Cooking for conversational English p. 4

A new online tool for the circular economy p. 12

These chestnut trees have defied the odds p. 18 THE ISSUE

Cooking for conversational English p. 4

A new online tool for the circular economy p. 12

These chestnut trees have defied the odds p. 18 THE ISSUE

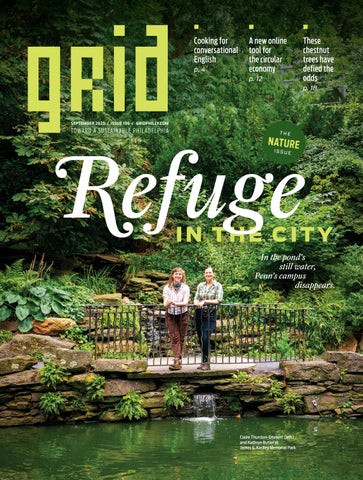

In the pond’s still water, Penn’s campus disappears.

NextFab is a Philadelphia-based membership-based makerspace for makers, creatives, & entreperenurs, providing shared workshops and education in the areas of woodworking, metalworking, laser cutting, 3D printing, textiles, jewelry making, and digital manufacturing tools. Learn more about classes, membership, & being part of our community at nextfab.com!

publisher Alex Mulcahy

managing editor

Bernard Brown

associate editor & distribution

Timothy Mulcahy tim@gridphilly.com

deputy editor

Sophia D. Merow

art director

Michael Wohlberg

writers

Marilyn Anthony

Kyle Bagenstose

Bernard Brown

Andrew Conboy

Patrick Kerr

Emily Kovach

Julia Lowe

Ed Rodgers

Jordan Teicher

photographers

Chris Baker Evens

Jared Gruenwald

Julia Lowe

Jordan Teicher

Solmaira Valerio

illustrator

April Finfrock

published by Red Flag Media

1032 Arch Street, 3rd Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107

215.625.9850

GRIDPHILLY.COM

Content with the above logo is part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. The William Penn Foundation provides lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation, and Philadelphia Health Partnership. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit www.everyvoiceeveryvote.org. Editorial content is created independently of the project’s donors.

Red-eared sliders are turtles that make bad pets, but that doesn’t stop them from being sold to people who don’t know better. They start off as cute hatchlings, but they can live 40 years and grow as large as dinner plates, at that point needing way more space than the usual aquarium.

Ill-prepared owners often dump sliders in the nearest accessible body of water, which for much of University City means the BioPond. The turtle owners turn and walk away, but Claire Thurston-Emmert, who manages the BioPond, is then stuck with them. “Just please, don’t drop off the turtles,” she says. The turtles are native to the Mississippi River watershed, not the Delaware’s. And an overpopulation of sliders is bad for them and the pond, no matter where they’re from.

Thurston-Emmert isn’t the only person frustrated at how humans dump red-eared sliders. Out on the West Coast they compete with the local pond turtle species. In Europe and in Asia they bully multiple species of native turtles. Thanks to humans releasing the adaptable critters into the wild, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) includes red-eared sliders on its list of the 100 worst invasive species

Pet rescue organizations are overcapacity with red-eared sliders for all of these reasons: there are tons of them, and everyone who wants one already has three. Plenty of overwhelmed turtle owners drop them in a nearby waterway and hope for the best.

The same happens too often with cats (also on the IUCN’s invasive species list). Desperate cat owners often end up doing what red-eared slider owners do. They drop the cat at a park and leave.

I met one such cat, named Tommy, when I worked a summer as a seasonal environmental educator for Parks & Recreation. Tommy, a fat, mellow, orange cat, had landed at the Wissahickon Environmental Cen-

ter (aka the Tree House) more than a decade before, and the staff at the time decided to let him stay. Tommy enjoyed the attention of visitors on the nature center’s big porch or at its picnic tables, except when he had had enough, which he signaled by biting. Like lots of cats, Tommy occasionally enjoyed stalking and killing small animals, which in a park like the Wissahickon meant native wildlife like white-footed mice.

Tommy, I learned, had developed a fan base whose romanticized rural idea of a lazy cat on a porch was at odds with his reality. One time a park visitor actually tried to take Tommy home, but Tommy’s fans objected, and the would-be adopter dropped Tommy back off at the nature center.

This July Tommy met a gruesome end. A larger predator (possibly a coyote or raccoon) mauled him, and Tommy was euthanized. Tommy had actually survived a similar encounter last year, which I would think would have been enough to convince those who cared about him to find him a safer home, but the idea of Tommy was more powerful than the reality of life and death in the woods.

All of this was avoidable. No cat has any business living in a park, whether for its impact on the wildlife or its own safety. If Tommy had been quickly rehomed upon arrival in the Wissahickon, both he and the wild animals he killed would have lived longer lives.

We tend to think of our pets as friendly and innocuous because that’s how we experience them, indoors. Too often we try to will the outdoors into being an extension of our living spaces, pets included, but that doesn’t make it so.

Our WeCycle program takes back single-use plastic containers from our Deli and Prepared Foods departments and sends them to Rabbit Recycling, a recovery facility that will ensure they are recycled or reused properly. By partnering with Rabbit Recycling, we will divert in-house plastic packaging toward more sustainable waste streams. Please bring in clean Weavers Way Deli and Prepared Foods containers ONLY and drop them into the yellow weCycle bins located in each store.

Thanks for helping us go greener with WeCycle!

Free Library of Philadelphia program combines cooking and conversational English practice story by marilyn anthony

The name Edible Alphabet might conju re images of sugary breakfast cereal or playful pasta shapes.

That’s not what has drawn more than 1,000 adult learners to this innovative series of free, fun English language classes at the Culinary Literacy Center in the Free Library of Philadelphia since 2016. Lindsay Southworth, senior program manager, traces the origin of the program to an idea that the “magic in cooking together” would incentivize non-native English speakers to practice conversational skills. A well-designed curriculum keeps the focus on talking during the sessions, which involve team cooking followed by eating and discussing the delicious result. There

are no tests and no deep dives into grammar, just lots of opportunities to learn new vocabulary, practice conversing and make both lunch and new friends.

To get students talking, Southworth, assisted by chef instructor Shayla Felton-Dorsey, opens each session with a welcoming question such as, “Do you like

spicy food?” Next, Southworth reads aloud key words in the recipe — “peel” or “seed” or “drain” — and Felton-Dorsey demonstrates their meaning. Students get into groups of three or four and, with help from Felton-Dorsey, start cooking. Once the dish is simmering or baking, they regroup to do a reading or a role-play or to engage in guided

What we’re eating is less important than the conversations we’re having.”

lindsay southworth, Free Library of Philadelphia

dialogue. Then it’s time for lunch, when students enjoy such made-it-themselves dishes as samosas, noodle salads or American favorites like pizza.

Southworth describes Edible Alphabet’s multiple goals. The first two are increasing conversational competence in English and introducing students to the many services the library system offers. She notes that some program participants have become library ambassadors and employees. Feedback from students attests to Edible Alphabet’s achievement of its third goal: building community. Students describe how the classes helped them feel less isolated and more connected to other new Americans and gave them increased confidence in their speaking skills. “I want to learn how to have a normal conversation, not just classroom English,” one Mandarin-speaking student says. “Cooking is a lifestyle activity, so it’s a good way to practice just talking.”

“What we’re eating is less important than the conversations we’re having,” Southworth says, but Edible Alphabet recipes do have to meet specific criteria. To respect religious and dietary concerns, dishes must be vegetarian. They have to be sufficiently difficult that it takes a team an hour or so to complete the recipe, and the ingredients must be affordable, both for students to make at home and for the library’s budget.

Funding for this free, open-enrollment program comes from the Free Library of Philadelphia Foundation, with additional funds from the City and corporate sponsors including Dietz & Watson and Comcast. Three-hour in-person classes — held variously at Parkway Central Library and the Northeast Regional and Lillian Marre-

Serves 3

Japchae is a traditional celebratory dish in South Korea and is commonly served as a banchan (side dish), although it can also work as a main dish for a light lunch or dinner.

