Addenda to ‘The Naming of Cebu’

IN OUR article on ‘The Naming of Cebu’ (in The Murillo Bulletin Issue No. 14) we wrote that Subuth was the earliest European name for the island, used by Maximilianus Transylvanus in his work De Moluccis Insulis, the first published account of the Magellan-Elcano expedition This work predated the c. 1525 Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo by Antonio Pigafetta, in which his maps show the name Zzubu

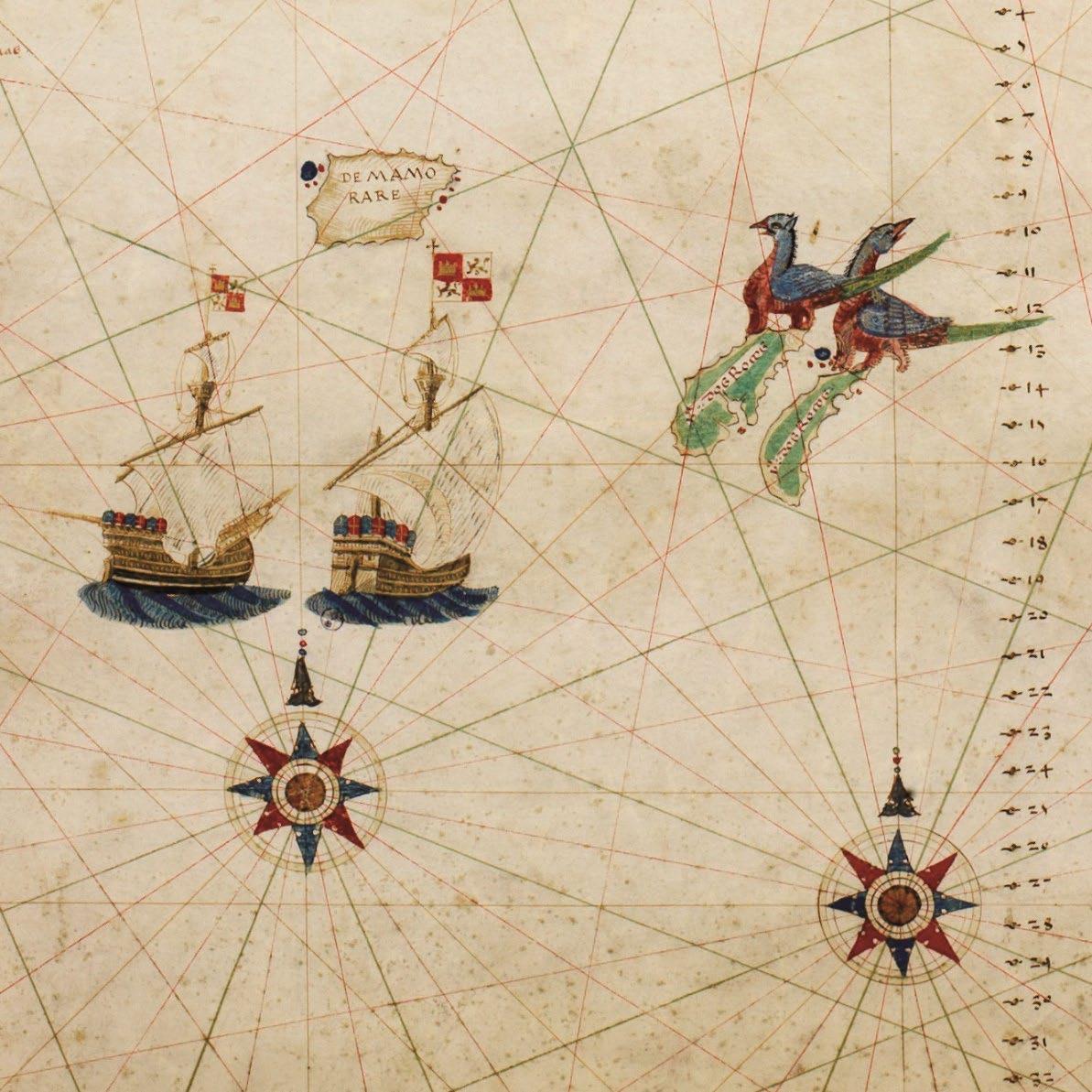

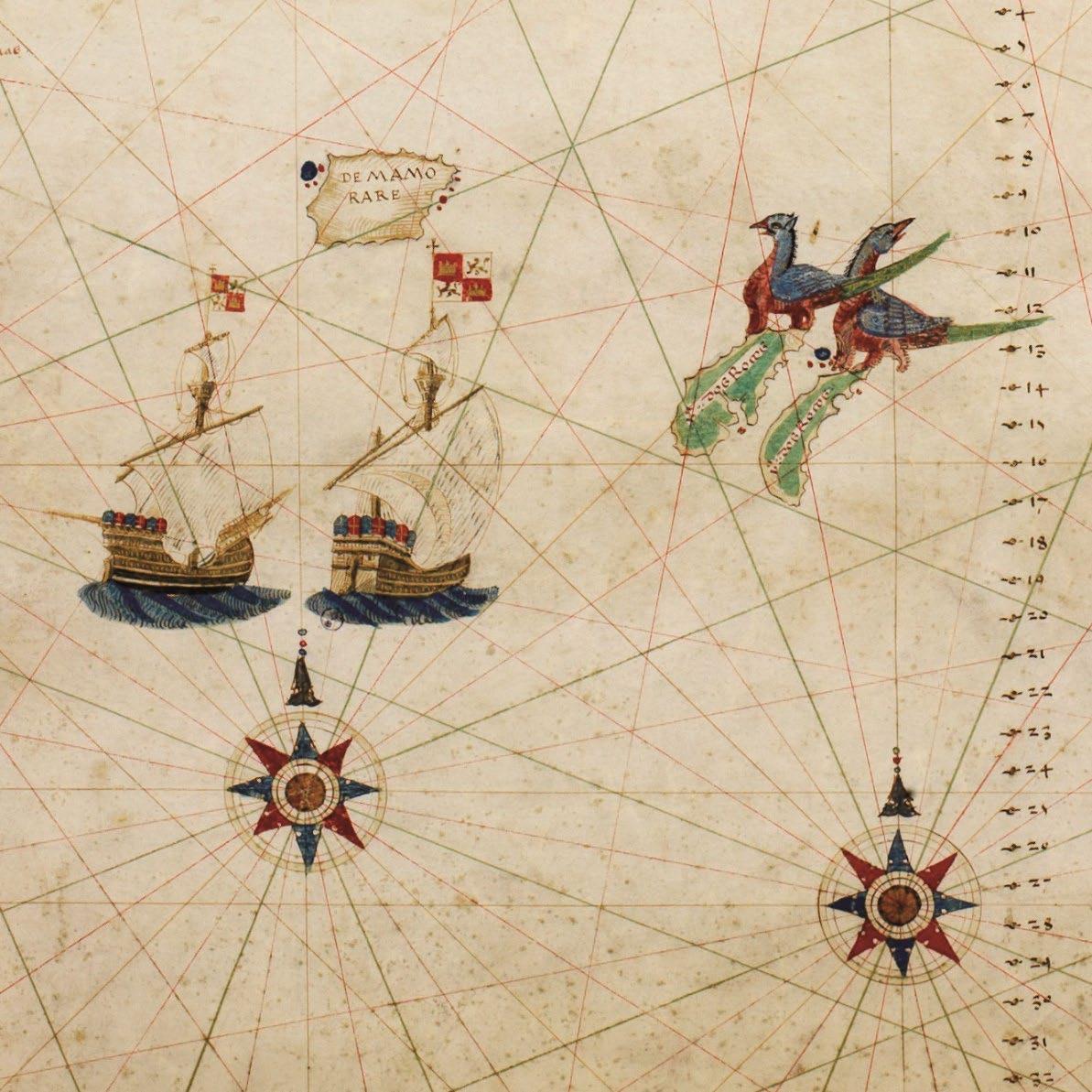

However, thanks to Noelle Rodriguez, we now know that the first map to be created after the return of the Victoria in 1522 was in fact the Carta Nautica delle Indie e delle Molucche by Nuño García de Toreno This manuscript map, held by the Biblioteca Reale, Musei Reali Torino, has been on display in the exhibition Non si farà mai più tal viaggio ‒ Pigafetta e la prima navigazione attorno al mondo (‘No such voyage will ever be made again ‒ Pigafetta and the first navigation around the world’) at the Gallerie d'Italia, Palazzo Leoni Montanari in Vicenza. The exhibition and its handsome catalogue were curated by Valeria Cafà and Andrea Canova

On his return to Seville on 6 September, 1522 Juan Sebastián Elcano delivered all the cartographic materials and travel notes from the expedition to the Spanish cartographer García de Toreno. His beautifully decorated and richly coloured map covers the Indian Ocean from Mesopotamia to the Insula de Gelolo in the Moluccas. It shows the equator, and the antimeridian of the Treaty of Tordesillas line of demarcation bisecting Sumatra, bolstering Spain’s spurious claim to the Moluccas For us, the most fascinating detail is the map’s name for the island of Cebu: Gebu, which was presumably pronounced with a soft G. This is the only map we have found with that spelling.

A collaborator of Amerigo Vespucci from 1508 onwards, García de Toreno was appointed master chartmaker at the Casa de la Contratación in Seville in 1519 There he worked with Juan Vespucio (Amerigo’s nephew) and the Portuguese mapmaker Diogo Ribeiro to produce some 25 charts for Ferdinand Magellan to take on his expedition.

Although we thought our initial list of over 30 names for Cebu was exhaustive, additional research has unearthed not only Gebu but several more variations in the spelling of Cebu that were either not included in the original article or appeared on other maps than those we did mention, as follows:

One of the 12 manuscript maps in the Boke of Idrography (aka the Rotz Atlas) made by Jean Rotz in c.1535-42 shows the island of Sezbo. Rotz was a hydrographer and navigator from Dieppe who probably took part in the expedition to Sumatra under the command of Jean Parmentier in 1529-30.

