Works by Rev. Solomon A. Dwinnell In the Reedsburg Free Press June 28, 1872 – December 27, 1872

Reedsburg in the War of the Rebellion

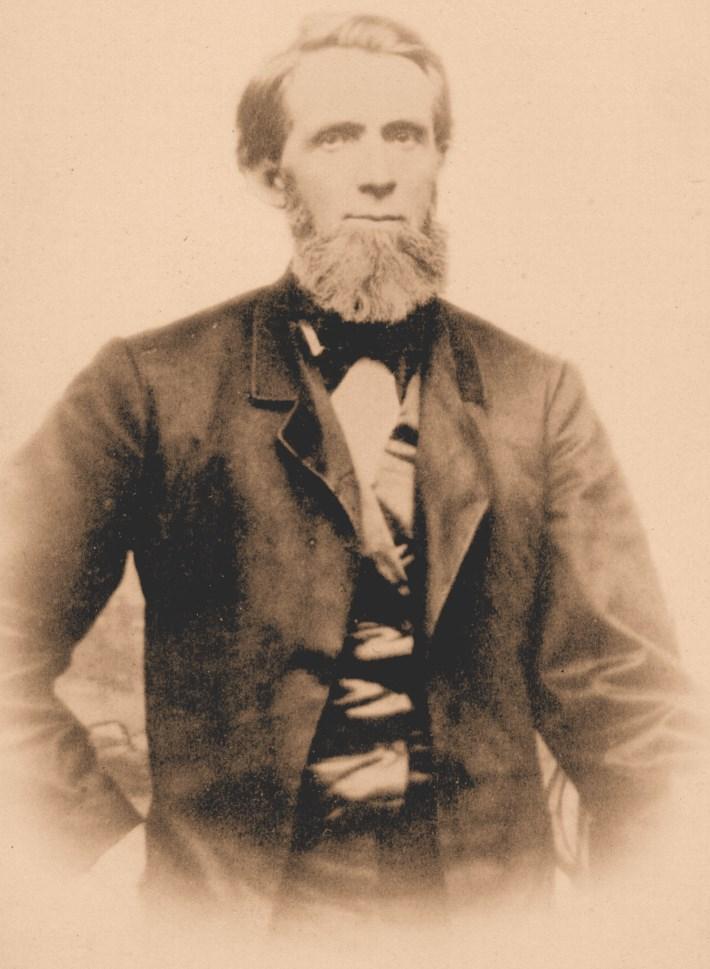

Solomon A. Dwinnell

Compiled by William C. Schuette 2025

Transcribed from the Reedsburg Free Press By John & Donna McCully 2002

Reedsburg Free Press June 28, 1872

THE DEAD OF REEDSBURG IN THE WAR OF THE REBELLION!

(1)

There appears to be no list of those from this town, who fell in the late war, yet made out. Believing it to be due to the memory of those who sacrificed their lives in defence of their country, as well as to the future historian of the town that such a record be made, I have taken considerable pains to perfect one. This required a good deal of labor, some of the names not appearing in the Adjutant General’s report of our dead, others being misspelled. It is possible that I have failed to report all; if so, let any person having a knowledge of the facts, send to me, and I will add to this list. Wm. Miller enlisted from Winfield, WI but removed his family to this town. Hugh Collins and J. Wesley Dickens died after their discharge, from disease contracted in the army. Three families lost two each: Collins, father and son; and Miles and Pitts, two sons each.

After the following names, k stands for killed in action, w for died of wounds, and d for died of disease. The number before the name indicates the regiment.

INFANTRY

6. Geo. C. Miles, k, South Mountain, Md., Sept. 14, 1862

7. Geo. W. Root, d, Arlington, Va., Feb. 28, 1862

11. Amariah Robotham, d, Pocahontas, Ark., May 8, 1862

12. Serg’t Spencer S. Miles, w, Marietta, Ga. July 26, 1864

12. Serg’t F. W. Henry, k, Atlanta, Ga., July 22, 1864

12. J. Wesley Dickens, d, LaValle, Wis.

12. Charles T. Pollock, d, Bolivar, Tenn., Nov. 30, 1862

12. Chas. Reifenrath, k, Kenesaw [Kennesaw] Mt., Ga., June 27, 1864

19. Serg’t A. P. Steese, d, Hampton, Va., July 20, 1864

19. Corp. Alvah Rathbun, w, Fortress Monroe, Va., Nov. 5, 1864

19. Dexter C. Cole, d, Madison, Wis., March, 1864 [March 7, 1863, ten days after enlistment]

19. Hugh Collins, d, Reedsburg, Wis., Aug., 1867

19. John Cary, d, Portsmouth, Va., Feb. 19, 1863

19. Charles Day, w, Hampton, Va., June 16, 1864

19. Dexter Green, k, Fair Oaks, Va., Oct. 27, 1864

19. Ephraim Haines, w, Portsmouth, Va., July 5, 1864

19. Wm. D. Hobby, d, Yorktown, Va., July 31, 1863

19. Wm. Horsch, d, Hampton, Va., July 29, 1864

19. James Markee, d, Portsmouth, Va., Oct. 12, 1862

19. Wm. Miller, w, Richmond, Va., Nov. 1, 1864

19. Newman W. Pitts, d, Salisbury Prison, N.C., Jan. 16, 1865

19. Benj. S. Pitts, k, Drury’s [Drewry’s] Bluff, Va., May 16, 1864

23. Erastus Miller, k, Blakely, Ala., April 8, 1865

23. Jason W. Shaw, k, Vicksburg, Miss., May 28, 1863

23. John Waltz, d, Memphis, Tenn., March 9, 1863

49. John McIlvaine, d, Reedsburg, Wis., March 3, 1865

CAVALRY

1. Erastus H. Knowles, d. St. Louis, Mo., April 8, 1862

3. Henry Bulow, k, Baxter Springs, Ark., [Kansas], Oct. 6, 1863

3. Geo. W. Priest, d, Camp Bowen, Ark., Nov. 6, 1862

1st Mo. Battery. John Collins, d, Cincinnati, Oh., Aug., 1862 N.Y. Regt. Boardman Roscoe, Davids Is., N.Y., Apr. 1865

Unknown. Holden Miller, Madison, Wis., 1864

From this list we find that Reedsburg lost a larger number than any one supposed, being about one-fourth of all who enlisted. Of these, eight were killed, six died of wounds, and eighteen of disease. The 19th Regiment took more from this town than any other, and consequently lost more.

Henry Bulow was murdered, with all the Regimental Band of the 3rd Cavalry, after surrender, and their bodies thrown under the Band Wagon and burned, by order of the infamous [William C.] Quantrill, who, with 500 rebels, were disguised in Federal uniforms. [A letter by Jesse Smith that tells about the Massacre at Baxter Springs is at the end.] Reedsburg, June 24th, 1872

S. A. DWINNELL

Reedsburg Free Press July 5, 1872

RECORD OF REEDSBURG IN THE WAR (2)

by S. A. Dwinnell

Reedsburg has a record of which she need not be ashamed too valuable to be lost. It will pass into history. It ought now to be collected, and put in form to be preserved, before it is lost from the memory of man.

There enlisted from this town, so far as I can ascertain, one hundred and forty persons. One went who was drafted. Others were drafted who commuted by the payment of three hundred dollars.

Of those who volunteered, one hundred and eleven entered the service during the first year of the war, when they received no other bounty than that paid by the United States, which was one hundred dollars.

Most of those who entered the service at a later period, were too young to be enlisted at the commencement of the war. As near as I can ascertain, this was true of about four-fifths.

Of those who entered the service as commissioned officers from this town, Capt. R. M. Strong was promoted to Lieut. Colonel; Lieut. Henry A. Tator to Captain; Lieut. A. P. Ellinwood to Captain; 2nd Lieut. Jas. W. Lusk to 1st Lieutenant; Sergt. John A. Coughran was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant; and Sergt. Chas. A. Chandler also to 2nd Lieutenant; the latter was appointed Captain, but not mustered.

It has been no easy matter to obtain the names of all our soldiers, together with the regiment in which they were mustered. I have done the best I could to make a correct list. My inquiries have been numerous. After all, it may not be perfect. Some names may have been overlooked that ought to have been set down to us. If any person knows of such, they will please oblige me, by forwarding them to me at once, together with their regiment; and if they were veterans or wounded say so.

Many families changed their residence just as the war commenced, and in some cases it is impossible to ascertain the exact time of their removal. For this reason, perhaps a wrong credit may have been given in two or three instances.

Thirty-three lost their lives eight of them were killed in action, five died of wounds incurred in battle, one by accident and nineteen by disease.

Twelve were wounded in action, and two by accident, who recovered. Of these, seven are entitled to pensions from the United States.

Twenty-nine are known to have re-enlisted as veterans, for three years, after having served two years or more. Of these, eight lost their lives, most of them in battle after their re-enlistment.

