Objectives

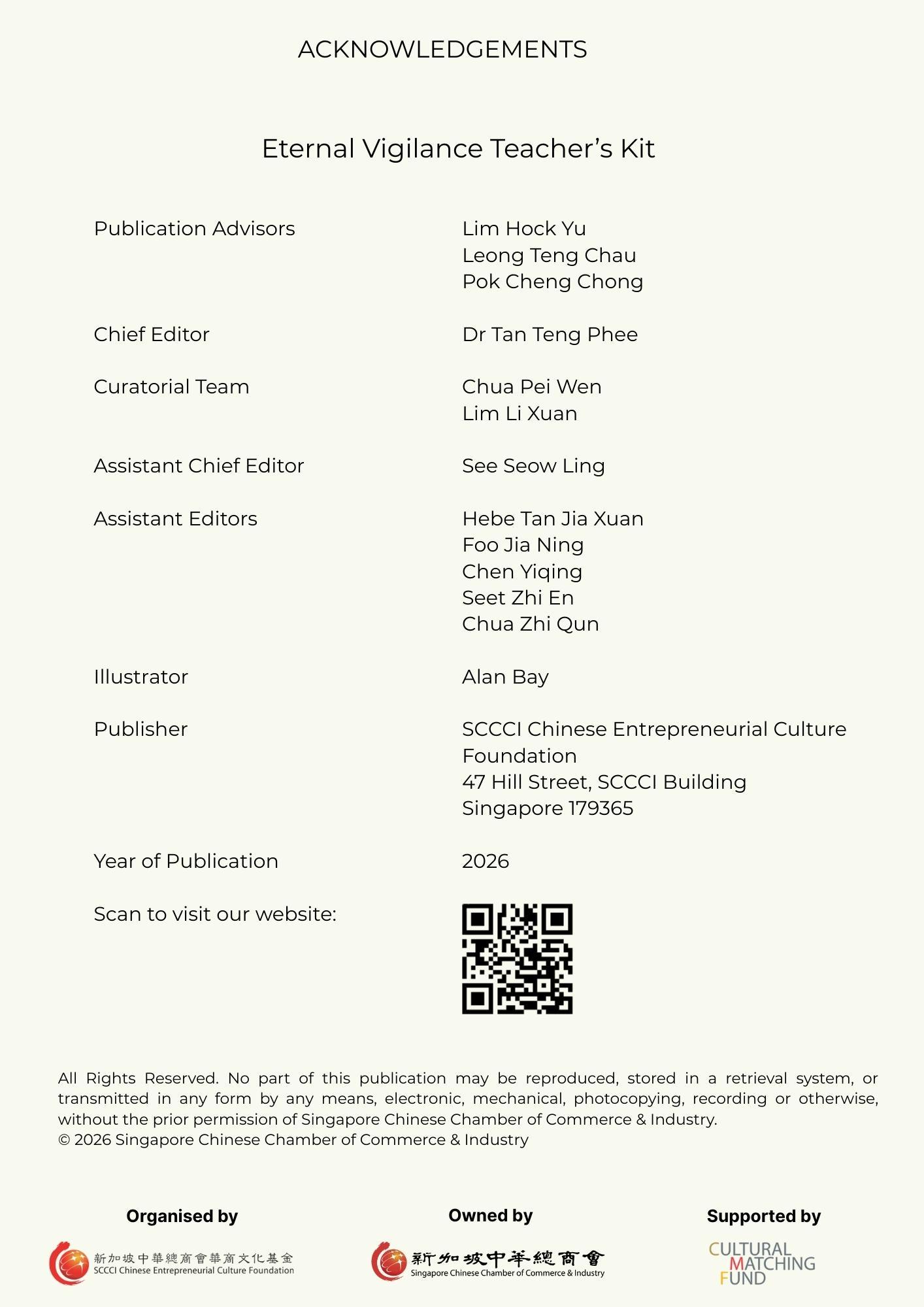

This Eternal Vigilance Teacher’s Kit is designed to provide teachers with a suggested framework and supplementary material in guiding the students through the Student Activity E-booklet, which aims to encourage further reflection on Singapore’s history during the Japanese Occupation in WWII, through a game-based learning resource.

