7 SHARK Teams Finish in the Top 12 Points Trophy Standings

At 25 Lbs. the Lightest Singles in Production

• Less Drag, More Speed

• Lighter Feel, Higher Stroke Rate

• Easier to Carry

Follow Rowing News on social media by scanning this QR code with your smart phone.

Embrace pain. Relax to excel. Love your rival. Win by losing. Go inward to be a champion. Yes, Frank Biller’s UVA crews do things differently. And it shows on the podium.

BY TOM MATLACK

For Sean Bamman, rowing was a path out of poverty. Thirty years later, he is helping raise money for a much-needed boathouse on the Arlington side of the Potomac.

BY TERRY GALVIN

News National Championships

Beach Sprint Finals Canceled

Crotty Steps Down at Princeton

Ry Hills Retires

Sports Science The Science of Swing Coxing Rules of Recruitment II

Best Practices Attention, Campers! Fuel In Praise of Good Fat

Training The Long and Short of Stroke Length

Coach Development Midsummer Dreams

14 From the Editor

66 Doctor Rowing

CHIP DAVIS

Great rowing coaches influence the athletes they teach and inspire for years—decades, really—after their last race.

In the heavyweight varsity grand final at this year’s IRA national championship, two crews coached by two Washington-Lee High School alumni finished one-two, just as they did at the same regatta last year.

University of Washington head coach Michael Callahan (W-L Class of 1992) and Harvard’s Charley Butt (W-L Class of 1979) never overlapped as teammates, but their crews have had nothing but overlap at the end of races for the last two years at both the IRA national championships and the early-season IRA Sarasota Invitational.

Inspired coaching animates the reborn rivalry of Harvard and Washington.

Now known as the Sarasota 2K, the regatta at Nathan Benderson Park is where the Bolles Cup contest between the first varsities of Harvard and Washington has been revived. Washington won it this year; Harvard, last year.

Washington won both the varsity final (for the national championship) and second varsity IRA final over Harvard by mere seats, while Harvard won the third varsity final over Washington—by three onehundredths of a second. (See Big News, beginning on page 25).

The overlaps don’t end there. Both current coaches were coached by the same coach at W-L: Butt’s father, Charlie Butt.

The senior Butt’s enduring influence on our sport goes far beyond today’s top collegiate crews, though. Another one of his former oarsmen, Callahan’s teammate Sean Bamman, is leading the decades-old effort to build another boathouse in the Washington, D.C. area to provide additional access to the water for future athletes.

Bamman credits the stabilizing influence of the W-L program with making it possible for him to overcome a challenging background, and he’s paying it forward, decades after benefiting from a great coach—Charlie Butt.

As a former college head rowing coach at both the University of Rhode Island and the University of Tampa and a former director of USRowing, I am deeply concerned about the consequences of the NCAA’s $2.8-billion settlement on non-revenue sports.

While revenue-sharing for athletes marks a step toward fairness, its unintended impact may be devastating for programs like rowing, track and field, swimming, and other Olympic sports.

With institutions now permitted to allocate up to $20.5 million annually toward athlete compensation, projections suggest that over 75 percent of these funds will go to football. As a result, many schools may slash budgets for uniforms, travel, coaching stipends, and even entire teams, undermining the student-athlete experience in non-revenue sports.

Rowing is a prime example. These programs often operate on lean budgets and rely on institutional backing and fundraising. A shift in funding priorities could lead to severe reductions in travel, equipment, and coaching salaries, jeopardizing the future of these teams.

Beyond rowing, athletes across

dozens of sports depend on these programs for personal, academic, and athletic development. Preserving their opportunities must be a priority.

Colleges must pursue equitable resource distribution that supports all studentathletes, not just those in revenue-generating sports. The diversity of collegiate athletics enriches campus life and fosters a broader culture of inclusion and achievement.

The NCAA settlement should not lead to the dismantling of the very programs that define the spirit of college sports.

Tom Feaster Tampa, Fla.

The Beach Sprints have been getting some negative comments related to setbacks in the lead-up to their Olympic debut. I hope to put these setbacks into a bigger picture.

The first thing that came to my mind after the recent cancellation of the Beach Sprints in Brazil was the Rio Olympics and all the controversy and organizational issues surrounding the lead-up to those

Games. When it comes to hosting, Brazil’s track record is not the best, and the cancellation of the Beach Sprint Finals shouldn’t reflect on Beach Sprints as a sport. Furthermore, it’s a reflection of the state of international sports in general. The world currently is not in a strong “let’s play together” mindset. As governments withdraw more into themselves, the “global community of sports” becomes a harder sell, and the economic demands of sport become less acceptable when national economies are in—or feel they are in—peril.

Rowing overall—and I’m including traditional flat-water rowing—is undergoing challenges. At the Olympic level, rowing is under pressure. Lightweights are out. Reduced athlete quotas are being looked at. What will the future of classic rowing look like, never mind new rowing disciplines?

No doom and gloom here, just saying that any conversation about the Olympics and Olympic cycles includes challenges, changes, adaptations, and, ideally, growth points.

The 2023 World Beach Games also have been cited as a flop for coastal rowing. Yes, Beach Sprints were canceled, but so were the entire Games, all sports included. So again, not an issue with Beach Sprints per se but rather with the entire event, and another example of the challenges

large international sporting competitions are facing. They are getting canceled and changed wholesale.

At the recent 2024 Beach Sprint Finals in Italy, there was a last-minute swap of venue, much to the event’s detriment. The city decided to do work on the approved beach and shut it down, without bothering to honor prior sporting contracts. Is this proof that Beach Sprints are struggling? Again, I attribute this to the reduced importance overall being assigned sports.

Certainly, it’s not easy to find perfect Beach Sprint venues. But look at LA 2028 and the venue for flat-water rowing; the course is 1,500 meters! Venues for elite 2K racing also are hard to find, so this is not just a Beach Sprint issue.

Some places are more suited inherently to flat-water racing; others, to coastal. The upcoming Summer Youth Olympics in Dakar, Senegal, will not feature 2K flat-water rowing because there was no suitable venue. It will, however, feature Beach Sprints since a practical coastal site exists.

Adding coastal is a net gain for rowing because it opens an array of environmental options that allow “different strokes for different folks,” without diminishing traditional rowing. Road cycling hasn’t been

harmed by mountain biking. Instead, the ways and places one can appreciate the sport have increased.

All sports need what they need. Surfing needs surf waves. Snowboarding needs snow and slopes. Flat-water racing needs a sheltered straight 2K course six lanes wide. Beach Sprints need a moderately exposed sandy beach, which leaves a lot of flexibility in its design.

While it’s easy to see the Beach Sprint snags in the Olympic run-up, since they are loud and public (e.g., the Brazilian cancellation), what is less public are the successes. World Rowing sees coastal rowing as a way to expand rowing into new demographics and territories.

This is happening. Tunisia has a strong coastal-rowing contingent. The tiny Bahamas are participating every year in world championship events. A wonderful group of local islanders from a poor fishing community have, for the first time, experienced the joys and challenges of international competition.

Even with the Brazilian flop, South America and Central America are embracing Beach Sprints. Peru holds an annual international competition. Costa Rica has recently entered the scene and has held

a couple years of racing. None of these countries is a hotspot for traditional rowing; they are growth points stimulated by Beach Sprints and coastal rowing.

World Rowing is an active agent of this growth. It is taking a chance on venue stability by bringing these races to new and untested territories. Good for them. Greatness requires risk.

Yes, there have been some hiccups in Beach Sprint rollout. It’s a new sport. It will have some hitches. It will make mistakes. And it’s insanely fun.

Beach Sprints and coastal rowing could well be the most fun one can have with oars in hand. I spent this morning in my coastal-rowing boat, surfing down the face of beautiful curling waves in the brilliant summer sun.

Ben Booth Dartmouth, Mass. Co-founder and coach, Next Level Rowing Co-founder, Next Boatworks

RowAmerica Rye defended its men’s youth eight title at the 2025 USRowing Youth National Championships in mid-June at Nathan Benderson Park in Sarasota. The New York club finished 1.17 seconds ahead of New England scholastic champions Deerfield Academy and 2.58 seconds ahead of California’s Marin Rowing Association.

