SMALL TOWN, BIG BEACH

1950s, City of Gulf Shores Fire Department Truck

small town, big beach

Published by PV Publications

©2025 City of Gulf Shores, Alabama

All other rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permission from the City of Gulf Shores, Alabama

ISBN: 978-1-7372192-2-4

Written and curated by PV Publications, Kristin Borden, in partnership with the City of Gulf Shores

Graphic design by Lane Bullard and PV Publications

This book was made possible thanks to the invaluable insight and contributions of Claude O’Connor, the Ward Family, the Gulf Shores Museum and many others who, over the years, have preserved and protected the history of this area — including Joy Busken and the collections compiled by the Gulf Shores Woman’s Club — whose materials formed the foundation for much of what is presented here.

For details, contact: www.pvpublications.com

PV Publications

PO Box 4752, Palos Verdes Peninsula, CA 90275 kristin.borden@pvpublications.com

For more information about the City of Gulf Shores: www.gulfshoresal.gov

Robert Craft has devoted the past two decades to serving the City of Gulf Shores. He was elected as the city’s ninth mayor in August 2008, following four years of service on the Gulf Shores City Council from 2004 to 2008.

As mayor, Craft has focused on enhancing the quality of life for all residents. Under his leadership, the city has made tremendous strides, including more than $272 million in capital improvements and the acquisition of $76 million in grant funding. Key accomplishments during his tenure include the establishment of Gulf Shores City Schools, the development of a state-of-the-art freestanding emergency room, the revitalization of Gulf State Park and Lodge, the addition of the Auburn University Education Complex, and significant infrastructure improvements across the city.

In addition to his role as mayor, Craft is one of 10 Alabama leaders serving on the RESTORE Council, which manages the distribution of $750 million from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill settlement for projects in Mobile and Baldwin counties. He also serves on the boards of the Gulf Coast Convention and Visitors Bureau, Gulf Shores Utilities, and the Gulf Coast Center for Ecotourism. He is an active member of the Gulf United Metro Business Organization (GUMBO).

Prior to his public service, Craft had a successful entrepreneurial career in agribusiness and real estate development. In 1986, he partnered with his parents, Jane and R.C., to develop Craft Farms—a master-planned residential community featuring nine neighborhoods, two Arnold Palmer-designed golf courses, a Courtyard by Marriott hotel, and Cypress Point Condominiums. He also founded Craft Turf Farms, a 2,000-acre operation providing premium turf grass to builders and landscapers since 1974.

Craft is a graduate of Foley High School and Auburn University, where he earned a degree in Agricultural Science. He is married to Trudy, a Mobile native, and together they share a blended family of four children and ten grandchildren.

Heritage n Honoring Our

On behalf of the residents, staff, and City Council, I am honored to introduce you to and warmly welcome you to Gulf Shores, Alabama.

Gulf Shores has become Alabama’s number one tourist destination and is home to some of the most picturesque beaches in the country. Whether you prefer a leisurely walk along our miles of coastline, a fitness-inspired trek down one of our many trails, or an exhilarating boat ride across our backwaters, bays, and lagoons, Gulf Shores offers breathtaking moments around every corner.

Gulf Shores blends its small-town, family-friendly atmosphere with a thriving big-beach economy, providing wholesome Southern hospitality and first-class attractions. Enjoy fresh seafood at locally owned restaurants, take a stroll through our charming shops, and explore the natural beauty of our parks, trails, and beaches.

Each year, millions of guests fall in love with our coastal community, with many developing long-standing family traditions of relaxing and reconnecting with loved ones while enjoying our expansive, white-sand beaches. Our city also proudly hosts numerous National Championship softball, baseball, track, and soccer tournaments at the state-of-the-art Gulf Shores Sportsplex and surrounding facilities—further establishing our community as a premier destination for both leisure and competitive events.

Whether you are seeking a beach escape for a day or a lifetime, Gulf Shores is an uncomplicated beach community, making it the perfect place for relaxed living. Some, the lucky ones, choose to stay—drawn in by the beauty, the pace, and the sense of belonging that makes Gulf Shores feel like home. So, what are you waiting for? Come and explore all that Gulf Shores has to offer and experience what our Small Town, Big BeachTM is all about.

Sincerely, Robert Craft Mayor, City of Gulf Shores (2008-present)

Introduction

Nestled along the Alabama Gulf Coast, Gulf Shores is a place where white-sand beaches meet laid-back coastal charm. It has the heart of a small town—filled with familyfriendly activities and a strong sense of Southern hospitality. Neighbors still look out for one another, and traditions of kindness and connection remain at the core of this close-knit community.

Even during the bustling summer months, when the beaches fill with vacationers, Gulf Shores stays true to its roots. It offers a welcoming, authentic atmosphere that feels like home.

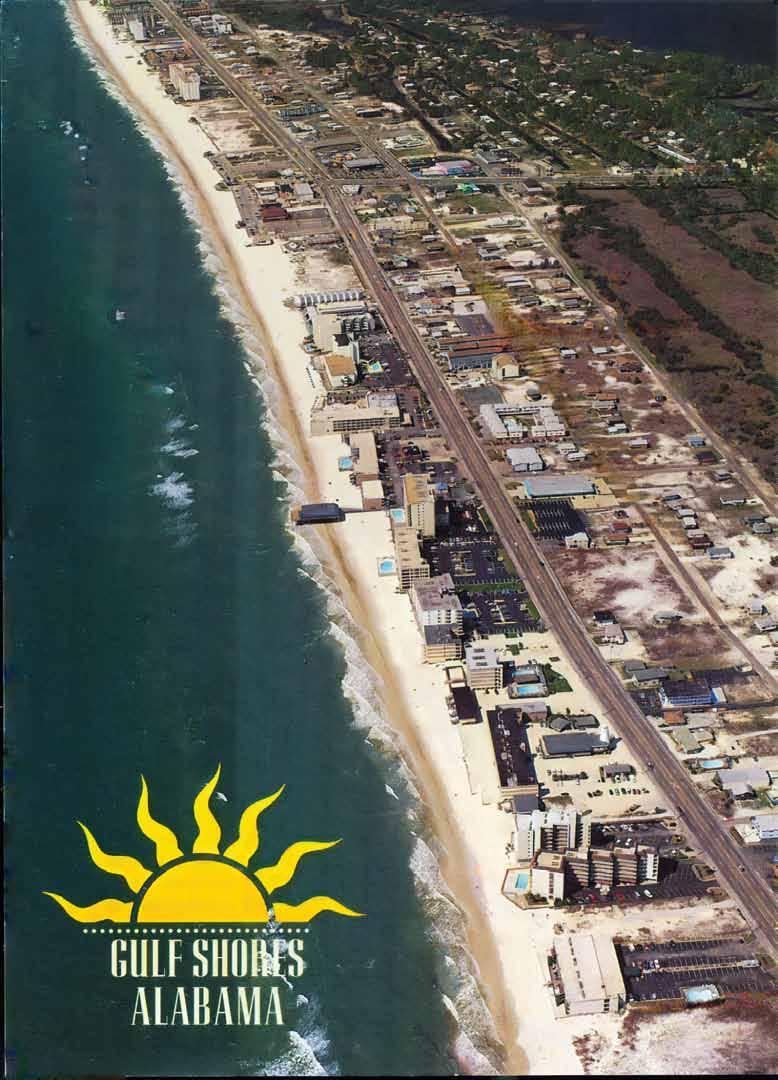

Over the years, Gulf Shores has grown into one of the South’s most desirable small-town destinations. Consistently ranked among the nation’s top beaches, it boasts miles of sugar-white sand and diverse ecosystems, making it a paradise for both relaxation and adventure.

But Gulf Shores is more than just a beloved vacation spot—it’s a thriving community with a rich history. The completion of the Intracoastal Waterway in 1937 and the opening of Gulf State Park in 1939 helped attract new residents and visitors alike. Before that, it was home to a small fishing village that dates back to the early 1800s. The town got its first post office in 1947 and officially became incorporated as a town with 120 residents in 1958. What began as a community rooted in shrimping, oystering, and fishing has since evolved into a vibrant resort destination shaped by tourism and real estate. While the beaches remain the biggest draw, there’s no shortage of

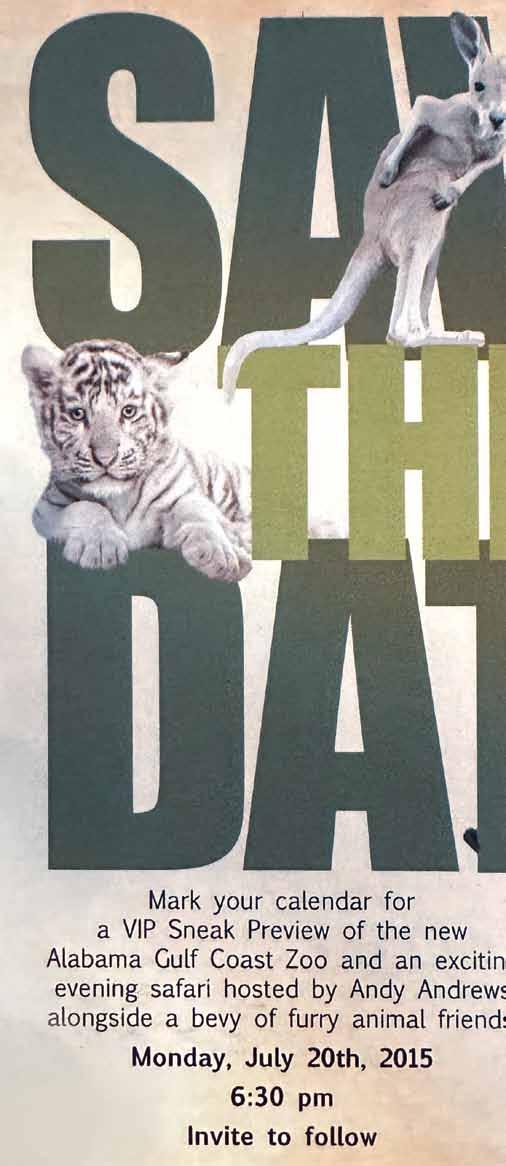

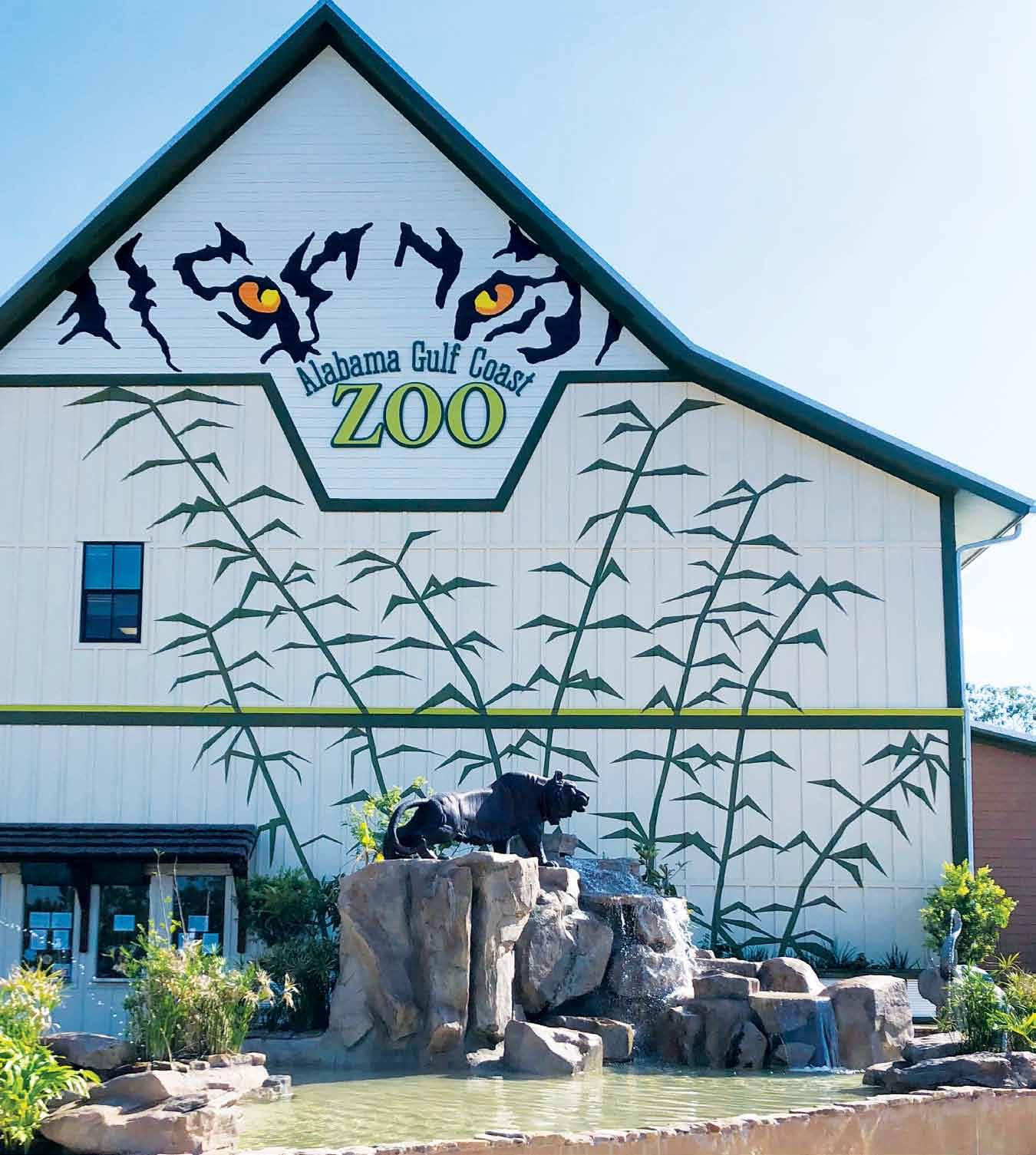

things to do. Visitors can take scenic cruises, watch dolphins gliding through the waves, or explore miles of hiking and biking trails. Families love the Alabama Gulf Coast Zoo, known for its hands-on animal encounters, while outdoor enthusiasts enjoy fishing, golfing, and the nature trails at Gulf State Park. For a more peaceful retreat, Bon Secour National Wildlife Refuge provides a sanctuary for sea turtles and migratory birds, and history buffs can step back in time at Fort Morgan, a 19th-century landmark overlooking Mobile Bay.

In recent years, Gulf Shores has also become a premier destination for sports. The City hosts major events like NCAA Beach Volleyball National Championship and numerous softball, baseball, track, and soccer tournaments at the Gulf Shores Sportsplex. With top-tier facilities and a stunning coastal backdrop, it attracts athletes and fans from across the country.

Whether you’re seeking adventure or a place to unwind, Gulf Shores offers something for everyone with its unique blend of history, hospitality, and scenic beauty. The City remains committed to thoughtful growth, balancing development with sustainability through conservation efforts, community engagement, and smart planning. This dedication helps preserve the coastal charm that draws both longtime residents and first-time visitors alike. Every sunrise over the Gulf and every walk along the shoreline serves as a reminder of the enduring natural beauty and welcoming spirit that make Gulf Shores a one-of-a-kind destination.

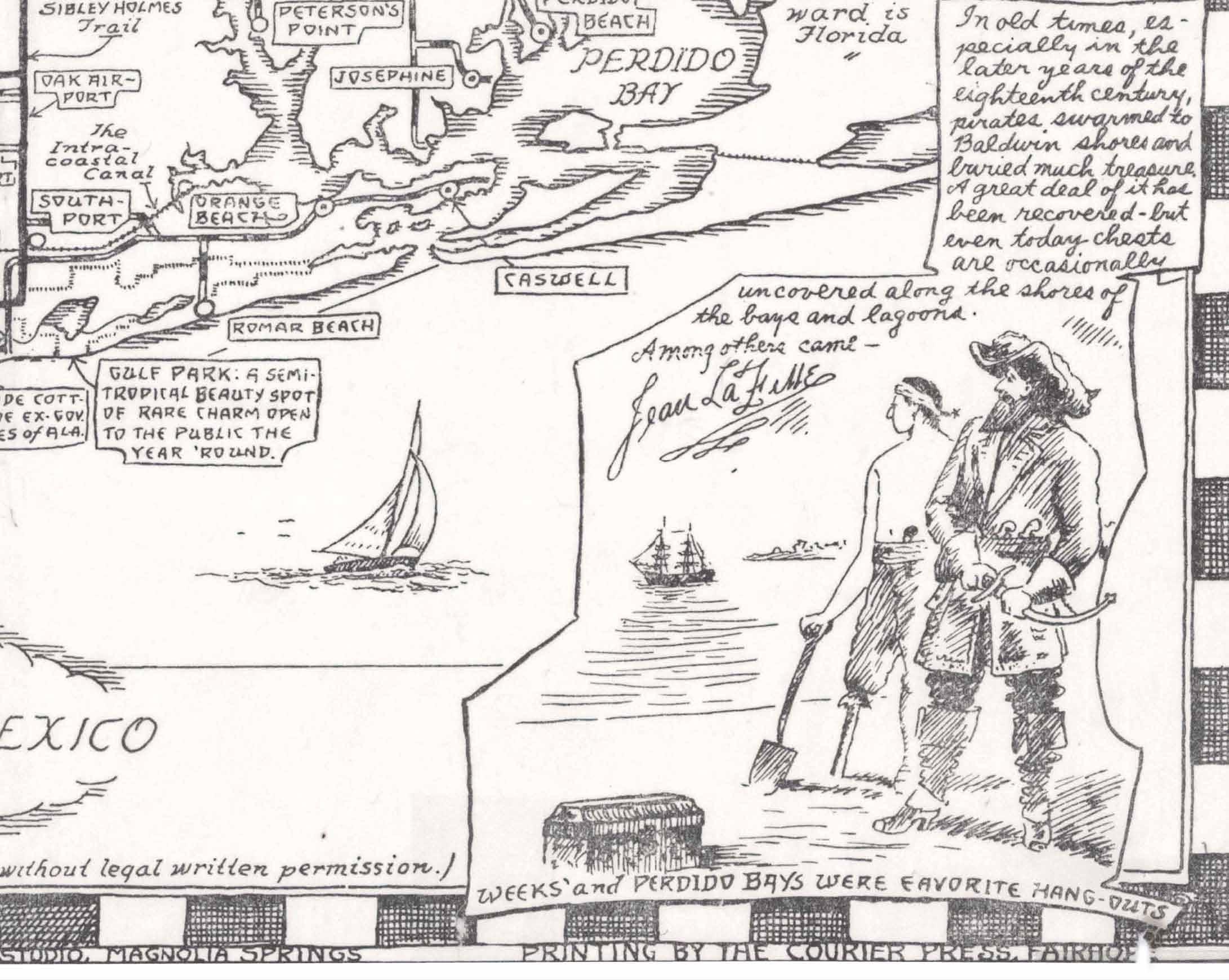

1939, Highlights and Highways of Baldwin County, Alabama, by Walter Overton

1920s, Gulf Shores Beach

Before the City: The Land that Shaped

Gulf Shores

As the sun rises over the Gulf Coast, the pristine white sand beaches of Gulf Shores evoke a sense of timeless beauty. Yet this coastal landscape hasn’t always looked as it does today. To fully appreciate the evolution of Gulf Shores, one must first delve into the deeper history that shaped this region long before it became the beloved coastal community we know.

In the aftermath of the Ice Age, the Gulf of Mexico stretched much farther south, and the land now known as Gulf Shores was covered in dense forests. Archaeological evidence suggests that human habitation began here around 11,500 years ago, with organized civilizations emerging by 1000 BC. Among them were the Mississippian tribes, who left behind shell and burial mounds— silent testaments to their presence and culture.

These early inhabitants were far from isolated. They were part of an expansive trade network, exchanging goods across vast distances. Around 566 AD, they even constructed a hand-dug canal to link the region’s waterways, improving transportation and trade. Often referred to as the “Indian Ditch,” this canal has become a valuable archaeological discovery. Portions have been partially rediscovered, offering rare insights into the complexity of life in the region. Local historian Harry King’s investigations revealed artifacts from across the continent—arrowheads, copper, and obsidian—highlighting Gulf Shores’ place in a broad prehistoric trade system. In 2023, under the direction of Wade and Pat Ward, The George C. Meyer Foundation donated the Indian Ditch to The Archaeological Conservancy to ensure its continued protection and study.

By the 17th century, European settlers began to arrive. While few established permanent homes directly on the beach due to poor soil conditions, nearby inland areas offered rich, fertile ground. These fertile lands in close proximity to the beach eventually contributed to Baldwin County’s longstanding reputation

as an agricultural hub. For many years, it was commonly referred to as “the agricultural county,” a title that speaks to the region’s deep farming roots. Though the sandy beachfront proved unsuitable for cultivation, adjacent inland areas—now within today’s Gulf Shores city limits—continued to support agricultural use well into the mid-20th century. One noteworthy example came in 1953, when R.C. and Jane Craft, along with their son Robert, began cultivating millions of potatoes and gladiolas in the area now known as Craft Farms. Their success further underscored the richness of the local soil just miles from the coast, and some of that land continues to be farmed to this day. Their son, Robert Craft, is the current mayor of Gulf Shores, continuing the family’s legacy of shaping the community.

It wasn’t until the 1906 hurricane reshaped the coastline— carving out the striking white sand beaches we now associate with Gulf Shores—that the area began to take on its identity. In the years that followed, the 20th century ushered in development. By the 1920s, very modest hotels and a few homes had begun to appear and by the 1950s, the start of a new chapter began, signaling the beginning of an evolution to what it is today. Once a quiet fishing and farming area, Gulf Shores gradually transformed as its natural beauty—with calm waters and refreshing breezes— began attracting new residents and visitors. The foundation was laid for the vibrant coastal destination that Gulf Shores has become.

Today, the legacy of that land endures. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Baldwin County is now the fourth most populous county in Alabama and ranks second in median household income, behind only Madison County, home to Huntsville. This remarkable growth is a testament to the enduring appeal of Gulf Shores and the surrounding area—a community shaped not only by time and progress, but by the very land that made it possible.

1950s, the end of West Beach Road

the early days

1800s

• A small fishing community is established.

1834

• Fort Morgan is completed.

1918

• Shrimping becomes a prominent industry, led by Little Lagoon families such as the Callaways, Wallaces, Nelsons, Childresses, Plashes, and many others.

1920s

• The first hotel opens in the area.

• Local fishermen begin offering one-day fishing charters.

• The first corduroy road is completed, leading to the beach. These roads were constructed by laying logs lengthwise through swampy areas, then covering them with sand and soil, creating a patterned effect resembling corduroy.

• In 1921, George C. Meyer establishes the first homestead south of the Little Lagoon.

1934

• The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) begins constructing buildings and trails in Gulf State Park.

1937

• The Intracoastal Waterway is completed, improving accessibility and encouraging commercial trade.

1939

• Gulf State Park opens with cabins and a beachfront casino.