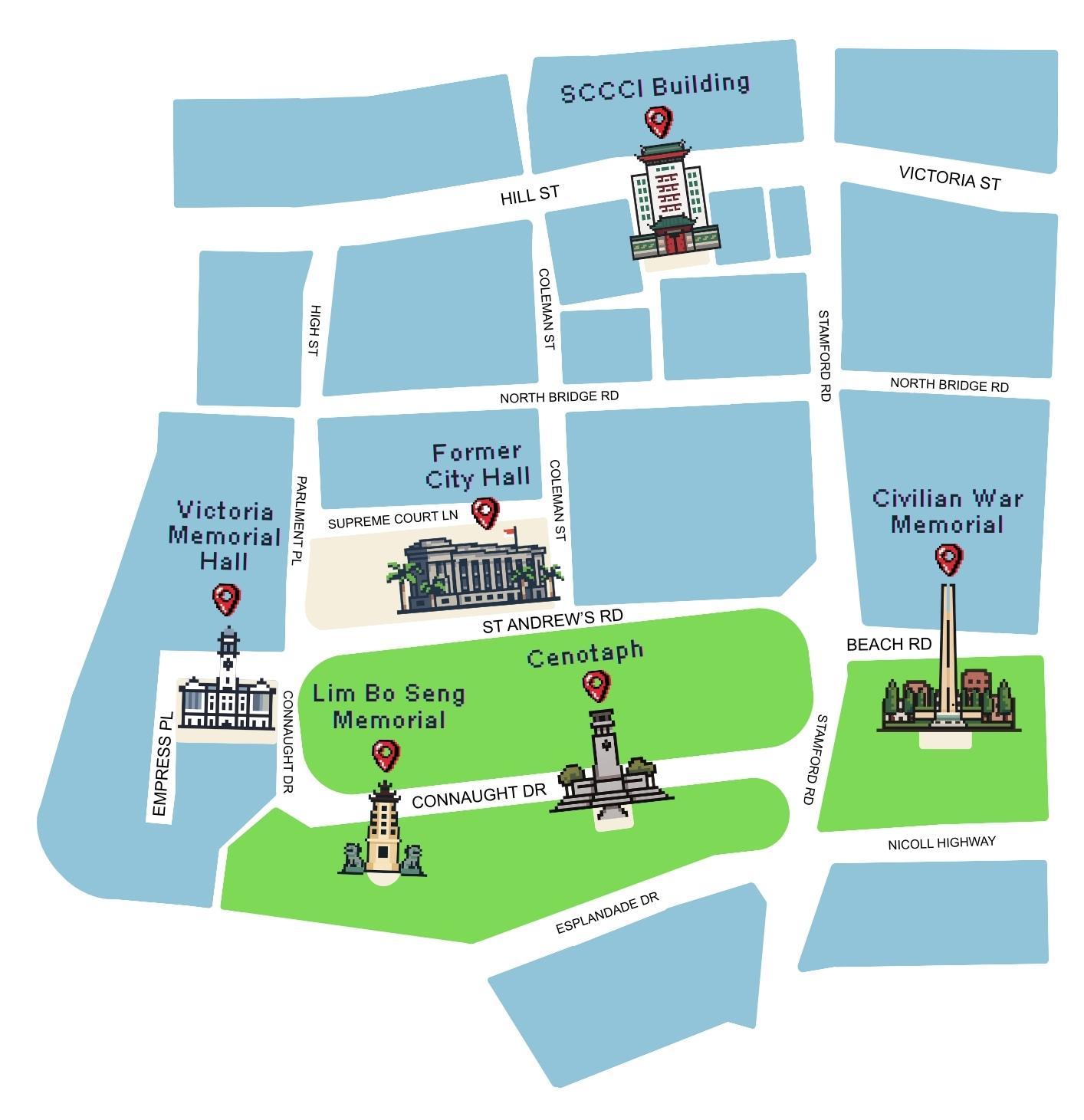

In the E-booklet, students will take on the challenge of restoring historical archives from WWII that are corrupted by a mysterious “virus”. Embarking on a journey with a cat archivist, Whiskers, students move through the five selected locations arranged in chronological order, each marking a significant historical event from the Japanese Occupation to the post-independence period. The E-booklet also introduces the importance of digital awareness, as younger generations may encounter new and evolving challenges within a highly digitalised society

