NPCA

PROGRAMS

CHESAPEAKE A WATERSHED MOMENT FOR THE

Establishing a new national park unit

Unveiling the Ecological Impacts of Air Pollutants in National Parks

The science behind NPCA’s Polluted Parks 2024 report

Vital Forests

Why and where to protect old-growth forests in and around parks

Most At-Risk Coastal Parks

Cutting-edge data evaluates four categories of coastal resilience in national parks

SPRING 2024 Science News

CONSERVATION

Science News

NPCA Science News is an internal newsletter highlighting the integration of science empowering our park protection. Our stories are inside stories – originating from close, collaborative work with Programs and Regions. By spotlighting science-related work throughout NPCA and with our many partners, we bring much needed attention to the important role of science in advocacy.

CONSERVATION PROGRAMS

Conservation Programs Vice President PRIYA NANJAPPA

CONSERVATION SCIENCE | NPCA Science News Editorial Team

Sr. Director RYAN VALDEZ, PH.D. (Editor in Chief)

Sr. Program Manager NIK MOY (Managing Editor and Content)

Geospatial Science Fellow AMY TIAN (Art Design and Content)

With Editing and Printing Support from:

Assistant Director of Advancement Communications KELLY BURTON (Copy Editor)

SCIENCE ADVISORY LEADERSHIP TEAM (SALT)

Conservation Science Sr. Director RYAN VALDEZ, PH.D.

Sun Coast Regional Director MELISSA E. ABDO, PH.D.

Conservation Programs Sr. Program Manager CHRISTA CHERAVA (Copy Editor)

Conservation Programs Deputy Vice President SARAH BARMEYER

Foundation Relations Senior Director JULIE L. HOGAN

Conservation Science Sr. Program Manager NIK MOY

Clean Air and Climate Sr. Manager DANIEL OROZCO, PH.D.

Please contact Nik Moy, nmoy@npca.org, if you would like to share with any audiences external to NPCA or if you would like to print a version of this newsletter.

Interested in helping advance Conservation Science at NPCA? To explore how your support can make a meaningful impact please reach out to:

Foundation Relations Senior Director JULIE L. HOGAN at jhogan@npca.org

To view this report digitally and access links:

1 NPCA

A Watershed Moment

by THERESA PIERNO President and CEO

Opening Note

In this issue of NPCA Science News, the feature story showcases NPCA’s powerful advocacy with conservation science partners to turn the proposed Chesapeake Bay National Recreation Area into a reality. You’ll hear stories of Chesapeake Bay’s wildlife, history and the essential scientific monitoring programs propelling its restoration.

The Chesapeake Bay has always been a meaningful place for me. Through family vacations I learned to sail and found it thrilling to be in control of a boat, though of course you’re not in control of the wind. I knew from these early experiences how important the Chesapeake and its tributaries are — to wildlife, to sport and even to way of life. Ultimately, I was able to parlay that into a career, working to protect our environment including the Chesapeake Bay.

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in North America. Thousands of years of history and one-ofa-kind natural wonders come alive there, and many generations of watermen have worked to protect them. Countless families, including my own, have sailed the Chesapeake’s beautiful waters, celebrated milestones on its shores, and tasted the famous blue crabs from its depths – including my own. For many of us, the Chesapeake Bay means home. And it’s so worthy of inclusion in the National Park System.

Also in this issue, you’ll learn more about coastal parks through our Water Team’s new and innovative conservation science partnership that helps identify the most vulnerable parks for coastal protection priorities. Even more on science, see key details from our Air Team’s 2024 Polluted Parks report showcasing how air pollution negatively impacts most of our national parks.

Enjoy the Spring 2024 edition of NPCA Science News,

Theresa Pierno President and CEO

Theresa Pierno President and CEO

SPRING 2024 2

A great blue heron majestically stands looking out over the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland.

Photo by Patrick Wolf. TOP

Theresa Pierno, President and CEO of NPCA, cruising on a boat on the Bay.

LEFT

5

Contents

Conservation Programs

Wildlife Polling

Ecological Impacts of Air Pollution on Parks

Science Advocates at NPCA

Visualizing the NPS Sustainability and Climate Adaptation Project Database

Creating An Informed Response to the BLM’s New Solar Plan

Side Feature

Vital Landscapes: Why and Where to Protect Old-Growth Forests In and Around Parks

Feature Story

A Watershed Moment for the Chesapeake: Establishing a new national park unit

3 NPCA

13

27

On the cover

Thomas Point Shoal Lighthouse is Maryland’s most recognizable lighthouse in the Chesapeake Bay. Built in 1875, it is also a designated National Historic Landmark. The lighthouse would be an iconic part of the proposed Chesapeake National Recreation Area. Photo by Brycia James.

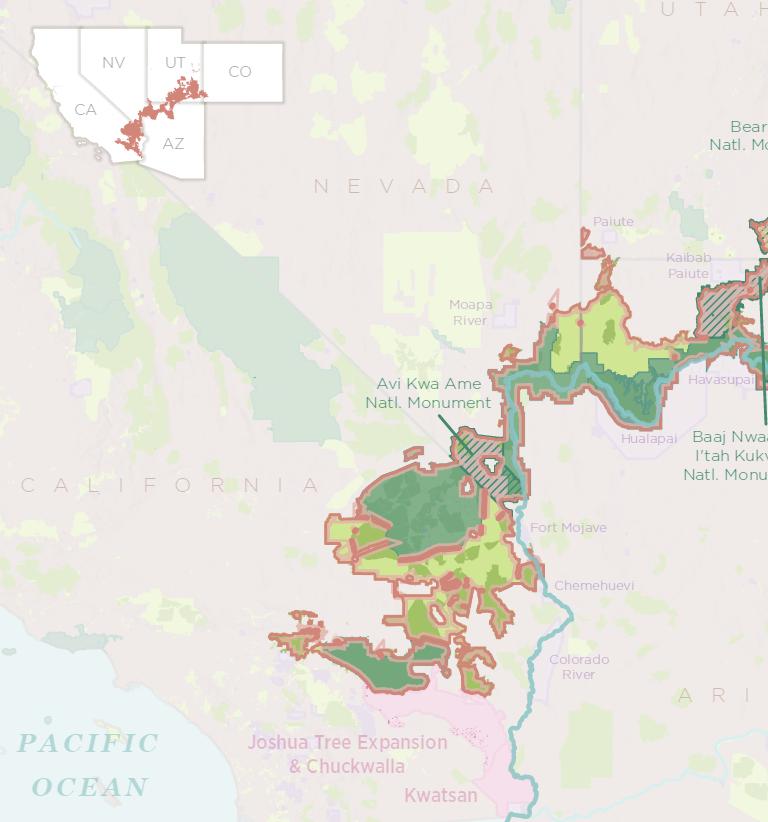

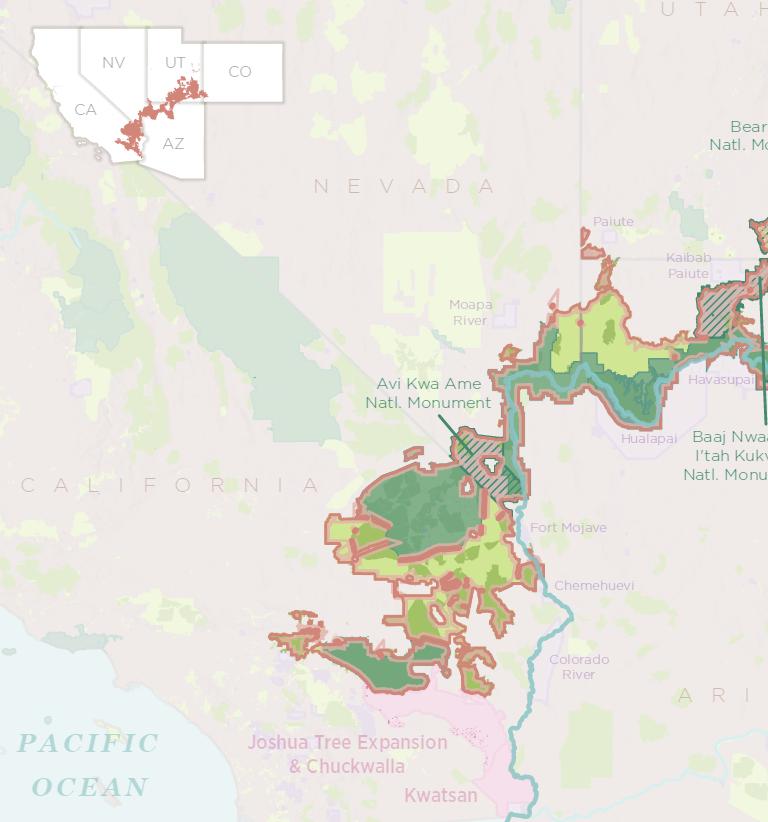

Southwest Protected Lands Corridor

Protected lands "managed for biodiversity" (PAD US 3.0 GAP I & II, USGS)

Proposed protected areas

National Park Service Units

Indigenous lands

Newly protected lands by the Biden Administration (2023) CO

17,506,480.93 Acres

19,034,888.72 Acres

Land & Seascape Conservation 31

Land and Seascape

Toolkit

Coastal Parks Data

Submission to Scientific Journal

Mapping Black

Community Resources in Birmingham, Alabama

The Lands Between Chuckwalla

43

GIS Lab

Highlight

Southwest Protected Lands Corridor 30x30 Landscape Conservation Atlas

ColoradoRiver

ARIZONA

NEVADA UTAH NEW MEXICO CA NV UT AZ Moapa River Havasupai Hopi Navajo Nation Kaibab Paiute Paiute Ute Mountain

CALIFORNIA

COLORADO

SPRING 2024 4

Conservation Programs

and unifies NPCA in achieving dynamic and equitable conservation solutions that protect and enhance the air, lands, water, wildlife, and climate of our national parks.

Leads

Leads

5 NPCA

Priya Nanjappa Vice President, Conservation Programs

Sarah Barmeyer Deputy Vice President, Conservation Programs

Christa Cherava Senior Manager, Conservation Programs

Matthew Kirby Senior Director, Energy & Landscape Conservation

Bart Melton Senior Director, Wildlife

Ryan Valdez, P.h.D. Senior Director, Conservation Science

Karen Hevel-Mingo Director, Sustainability

Stephanie Adams Director, Wildlife

Ulla Reeves Interim Director, Clean Air

Natalie Levine Interim Campaigns Director, Clean Air

Daniel Orozco, P.h.D. Senior Manager, Clean Air

Beau Kiklis Senior Manager, Landscape Conservation

Nik Moy Senior Manager, Conservation Science

Amy Tian Geospatial Science Fellow, Conservation Science

NPCA National Wildlife Poll

A new poll from NPCA explored public perspectives on threats and opportunities for conserving park wildlife. The survey shows bipartisan concern for the future of park wildlife populations and united support for solutions. Reach out to Bart Melton at bmelton@npca.org to learn more.

