850 miles of trails, one step at a time p. 12

Manayunk? p.

850 miles of trails, one step at a time p. 12

Manayunk? p.

WeCircle is the heart of our sustainability commitments - a community-powered circle of reuse, return, and renewal. We invite our shoppers to be part of a loop that reduces waste, rewards mindful habits and builds a more sustainable future.

Shoppers get a 25¢ credit for each reusable container they use while shopping. BYO container or get one from our Jar Library.

WeReturn is our circular reuse program. We will offer top-selling products in bulk, deli, and prepared foods departments in returnable containers. Shoppers pay a $3 deposit that’s refunded when containers are returned at the register.

Weavers Way and Rabbit Recycling are working together to recycle deli containers used for prepared and in house packed foods.

publisher Alex Mulcahy

managing editor

Bernard Brown

associate editor & distribution

Timothy Mulcahy

tim@gridphilly.com

deputy editor

Sophia D. Merow

art director

Michael Wohlberg

writers

Marilyn Anthony

Kyle Bagenstose

Tim Bennett

Anne Hylden

Emily Kovach

Adam Litchkofsky

Julia Lowe

Jordan Teicher

photographers

Chris Baker Evens

Matthew Bender

Jared Gruenwald

Adam Litchkofsky

Julia Lowe

Jordan Teicher

illustrator

James Olstein

published by Red Flag Media

1032 Arch Street, 3rd Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107

215.625.9850

GRIDPHILLY.COM

Content with the above logo is part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. The William Penn Foundation provides lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation, and Philadelphia Health Partnership. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit www.everyvoiceeveryvote.org. Editorial content is created independently of the project’s donors.

My daughter and i wended our way through the streets of our West Philly neighborhood, shunted block after block by fire department barricades. We were heading from a playground, where we had started the morning, to the supermarket, but there was a burning vacant apartment building in the way. As we followed the downwind side of the safety perimeter, me on my bike towing her in a trailer, the air grew hazy with smoke. We inhaled the gas and particulate remains of the apartment block’s wood, matter that had been locked in the timbers, walls and floorboards since they had been hammered into place inside the brick facade in 1928. It did not belong in our lungs.

That brief exposure made me glad we live a few blocks upwind and that, aside from that ride to the grocery store, my family wouldn’t have to breathe the smoke. We got lucky. All the families living downwind did not.

At that moment, families in Chicago and Detroit were inhaling smoke from black spruce, jack pine, larch, balsam fir and other trees burning in the boreal forests of Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Our smoky neighborhood and the footage of these cities in the news reminded me of Philadelphia two years ago when our air was filled with smoke from similar Canadian fires, trapping us in a toxic orange haze. So far this year the winds have blown most of the wildfire smoke to the Upper Midwest. Again I feel lucky in the face of other families’ misfortune.

Boreal forest fires are usually sparked by summer lightning strikes. Until recently they have been a routine but not catastrophic force in shaping the far-north landscape. Every 100 to 150 years fire would run through stands of black spruce and other conifers, clearing the way for new plant communities to establish themselves. That was before global warming. These days less snow piles up through the winter. The thinner snowpack then melts away quickly, drying out the deep layer of slowly decay-

ing wood and conifer needles on the forest floor, turning the damp, springy mass into a crunchy bed of tinder. Now fires start earlier in the season than they used to, and they easily roar out of control. The boreal forests north of the border are vast, and they will only be growing drier and warmer.

The firefighters extinguished the apartment fire the same day, and the smoke cleared from our neighborhood, but our future remains hazy. Canada has a long fire season ahead, and worsening fire seasons every year for the foreseeable future. The smoke will always blow somewhere: to eastern Canada, to the Great Lakes and sometimes to the Mid-Atlantic.

Mostly thanks to luck and privilege, my family occupies a location and a class that have felt buffered from the worst of climate change so far. Philadelphia does not often get hit by hurricanes, unlike Florida, or Bangladesh for that matter. Wildfires increasingly happen somewhere else, like Hawaii or Manitoba, but not here. We don’t rely on farming in a drying place like the people of Guatemala’s Western Highlands Likewise we happened to buy a house well above the floodplains that spread over much of Southwest Philadelphia. And we can afford to turn on the air conditioning whenever it gets too hot.

Of course it is incumbent upon us and on our leaders to help everyone adapt — to do everything we can to keep survival from being a matter of luck and privilege, but another smoky summer reminds me that there’s only so much we can do in the face of a disaster that is truly global, in which conflagrations on the other side of the continent can still reach us from 2,000 miles away.

bernard brown , Managing Editor

Jason weckstein cranks open one lane of the massive movable storage unit holding one of the world’s 10 largest collections of birds, revealing stacks of long drawers, each filled with rows of still, silent birds. The ornithology research lab at Drexel University’s Academy of Natural Sciences (ANS) is home to more than 200,000 of these taxidermied study skins from more than 7,000 bird species.

Some of the oldest window-strike birds in the collection date back to the 1890s — common yellowthroats, warblers who met their fate in Philadelphia and surrounding coun-

ties. One common yellowthroat died after striking “City Hall Tower” on October 9, 1900. Bird deaths due to window strikes are on the rise with modern architectural practices producing urban buildings with more and more glass. Birds can’t see that glass is not a passable surface, causing them to collide with it and often die. Without proper protective measures being taken to prevent birds from crashing into glass, the numbers are bound to continue increasing. Upwards of a billion birds die in window collisions in the United States every year, and a recent study by Muhlenberg College researchers indicates that the total number of avian ca-

litchkofski

sualties could be as high as 3.5 billion.

Weckstein is an associate curator of ornithology at ANS and an associate professor in the Department of Biodiversity, Earth and Environmental Science at Drexel University. Beyond the research at his lab, he takes part in managing the window-strike birds dropped off by Bird Safe Philly’s volunteers.

After a volunteer deposits a dead window-strike bird at ANS, it is put in a freezer until the time comes to process it. Academy scientists skin the bird and take samples of the muscle, heart and liver tissue and preserve any parasites — such as lice — that they find. They then stuff the skin with

batting and use pins and string to ensure that it dries in the form it had in life. The preserved bird then rests in a drawer of the expansive storage unit, waiting to be removed for future research.

“Our group has done everything from monitoring window strikes to identify problem areas in the city to treating glass on some smaller buildings to reduce strikes,” says Weckstein. “At the ANS we house the specimens that come from window strikes, as this documents these events in a way that researchers can go back to decades after the occurrence.” ◆

At the ANS we house the specimens that come from window strikes, as this documents these events in a way that researchers can go back to decades after the occurrence.”

jason weckstein, Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University

Fishtown Pickle Project highlights local seasonal produce and bold flavors with collaborations for a cause story and photos by julia lowe

On a typical monday at Fishtown Pickle Project, cucumbers are everywhere: being rinsed, flying through the spear cutter—affectionately named Britney Spears—and getting stuffed into jars with garlic and seasonings. The aroma of vinegar wafts down the hallways of their manufacturing center in the Globe Dye Works building in Frankford, where the staff processes roughly 3,000 pounds of cucumbers each week. Today’s cucumbers will become their Original Sour pickles, says Niki Toscani, co-founder and dietitian at Fishtown Pickle Project.

“We’re still very scrappy,” Toscani says as she squeezes through the narrow corridors of the kitchen, where every table is covered with glass jars and the walls are lined with produce bins and brine tanks.

Toscani co-founded Fishtown Pickle Project with her business and life partner chef Mike Sicinski in 2018. Seven years later, they pride themselves on making small batch, culinary-inspired pickles, where each cucumber is still “touched by hand.”

“A lot of the things that we do are rooted in our value system of sustainability, tradition, wellness, and making bold flavors,” says Toscani.

The couple met through their careers in the food industry, teaching healthy cooking on a budget at a local food bank. Sicinski always had a personal interest in pickling, and occasionally made pickles as gifts for friends and family. When the two got mar-

The project is to create joy, connect our people with small businesses, local farmers, and hone in our craft of making a better pickle.”

— niki toscani , Fishtown Pickle Project

ried, Toscani suggested giving out pickles as a wedding favor at their reception.

“People kind of lost their minds and wanted more,” Toscani said.

That first flavor from their wedding reception — Zesty Sweet Garlic —is still in production today.

“That’s the flavor that got us in business,” says Sicinski. “That just was the pickle.”

That fall marked the first annual Pickledelphia festival in Northern Liberties, so the “crazy newlyweds” incorporated as an LLC and joined as a vendor. Fishtown Pickle Project has since grown to eight employees, and their flavor lineup now includes four other core flavors: Original Sour, Philly Dilly Deli, Habanero Dill, and Sweet Onion.

