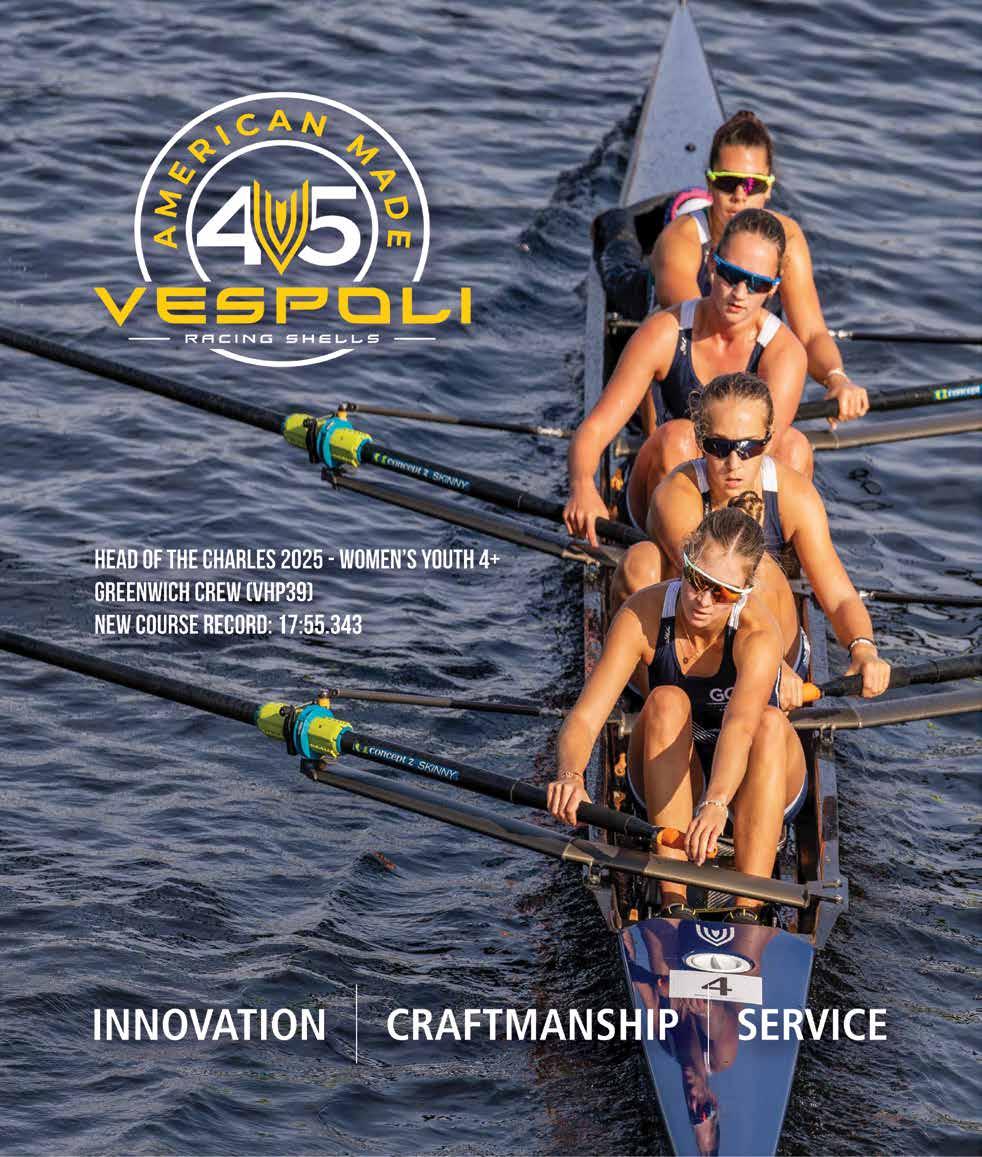

Focused on Winning

6 Course Records

23 Event Wins 70+ Podiums

Focused on Winning

6 Course Records

23 Event Wins 70+ Podiums

Maureen Harriman won her Women’s Veteran Singles

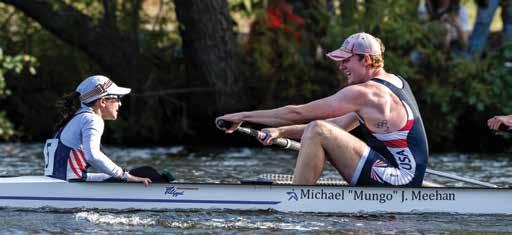

Lightweight Cooper Tuckerman switched into a Phantom 25 after rowing a different brand boat in 2024 and was 30 seconds closer to repeat winner, Finn Hamill. An impressive 4th place both years, Cooper was 47 seconds behind Hamill in 2024 and only 17 seconds back this year, rowing the Phantom 25.

Chip Davis PUBLISHER & EDITOR

Chris Pratt ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

Vinaya Shenoy ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Art Carey ASSISTANT EDITOR

Ian Parish ASSOCIATE

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Andy Anderson | Nancy Clark

Martin Cross | Mike Jensen | Volker Nolte

Marlene Royle | Robbie Tenenbaum

Madeline Davis Tully | Hannah Woodruff

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Jim Aulenback | Steve Aulenback

Julia Kowacic | Katie Lane | Karon Phillips

Patrick White | Amy Wilton | Lisa Worthy

MAILING ADDRESS

Editorial, Advertising, & Subscriptions PO Box 831 Hanover, NH 03755, USA (603) 643-8476

ROWING NEWS is published 12 times a year between January and December. by The Independent Rowing News, Inc, PO Box 831, Hanover, NH 03755 Contributions of news, articles, and photographs are welcome. Unless otherwise requested, submitted materials become the property of The Independent Rowing News, Inc., PO Box 831, Hanover, NH 03755. Opinions expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect those of ROWING NEWS and associates. Periodical Postage paid at Hanover, NH 03755 and additional locations. Canada Post IPM Publication Mail Agreement No. 40834009 Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Express Messenger International Post Office Box 25058 London BRC, Ontario, Canada N6C 6A8.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: ROWING NEWS PO Box 831, Hanover, NH 03755. ISSN number 1548-694X

ROWING NEWS and the OARLOCK LOGO are trademarks of The Independent Rowing News, Inc. Founded in 1994

©2025 The Independent Rowing News, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission prohibited.

Michelle Sechser, Will Porter, and the U.S. National Team women’s four achieved what the sport is all about: crossing the line first in the most important race of the year.

BY CHIP DAVIS

Women’s rowing at Tufts had been rising in NCAA Division III. Then Lily Siddall, at age 29, was asked to take it over the top.

BY MIKE JENSEN

DEPARTMENTS

News World Rowing Beach Sprint Finals

Race Reports Head of the Hooch, Head of the Schuylkill, Head of the Lake, Princeton 3-Mile Chase

Sports Science The Pause That Refreshes

Coxing Minister of Information

Recruiting I Want to Row in College

Fuel Advice You Can Trust

Training The Regeneration Phase

Coach Development Does it Make the Boat Faster?

CHIP DAVIS

Rowing is not an expensive sport. Often for free, you can hop on an erg (a.k.a. “indoor rower”) at practically any gym, CrossFit box, or YMCA, with no instruction, training, or prior experience, and just row.

If, like most of us, your first rowing experience comes in a school or club setting, the boats, oars, electronics, and coaching are all provided—that is, paid for already by others (and used by many, many more). Even if you start from scratch with the best brand-new equipment, you can have a Concept2 RowErg, the standard for our sport both indoor and out, delivered to you for about a thousand bucks. Try buying Olympic-level equipment in any other racing sport, or starting for free in any other NCAA Division I championship sport, before repeating the myth that rowing is “so expensive.”

Rowing is also not complicated—first one across the line wins, period.

Rowing is also not complicated—first one across the line wins, period, whether it’s the classic form of rowing, the oldest intercollegiate sport both in the world and in the U.S. (Oxford-Cambridge, 1829 and Harvard-Yale, 1852) or the newest Olympic sport of Beach Sprints (see page 25), which is proving to be a terrific hybrid—both not expensive (World Rowing provides standardized equipment for competitors on site) and not complicated (the start/finish line and entire racecourse are visible to all spectators—it’s literally a day at the beach).

So it’s fitting that we celebrate the best of our sport in 2025 in the same issue as we deliver Martin Cross’s authoritative coverage of this year’s World Rowing Beach Sprints Final, the world championship of rowing’s newest attraction.

In each category—boat, coach, and athlete—we’ve selected deserving recipients as well as a number of honorable mentions, all of whom achieved the same feat in 2025: They crossed the line first.

$445 $495

Large Configurable Display (2, 4 and 6 fields)

Optional Wireless Impeller & Accessories

Easy Data Transfer via the DataFlow App

Independent review of the ActiveSpeed - Sander Roosendaal, founder of the rowing analytics site rowsandall.com, takes a deep dive into the ActiveSpeed.

