TENNESSEE TRANSFERS TO THE TOP

SIR STEVE REDGRAVE

REFEREE CRISIS

July 28–August 4, 2024

St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada

New Date for 2024 as St. Catharines hosts the World Rowing Championships –August 18-25, 2024.

Follow web and social for important dates, accommodation and more information.

MASTERS

July 28

OPENING CEREMONY

July 29

RACE WEEK

July 30–Aug 4

Why a light boat?

• Less drag, more speed

• Lighter feel, higher stroke rate

• Easier to carry

How did we do it?

Single skin - kevlar/carbon

No paint on deck

I-beam frame

The lightest fittings:

• Dreher/Peinert rigger - 4.3 lbs.

• Dreher seat - 15.5 oz.

• Carl Douglas tracks - 15 oz.

• Carbon footboard - 15 oz.

• H2Row shoes - 19 oz.

• Molded bow ball - 1 oz.

$9,950

They have the most thankless job in our sport. Usually unpaid, often unappreciated, still unrated and unranked, referees are graying, and some regattas can’t find enough.

BY MADELINE DAVIS TULLYWhen three coaches and 17 rowers left SMU for Tennessee last summer, it wasn’t the beginning of a transfer-portal apocalypse.

BY CHIP DAVISThe most decorated oarsman of all time explains the enduring appeal of Henley, why World Cup participation lags, China’s Olympic prospects, and why Beach Sprints may split rather than save rowing.

February, when the work for this issue was done, brought far more interest and news than we have seen in recent past winters. The USRowing Speed Order at Nathan Benderson Park revealed a number of faster, younger rowers looking to earn places on the Olympic squad (see Big News, page 25). Our sport’s vital but under-resourced referee corps is reaching crisis stage, as Madeline Davis Tully explains in her latest feature on page 34. And as Steve Redgrave chairs his latest and probably greatest Henley Royal Regatta this year, he offers an alternate view on the as-yet-unfounded hopes that Beach Sprints will save Olympic rowing. Quite the opposite, as you can read in the exclusive Rowing News interview on page 48.

What’s not a problem is directing more resources to women’s rowing.

Collegiate rowing continues to evolve as the NCAA undergoes seismic changes. As I did the research, talked to people, and conducted the interviews that went into my feature story, “Follow the Money” (page 40), I came across two opposing themes, one factually correct—that rowing, especially women’s collegiate rowing, is better than ever—and the other an outdated and inaccurate attitude that our sport needs to leave behind. That ugly, negative attitude is that somehow something bad and immoral is going on when a particular part of our sport, and the women practicing it, finally get proper support and major resources.

There are a lot of things wrong with college athletics and the NCAA today, but what’s not a problem is directing more resources to women’s rowing. The money that comes from TV contracts to pay for scholarships ends up in university coffers, and coaches—especially assistants—are finally getting paid more than near-poverty wages to teach our great sport to the next generation of young women eager to row, compete, and develop into strong and healthy human beings.

Even the equipment trickles down through our sport, to clubs and junior programs. Division I programs get at least one new boat every year, and when I go to club regattas and head races, I see those perfectly good, previously wellmaintained handed-down shells providing high-value, lower-cost steeds for the much larger rowing populations in youth and non-NCAA rowing communities.

The women I interviewed who have made the move—literally hiring movers to put their belongings in storage, and then renting U-Hauls and driving them themselves—to Knoxville are not being taken advantage of. Quite the opposite, really. Many have come from foreign countries with tuition-free universities to row and study at a U.S. university because the opportunities here are even better than in the rest of the world.

The other, better attitude I came across was one of gratitude and carefulness not to denigrate what others have when describing one’s own good fortune. All the coaches and rowers I spoke to, most of them women, share a strong and healthy competitiveness toward their rivals, tempered by real respect and appreciation for the challenges others face.

It’s the best of our sport, even if we’re not all ready to accept things going well for others.

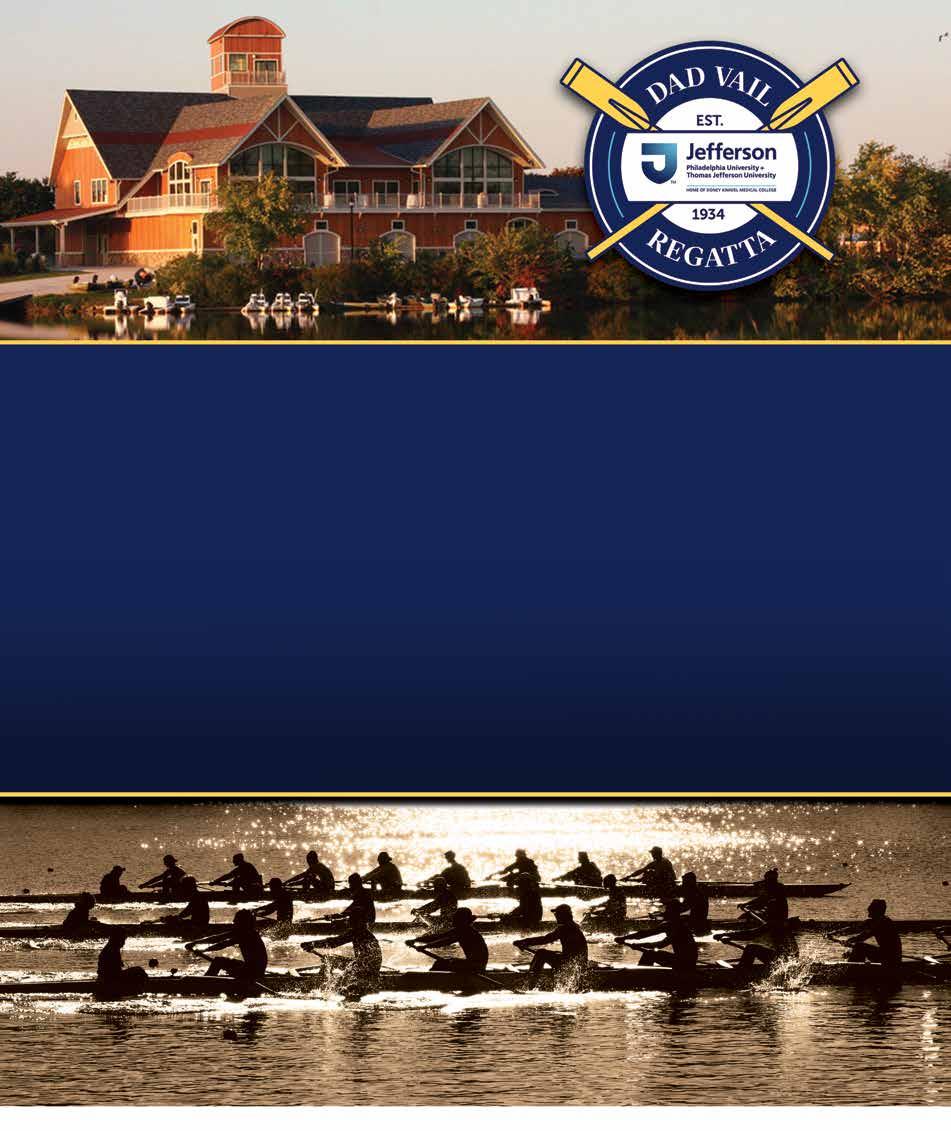

FRIDAY, MAY 10 and SATURDAY, MAY 11

Cooper River • Pennsauken, NJ

National Open Collegiate Rowing Championship with a Festival atmosphere

Live “on-stage” music, food, vendors and more!

New events added!

MEN’S

Club/DIII Varsity Eight

Club Varsity Four with Coxswain

WOMEN’S

Club Varsity Eight with Coxswain

Club Varsity Four with Coxswain

85th Dad Vail Regatta Anniversary Grand Celebration

85th

I read with interest Doctor Rowing’s article “A Model Worth Emulating.” While The Boys in the Boat movie hoopla has brightened the lights on the University of Washington crew, Eric Cohen has been doing the same year in and year out for decades. The level of detail, content, and entertainment is unmatched. Anyone who was at the BITB enclosure at last year’s Head of the Charles would concur—Eric’s emceeing Bill Miller (rowing historian extraordinaire) and Jim Pocock’s presentation was a highlight!

You are absolutely right to note that having an individual, or group of individuals, harness, appreciate, and celebrate any rowing program’s history is essential for it to thrive. Eric is to be congratulated for his hard work, as should everyone who is doing the same for their school, university, or club program. It is a core element of the rowing community to which we all belong.

P.S. Eric is a damn good coxswain as well!

Charlie Clapp Captain,1981 UW men’s crew Boston, Mass.

While Bill Manning’s column, “Talking Points,” is quite informative about effective communication with athletes, the penultimate paragraph is disappointing and irresponsible.

Coach Manning writes of athletes who “make excuses, complain, or criticize others,” and tells coaches to “consider ignoring their pleas by being visibly distracted” or “feigning indifference.”

