HENLEY ROYAL REGATTA

THREE GENERATIONS OF WOMEN PASSING ROWING ON TO THE NEXT

INTERNATIONAL RECRUITS: WHY SO MANY?

GENERATION

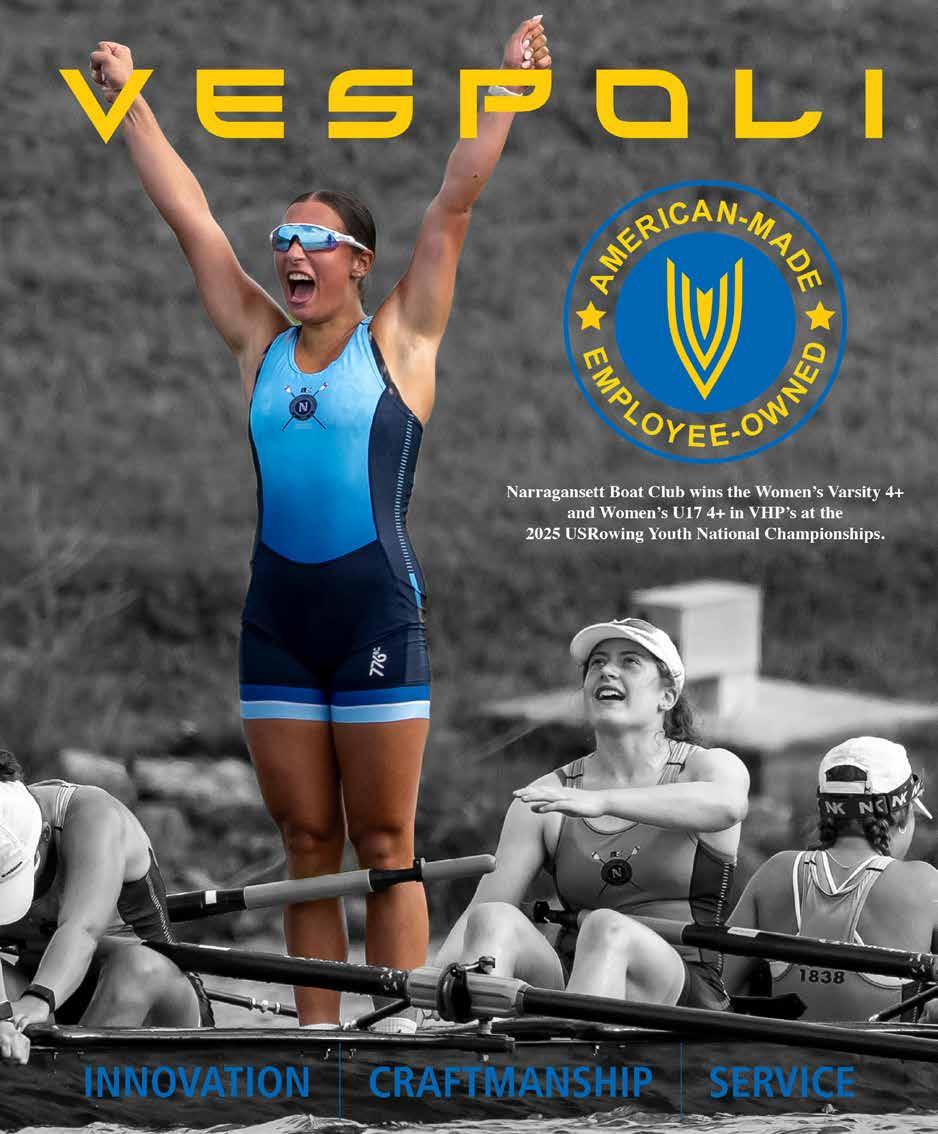

Official Boat Supplier of USRowing U19 and U23 Teams

USRowing National Champion, Men’s Youth Single Sculls // U1.42 Men’s JM1x, World Rowing Under-19 Championships

Tony Madigan, Potomac Boat Club

Photo Credit: AllMarkOne

E.R. Davis

Upper Thames Rowing Club

Congratulations to the Fastest Masters at the Independence Day Regatta!

Charlotte Dobry winning her flight and posting the fastest Womens’ Masters time while borrowing our Phantom 25 display boat.

Troy Howell winning his flight and posting the fastest Mens’ Masters time in the Craftsbury Phantom 25 demo boat.

• Less Drag, More Speed

• Lighter Feel, Higher Stroke Rate

• Easier to Carry

Chip Davis PUBLISHER & EDITOR

Chris Pratt ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

Vinaya Shenoy ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Art Carey ASSISTANT EDITOR

Ian Parish ASSOCIATE

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Andy Anderson | Nancy Clark

Madeline Davis Tully | Terry Galvin

Bill Manning | Volker Nolte | Marlene Royle

Robbie Tenenbaum | Hannah Woodruff

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Jim Aulenback | Steve Aulenback

Stewart Cohen | Katie Lane

Karon Phillips | Amy Wilton

Patrick White | Lisa Worthy

MAILING ADDRESS

Editorial, Advertising, & Subscriptions PO Box 831 Hanover, NH 03755, USA (603) 643-8476

ROWING NEWS is published 12 times a year between January and December. by The Independent Rowing News, Inc, 53 S. Main St. Hanover NH 03755 Contributions of news, articles, and photographs are welcome. Unless otherwise requested, submitted materials become the property of The Independent Rowing News, Inc., PO Box 831, Hanover, NH 03755. Opinions expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect those of ROWING NEWS and associates. Periodical Postage paid at Hanover, NH 03755 and additional locations. Canada Post IPM Publication Mail Agreement No. 40834009 Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Express Messenger International Post Office Box 25058 London BRC, Ontario, Canada N6C 6A8.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to:

ROWING NEWS

PO Box 831, Hanover, NH 03755. ISSN number 1548-694X

ROWING NEWS and the OARLOCK LOGO are trademarks of The Independent Rowing News, Inc. Founded in 1994

©2025 The Independent Rowing News, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission prohibited.

PLEASE SHARE OR RECYCLE THIS MAGAZINE

Follow Rowing News on social media by scanning this QR code with your smart phone.

FEATURES

Hundreds of thousands watched in person, and another 750,000 viewed the livestream, as national-team crews racing under traditional club names swept the premier events.

BY CHIP DAVIS

Three women, three eras, one enduring tradition. This family’s rowing story is a celebration of resilience, connection, and the power of shared passion.

BY AMY WILTON

Foreign Invasion Legacy on the Water Henley Royal Regatta

In national-championship crews at Division I programs, international athletes fill most of the seats. Here’s why—and what can be done to get more American kids recruited.

BY TERRY GALVIN

DEPARTMENTS

23 QUICK CATCHES

News U.S. National Team Wins in Europe

EMU Adds Women’s Lightweight Rowing The Oarsman Award Winners

UCLA Hires Vanessa Tavalero

57 TRAINING

Sports Science Weather or Not

Coxing Making the Right Decision

Recruiting The Many Paths to College Rowing

Fuel Natural vs. Commercial: The Latest Skinny

Training The Technique Session

Coach Development Prove It! 14 From the Editor 66 Doctor Rowing

CHIP DAVIS

The Best Views

Ididn’t get to Varese, Lucerne, or even Henley this year to see those great regattas in person, but I did spend about a quarter of May in New Jersey witnessing the IRA and NCAA nationalchampionship regattas.

For all five regattas, I, like thousands of others, had the best views of the astounding racing, fast times, and remarkable results achieved by some of the world’s greatest rowers.

At the European regattas, drones and multiple other camera angles delivered video images even better and more dramatic than you’d see in person.

On both the Cooper River in Camden County and Lake Mercer in Mercer County, you had to be there to appreciate fully how bad the wind and water conditions were—and how well most crews handled them, whether they should have been racing in those conditions, or not. And when you wanted to know what was happening at every point of the racing, all you had to do was look at the huge video screens showing the livestream coverage.

For the European regattas, drones and multiple other camera angles delivered video images even better and more dramatic than you’d see in person and in vivid high-definition clarity. At the World Rowing Cups, drones appeared to fly at, around, and in between the crews as they raced, providing an even better view than that of the coxswains.

From the continued dominance of the Romanian women’s eight at Lucerne to the outrageous and repeated upsets handed out by Finn Hamill at Henley, you could watch, and rewatch, why successful coaches warn their crews about getting overstroked and why the size of the fight in the dog is more important than the size of the dog in the fight.

It’s all possible thanks to the rapid improvements in video coverage, commentary, and digital delivery going on right now in rowing. Never has the myth “it’s not a great spectator sport” been less true.

Crab

“From The Editor” in the July issue prompted former Rowing News columnist George Kirschbaum to set the record straight:

Charley Butt (III) did not go to or row for Washington-Lee. He went to Langley High School in Fairfax, long before Langley ever had a team. However, he has always been a valued member of the W-L crew family (as are all his siblings).

CSB Jr. used to bring him to W-L practices regularly, and the W-L athletes adopted him as their “little brother.” Many W-L crew alumni have fond memories of him and still consider him a friend.

His skill as a coach is without question, and even CSB Jr. would consult him for advice as he prepared the last W-L crew to race at Henley in 1989. So Charley is W-L in spirit, if not by direct association.

This photo of Sean Baman, which appreared in the July issue, was not properly credited to George Kirschbaum.