SCAN FOR SPECIAL HOTELS RATES

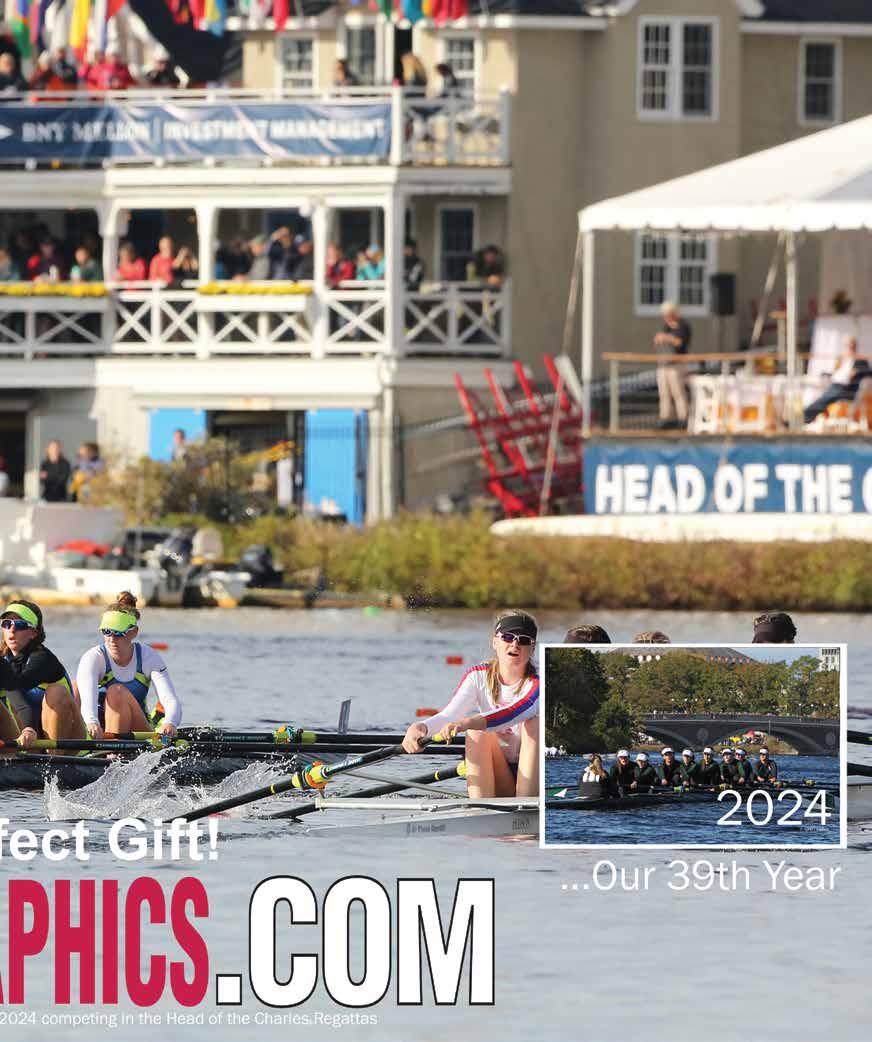

La Salle (left) clashed with MIT (right) in the men’s collegiate eights event at the Head of the Charles after swinging wide at the Eliot Bridge turn and into overtaking MIT’s path, hitting the buoys marking the closed arch and then rowing into the path of Williams. Two minutes worth of penalties relegated the Explorers to 42nd—and last—place.

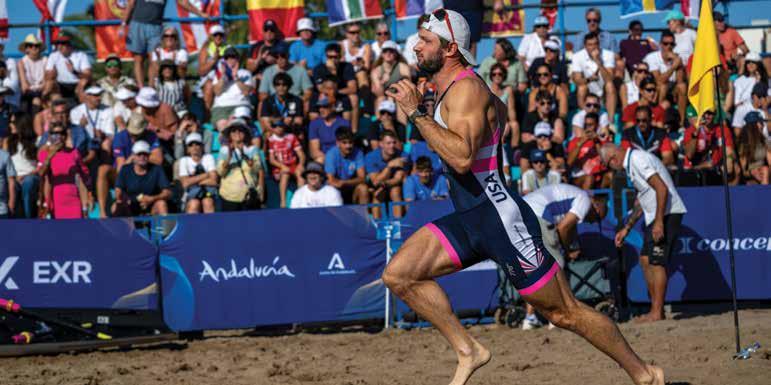

American Chris Bak became the most successful Beach Sprint rower of all time, winning gold in the men’s solo and silver in the mixed double at the 2025 World Rowing Beach Sprint Finals in Antalya, Turkey, in November. Bak’s total medal haul so far in the new Olympic sport that debuts at LA2028 stands at four gold, one silver, and one bronze.

The United States had its best world championships of any type since 2019 at the 2025 World Rowing Beach Sprints Finals in Antalya, Turkey, especially in soon-to-be Olympic events. Chris Bak defended his title in the men’s solo and added a silver in the mixed double with Sera Busse, both Olympic events for the 2028 Los Angeles Games. The U.S. mixed coxed quad of coxswain Coral Kasden, Kory Rogers, Annelise Hahl, Audrey Boersen, and Malachi Anderson also won gold in the nonOlympic event.

At Beach Sprints worlds, Chris Bak of the U.S. became the first threetime champion in the men’s solo. Two hours later, he won silver in the mixed double sculls, missing gold by inches.

Team USA delivered a sensational set of results on the final day of the World Beach Sprints Championships.

And that man from Cincinnati, Chris Bak, was right at the heart of an incredible medal haul.

On the sun-kissed waters, just off the beach in Antalya, Turkey, the 29-year-old was almost unstoppable. In the final of the singles, he beat his great friend and rival, Ander Martin of Spain, to win his second world title in a row, third in the event, and fourth overall.

Then just two hours later, Bak and his partner, Sera Busse, took a brilliant silver in the mixed doubles, losing out to the Lithuanian world champions in the sprint up the beach by centimeters.

The Stars and Stripes hadn’t stopped being waved over the beach all morning. Early on Sunday, the USA mixed quad

powered to a convincing victory over their Spanish opponents.

These championships showed why Beach Sprints is such a game-changing addition to the Olympic program. Before I had immersed myself in the world of Beach Sprints, I thought it came in a pale second to exciting new Olympic events like kayak cross, where paddlers launch off a ramp that’s 4.5 meters high. That contest was a smash hit at the Paris Games, but if promoted properly, Beach Sprints could be the standout event at LA 2028.

There is significantly more jeopardy, and therefore excitement, for the spectators and viewers in Beach Sprints. And so much of that was on display in the Antalya championships.

Take just one of the semifinals of the men’s solo. The German Olympic oarsman Moritz Wolff

The Brock University Badgers men’s crew won the Ontario University Athletics title—their fifth straight— on the Canadian Henley course in St. Catherines, Ont. in late October.

“Winning five banners in a row is a challenge,” said head coach Scott Anderson. “This team creates a great atmosphere to be a part of, and to have some of these athletes have their names on all five of these banners is really cool.” Brock earned a spot on the podium in nine of 10 events at the regatta, winning five gold, two silver, and two bronze medals. The University of Western Ontario finished second in points to Brock, with Queen’s University third.

was head to head against Martin of Spain. And the man from Berlin had a narrow edge on his rival at every stage of the course—until dramatically, with just meters to go before Wolff was going to win a final spot, the 25-year-old stumbled on the sand, his legs failing to carry him to the victory that was so close to his grasp. Anders passed by a prostrate Wolf to win a place in the final.

The jeopardy is there because the quarterfinals, semifinals, and finals are raced within a 45-minute window. There’s practically no time for the athletes to rest or recover. So the lactic acid builds up in the

muscles after a pulsating 80-meter dash over the golden sand of the Antalya beach; the sprint up to over 50 strokes a minute on the outward 250-meter leg into the ocean; the swerves to right and left around the slalom buoys; and then the shock of stopping dead for the 180-degree turn at the top of the course.

If the athletes have any energy left, it’s a sprint back to the beach, heart rates through the roof again, ending with a splash and rapid exit from the boat. Then an exhausting 80-meter sprint back to the red buzzer.

The closeness of Martin’s semi against

Wolff probably meant the Spainard had little to give against Bak, who had controlled his semi more effectively against Mathis Nottelet of France. Endurance is such a crucial issue in this event.

Just as crucial for the viewers and spectators is to watch the whole event unfold. Don’t make the mistake I did of just dipping in to watch the A final because you will miss all the thrills and spills of an incredible contest over the three final rounds.

Moreover, if you’d caught the earlier rounds, you’d have noticed that the men’s

solo was notable in that the two finalists were both coastal specialists. There were some big names from flat-water rowing whose reputations were left on the sands of Antalya.

The Kiwi Finlay Hamill, finalist in the Diamond Challenge Sculls at Henley and winner of the Head of the Charles, set off at a furious pace but messed up his navigation on a slalom buoy in his first head-to-head contest.

The Australian Olympic fours champion from Tokyo, Spencer Turrin, went out to Lithuania’s Zygimantas Galisanskis, an experienced coastal competitor.

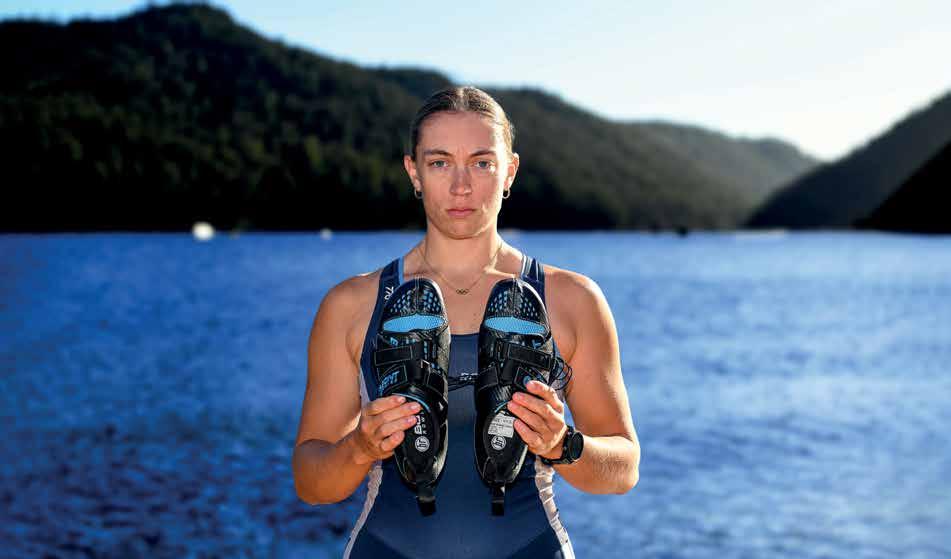

The same was not the case with the women’s solos, though. There, the final was contested by two legends of the sport: Emma Twigg of New Zealand and Magdalena Lobnig of Austria. Twigg had looked in great form through the championships, fastest in the time-trial round and serene through the early knockouts and quarterfinals.

