CONTENTS Editors’ Letter Introduction 2 The Sound of Dissonance by Anson Sathaseevan Reflection 3 Mirrors by Ansh Patel Poetry 5 Better From a Distance by Quintyn Farrar Artwork 6 Untitled by Tanya Narang Artwork 7 Shared Decision-Making Is... by Jenna Rossi Article 9 Death Knells of Family Medicine by Anonymous Opinion 11 Here Lies Wellness by Michele Zaman Artwork 13 Untitled by Benjamin Divito Poetry 15 Ode to Immigrant Doctors by Ashwin Rao Poetry 17 A Single Strand of Silk by Prashanth Rajasekar Artwork 18 The Doctor’s Orders by Mudia Iyayi and Joshua Bierbrier Article 19 Greening the OR by Rosephine Del Fernandes Article 21 Prescribed Greenery by Anonymous Artwork 23 A Book Review by Cynthia Qi Opinion 25 Photography by Frank Chen Artwork 27 To Speak is Not to Say by Josie Jakubowski Poetry 28 Sacred Seven by Danny Ke Reflection 29 Untitled by Michele Zaman Artwork 30 The Beholder by Simoon Moshi Artwork 31 Misconception by Sarenna Lalani Reflection 32 Depersonalization by Prashanth Rajasekar Artwork 33 Little Things Make the Light Shine Clearer by Isis Lunsky Reflection 35 The Fleeting Self by Simoon Moshi Artwork 37 The Hidden Curriculum by Devyani Premkumar Poetry 38 Mirror, Mirror on the Wall by Helen Lin Reflection 39 Obsessed with being Obsessed by Anonymous Poetry 41 Truth by Youssef Belal Artwork 42 Identity in Medicine by Imran Syed Reflection 43 Embracing my Distorted Existence in Medicine by Gajan Sivakumaran Poetry 45 Untitled by Michele Zaman Artwork 46 Moments in Medicine by Laura Wells Reflection 47 Murmurs by Simoon Moshi Artwork 49 Rising Stars by Ivneet Garcha Horoscopes 51 Book List and Spotify Playlist Misc. 53 References Index 55 Our Team/Contributors Credits 57 1

To our readers,

We present to you our final issue of QMR’s sixteenth edition - Distortions in Medicine.

We wanted to end our term as Editors-In-Chief with a bold statement, uncovering the altered perspectives of our reality and pushing our community to be more vulnerable. The pieces that live within the bounds of this journal were born outside of comfort zones. They are reflections, examinations, and representations of the twisted realities found in our personal lives and shared experiences in medicine.

If we pay close attention, distortion can be found all around us. It can be heard, seen, felt, and perceived in any sense of the word. We distort truths, appearance, music, biology… sometimes intentionally, and other times not. In healthcare, distortions appear as invasive medical procedures, silent patient stories or a hidden curriculum. Sometimes distortions act as masks that we need to unveil, so that we can look at each other once again and say, “I see you”.

We are so incredibly proud of all the contributors in this issue, specifically, their strength to be seen and perceived. We hope that the breadth of emotions within these pages translate to you, the reader, as you journey through Distortions.

Love, Devyani & Simoon Editors-In-Chief Queen’s Medical Review

EDITORS’ LETTER

2

THE SOUND OF DISSONANCE

Written by: Anson Sathaseevan

MAIN

A high-pitched ambulance siren. Nails on a chalkboard. A blaring car horn.

Birds chirping to the rise of a late summer sun. A solemn chorale resonating through an empty hall.

What makes some sounds pleasant and some sounds unpleasant? The idea of what is “dissonant” is a subjective matter that hinges more upon personal experience rather than a universally accepted maxim. Instead of trying to provide a definitive meaning of dissonance, I have outlined a set of principles to frame the idea of dissonance. It is important to note there is a lot of overlap among these concepts, and I have only compartmentalized them here for the sake of discussion.

EVOLUTION

Our brains are hardwired to respond to stimuli in our environment, and our sense of hearing helps inform what we view as potentially threatening and what is not. Being made aware of thunder rumbling in the distance was a good indication to our ancestors that rain might soon follow and that they ought to take shelter.

Having this acuity of hearing was advantageous, but we now live in a markedly different environment where unpleasant sounds are such a ubiquitous feature of our everyday lives that we even have a catch-all term for them: “noise pollution”. Multiple sources have linked noise pollution in highly urbanized areas to hypertension, cardiovascular disease and reduced cognitive performance1. Our evolutionary history and the rapidly changing environment around us have informed our ideas of dissonance and have direct effects on human health.

SETTING

Imagine you are attending a symphony performance. You have arrived early and you are sitting in the audience listening to the orchestral players warm up. Random notes from all manner of instruments are heard at the same time as the performers prepare for the concert. In reality, what you are hearing is just a cacophony of intermingling musical passages which do not have much context without their meticulous overlapping framework in the musical score. And yet we do not usually associate this as being noisy or unpleasant, at least not enough to warrant us plugging our ears. In fact, the opposite is probably more likely: that random jumbling of musical passages might be heard as pleasant to some audience members.

The setting we are in informs how we interpret sounds around us. We are much more likely to accept what we hear as natural (that is, not unpleasant) if the setting dictates it as such. Each of us is more easily swayed than we would like to admit.

DISPOSITION

As I absent-mindedly walk through City Park on a mild winter day after class, I can hear birds chirping overhead. As I feel the warmth of the sun, which every day persists just a little bit longer, I am reminded of the spring to follow and the promise of those much-missed lazy summer evenings. The birds singing overhead lull my state of mind from what was otherwise a long day.

In a crammed library in the middle of exam season, after extensive searching, I finally stumble across an empty desk in a corner on the third floor of the library. I unpack my laptop and prepare to bury myself into my notes, acutely aware of the paucity of time I have until final exams.

3

DISPOSITION CONT’D

As I try to focus, my attention is broken by birds shrieking outside. The window adjacent to my study desk is old and doesn’t insulate well against outside sound. I fruitlessly dig through my backpack for headphones I already know I forgot to bring with me. What was once a welcome reminder of the spring to come is now a nuisance I wish would end.

Context provides the interpretive platform through which we process the external world. Our mood and general state of being can make the same sound welcome in one instance and unwelcome in another.

INTENTION

Dissonance in music generally refers to two overlapping tones which, in conjunction, sound unsmooth. Why would anyone intentionally write music that is meant to sound abrasive? The answer lies in the general principles governing the harmonic structure of music.

The bane of every music student learning harmony for the first time is how to resolve seventh chords back to the harmonic root of a piece of music. Seventh chords, consisting of the seventh of a musical scale, are by their very design abrasive. This harmonic “charge” provides tension that naturally resolves back to the tonic. Without that contrast, there would be no variety and we would quickly lose interest. Seventh chords are a ubiquitous feature of most music.

Of course, this rudimentary idea of dissonance in music is just one example, and the intentional use of dissonant, charged harmonies has been expanded widely (and to great effect) in music.

While we often find it easy to describe a sound as pleasant or unpleasant, we frequently disregard the reasoning for that label. And as I have tried to argue, the idea of a dissonant sound is not as clear cut as we would be inclined to think. Having that perspective can allow us to delve into the nuances of the soundscape we encounter every day in a journey of discovery and self-discovery about our own aesthetics.

FIN

4

References on Page 55.