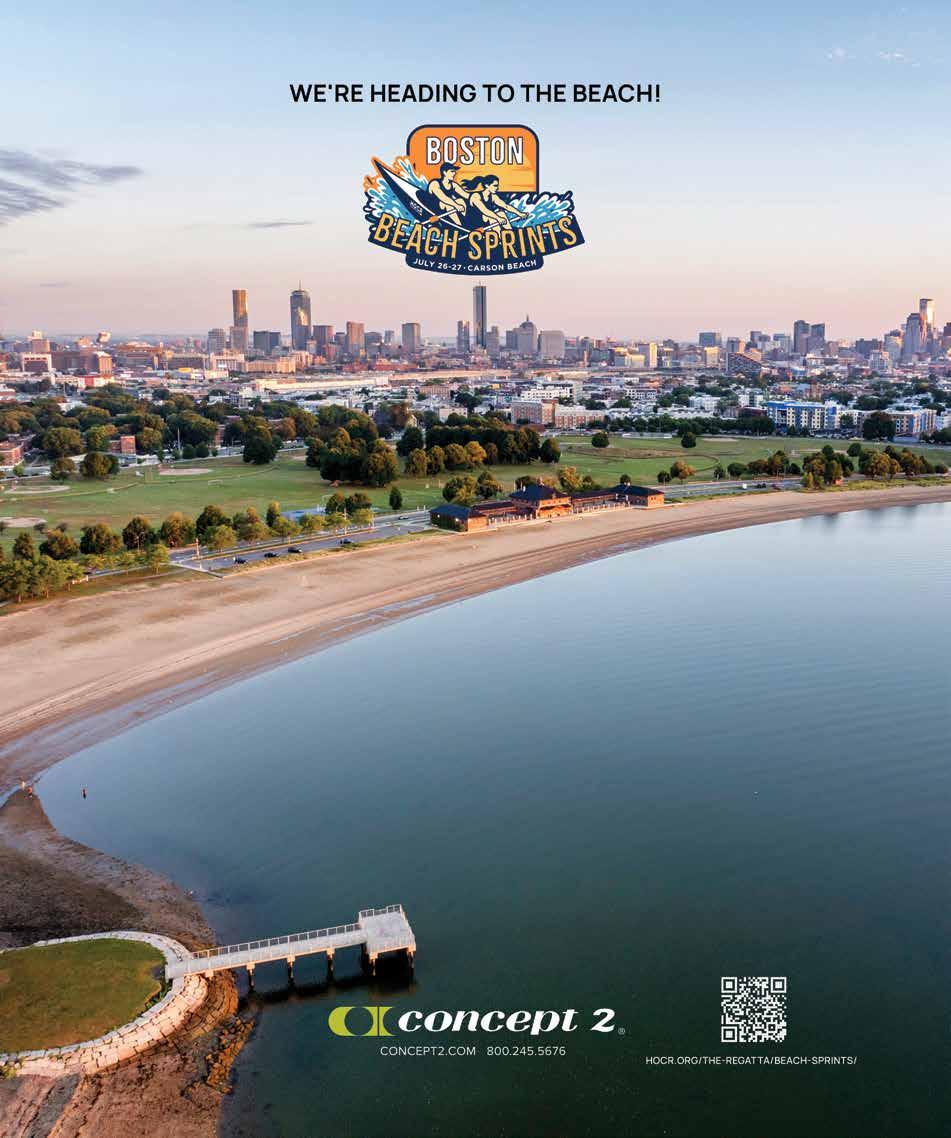

Future Olympians?

USRowing held the inaugural Youth Beach Sprint National Championships on Lido Beach in Sarasota in June. Ophelia Weiss from Next Level Rowing won the women’s single sculls. In the men’s single sculls, Ronan Maher of Oregon Rowing Unlimited clinched gold. In the men’s double sculls, Nicholas Griffin and Harrison Lee claimed gold, thanks to their explosive speed both on land and water. In the women’s double sculls, powering through the conditions led Elizabeth City Rowing Club’s Emma Mayer and Ella McFadden to win gold

PHOTO: LISA WORTHY.

Cheers!

Leander Club’s Ladies’ Plate crew celebrate victory at Henley Royal Regatta. Harvard’s heavyweights, a combination crew of IRA lightweights racing as Brigantine R.C., and Dartmouth’s heavyweights all raced in the Ladies’ Plate, with the Big Green coming closest—half a length—to the eventual winners.

PHOTO: LISA WORTHY.

FOCUS ON THE FINISH LINE WE’LL TAKE CARE OF THE REST!

Planning your next regatta? Nathan Benderson Park makes it easy. Seamless booking and complete logistical support means you can concentrate on the competition, not the complications.

BENEFITS OF BOOKING AT NBP

Permanent, Purpose-Built World-Class Rowing Venue

Ample Trailer Parking with Easy In and Out, 1 Mile from I-75

Course Setup & Management by On-site Professional Staff

Premier Safety & Emergency Services Coordination

550-Acre Park with 400-Acre Lake

Plenty of Tent & Vendor Space and Unobstructed Course Views

Parking & Traffic Flow, Course Maps, Practice Schedule

Location: 5 Miles from Airport. Walking Distance to Hundreds of Shops and Restaurants in a Safe Neighborhood. Minutes Away from the World’s Best Beaches

PLAN YOUR REGATTA!

NathanBendersonPark.org

NATHAN BENDERSON PARK

5851 Nathan Benderson Circle, Sarasota, FL

QUICK CATCHES

Season of Victories

A U.S. National Team women’s four won in Varese. U.S. crews won gold, silver, and bronze in Lucerne, and NYAC rowers won at Henley. Verdonkschot: “Great to have some racing to see where we are.”

U.S. National Team crews took the step from “heading in the right direction” to winning races in Europe in June and July.

A U.S. women’s four won at the Varese, Italy, stop of the World Rowing Cup on June 15. A different U.S. crew won the same event at the Lucerne regatta, and U.S. Olympians Madeleine Wanamaker and Claire Collins, rowing for New York Athletic Club, won at Henley Royal Regatta on July 6.

U.S. National Team boats earned four medals in total at the World Rowing Cup in Varese. In addition to the women’s four’s gold, Jacob Plihal won silver—his first World Rowing Cup medal—and the women’s eight took home silver, all on

Sunday, after the PR3 mixed four with coxswain took silver on Saturday.

The USA1 entry of Camille VanderMeer and Olympians Kate Knifton, Teal Cohen, and Azja Czajkowski trailed a Dutch four through the first half of the race before taking the win. The USA2 entry of Etta Carpender, Alexandria Vallancey-Martinson, and Olympians Jess Thoennes and Charlotte Buck finished fifth.

The two fours combined into an eight coxed by Olympian Nina Castagna to finish second to the Brits. Level with Australia and trailing both Germany and Great Britain through the first half of the race, the U.S. crew closed the gap to two seconds at the line, leaving Australia (third) and Germany (fourth) behind.

EMU Adds Women’s

Lightweight Rowing

Eastern Michigan University will add women’s lightweight rowing as its newest varsity sport, beginning in the 2026-27 school year. The expansion commemorates the 25th anniversary of EMU rowing and will bring Eastern’s total number of varsity sports to 20, including 13 women’s programs. It also represents EMU’s first addition of a women’s sport since lacrosse began competition in 2022-23. “It’s a privilege to be at a university that truly values rowing and is actively expanding opportunities for the sport and for women,” said EMU head coach Kemp Savage.

The U.S. National Team four of U.S. four of bow Alexandria Vallancey-Martinson, Camille Vandermeer, Azja Czajkowski, and stroke Etta Carpender won at Lucerne.

Back Issues are available online

QUICK CATCHES

Italy’s women’s eight missed catching Germany by .01 second. China finished sixth of the six total entries.

Plihal, who won the C final and recorded the fastest time ever for a U.S. single sculler at the Paris Olympics last summer, chased Olympic bronze medalist Simon Van Dorp down the course in the grand final after winning his heat and quarterfinal races.

In the semi, Plihal, a Northeastern alum, lost to Van Dorp, a Washington alum, by three-quarters of a second. Van Dorp extended the margin to two seconds in the final.

U.S. National Team boats earned four medals in total at the World Rowing Cup in Varese

But Plihal, who didn’t have a full four years to concentrate on the single going in to Paris, has narrowed the gap to the top impressively so far in the early run-up to LA 2028. This spring, he told Rowing News he was looking forward to concentrating on sculling and seeing what he could accomplish.

Any budding rivalry will have to wait, as Plihal entered the quadruple sculls and, combined with the four, the eight at Lucerne, while Van Dorp went on to Henley, and the U.S. National Team squad returned to New Jersey to select crews for September’s World Rowing Championships.

“Always good to keep people guessing,” said U.S. National Team boss Josy Verdonkschot, who led the coaching staff of new hire Fiona Bourke, women’s coach Jesse Foglia, and Olympic-champion men’s coach Casey Galvanek on the three-week training and racing trip that did not include Henley Royal Regatta. Said Verdonkschot: “It was a nice opportunity to try out some stuff.”

The Netherlands, with three golds and eight total, topped the medal table at the Varese World Rowing Cup but did not compete in Lucerne. Great Britain, also winners of three golds, was second with five total, but lost to Dutch and Australian competition at Henley. The U.S. was seventh on the Varese medals table but

fourth in the World Rowing Cup (not all medal events count).

U.S. National Team crews won gold, silver, and bronze medals at the second and final stop of the World Rowing Cup in Lucerne. The U.S. women’s four won gold over early-leading Australia, the women’s eight won silver, and the men’s quad won bronze.

“We did a really good job of executing our plan, just staying internal,” said Azja Czajkowski of the U.S. four (bow Alexandria Vallancey-Martinson, Camille Vandermeer, Czajkowski, and stroke Etta Carpender), which also raced as part of the women’s eight. “We just trust each other a lot.”

The men’s quad medal was the first for the U.S. in the World Rowing Cup event since 2014. U.S. Olympic single sculler Jacob Plihal joined Andrew Leroux, Cedar Cunningham, and Christopher Carlson in the quad, which also doubled up with the sixth-place U.S. men’s four to finish fifth in the final-only eights race.

The Lucerne regatta completed a successful training and racing trip for the U.S. National Team.

“Great to have some racing to see where we are and test some combinations,” said Verdonkschot.

Romania’s Olympic-champion women’s eight won at Lucerne, as did the German men’s eight, marking a return to the top for Germany. Recent University of Washington national champion Logan Ullrich jumped in the single after the IRA regatta and won at Lucerne.