Oronce Finé’s toponym Cobu, which appeared on his world map in 1531, was also used in the untitled world map published by Sebastian Cabot in 1544. Although Cabot was living in Spain at the time, the map was published in Antwerp as the Spanish government prohibited any proprietary dissemination of information regarding their New World.

On the 1555 manuscript map of the East Indies Mer de l’Inde Orientale et des Moluques, the island of Cebu (fused with Negros) appears with the name Cube. The map is contained in the Cosmographie universelle, selon les navigateurs tant anciens que modernes. Par Guillaume Le Testu, pillotte en la mer du Ponent, de la ville francoyse de Grâce

The name Cabu, used in Dutch maps at the end of the 16th century, first appears on the map of Asia by Giuseppe Cacchij dell'Aquila, published in Naples in 1573 in La Universal Fabrica Del Mondo, a book of treatises describing the cosmography of the four parts of the world.

Although Gerard de Jode initially used the name Ciabu on his map Tertiae partis Asiae of c.1566, this was changed to Cioba on the polar projection, twin hemisphere world map Hemispheriū Ab Aequinoctli Linea, Ad Circulū Poli Arctici published by Gerard and his son Cornelis de Jode in 1593.

7

8

Carta Nautica delle Indie e delle Molucche by Nuño García de Toreno (1522) (image courtesy of Musei Reali ‒ Biblioteca Reale, Torino, Dis.Vari.III_176)

Detail of ‘Gebu’ from Carta Nautica delle Indie e delle Molucche by Nuño García de Toreno (1522) (image courtesy of Musei Reali - Biblioteca Reale)

Detail of ‘Sezbo’ from the Boke of Idrography by Jean Rotz (c.1535-42) (image courtesy of the British Library)

Detail showing ‘Cobu’ from the untitled world map by Sebastian Cabot (1544) (image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Detail showing ‘Cube’ from Mer de l’Inde Orientale et des Moluques by Guillaume Le Testu (1555) (image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Detail of ‘Cabu’ from the map of Asia by Giuseppe Cacchij dell'Aquila (1573) (image courtesy of Barry L. Ruderman Antique Maps)

Detail of ‘Cioba’ from Hemispheriū Ab Aequinoctli Linea … by Gerard and Cornelis de Jode (1593) (image courtesy of Neatline Antique Maps)

9

John Bach

John Bach

Cartographer, collector and historian of maps of the Philippines by Peter

Geldart and Alberto Montilla

JOHN BACH (1) was born in Kristiansand, Agder, Norway on 10 February, 1872, the son of Hans Christian and Chatrine Johnson Bach. After seven years of education in public schools, he graduated in civil engineering from the Trondheim Technical School in 1892 and was then engaged in architectural drafting and the construction of private dwellings in Kristiansand.

He emigrated to the United States in March 1893 where for two years he worked as a draftsman and as an ironworker for the erection of elevators. From 1896 to 1901 he was employed by the Argentine government, in charge of a unit conducting surveys, triangulation and topography of the boundary between Argentina and Chile in the Andes Cordillera. In January 1902 he returned to the United States, became a U.S. citizen, and obtained a position with the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey (USC&GS).(2) In November 1902 he was posted to the agency’s Manila Field Station, which had been opened just a year earlier (with George R. Putnam as its first Director) and tasked with completing a comprehensive survey of the newly-acquired Philippine Archipelago.(3)

Bach’s duties in his early years in Manila are recorded in the annual reports sent to the U.S. government by the Director.(4) In the report for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1904 Bach is listed under Field Work as an ‘observer, triangulation and topography’ and under Office Work as em-

ployed ‘on computations necessary for the completion of the field work executed by [him] and while awaiting orders for the field’. His field assignments included being an observer in a shore party at Gubat, Sorsogon in 1902-03, and the chief of a party undertaking triangulation and topography on the west coast of Luzon in 1904. The report for the following year states:

Hydrographic verification division. ‒ John Bach, observer (now appointed cartographer), was detailed to this duty in December, 1904. The work consists of the examination and verification of hydrographic sheets, the examination and registry of all survey sheets, and assistance in the verification of chart drawings, and is indispensable in maintaining a proper standard of accuracy and system.

11

Kristiansand c.1900-1920

Photograph of John Bach in 1931 from the Graphic

In September 1905 Bach was put in charge of the chart construction division, assisted by a second cartographer, a draftsman, 12 junior draftsmen, and three apprentice draftsmen. The work included ‘the preparation of drawings for new charts and new editions of charts, the completion of unfinished field sheets, as the inking of topographic sheets and the plotting of hydrographic sheets, … and the verification of chart drawings’. In the report for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1907, Bach is described as ‘chief cartographer’ of the chart construction division.

In 1907-08 Bach was working in the office evaluating field reports when he had an argument with Asst. D.R Jewell, in command of the survey ship Marinduque, over the validity of the soundings taken at Burdeos Bay in the Polillo Islands. Perhaps as a result of this disagreement he again became involved in field work, and in 1911 ‘E.R. Frisby and John Bach made a survey of the subterranean river of

Palawan’.(5) In 1917 Bach is recorded as being employed by the USC&GS as a Draftsman with the title of Chief of the Drafting Division, at a salary of US$2,400;(6) by 1921 his salary had increased to US$3,000.

The earliest of Bach’s maps we have seen is dated August 1907 ‘corrected to Aug 26-07’, and is titled Map of the Philippine Islands / Compiled from the latest data by John Bach assisted by the Filipino draftsmen and engravers J. Gonzalez, G. Tichepco, P. Tabora, J. Velasquez, M. Navarro and V. Estrella The map, at a scale of 1:1,250,000, has a table of distances ‘in nautical miles by the shortest navigable routes’ to overseas and interisland ports, and a circular inset plan of the City of Manila at a scale of 1:30,000. The map, which measures 160 cm x 99 cm, was ‘Published at Manila P.I. by John Bach & O.O. Tweeth’ (7) and ‘Copyrighted in the Philippine Islands and Copyright applied for in the United States of America’

12

Map of the Philippine Islands published by John Bach and O.O. Tweeth in August 1907 with (right) details of the title cartouche and inset plan of the City of Manila (Alfredo Roca collection)

13

The first (1911) edition of John Bach’s map of the Philippine Islands (left) and an uncoloured proof state of the map with manuscript notations (right) (the latter image courtesy of the National Library of Australia)

Map To accompany ‘The Philippines ‒ The Land of Palm and Pine’, August 1911 (left) and the fifth (1926) edition of John Bach’s Philippine Islands (right)

Cover of the 1st edition of Bach’s Philippine Islands

In 1911 Bach produced the first edition of his best-known map, titled Philippine Islands, that would run to a total of nine editions published in 1911, 1917, 1921, 1924, 1926, 1929, 1934, 1937 and 1940. The map, drawn at a scale of 1:2,000,000, measures 79 cm x 57 cm. The first edition has two insets, one of the Batanes and Babuyan islands and the other, at a scale of 1:800,000, of the Vicinity of Manila. The Principal Authorities for the map are listed as: U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey; U.S. Army Surveys; Bureau of Constabulary; Bureau of Lands; Bureau of Science; Bureau of Forestry; and Atlas de Filipinas by Don Enrique d’Almonte (see below).

The map, ‘copyrighted in the Philippine Islands and the United States of America’, is a lithograph printed in pink, yellow, taupe and green, with the coasts and inland lakes outlined in shades of blue. A table, printed in red, shows distances ‘in nautical miles by the shortest navigable routes’ between Manila and 15 overseas ports, and between Manila, Iloilo, Cebu and Zamboanga and a list of interisland ports. Another table, also in red, gives the call signals of Wireless Telegraph Stations.(8) The maps were printed by ‘Imp. Lit. Carmelo & Bauermann, Manila, P.I.’.(9)

Essentially the same map, dated August, 1911 and with the title revised to Map To accompany “The Philippines ‒ The Land of Palm and Pine”, was issued to accompany a 214-page book by John R. Arnold, The Philippines ‒ The Land of Palm and Pine: An Official Guide and Handbook, published by the Department of Commerce and Police in 1912.

For the second and subsequent editions of the Philippine Islands the main map was made bigger (93 cm x 64 cm) to include the Batanes islands and the original insets were replaced, at first by a large inset map of Central Luzon at a scale of 1:800,000; from the fourth edition onwards a small inset map showing Trade Routes of the Orient was also added. The maps were issued folded into a cardboard cover together with a booklet, initially a 12-page ‘Postal Directory to Accompany Map of the Philippines’ which by the last edition had grown into a 72-page ‘Index of Names Pertaining to Bach’s Map of the Philippine Islands’.

The colourful cover of the first edition carries a striking image of the explosion of ‘Taal Volcano, Jan. 30th 1911’; those of the second, third and fourth editions show a circular map of the Pacific Ocean. The covers of the fifth to eighth editions are plain, with the title, John Bach’s name and the date; the cover of the ninth edition has an engraving of Ferdinand Magellan’s ship Victoria copied from Barent Langenes’s 1598 Caert-Thresoor, together with a translation of a poem by Abraham Ortelius.(10)

14

Cover of the 2nd edition of Bach’s Philippine Islands

A plan of the City of Manila, Philippine Islands dated ‘December 1913’ was published and copyrighted in January 1914 by John Bach and F.H. Jaeger ‘For the Philippine Publicity Committee of the Manila Merchants' Association and the Government of the Philippine Islands’.(11) Measuring 100 cm x 75 cm, the map shows the city at a scale of 1:11,000 from the Estero Sunog Apog, Binondo Cemetery and Cemetery del Norte in the north, to the San Juan River and San Felipe Neri (later Mandaluyong) in the west, and down to Pasay in the south. Many

neighbourhoods are shown as proposed or under construction, with the ‘Projected Streets’ indicated by dashed lines; ‘Street car lines’ are shown in red. The City Engineer, Coast & Geodetic Survey, Bureau of Lands and U.S. Army are listed as ‘Authorities’ A table with grid references provides a numbered list of ‘Places of Interest and General Information’: Amusements, Banks, Cemeteries, Churches, Clubs, Educational, Fire Stations, Government Offices, Hospitals, Hotels, Police Stations, Public Service, and Miscellaneous.

