The Murillo Bulletin

Journal of PHIMCOS

The Philippine Map Collectors Society

Issue No. 14 November 2022

A special issue on the Mapping and History of Cebu

PHIMCOS News & Events page 3

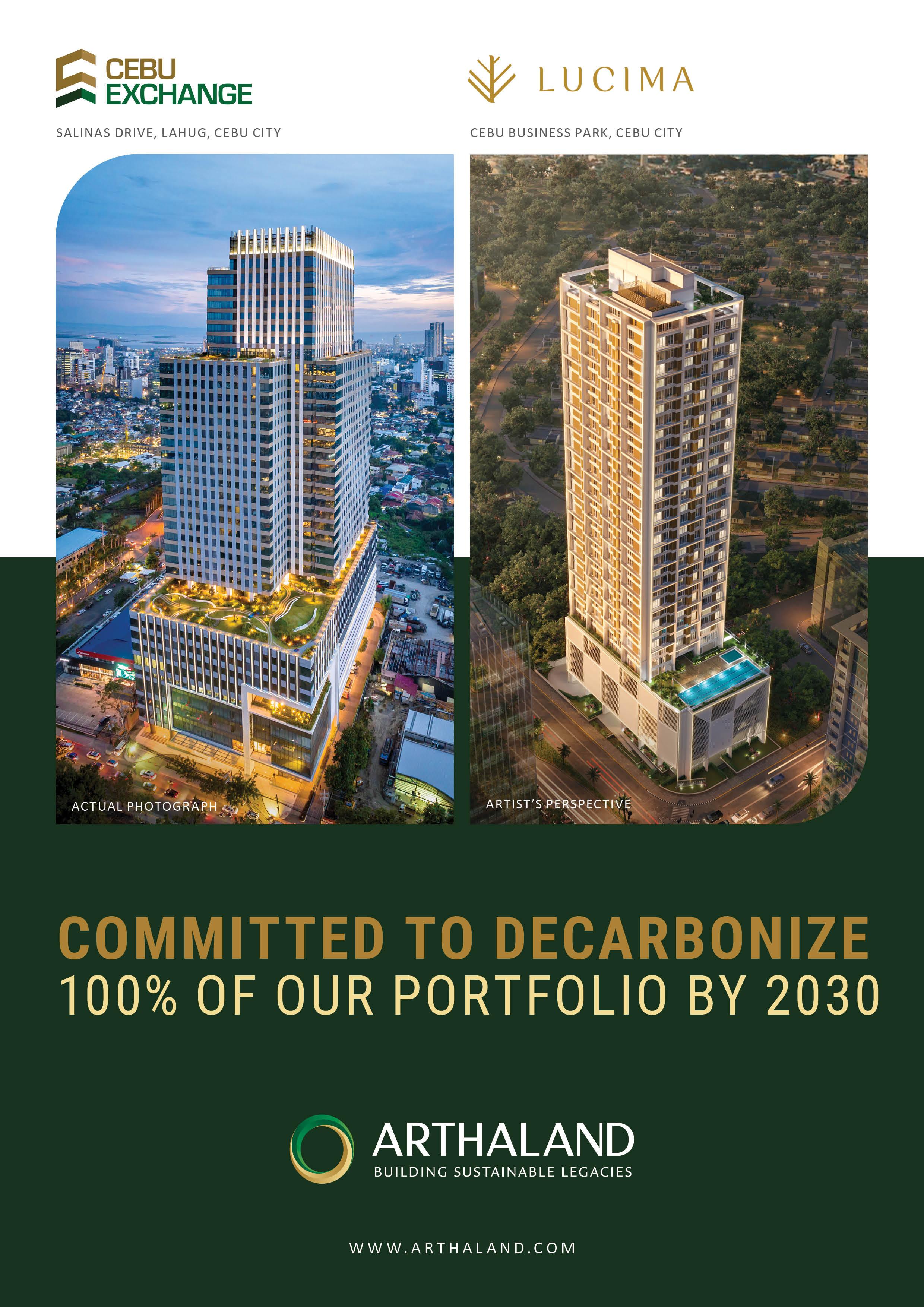

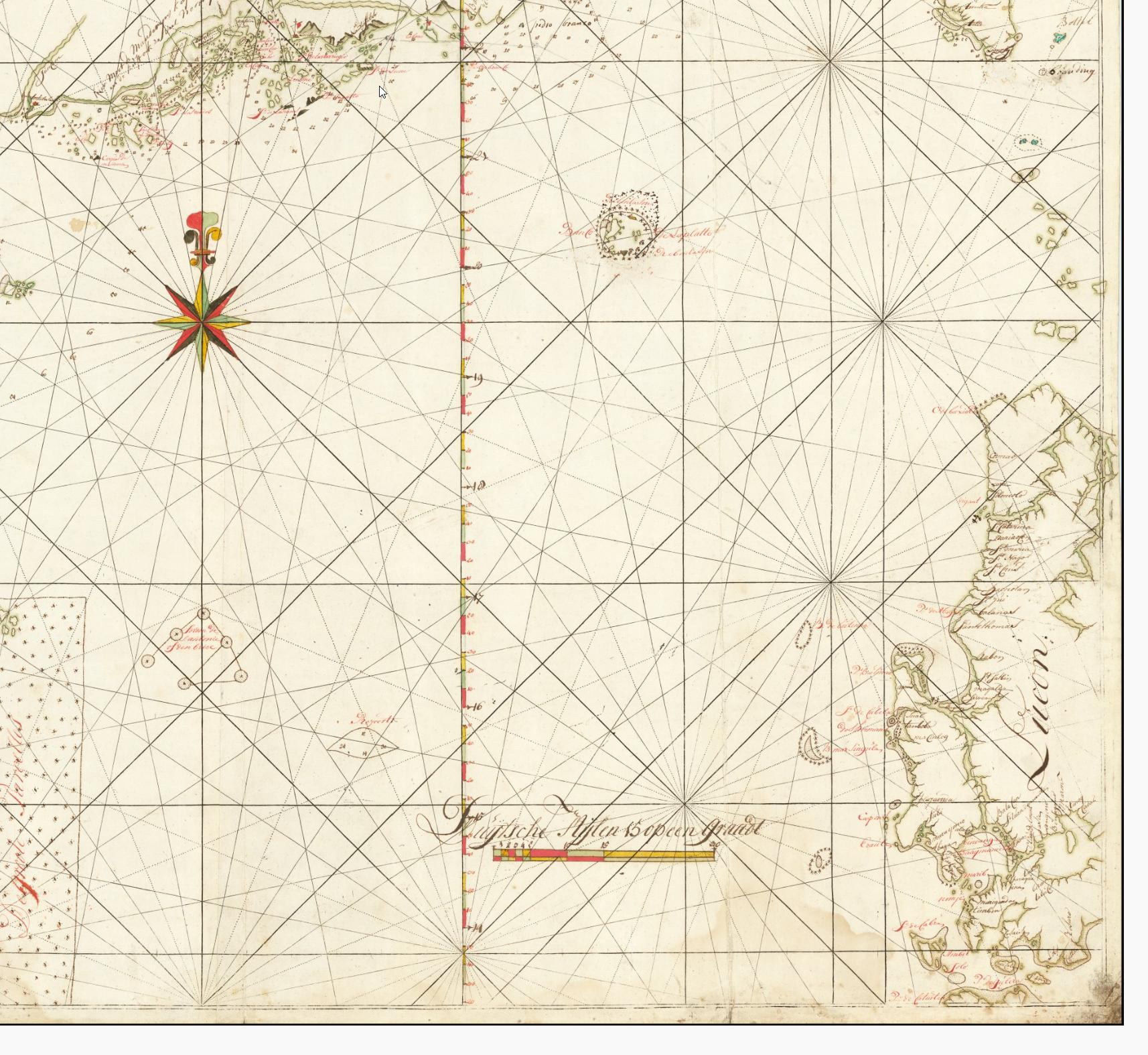

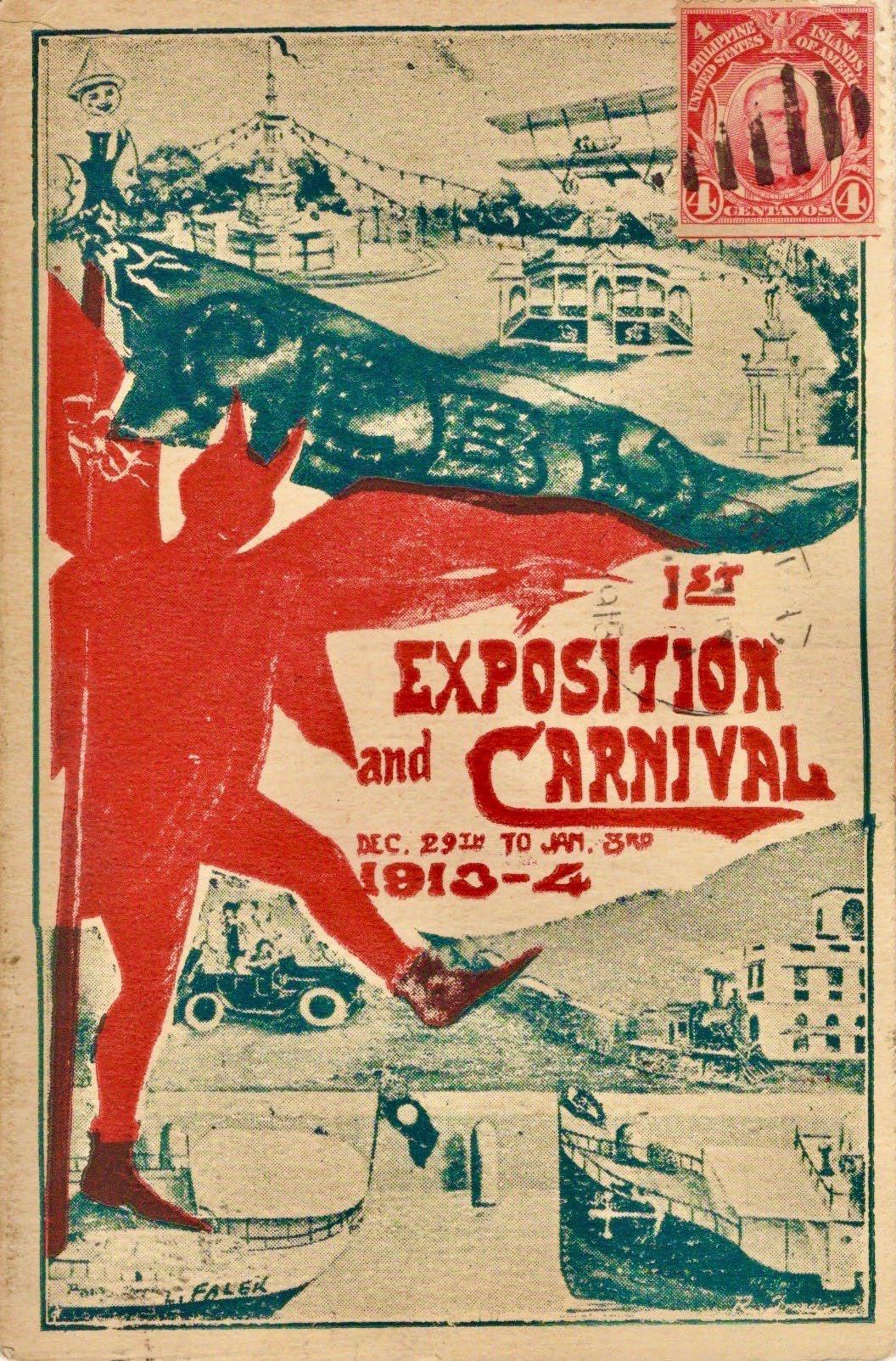

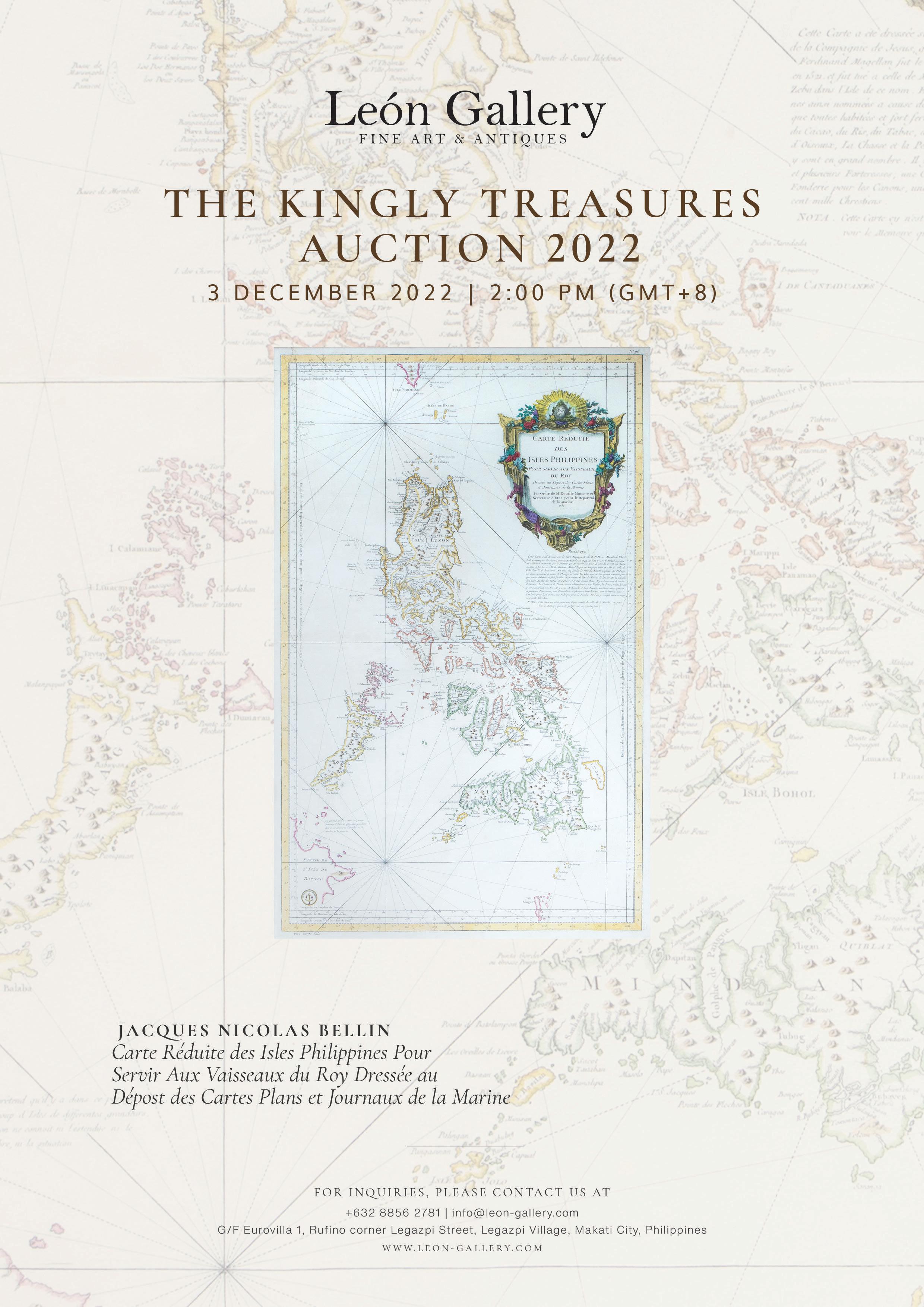

Our Cover 7

The Naming of Cebu by Margarita V. Binamira and Peter Geldart 11

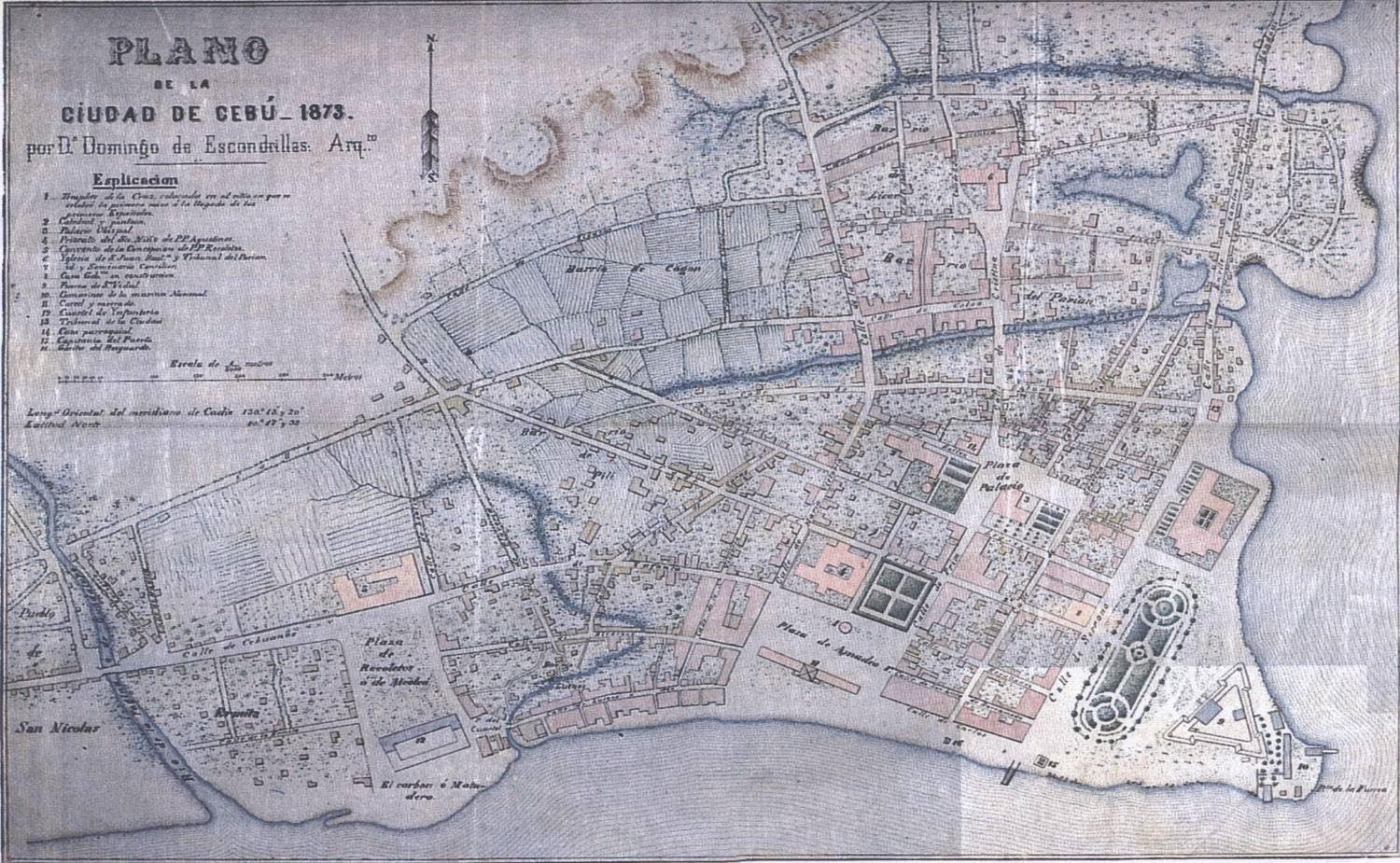

Cebu City: A Cartographic Chronicle by Margarita V. Binamira 21

The Lost Waterways of Cebu City by Dr. Maricor N. Soriano 45

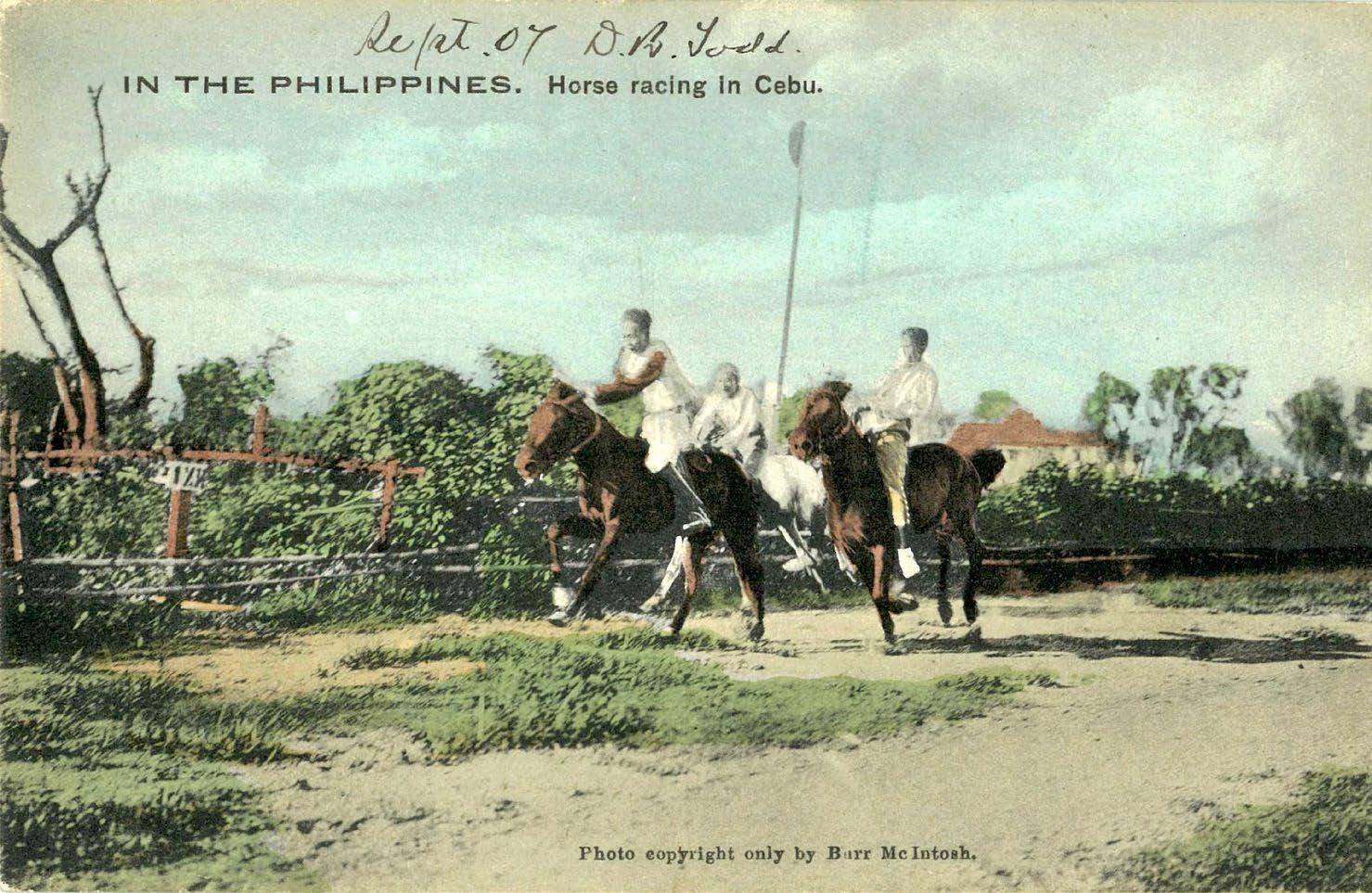

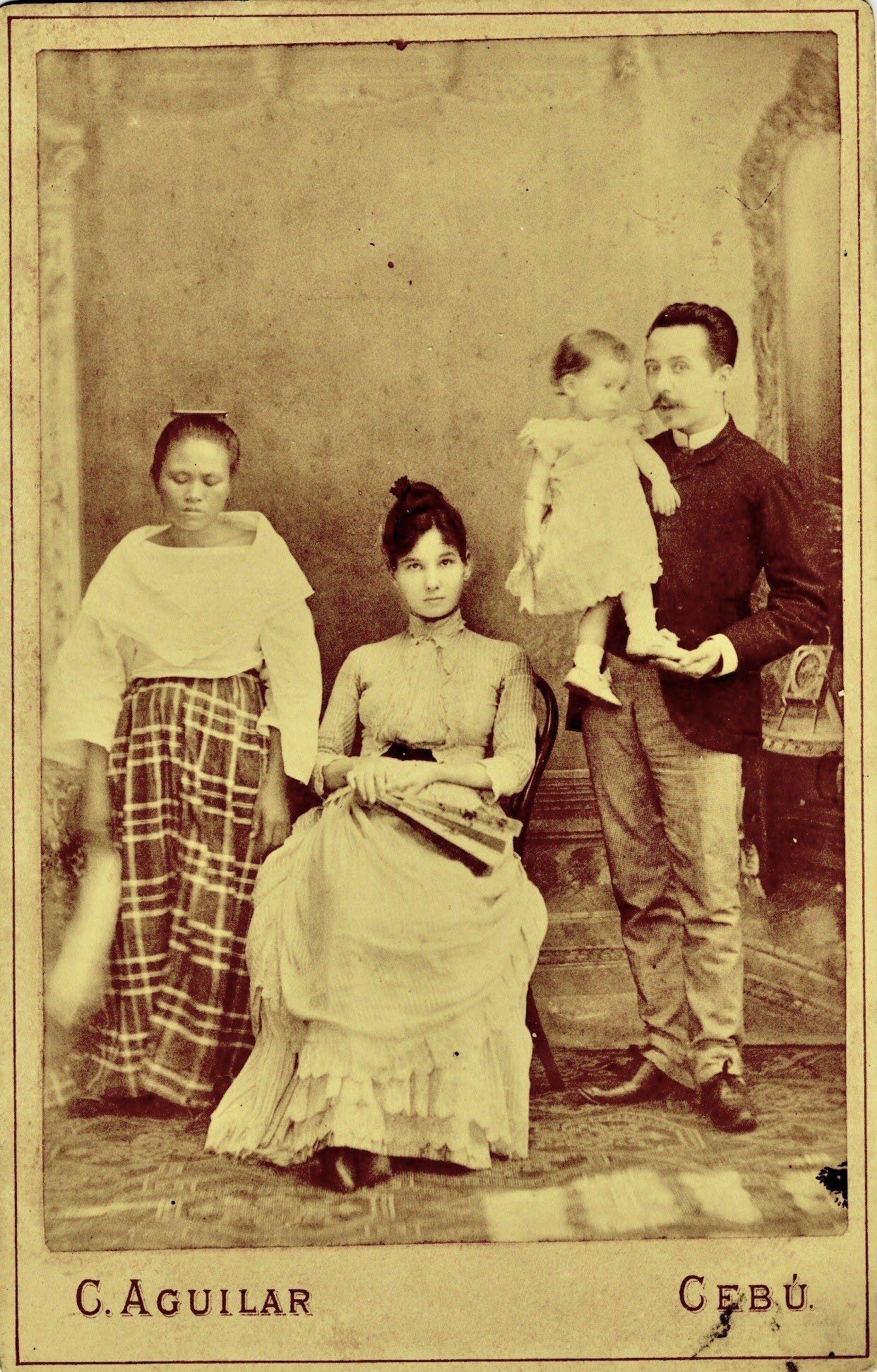