“I dreamed about this for years,” said New Zealand Olympian Ullrich. “I didn’t think it would come that quick in my sculling career. I’m just blown away.”

Great Britain’s Lauren Henry won the women’s single in Lucerne. Henry also won the European Rowing Championships and the Varese stop of the World Rowing Cup.

Romania topped the medal table in Lucerne after winning three golds, two silvers, and one bronze. Overall, Great Britain won the 2025 World Rowing Cup.

The year after an Olympic Games is typically a time for elite rowers and national teams to try new things. It’s also the only year the World Rowing Championships are held outside of Europe. This year’s Worlds will take place Sept. 21 to 28 outside of Shanghai.

CHIP DAVIS

HEAD OF THE SCHUYLKILL REGATTA

HOSR welcomes you back to Philadelphia October 25 & 26, 2025

Competition for Juniors, Collegiate, Masters, Veterans, Elite, Adaptive/Para, Corporate and Alumni.

Registration opens July 15th at RegattaCentral.

Purpose got us started. Passion keeps us going. Join us on the course for our 55th year.

Turkey to Host 2025 Beach Sprint Finals

With the new form of competitive rowing set to debut at the LA Olympics in 2028, World Rowing pushed to reschedule the event after it was canceled in Rio de Janeiro.

The Mediterranean resort city of Antalya, Turkey—the jewel of the Turkish Riviera and the Turquoise Coast—will host the 2025 World Rowing Beach Sprint Finals in early November, after the event was canceled at its original site in Rio de Janeiro.

“The level of interest we received following the Rio cancellation was both encouraging and energizing,” said World Rowing President Jean-Christophe Rolland.

“With the discipline now on the Olympic program for LA28, we felt it was absolutely essential to ensure that the 2025 Beach Sprint Finals could still go ahead. We are deeply grateful to the Turkish Rowing Federation and the local organizers in

Antalya for stepping up.”

In Beach Sprint rowing races, athletes run across the beach and jump into shells held in the water. They row to buoys 500 meters out and then back through the surf to the beach, where they sprint to hit a button in the sand.

Part of the coastal category of competitive rowing, Beach Sprints were created to generate more interest in the sport. The three Beach Sprint events— men’s solo, women’s solo, and mixed double sculls—replace Olympic lightweight rowing and will be included in the Los Angeles 2028 Olympic Games and the Dakar 2026 Youth Olympic Games.

COLLEGE

Tavalero Picked to Lead UCLA

The former Cal associate head coach rowed at Washington and is one of few to have won NCAA championships as both athlete and coach.

Vanessa Tavalero was named head coach of UCLA women’s rowing in July, following Previn Chandrarathna’s resignation in May after fours years as head coach of the Bruins. Tavalero was the associate head coach at the University of California, Berkeley for the 2024-25 season and was an assistant at Cal from 2011 to 2019. Tavalero also was an assistant coach at Saint Mary’s College of California from 2020 to 2022.

“Vanessa brings championship-level experience to our program, both as an assistant under some of the top coaches in the nation, and as a two-time nationalchampion rower,” said UCLA athletic director Martin Jarmond. “Her strong leadership qualities stood out immediately, and we are excited to bring her aboard to begin a new era of UCLA rowing.”

UCLA finished ninth of 11 teams at the 2025 Big Ten Championships and was ranked No. 25 in the nation at the time. The Bruins failed to qualify for the NCAA championship regatta for an 11th straight season.

“UCLA is extremely fortunate to have Coach Tavalero lead the next generation of Bruins,” said Cal head coach Al Acosta. “Vanessa was a huge part of our NCAA Championship and podium-finishing teams here at Cal. Vanessa is also one of the few who have won NCAA championships as an athlete and a coach. More important, she’s a great person, mother, and role model. “

Tavalero rowed at Washington on the Huskies’ back-to-back NCAA championship teams in 1997 and 1998. She led UW to a second-place team finish at the 2000 NCAAs. Tavalero also rowed on the U.S. Junior National Team women’s eight in 1994 and 1995.

PHOTO: LISA WORTHY.

Independent review of the ActiveSpeed - Sander Roosendaal, founder of the rowing analytics site rowsandall.com, takes a deep dive into the ActiveSpeed. Radley

Large Configurable Display (2, 4 and 6 fields)

Optional Wireless Impeller & Accessories

Easy Data Transfer via the DataFlow App

$445 $495

COLLEGE

Derrick Named Head Coach at Kansas

The University of Kansas has named Andy Derrick the third head coach in Kansas rowing history.

Derrick led Gonzaga to four straight West Coast Conference titles, top-20 national rankings in four of the last five seasons, and is a three-time WCC Coach of the Year. He signed a five-year contract that extends through the 2030 season.

“We couldn’t be more thrilled to welcome Andy, his wife, Karin, and their three children, Kathryn, Josephine, and Jack to the Jayhawk family,” Kansas director of athletics Travis Goff said.Before coaching at Gonzaga, Derrick served as the head coach at Seattle Pacific and Central Oklahoma and has worked also as an assistant coach at Oklahoma and the University of Central Florida. He rowed at the University of Washington, where he won a national championship in 2001. He also represented the United States at the 2001 World Rowing Under 23 Championships.

Kansas finished third of six teams at the 2025 Big 12 Rowing Championship in May at Nathan Benderson Park in Sarasota. UCF swept all six races at the championship, securing the program’s first Big 12 title in rowing and earning the conference’s automatic bid to the NCAA championship.

“I was blown away as I went from not looking to extremely impressed and interested,” Derrick said. “It was clear from a very early conversation that Kansas was serious about getting good at rowing. KU absolutely has the resources and now the willingness to use them to grow the program and I am very excited to have been entrusted to steward the team on what is going to be a great upward trajectory!”

COLLEGE

Penn’s Lewis to Coach Alabama Women

Alabama has appointed Kumari Lewis head coach of the Crimson Tide women’s rowing program.

Lewis goes to Tuscaloosa from Philadelphia, where she coached in the University of Pennsylvania’s women’s program for eight years, the last two as the associate head coach and recruiting coordinator.

“She is widely regarded as one of the top up-and-coming coaches in the sport and came highly recommended by many throughout the search process,” said Alabama athletics director Greg Byrne. “Coach Lewis has a proven track record of success in one of the most competitive rowing conferences in the nation and has been instrumental in Penn’s past recruiting efforts.”

While Lewis was a coach at Penn, the Quakers earned bids to the NCAA championship the last four years and won five medals at the Ivy League championships.

Within weeks of being named head coach, Lewis hired Erin Hayes as an assistant coach. Hayes, who coxed at Alabama from 2014 to 2018, was the head coach at St. Andrew’s in Roswell, Ga., perennially one of the top youth programs in the Southeast.

“I am really excited for the opportunity to work with Erin. Not only is it special to have an alumni coxswain returning to ’Bama, but I know Erin is going to be an integral part of this team and staff,” Lewis said.

“This team has the capacity to do something exceptional, and I am excited to help make that happen alongside an amazing staff. The university community is unparalleled, and I am humbled by the opportunity to be part of it. Row Tide!”

New Oarsman Award Salutes ‘Generational Talent’

Washington’s Ullrich, Harvard’s Erdmann, and Trinity’s Carr are first recipients of “rowing’s Heisman.”

Washington heavyweight Logan Ullrich, Harvard lightweight Brahm Erdmann, and Division III’s Trinity College captain Jack Carr are the first recipients of the Oarsman Award, the Intercollegiate Rowing Coaches Association’s new honor, meant to emulate the Heisman Trophy.

The Oarsman recognizes a generational talent—a rower whose collegiate record is not only impressive but also unprecedented within a particular program, according to the IRCA.

Ullrich, a New Zealand Olympian who won silver in Paris in the four last July, rowed on this year’s IRA national-champion

Washington heavyweight varsity in June and won the Lucerne Regatta in the single later the same month.

“At Washington, we spend a lot of time talking about what it takes to be a ‘true oarsman,’” said UW head coach Michael Callahan. “There’s a lot more to it than simply pulling an oar through the water, and Logan embodies everything that makes the ideal oarsman on and off the water.”

Erdmann was a member of the Harvard lightweight varsity that won Eastern Sprints, the IRA national championship, and the Temple Challenge Cup at Henley Royal Regatta.

“Brahm embodies the industriousness

of this program and helped lead it from its lowest point to unprecedented success,” said Billy Boyce, head coach of the Harvard lightweights.

Carr is a four-year letterman on Trinity College’s varsity, two-year captain, and this year undefeated Division III national champion. He routinely held the highest GPA on the team, assistant coach Nate Clark said.

“His preparation was second to none, and his leadership ensured others came with him. He is an outstanding scholar who lived up to the highest academic standards possible,” Clark said.

Images must be 300 dpi, and a minimum size of 4” x 6”.

At Henley, a Grand Royal Rite of Rowing

PHOTOS BY LISA WORTHY AND PATRICK WHITE | INTERSPORT IMAGES

Hundreds of thousands watched in person, and another 750,000 viewed the livestream, as national-team crews racing under traditional club names swept the premier events.

Henley Royal Regatta attracted some of the world’s fastest crews and record crowds for the sport’s grandest event, on and off the water.

The Leander Club reported serving 2,500 jugs of Pimm’s and 10,000 pints during the regatta, held over the first six days of July. Hundreds of thousands of spectators watched in person, and another 750,000 viewed the livestream on YouTube.

The premier events, for elite-level crews like national and Olympic teams, all went to the national-team crews racing under traditional club names. Harvard’s lightweights, Rutgers’ women, and the New York Athletic Club pair of Madeleine Wanamaker and Claire Collins crossed the Atlantic to win the Temple Challenge Cup, Island Challenge Cup, and the Hambleden Pairs Challenge Cup, respectively.

Rutgers women’s entry in the new Island Challenge Cup raced to a course record in winning Wednesday through Sunday in Henley Royal Regatta’s single-elimination bracket format, contested over 2,112 meters (the inspiration for the Olympic standard distance)

PHOTO: PATRICK WHITE | INTERSPORT IMAGES.