15

Road Map of Central Luzon (above) with its cover showing Sibul Springs Bridge (top right) and reverse plan of the City of Baguio (right) (images courtesy of the H. Otley Beyer collection at the National Library of Australia)

In 1917 Bach published a Road Map of Central Luzon at a scale of 1:800,000 with, on the reverse, a plan of the City of Baguio. Again, the map was issued folded into a cardboard cover, with an attractive, tinted photograph of ‘Sibul Springs Bridge, Bulacan Prov.’.(12) This map was used for the new inset of Central Luzon on the second and subsequent editions of Bach’s Philippine Islands map.

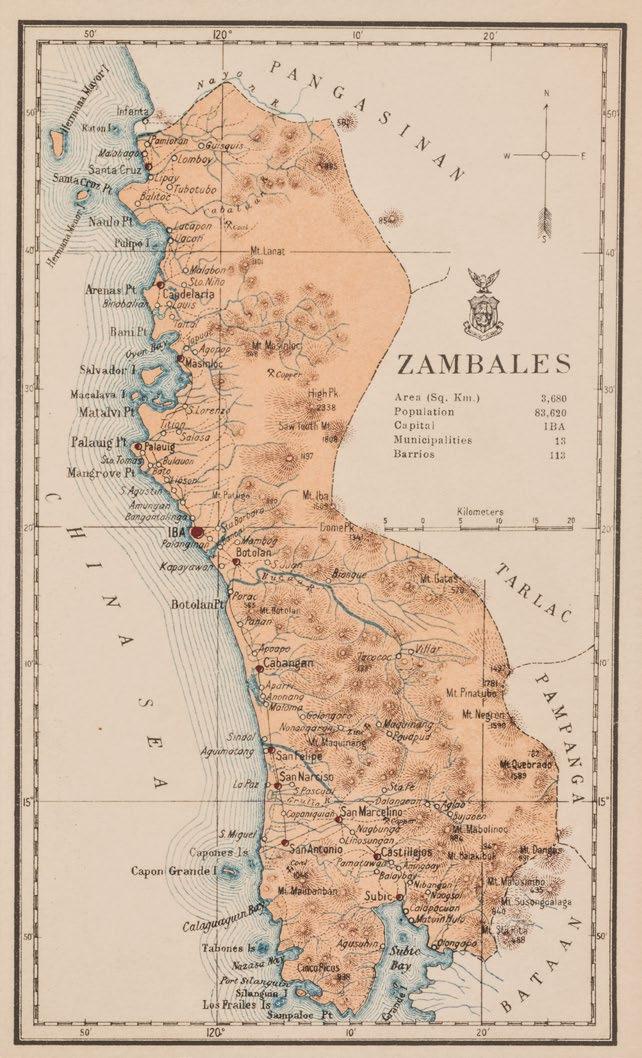

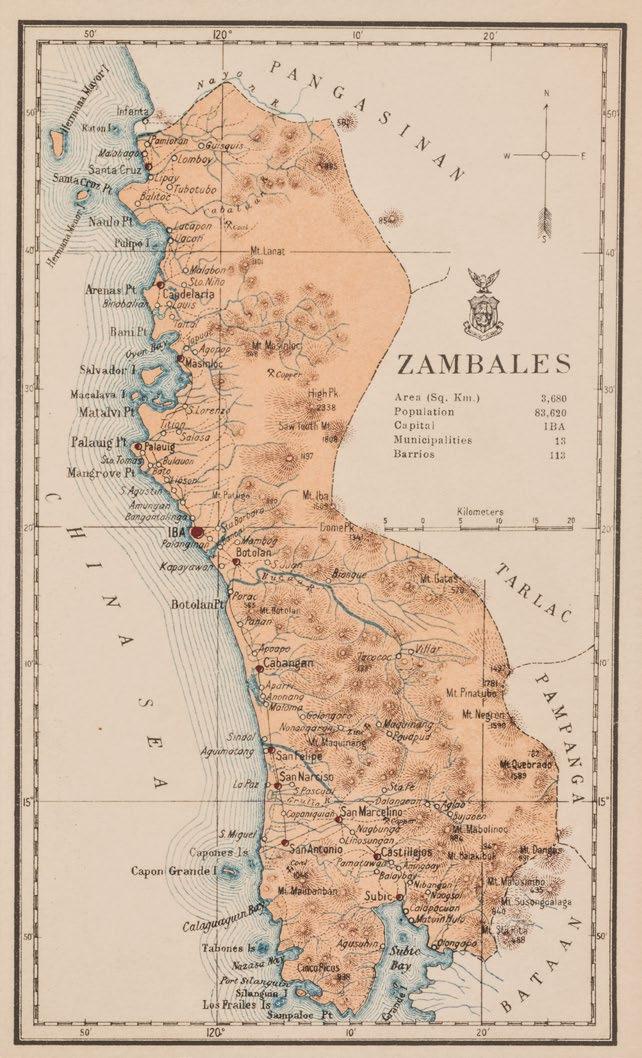

A milestone in Bach’s career occurred in 1920 when the Census Office of the Philippine Islands compiled and published the Census of the Philippine Islands Taken Under the Direction of the Philippine Legislature in the Year 1918, in four volumes. The report contains a total of 61 maps comprising two city maps of Manila and Baguio; 43 provincial maps; six maps of halfprovinces; seven maps of sub-provinces; and three maps of the Philippines ‒ one at a scale of 1:5,000,000 showing the provinces, a Relief Map showing seismic activity and volcanoes, and a Forestry Map showing forest areas, concessions and sawmills. These maps are bound into the Census Report, and were also published in a separate Atlas of the Philippine Islands. The maps are quite small (24 cm x 16.5 cm) and, apart from two ‘compiled by John Bach’, are not signed; however, Bach’s responsibility for their production is noted in the Introduction to Volume I of the Census:

The attention of the reader is drawn to the Atlas of the Philippines or provincial maps published in this volume of the Census. They were prepared especially for the Census, at the request of the undersigned [Ignacio Villamor], by Mr. John Bach, the able cartographer of the Bureau of Coast and Geodetic Survey, who used for this purpose, among other sources of information, the data recently collected by the Census officials. Every map of the series is a new production in the sense that it is a complete compilation of all information existing on the date of publication.

The Preface to the Census Volume I continues:

The maps in the following collection were prepared for the Philippine Census in the Office of the Coast and Geodetic Survey at Manila during the year 1919. The work of compilation of drawings and construction of lithographic stones was executed by a force of 12 Filipino draftsmen and lithographers under the supervision of Mr. John Bach. Each map is an entirely new compilation from the most authoritative original sources of information. The printing was done at the establishment of Carmelo and Bauermann, in Manila. Five colors were used in printing: black for outlines and names; brown for mountain shading; blue for coast fringes, rivers, and lakes; red for municipal symbols; and either pink, yellow, purple, green, or orange for the land-areas.

On each of the maps of the provinces, below the title, a table lists relevant information: the area in sq. km.; the population; the name of the capital; and the number of municipalities, municipal districts, townships, rancherias (settlements) and/or barrios (as relevant for each province). Versions of the maps without this information also exist; these may have been preliminary proofs.

The small map of the Philippine Islands at a scale of 1:5,000,000 ‘compiled by John Bach’ in 1919 for the Census Atlas is interesting because it includes (shown in red) the ‘Treaty Limits’, i.e. the boundaries of the Philippines designated by the 1898 Treaty of Paris between Spain and the United States, but without reference to the adjustments to the limits made in the 1900 Treaty of Washington. Both Pratas Reef and Scarborough Reef are shown, to the west of the Treaty Limits. In 1923 essentially the same map

16

Map of Zambales from the Atlas of the Philippine Islands (1920)

Bach’s small-scale map of the Philippine Islands from Beautiful Philippines (1923)

was published in Beautiful Philippines – A Handbook of General Information, but with the significant change that the two reefs have been removed and replaced by the same table of distances between Manila and interisland ports shown on Bach’s larger-scale map.

In 1920 Bach compiled a map of the Trade Routes from Manila for the Bureau of Commerce and Industry. Covering the Indian and Pacific Oceans, the map has two concentric circles centred on Manila with radii of 700 miles and 2,500 miles; trade routes are shown from Manila to ports in Arabia, India, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and North and South America. The map has tables of Principal Exports, Principal Imports, and the distances of Common Trade Routes. A simplified edition of this map, with the title revised to Trade Routes of the Orient, was included in Beautiful Philippines – A Handbook of General Information in 1923.

Another map compiled by Bach and published by the Bureau of Commerce and Industry was the detailed and colourful Economic Map of the Philippine Islands dated 1921. The map shows inter alia land use, colour-coded for Surveyed Forest, Unsurveyed Forest, Partly cultivated or open land, and Cultivated Land; sugar centrals; fishing grounds, with commercially-important fish; sawmills, in operation and proposed; forest / timber concessions; and, from the Bureau of Science, the locations of mineral resources. Tables also list statistics for foreign trade, geographic information, and distances to overseas and interisland ports.

ѵ Bach’s Trade Routes from Manila (1920) revised as Trade Routes of the Orient (1923) (image courtesy of the Gallery of Prints, Manila)

17

Economic Map of the Philippine Islands compiled by John Bach, second edition (1924)

18

A second edition of the Economic Map, with a number of revisions, was published in the Bureau’s Commercial Handbook of the Philippines for 1924, which also included the revised map of the Philippine Islands at a scale of 1:5,000,000, the original 1920 Trade Routes from Manila, and a map of the City of Manila copied from the 1918 Census map but with ‘in 1918’ added after ‘Population’, and with the table of References and the corresponding number keys comprehensively revised.