RowAmerica Rye’s women’s youth eight repeated as Youth National champions, winning all of their races by open water. Newport Aquatic Center finished second, with Winter Park third.

Sarasota Crew’s U17 men’s eight gave it their all, finishing third. Over 4,000 youth rowers from 231 programs raced in 886 boats, and USRowing recognized national champions in 43 events.

Potomac Boat Club’s Michael Madigan won the men’s youth single, and Mariia Prodan of Community Rowing, Inc. won the women’s youth single.

Strong wind wreaked havoc at the NCAA and IRA championships, but Stanford, Yale, Washington, Princeton, and Harvard rowed to victory.

The NCAA and IRA national championships featured clear winners and significant weather issues that called into question their formats and venue choices.

Stanford’s women seemed the prohibitive favorites to win the Division I NCAA championship all spring, and they did it for the third time in school history in a raging tailwind on a rough Lake Mercer with strong senior-class leadership.

“We have some phenomenal seniors,” said head coach Derek Byrnes, who also coached Stanford to the NCAA national championship in 2023, “just good kids that have grown up a ton in the program and are

doing a great job of leading it.”

The Cardinal won the varsity four and second eight, but Yale upset the favorites in the first eight grand final, jumping out to an early lead and hanging on in a strong tailwind that made the water so rough that waves broke over the riggers.

It was a brilliant strategy for beating the previously undefeated Stanford varsity that vanquished the Canadian National Team and Texas—both by open water— in April, before breaking six minutes on Clemson’s Lake Hartwell at the ACC championships.

Length and power were the keys to Yale’s success

For the first time since the NCAA’s founding in 1906, colleges may pay athletes directly, after a federal judge in early June approved the settlement of an antitrust suit against the NCAA. Beginning July 1, colleges can pay up to $20.5 million a year to their athletes, with football players expected to receive 75 percent of the money; basketball players, 20 percent; and athletes who play other sports, such as rowing, splitting the remaining five percent. Leagues can opt out of the settlement, and the Ivy League has indicated that it will.

“You gotta accommodate the athletes to let them perform on a championship level.”

—Will Porter

in the grand final, said Will Porter, who has been the Bulldog head coach for 25 years.

“Some athletes can do it, some athletes can’t row with that much length” to sustain a lead taken aggressively from the start. “We were lucky enough to put together a combination that could sustain it.”

But it was the conditions, which forced delays and schedule changes throughout the regatta, that had the biggest impact on racing.

“It’s Mercer,” Porter said. “Getting a margin is important, and it’s hard to come back” in such rough water and with such fast times (Yale went 6:08, an NCAA

record, despite the rough water, and Stanford’s four broke seven minutes, going 6:56).

Finals racing on Sunday had been moved up to a chilly 7:12 a.m. start to avoid the worst of the conditions, which deteriorated as the morning wore on. With some crews staying in hotels an hour away, the earlier start meant getting up at 4:30 a.m. after some crews finished late (the last DI race the night before started at 6:40 p.m.).

“For athlete welfare, that’s not OK,” Porter said. “That 7:12 start was questionable. You gotta accommodate the athletes to let them perform on a championship level.”

Tufts University repeated as NCAA Division III national champions after winning the Jumbos’ first-ever title last year.

Head coach Lily Siddall and her assistant coaches, Ethan Maines, Kaitlyn Severin, and Emelie Eldracher, earned regional and national coach and staffof-the-year honors from the Collegiate Rowing Coaches Association after the championship, where Tufts won both the first and second eights.

“It truly takes a team,” Sidell said. “Each coach brought something special to the group this year with the diversity of backgrounds and expertise.”

Women’s rowing became the first program in Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University’s NCAA Division II era to win a team title. Embry-Riddle is the eighth program to win the NCAA II women’s rowing championship, which has been held every year since 2002 except 2020.

“This group has truly earned every moment of this national championship,” said head coach Grant Maddock. “Two years ago, we made a deliberate choice to raise the bar by training harder and racing at a higher level. That commitment set the course for where the program is today. What we’ve accomplished is special, but it’s just the beginning of what this team is capable of.”

That Embry-Riddle won its first-ever Division II rowing championship at the same regatta is significant; rowing is the only NCAA sport to hold its Division I, II, and III championships at the same venue at the same time. The events of the three divisions intermingled in the schedule on the first two days of the regatta, with the DII and III Saturday finals coinciding with the DI semifinals.

When Lake Mercer’s rough conditions

caused schedule changes, nationalchampionship finals took priority over semifinals, and practices times were canceled.

“The schedule change was tough,” said Tennessee head coach Kim Cupini, who made significant changes to her second varsity but wasn’t able to try them out because of canceled practice times. “I appreciate that they are trying to get the racing off, but not having a pre-race row was huge.”

“There are racecourses that have beautiful conditions, that don’t get blown off,” said Cupini, a proponent of separating the championships of the three divisions— at least the schedules, if not the venues.

“Are we selecting these places the right way? I can’t believe we chose that racecourse,” Cupini said.

“There are maybe two or three racecourses in the country we should be using,” Porter said of site selection for the NCAA championships. “There’s not a rowing course in every state, like there is a basketball or football stadium.”

The NCAA championship was not the only regatta in New Jersey struggling to run races in extremely challenging conditions. Thirty miles away in Camden, at the IRA national championship, which has grown to include multiple lightweight events as well as the men’s Division III national championship, a raging tailwind and varying water levels disrupted proceedings.

In the end, Washington won the men’s varsity heavyweight eight grand final over Harvard and Dartmouth to secure the Huskies’ 21st national championship.

“It’s harder to defend the national championship than to win it in the first place,” said UW head men’s coach Michael Callahan. “The depth of the field is outstanding.”

Washington had Olympic silver medalist Logan Ullrich back in the boat after he took a year off to train with New Zealand’s Olympic squad.

“The fact that Logan came back into our crew put so much pressure on him and also on the crew. You’re coming back into a crew that’s already won,” Callahan said.

The IRA regatta got off to a rough start on Wednesday, the first day of practice, with the Cooper River’s water level lowered in anticipation of rain. Seven crews knocked fins off their shells in the shallows, leading to the closing of the course until the water level rose later in the day.

Things got only worse for top-ranked Cal on the weekend. The IRA semifinals on Saturday offer some of the most exciting racing in all of rowing as 12 crews—most of them legitimate finalists—race for six lanes in the final. Top finishers from the heats race in the typically advantageous middle lanes. But on this year’s IRA Saturday, as the wind picked up, the middle lanes were plagued by the worst of the rough water.

The No. 1 Cal varsity, which had rowed through Washington to win the Mountain Pacific Sports Federation championship two weeks before, dealt with waves breaking over the riggers on both sides of the shell before catching a boatstopping crab,

rowers - indorowers - coastal rowers open ocean rowers - coxies - coaches race/regatta officials

1,783 members in 45 countries

connecting individuals with member groups - regattas - galleries news - events - forums - rowing club links

Register today - it’s free!

Gay + Lesbian Rowing Federation

No more wings and back stays sitting awkwardly on arms. Whether a boat is port rigged, starboard rigged, bucket rigged, stern mounted or bow mounted. If an arm needs to be shifted to the left or to the right, simply loosen (4) nuts and slide the arm (on rollers) to the desired location, then tighten the (4) nuts - PROBLEM SOLVED!

Focus would like to give thanks and appreciation to the amazing rowing community for making Focus Racks the #1 shell rack provider in North America for the last 25 years!

BIG NEWS >>> which relegated Cal to the petite final on Sunday.

Asked if he thought the lanes were fair on the Cooper River under those conditions, Syracuse head coach Dave Reischman, whose varsity made the IRA grand final for a fifth-straight year, said, “Where is? The wind across the lanes was more fair than we’ve seen at Mercer the last couple of years. It’s a bit of mystery to me why we haven’t considered Sarasota.”

Next year’s IRA regatta will be held on Lake Natoma, in Gold River, Calif., where the forecast high was 102 degrees on the same weekend.

In varying conditions, Cal set the fastest time of the regatta—5:24.0—in winning the petite final on Sunday. (Washington won the grand final 20 minutes later in 5:29.8.)

