CITY . PLANET . Your Your Your

publisher Alex Mulcahy

managing editor Bernard Brown

associate editor & distribution

Timothy Mulcahy tim@gridphilly.com

deputy editor

Sophia D. Merow

art director

Michael Wohlberg

writers

Marilyn Anthony

Kyle Bagenstose

Tim Bennett

Costance Garcia-Barrio

Dawn Kane

Emily Kovach

Julia Lowe

Jenny Roberts

Jordan Teicher

photographers

Troy Bynum

Jared Gruenwald

Julia Lowe

Jordan Teicher

Tracie Van Auken

published by Red Flag Media

1032 Arch Street, 3rd Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107

215.625.9850

GRIDPHILLY.COM

Content with the above logo is part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. The William Penn Foundation provides lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation, and Philadelphia Health Partnership. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit www.everyvoiceeveryvote.org. Editorial content is created independently of the project’s donors.

Unguarded Waters

Lately, as i’ve walked through the city, I’ve found myself crisscrossing from one side of the street to the other based on the angle of the sun and how much shade the street trees offer. We’ve had a hot, humid stretch here in July, recalling the fierce heat wave in June.

It did occur to me to jump in the water, and I have done so quite a bit this summer, but it has all been chlorinated and in swimming pools. Longtime readers of Grid might remember that I’m a big fan of swimming in natural bodies of water, as indicated when I wrote back in 2010 about taking a dip in the Schuylkill River.

Much more recently, in 2022, I talked with boaters and swimmers at a Northeast Philly boat ramp about water quality in the Delaware River. It was a painfully hot day, and the water was right there. After two of my interview subjects, young men from Brazil who worked in a nearby tire shop, jumped in, I had to follow them. It was magnificently refreshing to plunge into the cool river water, the perfect antidote to the heat.

So I totally get it that on hot summer days plenty of other Philadelphians jump in our creeks and rivers, prohibitions be damned. Devil’s Pool is the most famous swimming hole, but plenty of people wade into the Wissahickon and other creeks at shallower spots that don’t have sexy/scary names that trend on Instagram. And they’re not all thrill seekers drawn in via social media. From what I’ve seen, plenty are families out for a picnic on a hot day doing what comes naturally, and, as Kyle Bagenstose writes in this issue, has been common practice for most of Philadelphia’s history.

Currently swimmers violate park regulations that ban swimming, since virtually all of the accessible Philly waterfront is parkland. Philadelphia Parks & Recreation seems to do little to enforce the swimming ban, though. Plenty of people take the absence of enforcement as tacit permission to get in the water, or

at least find themselves faced with no practical disincentive. The City also recognizes no obligation to make the illegal activity safer or cleaner; why would it need to assist people breaking a rule?

I sympathize with park leaders stuck in a bind. They can barely afford to staff the legal swimming spots (pools). Last we checked, the park system had 28% of its positions unfilled across the board. Even if it were fully staffed, I doubt the department would have the rangers and maintenance crews to manage swimming in waterways. If I lacked the money to do my job, as park leadership does, I wouldn’t want to make it even bigger and more complicated.

But the result is lawlessness, a situation in which people routinely drown or get injured. When the City ignores the swimming happening in our creeks and rivers, swimmers are left on their own, swimming at their own risk, and park partners such as friends groups are stuck with the hard task of cleaning up.

Anyone who swims at the Jersey Shore knows that models, such as beach tags, exist for regulating and financing the oversight and maintenance of shorelines. I could imagine fencing in Devil’s Pool and charging people to enter and swim, then using the proceeds to hire lifeguards, direct traffic and pay for cleanups. Of course, sitting here as an armchair park administrator, I can’t say for sure that that would be the best option, or what would work elsewhere along the banks of our creeks and rivers. But I do feel confident that continuing to avoid the issue won’t generate any better solutions.

bernard brown , Managing Editor

WeCircle is the heart of our sustainability commitments - a community-powered circle of reuse, return, and renewal. We invite our shoppers to be part of a loop that reduces waste, rewards mindful habits and builds a more sustainable future.

Shoppers get a 25¢ credit for each reusable container they use while shopping. BYO container or get one from our Jar Library.

WeReturn is our circular reuse program. We will offer top-selling products in bulk, deli, and prepared foods departments in returnable containers. Shoppers pay a $3 deposit that’s refunded when containers are returned at the register.

COMING SOON!

Weavers Way and Rabbit Recycling are working together to recycle deli containers used for prepared and in house packed foods.

The Best Medicine

Hospital clowns bring a dose of joy for patients of all ages

At st. christopher’s Hospital for Children, a tantrum looms. Scalp bristling with electrodes, a three-year-old boy remains stubbornly unmoved by his parents’ pleas that he take his medication.

Then his nurse proposes a deal.

“Yeah,” the boy responds to her question, “I’ll take the pills if the clown comes to see me.”

Within moments, Marilyn D., aka DR Marebow, a longtime clown at St. Christopher’s and Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, arrives, complete with red nose, tea-bag earrings and a rainbow of a hat. She rewards the child with a smiley-face sticker for taking his medicine.

“I like her,” says Dion, age four, a patient across the hall. “She’s funny.”

DR Marebow — many style their clown names thus to distinguish themselves from physicians — and other therapeutic clowns serve up levity, often in short supply in medical settings. “Hospital clowns are a cross between improv comedians and social workers,” Marilyn says. “You don’t have a memorized script. You respond to the moment. Sometimes people just want a listening ear.”

Even after years, medical clowning can still spring surprises on Marilyn. She was lunching in Jefferson University’s cafeteria one day when a woman ran up to her. “She told me, ‘My mother wants to see you,’” Marilyn remembers. “‘She’s dying, and she wants a clown to be the last person she sees.’”

Hospital clowns’ empathy can soothe patients from elders to infants. A 2017 study found that clowning can help people with dementia because humor can calm them and strengthen their social bonds.

Likewise, babies also respond to clowns’ compassion. “With patients two to three months old you could hum a lullaby, just create a presence,” says James Ofalt, a clown at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) for seven years. A slew of studies show that interaction with clowns can ease children’s anxiety, improve their sleep and shorten their hospital stays.

story by constance garcia-barrio

DR Marebow brightens the days of pediatric patients like Dion.

Hospital clowns are a cross between improv comedians and social workers.”

marilyn d., medical clown

Hospital clowning in the United States began in the early 1970s with Hunter “Patch” Adams, M.D., who incorporated humor in caring for patients near his West Virginia home. This dimension of care reached the Delaware Valley some 35 years ago when George W. Edward, aka DR Bumper “T” Clown, donned outlandish clothes to visit his father in Cooper University Hospital’s cardiac unit. A smash hit with patients and staff, he ended up staying for hours. The first Bumper “T” Caring Hospital Clown training took place in September 2001. Today, Bumper “T” Caring Clowns has grown into a nonprofit that teaches therapeutic humor.

Nonprofits like New York City-based Healthy Humor train professional performers, like CHOP’s Ofalt, for healthcare settings.

“If one would like to volunteer as a medical clown, the first step is to contact the Volunteer Department,” says Dina Melchiorre, St. Christopher’s director of volunteer services. Pennsylvania Act 153, the Child Protective Services Law, requires a rigorous back-

ground check, she notes.

With clearances in hand, volunteers start training. At St. Christopher’s and Thomas Jefferson, this step involves, in part, shadowing an experienced clown one day a week for eight weeks. “New clowns learn about hygiene, protecting patients’ privacy and other essentials,” says Tim Slattery, who retired from working in commercial credit years ago to do medical clowning. “I always loved clowns since … making others laugh is one of the best things you can do,” he says. “In training, you learn to use just enough makeup for people to recognize you as a clown. You don’t want to scare them. Your job is to get patients to focus away from their illness.”

Marilyn D., a psychologist who began clowning because she enjoys volunteering, emphasizes learning to “read” patients’ body language: Do they look welcoming, glance away from you, seem to be in pain, offer a smile?

“Patients can tell us no,” Ofalt says, noting that accepting or declining a clown is

a rare opportunity for a patient to make a unilateral decision during a hospital stay. “It gives them a sense of power,” he says. Clowns may see a patient only once or twice, but repeated encounters can ripen into deeper connections. “In chemo, you see people over and over again,” Slattery says. One woman in chemo, a former seamstress, offered to make Slattery a clown suit. She finished one suit but kept on making them. “I finally told her that I was the best dressed clown in town, that I didn’t need more,” Slattery says. “She said, ‘That’s all right. I enjoy what you do’ and kept right on making them.”