Coach Manning further says that ignoring them shows that their concerns are “no big deal,” but the examples he cites often are big deals. In the preceding paragraph, he writes that “coaches show they care for athletes by giving them their full attention.” Are we to understand that he’s advising us to show an athlete that we don’t care?

Coaches should not be ignoring athletes who are criticizing others inappropriately. That’s not a culture anyone should allow to fester on their team and should be addressed in private. Athletes who makes excuses might not be cut out for whatever the standards are, or they may need help contextualizing the challenges they’re facing. Either way, this is an opportunity to teach them to rise to the occasion or guide them toward the reality that maybe their time would be spent better elsewhere.

When athletes complain, it can mean many things. Maybe they don’t like rowing in the rain. Or they could be complaining about a legitimate safety concern, a possible injury, negative culture, misunderstanding the direction of the program. None of these possibilities is mentioned in the column.

Coach Manning is well regarded in the rowing world, rightfully, and his words carry weight. What he’s recommending may be perfectly appropriate in some circumstances, perhaps when working with elite adult athletes at Penn AC, but it’s a tool that requires training and understanding when it should be used.

While I’m confident Coach Manning knows when and when not to ignore his athletes, I shudder at the thought of a young junior coach, just getting his feet wet and without a mentor, reading this article and ignoring an athlete who’s complaining about a teammate who says he isn’t good enough.

Nate Clark

Assistant Coach and Recruiting Coordinator Trinity Men’s Rowing

Bill Manning Replies:

Coach Clark raises some good points in his comments about my column. I appreciate his sharing them and getting me to think more about what I wrote. I could have done a better job.

Unfortunately, in 500 words, I can’t fit all the necessary nuance or address all types of rowing (juniors, club, collegiate, masters, para, National Team). Bold, simplistic statements sometimes get made, I regret to say. Often, more explanation and examples would be beneficial.

That said, I stand by the core idea that occasionally the best approach with an athlete is

benign neglect. I see two potential benefits.

By not engaging the athlete about the matter, he/she will see that it’s unworthy of attention; the coach’s inattention signals that the athlete should give it no attention, either. This is true of many excuses, criticisms, and minor complaints.

When children stumble and fall, typically they look instantly to their parents for guidance about how to react. If parents show concern, children take it seriously and wail away. If parents don’t fret about it, children often pick themselves up and carry on. The key, obviously, is parental judgement. It must be established first that the child is safe and that there’s nothing to worry about. Coaches must do the same.

The other benefit is that athletes are left to figure out things for themselves. It’s better coaching practice to recognize these learning opportunities and give athletes the space to figure things out on their own. More often than not, it’s necessary to explain things to athletes and guide their learning explicitly, but when the situation allows, it’s best to let them learn for themselves.

Most athletes will solve problems on their own when given the opportunity to do so rather than being spoon-fed solutions. When they race, there will be no coach giving them advice or changing the race plan; the athletes need to take control and act independently. Sometimes, providing small opportunities to do so prepares them better for the independence they’ll have when racing (and when on their own without a coach’s caring presence).

To stop athletes from making excuses, don’t entertain the excuses. Instead, stay focused on performance. Many instances of poor behavior are driven by an athlete’s desire for attention. Refrain from giving this attention and the athlete learns that the behavior doesn’t generate the desired response, and so is not worth engaging in.

As Coach Clark highlights, the key is exercising good judgement. Coaches need to appreciate the difference between an excuse and a legitimate handicap. They need to recognize when bad behavior is rooted in a significant personal problem and when it’s just superficial and selfish. With seasoned good judgement, benign neglect becomes another useful coaching tool.

Excellent Q & A with Matt Smith. He hits on most of the topics affecting U.S. and international rowing over the last 30 years— universality, lightweights, TV coverage, racecourse-construction costs, number of rowing athletes at the Olympics—with the cool precision of an experienced executive.

Great article!

Bob MaddenPhiladelphia, Pa.

Although I enjoyed the article and interview with Matt Smith, I was annoyed to see a repeated error. The bridge in Long Beach that affects the length of the course is on 2nd Street, not 7th Street. You can trust me on this; I’ve lived in Long Beach and have rowed under that bridge since 1984.

Ellen Kirk Long Beach, Calif.From Doctor Rowing: My apologies for hastily done work in the December column. I so often praise Peter Mallory’s magnum opus, The Sport of Rowing , that somehow, when listing places to find excellent writing about rowing history, I neglected to mention how valuable his book is.

An alert reader also brought to the attention of Rowing News that in mentioning the 1956 Yale Olympic eight, the first to win gold through the repechage, I did not call attention to the second USA eight to do so, the Vesper 1964 crew. Of course, I know better, especially since one of the crew’s members, Emory Clark, is a graduate of Groton, where I teach and coach, and has been a frequent visitor to campus. All three of my children have had the pleasure of wearing his gold medal around their necks for a few moments. His book, Olympic Odyssey, is a favorite.

All I can say is, “Oops, I screwed up!” I sometimes mix up my children’s names, but they still love me. I’ll do better checking in the future.

Frank Rothwell, 73, completes his second row across the Atlantic, from the Canary Islands to Aruba, on Feb. 15, after 64 days. Story, page 30. The record for the fastest Atlantic-crossing crew is held by The Four Oarsmen, who made the journey in 2017 in 29 days, 14 hours, and 34 minutes. In 2016, solo oarsman Daryl Farmer took 96 days to do it, rowing without a rudder for nearly 1,200 miles over 40 days. Ocean-crossing rowing continues to grow in popularity, with a race-record 43 crews setting out in the 2022 Atlantic edition of “The World’s Toughest Row” (Forty-two completed it).

California Rowing Club’s Sorin Koszyk was the fastest sculler every day at the winter Speed Order, Feb. 15-17 at Nathan Benderson Park in Sarasota-Bradenton, Fla. and won the A final. “Today was a solid effort,” said Koszyk. Story, page 25.

PHOTO: LISA WORTHY

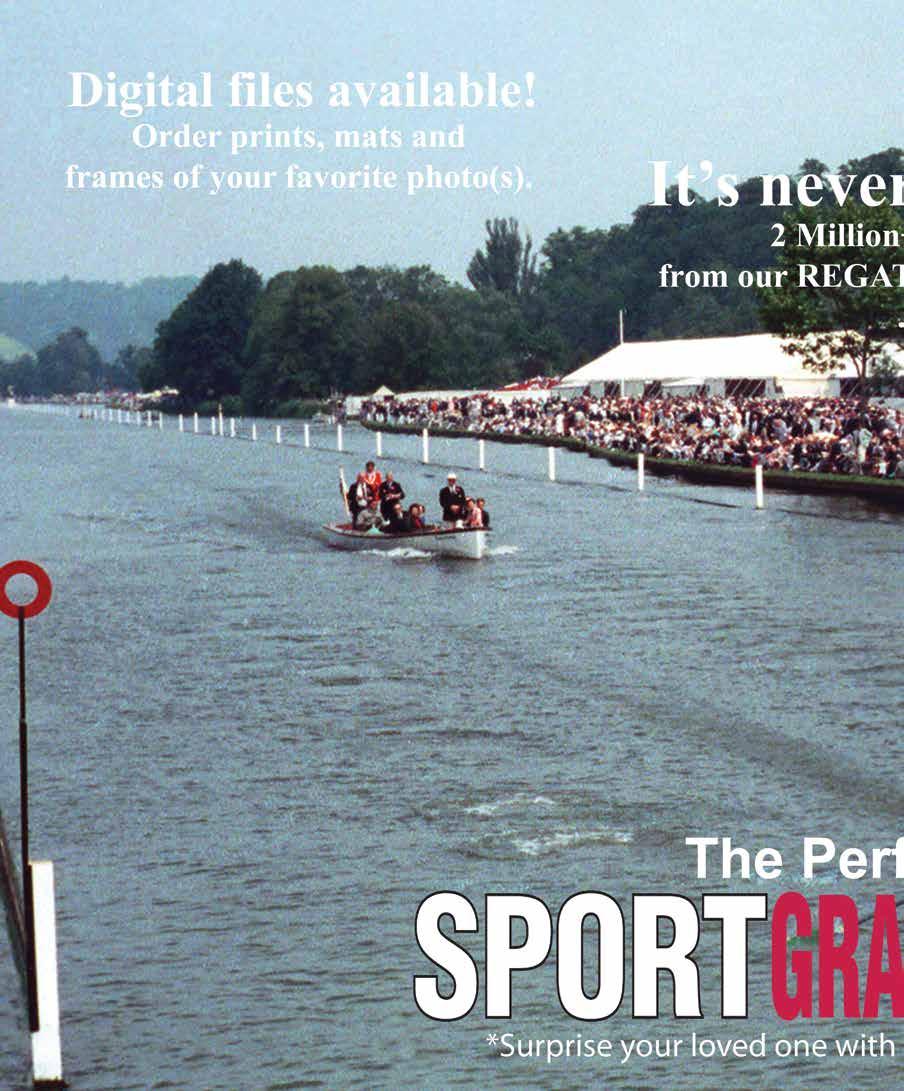

Cambridge leads Oxford in the 2023 Gemini Boat Race on the River Thames. Cambridge won both the men’s and women’s races last year, and the overall record stands at 86-81 in favor of the Cambridge men and 47-30 in favor of the Cambridge women. The crews for the 2024 Gemini Boat Race will be unveiled at the Battersea Power Station on Wednesday, March 13.

