Figures List of

Figure 1: Contemporary picture of Johannesburg

Figure 2: Historical map of Johannesburg, 1897

Figure 3: Racial hierarchy in apartheid South Africa, 1980

Figure 4: Social hierarchy in apartheid South Africa

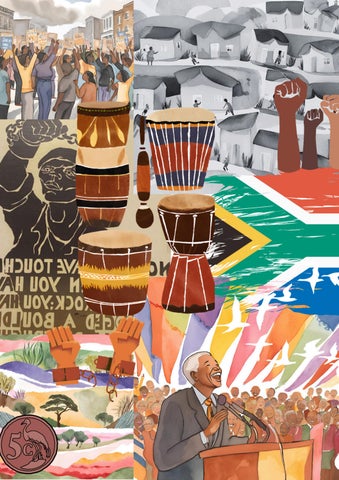

Figure 5: Scenes of apartheid

Figure 6: Scenes of apartheid

Figure 7: Scenes of apartheid

Figure 8: Apartheid background and timeline

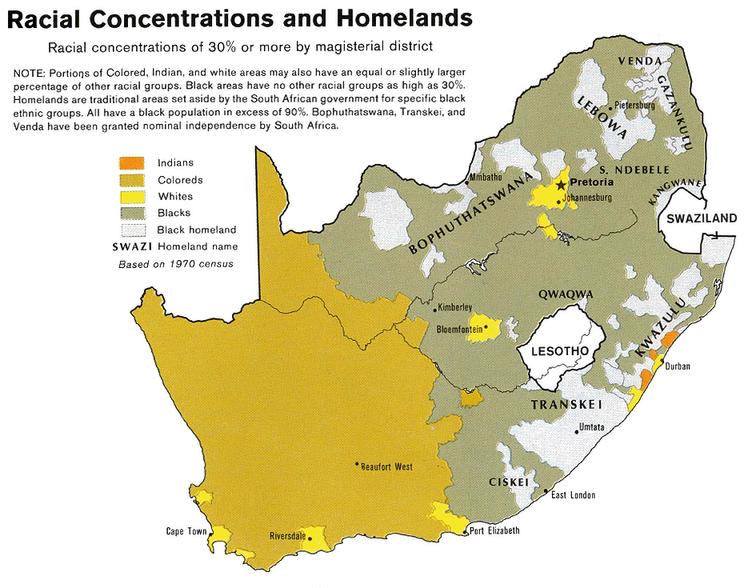

Figure 9: Racial concentrations and homelands in South Africa, 1970

Figure 10: Historical photograph of Soweto townships

Figure 11: Historical photograph of Soweto townships

Figure 12: Locations of informal settlements in Johannesburg

Figure 13: Historical map of Johannesburg and surrounding areas, 1902

Figure 14: Constraining suburbs in Johannesburg

Figure 15: Historical photograph of Alexandra township

Figure 16: Historical photograph of Alexandra township

Figure 17: Floor plan and elevation of an apartheid-era housing scheme

Figure 18: Photograph of an apartheid-era housing unit

Figure 19: Historical form of apartheid resistance

Figure 20: Historical form of apartheid resistance

Figure 21: Photograph of the Regina Mundi Church in Soweto township

Figure 22: Wall murals reflecting an important period of history and resistance

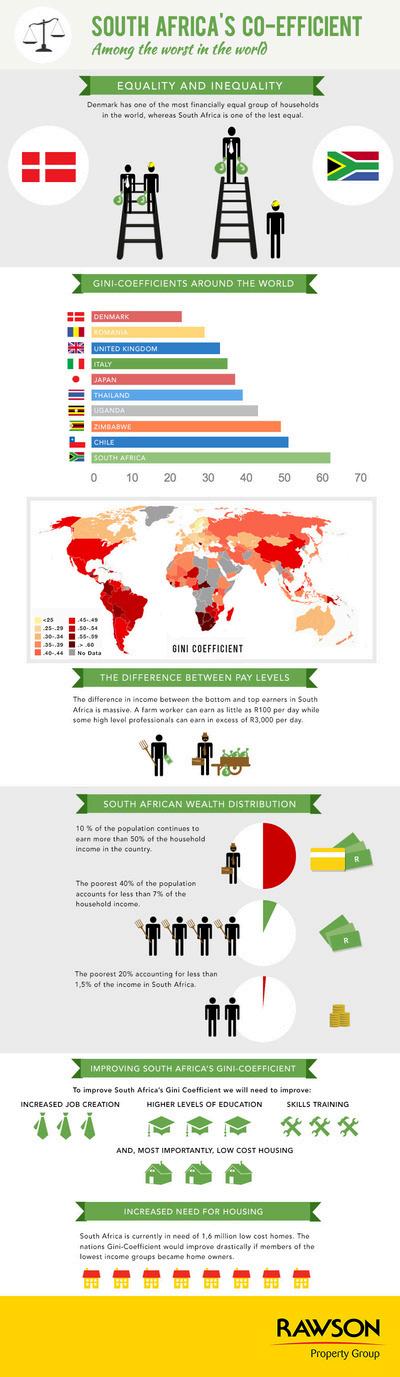

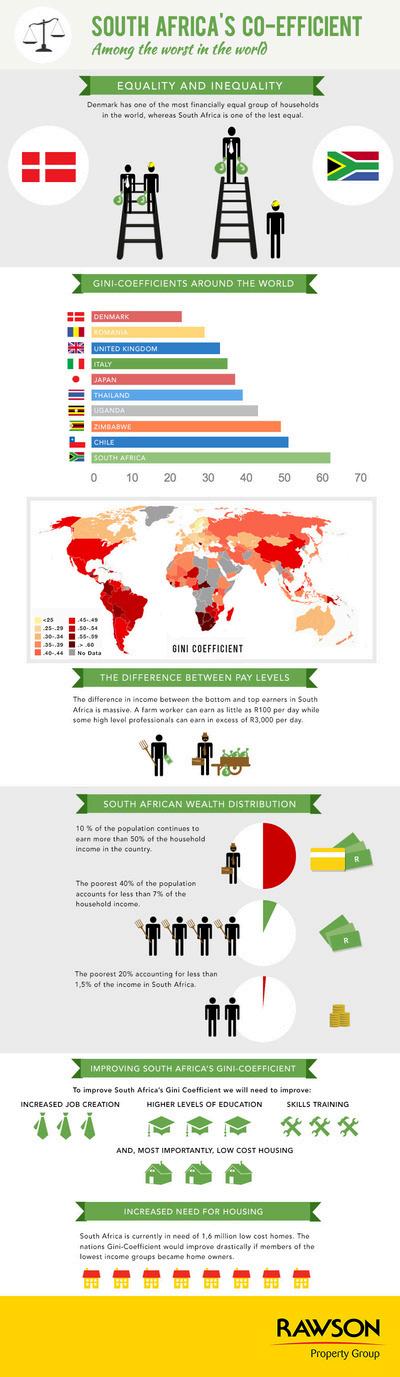

Figure 23: Infographics highlighting South Africa's Gini coefficient and wealth inequality

