Ocean Knowledge and Governance Capacity Changes and Trends

CREDITS

Ocean Nexus Research Team

OVERVIEW

The Ocean Nexus Interim Report highlights alarming reductions in ocean governance and science capacity across the United States, amidst compounding global crises climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution, and social inequity The report warns of an “epistemicide,” the systematic dismantling of ocean-related knowledge infrastructure and governance capacity, with long-term consequences for communities and ecosystems

AUTHORS | CREDITS

Lead:

Anna Zivian, PhD

Research Associate, Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus

Yoshitaka Ota, PhD

Director, Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus

Professor, Department of Marine Affairs, University of Rhode Island

Assistant:

Richard Okelola

Student Fellow, Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus

Undergraduate, University of Rhode Island

Sophie Kissimba Kassini

Student Fellow, Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus

Undergraduate, University of Rhode Island

Luciana Bueno

Student Fellow, Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus Undergraduate, University of Rhode Island

Editor:

Cinda Scott, PhD

Co-Director, Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus Department of Marine Affairs, University of Rhode Island

Ricardo de Ycaza, PhD

Postdoctoral Fellow, Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus Department of Marine Affairs, University of Rhode Island

Summary

The Ocean Nexus Interim Report highlights alarming reductions in ocean governance and science capacity across the United States, amidst compounding global crises climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution, and social inequity. The report warns of an “epistemicide,” the systematic dismantling of ocean-related knowledge infrastructure and governance capacity, with long-term consequences for communities and ecosystems.

A. Key Findings:

• Staff and Budget Cuts:

Over 135,000 federal employee positions have been terminated, with over 107,000 more planned. Key agencies such as NOAA, EPA, and USAID face major reductions in staff and budgets (e.g., EPA by 54%, USAID by 83.7%) posing risks to forecasting and monitoring capabilities

• Institutional and Programmatic Losses: Thousands of federal programs are being terminated, including:

o Disbanding of advisory committees on climate, science, and environmental justice.

o Elimination or defunding of long-standing programs like IOOS, Sea Grant, and the Marine Mammal Commission.

o Closure of key databases (e.g., climate.gov, Billion-Dollar Disaster database) and research tools.

• Targeted Defunding and Ideological Shifts: Budget and staffing reductions are particularly focused on climate change, equity, and public health. Grants for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in marine science (over $13.5 million) have been terminated.

• Loss of International Leadership:

The U.S. withdrawal from UNESCO, ending USAID programs, and disbanding the Office of Global Change undermine global partnerships critical for ocean sustainability.

• Regulatory Rollbacks: Deregulation efforts include:

o Repealing protections for marine monuments and endangered species.

o Promoting offshore oil/gas development and rescinding clean water protections.

o Abandoning the Paris Agreement and scaling back climate risk disclosures.

• Impact on Research Institutions: Cuts to NSF, NASA, and other research agencies have led to canceled fellowships,

halted REU programs, and the loss of long-term ecological datasets. Restrictions on foreign researchers worsen the talent drain.

B. Implications:

• The cumulative effect of these changes across federal agencies, academia, and NGOs represents a major decline in the U.S.'s ability to respond to ocean and climate-related challenges. The report calls for immediate reinvestment, crosssector collaboration, and prioritization of community needs to rebuild ocean governance and knowledge systems before irreversible damage is done.

C. Key Numerical Highlights:

• Federal Workforce Reductions (as of May 2025):

o 135,000 federal employees cut, with 107,000 more planned.

o 51,000 firings, 57,900 retirements, and 75,000 deferred resignations reported.

o NOAA alone lost staff representing 27,000 years of experience through early retirements.

Table 1. Agency-Specific Staff & Budget Cuts:

Cut

2,000 + 6,000 planned $10B+

• Programs and Contracts Terminated:

o 2,600+ federal programs slated for cancellation.

o 418 federal leases ended (including 19 NOAA facilities).

o 1127 contracts terminated in February 2025, including $77.7M in NOAA contracts.

o $13.5M in NSF DEI-related grants in marine/ocean science terminated (see Appendix A in report).

• Research Infrastructure at Risk:

o NOAA’s climate.gov, FEMA’s Future Risk Index, and NOAA’s Billion-Dollar Disasters database decommissioned.

o NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research and Sea Grant program proposed for elimination.