Oxford men’s and women’s boat clubs have joined forces this year for the first time in their history. The Cambridge clubs combined in 2020. First raced by crews from Oxford and Cambridge in 1829, The Boat Race is the world’s oldest intercollegiate sporting event and is attended regularly by over 250,000 spectators on the riverbank and watched by millions more on television.

speeds” and “better small-boat skills.”

Alarge field revealed a deep talent pool as the first official step in selecting U.S. Olympians—the winter Speed Order—concluded Feb. 17 at Nathan Benderson Park in Sarasota-Bradenton, Fla.

“It’s a good reflection of where we are,” said Josy Verdonkschot, USRowing’s chief high-performance officer. “We see more depth and we see better small-boat skills. I’m pretty pleased, especially because most finals were competitive.”

Men’s pairs racing for California Rowing Club took the top five spots in the A final, with a sixth CRC pair winning the

B final. On the women’s side, USRowing Training Center-Princeton pairs took first, second, and fourth through sixth in the A final, with CRC’s Ali Rusher and Megan Musnicki, who qualified the U.S. for the Olympics in the event at last year’s Worlds, third. (Some pairs were actually composite crews. According to Verdonkschot, “in the end we all train together as one team.”)

In both the men’s and women’s pairs, a little over five months ahead of the Olympics, all six A-final crews were within at least 95 percent of the established Competitive Standard Time, the speed

The Atlantic Coast Conference announced its first-ever Rowing Watch List for the upcoming campaign. The watch list consists of one studentathlete from each ACC program, nominated by her respective college or university. The ACC is the only conference with a preseason rowing watch list, which is designed to draw more attention to ACC rowing. Multiple websites picked up the story within hours of its release. The 2024 ACC season gets under way on Saturday, March 16, when Louisville hosts the Oak Ridge Cardinal Invitational in Oak Ridge, Tenn.

at which they might be expected reasonably to win.

“There was almost no wind, flat water, but still, in order to row fast times, you have to be fast,” said Vedonkschot. “In that respect, I’m happy with the results.”

In all, 95 single scullers and 27 pairs competed in the regatta.

“It’s always a bit tougher to hit a time standard when you’re in a small boat,” said Verdonkschot. “So that’s a good indication. And if you look across the fields, men’s pairs as well as women’s pairs as well as singles, all good, decent speeds. So we can only be happy about that.

“You get what you invest in. So if everybody is aware of the fact that they have to not just pull hard on an erg but also show that they can move small boats, people step up and understand and they focus on the right things.”

Unlike some previous Speed Orders, every competitor raced in a six-boat final, whether they qualified for the quarter finals (singles) or semifinals (pairs) in the opening time trial or went straight to the lower E-through-H finals on Friday, the second day of the regatta. Upper-level finals were held on Saturday, a day earlier than originally scheduled, to accommodate the America Youth Cup regatta, which was previously scheduled for the venue.

“If you look at the general level, people understand the importance now of small boats; they enjoy the training and they enjoy the competition,” observed Verdonkschot. “Everybody who was here, down to D-finals and below, had fun with their racing because it was competitive. It’s great development.”

Besides the CRC and USRowing training centers, clubs— including Cambridge Boat Club, New York Athletic Club, ARION, Whitemarsh, Green Racing Project, and Penn AC— trained athletes who have raced their way into Olympic consideration.

“I’m very encouraged with the overall performance,” said Bill Manning, highperformance head coach at Penn AC and a Rowing News columnist. “The clubs are doing an excellent job of preparing athletes to row for the United States.”

Scullers who have already made National Teams turned in the best performances in the singles. Lightweight sculler Molly Reckford, a Tokyo Olympian

in the women’s lightweight double, won the combined open and lightweight-singles time trial Thursday morning and then set the fastest time in the afternoon quarterfinals.

“I don’t know how this is happening,” said Reckford. “There are some damn fast women in this race, and I have no doubt they’ll just get faster over the next couple of days.”

Maggie Fellows, a veteran of the 2022 U.S. squad, proved Reckford right, winning the singles A final ahead of Sophia Vitas, who won bronze in the double at last year’s Worlds. Reckford finished third. Lauren O’Connor, Michelle Sechser, and Teal Cohen completed the A final.

Sorin Koszyk continued his winning streak in the single, finishing first in the men’s-single time trial, his quarterfinal, semifinal, and the A final. Ben Davison, Koszyk’s partner in the double at last year’s Worlds, finished second, with William Legenzowski third, giving CRC the top three spots. Jacob Pihal, Andrew LeRoux, and Michael Knippen rounded out the A final.

Several men and women who raced on last year’s U.S. National Team at Worlds were relegated to C finals and lower, as younger athletes rise in the ranks and competitive standards go up in the Olympic year. This year’s pool of athletes includes 25 women who have gone under 6:45 for 2K on the erg and 33 men under 6:00, a dozen of whom are under 5:50.

The Speed Order helped determine invitations to Olympic selection camp, to be held at Nathan Benderson Park in March. USRowing qualified for two Paralympic and eight Olympic events at the 2023 World Rowing Championships in Belgrade, Serbia. The U.S has spots in six of the seven women’s Olympic events but in only two men’s events. The women’s quad and all but the men’s pair and four, along with three Para boats, will have to earn qualification for Paris at the 2024 World Rowing Final Olympic & Paralympic Qualification Regatta, May 19 to 21 in Lucerne, Switzerland, before Rowing World Cup II. If the crews USRowing sends to Lucerne don’t finish in the top two, the U.S. won’t have an entry in those Olympic events.

Invitations to attend the Olympic selection camp went out after the completion of the Speed Order. Athletes don’t have to attend that camp to represent

the U.S. at the Olympics in some events. The women’s single and men’s and women’s pairs will be the winners of Olympic trials. The other seven qualified boats will be picked through selection camp, although Koszyk and Davison will most likely be named the men’s double and train at CRC. But five of the non-qualified boats—all but the men’s eight—will be the winners of Olympic trials, who then have to finish toptwo at the final qualifier in Lucerne.

Verdonkschot said team boats—quads, fours, and eights—will be selected from invited athletes at the selection camp, but the athletes have the option to choose their own paths.

“People who decline the invitation and want to go to trials—I don’t mind, as long as we communicate it early, because I would want to have the athletes for the quad camp.”

Similarly for the fours and eights: “Everybody who feels uncomfortable or wants to self-remove and create a pair, they can do that. At the end of the camp, people who are not selected will also be able to prepare for trials in the pairs.”

Based on results at last year’s Worlds, the eight will be the priority sweep boat for the women, with the coxless four selected from the same pool. Both will race in Europe this summer, with the opportunity to fine-tune line-ups between boats, if warranted, since Olympic rules allow changes to qualified boats.

The four will be the priority sweep boat for men, and the eight, to be selected by USRowing Training Center-Sarasota head coach Casey Galvanek, will try to recreate The Boys in the Boat. Plans call for them to train in Seattle with University of Washington head coach Michael Callahan during the spring before attempting to qualify in late May and, if successful, stay to race the World Cup in Lucerne before returning to the Princeton area to train with the whole Olympic squad before the Games.

U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Team Trials take place at Nathan Benderson Park, April 2 to 7. Olympic selection camp begins March 3.

As Verdonkschot said at the completion of the Speed Order, “Now the trouble starts.”

CHIP DAVIS

The oil-rich kingdom is spending billions to promote sports and tourism and hopes to host championships in indoor rowing and Beach Sprints.

Saudi Arabia—the richest Arab country, with a thriving economy driven by huge oil revenues —is aiming to become a player in international rowing by vying to host the 2025 indoor-rowing championships and the 2027 Beach Sprint championships.

Rowing “encourages a competitive environment in the country,” said Husein Alireza, an Olympian and captain of the Saudi Rowing Team during an Arab News podcast.

“To host world-class athletes, to demonstrate world-class performances and expose the people to what it takes to perform on the world stage, that’s priceless. It inspires people.”

The Saudi Rowing Federation, formed three years ago, has ambitious plans to discover, recruit, and develop promising

rowers in the nation of 36 million people. Scouts have visited some 50 schools to conduct fitness assessments and identify students who, because they are tall and long-limbed, are suited biomechanically to excel in the sport.