CONSERVATION PROGRAMS SPRING 2024 6

Unveiling the Ecological Impacts of Air Pollutants in National Parks

Written by DANIEL OROZCO, P.h.D., NPCA Senior Manager, Clean Air

View the Polluted Parks Report 2024

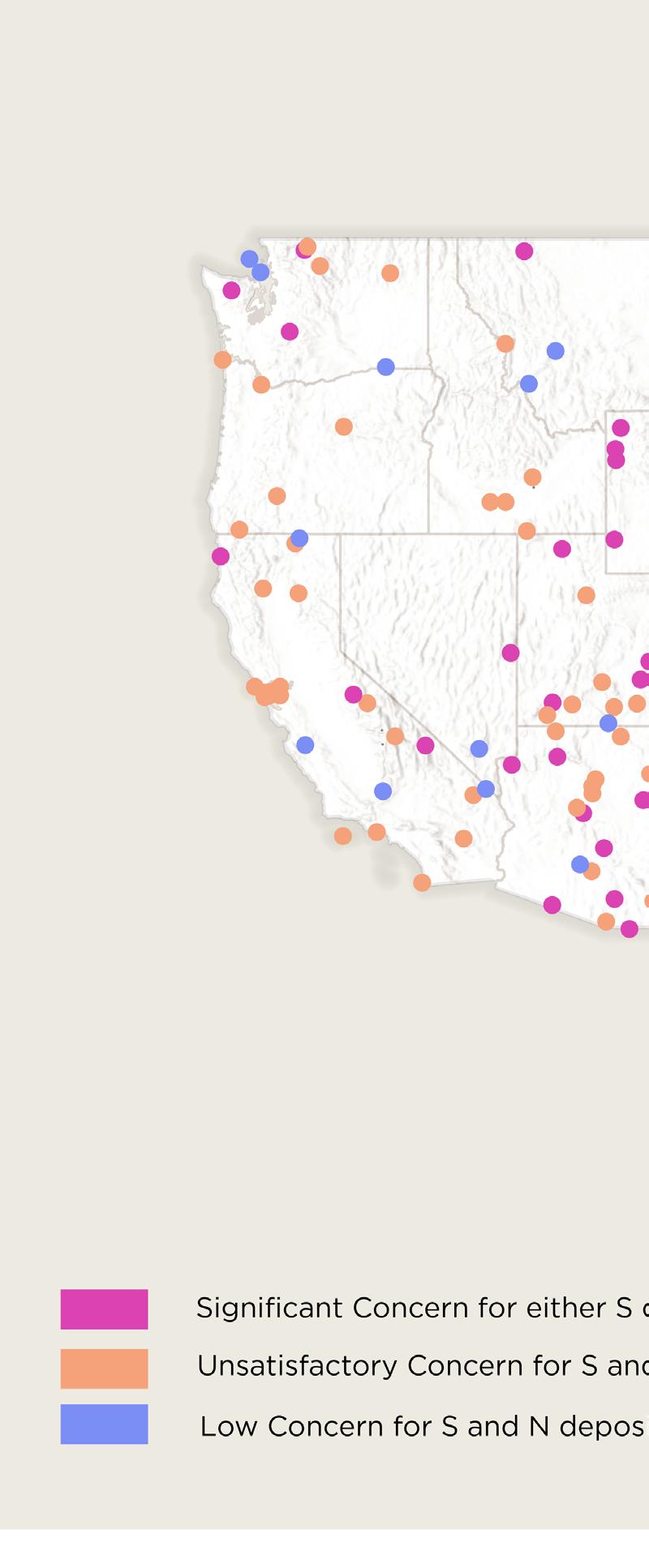

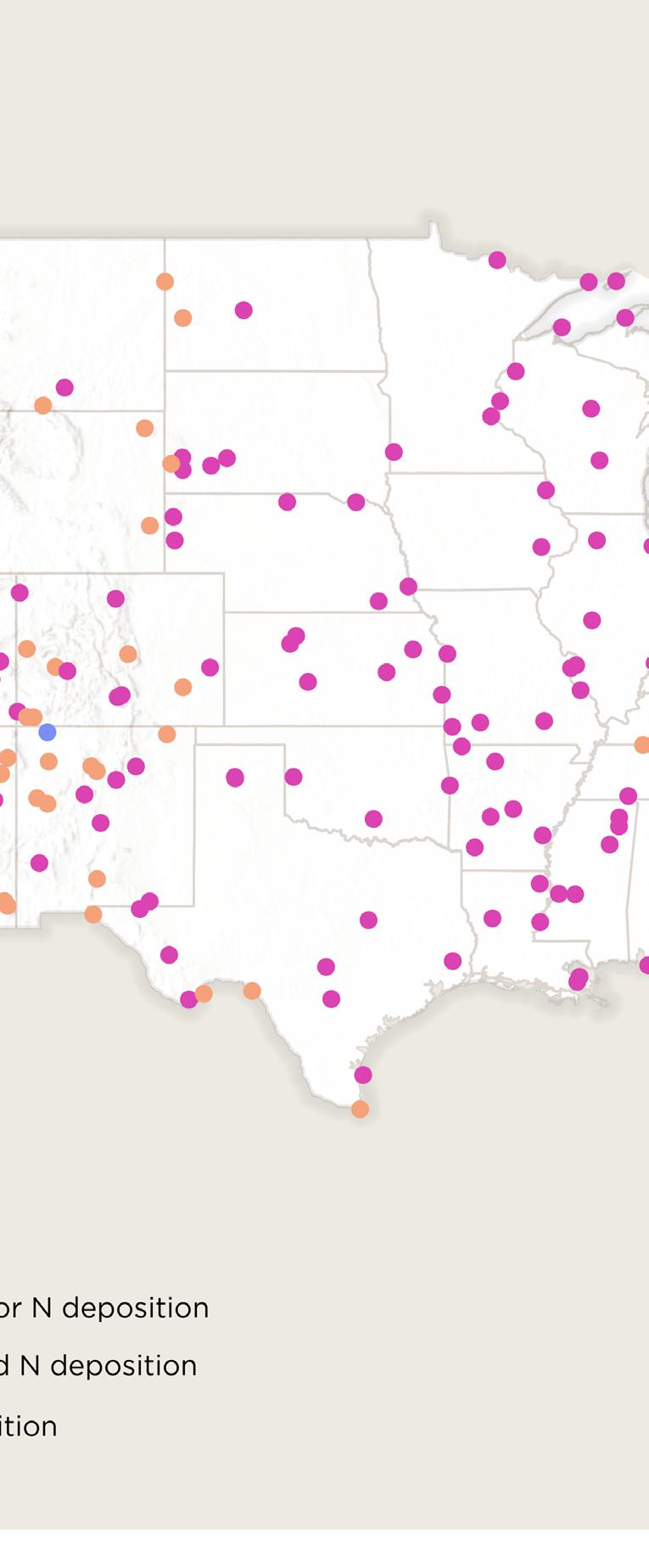

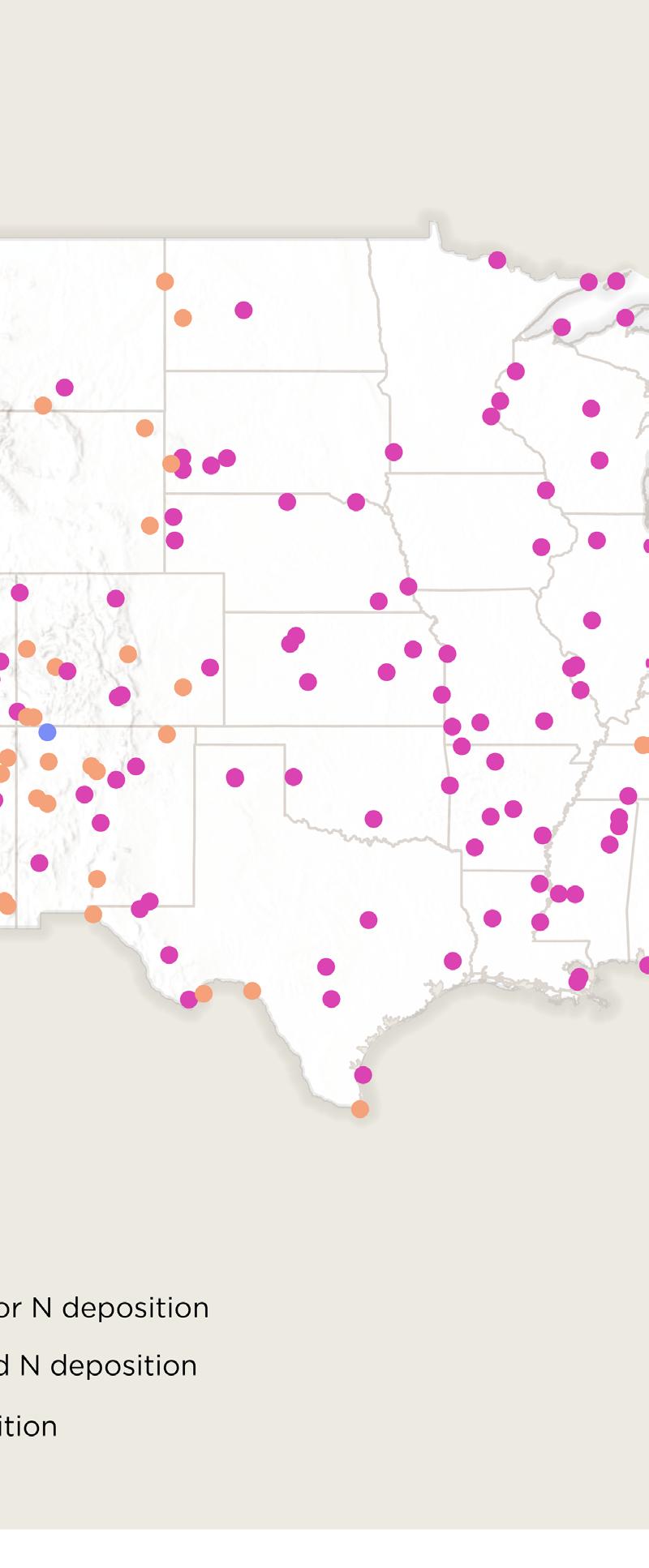

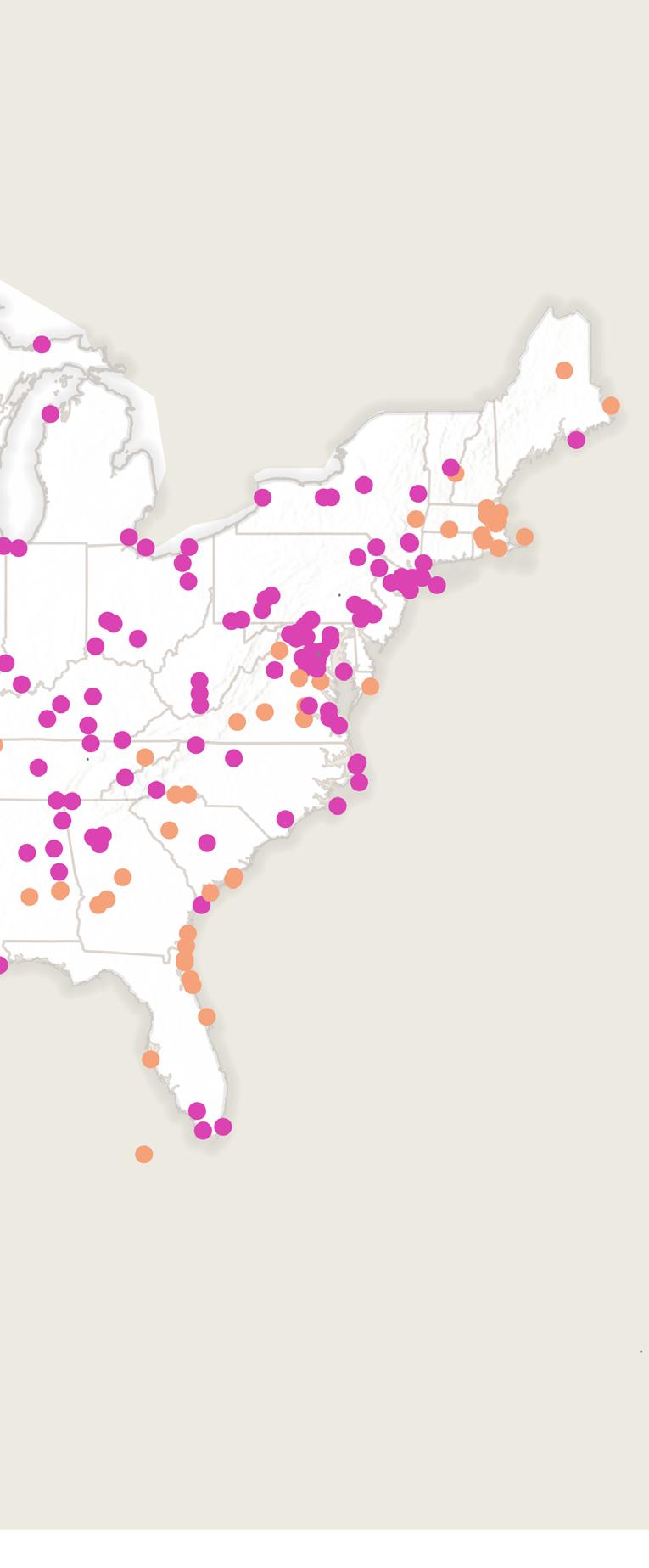

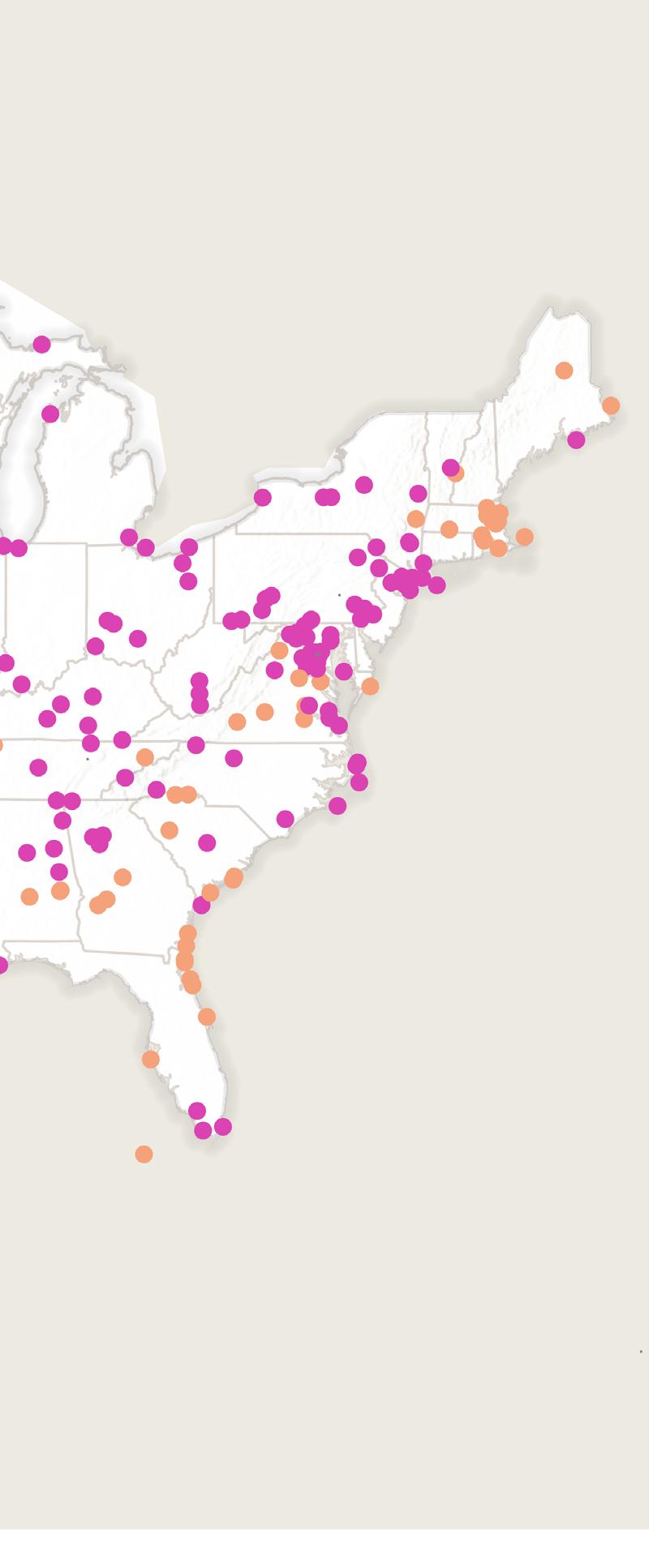

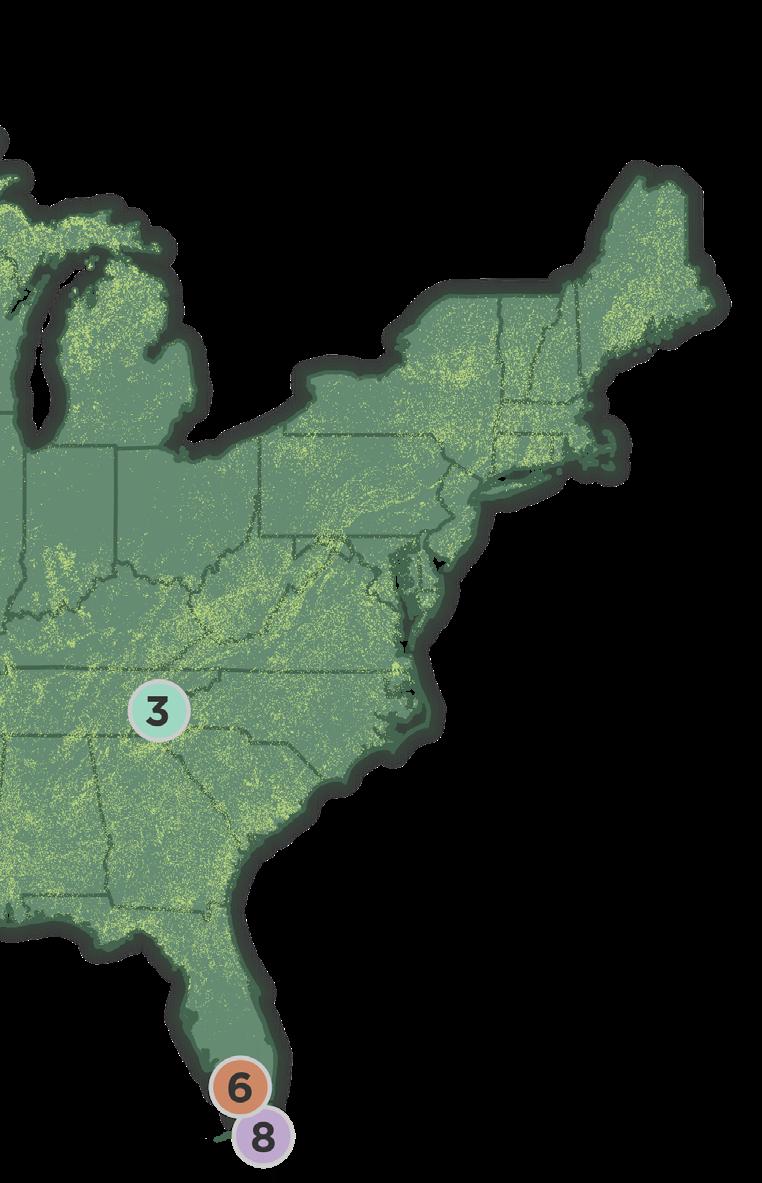

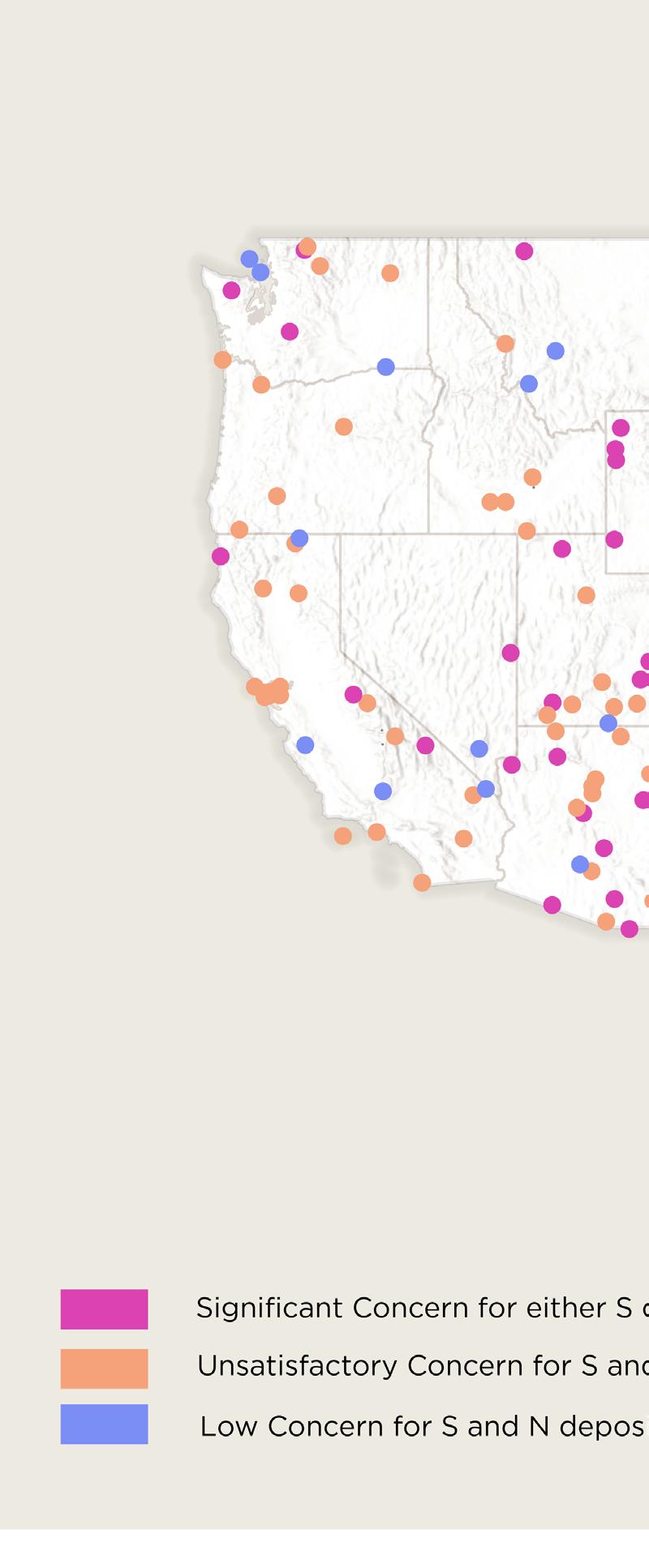

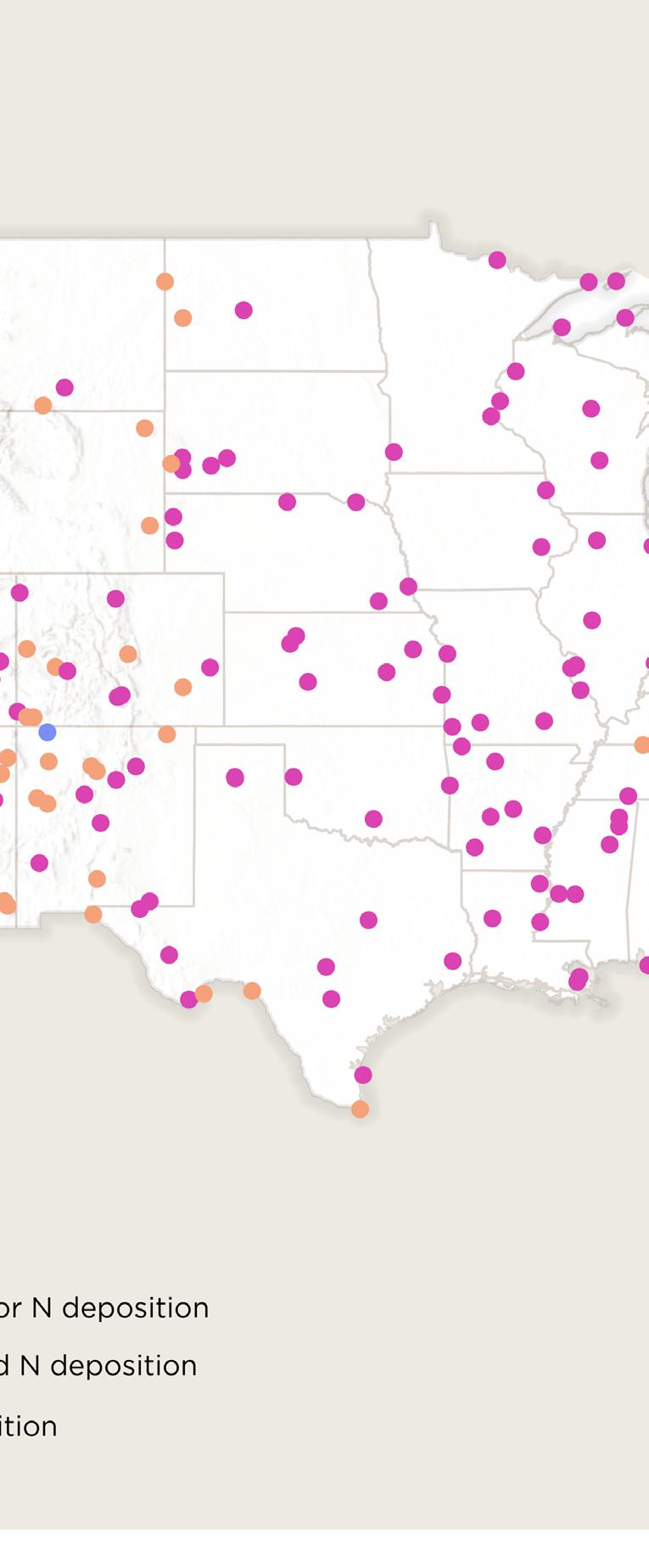

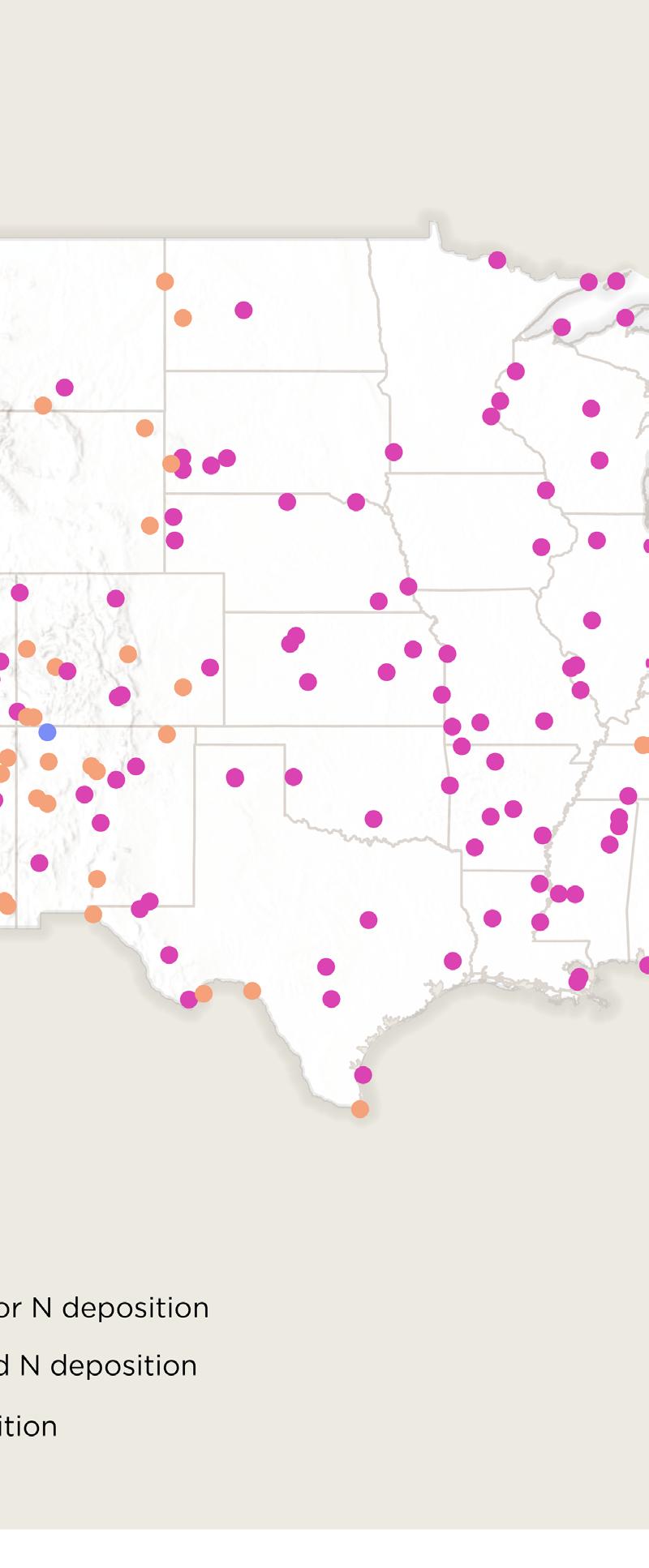

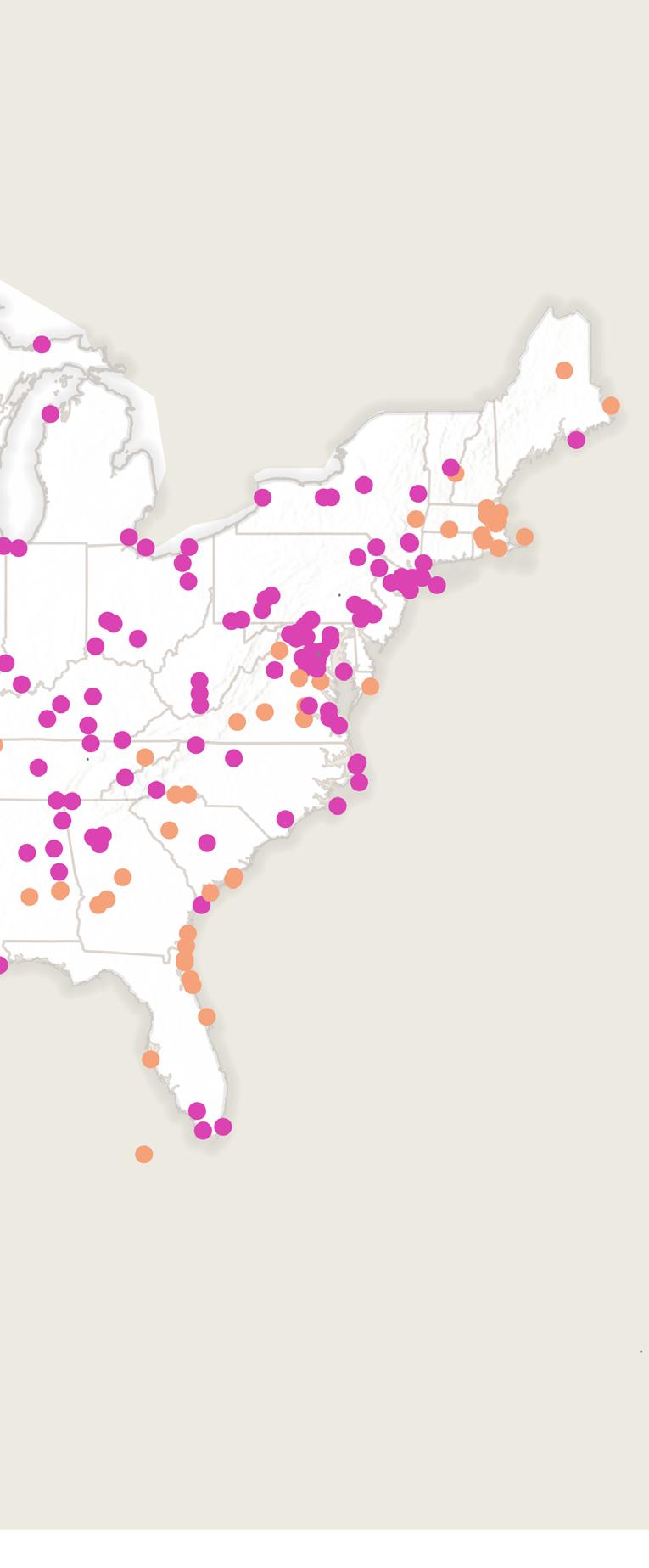

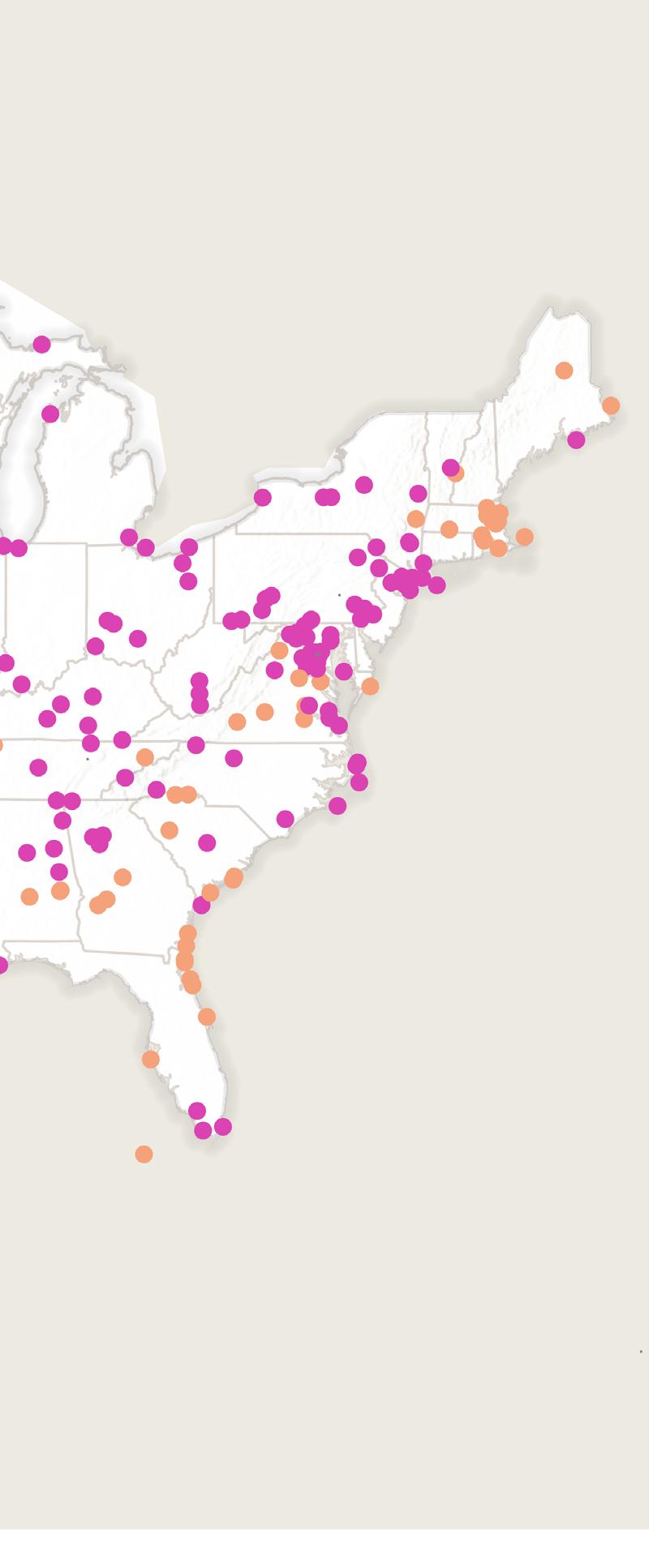

NPCA’s 2024 Polluted Parks report reveals the persistent effects of sulfur and nitrogen pollution on national parks across the U.S. Industrial facilities and vehicles emit these air pollutants into the atmosphere which are eventually deposited in the soil and water disrupting delicate ecosystems and threatening biodiversity. Our analysis of National Park Service data found that 94% of parks experience nitrogen deposition at significant or unsatisfactory levels and 70% of parks for sulfur deposition.

What is sulfur and nitrogen deposition and how does it impact parks?

While sulfur and nitrogen deposition are natural processes, human activities have produced immense excess causing imbalances in nutrient cycling and

Sulfur (S) is emitted as sulfur dioxide (SO2) and Nitrogen (N) is emitted as nitrogen oxides (NOx); both originate from sources like power plants, industrial processes, and vehicles. Ammonia (NH3) is another major nitrogen-based pollutant primarily emitted from agriculture processes in animal manures and fertilizers.

These sulfur and nitrogen compounds can undergo chemical reactions in the atmosphere to produce acidic compounds like sulfur dioxide, nitric acid, and nitrate particles. Acidic compounds can be transported long distances and ultimately settle back on soil and water, through precipitation as acid rain, or through dry deposition.

71% of parks experience S and N deposition at significant concern levels

Impact on Soil, Water, and Wildlife

When too much sulfur and nitrogen settle out of the atmosphere and is deposited into the soil and water, it degrades soil health and water quality causing biodiversity loss.

In soil, these pollutants decrease pH causing soil to become more acidic. Acidification can lead to the excess release of toxic elements such as aluminum and manganese. Toxic levels of these elements inhibit plant’s root growth reducing crop yields and contribute to forest decline affecting biodiversity across the food web. Acidified soils also intensify nutrient imbalances and disturb microbial communities. For instance, the spread of invasive species in national parks like Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) and Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) are exacerbated by excessive nitrogen deposition that allow invasives to outcompete native vegetation.

In water, Sulfur and Nitrogen deposition is changing water chemistry—acidifying lakes, rivers and streams. This can cause various threats to wildlife. When freshwater bodies become acidic, calcium concentrations decline and harm aquatic organisms that depend on high levels of calcium for their shell and bone formation.