On a number of occasions Bach also produced maps for the Bureau of Science. A reduced version of his 1911 map at a scale of 1:4,000,000, with the title Map of Philippine Islands and the addition in red of the ‘Principal Mineral Localities’, was published by the Division of Mines, Bureau of Science in The Mineral Resources of the Philippines Islands for the Year 1911. An article in The Philippine Journal of Science in 1924 contained an Isobathic Map of Panay, Negros, and Cebu ‘prepared by Mr. John Bach’.(13) He is also mentioned in the Preface to Monograph 21 of

the Bureau of Science, Distribution of Life in the Philippines, published in October, 1928:

The hearty coöperation of the Philippine Bureau of Coast and Geodetic Survey was particularly helpful in the preparation of the maps and charts upon which the hydrography chapter was based. Capt. H.C. Denson, former director of the bureau; Capt. E.H. Pagenhart, director; and Mr. John Bach, supervisor of the geographical division, were always ready to contribute their excellent data.

In 1918 Bach published and copyrighted (in his own name) a new edition of the City of Manila. There is no mention of Ferdinand Jaeger, the U.S. Army was deleted as one of the Authorities, and the map was ‘Issued by Authority of the Bureau of Commerce and Industry’. The plan is the same size and covers the same area as the 1913 map but shows considerably more detail in many districts, with street names added in neighbourhoods under development such as Tondo and Rizal Park, and the new roads laid out in Sampaloc drawn in

19

Details from the 1913, 1918 and 1920 editions of Bach’s map of the City of Manila showing the development of the railway tracks and streets adjacent to Tutuban station (images courtesy of the Huntington Library, the Biblioteca Nacional de España and the Library of Congress respectively)

City of Manila ‒ Philippine Islands second edition (1918) (image courtesy of the Biblioteca Nacional de España)

Concentric circles are placed at distances of one, two, three, four and five kilometres from Plaza Goiti (today Plaza Lacson). An extensive Index of Street Names, with grid references, was added in the top-right corner, replacing the title which

was moved to the bottom-left corner. The list of ‘Places of Interest and General Information’ was expanded with the addition of Lodges, Bureaus, Industries, Markets, and United States Army locations.

20

A second state of the revised City of Manila map appeared in 1920, with updated details such as the expanded rail tracks and train depot running from the central railway station in Tutuban. Further additions were made to the tables, including telephone numbers for many of the Places of Interest. The map was sold folded into a cardboard wallet with the title Official Map of the City of Manila. In 1923 a smaller, black-andwhite version of the plan was included in Beautiful Philippines – A Handbook of General Information which was ‘Prepared by the Philippine Commission of Independence’ and published by the Bureau of Printing, Manila. In 1924 the Bureau of Commerce and Industry also included a smaller (56 cm x 43 cm) edition of the map as a fold-out in its Tourist Handbook of the Philippine Islands, which has a cover illustration attributed to Fernando Amorsolo.

Yet another edition of the City of Manila was published by Bach in 1930, with the title shortened to just Manila, no reference to the Bureau of Commerce and Industry, and a different colour scheme. New barrios are shown to the north of the city; the Pasay Race Course has become a residential district with streets marked out; the new South Cemetery appears to the south of the much smaller English Cemetery; and the table of ‘Places of Interest and General Information’ has been deleted.

In 1932 Bach produced a revised and enlarged plan of the metropolis. Titled Manila and Suburbs, the map is at the same scale of 1:11,000 but covers a wider area than the earlier City of Manila: from the Sangan Daan, Rizal Avenue Hills and Balintawak Subdivisions in the north, to Wack Wack Golf & Country Club in the west, and to Fort William McKinley and Pateros in the southwest. Consequently the map is considerably bigger, measuring 153 cm x 107 cm. The table of Places of Interest and General Information was retained, but the street names are shown either on the map or in a number of small tables by locality, with grid references. Two tables list the bus lines of the Pasay Transportation Company, Inc. and the Manila Electric Co. On another state of the map, 26 small photographs of churches, monuments and other buildings in Manila, with captions, have been added in various empty spaces. The map was ‘Copyrighted and all rights reserved by Frances L. Bach’, John’s daughter,

A revised state of the 1930 plan, again with the title Manila, was published by Bach in 1935. Having been printed by Carmelo & Bauermann, using a ‘Photo Litho Process’, this edition is more colourful than the earlier ones, with builtup areas in orange, open spaces such as parks and cemeteries in green, and rivers in blue. Like the 1932 map it was copyrighted by Frances L. Bach. Of particular interest is the addition of an area of reclaimed land off the waterfront in Pasay marked ‘Proposed Airport (Under construction)’ with, adjacent on the north side, the ‘Seaplane basin’ and the ‘Yacht Club basin’. In 1941 a close copy of this map with the title and names in Japanese, but without Bach’s name, was published in Tokyo.

21

The cover of the 1924 Tourist Handbook of the Philippine Islands attributed to Fernando Amorsolo

22

Manila and Suburbs (1932), with photographs added, copyrighted by Frances L. Bach

Following the Economic Map of the Philippines of 1921/24 another, larger, map packed with economic information was produced in 1937 by John Bach and the economist Hugo H. Miller.(14) Measuring 118 cm x 82 cm, Philippine Islands Physical – Economic – Political covers the archipelago at a scale of 1:1,600,000. The map is colour-coded to show lowlands, uplands and plateaus, mountains, and the depths of the surrounding seas. Local produce is named in red, and symbols indicate important sawmills, sugar centrals (15) and rice milling towns; hemp presses; and oil mills and coconut mills. Around the borders, ten small inset maps cover minerals and mining; population; soil cover; climate; and the regions growing sugar cane, rice, abaca (Manila hemp), coconut palms, tobacco, and corn. The map was re-issued in 1941.

Bach was employed by the USC&GS but he must have been allowed to publish his work commercially since many of his maps were copyrighted, usually in his own name but on three occasions jointly;(16) at least three of the maps were copyrighted by his daughter, Frances L. Bach.(17) But not all of Bach’s maps were copyrighted by him or his family, for example the various maps published by the Bureau of

Commerce and Industry which were ‘compiled by John Bach’ but did not carry his copyright.

There is limited information available about Bach’s private life. He married Fannie L. Daily, an American born in New York in 1876, and they had two daughters: Frances L. Bach and Anita C. Bach, born in Manila in 1904 and 1908 respectively. In 1914 the family visited Norway via the United States to see John’s sister Hulda, who was still living in Kristiansand. In April 1927 Bach took a year’s leave of absence from the Manila field station to visit the United States, again with his family. There he was detailed on a temporary basis to the USC&GS office in Washington D.C., from October 1927 to March 1928, before returning to Manila.(18) On his return he reassumed his position as Head of the Drafting Division and also, concurrently, became the technical supervisor of the bureau’s Geographic Division.(19)

The Bachs apparently led an active social life. John Bach was a member of the Free and Accepted Masons Lodge No. 1 (Scottish Rite);(20) the Manila Polo Club, then located on the seafront in Pasay; and the National Geographic Society. The Tribune newspaper recorded that

23

Manila (1935) (left) with the Japanese version published in Tokyo in 1941 (right)

Philippine Islands Physical – Economic – Political by John Bach and Hugo H. Miller (1941)

‘Mrs. J. L. Bach [and] Miss Anita Bach’ attended a tea at Malacañang on 24 July, 1933 hosted by the Philippine Anti-Tuberculosis Society for the Catholic Women’s Club of Manila. The Tribune also reported Frances Bach’s social activities

between 1934 and 1937 ‒ playing bridge and attending society tea parties ‒ and she visited the United States again in 1935-36.(21) A portrait photograph of John Bach appeared in an article in the magazine Graphic published in 1931.(22)

24

As reported in an article in the magazine Philippine Touring Topics, in August 1934 Major General Frank Parker, Commander of the Philippine Department First Division, flew over a mountainous region in eastern Mindanao between Cotobato and Sarangani Bay marked on the maps as ‘unexplored’.(23) There he spotted the crater lake in the caldera of Mount Parker (today Mount Melibengoy), and on his return to Manila he organised an expedition to explore the volcano on which ‘Captain E.H. Pagenhart (Superintendent of the Coast and Geodetic Survey in Manila) and Mr. John Bach (Assistant to Captain Pagenhart) were members of the advance party’.

In February 1934 Bach had reached the mandatory age of retirement for civilian employees of the U.S. government; however, an Executive Order signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 21, 1934 stipulated:

Whereas the public interest requires that John Bach, Chief, Drafting Division, Coast and Geodetic Survey, Department of Commerce, Manila, Philippine Islands, who, during the current month, will reach the retirement age prescribed for automatic separation from the service, be exempted from the provisions of this section and continued in the service until February 28, 1935; Now Therefore by virtue of the authority vested in me by the aforesaid statute,(24) I do hereby exempt John Bach from the provisions thereof and continue him in the service until February 28, 1935.

However, Bach did not in fact retire in 1935. In his history of the Bureau of Coast and Geodetic Survey, Raul de Leon records that: “Although John Bach retired on February 28 [1935], he had consented to stay on for the balance of the year

and train an understudy, Castor G. Lim, to take charge of the Drafting Division.” De Leon also writes that, after the Department of National Defense had been organised in November 1939, notable changes in Coast Survey personnel took place on 1 June, 1940 but: “For unexplained reasons, J. Bach continued to take charge of the Drafting Division despite his retirement, but no mention was made regarding his emolument.”(25) An encyclopedic directory published in 1939 (26) still lists ‘John Bach, Chief, Drafting Division’ under ‘Federal Offices in the Philippines ‒ Bureau of Coast and Geodetic Survey’. At that time, Bach also remained a member of the board of directors of the savings and loan association of the Bureau of Coast and Geodetic Survey.

On January 14, 1941, the Bureau of Printing in Manila published, on behalf of the Commonwealth of the Philippines Commission of the Census, the 1939 Census Atlas of the Philippines as Volume V of the Census The Introduction to the atlas states:

The preparation of the Census Atlas was agreed upon in 1937, on a coöperative basis after several conferences between Assistant Commissioner of the Census Vicente Mills; Director Thos. J. Maher, Mr. C. F. Maynard, and Mr. John Bach, of the Bureau of Coast and Geodetic Survey; and Director Reverend Father Miguel Selga, S.J. of the Weather Bureau. The geographic maps and data were prepared and compiled by personnel of the Commission of the Census, working under the immediate supervision of Director Thos. J. Maher, designated as Adviser on Hydrography under the provisions of the Census Act; and his successors, Directors F. B. T. Siems and R. R. Lukens, assisted by Mr. C. F. Maynard and Mr. John Bach, designated as Advisers on Cartography.