Prospects will begin by learning how to row and will progress through several stages of development until they’re capable of competing and winning at the elite level. The coach of the Saudi team is toptier—Matthew Tarrant, a two-time British Olympian who rowed in the coxed pair, coxed four, and eight and won medals in five world championships, two of them gold.

Alireza, Saudi Arabia’s first rowing Olympian, competed in the single scull in Tokyo in 2021. He began rowing at Cambridge University, where he was coached by the esteemed oarsman Bill

Barry, who continued to guide Alireza when he earned an Olympic spot after capturing a gold medal at the Saudi Games. (Barry attended another Tokyo Olympics—in 1964—as an athlete, winning silver in the coxless four.)

During the four years he prepared for the Olympics, Alireza trained relentlessly, rowing three times a day, and taking a day off only once every two weeks.

Alireza views rowing as a way to diversify further Saudi Arabia’s booming sports scene (the number of sports federations in the kingdom has tripled, soaring to 97 from 32 in 2015) and dilute the dominance of football (soccer). He’s excited especially about the potential appeal of spectatorfriendly coastal rowing and Beach Sprints.

Coastal rowing, which debuts at the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics, “opens up a whole

new world,” he said. “It’s a little easier to get a hold of and to master than traditional rowing, so it’ll involve a lot more Saudis.”

With its many beaches, Saudi Arabia is an ideal venue for such contests, he added.

“The social and economic benefits of hosting these events are undeniable and well-documented,” Alireza said. Sports participation “decreases stress and improves the health of the general population, which in turn decreases the costs of health care. It’s intrinsically linked to the quality of life.”

Saudi Arabia is moving aggressively to broaden its economy and reduce its reliance on oil by promoting sports, entertainment, and tourism and is spending billions to do so as part of Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman’s Vision 2030. The country is liberalizing its laws and investing in the traditionally marginalized, such as youth and women. In 2018, women were allowed to drive for the first time in history.

The two pillars of fostering sports like rowing are opportunity and support, and the Saudi government, through its Sovereign Wealth Fund, is putting its money where its mouth is, channeling $427 billion into bolstering its various sports federations.

In 2021, the kingdom shook up the world of golf when it ponied up $2 billion to launch the LIV Golf Tour, luring star players from the PGA with lucrative cash payouts. That same year, the first Saudi Arabian Grand Prix, a Formula One race, took place, a contest that recurs this month.

Late last year, Jeddah was the site of an America’s Cup preliminary regatta, and in 2034 the kingdom will host the Asian Games and the 25th FIFA World Cup. Saudi Arabia has been staging professional wrestling events since 2014 and purchased a $100-million stake recently in a mixedmartial-arts league.

The nation has become the home of elite boxing and is negotiating to host a new Masters 1000 professional tennis tournament as early as January of next year.

“It’s amazing the diversity of the events we are hosting,” Alireza said. “If we are ready to host world-class events, then why not? We don’t have to explain why these events are happening here. It’s because we can.”

ART CAREYThe 2027 NCAA National Championship will likely be the last to crown a Division II women’s champion.

At the recent 2024 NCAA Convention, the Division II delegate body approved a proposal to change the minimum sport sponsorship number and, crucially, to remove the current exception for Olympic sports, which applies to rowing. This means that any sport with fewer than 35 sponsoring institutions will no longer have an NCAA national championship after a three-year grace period. Though not listed in the media alert, women’s rowing, with only 15 institutions sponsoring a team, is the only sport affected by the new rule change.

The options going forward are limited. The most direct way to regain a national championship would be to meet the minimum required number of sponsoring institutions. However, the sudden addition of 20 new DII rowing programs is nearly impossible, especially given that the number of DII teams has remained relatively constant over the past years.

In a “Question and Answer Guide” published by the NCAA in December 2023, it is clearly stated that no sports will be “grandfathered” in, so there is no chance of the current exception being extended.

The guide does, however, state that there is a waiver opportunity for sports that fall below the 35-team minimum. This is perhaps rowing’s best chance, though the likelihood of this being successful is unknown.

Beyond that, DII schools are left without a championship, without a structure or focus for their seasons, and therefore little motivation for schools to continue to sponsor rowing teams. According to Kim Chavers, head coach of women’s rowing at Nova Southeastern, a few schools may try to move up to DI if a waiver is not approved. However, the more likely outcome for the majority of DII institutions, said Chavers, will be to downgrade their women’s rowing team to club status or cut it outright.

“The real issue here is that the NCAA is eliminating 400 opportunities for women with no plan to replace them elsewhere,” Chavers emphasized.

MADELINE DAVIS TULLY

It was the second crossing for the owner of a British pro soccer team.

Frank Rothwell, the 73-year-old owner of British professional soccer team Oldham Athletic, completed his second solo row across the Atlantic to raise money for Alzheimer’s Research UK, on Feb. 15 after 64 days at sea.

“You can’t put into words how hard it is to do this,” Rothwell said.

He’s completed the crossing before, raising over a million pounds ($1.2 million) after a 56-day row. This year’s attempt was hampered by unfavorable winds. To complete The World’s Toughest Row, Rothwell sculled for 3,000 nautical miles from the Canary Islands, off the coast of Africa, to Antigua in the Caribbean.

“There aren’t many harder things than running a football club, but this probably is.”

CHIP

Once again, Swing is looking for college undergraduates interested in a summer spent on the front lines of venture capital, entrepreneurship, and business building.

You will be sent to fetch zero coffees, ever.

info@swing.ventures | www.swing.ventures

Interns will be based remotely, and applicants from all timezones are encouraged to apply.

An early stage venture capital fund dedicated to supporting innovation and high-impact entrepreneurs, Swing Ventures has invested across an array of industries and models including financial and health technology, consumer hardware, and e-commerce. Swing is deeply networked and well-positioned to help businesses at a variety of life stages.

info@swing.ventures

THEY HAVE THE MOST THANKLESS JOB IN OUR SPORT. USUALLY UNPAID, OFTEN UNAPPRECIATED, STILL UNRATED AND UNRANKED, REFEREES ARE GRAYING, AND SOME REGATTAS CAN’T FIND ENOUGH.

STORY BY MADELINE DAVIS TULLY PHOTOGRAPHY BY LISA WORTHY

During the 2023 NCAA National Championship, a dozen geese planted themselves on the racecourse before the final of the Division I second-varsity eights. Despite warnings from at least one coach, the referees did nothing to remove the geese or delay racing.

Less than a minute into the race, the Texas crew rowed directly into the flock, a completely avoidable obstacle that the team protested immediately after crossing the finish line—to no avail.

That same year, at the Head of the Charles, in addition to pride, money was on the line for the top three finishers in the Championship Singles events. Afterward, Emma Twigg, who earned $5,000 by finishing second, was overheard saying she had missed a buoy and was not penalized.

This, presumably, did not sit well with Kara Kohler, who finished fourth, just out of the money and a mere 3.4 seconds behind Twigg. She raised the issue with regatta officials, who directed her to the referees. But because an umpire hadn’t seen a violation and assessed a penalty during racing, the call could not be appealed.

Every coach has tales to tell of referees who do not take action in a crucial race or stepped in when it didn’t seem necessary. But the sport of rowing would not be possible without the presence of referees to ensure the safety and fairness of racing. And yet they’re often a source of frustration for rowers, coxswains, and coaches alike—when they’re noticed at all.

Every rower or coxswain can recall times when a referee harangued them unnecessarily for their steering or, worse yet, did nothing to address the sloppy steering of a competitor. While these stories are attention-grabbing and certainly a source of consternation, they represent only a small part of what referees do and the difficult realities they face.

Referees have the most thankless job in our sport. Most in the rowing world rarely look past their surface interactions with referees to understand all that goes into being an official, the challenges individual referees and the corps as a whole face, and the active efforts being undertaken to improve the practice.

Financial barriers to entry, low numbers, an aging demographic, lack of consistent compensation, and no standardized system for evaluation combine to limit the current and future effectiveness of referees. With each passing year, these

problems are becoming only worse. Said Tom Rooks, USRowing’s Director of Sport Safety and Operations: “There’s an alarm on the dashboard.”

Today, the role of referee is being redefined.

“We’re in a challenging and everchanging landscape,” said Gary Caldwell, commissioner of the Intercollegiate Rowing Association, “where some folks inside and outside the referee corps consider it avocational, and some people consider it vocational.”

The good news is that many in the referee corps, with renewed support from USRowing, are working behind the scenes to make things better, because they realize the stakes are high. Without an educated, energetic, accountable, and supported referee corps, the entire sport of rowing will suffer, becoming less safe, less fair, and ultimately less competitive.

