Editedby: ElsLecoutere, CGIARGenderPlatform-International LivestockResearchInstitute (ILRI),Kenya

Reviewedby: KerryRenwick, UniversityofBritishColumbia,Canada SatoshiYamazaki, UniversityofTasmania,Australia

*Correspondence: MuliaNurhasan m.nurhasan@cgiar.org

Specialtysection: Thisarticlewassubmittedto NutritionandSustainableDiets, asectionofthejournal FrontiersinSustainableFoodSystems

Received: 04October2021

Accepted: 15December2021

Published: 29March2022

Citation: NurhasanM,MaulanaAM,AriestaDL, UsfarAA,NapitupuluL,RouwA, HuruleanF,HapsariA,HeatubunCD andIckowitzA(2022)Towarda SustainableFoodSysteminWest Papua,Indonesia:ExploringtheLinks BetweenDietaryTransition,Food Security,andForests. Front.Sustain.FoodSyst.5:789186. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2021.789186

published:29March2022

doi:10.3389/fsufs.2021.789186

TowardaSustainableFoodSystemin WestPapua,Indonesia:Exploringthe LinksBetweenDietaryTransition, FoodSecurity,andForests

MuliaNurhasan 1,2,3*,AgusMuhamadMaulana 1,DesyLeoAriesta 1 ,AvitaAlizaUsfar 3,4 , LucentezzaNapitupulu 5,6,AserRouw 7 ,FerdinandusHurulean 3,AzizahHapsari 8 , CharlieD.Heatubun 3,9,10 andAmyIckowitz 1

1 CenterforInternationalForestryResearch,Bogor,Indonesia, 2 DepartmentofNutrition,SportsandExercise,Universityof Copenhagen,Copenhagen,Denmark, 3 ResearchandDevelopmentAgency(Balitbangda)ofProvincialGovernmentofWest Papua,Manokwari,Indonesia, 4 IndependentConsultant,Jakarta,Indonesia, 5 FoodandLandUseCoalition,World ResourcesInstituteIndonesia,Jakarta,Indonesia, 6 DepartmentofEconomics,FacultyofEconomicsandBusiness, UniversitasIndonesia,Depok,Indonesia, 7 AgencyforAgriculturalResearchandTechnology(BPTP)ofWestPapuaProvince, Manokwari,Indonesia, 8 EcoNusaFoundation,Jakarta,Indonesia, 9 FacultyofForestry,UniversitasPapua,Manokwari, Indonesia, 10 RoyalBotanicGardens,Kew,Richmond,UnitedKingdom

Naturaltropicalforestscover89%ofthelandareaofWestPapuaProvince,Indonesia. ForestshavetraditionallybeenanimportantpartoflocalfoodsystemsforIndigenous Papuans.Despitethecontributionofforeststofoodsecurity,WestPapuahasbeen rankedasoneofthemostfood-insecureprovincesinIndonesia,withhighratesof bothunder-and-overnutrition.Thispaperaimstodiscussthedietarytransitiontaking placeinWestPapuaanduseslocalperspectivestoexplorethelinkbetweenchanges indiets,foodsecurity,andforests.Weusedmixedmethodswithatriangulationdesign tocorroboratethequantitativedatathatwepresentfromtworoundsoftheNational SocioeconomicSurvey(SUSENAS)onfoodconsumptionforWestPapuafrom2008 and2017,withinformationfromfourfocusgroupdiscussionswithinstitutionaland localstakeholders.Thequantitativeanalysisshowedthat WestPapuaisexperiencing adietarytransition,movingawayfromtheconsumptionoftraditionalfoods,suchas sago,tubers,wildmeat,andfreshlegumes,towarddietswithmorerice,chicken, tofu,andtempeh.Theconsumptionofprocessedandultra-processedfood(UPF)has increasedwhiletheconsumptionoffreshfoodhasdecreased.Thequalitativeanalysis confirmedthesefindings.TheinstitutionalstakeholdersexpressedadesireforPapuans toreturntoeatingtraditionaldietsforbetterfoodsecurity,whereasthelocalstakeholders worriedabouttheirchildren’shighconsumptionofUPFs.We alsofoundadisconnect betweenhowfoodsecurityismeasuredbythenationalFoodSecurityIndex(FSI) andthepointofviewoftheinstitutionalstakeholders.WhiletheFSIindicatorsare moreinfrastructure-relatedmeasures,theinstitutional stakeholderslinkfoodsecurity withtheavailability,accessibility,stability,andsustainabilityofthefoodsourcesintheir surroundingenvironment,especiallytheforests.Theinstitutionalstakeholderssupport thecommitmentoftheprovincialgovernmenttomaintainatleast70%oftheforestcover

inWestPapua,asstatedintheManokwariDeclarationalthoughtheyexpressedtheneed formoreclarityonhowthiswillimpacttheirfoodsecurity. TheIndonesiangovernment andtheinternationalcommunityshouldsupportthisinitiativeandcarryitoutwith substantialinputfromlocalPapuanstakeholders.

Keywords:WestPapuaIndonesia,dietarytransitions,forest,sustainablefoodsystem,Indonesia,foodsecurity, nutritiontransition,ultra-processedfood

INTRODUCTION

Theworld’sdietsaretransitioning.Globally,dietsarebecoming dominatedbyhigherintakesofanimal-sourcefoods,fats,and sugarandlowerintakesoffiber(Popkin,2006).Thispatternis foundinmanypartsoftheworld(Popkinetal.,2012).Inlowandmiddle-incomecountries,dietarytransitionshaveconverged onwhatisoftencalleda“moderndiet”or“Westerndiet.”The termsusedheredonotnarrowlyrefertoWesterncuisinesbut insteadrefertoahigherintakeoffat(particularlyvegetableoils), addedsugar,animal-sourcefoods,refinedcarbohydrates,and lessfreshvegetables,legumes,andcoarsegrains(Popkin,2006). Dietarytransitionislinkedwithoverweight,obesity,and various non-communicablediseases(Popkinetal.,2012;PopkinandNg, 2021).

ForIndigenouscommunities,whichhistoricallyhaveahigher dependenceonfoodsourcesfromthesurroundingnatural environments,dietarytransitionsareassociatedwithmarket penetration/integrationandthecommodificationoftheirfood systems.Thisincludesmovingawayfromtraditionalfoods towardmoreprocessedfoodshigherinfat,addedsugar,andsalt (Kuhnlein,2009).InastudyofthedietarypatternsofIndigenous peopleinforestedareasofBolivia,Cameroon,andIndonesia, Reyes-Garcíaetal.(2019) foundthatIndigenouspeoplewho livedfarfrommarkettownshadmorediversedietsthanthose livinginvillagesclosertomarkets.Theyalsofoundthatthe consumptionofnutritionallyimportantfoods,suchasfruits, vegetables,andanimal-sourcefoods,decreasedwithincreasing marketintegration.Incontrast,theconsumptionoffoodssuch asfatsandsweetsincreased(Reyes-Garcíaetal.,2019).

Studiesonthecontributionofforeststofoodsecurityshow thatforestsprovidewildplantfoodssuchasfruits,mushrooms, leaves,andtubers.Inaddition,forestsprovidehabitatsforedible insects,animalshuntedformeat,andfishacrossthetropics, whichareessentialforfoodsecurity(Rowlandetal.,2017).They provideecosystemservicesthatindirectlyaffectfoodproduction, suchashabitatsforpollinators,waterregulation,soilprotection, nutrientrecycling,andmore(HLPE,2017).Forestsalsoprovide thewoodfuelusedtopreparefoodandproductsthatcan

Abbreviations: COICOP,ClassificationofIndividualConsumptionaccording toPurpose;F&B,Foodandbeverage;FGD,Focusgroupdiscussion; FSI,Food SecurityIndex;FSVA,FoodSecurityandVulnerabilityAtlas;GI,Glycemic index;HDDS,HouseholdDietaryDiversityScore;IDR,Indonesian rupiah; MIFEE,MeraukeIntegratedFoodandEnergyEstate;OAA,Otheraquaticanimal; POH,Processed-preserved-prepared-outside-home;RDA,Recommendeddietary allowance;RTE,Ready-to-eat;SD,Standarddeviation;SSB,Sugar-sweetened beverage;SUSENAS,SurveiSosialEkonomiNasional(NationalSocioeconomic Survey);UPF,Ultra-processedfood.

besoldforcashtopurchasefoods.However,therearefew studiesdocumentingtheprovisioningservicesofforeststofood productionordietsinWestPapua.

Changinglandscapesmaybeanimportantfactoraffecting dietarychange(Broegaardetal.,2017;Ickowitzetal.,2021). Thiscanbeduetoalossofwildfoodsifcultivatedlandscapes replacewildonesoralossofagrobiodiversityifmoreintensive monoculturesreplacepolyculturallandscapes(Ickowitzetal., 2019). HerforthandAhmed(2015) alsosuggestthatforpeople withahighdependenceonsurroundingfoodsources,suchas thoselivinginforestedareas,changesinlivelihoodactivities affectthetimeallocationforfoodproduction.Thiscouldmean thatpeoplenolongerhavethetimetocollect,hunt,orprocess traditionalfoods. Rasolofosonetal.(2018) assessedtheimpact offorestsonchildren’sdietsinruralareasof27countries and foundpositiveassociationsbetweenforestsandfoodsecurity, dietarydiversity,andevenstunting. Galwayetal.(2018) foundthatdeforestationinWestAfricadecreasedthedietary diversityofchildrenlivingnearforestsandtheirconsumption ofhealthyfoods.

Therecentadditionof“agency”asanimportantdimensionof foodsecuritywasproposedbytheHigh-LevelPanelofExperts onFoodSecurityandNutrition(HLPE,2020).Includingagency highlightstheneedtotakelocalperspectivesandpreferences intoaccountinfoodandnutritionanalysesandinterventionsto achievefoodsecurityandnutritiongoals:“Agencyrefersto the capacityofindividualsorgroupstomaketheirowndecisions aboutwhatfoodstheyeat,whatfoodstheyproduce,howthat foodisproduced,processedanddistributedwithinfoodsystems, andtheirabilitytoengageinprocessesthatshapefoodsystem policiesandgovernance”(HLPE,2020).Afocusonagencyis highlyrelevanttoIndigenouspeoples’foodsystemsbecausetheir foodculture,knowledge,andpracticeshavebeenandcontinue tobemarginalizedinfoodsecuritypolicyforums(FAO,2021). Agencycanalsobeveryusefulforunderstandingissuesofdietary transitionandfoodsecurityinIndigenouscommunities.

Addressingagencyinfoodandnutritionisparticularly relevantfortheIndonesianprovinceofWestPapua.1 WestPapua hasalargeIndigenouspopulation,andtheprovincehashigh ratesofpoverty,malnutrition,andfoodinsecurity.Thereare40 Indigenousethnicgroupslivingacrosstheprovince(Wambrauw, 2017;StatisticsWestPapua,2021d),withaverydifferenthistory, ecology,andtraditionaldietaryculturethanthosefoundinother

1Fortherestofthepaper,whenwereferto WestPapua, werefertotheWestPapua ProvinceofIndonesia.Thisissometimesconfusedwiththeterm WestPapua used internationallytorepresentthewesternpartoftheislandofNewGuinea,including bothWestPapuaandPapuaProvincesofIndonesia.

regionsofIndonesia.WestPapuaiscoveredbynaturaltropical forestson89%ofthelandarea(Figure1; Hansenetal.,2013).It islocatedonthefurthestislandfromJava—thecenterofpolitics andeconomicdevelopmentinIndonesia.ForPapuans,forests areinextricablylinkedtofoodsecurityandtheidentityof the Indigenouspeople(Pattiselannoetal.,2019).Papuans,especially thosewholivenearforests,huntandgatherfoodintheforests (Pattiselanno,2004;Pangau-Adametal.,2012;Pattiselannoand Nasi,2015).

Previousstudieshaveindicatedthatland-useinPapuais linkedtoadietarytransition(Purwestrietal.,2019).Research onthedietsofIndigenoushouseholdsinMerauke,Papua Province,foundthatthosewhocollectedfoodandhuntedin theforestsatemorefruit,fish,andmeatthanfellowPapuans workinginoilpalm.Womenworkinginoilpalmalsosuffered fromhigherratesofanemiacomparedtowomenwholived amoretraditionallifestyle(Purwestrietal.,2019).Anecdotal evidencesuggestsanincreasingtrendintheconsumptionof ultra-processedfoods(UPFs)amongPapuans.AlthoughUPFs aretypicallysoldinplaceswithaccesstomodernmarkets, theyhavealsopenetratedtheruralcommunitiesofPapua (Hidayat,2017;Rachmawati,2020).Participantsinfocusgroup discussions(FGDs)inMerauke,PapuaProvince,reportedthat theconsumptionofwildfoods,particularlywildmeatandsago,2 hasdeclinedwiththedecreaseinforestedlandscapes.Toharvest sagoorhuntanimals,suchasdeerandkangaroos,theyreportedly nowneedtowalklongerdistancesthantheydid10yearsago (Purwestrietal.,2019).