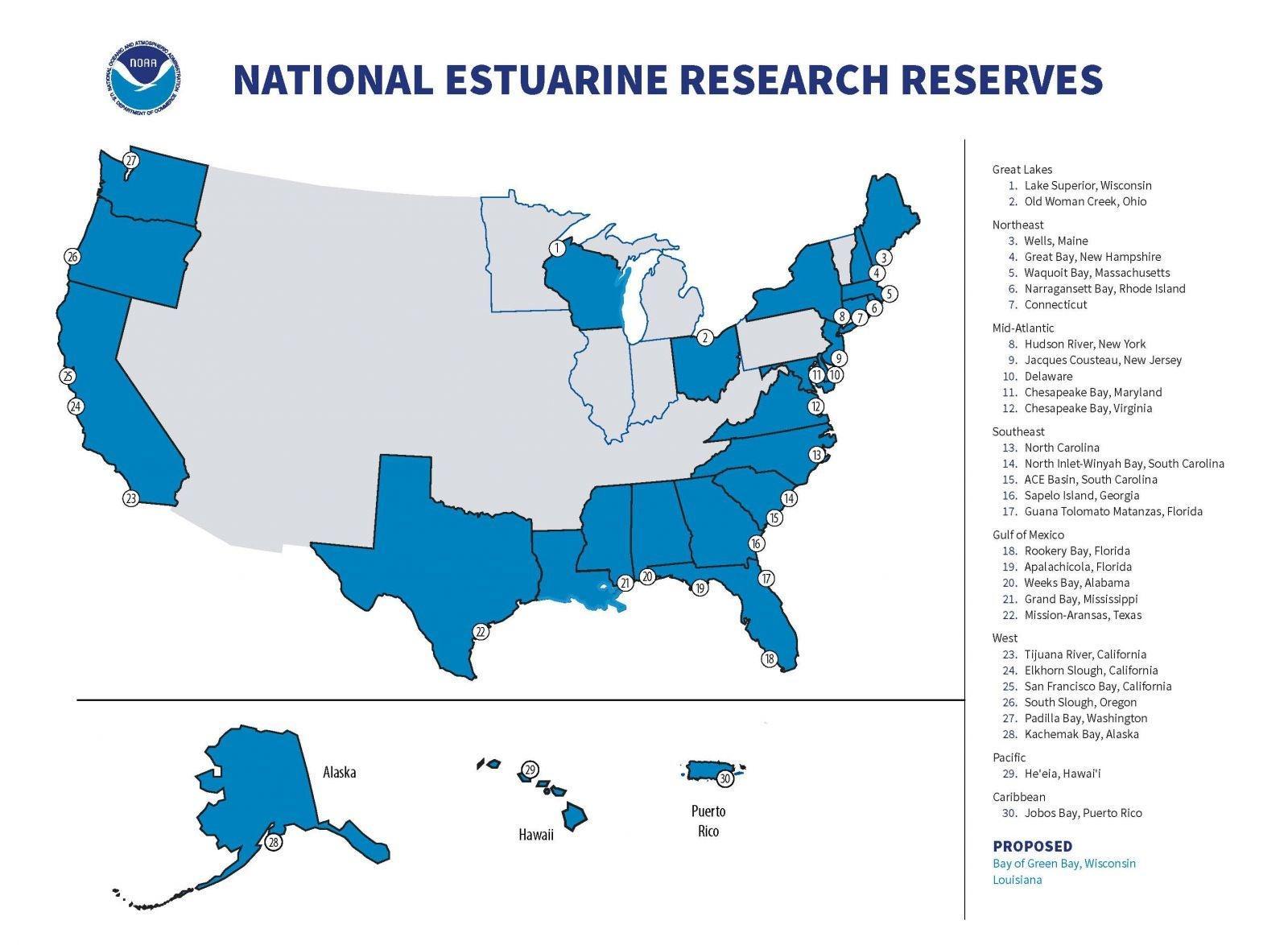

o National Estuarine Research Reserves system (30 reserves in 23 states & PR) faces defunding

I. Introduction

Ocean Nexus is conducting ocean governance capacity research to understand the impact of the loss of governance capacity considering recent reductions to the US federal workforce and funding. Understanding global ocean governance capacity is vitally important since it involves the implementation of laws and policies and involves multiple countries working in concert to ensure cooperation across boundaries. Thus, documenting and monitoring any changes to ocean governance capacity, particularly in the US which previously supported national and international efforts to build capacity, is critical for understanding what capacity has been lost, and how, if at all, this capacity can recuperate in the future. The reduction of federal funding to environmental agencies across the United States poses a myriad of challenges to ocean governance and science capacity both nationally and internationally. This research is particularly imperative considering cuts are occurring across multiple agencies thereby weakening regulations, terminating partnerships, and reducing human capacity via the elimination of federal employees with niche expertise and institutional knowledge. The research outlined in this report is limited in its scope due to lack of public administration of several agency websites, and funding. The data was gathered using multiple sources and are all publicly available. The research, led by Drs. Anna Zivian and Yoshitaka Ota, was conducted by an interdisciplinary team of researchers. The research and subsequent analyses focus on topics including staffing reduction and budget cuts, areas of capacity loss at each government agency, and regulatory rollbacks.