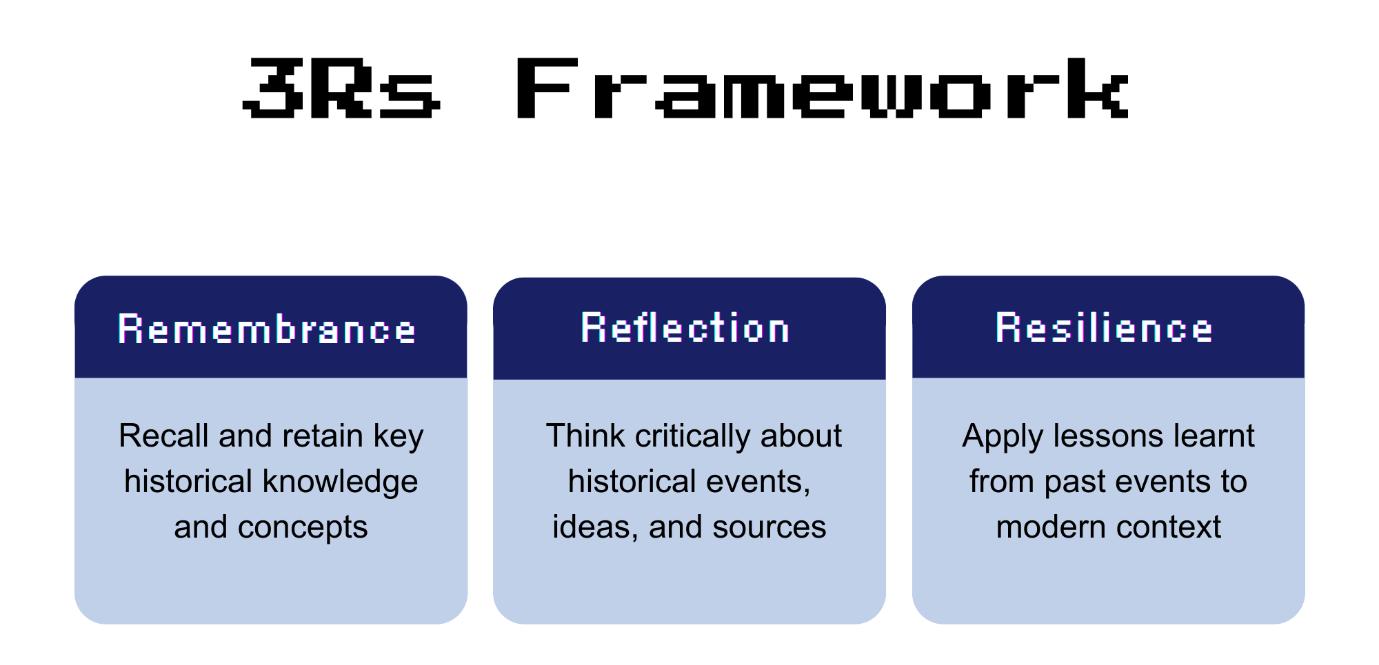

This E-booklet is designed based on the 3Rs framework – “Remembrance, Reflection, Resilience” – guiding students through a process of constructing, interpreting, and evaluating knowledge from different perspectives (see Figure 1). This framework aims to deepen historical understanding by cultivating critical thinking, drawing connections between past and present, and promoting the application of historical knowledge to contemporary contexts.

Why are digital awareness and cybersecurity important? Hear from our nation's leaders:

“As we are entering an age where the digital and physical realms converge, the theme of cyber security is increasingly critical with cyber disruptions possibly spilling over to the physical domain with real-world consequences.”1

“Security threats can be real and physical like terrorism or, just as damaging, can come through the cyber world. Malicious malware can cripple our systems. Fake news can cause racial riots and divide our people.”

– Former Defence Minister, Dr Ng Eng Hen, Total Defence Day message on 14 February 2019.2

“To reap the benefits of the digital age, we must pay heed to the seemingly invisible threats in the cyberspace, and safeguard our digital realm. The world of cybersecurity is one that is dynamic and complex, marked by constant emergence of new, sophisticated threats, and the continuous improvement of existing ones…we all have an important role to play here in Singapore in the digital cyberspace.”

– Senior Minister of State for Defence, Mr Zaqy Mohamad, Sentinel Programme Official Launch on 20 January 2024 3

Lastly, we hope this E-booklet will encourage students to take personal responsibility in defending against cyber threats, fostering both awareness and civic duty in safeguarding national security.

