Moving Rowing Forward as the Official Boat Supplier of the A Most Beautiful Thing Inclusion Fund Rowing Programs

Atlantic City High School Rowing

Baltimore Community Rowing

BLJ Community Rowing

Brick City Rowing

Chicago Training Center

Dallas United Crew

Delta Sculling Center

DeMatha Catholic High School Crew

Evanston Township High School Rowing

Hackensack High School Crew / Hope On Water

San Miguel Academy Rowing Team

Riversport OKC

RowLA

Unity Boat Club

Xavier University Rowing Club

2025

May 18:

BIG 12 Rowing Championship

June 12 - 15:

USRowing 2025 Youth National Championships

October 11-12

Benderson Chase & Oktoberfest - A Day of Oars & Pours

FISA Class A certified, 10-lane protected, buoyed course with coaches lane

Adjacent 1500m practice course

Aluminum gangway with low profile floating docks

Hotels, restaurants & attractions within walking distance

TRAINING LOCATION OF THE NATIONAL TEAM DATES FILLING UP FAST. BOOK YOUR TEAM

Trusted by referees and coaches to keep every stroke, start, and sprint on point.

Whether you’re calling a clean start or commanding a lineup, one thing is certain: your voice matters. Referees rely on crystalclear communication to keep races fair, safe, and on schedule. Coaches count on timing and tone to sharpen technique and focus. The NK Blue Ocean® Megaphone + Interval® 2000 Split/Rate Watch combo delivers the power, clarity, and precision both roles demand— rain or shine, start to finish.

• Long-range, waterproof megaphone with unmatched audio clarity

• Built-in rechargeable battery for all-day regattas

• Pair with the NK Interval Rate Watch for precision timing and feedback

• Designed for performance on and off the water

Grace Joyce

Chip Davis PUBLISHER & EDITOR

Chris Pratt ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

Vinaya Shenoy ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Art Carey ASSISTANT EDITOR

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Andy Anderson | Nancy Clark

Bill Manning | Terry Galvin

Volker Nolte | Marlene Royle

Robbie Tenenbaum | Madeline Davis Tully

Hannah Woodruff

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Jim Aulenback | Steve Aulenback

Julia Kowacic | Karon Phillips

Patrick White | Lisa Worthy

MAILING ADDRESS

Editorial, Advertising, & Subscriptions PO Box 831 Hanover, NH 03755, USA (603) 643-8476

ROWING NEWS is published 12 times a year between January and December. by The Independent Rowing News, Inc, 53 S. Main St. Hanover NH 03755 Contributions of news, articles, and photographs are welcome. Unless otherwise requested, submitted materials become the property of The Independent Rowing News, Inc., PO Box 831, Hanover, NH 03755. Opinions expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect those of ROWING NEWS and associates. Periodical Postage paid at Hanover, NH 03755 and additional locations. Canada Post IPM Publication Mail Agreement No. 40834009 Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Express Messenger International Post Office Box 25058 London BRC, Ontario, Canada N6C 6A8.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: ROWING NEWS

PO Box 831, Hanover, NH 03755. ISSN number 1548-694X

ROWING NEWS and the OARLOCK LOGO are trademarks of The Independent Rowing News, Inc. Founded in 1994

©2024 The Independent Rowing News, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission prohibited.

Follow Rowing News on social media by scanning this QR code with your smart phone.

For sports entrepreneur Kevin Scott, it’s not about profit but purpose. By fostering a love of rowing among Tahitian youth, he’s planting seeds for a healthier future.

BY ADAM KREEK

Unescorted and unsupported, the Maclean brothers aim to row 9,000 miles across the Pacific in four months, avoiding storms, cargo containers, hull-piercing marlin, and sore bottoms.

BY TERRY GALVIN

News Replacement Refs Cambridge Wins Michael “Mungo” Meehan

Sports Science Now or Never Coxing Chance Favors the Prepared Crew

Training The Many Modes of Practice

Fuel Quieting the Food Noise

Recruiting It’s Never Too Early to Prepare Coach Development The Rule of Thirds 14 From the Editor 66 Doctor Rowing

CHIP DAVIS

Setting out to row 9,000 miles across the Pacific Ocean unsupported takes courage, among other things. The Maclean brothers, as chronicled by Terry Galvin, beginning on page 38, developed that courage by bravely taking to the waters off their native Scotland as boys, as well as conquering the Talisker Whisky Atlantic Challenge. Their current challenge, rowing from South America to Australia, will develop their courage further—as long as it doesn’t kill them.

Little in life will be defined so clearly as the results of a regatta.

For rowers across North America, especially the youngest and least experienced, taking to the water with boatmates to race this spring requires bravery, too—the bravery to line up against peers from rival schools and clubs and push themselves beyond their assumed limits, opening an exhilarating sense of what’s possible through exertion, resiliency, and a practiced tolerance for physical pain and mental strain found in few other pursuits in life.

Win or lose, through the competitive adversity to which they and their boatmates subject themselves, they’ll become stronger, more experienced, and a bit more courageous for having been brave enough to line up at the start and match their training, teamwork, and effort against rivals doing the same. Each will suffer, and only one boat will win, but all will come out of the race changed, improved, and better prepared for the next race.

Rowing News celebrates the winners, recognizes excellence in our sport, and, we hope, inspires the rowing community we serve. Most crews get to do it again next weekend, and then, all too soon, the last championship weekend arrives and the final speed order is determined on the racecourse—as it should be.

Little in life will be defined so clearly as the results of a regatta, but every rower will lead a better life from having had the bravery to develop courage in a boat.

Now, more than ever, the Gay + Lesbian Rowing Federation (GLRF) is essential as a safe space for rowers, coxies, coaches, and race officials. As an individual membership online community, GLRF offers a continuous connection between members of the LGBTQ rowing community and clubs, programmes, organizations and vendors in the broader rowing community.

We want to highlight a powerful tool on our community platform: the Share A Link feature. It provides an opportunity for LGBTQ rowers and supportive allies to promote rowing clubs or programmes, and other rowing-related entities that genuinely support acceptance and inclusion. The goal is to help both GLRF members and website visitors to find a rowing home, vendors, and other resources where they can trust they will feel welcomed and comfortable in their identity.

Every Share A Link listing provides a descriptive text space to describe the club or programme, vendor, or organization and any supportive language for LGBTQ acceptance and inclusion. Share A Link users can search by categories, geography, and by tags, helping them find an accepting space to row and participate in the sport. The categories, covering all aspects of the rowing experience, include:

• Clubs & Programmes

• Open Ocean Race Teams

• Boat, Oar, and Erg Manufacturers

• Rowing Retailers

• National and Regional Rowing Federations/Associations

• Rowing Resources

• Training and Fitness Resources

• Rowing 101

Representatives of LGBTQ-inclusive clubs and programmes, vendors, and organizations are welcome to add a link for their entity.

Why does this matter now?

The current political climate, the assault on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion policies and programmes, and threats against LGBTQ participation in sports in the United States will (among many other things) make it harder for LGBTQ individuals to find places where they can feel comfortable and safe, and for organizations to express support for the LGBTQ community.

Although we believe there is an urgent need to show support from the North American rowing community, it is equally important for this resource to be built out worldwide. We call on the global rowing community to support our Share A Link feature. With robust input from both the LGBTQ rowing community and allies, Share A Link will be a powerful tool.

The Gay + Lesbian Rowing Federation isn’t just for LGBTQ individuals. We warmly welcome allies. Our registration system doesn’t ask anyone’s sexual orientation, just a person’s gender identity. Belonging to the Gay + Lesbian Rowing Federation helps expand our network and strengthen our community.

Registering with GLRF is free, as is adding Share A Link listings (you must register to be able to add to Share A Link).

Gay + Lesbian Rowing Federation - https://glrf.info

During the last Sarasota Invitational regatta, a nearly fatal heart attack occurred during the eights race in the boat in which I was rowing.

Fortunately, I’m a physician and was able to recognize the situation and begin CPR on the referee’s launch. Another rower, the paramedics stationed at the venue, and I were able to restore the pulse of my crewmate, who was transferred to the hospital, where his life was saved by the physicians on duty. Thank God he is alive and recovering.

Rowing and competing are a passion for rowers of all ages, but a cardiac event can happen at any age for different reasons. The International Olympic Committee has guidelines for youth and elite athletes, to which I believe USRowing adheres.

The guidelines for master athletes, however, vary in different countries in terms of requirements and strictness. I know of many masters athletes who have cardiac conditions, are taking anticoagulant medication—even some who have had heart attacks—and who, against medical advice, are still competing.

Among scientists and medical professionals, there’s disagreement about the guidelines. Some medical journals support doing electrocardiograms, stress tests, and other evaluations, while others call for these interventions only in particular circumstances.

The American Heart Association, the authority on cardiovascular health, recommends that athletes answer 14 precompetition screening questions. A positive answer to any one is supposed to trigger a more extensive evaluation.