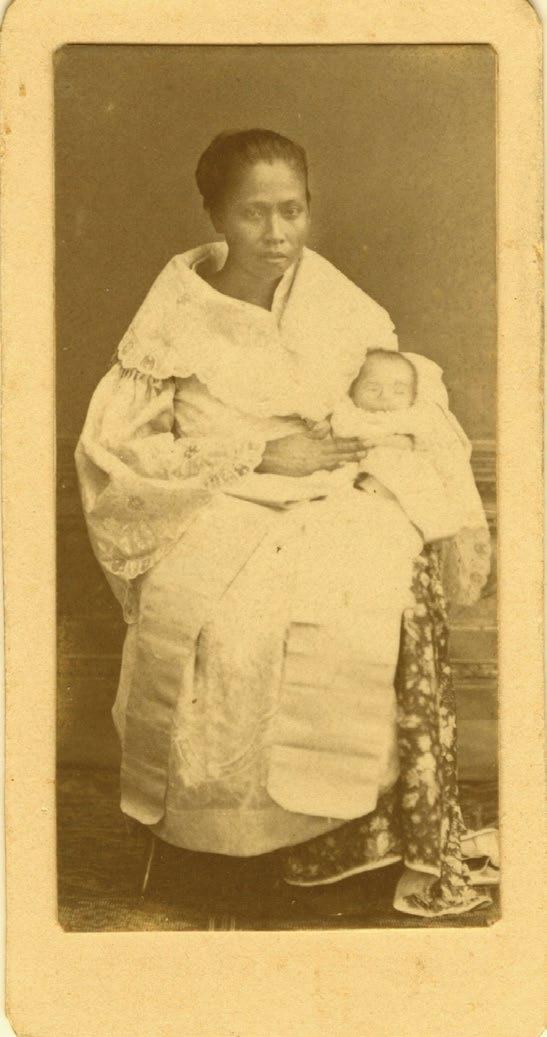

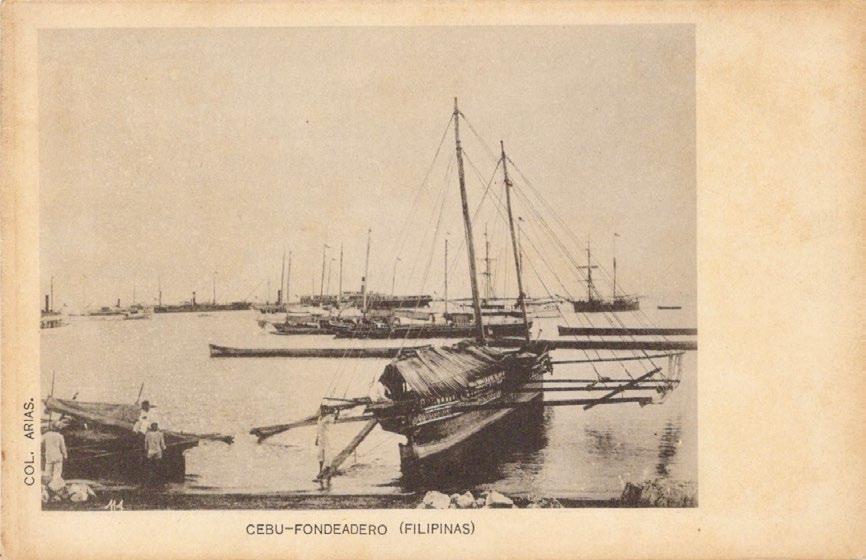

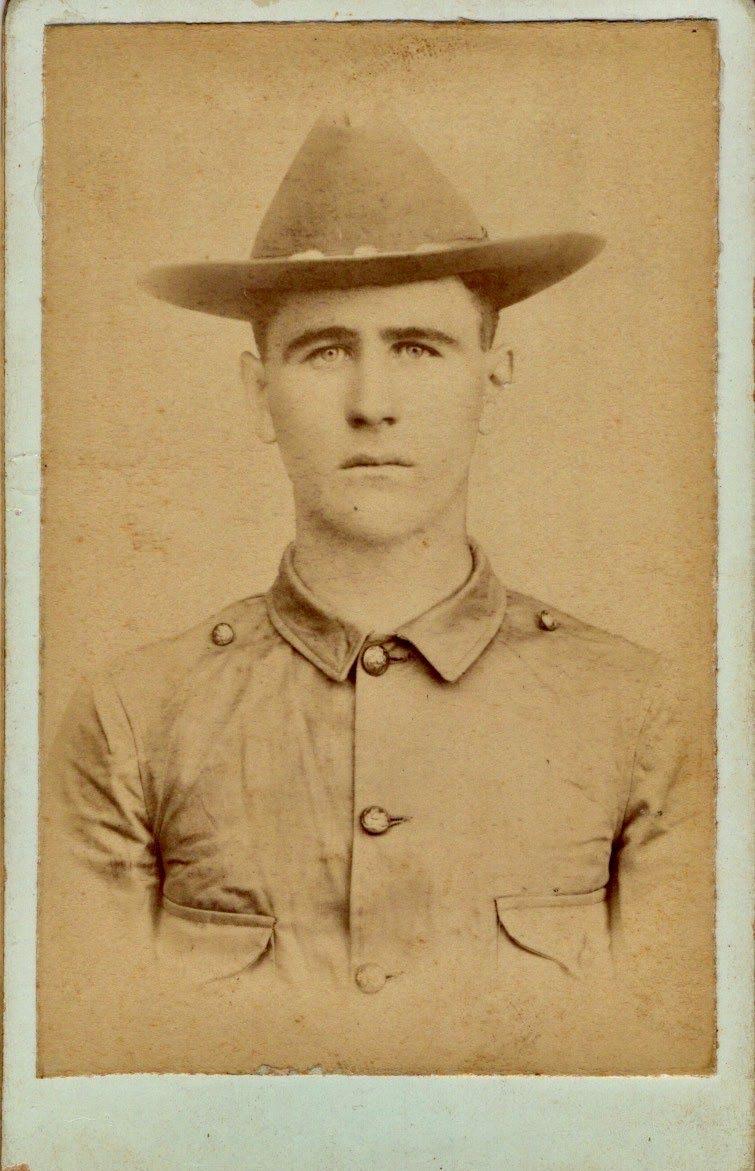

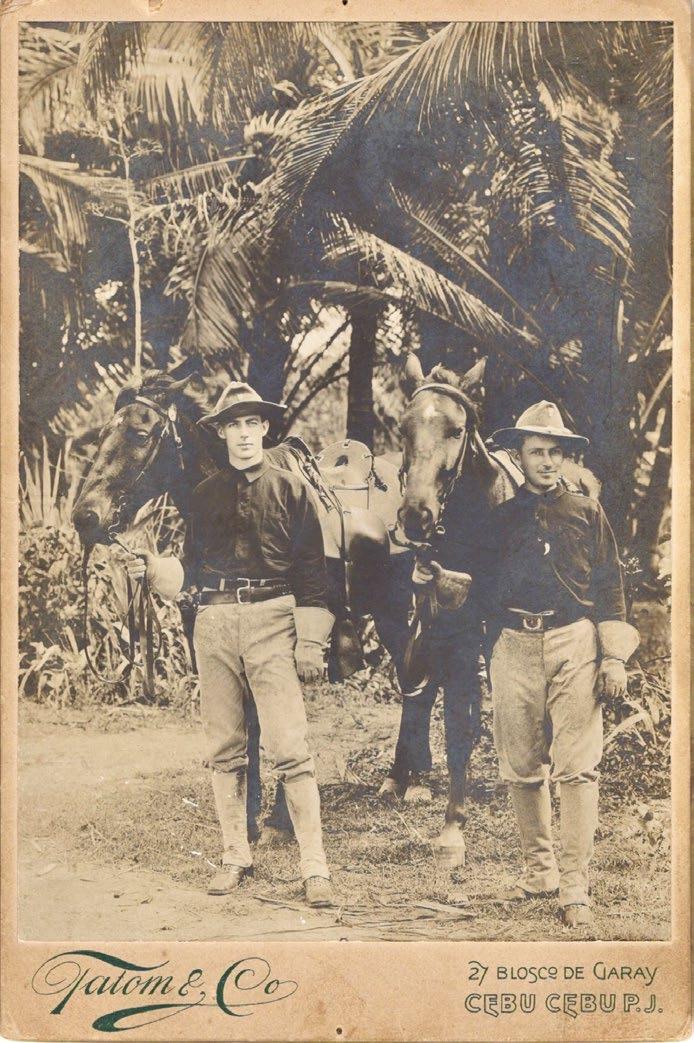

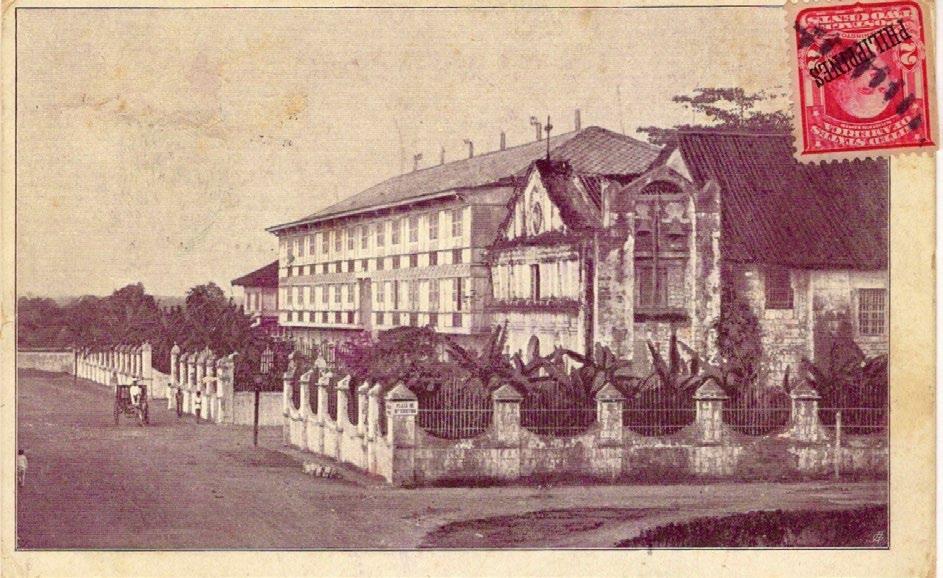

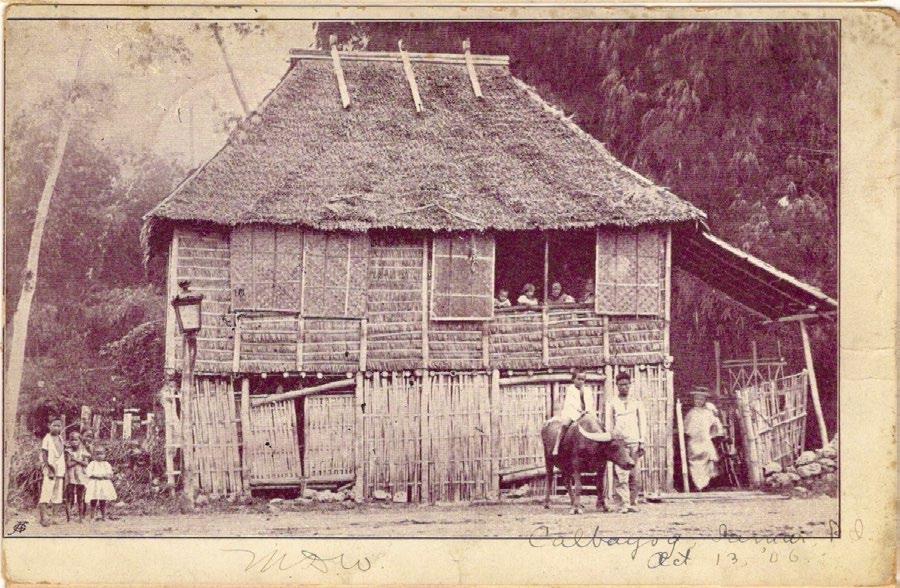

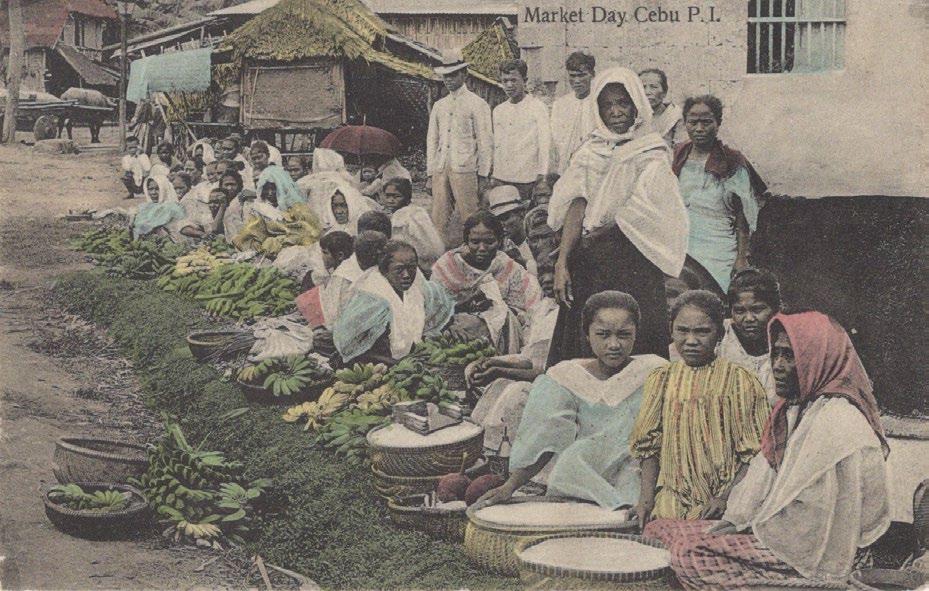

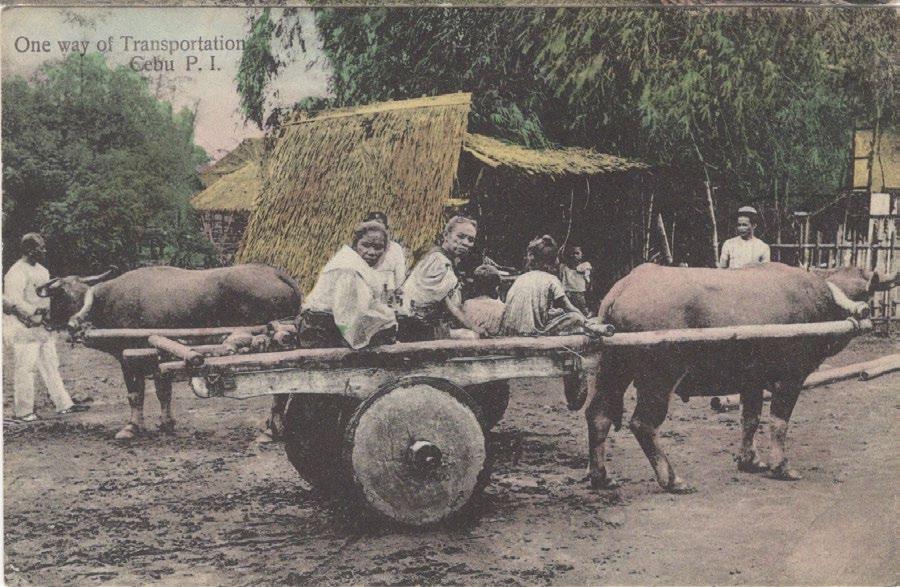

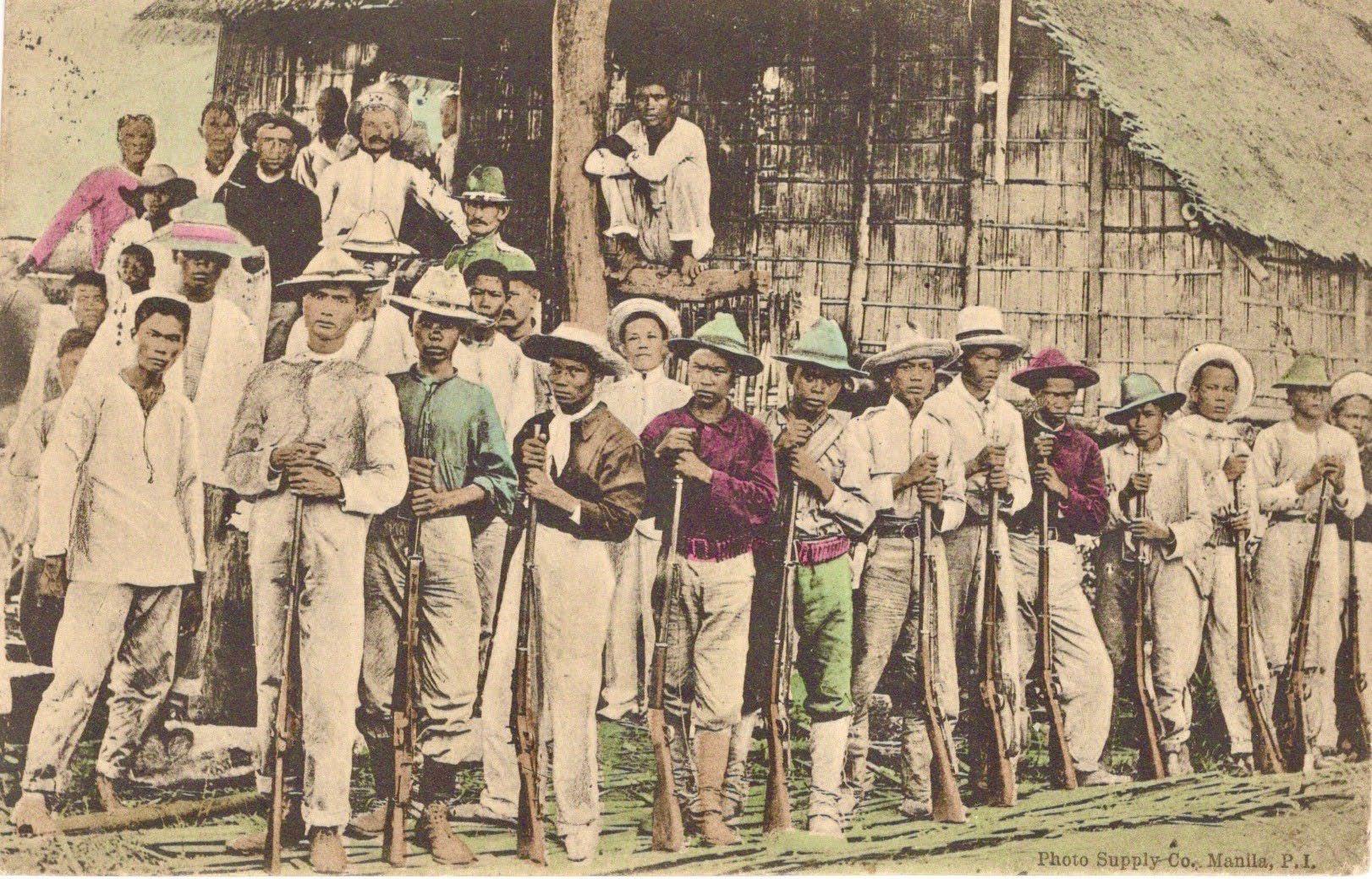

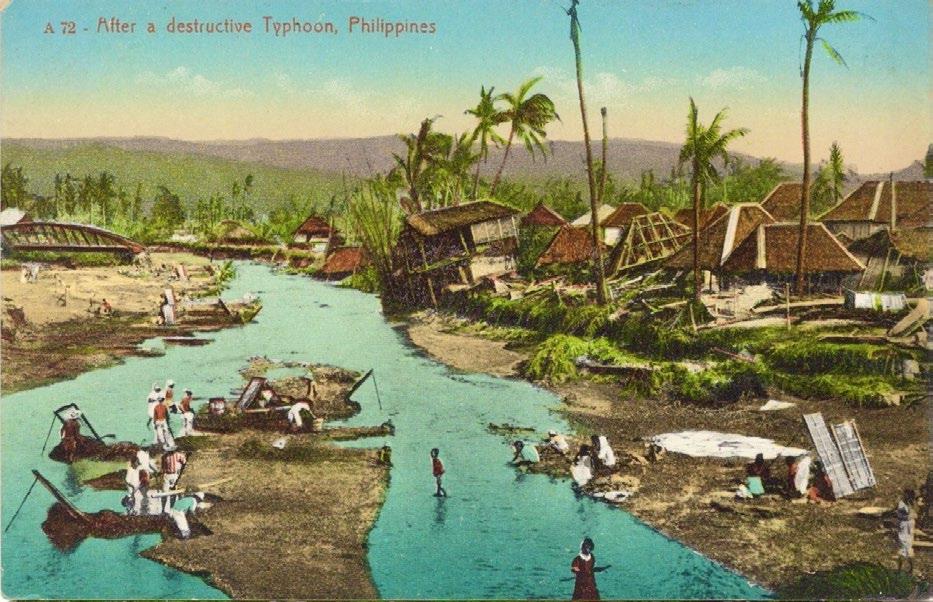

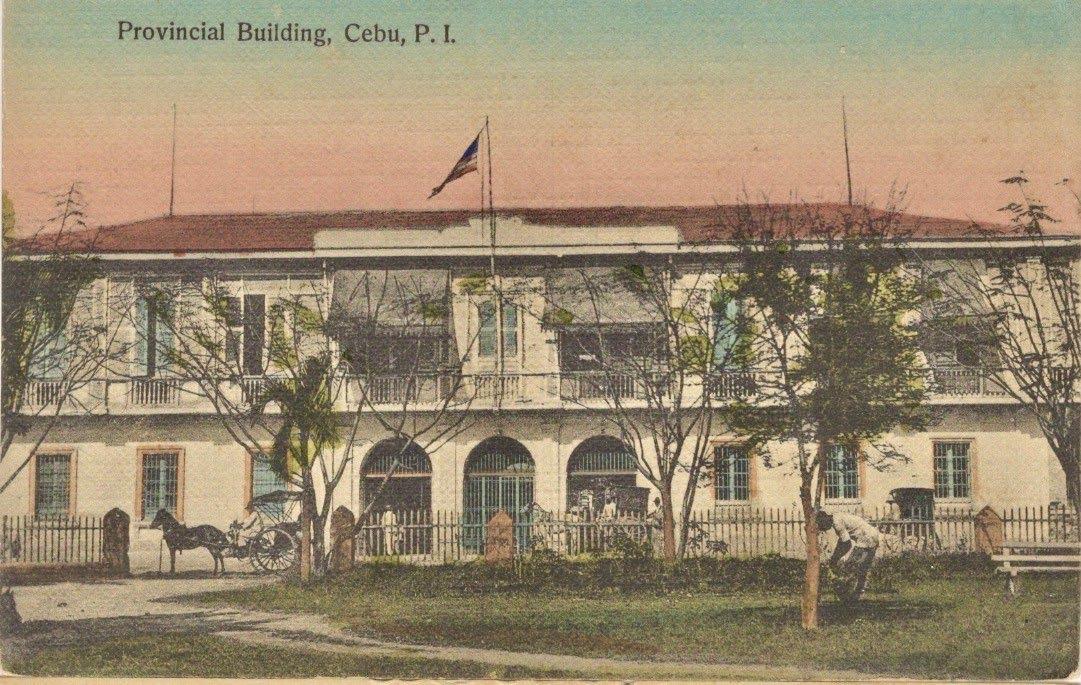

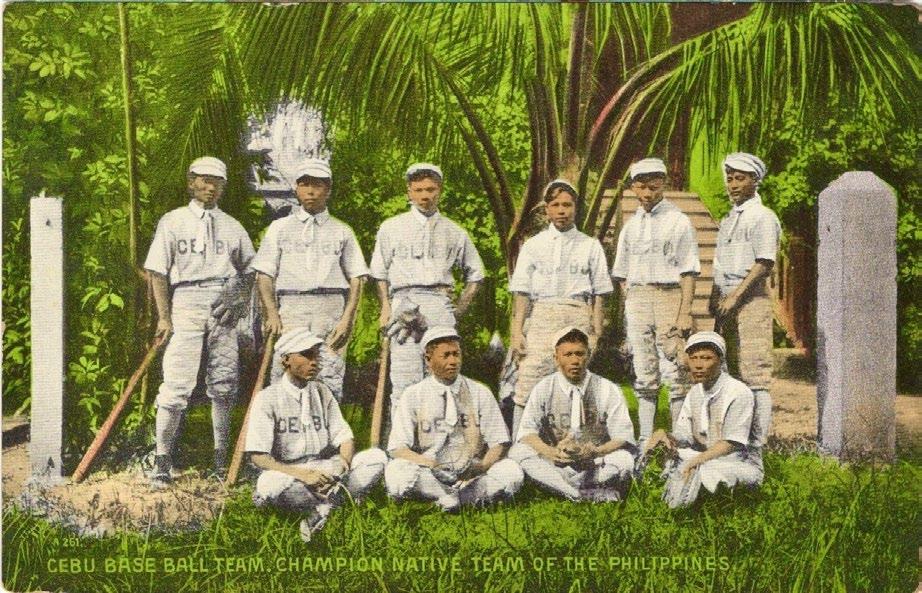

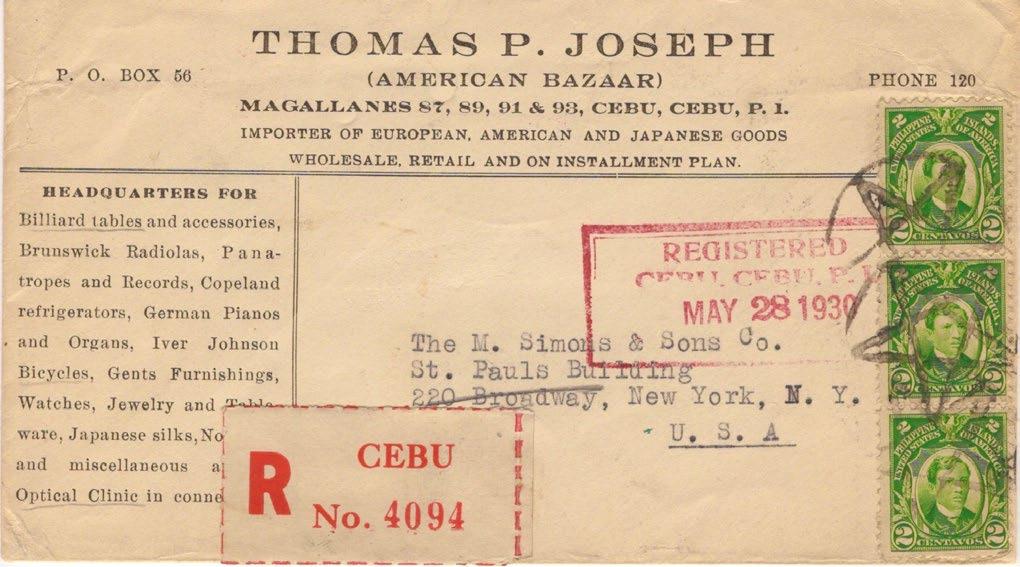

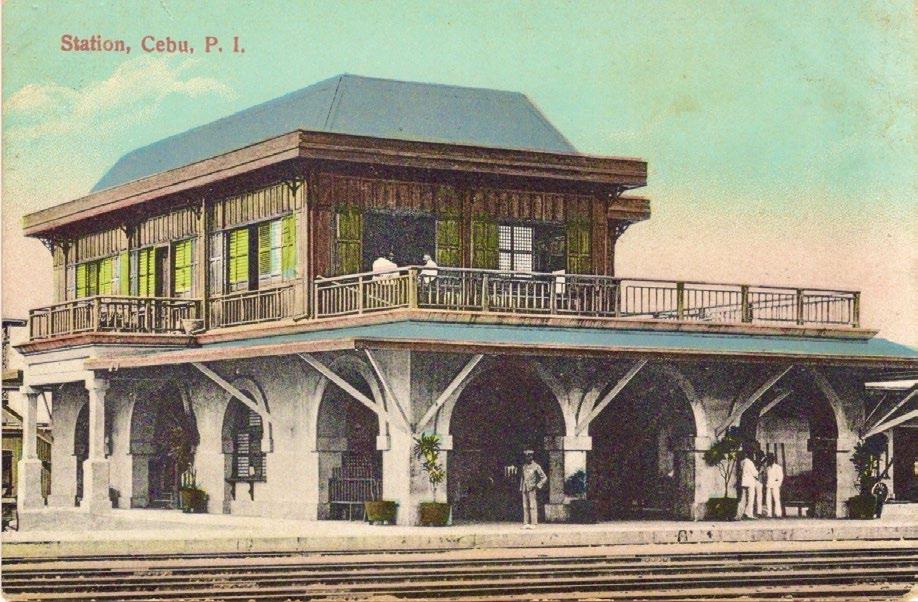

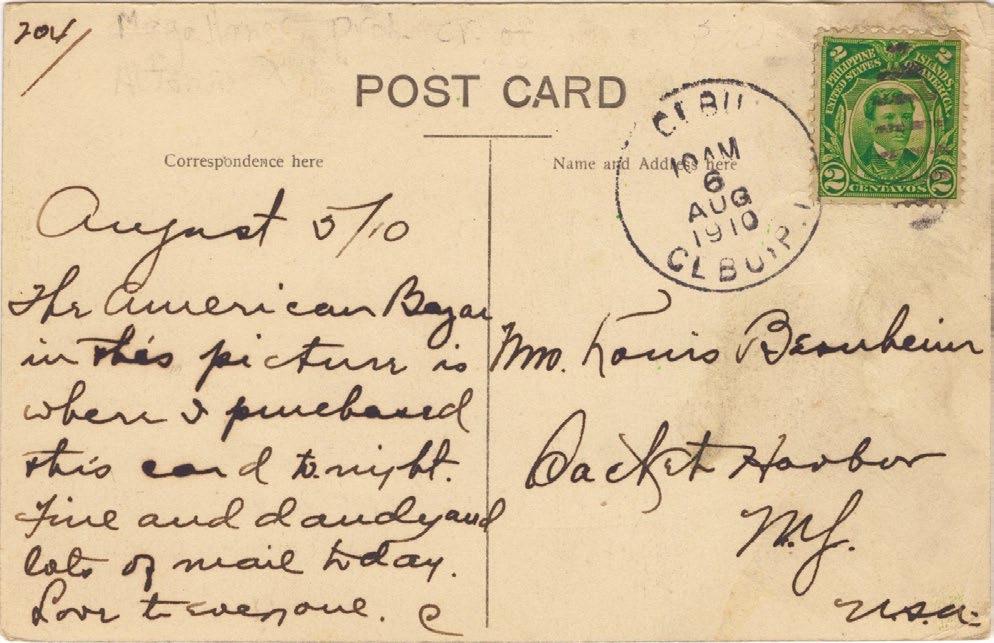

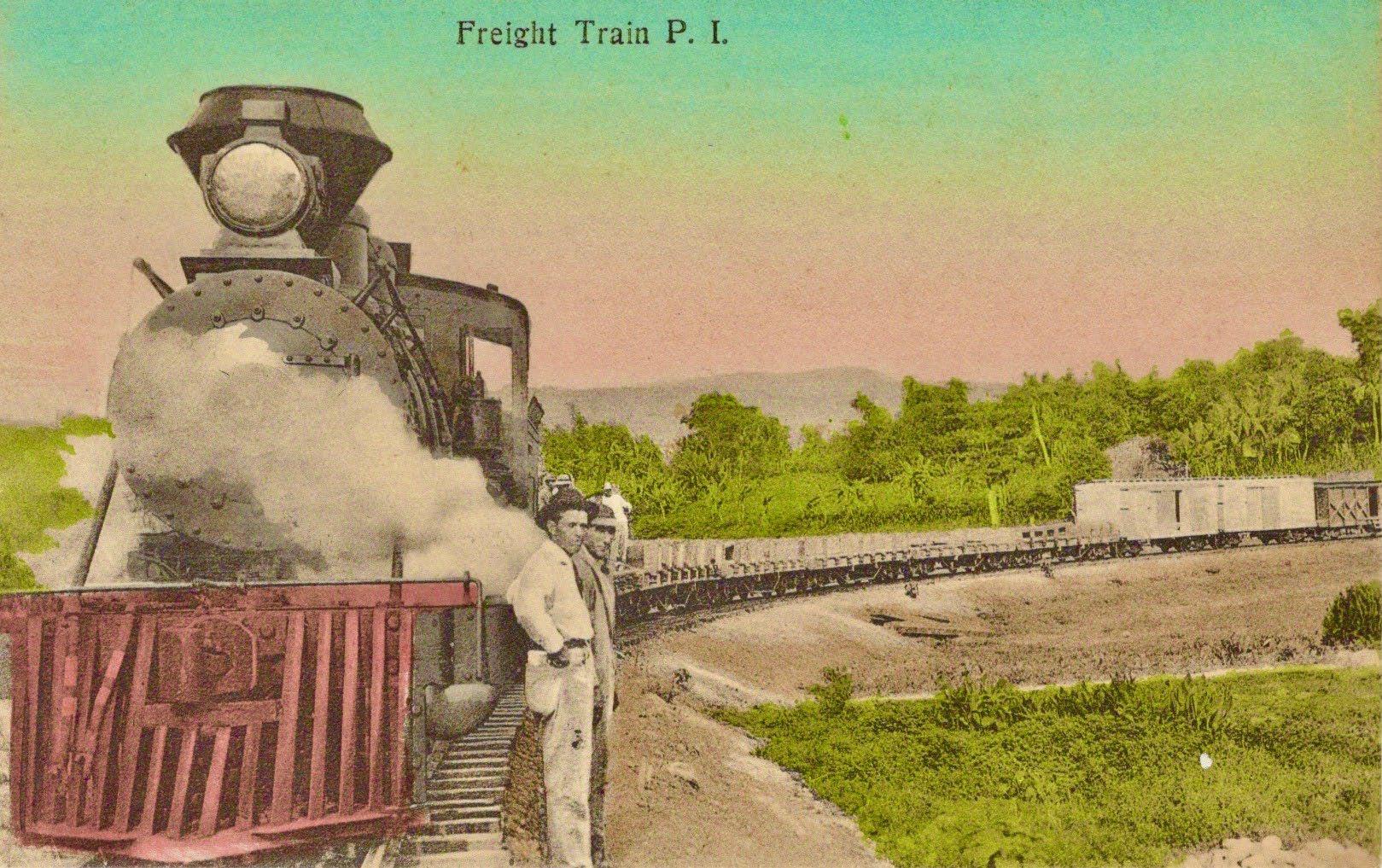

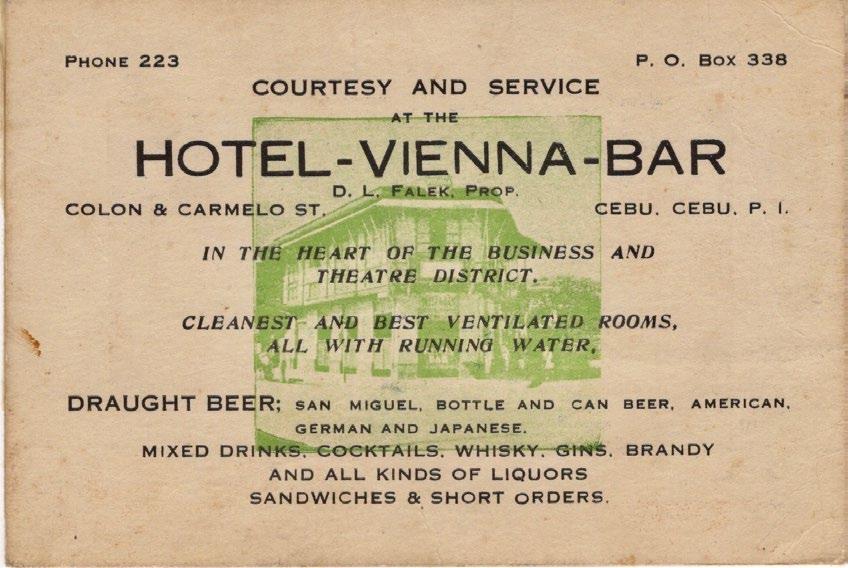

