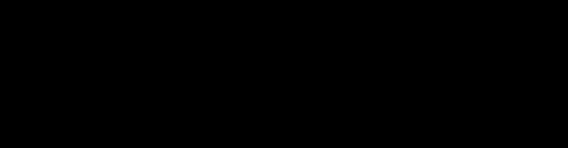

MY BODY & A BROKEN

EDITORS-IN-CHIEF

C Icart and Michelle Young eic@the-peak.ca

COPY EDITOR

Michelle Young copy@the-peak.ca

FACT CHECKER

Karly Burns factchecker@the-peak.ca

NEWS EDITOR Hannah Fraser news@the-peak.ca

NEWS WRITERS Corbett Gildersleve and Lucaiah Smith-Miodownik

OPINIONS EDITOR Zainab Salam opinions@the-peak.ca

FEATURES EDITOR Daniel Salcedo Rubio features@the-peak.ca

ARTS & CULTURE EDITOR

Phone Min Thant arts@the-peak.ca

HUMOUR EDITOR Mason Mattu humour@the-peak.ca

STAFF WRITERS Noeka Nimmervoll, Ashima Shukla, and Yildiz Subuk

WEB MANAGER Subaig Bindra web@the-peak.ca

The Peak MBC2900 8888 university Dr. Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6

PROMOTIONS MANAGER

Juliana Manalo promotions@the-peak.ca

PROMOTIONS ASSISTANT

Petra Chase

PRODUCTION & DESIGN EDITOR Abbey Perley production@the-peak.ca

ASSISTANT PRODUCTION EDITORS Mary Gigiberia and Minh Duc Ngo

PHOTO EDITOR Gudrun Wai-Gunnarsson photos@the-peak.ca

BUSINESS MANAGER

Yuri Zhou business@the-peak.ca (778) 782-3598

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Juliana Manalo, Liam McKay-Argyriou, Yildiz Subuk, Olive Visser, and Yuri Zhou

PEAK ASSOCIATES Sonya Janeshewski, Victoria Lo, Yan Ting Leung, and Katie Walkley

COVER ARTWORK Sonya Janeshewski

Follow us on Instagram, at @thepeakatsfu and check out our YouTube channel, The Peak (SFU).

READ THE PEAK Pick up paper copies at any SFU campus Find extended, cited, and web-accessible articles at the-peak.ca Download digital issues at issuu.com/peaksfu

The Peak is SFU's weekly student newspaper published every Monday, by students, for students. We’re funded by a student levy and governed by a Board of Directors. Any SFU student can apply to become staff.

We reserve the right to edit submissions for length, as well as style, grammar, and legality. We also reserve the right to reprint submissions at any time, both in print and on web. We will not publish content that is sexist, racist, or otherwise prejudiced.

TSSU speaks on latest updates to IP policy

Inclusion, not consultation, is what TSSU expects for a policy affecting its members

CORBETT GILDERSLEVE · NEWS WRITER

As recently reported by The Peak, the Senate reviewed and discussed a new draft version of its intellectual property (IP) policy solely focused on the commercialization of inventions and software. Based on community feedback, they split the IP policy into two: one for inventions and software, and the other for educational material and general IP issues. The Peak spoke with Ciaran Irwin, Teaching Support Staff Union (TSSU) trustee, and Derek Sahota, TSSU member representative, to learn about their thoughts on the latest updates.

Sahota said they met with Dugan O’Neil, SFU vice president research and innovation, and Kamaldeep Singh Sembi, director of technology licensing and IP legal counsel, to relay their concerns. Irwin said, “It’s nice to see that a lot of the concerns that we raised in the last policy/previous proposal have been addressed,” but “we still have issues not just with some of the aspects of this new policy, but in the process that they’re embarking on.”

When asked about their specific concerns, Irwin said that given TSSU wasn’t invited to be more involved, and with “glaring issues” like ambiguous language in the policy back in March, SFU scrapped that draft, which he deemed a “large waste of time and resources.” He added that SFU has now reworked the language in their policy and “explicitly addressed some of the issues around ownership.”