As far as I know, no rowing club or rowing society requires competitors to answer the simple AHA questions, which would help avoid problems like the one we had in Sarasota.

The fact remains, however, that some rowers may answer all the AHA’s questions negatively and, like our crew member, still have a heart problem. The extreme physiological demands of rowing make it unique and different from other sports.

Although I intend to ask my doctor for an extensive cardiovascular evaluation, the 14 AHA questions are a good first step to safety.

Rodrigo N. Banegas, M.D. Boca Raton, Fla.

Crews from all 11 Big Ten rowing programs, along with 12 other invited crews, raced on the 2017 World Rowing Championships course at Nathan Benderson Park at the Big Ten Invitational. The field was stacked, with 13 of the top 25 crews ranked in the Pocock CRCA Poll—Big Ten crews No. 3 Washington, No. 9 Rutgers, No. 12 Michigan, No. 14 Ohio State, No. 21 Indiana, and No. 24 USC as well as No. 6 Tennessee, No. 7 Brown, No. 11 Penn, No. 16 Duke, No. 17 Oregon State, No. 18 Harvard/Radcliffe, and No. 20 Oklahoma—racing three times each.

PHOTO: JOE MEISCHKE JR.

After getting swept by No. 2 Stanford in late March, Tennessee—including stroke Hannah Smith and coxswain Patricia Menendez—dropped from No. 3 to No. 6 in the Pocock CRCA Poll, before beating new No. 3 Washington in the first varsity eight at the Big Ten Invitational in April at Sarasota’s Nathan Benderson Park.

PHOTO: DREW GARRISON/TENNESSEE ATHLETICS

The Knecht Cup Regatta welcomes college crews—including St. Joseph’s University in 2023—to New Jersey’s Cooper River racecourse, honoring the late William J. “Bill” Knecht, the man behind the development of the venue as well as a founder of the National Rowing Foundation. This year, the regatta featured the inaugural race of NCAA Division I’s newest program, the University at Albany Great Danes.

“We’re incredibly proud to make our debut at the Knecht Cup,” said UAlbany head coach Kim Chavers. “This is the first collegiate race not only for our program but also for every student-athlete in our boats. It’s a huge milestone.”

The National Association of Collegiate Rowing Officials, an alternative source of trained referees, makes its debut at the Sarasota 2K regatta.

At the Sarasota 2K regatta in late March, the referees were not wearing the standard light-blue tops, navy-blue blazers, and emblems of USRowing. All were USRowing referees but they were wearing navy-blue polo shirts with the acronym NACRO on the left side of the chest.

That’s because the regatta at Nathan Benderson Park included teams racing under the umbrella of the Intercollegiate Rowing Association, which has sought another source of officials and insurance coverage.

The National Association of Collegiate

Rowing Officials is one such alternative, and the Sarasota regatta that drew IRA and other college teams was the first significant event where its acronym appeared.

The organization, founded in January by IRA Commissioner Laura Kunkemueller and two other NACRO board members, has no employees and no website but it has a powerful ally, the 32,000-member National Association of Sports Officials.

The nonprofit NASO, founded in 1980, provides insurance coverage and other benefits for members who officiate many sports in the U.S. and Canada. NASO’s managers

Cambridge University won both the women’s and men’s Boat Races on the four-mile, 374-yard (6.8 kilometer) course on London’s Thames River Tideway. The Light Blue men’s crew beat Oxford’s Dark Blues by 5.5 lengths in a time of 16:56 to win the 170th edition of the men’s race. The Cambridge women beat Oxford by 2.5 lengths with a winning time of 19:25 to take the 79th Women’s Boat Race. The race featured the first restart of the women’s race after the crews crashed into each other. This year marked the 10th anniversary of the women’s race on the Tideway.

Cambridge completed a sweep, winning the reserve-crews races as well as the lightweight races.

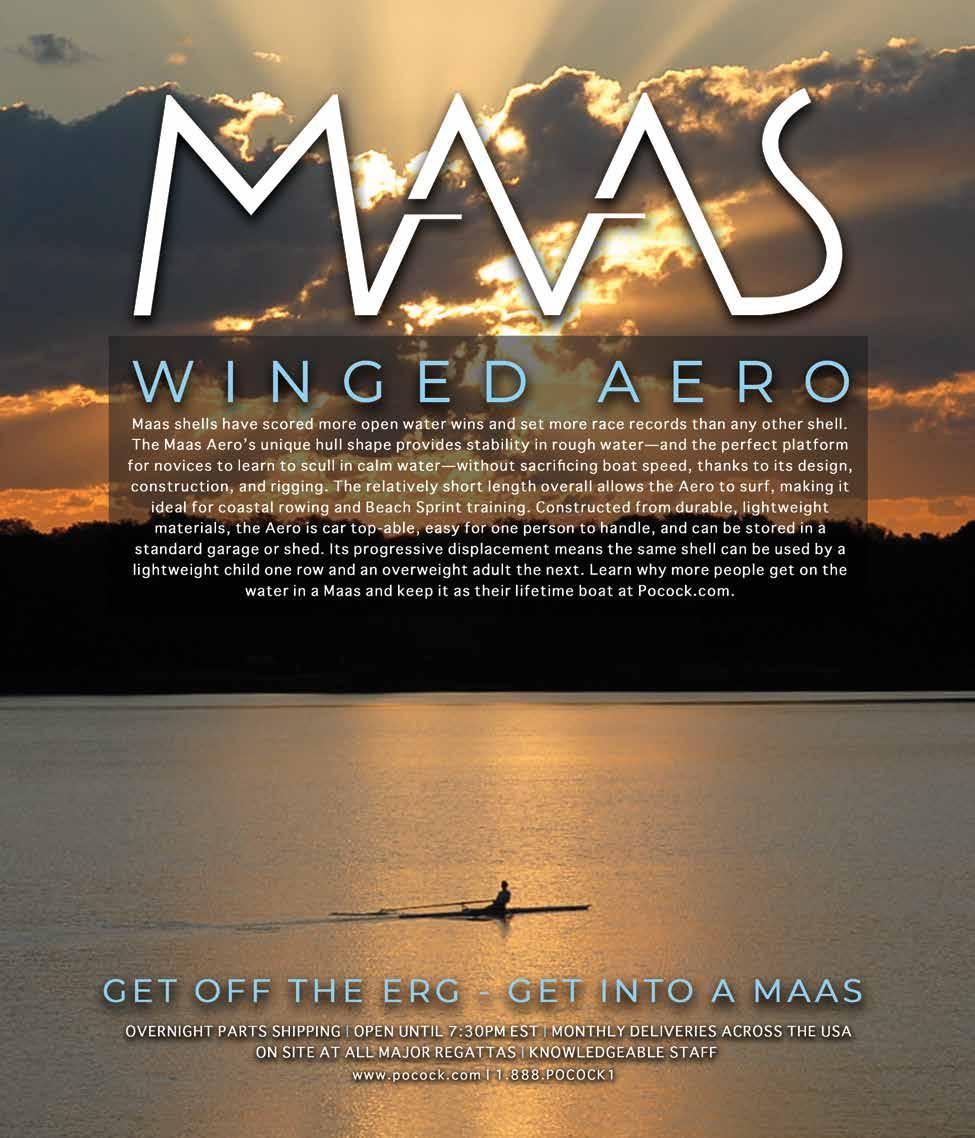

Unrivaled performance in waves. Excellent straight-line speed. Stable learning platform. Now in stock – Hit the beach this Spring in our revolutionary new coastal scull. Free shipping in Lower 48 for Rowing News readers until April 30 on in-stock boats. Use coupon code RNEWS at checkout.

are the staff of Referee Enterprises Inc., the for-profit company that publishes Referee magazine.

NACRO uses a company called RQ+ to assign referees to regattas, track their schedules, and perform other clerical functions, Kunkemueller said. RQ+ is used by most NCAA athletic programs.

Kunkemueller, a USRowing and World Rowing referee and one of the few people who has worked at the last 25 IRA championships—first as a referee and since 2015 as chief referee—is a past USRowing board member who rowed for Princeton.

Since NACRO requires all its referees to be USRowing officials, what’s the point?

Kunkemueller’s answer: NACRO allows colleges to have trained, high-quality officiating and the insurance coverage necessary to run regattas while avoiding USRowing requirements—notably, that they abide by U.S. Center for SafeSport rules, that regatta-sponsoring groups be organizational members of USRowing, that all athletes in a regatta be individual members, and that all coaches are USRowing-certified.

NACRO does require members to complete abuse-prevention training (SafeSport is acceptable) and a background check, she said.

USRowing requirements might work well at events for masters, juniors, and smaller collegiate programs, Kunkemueller said, but larger more established college programs have their own staffs and procedures to ensure safe, high-quality athletic experiences.

“Having to do both bogs down the works,” she said. “What colleges object to is outside organizations telling them how to deal with their employees.”

Kunkemueller said a decision by the IRA stewards led her to form NACRO. The decision was made in October, the same month she was named commissioner.