Thispaperaimstoprovideevidenceshowingthata dietarytransitionistakingplaceinWestPapuaanduseslocal perspectivestoexplorethelinkbetweenchangesindiets, foodsecurity,andforests.Todoso,weusehouseholdfood consumptiondatafromtworoundsoftheIndonesianNational SocioeconomicSurvey(SurveiSosialEkonomiNasional; SUSENAS)from2008and2017toshowquantitativechangesin foodconsumptionovertime.Wethencorroboratetheevidence fromthequantitativeanalysisofSUSENASdatawithdatafrom FGDswithlocalstakeholders.Wealsoincludeadiscussion ofstakeholders’perspectivesonwhataspectsoffoodsystems mattertothem,withafocusonhealthandnutritionalissues, foodsecurity,andforests.

METHOD

StudySetting

TheislandofNewGuineaisadministrativelydividedintotwo countries:IndonesiainitswesternhalfandPapuaNewGuinea initseasternhalf.Indonesiahasdivideditspartoftheisland intotwojurisdictions,specificallytheprovincesofPapuaand WestPapua.WestPapuaislocatedjustbelowtheequator.Its altituderangesfromsealevelinthelowlandstomorethan2,000 metersabovesealevelinthemountains(StatisticsWestPapua, 2021d).WestPapuaisamongthepoorestprovinceinIndonesia, where22%ofthepopulationlivesunderthepovertyline

2Sagoisastarchthatisharvestedfrompalmsthatgrowmostlyinthelowland forestedareasofPapua.

(StatisticsIndonesia,2021b).Theprovincealsohashighrates ofunder-andovernutrition;almostone-third(27%)ofchildren under5yearsoldinWestPapuaarestuntedintheirgrowth,and 40%ofadultsareeitheroverweightorobese(MinistryofHealth, 2019a).

ThemajorityofthepopulationinWestPapuaadheresto Christianity(63%),andMuslimscompose37%ofthepopulation (StatisticsWestPapua,2021d).Papuantraditionaldietsinclude sago,tubers,freshfruits,wildmeat,andfish.Theirmeals generallydonothavemanyingredients,andtheyusefewer spicesthanmostcuisinesfromtheothermajorislandsof Indonesia(Tempo,2018).WestPapuaachievedasubstantial economicgrowthrateof8%in2020,supportedmainlyby themanufacturing,mining,andquarryingsectors.Despitethis substantialgrowthrate,thepovertyratereached22%in2020 (StatisticsWestPapua,2021d).TheHumanDevelopmentIndex was65%(StatisticsWestPapua,2021d),belowthenational averageof72%(StatisticsIndonesia,2021b).Moreover,the provincewasclassifiedasafood-insecureareain2018(Food SecurityAgency,2018).

AspartofNewGuinea,thesecond-largestislandandthe largesttropicalislandintheworld(Newboldetal.,2016), WestPapuahasarichdiversityoffaunaandflora(Marshall andBeehler,2011).Recognizingtheimportanceofforestsfor biodiversity,climatechange,andlivelihoods,theprovincial governmentofWestPapuasignedtheManokwariDeclaration: CustomaryArea-BasedSustainableDevelopmentinPapuaLands onOctober10,2018(ManokwariDeclaration,2018).The provincialgovernmentdeclareditscommitmenttoconserving atleast70%ofthelandandintegratingsustainabilityprinciples intoitslong-termdevelopmentplans,includingacommitment topromoteandacceleratetheformulationofgubernatorial regulationsonfoodsecurity.

DataandAnalysis

Weusedmixedmethodsinthisstudywithatriangulation designfollowingtheworkof PlanoClarketal.(2008) to bringtogetherdifferentbutcomplementarykindsofdata.This enabledtheauthorstocorroboratetheevidenceandexpand theinterpretations.Thequantitativeandqualitativedata were collectedinparallelandanalyzedindependently.Theresults fromeachanalysiswerethenmergedtovalidateandidentifythe discrepanciesbetweenthedatasources(PlanoClarketal.,2008).

DataSetforQuantitativeStudy

Usingtworoundsofweeklyhouseholdfoodconsumptiondata fromthe2008and2017SUSENAS,weexploredthedifferences inthefoodconsumptionpatternsinWestPapuaoverthose2 years.Thesesurveysprovidedataaboutthefoodconsumedby theentirehouseholdasrecalledbyonerespondentfromthe household.Thedataarerepresentativeofthepopulationdown totheregencylevelandinclude2,196householdsin2008and 3,981householdsin2017.However,comparativeanalysisatthe regencylevelwasnotpossibleduetotheexpansionandchanges injurisdictionsoftheregenciesbetween2008and2017.

FIGURE1| PrimaryforestcoverlossofWestPapuaProvince2000-2020a a GreencolorshowstheprimaryforestcoverinWestPapuayear 2020,covering9.2 millionhectaresoflandarea,orabout89%oftheProvince;Redcolorrepresentstheareaofdeforestationfrom2000to2020,coveringabout205thousandhectares cumulatively;Thedatawasbasedon Turubanovaetal.(2018),accessedthroughtheGlobalForestWatchwebsite.Thereis anotherdeforestationdataprovidedby theMinistryofEnvironmentandForestry(MOEF)inhttps://geoportal.menlhk.go.id/whichshowdifferentdeforestationrate.However,bothdatasetssuggestthatthere hasbeendeforestationinWestPapuaProvinceduringthesameperiod.Thispaperuses Turubanovaetal.(2018) duetotheavailabilityandaccessibilityofthespatial database.

QuantitativeAnalysis

WecreatedthefoodgroupsfromtheSUSENASfoodlistswith fourobjectivesinmind.First,tounderstandthegeneralchanges infoodconsumption,wecreatedfoodgroupsbasedon Kennedy etal.(2013),modifiedtomatchthefoodlistprovidedinthe SUSENASandWestPapuacontext.Wecalculatedthequantity consumedfromeachfoodgroupandthepercentchangeof foodconsumedoverthe2years.Second,toassessiftheability ofahouseholdtoaccessavarietyoffoodshaschangedover time,wegroupedthefooditemslistedinSUSENASbasedon theguidelineformeasuringhouseholdandindividualdietary diversity(Kennedyetal.,2013).Wemadeasfewmodifications aspossibletomatchthefoodlistprovidedinSUSENASand thefoodlistinthehouseholddietarydiversityguideline. We usedtherecalldatatogeneratedummyvariables,indicating whetherthehouseholdconsumedeachfoodgroupinthepast sevendaysornot.ThenwecalculatedtheHouseholdDietary DiversityScore(HDDS)bysummingthenumberoffoodgroups consumedinthehousehold.TheHDDSisavalidatedtoolto assessahousehold’seconomicabilitytoaccessavarietyof foods using24-hrecallintakedata(Kennedyetal.,2013).However, wereferto MehrabanandIckowitz(2021) ontheuseofsimilar

7-dayfoodconsumptiondataatthenationallevelinIndonesia fortheHDDS.

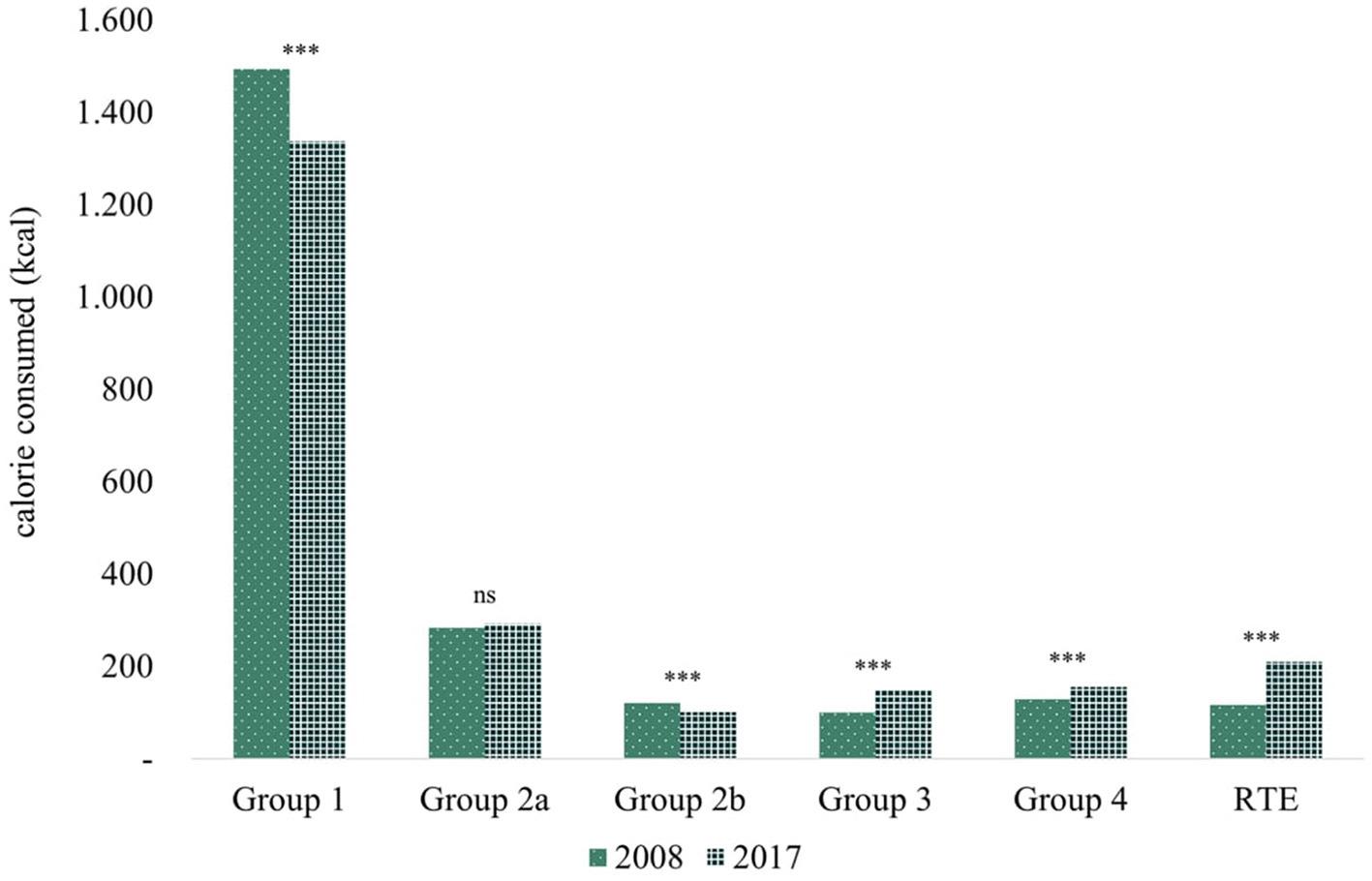

Third,tounderstandwhetherthedietarytransitionhasmoved towardincreasedconsumptionofUPFsandlessfreshand minimallyprocessedfoods,wecategorizedthefoodslistedin SUSENASbasedontheNOVAfoodprocessingclassification (Potietal.,2017).TheNOVAclassificationcategorizesfood intofourgroups:freshandminimallyprocessedfoods(Group 1);oil,sugar,andsalt(Group2);processedfoods(Group3); andUPFs(Group4).Here,wedivideGroup2intoedible fats(2a)andsugarandsalt(2b)toanticipatethedifferent trendsinconsumptionasindicatedbyanotherstudyNurhasan etal.3.UPFsandbeveragesweredefinedasmulti-ingredient industrialformulations.Thisincludessugar-sweetenedbeverages (SSBs),packagedbread,cookies,savorysnacks,candy,icecream, breakfastcereal,andpre-preparedfrozenmeals(Potietal.,2017).

3Nurhasan,M.,Fahim,M.,Aprillyana,N.,andIckowitz,A.(forthcoming). ChangingFoodConsumptionPatternsinIndonesia’sMostand LeastDeforested Areas.Bogor:CenterforInternationalForestryResearch(CIFOR),Statistics Indonesia(BPS).