The elephant folio atlas contains a map of the Commonwealth of the Philippines, 24 provincial maps, two maps on the distribution of population, four maps on climate and weather, four maps on economic areas and resources, and seven maps portraying the history of Philippine cartography. The economic maps include an Economic Map of the Philippines ‘Courtesy of Hugo H. Miller and John Bach’ which is copied from their 1937 map, but without the small inset maps.

25

Photograph of Vice-Governor Hayden and General Parker exploring Mount Parker in 1934; the figure in the background could be John Bach

After they was printed most copies of the 1939 Census Books and Atlas were destroyed when the warehouse in which they were stored was bombed by the Japanese during the opening days of the war. However, a small number of copies of the atlas have survived from a batch that had been distributed in advance According to the Library of Congress:(27)

A request was in Manila asking that 1,000 sets of the volumes be sent to the United States and distributed to libraries. A careful inventory of the volumes and special bulletins which reached the United States just prior to the outbreak of war indicates that a few over 50 sets of four [which included Vol. V, the atlas] of the five contemplated volumes of the census are in the United States, most of which are in United States Government offices.

Copies of the atlas were also acquired by Japanese officials; one of these bears a stamp with the name and address of Hōki Saburō, a member of the Kenkyu Chosa Kyoku (Research Office) of the Manchuria Railway Company, a civilian research institute that conducted studies of the Philippines before the war.

Bach’s importance for Philippine cartography lies not only in his long career with the USC&GS and his abilities as a prolific compiler and publisher of maps; he was also a keen researcher and avid collector of maps of the Philippines. In the words of Captain Earle A. Deily of the USC&GS, writing in June 1953:(28)

The late John Bach, who was connected with the cartographic section of the Manila office of the Coast and Geodetic Survey during most of its years of operation, conceived the idea of producing a map history of the island group. He made personal visits to museums, art galleries, and the hydrographic bureaus of various European nations. Through further correspondence with these organizations and with dealers in old maps, he accumulated at his own expense a great number of original prints and photographic reproductions of maps of the Philippines. The bombing of Manila during World War II caused the irreparable loss of this great collection before the dream of an atlas of maps arranged in chronological order could become reality.

The results of Bach’s research had been presented in Vol. 22, No. 124 (July-August, 1930) of The Military Engineer, published by the Society of American Military Engineers. His ninepage article ‘Philippine Maps from the Time of Magellan’ was the first publication on the cartographic history of the Philippines in English. Bach discusses the archipelago’s cartography in some detail, from Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition in 1521 to the work of the USC&GS.

26

In the article Bach discusses many of the most important maps of the Philippines, including those by Pigafetta, Mercator, Ramussio (sic), Legaspi (sic), van Linschoten (attributed to [Jacob Floris van] Langren), Sanson D’Abbeville, Marcos de Orozco / Colin, Romero / Chandia (sic), Pedro Murillo Velarde, William Nichelsen, Robert Carr, the Malaspina expedition, H.K.W. Berghaus (which he attributes to Ildefonso de Aragon), Francisco Coello, and José Algué. He concludes with a descriptive list of ‘the four most popular topographic maps that ministered to the wants of the public during the nineteenth century’, concluding with the following unique manuscript atlas:

Atlas de Filipinas, 1899, compiled by Don Enrique d’Almonte y Muriel.(29) This is a manuscript atlas in the file of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey which has never been reproduced. It contains 23 sheets (each 13 inches by 21 inches), and elicits no little esteem for its map presenting the entire Philippine Archipelago on a scale of 1:800,000. This masterpiece of cartography may be regarded as the climax of maps bequeathed to posterity by the scores of Spanish geographers. From numerous comparisons with the explorations which occurred during the American administration, it has been proven beyond a shadow of doubt that d’Almonte’s atlas and his series of maps of the principal islands eclipsed both in accuracy and completeness all the other topographic maps of the period.

This atlas is listed as one of the sources Bach used for the first (1911) edition of his map of the Philippine Islands. Exactly how it was acquired by the USC&GS is unclear. Carlos Quirino wrote that: “When the Americans occupied Manila on August 13, 1898, they found a manuscript atlas of the country by Enrique d’Almonte y Muriel, a Spanish map-maker who had been occupied with that task for the preceding decade.”(30) However, in his 1905 annual report to the U.S. government George Putnam, the Director of Coast Surveys in Manila, recorded that he went to the United States in March 1904 and returned to Manila in August by way of London and Spain where: “I was fortunate in meeting in Madrid Mr. Enrique d’Almonte, the leading Spanish geographer of the Philippines, and secured from him the remainder of his collection of Philippine maps,

partly in manuscript.”(31) The atlas has now disappeared, presumably destroyed in the wartime bombing of the USC&GS’s premises.

Bach’s article contains images of 15 of the important maps he describes, and the author explains his sources:

The Library of Congress has a remarkable collection of old maps and atlases. There is also an extensive file of old maps in the Manila office of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, most of which were acquired in the early days of the American Occupation, in the course of compiling information for the production of modern charts and maps of the islands. Another source of information is the collection of the late Dr. Trinidad Pardo de Tavera, distinguished Filipino philosopher and authority on Philippine history. The cuts accompanying this article are reproductions from copies in these collections.

Bach also acknowledges that: “Very valuable assistance in the preparation of this article was given by Rev. Father Miguel Selga, Director of the Philippine Weather Bureau,(32) and by Lieutenant Commander L.O. Colbert, Director of Coast Surveys, Manila, P. I.”

In 1894 the renowned physician, historian and politician T.H. Pardo de Tavera (1857-1925) had published a 19-page monograph on the 1734 Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica delas Yslas Filipinas by Fr. Pedro Murillo Velarde,(33) of which he had acquired a facsimile from the Bibliothèque nationale de France when he was living in Paris from 1875 to 1887. In 1934, to commemorate the map’s bicentenary, the National Library of the Philippines (which had acquired his collection) printed a reproduction from this copy, accompanied by a brief explanation of the map and its side panels from Pardo de Tavera’s monograph.

Since this commentary was in Spanish, John Bach produced his own 11-page booklet containing ‘brief notes on Murillo Velarde and his map … to accompany the reprint of this map in 1934’. The booklet, titled Two Maps of the Philippines, Murillo Velarde 1734, John Bach 1934, contained the Murillo Velarde facsimile and the 7th (1934) edition of Bach’s map of the Philippine Islands. The Field Engineers Bulletin No. 8 issued by the USC&GS in December 1934

27

commented that: “Most of us are familiar with Mr. Bach’s excellent map of the Philippines, and this new edition is even more complete than the former ones.” They also wrote that: “In spite of the great improvements in cartography during the 200 years between these two maps, we note that our old friend the carabao hasn’t changed much.”

We have been unable to establish when or where John Bach died. His Commonwealth of the Philippines, ninth edition, was published and copyrighted in 1940, and the Philippine Islands Physical – Economic – Political was republished in 1941. The Manila telephone directory for 1938 lists his address as ‘1022 Penn Avenue’; The Tribune for 24-25 February, 1940 reported that Bach and his wife were living at ‘1054 Pennsylvania’,(34) and by February 1941 the couple appear to have moved again to 1167 Carolina Street, still in Malate.(35)

For most of the pre-war period the offices and plant of the USC&GS were in the Intendencia Building (aka the Aduana or Customs House) in

Intramuros overlooking the Pasig River. But in 1937 ‘Commonwealth officials expropriated the Intendencia Building for the use of a [newly organized] government bureau’ and, although the senior staff remained in their old offices, the USC&GS’s printing presses, equipment and stores were relocated ‘over the most energetic protest of Director Maher’ to the old, twostorey masonry Administrative Building on Engineer Island at the mouth of the Pasig.(36)

Because the Intendencia Building was being used by the Treasury Department and was therefore a primary target, it was bombed by the Japanese on 24-26 December, 1941 and heavily damaged, together with the Santo Domingo church across the street. The building on Engineer Island was also a target of the bombing raids and was flattened; all of the USC&GS’s records, instruments and equipment were completely destroyed. We know Bach’s entire collection of maps was recorded as lost in the bombing of Manila, perhaps in the destruction of either of these buildings if he had left them with the USC&GS.

28

The USC&GS building on Engineer Island in c.1937

The Engineer Island (left) and Intendencia (right) buildings after the bombing in 1941

Although a number of USC&GS employees either died in the air raids in late-December 1941 or became prisoners of war (37) Bach’s name does not appear among them, probably because by then he was no longer an employee. Nor does his name appear in the records of the American cemetery in Manila, or among the internees listed by the Center for Research for Allied POWs Under the Japanese. As there is no record of Bach having returned to the United States, it is therefore quite likely that he was still in Manila when war broke out and he died or was killed there, with his death left unrecorded in the fog of war.

Bach’s fondness for the Philippines is apparent from the opening paragraph of his monograph:

To those who have spent part of their lives in the Philippines, partaken of the bounteous yield of its land, or marveled at the subtle charm of its mystic scenery and the generous

hospitality of its kind people, a good map of those islands will always be of interest. On it they may seek the familiar names of places which they visited, whether in civil or military life, the lakes and rivers that they traversed, and the imposing mountains and volcanoes which they scaled. To one who knows how to read it properly, a faithful map not only revives fond recollections of one’s personal experiences and adventures at the localities indicated thereon, but also reveals an interesting story of the country it illustrates, the distribution of its people, and the successful development of its resources.