1946

• Bus service from Mobile to Gulf Shores begins, increasing tourism.

1947

• The First Gulf Shores Post Office opens.

1950s

• In 1956, residents of Gulf Shores began petitioning for incorporation, seeking official recognition as a municipality. After two years of efforts, the Alabama Supreme Court granted the incorporation in 1958, officially establishing Gulf Shores as a town.

Stretching 32 miles from Mobile Bay and the unincorporated Fort Morgan Peninsula to Perdido Key, Florida, this coastal stretch of Baldwin County—now Alabama’s largest county by land area and the fourth most populous— was, in the early 1920s, an untamed and largely unexplored wilderness. The coastline, lined with pristine white sand dunes and dense maritime forests, was virtually uninhabited. Beyond a handful of homes scattered along the Gulf and modest settlements like The Ridge on Little Lagoon and the fishing village of Bon Secour, the area remained a wild and roadless expanse, with little to no infrastructure in place.

It was during this era—at the height of the Roaring Twenties—that George C. Meyer first visited the region. A self-made and visionary real estate developer, Meyer had explored numerous coastal locations across Florida in search of the perfect site for a family-friendly beach town. But it wasn’t until he laid eyes on the untouched beauty of the Gulf Shores area that he found what he had been looking for. To him, the swampland wasn’t a barrier— it was a blank canvas full of potential.

Meyer’s persistence in acquiring land along the Gulf Coast would spark the early development of Gulf Shores. Through his vision and efforts, the groundwork was laid for transforming this isolated stretch of Alabama shoreline into a welcoming coastal community, setting the stage for what would eventually become one of the state’s most beloved beach destinations.

A Rich HeritageFishing

Gulf Shores and the surrounding area have a deep-rooted history in fishing that stretches back to the early 1800s, when a small community of farmers and fishermen first settled in the area. Long before their arrival, Native Americans thrived here, taking full advantage of the abundant marine resources in the bays and inlets. For countless generations, Indigenous people expertly harvested fish like croakers and mullets using tidal traps and nets, and collected oysters, clams, and other shellfish in vast quantities. A large Native population once inhabited the region, with evidence of a seasonal or intermittent settlement at the north end of Oyster Bay. The presence of the Ancient Canoe Canal—cut across the Fort Morgan Peninsula from Oyster Bay to Little Lagoon—further illustrates their lasting influence. The Canal’s discovery and preservation were not the result of a single moment in time, but rather the outcome of continued efforts by numerous individuals and organizations over the years, reflecting its enduring historical importance. Remnants of shell mounds and burial sites can still be observed today.

Fishing has long been central to Gulf Shores’ economy and cultural identity. For generations, the rich waters provided a steady source of income and sustenance. Early settlers relied on small, family-owned boats to catch fish for local consumption and trade. Families such as the Nelsons, Callaways, Wallaces, Smiths, and Plashes settled near Little Lagoon and along the bayous—many of their descendants still call the area home today.

These pioneering families not only fished the abundant waters but also faced the harsh realities of life along the humid, swampy Gulf Coast. Disease was common, and access to medicine was scarce. In an era before modern forecasting, hurricanes struck without warning, giving families little time to prepare. The storms brought not only destruction but heartbreak—floodwaters that swept away homes, belongings, and, in the most tragic cases, beloved family members.

Through the difficult times of the early to late 1800s, these families persevered, doing their best to survive and build a stable life in a challenging and often unforgiving environment. They are just a few of the many families who gave so much to this area. We couldn’t possibly name them all, but in our hearts, they are recognized and honored.

Through all the hardship, fishing remained at the heart of life in Gulf Shores. It wasn’t just a way to make a living—it was a way of life. The bayous, inlets, and open Gulf waters provided not only food but a sense of identity and connection to nature. From hand-tied nets to homemade traps, from long days under the sun to quiet mornings on the water, generations of fishermen and their families helped shape the culture of this community. That legacy still echoes today in every cast line and every story passed down by the water’s edge.

Opposite page: 1900s, fishing on the Bon Secour River Above: 1800s, Captain Jim Callaway shown with conch shells

The advent of commercial fishing in the 1930s significantly elevated Gulf Shores’ profile, establishing the town as a major seafood supplier during World War II. The industry brought not only economic prosperity but also deeply influenced the area’s culture. At the heart of this growth were local fishing families— among them the Callaways, Wallaces, Nelsons, Childresses, Plashes, and many others—who helped build a close-knit community grounded in hard work and maritime tradition. Their deep knowledge of the waters, time-honored techniques, and cherished recipes have been passed down through generations and remain a vital part of Gulf

identity today.

Shores’

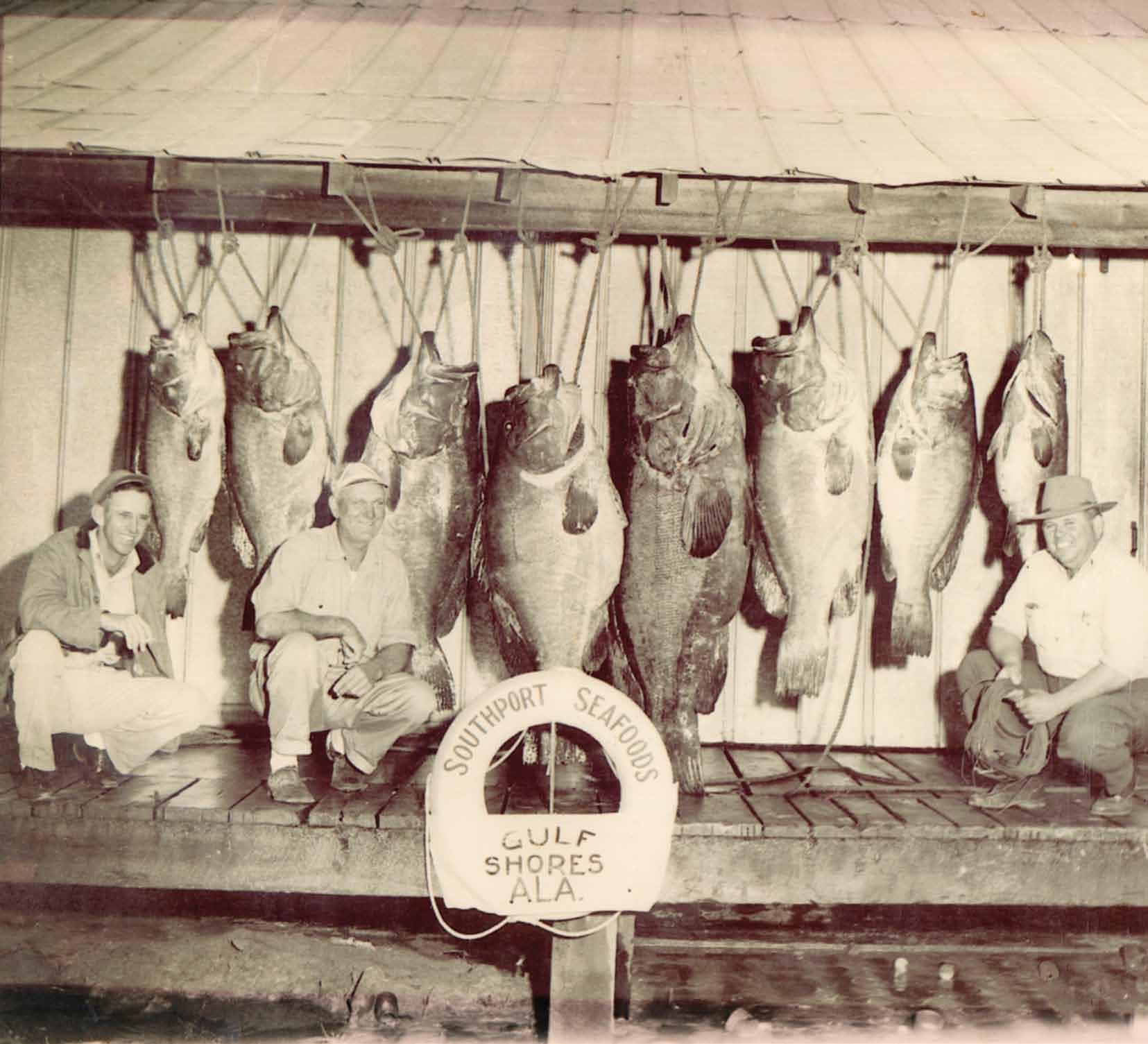

Above: 1950s, Callaway Seafood, Vivian Lee Callaway Opposite page: 1950s, a large catch of grouper on the dock of Southport Seafood, where Lulu’s Gulf Shores Restaurant is located today

1950s, Son’s and Daughter’s Day: Dot Salley (back row, left) with local children holding fishing poles; Mike Miceli (front row, left) looks unhappy holding a stick instead of a pole.

Shrimp Boat Vivian Lee

Being in the fishing industry since the early 1970s, I’ve seen firsthand how everything in Gulf Shores revolved around fishing. My father opened a shop on the north end of what is now Lulu’s, and we worked side by side, repairing boats, building vessels, and keeping the local shrimping fleet going, along with a few others. Fishing wasn’t just a job—it was a way of life that shaped the entire community. Most of the boys played sports around their shrimping schedules because in the summer, they were out on the boats helping their families. If a family was in need, we’d take the boat out, catch a load of fish, and host a fish fry at the Methodist Church to raise money. That’s just how it was—neighbors helping neighbors. Gulf Shores may have grown over the years, but that deep connection to the water and to each other is still at the heart of this town.

—Joe Garris

Pulling in the catch as a shrimper brings up a basket of shrimp caught in the Gulf

City Councilmember (2004-present)

Left: 1963, Lurleen Wallace, the first female Governor of Alabama, presents the Daily Prize Winner trophy to the Speckled Trout Rodeo Champion

Top: 1951, Betty Egbert Holt holding the winning speckled trout Bottom: 1950s, winners Virginia James of Centreville, Alabama, and Virginia Clinton of Florence, Alabama. Prizes included an Evinrude outboard motor.

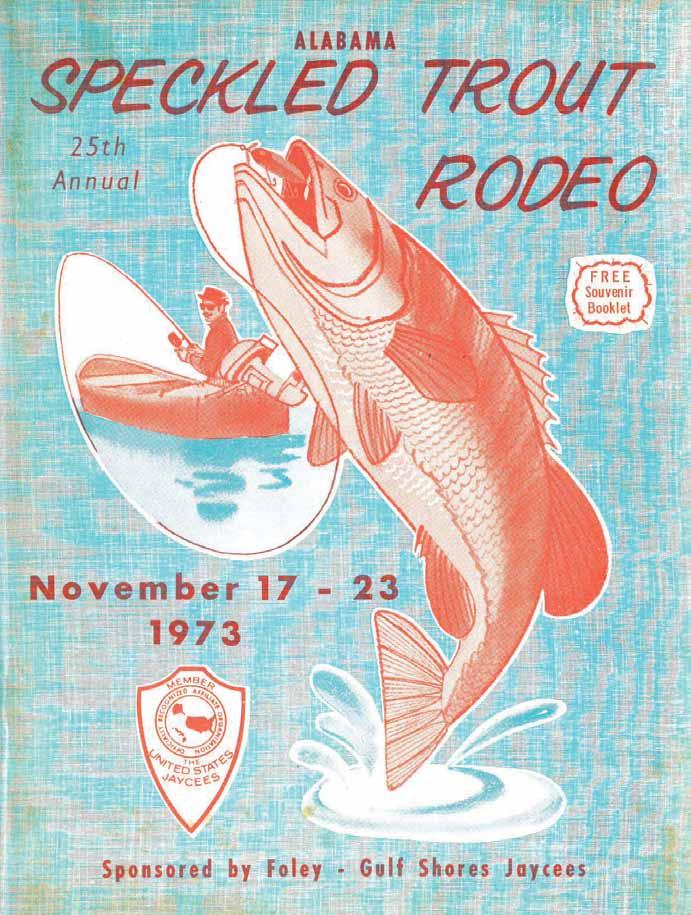

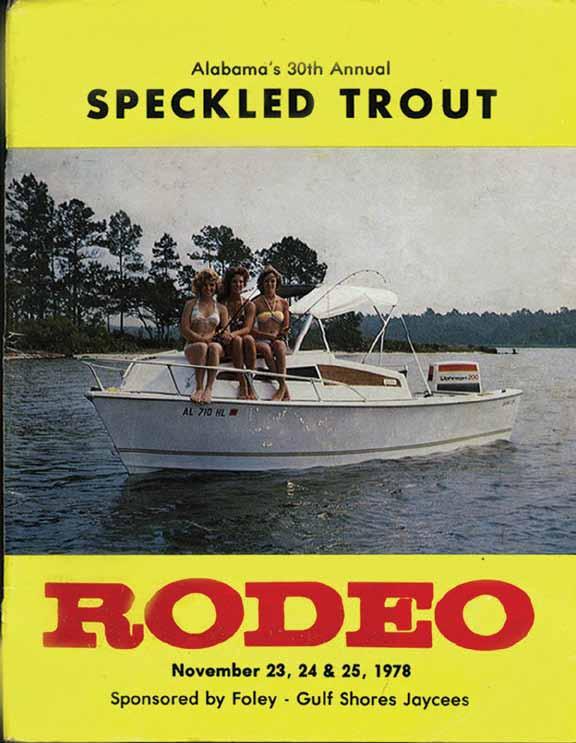

The Baldwin County Speckled Trout Rodeo began in 1948, and by 1973, it had reached its 25th anniversary, marking a quarter-century of fishing, community camaraderie, and spirited competition. Sponsored by the Gulf Shores Lions Club, this highly anticipated event spanned an entire week in midNovember, drawing anglers eager to showcase their skills in the waters off Gulf Shores, Alabama. More than just a fishing tournament, the rodeo was a true celebration—bringing together locals and visitors for a week of excitement, prizes, and tradition. In addition to the fishing competition, the event featured a beauty contest and even a turkey shoot, making it a highlight of the season.

Fort Morgan

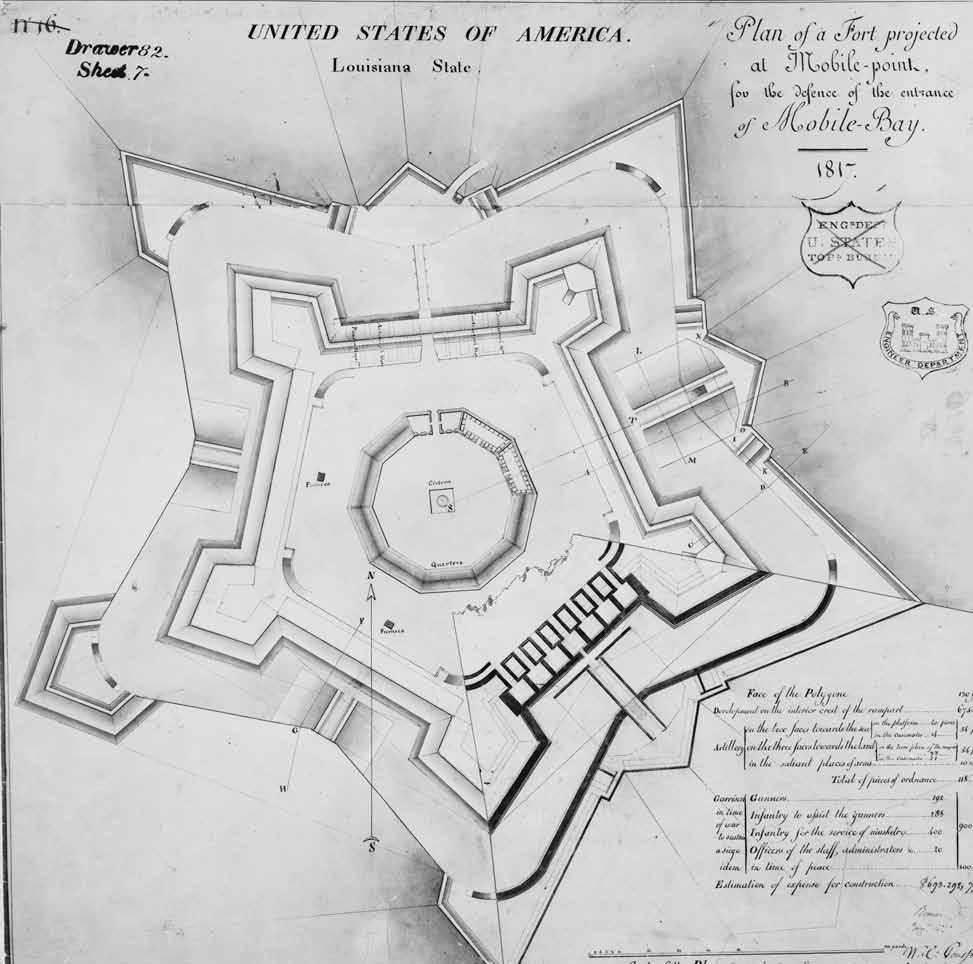

Perched at the entrance of Mobile Bay, Fort Morgan stands as a testament to the strategic military history of the Gulf Coast. Constructed between 1819 and 1834, this imposing masonry fortification was named in honor of Revolutionary War hero General Daniel Morgan. Its pentagonal design and robust structure were intended to bolster coastal defenses following the War of 1812.

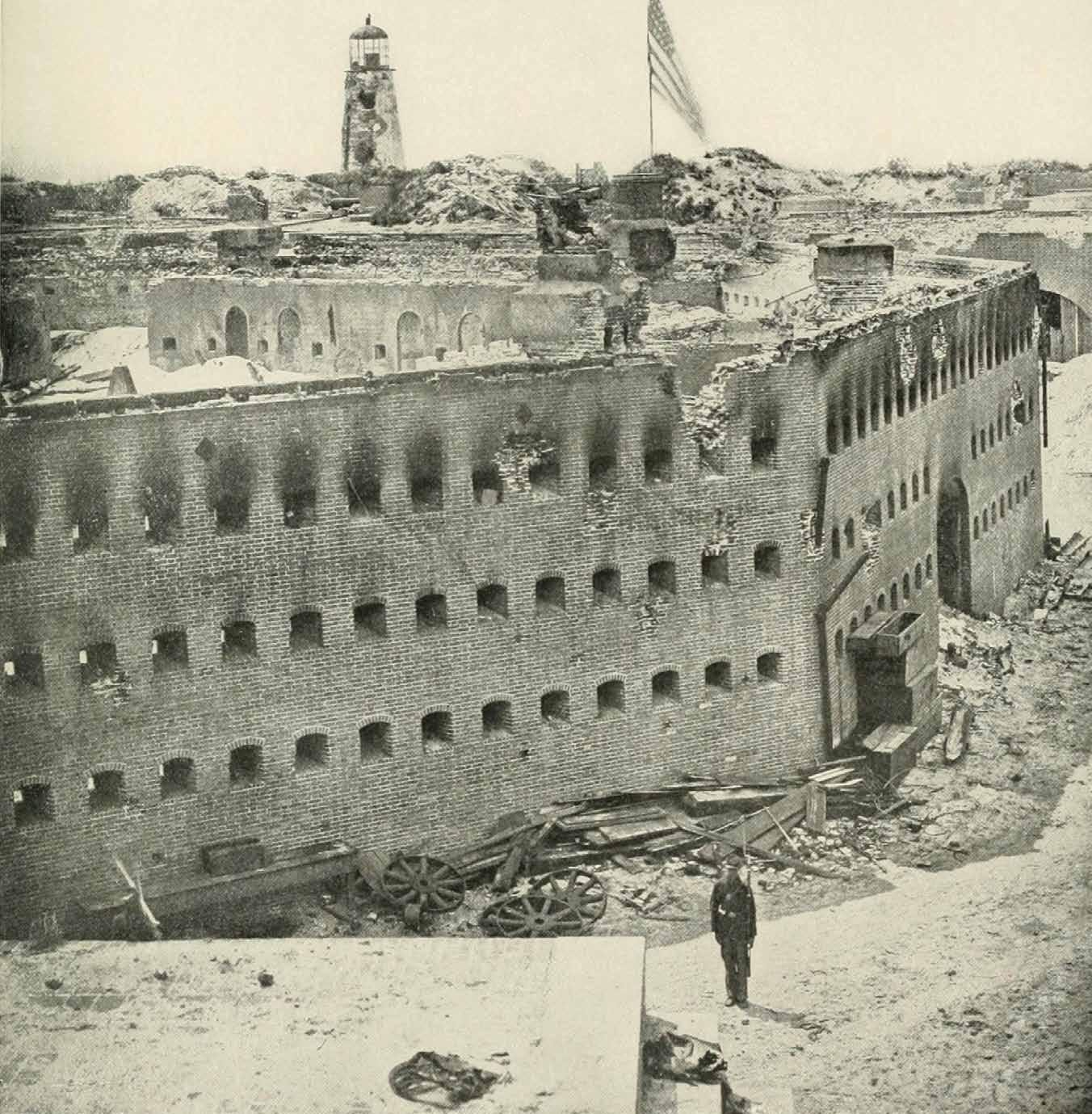

The Fort’s significance is perhaps most prominently highlighted during the Civil War, particularly in the Battle of Mobile Bay in August 1864. Union Admiral David Farragut led a daring naval assault against Confederate forces, famously declaring, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” This decisive engagement led to the Union’s control over Mobile Bay, a critical Confederate port.

Beyond the Civil War, Fort Morgan played roles in subsequent conflicts, including the Spanish-American War and both World Wars. Its strategic position made it a focal point for coastal defense and military training activities. During World War II, enemy submarines patrolled the Gulf of Mexico, threatening vital shipping lanes. Notably, German U-boats, such as U-166, operated in these waters, underscoring the Fort’s continued importance in coastal defense.

The preservation of Fort Morgan owes much to the dedication of William Temple “Hatchett” Chandler. Serving as the Fort’s custodian from World War II until 1957 and as secretary of the Fort Morgan Historical Commission, Chandler was instrumental in developing the site into a historical park. His efforts in restoring the Fort and promoting its history have left an indelible mark, ensuring that visitors today can experience this piece of American heritage.

Today, visitors to Fort Morgan can explore its well-preserved structures, including the original brickwork, artillery batteries, and the museum that houses artifacts spanning its operational years. Walking through its corridors and ramparts offers a tangible connection to the past, providing insight into the Fort’s role in shaping the region’s history. As a designated National Historic Landmark, Fort Morgan serves not only as a monument to military engineering but also as a reminder of the complex narratives that have defined the Gulf Shores area. Its enduring presence continues to educate and inspire, offering a window into the coastal defenses that once stood as the nation’s guardians.

