Chimera 2013

Issue 14

chimera

1. An illusion of the mind.

2. A fantastical creature composed of disparate parts.

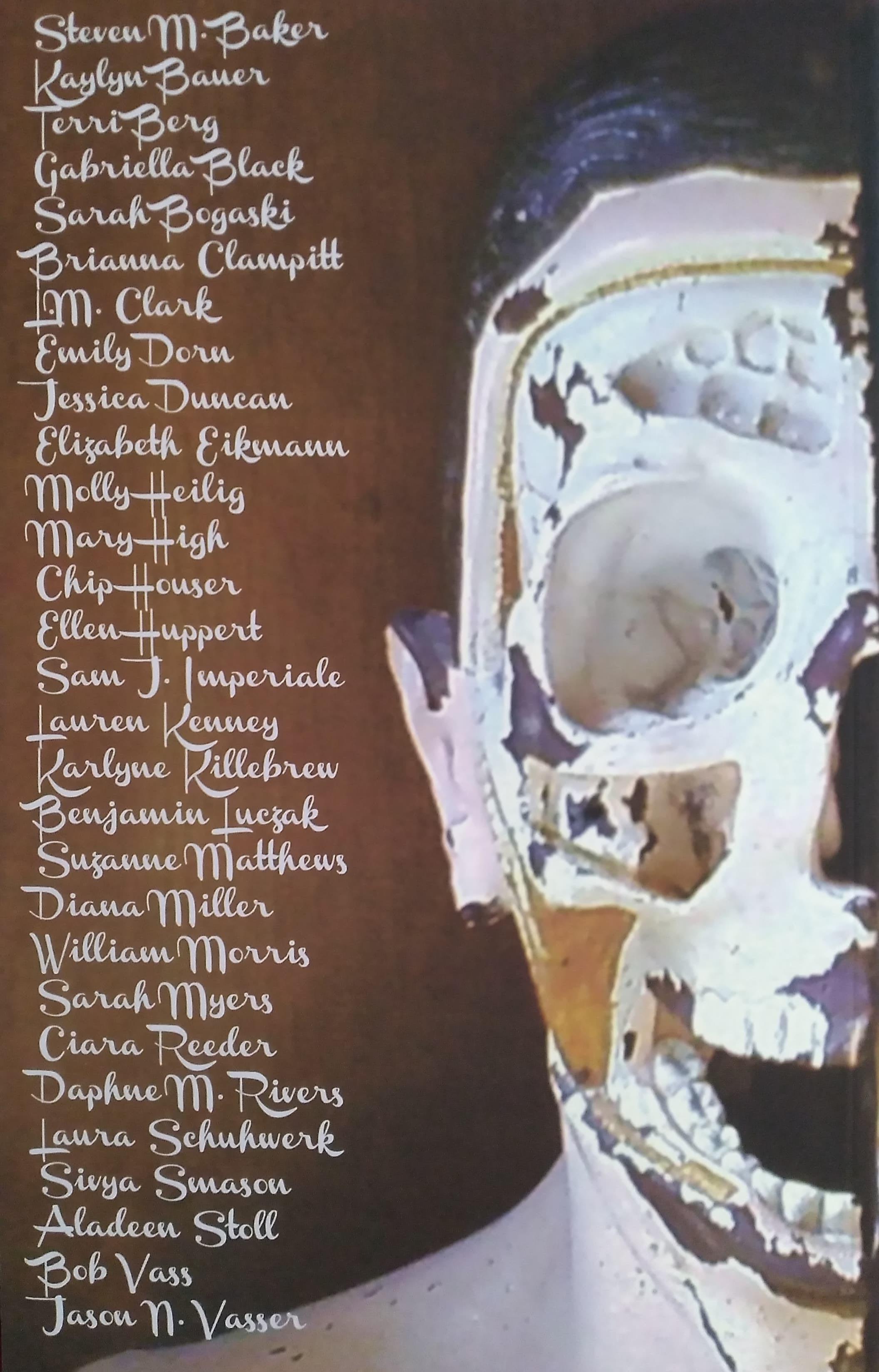

CoverArt:

Gabriella Black

Pierre Laclede Honors College

University of Missouri-St. Louis

TableofContents

Handsome Stalin, 1902

Divide

Membrane

Unseen, Unheard

The Lady of the Sidewalk

Springtime on the Shuttle

A Boy

I Remember You

Dennis the Philosopher

Consider the following scenario:

The Hipster

For Ira Kaplan

Kamikaze Clowns Coming in the Clouds

Zombie

Creep

The Boy in the Crimson Veil

Chartres

The Hog Farmer

It’s Killing Her

I have a rough number

Amusride

Tornado Song of a Wayward Daughter

Grocery List

Roderick Now

Hunger

Grateful, Saved from Cat

Mrs. Knaudi

Reach e

Eric to Battle

On becoming men

Psych Ward

Stickery Thicket

Somewhere between Eisenhower and Nixon

Mini Mushrooms

Brianna Clampitt

Gabriella Black

William Morris

Diana Miller

Sam J. Imperiale

Brianna Clampitt

Ellen Huppert

Jessica Duncan

Terri Berg

William Morris

Sivya Smason

Benjamin Luczak

Sam J. Imperiale

Sarah Bogaski

Lauren Kenney

Daphne M. Rivers

Kaylyn Bauer

Karlyne Killebrew

Molly Heilig

Aladeen Stoll

Mary High

Brianna Clampitt

William Morris

Terri Berg

Jason N. Vasser

Sarah Myers

Sivya Smason

Gabriella Black

Benjamin Luczak

Terri Berg

Jason N. Vasser

Bob Vass

Chip Houser

Sam J. Imperiale

Steven M. Baker

TableofContentsStaffAcknowledgements

William Morris

Daphne M. Rivers

Terri Berg

Brianna Clampitt

Ellen Huppert

Aladeen Stoll

Steven M. Baker

Laura Schuhwerk

Benjamin Luczak

L.M. Clark

America: Inception, Evolution, Purpose, Impact, and Law Biographies

Staff Photograph

Staff Notes

Faculty Advisor

Gerianne Friedline

Art Committee

Emma Figueroa, chair

Aaron C. Clemons

Michael Goers

Editing Committee

Courtney Henrichsen, chair

Nicole Bonsignore

Andy Henderson

Suzanne Matthews

Hung Nguyen

Melissa Somerdin

Hope Votaw

Layout Committee

William Morris, chair

Brett Lindsay

Colleen O’Neil Milne

Public Relations Committee

Sam J. Imperiale, co-chair

Karlyne Killebrew, co-chair

Alex Hale

Handsome Stalin, 1902

half-smiles from a grey photograph, straddling a divide between a childhood beaten and maimed and stark Bolshevism—happy in his distance from his scars, broken arms, alcoholic fathers, exile and expulsion—blissful in his nearness to crime and revolution

there is a balance to him, or so he believes—he traces the careful lines of capitalism across the Tsar’s economy and sees within it the echo of his own life; there is a power that sucks dry the son, the student, the citizen, the bank account, the sweat of the brow, and leaves its husks to die on the street

he learns, and learns to want to grip the workers of his state with an iron fist, to wield them as a hammer to strike and take his due

Stalin half-smiles, young and grey— thirty million deaths a gleam in his eye

Brianna Clampitt

He pressed his weight against the door, sighed and clenched his eyes shut tight; thought he could hear her breathing on the other side. No. No, no, no. That’s not right. It wouldn’t be.

Unseen, Unheard

Tiptoeing through the room lithe legs pirouetting upon floorboards polished with dust motes dancing joining in to partner where arms once held the two; sunbeams softly streaming, curtain panels weathered fine hang delicate, yet regal, match the ethereal flutter of her hands— fingers placed just so; silence sounds as whispered tunes while music plays for her ears only— a distant memory.

Limbs glide, there’s harmony feet deftly arch and lift still—breaths exhaled, weep a soul remembers laughter, love, gone these many years. Eyes of gray that rarely gleam; Their light seen dimly lit reveal another lost soul unseen— her heart beats, bereft.

The Lady of the Sidewalk

Rare indeed you are, among the wooden ladies on the street. Fair-framed like a noble woman tall and proud, standing between the curb and the cracked sidewalk, clutching fiercely at the ground with elegant earthly feet, arms bent, but upraised in cosmic understanding.

Gentle, veined hands wave at the world, then age as brown flakes of skin mark the passing of your years. They fall like ragged pieces of dark paper with hidden heroic stories, whistled to children in the wind who rake the pages of your life into piles like playthings.

Grey guests dance as necklaces about your throat, gathering your young, who fall slowly and silently, and the rocky ground becomes their stony pillows for sleep. Their spines stretched out slowly like little defiant lances, pleading for life-giving graves in the ground.