That decision, according to a memo to coaches Kunkemueller wrote at the time and that’s posted on the IRA website, says, “USRowing organizational membership is NOT required for an IRA member school to participate in IRA-run regattas.”

But that doesn’t mean the IRA or NACRO are “pulling people away from USRowing,” Kunkemueller contended.

“This is a parallel enterprise that serves a segment that USRowing has chosen to

exclude,” she said, by imposing requirements the schools don’t want to fulfill.

NACRO’s emergence, however, has put USRowing referees in an uncomfortable position, said Letcher Ross, chairman of USRowing’s Referee Committee.

“It’s unfortunate that we find ourselves caught between these factions that haven’t been able to find common ground without it coming to this,” said Ross, a referee for nearly 30 years.

“We are all committed to being USRowing referees because that is our sanctioning body. I don’t see that changing,” he said, pointing out that NACRO depends on the training and vetting that USRowing provides its officials.

He said he’s satisfied with USRowing’s insurance, which includes explicit coverage for such things as liability for errors and omissions in officiating.

NACRO “adds to my overhead,” he said, because it is “another organizational task you have to deal with” to officiate for some collegiate regattas.

Regardless of how NACRO grows or how many refs join so they can serve the sport and its athletes at some regattas, USRowing isn’t going anywhere, and referees who join NACRO will remain USRowing referees, Ross said.

USRowing membership is mandatory for teams competing in international regattas, such as England’s prestigious Henley Royal Regatta. World Rowing requires teams that compete in its events be in good standing with their national governing bodies.

Being the sports’ NGB also means USRowing is responsible for choosing and developing the U.S. National Team that competes in world championships, the Pan American Games, Olympic Games, and Paralympic Games—goals to which many top American college rowers aspire. As the NGB, USRowing also is subject to the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee’s rules and requirements, including SafeSport.

USRowing was created in 1982 by the merger of the National Association of Amateur Oarsmen, founded in 1872, and the National Women’s Rowing Association, established in 1963. TERRY GALVIN

After success on Wall Street, Meehan began “paying back” the sport he loved, enlisting other rowing buddies in finance and making donations with no strings attached.

Micheal J. “Mungo” Meehan 2d, a tireless and enthusiastic supporter of the sport of rowing, died Tuesday, April 15. He was 87.

The longtime president of the National Rowing Foundation and one of the most generous donors ever to American rowing, Mungo was inducted into the National Rowing Hall of Fame as a patron in 2022.

After graduating from the University of Pennsylvania in 1963, Mungo was approached by legendary Penn coach Joe Burk and asked to head the Friends of UPenn Rowing, recounted rowing historian Bill Miller. Mungo said it was “a thrill, the greatest honor of my life.”

After achieving success on Wall Street, Mungo began “paying back” the sport he loved, enlisting other rowing buddies in finance and making substantial donations with no strings attached.

“He always wanted the donations to be used where they were needed most,” said fellow NRF member Jamie Koven.

“Mungo was the heart and soul of the

NRF board for decades as our president. He brought a huge amount of enthusiasm for the U.S. National Team and organized his friends to provide support through the NRF,” said Koven, a former world champion in both the single (1997) and eight (1994).

“Decades of athletes had the chance to compete at the Worlds and Olympics due in large part to Mungo’s contributions. Mungo was a great friend of mine for the past 30 years and helped me every step of the way. We are really going to miss him.”

Mungo served as the president of the National Rowing Foundation for decades. Seeking to make the NRF more inclusive, he added women and lightweights to the board of directors and worked diligently to ensure that women’s rowing and lightweight rowing were treated fairly.

In the mid-1970s, with the late Frank Shields, he co-founded the Power Ten New York, Inc., a social and fundraising organization. He continued to row late in life, racing in masters events “until aching bones left me on the embankment.”

No. 1-ranked Texas won the JessopWhittier/Cal Cup Collegiate Invitational at the San Diego Crew Classic, topping a stacked field that including No. 5 Washington, No. 8 California, No. 20 Notre Dame, No. 23 Southern California, and No. 24 Washington State.

We expected some hard-fought races and close margins today, and that’s exactly what we got,” Texas head coach Dave O’Neill said after the Longhorns outlasted Washington to win by less than a second.

“We got exactly what we came here for: tight early-season racing at a big-event regatta,” said UW head coach Yasmin Farooq. We were really glad for the opportunity to race Cal in both the heat and the final and were excited and ready for some sideby-side action with Texas,” Farooq added. “The first and second varsity eights had strong races with many positive takeaways. The varsity four win was definitely gratifying.”

Cal’s men’s freshman eight won the varsity eight Cal Cup in morning racing before losing a close race to Club Nautico De San Juan in the afternoon in the open eight Anderson Borthwick Memorial Trophy.

With 423 entries from 93 programs competing in temperate conditions on San Diego’s Mission Bay, this year’s Crew Classic was the biggest and best yet, said executive director Bobbie Smith.

“We saw a record-breaking number of entries,” Smith said. “We hosted more races and on-the-water events than ever before, making this our most ambitious and exciting schedule to date. It was an exceptional year.”

Newport Aquatic Center raced to a clear victory over Saugatuck and Marin— second and third, respectively—in the women’s youth eight. Marin won the San Diego Rowing Club Cup for men’s youth eights by eight seconds over Norcal crew, with Newport Aquatic Center half a second back in third.

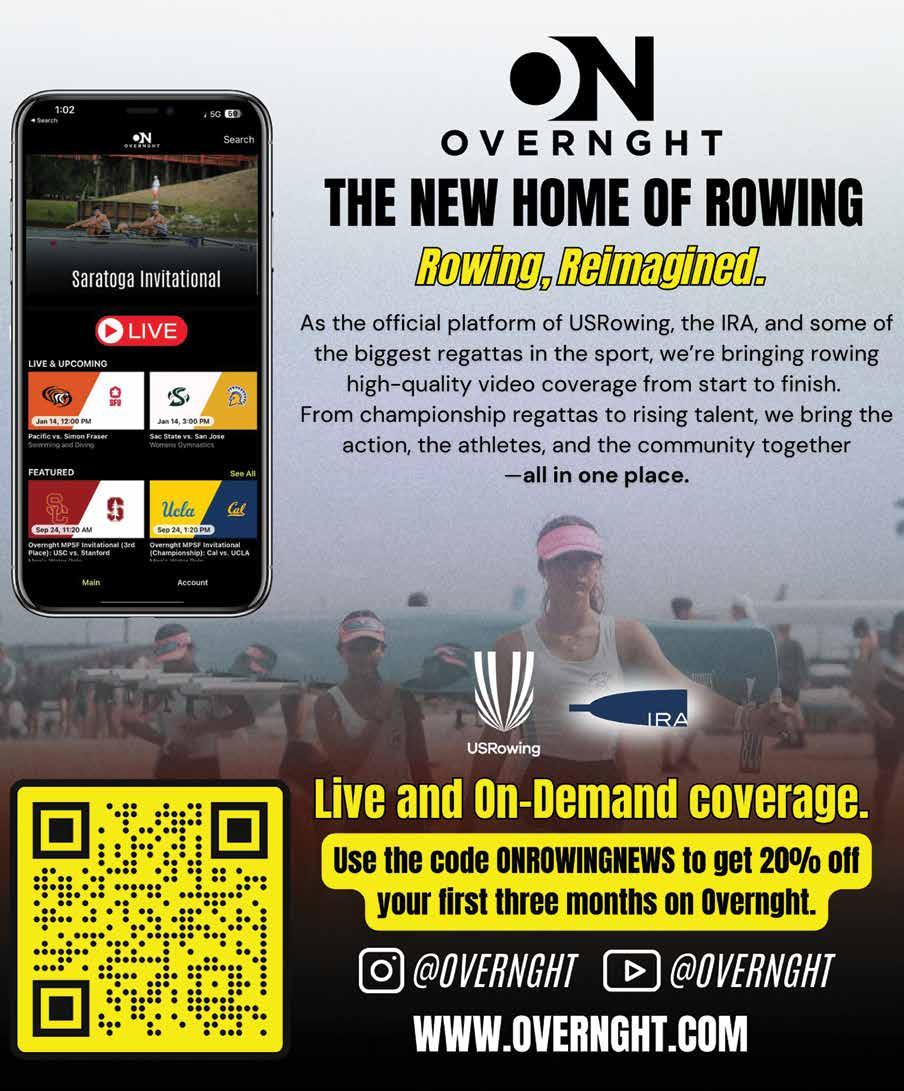

The live-sports streaming service that’s dedicated to increasing the visibility of Olympic sports aims to cover 40 regattas this year, including the IRA and all USRowing events.

Overnght, the online live-sports streaming platform, has signed new rowing events and added Olympic rowing champion Justin Best, Hydrow founder Bruce Smith, and Rowing Industry Trade Association chair Andrea Buch to its board of advisors.

Founded by former UCLA defensive lineman Kevin McReynolds, Overnght livestreamed 20 rowing events in 2024 and aims to double that number in 2025, including the IRA and New England Interscholastic Rowing Association championships and all USRowing regattas.

