sustainability

Review

AgroecologicalNutrientManagementStrategyforAttaining

WindaIkaSusanti 1,2,*,SriNoorCholidah 2 andFahmuddinAgus 3

1 J.F.BlumenbachInstituteofZoologyandAnthropology,UniversityofGöttingen,UntereKarspüle2, 37073Göttingen,Germany

2 WorldResourcesInstitute(WRIIndonesia),Jl.WijayaINo.63,Petogogan-KebayoranBaru,SouthJakarta, Jakarta12170,Indonesia;sri.chalidah@wri.org

3 NationalResearchandInnovationAgency,Cibinong16911,Indonesia;fahmuddin.agus@brin.go.id

* Correspondence:winda.ika-susanti@biologie.uni-goettingen.de

Abstract: Riceself-sufficiencyiscentraltoIndonesia’sagriculturaldevelopment,butthecountryisincreasinglychallengedbypopulationgrowth,climatechange,andarablelandscarcity.Agroecological nutrientmanagementofferssolutionsthoughoptimizedfertilization,enhancedorganicmatterand biofertilizerutilizations,andimprovedfarmingsystemsandwatermanagement.Besidesproviding enoughnutrientsforcrops,theagroecologicalapproachalsoenhancesresiliencetoclimatechange, reducestheintensityofgreenhousegasemissions,andimprovesthebiologicalfunctionsofricesoil. Organicandbiofertilizerscanreducetheneedforchemicalfertilizers.Forexample,blue-greenalgae maycontribute30–40kgNha 1,whiletheapplicationofphosphatesolubilizingmicrobescanreduce theuseofchemicalphosphorousfertilizersbyupto50percent.Thecountrycurrentlyexperiences substantialyieldgapsofabout37percentinirrigatedand48percentinrain-fedrice.AchievingselfsufficiencyrequiresthatIndonesiaacceleratesannualyieldgrowththroughagroecologicalnutrient managementfromahistorical40kgha 1 year 1 to74kgha 1 year 1.Theaimistoraisetheaverage yieldfromthecurrent5.2tha 1 year 1 to7.3tha 1 year 1 by2050.Simultaneously,controlling paddyfieldconversiontoamaximumof30,000hectaresperyeariscrucial.Thisstrategicapproach anticipatesIndonesia’smilledriceproductiontoreacharound40millionmetrictonnes(Mt)by2050, withanexpectedsurplusofabout4Mt.

Citation: Susanti,W.I.;Cholidah,S.N.; Agus,F.AgroecologicalNutrient ManagementStrategyforAttaining SustainableRiceSelf-Sufficiencyin Indonesia. Sustainability 2024, 16,845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020845

AcademicEditors:MdRomijUddin andUttamKumerSarker

Received:2December2023

Revised:27December2023

Accepted:2January2024

Published:18January2024

Copyright: © 2024bytheauthors. LicenseeMDPI,Basel,Switzerland. Thisarticleisanopenaccessarticle distributedunderthetermsand conditionsoftheCreativeCommons Attribution(CCBY)license(https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ 4.0/).

Keywords: agroecology;biochar;biofertilizers;climatechange;greenhousegases;inorganicfertilizers; nutrientmanagement;organicmatter;paddyfieldconversion;riceself-sufficiency;stonemeal

1.Introduction

Indonesiaheavilyreliesonriceasastaplefood,servingasthemaincomponentof almosteverymealandconstitutingafundamentalpartofthedailydiet.Ricecultivation playsapivotalroleinthecountry’seconomy,providingemploymenttomillionsinruralareasandsupportinglivelihoodsandlocaleconomies.Foodsecurity,definedasequalaccess tosufficient,safe,andnutritiousfoodnecessaryforallpeople[1],hasbeenaneconomic, social,andresearchinterestinthepastfewdecades.However,riceself-sufficiencyhas remainedtheprimaryindicatoroffoodsecurityinIndonesia[2].

Riceproductionfaceschallengesduetothehighandincreasingpopulation[3],land scarcity,andclimatechange.Itslowmanagementlevelresultsinawideyieldgap,representing thedifferencebetweentheactualyieldandtheattainableyieldinriceproduction[4].We believethatagroecologicalnutrientmanagement,combinedwiththecontrolofpaddyfield conversion,willbethesolutionforattainingsustainablericeself-sufficiencyinIndonesia.

Agroecologicalnutrientmanagementreferstoasustainableandholisticapproach tomanagingnutrientsinagriculturalsystems.Itinvolvestheintegrationofecological principleswithagriculturalpracticestooptimizenutrientuseefficiency,minimizeenvironmentalimpacts,andenhancelong-termagriculturalsustainability.Ittakesintoaccountthe

complexinteractionbetweencrops,soil,microorganisms,andtheenvironmenttopromote nutrientcycling,reducenutrientlosses,andimprovesoilfertility.Itisamanagement approachbasedonagroecologicalprinciplesthataimtoincreasefarmproductivitythrough thewiseuseofexternalinputs,sustainingecosystemservices,andvalorizingecological processesandecosystemservices[5,6].Thisapproachreducesrelianceonchemicalfertilizersandenhancestheuseoforganicmatter,biofertilizers,andtheefficientuseofwater[7]. Arecentstudyshowedthatagroecologicalnutrientmanagementwithahigherinputof organicmatterincreasedsoilpH,theavailabilityofpotassium,calcium,andmagnesium, potassiumconcentrationinleaves,andmycorrhizalcolonization[8].Anotherstudythat increasedrelianceonlegumes,integratedcrop–livestockproduction,anduseofsoilamendmentsresultedinenhancedsoilorganicmatter(andsoilcarbon)accrual.Theeffectsin thelongtermweremoreconsistentintermsofincreaseyields,yieldstability,profitability andfoodsecurity[9].Anagroecologicalapproachisimportantforrestoringdegraded lands[5,10]andovercomingtheyieldgap[4].Increasingconcernsaboutthelossofnatural habitatsandbiodiversityemphasizetheimportanceofproducingmorericeonexisting croplandbyimprovingtheefficienciesofnutrients,energy,water,andotherinputsinan agroecologicalprocess[5,11,12].

ThericeharvestareainIndonesiawasabout10.6millionhectares(ha),andunhusked (paddy)rice(subsequentlycalled“rice”)productionwasabout54.5milliontonnesperyear (Mtyear 1)(equivalentto31.4Mtmilledrice—theaveragefor2020–2021).Riceyieldwas about5.2tonnesperhectare(tha 1).From2000to2021,Indonesiaimportedaminimum of0.25Mt(in2009)andamaximumof2.75Mt(in2011)ofmilledrice.In2021,themilled riceimportwas407,741tonnes,andthenationalproductionwas31.36Mt(information aboutthemilledriceimportandnationalproductionisfromIndonesia’sCentralBureauof Statistics, www.bps.go.id,accessedon11November2022).ThismeansthatIndonesiais barelyreachingriceself-sufficiency.

Asapopulouscountry,dependenceonriceimportmaymakeIndonesiavulnerable tointernationalmarketpricefluctuations.AlthoughDawe(2008)[13]doubtedthatprice volatilityandworldmarketpricedistortionwouldbesignificant,thegovernmentpolicyis thatnationalproductionmustbeincreasedtomeetdemand,andimportmustbeeliminated orkepttoaminimum.

Indonesiawilllikelybecomemoredependentonriceimportasitspopulationincreases[14]andtheeffectsofclimatechangeanduncontrolledpaddyfieldconversion worsen[15].ThepopulationgrowthrateinIndonesiamaybedecreasingwithincreased educationlevel(populationgrowthdataarefromWorldBankOpenData, https://data. worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.GROW?locations=ID,accessedon11November2022), butitwilltendtostaypositiveuntil2050.

Theeffectsofclimatechangemaybeintensifying,andwilldependontheabilityof countriestoadaptandcomplywiththeirpledgesonclimatechangemitigationasstipulated inthe2021GlasgowClimatePact(tolearnmoreaboutthe2021GlasgowClimatePact,see https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/cop26,accessedon3January2023).Meanwhile, controllingpaddyfieldconversionappearstobemoreandmorechallenging,notonly inIndonesia[16]butalsoelsewhereintheworld[17].Thesethreefactors—population growth,climatechange,andlandconversion—areobstaclestoattainingriceself-sufficiency. Adaptingtoandmitigatingclimatechangeisessential[18],andfailingtocontrolricefield conversionwillhinderthericeself-sufficiencyobjective[19].

Therearetwoapproachestoincreasingriceproduction:extensificationand(sustainable)intensification.Extensificationisbecomingmoreandmoredifficultduetoarable landscarcity[19].Furthermore,theconversionofexistingrice-producingareasisoccurring atanalarmingrate[20],resultinginshrinkingpaddyfieldareas.Hence,intensification hasagreateropportunitytocontributetoincreasedriceproduction.Theactualaverage riceyieldofabout5.2tha 1 isfarbelowthepotentialyieldofirrigatedrice,rangingfrom 8.3tha 1 to11.7tha 1,ortherain-fedriceyield,rangingfrom7.9tha 1 to12.1tha 1 [21].

Thesedataclearlyshowagreatopportunitytoclosetheyieldgaptoincreasenational riceproduction.

Yuanetal.(2022)[14]suggestedthatyieldisattainableupto80%ofpotentialyield underirrigatedor70%ofpotentialyieldunderrain-fedricesystems.Increasingyieldto above80%ofthepotentialyieldmaynotbefeasibleeconomically,anditmayposeathreat totheenvironmentduetotheexcessiveinputitrequires[11,12].

NutrientdeficienciesandimbalanceshavebeenthemainprobleminIndonesianrice fields[22,23].Thisaspectwillbediscussedasanavenuefornarrowingthericeyieldgap fromanutrientmanagementperspective.Thebenefitsandfeasibilityofusingbiocharare alsodiscussed.Theeffectsofclimatechangeonfoodsecurityrequireseriousattention; hence,wediscussadaptationandmitigationstrategiesformanagingpaddysoils[18].We alsotouchupontheproblemofpaddyfieldconversion,whichmayhinderachievingthe riceself-sufficiencytarget.Finally,weproviderecommendationstoimprovethecurrent policy,includingthechallengesthatmustbeovercome.

Thispaperpresentsaliteraturereviewofpaddyfieldnutrientmanagementsystems, linkingthemwithagroecologicalprinciples.Itprovidesanoverviewofpaddyfieldnutrient statusandfertilizationanddiscussestheenhancementofagroecologicalfunctionsresulting fromagroecologicalnutrientmanagementpractices.

Weconductedacomprehensiveliteraturereviewonagroecologicalnutrientmanagementaimedatachievingriceself-sufficiencyinIndonesia.Thisinvolvedasystematicsearch andanalysisoftheavailableliterature,includingrelevantjournals,reports,andscholarly articlesrelatedtoagroecologicalapproachestonutrientmanagementforricecultivation andself-sufficiencyinriceproductioninIndonesia.Whileweprioritizedpublicationsfrom thelast20years,olderrelevantliteraturewasincludedwhennecessary.

OurliteraturesearchutilizeddatabasessuchasScopus,WebofScience,GoogleScholar, andrelevantinstitutionalrepositories.Weusedkeywordsrelatedtoagroecology,nutrient management,ricecultivation,riceself-sufficiency,watermanagement,methaneemissions, nitrousoxideemissions,biofertilizers,biochar,andIndonesia.Thecollectedliterature wasscreenedbasedonthefocusofourreview.Keyinformationwasextractedfrom selectedstudies,andfindingsweresynthesizedtoidentifycommontrends,challenges, andsuccessfulapproachestoagroecologicalnutrientmanagementforachievingriceselfsufficiency.Thesummarizedfindingswereinterpretedintermsoftheirimplicationsfor riceproductionandself-sufficiencyinIndonesia.

Limitationstothisreviewprocessmayariseduetopublicationbias,inwhichcertain topicsmightbeoverrepresentedwhileothersareunderrepresented,potentiallyskewingthe overallfindings.Despiteevaluatingtherobustnessofthereviewedstudies,variationsin thequalityandreliabilityofstudiesmaypersist,possiblyleavingoutcrucialdevelopments unsupportedbyscientificpublicationsorlackingpublishedtimeseriesdata,especially concerningnutrientstatus.

Additionally,weofferabriefscenarioanalysisregardingclosingtheyieldgap,controllingpaddyfieldconversion,andimplicationsforriceself-sufficiencyuntil2050,including calculationsfornationalriceconsumptionandlandconversionrates.