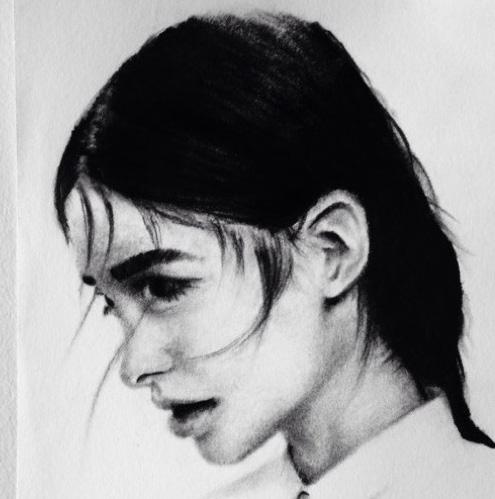

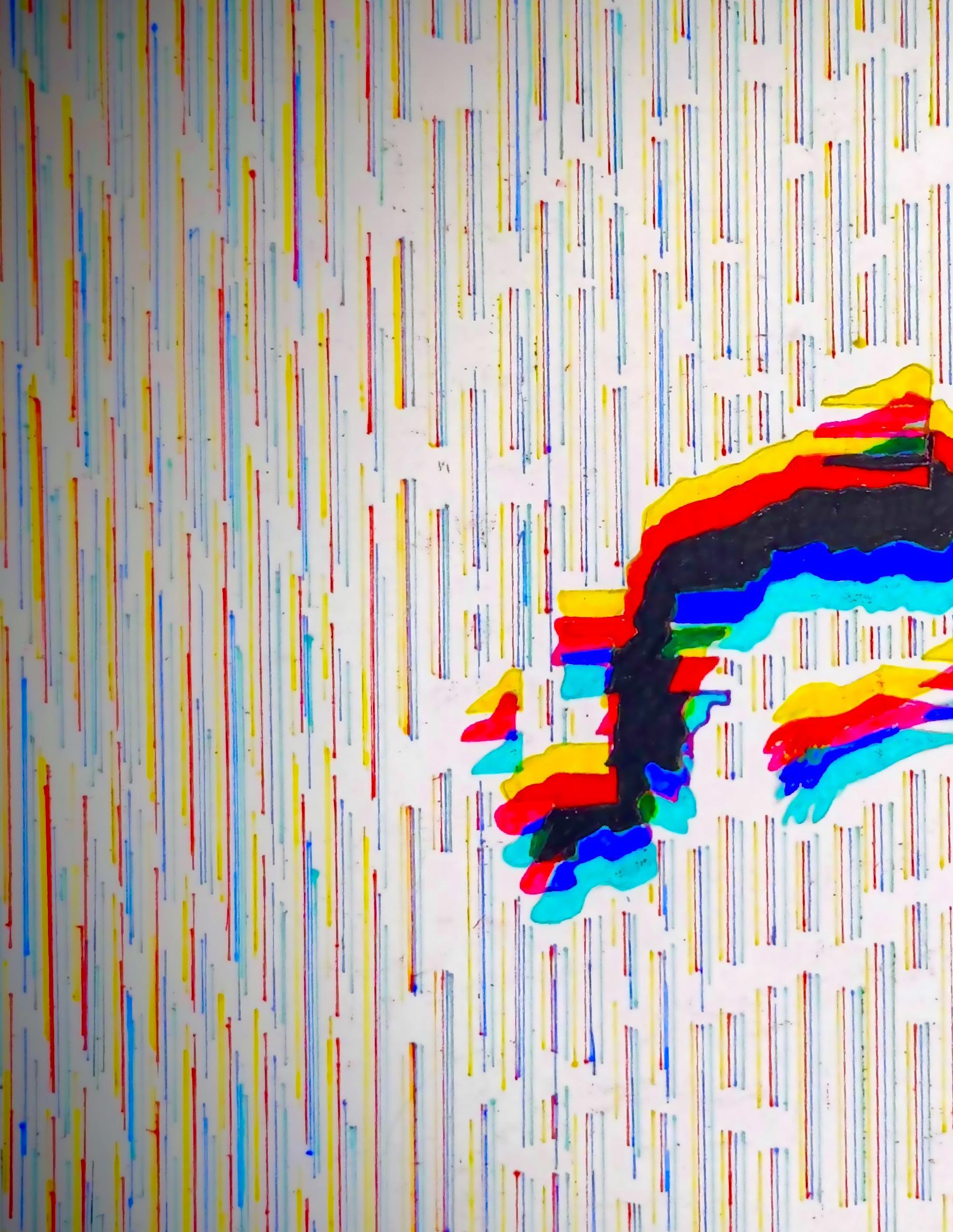

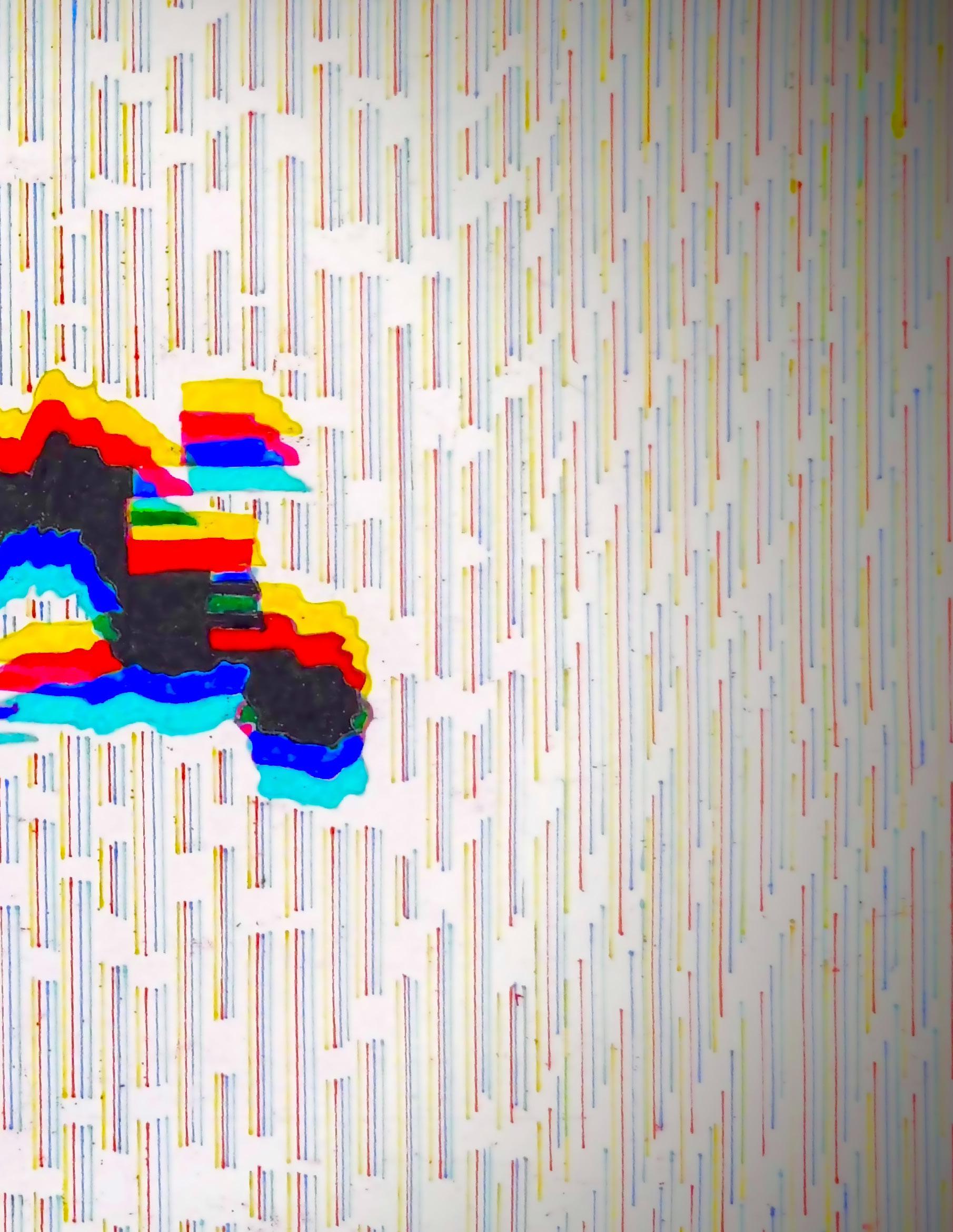

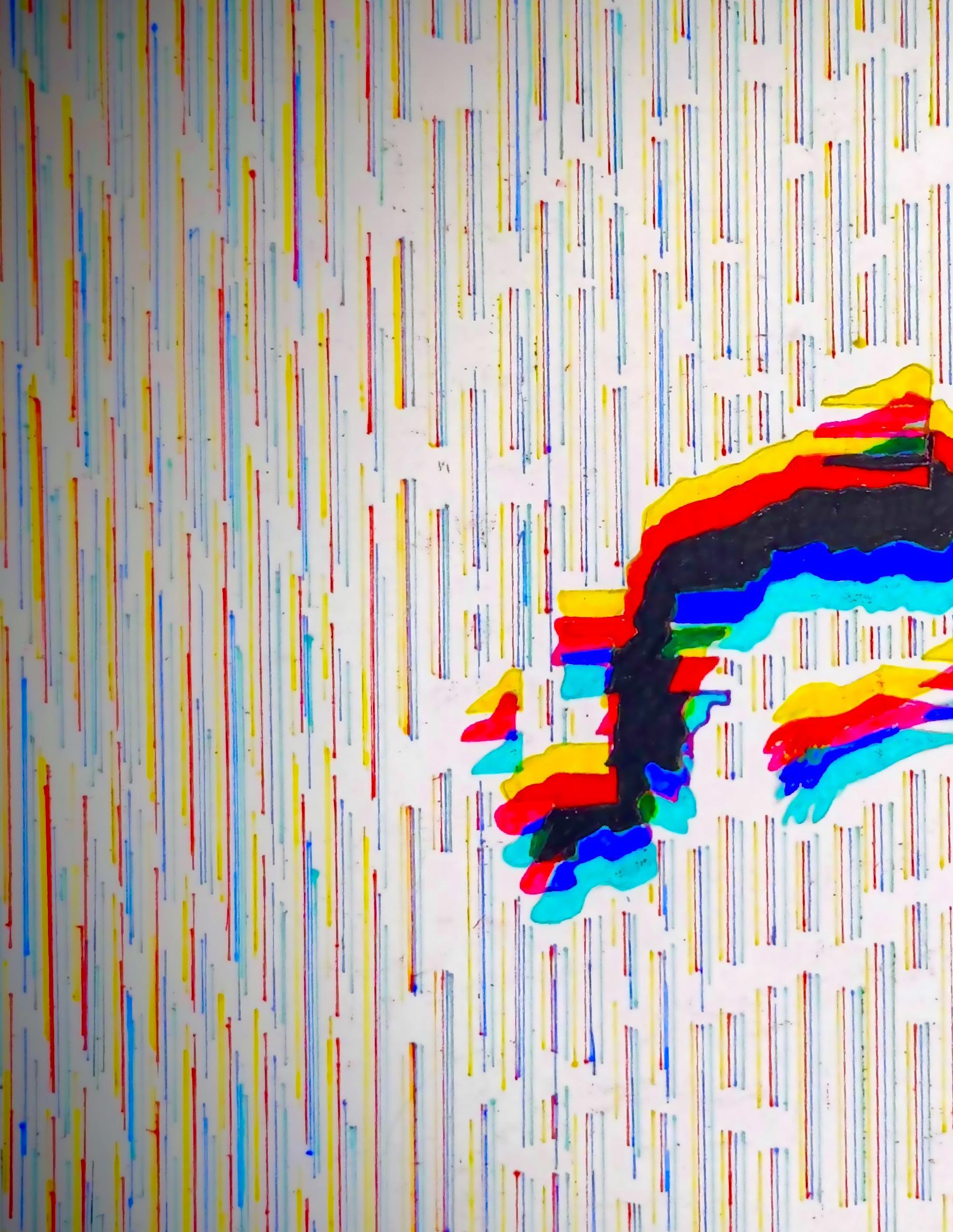

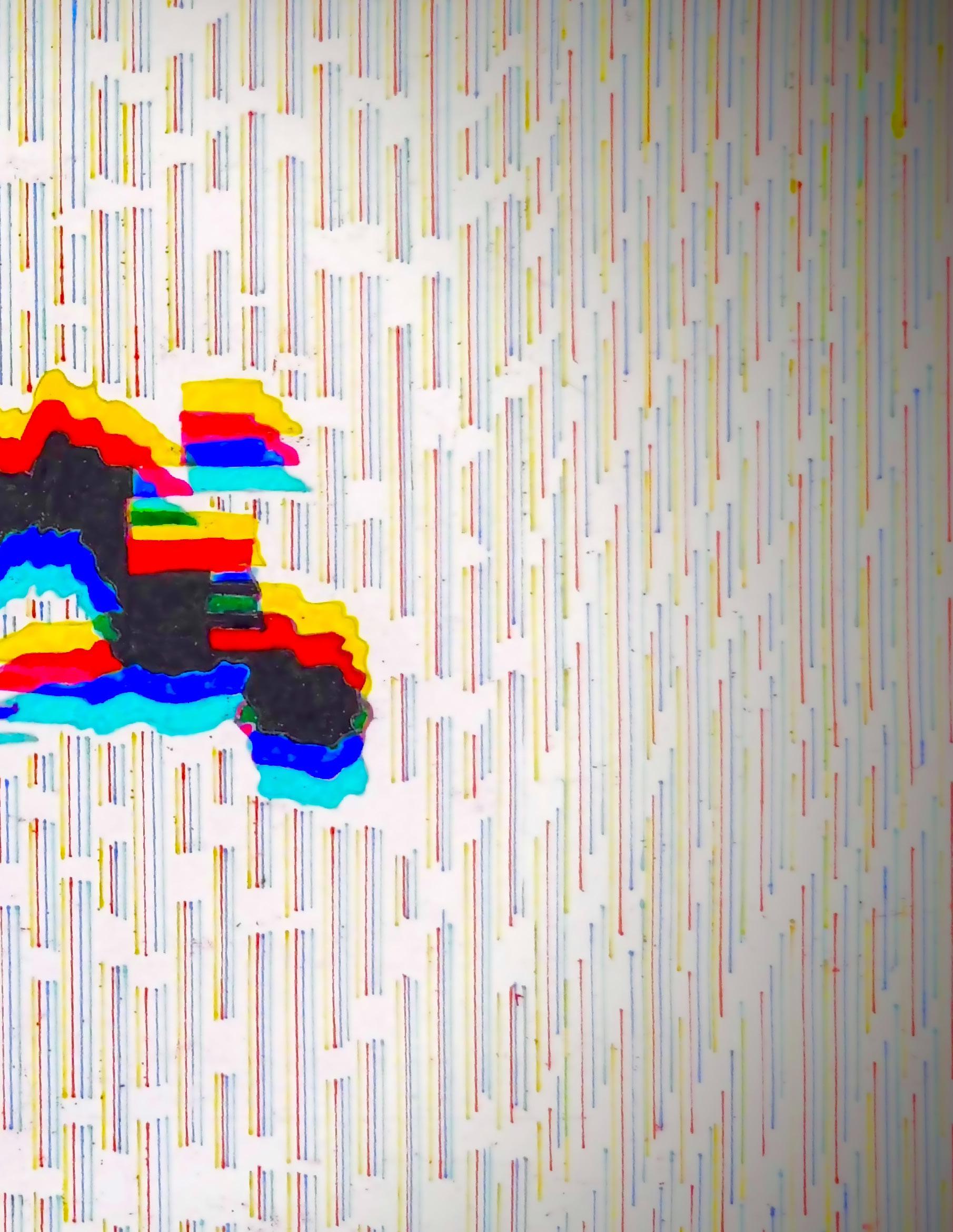

Artwork by: Michele Zaman

MIRRO S

Written by: Ansh Patel

Mirror mirror on the wall, Holds no secrets, none at all

R

A perfect reflection of each imperfection A visual circus of mental contortion

Staring at this clear facade it’s hard to believe that I’m not flawed Because the mirror hides my essence highlighting my appearance as quintessence But the mirror doesn’t see the beauty within the kindness, the love, the strength beneath my skin It obscures a soul pure and free showing only what i am, not who I can be

So let us not be fooled by what we see Gaze deeper into the reflection to unravel this tortuous distortion

5

From a Distance”

“Better

6

Artwork by: Quintyn Farrar

7

Artwork by: Tanya Narang

8

Artwork by: Tanya Narang

SHARED DECISION-MAKING IS.... DEBUNKING MISCONCEPTIONS

Written by: Jenna Rossi

Written by: Jenna Rossi

Shared decision-making (SDM) is a process whereby patients and their health care team collaborate to make medical decisions, based on the available evidence, that align with patients’ values, preferences, and goals1. SDM has gained popularity in the medical community as it seeks to move towards more patient-centered care approaches which have been prominent in the medical literature since the 1980s2,3. However, SDM remains poorly understood and applied in clinical practice. In this piece, we will explore the concept of SDM, as well as dispel some common misconceptions about this decision-making model and its integration into practice.

Patient centered care encourages collaboration between patients, their families, and healthcare providers to make decisions about the management of a patient’s condition4. This represents a shift away from the traditionally passive role of the patient and their family in the decision-making processes, towards that of an active team member4. SDM is an integral part of patient-centered care; it empowers patients to be active collaborators and decision-makers in relation to their care. This decision-making process involves both the expertise of the healthcare provider and the patient for, after all, patients themselves are the experts on their experience of their disease. In SDM, when a decision needs to be made, patients are provided with comprehensive information regarding the risks and benefits of the options available to them in relation to their disease and personal preferences5. This is often done through information provided by the physician and the use of decision support tools such as decision aids1,5. The healthcare provider can then counsel the patient’s decision-making by reviewing, clarifying, and discussing this information with them, all the while respecting and considering their individual competence, expertise, and values5. Several positive outcomes have arisen as a result of SDM use. Importantly, treatment plans may better reflect patient goals6, patient and physician satisfaction can be increased7, patient-physician communication may be improved6, and in some cases, costs can be reduced8–10.

While the presence of SDM in the medical literature has burgeoned, the uptake in clinical practice has been slow11 Despite the demonstrated benefits, there remain many misconceptions surrounding the implementation of the SDM

process among patients and healthcare providers alike3 that may be a barrier to its integration in practice. We will address 5 of the most common misconceptions around the implementation of SDM.

...is well understood by healthcare professionals?

A common misconception regarding SDM surrounds what exactly it entails. The findings of a systematic review exploring SDM in surgery suggest that there may be insufficient knowledge on the part of both physicians and patients as to what SDM really is12. For instance, they found that when subjective measures of SDM were used, both physicians and patients commonly perceived decision-making processes as shared, or patient driven. Whereas when objective measures of SDM were adopted, these indicated a low level of SDM in surgical settings. This conflicting information likely stems from a lack of understanding with respect to what SDM is and/or that it is mistakenly equated to informed consent. This finding points to a need for further education to ensure SDM is being properly integrated in patient care12.

… difficult to integrate into practice?

Another misconception surrounding SDM relates to its format and implementation. It is commonly assumed to be a process that is difficult to integrate into practice. For example, due to patient characteristics such as low level of education, or the clinical situation such as when specific guidelines exist3,13. Instead, SDM is not a one-size-fits-all approach.

The process can be tailored based on the patient’s characteristics and abilities, as well as the context in which it is being offered. This ensures all patients have the opportunity to be involved in shared decision-making13. Various tools

9

and approaches, such as the SHARE Approach exist to facilitate the implementation and adaptation of the SDM process14. Many decision-making aids also exist to facilitate this process and help provide information to patients to help them correlate their personal values to the harms and benefits of the evidence-based options5. These interventions are useful in the context of SDM and can help support patient-oriented decision-making conversations.

…time consuming?

SDM is often perceived by medical personnel as too time-consuming to implement in clinical practice3. In actuality, a 2017 Cochrane review showed that SDM using a decision-making aid only takes an average of 2.6 minutes longer compared to usual care, with a range from 0.4 minutes shorter to 23 minutes longer than usual care15. The variation in time depended on the topic of the consultation as well as the types of decision-making aids used.

…not going to change outcomes?

It is important to recognize the positive impact of SDM on patients when compared to usual care. It has been shown that informed patients tend to make more conservative treatment decisions15. This translates to improved patient satisfaction15 as well as reduced healthcare costs in certain contexts15. It has also been suggested to reduce rates of certain elective surgeries, which can be costly compared to non-surgical alternatives9.

…a one-time conversation?

Many perceive the SDM process as only limited to the conversation that occurs between the healthcare provider and the patient16. Rather, SDM frameworks often recommend a series of discussions to 1) discuss management options, 2) further analyse the different possibilities (pros and cons) and provide decision-making aids, and 3) support the patient in their decision-making5. While this approach seems straightforward in theory, there are many factors outside of these conversations that may affect a patient’s decision-making16. Emotional factors that surround a diagnosis and the patient’s healthcare experience, social expectations, and relational pressures may all influence a patient’s decision. For example, a patient may be more predisposed to choose a surgical management option compared to a non-surgical alternative

simply because a referral to a surgeon by another physician suggests it is necessary16 or that the surgical option had been suggested as the optimal option throughout the patient’s healthcare journey… This is why it is important to consider SDM throughout a patient’s journey in healthcare from screening to surgery!

While several challenges exist around the incorporation of SDM in practice that need to be addressed, a first step is to refute some of the misconceptions around its implementation. SDM has the potential to actively engage patients in their care and give patients more agency in their healthcare decisions. It can help patients and healthcare providers make decisions in line with patient priorities and values. This is important in all specialties, including surgery where decisions are oftentimes irreversible12. As students and physicians, we can contribute to the implementation of SDM into widespread clinical practice by learning and teaching about this decision-making model at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels, contributing to research on this topic and its use in various fields, as well as developing tools such as decision-making aids and other resources to help ease its integration into each physician’s practice. Importantly, taking the effort to reflect on how to best fit SDM into our own practices and actively using this method with patients will allow each of us to understand how SDM can best benefit our patients. SDM is an important component of healthcare’s evolution towards patient centered care, and it is important for us to reflect on and evolve our practice in the coming years so we can learn to adopt it seamlessly in our patient encounters17.

This article was inspired by the 2014 article, “Twelve myths about shared decision making” by France Légaré and Philippe Thompson-Leduc.”

Thank you to Dr. Karine Toupin-April, Associate Professor at the University of Ottawa in the Occupational Therapy program, for your suggestions regarding this article.

References on Page 55.

10

THE DEATH KNELLS OF FAMILY MEDICINE ARE RINGING: YOUR TONE MATTERS

Written by: Anonymous

Written by: Anonymous

When I decided to give medicine a shot, I dreamed of becoming a family doctor. Everything about it seemed appealing to me, the long-term relationships with patients, the ‘boots on the ground’ mentality. The idea of being the centre of a patient’s care journey. The variety of presentations. The ability to work with other healthcare providers in a team. Minor procedures. The capability to work anywhere. Being able to see a newborn baby and then an 85 year old patient in the same hour. It sounded like a dream career that would leave me fulfilled, happy, and content.

Fast forward (ideally 2x speed past many rejected applications, MCAT rewrites, and a pandemic) and after almost 2 years of medical school here I am, desperately hoping that I can see myself doing any other type of specialty.

The death knells of a happy, meaningful, mostly burnout-less career in family medicine seem to get louder every day.

They started off small in our first year. Subtle remarks from specialist lecturers referencing shoddy primary care. Offhand, dismissive comments about family medicine on observerships.

Lecturers excluding the relevance of family doctors in very complex niche procedures with ‘obviously you’d never do this as a family doctor’ even though most other specialties would not do that procedure either. Tone matters. I realized that part of the hidden curriculum is to think of family medicine as a specialty that is ‘lesser than’. Among peers it is a ‘parallel plan’ aka ‘backup’. It is rarely treated with the same respect, appreciation, or admiration that other specialties seem to garnish.

Obviously, our fractured healthcare system is partially to blame. It is long past groaning, it is screaming. People aren’t just falling through cracks anymore; they are being left to drown.

I see it in my FSGL and clinical skills tutors, both family medicine physicians; they are tired. It makes me tired, and I’m not even doing anything.

Family medicine sounds rough. As much as I hate to admit it, there is an element of pride and ego that weighs into my specialty choice decision. I would wager to say this factor plays into the majority of medical students’ decisions. Or maybe this is the unintentional hidden curriculum working? Or maybe this is the type of people medicine attracts - who knows. Still, Tone Matters.

11

Dr. Sanfilippo once wrote in a completely unrelated blog post that people vote with their feet. There were over 250 unfilled R-1 first iteration CARMs spots for family medicine this year1. He, Dr. Philpott and Dr. Schultz also wrote in a completely related blog post that part of the negative hidden curriculum is that medicine culture is hierarchical, and that some disciplines are inadvertently taught to be more valued than others2.