“Overnght is a live-sports streaming platform built to give Olympic sports—and the athletes, coaches, and communities behind them—the visibility they deserve,” McReynolds said.

The inspiration for Overnght grew out of seeing friends come home from the Olympics with medals, McReynolds said, and there was no spotlight or media infrastructure for sharing their performances.

“The future of sports media lies in serving communities with depth, storytelling, and experience, while aligning with the athletes—not just the algorithms.”

In March, Cal men’s rowing announced an exclusive streaming agreement with Overnght, which is also the official livestream partner of the Mountain Pacific Sports Federation, a successor to the Pac-12 athletic conference that Cal joined this year.

The inaugural MPSF Rowing Championship will take place May 17 and18 on California’s Lake Natoma and feature the men’s rowing programs formerly with the Pac-12—including defending IRA national champions Washington—plus rowing programs from the Western Sprints, including Gonzaga, Oregon State, San Diego, Santa Clara, and UC San Diego.

Overnght’s initial success came in water polo. Rowing is one of six Olympic sports—including artistic swimming, fencing, gymnastics, rugby, and swimming and diving—featured on the pay streaming service.

In March, Overnght announced that Hydrow founder Bruce Smith would join its board of advisors. A month later, Olympic champion Justin Best also joined the board. Smith founded Hydrow in 2018 and developed indoor rowing machines that show live outdoor video content. Previously, he led Community Rowing, Inc., and started VitalSpark, which provides AIdriven personalized motivation to help people achieve their fitness goals

A 2019 graduate of Drexel University, Best rowed two seat in the U.S. four that won gold at the Paris Olympics. A seventime U.S. National Team member— including junior, under 23, and senior teams—Best works as an analyst at Union Square Advisors, a technology-focused investment bank.

Andrea Buch has over 30 years of experience in rowing as an athlete, coach, and industry leader. She began rowing with Old Lyme Rowing Association/Blood Street Sculls in Connecticut before joining the inaugural recruiting class at the University of Kansas.

Her coaching career includes serving as an assistant coach and recruiting coordinator at Louisville and Syracuse as well as working with USRowing’s Junior National Team Development and Olympic Development camp programs. She also was the junior women’s head coach at Pocock Rowing Center in Seattle.

Besides coaching, Buch spent seven years at Pocock Racing Shells, rising to vice president of customer sales and support. Now, as senior director of production operations at Hydrow, she leads on-water

production and global content creation. Since 2020, she’s been on the Rowing Industry Trade Association board, of which she is currently chair.

Overnght pays regattas a share of the revenue from subscription sales—the full-year all-inclusive “premium plan” is $105—and, for some, offers yearly financial guarantees. Regattas use the money to pay for video production, which can cost tens of thousands of dollars.

McReynolds said Overnght’s strategy for rowing is based on eliminating three of the biggest barriers to the sport’s growth: no true media partner; no technical infrastructure for live video broadcasts; and limited financial resources.

“Overnght’s approach to rowing fundamentally differs from the major media companies and tech providers that disregarded it entirely,” McReynolds said. “We’re actively engaged with the community and understand what legacy means to rowing participants—from the athletes to the parents to the governing bodies.”

HOSR welcomes you back to Philadelphia October 25 & 26, 2025

Competition for Juniors, Collegiate, Masters, Veterans, Elite, Adaptive/Para, Corporate and Alumni.

Registration opens July 15th at RegattaCentral.

Purpose got us started. Passion keeps us going. Join us on the course for our 55th year.

When a masters rower had a heart attack at Nathan Benderson Park, everything was in place to save his life.

Darrel Davidson’s heart stopped and he pitched forward— unconscious, not breathing—after the eight in which he was racing crossed the finish line at the Sarasota Invitational Regatta in late February at Nathan Benderson Park.

Davidson’s heart attack occurred as he sprinted to the finish in a hotly contested masters race. It was the third race of the day for the retired carpenter from Vero Beach, who customarily rowed three times a week.

Because his feet were tied in the boat’s shoes, he didn’t fall out of the boat completely when he suddenly blacked out and pitched forward, his body half out of the boat.

With the help of other rowers in the eight, a park safety launch driver was able to hoist him out of the boat and get him to shore quickly.

One of the rowers in Davidson’s boat was Rodrigo Banegas, a Palm Beach orthopedic surgeon, who began chest compressions on the short ride to shore, where emergency medical personnel were waiting.

The emergency medicine specialists continued chest compressions, used a defibrillator, and administered oxygen and vasodilators to keep Davidson alive.

“The stars were aligned,” said Joanne Fava, chief medical officer at the busy rowing venue.

But the stars had to be there first, and NBP has a few of them. His survival was largely due to the park’s staff and its efforts to keep the venue safe for the tens of thousands of athletes who participate in events there yearly. Fava has been instrumental in those efforts since 2010, first as deputy to Dr. Valli Gambina, then as chief beginning in 2019.

“My focus at NBP has always been on

keeping our athletes safe both on and off the water,” said Fava, who has created medical plans and been part of support teams for sports events internationally, including Olympics qualifiers, in a variety of sports.

She said she employs best practices based on a national governing body’s requirements and tailors the number of medical staff and the amount and type of equipment to the size and conditions of each event.

The park, owned by Sarasota County and operated by the nonprofit Nathan Benderson Park Conservancy, holds dozens of events a year, many of them on the 2,000-meter, fully buoyed racecourse that has made it the top rowing venue in North America and one of the best in the world. Rowers competing in regattas there range from middle school students to athletes in their 80s.

NBP formed a Safety Squadron to check out and train launch drivers. The group, led by Mason Johnson, NBP programs and aquatic manager, emphasizes past boating experience in selecting people to train. Trainers stress safe boat handling and the need for teamwork with event officials, whether at rowing events or at the venue’s growing number of dragon boat and other paddling events, plus triathlons and open-water swimming competitions.

“It is a gift to have such well-trained boat drivers,” said Debbie Grossman, who has worked at many regattas at NBP and elsewhere in her 36 years as a USRowing referee. “In the unfortunate event of an emergency, the referees can feel confident

that the NBP launch drivers will know what to do.”

The Lakewood Ranch Medical Center, which is 10 miles away and specializes in cardiac care and dealing with heart attacks, was ready to receive Davidson before the ambulance had begun the 10-minute trip.

At the hospital, Davidson’s heart was restarted several times. The head of the cardio catheter lab was working that Sunday afternoon, and he and his team were able to clear the blockages that had shut down Davidson’s heart.

Davidson, who began rowing less than two years ago, suffered a heart attack in 2023 after getting home from a bicycle ride. Doctors found two blockages, but said they weren’t serious enough to require stents.

Davidson quit seeing cardiologists because they wanted to put him on a blood thinner and statin to lower his cholesterol.

At a masters regatta a year ago, he rowed in a race for the first time.

“At race pace, when you’re going all-out for 1,000 meters, it’s a whole different level of effort.”

Davidson, who turned 72 during 18 days of treatment and rehabilitation, surmised that his heart attack in the eight may have resulted from doing three races in one day.

“If I’d done only two …”

Terry Galvin is a longtime volunteer at Nathan Benderson Park and a member of its Safety Squadron

STORY BY ADAM KREEK

PHOTOS: KEVIN SCOTT

Rowing has a way of bringing clarity to life. Maybe it’s the rhythmic pull against resistance or the way the water refuses to yield unless you do the work.

For Kevin Scott, a man from the serene banks of the Gardon as it flows through Montfrin in southern France, rowing is more than a sport—it’s a philosophy of life. And in French Polynesia, he’s turned that philosophy into a force for generational change through sports entrepreneurship driven by values.

Scott’s rowing journey began at a humble club in Beaucaire, the same training ground that produced Olympic champion Adrian Hardy. A 2016 holiday to Tahiti, planned as a brief escape to teach rowing, changed his life. What began as a short trip turned into a permanent embrace of island life, thanks to Scott’s ability to

blend sport, education, and communitybuilding.

Scott adopted rowing during his teenage years when health challenges, including a growth-related illness and scoliosis, sidelined him temporarily from sports. Prescribed rowing as a low-impact form of rehabilitation, he quickly discovered its transformative power. The sport not only strengthened his body but also instilled discipline and resilience. These formative experiences fueled a passion for rowing as a vehicle for personal growth—one he now uses to empower others facing their own obstacles.

A Teacher with an Entrepreneurial Oar

Scott’s move to French Polynesia marked a turning point in his journey as a sports educator and innovator, as he channeled his personal lessons into

programs that change lives across the islands.

In France, Scott had worked with the French Rowing Federation, introducing students to ergometers and collaborating with prisoners, guards, and other unlikely rowers. In Tahiti, he found a blank slate. The local rowing club was sparse—barely any boats and no structured programs—yet Scott saw potential. His mother-in-law’s roots in the Marquesan Islands gave him a sense of belonging, and after two months of initial exploration, he met with local officials, crafted a strategic plan, and outlined how rowing could uplift both kids and communities.