The Tokyo Olympic champion’s only error came when she misjudged the jump into her boat at the start of her semifinal against the Scot Laura McKenzie. The British athlete led out. But Twigg was fearsome on the 180-degree turns.

“Today I decided I was going to take the turns pretty hot,” Twigg said, “and it worked out for me.”

On the other side of the draw, Lobnig had arrived at the championships following a night spent in a cell at Antalya airport because of a visa irregularity. The Tokyo Olympic bronze medalist had to fly back to Austria, get her papers in order, and return to Turkey. It was hardly the ideal preparation for the 2024 world Beach Sprint champion. But the 35-yearold clearly improved each day. In the quarterfinals, she dispatched the USA’s Christine Cavallo in a tight contest.

By the final, Lobnig was flying. There was little to choose between the two scullers on the outward leg. Twigg had just shaded the sprint, but Lobnig was not fazed. It was the 180-degree turn that proved crucial. The 38-year-old Kiwi came out with a length’s advantage and began to pull away.

At the finish, the 2025 champion gave her thoughts: “LA seems a long way away, especially at my age. But I’m loving it.”

Lithuania’s mixed double of Martyna Kazlauskaite, and Dominykas Jancionis were clearly loving things, too. The 2024 world champions in the mixed double (an event on the program in LA) displayed incredible endurance, holding ratings of 50 or more for much of the 500-meter course. They had seen off Poland and France to reach the final. Waiting for them would be the Green Racing Project athlete Sarah Busse, just out of the USA quad from the Shanghai World Rowing Championships, and Chris Bak—about to embark on his sixth race of the day.

On the surface, it looked like mission impossible. But Bak and Busse had other ideas. They recovered from a slower sprint to lead at the turn by the narrowest of margins. For the first 100 or so meters back to the beach, it looked like Lithuania’s high rating would take them away. But as they approached the beach, Busse and Bak found something. The afterburners went on, and the U.S. crew hit the beach almost level. It looked like Bak might outsprint Jancionis. The American made a full-length dive for the buzzer and missed out by just 0.24 seconds. The race was incredible.

The USA mixed quadruple scull was more dominant in its contests. The quad is not in the Olympic program, but the importance of a strong squad to choose from is clear. So Malachi Anderson, Audrey Boerson, Annelise Hahl, and Kory Rogers, together with cox Coral Marie Kasden, can consider themselves key parts of Team USA’s Olympic setup. And their victory over Spain in the gold-medal race was never in doubt.

For the crowds, too, it was an amazing atmosphere, where the spectators have the chance to experience a much closer relationship with the competitors than is possible in flat-water rowing. That much is apparent when leading athletes run in ahead of their opponents and have the chance to salute and acknowledge the crowd. The word most mentioned is the Beach Sprint “vibe.” With music pumping out, the atmosphere is joyous.

Part of Sunday’s crowd were the U19 athletes who had finished their finals the day before. The men’s contest was especially memorable as, on this very beach, during the European semifinals a month before, the Spanish athlete’s legs had given way. He had collapsed on his final sprint into the buzzer—while in the lead.

This time, though, Ignacio RamonBorja Garcia’s nerve, and legs, held. He took the gold from Germany’s Felix Krones. France’s Lou Phillipe took gold in the women’s U19, and Austria took a brilliant gold in the U19 mixed doubles event.

The U19 racing was thrillingly close and gave the crowd the chance to see what a crucial role boat handlers play in this sport. Often former coastal rowers turned coaches, they play a crucial role in helping athletes into the boat, giving them a push off the beach, and steering them around the buoys by using their arms. They are like Formula One pit crews, and their participation adds a brilliant dimension to this sport.

The USA’s boat-handling team shared in all the glory of those Sunday medals. And it’s no exaggeration to say that, with less than three years to go until the crews line up on the sands of Long Beach to go for Olympic gold, it’s the USA that has taken an early advantage.

The Next Level rowing program run by Marc Oria has benefited not only Chris Bak but also Kory Rogers, who was part of the winning quadruple. Oria had taken his team out to the European championships–in Antalya—where they raced in the coastal endurance event so they could get used to the conditions ahead of the worlds.

For Niki Van Sprang, a Dutch Olympic oarsman doing the post-race interviews for World Rowing, it was an amazing experience, and not just because it was Van Sprang’s first exposure to Beach Sprints.

“The course and beach are cool, the atmosphere is cool, and the athletes are super cool,” he said. “Just before the men’s final, there was Chris Bak and Anders Martin sitting next to each other and chatting. Then Anders put his head gently on the shoulder of Chris. It was a beautiful gesture that typifies the relationship between the athletes, and what’s so great about this sport.’

Let Bak, a student of authors like Eckhart Tolle and Paulo Coelho have the last word.

“It’s a title that’s only borrowed; I’m happy to borrow it one more year. This competition is insane. Every competitor this year was absolutely phenomenal.”

MARTIN CROSS

Vanderbilt won the women’s collegiate eight by more than 30 seconds over second-place Florida, with Clemson third.

Alabama won the men’s event, ahead of UNC and Georgia Tech.

Hundreds of the top junior and college clubs crews traveled to Chattanooga for the Head of the Hooch Regatta, which, coming at the end of the fall season for many crews and featuring a fun and festive vibe, truly is “The Last of the Great Fall Regattas.”

“We had another great event in spite of a little fog Saturday and some rain Sunday,” said Ulrich Lemcke, president of the regatta. “Water was good in spite of it all, so all competitors were in good spirits and we heard nothing but compliments.”

Vanderbilt won the women’s collegiate eight by more than 30 seconds over second-place Florida, with Clemson third. Alabama won the men’s event, ahead of UNC and Georgia Tech.

Cincinnati Juniors nipped Chicago by less than two seconds to win the women’s youth eight event, which included 72 finishing crews. Chicago finished second also in the men’s 92-boat event, won by Belen Jesuit.

An Atlanta Composite entry averaging 50 years of age won the women’s masters eight on both raw and adjusted time. Catawba’s age-64 crew won the men’s event by 10 seconds (adjusted time) ahead of Atlanta, with the fastest raw time.

PHOTO: KENDALL ILER.

Seventy clubs competed in Seattle’s Head of the Lake regatta, racing from Lake Union through Portage Bay and the Montlake Cut and finishing near Conibear Shellhouse.

The University of Washington, which co-hosts the regatta with Lake Washington Rowing Club, won both the men’s and women’s premier eights events, with the Husky women also finishing second.

In the men’s event, Oregon State took second, just over a minute behind UW’s varsity eight, made up entirely of members of the defending IRA nationalchampionship squad, including four oarsmen from the IRA-winning varsity.

In the champion women’s collegiate/ open eight sponsored by Pocock Racing Shells, Washington State took third behind the Washington one-two.

Brentwood won the men’s junior eight cup in the 18-boat field. Green Lake won the women’s event.

The University of Washington won the team points trophy with 16 gold, silver, and bronze. Sammamish Rowing Association scored 11 for second, with Lake Washington and Pocock Rowing Club tied for third with 10 each.

Although Canadian entries were down 22 percent, St. Catharines Rowing Club brought a formidable armada of sculling boats and won several events.

The University of Pennsylvania women finished first and second in five events at the Head of the Schuylkill Regatta in late October in Philadelphia.

“Penn women’s crew enjoyed another exceptional Head of the Schuylkill Regatta,” said head coach Bill Manning. “The City of Philadelphia, the Philadelphia rowing community and Boathouse Row, our alumnae, and the weather all turned out to make a great day.”

RowAmerica Rye racked up 11 wins, including men’s high-school trainer singles (JV), men’s high-school quads (frosh/ novice), men’s high-school fours with cox (varsity), women’s high-school fours with cox (varsity), The Michael O’Gorman women’s high-school eights (frosh/novice), The Paul Coomes women’s high-school quads (varsity) and women’s high-school quads (JV), women’s high-school fours with cox (JV), men’s high-school fours with cox (frosh/novice), women’s high-school eights (varsity/first boats), and women’s highschool eights (JV and lower boats).

St. Joseph’s Prep won the men’s

high-school eights (varsity/first boats), the Michael O’Gorman men’s high-school eights (frosh/novice), and men’s high-school fours with cox (JV).

Mirroring national trends in tourism, in which Canadian visits to the U.S. by car fell 35 percent in September, Canadian entries in this year’s regatta were down 22 percent (138 crews versus 175 in 2024). Still, St. Catharines Rowing Club brought a formidable armada of sculling boats, winning the men’s high-school coxed quads varsity and JV events, as well as the men’s high-school doubles (JV).

Potomac’s Michael “Tony” Madigan scored an eight-second victory against his friendly rival, CRI’s Simeon John, who had won the Head of the Charles by seven seconds over Madigan the previous weekend, resetting his own course record.

Madigan is the defending youth national champion and finished fifth at the 2025 World Rowing Under-19 Championships. Both have won multiple Canadian Henley golds and have developed a healthy rivalry and could be the future of American sculling on the elite level.