From this town there entered the army, six fathers with one son each, two fathers with two sons each, and one father with three sons. There went also, twenty pairs of brothers. In addition to this, there were five instances where three brothers went from a family, and in one case four; making seventy-nine in all, who stood in the relation of father, son and brother to each other.

This case is probably without a parallel in a town of twelve hundred inhabitants in the entire land, where they entered the army voluntarily, and shows how very heartily fathers and sons and brothers threw themselves into the work of saving the nation in the hour of danger.

The following individuals volunteered in the Army. Those who removed their families here before they were sworn into the service of the United States, I have credited in this town.

5th W. I. Carver

6th Sergt. John A. Coughran

Theodore Joy

Geo. Morgan Jones

12th Capt. Giles Stevens

Lieut. Jas. W. Lusk

Sergt. Frank W. Henry

Sergt. Spencer S. Miles

Corp. Reuben W. Green

Corp. Morris E. Seeley

John Barnhart

Levi J. Bemis

Charles Bulow

16th Alfred S. Devereaux

INFANTRY

6th Alfred Darrow

Geo. C. Miles

7th Albert C. Hunt

Geo. W. Root

12th Edward Bulow

Francis Colgan

Frank E. Dano

Wesley Dickins

Leroy Dickins

Geo. W. Dickins

John Dongal

Aug. H. Johnson

Philo Lane

8th Samuel Fosnot

11th Amariah Robotham

12th James Miles

John Oliver

Charles F. Pollock

Elias Pond

Baldwin Rathbun

Chas. Reifenrath

John Sanborn

Wm. W. Winchester

19th Capt. Rollin M. Strong

1st Lieut. Henry A. Tator

2nd Lieut. Alex. P. Ellinwood

Sergt. Chas. A. Chandler

Sergt. Eugene A. Dwinnell

Sergt. John H. Fosnot

Sergt. Alfred P. Steese

Sergt. Geo. Waltenberger

Corp. Jas. M. Hobby

Corp. Benj. S. Pitts

Corp. Alvah Rathbun

Corp. Martin Seeley

Isaac N. Bingman

Peter Brady

John Carey

James Castle

Julius Castle

Dexter C. Cole

Rufus C. Cole

Cassius M. Collins

Hugh Collins

Clarence A. Danforth

23rd Erastus Miller

Jason W. Shaw

Wm. W. Pollock

John Waltz

1st Erastus H. Knowles

3rd Oscar Allen

Henry Bulow

W. Nelson Carver

Philemon Devereaux

4th Battery Geo. Fosnot

Oliver E. Root

David Sparks

10th Battery

Edwin E. Shephard

19th Charles Day

Albert E. Dixon

Osgood H. Dwinnell

Peter Empser

Christoph Evers

Joseph C. Fosnot

Nelson Gardner

Giles Graft

Dexter Green

Martin Greenslit

Ephraim Haines

Edward Harris

Wm. D. Hobby

Chas. Holt

Thos. J. Holton

Wm. W. Holton

Wm. Horsch

Edward L. Leonard

Giles Livingston

Jas. Markee

Geo. Mead

Erasmus Miller

35th A. F. Leonard

37th Horatio N. Day

41st Zalmon Carver

43rd J. Israel Root

CAVALRY

3rd Hiram Gardner

Geo. Hufnail

Geo. W. Priest

Henry Southard

John Winchester

ARTILLERY

1st Battery Mo. Lt. Artillery

Lieut. William Miles

Q. M. Sergt. Geo. H. Flautt

John Collins

19th William Miller

Amos Pettyes

Frank Pettyes

Newman W. Pitts

Wm. Pitts

Walter O. Pietzsch

Russel Redfield

H. Dwight Root

Hiram Santus

Hermon V. V. Seaman

Dewelton M. Sheldon

Chas. F. Sheldon

Kirk W. Sheldon

Wm. Steese

Julius M. Sparks

Chas. H. Stone

John Thorn

Richard Thorn

Henry E. Waldron

Orson S. Ward

Frank Winchester

Menzo Winnie

43rd Albert Winchester

49th John McIlvaine

Russel T. Root

3rd Moses Van Camp

4th Norman V. Chandler

Milo Seeley

John Downing

Jay Jewett

M. L. Jewett

The following persons enlisted in regiments of other states, or of unknown regiments of our own state: Allen Brooks, Oliver B. Christie, S. S. Clark, John Culbert, Henry C. Hunt, Isaac Lyon, Geo. Pollock, Boardman Roscoe. Samuel Ward is said to have been drafted.

Reedsburg Free Press July 12, 1872 RECORD OF REEDSBURG IN THE WAR (3) by S. A. Dwinnell Fathers, Sons and Brothers Who Enlisted.

From this town there entered the union army the following named fathers with their sons: Amos Pettyes and son Frank, Erasmus Miller and son Erastus, A. F. Leonard and son Edward, Wm. Steese and son Alfred, M. L. Jewett and son Jay, Orson Ward and step-son E. Haines, John Collins and two sons Hugh and Cassius, Horatio N. Day and two sons Charles and Addison, Wm. Pitts and two sons Benjamin and Newman, and Wm. Winchester and three sons Franklin, Albert and John.

There also went twenty-one pairs of brothers: Osgood and Eugene Dwinnell, Addison and Charles Day; Holden and Erasmus Miller, James and Wm. Hobby, John and Joseph Fosnot, George and Samuel Fosnot, Henry and Albert Hunt, John and Richard Thorn, Alvah and Baldwin Rathbun, Menzo and Edwin Winnie, Rufus and Dexter Cole, Norman and Charles Chandler, Israel and Oliver Root, Thomas and Wallace Holton, Hiram and Harvey Santus, Benjamin and Newman Pitts, Orson and Samuel Ward, Hugh and Cassius Collins, Philemon and Alfred Devereaux, James and Julius Castle, Julius and David Sparks

From five families went a trio of brothers as follows: Edward, Henry and Charles Bulow; Wesley, Leroy and George Dickins; Dewelton, Charles and Kirk Sheldon; Frank, Albert and John Winchester; Charles, William and Geo. Pollock.

From one family were four volunteers all of whom entered the army early in the war, viz: William, George, Spencer and James Miles. This enumeration shows that seventy-five different individuals sustained the relation of father, son and brother to each other.

Of these, John and Hugh Collins, father and son; George and Spencer Miles, Benjamin and Newman Pitts, and Charles and Wm. Pollock, brothers; and Holden and Erastus Miller, Uncle and Nephew, lost their lives.

Thomas Rathbun had another son, Garrett, who enlisted elsewhere, making three in all. And Dea. Israel Root had two sons who enlisted in other towns, Harrison and Wade, making five in all from his family. From J. S. Strong’s family, two sons went as Captain of companies, one of which was enlisted in eleven days.

If any other town, East or West, of two hundred and fifty voters, can present a better record on this head, let them speak and they shall be heard.

THE VETERANS

The following named forty-seven soldiers re-enlisted as veterans, after a service of two years or more, receiving from the United States a bounty of three hundred dollars and a furlough of forty days. A part of these veterans gave their names to be credited to Reedsburg and received a bounty of one hundred dollars each, by vote of the town some months afterwards. Some were credited to other towns and cities, trusting to their sense of justice to grant them bounty. It is believed that nearly all of this latter class failed to receive a farthing of their expected bounty. Not one who gave to Madison their credit, received a dollar, although it cost the city at that time as it did the towns generally, three hundred dollars each to hire men from home to fill their quota.

The veteran boys felt that great injustice was done them by these towns, in which opinion we all share.

VETERANS

NINETEENTH INFANTRY

Capt. A. P. Ellinwood

Lieut. C. A. Chandler

Isaac N. Bingman

Clarence A. Danforth

Eugene A. Dwinnell

Osgood H. Dwinnell

Charles Day

James Castle

Julius Castle

Peter Empser

Edward Bulow

Leroy Dickins

Wesley Dickins

John Dongal

Frank Henry

Christoph Evers

John H. Fosnot

Nelson Gardner

Dexter Green

Ephraim Haines

Charles Holt

James M. Hobby

Wm. Horsch

Edward L. Leonard

Giles Livingston

TWELFTH INFANTRY

Aug. H. Johnson

James Miles

Spencer S. Miles

Elias Pond

Morris E. Seeley

TWENTY-THIRD INFANTRY

G. Morgan Jones

FOURTH CAVALRY

Milo Seele

FOURTH BATTERY

Addison Day

Wm. Miller

Walter O. Pietzsch

Frank Pettyes

Benj. S. Pitts

Newman W. Pitts

Alvah Rathbun

Julius M. Sparks

Alfred Steese

Richard Thorn

Franklin Winchester

John Sanborn

Baldwin Rathbun

Chas. Reifenrath

THE DEAD

Of the one hundred and forty-six who enlisted from Reedsburg, thirty-three lost their lives, being about one in four. Of these, five were sons of ministers of the gospel, one of them, Wm. Pollock, died of disease at Young’s Point, Miss., Jan. 24th, 1868, whose name was omitted in the list heretofore published.