Tothebestofourknowledge,noscientificpapershavecomprehensivelydiscussed variousaspectsofpaddyricenutrientmanagementsystemslinkedwithagroecological principles.Therefore,thispaperisrelevantnotonlyforIndonesianconditionsbutalsofor othercountrieswherelowlandriceconstitutesasignificantagriculturalsystem.

2.PaddyRiceSoilsandTheirNutrientStatus

2.1.PaddyRiceSoils

About70%ofIndonesianpaddysoilsbelongtotheInceptisol,Entisol,andVertisol soilorders.Vertisolscompriseabout7%ofIndonesianpaddysoils[24].About22%are paddysoilsofhigherelevationinvolcanicareas,andtheybelongtotheUltisol,Inceptisol, Andisol,andAlfisolorders.

2.1. Paddy Rice Soils

About 70% of Indonesian paddy soils belong to the Inceptisol, Entisol, and Vertisol soil orders. Vertisols comprise about 7% of Indonesian paddy soils [24]. About 22% are paddy soils of higher elevation in volcanic areas, and they belong to the Ultisol, Inceptisol, Andisol, and Alfisol orders.

Inceptisols generally have a low pH, low cation exchange capacity (CEC), and low soil organic C and N contents. However, the fertility of Inceptisols derived from alluvium varies depending on the nutrient status of the parent materials. Vertisols have a relatively high pH, high cation exchange capacity (CEC), and high macro- and micronutrient content [24,25]. For example, the percentage of soils with a high K status is high in Central and East Java (Figure 1), where Vertisols are the dominant paddy soils, although management factors could also lead to a high K status. Rice fields of the Vertisol order are high in clay content and hence very likely have a low saturated hydraulic conductivity, which makes the leaching of cations and anions, such as potassium (K+) and nitrate (NO3 ), typically minimal [25]. This indicates a better nutrient efficiency in Vertisols compared to that in Inceptisols and Ultisols [26]. Ultisols are mostly low in CEC and exchangeable cations [25]; hence, they require relatively high inputs of basic cations.

InceptisolsgenerallyhavealowpH,lowcationexchangecapacity(CEC),andlowsoil organicCandNcontents.However,thefertilityofInceptisolsderivedfromalluviumvaries dependingonthenutrientstatusoftheparentmaterials.VertisolshavearelativelyhighpH, highcationexchangecapacity(CEC),andhighmacro-andmicronutrientcontent[24,25]. Forexample,thepercentageofsoilswithahighKstatusishighinCentralandEast Java(Figure 1),whereVertisolsarethedominantpaddysoils,althoughmanagement factorscouldalsoleadtoahighKstatus.RicefieldsoftheVertisolorderarehighinclay contentandhenceverylikelyhavealowsaturatedhydraulicconductivity,whichmakes theleachingofcationsandanions,suchaspotassium(K+)andnitrate(NO3 ),typically minimal[25].ThisindicatesabetternutrientefficiencyinVertisolscomparedtothatin InceptisolsandUltisols[26].UltisolsaremostlylowinCECandexchangeablecations[25]; hence,theyrequirerelativelyhighinputsofbasiccations.

Figure 1. Maps showing the percentage of paddy field areas with high phosphorous (P) status (>174 mg kg 1 P) (upper) and the percentage of paddy field areas with high potassium (K) status (>166 mg kg 1 K) (lower) (adapted from Widowati et al., 2021) [26].

Figure1. Mapsshowingthepercentageofpaddyfieldareaswithhighphosphorous(P)status (>174mgkg 1 P)(upper)andthepercentageofpaddyfieldareaswithhighpotassium(K)status (>166mgkg 1 K)(lower)(adaptedfromWidowatietal.,2021)[26].

When the dry (unflooded) land systems are converted to paddy field systems, the soil undergoes physical and chemical transformations. Flooding leads to a decrease in soil redox potential and increases the availability of phosphorus (P) and calcium (Ca) for plant uptake. Further, plow pan forms in paddy fields when soil is compacted by heavy equipment, humans, or animals [27], reducing water loss through percolation and nutrient loss through leaching. C stock tends to increase [28] and soil pH tends to reach near neutrality in paddy soils [29].

Whenthedry(unflooded)landsystemsareconvertedtopaddyfieldsystems,the soilundergoesphysicalandchemicaltransformations.Floodingleadstoadecreasein soilredoxpotentialandincreasestheavailabilityofphosphorus(P)andcalcium(Ca)for plantuptake.Further,plowpanformsinpaddyfieldswhensoiliscompactedbyheavy equipment,humans,oranimals[27],reducingwaterlossthroughpercolationandnutrient lossthroughleaching.Cstocktendstoincrease[28]andsoilpHtendstoreachnear neutralityinpaddysoils[29].

2.2.EssentialNutrients

ThenutrientsN,P,K,Ca,sulfur(S),Mg,C,oxygen(O),andhydrogen(H)aregrouped intomacronutrients,i.e.,nutrientsessentialtoplants,andareneededinrelativelylarge amounts.Ofthese,Ca,Mg,andSarealsocalledsecondarymacronutrientsbecausetheyare neededbyplantsinrelativelysmalleramountsthanN,P,andK,andareusuallyappliedto thesoilfromorganicmatter,lime,andothersources.ThemacronutrientsC,H,andOare

abundantinnatureandaretakenupbyplantsintheformsofcarbondioxide(CO2),water (H2O),oroxygen(O2)throughrootsandleaves[30].

MicronutrientssuchasZn,Cu,boron(B),manganese(Mn),molybdenum(Mo),Fe, silicon(Si),andchlorine(Cl)areimportantinmetabolicactivitiesandenzymaticprocesses andhelpinplantgrowthandproduction[31].Micronutrientavailabilitytoplantsis regulatedbyvarioussoilfactors,includingsoiltexture,soilpH,organicmattercontent, claycontent,soilmoisture,nutrientinteractions,microbialactivity,redoxpotential,and aeration[32].

Micronutrientcations,suchasFe,Zn,Cu,andMn,areeitherinthesoilsolutionorare adsorbedatsoilmineralexchangesites[33,34].Organicmatterisanimportantsecondary sourceofmicronutrientsinsoil.Soilsthatreceiveregularadditionsoforganicresiduesor manurerarelyshowmicronutrientdeficiencies.Incorporatingsoilamendmentsandfertilizersintothesoilcanalsocontributetomicronutrientavailability[32]andmicronutrient efficiency[35,36].BalancedPandKfertilizationalsoimprovesthemicronutrientbalance, especiallyofZnandCu[26].

TherearetwotypesoflowlandricefieldsinIndonesia:irrigatedandrain-fedrice fields.Irrigatedfieldsarenormallyfloodedduringthecropseason,withthewaterhead twotofivecentimetersabovethesoil’ssurface.Ofthetotalpaddyfieldareaofabout 7.4millionha acrossIndonesia,about4millionhaareirrigated[37].Irrigatedpaddyfields benefitfromasecurewatersupplyandthetransportofnutrientsfromirrigationwater,but thatisnotthecaseforrain-fedpaddyriceareas[38].

2.3.NutrientStatusofIndonesianPaddyFields

ThemacronutrientsN,P,andKareimportantforriceproduction.Amongthethree,K isthemostabundantontheEarth’ssurface.However,about90–98%ofthisKisintheform ofprimarymineralsthatarenotavailableforplantuptake,andonly1–2%ofthenutrient isintheformavailabletoplants[39].Inlow-activityclaysoils,suchasmostUltisolsand Inceptisols,Kcanmovethroughthemassflowprocessandleachfromthesurfacetothe lowerlayersduringandafterheavyrains.However,inpermanentricesystems,Kleaching canbeminimizedbythepresenceofaplowlayer[22].

Insoil,Nisverymobileandcanbeeasilylostduetoevaporationorleaching;italso changesfromoneformtoanother,suchasammonium(NH4 +)toNO3 ,nitrousoxide (N2O),orammonia(NH3).RiceplantsareveryresponsivetotheapplicationofNfertilizer, butthefertilizer’sefficiencyisverylow(i.e.,<30%)[40].SplitapplicationofNisacommon practicetoreduceNloss[26].

Insoil,PexistsasaninorganicformoriginatingfromP-containingminerals(suchas apatite)andanorganicformoriginatingfromorganicmatter.TheavailabilityofPinsoil islowbecauseitisboundtoclayororganicmatter.InsoilswithalowpH(4–5.5),Pis fixedbyiron(Fe)andaluminum(Al)oxides,whereasinsoilswithahighpH(7–8),itis fixedbyCaandMg.ContinuouslyapplyinglargequantitiesofPfertilizermaycausePto accumulateinsoil.AccumulatedPcanbetakenupbyplantsifthesoilreactionreaches optimalconditionsforitsrelease[22].

Inthe1990s,ricefieldsinJavawereconsideredtobesaturatedwithPandKbecause ofthecontinuousapplicationoftriplesuperphosphateandpotassiumchloride(KCl). However,asurveyinSumatra,Java,Sulawesi,andNusaTenggaraindicatedareverse trend,whereKapplicationtendedtobelowerthanthecropneeded[41].

NutrientstatusmapsforPandKwithscalesof1:50,000havebeencompiledfor 7259subdistrictsinthe34provincesofIndonesia[26].InFigure 1,wepresentonlythe highPandhighKstatusmapsofIndonesia.Thisnutrientmapwasdevelopedbasedon potentialsoilPandKextractedwith25%hydrochloricacid(HCl).ThePandKstatuses werecategorizedaslow(mgkg 1)(<87P;<83K),medium(87–174P;83–166K),andhigh (>174P;>166K).

ThePstatusmapshowsthatmostpaddyfieldsinJava,BaliandWestNusaTenggaraexhibithighpercentagesofareaswithhighPnutrientstatus,attributedtointensive

managementintheseareas.However,inSumatraandthewesternandeasternpartsof Kalimantan,mostpaddyfieldareasshowalowPstatus,duetohighsoilacidityand minimalinfluenceofvolcanicash,especiallyinKalimantan.

TheKstatusmapshowshighpercentagesofpaddyfieldswithhighKstatusinWest Java(maybeduetomanagementfactors).CentralJavaandEastJavaalsohavemoreareas withahighKnutrientstatus,whereasNTT,Riau,andSouthSulawesiweredominatedby lowKnutrientcontent(Figure 1).

Besidesnutrientstatusmaps,Indonesiaalsoutilizesapaddysoiltestkit(PUTS). PUTSscanbeusedbyextensionworkers,orevenbyfarmers,toassesssoilPandKstatuses, andaleafcolorchartcanbeusedtodetermineNstatusinplanttissue[42–44].Basedon PUTSs,NPKfertilizerapplicationis16–48%moreefficientinareaswhereitsapplicationis excessivecomparedtocommonfarmerfertilizerrates,andtheyieldincreaseis6–13%.Asof 2019,around18,325PUTSshadbeendistributedinIndonesia,mainlythroughgovernment projectsandprogramsaswellasasmallportionthroughindividualsales[43].However, effortsareneededtointroducethisdevicetofarmergroupsincentralriceproductionareas ofIndonesiaformoreefficientandmorebalancedfertilizerapplication,i.e.,ensuringthat plantshaveaccesstoanadequatesupplyofeachnutrientateverygrowthstage.

Nutrientstatusmapsarenecessarytoguideextensionservicesonrecommended domainsandpolicymakersonfertilizerdistribution.Previouslyavailablenutrientstatus mapsforIndonesiawereatascaleof1:250,000,whichcouldbeusedasabasisforfertilizer distributionattheprovinciallevel.Moredetailedsoilnutrientstatusmapswithascale of1:50,000cannowbeusedasabasisforfertilizerrecommendationsatsubdistrictand villagelevels[45,46].

Manureandinorganicfertilizerssignificantlyaugmentsoil-availableFe,Mn,Cu,and Zncontent.Long-terminputsoforganicamendmentsalterthepropertiesofsoiland increaseitsplant-availablemicronutrientcontent[36].

3.AgroecologicalNutrientManagement

Inthissection,wediscussseveralaspectsofnutrientmanagement,includingsoil nutrientstatus,fertilizationusingchemical,organicandbiofertilizers,aswellasother potentialnutrientsthatcanbeexploitedfromlocalsourcessuchasbiochar.

