Fri 2 May 2025 • 20.15 Sun 4 May 2025 • 14.15

Fri 2 May 2025 • 20.15 Sun 4 May 2025 • 14.15

conductor Andrés Orozco-Estrada

piano Fazıl Say

Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809-1847)

Overture A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Op. 21 (1826)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

Piano Concerto No. 21 in C major, K 467 (1786)

• Allegro maestoso

• Andante

• Allegro vivace assai

intermission

Carlijn Metselaar (1989)

Herinnering (2024; world premiere)

Commissioned by the Rotterdam Philharmonic with funding by the Rudi Martinus van Dijk Foundation

Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy

Symphony No. 5 in D major, Op. 107 ‘Reformation’ (1830/32)

• Andante - Allegro con fuoco

• Allegro vivace

• Andante

• Andante con moto - Allegro maestoso

Concert ends at around 22.15/16.15

Most recent performances by our orchestra:

Mendelssohn Overture A Midsummer Night’s Dream: Nov 2012, conductor Philippe Herreweghe

Mozart Piano Concerto No. 21: Mar 2013, piano

Imogen Cooper, conductor Ludovic Morlot

Metselaar Herinnering: World Premiere

Mendelssohn Symphony No. 5 ‘Reformation’: Nov 2015, conductor Jérémie Rhorer

One hour before the start of the concert, Gijsbert Kok will give an introduction (in Dutch) to the programme, admission €7,50. Tickets are available at the hall, payment by debit card. The introduction is free for Vrienden.