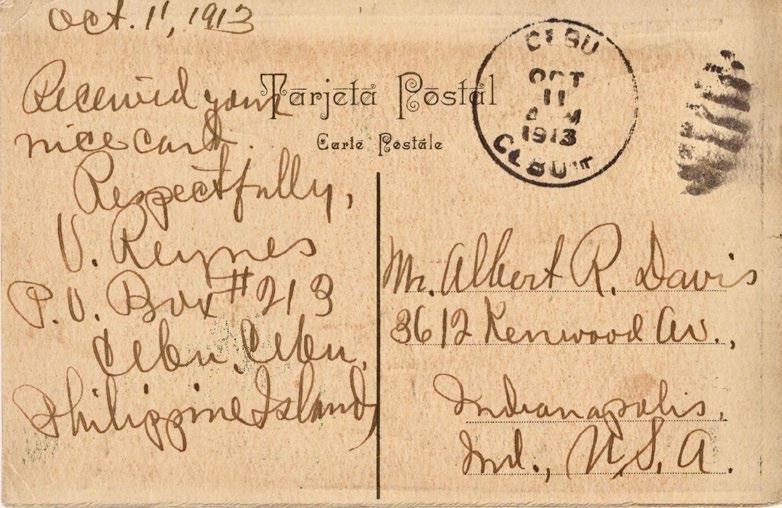

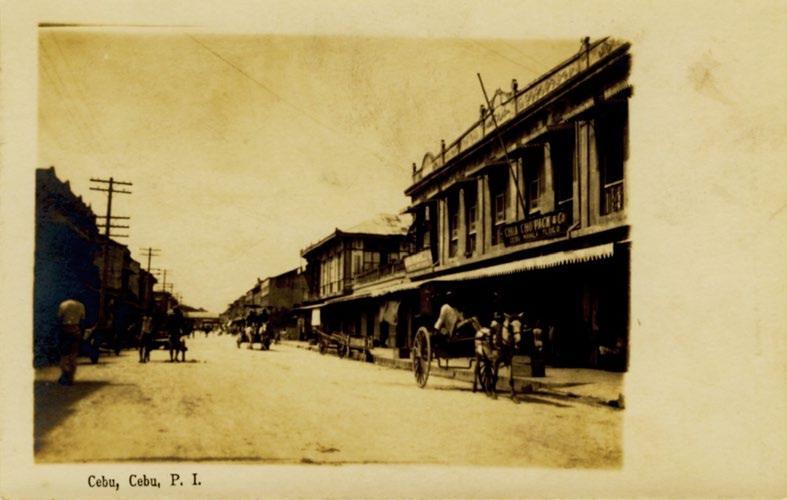

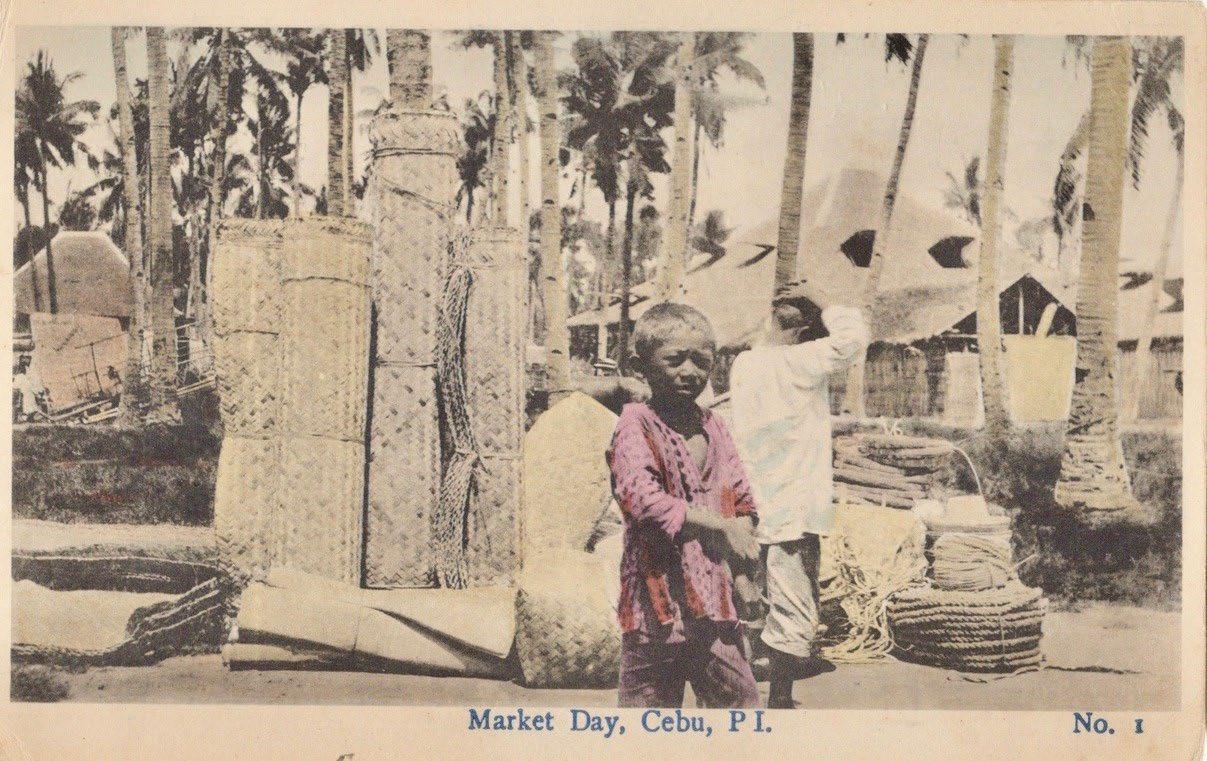

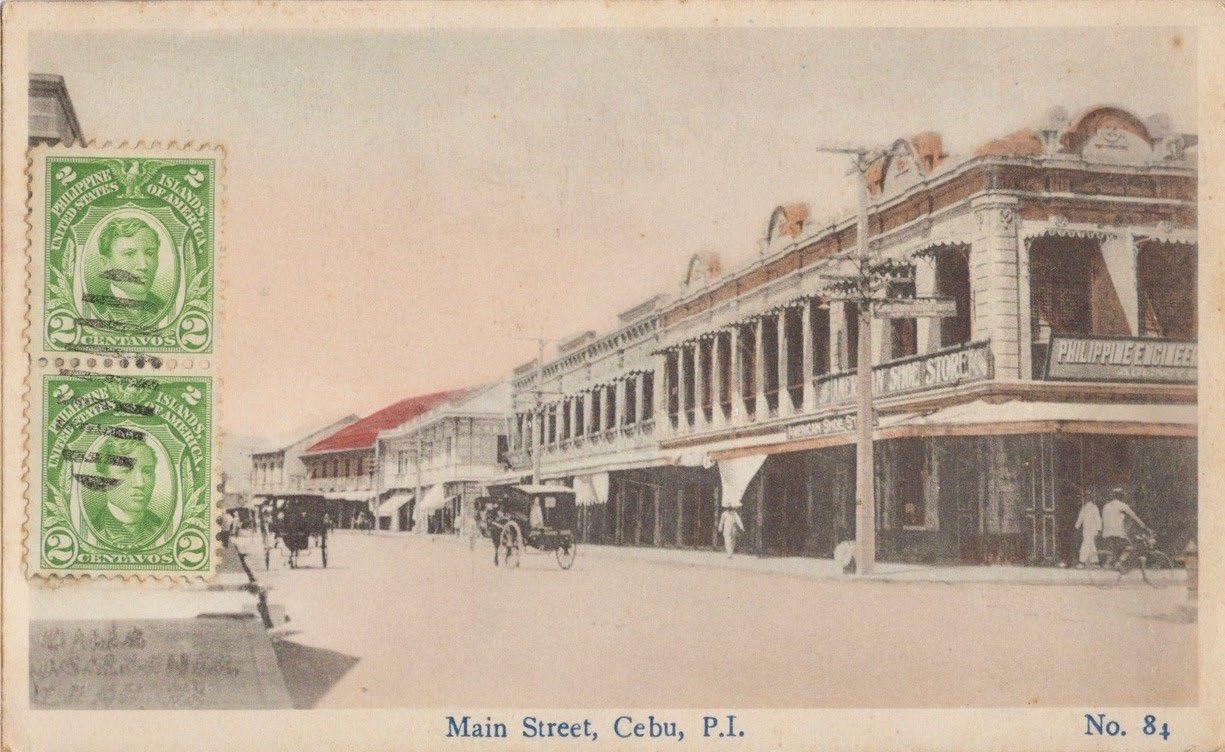

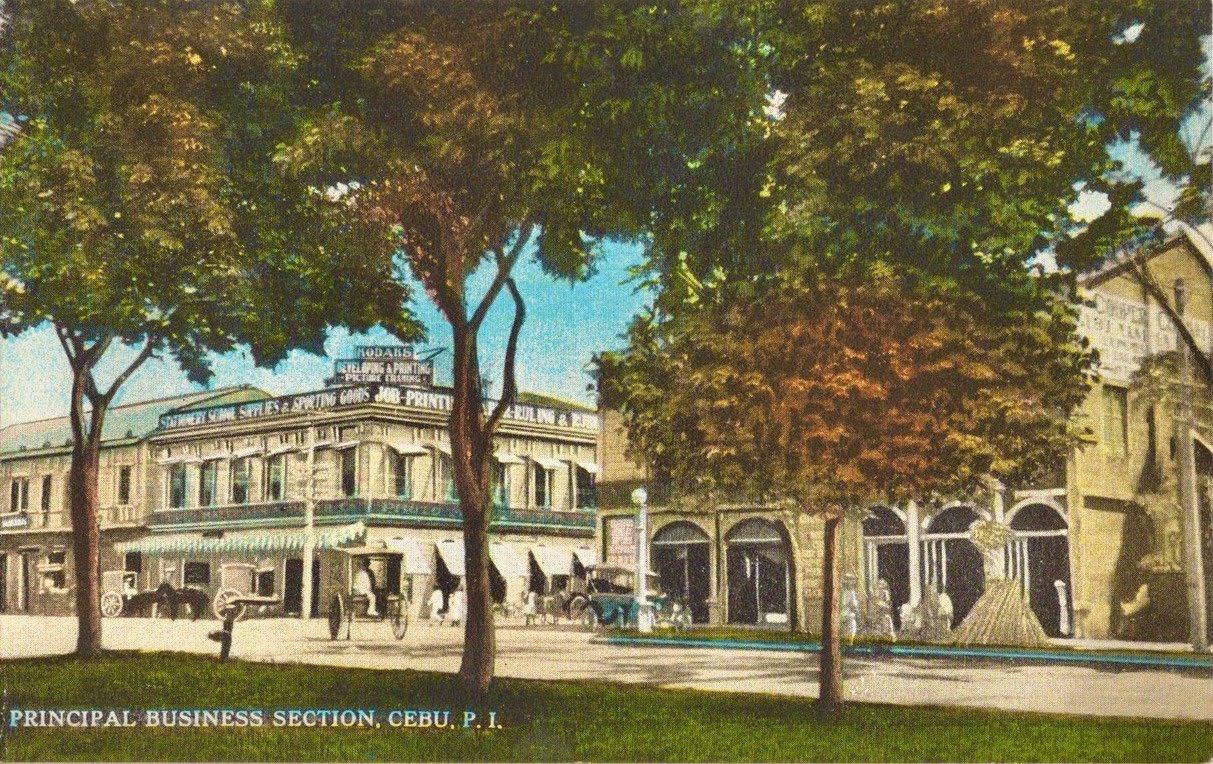

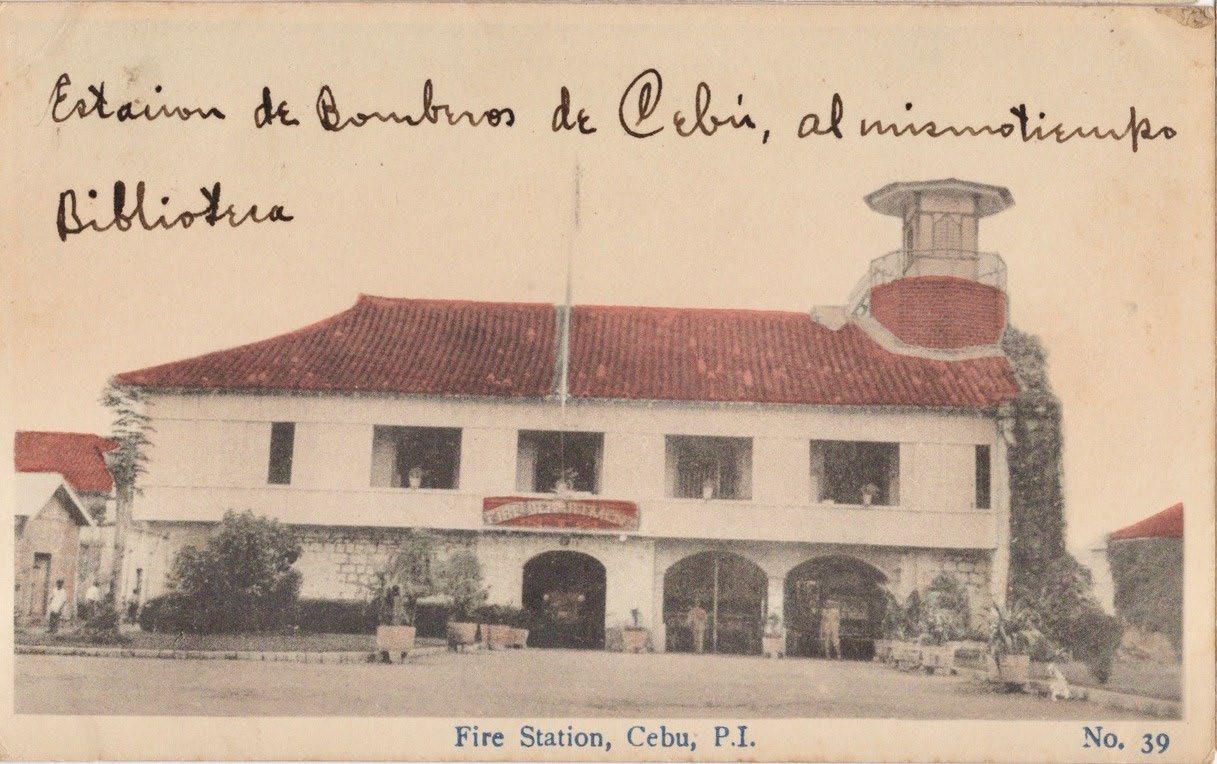

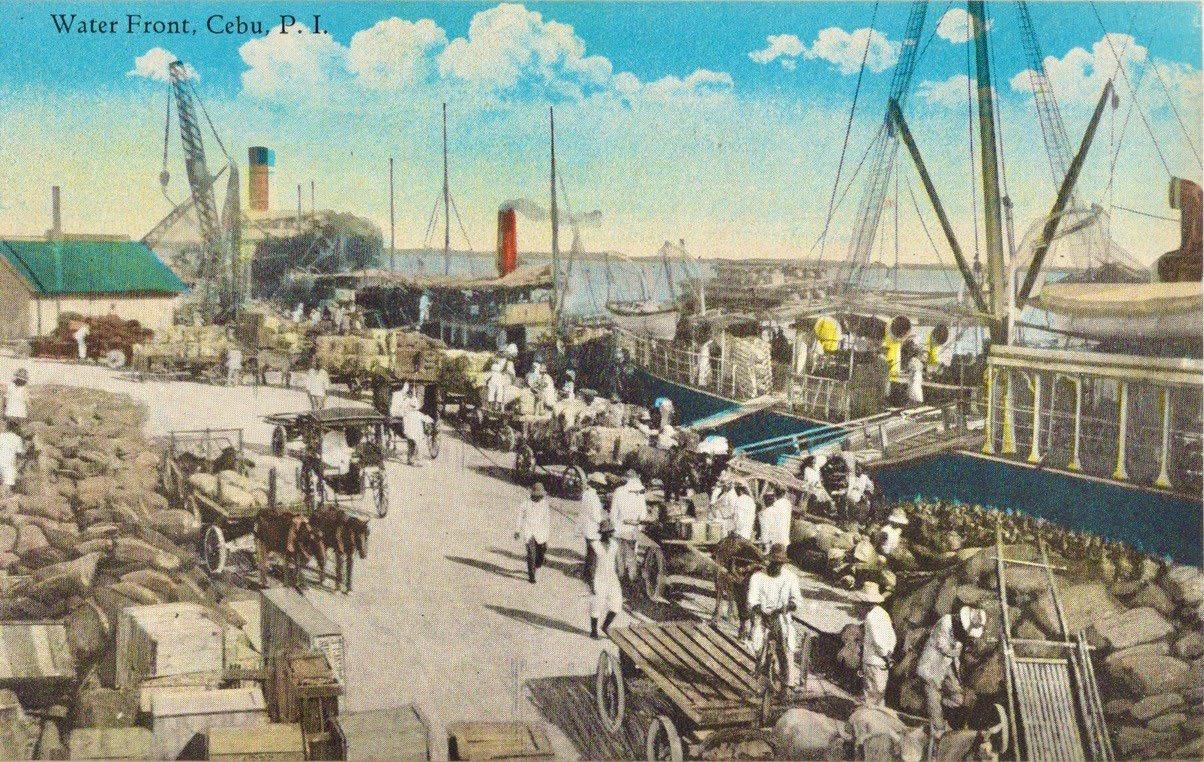

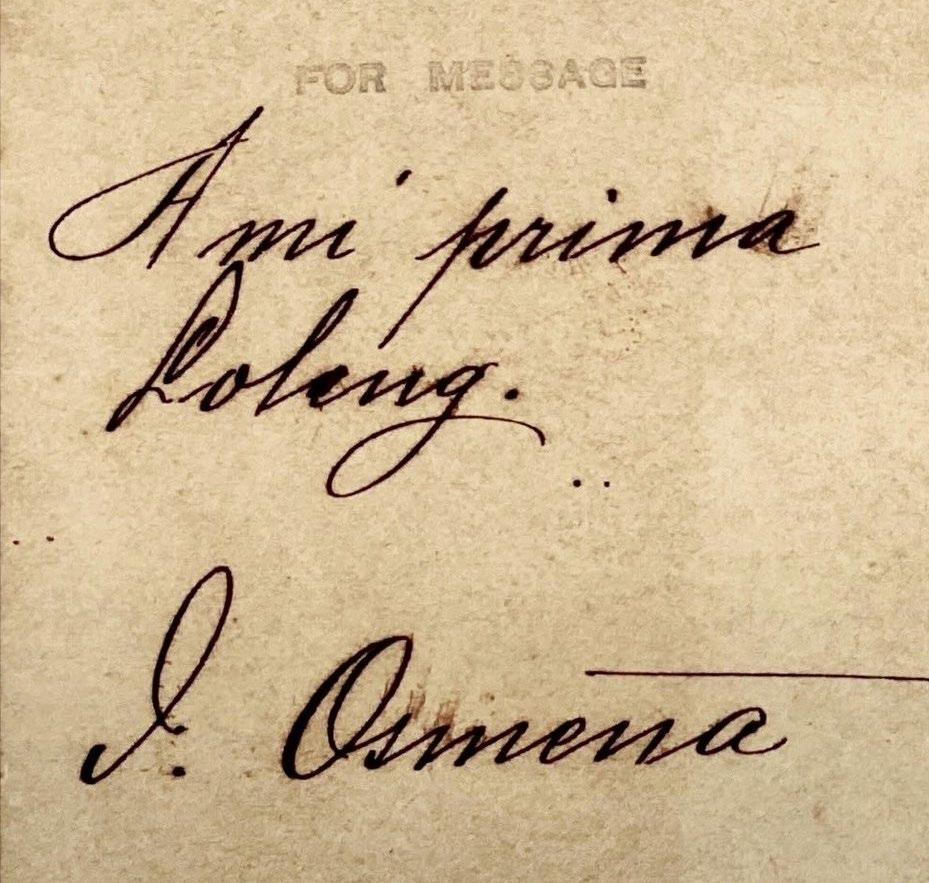

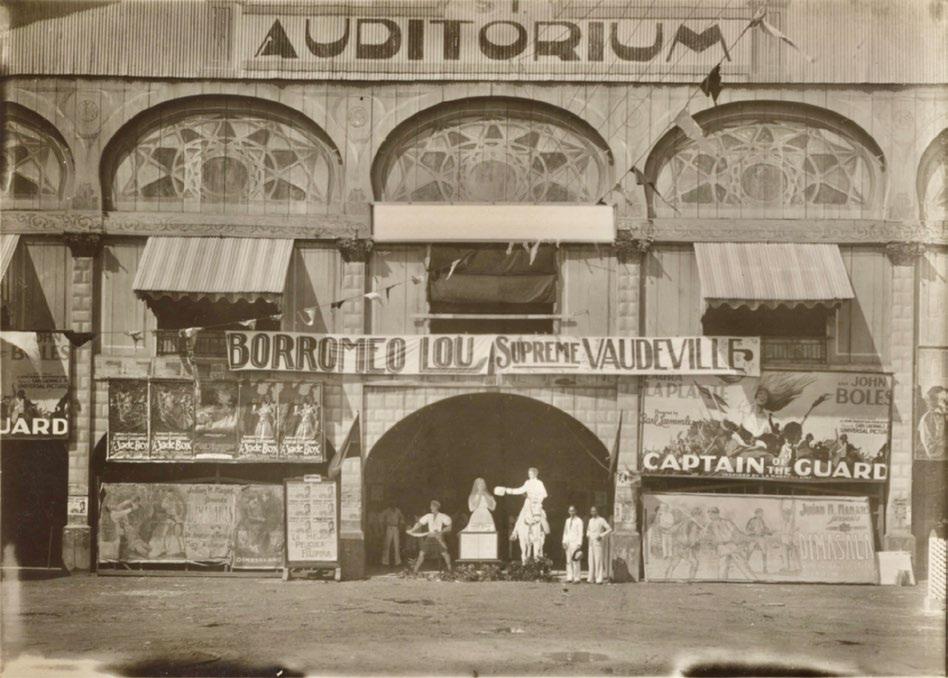

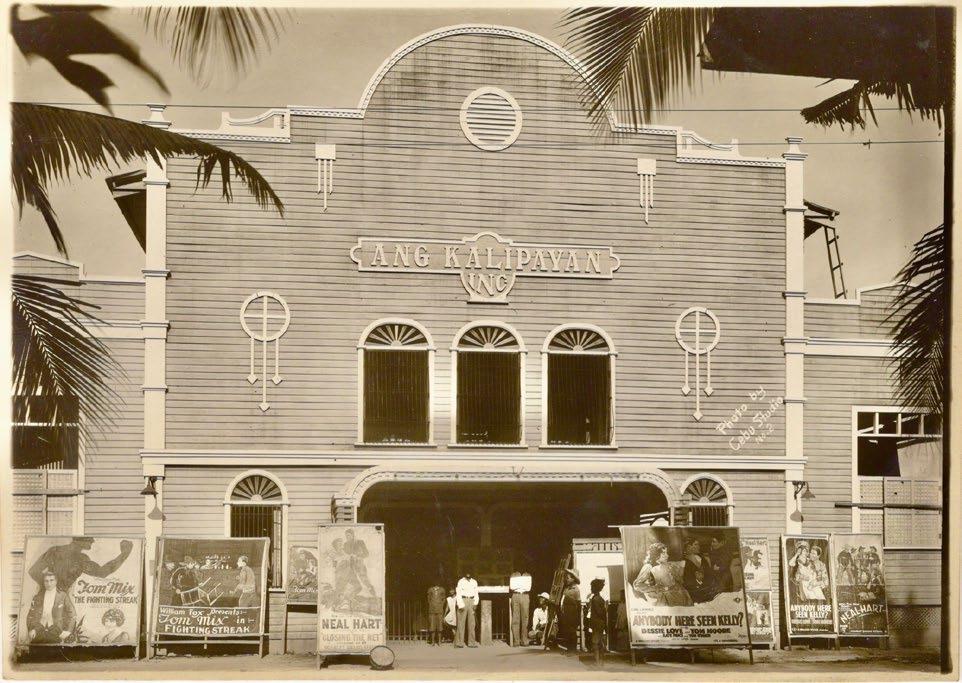

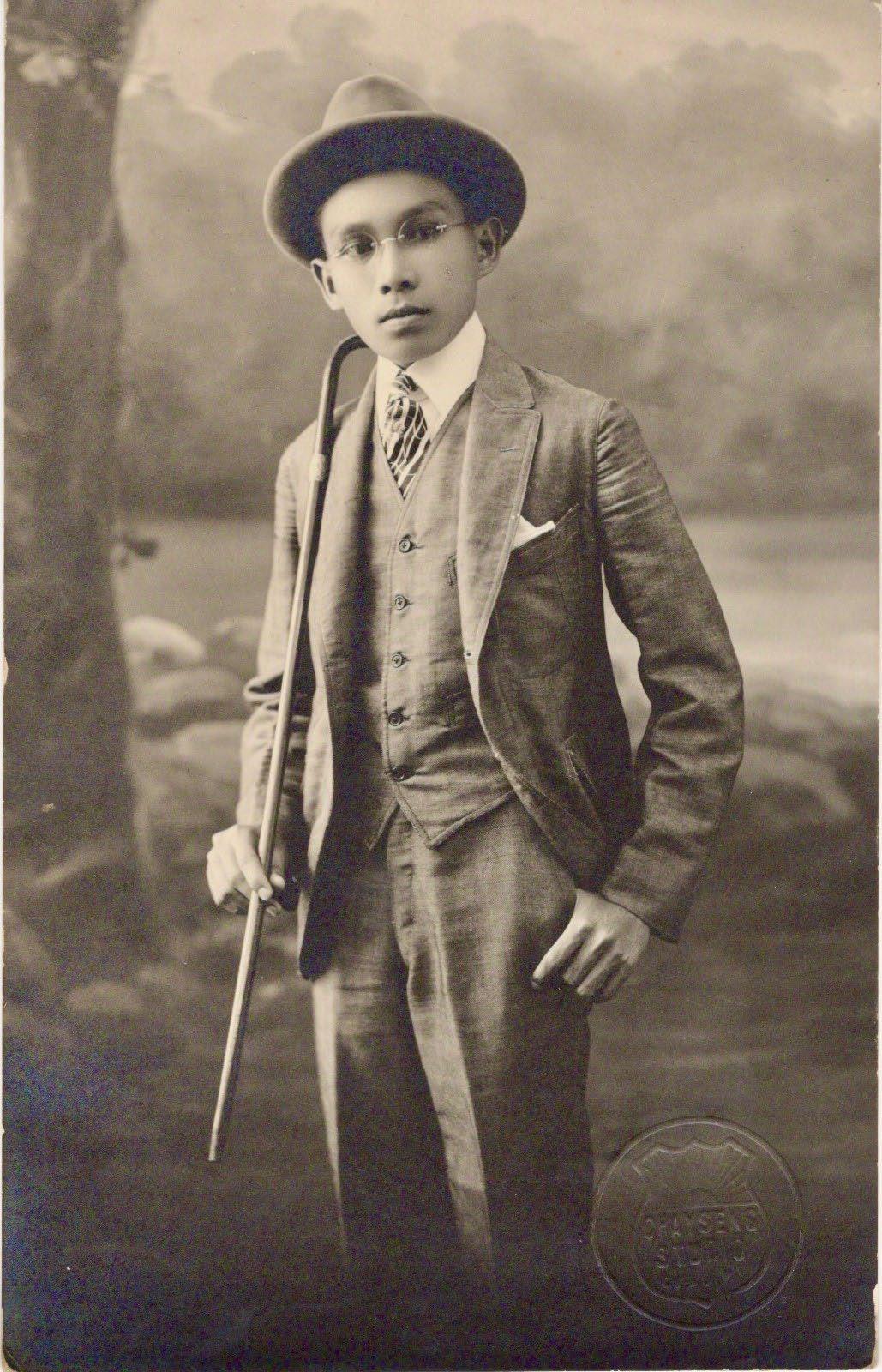

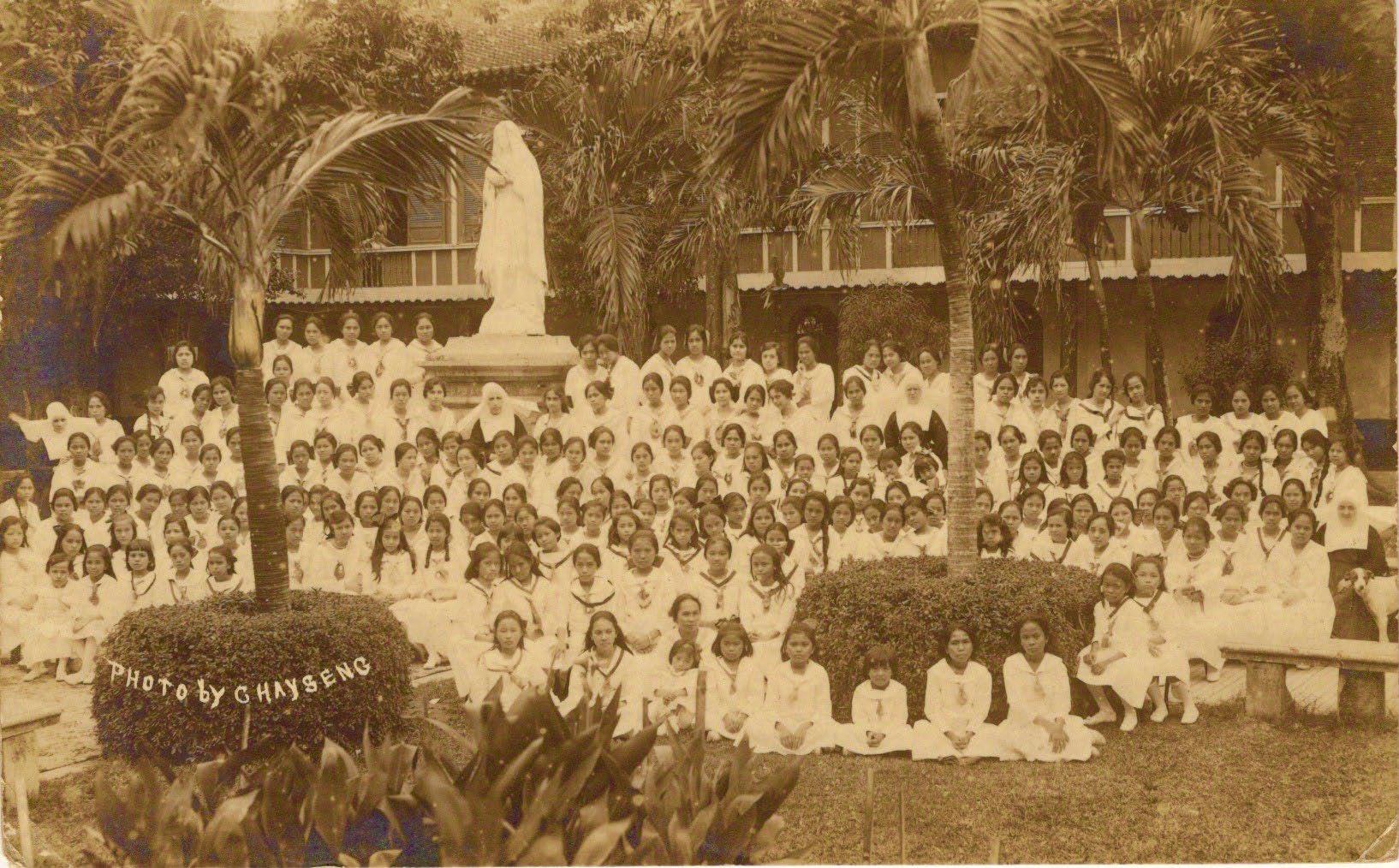

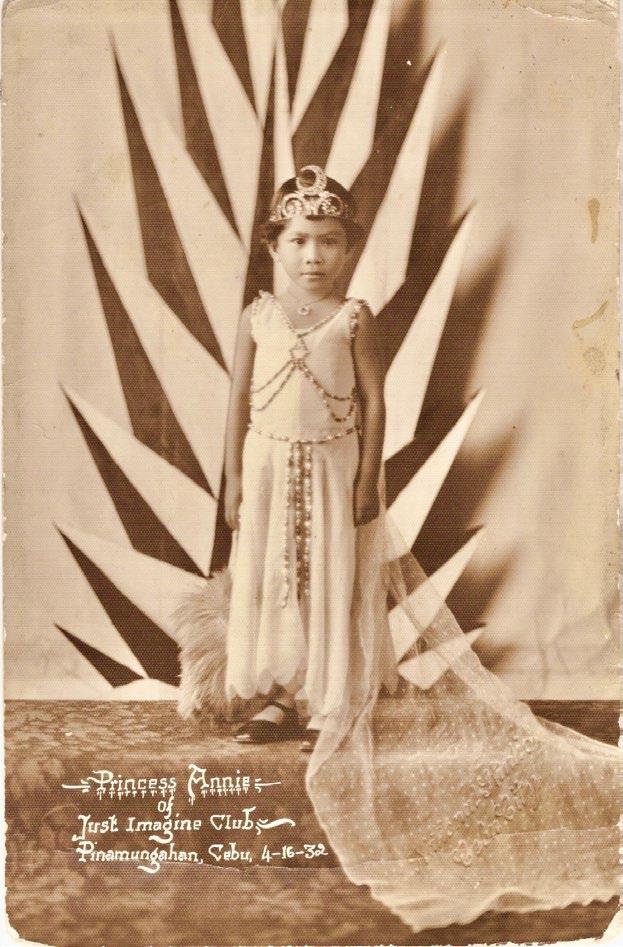

Photographers of Colonial Cebu by Michael G Price 49

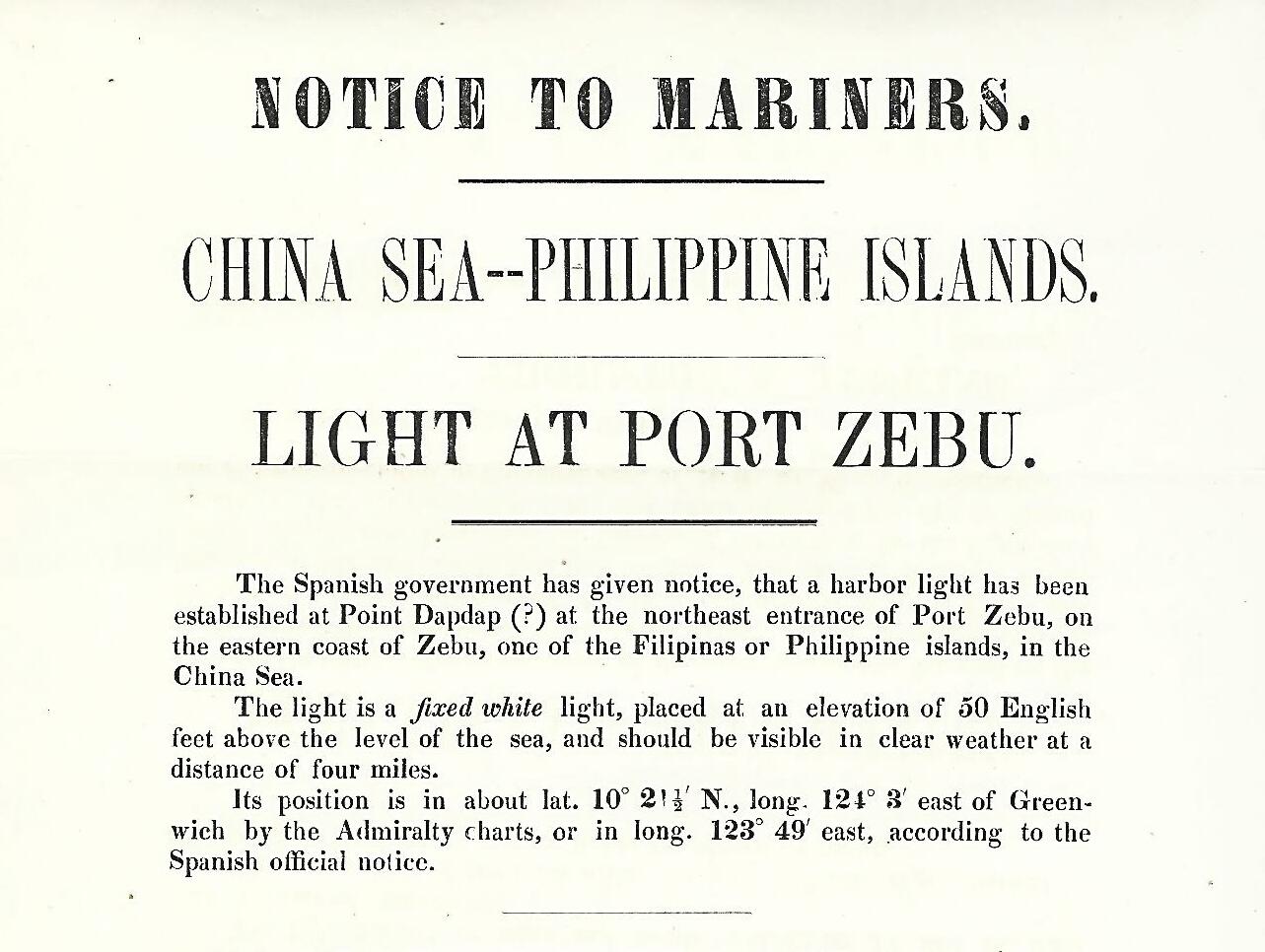

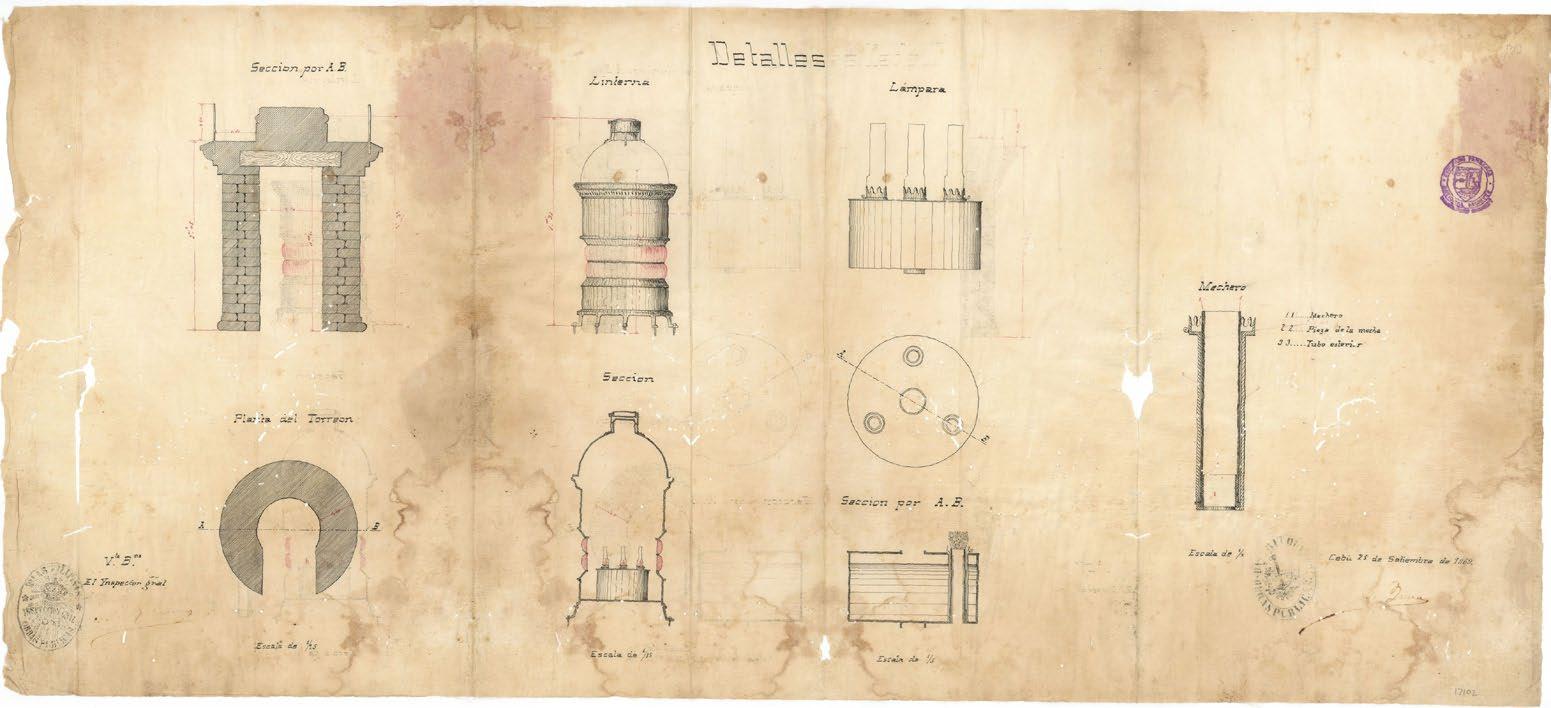

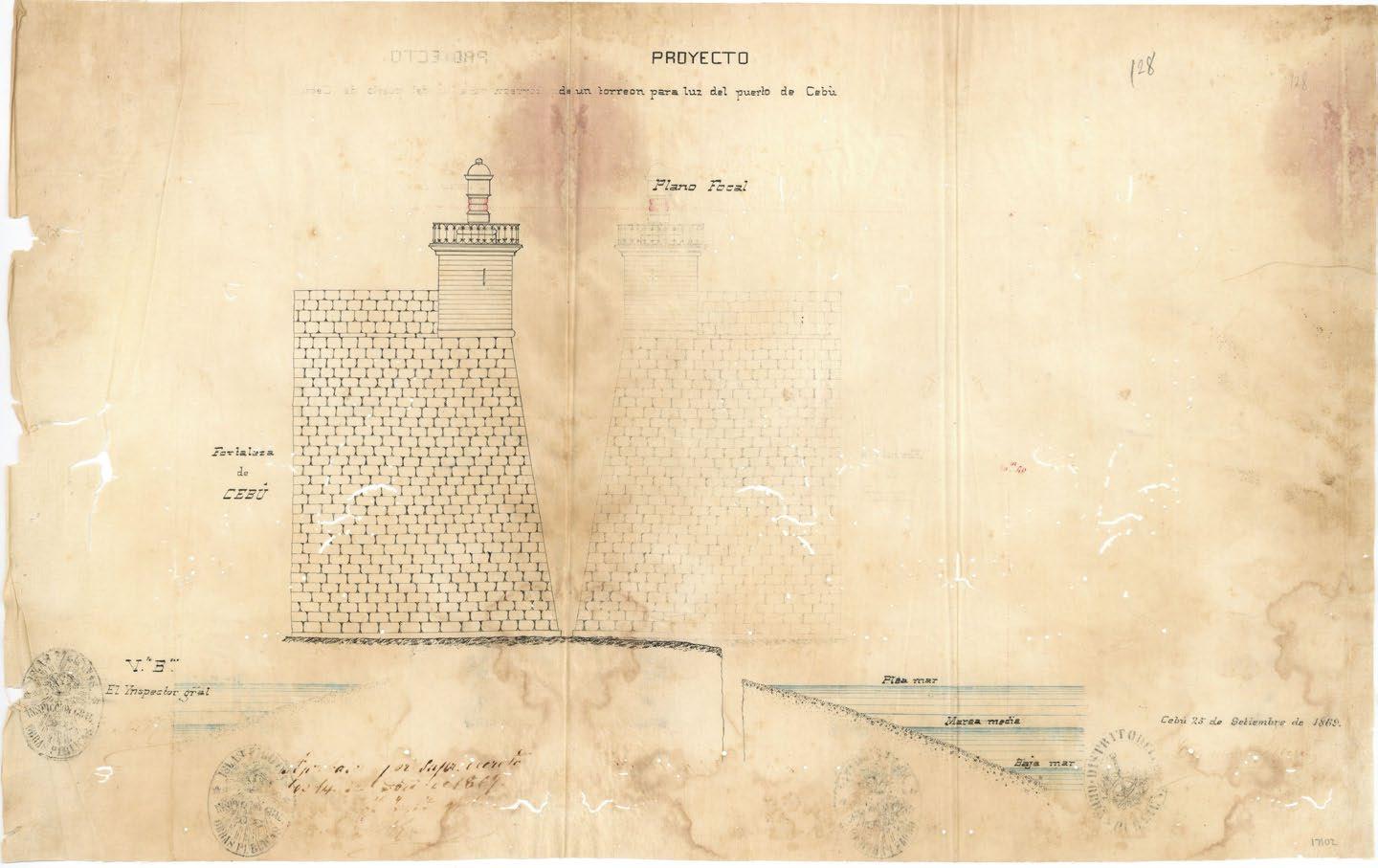

