T he Murillo Bulletin

About PHIMCOS

The Philippine Map Collectors Society (PHIMCOS) was established in 2007 in Manila as the first club for collectors of antique maps and prints in the Philippines. Membership of the Society, which ha s grown to a current total of 47 individual members, 8 joint members, and 2 corporate members (with two nominees each), is open to anyone interested in collecting , analysing or appreciating historical maps, charts, prints, paintings, photographs, postcards and books of the Philippines.

PHIMCOS holds quarterly meetings at which members and their guests discuss cartographic news and give after- dinner presentations on topics such as maps of particular interest, famous cartographers, the mapping and history of the Philippines, or the lives of prominent Filipino collectors and artists. The Society also arranges and sponsors webinars on similar topics. Most of the talks are recorded and can be accessed by members through our website. A major focus for PHIMCOS is the sponsorship of exhibitions, lectures and other events designed to educate the public about the importance of cartography as a way of learning both the geography and the history of the Philippines. The Murillo Bulletin, the Society’s journal, is normally published twice a year, and copies are made available to the public on our website.

PHIMCOS welcomes new members. The annual fees, application procedures, and additional information on PHIMCOS are available on the website: www.phimcos.org

Front Cover: Detail of the Philippines from the 1935 Theodore Roosevelt Spanish War Memorial Map (image courtesy of the Osher Map Library, University of Southern Maine)

CARR, Captain Robert. A chart of the China Sea and Philippine Islands with the archipelagos of Felicia and Soloo.. [London, c.1778].

PHIMCOS News & Events

THE FINAL PHIMCOS meeting in 2024, held on 13 November, was attended by a record number of 61 participants: in person by 16 members and 19 guests, and via Zoom by 4 members and 22 guests. Our guests of honour were Mayor Sitti Djalia Turabin Hataman (known as Mayor Dadah), the Local Chief Executive of the City of Isabela, Basilan, and her husband Congressman Mujiv S. Hataman, Representative for the Lone District of Basilan After dinner, Mayor Dadah gave a talk and video presentation on ‘Basilan: A Tapestry of Tradition and Diversity’, and this was followed by a presentation by Felice Noelle Rodriguez and Peter Geldart on ‘The History and Mapping of Basilan and the Basilan Channel’.

The island of Basilan, across the Basilan Strait from the City of Zamboanga, is home to a vibrant blend of cultural traditions shaped by centuries of indigenous customs, Islamic heritage, and regional influences. Known for its picturesque landscapes and seascapes, Basilan’s cultural heritage is a rich tapestry woven from the traditions of the Yakan, Sama Bajau, Tausug, and other ethnic communities which continues to thrive and evolve. Since the 16th century both the island and the channel have featured prominently on maps and charts, and in visitors’ accounts of their travels around the Sulu Sea.

On 28 February, 2025, Mayor Dadah generously hosted the PHIMCOS group which visited Zamboanga and Basilan (see below). The Mayor is also the main sponsor of a special issue of The Murillo Bulletin dedicated to Basilan to be published later this year.

The first meeting of 2025, held on 19 February, was attended in person by 17 members and 12 guests, with 3 members and 3 guests joining via Zoom. As this was our Annual General Meeting, Jimmie González recapped PHIMCOS activities over the preceding year; reported the recent decisions taken by the Board of Trustees, including changes in the board members and officers (see p. 44); and asked the members to ratify the ten board resolutions that had been circulated to them.

Following the AGM and dinner, John Silva gave a talk about ‘Philippine Colonial Photography in the Philippines’ in which he explained how the use of photography was a defining moment for the various peoples living in the highlands in the late- 19th and early- 20th centuries. He covered the convergence of photographs as a tool for anthro pologists with the active preservation of the heritage of the indigenous peoples of the Cordillera in Northern Luzon. Photography allowed them to maintain extensive documentation of their lives and, to a great extent, retain their traditional cultural practices well into the 20th century.

In a ‘show- and- tell’ session held a fter John’s presentation, Jimmie González exhibited a big sea chart titled Loran C / Asia / Philippines Central Part, which covers a large part of Luzon, Palawan and the Visayas. Loran C was a hyperbolic radio navigation system which was developed by the U.S. Coast Guard and widely used by the military and navigators from 1957 until satellite navigation was introduced in the 1990s Loran C charts are no longer produced but remain popular with fishermen and commercial divers The chart was issued by the U.S. Office of Coast Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

On 21 January, 2025 PHIMCOS members went to see ‘ Manila: Nexus of Empire’ , an exhibition by the National Archives of the Philippines (NAP) in collaboration with the Philippine Normal University. Through facsimiles of administrative, architectural and urban documents, plans and maps, the NAP presented Manila’s role as the ‘ seat of governance’ for Spain’s empire in Asia from the 16th to the 19th c enturies. Ino Manalo, the NAP’s Executive Director, led the members around the exhibition and highlighted the NAP’s objectives of bringing old documents to life through interactive displays, thereby making history come alive for today’s youth.

After the visit to the exhibition, the members went to the National Museum of the Philippines to see the newly- acquired clay sculpture by José

Rizal titled ‘ Josephine Sleeping ’ . Made during his exile in Dapitan, the statue is a tribute to Josephine Bracken, who m Rizal married a few hours before his execution on 30 December, 1896. The sculpture, offers an intimate glimpse into the humanity and personal lives of Rizal and his last love, and is believed to be a memento intended to be kept close to its creator.

Other exhibitions and events to which PHIMCOS members were invited included:

The opening on 11 December, 2024 of Kultura, Kasaysayan at Kapangyarihan ‘Homage to the Revolutionary Spirit and Cultural Memory’, an exhibition of anting- anting (amulets), maps, flags and bladed weapons from the Edwin and Aileen Bautista Collection at Museo De La Salle

‘ War & Memory: 80 Years After’, an international conference and associated talks, tours and films organised by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) and the Philippine World War II Memorial Foundation from 18 February to 1 March, 2025, to mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II in the Philippines.

In April, ‘The Battle for Manila: World War II in the Pacific ’, an exhibition at the Ortigas Greenhills Mall of o ver 80 large framed photographs from the collection of fellow members Albert Montilla and Rosario Ortigas. On display were photographs of pre- War Manila, its destruction and liberation, and contemporary maps.

‘The Philippines in the Nusantara: Connections and Exchanges’, a talk on 26 April, 2025 at the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur by Dr. Felice Noelle Rodriguez in which she explores the Philippines in Nusantara waters, tracing island and sea connections in the Malay and Indonesian archipelagos through time

On 1 May, 2025 the inauguration of the De La Salle Center for Heritage Conservation at the campus of De La Salle University in Dasmariñas, Cavite The center, set up by Ephraim ‘ Eddie’ Jose, will provide facilities and services needed for the holistic and scientific c onservation of the cultural heritage of the Philippines, especially works on paper and fabric

From 25 February to 1 March, 2025 a group of 20 PHIMCOS members, including family and friends, travelled to Zamboanga for the opening of ‘Zamboanga Encounters: Where Land and Sea Meet’, an exhibition arranged and sponsored by the Universidad de Zamboanga (UZ), the National Museum of the Philippines, PHIMCOS and the Tourism Office of Zamboanga City

Curated by Dr. Felice Noelle Rodriguez, the exhibition has been described by the UZ as providing ‘an immersive walkthrough of Zamboanga’s shared history and cultural identity … and the deep connection between the city’s landscapes and the maritime world that shaped it ’. It will remain open until 28 February, 2026.

On arrival we checked into the new Garden Orchid Hotel and then proceeded to the Alavar Farm House, a private restaurant in barangay Lumbangan. Our delicious dinner, arranged by the Universidad de Zamboanga and the City Tourism Office, showcased Zamboangan specialities ‒ notably the famous local curacha (spanner crabs) with Alavar sauce.

Next day was the Dia de Zamboanga, celebrating the anniversary of the City’s charter when the first city officials were sworn into office on 26 February, 1937. We started our tour by visiting Fort Pilar, the Spanish fort founded in 1635, deserted in 1663, reoccupied by the Spanish from 1719 to 1898 and by the U.S from 1899, seized by the Japanese in 1942, taken over by the Republic of the Philippines in 1946, and restored by the National Museum of the Philippines in 1980- 86. Outside the fort’s eastern wall is the open- air Marian shrine dedicated to Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Zaragoza, where we lit candles and made offerings before admiring the statue of the Virgin and the restored relief of the apostle James the Elder’s vision on the banks of the river Ebro.

Waving from the balcony of City Hall

We were then treated to a private tour of the BPI Zamboanga Museum, which is normally closed to the public, led by Carmina Marquez (Head of the BPI Foundation), Charlene Marinas (Zamboanga Area Business Director) and Anne Marie Ramirez (Branch Manager). The museum occupies the upper storey of the house in which the original branch in Zamboanga was opened by Francisco Barrios in 1912; this was only the second of BPI’s branches outside Manila, and the original counters on the ground floor are still in use today. On display were maps, photographs, paintings, furniture, textiles, porcelain, glassware, kitchenware, and colonial fixtures including Zamboanga’s oldest bathtub and bidet.

Our city tour continued with a visit to City Hall, where we were able to meet the Mayor, John Dalipe, and present him with copies of The Murillo Bulletin. After lunch at the Hacienda de Palmeras it was time for some retail therapy, and a visit to the Yakan Village resulted in most of us purchasing colourful placemats, bags, table runners and clothes woven in their traditional patterns by Yakan women from Basilan. To round off the day we had merienda while waiting for the sun to set at La Vista Del Mar, followed by another scrumptious dinner at Alavar Seafood Restaurant in barangay Tetuan.