In another example, stream acidification within Shenandoah National Park is an ongoing concern. If aquatic systems within the park acidify below a 4.5 pH, species like the brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) will no longer be able to reproduce. Nutrient imbalances in the water also cause disruptions higher up the food chain. For instance, increased nitrogen deposition has been linked to declines in bird populations tracking declines in aquatic food availability such as pH sensitive aquatic macroinvertebrates.

Sulfur and Nitrogen deposition pose a significant threat to the health and integrity of national parks’ ecosystems. As unveiled in the 2024 Polluted Parks report, 288 and 376 parks across the country have reached significant or unsatisfactory levels of sulfur and nitrogen deposition, respectively. This report underscores the urgent need to reduce emissions to mitigate these cascading effects. Check out the report to find out more about other air pollution categories including Hazy Skies and Unhealthy Air affecting national parks.

Reach out to Daniel Orozco, P.h.D. at dorozco@npca.org for more information.

Species impacted by Sulfur and Nitrogen deposition

Brook trout

Salvelinus fontinalis

Red spruce Picea rubens

American beech

Fagus grandifolia

Atlantic salmon

Salmo salar

Eastern bluebird

Sialia sialis

CONSERVATION PROGRAMS

CARTOGRAPHY BY AMY TIAN, NPCA. PHOTO CREDITS: American beech by treemontgomery.org, Brook trout by Jay Fleming NPS, Atlantic salmon by NOAA, Eastern bluebird by Steve Byland | iStock, red spruce by Keith Kanoti | Maine Forest Service.

Visualizing the NPS Sustainability and Climate Adaptation Project Database

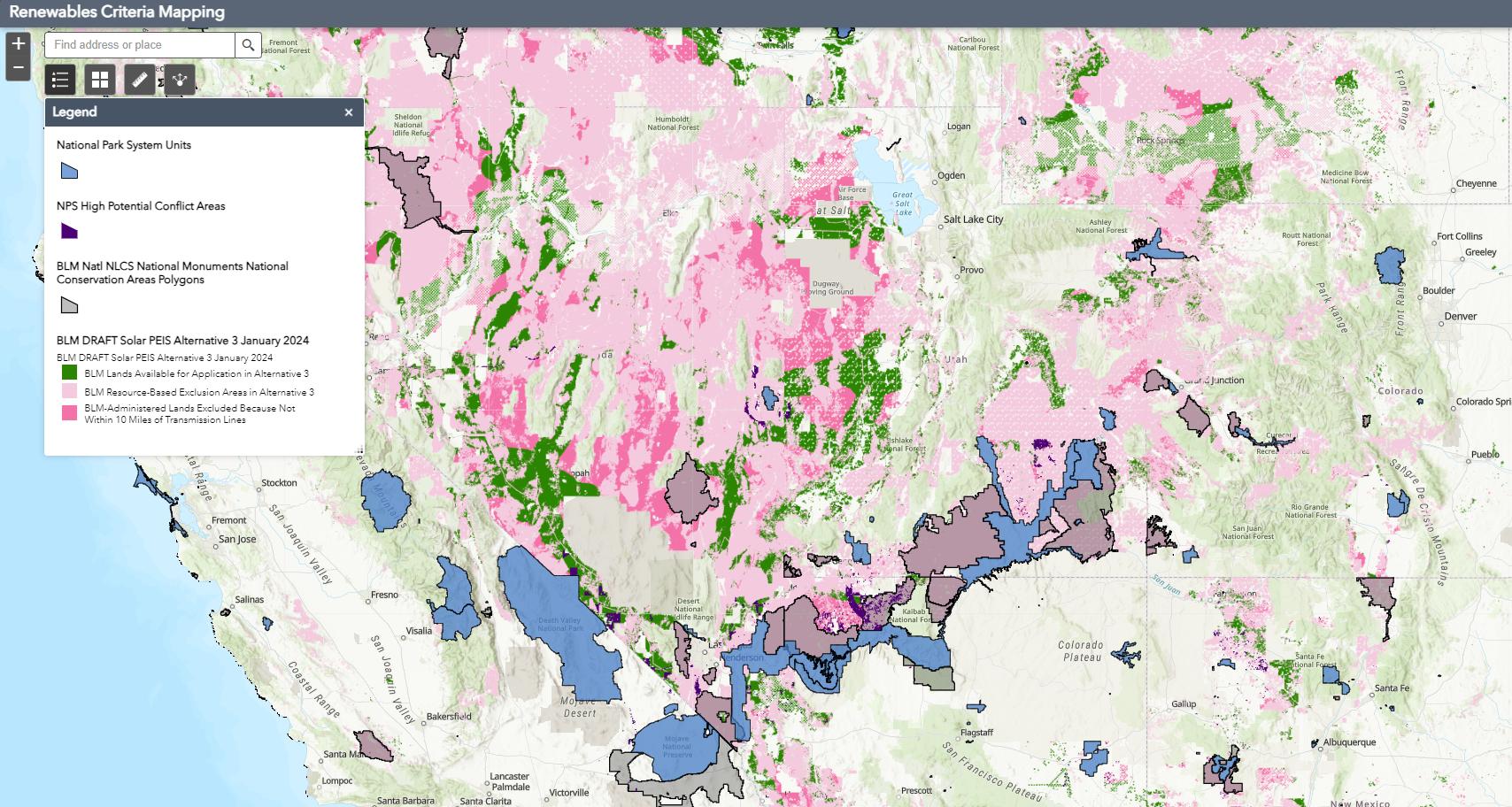

Creating an Informed Response to the Bureau of Land Management’s Solar Plan

9 NPCA

NPCA’s Sustainability Program worked with researchers at the University of Montana to create a geodatabase of all cataloged sustainability and climate change adaptation projects at each national park unit. The Park Service Climate Change Action Plan (National Park Service, 2012) outlines eight high-priority actions that the NPS is utilizing or plans to implement in the coming years to meet the challenges of climate change through adaptation. The Park Service Green Parks Plan (National Park Service, 2016) lays out a strategic plan with 10 specific goals for sustainable management of operations across parks. This geodatabase explores how these projects are distributed across goals and emphasis areas, as well as where they’ve been implemented.

Check out the NPS Sustainability and Climate Adaptation Project Database.

To learn more about the work contact Karen Hevel-Mingo at khevel-mingo@npca.org

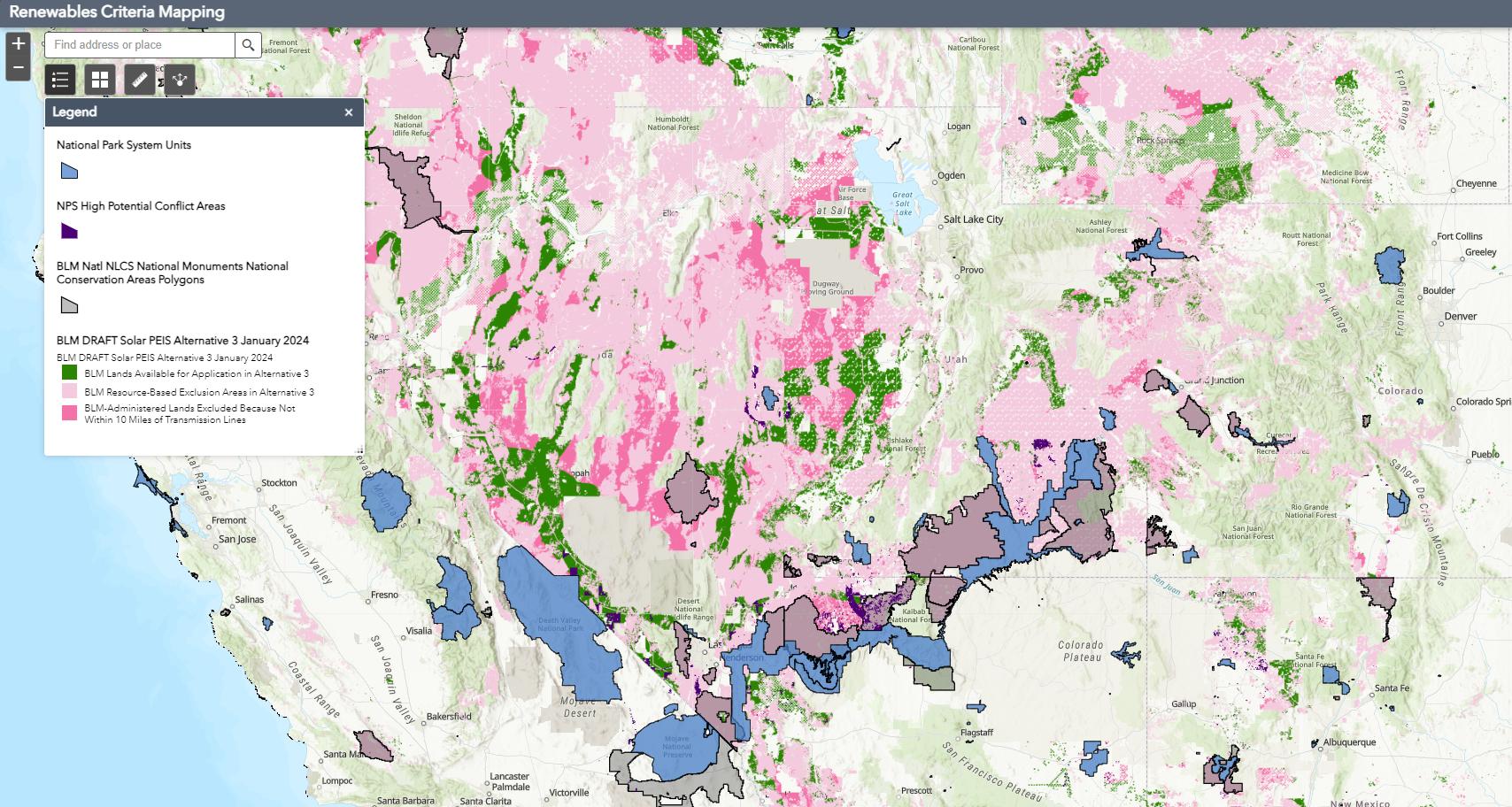

NPCA’s Energy Program is working to dilligently respond to an open comment period for the Bureau of Land Management’s 2023/2024 Draft Utility-Scale Solar Energy Development Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (Solar PEIS). The proposal highlights the Bureau of Land Management’s lands that will be made available for application for solar endergy development. The goal of the large-scale planning effort is to expedite implementation of national clean energy goals of siting 25GW of renewable energy on public lands by 2025.