SFU told The Peak that the current timeline is for the policy to be approved by the Board of Governors on September 25. However, Irwin said “it’s hard to feel confident that all the I’s are being dotted and all the T’s are crossed.”

One of the “fundamental problems with this new model is that it silos things. It tries to put software and innovation in one bucket with one policy, and then everything else aside,” said Sahota. However, “in an interdisciplinary university, in a university with emerging technologies like generative AI, these things are connected — not in all cases, but in some,” he continued.

The newest draft also recognizes that the collective agreements for TSSU and the SFU Faculty Association (SFUFA) apply, each with their own IP policies. Sahota explained that when faculty, graduate students, and staff conduct research, they need to navigate two separate IP policies and collective agreements when they have an invention. Now, when someone wants to license their invention, they’ll need to understand which policy it falls under — the SFUFA or TSSU collective agreements, the IP policy for inventions and software, or the upcoming IP policy for teaching materials that is yet to be developed. Sahota said it “is really unclear how that would play out on the ground.” He stressed these problems “need to be laid out before anything goes before the Board, because the Board needs to know what they’re actually implementing.

Corporate cuts for the Vancouver Pride Parade

Michael Robach, QMUNITY, explains why companies are pulling back PRIDE AND PAPER

LUCAIAH SMITH-MIODOWNIK · NEWS WRITER

This August, the Vancouver Pride Parade will look a little different. The event, hosted annually by Vancouver Pride Society, recently lost half of its corporate sponsorships for this year’s celebration. Companies like Lululemon and Walmart have withdrawn. The Peak spoke with Michael Robach, director of development at the non-profit QMUNITY, for more information.

QMUNITY was founded as “a community center for queer, trans, and Two-Spirit people to access low-barrier frontline mental health and social services, and that’s what we continue to do today,” he said. The initiative also “delivers programming all across BC,” and marches in different Pride events around the province.

“We’re one of the oldest LGBTQ organizations in Canada, and so by virtue of that, we’ve always been very involved in the Pride movement and Pride advocacy, ensuring equal and basic human rights for queer and trans folk,” Robach added.

QMUNITY has been involved in the Vancouver Pride scene for decades, helping to facilitate the original Vancouver Pride Parade, which Robach described as a protest, around 50 years ago. Fast forward to 2025, and the organization still plays a significant role in the August celebration. “Most recently, we entered into a partnership with the Vancouver Pride Society and the West End Business Improvement Association to really ensure and secure Pride this year,” he said, speaking to the recent loss of corporate sponsorships.

Like Vancouver Pride Society, Robach shared that QMUNITY also recently lost four sponsors for an annual breakfast the organization hosts. These groups were partners “for almost 17 years in a row.”

As to why companies may be shying away from involvement, over the last “year and a half, there’s been a very transphobic and homophobic rhetoric that has been permeating all across North America, particularly outside of larger cities, and we see this in the cases that come through our door, we see this in the news,” he said.

This built up tension and this overpoliticization of gender, and trans people, and trans bodies, and trans kids has sort of really been the driving force behind shifts in attitude.

MICHAEL ROBACH DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT, QMUNITY

Robach believes that large amounts of anger and frustration towards the government “on the more conservative side of the conversation” were heaped onto the trans community, and have been rising steadily. “This built up tension and this overpoliticization of gender, and trans people, and trans bodies, and trans kids has sort of really been the driving force behind shifts in attitude.”

When asked about the policy process, Sahota said they asked SFU not for consultation, but for inclusion in a policy affecting TSSU’s members. “We should be the ones that are talked to first before [they] consider any changes, and be included from day one in the thought process and development of what might be a policy change.”

Irwin added, “You’ve got experts here, you have stakeholders at your fingertips [ . . . ] and to not leverage that resource and to not engage these folks early in the process makes no sense to me.”

SFU pointed to the Policy on Policies within Board of Governors Jurisdiction and Associated Procedure as support for “policy developers and all members of the university community in streamlining the policy-making process while promoting consistency and coherence across the university.” They also acknowledged, “Outside the formal policy process, we recognize that informal discussions at early stages of policy planning could be helpful for some policies. We plan to keep that in mind as we plan our policy revisions in the future.”

