Project title: The Coast’s Bailout: Coastal Resource Use, Quality of Life, and Resilience in Southeastern Puerto Rico

Date: September 2, 2013

Project Number: assign

Investigators and affiliation:

Carlos G. García-Quijano, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Rhode Island

John J. Poggie, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Rhode Island

Ana Pitchon, Department of Anthropology, California State University-Domínguez Hills

Miguel Del Pozo, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Rhode Island

José Alvarado Biostatistical Consulting Services

With the collaboration and assistance of: Víctor Pagán, Natalia Rodríguez, and Yasmín Pérez Ortiz.

Dates Covered: June 1 2010-March 1 2013

Executive Summary:

This document reports on the final results of a three year-long, University of Puerto Rico Sea Grant-funded research project investigating the relationships between the use of Coastal Resources (CR) and the well-being and quality of life (QoL/WB) of people living along the coast of Southeastern Puerto Rico (SE PR). SE PR comprises some of the most rural coastal regions of Puerto Rico and has a rich history of intensive and extensive reliance on local coastal environments, which range from offshore reefs and seamounts to extensive estuaries and inshore coastal forests. Residents of this region have been using local coastal resources for generations: CR-based activities form integral part of many SE PR household economies, but the extent and shape of these are not precisely known.

CR use refers to the small-scale harvesting, processing, and exchange of coastal resources like commercial small-scale fishing, subsistence fishing, commercial and subsistence land crabbing, mangrove oyster and clam harvesting, and non-timber coastal forest resource uses such as picking coconuts. We define QoL/WB broadly as “participation in a social form of life that depends not only on physical health but also on healthy (social) relationships” (after J. Velazco’s 2009). QoL/WB is the REAL objective of public policy, and the various indexes and figures used to estimate and formulate policy for (such as the GDP and ICP), are usually limited in scope (e.g. GDP=formal economic activity) and rely on large assumptions about the relationships, expenditures, and QoL/WB of people. However, a considerable part of the value derived from small-scale CR use is manifested outside the scope of officially reported, formal economic activity. However, this information is usually not available for coastal policy makers as they make decisions about the future of the coast. The main goal of this research is to scientifically document the contribution of the coast (productive coastal communities and the physical environment they depend on) to QoL/WB and to make that information available to policy makers and the public as they evaluate alternative uses of coastal environments.

Many families and communities along the rural coasts of Puerto Rico make a living by combining coastal resource use, preparation, marketing, and selling with mainstream jobs in agriculture, retail, services, government, and local industries. This mixed coastal subsistence pattern has existed and persisted for hundreds of years in Puerto Rico’s coasts and dates at least as far back as the time of sugarcane-dominated Caribbean economies. Coastal communities in Puerto Rico have continued to rely on local CRs for at least part of their subsistence and everyday activities throughout the sweeping social, economic, and cultural changes of the last century. Our project builds on a body of research in the last two decades that has profiled fishery and coastal dependency of people all around the coast of Puerto Rico.

This report is based on three years of field research and analysis conducted between June 2010 and July 2013. These included two long-term field visits June-August 2010 and June-July 2011, coupled with several shorter field visits over the duration of the project to conduct focused research, give presentations, and share the results of our work with local communities. This target audience of this report is policy makers, coastal social science researchers, and others (most importantly local communities and community organizations themselves) with an interest in understanding human reliance on CRs and associated phenomena, to make better policy decisions. It also intends to serve as a blueprint for future research and evaluation, for the continued study of small-scale coastal resource dependence in Puerto Rico and elsewhere in the world.

Summary of Research Impacts: Coastal regions around the world are increasingly under population and development pressures. To achieve policies that carefully balance economic development with environmental and livelihood sustainability, it will be essential to empirically assess the contribution of locally-based, small-scale CR use to WB/QoL in communities and beyond. Links between the coast and QoL/WB are evident in practically all realms of SE PR residents’ lives: in commercial and household economies, risk reduction and resilience strategies, food security, family and community relationships, social problem (poverty and crime) avoidance, life and job satisfaction, and aesthetic enjoyment. Many of these links (including those related to production and exchange of coastal products) are manifested outside of formallyreported economic activity: assessments of policy trade-offs that only take into account formally reported economic exchanges will undoubtedly underestimate most benefits of CR use and engagement and thus risk policy failure.

This research shows that the quality of life and well-being of a large proportion of SE PR coastal residents of all walks of life is inextricably linked to the use of -and access to- the coast and its resources. It also provides a methodological blueprint to engage mixed qualitative and quantitative methods to provide policy makers with critical information for fulfilling the true objective of public policy: to enhance people’s total quality of life and well-being. These methods can be applied in other locales on the coast of Puerto Rico and beyond.

Objectives and How They were met:

The original objectives of this research were as follows:

1. To map small-scale coastal resource use in the municipalities of Salinas, Guayama, Arroyo, and Patillas, Puerto Rico.

2. To develop culturally-valid measures of WB/QoL and comunity resilience for the study region.

3. To study the (commercial and non-commercial) harvest-to-consumer movement of local CRs and derived products through social networks.

4. To assess the role of CRs in household economic histories with emphasis on CR use impact on resilience and mitigating economic and environmental uncertainty.

5. To survey the extent to which coastal Puerto Ricans in the study region participate inand benefit from- local small-scale CR harvesting and production.

6. To use modeling and scenario simulation techniques to test hypotheses about the impact of small-scale CR use on coastal communities and beyond.

7. To organize and conduct two multi-sector workshops about the importance of small-scale coastal resource use for Puerto Ricans' well-being, quality of life, and resilience.

Note on Methods and objectives: The overall methodology of this research is that of mixed methods, multidisciplinary ethnography. The principal investigators worked with local undergraduate and graduate students, a bio-statistician (J. Alvarado), and a post-doctoral associate (M. Del Pozo) to use a variety of methods to collect data, including 1) CR use mapping, 2)

Ethnographic Interviewing, 3) Participant Observation, 3) Structured Interviewing, 4) archival and secondary data collection.

We conducted 50 ethnographic, semi-structured interviews, 23 with coastal resource users, 22 with seafood sector, and 5 with community environmental activists. In addition, 47 structured interviews were conducted with a randomly selected sample of coastal resource users, as well as 47 separate interviews with randomly selected coastal community households. A variety of methods of analysis were applied to the different types of collected data, with the goal of achieving multi-layered convergent validity for our increased understanding of QoL/WB and resource use in the region. Data to fulfill the different objectives were gathered sometimes simultaneously, sometimes separately, during the different stages in the research process. This is different from other scientific research designs in which specific, separate procedures are used to gather data for specific objectives. Thus in the interest of brevity and readability the objectives discussion below will focus on identifying important results reached by applying the methods discussed in this paragraph.

Significant activities and findings include the following:

1) A large variety of signs of CR use and dependency can be seen in multiple locations up and down the coast, to the extent that we would characterize the coast of SE PR as a coastal resourceengaged coastal landscape.

2) Many residents of coastal SE PR view the identity of their communities as tied to being CR –engaged, “fishing communities”, to the extent that the communities would change in their very essence if CR-use patterns changed.

3) CR users tend to use coastal environments extensively as well as intensively, harvesting a variety of resources over space and time. Beside the more than 40 species of fish species routinely harvested, local people target a variety of coastal forest resources, sometimes in sustained fashion and other times in episodic or opportunistic fashions. This suggests a large degree of reliance on local environments for income and food security.

4) All CR users interviewed reported engaging in a variety of economic activities, together with CR harvesting. This pattern is well-described for Puerto Rico and other tropical small-scale coastal locations, and is a result of adaptation to local ecological conditions as well as economic uncertainty associated with employment availability in rural coastal locations.

5) A particularly important finding is the identification of a regionally- and culturally significant category of CR-use mode related to the use of mangrove and coastal forest resources known as “Pesca de Monte”. This constitutes a parallel use of the coast to offshore, “commercial” fisheries that has gone unreported in official fishery statistics and is thus a largely unknown value to coastal policy makers.

6) 92% of households routinely consume local CRs. 92% of the fish, 98% of the land crabs, and 97% of the bivalves consumed by interviewed households are locally-harvested.

7) All CR harvesters interviewed have household and/or extended family members who participate in the processing, value-adding and marketing of the CRs they harvest. These family members can benefit by earning money or by receiving part of the catch as payment.

8) In our sample of randomly-chosen local households, the most important ways they accessed CRs for consumption was 1) by being captured and brought home by a household member or 2) by a community CR harvester giving CR products to them as gifts. Even when CRs were bought with money, CRs were bought at either the harvester’ or the buyer’s home, which indicate relatively close social relationships. All of these exchanges are very unlikely to be recorded in official expenditure records, which leads to underestimating the real value of CR use.

9) In a randomly selected sample of 47 coastal resident households in the study region, 17 (36%) engaged in CR harvesting as a source of income. In some communities, like Barrancas in Guayama, virtually all randomly chosen households were CR users.

10) 95.7% of surveyed CR users report routinely giving away as a gift an average of 7% of the products of their harvest to people in their communities including family, friends, or those in need.

11) 45% of surveyed residents report routinely receiving products of local CR harvesters as gifts.

12) In seafood restaurants throughout the Coast, CRs sold are overwhelmingly local (95% routinely sell local CRs, which constitute a mean income of 59.8% (not adjusted for beverages). Seafood-based restaurants that sell local CRs report employing more than 250 people in the study region.

13) Seafood restaurant operators have developed mutually beneficial relationships over time with particular CR harvesters that rely on dependability and quality of harvest products in exchange for guaranteed purchase of total harvest. The most important ways that seafood establishments get the CRs they sell is by close, contractual relationships with local CR users and by personal, local, non-contractual relationships.

14) Interviewed SE PR informants have defined WB/QOL as a multi-faceted phenomena, composed of a variety of domains, including health (not measured in this study), wealth, economic security for household reproduction, participating in reciprocity networks and socially beneficial activities, minimizing the impact of socially-destructive activities (such as crime) in their communities, independence, and enjoyment of the environment.