Figure 24: Map of Alexandra Renewal Project area

Figure 25: Map depicting commercial, industrial, and residential development in Johannesburg (2001–2010)

Figure 26: Photograph of high-rise residential solution attempt in modern Johannesburg

Figure 27: Photograph of the modern neighbourhood of Braamfontein

Figure 28: Photograph of the modern neighbourhood of Maboneng

Figure 29: Photograph of the Gautrain rail system

Figure 30: Photograph highlighting the challenge of long commutes for vulnerable communities

Figure 31: Photograph of the Rea Vaya Bus

Figure 32: Infographic of the cost of living in Johannesburg, 2024

Figure 33: Photograph of modern-day Ponte Towers

Figure 34: Photograph of Ponte Towers’ downfall

Figure 35: Ponte Towers interior view

Abstract

This dissertation explores the urban planning and architecture principles in apartheid-era South Africa It highlights how these respected fields were manipulated to be used as tools of segregation and control. Based on an analysis of the transformation in Johannesburg, it examines the deliberate design and implementation of urban spaces that reinforced apartheid's legally sanctioned racial divides The research further investigates how those problematic Architectural and Urban planning methodologies continue to shape urban environments in the post-apartheid context and discusses possible ways of pursuing social justice and restoration through inclusive urban design.

Figure 1: Contemporary picture of Johannesburg

1. Introduction

To begin this tale of time, we must acknowledge a fundamental concept: architecture and urban design are instrumental tools that not only shape the physicalities of our cities, but they also lay the foundation to our quality of life as inhabitants. These tools can either connect and include or segregate and control Unfortunately, in the case of the Apartheid South African regime, they were both used to illustrate the darker potential of such powerful instruments, enforcing a divisive, unjust system that resulted in segregated environments creating foul social hierarchies and controlling movement for certain communities under the false guise of urban planning.

Using the city of Johannesburg as a case study, as it was originally established as a temporary mining camp, emerging chaotically in 1886 amid a gold rush, local and global miners crowded the area in hopes of striking the jackpot. This led to its chaotic early growth and the nickname "City of Gold." This unexpected sprawl enabled ill-willed city planners and architects to draft a discreet agenda that would divide the rapidly growing city into a stark example of controlled segregation. Developed urban zones and infrastructure were exclusively designed to separate racial groups, confining the non-white population to isolated townships like Soweto, far from economic opportunities and essential services. In these designed spaces of exclusion, the non-white residents lived in a landscape that was as much a barrier to social mobility as it was a physical reality, with every urban feature from bus stops to park benches encoding a strict racial hierarchy of living conditions. As Murray, Shepherd, and Hall (2007) mention, the very framework of Johannesburg was carefully engineered not just to segregate but to suppress, turning urban planning into a tool of social control.

Figure 2: This map provides a detailed view of Johannesburg and its suburbs in 1897, illustrating the city's layout during its early development following the gold rush. It highlights areas such as Braamfontein and Doornfontein, along with designated residential zones and industrial sites. The map reflects the spatial planning challenges and opportunities of a rapidly expanding urban area, offering insights into the foundation of Johannesburg's later segregated urban landscape

Figure 2: Historical Map of Johannesburg (1897)

The deeply entrenched racial stratification of apartheid South Africa reveals a society where privilege and oppression were institutionalised based on race and skin colour. At the apex of this hierarchy were White South Africans, comprising 17% of the population in 1980. This minority enjoyed unrestricted access to prime land and resources, full political control, and economic dominance. Below them were the “Coloured” and Asian communities, representing 12% of the population, who went through major restrictions on land ownership, education, and economic opportunities. At the base of the pyramid was the Black majority, constituting 73% of the population, subjected to extreme systemic oppression, forced into overcrowded and underdeveloped townships, deprived of basic rights, and relegated to hard manual labour. This racial hierarchy is a defining feature of apartheid’s legacy (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Figure 4

Throughout the course of this dissertation, the terms 'Coloured' and 'Asian' will be used strictly in accordance with legally defined categories of race during apartheid South Africa and will be seen as part of an oppressive system of apartheid racial classification techniques These terms are outdated and insensitive, and society has thankfully moved away from using them

This division along racial lines was compounded by an internal class stratification within each racial group Among White South Africans, the upper class controlled most of the wealth and political power, while the lower class, though still benefiting from racial privilege, occupied roles as skilled workers and tradesmen A similar structure existed within the “Coloured” and Asian communities, where an upper class gained limited access to education and small business opportunities, while the lower class struggled with economic precarity and limited prospects Within the Black population, systemic oppression largely flattened class distinctions, with the vast majority relegated to survival-level labour and impoverished conditions However, a small, educated Black middle class emerged as leaders in resistance movements, demonstrating that even within rigid structures of repression, agency and defiance persisted (see Figure 4).

Some of the most consequential political, economic, legal, and social forces in the colonial, pre-apartheid, and apartheid periods have profoundly shaped spatial injustice and urban residential segregation in South Africa (Strauss, 2017). These injustices have persisted over time, embedding systemic exclusion as a defining feature of many urban areas today. This is evident in the form of spatial inequalities, restricted access to housing, and socio-economic deprivation. As Strauss (2001) highlights, adopting a spatial lens to analyse legislation, case law, and historical contexts is crucial for addressing these enduring inequalities (Strauss & Liebenberg, 2014). This dissertation builds on such arguments to investigate the integration of spatial awareness in post-apartheid urban planning and to determine whether current approaches require reevaluation.

Figure 5: Scenes of Apartheid

Figure 6: Scenes of Apartheid

Johannesburg stands as a stark example of the costs of apartheid-era spatial separation, particularly in the form of over 25 townships collectively known as Soweto Many of these areas, initially labelled “Black spots,” arose from mass dispossessions and forced removals often rationalised by crises such as outbreaks of bubonic plague Colonial and apartheid legislation, including the Natives Land Act of 1913, which allocated 90% of land for White ownership, entrenched these processes (Findley & Ogbu, 2011). As a result, Soweto offers a valuable case study for examining the spatial mechanics of apartheid and its enduring consequences.

Building on this foundation, my dissertation investigates the tools of segregation and oppression that shaped architectural and urban design strategies during apartheid in Johannesburg. It also examines how these same disciplines can now serve as instruments of social justice and reconciliation in post-apartheid South Africa. By reflecting on this dark chapter in history, the research seeks to uncover lessons that can guide future cities and societies toward greater inclusivity and respect, dismantling the legacies of division that apartheid left behind

Figure 7: Scenes of Apartheid

2. Literature review

Deliberate patterns of spatiality during apartheid have been extensively explored and are well-documented by Murray, Shepherd, and Hall (2007). Their work shows how urban planning was weaponised to implement systemic oppression repurposing a neutral tool into a mechanism of control They chronicle how zoning legislation, segregated infrastructure, and spatial hierarchies were purposefully crafted to maintain socio-economic inequalities and limit mobility, relegating non-white populations to marginalised, resourcescarce locales. Central urban areas were reserved for white populations only, resulting in a glaring urban divide. Their analysis emphasises the deep entanglement between architecture and the structural injustices of apartheid, suggesting that architecture can act both as an agent of systemic inequality as well as a symbol.