The following morning we boarded bancas for the short ride to Great Santa Cruz Island, located in the Basilan Strait 4 kms south of Zamboanga. Arriving on the beach ‒ said to be one of the best in the world, with pinkish coralline sand ‒ we were greeted by ladies from the Sama Bangingi community, brightly dressed in red, blue and yellow costumes, who performed the traditional ‘fingernail dance’ of the Tausug people called pangalay. After merienda and another short boat ride we transferred to a fleet of small boats provided by the Yellow Boat of Hope Foundation to explore the island’s protected mangrove

lagoon, where we saw a large number of stingless jellyfish and were even given permission to touch them. The vivid patterns of the sails on the vintas (outrigger boats used across the Sulu Sea) along the shores were the ideal background for our photographs.

In the afternoon we were taken to the main campus of the Universidad de Zamboanga (UZ), where we admired the summit centre, the chapel of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the koi pond and the statue of Arturo F. Eustaquio, who founded the college in 1948. Today UZ is the largest private educational institution in western Mindanao, with some 11,000 students and a reputation for providing top- tier secondary, tertiary, technical and graduate programmes for its multicultural students through a variety of learning modalities. After touring the state- of- the- art teaching laboratories, we proceeded to the Rosa Function Hall for a sumptuous sit- down dinner prepared by Chef Aldwin Sahirul, with the former Mayor of Zamboanga, Beng Climaco, as sous- chef. Before the dinner, hosted by the university’s Centre for Local History and Culture (CLHC) led by Noelle Rodriguez, UZ President Abram M. Eustaquio (the grandson of the founder) invited the guests of honour to sign the UZ Guest Book.

On 28 February we assembled early for our trip across the strait to the island of Basilan. On arrival in Isabela City after a rather bumpy 40minute ride on speed boats we were met by our hosts, Mayor Sitti Djalia Turabin Hataman (known as Mayor Dadah), Lone District Representative Mujiv Hataman and City Tourism Officer Claudio Ramos II. Having transferred to sakayans (small fishing boats) we crossed to the barangay of Marang- Marang on the island of Malamawi, where we were welcomed on one of the floating cottages in the mangrove sanctuary by colourfully- attired Sama Bangingi ladies from the Marang- Marang Women’s Association and the Bajau Women Weavers Association of Tampalan, who performed the traditional Sama - Bajau igal tariray dance for us.

We watched the weavers at work and, inevitably, bought most of the finished tepo or baluy mats (made of dyed dwarf pandan leaves) that were on display. An even more welcome sight was the huge spread of Sama and Tausug heirloom dishes, which were new to most of us, including oko- oko, rice cooked in a whole sea urchin shell;

Weaving a tepo mat at Marang -Marang

utak- utak, a spicy fish cake with grated coconut; junay, rice with burnt coconut meat and spices wrapped in banana leaf; panyalam, a deep-fried pancake made of glutinous rice, brown sugar and coconut milk; putli mandi, steamed balls made of glutinous rice or cassava filled with sweetened coconut; and lokot- lokot or jaa, a crispy fried pastry made from glutinous rice flour and sugar.

Our journey then took us by boat through the channel that divides Isabela City, where we admired the multi- coloured Bajau houses built on stilts, and then by bus to Mayor Dadah’s Pahali White Beach Resort on the northern coast of Malamawi. There we were greeted with a display of music and dancing by the Pasangan Cultural Dance Group, and enjoyed a phenomenal seafood buffet with mounds of sushi, fish, scallops, clams, crabs and lobsters. And more shopping ‒ not only mats and textiles, but also traditional Yakan pirahs (a local type of bolo knife) forged by the renowned blacksmith Datu Halun Al- Rashid B. Asakil. Before returning to Zamboanga we visited the hill- top hotel under construction by Mayor Dadah overlooking the resort, with spectacular views; the soon- to- open Isabela de Basilan Museum curated by Marian Pastor- Roces, who had kindly arranged to join our Basilan trip; and the Tourism Information Center.

The week culminated with the gala opening of the exhibition ‘Zamboanga Encounters: Where Land and Sea Meet’. Formally dressed in our gowns and barongs, we assembled at the National Museum of the Philippines in Fort Pilar. At the opening ceremony we were entertained by the Coro Universidad de Zamboanga choir, and then heard speeches by former Zamboanga Mayors Manny Dalipe and Maria Isabelle ‘Beng’ Climaco- Salazar; City Tourism Officer Sarita Sebastian (representing Mayor John Dalipe);

UZ President Abram Eustaquio; PHIMCOS President Jaime González; National Museum Chairman Andoni Aboitiz; and CLHC Director Felice Noelle Rodriguez.

After cutting the ribbon, Noelle conducted a tour of the many exhibits ‒ reproductions of maps, prints, paintings and photographs ‒ housed in the ground-floor vestibule of the museum. A guidebook and postcards were made available, and interactive displays of visitors’ comments were displayed; the sponsors welcome donations to provide funds for paper and coloured pencils for use by children. There were so many people in attendance that many of us returned the following morning for a more leisurely viewing of the exhibition, as well as the permanent exhibits displayed elsewhere in the museum. A buffet dinner was served in the Fort’s great courtyard, where a stage had been erected for the spirited danc e entertainment provided by the Nawan Cultural Dance Ensemble. A wonderful evening was enjoyed by all.

Our trip to Zamboanga and Basilan was as successful as any organised by PHIMCOS, and we thank all who participated; our gracious and generous hosts at the Garden Orchid Hotel, BPI Zamboanga Museum, City Hall, Great Santa Cruz Island, the Universidad de Zamboanga, Isabela City, Malamawi, and the National Museum of the Philippines; the Tourism Offices of Zamboanga City a nd Isabela City, John Lester Lopez at UZ and Derek Lim for arranging all the logistics; our photographer Jay Molina; Dynah Gochuco for helping organise all our meals; and above all Noelle Rodriguez for all the months of hard work she spent in both curating the exhibition and organising this most memorable trip. Next stop: Cebu!

The PHIMCOS group outside Fort Pilar, all of us dressed for the opening of the exhibition

OU R COVER shows a detail of the Philippines from an amusing pictorial map that celebrates the life of Theodore Roosevelt. The map, titled Theodore Roosevelt Spanish War Memorial Map, depicts the story of the SpanishAmerican War of 1898 and American expansion into Cuba, the Philippines, China and Puerto Rico. Included are images of military figures who participated in the war and were part of the efforts to increase the interests of the U.S. in other countries An image of President William McKinley, who declared war on Spain on 21 April, 1898, is shown next to a map of Cuba.

At the top of the map a portrait of Roosevelt ‘The Rough Rider’ is surrounded by flags and flanked by vignettes of his life from rancher to becoming President after the assassination of McKinley in 1901 In the center is the Spanish War Veterans’ Memorial building , superimposed on a compass rose. Around the map of the Philippines Islands

are portraits of Admiral George Dewey, General Henry Ware Lawton, General Wesley Merritt, Colonel Frederick Funston, and Emilio Aguinaldo. Vignettes show the Battle of Caloocan; A Spanish Prisoner; the Fall of Manila; the Battle of Manila Bay; the Entrance to the Arsenal, Cavitè, with Wreck of Spanish Fleet in the background; Stretcher Bearers; Insurgents; and the Rainy Season. Some of the accompanying comments would not be considered appropriate today!

This rare map measures 43 cm x 57 cm and was compiled by Josephine Wilhelm Wic kser, designed by Carlo Nisita, published in 1935 by The Theodore Roosevelt Spanish War Veterans’ Memorial Association, Inc., Buffalo, N.Y., and printed by The Holling Press, Inc., Buffalo, N.Y. This example is held in the Osher Map Library, Smith Center for Cartographic Education, at the University of Southern Maine: https://oshermaps.org/map/58757.0001

Theodore Roosevelt Spanish War Memorial Map (image courtesy of the Osher Map Library )

Fr. Vittorio Ricci’s map of Australia Manila, 1676

by Daniele Quaggiotto and Peter Geldart

ON 4 JUNE, 1676, Fr. Vittorio Ricci, O.P. sent a letter from Manila to the Sacra Congregatio de propaganda Fide (Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith) in Rome, in which he says:

I am trying to discover and enter the Austral Land which is known as incognita , which is the fifth part of the word. This land contains many kingdoms and nations whose rough drawing I enclose with this letter. Because there is no part of the world subject to the Catholic religion from which it would be easier to organise this mission as from here (as one can see from the map), for this reason I would like to go to those kingdoms to announce that there is a God.(1)

A curious map

Titled Terra Australis Quinta Pars Orbis (Terra Australis Fifth Part of the World) and addressed Sacræ Congregationi de propaganda Fide (sic ), the map is dated ‘Manila 1676’ and signed Humillimus Subditus Fr. Victs . Riccius. Ord. Predicat (Your Most Humble Subject, Father Victorio Riccio of the Order of Preachers). It is drawn in ink and watercolour on paper, measures 31.2 cm x 41 cm, and is now held in the Borgia Collection at the Congregazione per l'Evangelizzazione dei Popoli (Congregation for the Evangelisation of Peoples) in the Vatican.