15) Throughout the study region, various forms of CR harvesting, processing, value-adding, marketing, and selling, figure importantly in the informants’ narratives of QoL/WB, or what they often call “a good life.”

16) Overall, domains related to enjoyment of close social relationships were more highly rated/valued for QoL/WB than material wealth domains (as long as, as one informant put it, wealth “is enough to pay the bills”). This pattern was more marked for people who make a living with CR use.

17) The majority of ethnographic informants viewed their QoL/WB as significantly affected by access to coastal resources in their communities. As one community activist informant put it: “one way or another, everyone around here depends on the coast and fishing”.

18) CR use and related economic activities are widely valued as contributing to avoidance of social problems, specially crime, by providing “honorable work” alternatives to a life of crime. This was one of the most widely mentioned and discussed topics in our interviews. Professional CR users mention specifically seeking out at-risk youth in their kin and neighborhood networks to offer them opportunities for honorable employment.

19) Local communities seem to be keenly aware of the links between CR use and the QoL/WB of their communities. Grassroots community groups pursue enhancing CR use and access as part of their local beneficence agendas. This includes actively organizing and collaborating with local fishing associations and other CR users.

20) Although CR users reported economic histories of occupational multiplicity, they tended to consider CR harvesting as the most beneficial and desirable occupation for their QoL/WB and tended to judge other occupations by their similarity to fishing or by the free time that they allowed to engage in CR use. Thus, they tended to report low occupational fungibility (ability to find satisfactory alternative employment to CR use) even though they clearly had a range of skills and occupational experience.

21) We assembled a range of WB/QOL measures, both developed by us and standardized, that we used in structured questionnaires and that were validated by pre-testing.

22) Responses to questions in a Community Solidarity Index indicate that overall coastal communities in SE PR are face-to-face communities with relatively high cohesion and solidarity.

23) People involved in CR use seem to specially invest in solidarity-enhancing activities and experience relatively higher community solidarity. This seems to reflect a greater engagement with reciprocity-based, rather than market-based, exchanges. As one fisher put it, “ I take care of my community so that the community will take care of me when I’m in need”.

24) Material Style of Life (MSL) data gathered with surveyed SE PR coastal residents indicates that material wealth is generally adequate for basic material needs throughout the coastal region. However, residents working in non-CR use jobs in the formal economy showed significantly higher material wealth than CR users.

25) Does their higher material wealth make residents with non-CR use jobs more satisfied or happier than those who work as CR users?: The answer is NO: In our probability samples, NonCR users reported statistically significant lower scores than CR users in their: i) Satisfaction with Life (using Diener’s SWLS scale), ii) Job Satisfaction (using Pollnac and colleagues’ Job Satisfaction Scale), iii) enjoyment of community relationships (using our Community Solidarity Index).

26) Non-CR users also reported spending relatively less time with family and close friends (one of the most important Qol/WB domains) and reported being less inclined to choose the same way of making a living if they had the chance to live their life over again.

27) The convergence of our data indicates that there is a strong overall positive effect of engaging in CR use as a job on subjective well-being and life satisfaction. This comparison is especially valid because it compares people living in the same communities who report similar life priorities and important domains of QoL/WB.

28) Many Non-CR users nevertheless also perceive coastal resources as important for their QoL/WB. 74% (along with 96% of CR users) agreed with the statement that “sin recursos costeros, esta comunidad estaría muerta y triste” (without coastal resources, this community would be dead and sad).

29) An active CR use sector enhances community resilience and access to high-quality food for those beyond CR user families. Vulnerable residents such as the elderly, infirm, or unemployed seem to benefit specially from CR-based reciprocity.

30) At the writing of this report, we are working with programming and coding of the simulation modeling for objective # 6. The full-blown simulations of different coastal policy scenarios are not yet complete. We have however developed the algorithms and weighting procedures for estimating policy impacts of different coastal use policies on a range of SE PR coastal households. Initial runs of the algorithms using a simple database model indicate that QOL/WB or SE PR coastal residents would be maximized by policies that balance formal economy jobs with CR use opportunities and access. Simulations using SIMILE and NETLOGO software are expected in the next few months.

31) Due to field conditions and the timing of research activities, the dedicated multi-sector workshops that were expected to be conducted were replaced by participation and presentation of our project and partial results in two multi-sector environmental community meetings in June and July 2010, and in further collaboration with community representatives regarding socialenvironmental issues over the last two years of this project.

32) The results of this research are being freely shared with local community organizations such as IDEBAJO and Accion Ambiental that have an interest in the communities’ QoL/WB and their relationships to a sustainable coast.

33) Realizing the links between coastal environmental sustainability and the continued Qol/WB of the communities, these groups pursue agendas of environmental sustainability along with their social organizing. The results of our research are presently being used in court and political battles with industrial, large-scale tourism and urbanization developers whom these organizations perceive are threatening the integrity of coastal habitats.

Students Supported:

1. Name: Victor PagánAddress: HC-03 Box 11115, Camuy, PR 00627

Email: < priverabistol@gmail.com>

Degree Sought: M.S. in Social Work, UPR-Río Piedras

Amount paid: $2250

Time period: 1-1-2011 to 12/31/2012

Effort: 180 hours (Sea Grant)

2.Name: Yazmin Pérez Ortiz

Address: Calle 2 ext. 3 urb. Toa Linda, Toa Alta Puerto Rico 00953.

Email: <yasperort@gmail.com>

Degree Sought: B.A. in Biology, UPR-Cayey

Amount paid: $2250

Time period: 1-1-2011 to 12/31/2012

Effort: 180 hours (Sea Grant)

3.Name: Natalia Rodríguez

Address: Calle 8 M-7 El Torito Cayey, PR 00736

Email: < lalapr7@gmail.com >

Degree Sought: M.S. in Environmental Sciences, UPR-Río Piedras

Amount paid: $500

Time period: 6-1-2012 to 12-31-2012

Effort: 40 hours (Sea Grant)

Post Doctoral Associate Supported:

1.Name: Miguel Del Pozo

Address: Almácigo H-25, Urb. Arbolada, Caguas, Puerto Rico 00727

Email: < Miguel.delpozo@upr.edu>

Amount paid: $7500

Time period: 1-1-2011 to 12/31/2012

Effort: 500 hours (Sea Grant)

Principal Investigators:

PI Carlos García-Quijano

Time period: 6-1-2010-3-1-2013

Amount Paid: $12360 (2 months Sea Grant); $19164.86 (2 months plus benefits match)

PI John Poggie

Time period: 6-1-2010-3-1-2013

Amount Paid: $23452 (2 months Sea Grant); $32630.25 (2 months plus benefits match)

Associate Investigator: Ana Pitchon

Time period: 6-1-2010-3-1-2013

Amount Paid: $5000 (1 month Sea Grant)

Publications:

García-Quijano, Carlos, Miguel Del Pozo and John Poggie (submitted to Journal Revista de Ciencias Sociales, University of Puerto Rico) “La pesca de monte: subsistencia y oportunidades de vida en los bosques costeros del sureste de Puerto Rico” (“Pesca de Monte”: Subsistence and Livelihoods in Southeastern Puerto Rico’s Coastal Forests). Expected Fall 2013

Valdés-Pizzini, Manuel and Carlos García-Quijano (submitted to Journal Revista de Ciencias Sociales, University of Puerto Rico) “Indicios y formas de saber: el conocimiento ecológico local de los pescadores puertorriqueños” (Markers and Ways of Knowing: Puerto Rican Fishers’ Local Ecological Knowledge”). Expected Fall 2013

Griffith, David C., García-Quijano, Carlos G., and Manuel Valdés-Pizzini (2013). A Fresh Defense: A Cultural Biography of Puerto Rican Fishing. American Anthropologist 115(1):17-28.

Garcia-Quijano, Carlos, John Poggie, Ana Pitchon, and Miguel Del Pozo (2012) “Investigating Coastal Resource Use, Quality of Life, and Well-Being in Southeastern Puerto Rico”. Anthropology News: March 2012, 6-7.

Project-based Refereed Talks and Presentations: Quality of Life, Well-Being, and Resilience in the Puerto Rican Coast. Carlos García-Quijano, invited Speaker. IGERT Colloquium Series, Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Puerto Rico-Río Piedras, April 18, 2013, Río Piedras, PR.

Roundtable Session: Developing Measures of Well Being for Evaluating Projects. 72th Annual Meeting of the Society for Applied Anthropology, March 29, 2012, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Researching Quality of Life and Well-Being for Coastal Puerto Rican Communities. With John Poggie and Ana Pitchon, 72th Annual Meeting of the Society for Applied Anthropology, March 30, 2012, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Ecosystems-Based Tropical Fisheries Management: Convergence Between Western and Traditional Ecological Knowledge Systems. University of Rhode Island Anthropological Student Society Lecture Series, February 24, 2012, Kingston, RI, USA.

Connected by Water: Coastal Peoples and Human Ecosystems in the Inter-American Seas. Invited Keynote Speaker, Inaugural Symposium of Inter-American Seas Institute for Sustainability Science and Policy, Florida State University. December 8, 2011, Tallahassee, Fl, USA.

Community Perspectives on Natural Resource Dependency and Resiliency. Co-Organized with Ana Pitchon and John J. Poggie. 71th Annual Meeting of the Society for Applied Anthropology, March 30, 2011, Seattle, WA, USA

Coastal Resource Use, Quality of Life and Resilience in Puerto Rico. With Ana Pitchon and John J. Poggie. 71th Annual Meeting of the Society for Applied Anthropology, March 30, 2011, Seattle, WA, USA.

The Value of Local Ecological Knowledge: Success, Well-being, and Management of Environmental Complexity in Puerto Rican Small-scale Fisheries. Invited Talk, Methods of Analysis Program in the Social Sciences Colloquium Series, Institute for Research in the Social Sciences, Stanford University. March 11, 2011, Palo Alto, California, USA.