Harvard lightweights won the Temple Challenge Cup, capping a perfect undefeated, HYP, Eastern Sprints, and IRA national-championship season

PHOTO: LISA WORTHY.

Princeton’s Theo Bell and Marcus Chute, fresh off the Princeton heavyweight men’s 2025 season in which they won bronze at Eastern Sprints, advanced to the final of the Silver Goblets and Nickalls’ Challenge Cup. “It’s been impressive to watch these two as they have worked their way through the week’s racing,” said Princeton heavyweight head coach Greg Hughes, “coming from behind in every race so far to find the lead and never let up.”

PHOTO: PATRICK WHITE | INTERSPORT IMAGES

New Zealand’s Finn Hamill (right), the 2023 World Rowing Under 23 Championship silver medalist in the lightweight single, tore apart both the Diamond Challenge Sculls and the Double Sculls Challenge Cup (with Benjamin Mason) brackets. In the single, Hamill eliminated Olympic bronze medalist Simon Van Dorp in the Friday quarterfinal dual, beat 6-foot-8 German Olympic champion Olli Zeidler in the Saturday semifinal (having raced and won already in the double each day) and fell finally to The Netherland’s Melvin Twellaar—who set a new course record—in the final. Hamill then won the double, racking up six total wins in four days on the Thames

PHOTO: PATRICK WHITE | INTERSPORT IMAGES.

The Dutch women won the Remenham Challenge Cup ahead of Great Britain’s eight, who had eliminated Australia the day before.

PHOTO: PATRICK WHITE | INTERSPORT IMAGES

Racing for New York Athletic Club, Olympians Madeleine Wanamaker and Claire Collins won the Hambleden Pairs Challenge Cup, outdistancing the Jurkovic sisters, who finished third for Croatia at the 2024 European Rowing Championships. Wanamaker and Collins raced in the U.S. women’s eight in Paris, the four in Tokyo, and won a bronze medal as a pair at the 2022 World Rowing Championships.

PHOTO: PATRICK WHITE | INTERSPORT IMAGES

Legacy on the Water

Three women, three eras, one enduring tradition. This family’s rowing story is a celebration of resilience, connection, and the power of shared passion.

STORY AND

BY AMY WILTON

PHOTOS

Susan Sunda, 83, Melissa Dow, 58, and Amanda Dow, 25 represent three generations of rowers from one family.

In a sport where endurance, timing, and teamwork are everything, they prove that age is no barrier to passion or performance. Each has carved her own path in rowing while staying connected through the shared rhythm of the stroke.

Theirs is a story about not only competition and fitness but also legacy, resilience, and the quiet power of women showing up—on the water and for each other.

The three women hail from northern Michigan, and I met them last spring while coaching a rowing camp at Craftsbury Outdoor Center in Vermont.

The first thing you notice about Susan is her sprightliness. She doesn’t walk— she bounces, she floats, she springs. She carries her petite frame with the energy of a 10-year-old. Unlike the rest of us, she has managed somehow to defy aging.

Ask her how old she is and she’ll say, “Oh, I don’t know. That’s not important to me. I never pay attention to that,” and it shows.

Maybe that’s the key to aging gracefully—not assuming certain things happen at certain ages and just going about your business, ignoring how many candles will melt on the top of your next birthday cake.

Oh yeah, and there’s the rowing. For Susan, that was the key.

Susan was born and reared in Arlington, Va., in the days before Title IX when girls could be cheerleaders but weren’t allowed to participate in most school sports. She had a boyfriend on the rowing team at Washington-Lee High School (now Washington-Liberty), coached by D.C. rowing legend Charlie Butt.

Charlie would let the girls wash the boats, take the oars out, and one time he even let them sit in the boat at the dock as he held the bow so they could take a few strokes. As soon as the boys came back, of course, they had to hop out. Still, that was enough to ignite Susan’s lifelong passion for rowing—even if she had to wait another 22 years to get back in a boat again.

One day in 1982, when Susan and her family were living in Indianapolis, she saw a video of the Purdue University men’s crew on the news and was excited to learn there was rowing nearby.

A short while later, she responded to a newspaper ad for a Learn to Row class sponsored by the new Indianapolis Rowing Club (IRC). When she called and asked whether 40 was too old to learn how to row, the answer was no, and she signed up immediately.

Members of Purdue men’s crew taught the class by putting collegiate rowers in the bow and stern and novice rowers in the middle of the boat.

“It was incredible!” Susan said. “You could feel the run of the boat. I’m getting goose bumps now thinking about it. I remembered hearing Charlie Butt talk about that, and now I knew what it felt like.”

After that class, she was invited to join the club, which is based on Eagle Creek Reservoir. Because everyone was required to perform a job within the club, Susan volunteered to help run all the regattas, including at the Pan American Games, where she was in charge of weighing lightweights.

Eventually, Susan found a pair partner who had coxed in college and she began rowing regularly. Soon, they recruited two more rowers and made a four.

Clete Graham—founder of the Notre Dame women’s club team, impresario of the Schuylkill Navy and Stotesbury Cup Regatta, and a teacher at Philadelphia High School for Girls—began coaching at the club.

“You’re going to row six days a week and row six races a season,” he announced. “If someone is missing or the weather is bad, we will do land training.”

The response of Susan and others: “We’re in!”

But they needed a coxswain. Susan thought she might have one at home.

Susan often brought her 10-year-old son, Mark, to the reservoir to look at the boats. One day, as he was watching a crew getting off the water, he asked what the little guy in the back of the boat was doing. Susan explained that he is the coxswain—the brains of the boat, the one who can talk, has the strategies, and can steer. Mark thought that was really cool.

So she introduced her son to Graham, who agreed to coach them with Mark in the coxswain’s seat. Mark’s perseverance in the boat surprised everyone. A quiet, dyslexic, introverted boy, he gained a lot of confidence from his coach.

After a few years under Coach Graham’s tutelage, Mark coxed the Head of the Charles six times before the age of 18. Susan calls him a coxswain savant. He went on to cox for

Purdue University. At 5-foot-8, the freshman was taller than all the other coxswains, but the varsity men’s eight had seen him work his magic in many races and wanted only him. A steady, calming presence, he consistently steered his crews to victory.

Susan’s daughter, then 16, had a different introduction to rowing. Graham’s threat of dry-land training motivated Susan to recruit Melissa. Susan would shake the teenager awake before dawn and say, “Get up, you have to come. Rosemary [a teammate] can’t make it today!”

At the time, her daughter was a selfdescribed “rebellious teenager.” She didn’t like to get up early, but after rowing with very competitive, confident rowers, she was able to fill in when necessary. Melissa was also a dancer, which is why Susan, in a bid to convert her, described the grace of rowing as “a dance on the water with power.”

After a few months of rowing in a four with her mom, Melissa was invited by Susan to go out in a double for some oneto-one coaching so she could really learn the stroke. They set out from the dock on a beautiful sunny day that turned stormy quickly, with foot-high waves crashing over the gunnels.

Susan ordered Melissa to hold on to her oars and not let go. As her blades kept getting caught on the water, she was certain they both would end up in the drink. On their way in, when Susan asked Melissa whether she was having fun, she responded with a firm “NO!” After they made it back to the boathouse upright, Melissa swore she would never get into a sculling boat again.

At about the same time, in the late ’80s, Susan began coaching the IRC novice women. After a few weeks of practice, they were rowing in synch. She asked whether they felt the oneness when they were all moving in the boat together. They did. As they came off the water that day, they were excited, hugging each other and exclaiming, “We were all one!”

Susan loved watching the girls come from nothing to rowing as a team and being able to race together.

In 1990, Susan went with IRC to the masters nationals in Miami in a double. She and her partner made a plan ahead of time, visualizing every stroke the night before. During the race, they replayed it exactly and won handily over their much taller competitors from Washington.

After the regatta, a friend told her their boat had been losing at the halfway point and wondered how she was able to surge ahead at the end.

“We didn’t even notice,” Susan replied. “Our heads were in the boat, and we were following our race plan. We had won that race already in our heads. Your brain doesn’t know whether you’re just thinking about it or really doing it.”

Right after that regatta, this 5-foot2, 107-pound woman was dogsitting a neighbor’s Rottweiler. In the morning, when she went downstairs to let out the dog, it charged at her, knocked her to the ground, and sunk its teeth into her arm.

Knowing that if she tried to yank her arm away, it would break, Susan dragged the 150-pound beast through the house to the front door. With the animal still attached to her arm, she managed to turn the deadbolt and get outside, where a neighbor saw here and called the police.

When officers arrived, they removed the dog and put it in the house to wait for animal control. But it escaped.

Susan remembers standing in the front yard, her arm in the air and blood streaming down her side, looking at the exposed tendon in her arm.

Suddenly, she noticed the officer next to her crouching low, arms out straight, gun pointed toward the house. The dog was charging at Susan. The officer fired; the dog went down. He had no choice.

Had rowing not made Susan so strong and fit, she would have died that day. She was back in the boat a mere four months later.

During the years Susan rowed with IRC, she won over 60 medals and competed several times at the Head of the Charles. She displays her medals in her home on a set of deer antlers. When Susan moved to Utah in 2004, there was no rowing club, so she rowed by herself on Pine View Reservoir in the Ogden Valley, initially in her Maas and later a Peinert.

Meanwhile, Melissa married and settled in Washington, D.C. She didn’t get into a boat again until years later while living in northern Michigan, when her daughters, Amanda and Rachel, were 13 and 11, and she was 46. She attended a few Learn to Row classes but couldn’t commit to a team because her husband traveled and she had children to care for.

In 2019, Melissa overcame her sculling trepidation and bought a single. Rowing in the early morning, she noticed other rowers on the turquoise waters of Glen Lake in Glen Arbor, Mich. Tired of rowing alone, she brought these people together and launched the Northern Michigan Rowing Club.

