remote sensing

Article

ElevationRegimesModulatedtheResponsesofCanopy StructureofCoastalMangroveForeststoHurricaneDamage

QiongGaoandMeiYu*

Citation: Gao,Q.;Yu,M.Elevation RegimesModulatedtheResponsesof CanopyStructureofCoastal MangroveForeststoHurricane Damage. RemoteSens. 2022, 14,1497. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14061497

AcademicEditor:ChandraGiri

Received:9February2022

Accepted:18March2022

Published:20March2022

Publisher’sNote: MDPIstaysneutral withregardtojurisdictionalclaimsin publishedmapsandinstitutionalaffiliations.

Copyright: ©2022bytheauthors. LicenseeMDPI,Basel,Switzerland. Thisarticleisanopenaccessarticle distributedunderthetermsand conditionsoftheCreativeCommons Attribution(CCBY)license(https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ 4.0/).

DepartmentofEnvironmentalSciences,UniversityofPuertoRico,RioPiedras,SanJuan,PR00926,USA; q.gao@ites.upr.edu

* Correspondence:meiyu@ites.upr.edu

Abstract: Mangroveforestshaveuniqueecosystemfunctionsandservices,yetthecoastalmangroves intropicsareoftendisturbedbytropicalcyclones.HurricaneMariasweptPuertoRicoandnearby CaribbeanislandsinSeptember2017andcausedtremendousdamagetothecoastalmangrove systems.Understandingthevulnerabilityandresistanceofmangroveforeststodisturbancesis pivotalforfuturerestorationandconservation.Inthisstudy,weusedLiDARpointcloudstoderive thecanopyheightoffivemajormangroveforests,includingtruemangrovesandmangroveassociates, alongthecoastofPuertoRicobeforeandafterthehurricanes,whichallowedustodetectthe spatialvariationsofcanopyheightreduction.Wethenspatiallyregressedthepre-hurricanecanopy heightandthecanopyheightreductiononbiophysicalfactorssuchastheelevation,thedistance torivers/canalswithinandnearby,thedistancetocoast,treedensity,andcanopyunevenness. Theanalysesresultedinthefollowingfindings.Thepre-hurricanecanopyheightincreasedwith elevationwhenelevationwaslowandmoderatebutdecreasedwithelevationwhenelevationwas high.Thecanopyheightreductionincreasedquadraticallywiththepre-hurricanecanopyheight,but decreasedwithelevationforthefoursitesdominatedbytruemangroves.ThesiteofPalmadelMar dominatedby Pterocarpus,amangroveassociate,experiencedthestrongestwind,andthecanopy heightreductionincreasedwithelevation.Thecanopyheightreductiondecreasedwiththedistance torivers/canalsonlyforsiteswithlowtomoderatemeanelevationof0.36–0.39m.Inadditiontothe hurricanewinds,therainfallduringhurricanesisanimportantfactorcausingcanopydamageby inundatingtheaerialroots.Insummary,thepre-hurricanecanopystructures,physicalenvironment, andexternalforcesbroughtbyhurricanesinterplayedtoaffectthevulnerabilityofcoastalmangroves tomajorhurricanes.

Keywords: urbanmangroves;LiDAR;canopystructure;hurricanedamage;Caribbean

1.Introduction

Growingundermultiplephysiologicalstresses,coastalmangrovespossessunique ecosystemfunctionstomaintainhighcarbonsequestration[1,2],topurifycoastalwater, tohostanumberofvertebrateandinvertebratespecies[3],tooffsetthesealevelrisevia verticalaccretion[4,5],andtoprotectsocietalpropertiesofcoastalcommunitiesduring tropicalstorms[6].However,thecanopiesofcoastalmangrovesarelikelytobeseverely damagedbytropicalstorms,thusgreatlyreducingthefunctionsofmangroveforests[7–9]. Understandingthevulnerabilityandresistanceofmangrovesunderstormdisturbanceis vitaltorestoreandtoconservecoastalwetlands.

Inadditiontothegreatwindspeedofstorms,severalbiophysicalfeaturesmay elucidatethevulnerabilityoftropicalforeststodisturbance;emergenttreesorhigher canopy,smallertreediameter,lowertreedensity,andlowersoil-rootanchoragemayincur morecanopydamage[10,11].Mangroveswithhighercanopytendtointerceptmorewind force,treeswithsmallerdimeterhaveasmallshearmodulus,alowertreedensitymakes thewindeasiertotraversethecanopy,andalowersoil-rootanchoragemakesthecoastal

foresteasiertofallorslantunderstormwind[11].Inaddition,stormsoftenbringagreat amountofrainfallandseawatersurge[12],whichmayfloodcoastalmangrovesand immersetheiraerialroots,andtheprolongedimmersionmayleadtodelayeddeathof mangrovetrees[13].

Canopyheight,stemdensity,andtreediameterarelikelytobeshapedbythephysical environment,aswellastropicalstorms[14].Formangrovesinthetropics,salinityisa majorlimitingfactorinmostcircumstances[15–17].Althoughmangroverootscanexclude andleavescanexcretevariableamountsofsalts,thecanopyheightwasfoundtodecrease withsoilsalinity,whichisaresultofinterplaybetweensaltbroughtbytheseatidesor groundwaterandthehydrologicalprocesses[18,19].Amplerainfall,overlandflow,and riverdischargemaycarrysaltawayordilutethesaltconcentrationinsoil,whereastides bringthesalttomangroveforest,andevapotranspirationremovesmostlypurewaterand letssaltaccumulatewithinthesoil.Hence,thesoilsalinitydependsonboththeclimate regionandthefrequencyoftides[20].Inadditiontosalinity,mangrovegrowthmayalso bethreatenedbydeficiencyofnutrients,whichdependsnotonlyontheparentmaterials andmineralization,butalsoonexternalsourcessuchasurbanprocesses.

Theimpactofhumanactivitiesmayalsoaffectthemangrovegrowthandthevulnerabilityduringtropicalstorms.Mostoftheworldpopulationlivesnearcoastsand oftencompeteforhabitatwithmangroves.Mangroveforestsandneighborhoodurban areasmaybeconnectedviaaerodynamicsandhydrology,andtheconnectionsviasewage canals/pipesprovidefreshwaterandnutrientstomangroveforests,thusaffectingtheir growth[21].Thisisespeciallyimportantforcoastalmangroveforestsinheavilypopulated islands,wheremangrovesareinclosedistancetourbancommunitiesandwerehistorically drainedforagricultureandurbandevelopment[22].

Theeffectsofsalinityandnutrientsonmangrovegrowthdependonthespeciessalt toleranceandnutrientbudget[15,23].Threemajorspeciesoftruemangroves[24]are foundonCaribbeanislands:redmangrove(Rhizophoramangle)withstiltrootsgrowing inthecoastalwater,blackmangrove(Avicenniagerminans)oftenfoundinshallowwater ormuddysoilwithpneumatophoresgrowingfromhorizontalcableroots,andwhite mangrove(Lagunculariaracemosa)growinginslightlydrierconditionsthanblackmangrove. Redandblackmangroveshaveahightolerancetosalt,whereaswhitemangroveshave moderatetolerance[15].Inadditiontotheabovetruemangrovespecies,therearemangrove associateswhichwereonceclassifiedasmangrovesinhistory[25].Buttonwoodmangrove (Conocarpuserectus)isoccasionallyfoundinrelativelydryspots,and Pterocarpusofficinalis as ahardwoodisalsofoundinbrackishwater.Thesespecieshaverelativelylowertolerance tosalinityandoftengrowtogetherwithtruemangroves.Therefore,whenwemention mangroveforests,weimplybothtruemangrovesandmangroveassociates.

Theimpactoftropicalstormsoncoastalmangrovescanbeassessedbygroundinventory,aswellasremotesensing[26,27].Groundinventoryisoftenlimitedbyscales[28]. Remotesensing,usingaerialphotosandsatellite-basedmultispectralimagesas2Dtools, isoftenlimitedtotheassessmentofgreennessandfallsshortintheassessmentofthe verticaldimension[7,29–31].AirborneLiDAR(lightdetectionandranging)providesan idealtooltomeasurethe3Dchangesinthemangrovecanopyatlandscapescales.A LiDARinstrumentonboardanaircraftemitsnear-infraredlaserbeamswhichhittheleaves, branches,trunks,andground,resultinginmultiplereturnsofthelaserbeams[32].The heightofthereturnsisrecordedbytheLiDARinstrumentsasameasurementofthetop andinternalcanopystructure.

