THE ORCHID CRISIS

Science News

NPCA Science News is an internal newsletter highlighting the integration of science empowering our park protection. Our stories are inside stories – originating from close, collaborative work with Programs and Regions. By spotlighting science-related work throughout NPCA and with our many partners, we bring much needed attention to the important role of science in advocacy.

CONSERVATION PROGRAMS

Conservation Programs Vice President PRIYA NANJAPPA

CONSERVATION SCIENCE | NPCA Science News Editorial Team

Sr. Director RYAN VALDEZ, PH.D. (Editor in Chief)

Sr. Program Manager NIK MOY (Managing Editor and Content)

Cartographer and GIS Analyst AMY TIAN (Art Design and Content)

With Editing and Printing Support from:

Assistant Director of Advancement Communications KELLY BURTON (Copy Editor)

SCIENCE ADVISORY LEADERSHIP TEAM (SALT)

Conservation Science Sr. Director RYAN VALDEZ, PH.D.

Sun Coast Regional Director MELISSA E. ABDO, PH.D.

Conservation Programs Sr. Program Manager CHRISTA CHERAVA (Copy Editor)

Conservation Programs Deputy Vice President SARAH BARMEYER

Foundation Relations Senior Director JULIE L. HOGAN

Conservation Science Sr. Program Manager NIK MOY

Clean Air and Climate Sr. Manager DANIEL OROZCO, PH.D.

Please contact Nik Moy, nmoy@npca.org, if you would like to share with any audiences external to NPCA or if you would like to print a version of this newsletter.

Interested in helping advance Conservation Science at NPCA? To explore how your support can make a meaningful impact please reach out to:

Foundation Relations Senior Director JULIE L. HOGAN at jhogan@npca.org

To view this report digitally and access links:

Science in Practice

by NIK MOY | Senior Manager of Conservation Science

Opening Note

Where I grew up outside of Chicago, climbing over and under fences was a necessary part of getting outside. To sled on the nearby hill, fish at the stocked pond, or swim at the good beach, we had to cross onto private land. Doing basic outdoor activities led to run-ins, scoldings, tickets, and car rides home from land owners and law enforcers. This was a tax my childhood friends and I reluctantly accepted to answer the call of nature.

At the Southern Appalachian Landscape Coalition meeting in August, conservation partners gathered for two days to seek shared values on the landscape. The meeting was convened by Olivia Porter, NPCA’s Southern Appalachian Landscape Project Director, who also invited me to represent NPCA Conservation Programs by facilitating mapping discussions with the coalition.

The event culminated with a hike to Deaverview Mountain, a stunning peak that gives 180 degree views of the French Broad River Valley. We were told this private land is often trespassed because it is so locally beloved. Coalition partner Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy is working to make this 343-acre mountaintop tract into a public park. This work will make one less place where local Asheville kids have to trespass to play in nature. Needless to say, my childhood self was proud to be in a room with such remarkable humans.

The Great Smoky Mountains is a National Park at the heart of the Southern Appalachian Landscape, where NPCA and conservation partners gathered for a first ever coalition meeting this August. PHOTO: WerksMedia, iStock.

To me, this is what national park landscape conservation is all about—that small tracts can be just as meaningful as the Yellowstones and Denalis. This issue of Science News shares how NPCA is using science and landscape conservation best practices to lend the power of parks to support locally important places just outside their boundaries.

This issue also features a call-to-collaboration. In the face of the duel climate and biodiversity crisis, the need for parks to collaborate with scientists is more urgent than ever. We share an example in the Everglades where Melissa Abdo of the Sun Coast Regional Office is helping illuminate a story of orchid scientists connecting with agency officials.

Bridge-building, connecting people to eachother and to the land, is something that Melissa, Olivia and many others at NPCA have shown me is an effective and beautiful way to do this work. We hope you enjoy this edition of NPCA Science News.