Regardless of whether Bach’s death occurred during or after the war, in the Philippines or the United Sates or elsewhere, his legacy survives Today his maps are widely collected and his pioneering work on the history of the cartography of the Philippines has not been forgotten

This article is based on the presentation given to PHIMCOS by the authors on 23 June, 2022. The authors thank Loreto Apilado, Jonathan Best and Beatriz V. Lalana of the Ortigas Foundation; Efren P. Carandang, Deputy Administrator, and his colleagues at the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA); Dr. Ricardo T. Jose of the University of the Philippines; Rudolf J.H. Lietz and the Gallery of Prints, Manila; Raphael P.M. Lotilla; Michael G. Price; Richard Wilhelm Ragodon of the National Archives of the Philippines; and Alfredo Roca for the information and images they provided for the presentation and this article. Unless otherwise stated, images are of items in the authors’ collections.

Notes & references

1. John Bach had no middle name, which is not uncommon in Norway.

2. The United States Survey of the Coast was created within the U.S. Department of the Treasury by an Act of Congress in 1807. Renamed the United States Coast Survey in 1836 and the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey in 1878, the agency opened a field office in Seattle, Washington in 1899 and, in 1900, its sub-office in Manila.

3. The primary source of biographical information on John Bach is Who’s Who in the U.S. Coast & Geodetic Survey, published in December 1931.

4. Reports of the Bureau of Coast and Geodetic Survey, Manila, included in the Fifth / Sixth / Seventh / Eighth Annual Report of the Philippine Commission, 1904 / 1905 / 1906 / 1907, Part 3, Bureau of Insular Affairs, War Department, Washington D.C., 1905 / 1906 / 1907 / 1908 respectively.

5. Raul A. de Leon, Islands on Paper ‒ A Brief History of the Bureau of Coast and Geodetic Survey 1900-1978, Ministry of National Defense, Manila, 1980.

6. Official Register of the United States 1917, Directory, Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Washington D.C., 1918.

7. Ole O. Tweeth was a fellow Norwegian-American, whose surname may have been an Anglicised form of the Norwegian name Tveit. He lived in the Philippines for a number of years, where he was appointed in October, 1903 as an Inspector in the Bureau of Public Works, Provincial Division. Tweeth returned to the United States in c.1914, and died in Portland, Oregon in 1919.

29

8. The H. Otley Beyer map collection in the National Library of Australia holds a printed draft of the map before the table of distances was added, with manuscript names, locations and routes between the island ports marked in red ink The Harvard Library holds a version of the map printed in black and brown, without the tables printed in red

9. Carmelo & Bauermann, a major publishing house, was co-founded in Manila in 1887 by the artistengraver Eulalio Carmelo y Lacandola and Wilhelm Bauermann, a German lithographer and cartographer who was working for the Bureau of Forestry. Don Eulalio died in 1906 and the business was later headed by his son Alfredo Carmelo, a famous Filipino aviator, until 1938.

10. For the ninth edition the titled was changed to Commonwealth of the Philippines to reflect the creation of the Commonwealth in 1935.

11. Copies of the map are held in the National Archives of the Philippines and at the Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. In 1912 Ferdinand H. Jaeger is listed in the Official Roster of Officers and Employees in the Civil Service of the Philippine Islands as a Draftsman-cartographer at the Bureau of Coast and Geodetic Survey; Rosenstock's Manila City Directory 1917 lists him as Chief of the Geographical Division.

12. Sibul Springs in San Miguel, Bulacan was at one time regarded as the ‘Summer Capital of Central Luzon’.

13. Roy E. Dickerson, ‘Tertiary Paleogeography of the Philippines’, in The Philippine Journal of Science, Vol. 25, No. 1, Bureau of Science, Manila, 1924; an isobath is a line on a map or chart that connects all points having the same depth below a surface of water such as the sea.

14. Dr. Hugo Herman Miller (1883-1944) was ‘head of the department of industrial information in the Manila Bureau of Education’, and co-author with Charles H. Storms of Economic conditions in the Philippines (Ginn & Co., Boston, 1913).

15. A sugar central, located near the centre of a sugarcane-growing district, is where sugar is processed. Most sugar centrals consist of a sugar mill, where the juice is pressed out of the sugarcane and concentrated, and a refinery where the raw sugar is purified; some also have additional plant such as a distillery.

16. The 1907 Map of the Philippine Islands with O.O. Tweeth; the 1913 City of Manila with F.H. Jaeger; and the 1937 Philippine Islands Physical – Economic – Political with Hugo Miller.

17. The 1932 Manila and Suburbs, the seventh (1934) edition of the Philippine Islands, and the 1935 Manila.

18. Bach’s visit to the United States is recorded in the monthly issues of the Coast and Geodetic Survey Bulletin for April and October, 1927 and March, 1928.

19. Raul A. de Leon, op cit.

20. The first American Masonic lodge in the Philippines (Manila Lodge No. 342) was constituted in 1901; in 1912 the three lodges in the Philippines under the jurisdiction of the Grand Lodge of California amalgamated to form the Grand Lodge of the Philippines, with the first renumbered as Manila Lodge No. 1

21. The Tribune of 14 January, 1936 lists ‘Miss Frances L. Bach’ as one of the passengers on the American mail liner President Jefferson when it docked in Manila from Seattle.

22. ‘The Bureau Of Coast And Geodetic Survey ‒ Its Work In The Philippine Islands’, in Graphic, Manila, February 4, 1931. Photographs of Bach were also published in The Tribune ‒ one of a despedida luncheon for General Creed C. Hammond (24 June, 1933), and another of a dinner in honour of Antonio G. Perez being appointed Assistant Director of Coast Surveys (3 March, 1938) ‒ but the images are not clear.

23. ‘The Philippine Crater Lake’, in Philippine Touring Topics, Manila, February 1935.

24. Section 204 of the Economy Act of June 30, 1932.

25. Raul A. de Leon, op cit.

26. Cornejo’s Commonwealth Directory of the Philippines, 1939 Encyclopedic Edition, compiled and edited by Miguel R. Cornejo, Manila, 1939.

27. Lloyd S. Millegan, Library of Congress, ‘Census of the Philippines: 1939’, in The Far Eastern Quarterly, Vol. II, No. 1, The Far Eastern Association, Inc., New York, November, 1942.

30

28. Captain Earle A. Deily, ‘Maps of the Philippine Islands’, in The Journal – Coast and Geodetic Survey, Number 5, Department of Commerce, Washington D.C., June 1953. Lieutenant Deily arrived in Manila in March 1937.

29. Enrique d'Almonte y Muriel (1858-1917) worked in the Philippines for the Inspección General de Minas de Filipinas from 1880 to 1899; see Raphael P.M. Lotilla, ‘Enrique Abella y Casariego’s Isla de Panay –Bosquejo Geologico’, in The Murillo Bulletin, Issue No. 11, PHIMCOS, Manila, May 2021.

30. Carlos Quirino, Philippine Cartography 1320-1899, 2nd revised edition, N. Israel, Amsterdam, 1963; Fourth Edition, edited by Dr. Carlos Madrid, Vibal Foundation, Quezon City, 2018.

31. G.R. Putnam, ‘Report on the Work of the Coast and Geodetic Survey’, in the Sixth Annual Report of the Philippine Commission 1905, Bureau of Insular Affairs, War Department, Washington D.C., 1906.

32. Fr. Miguel Selga, S.J. was the author of ‘Los mapas de Filipinas por el P. Pedro Murillo Velarde, S.J.’, in Publications of the Manila Observatory, Vol. II, Issue 4, Bureau of Printing, Manila, 1934.

33. T.H. Pardo de Tavera, El Mapa de Filipinas del P. Murillo Velarde, Tipo-Litografía de Chofré y Comp., Manila, 1894.

34. After the war, Calle Pennsylvania in Malate was renamed León Guinto Street. The Tribune reported that on 23 February, 1940, the Bachs were burgled and ‘jewels, insurance policies, valuable documents and other articles with a total value of ₱2,355’ taken; part of the loot, ‘jewels worth about ₱800’, was recovered the next day ‘from a crevice near the Bach residence’.

35. C.W. Rosenstock, Manila City Directory, Volume 46, Manila, 1941.

36. Raul A. de Leon, op cit

37. Raul A. de Leon, op cit, and official USC&GS reports.

WATTIS FINE ART Est. 1988 Specialist Antique & Art Dealers

www.wattis.com.hk

Antique maps, prints, photographs, postcards, paintings & books

31

Philippinae Insulae by Jodocus Hondius Junior from P. Bertii Tabularum geographicarum contractarum, Amsterdam 1616

The Jinrikisha Puller Is There

by Felice Noelle Rodriguez

THE NAME ‘rickshaw’ originates from the Japanese word jinrikisha (人力車), where 人 jin = human, 力 riki = power or force, and 車 sha = vehicle, literally meaning ‘human-powered vehicle’.

Only a few older folk can identify the place pictured in the postcard opposite as Zamboanga in Mindanao. In the background is the Roman Catholic Church, bombed during World War II. In the forefront is a jinrikisha, a two-wheeled cart usually for one, pulled by an Asian man described as a ‘Moro Coolie’, barefoot, wearing loose shorts, a simple plain shirt and a turban. The passenger is a white man dressed in a white suit with a boater hat who we can presume is American as the postcard hails from the U.S. colonial period (1898-1946).

The church, jinrikisha, white man and Asian puller are all gone now. The stories of those who pulled these foreign contraptions are not mentioned in Philippine history books and are all forgotten. Many may even be surprised that these wretched laborers even existed. The story of the rickshaw ‒ to use the term popularized by the Americans instead of the more officious and original jinrikisha ‒ in Zamboanga reminds us of how life there was quite different from in the capital, Manila.

During the Spanish-American War the United States had arrived to wrest control of the Philippines. Following the one-sided Battle of Manila Bay on May 1, 1898, Spain surrendered to America. Although Manila had been under siege by Filipino revolutionaries and, on June 12, 1898, the Philippines proclaimed its independence from Spain, neither Spain nor the U.S. acknowledged the Filipino Government led by President Emilio Aguinaldo. Under the 1898 Treaty of Paris the U.S. purchased the Philippines and other territories from Spain for US$ 20 million, and American rule began. The Filipinos continued in their struggle with the new enemy, but in 1901 the capture of Aguinaldo marked the end of the Philippine Revolution and the start of U.S. colonial rule.

