■ Making SEPTA more accessible for the deaf p. 6

■ Don’t buy your next power tool — borrow it p. 8

■ Can a food co-op reclaim its collectivist roots? p. 18

THE ISSUE CO-OP

■ Making SEPTA more accessible for the deaf p. 6

■ Don’t buy your next power tool — borrow it p. 8

■ Can a food co-op reclaim its collectivist roots? p. 18

THE ISSUE CO-OP

For 20 years, Weavers Way Co-op and Saul High School have grown something beautiful

publisher Alex Mulcahy

managing editor

Bernard Brown

associate editor & distribution

Timothy Mulcahy

tim@gridphilly.com

deputy editor

Julia Lowe

art director

Michael Wohlberg

writers

Marilyn Anthony Bernard Brown

Gabriel Donahue

Emily Kovach

Julia Lowe

Jordan Teicher

photographers

Chris Baker Evens

Jared Gruenwald

Julia Lowe

Jordan Teicher

Tracie Van Auken

published by Red Flag Media

1032 Arch Street, 3rd Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107

215.625.9850

GRIDPHILLY.COM

Content with the above logo is part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. The William Penn Foundation provides lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation, and Philadelphia Health Partnership. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit www.everyvoiceeveryvote.org. Editorial content is created independently of the project’s donors.

Ahuman wrote this, and a human edited it. A human laid out this page too.

I could have asked one of the popular generative artificial intelligence models to compose a 600-word essay, in this case about the concerns a middle-aged writer and editor holds about a flood of environmentally destructive new technology that threatens his industry and livelihood.

But I have always been a late adopter. I prefer to see how other people misuse new technology so that I can avoid their mistakes, and I like to take some time to weigh the costs versus the benefits. Yet try as I might, it is becoming difficult to avoid the new wave of AI as tech companies thrust chatbots and enhancements into every app and interface.

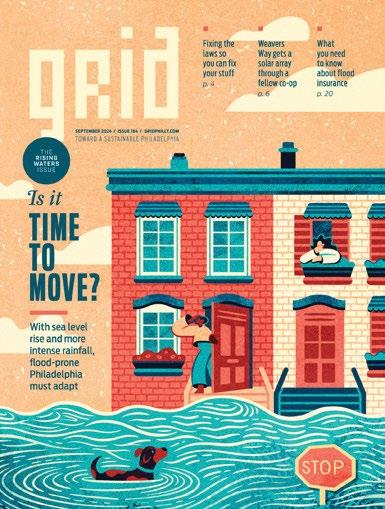

You’ve probably heard and read about the latest existential crisis that publishers like Red Flag Media, Grid’s parent company, find themselves in thanks to the generative AI boom. Red Flag Media hasn’t licensed the use of its Grid opus to any AI companies, and the same is true for thousands of other publishers and writers. But that hasn’t stopped AI companies from using our articles to develop their models, nor does it stop them from using our content to deliver summaries to readers who then might not bother to pick up a copy of Grid or visit the website. The question of whether this is theft or fair use is working its way through the courts, but, as Jordan Teicher’s article in this issue explores, the environmental impacts of the new models are devastatingly clear.

Generative AI seems low cost, like everything else we do in the “cloud,” the harmless-sounding name for the vast networks of computers housed in data centers owned by Amazon, Alphabet and other huge corporations. I don’t have to pay to see Gemini’s answers to my questions, and the same would be true if I asked Claude or ChatGPT to lend me a hand — although there are paid tiers available that boast unlimited use and the best AI models on offer. But one “free” ChatGPT query uses 10 times as much en-

ergy as a traditional Google search, and tech companies are building data center complexes covering hundreds of acres to handle the anticipated increase in traffic. Those vast banks of computers, however, aren’t fueled solely by the aspirations and egos of tech entrepreneurs and venture capitalists.

Data center complexes can suck up as much electricity as hundreds of thousands of homes And as Grid has reported , the regional electrical system does not expand at the speed of AI. New power plants — whether powered by renewables or fossil fuels — take years to plan and then build. PJM Interconnection, the entity managing the grid that connects power suppliers with consumers, can take years to approve the connections that allow new producers to bring their electricity to market. Electricity prices will increase for everyone as demand from new data centers (on top of the rising demand for green technologies such as electric vehicles and electric heat pumps) outpaces the rate at which new producers can expand the supply. Even if the companies operating the data centers buy renewable electricity, doing so bids up the cost for other users, delaying decarbonization overall. Ultimately, the AI boom will require lots of climate-wrecking fossil fuels, principally the methane that Governor Josh Shapiro is so eager to see burned.

You could understandably wonder if I am picking on the environmental impacts of AI because I am a worker particularly threatened by it, like a stable owner 100 years ago complaining about automobile emissions. But my self-interest notwithstanding, we all need to recognize that even if the services seem free, the costs are more than our planet can bear.

bernard brown , Managing Editor

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 2

Summer is over, but it’s not too late to capture its flavors in a jar. Scoop up late-season veggies at your farmers market and lean into the magic of pickling. Amina Aliako is eager to share her Syrian-style pickling secrets with you.

marilyn anthony

Syrian-style pickling is a rich and delicious tradition you can do at home story by

At its most basic, pickling requires only four ingredients: water, salt, vinegar and produce. Although pickling as a method for preserving foods has been practiced around the globe for centuries, its history has some fun local ties. Born in the U.S. to German immigrants, Henry J. Heinz founded the Pittsburgh-area company that became one of the first commercial pickle makers in the United States. Heinz pickles came to prominence during the 1893 World’s Fair as a result of a brilliant marketing scheme: Heinz advertised that anyone visiting his booth would receive a free pickle pendant. These small plastic charms were designed to adorn a watch chain or woman’s brooch. According to company history, Heinz gave away more than 1 million pickle charms during the five months of the fair, bringing the Heinz name and product into households across the country.

Less spectacular but still significant to pickle enthusiasts, John Mason, a tinsmith from Vineland, New Jersey, made home pickling safer in 1858 by inventing a square-shouldered jar with an airtight screw-top lid and rubber ring to replace unreliable sealing wax. Pickles later got unexpected acclaim from the September 2000 “Pickle Juice Game” in Dallas, so named after the Eagles beat the Dallas Cowboys 41-14 in temperatures topping 105 degrees Fahrenheit. The Birds credited drinking pickle juice with giving them their edge.

I would like to write everything about my product … to teach people about it.”

amina aliako

Amina Aliako has her own pickle history. Her mother, an acknowledged gifted pickler in Aleppo, taught her how to make the sour pickles Syrians expect at every meal. In 2017, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) brought Aliako and her family to Philadelphia. Aliako found work doing housekeeping at the Reading Terminal Market, where she saw a gap in the foods on offer, and approached general manager Anuj Gupta with an idea. The market management helped Aliako complete the requirements to become a vendor, and by 2019, she was selling authentic Syrian foods such as baba ghanouj, hummus and assorted pickles. The COVID-19 pandemic ended that dream when market operations were suspended.

These days, Aliako continues her family pickling tradition in her Northeast home kitchen, making gallons of pickled mixed vegetables for family and friends. “My kids are 16, 20, 22 and 24 and they love my pickles. They are always asking for some to be ready,” she says. She cooks many Syrian dishes for her children so they “don’t forget what is their country’s food.”

Aliako has discovered that “too many people don’t know about pickles. I would like to write everything about my product and spice to teach people about it. I want to share my recipe with people.” Here’s your chance to venture beyond the cucumber and taste pickled summer in the cold months ahead. ◆

Makes 6 to 7 pounds of assorted pickles, enough to fill a 1 gallon jar

10 medium cucumbers, unpeeled, cut into ½” slices (approx. 12-15 cups)

6 large carrots, peeled, cut into ¼” slices

6 green peppers (spicy or mild), cut into 1” dice

1 small green cabbage, rough chopped

6 cloves finely minced garlic

1 Tbsp. ground dried coriander ¼ cup salt

1 Tbsp. sugar

3 cups white vinegar

A large pinch of dried mint

• Wash and cut the vegetables thoroughly, mix together, then layer them in the jar.

• Fill the jar with cold water, then pour the water into a large bowl to measure the exact amount needed. Remove 3 cups of water and discard.