To understand referees, it helps to know how they are made. First, referee candidates must complete the five-hour Referee Online Training Program. As the name suggests, the program is entirely virtual and is created by the Referee College, a consortium of senior referees from across the nation. After completing the program, along with passing a background check and SafeSport training, candidates move on to observations. They participate in ride-alongs with licensed referees at regional regattas, witnessing first-hand the unique responsibilities of the various referee positions and learning from more experienced officials.

Once they’ve accumulated enough observation hours, candidates move on to the licensing exam. This 50-question test is multiple-choice and open-book. After completing this final step, candidates become officially licensed assistant referees. After completing another round of practical testing, they can advance to becoming a full referee. By working at least four regatta days per year and completing annual continuing education, referees can keep their license active.

The process is straightforward and, notably, is executed without the involvement of USRowing until it’s time to confer the actual license.

The system, say some of the most established referees in the game, works. Kirsten Meisner has been a referee for nearly 25 years, serving as an umpire at numerous national and international regattas,

including, this year, the Olympic Games. She’s also a member of the Referee College and knows the ins and outs of referee education.

“We have the background knowledge. It’s easier for us to just roll with it,” Meisner said, by way of explaining why the Referee College manages the training program. While turnover in USRowing staff can cause inconsistency, the referee corps remains stable, resulting in consistent educational standards for onboarding recruits.

“People who get the referee bug tend to stick around for a very long time,” Meisner said. “We have survived numerous different CEOs, numerous different boards, numerous different staff people. We have that perspective that they don’t necessarily have.”

Now for that “alarm on the dashboard.” It boils down to one word: compensation, a constant topic among referees and regatta directors. Though the position is volunteer, many referees can incur significant personal costs working a regatta, which discourages new candidates, especially younger ones. They’re required to travel long distances, stay overnight, which means often missing meals, time with family, and even paying workdays. For this, they may receive nothing more than a cup of coffee or, if they’re fortunate, complete travel reimbursement and a stipend. The time and economic barriers to entry are significant.

In 2023 when the Referee Committee, a group of referees who voluntarily advise USRowing, conducted a study of compensation at 97 regattas, they found that 97 percent provided some form of compensation but that nearly three-quarters provide no reimbursement for travel. The median daily compensation was $100, with a few offering up to $400 per day—and just as many offering zero.

The committee proposed a standard compensation rate ranging from $100 to $200 based on the number of hours worked. They proposed also that regattas should cover travel expenses, meals, and single-occupancy hotel rooms and advised that referees should have reasonable breaks throughout days that can last longer than 12 hours. USRowing already follows such practices for its nationalchampionship regattas, but its example does not dictate how registered regattas handle compensation.

IRA Commissioner Caldwell stages five championship regattas every spring— Eastern Sprints, Women’s Sprints, National Invitational Rowing Championship, New England Rowing Championships, and the IRA National Championship. Just to accommodate moving referees to singleoccupancy rooms, he said, increased hotel costs for the IRA National Champiobships from $11,000 to $23,000–a massive jump that resulted in higher regatta fees for participating teams.

it’s simply not the right thing. God love ’em, they’ll continue to make the same mistakes over and over again.”

Many referees are older—average age, 60–and have been doing it for a long time. Some have no background in competitive rowing, and others became referees only because their children began rowing and reffing afforded a better view of the action than the parents’ tent on shore.

Without a formal evaluation mechanism, there’s no reliable way to

“IF YOU LOOK AT OUR NUMBERS—WHERE WE’RE GOING, AND WHAT WE’RE TRYING TO ACCOMPLISH—IT DOESN’T WORK.” —TOM ROOKS

Terry Friel Portell, the current chair of the Referee Committee, while acknowledging the financial impact of the proposed compensation model on regattas, believes it’s worth it.

“We have to address the fact that referees are volunteers and need fair compensation for our time, which unfortunately puts monetary stress on the local organizing committees and ultimately the athletes. We recognize that. But to attract younger people to refereeing, we can’t expect them to give up workdays, give up vacation days, go somewhere and do this for a weekend and not get paid, or at least not walk away even.”

Another issue plaguing the referee corps is evaluation. Currently, there is no standardized way to grade referees, and the opportunities for constructive feedback are limited. Chief referees are responsible for creating their own team of refs for a given event. The selection is made often through networking and word of mouth, since there’s no objective ranking of referees—a constant source of frustration in the sport.

“That’s something that I’d love to improve,” Meisner said. “There are definitely people who would benefit from some feedback and opportunities to do different things.”

Added Caldwell: “There are some wonderful folks who are in refereeing, and

identify referees who are making errors consistently or mismanaging events. Chief referees must rely on their personal experience of the referees they’ve worked with or recommendations from trusted colleagues and then do the best they can with the people available.

“If you know you need 20 people and you can find only 15 that you’d classify as ones you don’t have to worry about, you still need five more,” Meisner said. “You take what you can get if you really need it for safety purposes. You just become very particular about where you assign them.”

These two issues –compensation and evaluation–bear on the most pressing issue facing the referee corps: recruiting.

Rowing is undergoing tremendous growth, and there are too few referees to keep up. In 2023, there were 224 USRowing registered regattas, up from 168 in 2019. During the same period, the number of referees actually dropped. Today, there are about 450 active referees, and some regattas are struggling to find enough refs, let alone those who are accomplished and regarded highly.

“If you look at our numbers—where we’re going, and what we’re trying to accomplish—it doesn’t work,” Rooks said. “This cannot continue for very long.”

To address the problem, USRowing last summer created the Referee Programs Associate—a full-time staffer whose job is to deal with referees. Hugh McAdam, a former National Team rower, was tapped for the position and has been collaborating with the Referee Committee members, all of whom have 15 to 20 years of experience, to formulate a practical vision for the corps.

Rooks, who oversees McAdam, describes the role as 51 percent supporting the referees and 49 percent leading them. The refs have operated with a high degree of autonomy for a long time and would benefit, Rooks and other believe, from more involvement by the sport’s governing body.

Recruiting referees is a perennial challenge. Experienced young rowers and coxswains are discouraged from becoming referees often by the expense and the perception that reffing is for retirees.

“There aren’t enough college coaches pulling kids aside and saying, ‘If you want to stay with this but you don’t have time to row at a club or you’re not National Team material, try reffing. It’s the best seat in the house,’” Caldwell said. “I don’t think we do enough proselytizing.”

The goal of USRowing and the Referee Committee is to approve a new recruiting plan by October and implement it in January. Their resolve is such that it’s cemented in the 2025 budget.

Meanwhile, USRowing is recommending compensation for referees sufficient for them to break even, and perhaps pocket some extra cash for their time, skill, and effort. This would help attract more and higher-caliber referee candidates. But at this point, it’s just a suggestion; USRowing will not require its registered regattas to comply, so deciding whether and how much to pay refs still rests with organizers of individual regattas.

Also being discussed are formal means of evaluating referees, despite reluctance and resistance from some corners of the corps.

“By and large, referees are very professional, and the corps does a good job of representing USRowing,” McAdam said. “But there are always a couple of bad apples. I’d love to have a way to minimize those.”

“It’s going to require culture change to get to that because we haven’t had that,” said Referee Committee chair Friel Portell. “There are a lot of people who don’t care to have any feedback.”

WHEN THREE COACHES AND 17 ROWERS LEFT SMU FOR TENNESSEE LAST SUMMER, IT WASN’T THE BEGINNING OF A TRANSFER-PORTAL APOCALYPSE. IT WAS THE PREDICTABLE RESULT OF A TOP ATHLETIC PROGRAM DEVOTING MAJOR RESOURCES TO WOMEN’S ROWING.

And just like that, they were gone. Less than two weeks after coaching Southern Methodist University to a historic top-10 finish at the 2023 NCAA Rowing Championships, Kim Cupini left Dallas for the University of Tennessee. But she didn’t just leave. A good portion of the SMU team—athletes and coaching staff—went with her.

In all, 17 student-athletes and three coaches went from Dallas to Knoxville to become the core of the 2023-24 Tennessee Volunteers women’s rowing program.

Unprecedented in size, it was the boldest mass transfer in NCAA rowing history, and it reflected how collegiate rowing at the highest levels operates now under the new and evolving reality of the transfer portal, extended Covid eligibility, and the trickle-down effect of NCAA rules on rowing.

STORY BY CHIP DAVIS PHOTOS COURTESY OF TENNESSEE ATHLETICS

Despite appearances and the teethgnashing of doomsayers, it was not, however, the beginning of an NCAA rowing transfer-portal apocalypse. Rather, it was the predictable result of a top athletic program demonstrating real support and directing major resources toward women’s rowing.

Behind Tennessee’s move is the same factor that for decades has powered top programs, from East Coast Ivies to West Coast state schools: institutional support.

Financial support for coaches’ salaries.

Admissions support for recruits.

Cultural support that makes studentathletes, coaches, and staff feel like what they’re doing matters—to the university, to the powers-that-be.

The annual migration of coaches, coaching staffs, and student-athletes among NCAA athletic programs has transformed big-time college sports, especially football. Beginning in 2021, the NCAA removed the requirement that student-athletes skip a year of competition when they transfer.