Sincerely, Nik Moy

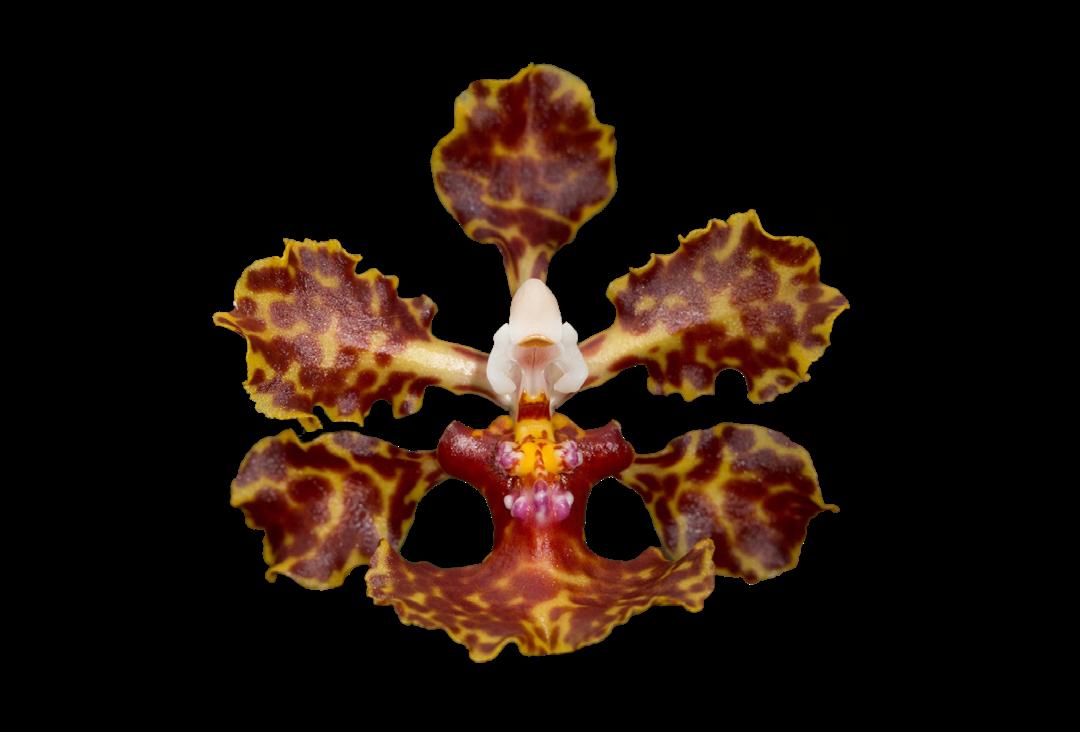

On the cover

The mule ear orchid, named for its large, thick petals resembling a mule’s ear, is a striking and rare orchid native to Florida and the Caribbean. With fewer than 50 adult orchids remaining in the Everglades, it is a race against local extinction.PHOTO: Keith Bradley.

Contents

5

11

Conservation Programs

Protecting Paleo in Parks

Conservation Science Toolkit For the Love of Dog

Summer of Connection

NPCA Getting Green

Feature Story

The Orchid Crisis in the Everglades: A Race Against Local Extinction

Land and Seascapes

NPCA and Park Institute of America Forge Partnerships 25

Conservation

Science for Advocacy: Southern Appalachian Coalition Meeting

National Park Service Engaging in Landscape and Seascape Conservation

NPS Park Science Roundup

CONSERVATION PROGRAMS

Leads and unifies NPCA in achieving dynamic and equitable conservation solutions that protect and enhance the air, lands, water, wildlife, and climate of our national parks.

Ryan Valdez, P.h.D. Senior Director, Conservation Science

Karen Hevel-Mingo Director, Sustainability

Nik

Ulla

Amy Tian Cartographer & GIS Analyst, Conservation Science

Priya Nanjappa Vice President, Conservation Programs

Sarah Barmeyer Deputy Vice President, Conservation Programs

Christa Cherava Senior Manager, Conservation Programs

Matthew Kirby Senior Director, Energy & Lands

Bart Melton Senior Director, Wildlife

Stephanie Adams Director, Wildlife

Reeves Director, Clean Air

Natalie Levine Campaign Director, Clean Air

Daniel Orozco, P.h.D. Senior Manager, Clean Air & Climate

Beau Kiklis Associate Director, Energy & Lands

Moy Senior Manager, Conservation Science

Protecting Paleo in Parks

In July, Christa Cherava embarked on her 2nd Paleo-themed sabbatical! This time, taking her into Alberta, Canada where she focused on dinosaur fossil exploration. Canada has some of the strictest paleo protection laws in the world, and she met with experts, professors, communicators, amateurs, volunteers and others who have made significant impacts in this field.

Her visits to various protected areas throughout the province led to a further understanding of how these resources are considered part of the Canadian heritage to Albertans and First Nations communities’ cultures.

Christa enjoyed both lab and field time, unearthing a frill section of a rhino-like dinosaur called Pachyrhinosaurus lakustaii. This piece makes it the 11th member of the herd found thus far at the Pipestone Creek Bonebed.

The Pipestone Creek bonebed in Alberta, Canada, is a significant paleontological site known for its rich concentration of dinosaur fossils, particularly those of the horned dinosaur Pachyrhinosaurus. PHOTO: Chris Istace, The Mindful Explorer.

The NPCA Conservation Science Toolkit is now available—and serves as an internal resource for staff, overseen by the Science Advisory and Leadership Team (SALT). The toolkit furnishs staff with pertinent and practical scientific tools and resources that empower advocacy, while also extending expertise and fostering collaboration.