Sam J. ImperialeA Boy

Springtime on the Shuttle

and she boards from the Meadows— boots at mid-calf, deep pink dress at mid-thigh, legs bare. She stretches them, seated with book in hand, brown hair hanging in loose waves, cloud-soft and spilling down her shoulders, drifting round her face, silver piercings glinting in her nose and ears and lips like rain. The shuttle ghosts over the morning dewcooled pavement, and she reads— alone in a bubble of quiet vitality, a modern urban Venus at ten in the morning on South Campus.

I Remember You

You were like a summer afternoon. I took a nap in you, and in an attempt to sleep, I searched for all your cool spots, but could find none.

And when I woke up, I was startled because I could have sworn I heard the screen door slam, but the only noise was the humming of the fan above me.

And when I woke up, my lips were stuck together and there was a bad taste in my mouth.

Like a fat cat in the corner, you yawned and looked up at me. “Fool,” you said.

You were like summer. Slowly, you dwindled away from me.

And as the wind grew colder, I began to remember all the things I liked about you. And then you were like winter.

Dennis the Philoso-

Terri BergConsider the following scenario:

Girls A and B come into the classroom together, just before the Professor, laughing and talking about something they had done over the weekend. Shortly thereafter, Girl C comes jauntily into the room, thrusting her bag to the ground and taking a seat in front of Boy A. Boy A recalls smelling Girl

C’s heavy, rustic perfume on her many times, as she often comes jauntily into the room, thrusting her bag to the ground and taking a seat in front of him, but he cannot identify the smell by anything other than its belonging to Girl

C. Girls A and B continue their conversation as the Professor glances over the class to take attendance, and Boy A wonders if Anyone Else smells Girl

C’s heavy, rustic perfume. Boy A asks himself, Why would Girl C, who appears to be my age and does not carry herself in an especially odd manner, wear a perfume that has such a particular effect? He begins to wonder if Girl

C’s perfume is, in fact, Old Woman perfume, and tries to recall his many encounters with Old Women in beauty salons and department stores, when he was a younger boy—encounters that had familiarized him with the pungent strength of Old Woman perfume and had made it one of the stock qualities he could use to describe certain smells (much in the way of words such as Musky or Citrus or Vanilla for most people), but cannot remember what Old Woman perfume smells like because he is overwhelmed with the power of Girl C’s perfume. As a result, Boy A decides to make a snap judgment and associate Girl C’s perfume smell with that of Old Woman perfume, effectively nullifying his concern at being unable to identify said smell by any descriptors other than those that are already in the smell’s name (i.e. Girl C perfume). Somehow, still, Boy A is dissatisfied with his conclusion. He quickly realizes, as the Professor begins discussion, that he (Boy A) does not understand why Girl C would wear such a scent, when other, less intrusive perfumes should be readily accessible for someone of her sort. This brings Boy A to an impasse, where he must ask himself, What is ‘her sort’? Asking this allows Boy A to, via another snap judgment, conclusively identify Girl C as a particular type of person, thus justifying her choice of perfumes. Boy A reflects on his few encounters with Girl C. Most recently, Girl C knocked

Boy A’s thermos off of his desk, while stretching her arms. Previously, Girl C asked Boy A if he burned Vanilla incense, because he (according to Girl C) smelled like the Vanilla incense that she often burned. Boy A wrote this interaction off as meaningless at the time because he often drank coffee that was lightly flavored with Vanilla. Otherwise, the only things Boy A could say about Girl C were that she was often late to class, and her hair was usually wet and in disarray. These statements, though faulty and based on a short range of interactions, were all that Boy A had to make his snap judgment by, and (though a snap judgment was, by virtue of its limited and hastily gathered evidence, not guaranteed to be accurate) Boy A felt the need to make such a judgment in order to satisfy the inner questions that were clouding his thoughts. Boy A concluded that Girl C was a frequent smoker of marijuana. He justified this by way of further defining the heavy, rustic smelling Girl C/Old Woman perfume as the ideal scent to mask the powerful odor of marijuana, making it the ideal perfume to douse herself in as she hurriedly trotted her way to class, late, because she had been up smoking too late the night before. Girl C’s hair was always washed (Boy A derived) because she wanted to keep the odor out of her hair as well as her clothes, in order to keep a more respectable appearance in the collegiate atmosphere. Finally, her knowledge of incense was an extension of her marijuana usage, as both are burned and produce an odorous smoke. The interaction in which Boy A’s thermos was knocked off of the desk by Girl C as she stretched her arms did not seem to be of particular importance in his case against Girl C (though he believed the other evidence to be strong enough to justify withholding this one piece of potentially faulty logic), as it could be an extension of:

A. His bad luck with coffee

B. Her muscle stiffness due to sleeping uncomfortably on a futon in someone’s basement after a long night of smoking marijuana

C. Her lack of attention/motor control, as a result of smoking earlier that morning

D. His placing the cup too close to the edge of his desk that morning

Thus, Boy A could not necessarily use this last incident as evidence one way or another in the case of her marijuana habits and perfume choice. Satisfied, Boy A joined into class discussion and used the aroma of his coffee, which coincidentally smelled of Vanilla, to block out that of the Girl C perfume for the rest of the hour.

The Hipster

Sivya SmasonFor Ira Kaplan

A pashmina afghan coiled around his neck. Felt fedora propped atop his shaved head. Tangerine-colored sunglasses shield his eyes should the sun pierce the walls of the shop.

In square-toed shoes of animal skin he moseys about, rummaging through the bins and bargains.

A spyglass and a boogie board. Tattered sweaters and floral nighties. A toy cash register.

Penguin-decorated wrapping paper.

He saunters by, eyeing the goods. Which object will next be examined?

Which recycled item tickles his fancy?

He locks eyes with a distressed piece of furniture.

His finicky fingers linger on the surface of the secondhand nightstand, revealing a moustache drawn on the seam of his index finger.

“Excuse me, sir, how much for the bedside table?”

“29.99, just as the tag says.”

He lifts his fedora and strokes his luscious mane.

“I’ll take it for 15.”

“25 and you’ve got yourself a nightstand.”

“20 and you’ve rid yourself a nightstand.”

Never underestimate a hipster in his natural habitat.

Benjamin LuczakAnd suddenly the guitar writhes and shakes and the feedback builds like a wave rising and cresting. Undoing strings and turning knobs like a mad, frantic Dr. Frankenstein and suddenly you’re dancing, you crazy old man. You sage. You’re dancing and it’s not noise but a pristine chaos, a joyful wailing and the guitar bucks and rears like an untamed stallion and for a moment it looks as though you might take flight higher and higher on the jet trails of your beat up guitar but the sleepy bassist and sloppy drummer keep you safe and sound. And it is now perfectly, joyously clear what you mean. What you said without lyrics or words or schematics or structure. And the guitar is up, up, above your head twirling and whirling and the throng is right there with you, high above it all.

Kamikaze Clowns Coming in the Clouds

(From a manual found in the front seat of a tiny clown car)

Sam J. ImperialeDo not waste your laugh lightly or lisp a long line badly. Run willy-nilly around the center ring with a silly song to sing. Rid yourself of earthly cares; peddle smartly your whimsical wares. As Kamikaze clowns, it is our mode to remain true to this comic code.

Keep your rubber nose in the best position; exercise constantly your clown condition. Squirt one another with water flowers, jump into small pools from tall towers. Three feet before impact’s dash, smile and make a great big splash. Many have landed with eyes wide open, children’s smiling faces a lasting token. Of your dedication your brothers will know so, after twenty years, you may honorably go.

No puny parachutes for us!

In pink and purple parasols we trust! Floating down from big top’s heights, giving boys and girls such a fright. It’s for them our lives we give. In comic fashion, we hope to live. And, when a Kamikaze clown dies, it’s in a tiny car that the body rides. No pallbearers or ornate earthly casket; just put him in a false-bottomed basket. Lift it up at the grave’s side and into the hole our brother will slide.

Creep

You’re so close.

I want to drive to your house stare longingly at your door and break through the broken screen just to close more of the distance. I won’t go in or disturb you; you shouldn’t have to worry that something is wrong. But I need to feel my arms wrap around something familiar. I try so hard to be independent but after all this time I just crave your attention your eyes your time.

I promise I’ll be nice if you make me young again.