Trinity won the Division III national championship on Saturday, over Tufts and Bates, in rough conditions.

“The water at the end of the day for DIII racing was atrocious,” said Dartmouth lightweight coach Trevor Michelson. “Those were Biblical conditions, and I don’t say that lightly.”

But the conditions didn’t upset the Sunday performances of both defending lightweight national champions, the Princeton women and Harvard men. The Tigers capped another undefeated year with a 3.4-second victory over Harvard and Georgetown’s lightweight women.

The Crimson lights, no less dominant over the past two years, managed to defend their IRA national championship in the Sunday final by a margin that was tighter, with Dartmouth and MIT chasing them in second and third.

“I’m glad our dream of winning a medal at the national championship was not on the water Saturday morning on the Cooper,” Michelson said.

This spring, all three collegiate national championships—ACRA for club crews; NCAA for DI, II, and III openweight women’s varsities; and IRA for heavyweight men’s DI and III and men’s and women’s lightweight varsities, suffered significant disruption from severe weather, which now affects racing regularly.

The climate has changed. Will national championship regattas change, too?

CHIP DAVIS

Williams Family $1.5-million gift to Berkeley’s flourishing rowing program reflects their admiration for Scott Frandsen, who insists on excellence on the water and in the classroom.

The University of California, Berkeley’s men’s rowing head coach position has been endowed, thanks to a $1.5-million gift from Cal alums Jeff and Patty Williams. The gift is part of the matching endowment challenge led by the Rogers family.

The Williams Family Men’s Rowing Head Coach endowment precedes next year’s celebration of the 150th anniversary of the Cal men’s rowing program.

“We are immeasurably grateful for Jeff and Patty’s generosity,” said Cal Athletics Director Jim Knowlton. “Our program has set the standard for intercollegiate men’s rowing, and their gift will help us enormously as we strive for continued financial stability.”

The Williamses’ love of rowing generally, and the leadership of Cal head coach Scott Frandsen specifically, led to their supporting the men’s rowing program.

“Scott is a great leader, molder, and educator of young men. We like how the program is flourishing under him,” Jeff Williams said. “It’s manifested in success both on the water and in the classroom. Having a program that has six and seven

boats on the water in practice each day— that’s a lot of guys who aren’t in the first or second varsity and who get to race only a handful of times each year. But they still want to continue to put in the time and the effort necessary to row at Cal, and that speaks volumes about the health of the program under Scott.”

Frandsen, a 2002 alumnus, won three consecutive IRA national championships with Cal between 2000 and 2002 and represented Canada in the 2004, 2008, and 2012 Olympics, winning a silver medal in the pair with Dave Calder in Beijing in 2008. He is in his 13th year of coaching at Cal, the last seven as head coach.

After Cal won the first-ever Mountain Pacific Sports Federation (MPSF) championship, Frandsen was named MPSF Coach of the Year, and Cal varsity stroke Frederick Breuer was named MPSF Athlete of the Year. (MPSF succeeded the Pac-12 men’s rowing conference).

In May, Breuer also received Cal Athletics’ Jake Gimbel Award, given to the graduating male student-athlete with the highest GPA.

Helping rowers worldwide get scholarships

Helping high school rowers and families navigate the university recruiting process- Coaches and parent groups reach out to us!

Robbie Consulting will meet your team, coaches and parents at your home club or school. Go to www. robbieconsulting.com to get in touch and schedule a visit

“His assistance was essential to get prepared for such a big step and to get to know the school and team I would compete for.”

www.robbieconsulting.com

1-614-330-2879 • Robbie@robbieconsulting.com

He coached the lightweight men to two IRA national championships, and won two more as a Tiger heavyweight oarsman.

Varsity men’s lightweight coach Marty Crotty has stepped down to pursue other professional opportunities, Princeton announced in June.

“The Princeton boathouse has been part of my life for over 30 years and always will be,” Crotty said. “I want to thank especially Mike Teti, for introducing Princeton to me; Curtis Jordan, for giving me the chance to coach at Princeton; and my current colleagues Lori Dauphiny, Paul Rassam, and Greg Hughes, with whom I have worked for more than 20 years.”

In his 15 years as the head lightweight coach, Crotty coached the Princeton

“I

will always be Princeton Rowing’s No. 1 fan”

—Marty Crotty

lightweight men to two IRA national championships, and he won two more as a heavyweight oarsman at Princeton, from which he graduated in 1998.

“Stepping away from coaching, and from Princeton University, was a difficult decision, said Crotty, “but I’m looking forward to the new opportunities that lie ahead. And I will always be Princeton Rowing’s No. 1 fan on the shores of Lake Carnegie.”

Crotty is the founder and an owner of Princeton Carbon Works, one of the world’s leading manufacturers of carbon-fiber bicycle wheels for competitive cycling and triathlons.

Planning your next regatta? Nathan Benderson Park makes it easy. Seamless booking and complete logistical support means you can concentrate on the competition, not the complications.

Permanent, Purpose-Built World-Class Rowing Venue

Ample Trailer Parking with Easy In and Out, 1 Mile from I-75

Course Setup & Management by On-site Professional Staff

Premier Safety & Emergency Services Coordination

550-Acre Park with 400-Acre Lake

Plenty of Tent & Vendor Space and Unobstructed Course Views

Parking & Traffic Flow, Course Maps, Practice Schedule

Location: 5 Miles from Airport. Walking Distance to Hundreds of Shops and Restaurants in a Safe Neighborhood. Minutes Away from the World’s Best Beaches

PLAN YOUR REGATTA!

NathanBendersonPark.org

NATHAN BENDERSON PARK

5851 Nathan Benderson Circle, Sarasota, FL

Barb “Ry” Hills helped launch women’s rowing at UNH, was the first women’s rowing coach at the Coast Guard Academy, and coached crews to many championship medals.

Barb “Ry” Hills retired from a long and successful coaching career this spring, more than 50 years after playing a major role in establishing women’s rowing at the University of New Hampshire.

As an athlete, Hills won both the pair and eight at the 1976 United States Rowing Association national championships and finished third in the Olympic trials, missing a spot on the team by 1.3 seconds.

She became the first women’s rowing coach at the United States Coast Guard Academy in 1978. In the early 1980s, she coached Dartmouth’s novice women to two Eastern Sprints wins. She also coached the U.S. Junior National Team, UNH, and Pioneer Valley.

For the past seven years, after founding Megunticook Rowing in Camden, Maine,

Hills coached at Bowdoin College with head coach Doug Welling.

“They have truly functioned as co-head coaches,” said retired Bowdoin coach Gil Birney.

In total, Hills coached crews to 15 New England Rowing Championship medals (11 gold), a women’s team-points trophy and seven medals at Dad Vails, and five medals (three gold) at ACRA championships. Bowdoin won the women’s point trophy at this year’s ACRA championship.

Mills is the sister of longtime Radcliffe coach Liz O’Leary and the mother of three children, including Lizzie Mitchell, associate head coach at Boston University.

“All in all, Mom, you are a total badass,” Mitchell said at a retirement gathering. “You are my daily inspiration, my guiding light, and the reason I am coaching today.”

It’s the latest development in a continuing struggle to establish the new Olympic discipline, which will account for 20 percent of the rowing medals at the LA 2028 Games.

The 2025 World Rowing Beach Sprint Finals in Rio De Janeiro have been canceled and will be held at another location at a future date.

The Brazilian Rowing Federation backed out of its commitment to host the October regatta, and World Rowing was unable to find a viable local alternative.

The cancellation is the latest development in a continuing struggle to establish the new Olympic discipline. Last year’s Beach Sprint Finals in Genoa, Italy, changed locations at the last minute when the original Italian site couldn’t be used. The event was held instead on a crowded, rocky beach that drew complaints from attendees.

The 2026 Commonwealth Games, including Beach Sprint rowing events, originally hosted by the Australian state of Victoria, have been moved to Glasgow, Scotland, and Beach Sprints have been cut.

The 2023 World Beach Games, including Beach Sprint rowing, were canceled when the Indonesian government withdrew support.