• Dissolve salt in the water. To ensure the perfect balance, place a whole uncooked egg in the water. If it floats to the surface, the brine is just right. If not, add more salt.

• Add vinegar and sugar to the brine.

• Stir in garlic, coriander and dried mint.

• Optional: Citric salt (known in Syria as milh al-lemon), available in the Middle East, is what allows pickles to stay fresh for longer.

• Pour the brine back into the jar, seal tightly, and leave in a cool place at room temperature for one week.

• After seven days, the pickles will be ready to enjoy.

• Note: Once the jar is opened, do not return any leftovers back into the jar. Exposure to air weakens the brine and may spoil the rest.

Advocates push SEPTA to provide sign language interpretation services story and photos by julia

lowe

Like many deaf americans, Igor Khmil usually uses American Sign Language (ASL). But when he is helping another deaf individual access public transit information — about routes or fares or schedules — he cannot communicate with SEPTA staff in ASL, as there are typically no interpreters in the transit authority’s stations. Instead, he has to write back and forth with SEPTA staff in English, which can — thanks to mistranslations and logistical complications — lead to service delays.

For many deaf and hard of hearing Philadelphians, these miscommunications with

public transit staff are a regular occurrence. But one local nonprofit says that bringing ASL interpretation to SEPTA could be as simple as scanning a QR code.

Liberty Resources, a Center for Independent Living supporting individuals with disabilities, is advocating for SEPTA to invest in video remote interpretation (VRI) services at its 1234 Market Street headquarters.

VRI uses video conferencing technology to provide a live ASL interpreter when an in-person interpreter is not available.

Liberty Resources advocates for the independence of disabled people through a combination of peer support, information

and referral services, and both individual and system-wide advocacy.

Khmil, a deaf advocacy and independent living specialist at Liberty Resources, leads a deaf advocacy peer group. On “probably about 10” occasions, he has helped deaf SEPTA riders who have had difficulties communicating with SEPTA staff when attempting to apply for a reduced fare card or locate route information.

“We’re wanting the VRI set up there, so that if the people there are speaking, the deaf individual can understand without having to write back and forth,” says Khmil.

Using written English can lead to miscommunications and frustrations for deaf riders, Khmil says. Writing or typing out questions and waiting for the staff member to respond in kind takes a long time and creates gaps in the conversation, whereas VRI would offer a live ASL interpreter, making the conversation more efficient and effective.

“ASL is its own unique language. It’s not like English. Completely different verbiage,

they need in Philadelphia. That’s the same thing I’ve been reaching out to them for.”

Khmil says that SEPTA has been “dragging out” the process of setting up VRI. He hopes to see the agency follow the MTA’s lead and explore the possibility of a QR-code based system that relies on riders’ phones instead of a tablet or laptop for VRI use.

In an emailed statement to Grid, SEPTA did not comment on the possibility of a QR-code system as an alternative to tablets. Agency spokesperson John Golden wrote that the agency’s funding crisis “has halted any IT enhancements regarding the implementation of new technologies.” But with the recent fare hike, plus service cuts and quick rollbacks in September, access to updated route information and reduced fares is more essential now than ever.

“Regardless of if they have the money or not, it’s just things that should be provided. Accessibility, communication for the deaf is just something that’s necessary,” says Khmil.

We’re wanting the [video remote interpretation] so that … the deaf individual can understand without having to write back and forth.”

igor khmil, Liberty Resources

sentence structure,” says Morgan Hugo, senior independent living specialist at Liberty Resources.

As with any technology, VRI has limitations, namely that it relies on a high-speed internet connection to visually display interpreters’ signs clearly and without freezing or lagging.

Khmil first reached out to SEPTA about setting up VRI access in 2022 and was in talks with the agency about setting up a tablet with VRI access, but the installation has yet to take place.

Earlier this year, New York City’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) began piloting VRI at its customer service centers with the help of deaf-owned company Convo, which allows riders to scan a QR code and connect to live ASL interpreters anytime.

Khmil saw a news story about New York’s program. “I was thinking, that’s what

With the city poised to host the FIFA World Cup and many other events in 2026, Khmil and Hugo would like to see VRI in place at SEPTA HQ at 12th and Market streets as soon as possible and expand to other places — like 30th Street Station, Philadelphia International Airport and other major transportation hubs — by next summer.

“As a city of brotherly, sisterly love, no matter how our visitors come in here, and what modes of transportation that they use, if it’s SEPTA, Amtrak — all of those modes of transportation should be accessible to those who are deaf and hard of hearing,” says Hugo. ◆

With a membership to the West Philly Tool Library, you don’t need an arsenal of expensive equipment to do it yourself

by bernard brown

In early september I dropped by the West Philly Tool Library to return a detail sander I had borrowed for a canoe I’m working on. I can’t remember the last time I used a detail sander before that, and I imagine it will be a while before I need to use one again. The same could be said for the steel tamper I used 10 years ago when we set the flagstones in our backyard, and for innumerable clamps, saws, landscaping implements and power tools I’ve borrowed since.

The Tool Library functions pretty much as you might guess from the name. Members, who pay an annual fee based on their income

level, borrow tools for a week at a time.

Rob Roy, who was borrowing a ladder when I dropped off the sander, became a member in 2016 and visits frequently when he is working on a home improvement project. “I built copper kitchen counters and used pretty much all tools from the tool library to do that,” he said.

Michael Froehlich started the library in 2007 after seeing similar tool libraries in San Francisco and Seattle. Ash Jones, who was returning some tools for a friend, joined three years later in 2010. “I’ve renovated my house and other houses with tools from the tool library,” he says.

Jason Sanders of the West Philly Tool Library believes connecting people with tools they couldn’t otherwise afford can be empowering and life-changing.

Executive director Jason Sanders first got involved with the tool library as a volunteer during the pandemic. (Aside from four part-time tool librarians, all positions at the library are volunteer.) Sanders, a mechanical engineer who had long done car and home repair work for friends and family members, started off helping at fundraising events such as tool sales. Soon he was working shifts at the front desk. Within a couple years, he had joined the board.

The tool library has always offered classes in home repair to go along with the tools, but Sanders has prioritized increasing the number and scope of offerings. Currently, the library offers more than 50 classes on topics including sewing and bike repair, in addition to home improvement basics such as tiling a backsplash.

“We’re sitting at about 1,300 members,” Sanders says. “Some come in frequently. For other people, they can borrow a carpet cleaner for 20 bucks [the membership fee for the lowest income tier] and it pays for itself.”

Clearly, I am not the only one who finds it to be a convenient way to avoid investing unnecessary money and space on tools I would barely use. Ryley Wilson lives in Roxborough but works in West Philadelphia and drops in on their way home. When I ran into them at the library, they were picking up an electric lawn mower. “For a tool that you would only need once or twice, it would be silly to buy it, and I would never have the space to store it.”

Sanders says the tool library isn’t simply meant to be convenient. Having access to the knowledge and tools to make repairs independently can be especially empowering for low-income members. “A lot of people might think someone should own a cordless drill or screw driver,” Sanders says. “But [borrowing tools] can really change the life of someone who doesn’t.” ◆

A lot of people might think someone should own a cordless drill or screw driver, but [borrowing tools] can really change the life of someone who doesn’t.”

jason sanders, West Philly Tool Library executive director

At press time, West Philly Tool Library learned that their lease will not be renewed. Visit westphillytools.org to learn about fundraising efforts to help find a new home for the nonprofit.

Can Pennsylvania be both a data center hub and a climate leader?

by jordan teicher

In june, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro stood on the lawn of the historic Jackson Mansion in Berwick, Columbia County, to make an announcement in the works for nearly two years: Amazon, he said, would spend $20 billion to build two cloud computing and artificial intelligence (AI) data centers in Pennsylvania, one in Bucks County and another in Luzerne County.

For Shapiro, the announcement marked a crowning achievement in a long cam-

paign to position Pennsylvania as an AI and data center hub. It also served as an advertisement of the state’s eagerness to attract even more data center development. In making the case, Shapiro emphasized Pennsylvania’s technology-focused universities, his administration’s fast new permitting process and — crucially — the state’s energy resources.