Fourth,tounderstandwhetheradietarytransitionhas movedtowardtheincreasedconsumptionoffoodsprepared byvendorsbutnotnecessarilyprocessedfoods,weanalyzed theconsumptionofready-to-eat(RTE)foods(Bhuttaetal., 2013).TheRTEfoodcategorywasbasedontheClassification ofIndividualConsumptionaccordingtoPurpose(COICOP) Division11(UnitedNations,2018).Thisfoodclassification includesallofthefoodsservedorpreparedbythefoodvendors andthefoodfromRTEvendors,restaurants,cafés,andstreet foodvendors,includingfactory-producedfoods(e.g.,vegetable sautés,friedsnacks,chickenskewers,carbonateddrinksserved withiceinacafé,etc.).RTEfoodscanincludeprocessedfoods andUPFs.IntheIndonesiancontext,small-scalefoodvendors providefreshandminimallyprocessedfoodsandsellthem ataffordablepricestoconsumersofvariouseconomicclasses. IncreasingtheconsumptionofRTEfoodsinIndonesiahighlights theimportanceofimprovedfoodsafetyandqualitywhenit ispreparedbymicro-andsmall-scale,informalfoodvendors (Vermeulenetal.,2019).

Wecalculatedtheenergyintakefromtheconsumptionof eachfoodgroupinNOVAandCOICOP11.Wepresented theaveragedailypercapitaconsumptionforbothyearsat theprovinciallevel.Thedifferencesintheenergyconsumed perfoodgroupbetweentheyearswereassessedbasedona two-sampleindependent t-testwiththesignificancedeclared at p < 0.05.Thefoodlistedforeachfoodgroupispresented in SupplementaryTables1–3.Thereweredifferencesinthe SUSENASfoodlistsfrom2008to2017.Somefooditemswere excludedfromourfoodlistifnotrepresentedinbothyears.For easeofcomparison,wegeneratedanapproximateconsumption percapitaperdaybydividingthetotalhouseholdconsumption bythenumberofhouseholdmembersandthenumberofdays inaweek.Duetodatalimitations,itwasnotpossibletoconsider theageandsexofallhouseholdmembers.

Inadditiontotheanalysisofthefoodconsumptiondata,we alsousedSUSENASdatatoconfirmfindingsfromourqualitative dataonpricechangesfordifferentstaplefoods.Wedidthisby calculatingthemeanpriceofstaplefoodsfromthe2008and2017 SUSENAS.Wethenmeasuredthechangeofeachstaplefood overtimeagainstthepriceofinstantnoodlesin2017.Wechose instantnoodlesasourcomparatorbecausethisfoodisamarketbasedcommodityconsumedalloverIndonesia,anditsprice isreadilyavailablefromtheSUSENASdataset.Intheresults section,wealsoincludeacalculationonthepercentageofstaple foodsconsumedfromownproductioncomparedtopurchase. Thedifferencesinconsumptionandpricesperfooditemorfood groupbetweentheyearswereassessedbasedonatwo-sample independent t-testwiththesignificancedeclaredat p < 0.05.

QualitativeStudy:FGDs

WeusedthedatafromthetwosetsofFGDsinvolvingdifferent stakeholders:twoFGDswithinstitutionalstakeholdersandtwo FGDswithlocalstakeholders(mothersandcaretakersofyoung childreninvillages).

InstitutionalStakeholders

WecarriedouttwoFGDswithstakeholdersfromvarious institutionsinWestPapuawhosemandateswererelatedto

foodsecurityandlanduse(laterreferredtoas institutional stakeholders).Theinvitedinstitutionswerethoseworkingin foodsecurityandnutrition-relatedareas,suchasagriculture, health,women’sgroups,anduniversityfaculty.Thelistof invitedinstitutionswasdiscussedwithalocalnon-governmental organizationpartner,theEcoNusaFoundation,andalocal governmentpartner,theWestPapuaCenterforResearch andDevelopment(BadanPenelitiandanPengembangan Daerah;Balitbangda).Theinvitedinstitutionsofficiallysentthe stakeholderswhoattendedtheFGD.However,theopinions sharedbytheparticipantsmightrepresenttheirpersonalviews andnotnecessarilytheviewsoftheirinstitutions.

TheFGDswereheldtwice—onFebruary7andMarch13, 2019—inManokwari,thecapitalofWestPapua.TheFGDs werepartofaseriesoflargerfoodandland-useworkshops organizedbyBalitbangda.ThefirstinstitutionalstakeholderFGD wasattendedbysixpeople(fourmenandtwowomen)from sixinstitutionsandlastedaround2h.Thesecondinstitutional stakeholderFGDwasattendedby16people(sixmenand tenwomen)from13institutionsandlastedaround3h.The groupdiscussionswereaudiotapedwithverbalconsent.The participantsreceived150,000Indonesianrupiah(IDR; ∼10 USD)fortransportationfees,exceptforthosewhocamefrom PegununganArfak,whoreceived500,000IDR(∼35USD)to coverthehightravelcostfromtheirhometothemeetingvenue.

LocalStakeholders(MothersandCaretakersofChildren) ThesecondsetofFGDstargetedthemothersandcaretakers ofchildrenfromtwovillageswithdifferentlandscapes(later referredtoas localstakeholders).Motherswerepurposively selectedbecausetheresearcherswantedtogatherinformation abouthouseholddietsandchildfeeding.TheFGDswereheld onFebruary9–10,2019,inthevillageofBamahainPegunungan ArfakRegencyandthevillageofArowiinManokwariRegency. Theregencieswereselectedtorepresentacoastalcommunity withamixed-racepopulationandbettermarketaccessanda highlandcommunitypopulatedmostlybyIndigenouspeople whowererelativelyremotewithpooraccesstomarkets.The villageswereselectedwheretheresearchershadalinkwiththe civilorganization(BentarainPegununganArfakandthehealth careatManokwari)inthearea.

Theheadsoftheorganizationsverballyinvitedthemothers andcaretakersofthepreschoolersandelementaryschoolchildren inthevillage.TheFGDinArowitookplaceinthehouse ofthevillagechief,wasattendedbyeightparticipants,and lastedaround2h.TheFGDinBamahawasconductedin theBentaralibrarywitheightparticipantsandlastedaround anhourandahalf.TheFGDswereaudiotapedwithoral consent.Eachsessionbeganwithintroductionsbythefacilitators andtheparticipants,followedbycriticalquestionsand discussions.Itendedwiththethankingoftheparticipants.Every participantreceived50,000IDR(∼3.5USD)tocompensatefor theirtime.

QualitativeDataAnalysis

Theobjectiveofthequalitativedataanalysiswastocorroborate evidenceofdietarytransitionsfromthequantitativeanalysisand documenttheperspectiveonwhataspectsoffoodsystemsmatter

tothestakeholders,withafocusonhealthandnutrition,food security,andforests.Weusedthescissor-and-sorttechnique fortheanalysisdrawnfromtheworkof Stewartetal. (2007).Wedeterminedwhichsegmentsofthetranscriptwe consideredessentialanddevelopedacategorizationsystem for thetopicsdiscussedbythegroup.Followingthis,weselected therepresentativestatementsregardingthesametopicsfrom the transcriptandinterpretedthefindingsbasedonthestatements ineachcategory.Toavoidpersonalbias,theanalysiswas conductedseparatelybycoauthorsMNandAMMonthesame transcripts.Bothofthecoauthorsthencomparedanddraftedthe findingstogether.

RESULTS

QuantitativeAnalysis

GeneralTrendsinFoodConsumption

Theamountoffoodsconsumedperfoodgroupfor2008and 2017ispresentedin Table1.Thetrendinfoodconsumption ispresentedasthepercentagechangeofthequantityperfood groupconsumedinWestPapuain Figure2.Consumptionof thefollowingfoodgroupsincreased:rice-andwheat-based staples,avianmeats(dominatedbybroilerchicken),dairy foodsandbeverages,vitaminA–richvegetables,vitaminA–rich fruits,processedlegumes,processedingredients,caloricsnack crackers,andSSBs.Conversely,consumptionofthefollowing foodgroupsdecreased:“other”staples,includingtraditional staplefoods;freshmeatand“other”freshmeat,whichincludes wildmeats(butnotexclusively);processed-preserved-preparedoutside-home(POH)meat;eggs;dark-greenleafyvegetables; “other”fruits;freshlegumesandnuts;andbeveragematerials. Table1 alsoshowsthattheHDDSin2008and2017increased from8.5to9.0.

TrendsTowardConsumptionofUPFsandRTEFoods

Figure3 presentsthecalorieconsumptionperfoodgroup basedonNOVAandtheCOICOP11classificationin2008 and2017.Theconsumptionofprocessedfoods(Group3), UPFs,andRTEfoodsincreased,andtheconsumptionoffresh andminimallyprocessedfoods(Group1)andsugarandsalt (Group2b)decreased.ThecaloriecontributionfromUPFsin 2008was130kilocaloriespercapitaperday(kcal/capita/day), whichis6%oftherecommendeddietaryallowance(RDA)of 2,100kcal(MinisterofHealthRegulationNumber28,2019). In2017,thecaloriecontributionfromUPFsincreasedto156 kcal/capita/day,contributingto7%oftheRDA.Thecalorie contributionfromRTEfoodsin2008was117kcal/capita/day, whichwas6%ofRDA.In2017,thecaloriecontributionfrom RTEfoodsincreasedto210kcal/capita/day,whichwas10%of theRDA.

ChangesinStapleFoodPricesandConsumption FromOwnProduction

Table2 showsthatthepriceofsagodoubledcomparedto thepriceofricefrom2008to2017. Figure4 showsthat thepercentageofriceconsumedfromownproduction increased,butconsumptionoftraditionalPapuan

TABLE1| Consumptionperfoodgroupandhouseholddietarydiversity in2008 and2017inWestPapuaProvince,Indonesia.

Consumptioninquantityunit percapitaperdaya atthe Provincelevel

(n = 2,196)

(n = 3,981)

Averagehouseholdmember44

Householddietarydiversity

Mean ± standarddeviation 8.5 ± 1.69 ± 1.7

Median89

Staplefoods

2017b

Rice-basedstaple(g) 204 ± 122229 ± 97***/+

Wheat-Basedstaple(g)18 ± 2821 ± 25***/+

Otherstaples(g)189 ± 239103 ± 137***/–

Animal-Sourcefoods

Freshandpreservedfishand otheraquaticanimals(g)

112 ± 98111 ± 94ns/–

Freshredmeat(g)10 ± 277 ± 19***/–

Freshavianmeat(g)5 ± 1810 ± 25***/+

Otherfreshmeat(g)6 ± 273 ± 13***/–

PreservedPOHmeat(g)4 ± 232 ± 8***/–

Eggs(g)14 ± 3712 ± 16**/–

Dairyfoodandbeverages(g)4 ± 144 ± 15*/+

Vegetables,legumes,and fruits

Dark-Greenleafyvegetables(g)

100 ± 10167 ± 60***/–

OthervitaminA–richvegetables (g) 1 ± 62 ± 9***/+

Othervegetables(g)58 ± 7558 ± 75ns/–

VitaminA–richfruits(g)7 ± 2813 ± 36***/+

Otherfruits(g)88 ± 11359 ± 79***/–

Legumesandnuts(g)5 ± 202 ± 9***/–

Processedlegumes(g)18 ± 4022 ± 37***/+ Sidedishesandbeverages

Beveragematerials(ml)

275 ± 379153 ± 143***/–

Spices(g)21 ± 1820 ± 16ns/–

Processedingredients(g)4 ± 65 ± 5***/+ Snacksandcrackers(g)21 ± 3037 ± 42***/+ Sugar-Sweetenedbeverages(ml)38 ± 8554 ± 89***/+ Alcoholicbeverages(ml)2 ± 312 ± 23ns/+ ns,notsignificantstatistically;POH,processed-preserved-prepared-outside-home;SS, statisticalsignificance.

aUnlessstatedotherwise.

b***showsastatisticallysignificantdifferenceat < 0.001; **showsastatistically significantdifferenceat0.001–0.01; *showsastatisticallysignificantdifferenceat < 0.05. Additionally, +indicatesthatthemeanof2017isgreaterthanthemeanof2008,while –indicatesthemeanof2017issmallerthanthemeanof2008.

staples(suchassagoandtubers)fromownproduction decreased.

QualitativeAnalysis

TheanalysisoftheFGDtranscriptsoftheinstitutionalandlocal stakeholdersrevealedfourdominantissues:adietarytransition fromsagotorice,thehigherconsumptionofUPFsandSSBs,the stakeholders’viewthatWestPapuaisnotfoodinsecure,andthe linkbetweendietsandforests.

FIGURE2| FoodconsumptiontrendsinWestPapuaProvince,2008–2017a a Measuredaspercentchangeofthefoodgroupsconsumedinthe WestPapua provincein2008and2017;OAA,otheraquaticanimals;POH,processed-preserved-prepared-outside-home;F&B,foodandbeverages;SSB,sugar-sweetened beverages;bev,beverages;ns,notsignificant;***showsastatisticalsignificanceat <0.001,**at0.001–0.01,and*at < 0.05.