THE WOUNDED

Col. R. M. Strong and Capt. Giles Stevens were wounded in battle and recovered. Also, Clarence Danforth, Eugene Dwinnell, Joseph and John Fosnot, Geo. Fosnot, Irving Carver, James Miles and Wallace Holton. G. H. Flautt and Richard Thorn were wounded accidently.

PENSIONERS

The following named soldiers are entitled to pensions, most of whom applied for, and are receiving it. Col. R. M. Strong, E. A. Dwinnell, C. A. Danforth, Joseph, George and Samuel Fosnot, James Miles, and Wallace Holton.

PRISONERS

The prisoners of war were Col. R. M. Strong, confined at Libby prison, Richmond, VA; and Isaac Bingman, Osgood Dwinnell, Peter Empser, Nelson Gardner, Wm. Miller, Walter Pietzsch, Newman Pitts, Giles Livingston, and Franklin Winchester, all of whom were of the 19th Regiment and captured with Col. Strong at Fair Oaks, VA, Oct. 24th , 1864, confined a short time at Libby and then transferred to Salisbury, N.C., where they were kept four months. Wm. Miller died of wound, at Richmond, and Newman Pitts of disease while prisoner.*

Frank Henry was for a short time a prisoner. Albert Dixon alleges that he was for some months a captive and endured severe sufferings in rebel prisons, but his comrades did not award him a large amount of sympathy, for the reason, as they say, that it was the result of his own wrong.

In August, 1864, several of our citizens entered the service of the government as mechanics, and were sent into the South, where most of them soon were attacked with disease and were discharged. Sidney West died on his journey home. His body was brought here for burial.

HOW THEY VOTED

At the breaking out of the war, the voters of this town were divided about equally between the Republican and Democratic parties. The political attachment of the soldiers as they entered the army was as follows, classing those who were minors, with the fathers of each in political preference. Unknown, seven, Democrats, thirty-three, Republicans one hundred and six.

(* Salisbury military prison was situated in one of the best agricultural counties of the state, where there was plenty of grain, while the prisoners were starving. The United States authority and sanitary commission, forwarded for their use and comfort, through rebel hands, a good supply of clothing and blankets, which were never delivered to them. It cannot be doubted that the Southern leaders deliberately starved their prisoners in order to weaken the Federal army.)

Reedsburg Free Press July 19, 1872

RECORD OF REEDSBURG IN THE WAR (4)

By S. A. Dwinnell

History of Company B, Twelfth Regiment. (Chapter first)

On the second day of September 1861, Giles Stevens, a lawyer of this village, having received a commission from Gov. Randall for that purpose, commenced enlisting a military company, called “The Pioneer Rifles.” At the end of the first week, forty had been enrolled and sworn into the State service. In a short time the company was filled up, mostly from the towns of Winfield, Westfield, Ironton, LaValle, Reedsburg, Wonewoc and Hillsboro, Wisconsin. This village was its place of rendezvous and drill. Giles Stevens was chosen Captain, B. F. Blackmon, of Ironton, 1st Lieut., and J. W. Lusk, of this town, 2nd Lieut., and were duly commissioned by the State.

On the evening of October 28th, a meeting was held in the Basement of the Presbyterian church, at which swords were presented to the officers by the citizens, and presentation speeches made.

On the morning of October 30th, the people and friends of the soldiers assembled to bid them adieu, and in some instances, as the result proved, a last greeting. They were taken in wagons to Spring Green, on their way to Camp Randall, at Madison, WI. As they passed out of the village, the citizens, under direction of Captain F. A. Wier, lined the street south of the flouring mill of S. Mackey & Co., and gave them three cheers at parting. This was the first company which had then left the north-western portion of Sauk County for the war, and it awakened new and sad emotions in many souls.

The company was mustered into the United States service and assigned to the 12th Regiment of Infantry as company B., George E. Bryant was their Colonel.

The Regiment left Camp Randall for Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, January 11th, 1862, 1,049 in number, the largest

that had then left the state. There was considerable religious interest in the regiment. Prayer Meetings were regularly held, and a number professed conversion to Christ. It was armed with Belgian rifles and had Sibley tents and was well equipped throughout.

The Regiment was unable to cross the Mississippi at Quincy, IL on account of the condition of the ice, and marched down to Douglassville, IL, opposite Hannibal, MO, a distance of twenty-two miles. There they spent the night of the 13th, with the temperature twenty degrees below zero, and had no place of rest after their tedious march, but to lie down on the frozen ground, without tents, on the banks of the river.

Crossing the Mississippi, they rode from Hannibal to Weston, Missouri, for twenty-four hours, chiefly in open cars, without fire, lights, or warm food, and as a result over one hundred were in a few days on the list of the sick. Captain Stevens’ company being on the left of the regiment and being the last to cross the river, were detailed to take charge of the baggage and load it upon the train. This they did in a driving snow storm. The other companies having proceeded on their way as before stated, company B was left to take the regular passenger train, and thus was not exposed to the perils and sufferings of their companions in arms.

From Weston they marched early in the spring, one hundred sixty miles south, to Ft. Scott, then back to Lawrence, Kansas, which place they left April 20th, for Fort Riley, one hundred and five miles west, by way of Topeka, KS, where they shared with many other troops in a general review.

The great Southwestern expedition to New Mexico, to which they were destined, having been abandoned, the company with the whole command, was ordered back to Leavenworth, KS, which they reached May 27th, and joined in another grand review. On the 29th, they moved to St. Louis, MO on the way to Corinth, MS, landed in Columbus, Kentucky June 2nd, and were engaged for some months in repairing the Mobile and Ohio Railroad, and scouring the country in search of bridge-burners and bushwhackers. They subsequently moved to Union City, TN, thence to Humbolt, Tennessee. While at that post, Captain Stevens, in command of his own and two other companies, was ordered to Huntington, in that State, to drive out a force of the enemy. This they effected, pursuing them until they crossed the Tennessee river, when they returned to camp.

On the 4th of October the regiment was removed to Pocahontas, TN to take part in the battle of Hatchie, then in progress, to prevent Van Dorn in his northward movement, which was effected. They formed the reserve and were not in action and thence marched to Bolivar, Tennessee. They continued at that place till November 3rd, when they commenced their march to the South with the “army of the Mississippi,” under General [Ulysses S.] Grant. On the 4th they reached La Grange, TN, and on the 8th the twelfth led the advance of a large force under command of Gen. [James B.] McPherson, on a reconnoitering expedition, towards Holly Springs, MS, near which a heavy rebel force was known to be encamped. They marched within eleven miles of that place, when companies A and B were deployed as skirmishers, and advanced to the supposed position of the rebels, but they had retreated, and the regiment moved up and bivouacked on the site of the rebel camp. The expedition returned the next to La Grange, having captured one hundred and fifty prisoners. November 28th, they moved southward to Holly Springs and Lumpkin’s Mill, and December 12th, to Yocona Creek, having a severe march down the line of the Mississippi Central Railroad, with the probable object of attacking Vicksburg, MS in the rear. Holly Springs, which cut them off from their base of supplies, having been captured by Van Dorn, obliged General Grant to retrace his steps, and the 12th went into camp again at Lumpkin’s Mill, on the 27th of December.

In January 1863 they moved to Moscow, Tennessee, thence to Lafayette, then to Collinsville, and March 14th to Memphis, TN. April 18th, Col. Bryant commanded an expedition to attack the rear of the rebel General [James R.] Chalmers’ forces, while General Smith should attack in front. In a skirmish in which seven rebel officers and sixty men fell into our hands, Captain Stevens’ company was under fire, but sustained no loss. The next day they came upon the enemy eight miles south of Hernando, MS in a strong position, but being too weak in numbers and awaiting reinforcements, did not attack all which movements were intended to hold the enemy in that vicinity while Colonel [Benjamin H.] Grierson made his famous raid through Mississippi. May 11th they embarked at Memphis, disembarked just out of range of the enemy’s guns above Vicksburg, MS, marched across the peninsula opposite the town, embarked again and landed at Grand Gulf, MS. After the valuable army stores had been removed from that place, the regiment proceeded up the river to Warrenton, where they joined the fourth division, under General [John G.] Lauman, and took position in fortifications before Vicksburg, MS. They were engaged in reducing that important fortress until the surrender of that place by Pemberton to Grant, July 4th

As illustrating the nature and perils of the siege, the following incidents may be related. One night Captain Stevens received orders to advance his line of works to a distance of some rods towards that of the rebels, to a certain designated locust tree. Preparatory to doing it, he detailed ten men, among them James Miles, to form a skirmish line and proceed to the spot and feel for the enemy. Giving orders to another detail of twenty men to take their entrenching tools and prepare for an advance to dig a new line of rifle pits, he proceeded alone to reconnoiter. When within some twelve feet of the tree above named, he received an order to halt, which he at once obeyed, supposing at first, however,

that it came from one of his own skirmishers. He soon discovered from the sound of their voices, his mistake, and knowing that if he allowed himself to be taken prisoner without any alarm, the details of men that were about to proceed to the spot, might one after another, suffer a similar fate, until his whole command would be “gobbled up.” He resolved to retreat at double quick at all hazards, in doing which the rebels fired a volley upon him; but he escaped unharmed.