Robach also noted that in precarious financial times, businesses tend to cut down on their philanthropy and social investments.

Returning to the topic of funding for the Pride Parade, Robach considered what it meant to need to rely on large corporations in the first place. He spoke to pinkwashing, when groups or organizations support 2SLGBTQIA+ initiatives as a way to distract from harm or wrongdoing. “We should always hold conversations and be critical about understanding the ways that funding structures work and operate,” he said.

Still, QMUNITY’s services are “so important to people’s livelihoods and sense of self, and ultimately in order for that to happen and for spaces like those to exist,” and the organization depends on the “funding structures that are in place to support it.”

PHOTO: VICTORIA LO / THE PEAK

PHOTO: DERICK MCKINNEY / UNSPLASH

Resolving that issue with an operation wasn’t the end of my problem. Only eight months later, compounding issues began to occur with my kidney. One thing led to another, and I went from being a healthy-bodied individual to a chronically ill person. When I started to seek support from SFU, I found myself navigating a system that was fragmented, inconsistent, and ultimately unfit to address illness. By the time I accepted my new reality, it was too late to apply to receive accommodations from the Centre for Accessible Learning (CAL). There was no immediate, alternative institutional pathway. My case was left for my then four professors to decide. Two of them were very kind and understanding — the other two, not so much.

The fight for my rights and protection that followed introduced me to the devastating gaps in SFU’s approach to student illness. This isn’t a novel realization, I fear. Having to fight for accommodations is likely on the forefront of every chronically ill student. It made me grasp the urgent need for SFU to implement a comprehensive, standardized system to manage illness and disability — both short-term and prolonged — that goes beyond the limited scope of CAL.

Even in my conversations with a CAL representative, I was told that my health issues, which had been on-going for nine months at this point, would not qualify me for CAL accommodations. So where was I supposed to turn? There was no centralized process for handling these grey-zone cases. I was left to advocate for myself with individual instructors, each with their interpretations of fairness and responsibility.

It’s clear that the lack of an institution-wide framework for instructors and students to follow not only allows but enables such transgressions to occur. The discrepancy in the interactions we as students have with our instructors is frustrating and discriminatory. Students don’t know what to expect when they reach out to instructors. And without a clear, universal protocol, accommodation becomes a lottery of luck rather than a guaranteed right.

If my medical documentation was not enough to prove the legitimacy of my health issue, and did not garner enough empathy from my professors, what does that communicate about SFU’s values? There was no way for me to understand SFU’s values, other than upholding able-bodied norms as the only acceptable form of existing. In the absence of a unified policy, SFU effectively communicates that illness is rejected from educational spaces.

birthday, along with my medical history. Information I don’t feel entirely comfortable divulging. Yes, instructors most likely don’t care about my personal health number or birthday, but I still feel a sense of invasion of privacy handing that medical note. Which I assume is kept in some file to document my extension. And for what? There’s no guarantee my vulnerability will be met with support.

On top of the emotional and academic toll, there’s also the financial cost of being sick. I couldn’t work for months and had to go on sick leave — a break that significantly reduced my income. And then there’s the price of being believed: every medical note I submitted cost $50. Since I was expected to provide documentation every couple of months, this added up quickly. I was paying hundreds of dollars just to prove I was unwell.

Worse still, the academic penalties I’ve faced due to this lack of systemic support have begun to impact my eligibility for post-bachelor programs. Missed deadlines, inconsistent attendance, and lowered grades — all stemming from circumstances beyond my control — now live permanently on my transcript. In essence, I’m being punished for being sick. My future academic and professional opportunities are being narrowed, not because I lack potential, but because I lacked institutional protection. And because SFU lacks a clear, compassionate system for dealing with medical crises.

The truth is, I’m no stranger to the ableist world we live in. Disability justice clearly outlines that accessibility shouldn’t be a luxury but a baseline — a shared commitment to collective care, autonomy, and interdependence. Yet, SFU continues to operate under a reactive model that individualizes crises and burdens students with the responsibility of proving their pain.