Current funding cuts amount to limited science and knowledge capacity, especially concerning climate change and equity issues. This calls for immediate action as well as long-term strategy. Over the near term, understanding what is being limited is critically important to establish a baseline dataset to inform future recouperation and (re)creation of affected programs. Recuperation and (re)creation of programs will involve maintaining datasets or shifting how and by whom information is tracked, held, and disseminated. Some knowledge limitations are less evident, however, and are held largely by individuals. For this reason, supporting topical working groups on key knowledge and governance areas (with a strong element of cross-cutting to avoid creating new silos) could be an important first step in documenting what remains and what has been limited; prioritizing areas for (re)building; maintaining partnerships and connections; and thinking of and creating ways to act on the identified priorities.

The impact of the elimination of funding is yet to be determined, but could result in long-lasting changes for the ocean, coasts, Indigenous and coastal dependent peoples,

local communities, businesses, and the health and safety of citizens. This report highlights trends across agencies in staff and financial reductions and the importance of tracking these changes to ensure the prioritization of actions to meet the current existential threats facing us.

A. Overview of US capacity

Two key trends stand out in the current ocean knowledge and governance environment: staffing reductions and budget cuts. While both are still being contested, the emerging picture is of unprecedented loss of financial resources, knowledge, and human capacity.

Table 2 Approximate numbers of staff and financial reductions across US federal government environmental agencies.

Agency Staffreductions*

Financialresources(Administration’s FY26budget) – reductionsoverFY25 budget** All federal agencies

with additional 107,000 planned°

NOAA 2,300^, with additional 17% planned

with reduction to 15 employees total planned

($1.8b)

*Including terminations, early retirement, deferred resignations, etc.

** note that these are proposed budget reductions included in the President’s budget, not the final enacted numbers, which are trending towards less dramatic cuts (e.g., 5% cut to NOAA, 23% cut to EPA). The President’s budget, however, is indicative of the goals of the Administration in terms of future plans for the agencies

° planned cuts are per President’s budget request and may not be enacted in full ^ over 27,000 years of cumulative experience in early retirees

Table two highlights the approximate numbers of staff and financial reductions across US federal government environmental agencies. Other agencies that have ocean and coastal management roles are also losing staff and budget resources, including NSF,

NASA, the Department of State, FDA, FEMA, NIH, and CDC. Science and research branches of all federal agencies are particularly hard hit, and the Congressional budget resolution includes $9b in previously approved funding, much of it for scientific research In addition, there are many indirect effects to partners including universities, businesses, and NGOs/community-based organizations. These, too, remain uncertain and contested, but include:

o 2600 federal programs originally slated for termination (The Upshot, NYT, 1/28/25); OMB lists just 2623 federal programs in its entire inventory of federal programs (see OMB).

o 418 federal leases terminated (JLL, 7/2/25),with plans to eliminate 1000 of the 7000 or so federal leases, including over 100 Department of Interior offices (USF&W, USGS, BIA, OSMR, BLM, Reclamation, MMS, etc.) (Huffman, 2025) and at least 19 NOAA facilities (of over 600 NOAA facilities total).

o All NSF grants to universities and NGOs related to ocean equity (totaling $13.5m) canceled

o $77.7m in NOAA contracts terminated (of approximately $2.75b), with all contracts of over $100K having to be reviewed directly by the Secretary of Commerce.

o Databases and websites discontinued, including climate.gov and U.S. Global Change Program website

o Withdrawal from IOC/UNESCO, which coordinates the UN Ocean Decade

II. Background And Current Trends

In the last several years, governments around the globe have taken greater action to include the ocean and its coasts in policy and governance. Examples include participation in the UN Decade for Ocean Science; greater inclusion of the ocean and coasts in international reports by the IPCC and IPBES; and calls for the creation of an International Panel for Ocean Sustainability. Similarly, global philanthropic funding for marine conservation has increased over 100% over the last 15 years (from $430m in 2010 to just over $1b in 2022), but this is still less than 1% of all global philanthropic funding (Our Shared Seas, 2023). In this context, any reductions in capacity are concerning, and current trends are particularly worrying.

There are several key actions that are weakening research and governance for ocean and coastal issues in the context of North American ocean governance capacity (US). Foremost among these is staff reduction in the federal agencies that address ocean science, knowledge, and management both directly and indirectly. These reductions are extreme and will have long-lasting impacts, because it will be difficult to replace the expertise of the human capital being lost. Federal hiring processes take a long time and newly hired staff also need time to learn the details of any position, thus if staff reductions were reversed, it would be several years before agencies regained full capacity.