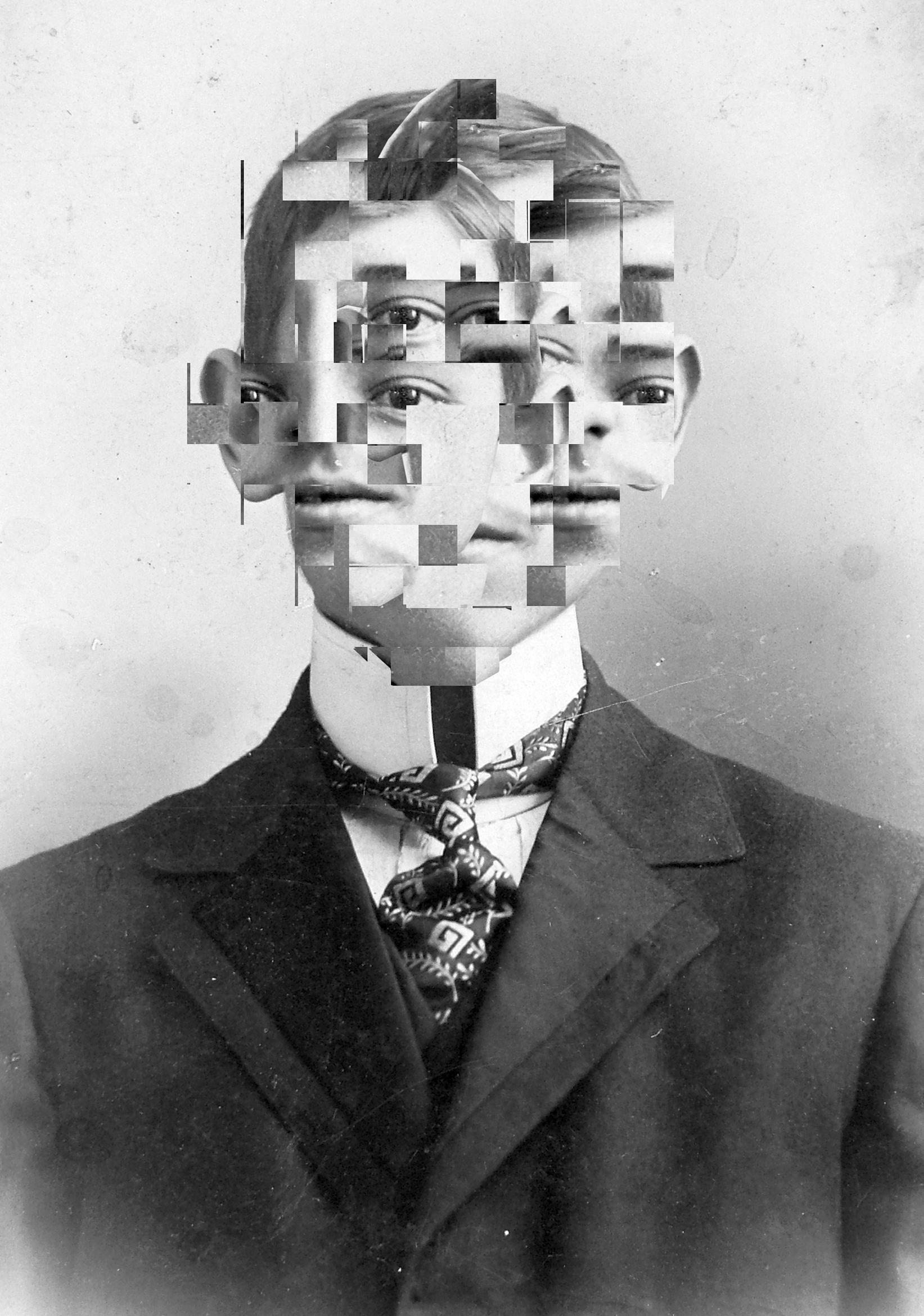

Cover: Photo Mark Kamalov (Unsplash)

Felix Mendelssohn was born into a Jewish family, which was reason enough for the Nazis to ban the performance of his music. Eighty years since liberation, we recall how voices such as his could be silenced, and how vital our remembrance is to ensure that history does not repeat itself.

The brilliantly orchestrated opening chords of the overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream are like four steps that lead immediately into a higher dream world. At the age of seventeen, Felix Mendelssohn composed this music sitting in the large, park-like garden at the back of his family home in Berlin. It was the summer of 1826, a time he would later recall as ‘one endless celebration, filled with poetry, music, games, plays, and fancy-dress parties.’ Every so often he would break away from the high jinks to scribble down some notes on paper. Thus he created his fairytale overture inspired by Shakespeare play of the same name. The young Mendelssohn described his idea to set the masterful comedy to music as ‘bordering on reckless’. Fortunately, he did not let the challenge hold him back: his overture is woven from the fabric of which dreams are made.

‘Bravo, Mozart!’ called out the emperor from his theatre box, waving his hat. In the season 1784-1785 Mozart could rely on the support of all of Vienna. At the age of 29, the composer was at the height of his fame. As a pianist he was celebrated throughout the city: over the winter of that year he had kept his audience

satisfied with as many as six new piano concertos, performed by himself as soloist, at the special ‘Academies’ – public concerts that he organised personally at his own expense. The fact that Mozart performed as soloist had its advantages. He did not need to write out the solo part, which he knew by heart. How did the conductor cope with this arrangement? There was no conductor: Mozart led the orchestra himself from the piano. He was a huge attraction.

Mozart’s father, who had travelled from Salzburg to Vienna to see if Wolfgang was making a success of his life, could be proud. His son was earning good money: ‘Your brother’s concert evening earned him 559 florins,’ their father wrote to his daughter Nannerl, following the premiere of the Piano Concerto No. 21. Wolfgang’s busy concert schedule left his father reeling: ‘At the end of each Academy performance it is impossible to describe all the chaos and commotion; since I have been here your brother’s fortepiano has been transported from his home to the theatre and back, or to some other place, at least twelve times.’ Fortunately, in those days fortepianos were somewhat smaller and lighter than the grand pianos of today.

Carlijn Metselaar was commissioned to write Herinnering (‘Remembrance’) by the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra for the Remembrance Day commemorations in May. About the work, she reflects: ‘I thought about the physical nature of remembrance, and how something such as a wartime experience can endure within the human body. The work is

based on a cantus firmus [a simple, repetitive melody that forms the base against which other voices counterpoint, ed.] that runs through the piece, perhaps like the human nervous system, which becomes increasingly disrupted. There is a sense of the music reaching out and trying to connect, but being constantly held back. The image that came to me is crown shyness, where the crowns of trees stop growing to avoid touching each other, creating beautiful lines of sky between each of them.’