Respect, appreciate, admire, and support your family medicine colleagues. A little extra kindness supposedly goes a long way for patients – as physicians, a little extra kindness could go a long way for each other. Resist the hidden curricular hogwash and be a better human.

I am not here to step out of ranks and tell unyielding attendings how to speak about their family medicine colleagues. I am asking you to think about your own biases, your own perception, your own identity. Most importantly, I am asking you to check the tone you use in conversations about family medicine.

There are many things that need to change, and people are doing good work to address this. For example, Dr. Danielle Martin (the queen of classy opposition)3 and others (Dr. Philpott hot off the press again) just published an urgent to-do list for more equitable primary care. The majority of the points are bang on and will make a huge difference4. But the implementation will tragically get caught in the 401-rush hour-traffic-speed of political proceedings and chronically atrophying budgets.

Reading their call to action made me moderately hopeful, but impatient. And I feel like it missed one more point that is actionable by one group of people and is free to implement. Here is a hint: Tone Matters.

To give you a practical example, if someone tells you they are interested in family medicine, do not say “Oh wow, that could never be me. But good for you’. It is patronizing and derogatory and isolating. Tone matters.

Think about it, check your assumptions, be part of the solution. Because as future doctors in this country, the family doctor shortage is our problem to deal with whether we like it or not.

So, here’s to heading into clerkship, the CARMs shark tank, and the rest of our careers. Hopeful, Impatient, and telling you that Tone Matters. I am begging you to turn those death knells into anything less ominous.

References on Page 56.

“People aren’t just falling through cracks anymore; they are being left to drown.”

12

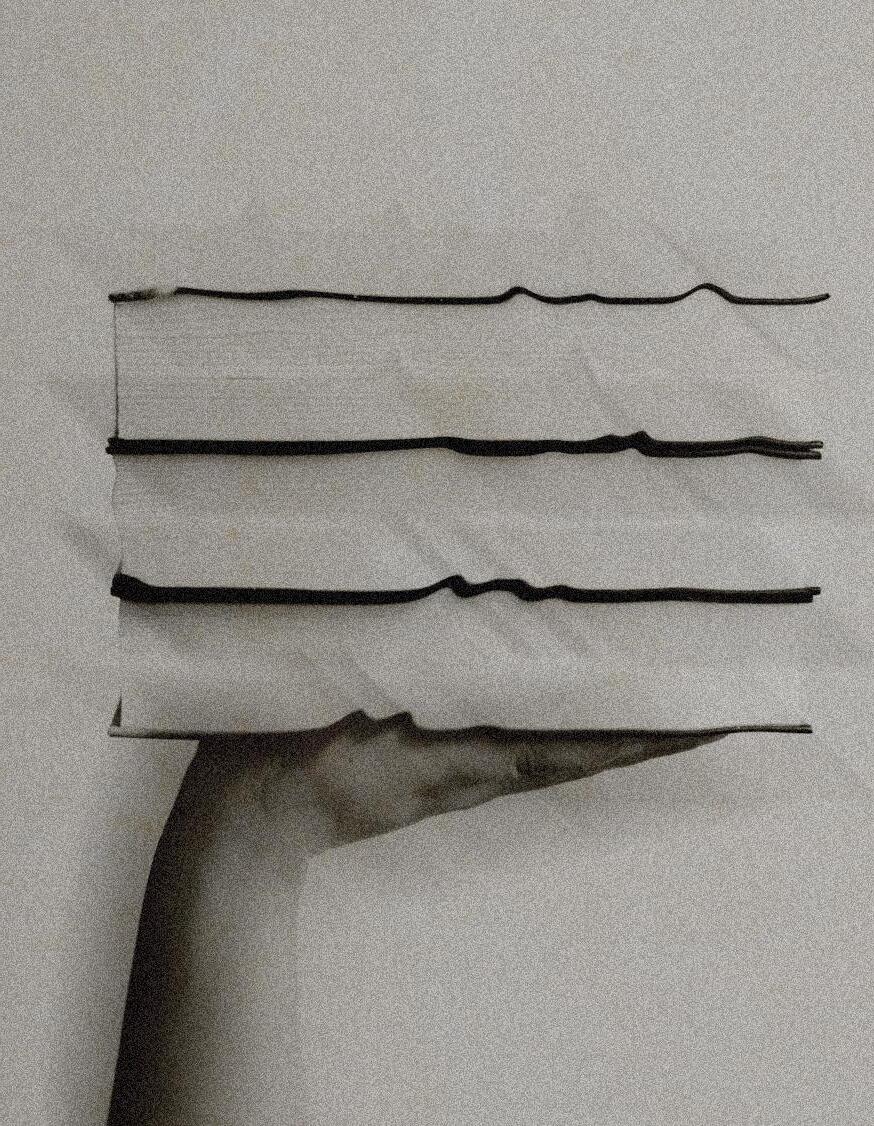

“Here Lies Wellness”

13

Artwork by: Michele Zaman

have u called mom?

be a better partner

manuscript finished?

were u productive?

Gym tn?

ur soap note is late

C ur friends!

Do better

U should study

14

Written by Benjamin Divito

“This is going to be a difficult conversation.”

We walk through the emergency department, busy with noisy chiming and moving bodies, towards a small room tucked away in a corner.

As we enter the room, the bustle of the emergency department is replaced by the quiet hiss of high-flow oxygen. The room is filled with soft dim lights, decorated by the flashes of monitors.

I am met by deep brown eyes. A small middle-aged woman, dwarfed by the comparative enormity of her bed, sits across from where I stand. Sitting with her is her husband and her father, neither making a noise.

The physician squats next to her, approaching her at equal height, and they begin to talk.

“The patient we are about to see has [incurable lung cancer] that is rapidly advancing. She is presenting today with worsening dyspnea.”

The physician asks about her symptoms, discusses the progression of her disease, and carefully says that she may pass in only a few days.

Her prognosis of weeks cut to days.

Her husband watches from her side, scratching his arm anxiously from under a white hospital blanket. His already dark eyes deepen further as he listens.

Her father sits in a chair to her bedside, still as glass, except for his heavily moving eyelids that reveal quiet tears.

Untitled

15

Her response is different. She is calm, her dialogue clear and without strain. She does not seem afraid.

Where does she draw her strength from?

She wants to die.

“I want to be comfortable. Without pain.”

Her prognosis of days cut to hours.

Over the next minutes, they discuss the manner of her passing. The removal of care and the addition of drugs that will let the disease finish its aggressive course. “It will feel like you are drifting into sleep.”

He asks if she would like to hold off until more of her family can arrive, their plane having not yet landed.

“This is what I want. They would only see the same thing as they would over this” as she holds up her phone.

The physician offers kind words and promises to monitor her closely.

As we leave, the quiet atmosphere of her corner room is replaced with the chiming of machines and the movement of busy bodies.

We descend into the chaos, to find our next patient.

16

Written by: Ashwin Rao

Artwork by: Michele Zaman

Ode to Immigrant Doctors

my dad was a surgeon with countless stories of sleepless nights, sacrifice, and exertion but what else could make him smile like this?

my dad was a surgeon whose titles were stripped by this “land of opportunity” his operating theatre productions drowned leaving acts of desperation to surface

my dad was a surgeon who distorted my view of medicine how could a man who devoted thirty years advise so strongly against the scalpel?

but his resilience kept me afloat and led me now to where he once was my dad is a surgeon his passion lives on through me

17

“A Single Strand of Silk”

18

Artwork by: Prashanth Rajasekar

THE DOCTOR’S ORDERS

Correcting Misconceptions about Medical Specialties

Written by: Mudia Iyayi and Joshua Bierbrier Medicine

is composed of a myriad of specialties, each with unique aspects and nuances. Entering medicine, it is common to have misconceptions about what these specialities entail. Our ideas about specialties can be guided by media or physician stereotypes, rather than the experiences of doctors in the field. This may leave us feeling misguided on decisions around residency or general career exploration. In line with the theme of Distortions in Medicine, we consulted eight physicians to discuss common misconceptions about their specialties.

EMERGENCY MEDICINE

Emergency medicine is not just acute resuscitation, trauma and overdoses. It’s a lot of thinking on your feet and troubleshooting unique problems that no textbook can prepare you for. The emergency department is the safety net for society. We spend a lot of time advocating for patients in crisis, patients with no support and patients with no voice. Collaboration - with patients, consultants, allied health and upper leadership - plays a huge role in our daily work. Being an effective emergency physician requires creative thinking, humility and a good sense of humour!

Dr. Isabelle Gray, Emergency Medicine

PATHOLOGY

Before I did an elective in Pathology in QMed4, I didn’t really understand that pathology was, in fact, practicing medicine. I discovered that, much like radiology, pathology is a visual interpretation-based diagnostic specialty. Our interpretations of biopsies and surgical specimens largely dictate the most appropriate further investigation or treatment. You may not get many boxes of chocolate in December from your patients, but if you want a practice enriched in impactful (ie. cancer vs not cancer!!!) decision making based on your knowledge and visual interpretive skills, pathology may be for you!

Dr. Christopher Davidson, Pathology

PALLIATIVE CARE

Only a part of Palliative Medicine is end-of-life or hospice care. In reality, Palliative Medicine can be involved at any point in a patient’s illness trajectory, right from the time of diagnosis until the time of death. Often, we work in multidisciplinary care teams where patients are concurrently receiving disease-directed therapies, such as chemotherapy or dialysis. The core of our work is helping patients find relief from distressing symptoms, whether physical, spiritual, emotional, or social. Palliative Medicine aims to help people live as well as they can - early involvement has been shown to improve quality of life and in some cases may even help people live longer.

Dr. Julianne Bagg, Palliative Care

OPTHALMOLOGY

Ophthalmologists share their time between clinics and ORs. And you can adjust that to your liking. There are so many different surgeries and sub-specialties. Probably the specialty that performs the highest number of different tests/exams per appointment (visual acuity, tonometry, pupillary reflex, fundoscopy, gonioscopy, ocular motility, etc.). And we are privileged, fundoscopy is the only exam that you can see with your own eyes, a nerve and pulsating arteries.

Dr. Newton Duarte, Opthalmology

“ 19

THORACIC SURGERY

As a medical student, I wish someone had told me the following: 1) As a thoracic surgeon, I am as much a physician as a surgeon. Before offering invasive treatment such as surgery to a patient, I need to understand and treat severe medical refractory disease non-operatively with lifestyle modification and medical treatment. I am the gatekeeper before offering surgery to my patients. 2) As an academic thoracic surgeon, I operate only 3 days a month. Unlike community thoracic surgeons who have 3 OR days a week, I spend the rest of my time assessing patients in the clinic, teaching medical students or residents, conducting research, and working in administration. 3) It doesn’t take 7 years to train to be technically competent as a thoracic surgeon. Most procedures can be learned with enough exposure in much less time. The training takes that long because you need time to learn the art of patient selection and who you should not operate on. You also need lots of patient volumes over a long time to learn how to take care of your patients postoperatively, manage intra and postoperative complications, and optimize your patients for surgery. 4) Thoracic surgery is not a fellowship program. It is a 2-year residency program after a 5-year general surgery residency program. Thoracic surgery fellowship starts in your 8th year of training. It is a long journey but it is certainly one of the most rewarding specialties.

Dr. Wiley Chung, Thoracic Surgery

PEDIATRICS

A common misconception is that pediatricians are “baby doctors”. Pediatricians see and treat children from birth (in fact, many do prenatal consultations too) through late adolescence. In most cases, pediatricians stop seeing patients when they turn 18 years of age, but in some cases they continue seeing patients until their early 20’s, particularly for chronic illnesses. In Canada, pediatricians are trained to be consultants, whether as general pediatricians or a subspecialty pediatrician (pediatrics encompasses a very wide range of medical specialties, plus things like critical care, neonatology, emergency medicine, pediatric oncology, developmental pediatrics and adolescent medicine). While some pediatricians practice primary care pediatrics, particularly in larger cities in Canada (unlike the United States, where primary care pediatrics is the norm), most practice consulting pediatrics, and see patients by referral from other practitioners (such as family physicians) for complex and multi-system problems. While Pediatrics is a medical specialty of its own with its own subspecialties (for example, cardiology, respirology, gastroenterology, rheumatology, infectious disease and more), many other fields, such as the surgical specialties, have pediatric subspecialty training or certification after completing an initial specialty (for example, pediatric general surgery, pediatric ophthalmology, pediatric anesthesia, pediatric radiology, pediatric urology and more). It is also commonly thought that most specialty pediatrics is practiced in large children’s hospitals. While certainly this is where much of the very highly specialized pediatric care is provided, most pediatric care is provided in a variety of hospital and community settings.

Dr. Richard van Wylick, Pediatrics

OTOLARYNGOLOGY/ENT

The simplest way to describe ENT, or more formally known as Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, is the care of medical and surgical disorders from the head to the collarbones, excluding the eyes and brain. Of course, that’s not strictly true as some of our sub-specialists contribute to management of lesions in the posterior and anterior cranial fossa, and we are still occasionally called on to provide rigid endoscopy of the trachea and esophagus. However I think the one common misconception of ENT I see is that we are mostly a surgical specialty, while in fact much of ENT involves medical care, so I see it as a specialty that is nicely balanced between procedural interventions, and medical care of acute and chronic conditions.

Dr. Russell Hollins, Otolaryngology

Dr. Russell Hollins, Otolaryngology

The insights from physicians illustrate the importance of appreciating a specialty for what it truly offers as opposed to misconceived stereotypes. We hope they can help guide your residency and career decisions and serve as a reminder to see through Distortions in Medicine.

??

20

GREENING THE OR:

THE UNDERSTATED IMPACTS OF SURGERY ON THE ENVIRONMENT

Written by: Rosephine Del Fernandes

The picture displayed depicts a woman in a surgical gown surrounded by surgical waste.1 The woman’s name is Maria Koijck. She is a patient and artist who was shocked to discover the amount of surgical waste produced from her single operation – a double mastectomy, which she had undergone after receiving a diagnosis of breast cancer. She used art expression to raise public awareness of the impacts of surgery on the environment, which ultimately affects our health.1

SURGICAL WASTE

Although the health impacts of pollution and environmental changes are well known to many, the environmental impacts of healthcare are disregarded more often than not.2 Operating rooms are particularly resource intensive. Many surgical devices are single-use, require batteries, and are neither biodegradable or recyclable. At the end of an operation, numerous large plastic bags are filled with drapes, gowns, plastic instruments, tubing, and disposable devices that release environmental toxins when they are disposed of. One study found that disposable linen, paper, and recyclable plastic accounted for 74% by weight of total surgical waste.3 Recycling these items and using reusable linen products could lead to significant reductions in surgical waste.3 Yet, this is typically not practiced in the operating room, and there are few studies available to inform the safety of recycling and reusing in the OR. Additionally, there are many opened and unused one-time use items, including surgical sponges and blades, that not only contribute to financial expenditure loss, but also a carbon footprint.4

RICHARD SAMUELS

A second major impact of surgery on the environment is the carbon footprint of anesthetic gases and the large consumption of non-renewable energy. Desflurane is one of the most used anesthetic gases, now out of favour with its known environmental impact. Using a single bottle of desflurane has the same global warming effect as burning 440 kg of coal.5 Physicians should be made aware of the potential environmental hazards of anesthetic gases, and these should be considered when deciding between anesthetics for a procedure.

Equipment including HVAC systems, monitors, heaters, and surgical tools alone consume copious amount of energy, which in many regions is derived from the burning of fossil fuels.6 In North America and Europe, the healthcare industry is responsible for producing an astonishing 10% of greenhouse gas emissions.7 These same countries often set global standards and inspire surgical practices in other regions. It is well known that changing climate due to

21

an increase in greenhouse emissions will contribute to an increasing number of major environmental events, such as heat waves, cyclones, floods, and droughts, which in turn, cause significant health crises, often in an inequitable population distribution.2 Alarmingly, those most often harmed live far from those who benefit from healthcare provided.2

Doctors and other hospital leaders have a practical and ethical responsibility to address the environmental footprint of surgery. The healthcare evaluation should consider the use of new gas, equipment, technique, and the costs of the environmental footprint, which has largely been ignored, in addition to health outcomes and financial costs.