Princeton heavyweight men’s eights finished first, second, and fifth at the Princeton 3-Mile Chase in early November. Princeton’s women won their open eight event by less than a second over Virginia, whose A and B entries finished second and third. Virginia also won and finished third in the women’s coxed four event.

“We had a great day of racing on Lake Carnegie,” UVA head coach Wesley Ng said. “The coxing was fearless and decisive. I’m very encouraged by our focus and approach this fall.”

While the head race is neither a championship event nor counts toward anything, the college-only Princeton Chase has long been used by coaches as a benchmark at the end of the fall training season because it offers better, more controlled racing conditions than huge head races like the Head of the Charles.

“I am proud of how our athletes went out and attacked the challenge this weekend. We showed really solid performances from all boats this weekend, and I am excited about the progress that the program is making,” said Iowa head coach Jeff Garbut, who brought his top two eights to New Jersey, while less experienced oarswomen stayed home to race in the Iowa Chase, which includes juniors and masters.

Cornell won the men’s lightweight eight event, eight seconds ahead of Penn in second, and more than 20 seconds ahead of hosts Princeton in third and fourth. Georgetown was fifth in the field of 20 eights.

Train like champions at Nathan Benderson Park. Recognized as North America’s best rowing venue, NBP provides elite facilities and seamless support—so your team can focus on results.

Benefits of Training at NBP

• World-class rowing venue in Sarasota, FL

• Perfect training climate, with great weather and calm conditions

• Just 1 mile from I-75 with ample trailer parking

• 550-acre park with trails for walking, running and fitness

• 5 miles from airport, walking distance to shops and dining, minutes from world-renowned beaches

As Yale’s first varsity eight locked in at the start of the Division I grand final of the 2025 NCAA National Championship Regatta on New Jersey’s Mercer Lake to race the heavily favored ACC champions from Stanford, plus Big 10 champs Washington, SEC champs Texas, Tennessee, and Brown, the Eli women had an advantage.

Before the race, their coach, Will Porter, had instructed them to execute a risky strategy: Go out fast and row hard to grab an early lead, then hang on against the fastest NCAA crew ever. (Known also as “fly and die” when it doesn’t work.)

It worked. Yale blasted out of the start, surprising the field, and in terrible conditions that make moves even more difficult, put in long powerful strokes that kept them in the lead all the way to the finish.

“Watching that race, someone made the comment that they thought they were gonna get caught,” recalled Syracuse head coach Luke McGee. “I whipped around, and was like, ‘There’s no way. There’s too much talent, too much skill that he helped build, for that to happen.’”

“He” is Will Porter, the Yale women’s rowing head coach for 25 years, and the 2025 Rowing News Coach of the Year.

“He’s the best, most unrecognized rowing coach in the country. What the hell?” said Yale lightweight coach Andy Card, who has coached in the same boathouse as Porter since 1999. “Will was a men’s heavyweight coach first, and his crews were good, too!

“Drop Will into any boathouse and have him coach men or women, doesn’t matter, that boathouse will be a winning one in short order.”

Stanford earned the 2025 NCAA title, decided by team points, with the Cardinal second eight and varsity four each winning their events at the championship regatta. Stanford’s first varsity eight had been the fastest all spring, beating both Texas and the Canadian National Team (the Olympic silver medalist, albeit with a very different lineup) by open water in April.

They were undefeated in the regular season and won the ACC championships by sweeping the regatta on Lake Hartwell in

Clemson, S.C. in May, with no one coming within five seconds of their NCAA boats, and the first varsity turning in a record time of 5:58.6—the fastest NCAA eight, ever.

But Porter had been developing his group through two- and three-crew cup races every weekend throughout the spring

“We have that tri race with Yale and Cornell and Syracuse. He’s a big proponent of keeping those cup races going in the tradition of the sport,” McGee said. “Even when we’re competitors, he’s always got time for discussing ideas, a willingness to talk and to share, which is certainly appreciated.

“Since I first started coaching women, he’s been super supportive. But he’s a real competitor. He makes boats go really fast, and I know every time you race against him, you get the full measure of it. Hard to beat, that’s for sure. We got close once, but definitely, definitely hard to beat.”

Stanford won its Friday heat at the NCAAs and its Saturday semifinal, going a second faster than Yale’s winning time in the other semifinal. For the grand final, racing was rescheduled for early Sunday morning in an attempt to avoid the worst of the windy weather, but the water was rough, whipped up by a stout and gusty tailwind. It was race-able—if only just—in conditions that compress finishing times and margins, something Porter recognized, and took advantage of, to win the race of the day.

“It’s Mercer,” Porter said. “Getting a margin is important, and it’s hard to come back” in such rough water and with such fast times—Yale went 6:08 for the win, an NCAA regatta record, despite the rough water.

Length and power were the keys to Yale’s success in the grand final, Porter said. “Some athletes can do it, some athletes can’t row with that much length” to sustain a lead taken aggressively from the start.

“Will obviously did a great job developing that group,” McGee said.

“Will keeps it simple but not simplistic,” Card said. “Since rowing demands high fitness, technical skill, and mental toughness, that is what he expects from each of his rowers and coxswains on the water daily. He’s matter-of-fact about it, just gives ’em the information they need, and his best crews—that is, most of his crews—act on that decisively.

“Will is the first to say that good rowers make good coaches, not the other way around, and that’s true,” Card said. “Will is good at finding good rowers and bringing out their best.”

“We knew the final would be a drag race and we wanted to be part of it,” Porter said. “It’s one of those things you need to have the fitness base to give you the confidence to really send it, and we did. I am proud of them.”

Afew short years ago, at the 2022 Eastern Sprints, Harvard’s lightweight men finished seventh of nine teams in the Jope Cup points standings, with the varsity second to last in the petite finals. Some supporters of the program were asking if it was time to move on from coach Billy Boyce, who had been the head coach since 2016, following five seasons as an assistant on the heavyweight staff.

They were wrong; it wasn’t. It might have been time for more training volume and other adjustments made by Boyce and associate head coach Ian Accomando. It was also the last time the Crimson lights weren’t competitive, peaking in 2025 with a second consecutive undefeated season at Eastern Sprints and the IRA national championships, followed by the program’s first-ever Temple Challenge Cup victory at Henley Royal Regatta. Boyce’s lightweights added wins in the lightweight four and eight at the Head of the Charles to round out the year.

Lily Siddall coached the Tufts women to back-to-back NCAA Division III national championships, winning both the first and second eights at the 2025 regatta. Read more about her in our feature story beginning on page 44.

Just about all Washington coach Michael Callahan has done since being named last year’s Rowing News Coach of the Year is continue to win. A defeat against archrival Cal at the Mountain Pacific Sports Federation (successor to the Pac-12) championship after Washington’s dramatic come-from-behind win in the Schoch Cup set up a much-anticipated third meeting at the IRA national championships. White-cap conditions in the semifinal caused a crab that kept Cal from advancing to the grand final, which Callahan’s Huskies won, again.

Will Porter. “Since I first started coaching women, he’s been super supportive,” said Syracuse head coach Luke McGee. “But he’s a real competitor. He makes boats go really fast, and I know every time you race against him, you get the full measure of it.

The USA’s women’s four. “The result of the women’s four shows that we are back on track with women’s sweep,” said Josy Verdonkschot, The McLane Family Chief High Performance Officer for USRowing.

After the U.S. women’s eight’s 11-year streak of world championships and three Olympic golds, from 2006 to 2016, it was a long five years from the last time any USRowing senior National Team boat won a worlds gold, in 2019, and a tough couple of Olympics in which the U.S. women didn’t win a single medal during the same five years.

The USA’s women’s four of bow Camille VanderMeer (Princeton), Azja Czajkowski (Stanford), Teal Cohen (Washington), and stroke Kaitlin Knifton (Texas) ended that streak, winning the 2025 World Rowing Championships in Shanghai by racing through the field in the A final

with a demonstration of power and speed.

“The result of the women’s four shows that we are back on track with women’s sweep,” said Josy Verdonkschot, The McLane Family Chief High Performance Officer for USRowing.

While three of the four are Olympians from the Paris Games—Knifton in the fifth-place four, Cohen in the ninth-place quad, and Czajkowski in the fourth-place pair—they are part of a squad of relatively fresh faces who announced their arrival at the top of elite international rowing this summer with wins and medals in fours and the eight at the World Rowing Cups in Varese and Lucerne.

“Four young athletes, from four different programs, who lead the way for the new generation,” Verdonkschot said. “I want to thank their coaches—Dave O’Neill, Yaz Farooq, Derek Byrnes, and Lori Dauphiny—for their support of our system

and for the way they work together with Jesse Foglia. It gives me a lot of confidence in the future.”

The next stops in that future are the World Rowing Championships in Amsterdam next year and then Lucerne in 2027, before the U.S. hosts the Games of the XXXIV Olympiad in Los Angeles in 2028.

Fast eights: Comparing times in the sport of rowing is a fool’s errand, since conditions, including currents, winds, and water temperature, can distort the numbers. At times this spring, Princeton’s Carnegie Lake was more like the Carnegie River, as heavy rains raised the water level, and strong winds pushed both crews and water down the course.

Still, the Tennessee women’s sub-six winning time (5:57.6) against Princeton, Syracuse, and Ohio State in late April was incredible. The Harvard lightweights covered the same course in 5:28.5 (World Rowing’s world-best time is the German National Team’s 5:30.2 at the 1992 Worlds in Montreal) to win the Goldthwait Cup against Princeton and Yale before winning everything else

for the rest of the year. Included in that winning streak was a Henley match race against the Virginia’s men’s eight , the ACRA club national champion, in which sisters Anya Chang (Harvard) and Celia Chang (Virginia) coxed against each other.