Top left: 2024, aerial of Fort Morgan

Top Right: 1817, “Plan of a Fort projected at Mobile Point”

Bottom:1864, view of parapet, looking north, showing Union Fleet at Mobile Bay

1864, Fort Morgan after the Battle of Mobile Bay

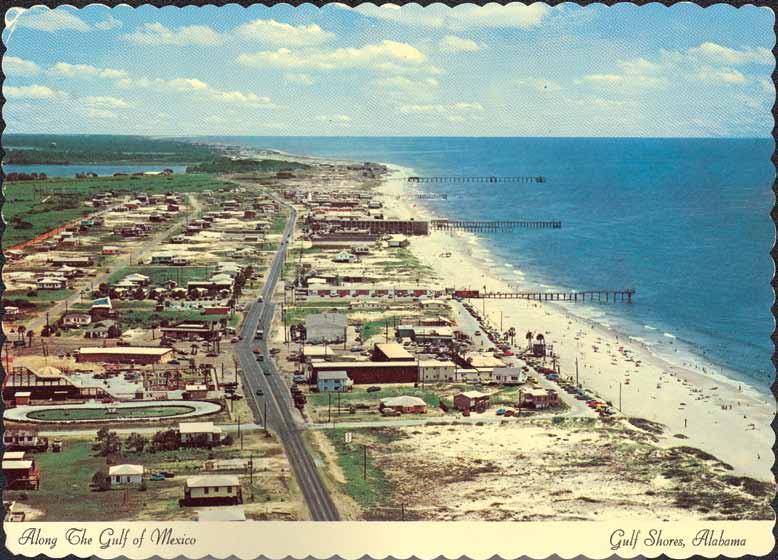

1950s, beach, looking eastward

George C. Meyer A

Founding Visionary

George Charles Meyer, born on September 21, 1878, in Minnesota, was the son of German immigrant parents, Christopher Meyer and Caroline Rosine Sophie Blume. With a spirit of adventure and a dream to create a coastal paradise, Meyer embarked on a remarkable journey that would forever shape the history of Alabama’s Gulf Coast. Meyer’s early life in Le Sueur, Minnesota, gave little indication of the transformative impact he would later have on Baldwin County, Alabama.

Meyer’s vision for Gulf Shores began in 1921 when he established the first homestead south of Little Lagoon in what was then a nearly uninhabited region. Described as a “visionary” and a “man ahead of his time,” he dreamed of building a world-class resort destination rivaling the great spas of Europe. Touring the lush coasts of Florida before heading west to Alabama, Meyer envisioned a family-friendly beach community where people could live, play, and thrive.

Meyer’s foresight extended beyond private development. He was instrumental in the establishment of Gulf State Park, recognizing that state ownership of land would lead to the construction of vital infrastructure. He donated approximately 1,000 acres—about one-sixth of the park’s total area—and provided funds to assist in its development. This effort not only protected the natural beauty of the area but also laid the groundwork for accessibility and sustainable growth.

Access to Gulf Shores in those early days was challenging, restricted to a pontoon barge at the southern end of what was then Highway 3. Despite these limitations, Meyer pressed on, acquiring and developing land to create a thriving community. His wife, Erie Hall Meyer, was equally committed to his dream, and after his passing on February 1, 1959, she continued his work, ensuring the growth of Gulf Shores as a vibrant coastal town.

George C. Meyer’s legacy is an integral part of Gulf Shores. From the land he donated to the dreams he pursued, his vision continues to shape the Community’s foundation. When residents and visitors worship, study, or play in Gulf Shores, they do so on the very soil and sand that Meyer and his family generously provided to help build a better future.

Meyer’s contributions were not only transformational for Gulf Shores but also for Alabama’s Gulf Coast, solidifying his reputation as a humanitarian and visionary whose impact endures to this day. He is laid to rest with his wife, Erie, in a mausoleum at Pine Rest Cemetery in Foley, Alabama. His remains were moved there in the early 2000s, further honoring the legacy of innovation, generosity, and community building he left behind.

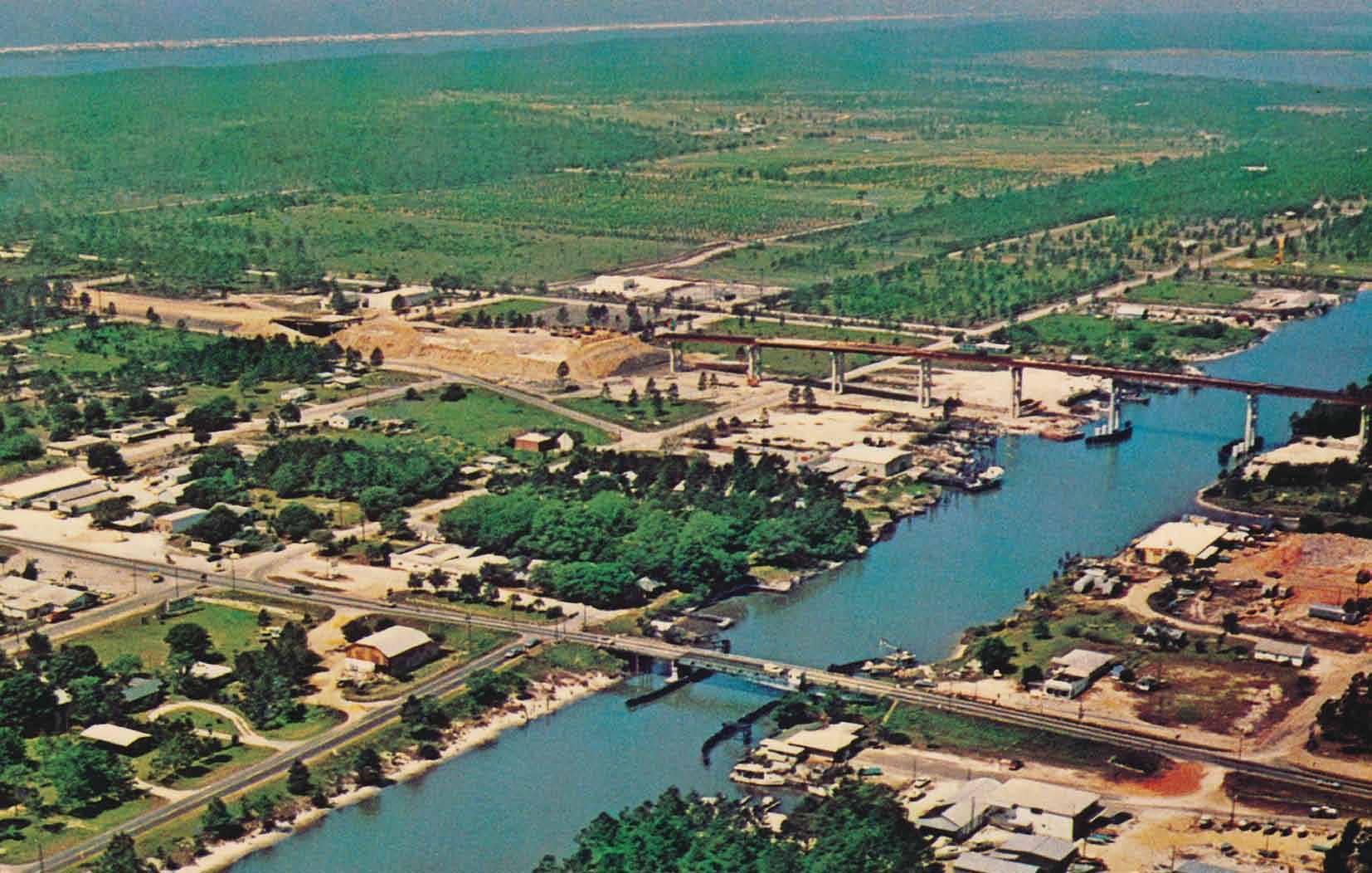

Intracoastal Waterway

The creation of the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) was a milestone in the history of Gulf Shores, reshaping both its geography and its economic future. The waterway was envisioned as part of a broader national effort to develop navigable inland routes along the coast, offering both commercial and recreational opportunities. George C. Meyer played a critical role in bringing the ICW to life. He worked in close collaboration with the federal government, granting a perpetual lease for the necessary land and championing the project’s potential to connect Gulf Shores to state and national resources.

Construction of the ICW was completed in 1937 at a cost of $443,000, drawn from an allocated $600,000 budget. This monumental effort linked Mobile Bay, Bon Secour Bay, and Oyster Bay to Wolf Bay and Perdido Bay, effectively altering the landscape. The new waterway separated two sections of land from the mainland, creating Pleasure Island—now home to Gulf Shores and Orange Beach—and Plash Island, a smaller area named after the Plash family, who were prominent in local shrimping and fishing industries.

While the ICW’s original purpose was to facilitate commercial shipping, enabling barges to transport petroleum, foodstuffs, building materials, and manufactured goods, it has since evolved into a favored route for recreational boating. Today, it stands as both a functional waterway and a testament to forward-thinking initiatives that laid the groundwork for Gulf Shores’ development. Meyer’s efforts to secure the project ensured that Gulf Shores was positioned for growth, connecting the region to vital state and federal resources that spurred its transformation into a thriving coastal community.

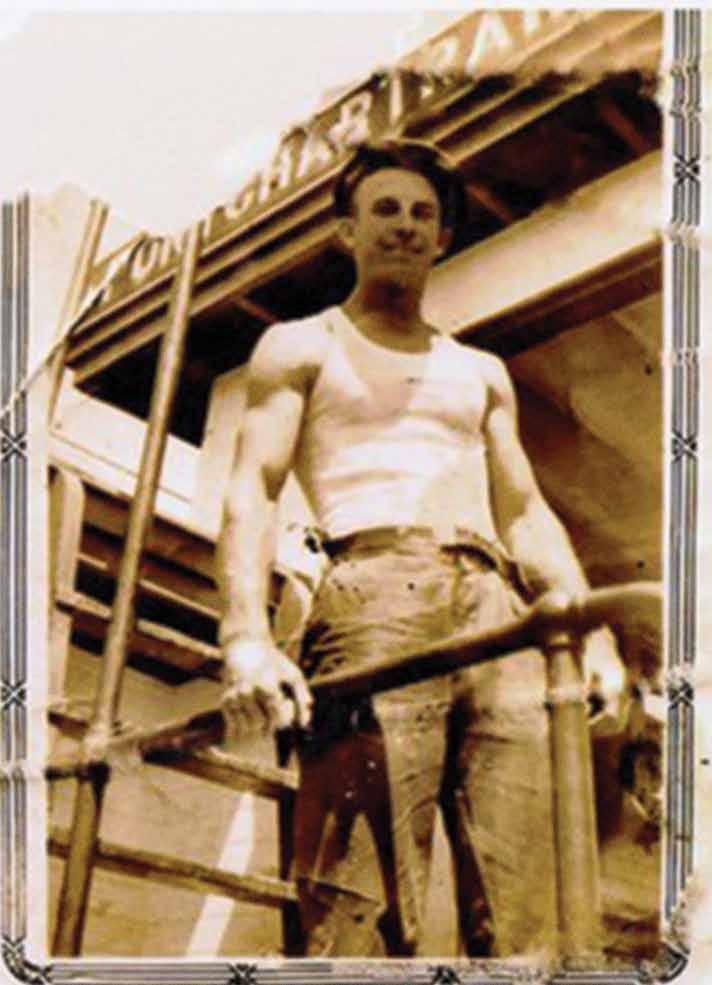

Center: 1933-1937, the Dredge Ponchatrain which was used to build the Canal Top: 1933, Joseph Quilliber working on the Dredge Ponchatrain during the building of the Intracoastal Waterway which opened in 1937

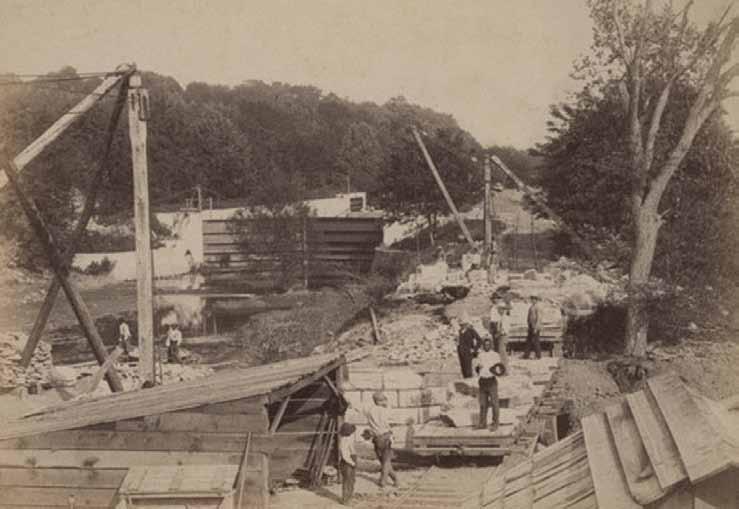

Bottom: 1930s, construction on the Intracoastal Waterway

Above:1980s, originally built for commercial use, the Intracoastal Waterway gradually became a route for recreational boaters alongside commercial barges

Opposite page: 1980s, Intracoastal Waterway, looking westward towards Oyster Bay

Mr. Meyer was 70-plus years of age, and I was a high school student. I would listen and learn. How grateful I am for his faith in me. He taught me to love Gulf Shores and to work for it. He urged me to always learn, to continue my education, to ask intelligent questions, and to give back to the community.

I went to work for Mr. Meyer when I was just sixteen, living in Mobile. For three years, I worked every weekend and all summer long. I would come to his office, eager to help and absorb everything I could—watching and learning. I felt like a young Italian painter at the foot of Michelangelo as he began his masterpiece.

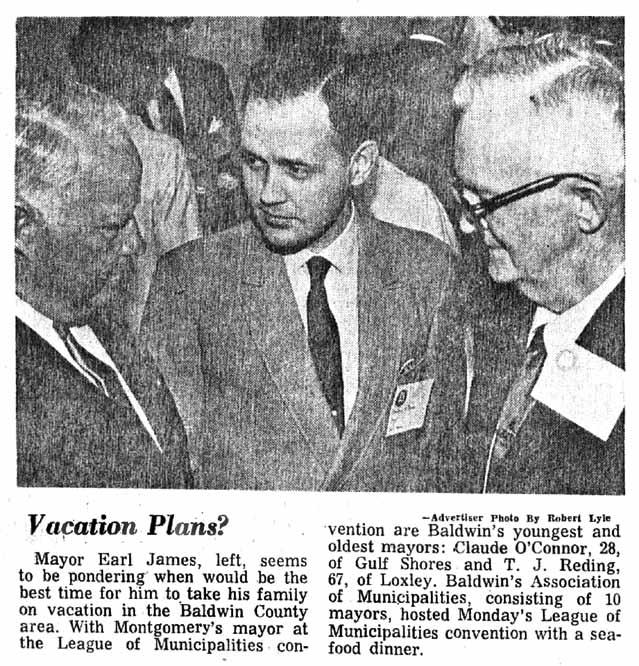

When I was elected mayor of Gulf Shores at the age of twenty-seven, John Watkins, then Executive Director of the Alabama League of Municipalities, summoned me to Montgomery. He appointed me to both the League’s Executive Committee and Legislative Committee, where I learned how to write bills and shepherd them into law.

I worked furiously on submitting bills to annex additional territory into Gulf Shores— though I never did so without the full agreement of the property owners involved.

My aim was always to build a stronger community, with respect and cooperation at its foundation. Looking back, I realize I wasn’t here a week before the sand landed not only in my shoes—but also in my heart.

—Claude O’Connor Second and youngest Mayor of Gulf Shores (1966-1968) City Councilmember (1972-1982)

Monroe “Mac” McLeod and George C. Meyer

Erie H. Meyer with picture of George C. Meyer in foreground

The Meyer Foundation And

When George C. Meyer passed away in 1959, the City of Gulf Shores had been incorporated for just three years. By then, City Hall, Meyer Park, Johnnie Sims Park, and Wade Ward Park were already part of the growing Town’s identity. In 1953, George C. Meyer established the George C. Meyer Foundation to support the development of Gulf Shores as a thriving family town and vacation destination through significant donations of land and financial resources. After his death, leadership of the Foundation continued under Erie Meyer and her nephew, Wade Ward.

The unwavering generosity of the Meyer and Ward Families provided the foundation for the City’s transformation—from a small beach community into a vibrant, familycentered municipality. Today, the Foundation remains committed to supporting the Gulf Shores community through various charitable initiatives.

The Meyer Foundation has faithfully carried out George C. Meyer’s vision, but just as impactful has been the legacy of community involvement and dedication set by George and Erie. Their generosity shaped much of the City’s landscape, with contributions playing a pivotal role in the City’s growth. Nearly every church in Gulf Shores was built on land donated by the Meyer family. One of their most significant gifts was a 500-foot-wide portion of the City’s public beach at the end of Alabama State Road 59, along with several smaller public beach accesses. The Foundation also provided property for City Hall, the Civic Center, and schools—including the Middle School and Coastal Alabama Community College.

In addition to these civic contributions, the Meyer Foundation helped preserve the City’s natural beauty. The family donated 1,000 acres of beachfront to what is now Gulf State Park and provided land for the Gulf Shores Golf Course. The City’s industrial park was made possible through a donation of approximately 100 acres, while numerous public parks—including Meyer Park, Johnnie Sims Park, Wade Ward Park, and Lagoon Pass Park—were established on land gifted by the family. The Foundation also played a key role in developing the City’s infrastructure, making significant monetary contributions to the

Erie H. Meyer

construction of both the Civic Center and the Recreation Center, and funding the installation of street lights on the Intracoastal Waterway bridge.

Beyond these substantial gifts, the true legacy of the Meyer Foundation lies in the spirit of community service it fostered. Erie Meyer, in particular, demonstrated an enduring commitment to the City through her service on the South Baldwin Board of Trustees and the Gulf Shores Planning and Zoning Commission.

A lasting dream of Erie’s was to establish local schools in the City. For years, she offered Meyer Foundation land to the Baldwin County Board of Education to build schools—a proposal that was finally accepted in February 1977. Her perseverance also led to the creation of the Gulf Shores Middle School and the local campus of Faulkner State Community College. That effort was supported by community members like City Councilmember Claude O’Connor, who persistently petitioned the Baldwin County School Board despite firm resistance from the superintendent. His advocacy eventually led to a federal court case in which Claude stood as the sole petitioner. By 1979, the City had its own county public school—a transformative victory that changed the Town’s future and reflected O’Connor’s personal investment in the well-being of the community. This commitment to education and local control would continue decades later. In 2017, Mayor Robert Craft and the Gulf Shores City Council made another bold move by officially breaking away from the Baldwin County School System to establish the Gulf Shores City School District.

Through the Meyer Foundation and Erie’s steadfast efforts, the City of Gulf Shores has grown into the vibrant, family-centered community envisioned by George C. Meyer. Under Wade Ward’s leadership, the Foundation continues to invest in the City’s future, ensuring that Gulf Shores thrives for generations to come. The unwavering generosity of the Meyer and Ward Families provided the foundation for a strong, connected community—one that continues to benefit from their vision and dedication.

• Lots for almost every church in Gulf Shores

• A 500-foot wide portion of the City’s public beach area at the end of Alabama State Road 59, and several smaller public beach accesses elsewhere

• Property for the Gulf Shores City Hall complex, Civic Center, Elementary School, Middle School, and Coastal Alabama Community College

• 1,000 acres of beachfront in Gulf State Park

• Land for the Gulf Shores Golf Course

• About 100 acres of the City’s Business and Aviation park

• Land for the City’s public parks which included: Johnnie Sims Park, Wade Ward Nature Park, Meyer Park, and Lagoon Pass

• Significant monetary contributions to build the Civic Center and Recreation Center

• Street lights for the Intracoastal Waterway Bridge M E y E r FAM i L y C ONT ri B u T i ONS

1946, Big Casino shown, which was part of the Gulf State Park, not to be confused with the Little Casino which was privately owned by a local family. (In the 1950s, the word “casino” did not always refer to a gambling establishment as it does today. Instead, it often referred to a social club, music hall, or entertainment venue where people gathered for recreational activities.)

Gulf State Park A Legacy

of Vision, Leadership, and Preservation

Gulf State Park stands as a testament to visionary leadership and determination, beginning with George C. Meyer’s dream to preserve Alabama’s pristine coastline. Recognizing the importance of public access and environmental protection, Meyer donated nearly 1,000 acres of beachfront land—approximately one-sixth of the Park’s total acreage—and provided financial support to assist the State in its development. His foresight extended to the understanding that state ownership would spur much-needed infrastructure improvements, such as roads to access the parkland.

According to Erie Meyer, “One of the most difficult things George Meyer ever did was persuading the State Legislature to create a state park out here, because they couldn’t understand why he was so determined. George said the day will come when you will understand.” Meyer’s year-long effort to persuade the Legislature to accept his donation laid the foundation for Gulf State Park’s creation. Once the State embraced his vision, they acquired additional property, and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was brought in to develop the Park. By 1939, Gulf State Park was completed, becoming a centerpiece of Alabama’s Gulf Coast and a transformative force in the development of Gulf Shores.

The Park’s growth and success owe much to the long-term dedication of its leaders. In 1942, Monroe “Mac” McLeod, a high school teacher from Wedowee, accepted a summer position as the Park’s manager. Although initially planning to return to teaching, McLeod and his wife, Thelma, fell in love with the area and decided to stay. McLeod became Gulf State Park’s first superintendent, a role he held for 34 years. Under his stewardship, the Park flourished and became so popular that by 1944, its revenue supported the majority of Alabama’s state park operating costs.

In the late 1960s, Governor Lurleen Wallace sought to elevate Alabama’s parks to rival the state park resorts of Kentucky. Her push for legislative support led to a bond issue in 1967, resulting in significant enhancements to Gulf State Park. These included the Fishing Pier, Campground, Golf Course, Beach Pavilion, and eventually a hotel. Though Governor Wallace passed away before witnessing the Park’s transformation, her vision left a lasting legacy.

When McLeod retired in 1976, Hugh Branyon assumed the role of superintendent. Over his tenure, the Park faced numerous challenges, including hurricanes and a devastating fire, yet it consistently rebounded with new improvements. Branyon’s leadership also oversaw the development of the Park’s extensive trail system, which took decades to complete due to competing priorities.