Current and proposed funding cuts are equally damaging. These have both direct effects (agencies are unable to perform functions they had planned – including mandated requirements) and indirect effects (research institutions are unable to take on new students, partners are losing funds they were relying on to meet the needs of their communities and to fulfill their missions). Table three provides a non-exhaustive list of US agency offices that have been terminated. The targeting, on ideological grounds, of certain types of research – and researchers – threatens knowledge generation globally, not to mention the position of the United States and its institutions (academic, government, business) as leaders in science and technology. For instance, cuts to the Fulbright program, a nearly 80-year-old program that supports cultural exchange, including academic research, appear to have targeted research that touched on gender or race and on climate change (Knox, 5/29/25). In 2025 federal funding cuts broadly have been especially severe for diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives and research, climate change and renewable energy research, research on health impacts of pollution, biodiversity conservation research, and others.

International cooperation is also being affected, particularly in areas like climate change, where, for example, the US Department of State is eliminating the Office of Global Change, which leads international climate change for the United States (FoodTank, 2025). This move away from international cooperation will also directly affect ocean and science knowledge, as the current U.N. Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021-2030), currently entering its second half, is coordinated by the International Oceanographic Commission, which is housed at UNESCO, one of the UN institutions the US has now withdrawn (Irish and Chiacu, 7/23/25).

Table 3 Federal agency offices terminated (this list is non-exhaustive)

● EPA Office of Research and Development*

● EPA Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights

● Department of Defense social science research

● DOJ Environmental Justice Unit

● State Department Office of Global Change, UNESCO staffing

● NOAAOfficeofOceanicandAtmosphericResearch(proposed)

*The EPA has said it will create a new office of applied science and environmental solutions Information from Busiek, 6/26/25; The Guardian staff, 7/19/25; Columbia Law School Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, 2025; Peck and Glasser, 7/23/25; EPA, 3/12/25; McElfish, 4/10/25; Irish and Chiacu, 7/23/25

These are the most obvious impacts, but other actions will also have long-term effects: federal buildings terminating leases and in some cases being sold. Physical space, like staff, is much easier to get rid of than to rebuild. Scientific committees are being disbanded; for instance, advisory committees at NOAA for climate, coastal area management, and fisheries have all been disbanded (Katz, 3/3/25). Management protocols are in limbo, leaving those who rely on them, like fishermen, uncertain about their businesses. Long-term datasets are at risk of being discontinued or even destroyed, putting at risk knowledge that can help communities adapt to the accelerating changes facing them; for example, the Billion Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters database maintained by NOAA will no longer be updated (Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, N.D.). Other government information has been removed from websites (and some sites, like climate.gov, have been removed altogether), reducing public access to information

Cutting or eliminating risk forecasting, assessment, and emergency response systems like weather satellites, infrastructure, and oil spill response staff can affect responses to natural and human-caused disasters. Contradicting agency assessments and repealing EPA and other regulations on dangerous chemicals like PFAS, harmful metals like mercury, and greenhouse gasses will likewise increase health risks (Stand up for Science

2025). Similarly, changes to or removals of regulations can both decrease knowledge holdings through ending monitoring and increase risks to human and ecosystem health.

Other indirect effects include the ability for current federal agency staff to innovate and work cross-programmatically, as they will have to be fulfilling agency mandates with less staff capacity (personal communication). Fears about research competitiveness on the international level are also widespread; beyond cuts in agency grants to universities broadly, some universities are being subjected to additional federal cuts (for example, Harvard University, where labs are killing research mice rather than spend money to feed them (Kohti, 6/25/25)).

In addition, cuts to grants to states, local governments, and community partners will affect the ability of these entities to do environmental protection, environmental justice, planning, and resource management work that they previously were able to fund through federal grants and loans. Just one example of this is over $45 million in cuts to non-profits and local governments in Virginia for hazard mitigation and flood protection (Heckt, 6/25/25). Similar cuts around the country are affecting local disaster preparation and prevention projects.

Further, decreases in federal staff are having a “hollowing out” effect. Terminations have most affected recent hires and recently promoted staff (these categories are categorized as “probationary” for two years even though recently promoted staff may have been in other positions in the federal government for many years). Both categories often include some of the most energetic and effective employees (thus the reasons for hiring and promotion) (personal communication). At the same time, because of incentives for “voluntary retirement” programs, and the disincentives for remaining at their existing positions (for instance, the threat of losing retirement and health benefits), many long-time employees are taking ‘voluntary’ retirement (many of these employees felt pressured to accept the early retirement offers (personal communication)) through VERA (voluntary early retirement) and VSIP (voluntary early separation) and leaving their positions.