TwomajorhurricanesinSeptember2017impactedtheCaribbeanregion,especially theislandofPuertoRico[7,33].HurricaneIrmapassedbyon6SeptemberasaCategory5, whileHurricaneMariatraversedPuertoRicoon20Septemberasahigh-endCategory4, whichresultedintremendousdamagetothecoastalmangroveecosystems.Treeswere defoliatedandstemswererupturedorslanted(photosinAppendix A),thuslargely reducingthecanopyheight.LiDAR-basedassessmentofthehurricanesdamageoncoastal mangrovesisvitaltounderstandtheirvulnerabilityatlandscapescales.Theapplication

ofLiDARdatatothelargestbasinmangrovesinPuertoRicoshowedthatelevation,tree density,anddistancetofreshwaterorsewagecanalsareimportanttoexplainthespatial variationsofthepre-hurricanecanopyheight,aswellasthecanopyheightreductionby thehurricanes[34].However,itisunknownwhetherthesefindingscanbegeneralizedto themangrovesofvarioustypeswithdiverseenvironmentalsettings.

Theobjectiveofthisstudywastoexplorethespatialvariationofthepre-hurricane canopystructureofmultiplemangroveforestsalongthePuertoRicocoast,aswellasthe damagetothecanopyduetothemajorhurricanesin2017.Wehypothesizedthatthe pre-hurricanecanopyheightofcoastalmangroveforestsisafunctionofthetopography, thedistancetotherivers/canalswithinandnearby,andthedistancetothecoast,asthese variablesmaymodifythehydrology,salinity,andnutrientsupply.Wealsohypothesized thatthecanopyheightreductionbyhurricanesisalsoafunctionoftheabovefactors,but moreimportantlydeterminedbythepre-hurricanecanopystructure.

2.MaterialsandMethods

2.1.SiteDescription

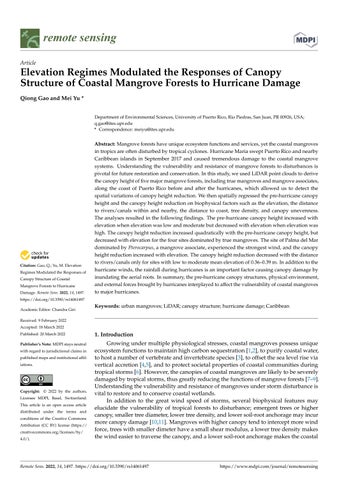

PuertoRicoliestotheeastendoftheGreatAntillesislands(Figure 1,upperpanel) withacentrallatitudeof18.22◦N.RainfallinPuertoRicovariesgreatlyfrom~1000mmin thesouthwestto~4000mmintheeastmountainpeak,whichshieldstherainfallbrought bytheeasterlytradewinds.Ingeneral,thenorthernandeasterncoastsreceivemore rainfallthanthesouthernandwesterncoasts.Amplerainfallonthenorthcoasttends toproducemorestreamdischargeandoverlandflowthanthesouthcoast,whichdilute thesalinity.Thedifferencebetweenthenorthernandsoutherncoastsalsoarisesfrom bathymetry.ThenortherncoastisboundedbytheAtlanticOceanwiththedeepesttrench, whereasthesoutherncoastfacesthemuchshallowerCaribbeanSea.Thus,thetidalenergy onthenortherncoastishigherthanthatonthesoutherncoast.Theconsequenceisthatthe northerncoasthasdevelopedmoreandlargefluvialplainsandsandybeachesthanthe southerncoast.Basinandriverinemangroveforestsaremostlyfoundonthenortherncoast, whereasfringeandover-washedmangroveforestsareusuallyfoundonthesoutherncoast. Historically,PuertoRicooncehadabout11,000haofmangrovesin1800s,whichdeclined toabout6000hain1960sduetotheexpansionofagricultureandurbandevelopment[22]. Theconservationofwetlandsguidedbyinternationalandnationallawsledtotherecovery toabout8000hainlarge,aggregatedpatches[5,22,35,36].PuertoRicohasallthreetrue mangrovespecies,aswellasthemangroveassociates,foundintheCaribbean.

Thisstudyanalyzedfivemangroveforests,includingtruemangrovesandmangrove associates,alongthePuertoRicocoast,fourofwhichwereintheeastandnortheast,along withonesiteinthesouthwest(Figure 1,thelowerpanel).Thesesiteswereselectedmostly onthebasisofdataavailability.Thefoursitesintheeastandnortheast(PalmadelMar, Fajardo,CañoMartínPeña,andToaBaja)werealsoclosertothepathofHurricaneMaria thanLaParguerainthesouthwest.TheforestinPalmadelMarisdominatedby Pterocarpus officinalis,amangroveassociate,whereastheotherfouraredominatedbytruemangroves.

2.2.DataSource

Toinvestigatethespatialpatternsofthemangrovecanopyandtoassessthehurricanes damage,weusedairborneLiDARdataprovidedbytwocampaignsbeforeandafterthe hurricanes.InMarch2017,thecampaignofGoddard’sLiDAR,Hyperspectral,andThermal Imager(G-LiHT)[37]bytheNationalAeronauticsandSpaceAdministration(NASA) coveredanumberoftransectstripsinPuertoRico.AfterthehurricanesinSeptember 2017,USGSLiDARcampaignsin2018(https://nationalmap.gov/3DEP/,accessedon 15March2022)coveredmostoftheisland.Bothcampaignsprovideddataintheform ofpointclouds.Hence,theboundariesofthefivesiteswerederivedonthebasisofthe intersectionsofcoverageofG-LiHTandUSGSLiDARandtheforestedwetlanddelineated bytheNOAA2010C-CAP(CoastalChangeAnalysisProgram)land-covermap,andthen wereshrunkforsimplicity[38].TheLiDARdataoftheG-LiHTtransects(Table 1)were

usedtoderivethecanopyheightbeforethehurricanes,whichwehereafterrefertoas the‘pre-hurricanecanopyheight’,whiletheUSGSdatawereusedtoderivethecanopy heightafterthehurricanes(Table 1),whichwehereafterrefertoasthe‘post-hurricane canopyheight’.ForG-LiHTdata,thenormalpointspacingofthepointcloudis0.24m withhorizontalandverticalaccuraciesof1m(https://glihtdata.gsfc.nasa.gov/,accessed on15March2022),whereasthenormalpointspacing,verticalaccuracy,andhorizontal accuracyofUSGSLiDARpointcloudare0.34,0.1,and1m,respectively.

Figure1. PuertoRicogeographicallocation(up)andlocationoffivesitesalongitscoast(low).Red andbluelinesdepictthepathsofHurricaneMariaandHurricaneIrma,respectively.

Table1. Pre-andpost-hurricaneLiDARpoint-cloudimagesprovidedbytheNASAG-LiHTandthe USGS3DElevationProgram.

SitePre-HurricaneGLiHTTransectsPost-HurricaneUSGSTiles

CañoMartínPeñaPR_10March2017_118

E_2018_19QHA37506600, E_2018_19QHA39006600 FajardoPR_15March2017_75

PalmadelMar

PR_12March2017_58a, PR_12March2017_58b

H_2018_20QKF81005700, H_2018_20QKF81005850

H_2018_20QKF66002850, H_2018_20QKF67502700, H_2018_20QKF67502850

LaPargueraPR_8March2017_114A_2018_19QFV28001200

ToaBaja

PR_10March2017_117, PR_17March2017_199

G_2018_19QGA22506750, G_2018_19QGA22506900, G_2018_19QGA24006900, G_2018_19QGA25506900

EachG-LiHTtransectconsistsofafewtiles,andeachtileisapproximately80mby 500m;onlythosetileswithinthesiteswereanalyzed.TheUSGSLiDARtilesforthe post-hurricaneanalysesarealsolistedinTable 1.InadditiontotheLiDARpointclouds, weusedthedigitalelevationmodel(DEM)of1mresolutionprovidedbytheUSGS3D

ElevationProgram(https://www.usgs.gov/3d-elevation-program,accessedon15March 2022),whichhasaverticalaccuracyof10cm(RMSEz,RootMeanSquareErrorinz).

2.3.AnalysisofPre-HurricaneCanopyHeightandCanopyHeightReductionbytheHurricanes Mangroveforestcanopieswerederivedasfollows:WefirstclippedtheLiDARtiles accordingtotheboundaryofeachsite.Thecanopyheightbeforeandafterthehurricanes werederivedat1mresolutionfromtheG-LiHTandUSGSpointclouds,respectively,using thegrid_canopy()andnormalize_height()functionsprovidedbythe‘lidR’packageversion 3.1.3[39].Tohelpexplainthecanopyheightreduction,wealsotriedtodetecttreesand treeheightsusingthefind_trees()functionusinglocalmaximumalgorithm.Thisalgorithm maynotbeabletoidentifysmalltreeswithcrownsoverlappingwiththeadjacenttrees. However,theparameterssetinapreviousstudyallowedustoverifythedensityderived againstagroundsurveyfortreeswithstemdiametergreaterthan10cm[34].Wenamedthe treedensityderivedusingthismethodas‘algorithm-derivedtreedensity’.Thereduction incanopyheightbyhurricaneswasfurthercomputedasthepre-hurricanecanopyheight minusthepost-hurricanecanopyheight.