3.5 ounces Korean sweet potato glass noodles (dangmyeon)*

1 small carrot

1 small onion

2 scallions

4 mushrooms

1 cup spinach

2 tablespoons soy sauce

1 tablespoon sugar

• Boil a pot of water.

1 tablespoon sesame oil

2 teaspoons sesame seeds

vegetable oil

salt

black pepper

* You can also substitute regular glass or cellophane noodles, vermicelli or angel-hair pasta.

• Peel and cut the carrot into matchsticks.

• Thinly slice the onion. Cut the scallions into similar lengths.

• Slice the mushrooms.

• Blanch the spinach in boiling water for 15 to 30 seconds. Remove the spinach with a slotted spoon and shock it in cold water.

• Squeeze out excess water from the spinach, cut it into about 2-inch lengths and lightly season with salt and pepper.

• Measure and combine soy sauce, sugar, sesame oil and sesame seeds in a small bowl. Mix well until the sugar is dissolved.

• Bring the same pot of water to a boil again and cook the noodles for 6 to 7 minutes. Rinse in cold water and drain. Cut the noodles into 6- to 7-inch pieces.

• Mix the noodles with 1 tablespoon of the prepared sauce in a large bowl.

• Stir-fry the noodles over medium heat in a large skillet, stirring frequently, until translucent and a bit sticky (about 4 minutes). Transfer back to the bowl.

• Add 1½ teaspoon of oil to the pan and stir-fry the onion and mushrooms together over medium-high heat until the onions are translucent. Lightly season with salt and pepper. When the onion is almost done, stir in the scallion and cook briefly. Transfer to the bowl with the noodles.

• Stir-fry the carrot for 1 to 2 minutes until softened. (Do not overcook. The vegetables should be crisp.) Transfer to the bowl.

• Add the spinach and the remaining sauce to the bowl with all the other prepared ingredients.

• Toss well by hand. Adjust the seasoning to taste by adding a little more (start with ½ teaspoon) soy sauce and/or sugar as necessary.

ro branches — run for six weeks at a time, while an online version of the program offers two-hour sessions for eight weeks.

Edible Alphabet students come from around the globe but often make the same observation. In their cultures, unlike in the United States, cooking and eating with

family, friends and neighbors is common. Southworth says that Edible Alphabet offers a return to that cultural practice in which “there’s something so warming and nourishing about the collective effort of preparing and sharing food. The food tastes good because we cook it together.” ◆

Mycopolitan Mushroom Company grows tons of fungus in North Philadelphia warehouse basement story and photos by julia lowe

It’s a balmy day in late August, but the Mycopolitan Mushrooms grow room feels more like a forest floor in midOctober. A thick mist sprays from the ceiling, casting a glowy haze across shelves filled with blooming oyster mushrooms, lion’s mane and a handful of other exotic species.

Pennsylvania is home to the majority of the country’s mushroom production, with

most farms concentrated in Chester County. But, strangely enough, instead of Kennett Square, Mycopolitan co-owner Tyler Case drives into the Juniata Park neighborhood of Philadelphia to his farm.

“It’s bizarre, but it makes sense for a mushroom farm to be here,” says Case of the subterranean production space in the basement of the Common Market building. The earliest mushroom farms were in caves,

and with an apparatus of lights, misters and air conditioners, Mycopolitan has created a strikingly cave-like environment where mushrooms can thrive.

“Mushrooms, in nature, make use of unused space and refuse,” says co-owner and production manager Dan Howling. “I feel like the basement is sort of like that — it would otherwise go unused.”

Case and Howling, along with co-owner

Brian Versek, started building this grow room in 2013, and officially started growing and selling their exotic gourmet mushroom varieties under the name Mycopolitan Mushrooms in 2014.

The grow room currently holds eight mushroom varieties sprouting from substrate blocks: blue oyster, Phoenix oyster, shiitake, chestnut, Pioppino, lion’s mane, coral tooth and reishi. But in the cooler months, Mycopolitan operates a second grow room to make room for increased production and seasonal varieties like golden enoki, king trumpet and black pearl oyster mushrooms. Here, you won’t find commercial varieties like creminis or portobellos.

“We’re more artisanal compared to some of the more massive farms, which means that we can have a higher attention to detail: we can harvest at the perfect time, refrigerate immediately, [and] get it out to our customers as soon as possible,” says Versek.

Case first came up with the idea of starting a mushroom farm while working with Versek at a previous job. As Versek tells it, the whole process of starting the farm came together in just a few months. They put their idea “out into the universe” — on a nowdefunct urban farming listserv — and quickly got connected with nonprofit food wholesaler Common Market as they were moving into the Erie Avenue warehouse. Soon, Mycopolitan became the building’s first tenant.

“They immediately recognized, almost casually, to themselves, somebody should be growing mushrooms in this basement,” says Versek.

Over a decade later, Case and his team have refined the entire process for growing mushrooms, down to the substrate. Each block of mushrooms starts off as an 11-pound plastic bag filled with a woodbased substrate. Every day, staff members fill at least 60 bags with pellets of red oak sawdust and soybean hulls before hydrating them and preparing them to be sterilized.

Once the bags have been cooked to about 98 degrees Celsius [208 Fahrenheit], they are cooled, then inoculated with mushroom spawn. The bags are then taken into a dark room where the mycelium — the branching structure that makes up fungal colonies — can grow. The mycelium consumes the substrate block in its entirety, growing itself in the process.

Once the bags are fully myceliated, they are ready to be moved into the grow room

The leftover material is actually wonderful stuff. It’s high mycelial biomass, which everything wants to gobble up and turn into really fertile soil.”

tyler case

and cut open to sprout their fruiting bodies, the actual mushrooms. And in a few days to a couple weeks, depending on the species, a full flush of mushrooms will have grown and be ready to harvest.

Much of Mycopolitan’s real estate is taken up by shiitake blocks, which take around three months to incubate, much longer than most other species they produce. Once ready, the shiitake mushrooms themselves can grow in seven days, Case says.

“Eight months out of the year, we have probably about 2,700 blocks in this room,” says Case. The incubation room takes up the length of the basement — 150 feet of shelves in near-darkness. Case quickly calculates: “there’s about 15 tons of mycelium in here.”

Mycopolitan produces an average of 900 pounds of mushrooms per week in the summer, and as much as 1,500 pounds during the rest of the year, spanning their 12 unique varieties.

“There’s a lot of different flavors in here,

but all of them have umami,” says Case. Flavor is huge at Mycopolitan, which supplies mushrooms to over 20 restaurants in the Philadelphia area. Case and Versek throw out words like “cheesy,” “porky,” “musty” and “nutty” to describe the aroma and taste of each species.

Mycopolitan also distributes to locals through a farm share subscription program. After harvest, the spent substrate blocks are composted or donated to community partners.

“The leftover material is actually wonderful stuff,” says Case. “It’s high mycelial biomass, which everything wants to gobble up and turn into really fertile soil.”

Mycopolitan Mushrooms can be found at the Phoenixville, Wyomissing and Collegeville locations of Kimberton Whole Foods, with fresh deliveries weekly and available for purchase every Friday. “We’ve had a great relationship with Kimberton Whole Foods. They’ve really drummed up a lot of interest in lion’s mane,” says Case. ◆

Advocates believe Philadelphia’s waterways could be the next great playground — if the City prioritizes it by kyle bagenstose

In last month’s edition of Grid, we shared the perspectives of advocates who want to see more recreation in Philadelphia’s rivers, creeks and lakes. But do powerful stakeholders share this vision of a water-happy Philadelphia? Turns out, it’s complicated.

The federal Clean Water Act created a regulatory system in which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and state deputies like the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) determine which recreational activities should be available in a particular waterway, and thus

The first part of this story appeared in the August 2025 issue of grid

to what degree they need to crack down on nearby polluters.

Presently, most attention in Philadelphia is on the Delaware River, where the interstate Delaware River Basin Commission has debated in recent years whether to upgrade the regulatory designation of the stretch of river passing through Philadelphia to match that upstream in Northeastern Pennsylvania and downstream in the Delaware Bay. Doing so would require water quality suitable for such “primary contact” recreational activities as swimming and tubing. Environmental groups and some members of City Council, led by Councilmember Mark Squilla, have advocated in support, stating their belief that the river has improved

enough in recent decades to warrant a regulatory upgrade. That could force industrial polluters and sewage plants to spend more money on newer treatment methods.

