Keys to resilient supply chains

Increasing supply chain resilience: OECD policy toolkit

Increasing supply chain resilience: OECD policy toolkit

Supply chain disruptions are becoming the new normal. Conflicts, wars, extreme weather events leading to natural disasters, ongoing geopolitical tensions, regulatory uncertainty and economic fluctuations and threats of cyber-attacks have highlighted the importance of boosting resilience. Increased pressure on the logistics and transport industry coupled with frequent congestion, labour and container shortages and rising prices have put additional strain on supply chains.

The persistence of these events increases pressure on companies, but also on governments to anticipate, respond and recover from acute external shocks. Supply chain resilience can therefore be defined as the ability of a supply chain to return to normal operations following a disruption.

Governments are increasingly expected to play a significant role not only in ensuring the resilience of critical supply chains, but also in co-ordinating with the private sector to respond to similar events in a more effective and rapid way. It is a challenge faced by governments at all levels of development.

This document provides policy makers with tools to navigate relevant decision-making processes on key aspects of building supply chain resilience. While policy makers do not play a direct role in managing supply chains, they can support the private sector’s efforts by creating a stable, transparent and predictable framework for business to operate in.

The policy makers’ role is complementary to the private sector’s efforts and focuses on fostering co-operation, collaboration and co-ordination on all three levels: international, national and individual supply chain.

As such OECD identifies four key concepts on which any policy toolkit for supply chain resilience should build on:

Deploying domestic policy tools

Keeping markets open

Building trust

Understanding the diverse nature of potential disruptions can help governments anticipate the costly and disruptive effects of external risks and undertake early response planning.

Given the diverse nature of shocks that have the potential to disrupt modern supply chains, the first step for policy makers is to understand how the various types of developments are likely to impact domestic and international stakeholders.

While it is impossible to fully predict future shocks, risk management strategies could involve 1) identification of possible risks and their likelihood, 2) early warning and detection metrics, and 3) early response procedures. These steps can help policy makers to respond to the first signs in a timely and efficient manner. Data and scenario analysis are important to construct these strategies

Categorising and identifying potential risks allows national governments to understand how various types of disruptions are likely to develop and impact supply chains.

There are different ways to categorise risks. One of them is based on their likelihood and impact. An example of a high-likelihood, low-impact occurrence would be a sudden disruption leading to delays in one or a few ports. An example of a low-likelihood but severe impact event would be the next global pandemic.

Each type of risk requires a different set of responses from policy makers. Whatever the classification system used, early identification would allow governments to act fast.

Loss of key supplier

Transportation link disruption

Single port closure Computer virus

Flood Wind damage

Low Light Impact Likelihood

Economic recession

IT system failure

Multiple port closure

Earthquake Pandemic

Severe High

• Natural disasters: Such as earthquakes, tsunamis or floods can halt domestic production and affect international trade. These risks generally affect a specific area but can have a prolonged impact as the local economy and infrastructure recover.

• Accidents: Such as fires, crashes or explosions are also generally localised. Like natural disasters, they can have a knock-on effect on supply chains when they affect a key resource or an area of strategic importance. The Evergreen accident in the Suez Canal could be an example. With roughly 10% of global maritime commercial traffic passing via the Canal, the event highlighted potential bottlenecks in global shipping lanes.

• Intentional shocks: Such as wars or terrorist attacks can severely disrupt international supply chains. The Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine and the sanctions which followed against Russia led to temporary price shocks across the energy and food supply chains in Europe. In some cases, supply chains (e.g. food or energy production) or locations of strategic importance can be targeted to maximise the disruption.

• International crises with contagion effects: Such as the COVID-19 pandemic or the 2007-2008 financial crisis. Events of this nature have a broad impact and can affect several economies at the same time.

• Prolonged geopolitical tensions: Such as unilateral protectionist measures, retaliatory tariffs or trade wars rarely represent a significant disruption to supply chains in themselves. However, they can escalate and put substantial pressure on supply chains making them less agile in responding to other external events.

Routine disruptions and minor shocks rarely require government intervention. Accidents and even some natural disasters may be localised to the point where they do not affect a large number of companies nor lead to serious disruptions to wider supply chains. Disruptions resulting from such events can be mitigated through companies’ internal risk management strategies, with the support of local authorities when needed.

However, other external shocks can have a widespread and severe impact on society and the economy. These events cannot be fully addressed by firms’ internal strategies. Governments are required to intervene and complement the private sector’s efforts.

Before disruption: Risk management

Assessing resilience

Enhancing resilience

Reducing the probability of foreseeable bad events by identifying and monitoring sources of endogenous vulnerabilities and taking measures to stem their build-up.

Preparing to absorb the impact of a shock through buffering mechanisms put in place ex ante and ready to be activated.

