Roche Limit

Bellerive 2018

Issue 19

Roche Limit : how close an orbiting body can get to a planet before being torn apart by its gravity

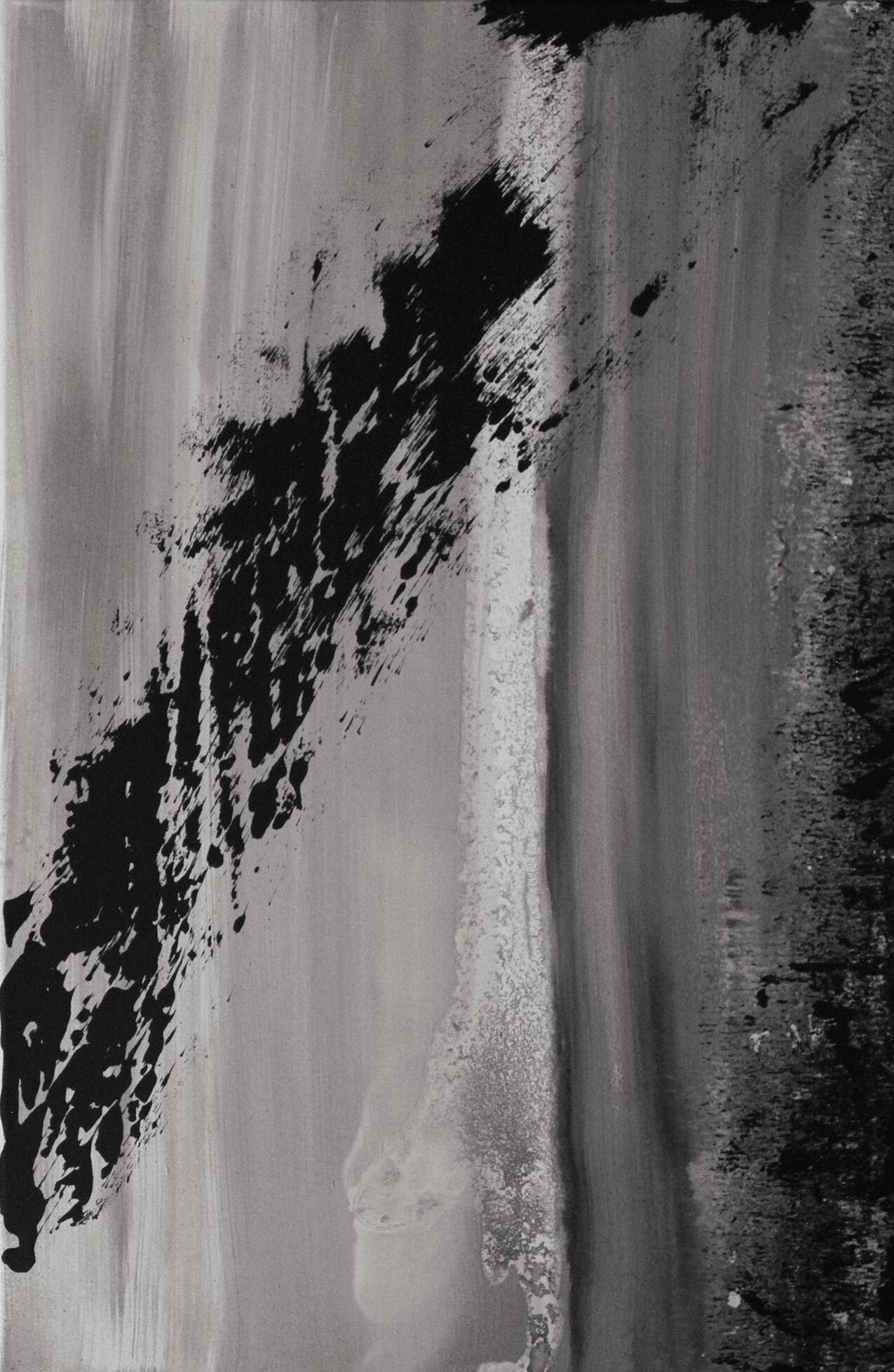

Cover Art: #29 Landscape Monochrome Ramsay Wise

Pierre Laclede Honors College University of Missouri–St. Louis

Cover Art: #29 Landscape Monochrome Ramsay Wise

Pierre Laclede Honors College University of Missouri–St. Louis

ART

Cody Barton, Zyra De Los Reyes*, Tori Dieckman, Eric EggersEDITING

Haley R. Graham*, JoHannah McDonald*, Chloe Simpson, Regan Slaughter, Daisha T. Smith

LAYOUT

Kristy N. Burkemper*, Kevin Kuchno, Brandon Vestal

FACULTY ADVISOR

Geri Friedline

*Denotes committee chair

Current and past copies of Bellerive issues are available to purchase for $7 each or two for $12. To purchase, contact Geri Friedline at (314) 516-7874 or via email at friedlineg@umsl.edu. Alternatively, visit the Triton Bookstore. Please note that limited copies are available for each issue, and once they have all been sold, no further copies will be produced.

All University of Missouri–St. Louis students, faculty, staff, and alumni are invited to submit original creative works that have not been previously published. Submissions are accepted from March 1 through October 1. We invite eligible individuals to submit up to 5 poems, up to 2 prose pieces (each at 4,000 words or less), up to 5 digital images of photography/art, and up to 2 original music works (as audio files).

To learn more about submitting to Bellerive, inquire at BelleriveSubmit@umsl.edu or visit facebook.com/BellerivePublication.

Submissions review is a blind process. Submitters’ names are not disclosed during review. The new issue of Bellerive is launched at a reception in Provincial House each February. This open reception also kicks off the next issue’s submission period.

Offered every fall, the Bellerive Workshop course is open to Pierre Laclede Honors College students, sophomores to seniors, interested in all aspects of producing Bellerive. The class focuses on all steps of publishing: reading and selecting works to be included, copy editing, communicating with submitters, designing layout, digital image editing, and marketing and selling of the publication. Individuals in the class choose which areas of contribution best suit their interests and talents.

facebook.com/BellerivePublication

Table of Contents

iv Introduction

1SARAH MULLIN wood pulp

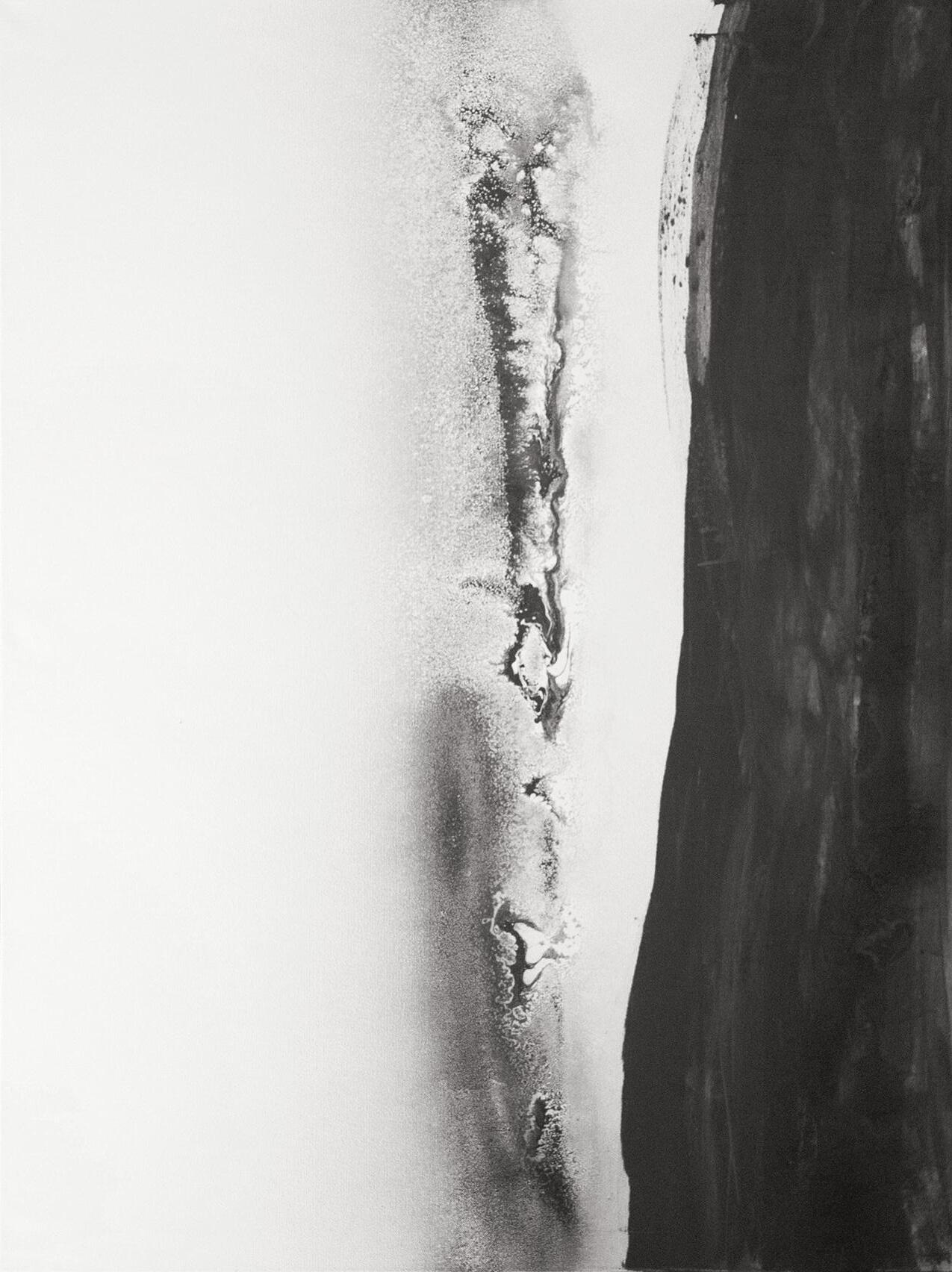

2KELLY STOLLE Tar

3RAMSAY WISE #29 Landscape Monochrome

4ABBY N. V. Grasping

5JESSIE EIKMANN Something Stolen

9ERIC EGGERS Unveiled

10KELLY STOLLE Mortal Wounds

11MALIK LENDELL mississippi

12SARAH MULLIN anyeverythere

13TORI DIECKMAN Anthrobotany

14HALEY R. GRAHAM log 14

15SARAH MULLIN .5mg split

16JESSIE EIKMANN Jackson Pollock is a 19-year-old girl

18DAI T. SMITH Just Ride

23KIT ANDREASEN Cloud Nine

24NICOLE GEVERS Lafayette Square

25VICTORIA SCHEFFLER A Lone Piano Song

26SARAH JANE MATT Means to an End: Honor and Morality in the Analects and The Thousand and One Nights