“This outcome is disappointing for the international rowing community,” World Rowing stated in a press release, “especially for athletes, coaches, and fans who were preparing for a pivotal competition on the pathway to the 2026 Youth Olympic Games in Dakar, Senegal, and the Los Angeles 2028 Olympic Games.”

Beach Sprints, the newest form of coastal rowing in World Rowing’s scheme to increase the popularity of rowing, will account for 20 percent of Olympic rowing medals at the LA 2028 Games.

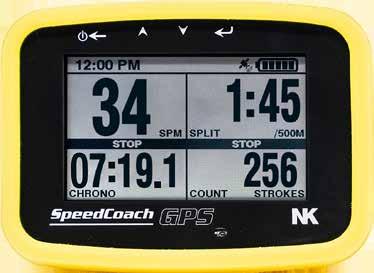

Large Configurable Display (2, 4 and 6 fields)

Optional Wireless Impeller & Accessories

Easy Data Transfer via the DataFlow App

Independent review of the ActiveSpeed - Sander Roosendaal, founder of the rowing analytics site rowsandall.com, takes a deep dive into the ActiveSpeed.

Embrace pain. Relax to excel. Love your rival. Win by losing. Go inward to be a champion. Yes, Frank Biller’s UVA crews do things differently. And it shows on the podium.

They are beginning to feel this,” Frank Biller whispers as we pull up to the three Virginia men’s eights crossing the line, completing their fourth of five 2,000-meter pieces. All the oarsmen gasp for breath, noticeably less fresh than when we left the dock. It is exactly three weeks before the ACRA championships, a moment to push one last time before a final taper.

The 2025 American Collegiate Rowing Association Championship in Oak Ridge, Tenn., was more than just a rowing race; it was the culmination of a life’s work. It attempted to resolve the paradox of embodying a growth mindset in life in general and rowing in particular: Greatness is relative only to oneself, yet competition can bring out the full expression of oneself. It is only by losing that one can truly win. Yet it’s only by focusing inward that we become champions, both on the water and in life.

The UVA boats are not filled with sub-six-minute ergs or scholarships. Every one of these athletes got to these waters on their academic merit alone, earning a spot at one of the most selective universities in the country, and then were recruited to rowing after they arrived on “the Grounds,” competing as novices in their first year and having to raise money for equipment and travel. They pay $1,000 as freshmen and $2,500 on the varsity in dues for the privilege of rowing. No one is paying their tuition or giving them a leg up in admissions for rowing.

No extra-large humans in the boat, either. The boat average appears to be 175 pounds. Just chiseled muscles moving in unison, making the boat take off at each catch, as Biller had explained during a deep dive on the meaning of telemetry data.

“Getting the blade in directly is hugely important,” he said. “Nothing happens once the stick is perpendicular to the boat; the power is all in the front half of the stroke, so getting the blade in and connected is the key.” His varsity is achieving that with resulting speed on this Saturday in late April on the Rivanna Reservoir, which is pastoral and flat— wonderful water for rowing. It had been sprinkling, but now the sun promises to break through as a gentle breeze washes over the course.

I think back to a recent conversation with the Swiss Olympian and 2017 world

champion Jeannine Gmelin about Biller, about his approach here at UVA.

“He’s the only coach I know that is so big on supporting the holistic athletic journey. You’re an athlete, but you are also a human being. You have to integrate the psychological aspect into training. You get to know yourself from a different angle. The better you know yourself, the better you can navigate good times and also hard times. What he’s doing is not just for rowing.”

Frank Biller is a large man with broad shoulders, big hands, and long arms. He flashes a quick smile and offers a bear hug to just about anyone who needs it.

This is his 16th year as Virginia’s men’s head coach, and on land Biller speaks about the team, in his native Swiss accent, readily and enthusiastically. Under his guidance, Wahoo crews have won multiple ACRA national championships, Dad Vail golds, and six Head of the Charles titles. Biller has taken UVA crews to Henley in 2011, 2013, 2015, 2017, and 2023, and several of his UVA rowers have represented the U.S. internationally.

In the launch, however, Biller is quiet, checking ratings and boat speed, observant, joking occasionally with his coaches. He is careful with his words to the athletes, allowing his assistants Cailly O’Toole and Frank Vasquez to do most of the talking. They stand behind me in the launch, often reading each other’s minds.

“The impulse felt better on that one in the last 500,” varsity coxswain Celia Cheng reports. “We were hovering around 1:25, and it felt pretty solid.”

But she seems to be talking to the two assistant coaches behind me in the launch, not Frank, who remains silent.

“Great, turn’ em around,” assistant coach Vasquez commands.

There are visible signs of exhaustion on the rowers’ faces now, but they won’t give in. They know this is the part that matters—finishing the workout strong.

“My dream,” Biller confides just after his team goes back into maximum exertion for their last piece of the day and he eases the launch throttle forward to follow them, “is that at the starting line of the grand final, the Virginia stroke leans over and says to the Purdue stroke in the next lane, ‘I really hope you guys row faster than we do,’ knowing full well that it would take an extraordinary effort for that to happen.”

Biller arrived at UVA in 2009 on the cusp of a new league in rowing and at a moment during which UVA men’s rowing was on the brink of disaster as the team dwindled in size and the club’s finances deteriorated. The year before, they had endured embarrassing losses to traditionally inferior teams.

“I came to UVA when the American Collegiate Rowing Association was in its third year, after all the club teams were kicked out of the IRA,” Biller said.

Biller had rowed on Switzerland’s junior national team, then worked on Wall Street, then returned to Switzerland, and eventually moved to Philadelphia in 2002 for his MBA, where he met his wife in a boathouse and decided to stay.

Matt Miller, the current UVA men’s rowing board chair, was a third-year when Biller showed up in Charlottesville in 2009.

“They took a big risk in hiring Frank,” Miller recalled. “They decided to run a deficit, eat into our small endowment, and try to turn the program around.”

Biller was way ahead of the curve in understanding physiology. He was among the very first to do lactate testing in rowing. He set heart-rate zones and enforced zone-two steady state as the foundation for everything.

“No, Matt, you have to go lighter!” Biller would tell him. “You will be sitting on the erg for 90 minutes today.”

On the water, Biller would stop the boat and have everyone take a pulse for 10 seconds and shout it out. Then, he would write all the numbers down in his notepad and get frustrated.

“You guys are going the speed I want you to go, but you’re working way too hard to do it.”

Under Biller’s new training regimen, Miller “started dropping time on my 2K and 6K real fast,” despite having been convinced he had reached his potential already. He broke six minutes the November after Frank arrived, and by the time he graduated, he had gone 5:54.7.

After graduation, Miller worked fulltime in energy trading, lived at home, saved money, and trained with an elite group at the Potomac Boat Club. In January 2014, with an invitation to the U.S. National Team training camp, Miller quit his job and eventually represented the U.S. in the four at the Rio Olympics. A collegiate club rower who made it to the Olympic Games. In the process, Miller also achieved a 5:40 erg score, breaking the U.S. record.

He said he could not have done any of it without Biller. But in the end, what Biller taught Miller—what he teaches anyone— has nothing to do with heart-rate zones or even record-holding erg scores.

In fact, the biggest changes to Biller’s coaching style, and clues to him as a man, happened after Miller graduated, I discovered.

Biller described how UVA men’s rowing lost team member Jake Cusano on Feb. 15, 2013 to suicide.

“I got the whole team together,” Biller told me over breakfast in downtown Charlottesville. “It was at the boathouse. I said, ‘Just so you know, this has happened; he’s dead.’ I let that sink in for a moment, and that just let the emotions flow, and then we just spent time together.”

He went on to tell me how the most excruciating thing he has ever had to do is tell a mother that her son had passed away. How the whole team got on a big bus dressed in their Henley blazers and traveled up to New Jersey for Jake’s funeral.

“We showed up as a team, and it was a huge deal for the family.”

The whole experience was a huge deal for Biller, too.

Afterward, he turned to August Leming, a psychologist specializing in human motivation and athletic performance

whom he’d met through a rower who worked with Leming in high school. Biller needed help—for his team and himself.

