Cultural Resources Research Design and Survey Methodology

Crossroads Solar Project 1

Cardington, Lincoln, and Westfield Townships, Morrow County, Ohio

Prepared for:

Crossroads Solar I, LLC 1105 Navasota Street Austin, TX 78702

Contact: Patrick Buckley, Vice President, Development (713) 962-2933 patrick@openroadrenewables.com

Prepared by:

Environmental Design & Research, Landscape Architecture, Engineering & Environmental Services, D.P.C. 5 E Long St, Suite 700 Columbus, OH 43215 www.edrdpc.com

April 2023

1 Since submittal of this report in April 2023, the Project name was changed to Crossroads Solar Grazing Center.

Involved Agencies:

Phase of Survey:

MANAGEMENT SUMMARY

Ohio Power Siting Board (OPSB)

Ohio State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO)

Research Design and Survey Methodology

Location Information: Cardington, Lincoln, and Westfield Townships, Morrow County, Ohio

Project Description:

Project Area:

A utility-scale solar project consisting of ground-mounted photovoltaic panels and associated infrastructure.

An approximately 604-acre area that will host all components of the Project.

Historic Resources Study Area: Area within a 2-mile radius of the Project Area.

Area of Potential Effects (APE):

The APE for Direct Effects consists of the direct Project footprint with potential to experience ground disturbing activities, occurring within the boundaries of the Project Area

The APE for Indirect (Visual) Effects represents portions of the Historic Resources Study Area where there is potential Project visibility.

USGS 7.5-Minute Quadrangle Map: Ashley, OH (1995)

Archaeology Resources Overview: There are no Ohio Archaeology Inventory (OAI) sites mapped within the Project Area. Fifty-five OAI sites are mapped within the Historic Resources Study Area.

Historic Resources Overview:

The Historic Resources Study Area includes one property that was formerly listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), one property formally determined NRHP-eligible, 87-properties listed in the Ohio Historic Inventory, nine cemeteries designated by the Ohio Genealogical Society, no Ohio Department of Transportation historic bridges, and no National Historic Landmarks None of the previously recorded resources are located within the Project Area.

Report Authors: Michael Way, RA; Janna Napoli, RPA

Date of Report: April 2023

Cultural Resources Research Design and Survey Methodology

Crossroads Solar Project i

1.0 INTRODUCTION

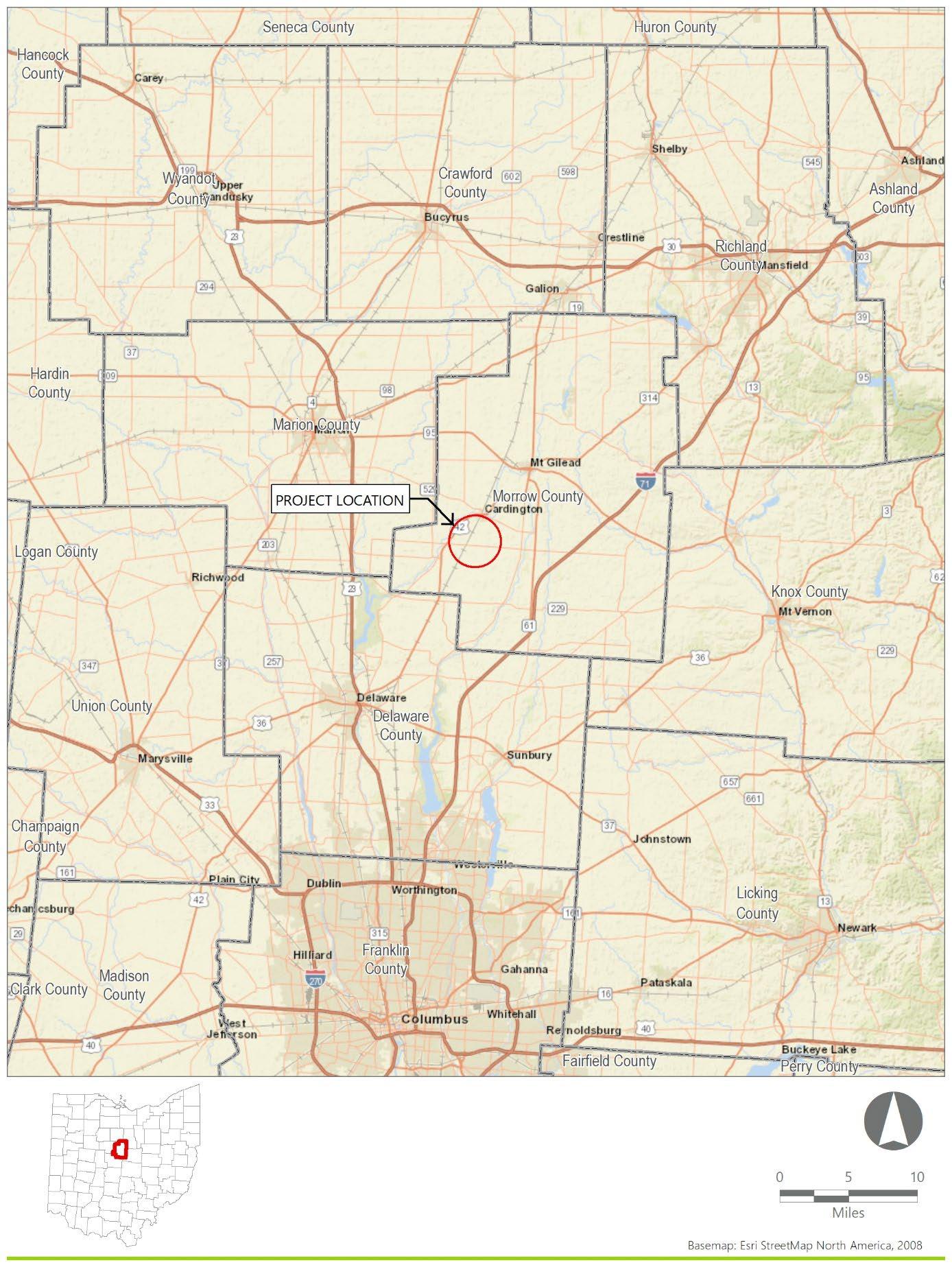

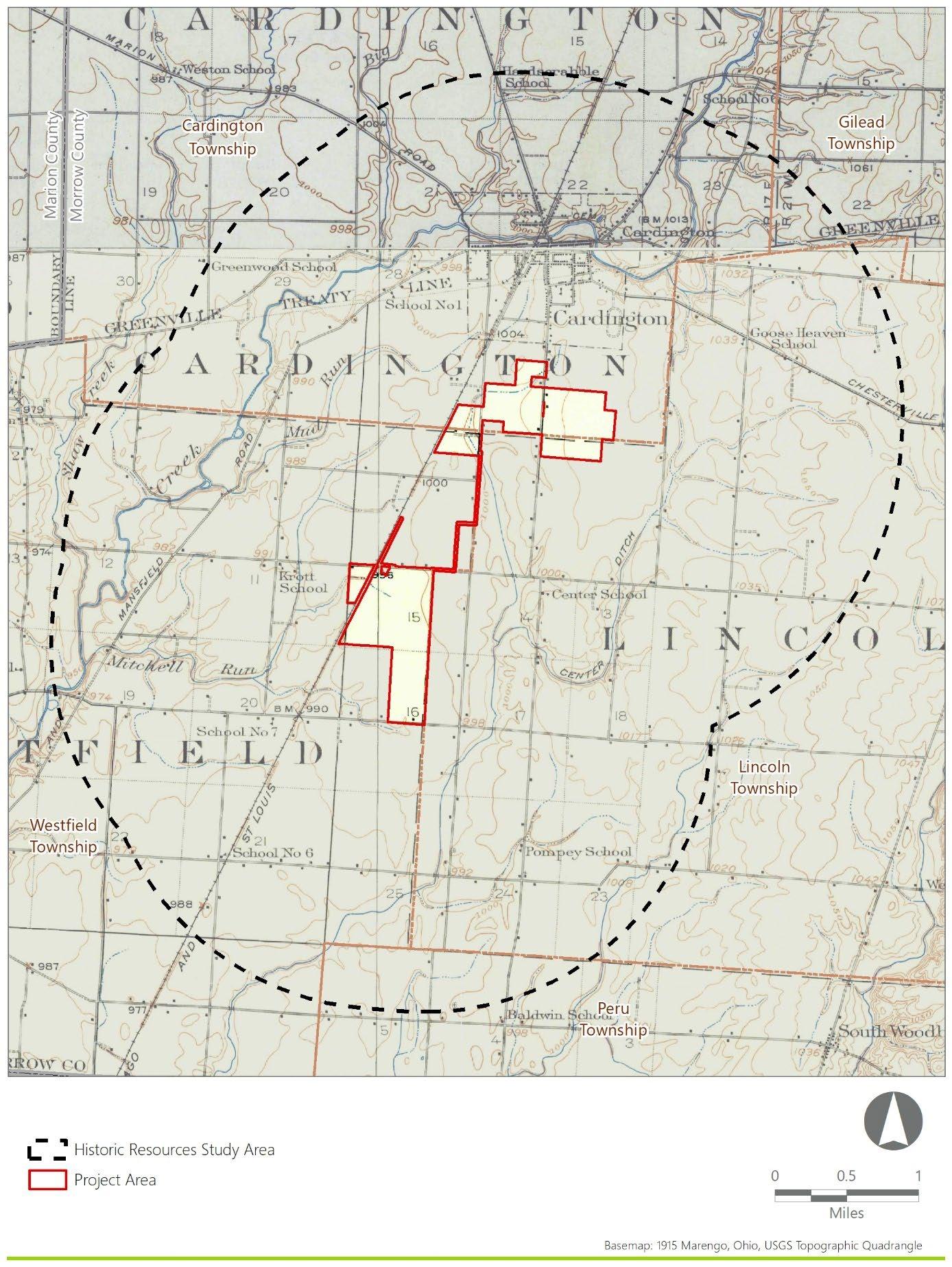

On behalf of Crossroads Solar I, LLC (the Applicant), Environmental Design & Research, Landscape Architecture, Engineering, & Environmental Services, D.P.C. (EDR) has prepared a Research Design and Survey Methodology for the proposed Crossroads Solar Project located in Cardington, Lincoln, and Westfield Townships, Morrow County, Ohio (the Project; Figure 1). The information and recommendations included in this report are intended to assist the Ohio State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) with its review of the Project for the Ohio Power Siting Board (OPSB). Specifically, this Research Design and Survey Methodology report has been prepared to satisfy portions of Section 4906-04-08(D) of the Ohio Administrative Code (OAC).

1.1 Purpose of the Investigation

The purpose of the Research Design and Survey Methodology is to describe previously identified cultural resources and/or sites of cultural or religious significance that are located within the vicinity of the Project. In addition, the report proposes a methodology to identify previously unrecorded cultural resources, evaluate their eligibility for the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), and assess the potential impacts on those resources.