FIGURE3| Calorieintakefromconsumptionoffood—groupedbasedonnovafoodprocessingclassificationsin2008and2017a a Group1:Unprocessedor minimallyprocessedfoods;Group2a:Oilsandfats;Group2b:Saltandsugar;Group3:Processedfoods;Group4:Ultra-processedfoods;RTE,Ready-to-eatfoods; ns,notsignificant;***showsstatisticalsignificanceat < 0.001.

ADietaryTransitionFromSagotoRice

Generally,theinstitutionalandlocalstakeholdersbothagreed thatriceisnowWestPapua’sprimarystaplefood.Onlythe elderlymembersoftheIndigenouscommunitieswherewe

conductedtheFGDsarestillconsumingsagodaily.Inthelocal stakeholdergroups,theparticipantsstatedthattheyeatrice daily. MostmothersinBamahaseemedtoconsumelocalstaplefoods moreoften(threetimesaweek)thanthemothersinArowi(once

TABLE2| Changeinpriceofstaplefoodsbetween2008and2017relativetothepriceofinstantnoodlesin2017.

Theproportionofriceandothertubersconsumedfromownproductiontototalconsumptionin2008and2017. ortwiceaweek).OnestakeholderinBamahasaidwithhumor, “If wedonoteatrice [everyday], wewilldie.” Thelocalstakeholders inbothsitessuggestedthatchildrenpreferricetotraditional staplefoods.AstakeholderinArowisaid, “Onlytheelderlyliketo eattubers.” Furthermore,astakeholderinBamahasaid, “During afamilymeal,childrenonlywanttoeatrice.Ustheelders,wecan stilleatwithoutrice.Weeattuberswhichhassupportedussince wewerechildren.”

Theinstitutionalstakeholdersexplainedthateatingriceis alsoamatterofprestigebecausericeisconsideredthepremium staplefoodcomparedtothelocalstaplefoods.Theinstitutional stakeholdersinthisstudyalsoexpressedthatprestigeplaysa role inincreasingriceconsumption.Onestakeholdershared, “Iused todoresearchintheruralarea [ofPapua]. Ifoundthatricewas notjustaregularstaplefood.Itwasaprestigiousstaplefood.” The institutionalstakeholderssuggesteditinanegativelight.

Riceisalsopreferredoversagobecauseofitsrelatively lowercost.IntheFGDwiththeinstitutionalstakeholders, the participantsmentionedthatthedailyconsumptionofsagois moreexpensivethanriceifitispurchased.Asonestakeholder stated, “Whenwebuysagointhemarket,justthismuch [hand gestureshowingsmallamount], is20thousandandthecontent isnotdense...” Thesamestakeholderthencontinued, “Ifwebuy rice,youknowhowmuchitcosts?Raskin [agovernmentprogram thatsubsidizesriceforthepoor] costs7thousand,right?The sameamountofmoneyismorethanenoughtobuytwokilograms [ofrice].”Governmentprogramssuchas Raskin,whichprovide freeorsubsidizedriceforthepoor,werediscussedasoneofthe causesofadietarytransitionbytheinstitutionalstakeholders. Oneparticipantarguedthatricecouldreplacethelocalstaple foodsoftheWestPapuansbecauseofsubsidies.Thestakeholders recommendedthattraditionalstaplefoodsshouldbesubsidized

toboostproductionandconsumption:“Riceusedtobeexpensive, butbecauseofthesubsidyprogram,itstartedtobecheaper.”

Oneinstitutionalstakeholderblamedriceformakingthe WestPapuanslosetheirskillstoprocesstheirlocalfoods. “Ourdietarypatternhasshiftedtorice-based.Toreturnto that [sago-ortuber-baseddiet] isratherdifficult.Ithinkitmustbe donegradually.Itisnotaseasyasturningyourpalmaround. Ithastobestartedfromkindergartenstudents;theyhaveto bemotivated [toconsumetraditionalfoods].”Thefactthat riceisnowwidelyavailablewassaidtohavecontributedto creatingtheWestPapuandependenceonrice.Oneparticipant stated, “TheavailabilityofricemakestheIndigenouspeople consumerice.Theyarenotgardening,hunting,andgathering anymore.” Theharvestingandprocessingofsagowerealso mentionedseveraltimesasbothaproblemandasolutionin thestaplefoodtransition.Theinstitutionalstakeholders saidthat processingsagoforstaplefoodconsumptionisstilltraditional. Thisismorecomplicatedthancookingricewitharicecooker. Therefore,riceisoftenchosenoversagoforitspracticality.One institutionalstakeholderexpressedthephysicalhardshipofthe traditionalsagoproductionactivities.Subsequently,this limits sagoproductionandconsumption.Thestakeholdersuggested thatitshouldbemadeeasiertomakeitmoreattractive.

Riceisalsoviewedasamoresuitablestapletoservewithmore sidedishes.ThelocalstakeholdersinArowiandBamahavillages preferredtoeatsagoasastaplewithfishand“yellowandsour soup.”Thisrecipewasalsoviewedasamorecomplicateddishto servethanrice.Someoftheinstitutionalstakeholdersalsoargued thatthegrowingindustryintuber-basedsnackproductionfor oleh-oleh (foodsouvenirs)hasalsochangedtheperceptionof WestPapuans.Tubers,traditionallyconsumedasastaplefood, havegraduallybecomeknownandconsumedassnacks.

ConsumptionofUPFsandSSBs

Someinstitutionalstakeholdersandalllocalstakeholdersraised concernsregardingthemarketingofUPFsandSSBs.For example,thelocalstakeholdersinArowiandBamahavillages complainedabouttheirchildren’s“pesterpower”whennagging fortheUPFsnackssoldbyfoodtraders.InBamahavillage,where accesswasonlypossiblefromManokwaribyeitherfour-wheel vehiclesorspecialtrucks,themobilesnacktraderscomeand go aboutfourtimesadaybymotorcycle.Whenaskedwhatthey usuallybuyfromthemobilesnacktrader,thelocalstakeholders inBamahaanswered, “Candies,biscuits,Supermi [abrandof instantnoodles], SuperMama [abrandofUPFsnacksmarketed tochildren], grilledcorn [extrudedsnacks].”

ThelocalstakeholdersinBamahavillagereportedspending upto50,000IDR(∼3.5USD)everydayonsnacksfortheir children. “IboughtSupermi,sometimesfivethousand,biscuits, ten thousand,chiki,fivethousand.Thatpopcornwasten [thousand]. TodayIspentfifty [thousand]. Tomorrowagainanother50 thousand.” Anotherlocalstakeholdersaidthatshespent20,000 IDR(∼ 1.4USD)inaday.Whileexplainingthis,thestakeholders seemedupset. “Whenthemobilesnackvendorcomes,children cry [beggingfortheparentstobuysnacks]. Whenthemobile snackvendordoesn’tcome,childrenwilleatjustlocalfoods.They don’tcry.” Thestakeholdersalsoreportedthattheyhavedirectly

complainedtothemobileUPFsnacktradersforcomingtotheir areafourorfivetimesadayfromtheearlymorningonward. However,thecomplaintdidnotresultinthemobilesnackvendor cominglessoften.

ThelocalstakeholdersinArowiexplainedthattheirchildren usuallyaskedthemtobuyUPFsnacksandSSBs,suchasinstant juicepowder,biscuits,andjuiceinaglassfrommicro-andsmallscalefoodkiosks.ThestakeholdersalsoincludedRTEfoods, suchasmeatballs(bakso)andtapiocaballs(cilok),asthesnacks commonlypurchasedandconsumedbytheirchildren.The stakeholdersalsoreportedthatthechildreninArowiusedtocry whenaskingtheirparentsforUPFsnacks: “WhenIwasachild,I didn’tusuallybuysnacksbecausemyparentsgavememaybe50 or 500rupiahsforonewholeday.Butnow,therearesomanysnack kiosks,childrenwouldcryaskingformoney [tobuysnacks].”The stakeholdersreportedspendingabout10,000–30,000IDRperday ontheirchildren’ssnacks.

“TheMalnutritionIsActuallyDuetotheDietary Transitions”

Theinstitutionalstakeholdersadmittedthatthereareproblems regardinghealthandundernutritioninWestPapua.However, theydidnotbelievethattheproblemswerecausedbyinsufficient foodavailability.Theparticipantsdoubtedthattheproblems had anythingtodowiththeirlocalfoodsupplybecausetheyargued thatthelandscapeofPapuacouldsupporttheproductionof foodforthelocalpeople. “InPapua,therearenomalnourished orstarvingpeoplebecausetheydon’thaveenoughfood.What happensisahealthproblem,”saidonestakeholder,blaming healthissuesasthecauseofmalnutritioninsteadoflackof food. Therewasconcernexpressedbytheinstitutionalstakeholders thatadietarytransitionintheircommunitieshadreducedthe abilityoflocalpeopletoprocesstheirownstaplefoodsandthat thiscouldleadtostarvation,assuggestedbyonestakeholder: “That [malnutrition]isactuallyduetothedietarytransitions. Peopleusedtoeatlocalfood.Andnow,whentheRaskinisrunning out,theycannotmakeorprocess [localfoods].”

TheinstitutionalstakeholderswereconfidentthatWestPapua couldbeself-sufficientinitsfoodsupplybecauseithasalarge landbasethatcouldbeusedtogrowlocalfoods.Thismessage wasdeliveredconsistentlybydifferentparticipants.Statements sayingthatthereisnoproblemwithlocalfoodsufficiencywere oftenheard,suchas, “...wehaveeverything.Theproductionof tubers,theproductionoflocalfoods,is [enough] tofulfillthe needofthelocalpeople.Thus,inmyopinion,theproblemoffood securityisnotduetolandissues.”Mostofthestatedassumptions aboutself-sufficiencyincludedargumentsabouthowlargePapua isanditsrichnessintermsoffooddiversity.However,therewas somedoubtwhenitcametothesufficiencyofthefoodfornonIndigenousPapuansinurbanareas: “....Ithinktheavailabilityof thelocalfoodsissufficienttofulfilltheneedsofthe [local] people wholiveinthevillages.Theproblemisforthenon-indigenous Papuan,includingmyself,isitsufficientornot?”

Onestakeholderexpressedhisconfidencethatmalnutritionin WestPapuaisindependentoffoodsufficiencyandavailability. “IoncewenttoacoastalvillageinKebar.Therewerefewer teenagersthantheunder-five-year-oldchildren.Also,therewerea

lotofundernourishedpregnantmothers,andnoneofthechildren werechubby.However,ifwelookattheavailabilityofthefood resourcethere,theyweregood,sufficient.Theyhadplentyof deers [wildanimal-sourcefood], andthewatersourcewasgood.” The stakeholderfurtherexplainedthatthelocalagencyinthearea didnotknowwhythevillagersweremalnourishedandthatsuch issueshadneverbeendiscussedwithrelatedagencies.Thereisa needformembersofthehealthandagriculturalagenciestosit togethertodiscusstheproblemfromvariousperspectives.

TheLinkBetweenDietaryTransitionandForests

Theinstitutionalstakeholdersexpressedtheirconcernsaboutthe land-usemanagementinWestPapuaandhowitaffectedfood security.Therewasanintensediscussionaboutthe cetaksawah program(literallytranslatedasapaddyfieldprintingprogram). Thisisapolicyenactedbythecentralgovernmenttoboost riceproductionandhasresultedintheconversionofforests inPapuaintoricefields.Astakeholderstatedtheconcernthat theimplementationofthisprogramencourageslocalpeopleto converttheirlandtopaddyfieldsandtoconsumerice: “The cetaksawahprogramencouragesthelocalcommunitiestoclear theirland [forpaddyfields]. Thismeanssupportingtheindigenous peopletoconsumerice.” ThestakeholderindicatedthatPapua isthetargetareaforpaddyfieldsbecauseJavahasnomore agriculturalland. “BecauseinJavathereisnomore [agricultural] land.[TheyhavetolookforlandoutsideJava.] Whereisoutside Java?It’shere [Papua]!Anditisreducinglocalfoodproduction.”

Theinstitutionalstakeholdersexpressedconcernsregarding thesuitabilityoftheconvertedlandforgrowingrice.One participantsaid, “Don’tconvertourlandwhichissuitablefor localfoodintoricefields.” Thestakeholdersexplainedthatthe forestareasclearedforthe cetaksawah programwerewidely abandonedinthepast. “Theagricultureagencyclearedthe land,buttheydidn’tcontinuetoplantit.Betternottoburden WestPapua.Thenumberofclearedlands [foragriculture] is increasing,butnotproductive.” Therepresentativefromthe OfficeofAgricultureadmittedthattherewereobstaclesthat delayedplantingontheclearedland.However,hearguedthat theclearedlandcanbeplantedwithanythinginpracticeand thatitdoesnothavetoberice.Theyalsocomplainedthatthe premiumlands(forestedareasorclearedlandssuitableandfertile foragriculture)areallocatedforoilpalmandtransmigration programs.Theyfearedthattheremainingavailablelandswere notthemostsuitableforagriculture,suchasslopeyareas.As oneparticipantstated, “Flatlandsbecomethegovernment’starget foroilpalmplantation,pushingawaytheland-usedforplanting localfood.”