1 Cyber Security Agency of Singapore, The Singapore Cybersecurity Strategy 2021 (Singapore: Cyber Security Agency of Singapore, 2021), https://isomer-user-content.by.gov.sg/36/6318c1f5-3257-4c99-80e527339cf41883/The-Singapore-Cybersecurity-Strategy-2021.pdf

2 Hariz Baharudin, “Digital Defence to Be Sixth Total Defence Pillar, Signalling the Importance of Cyber Security,” The Straits Times, February 14, 2019, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/digital-defence-to-be-sixth-totaldefence-pillar-signalling-the-importance-of-cyber

3 Zaqy Mohamad, “Speech by Senior Minister of State for Defence Mr Zaqy Mohamad at the Sentinel Programme Official Launch on 20 Jan 2024, 1300hrs, at Temasek Polytechnic,” Ministry of Defence, January 20, 2024, https://www.mindef.gov.sg/news-and-events/latest-releases/20jan24_speech/

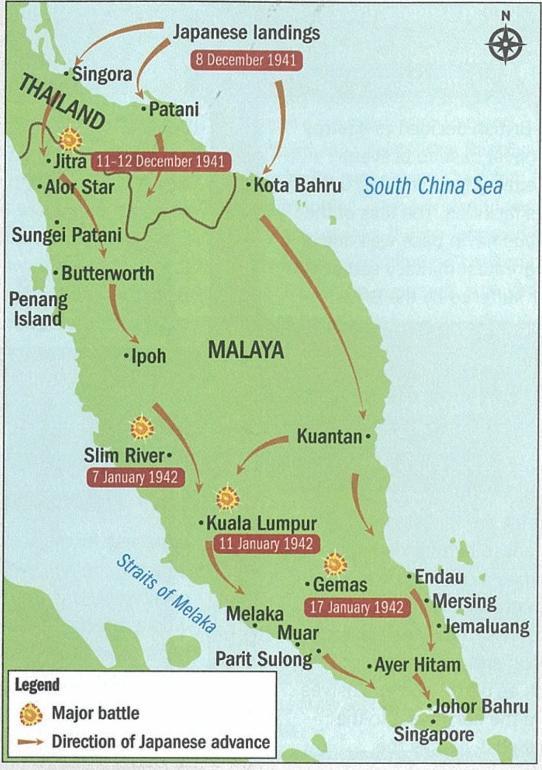

The British initially believed Singapore could not be attacked from the North due to thick jungles and therefore, set up defences to protect Singapore from the South and East.

However, by the 1930s, the British military commanders realised that their assumptions were untrue and started to build airfields in Malaya to stop any invasion Despite making plans to defend Singapore and Malaya, outdated British warplanes failed to stop Japanese landings in Southern Thailand and Northern Malaya. The Japanese then advanced swiftly down Malaya and invaded Singapore (see Figure 2).

4 Ministry of Education, “The Japanese Advance down Malaya,” map, in Singapore: A Journey through Time, 1299–1970s, 197 (Singapore: Star Publishing Pte Ltd, 2021).

The E-Booklet will be covering the following locations:

Key Theme Skills and Values

Interpreting propaganda and identifying its purpose, audience, and intended effect

Propaganda

Being aware of how information can be manipulated to influence beliefs and actions

Background Information

Victoria Memorial Hall (VMH), now known as Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall, played a significant and multifaceted role throughout the tumultuous period of WWII in Singapore.

Shortly before the fall of Singapore, the VMH was converted into a makeshift hospital to treat the wounded and to house survivors of Japanese air raids 5

During the Japanese Occupation, it was repurposed as a cultural centre to align with Japanese propaganda efforts to promote their culture and the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” (GEACPS) 6

Syonan Symphony Orchestra (also known as Syonan Kokkaido Orchestra) performed at its headquarters in VMH, Cathay Cinema, and Japanese military camps. The public and POW Prisoners got to watch these performances as well.7

After the end of the war, the VMH was used as the location for the trial of Japanese war criminals 8

5 National Heritage Board, “Victoria Theatre and Victoria Concert Hall,” Roots.sg, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.roots.gov.sg/places/places-landing/Places/national-monuments/victoria-theatre-and-concert-hall

6 Zhen Tian, Tian Zhang, Wei Li, and Wei Qiu, “Iconic Architecture as Vessel for Political and Cultural Expression: Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall Changing with Singapore Cultural Icon,” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 24, no. 5 (2024): 3542–57, https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2024.2397123

7 Phan Ming Yen, “The Syonan Symphony Orchestra: A Case of Musical Collaboration in Wartime Singapore,” Cultural Connections 6 (2021): 42–51, https://isomer-user-content.by.gov.sg/130/a7bff560-ee6f-4497-91ce520b9c339c75/Phan%20Ming%20Yen.pdf

8 Bonny Tan, “Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall,” Singapore Infopedia, National Library Board, 2016, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=8472b2d8-5549-4858-912b-f6150b4bcae6

Suggested Guiding Questions

• Why did the Japanese utilise propaganda during their occupation of Singapore?