The Stanford women’s 5:58.6 at the ACC Championships on Lake Hartwell was real, with no assistance from abnormal currents. The Cardinal sent seven current and former rowers to represent their countries at worlds, and none went that fast there.

The Netherlands won both the men’s and women’s eights at worlds, for the first time ever in the country’s history of great rowing. Their women didn’t even have an eight for the Paris Olympics but put one together for this year, won Henley, and then beat the Olympic champion Romanians at their own game with clean relatively short strokes at high ratings.

The Gemini.com Beach Sprint [U.S.]

National Team won “three medals out of the four senior events, that’s almost grand slam” said Josy Verdonkschot. “Christine [Cavallo] was very unlucky in the draw, but that is also part of the Beach Sprints format. Like the rest of the team, she showed that we are competitive in all events. All credit to this group and of course our coach, Marc Oria.

“This year we invested in the senior team athletes and their program, including domestic camps, and camps and races in Europe. The selected team was a healthy mix of established names, young talents, and cross-over athletes. And they delivered” Vanderbilt’s women repeated as ACRA club national champions, RowAmerica Rye took repeat national championships a step further at the 2025 USRowing Youth National Championships—the biggest and best version ever—winning both the men’s and women’s youth eights, again.

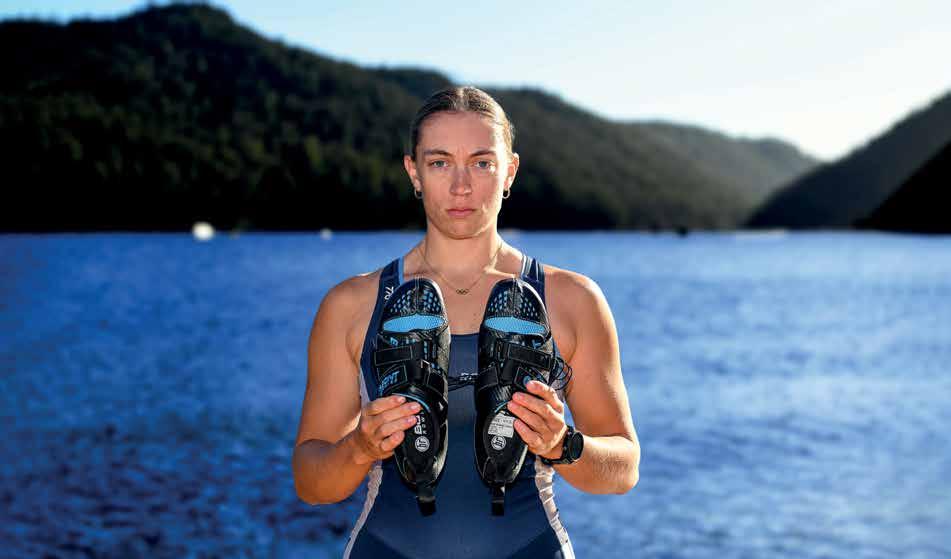

Outlasting China’s Dandan Pan to win the Shanghai World Rowing Championship in the lightweight single, Michelle Sechser didn’t please the local crowd but she put smiles on the faces of all those who have cheered for and supported her during her 13-year (and counting) U.S. National Team career.

“I was so happy for her,” said Molly Reckford, Sechser’s lightweight double partner in two Olympics. “I know that winning a world championship is a very special thing and I’m so glad that after her career and all of her visits to the Olympics and the world championships she finally got that top podium spot.”

“It has been a difficult year for Michelle,” said Verdonkschot, referring to injury and illness setbacks Sechser overcame in 2025. “Therefore, I am extremely happy that she got the reward she deserved.”

“Michelle is such an impressive athlete,” Reckford said. “She takes every aspect of training—whether that’s getting enough sleep, focusing on nutrition, weightlifting, going to PT and doing rehab—very seriously. Her diligence is something to be admired and something that a lot of young athletes can really learn from.”

“Way back, 15 years ago when I was working in Italy,” Verdonkschot said, “Kris Korzeniowski asked me if he could send over an athlete to train a couple of weeks with me and my team. He told me she was strong but still had to learn a lot about sculling. Michelle has come a long way since then, and I am sure Korzo is super proud—as he should be.”

“She’s an amazingly fierce competitor,” Reckford said. “I have always said I would rather be in the boat with her than trying to race against her.”

The University of Washington’s Logan Ullrich returned from an Olympic year away, during which he won a silver medal in the four for New Zealand, to capture the IRA national championship with the Huskies. He then jumped in the single to win at the Lucerne World Rowing Cup and is the inaugural recipient of The Oarsman Award, the Intercollegiate Rowing Coaches Association’s version of the Heisman.

Finn Hamill picked up where he left off last year, winning across continents and disciplines. The 2024 World Rowing Coastal Championships winner in the men’s solo event won the double sculls event at Henley Royal Regatta while also racing the single in the same regatta, nearly winning the Diamond Challenge Sculls and knocking out current Olympic champion Olli Zeidler in the process.

The former lightweight raced the open double at the World Rowing Championships in Shanghai in September, then successfully defended his Head of the Charles championship single title in October, before heading to Turkey, where he competed at the World Rowing Beach Sprint Finals.

BY MIKE JENSEN PHOTOS BY TUFTS ATHLETICS AND SPORTGRAPHICS.COM

It wasn’t imposter syndrome exactly. Or maybe it was that exactly. Lily Siddall didn’t expect to be a college head rowing coach so young. She wanted it, was preparing for it—she’d created her own college major with such a job in mind—but that call came four months before her 30th birthday, and five days before her wedding in August 2023. Now? RIGHT NOW? Can I at least take my honeymoon? Get to Cape Cod for a few days?

The women’s rowing program at Tufts University had been bubbling up toward the top of NCAA Division III for all sorts of foundational reasons, including a bestin-DIII boathouse and the institutional

attitude of Tufts toward athletics. Siddall’s predecessors had laid down a foundation carefully. Now Lily was being asked not just to maintain what had been built but to take it over the top—ASAP.

Siddall didn’t know she was ready until she found out she was. Her resume was non-traditional but included many little stops that led to watching her rowers stand on podium after podium over the last twoplus years, with Tufts emerging as the new powerhouse of DIII women’s rowing.

Talking about her jump from assistant coach working with Tufts novices to making decisions involving the top rowers, Siddall points to the rowers themselves

and how they dealt with her elevation. Siddall already knew that a head coach must make hard decisions. She uses the word grateful to describe the reception she got from team members.

“Whatever you say, we trust you,” was the message she heard back. “We believe in you.”

Part of it, she believed, had to do with her gender.

“It was really motivating for them to have a female head coach,” Siddall said, adding that team members loved the previous head coach, Noel Wanner, and understood that his departure had everything to do with his own family

reasons.

There was no bad blood in any direction. Wanner had taken the team to new heights. It was he who had called Lily and shocked her: He was moving to Vermont; the job would be hers if she wanted it.

“I almost wished at the time there were fewer expectations,” Siddall said.

Tufts almost got rid of rowing, both men’s and women’s. That had been the plan around 1990.

“The university was going through a financial squeeze,” said Gary Caldwell, who took the job as head men’s and women’s rowing coach just as the athletic department was feeling that squeeze, with an athletic director looking around trying to find where he could make the cuts the school was demanding. Rowing and ice hockey were the sports he decided to axe. The AD didn’t hide that fact from Caldwell, then a Northeastern men’s assistant.

“He let me know he understood if I didn’t want to come for a year,” Caldwell said.

Caldwell had a different idea. Could he have access to the rowing alumni and parent list to see if he could raise money? Since the answer was yes (“let the kid knock himself out”), that suggested the door wasn’t closed fully on cutting the sport.

A benefactor working on Wall Street stepped up with a challenge gift—$60,000, if an equal amount could be raised to match it.

When that sum was reached, said Caldwell, “That was the end of canceling the program.”

There were reasons rowing had been targeted. Rowing had been a Tufts sport in the ’60s–the 1860s–and had kept going into the 1880s, before, Caldwell said, “it went dormant, and laid dormant for close to 100 years.”

Though it came back in 1979, it was a team often in search of a home around rowing-steeped Boston—sometimes working out of a tent along the river; sometimes taking up space in Harvard’s boathouse on the Charles; sometimes operating out of a warehouse on the narrow Malden River, which had the advantage of being closer to the Tufts campus in Somerville.

There was a push to build a Tufts boathouse on the Malden, which fell short when the Tufts president and the owner of a piece of land “came to loggerheads,” as Caldwell put it, over the length of the lease. Eventually, another site popped up, part of an urban-renewal project.

“I’ll give you a 20-year lease,” was the

offer this time.

“That’s what the other guy offered.”

“With four 20-year renewals on your end.”

Yes, that was more like it. The clincher: “100 years for 100 bucks.”

Everyone understood the deal was too good to pass up.

“Our real-estate guy pulled out his wallet, handed the guy 100 dollars,” Caldwell said. “It opened in 2006.”

Almost two decades later, Caldwell believes that it is, undeniably, “the most beautiful DIII boathouse in the country.”

For a time growing up, Siddall lived in Princeton, where her father was an engineering professor. She noticed not just the college’s rowing facility but the nearby U.S. national training center. She always saw the rowers. She also saw Princeton coaches around her neighborhood, even had Princeton women’s ice hockey players as babysitters. Siddall herself was a competitive Irish step dancer. Her mother had been a world-champion step dancer.

“There’s definitely an aspect of posture and rhythm,” said Siddall, of similarities between the disciplines. “People don’t understand just how intense it was—six days a week.”