Every six to eight weeks, they also rotate in

a new limited batch of pickles. These limited batches are where the “project” part of the business name becomes obvious: they often feature unique seasonal pickled produce, experimental flavor profiles, or collaborations with local farms or small businesses.

“We just released our ginger lemonade pickles, and our friends at Nourish Cold Pressed Juice made a Philly Dilly pickle lemonade,” says Toscani. Both businesses will donate a portion of proceeds from this collaboration to The Attic Youth Center, an organization that works to create opportunities for LGBTQ+ youth in Philadelphia.

Previous limited batches have featured produce like okra, jicama, and asparagus. But highlighting seasonal local produce is not just a culinary goal for Fishtown Pickle

Project. Sourcing ingredients as locally and sustainably as possible is central to their mission. For most of the year, cucumbers are not grown locally, but from July through September, FPP partners with Muzzarelli Farms in Vineland, New Jersey to pickle only local cucumbers.

“The project is to create joy, connect our people with small businesses, local farmers, and hone in our craft of making a better pickle,” Toscani says.

Unlike many other pickles on the market, Fishtown Pickles are acidified or “quick pickled” rather than fermented. This method uses a vinegar-based brine instead of saltwater and is followed by immediate refrigeration, leaving the acid to build flavor and retain crunch.

“That’s how we get big, bold flavors and crunchy pickles,” Toscani says.

Packing their product in glass jars was an important sustainability practice for Fishtown Pickles from the start. “Glass is very hard work. It’s very heavy. It’s expensive. It breaks. It has a lot of challenges, but it also lasts forever,” says Sicinski. They accept empty jars back from customers, and also work with Bottle Underground to collect used jars. “They get sanitized and put right back into production.”

Reducing food waste is another one of their key sustainability initiatives. Any cucumbers that are misshapen or too small get cut into bite-size pieces and added to the tops of each jar. They also compost food scraps with Bennett Compost.

“We’re nearly zero food waste, which is something that we’re very proud of,” says Toscani.

Toscani and Sicinski also host pickling classes in their production kitchen, where they teach customers not only how to make their own pickles, but also how to reuse brine and seasonings for other cooking purposes.

“It’s so refreshing to connect with people face to face and have people say things like, there’s no other pickle like this pickle,” says Toscani. “The process is what makes this product so special.”

Fishtown Pickles are available at all locations of Kimberton Whole Foods. “They are very dear partners of ours.”

by marilyn anthony

Estere alveno-marius remembers the first time she tasted comparette (also known as konparèt), the sweetly spiced gingerbread-like treat that originated in Jérémie, the capital of Haiti’s Grand’Anse region. A friend visiting Alveno-Marius in her hometown of Saint-Louis-du-Sud brought the pastry as a gift. One taste and Alveno-Marius understood how the fragrant coconut sweet

bun got its name, a Creole interpretation of the French phrase, “quand’l paraît’t,” roughly translating to “eat it quickly when it shows up.”

In 2018, at the age of 45, Alveno-Marius left Haiti to join her husband, Jude Patrick Marius, in the United States. He had initially looked for work in Florida but found more opportunity in Philadelphia. Alveno-Marius left a good accounting job in Haiti to reunite

with her husband. They settled in a Northeast Philadelphia neighborhood, home to a vibrant and growing Haitian community. Still, Alveno-Marius is keenly aware of all she gave up. “The hardest part of coming here was leaving behind all my traditions, my language and my culture,” she says. “Everything was different for me. I had to start at the bottom of my profession to find work.”

One bit of continuity came in the form of baking. Just over a year ago Alveno-Marius returned to her mother’s recipe for a family favorite, bonbon sirop, and began experimenting with comparette, too. As a child she helped her mother make bonbon sirop, a soft bun or cookie flavored with

The hardest part of coming here was leaving behind all my traditions, my language and my culture.” estere alveno-marius

ginger and cinnamon and sweetened with sugarcane syrup. She watched her mother mix the dough — judging by eye and feel, not measuring cups — to get the right consistency. Then her mother baked the pastry in a makeshift outdoor oven she had built from a box lined with aluminum foil and heated with burning coals. Alveno-Marius and her six brothers and sisters would devour the cookies, but some were set out on a roadside table where passersby could purchase them.

Recently Alveno-Marius has been looking for ways to realize her childhood dream of owning a bakery. For now she is baking small batches of Haitian cookies and breads, selling them at her church and a nearby beauty salon. Alveno-Marius, who last year completed an entrepreneurship

class at The Welcoming Center, has a ready answer for why an accountant would start a bakery: “I know people like eating food, and I like making it for them. When you know someone likes something, then you make it.” She confesses, though, that she doesn’t enjoy cooking as much as baking. “My husband sometimes cooks for me, so I am very lucky,” she says.

Alveno-Marius envisions offering customers her sweet tooth-satisfying comparette and bonbon sirop but ultimately aspires to more than a bakery. “I’d like to have a big, beautiful place in Philadelphia that helps people from every nation, not just Haitians, with various services and immigration needs,” she says. “I think one day I don’t just want to get a paycheck. I want to have my own business. This is my dream.” ◆

Serves 6

1 ½ cups unsalted butter (3 sticks)

1 cup sugar

1 tablespoon lime juice

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1 ½ cups unsweetened shredded coconut

2 ¼ cups all-purpose flour

1 tablespoon ground cinnamon

¼ teaspoon nutmeg

1 teaspoon coarse kosher salt

2 teaspoons baking powder cup finely diced ginger

1 teaspoon almond extract

1 teaspoon finely grated lime zest

• Preheat the oven to 350 degrees.

• Using an electric mixer, beat the butter and sugar in a large bowl until well blended. Add the lime juice and vanilla extract and mix in.

• Add the shredded coconut, flour, salt, lime zest, ginger, nutmeg, cinnamon, almond extract and baking powder, and beat on low until the mixture clumps together.

• Use your hands to form the dough into a ball. On a lightly floured surface, roll the dough out to ¼-inch thickness. Using a glass or a biscuit cutter, cut into rounds about 2 to 3 inches across.

• Bake on a greased sheet pan for 20 to 30 minutes or until golden brown.

My first four columns covered different ways to collect food waste from residents. But collection is only the start. Once food scraps are collected, they need to be composted. This is where it gets tricky. We don’t currently have enough permitted composting facilities in the region to handle all of the food scraps. So what can we do about this?

First, some background. Any composting facility that is larger than a backyard system and accepts outside food scraps needs to be permitted by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). Prior to 2022, if you weren’t a farm or a quarry — which had their own permits — it was difficult to obtain one. In 2022, guidance from the City of Philadelphia and Bennett Compost prompted the DEP to amend the farm permit to allow small- and medium-scale composting facilities to exist anywhere in the commonwealth provided they met reasonable requirements. This led to the creation of Philadelphia’s only two permitted composting facilities.

by

tim bennett

And opened the door for more. Building a network of small-to-medium facilities throughout the city would create a resilient composting infrastructure not dependent on one mammoth or two large regional ones. The closure of Wilmington, Delaware’s largescale Peninsula Compost Facility in 2015 for odor and other public nuisance was a major setback for composting in this region, and we must heed the lessons of that history. Small-to-medium facilities have lower risks of nuisance, reduce the distance food waste has to be transported and are easier to build. Local composting creates more jobs and is

Local composting creates more jobs and is more likely to connect the finished product (soil) to local community gardens and farms.

more likely to connect the finished product (soil) to local community gardens and farms. Small-to-medium facilities are more likely to be operated by local businesses committed to composting rather than large, multinational corporations that too seldom deliver on their promises related to composting and recycling. The reasons go on and on.

The main challenge with small-to-medium facilities is the initial investment necessary for construction. This is where the City could play a role. Identifying public land where composting facilities could be set up, helping to build the sites out and then operating these in partnership with local companies would lower some of the costs. The City could reap such benefits as free collection of material from City properties, access to high-quality finished compost and opportunities for compost education, training and workforce development.

The most obvious place for such a public-private partnership to take shape is the Fairmount Park Organic Recycling Center, the City’s leaf and yard waste composting facility. An EPA grant that would have funded laying the groundwork for a food waste composting system on the site fell victim to the recent DOGE cuts. The City has — to its credit — expressed interest in finding outside monies to fill the gap, but I’d argue that the work should proceed even without a replacement influx of cash: $150,000 is a lot of money for you or for me, but not for a city government serious about composting.

The grant also would have funded identification of other potential locations for composting facilities. Underutilized public land on Water Department and Parks & Recreation properties could fit the bill. The City’s Rising Sun Avenue Composting Facility is a demonstration of how small-to-medium facilities can be operated on smaller parcels, closer to other businesses and residents, thus expanding the portfolio of available spaces.