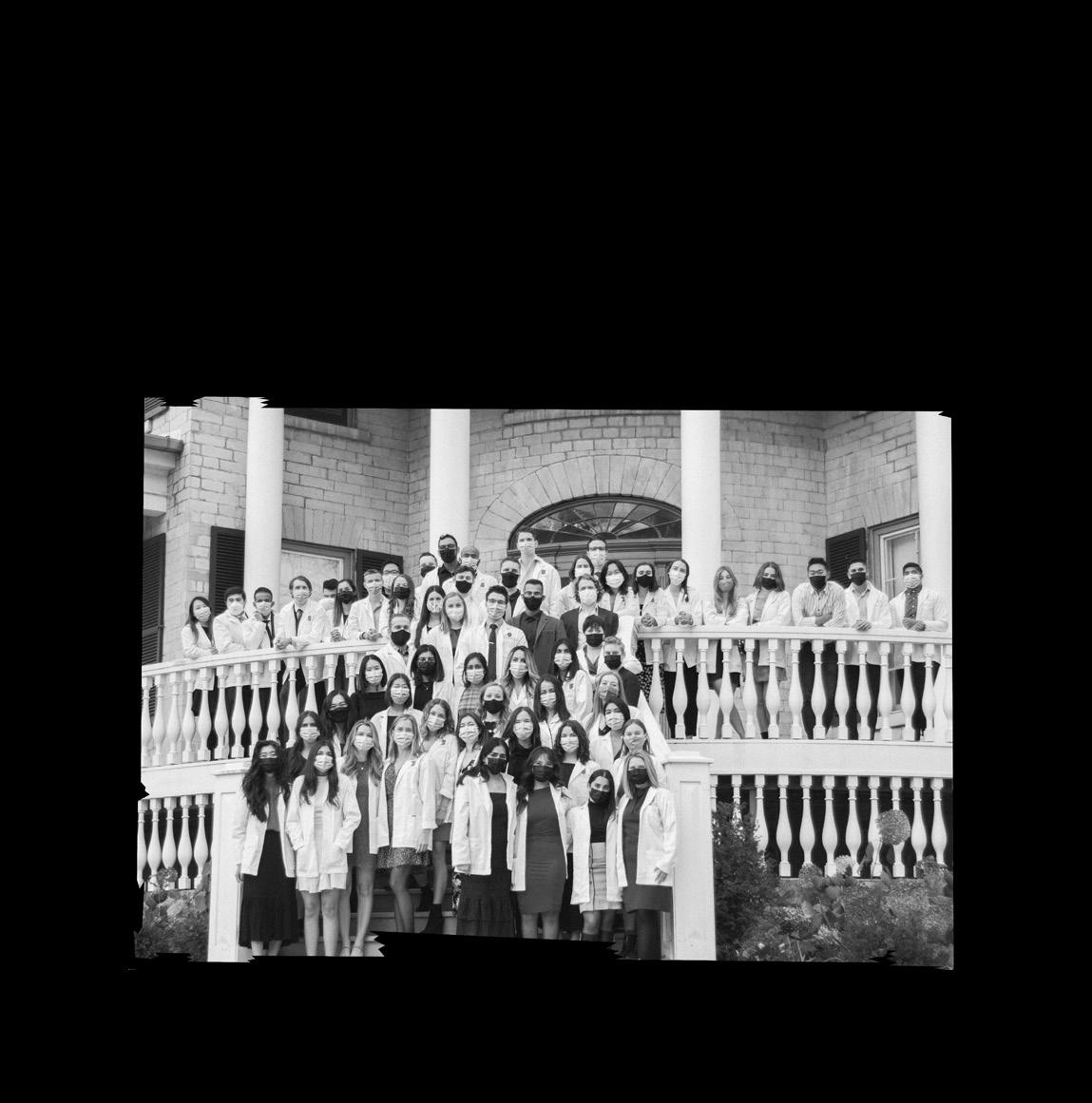

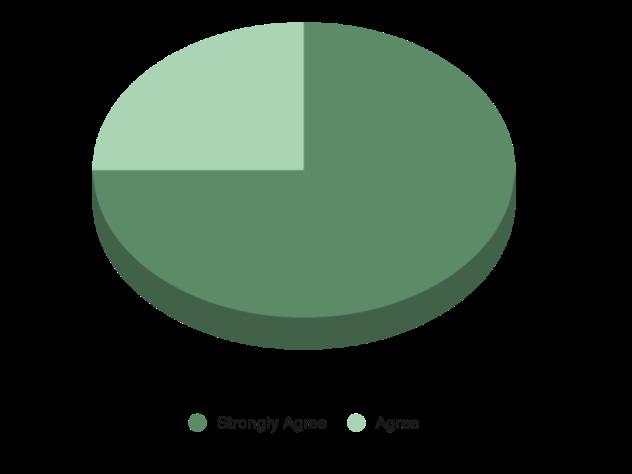

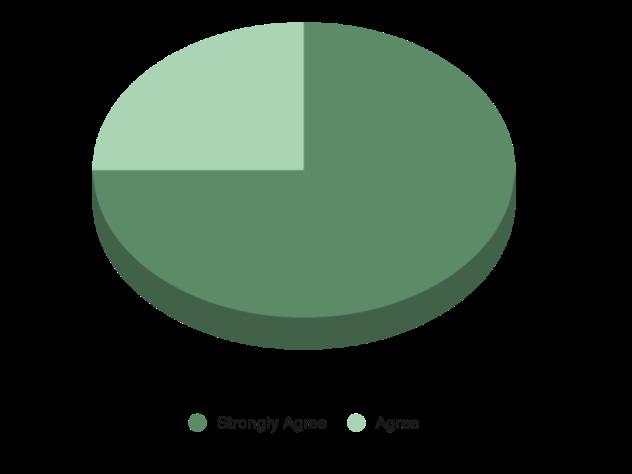

During the week of SSTEP in the summer of 2024, new clerks were asked questions to reflect on their learning of environmental sustainability during pre-clerkship. Here is what they submitted:

As a new clerk, do you feel you were taught adequate knowledge about the environmental impacts of healthcare to become an advocate? If not, are you interested in learning more?

“Having been in healthcare previously, I don’t feel students have a true comprehension of the waste that occurs until they start clerkship and see it firsthand.”

“No I don’t think there is enough conversation but I would like to know more.”

All (4) respondents felt the education they received was inadequate and were interested in learning more.

Avoiding the use of gloves and swapping one-time use tools for reusable tools did not impact my learning during SSTEP.

Three clerks strongly agreed (75%) and 1 clerk agreed (25%).

ACTION ITEMS

In effort to address some gaps in knowledge regarding environmental sustainability in surgery, here are some Action Items and suggested resources to become a Student Advocate and to incorporate changes to future practice.

Become a Student Advocate for Planetary Health

1. Review available resources, such as the CFMS Planetary Health Competencies, that address the local and national health impacts of climate change and other environmental changes targeted to medical students.

2. Support student initiatives to improve planetary health projects and improve planetary health education, such as the QMed Environmental Advocacy in Medicine group.

3. When medical conditions made worse by environmental changes are discussed in lecture or small group learning, share resources with your classmates to supplement their learning. Additionally, approach the lecturer to suggest environmentally conscious learning points for future years.

4. Become proficient in sterile technique to avoid discarding one-time use items if a break in the sterile field occurs.

5. When you notice hospital staff disposing single-use recyclable products, advocate for more easily accessible recycling receptables to help break the cycle. If staff are not aware of the ability to recycle certain products, such as the plastic bags holding scrubs, kindly inform them!

Incorporate Planetary Health Advocacy into Your Future Practice

1. Select anesthetic techniques that minimize greenhouse gases and consider the global warming potential of desflurane.

2. Reduce plastic use to discourage its production. Plastics are nearly indestructible, water resistant, and do not conduct electricity. While these attributes are useful in the OR, they make them uniquely harmful to the environment.

3. Reuse equipment if indicated, such as reusable laparoscopic trocars, or laundered gowns and drapes.

4. Minimize the use of surgical staplers powered by single-use lithium batteries.

5. Advocate for the use and development of environmentally conscious technology and materials. Collaborate with building resources and hospital management in the decision-making for these items and consider environmental footprint in addition to health outcomes and financial cost.

References on Page 56.

22

23

“Prescribed Greenery” Artwork by: Anonymous 24

THE SPIRIT CATCHES YOU AND YOU FALL DOWN: A BOOK REVIEW

Written by: Cynthia Qi | Artwork by: Kiera Liblik

Written by: Cynthia Qi | Artwork by: Kiera Liblik

What does good care mean to you? To some, it means timely access to interventions, delivered by competent specialists at a medical establishment stocked with the latest technology, medications, and treatments. To Lia Lee’s family, good care takes place in their home, surrounded by people they trust, and involves a spiritual shaman called a txiv neeb who rides a winged horse over twelve mountains between the earth and the sky, crosses an ocean inhabited by dragons, and negotiates with the spirits in the underworld to restore health back to their patients. If that’s not patient-centered care, then I don’t know what is.

The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down is a true story written by Anne Fadiman about a Hmong family living in the United States who care for their daughter, Lia Lee, who was diagnosed with epilepsy as an infant. Readers are immediately drawn into the rich and intricate world of the Hmong. The Hmong people are an indigenous group who originated in East and Southeast Asia. Presently, they reside in China, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand, and in the case of Lia and her family, in a small town in California called Merced. The book explores the clash between the Hmong way of living and the American medical system as both sides attempt to navigate Lia’s medical condition.

Lia’s family had a drastically different understanding of her illness compared to her doctors. Her doctor saw an 8-monthold female who was brought into the emergency room after her parents noticed her shaking and not breathing for 20 minutes at a time. He recognized these symptoms immedi ately and diagnosed her with epilepsy. No one would fault this doctor for his actions. He was prepared, asked the right questions, performed the right assessments, and came to the right conclusion. However, Lia’s doctor had no way of know ing that Lia’s parents had already diagnosed Lia’s condition as qaug dab peg, which translates to the illness where “the spir it catches you and you fall down”. Her parents had noticed her shaking and not breathing for 20 minutes at a time. They recognized these symptoms immediately and knew that this meant that Lia’s soul was lost. Her soul was frightened by a loud sound, fled her body, and had become lost in the spirit world. Lia’s parents would have been surprised to hear that her doctor thought her condition was caused by

an electrochemical storm inside their daughter’s brain as a result of the misfiring of atypical neurons. They would have thought that her doctors were crazy.

I love this book because it explores both sides of the conflict in detail and concludes that no one is to blame. Much like a Shakespearian tragedy, Lia’s story is devastating because her doctors were excellent, and her parents were loving, yet the conclusion you knew was coming kept barreling steadfast through the pages. Lia’s parents did not speak English and had a limited understanding of Western medicine, so they struggled to comply with the doctor’s instructions, which led to miscommunication, medication errors, and ultimately, a tragic outcome. Meanwhile, her doctors, who were trained and taught to think through a purely biomedical lens, were frustrated with Lia’s family in what they perceived to be intentional noncompliance and distrust in the medical system. Despite years of top-notch medical training and the best of intentions, readers are left wondering if they did more harm than good.

25

This book taught me that the truth becomes distorted amidst a clash between cultures. It’s easy for us to dismiss the Hmong way of knowing as “wrong” since their beliefs are not rooted in evidence-based science. The difficult question that we ought to ask ourselves is whether our points-of-view are also considered distortions when viewed through another lens. It’s undeniable that “Western” or evidence-based medicine saves lives, and I am not arguing against scientific rigor. However, it’s important for us to recognize that what we believe to be “truths” can seem unbelievable to many. For some, like Lia’s family, the biomedical point-of-view is the unimaginable, inconceivable, and sometimes inhumane point-of-view. It is a dangerous mentality to assume otherwise, and ignorant to think that our view is the objective “truth” that is untouchable and removed from all biases.

As we continue to gain knowledge to become competent physicians, it is imperative that we continuously criticize our lens, and remind ourselves that sometimes, an objective truth matters less than the meaning each party assigns to it. Only when we become aware of our worldview, question it, and seek to understand the worldview of others, can healing truly begin.

The book provides readers with 8 questions that we can ask our patients to try to unravel and reveal distortions experienced from both sides. The questions are as follows:

1. What do you call the problem?

2. What do you think has caused the problem?

3. Why do you think it started when it did?

4. What do you think the sickness does? How does it work?

5. How severe is the sickness? Will it have a short or long course?

6. What kind of treatment do you think the patient should receive? What are the most important results you hope she receives from this treatment?

7. What are the chief problems the sickness has caused?

8. What do you fear most about the sickness?

Overall, I rate this book 5/5. It is one of my personal favourites because it changed the way I think and view the world, and isn’t that, after all, the goal of reading?

26

27

Photography by: Frank Chen

to speak is not to say

Written by: Josie Jakubowski

You may never hear me speak, but I have a lot to say Oh, and don’t judge the chair, or my outward display

To you, I am different, but to my friends I am one and the same Like any other child, laughing and playing is my aim

I can’t say “I love you”, but I will show you in my embrace I can’t say “I’m happy”, but you’ll see it on my face

Other people ask, “why is he not like us?” They can’t understand, and sadly, we can’t discuss

But I skate, ski, and sail, there’s so much life to live My spirit soars, I have so much love to give

So how can you change a life without ever using your voice? I speak with my hands and face, every action is a choice

In a place not built for me, I see the world from a different seat

My chair might change how I do, but it will not limit who I’ll be, I will show you a different path, it is my destiny

So take my hand, I’ll lead the way, Come see the world through my eyes today

28

Artwork by: Michele Zaman

SACRED SEVEN

Written by: Danny Ke

“I want derm so badly, but there are so few spots. Low-key and high-key freaking out…. I think I should back up, but I really don’t want to….”

Why is this even an issue? How stressed could these med students possibly be? They’ve made it! My entire life right now revolves around just being in the same room as they are one day. Premed 101 really hammers down this idea: Once you’re in, you just ride this wave towards a rich and fulfilling life.

I work with some medical students in an organization we co-founded. Being the only pre-med in a room of ten med students is… overwhelming, to say the least. I worship the ground these titans walk on every time I’m gifted with their presence. Their immense power radiates toward me like chest pain to the arms, imbuing me with an energy to work harder and faster. So it baffles me every time CaRMS is even brought up. What does a titan possibly have to worry about?

3 years later

A wise man once said, “Most people across cultures wake up at a 7/10. We don’t have absolute scales, and everything is in relation to something else. These anchors are arbitrary, and with time, we get to choose what they are.” Now a titan myself, I see what life has to bring with a much clearer lens. Have all of my pre-med worries disappeared? Yes. But am I still stressed about exams, research, ECs, adulting, clerkship streams, and how in three short months, the med building will no longer be our hub world? Also yes. How can both of these statements coexist? Distortions. Why can’t I forever be as happy and ecstatic as I was the moment I got in, instead now waking up again at around a 7/10? Distortions.

Distortions to me reflect Sisyphus’s need to always focus on pushing his boulder, for why focus on what’s behind him? There is a lens with which we see the world that is optimal for our own personal development, and this lens changes, or “distorts,” over time. Medicine is the epitome of a career that provides continual growth. No matter where I am, there is always a next step, and that is a privilege. It is one of the points many of us brought up in our “why medicine” spiels. In my pre-med years, my mom always reminded me that medical school is not an end, but a new beginning. Of course, I had no choice but to see it as an end, distorting my life to focus on the task at hand. We all do this at different stages of life. We’re even doing this now, focusing just on how to be great students, clerks, and CaRMS applicants. There will be bigger fish to fry in residency, but we don’t have to heat up that pan quite yet.