In NOAA alone, the early retirements mean a loss of over 27,000 years of experience total with the agents left from their positions (Greenwire, 4/29/25). With them, retirees are taking vast amounts of organizational experience, knowledge, and history. The level of knowledge loss across the federal government amounts to an “epistemicide,” or elimination of knowledge – for instance, the wholesale disbanding of USAID has destroyed a “global public good” of providing knowledge that aids human well-being across the

globe, for instance, helping adapt to climate change or promoting gender equity (Cummings, White, and Boyes, 2/27/25).

In addition, the loss of personal connections and the uncertain environment are taking a toll on morale within federal agencies (personal communication). Indeed, this effect on morale – “Promoting a culture of fear, forcing staff to choose between their livelihood and well-being” – is one of five concerns raised by EPA employees in an open letter to EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin, alongside loss of public trust, ignoring evidence to benefit polluters, harming EJ communities, and destroying research capacity (standupforscience.net, N.D.). The 139 staff members who signed the letter openly have since been placed on administrative leave (Sorg and Azhar, 7/3/25).

Some specific concerns about capacity loss are listed below. Much of what has happened in the first six months of the current administration is still in flux, with legal challenges playing out in the courts, decisions being reversed (or accelerated) by the executive branch, and unclear engagement by legislators in Congress and in the states. Increasingly, however, trends indicate that these changes will continue to be implemented, with recent rulings by the Supreme Court having upheld the executive branch’s authority (for instance, in allowing the dismantling of the Department of Education via mass employee terminations (VanSickle, 7/14/25)) and with Congress’s recent passage of the Administration’s budget bill (congress.gov, accessed 7/15/25).

Examples of areas defunded, eliminated, or decreased are listed in Table four

Table 4 Examples of areas defunded, eliminated, or decreased

Area of capacity loss

Disaster preparedness

Climate research

International cooperation

Public health

Coastal adaptation

Long-term datasets

Environmental justice

Examples of project/program cuts

EPA grants from IRA

US Global Change Research Program

State Department eliminating climate negotiation staff; ending USAID funding

Water quality monitoring

C-CAP USAID program; University of Hawai’i at Manoa’s Coastal Research Collaborative

Funding for Long-term Ecological Research

Sites

Complete shuttering of EJ offices at EPA, firing staff working on EJ, termination of the National

Climate change awareness

Environmental Justice Advisory Council (NEJAC)

Removing climate.gov website; removing 5th National Climate Assessment website; Climate literacy guide removed from NOAA website

Climate education B-WET program (Chesapeake Bay Watershed Education and Training)

Fisheries management

Staff reductions at NMFS

International leadership/soft power USAID, State Department budget and staff cuts

Science and knowledge capacity NSF cuts

Research, development, and innovation

Public access to information

III. Key Statistics

Workforce reductions limit staff capacity to innovate; funding cuts across science programs at federal agencies

Signage at Muir Woods National Monument removed, other sites in DOI’s jurisdiction slated to have signage removed and/or changed

A. Total planned and effectuated staff cuts

As of 5/12/25, nearly 135,000 federal employees from across multiple agencies were confirmed to have been cut or taken early retirement (Shao and Wu, 5/12/25). This includes over 51,000 federal employees who were fired (Choi, Gainor, and Carroll, updated 7/14/25). OPM reported that 57,900 employees have retired in the first half of 2025 (OPM, accessed 7/15/25). Between 2005 and 2023, federal retirements have averaged just over 100,000 per year (OPM, accessed 7/15/25). This is in addition to about 75,000 employees who have taken deferred resignation (“Fork in the Road”) offers instituted by DOGE (Fabino, 2/18/25).

Government agencies are seeking to reduce the number of employees dramatically (by at least a third (or about 700,000 employees, (approximately 1/3 the federal civilian workforce (excluding USPS))), per Office of Management and Budget and Office of Personnel Management guidance (Govex staff, 5/15/25), and are doing this via layoffs and firings of probationary employees (many of these decisions are being contested in the courts), reduction-in-force (RIF) notices, and early retirement incentives.

At NOAA specifically, at least 600 employees have been fired (Frazin and Budryk, 3/1/25), some of them rehired, and fired again (Freedman, 3/17/25; personal communication, former NOAA employee, 4/11/25). A Reduction in Force (RIF) plan for

NOAA intends to cut an additional 10 percent of agency staff, or approximately 1000 more positions (Kemp, 3/14/25), and overall, the FY26 budget plans for additional cuts of 18% (Pulver, 7/1/25).