The reality is this: SFU’s current accommodation system is broken — it leaves students with health issues and disabilities at the mercy of instructor discretion and reinforces ableist norms. We need a centralized, and transparent process — one that trusts students, protects privacy, and acknowledges that illness and disability do not follow tidy deadlines. SFU must stop putting students in the vulnerable position of begging for basic support, and instead build a system that reflects respect for our shared humanity. Anything less is unjust.

The Bright-er Side

Iced lattes

A certain headiness comes with the first sip of a latte. It’s not just the taste — it’s the warmth, the anticipation, the ritual that precedes it. I usually start my day yearning for my iced brown sugar and honey latte. I queue the espresso shots in a shot glass — double and blonde. Then add a spoonful of honey to a cup, with a cube of brown sugar, and two dashes of cinnamon. Pour the shots right over them. The waft of that coffee goodness rises, swirling softly through the air. I stir it together until it all melts and becomes an elixir of comfort; dark, sweet, and enticing. Then I add oat milk until it’s my favourite shade of beige — rich and golden. Top it up with ice. A few gentle clinks, and just like that, my day is set.

The day cannot be heavy. A simple drink, and everything feels right. I can take anything on. Everything is possible.

I feel attuned to everyone who starts their day with a simple ritual. To all who existed decades before me. Centuries before me. Maybe the way of preparing coffee changes from one culture to another, and it changes from one time to another, but the comfort remains the same. The intention remains the same — to consume something grounding, and sacred.

PHOTO: AMY HUMPHRIES / UNSPLASH

ZAINAB SALAM OPINIONS EDITOR

LOCAL GARDENS F OR LOCAL HARVEST

COMMUNITY GARDENS ARE A KEY TO FOOD SAFETY AND SECURITY

DANIEL SALCEDO RUBIO FEATURES EDITOR

Walking around Metro Vancouver, it’s likely you’ve found community gardens full of vegetables and plants. These spaces aren’t just pretty; they are a great way for people to strengthen their relationship with the land they inhabit, build community, and eat local food — how much more local can it get than harvesting with your own hands?

Developing these plots of unused land into sources of locally produced food is one of Vancouver’s food security efforts. As part of the Vancouver Food Strategy and the Local Food Action Plan, the city harbors over 110 community gardens spread across parks and public spaces.

One of the biggest barriers to community gardens in Vancouver is the competition over available plots of land. In a city where every square foot is sought by developers to build high rises or is set apart for public infrastructure by the government, it’s likely community gardens aren’t very high on the priority list. Not only is developing new gardens an issue, but the process of being accepted into one can take a very long time as well. With limited spots available and long waitlists, many Vancouver residents are locked out of them. This is especially considering two-thirds of renters in Metro Vancouver live in apartments, most of which don’t have proper gardens for this activity. These factors make any community garden a highly coveted award.

However, solutions are already being implemented. Basel, Switzerland, started a program in the ‘90s mandating green roofs on new and renovated buildings. Not only is the mandate in place, but the city has provided subsidies and insists on using native seeds for the gardens. In San Francisco, another example of green roofs, started requiring solar panels on rooftops for most new constructions, so buildings will either have green rooftops, solar panels, or a combination of both. Not far from us, Toronto became the first North American city to require new buildings to incorporate green gardens in 2009. Unfortunately, this isn’t the reality of Vancouver. In a survey conducted by Living Architecture Monitor, only 283 of 9,526 of the mapped buildings had gardens in them. While it’s great that some buildings have dedicated space for gardening, these initiatives should really be implemented by the government. This can

HOW MUCH MORE LOCAL CAN IT GET THAN HARVESTING WITH YOUR OWN HANDS

?

look like incentivizing or outright requiring developers to dedicate spaces for a community garden, whether it be on the rooftop or a dedicated amenity inside the building.