It was in the following year, 1902, that American businessman Carlos S. Rivers proposed the introduction of rickshaws to Manila, a move welcomed particularly by American officials who felt the need for easier transportation from home to work. Rivers proposed the importation of several hundred of the vehicles and 1000 Japanese pullers; in those days, Japan was a source of cheap migrant labor. However, in response to the request by the Luzon Jinrikisha Company, on March 21, 1902 Collector of Customs W. Morgan Shuster ruled that the importation of Japanese pullers was against the law. The law cited was the 1885 Alien Contract Labor Law, an act ‘to prohibit the importation and migration of foreigners and aliens under contract or agreement to perform labor in the United States, its Territories, and the District of Columbia’.(1)

The rickshaws were also met with protests from local Filipinos. Historian Michael D. Pante has written about the Manila rickshaw controversy, explaining how protests came in from the cocheros (drivers of horse-drawn carriages) who banded together as a section of the Unión Obrera Democrática Filipina, the first Philippine labor federation. They came out with a statement claiming ‘Los Filipinos no son brutos’ (Filipinos are not beasts).(2) Filipino protesters were against the rickshaws for fear of becoming ‘slaves of foreigners’ if they agreed to be pullers. Despite already being colonized, the union drew a distinction (however arbitrary) between being conquered and becoming slaves; to be pulling a white man, sweat running off the Filipino back under an oppressive sun, crossed this line. Of course, there were also economic incentives as the jinrikishas would present a cheaper alternative to the horse-drawn carriages.

Despite the protests, the company started operations on May 24, 1902 but with only 20 of the 300 rickshaws stored at the company’s godown, and with Chinese coolies employed as pullers. Pante continues that ‘on the second day, no puller reported for work, and the following day, only one did so’, the absence of

32

‘Rickshaw and Moro Coolie, Zamboanga, Mindanao, Philippines’ (from the author’s collection)

the coolies being ‘due to pressure from the Manila Chinese community [many of them from the merchant class] which felt humiliated by their compatriots who chose to be pullers’.(3) In the end, the rickshaw business failed to take off in Manila.

Down south, however, a different tale unfolded. Unlike other Asian cities such as Singapore (4) and Hong Kong, which used Chinese coolies, in Zamboanga ‘Moros’ or ‘pagans’ were employed as pullers

Under the new American colonial rule that had come to Zamboanga in 1899, Moros and pagans belonged to the newly-created Bureau of NonChristian Tribes. The ‘non-Christianized’ usually referred to those that had lesser contact with earlier Spanish colonials, including ethnic groups in the northern part of the Philippines, the unhispanized indigenous groups (pagans), and those that practiced Islam in Mindanao (Moros). The wide umbrella term ‘Moros’ included the Bajau or Samal Balangingi, Tausug, Magindanao, Maranao, Kalibugan and Yakan people. Considered ‘uncivilized’, they were segregated from the civil government. This Bureau was tasked with the making of ‘systematic investigations with reference to the nonChristian tribes of the Philippine Islands with special view to determining the most practicable means for bringing about their advancement in civilization and material prosperity’.(5)

It was through the patronizing colonial lens of the ‘White Man’s Burden’ (6) that Major John P. Finley, Governor of the District of Zamboanga, Moro Province, wrote his article on ‘Race and Development by Industrial Means among the Moros and Pagans of the Southern Philippines’, in which he juxtaposes the reception of the jinrikishas in Zamboanga and in Manila:

Industrial coöperation led to the introduction and successful operation of jinrickishaws [sic] by Moros and Pagans at Zamboanga in 1906. The use of such carriages in Manila where 500 were introduced in 1905 had been found to be practically impossible, and much of the property was destroyed by rioting Filipinos, who were enraged against the Chinese for pulling the carts, and competing with their native ponies in hauling the quilez and carromato (7) The Filipinos also pretended to resent the proposition of the American and Spanish owners that they should be employed as horses in pulling Japanese carriages. Thereupon the Moro Exchange at Zamboanga took up the jinrickishaw question with the Moros and Pagans who, after a full presentation of the matter, including the failure in Manila and its causes, deliberately agreed to operate such carriages in the capital of the Moro Province. The Filipinos made strenuous efforts to dissuade the non-Christians from operating the Japanese carts, but all to no purpose, and Zamboanga remains today the only city in the Philippine Islands where jinrickishaws are operated.(8)

33

In his colonial treatise offering an explanation of the ‘backwardness’ of the natives and prescribing policy suggestions, Finley dismissed the Manila union’s protests against ‘becoming beasts’ as mere excuses to stave off competition. We can only surmise the reason why the Moros and pagans in Zamboanga agreed to become pullers, but we can speculate that the experience and issues of the Moro in Mindanao were different from those of the Filipinos in Manila.

As the city is situated at the tip of the peninsula, with almost all settlements located along the coastal areas, traveling from one place in Zamboanga to another was usually by boat ‒the banca or the prahu. Travelers would pay to be brought from one coastal town to another. The boats were rowed, using manpower. With the population rising during the American colonial period there was a need for transportation to go around the town. What is the difference between using one’s arms to row a boat to that of pulling a carriage? Possibly, for the Moro, they did not look at the work of a puller as demeaning. The act of pulling a rickshaw could have been no different from paddling a boat to take passengers from one place to another.

Five years later, in 1911, the first Moro Province Fair was held in Zamboanga. According to the Annual Report of the Governor of the Moro Province for the Year ending June 30, 1911: “Representative delegations from all the different districts and tribes peaceably assembled together for friendly intercourse.” For eight days, from February 7 to 14, various activities were lined up for the more than 20,000 visitors from different ethnic groups, categorized by the Americans as ‘Moros’ and ‘Pagans’ as well as the (Christian) ‘Filipinos’. Industrial exhibits and agricultural products were on display and exchanged.

Interestingly, among the different activities in the program, aside from the speeches, parades, dances and sports contests were also races. On February 14 there were exciting contests of speed galore: races by goat-cart, pony, carabao, and bicycle, a three-legged race, a sack race for children, and others. Topping the list was the jinrikisha race! Unfortunately, we do not have photographs of the race, but we can imagine the sight of lean but muscular coolies, sprinting at full speed with all their upper body strength to carry the carriage, and leg muscles to pull it to the finish line.

The printed program for this 1911 Moro Province Fair listed its different attractions. To get around, one could avail of the jinrikishas for 30 centavos per hour. They were the cheapest means of public transportation, compared to automobiles at five to eight pesos an hour, Victorias for three pesos an hour, calesas for one peso an hour, or bicycles for 40 centavos an hour.(9)

Five years later, in 1916, there was another printed program, this time for the East Visayan Athletic Meet. The price of hiring a rickshaw had gone up to 40 centavos for the first hour with 30 centavos for every succeeding hour. From these fairs, we can judge that the Zamboanga rickshaws had become a cheap alternative form of transport as well as a cultural attraction ‒defying the curse of the Manila rickshaws.

A photograph in the collection of Glenn Whitman Caulkins, a former U S Education Superintendent for Mindanao and Sulu, is labeled as the Government Building. Built in 1906 as the central seat of power for the Moro

34

Program of the 1911 Moro Province Fair (from the collection of Michael G. Price)

Province, the building is barely visible behind the large tree in front of it. Not labeled, but clearly visible under the shade of the tree, parked rickshaws with their pullers are standing by, waiting there to serve the needs of notables or for passengers from nearby establishments. The attraction is the Provincial Building, the seat of power, but the rickshaw pullers are there too, unacknowledged and undeserving of mention.

In one of her letters to her family back home Mertie Beard Heath, a young bride who had joined her husband assigned to Zamboanga as an adjutant in the American army, wrote of her experience riding a rickshaw in 1910:

Had a brand new experience going down to the dock. I rode in a rickshaw, with a Moro between the shafts. They are plenty in Zambo town, rickshaws I mean, but I had never ridden in one before. It wasn’t bad, Charlie told him to go ‘poco tempo’ and it was only about four blocks from home, so I didn’t feel sorry for him. They trot along usually though, at a good round pace.(10)

Mertie used the abbreviation ‘rickshaw,’ and describes the puller as a ‘Moro’, indicating that the rickshaw pullers were not Chinese, unlike elsewhere in Southeast Asia. And yet, she felt a certain guilt, hastily professing empathy: ‘it was only four blocks so I didn’t feel sorry for him’. She felt she had to explain to the readers of her letter, who might have disapproved of her riding in the carriage as the puller was not a beast, but human. The language Charlie used to instruct the puller was probably Chavacano, poco tempo meaning ‘go slow’ in Chavacano rather than the Spanish ‘little time’ which would otherwise be understood as ‘go quickly’.

Unfortunately, aside from these documents, we have no records of the names of the pullers, or what their lives were like. Where did the rickshaws come from? Who imported them to Zamboanga? If this occupation was reserved for ‘Moros and pagans’, why was this so? Who were the pullers: the Samal Balangingi or the Bajau who lived by the coasts of Zamboanga, or were they possibly from the village of Magay? Or did they migrate to Zamboanga from nearby areas like Basilan or Sulu? What were the working arrangements with the pullers and their terms of pay? I have not been able to find any documents suggesting why the use of rickshaws fell into disuse. When and why did it stop?

I am afraid the photos and documents we have leave us with more questions than answers. But it is important to ask these questions as they remind us of how little we know about the lives of the ordinary people who formed part of the fabric of society in Zamboanga and the Philippines at the time. As with the photo of the Provincial Building, the jinrikisha pullers are still there. They may remain unlabeled, unnamed, and unacknowledged, but they are there.

This article is an edited version of the author’s article first published on 25 September, 2020 by ‘O For Other’, a collective blogging project by the Malaysia Design Archive & Visual Art Programme, University of Malaya, that explores histories, narratives and cultures that might say something different about the world.

35

‘Government Building, Zamboanga, Mindanao, P.I.’ (from the collection of Glenn Whitman Caulkins; image courtesy of Brenda Hall and Erwin Tiongson)

Sources and notes

1. Elihu Root, [Collection of United States documents relating to the Philippine Islands], Government Printing Office, Washington D.C., 1898-1906.