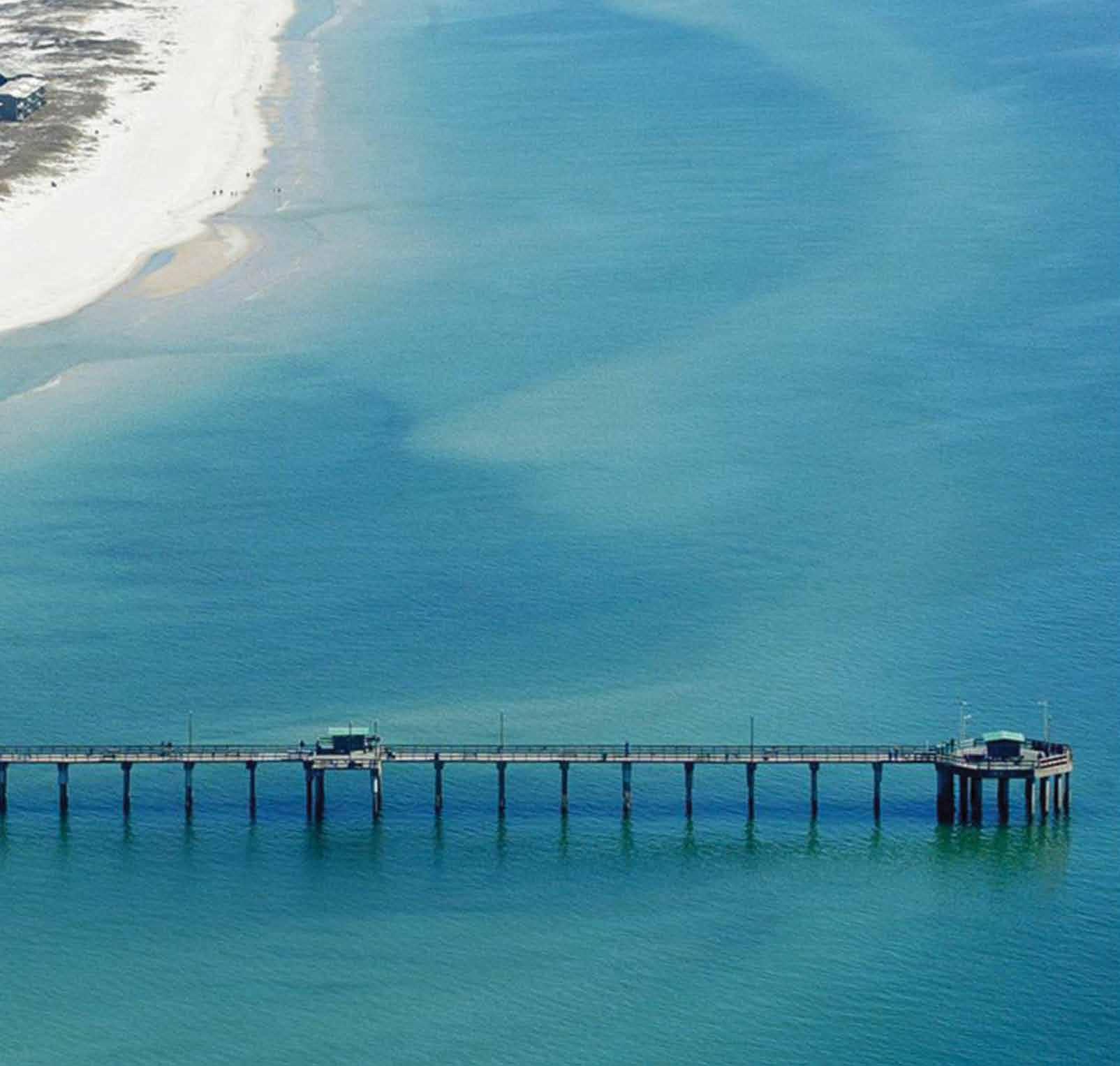

The Hugh S. Branyon Backcountry Trail, named in his honor, spans approximately 29 miles across 6,180 acres within Gulf State Park. For the third consecutive year, it secured the number one spot in the 2025 USA Today 10 Best Readers’ Choice Awards.

In 2004, Hurricane Ivan destroyed the original Lodge at Gulf State Park. After years of planning and redevelopment, it reopened in November 2018 under Hilton’s management as The Lodge at Gulf State Park, a Hilton Hotel. The new eco-friendly facility, featuring 350 guest rooms, now serves as a centerpiece of the Park’s commitment to sustainability, education, and public access. Today, Gulf State Park has evolved into a world-class destination, offering the largest pier on the Gulf of Mexico, an environmentally conscious Lodge and Conference Center, and innovative educational programs that highlight the region’s fragile ecosystem.

The Park’s continued success is a reflection of visionary leadership. As Gary Ellis retired in 2022 from his role as Director of Community Relations and Administration, Matt Young joined the Alabama State Parks Division to continue that legacy. Since 2019, Ellis had served as a community liaison for Gulf State Park, helping coordinate the establishment of The Lodge, assisting in the planning of new amenities, and working to position the Park as an international ecotourism destination. His leadership fostered strong connections between the Park, the local community, and hotel management, ensuring it remains an integral part of the City’s identity. Gulf State Park’s creation and growth honor the dedication of individuals like George C. Meyer, Mac McLeod, Hugh Branyon, and Gary Ellis—whose lasting efforts have preserved this natural environment for generations to come.

• 1933, construction began on the Gulf State Park led by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and it officially opened May 20, 1939

1967

• Governor Lurleen Wallace received legislative approval for bond money to turn Gulf State Park into a resort park

1968

• 825-foot saltwater pier added 1972

• 468-site campground, 18-hole golf course, and beach pavilion additions 1974

• 144-room Gulf State Park Hotel/Convention Center opens

• Hurricane Frederic destroyed all the CCC built lakeside cabins

•New lakeside cabins and a store was added

• Hurricane Ivan destroyed pier and hotel, damaged the cabins, and flooded entire park 2006

• 11 new 3-bedroom cottages, 2 playgrounds, and new saltwater pavilion open 2007

• Hugh Branyon Trail opened; the old Gulf State Park Hotel was demolished and rubble used to create an artificial reef in the Gulf; plus new parking and bathrooms at Romar Beach, Cotton Beach, and Florida Point access

• New 1,540-foot-long saltwater fishing pier

•

and

• The Lodge at Gulf State Park opens along with the Park’s new Conference Center and three restaurants. The new lodge was managed by Hilton Hotels, the eco-friendly facility features 350 guest rooms and marks a major milestone in Gulf State Park’s commitment to sustainability and public access. 2019

• Eagle Cottages designated as part of National Geographic’s Unique Lodges of the World

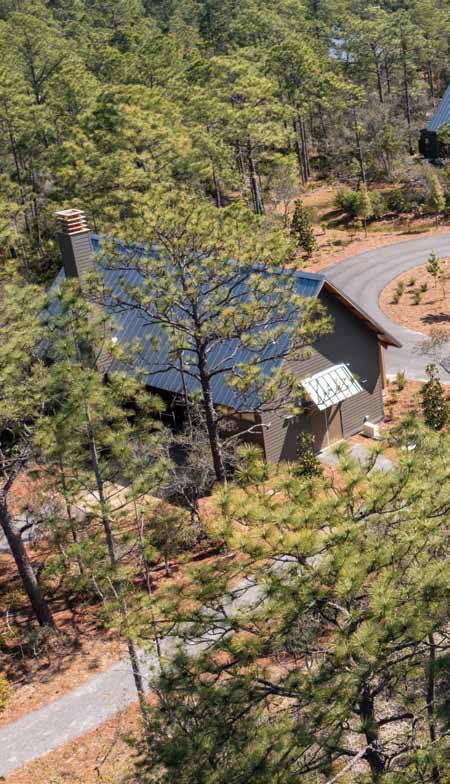

1950s, original entry building to Gulf State Park, which still stands today

Above: 1980s, aerial view of Gulf State Park Resort and Convention Center which officially opened in 1974

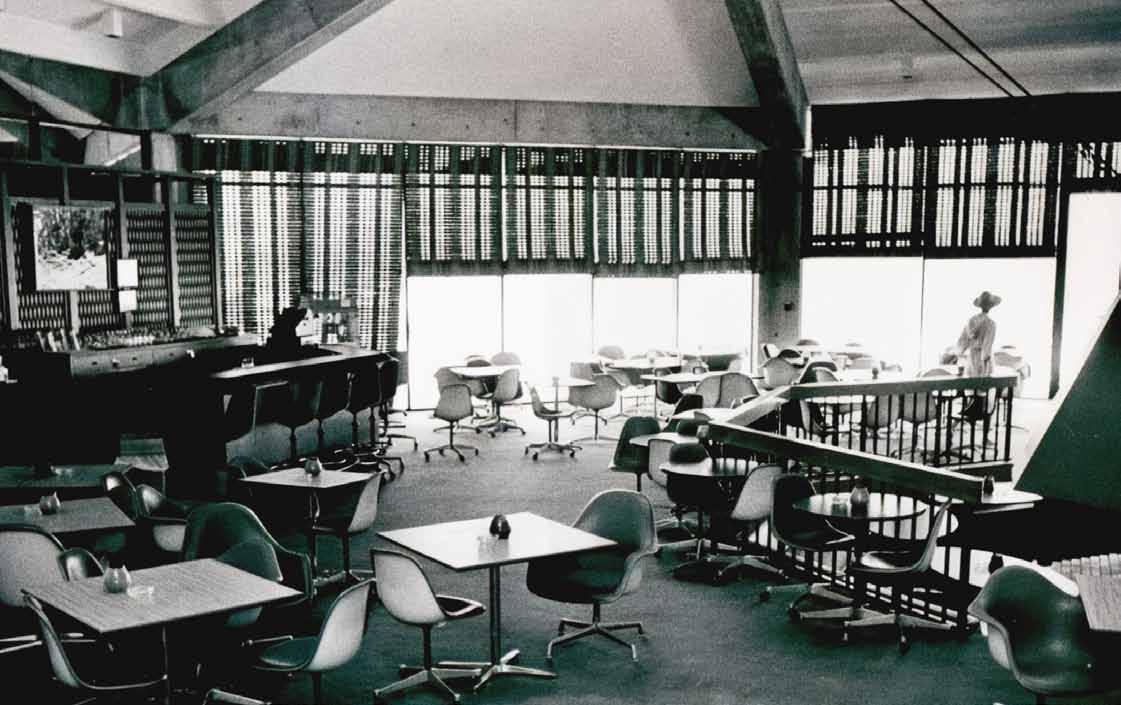

Left: 1980s, Gulf State Park Resort Dining Room interior

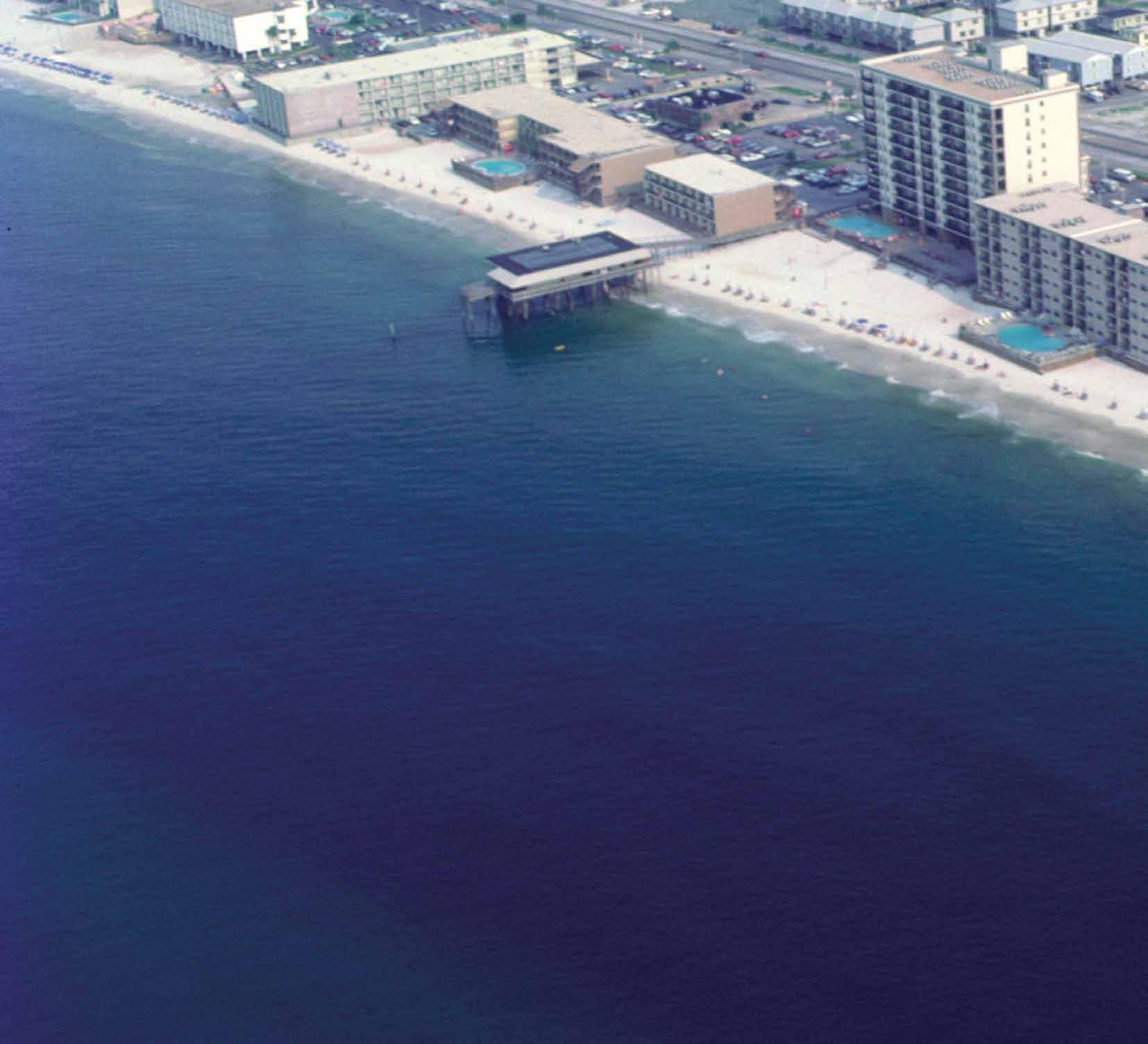

1980s, aerial view of Gulf State Park Pier, Resort and Convention Center

Opposite page: 1950s, Dr. Oswald’s home on beach shown with windmill

Above: 1950s, Gulf Shores Hotel

1970s, Gulf Shores Post Office, the first Gulf Shores Post Office opened in 1947

In January 1965, the Lions Club Park and Recreation Society of Gulf Shores deeded the land— originally gifted to them by George C. Meyer in January 1954—to the town of Gulf Shores for $10.00. The Community House on this land became a central gathering place for local events, including early church services such as those of St. Jude’s by the Sea Lutheran Church, which held Sunday worship there until moving into its own building in 1984. The Community House also hosted the first Gulf Shores Town Council meeting on February 5, 1957.

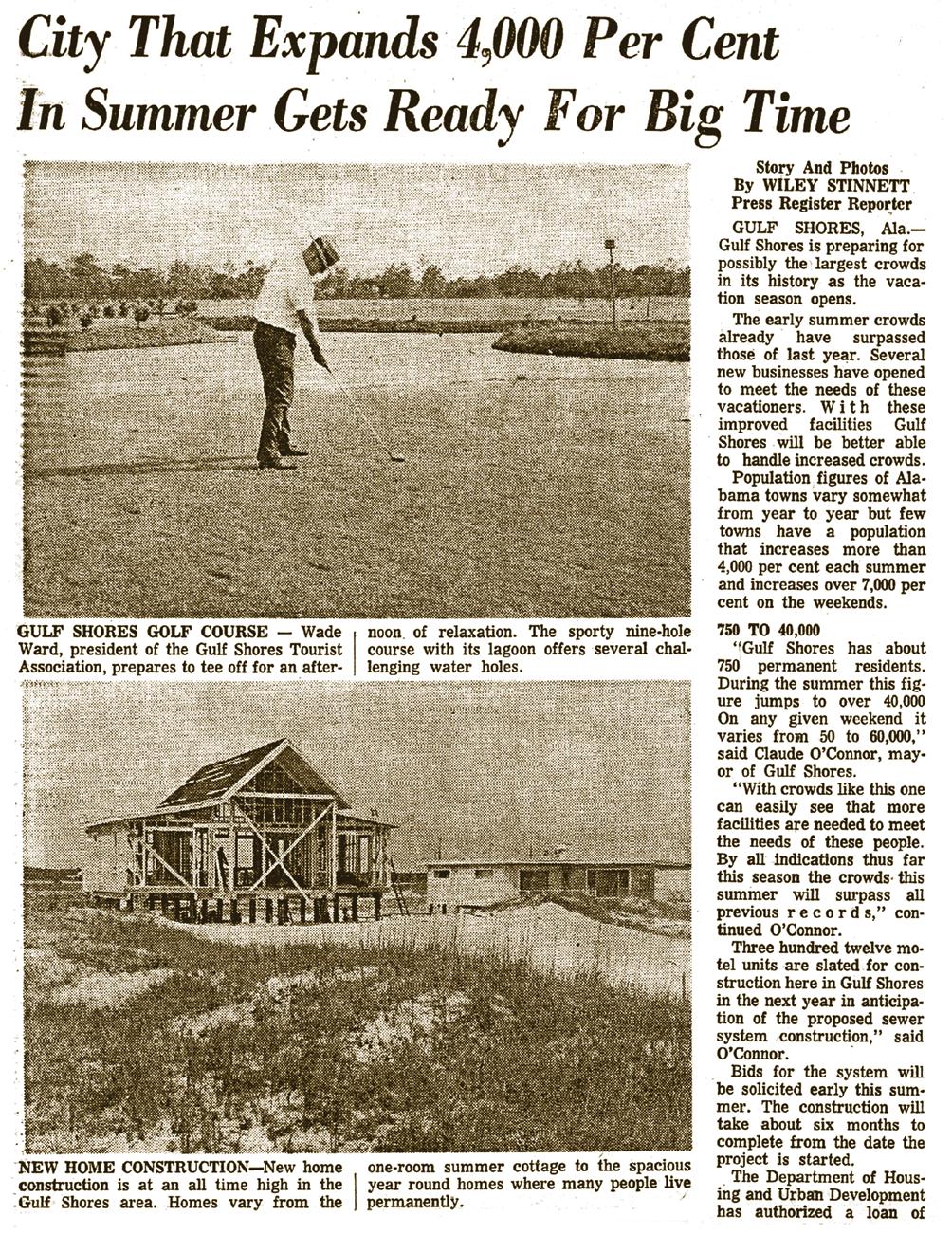

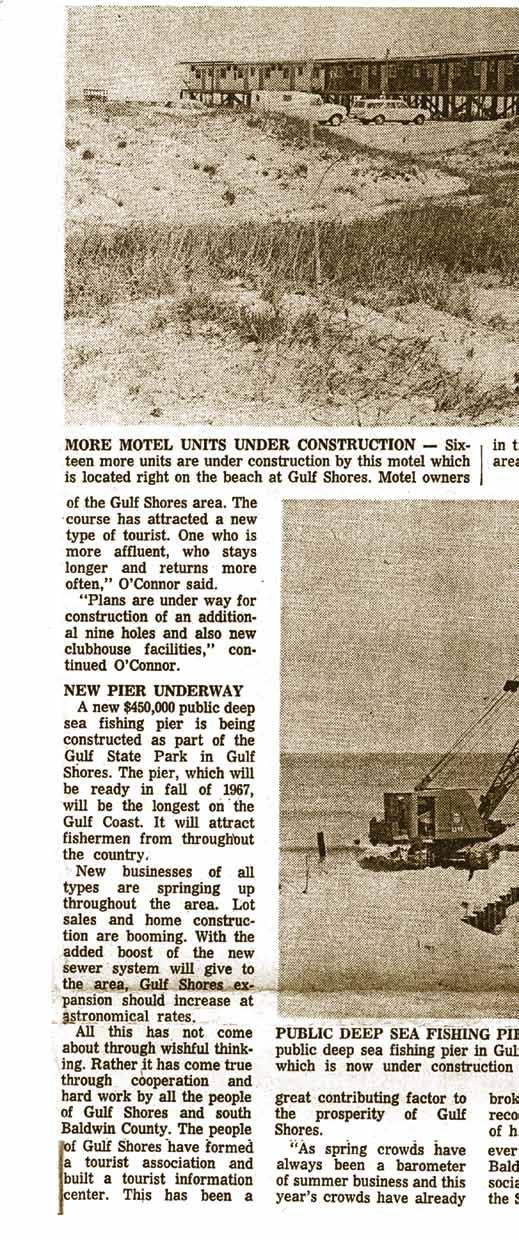

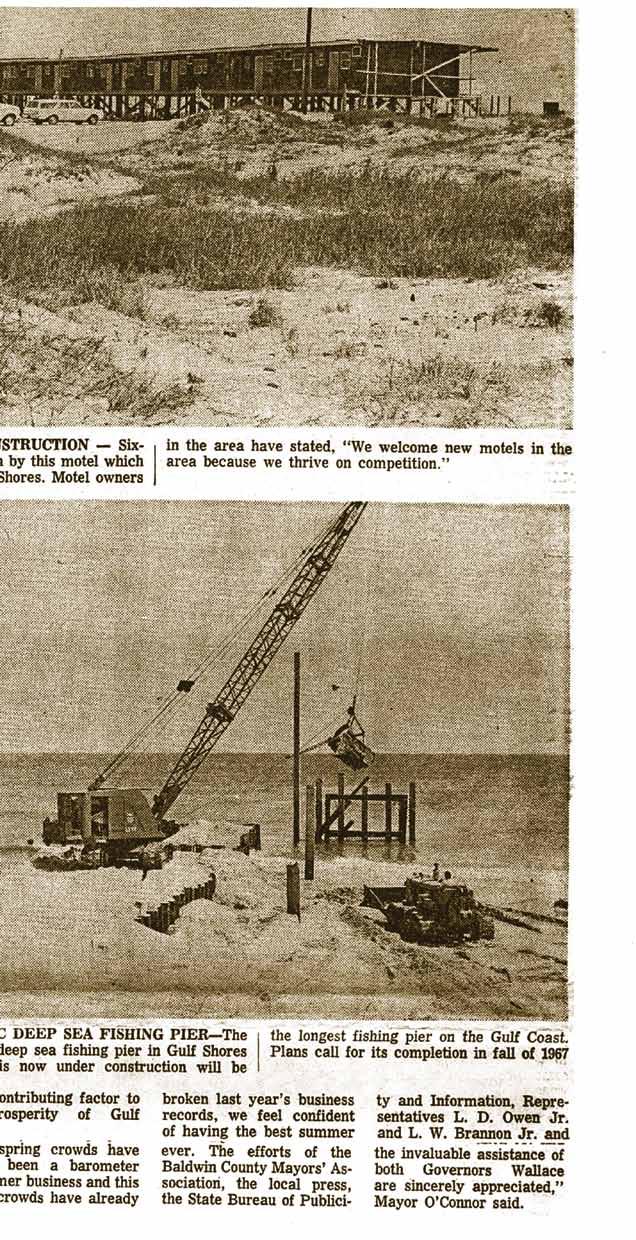

1967, Foley Onlooker

1950s, Little Casino, looking northeast

1950s, Little Casino, looking southeast

1960s, Gulf Shores Fire Department vehicles

Fire Department Gulf Shores

The Gulf Shores Fire Department has evolved in step with the city’s remarkable growth, transforming from a volunteerrun operation into a fully staffed, modern emergency service.