3.1.Nitrogen,PhosphorousandPotassiumFertilization

N,P,andKfertilizersareessentialforincreasingpaddyriceyieldandnationalrice production.However,fertilizerapplicationsthatareunbalancedandinsufficienthave contributedtolowfertilizerefficiencyandareineffectiveforincreasingcropyield.

Untilatleastearly2010,theuniformrecommendationof600kgureaha 1 (276,N), 300kgSP-36ha 1 (47,P),and150kgKClha 1 (78,K)wasstillcommon[47],andthismay haveledtotheexcessiveordeficientstatusofsomeorallnutrients.Inearly2020,Indonesia developedasoilnutrientstatusmapatascaleof1:50,000.InFigure 1,wedemonstrateonly themapofhigh-statusphosphorous(P)andpotassium(K)forIndonesia.

ThenationallevelsoiltestapproachinIndonesiaclassifiedthesoilnutrientstatus intosoilswithlowsoiltestP(<87mgPkg 1),forwhichtherecommendedPfertilizer is17kgPha 1.Soilswithmedium(87–174mgPkg 1)andhigh(>174mgPkg 1)P statusarerecommendedtohave13and11kgha 1 Pfertilizer,respectively.Likewise,soils withlow(<83gkg 1 K),medium(83–166gkg 1 K)andhigh(>166gkg 1 K)soiltestK arerecommendedtohaveKfertilizerinamountsof38,30,and25kgha 1,respectively (Table 1).

RicestrawservesasanimportantsourceofK,allowingforareductioninKapplication tohalftherecommendeddose(only30kgKha 1)incasesoflowsoilKstatus,oracomplete waiverincasesofmediumandhighKstatussoil[26].

Table1. Recommendedphosphorous(P)andpotassium(K)fordifferentpaddysoil(PandKsoil) teststatus(modifiedfromWidowatietal.,2021)[26].

SoilNutrientStatusFertilizerRecommendation

Pstatus(mgPkg 1)Fertilizerrate(kgPha 1) Low(<87)17 Medium(87–174)13 High(>174)11

Kstatus(mgKkg 1)Fertilizerrate(kgKha 1) Low(<83)38 Medium(83–166)30 High(>166)25

Nitrogen(N)fertilizationisbasedonyieldtarget,wherebyNratesare112.5,135,and 157.5kgha 1 toattainyieldtargetsof<6,6–8,and>8tha 1,respectively(Table 2)[26].

Table2. Nitrogen(N)fertilizerratesbasedonyieldtargets(modifiedfromWidowatietal.,2021)[26].

YieldTargets(tha 1)NRates(kgha 1) <6112.5 6–8135.0 >8157.5

Planttissueanalysis,alsoknownasplanttissuetesting,isrecommendedtocomplementsoiltestsorsoilnutrientstatusmaps.Bymeasuringthenutrientlevelintheplant tissue,onecanevaluatenutrientdeficiencyornutrientsurplusandaddresstheseimbalance problemsaccordingly.Whenfarmersencounterunexplainedissueswithaplant,such asstuntedgrowthordiscolorization,tissueanalysiscanprovidevaluableinformationto diagnosetheseproblems[48].

Planttissuetestscancomplementsoiltests.Planttissuetestresultsarecompared againstspecificnutrientcriticallevelstoguidefertilizationpracticesaimedatadjusting planttissuenutrientconcentrationstomeetthesecriticallevels.Forinstance,Dobermann andFairhurst(2000)[49]proposedcriticallevelsofN,PandKforriceat2.2%,0.20%,and 1.4%,respectively.

Inastudyonnutrientsufficiency,P.Grassini[50]analyzedtheconcentrationsofN,P, andKinriceplanttissuesfromsamplescollectedinmajorpaddyfieldproductionareas. ThefindingsshowedhigherconcentrationsofNandP,butlowerconcentrationsofKthan thecriticallevels.Thisdiscoveryemphasizesthenecessityofregularlyconductingsoil testsinconjunctionwithplanttissuetests.

3.2.MicronutrientFertilization

OneofthemostlimitingfactorsinricetilleringandspikeletsterilityisZndeficiency. ThecriticallevelofZninsoilis0.8milligrams(mg)kg 1 usingdiethylenetriaminepentaaceticacid(DTPA)extraction[49].Insoil,Zndeficiencycausesstuntedplantgrowthand reducescropyield[51,52].TherecommendeddoseforZnfertilizationis5–10kgZnha 1 andcanbeappliedintheformofzincoxide(ZnO),zincchloride(ZnCl),orzincsulfate (ZnSO4)[53],orbydippingricerootsintoasolutionof0.05%ZnSO4 forfiveminutes[52]. Zndeficiencycanalsobealleviatedbyrecyclingricestrawbecause60%ofZninplant tissuesisstoredinstraw[49].

CopperplaysanimportantroleinN,protein,andhormonemetabolisms;photosynthesisandrespiration;pollenformation;andactivatingtheligninoliticenzymes[49].Cu deficiencyaffectsgrainformation,causeschlorosisandalossofturgorinyoungleaves, andmayfavortheincidenceofdiseaseoutbreak[51,52].Asmuchas5–10kgCuha 1 can beappliedforafive-yearperiod,orriceseedlingrootsorriceseedscanbesoakedin1% coppersulfate(CuSO4)solutionforonehour[49].

PlantsrequireBforcarbohydratemetabolism,sugartransport,lignification,nucleotide synthesis,respiration,germination,andseedproductionextraction[44].Itisessentialfor thegerminationofpollengrains,thegrowthofpollentubes,andseedandcellwall formation,anditpromotesplantmaturity[33].Borondeficiencyreducesplantheightand mayleadtothefailureofpanicleformation[52]andlightchlorosis,thedeathofgrowing points,anddeformedleaveswithareasofdiscoloration[51].

Inplants,Fepromotestheformationofchlorophyll.ThereactionsassociatedwithFe includetheredoxreactionsofchloroplasts,mitochondria,andperoxisome[54].Thecritical limitofFeislessthan5mgkg 1 soil(usingDTPA+calciumchloride[CaCl2],pH7.3 extraction).Thisconditionisgenerallyfoundinalkalinesoilsorinsoilswithaveryhigh Fe-to-Pratio[49].AdeficiencyofFecanbeseenaschlorosisoryellowingbetweenthe veinsofyoungleaves[51].

Manganesefunctionsasapartofcertainenzymesystems.Ithelpsinchlorophyll synthesisandalsoincreasestheavailabilityofPandCa.IthassimilarpropertiestoMg andcansubstituteforMginsomeenzymesystems[54].TheoptimumMnconcentration inplantsalsodecreasestheincidenceofdiseases.AdeficiencyofMnischaracterizedby chlorosisoryellowingbetweentheveinsofnewleaves[51].

Molybdenumisrequiredinthesmallestamountofalltheessentialmicronutrients. Itisrequiredtoformthe“nitratereductase”enzyme,whichreducesNO3 toNH4 + in plantsandisthefirststepofincorporatinginorganicNOintoorganicNcompounds.Other functionsofMoarepresentinnitrogenase(Nfixation)andnitratereductaseenzymes;it playsanimportantroleinplantnodulationandisneededtoconvertinorganicphosphates toorganicformsinplants[33].AdeficiencyofMoresultsinadisruptedNmetabolism[54].

Chlorineisrequiredforturgorregulation,electricalchargebalance,resistingdiseases, andphotosynthesisreactions[33].AdeficiencyofClmaycausechlorosisandwiltingin youngleaves[51].

Siliconisbeneficialtothemechanicalandphysiologicalpropertiesofplantsand helpsthemovercomebioticandabioticstresses.Itenhancesrootwateruptake,which helpsregulateaquaporinactivityandgeneexpression[55,56].Inaddition,Siprovides resistanceagainstpathogensandpestsaswellastoleranceofdroughtsandheavymetals, andenhancesqualityandyield[51].

Mostmicronutrientscanbesuppliedbyorganicmatter[57];hence,itisgoodpractice toutilizeorganicmatterwhereavailable.Althoughirrigationwatercanalsocontain micronutrients,caremustbetakenwithwaterquality,especiallyfornonconventional irrigationwatersources,becausethewatermaycontainheavymetalsandotherharmful elements[58].

3.3.EnhancedUseofOrganicFertilizers

Organicfertilizerscanbeusedintheformoforganicmatter,biofertilizers,orbioorganicfertilizers.

3.3.1.OrganicMatter

Organicmatterplaysanimportantroleinenhancingsoilpropertiesandcropyield. Theleveloforganicmatterinsoilcanbeincreasedbyaddinghigh-qualityorganicmatter, suchascompostedplantresiduesorbarnyardmanure,intoricesoils.Organicmatterhas manybeneficialfunctionsforsoil,suchasincreasingsoilwater-holdingcapacity,improving soilstructure,releasingmacro-andmicronutrients,improvingsoilbiologicalactivities,and increasingsoilcarbonstock[26,59,60].Forexample,theapplicationof2tha 1 dryweight ofmanurewouldprovideabout16kgN,14kgP,31kgK,and16kgCa[61],inaddition toothermacro-andmicronutrients.OrganicmatterapplicationcanincreaseorganicC contentfrom0.78%to0.83%,aswellasincreasesoilCEC.Meanwhile,theapplication of 5tha 1 ricestrawcontaining9kgNand26kgKincreasedthericegrainyieldfrom 2.39tha 1 to4.14tha 1 comparedtoplotswithoutricestrawrecycling[62].

Ricestrawtypicallycontains0.5%to0.8%N,0.07%to0.12%P,and1.16%to1.65% K[63].Ifallthericestrawyield(atanationalaverageof5tha 1)isrecycled,thisequates torecycling25kgha 1 to40kgha 1 ofN,3.5kgha 1 to5.9kgha 1 ofP,and58kgha 1 to 83kgha 1 ofKpercropseason.Almost80%ofKabsorbedbyriceplantsisstoredinrice straw.Therefore,itishighlyrecommendedtoreturnstrawtothepaddyfieldtoprevent potassiumdepletionandprovideasubstantialamountofN,aswellasadecentamountof P[26].

However,undersaturatedconditions,theadditionoffreshorganicmattermayinduce methane(CH4)emissions.Furthermore,theapplicationofeasilydecomposableorganic matter,suchasthatcontaininghighcarbohydrates,canenhanceNmicrobialimmobilization.Conversely,theadditionoforganicmattercontaininghighcellobioseandcellulose (intermediatelydecomposablecompounds)willleadtoalowerrateofNimmobilization. Onthecontrary,whentheaddedorganicmatterisdominatedbyrecalcitrantcompounds, suchasligninsandtannins,itdoesnotaffectNimmobilization.Notably,theC-to-Nratio perseisnotadeterminantofNimmobilization[64].

Beforeapplyingorganicfertilizerstosoil,partiallydecomposedstraw(compost)is recommended.StrawcompostingcanbeacceleratedbyaddingNtoreducetheC-to-Nratio. Thedecompositionprocesscanalsobeacceleratedbyaddingmolassestothewindrowsof straw[65].Thisallowsdecompositiontotakeplaceinsitu,hencereducingthelaborneeded forprocessing.Bydoingso,transportationcostsandassociatedgreenhousegas(GHG) emissionscanbereduced.Combiningtheuseoforganicfertilizersandinorganicfertilizers canincreasericeyieldsignificantlycomparedtoonlyorganicmanureapplication[31,66].

Andoetal.(2022)[66]reportedthatapplyinginorganicfertilizer(NPK)withaproper amountofslakedlime(Ca(OH)2)andricestrawcompostisthemostefficientfertilizer managementsysteminpaddysoils.Further,theapplicationoflimeandtherecyclingof strawincreasedriceyield,likelyduetotheireffectonsoilfertilityandplantNuptake[67]. Anotherstudyalsoreportedthatincorporatingricestraworcropresiduesenhancesboth soilorganiccarbon(SOC)contentandsoilhealth,amelioratesclimatechange,andalso increasesbeneficialsoilmicrobeactivities[68,69].Ricestrawapplicationincreasedsoil microbialrespirationintherhizospherebecauseitfunctionsasasubstrateandenergy sourceformicrobes[69].ApplyingricestrawincombinationwithinorganicNfertilizer (80%Nthroughricestrawand20%throughmineralfertilizer)resultedinmaximum enzymaticactivitycomparedtoonlycropresidueoronlymineralfertilizerapplication[68].