This report includes a review of maps and documents for records of “registered landmarks of historic, religious, archeological…or other cultural significance,” i.e., those “districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects that are recognized by, registered with, or identified as eligible for registration by…the state historical preservation office” located within the Project Area and surrounding 2-mile radius (Historic Resources Study Area) that could potentially be affected by the construction and/or operation of the Project (OPSB, 2021). Please note that the requirements of OAC 4906-04-08(D)(1) and (2) addressing “formally adopted land and water recreation areas, recreation trials, scenic rivers, scenic routes or byways” and “registered landmarks of…scenic [and] natural…significance” are not addressed in this report. This Research Design and Survey Methodology report has been prepared by professionals who meet the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Professional Qualifications (per 36 CFR, Part 61) in their respective fields and the report has been completed in accordance with applicable portions of the Ohio SHPO’s Guidelines for Conducting History/Architecture Surveys in Ohio (2014) and/or the Ohio SHPO’s Archaeology Guidelines (2023), as applicable.

1.2

Project Location and Description

The Project is a proposed solar-powered electric generating facility located in Cardington, Lincoln, and Westfield Townships, Morrow County, Ohio (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The following terms are used throughout this document to describe the proposed action:

Project: Collectively refers to all components of the Project and associated infrastructure (such as solar panels, collection lines, substation, and other equipment).

Project Area: An approximately 604-acre area of land that will host all components of the Project.

Historic Resources Study Area:

APE for Direct Effects:

APE for Indirect Effects:

The area within 2 miles of the Project Area which accounts for potential visual effects on historical resources. The Historic Resources Study Area includes portions of Gilead and Peru Townships, Morrow County, Ohio.

The direct Project footprint with potential to experience ground disturbing activities. The APE for Direct Effects will occur entirely within the Project Area.

The portions of the Historic Resources Study Area where there is potential Project visibility as determined by viewshed analysis.

The design and engineering are ongoing concurrent with environmental studies (including cultural resources) to identify sensitive resources and allow for avoidance and minimization of potential impacts. The Project will consist of, but is not limited to, the following components:

• Rows of photovoltaic panels (arrays) producing direct current electricity mounted on single axis tracking structures

• Inverters placed within the panel arrays to convert direct current electricity to alternating current electricity.

• A medium voltage collection system that will aggregate the alternating current output from the inverters

• A substation and electrical switchyard where the Facility’s electrical output voltage will be combined and increased to the transmission line voltage via step-up transformers.

• A generation tie line that will connect the Facility to the designated point of interconnect

• Internal infrastructure including access roads, driveways, and security fencing

• Temporary laydown areas for equipment staging during construction.

The Applicant anticipates that each section of the Project’s solar arrays will be surrounded by fencing and select sections may include landscape buffering/vegetative screening outside the fence.

The Project Area is rural and set in an area of generally low topographic relief, mostly consisting of open agricultural fields interspersed with woodlots, tree lines, and wooded streams. Most of the landscape within the Historic Resources Study Area is flat to gently rolling agricultural fields. These fields are bisected by long, straight rural transportation routes, tree lines, woodlots, creeks, and minor tributaries to Sycamore Creek While the majority of the landscape within the Historic Resources Study Area is open agricultural fields, pockets of residential, commercial, and industrial development are present along the main thoroughfares, with the northern section near the village of Cardington more developed Existing developed features in the Historic Resources Study Area include electric transmission lines, public roads, single family homes and agricultural complexes, as well as public and commercial buildings and established cemeteries.

2.0 BACKGROUND AND SITE HISTORY

This section includes a discussion of the geology and soils of the Project Area, and a review of previously documented resources in the Historic Resources Study Area, as required in the Guidelines for Conducting History/Architecture Surveys in Ohio (SHPO, 2014) and the Archaeology Guidelines (SHPO, 2022).

2.1 Geology and Soils

The Project Area consists of relatively level terrain with an undulating landscape and slopes that range from 0 to 6%. Elevations within the Project Area range between approximately 990 and 1,025 feet above mean sea level (amsl). Mapped waterbodies within the Project Area include an unnamed tributary of the West Branch Alum Creek and an unnamed tributary to Mitchell Run. Both waterbodies drain into the Scioto River.

The Project Area is within the Central Ohio Clayey Till Plain section of the Central Lowlands Physiographic Province The Central Ohio Clayey Till Plain section consists of well-defined moraines with intervening ground moraines and intermorainal lake basins. Elevations range from 700 feet amsl to 1,150 feet amsl (Brockman, 1998).

EDR reviewed online data from the Natural Resources Conservation Service to identify soil series mapped within the Project Area (NRCS, 2023). The Project Area contains six soil series, which are detailed in Table 1.

12%

Ap: 0-25

A: 25-33

Btg1: 33-64

Btg2: 64-94

Cg: 94-152

Ap: 0-18

Btg: 18-30

Bt: 30-58

BCtg: 58-76

CBd: 76-107

Cd1: 107-137

Cd2: 137-200

Ap: 0-18

E: 18-23

BE: 23-30

2Bt1: 30-41

2Bt2: 41-51

2Bt3: 51-58

2BC1: 58-69

2BC2: 69-81

2Cd: 81-203

10YR 2/2 clay loam

10YR 2/2 clay loam

10YR 4/1 silty clay

10YR 5/1 silty clay

10YR 5/2 silty clay loam

10YR 4/2 silt loam

10YR 5/2 silty clay

10YR 4/4 clay

10YR 5/2 silty clay loam

10YR 4/3 clay loam

10YR 5/3 clay loam

10YR 4/3 clay loam

10YR 4/2 silt loam

10YR 4/3 silt loam

10YR 4/4 silty clay loam

10YR 4/4 silty clay

10YR 4/4 clay

10YR 4/4 silty clay loam

10YR 5/4 silty clay loam

10YR 4/4 silty clay loam

10YR 5/4 clay loam

0-1% slopes; Very poorly drained soils formed on moraines, near-shore zones (relict), and lake plains.

0-4% slopes; Very deep, somewhat poorly drained soils formed on till plains, till plains, and near-shore zones (relict)

2-6% slopes; Moderately well drained soils formed on ground moraines and end moraines

Soil

Milford silty clay loam 4%

Ap: 0-23

A: 23-46

BA: 46-56

Bg1: 56-79

Bg2: 79-107

Bg3: 107-127

Cg: 127-152

Ap: 0-20

BE: 20-28

Bt1: 28-51

Bt2: 51-76

Gallman silt loam, loamy substratum 2%

Sleeth silt loam, loamy substratum 1%

Bt3: 76-94

Bt4: 94-132

Bt5: 132-168

Bt6: 168-190

C: 190-229

Ap: 0-23

E: 23-36

Bt1: 36-56

Bt2: 56-96

Btg1: 96-114

Btg2: 114-127

2Cg: 127-152

10YR 2/1 silty clay loam

10YR 2/1 silty clay

10YR 3/1 silty clay

5Y 5/1 silty clay loam

5Y 5/1 clay loam

5Y 4/1 silty clay loam

5Y 5/1 clay loam

10YR 4/3 loam

10YR 5/4 loam

7.5YR 4/4 sandy clay loam

7.5YR 4/4 gravelly clay loam

7.5YR 4/4 sandy loam

7.5YR 3/2 gravelly sandy clay loam

10YR 3/3 gravelly sandy clay loam

7.5YR 4/4 sandy loam

10YR 5/2 loamy sand

10YR 4/2 loam

10YR 5/2 loam

10YR 6/3 clay loam

10YR 6/3 clay loam

10YR 6/2 gravelly clay loam

10YR 5/2 gravelly clay loam

10YR 5/1 gravelly sand

& Landform

0-2% slopes; Poorly drained to very poorly drained soils formed on glacial lake plains.

2-6% slopes; Well drained soils formed on outwash plains, outwash terraces, kames, and moraines

0-3% slopes; Somewhat poorly drained soils formed on outwash terraces, stream terraces, and outwash plains

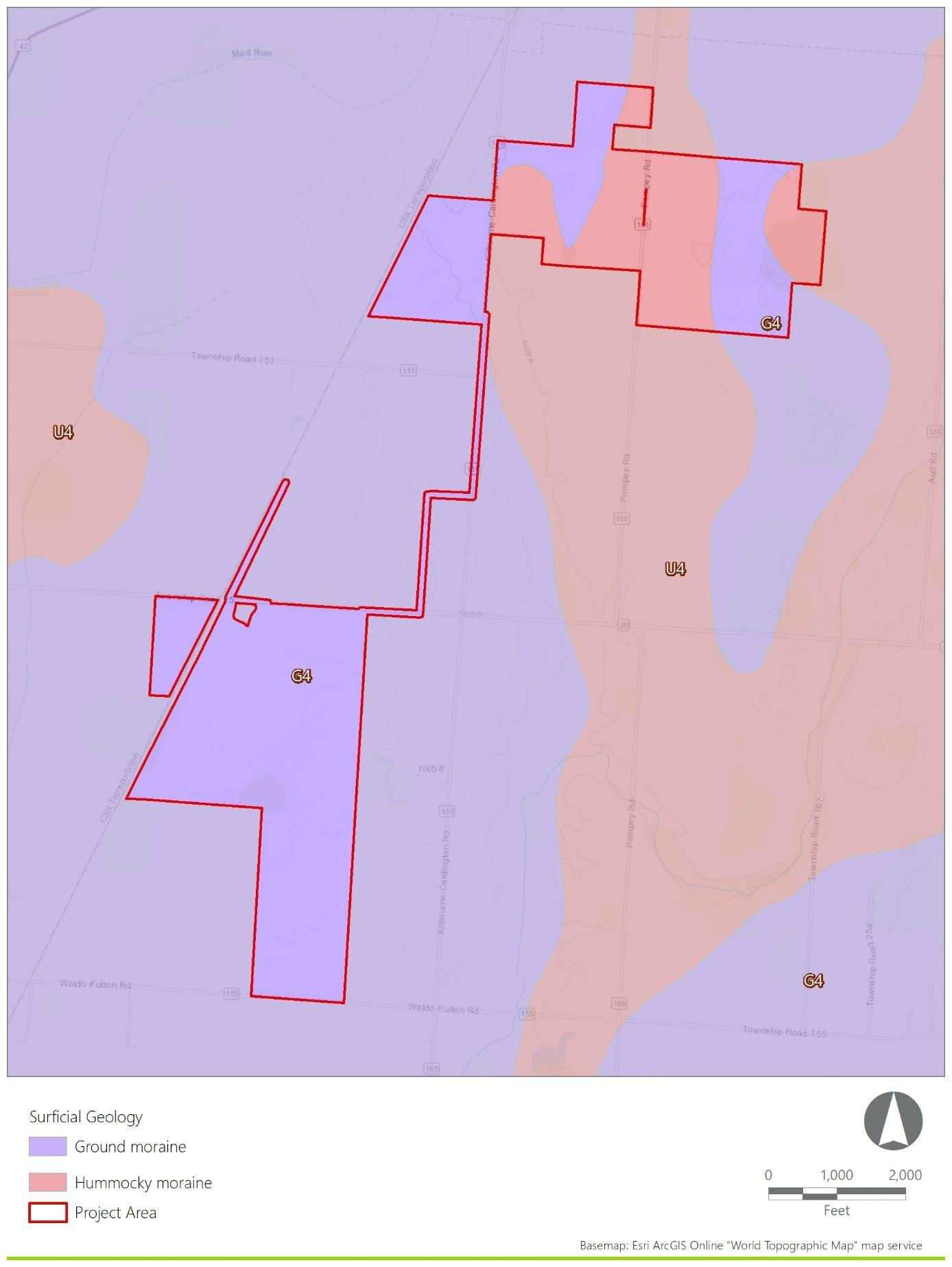

The surficial geology of the Project Area is summarized in Table 2 and depicted in Figure 3. It consists of ground moraine and hummocky moraine deposits dating to the Late Wisconsinan period, which extended from 70,000 years Before Present (B.P.) to 14,000 B.P within Ohio (Pavey et. al, 1999; OHC, n.d.a). The soils from moraine deposits are formed in glacial deposits, which are unlikely to contain deeply buried cultural horizons. Archaeological testing in these soils should extend to a minimum of 10 centimeters into sterile subsoil.