But in 2023 the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) released a study on recreation in the river that reads a bit like a 178-page laundry list of all the reasons it’s not a good idea: regular traffic of huge commercial container ships, powerful currents, floating debris and too few points of ingress and egress chief among them.

“Without the ability to maintain a safe distance from the federal navigation channel, swimmers and paddlers are especially vulnerable to maritime hazards,” the report concluded.

frequently enough to evaluate changing conditions. Instead, the Pennsylvania Department of Health often regulates public swimming beaches via more regular sampling. But the City conducts no such regimen in the Wissahickon.

The fact that neither federal nor state entities have forbidden recreation on Philadelphia’s waterways, and indeed to varying degrees support adding more of it, adds to the frustration of some advocates about the City’s policies and priorities.

Despite data collected by Riverways (a consortium of advocates for water recreation) suggesting low levels of E. coli at FDR Park, the park’s aging dock, patched with wooden panels and beset by weeds, was not included on the initial list of major repairs and upgrades as part of the park’s $250 million renovation, led by the Fairmount Park Conservancy in partnership with Parks & Recreation.

A new tide gate installed at the south end of the park in 2024 keeps out sewage-contaminated river water that may have helped lower pathogen levels, says Adam Forbes, founder of Discovery Pathways, a nonprofit that hosts free public paddling sessions there. But it also appears to have cut off the lake’s waters from tidal influences, which Riverways believes stagnated the water and contributed to an algal bloom that plagued the lake in the summer of 2024. Similar lakes elsewhere use chemicals or aerators to address such problems.

We support recreation where and when it’s safe to do so.”

kelly anderson, Philadelphia Water Department

The dynamics are also complicated in smaller Philadelphia waterways like the Wissahickon, where the DEP’s regulations technically say the water doesn’t meet safe pathogen levels for recreation. But in an email, DEP press secretary Neil Shader said the state’s findings do not automatically create legal prohibitions on swimming, which

are instead determined by state or local regulations, such as the City’s swimming ban.

Asked about data suggesting that pathogen levels may actually be low enough to safely swim under the right conditions, Shader also said the DEP’s designations are “not appropriate to be used to determine if it is safe to swim,” as data is not collected

For its part, the Fairmount Park Conservancy says the tide gate is working to achieve objectives of FDR’s redesign, including reducing flooding, allowing stormwater with pollutants from nearby roadways to flow out of the park and helping to establish a 33-acre tidal wetland. The organization referred further questions about the tide gate to Parks & Rec and the Philadelphia International Airport, and questions on water quality to state regulators.

Conservancy spokesperson Cari Feiler Bender said that the lake’s dock is “safe” and “functional” and that efforts are currently focused on amenities such as basketball, football and soccer. The organization’s chief of staff, Kevin Roche, added that renovation plans call for eventually restoring Shedbrook Creek in FDR’s western half, opening the little-known waterway to activities like kayaking for the first time.

Boating on the Schuylkill is perhaps

the city’s most visibly robust form of water-based recreation. But even there, public access points and boat launches remain few and far between. Over the past decade, PWD and Parks & Rec collaborated on two multimillion-dollar projects along the waterfront in Manayunk: one to overhaul a recreational area on Venice Island and another to perform a major restoration of water flow into the Manayunk Canal. Neither facilitated access for on-water recreation.

But Kelly Anderson, director of PWD’s Office of Watersheds, points out the two city agencies did support the construction of a new kayak launch in 2021 just downriver in East Falls. The Water Department also created and continues to maintain RiverCast, a website that provides real-time assessments of whether the Schuylkill’s water quality is safe for activities like kayaking.

“We support recreation where and when it’s safe to do so,” Anderson says.

She also says that the department remains committed to reducing combined sewer overflows and that pipes that directly pollute parks like Bartram’s Garden and Tacony Creek Park are “top priorities.” But, Anderson says that getting all of Philadelphia’s waterways to swimmable standards would cost funding in excess of the billions of dollars it is already spending to reduce combined sewers, and may also be beyond PWD’s powers to control, as pollution such as stormwater runoff filters into the rivers from upstream.

“The job is never done,” Anderson says. “But we’re also managing PFAS [“forever chemicals”], right? Also managing climate change. Also managing biosolids. The list goes on and on…. At some point you really have to, you know — thinking about ratepayers — pick what makes the most sense.”

Asked if the Fairmount Park Conservancy, which serves as the City’s primary nonprofit parks partner along the Schuylkill, ever has conversations about installing more boat launches, Roche demurred. Instead he suggested that perhaps it was time to consider the development of some kind of comprehensive water recreation strategy, by bringing together public and private stakeholders across the city, similar to ongoing initiatives for hiking and biking trails.

“I think that’d be a great idea for water-based organizations,” Roche says.

Can we be at a point where we can say as a city that [our waters] are safe to swim in? I don’t think that’s realistic.”

Tookany/Tacony-Frankford Watershed Partnership

Still, Stefanie Kroll, director of Riverways, and Tim Dillingham, executive director of the American Littoral Society, a nonprofit focused on cleaning up waterways in the Delaware River watershed, doubt that key stakeholders are as interested in increasing public access to the water as they are. For them, the dynamics feel like a far cry from days when Philadelphia spent money to create public bathing areas on waterways and staffed Cobbs and Pennypack Creeks with lifeguards, or the contemporary efforts of peer cities like Chicago and Washington, D.C., to achieve swimmable and fishable waterways more quickly.

“I’m not sympathetic to it at all,” Dillingham says of the argument that water-based

recreation is too difficult or expensive to prioritize. “Yes, everyone wants to be cognizant about the impact that [higher utility] rates might have on lower income folks. But for too long, it’s been an excuse to not be aggressive or visionary about how we treat the water.”

So just where is the ceiling on Philadelphia’s water recreation potential? Other players in the space vacillate between optimism and realism.

Stuart Clarke, manager of the Environment and Public Space program at the William Penn Foundation, says improving water quality around the city and providing

increased access and water-based programming are all objectives of the foundation. He sees the right conditions — advocacy, a regulatory framework and federal and state funding sources — to improve water quality and notes that the foundation has a grantmaking objective to dramatically reduce combined sewer overflows by 2035. The foundation also provides funding to groups like Discovery Pathways and Riverways to support their growing programming.

But Clarke’s view isn’t all roses. He acknowledges that sewage pollution is just one of several recreation hazards in a river as robust as the Delaware and says that he too wonders about the level of interest citywide, particularly among entities “in a position to make investments or prioritize” the issue.

“We’re seeing substantial enthusiasm within the Greater Philadelphia community for this work,” Clarke says. “What I don’t think we see as much as we might is an understanding that access to the natural environment — access to programming — is public health infrastructure. These are critical investments to ensure the health and flourishing of the regional population.”

Justin DiBerardinis, executive director of the nonprofit Tookany/Tacony-Frankford Watershed Partnership, which supports the 300-acre Tacony Creek Park, has visions of turning it into the “Wissahickon of North Philadelphia.” He’s actively seeking grant money to help address large overflows of sewage into the creek and hopes that one day it will be clean enough to stock sport fish.

But swimming? Given the crowds and littering problems he knows exist at Devil’s Pool, along with all of the other inherent challenges for this holy grail of water recreation, DiBerardinis has firm doubts.

“Boatable, fishable, that’s there and that should be encouraged at the highest levels,” he says. “Can we be at a point where we can say as a city that [our waters] are safe to swim in? I don’t think that’s realistic.”

Opinions are even split in Philadelphia’s cleanest watershed, the Wissahickon. Erin Landis, water programs manager for Wissahickon Trails, a nonprofit that stewards the creek’s watershed in Montgomery County, says the organization currently adheres to a no-swim standard based on DEP’s guidelines. However, the group is focused on reducing stormwater runoff that carries pollutants into the creek and is open to the idea of a swimmable future.

