Milestones deserve to be celebrated. Congratulations to the many members of our community who have contributed over the years to reach the milestone of ten published editions of Pymble’s Research and Innovation Journal, Illuminate.

Our inaugural edition was published in 2018, when the College had recently celebrated its Centenary and was in the final years of implementing a strategic direction known as Towards 2020 – Striving for the highest. Back then, the pillars of teaching and learning were defined as Personalised Learning, Community, People and Culture, and Sustainability, and the purpose of this journal was to celebrate our teachers as designers, innovators and thought leaders in education, specifically within the context of an all-girls’ school. Illuminate was conceived as a platform for sharing the depths and discoveries of the creative, connected and engaged practice of teaching and learning at Pymble

Ten editions later, we are in the second triennial of our current strategic direction for 2021 to 2030, Watch Us Change the World. Our four teaching and learning pillars are defined as Academic, Emotional, Social and Digital Intelligence, and the College footprint has evolved with the acquisition of our outdoor education campus, Vision Valley, and the commencement of an ambitious Master Plan to create new and enhanced learning spaces across both campuses. We have launched the Pymble Institute, hosted numerous research conferences, established an Ethics Committee and participated in a variety of internal and external research projects. While the changing global environment calls for continual reflection, adjustment and innovation in education to equip our students for their futures, the purpose of Illuminate remains the same: to shine a light on the pedagogy that makes Pymble an exceptional place to teach and learn.

Across ten editions, our incredibly generous academic staff, students and professional partners have found the time to contribute approximately 90 articles exploring topics ranging from Artificial Intelligence to Wellbeing, and everything in between.

Fittingly, the theme of our 10th edition is Social Intelligence. At the core of this focus is our community’s commitment to embracing opportunities to learn in collaborative environments where different perspectives are encouraged and valued. This is so important in research and inquiry, not to mention life in general. We look forward to continuing to provide opportunities for staff to present and publish their work and promote the dissemination of ideas.

To all our past, present and future Illuminate authors, thank you for playing a role in building our collective research muscle. To our professional services staff who have been involved in designing and editing these editions over the years, we are grateful to have your expertise in bringing Illuminate to life in printed and digital form. To Dr Sarah Loch, thank you for your vision and commitment to building a dynamic and evolving research community at Pymble, and for continuing to focus on our students at the heart of all you do. And finally, to our students, this and every edition of Illuminate is dedicated to you and your bright, shining futures.

DR KATE HADWEN PhD, MEd, BTeach, MNTCW PRINCIPAL, PYMBLE LADIES’ COLLEGE

Welcome to the latest edition of Illuminate: Research and Innovation, the research journal of Pymble Ladies’ College. This edition is a cause for celebration as it is our 10th edition and we can look back on the research-focused educational stories we have shared over the past six years.

Our focus for this issue is Social Intelligence, one of the College’s four strategic pillars, which appropriately for an anniversary edition, highlights interrelatedness and connections between people. The main tenet of the Social Intelligence pillar is that through seeking and embracing diversity, including diversity of thought and background, a community comes together with a stronger sense of purpose. The articles in this edition continue the College’s story of the impact we can have in the educational landscape of Australia and beyond through bringing our diverse interests to the fore.

In the following pages, you will find research that takes you inside our commitment to the power of learning and teaching in the social, relational and intrapersonal domain. Following completion of her Global Action Research Collaborative research project with colleagues from the International Coalition of Girls’ Schools, Kate Giles shares her paper on fostering social and emotional learning among Junior School girls. Kate Brown, Head of Junior School looks strategically at the progress of the Junior School’s kindness initiative and evaluates its growing impact on students. Similar threads are explored by Imogen Kennett, who utilises positive experiences in a reading aloud initiative to investigate ways of expanding literacy skills in young children, and Melinda Pedavoli writes about encouraging interdisciplinary ways of teaching to prepare our students for complex future contexts.

Authors have also interrogated some of the many and varied professional learning environments and opportunities available in our profession. Writing with the Pymble Institute team, Dr Meera Varadharajan shares her research into career change teachers. These are people who opted to re-train as teachers following a career which

began in a different domain. Dr Joshua McDermott and I present a literature review conducted on kindness and prosocial behaviours, and take a step back to explain the wider relevance of using literature reviews in a school improvement context.

Leadership is also in the spotlight, with Tom Riley and Vanessa Petersen reflecting on key opportunities that have enriched their perspectives on their roles. Tom participated in the Flagship Leadership Program with the Association of Independent Schools (NSW) and Vanessa presented at an international outdoor education conference in Tokyo, Japan with academics from Western Sydney University. Carolyn Burgess, Pymble’s Head of Boarding, reflects on the experiences gained during an overseas tour of boarding schools which afforded her the opportunity to recognise the important cultures and traditions that build effective boarding environments.

As you read, consider the highly relational, interconnected and complex work being undertaken each day in schools around the world. These articles are examples of some Pymble stories which we hope will inspire and inform others in their search for diversity of thought and action. Together, this collection of articles and the authors behind each initiative and paper, seek to embody the change we aspire to see in the world — one story, one research project, and one learning experience at a time. The authors and I hope you enjoy the papers which make up our tenth edition!

DR SARAH LOCH PhD, MEdSt, MTeach, BA, HFTGN DIRECTOR – PYMBLE INSTITUTE

Victoria Adamovich moved from Taipei to London at the age of eight and studied French and Politics at The University of Edinburgh. After working for a decade as a marketing executive in Asia, she retrained as a teacher at the University of Hong Kong. She taught in bilingual EnglishChinese schools in Hong Kong and Shanghai before returning with her family to Sydney in 2017 to work at Pymble Ladies College as an EAL/D teacher. To better understand the students and families she supports; Victoria embarked on a Master of Research at University Technology Sydney to study the wellbeing of migrant children. Victoria also works as the Research Associate with the Pymble Institute and she has also authored a children’s picture book, The Story of My Names

Kate Brown has been teaching across Kindergarten to Year 8 for more than thirteen years, since changing careers from law to education. In her career as an educator, Kate has been a class teacher, Year Co-ordinator, K-6 English Co-ordinator, Deputy Head of Learning and Head of Student Wellbeing K-6. Her approach to teaching and learning centres around the philosophy that creating a culture of kindness provides an environment in which each child feels happy to be who they are and, therefore, ready to learn and ready to embrace challenge, as well as learning. This enables Kate to inspire Pymble students to be kind, not only to themselves, but to then share their ideas with others and positively impact their world.

Carolyn Burgess is a dedicated educator with over 30 years of experience shaping young minds and fostering educational growth. For the past seven years, she has served as the Director of Boarding at Pymble Ladies’ College, where she passionately invests in creating a supportive and enriching environment for boarders. Carolyn is deeply committed to community life and continually strives to provide the best possible opportunities for our boarders, ensuring they thrive both academically and personally.

Kate Giles is the Head of Wellbeing K-6 at Pymble Ladies’ College. With a background in primary teaching and law, Kate has worked in both government and independent schools, predominantly in girls’ education. Prior to moving to education, Kate practised as a professional indemnity litigator in health law. She also holds qualifications in psychology. Kate is currently undertaking a Master of Education with a specialisation in student wellbeing. Kate is passionate about personalised learning and the importance of student wellbeing. She is currently undertaking action research projects on student wellbeing in the primary classroom.

Imogen Kennett is a Grade Co-ordinator and Compass Teacher in the Junior School at Pymble Ladies’ College. With a background in primary teaching, Imogen has worked in both government and independent schools. She is passionate about student wellbeing and dedicated to enhancing student learning and engagement. Imogen’s experience in various educational settings has equipped her with a deep understanding and commitment to fostering a supportive and stimulating learning environment, ensuring that every student thrives both academically and personally.

Sarah Loch is the founding Director of the Pymble Institute at Pymble Ladies’ College, the school’s hub of researchrelated activities. She works with students, staff and alumni, along with academics and partners from external organisations, to create opportunities for research. Sarah gained her PhD in education with a thesis examining ways young adolescent girls select school subjects and plan for their futures. She teaches History, where she loves helping her students develop a passion for scholarship. She leads the College’s Social Intelligence strategic pillar and is responsible for the College Libraries, Archives, Social Impact and Careers programs.

Joshua McDermott has been teaching History and English for more than fifteen years for a diverse range of students in Korea, London Melbourne and Sydney. It was as the Head of History at St Thomas More in London that he gained a keener sense of the need for holistic responses to the social, psychological and emotional needs of students. He found that schools can support students in not only reaching their academic goals, but also in finding their passions. His postgraduate journey in research began at Macquarie University with a Master of Arts and a Master of Research before he completed his Doctorate summa cum laude in Ancient History at the University of Sydney. He currently teaches History and performs research at Pymble Ladies’ College, a place which nurtures students’ individual learning journeys.

Melinda Pedavoli is the Head of Drama and Theatre Production at Pymble Ladies’ College, having previously served as Head of Teacher Development and Head of English at St Catherine’s Sydney. With sixteen years’ teaching experience, Melinda has consistently demonstrated her ability to drive educational change through an innovative and practicebased approach to pedagogy. Her leadership has fostered a culture of lifelong learning, achieving significant growth and success across the teams she has led. Holding a Bachelor of Education with First Class Honours and the University Medal from Sydney University, and a Master of Educational Learning and Leadership from UTS, her strengths lie in empowering and developing others, championing best practices, and fostering positive school-wide change in response to the evolving educational landscape.