Governments have three broad tasks to undertake, the exact nature of which may vary according to the type of risk. These tasks are to: (i) prevent risks; (ii) detect and anticipate crises; and iii) prepare policy responses. Determining the role of governments in ensuring wellfunctioning international supply chains is a challenging task, particularly as these supply chains involve cascading tiers of suppliers in many countries. Early warning and detection frameworks as well as clear attribution of responsibilities can allow policy makers to understand at which point policy intervention is required. This could involve developing metrics to understand the likelihood of a widespread impact.

Resilience management steps

During disruption: Crisis

Maintaining

After disruption: Bouncing forward

Recovery through adaptation/transformation

Actions to regain lost system functions as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Creating market, rule-making and institutional conditions for the economic system to adapt and transform so as to bounce forward and lower vulnerabilites to similar threats in the future.

When government intervention is required, early response procedures would enable policy makers to respond to evolving crises in a timely manner. Effective response strategies should be put in place prior to disruptions occurring and dependent on different types of potential shocks.

Ministries and agencies should receive clear guidelines that define risk management processes, roles and responsibilities of different governmental and other public sector actors. The occurrence of a risk situation should immediately trigger a specific government intervention.

These early response strategies aim to minimise the initial response time and are not meant to be set in stone. They should be reviewed and adapted as the situation develops. In order to be able to reassess and adjust the response in light of changing needs, policy makers will need to adopt data-driven monitoring and risk-assessment procedures. This will also require appropriate communication channels and strong co-operation and co-ordination on a number of levels: between and across national governments, regional and local authorities, and private sector actors. Governments often hold information in silos. Lack of effective crossdepartmental communication can thus be an additional obstacle in a time of crisis. It can lead to duplication of work and minimise the effectiveness of the response. The government should ensure that legislation enabling information sharing between departments is in place.

Both early response planning, as well as subsequent policy adjustments in the face of a developing crisis, require data. Access to accurate, reliable and current data can help policy makers anticipate risks as well as respond to them by enabling modelling and scenario analysis.

At the firm level, scenario analysis aims to measure the likelihood of occurrence and the magnitude of impact of potentially disruptive events. Governments could supplement the private sector’s efforts by developing a data-driven scenario analysis that extends beyond the traditional firm-level and national view. This would enable greater visibility across various supply chains and could help better understand the challenges, including in the areas of transport and logistics. With advanced data and

supply chain mapping capabilities, governments could significantly improve their ability to analyse the current state of play, potential risks and bottlenecks.

Insights should be shared, if possible, with other actors –whether on an international or national level to support policy formation or with the private sector to support firmlevel resilience-building activities.

Obtaining data required to map global supply chains and develop scenario analysis is not an easy task. This is another area where public-private sector partnerships can prove useful in building resilience. This could take the form of partnerships with supply chain mapping companies and platforms.

The OECD’s trade model, METRO, is a computable general equilibrium model of the world economy that uses data to explore the economic impact of changes in policy, technology and other factors. The METRO model has been used to simulate the impact of shocks under different supply chain scenarios.

Panel A: Interconnected regime

Panel B: Localised regime

Note: The figure shows model simulations on the impact of trade shocks on the level of output and its variability under two different supply chain scenarios, globalised and localised. All changes in variables are relative to the level of the interconnected (aka globalised) regime base scenario which is set to equal 100. Blue dots show the base in the given regime relative to the interconnected base, and whiskers show average deviations for negative and positive trade cost shocks.

Source: Figure 13, Arriola, C., et al. (2020), Efficiency and risks in global value chains in the context of COVID-19, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1637, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3e4b7ecf-en

Categorise and identify risks:

• Create a system to categorise potential risks. Identify the types of risk that can have a severe impact on supply chains.

• Establish early warning signs for different types of risks.

• Identify critical supply chains that require continuity of supply or could face surges in demand in the context of specific risks and crises (e.g. specific supply chain risks in the provision of essential goods and services).

Determine the role of government:

• Identify relevant government bodies and assign national leadership roles for risk governance, monitoring and management. A specific government agency or department can be in charge of overall risk management or a dedicated agency can be responsible for managing specific supply chain risks. Equally, a specific government agency can be in charge of a particular type of risk, e.g. disruptions related to health, logistics.

• Based on the above structure, identify different agencies and local administrations responsible for responding to the early warning signs and implementing risk management strategies that would report to the government bodies managing overall risk.

• Identify and agree on a diverse set of indicators that encompass a wide range of potential risks. This includes mechanisms to detect and anticipate crises (e.g. monitoring the vulnerabilities in supply chains, international exchange of information, and early warning indicators).

• Develop a methodology to identify the right time for the government to intervene based on the above indicators – when the level of disruption to supply chains exceeds “routine risks”.

Establish early response procedures:

• Develop high-level national risk management strategies for each type of risk identified as part of the categorising risks exercise. Develop a methodology to identify whether or not governments should act. The occurrence of a risk where government intervention is required should immediately trigger action.

• Ensure that government departments, agencies and local government are involved in the process of developing these strategies, response frameworks and guidelines.

• Ensure that risk management strategies are routinely updated and properly communicated to all government staff.

• Develop practical guidelines and response frameworks for implementing these strategies in case of a critical risk.

