Napoleonic Soldiers Buried

In and Near Sauk County

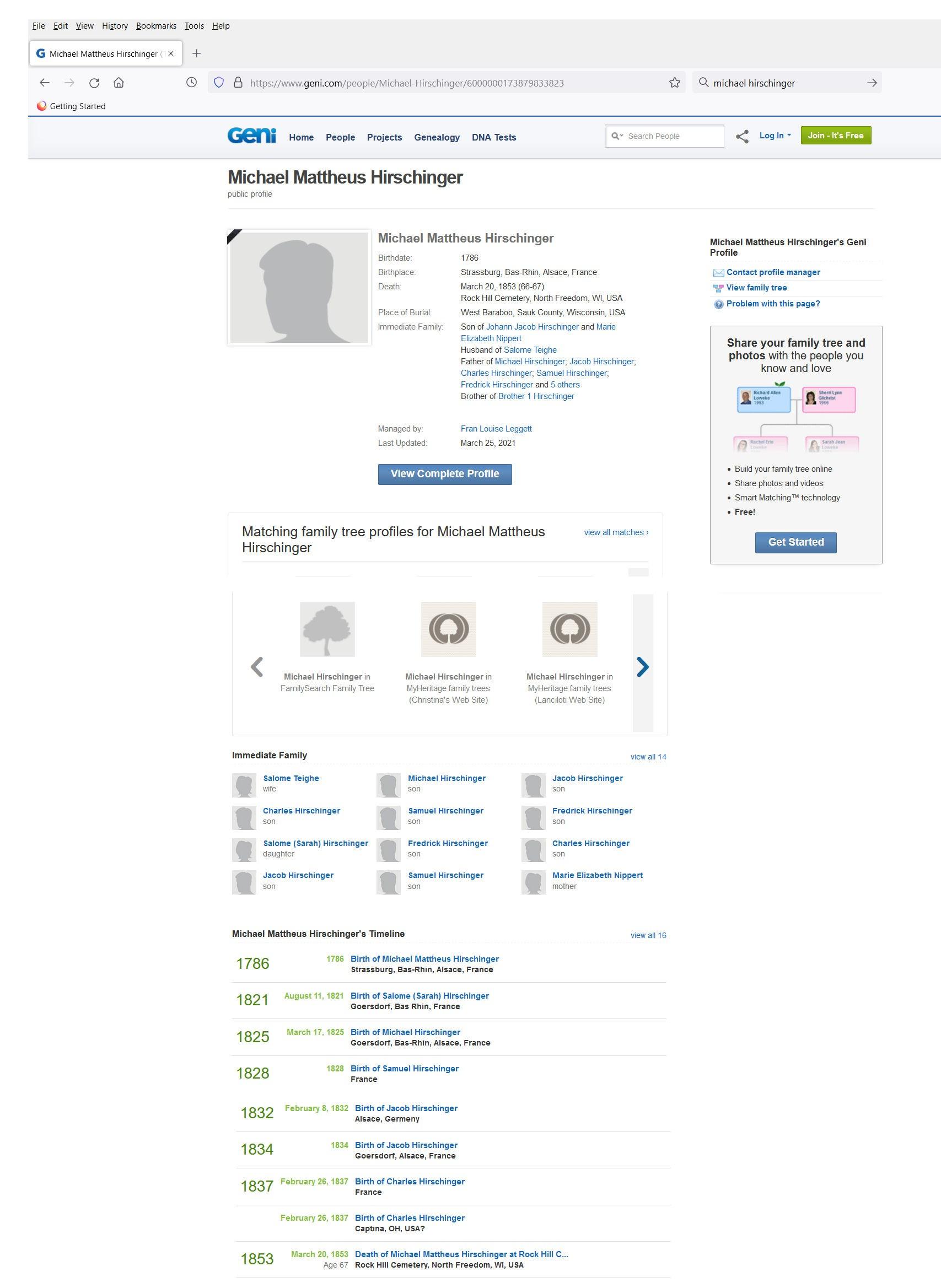

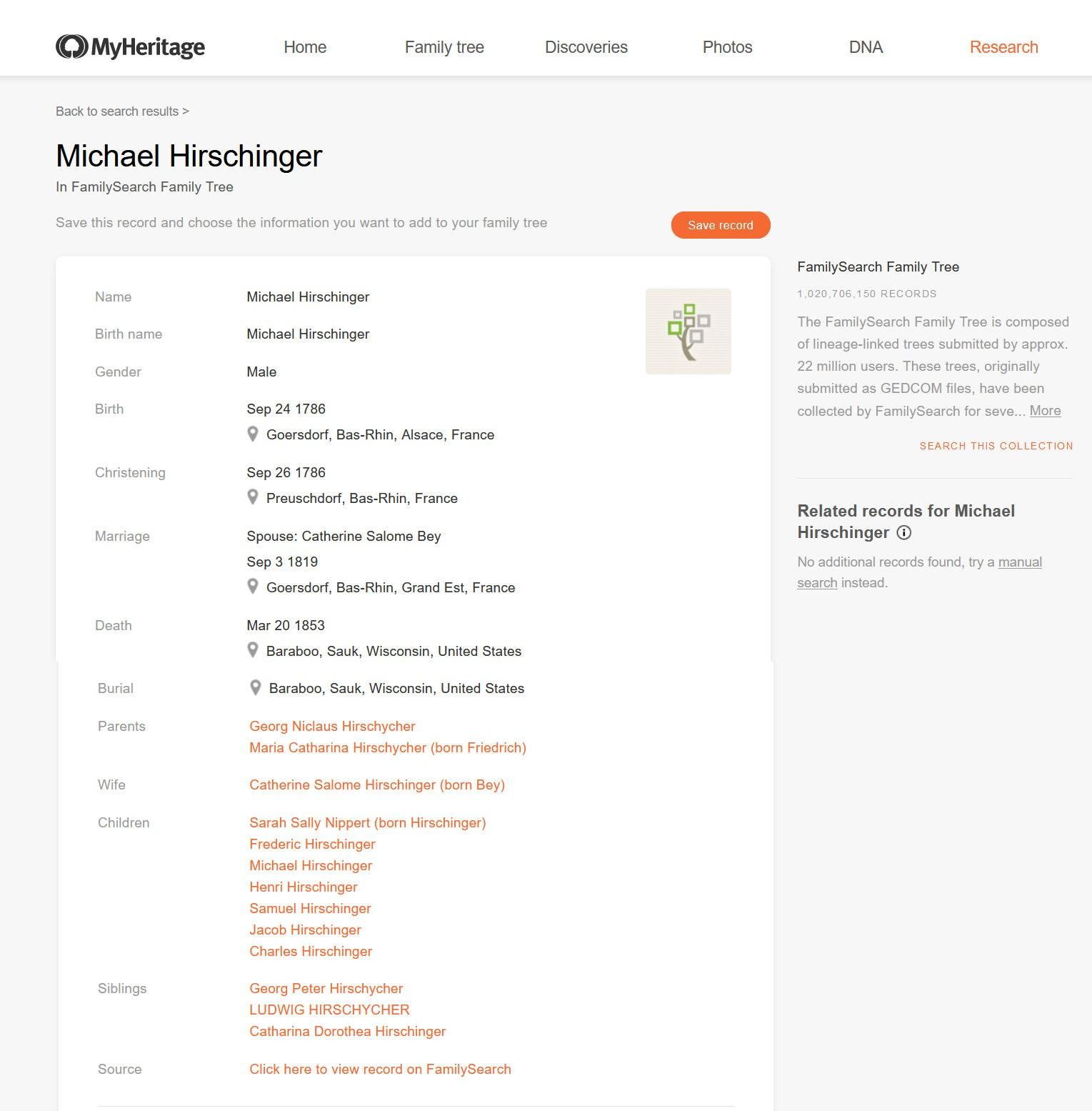

Michael Hirshinger

Michael Klaes

George Meyer

Michael Nippert

Peter Pauli

Michael Hirshinger

Michael Klaes

George Meyer

Michael Nippert

Peter Pauli

Napoleon ruled for 15 years, closing out the quarter-century so dominated by the French Revolution. His own ambitions were to establish a solid dynasty within France and to create a French-dominated empire in Europe. To this end he moved steadily to consolidate his personal power, proclaiming himself emperor and sketching a new aristocracy. He was almost constantly at war, with Britain his most dogged opponent but Prussia and Austria also joining successive coalitions. Until 1812, his campaigns were usually successful. Although he frequently made errors in strategy especially in the concentration of troops and the deployment of artillery he was a master tactician, repeatedly snatching victory from initial defeat in the major battles. Napoleonic France directly annexed territories in the Low Countries and western Germany, applying revolutionary legislation in full. Satellite kingdoms were set up in other parts of Germany and Italy, in Spain, and in Poland. Only after 1810 did Napoleon clearly overreach himself. His empire stirred enmity widely, and in conquered Spain an important guerrilla movement harassed his forces. Russia, briefly allied, turned hostile, and an 1812 invasion attempt failed miserably in the cold Russian winter. A new alliance formed among the other great powers in 1813. France fell to the invading forces of this coalition in 1814, and Napoleon was exiled. He returned dramatically, only to be defeated at Waterloo in 1815; his reign had finally ended. Source: Britannica1

Four men, who eventually emigrated to America and the Sauk County area, accompanied Napoleon to Moscow during his disastrous campaign of 1812: Peter Klaes, Michael Hirshinger, Michael A. Nippert, and Jurgen Meyer, who are all profiled in this publication The following is a chronicle of their sojourn on that trip to and from Russia. All four survived. Also included in this profile, is Peter Pauli, who was with Napoleon at Waterloo, during his disastrous defeat in1815. He also survived and came to America.

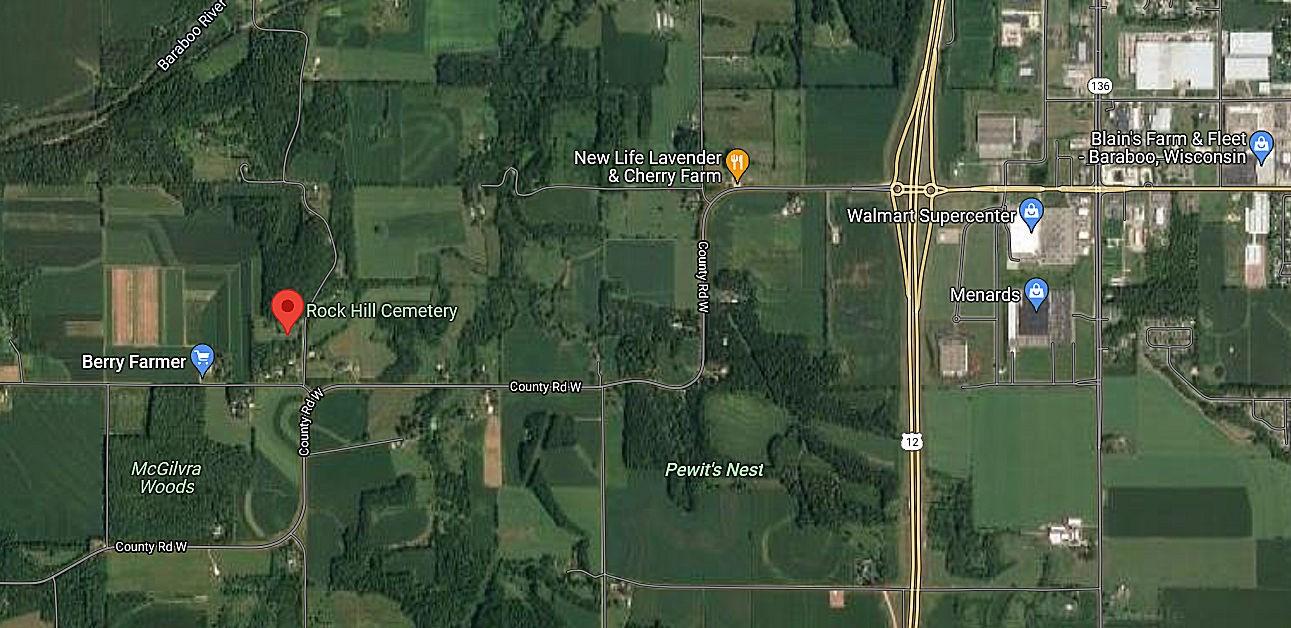

Pauli is buried in St. Norbert’s Cemetery, Roxbury, Dane County, Wisconsin. Klaes is buried somewhere in the Roxbury area. Hirshinger and Nippert are buried in Rock Hill Cemetery, Baraboo, Sauk County, Wisconsin, and Meyer’s final resting place is in St. John Cemetery, Westfield, Sauk County, Wisconsin.

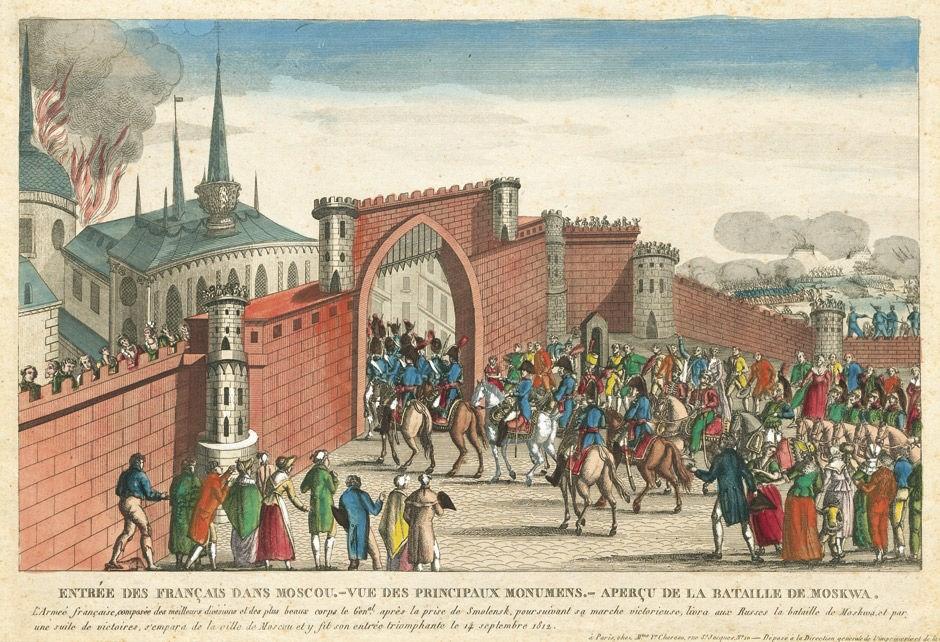

ON The MORNING of September 14, 1812, the Grand Army reached its supreme goal. The advance guard came to the top of rising ground, looked out over the flat plain beyond. There under a leaden sky a dingywhite line stretched half across the horizon. Above it, floating like bubbles, were the soaring cupolas of an Oriental city. Moscow.

The Emperor’s keen eyes picked out a group of towers higher than the rest the Kremlin. Napoleon was well content. He dismounted and prepared to receive the deputation that would come from the city begging terms.

It was the climax of the greatest blitzkrieg in history before or since. In 82 days, the Grand Army had fought its way 700 miles amazing speed for horse transport and men afoot.

It was the largest organized fighting force since the time of Darius [Darius led military campaigns in Europe, Greece, and even in the Indus valley, conquering lands and expanding his empire. Ca 522 BC.] Half a million men had crossed the Niemen on June 24 and the days following. Among them were armies from most of the conquered states of Europe; Prussia, Austria, Italy, Poland, Switzerland, Saxony, Hesse, Westphalia. But the core of the Grand Army was the French, those men who had never been beaten, whose best weapon was their legend of invincibility.

They had driven on through the heat and dust of the summer, pushing the Russians before them, at last forcing battle at Borodino. There, almost as a matter of course, they had won. The victory was costly, 35,000 Frenchmen killed and wounded. But it had opened the road to Moscow and here they were.

Now only one obstacle to world conquest remained Britain. Britain, who had thwarted him before, who had refused the secret truce which he had sent his brother to negotiate, who had pulled strings here in Russia to set the Czar against him.

Thus, Napoleon Bonaparte stood before Moscow, a dark, scowling, hard little man in a fair way to rule the world.

If he had a weakness, it was a rather vulgar love of pomp, of the spectacular and dramatic. He loved especially occasions like this, when conquered princes and deputations bowed before him.

This particular deputation was unaccountably delayed. The Emperor, impatient, sent couriers to hurry it up. After a long time, they returned with a strange tale, so strange that Napoleon went to see for himself.

He entered the city by the great double gate. There was no one there to meet him. He rode through the streets. No one stood at the curbs, none looked from the windows. Over all was heavy silence. Patrols were sent into houses, to bring out the inhabitants. There was nobody to bring. Palaces, hovels, churches, stores stood empty.

The Emperor went into the great enclosure of the Kremlin. He entered the royal apartments. The clocks were still ticking but there was not one human being. Searchers through the city rounded up a mere handful of poor and ignorant folk. From them nothing could be learned.

An uneasy feeling took hold of Napoleon. Things that he had seen since he entered Russia assumed new meaning. The devastation, for example peasants and livestock gone, their houses burned, their crops destroyed.

He began to wonder a little what was in store for him in this strange country.

But he dealt with the situation in his usual methodical way. He established quarters in the Czar’s apartments, gave orders to occupy the city, sent a force to make contact with the enemy.

The soldiers, too, dealt with the situation in their way. They broke into stores and palaces, loaded themselves with furs, silks, paintings, silverware. They found great stocks of wine and brandy made full use of them. Discipline relaxed.

At noon next day the 15th the guard on the walls of the Kremlin saw wisps of smoke in the northern section of the city. Presumably chance fires started by careless, drunken soldiers. Sappers [combat engineers] sent to keep the fires from spreading returned with a disquieting report. The city’s fire engines had disappeared.

Other fires were seen in the east. Then in the south. Finally, a patrol caught a Russian setting a blaze. A rising wind merged the separate fires until the whirling smoke was a flat ceiling over all the city. All that night Napoleon stood on the Kremlin walls watching silent. Next day he was persuaded to leave. The city was one great plain of fire, four miles across. For a whole week it burned. The Kremlin alone escaped. The Emperor returned to it.

In those days Napoleon spoke little. He seems to have been in a puzzled state of mind. He couldn’t believe that the rulers of even a barbarian nation could have ordered such a deed at one stroke to have made 300,000 of its people homeless. Even he couldn’t grasp so vast an indifference to the lives of individuals. He began to think too of the hundreds of miles of burned villages and devastated fields that lay behind, on the road home.

Moscow’s grain warehouses had been burned and foraging parties sent out into the country brought back little. In other conquests Napoleon had always found traders who, for gold or paper, would supply all he needed. He didn't find them in Russia. The army began to be hungry. Discipline relaxed a little more.

Even now Napoleon believed that his defeat of the Russian army, his occupation of the Russian metropolis, marked a decisive end of the war. It always had. He sent a mission to St. Petersburg to offer peace terms to the Czar terms a little more generous than he had first intended.

There was comfort in the fact that the weather stayed fine. It was a lovely October crisp in the morning, but calm and sunny all day. Once a few flakes of snow fell, but then it turned warm again.

Weeks went by and no reply came from the Czar. It became increasingly apparent that no reply was coming.

Napoleon broke out in a petulant fury of exasperation. He summoned his generals and announced that he would march on St. Petersburg. Always in the past Napoleon’s decisions had been final. But this was an impossible plan. His line of communication was already strained to the breaking point and winter was coming. His generals didn’t so much argue against the project as kill it by their silence. Nothing was done about it.