Scott’s approach combined his background in sports education with keen entrepreneurial instincts. By his second year in Tahiti, he had transitioned from teaching as a physical educator to running ergometer

training classes full-time. He didn’t just teach rowing; he designed programs that were socially and financially sustainable. Schools provided free spaces, students used the ergometers during the day, and adults paid for affordable evening classes. The fees from the adult sessions helped subsidize the youth programs, creating a virtuous cycle of impact.

Rewriting Rowing’s Rules

French Polynesia, with its tradition of racing outriggers, might seem worlds apart from the flat-water sculling Scott once knew. Yet he didn’t try to change the culture; he adapted to it. Instead of clinging to traditions that made rowing in

Australia, to participate in the inaugural Oceania Youth Development Indoor and Beach Sprint Rowing Championships. Despite limited experience and less refined technique, the team demonstrated remarkable determination and raw power. Their aggressive passion was evident as they competed against more seasoned rowers from across Oceania. Notably, Teranihere Pater secured a silver medal in the U17 500-meter individual indoor rowing event, while Remine Tchang clinched gold, and Elikaï Manuel took silver in the same category. Additionally, the Polynesian team won gold in the mixed relay event, covering 4,491 meters in 16 minutes and surpassing their closest competitors by 143 meters.

France rigid and exclusive, Scott introduced inclusive programs.

Beginning with ergometers and then using fun, inclusive equipment like the Oar Board stand-up paddleboard rower, Scott created a bridge for on-water rowing. Parents who dropped off their kids were invited to join beginner-friendly classes. His message was clear: Rowing is for everyone, not just elite athletes. More adults pulling on ergometer chains led to the embrace of the program by more schools, where Scott introduced virtual rowing-machine competitions across the islands.

Scott wasn’t teaching just technique; he was cultivating a community. His programs nurtured middle-schoolers through fun fitness-focused activities on the ergometers and prepared high-schoolers for serious training. His ultimate vision? To send highperforming rowers overseas for universitylevel development, with the hope they’d return as community leaders and coaches.

Scott recently led a group of young athletes from French Polynesia to Sydney,

This experience not only highlighted the athletes’ physical prowess but also underscored the importance of technical finesse in rowing. Scott shows his commitment to nurturing these young talents by continuing to provide opportunities to compete internationally, thus fostering both their athletic and personal growth. The team’s achievements in Sydney were proof of their potential and the effectiveness of Scott’s coaching philosophy, which emphasizes passion and perseverance along with developing skills.

One of Scott’s most innovative moves was adopting the Oar Board, a portable rowing apparatus he discovered on Facebook. With these lightweight tools, he brought rowing to remote islands that lacked access to traditional boats or facilities. This made rowing more accessible and gave communities a new way to connect with their stunning natural surroundings. Scott’s entrepreneurial mindset made him a leading influencer on Kinomap, a platform offering interactive training videos

for indoor fitness enthusiasts. By filming nearly 200 GPS rowing sessions in French Polynesia, Scott has inspired a global audience, blending fitness with the beauty of the islands.

A significant aspect of Scott’s influence is his innovative use of the Oar Board, the inflatable, collapsible, portable rowing apparatus that transforms stand-up paddleboards into rowing boats. This clever device has enabled him to capture unique rowing experiences over the crystal-clear lagoons and reefs of Tahiti.

Scott’s mission to promote health and well-being across French Polynesia is as innovative as it is impactful. Obesity is common in this island paradise, and Scott uses rowing to teach kids the impact of their dietary choices. He provides a deck of cards showing various foods and their caloric density and challenges them to “row off” the calories on an ergometer.

The experience is eye-opening. Many kids are shocked by how difficult it is to row off the calories in a single candy bar. Scott doesn’t lecture them about the dangers of sugary drinks and junk food; instead, he lets the rowing experience speak for itself, proving that the oar can be a tool for transformation.

He punctuates the lesson by asking provocative questions, such as, “Who is closer to death? Me, a guy in my 40s, or you, kids in your teens?” This leads to a discussion about how exercise and diet can influence their health and longevity. By blending physical activity with experiential learning, Scott is educating and inspiring the next generation to adopt healthier, more mindful lifestyles.

For Scott, sports entrepreneurship is not about profit; it’s about purpose. By fostering a love of rowing among Tahitian youth, he’s planting seeds for a healthier, more connected future.

“Rowing taught me to embrace discomfort and grow through it,” he often reflects. And now, he’s sharing that lesson, one stroke at a time, with the next generation.

Unescorted and unsupported, the Maclean brothers aim to row 9,000 miles across the Pacific in four months, avoiding storms, cargo containers, hull-piercing marlin, and sore bottoms.

STORY

TERRY GALVIN

It sounds like the setup for a joke— “Three Scottish brothers decide to row across the Pacific Ocean”—because it seems so outlandish.

But it’s no joke. The brothers left the afternoon of Saturday, April 12, from Lima, Peru, on a 9,000-mile voyage to Australia.

Ewan, Jamie, and Lachlan Maclean, born in Edinburgh, are planning to cross the widest and emptiest part of the world’s largest body of water in a 30-foot boat that looks like a bath toy Jules Verne drew up, with only their muscles, skills, and wills to propel them across thousands of miles of open ocean.

Their expedition will be without escort or support. If disaster strikes, their only hope is that they’ll still have satellite communication and that a ship that happens to be in the region can be diverted in time. They’ll be well beyond the reach of the nearest rescue service.

They plan to reach their destination before the food they’re carrying runs out. The trip is expected to take 130 days—more than four months—at two to three miles per hour. The brothers plan to row two at a time in shifts of two to three hours, 24 hours a day, at a stroke rate in the mid 20s.

The Maclean brothers’ goals, beyond survival, are to set an elapsed time record for an unsupported human-powered crossing of the mid-Pacific and to raise one million pounds, or $1.2 million, to provide clean water for villages on an island off Africa.

When he was reached on a WhatsApp call in Peru, Jamie Maclean was putting vinyl sponsor names on their boat, named Rose Emily to honor a sister who died before birth.

The brothers—Ewan, 33, Jamie, 31, and Lachlan, 26—and their small team were preparing for the departure from Yacht Club Peruano in Callao in metropolitan Lima, the nation’s capital. It’s on the Pacific coast in La Punta, next to Club de Regatas Lima, which began as a rowing club in 1875.

They know what they’re getting into. Sort of.

The Pacific won’t be the first ocean the brothers have rowed across. They completed the 2019-20 Talisker Whisky Atlantic Challenge, now known as The World’s Toughest Row, but that route across the Atlantic from the Canary Islands to Antigua

was only 3,000 miles and took 35 days, nine hours, and nine minutes, according to the Ocean Rowing Society.

They finished in six fewer days than any other three-rower boat in the race’s history; theirs was the youngest crew to cross the Atlantic; and it was the first crossing of any ocean by three brothers. (Jamie called some of the records “low-hanging fruit”; most rowing expeditions have one, two, or four rowers and, well, they aren’t usually siblings.)

Although it was an organized event with 35 boats, it was no small undertaking. Surely, they already were experienced rowers who’d long dreamed of tackling such a challenge.

Nope.

Lachlan learned about the Talisker challenge in 2018. At that time, none of the brothers had rowed a boat with a sliding seat. Jamie’s reaction when Lachlan told him about it: “Wow. What an insane thing to do.” And when Ewan, the elder brother, learned what they were discussing, he immediately said, “There’s no chance you’re going to do this without me.”

Though not rowers, the brothers had “always been sporty,” Jamie said, playing rugby and running, among other athletic pursuits. Scotland has more than 11,600 miles of coastline, if you include its islands, and a long seafaring tradition. The brothers were born in Edinburgh but spent every summer and Easter in Nedd, a small fishing village. Nedd is in the northwest Highlands on the shore of Loch Nedd, one of the deep fissures in Scotland’s coast gouged out by Ice Age glaciers. Lachlan and Jamie live and train there now when they aren’t in Edinburgh visiting their father or off crossing oceans.

Growing up, they spent much of their time there puttering about in a small fishing boat that had an engine, Jamie said, which fostered a love for the water, a lust for adventure, and a feeling they could go anywhere together.

After deciding to do the Atlantic challenge, the brothers trained for 12 months by rowing, when they weren’t busy finding a boat, sponsors, and groups worthy of the money they hoped to raise. They chose Children First, a Scottish organization, and Feedback Madagascar, which works to provide clean water and

other aid to that island nation in the Indian Ocean off the southeast coast of Africa. They did a training row of about 200 miles from the Isle of Aaron to the Isle of Skye.

As a result of the Atlantic challenge, they raised 200,000 pounds, or more than $256,000. Because they had sponsors covering their expenses, all the money raised went to the charities. The trip had planted the idea of a bigger challenge even before they arrived in Antigua, something they had plenty of time to talk about as they spent a month together, day and night, on a small boat, Jamie said.