Nord (2022) expands this critique by demonstrating how modernist planning principles were appropriated to justify geographically segregated enclaves. Although these principles were initially developed to improve societal efficiency, they became tools for entrenching racial hierarchies. For example, the "matchbox houses" of apartheid townships echoed Le Corbusier’s concept of temporary workforce housing, while township layouts mirrored Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City principles. However, these designs were subverted to serve segregation rather than community building. Nord also highlights a gap in existing literature insufficient attention to how resistance to these oppressive structures has influenced contemporary urban practices. This omission leaves room to explore how defiance during apartheid helped shape more inclusive urban strategies post-apartheid

Extending the discussion to post-apartheid Johannesburg, Herbert and Murray (2015) critique the uneven urban development that followed apartheid. Their research shows how so-called value-added policies for urban advancement often reflect neutralised narratives that fail to dismantle the spatial hierarchies established during apartheid Redevelopment efforts, they argue, frequently overlook the integration of economic development with social equity, permitting injustices to persist This disconnect is particularly evident in Johannesburg, where urban renewal initiatives often cater to market-based interests rather than addressing the needs of marginalised communities. Their comparative analysis with other post-conflict urban contexts underscores the necessity of embedding social justice within urban planning practices.

Totaforti (2020) builds on this by assessing the inclusivity of post-apartheid urban planning. Her findings highlight that while apartheid formally ended decades ago, its economic and infrastructural marginalisation persists for Black communities She advocates for sustainable community development initiatives that prioritise the needs of marginalised groups, aligning with global movements to create equitable and inclusive urban spaces

Findley and Ogbu (2011) offer a complementary perspective by focusing on the transformation of townships like Soweto. They illustrate how entrepreneurial residents have begun turning these historically marginalised settlements into hubs of commerce and culture Businesses operate from homes, shacks, and new commercial centres, while large developments such as Maponya Mall and Jubalani Mall have introduced economic opportunities closer to home. However, despite these advancements, many township residents remain dependent on city centres for work and resources, perpetuating apartheidera spatial inequalities

The role of health policies in enforcing segregation is another dimension explored by Swanson (1977). He introduces the concept of the "sanitation syndrome," explaining how public health laws were used to justify the forced removal of Black communities from urban centres Settlements like Ndabeni in Cape Town emerged as a result, demonstrating how health narratives reinforced spatial exclusion under the guise of urban hygiene.

Murray (2015) critiques the proliferation of privatised urban spaces in Johannesburg, arguing that such developments often prioritise economic gain over social equity. These spaces, designed to attract investment, fail to address the needs of marginalised populations, thereby perpetuating the spatial and economic divides established during apartheid. His work underscores the importance of adopting bottom-up approaches to urban development, advocating for frameworks that prioritise the needs of vulnerable communities over market interests.

Shepherd (2007) brings a symbolic dimension to the discussion, examining how apartheid’s architectural legacy shapes collective memory and reconciliation efforts He posits that urban spaces act as repositories of historical trauma while offering opportunities for social healing. By re-envisioning these spaces, architects can foster a more inclusive and cohesive society.

Despite these significant contributions, critical gaps remain in the literature. The potential role of architecture as a form of resistance during apartheid both in its performativity and sustainability has yet to be fully interrogated. Exploring these acts of defiance could provide valuable insights into how contemporary urban practices can address historical injustices. Additionally, there is a scarcity of comprehensive evaluations of post-apartheid redevelopment projects, particularly regarding their effectiveness in reducing entrenched spatial inequalities and promoting integration

This dissertation aims to address these gaps by critically examining redevelopment projects in Johannesburg. It will assess whether and how these initiatives successfully address apartheid's spatial inequalities and facilitate just urban futures. By synthesising historical analysis with critical evaluations of current policies, this research seeks to contribute to the discourse on urban justice and advocate for transformative approaches prioritising equity, reconciliation, and care

3. Methodology

In order to explore the research question in a systematic manner, this dissertation adopts a mixed-methods approach, utilising qualitative and quantitative research. The qualitative part signals a broad reading of architectural design projects, urban planning, legislative text and anecdotal evidence from Johannesburg. This includes the articulation of how architectural strategies and urban planning emerged during apartheid, explored through case studies such as Johannesburg’s townships and iconic buildings like Ponte Tower Where relevant this qualitative research will be situated against socio-economic and demographic data in order to derive insights about spatial distribution patterns through a bio-socioeconomic lens

While this approach presents significant opportunities, it is not without challenges, particularly given the extensive body of literature on these themes. There is considerable literature available related to the formal characteristics of apartheid architecture, but this dissertation aims to critically engage existing literature to indicate gaps in research that can be taken up.

A close analysis of the historical contexts in which these issues were, and often still are framed, might reveal deeper layers and provide fundamental insights especially when it comes to social justice within urban design in post-apartheid Johannesburg. Utilising comparative case study analyses, and informed by critical assessments of urban redevelopment projects, this investigation seeks to formulate critical consideration about the barriers and potentials in achieving just cities in the modern post-apartheid context. This dissertation adopts a structured critical process to refine the prevailing narrative and position within the broader research landscape. Ultimately, this study aspires to contribute meaningful solutions to the ongoing discourse on urban equity and justice.

4. Apartheid Background

Apartheid was a policy of racial segregation, oppression, and discrimination that was systemically institutionalised by law in South Africa from 1948 to as recently as the early 1990s. The National Party a minority party comprising Afrikaans people, descendants of the Dutch settler population ensured the repression of this regime Apartheid was an institutionalised system for both economic and social discrimination along these lines, aimed at ensuring the minority white settlers of South Africa maintained control over a non-white majority population, composed primarily of native Africans and Indians, in addition to the sizeable "Coloured" community.

Spatial segregation originated with colonial practices and the early European settlements’ systematic use of segregated locations to control indigenous populations For instance, the Dutch introduction of res nullius (unclaimed land) enabled the displacement of indigenous communities and restricted their access to arable land (Van Wyk, 2012).