Access the toolkit at science.npca.org

For the Love of Dog

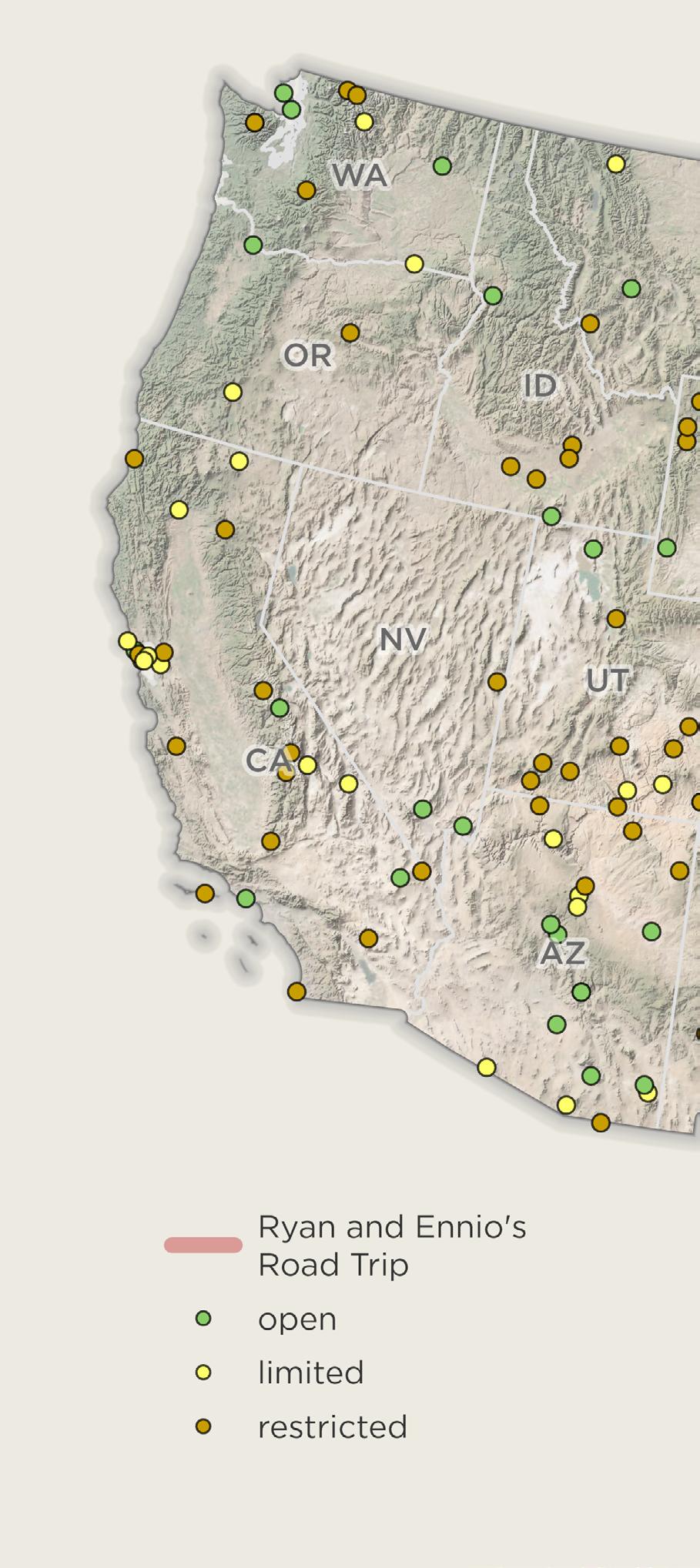

A new guide to dog accessibility at national parks can help people traveling with pets know what to expect at 430+ park sites across the country.

Our pets are family, and when we travel, it only makes sense that we want to bring our dogs with us. Many national park sites are ideal places for our canine companions, with accessible trails and programs geared just for them — but not every site is a good choice for a dog, and many can present serious dangers to our pets.

A new system-wide map and guide to dog accessibility can take some of the mystery out of planning a park trip, and knowing the park regulations and best practices can make trips safer and easier for pet owners and their furry family members.

Enjoy this StoryMap to explore best practices, topical issues — and a few odd stories to keep in mind — when visiting parks with our furry best friends.

Also enjoy the podcast – The Secret Lives of Parks: For the Love of Dog, by Jennifer Errick

Dog accessibility at park

PHOTO: Ryan Valdez.

A new interactive database to plan your park trip with your furry triend!

MAP: Amy Tian, NPCA.

NPCA Getting Green

For the Fall Semester of 2024, NPCA’s Green Team will collaborate with Harvard University’s sustainability curriculum to complete a Greenhouse Gas Inventory and Reduction Plan. The results will be based on internationally accepted standards and protocols for addressing Scope 1-3 emissions and will be using the US EPA’s analytical tools that are science based so that NPCA can voluntarily and effectively contribute to mitigating climate change impacts.

PHOTO: NanoStockk, iStock.

Summer of Connection

Swimming through a sea of 20,000 other mappers, Nik and Amy charted new territory at the Esri User Conference in San Diego this July—the world’s largest GIS conference.

Nik gave a talk to over 200 attendees on the importance of applying a data-driven national park landscape framework with partner NatureServe. Amy showed a map at the conference’s Map Gallery. The cartography was done in collaboration with NPCA’s Mid-Atlantic Regional Office to advocate for the new Chesapeake National Recreation Area, which thousands of conference goers had the chance to interact with across the week.

Later in August, Amy attended the Society for Conservation GIS meeting, where she had the chance to meet with the National Park Service cartographer responsible for the maps inside those iconic park brochures.

PHOTO: Amy Tian, Nik Moy, NPCA.

THE ORCHID

CRISIS

A RACE AGAINST LOCAL EXTINCTION

PHOTO: Jake Antonio Heaton, iNaturalist.

NPCA SUN COAST REGIONAL OFFICE

Everglades National Park has the highest orchid diversity of any park in the continental US. Despite this, orchid species have been disappearing from the park. The mule-ear orchid, with its brilliant yellow and red spots, is an orchid that scientists are racing to save.