30BAILEE WARSING Paint Pots of Kootenay National Park

31MICHAEL HALL swim

32MORIAH SWOBODA It’s a Big World Out There

33SARAH MULLIN opal

34CURTIS J. HOWD Cairn: In Memory of David Maslanka

35BAILEE WARSING Northern Cascades

36KELLY STOLLE Reverie in Green

37TARA CLARKSON American Sycamore

38JESSIE EIKMANN Stegosaurus

40MARLEY SMALL Growing Up

41JESSIE EIKMANN Doubletree

42MORIAH SWOBODA Summer Daze

43SARAH MULLIN untitled

44JESSIE EIKMANN Love Poem: Inadequate Spider

45ISAK SAMSUHANG RAI untitled

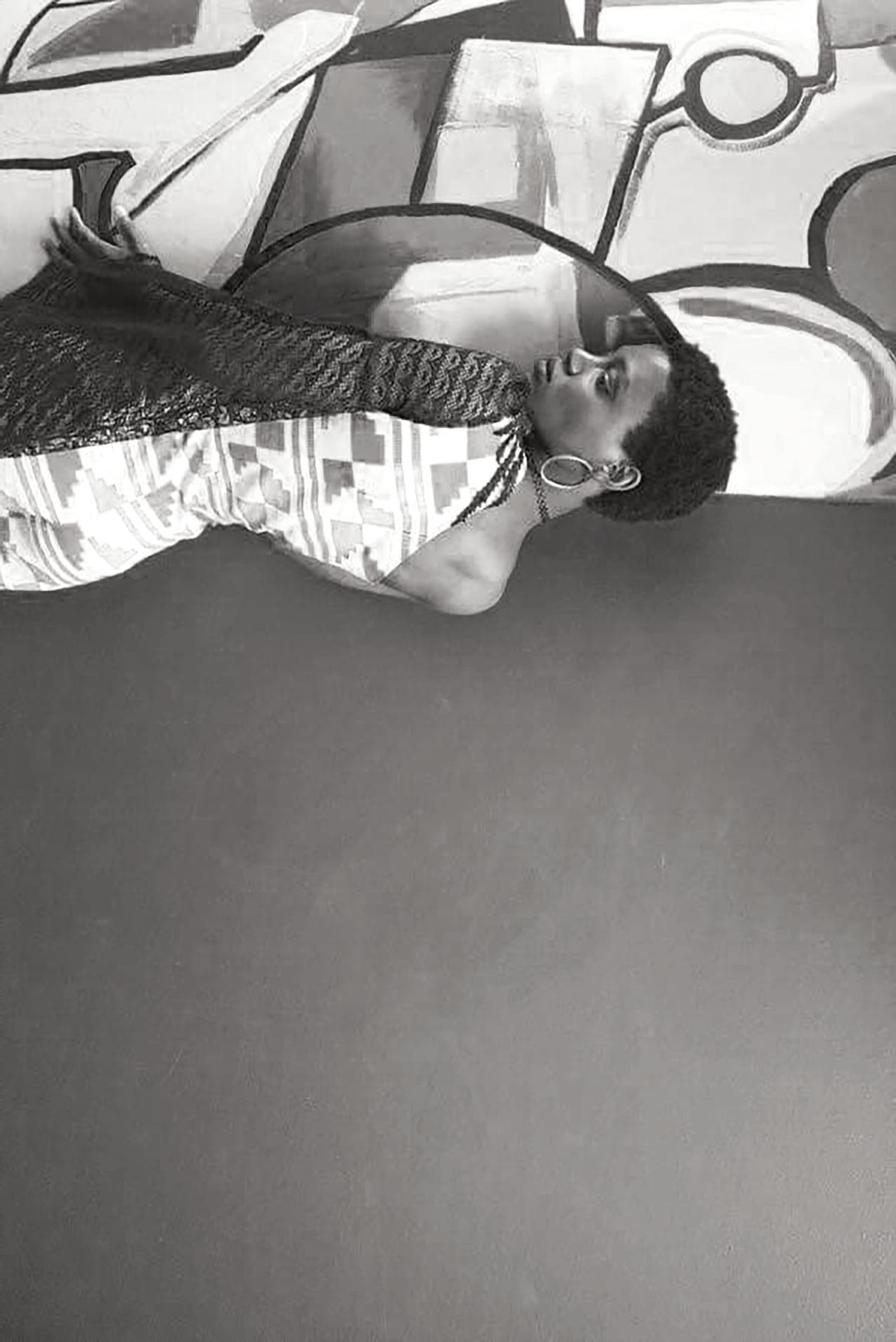

46EVELYN TETA KUMEH Camouflage

47S. HART Ladylike

48TANNER EARLY I Was Once Your Painter

50MORIAH SWOBODA Opportunity Knocks

51CHELSEA WESTHOFF attached.