The Boy in the Crimson Veil

Chartres

Daphne M. Rivers

Daphne M. Rivers

Gun smoke, panic, and flashing lights—it’s the sort of thing of celluloid fantasy, a tide of anger slams into the shores of our fear and complacency. When it washes out there is only you, the boy in a crimson veil. Neighborhood heroes and saviors line the pavement, purposeless because of the hole in your face. The real tragedy is them picking up your pieces, arranging them so they are presentable to those who knew you best. But they won’t know you—boy in a crimson veil, gunned down in the ghetto of our dying hopes and dreams. In the morning the light will touch everything the night made dark, except you, except us. The villain who gave your soul to God or the Devil will retreat to the shadows, though nameless, though faceless, he will not be forgotten. The stain of your existence shall forever be embedded upon these concrete stairs; my child will endure concrete stares from those who watch her play there. The chorus of that night will replay in our waking thoughts: your pointless cries for help; fists slamming violently against the door; then silence, a moratorium on fighting to live. I would not open the door, wanting no part in the hell that followed. I could never have helped you. Believing that a soul lost is not gone, I wed myself to your last moments and whisper these words to you in my dreams, “Do not fear the shadows; God dwells amongst villains too.”

The Hog Farmer

Karlyne KillebrewAnother dreary day is drifting by me in the town of Quiet, Oklahoma. Wake up and get fed by the wife, along with the rest of the mice, then head ten miles down the road in a beat-up red Ford pick-up to the shed where we keep the hogs and feed them. Old Harold Mason the Hog Farmer is my official title in this town—not that it ever gets used much. I’ve been living here for all thirty-three years of my life, and save two deceased parents and my peculiar little wife, Mercy, no one has ever had too much to say regarding me except that I did what was asked of me and stayed out of the way.

It’s Tuesday, so after I toss the feed to my herd I’ll head on over to the bank to take care of my biweekly business. I had to sigh with a spoon full of oatmeal in my mouth as I went through the day’s events in my head: go see Hank, make small talk, look over records, strike a deal of some sort that gave him an extra holiday ham and me more tax season pocket money. It was predictable and unavoidable. I made my way to the door, glanced back at Mercy standing idly by the sink, staring into space in a ratty pink bathrobe, and shook my head.

The bank didn’t go anything like I planned. First of all, Hank apparently didn’t work there anymore. He had ran off to Kansas City with that hussy he’d been seeing, leaving his wife and two boys. The whole town knew about her, but I still acted appropriately surprised when I heard. Instead, I was greeted by some heavily made-up girl who appeared to be in her early twenties with proportions so full she looked like she’d been drawn by a Disney cartoonist.

“Harold!” she squealed.

I couldn’t believe it. It was our neighbor’s daughter Lila Anderson. I thought she’d gone off to school. I had heard she matured a lot there, too. Looking at her now, I see the rumors are right. She smelled like trouble: a jezebel’s perfume and a wandering eye on a young, virile, overly-sheltered girl. I tried to keep the talking brief, wondering how much she knew about the business Hank and I were in. She knew what she was doing and business

continued. She finished up the transaction and I made my way home.

It seemed like a long drive home. I could barely see the road in front of me for imagining the curves on the Andersons’ little girl. Praising God that I had made it home safely, I eventually manage to pull into my driveway, deciding it was best to take a cold shower or perhaps just see my wife.

After calling around for her a few times, I found her note on the refrigerator door. It said she’d gone out for a moment, and that I’d missed a phone call. Checking the answering machine, I’d found out it was from Lila. I didn’t know what she wanted, but I could tell it probably wouldn’t be worth the trouble if I called back to find out.

I looked between the phone and the note for a minute. Prematurely exhausted by the sheer amount of thought going on in my head, I decided to just go feed my hogs their evening meal and push them both from my mind. I lugged the sack of feed around and dropped generous servings into the multiple troughs in the pen. They weren’t eating but instead were crowding around something else. I walked into the pen and pushed through a few of them to see my wife’s half-eaten body lying in the center, her broken neck cocked to a very uncomfortable-looking angle. The only possibility I could surmise was that she maybe had jumped from one of the ceiling beams. I could come up with no reasons why. I guess it wouldn’t be too much trouble to call Lila back after all.

It's Killing Her

Words bubble up, and tumble from her mouth. Letters sticking to her lips, ripping; tearing.

They slither to the pages, black and red and slick.

All around her, colours fade and blur, as the world disappears.

The words keep pouring out, she cannot slow, she cannot stop. Fingers stained and aching, she has to let it out.

Words smear and bend and stretch.

They take a life of their own. They shift and stir, to fill the page. Finally coming to rest. She sits back shaking, wipes the ink from her lips. She sees all that she has done. This sickness, this madness. Creativity is a disease.

She’ll purge her soul, penning it to paper.

No cure in sight, it never ends.

She’ll write until her life is spent.

Molly HeiligI have a rough number, ballpoint on pink cardstock, tucked between my chest and bra. Thick lines from a girl, a siren with her plaintive wail, made lonesome singing love songs to hot spotlights over pretty heads. What the card has is a number, a name; what the card holds is a direct line to a warm body in this city, tonight. I did not mean to keep it. It was placed and forgotten before the late late night became the very early morning. I can feel it now. I can feel the outline. Now I have remembered. The corner needles the slope of my breast, every breath.

Before my sliver of sleep between cab door and deadbolt, I listened to 4:47 a.m. and every songbird sounded like a crow. I am tired. I am sleeping with laundry and longways twisted comforters, anything soft and space-consuming.

Think: large thoughts, think: surrounded, think: full.

Aladeen Stoll

I have a rough number

Tornado Song of a Wayward Daughter

She wanders highways soundless as a cloud And follows where her guiding breezes blow, Grey eyes on the horizon, head unbowed.

She takes her pleasure far from any crowd; Her backroads wind where fewer motors go. She wanders highways soundless as a cloud.

When moonless nights fall thick as any shroud, She rounds the curves before her wide and slow, Grey eyes on the horizon, head unbowed.

This is her escape. She never vowed To trust all that the Bible says is so. She wanders highways soundless as a cloud.

When whirlwinds come and sirens wail aloud, She breathes the tumult from the ground below, Grey eyes on the horizon, head unbowed.

She is free and rapturous and proud And knows all that she’ll ever need to know. She wanders highways soundless as a cloud, Grey eyes on the horizon, head unbowed.

Brianna ClampittWilliam Morris

Milk Eggs

Bread

Orange Juice

Protein Bars

Whiskey

Clever ways to describe the bits of memory that still pop up occasionally without sounding too Victorian for struggling with the loss of a metaphorical “you” that really represents myself

Yogurt

Bananas

I have eaten the hamburgers, and hot dog— at the stadiums, in the parks. Even the healthy Kosher dogs with a dill pickle— on the side. I’ve consumed them, the way the roar of the crowd at the ballpark swallows the cries of those searching for their own past time— the one their ancestors played before their names were replaced by mascots adorning ball caps, jerseys, and the inevitable stuffed animal waiting to be sold.

I have savored the smokiness under American cheeses with Dijon, like a wolf might consume the insides of rabbits unaware of their demise.

I have eaten my way up and down the coast respecting the local fare—the way a pimp might consume the bodies of women destined for lives beyond street corners and hotel rooms, that wear a glaze of sweat like a sheet, a dental dam preventing orgasms to surface the oceans of their shame.

I have eaten the fish and chips too, without fail accompanying a Guinness, the way I imagine Irishmen do in Pubs worlds away, where I have yet to grasp their concept of what green really is. I did it in festivals, and pseudo–hole–in–wall restaurants serving their fish and chips wrapped in imitation newspaper. And I attacked my food head first like a grand African American moose, whose nappy antlers pick and pry, looking for the truth inside

the flaky flesh of fish, tempered and matched with the crisp of fries—with the satisfaction of the Guinness chasing my meal, looking for something anything real— even the bratwursts, explosive like the cherry bombs in the hood on “independence day.”

I have eaten them all except for one, sick as I slouched like a bag of potatoes in the corner of a room, I ate them as surely as England ate Ireland, and regret too the way I devoured their treats like ants in a colony eat one leaf, yearning so much for yams, cassava, and beer made from kola nuts, instead I devoured this stuff like Jesse Owens gobbled hurtles in “L-shaped” leaps into the Ohio Sky. I am riding lips first across my life, as if my hunger—my hunger were the only way out of this lonely skin I’m suck in.

Mrs. Knaudi

When Mrs. Knaudi pranced into class her quirks were met with teasing, She didn’t mind the children’s sass in fact she found it pleasing.

She encouraged her students to be creative and aroused their imaginations. She called on the ones who were vegetative and used sock puppets for visualization.

It surfaced one day her husband at play in bed with another woman

When she stapled her finger and didn’t wince and laughed, “High tolerance to pain.”

I should have known she was lying since she put a bullet right through his brain.