Theinstitutionalstakeholdershadastrongsenseofsolidarity fortheIndigenouspeopleandlocalsmall-scalefarmers,as elaboratedonbyoneparticipant: “Actually,people,ingeneral, arestilldependingontheforest,fornow.So,itisimpossible to implementactivitiesthatwouldchangeournatureonalarge scale. Forexample,large-scaleplantingofcassavaandsweetpotatoesis thesameasplantingoilpalm.Theycandamagetheforest,too. Theindigenouspeoplestilldependontheirforests.Therefore,we shouldregulateland use,tostoptheexploitationofforestsona largescale.” Thestakeholdersseemtobelievethatexploitingthe

locallands,includingthePapuanforest,foragricultureshouldbe implementedincollaborationwiththetraditionalchiefs.

Therewasconfusionsurroundinglandallocationfor conservation,large-scaleplantations,andlocalfoodproduction. Participantsrepeatedlyexpressedtheirconcernsthattherewould notbeenoughlandforfoodproductiontofeedWestPapuans aftertheallocationforconservationandlarge-scaleplantations. “Thereareintactforestswhichwillbehandedovertotheprivate sector,buttheprivatesectorwillonlyget30%,andthe70%will notbecleared.”One stakeholderreferredtotheManokwari Declaration,aprovincialcommitmenttoconserveatleast70% oftheirforests.Thesamestakeholdersspeculatedabouthow the percentageoftheconservationareawasdetermined:“However, itisnotthenumbersthatweareconcernedabout.Instead,it is moreabouthowitwillbeexecutedspatially.Noonecananswer thatuntiltoday.”Thestakeholdersdiscussedthestatusofthe declaration,whichhasnotyetbeenembodiedintheWestPapua Provinceregulationsatthetimeofthisstudy.

DISCUSSION

TheresultsfromthequantitativedatashowthatdietsinWest Papuaaretransitioningtowardlessconsumptionoffreshand minimallyprocessedfoods,traditionalstaplefoods,wildmeat, dark-greenleafyvegetables,freshlegumes,nuts,and“other’ fruits.Dietsarealsotransitioningtowardmoreconsumption ofprocessedfoods,avianmeat,vitaminA–richfruits,UPFs, andRTEfoods.Someoftheresultsfromthequantitative analysiswereechoedbythefindingsfromtheFGDsinvolving institutionalandlocalstakeholders,particularlythatdietswere transitioningawayfromtraditionalfoodsandtowardmorerice andUPFconsumption.Whereas,theinstitutionalstakeholders weremoreconcernedaboutthetransitioninstaplefoodsand thelinktolanduse,thelocalstakeholdersseemedtoacceptthat theirdietsarenowricebased.Thelocalstakeholdersseemedto bemoreconcernedabouttheirchildren’shighconsumptionof UPFsandSSBsandthesocialandeconomicdifficultiesthatthis hascreated.

ADietaryTransitioninWestPapuaToward Javanese-InfluencedDiets

InearlierresearchonthedietarytransitioninIndonesia,a shiftindietarypreferencestowardWesternfoodwasreported amongpeoplewhomovedtoJakarta,thecapitalcity(Colozza andAvendano,2019). Lipoetoetal.(2004) foundanincreasein expenditureonmeat,eggs,milk,andpreparedfood,following asimilarpatternofdietarytransitioninotherdeveloping countries.AnotherstudysuggestedthatSoutheastAsiansare retainingtheirtraditionaldiets.However,moreanimalfoods, sugar,andvegetableoilsareaddedtotheirtraditionalrecipesdue toincreasedpurchasingpower(Lipoetoetal.,2013). Paweraetal. (2020) suggestedthatalthoughtraditionalfoodsarestillpreferred overWesternfoodsinruralIndonesia,concernsareraisedover theincreasedavailabilityoffriedsnacksandUPFs. Oddoetal. (2019) foundthatconsumptionofUPFiscommoninIndonesia, andphysicalactivityhasdecreasedoveradecade.

ThedietarytransitionthatweseeinWestPapuahassome contextualdifferencesfromthe“typical”dietarytransition.First, weseeachangeinthecompositionofstaplefoodstowardrice andwheat,awayfromtubers.Fromtheinstitutionalstakeholder pointofview,thiswasanimportantconcern.Second,instead ofanincreaseinanimal-sourcefoodsingeneral,weseea decreaseinfreshmeatconsumption,nosignificantchangein fishconsumption,andanincreaseinavianmeatconsumption, whichisdominatedbybroilerchicken,presumablyimported frozenfromJava(Isnantoyo,2016).Therewasalsoanincrease intheconsumptionofprocessedlegumes,whicharetraditionally rootedinJavanesefoodculture(ShurtleffandAoyagi,2007). ThesechangesreflecttheratherspecialcharacterofthePapuan diet,whichhastraditionallybeenbasedonharvestingsago and tubersandhunting,gathering,andfishing.

IntheWestPapuacontext,dietsappeartobetransitioning towardbeingmore“Javanese.”Javanesedietsaredominated by ricewithsmallerportionsofmeatandfishandprocessedsoy productssuchastofuandtempeh.Thefollowingconversation, whichoccurredamongthelocalstakeholdersinArowi,describes thesituation: “Nowweeatchicken,inthepast,weatefish.” Anotherstakeholderansweredthattheydidnoteattofuinthe past,andnowtheydo.Adietarytransitioninwhichcoarsestaple foodsarereplacedbytheconsumptionof“primestaplefoods,” suchaswheatandpolishedrice,hasalsobeenreportedaspart ofthemodernizationofdietsinChina,particularlyinrural lowincomesettings(Popkin,1999;Changetal.,2018).InIndonesia, theadoptionofricehasbeennotedformorethan20yearsona remoteislandinSiberut(Persoon,1992)andmorerecentlyon theislandsofMoluccas(DamanikandTahitu,2011)andRiau (Syartiwidyaetal.,2019).

Fromanutritionalperspectivealone,themodernizationof dietshaslikelybroughtsomebenefitsforWestPapuans.The increasedconsumptionofbroilerchicken,tofu,andtempehhas likelyincreasedtheproteinintake.Theconsumptionof“other” fruitshasalsoincreased,plausiblyduetothetradebetween West Papuaandotherprovincesintheregion.Thedataalsoshow thatconsumptionofprocessedfoodhasincreasedsubstantially, indicatingthemodernizationoftheregion’sdiet.Theincreased consumptionofprocessedfoodsdoesnothavethesamenegative healthimplicationsastheconsumptionofUPF.Preservingfish andprocessingsoybeanscouldhelpimprovetheleveloffood security(Fuscoetal.,2017)byincreasingtheintakeofprotein fromtofuandtempeh.Proteinconsumptionwaswell-belowthe recommendation(57.0grams/capita/day)inseveralregenciesin WestPapua,suchasPegununganArfak(38.5g)andSorong Selatan(43.4g)(StatisticsWestPapua,2018b).

Further,analysisoftheHDDSshowsthatdietarydiversity increasedfrom8.5to9.0,indicatingimprovementinhousehold accesstodiversefoods.However,theinstitutionalstakeholders expresseddissatisfactionwiththecurrentdietarypattern. They describedthemoveawayfromtraditionalfoodsaslosingthe poweroftheirfoodsystems.Thisfindingsuggeststhatthedietsof apopulationcanbeimprovedinqualitybuttowardconsumption offoodsthatarelesspreferredbythelocalcommunitiesfor reasonssuchascultureandvalues.Ifagencyistobeconsidered asoneofthefoodsecuritydimensions,measuringdietquality

fromanutritionalperspectivealoneisnotenough.Forexample, theMinimumDietaryDiversityforWomen(MDDW)indicator considerstheconsumptionofsago,tubers,andricetobe thesame(underthestarchystaplesfoodgroup).TheHDDS differentiatesbetweenriceconsumption(recordedunderthe cerealgroup)andsagoandtubers(underthewhiterootsand tubersgroup),butitscoresthemequally.Anefforttodevelop metricstoassessfoodagencyinWestPapua,suchasinthe FoodConsumptionAgencyMetricsforBurkinaFasocontext,is needed(Tkaczyk,2021).

UPF:ASignificantSocialandEconomic Burden

Inotherrespects,thedietarytransitioninWestPapuaalso reflectsthemore“typical”patternoftheincreasedconsumption ofUPFs.OurfindingontheincreasedconsumptionofUPFis consistentwithotherstudiesfocusedonthehighconsumption ofUPFinIndonesia(Greenetal.,2019;Oddoetal.,2019).The increasedconsumptionofUPFsraisesconcernsoverpotential healthimpacts.UPFs(e.g.,bakedgoods,savorysnacks,and packagedextrudedsaltedsnacks)tendtohavepoornutritional profiles(Potietal.,2017).Theymayreplacefreshandtraditional minimallyprocessedfoods.UPFsnacksandSSBsdeliverhigh energyintheformofsimplecarbohydratesandarealsohigh inpreservativesandsodium(Moubaracetal.,2017).Our findingsindicatethattheconsumptionofUPFs(Group4NOVA classification)hasincreasedsignificantlyinWestPapua.The consumptionofSSBs,caloricsnacks,andcrackershasalso increased.Andtheincreasewasdetestedbythestakeholders.

Thedisplacementofminimallyprocessedfoodsandfreshly prepareddishesandmealsbyUPFsisassociatedwithunhealthy nutrientprofiles.TheconsumptionofUPFsislinkedwith varioushealthproblems,includingtheincreasedriskof all-causemortality,overallcardiovasculardiseases,coronary heartdiseases,cerebrovasculardiseases,hypertension,metabolic syndrome,thestateofbeingoverweightorobese,depression, irritablebowelsyndrome,overallcancers,postmenopausalbreast cancer,gestationalobesity,adolescentasthmaandwheezing, andfrailty(Chenetal.,2020).InWestPapua,40%ofadults areoverweightorobese.Thisishigherthanthenational averageof35%.From2007to2018,theprevalenceofdiagnosed hypertension,stroke,andheartdiseaseincreased,noticeablyfor diabetesmellitus,therateincreasedbymorethanthreefolds (MinistryofHealth,2008,2019a).Duetochangesinjurisdictions andlimiteddataavailabilityduringtheobservedyears,we cannotcomparethedataattheregencylevel.However,from theavailablediabetesmellitusdata,sixoutofeightregencies withcompletedatahadincreasedprevalencein2007and2018: Kaimana,Manokwari,RajaAmpat,Sorong,SorongCity,and TelukBintuni(MinistryofHealth,2009,2019b).

Althoughthisstudyprovidesnoevidenceoftherelationship betweendietarytransitionsandhealthproblems,theincreased consumptionofUPFsandtheincreasedprevalenceofnoncommunicablediseasesduringthesameperiodsuggestsa plausibleconnectionthatshouldbefurtherstudied.Increased prevalenceofoverweight,hypertension,diabetes,andcholesterol

wasfoundamongformerhuntersinBorneoaftereasieraccess tofoodmarkets.Improvedaccesstomarketshaspresumably stimulatedanincreaseintheconsumptionofunhealthysnacks thatarehighinfatandfreesugarsbutlowincomplex carbohydrates(Douniasetal.,2007).

UPFscanalsohavenegativesocialandeconomicimpacts (Monteiroetal.,2018).InWestPapua,thelocalstakeholders complainedaboutthecirculationofultra-processedsnacksand beveragesintheirvillagesandhowtheirchildrenusepester powertomakethembuysuchfoods.Theyreportedspending upto3.5USDperdayonUPFsnacks.Comparedtotheaverage percapitaexpenditure,thespendingonUPFsnacksissignificant inManokwariRegency(whereArowiislocated),anditisalso paramountinPegununganArfakRegency(whereBamahais located)(StatisticsWestPapua,2018a).Thehighexpenditureon nutritionallypoorfoodcanbeasubstantialeconomicburden forhouseholds.

Furthermore,aconcernwasraisedbytheinstitutional stakeholdersregardingtheincreasingproportionoffood producedoutsideofPapuathatispartoftheoverallfoodintake. Theyexpressedconcernsabouttheirweakeningpowerovertheir ownfoodsystemsamidtherice-basedfoodassistance,imported products,andthemarketingofUPFsnacks.Interestingly, supermarkets,hypermarkets,andconveniencestoresareknown astheincreasinglydominantchannelsforthedistributing UPFs (BakerandFriel,2016).InWestPapua,wheretherearefew supermarkets(oneinManokwari,sixinSorongCityin2021) andagrowingnumberofminimarkets(Nursalikah,2015),the localandinstitutionalstakeholdersexplainedthatmicro- and small-scalefoodstallsandmobilefoodvendorsweretheprimary channelsforUPFdistributionatthetimeofthestudy.