Clowns raise the spirits of not only patients and their families but the staff too.

“Say, there’s a debriefing after a difficult incident,” says Heather Lavella, St. Christopher’s director of nursing. “Clowns can brighten up everyone’s day.”

Rapport between clowns and staff benefits the patient. In a case recounted in a 2000 book, “The Joyful Journey of Hospital Clowning,” a doctor wanted to look at the lower part of a girl’s eyes to evaluate her for a possible concussion. The girl refused to cooperate. A nearby clown began blowing bubbles toward the ceiling. When the child looked up at the bubbles, the doctor was able to complete his examination.

Sometimes, emotional attunement can prove hard work. “What do you tell a child with serious burns or one who is awaiting an amputation?” asks Ofalt. “What do you tell their family?”

Some clowns bring skills like puppetry, juggling or playing the kazoo to medical settings, but even these abilities don’t guarantee a smile. “You don’t always succeed,” Slattery says.

On the other hand, clowns may succeed too well. “My partner and I had a kid laughing so hard that it started pulling on his stitches,” Ofalt says. “We had to leave the room.” ◆

The number of medical clowns in Greater Philadelphia dropped during COVID-19 and has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels, Marilyn D. says. More clowns are needed nationwide, according to the North American Federation of Healthcare Clown Organizations. For details about medical clowning, call the hospital you’ve chosen or visit bumpertcaringclowns org

BREAD AND BELONGING

How Merzbacher’s built a community — one loaf at a time story and photos by julia lowe

When Peter Merzbacher first started delivering loaves of bread around the city on his bicycle, he had no five-year plan to grow his small baking project into a wholesale business. But today, Merzbacher’s processes 12,000 pounds of dough into bread every week out of its Germantown warehouse. And still, the mission remains the same: nourish and delight the community through

a love of bread.

“Bread, to me, is the perfect symbol of community,” says Merzbacher.

Merzbacher launched the bakery under the name Philly Bread in 2013. At the time, it worked similarly to a community-supported agriculture model: for $25 a month, subscribers could buy loaves in advance, and Merzbacher would haul a bike trailer full of bread to meetup spots around the city for

pick up. It was at those meetup spots, where his subscribers would also sometimes hang out for a beer after picking up their bread, that Merzbacher — then a recent transplant to Philadelphia from Massachusetts — began discovering a newfound sense of home.

“By making bread, I was very quickly building community.”

And that community soon helped grow his subscription model into a more formal

Peter Merzbacher started baking bread out of his home kitchen; now his business processes 12,000 pounds of dough per week.

business, one where customers could buy their bread on demand instead of waiting for his delivery. Once demand outgrew his home kitchen, he began knocking on the door of “every pizzeria in West Philly” looking for an oven to bake in, and managed to find a pizzeria owner who would rent out his kitchen for $100 a week. But in a few short months, Merzbacher’s business again outgrew the space.

“I came in for one day a week, then two days a week, then most days of the week,” says Merzbacher. He soon found himself kicked out of the pizzeria, with nowhere to go, and a growing roster of wholesale customers. “It felt really unfair to pull the rug out on them.”

After another expeditious search for a new space, he “lucked out” with an empty Tunisian bakery in Olney. It was fully-fitted for artisan baking: with imported French ovens and imported German mixers, it was perfect for Merzbacher’s intuitive approach, in which he tinkers with each step in the baking process to form creative loaves. He believes that “the dough is the boss” — he prefers to feel the dough and rely on tactile intelligence for improving it, rather than following strict measurements or a technique from a cookbook.

Merzbacher lived above the bakery while scaling up the business, and, by Philly Bread’s sixth birthday, the operation grew from just Merzbacher to having two dozen employees.

Now, another six years have passed since they moved in March of 2019 to what Merzbacher calls his “dream bakery,” a Germantown warehouse they renovated into a bakery that tripled their production space and now has a retail window for walk-up and pick-up orders.

The move also came with a name change from Philly Bread to Merzbacher’s. After hiring different firms to come up with a more memorable and creative name, it soon became obvious how well Merzbacher’s own last name would fit: having a German name for the business in their new home of Germantown, plus the similarity in sound between “-bacher” and “baker” proved “too good to be true,” as he puts it. At first, he thought naming the bakery after himself would seem like an egotistical move, but seeing the logo, which reminded him of a trustworthy, old-school bread brand, changed his mind. Five years later, he says

it was the right call.

“People mispronounce it, but they do remember it,” Merzbacher says.

Since settling in Germantown, they’ve more than doubled their production and have introduced several new products from their ovens. Each week, Merzbacher says he can count on the high demand for their tender Sweet Potato Buns and their famous Philly Muffins, their signature healthier square-ish version of an English muffin. Their newer releases are also popular, like the Citywide Sourdough and their newest product, Healthy Vibes: a bread made with roasted sweet potatoes and cooked red lentils that boasts 10 grams of protein and 9 grams of fiber in two slices.

Merzbacher’s idea behind developing Healthy Vibes was to make a hearty, high-protein bread without using a processed nutrient such as pea protein isolate. It was also a great way to use the sweet potatoes that they already had in their inventory

for their Sweet Potato Buns.

“I want it to be a daily bread,” Merzbacher says of the Citywide Sourdough, which contains toasted cornmeal that imparts moisture to the bread and extends its shelf life. The cornmeal is sourced from a mill in Manheim, Lancaster County, that provides to the scrapple industry. That local pride is central to much of their sourcing: all of their white, wheat and rye flours come from Snavely’s Mill in Lititz, also in Lancaster.

Merzbacher’s ultimate goal is to keep the greater Philadelphia community at the center of what they do, which means growing thoughtfully and sustainably.

Merzbacher’s breads and baked goods can be found at all locations of Kimberton Whole Foods. “They’ve figured out how to achieve the scale you need to offer food at a fair price without losing a sense of humanity and community and regional pride that one could easily lose in that process of scaling up.”

Bread, to me, is the perfect symbol of community.”

peter merzbacher

sweet

Savoring Tradition

Grad student gardener sees the value in homegrown, culturally-relevant sustenance by

marilyn anthony

fore cultivating her own plot at the Glenwood Green Acres community garden. That’s when the real learning happened.

“I was welcomed with open arms, surrounded by elders who are very knowledgeable about growing food that has cultural relevance.” Of her four seasons at Glenwood, Clark says, “I have learned so much from people who have been land stewards in North Philly for most of their lives.” Her fellow community growers cultivate foods with cultural ties: callaloo, collard greens, butter beans, peanuts, lima beans, Scotch bonnet peppers, sweet potatoes and more. Clark gets tips on what to grow and how to grow it. “They might watch me work and say, ‘You’re wasting energy. Let me show you how to do that,’” she says, adding that in every instance these interactions are done with “so much love.”

Bakari clark describes herself as a student and a gardener.

As the 2025 recipient of the prestigious Douglas Dockery Thomas Fellowship in Garden History and Design, Clark can now claim to be a student of gardens.

The 25-year-old Virginia native came to Philadelphia to study at Temple University, where she became interested in many aspects of food — its history, systems and access. It wasn’t long before Clark decided she “wanted to have [her] hands in food.” She worked on an urban farm and at a farmers market be-

Currently Clark is pursuing a master’s degree in city planning and landscape architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. The fellowship she received is sponsored by the Garden Club of America (GCA) and is awarded annually to one exceptional graduate student whose proposal reflects GCA’s interest in garden history and design and in

Bakari Clarke finds connection to her past and her community through her grandmother’s

potato pie recipe.

I was welcomed with open arms, surrounded by elders who are very knowledgeable about growing food that has cultural relevance.”

bakari clark

promoting the future of gardens and their role in the environment.

Clark’s fellowship funds her research into the deeply rooted history of several gardens, including historic Grumblethorpe and the thriving community gardens at Norris Square and Queen Village. Her project explores the origins of these gardens along with information about the people stewarding them today.

Among the many things Clark has learned so far is what motivates people to tend their neighborhood plots. “I feel like for a lot of people what keeps them coming out is the sense of community in the garden and the opportunity for people to grow what they eat, to sustain themselves in a way that is culturally relevant.” The vegetable Clark is most

excited to raise is one rich in personal history: sweet potatoes. The sweet potato pies

Clark’s aunts brought to family gatherings throughout her childhood were so delicious that she would ask to take a whole pie home to share and savor with her sisters. Now she grows her own sweet potatoes and honors a cherished family tradition by baking Grandma Juanita’s sweet potato pie.

