HUES IN MEDICINE

Editors’ Letter Introduction 2 Untitled Artwork 3 My Hues Poetry 4 The Intersection of Art and Medicine Article 5 10 Things I Felt During My First Year of Medical School Reflection 7 To Hue or Not to Hue Opinion 9 Green Moments Photography 10 Hues of the Hematoma Article 12 Hues of Mania Artwork 12 The Art of Surgery Article 13 In My Garden Poetry 17 Some Lessons from the Festival of Lights Reflection 19 No, I Don’t Want No (Ugly) Scrubs Opinion 21 From Sunrise to Sunset Poetry, Photography 23 History and Use of Medical Illustrations Article 27 Shades of Melancholy Artwork 29 The Colours of Life Poetry 30 An Ode to the Colour Green Photography 31 Blueberry Lemon Ricotta Cheesecake Recipe 32 Windows Photography, Digital Art 33 Power Colours Horoscopes 35 Spotify Playlist Music 37 Our Team, Special Thanks Closing 39

We present to you the first issue of QMR’s sixteenth season… Hues in Medicine.

The two of us embarked on this journey in a crowded coffee shop in September, a rush of excitement coursing through us as we sifted through ideas and jotted down plans. Since then, our collective has grown with writers, editors, artists, and managers- all of whom have poured their talent into the pages of this issue. A big thank you to our team, we could not have done it without you. And to each reader who opens this journal, we thank you for trusting us and hope that you can take a piece of it with you.

Now, onto “Hues”. How do we capture the palette of our day-to-day life in medicine? From the shifting tones of patient encounters, to the rush of blue scrubs we see in the hospital hallways, there is vibrancy all throughout the Queen’s Medicine community.

We recognize that colour, even a lack thereof, has a significant place in healthcare. Bruises change hues, helping us identify the timing of injury or trauma. Diversity in our patients tells us there is more to study than a single skin tone. Shades of the sun change, peaking through big windows as we run to a call, finish a surgery, or complete our charting for the day.

What evokes brightness and intensity in one, may bring somber and solitude in another. Colours can describe stories from the past, symbolize the start of revolutions and challenge norms. Through thought and imagery, we endeavored to capture the different hues people share in this world and reflect on the meanings they summon. We hope it brings some light and radiance to your day.

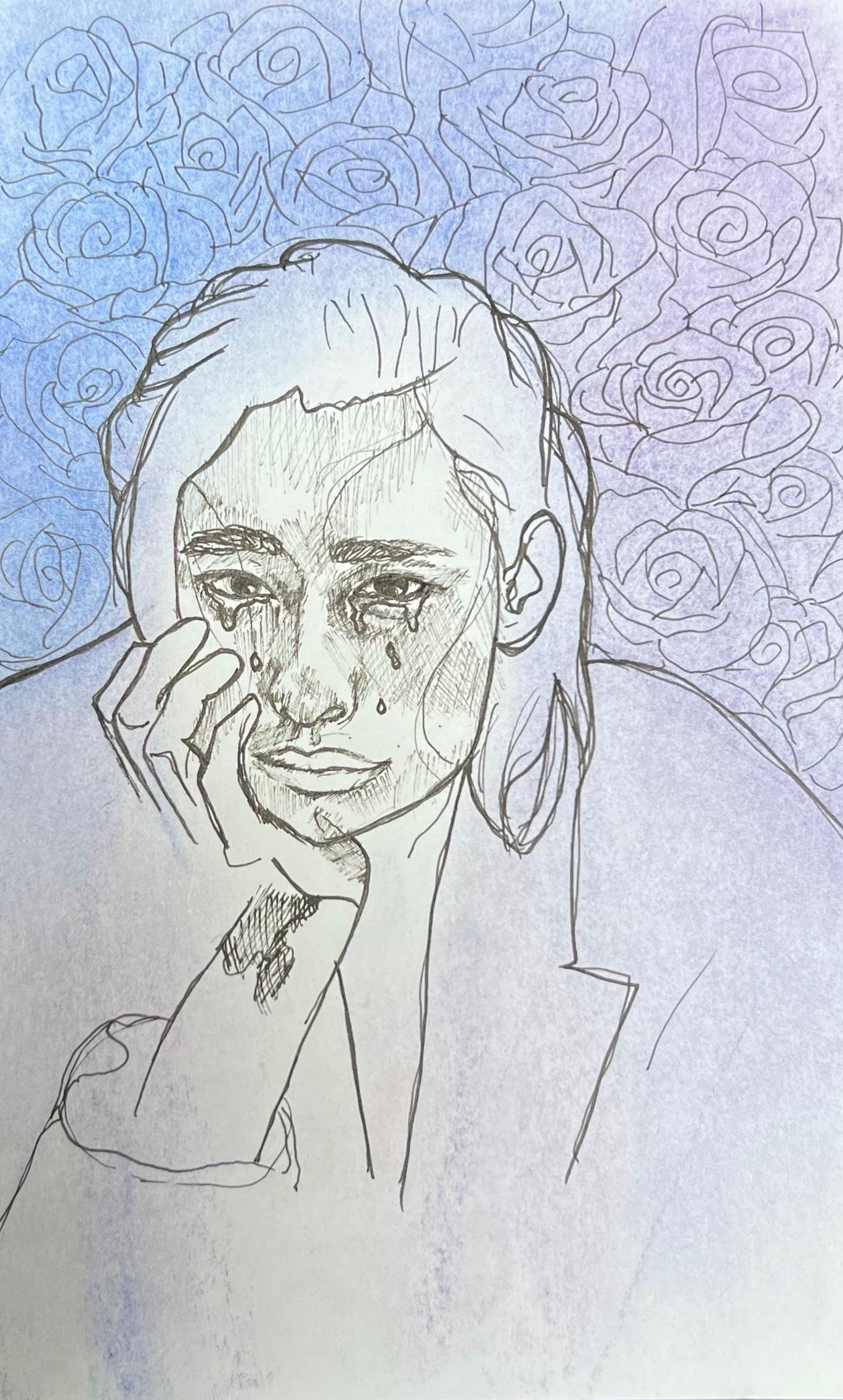

my hues by sabra salim

you once told me you loved the vastness of the ocean blue

i changed the colour of my eyes so you would think me glimmer

you once told me that you loved the sun, illuminating every corner touched by its reach, golden and jocund

i dyed my hair so you would think me radiant you once told me you loved the billow of the cherry blossom, born to bloom in vivacious pink

i painted my cheeks so you would find me warm

you once told me you loved the white of snowflakes, dancing down the sky as they settled to their resting

i scrubbed my skin endlessly, wearing down my layers so you would find me pure

today you told me that your love has left, with it the colours i owned

i sought to become the palette you so desired, but in it i lost mine

but with time again the ocean will crash, the sun rise, the flowers bloom and into it the winter fall

and soon too will my eyes soften, my hair grow, and my skin shine in its glory so that my colours may be once more

By Mudia Iyayi

By Mudia Iyayi

and the arts are usually viewed as two distinct streams of practice. Each with its own unique rules and norms with no intermingling. Medicine is a science and deals with the treatment and care of a patient. There is no showcasing of creativity or artistic skill; instead, objective knowledge of biology and patient communication is valued. A good physician is not measured by their ability to tell stories nor are they defined by their ability to create stunning visual art. Right?