The man woke up one morning to find a tree in his apartment. The combination of the smell of wood and the angle of the morning light on his forehead gradually brought him around. Still in a daze the man sat up, yawned, and moved to the bathroom. The bathroom was originally a broom closet, but the apartment’s previous owners had installed plumbing. The combination of limited mobility and recently installed plumbing made the bathroom feel like a public restroom stall, but without the invitations to a good time scrawled on the walls. In fact, instead of obscene graffiti, the bathroom walls were covered by a string of numbers which ended underneath the toilet. After relieving himself while blankly staring at the numbers, the man returned to his room and promptly tripped and fell over a root, hitting the ground with the palms of his hands and rapping his head on the floor. The man sprawled on the ground, cursing his cat for serving no other purpose than being a road block. Not quite ready to get up yet, the man turned over onto his back and it was then he noticed the tree. At first, he marveled in the beauty of the tree’s canopy. The midday sun was streaming through the maze of branches and vibrant yellow, almost gold, leaves. For a moment, the man forgot about how much he hated his cat. This peace was quickly replaced with stupefaction at the sight of the tree. Then the hangover descended, causing a dull ache. The man struggled to stand, inching towards the tree and using the trunk to pull himself up.

Here is a tree in my apartment, the man thought dully. Was it here last night? He attempted to pierce through the veil the alcohol had mercifully used to cover the events of the previous evening. After getting back earlier than usual, around 3 a.m., from helping a colleague with hypersurfaces, he proceeded to get wine drunk at the bar near his house and had attempted to impress a redhead with his knowledge of transcendental numbers. This quickly deteriorated into him shouting the volume of the redhead’s breasts, which he calculated on a spherical coordinate field. He was promptly thrown out.

Unbeknownst to the man, around 2 a.m. the tree had burst through

the floor, spread its roots out as far as they would go, and stretched toward the ceiling. One root had snaked under the bed and spooked the cat which ran hissing to the refuge of the space between the refrigerator and the wall. Another root had curled around the armchair. A third root had managed to pry the liquor cabinet open and drink two bottles of whiskey. The man stumbled into his apartment, dead drunk after being thrown out of the bar, and collapsed on his bed, completely missing the tree. That night the man had dreamt of math and fractals, seeing patterns twirl and twist in his mind. The man also, rather strangely, dreamt of the woods of his childhood. The man often dreamt about math, but this time it was different.

No, thought the man, there definitely wasn’t a tree here last night. The man felt the tree with his hands, carefully at first as if the tree might suddenly react, and then roughly as if challenging its very existence in his apartment. The man pulled some branches. The man pulled a leaf off and smelled it. Yep, the man thought, sure smells like a leaf. There’s a tree in my apartment. Jesus. Well, thought the man, might as well accept it. The man stepped back.

It appeared as though the tree had been growing in the center of the man’s studio apartment the whole time and just now decided to vault into maturity. The tree was positioned centrally, and its roots could touch all four walls. The man’s apartment resembled a rather spacious cell block or a very luxurious interrogation room, but the man had managed to turn it into something resembling a monastic cell. The walls had been plain cement blocks until the man covered them with white paint and, in a flash of creativity, bought some black paint and absolutely covered the walls in mathematical diagrams, pictures, scrawls. The man had derived the constant for logistic growth, e, to so many decimal points that the north wall of the apartment was covered floor to ceiling in numbers. These numbers continued marching on into the bathroom on the east wall. They gave the man something interesting to look at while taking a dump. A heap of construction supplies next to the east wall resembled a bed. The west wall of the apartment gave refuge to a chifferobe-turned-liquor cabinet, a makeshift desk he had found in an alley, and a bookshelf from his college residency at Cambridge. The bookshelf was covered in books. The man liked to read. The space between the

walls was now occupied by the tree. The canopy of the tree covered 95.7 percent of the ceiling. Due to some construction error, the apartment had one window that was just about head level, and the tree had thoughtfully covered it with its branches so as to bathe the apartment in splendid yellow light. A more artistic soul might remark that the window now resembled stained glass. The tree kind of fits, the man remarked, and he wondered idly if he could model the branches’ arrangement using the fractal math he had dreamt about.

The man had few friends and lived alone, except for his despotic red tabby named Gödel, after the Austrian mathematician who found the gaping hole in the center of mathematics. The man hated both the cat and Gödel equally, one for being a roadblock and the other for marring the only thing the man found beautiful in this life.

The man’s occupation, if one could call it that, was as follows:

Every couple of days or so the man would get a call. The callers would introduce themselves and tell him about their dissertation. One would have trouble proving a theory about optimization of triangles in graph theory. Or trialitarian algebraic groups. The man would usually ask just one question. If this didn’t work, the person on the other end of the line would invite the man over for dinner. The man would arrive, usually by bus, be treated to a nice dinner of either steak or pasta and then, with amounts of coffee and amphetamines that might induce epilepsy in others, help with their dissertation. These sessions would usually go long into the night, often with the two of them solving the problem around the 4 a.m. euphoria. They would put on the finishing touches when the first rays of light would peek into the house. Then the man would receive a paycheck or bundle of cash which he would promptly spend on alcohol before staggering home to sleep. This Spartan-esque lifestyle devoted to the cult of mathematics had turned him into a sort of medicine man of academia. The man would meet some 100 or 150 people a year and remember none of them, but he could remember each and every paper he worked on. His name was passed in secret around the cramped desks of doctorates of mathematics and written on slips of paper which were promptly destroyed. The man, rather naturally, was oblivious to it all. In fact, he was oblivious to anything that wasn’t related

to mathematics.

The man was oblivious to the days of the week. The man was oblivious to the months in the year. The man was oblivious to the outside world. He was oblivious to technology. The man did not own a computer or a cell phone. The man was oblivious to the fact that he didn’t pay any rent. The landlord of the building had a humanitarian streak in him and let the man stay for free in the studio apartment, mainly because the landlord thought the man was homeless or mentally deranged. As far as he could tell, the man had no family, friends, or close relations. Besides his cat, the man didn’t really have anything.

However, the man had mathematics, and she was a cold mistress. The man would wake up every day, and where others would start the day with coffee, the man would start the day with a proof. Sometimes it would be the Fundamental Theory of Calculus. Other times the man would be at the store, purchasing alcohol, and would be suddenly filled with the inexplicable desire to calculate the volume of all the alcohol on the shelf—a calculation the man could do rapidly and without effort. The man had no need to keep abreast of the current world of mathematics; the man was the current world of mathematics. One day, while helping a colleague out with a basic number theory paper, the man absentmindedly scribbled something he had been thinking about on a napkin. The man had developed a heretofore unheard of solution for endless generation of prime numbers. The colleague, flabbergasted, preserved the napkin and brought it to a cohort of his, who promptly converted the idea into a paper that revolutionized mathematics. The man, characteristically, was oblivious.

Now there was this tree. The tree kept mostly to itself throughout the last few weeks of winter. Occasionally the man would find a book open on the ground to a certain page with a root lying away from it. The tree managed to find the man’s college copy of Walden, and it irked the man to consider the possibility that the tree liked reading about itself. At first he had a problem keeping alcohol in the house. The tree was a thirsty soul. At times the man would return with a handle or two of whiskey, later to find both bottles empty and a number of glasses strewn about the floor. He solved this problem by leaving a saucer of whiskey next to the cat’s milk. Gödel was

suspicious and did not appreciate the new rooming arrangements, often using the tree’s trunk or roots as a scratching post. The man would sometimes wake in the middle of the night to the frenzied yelpings of Gödel, who had been imprisoned in a cage of branches towards the top of the tree. The man believed Gödel deserved it.

The man had been doing fine until this winter when he looked in the mirror and noticed the cross hatching of lines on his forehead, like a deeply etched Cartesian plane. It was at this point that he wondered about his age. Then the feeling of vacancy started.

Something was absent. Sitting in his room, looking at his frantic artwork and wrinkled forehead, the man felt a vast hole in his being. He could feel the dust begin to collect on his shoulders. The man tried to console himself with mathematics, but mathematics began to feel cold, where it once had felt warm. The man felt incurably lonely, abandoned on a mountaintop in the wilderness. He threw himself into his work, going a whole week without sleeping, working on three or four papers a day. He began making small mistakes, rounding errors, which soon culminated in full blown logical errors. The small, potted plant he had kept before the tree, instead of wilting and dying, broke the pot with its roots, overextended itself, and died. One day he opened the blinds when he meant to flush the toilet and flushed the toilet when he meant to open the blinds. He forgot where he lived and relied on his drunken muscle memory to lead him home. Soon he would become another nameless casualty. No one would remember him.