Vanessa Petersen is a passionate and innovative educator. Graduating at the top of her course with First Class Honours from the University of Sydney, and has consistently demonstrated her creativity and leadership in teaching. Vanessa’s teaching experience began with HSC and IB Science (Biology and Chemistry), before pioneering STEM and integrated learning initiatives across tertiary, secondary and primary education institutions. Vanessa has held leadership roles in curriculum, pastoral care, and more recently in the unique learning environment of Vision Valley, Pymble’s second campus in Arcadia, NSW. Her pursuit of excellence spans beyond the traditional classroom to ignite courageous and adventurous young adults.

Tom Riley is the Head of Campus - Vision Valley and was previously Head of Upper School at Pymble Ladies’ College. He grew up in the United Kingdom in a family of teachers and attended boarding school before moving to Australia for university. He began teaching Biology and has since held leadership roles in pastoral care, academia, and outdoor education, both in Sydney and regional Australia. With a Master’s degree in Organisational Learning from Monash University, Tom believes education fosters progress and connection. He is passionate about inspiring curiosity and aligns with Pymble’s mission to empower young women.

Meera Varadharajan is a Senior Research Fellow at La Trobe University in Victoria. She is Research Lead of the Commonwealthsupported award-winning Nexus Program - an innovative employment-based pathway to join the teaching profession. Meera has over 15 years of experience in the education field. She is an experienced qualitative researcher, and her research focus and expertise are in the areas of education equity; education policies impacting schools; teacher retention and career change professionals. Prior to joining La Trobe in March 2024, Meera worked at the University of New South Wales for five years as a Research Fellow at the Centre for Social Impact (CSI) where she was involved in leading and managing complex research projects and programs. Meera is passionate about connecting human stories and experiences in her work to drive purposeful change in society.

Kate Giles, Head of Wellbeing K-6, Pymble Ladies’ College

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted the social and emotional learning skill development of many students, and addressing the adverse effect of distance learning and the limited social interactions has been recognised as a priority in education (Reimers et al., 2023). Social and emotional skills are vital to student wellbeing, particularly for girls (Kuriloff et al., 2017), and research has demonstrated the significant relationship between student wellbeing and academic outcomes (Fitzpatrick & Page, 2022). This finding has made the teaching of social and emotional skills a priority

in education generally and is a specific focus in the Junior School at Pymble Ladies’ College.

The influence of key adult figures at home and at school has been shown (Howard et al., 2017) to shape children’s social and emotional development. It is suggested that the creation of consistent environments both at home and school, where parents, teachers, and students work together to build a shared language and understanding of social and emotional skills will aid in the growth and development of those skills. When looking at the Global Action

Research Collaborative (GARC) action research topic of collaboration, I reflected on what this meant when teaching social and emotional skills, and my focus became the issue of how to build this shared language and understanding through collaboration. This led me to my research question: How does active collaboration in Compass Directions lessons strengthen girls’ social and emotional skills?

Action research enables educators to undertake a systematic inquiry into their own practice (Mertler, 2020) to improve and refine their

teaching. Utilising an action-research methodology for this project allowed me to create a series of interventions, based on research, where the girls collaborated with each other and their parents to explore different strategies for selfmanagement and self-awareness. Using this methodology allowed me to focus specifically on how social and emotional skills are taught to the girls in Year 3 and provided the opportunity to systematically implement and evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions for developing these skills.

Considerable research emphasises the positive impact of social and emotional skill development on student outcomes, demonstrating that effective social and emotional learning programs enhance academic performance (Dix et al., 2020; Durlak et al., 2011; Greenberg et al., 2017; Paige, 2021; Wong et al., 2018). Cipriano et al. (2023) extend this body of evidence, showing improvements in behaviour, peer relationships and academic achievement through such interventions. Notably, Fitzpatrick et al. (2022) emphasise that this is particularly important for girls.

The CASEL (Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning) Framework (2012) takes a systemic approach across several key settings (classrooms, schools, families and communities) to enhance social, emotional and academic learning. Key social and emotional competencies identified by CASEL include selfmanagement and self-awareness. The development of these skills is particularly important for girls, who have been shown to have difficulty

expressing and regulating emotions, building resilience, and, therefore, have a greater rate of anxiety symptoms (Australia Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA), 2008). The World Health Organisation (2000) further identifies coping and self-management skills – skills for managing feelings and skills for managing stress – as being essential for the healthy development of children and adolescents. These two areas, self-management and self-awareness, were identified by the Year 3 teachers at my school as areas in which the girls needed further development, so these became the focus for this research project.

Albright and Weisberg (2010) suggest that evidence-based social and emotional learning programs are more effective when they extend into children’s home lives. This notion is confirmed by Dent (2022), who states the importance of parents being involved in their daughters’ social and emotional learning, as well as the need to help girls to understand their own emotions and the emotions of others to successfully navigate relationships. Dent further articulates this importance for girls in particular: “Helping our little girls identify when they are feeling stuck in a mood and helping them work out ways that they can escape the mood, is a really helpful life skill’ (p.84).

Research further demonstrates that collaborative learning, where groups of learners work together to solve a problem, complete a task, or create a product, has major benefits, particularly for girls (Griffiths et al., 2020). These benefits include social benefits, such as the establishment of shared understanding and learning

communities; psychological benefits, such as a reduction in anxiety; and academic benefits, such as the promotion of critical thinking skills (Laal & Ghodsi, 2012). Tolmie et al., (2010) take this concept further, indicating that collaborative learning in primary school students not only builds understanding of a given topic, but also provides powerful social effects by improving social skills in students. In the classroom, collaborative lessons, activities and projects provide girls the opportunity to take responsibility for their learning and foster conditions where girls can confidently share understanding and express their ideas without fear of damaging their relationships. It is these relationships that not only help learning but also provide skills development for positive peer interactions (Roffey, 2011).

One strategy that has been used to develop social and emotional learning in the primary school classroom is Circles (also referred to as Circle Time) (Mosley, 2009). This strategy involves the teacher being more of a facilitator once the circle structure and agreed norms are established. Here, the students collaborate within that safe structure, listening to each other, appreciating each other’s perspectives and collaboratively problem-solving together. Visible thinking routines (Richhart & Perkins, 2008), such as “Think, Pair, Share,” are also effective collaborative strategies that can be utilised to explore and deepen thinking and understanding around topics. Teaching girls how to collaborate can also aid the development of important skills such as cooperation, positive interdependence, and peer relationships (Laal, 2013).

In addition to collaboration between students in the classroom, collaborating with families has been shown to be a key factor in determining school success, both academically, socially and emotionally for students and that these partnerships, if effective, also provide significant protective factors to support student mental health:

Schools play a vital role in promoting the intellectual, physical, social, emotional, moral, spiritual and aesthetic development and wellbeing of young Australians, and in ensuring the nation’s ongoing economic prosperity and social cohesion. Schools share this responsibility with students, parents, carers, families. (MCEETYA, 2008, p. 4).

It is the importance of creating a consistent supportive environment, both at school and at home, to support the development of girls’ social and emotional skills that this project sought to explore. The continued development of girls’ social and emotional skills is essential, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic. These skills underpin effective learning, enabling emotional regulation, problem solving, and positive peer relationships (Durlak et al., 2011). By fostering collaboration between students and between students, teachers, and families, a consistent environment and shared responsibility for social and emotional development can be established (Byrne et al., 2020).

Pymble Ladies’ College, situated in Sydney, Australia, is an independent school catering to girls from Kindergarten to Year 12 (ages five to 18 years old). The Junior School encompasses over 800 students,

including 125 girls in Year 3. This research involved a Year 3 class of 22 students, aged eight and nine years-old, and was undertaken from August to December. I conducted two (sometimes three) hour-long afternoon sessions per week, integrating the project into existing Compass Directions lessons to avoid disrupting the curriculum and ensuring there was no disadvantage to the class. The class was selected due to my prior teaching experience with them in Year 2 and my current role overseeing student wellbeing in the Junior School. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the year group’s wellbeing and social-emotional development also influenced the selection.

Participation in the research project was optional; however, all students in the class participated in the lessons. Parents provided consent for their daughter to be involved in the project, and were sent communications containing information about the project, including how to withdraw their daughter at any time during the project. In addition, the girls were informed of the project, what was involved, and that their participation was voluntary. Parents were separately asked to provide consent for the girls to be photographed and videoed during lessons and interviews and, to ensure anonymity, all names have been omitted from this report.

The main action of this project was to facilitate the development of selfmanagement and self-awareness skills in the girls. The initial plan was to create a series of lessons where the students collaborated with each other to learn a variety of techniques to regulate their emotions. It was then planned that the students would share

these strategies with their families at home on the basis that, to ensure the development of social and emotional skills, there needs to be consistency between the home and school environments (Griffiths et al., 2020).