The result proved that he had encountered a regiment of the enemy, out between the lines of the two armies on reconnaissance. Inman and his men having filed too far to the right, and having advanced to a point between the rebel works and this regiment of the enemy, had just discovered them, and mistaking them for a picket post, were preparing to take them prisoners and bring them into camp, when the firing revealed their mistake, and led them to retreat to their line of works for protection. Their rifle pits were at once attacked by the enemy, a brisk firing on both sides was kept up for two hours, when the rebels retreated to their entrenchments.

During this attack, James Miles after drawing up and firing at the flash of one of the enemy’s guns, discovered upon attempting to reload, that the ramrod of his rifle had been hit by a rebel ball, and bent the upper band being shattered, the ball glancing down to the ground, thus saving his life.

Closely related to the fall of Vicksburg was the second battle of Jackson, the Capital of Mississippi. On the 12th of July, Captain Stevens being in command of the regiment, received an order to detail three hundred men to act as skirmishers, his whole command numbering but four hundred and fifty at that time. He afterwards received orders to join his regiment to the assaulting column. In reply to the order, he asked that the three hundred detailed skirmishers might first be returned to his command, but it was found that they were three miles away. Another regiment was then ordered into the charge in place of his. That regiment was repulsed with terrible loss. Thus the 12th was Providentially saved from being fearfully decimated.

Returning to Vicksburg, MS they suffered much from sickness. August fifteenth, the regiment embarked for Natchez, MS. September 1st they had the advance in an expedition to Harrisonburg, Louisiana, commanded by General [Marcellus M.] Crocker. November 22nd they embarked at Natchez for Vicksburg, and went ten miles east, to guard the railroad near the Big Black [River]. December 4th they returned to Vicksburg and embarked for Natchez again, where they joined a strong force sent out in pursuit of Wert Adams’ command. January 23rd, 1864, they embarked for Vicksburg, where five hundred and twenty of the men re-enlisted. In February they formed a part of Sherman’s celebrated Meridian expedition, marching more than two hundred miles eastward and back, Captain Stevens, in command of six Companies, forming the rear guard. General [William T.] Sherman had directed that the troops should subsist from the country through which they passed. On the outward march, Sergeant Inman, James Miles, and one other, man were detailed on a foraging expedition, to bring in subsistence. Passing down the Railroad track, at a point where it diverged from the traveled road, over which the troops were marching, they were soon widely separated from any support from their companions in arms, and near the confines of a little town in which rebel troops were seen. Turning aside to a neighboring plantation, they confiscated a four mule team and wagon, loaded it with bacon and other supplies, and joined their command in safety. It was regarded by all, as a feat of great daring. On the 13th of March, the re-enlisted men went home on veteran furloughs of forty days.

(NOTE. In writing this chapter, I have used in some instances, the language of “Love’s History of Wisconsin in the War of the Rebellion,” without giving credit by marks of quotation his language and my own being often so intermingled as to render it difficult to do it. I may do the same in the future.)

Reedsburg

Free Press July 26, 1872

RECORD OF REEDSBURG IN THE

WAR (5)

By S. A. Dwinnell History of Company B, Twelfth Regiment.

(Chapter Second)

On the 10th of April, 1864, General Sherman received instructions, from Lieutenant General Grant, to proceed on his campaign, from Chattanooga, Tennessee, through Georgia. His forces had been re-organized, and consisted of the army of the Ohio, under Major General Schofield, the army of the Cumberland, under Major General Thomas, and the army of the Tennessee, under Major General McPherson, and consisted of 97,797 men, infantry, cavalry and artillery, and 254 guns. The rebel army under Johnson, marshalled to meet them, numbered about 54,000 under Hardee, Hood and Polk.

The first design of the Campaign was to reach Atlanta, one hundred and thirty-eight miles distant, an important town and a large manufacturing place where an immense amount of arms, ammunition and clothing, for the rebel army, was made. The country to be passed over, was part of the way, mountainous, and at the most important points and passes on the route, such as Resseca [Resaca] and Kennesaw mountain, GA, the enemy was strongly entrenched.

The last chapter left Captain Stevens’ company the veterans at home on furlough, and the non-veterans and

recruits near Vicksburg. The latter class received orders to rejoin the former at Cairo, and all proceeded on their way to take their place again in the seventeenth corps, under Blair, in the army of the Tennessee, under McPherson, which they effected on the 8th of June, at Ackworth [Acworth], Georgia. From this time they were engaged in battle or skirmishes much of the time being under fire more or less, as Captain Stevens says, every day until early in September following.

A few miles on this side of Kenesaw [Kennesaw] mountain, Charles Reifenrath, of this town, was mortally wounded on skirmish line, and died soon after.

BEFORE ATLANTA

Jefferson Davis had long been unfriendly towards General [Joseph E.] Johnston, and desired to witness his public disgrace. His failure to hold the Federal army in check in their campaign from Chattanooga, TN, afforded Davis an opportunity to carry out his design, although it is doubtful whether any other of his Generals, with a force so much inferior to that of the Union army, would have done better for the weak and waning cause of the Confederacy.

On the 17th of July, Johnston was removed and Hood, who was one of their best fighting Generals at that time although impetuous, rash and unfit to command a large army was appointed in his place. Hood, evidently desirous of striking quick and brilliant blows upon Sherman’s army, immediately upon taking command of the Confederate troops, commenced some of the most dashing and furious onsets upon our arms, experienced during the war.

Sherman, instead of attacking the place from the south-west, as the rebels evidently expected, moved around to the north-east, where the battle of Peach Tree Creek was fought, on the afternoon of July 20th, by which the rebels were forced back to their last general line of defences, on that side of the city, on the night following.

Bald Hill, which was evidently considered by the rebels as a commanding position, is upon the East of Atlanta, GA, and the attack of the July 21st, was made from that side, where the altitude was not high, and the ascent was easy. The Twelfth and Sixteenth Wisconsin Regiments were in the first Brigade of General Leggett’s division, on the extreme left of the line, towards the South. In the assault upon the enemy’s work on that morning, by these regiments, Company B of the 12th, were deployed as Skirmishers, three rods in front of the 16th Regiment. They crossed a cornfield and charged up the hill under a withering fire from the enemy’s entrenchments. When near the works of the enemy, it is according to the rules of war, for skirmishers to drop upon the ground and allow the main body to pass over them, before uniting in the charge. But Company B, mistaking a word of encouragement, from their Captain, addressed to the men of the 16th Regiment, for a command, still rushed on, and pushed at once into the enemy’s entrenchments. But the 16th was soon to their support, and the rebels fled to another line of works.

Love’s History says of this assault: “The men pressed forward without wavering, entered the rebel works with loud cheers and then commenced a hand to hand fight, with bayonets and the butts of their muskets. When finally they drove out the desperate rebels and held the works, the ground was strewn with dead and wounded.” There was no bayonet fighting, however, on the left wing where Company B was engaged.

In this charge, L. B. Cornwell, of Winfield, WI, J. E. Wickersham and Amos Ford, of Ironton, WI were killed, and Spencer Miles mortally wounded. James Miles was severely wounded on picket duty, previous to the charge on that morning. During the night following, the captured entrenchments were changed, so as to face Atlanta. A slight earthwork was made on their left, running South, and about three feet high, after the battle of the next day commenced, to prevent an enfilading fire from that side.

Captain Stevens’ Company was on the extreme left of the line, at the angle of these earth-works, extending along those that faced to the west, and also those that faced south. The events of the following day proved their position to be one of great importance in the estimation of the rebels and one of extreme peril to themselves.

About noon on the 22nd, there were indications that Hood was about to make an attack. The infuriated rebels soon moved to a charge, both on the west and south. It was the intention of General McPherson to prevent an attack from the South, by stationing a large force on that side, but the enemy discovered a gap between General [Grenville M.] Dodge’s moving column and General [Francis P. Jr.] Blair’s line, and pouring through it, commenced a furious attack from that quarter. General McPherson heard the firing, and riding through the woods to discover the cause, came suddenly upon a body of rebels who ordered him to surrender; but he put spurs to his horse and dashed into the forest. The deadly aim of rebel bullets was too certain, and he fell. His body was taken within the Confederate lines and held for a time.* His last command was to fill up that gap; but it required most desperate fighting to do it.