The club has two locations, with more possible in the future. Sharing equipment and resources, they are more like chapters than separate clubs. The goal is to spread organized rowing to many of northern Michigan’s lakes so people who love the sport can enjoy the convenience of rowing where they live.

Susan, the family matriarch, has learned many lessons from rowing that she’s passed on to her children and grandchildren—tenacity, the conviction that hard work pays off, the importance of planning ahead to achieve the desired outcome.

“That’s why I am who I am,” Melissa said. “I’ve tried so many things in my life because I think through each one and I know it’s going to work. Rowing is where that came from.

Melissa’s older daughter, Amanda, says the example set by her mother and grandmother has given her the confidence to be more adventurous in life.

Melissa got her firstborn on the water a couple of years ago, but it wasn’t until last summer that Amanda committed to learning by joining her mom and grandmother at Craftsbury for a week of rowing camp. Because Amanda’s sister, Rachel, was introduced to rowing on the erg at a CrossFit gym, she isn’t convinced rowing can be a Zen sport. Melissa hopes that if she promises to try pickleball, Rachel will hop in a boat.

“Full of determination” is how Melissa describes every member of her family. Growing up, they didn’t have a lot of money, so they worked with what they had to get the most out of life. She and her brothers had a happy childhood because of Susan’s exceptionally positive attitude. As with rowing, if you have the determination to dedicate yourself to practicing the technique, she says, you will succeed.

The year 2022 was big for secondgeneration Melissa. Not only did she complete USRowing’s Level 2 coaching course but also she convinced her mom to move to Michigan so they could row together again.

The cycle is complete.

“People say it’s in our blood, and maybe it is,” Melissa said, “but maybe it’s just so beautiful that we all want to do it.”

Coda

Susan claims that in her 43 years of rowing she’s never caught a crab.

Melissa finally lured Rachel into a boat and out on the water to row. Now she owes her a game of pickleball.

FOREIGN INVASION

IN NATIONAL-CHAMPIONSHIP CREWS AT DIVISION I PROGRAMS, INTERNATIONAL ATHLETES FILL

MOST OF THE SEATS. HERE’S WHY—AND WHAT CAN BE DONE TO GET MORE AMERICAN KIDS RECRUITED.

STORY BY TERRY GALVIN

PHOTOS BY LISA WORTHY AND KATIE LANE

At the 2025 IRA National Championship heavyweight A final, only 40 percent of the studentathletes were U.S. citizens.

Of the top three finishers, Washington, the winner, had one American. Harvard won silver with two Americans, and bronzewinning Dartmouth had six. In the rest of the A final field, Princeton had three; Brown, four; and Syracuse, six.

In recent years, both Yale and Cal have won the IRA national championship with crews made up entirely of international oarsmen.

Top collegiate rowing programs in the United States have more international athletes than Americans in their boats for many reasons, interviews with several prominent coaches show.

It’s a situation that has puzzled and

concerned many for years, and it even prompted rower Carlo Zezza to write a 2017 book that explored “why our top college crews are rowed by foreigners.”

Measuring by Olympic performance and medals, Zezza plots the decline in U.S. rowing talent from its nearly 40 years of highs to the low of zero medals for U.S. men at the Rio Olympics in 2016 (U.S. women won gold in the eight, and American Gevvie Stone captured a silver in the single).

The simple explanation for the large presence of international athletes in top crews at U.S. collegiate regattas is obvious: They help their crews win races.

But many other factors also contribute. In other countries—primarily the U.K., Australia, and New Zealand, but also Germany and other European nations— rowing thrives because:

Nearly half—25 of 58—of the hometowns listed on the roster of the 2025 IRA national champion University of Washington men’s program fall outside of the U.S., and only one member of the winning varsity crew is an American. PHOTO: Lisa Worthy.

Six of the women in 2025 NCAA Division I national champion Stanford’s first eight, and half of the Cardinal’s second eight, are internationals. PHOTO: Katie Lane.

• Their cultures and traditions recognize and celebrate the sport more than the U.S. does.

• There’s less competition from other major sports than in the U.S.

• Athletes participate in other sports, compared with the tendency of U.S. athletes to specialize, which often results in burnout.

• They introduce rowing to younger athletes and in smaller boats that reinforce good rowing technique, whereas most U.S. youth and junior programs emphasize eights.

In addition, the number of U.S. collegiate rowing programs has increased, boosting demand for athletes. Colleges with rowing programs have more than doubled in recent decades, if for no other reason than Title IX’s support of women’s rowing.

“It’s a simple numbers game,” said Syracuse men’s head rowing coach Dave Reischman. “Every year, the country produces top U.S. rowers in erg scores and body type, probably eight to 10 a year.

“Rowing isn’t any different.”

Manning, named head coach of Penn’s women’s team last year, has been a high-performance coach at Penn Athletic Club and a senior U.S. National Team coach. He also spent 23 years coaching and recruiting at Princeton and Harvard.

For him, a major reason for the high number of international students on top U.S. college crews is the abundance of sports with higher profiles in the U.S. Those sports naturally draw the most athletically gifted young people.

“In Australia and the U.K., you will find some of their best athletes rowing,” Manning said, compared with the U.S., where many of the best athletes are drawn to “the big three”—football, basketball, and baseball.

“I personally don’t think an international kid is better than a U.S. kid,” he said, “but often they are coming out of a program where they were very well coached and supported.”

Because the U.K., for instance, doesn’t have nearly as many universities with major rowing programs as the U.S., Manning said, many of the top U.K. coaches have good-paying jobs at the more plentiful secondary schools.

“The majority of the best coaches in the U.K. coach juniors.”

“We have had rowing since 1874, but when I tell people, even here, that I’m the Syracuse rowing coach, they’ll say, ‘I didn’t know Syracuse had rowing.’ ” —Dave Reischman

“If you can recruit the best eight to 10 kids from every country, it helps.”

Reischman, who led all four of his boats into the A finals in this year’s IRA championships, acknowledged that the international trend has grown, leaving older alumni who might have begun as walk-ons concerned about the change.

Bill Manning of the University of Pennsylvania, however, pointed out that colleges recruit internationally for many sports —tennis, soccer, basketball, etc.

This, of course, makes the rowers they train prime targets for U.S. university recruiters.

Reischman expressed a similar view. In the four countries that supply the most athletes to U.S. college crews, rowing is “a higherprofile sport. It’s not competing with as many sports as in the U.S. It’s a bigger part of the culture and is closer to the surface of popular consciousness.

“We (Syracuse) have had rowing since 1874,” he continued, “but when I tell people, even here, that I’m the Syracuse rowing coach, they’ll say, ‘I didn’t know Syracuse had rowing.’ ”

To cement the argument that athletic young Americans strive to excel in the glamorous spectator sports rather than

rowing, Manning said: “There’s not a single rower who could be a starting quarterback for a Division I college team.”

Beyond heavyweight men

The prevalence of international athletes is less pronounced in lightweight men’s and women’s teams.

But the percentage of international athletes in the women’s openweight NCAA Division I varsity eight A final this year was identical to that of the men’s heavyweights: Only 40 percent of the rowers were U.S. citizens.

First-place Yale had four U.S. citizens; second-place Stanford had three, as did Texas, in third; Tennessee, in fourth; and Washington, in fifth. Sixth-place Brown had six.

“International rowers have been a part of the Washington rowing legacy since the ’80s, including a woman who defected from the Romanian team during Communism when they came to Seattle for the Windermere Cup,” said women’s team head coach Yasmin Farooq, a twotime Olympian and a world champion as a cox.

“That said, the sport has grown and evolved since then, including scholarships across many schools, and there certainly is a trend of more international rowers across the board, especially in teams’ varsity eights.”

Women’s rowing has many more opportunities for rowers, Farooq noted.

“The difference in women’s rowing is that you have to be three boats deep to win an NCAA [Division I] championship and you need to be seven boats deep in the Big Ten. That leaves a lot of room for development here at Washington, and we’re working really hard to be able to continue that grassroots work.

“We are also one of the last places that is truly developing walk-ons. We actively recruit top athletes from other sports in and out of state and teach them to row. There are also a lot of local kids on area teams who dream of rowing for the University of Washington, and they are also a key part of our program.”

Why U.S. schools appeal to international students

The presence of international students in U.S. college crews benefits both sides, coaches stressed.

Attending a top U.S. university is the

“We need to work on our culture. We can do a better job exposing young people to the sport. We need as a community to get our young people to see it’s awesome to row.”

—Kim Cupini, head women’s rowing coach, University of Tennessee.

goal of many international students and their families, and athletics—whether rowing or another sport—is a way to make that happen.

“It’s a uniquely American notion that a university will pay for your education just because you are good at a sport,” Manning said. With or without a full or partial scholarship, being a good athlete can guarantee entrée to a top school.

“A lot of families overseas see an education at a U.S. university as their golden ticket,” Manning said, because of the quality of the academic instruction and athletic coaching, the experience and prestige of studying abroad, the international connections that can be made, and the opportunity to perfect their English if it isn’t their first language.

“American universities are incredibly appealing,” he said.

Furthermore, there’s the impressive quality and quantity of coaching and other resources provided to athletes in top American collegiate programs.

“They get to train at a high level and go back to join their country’s national team, if that’s their ambition,” Reischman said.

Speaking of her own school’s goal of “sending them back to national teams ready to go,” Farooq put it this way: “A lot of aspiring international junior rowers see the University of Washington as a means of achieving those dreams, so we are a destination.

“In general, American educations are still highly sought after, and the opportunity for scholarships is attracting more and more internationals.”

Universities not named Washington, Stanford, Yale, or Princeton also impress international students with what they offer rowing recruits, said Kim Cupini, head women’s rowing coach at the University of Tennessee.

“At Tennessee, we’re building a program that provides a lot of coaching and athletic and academic resources,” Cupini said. “We really do give you everything international students look for and are really grateful to have.”