The history of medicine itself is intrinsically attached to the arts, most notably in the form of medical illustration. In the early days of medicine, open dissections were a staple of understanding human bodily function and anatomy. In the second century, Claudius Galenus, a Greek physician, was a notable innovator in the field of anatomy and performed dissections on animals, such as pigs and monkeys to gain a better appreciation of mammalian anatomy.1 In the fifteenth century, Persian scientist, Mansur ibn Ilyas, published one of the first coloured atlases of human anatomy which would greatly shape the understanding of the human body for centuries to come.2

In the Western world, Galenus’ innovations paved the way for the anatomical-artistic revolution that would occur during the Renaissance period such as Leonardo da Vinci and Andreas Vesalius.1 During the Renaissance, as more human dissections were being performed, scientists gained a more intricate under-

standing of human muscles, organs, and even individual nerves. Not only were these drawings labeled with immense scientific detail but represented a stunning achievement in human art and were nothing short of visually stunning. These artists blurred the lines between knowledge translation and creative expression. It allowed learning human anatomy to become more accessible and increased the general anatomical knowledge of practicing physicians. It also paved the way for today’s medical textbooks we currently use such as Gray’s Anatomy or the Netter’s Atlas—which themselves are miniature art collections in their own rights. Medical education would be very different without the artistic innovations of these founding artists–anatomists.

Modern medical technology could be considered an art of its own. Just as stated, medical illustrations greatly advanced the field of medicine and provided immense improvements to medical education and human anatomical understanding. The evolution of medical technology and equipment can be viewed similarly. Art is the expression of creativity and imagination. Medicine could not have evolved without the creative and imaginative ideas of its innovators. Is there a distinction between a painter and a physician? Both have their tools—a paintbrush and a stethoscope, respectively. And both have their ideas about the natural world—a stunning landscape to create and a differential diagnosis to investigate, respectively.

Analogies aside, imaginative boundlessness and limitless creativity in medicine is evident in the ground-breaking technologies that arose in the past few decades. We can now better understand neural pathway firings by using fMRI. Point-of-Care Ultrasounds can allow for quick patient diagnoses and are even more crucial in rural/underserved areas. Angiograms can allow you to visualize the coronary arteries and make important decisions regarding treatment and therapy.

How are these medical technologies distinct from the great works of Vivaldi, Picasso, or Dickens? The only distinction is that in the case of medicine, the human body is the canvas, and the consumption of its creative expression is the patient’s well-being.

The most important aspect of medicine is the physician-patient relationship. Art is not only helpful in the practical aspect of medicine, but studies have shown that it can help medical students become better physicians.3,4 The consumption of art allows medical students to be more observationally aware and learn the importance of a deep and thorough investigation of patient concerns. The importance of this translation to the clinical setting cannot be understated, as it is crucial that physicians examine patients in detail, and without overlooking findings. Art consumption by medical students was also found to increase inter-physician collaboration and decrease burnout.4

Art and medicine have been and will continue to be intertwined. The physician and artist are different only in name. References

1. Gurwin, J., Revere, K. E., Niepold, S., Bassett, B., Mitchell, R., Davidson, S., DeLisser, H., & Binenbaum, G. (2018). A Randomized Controlled Study of Art Observation Training to Improve Medical Student Ophthalmology Skills. Ophthalmology, 125(1), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.06.031

2. He, B., Prasad, S., Higashi, R. T., & Goff, H. W. (2019). The art of observation: a qualitative analysis of medical students’ experiences. BMC medical education, 19(1), 234. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-0191671-2

3. Savage-Smith, E. (2016, August 26). Historical anatomies on the web: Mansur Ibn Ilyas: Author & title description. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/ historicalanatomies/mansur_bio.html

4. The history of anatomy - from the beginnings to the 20th century. Body Worlds. (2018, December 19). Retrieved from https://bodyworlds.com/about/history-of-anatomy/

Excitement: Fresh air blowing through the window of a car that has my life packed in its trunk on the way to a new town where I’ll begin my medical journey. This week I’ll meet hundreds of people who I will share this new experience with, learning new things, experiencing this together. My favourite artist plays on the radio, tomorrow is my first day.

Pride: Stethoscopes and short white coats. This week we are learning our first physical exam. Weeks after our first encounter with an SP, days after our first time using a otoscope and months before our first interview with real patients on an observership, we are here together. Years pass, and there are so many firsts to come: first sutures, first intubations, first day of clerkship. Time passes, and you remember this feeling that was captured by an Instagram memory.

Euphoria: It’s the night of halloween, homecoming, MVN, the first night of a class trip. We’ve since left the responsibilities at home, because this is a well deserved break after a ton of hard work. Tonight is about celebrating and enjoying with friends on the same journey.

Anxiety: What did I do again? I don’t remember it like that. At least that wasn’t my intention anyway. Sometimes this town feels too small. I want to put my hand up in lecture, but I wonder if I sound stupid. I want to tell a dumb joke, but I don’t want to be the ass of it. And other days, I feel like these risks are always worth it.

Disappointment: We are reminded again of the dark history of this profession; it hasn’t always been innocent. So much disgust for the past atrocities in the name of education, and how much of it is still rooted in our day to day. I try to reconcile my privilege, but I also realize it is what has brought me here. Will I ever be the change I hope to see? Where can I begin to change when even thinking about it is so uncomfortable? I try to distract myself, because alone I can’t solve these problems.

Like an Imposter: I move my stethoscope quickly between auscultation points. “Yeah, I can hear them.” I can’t, but I don’t want to admit it. My ego won’t let me. Sometimes I worry that asking for help is admitting failure even if I know better. I start to think that I don’t deserve to be here, or that I don’t belong. Sometimes I feel it when a preceptor pimps me, when a young pre-med asks me for advice or at the end of a difficult final. Other times, I know better.

Isolation: It’s a cold Kingston day. My warmest jacket isn’t warm enough, and today, I just don’t feel like skating on a lake. What would it would be like if this town was a bit closer to home. If I tried to make it back tonight, I wouldn’t have been on time. The distance was just too much for us. Nothing is open tonight, and all my friends are asleep in this small town. I try to spend time by myself instead.

Awe: A late October day, I walk through a park I have walked a dozen times the week before, on my way to an 8:30 class in my first year. The leaves are shades of red, yellow, orange and a dying green. They haven’t started falling yet. Kingston is beautiful, I tell folks at home: trees throughout a city that sits on a lakefront that invites swimming throughout most of the year. The buildings tell a story of history, and give the feel of a small welcoming town. I don’t imagine my honeymoon with the city ending.

Hope: We are at a crossroads in society. I’m not even 30 but I think about the amount of change our day-today conversations have seen. I am reminded of how much more we have left to do: to be more inclusive, more representative, and more equitable as a profession. We see institutional changes, and we question if it is enough or just publicity. Still, I have hope that these are difficult conversations that we have in the early stages of something truly meaningful.

Empathy: My preceptor brings me into a clinical room in the middle of my week long observership. “This guy has cancer, I have to break the news to him.” He does. “I had a feeling in all honestly, okay Doc, what’s next.” I need a moment to collect my breath, and I’m not the patient here. Right now, I am just an NPC in someone else’s nightmare today. I think this patient saw it differently though. He is incredibly optimistic, appreciative, and ready to take on his treatment, as well as any challenges it might bring. I think I learned more from being in this room than anything else in my first year of classes.

Stepping into a first (or second) year clinical skills class, you’ll probably notice all of us dressed as if we are mourning or attending a sombre event. The truth is we’re all dressed in what we and the institution consider to be “formal”, or “professional”, or “business” clothing. Business attire is black, grey, white, light blue, and other “neutrals”. Dark clothing goes with everything we tell ourselves. Black is slimming we say, it isn’t too much or too out there. We don’t want to stand out, or look different from our peers, or be noticed as a target for tutors to call on. We want to look the same as each other despite our profession becoming increasingly diverse.