SeveralbrandsdiscussedduringtheFGDswiththelocal stakeholdersarepartofthenationalandtransnationalfood and beveragecorporations.Thebrandsmentionedcanrefertoa specificbrandortootherbrandsconnectedtosimilarproducts Itiscommontonameaproductafterthemostpopularbrandin theIndonesiancontext. BakerandFriel(2016) suggestedthatas thegrowthofmarketsinhigh-incomecountrieshasstagnated, UPFproducersaretargetinglow-incomeandmiddle-income countries.InAsiancountries,themarketpowerofcorporations shapesboththeglobalandlocalfoodsystemsbyalteringthe availability,price,nutritionalquality,desirability,andultimately theincreasedconsumptionofUPFs(Bakeretal.,2020).Thisalso couldbethecaseinWestPapua.

LocalPerspectivesontheRiseofRice ConsumptioninWestPapua

Thedietarytransitiontowardriceandawayfromsagoand tuberswasmentionedrepeatedlyandconsistentlybythe institutionalstakeholdersassomethingthattheyperceived negatively.Whereas,theinstitutionalstakeholdershadstrong feelingsthatWestPapuansshouldreverttotraditionalstaple foodsandexpresseddissatisfactionwiththecentralgovernment policiesthatsupportriceasastaplefoodinWestPapua,thelocal stakeholdersseemedtoacceptthistransition.Boththelocaland institutionalstakeholdersrecognizedseveralfactorsthatsupport

thetransitionfromricetosago:(i)theimportanceofnutrient content(healthaspect),(ii)theperceptionofriceasa“prestige” food,(iii)cookingpracticality,(iv)thewidemarketavailability, and(v)therelativelylowprice(accessibility).

BasedontheinstitutionalFGD,weidentifiedthefollowing concernsfromstakeholdersregardingtheriseofrice consumption:(i)riceconsumptioncouldhaveanegative healthimpactonPapuanswhoarebiologicallyadaptedto consumesagoandothertubersinsteadofrice,(ii)Papualand isunsuitableforgrowingricewhichwouldcreateadependence ontheexternalproductionofstaplefoods,makingWest Papuansvulnerabletoshocksinthericesupply,and(iii)thatthe knowledgeofthehowtoproduceandprocesslocalstaplefoods isdisappearing.

TheHealthCharacteristicsofStapleFoods

Thestakeholdersgenerallyviewedsagoashealthierthanrice. Althoughriceprovidesaboutthesameamountofenergy assago,itcontainsmoreprotein:8.4gper100.0gofrice comparedto0.4gper100.0gofsagoflour(Nilaigizi.com.,2021). Furthermore,riceisagoodsourceofvitaminsB1andB3,which arebarelypresentinsago.However,sagohasalowerglycemic index(GI)thanriceandthereforehasabetterimpactonblood glucoselevels(Wahjuningsihetal.,2016;Syartiwidyaetal.,2019). OneFGDparticipantmentionedthatmanyPapuanswhose bodieswereusedtoconsumingsagosuffereddiabetescausedby thetransitiontorice,astaplefoodwithahigherGI.Because sago andtubersarehigherinfiberthanrice(Nilaigizi.com.,2021), theytendtodelaygastricemptyingandthusprolongsatiety. Additionally,emergingevidencealsosuggeststhattheprobiotics derivedfromsagocouldhavearoleinreducingdiabetes(Ahmadi etal.,2019).

AccordingtotheMinistryofHealth,theprevalenceof diabetesamongWestPapuansaged15yearsoldorolder increasedfrom0.6%in2007to1.9%in2018(Ministryof Health,2008,2019a).Astudyusinganimalmodelsshowed adecreasedlipidprofileandanimprovementintheinsulin resistanceofratsfedwithsagoanalogriceduetotheroleof resistantstarch(Wahjuningsihetal.,2018).Thus,therelative healthandnutritionalbenefitsofriceandsagoaremixed.The dietarytransitionfromsagoandtuberstoricemayincrease proteinandcertainmicronutrientsfromrice,butitmayalso triggernegativehealthimpacts.

TheAvailability,Accessibility,andStabilityofStaple Foods

AstudyinPapuaProvinceshowedthatthedietarychangesof thepeoplewholivedinMeraukecanbeexplainedbychangesin theavailabilityoftraditionalandwildfoods,accesstomarkets, howthewomenusetheirtime,andpreferences(Purwestrietal., 2019).Theresultsfromthequalitativeanalysisareinlinewith thesehypothesesandfindings.Theinstitutionalstakeholders pointedoutthatsagoflourismoreexpensivethansubsidized rice.Theinstitutionalstakeholdersexplainedthatriceis more availableandaffordableinWestPapua,partlyduetosubsidies. Whenricebecamefamiliartolocalpeople,thedemandforrice increased,andthedemandforotherstaplefoodsdecreased.

Nationally,rice-basedfoodassistanceprogramsappeartohave lessenedrice’seconomicburden.

However,accordingtothestakeholdersinthisstudy,the financialmechanismthatimprovesriceconsumptioninWest Papuahashadanegativeimpactbyreducingtheconsumption oftraditionalstaplefoods.Quantitativeanalysisofthechange inthepriceofriceandtraditionalstaplefoodsshowsthatfrom 2008to2017,whereasthepriceofricewasmorestable,the priceoftraditionalstaplefoodsincreasedmoresubstantially. Further,theproportionofstaplefoodsconsumedfromown productionincreasedforricebutdecreasedfortraditional staple foods.Althoughthefindingsdonotprovideevidenceofa causalrelationship,theyconfirmtheinformationconveyedby institutionalstakeholders.

ThePrestige,Preference,andPracticalityofRice Preparation

TheFGDwiththelocalstakeholdersfrombothvillages (mountainousandcoastal)confirmedtheirdependenceonrice andtheirlowsagoconsumption.Theinstitutionalstakeholders raisedconcernsthatthetransitionfromsagotoricecontributed toachangeinthepalateofWestPapuans,withsagobecoming lessfamiliarcomparedtorice.Incontrast,thelocalstakeholders inArowididnotshowanyconcernsoverthetransitiontorice Instead,theysuggestedthatonly“theoldpeople”eatsagoevery day,inatonethatseemedtolookdownonthisbehavior.In Bamaha,therewasmoreofasenseofpridewhenthelocal stakeholdersstatedthataselders,theystillconsumetubers: “We eattuberswhichhavesupportedussincewewerechildren.” The desiretoreverttoatraditionaldietwasnotequallyexpressedby allofthestakeholdersinourstudy.

Somestakeholderspreferredriceoversagoandtubersbecause theycouldeasilypurchasericebeforecookingratherthan harvestingandprocessingsagoandtubersfromtheforests orbuyingthematahigherprice.Particularlyforsago,local Papuansgenerallyharvestedfromthesagopalmtrunkwhich growsmostlyinforestedandswampyareas.Thepalmneedsto becleaned,cutdown,andsplitinhalf.Thesagopalmfiberis thencrushedwithahoeoranax-likedevice.Themoremodern processusesamechanicalshreddertocrushthecutoutsagopalm fiber.Wateristhenaddedtotheshreddedsagopalmfiber,and thenitissqueezedandfilteredforthestarchbeforeitfinally settlesorissedimentedinabucketmadeofsagopalmleaves (DewiandBintoro,2016).Theprocessislaboriousandtimeconsuming(Persoon,1992),whilepracticesandtechnological innovationsforfacilitatingthepreparationofsagoarestilllimited (Akzaretal.,2020).

Someofthestakeholderspreferredsagoforitssuitability toaccompanylocaldishes.However,ricewassaidtobemore practicalasitcanbeservedwithmorevarieddishes.With increasingbutstillrelativelylowamountsofenergyfromUPFs andRTEfoods,home-cookedmealsstillplayaprominentrole inthedietsofWestPapuans.Itisalsoimportanttonotethat thelocalstakeholderswhoexpressedtheirpreferenceforrice werewomen,whoarealsotheonesresponsibleforpreparing foodfortheirfamilies.Statementsmadebythemaleinstitutional stakeholders—suchas “Thescenariotoshiftbacktothetraditional

foodconsumptionpattern,dependsonthemothers”—hintsatthe genderednatureofthediscourse.Therepresentationofmale and femaleparticipantsattheinstitutionalFGDswasrelatively equal. However,werightlynotedthatwomenhandledfoodpreparation inPapuanculture(Kasniyah,2006).Thestatementimpliesthat tosomemembersofsociety,thiscomplexchallengeisthe responsibilityofwomenratherthanamultifacetedchallenge that needstobeaddressedsystematically.

Sustainability

The HLPE(2020) reportdefinessustainabilityinfoodsecurity asthelong-termabilityoffoodsystemstoprovidefoodsecurity andnutritionthatdoesnotcompromisefoodsecurityand nutritionforfuturegenerations.Concernsoversustainability expressedbyinstitutionalstakeholderswerecenteredontheissue oflandsuitability.StakeholdersstatedthatPapuanlandis not suitableforgrowingrice.Fromtheperspectiveoftheinstitutional stakeholders,traditionalfoodsgrownandproducedlocally are moresustainablethanfoodsimportedfromotherregionsor UPFs.Thus,intheirviews,dependenceonricemeansthat Papuanscannotbefoodsecurebecausetheirlandisnotsuitable forgrowingrice.RiceproductioninWestPapuaislow,with alowproductivityrate.Productiondecreasedfrom17,899tons in2019to14,572tonsin2020(StatisticsWestPapua,2021b). Theaverageconsumptionofrice-basedstaplefoodsin2017in WestPapuawas204grams/capita/day(Table1),and1.13million peopleliveinWestPapua(StatisticsWestPapua,2021a).Thus, localproductionisfarfromadequatetofulfilllocalneeds.

Fromanenvironmentalsustainabilityperspective,sago ismoreclimateresilientthanrice(Bantacut,2014).Rice contributesto30and11%ofglobalagriculturalgreenhouse gasemissionsofmethaneandnitrousoxide,respectively.Sago mainlygrowsnaturallyinswampyforestareasandcanalso becultivatedwithoutpesticidesandchemicalfertilizers. Sago canbereharvestedfromthesameclumpafter2–3years (Novariantoetal.,2020).Fromthisviewpoint,thedietary transitionthatmovesawayfromsagotowardricewillworsen theimpactofclimatechange;hence,itisnotenvironmentally sustainable(Guptaetal.,2021).Studiesonthesustainability aspectofIndonesiandietshavesuggestedacutinriceand sugarconsumption.Therefore,theopinionoftheinstitutional stakeholdersinthisstudyisalignedwiththesustainablefood systemsagenda(Vermeulenetal.,2019;dePeeetal.,2021). Further,itisalsoalignedwiththerecommendationfromthe centralgovernmenttoreducepercapitariceconsumptionand todiversifystaplefoodsbeyondriceandwheatasstatedin PresidentialRegulationNumber22(2009), MinisterofHealth RegulationNumber41(2014),and MinisterofAgriculture DecreeNumber64.1/KPTS/RC.110/J/12/2017(2017)

AreWestPapuansFoodInsecure?

WhenmeasuringandunderstandingfoodsecurityinWest Papua,thereseemstobeadisconnectbetweenthefoodsecurity indicatorsusedbythecentralgovernmentandtheperspective oftheinstitutionalstakeholders.TheFoodSecurityIndex (FSI) usedbytheIndonesiangovernmentconsistsofnineindicators, including(1)theratioofpercapitaofnormativeconsumptionto

netavailability4,(2)thepercentageofthepopulationlivingbelow thepovertyline,(3)thepercentageofhouseholdswherethe proportionofexpenditureonfoodismorethan65%ofthetotal expenditure,(4)thepercentageofhouseholdswithoutelectricity, (5)theaverageschoolyearsforwomenolderthan15yearsold, (6)thepercentageofhouseholdswithoutaccesstocleanwater, (7)theratioofhealthcareproviderstothepopulation,(8)the percentageofstuntedchildren,and(9)lifeexpectancyatbirth.

TheindicatorsoriginatefromtheFoodSecurityand VulnerabilityAtlas(FSVA)indicators,initiatedbytheWorld FoodProgram.WhenadoptedbytheFoodSecurityAgency undertheMinistryofAgriculturein2018,thenamebecame IndeksKetahananPangan (IKP),ortheFoodSecurityIndex (FoodSecurityAgency,2018).SincetheFSVApublishedits firstatlasinIndonesia,WestPapuahasalwaysbeenamongthe provinceswiththelowestscore.