Figure 8: Apartheid background and timeline

The establishment of Native Locations is another example, with Black labourers being forced into locations such as the Native Strangers' Location, severely restricted by laws curbing their movements These territories typically featured reduced infrastructure and prohibited residents from improving their houses, making them overcrowded and perilous (Kirk, 1991). Townships were designed as “bedroom communities,” distant from White urban centres and devoid of basic civic infrastructure. "Architecture and planning were critical to implementing apartheid policies. Design practices became cultural extensions of state power" (Findley & Ogbu, 2011)

The socio-economic inequalities codified under apartheid were not limited to spatial segregation, however. White South African elites, despite constituting a minority of the population, dominated political and economic systems, granting them privileged access to land, employment, and education, and placing all other racial and ethnic groups in positions subordinate to White South Africans. Even working-class Whites benefited from secure jobs, higher wages, and housing policies underwritten by the state In contrast, “Coloured” and Asian communities, while squeezed into the economy, were not given full economic participation, nor allowed access to land, education, and a skilled labour market. At the bottom of this hierarchy were Black South Africans who, under exploitative conditions, were forced to perform menial manual labour (sometimes in the mining or domestic work industries) with little to no legal protection

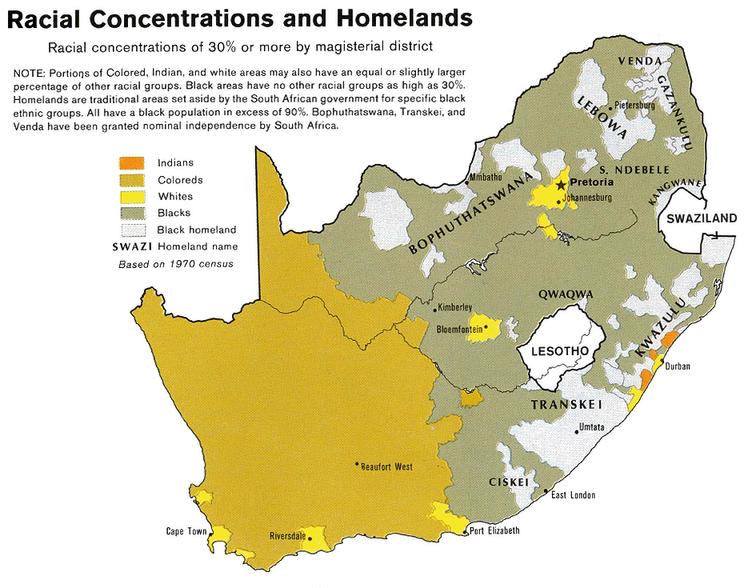

Figure 9: Racial Concentrations and Homelands in South Africa (1970 Census)

While apartheid evolved from earlier segregation laws, it was the National Party that established the legal definition of civil distinctions in society, based on racial identity. This allowed the establishment of wide-reaching and state-defended systems of repression, including the Group Areas Act, the Pass Laws, and other repressive legislation. The laws governed and dictated nearly every aspect of life in the country, continuing to entrench the separated society that was apartheid. The Pass Laws, for instance, served as a daily tool of disempowerment and humiliation, demanding that Black South Africans travel with permits to access areas of cities reserved for White residents This ensured their social and economic oppression while fortifying a spatial divide clearly favouring the White minority over the non-white majority, which became a hallmark of colonial capitalism in South Africa.

The deliberate design of these systems reflects how apartheid extended beyond political oppression into every facet of urban and social life The combination of spatial, economic, and legislative controls created a structure that enforced systemic inequities, the effects of which are still visible in South Africa's cities today.

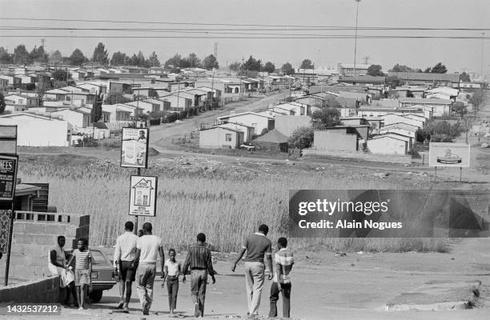

Figure 10: Historical photograph of Soweto township

Figure 11: Historical photograph of Soweto township

5. Control Mechanisms and Spatial Segregation

Apartheid-era urban planning and architecture in South Africa were not only tools of racial division but also active enforcers of economic dependency and social disempowerment. These fields were meticulously wielded to shape a society where privilege and opportunity were reserved for white South Africans, while non-white communities were confined to spaces deliberately designed to limit their potential and visibility. By embedding segregation into the very fabric of cities, apartheid planners created enduring systems of control that have left a deep imprint on South Africa's urban landscape.

Key to this strategy was the spatial relegation of Black South Africans to marginal and economically viable areas, as mandated by apartheid laws. The Native (Urban Areas) Act of 1923 and the Natives Land Act of 1913 laid the groundwork for this exclusion, but it was the deliberate use of urban design buffer zones, isolated townships, and fragmented infrastructure that turned policy into an oppressive reality. Buffer zones, in particular, became stark physical symbols of segregation Highways, industrial corridors, and greenbelts were not neutral spaces but deliberate barriers that restricted movement and interaction between racial groups These zones, such as Johannesburg’s mining belt, were strategically placed to separate affluent white suburbs in the north from impoverished Black townships in the south, reinforcing both physical and psychological divisions (Davies, 1981)

This map highlights the distribution of informal settlements across the City of Johannesburg The red dots represent the locations of these settlements, concentrated in areas such as Soweto, Orange Farm, and Lenasia These settlements often lack adequate infrastructure and services, reflecting the ongoing spatial inequalities rooted in apartheid-era planning. Major roads and urban nodes like Sandton and the Johannesburg CBD are also marked, illustrating the contrast between economically thriving areas and marginalised communities.

Figure 12: Locations of Informal Settlements in Johannesburg

This spatial fragmentation extended into the design of public spaces and transport systems, where segregation was embedded at every level Parks and recreational facilities were accessible only to white residents, while transport infrastructure functioned as a one-way system. Railway lines and bus routes were engineered to transport Black labourers into white economic hubs during the day, only to funnel them back to segregated townships at night This rigid system not only reinforced racial boundaries but also ensured the economic dependency of non-white populations on white-controlled industries (Christopher, 1990)

Architecture also played a significant role in enforcing apartheid’s control mechanisms The hostels built for Black workers near industrial areas were designed with stark simplicity, prioritising surveillance and control over human comfort. These buildings, often devoid of social spaces or privacy, dehumanised their residents while ensuring they remained under constant watch. Similarly, township layouts mirrored this ethos, with winding streets and restricted access points that made movement difficult and facilitated surveillance by authorities. The design of these spaces served not only to control the population but also to embed a sense of confinement and disempowerment into the everyday lives of non-white residents (Swilling et al , 1991)

Apartheid-era urban planning and architecture in South Africa were not only tools of racial division but also active enforcers of economic dependency and social disempowerment. These fields were meticulously wielded to shape a society where privilege and opportunity were reserved for white South Africans, while non-white communities were confined to spaces deliberately designed to limit their potential and visibility. By embedding segregation into the very fabric of cities, apartheid planners created enduring systems of control that have left a deep imprint on South Africa's urban landscape.