“Over the course of the next four years, you will embark on a personal journey which will change and shape the rest of your life.” Amid my excitement of realizing that I’ll be a physician, this one line in my acceptance letter stuck out. I just got in, so thinking about my life for the next four years was beyond me. But throughout that week, I felt my mind actively distort. Excitement about admissions gradually morphed from a 10/10 (yay!!) to an 8/10 (time to find a new place and fill in my vaccine forms!). Since we hit the ground running and have adjusted to our new lives, maybe now I’m at a 7.2/10. This 0.2 is the satisfaction that still lingers long after having achieved such a difficult goal. It is Sisyphus looking back during his coffee break and admiring how far he has come. It is a slow burn of gratitude for the privilege we will have as physicians. Amid all these distortions, maybe this 0.2 can stay, at least for a little longer.

29

30

Artwork by: Michele Zaman

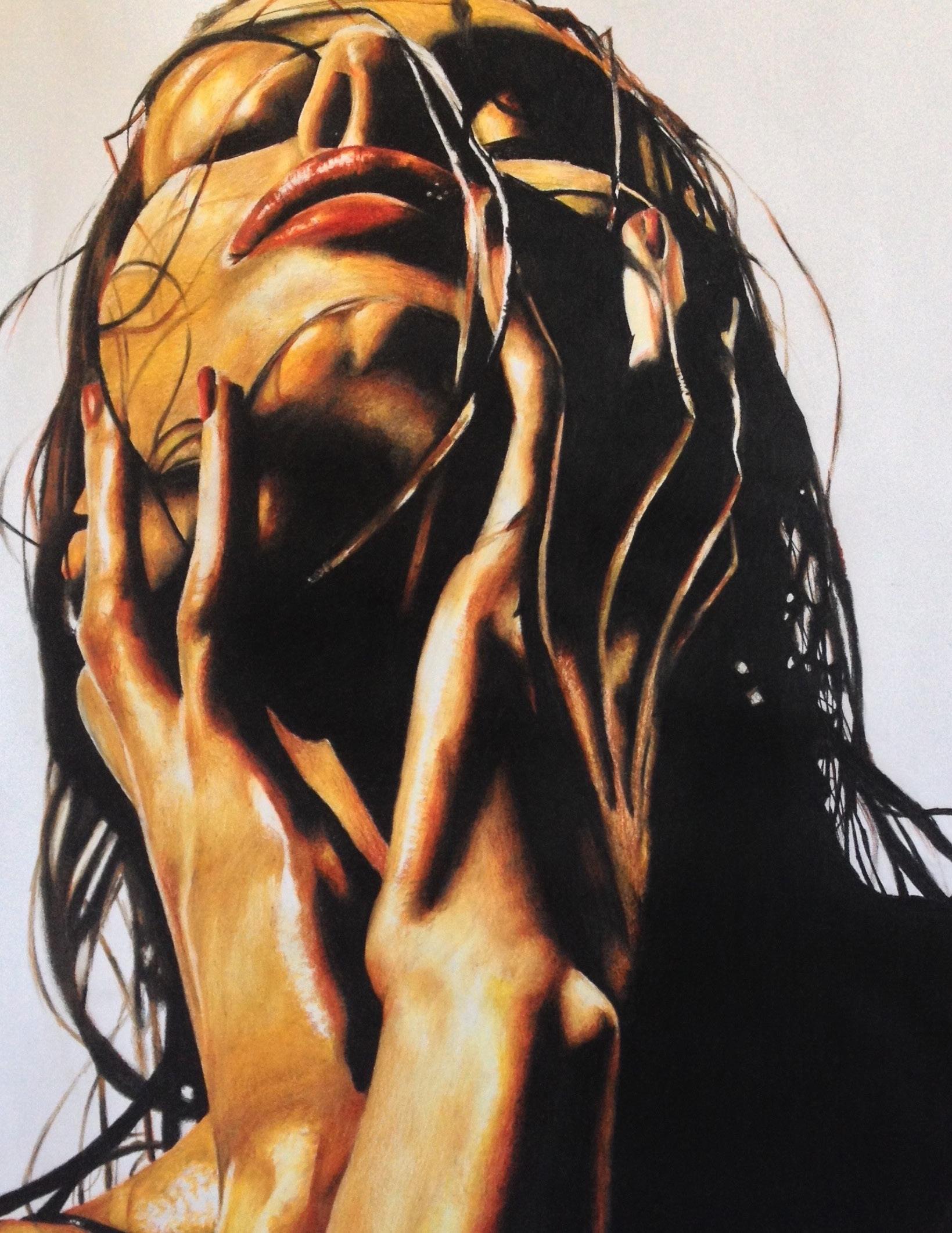

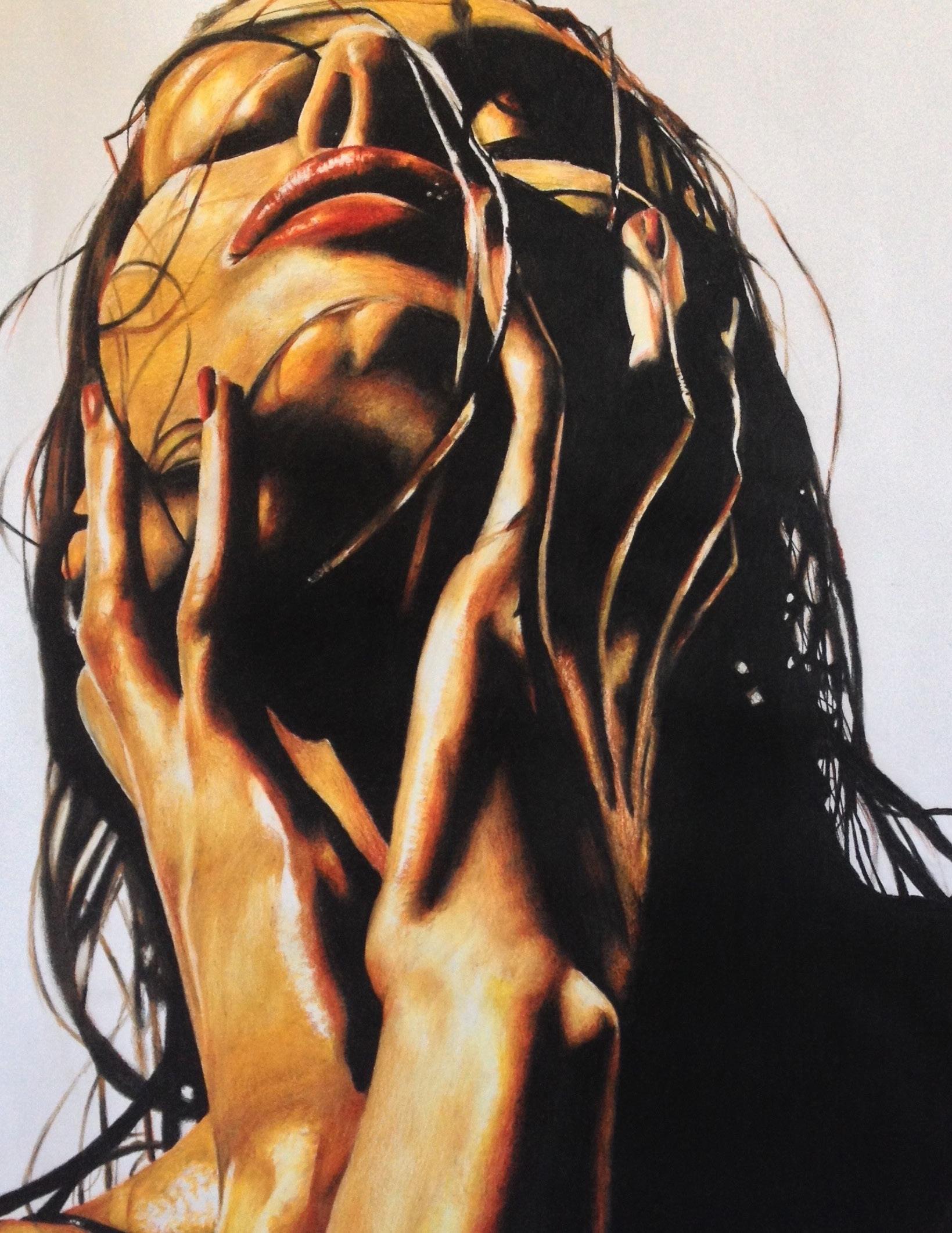

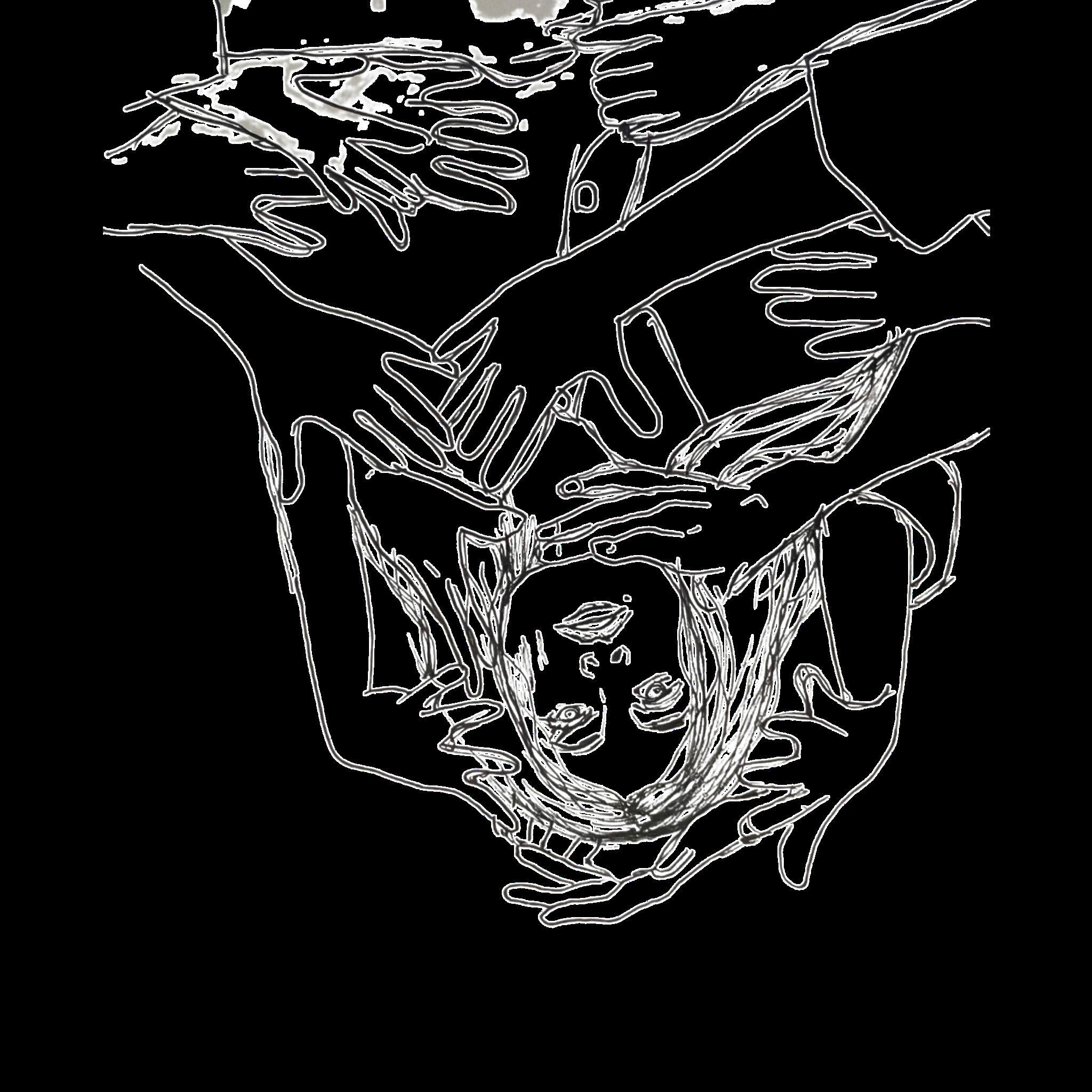

“The Beholder”

31

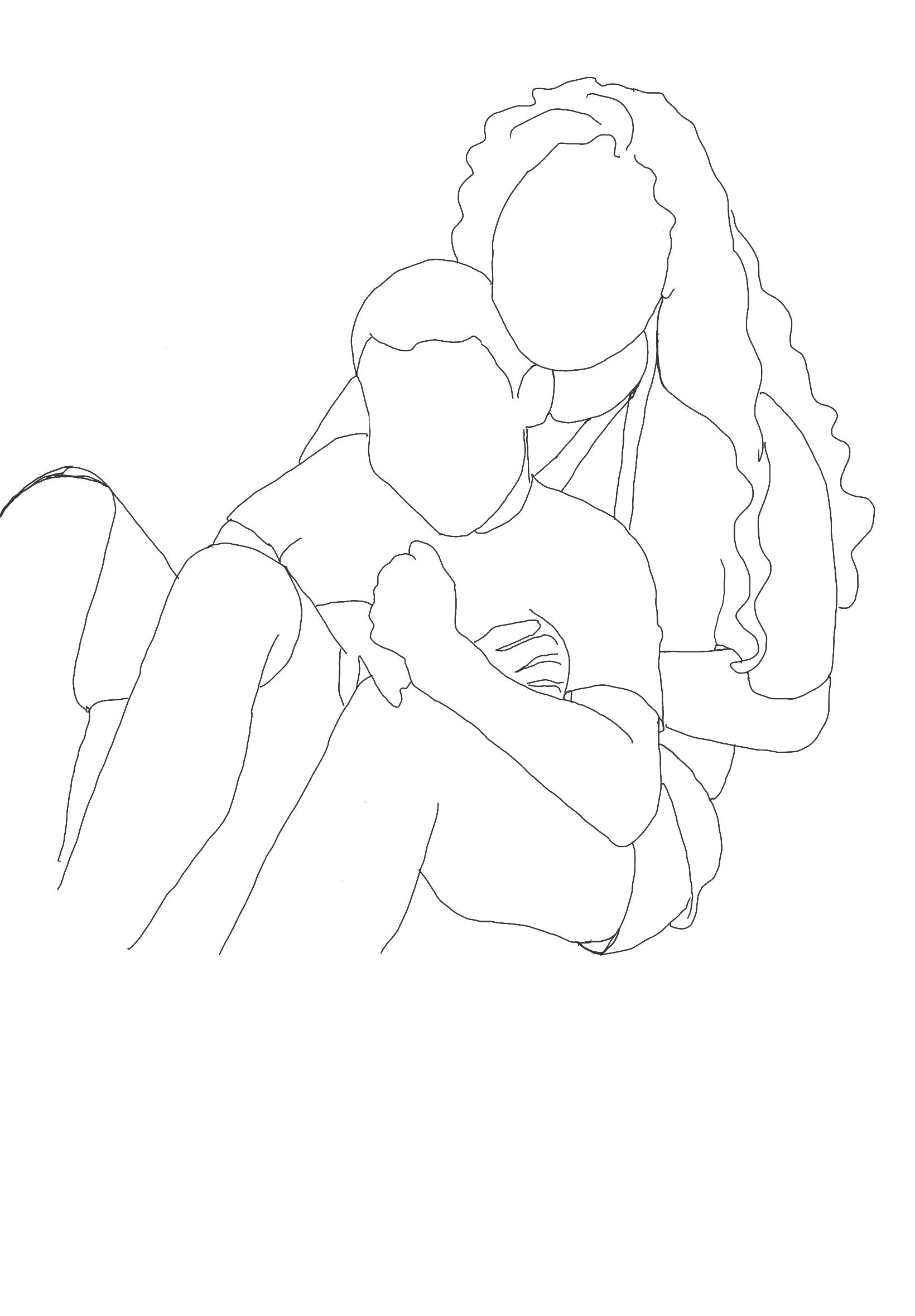

Artwork by: Simoon Moshi | Model: Dan Dilliot

MISCONCEPTION

A CLERK’S REFLECTION ON THE CaRMS PROCESS

Written by: Sarenna Lalani

Hindsight builds perspective. In each moment, we make the best decisions we can with the information we have. However, when we distance ourselves from these points in time, we are better able to identify the flaws in our reasoning. As my class continues to brave this CaRMS season, I find myself hoping there is a crack in this logic. The further away I get from each interview, the worse I feel; not just about my responses, but also about myself. Each day, new insecurities crawl out of the woodwork, manifesting in self-doubt and what feel like unrelenting tidal waves of anxiety. I had known that this process would be painful, but never could I imagine just how exhausting it would be. Throughout the past few weeks, I have joked with my friends about feeling like a shell of a human; alarming, however, is the level of truth within that statement.