Cupini has led the Lady Vols to impressive speed and victories since she was appointed in 2023 after nearly 20 years of coaching elsewhere. She was named Big 12 Coach of the Year in 2024, and Tennessee was fifth in team standings at this year’s NCAA Division I championship, just behind Washington, after finishing third in 2024—with a lot of international recruits who followed her from SMU (where she had also been historically successful).

“In our team culture, we love a lot of diversity, and a lot of internationals embrace that,” she said. “The different backgrounds increase the richness of our program.

“International students are not as caught up in attending a big-name school,” she added.

The question of money

Many international students need to enroll where their talent can snare scholarships.

“Their families saved and expected to pay $10,000 to $15,000 a year for college” in their home countries, Reischman said.

“They weren’t expecting $90,000. You don’t find many college students who can afford that.”

That tends to be true of the main sources of talented recruits, Reischman said, and across Europe.

Schools with less scholarship money to offer, however, benefit from recruiting international students who are full-pay.

“In certain countries, the elite in those countries have money,” he noted.

Changing the U.S. rowing culture

Can Americans develop more appreciation for rowing?

“We need to work on our culture,” Cupini said. “We can do a better job of exposing young people to the sport. We need as a community to get our young people to see it’s awesome to row.”

Although concerned about whether the quality of the coaching can keep pace with the surging growth in rowing programs, Cupini is encouraged that so many high-school and middle-school programs are popping up.

Reischman pointed to a major difficulty in creating broad public appeal for rowing here.

“Good rowing looks easy,” he said. “It’s certainly tougher to get the drama of our sport on a TV screen.”

Obstacles to generating more interest in rowing among young people include not having access to water and a nearby rowing program as well as the availability of boats and equipment.

Rowing has grown significantly since the days when it was practiced only among elite prep schools in the Northeast and a couple of schools in California and Washington State. Today there are many high-school, club, and college rowing programs in Florida and Texas and across the South and Midwest.

But as our sport tries to increase its visibility and attractiveness, competing for attention with America’s “apple pie sports” remains a high wall to climb.

Said Reischman: “How do you move ahead of the majors?”

TERRY GALVIN spent his professional life as a writer, editor, and designer at newspapers, largely in the U.S. Virgin Islands and in Sarasota. He learned to row as an adult and while he was business editor at the Sarasota Herald-Tribune covered the development of Nathan Benderson Park. Since its inception, he has volunteered at the park as a launch driver.

Weather or Not

Are more races being canceled today because of climate change, better safety protocols, or rigger design?

Doesn’t it seem like races at North American rowing regattas are being canceled more often today because of weather than 20, 30, or 40 years ago?

Such cancellations are frustrating for everyone involved, not just the athletes who’ve trained for countless hours and wind up empty-handed.

Races are canceled commonly because of thunderstorms, strong wind, torrential rain, or water levels that are too high or too low. Safety is, and should be, a priority— always.

When strong winds and high waves threaten rowers, officials, spectators, or equipment, regatta officials no longer take the risk. We are all more cautious now, rightly, and thanks to modern technology, we can detect approaching bad weather sooner and take appropriate precautions.

Our changing climate is certainly a cause of more volatile weather, but what about changes in the design of racing boats? Are they contributing to more race cancellations?

Worth considering is the use of wing riggers, which are mounted on the gunnel instead of the side of the boat. This rigger design limits the height of the gunnel so rowers can move their hands over the crossbars of the wings.

Glen Burston, chief engineer at Hudson Boatworks, believes wing riggers make rowing in rough water safer.

“There are two main reasons for this,” he said. “First, side-mounted riggers were much closer to the water surface, so even smaller waves hit the riggers and splashed water into the boat.

“Second, modern boat designs have horizontal lips at the top of the gunnels

that effectively act as a splash guard, pushing water away from the boat when the waves get high enough to reach the top of the gunnels.”

National and international racing rules require boatbuilders to construct watertight compartments in the cockpit so boats won’t sink when they fill with water and rowers can remain aboard and wait for help.

Fortunately, weather-related accidents are rare in rowing, owing to better education about observing and assessing conditions and increased readiness in exercising caution.

That’s a sign not of cowardice but of prudence.

VOLKER NOLTE, an internationally recognized expert on the biomechanics of rowing, is the author of Rowing Science, Rowing Faster, and Masters Rowing. He’s a retired professor of biomechanics at the University of Western Ontario, where he coached the men’s rowing team to three Canadian national titles.

Olympian Billy Bender (stroke), a finalist for the Oarsman Award, and his IRA bronze medal-winning Dartmouth teammates at the 2025 IRA National Championships.

TRAINING

Making the Right Decision

If you’re in the enviable position of choosing among multiple offers, be thoughtful. Think about the people you’ve met. Do you want them to be your coaches and teammates?

You’ve spent months building relationships with college coaches, and now it’s time to get down to decisions.

Be open-minded, but don’t talk to coaches (or take visits) at a school you absolutely won’t consider. That’s a waste of everyone’s time, including your own. If you decide during the process that a school isn’t the right fit, tell the coach politely. I’ve heard many coaches say that the best answer a recruit can give them is “yes,” but the second-best is always a “no.” That allows the coach to go find coxswains who want to fill that spot.

The more authentic and honest you are in the process, the better. If a school is your first choice, make that known. The worst that can happen is there’s no spot for you. If you’re dragging your feet

because you’re not sure about a program, the coaches can tell. Rather than avoiding the issue, initiate a candid conversation about where you stand and try to address your qualms. The point isn’t to have every coach fall in love with you; it’s to find the right environment for you.

This is also when to explore logistical sticking points standing between you and the school. By talking about academic standards and finances with the coach, you can avoid falling in love with a school that’s clearly not an option. Be pragmatic and move on once you’re sure something isn’t going to work.

If you’re not recruited to your dream school, you can always talk to the coach about the possibility of walking on. Most schools are thrilled to have a walk-on coxswain with experience. If you’re

looking into this, ask questions about the tryout process (will you have a guaranteed spot on the team?) as well as the number of coxswains and boats the coaches expect. That way you can assess how likely you are to make the squad and to be boated.

“Walk-ons need to be willing to put in the time and effort,” said a coach I spoke with, “but if you’re a good coxswain, it will come out. We’ve had recruited coxswains flame out because they came in without realistic expectations, and walk-ons who succeeded because they were willing to be patient.”

If you’re in the enviable position of choosing among multiple offers, be thoughtful. Think about the people you’ve met. Do you want them to be your coaches and teammates? It’s important to reflect on the reality of the school, not just the

Wharton School’s Rebekah Sun ‘26 walked on to Penn’s women’s rowing program and coxed the second eight at the 2025 NCAA National Championships.

idealized version of it.

Sure, you’ll almost certainly have the time of your life in college. You’ll form lifelong bonds, study fascinating subjects, and get to cox faster boats than you’ve ever been in. But you’ll also get sick probably, face academic disappointment, and endure tough practices. You want to attend a college where you can grow from these challenges and enjoy your successes.

When it comes to making this decision, a visit, unofficial or official, is extremely helpful. First, traveling to and from the college will enable you to assess how you feel about its location vis-a-vis your home. Some athletes want to be far away; some want to be able to come home on weekends. Listen to your gut, and remember: It’s normal to be nervous before a visit.

During the visit, make sure you sit in on a class or two. Look around and see how the students behave. Are these the kind of people you want to have as peers in the classroom?

Attend a practice, of course. If the session is amazing, great! It’s fun to watch fast college teams practice. If the practice doesn’t go so well, even better; you have an opportunity to see how the coaches and team handle a difficult circumstance.

Pay attention to what the athletes say in the locker room and in the dining hall. If you notice things that don’t jibe with what the coaches tell you, it doesn’t mean deception is taking place but it could indicate that the coaches and team aren’t on the same page..

As soon as your visit is over, write down things that stood out, both positive and negative. Record the feeling you had while on campus and make note of questions so you can follow up with the coach.

Whether you’re basing your choice on a list of pros and cons or relying on your gut, the same skills that lead to success in coxing—asking questions, being thoughtful, planning ahead—will help you make the right college decision.

ROBBIE CONSULTING

Helping

HANNAH WOODRUFF is an assistant coach and recruiting coordinator for the Radcliffe heavyweight team. She began rowing at Phillips Exeter Academy, was a coxswain at Wellesley College, and has coached college, highschool, and club crews for over 10 years.

The Many Paths to College Rowing

Coaches build their teams in a variety of ways, pulling talent from multiple sources, not just traditional high-school programs.

When high-school athletes begin the college-recruiting process, one of the first questions they often ask a university coach is: “How many rowers are you recruiting in my class?” or “How many coxswains are you looking for?” While these are valid questions, the answers are rarely straightforward. That’s because college rowing coaches build their teams in a variety of ways, pulling talent from multiple sources, not just traditional highschool programs.

Traditional High-School and Club Recruits

Many college rowers follow a familiar path: They compete in high-school or club programs for several years, gaining valuable race experience and technical skill. Some may even attend national selection camps or earn spots on the U.S. U19 national team. These athletes are on the radar early and often form the foundation of a recruiting class.

Athletes From Other Sports

In some programs, coaches actively recruit athletes who have never rowed before. These are high-performing competitors in other sports—such as swimming, basketball, or track and field—who show the physical and mental attributes needed to succeed in rowing. With the right coaching and commitment, many of these walk-ons have gone on to represent the U.S. at the U23 and even senior national team levels.

On-Campus Recruiting

Some coaches keep an eye out for potential talent already on campus. During summer orientation or in the early weeks of the fall semester, they identify students who may have been athletes in high school and are open to trying something new. With strong development, these late additions can become vital contributors.

International Recruits

Rowers from outside the United States represent another important pipeline. Many

international recruits have years of rowing experience and have competed at a high level in their home countries—sometimes even representing their national teams. Their maturity and technical skill can bring depth and international perspective to a team.

Transfer Student-Athletes

The NCAA transfer portal has created a new dynamic in college recruiting. Increasingly, coaches are leaving room in their budgets and roster plans to recruit transfer students—athletes who have already rowed at the collegiate level and are seeking a new opportunity. These transfers can bring valuable experience and leadership to a new team.