‘I can no longer abide the Reformation Symphony. I would rather burn this than any other work I have written.’ Mendelssohn might not have gone to such extremes, but he did withdraw the symphony. Not until twenty years after his death did the score again see the light of day. The symphony became known as Mendelssohn’s Fifth Symphony, Opus 107. These numbers are rather misleading, because in truth the Reformation was the second symphony composed by Mendelssohn: his Song of Praise, Scottish and Italian symphonies were all composed later.

His Reformation Symphony was born under an unlucky star. It took a full two years following its completion for it to actually be played. However, following early rehearsals of the work in Paris, in spring 1832, it was promptly pulled from the concert programme. ‘Too learned’, was the judgement of some, ‘lacking in melodies’. Too Protestant as well, maybe. Mendelssohn revised the symphony and in autumn of the same year the work was finally premiered. However, for Mendelssohn the magic was already lost: he could no longer enjoy the work.

In fact, things had gone wrong much earlier. In June 1830 Germany celebrated the 300th anniversary of the Augsburg Confession in

grand style. This confession of faith was a key document for Lutherans. Its submission to Emperor Charles V in 1530 had been a hugely significant event for the Protestant Reformation. With the anniversary approaching, Mendelssohn – born, it is true, into a Jewish family, but who had been baptised as a protestant at the age of seven –began work on his Reformation Symphony. At the end of the slow introduction he introduces the melody from the Dresden Amen; and in the last movement inserts Luther’s chorale Ein feste Burg in a glittering, fully orchestrated form. But whilst he was working on the symphony, he caught measles. This delayed completion of the composition, and Mendelssohn was unable to have the work ready in time for the anniversary celebrations. When the work eventually did get performed, two years later, the right moment had already gone.

‘Chaos and commotion; your brother’s fortepiano has been transported from his home to the theatre and back at least twelve times’

The disappointed Mendelssohn would later characterise the symphony as a ‘juvenile work’. We cannot really take such self-criticism seriously. From a composer who, at the age of seventeen, wrote the brilliant Midsummer Night’s Dream one can hardly label a work composed four years later as immature. In any event, there is within the Reformation Symphony so much that is beautiful to the ear that one quickly forgets that this is the work of a 21 year old daring to tackle his second great symphony.

Stephen Westra

Andrés Orozco-Estrada • conductor

Born: Medellín, Colombia

Current position: Music Director Orchestra

Sinfonica Nazionale della Rai, Music Director Designate of the Gürzenich Orchestra Cologne

Education: Instituto Musical Diego Echavarria; Vienna University of Music and Performing Arts, composition with Uroš Lajovic

Breakthrough: 2004, debut TonkünstlerOrchester Niederösterreich

Subsequently: Music Director Orquesta Sinfónica de Euskadi, Houston Symphony Orchestra, hr-Sinfonieorchester Frankfurt and Wiener Symphoniker; principal guest conductor London Philharmonic Orchestra; guest appearances with Cleveland Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Wiener Philharmoniker, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Staatskapelle Dresden, Münchner Philharmoniker, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; professor of orchestral conducting at the Vienna University of Music and Performing Arts Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2013

Born: Ankara, Turkey

Education: first piano lessons at age three, piano and composition at the Ankara State Conservatory, further studies with David Levine at the Robert Schumann Hochschule Düsseldorf and the Universität der Künste Berlin

Breakthrough: 1994, as winner of the Young Concert Artists International Auditions

Subsequently: Le Monde Award 2000, Echo Klassik 2001, 2009 and 2013, International Beethoven Prize 2016, Music Prize Duisburg 2017; Artist in Residence Konzerthaus Dortmund 2005–2010, Konzerthaus Berlin 2010–2011, hr-Sinfonieorchester Frankfurt 2012–13, Rheingau Music Festival 2013, Bodenseefestival 2014, Alte Oper Frankfurt 2015–2016, Zürcher Kammerorchester 2015–2016, Composer in Residence Dresdner Philharmonie 2018–2019