However,fromtheperspectiveoftheinstitutional stakeholders,thereisnofoodinsecurityinWestPapua. Theyclaimedthatmalnutritionisnotcausedbyunavailability andinaccessibilityoffood,suchasdietarytransitionand diseases.Fromtheirexplanation,itseemsthattheinstitutional stakeholdersdefinefoodinsecurityastheabsenceofavailability andaccessibilitytofoodsources.Thisisacommonperspective. TheFSIseemstobemoreanalogoustoahumandevelopment indexbecauseitmeasuresmorethanjustfood-relatedissues.In WestPapua,fromthestakeholders’perspective,theabundance ofnaturalresources,especiallytheoften-mentionedforests,can provideallofthefoodneededbylocalPapuans.Thedifferences betweentheFSImeasuresandtheviewsofthestakeholdersin ourstudysuggestdisagreementindefiningandvaluingfood securitybetweenthegovernmentandsomeWestPapuans.

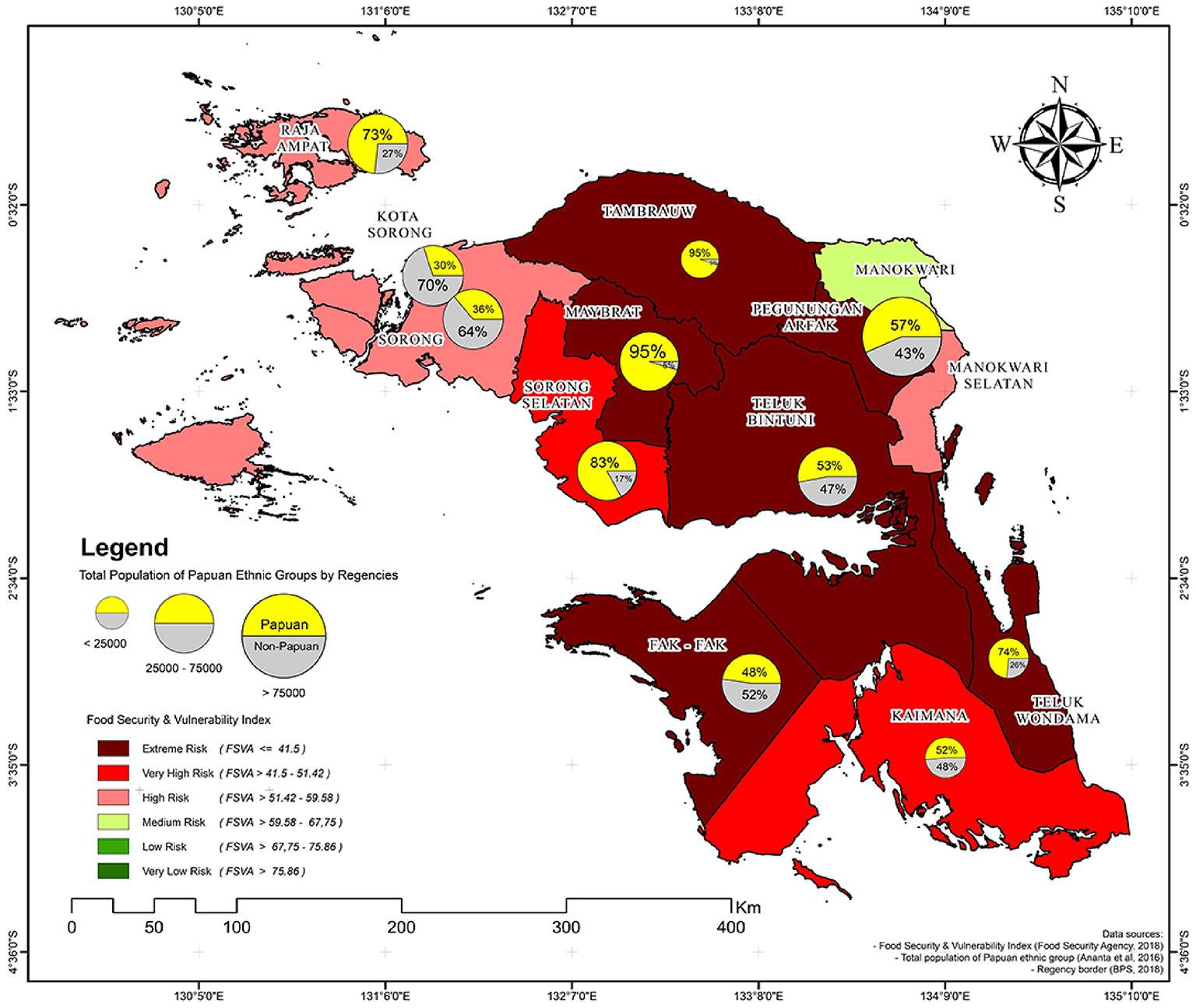

TheanalysisoftheHDDSindicatesanimprovementin householdaccesstodiversefoods.Further,thestuntingrate ofchildrenundertheageof5yearsinWestPapuadecreased from39%in2007to28%in2018(thenationalaverageis31%) (MinistryofHealth,2008,2019a).Theimprovementsinaccess tosanitationandeducationareplausiblefactorsforreducingthe stuntingratenationally(Arifetal.,2020).InWestPapua,the accesstoimprovedsanitationhasincreasedfrom26%in2007 to74%in2018(StatisticsIndonesia,2021a).Themeanyearsof schoolinghavealsoincreasedfrom6.8yearsin2010to7.3years in2018(StatisticsWestPapua,2021c).However,evenwiththese improvements,almostallareasofWestPapuaareconsidered tohaveanextreme,veryhigh,orhighriskoffoodinsecurity accordingtotheFSI(Figure5).

ThepatternsoffoodinsecurityinIndonesiadefinedbyFSI measureshaveastronggeographicaldimension.In2015,90% oftheregenciesidentifiedas“severelyvulnerabletofoodand nutritioninsecurity”werelocatedinthefareastofIndonesia, suchasthePapua,Maluku,andEastNusaTenggararegions. UpuntilthelastFSI2020,almostalloftheprovincesonthe westernsideofthecountry(JavaandSumatraislands)haveat leastamediumrisktofoodinsecurityorbetter(verylowrisk orlowrisk)(FoodSecurityAgency,2020),buttheprovincesof PapuaandWestPapuaremainunderextremeriskandveryhigh

4Thisindicatoronlyappliedtoregenciesandnotcities.

riskcategories.However,thismaybearesultofthefactthatthe componentsoftheindexcaptureaccesstobasicinfrastructure andgovernmentservices,includingelectricity,education,access tocleanwater,andhealthcare.Theregenciesidentifiedashaving highfoodinsecurityin2018,includingMaybrat,Pegunungan Arfak,andTambraw,werealsotheregenciesinhabitedby proportionallymanyIndigenousPapuans;theregencieswith betterfoodsecurityscores(Manokwari,theprovincecapital,and SorongCity)areurbanareaswithbetterinfrastructure(Ananta etal.,2016; Figure5).

IncontrasttothescoresoftheFSI,theinstitutional stakeholdersviewlocalpeopleandIndigenousPapuansasfood secure.Forexample,oneoftheinstitutionalstakeholderssaid, “In Papua,therearenomalnourishedorstarvingpeoplebecause they don’thaveenoughfood”.Anothersaid, “...wehaveeverything. Theproductionoftubers,productionoflocalfoodsis [enough] tofulfilltheneedofthelocalpeople.” TheFSIdoesnotcapture theissuesofavailability,accessibility,utilization,stability,and sustainabilityregardingfoodinthesurroundingenvironmentof WestPapua.TheFSIalsodoesnotcapturetheaspectofagency, definedhereasthecapacityofWestPapuanstomaketheirown decisionsaboutwhatfoodstheyeatandproduce,howthatfood isproduced,processed,anddistributedwithinthefoodsystems, andtheirabilitytoengageintheprocessesthatshapethefood systempoliciesandgovernance(HLPE,2020).Thesearethe aspectsoffoodsecuritythattheinstitutionalstakeholdersappear tohaveinmindwhendiscussingfoodsecurity.Theabsenceof indicatorsthatdirectlymeasuretheseaspectsindicatestheneed torevisitandproposemoresuitablefoodsecurityindicators

ConservingtheForest,SecuringFoodfor WestPapua

Forestsprovidevariousbenefitsthatcanbeuseddirectlyor indirectlyforfoodprovision.Directbenefitsarethefoods thatpeopleharvestandcollectfromtheforest,suchasfruits, insects,tubers,wildmeat,andmushrooms,makingforests“free organicsupermarkets”forthepeoplewholivenearby.Several studieshaveshownlinksbetweenforestsanddiets(Powell etal.,2015;Rowlandetal.,2017)andothershaveshownhow changesinlandusecanaffectdiets.InIndonesia,changesin farmingpracticesfromtheproductionofdiversecropstogreater specializationislinkedwithlowerdietarydiversityofrural Indonesianhouseholds(MehrabanandIckowitz,2021).Another studyinNorthernLaosfoundthatadecreaseofuncultivated landsduetocommercializationreducedwildfoodconsumption andsubsequentlyalsoreduceddietarydiversity(Broegaardetal., 2017).

WestPapuanlandiscomprisedofforestsandotherintact ecosystems,with89%forestcoverin2020(Figure1).Livingin aprovinceprimarilycoveredbyforest,thestakeholdersinthis studyexplainedthat “Theindigenouspeoplestilldependontheir forests.” Eventhelocalstakeholdersinthecoastalareanearthe citycentersaidtheyoftengotoforeststocollectwoodfuel and foods,suchasvegetables.Whenaskedaboutforestownership, theylaughedandsaid,“Theforestbelongstothecommunity.No onewillbeangry [atthemtakingwoodandfoodfromtheforest].”

FIGURE5| Distributionofpapuanethnicgroupsandfoodsecurityindex(FSI)inWestPapuaa a Thepositionandsizeofthecircleonthemapdescribesthetotal numberofpopulationsbyregencyaccordingtothe2010populationcensus;In2010,theregenciesofPegununganArfakandManokwariSelatanwerepartofthe ManokwariRegency;Thepiechartrepresentsthepercentage ofPapuan(yellow)andnon-Papuan(gray)inthepopulation, basedon Anantaetal.(2016)

Thechanginglandscapes,suchastheconversionofforestsinto plantations,couldaffecthuntingandgatheringactivitieswhich areanessentialpartofthefoodcultureofWestPapua.

Theinstitutionalstakeholdersexpressedconcernregarding thefutureuseoftheirforestsforplantationsandlarge-scale agriculture.Thisconcernmaybewell-groundedbecausethere hasbeenrecentdeforestationdueinlargeparttotheexpansion ofoilpalmandtimberplantations(Andriantoetal.,2019; Runtuboietal.,2021).Additionally,anationalgovernment programthatconvertedforeststoproducefoodandothercrops intheneighboringprovinceofPapua(Hadiprayitno,2017)is seenbymanylocalpeopleasanexampleofsomethingthatWest Papuashouldnotfollow.Thestakeholderssuggestedthatthey shouldavoidsimilarlargescalelandconversionforanykindof plantationbecauseofthedamageitcouldcausetoforests,as one stakeholdersaid“...itisimpossibletoimplementactivitiesthat wouldchangeournatureonalargescale.Forexample,large-scale plantingofcassavaandsweetpotatoesisthesameasplantingoil palm.Theycandamagetheforest,too.”

Thestakeholdersalsowereconcernedaboutthepotential impactsofgovernmentplansforforestconservationontheir foodsecurity.Theirworriesaboutconservationarelinked totheadoptionattheprovincialleveloftheManokwari

Declarationin2018,animportantmilestoneintheeffortto conservePapuanforests.Theinstitutionalstakeholderslargely approvedtheplantomaintain70%oftheirforestsasstated inManokwarideclaration.However,theyvoicedconcernsthat conservingforestscouldmeanfencingoutlocalpeoplefrom theirownforestsandtheirfoodsources.In2019,theManokwari Declaration,wasembodiedin SpecialProvincialRegulation Number10(2019) aboutSustainableDevelopmentinWest Papua,issuedbytheGovernorofWestPapua.Theregulation, whichaimedtoaccommodatethedeclaration’sgoals,stated thatWestPapuawillmaintainaminimumof70%oftropical forestecosystemareasandotheressentialecosystemsinthe land areaoftheprovince.Thisseemstoindicatethattheprovincial government’sintentionistomaintainthenaturalecosystem,with therightsoftheIndigenousPapuansinmind,andnotnecessarily tochangethestatusoftheforestintoaconservationarea.