Written by MELISSA ABDO NPCA Sun Coast Regional Director

Designed

by

AMY TIAN

NPCA Cartographer and GIS Analyst

ORCHIDS HAVE LONG CAPTIVATED

the imagination of botanists and nature enthusiasts alike. As one of the largest and most diverse plant families, orchids stand out even amidst the renowned treasure trove of biodiversity in the Everglades. With 46 known native orchid species, Everglades National Park is the park unit with the highest orchid diversity in the continental US. Tragically, many of these species are threatened. Some haven’t been observed in decades and are likely locally extinct in the park.

The loss of orchids in the Everglades is alarming. Beyond their alluring colors and designs, orchids have immense ecological and cultural significance. Many orchid species have evolved complex mutualistic relationships with specific pollinators due to their precisely shaped flowers or compelling fragrance. These niche pollination strategies create unique interaction webs within their ecosystems. This complexity has motivated close study and breakthrough understandings of plant ecology. Additionally, orchids have captivated human interest since time immemorial, inspiring countless artworks, books, and films.

Everglades National Park holds a special place in

conservation as the first national park established specifically to protect biodiversity. It is home to over 750 native plant species, nearly a quarter (25%) of which are considered imperiled or endangered. Protecting orchid species and other imperiled species is not just an isolated effort, but a fundamental part of the park’s mission.

While NPCA, the National Park Service, and many partners work to revive and protect the whole Greater Everglades Ecosystem, it is also important to dedicate

resources to species-specific conservation efforts that ensure every organism has a place in the restored landscape.

In neighboring Big Cypress National Preserve, NPCA and our allies secured a legal victory that will expedite the Endangered Species Act listing decision for the elusive and rare ghost orchid, Dendrophylax lindenii. Now, another orchid of the Greater Everglades ecosystem teeters on the brink of local extinction: the mule ear orchid, Trichocentrum undulatum

Orchids thrive in the Everglades due to its warm, humid climate, abundant rainfall, and nutrientrich swamps. Many orchids are epiphytic, meaning they grow on trees alongside the bromeliads pictured here (Tillandsia spp.).

Hong Liu, Florida International University.

PHOTO:

Ghost orchid Dendrophylax lindenii

The ghost orchid is one of the rarest flowers in North America.

A symbol of the Greater Everglades Ecosystem flora, this mysterious flower is pollinated at night by a giant sphinx moth.

The moth’s long proboscis perfectly reaches into the orchid’s flowers to gather nectar and transfer pollen.

Dingy-flowered epidendrum Epidendrum anceps

Butterfly orchid Encyclia tampensis

Grasspink orchid Calopogon tuberosus

PHOTOS: Joshua Hall, Jeff Stauffer, Rudy Wilms, John L. Clark, Arvind Balaraman, Logan Crees, Aidan Campos, iNaturalist.

JEWELS OF THE EVERGLADES

Everglades orchids come in all shapes, colors, and sizes. The dazzling orchids here are all found in the Greater Everglades Ecosystem and are pollinated by a variety of species, including bees, wasps, flies, butterflies, and even giant moths.

Mule ear orchid Trichocentrum undulatum

Dollar orchid Prosthechea boothiana

Clamshell orchid Prosthechea cochleata

Longclaw orchid Eltroplectris calcarata

Spring ladies’ tresses Spiranthes vernalis

THERE ARE FEWER THAN 50 ADULT MULE EAR ORCHIDS LEFT IN THE US

The mule ear orchid is a large and flamboyant tropical orchid native to South Florida and the Caribbean. With its dramatic yellow and red flowers and large size, this orchid drew attention from orchid harvesters at the turn of the last century and was overcollected before Everglades National Park was formally established.

Within the United States, mule ear orchids exist only in the southern Everglades—the only place the orchid can be found in North America. However, the mule ear orchid remains federally unprotected in the US after federal wildlife managers rejected a request for it to be listed under the Endangered Species Act in 2020. At this time, it is only afforded limited protection by virtue of being within Everglades National Park and state listed as endangered.

Recent research reveals a disturbing trend: the only known population of this orchid in Everglades National Park has declined by 90% over the past two decades (1). This species makes its home in the dynamic coastal buttonwood hammock of the southern Everglades, a resilient landscape where twisted trees and saltloving plants must adapt to rising seas and hurricanes.

Fewer than 50 adult mule ear orchid plants remain as of 2021, a stark reminder of the urgent conservation efforts needed to prevent this magnificent orchid from disappearing entirely from Florida—and the United States.

The Everglades mule ear orchids are hanging by a thread and burdened with a list of threats. Historically, unregulated collection wiped out its populations and widespread drainage dried its habitat. Additionally, predation by native herbivores, infestations by invasive insects, and climate change is broadly degrading their habitat through hurricanes and sea level rise.

Beyond these known threats, there are also unknown factors contributing to the sharp decline of mule ear orchids that scientists are racing to understand.

Citation (1) Borrero H, Alvarez JC, Prieto RO, and Liu H (2023) Comparisons of habitat types and host tree species across a threatened Caribbean orchid’s core and edge distribution. Journal of Tropical Ecology 38, 134–150

PHOTO: Russ Jones, iNaturalist.