The map is drawn on an unusual, semihemispherical projection, with its two lenticular halves meeting and centred on the Polus Antartic (South Pole) positioned in the middle of the Australian landmass. Three latitudes are indicated by concentric circles: the Circulus Antarticus (Antarctic Circle), the Tropicus Capricor. (Tropic of Capricorn), and the Linea Æquinoct (Equator). From the top to the bottom of the continent TERRA AUSTRALIS olim INCOGNITA nunc ex parte COGNITA (TERRA AUSTRALIS once UNKNOWN now partly KNOWN) is written.

In the top- left corner of the map the islands of Gilolo (now Halmahera) and Ceram (now Seram) are depicted, next to Papuas and Nova Guinea

(New Guinea). The latter two are shown as connected to the Australian landmass, and the word Pigmes (Pygmies) is written to the north of the Tropic of Capricorn. Further to the east are the Ins. Salomon (Solomon Islands). Two toponyms are shown along the western coast: at bottom- left, C. Concordia, with the annotation hic sunt homines precellens statura (here there are men of rema rkable stature); and at bottomright C. Landt

To the north, straddling the equator, the following islands are shown: Insulæ Philippinæ, Mindanao, Paragua (Palawan), Timor, Celebes, Flores, Borneo, Java and Sumatra. Outside Terra Australis the map also shows parts of Peru, Chile and Brasil (sic ), a number of cities in South America, and (below) Afric æ Pars (the southern part of Africa ) and the Ins. Maldivæ (Maldives).

A legend in two cartouches at the sides of the map reads: Tabula hæc cum in minimo puncto facta sit desunt penes innumerabiles Insulae, cum finis noster sit tantum ostendere ubi sit Terra Australis et quanta (Since this chart has been made on a very small scale innumerable Islands are altogether missing, since our only purpose is to show where Terra Australis is and how vast it is). Another legend, below the islands at bottomleft, reads: Ex istis Insulis haud difficilis est aditus ad Terram Australem (From these Islands the access to Terra Australis is not difficult).

Some Italian scholars believe that Ricci's is the first map where Australia is shown in its entirety, although it is probably more accurate to say that it is the first readily- recognisable map of Australia as a whole. However, the Australian map collector and author Dr. Robert Clancy, contacted by email, is of the opinion that the first map to show Australia as a whole is probably Description de la Terre Soubs.Australe , which shows Magallanica sive Terra Australis Incognita. First published in Amsterdam in 1616 by Jocodus Hondius Jr. in the Latin edition of the pocket atlas Tabularum Geographicarum by Petrus Bertius, the map harks back to the world map of 1531 by

Terra Australis Quinta Pars Orbis by Fr. Vittorio Ricci, Manila 1676 (copyright © Archivio Storico di Propaganda Fide)

Oronce Finé and other 16th- century doublehemisphere world maps that name the continent of Antarctica as Terra Australis.

Missionary and envoy

Ricci was born and christened Francesco Angelo in 1621 in Santa Maria a Cintoia , near Florence. At the age of ten he joined the monastery of St. Dominic in Fiesole as a friar and took the name Vittorio. Having been sent to study at the Dominican colleges in Rome, he was ordained and returned to the monastery at Fiesole to teach philosophy.

In 1644 he was recruited for missionary work in the East by Fr. Juan Bautista Morales, O.P. Recognising Ricci’s talents, the missionary sent him to Rome to petition Pope Innocent X for pontifical university status to be granted to the Dominican college in Manila (founded in 1611), which thus became the Pontifical and Royal University of Santo Tomas, the oldest university in Asia with a European charter.

Ricci travelled to the Philippines via Mexico in 1648, and in Manila he worked with the Chinese of the Parián. Having learned Chinese, in 1655 he transferred to the Dominican mission in Amoy (now Xiamen), where he served as procurator of the Spanish Dominicans and formed a close alliance with Cheng Ch’eng Kung (Zheng Chenggong), known as Koxinga, the rebel general who ruled Fujian, invaded Taiwan and raided the Philippines. In 1662 Ricci returned to Manila as Koxinga’s envoy, conveying his threat to invade the Philippines if the Spanish did not submit to his rule. However, Koxinga died in June 1662 and the invasion did not take place.

After another diplomatic mission to Manila in 1663, Ricci settled in Fuzhou in 1665 and, to escape deportation to Beijing after an imperial edict, he offered his services to the local representative of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (the Dutch East India Company, known as the VOC) as a trade facilitator with the Spanish. His mission failed and, on his return to Manila, Ricci was punished by Governor- General

Diego de Salcedo for his unauthorised trading initiative until Salcedo was removed from power two years later. In 1667 Ricci completed an account of the Dominican mission in China, Hechos de la Orden de Predicadores en el Imperio de China, but it remained unpublished.

Cartographic sources

We do not know for sure what cartographical sources Ricci used for his map of Terra Australis, but we can speculate. In the first half of the 17th century a succession of Dutch navigators explored the northern, western and southwestern coasts of Australia , in particular Willem Janszoon in 1606; Dirck Hartog in 1616; Jan Carstenszoon in 1623; and François Thijssen in 1627. These Dutch explorations culminated in the circumnavigation of the area by Abel Tasman in 1642- 44. This was during the Golden Age of Dutch cartography, and Australia began to be depicted in some detail in the post- Tasman maps of the East Indies published in Amsterdam, notably those by Claes Janszoon Visscher, Joan Blaeu, Arnold Colom and Hendrick Doncker, and in later editions by Pieter Goos, Frederick de Wit, Joannes van Keulen and others.

Ricci had become interested in cartography soon after his arrival in Manila in 1648. In a letter he sent to the Sacra Congregatio dated 27 June, 1651, Ricci commented on Spanish mapmaking :

Your Excellency who sits in Rome ordered that I should send him some maps of this part of the world. I am endeavouring to draw it and send it, but because the Spanish are not talented in these things, but only in matters of war, they did not produce maps of the Philippine Islands but only hydrographic ones for sailing. ... In the meantime I am sending you a very big map of the entire world which was brought to me from Beijing, the Court of Great China, which was made by Father Matteo Ricci, which you will enjoy seeing as it is with Chinese characters.(2)

In a following letter dated 15 July, 1652, Ricci continues:

I happened to talk to some people who have sufficient information about geography and hydrography, and in talking about the land which they call Australe Incognita (of which I had already reliable information from different sources) they assured me that many islands have already been discovered, some of which are so big that they think they are a landmass such as Europe and other parts of the world. They added that the Mahomedan sect has reached until 14 degrees towards the Antarctic Pole and is spreading at great speed in that region They [the islands] are very far and sailing is difficult because there are many islands in the Archipelago; we will pass the equinox line which lies 14.5 degrees from here and from the line we will head [south] until 20 (or possibly 25) degrees.(3 )

de la Terre Soubs.Australe by Jocodus Hondius Jr. / Petrus Bertius , Amsterdam 1616 (image courtesy of Sanderus Antique maps & books )

Description

The ‘people who have sufficient information about geography’ may have included the Jesuit missionary, historian and cartographer Martino Martini, who was in Manila when the second letter was written; in another letter Ricci mentions meeting him. During his years in Amoy Ricci may also have obtained access to Dutch maps showing Australia through his contacts at the VOC. The fact that he got into trouble with the Spanish authorities because of his dealings with the VOC may explain his reluctance to mention these as the source of his own map of Terra Australis

Another source of information is mentioned in the letter of 4 June, 1676, in which Ricci recounts talking to some natives ‘of the said Austral Land’ who had been ‘captured and made slaves by the Dutch who discovered parts of the said land’. He describes the men ‒ who were more likely to have been natives from Papua New Guinea,

enslaved in Tidore, rather than aboriginal Australians ‒ as ‘of dark complexion (some are black), brave and strong’. He goes on to explain:

They say that if one penetrates the interior [of Terra Australis ] one can walk for more than two years without seeing the sea, and that there are white and red nations like us, and this is plausible because they are in that part of the South in high latitude up to the Antarctic Pole.

Ricci’s map is quite crude, inaccurate and with little detail. The general shape of the continent is likely to have been copied (directly or indirectly) from Dutch maps, with the Gulf of Carpentaria recognisable at top left, and the peninsula at top right representing Tasmania (at that time not known to be an island). The theory that the likely sources for Ricci’s map were Dutch is supported by his use of the toponym ‘C[ape] Landt’ on the southwest coast of Australia .

Polus Antarcticus by Henricus Hondius, Amsterdam c.1637 (image courtesy of Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc.)

The projection used for the map, and the location of the South Pole as somewhere in Western Australia, can be traced to an earlier, pre- Tasman map. In c.1637 Henricus Hondius published the first edition of his important and popular hemisphere map Polus Antarcticus. The map is centred on the South Pole, which is shown surrounded by partial coastlines outside the Antarctic Circle and with the southern continent named as Terra Australis Incognita. A separate landmass is shown straddling the Tropic of Capricorn with (on the early, pre- Tasman editions) toponyms that include t'Lant van d’Eendracht, d’Edel's Lant and t'Lant van P. Nuyts, dated 1616, 1619 and 1627 respectively. On later editions of the map this landmass is identified as Nova Hollandia, the name given to Australia by Tasman.

Conclusion

By conflating the Polus Antarcticus map with the later Dutch maps showing most of the Australian coastlines, Ricci’s map is erroneous and misleading. The narrowness of the Pacific Ocean, which had already been well explored by 1676, is an obvious mistake. However, Ricci was not striving to produce an accurate map or sea chart of Australia, and although the map can be dismissed as a mere curiosity it did successfully

meet its author’s intentions. As stated in his letter, the purpose of Ricci’s ‘rough drawing’ was to show that the fifth, southern continent was both big ‒ containing a large number of ‘kingdoms’ and native inhabitants who needed to be evangelised ‒ and close to Spain’s colony in the Philippines, the easiest place from which to launch an evangelising expedition.