Consideringthesalinityandnutrientavailabilitywhichareaffectedbytherivers,the freshwaterorsewagecanalswithinornearby,aswellasthecoastalwater,wecalculated thedistancetotherivers/canalsandthedistancetothecoastat1mresolution.Average gustwindspeedandhurricanerainfallforeachsitewereestimatedonthebasisofground measurementsandkriginginterpolations[31,40].

Totestourhypothesesandtoexplainthespatialvariationinpre-hurricanecanopy height,aswellasthecanopyheightreductionbythehurricanes,weappliedspatialregressiontomodeltheresponseofpre-hurricanecanopyheightandcanopyheightreduction totheabovementionedcovariatesforeachsite.Thespatialerrormodeltookthefollowingform:

y = xβ + u, u = λWu + ,(1) where y isthedependentvariablerepresentedasan n × 1matrix(n,numberofrecords inthedataset), x isoneormultiple(m)independentvariables(covariates)representedby an n × (m +1)matrix, β isan(m +1) × 1coefficientmatrixtobeestimated,and u isan n × 1 spatialerrormatrix. W isan n × n weightmatrixdeterminedbytheneighborhood structure, λ isthespatialautocorrelationcoefficient,and ε isthenormali.i.d.(independent andidenticallydistributed)residual.

Toapplythespatialerrormodel,allthespatialvariableswereaggregatedinto20m gridstoobtainthemeanquantities.Inaddition,wecomputedthestandarddeviationofthe pre-hurricanecanopyheightforthe20mgridtoreflecttheunevennessofthepre-hurricane canopyheight.Thevariablesat20mresolutionwerenormalizedintherangeof0to1,so thatwecouldcomparethecoefficientsestimatedbytheregressions.

Toexplorethespatialresponsesofthemangrovesacrosssites,wealsopooledthedata ofallsitesforthesamesetofspatialregression.Thiswasdonebysampling150gridcells of20m × 20mfromeachsiteinthreestratadefinedas0–33,33–67,and67–100percentiles ofthepre-hurricanecanopyheight.Thespatialregressionswerethenconductedforthe pooleddatasets.

Thecovariatesincludedintheregressionofthepre-hurricanecanopyheightwerethe elevation,thedistancetowithinornearbyrivers/canals,thedistancetocoastalsaltwater, andthealgorithm-derivedtreedensity.Theadditionalcovariatesfortheregressionofthe canopyheightreductionbythehurricaneswerethepre-hurricanecanopyheightandthe canopyroughness.Thepooledregressionalsoincorporatedthemeangustwindspeed andtotalrainfallduringthehurricanetoexplainthedifferenceacrosssites.Allthedata analysesandmappingweredonewithR[41]andArcGISPro(ESRI,Redlands,CA,USA).

3.Results

3.1.SpatialVariationandSummaryStatisticsoftheCanopyHeightsbeforeandafter theHurricanes

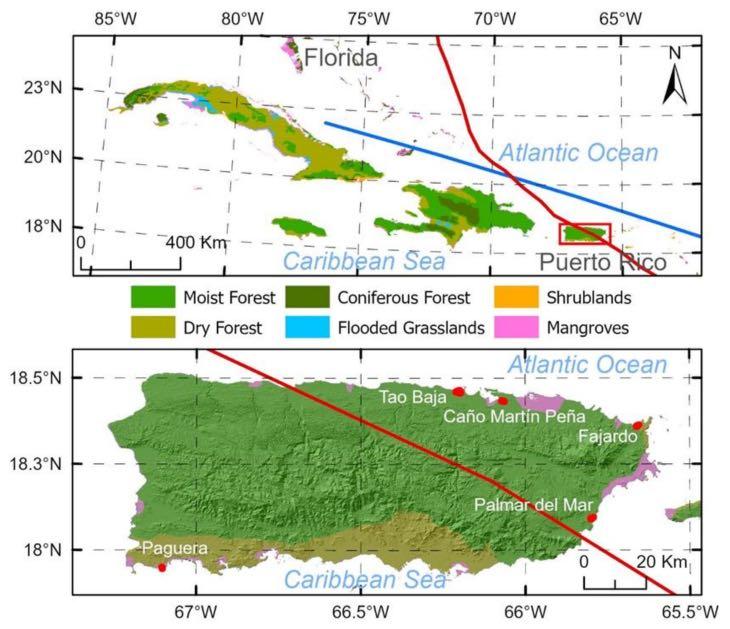

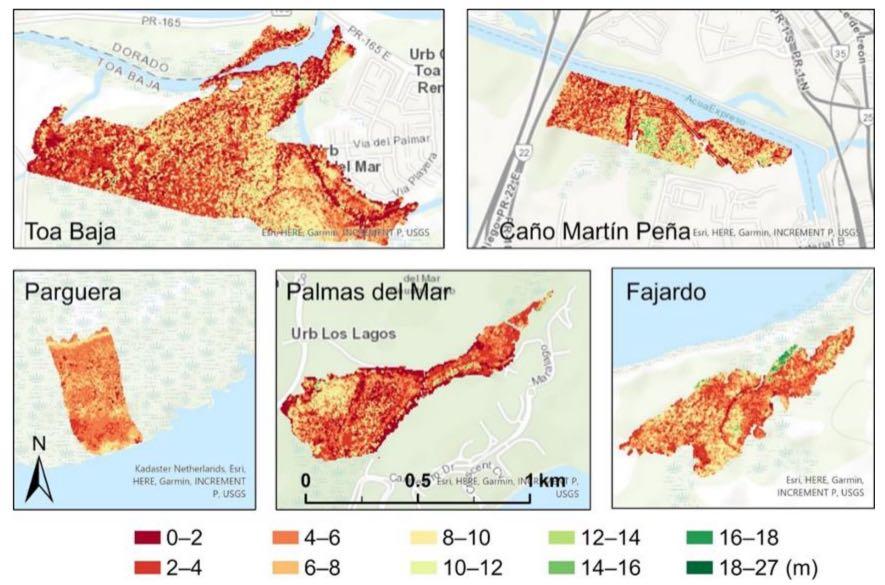

Elevationwasfoundtobethemostimportantenvironmentalvariableexplainingthe pre-hurricanecanopyheight,aswellasthecanopyheightreductionbythehurricanes[34]. Theelevationprofilesofthefiveforests(Figure 2,Table 2)showedgreatvariationsacross thesites.TheFajardositehadthehighestelevationwithamean ± SDof1.61 ± 1.07m, followedbyPalmaDelMarwith1.03 ± 0.38m.LaParguera(fringemangroves)inthe southwesthadthelowestelevationwithamean ± SDof0.16 ± 0.07m.CañoMartínPeña andToaBajahadmoderateelevationswithmeans ± SDof0.36 ± 0.32and0.39 ± 0.31m, respectively.

Figure2. DEMofthefivemangroveforests.Blueandlight-greenlinesdepictriversandcanalsof freshwater/sewage,respectively.

Table2. Summaryofthecanopyheightsbefore(CHM_2017)andafterthehurricanes(CHM_2018), canopyheightreduction,algorithm-derivedtreedensity,andthecovariatesofDEM,distanceto rivers/canalsandtocoast,andhurricanerainfallandgustwindbasedonthe20mgridmaps.