Of all the cuts, many are in agencies that have at least some interest in ocean and coastal issues, including climate change, fisheries, plastic pollution, and equity (Table five numbers below are approximate):

Table 5. Staff reductions for US federal agencies with all or partial focus on climate change, fisheries, plastic pollution, and equity.

Agency

Staffreductions(terminations,resignations,retirements)

All federal agencies 135,000 with additional 107,000 planned°

NOAA 2,300, with additional 1,000+ planned

USAID 10,000, with reduction to 15 employees total planned

(including NOAA)

with an additional 6,000 planned

planned

B. Independent advisory committees

Committees at several agencies have been disbanded and/or their members dismissed; particularly those addressing science, climate change, and equity (Barbati-Dajches, 2/6/25). Federal advisory committees (FACs) allow for experts from various fields outside the federal government to give input and advice to federal agencies, bringing concerns from relevant fields and the public at large directly to policymakers at federal agencies. Executive Order 13875 called for at least one-third of all federal advisory committees to be eliminated.

EPA National Environmental Justice Advisory Committee (NEJAC)

EPA Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee (CASAC)

EPA Science Advisory Board

HHS National Vaccine Advisory Committee

NIH complete pause on all FACs

C. Overall budget cuts for FY 2026

More than with staff cuts, which have been moving forward under the Administration’s oversight and at its behest, budget cuts remain uncertain. The proposed budget contains dramatic and unprecedented reductions, including reducing the EPA budget by more than half, cutting NOAA’s budget by at least 30%, cutting the NSF budget from about $10b to less than $4b, cutting NASA’s budget by over $10b, but Congress has proposed smaller cuts, including 25% cuts to NSF, keeping NASA’s overall budget flat (as opposed to the nearly ¼ cut proposed in the President’s budget) but cutting its science budget by 18%, and cutting NOAA’s operations, research, and facilities budget to $4.15b, or about a 6% cut (Garisto and Witze, 7/10/25, Cusick, 7/14/25).

On the other hand, proposed cuts to USAID have been largely unchallenged in Congressional budget negotiations (Pecorin, 7/14/25); USAID funding has been instrumental in supporting research and action on several ocean and coastal issues, such as fisheries management and aquaculture development, including the Oceans and Fisheries Partnership (SEAFDEC/USAID, 2020); developing international partnerships to address plastic pollution, like the Alliance to End Plastic Waste; support for offshore wind development (for instance, in the Philippines (RTI, October 2023)); and coastal adaptation (such as the C-CAP project in more than Pacific Island communities across 12 countries (USAID, last accessed 7/14/25).

Current proposals would decrease the EPA budget from $9.14b to $4.16b; environmental justice programs will be eliminated completely (Melburg and McCabe, 6/27/25). It would cut NOAA’s budget by $2.2m, or about 30% (Cusick, 7/3/25, including zeroing out the Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR) and eliminating the Sea Grant program; overall impacts on research would be dramatic (Pulver, 7/1/25). Cuts to the Department of Energy in the budget would hit non-defense spending, with a cut of over 25% proposed (DOE, May 2025). Renewable energy, including offshore wind, is a particular target, with support for wind energy completely cut and also defunded within the Indian Energy Policy and Programs budget lines (ibid.). The proposed budget also has dramatic cuts to NIH and CDC (which monitors and seeks to prevent waterborne disease, including diseases in ocean and coastal areas).

Overall, research and development budgets across the federal government are particularly hard hit in the current budget proposal. Total non-defense R&D budget

requests are down nearly 36% from FY25 budgets (Zimmermann, 7/15/25). STEM education and engagement budgets are also dramatically cut in both the President’s request and in Congress, with the House zeroing out funding from NSF and NASA in these two areas.

D. Regulatory rollbacks with ocean and coastal implications

There has been regulatory withdrawal from defending regulations in court, agency redefinitions, and other executive actions to roll back regulations that address climate, biodiversity, and human health. This also affects knowledge and policy capacity by decreasing research (e.g., ending monitoring; ignoring existing knowledge on, for example, effects of federal actions on species; developing new knowledge on climate) and ending international partnerships.

● There has been withdrawn areas for federal offshore wind leasing, paused new approvals and renewals of approvals, and ordered a review existing leases.

● Marine monument protections are being rolled back, with a call to review existing monuments and a proclamation allowing commercial fishing in the Pacific Island Heritage Marine Monument

● Through executive order, DOI is directed to encourage development of offshore oil and gas leasing, including in areas previously partially protected; protections for Alaska’s National Petroleum Reserve are also being reversed (this decision is being litigated).

● Endangered Species Act regulations are being rolled back under the claim of a “national energy emergency”

● There is a plan to revise the definition of “Waters of the United States” (WOTUS) that defines what waterways and wetlands are protected by the Clean Water Act.