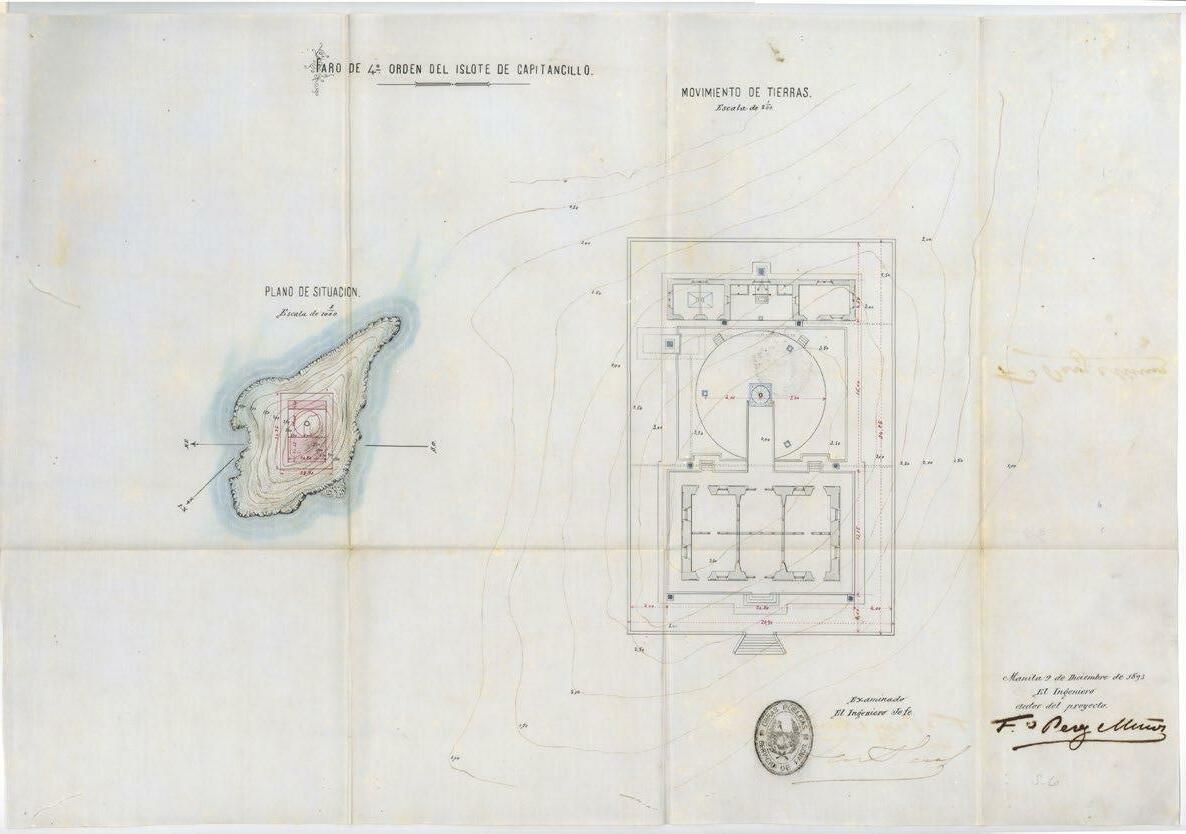

Faros y Fanales: Cebu’s Spanish Lighthouses by Peter Geldart 67

Straits: Beyond the Myth of Magellan reviewed by Andoni F. Aboitiz 73

PHIMCOS Trustees, Members & Committee Members 76

The Philippine Map Collectors Society (PHIMCOS) was established in 2007 in Manila as the first club for collectors of antique maps and prints in the Philippines. Membership of the Society, which has grown to a current total of 38 individual members, 7 joint members, and 3 corporate members (with two nominees each), is open to anyone interested in collecting, analysing or appreciating historical maps, charts, prints, paintings, photographs, postcards and books of the Philippines.