• Put in place monitoring and reporting procedures to adapt to changing situations.

• Develop a set of economic indicators to be put in place at the outset of a crisis to monitor its development and review against planned scenarios.

• Periodically review the indicators based on lessons learned at home and abroad.

Use data and scenario analysis:

• Create a system for collecting data about past supply chain disruptions from multiple sources, including from international organisations and other countries.

• Use data from various sources (public and private sector) for ongoing monitoring of supply chains. This data can be used against the metrics and indicators identified above.

• Create partnerships with private-sector organisations that maintain large databases (e.g. transport, logistics and supply chain management companies).

• Develop models for scenario building and analysis that go beyond traditional firm-level analysis. Ensure ongoing review and improvement of the methodology behind risk assessment and anticipation. Develop specific risk scenarios for essential products in co-operation with the private sector.

• Share, when possible, data about past supply chain disruptions with other countries and international organisations.

A range of domestic policy tools can support governments’ efforts to minimise exposure to shocks while also delivering a range of other benefits related to the flow of goods, services and investment.

Minimising exposure to external risks and promoting growth need not be a zero-sum game. Investing in infrastructure, enabling digital trade, sound public procurement procedures and improving the regulatory environment can promote the resilience of supply chains while also contributing to the country’s productivity and competitiveness. These actions represent an investment that is likely to have long-term benefits extending well beyond the time of a crisis. They also support the private sector by strengthening the external framework in which supply chains operate, indirectly helping to build resilience.

Investing in maintaining and improving the state of physical and digital infrastructure which underpins the flow of goods, services, data and people can help reduce exposure to shocks.

Recent supply chain disruptions have demonstrated how impacts on physical and digital infrastructure can generate cascading failures. Investing in infrastructure offers benefits that go beyond crisis management. It can improve the overall business environment and boost inward investment as well as facilitate trade in goods and services.

It is important for governments to develop a long-term strategic vision for infrastructure. This could include defining critical infrastructure based on risk and scenario analysis. International supply chains rely heavily on the integrity of critical infrastructure such as ports or airports. Disruptions in the functioning of these entry and exit points can lead to border delays and additional costs resulting from extended lead times.

Digital networks facilitate the co-ordination of production along globally interconnected supply chains and increase the ability to identify and react to unexpected shocks. Governments can support risk management strategies by creating the right regulatory environment for digital trade and data flows and by continuing to invest in digital infrastructure.

From a supply chain resilience perspective it is important for policy makers to: i) maintain well-functioning digital connectivity; ii) ensure access to goods and services that underpin digital networks (from computers to telecommunications equipment and computer services); and iii) ensure that the regulatory environment that underpins digital trade remains open and flexible to deal with unexpected shocks. The growing threat of cyber-attacks leading to blackouts or threats to subsea cables continues to pose risks to global supply chains. Recent cyberattacks targeting ports (for example Port of Nagoya, Japan in July 2023) highlight the high degree of interconnectedness between physical and digital infrastructure and the importance of policies aiming to minimise threats to their integrity.

Governments can support risk management strategies by creating the right regulatory environment for trade. The OECD STRI and Digital STRIs provide tools for governments to compare applicable legislation with international best practice. These indicators enhance transparency in applied legislation and also contribute to legislative reform.

The 2023 STRI data shows that transport sectors are prone to higher levels of regulatory barriers, especially on foreign investment (e.g. restrictions to ownership and control of domestic transport providers), barriers affecting competition at key transport nodes (e.g. ports and airports) and administrative barriers (e.g. customs). Furthermore, regulatory barriers also undermine multimodal transport (and integrated logistics providers) that depend on seamless interoperability across different transport modes. Reducing barriers to these services allows to overpass chokepoints and find alternative suppliers when needed.

STRI findings: Trade barriers are high across key supply chain services

Restrictions on foreign entry Regulatory transparency Other discriminatory measures Barriers to competition

Note: The STRI indices take values between zero and one, one being the most restrictive. The STRI regulatory database covers the 38 OECD Members, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Peru, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand and Viet Nam.

Source: OECD STRI (2023).

The lack of ability to adapt regulatory procedures and requirements in times of crisis can easily lead to significant delays in the mobilisation of local resources and production capacity. Improving regulatory systems to make them more agile and flexible when coping with crisis situations is essential to allow countries to mobilise all supply sources without undue constraints. Regulatory flexibility does not mean reducing safety or quality requirements, but rather temporarily lifting and streamlining certain requirements. It can also mean accelerating authorisation or license procedures for essential products or services.

Before introducing temporary changes to existing procedures, policy makers need to balance the interests that are protected by an existing regulatory framework with the benefits from its temporary suspension. Such flexibility should not lead to lower standards or undermine the predictability of the regulatory environment. The legitimacy of such measures is based on their temporary nature and the specific targeting of essential products. Retrospective reviews could also be introduced.