Professional attire is meant to elicit trust from patients. Many older patients, who are the majority of the population many of us will see in the future, prefer that their physicians look professional and wear a white coat. Perhaps it signals authority, knowledge, and power to them. Or perhaps it is a remnant of what was once a male-dominated profession. Traditional business attire was designed for men and women, women generally find it more challenging to fit into a model of business attire that was never meant for them in the first place. Black, grey, white, and neutrals may make the physician and patient feel as if the physician is part of the background, and the patient is the one in focus in our mental image of the physician-patient encounters.

Business attire colouring is also very cultural. Colourful business attire is more common in certain regions and cultures, particularly where black and white are considered colours of bad luck or mourning. Physicians may refrain from these colours to avoid conveying to their patients any inklings of negative prognosis and to promote a positive interaction.

Colours of clothing can have an impact on patients’ mood and outlook on their prognosis. Blue and green are considered more calming and tranquil colours, yellow elicits warmth and happiness, while orange or red may be received as more celebratory or intense. These emotions are important during patient encounters. Primary care visits can be as short as 15 minutes and every word, expression, change in tone, and body language matters when you are seeking to build a trusting relationship with someone.

In a world where hospital architecture is designed to elicit calmness and positivity among patients to improve patient outcomes (think large windows and open concepts in newer hospitals), perhaps we should offer more advice on what it means to dress professionally in medicine. Colour can have a positive impact on both the patient and the physician. It can change the idea of what a physician should look like, to the idea that a physician can look like anyone.

As the new season sets in, getting comfortable in its red, gold, and crimson skin, it leaves behind a trail of green summer moments To stride forward and achieve our potential this year, to grow as students, professionals, and a community; it’s important to remind ourselves that just like the earth’s colours, we will live through our own cycles. The green will come back, like it always does, but the maroon, and brown and grey are equally vital for our individual ecosystems.

Written by Mudia Iyayi Artwork by Kiera Liblik

Written by Mudia Iyayi Artwork by Kiera Liblik

One of the most colourful aspects of science is the concept of bruising. While bruising oneself is an unpleasant experience, one could appreciate the intricate biology behind the many colours that define the time course of a bruise.

A bruise refers to the discolouration of the skin that results from capillaries breaking due to trauma to the area.1 The breakage of these vessels causes blood to leak into surrounding areas underneath the skin and contributes to the red colour that defines the first stage of bruising. The bright red colour of blood—and the initial bruise—is a result of oxygen-carrying hemoglobin populating the injured tissue.2 Heme, the iron-containing component of hemoglobin, absorbs blue-green light and reflects red-orange light, thus appearing red to the eye. A few hours following the injury, the bruise becomes a darker red colour, secondary to the loss of oxygen. More specifically, the bruise loses oxygenated iron within its hemoglobin and thus its distinctive vibrant red colour diminishes.2

The next stage of bruising is defined by an indigo colour that is due to the continued loss of oxygen from hemoglobin. The blue-purple colour is simply the blood in the tissue darkening. This process usually occurs one to two days following the injury and can last up to five days.2

Following indigo, the bruise will turn into a green hue, thus representing the first stage of healing. This stage is characteristic of heme breakdown by heme oxygenase into biliverdin. The green colour of the bruise is due to biliverdin, which translates to“green bile” from Latin.2 The bruise then becomes yellow in colour, thanks to the conversion of biliverdin to bilirubin by the enzyme, biliverdin reductase.3 The yellow-coloured bruise can last from approximately the seventh to the tenth day post-injury.3

Following this, the bruise can turn to a brownish colour, following the metabolic processing of bilirubin due to a complex called hemosiderin. Hemosiderin is a remnant of macrophage breakdown of heme.4 Finally, the bruise should begin to fade, and the skin should return to its normal tint.

1. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/007213.htm

2. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/322742

3. https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/ajpgi.00026.2018

4. https://www.healthline.com/health/hemosiderin-staining

Written by Sigi Maho Artwork by Sigi Maho

Written by Sigi Maho Artwork by Sigi Maho

Surgery has experienced significant evolutions in the sophistication of technique, understanding of sterility, and approach to education –ultimately, establishing itself as a healing discipline within the medical curriculum. Anthropological studies have provided insight into surgical techniques that would have been employed by early civilizations to treat injuries and traumas, with early examples of suturing, limb amputations, and wound drainage.1 The age of antiquity brought significant establishments to the discipline – from Sushruta, the ancient Indian surgeon and “founding father of surgery” developing one of the oldest known surgical texts, to Galen, the Greek surgeon, physician, and philosopher.2,3 Galen’s views on anatomy, which were based on animal studies, dominated Western medicine for over 1300 years until Andreas Vesalius, a Belgian physician and professor of anatomy, published his seminal work that was based on human anatomy, De humani corporis fabrica. Vesalius was an advocate for a hands-on approach to surgical training by surgeons which involved surgeons engaging in dissections themselves.4

As surgery continued its development towards becoming an academic discipline within the medical curriculum, so did the approach to surgical training. Artists would often be commissioned to capture important surgical techniques, medical milestones, and distinguished physicians, as a form of record keeping and memorialization. It is through their work that we are left with a lens through which to observe and ana-

lyze the ongoing transformation that took place with surgery and surgical training.

Thirteenth-century Europe saw a separation between medicine and surgery with the emergence of the barber-surgeon, a skilled craftsman within towns that performed the practical work of surgery, such as setting broken bones and limb amputations.5 Despite their essential work, these barber-surgeons were not academically trained, and were of lower status than educated physicians trained within universities.6 During this time, human dissections became legalized and allowed for the further development of anatomical and medical training, however these dissections were infrequent and highly ritualized.7 An illustration from the Fasciculus medicinae by Joannes Ketham, depicts an exemplary scene of the separation between medicine and surgery within the context of medical education. The illustration portrays a medical professor sitting high above his students, reading aloud from the works of Galen. A dissected body rests below in the foreground, with a demonstrator or barber-surgeon conducting the dissection in tandem with the lecture. This illustration captures the power dynamics between the university-trained medical doctors, students, and barber-surgeons, using the visual hierarchy of the lecturing physician sitting above the rest. Additionally, it highlights the observation-based medical training that was prevalent within institutions at the time. Both physicians and medical trainees would examine and learn from dissections, without performing them on their own, as

this was viewed as an act “beneath” them, one for the barber-surgeons to perform. By the seventeenth century, the practice of using dissections to inform medical education became more acceptable. Paintings done at the time capture distinguished physicians standing closely beside the dissected cadavers, surrounded by their students.8 One of Rembrandt’s early masterpieces, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolae Tulp depicts Dr. Tulp describing the anatomy of the upper limb to a group of doctors or medical trainees through the dissection

of a cadaver. Unlike the previous illustration, this painting shows the medical professionals interacting closer with the cadaver, as Dr. Tulp clamps muscles and tendons of the dissected forearm himself. Interestingly, there are no other surgical instruments in the painting, and this is likely due to the cadaver not having been prepared by Dr. Tulp or any of the doctors in the painting, as the work of dissecting was still likely viewed as menial. Another change captured in this painting is a shift in the medical resources that are being used to guide the lesson. Some figures are depicted looking towards a large open book in the lower right corner of the painting as they follow along with the lesson. It has been suggested that this book is possibly Andreas Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica. The use of his text, which was based on careful observations of human anatomy instead of the animal dissections of Galen, demonstrates a second shift, one towards more anthropocentric evidence-based textual resources within medical training.