“He was able to normalize all my experiences,” Biller said, recalling Leming’s counsel during his darkest moments. “And express what I was trying to teach the guys, trying to teach people, period. There are just three gifts: love, empathy, and compassion.”

In Biller’s pain, and the team’s, everything changed when Leming showed up.

“It was a huge part of learning to understand what is going on inside,” Biller said. “And it reset the team completely. It opened everyone up.”

It was through Leming that Biller came to understand that his true job had nothing to do with rowing.

“One of the things that affects the speed of the boat most is how relaxed the bodies are during the recovery,” August Leming told me.

“If you’re in a state of sympathetic engagement, of fight or flight in any way, shape, or form, the body won’t relax, and so the tension that you’re carrying deep inside the body, the diaphragmatic floor, especially during your recovery, it’s energy that’s not going into the stick. It’s consuming glycogen, it’s consuming oxygen, it’s putting undue pressure and strain on your

connective tissue, and you’re slowing the boat down.

“So, the simple fact is, to make a boat go as fast as it can, everyone in this boat needs to be as relaxed, detached, and unconcerned as possible about how fast it’s going. That’s a big, big ask.”

Leming pointed out that any other physical endeavor of the human body involving maximal exertion cannot last longer than 10 seconds. Yet rowing has found a way to make maximal exertion last six minutes.

“So it’s torture.”

His point of departure is to embrace the reality of that torture, moment by moment, as a gift.

Leming must have seen the confusion in my eyes and tried a completely different approach.

“All warriors have broken hearts,” he began. “When I live from a wakeful state, sadness is always a part of my experience, and it doesn’t make anything less beautiful or less joyful or less anything. It’s just always there because there’s a sacredness and a value to sadness that is part of being human. In Western culture, if you tell someone you’re sad, they say, ‘What’s wrong?’

“If you want to be the best rower you can be, we can talk. But I suspect you just want to be better rowers than everyone else, and that’s a completely different ball game. I’m not your guy if that’s what you

want, because most people misconstrue a competitive mindset for a comparative mindset, and they are hugely different.

“Most folks judge the quality of their output compared to the output of others, and that’s a much lower ceiling than going on a path of exploration about what you are truly capable of being.”

Biller told me later that he changed his approach to the erg completely after he met Leming.

“We do these experiments every year where we do a series of really hard work pieces. Each time, we’ll give the guys a different focus point. And on the last one, when everybody is already pretty cooked, we ask them to just sit there next to each other. And before they start the last piece, we ask them each to reach out to their left and the guy on the right and say, ‘I wish you to go faster than me, and I love you.’”

Biller stopped talking here, overcome by emotion. Finally, he admitted that he had goosebumps trying to speak about this.

“The entire energy of the room changes. I have seen guys pull the best piece of their life, get off the erg, and just say, ‘What the fuck just happened?’ I stand on the side watching, and I would just have tears running down my face. And I couldn’t tell you why. It’s just the energy you could feel. Few people ever truly experience it. But when you go through that experience, as a coach or as an athlete, you’re like, ‘What

else is there?’”

In the end, Biller’s whole approach to managing pain, on the water and in life, as when Jake Caruso died, changed, thanks to Leming’s approach.

“You can’t magically push your body to do something that it’s just not capable of,” he told me. “But you can tap into the potential that you never knew was there.”

“We started recognizing,” Leming said, “that there are some illusions that we should probably address before we have a conversation about what it is we’re doing here.”

And that’s what Biller began to build the UVA program upon.

Biller and his team certainly enjoyed a measure of success as they implemented what they learned from Leming. But the final piece in Biller’s maturation involved his best friend, Robin Dowell.

In 2011, Dowell and Biller were both product consultants for Hudson Boat Works. They drank and shared stories, coaching ideas, and a common view on life. The bond was immediate and deep. Dowell was coaching Sir William Borlase’s Grammar School in Marlow, England, from obscurity into a rowing force. He became the junior national coach for Great Britain and then, after some phone calls from Biller, the head coach of the Swiss national team.

Dowell would come to stay with Biller each fall before the Head of the Charles. Biller stayed with him at Henley. They were brothers in all but blood. In 2019, Dowell brought Jeannine Gmelin, the 2017 World Rowing single sculling champion, with multiple World Rowing Cup golds, and the best female rower in Swiss history, to train in Charlottesville with Biller and UVA.

Biller and Dowell would text many times each day and talk whenever they could. And then one day two and a half years ago, the text messages stopped abruptly—and Biller’s life changed forever.

On a still December morning in 2022, Gmelin and a few fellow scullers pushed off from the dock at the Swiss national training center on Lake Sarnen. Behind them, Dowell stayed back, quietly clearing the fresh snow from the dock, as he often did, to make sure everything was ready for those who would come after.

About 300 meters out, Gemelin noticed something that didn’t sit right. Dowell’s launch was adrift, still and silent, where it shouldn’t have been.

She turned the boat. Rushed back. And found him unresponsive.

She dove in without thinking, swam to him, tried everything she could. But it was already too late. Dowell was 40, a presence so constant that for Gmelin and Biller he’d become part of the landscape. And so in a quiet, ordinary morning, the unthinkable

had entered without warning.

The lake held its calm. But everything had changed.

One of Gremlin’s first calls was to Biller. He had always stood in her corner— steady, encouraging, reminding her that what she was building was something rare. But in that moment, something shifted. “We weren’t just part of the same journey anymore—we were family.”

Biller stepped into the space that loss had carved out, not to replace, but to hold—“to be the older brother I suddenly, deeply needed.”

When the time came to announce her retirement from racing to the world, it was Biller who stood beside Gmelin. “Not in the spotlight, but close enough to steady me if the weight returned.”

Back at breakfast in Charlottesville, Biller pulled up his sleeve as, with tears in his eyes, he finished telling me about Dowell. He showed me a large tattoo on his forearm with the name “Robin” with a heart above it (“for the love we still have for each other, we talk often”) and ’22 below it for the Valhalla Class of 2022, the Norse mythological hall of the Gods reserved for slain warriors, where they can feast in paradise.

The memory of losing Robin Dowell is still fresh in Biller’s moist eyes. It has clearly changed him as a man and as a coach, broken open his heart in a new way that he brings to the boathouse every day and tries to share with his athletes.

Back at the Thomas Temple Allan Boathouse, I find the two current Virginia captains—Noah Amato and Tyler Remigino—stripped down, completely shredded, muscles rippling as they complete an endurance lifting session that has them moving between stations for 45 minutes.

Both Amato and Remigino are former Division I athletic recruits, but not in rowing. Amato was accepted by the Air Force as a gymnast and then medically rejected because of childhood asthma, which he has since outgrown. Remigino arrived at UVA as a middle-distance runner. Amato is 5-foot-10 and Remigino is 6-foot3, and neither weighs anywhere near 200 pounds. These are just a couple of normalsized Virginia boys who love to row.

As with all members of the UVA squad, both began on the novice team, Amato as a freshman and Remigino as a sophomore.

Amato’s novice boat won the national championship at ACRA, the first time UVA had won the event in a long while. Remigino’s novice boat finished third.

The varsity went to Henley that year and, as a sophomore, Remigino wanted to go, even though he was “still just figuring the sport out, I didn’t know how to row yet.”

That spring, Biller took Remigino out one on one every afternoon in a single until Remigino became skilled enough to make the eight that went to Henley.

With sweat dripping from their faces, Remigino and Amato tell me how Biller gives the team PowerPoint presentations about the physics of the stroke to help them understand what they’re doing on the water, emphasizing that “every little movement we make is going to change the force on the pin a certain direction.”

They discuss how Biller rarely seat races because he believes it’s unfair but he’s an open book about selection, showing athletes their Peach data. They mention Biller’s obsession with rigging and talk about shoveling gravel for eight hours at a time in their rent-a-rower program to raise money for their dues.

“The best way to do this is to be deeply present with every moment,” Amato says. “And that is not something you want to do when your present moment is painful.”

These are non-recruited college male rowers, their frontal cortexes still not formed, looking me straight in the eye with the wisdom of old men.

They tell me about how Biller taught them meditation, how they visualize their races beforehand and at the starting line, and how Biller doesn’t allow music during erg tests. Instead, before the test, he asks them to sit on the ergs in silence to get centered.