With the support of Conservation Science’s geospatial resources, NPCA’s Energy Team, Regions, and Government Affairs can quickly explore the extent of the proposed open lands, proximity to parks, and any interactions with diverse park resources that extend beyond park boundaries. This work showcases how NPCA is using geospatial science to effectively scale data-driven decision making.

Reach out to Matt Kirby at mkirby@npca.org to learn more.

Impact

SCIENCE ADVOCATES at NPCA

When Science Meets Art

Featuring Amy Tian, Geospatial Science Fellow

Literature Review

Infographics

Empower Campaigns

Illustration

Communications Collabs

Cartography

Regional Collabs

Develop Geospatial Resources

Remote Sensing

Science Communication

Conservation Programs Collabs

Beautiful Science Stories

Amy is a cartographer and science communications specialist who transforms data into engaging environmental stories. As NPCA’s Geospatial Science Fellow, she uses cartography, scientific illustrations, data visualization, and infographics to communicate conservation science to empower national parks advocacy.

Database Management

Geospatial Analysis

Government Affairs Collabs

Development Collabs

Innovative Data Products

Impactful Summary Statistics

Science is essential to guiding national parks conservation at NPCA. But science is only as good as how well it is communicated. Amy believes that by making information and maps beautiful, we can help build trust, educate, and inspire action for parks.

In her first year, she has brought expertly applied, innovative ideas to NPCA’s Conservation Science team. Amy hit the ground running by giving Science News a complete overhaul with beautiful cartography, infographics, scientific illustration, and pitch-perfect stories. Each expertly designed feature not only takes storytelling prowess, it takes ample collaboration — Amy brings a professional kindness and personability to all of her interactions with colleagues.

Skills

Cartographic Maps for Lawmakers

Amy is a geospatial new opportunities and analysis. She of maps and infographics campaign work. NPCA’s geospatial mapping style guide, for how the Science to support campaigns.

Amy is a builder. by making it beautiful, brilliant attitude

11 NPCA

geospatial data whiz and continues to spark opportunities for data management, visualization, She has helped colleagues create dozens infographics to empower regional and Her long-term goals aim to bulk out geospatial data hub, developing NPCA’s first guide, and creating a proof-of-concept Science team can leverage remote sensing campaigns.

builder. She advocates for science at NPCA beautiful, bringing her curiosity and to everything she does.

A WATERSHED MOMENT FOR THE

CHESAPEAKE

MID-ATLANTIC REGIONAL OFFICE

A blue crab lays on the sandy shores of the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. The blue crab is an iconic symbol of the Chesapeake. They drive regional culture and serve an important role in the food web of the Bay. Photo by Patrick Wolf.

Written by ED STIERLI

NPCA Mid-Atlantic Senior Regional Director

Designed by AMY TIAN NPCA Geospatial Science Fellow

The largest estuary in North America,

the Chesapeake Bay and its watershed spans 64,000 square miles across six states and the District of Columbia. The Bay is recognized as one of America’s Great Waters and one of the most biologically productive estuaries in the world.

With its ecological and cultural significance, the Chesapeake has become a symbol of the delicate balance between human activity and nature. This

expansive estuary, home to over 3,600 species, is not just a body of water — it’s a thriving ecosystem that has sustained Native peoples for centuries and played a pivotal role in American history.

The Chesapeake Bay is already home to more than 50 national park sites that tell the story of America’s diverse history. Chief Powhatan and the Algonquian people established their Tribal headquarters,

15 NPCA

Werowocomoco, along the York River. Captain John Smith voyaged throughout the Bay’s tributaries and the Jamestown colony settled on the banks of the James River. The region experienced major battles during the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and the Civil War. In 1619, the first Africans were traded into slavery on this continent in what is now present-day Virginia and in 1849, Harriet Tubman journeyed across the region to escape to freedom.

Over a span of just a few centuries, the majority of Native Americans found themselves displaced from their ancestral territories. The Bay watershed developed into cities and farms, and natural filters which served as the vital organs of the region’s ecosystem hovered on the edge of collapse.

A large group of Brown Pelican fledglings on the coast of the Chesapeake Bay. The Bay is a key part of the Atlantic Flyway and has over 1 million migratory birds every winter.

SPRING 2024 16

Photo by David Kay | Dreamstime.com.

Oysters have tremendous ecological value in the Bay. They purify the water of pollutants as they filter for their food. Historically, oysters could once filter the entire water volume of the Bay in a week. With the remaining oysters today, it would take more than a year. Photo by Daryl Ariawan.

“We’re at a critical juncture. the choices we make today will determine the fate of the Chesapeake Bay for generations to come...”

Renee Reber, NPCA Climate & Clean Water Program Manager

Beginning of the conservation movement

FOR A GENERATION, ENVIRONMENTALISTS HAVE BEEN TIRELESSLY working to safeguard the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. This conservation movement has evolved into a powerful force, fueled by innovative science and collaborative partnerships. These began during the 20th century with the establishment of new national parks, such as Shenandoah National Park, and many wildlife refuges and state parks across the watershed.

Air and water pollution from land-based activities degrade water quality and contribute to growing dead zones, depleting aquatic life such as blue crabs and oysters. Such pollution threats include stormwater runoff containing fertilizer, chemicals, and sediments; municipal wastewater and industrial wastes; and airborne nitrogen and toxic mercury from power plants and motor vehicles. Additionally, over harvesting and disease have reduced oyster populations that helped filter pollutants from water.

Renee Reber, NPCA Climate & Clean Water Program Manager and stormwater expert, reflects on the need for urgent action, “We’re at a critical juncture. The choices we make today will determine the fate of the Chesapeake Bay for generations to come, and it’s critical that we don’t lose momentum, especially in the face of climate change and development pressures.”

Over the last four decades governmental and nongovernmental groups have been working to restore the Chesapeake watershed. Notable successes include the reduction of point source pollution and the decreasing trends in nitrogen and phosphorus pollution levels. However, much work remains to restore the bay to the highly productive ecosystem from historical times.

Threats to the Chesapeake

Power plants and motor contribute to airborne such as nitrogen and pollutants fall back onto surface and waterways, to algal blooms, clouding and creating dead zones. Hal Bergman.

AIR POLLUTION

TOP LEFT

19 NPCA

The Chesapeake Bay faces numerous threats due to human activities. The following are a few examples of threats:

motor vehicles airborne pollutants mercury. These onto the earth’s waterways, contributing clouding the water, zones. Photo by POLLUTION

Dead zones are aquatic areas that are depleted of oxygen. Due to dead zones, underwater grasses, crabs, fish, and other marine life can devastate biodiversity and food chains. Photo by Aj_OP | iStock. com.

AGRICULTURE RUNOFF

Agriculture is essential to people but is also the largest source of nutrient and sediment pollution entering the Chesapeake. Overtilling, fertilizers, and pesticides contribute excess nutrients and chemical imbalances in the water.

STORMWATER RUNOFF

When rain falls on parking lots, roads, roofs, and driveways, it can wash harmful pollutants like fertilizer, pet waste, chemical contaminants, and litter into Bay’s waterways. Photo by Iri-s | iStock.com.

OVERHARVESTING

Overharvesting and disease have reduced oyster populations that helped filter pollutants from the water. Photo by wakila | iStock.com.

DEAD ZONES

TOP RIGHT

Photo by fotokostic | iStock.com.

BOTTOM LEFT

BOTTOM MIDDLE

SPRING 2024 20

BOTTOM RIGHT

Cutting-edge innovation

THE CHESAPEAKE WAS THE FIRST ESTUARY IN THE nation to be targeted for integrated watershed and ecosystem restoration. In 1998, the Chesapeake Bay was listed as impaired under the Clean Water Act for failure to meet water quality standards, specifically for nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment. Despite efforts to clean the Bay, it still does not meet the standards.

The Clean Water Act requires each state to develop Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDL) for their impaired waterways. The Bay states agreed that, in this case, a “state by state” approach would not be as effective as a regional approach and invited the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to develop a bay-wide TMDL.

Twelve years after being listed as impaired, in December 2010, EPA issued a bay-wide TMDL, which identified the maximum aggregate of pollutants possible for achieving water quality standards. The pollutant aggregates are divided among states, which give states the flexibility to decide which actions to take to reduce pollutants in the bay.

The health of the Bay is measured in part by the population of indicator species, such as oysters, blue crabs, and striped bass. Data on habitat health is also evaluated, including underwater grasses, forest buffers, wetlands, and forests.

Land conservation and restoration have had tangible and critical benefits for the Bay restoration and conservation movement — filtering water, recharging aquifers, sequestering carbon, absorbing nitrogen, in addition to wildlife habitat and access for recreation.

The Chesapeake Conservancy’s Conservation Innovation Center (CIC), established in 2013, has been on the forefront of data-driven strategies to inform land conservation. This includes precision conservation, where CIC analysts apply advanced spatial analysis techniques to prioritize conservation best management practices to ensure maximized ecosystem services and have the greatest impact.

Joel Dunn, President and CEO of the Chesapeake Conservancy, has led efforts to unite conservationists in the region around data-driven goals, such as launching the Chesapeake Conservation Partnership. “The CIC is empowering others to work smarter, not harder, through the latest technology. Just as the use of technology changed the corporate world to make it more efficient, technology is changing the conservation movement.”

Data and maps produced by the center have helped prioritize lands for conservation and restoration opportunities, as well as inform optimal solar siting or vacant lots in the City of Baltimore that can be transformed into usable green space.

A new national park unit

THERE ARE MANY NATIONAL PARK UNITS IN THE Chesapeake Bay watershed, and for decades NPCA’s Mid-Atlantic Regional Office has advocated for policies to protect water quality, reduce air pollution, and expand public access for recreation. This included helping to lead efforts to establish new national parks, such as Fort Monroe National Monument and Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park.

But none are dedicated solely to telling the powerful and unique story of the Bay, which is why NPCA and the Chesapeake Conservancy are leading efforts to establish the Chesapeake National Recreation Area (CNRA).

Pamela Goddard, Mid-Atlantic Senior Program Director, leads NPCA’s efforts to establish new parks, including Fort Monroe, recognizes that “the Chesapeake Bay watershed is celebrated for its iconic natural beauty, historic significance and diverse outdoor recreational opportunities. Creating a new national park in the Chesapeake will increase public access while sharing with park visitors the many unique sites and stories the region has to offer.“

Lawmakers have considered a national park unit for

the Bay since President Ronald Reagan declared the Chesapeake Bay a national priority in his 1984 State of the Union address, and the opportunity is finally here.

In July 2023, Senator Van Hollen and Representative Sarbanes of Maryland, along with a bipartisan congressional delegation, introduced the Chesapeake National Recreation Act. This legislation will designate a unified Chesapeake National Recreation Area as part of the National Park System, designating a collection of new and existing parks and public lands along the Bay as the new CNRA. Four key sites included are Whitehall, Burtis House, Thomas Point Shoal Lighthouse, and Fort Monroe North Beach (descriptions on next page 23).

“Just as the use of technology changed the corporate world to make it more efficient, technology is changing the conservation movement.”

Joel Dunn, President & CEO of Chesapeake Conservancy

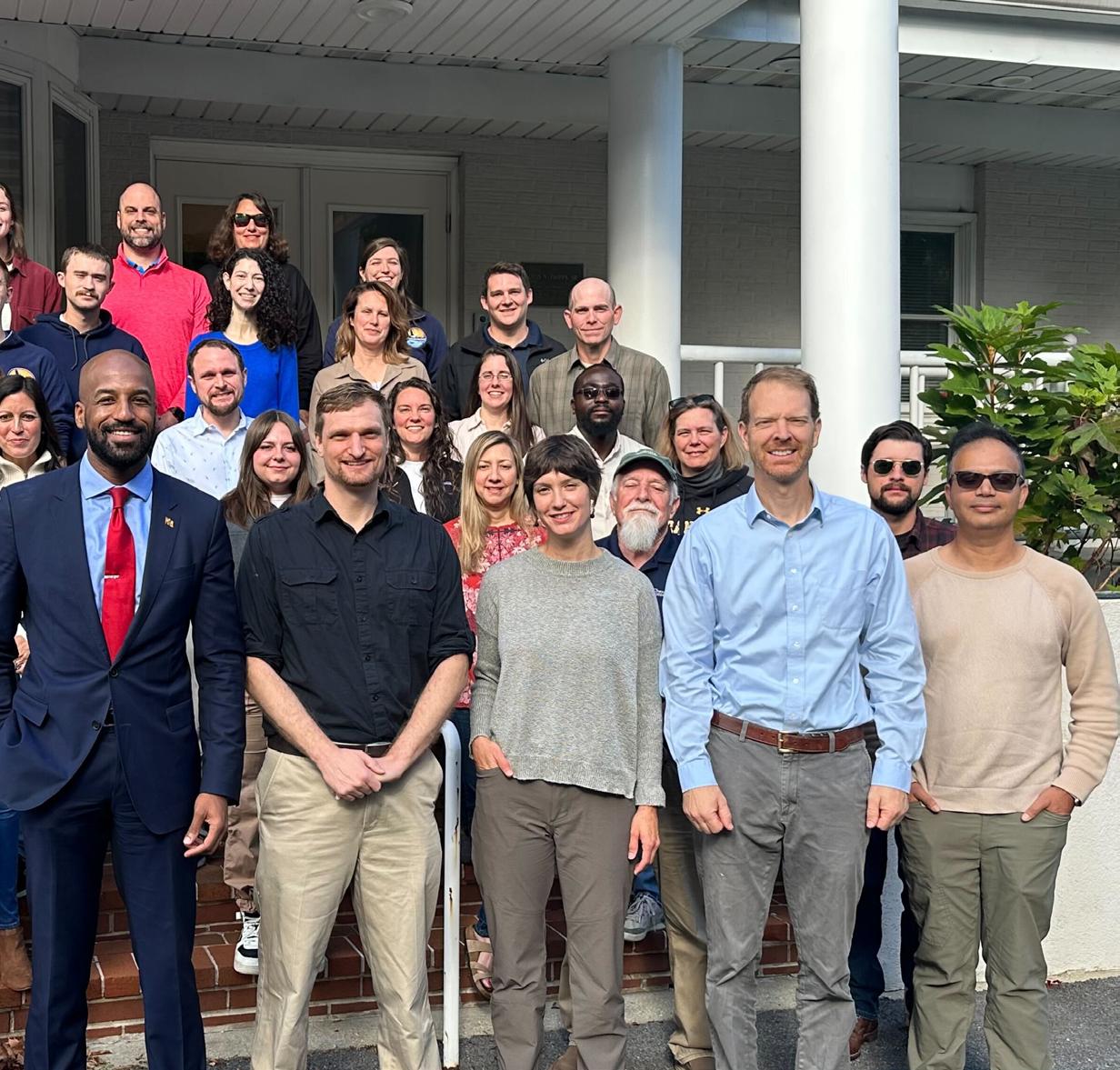

NPCA staff and volunteers visiting Thomas Shoal Point Lighthouse, a new park that would be in the CNRA.

NPCA MIDATLANTIC TEAM

LEFT

The CIC is a scientific powerhouse for the Chesapeake Bay, creating essential data to prioritize conservation management.

CONSERVATION INNOVATION CENTER

RIGHT

SPRING 2024 22

“Creating a new national park in the Chesapeake will increase public access while sharing with park visitors the many unique sites and stories the region has to offer.”

Pamela Goddard, NPCA Mid-Atlantic Senior Program Director

25 NPCA

THE CNRA WOULD ENABLE THE PARK SERVICE TO elevate the stories that too often go untold, including the story of Indigenous peoples who have inhabited the Chesapeake for more than 12,000 years, but whose land was taken from them, often violently. A new national park unit would bring opportunities to share ancestral connections to the land and water.

Places that highlight the Bay across Maryland and Virginia, such as state and local parks and wildlife refuges, could become part of the CNRA and benefit from the resources of the National Park Service to help improve the visitor experience, improve public access to the Bay, protect the natural environment, and advance landscape-scale conservation.

NPCA works with partners to improve equitable access to the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, such as the Anacostia River. These photos are from a partner paddle event NPCA co-sponsored at Anacostia Park. Photos by Annie Riker | NPCA.

As bipartisan support gathers for the CNRA, there’s a sense of anticipation for the historic moment that lies ahead. Passage of the Chesapeake National Recreation Act would be a culminating achievement for the Bay’s restoration efforts — a testament to the power of collaboration, innovation, and a shared commitment to safeguarding the Chesapeake Bay for generations to come.