“We are always balancing the recreational use of land and waterways with habitat and ecological protection,” Landis says. “In a developed watershed such as this, any water quality improvements are worth pursuing and delisting segments of the Wissahickon Creek and/or tributaries for … recreational use would be considered a huge accomplishment.”

However, FOW’s Marley says that her organization believes there are too many hazards — dams, submerged objects, flash flooding conditions — in the Philadelphia stretch of the creek and a lack of resources for lifeguards.

“Trying to obtain any kind of regular supervision of people either swimming or boating in such an inherently problematic area with often unpredictable conditions does not feel feasible or justifiable,” says Sarah Marley, interim executive director of Friends of the Wissahickon (FOW).

Joseph Syrnick, president of Schuylkill Banks, a nonprofit focused on waterfront recreation in Center City, says his organization originally formed more than twenty years ago out of a desire to push City officials to “get off their rear ends and do something” about reconnecting Philadelphians to the river as it passed through Center City.

He feels they’ve achieved that goal over the decades, but by actually developing a closer working relationship with the City. The skinny swath of land separating Center City from the east banks of the Schuylkill used to only be an industrial corridor, he says. The train tracks are still there, but much of the strip is also now a green oasis where people come to run, fish, relax and occasionally launch a kayak. Vendor Hidden River Outfitters, which offers kayak tours of Center City, regularly sells out paddling excursions that launch from Schuylkill Banks’ dock, and Syrnick’s organization plans to build another dock south of Walnut Street that would be flush with the water and thus more conducive to launching kayaks.

Maitreyi Roy, executive director of Bartram’s Garden, a 50-acre park abutting the Schuylkill in Southwest Philadelphia, says local interest in its paddling and fishing programs has grown exponentially over the past decade. Combined sewer overflows cancel about a quarter of their on-river programs due to unsafe levels of pathogens, but

Roy says she’s presently working in good faith with PWD to find solutions. Even if the Schuylkill’s waters were to become immaculately clean overnight, she feels much more is needed before Philadelphians can safely take to the river on their own in large numbers, given the river’s powerful currents and other hazards.

“We have to take the long view,” Roy says. “There’s no, you know, ‘Turn on this switch and it’ll be done.’ It’s a generational challenge.”

But she agrees wholeheartedly with Forbes that it’s worth doing. While some view kayaking and river swimming as appealing primarily to white and upper-class Philadelphians, both advocates say their programming draws a diverse mix of Latino, Black and Asian attendees eager to get onto the water. And providing those opportunities, they say, is an ideal way to get people thinking about the health of local rivers and creeks and the influence of humans.

Perhaps no one is more emblematic of that than 17-year-old Tha Oo. During a recent Discovery Pathways paddle at FDR Park, the rising senior at George Washington Carver High School of Engineering and Science in North Philadelphia supervised junior members of the organization as they helped visitors into and out of kayaks and rowboats. Like many of his peers, Oo had never been on the water prior to joining the group four years ago. He says his first time out was “scary” but that he learned to overcome the fear and began thinking about his relationship with the rivers, creeks and lakes that dot Philadelphia’s landscape. Now, he dreams of becoming an environmental engineer.

“Before I joined the program I had a bad habit of polluting and not being a really good environmental person,” Oo says. “But after joining, I’m seeing more opportunities for me in environmental protection and telling others to stop polluting.” ◆

This article was produced in partnership with Chestnut Hill Local and the online newsroom Delaware Currents with support from the Philadelphia Journalism Collaborative. Part I of this article, which ran in the August issue, incorrectly thanked Every Voice Every Vote.

Newly-launched website offers a smart, free database to help Philadelphians participate in the circular economy

by emily kovach

There are a lot of materials in our lives — from fabric to furniture to fire extinguishers — that can find continued usefulness outside of the waste stream. That’s the idea behind resourcePhilly (resourcephilly org), a new website that helps residents figure out where to donate, repair and recycle unwanted items responsibly.

Created by Circular Philadelphia, a nonprofit that aims to cultivate a low-waste, regenerative economy, in collaboration with The Resource Exchange, a creative reuse center in Kensington, this project is tackling Philly’s waste problem head-on.

“Philly sends 1.5 million pounds of trash to the incinerator every year, and the Southeastern Pennsylvania region sends 3 million tons that are either burned or buried,” says Circular Philadelphia cofounder Samantha Wittchen. “Our hope is that by giving residents the tools to find better solutions to things they no longer need or want, we can make a dent in that.”

resourcePhilly is a database that allows users to search by item or category. The tool pulls up a list of results across the region, each corresponding to a circle on an interactive map. Each entry gives the name, physical address and URL of a business or

organization and indicates where it fits in the circular economy, whether it will recycle, rehome or repair items, say, or empower you to buy, rent or borrow secondhand, bulk, recycled or otherwise more-sustainable-than-usual wares.

One notable feature of the site is that its custom-built algorithm prioritizes local options over national ones like Goodwill or Home Depot. So, a search for everyday items yields familiar Philly operations like Rabbit Recycling, Circle Thrift and the West Philly Tool Library. But you might also discover new names, like Rutabaga Toy Library, PARRecycle Works and the Philly Fixers Guild.

A database like this has long been a dream of Wittchen’s. When she discovered that Karyn Gerred, the founder/owner of The Resource Exchange, had for years been maintaining a physical map on the store’s wall listing reliable recycling/reuse centers and organizations, a light bulb went off.

“We started talking about how we could reach a lot more people if this was an online searchable resource,” Wittchen remembers. “The Resource Exchange staff did such a good job maintaining the list, so the foundation was laid for us.”

Circular Philadelphia knew that approaching the City of Philadelphia about funding would be a nonstarter, even though cities like Austin, Texas and New York have piloted similar programs.

“Our City has not chosen to prioritize waste minimization and reuse,” Wittchen says.

Instead, Circular Philadelphia and The Resource Exchange applied for a grant from the Green Family Foundation in fall 2024 and received funding from that organization at the end of the year. After what Wittchen calls “a sprint” to develop the platform, resourcePhilly launched in late June of 2025.

While Wittchen isn’t optimistic that the City will contribute funding for the site’s maintenance, she wonders if the recent labor union strike, which included sanitation workers, will give the issue new urgency.

“We launched at a kind of serendipitous time, right before the strike, when a whole bunch of people were suddenly confronted with the amount of trash we generate and were desperate for alternatives,” she says.

“I’m hopeful that this will offer an opportunity for us to reopen a conversation with the City about supporting resourcePhilly.” ◆

Community advocacy, public service, and leadership represent these graduates’ values

For a quarter of a century, PA Cyber alums have been making an impact in Pennsylvania and beyond. Graduates from every county in the commonwealth have chosen this cyber school as a foundation for their lifelong plans. We’ve had students like pop star Sabrina Carpenter, “Dance Moms” alum Nia Sioux, and country singer Gabby Barrett. As the most experienced public cyber charter school in Pennsylvania, PA Cyber continues to provide a new school experience to students looking for a better educational fit.

Here’s how some of our alums are making a difference in Pennsylvania.

Uplifting County Amid Population Decline

Christina Bingman ‘11 dedicates herself to building a brighter future for her family of five and her rural community. As a volunteer, she strives to prevent population decline throughout Warren County in northwestern Pennsylvania. She advocates for improved transportation and more accessible cellular and internet services. She collaborates with local businesses and organizations because “bringing people together is the first step to getting things done.”

Growing up, Christina changed schools often and experienced social anxiety. Her

life took a positive turn when she enrolled at PA Cyber, which she credits with “completely changing” her. She was relieved to graduate on time. “PA Cyber set me up with a good foundation of believing in myself,” she said.

Christina is on track to complete her bachelor’s in environmental science this fall. She plans to become an environmental technician in the oil and gas industry to protect the health and safety of folks in her county.

An incoming senior at Robert Morris University (RMU), Zayn Farooq ‘22 is studying political science and history. After earning his degree, he plans to attend law school and make an impact by working in public interest law. “I recognize the deep structural issues we face in housing, civil rights, and educational law and policy,” he said.