It was explained to the girls that they would participate in lessons where they learnt and explored different strategies and techniques that they could use to regulate and manage their emotions. The collaborative nature of the lessons was explained to the girls, where they would explore and practice the techniques together, discuss and share their thoughts, and reflect as a class. The project started with some explicit lessons on collaboration, building trust, and understanding active listening, before moving on to selfawareness and self-management skills. Each lesson had a specific focus and included activities, such as reading picture books, role plays, learning a specific skill such as belly breathing, discussions, brainstorming, and reflecting. Each lesson started with the girls seated in a circle on the floor. I also sat within the circle with the students to create a feeling of equality, teamwork, and collaboration (Roffey, 2011).

The action evolved over the course of the project following student opinions regarding some of the activities. For example, some of the mindful activities, such as colouring and meditation, evoked strong feelings from the girls, both positive and negative. This made me consider how personal it was when determining what techniques and strategies worked to manage our own emotions and I decided that it did not seem appropriate to simply expect the students to all use the same techniques and strategies. Consequently, I added an extra step

to the action whereby the lessons would culminate in the creation of personal toolkit (see Figure 1’) by each student that she could then use when needed.

The project started in August 2023 and, over the course of approximately 12 weeks, the students worked together to explore various social and emotional learning skills to develop their self-regulation and self-management. During this time, I collected both qualitative and quantitative data through a mixedmethods approach. This allowed polyangulation of findings and enhanced their validity, with the aim to create a data set that was credible, accurate and dependable (Mertler, 2020). I used a variety of different data collection techniques, including:

• questionnaires for students, teachers and parents;

• individual student interviews;

• focus groups of parents;

• researcher observations and field notes;

• student work samples;

• student self-reflections (videos).

I first collected data about the social and emotional skill development of the Year 3 girls, as observed by their teachers. This was collected via questionnaire, and I asked questions (using a five-point Likert scale) such as, ‘The Year 3 girls are able to regulate their emotions’ and ‘The Year 3 girls have tools and strategies they call upon to help regulate their emotions when needed’.

Following this, I also conducted a baseline questionnaire with the parents, seeking to understand their awareness of the social and emotional skills their daughter is taught at school and their role in their daughter’s social and emotional skill development. This information was used to inform the action that I was going to take in the project and assisted in providing part of the baseline data for the intervention. The same questionnaires were provided at the end of the project to both parents and teachers.

During the lessons, additional data were collected from student discussions, brainstorming using

butcher’s paper and post-it notes, and observational notes. Photographs and videos were also taken. It was during these lessons, that I recorded my observations using field notes on the discussions and responses to activities, as well as my observations about the collaboration between the girls. In addition, the girls also completed a questionnaire to share their views of the lessons at the half-way point of the intervention. This was to provide feedback about the different interventions and activities, and served to seek feedback from the quieter students who may have been uncomfortable providing their insights verbally.