3.3.2.Biofertilizers

Biofertilizersaremicroorganismscapableofincreasingnutrientavailabilityandimprovingsoilhealth.Theuseofbiofertilizerscanincreasesoilnutrientavailabilityandcan alsoreducesoilpathogens[69].Thefollowingsectionsdiscussseveraltypesofbiofertilizers thathavebeendevelopedinIndonesia.

3.3.3.N-FixingBiofertilizer

N-fixingbiofertilizercomprisesthebeneficialmiroorganismsthatconvertN2 into NH3 [70].TheprocessofconvertingN2 intoNH3 viadiazotrophicmicrobesallowsthetotal NcontenttobereplenishedandthefixedNregulatescropgrowthandyield[71].N-fixing biofertilizerhasbeendemonstratedinfree-livingmicroorganismswithanaerobicfixation (e.g., Clostridiumpasteurianum)andaerobicfixation(e.g., Azotobacterchroococcum).Other prokaryoticorganismsincludecyanobacteriaandarchaebacteria.Symbiosisintheroot systemsofnonleguminousplants(e.g., Frankia spp.)andleguminousplants(e.g., Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium)andanassociativefixationbetweennonsymbioticmicroorganisms (e.g., Azospirillum spp.)growingontherootsystemsofnonleguminousplants,butwithout formingnodules,alsoincreasesNavailabilitytoplants[70].N-fixinggroupsalsoinclude greenSbacteria,firmibacteria,actinomycetes,andproteobacteria.Nitrogenaseisthekey enzymethatcarriesouttheconversionofdinitrogenintoNH3 duringtheprocessofN fixation[70,71].

Biologicalnitrogenfixationplaysanimportantroleinrestoringsoilfertilityand ecosystemsustainability.N-fixingbacteriacanprovide50–70kgN-ureaha 1 tocrops[72] andisimportantforrestoringagroecologicalfunctionsandreducingtheyieldgapinstaple foodproductionbyincreasingsoilfertilityandgeneratingincomeforfarmers[73].

AstudybyRazieandAnas(2008)[74]showedthat Azotobacter and Azospirillum inoculationincreasedricegrowthwiththeirabilitytofixN2 fromtheatmosphere.The increaseinthetotalNcontentofsoilwasfollowedbyanincreaseinthetotalNcontentof theplanttissue. Azotobacter spp.and Azospirillum spp.alsoincreaserootandshootgrowth inriceplants.When Azotobacter isusedasabiofertilizerandiscombinedwith50%NPK fertilization,itsignificantlyincreasesthegrowthandproductionofgrainandmatchesthe growthandproductionofgrainwith100%NPKfertilization[75].

N-fixingblue-greenalgae(BGA),suchas Nostoc sp., Anabaena sp., Tolypothrix sp., and Aulosira sp.,havethepotentialtofixN2 andareusedinpaddyfields[76].BGA arephotosyntheticprokaryoticmicroorganismswhicharecapableofNfixationbecause theycontainnitrogenase.Theyalsobenefitriceplantsbyproducinggrowth-promoting substances[77].BGAmaycontribute30–40kgNha 1 totheecosystem.Grainyield increasedfrom2000kgha 1 to2300kgha 1 withalgalization,andfrom3000kgha 1 to 3200kgha 1 underthetreatmentof50kgUrea-Nha 1 withalgalization.Ingeneral,algal inoculation(whereeffective)increasesyieldbyabout14%[78].Intheplantstreatedwith BGA,Nuptakewashigherthanthoseoftheuntreatedcontrol[77].AstudybySetiawati etal.,2020[79],demonstratedthattheapplicationofgreenmanureincreasedsoilNcontent from0.10%to0.20%andorganicCcontentfrom0.8%to2.0%.

Theapplicationofa50%doseofNPKfertilizer,alongwith7tha 1 ofAzollaand 25tha 1 ofacompoundbiofertilizercontainingAzotobacter,Azospirillum,N-fixingbacteria,andP-solubilizingbacteria,matchedtheyieldoffull-doseNPKfertilizers.Thisimplies thatAzollaandthecompoundbiofertilizerscompensatedforabout50%ofN,PandK needs,relativetoafullNPKdose(138kgha 1 ofN,7.8kgha 1 ofP,and41kgha 1 of K)[80].

StudybySetiawatietal.,2020[79]reportedthatusing 10tha 1 ofgoatmanure and10tha 1 ofgoatmanureincombinationwitheither10tha 1 ofAzollaor2tha 1 Sesbaniagreenmanure,or5tha 1 Azollaplus1tha 1 Sesbaniagreenmanure,didnot showasignificantlydifferentresponseofricegrainyield,rangingfrom4.4to 5.8tha 1 . Thisimpliesthatnutrientssuppliedby10tha 1 goatmanuresufficedforthecrop’s needs,andthatadditionalgreenmanurewasnotnecessarywithsuchahigh-levelgoat manureapplication.

Similarly,anotherstudy[81]usingeither10tha 1 or20tha 1 fresh Azollapinnata orpowderedcompostofeither2.5or5of Azollapinnata didnotaffectricegrainyield relativetothecontroltreatmentwithoutAzollaapplication.Thispotstudyappliedblanket fertilizersequivalentto46kgha 1 ofN,8kgha 1 ofP,and41kgha 1 ofK.

Ingeneral,however,whenpaddyfieldsareinoculatedwithBGA,ricegrainyield increasesby7%to22%[82–85].

3.3.4.Phosphate-SolubilizingMicrobes

Phosphate-solubilizingmicroorganisms(PSMs)playacriticalroleinthesoil’sPcycle. TheyachievethisbymineralizingorganicP,solubilizinginorganicPminerals,andstoring asignificantamountofPinbiomass[86,87].

PSMs,whetherphosphate-solubilizingbacteria(PSB)orphosphate-solubilizingfungi (PSF),produceorganicacidssuchascitricacid,glutamate,succinate,lactate,oxalate, glyoxylate,malate,fumarate,tartrate,and α-ketobutyrate.TheseacidscanbindCa,Al, andFe,facilitatingphosphateavailabilitytoplantsintheformofdihydrogenphosphate (H2PO4 )[88].

PSMsisolatedfrombulksoilsandrhizosphereshavebeenshowntohydrolyzePby releasingphosphatases,playingamajorroleinPmineralizationinmostsoils[86].PuspitawatiandAnas(2013)[89]succeededinisolatingPSMcapableofdissolvingphosphate

sourcessuchascalciumphosphate[Ca3(PO4)2],aluminumphosphate(AlPO4),andferric phosphate(FePO4),increasingthesolubilityofPfrom65%to135%.Theapplicationof PSMtopaddysoilssignificantlyincreasedriceplantgrowthandPuptake,andreduced chemicalPfertilizerusagebyupto50%.

3.3.5.K-SolubilizingMicrobes

OnewaytoincreasethesolubilityofKfromK-containingmineralsorrocksinvolvestheuseofK-solubilizingmicrobes(KSMs),includingK-solubilizingbacteriaor K-solubilizingfungi.Variousgroupsofrhizobacteriaandfungiareinvolvedwiththe solubilizationofKmineralsinthesoilsystem[90].Aconsortiumofrhizobacteria,including Bacillusedaphicus, Bacillusmucilaginosus, Bacilluscirculans, Acidothiobacillusferrooxidans, Paenibacillussp., Pseudomonas,and Burkholderia demonstrateseffectiveK-solubilizingabilities[90]. Aspergillusterreus alsoexhibitsahighcapacitytodissolvemineralsandrocks containingK.Thesemicrobesareubiquitous,andtheirpresencedependsonstructure, texture,organicmatter,andrelatedsoilproperties[90,91].

Overall,biofertilizersthathavebeenwelldevelopedinpaddyfieldsincludefree-living orsymbioticmicrobeswhichhelpNfixationandPSMs.Amongthevariousbiofertilizers, N-fixingmicrobes(i.e.,BGA)aresomeofthemostcommonlyusedandcanincreasegrain yieldby200–450kgha 1 [78].Scalinguptheirapplicationisanimportantstrategyfor increasingriceyield.

3.3.6.BioorganicFertilizers

Bioorganicfertilizersareorganicfertilizersthatareimprovedbyaddingbeneficial microbessuchasN2 fixers,PSMs,KSMs,andantagonisticmicrobes.Bioorganicfertilizers areusedtoreducechemicalfertilizeruse,improvesoilproperties,andreduceenvironmentalpollution.

Theapplicationofricestrawenrichedwith Azotobacter wasabletoreducetheuseof NPKfertilizersby25%.Theuseoforganicstrawfertilizerenrichedwith Azotobacter without artificialfertilizersincreasedsoilNO3 andNH4 +.Theuseofricestrawenrichedwith Azotobacter anda100%doseofNPKfertilizerswasabletoincreasethericegrainharvest comparedtotheapplicationofN,P,andKwithoutorganicfertilizer[76].Bioorganic fertilizersreducedinorganicfertilizerusebyabout25–30%andincreasedriceyieldby about25%[92].Theapplicationof50%NPKandbioorganicfertilizerincreased 2.35tha 1 grainyieldand3.39tha 1 strawyieldcomparedtotheapplicationof50%NPKwithout bioorganicfertilizer.ThisyieldincreasewasattributedtothesupplyofPandKfromorganic fertilizersandtheincreasedavailabilityofthesenutrientsduetothesolubilizingmicrobes.

3.4.OtherLocallyExploitableNutrientSources

Besideschemicalandorganicfertilizers,therearemanyothersourcesofnutrients, includingsoilameliorantssuchasagriculturallime,biochar,andcrushednaturalminerals, alsocalledstonemeal.

Lime,especiallydolomiticlime,hasbeenwidelyusedinIndonesia.Dolomiticlime canimprovethemicrobialactivityofacidicsoilsandincreasecropyields[93,94].Besides providingCaandMg,dolomiticlimealsoincreasessoilnutrientavailability,suchasN, andP,inacidsoils[94–96].

LimingandapplyingstrawincreasedsoilNavailabilityandtheactivitiesofsoil enzymesinvolvedinbothCandNcyclingand,hence,riceyield[67].Theapplicationof dolomiticlimestoneincreasedK,Ca,Mg,andMncontentintheleaves[97].Additionally, calciteordolomitelimecanbeusedasasoilamendmentonrain-fedpaddyfieldswitha lowpHorlowCaandMgcontents[40].Limeapplicationalsocanreducecadmium(Cd) andlead(Pb)accumulationinrice[98–102].

Biocharisacharproducedfromorganicmatterviathermalprocessingunderdepleted O2 concentrations(pyrolysis)[103,104].Applyingbiocharincombinationwithcattle manureincreasedsoilorganicC;CEC;availableP;exchangeableK,Ca,andMg;and

nutrientuptakebycrops[105].Biocharalsocanbeusedasasoilamendmentinacidicsoils toimprovesoilPandreduceexchangeableAlandsolubleFe,aswellastosignificantly increasericebiomass[106]andyield[107].

Biocharimprovessoil’sphysical,chemical,andbiologicalproperties.Biocharimprovessoil’schemicalpropertiesbyincreasingnutrientretentionandavailability.Biochar decreasessoilbulkdensityandincreasessaturatedhydraulicconductivity.Incorporatingbiocharintosoilincreasesthemicrobialpopulationinthemicrospherebecausethe biocharsurfacechangessoilconditionsandmakesitfavorableformicrobialactivityinthe soil[108,109].

Ricehuskbiochar(RHB)contains1.12mgkg 1 ofN,0.98mgkg 1 ofP,184mgkg 1 of Mg,168mgkg 1 ofSi,225mgkg 1 ofCa,and176mgkg 1 ofK.Therefore,itsapplication tothesoilimprovesthesoil’snutrientstatus.Theapplicationof10tha 1 RHBsignificantly increasesricegrainyieldto4.6tha 1 comparedto2.6tha 1 underthecontroltreatment withoutbiochar.BoththeRHBandcontrolplotsreceived25kgha 1 ofK,26kgha 1 of P,and150kgha 1 ofN[110].Anotherstudyusingricestrawbiocharresultedin20–22% higherricegrainyield[111].

Stonemeal(i.e.,groundstonecontaininghighamountsofKandothermacro-and micronutrients)hasnotbeenwidelyexploitedinIndonesia.Consideringthehighprice ofconventionalKfertilizer(KCl),theuseofstonemealseemspromising.Stonemealcan rejuvenatenutrient-poorsoilsbecausesometypesofstonemealarerichinK,P,Ca,Mg, andvariousmicronutrients[112,113].