Ricci’s letter to his superiors was a request that he should be allowed to establish a mission in Terra Australis, with the entreaty: “To execute this plan it is necessary to have the authority of your Holy Congregation, which should prompt the Catholic King, so that the Government of these Islands does not embarrass him but instead helps and spurs him.”

It took nearly five years for Ricci’s letter and map to reach Rome. On 15 July, 1681 nine cardinals of the Sacra Congregatio met to discuss his request, which was summarised for them by Archbishop Edoardo Cibo, the Congregation’s secretary. The cardinals supported the proposal completely, and the Prefecture Apostolic of Terra Australis was created, with Ricci as its Prefect Apostolic. However, the decision came too late for Ricci to take up the mission, and he may no t even have known of his appointment when he died in Manila on 17 February, 1685.

This article is in part based on the presentation given to PHIMCOS on 18 October, 2023 by Daniele Quaggiotto, who has translated the passages from Fr. Ricci’s letters quoted above from the original Spanish and Italian.

Bibliography

Benno Maria Biermann, Die Anfänge der neueren Dominikanermission in China , Druck des Albertus -verlages, Münster, 1927.

Robert Clancy, The Mapping of Terra Australis, Universal Press Pty Ltd, Macquarie Park, 1995.

Jos é Maria González, O.P., Un Misionero diplomático: Vida del padre Vittorio Ricci, Ediciones Studium, Madrid, 1955.

T.M. Perry, The Discovery of Australia: The Charts and Maps of the Navigators and Explorers, Thomas Nelson Australia, Melbourne, 1982.

Dorothy Prescott, ‘A Little Master's Piece’, in The La Trobe Journal No. 79, Autumn 2007, State Library Victoria, Melbourne.

Ralph M. Wiltgen, ‘The Prefecture Apostolic of Terra Australis 15 July, 1681’, in Hemisphere, Vol. 26 No. 1, July/August 1981, Commonwealth Department of Education, Canberra.

References

1. Archivio Propaganda Fide, Scritture Originali riferite nelle Congregazioni Generali (SOCG), Vol. 493, f. 2 36 r.

2. Archivio Propaganda Fide, Scritture Originali riferite nelle Congregazioni Generali (SOCG), Vol. 1 93, f. 441 .

3. Archivio Propaganda Fide, Scritture Originali riferite nelle Congregazioni Generali (SOCG), Vol. 193, f. 193r.

Andrés de Urdaneta Did Not Discover the Tornaviaj e

by Jorge Mojarro, PhD

THERE ARE historiographical lies that tend to endure over time because they satisfy the need for myths on which nations are founded or legitimized. In the Philippines there are several examples, such as the hoaxes perpetrated by the swindler José E. Marco: the Kalantiaw Code, a purported pre- Spanish Philippine penal code; the false attribution of the novel La Loba Negra to Father José Burgos; and the manuscripts supposedly written at the time of the conquest that he sold to the National Library of the Philippines. These inventions were diligently refuted by William Henry Scott in his PhD thesis Critical Study of the Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History (1) However, the Kalantiaw Shrine that displays the code remains in Batan, Aklan.

Another of those disproved stories that seem to endure despite the lack of evidence is the one that attributes to the Augustinian friar Andrés de Urdaneta the discovery of the so - called tornaviaje , the transpacific route back to America eastwards from Asia. Finding this route was part of the royal instructions given by King Philip II to Miguel López de Legazpi. This was necessary because without a return route any further Spanish activity in Southeast Asia was simply impossible. The Spanish were mainly interested in the spice trade but were prohibited from sailing across the Indian Ocean, which had been assigned by the Pope to the Portuguese, as formalized in the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas.

Aged just 18, Urdaneta had taken part as a soldier in the disastrous second Spanish transpacific expedition led by Garc ía Jofre de Loaysa in 1525, in which the first European person to circumnavigate the globe, Juan Sebastián Elcano, also took part. Both died crossing the Pacific. Only two ships out of the seven that set off reached Asia, the Santa María del Parral in the Philippines and the Santa María de la Victoria in the Moluccas. Urdaneta, with a detachment of the surviving Spaniards, entrenched himself on the island of Tidore, whose kinglet had alliances with the Kingdom of Spain. In that tiny island Urdaneta resisted

for more than 12 years in the face of continuous attacks from the Portuguese, who were based on the neighboring island of Ternate.

In those years, the young soldier had a relationship with a native of Tidore with whom he had a daughter. Urdaneta took his child to his home town of Ordizia, in the province of Guipuzcoa. The young woman would get married years later and have seven children. Urdaneta, with serious physical disabilities as a result of the many battles he had fought ‒ a powder keg exploded on him during one of the hunts ‒decided to end his life of adventure and take the path of spirituality as a friar.

The Spanish tried twice more to cross the Pacific, this time setting out from New Spain: the expeditions of Álvaro de Saavedra in 1527 and Ruy López de Villalobos in 1542. Both failed for the same reason ‒ the impossibility of finding the longed- for tornaviaje , the return route. The issue was crucial, and without finding the way back to Mexico the Spaniards led by Legazpi in 1565 would never have established themselves in the Philippine archipelago.

This discovery has traditionally been assigned to Urdaneta. The first ones to do so were, of course, the Augustinian chroniclers, including those mentioned below. History books have kept repeating this attribution despite the fact that this assertion has been debunked since around 1970.

Luis Felipe Muro was a Peruvian historian who worked extensively in the Archivo General de la Nación in México City D.F. Having transcribed and studied dozens of documents dealing with the Legazpi expedition he found out then, and repeated in his 1975 book, (2) that there was no evidence to suggest that Urdaneta was the person who discovered the transpacific route. This issue has been researched again and confirmed recently by two other historians, Patricio Hidalgo Nuchera (3) and Juan Gil, (4) who have looked to the historical sources, just to arrive at the same conclusion.

The creator of this myth might have been an Augustinian historian, Fr. Juan de Medina, in his Historia de los sucesos de la Orden de N. gran P. S. Agustín de estas Islas Filipinas, desde que se descubrieron y poblaron por los españoles, con las noticias memorables, dated 1630. (5) His assertion was echoed by Fr. Juan de Grijalva in his Crónica, (6) by the most famous Augustinian historian of the Philippines, Fr. Gaspar de San Agustin, in his Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas, (7) and by most later historians until modern times.

There are two compelling reasons to assume that Urdaneta did not chart the return route successfully taken by all the ships of Legazpi's expedition that reached the Philippines. Firstly, while he was in the Moluccas, Urdaneta never took part in any of the attempts that were made to discover the return route. Secondly, Urdaneta took part in Legazpi's expedition under false pretenses; he thought he was heading for the island of Papua, which he considered to be in the hemisphere assigned by the Pope to the Spa nish Monarchy, and was told that they were heading for the Philippines only when they had already been on the high seas for three days. How was he

to know the return route from the Philippines if, in the first place, he thought they were heading for an archipelago much further south? His own report, signed in 1560- 61, has a detailed itinerary for go ing to and returning from ‘Papua Island’ . (8)

Supporting this there is an important fact. Urdaneta himself was not the first to complete the transpacific return but his fellow captain, Alonso de Arellano, who commanded the San Lucas, the smallest ship in Legazpi’s fleet, accompanied by the Afro - Portuguese Lope Martín as the pilot. After getting separated from the three other ships and wandering ‘ lost’ in the Philippines, Arellano successfully completed the first tornaviaje and arrived at Navidad, New Spain, on 22 April, 1565, beating Urdaneta by more than five months.

It seems likely that, as alleged by Legazpi and Urdaneta, Arellano had deliberately abandoned the expedition, although the American author Andrés Reséndez argues in his book that the San Lucas could have become separated through faulty navigation. (9) However, Reséndez's opinion does not stand up to scrutiny if we look at

Maris Pacifici (quod vulgo Mar del Zur ) by Abraham Ortelius , Amsterdam (1589) 1609 (Peter Geldart collection; image courtesy of Cohen & Taliaferro )

Arellano's own account; f ull of incoherence and contradictions, including divine apparitions and miracles, it seems more like a document written deliberately to excuse himself, especially when compared to other navigational accounts written at the same time. (10)

What does all this mean? I believe it means that all the members of the Legazpi expedition already knew of the route perfectly well. It should not be forgotten that the four previous expeditions cannot be considered completely unsuccessful, inasmuch as numerous reports and accounts were produced, maps were drawn, and they all contributed to the accumulation of experience- based knowledge about Pacific navigation

Who actually traced the tornaviaje ? We are not certain, but most probably Juan Pablo de Carrión, a captain from Valladolid who had taken part in the attempt to return to America from the Moluccas two decades earlier. An important anonymous document attributed to him describes the successful route. ( 11) The ill- fated Villalobos expedition failed to find the tornaviaje, but it did identify the strong Kuroshio Current that flows northeast from Luzon to the east coast of Japan, which they used for a few days to enter the North Pacific. Carrión's candidacy therefore seems to be solid, although not conclusive. Suspiciously enough, Carrión was excluded from Legazpi’s crew at the last minute and arrived back in the Philippines only in 1577. In 1582, at the age of 69, he led an army of Ibanag people (called cagayanes in the chronicles) which defeated a superior army of Japanese pirates in the surroundings of Aparri in northern Cagayan.