At last, it was manifest even to him that the only thing to do was to turn back. On October 18th [1812] the Retreat began.

Of the huge army that had crossed the Niemen the greater part had never reached Moscow. Some guarded the line of communication and garrisoned the cities on the route. Many had been lost in skirmishes and guerrilla fighting. More lay dead on the field of Borodino. The army that now marched out of Moscow numbered 100,000.

The road ran straight without a turn. As far as one could see, it a slow-moving stream of guns and wagons. On each side the infantry marched. On their flanks rode cavalry. An organized army, still.

From the very start they were hard-up for food. Now every driver had to watch his team to keep it from slaughter though there wasn’t much meat left on the animals. Whenever a thatched hut was found the straw was pulled out and fed to the starving beasts.

Behind the army the road was littered with abandoned loot books, pictures, silverware. Wagons and guns began to be abandoned too; not enough horses were left to haul them. But the French still had strength to fight off the Russians who were following at their heels.

Gloom settled over the marching army. There was one horrible day when they passed the battlefield of Borodino. The 35,000 French corpses and 40,000 Russians were still there rotted, half-eaten by the wolves.

On the night of November 5, the army lay bivouacked for miles along the road. A wind arose blew harder and then harder. It came from the northeast, from the frozen steppes, and for a thousand miles there was nothing to check it. Snow came with it heavier as the night went on. The snow drifted and the bivouac fires went out, one by one. The cold was such as these Frenchmen had never known.

Great numbers were frozen to death that night. From that time on the army never escaped for a moment the Russian winter.

The supply service went to pieces. The only way to get food was to leave the line of march and go foraging over the countryside. The long column began to break up into little groups going off on their own.

It has been said that Napoleon shared the hardships of his men. He did not. He kept fairly warm and well-fed on beef and mutton, white bread, even his favorite Burgundy. He rode in a carriage, bundled in furs. Sometimes the carriage would jolt heavily over the bodies of men lying in the road, frozen to death or not yet quite dead.

The hero of the Retreat was Marshal Ney, as he brought up the rear, protecting the struggling columns from the stabbing attacks of the pursuing Russians. Once Ney was cut off from the main body. Napoleon didn’t halt or try to reestablish contact. Eventually the Marshal, by a brilliant attack, fought his way back to rejoin his chief.

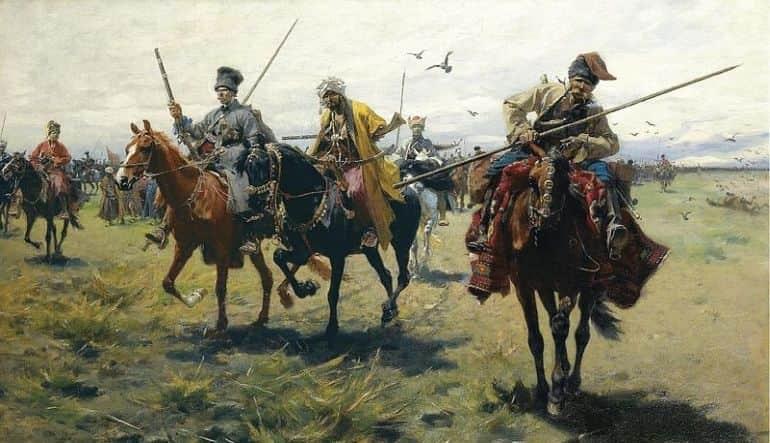

The Cossacks were the worst scourge of the Grand Army. They were tough, hairy little men, bearded to the eyes. They wore hairy caps and coats, rode shaggy little horses. They had short bowlegs and it seemed as if horse and rider had grown together. They carried long lances and rode to the attack with shrill, fierce cries.

They would hide in patches of woodland, ride out suddenly on cold, weary men looking for food, or gathered stiffly around a campfire. Sometimes they stripped their victims and herded them naked ahead of their horses until they fell and died. Sometimes the butts of their lances would rise and fall, the points stab down again and again. The snow would be crimson.

It got colder. The record shows somewhere between 30 and 40 below zero. But even in the bitter cold the soldiers would sweat as they struggled through snowdrifts. Then at night, as they slept on the ground, the damp clothes would freeze solid. The heat drained out of their bodies like a fluid. Each camp site was marked by hillocks covering the dead.

The route was cluttered by abandoned guns and wagons. Few horses were left. Their ribs stuck out and they staggered in the traces. Groups of men followed each team. When ahorse fell the crowd pounced on it, cutting it to pieces while it was still alive. They fought to drink the warm blood.

Snow blindness made hundreds helpless; others went mad.

Some few tried to help those who had fallen and were freezing. But the men on the ground would plead to be left alone, to be allowed to sleep.

The last encounter that could be called a battle was at the crossing of the Berezina River. They had hoped to find it frozen solid so that they could cross on the ice. But it was only half frozen, with big ice cakes churning down the current.

Sappers managed to construct two bridges, while the rear guard with difficulty held off the Russians. For a while an orderly crossing was maintained. The Emperor got safely across. Then one bridge broke and soon the Grand Army became a struggling mob, fighting to get on the other bridge. Russian cannon plowed lanes through the solid mass of men a target half a mile wide and two miles thick. It is said that in the spring 12,000 bodies were taken from the Berezina.

Across the river the remnant of the army staggered on.

The story has no one end, but a series of small, tragic endings, as little groups desperately seeking food were overcome by starvation or trapped by Cossacks.

It is not known how many straggled out of Russia. The organized army that finally reached Konigsberg numbered about 1000.

The Emperor was not with them. Early in December he had fled in disguise to Paris. To his companion on that journey he railed against England. He made new plans for attacking Britain impossible plans.

He knew that the news of the Retreat had reached Paris before him. He arrived like a dog who wonders whether he’ll be whipped. But the French and it must have astonished him were still loyal. He resumed the pomp and ceremony of his court still Emperor.

But the Retreat had finished him. Not at once. For more than two years he twisted and turned. It was no use the conquered races of Europe, seeing that he was not invincible, rose against him. His own people began to fall away from him. In the end he was beaten for good by the tenacity of the British at Waterloo.

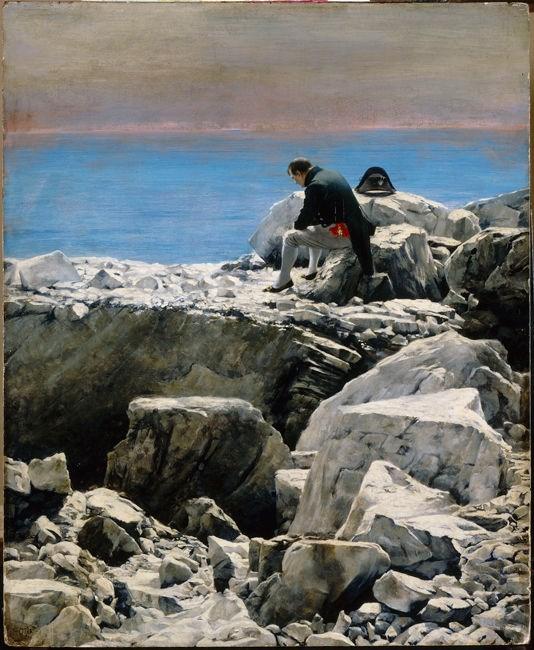

There were a few years left to him on his dreary little island where he perpetually explained how he had always been right. Then a dreary death.

As Victor Hugo said, God was bored with him.

Napoleon was ultimately exiled to St. Helena, a British colony 5,000 miles and a 10-week boat ride away from Europe. Napoleon spent more than five years on the island, arriving in October 1815. During his first couple of years on St Helena, Napoleon took regular walks, went riding and spent much of his time reminiscing. But as time went on, and the months turned into years, loneliness and boredom began to take its toll.

It's where he created his myth, dictated his memoirs and battled chronic pain from old battlefield injuries and, possibly, fatal stomach cancer. In 1840 his body was returned to Paris, where it was interred in the Hotel des Invalides. Source: Readers Digest2

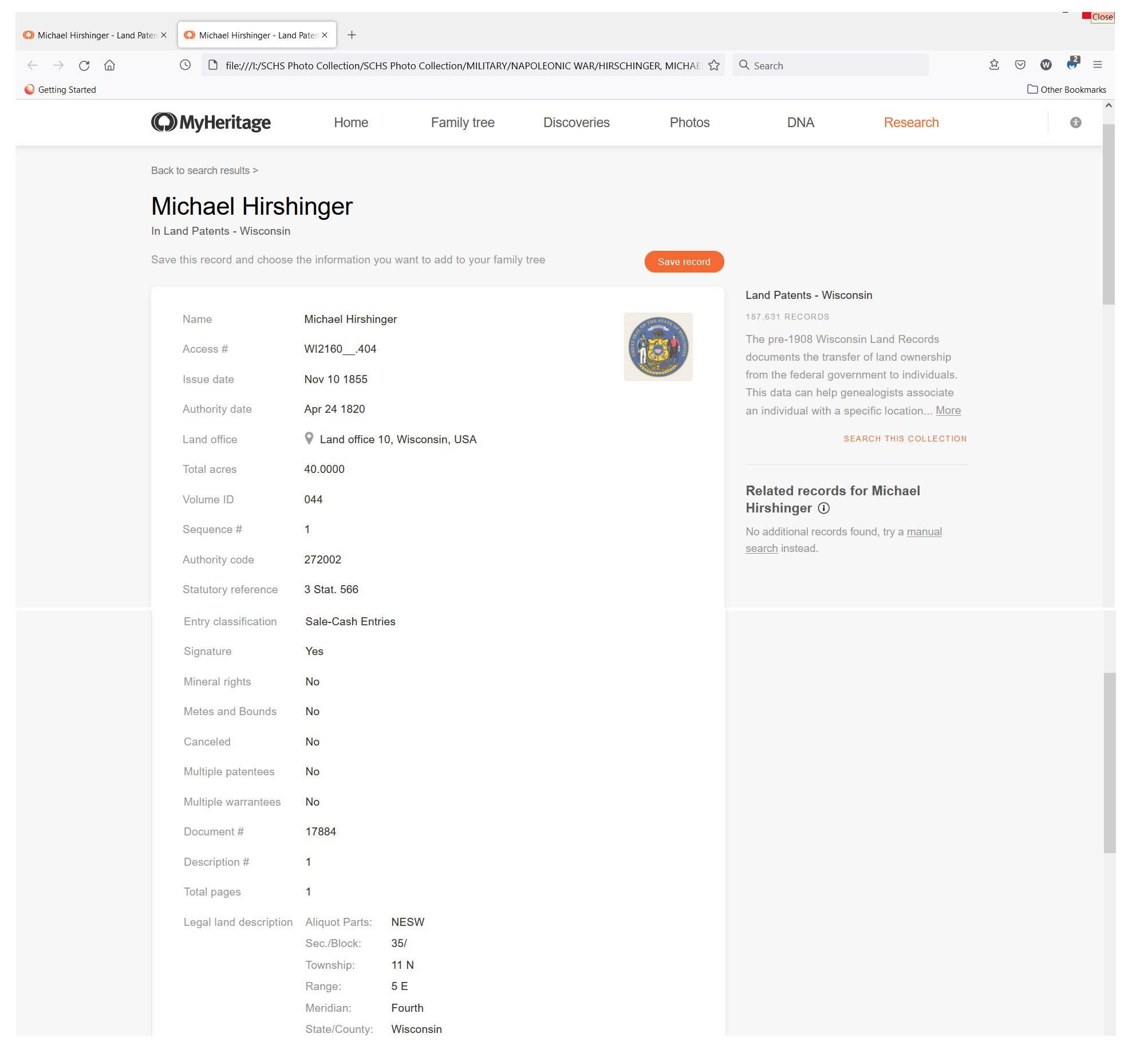

Michael Hirshinger served with Napoleon during the disastrous Moscow, Russia, campaign Jun 24, 1812

Dec 14, 1812. He was born on September 24, 1786, in Goersdorf, Bas-Rhin, Alsace, France. It is unknown whether he joined Napoleon's army voluntarily or was drafted. Nevertheless, he was with the army when Napoleon began his march to capture the Russian capital, Moscow, in 1812. He was one of the few survivors of that trip.

See Pages 4-11 for a complete description of Napoleon’s expedition to Moscow, and the disastrous return trip to France.

Rev. Waddell conducted this first worship service in the home of Michael and Selma Hirschinger. This was in the fall of 1847. Michael Hirschinger, along with Michael Nippert, had fought with Napoleon and were part of the emperor's march on Moscow in 1812. They are listed as part of a group of Germans who, in the mid nineteenth century, moved to an area of Eagle Township, which was transformed into Freedom Township, and later annexed to Baraboo Township. Cole explains, "Toward the close of the '50s and the beginning of the '60s two settlements of German people from Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, were made in Sauk County, one in the western part of the Town of Baraboo, including the Nippert and Hirschinger and other families, who organized a Methodist church or society. The other colony located in the western part of the Town of Freedom and East Westfield and they constructed a log church for the Methodist denomination." One apparent discrepancy is that "A Standard History of Sauk County" indicates that the Hirschingers and Nipperts migrated to Sauk County as part of the group from Pittsburgh in the late 1850s to the early 1860s. On the other hand, it is reported that the Hirschingers were already in the area in 1847 when they hosted the first worship service in Freedom Township. The following also gives the date of 1847 for the Hirschingers arrival in Sauk County. It is apparent that the Hirschingers came in advance of the subsequent groups.

"A Standard History of Sauk County" gives details on Michael and Selma Hirschinger moving to Sauk County:

“Michael Hirschinger was born in Germany in 1783 and married there Selma Beyx, who was born in 1797. Michael Hirschinger saw active service as a solider during the Napoleonic wars in Europe. In 1832 he left Germany, bringing his family to America, and they were thirteen weeks on one of the old sailing vessels that crossed the ocean. He first located at Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, subsequently lived in Ohio, and in 1847 came to Sauk County. That was a year before Wisconsin was admitted as a state and only a few clearings had been made here and there as evidence of the presence of white men in this county. Michael Hirschinger had bought a land warrant, and first used it to acquire 160 acres on the present site of Baraboo. He gave up that and located to another place in section 8 of Baraboo Township, where he had 120 acres. He did much development work on this land and lived there until his death in 1857. His widow survived him until 1881.”

The history of Methodism in Baraboo indicates that this church was built in 1850 in the Town of Freedom. One account of the history of the Westfield German Methodist Church mentions the German Methodist Church was started in Baraboo Township in 1853. Both may be correct since the church was built as a community church with the German Methodists taking over later. It is a fact that the last or one of the last of several restructurings of Freedom Township was the transferring of the easternmost sections of Freedom Township to Baraboo Township. That was in 1859. What was in Freedom Township at that time would be in Baraboo Township after 1859. Histories of the time use the names of the townships interchangeably. In any case, this church would have been founded under the banner of the German Methodist Church of the Town of Freedom. The Hirschingers owned land a little over a mile south of Rock Hill Cemetery. County Trunk W turns west below the cemetery, making that turn to bypass and preserve an idyllic spot known as Hirschinger Springs.

Later, William Canfield, for whom Charles Hirschinger, son of Michael Hirschinger, worked in the orchards, indicates that Charles “is a member of the German Methodist Church. They have a respectable church building within a mile of them to worship in." It doesn't indicate in which direction from the Hirschinger homestead the church stood. However, Bernadette Bittner reports:

“A Methodist Church was built in the east central part of section 7 in the early 1850s and was shown on the 1877 plat map as across the road from the school, now the community center. The structure is still standing (1977), having been used as a barn. It was a community church before the German Methodists took over…it was near Rock Hill Cemetery.”

iIn order to make the dates fit the other facts, it is necessary to understand that the new group who came from Pittsburgh, PA would have joined the Hirschingers and Nipperts who were already in the area. The late 50s and early 60s are mentioning the forming of the communities, not the dates of the arrival of the new settlers.

iiMost sources translate that German word Gemeinshaft as society. It means a group of people with something in common. In the case of churches, it would be better translated as congregation or fellowship.

iiiHarry Ellsworth Cole, ed., A Standard History of Sauk County, WI. Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Co., 1918. p. 582.

ivCole, op, cit. page 796.

vivhttps://www.baraboopubliclibrary.org/files/local/wardvol6/03%20Section%201.pdf, pg. 31.

viiWilliam Canfield, Sauk County, Including It's (sic) History from the First Marks of Man's Hand to 1891 and Its Typography. The Second Volume, Baraboo, WI

viiBernadette Bittner. The History of Churches in Sauk County Wisconsin featuring “Ghost Churches.” 1977., p. 19

Michael Nippert was also involved in the German Methodist Church of Freedom (Slentz District). His father once visited Michael and his family. His father then went to Germany where he started a German Methodist Church.

The Methodist Episcopal Church (now United Methodist Church) of North Freedom started in the blacksmith shop of Michael Nippert Jr, son of the Michael Nippert who fought with Napoleon. The blacksmith shop was on the northeast corner of today’s East Walnut and Depot Street in the Village of Bloom, now part of the Village of North Freedom.