When her father left academia for business and the family moved outside Boston, Siddall was ready to try different sports. None really took, she said, “until I stumbled into rowing.” She signed up for a Learn to Row program in seventh grade, part of Boston’s Community Rowing, Inc., not knowing how important Community Rowing would be to her future.

In high school, she raced competitively for Community Rowing, then went to Bucknell, where she rowed lightweight as a freshman

“In high school, I was, like, obsessed,” Siddall said. “Somebody would be closing up the boathouse, I’d still be in there.”

Unsure what she wanted to study, she left Bucknell after a year and worked in a City Year educational program in Detroit. That’s when her coaching career began, with a second-grade soccer team. At first, Siddall thought she wanted to teach but she soon realized that it was the two hours after school at practice that really excited both her and the kids.

She transferred to the University of Massachusetts, where she learned to cox, became a coxswain for the UMass men’s team, and joined an academic honors program that allowed her to create her own major in youth development and coaching. She could take classes across departments, adding psychology and military-leadership

courses. Leadership was the thread, not kinesiology.

Instead of student-teaching, she volunteered to help with the UMass women’s team, and while coaching the walk-ons, it became clear she hadn’t lost her obsession with the sport. After college, working in Boston, she returned to coach at Community Rowing, also serving as the community-events manager. Through that came a coaching internship with Tufts, which turned into an assistant coaching job. Her assignment: “Build the culture of the lower half of the team.”

Siddall liked the fact that at Tufts the goal was to build a culture that was collaborative, not simply competitive. “It wasn’t just boats pitting against each other to develop top-end speed.”

The recruiting challenge was to find rowers who wanted to be at Tufts. This meant looking to established programs but not recruiting based simply on erg scores and height. Most of all, it was necessary to find rowers who could get in academically, could afford it, and saw advantages in competing for Division III titles. Of the 16 rowers in the top two Tufts boats this fall, 15 had rowed in high school. Many chose Tufts over Division I rowing.

At Tufts, rowing is different from D1. The crew practices generally from 6 to 8 in the morning, and Tufts classes begin at 8:30 a.m., so nothing is usually missed on the front end. Rowers still have strengthtraining requirements, Siddall said.

“What’s great about DIII, you can give athletes a little autonomy.” If they have a class from 2 to 4, they can erg or work in the weight room after that.

“It would be different if they were 16 years old,” Siddall said. “Because we give them that time and space to build a schedule for themselves, they’re showing up.”

At the 2023 Head of the Charles, Tufts broke through and won the fall head race. They weren’t chasing success anymore, they tasted it. The following spring, with Siddall still officially the interim coach, “it was a little bit of a storybook year.”

By that, she meant undefeated in the first varsity eight, right into the NCAA championships. They’d won the New England Small College Athletic Conference, a huge breakthrough since the NESCAC regularly spawned national DIII champions. Tufts showed up in Ohio as the top national seed.

“It was cool and unique,” she said.

And they lost in the heat.

It’s easy to say in hindsight that finishing second to Williams in the heat had the benefit of taking the target off their

back. But the women in that boat were simply ticked off. Would frustration take their whole season apart?

Siddall didn’t try to talk to them right after the race; instead, she waited until after dinner. Her message: “We can’t race from a place of fear.”

All the things they’d done were great— cool memories, but just that. The team talked about needing to go in with thoughts of love and hope, not with set expectations.

“That’s when they won that championship,” Siddall said, “in that boat meeting.”

“We could have come off the water in a panic,” said Hannah Jiang, the coxswain of that boat. “We didn’t. Here’s what we’ve got to do. ‘What do you need to hear from me mid-race?’ Having that openness, that trust. We got our minds together. We prepared for this.

“That night, we were like, let’s just have fun. We went to friends’ rooms, playing games, listening to music.”

The next day, they led from the start— and built on that early lead.

“Pure belief,” Jiang said about the collective effort. “We were so internal. We’re going to focus on being the best crew out there, trusting the fitness, trusting what we had put into it.”

A second-place finish by the 2V locked up the points title and the program’s first NCAA title and also endowed the 2V returnees with a chip on their shoulder, something to build on.

Siddall lost the interim tag that summer. Now, Tufts has won consecutive NCAA titles, with the 1V and 2V both triumphing last spring. The depth is so strong that the 2V finished third overall in October’s Head of the Charles, with the 1V taking first overall, 15 seconds ahead of second-place Williams in the collegiate eights. They’ll be favored to win a third straight NCAA crown in the spring, the target now comfortably on their backs.

It takes more than a best-in-class boathouse to get to the top of the podium. The team recognizes Siddall’s essential role.

“She’s killing it,” said senior Rose Tinkjian, a captain who has been around all sorts of coaches by now. “She’s very human. I’ve had some very stoic coaches in the past. It’s frightening. You don’t know what they’re thinking until you see your name on a sheet.”

The lineup sheets are posted ahead of Tufts practices so that walking into the boathouse there are few surprises. Siddall seems to have pulled off the trick of giving her rowers ownership of their program while also holding them accountable. This may

be Division III but that doesn’t dampen her competitive drive.

“We’re here to make the fastest boats possible,” Tinkjian said.

“Seeing her grow into that headcoaching role–a lot of that, she leaned into the team culture,” said Lucy Howell, a 2025 graduate and two-year captain. “We have Fun Fridays. She leans into that, she loves that.”

That includes theme days (think Barbie Day.) “It’s a cool way to remind everyone,” Howell said, “that we’re just a bunch of friends who like to go fast together on the water.”

“It feels like we’re just chatting,” said senior captain Samara Haynes of conversations with her head coach. “She’s young enough that she can still connect with us as young athletes on a personal level. It’s been kind of incredible to watch Lily’s journey, to watch her become this strong and confident head coach we have now.”

To Haynes, the second NCAA title last spring defined Siddall’s career so far. “She really made last year’s success happen.”

Could they repeat? There were ups and downs. They no longer could see it all as some magical joy ride. “That easily could have cracked a lot of people,” Haynes said.

“A big motto of our team is ‘have fun doing the work’,” said Jiang, the coxswain, now a senior. “One of her strengths, she’s so positive all of the time. That’s something a lot of teammates buy into. We do talk about the mental aspect of rowing a lot. She tries to keep it very relevant. They are teaching technical things, helping us become students of the sport.”

This season, for instance, there’s emphasis on rotation, getting more length around the pin—“just one more inch of that blade being in the water,” Jiang said.

The head coach also has to make tough decisions. Siddall had a spreadsheet going for workouts so everyone would understand what was expected of them. They had to fill out their workout themselves.

“It was all in our face,” said assistant coach Ethan Maines. “It very much set us up for success.”

Siddall gives a lot of credit to Maines, now the recruiting coordinator, as she’s settled into being the head coach, including making tough calls. If someone slips up in meeting a team standard, nobody is immune from being called out.

Jiang is a particular gem, a two-time national champ, but there was one time Siddall sent her down to the 2V for a race after Jiang had been outspoken “just talking about lineups,” her coach said. Siddall put Jiang in the second boat for just the one race (“the 2V beat the 1V; she’s that good”). When Siddall talked about the support she’s

gotten from her veterans, she mentioned Jiang in particular.

“That was probably one of the best things that happened to me. I don’t think I was quite ready to be in the position I was going to be in,” Jiang said of her oneweek demotion, and of being a sophomore coxswain in a first varsity boat. “Now, getting older, understanding things more, talking to Lily about how to get there. How do I present myself in a way that’s going to help the team? It’s about growing as a person.”

The rowing culture extends to Siddall’s home. Her husband is a coach. They met coaching at a nonprofit community program in Springfield when she was just out of UMass.

Tom Siddall now is associate head coach at Harvard. They’ve been together for most of a decade, so rowing was their favorite early discussion topic. They’ve learned to have different interests, Lily said, to get away from the sport being all-consuming. But they’ll still stream big international competitions and watch over coffee.

“He’s been super-supportive, my No. 1 fan,” Siddall said of her husband. “He understands the work.”

What’s not to like? Caldwell, the coach who got the boathouse built, watches from afar. His old program is doing pretty good, huh?

“Pretty good?” Caldwell said, noting the progression from respectable to “ridiculously successful.”

His praise extends through his successors to the current coach, now two for two in getting the women of Tufts to the top of the NCAA podium.

Lily Siddall, it has been confirmed, is no imposter.

MIKE JENSEN wrote for The Philadelphia Inquirer for 35 years and was named Pennsylvania Sportswriter of the Year in 2023. He covered rowing on the Schuylkill River and at the Beijing Olympics and wrote the weekly Merion Mercy Academy crew newsletter for seven years while two of his daughters were champion rowers at the school. His book, Philly Hoops: The City That Shaped a Sport, will be published in late 2026.

ALL AVAILABLE WITH YOUR TEAM LOGO AT NO EXTRA CHARGE (MINIMUM 12)

UNITED STATES ROWING UV

VAPOR LONG SLEEVE $40

WHITE/OARLOCK ON BACK

NAVY/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

RED/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

PERFORMANCE LONG SLEEVES

PERFORMANCE T-SHIRTS

PERFORMANCE TANKS

Order any 12 performance shirts, hooded sweatshirts, or sweatpants and email your logo to teamorders@rowingcatalog.com and get your items with your logo at no additional cost!

There are good reasons to leave the boats alone for a while, but that doesn’t mean abandoning exercise and physical activity.

For most of our readers, the time has come to take the docks out and put the boats away for the season. The days are shorter, and the weather in many parts of the country is unsuitable for rowing. Therefore, we must turn to other sports. Even athletes who row in milder climates should consider this, since there are good reasons to leave the boats alone for a while.