SCIENCE COLLABORATIONS IN OTHER NATIONAL PARKS

Whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) is a keystone species in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. It is threatened by invasive species, climate change, and fire. The NPS Greater Yellowstone Inventory and Monitoring Network is an interagency team of scientists that track whitebark pine health. Here they are examining a whitebark pine tree for evidence of white pine blister rust, a non-native fungus killing the trees. The clusters of brown needles indicate potential infection. PHOTO: National Park Service.

IT WILL TAKE COMMITTED COLLABORATION

Across the country, parks are grappling with the difficult task of conserving species as climate change alters their habitats and ecosystems. These challenges require creative, science-driven solutions, making collaborations between park staff, researchers, and conservationists more vital than ever.

For example, at Yellowstone National Park, scientists are testing new strategies to protect the dwindling whitebark pine population, while in the Sierra Nevada, efforts are underway to safeguard the endangered Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog from the impacts of climate change.

However, many parks lack the resources or scientific capacity to implement conservation methods that require specialized expertise, underscoring the importance of academic and NGO partnerships.

THE LIU LAB FINDS SOLUTIONS

That’s where Dr. Hong Liu, an ecologist and professor at Florida International University (FIU), along with her students are taking action. The Liu lab is studying conservation methods to boost long-term survival for mule ear orchids in the wild. NPCA’s Sun Coast Region is partnering with FIU to get students involved in this initiative, strengthening the bridge between conservation science and advocacy.

Orchid conservation is complex and requires a lot of work. For rare orchids like the Everglades mule ear orchid, it’s important to protect their genetic diversity which helps them survive and adapt to changes in their environment. With less than 50 adult mule ear orchids left, it is best practice to duplicate and safeguard the wild population’s genetic diversity in a lab setting as soon as possible. Dr. Hong’s team is innovating two methods to do this, which can buy time for future conservation measures like reintroduction.

The first method involves cloning the orchids in a lab setting using modern tissue culture techniques. This would safely capture the genetic diversity of the wild orchid population with minimal human disturbance. Before they can collect samples from the park, the team is testing this process using the Caribbean mule ear orchid population. Currently, they are refining a cloning protocol shown on the next two pages that aims to yield a high success rate for cloning the mule ear orchid in a lab. Then, the team would need a permit from Everglades park staff to collect small plant tissue samples from wild orchids in the park. Finally, the team would clone the Everglades mule ear orchid samples using the protocol to preserve its genetic diversity and protect it in a greenhouse.

The second method involves hand-pollinating the orchids in the park to produce seeds. A portion of the seeds would be grown in the safety of a lab to form a living conservation collection and the remaining seeds to be stored for future use. With this method, the team must visit Everglades National Park multiple times, searching through thick swamp forests for the rare flowering plants. Since these orchids don’t bloom every year, this method often takes multiple years. Initially, this approach wasn’t approved by the National Park Service due to concerns of human interference, but the team may revisit this option if

the cloning method is not successful.

Dr. Liu’s team needs approval from Everglades National Park staff to implement both these conservation methods on the mule ear orchid. The park staff would likely need to partner with one or two botanic gardens that can host the orchid collection. The team has already identified three potential botanic gardens, including joint efforts with Dr. Jason Downing of Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, but they still need the park’s permission to move forward. This collaboration is crucial for

improving the species’ chances of survival, especially as climate change threatens its future. By allowing this research process, the Everglades National Park would take an important step in protecting its endangered orchids.

Dr. Liu and her field team of students from Florida International University.

PHOTO: Hong Liu.

INNOVATIVE ORCHID CONSERVATION

To help safeguard the mule ear orchid population, the best practice is to duplicate the wild population’s genetic diversity as soon as possible.

Dr. Liu’s team is prioritizing the cloning method in a laboratory first to minimize human disturbance in the park. Once the team develops a successful cloning protocol, the following steps will be followed:

1. COLLECT TISSUE SAMPLES FROM THE FIELD

Cloning the genetic diversity of wild Everglades mule ear orchids requires going into Everglades National Park one time to collect small plant tissue samples. This step requires a permit from Everglades park staff to move forward.

2. FIND BEST TISSUE STERILIZATION METHOD

Collected plant samples will be placed in a tube filled with various concentrations of bleach. This is to kill all fungal or bacterial contaminants.

3. FIND BEST RECIPE FOR TISSUE GROWTH

Dr. Hong’s team needs to experiment with agar recipes with different nutrients and growth hormones to grow the tissue. Here, the agar is an inky black because they used charcoal based on recipes from other scientists.

Infographic: Amy Tian, NPCA.

Photo: Luis, Florida International University.

Dr. Hong doing fieldwork

WHAT IT TAKES

Growing orchids is a tedious, and intensive task that can take approximately 2.5 years or more. The team is currently finding the best cloning protocol using the Carribean mule ear population. After the protocol shows a high cloning success rate, the team needs a permit from Everglades park staff to collect tissue samples from wild orchids one time only.

4. MULTIPLY TISSUE

The team checks under a microscope if the plant tissue shows growth. Then, the team will replicate the previous steps to multiply the number of plants being grown by placing them under specific lighting conditions.