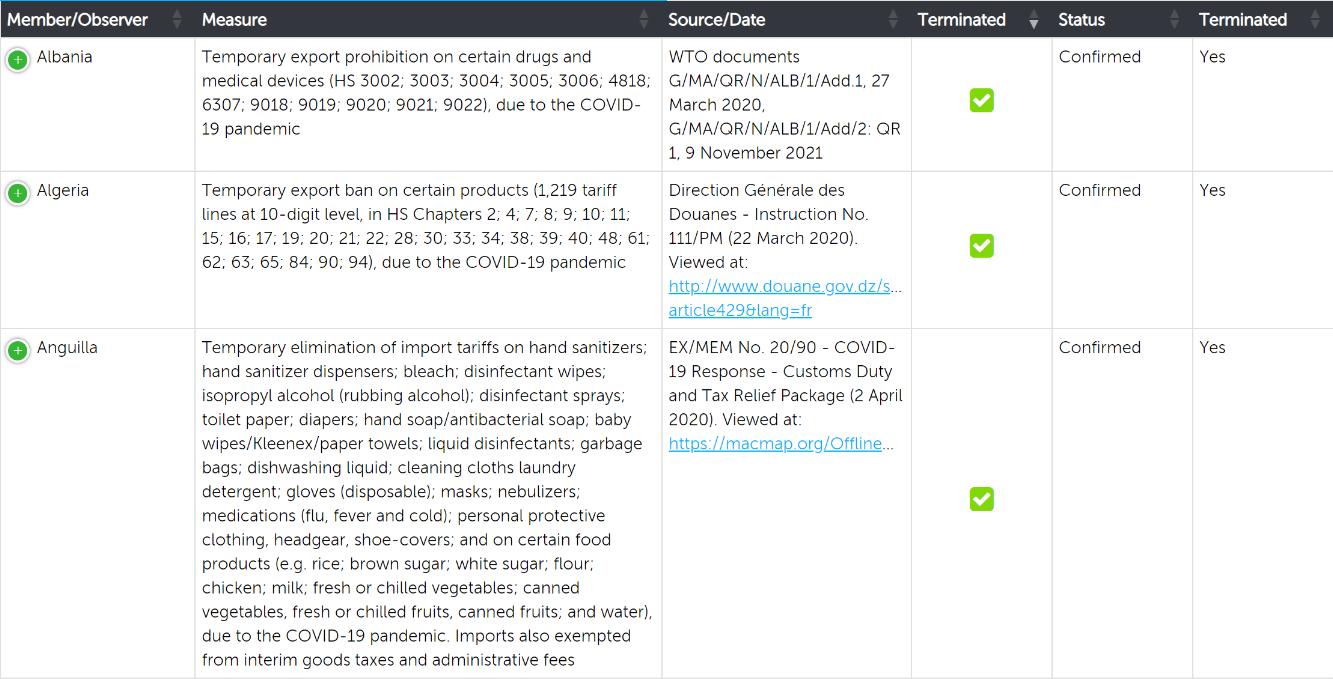

Providing transparency to any temporary suspension of regulation or new trade measure is important for both domestic actors and international partners. A number of temporary trade related measures were introduced during COVID-19 pandemic impacting imports and exports. Some of them were restrictive in nature, i.e. placed limits on exported or imported goods. Other were introduced to facilitate trade of certain key products across borders. In order to provide transparency around these measures the WTO Secretariat published the “COVID-19: Measures affecting trade in goods” database. This list of measures was periodically updated to reflect the latest changes.

Source: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/trade_related_goods_measure_e.htm

Governments should review the procedures in place and set up emergency protocols for government procurement. In the event of a crisis, procedures for issuing government procurement contracts should be simplified to avoid unnecessary paperwork. Ex ante agreements can be considered to boost the production capacity of essential goods.

Recent OECD work on medical supply chains gives examples of how emergency procurement procedures and template agreements can be put in place with domestic and international suppliers in preparation for a crisis1 .

Policy steps to respond to the COVID-19 crisis

As with temporary changes to the regulatory framework, contracts issued under emergency conditions should still be subject to quality control and monitored retrospectively. It is important to ensure that contracts issued under such conditions represent an efficient use of public resources and do not undermine public trust in the government’s ability to respond to a crisis. Safeguards preventing such practices should be built into emergency procurement procedures. Emergency procurement contracts should also reflect considerations around the security of supply.

Public procurement processes can also be strengthened through international collaboration with a view on their broader impact on supply chains.

Emergency, immediate responses (e.g. rapid procurement of essential items)

Maintain access to critical public services and infractructure

Taking stock of consequences and impacts whilst continuing emergency responses where needed

Adjustment of procurement and infrastructure strategies to the new challenges of the crisis

Building a new normal for post COVID-19

Procurement and infrastructure development actively contributes to the recovery of the economy and society

• Identify broadly defined critical infrastructure based on different categories of risk.

• Ensure that this infrastructure is regularly maintained to strengthen its resilience. Develop a long-term strategic vision for critical infrastructure to managing threats to its integrity.