When possible, PHIMCOS holds quarterly general meetings at which members and their guests discuss cartographic news and give after dinner presentations on topics such as maps of particular interest, famous cartographers, the mapping and history of the Philippines, or the lives of prominent Filipino collectors and artists. The Society also arranges and sponsors regular webinars on similar topics. A major focus for PHIMCOS is the sponsorship of exhibitions, lectures and other educational events designed to educate the public about the importance of cartography as a way of learning both the geography and the history of the Philippines. The Murillo Bulletin, the Society’s journal, is normally published twice a year.

PHIMCOS welcomes new members. The annual fees, application procedures, and additional information on PHIMCOS are available on our website: www.phimcos.org

Front Cover: Plano Topográfico de la Isla de Cebú by Enrique Abella y Casariego, 1884 (image courtesy of the Archivo del Instituto Geográfico Nacional, Madrid)

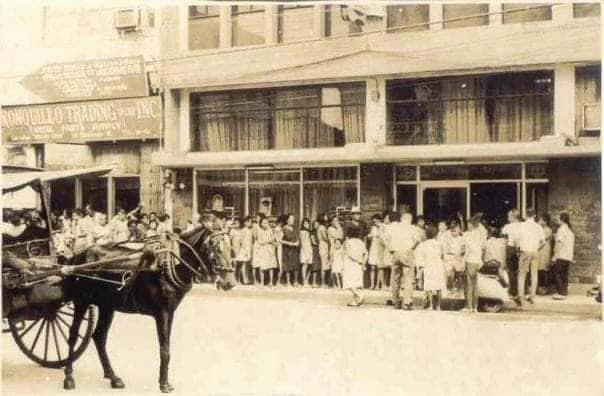

N 25 MAY, 2022 PHIMCOS was at last able to invite members to our first meeting for over two years, which was attended by ten members and four guests in person. After dinner, Marga Binamira gave a spirited and stimulating talk titled From Sugbu to Cebu A Cartographic View of Cebu City from the 16th to the 20th Centuries The presentation, which is elaborated in the article on page 21, was illustrated with many maps of the city, including rare items held by the National Archives of the Philippines. As well as those present in person, around 27 members and guests joined the talk by Zoom.

At the end of the meeting we made space on the floor for Peter Geldart to display the only known example of the Carta General del Archipiélago Filipino printed in Manila in 1897 by Chofré y Compania. The huge, detailed wall map is believed to be the largest map of the Philippines produced in the 19th century.

As well as restarting in person meetings for members, PHIMCOS continues to host webinars:

On 23 June Alberto Montilla and Peter Geldart gave a talk on John Bach: cartographer, collector and historian of maps of the Philippines. Bach was employed by the U.S. Coast & Geodetic Survey in Manila from 1902 until the outbreak of World War II. He was not only the most prolific cartographer in the Philippines during the American period but also an avid collector and historian of antique maps of the archipelago. The presentation covered Bach's life and work, illustrated with many of the maps he compiled and published.

On 10 August Ricardo Trota Jose PhD, Professor of History at the University of the Philippines, gave a presentation titled ‘You are Our Pals: Japanese propaganda leaflets and posters in the Philippines during World War II’ Dr. Jose showed us a comprehensive selection of leaflets and other ephemera that illustrated the efforts made by the Japanese army of occupation to win over the hearts and minds of the Filipinos, and also to try and persuade the American troops that defending the Philippines was impossible.

On 14 September Jorge Mojarro, a professor of Spanish at Instituto Cervantes de Manila and professor of literature at the University of Santo Tomás, presented ‘In search of the Spice islands: Spain and the Moluccas (1521 1667)’. His talk covered the history of Spain’s search for a presence in the Asian spice trade, the short history of the Spanish outpost in the Moluccas, the important role played in it by Filipinos, and the eventual abandonment of the settlement. The illustrations were maps featured in En el archipiélago de la Especiería. España y Molucas en los siglos XVI y XVII (Desperta Ferro, Madrid, 2020), edited by Prof. Mojarro.

On 19 May a delegation from PHIMCOS led by our President Jaime González visited the National Archives of the Philippines to present the NAP with a set of our past catalogues and issues of The Murillo Bulletin The visit was hosted by the NAP’s Director, Ino Manalo, who thanked PHIMCOS for our donation. Areas of potential collaboration between PHIMCOS and the NAP were discussed, including a possible exhibition in 2024 when the NAP inaugurates its new home in the restored and refurbished Intendencia Building in Intramuros.

From 12 June to 31 July the PHIMCOS Education Committee and Gari R. Apolonio, Curator at the Gateway Gallery, were partners in sponsoring the exhibition ‘Map to Freedom ‒ Putting the Philippines on the Map’ at the Araneta Center in Cubao. The exhibition used the panels made for the PHIMCOS Roving Exhibitions. In conjunction with the exhibition, on 9 July Prof. Ambeth Ocampo gave a talk on ‘Murillo Velarde the Mother of Philippine Maps’ that was attended by over 130 people.

On 30 August, PHIMCOS members were invited by Yale NUS College to join a Zoom webinar titled ‘Unlocking maps, Narrating the past: Historical Maps of Southeast Asia’. The webinar marked the launch of the Digital Historical Maps of Singapore and Southeast Asia Platform, a new online resource that brings together maps of the region from the collections of the National Library Board, Singapore; the Beinecke Library, Yale University; the Leiden University Libraries; and the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford The platform can be accessed at: https://historicalmaps.yale nus.edu.sg/

On 16 17 September PHIMCOS members were invited to attend the Annual Philippine Studies Conference organised by the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). This year’s conference was on ‘The 1762 British Invasion of Spanish Ruled Philippines: Beyond Imperial and National Imaginaries’ The conference explored ways of putting the British occupation of the Philippines into its historical context through issues of resistance, cultural repercussions and local history

We congratulate Raphael P.M. ‘Popo’ Lotilla on his recent appointment as Secretary of Energy. In view of the important responsibilities of his position in government, Popo tendered his resignation from the Board of Trustees on 15 July, 2022. He has been an outstanding and invaluable Trustee of the Society. In his place, the Board has approved the appointment of Felice Noelle Rodriguez, Visiting Professor at the Ateneo de Zamboanga University, who holds masters and doctoral degrees in History from the University of the Philippines and has published historical works on slave raiding, warfare, Christian discourses, nationalism and Zamboanga.

In recognition of its efforts to meet global environment, social, and governance (ESG) standards, Union Bank of the Philippines (UnionBank) was recently named the Philippines’ best bank for ESG 2022 at this year’s Asiamoney Best Bank Awards.

are complementary pursuits. By building strong, entrepreneurial and resilient communities, the thinking goes, there will be loads of new customers and deals coming UnionBank’s way,” Asiamoney said.

One of the initiatives recognized by Asiamoney in line with these goals is the Bank’s partnership with the International Finance Corp. to issue social bonds to finance small business loans, which has benefitted countless micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in the country.

Asiamoney also highlighted the Bank’s adherence to the United Nations’ sustainable development goals particularly through its sustainable finance framework, as well as its Tech-Up Pilipinas advocacy which contributes to the country’s digital transformation through inclusive and technologydriven co-creation and knowledge sharing.

In a statement, Asiamoney cited the five goals of UnionBank in promoting sustainability in the country, which are poverty reduction, improvement of education, making growth greener, climate change mitigation, and increased innovation and industrial efficiency.

“The bank’s commitment to ESG, and being an incubator for innovation and digitalization,

Two other initiatives highlighted by Asiamoney were UnionBank’s PeopleTech initiative aimed at helping stakeholders hone their digital literacy and know-how in reducing their carbon footprint; and the Xcellerator program which empowers internal and external talent with knowledge relevant in the digital economy.

“We at UnionBank believe that sustainability is the way forward, which is why we adopted ESG to become a component of everything that we do,” said UnionBank Chief Human Resource Officer Michelle Rubio. “To Asiamoney, we express our heartfelt gratitude for this recognition, and to UnionBankers, you made this happen. This is for you.”

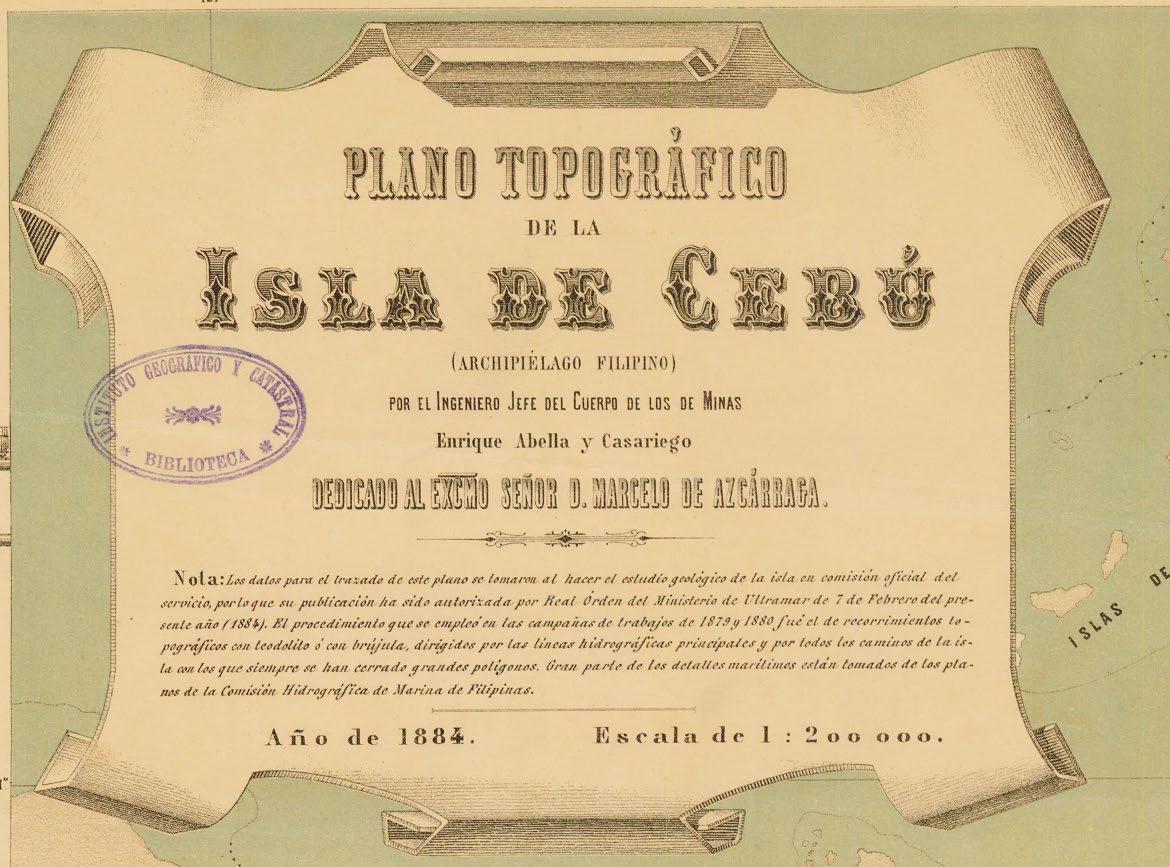

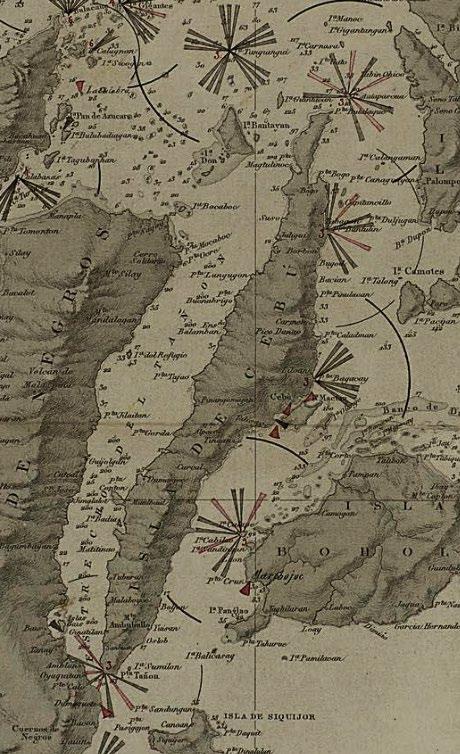

THE FINEST 19th century wall map of Cebu was published in 1884 by the Spanish cartographer Enrique Abella y Casariego. Titled Plano Topográfico de la Isla de Cebú, the map is dedicated to Don Marcelino de Azcárraga, a Spanish soldier and politician born in Manila in 1832 who would later become President of the Spanish Council of Ministers three times between 1897 and 1905. Measuring an imposing 123 cm x 90 cm, including its borders, the map was engraved by J. Mendez, and was printed in Madrid by the lithographic printing firm of Nicolás González

The main map, at a scale of 1:200,000, shows the topography of the island, indicated by shading and the heights of mountains; rivers; carriage roads and horse tracks; the size and status of the centres of population; and the location of mines, springs, hydrothermal mineral deposits and caves Offshore, hydrographic details include reefs, shallows and the direction of currents. A note at the bottom of the title cartouche explains that the data used in drawing the map came from the official topographic surveys of the island (in which Abella had participated in 1879 80) using theodolites and compasses. Hydrographic infor mation is from the Comisión Hidrografíca de Marina de Filipinas.

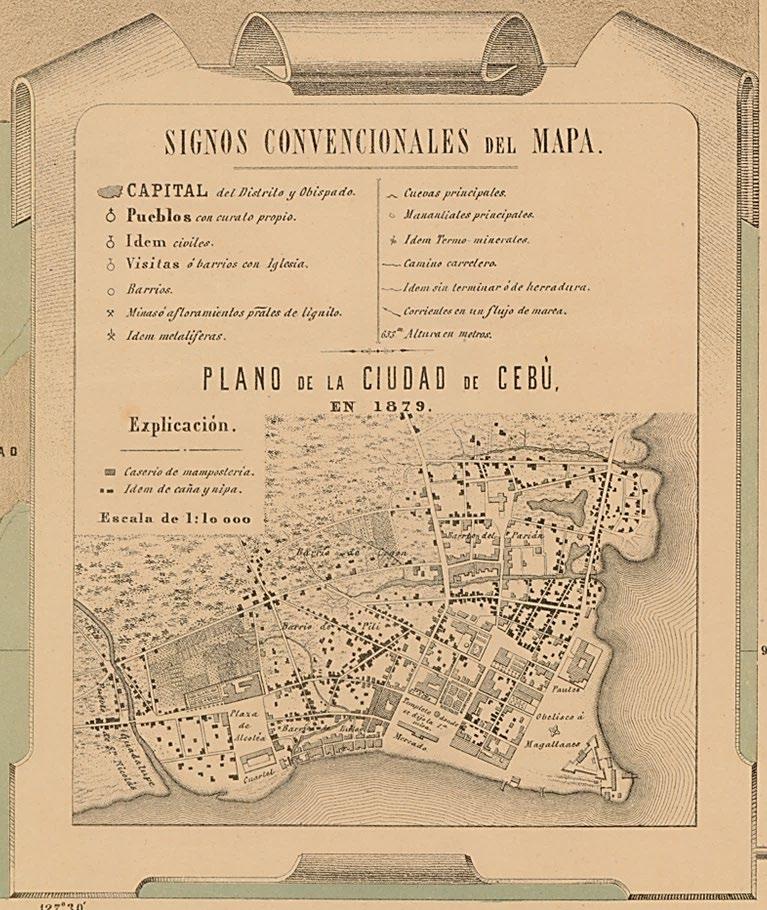

The map is framed by decorative elements in the style of early Modernismo (Art Nouveau) In the top corners there are portraits of Ferdinand Magellan (left) and Miguel López de Legazpi (right) with urns and surrounded by foliage. In the bottom corners there are vignettes of the Santo Niño church (left) and the Magellan's Cross Pavilion (right) supported by anchors. The title cartouche at the top is balanced by another cartouche at the bottom containing the legend of symbols used on the map and an inset map Plano de la Ciudad de Cebù en 1879 which is described in detail on page 36.

The map itself is flanked by two vertical panels, framed with bamboo, giving detailed Noticias generales (general information). The text of these panels is divided into sections on the

history of the discovery and settlement of the island; its size and location within the Visayas; the climate, with a comment on its healthiness; the race, language, customs and religion of the local inhabitants; the island’s population, including its growth and density, with a list of the individual parishes and their populations; agriculture; industry, with a focus on mining; commerce and trade; communications, by land and sea; public administration; and a note on the sources of information.

Enrique Abella was born to Spanish parents in Manila in 1847. He went to Spain for schooling, completed his studies at the Escuela de Minas (School of Mining) in Madrid, and joined the Cuerpo de Ingenieros de Minas (Corps of Mining Engineers) in 1870 as a second engineer. In 1877 he returned to the Philippines and joined the Inspección General de Minas de Filipinas (General Inspection of Mines)

As well as his Plano Topográfico of Cebu, in 1884 Abella produced a geological map of the island titled Bosquejo Geológico de la Isla de Cebú. Two years later this was published in Abella’s book Rápida Descripción Física, Geológica y Minera de la Isla de Cebú (Imprenta y Fundición de Manuel Tello, Madrid, 1886). This 189 page book contains two folded maps, two line charts, three sheets of geological profiles, and a detailed description of the island’s topography, geology and mineralogy.

After producing his work on Cebu, in 1890 Abella went on to publish an even more impressive and detailed geological map of the island of Panay, Isla de Panay Bosquejo Geológico, described in detail by Raphael P.M. Lotilla in his article published in Issue No. 11 of The Murillo Bulletin (May 2021). Having become involved in politics in the Philippines, Abella returned to Spain in 1897 and formally resigned from his Philippine post the following year; he continued in politics and died in Madrid in January 1913

Unless otherwise stated, images are courtesy of the Archivo del Instituto Geográfico Nacional, Madrid.

Bosquejo Geológico de la Isla de Cebú by Enrique Abella, 1884, from Rápida Descripción Física, Geológica y Minera de la Isla de Cebú (image courtesy of the National Library of Australia)

EBUANOS who know their Shakespeare may well ask: What's in a name? Over the five centuries since the first documented arrival of Europeans, on the Magellan Elcano expedition in 1521, their precious isle set in the silver sea has been given well over two dozen different names on maps of Asia and the Philippine archipelago.

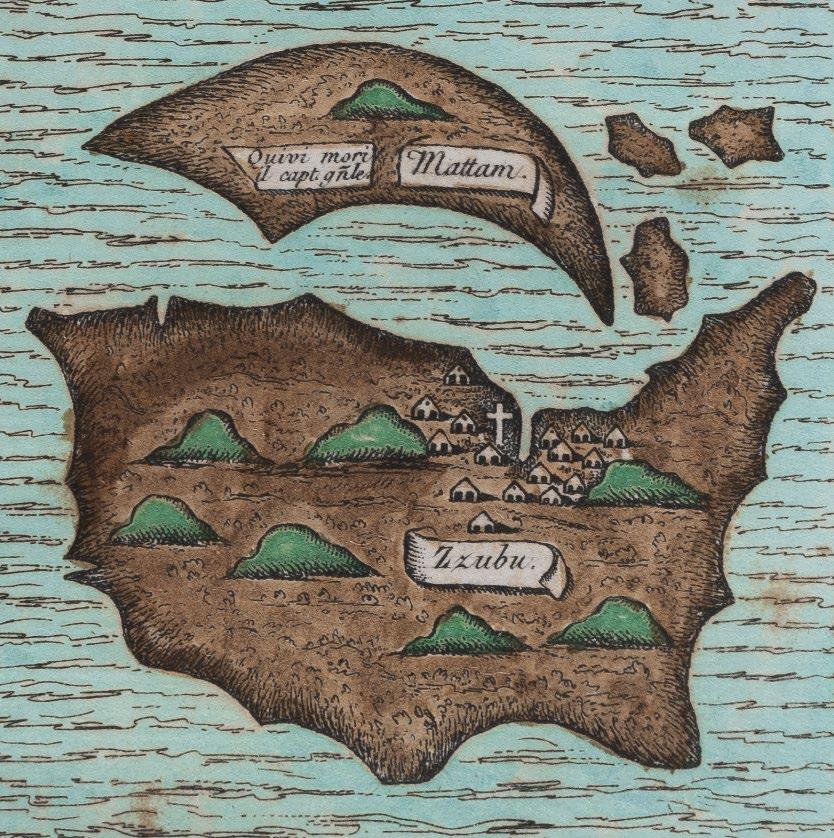

In the detailed manuscript account (and the accompanying maps) of the expedition by Antonio Pigafetta, Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo, written in c.1525, the island is named Zzubu, although Zubu also appears in some editions of Pigafetta’s work.(1) The name is believed to have been the Spanish version of that used by the inhabitants of the island and its main town: Sugbo, also pronounced Sugbu in Visayan, and with an alternative spelling of Sogbú (2) A possible explanation for Pigafetta’s spelling may be that, because he was Italian and worked in Sevilla after he moved to Spain, he learned to speak Spanish with an Andalucian accent, where the voiced sibilant ‘z’ is used instead of ‘s’.(3)

Sugbo is said to come from ‘a Visayan verb which means to walk in the water, which the people landing at this place used to do at former times when the water in front of the city was shallow’.(4) Although this is the most plausible etymology, other historians believe the name Sugbo came from Sibo or Sibu, an abbreviated form of the old Cebuano phrase sinibuay ng hingpit meaning ‘a place for trading’, referring to the settlement’s port area. Another theory comes from oral legends saying Sugbo meant ‘great fire’ from the scorched earth strategy used to repel the Moros who raided the area for slaves.

As the 16th century progressed, Sugbo morphed into a plethora of spellings. Carlos Quirino wrote: “This island has been variously called Subuth, Cabue, Zebu, Zsubu, Cubiene, and Çubur.”(5) Subuth is in fact the earliest European name for the island, used by the Emperor Charles V’s courtier Maximilian von Sevenborgen (aka Maximilianus Transylvanus) in his work De Moluccis Insulis. This was the first account of the

Magellan Elcano circumnavigation, written from interviews with the survivors of the ship Victoria and published in Cologne in 1523. Taking his cue from Transylvanus, the German mapmaker Johannes Schöner then used Subuth on a globe he made, also in Cologne, that same year.

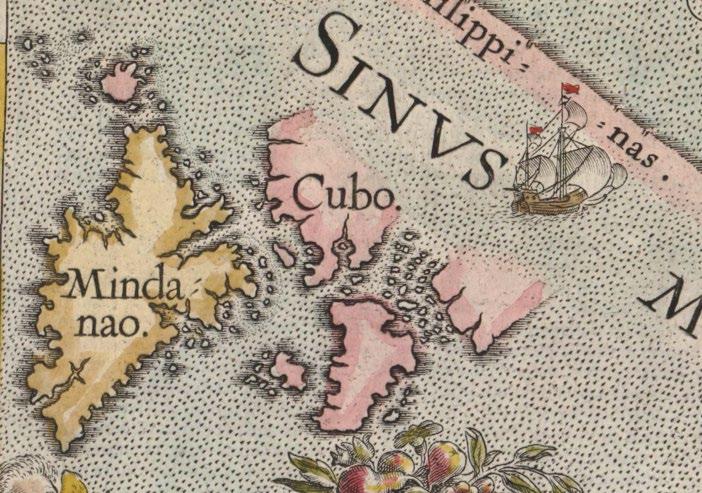

Some of the earliest European maps to show the Philippines are manuscript portolan charts by Iberian navigators, and early maps of Asia were also published in Italy. The ‘Carta Castiglioni’ of c.1525, attributed to Diogo Ribeira, shows Cebu as Çubu, as does the ‘Legazpi map’ attributed to Pierres Pli (aka Pierre Plin), a pilot in the Legazpi armada of 1564 65. The maps India Tercera Nuova Tabula by Girolamo Ruscelli (1561) and Descripcion delas Yndias del Poniente by Juan López de Velasco (1575, copied by Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas in 1601) use Cubu, without the cedilla. Gaspar Viegas opted for Çubo in his c.1537 chart of the western part of the Pacific Ocean, and the Costa de Cubo is shown by Fernão Vaz Dourado in the portolan atlases he produced between 1550 and 1575.

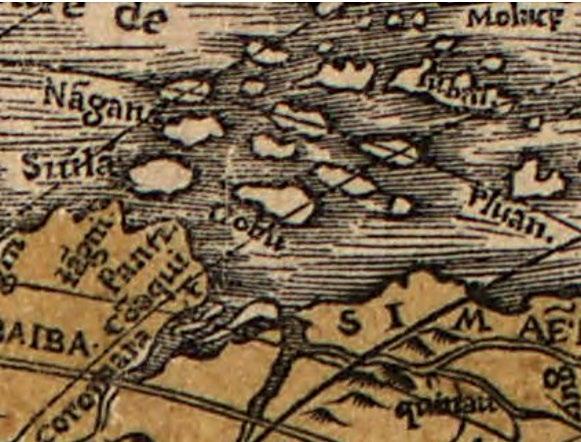

Detail of ‘Mattam’ and ‘Zzubu’ from Antonio Pigafetta’s map c.1525 (image courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Detail of ‘Çubu’ from the ‘Carta Castiglioni’ attributed to Diogo Ribeira (c.1525)

(image courtesy of Biblioteca Estense Digitale)

Detail of ‘Cobu’ from Nova, et Integra Universi Orbis Descriptio by Oronce Finé (1531) (image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Detail of ‘Çubo’ from the untitled chart by Gaspar Viegas (c.1537)

(image courtesy of Archivio di Stato di Firenze)

Detail of ‘Cubu’ from India Tercera Nova Tabula by Giacomo Gastaldi (1548) (author’s collection)

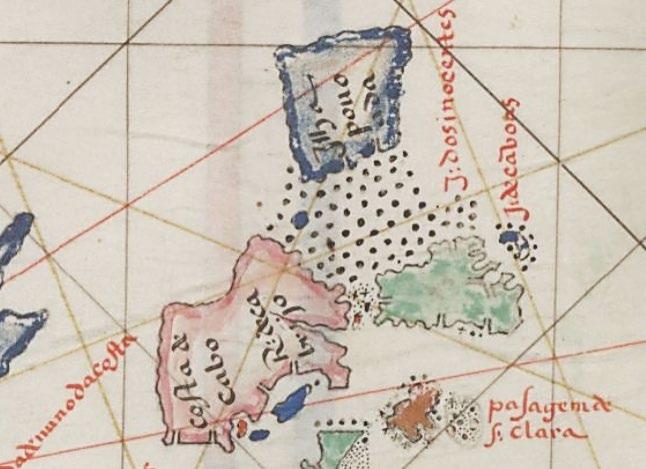

Detail of ‘Costa de Cubo’ from the atlas by Fernão Vaz Dourado (c.1560)

(image courtesy of The Huntington Library)

Detail of ‘Costa de Cabo’ from the chart by Bartolomeu Velho (c.1560) (image courtesy of The Huntington Library)

The occasional use of the cedilla (Spanish for ‘little zed’) in Çubu and Çubo is explained by the use in 16th century Spanish orthography of ‘ç’ to indicate the sibilant sound ‘s’ when it came before a hard vowel (‘a’, ‘o’ or ‘u’) rather than the ‘k’ sound represented by ‘c’ before those hard vowels.(6) By putting the cedilla under Çubu and Çubo the pronunciation became Subu and Subo, which was closer to the original Sugbo (Sugbu in Visayan) than Cubu or Cubo pronounced with a hard ‘c’ (as in ‘Kubu’ or ’Kubo’). In 1741, the Real Academia Española (Royal Spanish Academy) overhauled the orthography of many Spanish words and inter alia decided that the cedilla would be dropped;(7) the Academy’s proposals were officially adopted by royal decree in 1844.