They are aiming to raise five times as much money from their Pacific row. Again, every bit of it will go to a charity, the Madagascar organization. The money would be enough to provide sources of clean water for more than 30,000 people, the Macleans said.

Their Pacific expedition was delayed by the pandemic, which was at its peak when they finished the Atlantic voyage. The lockdown “exchanged one kind of isolation for another,” Jamie said, “but it gave us a chance to reflect on what we wanted to do and how to do it.”

The time also allowed them to establish a nonprofit, the Maclean Foundation, to handle donations and grants.

They know this challenge is much tougher than their Atlantic crossing.

“We feel like we are taking as big a step into the unknown as we did with the Atlantic row, when we started from nothing,” Jamie said. “No one has done it on this route, this long, and unsupported.”

Coincidentally, two women rowers left the same boatyard in Peru on April 8 on nearly the same route. Miriam Payne, 24, and Jessica Rowe, 27, expected to take six months to reach Sidney, but a broken rudder forced them back. The brothers spent time with the duo’s Seas the Day ocean-rowing team, exchanging tips and advice.

The boat

People have rowed across vast expanses of open water long enough to hone the design of their boats and, in recent years, to take advantage of such advanced materials as carbon fiber. The goal is to be light enough to be moved by humans with oars and strong enough to survive long exposure

to rough seas. The boats are unlike other seagoing craft because they must have a section of deck low enough for oar blades to reach the water.

A couple of companies have emerged to build such vessels. For their Atlantic crossing, the brothers used a boat made by Rannoch Adventure, which has a long record of building ocean rowboats. For their latest challenge, the brothers are using a new craft designed and built by Mark Slats, a Dutch ocean rower who founded The Ocean Rowing Co., based in Wassenaar, the Netherlands. Slats and Kai Wiedmer were first to finish of 21 teams in the 2020 Talisker Challenge, setting an elapsed-time record of 32 days, 23 hours, and 13 minutes in a boat Slats designed and built.

Rose Emily is a bit over 30 feet long and six feet wide and has three rowing positions with sliding seats. It weighs just over 600 pounds, and its bottom is flat for stability and to help it surf when the waves are coming from the right direction.

“The boat is state-of-the-art and incredibly strong and light, allowing us to keep up a good pace and carry enough food,” Jamie said. It cost 140,000 euros, or about $157,000.

It is equipped with solar arrays capable of generating 800 watts and three lithiumion batteries. Power is needed to run a small water maker, an autopilot, and navigation and communication equipment. The boat has areas of double hull with builtin bladders to hold drinking water. The electronics, some of it provided by a sponsor, Zelim, include AIS (an automatic shipidentification and tracking system), EPIRBs (emergency position-indicating radio beacons activated manually or when they become wet), and man-overboard alarms.

The cabin in the stern is devoted primarily to equipment, because that’s where the rudder, autohelm, and chart-plotter are. The bow cabin is primarily for storage. The brothers can sleep in either cabin.

The freeze-dried food—more than 1,300 pounds of it—will be stored in the bow as well as below the rowing deck, strapped in waterproof bags on top of that deck, and wherever else it can fit. Roughly half the food was prepared by the brothers with the aim of not only nutrition but also sufficient variety to stave off boredom and help boost their spirits.

The boat also will carry about 500 pounds of equipment, clothes, and other necessities. If that sounds like a lot for a 600-pound boat to carry safely, the Rose Emily actually becomes more stable as it sits lower in the water, Jamie said.

You could say the accommodations are spartan. They will use a bucket for a toilet and won’t use precious water to bathe. “You forget what clean smells like,” Jamie said.

Problems they could encounter include dangers an outsider might expect, such as storms, and many that are less obvious, such as hitting barely submerged cargo containers and eluding blue marlin that poke holes in hulls with their three-foot spear-like bills.

Rose Emily’s most vulnerable areas have an extra layer of carbon fiber to stop penetration by the 16-foot fish slashing their bills at prey attracted by the ecosystem created beneath the slowly moving boat. The vessel is designed to survive a capsize because its hatches are watertight and the crew is always tethered to it. The flat-bottom design should help it pass over everything that isn’t on the surface, where the hope is that it will be visible, and its slow speed should minimize damage if it strikes anything.

Pumps will enable the crew to empty one or even both cabins of water so the boat rights itself should a wave hit during the brief times watertight hatches are open, Jamie said. They have extensive medical supplies, have trained how to use them, and have a doctor with expedition training available to consult at all times via satellite communications.

A member of the crew will have to get out of the boat once a week to clean marine life from the bottom of their vessel so its additional friction doesn’t slow their progress, Jamie said. Overall, the possibility of a shark attack during these marine spacewalks outside the relative safety of their craft is less a worry than a wounded butt while rowing.

“You might encounter a shark or a storm but you know for certain that your body will be stressed in an intense, alien environment,” he said. “The greatest risk is not keeping on top of a sore on your bum that means you can’t row.”

Like all rowers, they have toughened their hands by exposing them to the friction and pressure of oar handles. They also have tested different seats and seat materials with different points of contact as well as gel pads and other ways to lessen problems caused by friction, pressure, salt, and sweat. A company called Formlabs Inc. helped 3D-print individually molded rowing seats.

The best prevention is “personal maintenance,” Jamie said. It’s crucial to notice problem areas quickly and act immediately to keep them from getting worse.

Ewan, the eldest brother, is an engineer who worked for Dyson, known for its innovative design of household appliances. He’s leading the technical aspect of the expedition.

Jamie is a professional designer-builder whose practical approach pays dividends.

Lachlan, who has a degree in philosophy from the University of Glasgow, is a talented chef and led the selection and preparation of the food they’re taking. He also tends to be the brothers’ moral compass and mediator, Jamie said, and manages the Maclean Foundation.

The brothers have trained intensively for months, rowing and working out, practicing capsize recovery, and consulting with Canadian extreme-sport expert Chloë Lanthier.

Family members don’t always make the best roommates, let alone teammates in close quarters and under stress for months. The Macleans are different, which is a good thing since “we haven’t managed to talk our friends into it,” Jamie said.

After the Atlantic event, Jamie said, they saw the harm done when other teams encountered conflicts.

“We thought a big factor was whether the people had been honest with their teammates. Were they racing or on an expedition? The worst time to discuss such things is when you are heavily sleepdeprived.”

“We have similar outlooks on life and grew up in a similar environment,” he said. “We have good team dynamics.”

The brothers know from their Atlantic row that they’ll be subjected to huge

emotional waves as well as physical ones.

“Day by day, you have a rollercoaster of everything from the extreme high of feeling good and going fast and strong and whole to focusing on still having thousands of miles to go.”

It’s what Jamie called “Type 2 fun.”

“In the moment, it is not enjoyable, but it’s the kind of thing, when it’s all said and done, that shifts your perspective in a positive way,” he explained.

“We like to combine our passions with a challenge and a purpose,” he said.

Their motivation —to supply clean water to people, supporting their agriculture and changing their lives, health, and general quality of life in big ways—is stronger now because they all have visited Madagascar twice to see the money at work.

“When we began our Atlantic challenge, it was a bit abstract. Over the last two years, we’ve grown more aware and seen the actual results on the villages. So that’s the motivation we will all draw upon over the next five months.”

The brothers’ progress can be followed by going to the expedition’s website, themacleanbrothers.com, which has a near real-time map and a place to sign up for daily updates and to donate.

GALVIN spent his professional life as a writer, editor, and designer at newspapers, largely in the U.S. Virgin Islands and in Sarasota. He learned to row as an adult and covered the development of Nathan Benderson Park while he was business editor at the Sarasota HeraldTribune. He also has volunteered at the park as a launch driver since its inception.

ALL AVAILABLE WITH YOUR TEAM LOGO AT NO EXTRA CHARGE (MINIMUM 12)

UNITED STATES ROWING UV

VAPOR LONG SLEEVE $40

WHITE/OARLOCK ON BACK

NAVY/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

RED/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

PERFORMANCE LONG SLEEVES

PERFORMANCE T-SHIRTS

PERFORMANCE TANKS

Order any 12 performance shirts, hooded sweatshirts, or sweatpants and email your logo to teamorders@rowingcatalog.com and get your items with your logo at no additional cost!

2-layer neck gaiters will protect you throughout the seasons. Stretchguard fabric with extreme 4-way stretch for optimal comfort. Super soft, silky feel that is lightweight and breathable. 100% performance fabric, washable and reusable.

$20

Plotting when and how to peak is more art than science, and always the overriding aim should be to help team members build confidence, not plunge them into a hole.

When the rowing season approaches its finale—the championships—it’s time for the coach to analyze the training plan one last time to make adjustments to achieve the best results possible.

When done correctly, the performance of the team will get a boost and the season will reach its peak. The consequence of not taking the right steps is that the final races of the season will fail to meet expectations.

At this point in the season, a large amount of information has been gathered about the team’s performance level. The development of each rower’s physiological capacity during the preparation phase was documented through various ergometer and perhaps even laboratory tests.