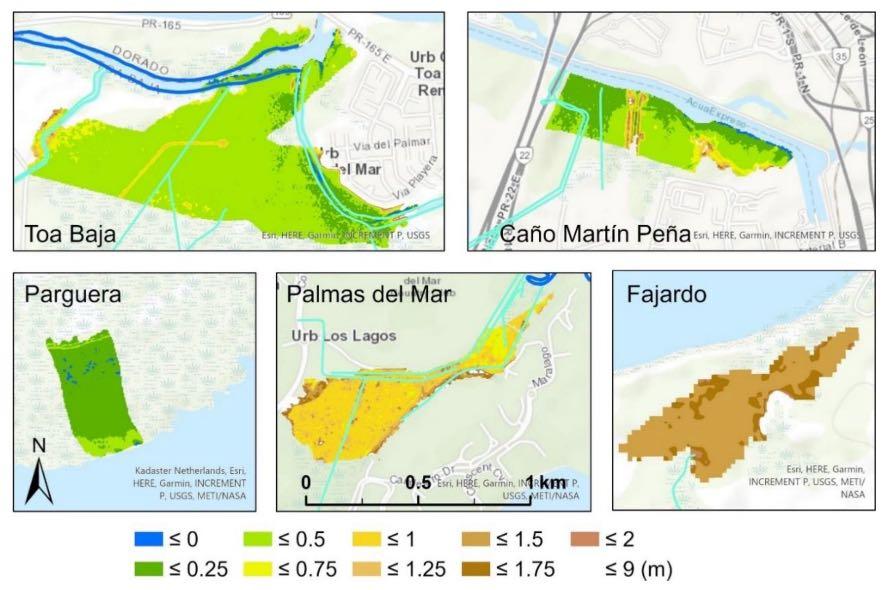

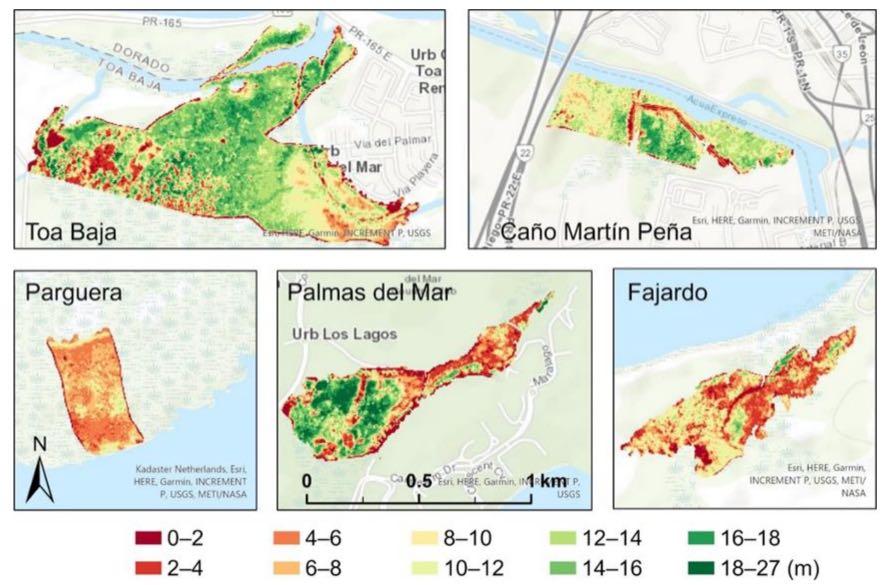

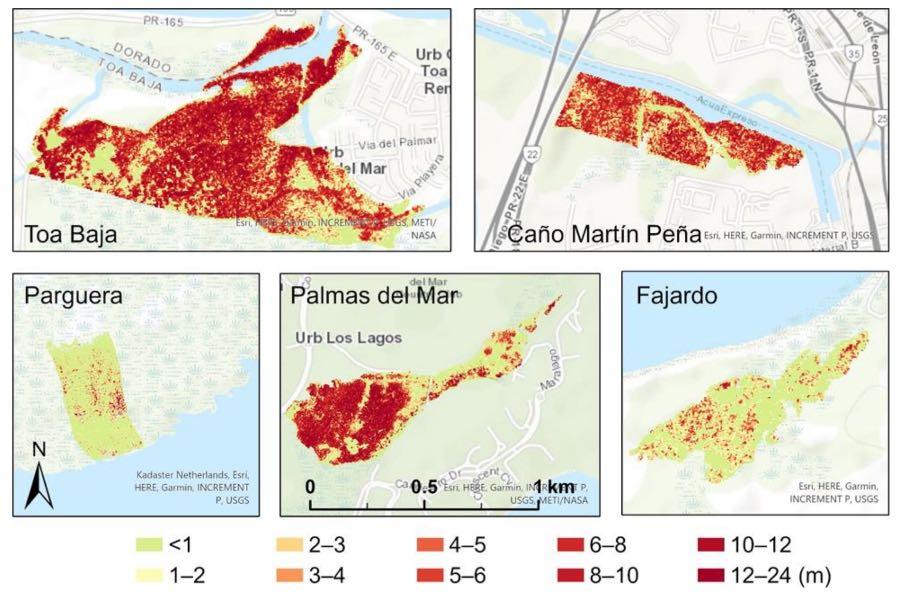

Thepre-hurricanecanopyheight(CHM_2017,Figure 3)showsthattherewerewide variationsinmangrovecanopyheightwithinandbetweensites(Table 2).Themeancanopy heightofCañoMartínPeña,PalmadelMar,andToaBajawereintherangeof9.3–11.7m, higherthanthatinFajardoandLaParguera(6.7and6.2m,respectively).Comparedto thepre-hurricanecanopyheight,themeanpost-hurricanecanopyheight(CHM_2018)was moreevenbothwithinandacrossthesites(Figures 3 and 4).Themeanheightvariedfrom 4.2minPalmadelMarto6.1minCañoMartínPeña.Wefoundapatternthatahigher pre-hurricanecanopyledtoagreaterreductionbythehurricanes(Figure 5).ToaBajawith thehighestmeanpre-hurricanecanopyshowedthegreatestreductionof6.1m,whereasLa Parguerawiththelowestpre-hurricanecanopyexperiencedthesmallestreductionof0.5m (Table 2).Themeanalgorithm-derivedpre-hurricanetreedensityreachedthegreatestlevel inCañoMartínPeñaandToaBaja(2135ha 1 and2132ha 1,respectively),butwaslower inLaPargueraandPalmadelMar(1674ha 1 and1682ha 1,respectively).

Figure3. Thepre-hurricanecanopyheight,derivedfromtheG-LiHTpoint-clouddata.

TheforestsinPalmadelMarandFajardoaretheclosesttorivers/canalswithmean distanceof57.8 ± 55.3and83.8 ± 60.8m(Table 2),respectively,whereastheforestin LaPargueradoesnothaveanyriversorcanalsnearbyandthenearestrivers/canalsare 948.1 ± 157.9m away.TheforestnearCañoMartínPeñahastheclosestmeandistanceto coastalwater(101.2m)becausewetreatedthewaterintheChannelofMartínPeñaassalty. The Pterocarpus forestinPalmadelMargrowsinwardtothelandandisconnectedtothe coastbychannelsandariver,suchthattheforesthasthefarthestmeandistancetothe coast(710.3m).Thegreatmeandistanceof516.9mtothecoastandthemediumdistance of341.5mtotheriver/canalsoftheToaBajaForestarelargelybecauseofitslargeareaof 71.1ha.

Windspeedandrainfallinterpolatedfromthegroundobservationsduringthehurricane[31,40]showedthatthemeangustwindspeedwasthehighestatPalmadelMar (49.5m s 1,Table 2),thesiteclosesttothelandfallofHurricaneMaria,whereasLaParguera inthesouthwestfarthestfromthehurricanepathhadthelowestmeangustwindspeed (34.1m s 1).Theotherthreesitesinbetweenalsohadgustspeedsofmorethan44m s 1 . Thehurricane-broughtrainfallshowedmorevariationacrosssitesthangustwindspeed.

ToaBajaandCañoMartínPeñaexperiencedthehighestrainfallof497.2and427.8mm, respectively,whereastheforestatLaParguerareceivedonly91.1mm.PalmadelMar,even closertothelandfallofMaria,onlyreceived286.5mmrainfall.

Figure4. Thepost-hurricanecanopyheight,derivedfromtheUSGSLiDARpointclouds.

Figure5. Canopyheightreductioncalculatedasthepre-hurricanecanopyheightminustheposthurricanecanopyheight.

3.2.SpatialRegressionModelsofthePre-HurricaneCanopyHeightandtheCanopyHeight ReductionbytheHurricanes

Thespatialregressionofthepre-hurricanecanopyheightyieldedequationswith significantcoefficientslistedinTable 3.Forexample,theequationforPalmadelMarwas

,(2)

where h isthenormalizedpre-hurricanecanopyheight, z isthenormalizedelevation, and d isthenormalizedalgorithm-derivedtreedensity.ForsymbolsinTable 3, sc isthe normalizeddistancetocoast,and λ isthespatialautocorrelationcoefficient.Thespatial errormodelforPalmadelMarhada λ of0.90and r2 of0.68.Exceptfortheforestin Fajardo,thepre-hurricanecanopyheightdependedsignificantlyontheelevation,butthis dependencedifferedacrosssites(Table 3).ForLaParguera,thepre-hurricanecanopy heightincreasedlinearlywithelevation.Similarly,thepre-hurricanecanopyheightofthe forestsinCañoMartínPeñaandToaBajaincreasedwithelevationwhenelevationwaslow, butthendecreasedwithelevationwhenelevationwashigherastheabsolutevalueofthe z2 coefficientwasgreaterthanthatof z.Thepre-hurricanecanopyheightofthesethree sitesalsosignificantlydecreasedwiththedistancetothecoast.Thepre-hurricanecanopy heightinPalmadelMardecreasedquadraticallywithelevation.

Table3. Spatialregressionofnormalizedpre-hurricanecanopyheight(h)onnormalizedcovariates. z,theelevation; d,thenormalizedalgorithm-derivedtreedensity; sc, thedistancetothecoast; λ,the spatialautocorrelationcoefficient; r2,thecoefficientofdetermination.Allcoefficientsweresignificant at α =0.05.

Thedependenceofthepre-hurricanecanopyheightonthealgorithm-derivedtree densitydifferedacrosssites;threesites(LaParguera,PalmadelMar,andFajardo)had pre-hurricanecanopyheightdecreaseswithdensity,whereasthepre-hurricanecanopy heightincreasedwithdensityinToaBaja.Thedensitywasnotasignificantexplanatorof thepre-hurricanecanopyheightinCañoMartínPeña.