If the cloning method does not yield a high success rate, then they will have to rely on a hand pollination method to obtain orchid seeds which will also require collaboration with park staff..

5. SEEDLING FORMATION 6. ACCLIMATE SEEDLINGS

A seedling has grown from the agar and is ready to be exposed to real world conditions in a greenhouse setting. If needed, the team puts the tissue onto another growth medium to become seedlings.

The seedlings are transferred from the jar to a greenhouse. The plants need time to acclimate and grow on their own without artificial nutrients. Dr. Hong’s team has already identified three potential botanic gardens to house the orchid collection. The team would need permission from Everglades park staff to house a collection in a greenhouse.

LAND and SEASCAPE CONSERVATION

Fostering connectivity across national park landscapes

Courthouse Falls in Pisgah National Forest in North Carolina shows one of the most valuable resources connecting the Southern Appalachian region: water. Streams, waterfalls, and rivers flow throughout Southern Appalachia with many species depending on them including fish, salamanders, amphibians, etc. Through NPCA and the Park Institute of America’s summer fellowship program, we examined aquatic connectivity to support the Southern Appalachian Coalition Meeting in August.

PHOTO: Alexeys, iStock.

LAND and SEASCAPE CONSERVATION

THINKING BEYOND PARK BOUNDARIES

National parks both support and rely on the integrity of surrounding land and seascapes. Applying a systematic and data-driven national park landscape conservation framework gives NPCA a foundation for working at a landscape scale, and allows us to adapt tools and strategies to diverse local realities.

FIRST STEPS

OUR APPROACH

Conservation Programs in direct collaboration with Regional Offices is using partner surveys, geospatial tools, and facilitated mapping discussions to better understand the role of parks in their greater landscapes.

Yellowstone National Park

SCIENCE FOR ADVOCACY

Southern Appalachian Coalition Meeting

THE SOUTHERN APPALACHIANS ARE anchored by two of the most visited national park units: Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the Blue Ridge Parkway. This living landscape is known for breathtaking mountain vistas, extreme biodiversity, and its treasured heritage. Despite substantial conservation efforts the landscape faces escalating threats, including land-use changes, habitat loss, pollution, climate change impacts, and invasive species inundation.

In August, the inaugural Southern Appalachian Landscape Coalition meeting was held in Asheville, North Carolina, with the goal of strengthening connections and developing strategies for collaborative conservation. The meeting brought together a group of local conservation leaders and the Eastern Band of Cherokee, including groups like The Wilderness Society and the Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy, who collectively have decades of experience protecting this region they call home.

Olivia Porter, NPCA’s Southern Appalachian

Landscape Project Director, convened the coalition, focusing on safeguarding the region’s biodiversity, climate resilience and way of life for its residents.

The first meeting was centered on relationship building, discussing coalition opportunities, and understanding shared values. For Olivia, the meeting marked the beginning of an inspiring new chapter for regional conservation.

npca’s landscape conservation approach fostered collaborative mapping and visual storytelling that fostered deeper engagement in the coalition.

OLIVIA PORTER

NPCA Southern Appalachian Landscape Project Director

Partners at the Southern Appalachian Coalition Meeting have conversations mapping their work and future hopes for collaborative conservation in the region. PHOTO: Olivia Porter, NPCA.

National Park Service

Engaging in Landscape and Seascape Conservation

“The Park Service recognizes that landscape and seascape scale conservation and protection, enhancement, and restoration of ecological connectivity are critical to fulfilling the NPS mission.”

Read the Memoradum here >

TYLER SAMMIS Director, Park Institute of America

NPCA and Park Institute of America Forge Partnerships

LAND AND SEASCAPE CONSERVATION FELLOWSHIP COASTAL RESILIENCE SYMPOSIUM

This summer, Nik Moy, Sr. Program Manager of Conservation Science, with Tyler Sammis of the Park Institute of America (PIA) designed a new fellowship program which engaged two Duke University graduate students in land and seascape conservation work supporting NPCA’s Southeast and Sun Coast Regional Offices. Read about the fellows’ work on the following pages.

According to Tyler, “The fellowship is unlike any program I have seen offered and provides a truly meaningful opportunity for Nicholas School students to build their science communication skills while supporting parks and protected areas.

Fellows were guided through a well-balanced practicum of needs assessment, data curation and analysis, guest lectures, and cartographic design. Both in its design and implementation, this program serves as a model for conservation data storytelling fellowships. PIA looks forward to growing this program with NPCA and leveraging to show why parks matter.”

Several regional teams converged on Beaufort, NC this September to attend the 2024 Coastal Resiliency Research Symposium organized by NPCA’s partner, the Park Institute of America.

Members of NPCA’s Sun Coast Region and Conservation Programs team joined Southeast Region staff, as well as members of the Southeast Regional Council and Young Leaders Council, at the Duke University Marine Lab to meet faculty and research teams from six universities, superintendents and resource management leads from both of North Carolina’s national seashores, US congressional staff, state coastal protected area managers, and coastal nonprofit leaders.

Participants discussed new research, policy, and outreach approaches to coastal resiliency being implemented locally that the state’s protected area managers should know more about, as well as those approaches already working for the state’s national seashores that could transfer to other coastal parks.