So, How Many Recruits Are Coaches Really Looking For?

With all these recruitment avenues, it’s easy to see why a coach might hesitate to give a specific number. The recruiting landscape is more fluid than ever. Coaches balance scholarships, roster needs, athletedevelopment timelines, and long-term goals along with roster caps.

If you’re a prospective student-athlete, the key is to be prepared and proactive. Ask clear, direct questions:

• How do you see me fitting into your team?

• What are you looking for in this recruiting cycle?

• What do I need to show you to earn a spot?

Most important, never be afraid to speak up. The more informed you are, the better decisions you can make—for both your athletic and academic future.

Natural vs. Commercial: The Latest Skinny

Research shows that commercial sports products offer no performance advantage over natural foods. Both help improve performance equally.

Professionals In Nutrition for Exercise & Sport (PINES) is an international organization whose mission is to educate athletes around the globe about how to fuel for optimal performance.

Each year, PINES members present cutting-edge information at the annual meeting of the American College of Sports Medicine. Here are highlights of this year’s meeting comparing natural and commercial sports foods.

Can athletes get enough creatine from a diet targeting creatine-containing foods without needing creatine supplements?

Likely yes, if they are eating a meat-centric diet; otherwise, no. The recommended creatine intake for athletes is five grams a day. Humans produce daily about one gram of creatine, and we eat about one gram of creatine a day from meats. A pound of raw meat contains about two to 2.5 grams of creatine; cooked meat has less.

Rowers, especially vegans, who listen to health advice to eat less meat can consume less than the recommended amount of creatine easily. Should you care? Yes, according to Eric Rawson of Messiah University. Creatine is linked with improved athletic performance as well as better brain function in people older than 60.

Is stevia an effective sugar replacement to reduce calorie intake?

Depends. Stevia, a calorie-free natural sugar substitute, can impart a sweet taste to a cup of coffee, tea, or soda. Eimear

ROBBIE TENENBAUM coached at the NCAA level for over 30 years and with the U.S. Junior National Team for eight. He now helps rowers and families navigate the university recruiting process.

FUEL

Dolan of the University of Sao Paulo says it’s unlikely that it reduces calories enough to contribute to significant weight loss. A teaspoon of sugar has only 16 calories, so replacing sugar with stevia in your morning brew could save you about 15 to 30 calories. Not much. However, if you’re a soda drinker who guzzles two cans of cola a day, you could save 300 calories. That’s significant!

A beef jerky stick or chocolate milk provides enough leucine, making Branch Chain Amino Acid (BCAA) supplementation unnecessary?

Plausible. Of the three BCAAs (leucine, iso-leucine, valine), leucine is the primary trigger for optimal muscle growth and repair. Consuming two to three grams of leucine a day maximizes protein synthesis in your muscles. Rowers who limit their intake of calories and/or protein can miss the twograms-per-day leucine target.

If you’re among the 37 percent of gymgoers who buy BCAA supplements, you could refuel more enjoyably with beef jerky (2.3 grams of leucine in 3.5 ounces of jerky) or chug 24 ounces of chocolate milk (2.3 grams of leucine) for your recovery food. Leucine is readily available in food, so think twice before paying $4.50 for a supplement with five grams of BCAA.

Is a homemade sports drink made from juice and a bit of salt as effective as a commercially available sports drink?

Plausible. Rowers can create a homemade sports drink easily that matches the nutrient profile of, let’s say, Gatorade: 55 calories, 105 milligrams of sodium in eight ounces. You can even add ingredients of your choosing, such as caffeine (brewed

coffee or tea?), honey, a splash of juice, or some other flavoring. Stavros Kavouras of Arizona State University warns: Don’t put a sports drink of any kind in a fluid carrier, such as CamelBac. Doing so creates a breeding ground for bacteria.

Can honey, apple sauce, or other foods replace carbohydrate gels for fueling exercise?

Yes. Research has compared different foods with commercial sports products, such as honey vs. gels; raisins vs. gummies; banana vs. sports drink; mashed potatoes vs. gels. In all cases, the commercial product offered no performance advantage over the natural food; both helped improve performance equally.

Catalina Fernandes of Costa Rica notes that “real food” might offer more fiber, be harder to carry, and bulkier (when matched for calories). Hence, each rower should experiment with both natural and commercial foods, paying attention to intolerances and gastrointestinal distress. For traveling athletes, knowledge that real food “works” can be helpful if their favorite commercial products are not available (or get lost with their luggage).

Is coconut water a sufficient replacement for electrolyte drinks?

Plausible. Coconut water is as good as rehydrating with plain water but it’s not better than a sport drink. Kinta Schott of ASU points out that coconut water is certainly a more natural beverage than a commercial sports drink. It’s higher in potassium and lower in sodium than most commercial sport beverages. Here’s how

eight ounces of coconut water compares with eight ounces of Gatorade:

Coconut water:

2 g Carb, 480 mg Potassium, 50 mg Sodium Gatorade:

14 g Carb,5 mg Potassium, 105 mg Sodium Coconut water can do the job for exercise of less than three hours that doesn’t cause high sodium loss from perspiration. If salt is a concern, sprinkle extra on your pre-exercise meal.

Do B vitamins and beet juice influence urine color enough to hinder accurate assessment of how well an athlete is hydrated?

Plausible. Urine color charts are useful tools that help athletes determine their level of hydration. Darker urine indicates more dehydration. Yasuki Sekiguchi of Texas Tech University reminds us that athletes who consume B-vitamin supplements or beets/beet juice have a slightly darker urine that could lead to assuming the athlete is under-hydrated. Hence, beet consumers shouldn’t rely on urine color to assess hydration status precisely.

Can athletes get enough calcium from dairy if they want to curb bone loss related to exercise?

Yes, but doing so may not be practical. Calcium in your blood drops at the onset of exercise, which triggers the release of calcium from your bones. Rowers and athletes in non-weight-bearing sports (such as cycling) have increased risk of poor bone health because of low bone density.

Researchers seeking to boost preexercise calcium intake (to curb potential bone loss) have employed calcium supplements. A study involving rowers and cyclists has shown that it’s possible to consume 1,000 milligrams of pre-exercise calcium from milk, yogurt, and cheese, but Louise Burke of Australia Catholic University says it’s not always practical

Weight-conscious and dairy-avoiding athletes might balk at the plan—and we don’t yet even know if doing so will translate into better bone health. That said, no harm in trying!

NANCY CLARK, M.S., R.D., C.S.S.D., counsels both fitness exercisers and competitive athletes in the Boston area (Newton; 617-795-1875). Her best-selling Sports Nutrition Guidebook is a popular resource, as is her online workshop. For more information, visit NancyClarkRD.com.

TRAINING

The Technique Session

By combining drills with low-intensity distance sessions, you can practice an exercise while integrating it continuously into your rowing.

Designate specific sessions in your weekly schedule to focus on improving your technique.

Drills can be combined with low-intensity distance sessions so that you practice an exercise and integrate it continuously into your rowing.

Here’s a sample technique session:

Row three repeats of 20 minutes, with three minutes rest in between. Alternate rowing four minutes at 18 to 20 strokes per minute with one minute of a drill.

For the first repeat, pause arms/ body away for a count of one 1,000, two 1,000—row. Knees are still down, and once feathered, wrists should be flat above the oar handle.

For the second piece, include a pause at half-slide, then focus on holding your body angle stable as you compress and square the blade.

For the third 20-minute piece, include a minute of one-quarter slide only, just breaking the knees on the recovery to work

on maintaining body-weight suspension during the last phase of the drive.

Try to “stand up in your shoes” to get the desired effect of holding the pressure on the foot stretcher, handle, and blade until you release.

Another technique-session variation is to include a “focus five”—a specific drill for five strokes at the top of each minute. For example, pay attention to your stroke rhythm crossover to crossover or exaggerate a clean release by holding the blade square until arms/body away, then feather off or include a bladework drill, keeping the top edge of the blade level and just under the surface of the water.

COACH DEVELOPMENT

Prove It!

At a time when college sports are changing rapidly, coaches must express clearly, concisely, and convincingly why the rowing team matters and what value it brings to the table.

Today, the very nature of sports is in flux. College sports are being redefined by House vs. NCAA , conference realignment, and the specter of student-athletes as employees.

At the same time, high-school and club programs are facing growing pressures, from earlier sport specialization to heightened scrutiny over costs and outcomes. More than ever before, Olympic sports at all levels are being asked to justify their existence. And that’s where you, as the coach, can and need to make a difference.

This is not a philosophical question or something that only coaches at the “big time” schools need to think about. It’s a reality for all of us. Coaches at every level need to be able to articulate clearly their team’s value. This is true whether you’re reporting to an athletic director, presenting to a high-school principal, or fielding questions from a parent about why rowing is worth the 5 a.m. wake-ups and weekendlong regattas.

Because if you don’t define your value, someone else will. And their version may be incomplete or inaccurate, leaving you, and your program, at risk.

Many rowing coaches want to believe that the impact of our sport speaks for itself. But at a time when budgets are getting slashed, programs are being cut, and the athletic world is being restructured rapidly, that’s not enough. If your team is not contributing explicitly to your organization’s bottom line—which no rowing programs are—you, as the leader, need to be able to express clearly, concisely, and convincingly why your team matters and what value it brings to the table.

To do that, you’ll need to define systematically your team’s value, hone your message, and get it out there.

MARLENE ROYLE who won national titles in rowing and sculling, is the author of Tip of the Blade: Notes on Rowing She has coached at Boston University, the Craftsbury Sculling Center, and the Florida Rowing Center. Her Roylerow Performance Training Programs provides coaching for masters rowers. Email Marlene at roylerow@aol.com or visit www.roylerow.com.

Canadian National Team member Shannon Kennedy at Henley Royal Regatta.

Begin with purpose. What is the purpose of your team? What do your athletes get out of being part of it? More broadly, what does your university or school stand to gain from the athletes on your team that they can’t get elsewhere? Be specific, and know your audience.