Propaganda was used to promote the Japanese narrative that they had liberated the locals from the British colonial rule and united them under the GEACPS.The GEACPS was Japan’s vision for Asia, with the goal of establishing a self-sufficient union of Asian nations led by the Japanese 9

Link: https://www.roots.gov.sg/Collection-Landing/listing/1122768?taigerlist=collections

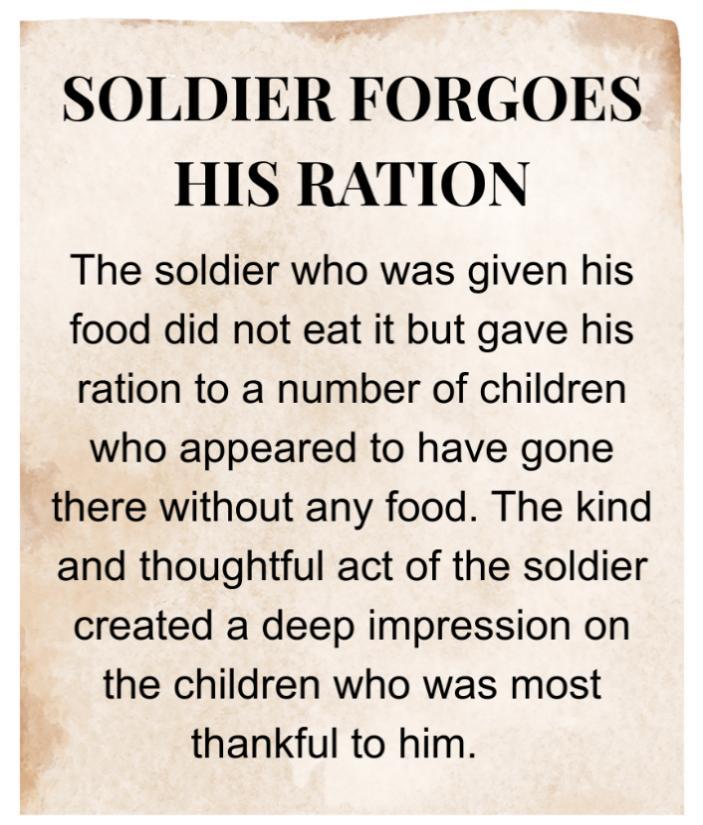

A propaganda postcard of a Japanese soldier from a set of five in the 1940s. Collection of National Museum of Singapore

• What details do you see in the postcard?

9 Antonette Magpantay, “‘Asia for Asians’: Revisiting Pan-Asianism through the Propaganda Arts of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere,” Manusya: Journal of Humanities 26, no. 1 (2024): 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1163/26659077-26010015

It depicts a Japanese soldier standing in an upright position with the face deliberately left blank for the card recipient to fill in The soldier is holding onto two children while two other children are hugging his legs 10 The children, visibly smiling, are of different races and are seen holding onto Japanese flags

• What message do you think the postcard is trying to convey?

The postcard conveys the message that different races accept and embrace Japanese rule, with “the Japanese military being revered as a guardian of Asian children” 11 It also presents a softer and friendlier image of the Japanese military by illustrating a joyful interaction between the Japanese soldier and children

• How does it support Japan’s propaganda narrative?

The postcard supports the GEACPS narrative of establishing a collective Asian identity under Japanese rule by presenting a peaceful and harmonious unity of different races. However, it also highlights “the rule of Japan above the people”, meaning that Asian nations have to depend on the Japanese to achieve coprosperity 12

10 National Heritage Board, Investigating History: Singapore under the Japanese Occupation, 1942–1945 (Singapore: National Heritage Board, 2021), PDF file, https://www.nhb.gov.sg/nationalmuseum//media/nms2017/documents/school-programmes/teachers-hi-resource-unit-3-japanese-occupation.pdf

11 National Heritage Board, Investigating History: Singapore under the Japanese Occupation, 1942–1945

12 Magpantay, “‘Asia for Asians,’” 1–20.

13 “Soldier Forgoes His Ration,” The Shonan Times (Syonan Shimbun), February 28, 1942.