Want to grow something delicious? Clark encourages novice gardeners to join one of the many community gardens around Philadelphia and is quick to reassure anyone worried about a lack of experience. “The gardeners are more excited to have you than you are nervous.” Growing your own food, she says, “is an experiment and an accomplishment.” ◆

GRANDMA JUANITA’S SWEET POTATO PIE

Recipe makes two 9-inch pies

2 frozen 9-inch pie crusts (keep frozen until ready to fill)

8 to 10 sweet potatoes, unpeeled

3 cups white sugar

1 cup light brown sugar

1 cup (2 sticks) butter

1 12-ounce can Carnation evaporated milk

1 tablespoon cinnamon, or to taste

large pinch nutmeg, or to taste

1 ½ cups self-rising flour

2 tablespoons vanilla extract

5 eggs

• Preheat the oven to 350 degrees.

• Bring a large pot of water to a boil.

• Add the unpeeled sweet potatoes and cook until soft (easily pierced with a paring knife).

• Combine the sugars and butter in a large bowl.

• Carefully peel the hot sweet potatoes over the sugars and butter.

• With a mixer or by hand, beat the potatoes, butter and sugar until smooth.

• Stir in the evaporated milk, spices, flour and vanilla.

• Add the eggs and mix until fully blended.

• Pour the mixture into two frozen pie shells.

• Bake for 30 to 40 minutes until the mixture is set and a toothpick or skewer comes out clean.

• Let cool completely before cutting.

Bakari Clarke offers a slice of pie to fellow gardener Shelly Hernandez at Glenwood Green Acres community garden.

Care Package

A new initiative is helping food service establishments think beyond single-use plastics by emily kovach

Ordering takeout from your favorite neighborhood spot is a treat. What’s not a treat? The disposable packaging that’s used for pretty much every to-go order. Whether you’re digging into a burger and fries or summer rolls and pad see ew, what you’re left with is a heap of unrecyclable trash that’s problematic for both the environment and our overburdened waste systems.

Philly Unwrapped aims to address the ubiquity of single-use packing waste in food service establishments. This local coalition was launched in early 2023 by ECHO Systems, a decade-old Philly-based nonprofit focused on designing circular systems for urban sustainability.

“This project brings restaurant owners/ operators, sustainability advocates and city stakeholders together in a way that’s collaborative, practical and financially realistic,”

says Alisa Shargorodsky, executive director of ECHO Systems. “We support business owners in reducing packaging waste through education, incentives, vendor connections and city policy engagement.”

The coalition kicked off its activities with a series of listening sessions that convened members of different small business communities. Owners and operators were invited to discuss single-use plastic waste solutions and the effects of the plastic bag ban and other similar legislation around certain packaging products.

“We wanted to understand: How are these bills going to impact our local business community? If the bans are an economic burden, how will we expect businesses to make these transitions?” Shargorodsky says.

From there, Philly Unwrapped developed a sustainable packaging toolkit for businesses. Once it has moved past the public

comment period, the toolkit — translated into Spanish, Mandarin and Cantonese — will be published with its own URL.

Philly Unwrapped also offers consulting services on reusable packaging logistics, like sourcing and sanitation. Part of this effort has been urging the Philadelphia Department of Public Health to adopt an updated food code that provides a clearer path toward reuse. They have done waste reduction projects with the Waldorf School of Philadelphia and Fishtown Montessori and a large packaging overhaul for Weavers Way Co-op, which Shargorodsky points to as a major success story.

“Weavers Way hired us to integrate a circular system called weReturn for its bulk, deli and prepared foods programs, which has already kept 40,000 single-use containers out of their waste stream,” she reports. “The coop hopes to level that up, with a goal to spend 40% less on single-use plastic by 2028.”

Philly Unwrapped has also partnered with Clean Water Action’s ReThink Disposable program to select local businesses for hands-on support to reduce disposable packaging at no cost. In collaboration with Trash Academy, they also plan to develop a creative research and visualization tool to help clarify the complexities of single-use plastic packaging. The progress of these projects hinges on obtaining new funding streams; previously awarded grants from the Environmental Protection Agency and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection are currently frozen or uncertain.

As Philly Unwrapped has educated various stakeholders, Shargorodsky has noted that people across the board, including consumers and food service operators, are invested in packaging beyond plastic. She believes that the next phase of awareness-building needs to focus on single-use plastic as both an environmental and public health threat.

“Most people have no idea that there are 16,000 chemicals of concern in single-use plastic — the materials are so normalized,” she says. “We must activate people around the idea of protecting ourselves from these chemicals. There are better alternatives, but it requires players from across the city to come to the table.”

Philly Unwrapped working group members, including Alisa Shargorodsky (front left), developed a sustainable packaging toolkit for businesses.

Scraps of Progress

Organizing and collective pressure can keep Philly’s compost momentum going by

tim bennett

In july, for the second time in five years, Philadelphia’s waste collection system stopped working and trash piled up in the streets. Five years ago there were staffing shortages caused by the pandemic; this time it was a municipal strike by the workers of District Council 33. When collection ceases, such issues as smells and pests prompt residents to start questioning the fundamentals. Our trash stinks and is attractive to bugs and rodents primarily because it includes food scraps. Now that the latest crisis is behind us, we need to lay the groundwork for a better system.

That planning was always the purpose of this series: to highlight the issues and show what is possible. And since my first article appeared in March, we have seen some progress from the City on composting food waste. Farm Philly (part of the Philadelphia Parks & Recreation) has expanded the City’s Community Compost Network to 19 sites — including some in new neighborhoods like South, West and Southwest Philadelphia — with a goal of as many of the new sites as

possible accepting public drop-offs at least one hour per week. In public meetings, the Department of Streets has discussed launching a 10-location public drop-off program using Bigbelly receptacles. The Department of Prisons has announced plans for two public drop-offs, one at their compost facility at the old Holmesburg Prison and another at the City’s State Road sanitation convenience center, in Northeast Philly. And with the current waste contract expiring in June 2026, the City released a request for information (RFI) about opportunities to diversify the handling of municipal waste.

So how do we keep moving composting forward? Via the age-old process of organizing, advocating and holding our elected and city officials accountable.

All of these are positive developments. But there is still a lot of work to be done. The City has neither a (public) master plan nor a point person to move the ball forward on composting in a systematic way. Questions remain about where the bins for the City’s public drop-off pilot will be located and how the material will be processed for composting. More pilot programs for both drop-offs and curbside collection are needed to figure out how to make composting work well across Philadelphia’s diversity of neighborhoods. This series of articles has made suggestions on these fronts, but there are many more possibilities to explore.

So how do we keep moving composting forward? Via the age-old process of organizing, advocating and holding our elected and city officials accountable. My conversations over the past six months have occurred in Kensington and Mount Airy. With individuals and groups in West Philly, Hunting Park and Holmesburg. With nonprofits and philanthropic organizations small and large. Rallying all the interested parties around a set of shared goals shows the decision-makers that addressing this issue can have a positive impact on all Philadelphians. Once these different groups are organized, they can advocate for expanded composting and apply pressure on elected officials to actually change how we manage food waste. Together we can make sure the City not only follows through on the initiatives described above but uses the input it is getting from concerned citizens, businesses and neighborhood groups through the RFI process to inform the launch of new and expanded programs to keep the momentum going.

Lower Merion Township just issued a request for proposals for a curbside collection program on the other side of City Line Avenue from Philadelphia. While small, it is the kind of pilot that Philadelphia can and should be doing. As I have said from the beginning, we can’t roll out curbside composting citywide today, but we can launch a number of smaller programs that will help us get there eventually. Don’t believe anyone who tells you otherwise. Let’s do this, Philly! ◆

tim bennett is the founder of Bennett Compost. Alex Mulcahy, publisher of Grid, is also a partner.

Trash piles up at a garbage collection site in July.

the fresh air issue

GET OUT

The concrete jungle isn’t for everyone, or welcoming to anyone, really. Especially in the summer, a landscape of asphalt, concrete, metal and glass doesn’t meet all of our needs. Nor do the indoor spaces — all stale air and artificial lighting — where we spend most of our sleeping and waking hours. ¶ But being outside — birdsong, cool waters, fresh air — that does us good. The physical and mental health benefits are clear. So what’s keeping you from getting out? And what would help you get out more? How about exercise classes under the blue sky? Accessible sidewalks? Air that won’t make you sick? A way to get on the water? ¶ We hope you read this issue (on a park bench, perhaps?) and spend some quality time outside. Get the exercise you need, fill your lungs with clean air and maybe even splash around in the water. And if you can’t, we hope this issue is an impetus to the advocacy needed to compel our public officials to prioritize improving access to quality outdoor spaces.