SPRING 2024 26

Forests Vital

Forests Vital

Protecting old-growth Forests in and around Parks

CONSERVATION PROGRAMS

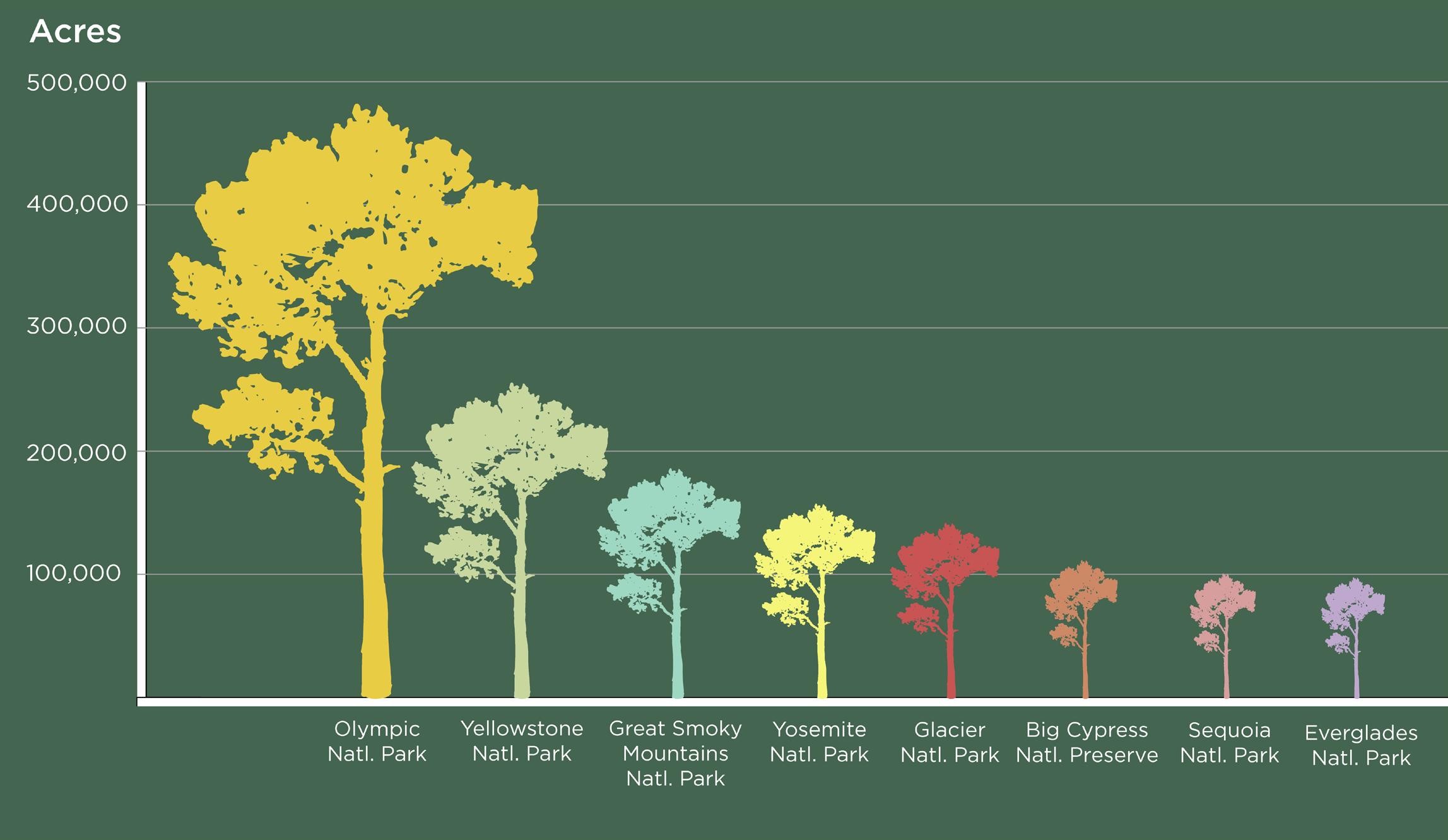

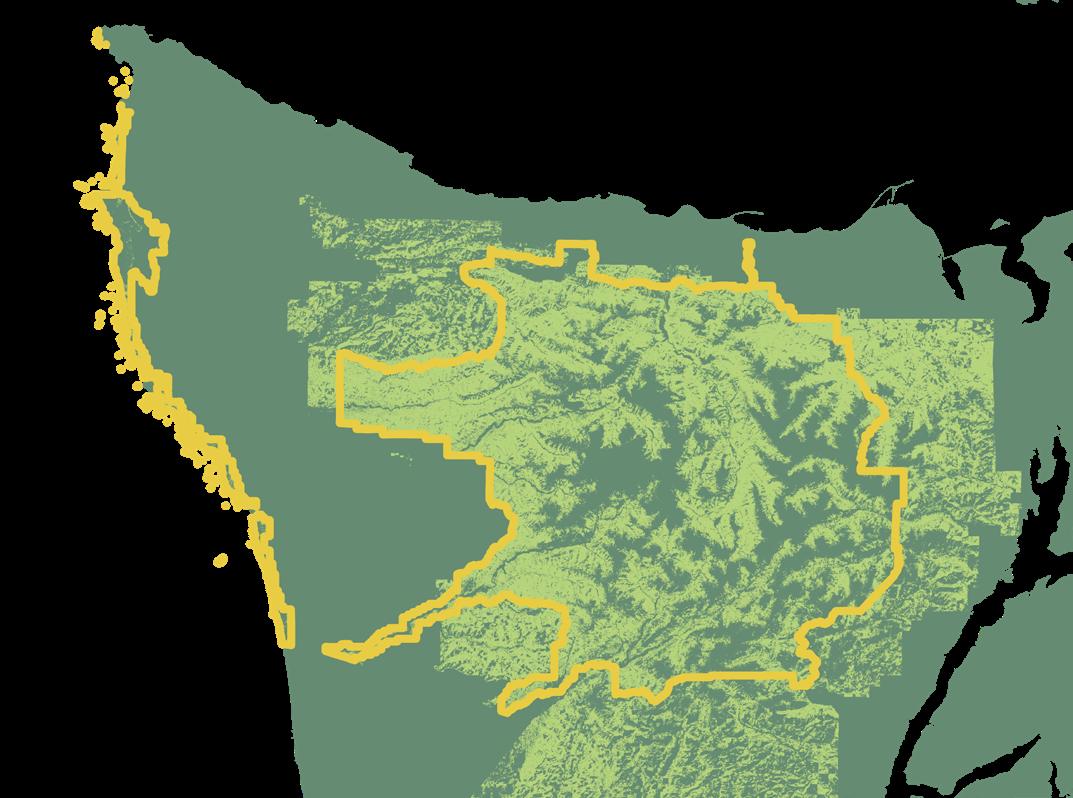

Olympic National Park is the National Park Service unit with the most mature and oldgrowth forest in the lower 48.

Photo by Nik Moy | NPCA.