Zayn recently completed an internship with the Allegheny County Department of Human Services, where he researched nationwide policy and legislation related to services for people at risk of experiencing homelessness. One of the most meaningful experiences of his college career so far was having his article on disparities in public education funding published in an academic journal.

Zayn was always a top-notch student. He enrolled in PA Cyber in sixth grade because “there weren’t any other viable middle school options in my area,” he said, “and PA Cyber offered a quality education from the comfort of my home.” He did so well that he earned a full scholarship to RMU.

Sarah Seader ‘21 has always prioritized service to others, from her time at PA Cyber through college and now at work. At PNC Bank, she is a risk management analyst and the community outreach and volunteer chair. She supports PNC’s initiatives with the American Heart Association, United Way, and employee-led groups that foster an inclusive workplace.

Sarah was a highly successful student at PA Cyber, and she only gained more steam in college. She earned two degrees in three years from PennWest California (CalU). Some of her extracurriculars included becoming student association president and editor-in-chief of the student paper. She was chosen as homecoming queen and commencement speaker.

Sarah has returned to PA Cyber’s Pittsburgh office for the past four summers to donate school supplies. “I hope that I can give back to others the way people at PA Cyber have impacted my journey,” she said.

Check out pacyber.org/news for more student stories.

Plant-based vendor proves Phillies fans don’t need to make concessions while at the game by

patrick kerr

Fifty minutes before the first pitch at a Friday night Phillies game in early June, the line at Greens and Grains already wrapped around and down the concourse at Citizens Bank Park.

Looking on, Kevin Tedesco, Aramark’s general manager at Citizens Bank Park, and Jason Firestone, Aramark’s senior director of concessions, shared the story of how Greens and Grains came to be at the Phillies’ stadium.

Established in 2015, Greens and Grains is a health-conscious, plant-based eatery founded by Nicole Jacoby-Psounos. A lifelong vegetarian, Jacoby-Psounos trained at the Institute for Integrative Nutrition in New York City in 2005, gaining experience in juice making and ayurvedic cooking. A few years later, she reignited her passion for healthy eating and ultimately launched the Greens and Grains concept.

Jacoby-Psounos’s husband, who has restaurant experience, is a formal partner

in the venture, the chain’s popular gyro sandwich a nod to his Greek roots. The pair initially opened Greens and Grains restaurants in Philadelphia’s Center City and in suburban New Jersey, but by 2022 only the New Jersey locations remained.

Through connections with South Philly’s Tony Luke’s and MBB Management, Firestone got in touch with Jacoby-Psounos ahead of the 2022 baseball season and arranged to bring the latest iteration of vegan options to the Phillies’ ballpark.

Before Firestone and Aramark signed on Greens and Grains, though, they had to try the food. “We went out to one of their restaurants,” Firestone remembers. “I’m not vegetarian at all. I tried some of their food. I wouldn’t have even known that it was vegetarian. I was blown away.”

Providing plant-based options at the park isn’t about tickling Firestone’s taste buds, of course. “It’s about having an experience for every fan,” he says. Vegan or vegetarian fans wouldn’t be able to eat at the game if the stadium didn’t offer food compatible with those dietary preferences, Tedesco says. “It’s a must-have.”

Aramark has situated all of its specialty food stalls — those catering to fans seeking vegetarian, vegan, gluten-free or kosher fare — behind home plate in the main lower level concourse section, adjacent to Phillies’ guest services.

In past seasons, Tedesco recalled, veg options were scattered throughout the concourse without a consistent season-over-season presence. Vegan hot dogs were available at the left field concession stand, but you had to ask for them. Such intermingling of vegan and non-vegan options made some customers nervous. A centrally located 100% plant-based vendor addresses these issues, says Tedesco.

“Having a dedicated location makes sure there’s no cross-contamination, and that we’re following all the standards,” Firestone explains.

Of the 10 or so Greens and Grains customers interviewed, only two said they follow a mostly or entirely plant-based diet. Most just wanted a healthier alternative to the main concourse food.

A mother buying a meal for herself and her daughter said, “It just seemed to be healthier than some of the other things. So we actually came specifically looking for that.”

A fan who largely avoids eating animal products frequents one of the Greens and Grains locations in New Jersey. Her go-to at the ballpark? The gyro. (Other hand-held, game-ready options available this season include a black bean burger and a buffalo chk’n hoagie.)

It’s about having an experience for every fan.”

jason firestone Aramark

The demand for plant-based options exists, Firestone emphasizes. “The next place we’ll go is probably for the guests upstairs so they don’t have to come all the way down here to the main concourse.”

In nature there is always something to discover. ¶ Maybe you’ll encounter a species living somewhere it has never been documented, perhaps an unexpected crayfish in a creek. What else could be swimming in there? ¶ You could find a chestnut tree growing strong where others are afflicted. Could that tree hold answers for how to overcome a century of blight? ¶ You might be entranced by a swallow as it zips and swoops, catching bugs over the surface of the water as you paddle by in a kayak. ¶ In the habitat of your home, you could explore cohabitation with a new-to-you plant. You don’t know if it will wither or thrive, but for now it offers promise. ¶ And a park with tall trees and a pond, even a small park tucked into a giant college campus, can offer peace when you need it. ¶ What will you discover?

A pair of chestnut trees in Wissahickon Valley Park are mysteriously unscathed by pathogenic fungus m BY ANDREW

CONBOY

In June 2023, I followed my friend Josh past old, arching oaks and tall tulip poplars along a path in Carpenter’s Woods in Wissahickon Valley Park in search of a rare and intriguing pair of trees he had heard about. We eventually arrived at two initially normal-looking trees: a 45foot tree that was growing towards a gap in

the forest canopy, and a smaller 20-footer nearby. The taller tree’s blooms were on the wane, and long, fragrant stalks of creamy white flowers littered the forest floor. I took a closer look. We had found what we were after — two healthy, apparently blight-resistant American chestnut trees. These were the largest ones I’d ever seen.

Just over a century ago, the American chestnut ( Castanea dentata ) dominated much of the woodlands east of the Mississippi River. The trees provided an abundance of nuts to wildlife and humans alike and supported pollinators with their plentiful summer flowers. The species was essentially wiped out in the early 1900s by an

The Carpenter’s Woods chestnuts are puzzling for a few reasons.

introduced pathogenic fungus called chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica).

The Carpenter’s Woods chestnuts are puzzling for a few reasons. First, it’s unclear if they are resistant to the fungal pathogen and thus considered “survivor trees,” or if they have somehow avoided being infected in the first place. Chestnuts that have been infected usually bear scars. Even resistant trees have cankers (patches of dead tissue) caused by the fungus. Josh and I didn’t see any cankers, though, which may suggest that the trees have never contracted the fungal infection. But this is quite unlikely, since the pathogen not only is spread far and wide by birds, insects, other animals, wind and rain but also can persist on oak trees, which are abundant in Carpenter’s Woods. American chestnuts found elsewhere in Wissahickon Valley Park exhibit

the growth patterns typical of trees susceptible to the blight; after dying back from the fungal canker, an infected chestnut uses any stored energy to resprout at its base. And if the Carpenter’s Woods specimens are indeed resistant survivors, questions about their origin arise. In the middle of the woods with no trees known to be resistant nearby, how did they get there?

In late 2023, I sent leaf and twig samples from both trees to the Pennsylvania-New Jersey chapter of the American Chestnut Foundation for testing, and both were confirmed to be pure American chestnuts. This exciting result ruled out the possibility that the trees could be resistant hybrids of Castanea dentata and Castanea mollissima (Chinese chestnut).

I revisited the trees in the fall of 2023 to see if the larger tree had yielded any nuts that could be grown, shared or perhaps

used for research plots. The findings were a bit disappointing but not unexpected: chestnuts develop inside husks, and most of the tree’s husks contained only shriveled, unfertilized nuts. An American chestnut needs to cross-pollinate with another chestnut tree to produce fruit. Although mostly unable to self-fertilize — the male and female flowers on a given tree mature at different times — a few fertilized nuts will appear on a standalone tree on occasion. I found one apparently viable nut — it appeared plump and healthy — but my attempts to germinate it failed.