• What do you think the author was trying to get the audience to think about the Japanese soldiers?

The author was trying to paint the Japanese soldier in a more positive and benevolent light, where he would give up his already meagre rations to help a child, who represents one of the most vulnerable groups in society.

• Why do you think the author portrays the Japanese soldiers in this manner?

They wanted to make Japan appear more acceptable and relatable to the population at that time. They also attempted to counter negative perceptions of Japanese brutality circulating in Singapore by presenting the soldiers as less cruel and more approachable.14

• What are the differences in how information was spread in the past as compared to today? Why?

In the past, traditional media such as newspapers and radio were the primary channels for disseminating information Today, information is mainly spread via digital platforms, particularly social media. These platforms allow us to communicate

14 Magpantay, “‘Asia for Asians,’” 1–20.

and share information more quickly and easily,15 while also enabling us to create content rather than merely consume information from media outlets 16

• What are the dangers of information being spread via digital platforms today?

Bombarded with an overwhelming amount of information over social platforms, users often end up sharing information with others without checking its accuracy. As a result, false information can spread widely and quickly, causing harmful impacts on human lives across social, political, emotional and economic aspects.17

• What are some strategies we can adopt to remain mindful of information consumed online?

As recommended by the National Library Board, the acronym S.U.R.E can be used to critically evaluate online information:18

1. Check the Source: Check the origin of the content and see if it is an authentic source. Beware of fake websites that imitate official ones.

2. Understand the Information you read online: Be wary if the content is vague in details and lacks facts (e.g. date, time, places). Look out for spelling, grammatical and punctuation errors.

3. Research the authenticity of an article: Search online beyond the initial source of the content received Find two or more credible sources to confirm if the information is real

4. Evaluate from different angles: Check if the information is fair and balanced. Consider that the content may be manipulated or edited to influence opinions.

15 M. W. M. Al-Quran, “Traditional Media versus Social Media: Challenges and Opportunities,” Technium: Romanian Journal of Applied Sciences and Technology 4, no. 10 (2022): 145–60, https://doi.org/10.47577/technium.v4i10.8012

16 Swastiningsih, Swastiningsih, Abdul Aziz, and Yuni Dharta, “The Role of Social Media in Shaping Public Opinion: A Comparative Analysis of Traditional vs. Digital Media Platforms,” The Journal of Academic Science 1, no. 6 (2024): 620–26, https://doi.org/10.59613/fm1dpm66.

17 National Library Board, “Prebunking,” June 10, 2024, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/site/sure-elevated/for-thepublic/prebunking

18 National Library Board, “To Stay Vigilant and Safe Online, here are 4 Steps to be S.U.R.E.” PDF file, 2023, accessed January 29, 2026, https://file.go.gov.sg/2023-sure-infographic-eng.pdf

Key Theme Skills and Values

Historical Significance of Buildings

Explaining the symbolic meaning of historical buildings and locations

Awareness of the importance of preserving historical memory for future generations

Background Information

The Former City Hall, completed in 1929, was originally known as the Municipal Building. It was an important British government office overseeing the maintenance of public infrastructure and the provision of public utilities 19

After Singapore fell to the Japanese on 15 February 1942, the Municipal Building became the headquarters of the Japanese municipal administration. Japanese forces gathered Allied prisoners-of-war in front of the Municipal Building and marched them to Changi Prison.

It was also the building where Allied forces accepted the surrender of Japan on 12 September 1945.

Suggested Guiding Questions

• What do you think the Former City Hall symbolises?

The Former City Hall was the main colonial administration building of the British which exhibited the prowess and might of the British Empire. Hence, after the British surrendered, the Japanese took over the building as their municipal administration headquarters to show their authority over Singapore.

19 Preservation of Sites and Monuments, “Former City Hall,” Singapore Infopedia, National Library Board Singapore, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=a310ec1d-fd39-4fd2bdc9-e530178f00a6

• How has the Former City Hall been preserved to reflect Singapore’s history?

The Former City Hall was gazetted as a national monument in 1992 to recognise its role in witnessing major historical milestones of Singapore’s independence journey, such as the swearing in of the first cabinet of the self-governed Singapore state in 1959 20

Today, it has been transformed into the National Gallery Singapore, which houses the world’s largest collection of Southeast Asian modern and contemporary art.21 The building now brings together history, art and civic pride, celebrating Singapore’s rich culture and heritage while reflecting national identity.