The rebel, Hardee, led this attack, but General Dodge repulsed him severely and captured many prisoners. The rebel, Stuart, who succeeded Polk, swept over a hill and captured some of our men, but was met by Generals Leggett and G. A. Smith and their forces, who fought him four hours, when he was about to withdraw. But at four in the afternoon a part of our forces having become weakened, was pierced and divided by the enemy, and at once the battle was renewed with great fierceness, but the Confederates were finally again repulsed. The yelling rebels swarmed around that hill like bees robbed of their hive. The smoke of battle and the missiles of death filled the air. Captain Stevens’ Company occupied a position, which more than any other, the enemy sought to possess. They were exposed to their fire

on the East, West and South, with only a slight protection, except on the West. It was only by the most determined resistance that the enemy were prevented from taking their works. During much of the entire afternoon, the missiles of death so filled the air, that one could hardly raise a hand or head above the embankment, without its being pierced. At the close of the day the rebel troops encamped upon one side of the entrenchments and ours on the other; but during the night the enemy fell back and left us in possession of the position. Here Captain Stevens was wounded, and Frank Henry fell, pierced through with several balls; and Caleb Clark, George Ford and Evert H. Hagaman were killed, and Wm. Richards mortally wounded. Company B was reduced, in the two days fighting, from seventy-four men and three officers, to twenty-three men and one officer. Their regiment, numbering less than six hundred in all, lost in the two days, one hundred and eighty-eight men. Our army, at the same time lost nearly 4,000. The rebel loss was some 12,000, of whom 3,240 were killed.

The twelfth regiment was in the movement, by Howard, toward the Macon Railway, July 28th, and when at noon, the fifteenth corps, two miles in advance were severely attacked, they moved rapidly forward, outstripping all other reenforcements, and joined in battle just in time to save the Federals from defeat. They lost on that day, nineteen in killed and wounded. Immediately after, they took position in the trenches before Atlanta, GA where they remained nearly a month. At Jonesboro, GA, August 31st, they joined in repulsing the enemy after a severe battle. September 1st they were also engaged, and the next day pursued the retreating foe. They next defended our communications against Hood, about which time the early enlisted non-veterans returned home, leaving the veterans and recruits to proceed with Sherman in his GRAND MARCH TO THE SEA, which commenced, from Atlanta, November 24th, 1864, with 60,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry and a large amount of artillery. On the march they destroyed 320 miles of railroad, severing thus the Confederate forces in Virginia, from those at the West. They burned railroad ties, heated and twisted rails, destroyed depots, shops, engine-houses and water-tanks. They burned 20,000 bales of cotton, besides capturing 25,000 at Savannah. There escaped from the plantations of their former masters, 10,000 negroes who followed our army to Savannah. Our entire loss was nine officers and 548 men, only about one half of whom were killed and wounded.

The army subsisted from the country through which they marched, chiefly on hogs, sheep, turkeys, geese, chickens, rice and sweet potatoes, foraged mostly from the plantations, and their subsistence was not scanty, even in a country where thousands of Union prisoners were starving in rebel stockades. There were issued to the troops, 13,000 head of beef cattle, 9,500,000 pounds of corn and 10,500,000 pounds of fodder. For the use of the army, 4,000 mules and 5,000 horses were taken.

The twelfth assisted, on the march, in the destruction of the Georgia Central Railroad, and reached the neighborhood of Savannah, GA, December 12th. They took position in the trenches and remained until the evacuation of the city. Proceeding with the seventeenth corps, by water, to Beaufort, SC they took part in the battle near Pocotaligo river.

In the campaign of the Carolinas, they crossed the Edisto river, marched through deep swamps, charged upon the rebels at Orangeburg, SC and drove them out of the place. They participated in the grand review of troops at Washington in May, and arrived at Louisville, Kentucky, June 7th, where they were mustered out, July 16th, and were paid and disbanded at Madison, Wisconsin August 9th, 1865.

(Note. In this chapter, as in the last, I have made free use of “Love’s History of Wisconsin in the war,” in most cases, without the usual marks of credit. *The statement that General McPherson’s body was taken within the Confederate lines and held for a time is authorized by Love’s History; but Elder F. I. Groat, of Ironton, who was a member of Company B, says that he was near by at the time; that as a member of the Pioneer Corps, he was not in the ranks, and had a good chance for observation, and is quite sure that his body was taken within our own lines and held.)

Reedsburg Free Press August 2, 1872

RECORD OF REEDSBURG IN THE WAR

(6)

By S. A. Dwinnell

History of Company A, Nineteenth Regiment. (Chapter First)

In December 1861, Rollin M. Strong having received a commission from Governor Randall for the purpose, resigned the office of Sheriff of the county, which he then held, and moving to Reedsburg, commenced enlisting a company, called the “Independent Rangers.” They proposed to unite with an Independent Regiment which the War Department had authorized Colonel Horace T. Sanders, of Racine, to raise and get in if possible, as Company A. The “independent” nature of the movement, together with the personal popularity of the recruiting officer among the boys, soon filled the company to its maximum, 108 in number, fifty-eight of whom enlisted from this town. Rollin M. Strong was elected Captain, Henry A. Tator 1st Lieutenant, and Alex P. Ellinwood 2nd lieutenant.

They remained in this village, for preparation and drill, until Sunday, January 26th, 1862, when much to the

displeasure and annoyance of the Christian people here they were ordered into camp at Racine, by way of Kilbourn City, WI [now Wisconsin Dells] to which place they were conveyed in sleighs by our citizens.

On the same day, at the close of services in the Congregational Church, a committee was appointed to communicate to Colonel Sanders, an expression of our deep sorrows, that the Lord’s day should have been unnecessarily violated by taking the company from our midst at such a time; to which he gave us a very respectful reply, attributing the movement to his adjutant, Van Slyke.

The regiment entered Camp Utley, Racine, WI, January 27th. Company A was mustered into the United States service February 22nd. By an order from the War Department, of the day previous, abolishing all Independent Regiments, Colonel Sanders’ organization was entered as the 19th Regiment of Wisconsin Infantry.

While at Racine the company was quartered near the bank of Lake Michigan and suffered considerably from the chilling winds from that body of water.

On the 20th of April the regiment was ordered to Camp Randall, at Madison, WI, to guard some 2,000 prisoners, which had then recently been captured at Fort Donelson, TN. Most of these prisoners were evidently from the poor whites of the South, rough in manners, degraded in appearance, and filthy in habits. It required the most rigid discipline to prevent their breeding a pestilence in camp. One company among them, the “Washington Artillery,” was from the educated classes of New Orleans, LA and refused to associate with their fellow prisoners.

Camp Randall, being the grounds of the State Agricultural Society, was surrounded by a high and solid board fence enclosing some twenty acres. The prisoners’ barracks were near the fence, whilst the quarters of the 19th regiment were in the central portion of the grounds. A guard was constantly on duty on the outside of the camp, as also on the inside, between the prisoners and the quarters of our troops. No intercourse was allowed between them and the soldiers, except in the line of duty.

Upon the removal of these prisoners to Camp Douglass, Chicago, IL, Company A accompanied them as a guard. Joining their regiment as it passed through that city, June 2nd, they proceeded at once, by way of Washington, to Fortress Monroe, VA in the vicinity of which place, they remained four weeks, performing guard and picket duty.

AT NORFOLK

About the first of July, 1862, they were ordered to report to General Viele, at Norfolk, VA where, and in the vicinity of which, they remained, in the performance of garrison and out-post duty, until April 14th, 1863. This regiment performed more of this species of service, it is believed, than any other of our State troops.

Although the men sometimes complained that they were kept so long from more active service in the field, yet they performed their duties with fidelity.

Norfolk was a city of about 15,000 inhabitants, with the suburban town of Portsmouth, with a population of 10,000 and nearly all of them were in deep sympathy with the rebellion. The regimental guard which had proceeded the 19th, in those cities, was understood to have used a good supply of “rose water treatment,” in dealing with the spirit of rebellion among the people, in which the commandant of the Post, General Viele, seemed to have more or less sympathy. The spirit of contempt and hatred towards the Yankee soldiers was especially manifest on the part of the females the men not daring to give expression of their feelings towards them. And the women manifested their hostility, more by acts and sneers and grimaces, than by words.

An incident, related by Sergt. C. A. Chandler, will illustrate their manners. Having business through the city in the line of duty, one day, he saw in advance of him upon the sidewalk, three young women conversing together. As he approached them they spread themselves across the entire walk, evidently intending to crowd him off the curbstone into the street; but he marched directly along, upon the outer portion of the walk, brushing quite hard the clothing, and jostling the person, of the most impudent of the trio; where upon she snarled out some expression of contempt for Yankee soldiers.