The tree, miraculously, brought him back. It brought him back through its tussles with the cat. It brought him back in the way it bathed the apartment in colored light. It brought him back in the way it almost seemed to lean over his shoulder when he was working at his desk. Or in the way there would always be a shot of whiskey waiting for him when he got home. It reminded him of something, of someone, but he could never name what or whom exactly. Whatever it was, it chased him through the last gasp of winter on towards spring.

On the first day of spring, after picking up the dropped copy of Walden, the man discovered an old box of books from high school. All memories of high school had been thrown out the balcony window of his brain

to make room for Euclid’s postulates and the homology of algebra. There was one memory though, and it came fluttering at him like a leaf in the wind as he beheld his battered high school copy of an obscure German publishing of Cantor’s Theory of Transfinite Numbers. But it wasn’t the theory that caused the man to pause; it was the memory of a girl he sat next to in homeroom.

The man struggled to remember her name. He grunted. Sweat broke out and began pouring down his brow. The cat, awakened from his nap, hissed and retreated into the corner. The tree, tensed up, withdrew its branches to the ceiling and waited. The man struggled and struggled until he felt the two sides of his very brain squeezing together to pluck this memory from the well of time. He struggled harder than he ever had on a math paper.

Her name was … what was it? What was her name? He thought desperately. It started with an M. He was sure of it. Mary? No, that wasn’t it. Mandelbrot? No, that was a mathematician. Mrr … mrr … Miranda. That was it. And like the click of a well made box, things fell suddenly and beautifully into place. Like watching the givens for a proof line up and point the way towards the solution, the man’s memories aligned themselves in perfect accordance to whom he was as a person, as a human. The man suddenly remembered his name. It was Paul. He remembered his age. He remembered his parents. He remembered everything.

It was as if someone had chucked a brick through the stained glass window of his musty, rotting, decrepit cathedral of mathematics, and all his memories of the outside world came pouring back with a burst of brilliant light. In high school, Paul had been the fifteen-year-old senior: a freshman, taking senior classes. In homeroom, he had met Miranda. Just saying her name, now, in his dank room, sent chills of joy and fear up his spine—something he had not felt in a long time.

Miranda had wanted to be a linguist, and Paul had fallen madly in love with her when she had proclaimed mathematics “a dead art” and calculus to be “organized cheating” because one can’t assume something has zero thickness in order to take a limit. She had taken him under her wing that first semester. They had kissed once, sitting on the bench outside the school in the falling snow, and Paul remembered the absolute joy and the simplicity of

it. The snowflakes had fallen in her hair, and she had looked so beautiful, so perfect. But not the beauty of a proof. This was a different beautiful, something he felt in his being—in his soul as opposed to his head. But it was on that day, cruelly, that both his parents died in a freak car accident. The roads were slick with black ice and so, Paul told himself, it was no small wonder they had died. The numbers were not in their favor. Having no relatives to tend to him, Paul was soon adopted by a pair of hard foster parents. On the surface, these parents looked fine, but underneath they angled for their foster son to be perfect. He would change the world, they said, whether he liked it or not, and he would change the world for them. They pushed and pushed him. He was rewarded with work and punished with work. Paul, standing in his room, had a brief and piercing memory of a next door neighbor, who was about his age, asking Paul if he knew what fun was. Paul honestly couldn’t tell him. He relaxed by deriving constants. He had derived π out to 11,000 decimal places by this point. Paul had retreated into his cathedral and locked himself away from the world. Life became easy for him: a series of proofs to solve and papers to write. He soon attended Cambridge. Then after graduating, with no incentive to find a job, he spent fifteen years ambling about helping people out for a living.

Paul felt dizzy and sat down. For once he was conscious of the time. It was midafternoon on a glorious spring day. It was, he thought happily, a Wednesday. Gödel cat-napped in a pool of light on the bed. The tree was still there, looking majestic. Paul looked at the tree. The tree looked at him. Paul felt like he owed the tree something and so he said: “Thank you.” The tree, almost imperceptibly, bowed, and then shrank. It now resembled a maple bonsai tree. For once, Paul was aware of the beauty of existence and he drank it in like whiskey.

“Damn,” Paul said, “this is a really shitty apartment.”

Eric to Battle

On becoming men

Jason N. Vasser

Jason N. Vasser

Remember Mickey D’s in the summers after track, it was 1989: before my parents divorced, before your pops got sick, back then we ran in heats, our young Pumas would barely touch the lane running, running fast, past time— for our parents, for the crowd, too fast to see the end coming— to all we understood about being boys and becoming men.

Going skating, we wore what we called “Cosby” sweaters, ball caps with flipped rims, and eyeglasses without prescriptions—all in the name of looking older like our fathers with beards, careers, and swag.

We’d talk to girls in hopes of understanding the mystery behind the French Kiss while every other weekend for a while, my sister and I would visit French Quarter Apartments to have Dominos with a stranger, my father, and some chick, and I would remember when all of us— would pile into your father’s van like logs—you know, the one with the TV and the blinds—and we’d ride all the way to Orlando for face paint, in matching shorts—you know the corny ones with the orange and green spots—and matching tube socks.

This was all we knew for years until gradually it stopped and was replaced by jobs. Remember when we had a beer with my dad and we spoke of yours? At the veteran’s home, alone, we went to see him that day, me and you, and watched the Olympic Track & Field events seemingly from the stands with him, the way he used to.

Psych Ward

The black man with the barrel chest, who used to spar with Spinks, wanders the fun house filled with frowning clowns and wavy mirrors. Having walked the serpentine path to the lounge in Ward F, he takes his meds and sits in his chair.

As the TV flickers, he sips his Coke. An aura of calm settles over his head and drifts down to his toes.

The river of voices ebbs and flows into a slow trickle.

As the chair’s cracked plastic arms morph into rabbit fur, and the static of the soap opera whispers into a white blur, silence settles into his soul.

Bob VassNo one told me that the years were golden, when Mom and Dad liked Ike. My world was a two-story definition of bricks, windows, and doors where comedies and tragedies played out on small stages with imaginary theater wings— the tiny places between rooms.

A backyard between small fences— the little piece of dirt that was our dream. Where captains sailed stick-masted ships and astronauts flew cardboard space capsules on limitless journeys through time. City farmers turned the earth in spring, yielding tomatoes and cucumbers, harvested with the utmost joy.

Then, icy blankets forgave the darkened world, and we played late in the white brightness at night. Explorers braved the cold in tennis-racquet-snow-shoes, trudging toward the pole, and slid down Art Hill on anything we could. It was Christmas then with real holiday smells: Mom’s room-mother cakes and little plates of pignolata. Time enough for her to play Santa.

Somewhere between Eisenhower and Nixon —46—

Sam J. ImperialePerhaps it was tears that marked the changes in the world. Not really old enough to understand why Mom was weeping over JFK, I watched cartoons in between the rider-less horse and John-John’s salute. And then suddenly awakened to the pain: Cousin Ronnie in ‘66, and we wept together over Bobby and Martin, then counted the body-count-cut-outs on Walter Cronkite’s graphic— a few every day slowly built up to Fifty-eight thousand two hundred and twenty. I saw Tricky Dick finally leave office.

The tree of my memories is almost bare; years have fallen like leaves between the small fences and now lay underfoot to be crushed into little shreds left to feel and comprehend. A few might remind me that it was real. My almost-forgotten youth existed somewhere between Eisenhower and Nixon.

Bowerbird

How little have I learned? Am I just a bower bird building boisterous nests for mates I can’t impress?

Bruce on the Black-

Dummy Doll Lover

Lothario, Lothario

Poor boy being flung around

By a two-foot terror in white ribbons.

He keeps a smile all the while, With pounding fists and parted lips. She beats that pretty face till it cracks then gives,

Spoiling her Sunday best as she stoops in the dust.

In a cotton dress baptized in tinctures of red, she severs

His playful extremities, squeezes his head

To pry it loose and leave him unmade.

Keep smiling, young Capricorn.

Smile while she screams.

Just the two all alone together

In the only child’s church, where

Daphne M. RiversEmpty swings sway in the breeze and Father’s watchful eyes close, Hallowed ground where the trees are living minarets

But the grass won’t grow

Poor boy, his armor, shield, and sword lay gleaming, Discarded in the sand.

Naked and confronted with godly rage—a toddler’s rage

Lothario says nothing, does nothing

He won’t say “I love you” like the box says he should

He won’t hug and kiss like it says he can

She sang to him—he didn’t dance

Poor girl, she had a dream, and he didn’t give a damn.

Gnarling baby teeth, saliva spraying

Lilly white ribbons cradling

Swollen eyes, wet cheeks

Fingernails grating plastic, breaking and bleeding

She wages war on his indifference

Keep on screaming.