Written by MATT KIRBY

NPCA Senior Director, Energy and Landscape Conservation

and NIK MOY

NPCA Senior Program Manager, Conservation Science

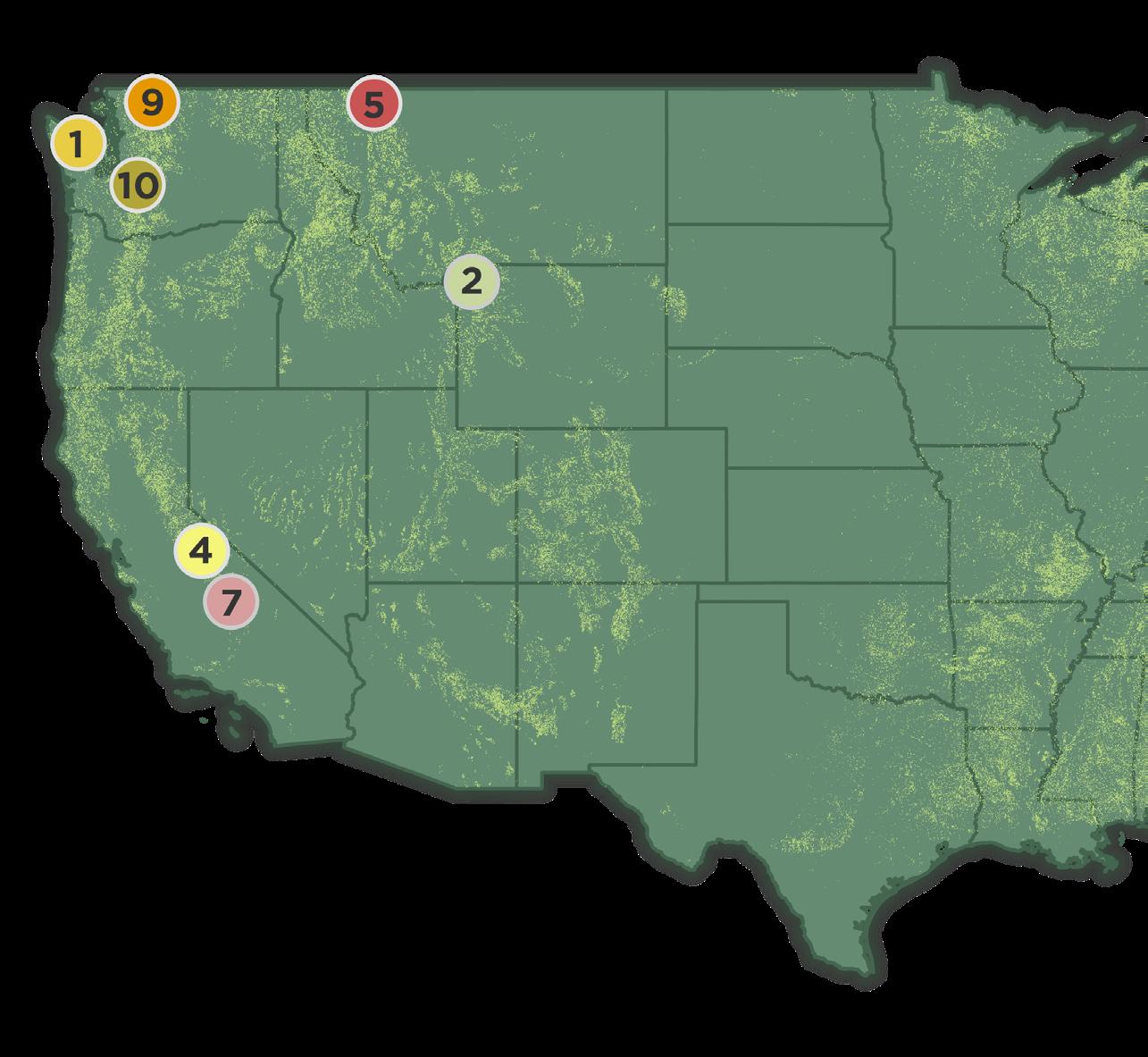

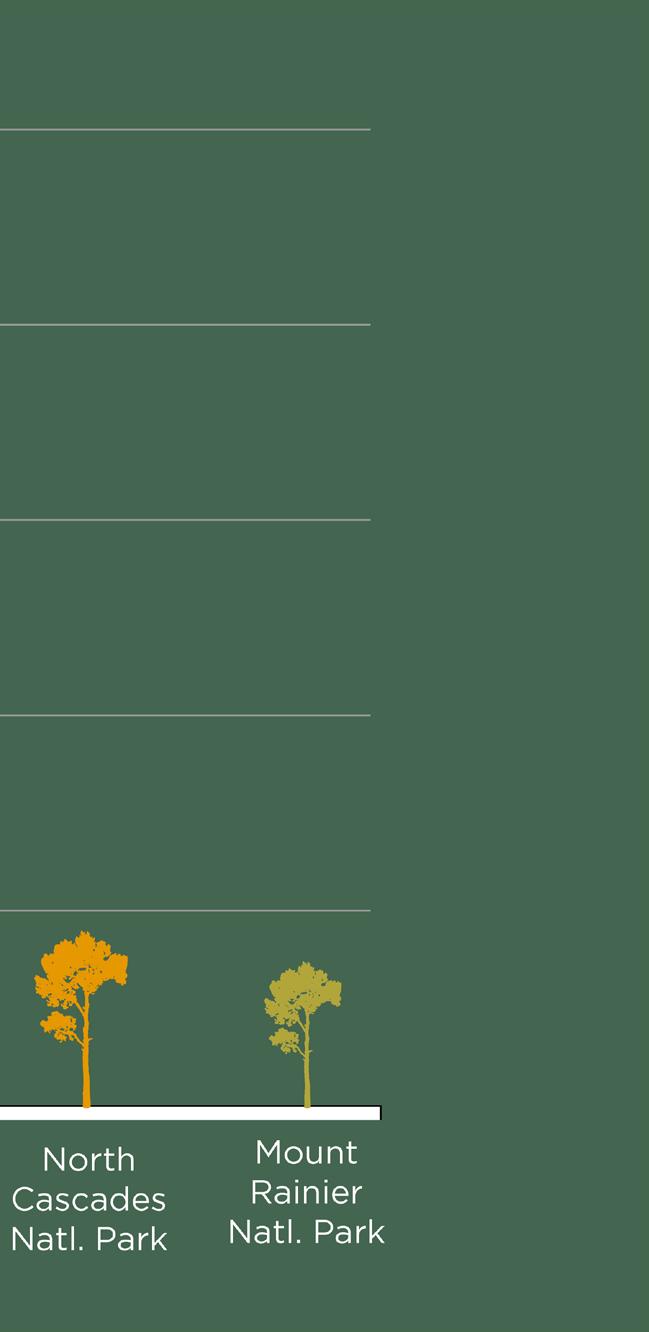

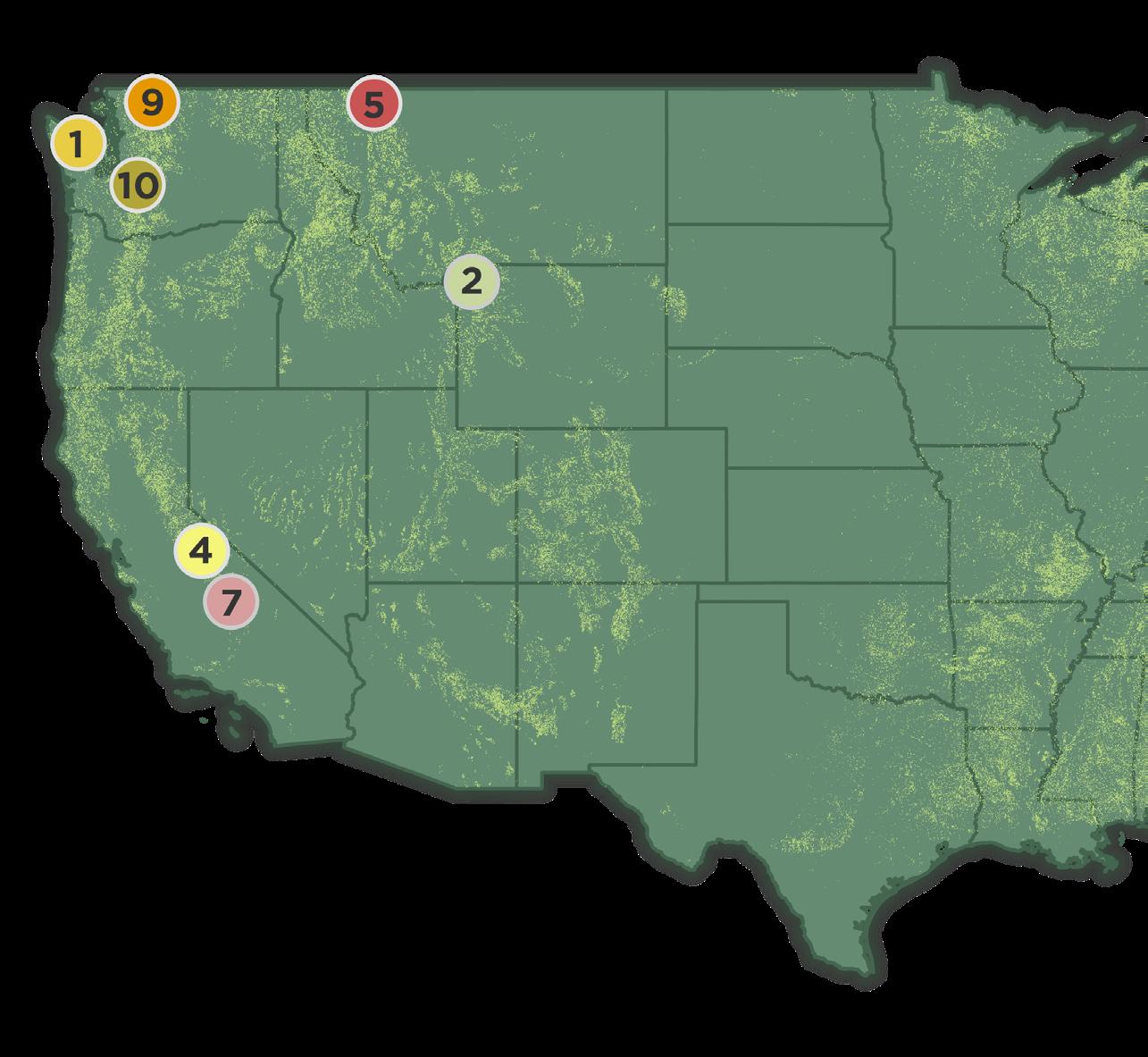

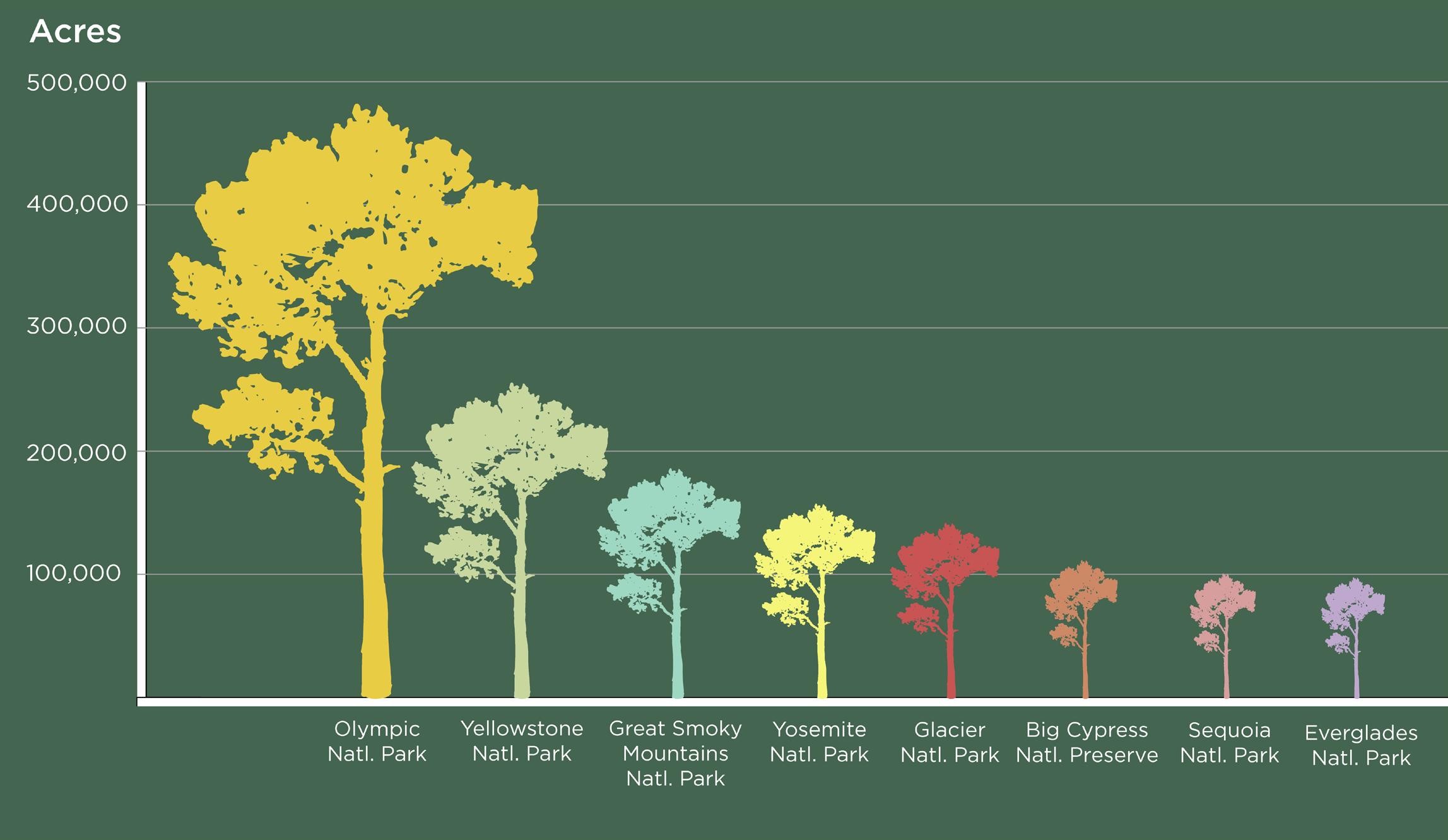

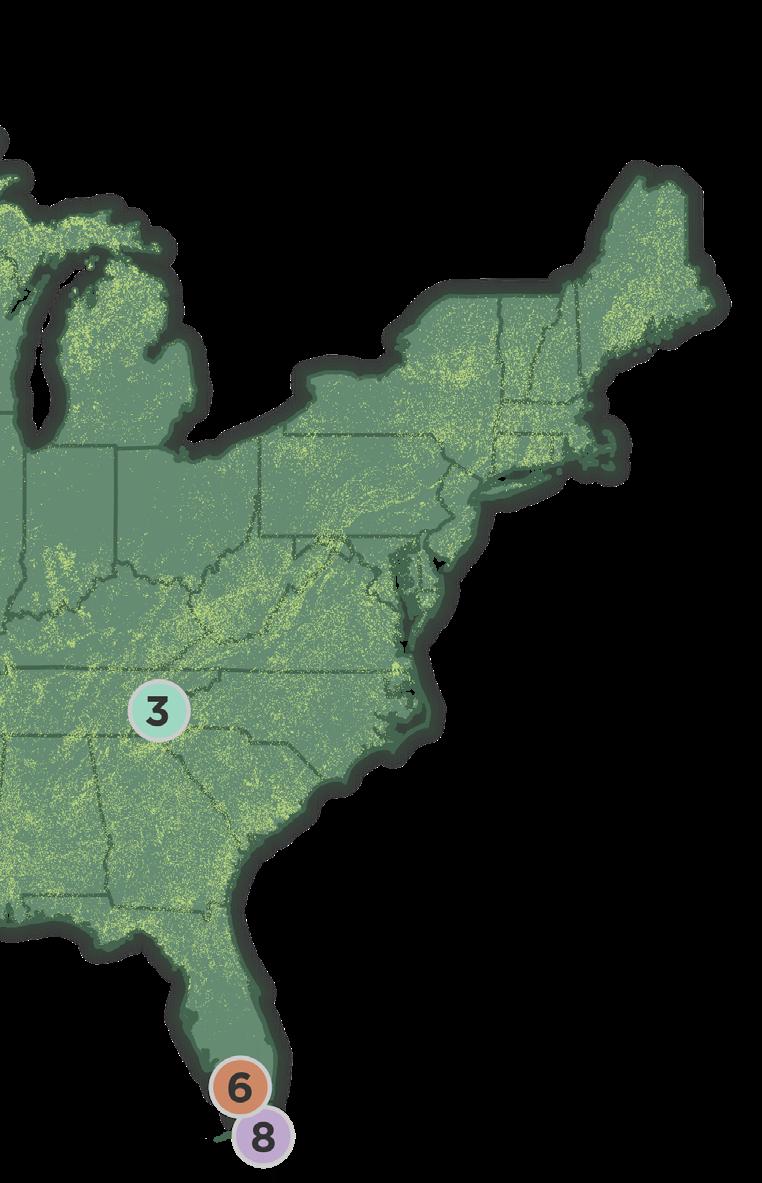

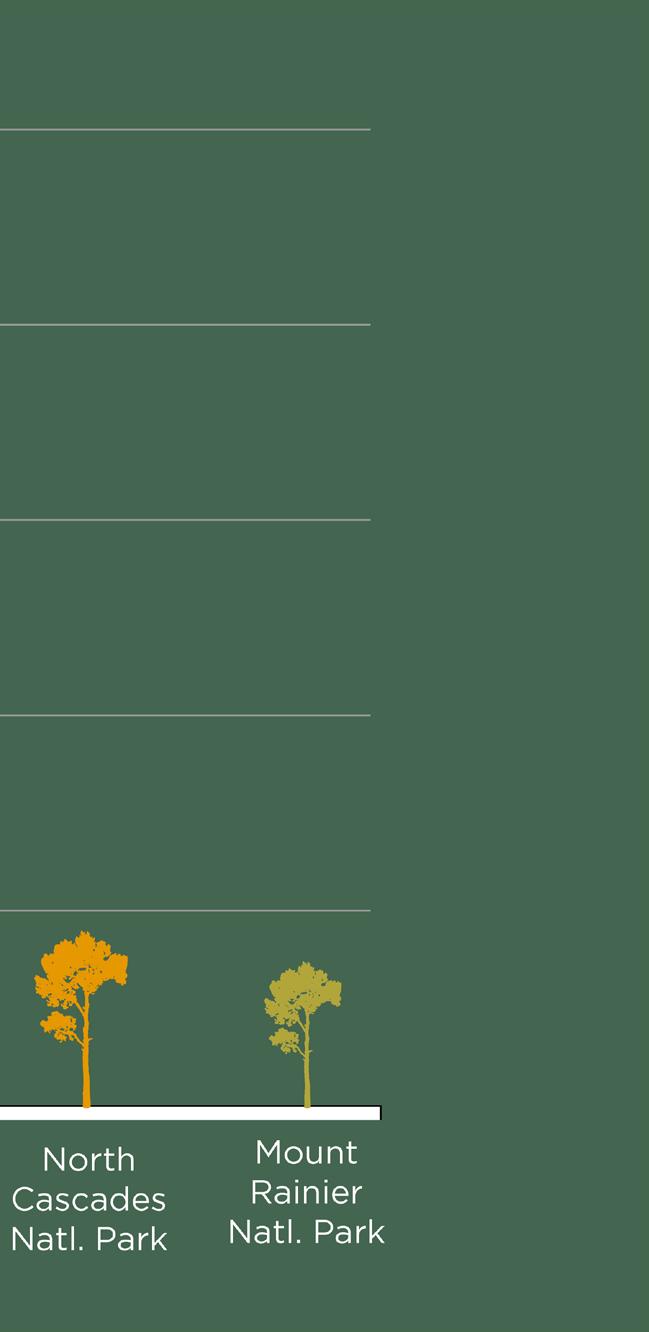

TOP 10 NATIONAL PARKS

with mature and old-growth forest in the Lower 48

Mature & old-growth forest in park and adjacent USFS land

Olympic National Park

Olympic National Park comes out on top with 480,977 acres of MOG in its borders and 345,087 acres on USFS land within 30 miles of the park.

DATA ANALYSIS BY NIK MOY, NPCA. CARTOGRAPHY AND INFOGRAPHIC PRODUCED BY AMY TIAN, NPCA. SOURCES: Mature and Old Growth Model presented in: D.A. DellaSala et al. Mature and old-growth forests contribute to large-scale conservation targets in the conterminous United States. Front. For. Glob. Change. 2022.

Old-growth forests are ancient. they protect us and biodiversity, but face many threats.

IN FEBRUARY, WE SUBMITTED COMMENTS TO THE U.S. FOREST SERVICE (USFS) on behalf of NPCA’s 1.7 million members and supporters about the agency’s notice of intent to amend all existing forest plans to better conserve and recruit old-growth forest conditions. These mature and old-growth forests play a critical and often overlooked role in maintaining the health and vitality of our national parks.

Seventy-six National Park Service units share partial boundaries with USFS land — the symbiotic relationship between these ecosystems is undeniable. The intricate web of wildlife, watersheds, and recreational resources zigzag and stretch across jurisdictional boundaries, emphasizing the need for collaborative and holistic management approaches.

It’s heartening to witness the Forest Service’s proactive stance in adapting policies to safeguard our national forests and grasslands in the face of climate change. The attention given to mature and old-growth forests in storing carbon, preserving biodiversity, improving aquatic conditions, mitigating wildfire risks, and enhancing climate resilience is not only commendable but essential for the well-being of our natural and cultural treasures. Notably, the proposed amendment to all forest plans would take the historic first step of ending all new commercial logging of old-growth forests.

While acknowledging the historic step taken to protect these forests from commercial logging, we also urged the inclusion of stronger protections. Specifically, the Forest Service should cease cutting old-growth trees everywhere, even cutting in old-growth stands where fire is infrequent, and especially in wet forests. Additionally, there should be no commercial exchange of old-growth trees allowed under any circumstance.

NPCA’s Landscape Team and Conservation Science Team analyzed a dataset out of the Unviersity of California, Berkeley that used modeled satellite imagery to determine the footprint of mature and old-growth (MOG) forest across the contiguous U.S. The study found that federal lands combined represented the greatest (35%) concentrations of mature and old-growth (MOG) forests, 92% of which is on national forest lands with 9% on Bureau of Land Management and 3% on national park lands (totals do not sum to 100% due to minor mapping errors in the datasets, and only includes the contiguous U.S.). This accounts for nearly 92 million acres (about the area of California) of MOG forests that persist on USFS land and over 3 million acres in Park Service units.

Our analysis shows that of these acres on USFS land, a staggering 23.7 million acres persist within 30 miles of Park Service units. The scale and scope of these forests across geographies are a testament to their vital importance in preserving larger ecosystems. This plan amendment is a monumental step toward safeguarding old-growth, and we look forward to working with the Forest Service to strengthen and extend these protections to mature forests.

WINTER 2023 24

SPRING 2024 30

Land and Seascape Conservation

Data-Driven Advocacy Beyond Park Boundaries

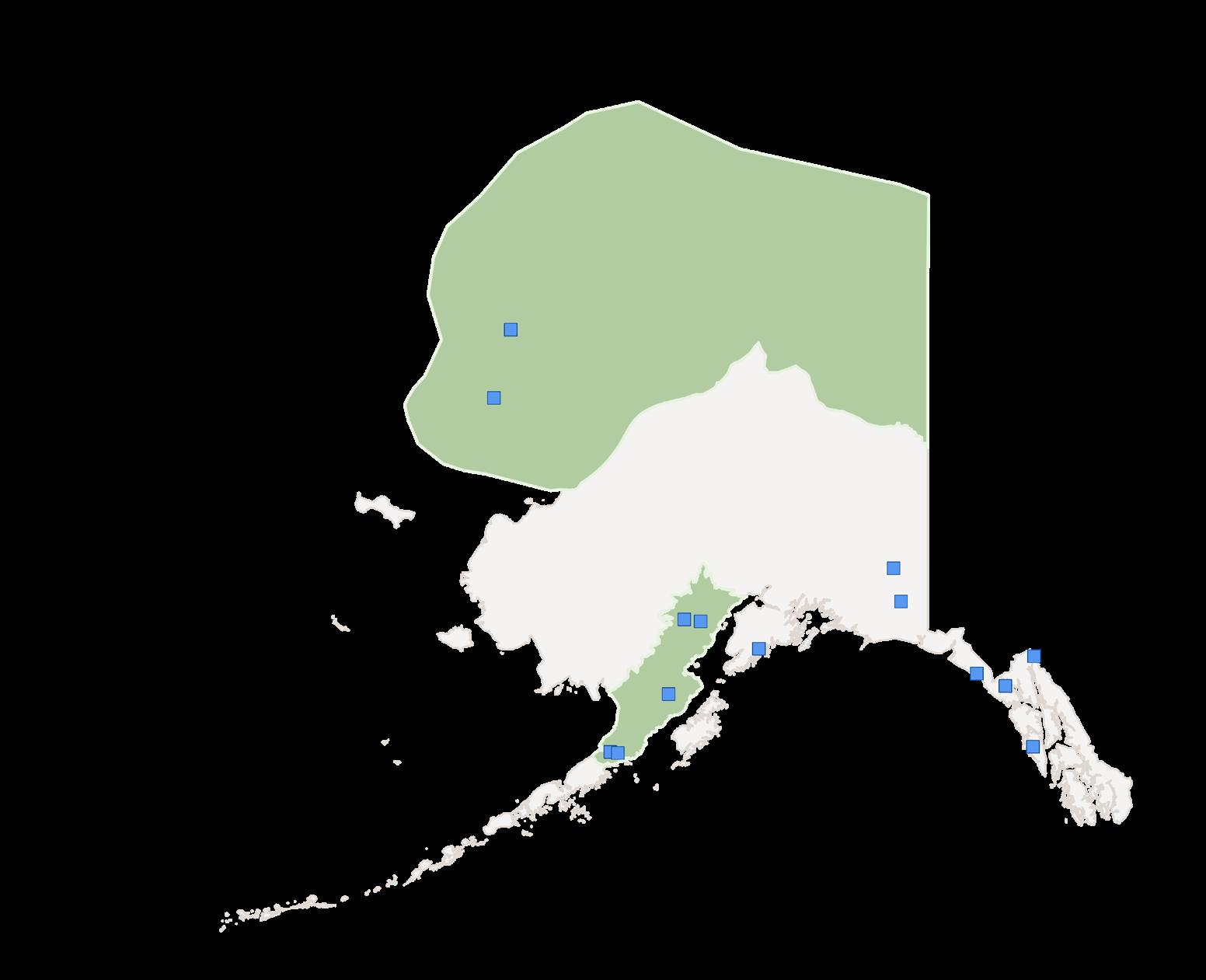

Conservation Programs is taking an information-centered approach to empowering beyond-park-boundary conservation across the organization. The result is a growing foundation of information that land and seascape initiatives at NPCA can build on.

We know that parks and their landscapes are equally reliant on eachother for healthy air, water, wildlife, and communities. Conservation Programs is asking the questions:

Where are the areas that represent the highest concentration of NPCA’s land and seascape conservation priorities and threats?

Who are the biggest conservation allies on the landscape?

Why is beyond-boundary thinking crucial to protecting our parks?

20 Focal Landscapes

88 Coastal Parks

Land and Seascape Toolkit Impact

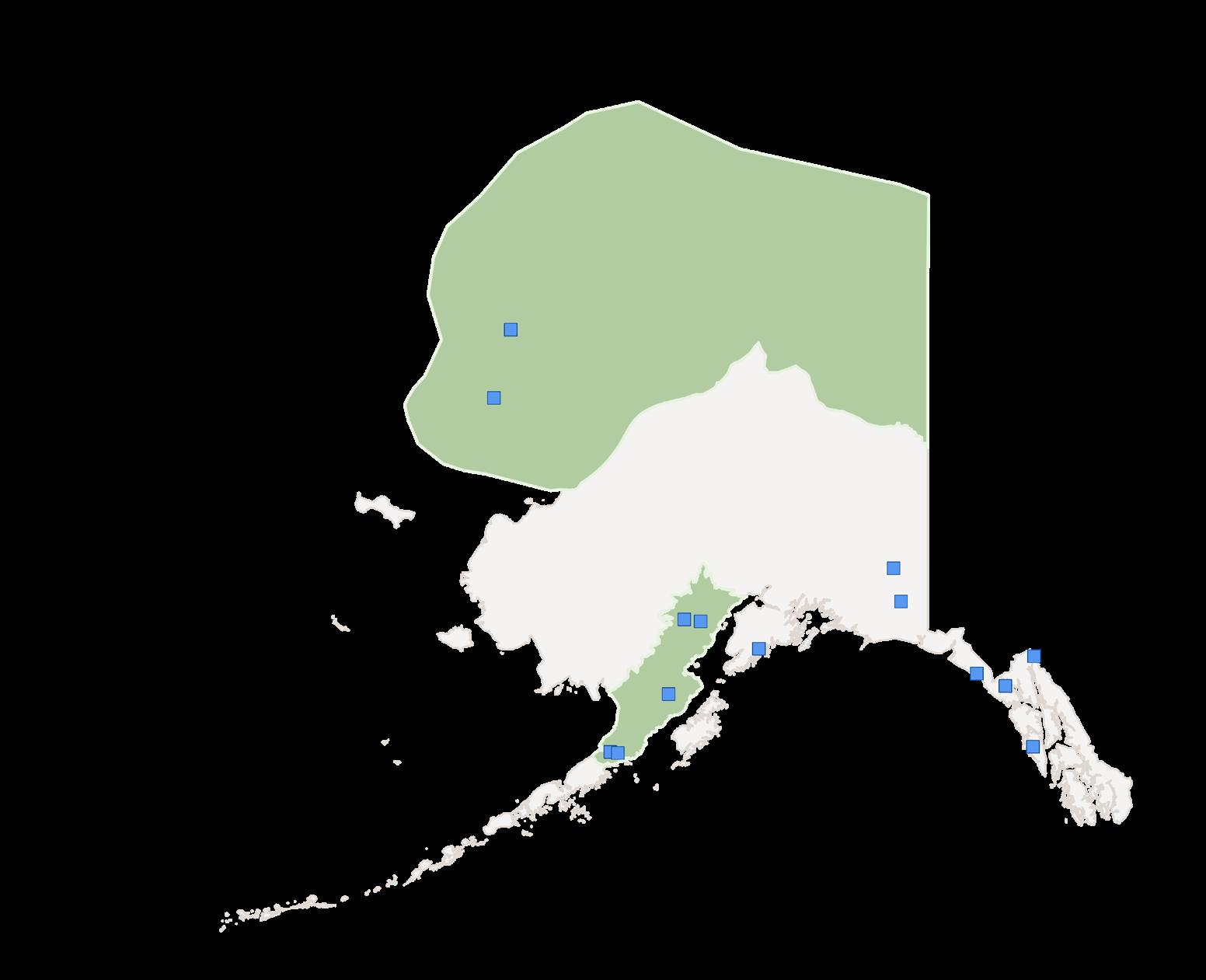

Conservation Programs has been building an information toolkit to support our 20 focal landscapes (shown in light green) and 88 coastal parks (shown as blue points), the icons on this map correspond with the status of the ongoing assessments.

North Cascades

Rim of the Valley

Arctic Landscape

Bear Coast

Geospatial Data Deep Dives

Facilitated by Nik Moy (nmoy@npca.org) and Conservation Science team in collaboration with NatureServe.

The team has completed national conservation value mapping of biodiversity, climate flow and climate resilience values. Additionally we have completed deep-dives for six landscapes, and have three more deep-dives underway with NatureServe.

First round of geospatial data deep dives completed.

Data deep dives currently underway

National Landscape

Facilitated by Matt Kirby (mkirby@npca.org) Landscape Team.

This team holds quarterly meetings support NPCA’s National Policy conservation

Priya Nanjappa represents NPCA Public Lands Workgroup for for All Coalition.

Newly added focal conversations and data

• Chesapeake Bay

• Joshua Tree and

31 NPCA

Crown of the Continent Ecosystem

Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

Dinosaur

The Lands Between Grand Canyon Landscape

Avi Kwa Ame

Joshua Tree & Chuckwalla

Calumet

Chesapeake Bay Watershed

Southern Appalachian

Alabama River Systems

Georgia River Systems

Maine 100 Mile Wilderness

Greater Everglades

Delaware River Watershed

Landscape Policy Support (mkirby@npca.org) and the meetings to share and Policy work around landscape

NPCA as the Co-Lead for the the America the Beautiful

focal landscapes with inital data gathering underway:

Watershed

Chuckwalla Landscape

Qualitative Landscape Assessments

Facilitated by Bart Melton (bmelton@npca.org) and Wildlife Team in collaboration with Washburn Consulting.

The team collected foundational information about the landscape’s human network in three landscapes with two more assessments underway with Washburn Consulting.

First assessments complete

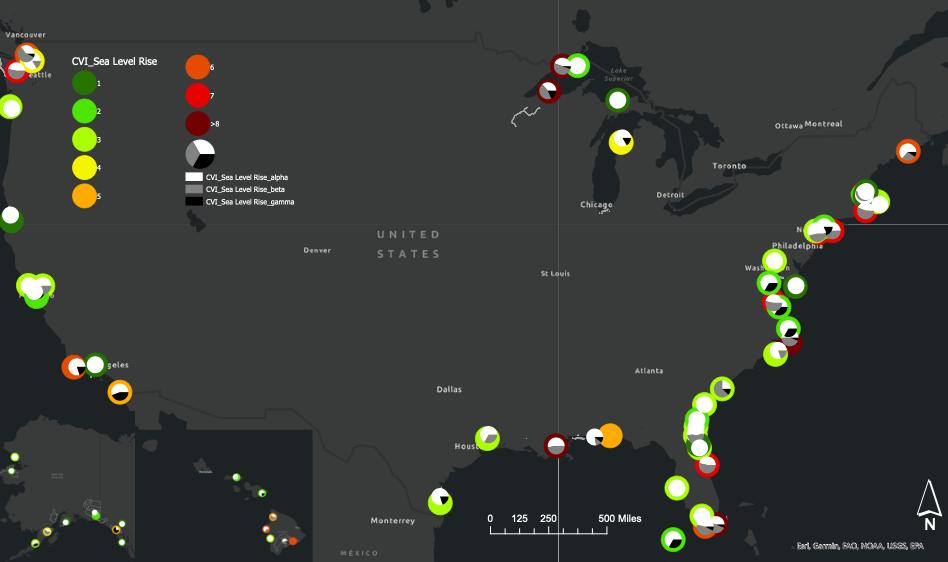

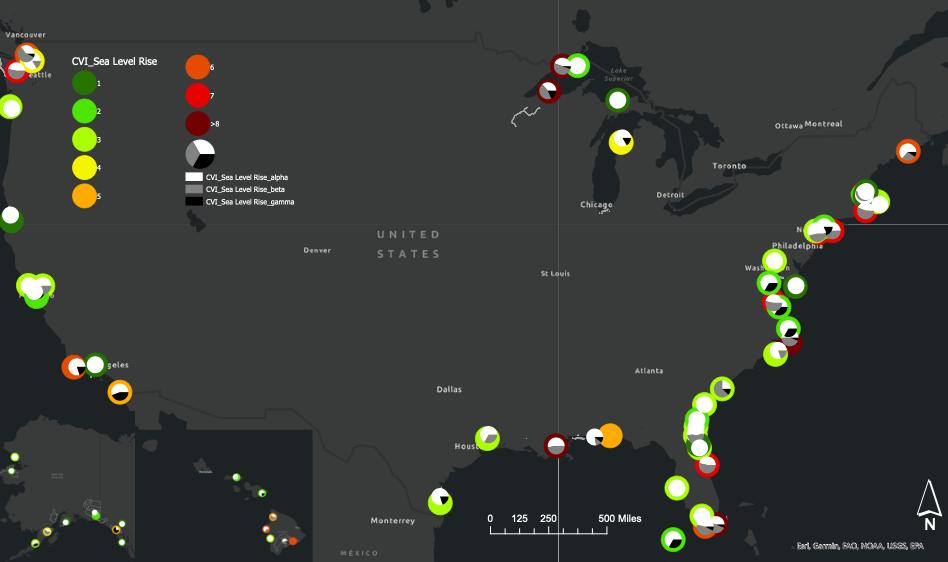

88 Coastal Parks

Facilited by Sarah Barmeyer (sbarmeyer@npca. org) and Water Team in collaboration with Applied Ocean Sciences.