The Sergeant stopped, and turning to the young women, told them that the soldiers had rights in that city as well as they that it was useless to attempt to crowd them into the gutter, and it would be much better to succumb to their fate, than to resist; to which they made no reply, and he passed on his way.

The soldiers would sometimes hang out the United States flag, over the sidewalk, in front of their quarters, if for no other purpose than to see the women leave the walk and take to the street, or pass to the other side, as they approached it. At one time, upon one of the large thoroughfares, some of their number hung a flag over the walks on each side of the street, so that to pass under it or take to the street and mingle with the passing vehicles, was the only alternative. This treatment on the part of the troops restrained these acts of hostility and contempt towards them, and their rights were some outwardly respected.

Reedsburg Free Press August 9, 1872

RECORD OF REEDSBURG IN THE WAR (7)

By S. A. Dwinnell History of Company A, Nineteenth Regiment. (Chapter Two)

Company A, with the regiment, continued efficient service at Norfolk, VA in guard and picket duty a favorite with the law and order portion of the citizens. They were commended by the Union, a newspaper, at that time published in the city, for “their exemplary conduct and quiet bearing.” By their gentlemanly and quiet deportment they commanded the respect, and by their vigilance in the discharge of their duty they excited the wholesome fear of those who hated them.

New Year’s day, of 1863, the Slaves became free, under the emancipation proclamation of President Lincoln. It was a high day in Norfolk. The negroes had a grand procession in commemoration of the event. A serious outbreak was feared by the excited populace. Extra guards were posted for preserving order and quelling the first symptoms of an outbreak; but none occurred. None need have been expected. It is not in man to avenge an act of merited justice done to themselves.

During the day the regiment called upon Colonel Viele, at his quarters, under whose command they had served for eight months. He made an appropriate address and commended them in these words: “Trusted with important duties and responsibilities, you have not in one instance failed to fulfill them. Stationed among those who felt little kindness towards you, you have daily exhibited a noble forbearance. When no courtesy was shown you, you have not failed magnanimously to show pity towards the many misguided people, whom the enemy have left here unprotected, who have made petty efforts to annoy you.”

General Dix, the commandant of that Department, had previously, in a letter addressed to Governor Salomon, of our State, made honorable mention of the regiment, and commended their conduct as creditable to themselves, and honorable to the commonwealth from which they came.

SIEGE OF SUFFOLK

Upon the banks of the Nansemond [River], VA, flowing to one of the inlets of the James river, and about thirty miles from Norfolk, is the little village of Suffolk. At the junction of the two Railways, it was an important strategic point, and was held by General Peck, with a force of 14,000 men. By the capture of a rebel mail, he learned of an intended surprise upon his forces, by Longstreet, one of the most able and daring of the rebel commanders. “Longstreet, Hill and Hood came rushing upon our lines,” says Abbott’s History, “with five divisions of the rebel army, expecting to sweep all resistance before them. They were met with solid shot, and bursting shells, and bristling steel. They had not cherished a doubt of their ability to cross the narrow Nansemond, seize the railroad in the rear of Suffolk, capture the city and its garrison, with all its vast stores, and then, after a holiday march, to occupy Portsmouth, and Norfolk.”

General Peck was on the alert, obtained a few wooden gun-boats from Admiral Lee, threw up defences, and sent to Norfolk, VA for guns and troops.

On the 14th of April, 1863, the Nineteenth received orders to move to Suffolk, to reinforce the place started by train at ten o’clock P. M. reached the place at three o’clock A. M. disembarked went two mile further in a drenching rain and Egyptian darkness, to the camp of the 21st Connecticut, a large detail of whose men were out on picket, where most of our men obtained shelter in the tents of the friendly soldiers, and others were exposed to the severity of the storm until morning. They now had 600 men on duty.

At five in the evening an order was received to march to Jericho Creek, where they pitched their tents, which had now been brought forward.

One night they spent in rifle pits on the Nansemond [River] boys had their first sight of rebs, in arms anxious to get a shot at them.

Saturday night, April 21st, a large detail was made from Company A, under Sergeant C. A. Chandler, and one hundred and sixty from the regiment, under Lieutenant Ellinwood and another officer, to build a corduroy road, three hundred yards over a miry marsh, and a rough bridge over a creek, thirty feet in width, for the transportation of cannon, to a piece of rising ground in the marsh. This was effected on that night and the one following, the soldiers carrying much of the timber for the road from half to three fourths of a mile.

On Friday night previous, company A, with five others, had marched down the river; and gone into rifle pits, under command of Major [Alvin E.] Bovay, opposite the rebel battery at Hill’s Point, on the Nansemond. The battery consisted of five splendid brass guns, four of them twelve pound Howitzers, and one twenty-five pounder. General Peck proposed to take this battery, and sent to Major Bovay for his men to join with other troops in the enterprise. Major Bovay plead that they were unfit for the dangerous expedition, having always been on guard and picket duty and never under fire, and thus obtained a countermanding order. When his men heard of this, they were fired with indignation at

their commander and called him a granny, unfit for his position. They were anxious for active work, and were just ready for such a daring feat.

Other troops two hundred in all were detailed for the enterprise, under command of Colonel John E. Ward, of the 8th Connecticut, who crossed over in a gun-boat landed unexpectedly rushed up the river-bank and along a ravine charged upon the rear of the fort, and captured men and guns without firing a shot on either side. This neat little affair has an honorable place in the history of the War and threw a halo of military glory around the actors in it. The men of the Nineteenth Regiment felt deeply chagrined, not only because they were not permitted to share in the hazard and the honor of the enterprise, but also because the conduct of Major Bovay gave countenance of a false charge preferred against them of shirking duty, and grumbling; which resulted in the publication of an order of the General commanding, soon after, relieving them from duty on the line of the river defences, and ordering them into camp at Suffolk, VA an order given, no doubt, in a moment of petulance arising from an incorrect statement of one of his staff officers, who fell out with Major Bovay.

From April 25th to April 30th, Company A, under Captain Strong, were on picket duty on the Nansemond in rifle pits the first thirty-six hours in the rain, without tents and without rest, except what they could get lying on the ground in their wet and chilled condition. Here they built and manned Fort Wisconsin, VA. There was a rebel battery on the opposite side of the river, about three fourths of a mile from them, between which and the river stretched a wide strip of marsh, covered with a growth of tall grass, through which the rebel sharp-shooters could crawl, concealed, to the river bank, and fire upon our men. Various unavailing efforts were made to shoot over combustible material and ignite the grass, when Nelson Gardner and Ephraim Haines, of Reedsburg, volunteered to swim the river, which was about twentyfive rods wide at that point, and set fire to the grass. They were accepted by Captain Strong, and concealing matches in their hair and wearing their hats, leaped over the ramparts plunged into the river swam over unobserved by the enemy set fire to the grass rested a short time under the bank and returned in safety; although subject, all the way, to a shower of balls from the enemy’s battery, and an enfilading fire from the rifle pits lower down the river. This dangerous feat has honorable mention in the history of the war; although the name of but one of the boys is given.

Soon after this, Company A, with about a brigade of other troops, were, for about two weeks, on a reconoissance [reconnaissance] towards the Blackwater their rations failing obliged to forage from the country found a crib of corn concealed in a swamp carried it to a rebel mill miller refused to grind gave him the alternative of surrendering his mill to their use, or being returned to headquarters as a prisoner he chose the former had two millers in Company A, Wm. Sweatland and Wm. D. Hobby set them to grinding the corn, confiscating pigs from the woods, lived in Southern fashion, on “hog and hominy” for several days.

From May 23rd to June 17th, the regiment were at Suffolk, performing ordinary fatigue duty and drill. June 18th at Yorktown, VA, encamped outside the old fortifications until the 25th, when they were ordered to West Point, where they remained until July 8th, when they received orders to return to Yorktown.

Reedsburg Free Press August 16, 1872

RECORD

OF REEDSBURG IN THE WAR (8)

By S. A. Dwinnell

History of Company A, Nineteenth Regiment. (Chapter Three)

AT YORKTOWN

Yorktown, VA is on the York river, 15 miles above Fortress Monroe. The stream at this point is about a mile in width, and the harbor will float the largest ships of war. It was strongly fortified during the Revolution. It was here that Lord Cornwallis surrendered his army of 7,000 men, with their munitions of war, to General Washington in October 1781, which in its results secured from Great Britain an acknowledgement of our independence as a nation.

The old fort contained an area of about twenty acres. In the early part of the war of the Rebellion the Confederacy built a new fort, enclosing the old one, and containing some forty acres.

With these and some other works, they frightened McClellan, when on his famous pick and spade expedition up the Peninsula in 1862, to spending a month in entrenching before he dared to move upon their works. Just as he got ready to do it, the enemy vanished, much to his disappointment and chagrin.