Even if you are lucky enough to have a private garden or balcony you could use to start your own harvest, it can be quite overwhelming. It’s not only the startup costs of soil, seeds, containers, watering systems, and whatnot — it’s the knowledge investment many people dread. Taking care of plants isn’t instinctive; not everyone has developed the skillset or acquired the knowledge required to bring a barren plot of land into a bountiful garden. If the City of Vancouver is really looking to ensure food availability, safety, and quality, then it must support residents not only with space, but with guidance. One solution could be the creation of an independent body dedicated to urban gardening support — offering practical education, hands-on workshops, and advice to individuals and communities. This same organization could serve as an auditor to ensure developers are meeting the requirements (if the city sets them) for harvest-friendly spaces in new buildings, while also being a consultant for residents. This initiative should also be built in collaboration with Indigenous communities; incorporating ecological and sustainable harvesting knowledge. Bringing Indigenous voices and expertise to the forefront is not only an act of reconciliation, it’s a way to ensure our gardens are grounded in respect for the land and the interconnectedness of the ecosystem living within. This way, the gap between barren plots and bountiful gardens can be closed while maintaining sustainable practices and even incorporating Indigenous knowledge into them.

While this might sound idealistic, it’s important to remember that gardens are living, breathing ecosystems. They rely on the care and commitment of people and therefore fully rely on human responsibility. However, they don’t necessarily need to rely on manual labour; there are countless innovations already in use, from automated irrigation systems to vertical growing setups, and even the tried-and-tested scarecrow. With the right infrastructure, knowledge, and expertise growing food in the city can become less of a luxury and more of a shared, sustainable practice.

Vancouver punk’s role in creating community

The music is the smallest part of it

KATIE WALKLEY · PEAK ASSOCIATE

When spending time in Vancouver’s public spaces, I notice it is common practice to avoid eye contact. Instead of engaging in other people’s lives, we tend to stay focused on our own.

I used to think all of Vancouver was like this — cold, distant, impersonal. Then, two years ago, I started going to some of the city’s punk shows. When my friends first introduced me to them, I did not understand the appeal of thrashing around with strangers, especially after hearing stories of bloody noses. However, once I finally built up the courage to join the mosh pit, I realized why they love it so much. It tends to the human need for community.

The focus everyone has on the present connects them all, unlike average interactions on the street, where people have their minds to themselves, thinking about their own worries. The punk dance style is so visceral that it takes us into an animal-like state where we have a rare opportunity to express ourselves freely beyond social norms in a public space. Since everyone there becomes connected through dancing together, it creates a place where you can go out by yourself and still feel like you belong.

At my first punk show, I discovered one of my now-favourite local bands: Luella. Their intense rhythm creates a hypnotic attachment to the music and the people around you. After their first song, they screamed at the crowd about how the world is awful and scary. They then reassured us that it is OK to be mad and invited us to let out our anger together. This was the first time in my life that I had seen an adult be fully honest about the painful state of the world and how it affects them. It wasn’t just aimless complaining — it was

righteous anger that made me realize rage is an incredible tool which opens the door to caring. Sometimes it’s uncomfortable to care, but when surrounded by people who make me believe in a better future, it feels like a great relief to finally allow myself to feel the pain I have always ignored in my efforts to stay comfortable. A

group of artists under the name of Dumpster Fire Distro. They are often seen at shows giving away free zines with a goal of bringing forward suppressed knowledge. The content spans topics from Indigenous stories to 2SLGBTQIA+ history to anarchism, and beyond. Although punk shows are mostly filled with levity and fun, they have always been a space for speaking up against injustice. For instance, back in 1993, there was a punk show at the Commodore Ballroom in support of the protesters protecting old-growth trees in Clayoquot Sound. The relationship between live music and politics makes so much sense because they are both crucial ways that we connect with each other.

When it feels like the world is cruel, that means it’s time to join a mosh pit to escape from our collective isolation.

The communities made in the mosh pit encourage a faith in humanity that inspires people to pick up the fight for human rights. It removes the separation we tend to create between strangers and reminds us we are all part of something bigger. Thinking about the impact that punk shows have had on me reinforces my belief in the importance of the time we spend in public. The way we see others has the power to completely shift our entire worldviews. So, when it feels like the world is cruel, that means it’s time to join a mosh pit to escape from our collective isolation.