Figure 13: Historical Map of Johannesburg and Surrounding Areas (1902)

This historical map illustrates Johannesburg and its surrounding regions during the early 1900s, providing insight into the city's rapid growth driven by the gold mining industry Key locations such as Pretoria, Rustenburg, and Witwatersrand are marked, along with prominent mining areas and transportation routes The map highlights the strategic importance of Johannesburg as a mining and economic hub during this period, setting the stage for its development into South Africa's largest city

Economic segregation was another cornerstone of apartheid’s spatial policies Non-white communities were forcibly located far from industrial and commercial centres, where job opportunities were concentrated Deprived of electricity, clean water, and sanitation, these townships became sites of entrenched poverty and limited upward mobility. In contrast, white neighbourhoods, positioned closer to economic hubs, were equipped with modern infrastructure and amenities, perpetuating the socio-economic divide. This imbalance in access and opportunity was a direct reflection of apartheid's intent to sustain white dominance through spatial and economic marginalisation (Hindson, 1987)

The stark contrast between white suburbs and non-white townships was a visible manifestation of apartheid’s racial hierarchy. Monumental civic buildings, wide boulevards, and lush parks in white areas symbolised privilege and power, while non-white settlements were reduced to basic, prefabricated housing with minimal infrastructure. This deliberate disparity in the built environment reinforced apartheid ideology by embedding inequality into the physical structure of society (Chipkin, 2008).

Although apartheid officially ended decades ago, its spatial legacies continue to shape South African cities. Informal settlements have emerged on urban peripheries, often replicating the exclusion and marginalisation of apartheid-era townships Also, historically white dedicated suburbs remain privileged by better infrastructure and economic opportunities. Addressing these enduring inequalities requires a reimagining of South Africa’s urban spaces, guided by principles of integration, equity, and justice

Figure 14: Contrasting Suburbs in Johannesburg

This aerial image vividly captures the stark divide between affluent, predominantly white suburbs and adjacent informal settlements in Johannesburg. On the left, well-developed neighbourhoods feature spacious homes, lush gardens, and orderly infrastructure, symbolising privilege and access On the right, informal settlements are densely packed with makeshift housing and lack basic services, reflecting the enduring spatial inequalities and socio-economic disparities rooted in apartheidera urban planning This visual contrast underscores the lasting impact of apartheid’s segregationist policies on Johannesburg’s urban fabric

6. Resistance and Resilience in Design up to 1994

Resistance often emerges from oppression, as seen in apartheid-era South Africa, where architecture and urban planning were used not only to control but also to resist. Faced with exclusion and disempowerment, marginalised communities showed remarkable creativity, transforming spaces meant to confine them into hubs of culture, resistance, and survival These examples show how people adapted to and resisted spatial restrictions, turning tools of control into symbols of resilience and defiance

6.1 Grassroots Urbanism and Informal Economies

Under apartheid’s oppressive urban design, informal economies and grassroots urbanism thrived despite the constraints In towns such as Soweto, which had infrastructure underdeveloped by design, residents built centres of entrepreneurialism. Spaza shops, shebeens, and informal markets were established as vital forms of economic opportunity, with areas like Meadowlands, Orlando West, Jabulani, and Vilakazi Street serving as notable hubs for formal and informal trade (Future Cities South Africa, 2021, pp. 91-93).

Soweto’s high population density averaging 10,206 people per km² further catalysed the vibrancy of these economies Local businesses flourished, creating dynamic communitydriven spaces that supported livelihoods and fostered resilience in the face of systemic exclusion These spaces did more than sustain livelihoods; they fostered community ties and cultural expression. Cultural interventions such as street art, murals, and music infused the urban landscape with vibrant expressions of identity and defiance. In Cape Town, street art in areas like Woodstock and District Six became a significant form of resistance, with murals portraying the voices of the oppressed and their resilience under apartheid (W., 2023). By reclaiming public space as a medium for storytelling and solidarity, these efforts transformed oppressive environments into canvases of empowerment, quietly challenging the spatial restrictions apartheid sought to enforce.

Figure 15 & 16 : Historical Pictures of Alexandra Township

6.2 Ad

The ar represe adapta genera into m intenti Standa unifor and su y adding to fit t symbo

Figure 17: Floor Plan and Elevation of an Apartheid-Era House

This diagram showcases the standard design of the NE 51/6 "matchbox" house, a common feature of apartheidera housing schemes

These houses were designed to accommodate a disproportionately high number of residents, often housing 7 to 9 people in cramped spaces The design reflects the apartheid government’s deliberate neglect of comfort and human dignity for non-white populations

Figure 18: Photograph of an ApartheidEra Housing Unit This image illustrates the real-life implementation of the NE 51/6 "matchbox" house

Apartheid-era housing policies enforced various oppressive housing types, each designed to maintain control and segregation. Hostels, for example, were another stark example of surveillance-based architecture Built mainly for Black male workers, these buildings offered shared dormitory-style rooms with no privacy or amenities for family life. Their utilitarian design prioritised monitoring over comfort Despite these conditions, workers used these spaces to organise politically, turning tools of oppression into platforms for resistance. Townships like Soweto were designed to isolate and marginalise non-white communities. With rigid grid-like layouts far from economic hubs, residents faced long commutes on poorly maintained transport systems. These houses often lacked basic services like electricity, running water, and sanitation, deepening the cycle of poverty. Yet, townships became vibrant cultural and economic hubs with collaborative efforts from the community.

Housing for Coloured and Asian communities was marginally better than township provisions but still reflected the racial hierarchy of apartheid In places like District Six in Cape Town, forced removals destroyed vibrant, mixed-race neighbourhoods, replacing them with segregated apartment blocks These displacements caused immense cultural and social loss, but they also sparked resistance. Displaced residents fought for their right to return, preserving memories of their communities and demanding justice.

These examples highlight how apartheid-era housing was a deliberate tool of systemic oppression Yet, those subjected to these conditions resisted and adapted, asserting their humanity and creativity. The very spaces meant to suppress became symbols of resilience and ingenuity. Marginalised communities transformed apartheid housing from instruments of control into spaces of empowerment, reshaping their physical environments and defying the system’s intentions.

Mining compounds were another oppressive housing type, built to confine migrant workers near industrial sites. These compounds were gated, sparse, and dehumanising, designed to isolate workers from their families and communities However, they also became spaces of solidarity, where workers organised strikes and protests, challenging their exploitation and the broader apartheid system. Figure 19 & 20

6.3 Community Spaces as Centres of Resistance

Churches, schools, and community centres in townships became focal points for resistance, serving as spaces for organising protests and fostering community solidarity. The Regina Mundi Church in Soweto is a good example of that, since it played a pivotal role during the anti-apartheid struggle, hosting clandestine meetings and sheltering activists These structures moved beyond their intended functions, becoming symbols of hope and resilience in the antiapartheid South African community (Oliver & Oliver, 2016)

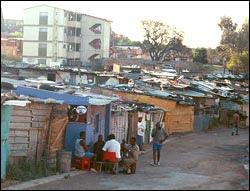

6.4 Informal Settlements as Acts of Defiance

Squatter camps and informal settlements, while often seen as chaotic or illegitimate sites, were, in fact, potent acts of defiance against apartheid’s spatial order. The settlements defied state control over urban territory by inhabiting land not sanctioned for its use Informal settlements such as Alexandra in Johannesburg became sites of resistance, with residents challenging evictions and laying claim to the area asserting their right to remain in close proximity to economic opportunities in the city.