Source: Allen Schroeder, July 2022

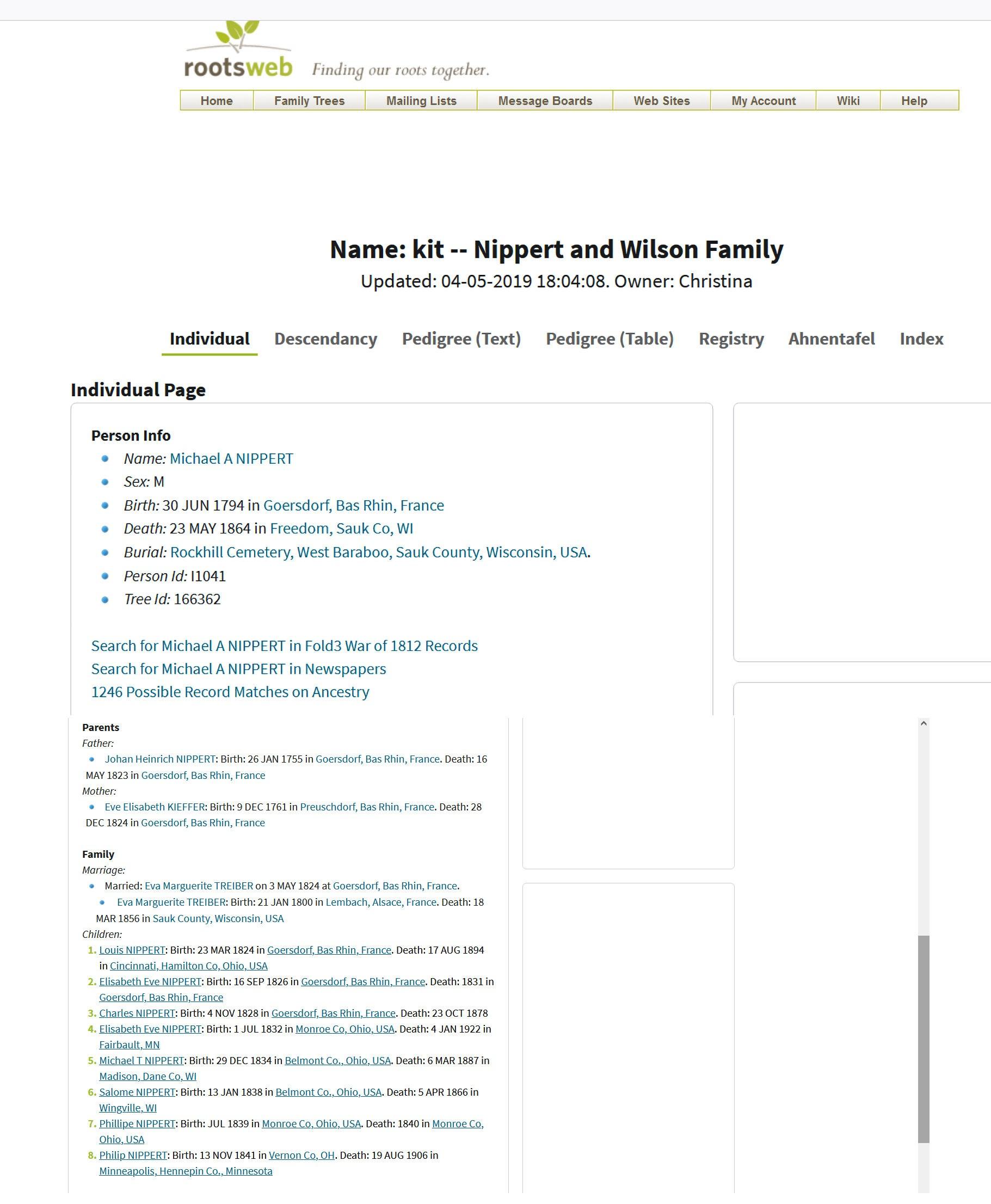

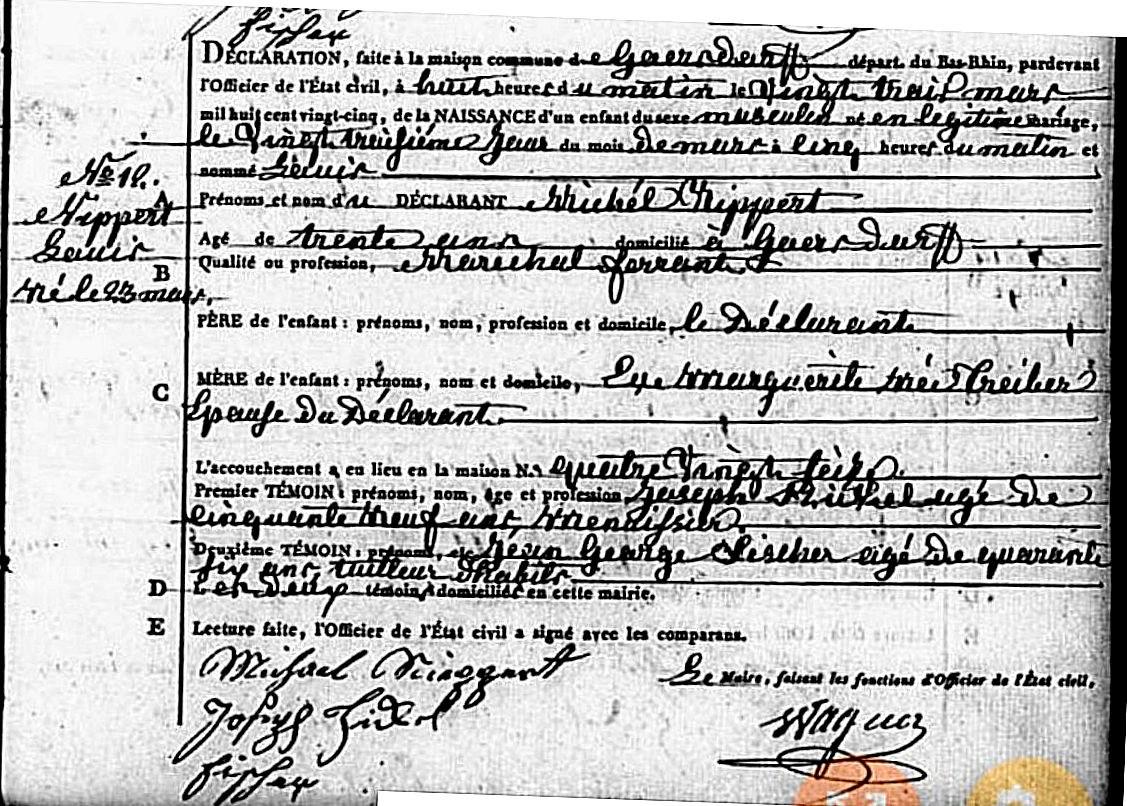

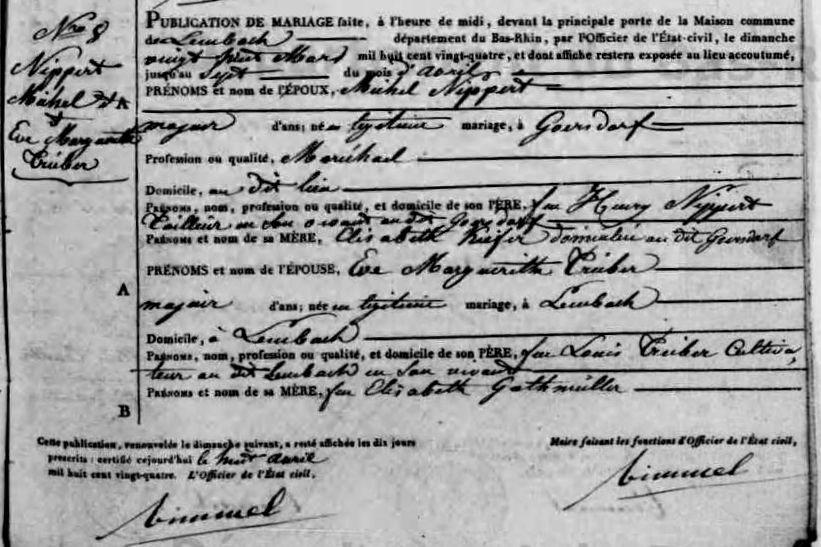

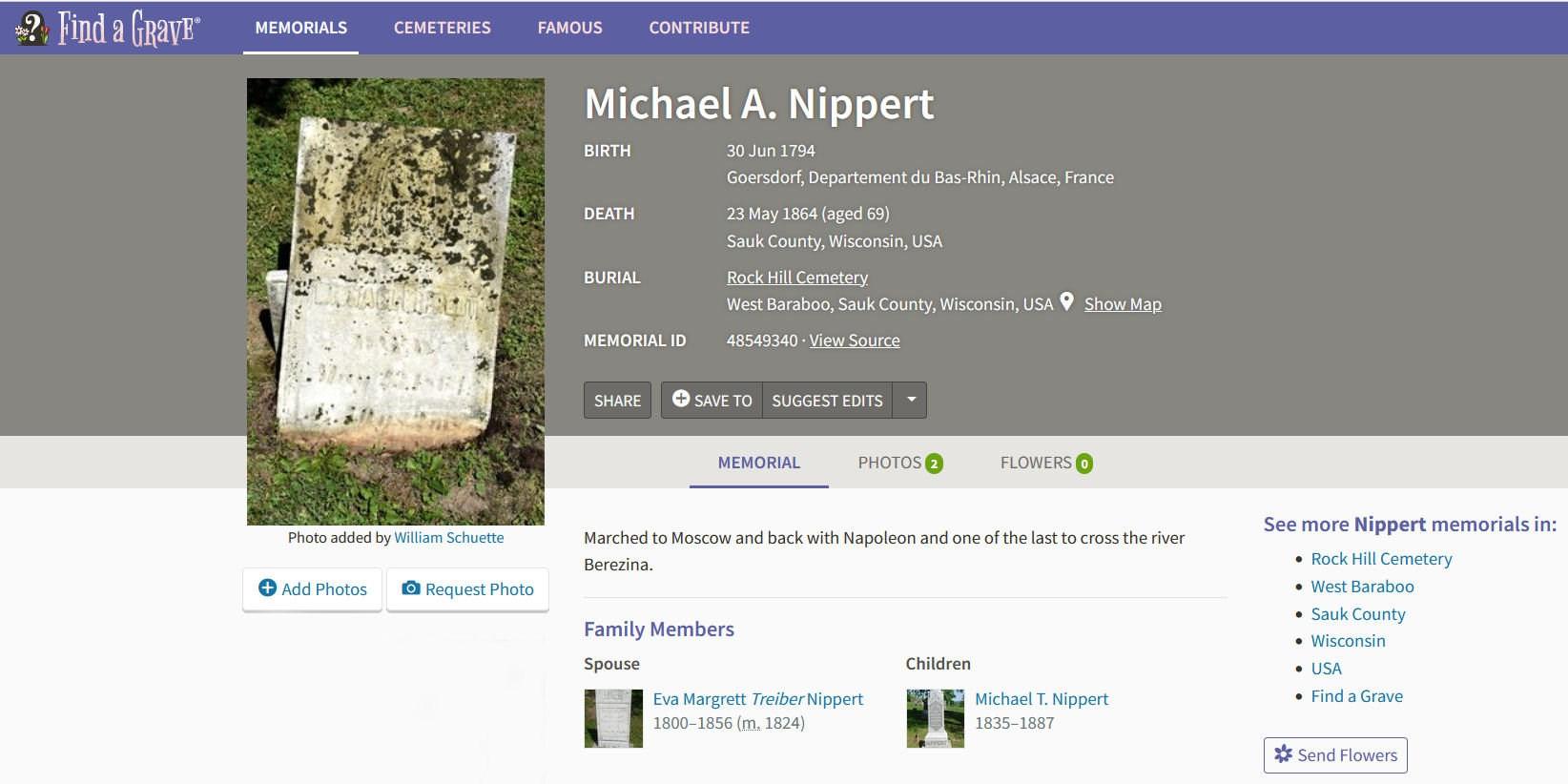

1794

1864

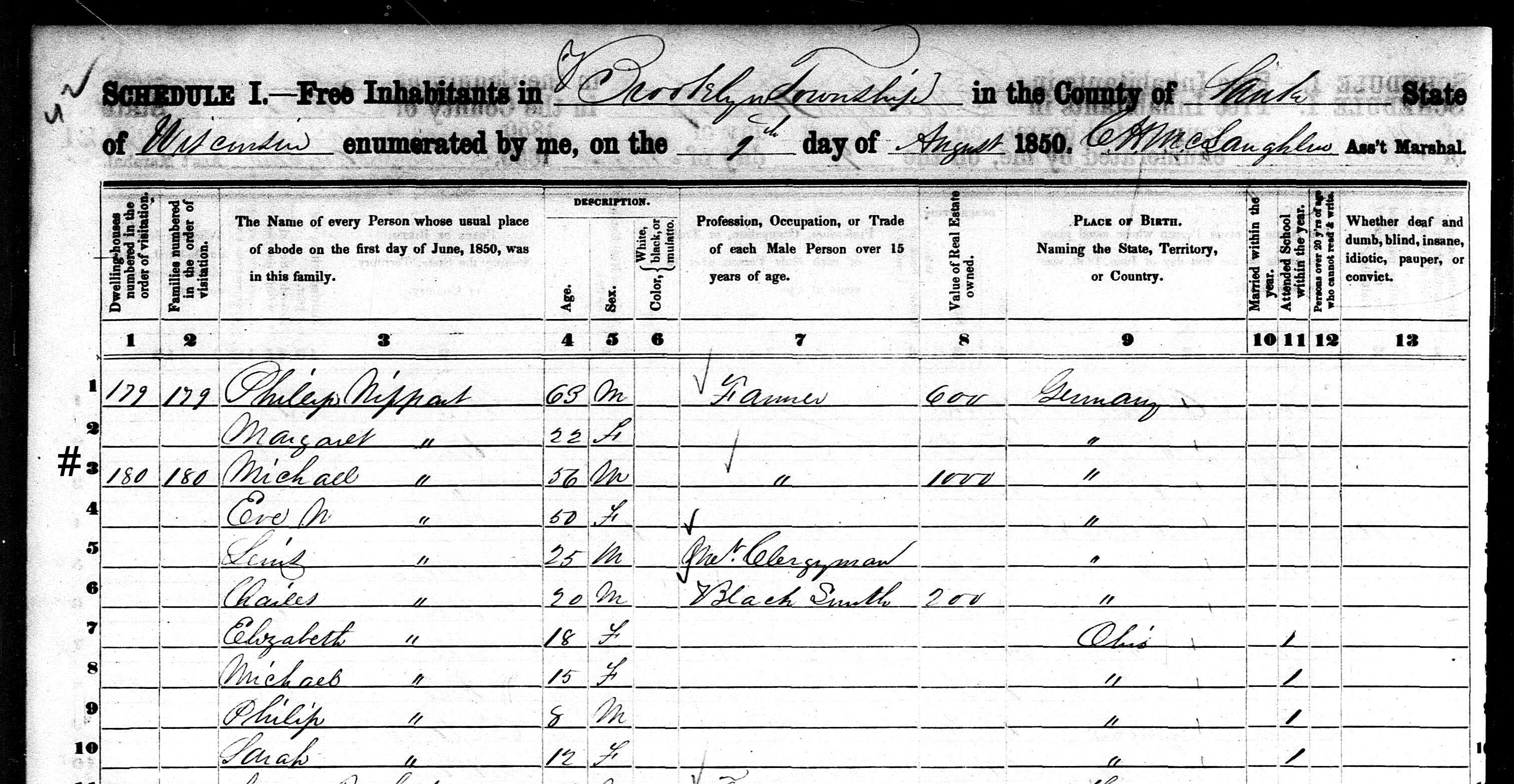

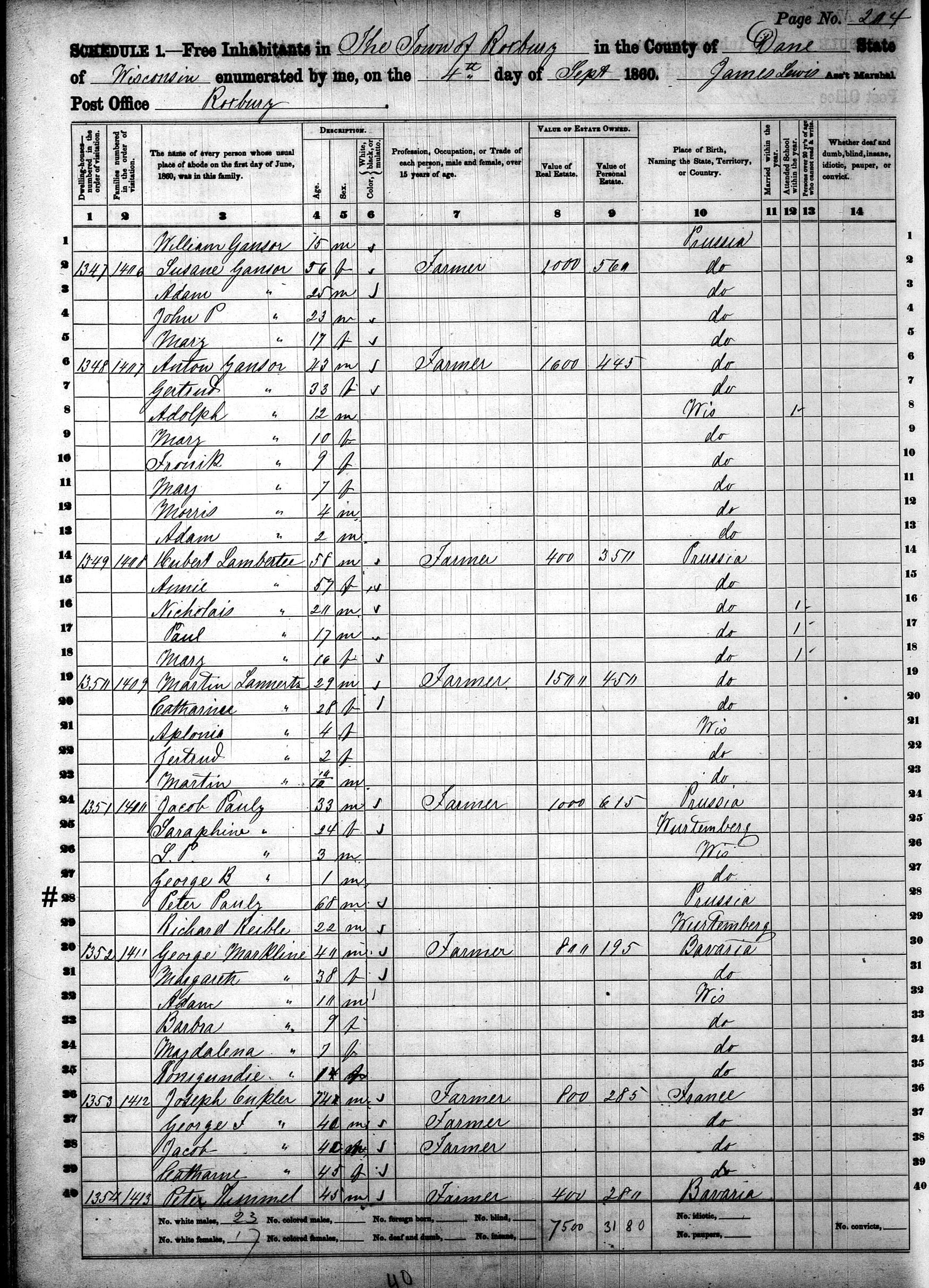

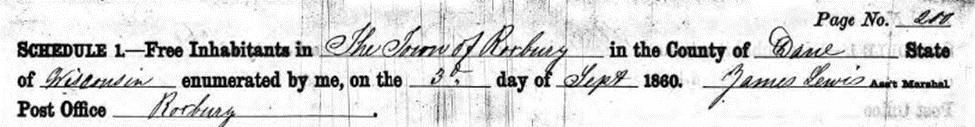

1850 Baraboo Township Census

1794

1864

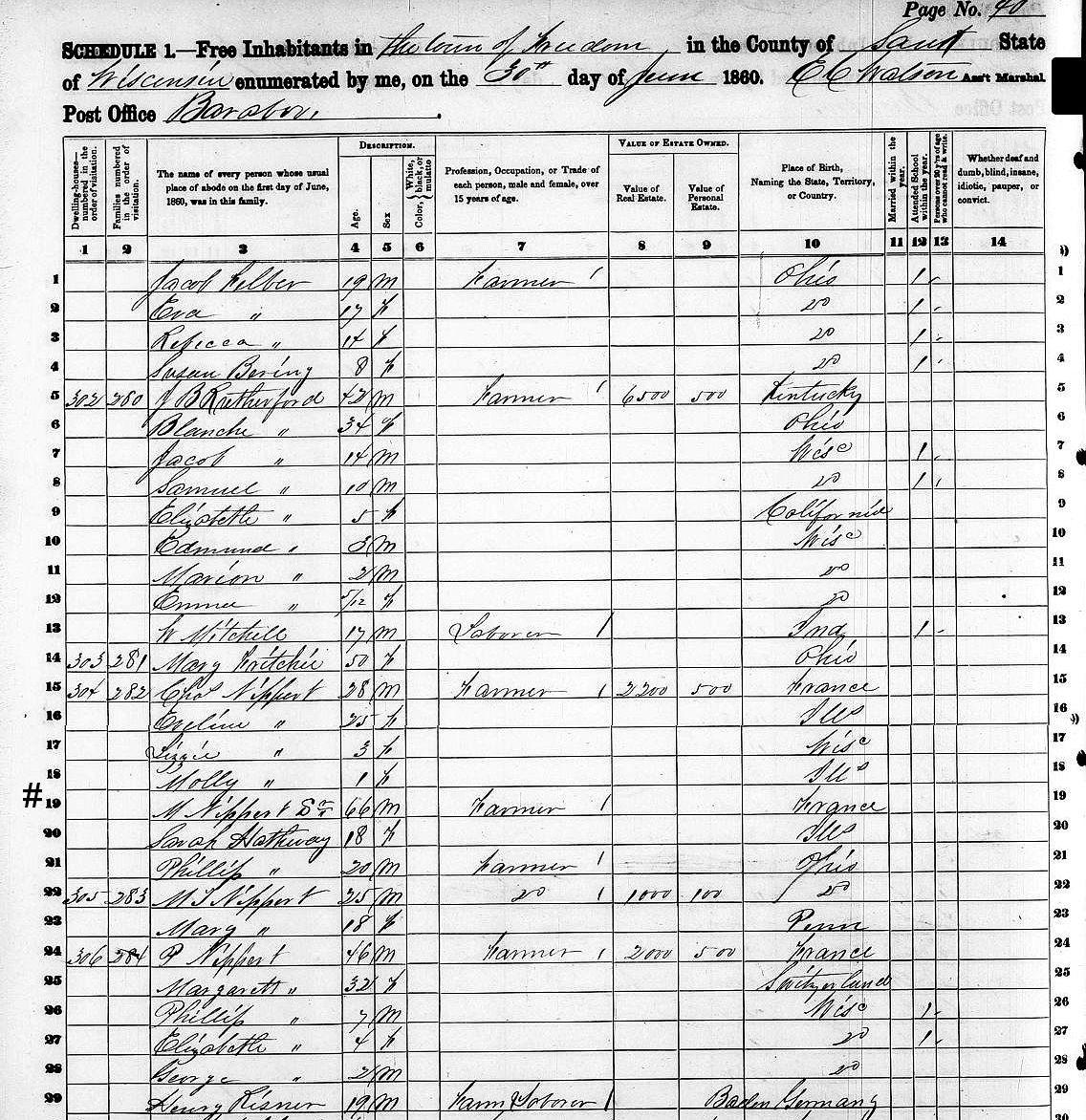

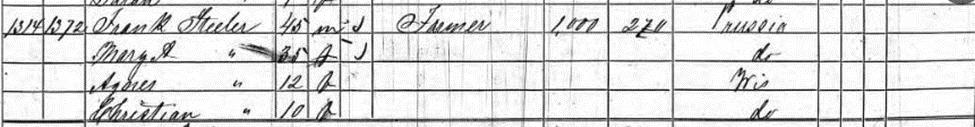

1860 Freedom Township Census

1794 1864

Declaration It appears this may be a declaration to depart from France.