A RIVER CITY AGAIN

Advocates believe Philadelphia’s waterways could be the next great playground — if the City prioritizes it ➜

BY KYLE BAGENSTOSE

On an unseasonably cool Saturday during one of this spring’s stretches of wet weather, Yazmine Acosta, a 14-year-old from South Philadelphia, greeted visitors at a lakeside dock at Franklin Delano Roosevelt Park, just across Broad Street from the Wells Fargo Center. Her slender arms out-

stretched, she demonstrated how to swoop a paddle’s ends in and out of the water in a figure eight fashion, instructing people twice her size and three times her age on proper kayaking technique.

Two years earlier, Acosta had never been in a kayak. In fact, at that point she barely knew that activities such as kayaking exist-

ed, especially so close to the boxed-in environs of her South Philly block. But when she saw fliers at her school for Discovery Pathways, a nonprofit with a mission to get more Philadelphians paddling on local waterways, she decided to try kayaking.

“I’ve learned so much about watersheds. I learned how to kayak properly. I

Boaters get on the water at FDR Park.

PHOTOS

even learned how to fish for the first time,” Acosta says from the dock. “I get to actually breathe air for once instead of just being cramped in a house.”

It wasn’t that long ago that Philadelphians regularly took to FDR’s lake — along with many of the city’s other waterways — to recreate. The lake was formed during an initial landscaping of FDR Park by the Olmsted Brothers in the 1910s, and historical photographs show hundreds of people at a time swarming its banks and wading into its waters to swim. The activity used to be so popular that residents of nearby neighborhoods began calling the park “The Lakes,” a history recent enough that it is remembered by some older visitors, according to Adam Forbes, founder of Discovery Pathways.

But Forbes isn’t focused on collecting memories of a bygone era. Instead he’s interested in making new ones for current and future generations of Philadelphians who want to boat, fish and perhaps one day swim in the city’s waterways. Often, though, he feels like he’s fighting to break the logjam of the status quo.

“It’s a city of rivers. There are lots of possibilities to get out on water. But there are very few established access points,” Forbes says. “And the biggest thing we deal with historically is people think of the Schuylkill and Delaware as dirty. Even the lakes at FDR, a lot of people just think the water is polluted, dirty and unsafe.”

Forbes is part of a band of advocates in the city who envision a Philadelphia with far more water-based recreation than currently exists. They picture waterways with less pollution and more boat launches, where all forms of water-based recreation are within reach geographically and financially for large numbers of the city’s residents.

Stefanie Kroll, director of Riverways, a consortium of groups — Discovery Pathways among them — devoted to connecting people to the region’s waterways, says Philadelphians who want to kayak often travel outside the city to do so. She wants to create the right conditions for them to stay.

“We need access points, and we also need signage … routes that we could publish, the same way as the Circuit Trails [network for bicyclists],” Kroll says. “People could leave a car and grab a bus, paddle back, you know?”

But some advocates say they feel that power players in the city don’t prioritize

water-based recreation as much as they do. At best, they reason, that’s because officials and government offices may be focused elsewhere in a big, poverty-stricken city with a multitude of competing priorities and not enough money to pay for them all. But others suspect something else: a desire to avoid the topic altogether, lest more attention be drawn to the condition of the city’s rivers and creeks.

“The official position is, or attitude is, don’t go on the water. Don’t go in,” says Tim Dillingham, executive director of the American Littoral Society, a nonprofit focused on cleaning up waterways in the Delaware River watershed. “To me, that is not the appropriate position for public agencies to take. The best interest of the public lies in clean water, and they should be doing everything they can to engage.”

Numerous Philadelphia city agencies, including the Office of the Mayor, Parks & Recreation, the Department of Public Health, the Office of Risk Management and the Philadelphia Police Department Marine Unit, declined to be interviewed or provide answers to written questions for this story.

Kelly Anderson, director of the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) Office of Watersheds, says that she has fond memories of family boat outings on the Delaware River while growing up in Riverton, New Jersey, just across from Northeast Philadelphia. She remains an “advocate” for river access and says PWD has worked with numerous nonprofits to promote free fishing days, build a kayak launch along the Schuylkill and support other programming. She rejects the idea that there is a binary

I get to actually breathe air for once instead of just being cramped in a house.”

// YAZMINE ACOSTA, Discovery Pathways

Yasmine Acosta teaches Philadelphians how to kayak at FDR Park.

decision to be made by PWD or other agencies around water recreation. The Water Department has worked to measurably improve the quality of the city’s waterways throughout its existence and continues to do so, she says. But, she adds, PWD must be judicious with ratepayers’ money and prioritize public safety.

“I’m coming at it from the perspective of a risk manager who is responsible for protecting public health and managing water quality,” Anderson says. “We have to be very clear-eyed about the risks that come from recreational uses.”

Councilmember Curtis Jones Jr., whose district includes both the Wissahickon Creek and Schuylkill River as it passes through Fairmount Park, has previously warned of the dangers of swimming in the city’s waterways, going so far as to call for filling in a notorious swimming hole with rocks. But he also says he views balancing industry and river recreation as an environmental justice issue. In 2018, Jones was among several councilmembers who participated in a Dad Vail rowing challenge on the Schuylkill. That led to a joint initiative with Temple University to get local kids, some of whom ended up with college scholarships, into rowing and crew.

“I think the river has the ability to transcend race, transcend economic classes and give people exposure not only to different views of the city, but different people from around the city,” Jones says.

A City on the Water

Today, Philadelphia’s public swimming pools dominate the water recreation space. But for centuries, it was the city’s rivers, lakes and creeks that residents flocked to in the summertime.

According to “Benjamin Franklin, Swimmer,” a 2021 book chronicling this lesser-known passion of Philadelphia’s favorite founding father, historical records suggest Franklin first learned to swim in the Schuylkill River, well before a modern-day prohibition went into effect. A century later came poet Walt Whitman’s numerous musings on the Delaware River and its natural beauties. And while Thomas Eakins’ famous paintings of rowers in Philadelphia’s waterways from the same era would look familiar to anyone passing by Boathouse Row today,

other historical depictions would not:

For example, a colorful account of an impromptu swimming race held in 1875 by the “Schuylkill Navy” in the river near Manayunk’s Flat Rock dam, tells the story of the winner receiving a gold medal and the loser one made out of cowhide.

Newspaper photos from 1947 show two boys near a waterfall in Pennypack Creek, with a caption noting that “several supervised swimming holes” dotted its course through Northeast Philadelphia — an amenity also available at Cobbs Creek into the 1950s.

Two years after that, there’s a picture taken of four rowboats, one helmed by a quartet of women in white dresses and hair ribbons, making their way up a flat stretch of the Wissahickon Creek

And then there’s this, perhaps the grandest account of the relationship that once existed between Philadelphians and their waterways: a Philadelphia Inquirer snippet from July 1927 noting that, in the midst of a heat wave that had killed at least nine

uptown, downtown, and on the Schuylkill to give the children and adults who wish to wade and bathe a chance to do so,” Moore told reporters. “They do it in Boston, in Chicago, Washington and other large cities and we ought to do it here.”

But this sentiment gave way by the mid20th century, coinciding with an increase in the pollution of urban waterways. News reports in 1963 announced a proposed City Council ordinance to ban swimming in the city’s rivers and their tributaries, citing Health Department measurements of harmful levels of bacteria and other pollutants.

“In addition, strong currents, deep holes, and other hazards make most of the old riverfront ‘swimming holes’ undesirable for public use,” read an editorial in the Inquirer supporting the proposed ban. The next year, a story in the same paper reported that City Council opted to instead place signage along the waterways warning of their contamination, as a subcommittee had determined that a ban and any subsequent arrests were

We have to be very clear-eyed about the risks that come from recreational uses.” // KELLY ANDERSON, Philadelphia Water Department

across the city, an estimated 6,000 people descended on FDR’s lake on a single day for a refreshing dip.

“It was a great day for the one-piece bathing suit,” the notice quipped.

Other records from that era tell of a love affair between the city’s elected officials and its major waterways. A 1920 Inquirer article announced passage of a City Council ordinance providing $48,000 ($772,000 in today’s dollars) to dredge the Schuylkill and establish a “public bathing beach,” located between the Fairmount Dam and a public boathouse. The same edition quotes Mayor J. Hampton Moore envisioning such public amenities stretching from FDR to the Upper Schuylkill, over the objections of councilmembers who found the prospect too expensive.