Increasing our capacity for composting in the city is necessary to move beyond pilot collection projects. There is an appetite for more collection of food waste and for more locally made, high-quality soil products. We just need to build the infrastructure. Let’s do this, Philly! ◆

tim bennett is the founder of Bennett Compost. Alex Mulcahy, publisher of Grid, is also a partner.

Since 2012, Circuit Trails has made strides connecting the region. Local governments and residents are on board, but will the Trump admin stymie its progress? by emily kovach

Almost any cyclist or pedestrian knows the pleasure of cruising down a trail without a car in sight. Usually, the open-road vibe only lasts for a limited time before the reality of near ubiquitous traffic reasserts itself. The mission of the Circuit Trails, one of the nation’s most ambitious multiuse trail networks — right here in our own backyard! — is to provide hundreds of miles of connected car-free paths across the region.

That might look like biking from Center City out to the bucolic woods of Bucks County, or from Camden’s waterfront to Bartram’s Garden, or from Fox Chase to the Pennypack Trail, without ever sharing the road with a motorized vehicle.

Circuit Trails was formed in 2012 by a coalition of nonprofits, agencies and foundations, springboarding off earlier successes like the Schuylkill Banks trail. The vision was to raise the public and political profile of bicycle and pedestrian trails and position the Circuit Trails concept as a high-level regional priority. It’s now overseen by leadership and steering committees; members include representatives from entities like Disability Pride Pennsylvania, Natural Lands, Fairmount Park Conservancy and the East Coast Greenway Alliance.

Patrick Starr, executive vice president of the Pennsylvania Environmental Council, is Circuit Trails’ chair. He has been involved with trail work since the early aughts and was one of the founding Circuit Trails members. The early Circuit Trails coalition set ambitious short- and long-term goals: to have 500 miles of completed connected trails by 2025 and 800 miles by 2040. There were around 225 miles already completed at the time.

“We knew it wouldn’t be easy,” Starr recalls. “The question is: How do you make this happen? How do you accelerate and

make the system respond and actually build those trail miles?”

They started by pounding the pavement, traveling to the various counties around Philadelphia, meeting with county commissioners and other stakeholders, touting the benefits of an expanded trail network, like increasing real estate property value, potential healthcare savings with a more active populace and positive environmental outcomes. Over the past decade, they secured the support of 120 municipalities in nine counties in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, which all passed resolutions in support of Circuit Trails’ goals.

Cut to June 2025: there now are 417 miles of fully completed trails with another 88 miles in active design or construction and a number of exciting projects in the planning stages.

A huge recent win is the Christian to Crescent trail project spearheaded by the Schuylkill River Development Corp. This new trail, which opened in May, is a key link in creating an off-road pedestrian and cyclist route along the Schuylkill River, with a trail access point on the east side of the 34th Street Bridge with a tunnel connection to Grays Ferry Crescent under the bridge and access to nearby Christian Street connecting to the existing segment of Schuylkill Banks. The Schuylkill Crossing swing bridge, slated to be completed by the end of 2025, will create a link to Bartram’s Garden and Southwest Philadelphia.

Cobbs Creek Trail, part of the East Coast Greenway and the September 11 National Memorial Trail, is another project in the works. This 4.2-mile trail currently ends at Woodland and Island Avenues. The second phase, led by the Philadelphia Streets Department, will extend the trail by another 1.3 miles, all the way to the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge.

Selling the vision hasn’t been difficult, according to Patrick Monahan, regional organizer with Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia, who has been on the Circuit

Trails steering committee since 2021.

“County commissioners get it. They see why it brings positive change to their county and connections to other counties,” Monahan says. “They’re seeing it less as a recreational feature, and more as an extension of the transportation network.”

A heavier lift is securing the funding to plan, design, build and maintain trails across hundreds of miles of terrain.

“At this point we get a lot of yeses from our elected officials, but there’s almost always a ‘but.’ Budgets are tight,” says Starr. “We can bring in money from the federal government and state dollars, but there ultimately has to be time and staffing and

some expenditure from local governments.”

Circuit Trails has indeed found success in securing government funding, including support from the Biden administration’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Federal Highway Administration’s Carbon Reduction Program.

Also, in July 2024 the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC) came through with $120 million in federal Carbon Reduction Program funding for the Circuit Trails as part of its Fiscal Year 2025 Transportation Improvement Program, with a focus on priority projects, like the Cross County Trail in Montgomery County, the Chester Valley Trail in Chester County,

County commissioners get it. They see why it brings positive change to their county and connections to other counties.”

patrick monahan, Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia

Spring Garden Street Greenway (a brandnew, off-road path connecting the Delaware River to Eakins Oval) and the Route 291 Trail/East Coast Greenway.

However, with the Trump administration signaling a lack of support for bicycle/pedestrian infrastructure and federal transportation programs like ReConnect and Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity coming under scrutiny, there is new uncertainty about the future of some of these projects.

The Wissahickon Gateway, at the sometimes confusing, hectic intersection of the Main Street and Ridge Avenue, was set to get a major facelift and functional upgrade. The concept was to install a new pedestrian bridge across the Wissahickon Creek that would thread along the Schuylkill River to the Pencoyd Bridge and provide pedestrians and cyclists a clear, safe way to continue into Manayunk.

The project was awarded a $13.7 million grant from the Biden administration in January 2025, but there has been no response from the Trump administration about the status of those monies.

“It’s been a massive turn,” says Monahan. “We’d picked up a lot of momentum toward the end of Biden’s administration with all the transportation funds and carbon reduction funds, and growing the partnership between county commissions, county planners, DVRPC and other organizations. Now, we have to identify a different pool of funds.”

The Circuit Trails coalition remains undeterred, actively urging Pennsylvania and New Jersey representatives to fight for transportation infrastructure funding, refocusing on allies in Harrisburg and Trenton for alternative funding streams. The goal of 800 miles by 2040 has increased to 850, and more local governments and citizens are expressing interest by the day. Starr is confident that the broad appeal and numerous benefits of trail networks like these are strong enough to keep political will galvanized and funds flowing.

“Some people think this is just about long-distance trails, but a trail network is really about making connections and gathering places, which people just love,” says Starr. “And ultimately, Circuit Trails is a multipurpose trail network that also serves pedestrians and cyclists, including people of all ages and abilities. No matter your political persuasions, trails are a happy place.”

It’s easy to feel hopeless. A global disaster-in-progress can do that to you. There are 8.2 billion of us humans on this planet, and we are each so tiny, and, on our own, we each have so little we can do to fight climate change and adapt, when adaptation so clearly requires large-scale action. ¶ In this section we hope you learn more about the nuts and bolts of how a shift to renewable energy would have to work, how electricity gets from a fossil fuel power plant or a solar panel to your house via the PJM grid. ¶ Unfortunately federal policy backslides could make it costlier to electrify your home or transportation or to improve the energy efficiency of a property. Going green is a massive undertaking, and it looks like this country isn’t undertaking it. ¶ So what can one 8.2-billionth of the world population do? We hope that the life and work of activists like George Lakey suggests a path forward: Keep trying, even when it feels hopeless.

A resiliency park along Manayunk’s waterfront could beautify, increase accessibility and mitigate flooding

➤ STORY AND PHOTO BY JULIA LOWE

The morning after Hurricane Ida devastated Manayunk in September 2021, John Hunter stood looking over the intersection of Main Street and Shurs Lane, watching floodwaters carry away the back deck of the former Mad River building.

“As the waters were flying by, it got to the point where this bar became detached from its foundations and started to move and float,” says Hunter, zoning chair for Manayunk Neighborhood Council (MNC). “This whole bar just floated down the street.”

Manayunk is one of Philadelphia’s most flood-prone neighborhoods. When the Schuylkill River floods, the adjacent corridor east of Shurs Lane — referred to as lower Main Street — can be engulfed by feet of water, as the floodplain extends as far as Station Street, about halfway between Main and Cresson Streets. And projections show that this corridor has extreme levels of flooding risk over the next 30 years.

Lower Main Street is a conundrum for development. Historically, much of the corridor has been zoned for industrial commercial mixed use, but it hasn’t been reclassified in over a decade, leaving the area “frozen in time,” as Hunter calls it.

“This is perceived as being run-down, neglected, not very attractive,” says Hunter. “And it’s the connection between the city from Kelly Drive to the commercial corridor [of Manayunk]. So there’s an obvious problem.”