“Here in Pennsylvania we’ve got a winning team. We also have a unique set of strengths that put us in a position to succeed, including

our abundant energy resources and Pennsylvania’s great track record of innovation that dates back centuries,” he said.

Those “abundant energy resources” are key to Pennsylvania’s value proposition for power-hungry data centers. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, data centers currently account for approximately 2% of total electricity use in the United States. By one estimate, that percentage could grow to as much as 9% by 2030. In 2030, per the International Energy Agency,

We’re getting into this business without even paying attention to what it’s really going to mean for the future of the planet and for our communities.”

karen feridun, co-founder, Better Path Coalition

data processing could consume more electricity than is required to manufacture all energy-intensive goods combined, including aluminum, steel, cement and so-called “primary chemicals” such as ethylene, ammonia and methanol. “We’re seeing load growth on the electric grid right now unlike we’ve seen since World War II,” Jackson Morris, the director of state power sector policy, climate and energy at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), tells Grid. “The lion’s share is from data centers.”

Data centers can be powered by renewables such as wind, solar and nuclear. But nuclear power plants are expensive to build and take far longer to get online than gas plants; they also pose safety and environmental risks. Wind and solar are locationand weather-dependent, presenting an issue for data centers, which need to run continuously. Given its abundance, dependability and flexibility, experts argue that natural gas is best suited to meet the industry’s demands. “In the short term, natural gas is the way to go. Many utilities consider it the most viable option for balancing the growing loads while ensuring reliability,” Karthik Subramanian, an analyst at Lux Research, told a data center industry publication.

In announcing the Amazon investment, Shapiro described himself as an “an all-ofthe-above-energy governor.” But experts and advocates say development of Pennsylvania’s data center industry is likely to lead to a boom for one energy source in particular — natural gas — making it harder for the state to transition away from fossil fuels.

“We’re getting into this business without even paying attention to what it’s really going to mean for the future of the planet and for our communities,” says Karen Feridun, co-founder of the Better Path Coalition and No False Climate Solutions PA. “It’s just wrongheaded.”

Gas companies fully expect to cash in on Pennsylvania’s data center boom, which is why they’ve been advocating for the growth of the industry in the state for years.

Former U.S. Rep. Tim Ryan (D-Ohio), who sits on the leadership council of the natural gas industry group Natural Allies for a Clean Energy Future, argued last October that natural gas-powered electricity is the “obvious choice” to power data centers and that AI data centers offer Pennsylvania a unique opportunity. “As the second-largest natural gas production state [outdone only by Texas], Pennsylvania is uniquely positioned to capitalize on this opportunity quickly, benefit from new job creation and investment, and power our high-tech future if we collectively embrace natural gas as part of that solution,” he wrote

That collective embrace has already begun, driven by an alliance between tech companies, the gas industry and governments. As a result, the development of gas-powered data centers has been progressing at breakneck speed. With Shapiro’s blessing, developers in April announced plans to build a $10-billion gas-fired power plant for data centers — it will be the largest gas-fired power plant in the United States — where the Homer City, Indiana County, coal-fired power plant used to be. “We’re sitting on top of one of the largest natural gas deposits in the world, and it makes all the sense to be doing this here and utilizing the space at Homer City to best produce the energy needed to drive these AI centers,” Jim Welty, president of the Marcellus Shale Coalition, told the Pittsburgh Business Times. “We have the production. We’ve always lacked both the ability to get the gas to market and develop those markets. This does both of those.”

That same month, Liberty Energy Inc., Imperial Land Corporation and Range Re-

sources announced plans to build a natural gas data center power plant in Washington County. “This strategic development will help to attract data centers and industrial operations to our region, bringing with it economic impacts for years to come,” said Stefani Pashman, CEO of the Allegheny Conference on Community Development.

Elected officials at the state and federal level are also part of the effort to lure data centers to Pennsylvania. In July, Senator Dave McCormick (R-PA) hosted a Pennsylvania Energy and Innovation Summit at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, which was designed to “showcase Pennsylvania’s incredible potential to power the AI revolution.” Governor Shapiro attended, and President Trump made an appearance alongside members of his cabinet. The gas industry had an outsized presence, with speakers including the head of EQT Corporation (the largest natural gas producer in the United States), the CEO of Exxon Mobil and the CEO of Bechtel (a major player in the liquefied natural gas industry).

The event was accompanied by the announcement of $90 billion in data center-related projects in the state, including huge amounts of new natural gas power generation. Blackstone committed to spend $25 billion on “digital and energy infrastructure” and announced a new venture with PPL to invest in new natural gas power generation facilities. Equinor said it’s investing $1.6 billion to enhance natural gas output and link it to data centers. Frontier Group said it will transform a former coal-fired power plant in western Pennsylvania into a new natural gas-fired plant.

“Unfortunately, many of these companies are either proposing to connect to the grid, which drives up costs for consumers, or they’re proposing to build new gas plants, which can mitigate the consumer impact, but they’re going to be adding a ton of pollution to the system and taking us in the wrong direction on climate,” says NRDC’s Morris.

Data centers have an immediate need for energy. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, meanwhile, has an immediate need to decarbonize. (According to the Department of Environmental Pro-

We’re sitting on top of one of the largest natural gas deposits in the world, and it makes all the sense to be doing this here … to best produce the energy needed to drive these AI centers.”

jim welty, president of the Marcellus Shale Coalition

tection’s 2024 Climate Action Plan Update, Pennsylvania has committed to reducing net greenhouse gas emissions to between 50% and 52% of 2005 levels — at least — by 2030 and achieving overall net zero greenhouse gas emissions by no later than 2050.) Is there a way to reconcile the two?

Morris says it all depends on state policy. He notes that in Georgia, now the second biggest data center market (behind Northern Virginia) in the world, “thousands and thousands of megawatts of new gas plants [are] being proposed to meet that new demand.” But Pennsylvania doesn’t necessarily have to do the same. The state, he says, could reduce the need for gas by procuring more renewables if Governor Shapiro’s Lightning Plan — introduced in April — is put into place. Parts of the legislative package are moving through the legislature but face opposition from Republicans. “If that whole package is adopted, it’s going to have a binding cap on emissions from power plants. It’s going to have an

augmented renewables platform to scale up zero emissions resources,” Morris says. “You can absolutely meet demand growth in a manner that protects consumers and prevents emissions increases. But you need those policies to do so.”

Feridun is more skeptical. Pennsylvania lags far behind most of the country in renewable energy production, she says, and the emissions from natural gas-powered plants for data centers are likely to cancel any ground gained in the renewables sector. At a time when the climate crisis is intensifying, she argues, we can’t afford to make the task of decarbonization any more difficult. “We have a lot of work to do,” she says, “and it seems like the state is interested in doing everything but that work.” ◆

• WEAVERS WAY CO-OP AMBLER

• WEAVERS WAY CO-OP CHESTNUT HILL

• WEAVERS WAY CO-OP MT. AIRY

• WEAVERS WAY CO-OP GERMANTOWN

• MARIPOSA FOOD CO-OP

• SOUTH PHILLY FOOD CO-OP

• SWARTHMORE FOOD CO-OP

The idea of ditching corporations that answer only to shareholders for missiondriven models that share power with workers can sound pretty appealing. ¶ But how would it actually work? Well, it might work like the cooperatives we already have all around us, and that have been around for ages. ¶ Do you bank at a credit union? Shop at Weavers Way or Mariposa? Then you are already taking part in the cooperative economy. Want to take your impact further? Explore the worker cooperatives — bookstores, landscaping companies, apartment buildings and more — where you can take your business as well. ¶ Does it always work? Growth can be challenging for cooperatives, just as it is for any organization. ¶ We hope you learn something new about an old model that’s ever more attractive. And, when you think about how you’d like to see your values in the marketplace, you know where to go.

A look at five of Philadelphia’s worker-owned enterprises story by

emily kovach

There are dozens of worker-owned cooperatives in Philly, where the employees are the owners and have the opportunity to share profits and participate in governance and decision-making. Here are five local businesses that follow this model, covering a range of services.

1.