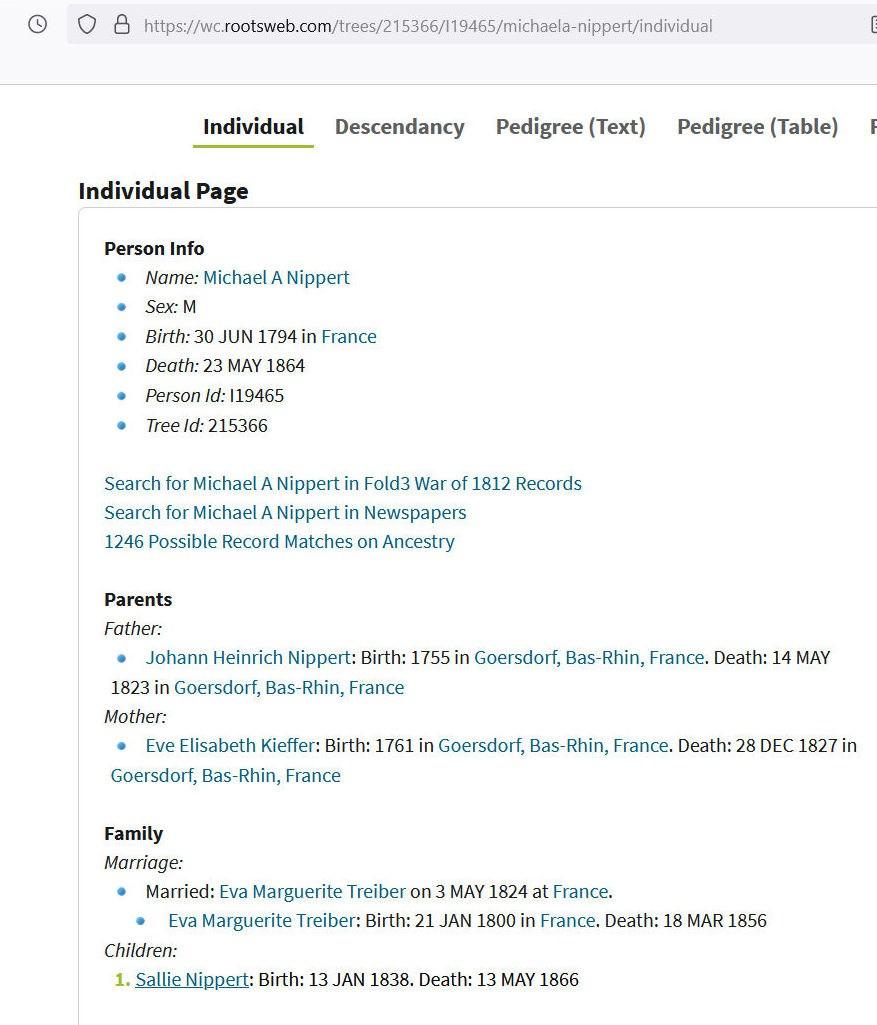

Notes on Nipperts of Baraboo, Wisconsin

(From Family Search-Unknown writer)

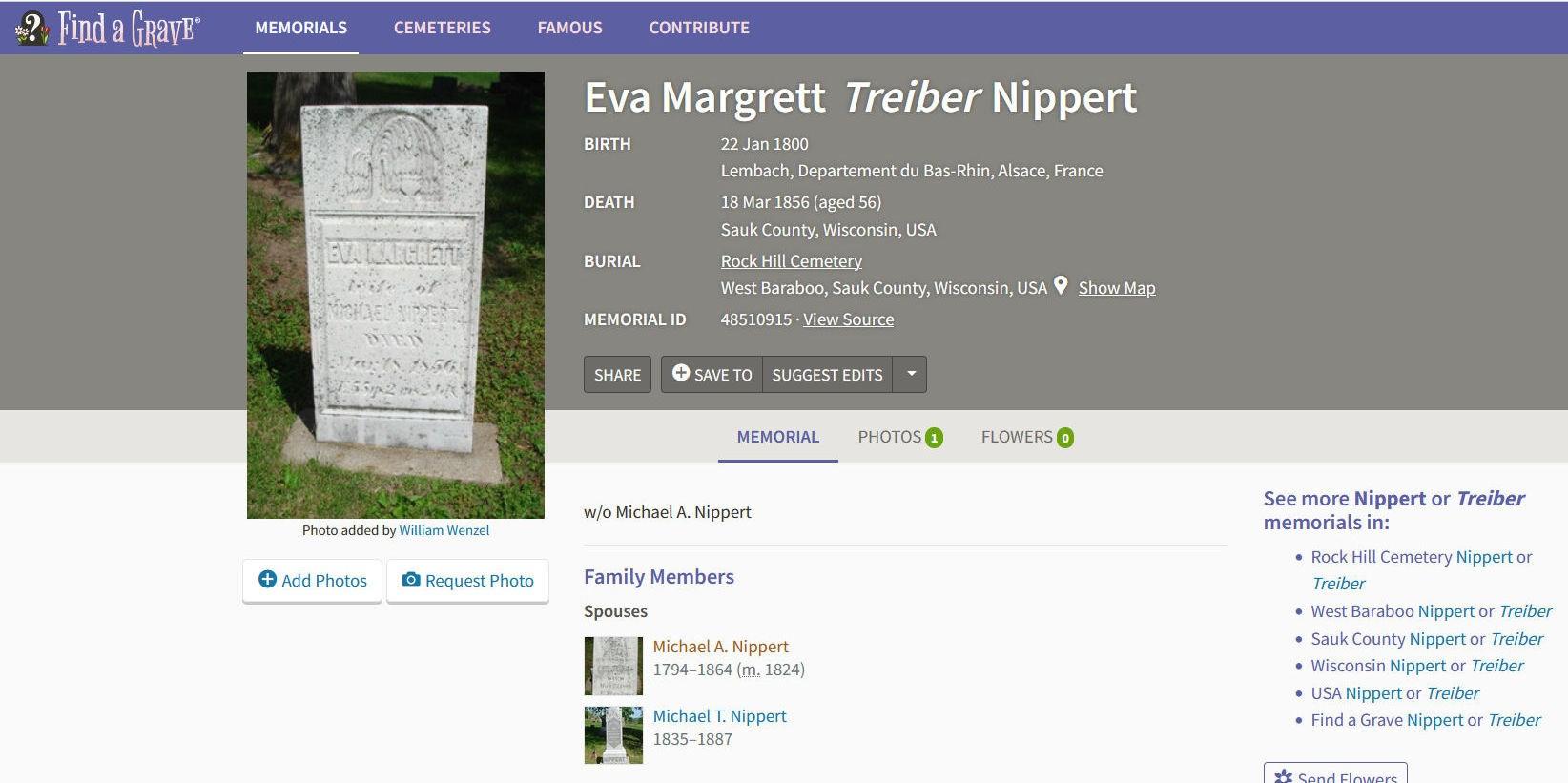

Rock Hill Cemetery: Nippert, Elizabeth, b. 1855, d. 1934, dau., s/w Philip Nippert, Row C18 Nippert, Eva Margrett, d. Mar 18, 1856, 55y 2m 24d, s/w Michael Nippert, Row C17 Nippert, George, b. Mar 26, 1858, d. Jun 25, 1876, son, s/w Philip Nippert, Row C17 Nippert, Jacob, b. 1861, d. 1934, son, s/w Philip Nippert, Row C18 Nippert, John, b. 1862, d. 1933, son, s/w Philip Nippert, Row C18 Nippert, Margret, b. Mar 14, 1829, d. Feb 18, 1903, wife, s/w Philip Nippert, Row C17 Nippert, Mary (Moog), b. 1842, d. 1860, Row N13 Nippert, Michael T., d. Mar 6, 1887, 52y 3m 10d, Co. G, 38th Reg. WVI, s/w Michael Nippert, Row C17 Nippert, Michael, d. May 23, 1864, 70y 2d, marched with Napoleon, Row C17 Nippert, Philip, b. 1854, d. 1933, son, s/w Philip Nippert, Row C16½ Nippert, Philip, b. Nov 29, 1814, d. Dec 19, 1873, Co. A, 6th Inf., Row C17 Nippert, Rebecca M., d. Oct 14, 1865, 8y 4m 7d, d/o M. J. & A. G., Row N19. His birthplace changed from France to Germany--the family of Nipperts seem to call themselves Germans more than French. The borders for those countries changed often and I am told they spoke German in their family.

NIPPERT NOTES: This is the man who marched with Napoleon. Inscription on Gravestone reads: Michael Nippert died May 23, 1864, aged 70 years, 2 months. This Michael is the one who has the GREAT BIGGEST stone at Rock Hill Cemetery. There are great big willow trees as the focus of the cemetery shading the huge stones which are the focus of the cemetery with all the normal size stones around them. Death entry at cemetery says: Nippert, Philip, b. 1854, d. 1933, son, s/w Philip Nippert, Row C16½ 1860 Census Michael lived with Charles and Eveline Nippert and their two little girls. Ohio descendants say he came to America in 1830 under a French passport, with 3 children. Louis, Eva and Charles. Reverend Louis Nippert says: Michael Nippert departed with his family in the spring of 1830 to make his way to America. On May 30, 1830 he landed in New York with his wife and 3 children after an ocean voyage of 64 days. Son Louis was only age 5. Little son Louis got lost in America on their way to Ohio. He was found entertaining a group of people with his simulated bird calls and was being rewarded with pennies. He was learning to be successful at an early age. He could have gotten scared and started crying. Instead, he decided he would do what it took to buy himself meals and take care of his own self.

1840 Census shows Michael, the father, with a wife and 6 kids in York Twp, Belmont County, Ohio was in manufactures and trades (not agricultural) Michael's gravestone says he died May 23, 1864. Michael T. Nippert's farm was" just west of Rock Hill Cemetery, opposite the Slentz place.” Michael came to America from Germany. His French name is Jean Michel. Left France on the 25th of Mar 1830. Came to US from Le Havre, France to Battery Park NY. Landed May 30th in New York with wife and 3 children after a 64-day voyage. At their arrival they went by wagon over land to Pittsburg and stayed for just a bit. Then crossed the Allegheny Mountains to Pittsburgh, took a flat bottom boat (Broadhorn) to Powhatten Point Belmont Co. OH where they spent a few years. Another source says they moved to Monroe County, Ohio in 1831 or 1832, Powhatten, Belmont County. A few years later moved to Captain or Capatan, Switzerland Twp, Monroe County, Ohio. Then in 1849 moved to Baraboo. Fish Lake, Ohio is mentioned too. Michael & family lived in Sauk Co. in 1850. Louis visited them there. His wife died in 1856 and he moved in with Charles Nippert. Was living there in 1860.

Michael was known as Michael A. or Michael Jean to the relatives in Ohio, but he was known as Michael T. to the Wisconsin folks. He is buried as one of the principal people at Rock Hill Cemetery. This is the guy that is Michael Hirschinger's cousin. "A great Corsican Warrior." In a history book it says, "The Corsicans are of Italian stock" and that several hundred thousand Italians live in southeastern France, especially about Nice. It also says that a great number of mules are raised in the sound of France. And of course, wine.

SOURCES: From the Cincinnati Nippert’s and many original certificates. Such as Goersdorf marriage records 1850-1900 Sauk Co WI census 1840(1830) Belmont Co. OH census 1910-20 census IL Louis's Bio, Eva Nippert's scrapbook. Birthdate also listed as 30 Jun 1794.

SOURCE: 1840 Census says Michael NEPERT, page 38, York Township, Belmont County, Ohio 1850 Brooklyn Township Census 1860 Census Freedom, Wis. p. 459. He lived with his son Charles and wife Eveline 1880 Census says Michael T told the census taker his mother and father were born in Germany not France Flora and Nora Lemke's letter to me in 1978. Michael T. was their grandfather. Came here with his wife in 1830 to Ohio, then Illinois, then Wisconsin. He was a blacksmith and taught his son Charles (Karl). He says his parents were born in Germany in the 1880 Census, Freedom, WI Alfred Kuno Nippert said in a letter that Michael came to USA in 1829 or 30, settled in Pennsylvania and about 1831 or 32 moved to Monroe County, Ohio. That he had 2 girls and 4 boys (who grew up, I suppose). This is what he said in his letter to someone. I have a copy of it, I think.

A Nippert was known to be the first to make ice cream in the United States. Sarsparilla too. Jerry Nippert told me these last two things. He specializes in Nipperts. And a Nippert was in the news for having a hot dog stand for the soldiers in WW2. There is a Nippert Stadium in Cincinnati, Ohio named after our ancestors. They were famous there. The stadium has been torn down in the 1990s to make way for a new one.

A Mr. Nippert was married to Maude Gamble, daughter of Mr. Gamble from Procter and Gamble.

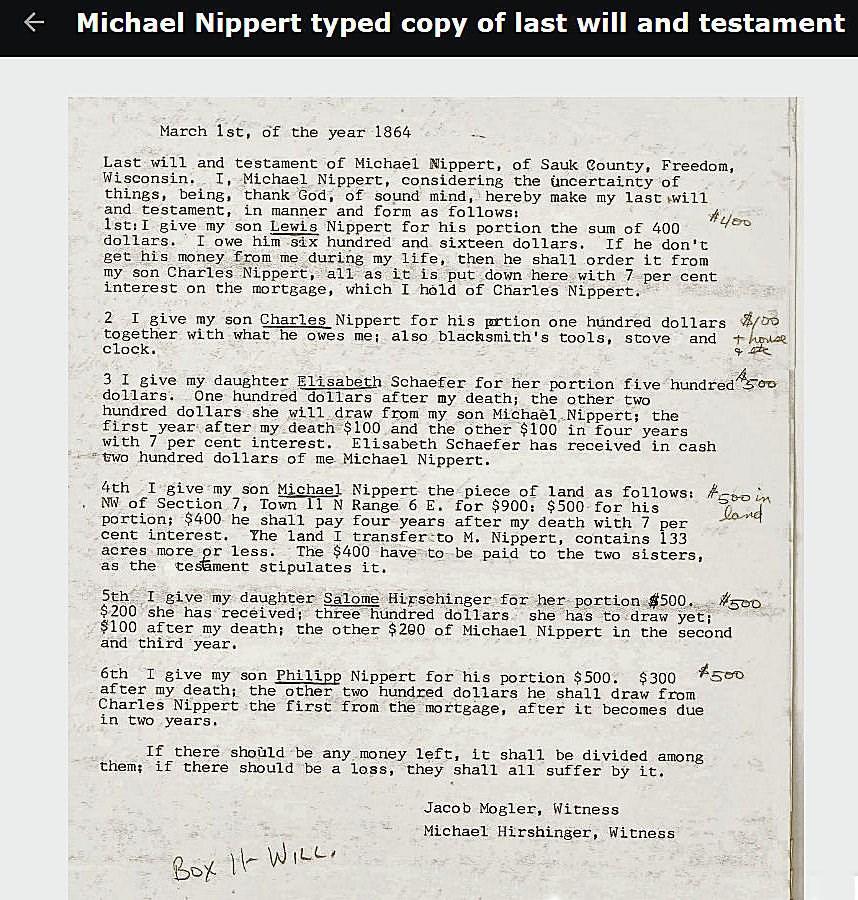

SOURCE: Vol. A, p. 506, Box 11, Will of Michael T. Nippert at Sauk County Courthouse, Baraboo in Baraboo: (Pat Decker) held and read the actual will plus other papers in his file. He gave Louis N. $400; Charles N. $100; Elisabeth Schaeffer $500; Michael got land; Salome Hirschinger $500; Philipp $500. All his children.

Michael & Eva Margareth came to Pennsylvania in 1829 or 30, then to Ohio in 1831 to 32, then to Wisconsin. Michael lived with Charles in the 1860 Freedom census no wife then. Michael's son, and Charles’s brother Philip lived there too.

MICHAEL HAS

1840 Census shows Michael, the father, with a wife and 6 kids in York Twp, Belmont County, Ohio was in manufactures and trades (not agricultural) Michael's gravestone says he died May 23, 1864 Michael T. Nippert's farm was "just west of Rock Hill Cemetery, opposite the Slentz place". Michael came to America from Germany. Left on the 25th of Mar 1830. Landed May 30th in New York with wife and 3 children after a 64-day voyage. At their arrival they went by wagon over land to Pittsburg and stayed for just a bit. Then by flatboat (broadhorn) to Powhattan Point Belmont Co. OH where they spent a few years. Another source says they moved to Monroe County, Ohio in 1831 or 1832. Michael & family lived in Sauk Co. in 1850. Louis visited them there. His wife died in 1856 and he moved in with Charles Nippert. Was living there in 1860. Michael was known as Michael A. or Michael Jean to the relatives in Ohio, but he was known as Michael T. to the Wisconsin folks. He is buried as one of the principal people at Rock Hill Cemetery. This is the guy that is Michael Hirschinger's cousin. "A great Corsican Warrior" In a history book it says "The Corsicans are of Italian stock" and that several hundred thousand Italians live in southeastern France, especially about Nice. It also says that a great number of mules are raised in the sound of France. And of course, wine. 1900 Sauk Co WI census 1840(1830) Belmont Co. OH census 1910-20 census IL Louis's Bio, Eva Nippert's scrapbook Henry Nippert a nephew not a son. POSSIBLE PROBATE: Will book A p. 506 box 11 at Baraboo Court House which I researched.