22: wall murals reflecting an important period of history and resistance

Figure 21: Photograph of Regina Mundi Church in Soweto

Figure

7. Post Apartheid Johannesburg

South Africa began its journey toward democracy, equality, and justice with the end of apartheid in 1994 and the historic election of Nelson Mandela as the country’s first Black president. Mandela’s leadership brought hope and unity, laying the foundation for efforts to dismantle systemic oppression and build a fairer and more inclusive society. The end of apartheid also led to significant social, political, and economic reforms, guided by a new constitution that guaranteed equal rights for all citizens

Johannesburg, as South Africa’s largest city and economic hub, became a focal point for these changes. However, the city’s deeply rooted spatial inequalities, a legacy of apartheid’s urban planning, created both major challenges and opportunities for redevelopment Historically white suburbs like Sandton benefit from advanced infrastructure and concentrated wealth, while areas like Soweto and Alexandra still struggle with limited resources and inadequate public services The Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, remains one of the highest in the world at 0.63, reflecting the city’s persistent economic and spatial disparities (Statista, 2024).

Figure 23: Infographic Highlighting South Africa's Gini Coefficient and Wealth Inequality

This infographic illustrates South Africa's position as one of the most unequal societies in the world, with a Gini coefficient of approximately 0 63 It highlights the stark disparity in income levels, where the top 10% of the population earns more than 50% of household income, while the poorest 40% account for less than 7% The graphic also emphasises the need for interventions such as increased job creation, affordable housing, higher education levels, and skills training to reduce inequality and improve socio-economic outcomes It provides visual context for understanding the systemic inequities deeply rooted in South Africa's history

This map highlights the boundaries and key focus areas of the Alexandra Renewal Project (ARP), a major urban renewal initiative aimed at addressing spatial inequalities in the Alexandra township The green outline defines the project area, while the icons represent critical points of interest, including educational institutions, medical facilities, and shopping centres The map also illustrates the township’s proximity to economic hubs like Sandton, underscoring the project’s goal of integrating Alexandra into Johannesburg’s broader urban framework Despite its potential, the ARP has faced challenges such as delays and funding shortages, limiting its impact on improving infrastructure and living conditions

Efforts to reduce these divides include initiatives like the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), which provided more than three million homes nationwide by 2016 (IEOM Society, 2018) However, most RDP settlements are located on the outskirts of cities, continuing the legacy of spatial exclusion seen during apartheid. Residents in these areas often face long commutes over two hours each way—to reach economic hubs like Johannesburg’s central business district, further limiting opportunities for upward mobility (City of Johannesburg, 2021). Additionally, many RDP homes suffer from poor construction quality, with studies showing around 30% requiring substantial repairs (SABC News, 2019) Urban renewal projects, led by organisations like the Johannesburg Development Agency, have focused on revitalising neglected inner-city neighbourhoods and upgrading informal settlements. Initiatives in areas like Diepsloot and Kliptown aim to integrate these communities into the broader urban framework. Yet progress remains uneven, as approximately 15% of Johannesburg’s population continues to live in informal settlements under precarious conditions. These challenges underscore the need for more inclusive urban planning to address entrenched inequalities and promote equitable development

Figure 24: Map of the Alexandra Renewal Project Area

Figure 25: Map Depicting Commercial, Industrial, and Residential Development in Johannesburg (2001–2010) This map illustrates the spatial distribution of new commercial, industrial, and residential developments in Johannesburg from 2001 to 2010. Colour-coded areas represent different forms of development: industrial and commercial growth is shown in red and orange, while residential areas, including formal housing, townhouses, estates, and informal settlements, are depicted in shades of pink, green, and blue The urban freeway network and key industrial zones are highlighted, emphasising the stark contrasts between welldeveloped areas and underdeveloped informal settlements This map provides a visual representation of the uneven urban growth patterns, which reflect the lasting spatial inequalities of apartheid-era planning

7.1 The Growth of Informal Settlements

Since the end of apartheid, Johannesburg’s population has grown rapidly, increasing by approximately 50% between 1996 and 2021 due to rural-to-urban migration and an influx of people from neighbouring countries (Statistics South Africa, 2021) This rapid growth has driven the expansion of informal settlements, which now house around 15% of the city’s population, or roughly 1.3 million people (City of Johannesburg, 2021). Areas like Diepsloot, home to an estimated 140,000 residents, and Zandspruit, with over 70,000 inhabitants, highlight the resilience of communities that build homes and lives despite limited resources (HDA, 2019) However, these areas face significant challenges, including inadequate sanitation, unreliable electricity access, and vulnerability to environmental risks such as flooding and fires

These settlements are emblematic of both the ingenuity of their residents and the government’s struggles to address housing shortages. Policies like the Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme (UISP) aim to provide basic services and infrastructure, but bureaucratic inefficiencies and funding limitations have often hindered progress (National Department of Human Settlements, 2020) Addressing these issues requires sustained investment and a more coordinated approach to integrating informal settlements into the urban fabric.

7.2 Gentrification and Urban Renewal

Gentrification has become a major issue in Johannesburg, especially in neighbourhoods like Maboneng and Braamfontein. These areas, once neglected, have been transformed into lively, modern hubs Maboneng, which means "place of light," spans approximately 6 hectares and now features over 50 businesses, including art galleries, colourful murals, cafés, and boutique shops, attracting an estimated 12,000 visitors monthly (City of Johannesburg, 2021). Braamfontein, home to the University of the Witwatersrand, has similarly been revitalised, hosting co-working spaces, trendy bars, and the well-known Neighbourhoods Market, which sees approximately 6,000 visitors every Saturday (Urban Studies Foundation, 2020).

While these changes bring significant investment and improve the image of these neighbourhoods, they also create challenges. Long-term residents are often displaced due to a 40% rise in rental costs in these areas over the last decade, leading to increased housing insecurity for lower-income groups (South African Cities Network, 2019). Many developments prioritise profit over inclusivity, leaving marginalised communities excluded from the benefits of these revitalised spaces.

Figure 26: Photograph of high rise residential solution attempt in modern Johannesburg.

Figure 27: Photograph of the modern neighbourhood Braamfontein.

Figure 28: Photograph of the modern neighbourhood Maboneng.

Infrastructure projects like the Gautrain rail system, launched in 2010, further illustrate the divide. The Gautrain connects Johannesburg, Pretoria, and O.R. Tambo International Airport, serving approximately 15 million passengers annually. However, its routes bypass many disadvantaged areas, making it accessible primarily to higher-income groups who can afford its fares, which are over five times higher than typical commuter rail costs (Gautrain Management Agency, 2022). This trend risks deepening socio-economic divides, as luxury developments and modern infrastructure coexist with sprawling informal settlements housing over 1 3 million residents (City of Johannesburg, 2021) These patterns underscore the challenges of balancing urban development with inclusivity, as profit-driven projects often overlook the needs of marginalised groups

7.3 Opportunities for Transformation

30: Photograph Highlighting the challenge of long commutes for more vulnerable communities

Johannesburg has the potential to address its spatial inequalities through inclusive urban development strategies that prioritise access and equity. Initiatives like the Alexandra Renewal Project, launched in 2001 with a budget of R1 3 billion, aim to improve infrastructure, provide affordable housing, and enhance public services in Alexandra township. While progress has been hampered by delays and funding shortages, the program highlights the potential of targeted urban renewal efforts to reduce inequality when combined with sustained resources and community participation (City of Johannesburg, 2021).