52ALEX GALINDO The Pooka Tale

54CHELSEA WESTHOFF Dee:med

55SAMUEL KILLION Ebbing into Nativity

56SAMUEL KILLION A Valediction

57EVELYN TETA KUMEH Skies

58JASON DULWORTH Gate B28

60SARAH MULLIN corporal

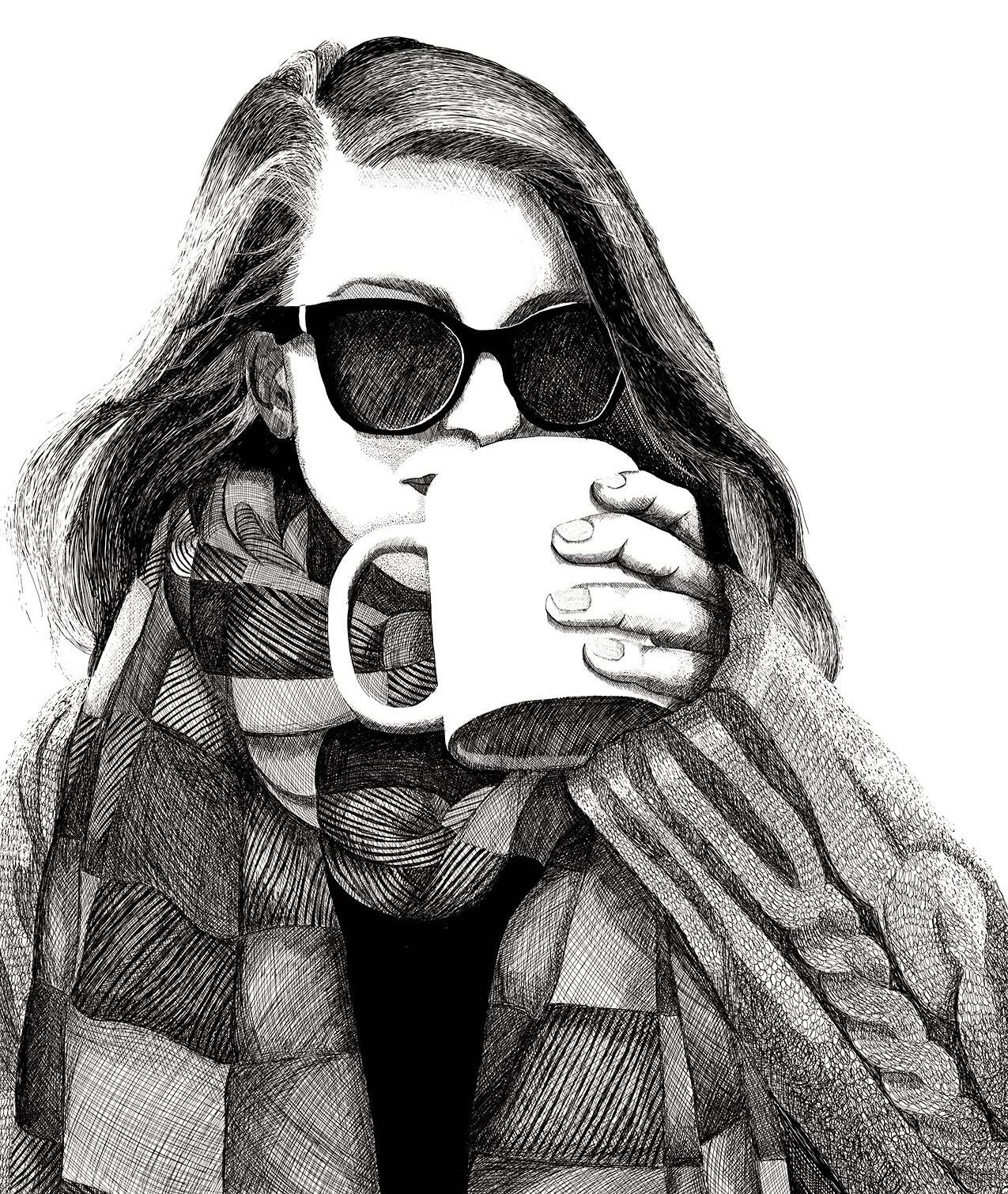

61NICOLE GEVERS Mugshot

62KIT ANDREASEN Saxophone

63NIKI CLOUTIER Speak Easy

67KATE VOTAW Rewrite the Stars

68SAMUEL KILLION Falling

69RAMSAY WISE #26 Landscape Monochrome

70TANNER EARLY The Cruel Mistress

71TARA CLARKSON The Snowy Day

72ABBY N. V. A Profoundly Female Experience

76BOBBY MEILE Distant horse whispers

78JESSIE EIKMANN Self Portrait: Inflatable Tube Man with a Hole in the Side

80CHELSEA WESTHOFF Robotic

81RAMSAY WISE #4 Stained GlassDetail Monochrome

82ABBY N. V. Better

83JASON DULWORTH Critique of Pure Reason

84EMESE MATTINGLY The Seventh Layer

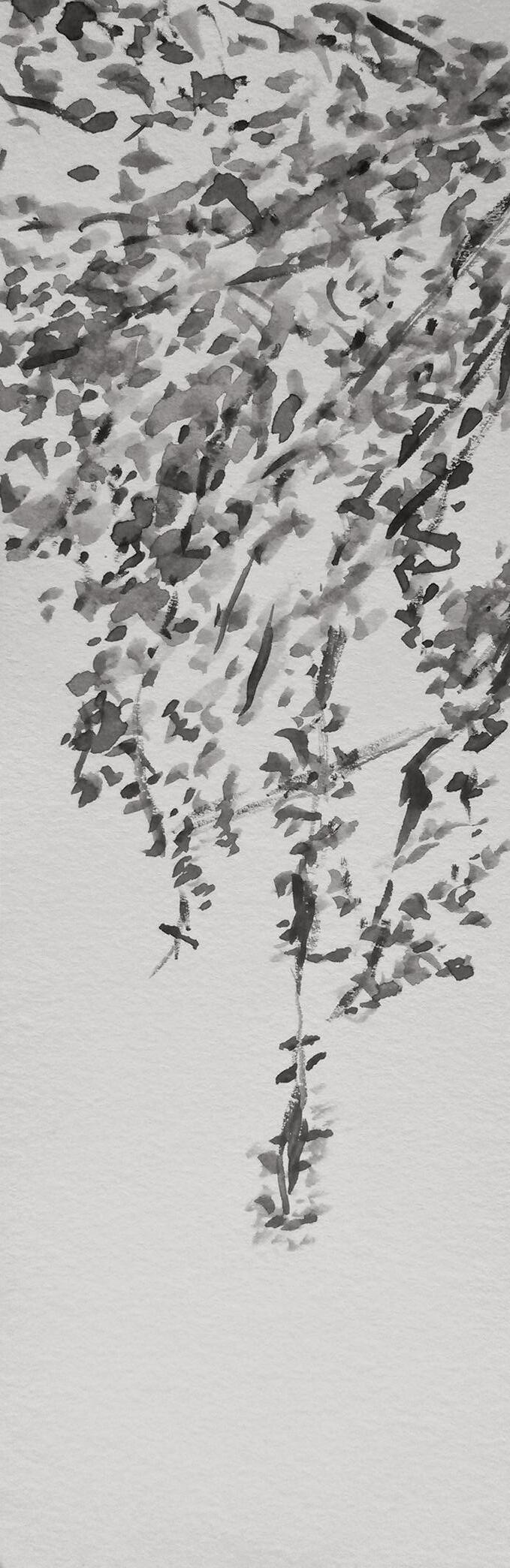

85TARA CLARKSON Birds in Tree 2

86TORI DIECKMAN To All the Fathers in My Life

87ZΔK Cr0w

88ABBY N. V. The Last Word

90 Excellence in Writing Winners 2017–2018

91REGAN SLAUGHTER Bringing Opera to the Visual: Perspectives on the Historical and Present Staging

Introduction

It is with great pleasure that I introduce Bellerive Issue 19, Roche Limit.

For nearly two decades, Bellerive has been blessed by the talents of those featured in the books, the dedication of those who produced the books, and the connection with those who continue to enjoy the books.

Roche Limit is the perfect title to hold together the collection of diverse and amazing works featured in the book. Many of these works expose human experiences that reflect a continuous tug of war between forward motion and being pulled in—with the very real possibility for personal loss or destruction as a result of getting too close. They explore the dissociation and disorientation that results from the tensions of this battle. Yet they also offer a view of increased self-awareness, growth, and progress that offers escape from the pull and the close calls and provides a return to stasis, if not resolution.

Roche limit, as a term in celestial mechanics, is also the perfect metaphor for the process of producing a book, like the one you now hold in your hand. Success requires a balance between forward motion and staying grounded. The enthusiasm and talents of the 2018 Bellerive staff certainly propelled this issue and the production process forward. Yet they also formed a solid production team that managed the gravitational pull of limits and deadlines with good humor, grace, and professionalism.

We hope you enjoy Roche Limit as much as we enjoyed bringing it to you. We are in awe of the risks taken by our submitters in creating and sharing works that draw us so close to the elements of human experience—please keep them coming. We hope to see you again in Issue 20!

wood pulp

you are raindrops on fresh ink turning the words i was going to say into blurry roses that my tongue cannot trace and my thoughts to pulp like they were before i pressed them neat and white for composition

Tar

My fingertips are like tar. I recoil when I remember, but it’s too late. I’ve torn off pieces of you as if I’m peeling for truth. I try to stutter my sorries, but my throat is either clogged or corroded, so I can only gurgle the bile on my tongue. I try to show you that I can be pure, so, I force up a smile and look like a monster.

#29 Landscape Monochrome

V.

Grasping

I am holding on, holding on to something If I let go

How far there is to fall I do not know

Tsukande iru

Nani ka o tsukande, tsukande

Tebanasu to Doko made ochiru ka

Wakaranai

掴んでいる

何かを掴んで掴んで 手放すと どこまで落ちるか 分からない

Something Stolen

This week, my younger sister resumes her courses at Missouri State, so my parents have offered me her room and her bed until she returns. Or, to be more precise, it is less an offer than a polite mandate: “You can sleep in Ally’s room now, so we can put that mattress back in the laundry room.” I can’t entirely blame them. The loose mattress is an eyesore, and there is no way to lean it up against the loveseat or the window without it falling over and occupying the entire basement floor. But I would prefer that unyielding rock of a mattress to this weird purgatory in a space that was mine until age eighteen. At best, it’s disorienting seeing the yellow-green walls and matching secretary desk crowded with lotions, tumblers, and posters I would never have chosen for myself. At worst, I feel like an interloper, a squatter, a thief.

I wake up and lock eyes with Ed Sheeran, who hangs over my bed and watches me all night. He holds his guitar in an odd way, by the neck and upside down, as if he is about to swing his arm down and club me with it. Elsewhere in the room Christina Aguilera looks absently at the corner, The Pretty Reckless sit on a stoop with vaguely menacing expressions, and various skylines of famous cities gleam without light. I momentarily forget how to turn off Ally’s alarm clock, blink at the too large numbers 7:31, and tumble out of bed. I open the door expecting the bathroom to be empty, but my other sister, Sydney, is bending into the mirror with her mascara brush. Today is her senior picture day. The theme is Hawaiian; accordingly, she has selected a hideous flowered orange shirt and a lei. I spend a few seconds fuming at Parkway North’s careless appropriation of indigenous culture before I remember to smile and say nothing. Unlike at my ex-wife’s apartment, that rant wouldn’t fly here.

The bathroom light across the hall is teasing me, so I readjust my bathrobe knot and go downstairs to wait. Every twenty paces of the living room there is a silence upstairs. In those silences, I creep up two steps hopefully. Then I hear the clink of a makeup bottle on the counter and squeeze my legs together again. I entertain the notion that I’ll surrender and end up peeing on the floor like our ancient dog. How can anyone stand to be in a bathroom this long? Elise spent no more than five minutes frowning with her concealer in the bathroom every morning.

At 8:02, right when I’m about to pound on the door, it huffs open and Sydney walks into her bedroom. She hears me barreling up the stairs and says, “Sorry. You could have just asked for a few minutes.” I close the door without saying that nothing could be more embarrassing. Even after three months, I am loath to do anything to assert my presence here. I’ll hide in my room for hours, look around before opening the cabinet or fridge, and

even bury my garbage deeper in the can. With each covert action, I think, this is how I respect their home. My therapist would hook onto that word their and call the thought self-invalidation or non acceptance. It’s as if the instant I say my house, a switch will flip and I’ll be magically bound inside the house until I’m forty.

My timeline for the morning is now compressed, but I decide I still have enough time for a shower. No sooner have I poured shampoo into my hand than I hear a knock on the door. I yell “What?” over the water.

Dad says, “Hey, how long have you been in the shower?”

I wonder why, if he’s awake, he doesn’t already know. “Like three minutes. Why?”

“Okay. Well, I still need to take a shower, so…” I can supply the rest myself. So you should have showered last night. So I need the shower because my job is more important than yours. So since I own the house, get out. I do a slapdash hair-washing job and grumble my way out of the shower. On the way back to Ally’s room I try not to make eye contact with the poster over her bed that says FALL IN LOVE…RUN AWAY TOGETHER…STAY IN BED ALL DAY…GROW OLD TOGETHER… REMEMBER WHY YOU FELL IN LOVE…THIS IS YOUR HAPPILY EVER AFTER.

The irony of me sleeping under that is nauseating. If all the romantic platitudes weren’t bad enough, they forgot the number one rule of cohabitation: for God’s sake, get on the lease. My greatest blunder in my 16month marriage was believing Elise when she assured me on the second day of living in the apartment that “oh, hon, it’s no problem. I’ll start on the lease and we can add you later.” We rode out the next two years that way, the real tenant and the fake tenant pretending that nothing bad was going to come of this.

On Mother’s Day, we got into a fight in Target. Unlike many last fights I’ve heard about, it was so absurd that people laugh or shake their heads when I try to explain. It involved her trip to the bathroom, a request for her car keys, an accidentally racist assumption about the safety of the neighborhood, and insults that kept shakily piling up like Jenga blocks. I decided the only thing to do was get out of the car, drink too much gin, and attempt to come home. Elise had other ideas and sent me to my parents’ house with an airline-trip suitcase of clothes. I lugged the clothes around on the bus the next day, jerking the bag in stagger-step so loud that everyone stared. The Chippewa bus driver smirked and said, “You must be going on vacation, huh, young lady?” I gave him the most dead stare I could manage and replied, “No. I’m homeless for the day.”

And that’s exactly what I hoped it would be: a day we would shake our heads about in ten years and say, my, wasn’t that close? But when I asserted my right to come back home, I got an immediate reply: No, I want you to stay away another night.

I sat back in the booth at the Mexican restaurant. Fingering the house keys on my lanyard, I fired back, But I’m dehydrated and exhausted. I’ve been carrying this damn suitcase all day.

Are you somewhere you could buy some water? The tap water at home suddenly seemed more attractive than my untouched glass of water and its sad slivers of ice—perhaps because the tap was now indistinct and forbidden. I left the restaurant, shading the phone screen from sun glare and banging out the promise that I didn’t care what she wanted. I was going back to take a nap in my home and get water from my faucet.

By the time I got home, the threats had escalated on both sides.

Me: I’m not going anywhere. How are you getting me to leave?

Elise: Please don’t do this.

Me: No, I’m so serious. Are you going to call the police? I dare you. Call them now.

Elise: You know I don’t want to do that.

Me: I feel I’ve been punished enough.

Elise: This isn’t about punishing you.

Me: It absolutely is.

Meanwhile I had pulled the handcuffs out of the kink closet and was planning how best to chain myself to a piece of furniture in the apartment. I remembered one of the three episodes of How I Met Your Mother I had watched—the one where Barney chained himself to the radiator because of Super Bowl spoilers—and thought it sort of worked until he panicked himself out of it. If it worked for a bro like Barney, why couldn’t I pull it off? I practiced squatting and cuffing myself to the apartment’s radiator, testing several hiding places for the key on my body. Under my thighs? Stuffed in my pants? In my mouth? The metallic prick of the key’s teeth under my tongue was pretty unpalatable, but if I had to I could live with it for a few hours. I got a message and spat the key out so I could unlock myself. I only unlocked the wrist piece, expecting that I would put it back in a few seconds. She had simply said, When I come home, you will leave. And I don’t want you coming back.