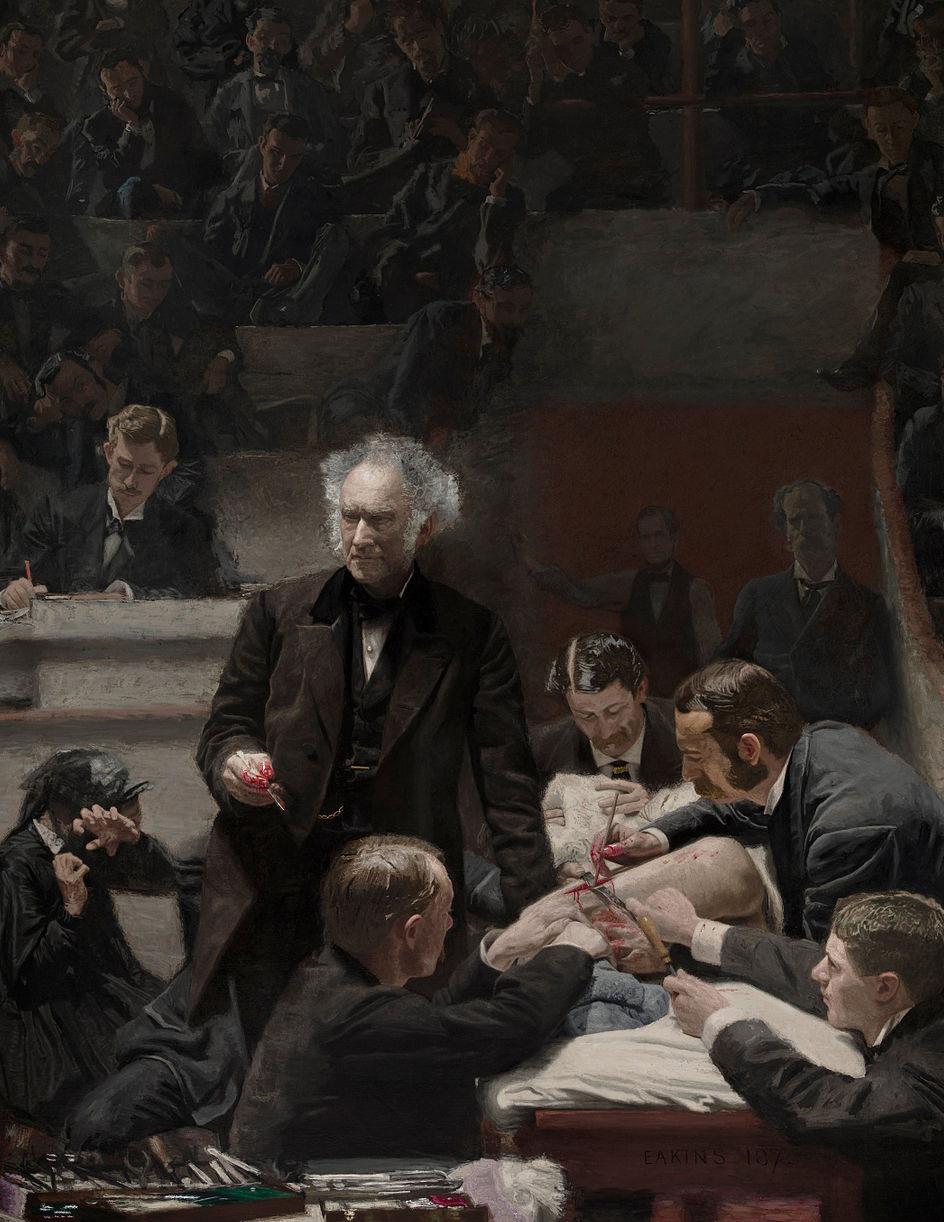

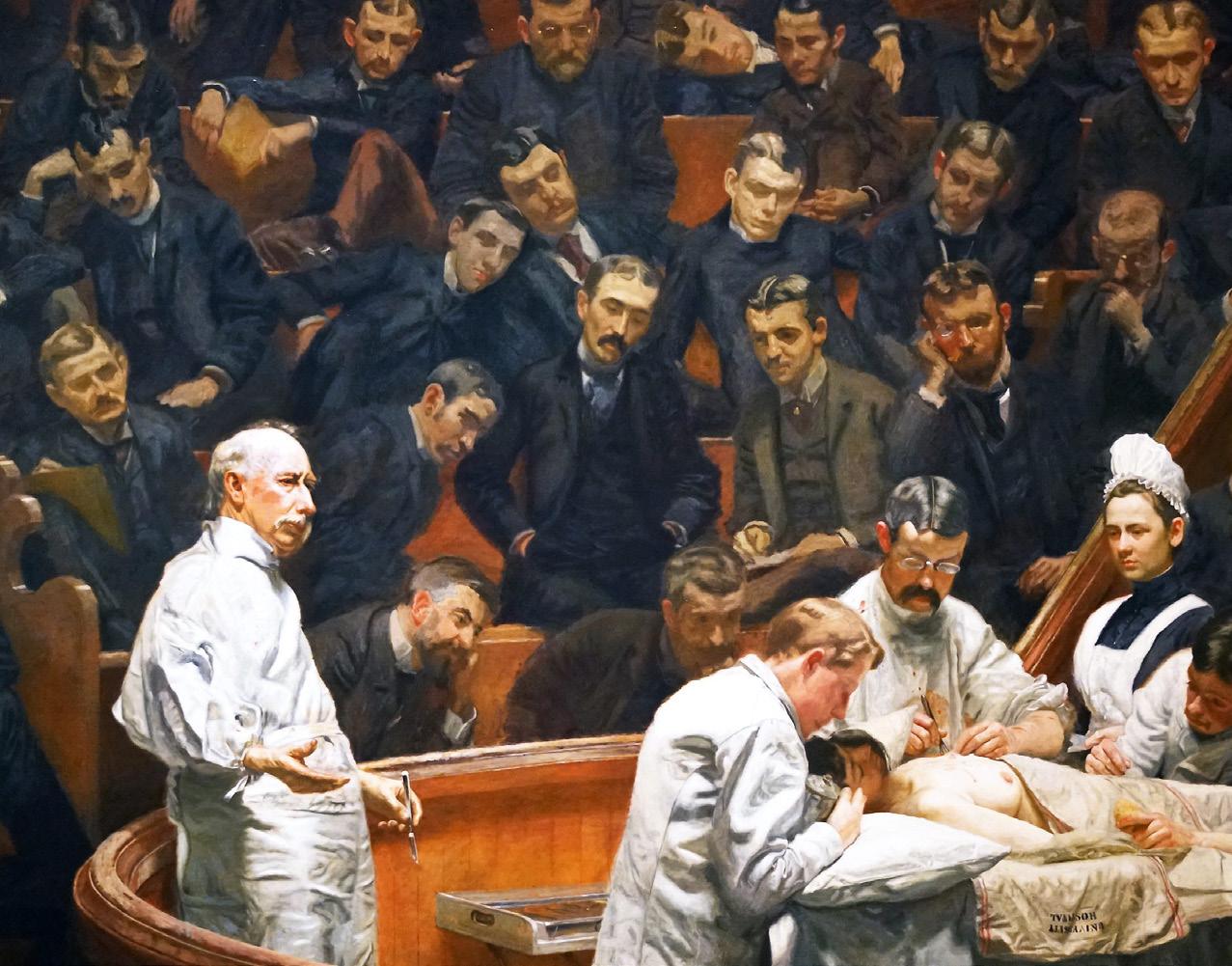

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, disease began to be reconceptualized, with the rise of disease classification prioritizing anatomical approaches to lesions in the body over symptom-based classificationss. This shift resulted in anatomy becoming essential within medical education. In Thomas Eakins’ The Gross Clinic, Eakins portrays Dr. Samuel D. Gross, a seventy-something year old professor lecturing to a group of medical students at Jefferson Medical College, as he treats a young patient for osteomyelitis of the femur. This painting contrasts the previous works examined – students are now being trained through observing real patients being operated on – highlighting education through the process of active treatment of disease instead of the passive observation of dissections. The surgeons encircle the patient in their black frock coats as the students in the background are immersed in keen observation, creating an atmosphere of academic fervor painted in somber hues. The only female figure in the painting is a woman sitting in the middle ground, assumed to be the patient’s mother, emotionally and physically withdrawing from the distress of seeing her child on the operating table. She functions as a contrast to the rest of the painting, her visceral and sensational reaction countering the stoic, detachment of the men surrounding her. While this painting honours the shift towards accepting surgery as a discipline within medical curriculum, it continues to perpetuate a paternalistic approach to medicine and surgical education.