2. Michael D. Pante, ‘Rickshaws and Filipinos: Transnational Meanings of Technology and Labor in AmericanOccupied Manila’, in International Review of Social History, Vol. 59, Cambridge University Press, 2014.

3. Pante op cit.

4. James Francis Warren, Rickshaw Coolie: A People’s History of Singapore 1880-1940, Singapore University Press, National University of Singapore, 2003.

5. An Act Creating a Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes for the Philippine Islands [Act No. 253], enacted by the United States Philippine Commission, October 2, 1901.

6. ‘The White Man’s Burden’ is a poem by Rudyard Kipling, published in 1899, in which he encourages the United States to colonize the Philippines and ‘civilize’ the people.

7. The quilez was a two-wheeled, four-seater carriage pulled by one horse, and the carromata was a twowheeled spring vehicle with a light roof for one passenger, pulled by a pony; see Michael D. Pante, ‘The Cocheros of American-occupied Manila Representations and Persistence’, in Philippine Studies: Historical & Ethnographic Viewpoints, Vol. 60, No. 4, Ateneo de Manila University, 2012.

8. John P. Finley, ‘Race Development by Industrial Means among the Moros and Pagans of the Southern Philippines’, in The Journal of Race Development, Vol. 3, No. 3, Clark University, Worcester, Mass., 1913.

9. A Victoria was an elegant, four-wheeled open carriage drawn by one or two horses, and a calesa was a two-wheeled carriage with a canopy, drawn by a single horse, that can accommodate two passengers.

10. Mertie Beard Heath, Mertie and Charlie: Selected Correspondence of Mertie Beard Heath An Army Wife in the Philippines 1910-1912, compiled by Jessie S. Heath, Trafford Publishing, Victoria B.C., 2005.

36

Discovery and Appreciation: The First Studies Dedicated to Pedro Murillo Velarde’s 1734 Map of the Philippines

by Agustín Hernando

ANYONE interested in delving into the treasured cartographic heritage of the Philippines is fascinated by the monumental Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica delas Yslas Filipinas published by the Jesuit P. Pedro Murillo Velarde in 1734. An eloquent proof of the attention given to this map is the title of the magazine in which this article is being published, further exemplified by the prominence the map has been given in recent exhibitions.(1) Given the depth of feeling it provokes, the curious will ask how the merits of the map were initially enumerated, and by whom its importance was first publicised. In the paragraphs that follow I will try to provide answers to these questions.

I would like to say that this brief essay emerges from a study dedicated to exploring the genesis of an awakened sensitivity to maps of the past in Catalonia, and to finding inputs that reveal an early investigative manifestation in Barcelona. The article is dedicated to showing the contribution of the Jesuits to cartography within the context of the cultural work carried out by members of their Order. A clear reference to the existence and qualities of the Murillo Velarde map, with a brief portrait of its author, is the oldest citation about the map we have found in Spain outside earlier Jesuit circles, by an author interested in unveiling and contributing a page to the history of cartography.

In investigating the subject I have found three worthy studies that give this map and its author notoriety and visibility. Published successively in the Philippines, France and Spain, these were the first contributions to the subject in each country. The authors had diverse profiles: a scholar interested in the history of the Philippines, an academic specialised in historical Spanish cartography and, as we shall see, an author about whose profile and the motivations that encouraged him to deal with this topic we lack significant information beyond his status as a Jesuit and the documentary rigor and soundness of his work.

The historiographic hatching of interest in the Murillo Velarde map took place at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, during the decades in which a curious public was encouraged to learn about the past of the Philippines and the history of cartography ‒ a discourse affected by the conventional colonial and nationalist concerns of the moment, and which sought arguments in cartography to forge some hallmarks of national identity. The views expressed are valuable and worth reading because of their chosen perspective, the data they provide, and the clarity and enthusiasm of their narration. Filled with great erudition and published after arduous research work given the precarious methodological conditions in which they were born, these accounts reflect the cultural and social conditions of the times.

The beginnings of a cultural revolution

The first work on the Murillo Velarde map we know of was published in the Philippines in 1894 by Dr. T.H. Pardo de Tavera (1857-1925) with the eloquent title El mapa de Filipinas del P. Murillo Velarde (2) This short, entertaining, scholarly and well-documented study shows the liking for maps of the Philippines professed by its author, who formed a splendid cartographic collection. Its publication took place after this doctor, journalist, politician and member of diverse cultural institutions had returned to Manila after a formative stage when he lived in Paris.

It can be assumed that it was in this city that he forged his fondness for cartographic images of the Philippines and discovered the map which he describes, with excessive prudence, as ‘a curious document’. As he explains, for his monograph he consulted the holdings of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) as well as those of the British Library, encouraged by his determination to know and examine maps pertaining to his country. It is worth remembering that, in order to provide authority and

37

Dr. Trinidad Pardo de Tavera

credibility to his story, he alludes to his possession of some cartographic specimens of interest that he had acquired, as well as his annoyance at not having been able to obtain one recently put on the market as it had already been sold ‒ an unpleasant experience we have all suffered. The fate of his patrimonial legacy is not known, but according to Carlos Quirino,(3) Pardo de Tavera’s collection consisted of about 40 items that went to the National Library of the Philippines but were destroyed during the Battle of Manila in 1945.

To make the importance of this cartographic jewel known to people interested in Philippine studies, Pardo de Tavera describes a copy of the wall map in the BnF as he believed that no copies were kept in the Philippines. The pleasant impression caused by its abundant and precise geographical information led him to be interested in the life of its author. He provides the reader with a brief profile of Murillo Velarde, whom he describes as an entendido geógrafo (expert geographer), and lists some of his works including the Geographia Historica in ten volumes which he describes as an obra apreciada (cherished work).(4)

One of the possibilities that he considers is that the map had been largely completed by the time Murillo Velarde received the commission from Governor-General Valdés Tamón (at the direction of the Spanish court) ordering its publication, since ‘otherwise, he could not have

completed it in such a perfect manner in such a short time’ But he considers this did not diminish its value or the meritorious role played by Murillo Velarde leading to the availability today of this 18th-century image of the Philippines. As I have pointed out, Pardo de Tavera’s praise stems from his amazement at the precision and richness of information the map exhibits, and his conclusion that it was the 'prime map of the Philippines', an assessment that would be taken into account and shared by other scholars. Logically, he considers such attributes in previously-published maps, notably those in books by P. Francisco Colin S.J. in 1659 (5) and by P. Andrés Serrano S.J. in 1707 (6)

His zealous interest lies in the wealth of valuable information the map reveals, pointing out its trove of data about the islands, provinces, boundaries, locations etc. He pays attention to the ornamental attributes of this 'beautiful work' with its splendid title cartouche adorned with two allegorical figures of Navigation and Astronomy. And he reproduces the information inserted in the medallion that appears in the lower part of the map (that served as inspiration for the design of the cartouche in its second edition) with its chronicle of the discovery of the Philippines and the enumeration of its riches, monasteries, inhabitants, and their activities. In short, some renglónes de lo más memorable (most memorable lines) from the past.

38

Carta

He also notes the charming display of boats and ships that dot the seas, including a depiction of the Victoria and the route followed by Ferdinand Magellan, as well as the course followed by the Manila galleon. Because of its design and harmonious composition, imbibed with good taste, he considers the map as an artistic work, rubricated by the care and expertise put into its engraving. However, the copy studied by Pardo de Tavera did not have the side panels with their elaborate vignettes, although the BnF did in fact have a complete copy in its collection.

As well as comparing the new map with those published earlier by P. Colin and P. Serrano, he also deals with those published by the later epigones who disseminated Murillo Velarde’s

new image of the Philippines. He cites the second edition, dated 1744 and published by Murillo Velarde in Manila in 1749, with changes introduced in its cartouche and ornamentation, commenting on the significance of the produce and people immortalised in the border that embellishes the title. He also dwells on the figure of San Francis Xavier, to whom he grants the title of 'prince of the sea'. And as the geographer who illuminates and propagates this novel image of the Philippines throughout Europe, clearly inspired by Murillo Velarde's, he cites the written memoire by Jacques-Nicolas Bellin in which the author dissects and ponders the instructive qualities of his source.(7) He also references the copy [by Georg Mauritz Lowitz] published in Germany by the Heirs of Homann.(8)

39

Hydrographica y Chorographica delas Yslas Filipinas by P. Pedro Murillo Velarde (1734) (image courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France ‒ ark:/12148/btv1b5963240f)

Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica delas Yslas Filipinas by P. Pedro Murillo Velarde (1734) (image courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France ‒ ark:/12148/btv1b53066953z)

40

Beyond underlining the map’s eloquent attributes and aesthetic charm, Pardo de Tavera invites the audience to pay attention to the details of this jewel of Philippine cultural heritage and discover the cartographic legacy of the archipelago. Having assembled an appreciable cartographic collection during his stay in Europe, he states that he would like to continue his study of other maps of the Philippines with the invaluable assistance of a good library. His erudite narration is illustrated by an image of the map’s title cartouche showing the ornamental charms of its design. As he affirms, the map is an aplauso tributado a la obra del misionero (acclaimed tribute to the work of the missionary) and the starting point for the appreciation evoked by this monumental and decorative work.

Documenting the vignettes in the side panels

Director of the Département des Cartes et Plans at the BnF between 1881 and 1908, Gabriel Marcel (1843-1909) would have met Pardo de Tavera on his frequent visits to the library and shared his interests. The latter's passionate search for documentary images of the Philippines probably aroused Marcel’s interest in the Murillo Velarde map and encouraged him to write his essay when he discovered the complete copies that Pardo de Tavera did not have the fortune to examine. Today, the BnF has two copies of the 1734 Murillo Velarde map: one complete with the 12 vignettes attached to its flanks,(9) the other without the side panels attached although these prints, fresh from the press, are held in an annex.(10) It was the impression caused by this find, considerably enriching the known merits of the map, that prompted Marcel to write his study and introduce the map to the French public.(11)