“Every single time I’ve won or lost, it’s my willingness to be present that has determined my success in achieving my best performance,” Amato says.

He talks about races in the past when he just wanted to get through it, when he blacked out and couldn’t remember what happened. He shut his brain off and just pulled.

“Whereas in the national final last year, I opened myself to the experience, locking in each catch, feeling everything that was happening, just so aware of the whole race. When I crossed the line, I remembered every second, which was amazing. When

you practice being willing to sit with the pain, you find this deep enjoyment, as backward as that sounds.”

Exactly what Gmelin had said she came to finally, too.

The UVA varsity defeated its chief rival, Notre Dame, last year at the regional championship. At the 2024 ACRA National Championship, however, UVA took the lead initially but was outgunned by the larger Notre Dame boat down the stretch.

They had lost, but did they really lose?

Biller called it one of the best races he had ever seen.

“As someone who has won the national championship twice [as a novice and in the JV] and lost it once, the loss was 10 times more meaningful,” Amato tells me.

“I worked my ass off, developed as a person, and so did our whole boat. We bonded, and it took all of that to get to where we did that day.”

Both Amato and Remigino tell me it was the biggest maturation moment in their lives.

Three weeks after my visit and ride in the launch in Charlottesville, Amato, Remigino, and boatmates, including their coxswain Celia Cheng, sat ready at the starting line for the 2025 ACRA grand final. Purdue was, in fact, in the next lane.

Even if it was not said out loud, which it might have been, I’m sure that the stroke of the Virginia boat was wishing for Purdue to go fast, for the gift of their competition to be rich and deep. Something to be cherished for a lifetime.

The UVA boat moved out to a lead. Purdue attempted to move back. But Biller’s crew was locked in, having the best race of their lives. The lead increased.

As they came across the finish line in first place, there was no slapping of water or overt celebration. Just Amato and Remigino thanking Purdue for such a magnificent race.

They had realized the gift of self from all the hard work they had put in to get to that moment, the gift of teammates, and the gift of strong competition on the day that UVA swept the men’s first and second varsity races.

“Many gifts,” Frank texted me afterward.

TOM MATLACK Is a mentor to men in business and life. He rowed for Will Scoggins at Wesleyan from 1985 to ‘87. His son, Cole, rows for Brown University.

For Sean Bamman, rowing was a path out of poverty. Thirty years later, he is helping raise money for a much-needed boathouse on the Arlington side of the Potomac.

STORY BY TERRY GALVIN IMAGES COURTESY OF ABF

High-school rowing teams often forge strong bonds among young people and, nearly as often, their families.

Organizing road trips to regattas, often with younger children in tow, parents augment the small coaching staff, feed voracious athletes, and share the emotions of victory and defeat. If they see a need, they fill it quickly.

When freshman Sean Bamman went out for the rowing team in 1989 at what was then called Washington-Lee High School in Arlington, Va., his needs were great.

Bamman had a season of rowing experience and good grades. But his single mother was a high-school dropout who had given birth to him when she was 15 and later became a heroin addict. Until he ran away to his grandmother’s home when he was in ninth grade, Bamman had moved with his mother from one crummy apartment and seedy motel to another, when they weren’t living in a car. For a college essay, he counted the places they had lived. He stopped at 43.

“It’s weird, because a lot of people describe the water of the Potomac as being rather choppy and chaotic,” Bamman said. “But to me, it was kind of like this safe haven from all the crap I was dealing with.

“It was magical.”

Although Bamman thought he was hiding his situation well, he was self-conscious and feared people were scrutinizing him for signs he was poor and parentless. His situation must have been obvious to anyone who cared to look; neither his mother nor grandmother ever attended any of his rowing events.

“A lot of the team, the team’s families, kind of adopted me in different ways,” he said.

Unbeknownst to him until much later, an anonymous family was paying his rowing fees and regatta travel expenses— costs he assumed his grandmother was covering. A teammate’s mother found him jobs that provided spending money for clothes and other things kids in normal situations enjoy.

In his junior year, when his grandmother lost a job and had to move out of the school district, Bamman lived with a

teammate’s family so he could continue to attend and row at W-L.

“There were other families, too, that were from the team who would provide for me in the nicest ways, like, ‘Hey Sean, I’ve got this extra pair of shoes. They don’t fit me. Do you want them? I can’t return them.’ You know, in a way that didn’t hurt your pride.

“So, it was a village, and it was a very supportive group, and I am again very fortunate to have had the friends and teammates and their families who did look after us.”

Because his grandmother lived nearly all her life in Arlington, it remained home base despite the many moves. The strong bonds formed on the team and the lifelong nature of the sport have helped keep many former teammates and W-L alumni in touch.

Arlington, and W-L in particular, have a long and distinguished rowing history, dating to 1949 when Charlie Butt began building his legend as founder and coach of the W-L rowing team. During the 41 years he coached, W-L varsity eights won the Princess Elizabeth Challenge Cup at the Henley Royal Regatta two times as well as many national championships.

“We had a really good freshman eight,” whose members included Michael Callahan, later an Olympic rower and today the head coach of the immensely successful men’s rowing program at the University of Washington. “There was a good energy to the team then, from varsity down to freshmen, and we had a lot of good wins and a lot of fun,” Bamman said.

Butt, an MIT graduate and engineer with the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics, coached until 1991, when he retired because of acute leukemia, from which he died the following year. His son, Charley Butt, is the Bolles-Parker Head Coach for Harvard Men’s Heavyweight Crew. In addition to coaching, he was instrumental in creating the rowing facility at the Occoquan Reservoir and devoted much of his energy late in life to establishing a boathouse on the Arlington side of the Potomac.

At the time, the W-L team was rowing out of the century-old Potomac Boat Club, with its walls of photographs of winning teams and famous rowers. Bamman, who lives in Arlington today, continues to row with Potomac.

It was there that in June 2024 he spoke with Nancy Butt Packard, one of Coach Butt’s daughters, and learned that the boathouse effort, an idea he’d heard about when he was a high school rower, was making quiet progress. Nancy Butt is a director of the Arlington Boathouse Foundation (ABF) that was formed in 1991 to fulfill Coach Butt’s vision. Last December, Bamman joined the ABF board to lead its fundraising campaign.

Since its founding, the all-volunteer ABF has been grinding through the regulatory process, seeking approval from multiple jurisdictions, advisory councils, and agencies, even as the need for a new boathouse—obvious in Coach Butt’s time—has grown with the local population and the surging popularity of rowing.

Arlington is walled off from nearby water by the George Washington Memorial Parkway, completed in 1932. As a result, rowers and other water-sports enthusiasts in Virginia must cross to the Washington, D.C., side of the Potomac to launch their boats.

“Arlington County does not have a single access point to the Potomac River,” Bamman said. “The Arlington County Boathouse would be that access point. Having this one boathouse would all of a sudden open it up to 800 acres of what we could call green space or water space.”

On the D.C. side are the Thompson Boat Center, dedicated in 1961, and the Potomac Boat Club (PBC), established in 1869. Farther away are the Anacostia Community Boathouse on the Anacostia River and the Dee Campbell Rowing Center, in Alexandria, Va., south of Arlington County. None of these facilities has the capacity to handle the increasing number of young athletes the sport has attracted in recent years, said Lena Wang, PBC president and a lifelong Arlington resident who rowed for Wakefield High School there as well as with a PBC junior program when the club hosted them.

These facilities house multiple clubs and high-school programs, and “there is no room for a school or club to grow due to the limited rack space,” she said, not to mention the fees charged by the corporate owners.

The Thompson Boat Center is home to 13 high-school crews, two college teams, and two masters programs, all of which store their equipment and launch from

there.

Washington-Liberty High School, as W-L is known now, keeps its boats currently at Columbia Island Marina, on the Pentagon Lagoon and accessed from the Virginia side of the river even though it’s part of the District of Columbia. Columbia Island, next door to the Pentagon and Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport, has no boathouse, and the W-L boats are stored there on roofless racks. The marina is managed by Boating in D.C. under a concession agreement with the National Park Service.