In 1978, Hartley Brokenshaw joined the department as a volunteer, one of two dozen dedicated men who responded to fires with only a siren alert and a phone call to an operator for details. They would converge at the fire station on East 22nd Avenue, where the engine was kept in a shed behind the main building.

That same year marked a significant turning point with the hiring of Tommy Thompson and Ed Curott as the department’s first paramedics. Their arrival was made possible by a state grant that also funded the purchase of a rescue vehicle—Baldwin County’s only unit equipped with the Jaws of Life. Alongside the efforts of the Pleasure Island Rescue Squad and an old ambulance operated by the local Lions Club, these additions ushered in a new era of professional emergency response. Over time, the various groups merged, creating a more unified and effective emergency service for the Gulf Shores community.

The early volunteers exhibited extraordinary commitment, often spending long nights battling fires only to report to their regular jobs the next morning. During Hurricane Frederic, the department had only a single engine, a tanker, a chief’s car, and one ambulance—but even with those limited resources, they met the growing city’s emergency needs with determination and grit.

By the 1990s, Gulf Shores had officially transitioned to a full-time fire department, though volunteer firefighters continued to serve until 2018. Today, the department operates from four fully equipped, modern fire stations that house engines, ladder trucks, rescue vehicles, brush trucks, and

specialized boats for accessing hard-to-reach areas. In peak season, the department expands to a workforce of approximately 90 personnel, reflecting both the City’s expansion and its commitment to public safety.

The City had recently constructed a new state-of-the-art training facility that includes live fire buildings, a combat training tower, and dedicated areas for trench and confined space rescue training. This facility is essential for the department to maintain its ISO Class 1 Rating—one of the highest honors a fire department can achieve nationwide. Today, in addition to fire suppression, nearly all department personnel are certified as Emergency Medical Technicians or Paramedics, enabling them to provide advanced medical care at the scene. The department also operates its own ambulance and frequently assists when local services are overextended.

Gulf Shores Fire Rescue further supports the community with trained open-water lifeguards, ensuring safety in the Gulf of Mexico and surrounding waterways.

A central figure in this legacy of service was Joseph L. McClusky, who dedicated over four decades to the City of Gulf Shores as both a realtor and the chief of the Gulf Shores Fire Department. In honor of his enduring service, the City of Gulf Shores named its flagship facility the Joseph L. McClusky Fire Station No. 1. Standing proudly at the front of the station is a statue of a firefighter—a powerful and lasting tribute to the courage, service, and sacrifice of those who have served in the Gulf Shores Fire Department. The statue not only honors Chief McClusky’s legacy but also serves as a symbol of the department’s journey from its volunteer roots to the highly trained, fully equipped emergency response team it is today.

Back then, it was just a handful of us, and we did whatever it took to get the job done. We didn’t have the manpower or resources, but we made it work. One of us drove the engine, the other the rescue unit, and we got started the best we could until help arrived — usually the volunteer firefighters from across the community. The old fire siren on the water tower would wail — so loud and unmistakable, you learned to listen for it. We covered everything from Fort Morgan to the Florida state line, even up into Bon Secour.

Many homes didn’t have addresses. People gave directions using landmarks — ‘two houses past the anchor on Fort Morgan Road’ — so we’d just start heading in that direction, hoping to find it.

Getting our first ladder truck in the early ’80s, a 1957 Mack truck, was a big deal. Before that, if a building was too tall, we got creative with extension ladders and whatever we had. We probably took risks that wouldn’t be allowed today, but we learned to be resourceful, and in the end, it made us better at what we did. We took chances, but we had each other’s backs, and we always found a way to get the job done.

1970s, the Lions Club operated an ambulance service which added to the very limited emergency response services that were available at the time

—Gary Sinak Retired Battalion Chief, Gulf Shores Fire Department (1980-2014), City Councilmember (2016-present)

Gulf Shores

Police Department

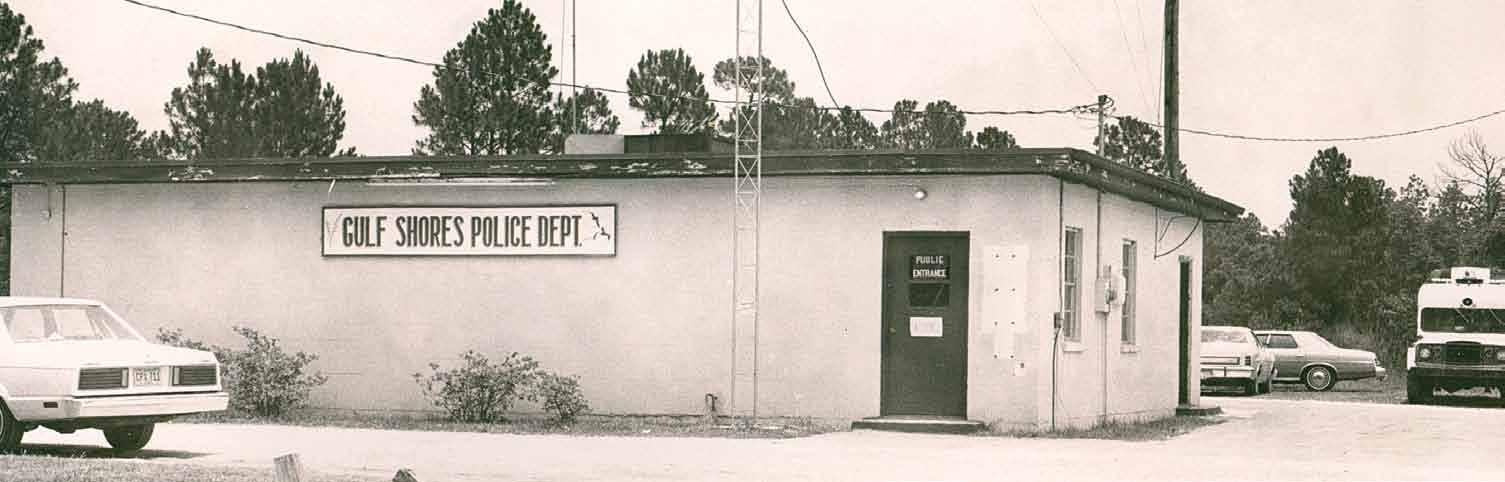

The Gulf Shores Police Department’s history is rooted in the growth of the City itself, with its first steps towards public safety taken in the early 1950s. Joe Smith, Gulf Shores’ first policeman, was hired in 1952 at a salary of $375 per month. Patrolling in his own car and wearing a donated uniform, Smith laid the foundation for what would become a dedicated and expanding police force. In 1953, Floyd Phillips was appointed as the City’s first police chief, marking the beginning of a more structured police department. At the same time, Gulf Shores established a volunteer fire department, further strengthening the City’s public safety efforts.

It wasn’t until nearly a decade later that the Police Department transitioned to a 24/7 operation. Over the following decades, the department continued to evolve in response to the City’s rapid growth, much of which centered around its popularity as a tourist destination. For over 20 years, Gulf Shores’ police and fire services covered an expansive area, stretching from Fort Morgan to the Flora-Bama and north to County Road 10. In the early years, summers brought an influx of visitors and, with it, higher demand for law enforcement, while winters remained quieter.

Arthur Bourne, who served as Gulf Shores’ Police Chief for 28 years and worked under six mayors, reflects on the department’s growth. “The Police Department grew with the City,” he says. “It did a good job of maintaining

Gulf Shores’ family-friendly atmosphere.” As the City’s population expanded and tourism grew, the department faced the unique challenge of balancing law enforcement with fostering an environment where visitors could enjoy themselves while ensuring public safety. Bourne recalls, “It’s a fine line to walk—enforcing the law, providing safety, and letting people enjoy themselves. As long as they didn’t infringe on someone else’s rights or cause a commotion, we’d work with them.”

Today, the Gulf Shores Police Department continues its mission to ensure the safety of both residents and visitors. The Department’s focus on community-oriented policing is reflected in initiatives such as the Gulf Shores Police Association, which strives to foster public support and raise awareness about the Department’s services. The Department remains committed to improving the quality of life for Gulf Shores’ citizens by providing a safe and secure environment. The City’s rapid development, coupled with its status as a major tourist destination, has shaped the Department’s role. Looking to the future, the Gulf Shores Police Department continues to prioritize the safety and well-being of the community, all while maintaining the welcoming, family-friendly atmosphere that has long defined this beloved coastal town.

Opposite page: 1970s, Gulf Shores Police Department Above: 1960s, Gulf Shores Police Car

From Barge to Bridge

Connecting Gulf Shores

With the completion of the Intracoastal Canal, Foley and Gulf Shores finally had a direct link—though its first iteration was far from conventional. A cement-filled barge on Old Highway 59 served as a makeshift bridge, relying on hand-operated winches to swing open for passing boats. Concrete ballast helped raise aprons at either bank, creating temporary barriers for traffic.

By the mid-1950s, the barge was replaced with a cantilever bridge powered by a V-8 Ford engine. This new design allowed the bridge to rotate on a turntable, enabling the tender to swivel it open whenever a boat approached. Tugboats, shrimp boats, and sailboats signaled their need to pass by sounding their horns three times, about a halfmile from the bridge. However, the bridge soon became notorious for mechanical failures—if it didn’t close properly, traffic came to a standstill. On busy summer weekends, cars often stretched for more than a mile, with drivers waiting an hour or longer for the bridge to reopen. Bridge operators worked tirelessly to keep traffic moving, though the job came with its share of challenges. Evelyn Sanders, whose husband was hired as an operator, recalled the constant worry that came with every malfunction: “If that bridge broke down and an ambulance was on the other side, you could just die,” she said. For locals, the unpredictable bridge was simply part of life. City Clerk Lois Gale Walker frequently traveled to Foley, “never knowing whether the bridge would be open or closed,” recalled Claude O’Connor. When it stalled, residents found creative solutions, including calling the police chief from a nearby business to intervene. Joe Garris remembered times when the drawbridge was so severely jammed that prisoners were brought in to crank it open by hand using a T-handle. Yet it wasn’t just inconvenience that ultimately led to the bridge’s replacement—it was also a bit of clever planning and local advocacy.

During the governorship of Lurleen Wallace, momentum began to build for a new bridge. Wade Ward, a civic-minded local leader and nephew of Erie Meyer, played a key role in the effort. He had recently overseen the opening of Gulf Shores’ first official visitor information center— an accomplishment that brought Governor Wallace to the coast for a ribbon-cutting ceremony. Ward picked the governor up from the airport in Foley, setting in motion a coordinated plan he had worked out with Mr. Lee Callaway. As their car approached the swing bridge, Ward radioed ahead, and Callaway contacted a nearby shrimp boat. Soon, the boat made its approach, triggering the bridge to open and leaving the governor and Ward stuck on the north side under the blazing summer sun. With the car heating up and cigarettes burning, Wallace asked about the delay. Ward seized the moment to describe the bridge’s constant mechanical issues, emphasizing the threat it posed to evacuation efforts during hurricanes. After the ceremony concluded, the two returned to Foley—only to encounter the same problem. Callaway had again coordinated a bridge opening, with shrimp boats drifting slowly through the channel. A few days later, the state announced that design and construction for a new bridge on Highway 59 would begin.

Relief finally came in 1972 with the opening of the W.C. Holmes Bridge. Named in honor of Dr. W.C. Holmes, a dedicated physician who had served Foley and Gulf Shores from 1927 until his passing in 1961, the bridge provided a much more reliable connection between the two communities. Its construction also led to the reconfiguration of Canal Road, introducing a sharp 90-degree turn to redirect traffic away from the water.

What had once been an unpredictable and often frustrating journey was now a seamless crossing, forever changing the flow of life between Foley and Gulf Shores.

Opposite page: 1972, City Leaders at the opening of the newly constructed W.C. Holmes Bridge

Above: 1970s, looking westward, W.C. Holmes Bridge under construction in background and old cantilever bridge can be seen in foreground

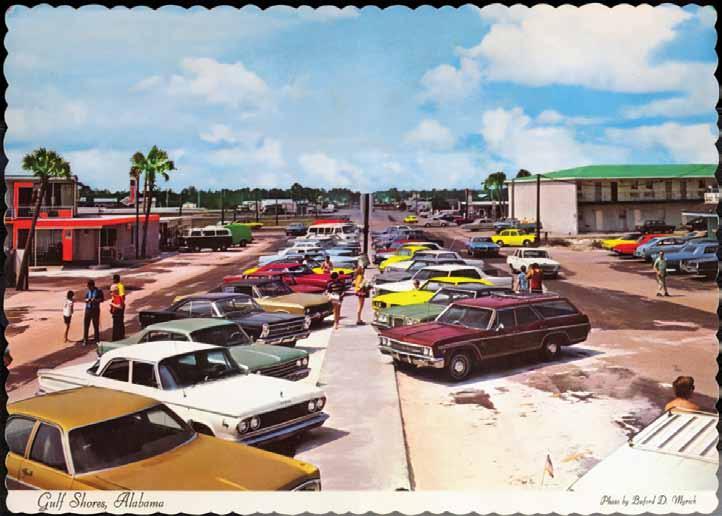

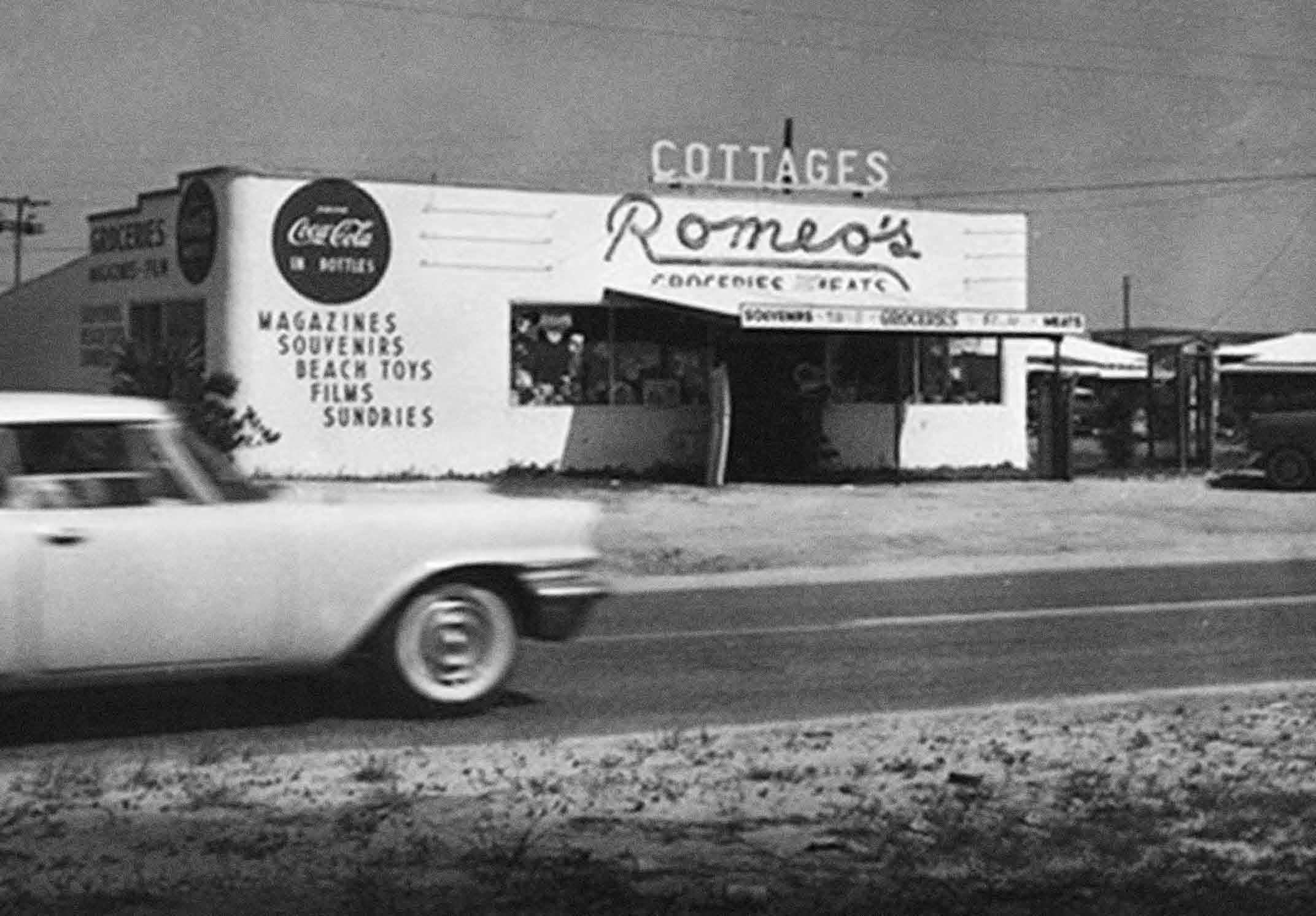

arrival of tourism

In the 1950s, locals built motel-style cottages like Romeo’s and Roberts’ Beach Cottages to accommodate visitors. Pictured in 1950 are Ernest Romeo, Bessie and Harry Roberts, with their son,Victor, shown in the window of the backseat of the car.

Gulf Shores was steadily growing, with more residents choosing to call it home each year. Family-owned grocery stores, restaurants, cottages, and motels created a lively summer playground. But life here was seasonal. As resident Leonard Kaiser described, “We lived life much like farmers. We harvested all we could during the summer and stored it up for the winter to survive until the next season.” Every Labor Day, visitors would leave, and the town would quiet down, leaving only residents until the next Spring Break, when the cycle would begin again. At that time, “snowbirds” had yet to discover the area, as there were few accommodations for them. During the fall, winter, and early spring months, income was scarce, but these were the times when residents worked to build the future of their city.

1960s, Lighthouse Motel

1970s, Oleander Motel

1950s, Romeo’s Restaurant and Cottages on the corner of Highway 59 and Highway 180

1960s, the original Souvenir City, founded by the Weir family

Souvenir City, an iconic Gulf Shores landmark, began as the Anchor Gift Shop—a modest space offering snow globes and postcards—established by Clyde Weir’s mother along Highway 59. In 1959, she passed the business to her son, who expanded it from 1,000 square feet to nearly 34,000 square feet at its peak. The shop’s name was borrowed from a Miami establishment, and its evolution has been shaped by customer demand, property changes, and challenges from hurricanes and fires. Over the years, Souvenir City sold everything from T-shirts and seashells to live monkeys, cayman alligators, and hermit crabs. Weir’s success stemmed from effective merchandising, customer service, and a keen eye for marketing. One of the most memorable additions was a giant seashell, later replaced in 1984 by the now-famous shark entrance inspired by Jaws. This creative touch transformed Souvenir City into a must-visit destination, cementing its status as a beloved beachfront attraction.

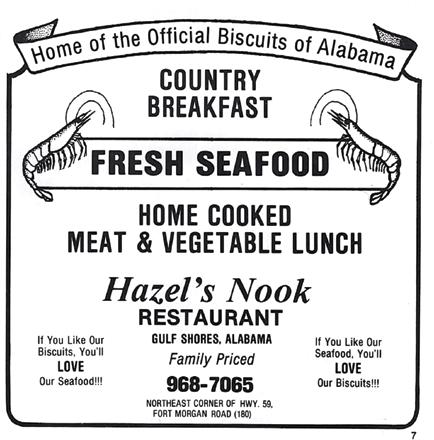

Top: 1960s, Hazel’s Drive-in Botom: 1950s, Pink Pony Pub

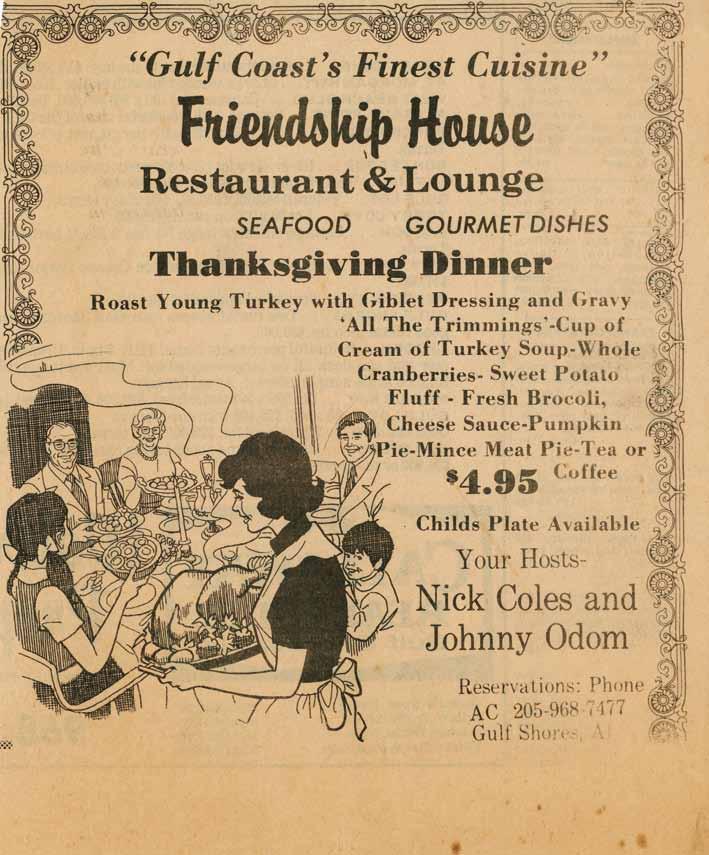

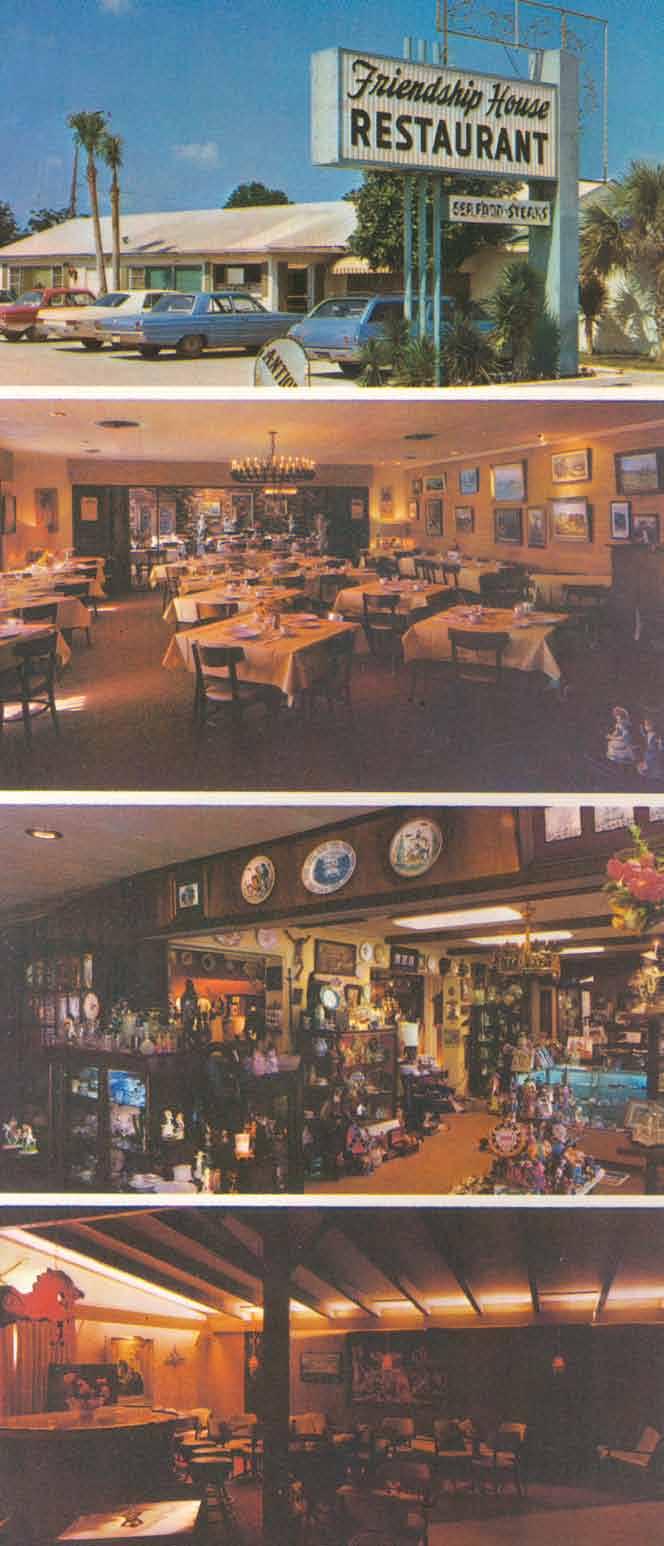

Top, right: 1960s, Friendship House Bottom; 1949, The Dunes

1960s, Hangout, a lively beachfront spot, offering an arcade, dancing, drinks, candy, films, beachwear, and supplies. It became a favorite destination for young beachgoers, reflecting the vibrant coastal culture of the era.