TheequationsofthespatialerrormodelforthecanopyheightreductionwithsignificantcoefficientsareshowninTable 4 andcouldbeexpressedasfollowsfortheToa Bajasite:

where ∆h isthenormalizedcanopyheightreduction, sh isthenormalizedstandarddeviationofpre-hurricanecanopyheightwithinthe20mgrid,and s isthedistanceto rivers/canals.

Thecanopyheightreductionofallsitesincreasedlinearlyorquadraticallywiththe pre-hurricanecanopyheight(Table 4).ThereductionatallsitesexceptPalmadelMar decreasedquadraticallywiththeelevation.ForPalmadelMar,thecanopyheightreduction increasedwithelevationwherethe Pterocarpus forestoccupiedahigherelevationcompared toothersites.ThecanopyheightreductioninPalmadelMarandFajardowassignificantly cutbackbythehightreedensity,whilethatinToaBajawassignificantlypromotedbythe unevennessofthepre-hurricanecanopyheight(sh).ThecanopyheightreductionatToa BajaandCañoMartínPeñawasloweredbythedistancetotherivers/canalssuchthata fartherdistancefromrivers/canalsledtolesscanopyheightreduction.Thecanopyheight reductionatCañoMartínPeñawasalsocutbackbythedistancetothecoastwater.

Table4. Spatialregressionofnormalizedcanopyheightreduction(∆h)onnormalizedcovariates: h,pre-hurricanecanopyheight; z,elevation; d,algorithm-derivedtreedensity; sh,standarddeviationofpre-hurricanecanopyheight; s,distancetorivers/canals; sc,distancetocoast; λ,spatial autocorrelationcoefficient; r2,coefficientofdetermination.Allcoefficientsweresignificantat α =0.05.

Poolingthedataofallsites,wefoundthatthepooledpre-hurricanecanopyheight hadthefollowingequation:

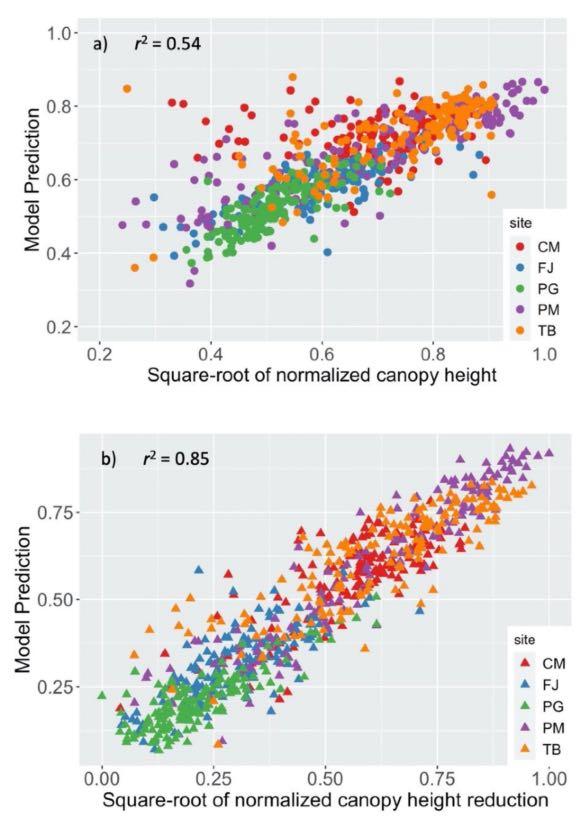

Hence,thepooledcanopyheightdecreasedquadraticallywiththeelevationand linearlywiththealgorithm-derivedtreedensityandthedistancetorivers/canals.The regressionhada λ of0.48and r2 of0.54.ThemodelfittothedataisshowninFigure 6a.

Figure6. (a)Model-predictedversusLiDAR-derivedpre-hurricanecanopyheight,and(b)modelpredictedversusLiDAR-derivedcanopyheightreduction.Codesforthefivesites:CM—CañoMartín Peña,FJ—Fajardo,PG—LaParguera,PM—PalmadelMar,TB—ToaBaja.

Theregressionofthepooledcanopyheightreductionresultedin

where p isthenormalizedrainfall,and w isthenormalizedgustwindspeed.Theregression hada λ as0.51and r2 as0.85.Hence,theprevailingpatternacrossthefivesitesisthatthe canopyheightreductionincreasedwiththepre-hurricanecanopyheightbutdecreased withelevation.Largerainfallandgustspeedincurredmorecanopyheightreduction; however,theimpactofthewindspeedwasgreaterthanthatofrainfallasindicatedbythe biggercoefficientbeforewindspeed.ThemodelpredictionversusLiDAR-derivedcanopy heightreductionisdepictedinFigure 6b.

4.Discussion

4.1.CanopyHeightbeforeHurricanes

Ouranalysessupportedourhypothesisthatthecanopyheightreductionsignificantly dependsonthepre-hurricanecanopyheight,asahighercanopybeforehurricanesmeans moreinterceptionofthewindforcetodamagethecanopy[42,43].Theeffectofprehurricanecanopyheighthasbeenidentifiedastheprimaryparameterinseveralmodels thatsimulatetheriskofwinddamagetoforeststands.

Thedependenceofthecanopyheightreductiononthepre-hurricanecanopyheight wasquadratic,ratherthanlinear,whichimpliesthattheslopedecreasedastheprehurricanecanopyheightincreased.Moreover,thepre-hurricanecanopyheightwasthe mostimportantfactordeterminingthehurricanedamagetomangroveforestasthecoefficientsofthenormalizedcanopyheightintheequations(Table 4,Equation(5))werelargest comparedtootherfactors.

4.2.Elevation

Ouranalysesbothatasitelevelandacrosssitesusingpooleddatasupportedourhypothesisthatboththepre-hurricanemangrovecanopyheightandthecanopyheightreductionbythehurricanesdependonelevation,butonlypartlyonthedistancetorivers/canals andthedistancetocoast.Theresponsesofcanopyheightandthecanopyheightreduction toelevationanddistancetorivers/canalsandcoastwaterdependedheavilyontheregimes ofthesevariables.

Theresponsesofthepre-hurricanecanopyheightofToaBajaandCañoMartínPeña toelevationweresimilar(Table 3)asthesetwositeshadthesameelevationregimewitha meanelevationintherangeof0.36~0.39m(Table 2).Thequadraticfeatureimpliesthatthe pre-hurricanecanopyheightincreasedwithelevationwhenelevationwaslowerandthen decreasedwithelevationatahigherelevationrange.Themaximumpre-hurricanecanopy heightoccurredatamoderateelevationaround1maccordingtoourmodelanddata.The placeswithlowestelevationwereclosertothecoastwithredmangrove.Aselevation wentfromlowtomoderate,thespeciesshiftedtoblackorwhitemangroves.Aselevation continuedtoincreasebeyondthemoderaterange,thefreshwatersupplydecreasedand salinityincreased[44,45],therebydecreasingthepre-hurricanecanopyheight.Itseemsthat thispatterncanbeextrapolatedacrosssiteswithdifferentelevationregimes.LaParguera hadthelowestelevationrangewithameanof0.16mandmaximumof0.2m,suchthatthe pre-hurricanecanopyheightincreasedwithelevation.The Pterocarpus growinginbrackish wateratPalmadelMarhadameanelevationgreaterthan1msuchthatthepre-hurricane canopyheightdecreasedwiththeelevation.

ThecanopyheightreductionofallsitesexceptPalmadelMardecreasedwithelevationmostlybecausetheareaswithlowerelevationweremuddierandthestemsofthe mangroveswereeasiertofalldownorbeslantedbythewind[11].Inaddition,thelower elevationwasmorelikelytobeinundatedtocauseadditionaldamage[13].Whenelevation increased,thelowerpre-hurricanecanopyheightandthestrongerroot-soilanchorage allowedthesystemtoresistandreducethewinddamagetothecanopy.TheforestatPalma

delMarhadgreaterthan1mmeanelevationandwasclosesttotherivers/canals(Table 2), whichbothhelpedtodrainthehurricanewaterand,thus,reducedtheriskofprolonged inundation.However,thissitewasclosesttothehurricanelandingpointandexperienced thestrongestgustwind.Withtheincreaseinelevation,thedominant Pterocarpus withhigh canopywasexposedtostrongerwindand,thus,sufferedmoredamage.