Transfers propelled the University of Washington’s quick rise to the top of college football. The Huskies had 26 transfers on their roster last year, and then 20 of 22 starters, The Wall Street Journal reported, left the program after the national-championship game.

Coaching staffs also move with head coaches. ClutchPoints reported that Jedd Fisch brought 21 staff members with him when he left Arizona to replace Kalen DeBoer as Washington head coach when DeBoer departed Washington after only two years to replace Alabama’s retiring Nick Saban.

Many of the same relaxed rules that enable such musical chairs in college football apply also to women’s rowing. The NCAA database of athletes eager to change schools is called the transfer portal, and it’s become, in effect, a free-agent marketplace.

“That’s what the NCAA wanted—to open the portal so athletes could move about and do what they want,” said Yale women’s head coach Will Porter. “For rowing, there’s always a trickle-down effect from the bigger sports.

“All of our transfers have been fifthyear kids, with an extra year of eligibility

because of Covid, going to get master’s degrees.”

As a large state school with a more flexible academic program, Washington is in a different and advantageous position, though it shares the same goal: developing a championship crew.

“There’s been a lot of interest from people in transferring,” said UW women’s head coach Yaz Farooq. “We get contacted constantly, but we still have the same standards as for the rest of our team. We want to know that this person is a good teammate, that they’re interested in actively contributing to our squad.”

Tennessee’s sudden influx of talented and accomplished rowers and coaches was different from the way Deion Sanders achieved quick (and short-lived) success with Colorado’s football team. All the women transferring to Tennessee had committed to being coached by Cupini and her assistant coaches, while Coach Prime assembled a team of free agents essentially from a variety of programs.

By rule, Cupini couldn’t recruit her SMU rowers to join her at Tennessee. Her assistants who had not yet left SMU could say what they wanted until they, too, departed. As for the athletes, they were free to talk among themselves, something they did at home, and around the world, once they heard the news.

“I honestly think each person made their own decision,” said Hannah Richardson, a sophomore from Australia who transferred from SMU to Tennessee. “I didn’t feel any peer pressure to go either way. It wasn’t really, ‘My teammates are leaving, so I’m going to leave.’ It was more like, ‘What are the opportunities for me at Tennessee?’

“Doing a little bit of research into the way Tennessee Athletics treats their athletes and the setup here, it didn’t take me long to figure out that I wanted to transfer.”

Richardson was home in Australia and slept through the team Zoom meeting when Cupini’s move was announced.

“I must have turned off the alarm in my sleep. So I woke up to a bunch of messages on my phone. ‘What is everyone going to do?’ And I was like, ‘Do about what?’”

In total, 17 rowers went to Tennessee,

something fifth-year captain Megan Hewison attributes to Cupini’s coaching, training techniques, and knack for breeding a winning team culture.

“I was a captain at SMU for three of the four years I was there, so I’ve got a close relationship with Kim and knew that I wouldn’t want to row my last year anywhere else. I also knew that a lot of the girls who had been in the eight and influential on the team at SMU would want to follow Kim as well.”

The transfer portal is open only for a certain period each year, but when a head coach leaves, the athletes in that program are granted a special window to enter.

“We need to get the ball rolling,” Hewison recalled thinking. “Not only do I want to go to Tennessee to be with Kim because she’s such a great coach but I also want Tennessee to be fast and I want all my teammates to come with me. That was the thought process.

“We had lots of Zoom calls without the coaches, just our SMU team talking through all the different reasons for people to stay or to go, and at the end of the day everyone made their own decision.

“The team understands that we’re not a Yale, we’re not a Washington or a Stanford. We’re not getting the best recruits, at least at the moment. We don’t have the best people coming in, so you’ve got to decide that you’re going to make the difference. You’ve got to make the best people through the training and the commitment.”

Hewison, who rowed out of Leander Club last summer as part of Great Britain’s national team, appreciates what Tennessee offers.

Unlike most other schools, Tennessee provides the maximum amount of socalled Alston money. Alston money is financial support for student-athletes that was allowed by the Supreme Court’s 2021 National Collegiate Athletic Association vs. Alston decision, which held that NCAA rules restricting certain education-related benefits for student-athletes violated federal antitrust laws. It’s $3,000 per semester, $6,000 per year, up to $24,000 over four years. Each school can choose how much is given to which sports.

“I’m not someone driven by money. I came here for the coaching and the

resources,” Hewison said. “But I’ve rowed at a lot of very good clubs, and the Tennessee boathouse is phenomenal. It’s crazy.”

The Wayne G. Basler Tennessee Boathouse sits right on campus, where the Tennessee River flows past Neyland Stadium in downtown Knoxville. The three-story facility, now undergoing renovation, is full of boats, ergs, and exercise equipment, of course, but also features offices, a kitchen, a lounge, a recovery room, and laundry services.

For all that, the main reason Hewison came to Tennessee was to be coached by Cupini.

Why?

“The results.”

“All of the training that every team around the country does is hard. It’s going to be hard no matter what team you’re on, so you might as well make it worth it. It’s nice beating big teams that have five-star recruits. We don’t; we just put in the work.”

At Tennessee, sports have always been huge, and the Volunteer brand is strong far beyond Knoxville, stronger than the brand of most professional sports teams and energized by zealous booster clubs across the country.

Spyre Sports, the Tennessee-focused college sports collective, or unofficial agency, has raised its annual fundraising goal from single-digit millions to at least $25 million. “We think that goal is absolutely attainable,” Spyre president Hunter Baddour told The Athletic.

Tennessee’s athletic director, Danny White, who moved to Knoxville from the University of Central Florida, where during his time women’s rowing was the top-performing academic team in the American Athletic Conference, takes athletic success across all sports very seriously.

In 2023, the Volunteers finished sixth, their best place ever, in standings for the Learfield Directors’ Cup. This award is given annually by the National Association of Collegiate Directors of Athletics to the college or university that is most successful in 19 sports that hold championships sanctioned by the NCAA and the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics.

In the Directors’ Cup contest, women’s NCAA rowing counts a lot.

Stanford, last year’s Directors’ Cup victor, earned 100 of its 1,412 points by winning the NCAA rowing championship. The year before, 2022 NCAA rowing champion Texas won the Directors’ Cup. Even last place (22nd) at the regatta earns 30 Directors’ Cup points. After the 2021 Covid season, Tennessee qualified for the NCAA championship regatta for the first time since 2010.

White gets paid for climbing the Directors’ Cup ladder; for last year’s sixth-place finish he received a bonus of $184,400, The Knoxville News Sentinel reported. Tennessee was 12.75 points behind fifth-place Florida, which doesn’t compete in varsity women’s rowing, and 26.75 points out of fourth place. Just qualifying for the NCAA championship regatta could be very good for Tennessee’s Directors’ Cup standings in general and for White, the top athletic decision-maker, in particular.

“It’s been unreal,” said Cupini of the support and enthusiasm she and her team have experienced at the University of Tennessee.

“When we go to Florida for training trips, people run out onto the docks. Certain cities set up things so high-school kids can come out and watch. The fan base is insane—like nothing I’ve ever seen.”

A wholesale team transfer like the one that followed her from SMU to the University of Tennessee is an anomaly, Cupini insists, and unlikely to become the new version of recruiting in NCAA rowing.

“All of our transfers either rowed for

me at SMU or already were transferring into SMU,” Cupini said.

More money at Tennessee has made a big difference for Cupini’s assistant coaches. After a career spent flipping rowing programs—first building up San Diego, then bringing SMU to new heights—Cupini now has the budget to pay her assistants well.

“I brought over people I’ve been working with for a while, including some people at SMU and then some people from other schools. We actually kept a gentleman on from Tennessee as well. So we have a really super, complete, diverse staff.”

Money for scholarships, however, is limited. Division I rowing programs are allowed a maximum of 20 scholarships, but minimum team size for the NCAA championships is 23 (two eights and a coxed four, not including spares and nonracing members of the team traveling for the experience).

That’s rare among NCAA sports. Basketball starts five players, but has 15 scholarships for women, and even football’s starting offense and defense combined number only 22, for which they can give out 85 full rides.

“Roster management is always a challenge,” Cupini understated.

“Because our sport is so new and unique, we need to educate the people who make the financial decisions about our sport, and the sheer numbers of our sport. We need to make sure that we’re treated the same [as every other sport] and that the women get what they need.”

THE MOST DECORATED OARSMAN OF ALL TIME EXPLAINS

THE ENDURING APPEAL OF HENLEY, WHY WORLD CUP PARTICIPATION LAGS, CHINA’S OLYMPIC PROSPECTS, AND WHY BEACH SPRINTS MAY SPLIT RATHER THAN SAVE ROWING.