For years, MNC members have been pushing to transform the lots between Main Street and the Schuylkill River into a resiliency park. Hunter, an architect and Manayunk resident of 35 years, has been working with zoning in the neighborhood for nearly two

decades. He maintains that this corridor is simply unsafe for residential development, as there are no evacuation routes from Main Street for nearly a mile from Shurs Lane to where Main Street meets Ridge Avenue.

“If you build anything here, people can’t get out. They’re stuck,” says Hunter. “The only people that can get in and out are first responders in dinghies. And even they are in danger because there’s all sorts of stuff flowing down the river: trees, dumpsters, all sorts of things.”

And yet, residential developments are in progress: the former G.J. Littlewood & Son textile mill at 4045 Main Street is set to be developed into a seven-story apartment building with two floors of parking on the ground levels. The developers appealed for a zoning variance to allow residential use of the site.

At a May 7 zoning hearing addressing the proposed development, Abby Sullivan, chief resilience officer for the City’s Office of Sustainability, stated in public comment that the office is “opposed to variances that bring more residents into the floodplain,” citing “significant risk to life and property.”

In an email to Grid, Sullivan wrote that although she couldn’t comment on specific proposals, a concept like the resiliency park is something the Office of Sustainability would support, as an alternative to “putting homes or businesses in a location with high flood risk.” She called the idea of a park a “common-sense approach,” a phrase also used by Hunter to describe this land use, as it would be compatible with the inevitable flooding.

“It is land which is relatively cheap at the moment to acquire. And it will then have a function which attracts and connects with Kelly Drive and Fairmount Park and the commercial district.”

Resiliency parks along waterfronts, in addition to providing recreational spaces for pedestrians and cyclists, can accommodate and recover quickly from flooding with minimal cost and disturbance, Hunter says. With flood-resilient design techniques and natural vegetation, such parks can mitigate stormwater and create drainage that reduces the impact of a storm or a flood event.

In July 2024, East Falls Development Corporation and Manayunk Development Corporation published a flood mitigation study that explored strategies like creating a linear park feature along the Schuylkill River. Such a park would “provide a buffer between the river and the neighborhoods, increase floodplain storage, incorporate other mitigation strategies such as berms and bank stabilization, and provide a space designed to flood and recover quickly.”

The study found that a resiliency park

would offer multiple benefits to the community and had a high amount of neighborhood support. But it also found that the project would likely require multiple grants and government funding, and that it would take many years for residents to see its flood mitigation benefits.

Hunter believes that the park could be incrementally developed over several years, by acquiring the lots along the river (many of which are vacant) on a piecemeal basis. MNC has been working to apply for grants, in partnership with Manayunk Development Corporation and with the City Planning Commission, to consider the park as a flood-resilient alternative to residential development.

MNC is not alone in supporting the idea of a transformed, flood-resilient riverfront: a group of second-year students from Thomas Jefferson University’s landscape architecture program created designs re-

It is land which is relatively cheap at the moment to acquire. And it will then have a function which attracts and connects with Kelly Drive and Fairmount Park and the commercial district.”

JOHN HUNTER Manayunk Neighborhood Council

imagining three parking lots at 4000 Main Street as a sustainable public nature park. Their projects, which were exhibited in the Manayunk Development Corporation’s welcome center this spring, explored strategies for managing stormwater runoff, enhancing the natural landscape and improving public access to the Schuylkill River. Hunter hopes that this exhibit can help garner more community support for the park.

“I think it would be great if we could somehow muster enough energy to get a grant to piggyback on the mitigation study, and do a resiliency park study that would give people some understanding of what we’re trying to suggest.”

In Hunter’s vision, the park would have a cycle path from Lock Street to the Pencoyd Bridge — a path that would run parallel to the proposed Schuylkill River Trail extension between Venice Island and Kelly Drive. This completed segment would cross the Schuylkill at Venice Island and follow the river on the Montgomery County side before crossing the Pencoyd Bridge back into Manayunk. Hunter says that there is enormous potential for a cycle path along Main Street, which would help direct cyclists away from the dangers of parked cars along the current narrow corridor.

The problem, Hunter says, is that, in the meantime, residential development is more likely to get financial backing than a public park. But there might be a way, Hunter says, for these two visions for lower Main Street to coexist.

On the north side of Main Street, if there were a way to construct flood evacuation routes behind the properties next to the railway, Hunter says residential development could be possible — and these potential units would be more valuable, he argues, as they would overlook a riverfront park.

Although many community members like the idea of the park, without a formal course of action or support from City agencies, it is, Hunter says, “a long, hard road.” ◆

Despite being within a floodplain, residential living is coming to the Navy Yard for the first time this fall. Will it stand up to greater rainfall and sea level rise? ➤

STORY BY KYLE BAGENSTOSE

EDITOR’S NOTE

A version of this story originally appeared in hidden city in 2024 and is shared courtesy of that publication.

For nearly two centuries, humans and Mother Nature have tangoed on League Island, the most southeasterly expanse of land in Philadelphia, known today as the Navy Yard. For the most part, humans have gotten the better of it. Over the centuries, engineers, sailors and industrialists turned what was

once a low-lying island at the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers into a 1,500-acre piece of modern urbanity, replete with giant shipyards and commerce of all types. But as the Navy Yard moves into its next chapter of human habitation — residential living — does it risk the tides turning in favor of Mother Nature?

This is a question that is swiftly moving beyond the theoretical and into the practical. In 2023, vertical construction began on two large apartment buildings at the Navy Yard, with a combined 614 units. With the

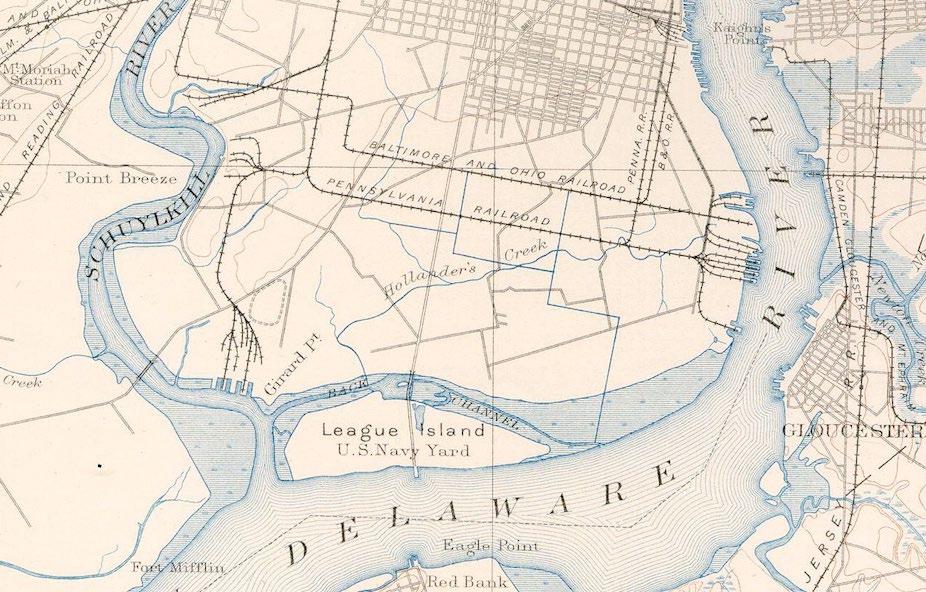

Apartment buildings under construction at the Navy Yard, which was originally built on the marshy and flood-prone League Island [shown on opposite page in 1891 map] will add residential units — and risk — as climate change raises sea levels and brings more-intense storms.

projects on schedule for a late 2025 opening, by the end of this year the area will see its first civilian residents in historical memory.

The projects’ proponents say that’s a great development. After the City largely assumed ownership of League Island from the U.S. Navy in 2000, the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC) assumed responsibility for its redevelopment. Early master planning was successfully executed: the Navy Yard now houses “15,000 employees and 150 employers who occupy 8 million square feet” across a variety of commercial enterprises, according to its website.

But what has been missing, its development team says, is residential. Due to a smaller, continued presence of the U.S. Navy, as well as a deed restriction, residential development was forbidden until just the past few years. Real estate development firms Ensemble and Mosaic were selected to bring it to fruition in 2019, and in 2023 the residential deed restriction was lifted, clearing the way for a groundbreaking in the fall of that year.

Jeffrey Brown, director of development for Korman Properties, the sub-development

firm constructing and managing the new buildings, views his firm as an integral part of the Navy Yard’s ongoing revitalization.

Korman’s vision, aligned with PIDC’s, is one of a thriving urban neighborhood where residents can live in close proximity to their places of work, as well as nearby commercial, cultural and recreational amenities.