I slumped against the radiator, unsure whether to feel nothing or everything. It had been pretty obvious that the marriage was broken for months, but to break up over something this stupid really stung. Needless to say the handcuffs wouldn’t win the argument. By severing everything at once she’d already won. Her message was a throat punch; mine was the whimper after the fist strikes. But this is my home.

No, she said, it was your home provided that you treated me nicely. If you don’t leave, I will move, and you’ll be left squatting in an empty apartment.

That word squatting stuck to me. It gave me a taste worse than the handcuff key, one nothing could gradually swallow away. I had been smacked in the face with the most inconvenient definition of “home.” It didn’t matter whether I was bound to someone by blood or a piece of paper.

It didn’t matter how much emotional support I was allegedly getting. It didn’t even matter that her mail snuggled up with mine in the box. What mattered was how much legal recourse I had now that my wife hated me— which was to say, none. For two years I thought my home was in the lofts above Pop’s Steak, Fish, and Chicken on South Grand, only to realize that my wife considered me a guest. A guest who was showered with material and sexual favors, but a guest nonetheless. I didn’t ask then if that was her plan all along, leaving me off the lease and paying the rent with her separate credit union account so I couldn’t even claim we jointly paid it. I expect I never will ask. Just the empty space in which I have to speculate hurts enough.

When I mentioned to Elise later that I still felt homeless, she laughed at me. That’s ridiculous, she replied. You have your parents. She probably thought I had it made here. I suppose that’s how it might look to anyone. Going from a tightrope walk on the poverty line to cable TV, a glass walk-in shower, and fluffy bedding is normally the right direction. But there’s no way I can tell her about the panic I felt my first night back in the house, when Ally opened the door in her underwear and let me in. That night I spent a sleepless hour on my old mattress in the basement, listening for the usual footsteps of my mom at 4 a.m. Then, with a sneakiness I pulled from nowhere, I stuffed the mattress behind the dog’s cage, opened the basement’s sliding doors, and ran with the suitcase across the yard. The motion tripped the patio light, which just barely missed my figure as I ducked into the woods behind our house. I lay prone behind a pile of grass clippings while she smoked and her Saturn idled in the carport. Mosquitoes descended on my ankles, but I didn’t move. All I had to do was break a twig and she would run up the hill, point at the woods with her lit cigarette, and yell “Is someone there? Who the hell are you?” But after half an hour, the cigarette tip disappeared, the car receded to the street, and Mom began her commute to O’Fallon completely oblivious.

Elise would think that was just like me. She’d tell people I always do this, elaborately plot to hide my mistakes, do it poorly, and get angry when I’m busted. But every day I remind myself that there were no better options. What else could I have done other than lie there and admit to using a stolen mattress and basically breaking into my parents’ house? And today, as I go back to my sister’s room wet but unclean, I wonder what, really, the difference is. The South Grand strip or Creve Coeur, the routine is the same: rising from a stolen bed, standing in a stolen shower, locking the front door with stolen keys, depending on other people’s generosity, and wondering when I’ll finally overstay my welcome. The only things in this room that are truly mine are the hundreds of clumsily punched holes in the wall between all the posters. They held up every poem I wrote a decade ago, when I called the walls and the room mine because I didn’t know any better.

ERIC EGGERS Unveiled

lost in my shadow stumbling, i lose footing my shadow goes on

KELLY STOLLE Mortal Wounds

I am the moon, just look at me looking at you. Eyes big, bright, and blue. Just look at the way I move in phases, looking down on, or shining light on you.

You are the sea. Just look at you, looking at me. You come in waves just like the way the tide brings life and destroys shoreline.

I lied.

We are mere mortals, sitting still, in place, trying desperately to read the other’s face. Out of the cold at my place, listening to the crashing waves by the light of the moon. But she is not me, and the ocean isn’t you. We’re just two heartbeats drumming out of tune.

MALIK LENDELL mississippi

anyeverythere

i have too many homes too many places i can never return to because they’re torn down or everyone’s gone travelling makes you comfortable everywhere but it doesn’t make leaving any easier it’s always gone when you are

if you go back you’ll be out of place so

absorb this location into your skin fill your lungs with a sense of place remember how the sunlight feels here and how the from-here-birds cluster remember the scent of these trees and this exhaust and the sound of nearby children and distant construction

it will be part of you forever one ring of the tree that you are for this moment only it is home

HALEY R. GRAHAM log 14

cabs won’t stop for you after 1a, apparently. no matter how lost, pathetic, you are. nothing will melt the heart of a cabbie about to get off. which is fair, i don’t blame them.

i’m lost in a city whose name i don’t know. each time i ask a person on the street where i am, they just say the street name. typical. it’s my third night here.

here is filled with potholes perpetually shining with gutter water. daytime feels unnatural. daytime in this city makes me feel the same confusion and discomfort as seeing a duck at night. just bad. it’s something you aren’t allowed to see, but do. not like an intimate moment barged in upon type of privacy, but a kid reading their big sis’ diary. something that sure as shit exists, but is only a reality you can peer into, not experience. a fish tank maybe? daytime is white sun and the hundreds of skyscrapers’ glares striping my vision. maybe it’s on purpose, maybe i’m not supposed to be able to see all that much during the day.

i’m not sure if i’m making it up, but this whole place feels...off.

isn’t the right word, but it’s the best i’ve got. it doesn’t feel much like alternate reality, just like the city itself scrutinizes you. but at the same time it doesn’t care about me. amused by nothing, it just looms and judges: an unsupportive parent breathing down your neck while you do homework. no people here, only cockroaches. i’m not trying to be mean, it’s just how it is around here. in daytime, if i’m lucky enough to spot someone, they scurry into crevices, like the sunlight makes them uneasy. they become shadows.

but nighttime. nighttime breathes. each afternoon, the sun practically throws itself down, the sooner to relieve here. it probably pities this town, and i do too, all its worth lurks in orange street lamps and hidden parties

.5mg split

are you okay? i've been wandering lost in my own body ever since panic set in hours ago and reality became neon and all i can think is- is- diz ziness clouds my view of your face i am lightheaded behind unblinking eyes and i need my quarter milligram of

JESSIE EIKMANN

Jackson Pollock is a 19-year-old girl

with unblinking eyes, scrubs, and three wristbands. Her latest painting is “Palette after Rain”: a broken yolk of yellow over the pink, a brown pupil in the white, the purple and blue switching skins.

The art therapist has asked her to paint the lifeboat she clings to when she’s stuck here: What gives you hope? Surely you have something. Her raft is an orange square,

or it was an orange square. It fights for space with black and gray waves on all sides—CODE GRAY. Alicia do you need a shot? Go back to your room—There is water in the sky, sky in the water,

sky blurring the edges of the raft. When the square is surrounded, she smudges the water and holds it up hollering, Do you like my boat? Do you like my boat?

The therapist pretends not to be annoyed about all the sky-water smeared on the table, saying, I like that style Alicia. It’s very Jackson Pollock.

Her entire palette will have to bleed in the sink, become an inextricable brown. The real Pollock knew colors shouldn’t be extricated. White was truly white when it was bloodshot blue,

marred by looping black tracks, dripped by sticks on a tumult of color. Do you want my boat? She jostles Ricky’s shoulder. Ricky looks up, his brush halted before it can add

a new stick to his picture, a chaotic coil of black and blue he calls “Burnt Wood.” The therapist stands and drops her clipboard on the table. Alicia, you know we don’t touch other patients.

Sure, Ricky says, I’ll take your boat. It’s very pretty. It isn’t the first time he has lied to her. He keeps saying he’ll visit when he’s out. HIPAA won’t allow that, and Ricky knows it.

Alicia says, They say I went into his room. They say I love him. That ain’t true. The therapist’s clipboard tells differently. It knows how she tries to distract him from the TV,

how she leans in to his chair in the lounge, how she demands he accept her artwork, how yesterday she followed him down the men’s hallway

and stood in the doorframe of his room until the nurses pulled her into solitary. The therapist clasps both hands together, praying Alicia will drop the issue.

We told you, that was yesterday and we’re not discussing it. Alicia moves away from her table. Her breath becomes audible. The nurses form a cautious circle around the room.

She yells louder, I ain’t done nothing. They’re lying on me. Her fist pounds the air with every word. Pollock’s fists closed on bottles at the Cedar, swung on his friends,

barely treaded water. He once said, I have no fears about making changes, destroying the image, etc., because the painting has a life of its own. He didn’t know he was the image

until the day when, wifeless, he hit the road, but the road was the sky and the sky was dark waves that swept him through the car window and smashed him into what looked like a raft. He hit the ground, a mangle of muscle, red droplets on the tree, the grass, his busted skull. Ricky will be free tomorrow. Alicia may never be.

She wheels on the therapist. She repeats, I don’t love him. I ain’t done nothing until she can say nothing else. She is swept out of art therapy as her raft pours orange into her hand.

Just Ride

Jordan was always a sure person. The way he poked out his chest and held his head high whenever he made a decision always told me so. He shined as the lead in both the junior varsity football team and the mandatory freshmen volunteer program, and he was the idol of the girls that swooned over his notorious misdemeanors. Once, a girl even told me how lucky I was to be his best friend. At the time, I’d been really pissed at him, and myself, for convincing me to take some girl’s virginity and break things of with her the next day, so I completely disregarded the comment altogether.

Me, I was the complete opposite of sure. I was a follower, his follower. But it was better than being a loner. I moved to Jennings, Missouri the summer before my freshman year, stepping foot into a predominantly black high school for the first time in my life. I had no friends, and I often sat alone. I was the “white boy” to them, until Jordan shoved a guy nicknamed Chiraq into a locker on my behalf. Nobody ever called me that again. I think about him often and that late night of January 2nd.

He’d reached for his mother’s car keys without much thought. They’d been resting on one of the wall hooks near the front door, glistening just enough to demand his attention in the living room’s dim light. We’d all been sitting, scattered, among the sectional couch and armchairs in our night clothes, covered by the fleece blankets his mother, Ms. Kyles, was hospitable enough to spare. We had been watching a horror movie, and as if that wasn’t daring enough, Jordan ordered us to find our shoes, get our coats, and follow him out the back door.