I remember first-year vividly. I blinked and nearly four years had gone by. I can picture myself in the lecture hall of the School of Medicine, feeling like a million bucks twirling in the crimson seats of 132A. I remember earnestly taking notes in the “Pearls of Wisdom” session, attempting to soak in as much information as I possibly could. A smile creeps onto my face as I write this, my cheeks unable to conceal my fondness of those memories. I vividly remember each moment of O-Week, from the cardboard boat rivalry to the friendships crafted over name-tags, the long summer nights to the eager excitement of our first day. I recall the whispers of CaRMS being uttered under people’s breaths. We were sitting at the kids’ table, quietly passing along a bad word, whispering so the adults wouldn’t hear. CaRMS was an enigma – nothing we heard then would prepare us for the tumultuous path to come. To say my construction of the ordeal was a misconception would be a monumental understatement.

This process is a cruel one, demanding every ounce of energy within your being. Those who have been through it offer pitying smiles, both acknowledging your pain and secretly grateful to not be in your shoes. You put your heart and soul on the line, first in a letter that details your foundational experiences and innermost dreams, then again in an interview that adjudicates your passion and personality. Each day you come to the surface gasping for air, only to be pulled back in by the undercurrent. Don’t get me wrong, it’s survivable (I mean, look at all the people before us who have done it),

but it definitely ain’t easy. CaRMS is the culmination point of four years of medical school and the years of dedication and preparation before that. It all comes down to a Gale-Shapely algorithm (thank you, Ricky), computed on some unknown device in an undisclosed location. So much feels out of your control. To my friends that feel this way, I see you. To those who don’t, please tell me your secrets!

Med school has been a journey, simultaneously the shortest and longest one of my life. Looking back, I see lifetimes compacted into a mere few years. First, I see an exponential amount of growth – brains that solved new problems and gained new knowledge, each intellectual morsel associated with a corresponding surge in confidence. I see friendships – brass-bonded by boundless days and late nights, solidified on a couch on the sixth floor overlooking the water. I see perseverance and grit – my colleagues and mentors overcame the insurmountable, and when faced with separation and isolation, continued to fight a broken system to serve those in need. Above all, I look back and feel an immense amount of privilege. I had the honour of learning in a community that both inspired and supported me. I have done life alongside kind colleagues and close friends, sharing in major milestones with screams of excitement and tears of joy.

“Each day, new insecurities crawl out of the woodwork, manifesting in self-doubt and what feel like unrelenting tidal waves of anxiety.”

A few months ago, I had no idea what obstacles the road ahead would bring. Similarly, a few years ago, I knew not what gifts the pathway ahead would bear. I conceived both in my head, spending hours crafting perceptions that would ultimately be proven incorrect. I would find it hard to believe that any human is prepared to have their heart exhumed and examined by a panel of humans in a hospital far away. But I also find it hard to believe that a better support system exists than this tribe of humans that I am proud to call family. QMed, particularly the class of 2023, I owe you a thank you; thank you for nurturing and supporting my dreams, for shaping the person I am, and for inspiring the doctor I hope to be. Consult ya on the other side!