Table 2. Project Area Surficial Geology

Flat to gently undulating; ranges from silty till

Occurs as nonlinear hummocky patches higher than surrounding terrain; occurs mostly in valleys but also found on plugs or benches; mixed with bedrock colluvium on slopes; ranges from silty till to clayey till

1: Derived from Pavey et. al, 1999

2.2 Previously Recorded Cultural Resources and Previous Cultural Resource Surveys

Previously recorded cultural resources within the Historic Resources Study Area identified on the SHPO’s Online Mapping System (OHC, 2023) are described in this section and include:

• National Register of Historic Places (NRHP)

• NRHP Determination of Eligibility (DOE)

• Ohio Historic Inventory (OHI)

• Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) Historic Bridge Inventory

• Ohio Archaeological Inventory (OAI)

• Ohio Genealogical Society (OGS) cemetery files

• Previous cultural resources surveys

• National Historic Landmarks (NHL)

In addition, EDR reviewed the Archaeological Atlas of Ohio (Mills, 1914) for documented American Indian archaeological sites. The findings of this review are also discussed in this section

2.2.1 National Register of Historic Places (NRHP)

The review of the SHPO’s Online Mapping System indicates that there are no NRHP-listed resources within the Project Area. One resource, the Exchange Hotel (ref# 79001907), was located within the Historic Resources Study Area. However, the SHPO’s Online Mapping System indicates that this resource was delisted due to the destruction of the hotel by a tornado on June 13, 1981.

2.2.2 NRHP Determination of Eligibility (DOE)

The review of the SHPO’s Online Mapping System indicates that there are no resources formally determined NRHP-eligible within the Project Area. However, one formally determined NRHP-eligible resource is located within the Historic Resources Study Area. The resource (DOE# 1150, MRW0009910), located at 521 South Marion Street, was determined eligible based on Criterion C.

2.2.3 Ohio Historic Inventory (OHI) Resources

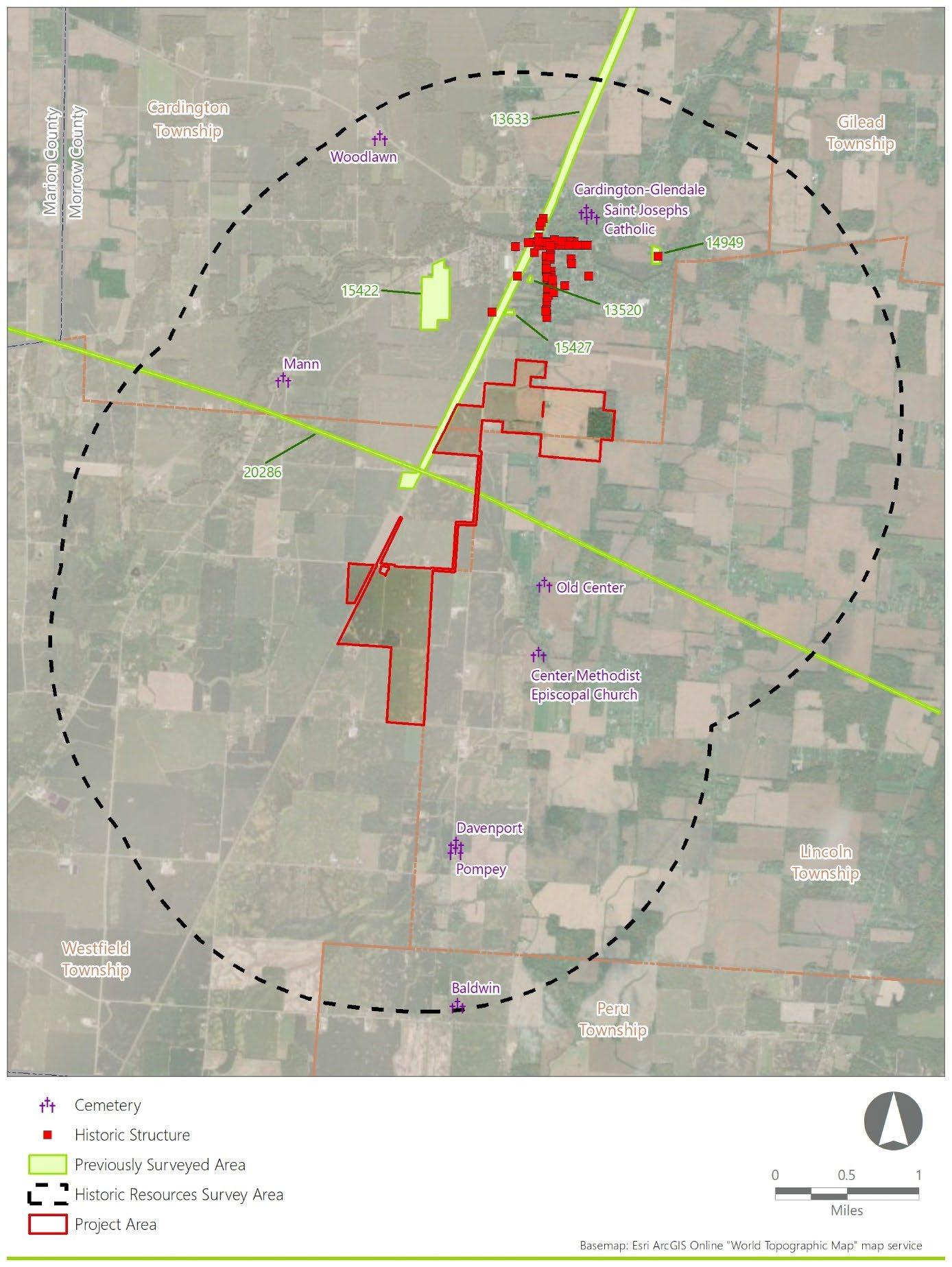

The review of the SHPO’s Online Mapping System indicates there are no OHI resources located within the Project Area. However, 86 previously recorded OHI resources are located within the Historic Resources Study Area (Table 3; Figure 4). None of these resources are NRHP-listed. However, one resource (MRW0009910) known as the Graham House, has been determined NRHP-eligible (see Section 2.2.2). The majority of OHI resources are concentrated within the village of Cardington located north of the Project Area.

Table 3. OHI Resources within the Historic Resources Study Area

4. Previously Identified Cultural Resources and Surveys

2.2.4 Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) Historic Bridge Inventory

The review of the SHPO’s Online Mapping System indicates that there are no historic bridges listed on the ODOT Historic Bridge Inventory located within the Project Area or Historic Resources Study Area

2.2.5 Ohio Archaeological Inventory (OAI)

The review of the SHPO’s Online Mapping System indicates that there are no previously identified archaeological sites within the Project Area. However, 55 previously identified archaeological sites are located within the Historic Resources Study Area (Table 4). Of these, four sites are located adjacent to the Project Area, all of which were identified for Survey 13633 discussed in Section 2.2.7: MW0149, MW0150, MW0151, and MW0152. Site MW0149 was identified as a multi-component site consisting of a small domestic scatter and one debitage fragment. The site dated from 1750 to 1900. Site MW0150 was identified as a multi-component site consisting of a small domestic artifact scatter dating from the eighteenth century to the twentieth century. Site MW0151 was identified as a historic-period site consisting of an architectural scatter of an unknown temporal period. Site MW0152 was identified as an American Indian site consisting of a small artifact scatter. Artifacts recovered included 11 debitage fragments of an unknown temporal period. Site MW0151 was recommended for avoidance with a 50-foot buffer.

4. OAI Resources within the Historic Resources Study Area

2.2.6 Ohio Genealogical Society (OGS) Cemeteries

The review of the SHPO’s Online Mapping System, as well as Findagrave.com, indicates that no cemeteries are recorded within the Project Area. However, nine OGS cemeteries are recorded within the Historic

Resources Study Area, (Table 5; Figure 4). The closest cemetery is located approximately 0.65 miles from the Project Area (Old Center Cemetery, OGSID 8667).

Table 5. OGS Cemeteries within the Historic Resources Study Area

8667

8666

1: Information derived from the SHPO’s Online Mapping System

2.2.7 Previous Cultural Resources Surveys

The review of the SHPO’s Online Mapping System indicates that there are two previous cultural resource surveys (NADB 13633 and 20286) located within the Project Area and four within the Historic Resources Study Area (Table 6; Figure 4). Survey 13633, completed in 1997, intersects through the northwestern portion of the Project Area and was conducted for a transmission line. The survey identified eight archaeological sites, including sites MW0149 through MW0151 which are detailed in Table 4 and discussed in Section 2.2.5. Survey 20286, completed in 2016, intersects through the central portion of the Project Area and was conducted for a substation and transmission line. The survey identified 10 archaeological sites, including sites MW0195 through MW0201 which are detailed in Table 4

Table 6. Previous Cultural Resources Surveys within the Historic Resources Study Area

NADB

13633

Phase I Cultural Resources Investigations for the Proposed Cardington-Galion Transmission Line, Morrow County, Ohio

Goodfellow, Susan T. 1997 Within 20286

Phase I Archaeological Investigations for the Approximately 18.5 km (11.5 mi) Fulton Station to Windfall Switch 138kV Rebuild Project in Richland Township, Marion County and Cardington/Westfield/Lincoln Townships, Morrow County, Ohio

Weller, Ryan J. 2016 Within 15427 Literature Review and Reconnaissance Survey of the Proposed Morrow County Schweikart, John F. 1992 0.3

13520

15422

Housing for Persons with Disabilities, Cardington, Morrow County, Ohio

A Phase I Literature Review and Cultural Resource Survey for the Proposed Cardington Meadows Apartments, Near the Village of Cardington, in Cardington Township, Morrow County, Ohio

Phase I Archaeological Investigations for the Proposed Manufacturing Facility in the Village of Cardington, Morrow County, Ohio

14949

Phase I Cultural Resources Management Investigation for a 1.28 (3.17 a.) Habitat for Humanity Development in Cardington Township, Morrow County, Ohio

2.2.8 National Historic Landmarks (NHL)

Blanton, David 1996 0.55

Weller Von Molsdorff, Ryan J. 1995 0.7

Weller Von Molsdorff, Ryan J. 2002 1.0

No designated NHLs are located within the Project Area or the Historic Resources Study Area (NPS, 2022).