Notes and References

Carrión spent the last days of his life living in the Philippines but, until recently, has been a relatively obscure figure.

The false attribution of the discovery of the tornaviaje to Urdaneta should make us reflect about the way history is written. As expected, in exercising their corporatism the Augustinians would praise themselves ‒ in this case Urdaneta ‒ in their chronicles, and the Catholic Church accepted it with the argument that it showed that the Catholic faith was the fate of the archipelago. Nationalistic historiography decided to forget Alonso de Arellano and his companions; they were considered traitors and, when it was discovered that they had deliberately abandoned the Legazpi expedition, they were sentenced to be executed on their return to the Philippines.

History should be a never- ending albeit always imperfect attempt to find the truth of the past and to better understand and interpret who we are. Historians with an ideological agenda provide cheap scholarship, with an early expiry date. ( 12) We must hold them to account.

Jorge Mojarro is a Research Fellow and Associate Professorial Lecturer III at the Research Center for Culture, Arts & Humanities, Department of Literature , University of Santo Tomás, Manila, and a professor of Spanish at the Instituto Cervantes de Manila. He holds a PhD in Spanish and Latin American Literature from the University of Salamanca, and has published more than 60 research papers in academic journals dealing with Philippine literature in Spanish, book history, missionary linguistics, and sources of Philippine history.

1. First published by the University of Santo Tomás Press in 1968.

2. Luis Felipe Muro, ‘La expedición Legazpi-Urdaneta a las Filipinas / Organización, 1557 –1564’, in Historia y sociedad en el mundo de habla española , ed. Bernardo García Martínez et al ., El Colegio de México, Mexico City, 1970, pp. 141 -216; reissued as an independent monograph La expedici ó n Legazpi-Urdaneta a las Filipinas , 1557 – 1564, Secretaría de Educación Pública, México City, 1975.

3. Patricio Hidalgo Nuchera, ‘La controversia Urdaneta versus Carrión sobre el destino final de la Armada de Legazpi según Luis Felipe Muro Arias’, in Archivo Agustiniano Vol. 95, No. 213, Valladolid, 2011, pp. 245 -7

4. Juan Gil, ‘El primer tornaviaje’, in La Nao de China, 1565 – 1815: Navegación, comercio e intercambios culturales , ed. Salvador Bernabeu Albert, Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, 2013, pp. 25 -64; in his article, Gil hipothesizes the attribution to Carrión for the first time.

5. The manuscript was eventually published as Vol. IV of the series Biblioteca Histórica Filipina , under the direction of José Gutiérrez de la Vega, Tipo-Litografía de Chofré y Comp., Manila, 1893

6. Juan de Grijalva, Cró nica de la Orden de N.P.S. Augustin en las provincias de la Nueva España en quatro edades desde el año de 1533 hasta el de 1592 , Mexico, 1624

7. Gaspar de San Agustin, Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas , Imprenta de Manuel Ruiz de Murga, Madrid, 1698 .

8. Andrés de Urdaneta, ‘Memoria delas cossas que M e paresçe que será bien que el Rey nuestro señor tenga notiçia d’ellas para que mande P robeer lo que más fuere servido’ (Report on the things that it seems to me it would be good for the King, our lord, to take notice of so that he may order the proof of what is most useful), undated c.1561, ref. Patronato 23, R. 15, Archivo General de Indias , Sevilla.

9. Andrés Reséndez, Conquering the Pacific: An Unknown Mariner and the Final Great Voyage of the Age of Discovery , Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston / New York, 2021, pp. 109 -111; reviewed by Marga Binamira in The Murillo Bulletin , Issue No. 16, PHIMCOS, Manila, November 2023 , pp. 27 -29, and by Kristie Patricia Flannery in Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 103, No. 2, Duke University Press, 2023, pp. 328 -32 9.

10. I analyzed Arellano´s account and dubious trip in my doctoral dissertation, ‘Crónicas de las Indias Orientales. Orígenes de la literatura hispanofilipina’, Universidad de Salamanca, 2016, pp. 303 -306.

11. Juan Pablo de Carrión (attributed), ’Parecer’, undated, c.1564, ref. Patronato 263, N.2, R.1 , Archivo General de Indias, Sevilla. It says: ‘están en mexor paraxe para la buelta por estar en altura y arrimadas a la banda del Norte, por donde se a de venir a descubrir la buelta’ (the Philippines are better located for the way back, closer to the North, which is the way to discover the return).

12. A historian writing with a nationalist view of history will ignore the evidence and make mistakes even if he has a doctorate, is a member of the Royal Academy of History, and has a long list of publications to his name, as shown by the academic Agustín R. Rodríguez González in Urdaneta y el Tornaviaje: el descubrimiento de la ruta marítima que cambió el mundo , La Esfera de los Libros, Madrid, 2021.

Admiralty Chart No. 3193 and the Cartographic History of Port Sebu by Andoni F. Aboitiz with contributions from Margarita V. Binamira and Peter Geldart

APROMINENT item in the list of favourite maps in my collection is the 1923 edition (with corrections to 1925) of British Admiralty c hart no. 3193, titled Port Sebu (Cebu Harbour) and Approaches. I have a deep connection with this chart as it ties me to the time and place where my family's holding firm, Aboitiz y Compania, was founded in 1920.

The chart was not a decorative map but a vital instrument in guiding a ship's navigator into and around the port of Cebu and the island of Maktan (Mactan) before the advent of computers and GPS systems. The map is also rather charming as the engraver, Davies and Co., London, put so much aesthetic detail into seemingly mundane items such as the reefs and coconut trees. I am particularly fascinated by the inset of Sebu Anchorage which lays out the urban area of the

municipality of Cebu, to be declared a city only in 1937. On this plan Cebu is still a sleepy, quaint entrepot.

Interestingly, we know the name of the vessel on which my chart was used. Tagged on its side is a label declaring the chart's owner as the S.S. Essex Lance , a merchant steamship built in 1918 with a gross tonnage of 6,625 tons. She was probably transporting coal for the city's electric plant when she entered sometime around 1928. We know she sailed into Cebu as a safe sailing path into the port is marked by red lines, done by hand, accompanied by some updates on the buoys. The Essex Lance later participated in the Atlantic convoys that fed Britain in World War II. She was sunk on 15 October, 1943 by the German submarine U - 426 in the middle of the Atlantic, fortunately with no loss of life.

Port Sebu (Cebu Harbour) and Approaches , Admiralty chart no. 3193, (19 0 3) 1925 (author’s collection )

Details of Port Sebu (Cebu Harbour) and Approaches , Admiralty chart No. 3193, (19 0 3) 1925 showing the bearings of the SS Essex Lance (author’s collection )

But I am getting ahead of myself. This article intends to place the 1923 edition of Admiralty chart no. 3193 in the middle of a series of charts, released by various national maritime agencies, related to navigating the port of Cebu. I have chosen eight maps to show the progression of the work done to collate information to serve mariners. I hope the reader will get an overview and impression of how Cebu progressed from having a beach a s its port to becoming a busy trade port using modern and dedicated infrastructure to accommodate the rise of its industry and commerce.

Early Spanish charts of Cebu

The earliest navigational map of Cebu I have chosen is the 1793 manuscript Carta Esferica ó Plano del Puerto de Zebú, (1) which displays many lines of soundings throughout the channel between the islands of Zebú (Cebu) and Matan ó de Opon (Mactan). It was prepared by Juan Díaz Maqueda, a Primer Piloto (Master) from the expedition to South America, the Pacific Ocean and the Philippines led by Alessandro Malaspina from 1789 to 1794 in the corvettes Descubierta and Atrevida.

After Malaspina’s ships left Manila in 1792 they did not visit Cebu, perhaps because it was then a tiny town still suffering from the retirada or

quasi- abandonment by the colonial Spanish Government. However, Maqueda and Segundo Piloto Jerónimo Delgado were left behind with orders to devote the next six months to a survey of the Visayas in the goleta (schooner) Santa Ana. Consequently this chart was intended purely for navigation and contains no urban detail. Dated 1793, it was drawn by José Felipe de Inciarte in Cadiz in 1805.

In 1843, the commander and officials of the Spanish Comision Hidrográfica produced another manuscript chart, drawn and signed by Guillermo de Aubarede y Pérez and titled Plano del Puerto de Zebú (2) The chart covers the coast of Cebu from the Castillo de Cauit and the Caserio de Canjuan in the southwest to Punta Bagatan (aka Bagacay) in the northeast, and contains significant information. In addition to the necessary soundings ‒ measured in brazas de á 6 pies de Burgos en bajamar (at low tide) ‒ and other maritime information, an outline of the town of Cebu is shown. This is notable for its semi- lunar shape, together with the locations of some adjoining landmarks: the tower and church of San Nicolas to the west; the Casa de Lazarinos (leper hospital) to the north; the village of Mandaui (Mandaue) and the Torre de Mandaui (still somewhat extant) further out to the northeast; and the village of Opon on the island of Magtan (Mactan).