The vowels in Cubo were reversed by the French cartographer Oronce Finé, who showed Cobu to the east of Pluan (Palawan) on the first (1531) edition of his world map Nova, et Integra Universi Orbis Descriptio. (8) According to cartographic historian Thomas Suárez (op cit), this is ‘the first appearance of any Philippine islands on a printed map’.(9) Curiously, this spelling would reappear in 1727, on a map by Alexander Hamilton. In 1545 Alonso de Santa Cruz of Sevilla presented his manuscript Islario general de todas las islas del mundo to the king of Spain. In this work, consisting of some 120 maps and a lengthy description of various parts of the world, Magellan’s visit to Cubucue is described, but on the accompanying map the name Matam (Mactan) is used.

In his 1548 map India Tercera Nova Tabula the great Italian cartographer Giacomo Gastaldi also shows Cubu, but in Terza Tavola the first map to show an island with the name Filipina (10) published in 1554 in the second edition of Giovanni Battista Ramusio’s book of voyages, Delle Navigationi e Viaggi, he not only changes the island’s name but confuses its location. To quote Suárez again: “Ramusio appears to have combined different sources which refer to the island by different spellings, for he charts Cebu twice: once as Cyābu and a second time as Zubut.” The map is oriented to the south, and Cyābu is shown to the north of Vendanao (Mindanao) and due east of Papuas (Negros); Zubut is located to the southwest of Papuas, between Vendanao and Palobā (Palawan).

Detail of the city of ‘Çiabu’ on the island ‘Philippina’ from Il Disegno Della Terza Parte Dell’ Asia by Giacomo Gastaldi (1561) (image courtesy of Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc.)

On Gastaldi’s third map of the region, Il Disegno Della Terza Parte Dell’ Asia, published in 1561, Zubut has disappeared, but the large island to the north of Vendanao has been given the name Philippina, and Ciabu is the toponym for the town on its southeast coast. The name of the city then becomes Chiabu on the spectacular 1587 world map by Urbano Monte.

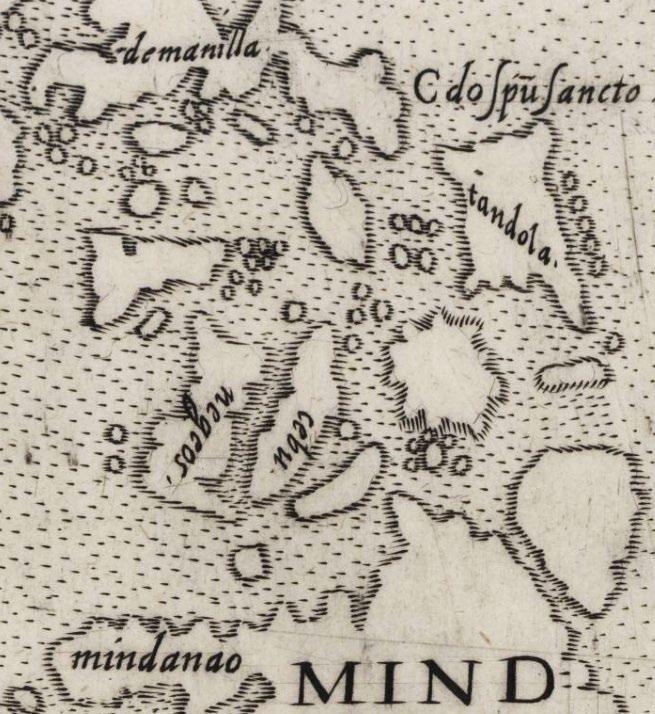

A manuscript chart of Southeast Asia dated c.1560, attributed to the Portuguese navigator Bartolomeu Velho, uses yet another spelling: a large, roughly trapezoidal island to the north of Mindanao and south of Ilha Pouoada (Panay) (11) is labelled Costa de Cabo with, towards the east of the island, the R: de Cabrijo Has this river been confused with the Cabrita shown in the Zamboanga peninsula on other 16th century portolan charts?(12)

The mapmakers of the ‘Golden Age’ of Dutch cartography were thoroughly inconsistent. When he published his map Tertiae partis Asiae in 1566, copied from Gastaldi’s 1561 map, Gerard de Jode included Ciabu; but his 1578 map Asiae Novissima Tabula shows Subut, presume ably copied from the seminal map of the world Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendate Accommodata by Gerard Mercator, published in 1569. Abraham Ortelius also shows Subut (13) on his map of Southeast Asia, Indiae Orientalis Insularumque Adiacientium Typus (1571), but uses Costa de Cuba on his map of Asia, Asiae Nova Descriptio (1574), and Cubo on his maps of China, Chinae, olim Sinarum Regionis (1584), and the Pacific Ocean, Maris Pacifici (1589). A spectacular 1599 portolan chart of Asia by Evert Gijsbertsz shows the Costa de Cubo.

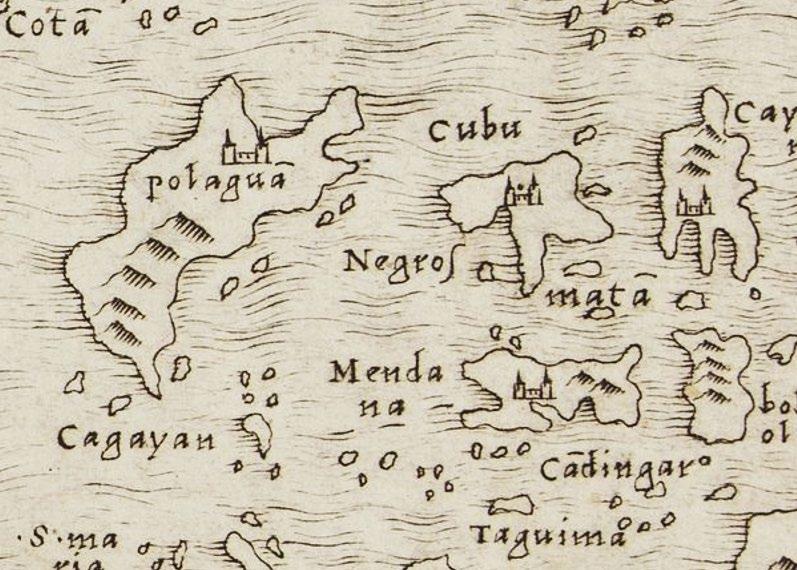

Detail of ‘Cabu’ on Insulae Philippinae by Petrus Kærius / Barent Langenes (1598) (author’s collection)

Cuba is the name used on Giovanni Mazza’s 1589 Asiae Nova Descriptio, the first printed map to show the island of Luconia (Luzon). The map of Asia by Arnoldo di Arnoldi, published by Matteo Florimi in Siena in c.1602, has the toponym Costa de Cuba along the northwestern side of an island southwest of Ponoades (Panay), although the town on the island itself is named S. Ioan. (14)

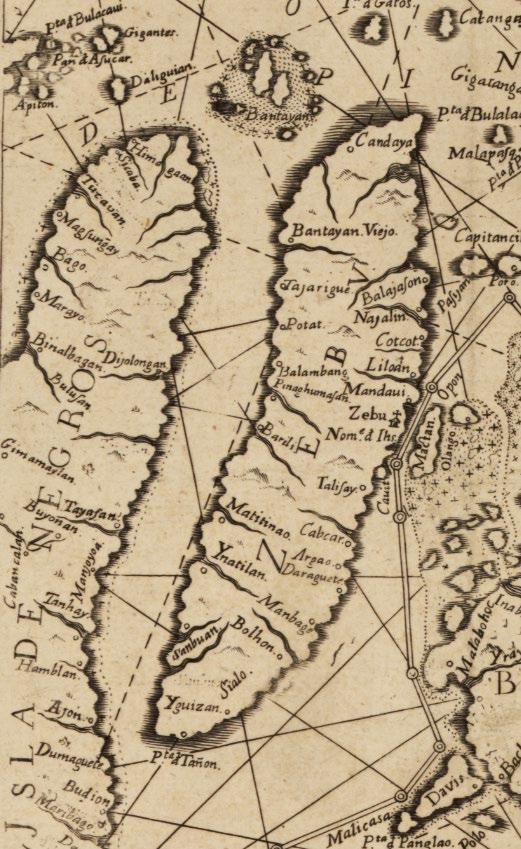

Towards the end of the 16th century another variation in the spelling of Cebu appears, on two important Dutch maps. Both Insulae Moluccae celeberrimae (the so called ‘Spice Map’) by Petrus Plancius (c.1594) and Exacta & accurata delineatio cum orarum maritimarum by Jan Huygen Van Linschoten (c.1596) name the island Cabu. These maps were the sources for the miniature maps of the Philippines that were the first to depict the archipelago on its own Consequently Cabu is the name shown on Insulae Philippinae by Petrus Kærius / Barent Langenes (1598); Philippinae Insulae by Johannes Metellus (1601); Insulae Philippinae by Cornelis van Wytfliet (1605); and Philippinae Insulae by Jodocus Hondius Jr. / Petrus Bertius (1616). Cabu is also used on Insulæ Indiæ Orientalis Præcipuæ by Hondius (1606) and an untitled map of Southeast Asia by Joris van Spilbergen (1619).

Somewhat surprisingly, the earliest map we have found that shows the island with its modern spelling Cebu is one of China. Sinarum Regni aliorumque regnorum et insularum illi adiacentium descriptio (description of the Kingdom of China and other adjacent kingdoms and islands) is a copperplate engraved map from a report on Jesuit missionary activities in China which used information from late 16th century Portuguese and Jesuit sources. It is believed to have been compiled by Fr. Michele Ruggieri, S. J. in Rome in c.1590 (15) The map shows China and its provinces, Korea, Japan, parts of Southeast Asia, and the Philippines, where Cebu is one of only six islands to be named. Some years later (c.1597) Cebu is found again, on a map of Asia by the Italian cartographer Fausto Rughesi, who had access to Jesuit sources of information in Rome; to the east the map also shows Cuba.

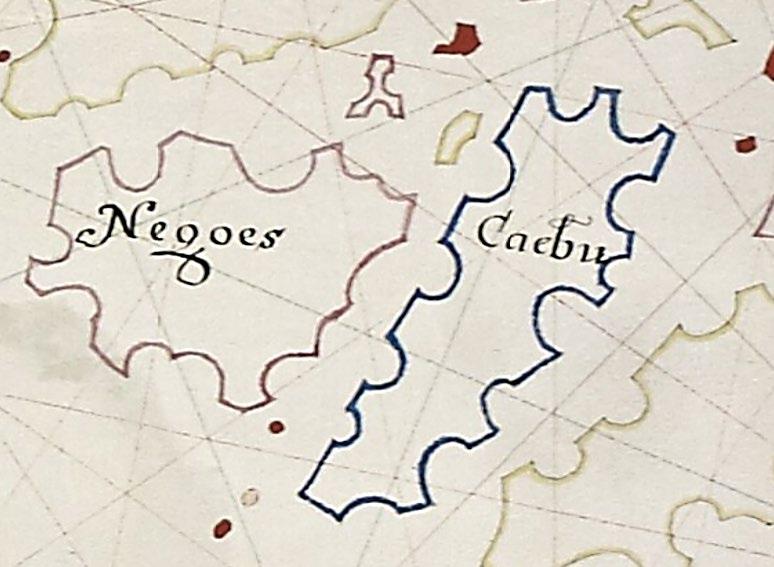

However, the arrival of the 17th century did not diminish cartographers’ appetite for the use of novel spellings for Cebu. The earliest known British map of the East Indies, a manuscript sea chart on vellum in the atlas produced by Martin Llewellyn in c.1598, features the island of Caebu. A set of gores for a terrestrial globe by Willem Nicolai titled Nova et integra universi Orbis descriptio, dated 1603, shows Suban (believed to be copied from a 1542 globe by Caspar Vopel)

Detail of ‘Cebu’ on Sinarum Regni aliorumque regnorum et insularum illi adiacentium descriptio attributed to Fr. Michele Ruggieri, S. J. (c.1588) (image courtesy of The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology Library)

Detail of ‘Cebu’ and ‘Cuba’ from a map by Fausto Rughesi (c.1597) (image courtesy of Barry Lawrence Ruderman)

Detail of ‘Çaebu’ from the Martin Llewellyn atlas (c.1598) (image courtesy of Digital Bodleian ©The Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford)

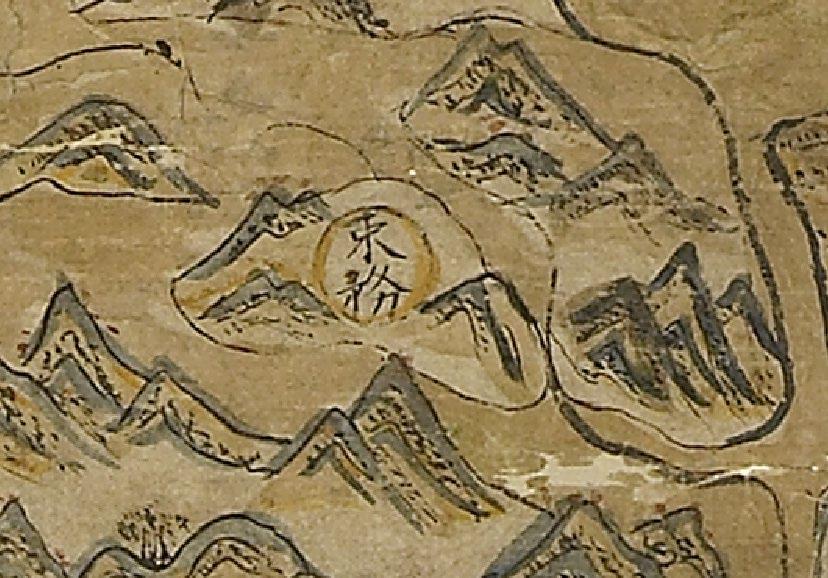

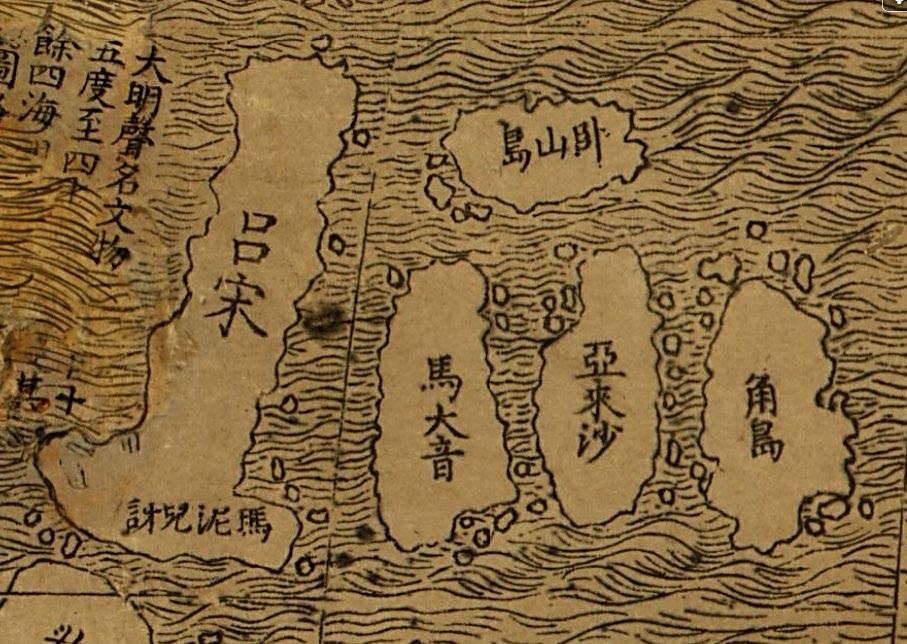

Detail of Cebu as 馬 大 音(ma da yin) from Matteo Ricci’s ‘Great universal geographic map’ (1602) (image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Detail of ‘Suban’ from a globe gore by Willem Nicolai (1603) (image courtesy of Leen Helmink Antique Maps)

Detail of Cebu as 束 務 (shu wu) from the Selden Map (c.1620)

(image © Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

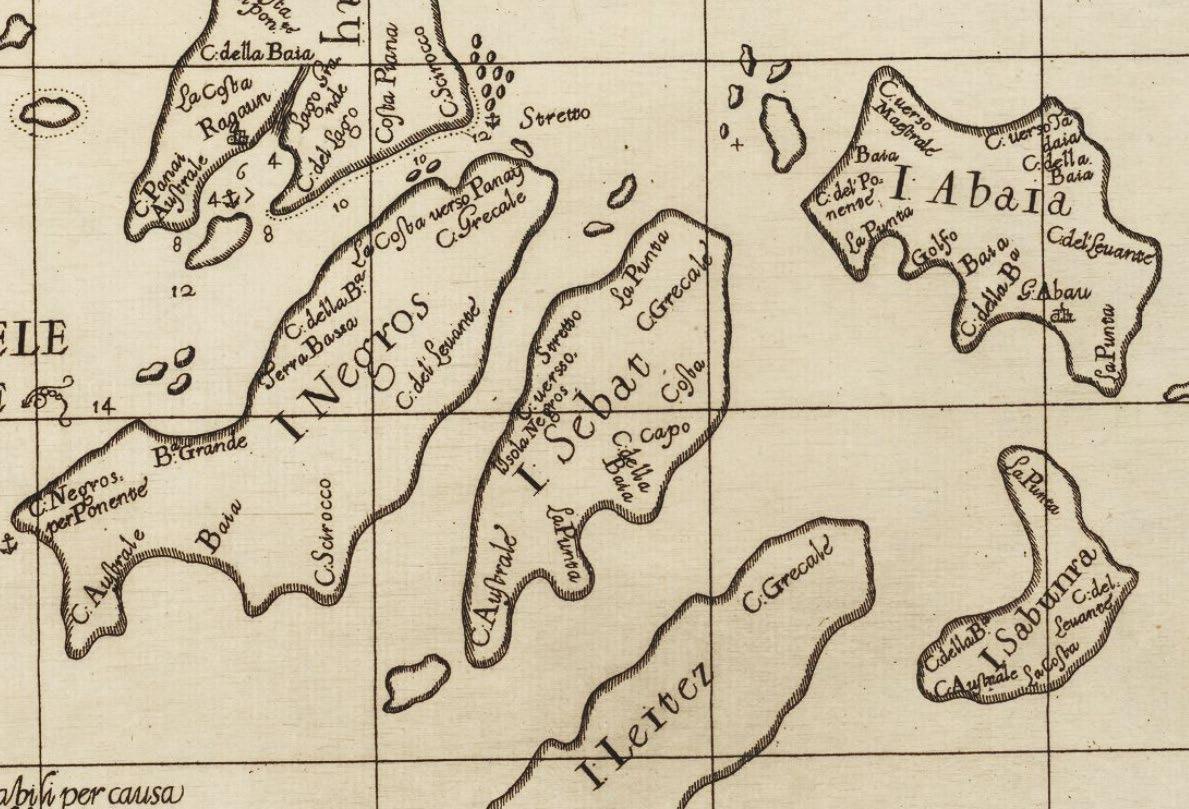

Detail of ‘Sebat’ from the Carta particolare dell’Isole Fillipine … d’Asia Carta X by Robert Dudley (1646) (image courtesy of Harvard University Map Collection)

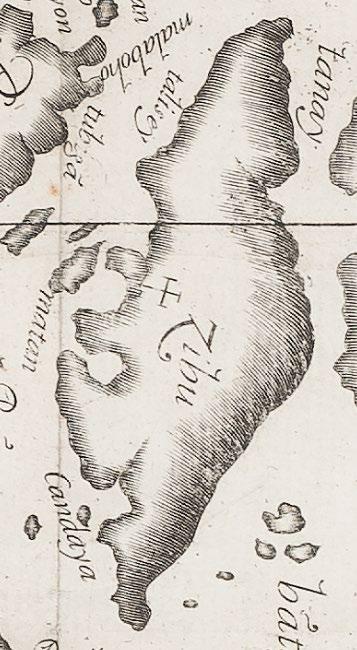

Robert Dudley used two variant spellings in the charts published in his nautical encyclopaedia Dell’Arcano Del Mare in 1646: Seba on the Carta seconda Generale del’Asia, and Sebat on the chart of the Visayas, Carta particolare dell’Isole Filipine è di Luzon … d’Asia Carta X. The Planta de las Islas Filipinas engraved by Marcos de Orozco in 1659 and published in 1663 in the Labor evangélica by Fr. Francisco Colin, S.J. exhibits the island of Zibu (see page 23)

In the 17th century the shape of Cebu became recognisable. On early maps the island appears rectangular, triangular, trapezoidal, rhomboidal, oval, kite shaped, D shaped or entirely irregular. As previously mentioned, some maps show a large island with Cebu and Negros fused together, and others have an amorphous landmass with only the southeastern coast delineated. Later maps show Cabu as a skinny, spiky amoeba. But Dudley, in 1646, and Orozco, in 1659, both made an attempt to draw the coastline with some accuracy, although the island still looks more like a pointed taro root than its true, elongated shape.

Chinese maps also named Cebu. Matteo Ricci’s K’un yu wan kuo ch’uan t’u (Great universal geographic map) of 1602 shows an elongated, rectangular island clearly recognisable from its position as Cebu, identified with the characters 馬 大 音 (ma da yin), a phonetic rendering of Matan (Mactan). The great manuscript Ming sea chart (c.1620) known as the Selden Map includes 16 ports in the Philippines with which China traded, including 束 務 (shu wu) as the phonetic name for Cebu.

In the mid to late 17th and early 18th centuries Cebu became the most common spelling, used on maps by Hessel Gerritsz, Nicolas Sanson, Melchisédec Thévenot, Pierre Duval, Vincenzo Coronelli and Herman Moll among others. However, the English mapmaker John Seller and the Dutch mapmakers Pieter Goos and Johannes van Keulen preferred Sebu. Then some new names materialised on certain English and Dutch maps. A chart of the Tradeing part of the East Indies and China by John Thornton (1703) identifies Cebu as Il. d. dios; a different chart with the same title by his son Samuel (1711) uses the name Nombre for the island, as does A Chart of Borneo Java and the Philippine Islands by Edmund Halley et al. in 1727.

Detail of ‘Celo’ with ‘Nombre [de] Dios’ from a map by Johannes Vinckeboons (c.1665) (image courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

The explanation is provided by an untitled, c.1665 manuscript map of Luzon and the Visayas produced by Johannes Vinckeboons for the Dutch Vereenigde Oost Indische Compagnie (VOC). This map, which was copied by François Valentijn in 1724 and (as Nieuwe Afteekening van de Philippynse Eylenden) by Johannes II van Keulen in 1753, gives the island the novel name of Celo and shows the toponym Nombre [de] Dios on the southeast coast. This name for the city of Cebu was derived from its Spanish name: ‘La Ciudad del Santisimo Nombre de Jésus’ (see ‘Cebu City: A Cartographic Chronicle’ on page 21).

The Carta Chorographica del Archipielago de las Islas Philipinas made by Francisco Diaz Romero and Antonio de Ghandia (aka Echeandia) in 1727 shows an elongated Isla de Cebu with the coast line inaccurately indented. When, in 1734, Fr. Pedro Murillo Velarde, S.J. produced his much improved Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica delas Yslas Filipinas he opted for Zebu, a name not previously seen. Murillo Velarde was born in Laujar de Andarax in Spain’s southern province of Almeria, and his adoption of the spelling Zebu may also be explained by his Andalucian accent.

Detail of ‘Isla de Cebu’ from Carta Chorographica del Archipielago de las Islas Philipinas by Francisco Diaz Romero / Antonio de Ghandia (1727) (image ©The British Library Board)

Following Murillo Velarde’s lead, Zebu was widely used on other 18th century maps, including those by Francisco Badaraco (copied by R.W. Seale in 1748 for George Anson’s A Voyage Round the World), J.N. Bellin, J.B.B. d’Anville, William Herbert, Georg Mauritz Lowitz, Pedro Freylin, Robert Sayer, Louis Brion de la Tour, Louis Denis, Antonio Zatta, the Duque de Almodovar, and Giovanni Maria Cassini. But Sebu still appears, for example in c.1751 on globe gores by Johann Friedrich Endersch and in c.1752 on A New Map of the Philippine Islands by Thomas Kitchin.

When the French cartographer J B. N. D. D’Après de Mannevillette published the first edition of his atlas of sea charts Le Neptune Oriental in 1745, he introduced a Gallicised name for the island of Cibou, which was in turn used by other French mapmakers such as Georges Louis Le Rouge and Gilles Robert de Vaugondy. In 1808 the Direccion Hidrografica in Madrid produced its Carta General del Archipiélago De Filipinas, based on the surveys made by the Malaspina Expedition in 1792 93. In accordance with the usage that had been standardised by the Real Academia Española, an accent was added to the Isla de Zebú.

Throughout the 19th century four spellings predominated. Aaron Arrowsmith and H.K.W. Berghaus followed the Direccion de Hidrografía with Zebú, but Ildefonso de Aragón, James Horsburgh, J.W. Norie, the French Dépôt général de la Marine, Jean Mallat and the Hydrographic Office of the British Admiralty all stayed with Zebu.

Some Spanish cartographers, notably Manuel Roldán, Lieutenant Claudio Montero (on the surveys he produced for the Comisión Hidrográfica de Filipinas), Enrique Abella y Casariego and José Algué also added an accent, to the name Cebú. On his map Abella notes that the island was Sugbú de los naturales (to the natives). Other Spanish mapmakers, such as Francisco Coello and the lithographic printers Chofré & Cie., retained Cebu. Charts of the East India Archipelago by James Imray & Son initially showed Zebu, but later switched to Cebu.