Home Care Associates

Home Care Associates (HCA) is one of the oldest worker-owned co-ops in the city, and also the largest, with approximately 160 employees. This women-led, B-Corp certified co-op specializes in providing quality, consistent in-home care across the city, including senior care, respite

and post-surgery care and companion care. It requires a lot of trust to bring in a caretaker into your home or the home of a loved one during a vulnerable time; because the caregivers at HCA are also company owners, they are deeply and personally invested in the quality of care they offer.

➜ hca.elevate.coop; (215) 925-0700

From its two campuses in Mount Airy and Germantown, Childspace Centers offers year-round child care for infants and kids, as well as Head Start programs, afterschool care and summer camps. Founded in 1988 by teachers, this worker cooperative delivers a carefully designed curriculum that encourages curiosity, problem solving and creativity in a nurturing environment. Childspace is accredited as a provider of quality care by the National Association for the Education of Young Children and has earned a STAR4 rating, the highest rating offered by the State of Pennsylvania.

➜ childspacedaycarecenters.org; (215) 248-3080

3.

Black Bird Rising

It’s an exhausting world out there, and Black Bird Rising provides a restful space for wellness and healing, with focus on Black, queer, LGBTQIA2S+ and trans-identifying people and their allies. This worker and producer co-op opened its storefront on Germantown Avenue in 2024, and has been serving the community through energy and body work, like acupuncture, herbalism and yoga, and herbal remedies sold through its apothecary. Blackbird also organizes and hosts workshops and events like Spiritual Bath Basics, Tea & Tarot and New Moon Intention Circles.

➜ blackbirdrisinghealing.com; (267) 270-7308

4.

Obvious Agency

Part-theater interactive company, part-experiential game designers, this artist worker cooperative’s offerings defy categorization; for instance, during Fringe Fest in 2024, Obvious Agency launched a production called “Space Opera,” which melded tabletop roleplaying games, democratic organizing practice and live theater. Over the course of the gameplay, the players created societies that worked together to “thwart existential consequences.” Another project, “Main Menu,” happens on a phone call, where the player interacts with “Annie,” a customer service bot. Check out @obviousagencycoop on Instagram for updates.

➜ obvious-agency.com

5.

Parula Gardens Cooperative

Parula Gardens formed after the landscaping company where the members worked shuttered in fall 2024. Instead of going their separate ways, the workers launched their own worker cooperative in March 2025. Its services include ecological landscape design, installation and maintenance, prioritizing native and edible plants and replacing invasive, nonnative species with native plants that encourage biodiverse habitats. Its name is a riff on the northern parula, a small migratory bird that is commonly seen in the Mid-Atlantic during spring and summer.

➜ parulagardens.com

story by emily kovach

While a worker-owned collective might not be everyone’s dream, these types of workplaces can be pretty dreamy. According to Corey Reidy, cooperative development director of the Philadelphia Area Cooperative Alliance (PACA), co-ops create long-term job stability, equitable wealth-building and are safer and more productive than non-cooperative businesses.

“Co-ops in the U.S. are two-thirds more likely to succeed and 14% more profitable compared to the average company,” Reidy says. “There is also a 2:1 pay average compared to the average 301:1 CEO-to-worker pay ratio in the U.S. The clarity in pay is a huge part of why people want to form co-ops.”

There’s also a profound sense of empowerment that comes with workplace democracy. It turns out that once people have a stake in a business, they’re more committed to it: the annual co-op employee turnover is just 14%, compared with industry norms of 40-60%.

“Workplace democracy is infectious: once you have it, you can’t ever go back,” Reidy asserts. “You know that if there are problems, you have the ability to change them.”

What kind of for-profit business can operate as a coop? Any kind, from ceramics studios to child care centers, grocery stores to gyms.

Here’s how to start your own worker-owned co-op, according to the pros at PACA:

❶ Do your homework: Think through the big picture. What do you want to do? Then, just like with any business, conduct market research.

❷ Find your people: Reidy suggests identifying at least two more people who are excited to form a co-op with you. This will become the steering committee which will explore the feasibility of the co-op, create governance and decision-making guidelines and organizational structures, and craft a budget.

❸ Get in formation: Recruit more members, if needed, to form a board of directors. Incorporate the co-op, develop financial projections, fine-tune your business plan and form committees.

❹ Raise capital: Money to seed the co-op can come from multiple sources, including member equity investments, loans, crowdfunding and grants.

❺ Implement your vision: It’s time to secure a location, lock down your financing, obtain any necessary license or permits, begin construction (if relevant), hire staff, develop HR policies, meet with clients and vendors and

start marketing your business to the community.

❻ Open for business: This is when your co-op is ready to start selling its products or services. Closely monitor financial performance and compare it with projections, adjusting as needed. There should be clear communication and transparency with all members about the numbers. Revisit group dynamics and decision-making policies as you see how the business operates in real life.

❼ Steady the ship: As the co-op progresses, adjust costs and pricing to achieve profitability. Examine systems, update financials and keep communication flowing between the members. Keep refining and clarifying decision-making processes.

❽ Grow the co-op: Once the co-op is stabilized, consider adding more services or products, growing the staff, opening additional locations and supporting other co-ops, while continuing to work on group dynamics.

Reidy reminds prospective co-ops that PACA is a resource that can support and help with technical assistance, from legal aspects, like bylaws and risk assessment, to financials, like loan readiness, to the business components, like writing business plans, incorporating and conflict resolution.

MARIPOSA FOOD CO-OP IN WEST PHILADELPHIA WAS FOUNDED IN THE 1970S AS A DEMOCRATIC ALTERNATIVE TO TOPDOWN CORPORATE GROCERY STORES.

TODAY, SOME WORKERS AND MEMBER-OWNERS SAY IT HAS STRAYED FROM ITS MISSION.

myriam sifter cried tears of joy. It was March 2012, and she was at the grand opening of Mariposa Food Co-op’s new home, a Greek-revival style former bank building on Baltimore Avenue in West Philadelphia. (Full disclosure: This author is a member of the co-op.)

For Sifter, it was the triumphant culmination of a journey years in the making. Originally founded as a buying club distributing out of basements and garages in 1971, Mariposa — like many co-ops that formed around that time — was meant to serve as an alternative to the growing corporate food system, with an emphasis on democratic control, local goods and community participation.

By the time Sifter moved to the neighborhood in the early ‘90s, Mariposa had bought a storefront at 4726 Baltimore Avenue and merged with another co-op. Like other members of the co-op, she had a key, and she’d simply let herself in to do her shopping. In the early 2000s, just after Mariposa hired its first paid staffer, she served on the personnel committee and helped develop the co-op’s first human resources policy.

In the years since, she’d observed the coop’s growth with excitement. By 2008, lack of space forced Mariposa to start a waiting list for new members and begin looking for a bigger space. The co-op’s new — and current — location, nearly five times larger than its former location, was the space they’d need to accommodate their 1,300 members and accept everyone on the wait list. The space would allow the co-op to actively recruit new members for the first time in its history, expand guest shopping for non-members, place larger orders and offer lower prices. In an area formerly a fresh food desert, it also felt like a victory for social justice. “I thought it

was amazing what the community, the board and the membership had done. Truly amazing,” says Sifter.

In the decade after, she continued to shop at the co-op, but didn’t keep up with its goings-on. Then, in 2022, Sifter spotted a flyer for a newly-formed group called Mariposa Liberation. Curious, she took the flyer and attended a meeting. There, she discovered that a lot had changed at Mariposa over the years, in ways that some people believed disempowered workers and member-owners alike.

In the years that followed, the attempts of both member-owners and staff to reclaim control of the co-op would ignite longstanding and ongoing debates within the food co-op movement: What is a co-op for? How should it operate? And perhaps, most importantly, who has the power to decide?

Back when mariposa was a members-only co-op in a small, 500-foot space, all decisions were made through universal consensus by membership. “At the time it was kind of a stranglehold model where anyone could veto any proposal,” says Andrew Zitcer, a longtime Mariposa member-owner and a professor at Drexel University whose book, “Practicing Cooperation: Mutual Aid beryond Capitalism,” considers Mariposa and other co-ops in Philadelphia. As the co-op grew, he remembers, that model couldn’t last. “It’s really hard to have hundreds or thousands of people giving input on decisions that have to be made within hours or by the next day,” he says.