I’ve been checking on the trees each year to see if the younger one will begin to flower. If it does, that could allow the two trees to cross-pollinate. Another option is to manually pollinate the flowers of the larger tree with the pollen of a known survivor tree from another location. This would require coordination, some tree climbing and careful hand-pollination skills. If anyone is interested in helping to pollinate the tree next spring, send me a message on Instagram @andrew the arborist ◆

BY BERNARD BROWN

Iparked my bike at nine in the morning on a heat-dome summer day and walked down the path into the University of Pennsylvania’s James G. Kaskey Memorial Park (better known as the BioPond). Under the tree canopy I immediately felt cooler after my sweaty bike ride. I paused to admire a stately American elm tree, dominating the landscape with its columnar trunk and spreading branches forming a massive umbrella, or, on that sunny day, a parasol. Most elms were wiped out by Dutch elm disease in the 20th century. Arborists have been treating this one to stave off the disease, a reminder that Penn’s entire campus is an arboretum, with trees grown as much for their heritage as for their shade.

Business-casual-clad workers paused at the pond on the other side of the elm tree, presumably enjoying the peace of water and greenery on their way to the offices where they’d spend the day staring at computer screens.

I strolled a lap around the pond and noticed a turtle — a red-eared slider — on the gravel path, probably a female looking for a place to dig a nest. Bullfrogs sang their deep, resonant “jug-o-rum” calls from the edge of the water below. A female mallard duck swam by with six ducklings in tow. A catbird warbled from within a nearby shrub.

Garden supervisor Claire ThurstonEmmert showed up to give me a tour, pruning shears in a leather holster on her belt. Thurston-Emmert says that the gardeners’ strategy is to promote native biodiversity, whether that’s with wildflower plantings or with trees like sweetgums intended to grow into the canopy as older trees in the garden reach the ends of their lives.

Some of the wildlife, such as the birds, arrive at the park on their own. Some stay and nest, like the mallard. Others are just taking a break mid-migration. Observations on eBird dating back to 1900 record 123 species. If I had visited in early May I might

“A lot of people say, ‘When I was at my most stressed out, I would come and study here, or cry here.”

CLAIRE THURSTON-EMMERT, garden supervisor

have seen blackpoll warblers on their way to the boreal forests of Canada.

Other wildlife can thank humans for their home at the park. The non-native redeared sliders are commonly (and illegally) sold as silver-dollar-sized hatchlings. Owners unable to care for them as they grow to the size of dinner plates regularly dump them in the pond, which is bad for the pond and the turtles.

Kathryn Butler, greenhouse and garden

manager, joined our walk, and we talked about the history of the park. At the end of the 1800s, botany professor John MacFarlane convinced the biology department to establish a research garden. Originally five acres, the garden had two ponds and long rows of beds. Eight greenhouses allowed students to study plants through the winter.

Over time new buildings whittled the five acres down to three, and only one pond remains. In 2000, according to the park’s web-

site, Richard and Jeanne Kaskey donated funds to renovate the pond and then endowed funds for the ongoing maintenance of the garden.

In the park, almost every plant has either been intentionally planted or permitted to grow, but in other ways the gardeners take a hands-off approach. “Except for plants of significant value and at particular risk, like our elm, we don’t really do pest management,” says Butler. “We find that most things start to just take care of themselves. We have a lot of aphids right now. That’s bird food. And other-insect food.”

Today the BioPond remains an oasis amid the traffic and never-ending building boom of University City, a place to take a break, watch birds and listen to frogs. Thurston-Emmert reports, “A lot of people say, ‘When I was at my most stressed out, I would come and study here, or cry here.’”

On an april morning , Nick Macelko was scouring the Assunpink Creek in Lawrence Township, New Jersey. It was a successful search. He found an acuminate crayfish (Cambarus acuminatus) on the creek bottom. “You can tell because he has that rostrum [part of the head that projects forward] that doesn’t have little spines on it. Cool.”

Biologists aren’t sure if the population in the Assunpink is a native species or invasive. Macelko is a project manager for the Pennsyl-

vania Department of Transportation and also the treasurer for the Neshaminy Watershed Association. In his spare time, he surveys and documents crayfish species in Delaware River tributaries. He first found this population of acuminate crayfish in 2024 near the confluence of the Assunpink and the Delaware River in Trenton. Macelko’s enthusiasm and passion for the work are apparent. “I immediately knew what it was, and I was just super hyped,” he says.

The acuminate crayfish was first de -

scribed in the late 1800s, but since then biologists have come to suspect that it is actually a species complex, or multiple species that are difficult to distinguish from one another. Similar crayfish have been discovered across the river in Bucks County and in the Schuylkill River watershed. Macelko says recent genetic testing shows that the crayfish found in the Assunpink are a separate population.

Investigation into the exact origin of this population continues, Macelko says. Since

BY NICK MACELKO

the acuminate complex has been documented in the Valley Forge area, the Assunpink population could simply represent an extension of the known range. But the crayfish are more numerous in Gold Run, a creek to the west of the Assunpink, than in either the Assunpink or Buck Creek, where they have also been found, indicating that the crustacean may have been introduced into Gold Run, from which it then moved into the other bodies of water. “We need to continue surveying, continuing to check out the other watersheds to see if it is present or not to determine if it is native or not native.”

Macelko has found today’s crayfish in a stretch of the Assunpink eight miles upstream from where he found the first acuminate crayfish last year. “It’s possible

“I immediately knew what it was, and I was just super hyped.”

NICK MACELKO crayfish enthusiast

that maybe this is established throughout the entire [Assunpink] watershed.”

There have been a number of efforts to improve water quality in the Assunpink Creek and other Delaware River tributaries. The acuminate crayfish is an indicator of good water quality, Macelko says, but the population is under threat from invasive species such as virile crayfish (Faxonius virilis). “That species … is larger than the acuminate crayfish. It is able to breed at a faster rate than the acuminate crayfish and is able to inhabit more areas in the stream.”

The use of road salt during winter months also creates problems. Macelko says that many waterways are slowly becoming more salty, which could have a negative impact on the crayfish and other aquatic species. ◆

Grades Pre-K and K

Tuesday, September 30, at 8:45 a.m.

Grades Pre-K-12

Saturday, October 11, at 9:30 a.m.

The only all-gender pre-K to 12 Quaker school in Center City friends-select.org 215-561-5900

Think Philly kids don’t care much for the city’s waterways? Think again m BY

KYLE BAGENSTOSE

Uber-urban South Philadelphia might seem an unlikely place to find the next generation of naturalists, environmentalists and outdoor aficionados.

But over the past four years, Adam Forbes, founder and director of the Philadelphia-based nonprofit Discovery Pathways, has done exactly that. After early career stops working with migrants, secondary school students and English language learners, Forbes stumbled upon water-based recreation as a catalyst for a diversity of city residents, particularly teenagers, to take an interest in the natural world.

The seed of the idea was personal — Forbes has long been a paddler himself and majored in environmental studies at Pitzer College in California. But things only started to come together after he moved to Philadelphia in 2009 and found work with the Nationalities Service Center, where he helped create community gardens for Nepalese and Burmese immigrants, and the Pennsylvania Migrant Education Program (PAMEP), through which he taught after-school English as a second language classes. Forbes’s manager at PAMEP had a key connection with Pennsylvania state parks.

“They hosted us for two camping trips every summer … as a reward for students who came to summer school,” Forbes says. “It was this kind of blip for our program, but it was the most powerful thing of the year, and a lot of the students who came on those camping

Adam Forbes of Discovery Pathways knows getting people on the water can build a bond with the natural world.

trips were the ones who stayed connected to us and graduated on time.”

Forbes later obtained a master’s degree in urban education from the University of Pennsylvania and began teaching health and Spanish at Mastery Charter Schools while staying involved in outdoor programming for kids on the side. It wasn’t until funding cuts curtailed PAMEP’s offerings and community leaders from diverse ethnic groups started reaching out to Forbes about ongoing opportunities for outdoor

attracted a few dozen participants now have hundreds. Forbes has upped his fleet to include dozens of kayaks, rowboats, canoes and paddleboards. A slick website shows off the free fishing and paddling days Discovery Pathways regularly hosts at FDR Park, in addition to the organization’s urban gardening, wellness, environmental education and field trip programs for public schools.