W-L’s rowing program moved out of PBC in late 2024 after the needs of the club and the youth program began to conflict.

Ground for the Arlington Boathouse won’t be broken for a while, but several developments represent great progress, said Paul Holland, ABF president since the middle of 2024 and a board member for almost 20 years.

“Recent developments—including Arlington County’s adding the project to its 10-year capital-improvement plan, an agreement between ABF and the Arlington Community Foundation, and ABF’s commitment to raising $2 million in support of the project—are very exciting,” Holland said. A senior program analyst with Reston-based Leidos, the defense industry’s largest IT services provider, Holland rowed starboard to his twin brother’s port for W-L before rowing as a Princeton heavyweight.

As part of its agreement with ABF, the Arlington Community Foundation will handle private donations, enabling the boathouse foundation to receive larger taxdeductible contributions.

The venture has been complicated by a lack of waterfront land and the tangle of overlapping jurisdictions involved, including Arlington County, the National Park Service, and the District of Columbia (overseen by Congress).

In 2018, after considering possible sites, the Park Service chose a slice of waterfront just north of the channel between Arlington and Roosevelt Island. Plans call for a 14,000-square-foot boathouse and a 300-foot-long floating dock.

The boathouse and dock will occupy the so-called “lower site,” a small area wedged between the parkway and the river. A building with locker rooms, showers, bathrooms and service-vehicle parking will be situated at the “upper site,” out of the

flood plain and on the other side of the parkway. That property of two-thirds of an acre is owned by Arlington County. The two sites will be connected by an existing pedestrian bridge.

An agreement for the use of the sites was signed in 2019 with Arlington County, the National Park Service, the National Capital Planning Commission, the D.C. State Historic Preservation Office, and the Virginia State Historic Preservation Office. The agreement gives the county until 2029 to complete the lower site.

While the plans do not include on-site parking, hundreds of spaces are available in parking garages in the Rosslyn central business district, half a mile or so from the lower boathouse site. The site also is less than a 10-minute walk from the Rosslyn Metro station, which connects with three lines. It’s also adjacent to a bike path and hiking trail.

The estimated cost of the lower site: $15 million (split 60-40 county and private funds).

In 1992, Arlington County voters approved a $1-million bond issue for the early stages of the project. In November 2022, Arlington residents approved a bond issue of $2.93 million for planning the boathouse, part of a larger budget item for park-related capital projects. The county’s capital-improvement plan for fiscal years

2025 to 2034 calls for $9.6 million in boathouse funding in fiscal year 2028, but the Arlington County Board will have to ask voters to approve that bond issue.

Said ABF President Holland, “I am optimistic the project will be completed and we will be rowing out of the facility in the early 2030s.”

“After decades of advocacy and planning, this boathouse is long overdue” said Jay Fisette, a supporter of the project when he was an Arlington County commissioner from 1998 to 2017. “The use of the Potomac River for non-motorized boats benefits everyone who wants to exercise in nature–especially our young adults.

“Let’s get this done.”

Bamman graduated from W-L and the University of Virginia, where he had a need-based scholarship. He rowed at first with UVA’s club team but realized he wanted to concentrate on his studies. At UVA, he made connections that helped him found a successful company that provides real-estate, zoning, permitting, and engineering services for wireless carriers. He and his wife have four children, including two sons who show signs already that they share their dad’s love of rowing.

He’s glad to help push the Arlington Boathouse over the finish line for the county and the sport.

“It’s like rowing—it kind of recharges me. I think not only of the connection I have with Charlie and his vision but also the future of rowing in the area and how much Arlington County has given me.

“The three primary high schools that row are rowing out of three different locations, and we need them to row under one roof. There’s such a great need because all the other places are at or beyond capacity and with expiration dates. New facilities are going to open rowing to the next generation.

“Rowing and Arlington gave me so much opportunity. To go from basically nothing to where I am now—working on this project some 30 years later—is like coming full circle.”

How you can help: Donations toward the boathouse project can be made via the Arlington Community Foundation’s website directly: tinyurl.com/5cbbsrsd

Further information about donations is available from the Arlington Boathouse Foundation’s website arlingtonboathouse. org or by contacting Sean Bamman at sean. bamman@arlingtonboathouse.org

2-layer neck gaiters will protect you throughout the seasons. Stretchguard fabric with extreme 4-way stretch for optimal comfort. Super soft, silky feel that is lightweight and breathable. 100% performance fabric, washable and reusable.

$20

ALL AVAILABLE WITH YOUR TEAM LOGO AT NO EXTRA CHARGE (MINIMUM 12)

UNITED STATES ROWING UV

VAPOR LONG SLEEVE $40

WHITE/OARLOCK ON BACK

NAVY/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

RED/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

PERFORMANCE LONG SLEEVES

PERFORMANCE T-SHIRTS

PERFORMANCE TANKS

Order any 12 performance shirts, hooded sweatshirts, or sweatpants and email your logo to teamorders@rowingcatalog.com and get your items with your logo at no additional cost!

Every rower knows the sensation when it happens, and doesn’t. When crews fail to swing, applying force at different times, the disharmony is felt throughout the boat.

We rowers are always striving for the perfect stroke, and everyone in the boat senses when it happens, though it’s never often enough. A perfect stroke not only creates a good feeling but also saves energy, which is always helpful in a race.

A crew that has to expend extra energy on movement that doesn’t serve propulsion will not only struggle to reach its top speed but also have difficulty in the second phase of the race. This is why physically stronger crews lose races against weaker but technically better rivals.

The perfect stroke happens only when several factors come together. One of the most important is what rowers and coaches call “swing.” Swing is achieved

when all crew members move their bodies in unison and transfer power to the boat in synchrony. Every rower knows the sensation when it’s done incorrectly. When inexperienced crews fail to swing, applying forces to their foot stretchers at different times, the disharmony is felt throughout the boat.

Paul Milde, an accomplished rower and the owner of Peinert Boat Works in Mattapoisett, Mass., had this to say recently about swing:

“Imagine that the whole eight is one big sliding rigger. If all rowers are not drawing it under them together and applying similar power through their feet to the pin [differential rigging can help here], then in effect they’re doing

calisthenics against each other.

“One way to get this across with less noise would be to rig a long weight bar and have all eight rowers doing cleans on the same bar.“

(For obvious reasons, I like the idea of the sliding rigger.)

The same experience can be had by taking a group of stationary ergometers and linking the slides. When rowers move together and exert force on the foot stretchers at the same time, everything feels solid and powerful. But if some athletes in the ergometer chain don’t row in synchrony, their foot stretchers will pull out from under them or they’ll be driven toward them, which will require extra force to push off for the drive.

Valery Kleshnev, who competed for the Soviet Union in the 1980 Summer Olympics, where he won silver in the quadruple sculls, calls this the “trampoline effect”—as when two people jump together on a trampoline. If they jump out of sync, their energy will dissipate, and they’ll struggle to spring high. But by jumping

When rowers move together and exert force on the foot stretchers at the same time, everything feels solid and powerful.

together, thus increasing the return force, they’ll go higher than if jumping alone.

Crucial to a well-executed swing is that the blades of each and every rower must enter and exit the water at the same time. Stroke length, the rotation of the upper body around the hips, the leaning forward and backward, and the use of force during the first part of the stroke also must be the same.

Differences in time of even hundredths of a second and unsynchronized body movements affect swing, so anticipation and sensitivity to coordination are essential. Crew members need to be exquisitely aware of each other and committed to making immediate adjustments to match motion and rhythm seamlessly for the next stroke.

Besides the rowers’ feel, the observations of the coxswain and coach, biomechanical measurements, and video recordings can help a crew perfect its swing—along with many miles of practice and hours of repetition

While the coach is learning about and evaluating you, you’re also assessing the coach. Do you want to work with this person? Imagine interacting day after day.

If you followed last month’s recruiting steps, you sent emails out to different programs and you filled out the questionnaires for your top choices. And now, great news: The replies are coming in!

The next step is to get on the phone (or Zoom) and talk with coaches. Inevitably, there will be a lot of “sameness” in the conversations. It’s likely you’re asking many of the same questions, and so are they. That’s OK.