Does this mean you should take

a break and rest? No! Regular exercise is important not only for maintaining your fitness but also your general health, whether you’re an ambitious competitive athlete of any age or a relaxed recreational rower. Numerous studies show that physical activity is the best thing you can do for your health and to prolong your lifespan.

If you want to maintain or improve your performance level, you should

continue training, since physical performance declines over time. If you don’t train regularly, your body will lose strength and endurance, and if you take a break from training, you’ll have to begin at a lower performance level when you return.

This doesn’t mean, however, that you must row or train with the same intensity as during regatta season. Instead, work on the fundamentals—basic endurance, general strength, agility, and flexibility—

since they form the foundation for successful, targeted rowing training.

Since you’re no longer bound to a planned and time-consuming rowing workout, you can focus on expanding your movement repertoire. Activate muscles that are neglected during focused rowing training. Improve your balance,

If you don’t train regularly, your body will lose strength and endurance.

coordination, reflexes, rhythm, etc.

Do what you enjoy or what challenges your agility. Play sports with special people— children, grandchildren, friends you haven’t seen in a while. Kick a soccer ball, swat a pickleball. Go jogging or crosscountry skiing together.

Such shared experiences are beneficial and enriching. They offer a mental and emotional break from stress, and varied activities are crucial for a happy, healthy life. They fortify you for returning to school or work and the strenuous training to come.

Just as important as exercising is engaging in activities that promote mental well-being. For recreational athletes, staying motivated is essential; for competitive athletes, being mentally prepared for training and competition is paramount. A conditioned mind is as critical to athletic success as a conditioned body. Taking a break from rowing can provide a surge of new physical and psychological energy.

All of the above applies to coaches as well. Coaching is often so time-consuming and strenuous that it’s difficult for coaches to integrate physical activity into their daily routine. Coaches, too, should use their time outside of regular training to do something good for themselves through exercise.

Recording and using your data well in the winter can help your rowers train well, perform better on erg tests, and see their own progress and potential.

During winter training, an expected duty for many coxswains is data management. What this entails varies dramatically from program to program. Some teams may have an integrated data app or system that records erg data automatically. Others may track everything in Excel, Google Sheets, or even with pen and paper.

Your coach may want every single piece of available data— heart rate, splits, meters, lactate-testing results—or just want you to record the occasional erg test. Regardless, you want to make

sure you’re poised to do the job efficiently and accurately.

I interviewed Gillian Selig, who coxed at Harvard-Radcliffe and is coxing at Oxford, about some data best practices.

If there’s no established procedure for data collection at your club, you can take that on. If you want to take charge, “take some time outside of practice to see how you can organize the data in the way that it makes the most sense to you and then have conversations with your coaches about what they’re looking for. Then you can come up with a model that you think works well and fulfills what [your

coaches] want,” Selig said.

For a well-organized Google doc or Excel file, make sure you have an accurate up-to-date roster (with everyone’s names spelled correctly!). This makes it easy to copy the roster for each new workout and ensures that you never drop a rower from the sheet or fail to record someone’s data—a cardinal sin.

“Copy your previous work when you can,” Selig said. “Have templates to work off. It’s never going to be anything that’s that different; it’s either going to be timebased or distance-based, so your columns are going to be generally the same.”

She’s right. Erg workouts are based on meters, splits, or watts. If you know the day’s workout ahead of time, set up the sheet in advance so you’re ready to go when it’s time to collect data. This also allows you to ask questions in advance: What information does your coach want broken out and readily available beyond the final workout averages? Does she want anything calculated or compared to previous workouts?

Speaking of which, keep a good record.

“Keeping a sheet where you have people’s PRs and updating them after every erg test is very helpful,” Selig said, so the information is always handy. You may want to create a reference of previous splits pulled on a workout so that if rowers ask how they performed two weeks ago, you can provide them with that data.

“Then you can go back and reference quickly in case someone asks what they went last time. They probably know their PR, but they may not know their most recent test,” Selig said.

With the advent of Google Sheets and other collaborative options, we’re now able to have many coxswains inputting data at the same time. Although this is convenient, it has its issues.

“If you feel like there are too many cooks in the kitchen, it’s because there probably are,” Selig said. “The fewer people you have on the Google sheet, the less likely it is that someone is editing the wrong cell.”

If the collaboration becomes overwhelming, you can rotate coxswains through data-collection duties on different days.

For any given workout, it’s wise to

assign each coxswain to collect data for a specific group of rowers.

“Then you know exactly who to go to if data is missing or hasn’t been put in yet, and that’s helpful for accountability,” Selig said. “You don’t want to be in a situation where you say: ‘Did anyone get her data?’, and everyone looks at each other with blank faces.”

It’s crucial that the data be accurate and complete so you can prove to your rowers and coaches that you can be trusted to do a thorough, careful job.

Even if your program uses an app to collect erg data, it’s still important that you have the skills to format the data, locate any missing data, and identify anything that doesn’t belong. No technology is perfect, so always give any results sheet a final once-over. If everyone’s scores start with a 1:00, that 10:00 is likely a typo.

Another benefit of data is that it enables your rowers to chart their progress and envision what they’re capable of in future performances. Selig’s favorite part of data management is using the information from previous workouts to make and refine predictions of what her rowers can accomplish on future erg tests.

“If you have ideas about data or things you can do with your spreadsheets or predictive models, bring them to your coaches and don’t be afraid to present your ideas.”

Even if you’re not spreadsheet-inclined, get involved and do your job well.

“It’s something to be excited about,” Selig said. “I would look at it as a challenge and responsibility rather than a burden. I know sometimes coxswains feel useless in the winter, but you can have a real purpose and a real impact, and I think data and spreadsheets are a solid way of doing that.”

Recording and using your data well in the winter can help your rowers train well, perform better on erg tests, and see their own progress and potential.

HANNAH WOODRUFF is an assistant coach and recruiting coordinator for the Radcliffe heavyweight team. She began rowing at Phillips Exeter Academy, was a coxswain at Wellesley College, and has coached college, high-school, and club crews for over 10 years.

Over the years, I’ve worked with athletes of all abilities and been inspired by how much they’ve learned through rowing about accountability, work ethic, and collaboration.

Iwant to row in college. I hear that phrase often in my work with Robbie Consulting, where I help high-school athletes navigate the college recruiting process. I also heard it countless times during my years as head coach at Clemson and associate head coach at Ohio State.

So, can everyone row in college? The honest answer is … maybe yes, maybe no. It’s a nuanced question that deserves an honest discussion.

Let’s consider the athlete who may be on the smaller side, not setting records on the erg, and still developing technical skills on the water, perhaps even without standout race results. Is there still a path forward?

Absolutely.

While not every rower will be recruited to a varsity program, opportunities still exist through club rowing or by leveraging the many transferable skills learned through the sport during the admissions process. College admissions officers, much like future employers, value student-athletes for their discipline, resilience, and ability to balance rigorous commitments.

Rowers have a well-earned reputation for academic focus and exceptional time management. Even if you’re not being

actively recruited, the skills you’ve built through rowing—dedication, teamwork, persistence, and leadership—can help distinguish you from other applicants.

I won’t promise that rowing alone will secure admission to a top academic institution. My goal, however, is for every high-school rower to stay engaged in the sport and recognize how much it gives back. Over the years, I’ve worked with athletes of all abilities and been inspired consistently by how much they’ve learned through rowing (often without realizing it) about accountability, work ethic, and collaboration. Your job now is to apply those lessons. Use the habits and discipline forged in early mornings and long practices to make your college application stand out. You may not be admitted everywhere you apply, but if rowing helps tip the scales even slightly, then this sport we all love will have served you well in more ways than one.

Nutrition podcasts can not only entertain you during yet another erg session or gym workout but also teach you how to fuel better so you can row better.

Listening to podcasts while exercising can be a convenient opportunity to educate yourself about all things nutrition. Nutrition podcasts can not only entertain you during yet another erg session or gym workout but also teach you how to fuel better so you can row better.

To help you select trustworthy podcasts, below are several options with topics of interest to rowers—health, energy, eating disorders, injury repair, current food controversies, and more. I hope you’ll avail yourself of the chance to learn from these top-notch nutrition researchers and clinicians from around the globe.

Since many sports nutritionists do not have their own podcasts, you also may want to Google “podcasts with___.” Fill in the blank with respected clinicians and exercise physiologists such as Louise Burke, Stu Phillips, Asker Jeukendrup, and Trent Stellingwerff. You’ll be able to listen to these guests on someone else’s podcast.

Sound Bites with registered dietitian Melissa Joy Dobbins.

Posted two times a month; around 60 minutes.

Melissa’s information is popular with both dietitians and the general public. You’ll learn about topics related to your daily diet, with a focus on current trends and controversies. For example:

How Safe Are Food Dyes? An Expert Weighs in on the Research and Regulations

The Sober Curious Movement: Embracing an Alcohol-Free Lifestyle

Plant-Based Performance Nutrition: Benefits, Challenges and Key Nutrients

Spot On! with Joan Salge Blake

Posted two times a month; 30 to 45 minutes

Blake, a registered dietitian and nutrition professor at Boston University, covers timely nutrition topics. In a lively style, she interviews top experts who offer practical health and wellness information. Examples:

Food Order: The Science Behind the Eating Pattern of a Meal and Your Health

How a Creatine Supplement May Boost Your Muscle and Your Mind

Why “Calories In vs. Calories Out” Is a Myth for Weight Management

Exam Room Nutrition with Colleen Sloan, a physician assistant and registered dietitian

Posted once a week, around 30 minutes.