• Reduce barriers that hinder access to information and communication technology (ICT) goods and services that underpin digital networks.

• Engage in domestic regulatory reform supporting open, non-discriminatory and transparent regulations for physical infrastructure related services and digital trade.

• Continue engaging in international discussions aimed at promoting services liberalisation, open markets and enhanced digital trade, whether at the World Trade Organisation (WTO), including in the context of the Joint Initiative on E-commerce, in trade agreements through more ambitious and numerous digital trade chapters, or in the context of digital economy agreements.

• Periodically review and update existing regulations in critical areas (e.g. safety regulations, enforcement of compliance with environmental and health standards).

• Ensure that the existing regulations allow for an agile and flexible response in the event of a crisis.

• Create emergency procedures for streamlining the regulatory procedures for essential products and services. Define the period for which emergency regulatory simplifications are available and the deadlines for their review.

• Ensure sufficient quality controls are in place under emergency procedures.

• Develop emergency procurement procedures and temporary suspensions of undue administrative and bureaucratic constraints. Define the period for which suspensions are available and the deadlines for their review.

• Ensure sufficient quality controls are in place under emergency procedures. Implement necessary safeguards to prevent fraud, mismanagement and unfair contract granting.

• Consider revising procurement criteria under emergency procedures to include considerations around the security of supply.

• Draft template supplier agreements to be used in the event of a crisis.

• Discuss regional or bilateral procurement co-operation and joint procurement agreements with key trade partners.

Close co-operation between the public and private sector is pivotal to the process of boosting supply chain resilience.

National governments provide a regulatory framework in which businesses operate. If done well, this can be conducive to private sector efforts to build resilience. Closer co-operation with the public sector and efficient information exchange can enable firms to better protect themselves against severe disruptions.

On the other hand, the private sector can share valuable data and insights into the functioning of supply chains which can help governments and other stakeholders shape national and international policies and respond to shocks.

Strengthening public-private co-operation can include supporting firmlevel risk management strategies, establishing public-private frameworks and developing a co-ordinated approach to stockpiling.

While firms generally strive for economic efficiency, they also manage business risks. Risk management, scenario planning and increasing supply chain visibility are part of best practices firms have been using to anticipate, prevent, prepare for, and respond to shocks, helping firms minimise disruptions. This benefits business operations, as well as broader supply chains.

Supply chain resilience is built at the firm level through efforts to gain greater visibility of the supply chain, agility and flexibility. As firms need to balance the economic consequences of disruptions with the costs of mitigating risks, they are often required to decide on the acceptable level of risk and to organise the production process accordingly.

Governments can support firms’ risk management strategies by creating the right policy framework for them to operate in as well as by offering help and guidance with the implementation of internal risk-management strategies. This could take the form of collaborative efforts in which private actors opt in to additional self-regulatory measures while receiving support and guidance from public bodies such as international organizations or national regulatory agencies.

In this regard, responsible business conduct (RBC) principles and standards provide a framework to enhance the visibility firms have of their supply chains. These principles can help achieve the dual objective of minimising the risk of supply chain disruptions and minimising the environmental, social and governance impacts of disruptions when the latter occur. Business need to internalise RBC principles in business practices. To enhance this, Governments could mainstream RBC in investment and trade agreements. This can help make supply chains more resilient, and sustainable and ensure that the gains from globalisation are more fairly distributed.2

Finally, there is also a limit to what a single firm can achieve in a silo. Greater co-operation amongst private sector actors including data and experience sharing, can help build resilience across the entire supply chain. To be truly effective firm-level strategies should be extended to entire supply chains. This should be done in compliance with applicable regulatory frameworks, notably with competition laws.

A strong foundation of public-private co-ordination, consultation, and co-operation can increase the capacity to successfully navigate crises, absorb and recover from shocks, and build collective responses. This requires appropriate frameworks to be set up before disruptions occur.

In most countries, stakeholder platforms are in place for industry representatives to communicate with relevant government departments. These structures are set up with a view to co-ordinate policy under business-as-usual

circumstances. For the purpose of crisis response or emergency planning, these frameworks would need to be redesigned to include a broader range of stakeholders, for example, individual companies instead of business or industry associations. Another example would be to create stakeholder forums involving representatives of key industries, local and/or regional authorities, as well as various intermediaries and service providers (e.g. logistics) to ensure coverage of the entire end-to-end process.

Preparedness conferences are an example of building private-public frameworks and increasing communication.

These conferences aim to assemble various stakeholders to collectively design mechanisms and procedures for response to a potential future crisis. During these work sessions stakeholders and government officials would jointly discuss and work through preparedness and response strategies and put together guidelines and playbooks that would be implemented when such event occurs. As such, they would allow private sector stakeholders to codesign government policy, improving transparency and increasing co-operation.

Preparedness conferences could be organised with different sets of stakeholders for different categories of external shocks. The OECD is working on how these conferences could be designed.