Detail of ‘Zebu’ from Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica delas Yslas Filipinas by Fr. Pedro Murillo Velarde (1734) (image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

To our surprise, a completely novel toponym appeared in 1847. A New Chart of the China Sea and East India Archipelago, published in London by R. Blachford & Co., shows the island of Czebu. In 1867 the Dépôt des Cartes et Plans de la Marine introduced a different accent for its chart of the Port de Zébu Finally, for the map produced (from sea charts) for the official publication of the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the U.S. Government Printing Office reverted to Sebu

Variant spellings would persist into the 20th century; as late as 1933 the British Admiralty published its chart no. 3193 with the title Port Sebu (Cebu Harbour) and Approaches. But with the advent of the charts produced by the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, and the atlases issued for the Philippine censuses of 1918 and 1939, the island whose names were not a few finally became forevermore Cebu

Detail of ‘Czebu’ from A New Chart of the China Sea by R. Blachford & Co. (1847) (image courtesy of Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc.)

1. Margarita V. Binamira, ‘A Venetian in the Visayas: Antonio Pigafetta’s Journey through the Islands’, in The Murillo Bulletin, Issue No. 2, PHIMCOS, Manila, June 2016.

2. Camilo de Arana, Derrotero del Archipiélago Filipino, Direccion de Hidrografia, Madrid, 1879.

3. John Moore, The Development of Spanish Sibilants, University of California, San Diego, 2005.

4. Norberto Romuáldez, Philippine Orthography, Visayas Printing Company, Iloilo, 1918.

5. Carlos Quirino, Philippine Cartography 1320 1899, 2nd revised edition, N. Israel, Amsterdam, 1963; Fourth Edition, edited by Dr. Carlos Madrid, Vibal Foundation, Quezon City, 2018.

6. André Martinet, ‘The Unvoicing of Old Spanish Sibilants’, in Romance Philology, Vol. 5, No. 2/3, Brepols Publishers, University of California Press, 1951 52.

7. Ortographia Española compuesta, y ordenada por la Real Academia Española, Madrid, 1741.

8. The first state of Finé’s map carries his name ‘Orontius F. Delph’ in the lower cartouche; the second state (also dated 1531) has the imprint of Hermannus Venraed.

9. Thomas Suárez, Early Mapping of Southeast Asia, Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd, Hong Kong, 1999.

10. John L. Silva, ‘Naming the Philippines: The Upside down 1554 Ramusio Gastaldi Map’, in The Murillo Bulletin, Issue No. 10, PHIMCOS, Manila, November 2020.

11. Raphael P.M. Lotilla, ‘The Naming and Mapping of Panay in the 16th & 17th centuries’, in The Murillo Bulletin, Issue No. 11, PHIMCOS, Manila, May 2021.

12. Felice Noelle Rodriguez, ‘Mapping the Growth of Zamboanga from Pigafetta to the 19th Century’, in The Murillo Bulletin, Issue No. 13, PHIMCOS, Manila, May 2022.

13. On his 1571 map Ortelius uses the spelling Subut for the island but Subuc for the town; Subuc is also the name of the town on the sheet of Asia in the 1587 manuscript portolan atlas by Joan Martines.

14. Margarita V. Binamira, ‘Illusions, Confusions and Delusions the mythical island of St. John’, in The Murillo Bulletin, Issue No. 6, PHIMCOS, Manila, August 2018.

15. Marco Caboara, ‘The First Printed Missionary Map of China’, in the IMCoS Journal, Issue No. 162, International Map Collectors’ Society, December 2020.

THE HISTORY of Cebu City begins long before the arrival of the Spanish, and even longer before the first maps and images of the city appear. Cebu Island, in the center of the Visayas, is relatively narrow, with coastal plains bordering rugged mountain ranges and limestone plateaus that traverse the island from north to south. Centrally located on the eastern coast of the island, the settlement of Sugbo, or Sugbu as it was also known to its inhabitants (see ‘The Naming of Cebu’ on page 11), grew around a sheltered harbor. As was then typical of the island’s communities, Sugbu hugged the coast in an elongated pattern, with its harbor allowing it to prosper as a pre colonial trading center.

Pre Colonial Sugbu

Archaeological evidence shows that Sugbu could have been settled as early as the 10th century A.D. The settlement became a central trading area for other nearby islands in the Visayas and Northern Mindanao, and historians believe that traders from Siam, Champa and other islands within the archipelago frequented Sugbu at this time However, as Cebu did not produce commercial quantities of tradeable goods, Chinese traders bypassed the port of Sugbu. Rather, pre colonial Chinese ceramics, pottery, iron tools, glass, lead ingots and commercial gold found in Cebu were probably brought in by local, inter island and Muslim traders, and exchanged for beeswax, cotton, pearls, tortoiseshell, betel nuts, and slave labor.

Trade became the driving force for the settlement’s growth, linking Sugbu to other islands in the archipelago as well as to other economies in Southeast Asia. Ceramics and other artifacts unearthed by archaeologists around Fort San Pedro show that to have been the main trading area before the arrival of the Spanish, and by the 16th century the settlement around the port already encompassed around 30 hectares of land. Because of its terrain, the settlement that developed was linear, with its houses and other structures spread out along the narrow coastal plain.

Pre colonial Sugbu was typical of settlements at the time. It grew from an aggrupation of peoples with a common goal, to live and work together to sustain their families. When they were not involved in active trade, fishing, agriculture and crafts provided the population with a sustainable livelihood. Sugbu’s geographic location, and the sheltered nature of its port, made it an ideal settlement for trade. Against this backdrop, the Spanish arrived.

A lot of what we know transpired during Ferdinand Magellan’s visit to Cebu in 1521 comes from the first hand account of Antonio Pigafetta, the scribe who accompanied the expedition. Pigafetta recounts that natives from other islands, the rajahs Kolambu and Siagu, suggested they visit Sugbu for provisions, and even guided them there. As our earliest observer of the village of Sugbu, Pigafetta talks of an open square where the king and other seniors met to discuss business, and describes the houses ’constructed of wood and built on planks and bamboo, raised from the ground on logs’.(1) We still see houses raised on stilts in some coastal villages today. In a map of Zzubu attributed to Pigafetta, he shows the clustering of houses around what is most likely the port area.

Interestingly, Pigafetta gives proof that Sugbu was already a thriving port when the Spanish arrived. He writes about a Siamese agent left behind in the settlement who was trading gold and slaves, and notes that the king and chieftains ate from (most likely Chinese) porcelain. Other 16th century accounts mention that the Chinese did eventually find their way to Cebu, and describe it as a place frequented by traders who exchanged their porcelain for gold, slaves and food supplies. Because Cebu is not a gold producing island, it most likely came from other parts of the Visayas, or even from as far as Camarines in Bicol or Butuan in Mindanao.

Not much is known about Cebu during the interim period from Magellan’s disastrous visit to the arrival in Sugbu of Miguel López de Legazpi on April 27, 1565, 44 years to the day after Magellan’s death. Other Spanish expeditions had made their way to the islands, but only Álvaro de Saavedra mentions Sugbu, in 1528; he describes the natives as pagans, still practicing pagan rituals. It was Legazpi’s expedition that marked the beginning of Spain’s centuries long influence over the archipelago.

When Legazpi arrived in Sugbu, he found a thriving settlement with around 300 houses and a population of more than 2,000 people. After diplomacy failed to get the natives to show allegiance to Spain as the new colonial power, and possibly as revenge for the killing of Magellan, Legazpi ordered the village burned and razed to the ground. Nevertheless, records show that he hoped Cebu would become a permanent Spanish settlement. Shortly after, he ordered the construction of a fort on the tip of a triangular piece of land that jutted out into the water, roughly the shape of the harbor promontory. The Jesuit historian Nicholas Cushner described the fort as a ‘mere palisade of dried palm leaves and logs, with sand used to bolster the corners’.(2)

Around the fort, Legazpi identified and measured the areas for the Spanish living quarters and, according to historical documents, used a line of trees to delineate the Spanish settlement. He drew a line in the sand which he told the natives not to cross because all indios (the indigenous inhabitants) were to be removed from within the area and relocated elsewhere, to an area south of the village which would be called San Nicolas.

In one of the burnt huts Juan de Camuz, one of Legazpi’s men, found an image of the child Jesus, believed to be the same statue given by Magellan to the Queen of Cebu in 1521. Seeing it as a sign, Legazpi ordered a church made of bamboo and nipa to be built on the location where the statue of the Santo Niño was found. The image and the church, named Nombre de Jesús in honor of the statue, were to be under the auspices of the Augustinian priests who accompanied the expedition.

Since these events all happened on the feast day of St. Michael, Legazpi called the settlement the Villa de San Miguel, the first Hispanic name for Sugbu. In 1571 the name was changed to the Villa del Santisimo Nombre de Jesús, after the Santo Niño. Then, in 1594, King Philip II of Spain promoted the Villa (town) to a Ciudad (city) and it was renamed again as La Ciudad del Santisimo Nombre de Jesús. To this day Cebu City is known to the older generation simply as ang syudad (the city)

Historian R.R. Reed described the small colony in Cebu with its palisaded fort as ’flimsy and liable to collapse under sustained attack’.(3) And for sure, there were sporadic attacks from various forces, including the indios who, until a peace treaty was signed, did not acknowledge the authority of the Spanish. On June 4, 1565 Legazpi and Rajah Tupas signed the one sided Treaty of Cebu under which the natives agreed to recognize Spanish sovereignty, pay tribute, trade with the Spaniards on a reciprocal basis, sell all the food supplies the Spaniards needed at local prices, and accept eviction from their homes and resettlement in San Nicolas. In return, the Spanish would defend the Cebuanos against their enemies.

Provisioning for the little settlement was problematic. With the addition of some 300 Spaniards to feed, food shortages became serious and, contrary to the treaty, the locals did not make it easy for them to source food. This threw off the balance of the settlement’s food equilibrium, achieved by subsistence farming and fishing. Many of the natives fled to the hinterland to avoid the Spaniards and the new settlement, taking with them their food and leaving little to feed the foreigners or those indios who chose to remain.

Security for the settlement was also a problem. Attacks and constant harassment by the Portuguese (who claimed Cebu Island for the Portuguese king) and the various unfriendly locals threatened to disrupt peace among the conquerors. Circumstances were difficult enough that in a letter written in 1569 Legazpi says that he moved his settlement from Cebu to Panay both to address the food supply problem and for better protection from Portuguese attacks. When reinforcements arrived from Spain, he returned to Cebu, with a new title as adelantado (governor) and Captain General of Cebu.

Legazpi did not stay long in Cebu or Panay. By 1571 he moved his administrative center to Manila, from where he would govern the Spanish colony. Even so, the Spanish kept Cebu as the base of operations for the Visayas and the southern islands, and it would remain a key political, administrative and military center for centuries to come. More importantly, Cebu served as an ecclesiastical center from where the word of God was spread. A papal bull in 1595 established Cebu as the seat of a diocese that encompassed the Visayas, northern Mindanao, and the Marianas Islands.

When the capital moved north to Manila, the town of Cebu faltered. Legazpi took not only the administration of the colony to Manila, but also the principal Spanish trade route from Cebu that had begun in 1565. With the relocation of the shipping hub for the galleons and their trade, Cebu started to decline as a major trading port, and Chinese and other Southeast Asian traders began to bypass the port.

In the 1590s, the Spanish living in Sugbu were allowed to build their own galleons and rejoin the lucrative galleon trade. It prospered for a while, but was short lived because of the many restrictions imposed by Manila regulating what could or could not be exported. Another barrier to trade, which caused collateral damage, was the looming war between the Spanish and the Dutch in search of spices. The trading ship San Antonio, built in Cebu, was hurriedly converted into a warship upon the orders of Antonio de Morga (Lieutenant to the Governor General) and renamed the San Diego. In 1600, in battle with the Dutch corsair Olivier van Noort, the San Diego sank off the coast of Nasugbu, Batangas, with all its cargo intact.

Another ship from Cebu sank on its way to Acapulco, and with an unprofitable and unlucky business environment, Cebu’s foray into the galleon trade ended in 1604. Without profitable enterprise, the Spanish began to abandon Cebu, choosing the more lucrative north to base themselves and their businesses. By the 1620s, Cebu City and its port were commercially inactive and had become ‘an economically depressed backwater’.(4) Ushered in by the loss of the galleon trade, emigrating population and other economic and political issues, Cebu’s decline and stagnation would last for two centuries.

Detail of ‘Zibu’ from Planta de las Islas Filipinas by Marcos de Orozco (1663) (from the collection of Rudolf J.H. Lietz)

God and the Virreinato will Provide The island of Cebu begins to appear on European maps and charts soon after the return of the Magellan Elcano expedition to Sevilla, under a variety of names. The town of Cebu is first shown by pictographs on the maps of Giacomo Gastaldi, on which it is unnamed in his maps of 1548 and 1554, and given the toponym Ciabu on his 1561 map Il Disegno Della Terza Parte Dell’ Asia Abraham Ortelius shows a pictograph for Subuc in 1571, and André Thevet and Gerard de Jode both have one for Subut, in 1575 and 1578 respectively. But later Dutch maps (including the first miniature maps of the Philippines by itself) have no toponym for the city of Cebu. Most 17th maps also do not show or name the city, although its presence is indicated by a large cross on the 1659 map by Marcos de Orozco.

Spain had two main reasons to settle and colonize these islands: trade and evangelism. So as not to be left out in the cold, Spain wanted a foothold to participate in the robust trade in spices from the Moluccas and Borneo that was tightly controlled by the Dutch and Portuguese, and also to profit from the on going trade in silks and other products from China and Japan. Magellan was in fact tasked to look for an alternate route to source spices, not to colonize, and (among other reasons) Legazpi moved his administration from Cebu to Manila to be closer to China and Japan.

The second reason for coming was to convert the natives to Christianity, and Legazpi’s expedition included a number of Augustinian friars. In the 1590s, the Spanish population of soldiers, civilians and missionaries in the Ciudad numbered from 50 to 100. With the collapse of the galleon trade, the majority of Spanish civilians left for Manila, but not all of the Spaniards abandoned the city; the missionaries, religious and some civilians remained, along with a handful of administrators to take care of Cebu and the areas under its responsibility.

Although Cebu was not a profitable settlement, geopolitics was in play and the town was made a city in 1594 and a diocese in 1595. In 1580 King Philip II of Spain had become King Philip I of Portugal, and all the Portuguese territories overseas were integrated into the Spanish empire. These included the Portuguese trading settlements in the Moluccas, which gave Spain a new opportunity to enter the trade in spices.

Despite the vast reduction in economic activity in the island and the city in the early 17th century, the Spanish continued to maintain Cebu as the military, religious and administrative center for the southern islands. The order to keep a colonial presence in Cebu was given because it was nearer to Mindanao and the Moluccas than was Manila, and it could be used as an outpost from which to convert the Muslims in the south. The objectives for colonization ‒ trade, missionary work and regional administration ‒ overlapped in the decision to maintain the settlement in Cebu.

Aside from the falling population, the Ciudad itself was in disrepair, and it was costing Spain and the Virreinato (Viceroyalty) in Mexico a tidy sum to maintain it. In fact, the royal fiscál

(attorney general) in Manila wrote to King Charles II suggesting Spain abandon the colony because of its economic dependence. In reality, the colony’s financial troubles really just mirrored those of Spain which, by the early 18th century, had bigger problems at home and was running out of funds.

Despite the terrible state Cebu was in, the twin objectives of administering the city and converting the natives continued, carried out hand in hand by the state and the church. The state assumed administrative responsibility, with the task of conversion assigned, in different areas, to various religious orders: the Dominicans, the Franciscans, the Augustinians, and the Jesuits.

Although the town of Villa del Santisimo Nombre de Jesús was established in 1571, and the parish of the indios was established by the Augustinians in San Nicolas 1584, the parish of the Ciudad del Santisimo Nombre de Jesús did not come about until 1598. The arrival of the Jesuits and their missionary work with the Chinese led to the establishment of a parish in the district of Parian in 1614.

Pueblos (villages) were set up, with each pueblo encompassing many barrios (barangays), in which churches and parishes were also estab lished by the religious orders. As these often suffered from a lack of converted almas (souls), the Spanish implemented the strategy of the reducciónes (resettlements) they had used in South America, with disastrous results.

As the Spanish went to the other islands, Mindanao included, to try and colonize and convert the natives, they noticed a number of non natives among the locals: slaves that had been taken during raids. For the raiders, slaves were simply a commodity, a tradable asset and a mobile symbol of prosperity. They were a source of labor and, in some cases, wives or concubines for the datus (chiefs) and Chinese. To the Spaniards, however, the Moro (Muslim) raiders were pirates, turning the conflict against the slavers into a religious war. It was perhaps naïve of the Spanish to think that they could eliminate slavery, which would remain a practice in Sulu until the end of Spanish colonial rule.

When Legazpi moved his administrative center to Manila, he left local administration in the hands of loyal Spanish subjects who remained in Cebu as part of the Encomienda System. These encomienderos, given responsibility over tracts of land and all the resources (including the indios) found within their borders, were tasked to defend the indios against their enemies, raiders included, and ensure their conversion to Christianity by the friars. The native inhabitants were scattered all over the place, so in order to locate and convert these almas the Spanish implemented the reducción policy whereby the indios were relocated and concentrated in villages where they could be easily administered bajo de las campanas (under the bells).

Because of the hilly nature of the island’s interior, the villages in Cebu were concentrated along the coasts, thereby issuing an open invitation for raiders to come and pillage the coastal settlements. The indios became prime targets for the raiders, who came in fast boats and easily took them away by the hundreds. The encomienderos were unable to defend the unlucky indios, who ended up as slaves.

As well as the Muslims from the south, Visayans also engaged in slave raiding. But during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when the frequency and gravity of the raids increased, most of the fierce, tattooed and daring marauders came from the Sulu Sultanate. To defend against these Iranun and Samal Balanguigui raiders, the Spanish, especially the friars, took to building forts and watchtowers along the shores to warn of approaching warships. They also formed a Marina Sutil (light navy) of fast, well armed sailing boats, manned by locals, that could fight back against the raiders. In the Visayas, the province of Cebu was equipped to command one of the four divisions of the Marina Sutil (5) The strategies employed by the Spanish deterred the raiders, but did not totally stop them from their pillaging and kidnapping. It was only with the arrival of steam gunboats in the 19th century that the Spanish navy eventually put a halt to the raiding.

Esta Mapa se hizo Esta Ciudad de Cebú el año de 1699 from a parishioners’ petition published in 1850 53 (image courtesy of the Archivo Histórico Nacional de Madrid) ѵ

Living under the threat of slave raiders, and with the tribute that the Spanish demanded from them often taken in the form of forced labor, it was inevitable that the natives would rebel. One rebellion that affected Cebu City was the Sumuroy Revolt in Samar of 1649. The Spanish would take men to the Port of Cavite to work in the shipyards, and in the town of Palapag, Samar, when news spread that the men were being rounded up to be brought to Cavite, a disgruntled man named Agustin (aka Juan) Sumuroy led an organized revolt. To quell the insurrection, which lasted a little over a year and spread to neighboring towns and provinces, including Cebu, the Spanish brought in reinforcements from Zamboanga, including 400 Lutao.

The Lutao, also called the Sama Bajau, are a group of people described as ’sea nomads’, people who live on water, in boats or houses on stilts. As they were excellent sailors and warriors, and many were converted Christians, they were recruited to the service of Spain and, when needed, helped in the defense of the Spanish crown.(6) In the case of the Sumuroy Rebellion, the Lutao were glad to assist the Spanish defeat their sworn enemies, the Visayans. After the uprising was put down, not all the Lutao returned to Mindanao; some decided to stay in the areas that they had defended for the Spanish, put down roots and built homes on land. One such place was Cebu, and a settlement of Christian Lutao, tired of their gypsy life on water, grew outside the city. Historian Bruce Fenner wrote that the Lutao could have arrived in Cebu ‘during the early part of the 17th Century’ and started a settlement there.(7) The settlement would grow in 1650, and again in 1663 when the Spanish garrison in Zamboanga was abandoned and another wave of Lutao arrived in Cebu.

While the friars were busy converting the non Christians, town building continued in the hands of the public administrators, usually Spanish. Probably the first map of the city, titled Esta Mapa se hizo Esta Ciudad de Cebú el año de 1699 …, shows the land ownership in 1699.(8) Well over a century after Legazpi’s arrival, and in the middle of a full blown economic crisis, the city was evolving and was built with a clearly marked grid pattern.

The Leyes de Indias (Laws of the Indies), signed by King Philip II in 1573, established the principles of settlement planning, and these rules were followed in Cebu City. The basic element was the grid design, with a rectangular street pattern, and the orderly arrangement of public and private structures. Most important was the creation of a plaza mayor (town square), which could function as a gathering place for the citizens and where monuments could be erected for all to admire. The town was to be set near a harbor (which Cebu was) and should establish links, either by land or by water, with other towns and trading areas.

In the case of the Ciudad de Cebu, the plaza mayor (called the Plaza de Armas on the 1699 map, later renamed the Plaza Mayor, then the Plaza Maria Cristina, and today the Plaza Independencia) is between La Fuerza (the fort), the Cabildo de Cebu (administrative center), and the religious center with the Cathedral (later to be managed by the diocese). The Augustinians were given land to build a church and a convent to house the image of the Santo Niño. Over time, as more religious groups arrived, they too were given property to establish schools and convents like the Jesuit school that would eventually become San Carlos University. At that time the boundaries of the Ciudad were not distinctly clear, but merged with the natural boundaries of marshes, swamps, rivers and the sea.

As earlier noted, the 17th century was a difficult time for Cebu City, and the infrastructure that had been built in the 16th century was falling apart. Records show that in 1628 a fire destroyed a huge portion of the city, including the Santo Niño Church and palisade fort; as described below, a larger fort was built, and its manpower strengthened.

Apart from descriptions of the emergence and rebuilding of the Ciudad, there are no clear images, prints or maps of the city until the end of the 17th century. By this time, we see that the Ciudad was not the colonial city envisioned by the Spanish. Plans to elevate Cebu into a proper Hispanic city with a wall around its Spanish enclave (like Intramuros in Manila) did not happen, and most of the lot owners were the religious orders. Nor did Cebu become prominent as a maritime center for the Visayas and Mindanao. Colonial rule disrupted a thriving

Plan de la Fuerza S.n Pedro de la Ciudad de Zebu (1738) from Planos de las Plazas, Presidios, y Fortificaciones … en las Yslas Filipinas (image courtesy of the Archivo del Museo Naval de Madrid)

settlement and, as the 17th and 18th centuries wore on, the Ciudad remained in the doldrums, with little commercial activity and reverted its focus onto agriculture and subsistence farming.

The Carta Chorographica del Archipielago de las Islas Philipinas made by Francisco Diaz Romero and Antonio de Ghandia (aka Echeandia) in 1727 has a large pictograph for the city of Cebu, with a number of churches and houses, and the 1734 Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica delas Yslas Filipinas by Fr. Pedro Murillo Velarde gives the city two names: Zebu and Nom.e de Ihs. (i.e. Nombre de Jesús)

In 1738 a Plan de la Fuerza S.n Pedro de la Ciudad de Zebu was published in a book on fortifications in the Philippines commissioned by the Governor General, Fernando Valdés Tamón.(9) As well as showing details of the fort itself, with its guardhouse, living quarters, store rooms and well, the plan famously displays the grid pattern of the city, with many of the landmarks from the map of 39 years earlier, albeit with a different

orientation. These include the Jesuit college and church, the cathedral, the Santo Niño church and convent, and the council and episcopal houses.

Beyond the boundaries of the Ciudad, across the estuary to the north, the buildings of the Parian de los Sangleyes (settlement of the Chinese mestizos) are shown, together with the church of St. John the Baptist and several pantanos (swamps). The church and convent of La Concepción is shown across the canal de fagina (now called Pagina) that delineates the south western border of the Ciudad. By this time, as shown by the number of religious establish ments, Cebu had become commercially insigni ficant and most of the activity was concentrated on the non violent conversion of the natives who had not fled to the hills to avoid being taken by the Muslim raiders.

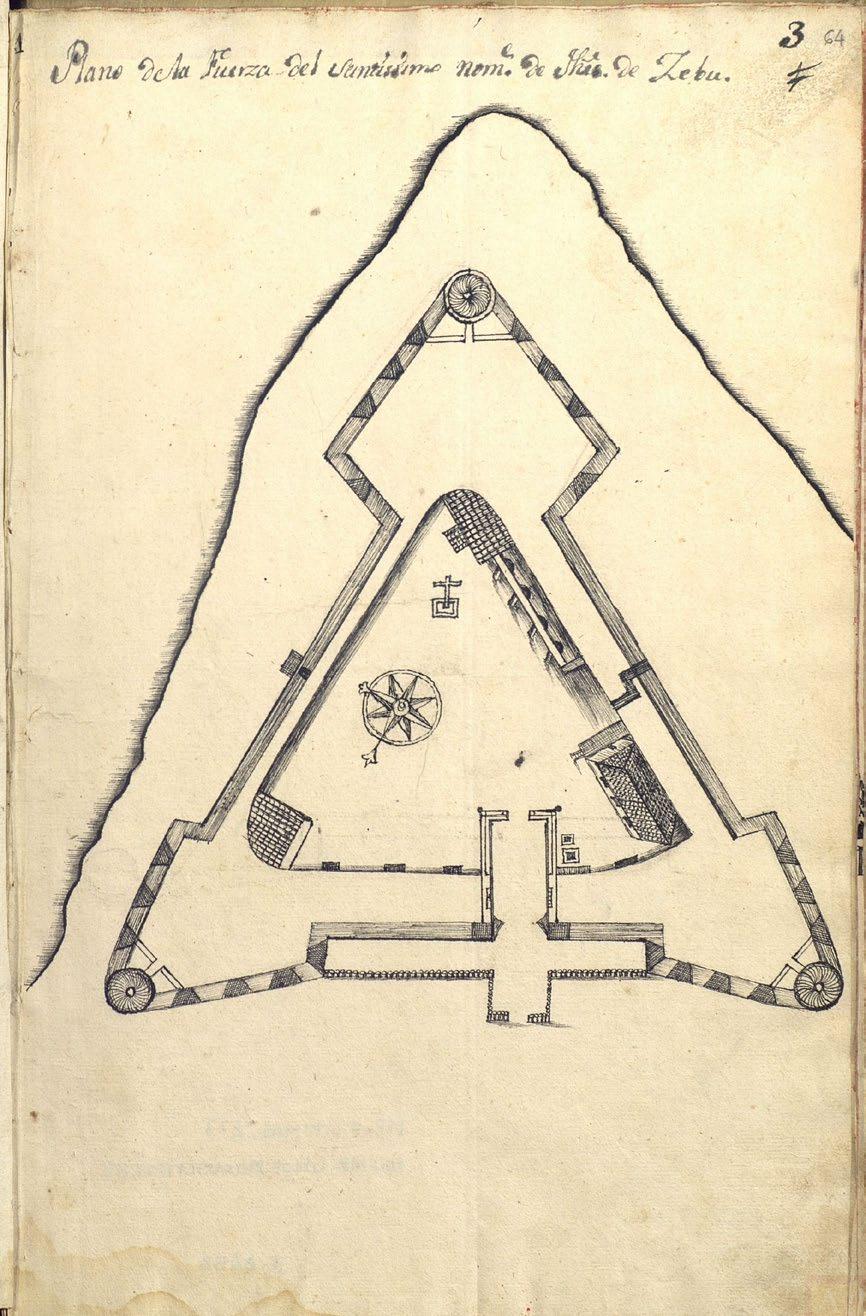

A slightly later book of plans of forts and presidios (fortifications) in the Philippines contains a detailed Plano de la Fuerza del Santíssimo (sic) nombre de Jesús de Zebú dated 1753.(10) After the original fort had been razed by fire in 1628, it

was rebuilt using stone and mortar. The date of construction of the new fort is uncertain, possibly as early as 1630, and it may have been repeatedly strengthened over the following century. Its triangular shape, conforming to the promontory that jutted out to sea, has two long sides of equal length seawards and a shorter side landwards, with three baluartes (bastions), one at each corner. This shape allowed the watchmen to look out for approaching threats on two sides and warn the soldiers accordingly. Entrance to the fort was across from the Plaza Mayor, in accordance with the planning rules of the Leyes de Indias.