When the co-op started hiring staff — by 2005, there were five of them — they began managing store operations as a collective. In 2009, Mariposa created a board of member-elected volunteer delegates to make big picture decisions. Shortly before the move to the new building, the board created an operations committee (OC), staffed by department coordinators, to support the staff collective.

But both the staff collective and the OC had problems with the arrangement. According to Jamila Medley, who joined Mariposa as membership coordinator in 2012 and served on the OC, members of the committee were not compensated for their work, and most didn’t want to serve. Since the committee’s role was ill-defined, and the rapidly growing staff collective wasn’t trained to take on

management responsibilities, the work kept piling up: the group came to be responsible for everything from determining whether a CSA could drop off boxes at the co-op to hiring a personnel coordinator.

Something had to change, but the way forward wasn’t obvious. In 2014, Medley and another OC member, Sam McCormick, proposed a new management structure: a two-person interim management team — Medley and McCormick offered to take on the roles — to “lead Mariposa’s staff through a transformational period after which it will have a workplace that is reflective of the democratic values identified by the Staff Collective.”

Tomason Payne, a staff member since 2005 and a former OC member, was concerned about the proposal. The OC, they say, had become increasingly out of touch with the sales floor due to the overwhelming workload. Further concentrating decision-making power in a couple of staff, they worried, “would run the risk of isolating management even further, making collective responsibility more elusive at the moment it is most necessary.” So they developed an alternate proposal with a handful of other staff members to redistribute operational responsibilities across separate committees, “rather than looking to only a few staff members to do everything.”

The board voted, Medley’s proposal won out, and immediately sparked backlash. Some staff members, Medley recalls, even organized a special membership meeting to have the decision of the board overturned. In the meantime, Medley began implementing a year-plus-long plan to guide staff in determining a new management structure for the co-op. But she says it struggled to move forward. “Some of the staff members who were called into supporting that work just didn’t do it. Meetings would get scheduled and people wouldn’t show up,” she says. Ultimately, the process proved so difficult, she resigned before it was complete.

“I learned a lot at Mariposa. And I think one of the important things that I learned about democracy is that it’s extraordinarily messy and it’s soul-sucking and it takes a lot of work,” Medley says.

Shortly after Medley left in 2015, her co-interim general manager, McCormick, left as well. A long-term staff member took

on the role of interim general manager that same year with the idea that he would soon make way for a longer-term transitional general manager. “As I understand it, there wasn’t an alternative,” says Medley. “So I think the board defaulted to it.”

In 2016 , mariposa looked beyond its current staff to hire a new manager. It found Aj Hess. Hess had been working in co-ops for decades, since they started volunteering at the People’s Intergalactic Food Conspiracy in North Carolina.

According to Payne, who served on a committee of staff and board members charged with coming up with a new management structure for the co-op, Hess was hired to finish the process Medley started: help the staff manage the store. A job description for the role reviewed by Grid shows that the hire was meant to “meet targeted goals for transition to Self Management.”

“A big part of what we hired Aj to do was to support and oversee the implementation of this new structure, and we wanted to ensure it would be fully established and operational by the end of their three-year contract,” says Payne.

Hess has a different recollection. They say their remit was to help “determine the management structure that would be put in place.” After conducting staff surveys and “observing a lot,” they say it was “clear that there was only a small segment of staff who actually were interested in collective management,” and a larger majority “wanted some sort of democratic workplace, but [felt] that collective management wasn’t necessarily the direction.”

Six months after Hess’ hire, collective management came off the table entirely. In September, the board voted to adopt policy governance, a governing model for co-ops developed by the consulting firm Columinate (formerly CDS Consulting), which provides consulting services for Mariposa and “exercises a near monopoly on board training and education in the food co-op movement,” according to In These Times

Under policy governance, according to Columinate, “governing boards establish their values and expectations in policy, delegate implementation to the board’s sole employee (typically the general manager) and monitor the outcome of operational activities against

S O me P e OP le th I nk O nly d I re C t dem OC raC y IS COOP erat I ve.”

ANDREW ZITCER, Drexel University

the stated policies.” In short, it put operational control of the store squarely with Hess.

This is not unusual. Weavers Way, a Philadelphia food co-op that has been in operation since 1973, also uses policy governance. According to Zitcer, policy governance has become the standard for most co-ops na-

tionwide. But the model is not without its critics. “Some people think only direct democracy is cooperative. So if I as a member don’t want the co-op to sell red grapes, and they do, and I didn’t get to make that choice, it’s not a democracy,” says Zitcer. But most people, he says, “don’t want to be involved

in the day-to-day,” and are content to cede a level of democratic participation as long as they can be assured their co-op is an “ethical place” that is “serving the community and the members.”

“I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with policy governance,” says Zitcer. “I think the question is: ‘Who’s watching it?’”

In the years since Mariposa adopted policy governance, the model’s effectiveness has been an open question. Those questions became pointed in September 2018, when a group of more than 20 current and recently departed staff mem-

bers wrote a letter addressed to the board, member-owners and the broader community. “The ineffective, unsupportive, divisive and overall poor management style enacted by Aj Hess has directly contributed to high staff turnover, abysmal staff morale, inefficient store functioning and financial risks incurred by both the co-op itself as well as our member-owners,” the authors wrote.

The letter included a bulleted list of 18 grievances directed at Hess, among them: “fostering a culture of fear, intimidation and retaliation,” “failure to publicly disclose money skimming affecting shoppers and member-owners,” “undisclosed and non-

t he BOard d O e S n’t knOw I t S Own POwe R .”

KITTY JAUREGUI, Friends of Our Co-op affiliate

consensual surveillance of staff and member-workers via video cameras installed in work areas without staff knowledge,” and “failure to work toward returning to staff governance by the end of their contract, a stated duty and objective of their job description upon hire.”

According to the letter’s authors, they’d made efforts to “communicate concerns to the Board and to resolve these issues internally with little to no action taken.” Now, they were publicly demanding the board remove Hess from their position, speed up the process to install a permanent general manager and help come up with a new management and governance structure that “empowers staff in collective decision-making.” (Hess says they only became aware of the letter recently; they declined to comment on its contents.)

The letter did not have its intended effect. Although the board acknowledged staff dissatisfaction and opened hiring for the manager role to outside applicants, in January 2019 it unanimously voted to offer Hess the permanent position of general manager. Three years later, the board would approve a new title for Hess: “Co-op Executive Officer” or CEO.

In the years after Hess’ hire, some Mariposa workers remained determined to exercise greater control of the co-op. Will Inglis was hired as a stocker at Mariposa in July 2019, and at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, he started organizing with his coworkers on the floor staff to demand hazard pay. That effort transformed into a union campaign, which resulted in a contract in March 2022. Inglis served on the organizing committee and the bargaining committee, and eventually became the shop steward for floor staff. “We intend to make Mariposa a workers’ paradise. We’re going to make it a place where you can make a good living. This first three-year contract is step one. We’re going to seize control of the place, the people who work there, through the board, and we’re going to run the place,” Inglis told The Philly Partisan. (Hess fired Inglis in 2023, and after detailing his negative experience with management at a member meeting, he got a letter from Mariposa’s lawyer threatening legal action for accusing Hess of “wage theft” in a public setting. The

letter also informed him he was banned from the co-op for life.)

The efforts of staff eventually dovetailed with those of member-owners like Austin Kelly. Kelly had been involved with the co-op movement since the 1970s, when he participated in the People’s Food System, a series of worker-owned collectives in the Bay Area. “I had experienced a different model that’s more about participatory power within the collective and worker dignity,” he says.

In 2022, when he found out Mariposa’s staff had formed a union, Kelly began organizing fellow member-owners, including Sifter, to advocate for them. Together, they talked with member-owners outside the co-op and attended board meetings. While Kelly’s concerns about the co-op initially stemmed from labor conditions, they quickly expanded. In an open letter sent to Hess in July on behalf of other member-owners under the umbrella of Mariposa Liberation, he decried a lack of transparency around Mariposa’s finances, labor policies and operations. “The future of our Co-op should be one that keeps Mariposa accountable to the greater community, clearly based in cooperative principles and social justice values generally, centering worker rights in particular,” he wrote.