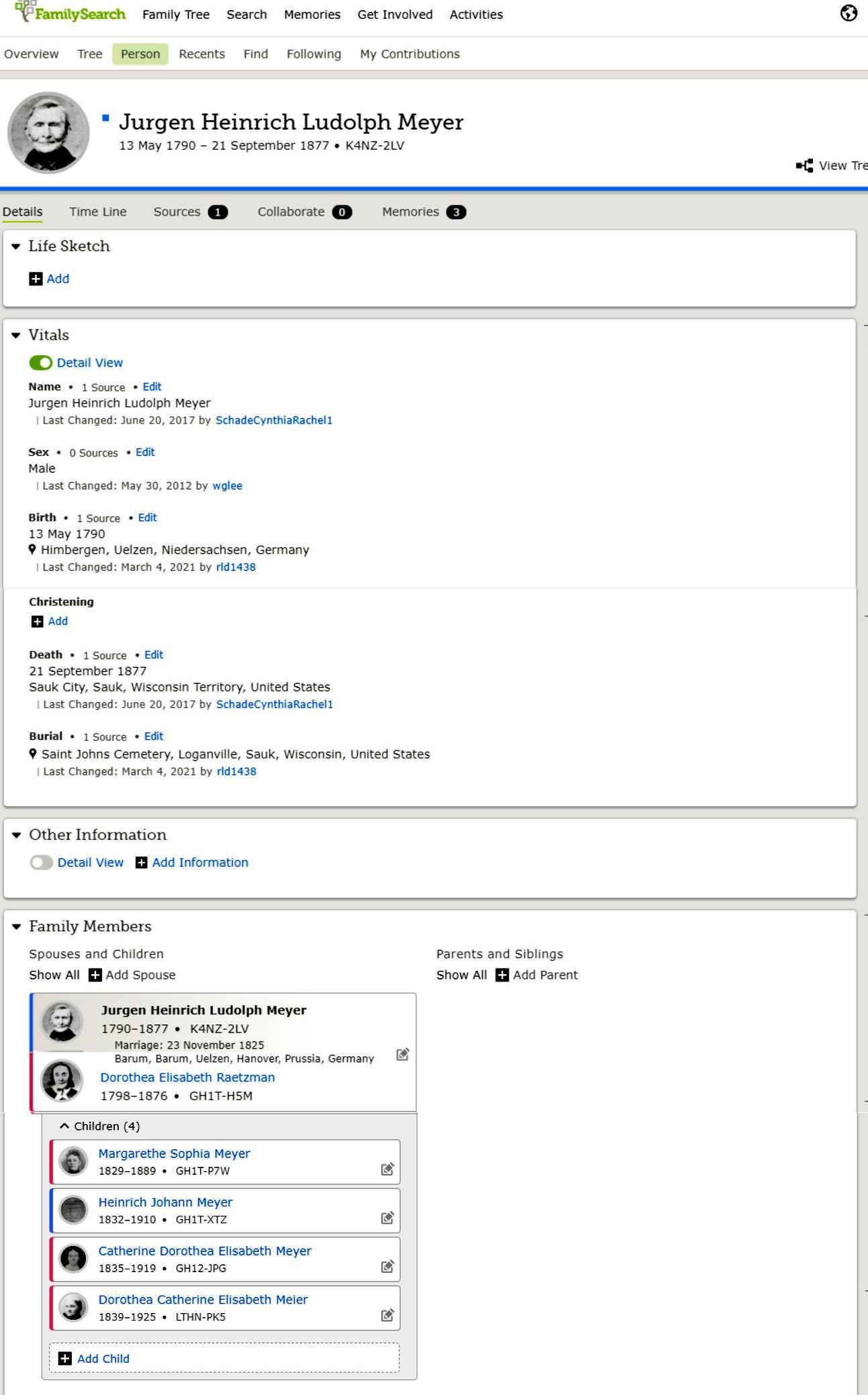

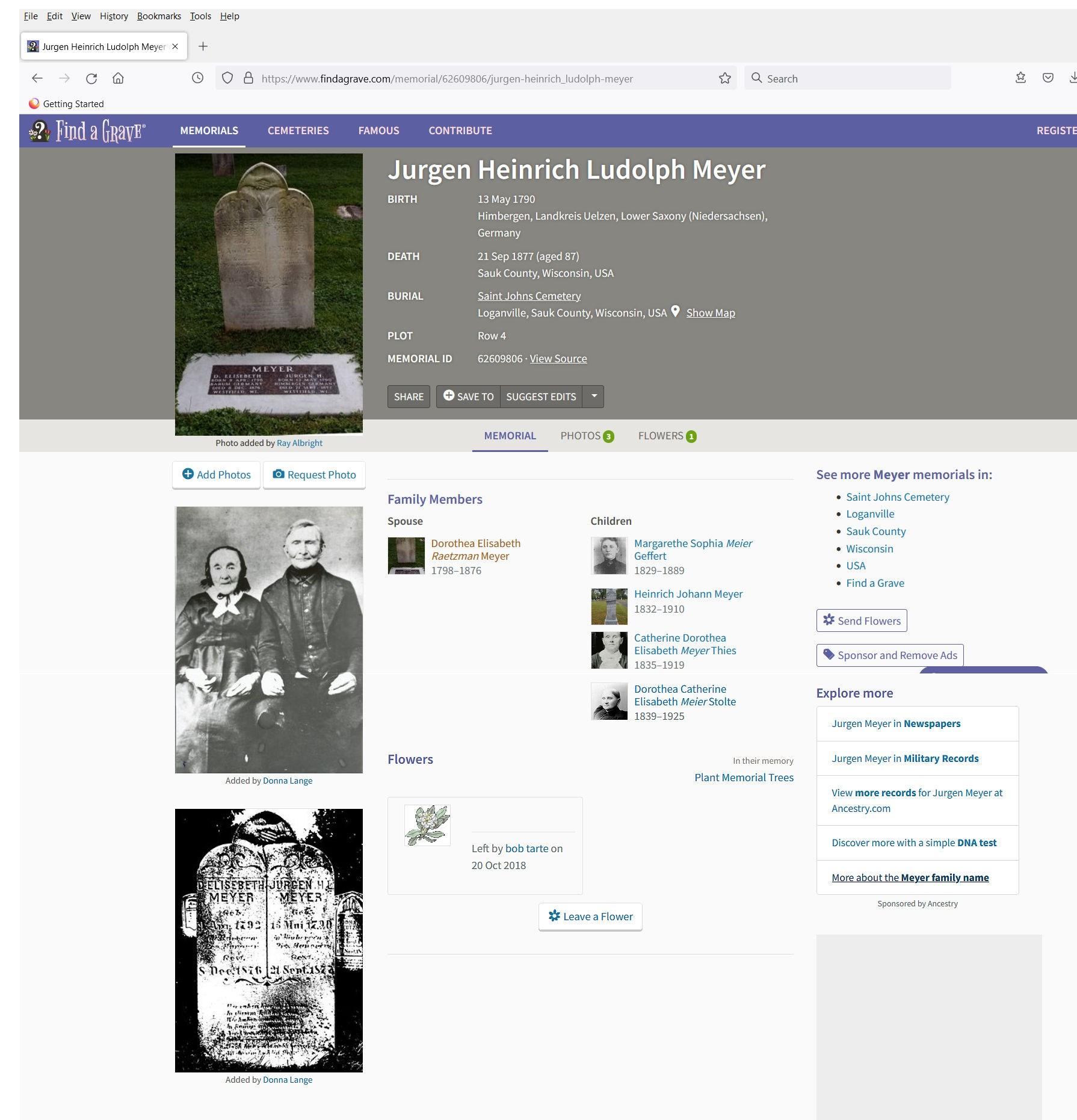

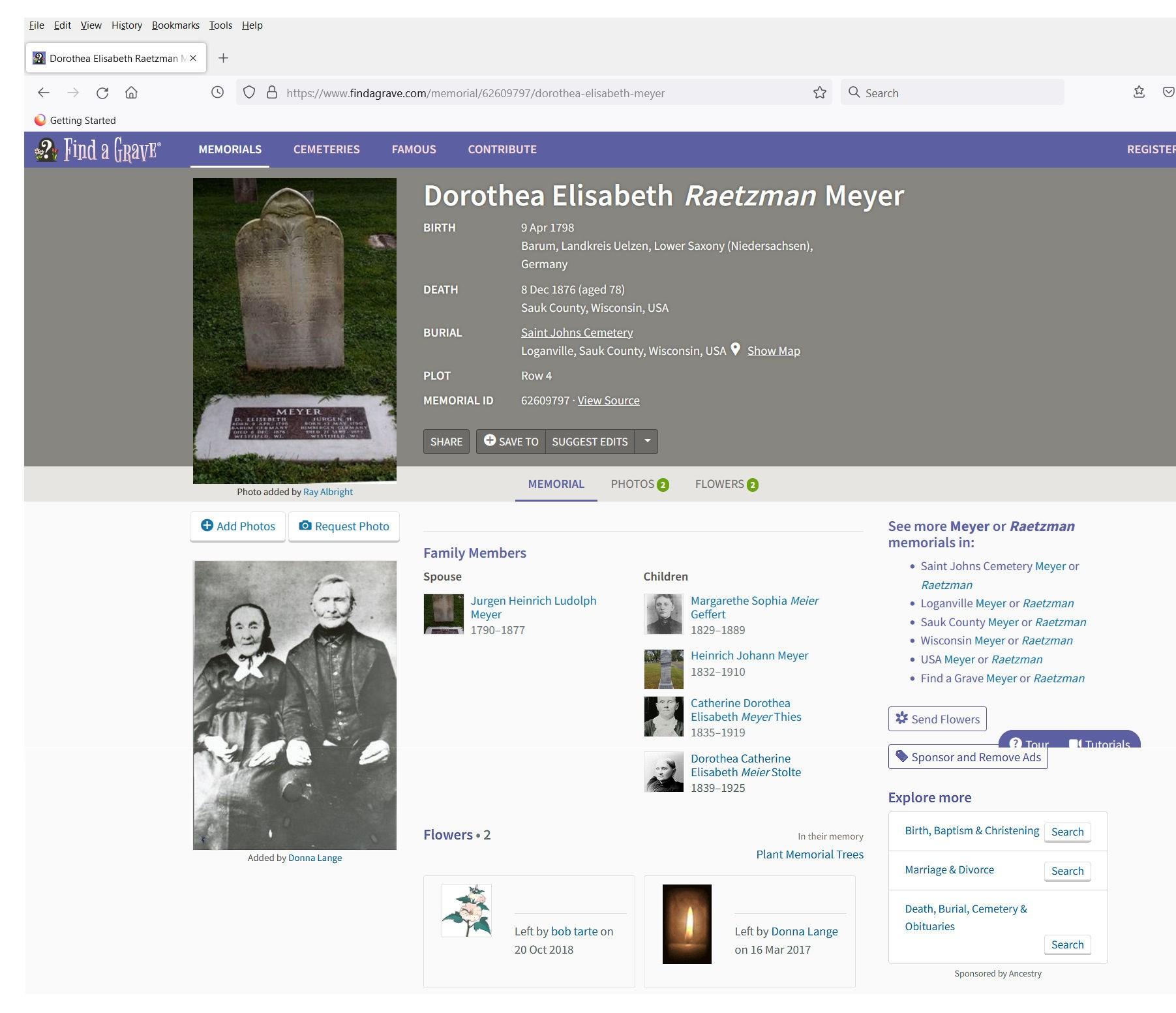

As mentioned in the obituary of Jurgen Meyer and in Merton Krug’s History of Reedsburg and the Upper Baraboo Valley, he was captured by Russian soldiers during the battle for Moscow in 1812. He was a prisoner of war for two years, and would have been treated as noted in the article below.

In early 1812, the Russian Ministry of War approved a new Statute on Commanding a Large Active Army that defined organization, structure and functions of the Russian military during the concluding years of the Napoleonic Wars. According to the statute, the Duty Office of the Main Staff handled all issues related to the treatment of the prisoners of war (Article 134). Once enemy soldiers were captured, they were supposed to be delivered to the division headquarters, which then conveyed them to the corps headquarters and finally to the Main Staff (Articles 55, 60). The Second Section of the Duty Office was responsible for providing immediate accommodation for prisoners of war (Article 72) while Gewaltiger-General, who served as chief of military police, handled enemy deserters (Article 165). All prisoners of war were presented to the commandant of the Headquarters, who then considered where to dispatch them. Once decision was made, the convoy of the Headquarters escorted prisoners to transportation points (Article 287). The Statute contained specific provisions to prevent abuse of POWs. Articles 403-404 and 435, thus, prohibited depriving POWs of clothing or buying from them any items or impressing them into service.

The question of prisoners of war became a major issue for Russia during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812. Just days into the conflict, Russians already began capturing prisoners of war (some of them deserters) who were treated in accordance with the Statute on Commanding a Large Active Army. The relevant Russian military authorities quickly processed prisoners and conveyed them to the nearby provinces – initially Kiev, Chernigov, Smolensk and Tver – for detention. However, as the Grande Armée penetrated deeper into Russia, the prisoners of war had to be evacuated further eastward, in some cases as far as Tambov.

Napoleon’s Grande Armée suffered tremendous losses during the campaign, and Russian military authorities struggled to deal with the ever-increasing number of prisoners. Aside from tens of thousands who perished on the battlefields or died of privation and cold weather, recent Russian studies show that Russians captured over 110,000 prisoners during the six-month long campaign. The harsh winter as well as popular violence, malnutrition, sickness and hardships during transportation meant that two-thirds of these men (and women) perished within weeks of captivity.

Source: Dans Napoleonica. La Revue 2014/3 (n° 21), pages 35 à 44

Russians didn’t really know what to do with all of those Frenchmen, as POW camps had not been invented yet. It was a major headache for the government and a catastrophe for the prisoners themselves. Many of them were killed by the Russian peasants who saw Frenchmen as the unholy bringers of the Apocalypse (basically, Mongol hordes). Peasants were even buying prisoners from soldiers to kill as many as possible, as they saw the eradication of the Frenchmen as their sacred Christian duty.

Many of the survivors died from illnesses and harsh climate, although the government tried to supply them with appropriate clothing and money for food. But they were sent to various regions of Russia to be guarded by local authorities, and Frenchmen were dying on the way en masse.

Source: Quora

French POWs during the War of 1812.

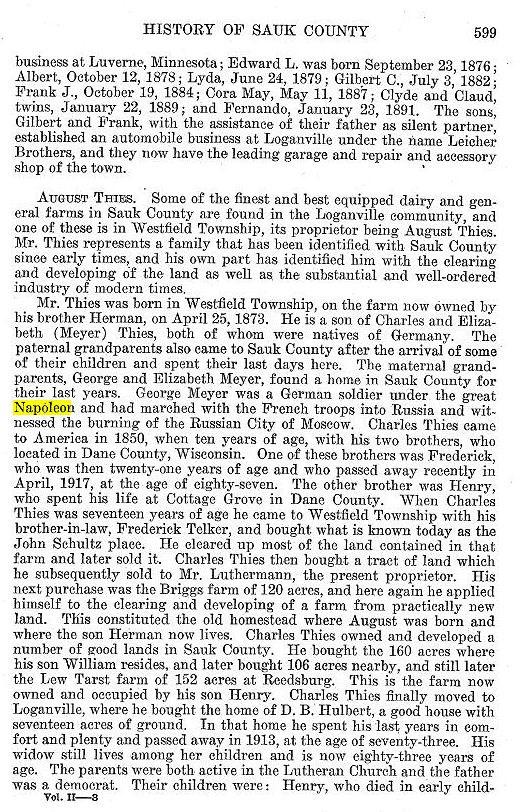

One of Reedsburg’s most active influential citizens, Mr. William Stolte II, is one of a few businessmen of this city who has spent his entire life in his native town. He was born in Hohenbunstorf, Hanover Germany, March 2, 1833, son of George and Dora (Evers) Stolte. The Stolte family was one of the two which existed in the vicinity of Hohenbunstorf as early as the year 1300. George Stolte grew to manhood on the ancestral farm, and upon attaining man’s estate, married. William I, came to America in 1860, his parents following him two years later. On December 21, 1862, William I, was married to Dorothea Meyer. She was born Nov. 15, 1839, a native also of Hohenbunstorf, and came to the United States with her parents, George [Jurgen Heinrich Ludolph Meyer] and Dorothea (Reitzmann) Meyer, while quite young. Her father was a native of Himbergen, Hanover, Germany, where his early years were spent. Upon becoming of age, he entered the Prussian Army, with which he served for several years. After the triumph of Napoleon, he served in the Napoleonic Army, and was with the Corsican Conqueror on his famous Moscow expedition. On this campaign he was taken prisoner by the Russian soldiers and kept in captivity for over two years.

On December 21, 1862, William Stolte I, was married to Dorothea Meyer. She was born Nov. 15, 1839, a native also of Hahoenbunstorf, and came to the United States with her parents, George and Dorothea (Reitzmann) Meyer, while quite young. Her father [George Meyer] was a native of Himbergen, Hanover, Germany, where his early years were spent. Upon becoming of age, he entered the Prussian army, with which he served for several years. After the triumph of Napoleon, he served in the Napoleonic Army, and was with the Corsican Conqueror on his famous Moscow expedition. On this campaign he was taken prisoner by the Russian soldiers and kept in captivity for over two years.

From: “History of Reedsburg and the Upper Baraboo Valley”, by Merton Krug, Feb. 1929. P. 436-438. Reedsburg Free Press

September 27, 1877, Page 3

MEYER At the residence of his daughter, Mrs. Theis, in the town of Westfield, Sept. 21st. Mr. Jurgen Heinrich Meyer, aged 87 years, four months and 7 days.

Mr. Meyer was born in Hanover, Germany, May 13, 1790. He was a soldier during the wars of Napoleon, and accompanied that great general on his campaign into Russia, in 1812. He was taken prisoner and kept in prison for two years; and of the soldiers from his native village who marched on that fatal campaign, he was the only one who returned. His children, one son and three daughters, live in Wisconsin. He was the father of Mrs. Wm. Stolte, of this village.