“It is my expectation to continue the bathing beach agitation until we have facilities

“of doubtful constitutionality.”

Indeed, navigable waterways such as the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers are technically under federal jurisdiction. Nevertheless, current regulations of Philadelphia Parks & Recreation, which manages the City-owned land through which the vast majority of the city’s waterways can be accessed, contain an explicit policy that “no individual may bathe, swim or wade in any waterway or body of water in or at any Parks and Recreation Facility.”

Dillingham believes that Philadelphia — “always … a river city” — took a wrong turn when creeks began to be paved over and industrial pollution was allowed to fester.

“It was only when we polluted it in the name of commerce that we lost that relationship,” he says.

But not everyone is staying out of the water.

A deal with the Devil

Symiya Taylor, a young woman from West Philadelphia, was keeping cool in the Wissahickon on June 24 when temperatures hit 100 degrees in parts of Philadelphia, the first such recording in 13 years. A friend of Taylor’s from New Jersey had previously visited the creek’s infamous Devil’s Pool, a natural swimming hole created by the drainage of Cresheim Creek into the Wissahickon. Now, on the hottest day of the decade, he had brought Taylor and two other friends to swim, jump from the large slabs of rock that ring the pool and just enjoy the outdoors.

They weren’t alone. Some two hundred people had gathered at the spot: a group of friends playing dominos on the rocky delta of the creeks’ confluence as smoke wafted from a grill, an immigrant from India keeping close eye on his three young boys wading nearby, scores of people swimming and two dozen more waiting their turn to cliff dive into the water.

“I like the thrill of it,” Taylor says after doing her first jump. “But I couldn’t feel the bottom and I was panicking on the first swim.”

Officially, swimming in the Wissahickon is prohibited by Parks & Recreation’s citywide swimming ban. The nonprofit Friends of the Wissahickon (FOW), which voluntarily maintains much of the park, notes that the ban is a City policy, not the organization’s. Nevertheless, FOW agrees that swimming is hazardous and posts warnings on its website.

“The waterways in Wissahickon Valley Park are not designated swimming areas, so they are unsupervised, and that alone makes them hazardous places to swim,” says Sarah Marley, interim executive director of FOW. “But there are many other dangers when swimming in the Wissahickon Creek and Devil’s Pool. Strong currents can lead to drowning, submerged objects can cause severe injury and poor water quality can result in skin infections and/or gastrointestinal distress.”

The dangers are not just theoretical. In June 2023, two visitors to the Wissahickon drowned less than three weeks apart: a 38-year-old man police say accidentally fell into Devil’s Pool and a 21-year-old man who

experienced distress while swimming on a 94-degree day. A decade earlier, the Wissahickon made international news when a father jumped into the creek in an attempt to save his struggling 13-year-old son; both drowned.

Historically, drownings and injuries have occurred across all of the city’s waterways, not just the Wissahickon. In June 1952, the Inquirer reported, an 18-year-old lifeguard in the Pennypack described as an “expert swimmer” drowned in the rain-swollen creek. He and other lifeguards had rowed to a log they mistook for a body and were sucked over an 11-foot dam.

Less well documented are potential harms from illness contracted while swimming. Public health experts say linking something like a stomach bug to swallowing a pathogen while swimming is notoriously difficult to do. The sick person might not even realize the connection, let alone report it to authorities. But scientists are able to provide estimates through modeling. A 2024 study of the Wissahickon, Tacony and Cobbs creeks led by Temple University researchers took sam-

A visit to Devil’s Pool is a family affair, despite a lack of facilities and a prohibition on swimming.

ples from popular areas of the waterways and found risks ranging from about 1 to 37 illnesses for every 1,000 exposures, depending on the creek and activity.

Still, risk is relative, and even acceptable under public health guidelines. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, for example, recommends that states set safety thresholds for freshwater recreation between 32 and 36 illnesses per 1,000 exposures. That raises the question of how far Philadelphia waterways are from such thresholds. The 2024 study, for example, found that the risk of contracting an illness from pathogens while swimming in Devil’s Pool may be just 1 in 1,000. It used assessment methods that differed from those used by regulators, however, and notes that risks depend on variables like recent precipitation.

This dynamic can be seen elsewhere across the city. In FDR Park’s lake, water testing performed in the summer of 2024 by Discovery Pathways for E. coli, a harmful bacteria linked to sewage, found that levels only exceeded the EPA’s guidelines for safe swimming during one week out of 15.

Kroll says such data highlight a potential gap between the actual conditions of some of the city’s waterways and publicly held beliefs. Visitors to the Wissahickon often hear that the creek is downstream from several municipal wastewater treatment plants. This is true: a series of municipal sewage plants in Montgomery County release treated sewer water into creeks that feed the Wissahickon before it flows into Philadelphia. Calculations have suggested that as much as half of the creek’s water may be attributed to these releases at certain points of time.

This does not make the creek inherently unsafe to swim in, however, as modern-day treatment plants effectively remove pathogens found in sewage before releasing treated water. Instead, dangerous pathogens found in the Wissahickon primarily come from sources such as feces from animals (and human visitors) that — along with pesticides, lawn fertilizers and motor oil — wash into it during rainstorms.

But many Philadelphia waterways are in fact polluted by the city’s aging combined sewer systems, which are designed to intentionally release raw sewage during rain-

... the biggest thing we deal with historically is people think of our rivers as dirty. Even the lakes at FDR, a lot of people just think the water is polluted, dirty and unsafe.”

// ADAM FORBES, Discovery Pathways

storms into waterways like the Schuylkill, Delaware and the Tacony-Frankford Creek. That causes pathogen levels to spike and can make the water undeniably hazardous even for fishing and kayaking in the days after a storm. A 2021 study of common recreational spots in the Delaware River and Cobbs and Tacony creeks found that nearby combined sewer overflows increased the risk of contracting an illness by between 39% and 79%.

These risks to life and limb can also have repercussions. Nonprofits that oversee many of the city’s watershed parks note that they can be held financially liable for accidents. In 2020, the Friends of Pennypack Park, a primary caretaker organization of that ribbon of green space in the Northeast for 40 years, disbanded after be-

ing sued twice in quick succession, once by the family of a girl injured by a falling tree branch and then by the family of a boy who drowned while fishing.

Joseph Syrnick, president of Schuylkill Banks, a nonprofit focused on waterfront recreation in Center City, says his group “gets sued more than you would think” by people who have claimed some form of harm after interacting with the water from their dock near Walnut Street. He joined others in saying the dynamic can create a disincentive for waterfront caretakers to officially open their facilities for public recreation.

There are also questions of cost. The Philadelphia Water Department is currently spending billions of dollars in an effort to decrease the volume of sewage overflows

each year — a cost passed on to residents via a fee on their monthly water bills. Anderson says the department would likely need to spend much more to get all of the city’s waterways to a swimmable standard.

Increasing access to the river would also mean spending money on new boat ramps, water patrols and perhaps even lifeguards, in a city where Parks & Recreation has already struggled in recent years to fully staff its 60-some public swimming pools.

Still, water recreation advocates believe these challenges can be overcome if the issue is prioritized and creative solutions are implemented. Syrnick says that something as simple as a locked gate on Schuylkill Banks’ dock helps provide legal cover if a person hops it and gets into an accident on the river.

“You don’t want to be paralyzed by fear of a lawsuit because then you’d do nothing,” Syrnick says. “But you need to make sure when you’re [facilitating access to water] you have best practices and have it secure.”

Kroll also acknowledges that water recreation comes with risks but says boating safety can be taught just like bicycle safety, noting that of the 150,000 paddlers whom Riverways has helped get on the city’s waters since 2017, not one has drowned.

She also says the health of the city’s waterways has already improved significantly since the 1972 passage of the federal Clean Water Act, which implemented new rules on pollution that drove vast improvements in water quality across the country, particularly near cities. She envisions a future where the legislation’s ultimate goal of “swimmable, fishable” rivers is fully realized in Philadelphia. After all, Paris just reopened the Seine to swimming for the first time in a century after a concerted cleanup effort.

“I tell people I’m 45 years old and my dream is to, before I’m too old, have beaches on the Delaware and the Schuylkill,” Kroll says. “If you’ve ever been to Chicago and you walk out of the city and go to the lake — that used to be really dirty, too. So I think it’s doable. ” ◆

Breathing Trouble

Philly’s air quality is bad and getting worse ➜

BY JORDAN G. TEICHER

The American Lung Association has released its latest annual report on the state of the nation’s air — and the news isn’t good for Philadelphia. In last year’s report, the Philadelphia-Reading-Camden metro area had the 65th worst air quality in the country; now it has the 26th worst.