(image courtesy of Archivo Histórico de la Armada - J.S. de Elcano, Madrid, MN-65 -10 )

(

Carta Esferica ó Plano del Puerto de Zebú by Juan Díaz Maqueda, (1793) 1805

Plano del Puerto de Zebú by Guillermo de Aubarede y Pérez, 1843

image courtesy of Archivo Histórico de la Armada - J.S. de Elcano, Madrid, MN-65 -6 )

Detail from Plano del Puerto de Zebú , Dirección de Hidrografía (1843 ) 1850 (image courtesy of Archivo Cartográfico de Estudios Geográficos del Centro Geográfico del Ejército Ar.Q-T.3 -C.1 221 )

To quote Marga Binamira:

To the northeast of Mandaui and in two locations on the northwest coast of Mactan, three vantay (coastguard stations, from the local word bantay for a watchman) are marked. Notes give details of the height of the tides and direction of the currents at these locations, and of the best anchorage during the northeast monsoon. In 1850, a printed edition of this chart was published in Madrid by the Dirección de Hidrografía, to which an inset Plano del Fondeadero de Tinaan by Claudio Montero was added in 1870.(3)

I assume the commission specifically introduced these landmarks to ease navigation around Cebu, and I ask the reader to take cognisance of them and the whole layout of this chart. You will see this model used again over the next decades for charts produced by the British Admiralty’s Hydrographic Office, the U.S. Hydrographic Office, and the United States Coast & Geodetic Survey (USC&GS), each updating subsequent maps with the latest corrections as they saw fit.

Admiralty chart no. 2391

On 1 October, 1855 the British Admiralty published chart no. 2391, Ports in the Filipinas. On the first edition the main chart (above the Hydrographic Office seal) is Port Zebú From a Spanish Survey 1843, which covers the port of Cebu and Mactan Island, and there are three

insets: Port Batan From a Spanish Survey 1842 at top- left; Port Iloilo From a Spanish Survey 1843, in the middle above Cebu; and Port Buluagan ó Sta. Ana From a Spanish Survey 1843 (on Guimaras Island) at bottom- right.

The soundings on the Admiralty chart have been converted from the Spanish brazas into fathoms, but otherwise the chart is a close copy of the 1843 Plano del Puerto de Zebú discussed above, with the same layout of the soundings, arrangement of the shoreline and Cebu’s buildings. It is striking that the lunar shape of urban Cebu is used again, along with similar images of San Nicolas church, Mandaui, Mandaui tower and Opon. This British chart of Cebu is, in essence, the Spanish map.

A second edition of the chart was published four years later, with ‘Large corrections April 1859’. Two insets were added at the bottom: Port San Miguel From a Spanish printed Plan 1842 (on Ticao Island) and Port Barreras or Lanang From a Spanish printed Plan 1842 (on Masbate Island). In July 1872 another new edition was produced, with the title changed to Ports in the Philippine Islands and the inset of Port Batan deleted. A new, extended chart of Iloilo is at a smaller scale, with the title re- positioned and changed to Panay I. / Port Ilo Ilo From a Spanish Survey 1864 The revised title for Cebu reads Port Zebú From a Spanish Survey 1843 / Additions and Corrections by the Officers of H.M.S. Rifleman 1869. (4)

In January 1875 HMS Challenger visited Cebu during the first global marine research expedition, sponsored by The Royal Society Jesse Lay R.N. , o ne of the official photographers on Challenger, took a photograph of Cebu (until now unpublished) in which the beach used for loading and unloading goods is prominent. The Tribunal de Naturales (city hall) appears in the centre, and the Smith, Bell & Co. complex is on the right of the image.

New editions of chart no. 2391 continued to be published. When re- issued in January 1896 with ‘Large corrections’, for Cebu the title was changed to Port Sebú (see back cover). Buoys and lights were added around Narvaez Bank and Lipata Bank, with notes warning that these were ‘not always to be depended on’. A close copy of this chart as published in January 1896 was produced by the U.S. Department of the

Ports in the Filipinas / Port Zebú From a Spanish Survey 1843, Admiralty chart no. 2391, 1855 (author’s collection )

Navy, Bureau of Equipment, and published by the Hydrographic Office at Washington, D.C. in June 1898 as chart no. 1723. With the arrival of Admiralty chart no. 3193, in April 1901 Cebu was removed, as was the inset of Port Barreras (by 1907), and chart no. 2391 (which is still in production today) was renamed Iloilo Strait.

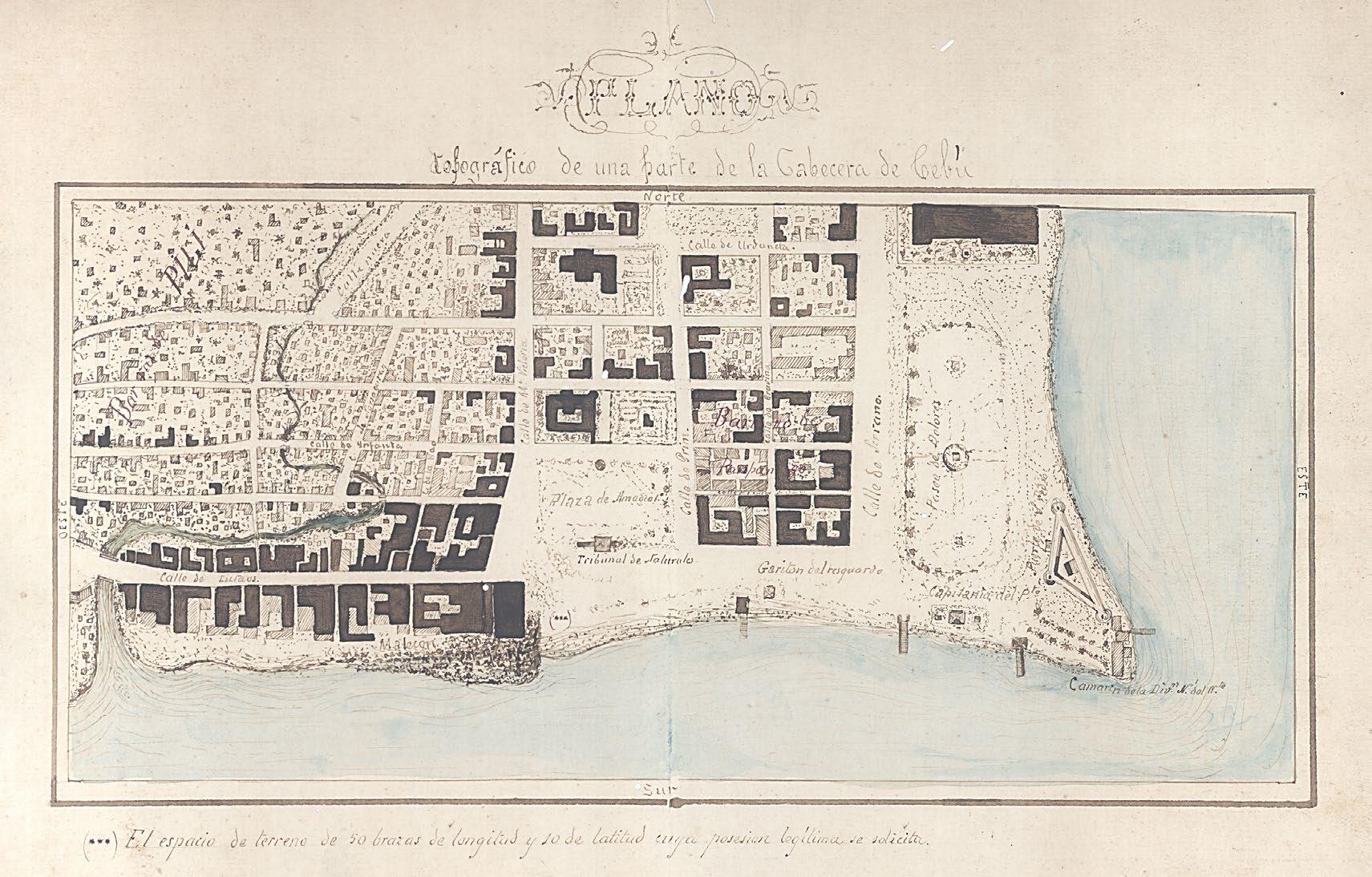

La Cabecera de Cebú

The National Archives of the Philippines keep a gorgeous map of Cebu titled Plano topográfico de una parte de la Cabecera de Cebú. (5) The map, which is undated but was probably made around 1882, shows a portion of the city that was the cabecera (capital) of the province of Cebu. The town's built- up area, the Ciudad centered on the

Tribunal de Naturales, is well illustrated. At this time, two prominent piers can be seen jutting out past the beaches; the one on the left is the government pier, while the one on the right is private.

The wide sandy beach to the left was still used extensively, as shown in photographs from the period. A third structure on the shoreline, in the middle of the beach, could be the private wharf for which Smith, Bell & Co. (6) had applied for building permission in 1879. The structure will become more prominent in future maps. At this stage in the history of the port, larger foreign ships were beginning to dock to pick up sugar, abac á (Manila hemp) and other agricultural exports as Cebu emerged as a trading centre. (7)

Photograph of Cebu with the beach, Tribunal de Naturales and Smith, Bell & Co. taken by Jesse Lay of HMS Challenger in January 1875 (image courtesy of the Natural History Museum, London )

Caseta de Carabineros y muelle en la playa de Cebu (police station and pier on Cebu beach), photograph by Francisco Pertierra, published in La Ilustració n Art ística on 28 March, 1887 (author’s collection )

(Top ) Plano topográfico de una parte de la Cabecera de Cebú , c.1882 with (bottom) detail showing the beaches and piers (images courtesy of the National Archives of the Philippines )

Admiralty chart no. 3193

From 29 November, 1899 to 19 March, 1900 the gunboat USS Bennington was assigned to Cebu as a station ship. (8) In addition to her duties supporting the operations of the U.S. Army, her crew conducted extensive soundings by sextant reconnaissance of the north and south approaches to the port of Cebu. The U.S. National Archives hold five manuscripts and a chart from these surveys of Cebu harbour: two rough sounding sheets, (9) three tracings showing corrections, and part of U.S. Hydrographic Office chart no. 1723.