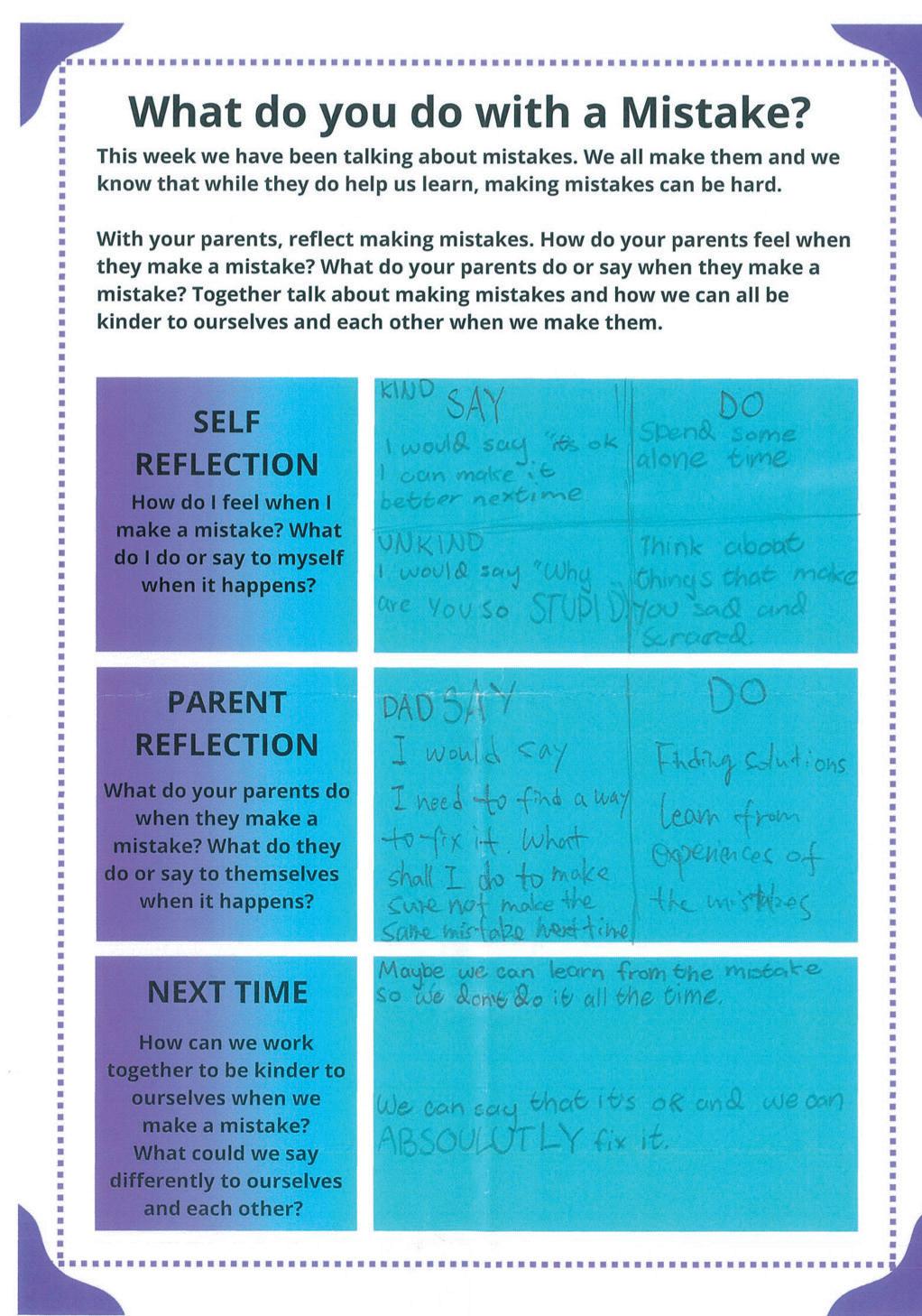

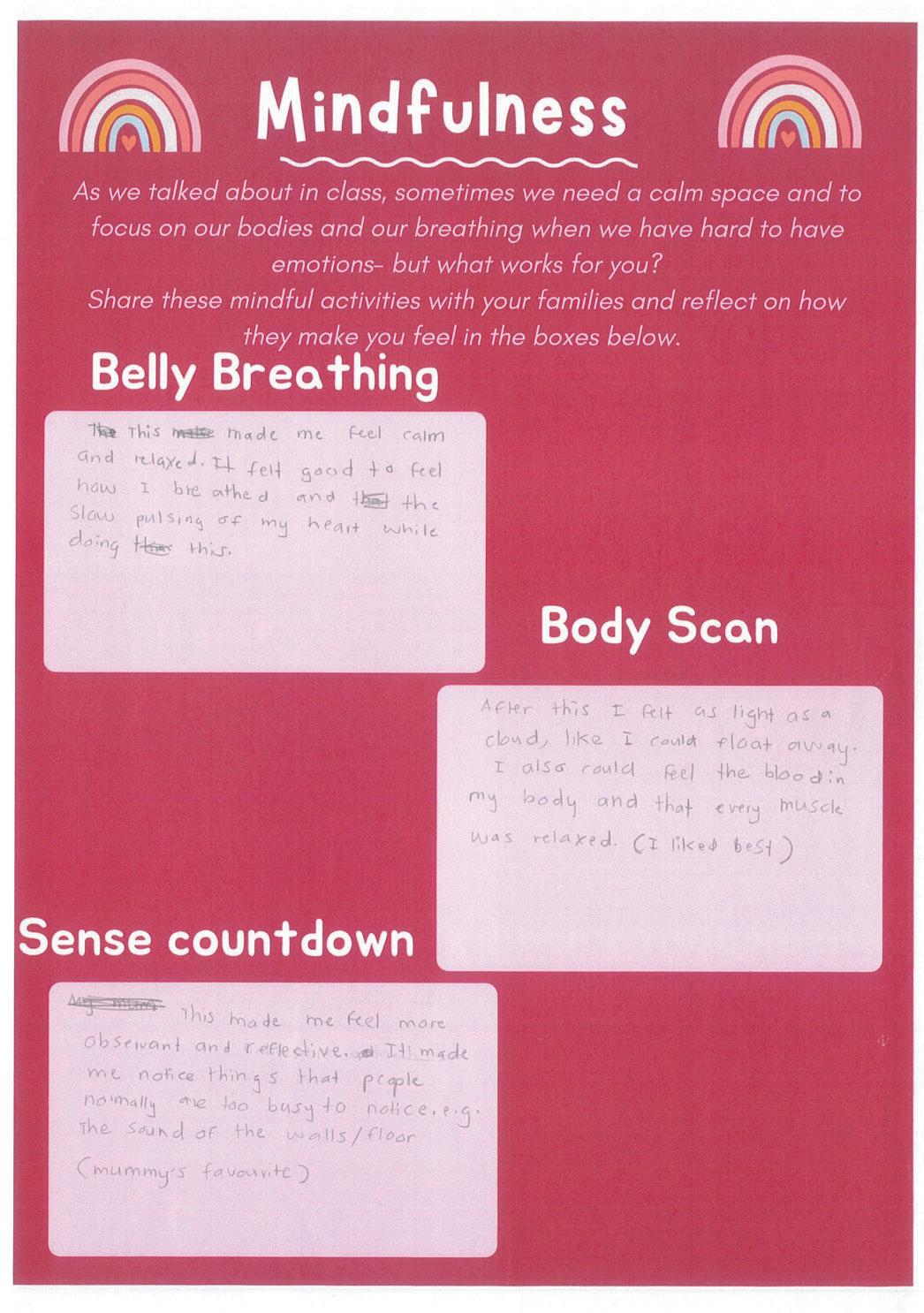

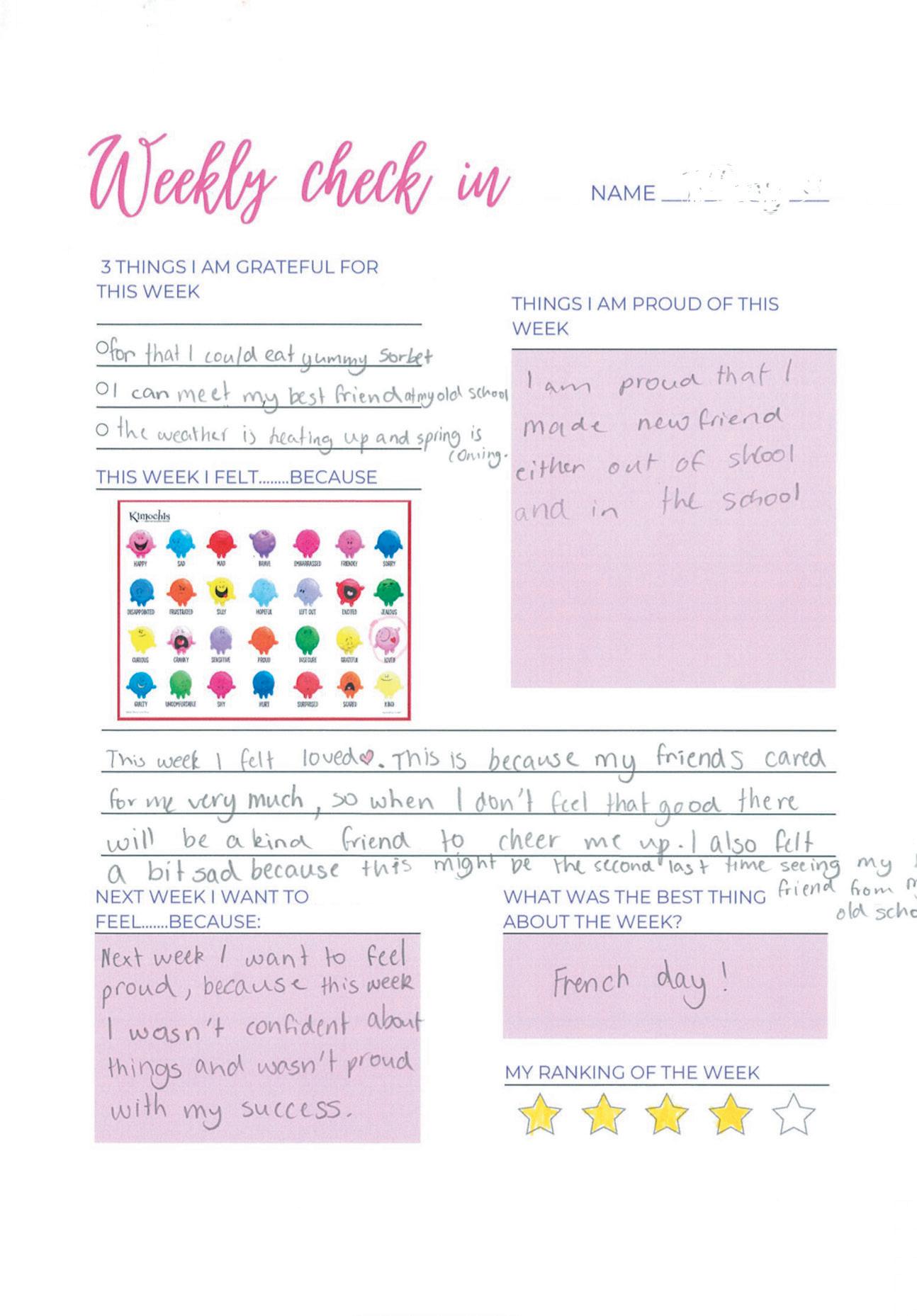

The students completed a selfreflection each week, which not only asked them to reflect upon the specific social and emotional skills learned that week, but also to reflect on their collaboration with their peers and family. This self-reflection allowed me to understand “students’ daily thoughts, perceptions and experiences in the classroom” (Mertler, 2020, p.138). This reflection was also useful in determining how much the students collaborated with their peers and families on these activities and it captured their thoughts and opinions regarding this collaboration. (See Figure 2 for examples of selfreflection done by students).

Another key part of the data collection process was the focus group interviews with students and with parents. The interviews with the girls were conducted in small groups of three or four, and included some prepared questions for consistency, but also allowed the girls to provide their own thoughts and insights, while providing me with the opportunity to ask any follow-up

questions as needed. These semistructured interviews (Mertler, 2020) focused on the activities in the lessons to develop self-regulation and self-management, plus sought the girls’ views on collaborating with their peers and families on the activities. The interviews with parents were beyond the scope of this research project and will be explored further at another time. Memberchecking and peer debriefing (Mertler, 2020) were also used as there was always a second teacher in the classroom during the intervention lessons. Following each lesson, time was taken to discuss the observations made and discuss thoughts about the activities. This was a useful step to ensure the accuracy of the data collected in the lessons.

The collection of a wide range of data before, during and after the intervention lessons in the project helped ensure that the results obtained about any change were clear and trustworthy. Once all data had been collected, I followed the process of inductive analysis to determine patterns and themes to make sense of the data (Mertler, 2020). This was completed by first transcribing any video interviews, merging and sorting the girls’ reflections, my field and observational notes, and the questionnaire results. I developed a coding system to assist processing and collating the data to make connections between the data and the research question and to

articulate findings and determine overarching themes.

Initial analysis of the data identified some clear themes, which were used to further analyse and distil my ideas. These themes and patterns were directly linked with my research question and supported my idea that active collaboration between the girls, their teachers and parents to create a personalised tool kit to support emotional regulation would benefit the girls’ development of social and emotional skills. Although there will be further work undertaken on this project, specifically related to the parental involvement, from this analysis, the following themes were identified:

“Joyful Learning” – Collaboration encourages high student engagement

The engagement of the students was essential for the project to be successful, given the personal nature of the lessons. Cooperative and collaborative learning has been shown to be important to aid the development of social and emotional skills by helping foster and build greater student engagement (Dyson et al., 2020). Further, Abla and Fraumeni (2020), reinforce the importance of student engagement with their learning, including social and emotional learning, for their long term physical and mental development. My initial observations of the girls were that, as soon as they saw me in their classroom as

they came in (lessons were held after lunch), they were extremely excited and immediately sat in the circular formation on the floor ready to start the lesson. This indicated a high level of engagement.

It was also clear from the interviews, self-reflections and surveys that the girls’ engagement with the lessons and the content was high:

“My favourite time of the week is these lessons as I like talking to the class and sharing my ideas and the activities are really fun” (Student D). The initial lessons set up the plan for the project and explored what collaboration looked like with the girls. Initially there was some trepidation from some of the girls when the concept of collaboration in relation to social and emotional learning was discussed. Some girls later commented that they felt nervous sharing their inner feelings with their classmates, with Student A saying, “At first I was really worried that if I shared how I felt about something people may not be nice to me. Normally I only share my feelings with my family and maybe some best friends, not the whole class.” The initial reservations from this student were alleviated, as her later reflections showed: “This has helped me, like, say my feelings out. Before I wouldn’t really say them out loud and people wouldn’t know what I’d be feeling like, but now they do.”

There were many joys during the

“There were many joys during the project, including hearing the girls talk about their toolkit with pride and an understanding of themselves, witnessing the growing trust in the classroom between the girls and hearing from the teachers that they had seen a change in the girls’ emotional regulation when using their toolkit strategies.”