Sea Maiden

Back when I’d only seen her from afar, Her distant form was cause for some surprise; But seeing her close, underneath the stars, I found myself more startled by her eyes. Some say they are the windows to the soul, Containing hints to one’s identity; And now I must believe that this is so, For looking in her eyes I saw the sea. Her irises were colored murky green, Her pupils dark as far-down ocean floors; Around her eyes, completing well the scene, Her face was tan as sandy island shores. I turned away, wishing for solid ground, From eyes that could lead anyone to drown.

Brianna ClampittOrchid

Aladeen Stoll

Ellie’s forehead had left a greasy imprint on the windowpane the night before. She positioned herself on the uncomfortable windowsill once again and tried to touch the glass in the same place. Watching for Patrick felt crazy, but books wouldn’t hold her attention, and the television was in the other room, much too far from the window. How would she make sure he came from the right direction? Something was happening with him, and she needed to know what it was. A week ago, Ellie had gently placed one of their wedding photos, the one with both of them wound up in her long veil, face down. Patrick hadn’t even noticed.

Ellie stretched her eyes open as far as they would go after squinting for so long into the night. “This is crazy,” she told herself over and over but did not move. It was dark outside, the street quiet and dull. Nothing interesting would happen; she knew that, as sure as she knew she would sit, selfdeprecating until his key was in the door. Patrick wasn’t cheating. He was in the med school’s library, studying until his own eyes crossed. “He wouldn’t cheat.” Ellie’s words were no comfort and disappeared as quickly as her breath on the windowpane.

She forced herself to look away from the street below. Their apartment was three stories up and looked out over a worn, brick road and many other squat apartment buildings. Behind her, within the apartment, Ellie was confronted with the major source of her suspicion—the flowers. She tried not to look at them, but they were there, in the darkness, dying. Patrick brought the first bouquet a month ago. He’d swung into the kitchen with them, braced by a hand grasping the door jamb. He held a fistful of fleshcolored peonies, each bloom the size of her face.

“I thought since we couldn’t have a garden, I might bring you the fruit of someone else’s labor,” he’d said.

She’d said, “Beautiful.” Patrick had been trying to be kind; they could have a garden. Their apartment had been chosen with that directive in mind. There was an accessible fire escape that received full sun. Unfortunately, Ellie couldn’t manage to grow anything. When Patrick started cracking jokes, Ellie Ellen Hup-

had stopped trying.

Headlights flashed across her eyes. Ellie slid from the windowsill until she was only peeking out. It wasn’t their car, but Ellie was relieved for the change of scenery. The car was an alarming shade of orange, even in the dark, and it pumped bass out into the night. Ellie’s wood floor picked up the vibration and tickled the arches of her feet. The car paused at the stop sign and then moved slowly on, leaving the world quiet in its wake.

She looked at the clock and thought that if she went to bed at this moment then she would get six hours of sleep, but she knew she wouldn’t, not until Patrick was home. This was crazy. She was acting crazy. Maybe Patrick enjoyed bringing home flowers every other day. Perhaps he stole them from people’s yards as he passed. That would explain why there were no purchases on their bank statement. The habit was getting out of hand though. She and Patrick were drinking out of the same glasses every day because they’d run out of vases. The damn flowers wouldn’t die fast enough.

Another car stopped at the sign below. It was their little white Corolla. Ellie backed away from the window and watched as her husband parked, climbed out, and removed his backpack from the passenger seat. There were no flowers tonight. Ellie turned on silent feet and made her way to the bedroom where she pretended to sleep until Patrick was warm and steadily breathing beside her.

Three days later, on Ellie’s day off, she decided to go to the little farmer’s market near Patrick’s university. She told herself it was an innocent venture and that she would call him later to see if he wanted to get lunch. She followed the route that Patrick normally took when he walked. It was a hot day, and within a few minutes the sweat was thick on her forehead and upper lip. She watched for victims of Patrick’s pillaging, examined flowering bushes, and checked alleys and gardens. She looked for pots and window boxes. There were a few tulip beds here and there, but they were not the same fluorescent shade of yellow as the ones in the stein behind her kitchen sink.

She considered giving up and calling Patrick for lunch, but as she pulled her phone from her pocket, Ellie spotted the source of the mystery flowers. There was a two-story brick house on a small hill with a crescentshaped sidewalk. The front slope of the yard was landscaped perfectly—long

but not very wide. Edging the sidewalk were poppies and along the front of the house were the bare heads of peony blossoms, come and gone. The second story had a wrought iron balcony, with more flowers in bloom. Baskets of begonias swayed beneath the balcony and their vines spilled over farther still. There was even a waxy-leafed magnolia tree at a corner of the house with tightly wound petals preparing to unfurl.

Ellie crossed the street and walked down the block to a small sandwich shop. There were a few students inside, but the tables outside were unshaded and thus empty. From a hot metal chair Ellie had a mediocre view of the brick house. She ordered coffee and waited. For a long time nothing happened. The waiter visited four times; lunchtime passed by, and Ellie didn’t call Patrick. Finally, when Ellie felt like the boredom had reached critical mass, the owner of the house came out onto the balcony.

A woman. Ellie considered her. The distance made it difficult to judge, but the woman looked older. The cut of her apple-green dress was reminiscent of the 50s and so was the set of her mass of black hair. The vibrant shade of the dress set off her dark skin beautifully. Ellie wanted a closer look so she decided to walk by. The woman caught Ellie looking at her and waved.

Ellie waved back, a quick motion, only once from side to side. She lowered her face but not before she noticed the woman’s thigh under the hem of her dress. Ellie tried not to compare the sight to her own pale, blotchy, freckled skin.

“Who is the woman you get the flowers from?” Ellie asked hours later as the door to their apartment opened. Patrick stood with his keys and backpack in one hand and some of the woman’s poppies in the other. The hand with the flowers fell.

“A friendly neighbor,” he said.

Ellie had planned what to say, but the scripted speech caught in her chest. She settled for asking “Why?” and opened her palm to the array of flora around them.

“El.” Patrick closed the door and walked to the sofa. He let the flowers fall from his hand; they brushed across the floor, their round heads deflating. “I thought you two could be friends. She knows how to get things to

grow. I thought she could teach you.” He paused. “It’s weird, isn’t it?”

“Yeah. It’s very weird,” Ellie said. She wanted a fight. To yell and throw things. But she didn’t want to scream at the top of his hanging head.

“I’m busy all the time; I wanted you to have a friend. Coralie’s … nice.” Her name came from the back of his throat, and he was anxious; Ellie could tell because he scratched the same spot on the side of his head every few seconds. “I didn’t want to tell you at first because I was worried you wouldn’t like her. Now, I think you would get along great, but I didn’t know how to explain.”

Ellie stared at him. Had he noticed yet that she’d eradicated all of the flowers? Pushed them deep into the dark recesses of a trash bag and scrubbed their watermarks out of every single one of her glasses? There wasn’t even a petal left, and the blood red poppies on the floor were the next to go. For the first time in weeks, their house smelled like bleach instead of floral perfume.

“You know what it looks like,” Ellie said, fists clenched.

“El, please. Do you think I would have brought the flowers home if that were the case?” Patrick looked disgusted. He had cheated once before, a few years ago when they’d first started dating. It was a worm in Ellie’s mind that she could not pull out.

Defeated, she sat next to him. “You could have spent that time with me. You could have come home.”

“You need a friend that isn’t me. You need a hobby.” He tried to take Ellie’s hand, but she moved it away from him.

“You can’t pick friends for me. I don’t even care about the stupid garden anymore.”

“You did.” Patrick’s voice was low.

The room was quiet. Ellie stared at the print of her forehead on the window a few feet away. Patrick stared at his hands.

“Maybe if you met her you would feel better,” Patrick said.

A few days later they stood on Coralie’s porch. Patrick held a bottle of Riesling, and Ellie held her purse so tightly that she left fingernail imprints in the soft, rose-colored leather. Coralie swung the door open. She wore a

gauzy yellow sundress, and her feet were bare. Her hair was pulled back and braided to one side.

Patrick beamed at Coralie, Coralie smiled brightly at Ellie, and Ellie tried not to run away. No recognition registered on Coralie’s face from their previous interaction, and for that Ellie was grateful.

Inside the house, they sat together in Coralie’s living room with glasses of tea, small disks of bread, and fruit jellies in porcelain jars. For an hour Patrick tried to subtly highlight why the two would make good friends. He said things like, “Her family is from North Africa, but she was raised in France. El loves French films,” and “Coralie’s a botanist, she specializes in orchids.” He scratched at the side of his head.