2.2.9 Mills Archaeological Atlas of Ohio (1914)

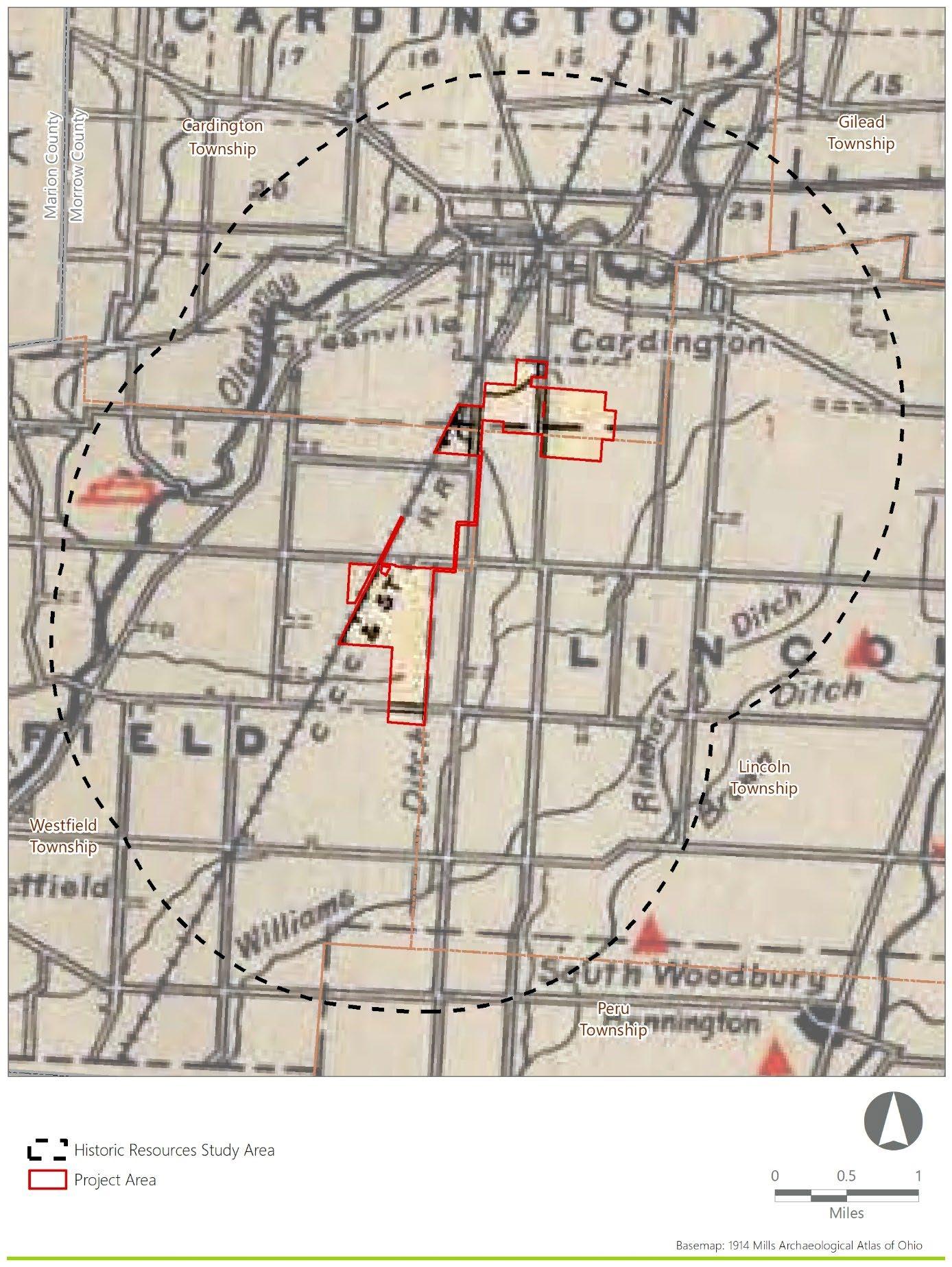

According to the Archaeological Atlas of Ohio (Mills, 1914), no American Indian resources are located within the Project Area (Figure 5). However, one resource is located within the Historic Resources Study Area and includes one village site. According to Mills (1914: 59), 32 American Indian sites were distributed across Morrow County and included 21 mounds, five enclosures, five village sites, and one burial Within Morrow County, the largest concentration of American Indian sites in 1914 was located along the Olentangy River, Alum Creek, and Owl Creek.

In addition to mapping American Indian archaeological resources, Mills (1914) also mapped known American Indian trails throughout Ohio. No trails are mapped within Morrow County. The closest trail illustrated by Mills is Trail 2, the Scioto Trail, located approximately 15 miles west of the Project Area. The Scioto Trail ran north and south through Ohio and connected Sandusky Bay (Lake Erie) with the mouth of the Scioto River (Scioto County, Ohio) (Mills,1914: VII).

2.3 American Indian Context for the Historic Resources Study Area

Present-day Ohio presents similar cultural chronological patterns to surrounding midwestern states. A commonly accepted chronology for Ohio history includes the following sequence of temporal periods: Paleoindian, Early Archaic, Middle Archaic, Late Archaic, Early Woodland, Middle Woodland, Late Woodland, Late Prehistoric, and Historic. The time periods used for changes in this chronological sequence are based on multiple factors including, but not limited to, environmental conditions, changing technologies, settlement patterns, subsistence, trade, and typological assessments. As such, chronological dates should be viewed as general guide points for changes occurring over time.

Paleoindian groups moved into the area encompassing present-day Ohio at the end of the Wisconsin glaciation, generally interpreted as small sized groups of highly mobile hunter-gatherers that were adapting to the changing environmental conditions of the Late Pleistocene - Early Holocene transition. Material culture associated with these groups in Ohio is usually found in the form of lanceolate, fluted projectile points with high densities occurring in the Ohio River drainage (Neusius and Gross, 2007:515). Typologically, these points are classified as “Clovis,” though other typological categorization schemes have been developed to capture variations, such as Cumberland, Barnes, and Crowfield (Justice, 1987:17-27; Neusius and Gross, 2007:515). Analysis of Paleoindian tool kits appears to indicate a preference for high quality raw materials (Seaman, 2006:46). This is supported by Boulanger and colleagues (2015) research on flaked stone tools at the Paleo Crossing site, where neutron activation analyses confirmed that the majority of the raw material for flaked stone tools at the site are comprised of Wyandotte chert from Harrison County, Indiana. As the raw material source for these tools is located 450 kilometers or further from the site, this certainly supports the concepts of long-distance retrieval for higher quality raw materials, as well as evidence of large social contact areas and territorial permeability (Boulanger et al., 2015:554).

Paleoindian subsistence and settlement patterns are lesser known. Seaman’s (2006:46) research focusing on the Nobles Pond site was interpreted as evidence for multiple groups occupying the site concurrently, most likely for social interaction. Other sites have been interpreted as short term hunter camps, such as Sheriden Cave (Redmond, 2006:48). Given the highly mobile interpretation of Paleoindian groups, they most likely had large home ranges for resource acquisition (Redmond, 2006:47). Now-extinct megafauna are often interpreted as valuable game during this period, evidenced by the association of Paleoindian tools with remains of mammoth and mastodons (Neusius and Gross, 2007:516). The terminus of Paleoindian activity in the Midwest is often marked by the presence of unfluted lanceolate points (Neusius and Gross, 2007:515). Significant Paleoindian sites in Ohio, though not exhaustive, include Paleo Crossing, Nobles Pond, Sheriden Cave, and the Burning Tree Mastodon Site.

Significant environmental changes associated with the end of the Ice Age marks the beginning of the Early Archaic period, often seen in the archaeological record by the changes that occurred in the Early Archaic toolkit (Lepper, 2006:51-54). A wider variety of diagnostic tools can be viewed as evidence of increasing population sizes as well as an early emergence of group identities (Lepper, 2006:54-56). The higher frequency of ground stone tools has also been interpreted as a need for heavier duty woodworking tools, representing some changes in behavior (Lepper, 2006:54-56).

Variations in Early Archaic diagnostic projectile point typologies often include side notching and serration, as opposed to the earlier lanceolate points of Paleoindian groups (Lepper, 2006:60). Hunting and gathering continued to be the predominate lifestyle, though the geographical movement seems to become more regionalized than earlier groups, as evidenced by an increase usage of localized raw materials (Lepper 2006:56). Burials in the Early Archaic are virtually absent in Ohio, potentially due to small population sizes and cremation practices (Lepper, 2006:62).

The Middle Archaic in Ohio presents little material culture, often attributed to the warming and drying climatic conditions of the Holocene leading populations to seek resources elsewhere (Lepper, 2006:63). Additionally, an increase in precipitation during this period is interpreted as having severe erosional effects on Middle Archaic sites, further impacting the ability to identify and recover material culture (Lepper, 2006:63). Middle Archaic activity is interpreted to have taken the form of larger base camps, potentially multi-seasonal in nature, with an increase in burial sites interpreted as evidence for continued population increases (Lepper, 2006:64). Hunting and gathering continued to be the primary mode of subsistence, with continued increases in plant species utilization, such as acorns and hickory nuts (Lepper, 2006:63). The Middle Archaic toolkit also presents increased variation, with continued side notched projectile point manufacture and increases in the variation of ground stone tools (Lepper, 2006:63).

Continued environmental changes consisting of a general cooling and increase in rainfall occurred during the Late Archaic, establishing the modern Ohio climate. A higher occurrence of Late Archaic sites across Ohio, focused on major river drainages, is viewed as evidence of continued population increases (Lepper, 2006:65). Distinct social groups appear to have formed, viewed archaeologically via regionally specific burial practices such as the termed Red Ocher Complex and Glacial Kame Complex (Lepper, 2006:74-75). Late Archaic site types typically range from small hunting camps and gathering sites to larger settlement/habitation areas (Lepper, 2006:69). There is an increase in the use of heavier and larger ground stone tools, along with the emergence of early pottery in the Late Archaic, interpreted as evidence that groups may have been occupying sites for longer durations (Lepper, 2006:70). The Davisson Farm Site, a larger base camp, presented earth ovens and structural features interpreted as potentially permanent structures, though year-round occupation of the site does not appear to have occurred (Purtill, 2006:66; Purtill, 2008:72). The Davisson Farm Site specifically yielded squash rinds, viewed as potential evidence for early plant domestication (Purtill, 2006:67). Other plants in the Late Archaic diet included sumpweed and goosefoot, as well as hickory nuts (Lepper, 2006:69).

The Early Woodland in Ohio saw the emerging reliance on agricultural practices for subsistence, as well as pottery usage and a flourishing of burial mound practices (Lepper, 2006:79). Plant domestication and the Eastern Agricultural Complex (EAC) became prevalent, including goosefoot, marshelder, maygrass, amaranth, squash, knotweed, and sunflowers (Abrams and Freter, 2005). The high value of nuts and meat in Early Woodland diets also continued (Lepper, 2006:81-86). Early Woodland pottery is often thick-walled with little decoration (Grooms, 2006:88).

The Middle Woodland period in Ohio is synonymous with Hopewell archaeological cultural manifestations, an expansional increase in many of the types of practices that began in the Early Woodland period. This is well represented at various significant sites throughout Ohio, such as at Newark, Seip, the Mound City Group (Hopewell Culture National Historical Park), Fort Ancient, Tremper, Fort Hill, Marietta, Portsmouth, Hopeton, and the Hopewell type site located in Ross County. Hopewell interaction covers a significant geography, stretching as far as Missouri in the west and Florida in the south (Lepper, 2006:114). In Ohio, significant Hopewell activity is often found in major river valleys, such as that of the Scioto, Muskingum, Licking, Little Miami, and Great Miami River valleys (Lepper, 2006:114). Generally speaking, the large geography reflects a widespread adoption of belief systems, including earthwork construction, artistic expression, raw material acquisition, and burial practices (Lepper, 2006:115).

Many significant Hopewell sites consist of large ceremonial centers, such as large geometric earthworks and hilltop enclosures. Rather than being used for habitation, earthwork centers are interpreted as vacant spaces that were repeatedly visited by the surrounding population, becoming a focal point for social activity (Pacheco, 1996:32). This is supported by the lack of refuse material that would be expected of longer-term habitations, as structures at these larger ceremonial centers may have been utilized as temporary housing for visitors (Lepper, 2006:146). Various ceremonial earthwork sites present astronomical alignments, such as the lunar extremes observed at Newark (Hively and Horn, 2006:160-161; Romain, 2000). Domestic sites are rather different, often referred to as hamlets, and were placed along rivers, streams, and associated tributaries, with adjacent gardens and cooking areas (Lepper, 2006:120). The EAC, hunting wild game, and gathering food plants continued to be important to subsistence (Lepper, 2006:121).

Continuing religious/ritual practice flourished in the Middle Woodland, with artistic and stylistic expressions of bears, birds, and deer (Lepper, 2006:123). Some of the most recognizable are the Wray Figurine, depicting an individual dressed in a bearskin that potentially represents shamanistic activity, as well as various animal effigy platform pipes that have been recovered from Mound City Group and Tremper (Lepper, 2006:123). It has also been suggested that “Big Houses” at earthwork sites may reflect three divisions or groups within Hopewell Society, evidenced by three distinct areas such as those found at Hopewell, Seip, and Harness (Lepper, 2006:129).

The Late Woodland is often marked by an abandonment or collapse of the practices observed at Hopewell sites across Ohio, as population sizes continued to grow and large villages were formed (Lepper, 2006:172). Village layouts began to take on the form of an open plaza surrounded by habitation structures and large earth ovens, presumably for larger numbers of inhabitants (Lepper, 2006:172). It is thought that these villages were occupied for longer durations, with stockades and ditches potentially being indicative of an increase in violence among populations (Lepper, 2006:172). Burial patterns show a transition to cemetery areas close to their associated villages, though burials are also noted to occur in middens, as well as intrusively into older Middle Woodland earthworks with pipes and red ocher (Lepper, 2006:190). Swidden agriculture and farming intensified during the Late Woodland, with continued usage of the EAC, and eventual increase in Maize agriculture (Lepper, 2006:176).

Significant changes in the Late Woodland include the transition to long term villages with an apparent inward focus and less interaction between populations than their Middle Woodland ancestors, which Lepper (2006:186) suggests may represent a growing “us vs. them” mentality, potentially indicative of the formation of tribal identities. Increased competition between villages competing for the same resources and a more sedentary lifestyle may have further expanded such a mentality (Lepper, 2006:186). There is also less stylistic expression, potentially indicating less need to visually communicate status within villages, along with the inward village focus potentially creating social stratification via achieved status (Lepper, 2006:191).

The large village layout expands further in the Late Prehistoric, with maize becoming the primary staple of subsistence, along with continued changes in ritualistic practices (Lepper, 2006:195). Cook (2017:235) suggests potential for Mississippian groups to have been migrating into the Ohio region, with a mixture of local Woodland cultural practices and Mississippian practices eventually migrating from southwestern Ohio in a northeastern fashion along major river tributaries. Triangular cluster points (Justice, 1987:224-230), shell hoes, large ground stone axes, and bone fishhooks become important aspects of the tool kit, along with increasing complexity in shell tempered, decorated pottery (Lepper, 2006:198-201). The “Three Sisters”, namely maize, beans, and squash, replace the EAC, with hunting continuing to be important for subsistence (Lepper, 2006:203).

Late Prehistoric villages are estimated to have contained between 100 and 500 individuals, occupied for between 20 and 30 years, and were most likely socially stratified (Lepper, 2006:203-210). Increased sedentism, increased competition between villages, and a need to manage food supplies are suggested to have potentially created a need to establish village leadership (Lepper, 2006:214-215). At some Fort Ancient villages, it has been suggested that the village authorities may have come from outside of the village (Cook, 2017:235). Overall, villages were thought to be egalitarian, evidenced by a centralized pole in the village layout that may have served to maintain the egalitarian setting (Cook, 2017:236).

Religion, ritual, and shamanistic activity are thought to have continued to play an important role for Late Prehistoric populations (Lepper, 2006:215). Religious and stylistic expression can be seen in the form of effigy mounds such as Serpent Mound and the Alligator Mound, and it is thought that some of Ohio’s petroglyphs date to the Late Prehistoric alongside those created by historical tribes (Pape, 2006:222-223). Lepper and colleagues (2019:52) indicate that serpent imagery becomes common in the Late Prehistoric, with Serpent Mound sharing comparable motifs to those from Picture Cave in Missouri, potentially representing some aspect of the Degihan Sioux genesis story. Cook (2017:236-238) suggests that during the Little Ice Age, population movements could have led to some Fort Ancient populations leaving the area that would eventually become parts of Degihan Sioux tribes, whereas local Woodland inhabitants would have been connected to Algonquian groups. Mississippian refugees potentially made their way into Ohio near AD 1100, around the same time that Fort Ancient villages and the effigy mounds representing “Beneath World” spirits were being created (Lepper et al., 2019:52).

Evidence of European presence within Ohio dates to as early as AD 1650, when French map makers depicted the southern shore of Lake Erie (OHC, 2022c). However, permanent European settlement in Ohio did not

occur until later. Prior to this, American Indians and Europeans entered into a trade relationship, exchanging goods such as copper, iron, and glass objects (Abel and Burke, 2014). Archaeologically, material sourcing for some of these artifacts, particularly those copper-based, are difficult to distinguish between foreign or native extractions, as native and European sourced copper has been recovered concurrently from various sites (Abel and Burke, 2014:190-195). This becomes increasingly more complex with evidence of American Indian groups dismantling European trade items, such as kettles, for the manufacture of traditional American Indian artifact forms (Abel and Burke, 2014:194).

Various American Indian tribes occupied portions of Ohio throughout the Protohistoric and Historic periods. This included groups with ancestral ties to Ohio, as well as groups being pushed into the Ohio country as a byproduct of European arrival (i.e., the Haudenosaunee) Haudenosaunee presence in the Ohio region increased beginning in the 1600s due to European presence within the northeastern United States and the seizing of American Indian lands (Brush, 2005:99). By the 1740s, the Wyandot had settled in northwest Ohio and continued to spread throughout much of the state (OHC, 2022c). Many American Indian groups spoke related languages, including those from the Algonquian language family, as well as the Iroquoian language family. Algonquian speakers include (but are not limited to) the Shawnee, Delaware (Lenape), Miami, Eel River, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Chippewa (Ojibwa; Anishnaabe), Peoria (Peoria, Piankashaw, Kaskaskia, and Wea), and Sauk. Iroquoian speakers include (but are not limited to) Mohawk, Wyandot, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca. It should be noted that while many of these groups share a common language family, individual group languages are often divergent and distinct.

Evidence of multi-group American Indian occupation is present throughout Ohio and includes Wyandot and Mingo occupation at Cochake in the mid-1700s (Brush, 2005:99-100; Darlington, 1893:37); Mohawk, Mohican, and Delaware occupation at Owls Town in 1775 (Brush, 2005:99-100; Smith, 1978:28-34); and Shawnee, Miami, and Wyandot occupation in the Maumee Valley in the 1780s (Lakomaki, 2014:602). The complexity of multi-group occupation is evidenced in the mixture of culturally diagnostic artifact styles, (i.e., projectile points and pottery) at American Indian habitation sites, which may be a reflection of population movements and interactions during the Protohistoric and Historic periods (Brush, 2005:99-100).

2.4 Historic Context for the Historic Resources Study Area

In the mid-eighteenth century, Virginia, New York, Massachusetts, and Connecticut each laid claim to sections of the Northwest Territory based on seventeenth- and early-eighteenth century charters. These lands encompassed parts of present-day Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin; however, land companies’ and speculators’ efforts to survey and sell these lands were hindered by the Seven Years’ War (1754-1763), Pontiac’s War (1763-1766), and the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). By 1786, the states ceded the Northwest Territory to the burgeoning United States federal government. This territory was augmented by American Indian land cessions, most notably in the treaties of Fort Stanwix (1784), Fort McIntosh (1785), Fort Finney (1786), Fort Harmer (1789), and Greenville (1795).

The Treaty of Greenville was signed on August 3, 1795, after Major General Anthony Wayne’s campaign against the native Northwestern Confederation, led by Miami chief, Little Turtle. The campaign, which culminated in the Battle of Fallen Timbers along the Maumee River near present-day Toledo, resulted in a victory for Wayne’s forces and constituted the last major American Indian resistance in present-day northwest Ohio (Beers, 1883). Throughout this period, U.S. policy encouraged American Indian groups to treat geographical areas and/or homelands as “exclusive tribal possessions” whereas many American Indians treated lands north of the Ohio River as collective, shared native land (Lakomaki, 2014:600, 602). The Treaty of Greenville undermined this belief in collective native land, as pressure to cede large portions of Ohio led some groups to begin voicing claim over specific territories (Lakomaki, 2014:603). By 1804, U.S. policy was actively undermining the belief in collective native land, exemplified by Governor William Henry Harrison’s (Indiana) drawing of intertribal boundaries, which tied ownership to specific American Indian groups. This resulted in land cession discussions with single American Indian groups rather than multiple and ultimately weakened displaced American Indian groups’ claims to territory which aided Euro-American expansion (Lakomaki, 2014:609).

As Ohio developed, federal expansion policies and settlers increasingly encroached on the American Indian reservations established in the Treaty of Greenville. By 1818, the Treaty of St. Mary’s led to further land loss by Ohio’s American Indian groups, ultimately resulting in only the Shawnee, Seneca, and Wyandot retaining small reservations within Ohio at Wapakoneta, Hog Creek, and Lewistown (Lakomaki, 2014:621-622). However, discussion of removal continued. By 1830, the Indian Removal Act displaced Ohio’s remaining American Indian groups and by 1842, the remaining tribes were forced to cede their reservations (Shetrone, 1970).

After their forced removal from Ohio, many American Indian tribes resettled within the Great Plains region. The Wyandot, removed from their reservation at Upper Sandusky, were sent to reservations in present day Wyandot County, Kansas before being forcibly moved to Oklahoma. Additional American Indian groups including the Miami and Shawnee were similarly relocated to Kansas and Oklahoma. Descendants from these groups today are members of federally-recognized tribes such as the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma and the Wyandot Nation of Oklahoma, as well as federally-unrecognized groups such as the Miami Nation of Indiana (OHC, n.d.b-n.d.d)

2.4.1

Morrow County History

Morrow County is located in central Ohio and is included in the Columbus, Ohio Metropolitan Statistical Area (US Census, 2012). While Euro-American settlement of Ohio generally increased between 1788 and 1798, it was not until the nineteenth century that Euro-American settlers moved into present-day Morrow County (Baskin, 1880:121) The first recorded Euro-Americans within the county were the Shaw family in Westfield Township in 1804, followed by Evan Holt in Chester Township in 1807 and Cyrus Benedict in Peru Township in 1809. In addition to these early settlers, other early settlers within the county were members of the Society of Friends (Quakers). In 1812, the Benedict family migrated from New York to Ohio and established the first Quaker settlement in Morrow County along Alum Creek (NPS, n.d.).

Early histories of the county state that springs were quite numerous, with early Euro-American settlers establishing cabins and “frontier farms” along these springs (Baughman, 1911: 33) Additionally, the landscape within the county consisted of dense vegetation and timber, which had to be cleared for agricultural purposes. As such, “frontier farms,” or early established farms, were typically non-sustaining for five years after land clearing (Baughman, 1911: 98). To supply the early settlers, the first Morrow County mills were erected between Cardington and Mount Gilead in 1819 and in Cardington Township in 1821 (Baughman, 1911: 113-114) However, due to scarcity of supplies, goods were transported via horseback from neighboring Delaware County and Owl Creek (Kokosing River) (Howe, 1907:315) Trails traversed by early settlers within Morrow County included pre-established American Indian trails, the earliest of which extended from Mount Vernon, Knox County, Ohio to the “Sandusky plains” located south and west of the Sandusky River By 1911 this trail was all but vacated; however, a small portion of the trail was still traveled between the towns of Pulaskiville and Chesterville, both located within Morrow County (Baughman, 1911:48).

The Ohio government officially authorized the creation of Morrow County in 1848 from portions of Delaware, Knox, Marion, and Richland counties. The village of Mount Gilead, Morrow County’s county seat, was laid out in 1824 as part of Marion County (Baughman, 1911:76) The community was first known as Whetsom and then Youngstown before it was renamed Mount Gilead in 1832. Between 1847 and 1880, Mount Gilead’s population increased from 400 to over 1,200 people, which differed from population trends in the county. Between 1850 and 1900, the population of Morrow County decreased from more than 20,000 people to less than 18,000 people.

During the 1830s and up to the Civil War, many locals, primarily due to their religious beliefs (Quakers), played an active role in the abolition movement with residents participating in the Underground Railroad (OHC, n.d.e). According to the National Park Service (n.d.), of the approximately 100,000 enslaved peoples who escaped via the Underground Railroad, at least 40,000 traveled through Ohio. Three stations of the Underground Railroad were located in Morrow County: South Woodbury (Peru Township), Friends’ Settlement (2.5 miles south of Mount Gilead, Gilead Township), and Iberia (Washington Township).

Agriculture was and continues to be a main industry within Morrow County. According to Baughman (1911: 32-33), the county was “fit for cultivation and for farming purposes.” Farms within the county were moderate sized farms, with the average acreage not exceeding eight acres. Improvements in farming reached Morrow County with the introduction of horse powered machinery in 1839, cast iron plows in 1849, the corn and cob grinder in 1856, and field drainage tile in 1859 During the nineteenth century, the primary system of agriculture was mixed husbandry, with livestock being the leading pursuit of most farmers within the county (Baughman, 1911:129). Crops grown within the county during the nineteenth century primarily included hay and apples, the latter of which saw increased production with the introduction of the railroad during the late nineteenth century (Baughman, 1911: 133). Prior to the railroad, agricultural products were transported via wagon and shipped to Cumberland, Maryland and neighboring counties in Ohio (Baughman, 1911:266).

Into the latter half of the nineteenth century, Morrow County entered the railroad era which facilitated economic growth within the county. The first railroad through the county was the Cleveland and Columbus Railroad constructed near the village of Edison, with rail traffic commencing in 1851. The railroad, later called the Cleveland, Akron, and Columbus Railroad (CA&C), connected the city of Cleveland to the city of Columbus and connected Morrow County to northeast Ohio. In the late nineteenth century, the Toledo and Ohio Central Railroad was constructed through the village of Mount Gilead, connecting Morrow County to northwest Ohio (Baughman, 1911: 275)

In addition to agriculture and its associated industries (i.e., mills), other industries during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries included pottery and tile works, dry goods manufacturing, banking, hotels, and postal services Significant industries within the county included the Mt. Gilead Tile Works, a tile factory and pottery works established in 1875, and the Hydraulic Press Manufacturing Company established in 1883 (Baughman, 1911:268-273). The tile factory burned down in 1907 and was rebuilt along a portion of the Toledo and Ohio Central Railroad, west of Mount Gilead. The tile works merged in 1922 with the McGowan and Company Pottery, a manufacturer of utilitarian earthenware and stoneware founded in 1888. The hydraulic press company was established in particular for apple cider and vinegar production in order to take advantage of the apple production within the county (Baughman, 1911: 279)

The population of Morrow County continued to decrease from 1900 to 1930. However, during the 1940s, the county’s population began to increase and continued to increase into the present (U. S. Census, 1930, 2020) Farming remains the largest employer in the county, with approximately 62% of the county’s acreage serving as farm fields. Manufacturing businesses are the county’s second largest employer, with governmental and retail finishing third and fourth, respectively. Oil drilling was also a major industry during the 1960s (OHC, n.d.e).

2.4.1.1

Cardington Township

Cardington Township was established in 1823 by the commissioners of Delaware County, Ohio. The first Euro-American settlement of Cardington Township is attributed to Quakers and Isaac Bunker, who arrived from Peru Township in 1822 (Baskin, 1880:322). News of Isaac Bunker’s success in Cardington Township led to a surge in migration to the area, particularly from former residents of Peru Township. Whetstone Creek became the focal point of the early settlement. Success of the milling enterprises became an important piece of the local economy further driving migration to the area (Baughman, 1911: 336-337) The largest town within the township is Cardington, which was formally established in 1836 (Baughman, 1911: 344). Early industry within the town primarily consisted of grist mills and carding mills, as well as carriage manufacturers, cooper shops, blacksmiths, and furniture factories (Baughman, 1911: 358).

2.4.1.2

Lincoln Township

Lincoln Township was originally part of Harmony Township. However, as the township expanded, a petition to create a new township was drawn Therefore, in March of 1828, Lincoln Township was formally created Much like the rest of the county, farming became the primary economy of Lincoln Township. Rich black soil at lower elevations provided large crop yields, with soils on higher ground utilized for grasses, corn, and

wheat (Baughman, 1911:510). Early Euro-American settlers of Lincoln Township consisted mainly of Quaker families from the surrounding townships (Baskin, 1880: 435). Due to the influx of Quaker settlers, Lincoln became an early adopter of church influence. Initially, the Meetings for worship were held in schoolhouses and cabins until 1853 when the Center United Brethren Church was erected followed by the Lincoln Christian Church in 1858 (Baughman, 1911: 440; Baskin, 1880, 516). The largest town within the township is Fulton, which was formally established in the early twentieth century due to the prevalence of stone quarries and its location near a train station for the Toledo and Ohio Central Railroad (Baughman, 1911: 439).

2.4.1.3

Westfield Township

Westfield Township was formally organized in 1822 as part of Delaware County, and later incorporated into Morrow County in 1848. Whetstone Creek divides the township roughly in half and served as an important natural resource for early settlers to the region. The first Euro-American settlement in Westfield Township was also the first Euro-American settlement in present-day Morrow County. The Shaw family of Chester County, Pennsylvania arrived in 1804 and settled on 400 acres of purchased land located in the northern portion of Westfield Township adjacent to the Greenville Treaty line (Baughman, 1911:488) Like Lincoln Township, religion played a major role in the early settlement of Westfield Township, as Quaker families composed a majority of the original settlers to the township (Baskin, 1880:385).

2.4.1.4

Gilead Township

Gilead Township was formally organized in 1835 as part of Marion County from portions of present-day Canaan, Cardington, Congress, Franklin, and Lincoln Townships, Morrow County (Baughman, 1911: 326) The township formally became a portion of Morrow County in 1848 when the county was formed. Early industries within the township that persisted throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries included agriculture, stone quarries, and mills. Crops grown within the county included grass, clover, hay, corn, wheat, rye, oats, flax, and fruit trees.

2.4.1.5

Peru Township

Peru Township was formally organized in 1848 from Sunbury Township, Delaware County (Baughman, 1911: 456). Similar to county trends, most early settlements within Peru Township were located along streams, such as Alum Creek. Additionally, like Lincoln Township, religion played a major role in the early settlement of Peru Township, with the first Quaker settlement in the county established in 1812 by the Benedict family (NPS, n.d.; Baskin, 1880:385). Within Peru Township, the Reuben Benedict House, constructed by the Benedict family, served as an ideal location for an Underground Railroad station as the area contained a sizeable free and fugitive black population, an active Quaker fellowship, and a “local community with strong convictions about the immorality and injustice of slavery” (NPS, 2023).

2.5 Historic Maps Research

Historic maps depict nineteenth- and twentieth-century settlements and development within the Historic Resources Study Area. The maps reviewed are discussed in subsection 2.5.1 and 2.5.2

2.5.1 Nineteenth Century Map Research

The Project Area and Historic Resources Study Area remained rural throughout the nineteenth century with the exception of the population center in the village of Cardington (Harwood and Watson:1857). Structures, most likely farmsteads, within the Project Area and Historic Resources Study Area are located along roadways connecting communities of the surrounding townships Structures are also present along Whetstone Creek which traverses the Historic Resource Study Area. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the population growth of the village of Cardington is depicted by the increased density of structures within the town proper, and the appearance of additional structures on the outskirts of town. However, the density of structures remains low throughout the Project Area (Lake,1871) (Figure 6) In addition to mapped structures, the Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati, and Indianapolis Railroad (CCC&I) is mapped along the western boundary of the Project Area, which was constructed in Morrow County during the late 1860s (Schmid, 1928).

2.5.2 Twentieth Century Map Research

Between 1871 and 1916, the Historic Resources Study Area changed little. Differences between the 1871 atlas map and 1915 and 1916 USGS topographic maps include the identification of schoolhouses within the Historic Resources Study Area and the change in ownership of the CCC&I Railroad to the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago, and St. Louis Railroad (Figure 7). By the mid-twentieth century, the Historic Resources Study Area included more roadways and more mapped structures along roadways. However, the structures still appear relatively sparse throughout the Project Area. Similar to the Project Area, the village of Cardington remains relatively unchanged (USGS,1915, 1916, 1943a, 1943b) (Figure 8). By the mid-twentieth century, the Historic Resources Study Area appeared very similar to the area’s current configuration. Developments within the late-twentieth century include the construction of electric transmission lines through the Project Area, as well as the railroad’s name and/or ownership change to the New York Central Railroad. The railroad’s present ownership is CSX Transportation, a freight railroad company. However, by the late-twentieth century the Project Area and Historic resource study area remain relatively unchanged (USGS, 1961a, 1961b).

3.0 PROPOSED ARCHAEOLOGY RESEARCH DESIGN AND SURVEY METHODOLOGY

Phase I identification is intended to discover unrecorded archaeological resources and confirm previously identified archaeological resources within the APE. This section includes a discussion of the proposed archaeology research design and survey methodology for a Phase IB archaeological survey as required by the Archaeology Guidelines (SHPO, 2022).

3.1 APE for Direct Effects

The APE for Direct Effects is defined as the direct Project footprint with potential to experience soil disturbance (or other direct, physical impacts) during Project construction. Potential Project components were discussed in Section 1.2. Given that the Project layout is currently in the preliminary design stage, the APE for Direct Effects is currently considered the Project Area in totality.

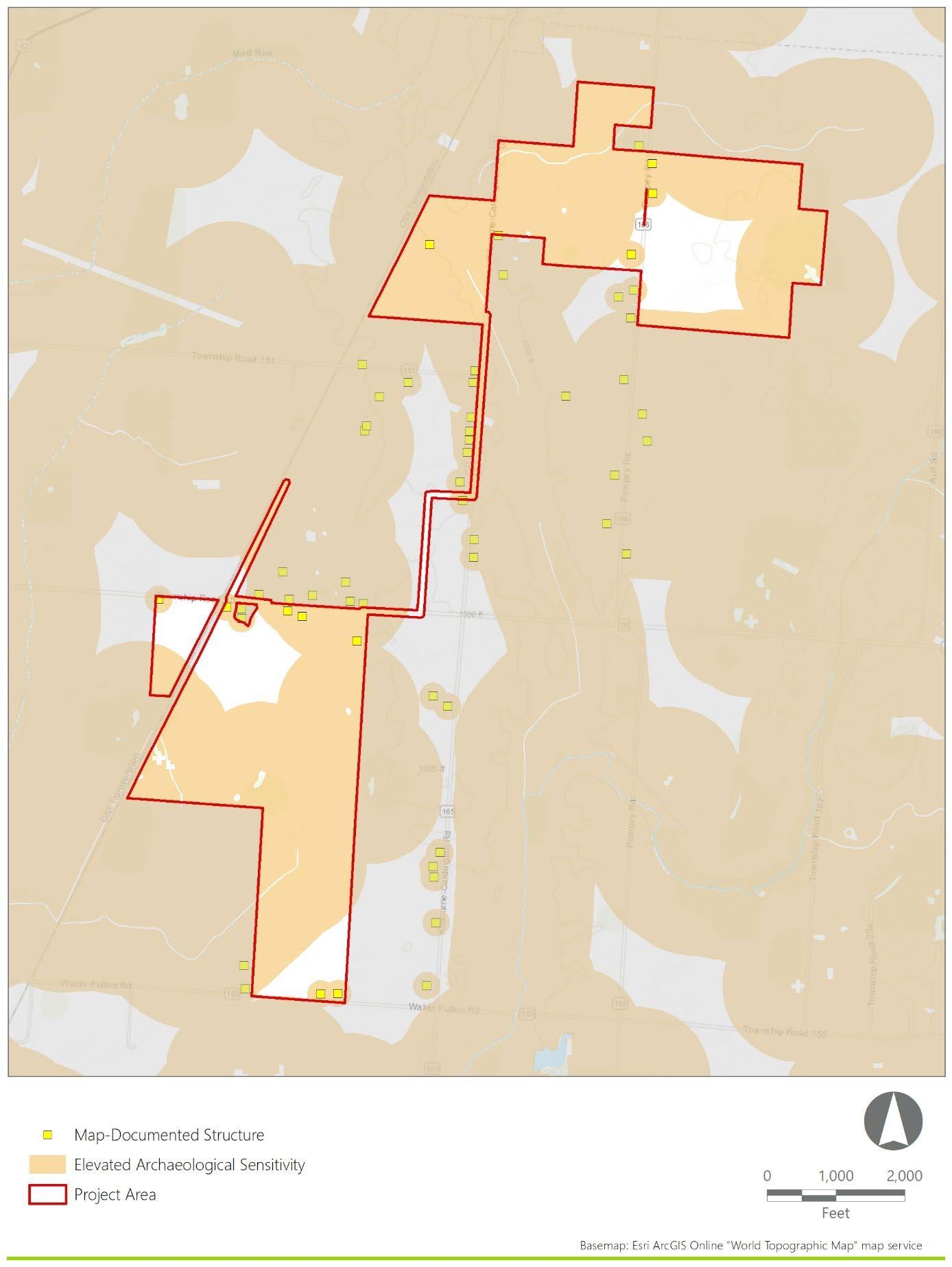

3.2 Archaeological Sensitivity Assessment

The Project has the potential to directly (physically) impact identified and unidentified archaeological resources. As described in Section 2.2.5, no previously recorded archaeological sites are located within the Project Area. However, 55 previously recorded archaeological sites and nine OGS cemeteries are located within the Historic Resources Study Area As part of the research design, EDR assessed the probability of encountering archaeological resources within the Project Area based on review of the SHPO’s Online Mapping System, the results of background research and historical map analysis, and desktop landscape/environmental analysis using Geographic Information System (GIS) tools and data. The results of this assessment for archaeological resources are presented in the following subsections and represented in Figure 9.

EDR prepared a GIS-based landscape analysis to identify areas of elevated archaeological sensitivity. Areas of elevated archaeological sensitivity meet one or more of the following criteria:

• Criterion 1: Within 1,000 feet of permanent water and on slopes equal to or less than 15%

• Criterion 2: Within or near known archaeological sites.

• Criterion 3: Locations of standing or demolished historic structures.

Each criterion is described in detail as follows

Figure 9. Archaeological Sensitivity Assessment

3.2.1 Criterion 1: Proximity to Waterways

Portions of the Project Area within 1,000 feet of naturally occurring rivers, streams, and wetlands are considered to have an elevated sensitivity for containing archaeological material Areas more than 1,000 feet from naturally occurring water sources are considered to have a reduced sensitivity for containing such material. Per the National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) mapping, aquatic resources are organized by type, and include riverine, pond, lake, emergent wetland, forested/shrub wetland, and “other,” waterways/bodies. In line with Nolan’s (2014) research, this analysis revealed that riverine aquatic resources are a much stronger predictor of American Indian site location than wetlands. Regardless, the Ohio History Connection (2020b) describes wetlands as some “of the most archaeologically sensitive areas in Ohio.”

Data sources used for streams and wetlands include the NWI mapped streams and wetlands. In order to eliminate as many artificial waterways or waterbodies from consideration, any mapped streams with Canal, Ditch, or Cutoff in the name were eliminated from consideration for archaeological material. Additionally, any unnamed mapped streams occurring in straight lines, containing right angles, and/or aligned with the road-grid were also eliminated from consideration. Any ponds which appeared to be human made were excluded. It is important to note that additional artificial streams or waterbodies may be identified in the field by archaeological survey crews and, therefore, the archaeological sensitivity model may be adjusted slightly as a result of the archaeological fieldwork.

Proximity to rivers, streams and wetlands appears to be a powerful environmental factor influencing human settlement in this area. Based on the analysis of similar sites and contexts, EDR has found that significant archaeological sites are often located within 1,000 feet (305 meters) of a mapped water source. In addition, least-cost pathways represent the shortest travel distance between archaeological sites, taking into consideration avoidance of steep topography and proximity to water resources.

Portions of the Project Area with slopes less than or equal to 15% were considered to have elevated archaeological sensitivity. Portions of the Project Area with slopes greater than 15% were considered to have reduced archaeological sensitivity.

3.2.2

Criterion 2: Proximity to Previously Recorded Archaeological Sites

Portions of the Project Area within 1,000 feet of previously recorded archaeological sites are considered to have an elevated sensitivity for containing archaeological material. In addition, portions of the Project Area within 1,000 feet of any features mapped in the Archaeological Atlas of Ohio (Mills, 1914) are considered to have elevated sensitivity for containing American Indian archaeological materials. However, no Mills Atlas features are located within 1,000 feet of the Project Area.

3.2.3 Criterion 3: Proximity to Map Documented Structures

Map-documented structures (MDS) in the vicinity of the Project are generally located adjacent to existing roadways. In some instances, they represent existing buildings and/or farms. In other instances, they are abandoned structures that may now be represented only by archaeological remains (e.g., foundational remains of domestic structures or outbuildings). Potential archaeological resources associated with these

MDS locations could include abandoned residential, municipal (i.e., school), and/or farmstead sites, where the complete residential, municipal, and/or agricultural complex (consisting of foundations, structural remains, artifact scatters, and other features) would constitute an archaeological site. In other locations, more limited remains of these sites, perhaps represented by only a foundation or an artifact scatter, may be present.

Areas located in the immediate vicinity (within approximately 200 feet) of MDS locations are considered to have high potential for the presence of archaeological resources. However, human occupation may not always be map documented. Archaeological sites not appearing on early maps would likely be located within proximity to the water resources. As such, the 1,000-foot buffer for permanent water resources would encompass early historic-period resources, as well. The remaining (non-MDS) portions of the Project Area are considered to have reduced sensitivity to contain historic-period archaeological resources.

The GIS-based sensitivity model resulted in the identification of approximately 483 acres (80%) of elevated archaeological sensitivity within the APE for Direct Effects. The application of this sensitivity model to the Phase IB archaeological survey is described in the following section

3.3 Phase IB Archaeological Survey Methodology

This Phase IB survey methodology was designed in accordance with the SHPO’s Archaeology Guidelines (SHPO, 2022) and will include archaeological investigations within all areas of the APE for Direct Effects, in accordance with the archaeological sensitivity model described in Section 3.2 and detailed in Table 9 Phase IB archaeological investigations will be conducted in 100% of areas with elevated archaeological sensitivity. Areas identified as having reduced archaeological sensitivity will be surveyed at increased survey intervals (i.e., 30 meters for subsurface testing and 20 meters for pedestrian survey), equivalent to a 50% sample rate compared to elevated sensitivity areas. During the Phase IB survey, any areas classified as having reduced archaeological sensitivity that present indicators of elevated archaeological sensitivity will be reclassified as having elevated sensitivity. Phase IB survey will then proceed utilizing the standard survey methodology as presented herein, in accordance with the Archaeology Guidelines (SHPO, 2022).

Table 7. Archaeological Sensitivity Model Summary and Recommendations

Elevated Sensitivity for Archaeological Material

Reduced Sensitivity for Archaeological Material

<1,000 feet from naturally occurring water body or previously recorded archaeological site and <200 feet from MDS

>200 feet from MDS and >1,000 feet from naturally occurring stream/wetland

100% Phase I survey

100% Phase I survey with increased shovel test intervals to 30 meters and increased pedestrian survey to 20 meters

It should be noted that the Project Area may change from the current acreage presented herein, as the Project layout may be modified following submission of this research design. However, any changes in the extent of the survey will be consistent with the archaeological sensitivity model and research design presented herein. The approach and level of effort proposed for the archaeological survey is expected to generate an adequate testing sample to evaluate the Project’s potential effect on archaeological resources.

3.3.1 Pedestrian Surface Survey

In existing agricultural fields with greater than 50% ground surface visibility within the APE for Direct Effects, EDR personnel will conduct pedestrian surface surveys to determine whether archaeological sites are present. In these areas, archaeologists will traverse the APE for Direct Effects while inspecting the ground surface for artifacts and/or archaeological features. In areas of elevated archaeological sensitivity, transects will be spaced at 10-meter intervals, while areas of reduced archaeological sensitivity will be spaced at 20meter intervals, or a 50% sample rate. If any artifacts or other indications of an archaeological site are observed on the ground surface, then the location will be recorded using professional-grade GPS equipment. Collected artifacts will be subjected to subsequent laboratory identification and analysis in accordance with standard archaeological methods. It is anticipated that the majority of the APE for Direct Effects will be investigated using pedestrian surface survey, as shallow disking (less than 15 centimeters) of previously plowed fields in the APE for Direct Effects is planned with landowners, following the guidance as outlined for disking in the Archaeology Guidelines (SHPO, 2022).

3.3.2 Shovel Testing

In addition to the pedestrian surface survey described in the previous section, archaeologists will excavate shovel tests in any portions of the APE for Direct Effects with less than 50% ground surface visibility in order to determine whether archaeological sites are present, per the Archaeology Guidelines (SHPO, 2022). Where conditions warrant, shovel tests will be excavated in 15-meter spaced intervals in elevated sensitivity areas, and 30-meter spaced intervals within areas of reduced sensitivity Close-interval shovel testing may be appropriate to further investigate soil conditions and/or to better assess the distribution and density of archaeological materials. Additionally, a minimum of one shovel test will be excavated at each significant archaeological site (i.e., recommended for Phase II excavations or avoidance) identified during the pedestrian survey in order to assess the subsurface stratigraphy and the potential for buried artifacts and features.

Shovel tests will be 50-centimeter by 50-centimeter squares, excavated to a depth of at least 10 centimeters into culturally sterile subsoil. Shovel tests will be excavated in 10-centimeter arbitrary levels and/or by natural stratigraphic levels, depending on the stratigraphy encountered. Archaeologists will record the locations of shovel tests with professional-grade GPS equipment with real-time reported sub-meter accuracy (with all field data post-processed), while also noting shovel test locations on field maps. All soils excavated from shovel tests will be screened through 0.25-inch hardware cloth to ensure uniform recovery of cultural material. Archaeologists will record shovel test stratigraphic profile data on standardized field

record sheets that include strata depth, Munsell soil colors, soil texture and inclusions, and any cultural materials.

3.3.3 Steeply Sloped, Wetland, and Disturbed Areas

No systematic archaeological survey work is proposed in steeply sloped areas (i.e., slope exceeding 15%), delineated wetlands, or areas where visual inspection confirms extensive ground disturbance. Examples of previous ground disturbance where no systematic archaeological survey will occur include road disturbance (e.g., gravel and/or paved roads, drainage ditches, and grading) and utility disturbance (e.g., water lines and natural gas pipelines), among others. These areas will be determined at the time of the Phase IB archaeological survey and therefore cannot be detailed in the archaeological sensitivity model described in this report.

3.3.4 Artifact Collection and Analysis

In the event that artifacts are collected during the survey, standard provenance information will be recorded in the field and the locations of all finds will be recorded using professional-grade GPS equipment and documented with field notes. All artifacts will be placed in temporary sealed plastic field bags labeled with provenance data. All collected artifacts will be retained by EDR for processing and placement in archivalgrade polyethylene artifact bags. Clearly modern materials will not be recovered. However, the presence of these materials will be recorded in field notes and representative photos taken in the field, as appropriate.

Following the completion of fieldwork, all recovered materials will be washed, dried, and cataloged per standard archaeological laboratory procedures. Artifacts will be described (to the extent possible) according to their count, material, type, metric attributes, decorative motif, form, function, and cultural/temporal association. Artifact identification will be conducted according to standard references for American Indian and historic-period artifacts. A complete listing of all recovered artifacts will be included as an appendix of the final Phase I report. Artifacts will be curated in accordance with Section V of the Archaeology Guidelines (SHPO, 2022).

3.4 Archaeological Site Avoidance/Minimization

It is anticipated that any potentially significant (i.e., potentially NRHP-eligible) archaeological site identified during the survey will be avoided by Project design. Because the Project Area includes large tracts of mostly open agricultural land, and the flexible nature of solar energy project components (in terms of siting constraints), it should be possible to avoid or minimize impacts to any potentially significant archaeological sites identified within the APE for Direct Effects through relatively minor modifications to the preliminary Project layout. In the event that a potentially NRHP-eligible archaeological site cannot be avoided by the Project, then additional site investigations and/ or mitigation would be explored with the SHPO.

In most instances, the types of finds noted below will not be considered NRHP-eligible. As such they are not expected to necessitate avoidance or additional archaeological investigations:

• Isolated American Indian finds

• Isolated historic period finds

• Small, low-density lithic scatters that lack diagnostic artifacts and/or indications of intact subsurface features

• Low-density scatters of historic-period artifacts (particularly in agricultural fields, which likely represent artifacts associated with manuring practices that cannot be associated with specific households or contexts)

• Artifacts/deposits of clearly modern origin

3.5 Phase IB Archaeological Survey Report and Inventory Forms

EDR will prepare a stand-alone Phase IB archaeological survey report detailing the results of the survey. The report will follow the format outlined in the Archaeology Guidelines (2022) and Survey Report Submission Requirements (SHPO, 2020). Per these guidelines, the Phase IB archaeological survey report will also include completion of Ohio Historic Inventory Forms (I-Forms) for all previously identified and newly identified OAIresources within the APE for Direct Effects using the SHPO’s I-Form Application Database. Prior to submitting the forms, EDR will contact the SHPO with a list of archaeological sites so that OAI numbers can be assigned.

4.0 PROPOSED HISTORIC RESOURCES RESEARCH DESIGN AND SURVEY METHODOLOGY

This historic resources research design and survey methodology was prepared in accordance with the 2014 SHPO Guidelines and based on the cultural resources records review results presented herein. The research design defines the APE for Indirect Effects on historic resources for the Project as a 2-mile buffer extending from the Project Area in which components of the Project may be visible. Additional details about the APE for Indirect Effects is provided in Section 4.1.

The goal of this historic resources research design and survey methodology is to:

• Define the APE for Indirect Effects on historic resources for the Project

• Establish the criteria by which historic resources will be evaluated

• Propose a methodology for a reconnaissance survey of historic resources.

• Establish expectations regarding resource typologies and survey results.

• Define the deliverables for the survey.

4.1 APE for Indirect Effects

The APE for Indirect Effects on historic resources includes those areas where the Project may result in indirect effects on cultural resources, such as audible or visual impacts. However, utility-scale solar facilities produce minimal noise, so auditory impacts resulting from the Project are not considered a significant type of impact to the setting of historic resources. The Project’s potential indirect effect on historic resources would be potential visual impacts (resulting from the introduction of solar panels or other Project components) in the historic resource’s setting.

In order to accurately determine the Project’s APE for Indirect Effects, a viewshed analysis for the proposed Project was prepared using ESRI ArcGIS® software with the Spatial Analyst extension. The viewshed analysis was based on a digital surface model (DSM), which accounts for the screening effects of topography, as well as existing vegetation and structures. This modeling provides an accurate potential viewshed of the proposed Project.

Through simulations prepared for several previous Ohio solar projects, EDR has determined that the practical limits of solar panel visibility end at approximately 2-miles due to their relatively low height (typically less than 15-20 feet). Even at distances closer to 1-mile, it is challenging for rows of panels installed on level ground to be discerned as such from the background and horizon. Furthermore, the visual effect of the substation is anticipated to be insignificant because the equipment will blend into the existing landscape from any open views beyond 2-miles and similar structures are common features of most landscapes. The generally flat topography in the area and absence of elevated vantage points further contributes to the lack of distant Project views more than 1-mile away In addition, dense development within populated areas, such as the development within the village of Cardington, will screen visual impacts introduced by the proposed Project within a few blocks, and the majority of previously recorded resources

within Cardington will not be visually impacted by the proposed Project Therefore, EDR proposes an appropriate APE for Indirect Effects for the Project includes those areas within a 2-mile buffer of the Project Area with potential visibility of the Project, as defined by the DSM viewshed results (Figure 10).

4.2 Criteria for Evaluating the Significance for Historic Resources

Historically significant properties are defined herein to include buildings, districts, objects, structures and/or sites that have been listed on, or determined eligible, for the NRHP. Criteria set forth by the National Park Service for evaluating historic properties (36 CFR 60.4) state that a historic building, district, object, structure or site is significant (i.e., eligible for listing on the NRHP) if the property is typically 50 years old or older and conveys certain characteristics (per CFR, 2004; NPS, 1990) as follows:

The quality of significance in American history, architecture, archaeology, engineering, and culture is present in districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects that possess integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association and:

(A) that are associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history; or

(B) that are associated with the lives of persons significant in our past; or

(C) that embody the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction, or that represent the work of a master, or that possess high artistic values, or that represent a significant and distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction; or

(D) that have yielded, or may be likely to yield, information important in prehistory or history.

The historic resources survey will be conducted by qualified architectural historians and historians who meet the Professional Qualification Standards in the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archaeology and Historic Preservation (per 36 CFR 61). Expectations about the kind, number, location, character, and conditions of historic properties within the APE for Indirect Effects is discussed in Section 4.4.

In addition to the historic context and historic maps review, additional research will be conducted during fieldwork and production of the subsequent historic resource survey report to further place identified resources within their historic context and assist in NRHP eligibility evaluations.

4.3 Historic Resources Survey Methodology

EDR will conduct a historic resources reconnaissance survey for the Project to fulfill the requirements of the OPSB Application. The historic resources survey will be conducted in accordance with the 2014 SHPO Guidelines. Field observations and photographs, in conjunction with viewshed mapping, will provide the basis for evaluating the Project’s potential effect on historic resources including buildings, structures, objects, sites, and districts.