IndonesiapossessesK-bearingminerals,suchasK-feldsparandleucite(analuminosilicatemineral),thatcontainmostessentialnutrients,including4–20%ofK[96].Various techniquessuchasmechanochemistry,leaching,alkalifusion,andbioleachingcanprocess thesemineralsintoKfertilizers[114].InPatiRegency,CentralJava,Indonesia,K-bearing rocksareprevalentinalkalineandsubalkalineformationscharacterizedbylowsilica contentandhighalkalinity.Theseformations,includingleucite,plagioclase,pyroxene,and opaqueminerals,exhibitapotassiumoxide(K2O)contentbetween1.94%and8.61%[115]. ThisalignswithapriorstudyinPatiRegencynotingK2Ocontentbetween1.92%and8.79% inleucite,augite,pyroxene,quartz,andsanidinerocks[116].

Itwillbenecessarytoconductasurveyofbasiccation-rich(especiallyK)minerals, followedbyfieldtestingandaneconomicfeasibilityassessmentofstonemeal.Ifthisstudy provessuccessful,itspotentialapplicationextendsnotonlytopaddyricebutalsotoother agriculturalsectors,suchasoilpalmandotherintensivelymanagedcrops.

3.5.ImprovedWaterManagementSystems

Sustainableintensificationtoincreasefoodsecuritywillrequireproperwatermanagementinadditiontotheuseofhigh-yieldingvarietiesandagronomicpractices[117,118].To increasewateravailabilityandmitigatetheeffectsofdroughtinagriculturalareas,irrigationmanagementwillneedtobeimproved,aswillthemanagementofproperplanting time[119–122].Waterisresponsibleforincreasedagriculturalproduction,soitiscrucially importanttoimproveirrigationandwateruseefficiency[123].

TheSystemofRiceIntensification(SRI)isonewateruseefficiencystrategy[124–126]. TheSRIemergedfromon-farmexperimentationinMadagascar,whereexistingnorms ofpaddyricewereradicallyamendedbyreducingplantingdensity,improvingsoilwith organicmatter,reducingtheapplicationofwater,andtheearlytransplantationofrice seedlings.Organicfertilizersareusedinadditiontochemicals.TheSRIcanincreaseN andPavailabilityandsoilmicrobialCactivity[127,128].TheSRImethodhasapositive influenceonricerootdevelopment,optimizingnutrientabsorptioninthesoil[129].Rice growthandproductionisbetterundertheSRIthanconventionalricecultivation[130–132], asshowninTable 3

Table3. ComparisonofriceyieldinconventionalcultivationandtheSystemofRiceIntensification(SRI).

tha 1 tha 1 %

6.07.932Bakrieetal.,2010[130]

3.64.322Razieetal.,2013[131]

7.09.029 HidayatiandAnas2016[132]

5.47.233Subardjaetal.,2016[133]

4.56.442MoserandBarrett2003[134]

3.84.622Tsujimotoetal.,2009[135]

4.87.658Stygeretal.,2011[136]

TheSRIimprovesplantphysiologicalprocessesandcharacteristics,includinglonger panicles,moregrainsperpanicle,ahigherproportionofgrainfilling,deeperandbetter distributedrootsystems,andahighernumberandlargerleaves[132,136],aswellas improvedwater-useefficiency[136,137].

However,despitethevoluminousresearchdatashowingthedramaticadvantagesof theSRI,itsadoptionatfarmerlevelissluggishbecausethemethodrequiressignificant additionallaborinputandspecificmanagementtechniquesthatarechallengingforsmallholders[134].Somestudieshavealsoreportednosignificantincreaseinpaddyyields undertheSRIcomparedtoconventionalricemanagementsystems[135].IncentivesforSRI implementationarelacking;SRIricedoesnotcommandapremiumpriceanditrequires greaterwaterregulationeffortsthanconventionalsystems[120,138].Controversiespersist intheliteratureregardingtheassociatedbenefitsofgrainyieldandtheSRI’sreducedwater use[139–141].

Fromtheabovediscussion,itisclearthattheoverallprincipleofimprovingagroecologicalfunctiontoincreasecropyieldcanbereachedbyimprovingnutrientbalance, optimizingsoilbiologicalactivities,increasingsoilorganicmattercontent,andimproving theefficiencyofagriculturalinputandwatermanagement.

3.6.FarmingSystemsandCropRotation

Inanagroecologicalnutrientmanagementsystemforpaddyrice,diversecroprotationscanbenefitsoilhealth,nutrientcycling,andoverallsustainability.Inirrigatedpaddy ricesystemsinIndonesia,therearetypicallytwotothreecropsperyear.Thethirdcrop usuallyconsistsofsecondarycropssuchasmaize,soybean,peanut,orvariousvegetable crops[16].Thisthirdcropimprovesnutrientutilization,cutsoffpestanddiseasepressure, andincreasesoverallyieldanddiversity.Forinstance,rotatinglowland(flooded)ricewith upland(oxic)maizeimprovesrootcolonizationbyArchaeaandbacteria[142].

Azolla,awaterfern,canbeusedasgreenmanureinpaddyfields.Itssymbiotic associationwiththecyanobacteriumAnabaenaazollaeenablesittofixnitrogenfromthe atmosphere.Azollaiseitherincorporatedintothesoilbeforericetransplantationorgrown asadualcropalongwithrice[143].Itcontributestonitrogensupply,asdiscussedin Section 3.3.

The‘Minapadi’,orrice–fishfarmingsystem,canbeaneffectivericefarmingsystem forincreasingprofitabilityifupto4tha 1 ofcompostisadded[144].Rice–duckculture isanotherexampleofanintegratedfarmingsysteminpaddyrice[145].Ducksfeedon weeds,deadleavesandpests(suchasplanthoppersandleafhoppers)inthefield,during whichprocesstheystirupthewaterandsoilandfertilizethefieldsothatsoilnutrients areincreasedandtheneedfortheapplicationoffertilizersandpesticidesislowered[146]. Furthermore,rice–fish–duckisapromisingingenioussystemworthtesting[147].

Treatments

Thekeytosuccessinthesefarmingsystemsistotailorcroprotationsbasedonlocal agroecologicalconditions,cropcompatibility,andthespecificneedsofthericepaddy system.Diversifiedrotationshelpmaintainsoilfertility,reducepestanddiseasepressure, andimproveoverallresilienceinpaddyriceagriculture.

SummarizingSection 3 onagroecologicalnutrientmanagement,theuseofchemical (synthetic)fertilizersremainsvitalfornationallevelriceproductiontoensurenutrientsufficiency.Indonesia’srecentsoilnutrientstatusmap[26]facilitatedtailoredrecommendations, specifyingfertilizerratesatsubdistrictlevelbasedonsoiltestresultsforphosphorous (P)andpotassium(K)statuses.Nitrogen(N)fertilizationalignswithyieldtargetsfor optimallevels.Formoredetailedsite-specificrecommendations,theuseofasoiltestkitis recommended.Complementingsoiltests,planttissueanalysisaidsindiagnosingnutrient deficienciesorsurpluses,andiscrucialforaddressingproductivityissues.

However,apartfromsyntheticfertilizerapplication,thereareothersourcesofmacroandmicronutrients,aswellasmaterialsthatcanenhancenutrientrecycling.Theseinclude organicmatter,biofertilizers,andotherlocalnutrientsourcessuchasbiochar,lime,and stonemeal.Thesesupplementarynutrientsourcescannotonlyreducedependenceon syntheticfertilizers,butalsoimprovesoilhealthandprovidevariousagroecologicalfunctions(seeSection 4).Theabilityofthesealternativenutrientsourcestosupplyorrecycle nutrientsvaries.Table 4 showspotentialamountsofnutrientcontributionsfromthese alternativesources.

Table4. Potentialnutrientcontributionsfromorganicmatter,biofertilizers,andothersoilameliorants.

PotentialNutrientContribution YieldIncrease (tha 1) References

Manure,2tha 1 (dryweight) 16kgha 1 14kgha 1 31kgha 1

Ricestraw (5tha 1) 25–40kgha

Azotobacter+50% ofNPKnormal dose

50%NPK(69kgN, 4kgP, 21kgKha 1)+ 7tha 1 ofAzolla+ 25kgha 1 powder ofAzotobacter, Azospirillum, N2-fixingbacteria, andP-solubilizing bacteria)

Blue-greenalgae 30to40kgha 1

Blue-greenalgae+ 50kgNha 1 30to40kgha 1

From2.0to 2.3tha 1 [78]

From3.0to 3.2tha 1 [78]

Blue-greenalgaeNANANANA7–22%[78,82–85] P-solubilizing microbes NA50%†NANANA[89]

Table4. Cont.

Treatments PotentialNutrientContribution

K-solubilizing microbes

Biochar

Stonemealof K-bearingrocks

(tha 1) References

NA=Datanotmeasuredornotavailable. † Percentcontributionrelativetoconventionalchemicalfertilizer application; ‡ Percentoftotalpotassiumofappliedstonemeal;ŁThevalueswereimpliedas50%ofappliedN,P, andK.

4.ImprovementinAgroecologicalFunctions

Theagroecologicalmanagementofpaddyricefieldsnotonlybenefitscropgrowth andproduction,butalsocontributestoclimatechangemitigation,improvespaddysystem adaptationtoclimatechange,andfacilitatesnutrientrecycling[18,148].

4.1.MitigationandAdaptationtoClimateChange

4.1.1.Mitigation

SeveralmanagementsystemscontributetoreducingGHGemissions,includingthe SystemofRiceIntensification(SRI),biocharapplication,organicmatterapplication,and theplantingoflow-methane-emissionvarieties.Theplantingoflow-methane-emission varietiesisnotdiscussedhereasitisbeyondthescopeofthisarticle,butreaderscanfinda listofsuchvarietiesinAgusetal.2022[18].

GHGemissions(especiallyCH4)ofnearly50Mtcarbondioxideequivalentperyear frompaddyricecultivationisthehighestamongemissionsfromtheagriculturalsector inIndonesia.EmissionsofN2Oarealsosuspectedtobehighfrompaddyricesystems becauseofthehighrateofNapplicationinintensivericeareas[18,28].TheseN2Oemissions fluctuatebecauseofwettinganddrying[149,150]resultingfromalternateanaerobicand aerobicconditions,theconditionfavorableforN2Ogasformation[18].However,the increasedN2OreleasedduringdryingiscompensatedbydecreasedCH4 emissions.Hence, itisthelengthofthesubmergenceperiodofapaddyricefieldthatreallydeterminesCH4 emissions,whiletherateofNapplicationismostimportantforN2Oemissions[151].When thepaddyfieldisdrained,CH4 emissionsdecreasebyabout1.22kgha 1 day 1 inthe drainedcondition.

TheSRI,withahighernumberofunfloodeddays,offerssignificantCH4 emission reductions.Thelongerfloodedsoilconditionsoftheconventionalricesystemleadto thehigheractivityofmethanogen(CH4-producingbacteria)comparedtotheprolonged aerobicconditionsintheSRI[152].Researchdemonstratessubstantiallylowerseasonal CH4 emissionsintheSRI(20kgha 1)incontrasttoconventionalsystems(32kgha 1)[153]. However,thefrequentdrainingofSRIplotsleadstointermittentaerobicsoilconditions, potentiallyincreasingN2Oemissionscomparedtofloodedfields[149,150].Yet,other studieshavereportedreducedN2OemissionsintheSRI[154–156].

Biocharhasbecomeincreasinglypopularbecauseofitslongresidencetimeand,hence, conservationofCinsoils[157–160].Forexample,theapplicationof25tha 1 ofbiochar increasedsoilCstockfromabout35tha 1 toabout57tha 1 [161].Similarresultswere foundinthestudyofSuietal.(2016)[162].

AstudybyShenetal.(2014)[159]reportedthattheapplicationofstraw-derived biochar(22.5–48tha 1)decreasedCH4 emissions.Anotherstudyalsoreportedthatthe applicationofbiocharamendmentwithNfertilizermaybeabeneficialstrategytoreduce netN2OandCH4 emissionsfrompaddyrice[160].