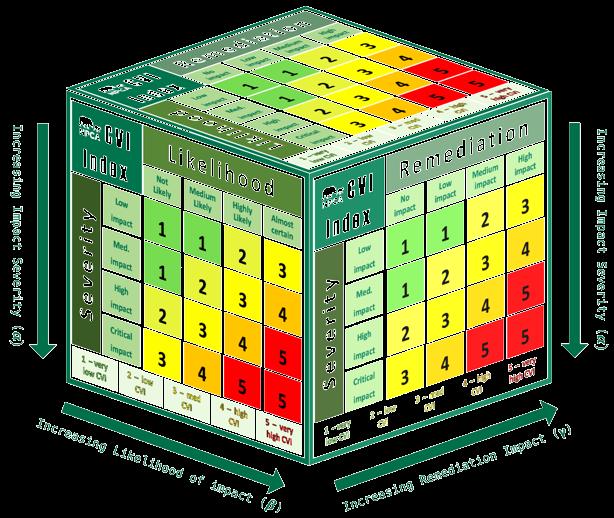

The team collected a large repository of data on conservation values and threats to these coastal parks and their surrounding seascapes into an easy to use mapping viewer. From there Conservation Value Indices (CVI) were developed to assess the parks.

The CVI’s combine dozen of datasets into indices assessing the values threats and opportunities of four topic areas:

• Sea-level rise

• Blue-carbon ecosystems

• Coastal erosion

• Marine Protected Areas

LAND AND SEASCAPE CONSERVATION

NPCA has added the proposed Joshua Tree Expansion Monument and Chuckwalla National Monument, as well as the Chesapeake Bay Watershed to our list of focal park landscapes. Photo: Joshua Tree NP | Nik Moy, NPCA.

JOSHUA TREE & CHUCKWALLA LANDSCAPE

NPCA has added the proposed Joshua Tree Expansion Monument and Chuckwalla National Monument, as well as the Chesapeake Bay Watershed to our list of focal park landscapes. Photo: Joshua Tree NP | Nik Moy, NPCA.

JOSHUA TREE & CHUCKWALLA LANDSCAPE

Data-Driven, Coastal Park Conservation

CAPE HATTERAS

Conservation Priorities for Coastal Resilience

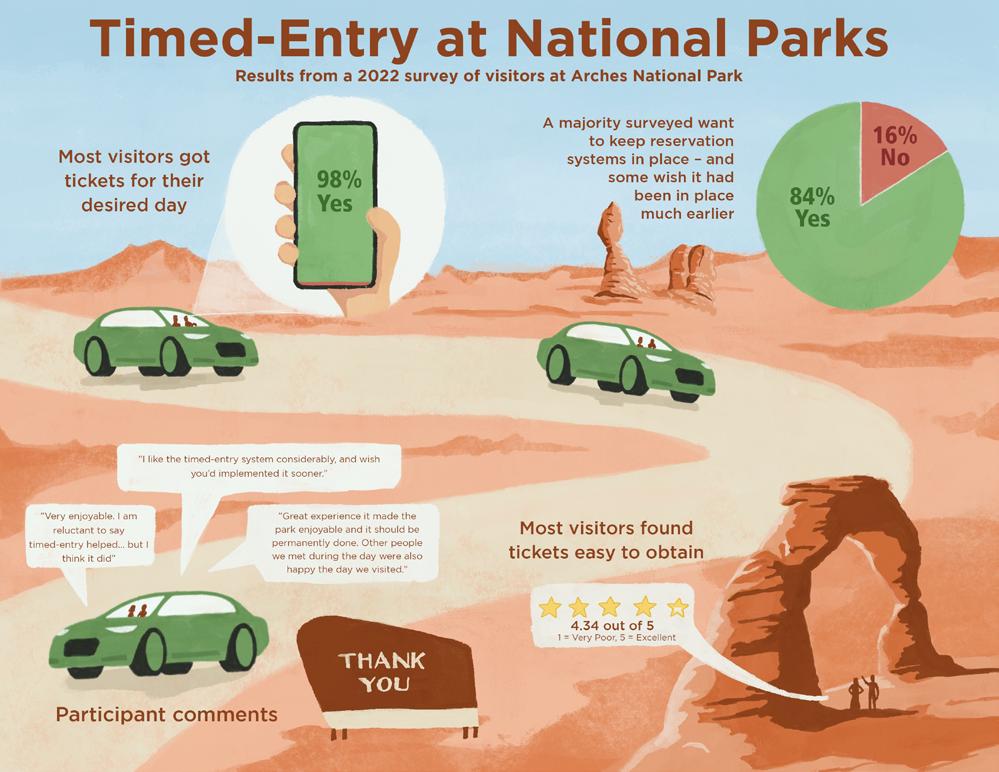

NPCA’s Water Program is collaborating with subject matter experts Applied Ocean Sciences to assess conservation priorities for the nation’s 88 coastal parks.

There are a multitude of environmental challenges facing coastal parks, and the nation’s coastal ecosystems in general, from sea level rise to degradation of blue carbon ecosystems such as kelp forests, coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangrove forests. There are limited resources for mitigating and protecting these ecosystems, and countless competing interests to consider when prioritizing conservation.

There is abundant data available for gaining insight into the values and threats of these remarkable places including modeled climate change impacts, projected sea level rise, ground cover, endangered species habitat, shoreline type, among a variety of others. This analysis takes a first attempt at building conservation value indeces that combine and simplify these data into actionable information.

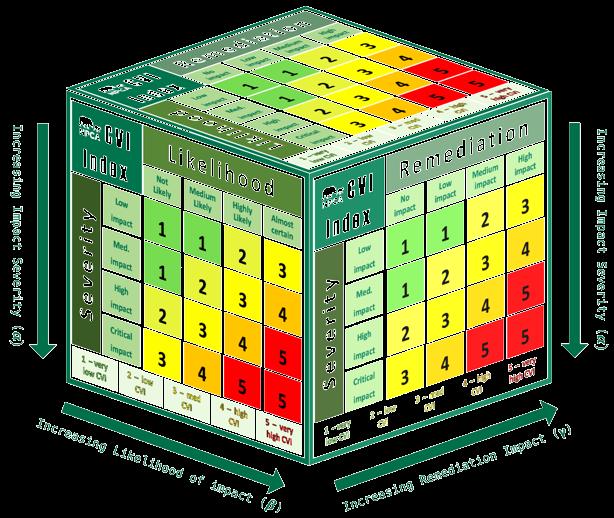

Conservation Value Index

Applied Ocean Science has created four deeply researched indices, each assessed across three axes — severity of the threat, likelihood of the threat, and remediation potential — represented in the scoring matrix below. If a park scored high on all three, it is scored as highest priority for conservation for the topic area.

The Four Topic Areas

The assessment included data to understand which of the 88 parks to prioritize for conservation based on Sea Level Rise, Blue Carbon Ecosystems, Coastal Erosion, and Marine Protected Areas

This is one of four maps representing just the data for Coastal Erosion. The coastal parks marked as darkest red should be highest priority for conservation when considering Coastal Erosion data because according to data the threat of coastal erosion is severe, has a high likelihood of happening, and because there is strong potential for remediation.

The work is still ongoing. To learn more reach out to Sarah Barmeyer at sbarmeyer@ npca.org

35 NPCA

Prior to its move in 1999, the Atlantic Ocean had encroached on the base of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. Photo by NPS

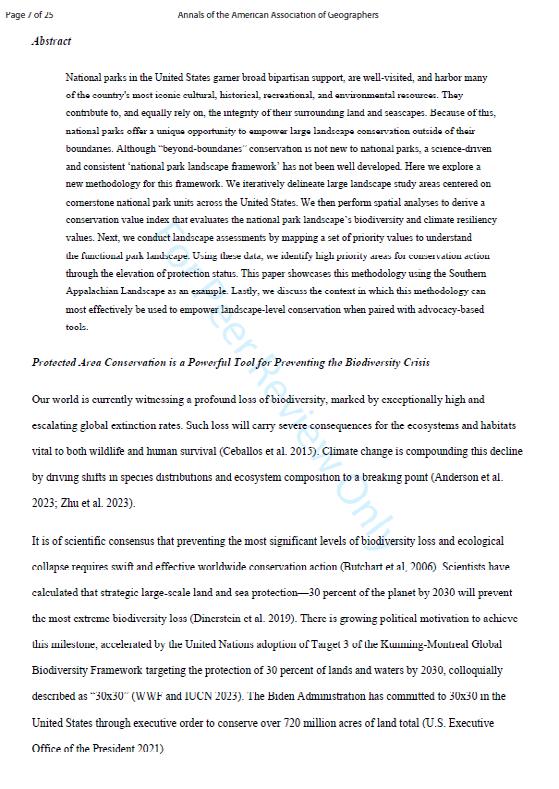

Landscape Methodology

Submitted to Peer-Reviewed Journal

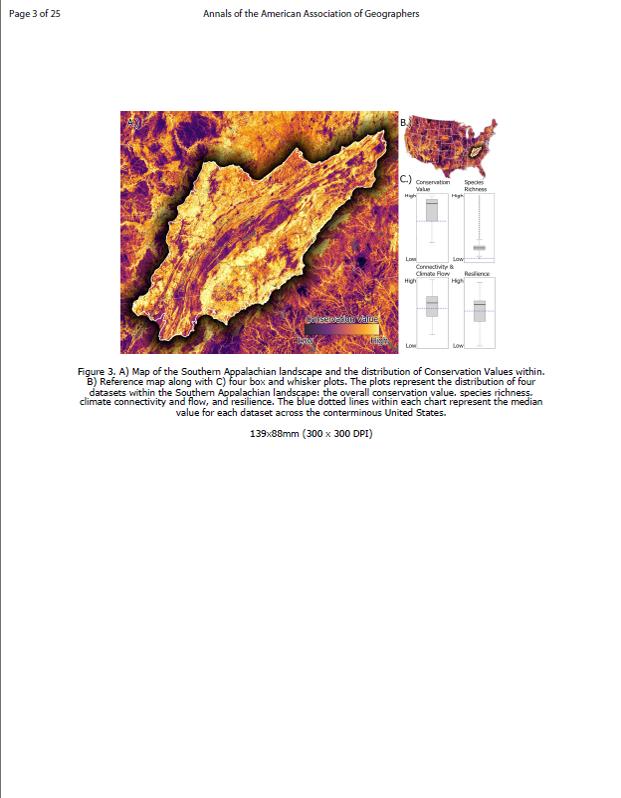

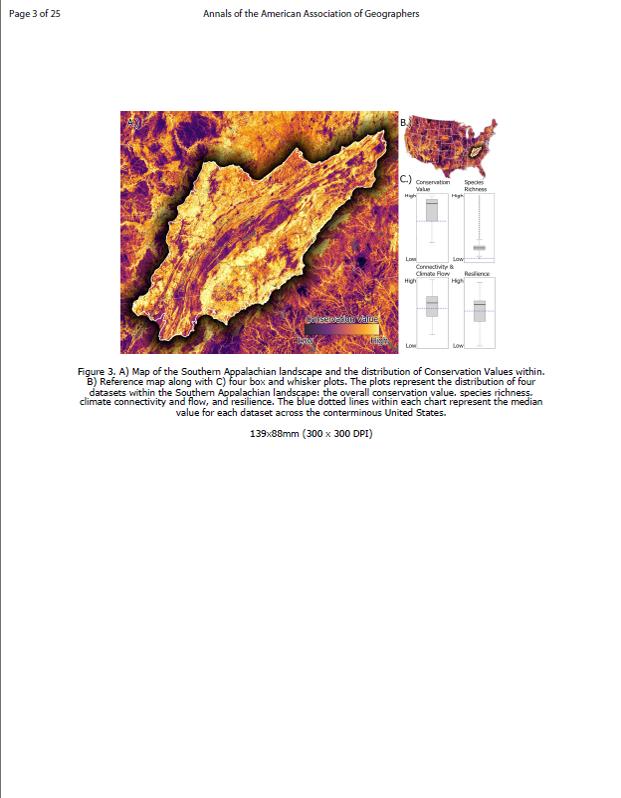

In Review at Annals of the American Association of Geographers: Empowering National Park Landscape Conservation by Connecting Science and Advocacy

N. J. Moy, H.R. Ceasar, C. Tracey, R.G. Valdez

Abstract

National parks in the United States garner broad bipartisan support, are well-visited, and harbor many of the country’s most iconic cultural, historical, recreational, and environmental resources. They contribute to, and equally rely on, the integrity of their surrounding land and seascapes. Because of this, national parks offer a unique opportunity to empower large landscape conservation outside of their boundaries. Although “beyond-boundaries” conservation is not new to national parks, a science-driven and consistent ‘national park landscape framework’ has not been well developed. Here we explore a new methodology for this framework. We iteratively delineate large landscape study areas centered on cornerstone national park units across the United States. We then perform spatial analyses to derive a conservation value index that evaluates the national park landscape’s biodiversity and climate resiliency values. Next, we conduct landscape assessments by mapping a set of priority values to understand the functional park landscape. Using these data, we identify high priority areas for conservation action through the elevation of protection status. This paper showcases this methodology using the Southern Appalachian Landscape as an example. Lastly, we discuss the context in which this methodology can most effectively be used to empower landscape-level conservation when paired with advocacy-based tools.

LAND AND SEASCAPE CONSERVATION

6SPRING 2024 36

LANDSCAPE VALUES

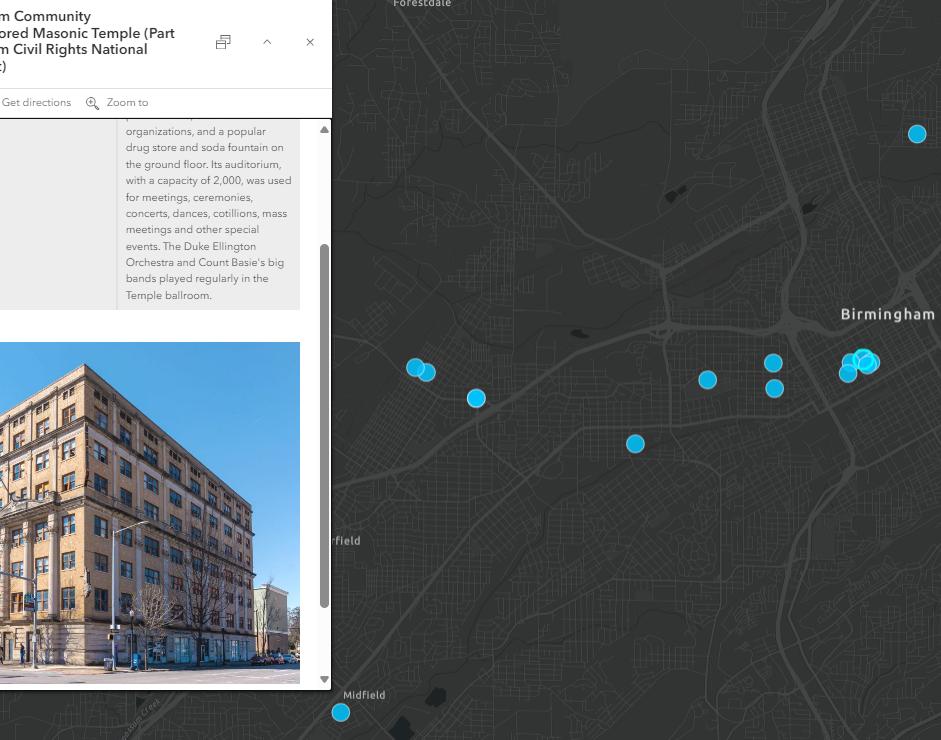

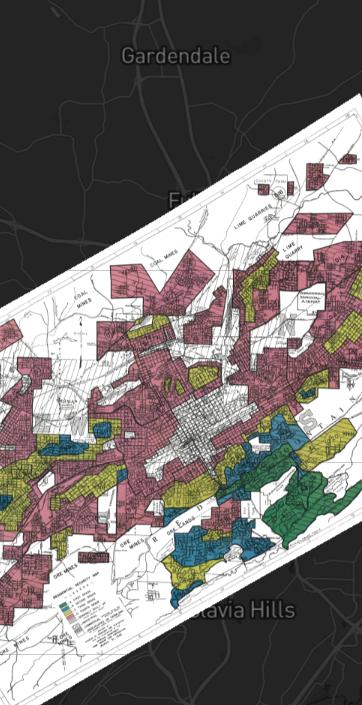

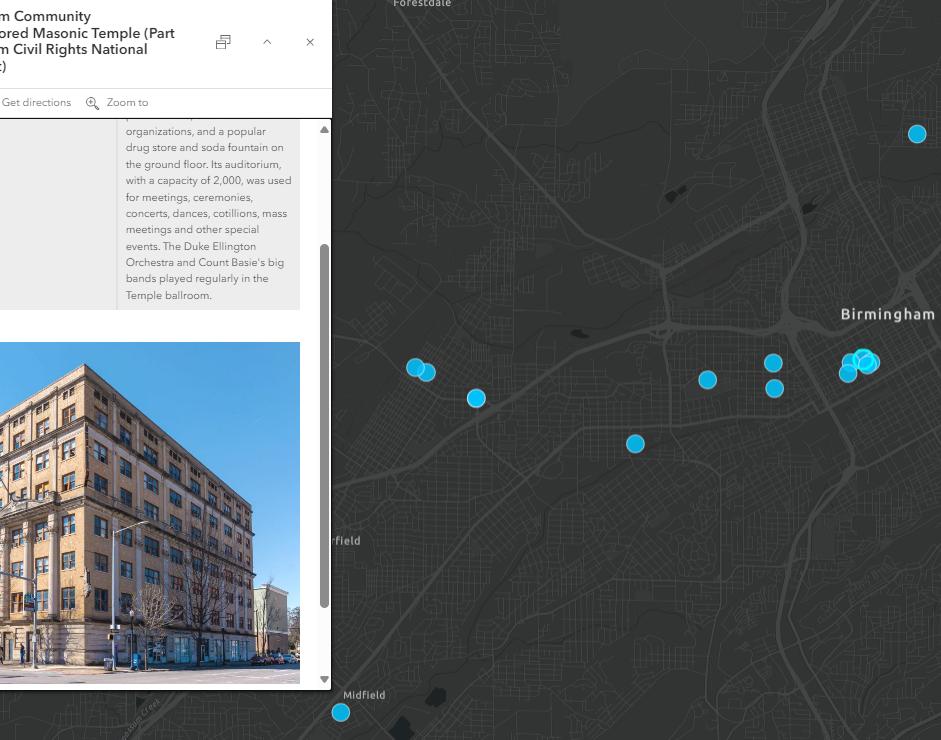

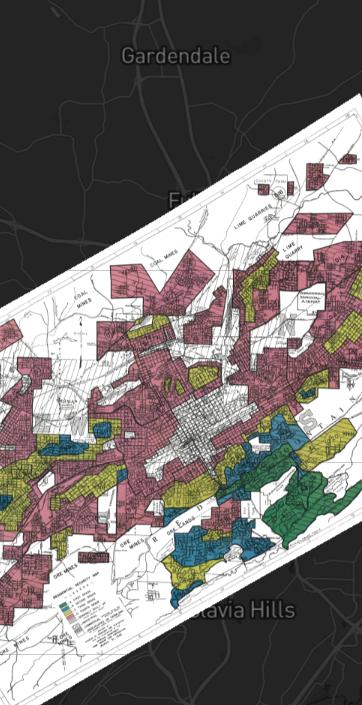

Mapping Black Community Resources in Birmingham, Alabama

In the tapestry of American history, Birmingham, Alabama bears witness to the interconnected threads of segregation, redlining, and environmental injustice.