The athletes underwent the process of being selected for various crews, which were then welded together in technical sessions. Technical modifications helped with boat balance and crew coordination that improved the boat’s run. The athletes

discovered their racing stroke rate and learned different tactical maneuvers. All this led to progress in the right direction. In time trials and races, the rowers were able to determine just how highly they could perform.

The aim in the final weeks of the rowing season is to bring the team’s performance to a peak. Physiological improvement is unlikely now since there’s no time for aerobic and strength gains. If done correctly, however, small gains can be made in anaerobic capacity, and technique still can be refined.

In this phase, the most important thing to work on is confidence—instilling the conviction in your rowers that they can rise to the occasion and achieve their goals

Confidence grows when the team “clicks” and begins feeling that the boat is moving well and that different boat speeds can be sustained in a way that seems light and easy. Other manifestations are improved training speeds and race results, boathouse harmony, soaring morale, and a

winning attitude.

By now, rowers are aware keenly of the coach’s feedback and sensitive to its nuances. Feedback that emphasizes improvement reinforces your athletes’ faith in their own perceptions. Criticism about things the team still needs to work on can be turned into optimism if communicated correctly and converted to progress.

The coach also must show confidence in the team and appreciation for all they’ve accomplished. All testing of equipment and various race strategies must be completed, and training sessions must reflect and support relevant decisions.

For example, the crew needs to execute, without hesitation, the agreedupon effort and stroke-rate sequence at the beginning of every training session. Similarly, rigging measures the crew has decided on in certain wind conditions must be applied in the same circumstances during practice. Frantic discussion of different race strategies or desperate rigging changes before training—or worse, before

racing—undermine the confidence of your rowers.

There have been times when drastic changes were made just before and even during championship races, and the outcome was happy. At the 1992 Olympics, the Canadian men’s eight changed their stroke seat at the last minute to win the gold medal. And let’s not forget the famous mutiny at the 1987 Boat Race, when half the reserve team was lifted into the first boat only to win against all odds. Both bold moves were exceptional decisions by experienced coaches.

In the final weeks before the last race, every training session must be planned carefully. A coach must weigh the still-required training loads against the necessity and likelihood of recovery. Can physiological progress still be made or will a longer recovery phase be more beneficial? Rowers gain strength from believing the coach is responding to their individual situation and addressing their specific needs.

In the end, plotting when and how to peak is more art than science, and always the overriding aim should be to help team members build confidence, not plunge them into a hole. One way to achieve this is to switch from long practices to short highintensity sessions.

When the goal is simply unachievable because of injuries or dominating competition, there’s still time to introduce restorative measures that can put the team on a positive path. Sometimes that means adjusting goals so they’re more realistic—a delicate endeavor because it requires maintaining confidence and not destroying hope. The new goals must be significant and exciting enough to ignite a fresh burst of enthusiasm to work hard for the last part of the season or the final race.

The last few weeks before a championship are difficult for a coach, and this is when experience and composure are crucial. The counsel of a wise mentor can help the coach make sound decisions. Sometimes an outsider sees things a coach misses, and all of us need encouragement and moral support.

Your rowers should know the race plan and where to make a move. That way, if the CoxBox goes out or if a novice coxswain must focus on steering, they can proceed confidently.

As we approach the championship season, let’s hope you’ve prepared for your crew to work like a well-oiled machine. It’s also wise to prepare for a race day when a wrench gets thrown into that machine and things don’t go according to plan.

The first thing to prepare for is the most common equipment issue for boats re-rigged at the racecourse: something that hasn’t been tightened fully.

Beyond checking the nuts and bolts after rigging, it’s also smart to stop during your on-the-water warmup and have your rowers check everything at their station that can come loose— tracks, footplate, oarlocks, etc. Make sure you have the necessary wrenches, washers, and nuts in case something is loose or missing.

If something more serious happens after launch, flag down an official. Regatta officials want to get all the boats to the start line for fair racing, and they may be able to help arrange a quick repair. In any case, always let an official know what’s happening so you’re not penalized for being late to the line. Not

every equipment failure will be fixable by you, so don’t hesitate to ask for help.

The second thing to prepare for is an electronic failure. As good as these systems are, they aren’t perfect. If you cox long enough, you’ll lose your audio at an inopportune moment. As with most things in coxing, don’t panic. Check all the plug connectors when you can, but don’t sacrifice your steering to do so. Keep coxing stern pair and get only the most vital information back to the rest of your boat.

It’s good to have a conversation with your rowers beforehand about what to do when this happens.

“Make sure that going into a race the coxswain and the rowers are crystal clear on where moves are and what the race plan is. That way, the rowers always know what to do if the CoxBox goes out or if a novice coxswain needs to focus on steering,” said Emilie Gross, a former Michigan State coxswain who coaches crew at Duke University.

It’s also good to rehearse what happens if the audio does go out. Practice not having a fully working CoxBox especially around the start and sprint, as changing rates and rhythms during

these phases make losing audio more problematic. It’s not something you and your crew need to do often, but doing it once or twice will enable your rowers to proceed confidently if they do lose your voice during racing.

If you’re a novice coxswain or in a novice boat, you should practice recovering from a crab or a missed stroke. As with the other situations, make sure your tone is calm and controlled.

For a small digger, your rowers may feel a disturbance but won’t know what happened, so re-establish the rhythm and reassure your rowers that you’re still on your race plan.

If you have a true boat-stopping crab—the kind that can turn the boat sideways in your lane—you may need to call the boat to stop, lean away so the rower in question can pop her oar out of the water, and then collect your boat back together. The adrenaline of the situation can either fuel a great recovery move or make your rowers frantic. As a coxswain, it’s your job to ensure it’s the former.

Whether a crab or a steering mishap, it’s wise to establish a call for your boat to come back together, something everyone recognizes immediately.

“Get them all on the same page for a technical call that will help them relax a little should anything go wrong, and define what that call means they each need to focus on,” Gross said.“The coxswain says the word, and on the next stroke, the focus is united on that spot, away from whatever distractions are happening outside the boat.”

With proper preparation, you shouldn’t encounter these situations often. But there’s nothing more satisfying for a coxswain than being able to bring a boat back together during one of these moments. If you can do that, you won’t need to practice for every contingency. Regardless of what happens, you’ll have the skills to respond under pressure.

Helping rowers worldwide get scholorships

Helping high school rowers and families navigate the university recruiting process- Coaches and parent groups reach out to us!

Robbie Consulting will meet your team, coaches and parents at your home club or school. Go to www. robbieconsulting.com to get in touch and schedule a visit

“His assistance was essential to get prepared for such a big step and to get to know the school and team I would compete for.”

www.robbieconsulting.com

1-614-330-2879 • Robbie@robbieconsulting.com

Practice is more than just the repetition of a movement; it should involve mastering specific tasks. TRAINING

Whether you’re teaching a Learn to Row program or preparing a crew for a championship race, multiple types of practice can make training sessions more effective. Here are six modes of practice that we use commonly when we coach, learn, or receive instruction.

Learning by doing stresses the active participation of the athlete. Practice is more than just the repetition of a movement; it should involve mastering specific tasks. Example: A novice sculler is taught to move the blade from feathered to squared, then row in a circle with one oar. When a rower learns through trial and error rather than guidance, it’s discovery learning. A goal may be to reduce the level of guidance a sculler or crew needs to perform a particular task. Example: Our novice learns how to adjust foot stretchers and to put the oars in correctly to get ready to scull but realizes when a mistake is made.

Working on one skill at a time is blocked practice. In early stages of learning, blocked practice is slightly more effective than random practice because an athlete concentrates on one thing at a time. Once the skill has been performed

successfully, however, random practice— introducing variety and challenge— provides more motor-learning retention.

Practicing racing starts by repeating the first stroke several times, then progressing to the first two strokes up to the first five strokes, is blocked practice. Random practice is practicing the full racing start sequence in various weather conditions.

Part-task and whole-task practice are equivalent to rowing’s part-stroke and whole-stroke. The stroke is taught as separate elements and reinforced with drills focused on that specific detail. Part-stroke includes drills with shorter slides, too. A continuous part-slide sequence evolves into a whole full stroke.

Practice stroke components (drills) as well as the whole cycle (full strokes) during the same session to advance skills from one outing to the next.

People choose foods based more on taste than healthfulness. There’s no such thing as a “good” or “bad” food. Rather, there’s a balanced or an unbalanced diet.

“Ieat way too many chips, even though I know they are bad for me”

“I get into the cookies all the time. I think I’m addicted to sugar.”

“I’m tempted to try GLP-1 weight-loss drugs. I’ve heard they put an end to food noise.”

We live in a tough food environment. I hear many athletes talk about food as if it is a drug that they try not to eat. You know:

“I try to stay away from bread.”

“I don’t keep ice cream in the house.”

“I don’t do pasta.”

I also hear athletes complain about “feeling hungry all the time,” eating “everything in sight” upon arriving home after work or school, and confessing they binge-eat a few times a week.