His mother was already asleep, but I really wish she hadn’t been. She worked intense shifts at a psychiatric facility in the city of St. Louis. Jordan often bragged that she endured twelve-hour shifts which called for him to stay at home alone at just the age of fourteen. He didn’t have any siblings, and his mother remained estranged from their family. Asking someone to keep an eye on him was the last thing she wanted to do. And this independence gave him plenty of opportunity to engage in misdeeds of all sorts.

Stepping onto that icy back porch in the burning chill was the last thing I’d wanted to do. I knew I probably should’ve spoken out but nothing moved me to do so. I’d always been the one to advise Jordan that even though his ideas seemed so marvelous to him, they always came at a price. Of course, I was often referred to as a coward by Ryan and Trent, who obeyed each Jordan Idea like they were part of the Ten Commandments. So instead, I pretended that my shivering was only due to the cold and not the fact that we were actually about to steal Ms. Kyles’ car.

“Maybe we should go back.” I’d finally gathered up enough nerve. By then, it was too late. We were already out of the suburban subdivision, cruising towards the unknown. My palms were sweating, and no matter how many times I wiped them off on my jacket, the moisture never left. Trent attempted to nudge me in the side with a hard elbow, but I had blocked the blow.

“Stop being a lame, Cody.” And so the criticism had begun.

“Yeah, why do you even hang with us if you can’t handle?” Ryan glanced back from the passenger’s seat. Much to my surprise, Jordan kept quiet. He observed the passing buildings, trees, and cars for quite some time. When he finally adjusted the rearview mirror, despite the darkness, I could tell those brown, often-narrowed eyes had found a way to land on me.

“Look, you need to relax. I’ve done this before. Once, I drove all the way from Florissant to Baden by myself and made it back in one piece. We’re just tryna get some fresh air. Chill out, ‘kay?”

I somehow found my voice, “But your mother—”

“What about her?” Jordan snapped.

“She could wake any minute and notice we’re gone.”

“So, what you’re sayin’? You don’t trust me?”

I stammered, my cheeks burning. “N-no, I do. I’m just saying stuff happens all the time.”

“Shit isn’t gonna happen, Cody.” Jordan replied nastily. “You do that crybaby-whining all the time. If you’re so scared to ride out tonight, get the fuck out and walk home! I don’t need you burnin’ bread on us. What I need is for you to shut up, sit back, and just ride. Got it?”

“No, you’re right.” I shut my eyes, overheated. “I won’t say anything else.”

I leaned back in defeat because, as expected, I lost another argument against Jordan. My heartbeat matched the mood of the song that was playing on the radio. It had strong bass that resonated throughout the compact-sized car. Jordan drove at an unnecessary speed with only one hand on the steering wheel. He seemed oblivious to the fact that all our lives were currently in his hands. He made horrible wide turns and carelessly hit a curb once or twice. It was enough to make my blond spikes fall limp on my forehead. I was soaked in sweat.

I cracked the window, a bit hesitant to stick my head out. When I did, it was only for a few seconds. I’d been scanning my thoughts and trying to think of an alibi that could save us if we did get caught, for when we did get caught. No matter how hard I swallowed, I always failed to get rid of the thick wad of anxiety that rested in my throat. We passed a cop’s cruiser, and I practically heard every single one of our hearts drop.

The profane music was silenced immediately.

Ryan kept twisting around in the passenger seat to glance past my

head. And willingly, I sunk into the plush, dark cushion, giving him the opportunity. If it hadn’t been for the headlights of a car unintentionally trailing us up the road, I would have never seen the twitch in his lips as he keenly stared.

“Jordan, d-drive! That cop’s turnin’ around!”

“No he’s not,” Jordan’s voice no longer held its severity, but it did crack. I chewed down on my lip when I heard the breaking off of every other syllable he spoke, “Oh, shit. He’s tur nin’ around. I’m gonna get us back to Hazelwood. Everybody act cool, okay?”

“’Kay.” Trent answered beside me. He was the only one that spoke, or at least the only one brave enough to speak. Nothing else was said as Jordan propelled us forward. He repeatedly raised his head towards the rearview mirror, constantly checking. I guess he never did see any way out at that point, because instead of slowing down and remaining composed, he didn’t fight his adrenaline. No, what he did do was speed profusely. Moments later, he managed to maneuver us into a foreign subdivision. The houses on either side of us were nothing but blurs. Cars parked along the stretch were barely missed because if Jordan had already been a horrible driver, he was even more disastrous now. I gripped my seatbelt despite already being buckled in. Something within me wanted to glance back to see if the cop was really following us but I couldn’t bring myself to do it. Instead, I watched in horror as Jordan made another misjudged turn, failing to apply the brakes. We headed straight into a large yard of a twostory brick house.

“Jordan, stop—” The impact of hitting the curb silenced me. I had wanted to close my eyes because I knew just how this would end but I was petrified. The car was sent into a whirlwind of shattering flips, diminishing the size of the already-small car. I heard screaming but I wasn’t sure which voice I was hearing. It could’ve been mine. It could’ve been all four of us. Either way, I never really wanted to know.

The smashing of metal distorted my ears, and my body endured every jerk. When we were finally at a standstill, I wasn’t sure if I was alive or not. I remained intact, dangling upside down. I glanced below and what I saw was horrific.

My friends’ bodies were sprawled out beneath me, distorted in shapes that suggested they were in absolute pain. There was moaning, smeared blood, and screaming…from outside the car. An unfamiliar voice spoke rapidly, trying to make sense of this, “Hello? Can anyone hear me? Everybody’s okay?”

I couldn’t find my voice at first but eventually, it came. “I don’t know. Please help us.”

Remarkably, I was left with only a few bruises and a migraine. I was able to undo my seatbelt and ease on down to the ground with the help of a

man. It was his yard we’d crashed on and, despite the cold and pale ghosts that formed with each of their breaths, he and his wife didn’t retreat back into their home.

For moments I sat on the hard, icy grass with a blanket the woman had given me, quiet. The police were phoned, of course, as well as the paramedics, and they would be arriving soon. I wanted to call out Jordan, Ryan, and Trent’s names, but I was too afraid I wouldn’t get an answer. My eyes stilled over, making it impossible to cry. But when Ryan and Trent’s parents, along with Ms. Kyles, arrived on the scene after being notified, I nearly did. When my parents appeared I figured I was in trouble. And if any of the boys had survived, they were, too.

Paramedics began moving each of them from the car. Ryan was first. He was expressionless for a moment but when placed on a stretcher, he winced and I knew somehow he would be okay. His parents kept hugging one another, saying, “Thank God he’s alright. Thank God.”

Next was Trent. He moaned immediately after being ejected from the squashed cube of metal. His parents walked alongside him all the way until he was lifted inside the ambulance. “We’re right here, son.” They had comforted. “We love you. You’re going to make it.”

And lastly, there was Jordan. He was more of a struggle to get to. I watched beside my parents for ten minutes while they fought to eject him. His mother was a wreck, her constant pacing around the scene made my parents even more speechless than they already were. They constantly kept gripping me and crying.

The lump that had managed to fade away in the wake of the accident was back again. Jordan was slowly removed from the car. There was a large crowd of spectators by then. Staring at the crystals in the green, frozen lawns was something I decided to do, just long enough until I could hear Ms. Kyles give confirmation that he was alright. But seconds had passed, and I didn’t hear so much as a rejoice. My insides had set ablaze in curiosity, and I finally looked up.

Jordan’s body remained limp the entire duration of being moved to its stretcher. Ms. Kyles was standing as close as authorities would allow her, pushing, but failing to break through. When the reality of all that was lost that night became apparent, she dropped onto her knees in the middle of the street. A female officer lowered to ground, hugging her in support. I’ll never forget her deep, sorrowful wail. It pierced right through me in that subdivision.

“Jordan?” She called, but there was no answer. “Jordan, please, say something!”

But Jordan Kyles was silenced everlastingly that night. In spite of a horrible decision that cost him his life, those who truly knew him honored him for the exceptional kid he was. He was the first freshman in thirty years

to earn the position of captain on our school’s junior varsity football team. He was also scheduled to take honors classes, alongside me, when we returned to school that upcoming semester. And lastly, out of all four of us in our squad, Jordan had already met the freshmen quota for community service hours.

When Jordan’s body left the scene, I was contemplating whether the entire incident was my fault. Maybe Jordan’s blood was on my hands. By the time Ms. Kyles was escorted away in an officer’s vehicle, I had accepted that I’d killed my own friend. I should’ve spoken up and held my ground, but instead, I was a coward.

Another group of paramedics eventually summoned me for an examination. Preparing to stand, my legs wobbled. The entire walk to the ambulance was a struggle. Somewhere in between the lawn and the street, I collapsed in my father’s arms.

I fell into unfamiliar warmth and immediately, I knew I was no longer in the yard of those helpful strangers, amongst my horrified parents, working paramedics, and nosey bystanders. Instead, I was in a vast openness of blinding light with a kaleidoscope of colors. I’ve never seen anything like it before. I felt comfort beyond any measure I’ve ever felt. I also wasn’t alone.

There stood a graceful, transparent Jordan in a sparkling meadow. He was several feet away, smiling and gesturing for me to follow in his lead. But I was far too distracted by what I saw in the distance. Hundreds of yards ahead, rested a breath-taking kingdom that showcased proudly all its shimmering glory. My…God. Its immense, golden gate. Not to mention, its skyscrapers—prestigious, pointed towers. The broad streets shined, every single gold plate. And as much as I wanted to go farther, I couldn’t. It was a firm, invisible force that stopped me. It wasn’t my time. So, from where I stood, I watched achingly as my best friend walked on to the beautiful city alone.

Cloud Nine

NICOLE GEVERS

Lafayette Square

VICTORIA SCHEFFLER

A Lone Piano Song

In front of a wall of swirled graffiti of city colors In a room of students, A man plays a piano The Audience does not care, But the man plays, I did not know the songs, but I knew their notes, The man kept playing, and playing, His audience still barely listening. Lost in their own lives and the man kept, Playing.

Means to an End: Honor and Morality in the Analects and The Thousand and One Nights

In many ancient texts, the idea of honor plays an important role. It is the ideal by which a soldier will live and die, the symbol of a powerful man, and the goal of a dedicated disciple. The human race collectively holds this value in high esteem, even across time periods and cultures that seem worlds apart. One well-known example hails from ancient China. Most of Confucius’ short sayings in his Analects appeal to humanity’s innate sense of honor. Whether addressing concepts such as hypocrisy or more concrete actions like respecting one’s parents, for Confucius it all comes back to honor and respect. To him, this honor is not only a value, but a responsibility—an honorable person has an inherent moral duty to follow this ethical code. Whether or not this honor is a responsibility, though, does not necessarily mean all the people will follow this code. Humans, despite their desire to achieve perfection, are flawed. In The Thousand and One Nights, nearly every character breaks this honorable code in some way, whether it be by breaking their word or defying their parents. Very few of the prominent players in the story could be described as fully moral people. The Analects see honor as an essential part of creating the ideal upstanding man, but in The Thousand and One Nights, characters often sacrifice their moral responsibility in favor of more convenient ways of achieving their goals.