Selective stockpiling can be an element of risk-management strategy for both firms and governments. Careful planning and design of these policies is necessary to prevent inefficiencies that can lead to unnecessary costs, product obsolescence or expiration.

OECD research suggests that just-in-time practices have led to fewer firms maintaining safety stocks due to the costs involved and the low effectiveness of such practices.3 On the other hand, companies should be encouraged to develop appropriate inventory strategies and contingency planning, in particular in critical industries.

From a wider perspective, stockpiling decisions should be made in the context of other policies such as crisis anticipation and response planning. There are a number of challenges and potential issues to consider on a national or international level:

• Choice of which essential products to stockpile: While some products (such as face masks) can be easily stored, this is not the case for all products. For some goods, the choice could be between stockpiling a final good versus critical inputs. In addition, depending on the type of shock, stockpiles of different types of goods can be required.

• Optimal risk-management strategy: There are opportunity costs of investing in stocks of goods as a risk- management strategy (e.g. strained health budgets). Cost-benefits analysis of stockpiling decisions should be based on the probability and potential magnitude of shocks.

• Role of public versus private sectors: Another consideration relates to the most cost-effective way to build stocks. Stock can be built centrally by the government or in co-operation with the private sector (see Co-ordinated stockpiling box below).

• Stock management and distribution planning: Stock management decisions should include considerations related to access and release. Scenario planning can help governments to better plan for the distribution of essential goods, and thus the level (and placement) of stockpiles needed to buffer demand surges. This should include last-mile delivery planning and co-ordination with delivery partners.

• International co-operation: Duplication of stocks or excessive purchasing may create shortages in other countries. This can aggravate the issue and contribute to price surges and shortages. Likewise, the simultaneous release of goods can cause prices to collapse and producers to exit the market, undermining future supply. Regional stockpiles of some essential goods may therefore be a cost-effective solution, notably for less developed economies.

Recent OECD research on medical supply chains indicates the importance of international co-operation in stockpiling. It demonstrates that the proliferation of national stockpiling policies in the face of a crisis, may have a negative effect.

Co-ordinated stockpiling on regional or international levels may be more beneficial in situations where rapid adjustments between supply and demand are required. This can be done in collaboration with companies where the stock is held or with the producer or manufacturer. OECD research suggests that international co-operation could help mitigate inefficiencies of stockpile initiatives by pooling procurement for stocks and co-ordinating more rational and equitable allocation of resources across countries according to pre-established guidelines.

Source: OECD (2024), Securing Medical Supply Chains in a Post-Pandemic World, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/119c59d9-en

Support the development of firm-level strategies:

• Support firm-level risk management strategies by creating a policy and regulatory framework that promotes transparency, and regulatory certainty.

• Employ a wide range of policies to support the participation of small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) in international supply chains. SMEs have fewer resources to devote to risk management strategies and therefore need higher government support.

• Provide help and guidance for companies with the implementation of their risk-management strategies –disseminate best practices and lessons learned.

• Promote greater traceability in supply chains and more sustainable practices through the use of responsible business conduct (RBC) standards and tools (such as due diligence).

Establish and maintain public-private frameworks prior to disruption:

• Set up public-private frameworks in various critical industries and on different levels. Ensure that these frameworks extend beyond individual firms and involve a wide range of stakeholders including local authorities, the logistics industry, public service providers, etc.

• Develop communication channels to ensure early consultation with stakeholders. Establish platforms to share information and promote public-private dialogue during crises.

• Organise preparedness conferences with the relevant actors for various types of potential shocks. Develop procedures for emergencies in collaboration with the private sector. Re-assess public risk management strategies based on feedback from the private sector.

Prepare for selective and co-ordinated stockpiling:

• Review domestic stockpiling decisions against a wide range of policies and assess on a case-by-case basis. Conduct an in-depth cost-benefit analysis.

• Work closely with the private sector to design efficient stockpiling systems. Coordinate with stock owners and/or manufacturers.

• Consider coordinating selective stockpiling on regional or international levels.

• Strengthen cross-border information-sharing practices on risk management, the availability of essential goods, prices and contacts to inform procurement strategies and lessen global supply chain disruptions.

Building resilience of international supply chains requires co-operation and co-ordination at an international level.

International economic co-operation can boost supply chain resilience through fostering collaboration, improving regulatory harmonisation and facilitating cross-border trade. It can help to create a more stable and predictable environment through strengthening the rules-based multilateral trade framework.

This can involve a full range of international economic tools, from multilateral, plurilateral and bilateral agreements, to softer forms of policy co-ordination and harmonisation.

These actions represent an investment that is likely to have long-term benefits extending well beyond the time of a crisis.

Global supply chains do not operate in a vacuum but against the backdrop of international trade rules and regulations. Departure from rulesbased trade, in the form of new, unexpected trade barriers, can have a snowball effect leading to further unilateral actions, retaliatory trade wars and increased support for protectionist measures. This can threaten access to inputs and markets and undermine confidence in global trade. It can also put an enormous strain on global supply chains making them less agile to respond to other external events.