Transit-oriented development (TOD) is another promising strategy By integrating housing, jobs, and services near transport hubs, TOD can improve accessibility and reduce spatial exclusion. However, high ticket costs for systems like the Gautrain limit their accessibility for low-income residents. Expanding affordable public transit options like the Rea Vaya Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system could bridge this gap, offering equitable access to economic opportunities while reducing reliance on distant informal settlements.

Figure 29: Photograph of the Gautrain rail system

Figure 31: Photograph of the Rea Vaya Bus

Figure

Efforts to upgrade informal settlements also present a significant opportunity for transformation For instance, initiatives in Diepsloot and Kliptown focus on improving infrastructure and integrating these areas into the broader urban framework. However, with 15% of Johannesburg’s population still living in precarious conditions, more investment is needed to upgrade these settlements rather than relocate residents to peripheral locations.

Developing affordable housing closer to economic hubs is essential Programs like the RDP have delivered millions of homes, but their placement on the urban periphery perpetuates socio-economic isolation Shifting focus to building affordable housing within city centres could foster integration and reduce inequalities.

This infographic provides an overview of the cost of living in Johannesburg, highlighting key expenses such as rent, utilities, food, and transport With a monthly average salary of $1,695 after tax and significant costs for housing and transportation, the data underscores the economic challenges faced by residents, particularly those in precarious conditions It aligns with the discussion on affordable housing and infrastructure development, emphasising the importance of integrating housing solutions closer to economic hubs to reduce socio-economic isolation and promote equitable living conditions

By aligning urban renewal efforts with investments in education, healthcare, and infrastructure, Johannesburg can move toward a more inclusive and equitable future

Collaborative efforts between the government, private sector, and local communities are crucial to ensuring that all residents benefit from the city’s development

Figure 32: Cost of Living in Johannesburg (2024)

8. Conclusion

Apartheid-era South Africa demonstrates how urban planning and architecture can be used as tools of oppression, embedding inequality into the very structure of society. Johannesburg, with its stark spatial and economic divides, is a testament to the long-term effects of such policies However, it also illustrates the power of resilience and the potential for transformation.

The research in this dissertation has traced how apartheid policies manipulated urban design to entrench social injustice, from the forced removals that shaped townships to the exclusionary housing and infrastructure that marginalised non-white populations These spaces were designed to control and segregate, but they also became sites of resistance, adaptation, and defiance Informal economies, grassroots urbanism, and the creative use of limited resources revealed the ingenuity of oppressed communities who refused to be defined by the restrictions imposed on them.

Today, Johannesburg’s landscape continues to bear the scars of apartheid, but it also offers a roadmap for building a more inclusive urban future The persistence of informal settlements and socio-economic inequality underscores the need for urban development that prioritizes equity over profit Programs like the Alexandra Renewal Project and transit-oriented development hold promise, but they must be scaled and adapted to benefit all residents, especially those who remain on the fringes of society.

Figure 33: Photo of modern day Ponte towers

Ponte City Tower exemplifies the complexities of Johannesburg’s journey toward spatial justice. Originally built as a symbol of apartheid-era exclusivity, its transformation into a community hub during the city’s most turbulent times highlights the resilience of marginalised populations. Ponte’s evolution from a luxury enclave to a contested symbol of urban resilience underscores the importance of designing spaces that adapt to the needs of diverse communities. While recent efforts to rehabilitate the building reflect Johannesburg’s aspirations for modernity, they also reveal the tensions between gentrification and inclusivity.

The legacy of apartheid architecture is both a warning and an opportunity. It reminds us of the profound consequences of design choices, not only for physical spaces but for the lives they shape. As architects and urban planners, there is a responsibility to learn from this history and create environments that promote equality, dignity, and opportunity for all. By prioritising community needs and embedding principles of social justice into every stage of the design process, future urban landscapes can move beyond the divisions of the past.

Ultimately, this dissertation calls for a reimagining of urban design as a tool for healing and inclusivity, ensuring that the mistakes of apartheid-era planning are not repeated. Johannesburg’s story, with all its challenges and triumphs, offers valuable lessons on how architecture and planning can be harnessed to build cities that reflect the values of equity and justice a goal that should guide the creation of all future spaces.

Figure 34: The Ponte downfall

Figure 35: Ponte towers interior view

References

Boaduo, A P (2017) Historic timeline – The mining settlement of Johannesburg.1Library. https://1library.net/article/historic-timeline-the-miningsettlement-of-johannesburg zwrrl07y

Jones, R. (2003). History of Johannesburg. Amethyst. https://www.amethyst.co.za/JhbGuide/Johannesburg.htm

Witwatersrand Gold Rush and the founding of Johannesburg. (n d ) Retrieved from https://goldmarketinsight.com/witwatersrand-gold-rush-and-the-founding-ofjohannesburg/

Findley, L., Liz, & Ogbu. (2011, November 17). South Africa after apartheid: From township to town. Places Journal. https://placesjournal.org/article/south-africa-fromtownship-to-town/

Christopher, A. J., & Elizabeth, P. (1997). Racial land zoning in urban South Africa.

ScienceDirect https://www sciencedirect com/science/article/pii/S0264837797000252

Wainwright, O. (2014, April 30). Apartheid ended 20 years ago, so why is Cape Town still 'a paradise for the few'? The Guardian.

https://www theguardian com/cities/2014/apr/30/cape-town-apartheid-ended-stillparadise-few-south-africa

Shepherd, N (2007) The world below: Postapartheid urban imaginaries and the remains of the. Retrieved from https://pure.au.dk/portal/en/publications/the-world-belowpostapartheid-urban-imaginaries-and-the-remains-o

Hall, M , Murray, N , & Shepherd, N (2007) Desire lines: Space, memory and identity in the post-apartheid city. Routledge.

https://uat taylorfrancis com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203799499/desire-lines-nickshepherd-no%C3%ABleen-murray-martin-hall

Herbert, J M , & Murray, C W (2015) Building from scratch: New cities, privatized urbanism and the spatial restructuring of Johannesburg after apartheid. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(3), 471–488.

https://deepblue lib umich edu/handle/2027.42/113120

Murray, M. J. (2015, January). Waterfall City (Johannesburg): Privatized urbanism in extremis Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 47(1), 3–22.

https://doi.org/10.1068/a140038p

Totaforti, S. (2020). Urban planning in post-apartheid South African cities: The case of Johannesburg Open Journal of Social Sciences, 8(6), 229–239.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2020.86018

Turok, I (1994) Urban planning in the transition from apartheid: Part 1: The legacy of social control. Town Planning Review, 65(3), 243–259.

https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.65.3.kq676164832433m1

Pirie, G H (1984) Race zoning in South Africa: Board, court, parliament Political Geography Quarterly, 3(3), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/0260-9827(84)90032-6

Christopher, A J (1990) Apartheid and urban segregation levels in South Africa. Urban Studies, 27(3), 421–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420989020080341

References

Chipkin, C (2008) Johannesburg transition: Architecture and society from 1950. STE Publishers.