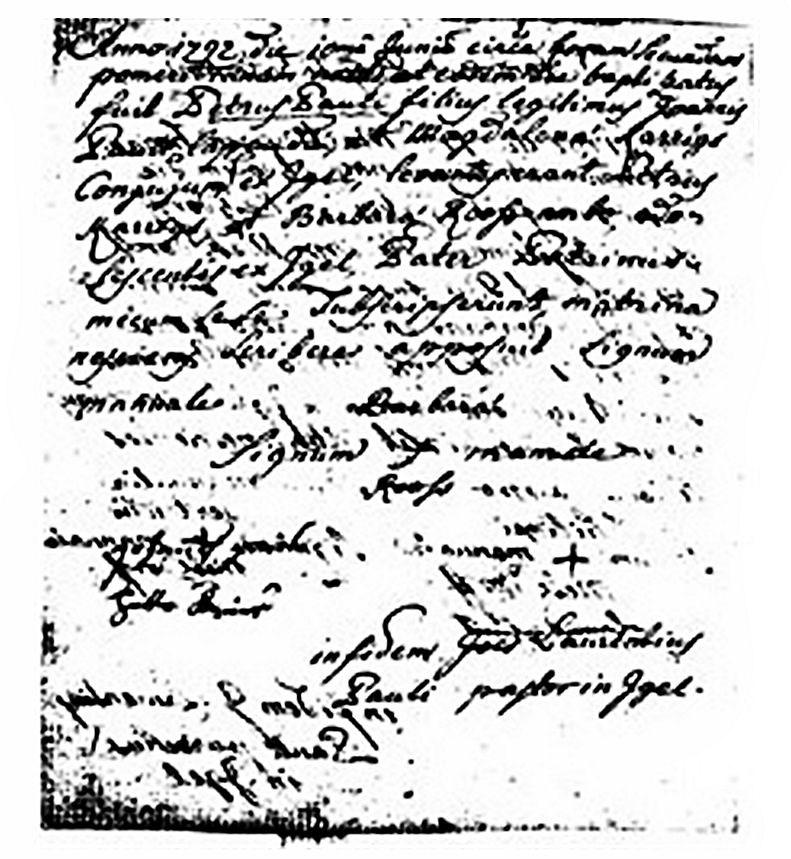

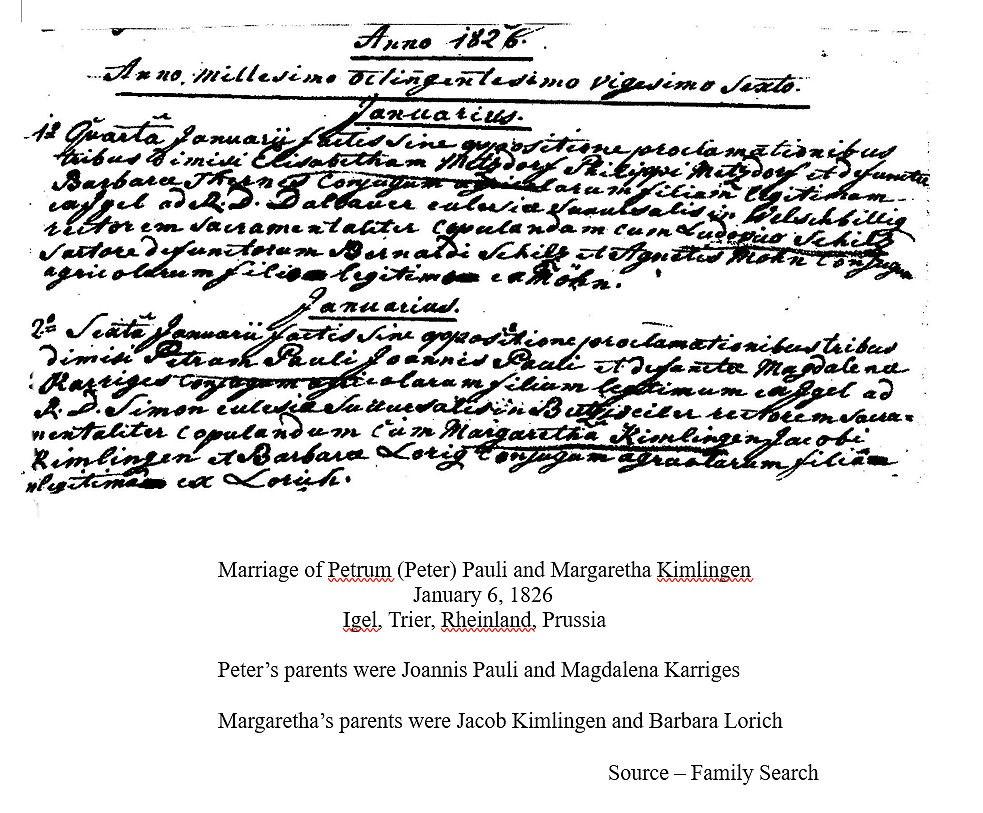

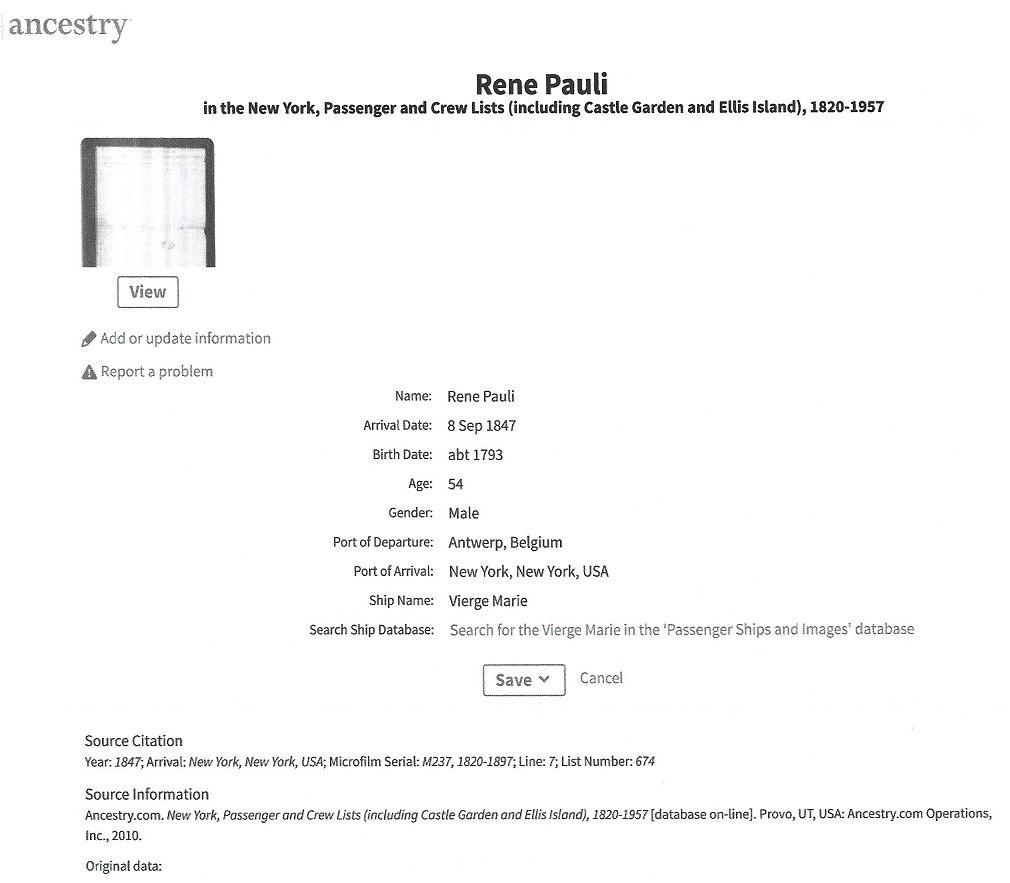

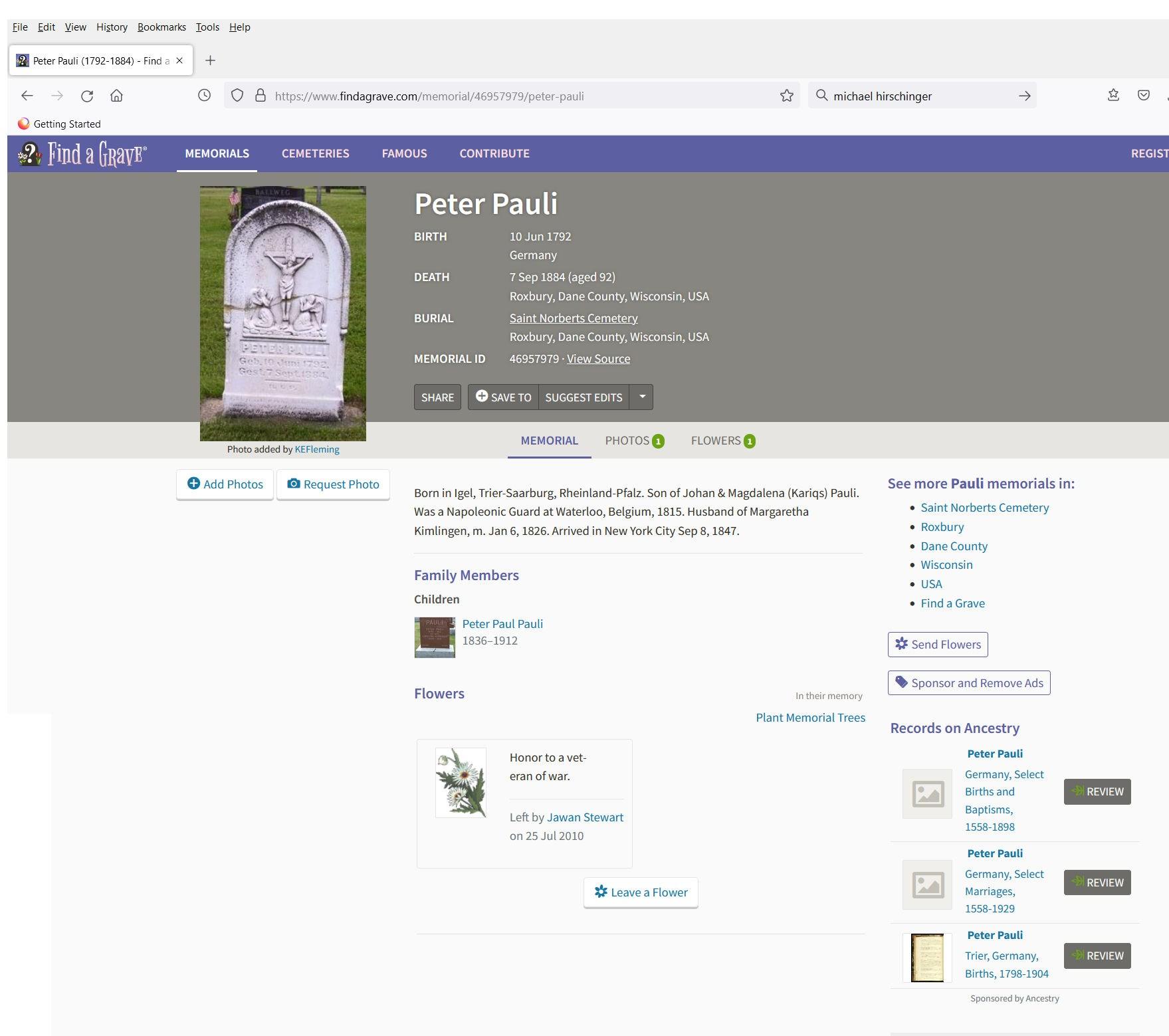

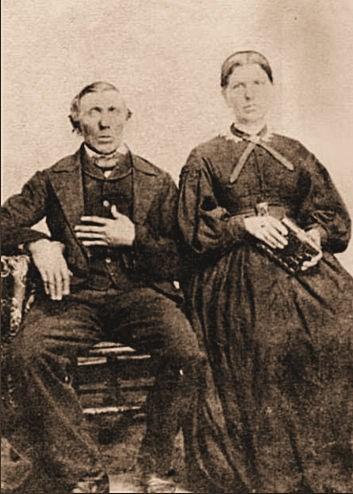

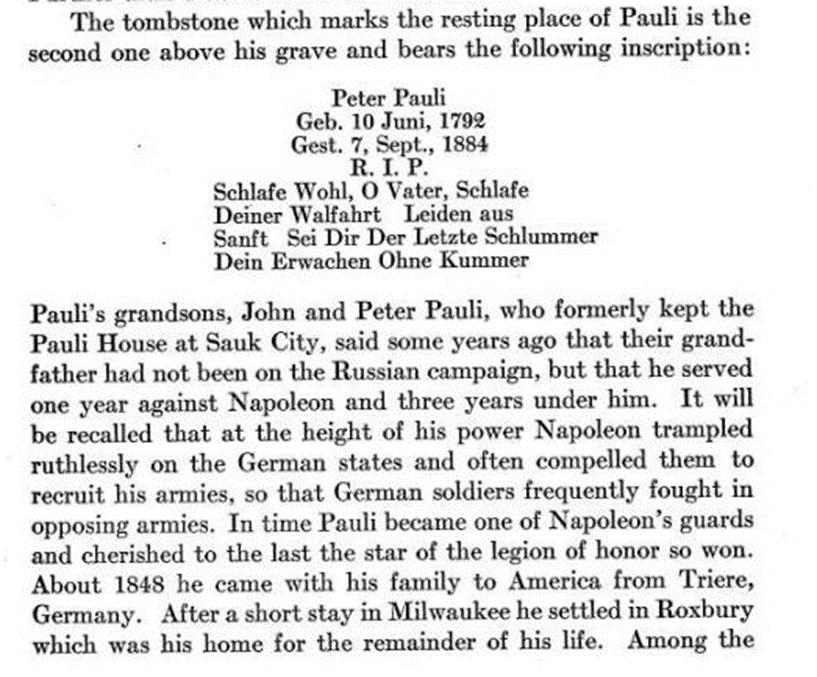

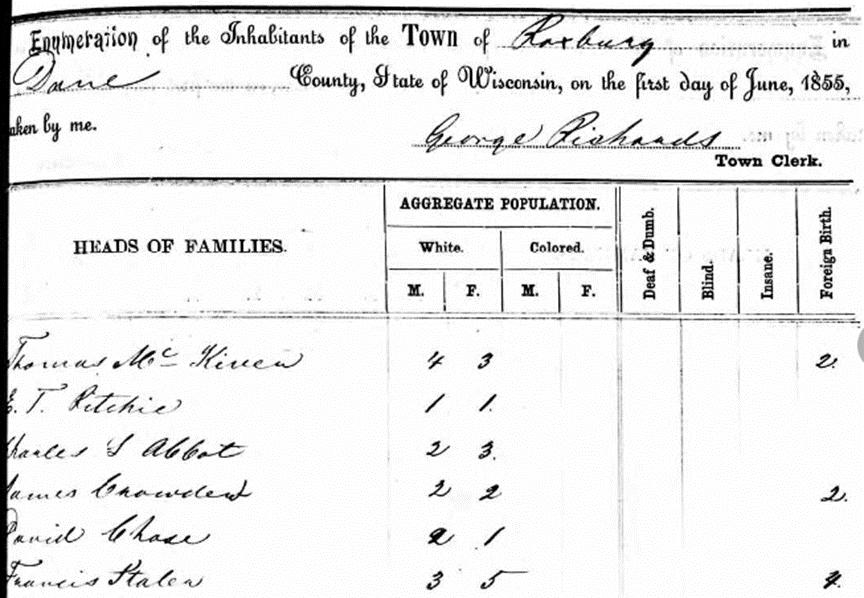

Peter Rene Pauli, son of Joannis Pauli and Magdalena Karriges, was born and christened on June 10, 1792, in Igel, Trier, Prussia. He married Margaretha Kimmlingen on January 6, 1826. She was the daughter of Johann Kimmlingen and Barbara Lorig.

Peter and Margaretha and their seven children immigrated to America in 1847. They departed out of Antwerp, Belgium on board the ship Vierge Marie and arrived in New York on September 8. From there they traveled west to Oak Creek, Milwaukee County, Wisconsin. Margaretha passed away in 1852 in Milwaukee County, after which Peter went to live with his son Jacob on Jacob’s 400 acre farm in Section 15 in the Town of Roxbury, Dane County Wisconsin.

Peter passed away on September 7, 1884 and is buried in St. Norbert Cemetery, Roxbury, Wisconsin. From Rhonda Enge 2022

Peter Pauli Birth Record

Born June 10, 1792

Christened June 10, 1792

Parents, Joannis Pauli and Magdalena Karriges

Igel, Trier, Rheinland, Prussia

Source: Family Search

The Imperial Guard was a small, elite army, directly under Napoleon's control. Like the corps, it had infantry, cavalry and artillery. It was comprised of the best veteran soldiers from every theater of war – Egyptian Mamluks, Italians, Poles, Germans, Swiss, and others, as well as French.

The Guard was made up of Napoleon's finest. They were the most seasoned soldiers of the French army and the best of his elite Imperial Guard. All were hand-picked volunteers of above-average height, each one hardened by years of campaigning. By the time of Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812, it had swelled to just under 100,000 men

As can be seen above, Peter Pauli was one of Napoleon’s Imperial Guards. He fought with Napoleon’s Army in the battle of Waterloo.

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on 18 June 1815 between Napoleon's French Army and a coalition led by the Duke of Wellington and Marshal Blücher. The decisive battle of its age, it concluded a war that had raged for 23 years, ended French attempts to dominate Europe, and destroyed Napoleon's imperial power forever. The adverse environmental conditions, the weak state of his army, the incompetence of his officers, and the superior tactics of his enemies all forced Napoleon to wage war from a disadvantageous position and eventually led to his demise.

Fought near Waterloo village, Belgium, it pitted Napoleon's 72,000 French troops against the duke of Wellington's army of 68,000 (British, Dutch, Belgian, and German soldiers) aided by 45,000 Prussians under Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher.

The battle of waterloo was a devastating event for the armies involved as well as the village itself. The combined number of men killed or wounded reached nearly 50,000, with close to 25,000 casualties on the French side and approximately 23,000 for the Allied army.

Out of 60,000 horses on the field of battle that day at least 7,000 were killed or wounded, with at least one estimate putting the figure as high as 20,000

The Battle of Waterloo brought an end to the Napoleonic Wars once and for all, finally thwarting Napoleon's efforts to dominate Europe and bringing about the end of a 15-year period marked by near constant warring.

Various sources

Most of the men in Napoleon’s Grand Armée were conscripts drawn from the poorer classes. Every ablebodied man of age in France was expected to willingly join the ranks to defend the Republic – or risk losing citizenship. In theory soldiers were eligible for discharge after five years, but after 1804, most discharges were only for medical reasons. Most new soldiers received little training, and had to learn their trade on the battlefield.

Supplies were usually scarce, since Napoleon’s armies traveled with small logistical trains to improve mobility. Uniforms were often ill-fitting and uncomfortable. Boots rarely lasted more than a few weeks. Soldiers learned by experience that marauding was often a more reliable source of food, horses and other provisions than the army’s supply system. Often hungry and eager to fight for the glory of France and their emperor, Napoleon’s soldiers were the most feared force in Europe.

Napoleon understood the hardships his soldiers faced. But he often forbade looting, and did not hesitate to order summary executions for disobeying his orders. But, for the most part, discipline was loose. Unlike most of his enemies’ armies, corporal punishment had been abandoned after the Revolution. The Republican ethos of liberty, equality and brotherhood was deeply rooted in the ranks.

ELTING: Imagine yourself carrying between 40 and 60 pounds of rations and musket and cartridges

Most of 'em were farmers' boys, grown up used to misery and walking and working from day to night He's got a bunch of the toughest, hammered down, ironed out roughnecks you ever saw, from generals down to buck privates. And he just said, "Sic 'em, boys."

HORWARD: And these men would march something like 30 miles in a day. They’d march for four hours, and stop and then march another three or four hours and then stop again.

But the ceaseless bloodshed eroded manpower and morale. Medical services remained inadequate. Four men died of sickness for every soldier who was killed in battle. Desertion and draft-dodging became rampant. Napoleon began to rely more heavily on troops drawn from conquered or allied states to provide units for his army.

Source: PBS Wisconsin5

Who were Napoleon's best soldiers?

The Imperial Guard were the most famous soldiers in Napoleon Bonaparte's army. An elite core of fighting men, they held a special place in the emperor’s heart and served a unique function in asserting his power.