● The US has withdrawn from the Paris Climate Agreement.

● The SEC is not defending the climate-related risk disclosure rule (a rule that requires companies to inform investors on the climate-related risks they are facing) from challenges in court.

● Columbia River Basin Native Fish restoration project established by Biden memorandum revoked.

● Executive order issued to deregulate commercial fishing.

● Four categories of funding for NOAA under the Inflation Reduction Act have been repealed by Congress, with unobligated funds rescinded: Investing in Coastal Communities and Climate Resilience (section 40001), $2.6b, Construction of NOAA and National Marine Sanctuaries Facilities (section 40002), $200m, NOAA Efficient

and Effective Reviews (section 40003), $20m, and Climate and Weather Research and Forecasting (section 40004), $150m.

(information on these rollbacks is from the Harvard Law School Environmental and Energy Law Program’s Regulatory Tracker, accessed 7/24/2025 ; Columbia Law School Sabin Center for Climate Change Law Climate Backtracker, accessed 7/24/25; Inflation Reduction Act Tracker, accessed 7/24/25)

E. Program terminations and pauses

Over 2600 federal programs were considered for termination before courts blocked the order (The Upshot Staff, NYT, 1/28/25 and 1/29/25), but many of these terminations have since moved forward, affecting agency actions and partners from the local to the international scale. For instance:

IOOS (Integrated Ocean Observing System) would be eliminated, reducing public access to data and forecasts (Wyden, 6/6/25; Tsantiris, 7/9/25)

A NWS student volunteer program in Kentucky has been cancelled (NWS Paducah KY on X, 3/4/25)

The proposed budget would cut the Brownfields program by 50% (Melburg and McCabe, 6/27/25). The Brownfields program leverages tens of billions of dollars for every billion spent and has created over 200,000 jobs over the past 30 years (Melburg and McCabe, 6/27/25). This funding cut is particularly concerning for coastal communities, as many brownfield sites (especially landfills and former industrial areas) are located in areas that are at risk from sea level rise and increased flooding (BCDC, ND).

The budget proposal, which is supported in the Congressional budget that is moving towards finalization, eliminates the Marine Mammal Commission, which was established in the Marine Mammal Protection Act passed by Congress in 1972. The FY26 budget proposes a cut from $4.5m to $1m, or 78% from the enacted FY25 budget; the $1m is intended to provide for “an orderly shutdown” of the MMC.

F. Loss of information/access to information/tools

Several federal websites and webpages have been or are being removed, reduced in size, or eliminated. Examples include climate.gov, which has been eliminated and which now redirects to noaa.gov; the 5th National Climate Assessment website (the report itself

remains available in the NOAA library, but the website contained information that is not available in the pdf report, such as metadata, additional charts, public comment letters with responses, and other clickable information); FEMA’s Future Risk Index, which showed projected county-level economic losses due to climate change; and EJscreen and the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST), two environmental justice mapping and screening tools that are widely used by communities and educators. A number of EPA staffers have expressed concern about the backtracking on environmental justice from the loss of these tools and from the cancellation of grants (Stand up for Science 2025; Sorg and Azhar, 7/3/25). Combined with a loss of communications staff, this means that the public is not getting information that (a) they have paid for through taxes and (b) they need for policy action or educational purposes.

The termination of the National Climate Assessment and the attempted end of the US Global Change Research Program (a Congressionally-mandated program) will affect states that rely on it for making decisions related to sea-level rise and other climate-driven change (personal communication, California OPC, 6/10/25).

G. Grant funding

NSF Grants

At least $13.5m in NSF grants for projects related to diversity, equity, and inclusion related to ocean, coastal, and marine science and policy have been cancelled (calculations based on data available from NSF) – see below for specific cuts (see Appendix A for table of terminated awards).

At NOAA, climate change research is being cut both in the agency itself and through defunding grant programs, like the Climate and Global Change Postdoctoral Fellowship Program Fellows. in this year’s grant have been put on unpaid leave, and fellows selected for this year have not received offers because the funding is too uncertain (Dzombak, 7/9/25).

At the EPA, grants provided under the Inflation Reduction Act through its Environmental and Climate Justice Program for disaster preparedness and flood control, among others, have been terminated. This will leave vulnerable communities even more at risk from extreme weather events (Lavelle et al., 7/3/25).

Even for already-approved funds, the requirement for sign-off by politically appointed agency heads for disbursement of funds for expenditures greater than $100,000

is significantly slowing operations and creating uncertainty as to whether those funds will be dispersed at all.