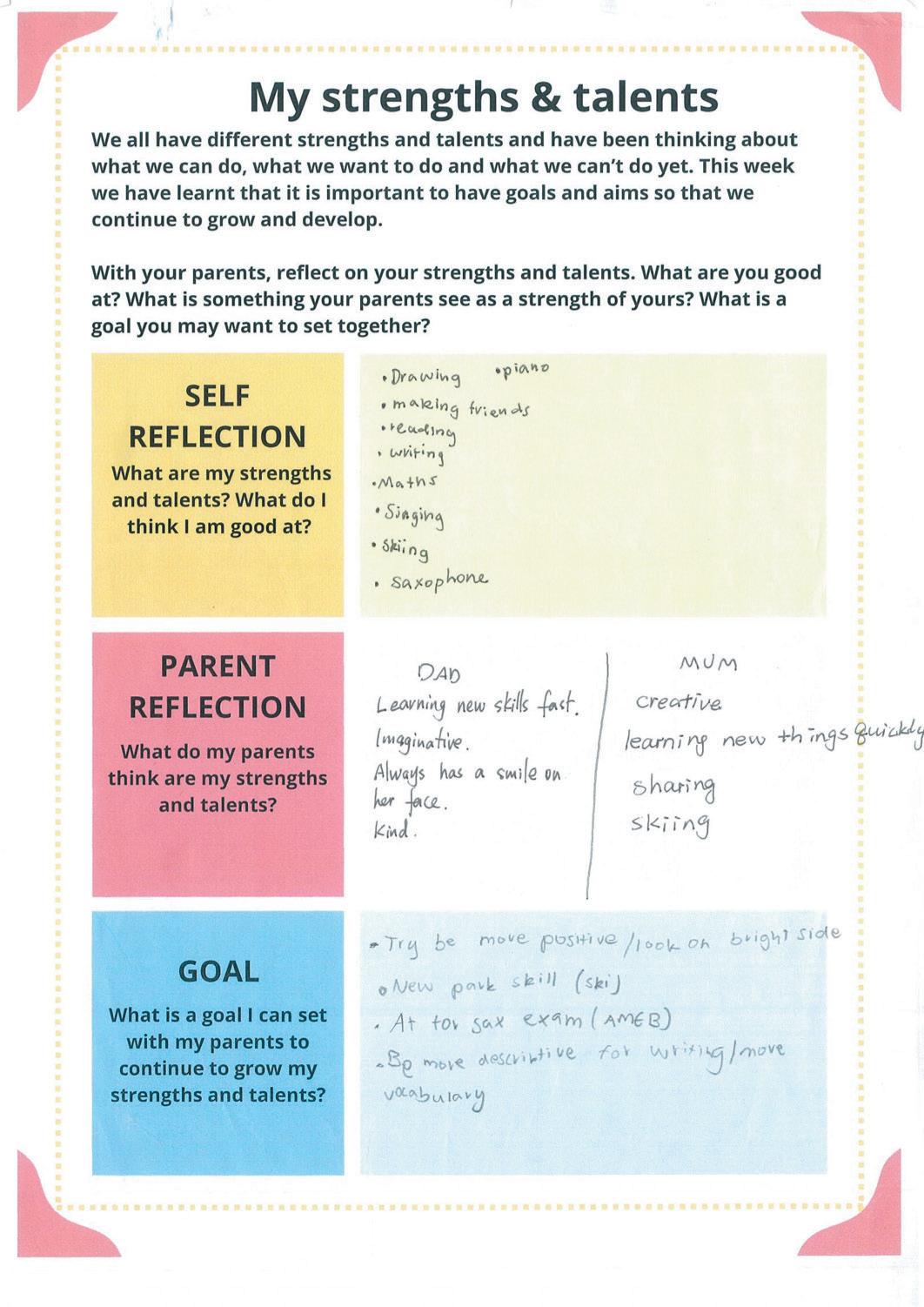

project, including hearing the girls talk about their toolkit with pride and an understanding of themselves, witnessing the growing trust in the classroom between the girls and hearing from the teachers that they had seen a change in the girls’ emotional regulation when using their toolkit strategies. The highlight, however, was hearing from the girls each Monday after they had shared their learning and reflections with their parents. One lesson, in particular, will stand out in my mind forever. This lesson followed the girls sharing and reflecting with their parents about their strengths and talents and setting some goals for themselves together. The girls were bursting with excitement to share their parents’ thoughts about their strengths and talents, some getting tearful sharing with pride what their parents had said about them and their strengths. Seeing the impact of the connections and trust grow between the girls and between the girls and their parents was something I had not really considered.

A safe classroom environment facilitates collaboration

When introducing the project to the girls, the creation of a safe environment in which they could share their personal feelings and thoughts was essential. We initially discussed what good collaborative learning looked like and the girls explained how the establishment of trust and respect is needed to facilitate cooperation and collaboration. As indicated by Griffiths et al., (2020), there are eight constructs identified that lead to collaboration, including trust, mutual respect, shared goals, and shared responsibility. It was clear throughout the project that Year 3 classroom had been created to be a safe space

for students to build trust and their mutual respect was reflected in their honest and vulnerable shared reflections. Student A commented, “My favourite thing about sharing with my friends is being able to get feedback and you can then improve and change your ideas. I liked how my friends were honest with me about how I could change things.” While Student D noted, “You get to spend more time with your classmates and can explain and understand more of what they are saying, and it helps to understand how they are really feeling.”

In addition, the girls expressed that they felt they had developed stronger connections with each other in the classroom through collaborating in the lessons. One of the girls reflected that this connection helped prevent some friendship conflict, too: “My favourite part of working together in Compass Directions is we can find out how each other feels and so we can understand each other more instead of having friendship fires” (Student C).

The girls showed maturity and honesty when reflecting with me during their interviews, noting the challenges of collaboration: “Sometimes it is tricky when we disagree as we then have a bigger challenge to overcome” (Student E), and “Working with other people can sometimes be hard as I don’t want anyone to get left out when they need a partner for discussion” (Student C). Student B also remarked, “Sometimes I feel uncomfortable talking in groups and sometimes I don’t really understand what they are talking about.”

A positive comment came from a student who initially found it really

challenging to share her thoughts and feelings with the class, her teachers and parents. Initially, she preferred to observe and listen, and only occasionally contributed to the group work when it involved writing things on post-it notes or the whiteboard. In her final interview with me, when she was reflecting on the tool kit she had made and how she felt, she said, “It is hard sharing our feelings with each other to start with but it got easier” (Student G).

Personalised management strategies enhance student agency Given the personal nature of the content of the lessons, and the need for students to connect with the strategies and activities to incorporate them into their routine to regulate and manage their emotions, it was vital that the girls collaborated when learning the tools and strategies to build their social and emotional skills. Such connection would able them to take ownership and have voice and choice when selecting the inclusions within their toolkit. The enablement of student agency is supported by the literature in the area, where students are empowered through the opportunity for voice in their learning and where learner voice and reflection positively impact learning (Landis et al., 2015).

Agency was demonstrated in the interviews with the girls during the creation of the toolkits and when the girls shared their toolkits with me. Student E commented, “I liked making my toolkit so I could think about the things that worked for me … some were different to my friends, and some were the same as my friends,” and Student A said, “It was funny that my friends really hated mindful colouring and drawing to help them calm down so they did

not use it in their toolkit but I have it in mine.” This ownership led to the girls being able to utilise these skills during times of emotional dysregulation, both at home and in the classroom or playground: “Yesterday I used my toolkit when I had a friendship fire with my friend. I got upset and angry and then I remembered the toolkit, so I did some belly breathing and read my positive affirmation. This helped me calm down and then talk it out” (Student D).

Although not part of this report, the development of the girls’ agency was further confirmed through parent and teacher interviews, where the parents and teachers noted the use of the specific strategies by the girls from their toolkits were positively impacting their emotional regulation in the classroom and at home.

Collaboration beyond the classroom enhances family connections

During the interviews and discussions with the girls, a clear theme emerged regarding the collaborative homework with their parents. The girls indicated, almost universally, that having personal homework to do with their parents, that involved discussions and joint input and output, meant greater connection time with their parents. Student F expressed, “I enjoyed that we were able to interact and share together, and my parents helped me to think about the activities and understand myself more.” Student B commented, “I liked listening to my parents and combining our ideas, but I was really surprised by what my mum wrote down about me (my strengths and talents). I didn’t know the things until we did the activity together” (See Figure 3 for an example of self-

reflection on strengths).

Although connecting with parents was a very positive result, as the girls loved this time, some of the girls were challenged by this collaboration, as it was not something that they had done before and was difficult for parents to fit into already busy schedules: “It is sometimes hard asking my parents for help and to work on things with me as they are busy” (Student C). This is a potential difficulty of any such collaboration and one that would need to be considered should this format be continued. Another challenge the girls expressed was being open and vulnerable with their parents about their emotions: “Something challenging was I was a bit scared to share my emotions with my parents but using the reflections and the toolkit helped me share with them” (Student G).

At the completion of the project, the girls asked if they could do something similar in Year 4. When I asked why, they expressed that it was lots of fun and helpful working with their friends and their parents about their feelings: “I really liked talking with both my friends and family about my feelings and I love how the homework is actually something that can help you. I really think working on these activities together made me understand my friends better, too” (Student F).

The development of selfmanagement and self-awareness skills in girls is a complex and ongoing process. As research has shown, long-term universal programs and interventions targeting these skills are needed to ensure these skills are embedded. The findings

from this action research project confirm that explicit teaching of these skills along with collaboration between the girls and their peers, as well as the girls and their families, creates an environment of shared understanding and trust. The girls were able to create their own personalised tool kit to assist them with emotional regulation by reflecting together and teaching these skills to their families. The teachers and the girls’ parents indicated improved self-management and self-awareness skills in the girls, particularly when managing feelings around making mistakes and friendship conflict, and it was clear that there was some consistent benefit in having strategies and activities across both the home and school environments that the girls could use.

The positive impact of this intervention was clear; however, it also had limitations. One was the difficulty managing the collaboration between the girls and their parents, given this happened at home. Some girls reported that the time needed to share their learning and reflect with their parents was difficult to find each week, which meant that the collaboration between the girls and their parents was not equal for each girl. Another limitation was the difficulty in seeing improvement in the girls’ self-management and self-awareness skills over the short period of the project, particularly as they moved into a new grade at the start of the year. It would be interesting to continue to track the girls over a longer period to see the true significance of this intervention. Finally, a third limitation of the project was the time available to implement the project given the need to fit in with the other timetabled lessons of

the teacher so as not to disadvantage the girls in any way.

A future direction for research in this area is to explore how to strengthen

the consistency across home and school environments in social and emotional skill development and I will be utilising data collected from parents here as a starting point to

References

Albright, M. I., & Weissberg, R. P. (2010). School-family partnerships to promote social and emotional learning. In S. L. Christenson, & A. L. Reschly (Eds.), Handbook of school- family partnerships for promoting student competence (pp. 246–265). Routledge.

Australia Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA). (2008). Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians

Byrne, D., Carthy, A., & McGilloway, S. (2020). A review of the role of school-related factors in the promotion of student social and emotional wellbeing at post-primary level. Irish Educational Studies, 39(4), 439–455.

Cipriano, C., Strambler, M. J., Naples, L., Ha, C., Kirk, M. A., Wood, M. E., Sehgal, K., Zieher, A. K., Eveleigh, A., McCarthy, M. F., Funaro, M. C., Ponnock, A., Chow, J., & Durlak, J. (2023). Stage 2 report: The state of the evidence for social and emotional learning: a contemporary meta- analysis of universal school-based SEL interventions https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/mk35u

Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL) (2012). Effective social and emotional learning programs: Preschool and elementary school edition. CASEL Guide.

Dix, K., Ahmed, S. K., Carslake, T., Sniedze-Gregory, S., O’Grady, E., & Trevitt, J. (2020). Student health and wellbeing: A systematic review of intervention research examining effective student wellbeing in schools and their academic outcomes. Main report and executive summary. Evidence for Learning, Melbourne.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based Universal Interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Fitzpatrick, R. & Page, E. (2022). The connection between socioemotional learning and girls’ educational outcomes. K4D Helpdesk Report. Institute of Development Studies.

Greenberg, M.T., Domitrovich, C.E., Weissberg, R.P. & Durlak, J.A., (2017). Social and emotional learning as a public health approach to education. The Future of Children, 27(1),13–32.

Griffiths, A.-J., Alsip, J., Hart, S. R., Round, R. L., & Brady, J. (2020). Together we can do so much: A systematic review and conceptual framework of collaboration in schools. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 36(1), 59–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573520915368

Howard, C., Burton, M., Levermore, D., & Barrell, R. (2017). Children’s Mental Health & emotional well-being in primary schools. Learning Matters, an imprint of SAGE Publications Ltd.

build upon. I am also excited to explore how to implement this project or similar initiatives across other grades.

Kurilof, P., Andrus, S., & Jacobs, C. (2017). Teaching Girls: How Teachers and Parents can reach their brains and hearts. Rowman & Littlefield.

Laal, M. (2013). Positive interdependence in collaborative learning. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 93, 1433–1437.

Laal, M., & Ghodsi, S. M. (2012). Benefits of collaborative learning. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 31, 486–490. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.12.091

Landis, C. M., Scott, S. B., & Kahn, S. (2015). Examining the role of reflection in ePortfolios: A case study. International Journal of ePortfolio, 5(2), 107–121

Mertler, C.A. (2020). Action research: Improving schools and empowering educators (6th ed.). Sage Publishing.

Mosley, J. (2009). Circle time and socio-emotional competence in children and young people. In C. Cefai & P. Cooper (Eds.), Promoting emotional education: Engaging children and young people with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. essay, J. Kingsley Publishers.

Paige, R. (2021). Creating a positive culture within primary schools: Whole school initiatives to foster effective social learning relationships. Social and Learning Relationships in Primary Schools, 73–92. https:// doi.org/10.5040/9781350096097.ch-004

Reimers, F. M., Bhuradia, A., Kenyon, C., Liu, Y. (Yoly), Nguyen, N., & Wang, M. (2023). Rebuilding resilient education systems after the COVID-19 pandemic. Creative Commons.

Ritchhart, R., & Perkins, D. (2008). Making thinking visible. Educational Leadership, 65 (5), 57–61.

Roffey, S. (2011). Introduction to positive relationships: Evidence-based practice across the world. Positive Relationships, 1–15. https://doi. org/10.1007/978-94-007-2147-0_1

Tolmie, A. K., Topping, K. J., Christie, D., Donaldson, C., Howe, C., Jessiman, E., Livingston, K., & Thurston, A. (2010). Social effects of collaborative learning in primary schools. Learning and Instruction 20(3), 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.01.005

Wong, R.S.M., Ho, F.K.W., Wong, W.H.S. et al. (2018) Parental involvement in primary school education: Its relationship with children’s academic performance and psychosocial competence through engaging children with school. Journal of Child Family Studies, 27, 1544–1555.

World Health Organization. (2000). Local action: Creating health promoting schools. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/ publications-detail-redirect/local-action-creating-health- promotingschools

By Dr Meera Varadharajan,

La Trobe University, formerly Centre for Social Impact, University of New South Wales

Additional content by Dr Sarah Loch and Victoria Adamovich (Pymble Institute)

Pymble Ladies’ College is committed to attracting excellent educators both into the College and the teaching profession generally. The need to attract people into teaching and encourage teachers to remain in the profession is increasingly urgent, with the Australian government identifying five key drivers: increasing the number of people who want to teach, strengthening initial teacher education, keeping the teachers we have, elevating the status of the profession and better understanding the needs of the teaching workforce (Education Council, 2020; National Teacher Education Workforce Plan, 2022).

To better understand the context of career-change teachers (those who elect to enter the teaching profession after first having a different career), we engaged an expert in the field to conduct a research project with a group of Pymble Ladies’ College staff who are career changers. Dr Meera Varadharajan is a Senior Research Fellow at La Trobe University. Previously, she was Research Fellow at the Centre for Social Impact (CSI), University of New South Wales (UNSW). This project was undertaken by Dr Varadharajan while she was at CSI and a report was submitted to the College in August 2023 (Varadharajan, 2023). This article summarises the report’s findings.

Dr Varadharajan has made a significant contribution to the understanding of career changers in the teaching profession. Her doctoral thesis and subsequent work focus on the contributions that career changers make to the teaching profession. Her book, Career Change Teachers Bringing Work and Life Experience to the Classroom (Varadharajan & Buchanan, 2021), provides practical recommendations to schools and jurisdictions on how best to leverage the skills and expertise brought by career changers. The book also serves as a useful guide to anyone contemplating a career change to teaching.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS UNDERLYING THE PROJECT

1. What motivates career-change teachers to make a career change into teaching?

2. What strengths and attributes do career-change teachers bring into the teaching profession from their past careers?

3. What steps can the education sector take to attract, engage and retain career-change teachers?

Project participants were six Pymble teachers who had a career in a different field before becoming a teacher and eventually joining Pymble. Participant details:

• Gender: One male and five female teachers

• Teaching level: Three in Junior School (Kindergarten to Year 6) and three in Secondary School (Year 7 to Year 12)

• Years teaching: Between five and 20 years

• Careers prior to teaching: Marketing, sales, accounting, research science and pharmaceuticals

Each participant was interviewed by Dr Sarah Loch (Director - Pymble Institute) or Kate Rimer (Chief People and Culture Officer). Five interviews were conducted face-to-face, on campus, in the interviewer’s office and one was held online.

Aligned with the research questions, participants were asked about their motivations for career change, strengths and attributes they brought to teaching, advice for prospective career changers and suggestions for the education sector on attracting and retaining this group of teachers in the profession. Interview data from all six participants were emailed to Dr Varadharajan in de-identified format. Participants had consented for their data to be provided to Dr Varadharajan for the purpose of analysis.

Dr Varadharajan utilised a thematic analysis approach to extract rich, meaningful interpretations from the interview data (Smith, Flowers, & Larkin, 2009), focused on participants’ everyday contextual lived experiences and circumstances.

Results examined the following four elements. Dr Varadharajan noted that results from this project aligned with previous research conducted in this area (for example, Varadharajan & Buchanan, 2021). Participant quotations are included where appropriate to highlight teachers’ voices.

1. Reasons for career change

2. Teachers’ strengths and attributes

3. Suggestions for prospective career-change teachers

4. Suggestions for education sector

KEY ASPECTS

Being ‘pulled’ to teaching

Four out of six participants were either intrinsically motivated due to personal values or had a longstanding aspiration to become a teacher.

Work-life balance

Four out of six participants also identified work-life balance as one of the reasons for changing careers to teaching. Out of the four, three also cited stress-related factors in their previous career which contributed to looking at other career options.

Influence of family and friends

Three participants spoke of the role that family and friends had on their career switch.

KEY ASPECTS

Theory-practice connections

Participants spoke of bringing practical, real-world knowledge from their previous careers. By using examples from their prior careers, they were able to make teaching more relevant and authentic for students. Theory-practice connections were particularly noticeable in the case of subjects like STEM and business.

Confidence and passion

Participants were passionate about their subject area and expressed desire to share their passion with students. They expressed confidence in transferring skills to extend student thinking and creativity.

PARTICIPANT QUOTES

“Education was valued and emphasised in the household, it was seen as a way of bettering yourself, becoming a better person and also increasing opportunities for betterment…”

“I had been working for about 10 years in marketing. The role had a lot of travelling so after I had my first child, we had to reevaluate how we wanted to be as a family. I talked to different people I knew and teaching came up.”

“…actually my mother’s ear was really in the back of my head saying, ‘You should be a teacher, you should be a teacher’”

PARTICIPANT QUOTES

“The way I teach a lot of my lessons is through stories and experiences. I have a bank of things that I can convey to students and really give it that real-world context”

“I’m passionate about science and STEM generally, but science in particular. I want to expose, particularly girls, to STEM early on so they don’t lose that love of it. You know, so they don’t gain that fear. That’s been a personal mission driven partly by my experience, but actually partly by life experience”

“…it also helps me to think about how I can extend students or get students to think about things differently…by introducing scenarios that I’ve actually been in or worked in. I find this can give them a different perspective when learning about these things”

Participants valued students’ diverse strengths and abilities and the importance of adapting or tailoring teaching practices to meet student needs.

Because of their wide career and life experiences, participants brought knowledge about workforce skills and a certain degree of maturity and wisdom to their teaching role. These attributes enabled them to build rapport and communicate effectively with parents and guide students on career paths and the type of skills required in the workforce.

“Recognise the perspective of others and that in teaching, all classes and all students are different and therefore there’s a real need to adopt teaching styles and pedagogy to those particular aspects; the differentiation aspect of teaching”

“I’m able to provide some informed commentary around what it is that employees are looking for in terms of the skill set in the 21st century. It’s never just facts or information that appeals to a prospective employer …. the importance of intellectual rigour. There is very much a need to deliver a more complete skill set. And I’m able to emphasise the importance of the soft skills, as well being able to deal with clients and colleagues”

“Leading a team, functioning within that team, opening lines of communication, those sorts of discussions that you have. Yes, absolutely. I’ve been able to transfer those”

KEY ASPECTS

Participants noted that prospective career changers must move to teaching for the right reasons (such as driven by passion and intrinsic motives) and must be aware of the potential implications of such a move, including impact on career trajectory or on family.

Visiting classrooms and getting as much exposure as possible to school and teaching environments prior to a career switch was also noted as a strategy in the transition and settling process. Aspects of autonomy and flexibility can work differently in the teaching profession and exposure to school environments can help career changers recognise and adapt to these differences.

PARTICIPANT QUOTES

“They [career changers] really do need to understand what’s going to drive them and what’s going to motivate them”

“If they could have real life experience and see if that’s something they want to do and really be sure that they want to work with children. Try it before you buy it”

“If you’ve had a lot of autonomy in your role, you’re going to lose some of that autonomy, and you’re going to have to be able to deal with that”

Be passionate about teaching and subject area

Participants noted the importance of being passionate about teaching and/or the subject matter which can also contribute to a smoother transition and better career preparedness.

Utilise past skills and experiences

Effectively drawing upon past skill sets in their teaching practices was also pointed out as a factor for career success and to be valued.

Implement mechanisms for recognising prior skills and experiences

Participants came to teaching with diverse skills and talents. They were keen for schools and the education sector to be aware of these skills so that they could be recognised and effectively utilised or tapped into.

“You need to have strength in developing rapport around engagement with students. It’s demonstrating a passion to them”

Make transition easier and smoother for career changers

Examples noted by participants included formally recognising prior qualifications so that they are able to obtain teaching credentials that match their expertise. They also called for the provision of tailored support, including mentors who are able to give targeted feedback. Making career-transition journeys smoother and simpler will help attract and retain more career changers into the profession.

“I’ve been able to look at all my previous jobs and think about the different skills that each job has, that has led to teaching. And I feel like teaching uses the most skills, not just one or two of them… I’ve landed in a place that actually values an awful lot of my skills”

“We all have a life outside of what we do here. Everyone has a story and it is important to be able to have the time and the space to actually get that story from them to tap into what their strengths and interests are”

“They [schools] should have career days or events where it’s like, you know, teachers from another life, something like that, just sharing that knowledge, not losing what they have, the skills that they gained in their previous lives”

“I would like for the department and the sector to recognise that while I may be a graduate teacher, I’m not a “new graduate”, and recognise that I’ve actually got more than that, that I came to teaching from an established career. I had to wait another five years to do my experienced-teacher accreditation [after gaining proficient teacher]”

“I had a very effective mentor with people … these are very experienced teachers that I almost piggybacked off for a good year or two. I was able to observe other teachers to a significant degree, and I was able to take a lot from that”

Compensate for financial and other loss of income

Career changers have given up on well-paying careers to take up teaching. Participants suggested that financial considerations should be prioritised if the teaching profession wants to attract and retain career changers.

Provide high-quality resources and a conducive work environment

Good teaching resources and a safe work environment was an important issue for participants who had worked in environments that were quite different to school workplaces.

Improve societal perceptions about teaching

Participants noted the importance of teachers being valued and respected by the broader community.

“Because I’m older and I’m not young, I didn’t have the luxury of living at home with Mum and Dad. I’m studying, but I still had a young family with three small children, and that was the challenge. If they want teachers to come into teaching from another industry, you need to make it easier”

“I could see it [lack of quality resources] being a problem in public schools in particular … I think that can lead to a sense of dissatisfaction with the role for those coming from a more comfortable and better-resourced corporate environment ... it certainly required a bit of a mind shift for me”

“We’re always battling as teachers… a lot has to do with society and what they believe we are as teachers. I think as teachers, we don’t have the respect that we used to”

INFORMED BY THE THEMATIC ANALYSIS OF RESULTS AS DISCUSSED ABOVE, DR VARADHARAJAN SUMMARISED THE KEY TAKEAWAYS AND NOTED SOME FINAL POINTS AS A WAY FORWARD IN THIS TOPIC:

The role of competent and well-qualified teachers, providing students with the right environment to thrive and succeed in learning and beyond, cannot be underestimated. As the data from this research project indicates, career-change teachers’ reasons for joining the teaching profession are typically driven by intrinsic motivation and a commitment for sharing knowledge gained through one’s career and life experiences. These teachers bring attributes of passion, creativity, maturity, flexibility and context awareness which are considered highly valuable in a classroom setting (Korthagen, 2004). Participants provided useful suggestions to prospective career changers. Having knowledge about the teaching profession and its various intricacies prior to entry would be invaluable to individuals before they make the decision to switch careers. The impact of such prior knowledge could be that they are less likely to experience a ‘culture shock’, are better prepared as a classroom teacher and more likely to remain in teaching.

As participants in this project alluded to, there is also a greater need for the education sector, including schools, to clearly understand career changers in the ways of their characteristics, contributions and unique needs. Innovative ways to make teaching attractive for career changers must be considered. Like other professional careers, teaching will need to be competitive if it is to attract and retain skilled personnel. Financial remuneration is important, but as participants noted, career changers’ expertise and experiences can be rewarded through other creative means. For instance, through leadership opportunities and having school events that celebrate their past career achievements and current contributions.

Students and the teaching profession stand to significantly benefit from career changers. By commissioning this research project and highlighting their contributions, Pymble Ladies’ College recognises career-change teachers to be game changers in our classrooms.

• Explain your reasons for the career change

• Communicate your passion for the subject and for student learning

• Explore chances for a school visit

• Ask about ways you can demonstrate your ability to work independently, flexibly and as part of a team

• Make sure you understand the teacher accreditation process in the school/system

• What opportunities will you have for professional learning?

• Schools are excited to bring the real world to students; highlight your experience and industry contacts by sharing how you can make connections between theory and practice.

TALK ABOUT TRANSFERABLE SKILLS FROM YOUR PREVIOUS

• Appreciate that your previous career has gifted you a mature mindset

• Give examples of your people and communication skills

• Discuss the leadership and project management skills you have acquired and give transferable examples in the school context

• Career-change teachers have often made a decision to move into teaching because of a passion for the subject and working with students.

• Ask the candidate about their subject knowledge, how it has been gained and why the candidate has chosen to apply their skills to teaching children

SHOW RESPECT FOR THEIR INDUSTRY KNOWLEDGE

Career-change teachers may have had years, or even decades, of experience in another industry. It is important to give them time to talk to this prior experience. This demonstrates respect for their previous career/s.

• Can you provide opportunities for a school visit for the candidate to see one of your classrooms in action?

• How will you ask the candidate about the degree of autonomy they enjoyed in their previous career? An idea is to ask about the candidate’s past reporting lines and expectations of flexibility.

• Discuss needs within the Teacher Accreditation Process

• Ask what sort of professional learning the candidate is looking for and career aspirations they might have. Remember that their need for curriculum and pedagogical growth may be out of sync with their existing leadership, communication and project management skills.

DISCUSS TRANSFERABLE SKILLS FROM THEIR PREVIOUS CAREER

Give career change teachers a chance to showcase examples of their:

• People and communication skills

• Leadership skills

• Project management skills

Figure 2

Education Council. (2020). , June 2020.

Korthagen, F.A.G. (2004). In search of the essence of a good teacher: Towards a moreholistic approach in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20 (1), 77-97.

National Teacher Education Workforce Plan. (December, 2022). Australian Government. Department of Education. https://www. education.gov.au/teaching-and-school-leadership/resources/nationalteacher-workforce-action-plan-publication

Smith, J.A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretive phenomenological analysis:Theory, method and research. London: Sage Publications.

Varadharajan, M. (2023). A project on career change teachers: An independent unpublished report prepared for Pymble Ladies College. Unpublished report. Centre for Social Impact, University of New South Wales.

Varadharajan, M., & Buchanan, J. (2021). Career change teachers: Bringing work and life experience to the classroom. Springer. https:// doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6038-2

numinous

(adj.) describing an experience that makes you fearful yet fascinated, awed yet attracted – the powerful, personal feeling of being overwhelmed and inspired.

Many readers may have, at first, suspected a misspelling in the title of this article. And while there is harmony with the terms numinous and luminous, the bright spark that makes an experience numinous may not be perceived by the human eye alone.

My own memories that are ignited when reading this definition come from a sense of the sublime and the feeling of something bigger than self (Casement and Tacey, 2006). Gazing up at the night sky, watching the sun glide into the water over the equator, stepping gently through ancient ruins,

crawling into the crater of a volcano, gliding fingers over unnatural grooves ground into rock, looking into the eyes of my children for the first time.

While the above definition will have provoked a different memory for

“Gazing up at the night sky, watching the sun glide into the water over the equator, stepping gently through ancient ruins, crawling into the crater of a volcano, gliding fingers over unnatural grooves ground into rock, looking into the eyes of my children for the first time.”

each reader, we all share in the deep emotional response that is numinosity. In my recent travels to Japan to represent Pymble at the 10th International Outdoor Education Research Conference (IOERC10), numinous was a nominal term poised by Dr Judith Blaine (University of Hong Kong) to describe the connection to nature that is at the core of outdoor education.

Traditionally, this feeling would have been associated with spiritual or religious connotations (Nörenberg, 2017). There is an underlying epistemological assumption separating religious language and numinous experience, which extends beyond the parameters of our uniquely human experience (Schlamm, 1992). The concept of nature as a medium to the divine presents a mosaic of examples and experiences, which Spratt simplifies as “to find God in nature” (2012, p. 155).

Recent literature notices a distinct shift in the language used by emerging generations regarding how they express this sense of awe and connection (Wittberg, 2021). For Generation Z (1997 – 2010) and Generation Alpha (2010 – 2025), connection is often confused with connectivity (Jha, 2020), and the digital landscape around them more likely to be artificially luminous than numinous. Some individuals in these generations are unsure how to articulate anthropomorphic beliefs and bigger-than-self experiences (Wittberg, 2021), with emotions reversely personified as a technology itself that can be charged or drained. But is this a language disconnection or an experience disconnection?

With my own children and the majority of our Pymble student community being part of what is termed Generation Alpha, there is a need to understand how this generational shift may reflect the communication of this feeling, one bit at a time.

Following Dr Blaine’s use of the word ‘numinosity’ in an outdoor education context, the intellectual dialogue amongst world-leading researchers cracked open a gap in current literature relating to the instruments used to measure a connection to nature. How do we measure that which cannot be seen, heard or experienced? This articulative confusion presents the recognised need to research the benefits of outdoor education, as an area that is not widely celebrated as traditional higher-order learning.

My intention in this article is to introduce examples of emerging outdoor education research across the world, and identify where our

Vision Valley Year 9 Residential Program and K-12 OEP Continuum fits in this big and beautiful natural world.

The International Outdoor Education Conference (IOERC) series began in 2001 to address a gap in the scholarly outdoor field, with a perceived need to see the outdoors develop as a significant discipline that engages with social, educational and cultural frameworks within critical dimensions. Remarkably, Pymble was the only school in the world to be represented at the 10th IOERC in Japan, placing us at the forefront of outdoor education research globally.

As I arrived in Japan on the first morning of the conference and entered the IOERC10 Welcome Event, the passion for outdoor education was apparent. From across the world, professors, innovators and pioneers in outdoor education research came together for the week to spark dialogue into the future of outdoor education in an increasingly built world. Researchers arrived wearing suits with hiking boots, or blouses and broad-brimmed hats,

laptops and carefully preserved research posters stuffed inside hiking packs. Our real-life Indiana Jones hybrid of researcher and explorer.

At the conference, I presented with Professor Tonia Gray and PhD candidate Helen Cooper from Western Sydney University on the research conducted at the Year 9 Residential Program. Titled Assessing the Impact of the Vision Valley Outdoor Education Pilot Initiative at Pymble Ladies’ College (Cooper et al., 2023), the research collaboration with Western Sydney University focused on the 2022 pilot program, where students from two singlesex schools joined together for the pioneering co-educational four-week Year 9 Residential Program at Vision Valley. In this project, quantitative methodology used unique, rigorous instruments to research three factors; students’ sense of belonging using the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scale (ACER, 2018); academic buoyancy using the Academic Buoyancy Scale (Martin and Marsh, 2008); and resilience using the Adolescent Girls’ Resilience Scale (AGRS) (Whittington and Aspelmeier, 2018). Immersive, qualitative methodology collected

The intentions of Pymble’s Residential Program are not for students to co-exist with static learning opportunities, but rather to become co-constructors of their learning and promote a deeper connection to self, others and the natural world. It was fitting that across the five-day conference and over a hundred and fifty presentations, the overarching theme of IOERC10 was connection. This included connection to nature through sustainability and beauty, connection to place by honouring First Nations voices and connection to the journey of our young people to find personal identity and belonging.

comfortable in nature. But can we map out the spectrum of comfort from those who gingerly ease themselves down to sit directly on grass, to others who use tiny bare hands to calmly grasp the leech crawling up their shoe? If we then look to relate connection with nature to numinous experience, comfort may lie a stone’s throw away or in the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

The need for connection to nature beyond the early years was highlighted by Mitchell and Sprague (Stramash Social Enterprise, UK) at IOERC10. Their presentation built on the WWF Natural Change

“As an evidence-informed school, the program continues to evolve, taking key findings and triangulated data from student, parent and staff experiences to allow the Vision Valley team to provide increasingly rich and rigorous learning opportunities.”

data at key points along the journey to learn from students, staff and parents over the four-week program. Findings from this research show increases across all three factors, with statistically significant increases in the AGRS subscale of Approach to Challenges (t(43) = -2.60, p. = 0.006).

Grounded research in connection begins in the early years setting with children in the pre-school years. This is where connection with nature is defined as comfort in nature (Lumber, Richardson and Sheffield, 2017). Anecdotally, it is simple to notice young children who are more

Project (Key and Kerr, 2017) and the Nature Relatedness (NR) scale constructed by Nisbet, Zelenski and Murphy (2009) to assess the cognitive and experiential aspects of individuals’ connection to nature for social change. This concept of going beyond knowing nature

to anthropomorphising nature for environmental action has been further explored by Lumber, Richardson and Sheffield (2017) for the creation of nine values of nature connectedness. Interestingly, the values align with a similar range of student personalities we often see at Vision Valley. Some students connect with nature by recognising its beauty (aesthetic), others want to know how, why and why not (scientific), or perhaps have a genuine fear of nature (negativistic). As educators, we must recognise which value each student prioritises to nurture their journey to forging self. In catalysing leadership, the ownership is transferred to our students who feel empowered and gain self-efficacy – the essence of what adolescents (and their parents) crave (Pritchard et al., 2020).

Another theme of connection probed by leaders in outdoor education research at IOERC10 was the enactment of place-

responsive outdoor education for connection. Place-based research has evolved from being in places to connecting with places, and with it the need to adapt place-responsive pedagogical frameworks to guide educators. Leong, Ho, and Seng Tay (Ministry of Education, Singapore) presented on a Singaporean case study implementing new curriculum framework for the interdependence of adventure, resilience and connection. The framework focuses on nurturing an ecological, social and physical sense of place to increase engagement and determine attitude to experiences (Adams et al., 2017). In our uniquely Australian setting, First Nations stories, histories and culture set the foundation for place-based connection.

The Year 9 Vision Valley Residential Program is a now a core component of students’ education at Pymble From our pioneering cohort in 2022, to the compulsory nature of the program in 2024, each shift, pivot

or jump in the program has been driven by research. As an evidenceinformed school, the program continues to evolve, taking key findings and triangulated data from student, parent and staff experiences to allow the Vision Valley team to provide increasingly rich and rigorous learning opportunities.