Fourteen years later, Eakins’ paints for us an operating theater once again, allowing the viewer to visually appreciate the progression in surgical training that occurred within those years. In this commission, he honors American surgeon Dr. Agnew, scalpel in hand, lecturing to a theater of students during a mastectomy. The Agnew Clinic contrasts the dark undertones of The Gross Clinic with cleaner and brighter tones. The choice of brighter colours and white

coats on the surgeons serves two purposes; visually depicting the evolving understanding of the importance of hygiene during surgical procedures as well as distinguishing surgeons from students. Similar to Dr. Gross, Dr. Agnew is represented larger and taller than most of the figures in the foreground, again using visuals to express the hierarchies within the surgical profession and education. However, unlike Dr. Gross, Dr. Agnew is painted away from the procedure, demonstrating the role he holds as more of an educator at the time. Standing across from Dr. Agnew and contrasting him in the painting, is nurse Mary Clymer. She serves not only as a feminine counterpart to him, but her presence also represents the advancements within the nursing profession at the time and the importance of interprofessional operating rooms. One other female is depicted in this painting – the patient – who is partially nude – while being observed by a room of male doctors and students. Despite the advancements within surgery and training captured by this painting, the patient presented in such a way suggests a general lack of concern for patient dignity within surgery at the time, a problem that we are working on improving upon even in today’s operating rooms.

Today, these surgical theaters remain historical landmarks that remind us of the advancements surgical training has undergone. We no longer sit on rows of wooden benches, surrounded by 50 of our peers, each trying to get a better view of the surgery while our professor lectures, scalpel in hand. Today as a medical student, we have the privilege of stepping into the modern-day operating room and learning from our preceptors at the bedside. We get to utilize the foundations that we have built upon during our first two years as well as the technical skills that we continue to refine through programs like the Surgical Skills and Technology Elective Pro-

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, Rembrandt, 1632, oil on canvasgram (SSTEP), in which I had the privilege of participating in this past summer. As a learner now having completed my core surgery rotation in clerkship, I can appreciate how SSTEP has helped me feel better prepared and more confident for the procedural skills that I have been asked to perform thus far in clerkship. These include, but have not been limited to assisting in laparoscopies, suturing incisions, and continuously maintaining sterile technique.

Analyzing and reflecting on surgical history through the lens of art history has revealed that surgical training is ever evolving. Through an exploration of our history, it is clear that surgical education has undergone numerous transitions, from improvements within professional hierarchies, patient care, and sanitization, and an approach to training that has shifted from passively observing surgeries from afar, towards actively assisting up close. I have contributed an additional painting to this reflection, one of my own. In this painting I play with the themes that have been prevalent throughout this analysis by depicting today’s medical students observing a modern-day surgery, yet still within the setting of a historic operating theater. My goal was to highlight the contrast of modern surgical advancements in education with historic forms of teaching, by having the students seated along the wooden benches, each trying to get a better look. I hope that students can see themselves in this painting and appreciate the evolution in surgical training, from the observation-based learning shown in this painting, to the hands-on approach we actually learn from in the hospital.

As a student in the operating room today, I am able to learn in a closer, more intimate manner, as I stand right beside the patient and assist the attending surgeon and residents, all the while promoting patient care and dignity in perioperative practice. For this reason, I believe that procedural skills training programs are essential within the medical curriculum, as they provide us with the practical knowledge and manual dexterity required in the medical and surgical settings to serve our patients. As a learner in a teaching hospital, procedural skills training has been essential to not only improving my confidence when performing such procedures, but most importantly, allowing the patient to feel more comfortable and looked after when in my care.

[1] Bishop, W. J. (1995b). The Early History of Surgery by W.J. Bishop (1995) Hardcover (1st ed.). NY: Barnes & Noble. [2] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2018, December 7). Sushruta. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sushruta

[3] Nutton, V. (2022, September 27). Galen. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Galen

[4] Florkin, M. (2022, June 20). Andreas Vesalius. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/ Andreas-Vesalius

[5] Hernigou, P., Hernigou, J., & Scarlat, M. (2021). Medieval surgery (eleventh-thirteenth century): barber surgeons and warfare surgeons in France. International orthopaedics, 45(7), 1891–1898. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-02105043-z

[6] Himmelmann L. (2007). Från barberare till chirurgie magister -steg på vägen mot en läkarprofession [From barber to surgeon- the process of professionalization]. Svensk medicinhistorisk tidskrift, 11(1), 69–87.

[7] Duffin, J. (1999). History of Medicine: A Scandalously Short Introduction (1st ed.). University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division.

[8] Duffin, J. History of Medicine: A Scandalously Short Introduction.

in my garden

late blooming in the autumn the ice frost keeps me still no time for growth for my translucent leaves to fill.

my petals stiffen with a heaviness i feel myself wither and close the trees whisper “it is going to be ok” but what do they know?

the hydrangeas sing their melancholic blues the lavenders blush as they dance the crimson roses find their place do I stand a chance?

this garden is a kaleidoscope of colour hues transcending past what colours do I bring how do I make them last?

the rich brown soil envelopes me pushing me to thrive i pray for silver, shimmering rainfall hoping to survive.

– devyani p.

Myfamily is a part of a very small minority of South Asians who don’t celebrate Diwali in any way, shape, or form. Growing up, it just wasn’t really a thing for us. You can imagine my surprise and ensuing trepidation when I had to bring a main for an evening potluck celebration arranged and hosted by our cohort. Eventually, I settled on chicken pukka, which is analogous to a fragrant and spicy risotto garnished heavily with hearty pieces of curried chicken breast.

I found myself in a somewhat strange state at that celebration, as a South Asian largely learning about the traditions of other South Asians. But not for a moment did I feel out of place as I shared in countless moments of laughter, enthralling conversation, a gut stuffed to the brim, fingers scalded from dripping candlewax and even some impromptu back porch singing and dancing.

Celebrating Diwali in Canada is particularly memorable because of its occurrence during the fall, when the leaves on trees are splashed in various shades of red, orange and yellow as they fall to the ground in a chaotic yet beautiful arrangement. And a full autumn twilight that seems to come earlier with each passing day casts a kaleidoscope of colors in the sky that transition from deep purple to peach. Afterwards, there is the moon which I have observed in various colors over the course of fall including bright orange, pale yellow, cream white and blue. The only thing missing is the nostalgic warmth of a greatly missed lazy summer evening. But there is certainly no absence of color nor variation therein.

The wonderful thing about celebrations like this is that they encourage people to come together and share in their unique customs and traditions. In fact, I learned about a lot more than techniques to keep a candle ablaze in a dimly lit backyard patio. Punjabi songs phonetically committed to memory, experimental (and highly successful!) home cooked dishes, and the arduous task of coordinating ritualistic puja over multiple continents with loved ones, which has since become a family tradition, are all unique experiences centered on Diwali.

When I think about the people served by our healthcare system, including their rich lived experiences, I understand that they share culture and traditions that give them a sense of identity. But beyond that, there are individual customs that make a person uniquely themselves, which are as multifaceted as the colors we associate with a Canadian Diwali. Having that appreciation of breadth is something that will serve us well as future clinicians, as we tread on the path towards optimizing our standard of care.