4.3.DistancetoRivers/CanalsandtoCoast

Riversandcanalssupplyfreshwater,andcanalsofsewagepurposesdelivernutrients andfreshwatertothemangroveecosystemstoalleviatethesalinityandnutrientstresses, especiallyforplaceswithlowelevation.Ouranalysissupportedthehypothesisthatthe pre-hurricanecanopyheightandthecanopyheightreductiondecreasewiththedistance torivers/canals.However,thishypothesiswasonlyapplicabletopre-hurricanecanopy heightwithpooleddataandtothecanopyheightreductionatsiteswithmoderateelevation. LaParguerahadthelowestelevation,butnoriversorcanalspassingthrough,andthe nearestcanalswereabout1kmaway.ForFajardoandPalmadelMar,theelevationregimes weretoohightoretainthefreshwaterandnutrientsderivedbytherivers/canals.Hence, thedistancetorivers/canalsdidnotappearsignificantintheequationsforthesethreesites. Thedistancetorivers/canalsonlyappearedintheequationsforToaBajaandCañoMartín Peña,wheretheelevationrangewaslowtomoderate.Furthermore,themeandistances torivers/canalsareinthemoderaterange,andwithin-sitevariationsofthedistanceto rivers/canalswerethegreatestatthesetwosites(Table 2).Itseemsthattheconditions forthedistancetorivers/canalstocomeintoplayareatleastlowormoderateelevation andlargewithin-sitevariationofthedistancetorivers/canals.Theseconditionsdidnot concurrentlyexistforothersites.

Ourequationsshowthatareaswithashorterdistancetorivers/canalswereassociatedwithhigherpre-hurricanecanopy(Equation(4))andmorecanopyheightreduction (Table 4).Soilsnearrivers/canalsmaybeassociatedwithlowersalinityorbetternutrient status,whichnotonlysupportbettermangrovegrowth,butalsochangetheallocation pattern [4,46–48].Thechangedallocationpatternwouldincreasetheshoot/rootratioso thatthemangroveswouldinterceptmorewindforceduringhurricanesbuthaveless soil-rootanchorage.Theconsequenceisthatthetreeswouldbeeasiertofallortoslant. Thebetternutrientsupplymayalsochangetheleaftraitsofplantssuchthattheleaves maygrowthinner.Thinnerleavesareeasiertobetornbyhurricanewinds,thusincurring moredefoliation[49].Thefloodingmapdetectedfromradarimagesshowedgreaterinundationalongtherivers/canals(unpublisheddata).Thesefactsexplainwhytheareaswith closerdistancetorivers/canalssufferedmorecanopyheightreduction,whereasthosewith fartherdistancewereassociatedwithlesscanopyheightreduction.

Thedistancetocoastmaybeassociatedwiththeelevationandsalinitygradients.For coastalwetlandswithriverinemangroves,thesalinitygenerallyincreaseswiththedistance tothecoast[44,50].Thehighersalinityatfartherdistancesallowsmorerootgrowththan shootgrowthtoresistwinddamage.Thefartherdistancetothecoastwasalsoassociated withlowerpre-hurricanecanopyheightinCañoMartínPeña,ToaBaja,andLaParguera, aswellaslowercanopyheightreductioninCañoMartínPeña.Inaddition,placeswith fartherdistancetothecoastmaybelesspronetoinundationfromstormsurges.

4.4.TreeDensityandUnevennessofCanopy

Thealgorithm-derivedtreedensityappearedintheequationsforPalmadelMarand Fajardotoalleviatethecanopyheightreduction.However,therelationshipbetweenthe pre-canopyheightandthetreedensitywasnotconsistentacrossallsites.Largerandtaller treesmaybeassociatedwithlowertreedensityduetoself-thinning.However,highertree densitymayalsomakethetreesgrowtallertocompeteforlightsothathighercanopy heightmaybeassociatedhighertreedensityormaynotbesignificantlyrelatedtothetree density[11].

Treedensityhasbeenidentifiedasafactorthatmodulatesthewinddamagetoforests inseveralstudies:Treesgrowingtogethercansupporteachothermechanically[8]by increasingtheinteractionamongneighboringtreesthroughfrictionofleavesandbranches indissipatingthewindenergy.Hightreedensityisespeciallyimportantformangroves withlowstemdiameters.Theoreticalandpracticalstudiesofwindbreaksystemshave indicatedthatdensityisoneofthemajorparametersforeffectivewindreduction[51].On theotherhand,forestswithlowertreedensityoftenexperiencemoredeadtreesandbent trunksaftermajorhurricanes[52].AhybridmodelofForestGalesdevelopedforsimulation ofwinddamageriskofforestsusedaseriesofimportantparametersincludingspacing amongtrees,whichistheinverseofthetreedensity.Thesensitivityanalysisfoundthat thecriticalwindspeedofstemruptureisinverselyproportionaltotheaveragespacing amongtreessothathigherwindspeedisneededtorupturecloselyspaced(highdensity) trees[10,53].

Acloselyrelatedconceptistheunevennessofthecanopy,whichappearedinour equationforToaBajatoenlargethecanopyheightreduction(Table 4).Boundary-layer theoryindicatesthatroughsurfacesassociatedwithunevennessofcanopiescanmakethe boundarythinnertofacilitateverticalconvections[54]suchthatthewindcanmoreeasily traversetheforestcanopyandcausemoredamage.Unevennessofcanopyheightisalso relatedtothetreedensity.Inadditiontotheheterogeneoussalinity/nutrientconditionsand thecompetitionamongtreesthatgivesdifferentcanopygrowth,thespatialheterogeneity oftreedensityislikelytocreatetheunevennessofthecanopyaslowtreedensitiesare likelyassociatedwithgapsinthecanopytoincreasetheunevennessofthecanopyheight.

4.5.HurricaneWindsandRainfall

Hurricanewindisthemostimportantforcedamagingthecanopy.TheforestatPalmar delMarexperiencedthestrongestgustwindandconsequentlyencounteredthemostsevere canopydamage,i.e.,55%relativecanopyheightreduction(Table 2).Inaddition,forthe coastalmangrovesdistributedinalowelevationprofileand,thus,susceptibletovarious floodingdrivers(coastalsurge,fluvial,orpluvial),rainfallduringthehurricanesappeared tobeanimportantdriverofcanopyheightreduction(Equation(5)).Thedrainagecapacity ofmangroveecosystemscan,thus,playanimportantroleinrainfall-driveninundation. Ourongoingworkonradar-detectedinundationshowedinundationsalongthecoast, alongtherivers/canals,andinlow-lyingareasafterthehurricanewhichlastedaround 10days.TheforestsatCañoMartínPeñaandToaBajaexperiencedstronggustwindsand theheaviesthurricanerainfall(Table 2).Thesetwositeshadlowtomoderateelevation withclosedistancetothecoastortherivers/canals,thusbeingpronetocoastalsurgeand fluvialorpluvialflooding.Theinundationcausedbythedownpour,stormsurge,andriver overflowisanimportantfactorresultinginadditionaldamage.

Wetlandrecoveryfromhurricanedamagewillbeafuturesubject.AirborneLiDAR datafromcampaignsafter2018shouldbeincorporatedwithmultispectralandhyperspectralimagestofulfilthistask.InadditiontoairborneLiDAR,spaceborneLiDAR dataarebecomingavailablerecently.Forexample,GEDI(GlobalEcosystemDynamics Investigation)onboardtheInternationalSpaceStationprovidesanalternativedatasource withlonger-termdataatalargerscale[55].Verticalcanopystructureandcomplexity playanimportantroleinprovidingmicrohabitatsforotherspeciessuchasinsectsand birds[56,57].Therefore,theassessmentofcanopyheightusingLiDARmighthaveimplicationsinbiodiversitystudies,especiallyforthosespeciesrelyingonforestsaspartof theirhabitats.

5.Conclusions

UsingLiDARpoint-clouddatabeforeandafterthehurricanesinSeptember2017, weanalyzedthepre-hurricanecanopyheight,aswellasthecanopyheightreduction, duringthehurricanesforfivecoastalmangrovesites.Therewerethreegroupsofvariables thatmighthaveinterplayedtoaffectthevulnerabilityofmangroveforestsundertropical

stormdisturbance:(1)pre-hurricanecanopystructureincludingcanopyheightandits unevenness,treedensity,andallometrypattern,(2)thephysicalenvironmentincluding elevation,rivers/canalswithinorpassingthroughtheforests,anddistancetocoast,and (3)theexternalforcessuchaswindspeedandrainfallduringthehurricanes.Mangrove forestswithhigher,unevenercanopyandlowertreedensitytendtoexperiencemorecanopy damagethanthosewithlower,evenercanopyandhighertreedensity.Thisbiologicalgroup isshapedbythesecondfactor,i.e.,thephysicalenvironment.Spatialvariationofelevation, climate,anddistancetorivers/canalsandtocoasttendtomodifythecanopystructure,the allometry,andtheleaftraitsasthesephysicalenvironmentalvariablescontrolthespatial distributionofthesoilsalinity.Amongthesephysicalenvironments,elevationisthemost determinativeasitsregimegovernsthesignificanceofthedistancetorivers/canalsand tothecoast.Inadditiontowindspeed,wefoundrainfalltoalsobeanimportantfactor affectingthemangrovecanopydamagebythehurricanes,especiallyinlowlandprone toinundation.