In addressing medical and nutrition questions, Sloan provides practical guidance on how to manage food for health. You’ll find food advice that bridges the gap between medicine and nutrition. Examples:

HDL=Good, LDL=Bad? It’s Not That Simple

Overcoming Nutrition Challenges for Women Over 40

“I’m Barely Eating. Why Can’t I Lose Weight?” The Hidden Factors at Play

Fueling Endurance: Nutrition for Runners, Cyclists and Athletes with Alan McCubbin

Posted one to two times a month; around 60 minutes.

McCubbin, a sports dietitian, nutrition researcher, and lecturer at Australia’s Monash University, addresses a rich variety of topics based on questions that endurance athletes commonly ask. Examples:

Are High-Carb Diets a Health Concern for Athletes?

Can I Trust AI With My Sports Nutrition Questions?

Are Omega-3s Important for Athletic Performance?

We Do Science with Laurent Bannock Posted once a week, around 60 minutes.

This podcast from the Institute of Performance Nutrition features a wide variety of leading experts who are clinicians and scientists with expertise in sports, exercise nutrition, and related fields. They take a deep dive into current trends and hot topics. Examples:

Nutrition for the Prevention and Treatment of Sports Injuries

Plant-Based Sports Nutrition

Advice About Nutritional Supplements

Unbiased Science with Jessica Steier and Sarah Scheinman

Posted once a week, around 30 minutes

The hosts take close looks at the science of health-related topics that may be a source of controversy. They debunk health myths and clarify the confusion with facts. Examples:

Cholestero-all In! The Role of Cholesterol in Heart Health

Protein, Creatine, and “Skinny Teens”

Food Dyes, Seed Oils, and Nutrition!

The Injured Athletes Club

Posted once a week; around 60 minutes

Hosted by mental-skills coach Carrie Jackson and health/fitness journalist and runner Cindy Kuma, this podcast offers support to athletes dealing with sports injuries. The podcast creates a community that offers hope to help make recovery easier. The hosts interview athletes who have recovered from an injury, as well injury after injury after injury. Examples:

Coping When Recovery Feels Overwhelming

Recovery from RED-S Expanding Your Identity

Whom to trust for nutrition facts

After listening to the weekly podcast Why Should I Trust You?, I understand why so many people mistrust messages about food additives, ultraprocessed foods, seed oils, and other public-health issues. The reason: Many nutrition professionals need to offer clearer information to the public. Two sources of clear messaging are Andrea Love and Jessica Knurick. They can help you distinguish between facts and hype You can follow @dr.AndreaLove and @drJessicaKnurick on socialmedia channels such as Instagram and Substack.

May these sources of science-based nutrition and health information address your questions and food concerns, enhance your health and athletic performance, resolve nutrition confusion, and add listening enjoyment to your long workouts.

CLARK, M.S., R.D., C.S.S.D., counsels both fitness exercisers and competitive athletes in the Boston area (Newton; 617-795-1875). Her best-selling Sports Nutrition Guidebook is a popular resource, as is her online workshop. For more information, visit NancyClarkRD.com

From Halloween to Thanksgiving is the perfect window to schedule some much-needed spiritual and physical rest.

Giving yourself permission to put your feet up for a bit, catch up on business that’s been on the back burner, and recharge leads to mental freshness and quality training. Feeling ready for a new set of challenges

Let your body heal from the hard work, rehabilitate a nagging injury, or address muscle imbalances.

in off-season training sets you up for a personal best.

Planned rest periods are an essential component of your annual training program. A periodized plan manages gradual changes in volume and intensity over the course of the year, including a rewarding regeneration phase after the racing season.

From Halloween to Thanksgiving is the perfect window to schedule some much-needed spiritual and physical rest. If you still have rowable water time, take

advantage, but shift your focus to technical base work. Plan a break closer to the holiday season.

During regeneration, let your body heal from the hard work, rehabilitate a nagging injury, or address muscle imbalances with a low-key strength program.

If you’ve noticed a discrepancy in strength from one limb to another when performing an exercise with one arm or one leg, you’ll want to balance this out. To correct the muscular imbalance, perform an exercise with your weaker limb first, followed by your stronger limb.

The repetitions on your stronger side should not exceed the repetitions you can perform on your weaker side. For example, if you can do eight reps of a one-arm dumbbell row with 20 pounds on your weaker side, do no more than eight reps on your stronger side until your weaker side becomes equally strong.

Light activity keeps you feeling mobile and balanced, but take regeneration seriously during this recreational time of year.

MARLENE ROYLE, who won national titles in rowing and sculling, is the author of Tip of the Blade: Notes on Rowing She has coached at Boston University, the Craftsbury Sculling Center, and the Florida Rowing Center. Her Roylerow Performance Training Programs provides coaching for masters rowers. Email Marlene at roylerow@aol.com or visit www.roylerow.com.

Asking whether something will make the boat go faster means being clear about your priorities and disciplined in your focus. Do your actions align with your values and goals?

Will it make the boat go faster?

It’s a common question among rowers, popularized by Ben Hunt-Davis and his teammates in the 2000 Olympic gold medal-winning eight.

It’s the ultimate filter for keeping athletes and coaches alike focused on what actually will improve performance.

Every decision athletes make—from how well they warm up before practice to how they spend their Saturday nights— can be run through this simple test.

Coaches, too, ask themselves this question when considering an adjustment to the practice schedule, equipment purchase, or a lineup.

But what if we applied that same question beyond the boat?

Because asking whether something will make the boat go faster isn’t really about rowing. (In fact, Hunt-Davis’s book by the same name was written for nonrowers and meant to apply to business and life.) It means being clear about your priorities and disciplined in your focus. It’s a way to check whether your actions align with your values and goals. And it presents an opportunity to look at what’s distracting you from what really matters.

Coaches are getting pulled constantly in a hundred directions— meetings, paperwork, equipment, travel logistics, recruiting, mentoring, fundraising. Most of these matters must be dealt with. But not all of them make the boat—or your program, leadership, or career—go faster. By applying this question to our work, we can better separate mere busyness from progress.

The first step is to define your boat. What are your guiding principles? What are you trying to move toward? If your reason for coaching is to develop confident, capable young people ready to take on new challenges, then you need to make sure you’re focused on doing exactly that and not getting distracted testing out the latest bit of technology or fighting with administration.

If your goal is to become a head coach in the next five years, you need to make sure you’re getting as much exposure to high-level responsibilities as possible, not sticking to your familiar, routine tasks.

Once you’ve defined your focus, you

need to take an honest look at how you’re spending your time. Where is your energy actually going? How much of that serves your big-picture goals? Think about ways you can spend more of your time and energy on what’s going to make your unique boat faster, and less on things that don’t.

The best leaders I know and work with, in and out of sport, come back time and again to a version of this question. Before taking on a new project, saying yes to another meeting, or adding one more thing to an already overflowing to-do list, they ask if it will make their own boat go faster. Will it allow them to move closer to

their goals or live in better accord with their values?

Like any skill, this takes practice. But sustained success comes from having the clarity and focus to put your energy where it contributes to both literal and figurative boat speed—and walking away from anything that doesn’t.

Basin with all the banter that goes on. People on shore are so supportive. There’s just so much excitement.”

“Perfect fall weather.”

“We came from Italy because we love rowing and want to be part of the world’s biggest regatta. You know that regatta is an Italian word, no?”

“I love seeing all the new gear, unis, jackets, but most of all boats, oars, and electronics. No wonder the crews are so much faster now.”

“The crashes!”

“When I was in college, I thought that the coolest people went to the HOCR. Then when I started rowing, I thought that I would never go to the regatta without my varsity jacket. Now I go because I realize how awesome the

whole day is.”

“Rowing is ideal for taking photos, and there is no better place to get close.”

“It was my first HOCR. I loved the excitement at the start—80 boats in my event, all trying to get ready. Looking at all of us was amazing! We got crashed into— just oars—and that was exciting, too. Kinda got my blood pumping. I was ready!”

To sum up, “it was a great day for the race, the human race.” It’s what we all need, this year more than ever.

Readers, why do you love it?

ROWING, a.k.a. Andy Anderson, has been coxing, coaching, and sculling for 55 years. When not writing, coaching, or thinking about rowing, he teaches at Groton School and considers the fact that all three of his children rowed and coxed—and none played lacrosse—his single greatest success.

ANDY ANDERSON

Is it the fall weather, friendships, and community? The excitement, enthusiasm, and sportsmanship? The babes, studs, and crashes? Or seeing great rowing up close?

At this year’s 60th Head of the Charles, Community Rowing, Inc., had a big tent draped with a huge banner that read “Why do you rowing?”

What a good question, I thought. Here we are at the world’s most fun regatta, so I think I’ll change the focus. I know what I love about the HOCR, but why not ask the multitudes? So I dug out my trusty pen and notebook and did just that. Here are some of the replies:

“I love it because it always falls within a day or two of my birthday, so it’s a birthday party with 200,000 of my best friends.”

“It’s the best place on Earth to see great rowing. You are so close to the action; you can really appreciate how athletic everyone is.”

“It’s like being at a horse race, right on the track. To see the power and grace is magnificent.”

“For me, it’s the friendships—a lifetime of camaraderie.”

“I love the enthusiasm of the announcers. I can’t imagine how they have the energy to be so positive.”

“For me, it’s the friendships—a lifetime of camaraderie.”

“I know that this year the weather is perfect, but believe it or not, it isn’t always. It sure feels like the gods are smiling on the HOCR almost every year.”

“I’m a coxswain and I love to get my boat out early in the week so that I can practice carving turns in the glassy water. I’ve got a tattoo of the course on my—I won’t tell you where—but I love the turns and negotiating the bridges.”

“I’m from LA, and it seems like no one my age rows anymore. I come here and I’m not even close to being the oldest person out there. It’s a fountain of youth for me. OK, I’m 82.”