To explore the profound impact, Joshua Jenkins, NPCA’s Mississippi and Alabama Field Representative is working with a local non-profit to trace the roots of systemic discrimination and the numerous examples of community resilience.

Continuation of a series on Civil Rights Mapping in Birmingham. Learn about redlining in Birminham in the previous issue.

Written by JOSHUA JENKINS Mississippi and Alabama Field Representative and NIK MOY Sr. Conservation Science Program Manager

37 NPCA

Birmingham’s history is marked by deep-seated racial segregation, from the segregation of Birmingham’s earliest Black residents through the Jim Crow Era, and perpetuated by redlining and zoning ordinances Birmingham witnessed pervasive segregation in housing, public spaces, schools, and transportation, perpetuating enduring social and economic disparities and resulting in abysmal environmental living conditions.

The struggle for justice in fair housing and environmental living conditions in Birmingham is not a footnote but a dynamic narrative of resilience and resistance. From 1945 - 1951, Black communities, organizers and the NAACP challenged racial zoning in three legal cases and finally won the hard fought legal battle to declare racial zoning laws unconstitutional. This was a major win for Birmingham, but the struggle for justice was far from over.

The city government and business leaders found new ways to preserve neighborhood segregation using strategies like urban renewal, slum clearance and the use of highway programs.

In early 1958, the United States Housing Home and Finance Agency (HHFA) funded a study that included the Tuxedo neighborhood and the surrounding areas. The consultant found that the Tuxedo neighborhood, part of a community that was over 80% Black, was in the worst condition. In an effort to stop “deterioration” toward the white neighborhood to the south, the report explicitly noted that the Interstate Highway 59 Project would “remove deteriorated areas” and initiate “substantial clearing of slum housing.”

SPRING 2024 38 LAND AND SEASCAPE CONSERVATION

Despite the description of Tuxedo as a blighted community, residents noted that the neighborhood thrived from the 1930s-50s. Kids in Birmingham 1963 member, Melvin Todd, recalls what it was like growing up in the Tuxedo Neighborhood, “The house I was born and raised in was a steel worker rental house 2 blocks from Tuxedo Junction and 1 block behind Holy Family Hospital in Ensley, which was the first and only hospital that allowed black nurses and doctors to practice there. There was a large intact Black community there when the interstate came through and cut the community in half in 1959.”

Melvin’s family, and other families, had to move when the highway came through and the only place they could afford was next to the Tennessee, Coal and Iron railroad tracks. Describing the condition of the air in the new neighborhood Melvin said, “On a sunny day, it looked clear, but if you put a newspaper down, you could hear particulate matter falling tap-tap-tap on the

paper.” The particulate matter rusted out cars where the chrome met the paint.

The Ensley urban renewal project was not the only one of its kind, and the result was the loss of population from those areas. Nine of ten neighborhoods with the largest population losses from 1960-70 were Black communities. Of these, eight had highways built through them in the 1960s.

While it is important to learn about the oppression Black communities faced in Birmingham and elsewhere, there is no doubt that it can be quite heavy and and

39 NPCA

This map shows aerial imagery from 1947 of College Hills, East Thomas, Enon Ridge, Graymont neighborhood, and Smithfield neighborhood— centers of Black life and culture. These neighborhoods were systematically ravaged by repressive infrastructure policy and development. Everything outlined in black was demolished and replaced with an impassable interstate highway.

discouraging. To counter the heaviness, it is important to highlight that In the face of this unrelenting repression, Black communities not only resisted but found ways to thrive. Through the construction and development of theaters, baseball leagues, football games, music traditions, and radio stations, communities found ways to play, worship, and care for each other in the face of oppression.

Joshua Jenkins of NPCA’s Southeast Regional Office with Conservation Science is working with community leaders at the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument and Kids in Birmingham 1963 to collect these stories of “Community Assets”. From this communityled process, we can learn how to best support the telling of these stories by contextualizing the broad impacts of segregation, redlining, and environmental injustice with the rich lives of Birmingham’s Black community life.

The exploration of these community assets uplifts the proactive spirit of individuals confronting oppression. These communities embody the resilience to not just survive but thrive amidst adversity. Recognizing such assets serves as a balm, providing comfort to those who resonate with the legacy of housing discrimination, enabling them to confront trauma by reconnecting with ancestral strengths and narratives.

With the support of NPCA, the story of Birmingham’s struggle and strength can reach National Park Service visitors, showing this story as a rallying cry for justice, equity, and a more sustainable tomorrow.

To learn more contact Joshua Jenkins at jjenkins@ npca.org.

SPRING 2024 40

The blue pins on both of these maps show a new database of Birmingham Community Assets collected by Joshua Jenkins (SERO) with community leaders at the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument and Kids in Birmingham 1963. These places stand as testament to the vibrance of Birmingham’s Black communities.

Park Science Magazine

by the National Park Service

A roundup of NPCA relevant articles from the National Park Service’s Winter 2023 Issue of Park Science.

Early Detection Is the Best Protection for Old-Growth Forests

Despite dire evidence of rising tree death, researchers found resilience and hope deep inside western Washington’s forests. But it will take 21st-century monitoring methods to keep that hope alive.

The 2009 study found tree death rates were doubling every 17 years throughout the Pacific Northwest. To discover if that trend held true in protected forests, researchers set up 45 long-term monitoring plots in Olympic, Mount Rainier, and North Cascades, as well as Lewis and Clark National Historical Park.

Federal land designations saved these parks from rampant logging. That left large swaths of forest intact, perhaps offering a buffer against dangers that emerged a century later.

Today, our best way to track and confront climate change impacts is information. A lot of information.

Continue Reading

41 NPCA

TOP LEFT

Two

A member of the monitoring team records data in the summer forest undergrowth at Olympic National Park. Photo by NPS.

How to Assess Air Pollution’s Impacts on Forests

The interconnectedness of living things is evident in a forest, where lichens act as pollution alarm clocks, and soil fungi help trees survive. Scientists gauged forest health by studying four types of organisms.

Continue Reading

Unlocking Earth’s Secrets, Layer by Layer

Those splendid rocks in our national parks aren’t just scenic wonders; they’re scientific and cultural treasures. A new geological inventory could help protect them.

Continue Reading

TOP RIGHT

LEFT

Reducing air pollution improves water quality and habitat for native animals like salamanders. Photo by NPS | Mike Bell.

Two geologists examining the Cretaceous Point Loma Formation with alternating beds of sandstone and mudstone. Photo by NPS.

TOP

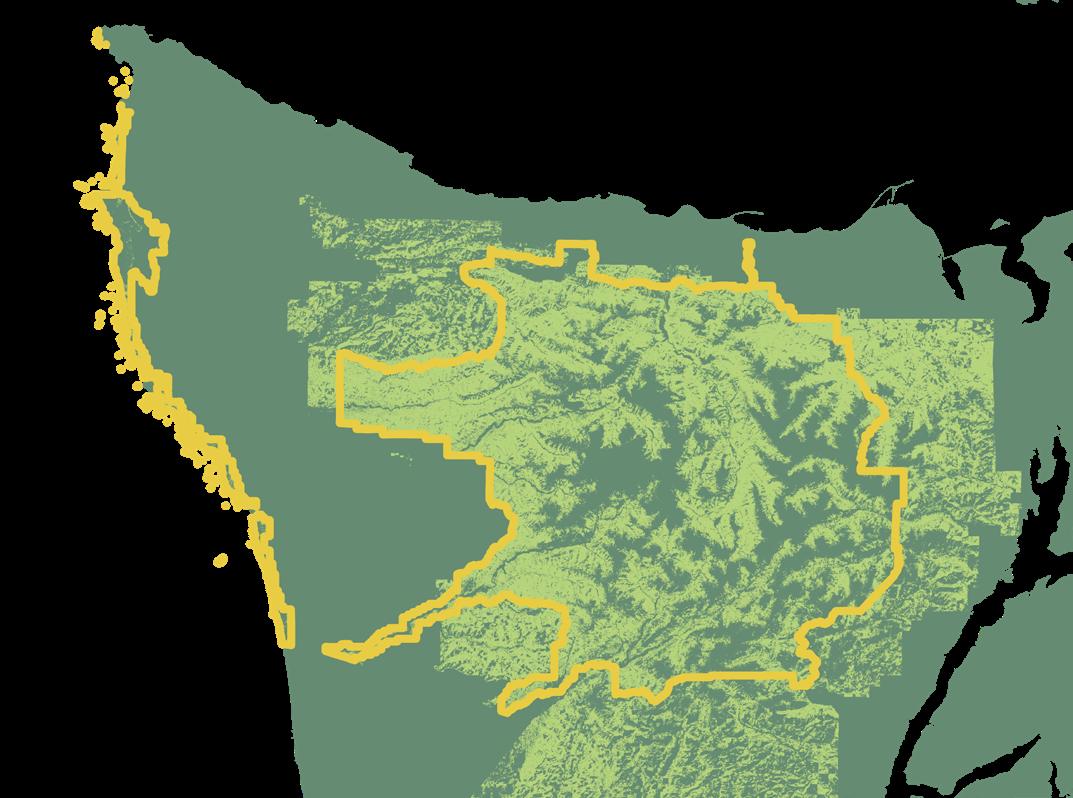

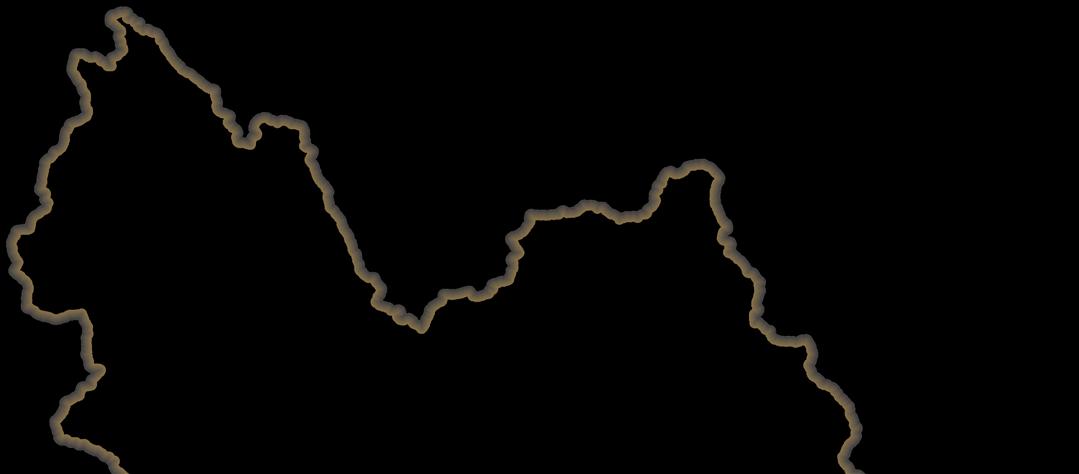

SOUTHWEST PROTECTED LANDS CORRIDOR

With Matt Kirby, Senior Director, Energy & Landscape Conservation This map was made for celebrating land protection successes showing the newly connected corridor of protected lands in the Southwest.

BOTTOM

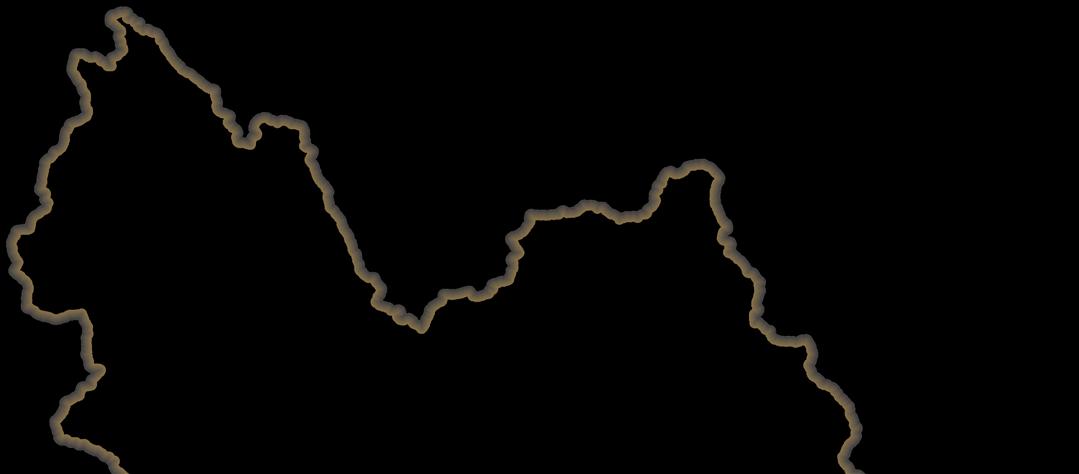

LANDSCAPE ATLAS MAPS

With NPCA’s Landscape Program and Development

NPCA’s Landscape program in collaboration with Development is producing a new Landscape Atlas. The publication will showcase the status of twenty focal landscapes. The following are sample reference maps Conservation Science created for the upcoming Atlas, showing the Dinosaur Landscape (left) and the Bear Coast (right).

43 NPCA COLORADO WYOMING UTAH Dinosaur National Monument Uintah and Ouray Reservation WY UT CO Ashley National Forest Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area Wasatch National Forest Vernal Routt National Forest Protected areas managed for biodiversity (GAP & 2) National Park Service Land status 0 20 mi Native American Lands

How to Collaborate

We’ve expanded our capacity with a Geospatial Science Fellow, contractors, and partnerships. Here is a refresher on what we can do and how we work.

What We Do

Mapping & spatial analysis Data visualization & infographics

Storytelling & science communication

What You Can Expect

+ Science consultation and resources

+ Help to connect with contractors, researchers, academic institutions

+ Respect for data sensitivities

+ Honest and clear communication about capacity and timelines

What We Expect

One month minimum notice or more before the product is due + Initial ideas for audience, purpose, and format of the product

+ Timely responses to questions and follow-ups

To collaborate, reach out to Nik Moy, nmoy@npca.org.

GIS

Highlight

Lab

SPRING 2024 44 Lake Clark National Park and Preserve Katmai National Park and Preserve Alagnak Wild River Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve Ugashik Natl. Wildlife Refuge Iliamna Lake PACIFIC OCEAN Bristol Bay Pedro Bay Kokhanok Port Alsworth Nondalton Iliamna Newhalen Igiugig Levelock Naknek King Salmon South Naknek Egegik Pilot Point Ugashik Kenai Fjords National Park AK Protected areas managed for biodiversity (GAP 1 & 2) National Park Service Land status 0 75 mi Native American Lands Seldovia Port Graham Ninilchik Kenaitze Salamatof Chenega Tyonek Knik Eklutna Chickaloon Lime Village New Koliganek New Stuyahok Ekwok Aleknagik Dillingham Portage Creek Clarks Point Twin Hills Togiak Platinum Goodnews Bay Kwinhagak Napaskiak Napakiak Bethel Akiak Tuluksak Lower Kalskag Aniak Chuathbaluk Napaimute Ouzinkie Port Lions Lesnoi Old Harbor Akhiok Karluk Uyak Larsen Bay Port Heiden

Science Resources

NPS Science Links

NPS Adaptation Resources

NPS Air Resources Division. Live weather and air quality data

NPS Alaska Park Science

NPS Connected Conservation Webinar Series

NPS Citizen Science

NPS Climate Change Science

NPS Continuous Water Data

NPS Science of Climate Change video series

NPS Coastal Adaptation

NPS Fossils and Paleontology

NPS Geology

NPS GIS Program

NPS GIS Cartography, GIS and Mapping

NPS Main Archival and Data Repository (IRMA)

NPS Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Directorate

NPS Natural Resources Science Resources (science by discipline)

NPS Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division

NPS Oceans, Coasts and Seashores

NPS Park Science

NPS Pollinators

NPS Research Learning Centers

NPS Research Permit and Reporting System

NPS Science of the American Southwest

NPS Science resources / Explore Nature

NPS Scientist in a Park Program

NPS Social Science

NPS Traditional Ecological Knowledge

NPS Wetlands

NPS Wilderness

NPS Yellowstone Science

45 NPCA

Professional Society Memberships at NPCA

AAAS: American Association for the Advancement of Science

AAG: American Association of Geographers

AESS: Association for Environmental Studies and Sciences

AFS: The American Fisheries Society

AGS: American Geographical Society

AGU: American Geophysical Union

ESA: Ecological Society of America

GSA: The Geological Society of America

GWS: George Wright Society

NACIS: North American Cartographic Information Society

SCB: Society for Conservation Biology

SCGIS: Society for Conservation GIS

SVP: Society of Vertebrate Paleontology

TWS: The Wildlife Society

JSTOR: Access to journal articles

For more information on accessing these memberships, please contact Ryan Valdez at rvaldez@npca.org

University-based National Park Programs

University of California, Berkeley: Institute for Parks, People, and Biodiversity

University of California, Merced: National Parks Institute

Clemson University: Clemson Institute for Parks

Duke University: Park Institute of America

Colorado State University, Salazar Center for North American Conservation: Conservation Conversations

WINTER 2023 46

Proposed Bahsahwahbee National Monument. Photo by Nik Moy, NPCA.

Science News

Spring 2024

Product of NPCA’s Conservation Programs.

Produced by: Conservation Science Ryan Valdez, Nik Moy, and Amy Tian

Contact Nik Moy, nmoy@npca.org, if you would like to share with any audiences external to NPCA or print a version of this newsletter. Additionally, please let us know if you have questions, suggestions, or story ideas for the next issues of Science News.

Interested in helping advance Conservation Science at NPCA? Please reach out to Julie Hogan at jhogan@npca.org to explore how your suppport can make a meaningful impact.

To view this report digitally and access links:

Theresa Pierno President and CEO

Theresa Pierno President and CEO

Leads

Leads

NPCA has added the proposed Joshua Tree Expansion Monument and Chuckwalla National Monument, as well as the Chesapeake Bay Watershed to our list of focal park landscapes. Photo: Joshua Tree NP | Nik Moy, NPCA.

JOSHUA TREE & CHUCKWALLA LANDSCAPE

NPCA has added the proposed Joshua Tree Expansion Monument and Chuckwalla National Monument, as well as the Chesapeake Bay Watershed to our list of focal park landscapes. Photo: Joshua Tree NP | Nik Moy, NPCA.

JOSHUA TREE & CHUCKWALLA LANDSCAPE