Students, faculty, and conservation practitioners including NPCA staff gathered for the Coastal Resilience Symposium.

PHOTO: Lily Zhang.

Appalachian elktoe

Alasmidonta raveneliana

Eastern hellbender Cryptobranchus alleganiensis

Southern Appalachia is a hotspot for aquatic species, but many face threats due to barriers which many partners are interested in removing. Ellie examined physical barriers to aquatic connectivity for several freshwater species of interest to the Southern Appalachian Coalition.

Four toed salamander Hemidactylium

scutatumonoff

PHOTO: Clockwise from top left, Dick Biggins (US Fish and Wildlife Service), Smithsonian Institute, Hazel Calloway (University of Virginia).

SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN LANDSCAPE

Aquatic Connectivity in Southern Appalachia

ELLIE HARRIGAN

Land and Seascape Conservation Fellow, NPCA Southeast Office

During my fellowship, I focused on supporting large landscape conservation within the Southern Appalachian Landscape. This region is not only a biodiversity hotspot for terrestial species but also a critical refuge for imperiled freshwater species.

My work centered on high-priority aquatic species in the area, evaluating how their habitats are threatened by barriers such as dams and roads. I used geospatial data to assess the proportion of protected lands in the study area, and which agencies are responsible for managing these lands. Further analyses highlighted what proportion of these barriers intersect with the species’ habitats, emphasizing habitats of highest vulnerability.

The goal of this project was to support NPCA and its partners with tools to guide conservation efforts, particularly as part of the broader global initiative to protect thirty percent of land by 2030. By using these data-driven tools, organizations can take proactive steps to protect the unique ecosystems of the Southern Appalachians, ensuring healthier and more resilient freshwater environments.

This experience has been so enriching, helping me get hands-on experience with conservation work using data science and creating impactful

visual representations of that data to tell a story.

ELLIE’S SUMMER WORK

The following are tools provided to support the work of the Southern Appalachian Landscape Coalition. These data are facilitating early conversations around collective story-telling, accounting for progress, and data-driven decision making.

GREATER EVERGLADES LANDSCAPE

Endangered Everglades Forests

HOPE LIU

I love the crucial relationships this experience helped validate, between data science and storytelling, biodiversity and anthropology, large landscapes and individual stories, all of which made this summer invaluable.

Land and Seascape Conservation Fellow, NPCA Sun Coast Office

This summer I had a wonderful time supporting the conservation of the Greater Everglades Landscape. Working alongside the Conservation Science team, the Sun Coast Regional Team, and many NPCA partners, I focused on the highly imperiled natural forest communities within this landscape.

My work involved processing various geospatial datasets to construct a database that explores conservation values and threats associated with forests in the Greater Everglades, while refining natural forest boundaries to help users identify the specific type and locations of these highly fragmented forest patches.

I also contributed to a science communication piece supporting advocacy for Greater Everglades wetland protection, particularly in response to last year’s Supreme Court decision on the Clean Water Act, Sackett vs. EPA. Wetlands have always been my favorite ecosystem, and it was deeply meaningful to contribute to their protection this summer. I hope my work helps regional conservation actions through science-driven toolkits that are communicated in an engaging way!

I love how this fellowship exposed me to so many diverse perspectives and stories that emerge from park narratives, and even taught me how to capture and write these stories.

Pine Rocklands are considered a globally critically imperiled habitat unique to South Florida and the Bahamas. Today, less than 2 percent of the habitat exists outside of Everglades National Park due to rapid urbanization and fragmentation in Miami-Dade county. Hope examined patches where these precious habitats still exist in Miami-Dade.

PHOTO: Stephen Wood, iStock.

EVERGLADES AT RISK: Clean Water Act protections severely

reduced

Drinking water for one in three Floridians depends on the Everglades But in August 2023, a Supreme Court decision drastically weakened the Clean Water Act, stripping protections from vital watersheds and wetlands across the country. Florida, already facing significant loss of wetlands and coastal watersheds due to sprawl development, sea level rise, and increasingly intense hurricanes, is now more vulnerable than ever. With vast areas of the Everglades and other treasured areas across the state no longer shielded by the Clean Water Act, it's critical for communities to understand the potential threats to their watersheds and how water quality could be impacted.

DRINKING WATER WAS ALREADY THREATENED

After the Supreme Court decision

South Florida’s drinking water relies on shallow underground aquifers, which are replenished by the Everglades. Wetlands play a vital role by allowing rainwater to filter into these aquifers and naturally purifying the water. The Clean Water Act regulates pollution and discharges that threaten water quality. Without these protections in place, wetlands and watersheds are at greater risk of increased pollution and degradation. Florida’s aquifers are already under pressure from urbanization, runoff, and rising sea levels that drive saltwater intrusion. If more wetlands are lost or paved over, less rainwater will recharge our aquifers, instead being diverted into runoff or drainage systems.

Alarmingly, nearly 100% of the waters within Everglades National Park and Big Cypress National Preserve are already impaired by pollutants. The loss of Clean Water Act protections in vast areas beyond park boundaries will further threaten water quality.

Kissimmee

HOPE’S SUMMER WORK

National parks aren’t isolated spaces — they are part of broader landscapes.