Honors/Awards related to this work: Carlos García-Quijano. 2013 University of Rhode Island Early Career Faculty Research Excellence Award.

The Coast's Bailout: Coastal Resource Use, Quality of Life and Resilience in Puerto Rico

Carlos G. García-Quijano

Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Rhode Island

John J. Poggie

Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Rhode Island

Ana Pitchon

Department of Anthropology, California State University-Domínguez Hills

Miguel del Pozo

Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Rhode Island

José Alvarado

Biostatistical Consulting

With the collaboration and assistance of: Víctor Pagán, Natalia Rodríguez, and Yasmín Pérez Ortiz.

“Fácil. Si no tuviera accesso a los recursos costeros, esta comunidad estaría muerta y triste”

“(the answer is) Easy. Without access to coastal resources, this community would be dead and sad”

--Coastal Resident, Puerto Rico.

In the epigraph quote above, a resident of the coastal village of Pozuelo in Guayama, Puerto Rico was responding to a question asked as part of our interviews with coastal residents, seafood business owners, and coastal resource (CR) users around the coast of Southeastern Puerto Rico (SE PR): “How would your community be affected if for any reason the residents of local communities ceased to be able to have access and harvest local coastal resources?”. This particular resident’s answer was remarkable for at least two reasons: one is that this coastal resident, chosen from a randomly chosen sample of Southeastern Puerto Rican households that were not necessarily involved directly with the local coastal resource economy, directly and unequivocally equated having access to coastal resources to any semblance of the community’s life, at least a life that would be worth living. The second reason this resident’s answer is remarkable is precisely because of how common, locally unremarkable, it was. As we traversed the coast of SE PR while interviewing, visiting, and conversing with residents of all walks of life during the last 3 years, time and again we heard highly similar, often identical answers to the question above. Clearly, many coastal SE Puerto Ricans derive significant value, material, social and symbolic, from the coast and, equally importantly, from the activities of those (like fishermen, crabbers, clam and oyster collectors, coconut harvesters) who harvest coastal resources and make them available for human use, exchange, consumption, and even aesthetic enjoyment.

Our endeavor for this UPRSG-supported research project has been guided and inspired by two overarching questions. 1) What is the importance of a healthy coast, one that includes engaged and productive human communities, for Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans, and 2) What does local

and greater society really lose if resource-engaged coastal communities are lost or severely changed by one of more of the variety of threats and challenges they face? If, as Costanza et al. (2007) point out, the real universal objective of public policy is not only about economic health but also to increase "well-being" and "quality of life", then to achieve adequate public policy and planning about the coast it will be crucial to understand the linkages between the use of coastal resources and the Quality of Life and Well-Being (QoL/WB) of Puerto Ricans. To produce this critically-needed knowledge, we designed and carried out a long-term, multi-methods and multidisciplinary research project to investigate the extent to which coastal resource use contributes to the well-being, quality of life, and resilience of people in four Puerto Rican municipalities located in the Southeastern coast of the island (Salinas, Guayama, Arroyo, and Patillas). While this report begins with an epigraph that could be considered “negative” because it talks about an scenario of a “sad” and “dead” community, we see the expressions of coastal SE Puerto Ricans as precisely an expression of the “positive” that CR-use and CR-based activities and culture contribute to the region. If loss of CRs and access to them would mean sadness and death to SE PR coastal communities, then this means that CR harvesting, use, and the socially and economically significant activities that radiate from these activities bring “happiness” and “life” to these communities. We thus view this research ultimately as an exercise in what could be called –borrowing from the “positive” psychologist Martin Seligmann-, “Positive Anthropology”: a ethnographic study of small-scale coastal resource use, and how, for coastal SE Puerto Ricans, it contributes to a life worth living.

Definitions

Coastal Resource Use- For the purposes of this study, Coastal Resource use refers to the small-scale harvesting, processing, and exchange of coastal resources. Specifically, this research concentrates on commercial small-scale fishing, subsistence fishing, recreational fishing for food, commercial and subsistence land crabbing, and non-timber coastal forest resource use such as mangrove root mussel harvesting and selling. Small-scale refers to resource use geared toward subsistence consumption and/or petty commodity production, usually carried out by the owners of means of production.

QOL/WB- Well-Being (WB) and Quality Of Life (QOL) are sometimes used in the literature as interchangeable terms with identical meanings and other times as separate constructs measuring different subjective and objective attributes. For the purposes of this research, QOL/WB are conceptually inseparable and refer to a range of attributes dealing with the fulfillment of human needs and functioning of social groups at various scales (nuclear family, extended familily , community, etc.). QOL/WB is broadly defined as “full participation in a social form of life that depends not only on physical health but also on healthy (social) relationships” (Velazco 2009). A more precise working definition is offered by Pollnac et al. (2007): “ Wellbeing refers to the degree to which an individual, family, or larger social grouping can be characterized as being healthy (sound and functional), happy, and prosperous”. Measuring QOL/WB involves the joint assessment of quantitative and qualitative, subjective and objective measures, ideally developed and interpreted in cultural context (Costanza et al. 2007; Pollnac et al. 2007; Velazco 2009). A key component of the proposed research is to use in-depth ethnographic research to achieve locally meaningful definitions and measures of QoL/WB (as well as community resilience (see below) that can be combined with measures used by researchers elsewhere.

Background of this research

The passing of Magnuson-Stevens Act’s National Standard 8 requiring research to… “account (for) the importance of fishery resources to fishing communities” (NMFS 1996) has been one of the most important events in the development of applied coastal social sciences and thus in the increased understanding of how people in U.S. Coasts depend on coastal resources and how CRdependent social groups might be affected by regulating or curtailing access to these resources. In this report herein, we will use Coastal Resources (CR) instead of “fisheries” to denote that people’s use and dependence on coastal environments and their resources often extends beyond the resources that are targeted as “fisheries”. Since the late 1990’s a considerable number of social and economic scientists have put their efforts and creativity towards identifying, measuring, and assessing precisely what shape does this “importance” of fisheries and coastal resources take and how it is manifested. In other words, looking at the value of costal resources for the people that engage in coastal-based harvesting and economic production.

The potential threat to CR-based economies and the communities that depend on them do not come only from catch regulations. The coast, specially biologically productive coastal areas such as a beaches and estuaries, have become focus of competitions for space, and resources for a variety of economic interest sectors, such as tourism (at all scales), recreation, urbanization, and industry, and even parks and conservation In many cases, the plausible alternative uses of the coast are not compatible with CR dependent-communities and if left unchecked or blindly supported can result in displacement of the communities, degradation or pollution of coastal habitats and resources, and/or the redirection of benefits from CRs away from local communities. Many coastal resources themselves (fish, crustaceans, bivalves) are objects of consumerist desire, as has happened with the coast itself as a place of recreation and conspicuous leisure (ValdesPizzini 2006; Brusi 2004; Griffith et al. 2007; Stonich 2000). These processes have on the one hand resulted in the inclusion of coastal resources in the luxury food economy (bringing money to CR harvesters but at the same putting focused pressure on a few highly desired CR’s) and on the

other changing the demographics of many coastal areas by the disruptive process of gentrification and associated processes such as coastal deforestation, construction, and generalized habitat degradation.

One of the realizations that have come about as people-CR interactions are better understood is that dependence on CRs goes beyond mere exchanges of money in the formal market. The value generated by CR use includes the social and cultural acts of productions and exchange that happen in CR users’ households, neighborhoods, and communities, whether the CR is sold commercially, bartered, gifted, or consumed directly (Pollnac et al. 2008; Dyer and Poggie 2000; García-Quijano 2006; Griffith 1999; Griffith et al. 2007; 2012). It has been thoroughly documented in other parts of the world that the satisfaction and enjoyment derived from CR use such as fishing exceeds purely monetary measures (Pollnac and Poggie 2006; 2008; Smith 1981; Gatewood and McCay 1990

Coastal Dependence in Puerto Rico

Recent works with marine fisheries in Puerto Rico have demonstrated that fishery dependence, as well as the impacts of fishing regulations, extend far beyond the specific households that depend directly on fishing (Griffith and Valdés Pizzini 2002; Griffith et al. 2007; Pérez 2005). This is because fishing (as we expect to be the case with other kinds of CR use) happens in the context of households, extended families, and communities that are ‘entangled’ with each other and with regional, national, and global social and economic processes.

A 2012 publication by Griffith, García-Quijano and Valdés-Pizzini (2012), based on a 5-year assessment of commercial fishery dependence around the coast of Puerto Rico, uses a “cultural biography” approach to show that an overall focus of quality (of product, of lived experience, of symbolic connection, of community reproduction) allows commercial fishers to add value to their catch and their activities in such a way that they can defend themselves against claims over seafood markets and coastal habitats made by more powerful actors that rely on economies of scale. Other studies have also identified a moral economy of household reproduction and community beneficence related to fishing that often causes the benefits from fishing to be distributed in the community beyond harvesters and their immediate families, while entrenching harvesters in reciprocity networks and thus enhancing their enjoyment of good social relationships (Griffith et al. 2007; 2012; Valdés-Pizzini et al 2008; García-Quijano 2009).

Griffith and Valdés- Pizzini (2002) show how due to the interplay between local and non-local (regional, global) histories and processes (e.g. Roseberry 1989), although small-scale fisheries are vulnerable to interaction with larger markets, participation (or having the option to participate) in fisheries affords individuals and households ways to partially resist the negative influence of the same larger markets in their lives. This is important because perceived powerlessness in the face of economic downturns can be a major Qol/WB issue.

Community Resiliency and Implications

Resilience is the capacity of a community to adapt to environmental, social, and economic change. The resilience of integrated human and nature systems, or social-ecological systems (SES) is based on three fundamental characteristics: the magnitude of shock that the system can absorb and remain within a given state; the degree to which the system is capable of selforganization; and the degree to which the system can build capacity for learning and adaptation (Folke et al. 2002). Adaptation fundamentally is the ability of humans to manage resilience, and it is the collective capacity of community members to do this with intention and planning (Walker et al. 2004). When a household or community is resilient, it can absorb shocks and still maintain function. The inability to deal with change through a lack of organic characteristics of resilience

makes a community vulnerable, where a small change in the system can lead to collapse. However, a community that builds and maintains resilience potential will have the components necessary to withstand shock, and instead use these changes to its advantage through development and innovation.

Common characteristics of resilient systems include redundancy, diversity, efficiency, autonomy, strength, interdependence, adaptability, and collaboration (Godschalk 2003).

The sociocultural factors that contribute to the resilience of coastal communities in the face of economic and ecological hazards are understudied when compared to more dramatic disturbances such as natural disasters (Pitchon 2006; Costanza and Farley 2007). These types of systemic shocks pose an equal threat, however, as restricted access to resources, local ecosystem degradation or a decline in an important subsistence species can devastate a community.

Ecological Edges

The concept of the “social-ecological edge” helps to explain why this is a valuable variable in resilience building. An ecological edge is an area that is in a transition zone from one ecosystem to another, and as a result tend to be rich in biodiversity (Odum 1971). The idea of socialecological edge explores how communities living on the edge of varied natural systems have access to diverse environments and species, thus enabling them to maintain the system through diversification and the creation of new opportunities (Turner et al. 2003). McCay’s discussion of the “edge effect” considers the social opportunities that overlapping systems can provide through “the brining together of people, ideas and institutions” (McCay 2000). As we will detail later in this report, this is the case for SE PR, where living on the edge of multiple ecosystems has allowed for diversification in species harvest and use.

In addition to new opportunities presented by accessible biodiversity, communities living on the edge of increasingly popular tourist zones are finding opportunities for resilience through programs in ecotourism and other non-resource dependent activities. For example, as we did our fieldwork in SE PR, an alliance of local community organizations, in collaboration with fishermen associations and funded by a quasi-governmental organization for rural community development (INSEC), were developing ecotourism initiatives around kayak and small-boat tours of the bays and keys along the SE PR coast, with local expert guides, many of them fishers or their children. During our three years of visits, these initiatives seemed to be doing well on their own after the initial period of funding, specially in the Salinas coastal communities.

While diversification is a key to resilience in many social-ecological systems, we must not discount the fact that diversity is dynamic. This can create uncertainty in another form when too many sources of potential stability are perhaps competing against each other or contingent upon the same variables. In addition, other elements of the system must be altered in order to increase diversity, which, if the system does not possess characteristics of resilience in the first place, it may not be able to withstand such pressures (Norberg 2008). Nonetheless, diversity is still a recommended if not fundamental characteristic of social-ecological resilience. As global systems are rapidly changing, both ecologically and socially, the capacity to adapt quickly becomes paramount, in which case having access to and an understanding of various opportunities is key.

Coastal Subsistence Patterns in Puerto Rico: Economic and Environmental Multiplicity

Many families and communities in the rural coasts of Puerto Rico and elsewhere in the Caribbean make a living by combining coastal resource use, preparation, marketing, and selling with mainstream jobs in agriculture, retail, services, government, and local industries (Comitas 1974; Griffith and Valdés Pizzini 2002; Griffith et al. 2007; Gutierrez 1982). This mixed coastal subsistence pattern of economic or occupational multiplicity has existed for hundreds of years in

Puerto Rico’s coasts and dates at least as far back as the time of sugarcane-dominated Caribbean economies, where formal employment for the majority of people was only available during the planting and harvest times, with no income during the down times of sugarcane agriculture, locally called “el invernazo” CR use was specially important for survival during the “invernazo”. The pattern has been perpetuated by the unpredictability of employment near rural coastal areas after sugarcane was replaced with coastal industries episodically hire and fire large numbers of non-skilled workers, as well as by long traditions of self-reliance and independence typical of rural coasts. Cultural identities strongly related to the use of coastal resources, which are partly results of this long standing dependency (Giusti 1994; Mintz 1960; Griffith and Valdés-Pizzini 2002; Valdés-Pizzini 1987).

The hydrological, geomorphological, and transportation characteristics that made rural coasts preferred places for sugarcane agriculture also made them preferred places for the establishment or large-scale pharmaceutical, manufacturing, and similar industries that came after sugarcane’s demise to provide needed employment but also undesired environmental degradation. The SE PR coast is home to at least 15 large-scale pharmaceutical, petrochemical and power generating industrial developments (Garcia-Quijano 2006).

Table 1. Large Coastal Industries in the study region. Data compiled from Enviromapper Server, United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2012.

Company name

Type of Activity

Location

Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Arroyo

Stryker Biomedical Arroyo

AES Jobos Steam Power Plant Electric Power Generation Guayama

Ayerst-Wyeth Pharmaceutical Guayama

Baxter Pharmaceutical Guayama

Chemsource, Inc. Pharmaceutical Guayama

Colgate-Palmolive Pharmaceutical Guayama

ICI Pharmaceutical Guayama

IPR Pharmaceutical Guayama

Phillips Puerto Rico Core Petroleum Refinery Guayama

Smithkline-Beechamn Pharmaceutical Guayama

Squibb Pharmaceutical Guayama

General Electric Manufacture Maunabo

AEE Aguirre Power Generation ComplexElectric Power Generation Salinas

Steri-Tech Inc. Biomedical Salinas

Allergan Biomedical Santa Isabel

Throughout these changes and processes, coastal communities in Puerto Rico have continued to rely on local CRs for at least part of their subsistence and socially-significant activities. We find Richard Stoffle and colleagues’ concept of Environmental Multiplicity useful to understand the resilience strategies centered around CRs. Environmental Multiplicity refers to the utilization of multiple resources for multiple uses, from a local environment (such as local coasts and estuaries), which includes the social relationships related to and deployed around the harvest, preparation, marketing, and consumption of the resources (Stoffle 1986; Stoffle and Minnis 2008). In the words of Stoffle and Minnis (2008): “The term environmental multiplicity builds on the narrower but established term occupational multiplicity (Comitas 1964), to describe their system of resilient adaptations. Conceptually these terms describe a range of multi-stranded and

redundant connections among the members of a traditional community and between them and their primary natural use areas (Stoffle 1986)”.

Thus, in this conceptual model, environmental, plus occupational, multiplicity, form a system of local adaptations that in general increase resilience of CR dependent communities in faced with an uncertain and dynamic social/economic/ecological environment. The key aspect, especially for policy making, is that the multiplicity makes the communities highly resilient, but only as long as they have access to a relatively healthy local ecosystem. A catastrophic loss of resilience can happen if the communities, for whatever reason, are excluded from access to their local ecosystems, like for example by being displaced by coastal development, gentrification or overly tough harvest regulations, or if resources become degraded by pollution, habitat destruction, or overharvesting. Or, as a crabber and community activist told us in 2011 “Jobs and industries come and go, but as long as the coast is healthy around here we will never go hungry”. This is something that coastal policy making and regulation should take into account.

One of the major finding of this research and previous works (e.g. García-Quijano 2006) is that many people around the SE PR coast build resilience through livelihood diversification and redundancy, combining participation in the formal job economy with use of local resources. Even though, in a given year, CR use contributions to the GNP might be very small (not including coastal tourism) compared to other economic sectors, a number of individuals, households, and communities still spend considerable time and energy harvesting, processing, and exchanging CR-based products. The total value of these activities needs to be documented for rational policy making about the future of coastal areas.

Methodology

This research deals with complex and multidimensional cultural phenomena, such as Coastal Resource Dependence of various groups of people, “emic” and “etic” (Pike 1967) measures of QOL/WB, and the value that CR use and associated activities have for SE PR Puerto Rico Ricans. This is a complex undertaking that necessitates an appropriately broad and flexible methodological framework coupled with diverse, nuanced techniques of elicitation, measurement, and analysis that are appropriate to the specific research objectives and social features being studied.

Our overall methodological approach is that of mixed-methods, multi-disciplinary ethnography

We use ‘multidisciplinary ethnography’ as an umbrella term for a variety of quantitative and qualitative, field -based and archival, exploratory and analytical techniques that we utilized to gather knowledge about the multiple topics related to CR use, as well as QoL/WB addressed in this study. These techniques are deployed around our core method of classical ethnography. Our overall methodology, rather than being discipline-based, is objective-based, and aims to balance the context-richness and attention to detail achievable with open-ended ethnographic methods with the predictive power and comparability of results acquired by exposing respondents to comparable stimuli (for example Kempton et al. 1995, Johnson 1998; 2000; Roos 1998; Harman 1998.

Qualitative Ethnographic Fieldwork

Although we used a variety of methods for data collection and analysis, this study’s central approach is based on qualitative ethnography and the discovery insights reached through ethnography. Ethnography, quite literally “writing culture”, is considered to be the methodological hallmark of Anthropology and is increasingly being used by other sciences, both social and environmental. The defining feature of ethnography, for us, is its “holistic empiricism”, the emphasis on systematically recording varied kinds of data about various interconnected aspects of a society’s culture and social life to develop complete, yet nuanced accounts of a group’s culture that are based on “being there” through systematic fieldwork (Fetterman 2010). Ethnography, and insights achieved through ethnography, are also being increasingly recognized as forming a very productive basis for simulation modeling, both systems and agent-based, because of the empirical “realism” of variable relationships, system logic, and realistic rules that can be achieved through ethnographic work (e.g. Agar 2007; Degnbol 2007).

In this study we used a variety of the techniques commonly associated with qualitative ethnography, including 1) systematic observation, including unobtrusive behavioral observation and “cultural mapping” of CR use in SE PR (Griffith et al 2007; Griffith 2011), 2) Participant observation, including field visits, attending community and CR user meetings and even community-based protests/activism, participating in CR use activities, and informal conversations, 3) Identifying key informants from whom to gather knowledge and perspectives related to the different uses of CR in the study region, QoL, WB, and the relationships between the two, 4)Oral histories and semi-structured interviews with identified key-informants, and 5) identification and analysis of archival and popular cultural material that exemplified CR use and its ties to QoL/WB

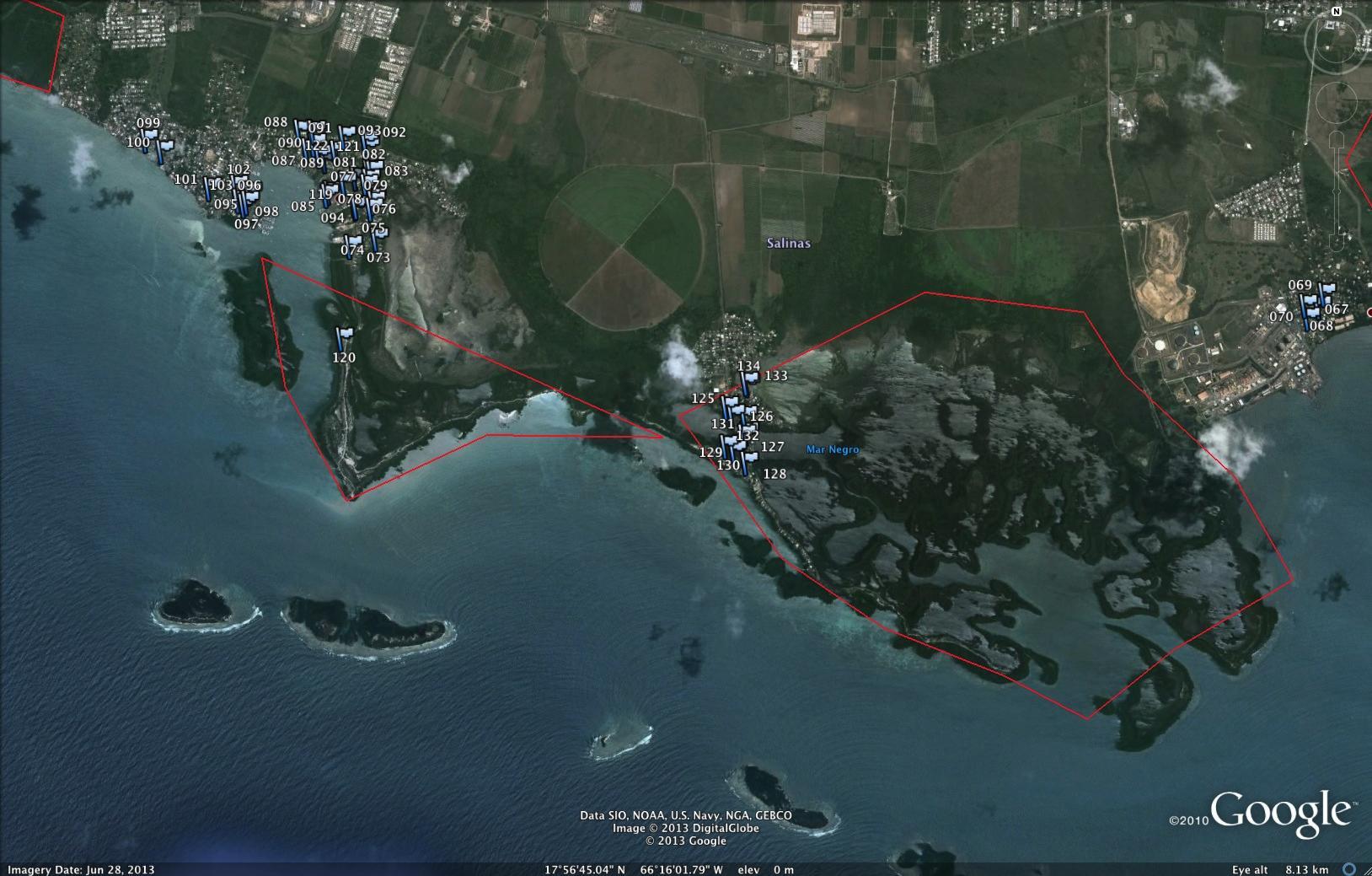

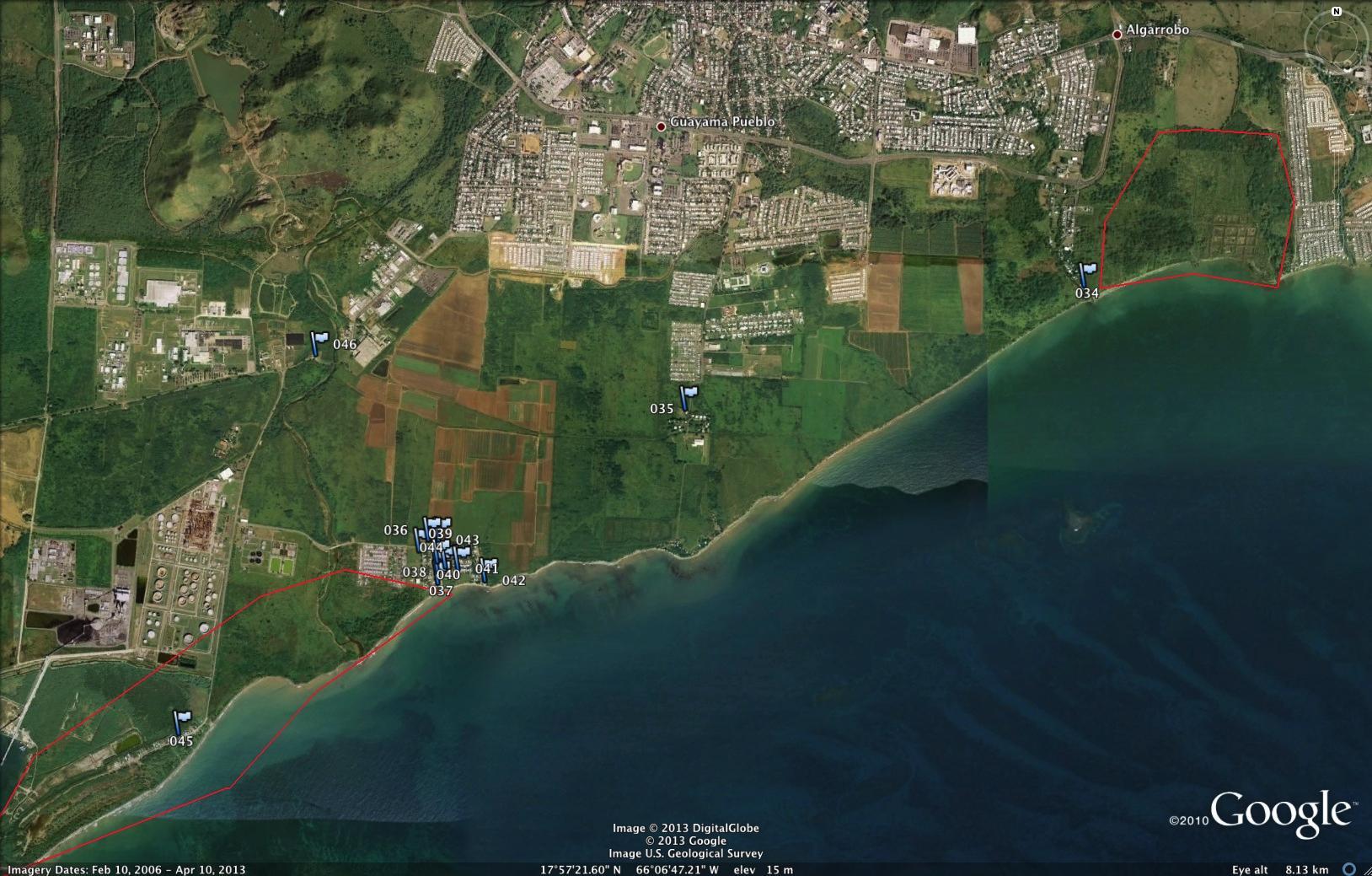

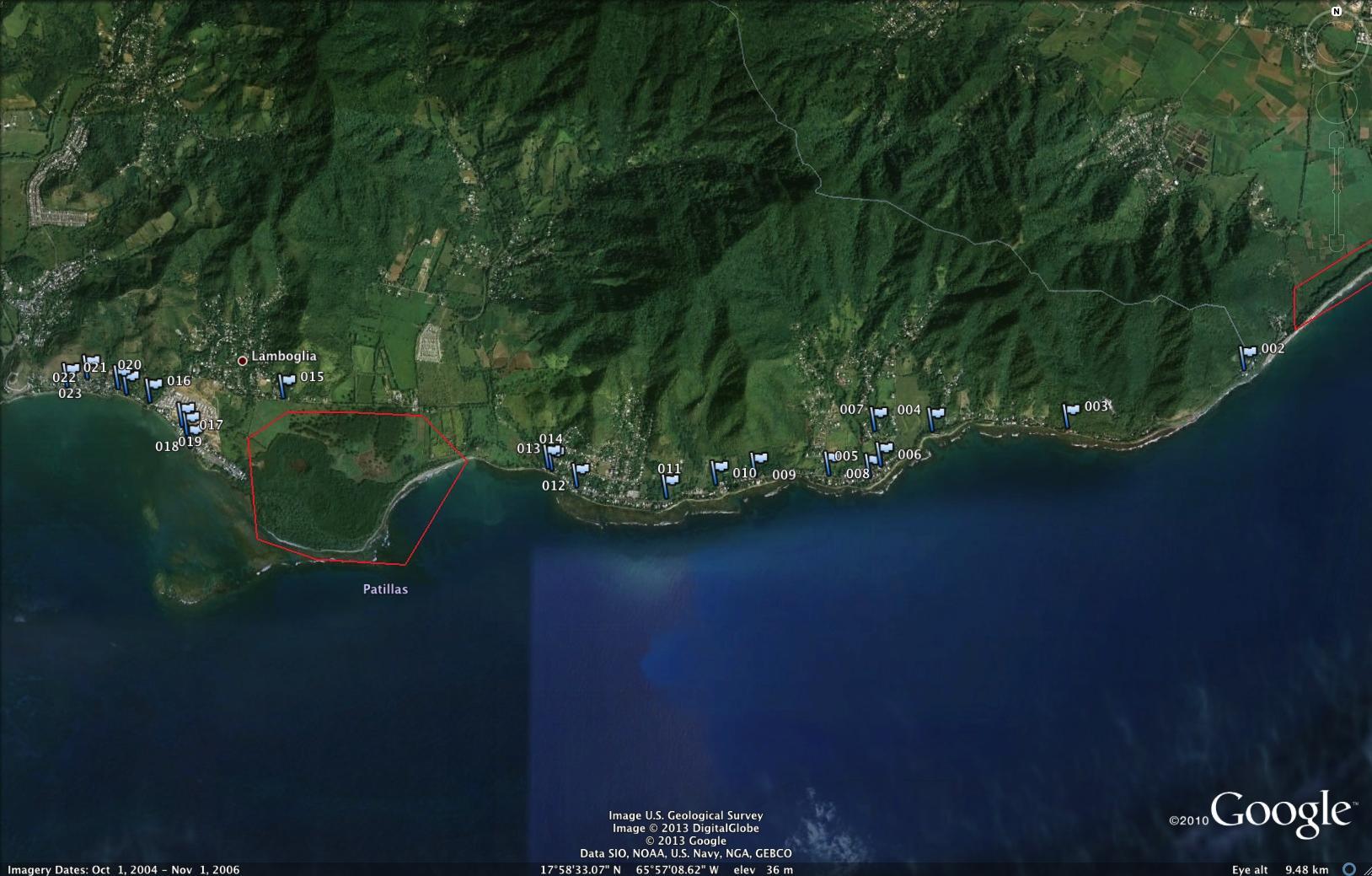

Coastal Resource use: cultural mapping

We take an interdisciplinary approach to “mapping”: In our mapping activities, we combined 1) the precise physical mapping of CR and its environmental context by noting and georeferencing CR use and signs of resource use, both observed and reported by field contacts and informants, with 2) “cultural mapping” (Griffith et al. 2007; Griffith 2011; Beebe 2001; Gutberlet et al. 2007), which consists of identifying and documenting the cultural (including material culture),

infrastructural, symbolic, and economic indicators of a human activity (e.g. coastal resource use). We combined two complete drive-throughs of the study region using a hand-held GPS to record signs, physical and cultural material, of CR-based activities with ethnographic, field-based interviews, analysis of archival, secondary data, reports, government databases, oral histories, photographic materials and other relevant sources. We were especially interested in determining what CRs are routinely used in the study area; who the resource users are, where they harvest them and perform other associated activities, and what consumer products result from CR use.

These methods work together to identify and place CR use, users, and their activities in the context of the physical and social total environment For example, one of the principal CRs harvested and marketed in the study region is the land crab (Cardisoma guanhumi) (GarciaQuijano 2006; Govender 2007). During our fieldwork we asked a variety of field contacts and ethnographic informants about the locations where land crabs are captured, processed, and marketed, as well as what the signs of land crab harvesting activities are, and where the land crab harvesters live and market their catch. Then, during our drive through mapping of the study region, we recorded and marked with a hand-held GPS unit the locations where we observed signs of land crab harvesting (crabbers trails through the mangroves, land crab traps), processing/marketing (crab processing tables, houses with land crab holding cages (jueyeras), roadside land crab vendors, se venden jueyes/carne de jueyes signs in local homes, etc.), and finally, signs of the cultural importance of land crabs (e.g. community murals of land crabs or land crabbers). Put together, these methods give us a broad, extensive view of the economic and cultural importance of land crabs for the region’s coastal communities. Se attachment A for a georeferenced database of field observations of CR use, signs and traces.

Key Informant Interviews

The overall intent of our interviews with key informants is to gain an in-depth understanding of coastal residents’ engagement with coastal resources as they relate to QoL/WB in the study region, and to collect information that will complement other research methods such as secondary data analysis. We identified and recruited 23 CR users and 5 community activists. Our sampling list of potential key informants was based on our ethnographic research, as well as on knowledge gained through previous studies in the region, (e.g García-Quijano 2006; 2009), combined with a snowball sample (Johnson 1990) in which we identified local experts in the use, marketing, and cultural importance of the different coastal resources harvested.

The Key Informant Interviews constituted one of the main sources of information of the ethnographic component of this research, and were designed to cover and elicit local information and ‘emic’ perspectives about a variety of topics related to CR use. The focus of these interviews was aimed at understanding the importance of these resources to the informants and their households, their communities, and the region. The interviews usually required several visits and between 3-6 total hours of interviewing and consisted of three parts

Table 2. Summary of characteristics of key informant interviews

Interview #

Protocol Title

I Background Information

Themes covered

Demographic information, types of Coastal Resource Use practiced, job satistfaction, labor history

II Patterns of Coastal Resource Use I

III Cultural models of quality of life, and wellbeing, emic perspectives

Coastal Resource use, Movement of CRs through social networks, CR-based community reciprocity patterns, problems and issues of CRS in area, meaning of CR use

What are the goals of CR users, meaning of WB, QoL, and success, personal and social indicators and determinants

QoL/WB

Interviews with Seafood Restaurant Sector

Types of questions

Demographics, open-ended questions, freelisting of locally-important fish species, snowball list of other expert fishers

Open-ended questions, list of social relationships related to CR use, following harvested CRs through social networks

Open-ended questions

We also conducted 22 semi-structured interviews with owners, managers, and cooks who work in the SE PR seafood restaurants and food vending establishments. From previous experience in the study region we knew that the seafood sector was an important link between local CR users and the wider economy in the study region and that some of the locally-harvested CRs were marketed in local seafood eateries, which constituted a reliable venue to add value to local CR production. Furthermore, over the years we had learned that, like in other coastal locations around the world, there are close social relationships between fishing and other CR user families and the families that operate local seafood eateries; with the same families in many cases being involved in CR harvesting and in the seafood eatery sector. However, we wanted more specific information about the actual levels and variability of engagement of local seafood eateries with local CRs and the importance of local CRs in attracting clientele and revenue from outside the region.

As part of our CR-use mapping activities we identified a total of 27 seafood-oriented eateries in the study regions. These local seafood eateries varied from formal, expensive “sit-down restaurants”, to less formal, medium price restaurant-bars and/or family-style restaurantscafeterias, to food trucks and seafood fritter and “pincho” (kabob) stands which often consist of a table, a portable fryer/grill and a seafood warming counter (see photo) located in the front of the seller’s home. We were able to conduct interviews with owners/managers/cooks in 22 of the 27 eateries. The seafood eatery interviews were shorter and more focused than the CR user ethnographic interviews, and most of them were done in one or at most two visits and 1-2 hours of interviewing. The interviews with the seafood eatery sector included: 1)Demographics, restaurant characteristics and interviewees role in the restaurant 2) Local CRs sold, how they were sold/prepared, and their importance to the eatery’s economy, 3) Relationship of eatery with local CR harvesters/suppliers, 4) Cultural models and definitions of QoL/WB. The PIs collaborated in writing the interview protocol and PI Garcia-Quijano tested the interview instrument. Our two local research assistants, Victor Pagán and Yasmín Pérez, were in charge of conducting the bulk of the interviews.

Analysis of Ethnographic Interview Data

Using Atlas.ti (Muhr 2004)1 as a qualitative analysis platform, we analyzed the different types of interview, secondary sources, and cultural mapping data together and treated them as sources of information for understanding CR dependency and its connections to QOL/WB that I would be testing in the exploratory phase of this research (cf Bernard and Ryan 1998). Because out principal goal was to elicit “emic” meanings and perspectives, we treated primary interviews data as the most important source of information.

Structured Interviews

Based on the cultural mapping, archival, and ethnographic data, we designed and conducted structured interviews with a randomly chosen sample of coastal SE Puerto Ricans. We chose six specific communities in the study region for the structured interviews: 1) Playa/Playita and Aguirre in Salinas; 2) Barrancas and Pozuelo in Guayama, 3) Playa/Malecon in Arroyo, and 4) el Bajo in Patillas. The six communities were chosen to maximize representation of CR engagement, linkages with local and regional economy, and types of CRs used.

The goal of the structured interviews was to assess variation in CR use, dependence, and impacts on QoL/WB and resilience among a probability sample of households, both CR users and others, chosen because they were residents, in the study region. The structured interviews designed to systematically gather data on CR use and dependency and variation in domains related to QoL/WB, specifically to shed light on the specific mechanisms (economic stability, enjoyment of coastal environments, enjoyment of satisfactory social relationships, sense of identity and community belonging, and others). By targeting and interviewing both CR users and coastal residents who are not necessarily CR users we achieved a comprehensive look at CR use and dependency throughout the study region.

The two types of structured interviews were designed to be complementary: although the different interview protocols included sets of questions that were specific to the two samples, a core group of questions about both CR use and QoL/WB were included in both samples so that we could compare between two targeted groups. As detailed below, sampling strategies were also different and designed to the specific group of respondents targeted.

Our analysis of structured interview data had three main goals: 1) to identify patterns of variation in CR users and coastal residents’ engagement with local CRs , 2) to identify patterns of variation related to QoL/WB and how it manifests, and 3 2) Build on ethnographic data to identify and understand the mechanisms (e.g. direct market participation, CR-Based reciprocity; household and community reproduction; social beneficence) by which the value generated by CR use in the region reaches people.

Structured Interviews with Resource Users

The CR user respondents were chosen randomly, stratified by the main resource used (commercial fisheries, land crabs, clams, mangrove oysters, etc.) and coastal communities. Because there are no comprehensive lists of CR users in the region (there are no license lists for many CR users, especially those who are part-timers and those who do “pesca de monte”,), our sampling universe consisted of a list of CR users compiled by combining 1) commercial fishing license record with, 2) lists of CR users for different CRs complied during our cultural mapping exercises, our ethnographic interviews, and conversations with local resource managers, and 3) Roadside CR vendors (specially jueyeros (land crabbers) and clam/oyster vendors) that we spotted regularly during fieldwork. Originally we planned to choose 10 CR users per each of the 6 coastal communities for a total of 60 respondents. However, due to unplanned fieldwork factors related to the availability of respondents and/or our ability to find them due to their laboral and geographic mobility, we ended up with a total sample of 47 CR user respondents with some

communities more represented (for example, Pozuelo in Guayama) than others. The PIs collaborated in writing the interview protocol and Garcia-Quijano tested the interview instrument. Postdoctoral Associate Del Pozo coordinated and performed the majority of the interviews.

The Structured Interview protocol for CR users consisted of 5: parts 1) Demographics, 2) Labor history and patterns of participation in Coastal Resource use, 3) Participation in activities related to the processing and marketing of CRS, 4) Variation in dimensions of QoL/WB identified from ethnographic research and literature (e.g. job satisfaction, life satisfaction, life domain weighted importance) 5) Open-ended questions about CR use and quality of life.

Structured Interviews with Coastal Residents

Doing probability samples of households in irregularly settled rural areas has long been a challenge for social scientists (Bernard 2005; Kumar 2007; Kilworth et al. 1998; 2003). Sampling can be specially difficult in a coastal region like the SE PR coast, where remote rural communities are interspersed with a few small urban areas, inserted in a diverse topography, with a meandering coastline and estuaries (see Garcia-Quijano 2006). Recent technological advances such as the widespread availability of georeferenced aerial photography have yielded promising new geographically-based sampling methodologies such as Geographical Cluster Sampling (GCS), (Kumar 200x). Combining georeferenced maps with US census data in regions with highly-clustered rural habitation has been used to further optimize GCS techniques (Alvarado and Gavillan, TRAMIL).

As part of this study, we collaborated with subcontracted GIS and Census statistics expert Jose Alvarado to create a GCS-based sampling methodology to randomly choose households for interviews using US Census blocks overlaid on Google Earth ™ freeware aerial photographs. An added advantage of this methodology is that it can be replicated easily and relatively inexpensively. We conducted complete interviews with a total of 47 coastal households. Local student researchers Víctor Pagán, Natalia Rodríguez, and Yasmín Pérez recruited households and performed the interviews.

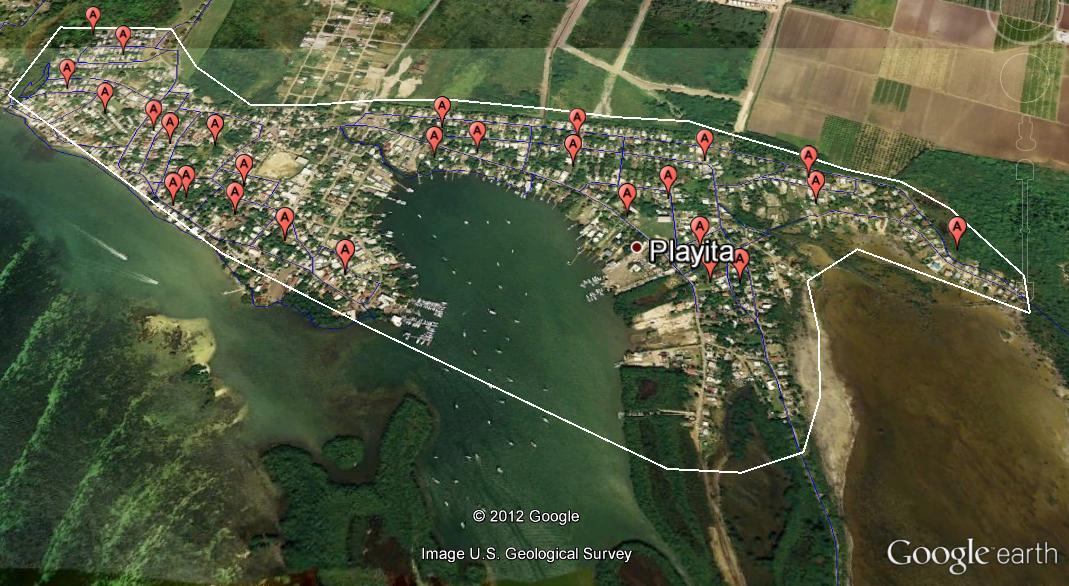

Coastal Household sampling methodology

The sample frame for this study was the total occupied house units in the following communities: Pesaco Arizona (Arroyo), El Bajo (Patillas), Barracas (Guayama), Pozuelo (Guayama), Aquirre (Salinas) and Playa Playita (Salinas). Every community was geographically delimited by the study PI Dr. Carlos Garcia-Quijano using Google Earth. Figure 3 shows the Google Earth geographic delimitation of Playa Playita Community. The Census Bureau 2010 Blocks Tiger Line Shape Files were downloaded from the Census Bureau FTP Site (www2.census.gov) and converted to Google Earth .kml files utilizing shp2kml version 2.0 free software. Once converted, the 2010 Census Blocks1 were used to approximate the communities’ geographical delimitation. Figure 4 shows Census Bloc approximation of Playa Playita Community. A total of 1,953 Blocks were used to approximate this community.

The Census 2010 Data was downloaded from the Census Bureau FTP Site and imported into MySQL (Open Source Relational Data Base Manager System). This data in combination with the Blocks Tiger Lines Files were utilized to estimate the number of occupied households unites for every Census Block inside the community geographical area. For each community a Cluster Sampling Methodology was used to select the Census Blocks’ households were the survey was conducted. The inclusion criterion was to select the Census Blocks with 10 or more occupied household units. Figure 5 shows the selected Census Blocks for Playa Playita. Only 28 Blocks had 10 or more occupied household units.

The intended sample interviews were equally distributed among the communities, each community with 10 interviews. For each community a list with the selected Census Blocks was created and sorted by the percentage of the households that were occupied by the household’s owner. The 10 interviews per community were distributed according to the following criteria:

• If the selected blocks for a community have at least 10 Census Blocks with 10 or more occupied house units then one interview would be conducted in each of the top 10 selected Census Blocks based on the percentage of owner occupied household unit.

• In the communities were the selected Census Blocks were less than 10, then two interviews would be assigned to the Blocks with the higher percentage of owner occupied household unit until the 10 interviews were allocated.

Figure X show the Blocks where the survey was conducted. These blocks were the top 10 Blocks of Playa Playita Community with more than 10 occupied house units and with the highest percentage of owners occupied house units.

Once the number of interviews where distributed among the selected blocks, Google Earth’s .kml files were created with the respective Blocks maps so the interviewers could use them as a reference to conduct the interviews in that particular area or sector of the communities.”

The Coastal Residents’ Households Structured Questionnaire consisted of 5: parts 1) Demographics, 2) Respondent and household patterns of consumption and use of local CRs, including participation in activities related to the processing and marketing of CRs, 3) Variation in dimensions of QoL/WB identified from ethnographic research and literature (e.g. job satisfaction, life satisfaction, life domain weighted importance) 4) Open-ended questions about CR use and quality of life.

Workshops and Meetings with Community Members

We conducted and participated in two meeting with coastal community members, one in June of 2010 and one in July 2011. During part of our ethnographic fieldwork we developed a working relationship with local environmental and social organizations (IDEBAJO and Cambio Ambiental), and we identified their regular meetings as a useful venue to reach a broad sector of the local coastal communities. The two times we participated in the meetings, we also invited

other community members that we identified as representing important stakeholders. During the meetings we engaged in both sharing information with the groups, as well as in gathering further ethnographic data.

The in June 2010 meeting, conducted in the Jobos Bay NERR, we shared our research approach and objectives with the a group that included local fishers, community organizers, youth, ecotourism venture operators, and environmental activists. Their feedback was very valuable an led us to very productive explorations of CR and QoL/WB linkages. In the July 2011 meeting, we shared our (up to that date) research results and solicited participants opinions and feedback, which was a key step in the verification and refinement of our research definitions and hypotheses. A third workshop in which one or more of the research team’s members will share the final results and establish plans for the regional dissemination of the project’s data will take place in January 2014.

Participating and linking/coordinating our activities with community organizations became a key component of our ethnographic fieldwork, and some of the most important insights about the value and importance of CR use in the region (for example, the links between CR use and reduced criminal activity in the region) came from our participant observation with these community organizations. We have actively cooperated in the environmental conservation agenda of these organizations by sharing out data about the importance of CRs for local economies.

Simulation Modeling

Based on the data and data relationships identified during the various phases of this study, we are at the time of this report preparing and conducting simulation modeling of the trade-offs in community and household QoL/WB effects of different policy-scenarios of coastal use in the region. The main unit of modeling is at the coastal household level: thus we are using an actorbased or agent-based modeling approach using Simile (Simulistics 2012) and Netlogo (Wilensky 1999) software.

An important characteristic of our approach to modeling is that it is ethnography-based: that is, we are using the insights from our mixed-methods ethnographic activities to 1) formulate the algorithms used for calculating Qol/WB levels and changes, 2) define the domains of QoL/WB used in modeling and the effects of levels of access to CRs in these domains, and 3) define the relative weights of these domains, for different types of coastal residents as they relate to overall QoL/WB. The algorithms, domains, and weights themselves are results of the research activities, thus they will be described in later sections of this report.

Research Objectives and Results

The original objectives of this research were as follows:

1. To map small-scale coastal resource use in the municipalities of Salinas, Guayama, Arroyo, and Patillas, Puerto Rico.

2. To develop culturally-valid measures of WB/QoL and comunity resilience for the study region.

3. To study the (commercial and non-commercial) harvest-to-consumer movement of local CRs and derived products through social networks.

4. To assess the role of CRs in household economic histories with emphasis on CR use impact on resilience and mitigating economic and environmental uncertainty.

5. To survey the extent to which coastal Puerto Ricans in the study region participate inand benefit from- local small-scale CR harvesting and production.

6. To use modeling and scenario simulation techniques to test hypotheses about the impact of small-scale CR use on coastal communities and beyond.

7. To organize and conduct two multi-sector workshops about the importance of small-scale coastal resource use for Puerto Ricans' well-being, quality of life, and resilience.

As detailed in the section Methodology above, a variety of methods of analysis were applied to the different types of collected data, with the goal of achieving multi-layered convergent validity for our increased understanding of QoL/WB and resource use in the region. Data to fulfill the different objectives were gathered sometimes simultaneously, sometimes separately, during the different stages in the research process. This is different from other scientific research designs in which specific, separate procedures are used to gather data for specific objectives. Thus in the interest of brevity and readability the objectives discussion below will focus on identifying important results reached by applying the methods discussed in this paragraph.

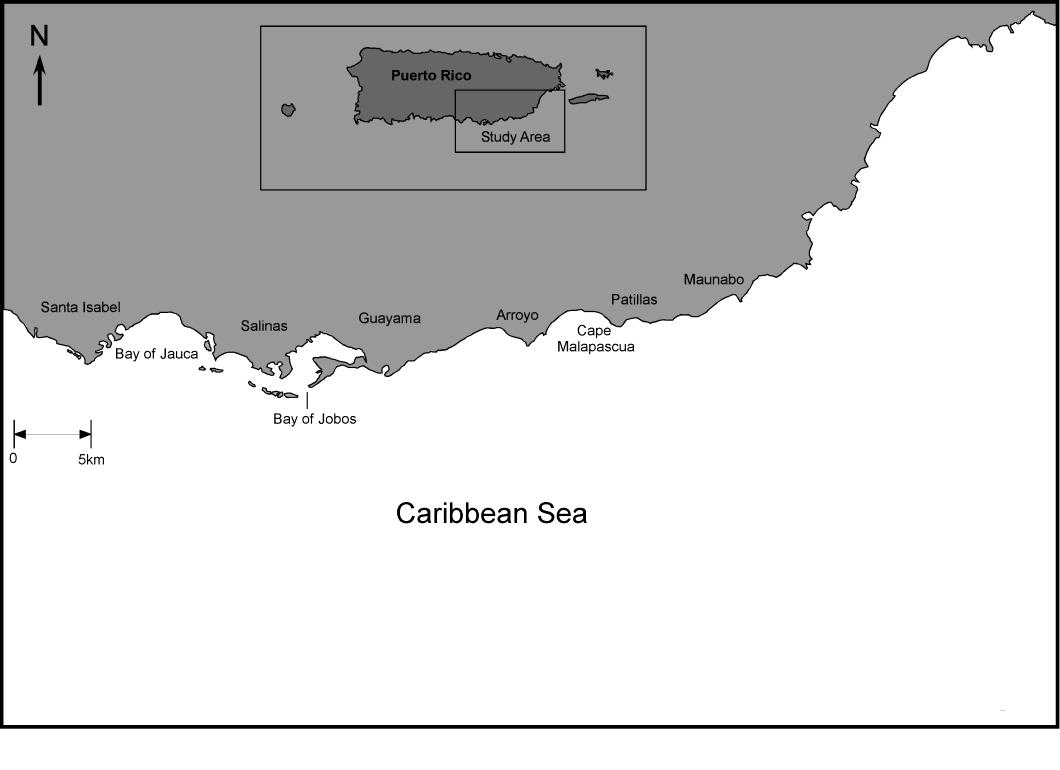

Physical and political geography

Puerto Rico is about 60 by 165 km, with an area of 9,104 km2 and 501 km of coastline (Cadilla 1988). Most people in Puerto Rico reside along the coastal plains. Our study regions, Coastal SE PR, is composed of the municipalities of (from East to West along the southern Coast of Puerto Rico) Patillas, Arroyo, Guayama, and Salinas. Politically, socially, and physically, SE PR can be called a coherent “region” of Puerto Rico’s Coast. An unifying characteristic of SE PR is being an ecologically rich and productive coastline that is also rural, relatively undeveloped with the accompanying lack formal economy opportunities and chronic unemployment that between 2000 and 2013 has hovered around 22-24% for the region, compared with between 12-17% for Puerto Rico as a whole (García-Quijano 2006, PR DTOP 2013). This is a key feature of the historical and continuing patterns of CR use and dependence as an economic strategy.

Physically, the SE PR coast is “a low-lying alluvial plain with a coastline either of beach plain or of mangrove, and wave erosion where alluvial cliffs form the coast eastward” (Morelock, Ramírez and Barreto 2002:5). The plain was formed by an extensive alluvial fan that extends from the mountain ranges to the north (Morelock, Ramírez and Barreto 2002). The plain extends from West to East until volcanic rocks from the Cuchilla de la Pandura mountain range reach the coastline. As with most coastal plains around Puerto Rico, much of the original flora has been removed to make room for coastal agriculture (specially sugarcane) and coastal development. More than 50% of this coast is suffering erosion (Morelock, Ramírez and Barreto 2002; JOBANERR 2002). This erosion is a major cause of marine ecosystem degradation through sedimentation of estuaries and coral reefs (Cambers 1998).

The three principal types of coastline that are found in Puerto Rico: rocky cliff and headlands, mangrove shoreline, and sand/gravel beaches are found interspersed throughout the study region.

Between Salinas and Guayama there are extensive mangrove forests, including the Bay of Jobos, site of the JOBANERR National Estuarine Research Reserve (NOAA) an important collaborating institution for this research project. Small mangrove islands, called Cayos (Keys), with associated fringing and patch reefs are found close to shore from Santa Isabel to Guayama. From Punta Las Mareas in Guayama eastward the coast is dominantly the result of wave erosion of the alluvial plain (Morelock 1978). Betweeen Arroyo and Punta Viento in Patillas, the coastline is predominantly beach-associated alluvial plain interspersed with mangrove shoreline and small estuaries.

Estuaries occur throughout the region, including the second-largest estuary in Puerto Rico, the Bay of Jobos. The estuarine zones of the region are important sources of nutrients for local marine life and are important nurseries and refuges for marine fish, mollusks, crustaceans, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Fringing reefs, patch reefs, and small barrier reefs occur at varied distances from the shore and throughout the area (JOBANERR 2002). These coral reefs, along with the Cayos, or mangrove islands, Thallassia sp. and Syrygodium sp. seagrass prairies, sand flats and muddy bottom areas make up a complex and productive underwater environment. The continental shelf (where most small-scale fishing in Puerto Rico occurs) is fairly wide by Puerto Rico standards (between 11-13 miles) south of Santa Isabel, Salinas, and Guayama, narrowing down from West to East until it gets as close as 1 mile to the shore near the coast of Patillas (Morelock 1978).

Table 3. Puerto Rican municipalities in this study’s area

Municipality Population (2010 United States Census)

Arroyo 19575

Guayama 45362

Patillas 19277

Salinas 31078

Coastal Communities Included in this Study

Pueblo de Arroyo (Arizona, Palmar, Callejon del Pescao)

Barrancas, Pozuelo, Jobos and surroundings

El Bajo and Guardarraya

Aguirre and surroundings, Playa, Playita

Descriptions of Coastal Communities

The following Descriptions of Coastal Communities are condensed and updated (through our cultural mapping activities) versions of community descriptions and profiles done by PI GarcíaQuijano as part of previous work in SE PR (Garcia-Quijano 2006), and as part of a Puerto Ricowide fishing community profiling research project (Griffith et al. 2007; 2012).

Arroyo

Arroyo was part of Guayama until 1855 (Toro-Sugrañes 1995). Arroyo’s commercial fishers landed approximately 45 thousand pounds of fish in between 2002-2003, worth more than 100 thousand dollars (Griffith et al. 2007; NOAA Fisheries). Unemployment in 2013 is reported at 24.9% (PR DTOP 2013). Arroyo was the most important seaport in the Southeast Coast until the early 20th century. Central Lafayette was a sugarcane mill that, along with the port of Arroyo, dominated economic life in this municipality (Lloréns 2005).

Arroyo Playa

The port of Arroyo is adjacent to the waterfront, and consists of a small embayment protected by a breakwater, about 30 small-boat slots used mostly by fishers. Arroyo has an active group of small-scale fishers, and pescadores de monte. There is a politically and socially active fishers’ association (Asociación de Pescadores Coral Marine), as well as at least two groups of loosely associated independent fishers. Coral Marine recently opened a restaurant to add value to their

catch by selling it cooked and prepared. Arroyo has a beautiful waterfront that Arroyanos take great pride on and which, with political and economic ebbs and flows, fluctuates from a bustling social center and to quiet or even depressed, with fishes and their activities being a constant presence over the years. There is a active commercial scuba shop near the waterfront where divers fill their tanks and which serves as a social meeting place for some groups of fishers. The waterfront in general during weekdays is a fisher meeting and socializing area, and we observed groups of fishers of various ages, including retired fishers meeting there on weekdays.

The coastal forests to the East of the port, specially the plain known locally as “Mar del Sur”, are reported to be used extensively by “Pescadores de Monte” for land crabs, coconuts, and other resources. Commercial fishers from Arroyo routinely fish a wide area along the southeastern coast, but the extensive seagrass shallows and some fringing reefs located 2-3 miles offshore between Guayama and Arroyo appear to be a preferred area.

Guayama