Based on data collected between 2021 and 2023, Philadelphia recorded a failing grade for all three measures of air quality — and all signs point to the city’s air quality getting worse. Philly averaged 6.3 days per year of unhealthy ozone smog, up from 5.5 days per year. The number of unhealthy days for short-term particle pollution, meanwhile, jumped from 1.5 days per year to 5.8. And levels of year-round particle pollution jumped above the federal standard from 9.1 to 10.0 micrograms per cubic meter.

Bad air quality is bad for everyone’s health. But for Philadelphians who are most at risk — including people under 18 or over 65, as well

wildfire risk there is,” Stewart says. “When there are major fires, and especially the closer they are, we are then more likely to experience significant observable problems from that.”

The report is sobering, Stewart says, but it is intended to be empowering. “We are issuing this report to make sure that people know what they’re breathing, what the problems can be as a result of that, but also to let them know that they can express their concerns and encourage their elected officials to do the right thing.”

For Alex Bomstein, the executive director of the Clean Air Council, lobbying elected officials to “do the right thing” in support of healthy air is his job. And he says that we’ve made progress in the past through, for instance, technologies that make fossil fuel-powered cars and power plants cleaner. But those advances have coincided with more cars on the road and greater energy demand, which means that we now need bigger systemic changes.

We have a great opportunity to clean up our air by switching away from fossil fuel-based heating and transportation. The technology is here. All we need to do is work to adopt it.”

ALEX BOMSTEIN, Clean Air Council

as people with lung or heart conditions — the consequences are particularly severe.

“One bad air day can be one bad air day too many for a person who is in one of the many higher-risk groups for air pollution,” says Kevin M. Stewart of the American Lung Association. “There are people who are especially sensitive to air pollution who really can’t go out when the air pollution levels are elevated, or can’t do some of the activities of daily life, let alone strenuous activity like sports or hard work. Those people are at risk of needing medical care or being hospitalized. Some people even die from exposure to air pollution.”

According to Stewart, much of the blame for the city’s declining air quality can be attributed to smoke from wildfires. As climate change accelerates, those wildfires are more likely to continue polluting the air in Philadelphia. “We know that higher temperatures, less rainfall and changes in wind patterns affect how much

“If you continue to burn fossil fuels, you can’t make that infinitely cleaner,” he says. “We have a great opportunity to clean up our air by switching away from fossil fuel-based heating and transportation. The technology is here. All we need to do is work to adopt it.”

Clean air is entirely achievable, Bomstein says, if we prioritize it. We can, for instance, shutter dirty peaker plants and replace them with batteries, expand funding for public transit to take cars off the road and decarbonize industrial facilities through programs like RISE PA. “There actually is a ton that we can do, but we need the political will and the political power,” he says. ◆

FEELING THE HEAT

Philadelphians speak on what high summer temperatures mean to them ➜ STORY AND PHOTOS

It’s a Wednesday afternoon in late June, and Philadelphia is on its fifth day of the first heat wave of the summer. As temperatures climb to 95 degrees, residents of Mill Creek flock to the best place in the neighborhood to cool down: Fletcher Pool.

Public spaces like Fletcher Pool are essential in a city that’s expected to get a lot more extreme heat in a warming world. Between 1971 and 2000, according to the City, Philadelphia had an average of four days per year that reached 100 degrees Fahrenheit. By 2099, the city could experience 55 such days annually. That kind of heat can cause serious health problems, especially for infants, children, people aged 65 years or older and those with certain chronic medical conditions.

Fletcher Pool — which is adjacent to a recreation center, a playground and a sprayground — is one of more than 60 outdoor public pools that will be open throughout the summer. For the Mill Creek community, it’s an especially meaningful place. In 2023, the pool and recreation center were renamed for Tiffany Fletcher, a Parks & Recreation employee who was killed by a stray bullet while working at the pool in 2022. The center has since received more than $3 million in upgrades.

At a commemoration ceremony in 2023, City Councilmember Jamie Gauthier underscored the role of Fletcher Pool — and public spaces generally — in making Philadelphians healthy, happy and safe. “The City must provide fully staffed and fully operational public spaces for young people — and the entire neighborhood — to safely gather, play and build community. Because when we give neighbors playgrounds, parks and pools they can be proud of, we are showing that we care, and an investment in their well-being is one worth making,” she said ◆

BY JORDAN TEICHER

↑SHARONA SMITH has brought her family to the pool for the first time today, and as a traveling nurse, she’s well-versed in the best strategies for staying safe and healthy in the heat. “Everyone just needs to stay hydrated and stay out of the direct sun and use sunscreen,” she says.

MALIA ALEXANDER is here with five members of her family to cool off. When asked for tips for other Philadelphians to stay cool, though, she says: “Stay in the house!”

A mother of four who is new to the area, SHAREEDA JACKSON says the Fletcher Recreation Center is a frequently-requested destination among her youngest children. “They beg me to come here after I pick them up from daycare,” she says.

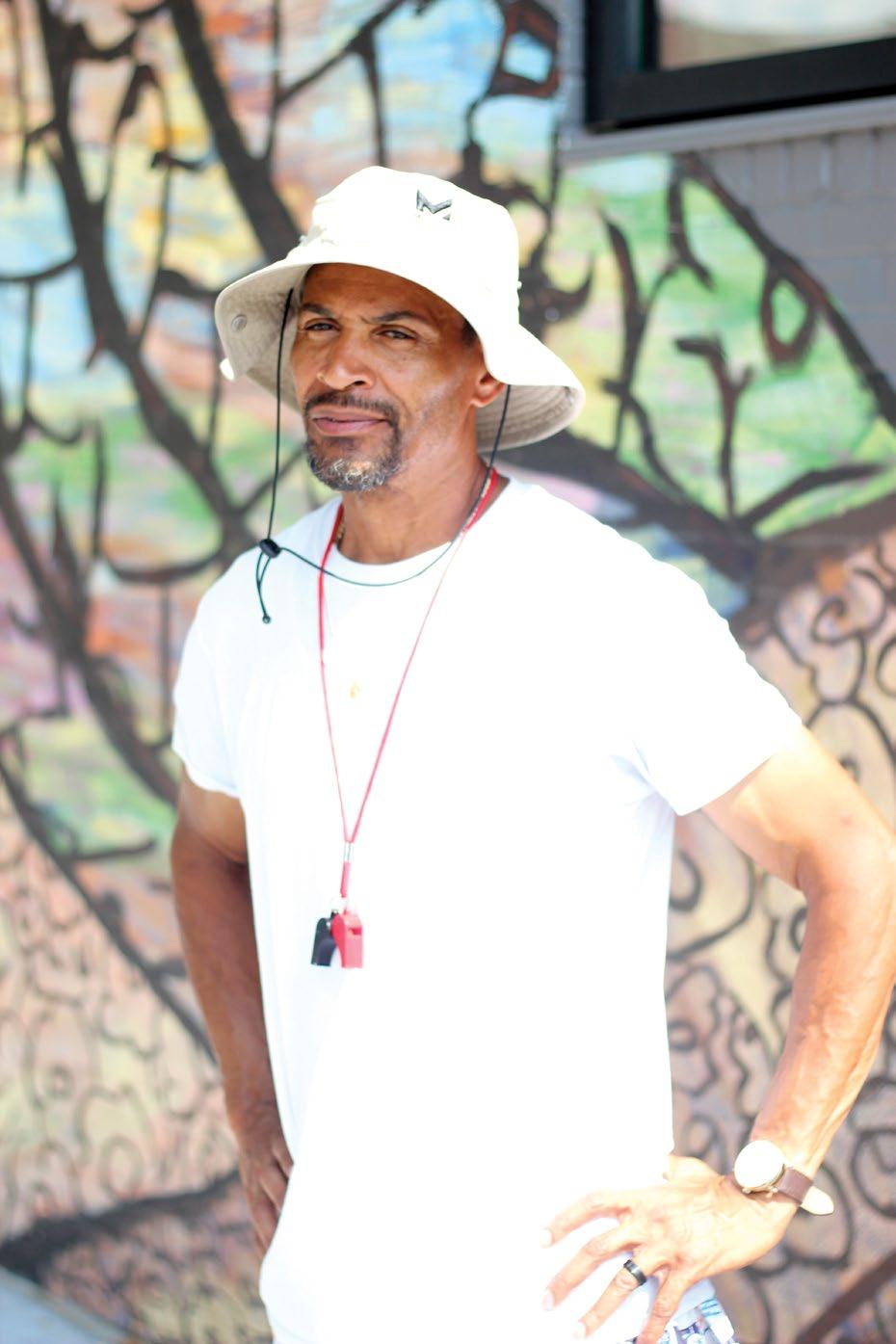

Born and raised in the neighborhood, SAM DAVIS brought his 13-year-old son to the pool today to beat the heat. But he has his own counterintuitive method for staying cool: boxing. On hot days, he trains outside across the street from Fletcher Pool. “The heat expands your lungs,” he says.