Becoming a City

George C. Meyer envisioned Gulf Shores as a successful family town, emphasizing elements that would attract and sustain families, such as churches, parks, and schools. This vision laid the foundation for what Gulf Shores would ultimately become. Once the area transitioned from scattered family neighborhoods to an official town and later a City, it has remained steadfast in its goal of being a family-oriented place to live and visit.

The journey from small settlements to an incorporated municipality was a lengthy and challenging process. Before World War II and during the Depression, Gulf Shores was characterized by small family clusters and a few families moving from other areas. The 1950s brought change, as new roads, the establishment of a state park, affordable automobiles, and greater family mobility led to an influx of tourists and new residents. Mom-and-pop motels and cottages accommodated visitors, while George C. Meyer and other developers focused on creating neighborhoods for a growing population. By the mid-1950s, these developments spurred residents to take legal steps toward incorporation.

In 1956, the Probate Court of Baldwin County approved a petition for a vote on Gulf Shores’ incorporation as a town. The vote took place on August 28, with 31 ballots cast—18 in favor and 13 against. Judge W. R. Stuart signed the official incorporation of Gulf Shores. Shortly after, the town held its first mayoral election. Johnny O. Sims ran against W.P. Pickett, Jr. Sims won the election by a single vote, prompting a re-vote, which he won by seven votes.

Johnny Sims, a North Alabama transplant and partner in Haddow & Sims Real Estate and Insurance Co., balanced his day job with his duties as mayor. Five council members were also elected, though one was immediately replaced due to voter eligibility issues. The early days of incorporation were fraught with conflict. Some residents opposed incorporation, attempting to intimidate the City’s leaders and disrupt progress. Meetings were held in the back of Mayor Sims’ real estate office, and the town clerk, Martha Sanders, used a donated typewriter from George C. Meyer to record proceedings. Accounts describe heated arguments and opposition that at times brought Sanders to tears. Sims himself faced threats but remained resolute, buoyed by Meyer’s optimism.

In 1957, opponents of incorporation filed a civil suit, and Judge Davis F. Stakely temporarily rescinded the town’s status. The town leaders appealed, and after much legal back-and-forth, the incorporation was upheld. Sims remarked, “We never looked back.” From then on, meetings followed Robert’s Rules of Order, and the town embarked on building its infrastructure.

In its early years, Gulf Shores operated on a limited budget, with revenue coming from a 2-cent beer tax and a cigarette tax. Property taxes were minimal, with beach properties assessed at rates as low as 50 cents per foot. Despite financial constraints, progress was steady. Mayor Sims oversaw significant advancements, including paving 20 miles of roads, installing streetlights, adding parks, establishing planning and library boards, and initiating plans for a sewer system, police headquarters, jail, and city hall. In 1966, Sims resigned due to health concerns.

MA y O r S OF G u LF SHO r ES

1957-1967

Johnnie O. Sims

1967-1969

Claude J. O’Connor

1972-1976

Eugene Ingram

1976-1980

Mixon Jones

1980-1988

Thomas B Norton M.D.

1988-2004

David L. Bodenhamer

2004-2008

George “Billy” William Duke

2008-2025

Robert C. Craft

Johnnie O. Sims was the first mayor of the new city of Gulf

Shores

Claude J. O'Connor A Champion for Gulf Shores A Life Serving with Heart

A native of Mobile, Alabama, Claude J. O’Connor was a pivotal figure in the formative years of Gulf Shores—both as a town and, later, as a city. His connection to the community began early; at just 16, he spent weekends and summers working for George C. Meyer. Under Meyer’s mentorship, O’Connor developed a deep appreciation for the value of land and the importance of long-term vision—principles that would go on to define his leadership style.

In 1966, at only 27 years old, O’Connor became the youngest mayor in Alabama—and one of the youngest in the nation—when he stepped in to complete the term of the resigned Mayor Sims. His early leadership reflected a unique blend of youthful energy and a mature understanding of Gulf Shores’ needs, cultivated during his prior service on the Town Council. At the time, tensions between the previous mayor and the City Council had stalled progress, and the town’s financial resources were severely limited. O’Connor inherited a divided government, but one of his most meaningful and demanding accomplishments was restoring cooperation among city leaders. This heartfelt effort laid the groundwork for progress, though it came with great personal strain— both emotionally and physically.

Despite the challenges, O’Connor helped lead the Council through a productive and forward-looking era. Among their most important achievements was securing a functioning sewer system—essential for Gulf Shores’ long-term development. The project was complex and grueling, and the sustained stress ultimately took a toll on O’Connor’s health. On the insistence of his cardiologist, he stepped down as mayor. But his commitment to Gulf Shores never wavered. Once medically cleared, he returned to public service and was re-elected to the Town Council in 1972. Even outside of elected office, he continued to serve with the same steady dedication—as a member of the Gulf Shores Planning Commission until 1980 and as a founding member of both the South Alabama Regional Planning Commission and the Gulf Shores Water Board.

O’Connor’s contributions to education were equally transformative. For years, he petitioned the Baldwin County School Board to establish a school in Gulf Shores. Despite persistent pushback—most notably from a superintendent who once declared, “Gulf Shores won’t get a school in my lifetime”—O’Connor refused to give up. Seven years later, following the superintendent’s passing, a new opportunity emerged. The incoming Superintendent, Aubrey McVay, agreed to file a petition with the federal court—on the condition that O’Connor serve as the sole petitioner. He accepted, and in 1979, Gulf Shores finally had its own public school—a milestone that reshaped the community’s future and underscored O’Connor’s unwavering advocacy.

His visionary thinking extended into local banking as well. In the late 1960s, when Gulf Shores’ only banking option was a small branch of the State Bank of Elberta, businessman Lee Callaway approached O’Connor about founding a full-service institution. O’Connor took the lead as organizing chairman, assembled a group of nine individuals, and traveled to Washington, D.C., to present their proposal to the FDIC. Approval led to the establishment of the State Bank of the Gulf—a catalyst for economic momentum that soon attracted four additional banks to open branches. The foundation of the City’s financial infrastructure was firmly established, and the boom that followed was undeniable.

O’Connor’s leadership style—marked by integrity, collaboration, innovation, and a deep love for his city—helped Gulf Shores grow from a quiet seasonal town into a thriving year-round community. His work in infrastructure, tourism, education, and financial development left a lasting mark, not just in policy but in the very spirit of the place. His legacy lives on in the schools, the streets, and the steady hum of a city he helped shape—always believing in its potential, always working to bring it to life.

To this day, O’Connor remains a devoted believer in Gulf Shores’ future. His vast knowledge of the City’s history, paired with his extraordinary attention to detail, continues to serve as a valuable resource—offering insight, wisdom, and perspective on how Gulf Shores became what it is today.

1966, first picture taken of Claude O’Connor and the City Council after he was appointed mayor

Left to right: Heath L. McMeans, Vada Baldwin, James Colidis, City Attorney James Howell, Mayor Claude O’Connor, George S. Salley, Otto Kaemmer Jr., Mayor pro tem Charles Rice

From the outset of his mayoral term, Claude O’Connor sought creative solutions to the City’s lack of funding. He traveled— at his own expense—to more established coastal communities like West Panama City Beach and Myrtle Beach, meeting with mayors and collecting copies of their beach and tourism ordinances. These leaders not only shared their policies but also offered guidance, helping Gulf Shores shape its own municipal code without the cost of hiring legal counsel. It was a testament to O’Connor’s resourcefulness and collaborative approach.

Early in his tenure, John Watkins, Executive Director of the Alabama League of Municipalities, recognized O’Connor’s promise and invited him to Montgomery. There, Watkins introduced him to influential state leaders and organizations, including the Montgomery Advertiser, which helped promote Gulf Shores as an emerging beach destination through press coverage and photography that highlighted its natural beauty. Watkins also appointed O’Connor to the League’s Executive and Legislative Committees, where he immersed himself in state governance. State Senator Louie Brannan mentored him on how to write legislation and navigate the Senate, while State House Representative Dick Owen helped him understand how to pass bills into law. These relationships not only elevated Gulf Shores’ profile but also established O’Connor as a respected voice in Montgomery.

Opposite page: 1980s, breaking ground for the first bank in Gulf Shores, State Bank of the Gulf Organizing Group for Charter for State Bank of the Gulf: Holding Shovel, front row; Lee Callaway, Mayor Clarence C. Horton, J. M. Lee, Bank President Andrew Cooper, Jimmy Gilbert, Chairman Claude J. O’Connor (shown behind Andrew Cooper) and Mixon Jones (shown behind Jimmy Gilbert, far right)

Top left: 1966, Mayor Claude J. O’Connor

Top right: 1968, The Montgomery Advertiser

Bottom: 1969, Mobile Press Register

ShrimpFestival

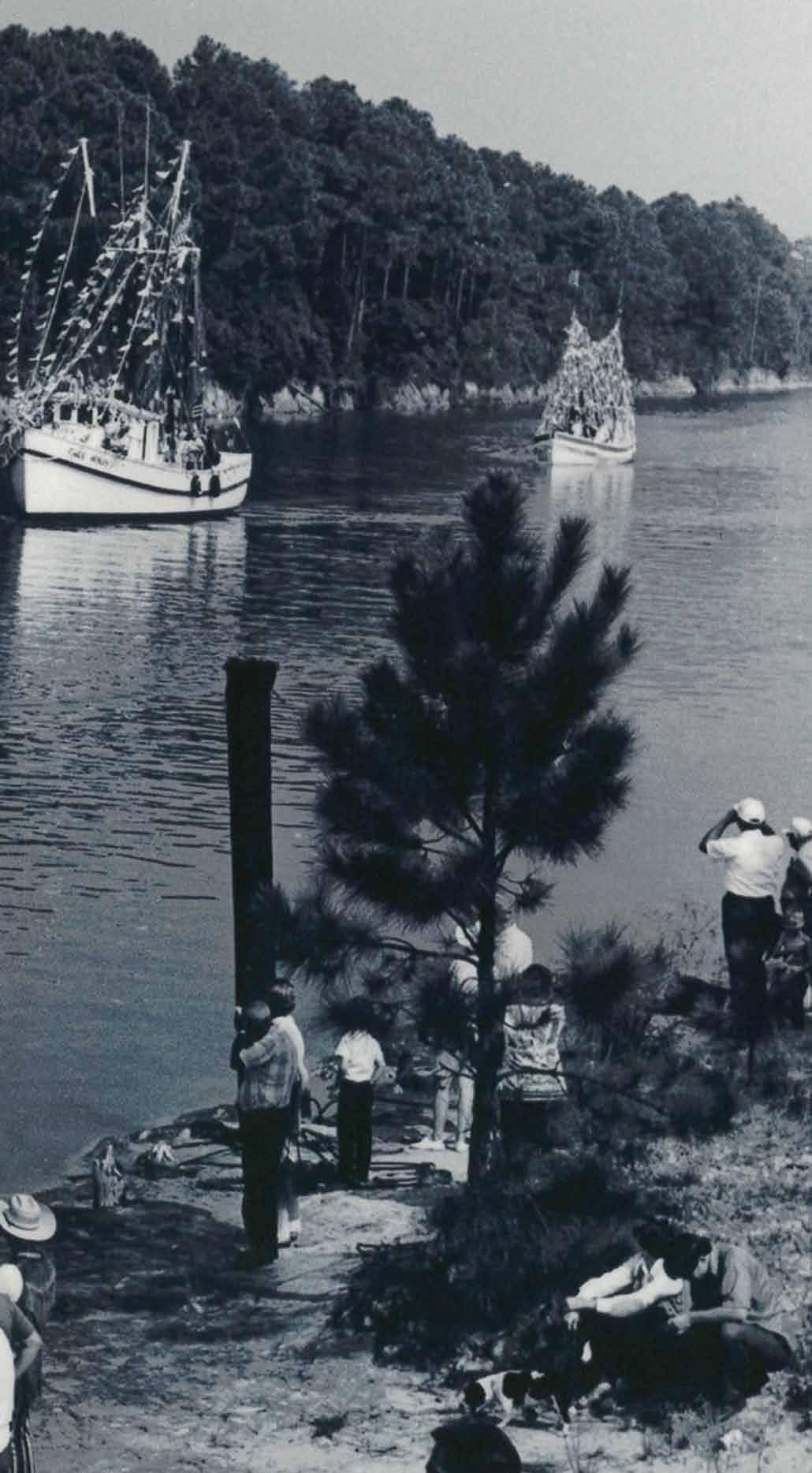

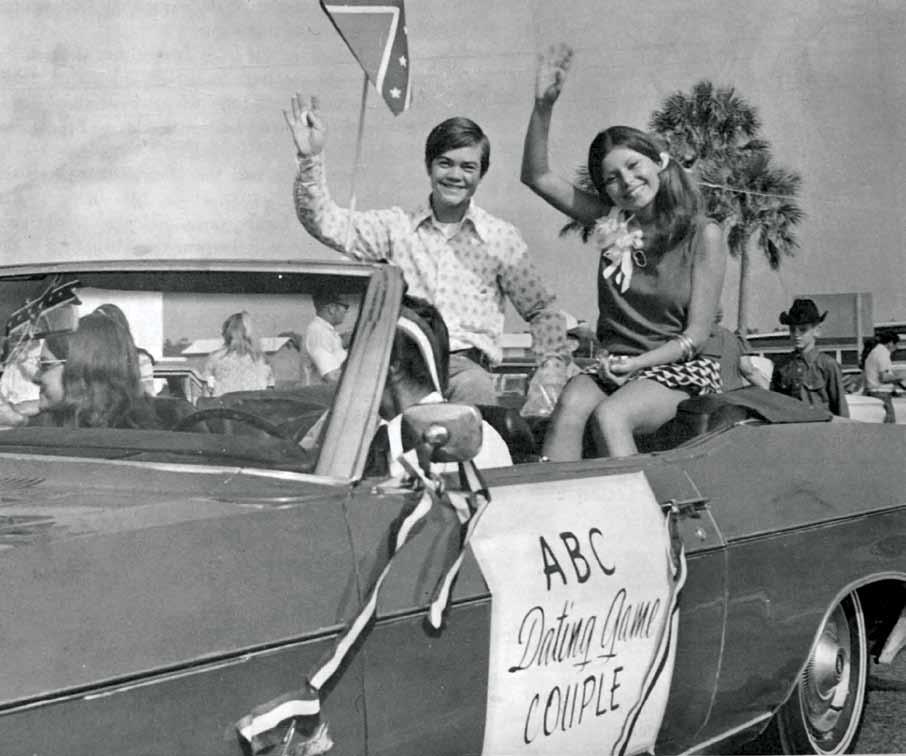

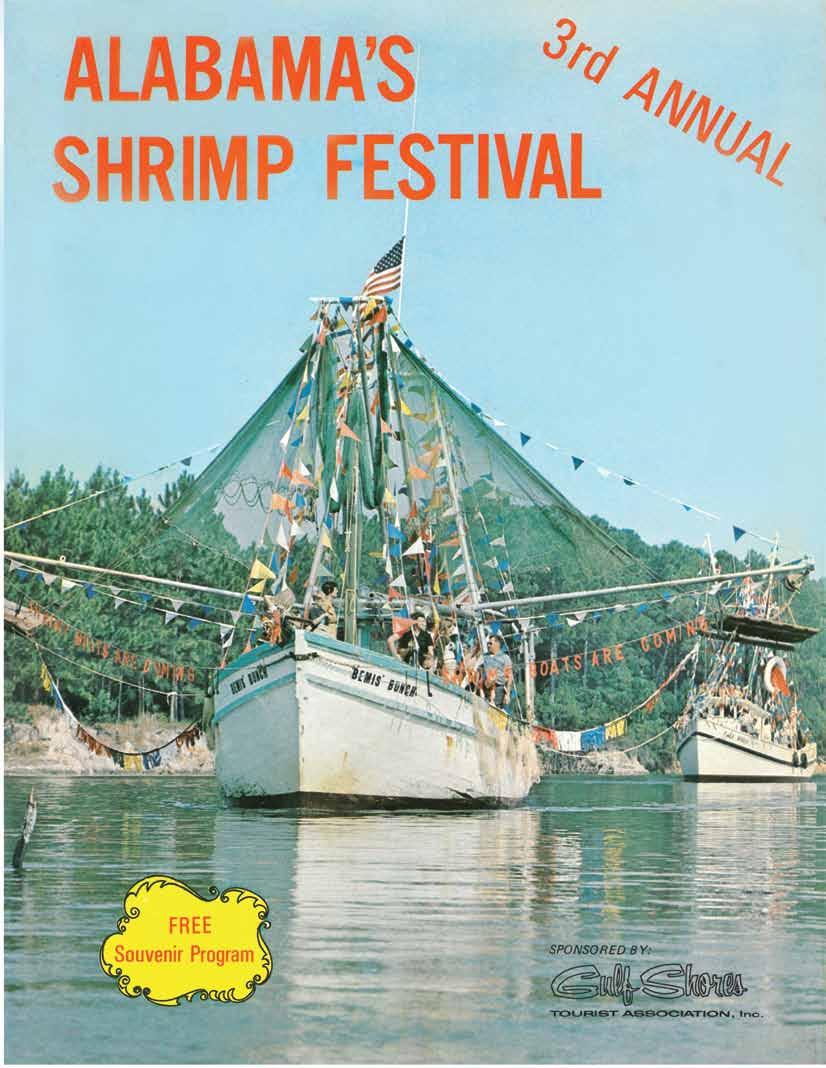

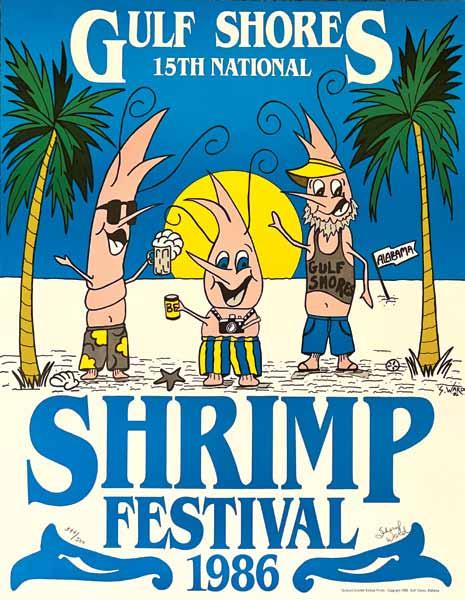

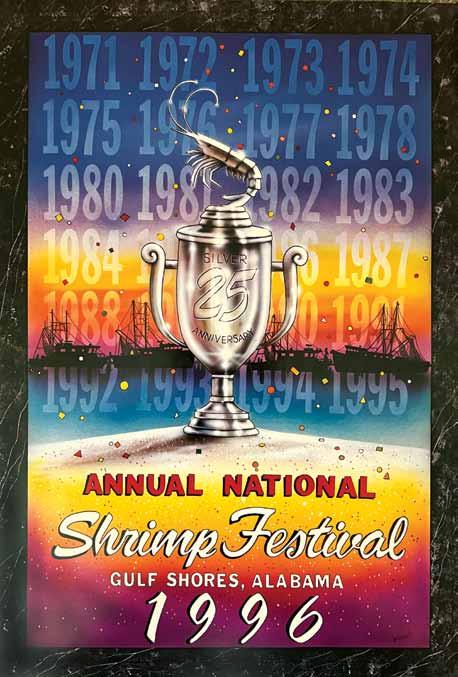

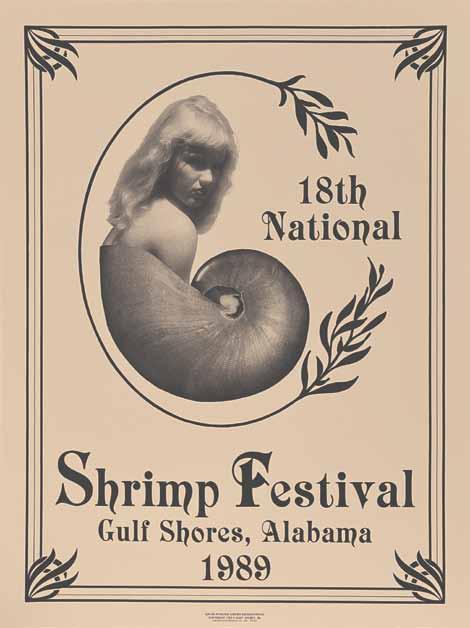

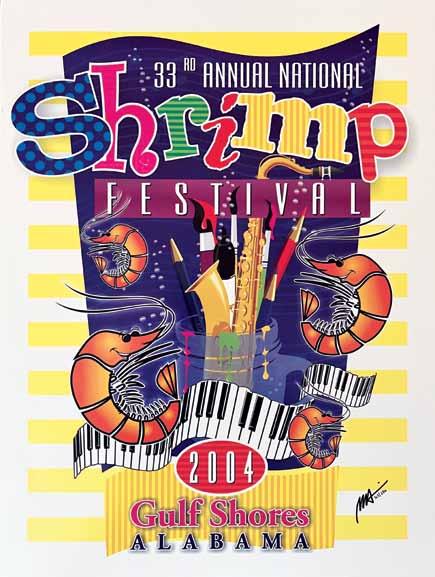

Gulf Shores has always sought ways to extend the tourist season, and in 1971, tying it to the local shrimping industry proved to be a winning idea. Lillian Callaway Bemis and her husband had been attending the Blessing of the Fleet in Bayou La Batre when inspiration struck—why not host a similar event in Gulf Shores? Armed with a newspaper article highlighting the success of the Bayou event, which drew 2,000 visitors, Bemis took the idea to the mayor and the local tourist association. “Then I forgot about it,” she later recalled. But the City saw the potential and ran with it, enlisting state support to help spread the word.