Stable, transparent and predictable rules-based international trade and investment regimes reduce uncertainty and costs for businesses. This strengthens global supply chains allowing them to spend less time responding to changing and uncertain regulations. Open and rules-based trade also facilitates supply chain diversification choices by firms, helping them to boost supply chain resilience. The World Trade Organisation (WTO), as the cornerstone of the multilateral trading system, needs to be able to ensure the continuity of rules-based trade.

Transparency is essential for well-functioning global markets. International organisations have the ability and capacity to collect information on trade-related measures and restrictions beyond the national level. They play a pivotal role in promoting transparency of trade-related rules.

This can take the form of intranational databases and repositories, as well as monitoring activities. An example of such activity would be the WTO Trade Monitoring Database or the WTO ePing Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) measures and Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) measures notification platform. These databases, however, face the challenge of being kept up to date. Another example of international efforts to improve transparency on trade measures is the OECD Export Restrictions Database on Industrial Raw Materials. This database contains information on export regulations in the raw materials sector, namely minerals, metals and wood, and shows the importance of international tools to enhance transparency on specific issues.

Transparency mechanisms can also play an important role once a crisis emerges. This includes informing trading partners in a timely manner of any new regulations or trade restrictions resulting from emergency measures as well as exchanging information on the state of supply chains and stocks. Such cooperation on an international level can help to avoid harmful policy choices such as panic buying or hoarding.

The Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS), created in the wake of the 2007-2008 food price crisis, allows governments to share information on markets, policies and stocks for key commodities. AMIS has underscored the value of timely information and transparency in preventing crises induced by panic buying, hoarding, or export restrictions. It is based on co-operation amongst major importing and exporting countries, with a commitment to providing timely information.

Bilateral, regional, and multilateral trade agreements include commitments by countries to keep markets open. Deep integration provisions are also increasingly common in trade and investment agreements. These contribute to the predictability and transparency of trade and investment regimes. Furthermore, tariff liberalisation provisions, under free trade agreements, support firms in diversifying their sourcing and organising production at an international level while reducing costs.

Many trade and investment agreements have exception clauses that allow governments to introduce emergency measures in the event of a crisis or for national security reasons. It is important to ensure that these built-in flexibilities are not used as protectionist measures or used to introduce significant export restrictions in times of

crisis. While flexibility is important, COVID-19 illustrated that trade and investment agreements did not prevent the introduction of restrictive trade measures that exacerbated supply chain disruptions. Such measures can also disproportionately affect developing and leastdeveloped countries.

New commitments in international agreements could be considered to reinforce the capacity of supply chains to operate during a crisis and to prevent the introduction of harmful measures. Such commitments could, for example: (i) limit trade and investment policy discretion on essential goods; (ii) enhance trade facilitation practices and regulatory co-operation; (iii) improve transparency; and (iv) create consultation mechanisms and co-operation in crisis situations.

In November 2023, the 14 members of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) signed the Agreement Relating to Supply Chain Resilience, referred to as the Supply Chain Agreement. It entered into force in February 2024.

The agreement introduced three bodies: The Supply Chain Council, the Supply Chain Crisis Response Network, and the Labour Rights Advisory Board.

The purpose of the agreement is to establish a framework for deeper collaboration to anticipate, prevent, prepare for and mitigate the effects of future supply chain disruptions. It aims to deliver a broad range of supply chain resilience measures. The members will support the private sector in accelerating diversification and prepare sector-specific action plans for critical sectors and goods. Furthermore, the agreement and its bodies will provide a co-operation and communication platform to prepare and respond to external supply chain shocks.

Source: https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/organisations/wto-g20-oecd-apec/indo-pacific-economic-framework/ipef-supply-chain-agreement

As supply chains span across borders, broader co-operation and harmonisation of regulatory environments can streamline international trade, both under business-as-usual conditions and during crises. Enhancing co-operation and harmonisation can also help avoid unnecessary friction when developing emergency measures in the context of rapid policy response. Development of common approaches saves time, for example by recognising the conformity assessment carried out by other countries.

International regulatory co-operation involves a variety

of public and private sector actors including lawmakers, regulators and standard-setting institutions. International organisations can also play a role in promoting best practices and common understanding in technical areas.

Trade and investment agreements increasingly cover international regulatory co-operation in stand-alone chapters or sectoral chapters. These agreements can include transparency mechanisms, mutual recognition of conformity assessment procedures, mandatory recognition of some technical regulations, or harmonisation measures.

Agreement on simplified procedures

Adoption of international standards

Unilateral

Bilateral

Regional

Multilateral

Recognising conformity assessment procedures

Mutual Recognition Agreements

Regulatory provisions in trade agreements

Participation in regional and multilateral fora (intergovernmental organisations, transgovernmental networks of regulators, etc.)

Source: OECD (2017), International Regulatory Co-operation and Trade: Understanding the Trade Costs of Regulatory Divergence and the Remedies, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264275942-en

Trade facilitation refers to a specific set of measures that streamline and simplify the technical and legal procedures for importing and exporting goods. Following the entry into force of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) in 2017, economies worldwide have been reviewing customs and regulatory frameworks to operationalise their commitments under the agreement.