Ellie nodded when she needed to. They talked a little about foreign movies but not about gardens. Ellie watched her husband interact with this beautiful stranger, looking for signs of an intimate relationship. There was no precedence for this where she came from. In her hometown, if your husband was meeting secretly with another woman, then he was cheating. End of story. Ellie’d seen it over and over again growing up—first from fathers, then high school boyfriends and baby daddies. She had believed that she and Patrick were different but doubted the wisdom of that now.

“What do you do, El?” Coralie asked.

Inwardly, Ellie’s body revolted against hearing Patrick’s pet name come out of the woman’s mouth. She held her ground, though it felt like most of her body wanted to leap away, even if it meant leaving the rest of her behind.

“I work in a call center.” Ellie was confused. She’d assumed that Patrick would have told Coralie all about their situation, about Ellie dropping out of college to support them while he was in med school.

“And later you want to …”

It was very difficult for Ellie to keep her emotions off of her face— not only the confusion but also the building anger. Ellie got the distinct impression that Coralie thought it was unfortunate that she worked guaranteed, good hours at two dollars more than minimum wage.

“I mean, as far as an end goal, I’d like to work on sustainability in the community I grew up in.”

Coralie smiled at Patrick. “You think you’ll move back to Kansas?”

“I know we will.” Ellie did not like the implication. Patrick was looking through the stack of books on Coralie’s glass coffee table. Both women watched him.

“Shall we eat?” Coralie suggested as she stood and, after adjusting the fall of her skirt, walked into an adjacent room. A minute later soft music eased the silence.

Patrick caught Ellie around the waist as she rose. “Thank you,” he said meaningfully. Out of habit, Ellie lifted her face toward his but he let go before their lips touched. “I don’t want to be rude.” He walked into the dining room. Ellie followed but only so she could ask for the restroom. Although the question was directed to Coralie, it was Patrick who answered.

“Up the stairs and to the left.”

Ellie intended to call her mother from the bathroom to try and get an outside opinion, even if it was a biased one, but the bathroom was aglow with a faint violet light, and she put her cell phone back into her pocket. She slipped inside and closed the door gently behind her. The purple lights were on tracks where the walls and ceilings met. A few feet beneath them, reaching into the dim night, were Coralie’s orchids. Directly across from Ellie there was a large window, a rectangle but for the top, which was round. A streetlight, filtered by the frosted glass, backlit the biggest of the orchids.

When she turned the light on, the scene was even more surreal. The flowers were in terra cotta pots with holes near their base through which the plants’ roots sprawled like green fingers. The pots were placed on a tiled shelf, and it looked like Coralie had the bathroom set up so that she could water the plants without moving them. There were drains every few feet along the floor. The tub and toilet were plain, and there was one small mirror above the sink. Ellie walked slowly around the small room. Most of the orchids had at least one spike heavy with flowers. But the largest, the one with the windowsill to itself, had four spikes, each with at least seven open, pink faces and one or two balled buds, waiting to bloom.

For the first time, Ellie considered asking Coralie about the flowers. She did want to learn how to keep beautiful things like these alive. Ellie moved toward the big orchid and reached out to caress a petal. It leapt from

the stem at her touch.

Ellie let out a soft “oh” and reflexively glanced at the closed door. After a few moments of deliberation, she pocketed the fallen flower head. Downstairs, she could hear laughter and Patrick singing loudly along with a man on the record. Ellie had heard Patrick sing only once before, on their second or third date in his tiny car. They’d pushed her curfew to the limit, and he sang so she would stay a little longer. Then, his voice had been soft and hesitant. According to her watch, she’d been in the bathroom for nearly fifteen minutes. He did not seem concerned. It was time to go back.

“Sorry I was gone so long,” Ellie said as she entered the dining room. The table was set, and Coralie was cracking an egg over a dish full of pasta noodles.

“Are you feeling well?” Coralie asked. She discarded the eggshell and moved around the table toward her. Coralie looked concerned. Ellie looked at the crow’s feet around Coralie’s eyes.

Coralie lifted a hand as if to check Ellie’s temperature, and Ellie caught a thread of cigarette smoke. It must have been nestled in the woman’s hair or the fibers of her dress. Her movement thrust it toward Ellie, who stepped away from the smell more than the extended hand.

“Pardon me,” Coralie said, and looked embarrassed as she pulled her hand away.

“I’m fine. I got caught up looking at your flowers.”

Patrick nodded at Ellie. He looked relieved.

“To answer your question from before, Coralie, I am interested in conservation. I think I would like to be a consultant on implementing environmentally friendly practices. I’ve done some research on colleges in the area, and a few look promising.” The words poured out of Ellie in a rush, and she could feel her heart gaining speed in her chest.

Coralie began stirring the raw egg into the noodles; the motion made an unpleasant squelching sound over the low scratch of the record player. “That’s great,” she said, distracted by something within the walls of the pot.

“When did this happen?” Patrick asked.

Ellie knew the easy answer. “I started looking at schools about a

month ago.” In truth she had an entire folder of bookmarks for local universities, National Geographic articles, and conservation blogs; it had been her hobby until Patrick had made the flowers a more pressing issue. The hard answer was it had not really “happened” until the words left Ellie’s mouth.

“I’ll still be in school next fall,” he said.

Sitting at the table with Coralie still stirring and Patrick waiting, Ellie shrugged and then she smiled. —62—

In the Cutlass

we could drive for miles without words a silver thread tying us together unseen, unspoken circled around our ears

I gaze out the window dreaming of former mountains and hills as you bite your lip and drive inside the memory of when you were a boy fearless climbing anything you were asked wondering where pieces of that might have drifted

Laura Schuhwerkwe can’t see from the sun in our eyes but we don’t care it just reminds us that we’re alive so we drive for miles the wind carrying us a silver thread circled around our ears

the sun starts creeping in, pulling us back to each other and with a sigh for a new day you roll the windows down and the air pours in like a warm blanket

I put my arm out the window and let my hand ride the wind like I always did as a young girl imagining where the wind stopped and my hand began as the day finds itself you reach for my leg making sure I know you’re there you must have forgotten about the silver thread so I let you

Uncle Walt

You came into my life bearded and hairy-chested With shirt undone and hat cocked and you told me— You told me flat out:

“This is how you do it, with both hands upraised And mouth bellowing, and you don’t give a Fuck

What other people think.” For a while, It was all too much. I hid when you came over. But in quiet moments, When the world writhed in Ecstasy at my feet, I saw the grass To be the beautiful uncut hair of graves. And then I went and found you, Sitting quietly on a bench, Waiting for me to catch up.

Benjamin Luczak

Esther, to Miss Russia

Shine your pearly whites, my dear— your glittering opals gleam. Those orbs of optical perfection reflect more than they take in. Your tiara is the star of Russia, the wonder of the world.

But listen; ease your ear to hear below the earth—in dust I lie. My pageant parade led to the king’s chamber. My prize? Brutish beast, manic monarch who fought with the sea.

Lashing and slashing always a threat— if not by my husband, his henchman Nooses and knives surrounded me, little princess, queen of the world. And what would you do? What did I do? Would you risk your breath in the name of World Peace?

My teeth are crumbs and my eyes are sockets, but I rest with sisters and brothers in expectation— my name is on the lips of millions.

Adventure

Suzanne MatthewsThe boy loved books. Even before he was born he loved books. His mother read to him throughout her pregnancy, passing on to him her brown eyes and love of language. Throughout those nine months, she nourished him with the nutrients of her body and the words of her favorite authors. And on the day he was born, as the nurses cleaned him off across the room, she could feel he was still connected to her.

In the first months of his life, while his father and the sun and the world still slept, the boy would beckon her with a soft cry, and she would go to him.

“Buenos días mi angelito. ¿Quieres una historia?”

The little infant would grab for his mother, hungry for her embrace. Smiling.

“

Sí, sí hijo, I have a story for you.” She rocked him slowly and read to him. In no time at all, he’d drift back to sleep to the soothing tones of his mother’s voice, still clinging to her breast.

As he grew, he saw the books in his mother’s hands and grew to love the sound of a page turning as much as he loved the sound of her voice.

He enjoyed the colorful pages of his books, filled with exciting, animated characters. They were trying to tell him something, but he didn’t know what. Soon he was telling his own stories, narrating whole plots in his unintelligible baby language. When he was big enough, he would grab his mother’s books from their shelves and enthusiastically turn their pages back and forth, listening to the sound. He liked his mother’s books better—they were bigger, and they had more pages to play with. Seeing this, his mother decided to dismiss the age-appropriate children’s books at bedtime and started, instead, to read him her favorites. This was their little ritual. And to the child, it was sacred. By the time he was four, he was actually beginning to read them.