Research institutions

NSF has cut funding for REU (Research Experiences for Undergraduates) programs; it remains unclear how large the cuts will be (Mervis, 2/27/25). Several universities have already cancelled programs this summer because of funding uncertainty; for example, both Johns Hopkins and UC-Merced cancelled this year’s programs (Insight into Academia, 2/27/25). California State University – Monterey Bay has also cancelled its 2025 REU program focused on ocean science (CSUMB 2025).

Cuts to NSF could also affect NSF-funded Ecological Research sites, such as the California Current Ecosystem and Santa Barbar Coastal Long-term Ecological Research sites. These programs provide long-term data from years of monitoring and research that aid understanding of coastal and marine ecosystem functioning and change (California OPC, 6/10/25).

In addition, the administration, through the Department of Homeland Security, has created uncertainty for the status of foreign undergraduates, graduate students, and postdoctoral researchers, both through charges against individual students as well as through attempts to ban enrollment of foreign students (e.g., Rose et al., 5/23/25). The atmosphere of uncertainty has already caused some researchers to enroll in programs or seek positions outside of the U.S. (personal communication, 5/26/25).

Subsidiesandsupport

Offshore renewable energy subsidies are slated to end and there is an environment of business uncertainty; Empire Wind received a stop work order in April that was lifted 5/19/25 (Equinor, 5/19/25). By contrast, protections from oil and gas drilling and leasing on outer continental shelf rescinded by Executive Order 14148 (order has been challenged, in, e.g., AlaskaEnv’tCtr.etalv.Trump).

Contract terminations

1127 federal contracts terminated by DOGE in February; some have been reinstated. The total value of contracts with NOAA that DOGE terminated on February 17th was approximately $77.7 million (Wikipedia, NOAA under the second presidency of Donald Trump)

Physicalproperty(leaseterminations,physicalpropertysales)

19 NOAA building leases are being terminated (AK, VA, FL, ID, OR, HI, LA, MD, NJ, WA, OK, RI, VA, CA) (Wikipedia, as above). If Congress approves the FY26 budget proposal, several laboratories would close, including the Global Monitoring Laboratory (which includes offices in Mauna Loa, where global atmospheric CO2 is monitored) and the Atlantic Oceanographic & Meteorological Laboratory in Miami (Pulver, 7/1/25).

Datacollection,databaseclosures,websiteremovals,otherpublicaccesstoinformation removed

Planned database closures at NOAA include the Shoreline/Coastline Resources page, the Coastal Water Temperature Guide, and six Regional Climate Center websites, and the Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters database, among others (Wikipedia, as above). Changes to National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service information at NOAA are noted on the NESDIS website.

EJScreen, EPA’s environmental justice tool, was removed from the EPA website. Diversity, equity, and inclusion websites and content have been taken down across agencies, including NASA, FDA, DOE, and NIST.

The FY26 NOAA budget would end funding for the National Integrated Heat Health Integration System (Pulver, 7/1/25).

The National Estuarine Research Reserves are under threat of being defunded. The 30-reserve system, illustrated below in Figure 1, monitors conditions in these reserves across the country; defunding the system would cause a gap in monitoring data at a time of rapid global change and would also cause job losses across the US (Cosman, 6/25/25).

Signage at sites in the Department of Interior’s jurisdiction is slated for removal if it “undermine[s] the remarkable achievements of the United States by casting its founding principles and historical milestones in a negative light;” this removal has already affected the Muir Woods National Monument (Wright, 7/23/25), where signs that discussed Indigenous history, racism, and women’s history have been removed.

Figure 1. Map of the National Estuarine Research Reserve system across 23 states and Puerto Rico (NERRS Science Collaborative, 2025).

Appendices

A. NSF grants for ocean-, coastal-, and marine-related projects terminated Terminated NSF awards

Recipient Title

Black in Marine Science Planning: Bringing the Ocean to the Streets: Strategic Approaches for Engaging Historically Excluded Communities in Geosciences

University of Rhode Island

Collaborative Research: Enhancing MPOWIR to Build a Diverse and Inclusive Oceanography Workforce

University of Georgia Research Foundation Inc. Collaborative Research: Enhancing MPOWIR to

University of South Florida GP-UP: Workshop to build collaboration & participation across DE&I programs in Ocean Science

University of Virginia Main Campus NSF INCLUDES Planning Grant: Coastal, Ocean, and Marine Enterprise Inclusion and Network-building (COME IN)

National Academy of Sciences Increasing Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Belonging, Accessibility and Justice (DEIBAJ) in the US Ocean Studies Community

University of Rhode Island

Washington

Coastal and Estuarine Research Federation

NSF-NFRF: Building resilience of coastal inhabitants in vulnerable regions of Bangladesh through a participatory, gender-transformative approach

University of the Virgin Islands Collaborative Research: IMPLEMENTATION: C-COAST:

88,281

13,546,097