TheapplicationoforganicfertilizercansignificantlyreduceGHGemissions.Specifically,theuseofmanuredecreasesN2Oemissionsbyabout4.98kgha 1 [163].Thisaligns

withotherresearchwhereplotstreatedwithricestrawandmanureexhibitedreductions inN2Oemissionsby43%and28%,respectively[164].Winetal.,2021[165],reportedthat cowdungmanurereducedCH4 emissionsby9.5%andN2Oemissionsby33.7%compared tothecontrol.Additionally,theapplicationofricestraw,poultrymanureandsugarcane bagasseresultedindecreasedN2Oemissions,offeringmitigationinricepaddies[166].The averageannualN2Oemissionsfromplotsreceiving50%inorganicNfertilizerandpigmanurewere51%lowerthanthosefromthe100%Ntreatment[167].Furthermore,compared withtheNPKtreatment,theapplicationoforganicfertilizeraloneledtoasignificant32% reductioninN2Oemissions[168].

AnotherstudyrevealedthatapplyingfreshandcompostedricestrawcanreduceN2O emissionsby49%and60%,respectively[169].InareaswhereNapplicationistraditionally excessive(e.g.,duetothehighsubsidyofNfertilizers),improvingtheefficiencyofNuse canreduceN2Oemissions[170].

Furthermore,paddyricecultivationalsomitigatesclimatechangebyincreasingsoilC stockbyabout35%ofitsinitiallevelover20years[28].

4.1.2.Adaptation

Climatechangeischaracterizedby(i)erraticweatherpatterns,includingchanges inrainfall,increasedfrequencyofextremeeventslikefloodsordroughts,andrising temperatures;(ii)risingsealevels,posingariskofsalinizationinlow-lyingpaddyfields, impactingsoilfertilityandcropgrowth;and(iii)outbreaksofpestsanddiseases,which threatenriceyields.Thesethreefactorsheightenvulnerabilityinpaddyfieldsandhinder thepotentialforincreasingriceyield.Therefore,adaptingtoclimatechangeiscrucialin Indonesiatoeffectivelymanagetheseclimate-relatedrisks[171].

Agroecologicalnutrientmanagementplaysapivotalroleinenhancingresiliencein paddyfarmingagainstclimatechangebecausebalancedfertilizationimprovescropvigor, andinturnscontributessignificantlytoaplant’sresilienceagainsttheimpactsofclimate change.Vigorouscropsexhibitbettertolerancetodrought,extremetemperatures,and changesinprecipitationpatterns.Theycanbetterwithstandperiodsofwaterscarcityor excess,temperaturefluctuations,andotherenvironmentalstresses.Vigorousplantstend toalsohavestrongerimmunesystems,makingthemmoreresistanttodiseasesandless susceptibletopestinfestations.Whenfacedwithstress,vigorouscropscanrecovermore efficiently.Theymightbouncebackquickerafteraperiodofdrought,heatstress,orother adverseconditions,allowingforabetterchanceofsuccessfulgrowthandyield[18,148].

Efficientwatermanagementthroughtechniqueslikealternatewettinganddrying (AWD)reduceswaterusagewhilemaintainingorimprovingyields.AWDhelpsadaptation toerraticrainfallpatternsbyallowingfarmerstoadjustwaterlevelsbasedonplantneeds. Diversifyingcropsinrotationhelpssoilfertilitymaintenanceandpestanddisease control,andreducesdependenceonsingle-cropcultivation.Thispracticeenhancesthe resilienceofricefarmingagainstclimate-inducedrisks.Furthermore,practicessuchas organicfertilizationandcovercroppingimprovesoilstructureandwaterretentioncapacity, makingfieldsmoreresilienttodroughtsandfloods[18,169].

Byimplementingtheseagroecologicalpractices,paddyfarmerscanenhancetheir resiliencetoclimatechange.Water-efficienttechniquesminimizetheimpactofchangingrainfallpatterns,whilecroprotationandsoilhealthimprovementmethodsreduce vulnerabilitytopestoutbreaksandenhanceoverallfarmresilience.Thesestrategiescollectivelyimprovetheadaptabilityofpaddyfarmingtouncertaintiesduetoclimatechange inIndonesia.

4.1.3.MitigationandAdaptationSynergy

Mitigationstrategiesshowtheireffectivenesswithintheframeworkofclimate-smart agriculture(CSA).CSAaimstoreduceGHGemissionswhilesimultaneouslyenhancing asystem’sresiliencetoclimatechange,therebyenablingincreasedcropproductionor,at theleast,maintainingcurrentlevelsdespiteclimatechange[18,172].CentraltoCSAis

integratedsoilhealthmanagement,suchasintegratedsoilorganicmatterandnutrient management,whichservestopreemptissuesassociatedwithclimatechangeandbolster agroecosystemresilience[172].Thisapproachintegratesagriculturaldevelopmentto ensurefoodsecurityandenableadaptationtoclimatechange.Forinstance,optimizing nitrogenfertilizerusenotonlyreducesnitrousoxideemissionsbutalsoenhancescrop resilienceagainstpestsanddiseases.Anotherexampleisalternatewettinganddrying, whichcurtailsmethaneemissionswhileconservingwaterforredistributionduringdry periods[18,173].

Overall,CSAcanbeappliedtoimproveandmaintainsoilhealthandincreasecrop productionandtheresilienceofsoilecosystemsagainsttheadverseeffectsofclimate change.

4.2.NutrientRecycling

Agroecologicalmanagementalsooptimizesnutrientrecyclingandorganicmatter turnover[174].Nutrientcyclingisavitalecosystemprocessbywhichavailableforms ofnutrientsmoveandexchangefromtheenvironmentintolivingorganismsandare subsequentlyrecycledbackintotheenvironment[175].Thecyclingofnutrientsbetween soil,plants,andanimalsisadynamicandcontinuousprocess.Chemicalelementssuchas C,O,H,S,N,andPareessentialforlife,andtheirrecyclingiscrucialforsustainingplant growthandyield[175].

Microbesinthesoilplayadynamicroleinreleasingmineralnutrientsthroughorganic matterdecompositionandmineralrecycling.Thesemineralizednutrientsarethenabsorbed byplantrootsalongwithwater,contributingtothecreationofneworganicmaterial[175]. Theyarealsocrucialinmaintainingsoilstructureandqualityforsustainableplantgrowth. Healthysoilactsasadynamiclivingsystemthatdeliversmultipleecosystemservices. Improvednutrientrecyclingisoneoftheimportantservicesinagroecologicalnutrient management[176].

4.3.WaterConservation

Indonesiaisblessedwitharangeofannualrainfall,varyingfromaround800mm inEastNusaTenggaratomorethan4000mminSumatra,Java,andPapua(rainfalldata canbeaccessedfromBMKG, https://dataonline.bmkg.go.id/home,accessedon3January2023).Thesesubstantialrainfallamounts,alongsideitswaterbodies,facilitateboth irrigatedandrain-fedpaddyfarming.However,wateravailabilityforpaddyfieldsiscompromisedduetothediscontinuityofirrigationnetworkscausedbygrowingurbanization andindustrialization,leadingtothedamageanddiscontinuityofirrigationnetworks[177]. Furthermore,approximately46%ofirrigationsystemsinIndonesiahavedeteriorateddue toaginginfrastructure[177].Urbanandindustrialdevelopmentsnearpaddyfieldareas alsoposeathreatofhazardouschemicalcontamination[177,178].Climatechangecan causechangesinrainfallpatterns,includingahigherfrequencyofextremerainfall,and couldfurthernegativelyaffectwateravailabilityandagriculturalinfrastructure[179],especiallyinrain-fedareas.However,water-efficientfarmingpracticeslikealternatewetting anddrying(AWD),precisionirrigation,andimprovedwatermanagementpracticescan conservewaterinricecultivation.AreviewbyIshfaqetal.(2020)concludedthatAWD cansavebetween25%and70%ofwaterusewithoutreducingyields[180].

4.4.BiodiversityConservation

Theimplementationofagroecologicalnutrientmanagement,asexplainedinSection 3, emphasizestheimportanceofusingaproperandbalancedamountofsyntheticfertilizers, enhancingtheuseoforganicfertilizerstocompensateforaportionofnutrientrequirements, incorporatingbiofertilizers,andutilizingnaturalnutrientsourcestomaintainsoilfertility andcropproductivitywhileminimizingenvironmentalimpacts.Thisapproachconserves thebiodiversityofmicroorganisms,whichsignificantlycontributestooverallecosystem

health,includingsoilorganisms,insects,andvariousaquaticfloraandfauna,suchas diversebirdspecies,amphibians,andaquaticplants.

Moreover,theagroecologicalnutrientmanagementsystempromotesbeneficialorganismslikepollinatorsandnaturalpredatorsofpests,thuscontributingtobiodiversity. Additionally,farmingsystemsandcroprotation,asoutlinedinSection 3.6,createvaried habitatsfordifferentspecies,therebyenhancingoverallbiodiversity.Thisdiversityincludesvariousbirdspecieslikeegrets,herons,andducks,fish,frogs,beneficialinsectssuch asladybugsandlacewings,arangeofaquaticplants,andsoil-dwellingorganismslike earthworms,beneficialbacteria,andfungi[181].

5.IntensificationandControlofPaddyFieldConversion

Tokeeppacewiththeincreasingpopulation,agriculturalproductionneedstobeincreased[182].However,manycountriesarefacingproblemsrelatedtotherapidconversion ofpaddyfieldsandinsignificantincreasesinriceyield[14,183],leadingtoawideninggap betweenriceneedandproduction.Thesetwoproblemsmustbeovercomesimultaneously toachieveself-sufficiencytargets.

Indonesia’spaddyfieldconversionrate,analyzedbyhigh-resolutionremotesensing techniques(includingIKONOS,QuickBird,orWorldview),isalarmingat96,500hayear 1 Ifthistrendcontinues,thetotalpaddyfieldareaof7.46millionhain2019[184]will decreasetoaround5.2millionhaby2045[16].

ThericeyielddatafromIndonesia’snationalstatisticsagency(riceyielddataare fromtheCentralBureauofStatistics, https://bps.go.id,accessedon10January2023) showanaverageyieldincreaseof0.04tha 1 year 1,fromaround4.4tha 1 in1993to 5.2tha 1 in2022.Thisyieldlevelcanfurtherbeincreasedbyimplementingsustainable intensificationtoattainayieldof7.28tha 1 year 1,whichis80%oftheyieldpotentialof 9.1tha 1 [14,185].