TheestimateofcanopyheightbyLiDARpointcloudsisbasedonthereturnedsignals bythesource.Thus,thecanopyheightreductionmostlyreflectsthedefoliationandraptures ofbranches,but,toalesserextent,thefallandraptureofthetrunks.Thesignificanceofthe covariatesintheequationsseemedalsodependentonthescales.Forexample,thedistance torivers/canalswasnotsignificantintheequationofpre-hurricanecanopyheightforany site.However,itwassignificantintheequationforthepooledequation(Equation(4)). Correlationamongcovariatesmayalsocausedifferencesinresponseequationsamong sites.Futureeffortsshouldbemadeongroundfieldmeasurementsandscalingfromplotto landscapesothatLiDAR-basedanalysiscanofferamorecertainandcompletemechanistic understandingofmangrovevulnerabilitytohurricanedisturbance.

AuthorContributions: Conceptualization,Q.G.andM.Y.;methodology,Q.G.andM.Y.;formal analysis,Q.G.andM.Y.;writing—originaldraftpreparation,Q.G.;writing—reviewandediting,Q.G. andM.Y.Allauthorshavereadandagreedtothepublishedversionofthemanuscript.

Funding: ThisresearchwasfundedbytheNOAAPuertoRicoSeaGrantNA18OAR4170089.

DataAvailabilityStatement: AllthedatasetsarepubliclyavailableattheUSGS3DElevation Program(3DEP)dataportal(https://nationalmap.gov/3DEP/,accessedon15March2022)andthe NASAG-LiHTdataportal(https://glihtdata.gsfc.nasa.gov/,accessedon15March2022).

Acknowledgments: WeacknowledgeUSGSforprovidingtheLiDARafterthehurricanes,publicly availableattheUSGS3DElevationProgram(3DEP)dataportal(https://nationalmap.gov/3DEP/, accessedon15March2022),andNASAforprovidingtheLiDARdatabeforethehurricanes,publicly accessibleatNASAG-LiHT(https://glihtdata.gsfc.nasa.gov/,accessedon15March2022).

ConflictsofInterest: Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictofinterest.Thefundershadnoroleinthedesign ofthestudy;inthecollection,analyses,orinterpretationofdata;inthewritingofthemanuscript,or inthedecisiontopublishtheresults.

AppendixA

Theaerialphotosofriverinemangrovestakenbeforeandafterthehurricanes(https: //glihtdata.gsfc.nasa.gov/puertorico/index.html,accessedon15March2022).

References

1. Alongi,D.M.CarbonCyclingandStorageinMangroveForests. Annu.Rev.Mar.Sci. 2014, 6,195–219.[CrossRef][PubMed]

2. Atwood,T.B.;Connolly,R.M.;Almahasheer,H.;Carnell,P.E.;Duarte,C.M.;EwersLewis,C.J.;Irigoien,X.;Kelleway,J.J.;Lavery, P.S.;Macreadie,P.I.;etal.Globalpatternsinmangrovesoilcarbonstocksandlosses. Nat.Clim.Chang. 2017, 7,523.[CrossRef]

3. Cannicci,S.;Burrows,D.;Fratini,S.;Smith,T.J.;Offenberg,J.;Dahdouh-Guebas,F.Faunalimpactonvegetationstructureand ecosystemfunctioninmangroveforests:Areview. Aquat.Bot. 2008, 89,186–200.[CrossRef]

4. Krauss,K.W.;McKee,K.L.;Lovelock,C.E.;Cahoon,D.R.;Saintilan,N.;Reef,R.;Chen,L.Howmangroveforestsadjusttorising sealevel. NewPhytol. 2014, 202,19–34.[CrossRef]

5. Yu,M.;Rivera-Ocasio,E.;Heartsill-Scalley,T.;Davila-Casanova,D.;Rios-López,N.;Gao,Q.Landscape-LevelConsequences ofRisingSea-LevelonCoastalWetlands:SaltwaterIntrusionDrivesDisplacementandMortalityintheTwenty-FirstCentury. Wetlands 2019, 39,1343–1355.[CrossRef]

6. Badola,R.;Hussain,S.A.Valuingecosystemfunctions:AnempiricalstudyonthestormprotectionfunctionofBhitarkanika mangroveecosystem,India. Environ.Conserv. 2005, 32,85–92.[CrossRef]

7. Cartier,K.HurricanesHitPuertoRico’sMangrovesHarderThanFlorida’s. EOS 2019, 100.[CrossRef]

8. Duryea,M.L.;Kamp,E. WindandTrees:LessonsLearnedfromHurricanes;SchoolofForestResourcesandConservation,University ofFloridaFASExtension:Gainesville,FL,USA,2017.

9. Smith,T.J.;Anderson,G.H.;Balentine,K.;Tiling,G.;Ward,G.A.;Whelan,K.R.T.CumulativeimpactsofhurricanesonFlorida mangroveecosystems:Sedimentdeposition,stormsurgesandvegetation. Wetlands 2009, 29,24.[CrossRef]

10. Gardiner,B.;Byrne,K.;Hale,S.;Kamimura,K.;Mitchell,S.J.;Peltola,H.;Ruel,J.-C.Areviewofmechanisticmodellingofwind damagerisktoforests. For.Int.J.For.Res. 2008, 81,447–463.[CrossRef]

11. Mitchell,S.J.Windasanaturaldisturbanceagentinforests:Asynthesis. For.Int.J.For.Res. 2012, 86,147–157.[CrossRef]

12. Ye,F.;Huang,W.;Zhang,Y.J.;Moghimi,S.;Myers,E.;Pe'eri,S.;Yu,H.C.Across-scalestudyforcompoundfloodingprocesses duringHurricaneFlorence. Nat.HazardsEarthSyst.Sci. 2021, 21,1703–1719.[CrossRef]

13. Choy,S.C.;Booth,W.E.ProlongedinundationandecologicalchangesinanAvicenniamangrove:Implicationsforconservation andmanagement. Hydrobiologia 1994, 285,237–247.[CrossRef]

14. Krauss,K.W.;Osland,M.J.Tropicalcyclonesandtheorganizationofmangroveforests:Areview. Ann.Bot. 2019, 125,213–234. [CrossRef][PubMed]

15. Lovelock,C.E.;Krauss,K.W.;Osland,M.J.;Reef,R.;Ball,M.C.ThePhysiologyofMangroveTreeswithChangingClimate. In TropicalTreePhysiology:AdaptationsandResponsesinaChangingEnvironment;Goldstein,G.,Santiago,L.S.,Eds.;Springer InternationalPublishing:Cham,Switzerland,2016;pp.149–179.[CrossRef]

16. Peel,J.R.;Sanchez,M.C.M.;Lopez-Portillo,J.;Golubov,J.Stomataldensity,leafareaandplantsizevariationof Rhizophoramangle (Malpighiales:Rhizophoraceae)alongasalinitygradientintheMexicanCaribbean. Rev.Biol.Trop. 2017, 65,701–712.[CrossRef]

17. Kodikara,K.A.S.;Jayatissa,L.P.;Huxham,M.;Dahdouh-Guebas,F.;Koedam,N.Theeffectsofsalinityongrowthandsurvivalof mangroveseedlingschangeswithage. ActaBot.Bras. 2018, 32,37–46.[CrossRef]

18. Waisel,Y.;Eshel,A.;Agami,M.Saltbalanceofleavesofthemangrove Avicenniamarina Physiol.Plant. 2006, 67,67–72.[CrossRef]

19. Reef,R.;Lovelock,C.E.Regulationofwaterbalanceinmangroves. Ann.Bot. 2015, 115,385–395.[CrossRef]

20. Lugo,A.E.;Medina,E.MangroveForests.In EncyclopediaofNaturalResources–Land;Wang,Y.,Ed.;Taylor&FrancisGroup: NewYork,NY,USA,2014;Volume1.

21. Branoff,B. UrbanMangroveBiologyandEcology:EmergentPatternsandManagementImplications;UniversityofPuertoRico:SanJuan, PR,USA,2018.

22. Martinuzzi,S.;Gould,W.A.;Lugo,A.E.;Medina,E.ConversionandrecoveryofPuertoRicanmangroves:200yearsofchange. For.Ecol.Manag. 2009, 257,75–84.[CrossRef]

23. Lugo,A.E.;Medina,E.;Cuevas,E.;Cintrón,G.;Nieves,E.N.L.;Novelli,Y.S.EcophysiologyofaMangroveForestinJobosBay, PuertoRico. Caribb.J.Sci. 2007, 43,200–219.[CrossRef]

24. Quadros,A.F.;Zimmer,M.Datasetof“truemangroves”plantspeciestraits. Biodivers.DataJ. 2017, 5,e22089.[CrossRef]

25. Miller,G.L.;Lugo,A.E. GuidetotheEcologicalSystemsofPuertoRico;U.S.DepartmentofAgriculture,ForestService,International InstituteofTropicalForestry:SanJuan,PR,USA,2009;p.437.