Underthearticleonagricultureandfoodsecurityin thespecialprovincialregulation,thefirstsectionstatedthat “agriculturallanddesignatedaspermanentricefieldsshallbe maintained,aslongasitstillfunctionsasricefields.” The statementaddressedtheissueoflandthathadbeencleared forpaddyfieldsbuthadneverfunctionedassuch,whichthe institutionalstakeholdersmentionedasa“burden”onWest

Papua(seesectionThelinkbetweendietarytransitionand forests).Thesectionindicatesthatnewlandclearingforpaddy fieldswillnotbesupported.Thefollowingsectionstated, “Local governmentsareobligedtopromoteandimprovelocalfood tomaintainfoodsecuritystabilityinWestPapuaProvince.” Together,thesectionsindicatethattheprovincialgovernment intendstoencouragemoreuseoflocalfoods.

In2021,theWestPapuaProvincegovernmentrevokedthe plantationpermitsof16oilpalmcompanies.Therevocationwas basedonanevaluationsince2018,whichshowedthatthelicense holdershadnotconductedanyoperationonthelandandhad notobtainedlandrights.Thissavedatleast346,000hectares ofland, ∼80%ofwhichisstillcoveredbyforests.5 Thereare ongoingeffortstoensurethereturnofrevokedconcessionareas totheIndigenouspeople,includingparticipatorymappingof communitylandandmappingofsocialandeconomicpotential intherevokedconcessionareas.Theintentionistoensurethat thelandwillbesecuredfortheIndigenouspeopleofWestPapua.

EffortstoconservePapua’sforestareinlinewiththecentral governmentpolicies,suchas:(i)theNationalMovementon SavingNaturalResources(Syarif,2020),(ii)theOilPalm Moratorium,whichwasbasedon PresidentialInstruction Number8(2018) regardingthepostponingandevaluationofOil PalmPlantationLicensing,and(iii)therevocationof192landusepermitson3,126,439.36hectaresofforestareainthecountry in2022through MinisterofEnvironmentandForestryDecree NumberSK.01/MENLHK/SETJEN/KUM.1/1/2022(2022).The challengesofmaintainingoverninemillionhectaresofnatural forestcovercomenotonlyfromprivateplantationcompanies, butcouldalsocomefromthedisharmonybetweentheinterest oflocalpeopleandgovernmentpolicies.ConservingPapua’s forestsrequiressubstantialinvestmentinhumanresources, extraordinarycommitmentfromallpartiesconcerned,improved scienceandmonitoring,andmoreeffectivelawenforcement (Cámara-Leretetal.,2019).Conservingtheseforestsmeans securingfoodsourcesforWestPapuans.Theseforestsare alsoimportantforIndonesiaandtheglobalcommunitysince theyplayavitalroleinclimatechangemitigationand biodiversityconservation.Hence,thecentralgovernment and theinternationalcommunitiesshouldstrengthentheirsupport ofconservationofthePapua’sforests.

CONCLUSIONS

TheevidencepresentedherefromtheSUSENASfood consumptiondatafor2008and2017andtheFGDsinvolving institutionalandlocalstakeholdersshowedthatthereisa dietary transitionunderwayinWestPapua.Thistransitionisaway fromfreshfoodsandtraditionalfoods,suchassago,tubers,fish, freshmeat,freshvegetables,andfruits,andtowardrice,broiler chicken,processedfoods,UPFs,andRTEfoods.Someofthe dietarytransitioncharacteristics,suchasthehigherconsumption ofrice,chicken,andprocessedlegumes,aremoretypicalofa

5PersonalcommunicationwithCindyJunickeSimangunsong,alegalexperton theWestPapualicensereviewprocessandthePolicyandAdvocacyManagerof EcoNusaFoundation,Jakarta,02/10/2021.

JavanesedietthanWesterncuisines.Inotherrespects,the changingdietinWestPapuaalsoreflectsthemore“typical” patternofdiettransitionsseenacrosstheworldtowardincreased consumptionofUPFs.

Fromanutritionalperspectivealone,themodernizationof dietscouldbenefitWestPapuans.Forexample,theincrease inchickenconsumptioncontributestoincreasedanimal-source foodintake,althoughitmayalsodecreasetheconsumption ofwildmeatsinsomeplaces.Anutritionalperspectivealone maynotcaptureotherundesirablefacetsofthetransition awayfromtraditionalfoods,asexpressedbytheinstitutional stakeholdersinourstudy.Furthermore,thedisplacementof minimallyprocessedfoodsandfreshlyprepareddishesandmeals usingultra-processedproductsisassociatedwithunhealthy nutrientprofiles.ThehighconsumptionofUPFswasalso problematicfromasocioeconomicpointofview.Althoughthe consumptionofUPFsandRTEfoodscontributedtoonly17% ofthetotalenergy,thestakeholdersraisedconcernsaboutthe health,social,andeconomicimpacts.Thestakeholderswere alsoconcernedthattheincreasingproportionofdietsfrom foodproducedoutsidePapua,suchasrice,broilerchicken,and UPF,weakenstheirpowerovertheirfoodsystems.Considering thewidelyrecognizedimpactofhighUPFconsumption, werecommendthatthecentralgovernmentregulatesthe productionanddistributionofUPFinIndonesia.Behavior changecommunicationprogramsshouldbeinitiatedthattarget allcommunitymembersandfocusontheriskofconsumptionof UPFsconcerningnon-communicablediseaseslaterinlife.

Theinstitutionalstakeholdersexpressedastrongdesireto reverttoatraditionaldiet.Thisdesire,aswellastheirconcern aboutthepoweroverthelocalfoodsystems,couldbeaddressed bycreatinglocal,sustainabledietaryguidelinesthatextend thecurrentIndonesiannationaldietaryguidelinesintothe localcontext,includingsustainabilityconsiderations.Thelocal stakeholdersinourstudytendtoacceptthatriceisnowtheir staplefood.Theselocalstakeholdersincludethewomenwho processandpreparefoodsinthefamily,whomaybemore concernedoverthepracticalitiesofpreparationandcooking time.Foodpoliciestosupportcommunitiesinincreasingsago andtuberconsumptionshouldconsiderthefoodprocessing andpreparationburdenonwomen.Additionally,researchto improvethepracticalityofsagoprocessingandpreparation shouldbeencouraged.

AlthoughWestPapuaiscategorizedashighlyfoodinsecure bytheFSI,theinstitutionalstakeholdersinthisstudytendto thinkotherwise.Thereseemstobeadisconnectbetweenthe foodsecurityindicatorsusedbythecentralgovernmentand the perspectiveoftheinstitutionalstakeholders.Thenational food securityindicatorsdonotadequatelymeasuredirectaspects of foodsecurity,suchastheavailabilityandaccessibilityofhealthy foodssurroundingtheWestPapuancontexts.TheWestPapuan foodsystemsarewell-supportedbythenearbyenvironment, whichisrichinnaturalresourcessuchasforestplants,wild meat,fish,andfertilesoilthatissuitableforgrowinglocalfoods. TheWestPapuanslivinginforestedareasunderstandthefood andnutritionalsecuritybenefitsthattheforestsprovide.These benefitsarerecognizedintheManokwariDeclaration,which

commitstoconservingatleast70%oftheforestcover,andthe SpecialProvincialRegulationNumber10Year2019(Perdasus No.10/2019)bytheGovernorofWestPapua.However,thelocal governmentneedssupporttooperationalizetheseobjectives.

Theglobalcommunityhasbeguntounderstandtheproblems associatedwiththecurrentglobalfoodsystem,includingits deleteriouseffectsonhealth,theenvironment,anditslack ofresilience(Willettetal.,2019;Fanzoetal.,2021).Oneof theproblemsassociatedwithmodernfoodsystemsistheir homogeneityinthetypesoffoodsproducedandhowtheyare produced.This,inturn,resultsinlimiteddiversityoffoods consumedandvulnerabilityoftheproductionsystemstoexternal shocks.Theinternationalcommunityshouldbeseekingtolearn fromthethousandsoflocalfoodsystemsthatstillexistaround theworldandtosupportpeoplewhochoosetomaintainthem beforetheydisappear.Thisdoesnotmeanrejectingallchanges intheproductionandconsumptionofnon-traditionalfoods. Instead,itmeansworkingwithcommunitiestomaintainthe characteristicsthatbenefittheirnutritionandhealth,support theirculturalidentity,andpromotesustainabilityandresilience. ThereismuchtobelearnedfromtraditionalWestPapuanfood systems—yetunlessactionsaretakensoon,manyoftheirunique featureswilllikelydisappear.

DATAAVAILABILITYSTATEMENT

Thequantitativedatasetspresentedinthisarticlearenot readilyavailablebecausethedatasetwasobtainedfromStatistics Indonesiaunderanagreementthatitwasusedonlyforthe purposeofrelevantresearchbytheinstitution.Interestedreaders canobtainaccessathttps://www.bps.go.id/.Thequalitative dataset(transcriptoftheFGDs)isnotpublisheddueto possibleidentifiableattributesinpartsofthecomments. Interestedreadersmaycontactthecorrespondingauthorfor furtherinformation.

ETHICSSTATEMENT

ThestudywasapprovedbytheResearchandDevelopment Agency(Balitbangda)oftheWestPapuaProvince,Indonesia, throughanofficialdecree.TheparticipantsoftheFGDprovided consenttoparticipateinthestudy.

AUTHORCONTRIBUTIONS

MNcontributedtothedesignofthestudy,conductedthe fieldwork,ledtheanalysisofthequalitativeandquantitativedata, andledthedraftingprocess.AManalyzedthequalitativedata, createdthemap,andcontributedtothedraftingprocess.DA

REFERENCES

Ahmadi,S.,Nagpal,R.,Wang,S.,Gagliano,J.,Kitzman,D.W.,Soleimanian-Zad, S.,etal.(2019).Prebioticsfromacornandsagopreventhigh-fat-diet-induced insulinresistanceviamicrobiome–gut–brainaxismodulation. J.Nutr.Biochem. 67,1–13.doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2019.01.011

analyzedthequantitativedataandcontributedtothedrafting process.AUcontributedtothedesignofthestudy,conducted thefieldwork,andcontributedtothedraftingprocess.LN contributedtothedesignofthestudyandcontributedto thedraftingprocess.FHcontributedtothedraftingprocess. ARconductedthefieldworkandcontributedtothedrafting process.CHcontributedtothedesignofthestudy,oversaw thequalitativedatacollectionprocess,andcontributedtothe draftingprocess.AHcontributedtothedesignofthestudy,and contributedtothedraftingprocess.AIcontributedsignificantly tothedraftingprocessandoversawtheoverallqualityofthe research.Allauthorscontributedtothearticleandapproved the submittedversion.

FUNDING

ThisstudywasfundedbytheBudgetImplementation DocumentforRegionalWorkUnitoftheResearchand DevelopmentAgency(DPASKPDBalitbangda)ofWestPapua Province,Indonesia,Fiscalyear2020—ProjectDevelopment andinnovationcollaborationwithdevelopmentpartners (universities,researchinstitutes,local/national/international NGOs);TheFoodandLandUseCoalition—ProjectinIndonesia administeredbyWRIIndonesia(2018–2020);TheForeign, Commonwealth&DevelopmentOffice—ProjectAScientific AdvocacySupportMechanismforSustainableDevelopment inPapuaandWestPapua;andtheUnitedStatesAgency forInternationalDevelopment—ProjectConservationand SustainableUseofTropicalForestBiodiversity.Thefindings andviewpointswrittenonthispaperaretheresponsibilityof theauthorsanddonotnecessarilyreflecttheopinionsofthe organizationsinwhichtheauthorsworkorthedonorswhofund thestudy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Wearegratefultoallstakeholdersfortheirtimeandactive participation.WealsothankthestaffofBalitbangda,the EcoNusaFoundation,andWRIIndonesiainWestPapua Provincefortheirkindsupportinorganizingthefieldwork.The studycontributestotheCGIARResearchProgramonForest, Trees,andAgroforestryledbytheCenterforInternational ForestryResearch.

SUPPLEMENTARYMATERIAL

TheSupplementaryMaterialforthisarticlecanbefound onlineat:https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs. 2021.789186/full#supplementary-material

Akzar,R.,Amiruddin,A.,Amandaria,R.,andDarma,R.(2020).Localfoods developmenttoachievefoodsecurityinPapuaProvince,Indonesia IOPConf. Ser.EarthEnviron.Sci. 575,012014.doi:10.1088/1755-1315/575/1/012014 Ananta,A.,Utami,D.R.W.W.,andHandayani,N.B.(2016).Statisticsonethnic diversityinthelandofPapua,Indonesia. AsiaPac.Pol.Stud. 3,458–474. doi:10.1002/app5.143

Andrianto,A.,Komarudin,H.,andPacheco,P.(2019).Expansionofoilpalm plantationsinIndonesia’sfrontier:problemsofexternalitiesandthefuture oflocalandindigenouscommunities. Land 8,56.doi:10.3390/land804 0056