Katie’s local punk recommendations

Favourite venue: The Alf House is an outdoor venue in someone’s backyard.

Favourite band: After the Fox has incredible stage presence. Find more punk events at vancouverpunkcalendar.

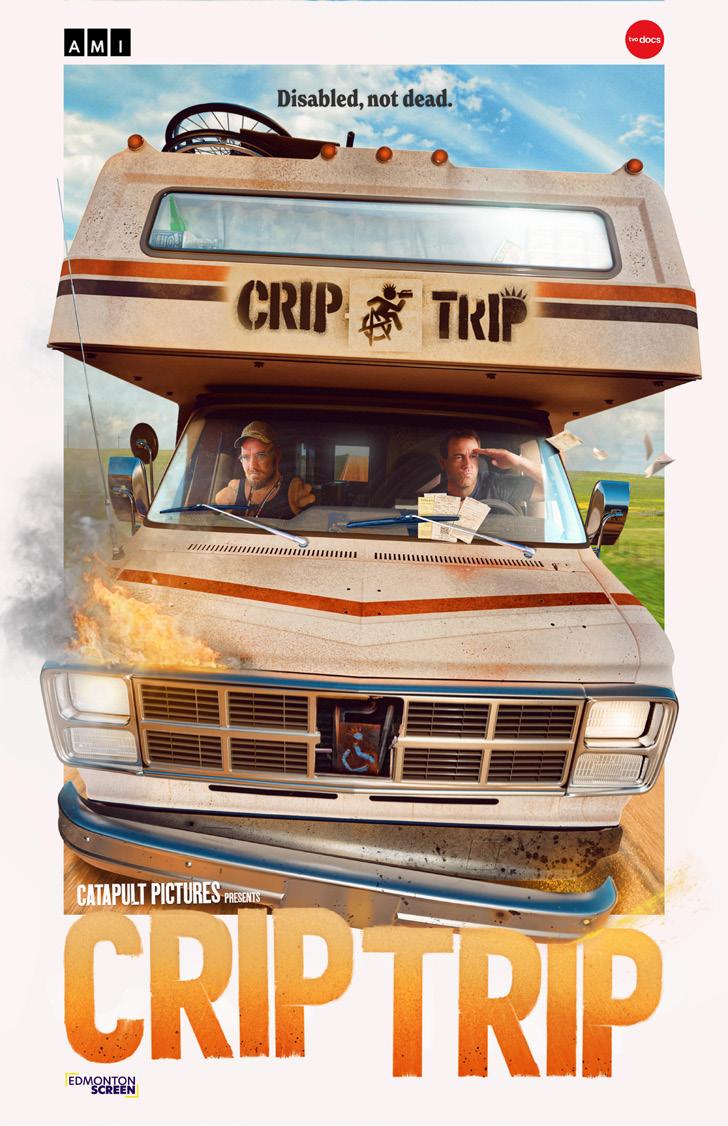

Crip Trip: a road trip against institutionalization

Two friends travel from Edmonton to New York, exploring the nature of care-giving

YILDIZ SUBUK · STAFF WRITER

Crip Trip is a docu-series about two friends and filmmakers, Frederick Kroetsch and Daniel Ennett, who set out on a road trip from Edmonton to New York. Ennett, a multidisciplinary artist and disability justice advocate, is a quadruple amputee trying to find full-time employment to avoid institutionalization. The series follows them on their trip as they meet other disabled people across North America who are facing issues regarding care and mobility.

The docu-series aired this year in April. Despite its comedic undertones, the series is raw and infuriating. Instead of focusing primarily on the specifics of disability, it focuses on the world around it — the institutional restrictions to mobility and access experienced by the disabled community in North America. Using the road trip, ideas about mobility, including a huge lack of access to proper mental care for disabled people in North America, are revealed. The two

travel in an old RV, which almost ends up breaking down in the first episode. This creates doubts about whether the road trip will even take off. The journey feels turbulent, as there is a lingering feeling that at any point something can go wrong — as exemplified by the RV constantly breaking down. The series becomes a fight for completion, exemplifying the crew’s dedication to spreading awareness of the main message behind the trip.

The series sheds light on core issues surrounding disability justice, such as bureaucratic red tape and inadequate financial support for caregivers. The themes surrounding the poverty trap of not allowing disabled people to work — lest they forgo their benefit payments — as well as the undue exploitation of family caregivers as unpaid forms of labour are explored. The clear lack of humanity when it comes to caring for those vulnerable becomes painfully visible, despite the chaotic fun

experience that is at the backdrop.

Kroetsch represents an outsider trying to learn about the struggles of disabled people and their support systems, while Ennett represents the insider inviting the viewer to see the world through the lens of the disabled community. Exploring disability through both of their viewpoints and the rest of the story, Crip Trip challenged me of my own perception of the privilege regarding my body and mobility while informing me of the many injustices still present for the disabled community today.

Watch Crip Trip on AMIplus.

PHOTO: EVGENIY SMERSH / UNSPLASH

EXCLUSIVE: McFogg the Dog comes out as gay

Left with more questions than answers

Katie Walkley · Peak Associate

With a studded collar and a lipstick stain on the cheek that he claimed to be from Gerard Way, McFogg the Dog sat in the doorway of a Lorne Davies Complex athletic storage closet for this exclusive interview. He’s called the closet home for the past seven years after mysteriously leaving the position of our school’s mascot. During this time, he was ferociously dodging Craigslist bidders who wanted to get his fabulous bod back into the mainstream for a revolutionary comeback tour.

Meanwhile, the retired legend stayed away, trying to find a sense of self outside of the limelight. Now, he’s here to tell us where he’s been and set the record gay — I mean, straight — on the countless speculations about whether he graces the 2SLGBTQIA+ community with his transcendent presence. After every SFU student has had a chance to label him, it’s time for this dog to label himself

Katie: Good evening, Mr. McFogg the Dog. Thank you for inviting me to your closet. So, please tell me about your look — is this new, or is it true that you felt forced to hide while under the ruthless scrutiny of the public eye?

McFogg: I knew the world wasn’t ready for a sexually ambiguous Scottish mascot. Stacking my emo identity on top of that would have created a controversy I could never return from. So, I had to cater to the norms for the time and go along with the presumptions that I was nothing more than a big bear in a kilt.

Katie: Wow. Speaking of identity, where do you stand on previous News Writer Chloë Arneson labelling you as a “queer icon” back in 2022? Does that label suit you?

McFogg: While I disagree with publishing my story in the humour section, my iconicness is undeniable.

Katie: Now, I hate to get so personal, but the people have to know — are you dating anyone?

McFogg: You know, it’s hard these days to find anthropomorphic creatures looking for a serious relationship. Mothman keeps leaving me on read.

Katie: Those beady red eyes must not be able to see what they’re missing.

McFogg: Exactly. I tried to find at least a hookup at a few furry conventions, but then I found out that there are people underneath the costumes.

Katie: Wait . . . is there not a person inside of you right now?

McFogg: How could you ask me that? Not everything is sexual, Katie! But yes, sometimes I do indeed have someone inside of me, wink, wink . . . You know what? This interview is OVER! I’m about to sashay away. Ugh!

He then kicked over his chair, did one iconic fur flip, and stormed out of the closet.

ILLUSTRATION: Yan Ting Leung / The Peak

Airport security vs. CAL: Welcome to the accommodated life

I think CATSA might be kinder than

CAL

My palms sweat as my student ID slides through my hands. Butterfingers. As I draw nearer to the checkpoint, I feel the weight of a thousand bullets piercing through my skin. I wipe away a pound of sweat.

I approach the Centre for Accessible Learning (CAL) checkpoint. “What’s your name?” demands an enraged lady with a clipboard. “Spit it out, I don’t have all day.”

“My name is . . .” I try to respond, but she’s just so intimidating.

“I said hurry up or else I’ll send in the dogs! They’re hungry for some students with accommodations; they have the best sweat glands,” she responds while barking and howling at the roof. She begins scanning the line to assess the other students, as if she’s telling me to hurry the fuck up in a non-nonchalant way.

“Matthew,” I tell her.

“Your ID. NOW. You don’t want the dogs in here, do you?” She begins to bark and howl again, this time getting on all fours and intimidating me. What the actual heck.

As I lower my hands and give her my ID, she places a plastic bin at my feet and demands that I put in any items I will need during my exam. This feels vaguely familiar, as if I have

gone through the exact same trauma in another environment.

I, then, follow this evil woman into a holding room. There, I am patted down not with physical force, but with condescending eye movement from another exam assistant. I carefully place two HB pencils, an eraser, and a bag with snacks in case my blood sugar goes low.

“DROP THE BAG! DROP THE BAG! HANDS UP!” the lady screams. She snatches the bag from my hand and begins inspecting . . . almost like I’m at airport security. Ah, bingo. That’s why this feels so fucked up and familiar. My bag gets handed back to me in a desecrated state, torn apart to find illegal study aids.

As I walk out of the holding room, I am scanned once again by a thousand exam assistants’ eyeballs, all watching me take the walk of shame into the exam room. There, plastered over all the walls, are signs of students posing. Mussolini’s propaganda had nothing on this shit. “YOU’RE UNDER SURVEILLANCE,” they read. “WE CAN SEE EVERY STEP YOU TAKE, EVERY MOVE YOU MAKE. YOU CAN’T RUN. YOU CAN’T HIDE.”

Above my head is a watermelon with a Sharpie-stained dot in the shape of a camera lens in the middle. I’m guessing that this is the surveillance.

Inside the room, rows of students are in a similar position as I am in. Hundreds of exam invigilators pace the room, giving them side-eyes and demeaning stares.

To go to the washroom, I have to put a question sign up. Yet when I put the question sign up, I am verbally attacked and berated until I put the question sign down. What kind of brutal conditions am I working under?

I slowly feel my eyes shuttering, a reaction to the horribly dimmed lighting. Almost a bit more to go, you can do this! You’ve got this! An exam invigilator hisses at me, accuses me of hiding notes in my eyelids, and I fall to the ground.

As I awake, I am at the security gate at YVR.

“Are you alright, sir? You collapsed when I asked you for your passport,” a voice calls out. I look up at a face. “Hey, are you from CAL? I work there part-time.”

“AHHHHHHH!” I get up. Then, the drug dogs come towards me as CATSA agents scream at me to drop the bag with my Diabetes supplies in it. I try to tell them that I can’t walk through a scanner because my insulin pump will malfunction — they literally don’t care.

All of this feels vaguely familiar. All roads in the airport security line lead back to CAL. Somebody call Carney, because I think more CAL staff could be hired at CATSA with little to no training required!

Matthew Cullings SFU Student

IMAGE: Gudrun Wai-Gunnarsson / The Peak

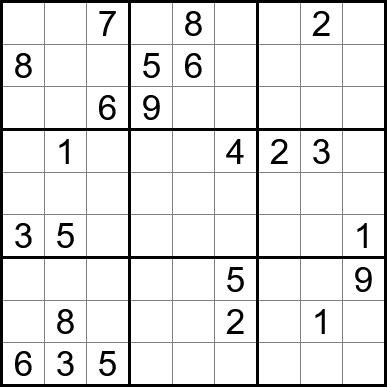

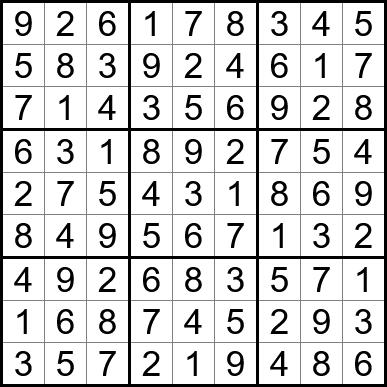

SUDOKU