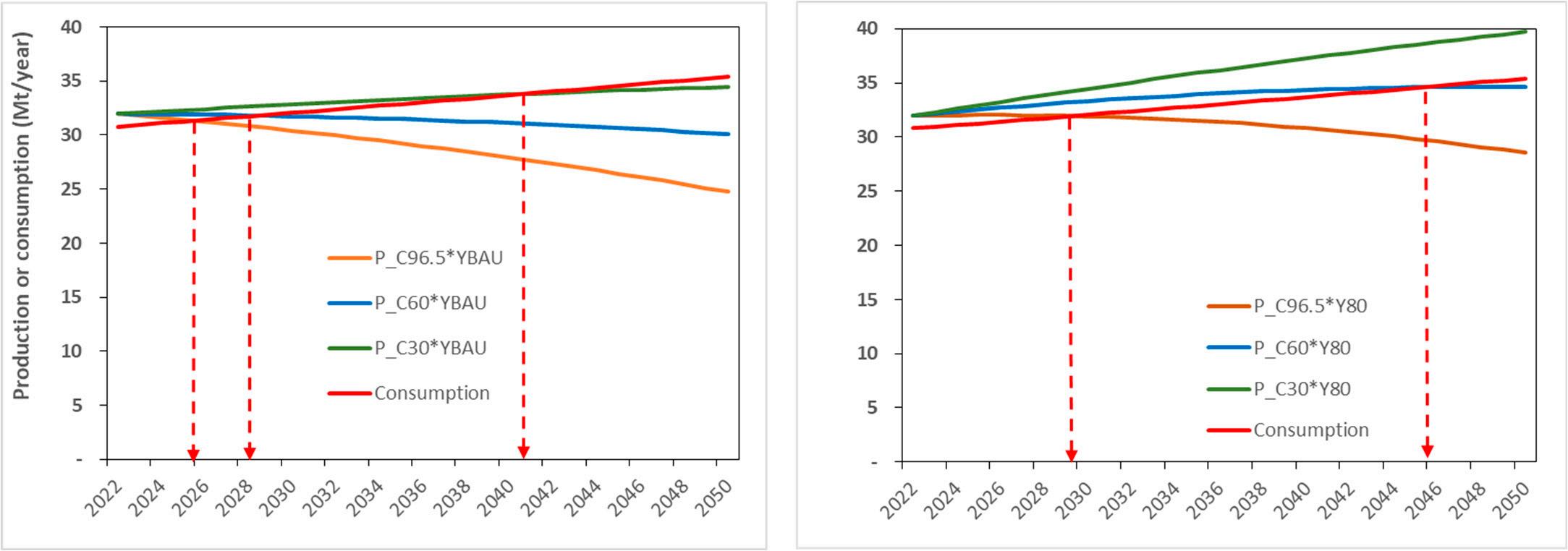

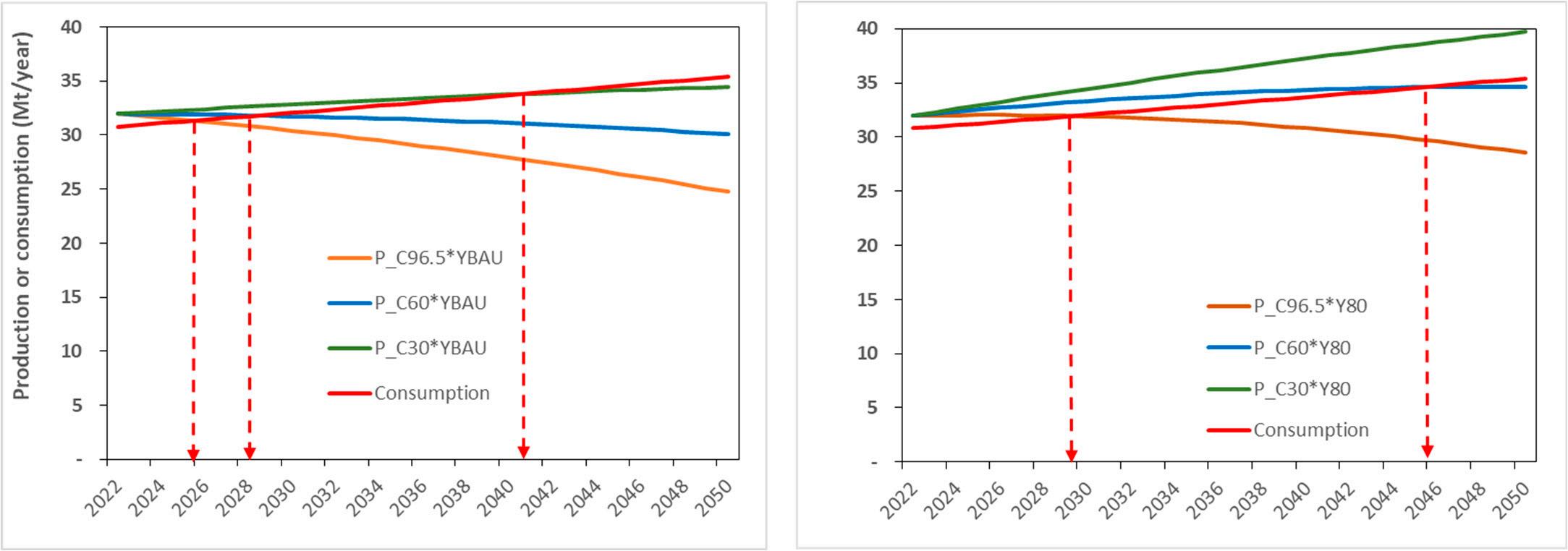

Todemonstratetheimportanceofyieldincreaseandthecontroloflandconversion,a two-variablescenarioanalysisisconductedasfollows:

• Riceyieldincreasescenario:

Y_BAU =Theyield,startingat5.2tha 1 in2022,increases40kgha 1 yr 1 inaccordance withthehistorical(businessasusual,BAU)trend(seetheCentralBureauofStatisticsfor moreinformation, https://bps.go.id,accessedon10January2023).

Y_80% =Theyield,startingat5.2tha 1 in2022,increases74kgha 1 yr 1 toattain80%of theyieldpotentialof9.1tha 1 (7.3tha 1)in2050(Yuanetal.,2022)[14].

• Paddyfieldconversionscenario:

C96.5=Thebusiness-as-usual(BAU)levelofpaddyfieldconversionof96,500hayear 1

C60=Themediumlevelofpaddyfieldconversionof60,000hayear 1

C30=Theoptimisticlowlevelofpaddyfieldconversionof30,000hayear 1

Theaveragecroppingintensityisfixedat1.43(croppingintensitydataarefromthe CentralBureauofStatistics, https://bps.go.id,accessedon10January2023),andthe annualpercapitaconsumptionisfixedat110kgmilledrice.Milledriceyieldisfixedat 0.576oftheunhuskedrice,andpopulationgrowthisassumedat0.5%annually,starting from280millionin2020to322millionin2050(milledriceyielddataarefromtheCentral BureauofStatistics, https://bps.go.id,accessedon10January2023).Underthethreepaddy fieldconversionscenarios,iftheconversionrateis30,000hayear 1,60,000hayear 1,or 96,500hayear 1,paddyfieldareain2050willbe6.62,5.78or4.76Mha,respectively.A summaryofthescenariosispresentedinFigure 2

(business as usual, BAU) and 74 kg ha 1 eld conversion rates of 96,500 ha

(businessasusual,BAU)and forattaining80%oftheyieldpotentialby2050,andpaddyfieldconversion ratesof96,500hayear (BAU),60,000hayear and30,000hayear

Figure 2. Scenarios of yield increase of 40 kg ha 1 year 1 (business as usual, BAU) and 74 kg ha 1 year 1 for attaining 80% of the yield potential by 2050, and paddy field conversion rates of 96,500 ha year 1 (BAU), 60,000 ha year 1 and 30,000 ha year 1

showstheresultsofthescenarioanalysisonnationalriceproductionand consumption.IftheyieldincreasefollowstheBAUtrend,Indonesiawillfacearicedeficit .Ifthe ,aricedeficitwilloccurin2026or2028, 1 whilepaddyfieldconversioniscontrolledatamaximumof30,000hayear 1.However,if thepaddyfieldconversionremainsat96,500or60,000hayear 1,riceself-sufficiencycan onlybemaintaineduntil2030or2046,respectively.

erent land conversion rates and yield in1; ; and P_C30 = milled . YBAU = rice grain yield increase for

s the milled rice production under the combined d dash arrows indicate the year when the conunder selected combined scenarios of conversion and yield in-

This analysis clearly shows that it is crucial to accelerate the yield increase and substantially decrease paddy field conversion to maintain rice self-sufficiency. Controlling paddy field conversion is one of the most difficult challenges to address. It requires interministerial and private sector coordination. The current trend of rapid infrastructural development—which often comes at the expense of highly productive agricultural areas— may be profitable in the short run, but it puts food self-sufficiency, which is the interregime’s main objective of agricultural development, at high risk.

Figure 3. Milled rice production and consumption at different land conversion rates and yield increase scenarios. P_C96.5 = milled rice production at paddy field conversion rate of 96,000 ha year 1; P_C60 = milled rice production at paddy field conversion rate of 60,000 ha year 1; and P_C30 = milled rice production at paddy field conversion rate of 30,000 ha year 1. YBAU = rice grain yield increase under the business-as-usual rate of 40 kg ha 1 year 1; Y80 = rice grain yield increase of 74 kg ha 1 for attaining 80% of the yield potential by 2050. * denotes the milled rice production under the combined different conversion and yield increase scenarios. Red dash arrows indicate the year when the consumption equals the production under selected combined scenarios of conversion and yield increase.

6. Challenges in Implementing Agroecological Management

Figure3. Milledriceproductionandconsumptionatdifferentlandconversionratesand yieldincreasescenarios.P_C96.5=milledriceproductionatpaddyfieldconversionrateof 96,000hayear 1; P_C60=milled riceproductionatpaddyfieldconversionrateof60,000hayear 1; and P_C30=milled riceproductionatpaddyfieldconversionrateof30,000hayear 1.YBAU=rice grainyieldincreaseunderthebusiness-as-usualrateof40kgha 1 year 1;Y80=ricegrainyield increaseof 74kgha 1 forattaining80%oftheyieldpotentialby2050.*denotesthemilledrice productionunderthecombineddifferentconversionandyieldincreasescenarios.Reddasharrows indicatetheyearwhentheconsumptionequalstheproductionunderselectedcombinedscenariosof conversionandyieldincrease.

The implementation of improved management systems that adhere to agroecological principles is challenged by the economic, social, institutional, and technical problems

Thisanalysisclearlyshowsthatitiscrucialtoacceleratetheyieldincreaseandsubstantiallydecreasepaddyfieldconversiontomaintainriceself-sufficiency.Controlling paddyfieldconversionisoneofthemostdifficultchallengestoaddress.Itrequires

This analysis clearly shows that it is crucial to accelerate the yield increase and substantially decrease paddy field conversion to maintain rice self-sufficiency. Controlling paddy field conversion is one of the most difficult challenges to address. It requires interministerial and private sector coordination. The current trend of rapid infrastructural development—which often comes at the expense of highly productive agricultural areas— may be profitable in the short run, but it puts food self-sufficiency, which is the interregime’s main objective of agricultural development, at high risk.

inter-ministerialandprivatesectorcoordination.Thecurrenttrendofrapidinfrastructuraldevelopment—whichoftencomesattheexpenseofhighlyproductiveagricultural areas—maybeprofitableintheshortrun,butitputsfoodself-sufficiency,whichisthe inter-regime’smainobjectiveofagriculturaldevelopment,athighrisk.

6.ChallengesinImplementingAgroecologicalManagement

Theimplementationofimprovedmanagementsystemsthatadheretoagroecological principlesischallengedbytheeconomic,social,institutional,andtechnicalproblemsfaced byfarmers.Table 5 listsexamplesofagroecologicalindicators,improvedmanagement systemsrequiredtoaddresstheseindicators,implementationchallenges,andstrategiesto overcomethesechallenges.

ApartfromthestrategiesexplainedinTable 5,therealityisthathigh-yieldingrice varietiesdominateIndonesia’spaddyfarming.Thesevarietiesexhibithighresponsiveness tosyntheticfertilizerapplications,leadingfarmerstoprioritizetheiruse.Consequently, theeffectsoforganicandbiofertilizersmightbemaskedbytheextensiveapplicationof syntheticfertilizers.

However,afteracknowledgingthebeneficialeffectsoforganicfertilizersonsoilhealth, emissionreduction,andadaptationtoclimatechange(asdiscussedinSection 4),itbecomes necessaryforthegovernmenttopromotetheiruse.Thisnecessitatestheimplementationof policiesaimedatsuchpromotion,includingthefollowing[186–189]:

• Financialincentivesintheformofsubsidiesand/orfinancialsupportforfarmers transitioningtoorganicfertilizers.

• Trainingandextensionservicestoinformfarmersaboutthebenefitsoforganicfertilizers,properapplicationmethods,andtheirimpactonsoilhealthandcropyield.

• Trainingontechniquestomakecompostandtheuseoflocalnutrientsources.

• Researchanddevelopmentfundingaimedatimprovingtheeffectivenessandefficient productionoforganicfertilizers,includingonthesimplerstorageandlongerviability ofbiofertilizers.

• Regulatorysupportthatfavorstheuseoforganicfertilizers.Thisincludessettingthe standardsfororganicfertilizersandcertificationprogramstoensurequality.

• Investingininfrastructuresuchascompostingandbiocharfacilitiesandorganicwaste managementsystemstofacilitatetheproductionanddistributionoforganicfertilizers.

• Theestablishmentofpilotprogramsatselectedfarmers’fieldstodemonstratethe effectivenessoforganicfertilizersisessential.Thesepilotsshouldaimtodemonstrate thebeneficialeffectsoforganicfertilizers,inadditiontoshowingtheidealcombination ofsyntheticandorganicfertilizers.

Implementingacombinationofthesepoliciescouldencouragetheadoptionandusage oforganicfertilizerswhilereducingdependencyonsyntheticones,promotingsustainable agriculturalpracticesinthelongrun.

Finally,withtheincreasingpriceofchemicalfertilizers,thereshouldbeanincreased emphasisontheuseoforganic,bio-,andbioorganicfertilizerswhilereducingthereliance oninorganicfertilizers.Thisshiftwillleadtomoreeconomicalandefficientfertilization practices.Furthermore,theenhanceduseoforganicfertilizersismoreenvironmentally friendly.Farmersshouldbeprotectedfromtheoverpromotionofcertainproductslacking proveneffectiveness.Finally,nutrientsufficiencyshouldbeensuredfromthecombined useofsyntheticandorganicfertilizersbecauseyieldincreaseisamustinattainingrice self-sufficiency(seeSection 5).