How much did Napoleon pay his soldiers?

Daily cost of maintaining a soldier under the Empire. The cost amounts to 1.91 francs (pay, equipment, engineering, travel, and military accoutrements included). Worth about $44. today.

What happened to Napoleon's soldiers in Russia?

The Russian army refused to engage with Napoleon's Grande Armée of more than 500,000 European troops. They simply retreated into the Russian interior

What did Napoleonic soldiers eat?

When all was going to plan, French rations included 24 ounces of bread, a half-pound of meat, an ounce of rice or two ounces of dried beans or peas or lentils, a quart of wine, a gill (roughly a quarter pint) of brandy and a half gill of vinegar.

Why did Napoleon burn Moscow?

The Moscow military governor, Count Fyodor Rostopchin, has often been blamed for organizing the destruction of the sacred former capital to weaken the French army in the scorched city even more.

Why was Napoleon annoyed with Russia's Tsar Alexander?

Alexander refused to comply with Napoleon's trade restrictions against Britain. Russia was trying to exert its influence over Austria, which Napoleon considered a part of its sphere of influence.

How many soldiers did Napoleon take to Russia?

The French emperor intent on conquering Europe sent 600,000 troops into Russia. Six disastrous months later, only an estimated 100,000 made it out. After taking power in 1799, French leader Napoleon Bonaparte won a string of military victories that gave him control over most of Europe.

How many of Napoleon's soldiers died of typhus?

As they have many times in their history, the Russians gave up their land to the invading army, encouraging the invaders to be drawn deeper and deeper into Russia. Just one month into the campaign, Napoleon had lost 80,000 soldiers to typhus and dysentery.

How did Napoleon's army die?

“The rest of this magnificent force, the majority of Napoleon's effectives, died of disease, cold, hunger and thirst.” And in wartime conditions, typhus can burn through an army.

How did the Russians beat Napoleon?

Alexander adopted a clever strategy: instead of facing Napoleon's forces head on, the Russians simply kept retreating every time Napoleon's forces tried to attack. Enraged, Napoleon would follow the retreating Russians again and again, marching his army deeper into Russia.

Why did Napoleon abandon Moscow?

Napoleon intended to attack and defeat the Russian army, and then break out into unforged country for provisions; however, short on supplies and seeing the fall of the first snows on Moscow, the French abandoned the city voluntarily that same night.

How many French soldiers survived the Russian campaign?

Only 120,000 men survived (excluding early deserters); as many as 380,000 died in the campaign. Perhaps most importantly, Napoleon's reputation of invincibility was shattered.

How many soldiers did Napoleon have when he left Moscow?

The Russians refused to come to terms, and both military and political dangers could be foreseen if the French were to winter in Moscow. After waiting for a month, Napoleon began his retreat, his army now only 110,000 strong, on October 19, 1812. Various Internet sources.

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on 18 June 1815 between Napoleon’s French Army and a coalition led by the Duke of Wellington and Marshal Blücher. The decisive battle of its age, it concluded a war that had raged for 23 years, ended French attempts to dominate Europe, and destroyed Napoleon’s imperial power forever. The French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte had escaped from exile in March 1815 and returned to power. He decided to go on the offensive, hoping to win a quick victory that would tear apart the coalition of European armies formed against him.

Two armies, the Prussians led by Field Marshal Gebhard von Blücher and an Anglo-Allied force under Field Marshal the Duke of Wellington, were gathering in the Netherlands. Together they outnumbered the French. Napoleon’s best chance of success was therefore to keep them apart and defeat each separately.

Attempting to drive a wedge between his enemies, Napoleon crossed the River Sambre on 15 June, entering what is now Belgium. The next day the main part of his army defeated the Prussians at Ligny and drove them into retreat, with losses of over 20,000 men. French casualties were only half that number. That same day, Wellington beat off a separate French attack on the crossroads at Quatre Bras. But the Prussian defeat at Ligny meant he also had to retreat or risk being outflanked and overwhelmed. The Prussian defeat might have been more decisive had not poor staff work led an entire French corps to march back and forth between Ligny and Quatre Bras without attacking either force.

Lady Butler's 'Dawn of Waterloo' (1895) depicting the Scots Greys on the morning of the battle, 1815

Purchased with the assistance of the Art Fund and the NAM Development Trust

Pursued by Napoleon’s main force, Wellington fell back towards the village of Waterloo. Unknown to the French, the Prussians, although defeated, were still in good shape. They retreated northwards towards Wellington’s position and were able keep in contact with him.

The 48,000-strong Prussian Army was experienced and professional, a mix of veteran, militia and reserve units. Its strength lay in the officer corps, especially its General Staff, who managed to reorganise the army and move it to Waterloo within 48 hours of its defeat at Ligny. Emboldened by their promise of reinforcements, Wellington decided to stand and fight on 18 June until the Prussians could arrive.

The French Army had their greatest military commander in Napoleon Bonaparte. The emperor was loved by his loyal troops, demonized by his enemies, feared and respected by all.

His army was composed of veterans who had rallied to his cause on his return from exile. Having detached 33,000 men to follow the Prussians after Ligny, Napoleon had 72,000 men and 246 guns at Waterloo.

Wellington also accepted that Napoleon’s presence on the battlefield made a huge difference to the morale and performance of his troops.

The Anglo-Allied army had 68,000 men and 156 guns. The men were a mix of inexperienced troops and veterans of the Peninsular War (1808-14). With such a mixed force there was no question of Wellington going on the offensive.

Wellington drew up his army along a ridge of Mount St Jean. Using tactics that he had perfected during the Peninsular War, he positioned most of his forces behind the ridge, so they were out of sight of the enemy and sheltered from artillery fire. The rest of his army guarded three outposts in front of the ridge.

To the west stood the Chateau of Hougoumont, which Wellington garrisoned with British Guardsmen and German Light Infantry. In the centre was the farm of La Haye Sainte, defended by more Germans and British riflemen. At the east end of the ridge lay the hamlet of Papelotte, occupied by German Duchy of Nassau troops.

Napoleon’s plan was simple. He would conduct a diversionary attack against Hougoumont. Then, once Wellington had sent reinforcements there, a main attack against the bulk of the Anglo-Allied army would begin.

At 11.30am, following a huge artillery bombardment - partly negated by Wellington’s position and the wet ground - Napoleon launched his diversionary attack against Hougoumont.

The French cleared the wood in front of the chateau but were shot down as they left its shelter. A small group did manage to break in via the north gate, which had been left open to facilitate resupply. But the defenders managed to shut the gates and kill them. The chateau remained in British hands all day.

By mid-afternoon, news of the Prussians' arrival forced Napoleon to form a defensive line on his right. Soon afterwards, believing the Allies were pulling back, the French cavalry charged the infantry of Wellington’s right centre who formed square.

Although more cavalry were committed to attack, the soggy ground hampered the French. They could not make an impression on the British squares, which held firm despite suffering casualties from artillery fire.

Meanwhile, the Prussians continued to arrive on Napoleon’s right, forcing him to detach more troops to steady the situation. At about 6pm the French captured La Haye Sainte, severely weakening Wellington’s position.

Under withering fire, Wellington’s centre began to collapse. The French commander Marshal Ney called for reinforcements to push home his advantage. But Napoleon decided first to send troops to recapture the village of Plancenoit from the Prussians. This gave Wellington time to strengthen his position.

At about 7pm, in a last bid for victory, Napoleon released his finest troops, the Imperial Guard. They marched up the ridge between Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte, but had chosen to attack where Wellington was strongest. Under a withering fire from British guardsmen and light infantry, the Imperial Guard halted, wavered, and finally broke.

Their defeat sent the rest of the French into panic and eventually retreat. This continued all night, with the French harried by the Prussian cavalry. Napoleon lost nearly 40,000 men killed, wounded or captured. The Allies suffered 22,000 casualties.

Napoleon was defeated. He spoke of fighting on, but was forced to abdicate when the Allies entered Paris on 7 July. He spent the rest of his life in exile on the island of St Helena in the South Atlantic.

Source: National Army Museum

“

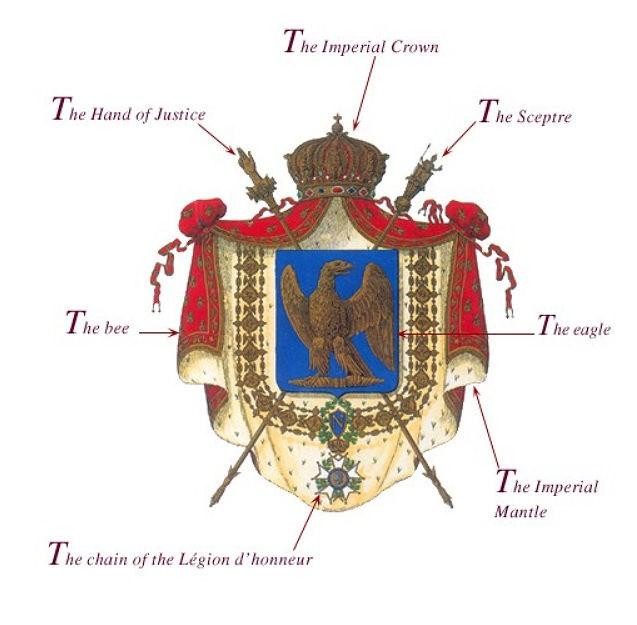

Legion of Honour, officially National Order of the Legion of Honour, French Ordre National de la Légion d’honneur, premier order of the French republic, created by Napoleon Bonaparte, then first consul, on May 19, 1802, as a general military and civil order of merit conferred without regard to birth or religion provided that anyone admitted swears to uphold liberty and equality.

True to the stated ideals of Napoleon when founding the order, the membership of the Legion is remarkably egalitarian; both men and women, French citizens and foreigners, civilians and military personnel, irrespective of rank, birth, or religion, can be admitted to any of the classes of the Legion. Admission into this order, which can be extraordinary military bravery and service in times of war. Admission into the Legion for war services automatically carries with it the award of the Croix de Guerre, the highest French military medal.

Peter Pauli proudly wore a similar medal on special occasions while living in the Roxbury area.

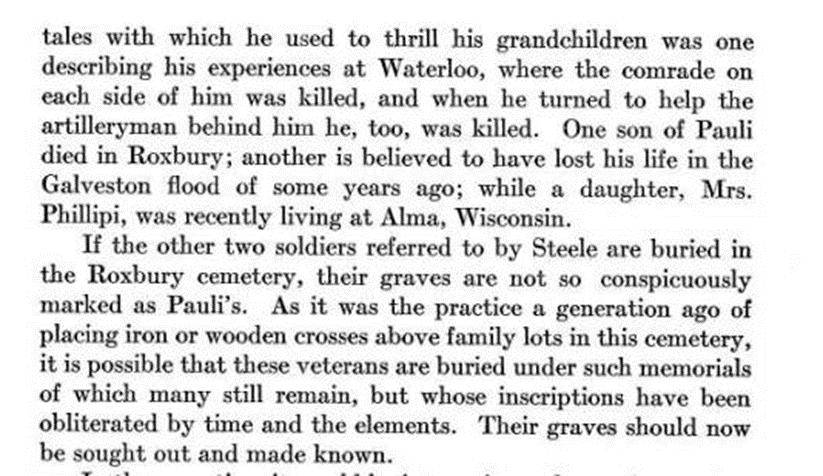

In the Catholic cemetery at Roxbury are buried three men, soldiers in the wars of Napoleon Bonaparte. Their names were Numiere [this is the son of Joseph Neumaier Sr. who was a Napoleonic soldier, and never came to America. This son did not fight in the war], Polly [Pauli] and Class [Klaes]. Numiere was under Blucher fighting against Napoleon, while Polly and Class fought under Napoleon on the plains of Waterloo against Wellington. Blucher coming up at night effected the overthrow of Napoleon. Polly wore the star of the Legion of Honor on his breast as one of Napoleon’s guards. The writer saw him while living at the age of ninety. He stood six feet, straight as an arrow. Mr. Class went at the age of fifteen as a substitute for his brother, who had a family, and served until the down fall of Napoleon. Being at the home of his daughter, I went out to where her father was dressing the grape vines. There stood the man who had shouted ‘Victory’ and suffered defeat on the blood-red fields of Spain, one of the army that crossed the Niemen 500,000 strong to invade Russia, one of the number who stormed the Russian entrenchments at Borodine, fighting uncovered in the open plain, causing Napoleon to exclaim at St. Helena, ‘You immortal heroes.’ He saw the burning of Moscow, the greatest conflagration of modern times lived and fought through that fearful retreat.”

Excerpt Source: Lodi Valley News by James R. Steele in 1896.

It should be emphasized that as stated in the 1896 article above, Joseph Neumaier Sr. never actually came to America. The author of the article, James Steele, erroneously assumed that the Joseph Neumaier Jr. who is buried in St. Norbert's Cemetery, was the Napoleon soldier. He was the son of the Neumaier who fought with Napoleon.

The following Pages 60 77 were Compiled by Lori Ploetz 2022

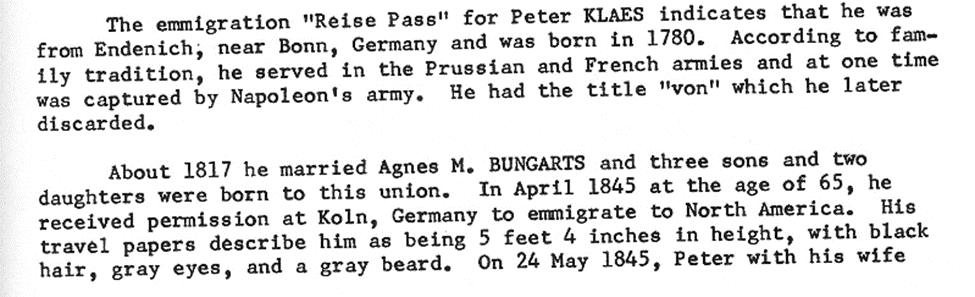

In order to track Peter Klaes and his wife Agnes Bungardt, we need to understand who his children were and where they lived, as Peter and Agnes lived with their children after they immigrated to America. In the March, 1921, issue of The Wisconsin Magazine of History, in an article entitled “Napoleonic Soldiers in Wisconsin” by Albert O. Barton, we find reference to three Waterloo soldiers buried in St. Norbert Catholic Cemetery, Roxbury, Dane County, Wisconsin. We quote Mr. Barton’s article without permission:

Source: The Wisconsin Magazine of History: Volume 4, Number 3, March, 1921, Albert O. Barton

We will concentrate on the soldier identified as “Class” or “Clause.” We are able to identify the soldier by the reference to his daughter, identified as “Mrs. Staler” in the article. The soldier referred to in the article is Peter Klaes, and his daughter Anna Maria Staeler/Stahler was quoted in the article.

Peter Klaes, also known as Peter von Klaes, was born 7 May 1780, at Endenich, Bonn, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany, to Jodocus Clees (1755-1821) and Maria Agnes Wallbruehl (1756-1814). He married Agnes Bungart/Bungardt on 7 September 1816 at Bonn. She was born in 1784 in Prussia to Jacob Bungart/Bungardt (-1787) and Catharina Heppenstritch (1754-1832).

Six children were born of the marriage of Peter Klaes and Agnes Bungardt:

Jodocus Klaes (1819-1890), died in Germany, did not immigrate to America

Unknown Klaes (born 1822-unknown death date), died in Germany

Gertrude Klaes (born 1823 in Germany, died 1910 La Crosse, Wisconsin), m. Jacob Rosche 10 September 1846 in Sauk County, Wisconsin

Anna Maria Klaes (born 1825 in Germany; died about 1885, probably in Wisconsin). m. Franz Staeler/ Stahler 1848

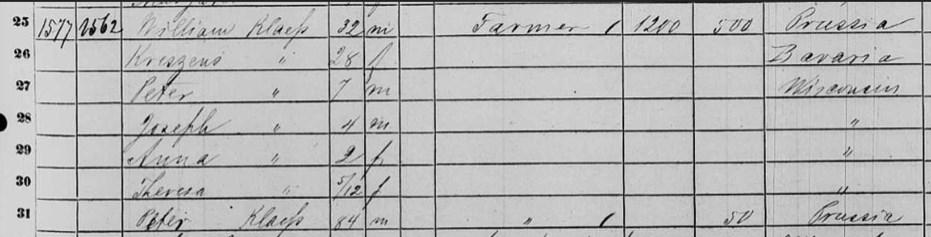

Wilhelm Klaes (born 1828 in Germany; died 1908 in Hebron Nebraska), m. Crescentia Franziska Beischel 4 November, 1852, Roxbury, Dane County, Wisconsin

Heinrich Klaes (born 1830 in Germany; died after 1850 probably in Wisconsin)

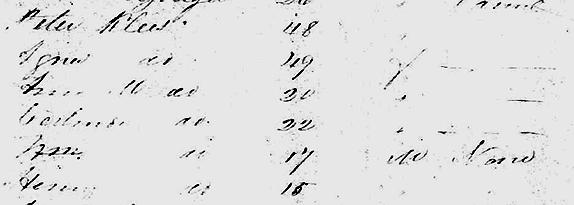

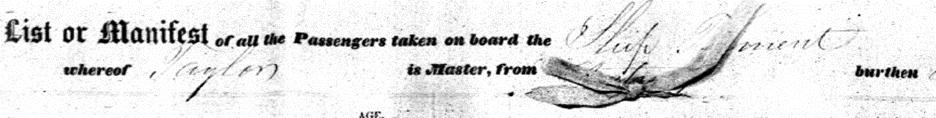

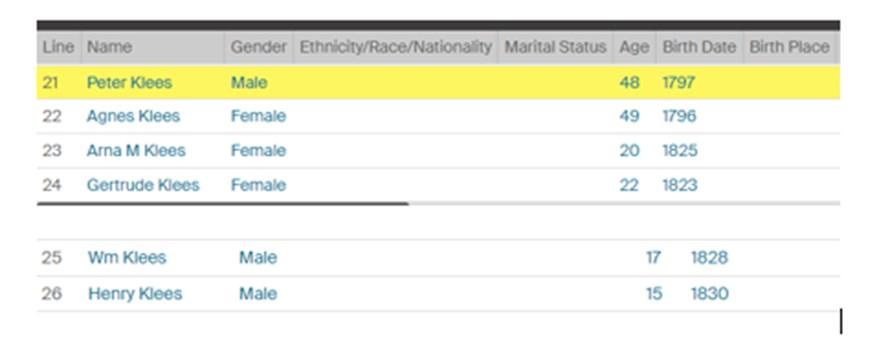

Peter Klaes, his wife Anges Bungardt/Bungart, and their four children immigrated to America in 1845. They departed Rotterdam/Antwerp on 3 June 1845 on board the Tremont. Their journey appears to have taken them from Rotterdam-Antwerp-Liverpool. The manifest for the Tremont indicates they left from Liverpool. This was a stopping point for more passengers to board. The voyage did not originate in Liverpool.

On the following page is a portion of the manifest of the Tremont. We note that Peter Klaes is listed as being 48 years old. In reality, he was 68 years old. We must remember that language barriers, minor education, and dialects made recording of the manifests difficult. We appreciate the record. We see that four of their children accompanied them on the journey. The arrived in New York on 16 July 1845. Their children were grown or mostly grown, and none of them were married. Although she was not the eldest, Anna Maria is listed first as being 20 years old. She would be the daughter quoted in the vintage article by Albert O. Barton as “Mrs. Staler,” as she eventually married Franz Staeler.