The results of this great effort were used in a small map produced in 1902: Sebú and Mactán / Port Cebú From a reconnaissance in 1899 and 1900, by the officers of the USS Bennington, with additions from a Spanish survey in 1843. The map was included as ‘ Senate Document 280, 57th Congress, 1st Session’ in A Pronouncing Gazetteer and Dictionary of the Philippine Islands prepared by the U.S. War Department in 1902. (10)

Using the Bennington’s surveys, on 1 June, 1901 the British Admiralty published the first edition of its chart no. 3193: Philippine Islands. Sebú and Maktan. / Port Sebú From a sketch survey in 1899

By USS Bennington, 1900 (image courtesy of the U.S. National Archives ) and 1900 by the Officers of the United States Ship “Bennington”, with additions from a Spanish Government Survey, 1843. A small inset on the upper- left side shows Sebú Island / East Coast Tinaan Anchorage from a Spanish Government Survey, 1864. Tinaan is located a few kilometres south of Cebu port, and I speculate that it served as an alternative spot to drop anchor in the event of high winds or rough seas, especially during the amihan (northeast monsoon).

It is interesting that the Spanish model from the 1843 Spanish map by Guillermo de Aubarede survives in both this iteration by the Admiralty and the 1902 map by the U.S. War Department. Clearly the Spanish model, with the lunar- shaped Cebu town and the other landmarks, was sufficient for its time as long as the cartographers used updated maritime information including soundings, buoys and lighthouses. For the expec ted English- speaking audiences the toponyms were anglicised.

In 1900 the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey (USC&GS), which had been created in 1807 and was headquartered in Washington D.C. , established its Manila Sub- Office. In July 1902 it produced chart no. 4447 Philippine Islands / Cebu Harbor and Approaches / Cebu, East Coast, at a scale of 1:30,000, with at top-left an inset of Cebu Anchorage , at a scale of 1:10,000. The chart states ‘Triangulation, Hydrography and Topography executed in 1902’ These surveys were made by the USC&GS’s

Pathfinder, a survey ship that arrived in Manila in late 1901 and joined the USC&GS under the command of Asst. J.J. Gilbert. The survey was described as follows:

The work at Cebu began on January 28 and was completed on March 21. A base line was selected and measured and the necessary geographic positions determined by triangulation. The greater portion of the topographic work was very difficult on account of the extensive coral reefs and the bordering mango (sic) swamps. The topographic survey was made on a large scale for the benefit of the military authorities, and one of the sheets included the city of Cebu.(11)

In the survey of Cebu Harbor and Approaches, Asst. Gilbert had proposed that “the included bay like most of the Philippine water is unnamed, and I suggest Mactan Bay. The broad expanse between the sheet and Leyte Island might be named Leyte Sound”. … [In] order to minimize optimism regarding the survey’s quality, the Manila Field Station was informed: “The sheet shows the densely built portions of the city, by shading, but no effort was made to locate them exactly, while the many native huts are sk etched in haphazard.”(12)

Sebú and Mactán / Port Cebú From a reconnaissance in 1899 and 1900, by the officers of the USS Bennington, with additions from a Spanish survey in 1843, 1902 (author’s collection)

Sheet II. Sextant Reconnoissance of Cebú Harbor

(Top ) Port Sebú From a sketch survey in 1899 and 1900 by the Officers of the United States Ship “Bennington” Admiralty chart no. 3193, first edition, 1 June, 1901 with (bottom) detail showing the channel and soundings (images courtesy of the Library of Congress )

(Top ) Port Sebu (Cebu Harbour) and Approaches from the United States Government Survey 1902 Admiralty chart no. 3193, second edition, 24 July , 190 3 with (bottom) detail of the inset of Sebu Anchorage (images courtesy of the Library of Congress )

On 24 July , 1903, the Admiralty released a new, re- sized edition of chart no. 3193, which was copied from USC&GS chart no. 4447 and titled Philippine Islands Sebu and Maktan / Port Sebu (Cebu Harbour) and Approaches from the United States Government Survey 1902. In this version, the urban areas of Cebu are more accurately engraved in the inset of Sebu Anchorage at topleft. The town's extensive lunar- shaped style was discontinued, and the pier belonging to Smith, Bell & Co. earlier mentioned is clearly drawn. There is also a smaller inset at top- centre: Sebu Island / East Coast Tinaan Anchorage from a Spanish Government Survey, 1864. On these early editions, as well as the chart number 3193 printed in the bottom- right corner, a second number (2674) is printed in parentheses in the bottom- left corner. (13)

New Iterations

Both the British Admiralty and the USC&GS continued to publish their charts, with periodic corrections and new editions. A copy of chart no. 3193 was also produced by the Intelligence Division of the British War Office and published

in the Confidential Military Report on the Philippine Islands Prepared by the General Staff, War Office 1904 (14) On the 1923 edition of chart no. 3193, titled Port Sebu (Cebu Harbour) and Approaches From the United States Coast Survey Charts to 1922, with small corrections in 1924 and 1925, the inset of Tinaan Anchorage was deleted.

By then the port of Cebu had grown and undergone tremendous improvements. The wooden wharves had been replaced by modern cement piers built around extensive reclamation to the southwest, away from Fort San Pedro. The upgrades included a Philippine Railway Co. branch line that ran alongside the Guadalupe River to reach the port area. The 1926 edition of chart no. 3193 (from the 1925 edition of USC&GS chart no. 4447), with additions and corrections to 1933, shows the Osmeña Fountain in Cebu City, built in 1912 to mark the opening of the Osmeña Waterworks, and the Asiatic Petroleum Co. (later Shell) refuelling station with its oil tanks on Maktan (sic ) Island. As discussed earlier, these highly atmospheric charts speak volumes on Cebu in the 1920s

Cebu Harbor and Approaches with inset of Cebu Harbor , USC&GS chart no. 4447, Dec. 1925 (image courtesy of the Office of Coast Survey, U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration )

Aerial photographs of Cebu taken in November 1936 showing (above) reclamations and the construction of piers in the port and (below) a view of the port from the southwest (images courtesy of the U.S. National Archives )

Detail from the (1926) 1933 edition of Admiralty chart no. 3193 showing the Osmeña Fountain, branch railway line, Asiatic Petroleum Co. station, and lights highlighted in yellow (Peter Geldart collection; image courtesy of Wattis Fine Art)

The U.S. National Archives hold aerial photographs of Cebu taken in November 1936. One of these has a view of the extensive reclamations and the construction of Piers 1, 2, and 3 of the Port of Cebu. The other shows the southwest portion of the port with (from right to left) Fort San Pedro, the Aduana (Customs House), warehouses, the Shamrock Hotel on the waterfront, and downtown Cebu.

During World War II the Japanese invaded Cebu and the c ity became a war zone. The port area was destroyed by Allied bombings in 1942 and further damaged by bombing in 1944 and during the Battle for Cebu City when the U. S. Seventh Fleet arrived in March 1945. After the war the rebuilding and rehabilitation of the c ity moved it away from the original shoreline settlement, but the revised charts capture further additions to the Port of Cebu. With the title revised to Cebu Harbour and Approaches From United States Coast Survey Charts to 1948, chart no. 3193 (with corrections to 1954) includes Piers 1, 2, and 3 (constructed in the mid- 1930s).

The urban areas around the piers received updates, and important edifices that dotted the City of Cebu were added. I posit that these additions were aids to navigation, as ships would have easily spotted these buildings from afar as they sailed towards the city. However, the vast reclamation works in the Banilad Shoals off Mandaue had not yet been carried out.

The layout of chart no. 3193 would survive until 1966, when the Admiralty introduced a new chart arranged in portrait format: Cebu Harbour and Approaches From the Philippine Government charts to 1962. For the new charts the printing method was no longer steel engraving but lithography. Over the next decades, the Admiralty added colour to the maps, making the charts more informative but much less charming. Chart 3193 was eventually discontinued, in September 2001, and replaced by chart no. 13 Approaches to Cebu Harbour.

Cebu Harbour and Approaches, Admiralty chart no. 3193, 1966 (author’s collection; image courtesy of Rudolf J.H. Lietz, Gallery of Prints, Manila )

This article is based on the presentation given to PHIMCOS by the author on 14 August, 2024.

Notes and References

1. Carta Esferica ó Plano del Puerto de Zebú formado entre la Ysla de este Nombre y la de Matan en el Archipiélago Filipino , (1793) 1805, Archivo Histórico de la Armada ‒ J.S. de Elcano, Madrid, ref. MN-65 -10.

2. Plano del Puerto de Zebú. Levantada por el Comandante y Oficiales de la Comision Hidrogr á fica en el Archipielago Filipino Año de 1843, Archivo Histórico de la Armada ‒ J.S. de Elcano, Madrid, ref. MN-65 -6.

3. Margarita V. Binamira, ‘Cebu City: A Cartographic Chronicle from the 16 th to the 20 th Centuries’, in The Murillo Bulletin Issue No. 14, PHIMCOS, Manila, November 2022.