Their concerns are not unique in the co-op world. In 2016, member-owners of La Montañita Food Co-op in New Mexico organized a “Take Back the Co-op!” group to reclaim democratic control, according to In These Times. Around this time, member-owners of the Honest Weight Food Co-op in Albany, New York, organized a similar campaign to “wrestle back their coop from a board that was working with the management team to strip authority from the membership.”

In the summer of 2022, Mariposa Liberation organized a series of public forums to discuss their concerns. Hess attended one of the meetings in August and took questions from attendees. “It was a bit eye-opening that we still had engaged members because, prior to that, members were never showing up to board meetings. We very rarely had contested board elections,” Hess told Grid. “That showed me that there were people who wanted to engage at a bigger level.”

According to staff, Mariposa Liberation’s efforts didn’t lead to improved conditions at the store. At the beginning of 2023, a group of current and former staffers once again sent statements to the board detailing additional complaints against Hess, including fostering a “toxic work environment” characterized by harassment and bullying. The staffers called for Hess’ removal and “the establishment of a committee, inclusive of union floor staff, to create a new management structure for the co-op.”

Alex Millard, a former staff member who had worked at Mariposa in 2018 when staff called for Hess’ removal, also wrote a letter. “It pains me to see that Mariposa is still having so many of the same problems with staff turnover and unhappiness that it was having five years ago,” Millard wrote.

Board members were confused about how to proceed. “According to the policy governance model, how is the Board supposed to respond to a significant level of dissatisfaction with management? Hether [Mariposa’s Columinate consultant] suggested that we ask Aj to reach out to staff to rebuild trust,” one board member, Elaine Fultz, wrote in an email to her fellow board members. “Is this the optimal approach in a situation where nine staff members are calling for their resignation? Should we be doing something in addition to that and if so what?”

In a group statement sent to The Philadelphia Inquirer by then-board convener and former Mariposa marketing and communications manager Meaghan F. Goodwin-Washington, current board members said they were “deeply concerned” about “dissatisfaction” they’d heard from about a third of the staff, and had, as a result, instructed Hess to complete an anonymous staff survey (already an annual requirement). According to a July 2023 document written by Hess reflecting on the survey’s results, “results indicate we have not met all the benchmarks” for a “minimum acceptable rating” set by Mariposa’s Columinate consultant. “At the time of the survey, there was quite a bit of negativity in and around the co-op,” Hess wrote, noting that “all of the questions had a high standard deviation, which really demonstrates the inconsistencies and shows that staff were having

very different work experiences.”

Since the staff survey, the report mentions, Hess had attempted to make improvements including open office hours, a periodic “Positive Vibes Wednesdays” initiative and the introduction of “staff appreciation vouchers.” Hess wrote that “there has been a palpable shift in vibes and energy at the co-op. In addition to the changes we’ve already implemented, the managers and many staff members have really been working on and committed to change the culture and morale.”

What further action was taken by the board is unclear. In a statement to Grid , Goodwin-Washington says that she “does not remember much that went into the process when the staff was unsatisfied.” She does recall encountering hostility from staff and efforts from the membership to “undermine” her leadership and that of the board. She also felt that “as a Black woman, I was putting out tons of emotional labor for an organization who elected me but didn’t feel I was worthy of leading.”

Hess declined to comment on the specifics of the letters of no confidence. “Sometimes you’re going to have staff that are unhappy. And if the board had larger concerns, they have avenues that they could go through to do further investigation, but at this point they have not, and they have determined that there’s nothing substantiated,” they told Grid. The staff, they point out, are unionized, and “if there were larger concerns, the union would bring them to me and that’s the staff’s process. The staff’s process is not to go to the board or to the press. It is to go to their union. And if nothing is coming out of that, then that indicates to me that, again, none of the claims are substantiated.” (According to Hess, the 2024 staff survey shows staff morale has improved substantially. “We saw tremendous improvement in the staff survey, to the point where the survey administrator said that she had never seen such remarkable results,” they say.)

Hess remained in place, and member-owners continued to organize. In April 2023, Kelly ran for the board and won a seat, and in October, Kelly’s group, now known as Friends of Our Co-op, gathered petitions to initiate a special membership meeting. Nearly 50 members, staffers, board mem-

bers and members of management attended. In a wide-ranging conversation, members discussed concerns about a lack of financial transparency, low staff morale and unsatisfactory shopping experiences. They decried a decline in member participation, including the working member program — in exchange for volunteering at the co-op, members could get a discount at the store — that ended during the pandemic and never returned. Taken together, these concerns, a report by Friends of Our Co-op found, “present a serious and unfortunate picture of financial risk, deterioration of shopping experience and erosion of satisfaction and confidence for members and employees.”

After the meeting, Kelly says, he continued to commit himself to improving the coop. But he often found himself at odds with the status quo of “deferring to executive power and executive privilege.” Ultimately, his time on the board was short. Three months after the meeting, the board voted to remove him due to “violations of the board code of conduct as well as numerous other board and co-op policies,” which he says were never explained to him.

Can mariposa’s board hold its CEO accountable? Kelly, ultimately, thinks not. He believes that the limitations of policy governance results in a board “deeply out of touch with autonomous worker voices as well as independent, grassroots member concerns relating to the structures and processes that shape and define our co-op.”

Kitty Jauregui, a Friends of Our Co-op affiliate, agrees. When she joined the board in April 2024, she says, she found it to be weak and passive, ill-equipped to effectively oversee Hess. The loss of institutional knowledge resulting from board turnover over the years meant that new members didn’t have a sufficient understanding of their roles. Ultimately, she found, the board had gradually ceded much of its authority. It had skipped reviewing crucial financial reports. It had neglected to complete an annual performance review for Hess on several occasions. Board members had no way to get in touch with the entire co-op membership; they neither had an email list of membership, nor the ability to update Mariposa’s website.

“The board doesn’t know its own power. Because of all the turnover, new board members look to Aj because of their experience. But ‘Can we do that?’ turns more into asking for permission than advice,” Jauregui says.

In recent years, Jauregui found, the coop had been falling behind on finances, membership and staff retention. Mariposa’s employee turnover rate, she found, was around 85% two years in a row. In six out of the last seven years, it had failed to meet its targets for membership growth, meaning it was 1,000 members below its goal. Sales,

she says, had fallen more than $2.5 million in the previous five years, and the store’s cash position had declined more than 50%, bringing the store close to a point where it would be “not enough to cover the investments our members have made in the coop.” When Jauregui raised these concerns to her fellow board members in an email, she was met with silence.

Jauregui’s time on the board, like Kelly’s, was short-lived. That fall, her partner, Tim Reimer — a longtime critic of Mariposa on social media — posted to Reddit about the co-op’s declining sales and cash reserves

and called for Hess’ firing. Jauregui shared the post. In November, the board voted to remove her from her position, and to terminate Reimer’s membership.

there are good reasons why many co-ops have chosen to empower their general managers, says Jon Steinman, the author of “Grocery Story: The Promise of Food Co-ops in the Age of Gromcery Giants” and the former board director of the Kootenay Co-op in Nelson, British Columbia. “Policy governance became as important as it is today because there were so many instances of general managers not being able to do their job because the board was trying to get too involved in the operations of the store,” he says.

In today’s highly competitive grocery market, he says, many co-ops wouldn’t survive without a general manager given as much leeway as possible. “Ideally, the general manager is an expert at what they do and the board’s job is to find that expert, make sure that they’re meeting the standards that are set by the board and allow that general manager to do their job well.”

That ideal scenario, he says, doesn’t always play out, and policy governance can create more separation between the member-elected board and the store. But it

doesn’t have to be that way. He says co-ops using policy governance can still effectively serve members’ needs and values through innovative engagement. “For a co-op that isn’t deeply engaged with its members, it probably has little to do with policy governance and more to do with there simply being a lack of skill, creativity or capacity among leadership at the operational or board level.”