Manifest of the Tremont, 1845, Klaes Family

Source: familysearch.org

A transcribed copy of the manifest, on the following page, makes it easier for us to read and understand. We note the different spelling of Klaes as “Klees.” We are tolerant of the efforts of long-ago captains, again, recording various accents, dialects, and languages.

Source: familysearch.org

Upon arrival in 1845, the family may have resided in the towns of Sauk City/Prairie du Sac, collectively referred to as “Sac Prairie.” Peter Klaes and his eventual son-in-law Franz Staeler were naturalized there in 1846. Gertrude Klaes married Jacob Rosche there in 1846, only one year after arrival. Jacob Rosche was a brickmaker in Sauk City, so it is entirely possible the Klaes family first lived in Sauk City, where Gertrude met Jacob Rosche and married in 1846. However, the 1850 Census for the Township of Berry, Dane County, Wisconsin, indicates that Peter, Agnes, Wilhelm, and Heinrich were living in the Township of Berry, Dane County, Wisconsin. The Township of Berry borders the Township of Roxbury, where Peter and Agnes would spend the remainder of their lives with their daughter Anna Maria Staeler and her family. We see the close proximity of the Township of Berry and the Township of Roxbury. To the northwest, across the Wisconsin River, would be the Sac Prairie area of Sauk City and Prairie du Sac.

Townships of Roxbury and Berry, Dane County, Wisconsin

Source: 1878 Snyder, Van Vechten & Co. without permission

Below we see the 1850 Census for the Township of Berry, Dane County, Wisconsin. We note the spelling of “Klaes” as “Classman.” Agnes is reported as “Ernest.” Gertrude was married to Jacob Rosche, and no longer living at home with her parents and siblings. In 1850, Gertrude and Jacob were living in the Township of Westfield, Sauk County. Anna Maria was married to Franz Staeler and no longer living at home either. The “Value of Real Estate Owned” by Peter Klaes was $400.

1850 U.S. Census, Township of Berry, Dane County, Wisconsin

Source: familysearch.org

Peter and Agnes’ first child Jodocus Klaes did not immigrate. Their second child was an unknown Klaes, born in 1822. We do not know the fate of this child. Gertrude, Anna, Wilhelm, and Heinrich all immigrated with Peter and Agnes in 1845.

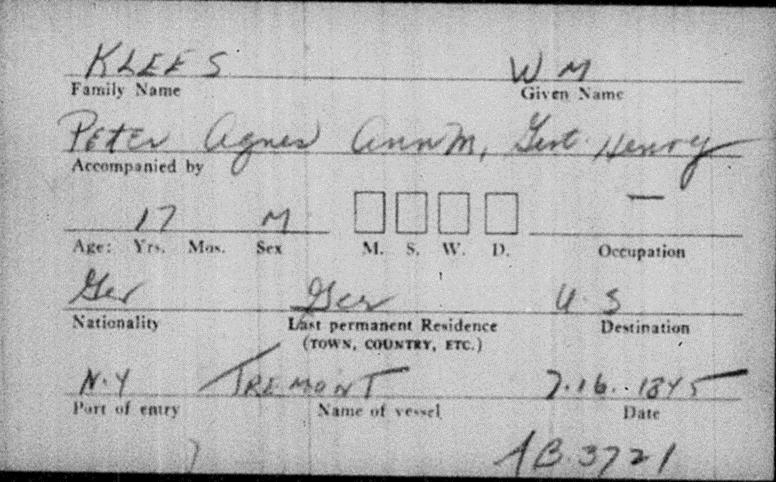

The immigration card of his son Wilhelm Klaes, who went by “William” in America, confirms their travel and arrival on board the Tremont. Wilhem’s travel with his parents and siblings is confirmed.

Immigration card of Wilhelm Klaes

Source: familysearch.org

On September 7, 1846, Peter Klaes was naturalized at nearby Prairie du Sac, Sauk County, which served as the county seat at that time. Sauk City was predominantly German Catholic; Prairie du Sac was Yankee Protestant. Residency was commonly based on religion, but Prairie du Sac served as the county seat at that time. Upon arrival in 1845, the family may have been living in Sac Prairie, probably in the German Catholic community of Sauk City vs. the Yankee Protestant community of Prairie du Sac, before relocating to the Township of Berry, Dane County, in 1850.

Naturalization card of Peter Klaes

Source: familysearch.org

Gertrude Klaes: Records indicate that Gertrude Klaes married Jacob Rosche on 10 September 1846 in neighboring Prairie du Sac, Wisconsin. They were married by Charles O. Baxter, Justice of the Peace.

Marriage Record of Jacob Rushe and Gurtrude Klas, 10 September 1846 (note spellings)

Source: http://genealogytrails.com/wis/sauk/marriages.html

We note that Peter was naturalized on 7 September 1846, and Gertrude was married on 10 September 1846 in nearby Prairie du Sac, which was the county seat. Peter was naturalized and Gertrude was married three days apart in Prairie du Sac.

Prairie du Sac was the county seat, but the county seat was eventually relocated to Baraboo, Sauk County, Wisconsin. When the Peter Klaes family arrived in Wisconsin in 1845, the nearby village of Prairie du Sac was considerably easier in which to obtain legal services than traveling the distance to Madison, the county seat of Dane County. He was naturalized prior to the family’s relocation to the Township of Berry, Dane County.

In 1843, Father Adelbert Inama, a Catholic priest born in the Tyrol region of Austria, came to New York. On November 25, 1845, Father Inama arrived in the Sac Prairie region of Wisconsin. In 1845-1846 he built his log cabin church in Roxbury, Dane County, Wisconsin, establishing the parish of St. Norbert. Many from Prussia and Bavaria followed Father Inama to the Catholic region of Roxbury. The Klaes family members were devout Catholics, although Gertrude was married by a Justice of the Peace.

Gertrude would have four or five children with Jacob Rosche. They would live in Minnesota, California, Iowa, eventually moving back to Prairie du Sac. Gertrude would spend the remainder of her life unmarried, living with her son John in La Crosse, Wisconsin. Gertrude died there in 1910. One census record indicates she was widowed. Another indicates she was divorced. She is buried in a Catholic Cemetery in La Crosse, Wisconsin.

Anna Maria Klaes: Family genealogy records indicate that Anna Maria Klaes married Franz Staeler in 1848 in Germany. This is unlikely. According to his naturalization card, Franz Staeler immigrated in 1842. Anna Maria Klaes and her family arrived in 1845. With the degree of difficulty in traveling and the expense, it is unlikely that Franz and Anna Maria traveled back to Germany to marry. They were most likely married in Wisconsin. We are unable to find a marriage record, but their first child Agnes Staeler was born in 1848, in Wisconsin. Records indicate that their second child Christina Staeler was born in 1849 in the Township of Lodi, Columbia County, Wisconsin. In the 1860 census, Franz and Anna Maria were living in the Township of Roxbury, Dane County, where Peter and Agnes Klaes would reside with them. It is likely that Father Adelbert Inama married Franz and Anna Maria in 1848. As we can see by Franz’s naturalization card, he was naturalized on 7 September 1846, at the county seat in Prairie du Sac, Sauk County, on the same day as his eventual father-in-law, Peter Klaes.

Naturalization card for Franz Stahler, 7 September 1846

Source: familysearch.org

Anna Maria and Franz would have five children. In the 1870 census, Peter Klaes was still alive, living with them. They farmed in the township of Roxbury, Dane County, Wisconsin, until 1877, when legal notice in the newspaper would seem to indicate bankruptcy and the loss of the farm. In 1880, they were living in Arcadia, Wisconsin, in Trempeleau County, with their married daughter and family. Peter Klaes was no longer listed as living with them, so we can assume he was deceased. They moved to Hebron, Nebraska, with their married daughter and son-in-law. According to the census dated 3 June 1885 for Hebron, Nebraska, both Franz and Anna Maria were living with their married daughter and

family in Nebraska. Family genealogy has Anna Maria dying in June, 1885, but this cannot be proven. No grave marker or burial record exists. They moved back to Wisconsin, where both Franz and his son-inlaw died in 1891. Franz Staeler is buried in St. Norbert Cemetery, Roxbury, Wisconsin. An iron cross marks his grave. This would further point to the likelihood of Peter Klaes also being buried at St. Norbert.

Marker for Franz Staeler, St. Norbert’s Catholic Cemetery, Roxbury, Wisconsin

Source: find-a-grave.com

Wilhelm Klaes: Wilhelm Klaes went by William in America. He married Crescentia Franziska Beischel, who went by Frances, on 4 November 1852. They were married by the Catholic priest, Adelbert Inama, who founded the Catholic parish of St. Norbert, Roxbury. Their marriage is recorded at Roxbury, Wisconsin.

According to Wilhelm Klaes’ 1908 obituary in Hebron, Nebraska, the family first “located at Sauk City, Wisconsin.” The Phelan history, quoted below, states that the family first settled in Sauk County. We know Wilhelm was unmarried and living with his parents in the 1850 census for the Township of Berry, Dane County. Wilhelm and Frances were married in 1852 by Father Inama in Roxbury, Dane County. Their first child Peter Klaes was born in 1853 in Roxbury. Their second child Joseph was born in Honey

Creek in Sauk County in 1856. Frances Beischel’s obituary states that her family first came to Jefferson, Wisconsin, and then to Roxbury, Wisconsin. She and Wilhelm Klaes were married by Father Adelbert Inama in Dane County on 4 November 1852. Sometime between 1853-1856, Wilhelm and Frances moved to Honey Creek, Sauk County. We do know that Franz and Anna Maria Staeler lived in Roxbury in 1855 by the census, and we do know that Wilhelm and Frances lived in Roxbury in 1853 when their first child was born.

This speculation is important because they lived in the largely German Catholic Township of Roxbury, Dane County, and this would point to the likelihood of Peter Klaes being buried at St. Norbert Catholic Cemetery, Roxbury, Wisconsin, where he lived most of the time after immigration, with his daughter Anna Maria Staeler. Wilhelm Klaes was married by Father Inama at St. Norbert Catholic Parish. Franz and Anna Maria’s daughter Agnes Staeler Nettekoven died at age 23, and is buried at St. Norbert. Their daughter Christina Staeler Lamberty died at age 33 and is buried at St. Norbert. The Catholic Church and the St. Norbert Cemetery were important to the family.

Wilhelm and Frances Klaes would have nine children. It was Wilhelm and Frances who moved to Honey Creek, Sauk County, in 1856. They would live in nearby West Point Township, Columbia County, Wisconsin. They would move to Missouri, which they did not like. They moved back to West Point Township and back to Honey Creek, Wisconsin, and eventually to Hebron, Nebraska, where they spent the remainder of their lives. They are both buried in a Catholic Cemetery in Hebron, Nebraska.

Heinrich Klaes: No record is found regarding the fate of their youngest child Heinrich Klaes, who immigrated with the family in 1845. According to the 1850 census, we know he was living in the Township of Berry, Dane County, Wisconsin, with Peter, Agnes, and unmarried Wilhelm.

The 1855 Census for the Township of Roxbury, Dane County, Wisconsin, for Francis Staler (Franz Staeler) indicates that Franz was living in the township of Roxbury, Dane County. Three males and 5 females were living with him and Anna Maria. This would most likely be Franz, Anna Maria, their daughter Agnes, their daughter Christina, their son Henry, their daughter Gertrude, and Anna’s parents Peter Klaes and Agnes (Burngardt) Klaes. Four individuals in the household were foreign born: Franz Staeler, Anna Maria (Klaes) Staeler, Peter Klaes, and his wife Agnes (Bungardt) Klaes.

Source:

Source:

On 3 September 1860, Franz Staeler, Anna, their children and her parents Peter and Agnes Klaes were living in Roxbury, Dane County, Wisconsin, according to that census.

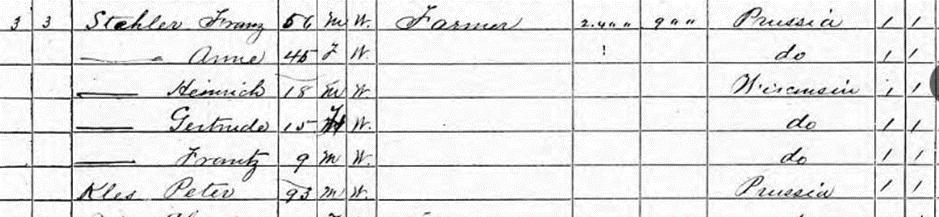

September 3, 1860, Federal Census for Frank Steeler (Franz Staeler), Town of Roxbury, Wisconsin

Source: Ancestry.com

Wilhelm Klaes, his wife Frances, and first child moved to Honey Creek, Sauk County, in 1856. In the 1860 Census for Honey Creek Township in Sauk County, dated 28 September 1860, Peter Klaes is listed as living with his son William (Wilhelm) Klaes and William’s wife and family. Agnes is not listed. Agnes’ death in family genealogy pages is listed as about 1860. Therefore, in the beginning of the month of September, 1860, Peter and Agnes were living in Roxbury, Dane County, with their daughter Anna Maria Staeler and family. By the end of the month, when the census was conducted in Honey Creek, Sauk County, Agnes was probably deceased, and Peter was now living with his son William/Wilhelm Klaes and wife and children in Honey Creek, Sauk County, Wisconsin.

1860 Federal Census for William/Wilhelm Klaes, Honey Creek, Sauk County, Wisconsin

Source: Ancestry.com

Agnes Klaes was probably buried in St. Norbert Catholic Cemetery in Roxbury, Dane County, Wisconsin. No record of her burial exists, and no cemetery marker exists. She lived with her married daughter Anna Maria Staeler in the predominantly Catholic township of Roxbury. Being devout Catholics, she was more than likely buried at St. Norbert Catholic Cemetery.

In the 1870 Census, Peter was again living with his daughter Anna Maria and her husband Franz Staeler in Roxbury, Dane County. There is no indication that he moved to West Point Township, Columbia County, Wisconsin, with Wilhelm and family, nor did he move to Missouri or Nebraska with them. It is believed that he died in 1875. More than likely, he was living with his daughter Anna Maria Staeler on the farm in Roxbury, Wisconsin, and more than likely, he is buried at St. Norbert Catholic Cemetery, Roxbury, Wisconsin. No record of his death or burial exists, nor does a grave marker exist.

1870 Federal Census, Town of Roxbury, Wisconsin, for Franz Stehler (Franz Staeler), with Peter “Kles” residing with them.

Source: Ancestry.com

In a family genealogy book entitled “Phelan Malone Kevill Stutz & Klaes Families,” by John T. Phelan, published in 1985, we find family lore which offers proof that Peter Klaes served in the military in Prussia during the Napoleonic War. A portion of the book is reprinted below, without permission. The author speculated that they were buried in Sauk County, but genealogy searches fail to verify dates of death and burial locations. They were speculating. Census information indicates Peter Klaes resided primarily in Dane County Wisconsin; first in the Township of Berry in 1850 and then with his daughter Anna Maria Staeler and family in Roxbury, Dane County, Wisconsin:

We are uncertain as to when Peter lost a leg farming in Wisconsin, but we know he was head of the family in the 1850 census while living in the Township of Berry, Dane County, Wisconsin. By the 1855 census, he is probably one of the eight individuals living with Franz Staeler and family. Peter was not head of the household in that census. In 1860, he was living with Franz and Anna Maria in Roxbury, and he is not the head of the household. Wilhelm and Frances Klaes were still living in Honey Creek, Sauk County, Wisconsin, in 1875 when their youngest child Josephine was born on 14 February 1875. In Honey Creek Township, a satellite parish called Our Lady of Loretto was established, in close proximity to Wilhelm’s farm. Father Alelbert Inama traveled to Honey Creek Township from Roxbury, Dane County, to administer to the Catholics living in Honey Creek Township. A permanent church building for Our Lady of Loretto was not built until 1880, but cemetery records indicate burials took place in the cemetery as early as 1862. However, Peter Klaes is not listed in the cemetery records. We know that in 1870, according to that census, he was living with Franz and Anna Maria in Roxbury. We assume that he was buried at St. Norbert Catholic Cemetery in Roxbury, Wisconsin, probably alongside his wife Agnes Bungardt Klaes.

The first cemetery at St. Norbert Catholic Church in Roxbury was established by Father Inama in 1846. According to the 1971 St. Norbert Parish anniversary booklet, “a plot of ground, about one block west of ‘St. Norbert House’ was set aside for cemetery purposes.” According to that same booklet, “44 persons were buried in this original cemetery; 26 were children.” The current cemetery was consecrated on November 1, 1857, according to the anniversary booklet. The booklet goes on to state that “when the present cemetery was opened, some graves were moved from the original cemetery, but many still lie buried in this now abandoned burial place.” It was used until 1853. No records exist for this cemetery. Parish history indicates that the creek flooded one spring, and those graves and markers were washed away. It is possible that Agnes and Peter Klaes were buried in that first, washed-away cemetery, if a deceased family member was buried there, in a family plot. It is also possible they were buried in the current St. Norbert Cemetery, consecrated in 1857, without grave markers. There are ancient iron crosses, such as the marker for Franz Staeler, in St. Norbert Cemetery where the elements have erased names and dates. We are left to speculate that Peter Klaes and his wife Agnes Bungardt are buried there, close to the farm where they lived with their daughter Anna Maria Staeler. Two of Peter’s adult granddaughters are buried near their father Franz Staeler, neither living in Roxbury at the time of their deaths. They were brought to St. Norbert Cemetery from other towns for burial. This further indicates the importance to the Klaes family to be buried together in this beloved Catholic Cemetery.

Respectfully submitted by Lori Ploetz, December, 2022

There is no tombstone for Peter Klaes, or his wife, in St. Norbert Cemetery, Roxbury, WI. Extensive research has failed to find any concrete evidence of his burial there. There is also no listing of them in the burial records of St. Norbert Church.

Lori Ploetz, has speculated that, “…the first-hand account of his service was supposedly made by his daughter Anna Maria Staeler/Stehler with whom he lived, pretty much full time, after the arrival in America. I believe he was living with the Staelers in Roxbury when he died, and he was buried in the old St. Norbert's cemetery. That's my guess.

“Another thought on no tombstone: Franz and Anna Maria Staeler/Stehler lost the farm in bankruptcy in 1877. If he [Peter] died in 1875 while living with them, they had absolutely no money to put up a stone, especially if they were losing the farm. But Father Inama [the priest at St. Norbert’s Catholic church at the time] would have buried him at the cemetery. If he was buried in the old one that washed away, the stone, if it had ever been there, was destroyed anyhow.

“Another thought on no tombstone, if there ever was one: Perhaps it was Peter Klaes' wish that his grave could not be identified, because he did not want his military service known.”

There were no burial records kept during the early years of St. Norbert Church. Also, during those early years, the cemetery, which was located near a creek, was completely washed away during a severe storm, and the tombstones were lost, if there was one for Peter. It is not certain if he was buried there, but it may be one reason that his grave can not be found.

1 Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-Europe/The-Napoleonic-era

2 Napoleon’s Retreat from Moscow, By Edwin Muller, Reader’s Digest, March 1942

3 National Army Museum: https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/battle-waterloo, The Battle of Waterloo

The following have contributed to the research and compilation of this publication:

Lori Ploetz

Rhonda Enge

William C. Schuette

Allen Schroeder

Edwin Muller

Juanita Wipperfurth

Father Michael Radowicz

Ancestry.com

My Heritage

Family Search

Roots Web.com

Find A Grave

St. Norbert Catholic Church, Roxbury, WI

Lodi Valley News by James R. Steele in 1896

Google Earth.com