20 Lee Hsien Loong, “PM Lee Hsien Loong at the Opening Celebrations of the National Gallery Singapore,” Prime Minister’s Office Singapore, November 23, 2015, https://www.pmo.gov.sg/newsroom/pm-lee-hsien-loong-openingcelebrations-national-gallery-singapore/

21 National Gallery Singapore, “Our Collections,” accessed January 29, 2026, National Gallery Singapore, https://www.nationalgallery.sg/sg/en/our-collections.html

Key Theme Skills and Values

Connecting historical sacrifices to modern-day peace and security

Digital Defence

Recognising civic responsibility in safeguarding present-day national peace

Background Information

The Cenotaph, derived from the Greek words “Kenos” (empty) and “Taphos” (tomb), is the only war memorial in Singapore that commemorates the sacrifice of individuals who died in both World Wars 22

Suggested Guiding Questions

Modelled after the Whitehall Cenotaph in London, England, the Cenotaph in Singapore was first erected as a memorial in honour of the 124 men from Singapore who died in action during WWI.23

After WWII, the reverse side of the Cenotaph was dedicated as a memorial for those who perished while defending Singapore during WWII. The words “They died that we might live” were cast in bronze plates in Singapore’s four official languages –English, Chinese, Malay (in Jawi script), and Tamil – and set on the structure 24

22 Zubaidah Mohamed and Valerie Chew, “Cenotaph,” Singapore Infopedia, National Library Board, May 2021, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=865fce29-fbe3-41d2-8bd6-4d65a49187fb ; Tan Yong Jun, “Monument Focus: The Cenotaph,” Roots.sg, April 15, 2025, https://www.roots.gov.sg/MUSE/articles/MonumentFocus-The-Cenotaph.

23 Mohamed and Chew, “Cenotaph.”

24 National Heritage Board, “Esplanade Park Memorials,” Roots.sg, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.roots.gov.sg/places/places-landing/Places/national-monuments/esplanade-park-memorials

Digital Defence is a new pillar of Total Defence that guards against threats from the digital domain. It reminds Singaporeans of the need to be able to respond to cyberattacks that target networks and infrastructure, as well as threats that can be perpetrated through the digital domain, such as fake news and deliberate online falsehoods. It highlights that every individual plays a key role in defending against these threats to maintain security, social cohesion, and public confidence.25

Some cyber practices that one can adopt, as recommended by the Cyber Security Agency of Singapore,26 include the following:

1. Use strong passphrases, e.g., use at least 12 characters with a mix of uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers and symbols

2. Enable two-factor authentication (2FA)

3. Spot signs of phishing scams, e.g., requests for personal information, suspicious attachments

4. Add ScamShield and anti-virus apps

5. Update software promptly.

• Why is a strong national defence important for Singapore?

As Singapore is highly vulnerable, a strong defence allows Singapore to enjoy security, peace, and stability while protecting its sovereignty, territorial integrity, and

25 Government of Singapore, “Digital Defence,” Total Defence, last updated July 14, 2025, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.totaldefence.gov.sg/about/the-six-pillars-of-total-defence/digital-defence/

26 Cyber Security Agency of Singapore, SG Cyber Safe Students – Secondary School Cybersecurity Poster, PDF (Singapore: Cyber Security Agency of Singapore, 2025), https://isomer-user-content.by.gov.sg/36/148e918170a7-473e-8087-f71463d6e579/sg-cyber-safe-students secondary-school-cybersecurity-poster.pdf

way of life. A strong defence also allows Singapore to act in its national interests without being swayed by external pressures 27

27 Government of Singapore, “Building a Strong Defence,” SG101, last updated October 6, 2025, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.sg101.gov.sg/defence-and-security/our-defence-and-security/building-a-strongdefence/

Key Theme Skills and Values

Recognising the contributions of individual resistance efforts to national history and identity

Resilience in the Face of Adversity

Reflecting on how values learnt from past lessons can inspire present-day choices and actions