Davies, R J (1981) The spatial formation of the South African city. Geoforum, 12(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7185(81)90034-6

Hindson, D. (1987). Pass controls and the urban African proletariat in South Africa. Ravan Press

Platzky, L., & Walker, C. (1985). The surplus people: Forced removals in South Africa. Ravan Press

Swilling, M., Humphries, R., & Shubane, K. (1991). Apartheid city in transition. Oxford University Press.

Lim, D L (2021) Remnants of Apartheid in Ponte City, Johannesburg. In N Shepherd & M. Hall (Eds.), The Politics of Design (pp. 188–210). Routledge.

https://issuu com/opresearch/docs/the politics_of_design/189

Hickel, J. (2014). Engineering the Township Home: Domestic Transformations and Urban Revolutionary Consciousness. ResearchGate.

https://www researchgate net/figure/House-types-NE-51-6-and-51-9_fig4_272164901

Oliver, W., & Oliver, E. (2016). Regina Mundi: Serving the liberation movement in South Africa HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies, 72(1), a3409.

https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v72i1.3409.

City of Johannesburg (2021) Joburg demographics and key socio-economic indicators Retrieved from https://joburg.org.za/documents /Documents/Statistical%20Briefs/Issue%2023%20Jobur g%20Demographics%20and%20Key%20Socio%20Economic%20Indicators pdf

IEOM Society. (2018). Challenges of RDP housing quality and its implications for sustainable development Retrieved from https://ieomsociety org/dc2018/papers/450.pdf

SABC News. (2019). Parliament concerned over quality of RDP houses. Retrieved from https://www.sabcnews.com/sabcnews/parliament-concerned-over-quality-of-rdp-houses/ Statista (2024) Gini coefficient forecast for South Africa. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/study/174049/socioeconomic-indicators-south-africa-report Housing Development Agency (HDA) (2019) South Africa’s Informal Settlements Status. Pretoria: HDA.

National Department of Human Settlements. (2020). Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme: Progress Report Pretoria: South African Government Statistics South Africa. (2021). Mid-year population estimates. Pretoria: Stats SA.

Gautrain Management Agency (2022) Annual Report 2021/22. Pretoria: Gautrain Management Agency.

South African Cities Network. (2019). State of Cities Report: Urban Transformation and Equity in South Africa Johannesburg: SACN

Urban Studies Foundation. (2020). The Social and Economic Impact of Gentrification in Johannesburg Pretoria: Urban Studies Foundation

Figure references

ResearchGate (n d ) Regina Mundi Catholic Church and the struggle for liberation Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Regina-Mundi-Catholic-Churchand-the-struggle-for-liberation fig1 310512359

CS Monitor. (2021). In South African architecture, women build on social justice. Retrieved from https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Africa/2021/0420/In-South-Africanarchitecture-women-build-on-social-justice Map360. (n.d.). Map of Johannesburg, 1897. Retrieved from https://johannesburgmap360 com/johannesburg-%28joburg-jozi%29-old-map Britannica. (n.d.). Johannesburg map, c. 1902. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/place/Johannesburg-South-Africa/History

Heritage Portal (n d ) Pyrites Panic Retrieved from https://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/pyrites-panic-when-one-three-citizens-leftjohannesburg

Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). South Africa racial map, 1979. Retrieved from https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:South_Africa_racial_map,_1979.gif

Gutenberg-e (n d ) Apartheid townships and resistance Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg-e.org/pohlandt-mccormick/pmh02w.html

Getty Images (n d ) Historical photographs of Soweto township Retrieved from https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/photos/soweto-township Britannica (n d ) History of Soweto Retrieved from https://www britannica com/place/Soweto

ResearchGate. (n.d.). Map showing land cover types in the Upper Vaal catchment. Retrieved from https://www researchgate net/figure/Map-showing-land-cover-types-inthe-Upper-Vaal-catchment fig5 265082409

OpenEdition (n d ) Exploring Alexandra Township Retrieved from https://books.openedition.org/africae/3485

Unequal Scenes. (n.d.). Johannesburg aerial views. Retrieved from https://unequalscenes com/johannesburg

MIT Urban Upgrading. (n.d.). Alexandra township case study. Retrieved from https://web mit edu/urbanupgrading/upgrading/case-examples/overview-africa/alexandratownship.html

Medium. (n.d.). The story of Sandton and Alexandra. Retrieved from https://giftmbanda medium com/the-story-of-sandton-and-alexandra-johannesburg723116ab97c1

Daily Maverick (2019) Alexandra renewal project: Search for the missing R1.6bn

Retrieved from https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-04-12-alexandra-renewalproject-search-for-the-missing-r1-6bn/

Figure references

Taylor & Francis (2020) Urban Transformation and Equity in South Africa. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03057070.2019.1602323#d1e168

Rawson (n d ) Gini coefficient and urban inequality in South Africa. Retrieved from https://blog.rawson.co.za/south-africas-gini-coefficient-is-the-highest-in-the-world Daily Maverick. (2015). Affordable housing in Johannesburg. Retrieved from https://www dailymaverick co za/article/2015-11-19-affordable-city-housing-a-modeland-building-joburg-must-maintain/

DYP (n d ) Diepsloot overview Retrieved from https://www dyp co za/what-andwhere-is-diepsloot/

IIED. (n.d.). COVID-19 housing crisis in the global south. Retrieved from https://www iied org/covid-19-housing-crisis-global-south-time-for-change

In Your Pocket. (n.d.). 10 must-do Maboneng experiences. Retrieved from https://www inyourpocket com/johannesburg/10-must-do-maboneng-experiences_77390f AndBeyond. (n.d.). Visit to Maboneng. Retrieved from https://www.andbeyond.com/experiences/africa/south-africa/johannesburg/visit-tomaboneng/

City Sightseeing. (n.d.). Braamfontein highlights. Retrieved from https://citysightseeing co za/en/joburg/braamfontein

Living Cost. (2024). Cost of living in Johannesburg. Retrieved from https://livingcost org/cost/south-africa/johannesburg

HDA (2019) Gautrain developments and urbanization Retrieved from https://thehda.co.za/pdf/uploads/multimedia/gau_alexandra_rev_gov.pdf

Gautrain Management Agency (2022) Annual report 2021/22. Retrieved from https://www.globalafricanetwork.com/company-news/gautrain-pioneering-towardsinnovation-and-future-sustainability/

SABC News. (2019). Rea Vaya’s travel fees and accessibility. Retrieved from https://www.citizen.co.za/soweto-urban/news-headlines/2013/10/22/rea-vayas-travel-fees/

The Guardian (2015) Ponte City: Johannesburg’s vertical slum Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/may/11/johannesburgs-ponte-city-the-tallestand-grandest-urban-slum-in-the-world-a-history-of-cities-in-50-buildings-day-33

Aperture. (2024). David Goldblatt: Documenting apartheid. Retrieved from https://aperture.org/editorial/david-goldblatt-legacy-apartheid/