→On a short break from his poolside post, lifeguard DON LONG stays cool in a small patch of shade outside the Tiffany Fletcher Recreation Center. During the heat of the day, he says, he drinks lots of water, and keeps his movements to a minimum. “It’s all about adjusting. We get all the seasons here,” he says.

SOPHIA THOMPSON sticks her “big ol’ jug of water” in the freezer so she has cold water throughout the day for herself and her children.

SMALL FUNDS, BIG STEPS

Mini-grants beautify and improve accessibility to gardens and commercial corridors ➜

BY JENNY ROBERTS

Amid the typical concrete of the cityscape, the Cecil Street Commucnity Garden offers a place for Southwest Philadelphia residents to enjoy green space, something often absent from dense, urban areas.

“Even though it’s in the middle of the city, it kind of gives you an escape,” says Unique Fields, executive assistant at the community nonprofit organization Empowered CDC. “It’s a breath of fresh air.”

Empowered CDC has recently made the community garden more accessible to people in wheelchairs and others who use mobility devices thanks to a $2,000 grant from the Clean Air Council’s Feet First Philly program in partnership with the Philadel-

phia Department of Public Health’s Division of Chronic Disease and Injury Prevention. The grants aim to improve walkability in and access to public spaces.

The grant allowed Empowered CDC to buy small stones to make the surface of the garden’s pathways compact and easier for people in wheelchairs to traverse. The grant also funded the purchase of concrete to update the aging sidewalks around the garden.

“We believe that everybody should have accessibility to [the garden], no matter who they are or what challenges they may be facing,” Fields says.

Empowered CDC was one of 10 Philly organizations that recently received a Public Space Enhancement Mini-Grant award.

“Our aim is to improve the pedestrian environment, making it more walkable for everyone,” says Titania Markland, Clean Air Council’s sustainable transportation program manager.

Since the grant program launched five years ago, 63 grants have been awarded. The most recent round of grants funded $18,000 worth of community improvements.

The next grant application round begins August 1 and will end by early October. Individuals, businesses and nonprofits can apply. Markland says that the selection committee looks to fund projects in low-income, underserved areas of Philadelphia.

SEAMAAC, a social services organization for immigrants and refugees, received a $2,000 grant for its 7th Street Corridor project between McKean and Porter streets in South Philly. The money will fund planters for flowers and small trees to put outside of businesses.

“It’s very important for us to work with the community to talk to them about the benefits of having a tree,” says SEAMAAC CEO Thoai Nguyen, adding that trees can help reduce the heat index, which quantifies how the human body perceives temperature when humidity is factored in.

He believes that beautifying the commercial corridor will draw more customers into local businesses, too.

Another grant awardee, ACHIEVEability, used its $2,000 to buy supplies for its Impact Day event in the spring. Volunteers beautified the West Philly neighborhood surrounding the anti-poverty nonprofit’s headquarters at 5901 Market Street.

Volunteers power washed the exteriors of homes, painted porches and gave residents planters. They cleaned over 50 city blocks and distributed more than 6,000 pounds of food. ACHIEVEability also installed 10 mini-libraries and opened a new community garden at 60th and Arch streets. Executive director Jamila Harris-Morrison says it will make the area a place where people “desire to walk.”

“All of this was really to improve the exterior appearance of the homes, to help our residents take more pride in their homes and [their] blocks, and to build community amongst our neighbors,” she says. ◆

A public space enhancement mini-grant paid for planters to beautify the sidewalk in front of Nor Farida Ahmed Jamil’s store on the 7th Street corridor. Clockwise from left: Dominic Brennan, Will Dunford, Thoai Nguyen and Nor Farida Ahmed Jamil.

PHOTO

“STRENGTH THROUGH NATURE”

Free yoga and line dancing classes on transformed piers reconnect Northeast Philly with the Delaware riverfront ➜ STORY AND PHOTOS BY JULIA LOWE

Ever since Elizabeth Luce b egan training to become a yoga teacher, she wanted to teach classes outside. Now, every Tuesday evening, she leads a class right on the Delaware riverfront. “The best part about being in this location is it’s so active,” says Luce. “Everyone is out. If they’re not here doing yoga, they’re out walking their dog, or fishing, or taking a hike or a bike ride.”

On a grassy pier at the southwest tip of

Pennypack on the Delaware Park, Luce tells her students to become aware of their natural surroundings. Between cues to “reach towards the pier” and to breathe in the cool breeze, she points out the park’s natural ambience: chirping cicadas, speedboat engines passing by and the wings of waterfowl flapping overhead.

Now in its sixth year, Yoga on the Pier is one of about 250 free public programs offered annually by Port Richmond-based

Riverfront North Partnership (RNP), says programs director Brian Green, and the nonprofit’s longest-running outdoor yoga program. The class is hosted by Roots2Rise, a nonprofit offering free and low-cost yoga and meditation programs across the city to learners of all ages and ability levels.

With yoga’s rise in popularity, Luce says the practice has become more commercialized, and therefore less accessible for those who can’t afford expensive studio member-

down and you can feel that little bit of air go over your face as your eyes are closed,” says Luce.

Everyone is out. If they’re not here doing yoga, they’re out walking their dog, or fishing, or taking a hike or a bike ride.” // ELIZABETH LUCE, yoga instructor

ships. Although teaching Yoga on the Pier is aligned with her mission of making yoga more accessible, she also sees it as an opportunity to help connect her students with the riverfront.

“To be part of something that is starting to bring people back to an outdoor space, both the green and the blue, I think is exciting,” says Luce.

Studies have shown that spending time in green spaces and in nature can provide both physical and mental health benefits similar to those of physical activity, with health outcomes like decreased stress and reduced risk of cardiovascular illness. “Green exercise” — combining physical activity with time outdoors — may also lower negative emotions like anxiety, anger and depression, while leading to improved moods and

relaxation. There is even evidence to suggest that exercising in and near blue spaces, like riverfronts and beaches, can yield similar health and wellness benefits or even result in better outcomes than exercising in green spaces alone.

“Being out on the river in these green spaces has a huge impact on folks’ mental health,” Green says. And with COVID-19 both increasing wariness of indoor proximity and highlighting the dangers of isolation, park spaces have become key venues for community programming.

Luce reports that being on the pier, surrounded on all sides by the Delaware River, brings a calming atmosphere to the yoga class.

“There’s been some evenings during shavasana [corpse pose] where the sun is going

The pier is also just feet from the Pennypack path, where runners and hikers often pass Luce leading a class. For her, those other park goers contribute to a sense of riverfront fellowship.

“When you see a community feeling comfortable enough to just come out, lay their mats down and do yoga, while you’ve got all these other community activities [going] on, I think that just adds a great element to it: seeing people coming together as a community on a Tuesday night,” says Luce.

Transforming Riverfront North

In several Northeast Philadelphia neighborhoods, including Port Richmond and Wissinoming, I-95 has cut off access to the Delaware waterfront for decades. Outdoor exercise classes like Yoga on the Pier are part of Riverfront North Partnership’s efforts to bring people back.

Since 2004, RNP has been working to reconnect Philadelphians with the Delaware River through the completion of an

Elizabeth Luce enjoys the natural surroundings and the communal feel that come from teaching yoga outside.

11-mile greenway system of trails and parks stretching from Port Richmond to Glen Foerd. RNP offers a variety of environmental, volunteer and community programming, including a diverse range of group exercise options in parks like Pennypack on the Delaware and Lardner’s Point.

Green says the former fishing pier where Yoga on the Pier meets was sitting “untapped” for years before the organization reactivated it. Several of the parks in RNP’s system, including the newly opened Robert A. Borski Jr. Park in Bridesburg, involved the transformation of vacant industrial property into green space for recreation.

“People think about Philly for industry, but not often for our green spaces, even though we have so many great ones,” says Green. “I think it was always the Schuylkill in the past. But now we’re seeing a surge of more opportunities on the Delaware River.”