Co-ops that don’t use policy governance, Steinman says, still experience interpersonal strife and often suffer financially. But there are some notable exceptions. The Olympia Food Co-op in Washington, for example, does not have a general manager; instead it’s operated by a non-hierarchical collective of 80 staff members, which makes decisions by consensus. “It’s not efficient in the very literal sense of the word, but the long-term payoff is worth the technical inefficiency of running collectively,” says Becca Bolo, who runs the bulk department. According to Bolo, the co-op is growing, with two retail locations and plans to expand.

lew baum, for one, believes Mariposa should stay the course. He worked as a member-owner volunteer in 2018, and got re-engaged in the co-op through the Friends of Our Co-op group. He began

serving on Mariposa’s board last year and became convener this June. (His views, he tells Grid, do not represent the board.)

“It would be a big and risky job to rebuild our structure and a functional culture without policy governance,” Baum says. “Policy governance is not holding us back, and spending time on it now would be a wasteful diversion from the core issues — bolstering our finances and engaging our members and the wider community.”

“Some people think that if we got rid of Aj, everything would be ducky,” he adds. “I think that’s very naïve.” Mariposa’s issues, he says, go deeper than personnel and management structure, and are tied to wider economic forces: inflation, the lingering impacts of the COVID pandemic and increased competition from corporate grocery consolidation. “We can work collaboratively with the executive. And ultimately, if we don’t like what’s going on, we can simply pass new policies that require the executive to do what we feel is necessary,” he says.

The board, under his leadership, is making progress, he says. It’s working on a performance review for Hess, and formalizing processes for monitoring the co-op’s finances. “The board is much more active now, and we are working more productively among ourselves and with management,” he says. “The Board has written plans and priorities. More is getting done in our committees. Finances are slowly improving. There is more to do.”

Sifter is less optimistic. While she wishes Mariposa well, she says she doesn’t recognize the co-op as it exists today. Organizing with Friends of Our Co-op, she says, is at an impasse, and she can’t imagine a path toward a future for Mariposa that resembles the place she once knew and loved. “If we can’t be a co-op anymore, then let’s just say it. Let’s not pretend,” she says.

Zitcer, however, believes Mariposa — and all cooperatives — always have the capacity for change. “I think it’s still in a transition that we could trace back to 2012 or 2015. And that’s the beauty of a cooperative, like the beauty of a democracy: so long as the structure of participation is intact, it can be re-imagined. I believe that cooperative structures always have that potential,” he says. “Instead of an organization, we have to think of it as organizing. It never stops.”

Cooperative bookstore in West Philly offers workshops and events to create community and spark political imagination

story by emily kovach

with a vintage tile facade and large glass display windows lined neatly with books, Making Worlds Cooperative Bookstore and Social Center’s storefront is ideal. However, this charming spot was not intended for retail; cofounder Malav Kanuga first identified the space as a storage facility for his independent publishing house, Common Notions.

“The original plan was to have storage in the back, and use the space in the front for public programming, film screenings and political education,” Kanuga remembers. “But it quickly got more ambitious — be-

cause we were already involved in social justice-oriented publishing, we decided to also use this space to feature other publishers we align with and respect.”

The location also felt like an organic fit. There wasn’t another bookstore in the immediate vicinity, and West Philly’s culture of activism made it feel like home.

“We wanted to learn from these histories, amplify them and give space for communities to come together and do some deep thinking about the problems on the city, national and international levels,” Kanuga says.

Making Worlds opened on Valentine’s

Day in 2020, and barely made it a month before businesses shut down because of the pandemic. The store began cautiously reopening a few months later, and received an outpouring of interest and support from the community.

“During the uprisings in Philadelphia that summer, we were flooded with requests to volunteer, and with ideas for teach-ins, read-ins and writer groups,” Kanuga says.

Since then, the shop has grown both its book selection and the scope of its programming. In any given week, you might find a writer’s group, a book launch by a local Black

Along with other member-owners, Malav Kanuga wanted to build a community space as much as a bookstore at Making Worlds.

graphic novelist and a Gaza medical mutual aid fundraiser and documentary screening.

Kanuga notes that, especially over the last two years, Making Worlds has hosted a lot of programming around Gaza and Palestine.

“The shop has also served as a space of grieving, where people are processing extremely complicated emotions around this unfolding and unmitigated catastrophe and genocide,” he says. “That programming has been deeply important for many of us who’ve been trying to make sense of this and can’t do so with any dependency on mainstream reporting.”

The store’s shelves are laden with current indie fiction, as well as books organized into numerous political categories, like Black, migrant and indigenous poetry, Asian American experiences, abolition, movement building, genderqueer and trans activism and many more.

MALAV KANUGA, Making Worlds cofounder

“The categories are invitations and portals into those topics that open into much larger rooms of imagination than we often have access to.”

Making Worlds is a co-op, currently with four cooperative members, all of whom also hold full-time jobs elsewhere. Kanuga notes that while it took a little while to iron out the co-op model because of the rocky start due

to the pandemic, a cooperative workplace was always the plan.

“For us, cooperatives, mutualism and reciprocity define what solidarity is, and those principles belong in the workplace. Our idea was to become a cooperative workplace and a cooperative place of learning and community engagement, a place where people’s ideas can come alive.”

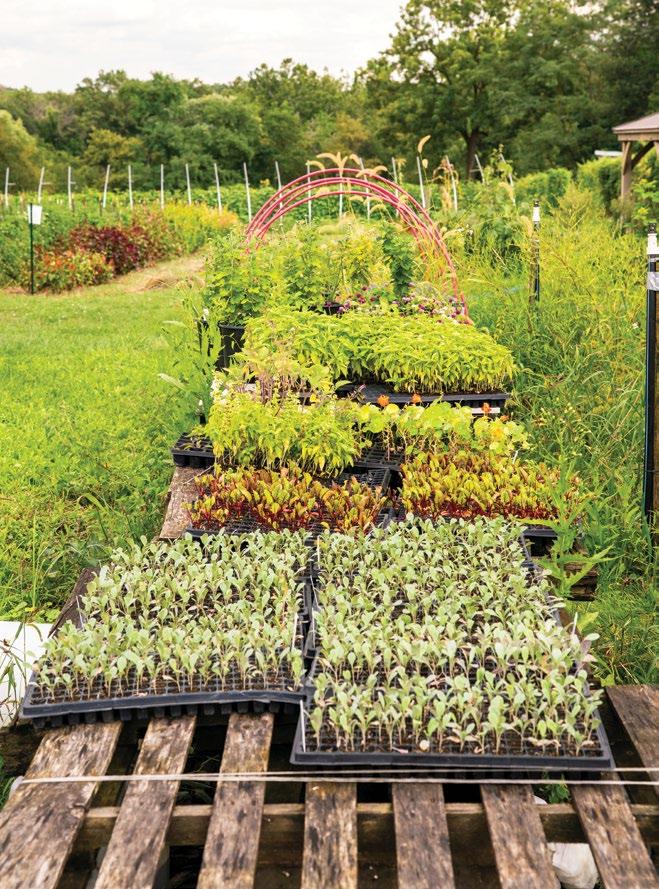

For 20 years, Weavers Way Co-op and Saul High School have grown something beautiful together

story by gabriel donahue

after nearly two decades, Henry Got Crops, the farm at the W.B. Saul Agricultural High School, still doesn’t turn a profit. But that doesn’t bother senior farm manager Ali Ascherio. The partnership between the school and Weavers Way Co-op pays off in other ways.

The vegetable farm takes up two acres behind the school. A hodgepodge of caretakers tend to its produce, herbs and flowers: staff members of the Weavers Way Cooperative, participants of state-sponsored apprenticeships, occasionally the working members of the co-op — and, most importantly, students of the high school.

“Our small vegetable farms and market generally are not profitable and are viewed more as a community resource — a way for folks to participate directly in the local food system, and an opportunity for young and beginning farmers to hone their skills and gain experience,” Ascherio says. “But, in the event that we became profitable, we have agreed to donate half of the profits to the school.”

Student interns voluntarily work on the farm in conjunction with their classes, and they can partake in paid internships during the summer. The farm also offers outside-the-classroom opportunities for students of all grade levels across Saul’s four majors to spend class time in the field.