The most important thing is to be yourself and be engaged in the

conversation. Take your calls in an environment without distractions and with reliable service or Wi-Fi. Research the school ahead of time. What majors are offered? What’s required for the application?

While you don’t need to know everything—that’s why you’re on the phone asking questions—you should show some familiarity with how the school operates. Please don’t rave about how excited you are to study a program that the school doesn’t offer. (You’d be surprised by how often this happens.) While you should

demonstrate that you’re serious, there’s no need to show off how much you know. You’re on the phone to prove your interest, not your knowledge of the school.

Make sure you’re using recruiting conversations to figure out what you want as well. Come prepared with questions, but don’t hesitate to deviate from them to ask about things that come up in conversation spontaneously. Remember: While the coach is learning about and evaluating you, you’re also assessing the coach. Do you want to work with this person? No one’s college career is totally smooth. Inevitably, there will be bumps in the road you’ll have to deal with alongside the coaching staff. Try to imagine what interacting with them will be like day to day.

By the end of your first few calls, you should have a good sense of who the coach is as a person and what he or she expects of coxswains. Begin picturing yourself on the campus and on the water. Walk yourself

through a day-in-the-life and think ahead about the next steps in the recruiting process.

If there are gaps in either visualization, where you aren’t sure what lies ahead, that’s a sign you should clear that up with the coach. This is also a good time to talk to your parents or guardians and ask what kind of financial and logistical questions they need answered. If your parents aren’t involved in the process, you can tell college coaches that, and they can walk you through some of the administrative steps of the recruiting process, especially regarding finances. We know that families are complicated, so don’t hesitate to be upfront.

Keep in mind that the recruitment process can be surprisingly different at different schools. Many schools offer (or require) academic or financial aid pre-reads. One of the most challenging elements of the relationship-building stage

of recruiting can be juggling different timelines with different schools. You might be having a first call and a fifth call on the same day, and that can make it tough to compare schools. Take notes after calls and keep track of both logistics (Coach A wants me to send a new recording) and your gut feeling (I feel like Coach B really supports her coxswains).

But what if the phone isn’t ringing and your inbox is empty? If you’re having trouble getting your emails answered, send another round to the same coaches. (Coaches are human, too; we miss emails, travel for training camps, and get backlogged.) But the uncomfortable truth is that it might be out of your control.

“There are just so few seats,” said one coach and recruiting coordinator. “Sure, the recording is going to differentiate you, but the sad truth is not everyone is going to listen to it. If you have a great recording and the two schools you want to attend won’t listen, you might need to expand your idea of where you want to go”—or be open to walking on.

If this happens to you, it’s a good moment for some introspection about what you’re looking for and why. For some coxswains, the outcome may be realizing that being recruited is less important than being free to apply only to the schools that really light a fire in you. For other coxswains, the security of a sure seat is the most important thing. If that’s the case for you, your job is to figure out where the overlap is between the programs you’re interested in and the programs that are interested in you.

If your phone is ringing, don’t get too excited just about getting recruited. This isn’t about who loves you more or the college decal you can display on the family car. It’s about where you want to spend four years of your life.

heavyweight team. She began rowing at Phillips Exeter Academy, was a coxswain at Wellesley College, and has coached college, highschool, and club crews for over 10 years.

Rowing camps can increase your recruitability—up to a point.

There are many reasons to attend a rowing camp, including the potential impact it has on your recruiting status. But like so many things, it comes down ultimately to the type of camp you choose and what you put into it.

Instructional camps affiliated with colleges are common and typically less than a week. Living on campus and meeting the coaching staff are a little like taking the college for a test drive. Depending on skill level and commitment, some rowers can improve significantly during these camps. They’re also an opportunity to show coaches how you row and how coachable you are. These camps will not, however, help you train like student-athletes. No college-based summer camp for high-school rowers comes remotely close to the demands of college rowing.

Unlike as in many other sports, rowing coaches generally do not use their camp as a primary tool for evaluating prospects. The camps of the top programs rarely help a prospect get recruited unless she’s an athlete from another sport and new to rowing. Instead, colleges use their camps mostly to supplement assistant coaches’ meager salaries.

Competitive racing camps offer increased opportunities and benefits. They are also longer, more demanding, and typically more expensive. College coaches frequently visit these camps scouting for talent. Performing well at club nationals or Canadian Henley increases a prospect’s

college options. These camps also give prospects a better sense of the athletic demands of college rowing. They cannot replicate the challenge of balancing one’s studies with rowing but they include two-aday practices, something many college teams do regularly.

Other camps are designed for more than rowing. Rowing is a vehicle for international travel, personal growth, and/ or long-term development. These camps can prepare you better for college rowing, but unless you improve on the erg during the camp, it won’t increase your recruitability substantially.

USRowing camps receive a lot of attention in the recruiting process. Attending a weekend identification camp will not, in and of itself, help, because the results are not shared with college coaches. Development camps are valuable but not necessarily a better option than staying home and racing with your local club. Junior national team selection camps are by invitation only and can help significantly. Nearly everyone who attends selection camp gets recruited by multiple colleges.

No matter where you go, however, behavior and attitude are all-important. Show college coaches that rowing is your passion and priority. Demonstrate a clear commitment to improve. Chip in, help out, and don’t play it too cool. Humility along with ambition impresses coaches.

BILL MANNING

People who eat antiinflammatory peanut butter and nuts five or more times a week can reduce their risk of diabetes by 25 percent and heart disease by 50 percent.

In my early years as a sports nutritionist, fat was a four-letter word. The mantra “Eat fat, get fat” scared athletes away from consuming any kind of dietary fat. I practically had to beg athletes to include some fat in each meal. After all, fat is an essential nutrient needed to absorb certain vitamins (A, D, E, K) and for normal brain functioning. Fat adds flavor (i.e., enjoyment) to food. Fat lingers in the stomach, helping you feel fed for longer than a fat-free meal.

Times have changed. We now know that fat-free foods that come with added sugar to improve flavor and acceptability, such as SnackWell cookies and fat-free frozen yogurt, can be detrimental to our health. Today, we encourage healthy fats, including olive oil, walnuts, almond flour, ground flax seed, pumpkin seeds, avocado oil, salmon, and sardines. These unsaturated fats are soft at room temperature, in contrast to saturated fats (beef fat, butter, stick margarine) that are solid at room temperature. Saturated fat is associated with an increased risk of heart disease.

How much fat is OK to

While there’s no limit on total fat intake (aside from calories), the American Heart Association recommends consuming less than six percent of total calories from saturated fats to lower the risk of heart attack and stroke. That’s about 15 to 20 grams of saturated fat, the amount in two tablespoons of butter. By choosing more beans, nuts, and fish (instead of fatty meats) and more olive oil (instead of butter), you can achieve that target.

What are the worst fatty foods to eat?

While there’s not a worst fatty food, I’d bet against a steady intake of greasy burgers, pepperoni, prime rib, French fries, chips, and fried foods. There’s no need to demonize fat. Rather, you want to look at the whole day’s intake and balance a McDonald’s Sausage Egg & Cheese Biscuit (17 grams of saturated fat) with a low-fat turkey sandwich for lunch, and fish for dinner.

Decades of science have shown that saturated fats raise your bad LDL cholesterol and put you at higher risk for heart disease. That said, the harm of saturated fat has become a topic of debate recently because saturated fats are not all the same. Some saturated fats (such as beef tallow) have long chains with 13 or more carbon atoms; others (coconut oil) have medium-length chains with seven to 12 carbon atoms, and some (dairy) have short chains with six or fewer carbon atoms. Different lengths of carbon chains impact health differently. For example, recent evidence suggests that the short carbon chains in dairy fat are not linked to heart disease.

What are the best fatty foods to eat?

Foods high in unsaturated fats, such as olive oil, salmon, and nuts, are at the top of the Good Fats List; they are known to fight the inflammation that comes with heart disease and diabetes. Research suggests that people who eat anti-inflammatory

peanut butter and nuts five or more times a week can reduce their risk of diabetes by 25 percent and heart disease by 50 percent. When you cook at home, you want to use olive oil (instead of butter) when sautéing and canola oil with frying and high-heat cooking.

Isn’t canola oil bad for you?