“This was an opportunity for us to really create a new neighborhood for the first time in a generation,” Brown says. “It’s really providing an opportunity for people of a wide variety of demographics, or socioeconomic status, to live, work and play in one place.”

But redevelopment of the Navy Yard is not without opposition. Josh Lippert, a professional floodplain manager and former chair of Philadelphia’s Flood Risk Management Task Force, doesn’t mince words about his concern for residential development at the Navy Yard. Currently, he points out, nearly the entire site exists within the federal government’s designated floodplains. Conditions are expected to only worsen over the coming century as climate change raises sea levels, which, in turn, will push the Delaware River’s tidal waters higher.

This was an opportunity for us to really create a new neighborhood for the first time in a generation.”

Combined with increasingly intense rainfall, as well as the relatively few access points between the Navy Yard and the rest of Philadelphia, the addition of residential units adds significant risk if people become trapped in the buildings by floodwaters, Lippert says.

A nine-to-five office use is one thing, but the risk escalates exponentially once people are living on-site and subject to floodwaters rising 24/7, especially as they sleep overnight.

“It’s unsafe. If there is a medical emergency, or any other compounding issue occurring — a fire in the structure — that is going to really increase life safety concerns in those buildings,” Lippert says. “Egress is the biggest issue. There is really only one way out of that site.”

Humans have been eyeing up League Island for some time. According to an 1898 description in The Philadelphia Inquirer, League Island got its name from the eponymous unit of distance, which equates to three miles by land or three-and-a-half nautical miles. Indeed, a satellite measurement of today’s land formation shows a length of just under three miles.

Also according to the article, League Island appeared to originally be attached wholly to what is now Greater Philadelphia before softer soils were eroded by action of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers and a channel was formed connecting them, separating a large patch of land from the main-

land. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP) further notes that League Island was one of just several in the vicinity dating to the Colonial era and earlier and that just offshore from the island were “once sandbars known as the Horseshoe Shoals.”

By the late 1600s, the “peculiarly advantageous position” of League Island was recognized by the land company of London, which built a fort there, the Philadelphia Inquirer piece reported. A century later, in 1783, the island was annexed by Pennsylvania in negotiations with New Jersey, after a delegation from both states agreed to award possession of Delaware River islands based on their proximity to the nearest shoreline.

HSP records that it didn’t take long for development to begin in earnest, in the early 1830s. According to research materials obtained by the organization, “Transcribed and printed letters between Charles Wharton Jr. and Richard Delafield, Captain of U.S. Engineers, and others, concern Wharton’s desire to build a causeway to connect League Island to Philadelphia at Broad Street.”

Wharton, a businessman with interests in the iron industry, wanted to make use of the island for the burgeoning coal trade coming from Pennsylvania’s interior. Delafield approved, explaining to Wharton how he might go about erecting the causeway and piers. Navy Commodore Charles Stewart also approved, HSP noted, as he believed development would also accommodate ice commerce in the winter and provide a safe harbor for ships. Wharton eventually won approval from the state, clearing the way for industrial development.

But the U.S. Navy itself soon had the island in its crosshairs. A brief history featured on the Navy Yard’s website highlights League Island’s role in the “Birthplace of the U.S. Navy,” as a second home for the service in Philadelphia.

“Dating back to the founding of the country in 1776, the Continental Congress leased land along Philadelphia’s Front Street docks to support naval defense,” the article first notes. By 1794, President George Washington signed the Naval Act to build six frigates for the United States, the first of which was built in a shipyard near Carpenter Street and launched in 1797. That shipyard quickly expanded into an official U.S. Navy facility, the Southwark Yard, which stretched from

Egress is the biggest issue. There is really only one way out of that site.”

Federal to Reed streets.

But by the arrival of the Civil War and subsequent ironclad ship technology, the Southwark Yard was in danger of obsolescence compared to piers in Massachusetts and Virginia. The U.S. Navy sought new grounds, and an idea for the Navy Yard at League Island was born. The City purchased the island in 1862 for $310,000, transferred its 923 acres to the U.S. Navy for $1, and construction of a new shipyard began in 1871. Over the next century, 53 warships were constructed and an additional 1,218 were repaired. The land was also further transformed, and League

Island became an island no more.

“The eastern portion of the small channel that still separated the island from the mainland was eventually filled in order to make room for a new airfield, Mustin Field, while a western portion of the channel was kept as a reserve basin for ships,” according to HSP.

Yet, by the late 20th century, time was also passing by for the Navy Yard. The last new ship to be built, the Blue Ridge, launched in 1970. A federal decision to close the base arrived in 1991, which officially occurred in 1996, precipitating the City’s redevelopment plans.

Work is underway at the Navy Yard to convert the former Receiving Station and Barracks Building into The Waylen, a 223-room full-service

Fortified against floods?

League Island has always been a place tied to the water. News reports as far back as 1889 describe storm surges causing the Delaware River to overflow into its meadows. In 1910, a Philadelphia Inquirer piece titled “Storm-swollen rivers invade city streets” described League Island as “practically cut off from the city” for several hours.

“The flood from both rivers widened the back channel and made a broad lake,” the newspaper reported, adding that workers were stranded until the tide went back out.

So can residential development really be made to live harmoniously in a place with such close proximity to Philadelphia’s two rivers, in a century when the climate is changing and seas are rising? The Navy Yard’s development team believes so.

A 2022 master plan envisions development of 3,900 total residential units at the

site, a significant expansion over prior plans. The two Korman properties, part of the company’s AVE portfolio, are the first to break ground. AVE Normandy, at 1200 Normandy Avenue, will have 267 apartment units, including 100 short-term rentals for corporate clients. A second building, AVE Constitution, at 1225 Constitution Avenue, will have 347 units, including 92 units designated for “mixed income” residents making 60-120% of area median income, says Brown.

Normandy will contain one, two and three-bedroom units, while Constitution will include studios, one and two-bedrooms. Extensive planned amenities include a fitness center, elevated pool deck, lounges, co-working and meeting spaces, bike storage, a café and ground floor commercial spaces.

Brown says Korman believes the $285 million development will have three target

customers: white-collar workers already employed at the Navy Yard who want to live where they work, Millennial-aged Philadelphians looking to relocate to a less-dense part of the city with a mix of urban and suburban amenities and retirees from the region looking to downsize.

There are not yet official plans for additional residential development beyond the two buildings, but Brown says Korman remains in talks with the development team and that nothing has been “ruled out” for residential, including the potential for home ownership. But what about flooding?

Kevin Lessard, vice president of marketing communications and government affairs for PIDC, says the corporation “acknowledges the importance of addressing flood risk,” and that the 2022 master plan “includes a comprehensive resilience strategy to address flood risk, climate change and

sea level rise.”

“This includes both short- and long-term sustainability initiatives and engineering solutions including elevating the land and infrastructure, incorporating innovative stormwater infrastructure including canals and swales along the streets on the east side of the campus to convey stormwater, and using dry ponds, green roofs and resilient landscaping, coordinating with public safety agencies on emergency preparedness, and regulatory compliance including compliance with building codes and zoning regulation,” explains Lessard.

In a comprehensive 2022 article on the issue, WHYY’s Sophia Sch midt polled numerous regional planners and flooding experts about the proposed safeguards, which also include an early alert system for residents to evacuate and an elevated roadway designed to maintain ingress and egress from the Navy Yard even in the event of four feet of sea level rise. Reviews were mixed, although numerous interviewees stated that it appeared the plans were about

as thoughtful as one could hope for when it comes to a parcel of land nearly entirely within federal floodplains. Lippert’s viewpoint stood out as the most critical and remains unchanged.

“The major elephant in the room is that this was an island … and it will once again be water in the future,” Lippert says.

He worries about a future event reminiscent of 1955’s Hurricane Diana, which Lippert calls the last major “catastrophic” event in the Delaware River’s history, having wiped out bridges, industry and other infrastructure along the river. With that kind of destruction a distant memory — indeed a Korman spokesperson noted that the Navy Yard has not experienced a “single significant flooding event” in the past 25 years — Lippert is anxious that developers are underappreciating the risk of what’s to come as sea levels rise and another storm of that magnitude lurks.

His biggest concern is trapped residents. The Korman buildings will elevate residential by leaving the first floor purely commer-

cial. But Lippert likens that to a piecemeal approach that raises properties out of the floodplain one “postage stamp” at a time. As is the case with recently developed residences in other flood prone areas of Philadelphia, like Manayunk’s Venice Island, that can still leave residents stranded within their buildings and potentially requiring rescue.