As a composer: four symphonies, various solo concertos, two oratorios, commissions by Salzburger Festspiele, Konzerthaus Wien, Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, BBC Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2007

Music for Breakfast

Sun 11 May 2025 • 11.30

Dudok aan de Maas

Musicians and programme rpho.nl

Memorial Concert

Wed 14 May 2025 • 20.00

Laurenskerk Rotterdam

conductor Lahav Shani

soprano Christiane Karg

baritone Thomas Oliemans

chorus Nederland Kamerkoor

Shalygin Canto Inferno (World Premiere)

Fauré Requiem

Fri 16 May 2025 • 20.15

Sun 18 May 2025 • 14.15

conductor Lahav Shani

soprano Christiane Karg

baritone Thomas Oliemans

chorus Nederland Kamerkoor

Brahms Symphony No. 3

Shalygin Canto Inferno

Fauré Requiem

Fri 23 May 2025 • 20.15

Sun 25 May 2025 • 14.15

conductor Lahav Shani

Mahler Symphony No. 9

Anima Obscura

Thu 29 May 2025 • 20.00

Fri 30 May 2025 • 20.00

Sat 31 May 2025 • 20.00

Sun 1 June 2025 • 20.00

Rotterdam, Nieuwe Luxor Theater

conductor Giuseppe Mengoli

chorus Laurens Vocaal

harp Remy van Kesteren

dance Scapino Ballet Rotterdam

choreography Nanine Linning

digital scenography Claudia Rohmoser

Brahms Ein deutsches Requiem

Kyriakides Ein Schemen

Chief Conductor

Lahav Shani

Honorary Conductor

Yannick Nézet-Séguin

Principal Guest Conductor

Tarmo Peltokoski

First Violin

Marieke Blankestijn, concertmaster

Tjeerd Top, concertmaster

Quirine Scheffers

Hed Yaron Meyerson

Saskia Otto

Arno Bons

Rachel Browne

Maria Dingjan

Marie-José Schrijner

Noëmi Bodden

Petra Visser

Sophia Torrenga

Hadewijch Hofland

Annerien Stuker

Alexandra van Beveren

Marie Duquesnoy

Giulio Greci

Second Violin

Charlotte Potgieter

Frank de Groot

Laurens van Vliet

Elina Staphorsius

Jun Yi Dou

Bob Bruyn

Eefje Habraken

Maija Reinikainen

Babette van den Berg

Melanie Broers

Tobias Staub

Sarah Decamps

Viola

Anne Huser

Roman Spitzer

Galahad Samson

José Moura Nunes

Kerstin Bonk

Janine Baller

Francis Saunders

Veronika Lénártová

Rosalinde Kluck

León van den Berg

Olfje van der Klein

Jan Navarro

Cello

Emanuele Silvestri

Joanna Pachucka

Daniel Petrovitsch

Mario Rio

Eelco Beinema

Carla Schrijner

Pepijn Meeuws

Yi-Ting Fang

Killian White

Double Bass

Matthew Midgley

Ying Lai Green

Jonathan Focquaert

Arjen Leendertz

Ricardo Neto

Javier Clemen Martínez

Flute

Juliette Hurel

Joséphine Olech

Manon Gayet

Flute/Piccolo

Beatriz Baião

Oboe

Karel Schoofs

Anja van der Maten

Oboe/Cor Anglais

Ron Tijhuis

Clarinet

Julien Hervé

Bruno Bonansea

Alberto Sánchez García

Clarinet/ Bass Clarinet

Romke-Jan Wijmenga

Bassoon

Pieter Nuytten

Lola Descours

Marianne Prommel

Bassoon/ Contrabassoon

Hans Wisse

Horn

David Fernández Alonso

Felipe Freitas

Wendy Leliveld

Richard Speetjens

Laurens Otto

Pierre Buizer

Trumpet

Alex Elia

Adrián Martínez

Simon Wierenga

Jos Verspagen

Trombone

Pierre Volders

Alexander Verbeek

Remko de Jager

Bass Trombone

Rommert Groenhof

Tuba

Hendrik-Jan Renes

Percussion

Danny van de Wal

Ronald Ent

Martijn Boom

Harp

Albane Baron