If I ask you what colours you think of when you think of scrubs, what colors would you choose? I believe the first thought that would come to your mind would be the colour blue or even green. Blue, notoriously made popular by Grey’s Anatomy, and green, also the colour of scrubs on the show ER, are possibly some of the most popular scrubs colours. But these colours haven’t always dominated the wards and clinics. Wouldn’t it be interesting to explore the history behind scrubs and their colours as well as try to understand what the meaning of these symbolic colours are?

The development of modern surgical attire was a direct effect of the acceptance of germ theory of disease that was theorized in the mid-16th century1. Back in the 1800s, physicians operated in the surgical theatre in nonhospital attire, often wearing suits and jackets on which some would wipe their blades on from case to case1. The very first iteration of what we now identify as “scrubs” were the white gowns and caps that were worn by surgeons and operating staff in the 1940s2. What they quickly realized was that the red from the surgical field clashed greatly with the white gowns and white surroundings and was very harsh on the physician’s eyes2. Also, as many of you may know, white stains atrociously, especially by blood. Green, which is red’s opposite color on the color wheel, was apparently soothing to the eyes. However, it wasn’t until the 1950s and 60s that light green scrubs began replacing the white gowns of the World War II generation2. This transition also coincided with the Korean and Vietnam wars.

So why do we call medical uniforms “scrubs?”. There’s an easy answer to this question: these garments are called “scrubs” because they are scrubbed clean through rigorous washing procedures2. The concept of scrubbing into a surgery also lends its name to these uniforms. This idea of sterility permeates the culture of medical garb.

Now as you might have seen before on Grey’s Anatomy, attendings wear scrubs in a darker shade of blue to signify their seniority while residents wear light blue scrubs. Although we don’t see this state of medical hierarchy in the form of scrub colors at Kingston’s various hospitals, this practice exists in other places. In England, NHS staff wear different colored scrubs to distinguish different branches of healthcare professionals3. For example, anesthesiologists in the NHS wear maroon3. There is also seniority designation according to the piping of different colors and patterns in NHS scrubs3.

As medical students, you’ve probably donned the classic navy blue scrubs available at Kingston General Hospital or Hotel Dieu Hospital. But what do patients truly think of these colours? According to a study done by Ohio State University, 341 randomly selected patients preferred light blue, light green, and darker blue, respectively, for medical professionals4. The patient surveys showed that blue and green were clearly viewed as “medical” colours, while other colours could confuse the patients about the role of the medical professional wearing them4. On the flip side, the Ohio study showed that professionals similarly preferred light blue, light green and darker blue4.

However, majority of participants believed the fit of scrubs needed improvement4. Many of the complaints about hospital issued scrubs are the shapeless boxy fit due to fact that these garments were designed to be universally worn by men and women. We’re not confined, however, to only wear hospital issued scrubs with advents of more “stylish” scrub manufacturers such as FIGS. Other popular brands include, Jaanuu, Koi, WonderWink and (much to my surprise) Grey’s Anatomy5. You’ll know FIGS if your targeted Instagram and TikTok ads have been shoving the brand down your throat with medical influencers dancing and crying in their trendy FIGS scrubs.

In May of 2021, FIGS went public with shares selling above an anticipated range, and with a valuation of approximately $4.5 billion5. They popularized the jogger-style scrubs, ribbed at the ankles, like sweatpants5. A quick peruse on the FIGS website shows a wide array of comfy/trendy scrubs in a multitude of pastel colours from “terracotta” to “lilac dawn”. I’d be lying if I didn’t find the idea of wearing joggers to an observership or a clerkship placement rather appealing. But you won’t find me shelling out $120 for a set of matching “ultra rose” coloured scrub top and joggers.

But the option of selecting more appealing colours to demonstrate individuality and personality is quite enticing. It begs the question if patients will enjoy a change of scenery when it comes to medical scrubs. Does pastel really soothe the mind and spirit? Or will it only work to confuse them more if one attending is wearing a mauve-coloured set of scrubs while all other medical staff are dressed in the commutable blue? At the end of the day, the utility of scrubs are to maintain a sterile environment for procedures and surgery. There is an argument to be made about not wearing scrubs outside of the hospital and clinic environment to prevent communicable diseases from spreading outside of the clinical setting, but that’s another article. I guess the jury’s still out on this one, but don’t even get me started on the Patagonia.

References:

1. Adams LW, Aschenbrenner CA, Houle TT, Roy RC. Uncovering the history of operating room attire through photographs. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(1):19–24.

2. Spellen S, says HK. Medical scrubs: A short history [Internet]. New York Almanack. 2020 [cited 2022Nov5]. Available from: https://www.newyorkalmanack.com/2020/09/medical-scrubs-a-short-history/

3. Scrubs (clothing) [Internet]. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation; 2022 [cited 2022Nov5]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scrubs_(clothing)

4. Aagard EA. A pre-design study of patient and medical professional attitudes and reactions towards the colors of medical scrubs [Internet]. OhioLINK ETD: Aagard, Erik A. [cited 2022Nov5]. Available from: https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_olink/r/1501/10?clear=10&p10_accession_num=osu1218038251

5. Friedman V. Health Care Workers Deserve Fashion, too [Internet]. The New York Times. The New York Times; 2021 [cited 2022Nov5]. Available from: https://www.nytimes. com/2021/06/09/fashion/healthcare-workers-scrubs-fashion. html

You wake up on a crisp October morning. The sky is a velvet blue; some leftover stars still glimmer.

Yesterday was a difficult day, maybe today will be different. You let out a little sigh, take a deep breath.

Your walks to and from work, they consist of the sun. Its radiance rising to start your day or its embers billowing to an end.

Some days, its golden hues remind you that the world is bigger than what’s between those hospital walls.

Some days, the deep purples make you realize how long your day truly can be.

Your vibrancy may change with the day, but trust that you will rest and rise again. The sun is unwavering, just like yourself.

– devyani p.

By Olivia Ginty

By Olivia Ginty

Throughout the history of surgery, art has been harnessed as a tool for knowledge dissemination and education. Famous physicians such as Frank H. Netter are well-known for the medical illustrations they created alongside their advances to the field of medicine. Today, physicians continue to use illustrations in publications to explain techniques, or simply rely on them to swiftly educate a student or patient with a visual aid. To demonstrate the fascinating, evolving relationship of art and medicine to the next generation of medical professionals, we must start at the origin of medical illustration.

First, let us travel back to the era of Guido da Vigevano, the first in his field to use illustrations rather than descriptive text to explain anatomy. This was accomplished in his work Anathomia, published in 1345, which included six drawings depicting the trephination of the head via a scalpel and hammer technique.1 Describing this visually rather than exclusively with text marked a revolutionary step in medical education. As the Renaissance period began, book printing became possible, enhancing the accessibility of medical illustration as it began to popularize. Along with the Renaissance period came Leonardo da Vinci, well known for multiple ground-breaking roles in art, science, and engineering. His incredible observation skills and talent in drawing extended to medical illustration. He produced cadaveric dissection illustrations, including but not limited to depictions of the fetal membranes, the reproductive systems of both sexes, the muscles of the extremities, and the proportions of the human body.1-4 He further contributed to the evolution of medical illustration as the first to illustrate the same anatomy from multiple viewpoints, a now commonly known principle which produces a far more comprehensive understanding of the subject to the viewer while remaining the boundaries of a two-dimensional medium.1 Michelangelo Buonarroti similarly participated in dissections and famously studied anatomy to produce sculptures with exceptionally accurate surface anatomy.1-2 Hieronymus Fabricius ab Acquapendente, a surgeon and chair of anatomy at the University of Padua in Italy, was responsible for the next notable turning point. Unlike previous anatomical illustrations which had an artistic agenda of maximizing the viewer’s interest, his atlas Tabulae Pictae in 1600 had a scientific focus, bringing us closer to the textbook illustrations we know today.1-3