As the Navy Yard currently only has a few access points to Philadelphia, Lippert worries about the complications of emergency response, especially during a major regional event where power can go down and citywide rescues stretch resources thin. If that did come to pass, he places the greatest amount of responsibility not on the building’s developers, but on the City for what he sees as a lack of forward thinking and present-day regulation on development in at-risk areas.

“We don’t want to think about the future. We don’t think out to 2100,” Lippert says. “There’s no long-range planning because, at the end of the day, it’s four-year political cycles. They want the tax base.” ◆

Home electrification and increased production of renewables are the goals, but challenges with infrastructure, policy and markets complicate the green transition ➤ BY ANNE HYLDEN

Now — the water is boiling,” says Jen Hamilton, calling attention to the pot on her stove. She lifts the pot and places her other hand flat on the cooking surface. She remains uninjured. “It’s safer!” she exclaims, explaining that her cats used to inadvertently turn on the gas on her old stove by bumping the knobs.

“We are now completely electric,” says Hamilton. With the induction stove for cooking and a heat pump for climate control, she

and her husband, Phil Salkie, have eliminated the need for natural gas in their home. They even called PGW to have someone cap the gas line to their house and remove the meter from their wall. “That was a wonderful feeling,” Hamilton adds with a smile.

Electrification, à la Hamilton and Salkie, is catching on. But the International Energy Agency cautions that for electrification to make any dent in global carbon dioxide emissions, energy generation needs to shift

to low-carbon sources. Think about it: if you buy electricity from a gas power plant, then your carbon footprint is about the same as if you had burned the gas in your kitchen. So, how do we know where our energy is coming from? And what can we do about it?

Unfortunately, whether you buy energy from PECO or a renewables-only provider, you can never control which generation sources you’re tapping, due to the complexities of the system we call “the grid.” But this doesn’t mean that consumers are helpless when it comes to choosing power sources. Far from it.

hamilton and salkie installed solar panels on their roof in 2017. On sunny days, the panels generate enough electricity to charge their Tesla Model S, an electric motorcycle and their electric bikes — and keep their lights and appliances on. But since some days aren’t sunny, they also purchase electricity from a company that deals only in renewables and buys surplus solar energy from customers.

Hamilton is under no illusions about

what happens when she buys “clean energy” from this provider. “It’s not like the individual electrons are tagged and they find their way from the wind generator,” she says. Rather, “they put that much energy into the grid, we draw that much energy from the grid and bookkeeping happens.”

The bookkeeping happens via renewable energy certificates, or RECs. When a renewable energy supplier generates one megawatt-hour of electricity and delivers it to the grid, they are issued one REC with a trackable serial number. They can then sell that REC in an open market, enabling customers to claim ownership of that amount of renewable energy — regardless of where the electricity in their power lines actually comes from. Utilities like PECO use RECs to show that they’re meeting the state mandate to have 8% of their power supply come from renewable energy sources.

The REC market, however, is separate from the wholesale energy market. Here in the Mid-Atlantic region, energy is traded by a profit-neutral entity called PJM Interconnection. Daniel Lockwood, a member of the corporate communications team at PJM, says that “PJM’s primary responsibility is to keep power flowing 24 hours a day, seven days a week for 67 million people in 13 states and Washington, D.C.” At their headquarters in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, PJM dispatchers monitor the power levels in the

We are now completely electric.”

JEN HAMILTON homeowner

high-voltage transmission system.

A video produced by PJM shows the inside of their control room, complete with wall-sized monitors covered in glowing text and meter bars. Operators at desks bearing smaller screens watch the readouts to make sure that, as the demand for power fluctuates, generating stations are putting out enough energy to meet that demand. Dispatchers decide when it’s time for different power plants to “spin up,” and the order of the queue is based on bids — or, how many cents per kilowatt-hour each generator is willing to sell its power for that day.

Certain kinds of power plants will bid very low, to make sure they always stay online. These include plants reliant on technologies that take a long time to ramp up, like nuclear and coal, or sources where the operating costs are very low, like wind. “Actually, wind will bid a negative number,” says Barry Mather, chief engineer in the Power Systems Engineering Center at

the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in Colorado. “Because wind, at least currently, gets production tax credits.”

Other types of power plants — natural gas combustion turbines, for instance — always bid the amount that makes them an acceptable profit. So-called “peaker plants” don’t run very much and are often expensive, but they help out on days of peak demand.

“The typical way a market runs is they just stack them from who bid lowest to who bid the highest, and they go up the list” until the current demand is met, Mather explains through a video chat. “What some people miss is: everybody gets that price.” Once enough generators have come online, the highest of the accepted bids is what everybody gets paid by the distribution providers — your local utilities — who buy the power. About two-thirds of electricity in the United States is sold on this type of market. (And there are more nuances to grid dispatch, especially in response to line congestion or equipment problems.)

Mather’s research group at NREL is designing the next generation of inverters, devices that convert direct current at the generating source into alternating current. The new inverters will reduce the number of transformers — a different electrical device — needed to “step up” the voltage before electricity travels along those tall, long-distance power lines. Reducing the

number of transformers needed will help with lingering supply chain issues from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“To me, the industry is at a little bit of an inflection point,” says Mather. “Wind and solar and renewables in general have been the lowcost leader and have been building massive, massive plants everywhere.” Now, with federal subsidies potentially becoming scarce, he says, “we get to see if some of the advantages pencil out without as much support.”

one such renewable energy project is located near Gettysburg, Adams County. In Straban Township, solar arrays dot the rolling farmland. Some families in the area have leased small sections of their land to Adams Solar, LLC, a subsidiary of Energix Renewables. A third-generation farmer named Brian Redding owns two of the 15 parcels that are part of this industrial solar project.

“If you’re any sort of a landowner, you’re constantly being approached by developers,” Redding says over the phone. He sees the lease with Adams Solar as a way to future-proof his farming operation, which can suffer intermittent losses due to crop market volatility. And the small portion of his family’s land currently occupied by solar panels — 70 out of 385 acres — can go back to being farmland after 40 years, which is not the case for other types of development like housing. Plus, the solar company is paying 13 times more in taxes for that land use than Redding’s family was. That money

Every time you pay an electricity bill, you’re voting for the kind of energy future you want.”

ZOË GAMBLE CleanChoice Energy

goes into the local government and school.

Other residents of Straban Township don’t have such a positive outlook on the installation. “The vast majority of what I saw in the newspapers wasn’t really valid,” says Redding. “And it did kind of get boring time after time, going to these township meetings, hearing the same thing over and over.”

People would complain about solar panels ruining their views or raise questions about water quality, erosion and decommissioning. There was so much opposition that, eventually, Straban and other nearby townships changed their zoning ordinances to severely limit new solar projects.

One recurring complaint was that the energy produced by these solar panels is going to Philadelphia, since the City has a power purchase agreement with Adams Solar that — on paper — now provides 25% of the electricity used by municipal buildings in Philly. “A lot of people thought that they were going to bury a cable from Adams County all the way to Philadelphia,” says

Redding. “That’s not true at all.”

Redding’s older brother Doug has an apt metaphor for the grid. “Visualize a lake of electricity,” he says. Generating stations are like springs and streams that feed the lake. Then homes and businesses pump out what they need. But all the resources get pooled together.

Our lake’s capacity, however, is limited by the system we’ve built to contain it. And this is becoming a problem as both the demand for electricity and the desire to build more clean energy generators continue to increase.

when a developer wants to build a new generating station in the PJM service area, they need an interconnection permit to access the grid. Getting a permit requires inspections to ensure that the surrounding infrastructure can handle the additional power. This infrastructure includes long-distance transmission lines as well as substations, where voltage is either stepped up or down as power enters or leaves the grid. And if the infrastructure is already operating at full capacity, the cost of building a new substation falls on the developer.

This may be an expected cost for corporations building industrial-scale projects, but it can be an unpleasant surprise for homeowners who find out that the solar panels they want to put on their house would overload their neighborhood substation. “Most every time, those upgrade costs get passed on to the customer,” says Brandon Woody, a project manager at US Solar. “And those costs can become astronomical quite quickly.”

PJM has been so overwhelmed lately with interconnection requests that they stopped accepting new proposals in 2022 to work through their backlog. Although they’ve been making a dent, many renewable energy developers have needed to withdraw their requests, since lengthy delays can

POWER SHIFT

mean that landowner agreements expire or other problems arise. Politico’s E &E News reports that PJM plans to start accepting proposals again in 2026 and thereafter keep the wait times under two years. Rather than using a first-come-first-served approach, the company has started prioritizing “shovel-ready” projects to accelerate the pace of new construction.