When Liz Tuppen, former president of the Collegiate Rowing Coaches Association, visited Washington to advocate for a group of Olympic sports, including rowing, she explained to congressional leaders, “These programs, including rowing, are essential not only for developing future Olympians but also for providing transformative educational opportunities, fostering gender equality, and shaping future leaders.”

When High Point University athletic director Dan Hauser made the decision to add women’s rowing as a varsity sport, he did so in part to “create uniqueness and differentiate High Point University from our peer competitors in the state and in the

region.”

High Point is only the third Division I program in North Carolina, and rowing is a sport that’s popular with the university’s demographic, with 60 percent of students coming from Virginia and points north.

As a leader of your program, you should be thinking as specifically as Tuppen and Hauser. Consider benefits such as increased graduation rates and alumni engagement, positive community relations, college-admission or post-graduation employment advantages, and more.

Need some help? Ask your current team members, alumni, and parents what benefits they see. Seek input from trusted campus partners and even coaches from other teams. How is the rowing team viewed on campus and how are rowers helping?

Once you’ve defined your team’s value, refine it into a concise pitch. Work with all the coaches on staff and team leaders to turn this into a message you

can use—three team pillars perhaps or a succinct mission statement of a few incisive sentences. Whatever you do, make sure it is true, clear, and repeatable. Could you, your staff, and team members say it back to you?

Now you need to get out the word. Share the crew’s mission with everyone you can, in alumni newsletters and recruiting conversations. Say it to your administrators or board members when you meet with them. And, most important, talk about it with your athletes. They are the team and therefore your best representatives.

Don’t leave this to chance. Define what your team stands for. Tie your impact to your institution’s goals. And then begin saying it out loud, often, and to everyone who needs to hear it.

U.S. National Team women’s coach Jesse Foglia’s fours won at both World Rowing Cups in 2025.

MADELINE DAVIS TULLY competed as a lightweight rower at Princeton and on the U-23 national team before coaching at Stanford, Ohio State, Boston University, and the U-23 national team. Now a leadership and executive coach, she is the founder of the Women’s Coaching Conference.

Re trat o Ope September 2025

November 1-2, 2025

Active Tools 31

Bont Rowing 4

Concept2, Inc 17

Fluidesign 6..7

GLRF 59

Head of the Hooch 64

HOSR 27

Hudson Boad Works 2..3

Leonard Insurance 65

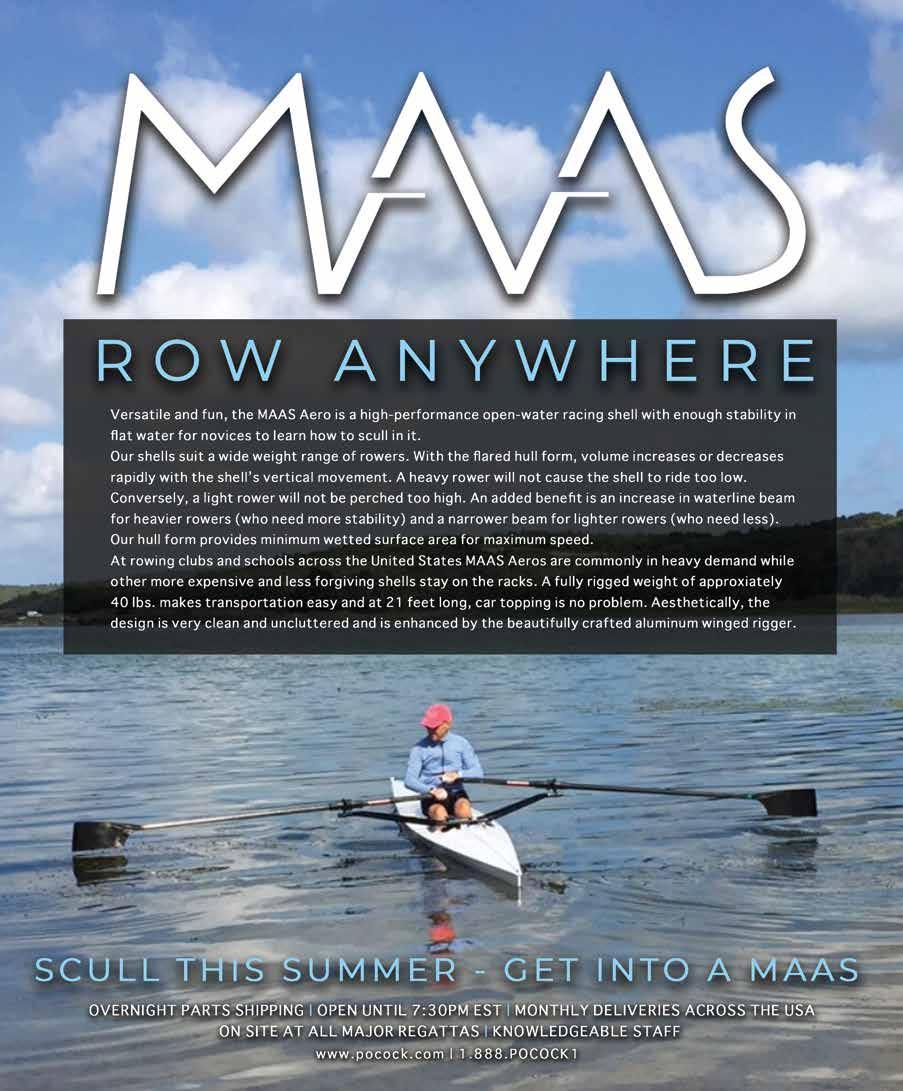

Maas Boats 67

NBP 24

Nielsen-Kellerman 5

Peinert Boatworks 10

Pocock Racing Shells 8..9

RegattaSport 16

Robbie Consulting 59

Row America 15

Shimano North America 56

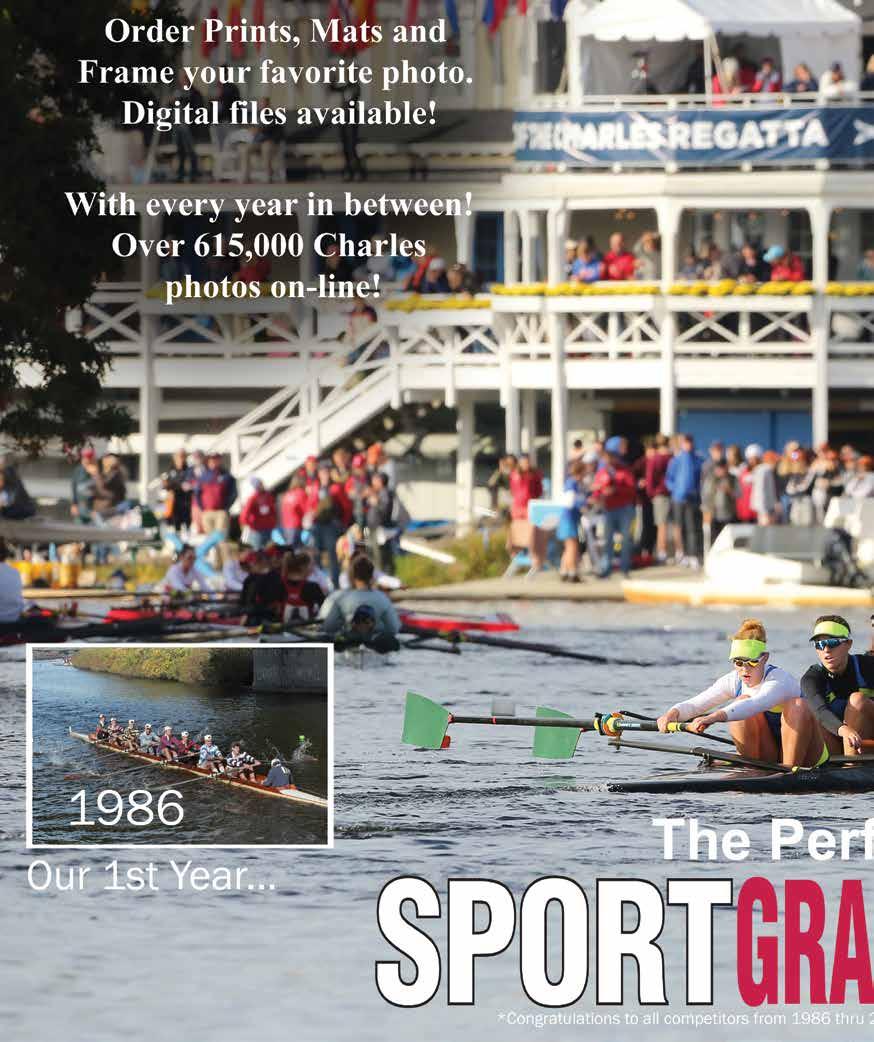

SportGraphics 12..13

Vespoli USA 68

then when winter came and I wasn’t allowed to coach, they set steps to reach their goal of winning a national championship.

“I’d say that their winter training really was the key to success. They were in charge; they pushed each other.”

In short, the chemistry on this team was incredible.

When the great Larry Gluckman coached at Trinity from 2004 to 2009, he inherited a squad that was less committed than he wanted them to be.

“Our biggest competition isn’t Wesleyan or Williams,” he said. “It’s the fraternities.”

Trinity had a tradition of “Hump Day” parties on Thursday nights, and the drinking was inconsistent with his goals for the oarsmen. Solution: 6 a.m. Friday practices. And because Saturday nights were also out of control, Sunday morning practices, too. Monday was the off day.

MacDermott, who was Gluckman’s assistant coach, hasn’t had to institute those rules. The guys row every morning; they like it, and it helps them achieve their goals.

There’s another thing that made this crew and DIII rowing in general special. They had two walk-on novices. The three man and the six man both learned to row at Trinity. When was the last time you heard of a championship crew that had two seats filled by guys who were novices their freshman year?

The bow pair were both lightweights;