Across the 17th and 18th centuries, anatomical illustrations continued to improve in their ability to depict a range of

anatomy in a more realistic, scientific manner. A Scottish anatomist and surgeon, John Bell, contributed to this evolution and is considered the “father of surgical anatomy.”1,5 He prepared both the descriptive text and surgical illustrations himself, unlike texts with hired artists, and published these in Anatomy of the Human Body in the late 1700s. He was followed by several more famous physicians publishing similar texts into the 19th century, including Jules Germain Cloquet’s text Anatomie de l’homme, known for detailed hernial disorder depictions, and Henry Gray and his text Gray’s Anatomy, widely regarded as a “Bible” of anatomy.1,3,5 Gray’s Anatomy has found its place on the bookshelves of numerous current medical professionals and students, and even inspired the name of a modern day medical drama television series. Together with his friend and professor in anatomy, Henry Vandyke Carter, who was responsible for the illustrations, they produced an impressive body of work.1,3,5 These texts were particularly popular for their emphasis on regional anatomy, depicting anatomy from sections rather than entire systems, just as one may approach it as a surgeon.

By the end of the 19th century, medical illustration was formalized as a discipline. Johns Hopkins School of Medicine established the first of its kind, Department of Art as Applied to Medicine, directed by Max Brodel, the “father of modern medical illustration.”1,4 This establishment led to the standardized training of medical illustrators and the creation of similar training schools across the world. Brodel also collaborated with famous surgeons, such as the neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing, with whom he depicted new surgical approaches to the pituitary gland.5

Cushing himself was known to enjoy illustration, recording his surgical techniques in the form of drawings immediately after surgery before even taking off his surgical gloves.2 Frank H. Netter was similarly a famous artist-physician, however, he was uniquely an artist prior to becoming a surgeon, supplementing his income as a medical illustrator.1,3 He was notorious for the meticulous research behind his illustrations, proudly proclaiming that a medical illustration was only as valuable as the medical point it delivered. In this way, he defined our modern-day definition of medical illustration as exclusively a tool for education. Into the 20th century and up to present day, the term medical illustrator has extended to include a community of animators, modellers, multimedia designers, and art directors, because of collaborations technology, but retains centuries of

history.6,7 Medical illustrators nowadays have pro gressed to creating educational tools in animated video, virtual reality, and 3D-models, expanding the dimensions of medical illustration; as well as molecular illustration which simplifies the visual depiction of complex envi ronments at the microscopic level.

Medical illustration began the fine arts, depicting anatomy for the delight as cadaveric dissection racy of the illustrations, of medical education. principles, such as depicting realistic views of content, and anchoring illustrations in clear objectives, further shaped medical illustration into a routinely used tool. The utility of medical illustration in the current day begins in training, just as historic experts like Cushing used it, to grasp concepts and study material. Medical professionals regularly use drawings informally to replicate anatomy and interventions for patients, enabling more effective education and for informed consent to be more reliably obtained.8-10 Medical illustrations also continue to be formally depicted, coupled to surgical technique descriptions in the literature, carefully simplifying procedural steps, providing anatomical landmarks and realistic viewpoints, to ultimately facilitate accurate dissemination of knowledge to other professionals.2,8 Furthermore, they improve communication with colleagues across departments, such as improving a surgeon’s description of a specimen to a pathologist, ensuring accurate review.8 This, of course, also extends to the communication between medical professionals and trainees, as more modern-day medical illustrations such as schematics provide visual structure to complex topics, and three-dimensional modelling promote spatial comprehension.2,6,8 Medical illustrations additionally overcome obstacles in communication such as in language barriers or handwriting legibility where words alone fail.10 So, when medical trainees use illustration as a study tool, they are both improving their education as well as building communication skills for their later careers. As the next generation of medical professionals face a field increasing in complexity, it is essential that medical illustration continues to be appreciated as an essential component of medicine’s history and future.

2. Athanasiou T, Debas H, Darzi A, Winderbank-Scott D. In: Key Topics in Surgical Research and Methodology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2010:741-751.

3. Netter FM, Friedlaender GE. Frank H. Netter MD and a brief history of medical illustration. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(3):812-819.

4. Hajar R. Medical illustration: Art in medical education. Heart Views. 2011;12(2):83-91.

5. Mavroudis C, Lees GP, Idriss R. Medical Illustration in the Era of Cardiac Surgery. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2020;11(2):204-214.

6. Ansary MA, el Nahas AM. Medical illustration in the UK: its current and potential role in medical education. J Audiov Media Med. 2000;23(2):69-72.

7. Bucher K. New Frontiers of Medical Illustration. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2340-2341.

8. Kearns C. Is drawing a valuable skill in surgical practice? 100 surgeons weigh in. J Vis Commun Med. 2019;42(1):414.

9. Kearns C, Kearns N, Paisley AM. The art of consent: visual materials help adult patients make informed choices about surgical care. J Vis Commun Med. 2020;43(2):76-83.

10. Krasnoryadtseva A, Dalbeth N, Petrie KJ. The effect of different styles of medical illustration on information comprehension, the perception of educational material and illness beliefs. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(3):556-562.

I once met a lady whose eyes were blue The kind of eyes that radiated virtue Her story however that was about to ensue Changed my look on life, it changed my view

See this lady had cancer, the terminal kind The kind of cancer that would put you in a bind And although her health slowly declined Her story portrayed her presence of mind

See her story was about her daughter’s distraught The pain that she felt, and the hatred she taught The anger you feel that makes you red on the spot As she started to pray and started to plot

As her mothers, white hair started to fall The daughter couldn’t stand it and started to bawl See it seemed that the curtains were starting to fall But the mom looked up and said, “my beautiful girl life gets us all”

See she told me she lived her life to the fullest She travelled the world as a yellow haired tourist And she made her amends and her soul was the purest And that life can be rough and she sure did endure it

See her point to me was that life is short And that sometimes jobs can start to distort The life you imagined, the goals you abort And forget about the ones who are there to support

So go travel and see the beautiful blue sea Sit down with your family, and have some green tea Stop and smell the roses and the lovely brown trees Or head to a snowy white mountain and go for a ski

“Don’t have regrets in life” that’s all that she asked Set goals in your life, and do any task So that at the end of life when you start to unmask Your life was indeed a rainbow, filled with colourful memories that last

By Sonu Varghese

By Sonu Varghese

Not because it’s bold

But because it represents something that we are all part of Nature and life

Neither of which we can recreate

Cake:

4 large eggs (room temperature)

2/3 cup granulated sugar

8 tbsp unsalted butter (softened)

15 oz ricotta cheese

¼ cup sour cream

1 tsp vanilla extract

1 cup of all-purpose flour

½ tsp of salt

2 tsp baking powder

1 1/2 tbsp lemon zest (approx. 1 large lemon)

8 oz fresh or frozen blueberries (approx. 1 ½ cups)

Icing:

1 – 1 ½ cups powdered sugar

2 tbsp lemon juice (freshly squeezed)

1. Preheat oven to 350°F. Grease the sides of a 7” or 9” springform pan with butter and line the bottom with parchment paper.

2. In a mixing bowl, beat together the eggs and sugar on high for approx. 2 minutes until light and frothy.

3. Blend in the butter until smooth.

4. Add in ricotta, sour cream, vanilla, and lemon zest and beat all ingredients together on high for approx. 1 minute or until well blended.