At a time when the Muslim slave raids were increasing, it was crucial to have warnings and alarm signals for approaching warships. Fort San Pedro was well stocked and provisioned in terms of arms and munitions, and its military complement was strengthened by bringing in recruits from Pampanga in Luzon to fortify the defenses, with Spanish and native troops taking turns to look out for raiders. Because of the large military presence at the fort, Cebu City and its immediate environs did not suffer from too many raids, unlike other coastal towns on the island.

Life in Cebu City in the 18th Century

Cebu City in the early to mid 18th century had become a veritable backwater and a really miserable place to be. Despite the town building and conversions, because of the raids, lack of commercial opportunities and absence of overall colonial leadership, the inhabitants of Cebu left in droves. The exodus of Spaniards continued, and by 1738 only two remained living in the Ciudad who were not public officials, soldiers or priests.(11) As there were hardly enough people to maintain the city, in 1755 Governor General Pedro Manuel de Arandía demoted the Ciudad del Santisimo Nombre to a mere pueblo. At the same time, the barrios of Lutao and Parian were also made pueblos. Historian Michael Cullinane estimates that in the 1770s the population of Cebu City and its environs, including the Ciudad, Parian, Lutao and areas of San Nicolas was only around 18,722, hardly enough to keep the city self sufficient.(12)

Complicating things further were two events. The first was the expulsion of the Jesuits from the Philippines, by order of King Charles III, in 1768.

Plano de la Fuerza del Santíssimo nombre de Jesús de Zebú (1753), from Descripciones con planos y figuras … de los presidios … en las Yslas Filipinas (image courtesy of the Archivo General de Indias)

As it was, there was a limited number of Spanish priests around to tend to the various parishes that had been established. After the Jesuits left, the Augustinians and Recollects, already stretched thinly, took over the parishes and schools abandoned by the Jesuits. The second negative event was the expulsion of the non Christian Chinese in 1773 by Governor General Simón de Anda. The Chinese had been responsible for keeping Cebu’s meager trade going during these tough times, and with their expulsion it was the Chinese mestizos that came to the rescue and kept the city commercially afloat.

The sangleyes (Chinese traders and settlers in the Philippines) and mestizos de sangley (of mixed Chinese and native Filipino ancestry) played an enormous role in the history of Cebu City. Their presence is noted in most maps of the city which show, to the north of the Ciudad, the pueblo of Parian, the designated area where the sangleyes and mestizos de sangley lived.

Chinese traders had been calling on the port of Sugbu for centuries, and it was inevitable that some stayed and married locals. When the Spanish arrived, their offspring, of mixed blood, were looked at as neither native nor Chinese but mestizos. Under the Spanish rules for ethnic segregation, the Chinese and the Chinese mestizos were set apart from both the Spanish and the natives, and segregated to the Parian area across the estuary, which was the natural dividing line. Parian was established in 1590, when Cebu still participated in the galleon trade, and quickly evolved into a market and trading center. The parish was established in 1614 by the Jesuits, who baptized the Chinese community and taught them reading, writing, arithmetic and Christian doctrine.

Always intrepid entrepreneurs, rich, industrious and active, it was the Chinese mestizos who helped Cebu City weather the difficult 18th and early 19th centuries. This was a small group who had both the foresight and the capital to invest. They numbered only a few thousand and continued to live apart from the Ciudad in Parian, but some historians go so far as to say Cebu City would not have survived without them.(13)

The Philippines was moving from a subsistence economy to an export crop economy. From Cebu, Chinese mestizos sent purchasing agents to Leyte, Samar, Negros and Panay in the Visayas, and to Caraga and Misamis in Mindanao, to buy up local products and raw materials for shipment to Manila, where they were sold to Chinese, European or other foreign merchants. These trade goods included agricultural and semi processed products such as sugar, tobacco, coffee, cacao, coconut oil, pearls, wax and gold. In Manila, the mestizos purchased imported manufactured wares to sell in the Visayas.(14)

The Spanish and Spanish mestizos were few in number, the native Filipinos had no capital, and the non Christian Chinese had been expelled in 1773. By the start of the 19th century, the Chinese mestizos had emerged as a different social class, neither indio nor Chinese, as they rose to prominence as comerciantes (merchants). They were also absorbed into Filipino culture and adopted Christianity. Wealthy and educated, by 1815 they dominated most commercial trade as well as civil, religious, and economic activities, and had influence over the natives.

The residents of Parian constituted only 25% of Cebu City’s population, but they had the best built homes and shophouses. They also began accumulating large tracts of land outside the city limits to plant tobacco, sugar, and other commodities that were highly in demand. The Chinese mestizos, in their zeal to expand agricultural output, began to enquire about purchasing the friar lands (cultivated and uncultivated) that abutted Cebu City. The Augustinians, who had ownership over these lands, felt threatened and moved to abolish the Parian parish, which they did in 1849.

Title cartouche of Juan Díaz Maqueda’s 1793 Plano del Puerto del Zebú (1805) (image courtesy of the Archivo del Museo Naval de Madrid)

Early 19th Century Maps of Cebu City

In 1792, the Philippines was visited by the five year expedition to South America and the Pacific Ocean led by Alessandro Malaspina. When the corvettes Descubierta and Atrevida left Manila in mid November for their return voyage to Cadiz: “Primer Piloto (Master) Juan Díaz Maqueda and Segundo Piloto Jerónimo Delgado were left behind with orders to devote the next six months to a survey of the Visayan Islands in the goleta (schooner) Santa Ana, important both in the interests of navigation in the archipelago and access to the Pacific Ocean.” (15)

As a result, the Museo Naval de Madrid holds a manuscript chart titled Carta Esferica ó Plano del Puerto del Zebú formado entre la Ysla de este Nombre y la de Matan en el Archipiélago Filiphino (sic).(16) The chart, dated Año de 1793 but ‘delineated’ by José Felipe de Inciarte in Cadiz in 1805, states that it was drawn from Maqueda’s surveys. Cebu City is shown, with the fort but no

other details, and San Nicolas to the west, separated from the city by the Pagina river. Lines of soundings crisscross the harbor and the whole of the channel between Cebu and Mactan. The channel between Mactan and the island of Olango is stated to be limpio y hondable (clean and suitable for anchoring), but the channel between Olango and Bohol segun noticias es sucio (is reported to be dirty).

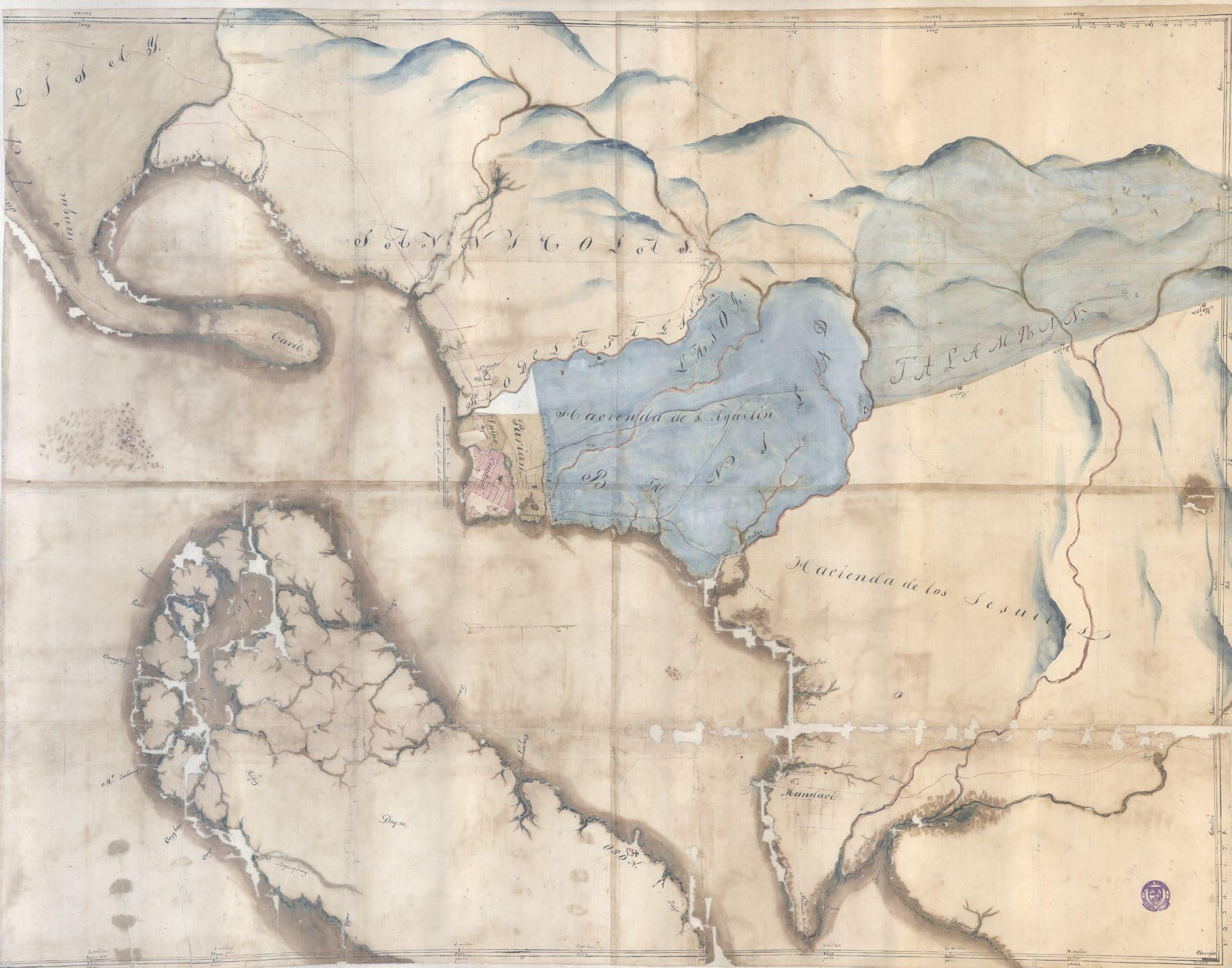

The National Archives of the Philippines has a manuscript map, dated 1833, whose legend and explanations say a lot about the city at the time. The Plano Topografico de la Ciudad de Cebú y sus barrios de los Lutaos y Parian con sus terrenos anecsos hasta los limites de los Pueblos S. Nicolas y Talamban is color coded. The purple area comprises the Ciudad. To the west, a brown area shows the pueblo of the Lutao, and the yellow area is Parian, also a pueblo, where the Chinese mestizos lived and worked; to the east of Parian, also in brown, is the Ysla del Tinago occupada por naturales del barrio de Lutaos. The word tinago means hidden, and the island was called ‘the island of the hidden’ because boats would take shelter out of sight in the inlet whenever there was a storm.

As explained by Dr. Soriano in her article on the lost waterways of Cebu (see page 45), the inlet has since silted up and the island is now connected to the mainland; however, the barangay is still called Tinago.

Boats and ships that came to trade would dock in an inland waterway close to Parian, bypassing the Ciudad, the Spanish enclave. These demarcations are clear on paper but, in reality, there were no physical barriers, and nothing to stop the Chinese in Parian, the Lutao ‒ who at this point were already called naturales (natives) as they had been in Cebu City for more than two centuries ‒ and even the Spanish behind their imaginary walls from commingling or intermarrying.

The native barrios of San Nicolas and Talamban are shown to the west and north, in light blue and blue gray respectively. San Nicolas, established at the time of Legazpi, was where all the original indios were told to stay behind the line of a largish estuary, La Fagina (Pagina). Talamban, on the other hand, was an area of the friar lands given to the Augustinians after all the Spanish encomienderos had left.

Plano Topografico de la Ciudad de Cebú y sus barrios de los Lutaos y Parian … (1833) (image courtesy of the National Archives of the Philippines)

The Plano Topografico de la Ciudad de Zebu … Año 1840 (image courtesy of the Archivo Cartográfico y de Estudios Geográficos del Centro Geográfico del Ejército)

Another manuscript map, Plano Topografico de la Ciudad de Zebu ‒ Barrios de Lutaos y Parian y parte del Pueblo de San Nicolas y limite del de Talamban Año 1840 is in the Archivo Cartográfico y de Estudios Geográficos del Centro Geográfico del Ejército in Madrid.(17) Made seven years after the previous one, this map highlights the fort, where the arms and ammunition for the province were kept, the seminary and the cathedral. It also shows the Barrios of Lutao and Parian, and part of the Pueblo de San Nicolas and the limits of Talamban. The explanations to the map say the houses and buildings colored red are made of mamposteria y teja (masonry with roof tiles), and those in yellow or straw colored are of piedra, tabla y nipa (stone, boards and nipa). Most of the houses and edifices in Parian are red, and the majority of those in the Ciudad are yellow.

The Plano Topográfico de la Ciudad de Cebú ‒Barrios de Lutaos y Parian parte del pueblo de Sn. Nicolás y límites de Tatambam is also an impressive, colored manuscript map of the city.(18) Housed at the Archivo del Museo Naval in Madrid, the map, dated 1842, was rectificado y aumentado (revised and augmented) by Captain

of Artillery J. Novello, and is initialed ‘J.N.’. Like the 1840 map, it highlights the red roofs of the masonry buildings, and shows the smaller nipa thatched houses in brown. The calzadas (roads) to Mandaue and Talisay are shown leading to the north and the south respectively, and the western border is the calzada to San Nicolas.

An addition to the 1840 map is a building on the waterfront on the south side of the city. Marked ‘R’, the legend states that this is an edificio que sera tribunal, carcel, y tiendas de generos (a building that will be a court, jail and goods stores). Nearby the letter ‘H’ marks the chapel curiously noted in the legend as where se halla depositada la primera cruz que puso Magallanes (where the first cross planted by Magellan is found). Historians believe it was actually the Augustinian friar Martin de Rada who erected the cross, not Magellan, as there are no records from Legazpi’s time that say they found a cross, only the Santo Niño. Fr. de Rada, ‘the apostle of the Christian Faith in Cebu’, arrived with Legazpi in 1565 and stayed until 1572, when he moved to Manila as the Augustinian regional superior in the Philippines.

Plano Topográfico de la Ciudad de Cebú : Barrios de Lutaos y Parian … año de 1842 (top), with the detail of the Ciudad and the Parian and Lutao districts (below) (images courtesy of the Archivo del Museo Naval de Madrid)

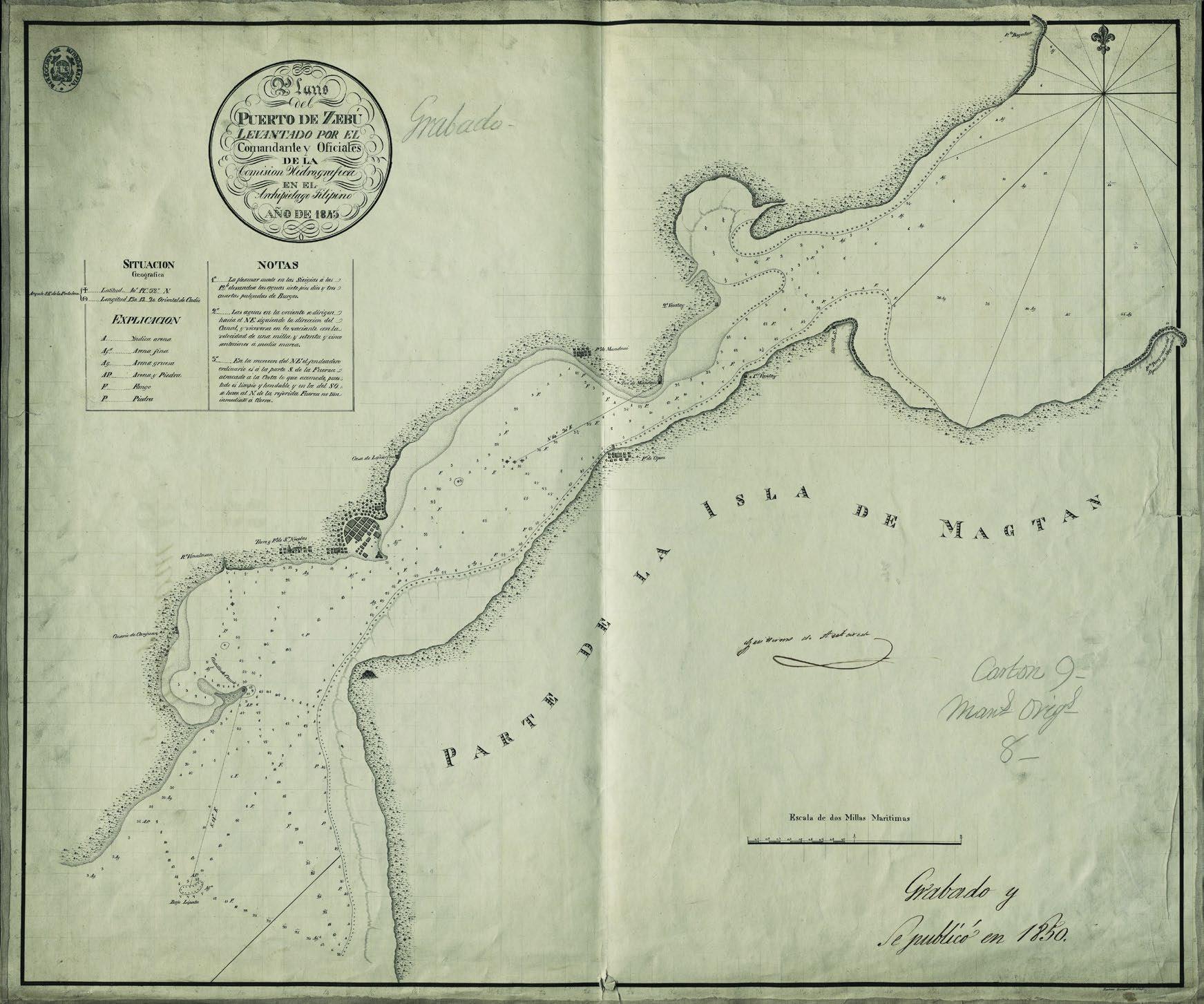

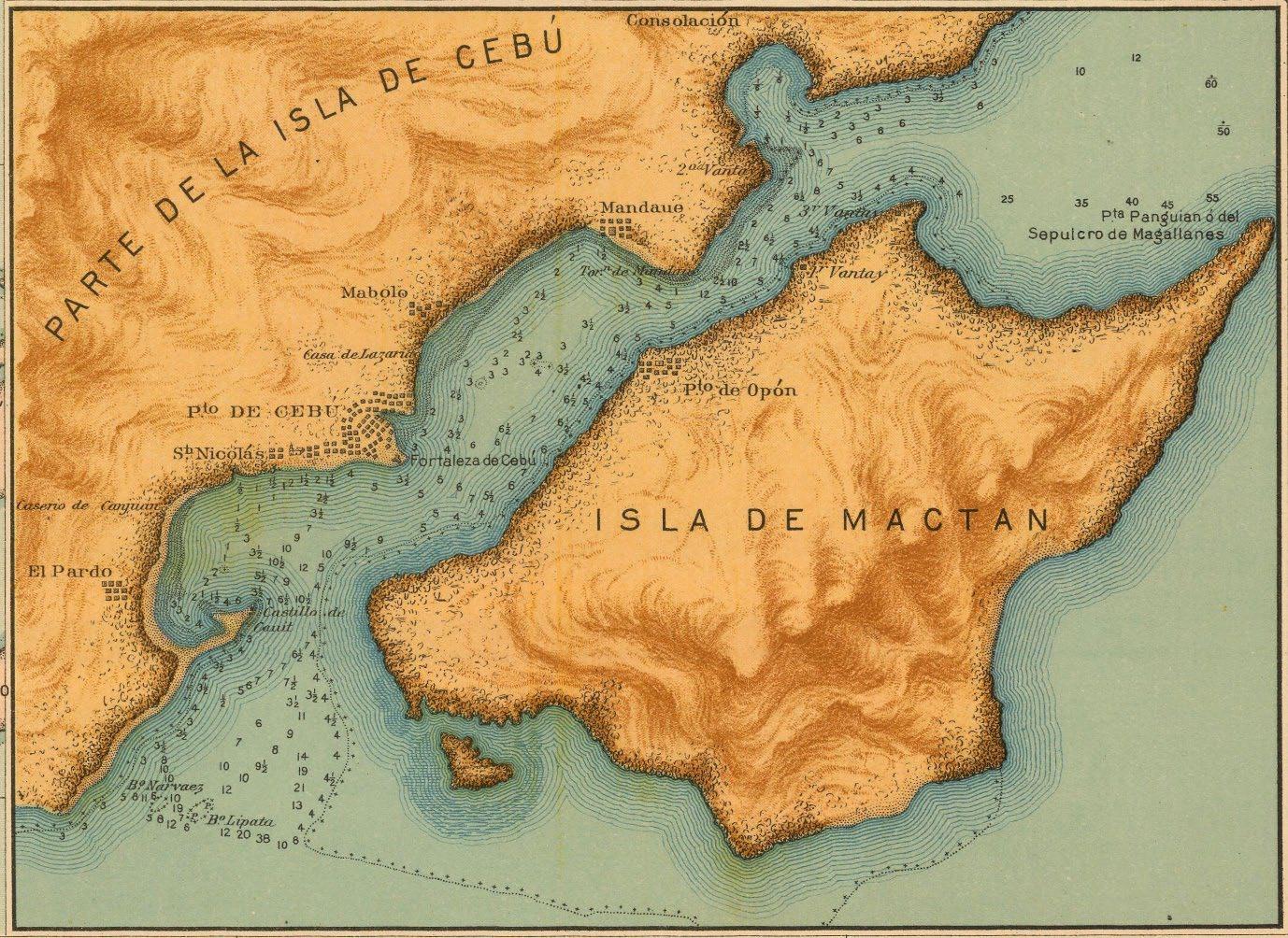

The Archivo del Museo Naval in Madrid holds a manuscript chart by Guillermo de Aubarede y Pérez titled (in a circular cartouche with elaborate scrollwork) Plano del Puerto de Zebú Levantado por el Comandante y Oficiales de la Comisión Hidrográfica en el Archipiélago Filipino Año de 1843 (19) The chart covers the coast of Cebu from the Castillo de Cauit and the Caserio de Canjuan in the southwest to Punta Bagatan (aka Bagacay) in the northeast. In the city, the fort and the grid pattern of the streets in the Ciudad are shown, surrounded by the buildings in the adjacent barrios in a semicircle. To the west are the Torre y Pueblo de San Nicolas, and to the northeast the Casa de Lazarinos (asylum for lepers); further out, we see the Pueblo and the Torreon de Mandaui.

The northern part of La Isla de Magtan (sic) is shown, including the Pueblo de Opon and Punta Panguian ó del Sepulcro de Magallanes. Lines of

soundings crisscross the channel between Cebu and Mactan, and reefs (including the Bajo Lipata) and shallows are drawn. Interspersed with the soundings are letters which indicate the nature of the sea floor: A for arena (sand), Afa for arena fina (fine sand), Ag for arena gruesa (coarse sand), AP for arena y piedra (sand and stone), F for fango (mud), and P for piedra (stone).

To the northeast of Mandaui (today Mandaue) and in two locations on the northwest coast of Mactan, three vantay (coastguard stations, from the local word bantay for a watchman) are marked. Notes give details of the height of the tides and direction of the currents at these locations, and of the best anchorage during the northeast monsoon. In 1850, a printed edition of this chart was published in Madrid by the Dirección de Hidrografía, to which an inset Plano del Fondeadero de Tinaan by Claudio Montero was added in 1870.

The 1847 Map of Cebu (image courtesy of the National Archives of the Philippines)

Another color coded manuscript map of Cebu in the National Archives of the Philippines is untitled and undated, but referred to as the 1847 Map of Cebu. Oriented to the west, the map covers the area from the mountains in the west to the channel between Cebu and Mactan to the south and east. The central portion of the map delineates the districts of the Ciudad, Parian, Lutao and Tinago. North of Parian, beyond the Linea de los Mojones de Banilad, lie the friar lands; the mojones (boundary stones) for the Hacienda de San Agustin and, further to the northwest, the Hacienda de los Jesuitas are located. San Nicolas is to the west, over the Rio de la Fagina, with Talamban further north.

By this time, a lot was going on in Cebu City and, by extension, the rest of the colony and the world. All these events led to Cebu City being poised to turn its economic fortunes around and, in the early 19th century, re emerge as a center of trade for products from the Visayas. Philippine agricultural crops were finding importance in the

world markets, the galleon trade had ended in 1815, Manila opened as a world port in 1834, and the indulto de commercio (license to trade) was abolished in 1844, all of which allowed provincial merchants increased economic activity and scope. Shipbuilding was also deregulated in 1842, and the following year a shipyard was opened in Cebu.

Against this worldwide backdrop, the Chinese mestizos remained extremely active in Cebu’s economy. Historian Edgar Wickberg states that it was the mestizos who made Cebu wealthy.(20) By this time, they had emerged into a ‘third class’, neither pure nor mixed Spanish, and neither pure nor mixed indio. Technically, they were not nobles, but nor were they commoners. Yet they had evolved into landed wealth, had readily adopted Spanish culture and Christianity, and had become Cebu’s ‘merchant elite’. Their connections to Cebu’s port centered commerce gave them social and economic prominence, and a social class to contend with.

Around this time, the Spanish began to return in search of economic opportunities as trade and agricultural ownership began to rise. More Spanish priests also came, filling the once abandoned parishes and churches. As the price of sugar was starting to increase in world markets and the Chinese mestizos wanted to participate in the boom, they were expanding their landholdings and extending beyond Parian and the city limits of Cebu. Feeling threatened, the Augustinians and other Spaniards wanted to limit the powers of the Chinese mestizos. In 1849, not only was the parish of Parian abolished, but so were the towns / pueblos of Parian and Lutao, with both incorporated under Cebu City

The Chinese were also allowed to return by the 1790s, though their participation in business was limited to farming and artisanal work. As such, few actually returned. By the 1850s, Chinese merchants who came to Cebu were Christianized and also settled in Parian. Cullinane estimates that in the 1840s there were only seven Chinese who lived in Parian, but by 1885 there were 1,032 merchants living in and around the district.(21)

It was a changing time in the Parian district. Through the centuries, the small Parian river that ran through the neighborhood had begun to silt up, making it difficult if not impossible for merchant ships to navigate. Instead, the ships docked in the Lutao area. The warehouses, offices and other commercial buildings associated with the port also moved out of the Parian area, which transformed itself from a commercial trading area to a residential area for mestizos and indios. From a population of about 100 people in 1744, Parian ballooned to about 2,500 people in the 1840s.(22) In 1849, some two years after the 1847 Map of Cebu was drawn, the Parian and Lutao districts had a population of 4,720, and the Ciudad had 5,576 people.

Although the Chinese and Spanish were now involved in trade, the Chinese mestizos still controlled most of it. Aside from trans shipments and wholesale procurement, they ventured into retail trade and, probably, shipbuilding after the shipyard opened in 1843. While the Chinese had to pay freight to carry the goods they bought and sold, the Cebuano Chinese mestizos owned their own ships, so the cost of sending goods to Manila was considerably less. Plus, they also engaged in credit lending, financing and tax collection.