The nonprofit’s financial growth — tax records show $25,000 in revenue in 2021 ballooning to $290,000 in 2024 — enabled

“A lot of people said they had an interest in accessing the water but didn’t know how. Boating is something they saw but was out of reach for them.”

ADAM FORBES founder and director of Discovery Pathways

recreation, though, that he realized just how valuable such programming is to so many. In particular, surveys Forbes conducted to gauge public interest revealed an untapped appetite for water recreation.

“A lot of people said they had an interest in accessing the water but didn’t know how,” Forbes says. “Boating is something they saw but was out of reach for them.”

So he and a few other volunteers collected some “broken rowboats” from a shuttering youth program and began hosting informal events at the lake at Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) Park in South Philly. Then, during the COVID shutdown in 2020, Forbes found the time to formally launch Discovery Pathways as a nonprofit.

Buoyed by grant money from the William Penn Foundation, the growth since has been impressive. Paddle sessions that once

Forbes to both leave his teaching job to become Discovery Pathways’ first full-time employee and compensate students for their work organizing paddling days. In 2024 the nonprofit also launched a youth dragon boat team to compete in local regattas. The team’s slogan: “They tried to bury us, but they didn’t know we were seeds.”

Forbes says he has been amazed to see the growth of the kids in the program. On one paddling day at FDR this summer, veteran participants — high school juniors and seniors, some preparing to major in environmental studies in college — oversaw the bulk of the operations as younger members trained visitors of all ages on proper paddling technique and launched them from a dock. Forbes stood by just keeping an eye on things, marveling at what he — and a few associates — have built. ◆

Plant lovers unite at the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society’s monthly gatherings m STORY AND PHOTOS BY

JORDAN TEICHER

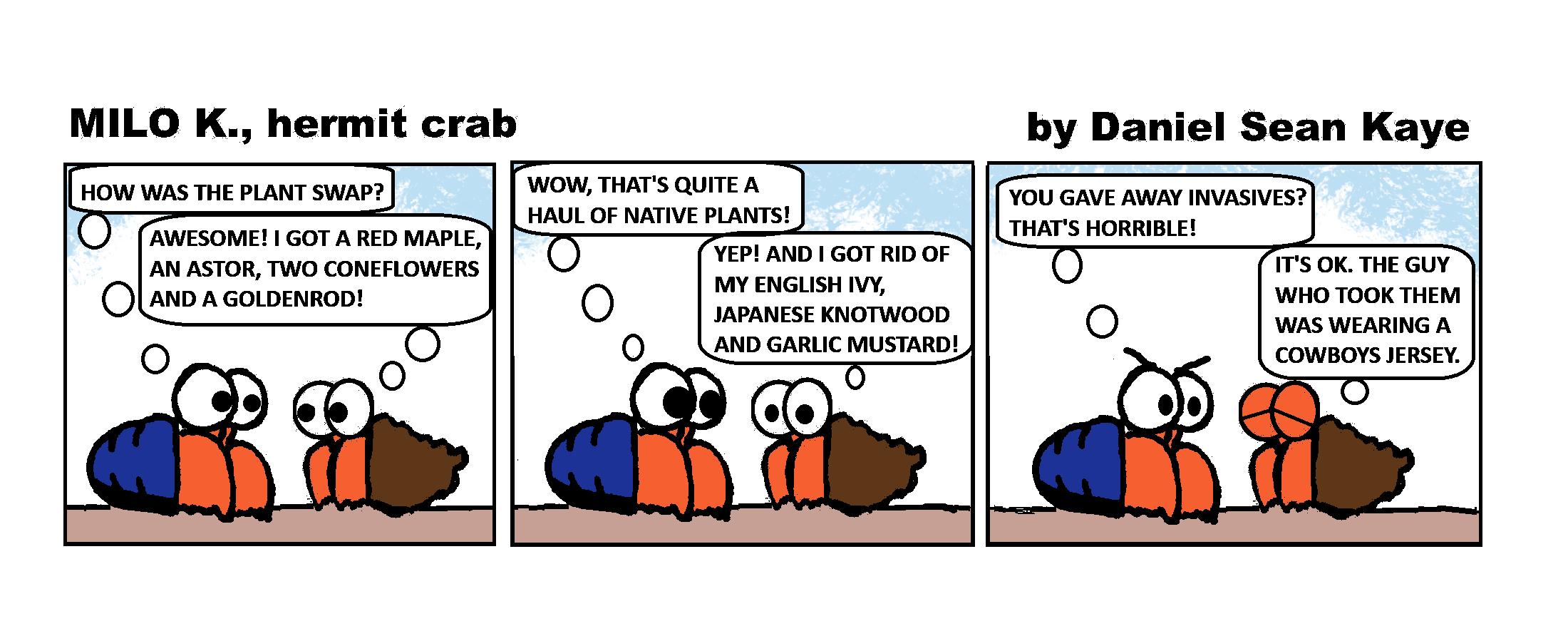

At the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS) Pop Up Garden at South Street one evening in August, two long picnic tables are covered in plants: philodendrons, lantanas, begonias and more. Around them, dozens of people anxiously hover, some picking up plants from the table to inspect them, others using their phones to look up the species. Then, after some announcements, the words they’ve been waiting for: “Let the plant swap begin!” The exclamation has the effect of a starter pistol. For the next few minutes, the garden is alive with activity as guests quickly snap up pots and jars.

PHS’s plant swaps are one-for-one exchanges: If you bring a plant, you can take a plant. If you bring more, you can take more. “It’s anything gardening-related,” says Cristina Tessaro, who heads up the plant swap programming at PHS. “You can bring that pot from the plant that you killed. Or maybe you’ve got that plant that really isn’t digging your house and it just needs a new home. Or maybe you have a big garden and you need to make room for something else. Or maybe you’re moving and you need to downsize.”

The free plant swaps are held monthly from April to October at PHS’s two pop-up beer gardens: on South Street and in Manayunk. Their goal, Tessaro says, is to make gardening more accessible and to build com-

munity around horticulture. “I’ve seen friendships blossom. I’ve seen people bring their co-workers. I’ve seen people — especially since COVID — being able to meet like-minded people and experience something new physically in person not behind a computer. That has been really special,” she says.

At the end of the night, many guests leave with large plastic tubs full of plants. And yet, there are still more on the tables. For Tessaro, that’s an opportunity to start more conversations and introduce some unsuspecting visitors to the joys of plant parenthood. “I’ll go through the rest of the garden and talk to the people just here having food or drinks,” says Tessaro. “I’ll be like, ‘Anybody want to take a plant? It’s OK if you kill it. We don’t want you to kill it, but there’s no financial investment. Come try something new.’” ◆

CARLEY JACKSON doesn’t have kids, but she does have plants. “They’re kind of like my children,” she says. “My monstera is my pride and joy right now. She’s my baby.” Today, at Jackson’s first PHS plant swap, she’s expanding her family with two new plants. “I’m not really sure what they are,” she says. “I’m hoping to take care of them and learn as I go.”

→LAVERNE COOK

started taking care of houseplants during the pandemic. Five years later, she has 260 houseplants — and counting. “My favorite plant is my vein plant [ Fittonia albivenis ], but it’s so picky. It’s like having another female in the house. I can only have one diva in the house and that’s me,” she says.

NATE FLETCHER started keeping houseplants nearly a decade ago, and now he has more than two dozen. He appreciates how they “make the inside feel like the outside,” and he likes to think they purify the air. “If I smoke weed, I end up cleaning them and rearranging them. I dust them and fidget with them,” he says.

→“I have been loving indoor gardening since college — which was 800 years ago or so — and it stayed with me all these years,” says NANCY BERMAN .

“I just love taking care of them, propagating them, sharing them. I had to pare down because it takes so long to water them that it’s become a little bit of a burden.”

When FELICIA BRYANT retired and moved to Willingboro, New Jersey, she started planting in her backyard — and never stopped. Today, she grows peppers, tomatoes, squash, herbs, cucumbers, peanuts and more.