5. Add flour, salt and baking powder into mixture and beat on low until well incorporated.

6. Pour the batter into the prepared springform pan and sprinkle blueberries evenly over the top.

7. Bake in the oven at 350°F for approx. 60 minutes or until edges are lightly browned.

8. In a separate bowl, add in the powdered sugar and lemon juice. Whisk until well incorporated. Add additional powdered sugar if a thicker consistency is desired.

Note: It is normal for the cake to be slightly jiggly in the middle. Once you remove the pan from the over, let the cake cool over a cooling rack for approx. 20 minutes.

While colour perception has emerged as an important human survival mechanism to convey essential information about the environment, it also serves as a ubiquitous form of non-verbal communication that elicits feelings, energies and sensations. Hence, the popular get-to-know-you question “what is your favourite colour” is often asked to reveal subtle hints about an individual’s psyche. Similarly, asking “what is your sign”, while eyerolling to some, can stimulate broader conversations about personality. Here we describe the intersection of both colour and astrology to describe the unique personality traits corresponding to the planetary patterns of when you were born.

Similar to the intense and bright red commonly used for emergency vehicles, Aries personalities are passionate, energetic and bold. This is the colour of assertion and excitement, which supports Aries’ ambitious and highly active nature. They are natural leaders who can easily take initiative. Red elicits a sense of urgency analogous to Aries’ distinctive impulsivity. They may not always think before they leap, but they are always willing to take the first step.

Geminis, like the glow of the sun, have a natural brilliance to them. They are highly intellectual and are great at communicating ideas. They can be very playful, uplifting and versatile in their interactions with others. There are quick witted and can read a room instantaneously, allowing them to quickly adapt to those around them making them very likeable. Their constantly mutability around others, while charming, may make it hard for people to feel truly connected to them. While they are exciting and clever, their flakiness and commitment issues can also cause others to feel burnt.

The Taurus spirit closely resembles an evergreen tree whose foliage remains consistently green and functional over several growing seasons. Taurus’s embody stability, practicality, and dependability. However, anything that alters their sense of stability and desire for control can be perceived as a threat. They can be stubborn, resistant to change and respond reluctantly to criticism. Like a giant sequoia tree, a great benefit of their grounded and rooted energy is that they can be very nurturing and resilient even in times of extreme chaos.

Similar to looking upon the waves of the ocean, Cancers may appear cold or uninviting at first glance. But beneath their surface is intense emotional depth and a highly sensitive and layered environment. Cancer’s superhuman power is their intuition. They naturally process the energies in a room and will act to care and nurture those around them in tender and subtle ways. However, their heightened self-awareness and awareness of others can cause them to be easily burdened by their own emotions and the emotions of those around them. Their feelings flow in and out like a tide. Depending on their emotional state, being around a Cancer can feel like being caught up in a thunderstorm or like the warm embrace of a summer breeze.

Leos are all who shimmer and shine. They naturally radiate confidence and optimism with their bold, charismatic and alluring personalities. Gold transmits brilliance and represents a colour that demands to be seen. Similarly, Leos do not shy away from the spotlight and welcome the praise of others. This can lead them to have an unhealthy dependency on external validation to feel self-worth. Like golden materials, Leos want to be perceived as unbreakable and may shield their vulnerabilities. But under their loud and proud exteriors lies a tender heart of gold.

Like a granny smith apple, Virgos strive to cultivate a healthy way of being in all aspects of their life. They are the ultimate perfectionists who set high standards for themselves and others. This can cause them to become anxious in fear of making mistakes. The tend to prefer routine and careful planning over spontaneity. They also possess a life-long commitment to self-growth which can be projected onto those they love. While Virgo’ criticism can leave a tart taste in your mouth, their intentions are all for the betterment of your well-being.

Libras are a sign of neutrality. They strive to cultivate harmony and can view all situations from multiple perspectives. They exude fairness and goodness towards others. These characteristics combined with their love for all things aesthetic gives them an elegant and graceful quality. Their neutrality may stem from an intense need to be liked. They carefully curate their words, actions and appearance to appeal to others. But this can come from a compassionate place, as Libras recognize how individual actions can impact other people’s happiness.

Scorpios are widely accepted as dark and mysterious. Their “darkness” is not notorious or bad. Rather, this speaks to their opaque exterior which makes it hard to know what they are truly thinking or feeling. If anything, their secretive nature is often very alluring and captivating by others. They exist behind a one-way mirror, always reading and analyzing those they interact with. They prefer to be the one asking the questions than being asked. This is because the only thing they fear in this world is being vulnerable with someone they cannot trust. They are always on guard and on the defense to avoid the pain of being hurt. But if you can get beneath their surface, you may be very surprised by what you see.

Sagittarius’s have a brazen spirit. They are the ultimate explorers who seek to cover extensive and unknown terrain. They are not afraid to go to places that others would do not dare to venture to. Their exploration extends beyond the physical realm as they equally quest for knowledge and a better understanding of the human condition. However, their relentless drive for adventure and searching the unknown may make commitment difficult for them. They are free spirits, who prefer spontaneity over solid plans. One benefit of this is they never will run out of wild stories.

Capricorns have a strong drive to succeed in very tangible and material ways. In turn, they are some of the hardest workers of the zodiac. They are natural leaders with strong ambition, determination and self-discipline. However, their relentless goal orientation can cause them to always put their ambitions ahead of others, making them appear cold and inflexible. They are very self-sufficient and may be quite reserved until they are sure someone can be trusted. But once a relationship is established, Capricorns are great people to turn to for practical advice.

Aquarians have a celestial air about them as they are often out-of-this world in how they think, act and dress. They thrive in their ability to be unique and comfortably hold contrarian views from the mainstream. However, this can cause them to feel a form of self-imposed alienation from others. They are visionaries who tend to focus their efforts on causes for the greater good. This may make them appear cold and aloof in their individual relationships. Regardless, they are highly cerebral and forward-thinking people that this world needs to make it a better place.

A Pisces’s personality is a tangerine dream. They are often very dreamy, imaginative and creative. They perceive the world through an idealistic lens containing big dreams tethered to their deep love for humanity and compassion. Conversations with a Pisces often feel more poetic versus hearing things matter-of-fact. They do not go about the world in an aggressive manner, and rather express themselves in a soft and ethereal way. As a sensitive sign they can easily get lost in their emotions and the emotions of others. In addition, their visions for the future, no matter how bold and beautiful, often sadly come at the expense of feasibility.

“Let me, O let me bathe my soul in colours; let me swallow the sunset and drink the rainbow.”

Editors-in-Chief Devyani Premkumar, 2025 Simoon Moshi, 2025

Layout Designers

Simoon Moshi, 2025 Gabriele Jagelaviciute, 2024

Managing Editor Helen Lin, 2025

Managing Illustrator Michele Zaman, 2025

Event Coordinator Adele Kim, 2025

Editors Mansi Dave, 2025

Omar Hajjaj, 2026 Kristina Ferreira, 2026 Simryn Atwal, 2026 Shangari Vijenthira, 2026 Haya Abuzuluf, 2025 Sarenna Lalani, 2026

In-House Writers

Mudia Iyayi, 2026

Imran Syed, 2025 Anson Sathaseevan, 2026 Yalinie Kulandaivelu, 2026 Helen Lin, 2025 Devyani Premkumar, 2025

Spread Illustrators

Visual Artists

Kiera Liblik, 2024 Michele Zaman, 2025

Frank Chen, 2026 Michele Zaman, 2025

Tanya Narang, 2025 Simoon Moshi, 2025

Sabra Salim, 2025

Nik Jelicic, 2026

Prashanth Rajasekar, 2025

Sigi Maho, 2024

Olivia Ginty, 2023

Farzan Ansari, 2025

Sonu Varghese, 2025

Raquel Oleksin, 2025

Jamie K. Fujioka, 2025

Photo by Mymind on Unsplash

Photo by Mymind on Unsplash