Shahrazad, the character that frames the famous tales of The Thousand and One Nights, is in a way the hero of the story, and yet through the lens of the Analects, she is anything but moral. Confucius places strong emphasis on the importance of honesty, saying of a true gentleman that “his word can be trusted” (391). He values above all a sort of unabashed openness, letting the world see the truth inside the man. Shahrazad, though with good intentions, certainly does not employ this type of blatant honesty. Her concern is with her goal—to free her country and the other women in it from the grip of their murderous, tyrannical ruler—and to her, the ends justify the means. Though she works towards a morally clean objective, her method primarily involves manipulation. She defies the Confucian virtue of honesty by conspiring with her sister behind the king’s back, setting up a conniving ploy to break the king’s murderous streak. Every night when telling her famous stories, she purposefully falls silent come sunrise, leaving the king dangling on a cliffhanger and forcing him to keep her alive to hear the end of the story. When the story is done, she

promptly begins a new one, to ensure that her cycle continues night after night. The plot is clever, well-mediated, and highly effective; yet when viewed through the Confucian ideals, it is a sacrifice of an essential honesty and cannot be considered fully moral. Motives aside, Shahrazad does not uphold her honor by her actions.

Another recurring theme in the Analects is filial piety—it comes up multiple times, even in a small collection. On any given page, respecting one’s parents is brought up at least once by either the students or the Master himself. Clearly, Confucius places great value in upholding family structure. Honoring and respecting one’s parents is one of his primary teachings. This is another Confucian value that Shahrazad throws by the wayside in her quest to achieve her goal. Far from following the lesson “never disobey” (Analects 381), Shahrazad openly defies her father’s wishes. Set in her plan to change the mind of the king, she entreats her father to give her hand to the violent ruler in marriage. Her father, a storyteller like herself, tries to dissuade her from her chosen path by telling her parables involving willful women and acting without thinking. While Shahrazad listens well to the stories, likely with a storyteller’s interest, she does not heed their message. Instead, she remains resolute, set in her path, despite all her father’s warnings. In the end, he gives in to her entreaties, though he fears for her life. Confucius emphasized that “the only time a dutiful [child] ever makes [their] parents worry is when [they] are sick” (381), but Shahrazad shows no concern for her father’s state of mind. Again, her motives are arguably pure; she has set her sights on a higher cause, giving herself up for the good of all the women in the land, yet in doing so she sacrifices personal morality.

Even the characters in Shahrazad’s tales break Confucius’ moral codes. In “The Tale of the Porter and the Young Girls,” all of the male characters take the same vow: “Speak not of that which concerns you not or you will hear that which shall please you not” (The Thousand and One Nights 624). The females of the house seem to have many stories to tell, but the vow prohibits the men from asking about their peculiarities. Finally, all but one of the men can no longer take the mystery and break their vow, demanding an explanation from the three girls. Through the eyes of the Analects, which place great importance on keeping one’s word, this is an offense that would cause the characters to lose their status of gentlemen. However, this implication was likely Shahrazad’s intent with this story. The king, so infuriated by his perception of immoral women breaking their vows of marriage, needed to be shown stories of men similarly disregarding vows. This hearkens back to Shahrazad’s strategic, careful manipulation. Not only her method but also her subject matter is designed impeccably to suit her needs, moral or not. She takes exactly what she knows will affect the king most and subtly uses it against him, so that he likely does not even notice

his imperceptibly calculated change of mind.

Ironically, the only character in The Thousand and One Nights who seems consistent with Confucius’ teachings is the bloodthirsty king himself. While his anger towards women renders his morals almost nonexistent, he is at least lined up with one of Confucius’ prime points: practicing what he preaches. When he finds his wife has been sleeping with slaves in a wellplanned, clearly well-practiced system, he condemns all women by the justification that “there is not a single chaste woman anywhere on the entire face of the earth” (The Thousand and One Nights 614). He blames the entire female population for the infidelity of his own wife. Taking one new woman per night and beheading her in the morning, he certainly upholds in action what he believes to be the tr uth. He makes no secret of his blackened heart, showing that same shameless honesty that Shahrazad declined to uphold. It is an unusual concept that Shahrazad uses immoral means to achieve a moral end, while the king employs honorable traits to further his bloody rule. This is, perhaps, the purpose to Shahrazad’s stories—to show the king that all people live among shades of gray, rather than black and white absolutes. He is too caught up in his anger to see this inconsistency within himself, but even the hardest of hearts is easily captivated by story. Even Shahrazad, while attempting to persuade her father, paused in her argument to hear his stories, though she remained resolute despite them. As a gifted storyteller, Shahrazad understands the power of story, and the authority it could hold even over someone like the enraged king. Taking this to heart, she is compelled to leave her personal morality by the wayside in order to achieve her righteous aim.

While the Analects glorify honor, respect, and honesty, The Thousand and One Nights turns these standards on their heads, creating an intriguing tale that plays out between motives and morality. The contrast between Shahrazad’s methods and those of the king begs the question of whether the ends do indeed justify the means—after all, Shahrazad’s end goal of saving the lives of multiple women is surely worth a few lies along the way. However, the Analects leave little wiggle room for motives. Confucius’ sayings collectively imply that it is the action, not the thought, that counts. After all, if one’s motives are pure, then employing Confucius’ desire for honesty, your words and actions, in theory, will follow. However, this is a highly simplistic argument, given that one of Confucius’ own sayings is this: “The gentleman considers the whole rather than the parts. The small man considers the parts rather than the whole” (382). Thus, by Confucius’ own teaching, he has labelled himself a “small man” by leaving motive out of his discussion of morality. Surely, the mere action of respectful ritual means nothing if the heart is not in the right place. However, the Analects were not meant to be taken apart in such a way. They were intended for everyday men living everyday lives, whose greatest moral concern was how best to

honor their parents. Shahrazad faced far greater challenge, and far greater peril, than any of Confucius’ devoted students. Real life is many times more complex than a cookie-cutter answer can possibly encompass. Perhaps it is the circumstances, and not the predetermined rules, that determine whether the ends justify the means.

Works Cited

"The Analects." Gateways to World Literature, translated by Simon Leys, edited by David Damrosch, Pearson, 2012, pp. 380-393.

"The Thousand and One Nights." Gateways to World Literature, translated by Husain Haddawy, edited by David Damrosch, Pearson, 2012, pp. 608-647.

Paint Pots of Kootenay National Park

As we swim in our oceanless depths we see the stars singing and swinging in the apple trees of our recent nostalgia. The time passed was like ever slowing oil through water. For if by death we may be. Because when it comes until a tidal eternal flow, it is like eyes burning under the sulphur.

Others have gathered supplies for the length of the falling storms of anarchy and feel confident in their confines.

The mountaintops filled and valley sink into rivers muddy and flowing, seas and oceans violent rage against base and wall of earth. Ground missing and replaced throughout its moving nocturnal plates.

The voices silent through deep song to Nirvana, the stumps to redwoods silent and resting firmly in set, the wildlife of land and sea silent and the fossils forming.

Chorus fluctuating of mighty star above; sabbatical anxiety of evolution.

It’s a Big World Out There

opal

feeling the somedays

itching under my skin

leaves rustling in autumn’s grass

fleeing their homes

it’s time for me to go fall brown to freedom

terrified on the precipice kick the window open

flowing down to yard swimming into grass

absorbing dew and moonlight

i am opal melting into delight in feeling the earth beneath me and the world surrounding drinking in this feeling is water in the desert of a sunday morning

Cairn: In Memory of David Maslanka

Bradley University Student String Quintet

Violin – Kelsey Klopfenstein and Heidi Schick | Viola – Erin Rocke Cello – Chris Adams-Wenger | Bass – Ian Brown *Conducted by Curtis J Howd

Ten years ago, I decided I wanted to be a composer. I spent some time writing and scrapping many different pieces before I composed my first decent fanfare—just a few measures played by my madrigal brass quintet. As I gained confidence, I decided to try my hand at a string piece. At the time, I had begun to greatly admire the work of David Maslanka. I’m not quite sure what possessed me to do this, but I completed the piece and sent it to Dr. Maslanka to see what he thought.

To my surprise, he responded with a full handwritten letter including a copy of my score full of his markings, advice on how to improve the piece, and general advice on how to become the best composer I could be. His kindness and confidence in me played a large part in propelling me forward.

When I heard of his death last year, I retrieved and read his letter, and listened to the piece again. I decided I ought to attempt to share this work with others. Dr. Maslanka’s most difficult criticism to satisfy was that the ending of the piece wasn’t striking enough. It didn’t “feel like a real ending.” I edited the ending many times, but he was never quite satisfied with my attempts, “The ending is not convincing. It sounds like you just wrapped it up.”

Thus, I have elected to remove even more of the ending, leaving the piece even more unsatisfying than it was prior. For me, Dr. Maslanka died suddenly. There was no closure—his life and legacy just rather wrapped up; it has yet to feel like a real ending. Thus, I leave the piece even more unfinished, and present it with gratitude and in memory of David Maslanka.

Northern Cascades

KELLY STOLLE Reverie in Green

You came to me in a dream, dripping in all your old ivy. The green was winding up your thighs, and when you opened your mouth that was all that tumbled out.

American Sycamore

JESSIE EIKMANN Stegosaurus

She collects things that melt and things that tick, circles and cubes and checkerboards in a drawer she can pull out from her navel.

-Kathryn Nuernberger, “The Strange Girl Asks Politely to Be Called Princess”Shortly after your tenth birthday, you hand a finger’s length of plastic to your mother, who immediately becomes hysterical and says, “Where did you get this

and why do you have it?” One of those questions is easy—off the sidewalk, school parking lot— but the other requires explaining to her

that this plastic tube is magical and people are not. Everyone has eyes like spears, and you get tired of their jabbing, so you take

your soda cans and screws and that one piece of metal that looks like an earring but isn’t

and hide in the tower on top of the slide. You run your fingernails over the rust and sit in the stifling red light

and blush whenever someone tries to crawl through and slide down. And when the teachers tell you “You can’t bring that inside. It’s trash,”

you cut dinosaurs out of notebook paper, give them names that rhyme, pair them off like in Noah’s Ark, say they hatched

from rocks. And of course, they all have to be stegosauri, because they are the most Platonic of dinosaurs, every trapezoid you strap to their backs

almost hypnotic to draw. You put one on their heads even though real ones didn’t have spikes there, and you use this as a perch to put festive hats on them,

like on St. Patrick’s Day when people laughed at you for putting little leprechaun hats on Mary and Gary when everyone else made clovers.