32

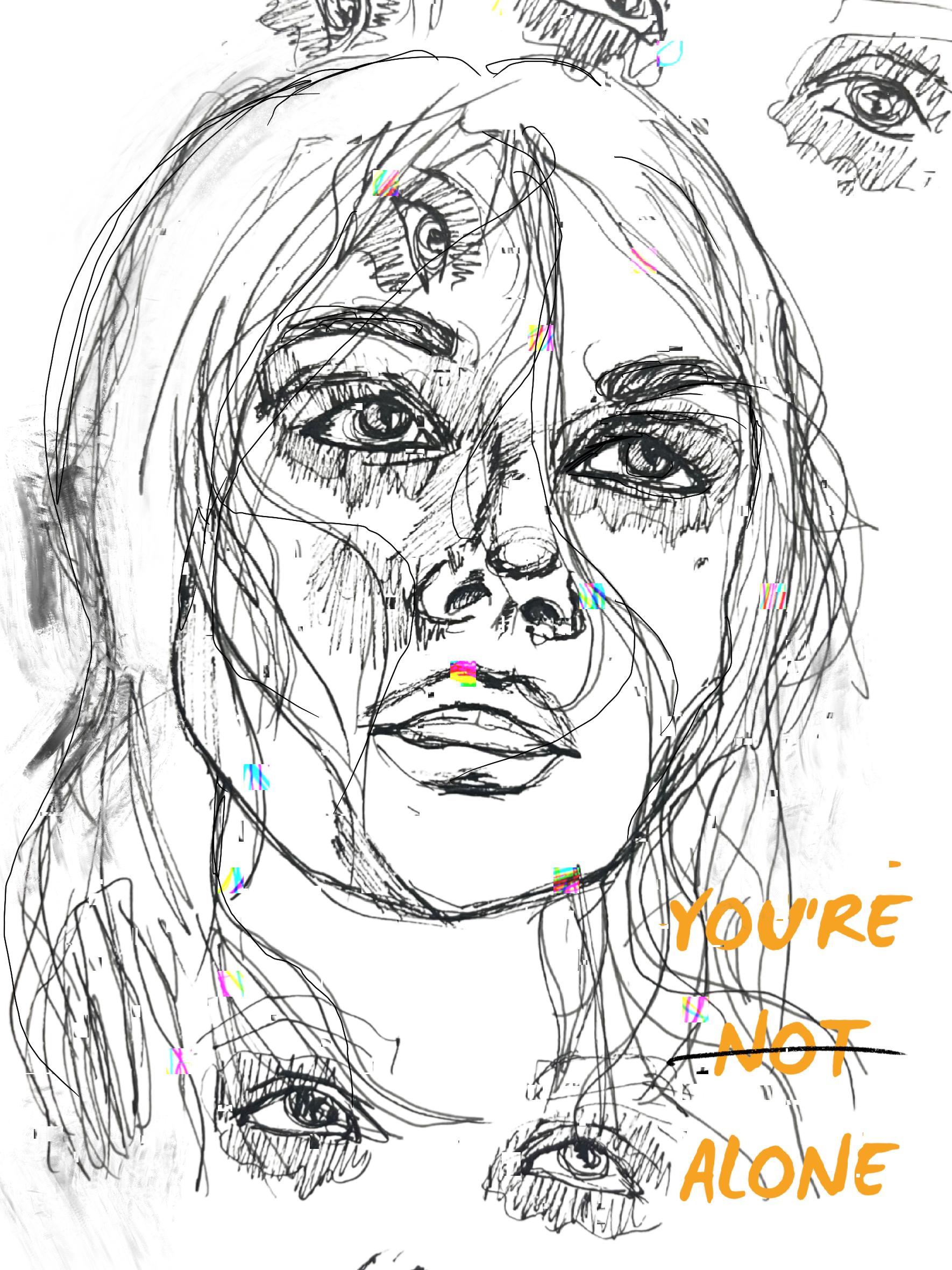

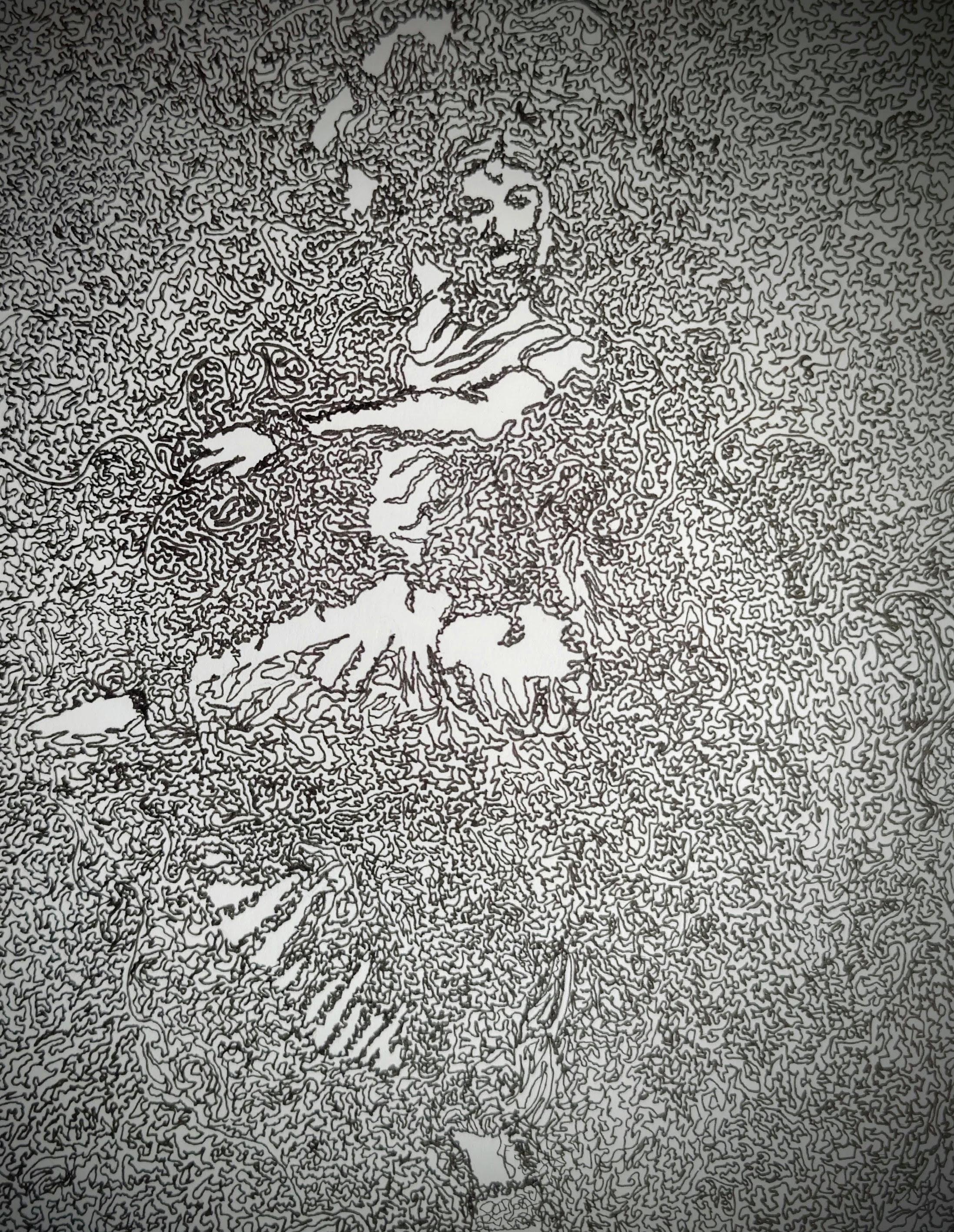

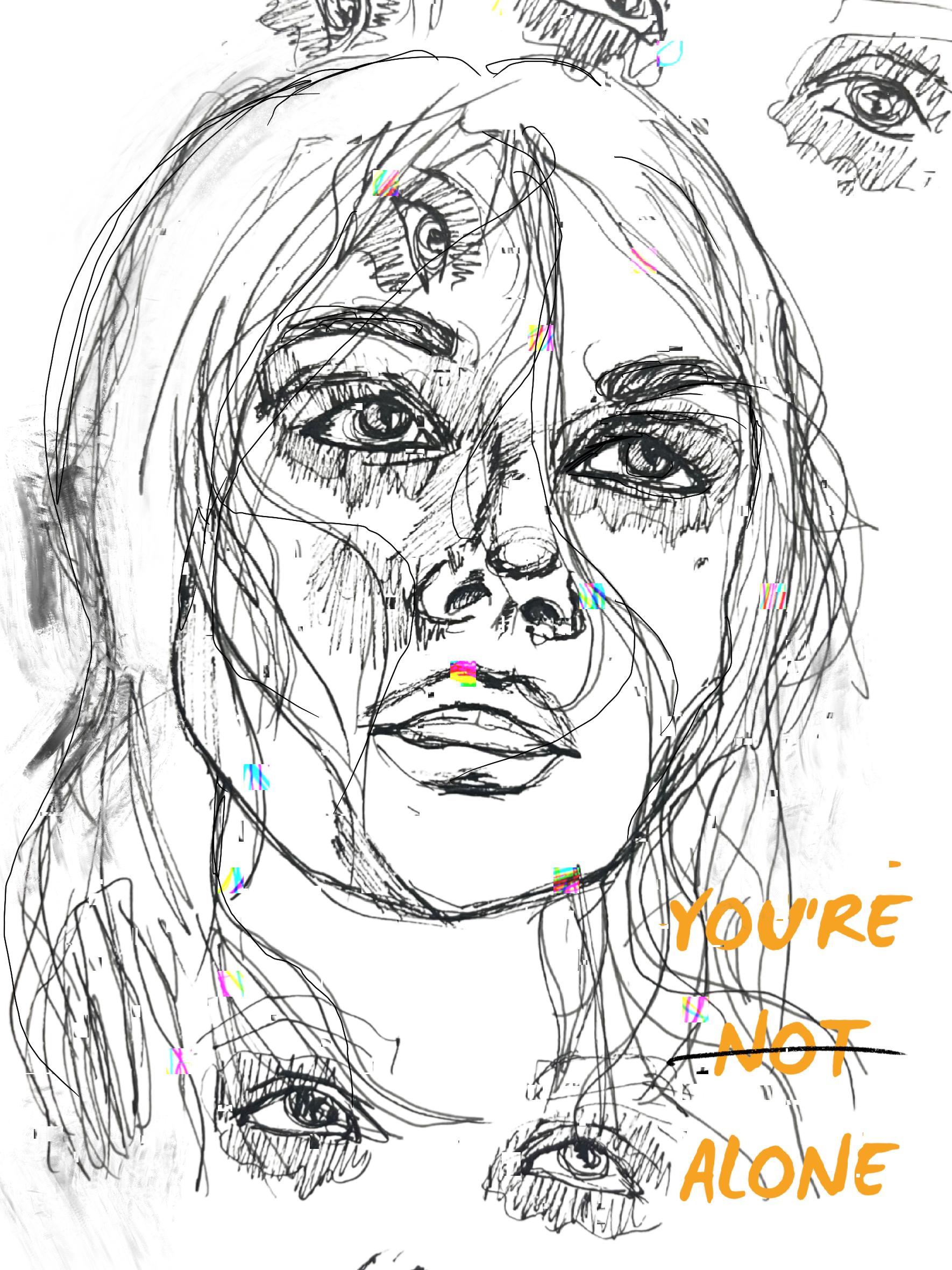

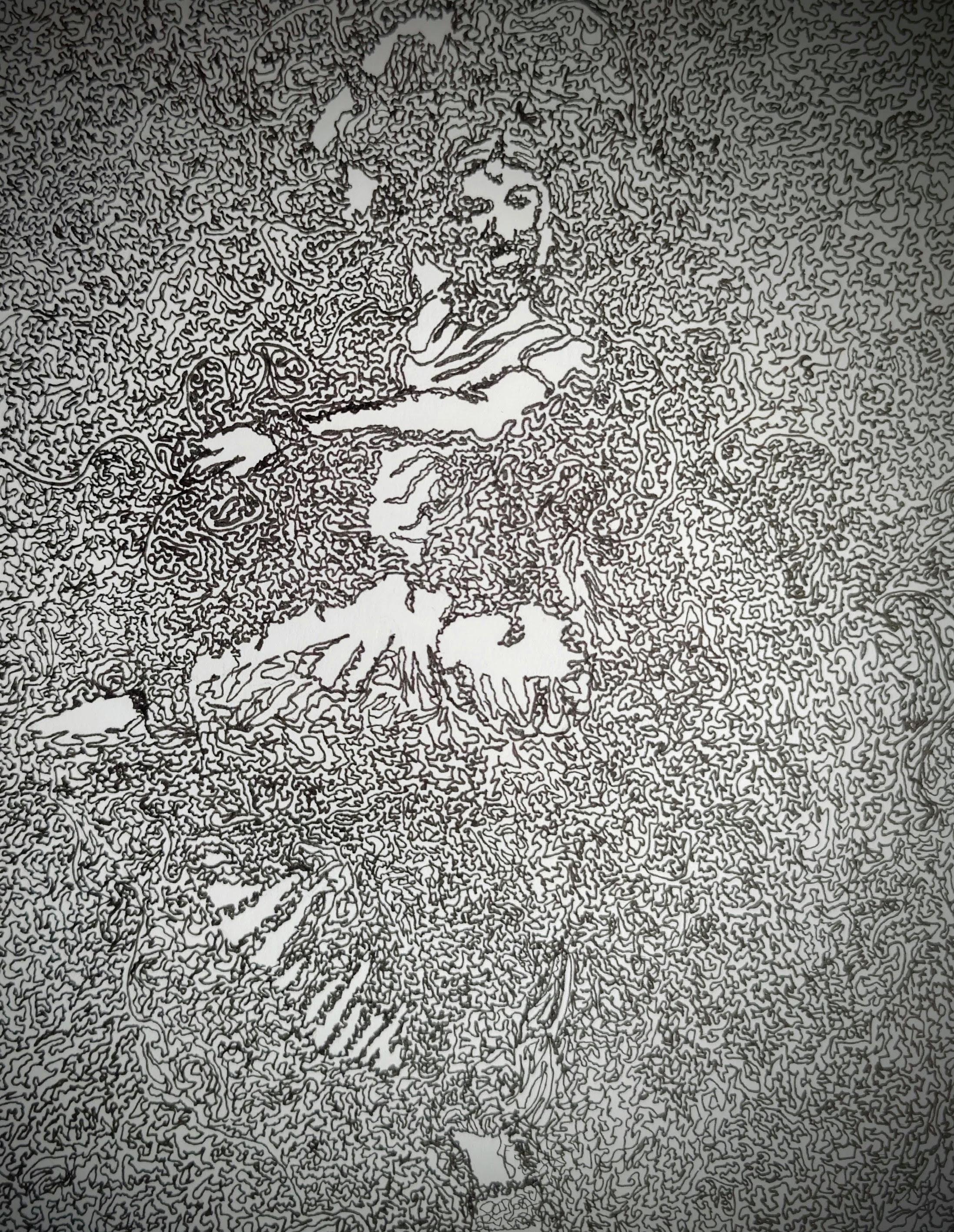

“Depersonalization”

33

Artwork by: Prashanth Rajasekar

34

LITTLE THINGS MAKE THE LIGHT SHINE CLEARER

Written by: Isis Lunsky

35

On the days that feel overwhelming, my views of life become negatively distorted, and clerkship seems to swallow me whole, I think about Jennifer.

Jennifer was a lovely older woman I met during my first rotation of clerkship. Over a few months, she started experiencing weight loss, night sweats, and dysphagia. She was diagnosed with a metastatic lung tumour that was growing into her trachea. While much was uncertain, there were some undeniable facts:

1) She was going to die.

2) She didn’t want any life-prolonging interventions.

3) She was at constant risk of her airway collapsing, and, without intervention, she was likely going to suffocate to death. To avoid this agony, she decided to pursue medical assistance in dying (MAiD).

This was my first time caring for a patient like her. She was so inspiring and gave me a new appreciation for the joy that one can get from even the smallest things in our day-to-day lives. As a matter of fact, one of the things I most vividly remember about her was the sheer joy she drew from finally passing a bowel movement.

The first day I met her, I had a hundred ideas of how to alleviate each of her symptoms and maintain the highest quality of life, but all she wanted was to feel a little less constipated. She knew she was nearing the end of life, and all she wanted was a sense of normalcy in her last few days. For her, that involved eating some Jello, speaking to her kids, and having her morning bowel movement.

So we increased her laxatives. We tried lactulose, but with her progressive loss of swallowing function, it didn’t work so well for her. We tried increasing her PEG. We tried increasing her senokot. We tried suppositories. And we watched. We waited.

But most importantly, we listened.

Because she was my patient, I got to visit her everyday and chat with her. I learned about her career, the books she loved, the places she’d travelled with her family, and the parts of her day that mattered most to her. I got to watch her progress,

and got to be the person who reliably checked in on her every day.

And one day, she turned and said to me, “Isis… I POOPED. Pardon my French but… All this sh*t came out. IT’S GONE!!”

Her smile was glowing, and there were tears in her eyes. For the first time in her stay, she felt human.

A few days later, she underwent MAiD, and all the while, maintained that same joy.

Moments like these are the reason I find myself able to continue, to persevere in this healthcare journey… but they’re not rare.

I met Connie, who, while recovering from an attempted suicide, smiled every day, talking about how much she wanted to adopt a cat. Those conversations built the foundation of trust that allowed her to open up about her mindset and start her recovery.

I met Jeremy, who after his radical cystectomy, couldn’t care less about urinating into a bag, as long as he could take a shower.

I met Audrey, who was willing to learn any technique to clean her tracheostomy tube, so long as it meant she would get to go home for a few hours. No one has ever been as grateful as she was when I put in the homecare paperwork. In the end, this brought her one step closer to one night in her own bed.

And as much as I’ll remember the 26-hour call shifts, the steep learning curves, and the seemingly perpetual exhaustion, the experiences that will shape me as a medical practitioner are these ones. As a clerk, you get to know your patients on such a deep, personal level, and learn to advocate for them in a meaningful way. Clerks have the gift of time – time to spend on your patient and their family, focusing on meeting their needs and making their journey easier, in whatever small way you can.

Because the small things make all the difference.

*Names and details have been changed to maintain anonymity.

36

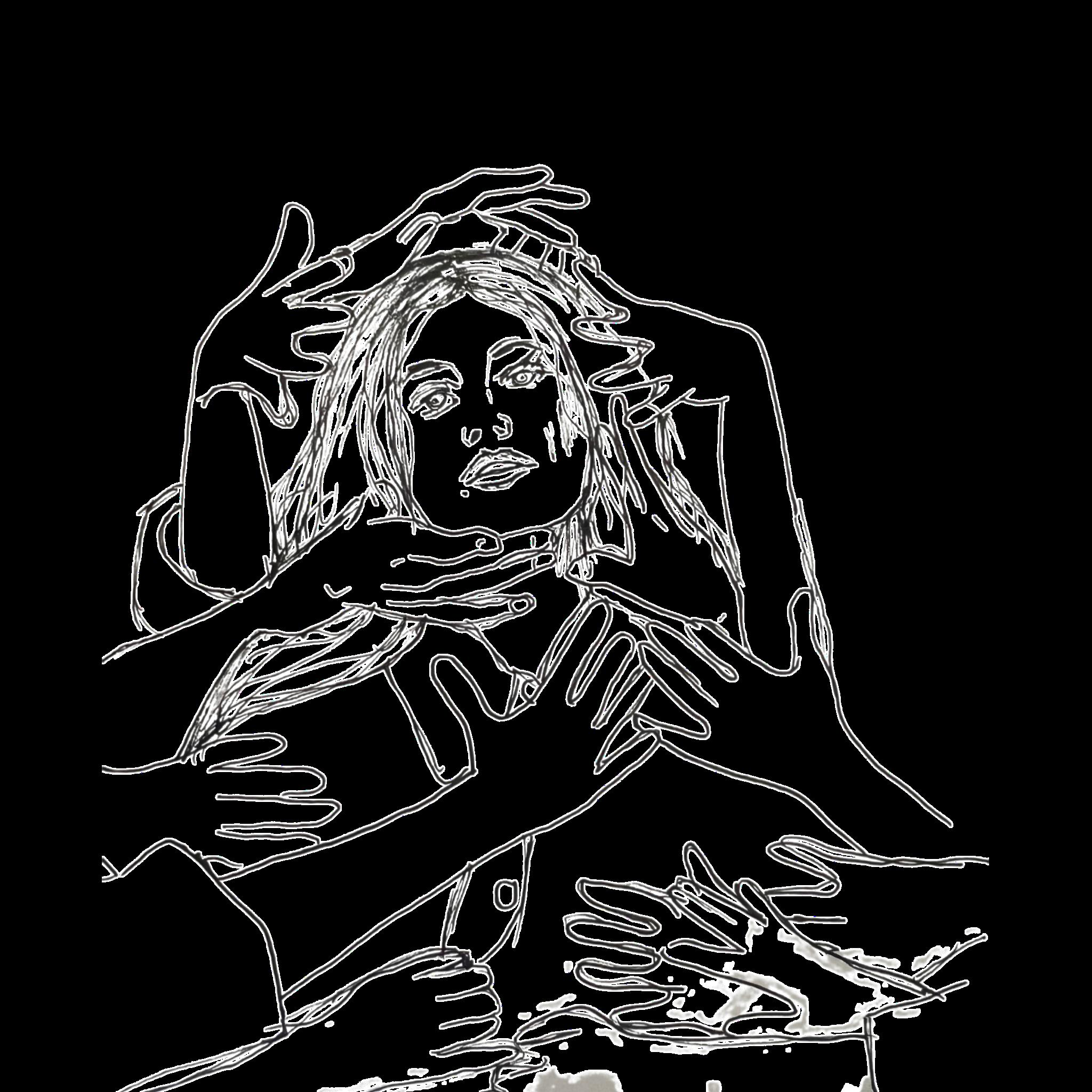

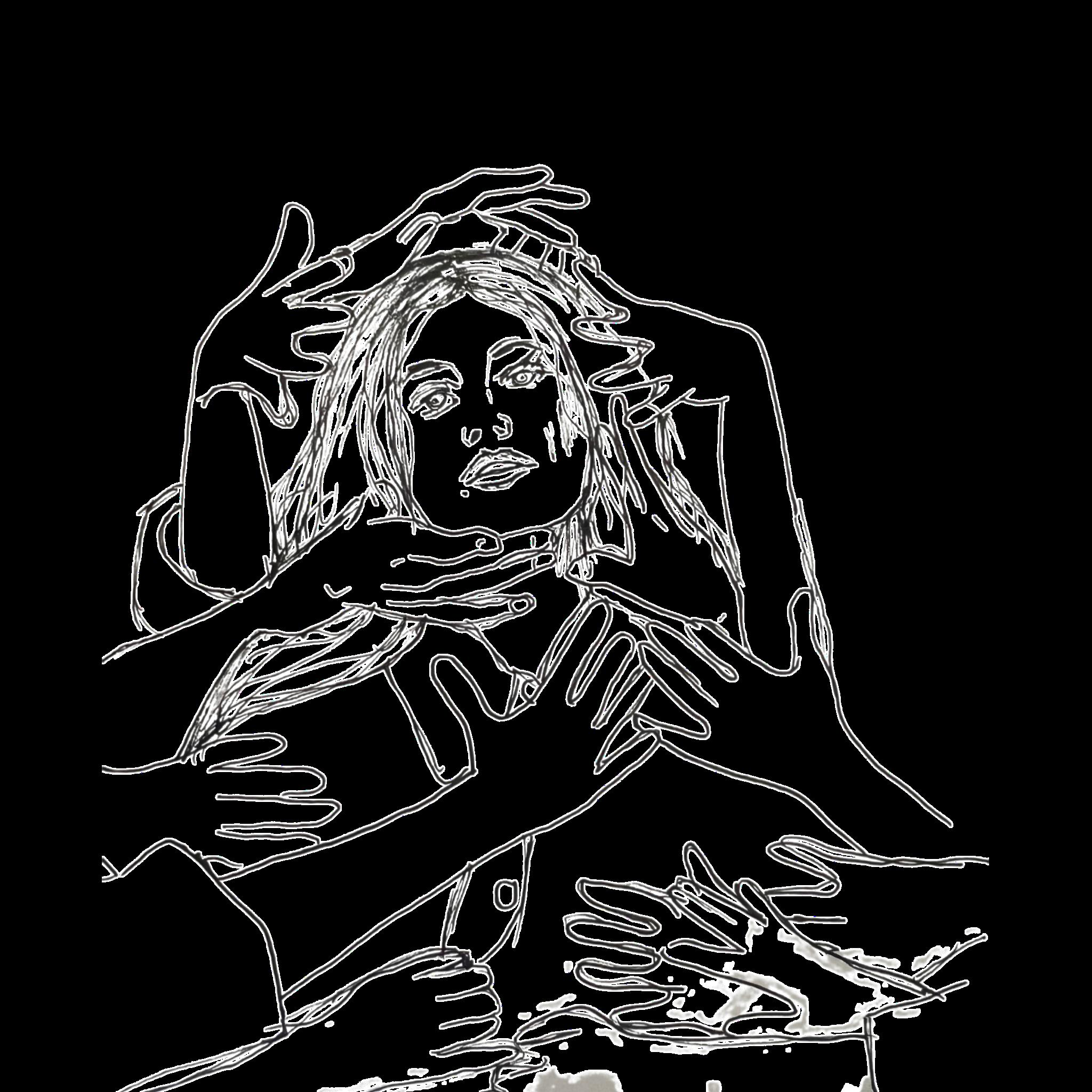

“The Fleeting Self”

“The Fleeting Self”

37

Artwork by: Simoon Moshi | Model: Mohamed Gemae

THE CURRICULUM hidden

Written by: Devyani Premkumar

your lives are immune to adversity to the severity of illness don’t you dare sit in stillness

your absence is seen as neglect we reject the idea that you are unwell well really, we ignore it

instead, we ask you to forfeit your peace your sense of self who are you if not well

dark brooding storms fill out this form

your request may be denied we tried to warn you

we expect greatness our empathy is empty pity under disguise when will you realize you, you are resilient when it rains it pours the silence of your suffering it’s deafening

we do not hear you

we absolve your feelings make you numb that’s what we call the hidden curriculum – devyani p.

I find that the relationship between system and student is well, distorted. They can feel overbearing; wanting what’s best for us, expecting only greatness, and in turn forcing you to hide your true feelings, your fears, your needs, so that you do not disappoint them. Instead, we suffer in silence. I truly question this form of resilience that we internalize.

As medical students, there is this misleading pretense that we are the epitome of health and wellness, or that we should always strive to be. To be considered with empathy requires us to be at our lowest, and even then, there are conditions and limitations in support.

So, I ask you this; why do you intend on making us bend, until we break?

38

MIRROR, MIRROR ON THE WALL:

A STORY OF A SELF-IMPOSED BATTLE AGAINST BODY DYSMORPHIA

Written by: Helen Lin Artwork by: Kiera Liblik

Trigger Warning: Mentions of body dysmorphia, eating disorders, and fat-shaming.

During spin class the other day, after a fast run, the instructor said: “What matters is that you showed up. It doesn’t matter what the scale says or what the mirror says.” While I agree with that, I do find that it is easier said than done. We all know we’ve been inundated with body positivity messages through social media, but how do we reconciliate Instagram models with their body positivity messages while pedaling fast slimming teas?

If you speak to any woman, they can tell you a history of being dissatisfied with their body. Something is always off. However, this doesn’t just affect women. Men are also affected by societal pressures to look a certain way. I, personally, have never been entirely happy about my weight and body, but it has not affected me to the point where I’ve stopped enjoying my life. Nonetheless, I don’t believe I’ve truly achieved contentment with my own self-image.

During undergrad, I was part of a YWCA after-school program that helped young girls transition from elementary school to high school. We discussed many obstacles young women face in the harsh realities of puberty and high school life and one of the most discussed topics was body image. As leaders, we had a script on what to say, but it only felt disingenuous; like merely paying lip service. What business did I have teaching young girls to accept themselves when it’s something I struggled with as well?