However, things changed when her esposo left. The cochino had taken nearly everything with him but the baby. The bookshelves, once endowed with tales of adventure and wonder, lay barren, and the house, stripped of its

family and furnishings, grew cold. In the following months, she slowly began to rebuild her collection of books—finding treasures where she could with the little money left over each month after the bills were paid. However, as time dragged on, she grew distant from the boy. She found it hard to even look at him, to see his father in his young face. She started drinking again. Soon she was drunk every day. She no longer read to him. Then, after he spilled her vodka on one of her books, she no longer allowed him to touch them. She moved the books into her bedroom, away from the clumsiness of young hands. He craved his mother, missed her. He longed to sneak into her room and lie next to her. To once again live in her world of books, to see their bindings perfectly aligned on the shelves, like a row of soldiers standing at attention. As the months passed and the bills piled up, she was forced to take a second job at the local bar, disappearing further from his life.

But on his first day of kindergarten, she came back to him—the boy saw a glimpse of the mother he once knew. His mother had woken early and made him breakfast. She was even singing. The morning passed too quickly for him. As the babysitter waited to take him to school, his mother came in with his jacket.

“You’re going to love school, mijo. There are so many things you will learn. So many books to read. And there will be many boys, just like you. You’ll make many friends.”

“I’m scared,” the boy said. He wasn’t really scared, but he wanted her to keep talking.

“You are so smart, mi amor, you’re not going to have any trouble making friends. But just in case, take this.” She handed him a copy of Huckleberry Finn—his favorite book. “Te amo, mijo. Be great.”

He left with his babysitter. He was sure that school was going to be the turning point that would bring his mother back to him. As he approached the classroom, he realized he really was scared and wished she were there to comfort him. He shuffled into his classroom. Children were running this way and that. Looking at the chaotic scene in front of him, he was unsure of where to go. He saw two boys talking nearby and thought he heard one of them say, “Tolstoy is my favorite!” Boys really were like him. Relieved and with renewed courage, he approached them.

“My mom loved Tolstoy! I never read him yet, though,” he said.

The boys looked at him with squinted, judging eyes.

“What? ... I thought you said you liked him?” He suddenly felt very embarrassed and shrank back inside himself.

“I said Toy Story,” said one of the boys.

“Yeah, weirdo, it’s not a him,” said the other.

The boy had never heard of Toy Story, and his tanned cheeks colored to a nice mauve. He thought as soon as he got home, he would go to his mother and ask her about this story. He lowered his head and walked away, too afraid to say anything further. He walked to the large round table and took a seat while the children played around him.

When it was time to begin, the teacher called for the class to settle down. Once everyone had found their seats, she began introductions. “Okay class, we’re going to start. When I call on you, stand up and tell the class your name loud and clear so they can know who you are.” She looked at the boy. She had noticed earlier how alone he was and thought she would help him out. “You there. Tell the class your name, honey,” she encouraged the boy.

“It’s Tollllstoy,” the boy from earlier shouted, dragging out the name in a taunting manner.

The class erupted with laughter.

“Tolstoy?” questioned one girl.

“What kind of a name is that?” said another.

“A weirdo’s name.” The whole class was talking about him. The young teacher, seeing that this was turning ugly quickly moved on, trying to spare him more embarrassment. He didn’t speak for the rest of the day.

When the last bell of the day sounded, the boy raced out of the school’s doors, hoping his mother would be there waiting for him. As he ran toward the doors, he thought of that morning and was full of hope. However, when he was met with the indifferent babysitter—and later, with his staggering mother—his stomach sank with the realization that nothing had changed. She had came out of it only long enough to send him off that day. Nothing would ever change.

He began to use this to his advantage. While his mother was at work or sick, he’d sneak into her bedroom and steal a book. She never noticed; she

never even read them any more. Every night he lay in bed and entered a new world. One in which he consorted with the characters of Hemingway, Faulkner, Hawthorne, and Twain. He knew also the names of Garcia Marquez, Fuentes, and Paz.

“It’s important to know where you come from, mijo,” his mother once said to him.

He was quite the prodigy. If he hadn’t gotten his books wet, maybe someone would have noticed. Now, away from the mess of the house and the strong, sharp odor of her chastising breath, he quickly grew to love his new secret life. These were his adventures. When he finished one book, he replaced it with another. However, there was something deeply unsatisfying in having only one book at a time. He missed the stacks of books that once surrounded him like a fort, making him feel safe.

But this was his life. Every year he started school with the hope that his mother had returned, and every year he was disappointed. He never made any friends. By the time he reached second grade, he barely spoke at all.

He was now seven years old. These days when recess was called, and the class ran to the playground, the boy walked, almost automatically, to the tree at the far end of the pavement. In his prior two years, he had tried to join them, but since that first day, he knew he didn’t belong. He preferred his books anyway.

He sat against the tree he had come to love and opened his book. He looked at the kids running around on the playground. Maybe he should try to join them, he thought. Maybe now, after all this time, they would give him a chance. He put his book away, walked back to the playground, and joined a game of tag.

“Can I play?”

“Sure. Get in the game,” said one of the boys. The boy felt exhilarated. He had taken his first step toward making friends. However, it wasn’t long until he realized that he had made a mistake. Every kid was running into him:

“Tag! You’re it!”

“Tag! You’re it!”

“Tag! You’re it!”

One right after the other. Each boy getting more forceful, pushing him harder and harder until he finally fell down. Defeated, he caught his breath, swallowed the lump in his throat, and walked back to the tree. He was Lennie, plain and simple.

His new teacher had been watching him for the first few weeks of school. She decided to approach him, “What are you reading?”

But the boy didn’t answer, and she was forced to look for herself. Of Mice and Men. The boy saw the puzzled look on her face. It was the same look he got from everyone at school. It said he was different.

That day, when he walked into his house with the sitter, they found his mother, kneeling in the bathroom. She looked like she was praying.

“Mami, are you okay?”

She didn’t answer him. Stumbling into the kitchen, she turned toward the girl.

“It’s okay, chica, you can go home.”

The girl left, and the mother resumed her post on the couch. The boy went to her bookshelves and grabbed a book. Maybe this would make her feel better. He brought her the book, but she looked right past him. Finally, he held it in front of her. She took another drink and slapped the book out of his hand, “¡Vete!” Go away, she said.

Tired of the rejection, of the puzzled looks, he ran to her room crying, and he grabbed his favorite books. He stuffed as many as would fit into his little duffle bag and, passing his sleeping mother, walked out of the little house.

Where would he go? He thought of Huck’s words: “You feel mighty free and easy and comfortable on a raft.” He loved Huck. Huck was his favorite character of all. He loved Huck’s sense of adventure. He knew he could get to the river undetected through the woods behind his house. He had walked it many times on his own adventures when his mother was sick. By the time he reached the river, the sun was beginning to set. He walked along, dragging the heavy bag. He wasn’t sure how he’d make a raft, but he knew he had to do it. Eventually, he stumbled along a little abandoned boat on the side of the river. He lifted his little duffle bag into the boat, finally relieved of its weight. He pushed the boat as hard as he could, moving inch by inch farther

into the water until the current began to take the boat, and he jumped into it. Safely ensconced in the little boat, he smiled. His adventure was starting. He didn’t know where he was going and, at that moment, he didn’t care. He would set out just like Huck; maybe he’d even make a friend like Jim. However, the river’s current grew rapid, and the boat started to rock furiously. He noticed a small amount of water puddling in the boat and realized why the boat had been abandoned. The water started to soak his bag. His books were getting wet. He struggled to move the books away from the water, pulling them out of the wet bag and placing them away from the leak; however, the weight of it all was too much, and the little boat tipped over. The boy and his books were spilled into the river. He was scared. However, as the world slowed down to a loud blur, he looked around and realized he was getting what he always wanted—a world in which he was surrounded by books. And, for a moment, he smiled.

The Broken Hearted Geisha ブロークンハーテッド芸者

Sam J. ImperialeOn a cool and foggy morning in the black volcanic soil, between the trunks of giant symmetrical pines, a geisha buried her diary, hidden in a bamboo box. She had written in dark characters on pages white as Fuji’s crest of ancient feudal wars and her forbidden love for a samurai.

Her proud warrior had wielded his sword against an opaline sky as sunlight glinted off the blades of shining steel, reflecting glimpses of crimson cherry blossoms which now temper the coldness of her beloved wounded tiger. Still clutching his sword, he searched for a sign of her.

An absent heart felt the blood of her fallen lover, and as his longing looks gazed into her eyes, she drew his knife from its scabbard and held it high to see the mirrored image of them both, forever frozen on its blade for an instant.

Something Stolen