4. H.M.S. Rifleman was a gun boat, launched in 1846, used by the Royal Navy as a surveying vessel. From 1861, under Master Commander John William Reed, she was dispatched to the China Seas to survey the Dangerous Ground (the Spratly Islands). During 1863 Commander J. Ward succeeded Reed in command of the Rifleman , but Reed returned to the ship in 1866 to complete a detailed survey of the Palawan Passage, from Singapore to Hong Kong. Reed’s 1867 -68 survey took him into the waters off Palawan, where he cooperated with Lieutenant Claudio Montero of the Comisión Hidrográfica de Filipinas . In 1869, after completing a large survey of the Balabac Strait, the Rifleman was condemned as unfit for further service, decommissioned and sold in Hong Kong. See: Commander L.S. Dawson, R.N., Memoires of Hydrography, Henry W, Keay, Eastbourne, 1885.

5. The map is part of a collection of manuscript documents held at the National Archives of the Philippines titled Terrenos de Cebu , which also contains a Vista del plano; see Binamira op. cit.

6. Smith, Bell & Co., a firm with origins dating back to 1838 principally involved in trading abacá , had opened its Cebu branch in 1866.

7. In 1860 the port of Cebu had been opened to worldwide trade.

8. USS Bennington (Gunboat No. 4/PG -43) was one of the U.S. Navy’s Yorktown class of steel-hulled, twinscrew gunboats. Commissioned at the New York Navy Yard on June 20, 1891, Bennington arrived in Manila on February 22, 1899. For a little over two years from her arrival she supported the U.S. Army's campaigns during the Philippine-American War, providing patrol and escort duty, and occasionally seeing action. See: Raymond A. Mann, ‘Bennington I (Gunboat No. 4) 1891-1910’, in Naval History and Heritage Command , U.S. Navy, 2006.

9. “Sheet I. Sextant Reconnoissance (sic) of Cebú Harbor, P. I. From St. Nicholas Church to Northern Entrance. Made by Lieut. F.M. Bostwick, U.S. Navy. Assisted by P.A. Paymaster J.H. Merriam, U.S. Navy. USS Bennington . Comdrs. E.D. Taussig and C.H. Arnold U.S. Navy Commanding. Soundings in Fathoms. Note: The scale used is three times that of H.O. Chart 1723. The black lines of this portion were enlarged from H.O. Chart 1723. The red lines indicate the approximate shore line as found.” Sheet II shows the coast “From St. Nicholas Church to and including Shoals off Southern Entrance.”

10. A Pronouncing Gazetteer and Dictionary of the Philippine Islands, United States of America, with maps, charts, and illustrations, Bureau of Insular Affairs, War Department, Government Printing Office, Washington D.C., September 30, 1902; the maps were photo-lithographed by The Norris Peters Co.

11. Report of the Superintendent of the Coast and Geodetic Survey showing the Progress of the Work from July1, 1901, to June 30, 1902 , Government Printing Office, Washington D.C., 1903, p. 161.

12. Raul A. de Leon, Islands on Paper ‒ A Brief History of the Bureau of Coast and Geodetic Survey 1900 -1978 , Ministry of National Defense, Manila, 1980, p. 17.

13. As explained (in email correspondence with Peter Geldart ) by Ann-Marie Fitzsimmons, Archives Research Manager at the U K Hydrographic Office, these additional numbers from 1 to 3437 (which were possibly shelfmarks,) were first added to all of the charts in the Catalogue of Admiralty Charts, Plans and Sailing Directions, 1900 A printed note at the front of the catalogue reads: "Caution. The New Numbers, given in brackets, being only intended for use in the Hydrographic Department, are not to be used by Mariners and others using the Admiralty Charts, and Charts are to be quoted as heretofore, by the old numbers only." The new numbers were discontinued in 1909.

14. Chart of Port Cebú To Accompany the Military Report on the Philippine Islands , numbered ‘I.D.W.O. 1897’ and dated June 1904; the chart was copied from Admiralty chart no. 3193 but re-engraved, rotated 34o to the east, and slightly truncated to the west of Talisai Point (sic), with the note on Tidal Streams deleted.

John Inskip and the charts of the ‘ London’ East Indiaman by

Peter Geldart

IN 2021 the London dealer in antique atlases, maps, plans and sea charts Daniel Crouch Rare Books (DCRB) offered a previously- unrecorded chart of the Billiton Straits by John Inskip. Measuring 55 cm x 76.5 cm, the chart is titled A Chart of Billiton Straits, with the Track, Soundings &c. of the London East Indiaman, John Eastabrooke Esq: Commander. by Mr. John Inskip, late Second Mate of the above Ship. To quote the entry in the catalogue:

This very detailed, large-scale chart, oriented with east to the top, shows the strait between the islands of Bangka and Belitung in the north Java Sea which, in turn, lie between Sumatra and Borneo. A route is plotted with numerous depth soundings navigat ing around the ‘Treacherous Islands’ that fill the channel. The ‘References’ [show two shoals, marked A and B, with navigation instructions and] specify that: ‘NB. It will be necessary to have a Boat on each Bow Sounding’.(1)

The DCRB catalogue also specifies that the chart is ‘ apparently the only recorded example of the only chart by John Inskip’. It was, therefore, quite a pleasant surprise when, at one of our recent meetings, a PHIMCOS member brought along a

fine chart of the Straits of Balabac and Sooloo Bay that none of us had seen before ‒ by none other than John Inskip.

This second chart measures 68.5 cm x 103 cm, and is oriented to the north. The title provides the dates when it was made: The Track of the London East Indiaman, I. Eastabrooke Esqr Commander. Across the China Seas, thro’ the Straits of Balabac; in October and November, 1786. Exhibiting, New Discoveries, of Rocks, Shoals, &c. with the Course of the Currents, so Prevalent at that Season. Also an enlarged Draft of the Bay of Sooloo, by Mr. I. Inskip, late second Mate, of the above Ship.

The track of the London is shown from P. Banca on Sept. 23 1786, sailing to the northeast past Pulo Condore (off the coast of Vietnam) to Pulo Sapata on Oct 4th. The ship then sailed eastwards into the ‘Dangerous Ground’ ‒ the archipelago of shoals, reefs, atolls and islets in the southern part of the South China Sea that would become known as the Spratly Islands. (2) Groups of ‘Rocks’ are shown on the chart, with a note: Upon some of these Rocks the Temple East Indiaman was supposed to be lost.

A Chart of Billiton Straits, with the Track, Soundings &c. of the London East Indiaman … by John Inskip (image courtesy of Daniel Crouch Rare Books )

The Track of the London East Indiaman, … thro’ the Straits of Balabac; in October and November, 1786 … (private collection; images courtesy of the owner)

Pushed by the monsoon winds and strong currents, the London followed an erratic course, sometimes backtracking and crossing over its earlier track; positions are shown on the 15th, 16th and 17th Oct. The ship eventually reached the Straits of Balabac, between the islands of Balabac and Mangee (to the south of Palawan), and the islands of Bangy and Balambangan (to the north of Borneo ) The track continues past Cayagan (sic ) Sooloo and Molagee island to Sooloo Island, to the north of the smaller islands of Dockan, Sooloo Lady, Cabay Ann and Pata.

A large inset displayed on a scroll at the bottom of the chart shows Sooloo Bay, with views of its features as seen from the ship’s anchorage. The Remarks list these as: a small Reef; a watering place; a Spring of Water; the T own and Flag Staff; the highest Peak; Tulian Isle; Three I slands ‘which appear as one’; and Menis Island.

After leaving Sooloo the London sailed eastwards along the south coast of Mindanao, past Bongo Bay, Bakulan Point and Sarangani Island, and southwards to round the islands of Sangier and Kabruang (northwest of Gilolo). She then continued eastwards before turning northwards, sailing to the east of the Palas Islands (Palau) on her route to China. The voyage is described in detailed Remarks signed ‘I. Inskip’:

When you have got the length of Pulo Sapata, and from the lateness of the season, find Variable Winds, with a swell from the N.E. you may then conclude the N.E. winds will soon prevail, and if you think it impracticable to get to Luconia [Luzon], stand imm ediately to the Southward into 7 Degrees N. Latitude, then steer away for the Straits of Ballabac (sic), and proceed on the passage described in this Chart.

I think, a moderate going Ship, may make her passage from Pulo Sapata, to China, in seven weeks at most.

An enlarged Draft of the Bay of Sooloo, by Mr. I. Inskip

NB. After leaving Sooloo, it will be naturally supposed that getting out to windward is best; but we tried 8 days without success; finding always a strong Current setting to the Westward, therefore, keep close under the South end of Sangier, and endeavour to make Kabruang, then hawl away to the Northward, as much as possible; until you see the East part of Morty , where we found a strong Current setting to the N.E. about 36 or 40 Miles a day, tho’ this was the case in the month of November, I do not take upon me to say it will be so at all times.

L aunched in 1779, the 836- ton East Indiaman London made seven voyages for the Honourable East India Company (HEIC) between 1780 and

1799, and was then sold for breaking up. On her third voyage she sailed from the Downs ‒ the roadstead and anchorage off the east coast of Kent ‒ on 2 February 1786, bound for Madras on the Coromandel Coast and China. She reached Madras on 13 July and Sulu on 9 November, and arrived at Whampoa on 17 January, 1787. Homeward bound she crossed the Second Bar on the Pearl River on 6 April, reached St Helena on 30 August, and arrived back in the Downs on 5 November, 1787. ( 3) Her officers were John Eastabrooke (Captain), Edward Boyce (First Mate), John Inskip (Second Mate), Richard Brunton (Third Mate), William Clootwyck (Fourth Mate), Philip Hawkes (Surgeon), and John Davies (Purser). ( 4)

The track of the London through the Dangerous Ground to the Straits of Balabac