26. Castañeda-Moya,E.;Rivera-Monroy,V.H.;Chambers,R.M.;Zhao,X.;Lamb-Wotton,L.;Gorsky,A.;Gaiser,E.E.;Troxler,T.G.; Kominoski,J.S.;Hiatt,M.HurricanesfertilizemangroveforestsintheGulfofMexico(FloridaEverglades,USA). Proc.Natl.Acad. Sci.USA 2020, 117,4831–4841.[CrossRef]

27. Taillie,P.J.;Roman-Cuesta,R.;Lagomasino,D.;Cifuentes-Jara,M.;Fatoyinbo,T.;Ott,L.E.;Poulter,B.Widespreadmangrove damageresultingfromthe2017Atlanticmegahurricaneseason. Environ.Res.Lett. 2020, 15,064010.[CrossRef]

28. Branoff,B.;Martinuzzi,S.MangroveforeststructureandcompositionalongurbangradientsinPuertoRico. bioRxiv 2018,504928. [CrossRef]

29. Field,C.;Osborn,J.;Hoffman,L.;Polsenberg,J.;Ackerly,D.;Berry,J.;BjÖRkman,O.;Held,A.;Matson,P.;Mooney,H.Mangrove biodiversityandecosystemfunction. Glob.Ecol.Biogeogr.Lett. 1998, 7,3–14.[CrossRef]

30. Giri,C.;Ochieng,E.;Tieszen,L.L.;Zhu,Z.;Singh,A.;Loveland,T.;Masek,J.;Duke,N.Statusanddistributionofmangrove forestsoftheworldusingearthobservationsatellitedata. Glob.Ecol.Biogeogr. 2011, 20,154–159.[CrossRef]

31. Yu,M.;Gao,Q.Topography,drainagecapability,andlegacyofdroughtdifferentiatetropicalecosystemresponsetoandrecovery frommajorhurricanes. Environ.Res.Lett. 2020, 15,104046.[CrossRef]

32. Huang,W.;Sun,G.;Dubayah,R.;Cook,B.;Montesano,P.;Ni,W.;Zhang,Z.Mappingbiomasschangeafterforestdisturbance: ApplyingLiDARfootprint-derivedmodelsatkeymapscales. RemoteSens.Environ. 2013, 134,319–332.[CrossRef]

33. Eisemann,E.;Dunkin,L.;Hartman,M.;Wozencraft,J.JALBTCX/NCMPemergency-responseairborneLidarcoastalmapping& quickresponsedataproductsfor2016/2017/2018hurricaneimpactassessments. ShoreBeach 2019, 87,31–40.[CrossRef]

34. Gao,Q.;Yu,M.ElevationandDistributionofFreshwaterandSewageCanalsRegulateCanopyStructureandDifferentiate HurricaneDamagestoaBasinMangroveForest. RemoteSens. 2021, 13,3387.[CrossRef]

35. Kennaway,T.;Helmer,E.H.TheforesttypesandagesclearedforlanddevelopmentinPuertoRico. Gisci.RemoteSens. 2007, 44, 356–382.[CrossRef]

36. Gao,Q.;Yu,M.DiscerningFragmentationDynamicsofTropicalForestandWetlandduringReforestation,UrbanSprawl,and PolicyShifts. PlosONE 2014, 9,e113140.[CrossRef]

37. Cook,B.;Corp,L.;Nelson,R.;Middleton,E.;Morton,D.;McCorkel,J.;Masek,J.;Ranson,K.;Ly,V.;Montesano,P.NASA Goddard’sLiDAR,HyperspectralandThermal(G-LiHT)AirborneImager. RemoteSens. 2013, 5,4045–4066.[CrossRef]

38. OfficeforCoastalManagement.C-CAPLandCover,PuertoRico.2010.Availableonline: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/ inport/item/48301 (accessedon15March2022).

39. Roussel,J.-R.;Auty,D.;Boissieu,F.D.;Meador,A.S.lidR:AirborneLiDARDataManipulationandVisualizationforForestry Applications.2019.Availableonline: https://cran.r-project.org/package=lidR (accessedon24August2021).

40. Pasch,R.J.;Penny,A.B.;Berg,R. NationalHurricaneCenterTropicalCycloneReport–HurricaneMaria(AL152017)September16–30, 2017;NationalHurricaneCenter:Miami,FL,USA,2019;pp.1–48.

41. RCoreTeam. R:ALanguageandEnvironmentforStatisticalComputing;RFoundationforStatisticalComputing:Vienna,Austria, 2021;Availableonline: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessedon15March2022).

42. Angelou,N.;Dellwik,E.;Mann,J.Windloadestimationonanopen-grownEuropeanoaktree. For.Int.J.For.Res. 2019, 92, 381–392.[CrossRef]

43. Peterson,C.J.;Ribeiro,G.H.P.d.M.;Negrón-Juárez,R.;Marra,D.M.;Chambers,J.Q.;Higuchi,N.;Lima,A.;Cannon,J.B.Critical windspeedssuggestwindcouldbeanimportantdisturbanceagentinAmazonianforests. For.Int.J.For.Res. 2019, 92,444–459. [CrossRef]

44. Wang,H.;Hsieh,Y.P.;Harwell,M.A.;Huang,W.Modelingsoilsalinitydistributionalongtopographicgradientsintidalsalt marshesinAtlanticandGulfcoastalregions. Ecol.Model. 2007, 201,429–439.[CrossRef]

45. Jiang,J.;Gao,D.;DeAngelis,D.L.Towardsatheoryofecotoneresilience:Coastalvegetationonasalinitygradient. Theor.Popul. Biol. 2012, 82,29–37.[CrossRef]

46. Chen,Y.;Ye,Y.EffectsofSalinityandNutrientAdditiononMangroveExcoecariaagallocha. PLoSONE 2014, 9,e93337.[CrossRef]

47. Nguyen,H.T.;Stanton,D.E.;Schmitz,N.;Farquhar,G.D.;Ball,M.C.GrowthresponsesofthemangroveAvicenniamarinato salinity:Developmentandfunctionofshoothydraulicsystemsrequiresalineconditions. Ann.Bot. 2015, 115,397–407.[CrossRef] [PubMed]

48. Peters,R.;Vovides,A.G.;Luna,S.;Gruters,U.;Berger,U.Changesinallometricrelationsofmangrovetreesduetoresource availability—Anewmechanisticmodellingapproach. Ecol.Model. 2014, 283,53–61.[CrossRef]

49. Reich,P.B.;Walters,M.B.;Ellsworth,D.S.LeafLife-SpaninRelationtoLeaf,Plant,andStandCharacteristicsamongDiverse Ecosystems. Ecol.Monogr. 1992, 62,365–392.[CrossRef]

50. Yang,S.-C.;Shih,S.-S.;Hwang,G.-W.;Adams,J.B.;Lee,H.-Y.;Chen,C.-P.Thesalinitygradientinfluencesontheinundation tolerancethresholdsofmangroveforests. Ecol.Eng. 2013, 51,59–65.[CrossRef]

51. Talkkari,A.;Peltola,H.;Kellomäki,S.;Strandman,H.Integrationofcomponentmodelsfromthetree,standandregionallevelsto assesstheriskofwinddamageatforestmargins. For.Ecol.Manag. 2000, 135,303–313.[CrossRef]

52. Jimenez-Rodríguez,D.L.;Alvarez-Añorve,M.Y.;Pineda-Cortes,M.;Flores-Puerto,J.I.;Benítez-Malvido,J.;Oyama,K.;AvilaCabadilla,L.D.Structuralandfunctionaltraitspredictshorttermresponseoftropicaldryforeststoahighintensityhurricane. For.Ecol.Manag. 2018, 426,101–114.[CrossRef]

53. Hale,S.E.;Gardiner,B.;Peace,A.;Nicoll,B.;Taylor,P.;Pizzirani,S.Comparisonandvalidationofthreeversionsofaforestwind riskmodel. Environ.Model.Softw. 2015, 68,27–41.[CrossRef]

54. Krogstadt,P.Å.;Antonia,R.A.Surfaceroughnesseffectsinturbulentboundarylayers. Exp.Fluids 1999, 27,450–460.[CrossRef]

55. Patterson,P.L.;Healey,S.P.;Ståhl,G.;Saarela,S.;Holm,S.;Andersen,H.-E.;Dubayah,R.O.;Duncanson,L.;Hancock,S.;Armston, J.;etal.StatisticalpropertiesofhybridestimatorsproposedforGEDI—NASA’sglobalecosystemdynamicsinvestigation. Environ. Res.Lett. 2019, 14,065007.[CrossRef]

56. MonmanyGarzia,A.C.;Yu,M.;Zimmerman,J.K.Effectsofvegetationstructureandlandscapecomplexityoninsectparasitism acrossanagriculturalfrontierinArgentina. BasicAppl.Ecol. 2018, 29,69–78.[CrossRef]

57. Mccormack,J.J.;Cotoras,D.D.BeetleDiversityAcrossMicro-habitatsonLizardIslandGroup(GreatBarrierReef,Australia). Zool. Stud. 2021, 60,12.[CrossRef]