PHOTOS BY Peter Spurrier | Intersport ImagesSteve Redgrave is the most decorated oarsman of all time, having won Olympic gold medals in five successive Games, from Los Angeles 1984 to Sydney 2000.

A Steward of Henley Royal Regatta, Redgrave served as chairman from 2015 until this year, a period during which the venerable rowing rite survived Covid, attracted record fields, and grew into a sixday event that attracts hundreds of thousands of live spectators and even more online with Henley’s innovative broadcast coverage.

Redgrave worked as China’s highperformance director when the nation’s men’s double won the first-ever Olympic medal for an Asian nation at the Tokyo Games in 2021. He spoke to Rowing News for an exclusive interview as he prepares for this year’s regatta, which takes place July 2 to 7.

Rowing News: Why the enduring appeal of Henley?

The history of the regatta is what it’s all about—186 years. That’s what resonates with the overseas entries, especially the American ones, and it's the highlight of the British rowing calendar. It’s a reunion of people who have raced the regatta in the past, and it's great to be able to continue that process.

Rowing News: Many small regattas in the United States didn’t survive Covid, but Henley certainly did. You even had one that was sort of out of season. Tell us about that.

It was a devastating decision that we made in March 2020 to cancel the regatta. Obviously, that it was the right thing to do and to do it early in the preparations for the regatta helped us financially. Our contractors that work with us on a yearto-year basis on all the different aspects of putting in the course, putting up the marquees, and maintenance all understood what we were going through, not just as a regatta but as a country, and where the world was at that point. Everyone pulled together to make sure that we got through that.

The greatest thing was our members. We have about 7,500 members, and they'd already paid their membership for that year, which helped us financially. Without that, I don't think we would have survived.

Coming into 2021, the world was beginning to open up, but there were still

quite a lot of restrictions. So there was no way we’d be able to stage a regatta at our normal time on the first weekend in July. So going later, having a more barebones regatta, got us back on our feet ready for staging the ’22 regatta. Financially, we were able to survive that, but it impacted our reserves. One thing we try to do as Stewards is bank financial reserves so we can get through whatever is thrown at us. Obviously, we didn't see Covid coming. Nobody really did. Good stewardship is what ensures our long-term survival. We want to keep our history going.

Over the years, Henley has grown longer. The first, in 1839, was a one-day event. Soon after that, it went to two days, and eventually three days. In 1986, it went to five days. And now we’re six days, which shows how popular the regatta is and also how the sport, worldwide, has grown as well.

I know that a lot of the British regattas are struggling with running the traditional regattas of knockout competition, because there are more competitors than there is time in the day. So things have been moving more to time trials and racing a final depending on your time trial, which is very different from when I was involved in the sport as a youngster. But that just shows the popularity of the sport. Obviously, the growth within junior rowing and women's rowing has been immense around the world, especially here in the UK. And that’s brilliant to see.

Rowing News: So why has the World Cup failed to attract even full finals?

The biggest stumbling block is that most countries don't have the funding to be able to compete internationally on a regular basis. In rowing, it's the work you do in the winter that determines how fast you go in the summer. So if you have three World Cup events within six weeks of each other, you're not going to get a big change in results. If everyone races to form, the results are very predictable.

If the World Cups were further apart and spread around the world, it would be more successful. But it comes down to finances, rowing being European-based. You Americans, the Canadians, the South Americans, Australia, New Zealand, even China, find it difficult to come to Europe for an extended period. It's very, very expensive to move big teams around.

Rowing News: How long until the women have a Ladies Plate-level university women’s-eight race at Henley? What's the holdup?

Time. At the moment there’s no appetite to become a seven- or eight-day regatta. We're limited by the time in a day but we’re looking long-term, and there’s a group of Stewards working on that process. It certainly won't happen this year, but I hope that will be the case in the future.

Rowing News: The regatta has been able to embrace other innovations faster than that. The camerawork, commentary, and free internet broadcast of the video coverage of the regatta have been the best in the world. How did that happen?

We've been talking about broadcasting since well back into the 1950s. We pride ourselves on the fact that if we do something we do it to the best of our ability. Covering rowing and water sports is difficult. In recent years, sailing has had quite a lot of initiatives—being able to track the boats and seeing the race on different visuals. We've been looking at it and working on it for a long time.

Our broadcast partner is Sunset and Vine. They're experienced in water sports and one of the top broadcasters in the world. International rowing really struggles with six lanes—a problem we thought we might have, especially with a panning shot. When you're sitting in a grandstand at a six-lane international regatta, it's difficult to figure out who's leading. If you're looking at it from an angle, you can't tell until the boats get closer.

At Henley, having two lanes has worked out really well, even with six cameras. You can tell who's leading the race, which was a bit of a surprise to me, but a pleasant one. The drone was a game changer with overhead shots, and we've got a hoist that offers an overhead shot as well. Side-by-side, two-lane racing is gladiatorial, and that works on broadcast really well. It has captured the imagination of people who love rowing and love to watch rowing.

Again, we're slightly different from other regattas because we survive on our membership. To get into the Stewards’ Enclosure, you’ve got to be either a member or a guest of a member. You can't go out and buy tickets. Henley tends to be

a celebration of the sport, and for schools and colleges it’s the climax of the year. Something like 300,000 people come to Henley and that kind of demand helps our finances so we can provide very high quality in all we do.

Rowing News: You were hired by China and got its program going for a while, but the Chinese seem to have fallen back. We don't see anything coming out of the other major populous countries of Asia, such as India, Pakistan, and Indonesia. What's that going to take? Is there any hope for rowing in that part of the world?

India has been improving over the last decade. There, and in other Asian countries, the people are relatively small, and rowing is a leverage sport where tall people have an advantage. There’s been rowing in India for a long time, and in recent years they've been showing some success in getting close to winning world championships, and that’s a big step forward.

In China, in the wake of the Beijing Olympics, the government wanted to promote sports. The rivalry among provinces is strong; of 30 some provinces, 20 compete at a high level and provide good talent to draw on for the national team.

I had a contract as the Chinese high-performance director until the Paris Olympics, but when Covid hit and you either got locked in the country or locked out, that was very difficult personally, so we came to an agreement whereby I changed my contract and became advisor. Then last year, my direct boss lost his job, and I lost my consultancy as well.

So far, China has qualified five boats for the Paris Games, and I know they’ll be sending some boats to the qualification regatta. We had six or seven boats in Tokyo and two very outstanding boats in the women's quadruple scull and the men's double scull. Both were world champions going into the Tokyo Games, which was the first time an Asian men's crew reached that level, and being the first Asian men's crew to win a medal at the Olympics was pretty special.

With the change of regime and China’s becoming not quite as focused internationally as when I was there, the Chinese have slipped a bit, but they're still competitive. The women's quad won the bronze medal at the world championships last year, and they've got the potential to be very successful.

Rowing News: Going back 20 or 25 years, if there had been Beach Sprints in the Olympics, would you have gone for a sixth gold medal in that?

Probably not. Even though I was a very good sprinter in running, I don't think it’s a format that would have suited my size and ability. Beach Sprints are for lighter, more mobile athletes, somebody who can run fast. The downside of Beach Sprints, at least in the races I've seen, is that whoever gets into their boats and rows first tends to win the race.

Would I have given it a go? Probably yes. But I'm very much a traditionalist. I love the 2,000-meter racing that’s been the international side of our sport for a long time—the dedication, the teamwork, the camaraderie. To me, the Beach Sprints singles or doubles aren’t as appealing.

But again, it comes down to finances. Will Beach Sprints change the sport on a long-term basis? It will be interesting to see. Also, the Olympic regatta in Los Angeles in 2028 is going to be held over a shorter distance—1,500 meters. That’s a big change. Will we survive?

Fortunately, after that the Games will be going to Australia, where they have a 2,000-meter rowing lake, so traditional rowing will continue there. But if we ever go to a country where they've got to build a new international course, it’s so expensive that I’m not sure whether rowing as we know it will survive. Rowing faces pressure because of the expense of putting on international events.

If you go back a few years, running, swimming, and cycling were combined to form the triathlon. When that became successful, it became a breakaway sport in its own right. If Beach Sprints are successful, they're not going to want to put money into keeping 2,000-meter rowing. So I don't see Beach Sprints as the savior of rowing. I think they will split the sport more than it is at the moment.

Rowing News: What's the next chapter in Sir Steve Redgrave's life?

As I sit here with a few months to go to the Paris Olympics, I don't have a role at the Games as it stands. So at the moment, I don’t have plans of going to Paris.

I would love to come to LA. That's where it all started. My Olympic career started back in ’84. So it seems to be a good rounding-up. But I don't know if that will be a broadcasting role, a coaching role, or an advisor’s role. But I would like to be out in LA.

The ability to teach the desired technique, not simply knowing it, leads to the best outcomes in the shortest period of time.