Table5. Examplesofagroecologicalindicators,improvedmanagementsystems,challenges,and suggestedimprovements.

AgroecologicalIndicator ImprovedManagement System Challengesin Implementation

Lowermethane(CH4) emissions

Lowernitrousoxide(N2O) emissions

Intermittentirrigation, includingimplementationof theSystemofRice Intensification

UseoflowCH4 emission varieties

Improveefficiencyofnitrogen (N)fertilization

Watermaybeexcessivewhen drainingisneededordeficient whenfloodingisneeded

Low-emissionvarietiesmay notbethehigh-yieldingor high-qualityvarieties;hence, theyarenotpreferable

Farmersaretraditionally happywithquickresponseof Nfertilizers

StrategiestoOvercomethe Challenges

Improvedirrigationand drainagesystems

Long-termgeneticprogramto producelow-emission, high-yieldingand high-qualityricevarieties

Improvedextensionand wideruseofleafcolorchart forNapplicationefficiency

Higheravailabilityofessential nutrients

Useinorganicfertilizersbased onlocalspecificor test-kit-assisted recommendations supplementedbyorganicand naturalfertilizers

Improvednutrientbalance, especiallybyhigher potassium(K)application

IncreaseapplicationofKfrom inorganicandorganic fertilizers

Unaffordabilityand/or unavailabilityoffertilizersat therightamountandtheright place

Increasedsoilcarbonstock

Improvedsoilhealthand nutrientavailabilityby microbes

Applicationofbiochar

Applicationoforganic fertilizer

Inoculationofmicrobes(N fixing,solubilizing,and antagonisticmicrobes)

• High-pricedKfertilizers

• Needtoregularlyupdate nutrientstatusmaps

• Regularlyupdatesoil nutrientstatusmaps

• Explorelocallyavailable sourcesofnutrients

• Ensuretheavailabilityof chemicalfertilizersatthe righttime,amount,and place,aswellasat affordableprices

• Optimizetheapplication oflocallyavailable organicmatter,especially straw

• Exploretheuseof naturalfertilizersuchas stonemeal

• ShiftaportionoftheN fertilizersubsidytoK fertilizers

• Scarcityoffeedstock becauseofcompetition withoff-farmutilization

• Extraworkandcoststo makebiochar

Scarcityoffeedstockbecause ofoff-farmutilization

Quickexpirationof biofertilizers,causingtheir ineffectiveness

• Explorealternative feedstock

• Providecarboncredit

Optimizetheuseofother organicfertilizers,suchas manure

Intensivetechnicalguidance ofhandlinganduseof inoculants

Sources:AdaptedfromAgusetal.(2022)[18]andLeimonaetal.(2015)[189].

7.ConclusionsandRecommendation

WehaveoutlinedIndonesia’schallengeinmaintainingriceself-sufficiency.Thisgoal hingesonenhancingriceyield,achievablethroughagroecologicalnutrientmanagement. Ourproposedstrategyemphasizesabalancedmixofsynthetic,organic,bio-,andbioorganicfertilizers.Improvedwatermanagementandintercroppingandcroprotationfurther amplifynutrientmanagementsuccess.

Soiltestsstandaspivotalindicatorsforfertilization,yetnutrientdynamicsarecomplex andareinfluencedbycropuptakeandsoilreactions.Hence,regularupdatesofnutrient statusmapsarevital,andshouldbecomplementedbyplanttissueteststofine-tune fertilizerrecommendations.Real-time,site-specificadviceisenhancedbyusingsoiltest kitsalongsideplantandsoiltests.Strategizingpotassiumfertilizerusethroughstraw recycling,increasedsubsidies,andexploringalternativesourceslikestonemealaddresses costconcerns.

Encouragingorganicfertilizerusagedemandsincentives,demonstrations,andstakeholdercollaborationtounderlinetheirefficacytofarmers.Biofertilizers,whicharewellsupportedintheliterature,requirepromotionthroughjointeffortsamongpolicymakers, researchers,andextensionservices.

Wehavealsodetailedtheenhancementofagroecologicalfunctionsresultingfrom agroecologicalnutrientmanagementinpaddyfarming.Theseimprovementsencompass climatechangeadaptationandmitigation,nutrientcycling,waterconservation,andbiodiversitypreservation.Theseaspectsmightbeintangibleforfarmers,thusrequiring governmentpolicyinterventionstobolstertheimplementation.

Ultimately,agroecologicalapproachesaimedatincreasingriceyieldmustbeaccompaniedbyastringentcontrolofpaddyfieldconversion.Implementingconsistentand coordinatedmeasuresisimperativetolimittheconversiontolessthan30,000hectaresper yearimmediately,whilegraduallyreaching80%oftheyieldpotentialby2050.Failingto dosowillrenderthericeself-sufficiencyobjectivemerelyrhetorical.

AuthorContributions: F.A.leadtheconceptualizationofthearticlewithcommentsprovidedby S.N.C.andW.I.S.;W.I.S.andF.A.wrotethedraft,andallauthorsreviewedandcommentedonthe manuscript.Allauthorshavereadandagreedtothepublishedversionofthemanuscript.

Funding: TheworkwasundertakenwithinthecontextoftheFoodandLandUseCoalitionIndonesiaplatformwithsupportfromNorway’sInternationalClimateandForestInitiative(NICFI), grant20/3447.

DataAvailabilityStatement: Alldatamentionedonthepaperareavailablethroughthecorrespondingauthor.

Acknowledgments: WethankAldiAiroriforassistingwithliteraturecollectionatthebeginningof thisreview.Thecontentsandopinionsexpressedhereinarethoseoftheauthorsanddonotnecessarily reflecttheviewsoftheassociatedand/orsupportinginstitutions.Theusualdisclaimerapplies.

ConflictsofInterest: Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictofinterest.

References

1. FAO(FoodandAgricultureOrganization);InternationalFundforAgriculturalDevelopment;UnitedNationsChildren’sFund; WorldFoodProgramme;WorldHealthOrganization. TheStateofFoodSecurityandNutritionintheWorld2019:SafeguardingAgainst EconomicSlowdownsandDownturns;FAO:Rome,Italy,2019.Availableonline: http://www.fao.org/3/ca5162en/ca5162en.pdf (accessedon10January2023).

2. Lestari,P.;Mulya,K.;Utami,D.W.;Satyawan,D.;Supriadi,M. StrategiesandTechnologiesfortheUtilizationandImprovementofRice; IndonesianAgencyforAgriculturalResearchandDevelopment:Jakarta,Indonesia,2020.

3. BPS(BadanPusatStatistik). StatisticalYearbookofIndonesia2023;BPS:Jakarta,Indonesia,2023.

4. Grassini,P.;vanBussel,L.G.J.;VanWart,J.;Wolf,J.;Claessens,L.;Yang,H.;Boogaard,H.;deGroot,H.;vanIttersum,M.K.; Cassman,K.G.Howgoodisgoodenough?Datarequirementsforreliablecropyieldsimulationsandyield-gapanalysis. Field CropsRes. 2015, 177,49–63.[CrossRef]

5. Wezel,A.;Casagrande,M.;Celette,F.;Vian,J.F.;Ferrer,A.;Peigne,J.Agroecologicalpracticesforsustainableagriculture.Areview. Agron.Sustain.Dev. 2014, 34,1–20.[CrossRef]

6. deMolina,M.G.;Casado,G.I.G.Agroecologyandecologicalintensification.Adiscussionfromametabolicpointofview. Sustainability 2017, 9,86.[CrossRef]

7. Garcia-Oliveira,P.;Fraga-Corral,M.;Carpena,M.;Prieto,M.A.;Simal-Gandara,J.Chapter2—Approachesforsustainable foodproductionandconsumptionsystems.In FutureFoods;RajeevBhat,R.,Ed.;AcademicPress:Cambridge,MA,USA,2022; pp.23–38.[CrossRef]

8. Martínez-Camacho,Y.D.;Negrete-Yankelevich,S.;Maldonado-Mendoza,I.E.;Núñez-delaMora,A.;Amescua-Villela,G. Agroecologicalmanagementwithintra-andinterspecificdiversificationasanalternativetoconventionalsoilnutrientmanagement infamilymaizefarming. Agroecol.Sustain.FoodSyst. 2022, 46,364–391.[CrossRef]

9. Drinkwater,L.E.;Snapp,S.S.Advancingthescienceandpracticeofecologicalnutrientmanagementforsmallholderfarmers. Front.Sustain.FoodSyst. 2022, 6,921216.[CrossRef]

10. Soane,B.D.;Ball,B.C.;Arvidsson,J.;Basch,G.;Moreno,F.;Roger-Estrade,J.No-tillinnorthern,westernandsouth-western Europe:Areviewofproblemsandopportunitiesforcropproductionandtheenvironment. SoilTill.Res. 2012, 118,66–87. [CrossRef]

11. Pretty,J.Agriculturalsustainability:Concepts,principlesandevidence. Philos.Trans.R.Soc.B 2008, 363,447–465.[CrossRef]

12. Balmford,A.;Amano,T.;Bartlett,H.Theenvironmentalcostsandbenefitsofhigh-yieldfarming. Nat.Sustain. 2018, 1,477–485. [CrossRef]

13. Dawe,D.CanIndonesiatrusttheworldricemarket? Bull.Indones.Econ.Stud. 2008, 44,115–132.[CrossRef]

14. Yuan,S.;Stuart,A.M.;Laborte,A.G.;RattalinoEdreira,J.I.;Dobermann,A.;Kien,L.V.N.;Thúy,L.T.;Paothong,K.;Traesang,P.; Tint,K.M.;etal.SoutheastAsiamustnarrowdowntheyieldgaptocontinuetobeamajorricebowl. Nat.Food 2022, 3,217–226. [CrossRef]

15. Liu,Y.;Yamauchi,F.Populationdensity,migration,andthereturnstohumancapitalandland:InsightsfromIndonesia. Food Policy 2014, 48,182–193.[CrossRef]

16. Mulyani,A.;Kuncoro,D.;Nursyamsi,D.;Agus,F.Analisiskonversilahansawah:Penggunaandataspasialresolusitinggi memperlihatkanlajukonversiyangmengkhawatirkan. J.Tan.Iklim. 2016, 40,121–133.

17. Andrade,J.F.;Cassman,K.G.;RattalinoEdreira,J.I.;Agus,F.;Bala,A.;Deng,N.;Grassini,P.Impactofurbanizationtrendson productionofkeystaplecrops. Ambio 2022, 51,1158–1167.[CrossRef][PubMed]

18. Agus,F.;Susilawati,H.L.;Surmaini,E.StrategiesforIndonesia’sagriculturalclimatechangeadaptationandmitigation. J.Sumb. Daya.Lahan.Indo. 2022, 16,67–81.[CrossRef]

19. Mulyani,A.;Agus,F.Kebutuhandanketersediaanlahancadanganuntukmewujudkancita-citaIndonesiasebagailumbung panganduniatahun2045. Anal.Keb.Pert. 2018, 15,1–17.[CrossRef]

20. Mulyani,A.Analisiskapasitasproduksilahansawahuntukketahananpangannasionalmenjelangtahun2045. J.Sumb.Lah. 2022, 16,33–50.Availableonline: https://garuda.kemdikbud.go.id/documents/detail/2690966 (accessedon6July2023).

21. Agus,F.;Andrade,J.F.;Edreira,J.I.R.;Deng,N.;Purwantomo,D.;Agustiani,N.;Aristya,V.E.;Batubara,S.F.;Herniwati;Hosang, E.Y.;etal.Yieldgapsinintensiverice-maizecroppingsequencesinthehumidtropicsofIndonesia. FieldCropsRes. 2019, 237, 12–22.[CrossRef]

22. Setyorini,D.;Widowati,L.R.;Rochayati,S.TeknologiPengelolaanHaraLahanSawahIntensifikasi.In LahanSawahdanTeknologi Pengelolaannya;PusatPenelitianTanahdanAgroklimat:Bogor,Indonesia,2005.

23. Husnain,H.;Masunaga,T.;Wakatsuki,T.Fieldassessmentofnutrientbalanceunderintensiverice-farmingsystems,andits effectsonthesustainabilityofriceproductioninJavaIsland,Indonesia. J.Agric.FoodEnviron.Sci. 2010, 4,1–11.