The ideals regarding weight and body type had been ingrained in my parents since childhood. It was a product of the culture and environment that they grew up in. My mother used to undergo extreme diets in university just to lose weight. There was no choice, but for that mindset to seep through and affect the way they interacted with me. Their persistent commentary on my weight may have been said out of an abundance of care and concern, but outwardly, it sounded like criticism. My grandmother is the most egregious perpetrator of this. My paternal grandmother is a take no nonsense, see something say something type of woman -

impressive with a sharp tongue, and an equally sharp wit. Every time she’d see me, eyeing me up and down, in Taiwan, her first comment would be: “You’ve gotten fatter.” And throughout the duration of my visit, the comments would become more and more frequent. “You eat so little, why are you still so fat?” “Your cousin lost weight recently, you just need to exercise more.” “Stop eating so much garbage, that’s why you’re fat.” Little else seemed to matter to her. Don’t get me wrong, I love my grandmother dearly, and I have no doubt of her affection towards me. Her words merely stung, but held no ill intent.

When I was younger, I took these comments hard, shedding tears over the dinner table (which, as a note, is the worst place to comment on someone’s weight). I would try to mitigate these “fat” accusations even before I left Vancouver for Taiwan. I would start dieting and exercising before the flight, counting down the days. Over the years however, in lieu of losing weight, I’ve developed thicker skin, decidedly trying to brush off the comments. But, this last summer, I experienced my first extreme bout of body dysmorphia unlike anything I have ever experienced in my life.

To give you a little context of the setting I found myself in, in Taiwan, fat-shaming is a common practice among mothers and well to do grandmothers. The ideal weight, as determined by the female population in Taiwan, for a woman, is universally considered between 45 – 50 kg. Everywhere I turned in Taipei, I was hit with dieting advertisements or gym membership posters of ladies with toned abs. It didn’t help that most Taiwanese women were quite slim and almost gamine like in stature. And over the course of just two months, the environment had effectively tricked my brain into thinking I was out of the norm. Abnormal.

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a disorder of self-perception1. Derived from Greek, dysmorphia means ugliness1. BDD was first presented in psychiatric literature in 1980 in the DSM-III1. The DSM5’s criteria of body dysmorphic disorder are as follows:

39

Preoccupation with 1 or more perceived defects or flaws in physical appearance that are not observable or appear slight to others.

At some point during the course of the disorder, the individual has performed repetivie behaviours (eg. mirror checking, excessive grooming, skin picking, reassurance seeking) or mental acts (eg. comparing his or her appearance with that of others) in response to the appearance concerns.

The preoccupation causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

a b c

dThe appearance preoccupation is not better explained by concerns with body fat or weight in an individual whose symptoms meet diagnostic criteria for an eating disorder.

BDD is considered and grouped under the obsessive-compulsive spectrum category1. This disorder even causes impairment of the patient’s life in social, occupational, and or other ways1. It can be understandable how someone can be so transfixed by their flaws that it bleeds through every aspect of their life. I felt it – the dysmorphia sink into my skin and crawl deep into me. I found any excuse to exercise in the sweltering 40 degree heat in Taiwan, and I refrained myself from pursuing any of the cravings I had. I found myself continuously checking myself in the mirror to see if my flaws had somehow disappeared. I kept looking, and I didn’t like what I saw.

I had never considered the fact that I could suddenly see myself in a different light just after one airplane ride. Suddenly, everything on my body became a flaw; it was as though a haze had entrapped me. Was it me? Or was it the culture? Was it the mass media I was being force fed? A greater number of East Asian adolescents were reported to judge their body image based on Korean, Japanese, and Taiwanese mass media2. The appearance of celebrities, all of whom are uniformly slim, are also influential in these countries2

So, I suppose I have reached the part of this story where I reveal the resolution to this madness. Like my creative writing professor once told me: for any good story, the resolution should be as compelling as the conflict. The truth of the matter is, I don’t have a cathartic resolution for this story. It’s ongoing. It’s a constant struggle. I suppose, the antidote for the poison that is body dysmorphia is more self-compassion. However, it seems to me that sometimes shame overwhelms any attempt at self-compassion.

An interesting study by Foroughi et al, explored the relationship between body dysmorphia and external shame against the mediating role of self-compassion3. What they found was

that shame, perfectionism, and negative affect are among the risk factors of BDD3. They believed that self-compassion serves as a protective factor against the psychopathology of BDD3. Self-compassion is a variable considered in relation to dissatisfaction with body image and eating behaviors in recent years3. Introduced by Kristin Neff in 2003, self-compassion indicates that a person treats themselves kindly in pain and difficulties, understands and acknowledges their transient nature, and considers their experience to be part of common human experience3. Foroughi et al. found that self-compassion can serve as a protective factor against perfectionism and negative affect, however it did not have a mediating role in the relationship between external shame and body dysmorphia3. Since external shame is an interpersonal component rather than a within person component, self-compassion would not be effective in this scenario3

So, you can’t control how others see you or how the culture will steer, but you can ultimately give yourself a little slack. I couldn’t push back against the oppressive “thin” culture in Taiwan, and when I returned to Canada – I did feel a little battle worn. I had been fighting myself over the entire summer. Did I lose any weight? Maybe, but I was too exhausted to bring myself to check.

Today, I am sympathetic to patient’s sensitivity towards topics such as weight loss. No one feels good about being told to lose weight. It feels as though we’re being hurled with accusations of laziness and lack of self control – as if there’s an innate defect that we have that prevents us from being the “right” weight or have the “right” look. As if we’re… abnormal. But maybe we can all give ourselves a little grace and approach our patients with a little more kindness and empathy. Ultimately, I think encouragement goes further than offhanded and judgemental comments.

Oh, and I completely disagree with Kate Moss’s quote: “Nothing tastes as good as pretty feels”. I think pretty will never taste or feel as good as a bowl of brown sugar shaved ice in the sweltering 40 degree heat of Taiwan.

References on Page 56.

40

Written by: Anonymous

Obsessed with being Obsessed

Awareness killed Compulsion. Knowledge gave birth to Obsession. Don’t confuse awareness for knowledge, avoid creating impulsive obsession, turn compulsion conscious, and conscious obsession subconscious. Obsession owns compulsion, but knowledge creates awareness.

I lost the point too, Or maybe just the objective one, Or maybe just the pretentious one. Does reflection make you feel intelligent? Or is reflection just obsession with yourself? But isn’t that the point, could be a game after all? Or is that just the compulsion looking for revenge on awareness? A page a waste of words, or have I struct your caution? And if I did I know you read it a “good feeling” number of times. Feel exploited? Few will. You know who you are. Or are you pretending to know? Compulsion to fit in at its finest either way. Ever wonder why one, now all the kids can’t focus? Well I just explained a sick hypochondriac. Hypocritical right?

and if you found this voice, read again until it feels right, it cannot be odd or end with e. Come back in time when odd or e start to haunt your obsession.

41

“Truth”

42

Artwork by: Youssef Belal

IDENTITY IN MEDICINE

Written by: Imran Syed | Artwork by: Kiera Liblik

“Do you remember the moment you first realized you got into medical school?” “How did you feel?” Truth be told, it is an unforgettable moment. No matter your path here, years of work have led you to this moment; whether it be multiple attempts at getting a good CARS score on the MCAT, rescuing your GPA from an English class, grinding away at that desk job you hated, or risking your life in service. In all honesty, the surrealness of matriculation does not speak to the emotional roller coaster you experience throughout the journey. You spend years dreaming, sit with your anxieties, and are often left uncertain as you wait to hear your fate. Then finally the time to celebrate and experience your next series of first; the first day, week, and year of school, meeting your class for the first time, the first friend you make.

As I reflect on my journey to this moment and consider my path forward I think about who I want to be in medicine, what kind of doctor do I want to be?

Imposter Syndrome: “Imposter syndrome is a psychological phenomenon in which an individual doubts their own skills, knowledge, or accomplishments and has a persistent fear of being exposed as a fraud. It is a common experience that can affect anyone, regardless of their level of expertise or accomplishments”

- ChatGTP

Someone once told me, “No matter your path here, you belong here.” I repeat that phrase to myself like a mantra when I feel uncertain. To me, there has always been so much you can learn about the world around you from the experiences of others. In medicine, this is my preceptors and mentors, as well as my peers and other professionals and everyone I interact with while I’m in school: patients, their families, my support network outside medicine, and strangers. We are bonded by a purpose of service.

“But what is my purpose?” When I feel insecure and unsure of my place I think of my strengths; what I can bring to the experience and patient care. What unique things do I offer others here? Even while everyone has a unique experience or perspective to offer, I often find myself rationalizing whether I deserve a place among my peers. Why me, when others didn’t get the same opportunity and privilege?

“But do I actually belong here?” Growing up, I often felt like a misfit. Whether it be a confederation of race, religion, or culture, I knew there were specific things that made me different. Although I focused on what made me different I grew to realize in many ways, I was so similar to everyone around me. Eventually we all grow up, we move out and begin to carve our own path. In some ways when you move on these feelings linger with you, cyclically popping up every few years for small periods of time or through different seasons of your life. On one hand, my life experiences have shaped who I am, and I couldn’t change that even if I wanted to – they shape who I am. They are what inspire my strength, enthusiasm, patience and knowledge. On the other hand, they can make me feel different and like I don’t belong.

“Am

I as smart as everyone else?”

“We have so many former athletes, and I’m just average”

“I’m not as extroverted as I need to be”

“Why aren’t I as accomplished as others”

What is my identity in medicine? How do I figure that out when I have struggled so much with my identity in the past? Who am I now to others in this program? A peer or a pest? A student or extra burden? What is my tribe here?

43

Imposter phenomenon is associated with female-identifying gender, younger age, and less work experience, and associates with greater burnout (emotional exhaustion and depersonalization), and less personal fulfillment according to one study. (Shanafelt et al. 2022)

And who will I be in a couple years? A father, a doctor, a surgeon and a good friend? Someone’s husband and a great physician? How many hats can I wear before I look silly?

Allowing insecurity to creep into the forefront of your thoughts can become a habit. As it happens I feel more withdrawn and insecure about my place here. Where did my confidence go? I honestly didn’t imagine it could feel like this; feeling like a failure even while accomplishing my biggest dream and conquering goals.

There’s another identity I throw into the balance: beyond medical student is, one day I hope, a medical doctor. Now I think of my mentors and preceptors: how did they balance this professional identity with their other identities? Will I be Imran the doctor, or Imran who happens to be a doctor? My professional identity is likely to be a core identity to me, but will it be my only identity?

I think of my past as it shapes who I am now, and who I will be in the future. “That idiot kid - really?” Sometimes I feel like too much of a degenerate to have the opportunities I have been granted, and that I inherited so many of the same qualities that have set me back in the past. Eventually, someone will realize that I am a fraud, and then my heist will finally end. But then I realize something else:

All throughout my journey I have failed so many times in my pursuit of medicine and I know that I still will fail countlessly. But with that in mind I don’t consider myself failure, because with each failure I learn a little more with hope that one day I will get it right.

Now is a moment of truth; I think of my goals, intentions, and again who I want to be in my career. How will I wear my hats in the specialty I pursue? Focusing on this future allows me to focus on a future where I have it figured out.

44

EMBRACING MY DISTORTED EXISTENCE IN MEDICINE

Written by: Gajan Sivakumaran

Does anybody else feel that med school has been a confining experience?

I am obviously very grateful and privileged to be here and yet,

Sometimes I feel like I cannot fully embrace my truest self in medicine.

Time after time, I find myself questioning whether it is worth

Outing myself as being queer and gender non-conforming in clinical settings,

Regrettably recognizing that my “coming out” journey never really ends.

Therefore, I must reflect on why I applied to med school – to distort the norms.

I will embrace my unapologetically distorted self in medicine,

Opting for my androgynous and bold outfits over a white coat because at the end of the day,

No one can take my identity away from me, not even medicine.

45

46

Artwork by: Michele Zaman

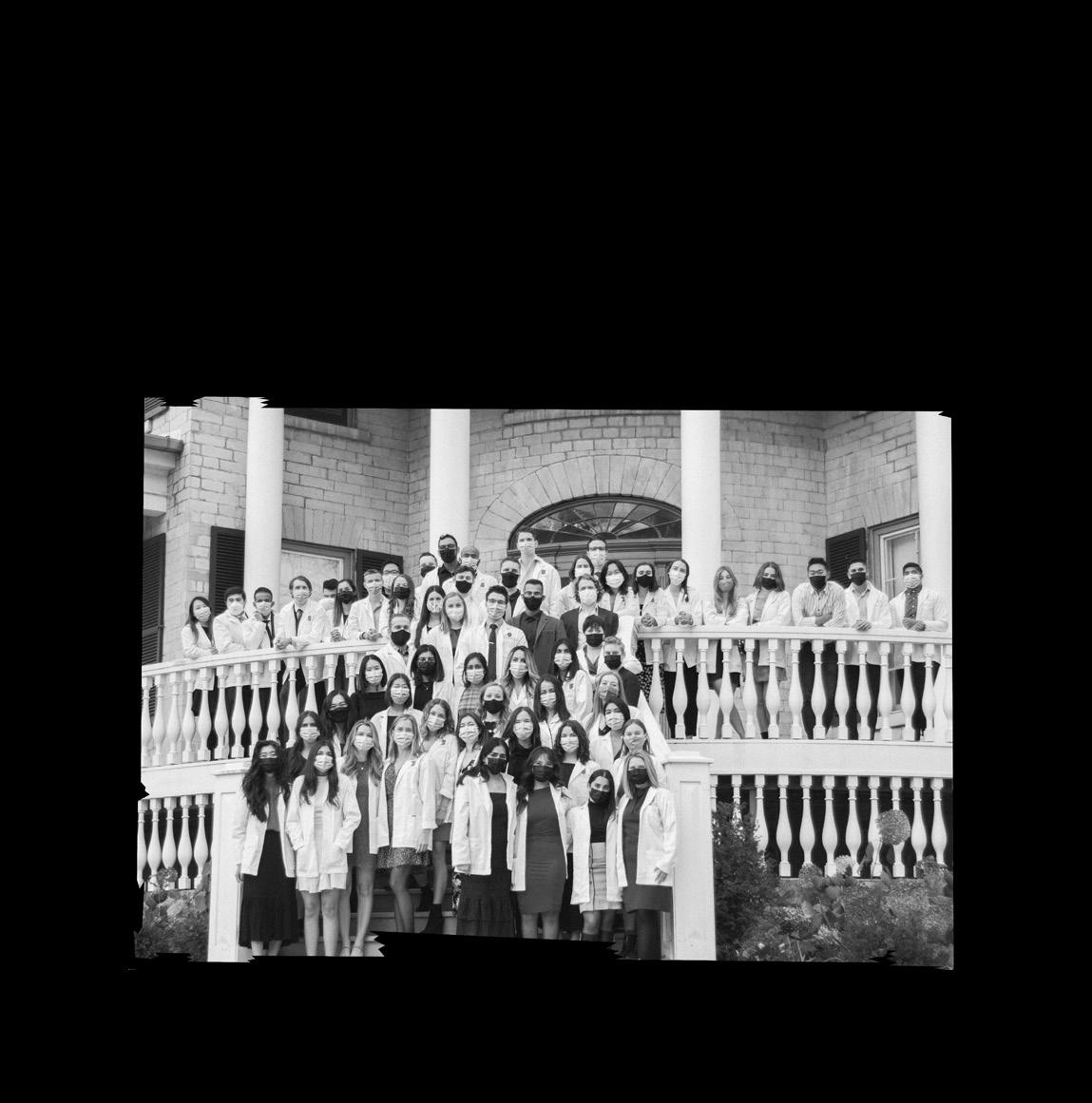

MOMENTS IN MEDICINE:

REFLECTIONS ON THE PASSAGE OF TIME IN MEDICAL SCHOOL

Written by: Laura Wells

Written by: Laura Wells

In medicine we tend to schedule our whole lives based on predetermined measurements of time. The days go by with the same unchanging truth that there will always be 60 minutes in an hour, 24 hours in a day, and 7 days in a week. Yet, somehow, our experiences and perceptions of time are distorted over the years. Spending minutes sitting in a lecture can feel like hours, and spending hours doing a job you love can feel like minutes. As I reflect on the passage of time during my four years of learning medicine at Queen’s, I’ve come to realize the importance of stopping to enjoy the beautiful fleeting moments inside and outside of medicine as time passes by.