The last chapter left the 19th regiment at Yorktown. This village, of some half dozen homes, is within the fort. Two of them built on brick, bore the marks of solid shot thrown into their walls during the bombardment of our army, previous to Cornwallis’ surrender.

The 19th, which occupied the fort in conjunction with several other regiments, were stationed in the north-west portion of the grounds, which had been used by the rebels as a kind of Ghehenna [Gehenna] or a place for the burial of horses and mules.

The regiment were supplied with the Sibley tent. For the purpose of giving a better circulation of air, stakes were driven in the earth and the tents pitched upon the top of them. A large portion of these stakes, when driven touched upon the carcass of some of the buried animals, and the boys were obliged to breathe, constantly, the miasma arising from them. One of the members of Company A says that he drove stakes in the earth, and placing a board upon them, slept upon it; and that he was the only member of the company who escaped sickness at that time. Some of the men who were quartered there, climbed into mulberry trees and fastening boards in secure positions to the limbs, slept on them.

The old fort had been a perfect breeding place and refuge for rats, and the town was over-run with them. At night they held high carnival. A person walking the street could often toss them with his toe. The boys were obliged to cover up face and ears with their blankets when they slept, to save them from being bitten. The three or four wells in the place were cleaned out every day or two, taking out from them, from half a dozen to half a bushel of dead carcasses each time.

There was a fine spring outside the fort, but no permission could be obtained from General Wistar to bring water from it. Sickness began to prevail. Rations were given away to the colored people. One very old man, formerly a slave, who said he lived there in the days of the revolution and remembered those scenes well, received one hundred loaves at one time. The ranks were thinned and Hampton hospital filled up. During four weeks in which they were in camp there, four hundred out of about seven hundred were sent there, nineteen-twentieths of whom were sick with miasmatic fevers. Col. Sanders made several applications to Gen. Wistar, the commandant of the Post, for the removal of his regiment to a more healthy locality; and although there seemed to be no good reason why it should not be done, as there was no enemy within sixty miles, his applications were unheeded. Colonel Sanders finally succeeded through his skill as a lawyer in working up a case in obtaining an order from higher officials, for their removal to Newport News, VA, from which place one hundred and fifty more were at once ordered to Hampton, VA hospital. The few who were left outside the hospital were all partial invalids, unfit for severe fatigue duty.

It is but justice to the members of the regiment, to say that they all regarded Wistar as an unfeeling brute.

From this recital we can see that the sufferings of army life are by no means confined to the battle field, or to active service before the enemy, and that immense suffering may come to an army from the wanton disregard of the health and life of his troops by a single officer.

On the 10th of October, 1863, the regiment left Newport News, VA, on transport, for NEW BERN, N. C., at which place they landed on the 11th. This is one of the finest towns in the State, containing about five thousand inhabitants and situated at the confluence of the Neuse and Trent rivers. The rebels considered it an important position, and had strongly fortified it early in the war. It was wrested from their hands by the bravery of the Union troops under General [Ambrose E.] Burnside and Commodore Goldsborough, in February 1862.

Upon the arrival of the regiment in New Bern, Company A was assigned to out post and picket duty at Evans’ Mills on Brice’s Creek, eight miles south of the city. At that place was a saw and flouring mill and a large plantation which had belonged to General Evans, of the Rebel army. The officers were quartered in the Evans mansion, and the soldiers in barracks erected for the purpose. From the west and south there was but one place of access, on account of intervening swamps, and that was across the mill-dam, and this enabled the Company to hold the position against superior numbers of the enemy.

At the time of the attack upon New Bern, NC, by the rebels, on the first of February 1864, Company A was attacked by a brigade of cavalry and a battery of artillery. They sent to New Bern for reinforcements and received three Companies of Cavalry and a twelve pound howitzer and men to work it. With this assistance they held the rebels in check three days. Captain Tator, who was in command of the out-post, and who was an efficient officer, sent out a cavalry scout several times a day, to watch the enemy and ascertain their position and what they were doing. At one time they found them building a bridge, evidently for the purpose of bringing over their artillery for an attack; but a severe shelling from the howitzer prevented their doing it. It is probable that the manifest boldness and daring of the Union troops, led the enemy to the conclusion that the force at the out-post was much superior to what it really was.

On the morning of February 3rd, Captain Tator received orders from General [John M.] Palmer, commanding at New Bern, to fall back to the city, soon after which, the rebels, guided by a Sesesh planter residing in the neighborhood, named Wood, marched around the swamps on the south, and coming in on the rear, took possession of the place. Company A was thus fortunately saved from being taken prisoners.

Upon their evacuation of the place, they burned their barracks and other property which they could not take with them. The rebels destroyed other property, and undertook to burn the Evans mansion, but the fire went out before much damage was done. The Confederates soon abandoned the position and Company A was reinstated. In rebuilding their barracks they tore down some buildings formerly used as slave cabins. In one of them was found an old rebel pay roll on which the name Wood, as a recruiting officer appeared; whereupon Lieut. Ellinwood and a small detail of men went out to his plantation and brought him in as prisoner. He was sent to New Bern, and from thence was delivered to the tender mercies of General [Benjamin] Butler, the commandant of the department at Fortress Monroe, who ordered him into confinement at the Rip Raps.

Reedsburg Free Press August 23, 1872

REEDSBURG IN THE WAR (9)

By S. A. Dwinnell

History of Company A, Nineteenth Regiment.

(Chapter Four)

In the latter part of April, 1864, the Regiment was transferred to Yorktown, VA, where a week was spent in reorganizing the army of the James. Company A was under the command of Captain Tator. The regiment was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Strong. It was assigned to the third brigade under Colonel Sanders first Division under General Brooks the Eighteenth Army Corps under General Baldy Smith the Army of the James under General Butler. Accompanied by a few gun boats, the whole army was taken by transports, to City Point and Bermuda Hundred, where they landed May 6th, taking the rebels completely by surprise. The whole movement, up to this point, was admirably planned and executed.

From May 5th to the 9th, the army lay at Bermuda Hundred, except a portion of the troops who were engaged in digging lines of entrenchments across the peninsula, from the James [River] to Appomattox, VA, a mile or so from their confluence. On the 11th and 12th, the Nineteenth, with other troops, tore up and destroyed eight miles of the Richmond and Petersburg railroad, burning the ties and bending the rails.

On Friday, May 13th, the Nineteenth assisted in taking a line of rebel works, in front of Fort Jackson, and on the next day another line of works still nearer, where George Fosnot was wounded. These entrenchments were in the neighborhood of Drury’s [Drewry’s] Bluff, VA, on the James. About four o’clock in the afternoon of Saturday, the rebels got the range of our troops and two men of the regiment were killed by shells.

On Sunday, loud cheering was heard by the Nineteenth, along the lines towards Richmond. Through rebel prisoners, afterwards taken, they learned that General [Pierre] Beauregard, with his troops from Charleston, SC had arrived, and that General R. E. Lee and Jefferson Davis were there reviewing their forces.

On Monday morning, May 16th, there was a dense fog and the rebels were early on the advance. Companies A and E, of the Nineteenth, were nearer the rebel lines than the others. Col. Strong, wishing to ascertain their position and give an order for their retreat to a position of greater safety, started out on reconnaissance. When but a short distance from his regiment, he found himself captured by four stalwart Tennesseeans. They were lost in the fog and did not know the direction of their own troops, from whom they were separated. Col. Strong at once entered into familiar conversation with them, and expressed the desire to be taken immediately within their lines, as he had been without rest for fortyeight hours and greatly needed sleep. Reposing some confidence in him as their guide, they were adroitly led in the direction of his regiment, who were lying down. When near his own men, he asked to be released from the grasp of his captors, sufficiently to take out his pocket handkerchief. The instant he was free, he bounded towards his regiment and gave the command, “attention!” in such a tone that they arose and brought their rifles upon the Tennesseeans, who cried out, “don’t fire,” and were soon sent to the rear as prisoners, expressing their satisfaction that they had fallen into the hands of the Union troops.

During the day the rebels pressed upon our troops and drove them at all points. During the afternoon the Nineteenth was ordered to dislodge the enemy, who was concealed in timber. To do it they were obliged to march across an open field, eighty rods, exposed all the way to a raking fire. For some reason they were not ordered to the charge upon the double quick as usual.

During the day the regiment lost thirty-two in killed and wounded. Company A lost 8. S. Pitts, killed, and W. T. Reynolds, J. H. Stull, A. C. Tuttle, John Fosnot, John Thorn, H. C. Feegles, and Charles Day, wounded. It was noticed that nearly all who were at this time wounded in the regiment, died, even where they suffered but slight flesh wounds, which led to the supposition that the balls of the enemy were poisoned.