But the new projects are not coming online quickly enough for growing demand. “Pennsylvania is on the same electric grid as Virginia, which hosts about a quarter of all data center capacity in the Americas,” write Penn State University professors Hannah Wiseman and Seth Blumsack, who study energy law and electricity markets, in an article for The Conversation. “Rising demand is also driven by the increase in electric vehicles and the replacement of gas- and oilbased furnaces with electric heat pumps.”

And the squeeze is starting to show up in electricity bills across the state, evidenced by a June 1 rate hike. These increased costs are due to both the imbalance in supply and demand, making energy a scarcer resource, and the need for local utilities to continue expanding and upgrading the physical wiring of the electrical system.

Lockwood, the PJM representative, says that PJM’s “key areas of focus” include keeping existing energy resources online as long as possible, reversing the retirement

of older power plants that have gone offline and supporting investment in natural gas pipelines. “It’s important to note that PJM remains neutral on energy policy or energy resources,” Lockwood writes. They’re just trying to keep the lights on.

what’s an eco-conscious consumer to do?

The Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission allows electricity customers to choose their supplier, meaning you can pick a utility company that buys RECs, as Hamilton and Salkie have done for their Manayunk home. “Every time you pay an electricity bill, you’re voting for the kind of energy future you want,” says Zoë Gamble, president of CleanChoice Energy. But as a recent Grid article explains, the process of shopping for a new provider can involve confusing options and misleading introductory contracts.

Putting solar panels on your house can reduce the net amount of electricity you draw from the grid, but there are tradeoffs. You can either pay high up-front costs to own your panels or essentially lease out your roof space — assuming you can find a solar company that operates in Philadelphia and is able to secure an interconnection permit.

Some states are seeing a rise in community solar projects, where households can pay a subscription fee to support a medi-

um-sized installation that feeds the grid. But Pennsylvania lawmakers have not yet agreed on how to legalize such developments. Apparently, though, there’s a different model that both is legal and bypasses the interconnection queue. Redding leases a small portion of his farm for community energy, in addition to his agreement with Adams Solar. “The energy is consumed within three miles of where it’s produced,” Redding says. “There’s no underground cables. There’s no substations.”

Creative solutions and new technologies will continue to offer hope for a carbon-negative future. But real change requires investment. “From a technical standpoint, it’s completely possible to operate the system however we want,” says Mather, the NREL engineer. “We can operate it with 100% coal if we want. We can operate at 100% renewable if we want. So it’s really a choice for us, as a society. But always the easiest choice is the economic choice.”

And renewable energy can be very economical — in the long run. Hamilton says, “We had to borrow money to put [the solar panels] on the roof, but they paid for themselves in five or six years” through RECs and savings in utility bills. And it sounds like she and Salkie just might keep blazing the trail toward energy independence.

“We keep talking … We’ve got the panels. Do we get the battery?” ◆

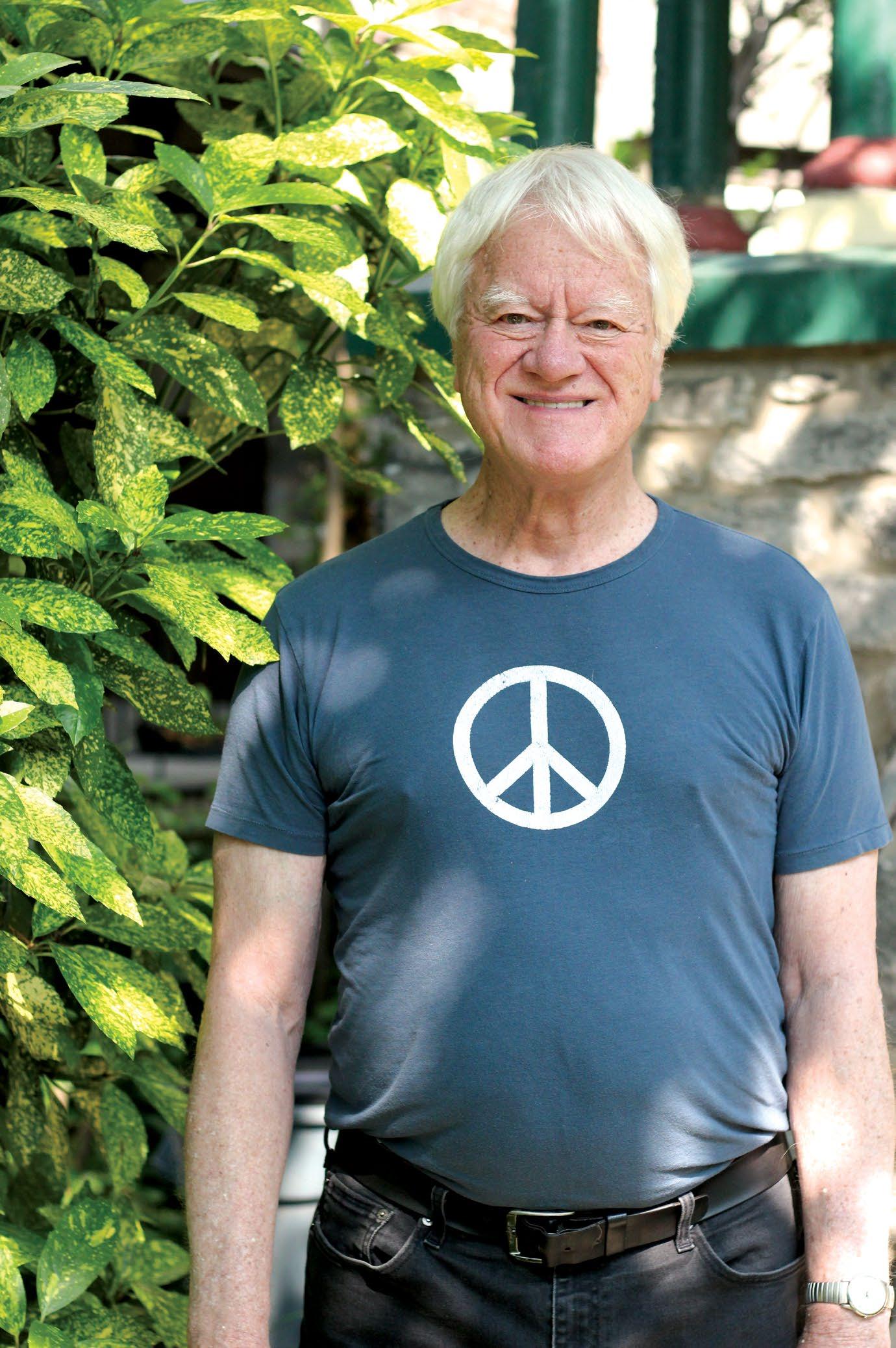

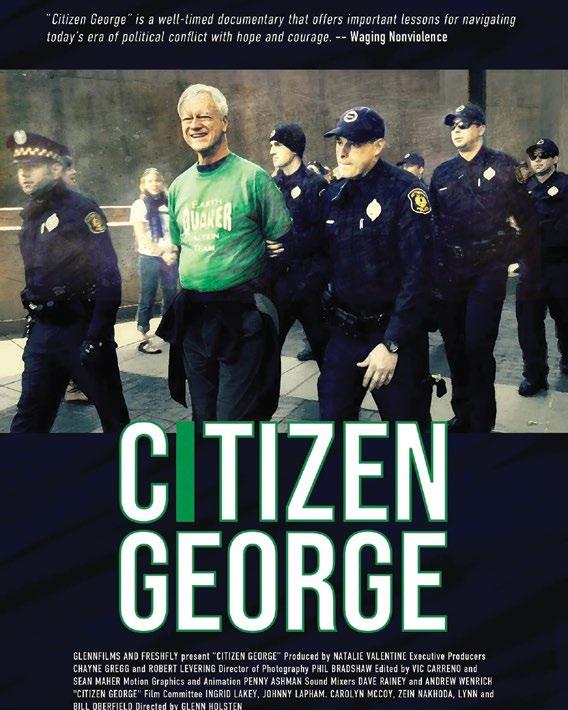

grid interviews legendary activist George Lakey on his inspirations, the current political moment and what keeps him motivated ➤ STORY AND PHOTO BY JORDAN TEICHER

George Lakey has seen his fair share of grim political moments. He has, after all, spent nearly seven decades fighting for civil rights, peace and environmental justice. At 87, Lakey recognizes that now is another one of those moments.

But his own personal experience as an activist and his research as a scholar of political movements — both examined in a 2024 documentary, “Citizen George,” which is now available to watch on Vimeo — tells him that our darkest hours can offer the greatest opportunity for radical change.