Jacob Turko says that roughly half of the 11th- and 12th-graders he teaches are interested in interning at the farm this year. Turko, a horticulture teacher at Saul, is considering adding more opportunities to his curriculum for the whole class to head to the farm, so that more non-interning students can reap the benefits of the resource.

“Besides actual interns and employees, we have classes that come out and supplement their curriculum [by] doing projects in our field,” Ascherio says. “We have a goose problem in the spring. A couple years ago, we had an animal science class sort of do goose mitigation research. They put up wildlife cameras and did surveys and tried different methods for mitigating geese.”

While Ascherio says that, in that instance, the students found there wasn’t much to be done about the geese, the recollection highlights the mutually beneficial nature of the partnership: bringing students

tomer service, developing social skills and simply getting familiar with vegetables.

ALI ASCHERIO, Henry Got Crops farm manager

out to the farm bolsters their classroom discussions, allows them to work through theories and gives them real-world opportunities to experiment in a setting that is sustained by their hands-on lessons.

“Even though they’re doing what we’re doing, there’s a way to do it where it’s still a generative experience for them. They’re not just hands for more work,” he says.

Interested students can also apply to work at the on-site Farm Market, a Weav-

ers Way storefront that repurposes an old chicken shack that is open four days a week The market sells produce from the co-op’s farms as well as locally sourced crops and grocery items. In this case, locally sourced means within 150 miles of Philadelphia, according to the co-op’s website.

Jenna Swartz, the Farm Market manager, says that student workers get Weavers Way employee benefits and, from her perspective, invaluable experience in sales and cus-

“A lot of students get to take produce home and try it, and experience different produce that they might not otherwise know about,” she says.

Because Henry Got Crops is a community-supported agriculture (CSA) program, consumers can purchase a share upfront and then receive weekly portions of the crops grown there and at Weavers Way’s Mort Brooks Memorial Farm. Students can participate in the CSA distribution, which allows shareholders to pick up produce weekly, with pickup opportunities occurring three times a week at the farm. There’s also a “ You Pick” option at Henry Got Crops, where CSA members pick directly from the field at designated opportunities.

Food Moxie, an educational offshoot of Weavers Way, creates tailored programs to get more students school-wide out onto the farm. Deja Edwards is an educational coordinator who says that this year — her first with the nonprofit — she aims to create programming that builds off of classroom curriculum, specifically focusing on topics that students need additional time to explore.

“I learned early on that teaching outside of the classroom really does show what students really remember,” Edwards says. “That repetition will help their brains actually retain that information.”

Conversations mapping out the program calendar for the current school year between Food Moxie, Saul faculty and other community players willing to help out are ongoing.

Edwards, who won’t work with the interns but rather with the rest of the student body, says she will also incorporate their interests, which is already a significant factor in bringing the kids onto the farm: similar to how the animal science students attempted goose mitigation, food science majors pick blackberries to make jam, and those in horticulture classes make floral arrangements with varieties blooming in the field.

Turko also says it is important to connect Black youth, who make up about 64% of Saul’s student body, with farming. “I think it’s a personal point too, helping to reframe what does farming, specifically agribusiness, look like for Black students… and changing that framing and mindset of its ties to slavery,” Turko says. “There’s a lot more to it in terms of ties culturally and, for some students, spiritually as well.”

Henry Got Crops has flourished in both ongoing student participation and CSA buy-in, which is at an all-time high of 282 shareholders, thanks to years of collective, intentional effort. “Nobody’s boss essentially decided that this partnership was going to happen — it was people who work for these organizations that saw potential, came together and made it happen, which I think is so special, but it also takes work to maintain,” Ascherio says. “This has become a really special place.” ◆

For more information and to sign up for Weavers Way community-supported agriculture, visit weaversway coop/stores/csa/

BEAUTY

Hair Vyce Studio

Multicultural hair salon located in University City servicing West Philly & South Jersey since 2013. We specialize in premier hair cuts, color & natural hair for all ages. (215) 921-9770 hairvyce.com

BOOK STORE

Books & Stuff

They can ban books in our libraries and schools, but they can’t ban the books in your home library. Grow your home library! Black woman-owned online shop for children, teens & adults. booksandstuff.info

Back to Earth Compost Crew

Residential curbside compost pickup, commercial pick-up, five collection sites & compost education workshops. Montgomery County & parts of Chester County. First month free trial. backtoearthcompost.com

Bennett Compost

The area’s longest running organics collection service (est 2009) serving all of Philadelphia with residential and commercial pickups and locally-made soil products. 215.520.2406 bennettcompost.com

Circle Compost

We’re a woman-owned hyper-local business. We offer 2 or 5 gallon buckets & haul with e-bikes & motor vehicles. We offer finished compost, lawn waste pickups & commercial services. 30 day free trial! circlecompost.com

The Franklin Fountain

The Franklin Fountain now offers returnable reusable pints of ice cream in Vanilla Bean, Chocolate & Caramelized Banana! Our ice cream is made with PA dairy & all natural ingredients. franklinfountain.com

Kimberton Waldorf School

A holistic education for students in preschool12th grade. Emphasizes creativity, critical thinking, nature, the arts & experiential learning. Register for an Open House! (610) 933-3635 kimberton.org

SunGate Educational Community

Microschool for up to age 15. Full academic curriculum, movement, nature & arts. Social learning, hands-on & project based. Learning differences welcome. Sliding Scale. sungatecooperative.org

Echo House Electric

Local electrician who works to provide high-quality results on private & public sector projects including old buildings, new construction, residential, commercial & institutional. Minority business. echohouseelectric.com

FARM

Hope Hill Lavender Farm

Established in 2011, our farm offers shopping for made-on-premise lavender products in a scenic environment. Honey, bath & body, teas, candles, lavender essential oil and more. hopehilllavenderfarm.com

Stitch And Destroy

STITCH AND DESTROY creates upcycled alternative fashions & accessories from pre-loved clothing & textile waste. Shop vintage, books, recycled wares & original fashions. 523 S 4th St. stitchanddestroy.com

GREEN BURIAL

Laurel Hill

With our commitment to sustainability, Laurel Hill Cemeteries & Funeral Home specializes in green burials and funerals, has a variety of ecofriendly products to choose from, and offers pet aquamation. laurelhillphl.com

GREEN CLEANING

Holistic Home LLC

Philly’s original green cleaning service, est 2010. Handmade & hypoallergenic products w/ natural ingredients & essential oils. Safe for kids, pets & our cleaners. 215-421-4050 HolisticHomeLLC@gmail.com

GROCERY

Kimberton Whole Foods

A family-owned and operated natural grocery store with seven locations in Southeastern PA, selling local, organic and sustainably-grown food for over thirty years. kimbertonwholefoods.com

MAKERS

Mount Airy Candle Co.

Makers of uniquely scented candles, handcrafted perfumery and body care products. Follow us on Instagram @mountairycandleco and find us at retailers throughout the region. mountairycandle.com

MENTAL HEALTH

Mount Airy Candle Co.

Makers of uniquely scented candles, handcrafted perfumery and body care products. Follow us on Instagram @mountairycandleco and find us at retailers throughout the region. mountairycandle.com

Philadelphia Recycling Company

Full service recycling company for office buildings, manufacturing & industrial. Offering demo & removal + paper, plastics, metals, furniture, electronics, oils, wood & batteries philadelphiarecycling.co

WELLNESS

Center City Breathe

Hello, Philadelphia. Are you ready to breathe? centercitybreathe.com

Kozak, MES ‘25 Senior Research Coordinator, Kleinman Center for Energy Policy

Join the MES program team from 12-1 p.m. on the first Tuesday of every month for an online chat about your interests and goals. Log in with us.

Arwen Kozak (Master of Environmental Studies ’25) was working as a physics and math teacher when she enrolled in the MES program three years ago. Her goal was to pivot into the environmental policy space. “I think to be a good policymaker is to be a good educator,” she says. Now a senior research coordinator at Penn’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy, Arwen is applying her teaching skills in a new way.

Arwen was attracted to the Penn MES for its interdisciplinary curriculum choices and the caliber of the campus community. “I wanted access to Penn’s network of people,” she says, “not only the faculty and students, but also the kinds of guest speakers and visiting scholars that would be available to me on campus.”