These athletes often blame ultraprocessed foods for being addictive; TV ads and social media for being triggers for food binges; and their own personality quirks for their obsession with food. Many express frustration at their lack of control over alluring ultra-processed snacks.

A paradox is that some of these snackattacking athletes track the healthfulness of their snacks on apps such as Yuka. Yuka judges a food based on a red-yellow-green light system. Does knowing a snack’s redlight ranking deter indulging? Generally not.

People choose foods based more on taste than healthfulness. Apps that rank foods as being “good” or “bad”miss an important point: There’s no such thing as a “good” or “bad” food. Rather, there’s a balanced or an unbalanced diet. Example: Lance’s ToastChee Peanut Butter crackers have a red-light (bad) ranking. But if you

or visit www.roylerow.com.

assess their 220 calories as part of an overall nutrient-dense 2,400-calorie diet, they have minimal negative impact.

That said, too many “bad” foods can indeed take their toll on health. Routinely devouring several packets of those crackers for dinner because you’ve gotten too hungry to cook a meal is self-sabotaging.

What is the solution to highly palatable ultra-processed snack foods, food cravings, and food noise? My simple suggestion is to stop snacking and replace those calories with a real meal, such as a second breakfast or a second lunch.

Meals should be hearty enough to keep you satiated for four hours. Hence, a rower who gets up at 5 a.m., trains, then eats a 7 a.m. breakfast will be ready for an early lunch by 10 or 11. a.m, followed by a second lunch at 3 in the afternoon. Instead of snacking on highly palatable foods with low nutritional value to “hold you over” to lunch or dinner, eat a real meal!

Being hungry at 9 a.m., after having eaten breakfast at 7, means you didn’t eat enough breakfast. Hence, you end up hankering for something to snack on. If the snack is healthful, no problem. But if it’s a pastry, think again. Eating enough wholesome food at meals curbs the hankering for quick energy (sweets), fats (concentrated calories), and convenient seemingly “addictive” ultra-processed snacks.

High-school rowers (and others) who train at 4 in the afternoon need a good breakfast, a hearty school lunch at 11ish, and an after-school second (lighter) lunch at 2:30ish to energize them for the workout. The second lunch will not only improve

their stamina and mood but also displace the post-exercise food frenzy of “eating everything in sight” that occurs when a rower gets too hungry.

Hunger is a major trigger for many food problems, including food noise, cravings for sweets, food “addictions” (a debatable claim), and eating too much junk food. When you know what you “should” eat but just don’t eat it (and instead devour the whole bag of whatever), it’s likely you’ve become way too hungry.

Now hear this: Hunger is a physiological request for food and appears in the form of incessant food thoughts, a.k.a. food noise. If we didn’t think about food, we would never think to eat. Rowers who disregard their body’s request for food can end up getting too hungry, which can lead to devouring lots of highly palatable, ultra-processed, nutrient-poor snacks (chips, cookies, candy).

Some obese people do have a genetically driven “big appetite” and have to work hard to control their food intake. For them, a GLP-1 weight-loss drug (Wegovy, ZepBound, Ozempic) seems to calm their appetite and put an end to food noise. But the majority of athletes need to front-load enough calories to prevent hunger, curb their appetite, reduce food cravings, and put an end to overindulging.

A key to managing hunger is to learn how many calories you’re supposed to eat, then divide the calories into four (more or less) even-sized meals. For a female rower, that could be four meals of 600 to 700 calories; for a larger male athlete, perhaps four meals of 800 to 900 calories. (Suggestion: Consult with a

sports nutritionist/registered dietitian to determine your calorie needs and help you create an effective meal plan.)

In my experience, most athletes eat far less than 600 to 800 calories at breakfast (and hence hanker for midmorning sweets). They may or may not eat 600 to 800 calories at lunch (a skimpy salad doesn’t do the job!). By 4, after having tried to stay away from snacks most of the afternoon, they’ve become too hungry and succumb to a snack attack. If only they had enjoyed a second lunch (peanut butter-banana sandwich) at 3 when they first began to think about food, they could have avoided this dietary disaster.

While front-loading calories sounds simple, it actually can be hard for rowers who fear they’ll eat just as much at night and end up gaining undesired body fat. Yet those willing to experiment with a four-meal food plan report to me:

• “My second breakfast/early lunch (bagel + peanut butter) keeps me away from mid-morning sweets. It’s nice to feel perkier all morning and not ruminate about food all the time.”

• “My second lunch is a game changer. I no longer crave chips or sweets in the afternoon. At 3, I enjoy 500 calories of an apple + cheese + crackers. I arrive home in a much better mood after work.”

• “By having a bigger breakfast, lunch, and second lunch, I curb my evening appetite. I no longer even want a huge dinner; I’m content to enjoy a lighter meal. I’m losing weight—while I’m sleeping. This is far preferable to my previous attempts to lose weight during training. The food noise in my head has gone away. And best of all, I feel better about my eating.”

Are you ready to experiment with eating four daytime meals that adequately support your active lifestyle? Be curious and enjoy the benefits: fewer cravings for sweets, more energy, and peace with food. Sports nutritionist NANCY CLARK, M.S., R.D., counsels both casual and competitive athletes in the Boston area (Newton; 617-795-1875). Her best-selling Nancy Clark’s Sports Nutrition Guidebook can help you eat to win. For more information, visit NancyClarkRD.com.

An important aspect of the recruiting journey is realizing that your personal timeline may not align with those of the coaches or programs that interest you.

Afew months ago, I emphasized a simple but powerful message: The time is now to begin the collegerowing recruiting process. That message remains just as important today. Early preparation is not only smart, it’s essential.

For student-athletes in the ninth or 10th grade who are just beginning their journey with a local rowing club or highschool team, now is the perfect time to lay the groundwork. This guidance is equally valuable for both athletes and their families as they prepare for the path ahead.

Begin

One of the first concrete steps you can take is registering with the NCAA Eligibility Center. Doing so will familiarize you with the core academic courses required for collegiate eligibility. Understanding these requirements early ensures there are no surprises later in your high-school career.

While NCAA rules restrict official and unofficial campus visits until junior year, ninth and 10th graders can and should begin researching programs. Begin building a list of colleges that interest you, and don’t be afraid if that list is long. It’s a starting point. Revisit your list every few weeks, adding new programs and removing others as your interests evolve and your understanding of different schools deepens.

As the summer before your junior year approaches (when communication with college coaches begins officially), it’s important to stay organized. Move deliberately. Take detailed notes on every conversation, email, or piece of advice you receive from programs. Develop a system that allows you to track each school’s culture, coaching staff, team dynamic, and academic offerings. At this stage, it’s helpful to divide

your list into a top and bottom half to focus your energy.

When you reach the point of scheduling official (paid) and unofficial (unpaid) visits, try to narrow your focus to your top four or five programs. This part of the process can be time-consuming, and investing your time wisely is crucial. Deep engagement with a few schools is often more productive than spreading your attention across too many.

One of the most important, yet often overlooked, aspects of the recruiting journey is understanding that your personal timeline may not align with those of the coaches or programs you’re speaking with. Especially during your junior year, don’t be afraid to communicate your goals and timing clearly. Transparency helps both sides navigate the process more effectively.

If you’re currently a junior and wondering whether you’ve missed your window, the answer is a resounding no. But the time to get organized is now. Create a structured plan, understand your priorities, and move forward with purpose.

Every university operates on its own recruiting schedule. Some programs may extend offers during junior year, while others wait until the fall of senior year. Tough decisions will arise, and it’s wise to prepare in advance. For example, know how you’ll respond to an offer from your second-choice school before hearing back from your top choice. This kind of strategic thinking will serve you well.

Recruiting is both exciting and challenging. With preparation, honesty, and a clear plan, you can navigate it with confidence. Whether you’re just launching your high-school rowing journey or already deep in the process, remember: The time is always now to take the next step.

Take the pressure off each individual day and keep the focus on the big picture—the season-long goal, four-year athlete development, career-long coach development.

Things don’t always go well. In fact, they go well only about a third of the time, I’d argue. And that’s right on track for achieving greatness.

We’ve all be there. The team pulls a big erg test and the results are…fine. Some big PR’s, some disappointments, plenty of people in the middle. Or your varsity eight follows up a great session on the water with a few days of mediocre rowing and a downright bad row thrown in, too. Who you thought was your top rower gets smoked in a seat race.

It’s easy to get down on yourself, your team, your training plan, when these things happen. We want our team, and ourselves, to be constantly building momentum. We want performance to be progressive, if not linear. But that’s not realistic, or even desirable—according to the Rule of Thirds.

Alexi Pappas, Olympic runner and artist, introduced me to this idea several years ago in her book, Bravey. After a bad training session in the lead-up to the 2016 Olympics, Pappas’s coach Ian Dobson, an Olympian himself, counseled her not to

worry.

“When you’re chasing a big goal,” he explained, “you’re supposed to feel good a third of the time, OK a third of the time, and crappy a third of the time.”