But you don’t tell your mother. You can’t because you can’t find the right words, you can’t say I came into this world

a bloody, wailing wad. I was discarded by your body and now I am discarded every day, and the only thing that keeps me from festering

in a dumpster like that cool thing you just made me throw away is a stegosaurus.

Growing Up

JESSIE EIKMANN

Doubletree

Your friends dare you to kiss the hotel room wall. You run your tongue over it and tickle it with your fingers—because this is how, yes, in every movie

fingers on the chin start the cataclysm, open the vortex where his tongue and mind will dive in and swim contentedly forever—and you linger so long there the wall seems to answer, crack open, push back. Then your friends call you back with whispers and whistles and you pull your mouth away. The lip print dissolves, but the passion doesn’t, and when you do your next dare, twirling your Aristocats pajama shirt around your arm and strutting shirtless in a circle, you see that everything loves you: your friends, your skittering shadow, the wall’s white internal eyes. So when two men knock on the door and ask, Can we party with you guys? You sound really fun, you don’t say no. They look inviting, the prickly plaster made flesh, pale collarbones and stubble. You pull the door open so they can see more than your eyes and—

Amber says over your shoulder, How old are you?

They look at each other. Twenty-seven. Does it matter? She screams, We’re fourteen!

The door slams on your chance at happiness. You snap at them all, Why? Can’t you just let me have this? They shake their heads and say things, but words like sketchy and predator don’t mean anything coming from them, the Judges, the ones who sit with only a flashlight on and tell you what parts they have clutched, how Aspen and Neal duck under covers when her dad’s not home, how Amber pretended to be impressed when Andrew slid into her, and when her blood pooled on the bed all she felt was bored. You live for these stories, but you can’t see your own body in them, the Judges won’t let you, they’ll shut the doors and pull the deadbolts every time because it’s delicious to dangle their boyfriends like glass beads and tell you your hands would just shatter them. You run crying to the ice machine. They are cold. The world is cold, a wall with no corners, and you can never hold it.

Summer Daze

untitled

chewing your way up my neck behind my ear eager to eat every last secret you can find inside my head and replace each with what,

your name like graffiti on the side of a train urgent sharpie truths in a bathroom stall no i think, shards of remembered dreams becoming dust in the sunbeam filling the space between us you breathe them into my hair until i’m drunk on all the possibility of you

Love Poem: Inadequate Spider

On our first two dates, we stood in the dim street, you looking around at nothing, wondering if you should kiss me. Our last date, your lip imprints were so indistinct they could have belonged to an old lover, my mother, a stranger. My insides still unraveled out of habit. I jumped from your gutters to porch pillars, cross-stitching so violently all my eyes were thrown out of focus. It was sloppy, and when you lifted a hand to bat it down, I’d already abandoned my handiwork. I thought you’d shred it—like all the others— and never think of it again. But when your palm broke the web’s pitiful resistance, my outermost eye caught you twirling its silvery strands a moment too long before they floated off your fingers and sank into the grass.

Camouflage

S. HART

Ladylike

There is a bruise on her inner thigh.

She uncrosses her legs. She adjusts her skirt, tucks her legs against her chest, hugs her knees. She faces towards me with her back against the bench armrest. She looks at the orange autumn ground. She listens to the quiet.

In a trance, she searches for something to say. Her mouth opens, prepared to talk, but nothing comes out. A dead leaf skims the sidewalk, her eyes follow.

“Did you see my new skirt?”

It’s magenta.

“It has pockets?” I find this fascinating. Women aren’t expected to carry anything that could have just fit nicely in a purse. She smiles. Her eyes squint in the light. She stands. Her whole body moves. One hand pushes the hair behind her ear. She turns to show me her other, a fist in the fabric. She twirls.

I’m excited for her, it’s nice to see her herself for once. But we need, I need, to focus on her pale thigh marked purple. The bruise grows larger in my mind. Growing until all I can picture is her whole flesh gone blue with blood broken. Contagious.

I can’t talk about it. I can’t kiss the soft neck behind her ear and smell the sunshine of her hair.

I can’t wrap myself around her like a magenta skirt of happy to hide all the bad. I can’t.

She smiles at me. Hands in her pockets.

TANNER EARLY I Was Once Your Painter

Your beauty is not real

Only an outer casing

Chosen every morning.

I view you across the room

You are so hollow

Were I to touch you

I’d feel a mannequin. You say very little To express much.

Your tear-away smile magnetizes

Once approached you become a canvas

Everyone paints who they assume You to be on first impression. It dries and you adapt to it

Acting the person you know Will attract them.

I know this

For I was once your painter.

Wrapped in your charismatic grip

They are yours

Any hint of retreat is anesthetized

By sweet tasting promises

Rolling from your tongue

Delivered with surgical precision

A cut not felt until it is too late.

You know the game

And play it to perfection.

After, the promises

Drop from your voice

To hit the floor

Breaking on impact.

I think of this

Tracing the inner scar

Inflicted by you

Condoned by me. As I do

A stranger enters Looking lost

A child in the crowd Your wandering ingénue. Eyes meet Smiles are put upon You have them Yours to lose.

SWOBODA Opportunity Knocks

CHELSEA WESTHOFF attached.

heart strings never tied.

fused together, cannot untwine. a mind of mine, you cannot find...

want. need. love.

walk away, again. this time, do not wait.

worry. waste. wither.

mend my mind. heal my soul. cut strings at the source. forget. progress. neglect.

peace is not found, rather, pieces of me. torn into three. was. am. will. when shall we be?

The Pooka Tale

“Damn. Took ‘em long enough,” I said.

That was how my last night in town ended. I’d been outside the bar for 30 minutes before finally flagging down a cab. The headlights rolled to a stop, and I was greeted by a shadowy driver and a cab more at home at a funeral parlor. Drinking alone felt like a poor way to spend a night, but I couldn’t think of anything else that made sense. I only knew that I had to do something on my last night; I couldn’t just sit around in a hotel room. It didn’t really matter with what was coming anyways.

“Where to?” said the unseen driver.

“Fischer Manor,” I said as I was getting settled.

“You’re the boss,” he said, eyes visible in the mirror. “By the way, feel free to take any of the water bottles back there. It’s made with lotus or something.”

“Thanks, but I’m good.” Something told me that would be a bad idea.

I felt myself relax as I settled into the leather seats, doing my best to take in the scenery. The city was beginning to close up shop for the day, and the brownstones were calling it a night. The fog began to shop its wares. The driver’s eyes seemed to pierce the fog with a glow only aided by the yellow lights of the dashboard and headlights. Soon enough, the surrounding blurred together with the same monotony of a metronome. I hadn’t even noticed that the driver had been wearing novelty rabbit ears the entire time until we were halfway there. Mostly because he felt the need to make small talk.

“So, what business do you have up there?” said the driver.

It irritated me that he would ask a question like that. I kept to myself and felt others should do the same. Talking was just a perversion of that natural silence. Unfortunately, it was too late to leave.

“My family has guarded it for generations. The last guardian was my uncle, but he died a month ago. I’m the next in line, and I was given a month to get my affairs in order,” I said.

“So, it’s that Fischer Manor?” said the driver. “Yeah.”

“…The one where—”

“I don’t really want to talk about it anymore.”

At that point, we had already left the city and entered that wasteland. I hadn’t expected anything different. Nobody was at the manor. The skeletal woods seemed to go on forever though. A graveyard of broken lances and ancestral promises.

“Kind of reminds me of that story about the Fisher King. A bit,” he suddenly said, not taking his eyes off the ashen road.

“I guess so.”

“Personally, I don’t think the King should have taken the charge, but that’s only my two cents. He had his own feelings,” he said. “He felt that he had to be the one to guard the grail,” he added mockingly.

“Maybe he felt obligated to his father or something,” I offered.

“No, it was his pride. Pride also got him that thigh wound,” he objected.

“Sure,” I curtly replied.

“Of course, in your case, you’re—”

“I guess,” I interjected, leaving the conversation to die.

“He just might not have been up to it,” he said as the cab rolled to a stop. “Well, we’re here. If you liked the ride, recommend me to your friends. My name is Brian, and don’t worry, it’s on me.” He paused for a moment before adding on one final bit.

“Have a good life,” he snickered.

I got out of the cab and looked at my keep. Underneath the gray sky, it looked more like a mausoleum than the castle it was. I turned to thank the driver only to be greeted by a crow. The crow’s glare chilled me to my bones. It stared right through me as if daring me, just daring me, choose anything else at all. At that point, I should have known it was too late for me. It had been an exhausting night, so I continued with my procession. As I made my way up the stairs, I thought about leaving. Twenty years later, as I sit underneath a gray sky, I wish I had. I wasn’t right for the job then, and I’m not now. Hopefully the next one learns.

CHELSEA WESTHOFF Dee:med

You once told me that happiness is a state of mind and handed me a little green book and told me that this would make me feel better and at the time it did but you did too but now you’re gone and so is the book and i’ve forgotten the words written inside and the advice you used to whisper in my ear late at night telling me that everything will be okay if i think it will and honestly i thought it would because you were there but you’re gone now and i feel like i have nothing left but memories and they flood my brain and wash away every good feeling i’ve ever felt and i’m left with a cold, shivering body and you’d think tears would fall but they don’t.

Not anymore.

Ebbing into Nativity

O Sea, embrace her worn and twisted frame; Guard her fair frame weary of wand’ring, Lyre; Play wistfully, let not waves thrash in fickle ire, Nor overpow’r thee, but swathe her sans disclaim. Relinquish her deed, relinquish her aim, Fallen and curtain’d from her former mire, Led by that blessed spire till her time of retire In depths reaching far past where gulls exclaim; A void still richer than the firmament, Ebbed into the eternal sunken abyss, Even her busied quarters hath ceased lament; Until the tides subside in infinite nativity, She will not ascend, nor descend, but be; And in her salvage not a piece shall be amiss.

A Valediction

I tended you from sapling’s breach With ne’er a realized dearth; I couldn’t guess you’d see my heart, And leave me in my birth.

Did you leave when flowers bloomed, When seeds were cast about? Or did you leave as heat surplused; The prelude to a doubt?

It couldn’t be when warmth had gone When winds assumed their place. And surely not when leaves grew dry, And greens grew ever trace.

Once succulent fruit lay grounded now From unwelcome sting of frost; It’s in the flight of bitterness That you were truly lost.