In the wake of the 2023 Sackett vs EPA Supreme Court decision that significantly reduced federal protections for wetlands, it became crucial to understand the potential impacts and inform communities.

To address this, NPCA teamed up with Stetson University’s Institute for Biodiversity Law and Policy, Institute for Water and Environmental Resilience, and Jacobs Law Clinic to study the Greater Everglades ecosystem under the new Clean Water Act ruling.

Thanks to the university’s experts and students, we now have a deeper understanding of the far-reaching consequences. Hope Liu, NPCA’s Land and Seascape Conservation Fellow, and NPCA’s Sun Coast Regional Office then communicated the results by producing this visually engaging fact sheet using the wealth of data produced by Stetson University to communicate the impacts to a wider audience.

This project brought together a diverse group of conservation practitioners, researchers, and students, highlighting the strength of collaboration from science to communication. This partnership supports NPCA’s ongoing advocacy for clean water protections in the Greater Everglades.

Park Science Magazine | Summer 2024

New

Research Shows Why Arctic Streams Are Turning Orange

In the pristine Brooks Range in Arctic Alaska, streams are turning bright orange and fish are disappearing, threatening the well-being of local communities. A recent scientific paper reveals why.

The Arctic is warming much faster than the global average, and it’s altering terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Warmer temperatures are causing permafrost to thaw and release substances that have been locked in the frozen ground for thousands of years.

O’Donnell and other scientists from the National

Park Service, U.S. Geological Survey, and several universities have since found many more streams that have turned orange across the Arctic. They used satellite images, chemical analysis, and fish population data to determine how biological system were being affected.

Read the article here >

Bird’s eye view of orange stream water mixing with clear water. To pinpoint when orange streams began appearing, the study authors zoomed out even further, and analyzed satellite imagery dating back to 1985. PHOTO: NPS / Ken Hill

BOTTOM

Researchers See Startling Brook Trout Declines in Shenandoah Streams

Brook trout function as an “early warning system” for environmental problems in Appalachian streams. They can alert us to broader ecological problems because they’re sensitive to things like pollution, non-native species, forest loss, and excessive heat.

If you’re exploring the mountains and you find a stream full of brook trout, you can be sure the water is clean and cold. But many streams across the eastern United States have lost their brook trout because of those stressors. In Virginia, brook trout are now largely confined to public lands protected from development. Even so, large-scale problems like air pollution and climate change can threaten protected brook trout. Were these threats harming populations in Virginia’s largest national park?

Read the article here >

Park staff and volunteers capture fish and gather data on brook trout abundance, age, and size before releasing the unharmed fish back to the stream. PHOTO: NPS

Science Resources

NPS Science Links

NPS Adaptation Resources

NPS Air Resources Division. Live weather and air quality data

NPS Alaska Park Science

NPS Connected Conservation Webinar Series

NPS Citizen Science

NPS Climate Change Science

NPS Continuous Water Data

NPS Science of Climate Change video series

NPS Coastal Adaptation

NPS Fossils and Paleontology

NPS Geology

NPS GIS Program

NPS GIS Cartography, GIS and Mapping

NPS Main Archival and Data Repository (IRMA)

NPS Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Directorate

NPS Natural Resources Science Resources (science by discipline)

NPS Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division

NPS Oceans, Coasts and Seashores

NPS Park Science

NPS Pollinators

NPS Research Learning Centers

NPS Research Permit and Reporting System

NPS Science of the American Southwest

NPS Science resources / Explore Nature

NPS Scientist in a Park Program

NPS Social Science

NPS Traditional Ecological Knowledge

NPS Wetlands

NPS Wilderness

NPS Yellowstone Science

Professional Society Memberships at NPCA

AAAS: American Association for the Advancement of Science

AAG: American Association of Geographers

AESS: Association for Environmental Studies and Sciences

AFS: The American Fisheries Society

AGS: American Geographical Society

AGU: American Geophysical Union

ESA: Ecological Society of America

GSA: The Geological Society of America

GWS: George Wright Society

NACIS: North American Cartographic Information Society

SCB: Society for Conservation Biology

SCGIS: Society for Conservation GIS

SVP: Society of Vertebrate Paleontology

TWS: The Wildlife Society

JSTOR: Access to journal articles

For more information on accessing these memberships, please contact Ryan Valdez at rvaldez@npca.org

University-based National Park Programs

University of California, Berkeley: Institute for Parks, People, and Biodiversity

University of California, Merced: National Parks Institute

Clemson University: Clemson Institute for Parks

Duke University: Park Institute of America

Colorado State University, Salazar Center for North American Conservation: Conservation Conversations

Proposed Bahsahwahbee National Monument. Photo by Nik Moy, NPCA.

Science News Fall 2024

Product of NPCA’s Conservation Programs.

Produced by: Conservation Science Ryan Valdez, Nik Moy, and Amy Tian

Contact Nik Moy, nmoy@npca.org, if you would like to share with any audiences external to NPCA or print a version of this newsletter. Additionally, please let us know if you have questions, suggestions, or story ideas for the next issues of Science News.

Interested in helping advance Conservation Science at NPCA? Please reach out to Julie Hogan at jhogan@npca.org to explore how your suppport can make a meaningful impact.

To view this report digitally and access links: