11 minute read

Napoleonic Soldiers Buried

The Napoleonic Era

Napoleon ruled for 15 years, closing out the quarter-century so dominated by the French Revolution. His own ambitions were to establish a solid dynasty within France and to create a French-dominated empire in Europe. To this end he moved steadily to consolidate his personal power, proclaiming himself emperor and sketching a new aristocracy. He was almost constantly at war, with Britain his most dogged opponent but Prussia and Austria also joining successive coalitions. Until 1812, his campaigns were usually successful. Although he frequently made errors in strategy especially in the concentration of troops and the deployment of artillery he was a master tactician, repeatedly snatching victory from initial defeat in the major battles. Napoleonic France directly annexed territories in the Low Countries and western Germany, applying revolutionary legislation in full. Satellite kingdoms were set up in other parts of Germany and Italy, in Spain, and in Poland. Only after 1810 did Napoleon clearly overreach himself. His empire stirred enmity widely, and in conquered Spain an important guerrilla movement harassed his forces. Russia, briefly allied, turned hostile, and an 1812 invasion attempt failed miserably in the cold Russian winter. A new alliance formed among the other great powers in 1813. France fell to the invading forces of this coalition in 1814, and Napoleon was exiled. He returned dramatically, only to be defeated at Waterloo in 1815; his reign had finally ended. Source: Britannica1

Four men, who eventually emigrated to America and the Sauk County area, accompanied Napoleon to Moscow during his disastrous campaign of 1812: Peter Klaes, Michael Hirshinger, Michael A. Nippert, and Jurgen Meyer, who are all profiled in this publication The following is a chronicle of their sojourn on that trip to and from Russia. All four survived. Also included in this profile, is Peter Pauli, who was with Napoleon at Waterloo, during his disastrous defeat in1815. He also survived and came to America.

Pauli is buried in St. Norbert’s Cemetery, Roxbury, Dane County, Wisconsin. Klaes is buried somewhere in the Roxbury area. Hirshinger and Nippert are buried in Rock Hill Cemetery, Baraboo, Sauk County, Wisconsin, and Meyer’s final resting place is in St. John Cemetery, Westfield, Sauk County, Wisconsin.

Reader’s Digest, March 1942

Napoleon’s Retreat from Moscow

By Edwin Muller

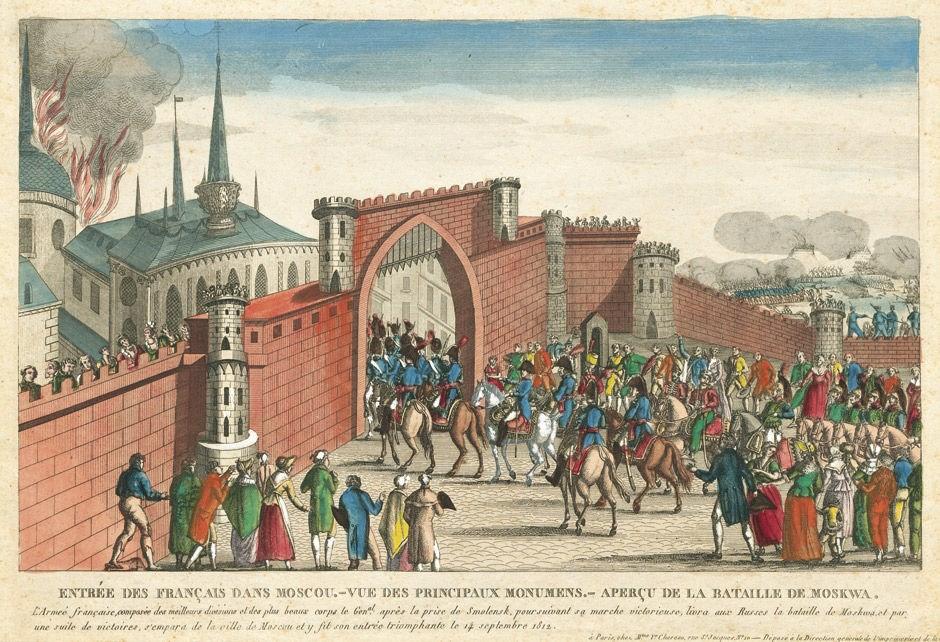

ON The MORNING of September 14, 1812, the Grand Army reached its supreme goal. The advance guard came to the top of rising ground, looked out over the flat plain beyond. There under a leaden sky a dingywhite line stretched half across the horizon. Above it, floating like bubbles, were the soaring cupolas of an Oriental city. Moscow.

The Emperor’s keen eyes picked out a group of towers higher than the rest the Kremlin. Napoleon was well content. He dismounted and prepared to receive the deputation that would come from the city begging terms.

It was the climax of the greatest blitzkrieg in history before or since. In 82 days, the Grand Army had fought its way 700 miles amazing speed for horse transport and men afoot.

It was the largest organized fighting force since the time of Darius [Darius led military campaigns in Europe, Greece, and even in the Indus valley, conquering lands and expanding his empire. Ca 522 BC.] Half a million men had crossed the Niemen on June 24 and the days following. Among them were armies from most of the conquered states of Europe; Prussia, Austria, Italy, Poland, Switzerland, Saxony, Hesse, Westphalia. But the core of the Grand Army was the French, those men who had never been beaten, whose best weapon was their legend of invincibility.

They had driven on through the heat and dust of the summer, pushing the Russians before them, at last forcing battle at Borodino. There, almost as a matter of course, they had won. The victory was costly, 35,000 Frenchmen killed and wounded. But it had opened the road to Moscow and here they were.

Now only one obstacle to world conquest remained Britain. Britain, who had thwarted him before, who had refused the secret truce which he had sent his brother to negotiate, who had pulled strings here in Russia to set the Czar against him.

Thus, Napoleon Bonaparte stood before Moscow, a dark, scowling, hard little man in a fair way to rule the world.

If he had a weakness, it was a rather vulgar love of pomp, of the spectacular and dramatic. He loved especially occasions like this, when conquered princes and deputations bowed before him.

This particular deputation was unaccountably delayed. The Emperor, impatient, sent couriers to hurry it up. After a long time, they returned with a strange tale, so strange that Napoleon went to see for himself.

He entered the city by the great double gate. There was no one there to meet him. He rode through the streets. No one stood at the curbs, none looked from the windows. Over all was heavy silence. Patrols were sent into houses, to bring out the inhabitants. There was nobody to bring. Palaces, hovels, churches, stores stood empty.

The Emperor went into the great enclosure of the Kremlin. He entered the royal apartments. The clocks were still ticking but there was not one human being. Searchers through the city rounded up a mere handful of poor and ignorant folk. From them nothing could be learned.

An uneasy feeling took hold of Napoleon. Things that he had seen since he entered Russia assumed new meaning. The devastation, for example peasants and livestock gone, their houses burned, their crops destroyed.

He began to wonder a little what was in store for him in this strange country.

But he dealt with the situation in his usual methodical way. He established quarters in the Czar’s apartments, gave orders to occupy the city, sent a force to make contact with the enemy.

The soldiers, too, dealt with the situation in their way. They broke into stores and palaces, loaded themselves with furs, silks, paintings, silverware. They found great stocks of wine and brandy made full use of them. Discipline relaxed.

At noon next day the 15th the guard on the walls of the Kremlin saw wisps of smoke in the northern section of the city. Presumably chance fires started by careless, drunken soldiers. Sappers [combat engineers] sent to keep the fires from spreading returned with a disquieting report. The city’s fire engines had disappeared.

Other fires were seen in the east. Then in the south. Finally, a patrol caught a Russian setting a blaze. A rising wind merged the separate fires until the whirling smoke was a flat ceiling over all the city. All that night Napoleon stood on the Kremlin walls watching silent. Next day he was persuaded to leave. The city was one great plain of fire, four miles across. For a whole week it burned. The Kremlin alone escaped. The Emperor returned to it.

In those days Napoleon spoke little. He seems to have been in a puzzled state of mind. He couldn’t believe that the rulers of even a barbarian nation could have ordered such a deed at one stroke to have made 300,000 of its people homeless. Even he couldn’t grasp so vast an indifference to the lives of individuals. He began to think too of the hundreds of miles of burned villages and devastated fields that lay behind, on the road home.

Moscow’s grain warehouses had been burned and foraging parties sent out into the country brought back little. In other conquests Napoleon had always found traders who, for gold or paper, would supply all he needed. He didn't find them in Russia. The army began to be hungry. Discipline relaxed a little more.

Even now Napoleon believed that his defeat of the Russian army, his occupation of the Russian metropolis, marked a decisive end of the war. It always had. He sent a mission to St. Petersburg to offer peace terms to the Czar terms a little more generous than he had first intended.

There was comfort in the fact that the weather stayed fine. It was a lovely October crisp in the morning, but calm and sunny all day. Once a few flakes of snow fell, but then it turned warm again.

Weeks went by and no reply came from the Czar. It became increasingly apparent that no reply was coming.

Napoleon broke out in a petulant fury of exasperation. He summoned his generals and announced that he would march on St. Petersburg. Always in the past Napoleon’s decisions had been final. But this was an impossible plan. His line of communication was already strained to the breaking point and winter was coming. His generals didn’t so much argue against the project as kill it by their silence. Nothing was done about it.

At last, it was manifest even to him that the only thing to do was to turn back. On October 18th [1812] the Retreat began.

Of the huge army that had crossed the Niemen the greater part had never reached Moscow. Some guarded the line of communication and garrisoned the cities on the route. Many had been lost in skirmishes and guerrilla fighting. More lay dead on the field of Borodino. The army that now marched out of Moscow numbered 100,000.

The road ran straight without a turn. As far as one could see, it a slow-moving stream of guns and wagons. On each side the infantry marched. On their flanks rode cavalry. An organized army, still.

From the very start they were hard-up for food. Now every driver had to watch his team to keep it from slaughter though there wasn’t much meat left on the animals. Whenever a thatched hut was found the straw was pulled out and fed to the starving beasts.

Behind the army the road was littered with abandoned loot books, pictures, silverware. Wagons and guns began to be abandoned too; not enough horses were left to haul them. But the French still had strength to fight off the Russians who were following at their heels.

Gloom settled over the marching army. There was one horrible day when they passed the battlefield of Borodino. The 35,000 French corpses and 40,000 Russians were still there rotted, half-eaten by the wolves.

Then, suddenly, the winter struck.

On the night of November 5, the army lay bivouacked for miles along the road. A wind arose blew harder and then harder. It came from the northeast, from the frozen steppes, and for a thousand miles there was nothing to check it. Snow came with it heavier as the night went on. The snow drifted and the bivouac fires went out, one by one. The cold was such as these Frenchmen had never known.

Great numbers were frozen to death that night. From that time on the army never escaped for a moment the Russian winter.

The supply service went to pieces. The only way to get food was to leave the line of march and go foraging over the countryside. The long column began to break up into little groups going off on their own.

It has been said that Napoleon shared the hardships of his men. He did not. He kept fairly warm and well-fed on beef and mutton, white bread, even his favorite Burgundy. He rode in a carriage, bundled in furs. Sometimes the carriage would jolt heavily over the bodies of men lying in the road, frozen to death or not yet quite dead.

The hero of the Retreat was Marshal Ney, as he brought up the rear, protecting the struggling columns from the stabbing attacks of the pursuing Russians. Once Ney was cut off from the main body. Napoleon didn’t halt or try to reestablish contact. Eventually the Marshal, by a brilliant attack, fought his way back to rejoin his chief.

The Cossacks were the worst scourge of the Grand Army. They were tough, hairy little men, bearded to the eyes. They wore hairy caps and coats, rode shaggy little horses. They had short bowlegs and it seemed as if horse and rider had grown together. They carried long lances and rode to the attack with shrill, fierce cries.

They would hide in patches of woodland, ride out suddenly on cold, weary men looking for food, or gathered stiffly around a campfire. Sometimes they stripped their victims and herded them naked ahead of their horses until they fell and died. Sometimes the butts of their lances would rise and fall, the points stab down again and again. The snow would be crimson.

It got colder. The record shows somewhere between 30 and 40 below zero. But even in the bitter cold the soldiers would sweat as they struggled through snowdrifts. Then at night, as they slept on the ground, the damp clothes would freeze solid. The heat drained out of their bodies like a fluid. Each camp site was marked by hillocks covering the dead.

The route was cluttered by abandoned guns and wagons. Few horses were left. Their ribs stuck out and they staggered in the traces. Groups of men followed each team. When ahorse fell the crowd pounced on it, cutting it to pieces while it was still alive. They fought to drink the warm blood.

Snow blindness made hundreds helpless; others went mad.

Some few tried to help those who had fallen and were freezing. But the men on the ground would plead to be left alone, to be allowed to sleep.

The last encounter that could be called a battle was at the crossing of the Berezina River. They had hoped to find it frozen solid so that they could cross on the ice. But it was only half frozen, with big ice cakes churning down the current.

Sappers managed to construct two bridges, while the rear guard with difficulty held off the Russians. For a while an orderly crossing was maintained. The Emperor got safely across. Then one bridge broke and soon the Grand Army became a struggling mob, fighting to get on the other bridge. Russian cannon plowed lanes through the solid mass of men a target half a mile wide and two miles thick. It is said that in the spring 12,000 bodies were taken from the Berezina.

Across the river the remnant of the army staggered on.

The story has no one end, but a series of small, tragic endings, as little groups desperately seeking food were overcome by starvation or trapped by Cossacks.

It is not known how many straggled out of Russia. The organized army that finally reached Konigsberg numbered about 1000.

The Emperor was not with them. Early in December he had fled in disguise to Paris. To his companion on that journey he railed against England. He made new plans for attacking Britain impossible plans.

He knew that the news of the Retreat had reached Paris before him. He arrived like a dog who wonders whether he’ll be whipped. But the French and it must have astonished him were still loyal. He resumed the pomp and ceremony of his court still Emperor.

But the Retreat had finished him. Not at once. For more than two years he twisted and turned. It was no use the conquered races of Europe, seeing that he was not invincible, rose against him. His own people began to fall away from him. In the end he was beaten for good by the tenacity of the British at Waterloo.

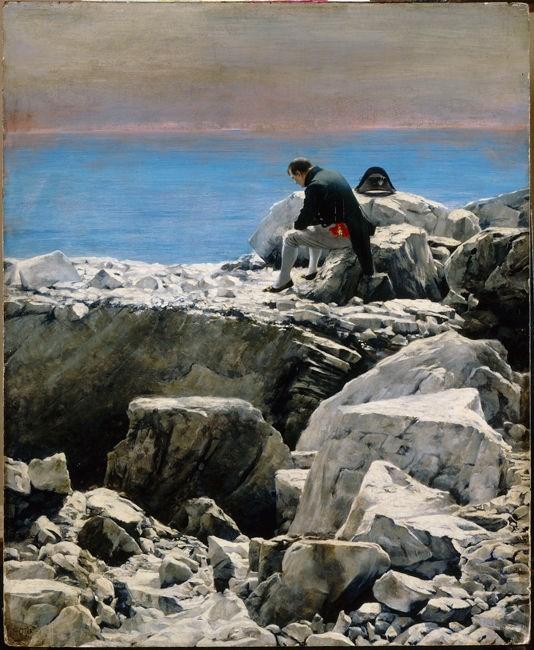

There were a few years left to him on his dreary little island where he perpetually explained how he had always been right. Then a dreary death.

As Victor Hugo said, God was bored with him.

Napoleon was ultimately exiled to St. Helena, a British colony 5,000 miles and a 10-week boat ride away from Europe. Napoleon spent more than five years on the island, arriving in October 1815. During his first couple of years on St Helena, Napoleon took regular walks, went riding and spent much of his time reminiscing. But as time went on, and the months turned into years, loneliness and boredom began to take its toll.

It's where he created his myth, dictated his memoirs and battled chronic pain from old battlefield injuries and, possibly, fatal stomach cancer. In 1840 his body was returned to Paris, where it was interred in the Hotel des Invalides. Source: Readers Digest2