But harvests are a fickle fiend, Though rich, and ripe, and mellow; They gush and syrup juices spry With oranges, golds, and yellows.

If plucked not at their pulpiest, The fruit rots black and feral, And even those that leave the vine Are consumed by winter’s peril.

It’s as though you never met my hands; Fair seed covertly lame. My careless cœur aches to confess You wilt there just the same.

JASON DULWORTH

Gate B28

Sue spilled my kid’s cheddar bunnies. They made it into the van. They made it through examination by careful, green-gloved hand. and as I buckle knees to begin my descent into my chair, Sue jerks me out of freefall by dumping seven-eighths of Mary’s only savory snack onto deco carpet.

Apologies spill out of her mouth as quickly as the rabbits scampered. We pick them up: Sue feeling she must apologize as long as we work, me feeling I must assure her she’s forgiven as long as she is asking. This task proves more laborious than cleaning up. *

Sue suffers a moment of shame, a moment of being a not-quite-elderly woman who’s done something clumsy. She is not silenced for long. She begins small talk with my toddler in a stubborn insistence to be human.

They have grandmothers in common (Mary having a couple and Sue being one a couple times over), so talk turns to grandmothers. I’m made superfluous. I sprinkle context on occasion.

My wife exits the restroom and I go for water.

* * * * *

Sue has closed the gap, breaking the “leave a seat between you and a stranger” rule. She holds a homemade calendar filled with pictures of her family: an obvious

Christmas gift for Grandma. Mary points to people. Sue fills her in. *

Conversation lulls without props. As always, we grow still before boarding, but it is a different stillness than I expected when we approached our seats.

SARAH

MULLINcorporal

i am poet hear me scratch words into paper with a pen out of ink the meaning of life is

sobering up in the back of a cop car he’s a sergeant with three chevrons who found me running down highland

retching and jumping fences and running off into the night to hide under a bush because i realized the meaning of life is

blacking in and out asking the cop about chevrons and M*A*S*H and vietnam i never did get his name

NICOLE GEVERS Mugshot

Speak Easy

By Leo’s standards, the night was young. He looked up, watching the smoke part around the moon. Sucking in a deep breath of his cigarette and spitting it back out, he watched it sink into the blanket of night. Jazz, he thought. The night needed a hint of jazz with a good old sax solo. Not by any blotto or lug either, but a good sax player tapping his toes and playing the song in his heart.

The town clock struck, dinging in sync with the church bells. Midnight. Leo smirked. His time of day. He dropped his cigarette, careful to grind it into the ground with his heel. It left a gray powder on the rim. He clapped his hands together, spinning around and leaving the lamppost he’d been guarding. He walked two buildings back, turned right, moved one more building down, and stepped down a small set of stairs, skipping every other step.

The door was locked as usual. He knocked twice, paused, and knocked twice again. He waited patiently, running his finger along the engraved heart symbol on the door. A lock unhitched and the door opened. A large, brutish looking man stood at least a foot taller than Leo. He wore a full suit, purple tie and work shoes.

“Name?” the man identified.

“Jose, you know it’s me,” Leo argued.

“Name and password.”

“Jose, c’mon. Don’t be a lousy goon.”

“No need to get all wet. I’m just doing my job.”

“A job I pay for!”

Jose rolled his eyes, stepping aside. Leo nodded, fixing his suit vest. He never wore the jacket, just the vest and tie with a good pair of suit pants. He stepped past Jose, entering the building. Jose closed the door.

“Nora just got in.”

“She what?!” Leo jumped, turning on his heels. “She’s supposed to be here by nine at the latest!”

“Lonnie already told her that.”

Leo sighed, continuing into the building. Pulling back the curtains, he took a deep breath. The air was thick with smoke and alcohol: two of his favorite things. He danced around all of the rounded tables, leapt onto the makeshift stage, and winked to the crowd. There were at least twenty people here tonight.

“Hello, attendance,” he purred, playing with the microphone stand. “I hear Nora just got in, much to my dismay.”

“She’s later every night, Leo!”

“Give her a good teaching!”

“Now, now,” soothed Leo, “I’ll see to it she starts when she’s supposed to.”

Part of the crowd whistled. Leo tipped his hat. He bounced off stage, moving around the tables again and shaking people’s hands. One man offered a cigarette, which Leo gladly took. It wasn’t his usual, but free was free. He stopped at the counter, leaning one arm on it and motioning for the tender.

“Lonnie, my main man, a French 75 if you don’t mind.”

“But I do mind, sir,” replied Lonnie, cleaning a glass as he approached.

“C’mon now, Lonnie.”

“No, sir. Every time you drink before two, you go and hit poor Nora before her act is done.”

“If she keeps showing late, she deserves it,” grumbled Leo. “Come now, Lonnie, lighten up.”

“No, sir. No drinks until well after two.”

“Not even a sip?”

“No, sir.”

“I could just fire you.”

“I’m the cheapest work you’d find ‘part from Chinese or other colored folk.”

“I hear Chinese are cheap.”

“Not as cheap as me, sir.”

Leo smiled, patting the counter. He would never fire Lonnie. The poor soul had more sense about him than anyone in the building. That went double for Leo. He sighed all the same.

“What’s the point of owning a speakeasy if I can’t drink?”

“How about avoid the—”

Jose threw open the curtains. He spun one finger in a circle, disappearing behind the curtain again. Leo turned to Lonnie, who had already snatched the bucket and a bottle of Coke. Leo sighed, reaching under the counter and gave the lever a mighty tug. The shelves revolved, hiding the liquor and replacing it with shelves lined with coke.

“Gents, it’s code sober time,” Leo called, passing Lonnie.

Lonnie was collecting the alcohol while refilling the glasses with coke. This was the worst part of his job because he had to get face to face with the clientele. They’d pour the cups of gin and alcohol into the bucket and accept the glass of Coke with a speechless frown, leaving the whole room quiet.

Leo moved backstage, entering Nora’s dressing room after knocking. She was brushing her hair, forcing a bobbed curl at the end of it. She barely glanced at Leo as he entered. He shut the door behind him.

“Hey-lo, my ritzy bim.”

“Leo, my lamb!” she cheered, standing up to greet him.

“You lousy Jane!” Leo turned, raising a hand. If he’d started with that, she’d have fought back.

“Oh, Leo. Don’t be like that.”

“Like what?”

She slipped her arms around his waist, soon wrapping them around his neck and brushing his hair. “Be a doll,” she’d whisper but never finish.

“I’ll talk about your tardy hide later. Right now, I need you on stage before the sober society kicks my door in.”

He marches back to the door, opening it as if to leave. He paused, looking back at her, pointing with his middle finger.

“Sing something peppy, boys been waiting all night.”

“Patriotic or flirt?”

“Flirt. There some sad fellows out there.” He glanced down the hall.

“‘My Man’ or ‘I Wanna Be With You’?” she hummed, reapplying her lipstick.

“The latter.”

He marched out across the stage, stepping down just as Jose let two rather short gentlemen in. One looked barely out of school while the other could’ve been his dad. Leo put on his best smile, offering a bow.

“Officers,” he greeted. “Can I help you?”

“We were told this here is a speakeasy!” chimed the young one.

“A juice-joint?” gasped Leo, hand to his heart. “Such…such bunk. I’ve never heard of about my shop.”

“What are you running here, mister…?”

“Forrest. Leo Forrest. I run a show if she’d ever get out. Flappers… what can you do?”

“A show?” the old one remarked.

At that moment, Nora strolled out in her red flapper and white boa. She had on red gloves and high heels. She took up the mic and sung sweet and quick. A few men whistled. Nora gave them a wink. Leo nodded, motioning for the officers toward Nora.

“Our prized singer. Not the best at timing or rules, but then again she’s a flapper if you’d ever seen.”

“Would you mind us looking around?” the young one snapped. Obviously new to the job.

“It’s late,” the old one sighed. “No sense disturbing the show.” He tilted his hat toward Nora then turned back to Leo. “No speakeasy in Sill Valley.”

“Too still in Sill Valley. Pleasure, officers.”

“Goodnight, Mr. Forrest,” they spoke together, exiting.

A few minutes of anticipated silence, except for Nora’s voice in the

mic. Leo wrung his hands, waiting for the all clear. Soon enough, Jose returned with a thumbs up. Leo sighed, turning to Lonnie.

“Let ‘em loose!”

The shelves spun around again, and Lonnie got to work on drinks as orders piled up. Nora broke out into her usual rhythm and dance, falling into some old blues songs. Leo sat at the counter, watching the clock and counting how long the good times would last.

Rewrite the Stars

SAMUEL KILLION

Falling

Falling, Mirrors surrounding, Who is who and who is me? I see three...or fifty; All the same, Ellipsing, Synchronously massing.

Rushing, Safely surrounded, Rolling downward, or upward; Destination ushered By gravity, Inevitability, Increasingly in precipitancy.

Sinking, Sky ascending, Harbinging the primordial sign, That heavenly design Winding to the boundary line. A secret; Slumbers restrict, Sinking in the thick of it.

The Cruel Mistress

Living with you Is a life caged. My jailer, Your liquid courage

Thinly masking Liquid rage.

Your judgment can never Be truly clear

Looking through frosted bottles

Filled to the brim with my fear.

I’ve learned to count time, Not by minutes, hours, or years, But through subtraction

Of your discarded beers.

Your whiskey is strong, Burning away every plea

Lacing your tongue with words To burn loved ones

Until they can only flee.

This addiction is a cruel mistress

Who takes as much as she gives. So convinced you are That you consume it. In truth, it consumes you as you live.

She is your first love

Who reigns above all others. A marriage pact in sin.

As long as you two Are intertwined together

It’s certain no one else can win.

TARA CLARKSON

The Snowy Day

A Profoundly Female Experience

One after another, I cautiously pulled off my sweaters until I was left standing in front of the locker in my bra and panties.

Moment of truth, I whispered before taking a deep breath and tossing the last articles of my clothing on the bench. I didn’t look around. To see the unabashed stares of the other women up and down my body would have chased all my blood into the tips of my cheeks and ears. Reaching down, I stuffed my wadded-up ball of clothes into the locker, turned the key, and snatched up my plastic basket of bathing accessories.

Then I turned and saw them—twenty-or-so women crossing the enormous yellow locker room in squishy plastic sandals and bare skin. Some had lengths of jet-black hair piled effortlessly atop the crowns of their heads. Others had salt-and-pepper locks pinned neatly behind the ears. All carried their own basket of supplies busily from locker to blow-dryer to benches. None spared a single glance for me, the gangly young foreigner in the corner, moseying shyly to the bath room door.