“My husband died in April 2024. For me, it’s comforting to watch things grow,” she says.

“I go out in my backyard every morning. I wake up and say hello to my dog and we go out in the back. I pick a cucumber and have it for breakfast, and I sit out on my porch and watch the bees. I saw a hummingbird for the first time. I didn’t know they were in our area.”

Artist examines the relationships between humans and the ecosystems we’re a part of with community-based, genre-defying projects m BY

EMILY KOVACH

In 2023, Cheltenham-based artist Retbecca Schultz completed a yearslong art project, “Mapping Our Watershed,” by stitching together tree bark rubbings, monotypes, soil-water watercolors, leaf prints, drawings and other media to construct a map of Cheltenham and the Tacony watershed. In total, more than 60 people contributed 90 pieces of artwork to make up this textural, layered collage in what Schultz calls a “participa-

It began with a series of free, all-ages outdoor workshops held in collaboration with the Tookany/Tacony-Frankford Watershed Partnership, the Cheltenham Center for the Arts and Friends of High School Park. People gathered on the banks of local streams to learn about such watershed-related subjects as riparian buffers and soil health; then they made art together using natural materials.

“Mapping Our Watershed,” which was

Viewers discuss “Mapping Our Watershed” at the project’s culminating celebration at Elkins Central.

and Fairmount Water Works, captures the essence of Schultz’s art-making philosophy and creative process.

“I explore what keeps ecosystems healthy and why they’re essential to our survival,” Schultz says. “I believe that this idea that we’ve become disconnected from the rest of the living world is at the heart of the [climate] crisis we’re facing.”

Originally from Pittsburgh, Schultz moved to the Bay Area in the mid-1990s and got involved with community-based theater and performance art. A decade ago, she recentered her practice around visual art, winding together her formal background in painting with her theater training and passion for community-engaged art.

Her return to visual arts also coincided with her growing awareness of, and anxiety about, the gravity of the climate crisis and

“After hitting a low point, I started looking at resources and engaging with women and queer scientists and thinkers who helped me shift that [mindset]. My artwork became a tool for me to process my ecological grief, to be aware of what is here and what we can save and what we can protect.”

When Schultz moved back to the Philly area in 2016, her personal/public practice grew to include site-specific installations in public parks and waterways, mural-making on the banks of the Schuylkill River and textile work inspired by community-gathered materials from a series of nature walks.

Over the past decade, she has become deeply connected with her Cheltenham community, getting to know her legislators

“I feel like there are a lot of parallels in the traditions of the scientific method and the creative process.”

REBECCA SCHULTZ artist

and sitting on the township’s Environmental Advisory Council. She’s also a Streamkeeper, helping to monitor streams in the Tookany/Tacony-Frankford watershed, and an active member of the Cheltenham Center for the Arts.

Her art practice continues to evolve around these relationships and making connections between humans and nature. She is a catalyst assembling scientists, environmental educators and residents of all ages to talk and learn about ecosystems — and then make art together.

“I feel like there are a lot of parallels in the traditions of the scientific method and the creative process,” Schultz says. “They’re both asking: ‘What are you looking for, what are you asking, what kind of meaning are you trying to create?’” ◆

BEAUTY

Hair Vyce Studio

Multicultural hair salon located in University City servicing West Philly & South Jersey since 2013. We specialize in premier hair cuts, color & natural hair for all ages. (215) 921-9770 hairvyce.com

BOOKS

“100 Things to Do in The Nude”

In this novelty cartoon collection, veteran illustrator and cartoonist Roy Miller Jr. suggests 100 fun and frivolous things for you to do. In the nude. Available on Amazon. tinyurl.com/NudeCartoonBook

Books & Stuff

The Giving Book Shop! Help me donate books next month by purchasing books I donated this month! books-stuff.com

Back to Earth Compost Crew

Residential curbside compost pickup, commercial pick-up, five collection sites & compost education workshops. Montgomery County & parts of Chester County. First month free trial. backtoearthcompost.com

Bennett Compost

The area’s longest running organics collection service (est 2009) serving all of Philadelphia with residential and commercial pickups and locally-made soil products. 215.520.2406 bennettcompost.com

Circle Compost

We’re a woman-owned hyper-local business. We offer 2 or 5 gallon buckets & haul with e-bikes & motor vehicles. We offer finished compost, lawn waste pickups & commercial services. 30 day free trial! circlecompost.com

EATS

Fifth of a Farm

Our jams are a tribute to Philly, capturing its rich heritage in every jar. Whether you’re a longtime resident or passing through, take home a taste of the local tradition. Find yours @ fifthofafarm.com

EDUCATION

Kimberton Waldorf School

A holistic education for students in preschool-12th grade. Emphasizes creativity, critical thinking, nature, the arts & experiential learning. Register for an Open House! (610) 933-3635 kimberton.org

SunGate Educational Community Microschool for up to age 15. Full academic curriculum, movement, nature & arts. Social learning, hands-on & project based. Learning differences welcome. Sliding Scale. sungatecooperative.org

Echo House Electric

Local electrician who works to provide highquality results on private & public sector projects including old buildings, new construction, residential, commercial & institutional. Minority business. echohouseelectric.com

Hope Hill Lavender Farm

Established in 2011, our farm offers shopping for madeon-premise lavender products in a scenic environment. Honey, bath & body, teas, candles, lavender essential oil and more. hopehilllavenderfarm.com

Stitch And Destroy

S&D creates upcycled alternative fashions & accessories from pre-loved clothing & textile waste. Shop vintage, books, recycled wares & original fashions. 523 S 4th St. stitchanddestroy.com

GREEN BURIAL

Laurel Hill

With our commitment to sustainability, Laurel Hill Cemeteries & Funeral Home specializes in green burials and funerals, has a variety of eco-friendly products to choose from, and offers pet aquamation. laurelhillphl.com

GREEN CLEANING

Holistic Home LLC

Philly’s original green cleaning service, est 2010. Handmade & hypoallergenic products w/ natural ingredients & essential oils. Safe for kids, pets & our cleaners. 215-421-4050 HolisticHomeLLC@ gmail.com

Kimberton Whole Foods

A family-owned and operated natural grocery store with seven locations in Southeastern PA, selling local, organic and sustainably-grown food for over thirty years. kimbertonwholefoods.com

Mount Airy Candle Co.

Makers of uniquely scented candles, handcrafted perfumery and body care products. Follow us on Instagram @mountairycandleco and find us at retailers throughout Greater Philadelphia. mountairycandle.com

MENTAL HEALTH

Cedar Park Therapy

In-person individual, relationship, and group therapy. Queer and Trans centered. Located in a residential neighborhood in West Philly so you can walk to therapy! cedarparktherapyphilly.com

Philadelphia Recycling Company

Full service recycling company for office buildings, manufacturing & industrial. Offering demo & removal + paper, plastics, metals, furniture, electronics, oils, wood & batteries philadelphiarecycling.co

WELLNESS

Center City Breathe

Hello, Philadelphia. Are you ready to breathe? centercitybreathe.com

Meet the experts who bring world-class academic research skills and real-world experiences to the MES

“Whatever technical skills you’re teaching, you can also teach students to communicate their work to a variety of audiences, and encourage group work and group projects, because we hear from industry that they need professionals who can work with a variety of different teams and people.”

Siobhan Whadcoat, MES Program Director

“I try to expose students to the many different avenues that they can go down with their Penn graduate degree, shining a light into some obscure corners of conservation. The goal is to get these students really thinking about not only what’s possible, but what’s practical.”

Lauren McGrath, freshwater ecologist and MES instructor

“Sometimes [students are] out of their comfort zone when it comes to what they want to learn—maybe they are more focused on science than policy, or more focused on economics than science. You don’t need to work on all of these subjects, but, if you are in the field of sustainability, it’s very important that you understand all of them. You need to see the big picture in order to work on your niche area, and more importantly to partner with the right people to make a better impact.”

Dr. Swati Hegde, sustainability research specialist and MES instructor

Join the MES program team from 12-1 p.m. on the first Tuesday of every month for an online chat about your interests and goals. Log in with us.