As each international transaction has two sides, trade facilitation measures work best when co-ordinated internationally. Co-operation between border agencies and customs authorities of trading partners can help to resolve practical and operational challenges to cross-border trade which result in delays, and increased direct and indirect costs for traders. This can significantly contribute to increasing the predictability and transparency of international trade.

In the event of a crisis, trade facilitation measures can play a pivotal role in ensuring the flow of goods and minimising border-related bottlenecks. Measures such as fast clearance procedures (“green lanes”) or increased pre-arrival processing can be deployed as part of a crisis response to help mitigate supply chain disruptions.

Another area of trade facilitation measures that can support building supply chain resilience is the digitalisation of trade documents and procedures. This relates to trading partners issuing and exchanging digital versions of trade-related documents such as origin or phytosanitary documentation (e.g. the International Plant Protection Convention’s e-Phyto Hub and Generic ePhyto National System). It also includes efforts to digitalise trade procedures and the exchange of information between public and private actors within international trade, such as the development of national trade Single Windows4. A trade Single Window aims to provide a one-stop-shop for all border procedures and actors ― a platform on which traders, logistics providers, government authorities and finance providers can submit and exchange documents and information eliminating duplication of processes.

Governments can support the digitalisation of crossborder trade by addressing institutional, technical and legal challenges to pursue the digitalisation of trade-related documents and processes.

The OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators (TFIs), which cover over 160 countries and is linked to the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement, highlight the areas where countries can do more. This includes transparency and predictability, streamlining and automating border processes, and co-operation amongst border agencies.

Information availability

Appeal procedures

Formalities – automation

External border agency co-operation

Note:

Source: OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators (2023).

Involvement of the trade community

Fees and charges

Formalities – procedures

Governance and impartiality

Advance rulings

Formalities – documents

Internal border agency co-operation

• Revitalise international trade and investment negotiations to reinforce a global rules-based environment. Strengthen confidence and commitment to the multilateral rules-based trading system.

• Engage in activities that increase the transparency of international trade policy measures such as various monitoring mechanisms, e.g. WTO notifications.

• Support gathering comparable information at an international level to be used for analytical purposes. Disseminate best practices and lessons learned to national governments and stakeholders.

Strengthen international agreements:

• Explore additional commitments in international trade and investment agreements to deal with the provision of essential goods and services during a crisis.

• Strengthen deep integration provisions in trade and investment agreements.

• Review general and specific exception clauses in international trade and investment agreements to create trust among parties and to encourage cooperation in times of crisis. Work with bilateral and multilateral parties to create a common understanding of “national security” and other terms that allow for the suspension of certain obligations in trade agreements.

• Co-ordinate efforts among governments, firms and international organisations to develop common approaches or adoption of international standards to facilitate the flow of essential goods.

• Co-operate with international organisations promoting common understanding in specific (including industrylevel) areas of regulatory policy.

• Work with trade partners and international organisations to facilitate product certification (e.g. streamlining certification procedures, use and adoption of international standards, more flexible application of product certification criteria in emergencies).

• Promote the inclusion of chapters on international regulatory co-operation in trade and investment agreements and the conclusion of Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs).

Facilitate trade across borders:

• Continue the implementation of national commitments under the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA).

• Support the work of National Trade Facilitation Committees set up under the WTO TFA. Use various sources of data, such as the OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators, to focus the work of the Committee on the areas which are lagging behind.

• Promote increased co-operation between border agencies. Enhance cross-border co-operation in border risk management.

• Promote the use of digital tools for customs clearance, paperless trade solutions and national trade Single Windows.

• Include trade facilitation measures such as emergency border procedures in international crisis response planning.

Arriola, C., et al. (2020), “Efficiency and risks in global value chains in the context of COVID-19”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1637, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3e4b7ecf-en.

Arriola, C., P. Kowalski and F. van Tongeren (2021), “The impact of COVID-19 on directions and structure of international trade”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 252, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0b8eaafe-en.

Arriola, C., P. Kowalski and F. van Tongeren (2024), “Shocks in a highly interlinked global economy”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, OECD Publishing, Paris (forthcoming).

Arriola, C., Cai, M., Kowalski, P., Miroudot, S. and F. van Tongeren (2024), “Towards demystifying ‘trade dependencies’: At what point do trade linkages become a concern?”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, OECD Publishing, Paris (forthcoming).

Jaax, A., S. Miroudot and E. van Lieshout (2023), “Deglobalisation? The reorganisation of global value chains in a changing world”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 272, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b15b74fe-en

Kowalski, P. and C. Legendre (2023), “Raw materials critical for the green transition: Production, international trade and export restrictions”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 269, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c6bb598b-en.

Miroudot, S. and B. Thakur-Weigold (2024), “Promoting resilience and preparedness in supply chains”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, forthcoming.