The inaugural Shrimp Festival in 1971 was a modest, one-day affair. “We went to Summerdale and borrowed hay bales from a farmer,” remembers Evelyn Sanders. “The Gulf Shores Building Supply loaned us a flatbed truck, and we set up the bales right in the middle of the red light at the intersection of Highways 59 and 182. That truck became our stage, and we danced in the circle.” The festival started with just four food booths, offering visitors a taste of fresh Gulf seafood.

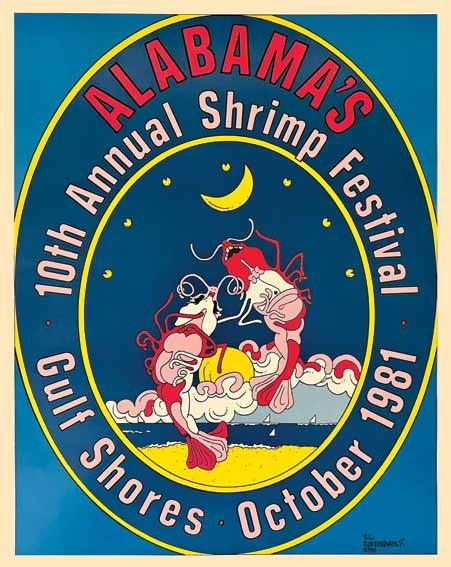

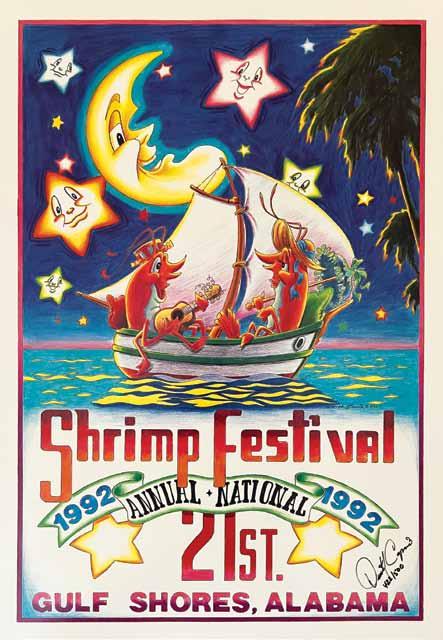

By the following year, the festival expanded to include a parade and more food options. Over the decades, what began as a small local gathering has transformed into one of the region’s most beloved traditions. Today, the Annual National Shrimp Festival—sponsored by the Coastal Alabama Business Chamber—draws tens of thousands of visitors from across the country for a multi-day celebration of fresh Gulf shrimp, southern cuisine, a juried art show, live entertainment, and family-friendly activities along the beachfront. The Festival remains a testament to Gulf Shores’ vibrant community spirit, its deep ties to the seafood industry, and its ability to turn a simple idea into a lasting legacy.

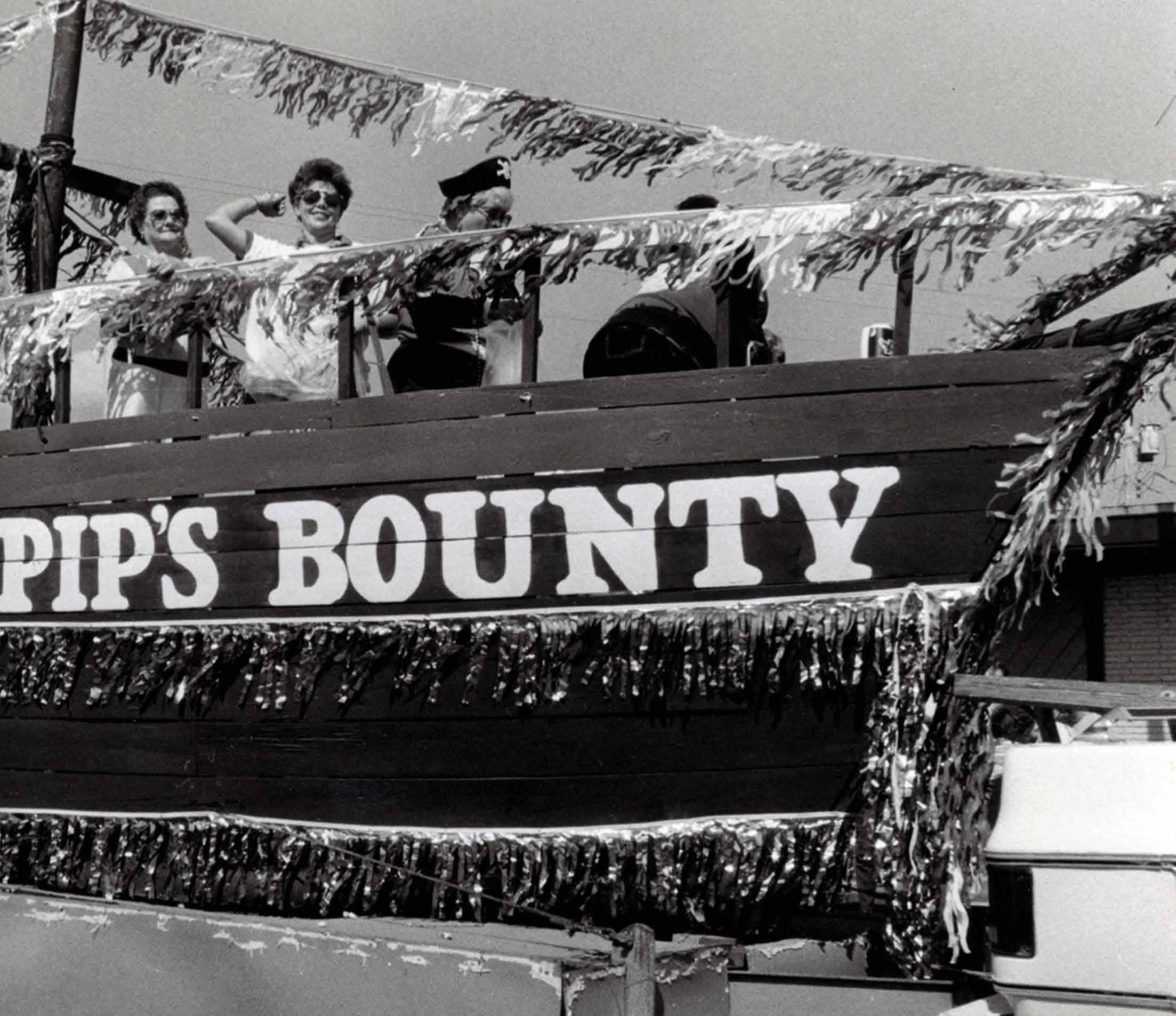

Shrimp Festival boat parade during the early days

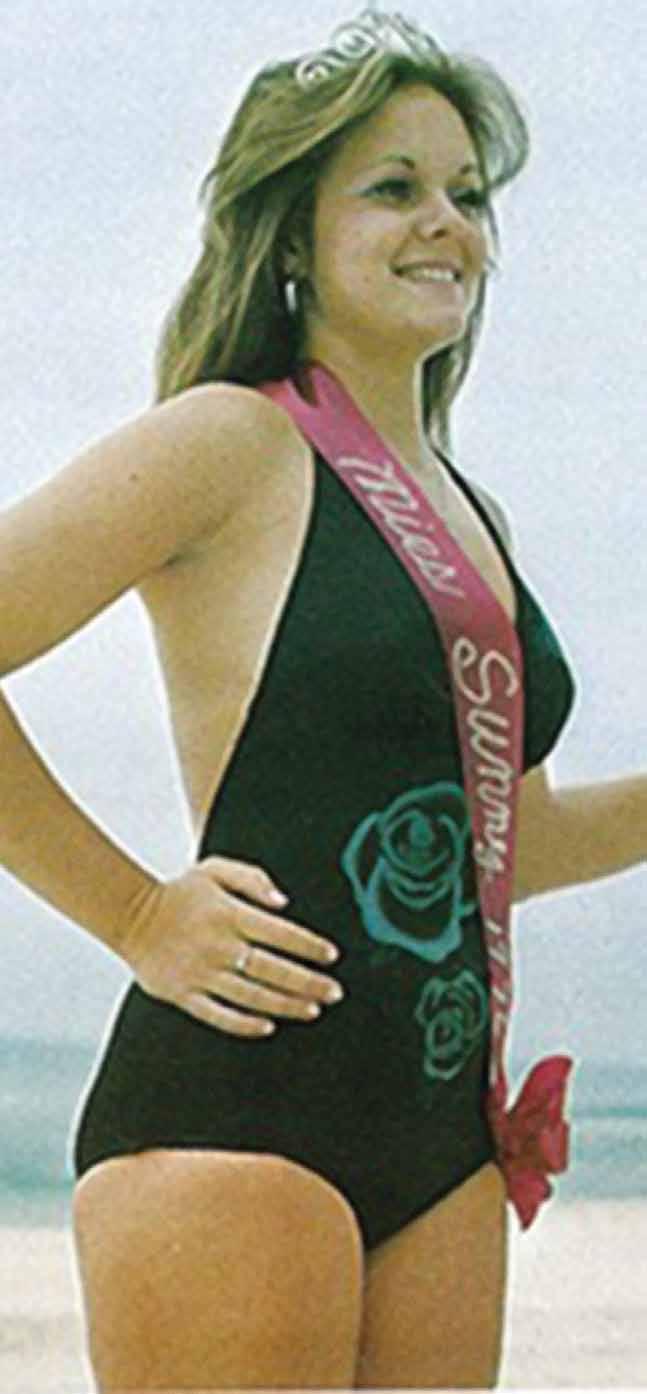

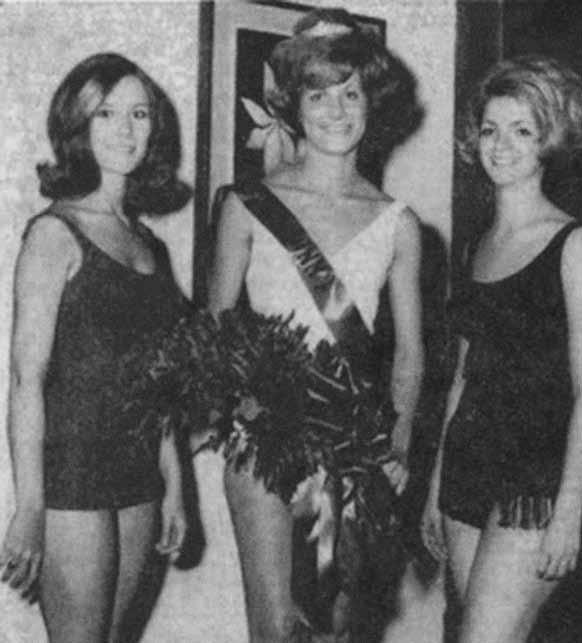

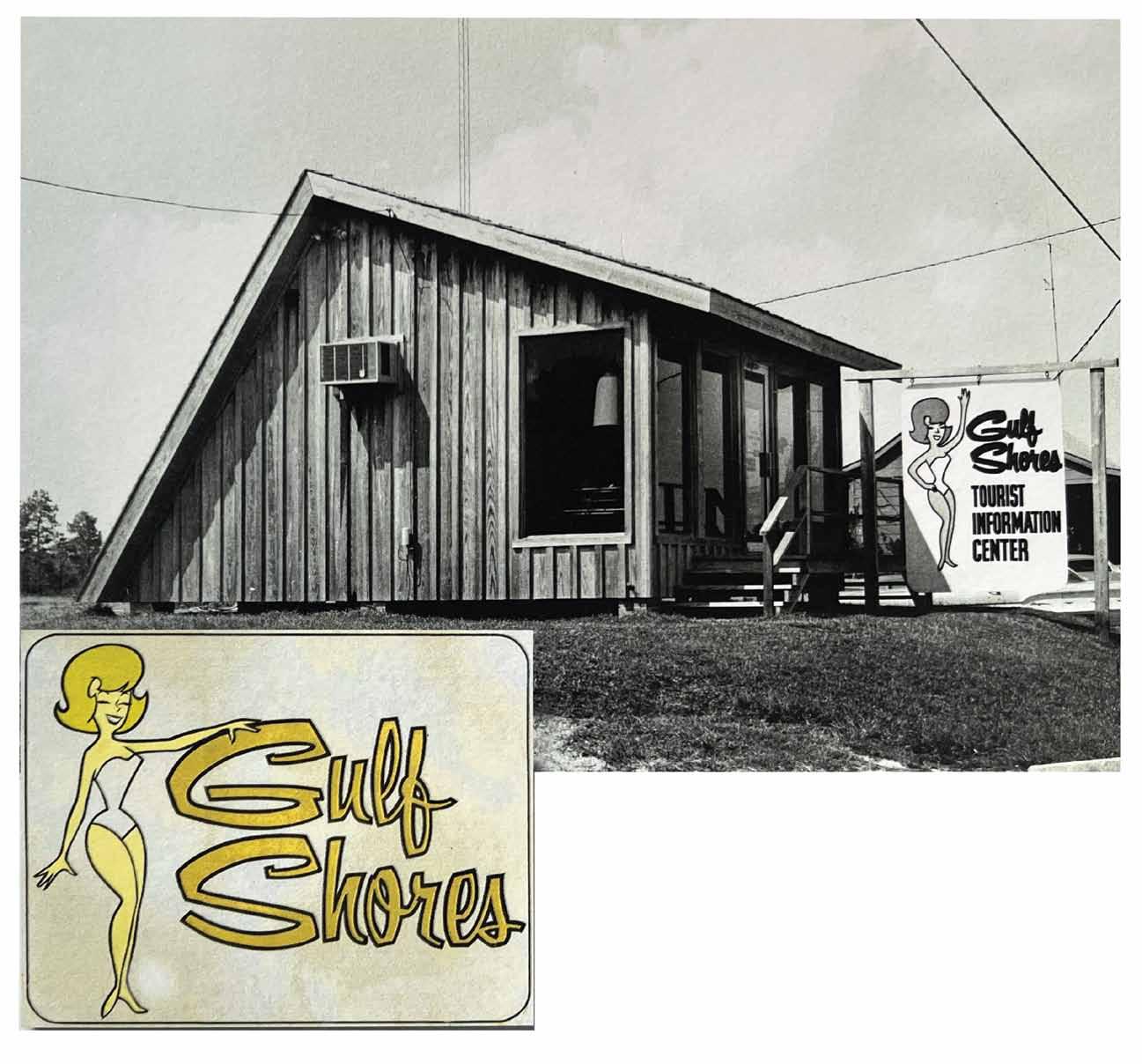

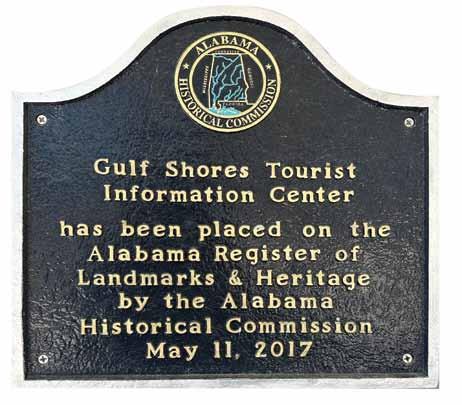

Miss Sunny, introduced in 1966, became the emblematic face of Gulf Shores tourism, gracing billboards and signs to attract visitors. In 1972, she transitioned into a live ambassador, participating in events like the ribbon-cutting of the Intracoastal Waterway Bridge and greeting guests at the Shrimp Festival. Her enduring impact was commemorated on June 4, 2016, with a dedicated exhibit at the Gulf Shores Museum, celebrating her pivotal role in promoting the region.

Left: 1976, Miss Sunny Winner Lisa Ludke

Top: 1966, Miss Sunny Runner-up Sylvia Polk, Miss Sunny Winner Brenda Rodgers, and Miss Sunny

Alternate Paula Trout

Bottom: 1971, Miss Sunny Winner Bobby Morris

Top left: 1973, Shrimp Festival parade featuring a couple from the television show, The Dating Game

Bottom left: 1970s, Shrimp Festival

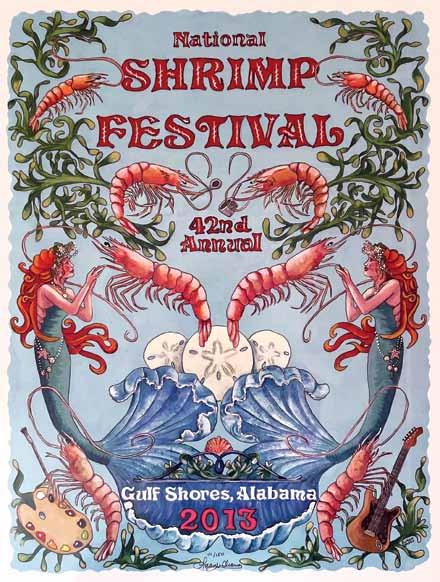

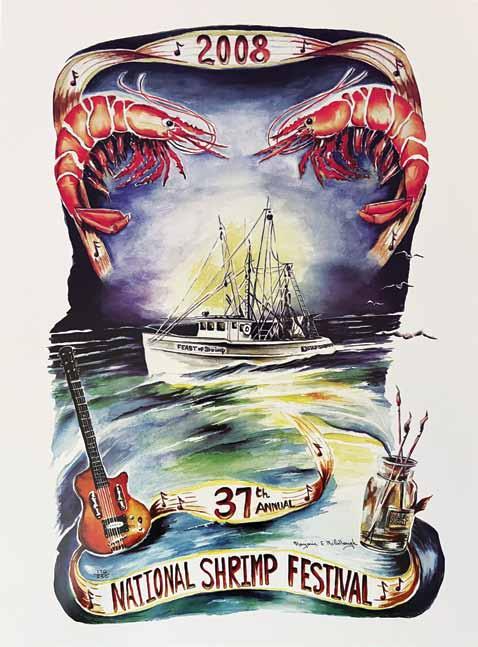

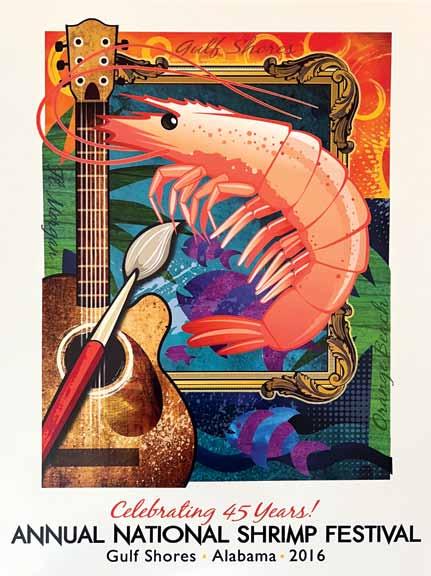

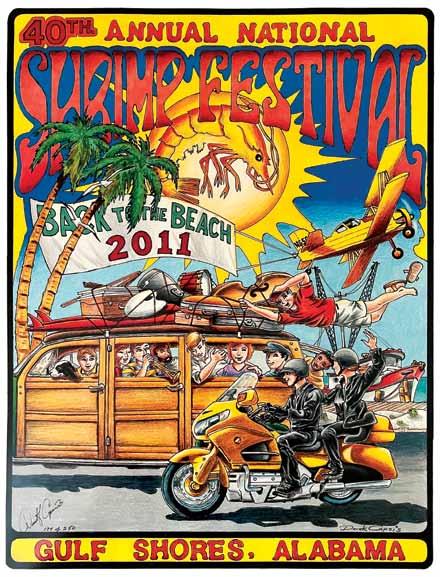

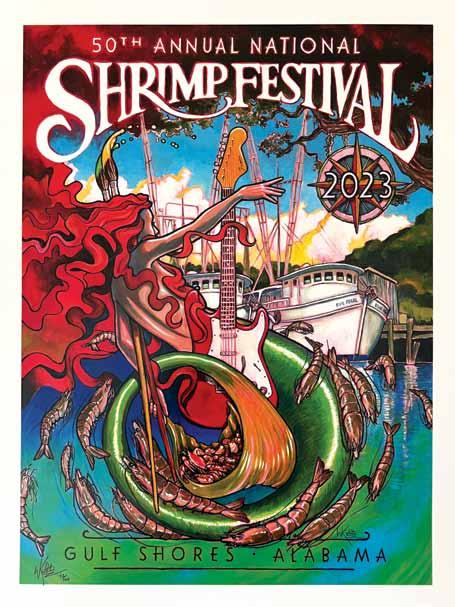

In past years, Festival program covers have featured the work of talented local artists. Each year, submissions are reviewed and one standout piece is selected for the cover.

The History of in Gulf Shores

Mardi Gras

Gulf Shores’ Mardi Gras celebrations began in 1978, organized by the Pleasure Isle Players, a charity club formed at the American Legion. The group initially performed plays and skits, often drawing inspiration from shows like Hee Haw. “Johnny Sims played his guitar, my husband played his guitar, and we had dances at the American Legion,” recalls Evelyn Sanders. “Snowbirds would come watch our skits,” she laughs.

The first Mardi Gras event was created as a fundraiser for the Gulf Shores Fire Department and the Gulf Shores School Library. Inspired by the Mardi Gras balls in Mobile, Sanders and her friends decided to host their own celebration. The following year, they crowned a king and queen, organized a volunteer court, and rented costumes in Mobile. Thanks to Gulf State Park Superintendent Hugh Branyon, the the State Park’s convention space was provided free of charge, and more than 250 people attended.

What began as a modest gathering has grown into a beloved Gulf Shores tradition. Today, Mardi Gras parades and balls fill event spaces across the region throughout the carnival season. Over the years, the festivities have included powder puff football games featuring stars like Kenny Stabler and Richard Todd, along with golf tournaments and other community events. Dozens of krewes host vibrant balls, while parades draw enthusiastic crowds eager to catch beads and Moon Pies. Gulf Shores and Orange Beach coordinate their celebrations—Gulf Shores holds its main parade in the morning, followed by Orange Beach’s in the afternoon—creating a full day of festivities. The City of Gulf Shores now leads the organization of its Mardi Gras parade, held annually on Fat Tuesday. The Mystic Order of Shiners, the oldest parading order in Baldwin County, has remained a central part of the tradition since 1979.

1980s, Pip’s Bounty Mardi Gras parade float

Top: 1978, Mardi Gras King Hugh Branyon and Queen Evelyn Sanders

Bottom: 1978, Mardi Gras PIPS pages carrying the King and Queen crowns

weathering the storms

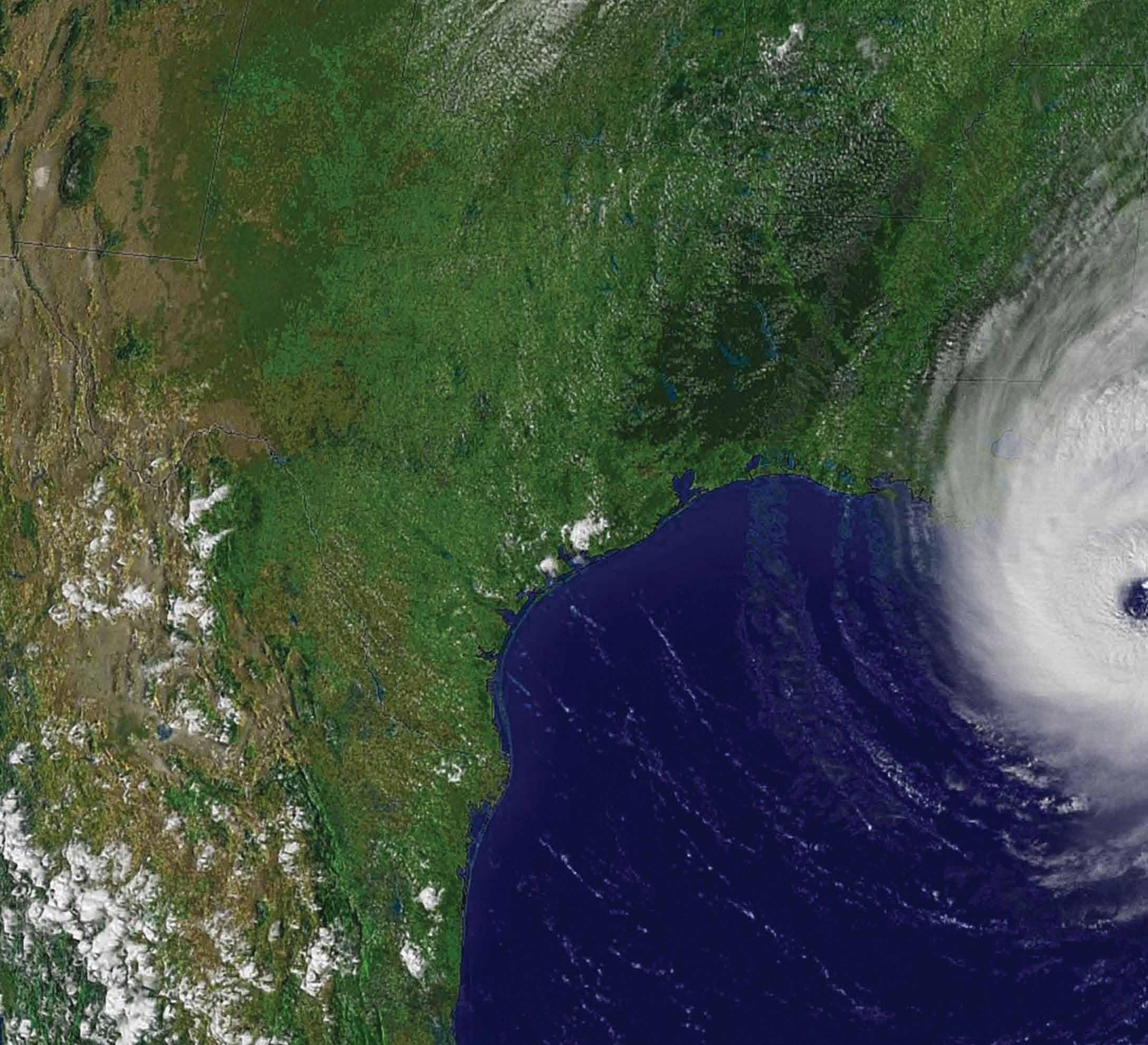

2004, Hurricane Ivan approaching the Gulf Coast

Top left: 1980 “Picture Book” of Hurricane Frederic damage

Top right: 1979, Gulf State Park Convention Center damage

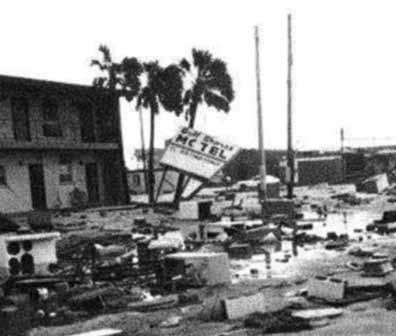

Bottom left: 1979, Hurricane Frederic, Gulf Shores Motel damage

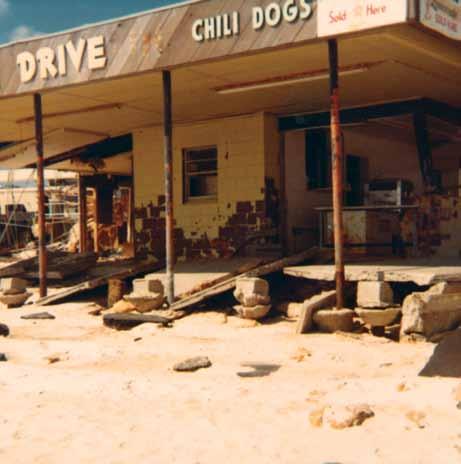

Bottom right: 1979, Hurricane Frederic, The Hangout damage

MajorStorms

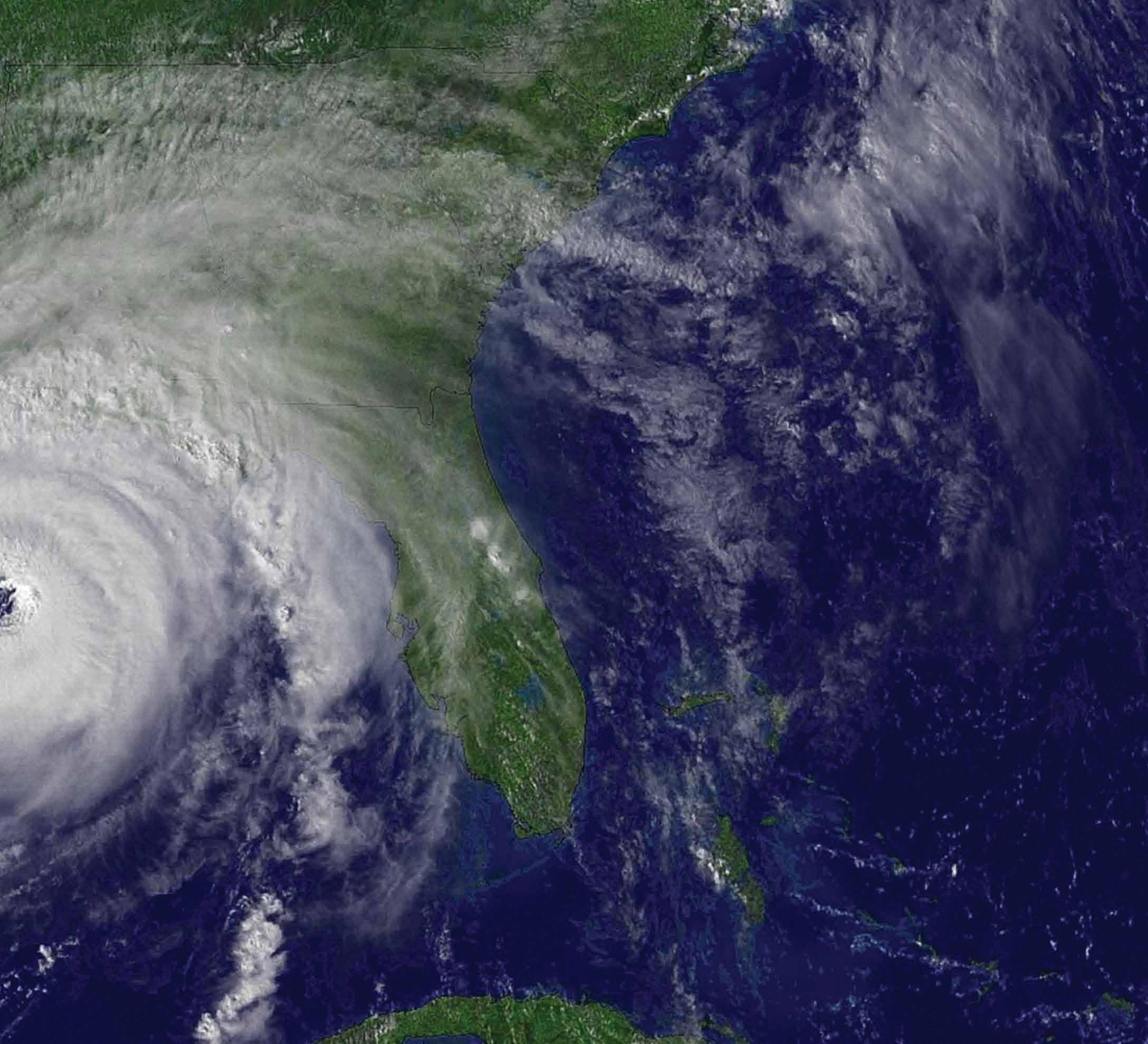

Although many more devastating hurricanes have impacted the area over the years—often blowing through without warning—these historic major storms were among the first to be documented in detail, occurring during a time when advancements in technology began enabling timely alerts and evacuation advisories. They not only caused widespread destruction but also signaled a new era in emergency response and community resilience.

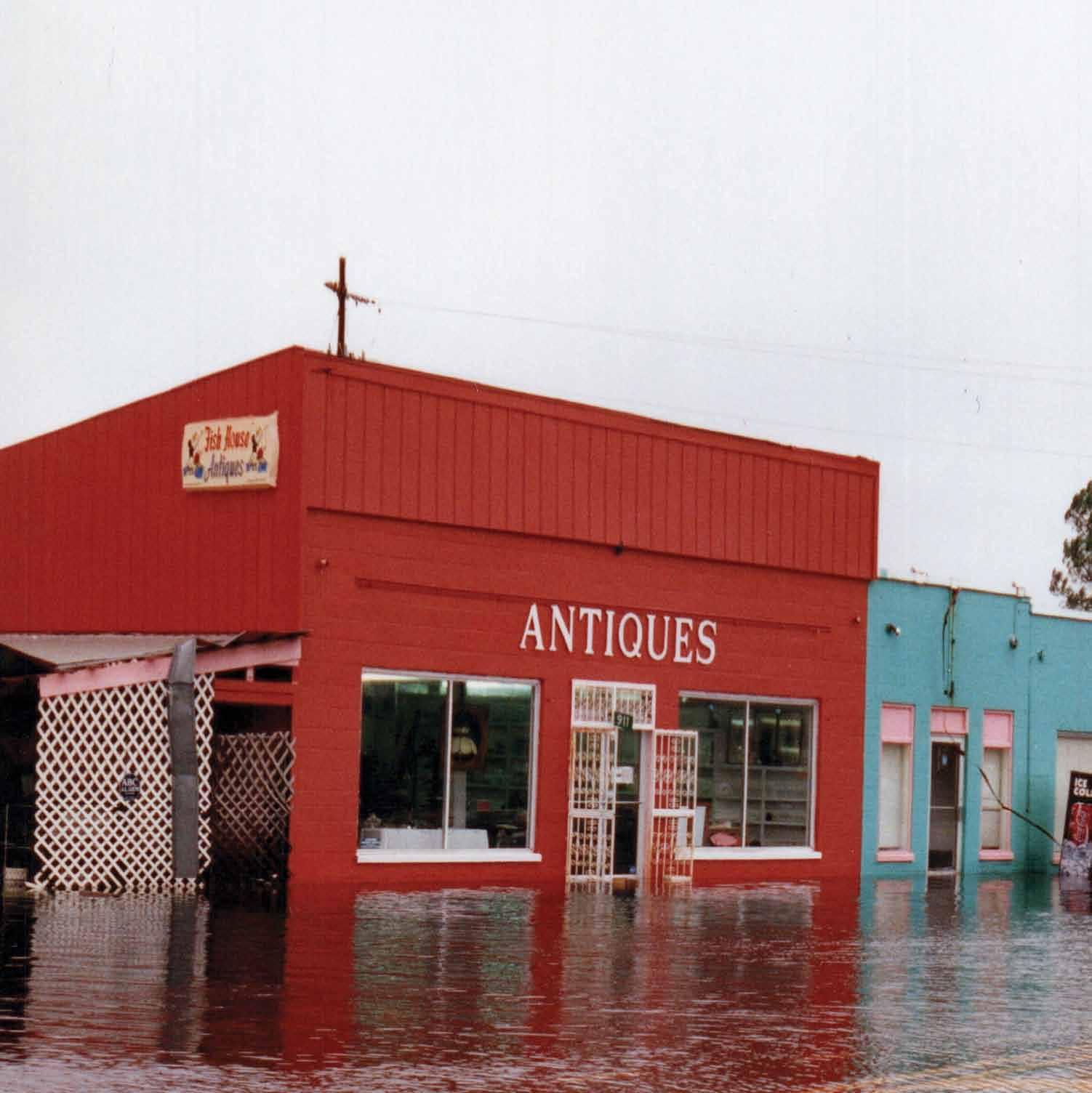

On September 12–13, 1979, Hurricane Frederic made landfall as a powerful Category 3 hurricane, bringing 130 mph winds and catastrophic destruction to Gulf Shores. The storm wiped out 80% of the City’s buildings, leveling homes, businesses, and beachfront structures. The landscape was left unrecognizable, with debris-strewn streets and thousands of trees snapped or leaning. Infrastructure was devastated, leaving the community without power, water, or communication for weeks. With $1.7 billion in damage (equivalent to $6 billion in 2023), Frederic was the costliest hurricane in U.S. history at the time.

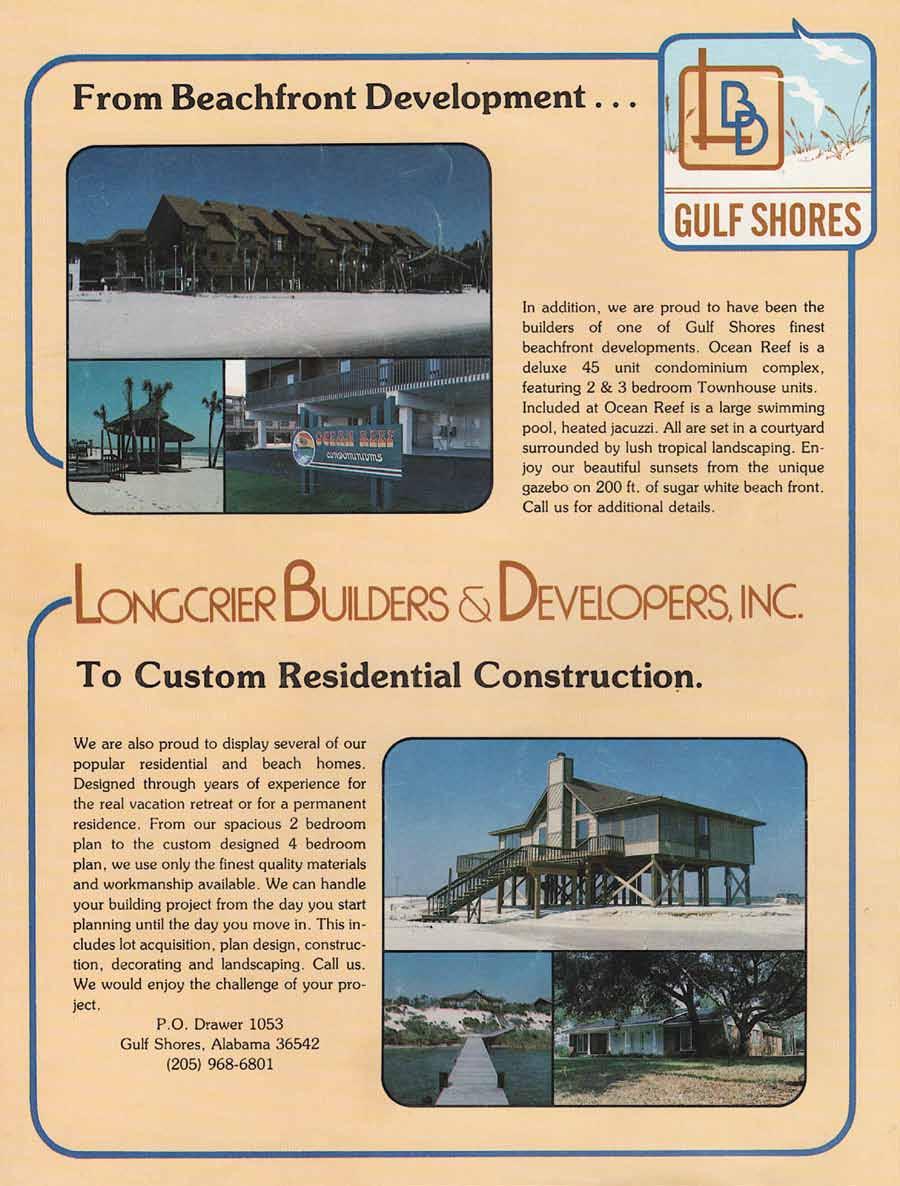

The destruction marked a turning point for the City. Federal aid and insurance payouts provided resources for rebuilding, and developers saw an opportunity to modernize. Before Frederic, the City had only one condominium complex; by the early 1990s, more than 100 had been built. The storm also led to stricter building codes and enhanced infrastructure, ensuring new structures were more resilient to future storms.

Nineteen years later, in September 1998, Hurricane Georges tested those improvements. Though the storm made landfall near Biloxi, Mississippi, as a Category 2 hurricane, its outer bands lashed Gulf Shores with sustained winds over 100 mph and a storm surge that flooded low-lying areas. Heavy rainfall compounded the damage, overwhelming drainage systems and leaving roads impassable. While Georges was less destructive than Frederic, it served as a reminder of the City’s vulnerability and reinforced the importance of continued investment in storm-resistant infrastructure. The recovery process, aided by federal assistance, was faster than in previous storms, demonstrating the effectiveness of the resilience measures implemented in the decades prior.

Six years later, Hurricane Ivan delivered another devastating blow. Making landfall on September 16, 2004, as a Category 3 hurricane, Ivan brought sustained winds of 120 mph and a storm surge up to 14 feet. Entire neighborhoods were submerged, roads were washed away, and the beachfront suffered extensive damage. However, the City was better prepared, having learned from Frederic and Georges. Strengthened building codes and improved infrastructure helped mitigate long-term damage, while federal aid and insurance funds facilitated a more efficient recovery.

Then, in 2020, sixteen years to the day, Hurricane Sally became the latest major storm to leave a lasting impact on the City. Making landfall on September 16 as a slow-moving Category 2 hurricane, Sally battered the area with sustained winds of 105 mph and torrential rainfall, causing record flooding. The storm surge, combined with prolonged downpours, led to historic water levels, submerging roads and damaging homes and businesses. The iconic Gulf State Park Pier was heavily damaged, and widespread power outages left residents in the dark for days. Despite Sally’s lower wind speeds compared to Frederic, Ivan, and Georges, its slow-moving nature resulted in catastrophic flooding, highlighting the ongoing vulnerability of the City to tropical storms.

Hurricanes Frederic, Georges, Ivan, and Sally reshaped Gulf Shores, transforming it from a quiet beach town into a modern coastal destination. Frederic set the stage for growth, Georges reinforced the need for storm preparedness, Ivan emphasized resilience, and Sally underscored the growing threats posed by water damage and flooding. Today, the City’s skyline of condominiums, resorts, and thriving businesses stands as a testament to decades of recovery and reinvention. Though these storms brought immense devastation, they ultimately propelled the City toward a future defined by adaptation and renewal.

1998, Hurricane Georges damage

Top: 2004, Hurricane Ivan, George W. Bush shown speaking with Mayor David Bodenhamer, assessing the damage

Bottom: 2004, Hurricane Ivan damage, along Main Beach road

Top left: 2004, Hurricane Ivan damage along West Beach

Top right: 2004, Lulu’s restaurant damage

Bottom left: 2004, Hurricane Ivan, Rusty Gilbert and Adrian Tanner with Brad Johnson from the Alabama Gulf Coast Zoo rescue an Asian fallow stag that escaped during the storm

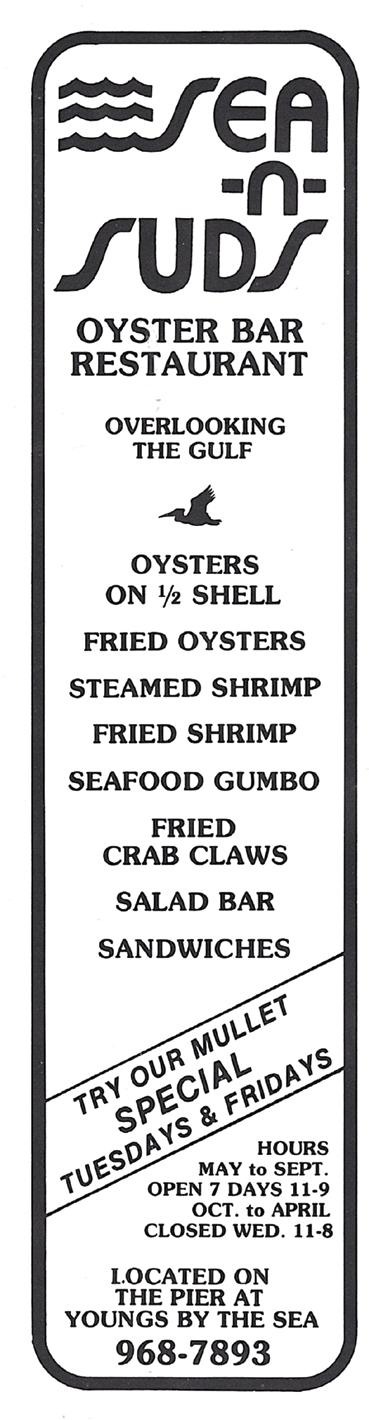

Bottom right: 2004, Sea N’ Suds damage after Hurricane Ivan

2004, Hurricane Ivan flooded and severly damaged Alabama Gulf Coast Zoo

resilience and the building boom

Building

Boom

Before Hurricane Frederic, Gulf Shores was a quiet coastal area with scattered cottages and the occasional two-story wooden structure lining the shoreline. While development had begun in the 1970s, it remained modest, reflecting the town’s small-scale, laid-back nature. Everything changed in 1979 when Frederic made landfall, bringing widespread destruction and reshaping the community in ways no one could have imagined. The storm served as a turning point, altering both the physical and social fabric of the island.