Grid spoke with Lakey about the challenges facing the environmental movement under Trump and the enduring power of nonviolent direct action. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The Trump administration is uniquely hostile to the interests of environmentalists. How do you see the environmental movement responding? I think we’re still in the stunned period. When so much is getting smashed, it’s harder to call attention to the environment. But I think things will settle down. Nature has a way of reminding us it exists. And not even Trump can distract us from that for very long. We will have comeuppances of various kinds — maybe even the heat this summer — that will remind us, “Oh right, there’s nature, and we have to deal with that.”

Do you think environmentalists learned anything useful about how to deal with Trump during his first term? I think we learned that he’s not Superman, and it’s possible to survive him. Fear is something we all have a lot of experience with now, and we know that fear is reduced when we’re with other

people. In fact, we know that when we’re kids. When we’re kids, the hand automatically goes out reaching for another hand. Sometimes as adults, we can get individualistic and imagine that we don’t need that. But we do. We need it all the more at times like this. We need to be in tighter solidarity than usual, not only because of the collision with nature, but also the collision with our president.

How much energy do you think environmentalists should be putting into intervening on the national level at this point? Well, in Scandinavia — which is a comparison I make a lot because I lived for a year in Norway — it makes a lot of sense for citizen action to work on the nation-state because the nation-state is responsive. They actually have democracy. I don’t think it makes that much sense here because democracy is not what we have. Our political structure is amazingly impervious, owned by the rich instead of by us. I think going after the corporations directly is actually a more sensible way of proceeding.

You’re a longtime advocate of nonviolent direct action. In the face of growing authoritarianism in the United States, should we still rely on nonviolent direct action? I looked into the Global Nonviolent Action Database that we built at Swarthmore Colmlege on that question recently because I thought it’d be handy if we had a list of some dictatorships that have been overthrown nonviolently. Even without a whole lot of searching in the database — which now has about 1,600 cases scattered over history — I found 40 cases in which dictators, most of whom had been in power for many years, were overthrown nonviolently. And a bunch of them were really vicious dictators. So it does seem to me pretty clear that if you’re going to go up against a really horrible enemy, nonviolence is the way to go.

You’ve been an organizer for a long time. What do you see as your role at this point in your life? At 87, I’m just sad sometimes. I even cry at the loss of energy that I have,

We will have comeuppances of various kinds — maybe even the heat this summer — that will remind us, ‘Oh right, there’s nature, and we have to deal with that.’”

GEORGE LAKEY

the loss of ability to concentrate over long periods of time on a particular thing. I can still jump up and make a speech. There’s other stuff I can do, and I’m happy to do it. But I also wear out really, really quickly.

What keeps you motivated? My greatgrandchildren are a reminder of all the young people who are inheriting this mess. What I hope is that we’re not only an example of a generation passing off a terrible mess to younger people, but we’re also a generation that is generating bright ideas and new ways of working and steadfastness and courage. Hopefully, that will inspire younger people to say, “Well, gee whiz, they didn’t give up.”

“Citizen George” features footage from the Rocking Chair Rebellion, a series of actions by older climate activists targeting banks that fund fossil fuel projects. Do you think there’s something unique that older people bring to the movement? I try to remind myself of that each time I’m being helped back up on my feet after lying on the pavement, or helped out of a jail cell. I was inspired by older generations as a young person. I knew Norman Thomas. I knew A.J. Muste and Bayard Rustin. I was just bowled over by the older folks who had been through so much s*** and still would actually listen to something that young people would say. Now, there’s a whole new set of young people and I get to be in touch with them. I’m so honored to be part of that continuity.

I know you consider yourself a hopeful person, but decidedly not an optimist. Why is that? Well, because the forces against us are so enormous. If I saw objective forces out there that were coming to save us, I would feel more optimistic, or if I believed in an interventionist God that would say, “All right, enough, you’ve put yourselves through enough misery, I think I’m going to give you a hand.” But I don’t think it works that way. I’m a big believer in God, but it’s not that kind of God. But I do think there’s hope.

Why? Partly because we never know everything that’s going on. I mean, there were very grim moments in the American Revolution. Not far from here, out at Valley Forge, there was George Washington with a bunch of tired and wounded soldiers. There have been so many moments like that in history when things looked just really, really grim and nevertheless turned out well. So, why discount that? Do I know everything that’s going on? No. I think in order to be pessimistic, I would have to be more arrogant than I am, more of a knowit-all than I am. All the victorious struggles I’ve looked into deeply have had moments when it really looked hopeless.

Does this moment feel like that? It does. ◆

The “One Big Beautiful Bill” aims to cut funding for electric vehicles and appliances by 2026 ➤ BY KYLE BAGENSTOSE

When Grid was planning a home electrification guide for the January 2025 issue, the uni0verse threw us a curveball.

Donald Trump’s reelection cast doubt on the longevity of federal financial incentives for homeowners across the country to purchase solar panels, electric stoves, heat pump HVAC units and other climate-friendly technologies.

So our guide, which walks readers through the who-what-how of electrifying their homes, came with a disclaimer: Repub-

licans may pull the plug on the money to pay for a whole lot of this.

Just months later, we’re standing on the precipice.

In May the U.S. House of Representatives passed Trump’s cornerstone budget bill, the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” which puts a range of climate change policies squarely in the crosshairs. The bill would seek to roll back former President Joseph Biden’s landmark climate policy, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, almost in its entirety. That legislation earmarked hundreds of

billions of dollars for the climate fight over a decade, primarily by providing economic incentives to juice an American clean energy revolution both on the supply side — think tax breaks for solar power manufacturers — and the demand side, with consumer rebates for electric vehicles and home appliances.

But the Big Beautiful Bill aims to kill. The carnage to clean energy sectors is too vast to review here. Heatmap, an online news outlet deep in the weeds, is tracking the proposed changes in detail. Generally speaking, the House bill seeks to end many tax breaks and rebates effective January 1, 2026, six years earlier than planned. In mid-June, just prior to Grid’s press time for this issue, the U.S. Senate Finance Committee offered an initial look at its version of the legislation. While softening the blow a tad for industries such as commercial-scale batteries, the committee’s bill would do little to avert a

swift and near-total sunsetting of funds for most climate-friendly technologies.

Both congressional measures seek to sunset at the end of this year 25C and 25D, tax provisions highlighted in Grid’s electrification guide that allow homeowners to deduct thousands of dollars annually for the purchase of home solar panels, heat pumps, electric hot water heaters and even weatherizing products such as new insulation, windows and doors. Also targeted are tax credits for the purchase of new and used electric vehicles. The House’s version would offer a one-year extension through

from everyday cars and trucks, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Home energy consumption accounts for another 10% of nationwide emissions, according to the Department of Energy. All in, the nonprofit Rewiring America calculates that about 42% of energy-related emissions in the United States flow from “kitchen table” decisions about what products homeowners and renters decide to buy.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) aimed to make serious progress on all of this, keeping the United States within striking distance of 2030 and 2050 emissions reduc-

We’ll continue to organize … I’m cautiously optimistic.”

FLORA CARDONI PennEnvironment

2026 for automakers that have sold fewer than 200,000 qualifying cars since 2010. But the Senate’s version — as of press time — would end credits after 180 days from passage, harming most EV automakers while potentially offering a brief reprieve (should those 180 days stretch into 2026) for companies like Tesla and General Motors, whose eligibility for credits would sunset on December 31 under the House bill.

The potential harm here is immense. Transportation is the largest greenhouse gas emitting sector in the United States at 28%, and more than half of those emissions come

tion goals that international climate scientists say are needed to avoid the most catastrophic climate scenarios. Its provisions for homeowners were crucial, as domestic electrification provides additional benefits by eliminating the toxic byproducts of gas combustion inside our homes and on our roadways, as well as lowering homeowner utility bills, says Flora Cardoni, deputy director of the nonprofit PennEnvironment.

“For us, the tax incentives are a huge priority because they’ve done a lot to fight climate change and protect our health,” Cardoni says.

So where are we now? The legislation is not yet law, and advocacy and interest groups like Rewiring America and PennEnvironment are waging lobbying campaigns to try to convince Congress to change course. Their strategy had focused on targeting moderate Republicans, especially those with clean tech manufacturers or other relevant economic interests in their districts. Hope was buoyed when, for instance, 18 House Republicans issued a letter to Congressional leadership last August making the economic case to keep at least some of the IRA’s measures intact.

But, those hopes were dashed in May when the Big Beautiful Bill passed the House with only three Republicans not voting yes, and none of them for IRA reasons. So the optimists among us then turned to the Senate, where at least six Republican Senators had signaled some level of interest in keeping some of the incentives.