Background Information

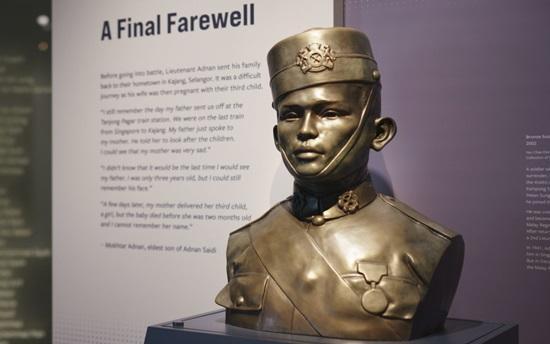

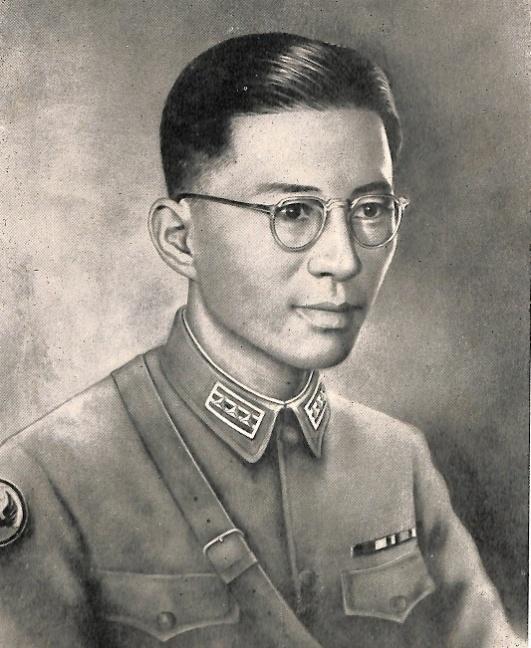

4. Photograph of Lim Bo Seng. SCCCI Collection. Lim Bo Seng was born in Nan’an, Fujian, China. When war broke out in China, he stepped forward and took on an active role in resisting Japanese advances. Before the fall of Singapore, Lim Bo Seng escaped to India and joined Force 136, a secret service unit established by the British and Chinese governments to resist the Japanese.28

28 Wong Heng and Valerie, “Lim Bo Seng,” Singapore Infopedia, National Library Board, June 2023, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=18b892a1-9b32-4f8c-a72a-6ad72122bdd4

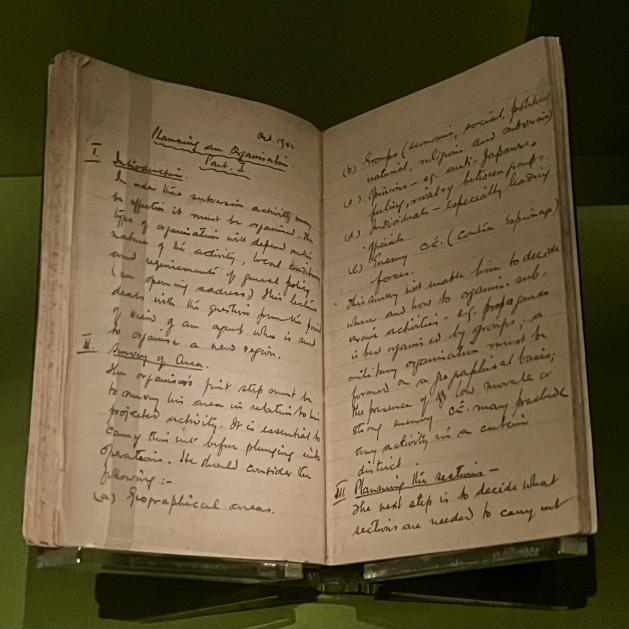

Figure 5. Photograph of Lim Bo Seng’s diary containing his personal experiences and detailed notes on Force 136 (c. 1942). Former Ford Factory Collection.

Due to blunders including missed supply runs from the sea that was Force 136’s main source of sustainment, their cover being blown by a captured communist guerrilla, and being sold out by an ally who fully cooperated with Japanese authorities,29 Lim Bo Seng was captured and tortured by the Japanese, eventually dying of torture, malnutrition and infection at 35 30

This memorial was built in memory of Lim Bo Seng. It stands as Singapore's only World War II memorial dedicated to a single individual.

29 Romen Bose, “Clandestine Forces,” in Singapore at War: Secrets from the Fall, Liberation and Aftermath of WWII, 293–320 (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2012).

30 National Heritage Board, “Lim Bo Seng,” Roots.sg, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.roots.gov.sg/stories-landing/stories/lim-bo-seng/story