Soulful line dancing

A pier a couple miles downriver from Pennypack on the Delaware hosts Green’s favorite RNP program: Monique Burrell’s Monday evening R&B Soul Line Dancing class at Lardner’s Point Park.

“It brings so many diverse audiences all together from all over the city,” Green says. The class even sometimes lures people right off the nearby Kensington & Tacony Trail; as hikers walk by, Burrell “strongly encourages” them to join in for a line dance.

“Folks are just walking by, and she somehow pulls them in,” says Green. “And then they come back [a] week later.”

R&B Soul Line Dancing is a community favorite and draws a committed crowd of weekly attendees. In the three years it has been offered, the class has always gone beyond the six-week session for which it was originally scheduled, usually running through most of September.

Burrell, who teaches under the name Mo’Smooth, first discovered R&B soul line dancing in the early 1990s, seeing dances like the Electric Slide performed at weddings and block parties. Watching groups of people falling into so many synchronized dances, she wondered what she was missing and signed up for her first line dancing class in Germantown in 2001.

Now a 24-year dancer and a teacher of

We have the outdoors, we have the scenery, we have what we all have been blessed with, which is nature.”

// MONIQUE BURRELL, R&B Soul line dancing instructor

three years, Burrell has always seen line dancing as a way to both build community and boost fitness. Going to the gym can be intimidating for some, she says, but she teaches line dancers of all body types, ability levels and age groups. Line dancing can also be a low-impact activity for those with injuries and chronic pain, like Burrell herself, who has a torn meniscus.

“How do I stay mobile? Because at the end of the day, you always still hear the doctor saying, ‘Stay active. Continue to work out,’” says Burrell.

Burrell says that being on the riverfront adds interest to the class. Recently, for instance, attendees witnessed the nearby Tacony-Palmyra Bridge opening for a cargo ship to pass.

“You can see people fishing, people walking on the trails, you have the bridge — that’s the experience that you’re not going to get inside a line dance classroom,” says Burrell. “We have the outdoors, we have the scenery, we have what we all have been blessed with, which is nature. We get most of our strength through nature.”

Monique Burrell gets line dancers moving at Lardner’s Point Park.

THE COOLING GAP

Ies, and her neighbors agree.

As Philly gets hotter, air-conditioned community spaces and weatherized homes are becoming essential ➜

n June at the Hunting Park Recreation Center, Ilianny Rodriguez, a senior at Esperanza Academy Charter School, was playing volleyball in the gym with her friends. She says that when it’s very hot, they cope by lying in front of the fan because the gym is not air-conditioned.

Rodriguez has noticed that people try to mitigate the heat by painting surfaces white, and she remembers efforts a few years back

BY DAWN KANE

when more trees were planted in the park and benches added, but she says these improvements haven’t been maintained.

Juan Díaz, who also enjoys going to the recreation center for volleyball, says that when it gets really hot, he steps outside for relief. “It’s draining,” Díaz says. “I come out here for a breeze and fresh air.”

Rodriguez says that the community needs to create more air-conditioned spac-

As documented in the 2018 report “Beat the Heat — Hunting Park,” community activists working with the Office of Sustainability heard from more than 600 community members that high heat was an important issue. This expression of concern led to a targeted effort to provide more resources, but more needs to be done, says Hunting Park United co-founder Leroy Fisher. He says more cooling centers are needed for teenagers and vulnerable populations. His organization is advocating for the Cityowned Logan House in Hunting Park to be used as a cooling center.

The need for such centers will only grow. The Philadelphia Department of Public Health (PDPH) declared two heat emer-

PHOTO BY TROY BYNUM

Charles Lanier, of the Hunting Park Neighborhood Advisory Committee, sees a connection between vulnerability to the heat and aging housing in need of repairs.

gencies in 2024, but, according to “Pennsylvania’s Looming Climate Cost Crisis,” a July 2023 report from the Center for Climate Integrity (CCI), that number is expected to go up. A heat emergency occurs when temperatures in the 90s or higher coincide with high humidity. The PDPH website states that this is when people can most easily suffer dehydration, heat exhaustion and heatstroke. And as the frequency of heat emergencies increases, it’s Philadelphians — especially those in neighborhoods like Hunting Park — who will be the most severely impacted.

According to the CCI report, the Pennsylvanians who will be at higher than the state average risk of heat-related illness, who will be “disproportionately burdened” by the effects of rising temperatures, include Philadelphia County residents and members of communities classified as Environmental Justice Areas or where high percentages of the population are foreign-born or speak languages other than English at home.

The City’s map depicting heat vulnerability, which it uses to plan door-to-door outreach and the placement of cooling centers, confirms that the most affected communities are largely divided by race and income. Hunting Park faces higher temperatures due to aging homes, fewer trees and fewer green spaces. As compared with sections of the city with newer housing and light-colored roofing, lower income neighborhoods frequently have dark roofing and more concrete, exacerbating the urban heat island effect.

“The housing situation has definitely impacted the health of residents,” says Charles Lanier, executive director of the Hunting Park Neighborhood Advisory Committee

What Is a Heat Emergency?

The June 22-26 heat wave baked Philadelphia in high temperatures between 88 and 100, with three days in a row topping out at 98 or above. The heat wave broke two high daily high temperature records and two daily low temperature records, offering no relief at night.

(HPNAC). Lanier works with HERE 4 Climate Justice, the Office of Sustainability and Built to Last, run by the Philadelphia Energy Authority, to advocate for upgrades to preserve older homes.

HPNAC coordinates community DIY workshops, providing tips on weatherizing homes and energy conservation. Residents who attended the workshops have received cooling kits with materials like caulk, weatherization strips and window insulation materials, says Lanier. Some received air conditioning units. “The funding doesn’t allow us to serve every household in the neighborhood, but we try our best to raise as many funds and serve as many people as possible.”

As temperatures rise, federal funding cuts make such work trickier to finance.

According to a May 15 Billy Penn report, recently “canceled grants include $500,000

for Esperanza’s tree-planting and climate resilience project in Hunting Park and $700,000 for the Overbrook Environmental Education Center’s program to help other groups secure grant funding for projects in disadvantaged communities.”

According to a March WHYY Climate Impact story, $13 million in cancellations and freezes “have hit projects to monitor air pollution, plant trees and protect residents from extreme summer heat in the Philadelphia region.”

The City is coming through, though, at least with funding to improve older housing stock. “We were successful in getting a $5 million increase in the City budget to upgrade more homes,” Lanier says. HPNAC and its partners, like Built to Last, will push for a $10 million increase going forward with a focus on electrification, solar paneling and heat pumps, he says.

“Built to Last is spending roughly $25,000 per home, and that funding leverages an equal amount of funding from partner programs, such as the Basic Systems Repair Program, the Weatherization Assistance program and aging-in-place, health and utility programs,” says Alon Abramson, vice president of Built to Last programs.

In the meantime, the City is working with 300 faith-based and community organizations to expand the network of libraries, recreation centers and other community spaces that serve as cooling centers from 48 to 55. According to a City representative, warming centers used during periods of extreme cold do not always serve as cooling centers in the summer. The City is updating its inventory of cooling spaces and is readying emergency workers for challenges like additional health crises and power outages.

And when the PDPH does, inevitably and increasingly often, declare a Heat Health Emergency, the City activates additional services including extended hours at cooling centers and assistance for those most at risk during a high-heat event: those over 65, infants, young children and those suffering from chronic health conditions, according to the PDPH Extreme Heat Guide

It is recommended that during a heat crisis, residents check on vulnerable community members and pets. During heat emergencies, the Office of Homeless Services declares a Code Red, and residents are encouraged to report anyone on the street who may be experiencing a health crisis to the homeless outreach hotline, (215) 232-1984.

In addition, the heatline, (215) 765-9040, is open during heat emergencies, and the Office of Emergency Management’s Hot Weather Preparedness information page provides links for additional resources and tips.

City residents can sign up for ReadyPhiladelphia, a system run by the Office of Emergency Management, by texting READYPHILA to 888-777 or by registering online to receive emergency alerts by text or email. Those alerts are translated in American Sign Language and 10 other languages. ◆

GREEN PAGES

BEAUTY

Hair Vyce Studio

Multicultural hair salon located in University City servicing West Philly & South Jersey since 2013. We specialize in premier hair cuts, color & natural hair for all ages. (215) 921-9770 hairvyce.com

BOOKS

“100 Things to Do in The Nude”