The regiment was ordered to Point of Rocks, on the south of the Appomattox [River], and some ten miles from Bermuda Hundred. While there, they were out on a raid upon the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad, and tore up and destroyed some six or eight miles of the track. Some of the men were detailed to guard a baggage train sent to Grant’s army at Cold Harbor.

On the 20th of June they were ordered into the trenches on the southeast of Petersburg, VA. These trenches were the advanced line of works next to the enemy. They were on duty forty-eight hours and off duty for the same length of time. They were relieved at midnight and ordered upon duty at the same hour; so they had but one night of unbroken rest in four. While upon duty, they were constantly exposed to the shells of the enemy, both night and day. During the day they suffered from sharp-shooters.

June 29th S. Searl was killed while reading the Baraboo Republic, a ball glancing from the limb of a tree, passed into his head.

July 5th W. W. Holton was wounded and Ephraim Haines mortally so the latter by a sharpshooter. About the

same time, and near the same spot, a ball from the same direction passed between the legs of Sergt. C. A. Chandler.

July 13th Corp. L. H. Cohoon wounded by a shell.

August 6th C. A. Danforth severely wounded by a sharpshooter while eating his supper, the ball passing in at the shoulder and out through the left cheek, shattering the lower jaw.

August 7th R. Cheek killed by a sharpshooter.

August 18th the Veterans, two hundred and fifty in number, left on a furlough of forty days; soon after which the non-veterans were ordered to Norfolk to engage in provost general duty.

Reedsburg Free Press August 30, 1872

RECORD OF REEDSBURG IN THE WAR (10)

By S. A. Dwinnell History of Company A, Nineteenth Regiment. (Chapter Five)

Upon the return of the veterans from their furlough, about the first of October, they were ordered to report at Chapin’s Farm, on the north of the James, before Richmond, VA. On the evening of October 26th, the men of the nineteenth, with Butler’s eighteenth corps, moved out from their line near Dutch Gap canal, advanced northward, and the next day, in the afternoon, formed near the old Fair Oaks battlefield, VA. They would easily have taken the defences had not the enemy learned of our movement and sent reinforcements rapidly from Petersburg. The Nineteenth regiment advanced with the other troops to assault the rebel works. Lieut. Col. Strong says: “The Regiment emerged from the pines and came out on a clear open field, about two hundred yards from the works. As we broke cover, the rebels opened on us furiously with artillery, and cut us up badly. Upon seeing the rebel works, the boys cheered lustily and advanced rapidly, closing up the breaks in the ranks made by the artillery, and preserving a splendid line. Thus for about one hundred yards, where we were met by a perfect tornado of shot, shells, canister and minnie balls directly in our faces, mowing us down by scores. The regiment was decimated mere fragments of the line remained; dead and wounded covered the ground passed over. The few brave boys pressed forward with the same old cheer, and closed upon the colors. The order, ‘lie down,’ was given. Flesh and blood could go no further. Nothing could withstand the perfect blast of lead and iron that most murderous, scourging, devouring fire. We lay down and made as thin as possible. No power to move forward or backward, or to assist in the least, our wounded comrades. The same fearful telling fire was passing over us; to raise a head was death; a hand to be hit. It was raining now, fine rain-mist and the early dark of a rainy evening was slowly enveloping us, and our earnest prayer was, ‘night or Blucher,’ when beyond our left a yell was heard, and the hurried tramp of men, and we were surrounded and prisoners.” The Regiment numbered eight officers and one hundred and ninety men who went into the fight. Forty-four men only came back. Col. Strong was wounded by a sharp-shooter as he was making some observations to see if there was any chance for his men to get to the rear, after the order to lie down. His leg was amputated at Libby Prison [Richmond, VA].

Company A went in with thirty-six men and came out with thirteen. Corp. A. Rathbun was wounded so near the edge of the field that he was brought off on a stretcher. Sergt. E. A. Dwinnell was wounded in the head, thigh, left arm, and right hand, the latter severely, a minnie ball passing through it, and yet he backed off the field, some sixty rods, drawing his knapsack at his head, and escaped to a place of safety. Two balls in addition passed through his clothing.

Sergt. C. A. Chandler escaped from the field entirely unharmed in this manner. When he received the order to lie down, he saw a dead-furrow near him and he fell into that. The field had been sowed in wheat the summer previous, and a small growth of weeds grown up after the harvest. This furnished some protection. He raised up his head several times to look over the field and saw men attempt to run to the rear, but they uniformly fell after running a short distance. He discovered, also, that when he raised his head, he attracted a shower of balls, and found it necessary to keep quiet. After a time he began to back down the dead-furrow, drawing his knapsack at his head for some twenty rods, when the rising ground brought him out in full view of rebel works. He then got up and run obliquely across the field, to a ditch some twenty rods distant, which he remembered to have passed over as they advanced to the charge. During all the time he was running, there was a perfect storm of bullets whistling all around him. He has no doubt that hundreds were fired at him, and yet not one touched his person, and but one his clothing. Once in the ditch he escaped without difficulty.

Edward L. Leonard was in this battle but was in a Company of sharp-shooters. They crept along a ditch to a position about twelve rods from the rebel fort, where they lay and picked off the gunners. Occasionally the Rebs would pour an ineffectual charge of grape or canister at them. There was but one of their number wounded during the action.

Wm. Miller was mortally wounded in the battle. When the prisoners were being taken from the field, he asked the rebel guard to allow one of them to remain with him and take care of him. He was answered that it could not be allowed, but that some of their own men would be along soon and take care of him, which was no doubt done, as he is reported to have died in Richmond a few days subsequently.

Sergt. F. B. Palmer, whose family resided in this village [Reedsburg, WI] during the war, and who were highly respected, was killed during the action, but none of his comrades saw him fall. He carried the guidon on the right of his regiment and next to the 148th New York. A soldier of the latter regiment told E. A. Dwinnell that he was shot through the head. Major Vaughn escaped from the battle-field just as the rebels were charging out to secure their prisoners, and was in command of the regiment at Chapin’s Farm during the winter.

On the morning of April 3rd, 1865, the Nineteenth, with their brigade, was the first to enter Richmond, and their flag was the first to float over the captured capital of the dead Confederacy. Colonel Vaughn planted it upon the City Hall. When the regiment was ordered to advance upon the works before the city, the men expected to storm them, but found them evacuated.

The non-veterans were mustered out at the close of their term of service, April 28th. The others moved from Richmond to Fredericksburg, and on May 1st were consolidated into five Companies. They were mustered out at Richmond, and August 9th, two hundred and sixty-five in number, they started for Wisconsin, where they were entertained at the fair, in Milwaukee, and were disbanded at Madison.

Reedsburg Free Press September 6, 1872

REEDSBURG

IN THE WAR (11)

By S. A. Dwinnell

Life in Rebel Prison, at Libby, and Salisbury, N. C.

Extracts from the Diary of a member of the Nineteenth Regiment.

(Chapter One)

Oct. 27th, 1864. Near old battlefield, Fair Oaks, Virginia. Drew up in line of battle charged out of the woods into the open field, where we were welcomed by a terrible shower of bullets from the rebel infantry, and grape and canister from their fort our ranks were quickly thinned some of our best and bravest men fell still on we went nearly half a mile, until we were left alone in the open field, directly opposite the rebel fort ordered to drop down here we lay, hugging mother earth and praying for darkness and release about half an hour before dark, the rebels charged out, flanked us and took us prisoners.

After a fatiguing march of seven miles, over a muddy road it had been raining all the afternoon we arrived at Richmond, VA at eight in the evening were quartered in Libby prison, and laid down to rest on the bare floor.

Friday, Oct. 28th . There are four officers: Strong, Holley, Schurff, and Wentworth, and seventy-four men here, out of two hundred and twenty of our regiment who went into the fight. Quite a number of these are wounded. [Of these prisoners there were from Reedsburg, Col. R. M. Strong and Isaac Bingman, O. H. Dwinnell, Peter Empser, Nelson Gardner, Wm. Miller, Walter Pietzsch, Newman Pitts, Giles Livingston and Franklin Winchester. S. A. D.] At 10 A.M. we received our first meal, consisting of a piece of corn-bread and a small piece of beef. Soon after, we were ordered to give up all the greenbacks in our possession knapsacks, haversacks, canteens and rubber-blankets were taken from us most of the boys were searched. This is the manner in which this “Southern Chivalry” treats Union prisoners. Cursed be a set of men who will rob a prisoner. At 5 P.M. our second meal was brought bean-soup and corn-bread. We are in a large room, on the third floor of a four story building, formerly used as a tobacco ware-house, but since the war, converted into a prison well known as Libby.

Saturday, Oct. 29th Pleasant. Quite a number of prisoners brought in to-day. Grant is reported to have taken the Danville Railway if this be true, we shall probably be sent off ere long either to some Southern prison, or back to our lines. The latter would of course be more acceptable to us. Our meals were the same as yesterday.