Coaches are teachers. Knowing the subject matter—rowing and sculling technique—is a prerequisite but also insufficient unless coaches know how to teach it. The ability to teach the desired technique, not simply knowing it, leads to the best outcomes in the shortest period of time. (There’s tremendous value in creating an environment in which athletes can mess around and figure it out on their own, but rarely is there enough time for this.) All coaches can follow a simple teaching progression to instruct their athletes more effectively.

Begin by telling athletes what to do. This is obvious and widely accepted but rarely yields good results alone. The

explanation must create a picture in their minds as crystal-clear as possible. It’s not enough to speak; a coach must communicate, and often this requires repeated and varied ways of stating the desired behavior.

Explain what should be done rather than what not to do. For instance, “Don’t sky” is less helpful because it’s less specific than “Keep the blade down before the catch.” Positive instructions are explicit and give clear direction toward the desired behavior. Negative instructions leave open too many other possible actions. Tell your rowers what you want them to do rather than one of the many things you don’t want them to do.

Next, explain why. When athletes understand the “why” behind the “what,” they’re more motivated to get it right. Doing so can be as simple as showing a much faster crew (“See what the varsity does that helps them go fast”) or as complicated as explaining the physics behind it (“By keeping the blade down, you miss less water and connect the blade better, thus moving the boat faster”). Too often, we underestimate the curiosity and intelligence of our athletes. By neglecting to involve these powerful traits, we miss learning opportunities. Understanding is empowering.

Knowing what to do and being motivated to do it, athletes now need help

learning how to do it. If “what” is direction, then “how” is instruction. Work back from the desired behavior to the underlying actions that can produce the correct outcome. Demonstrate and describe how to do what is wanted: “Square the blade down to the water by rolling the knuckles of your inside hand up and away….Keep the chin and chest up and thus the hands up.…Keep the lower edge close to the water by sitting tall and keeping the hands relaxed as the knees rise.…Loosen your grip.”

Too often, we underestimate the curiosity and intelligence of our athletes. By neglecting to involve these powerful traits, we miss learning opportunities.

Understanding is empowering.

Combining demonstration with description is the best way to convey how to do it correctly. Without verbal explanation, your athletes won’t know what to focus on or what actions bring about the desired result. After you show and tell the athletes, they should attempt to imitate; crucially, the coach should correct to refine the imitation and improve it. There must be accountability to the repetition, and it doesn’t serve your athletes to avoid correcting them. Negative feedback can be delivered when there’s a positive atmosphere and trust. Hold your rowers to the appropriate standard for their age, capabilities, and ambitions.

Typically, successful coaches introduce the “what,” explain “why,” teach “how,” and repeat until athletes get it right.

BILL MANNINGCOXING

Be self-aware and humble enough to know when you can do better, but don’t let perfect be the enemy of good.

.

Recently, I had the opportunity to write a letter of recommendation for a coxswain, and while I was working on it, I was pondering ideas also for this month’s column. All too frequently I think, “What is there to say that I haven’t said already,” and then an idea will land in my lap. This month is no different, and it’s a concept we all need to hear and sit with for a while before the season begins.

In the letter I wrote, I said this:

“She was confident in her strengths, open about her weaknesses, and willing to push through the discomfort that all soon-to-be recovering perfectionists experience when we lean into the reality that perfectionism isn’t a virtue. It’s a myth that robs of us of the joy and satisfaction we could otherwise experience in the face of a job well done.”

Let me say it again, and louder for those in the back who didn’t hear me the first time: Perfectionism isn’t a virtue, it’s a myth.

For many of us who find rowing and become coxswains, it feels like a role we were born for. It’s an outlet for the strong-willed, assertive women who are mislabeled “bossy” little girls, it’s a space for us to embrace mental athleticism when our physical attributes fall short (no pun intended), and it’s a uniquely challenging opportunity that excites us in ways that conventional ones don’t. There’s something special about being a coxswain that I’ve never been able to put my finger on; it’s just a feeling that you have to experience to understand.

But being a coxswain is also hard. It’s isolating, it’s complex, and it provides numerous opportunities for us to lean into the worst parts of ourselves—the overly critical, invalidating, discrediting, anxious perfectionist that kicks you when you’re down and never fails to find a way to talk you out of the successes you’ve earned.

Do you feel called out yet?

It wasn’t until a few years ago that

I acknowledged the toll that my own pursuit of perfection was taking on my mental health. When you’re already burned out and you feel unsupported and undervalued, it is shockingly easy to plant yourself firmly in your own way and tell yourself that you’re the problem. Things aren’t getting easier because you are not good enough, smart enough, capable enough, determined enough, and on and on and on. In most cases, though, you’ve set expectations so far outside the realm of reasonable possibility that no person could realistically attain them, let alone someone who is taking every opportunity to say to herself, “Hey, in case you forgot, you suck at your job”.

So how do we stop doing that? Well, I don’t know. I’m still figuring that out and probably will be for a really long time. But here are the things I’m committing myself to that have helped me begin seeing the light at the end of the very long tunnel. With the spring season right around the corner, I encourage you to come up with some commitments of your own to help guide you down the road of recovering perfectionism, and if you’re struggling to come up with any, I invite you to join me in mine.

1. Don’t let the idea of perfection get in the way of progress.

If you never make it to the execution phase because you’re stuck in the planning, or rather, procrastination phase, you’re intentionally stunting your own growth. Not just as an athlete but as a person. Not every “t” needs to be crossed and every “i” dotted before you try a new call or practice a new drill. The joy in learning comes from the process, not in doing it right the very first time.

2. Don’t talk yourself out of trying just because you might fail

Failure isn’t the mistake; it’s the idea that you shouldn’t bother trying again.

3. Get comfortable being uncomfortable.

The perfect line, the perfect call, the perfect drill execution, none of it

exists—and that is fine. Accepting that as a recovering perfectionist is uncomfortable, but it doesn’t mean that you’re settling for mediocrity (and coaches would do well to stop pushing that narrative). There’s far more growth to be gained in the flexibility of trying new things than there is in the rigid pursuit of perfection.

I’m a process person. I like the strategy of how to do something more than I care about the end result (not always, but usually). It was a harsh and humbling wake-up call when I realized that I was deliberately depriving myself of the thing I enjoy most simply because I’d convinced myself that if something wasn’t perfect, then the entire effort was a waste. Trust me: when you’re training for a 20-mile race and that moment of clarity hits you in the middle of an agonizing 12-mile run, it’s an unwelcome shock to the system. I felt called out by the part of myself that I’d been ignoring for a long time, the part that

just wanted to have fun doing the things I love without the need for it to be “perfect” for it to have been worthwhile.

I love coxing more than I love rowing, which is another thing that can be tough to explain (especially to rowers), but I want other coxswains to find just as much joy in our role as I do. In order for that to happen, though, we have to get out of our own way first. It’s easy to put the blame on our coaches and our teammates for making our jobs hard(er), but we need to take a step back and recognize that we put out the energy we think we deserve. If we undervalue ourselves, downplay the work we put in, and diminish the role of the coxswain on our teams, how can we possibly expect coaches and rowers to do any differently?

Chapter 64 of Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching includes the line “A journey of a thousand miles starts under one’s feet,” or, as it’s more commonly stated, “a journey of a

thousand miles begins with one step.” The road of recovering perfectionism is long and winding, and we have to be the ones to take the first step. In the time between now and the start of the season, let your guard down and give yourself the freedom to take that first step. Just do it. Don’t think about it, don’t overanalyze, just go. Commit to embracing the mistakes you make and learning enthusiastically from every single one. Be self-aware and humble enough to know when you can do better, but don’t let perfect be the enemy of good. Acknowledge the discomfort that you’ll experience and, most importantly, don’t be afraid to let people see you trying.

One last time: Perfectionism isn’t a virtue, it’s a myth. This season, let’s pursue the joy in excellence relentlessly and leave behind the myth that we don’t deserve it if we weren’t perfect in the pursuit.

KAYLEIGH DURMForget the outcome. What matters is the process.

Being “results-oriented” is a common and oft-lauded approach to coaching.

I’m sure many of you reading this have this phrase on your resume or have used it in an interview. I know I have. Today, I’m challenging you to put the results aside for a moment and focus on being process-oriented instead. Just as the best poker players do.

I know poker may seem like an unlikely source of coaching insight, but bear with me. The best coaches are open to inspiration and education from even the most unlikely sources—even casinos.

In professional poker, being focused on the results is detrimental to performance and will only distract from assessing your performance accurately. You can win with a bad hand and lose with a good one. For example, the best hand in Texas Hold’em, the most popular poker variant, is two aces. The worst hand is 72. If both those hands are allin before any other cards come, the two aces will win 87.4 percent of the time.

If that scenario plays out, and you lose while holding two aces against a player with 72, did you make the wrong decision? Of course not. So the biggest determinant of consistent success is not the outcome but the quality of your decisions. The challenge is understanding how and why the decisions were made.