Hale

In the Hawaiian language, hale (pronounced huh’-leh) translates to “house” or “host.” Hale is an intimate expression of the aloha spirit found throughout the islands and a reflection of the hospitality of Ko Olina. In this publication, you will find that hale is more than a structure, it is a way of life. Ko Olina celebrates the community it is privileged to be a part of and welcomes you to immerse yourself in these stories of home.

FEATURES

50

The Mating Game

O‘ahu’s only private snorkeling lagoon is also a wonderland for fish breeding.

64 Mountain Meditations

In the remote reaches of the Wai‘anae Mountain Range, a photographer finds moments of tranquility.

76

Rock Star

For this Mākaha-based celebrity, being multi-faceted means having more than one way to shine.

92

Westward Holoholo

A series of Hōkūle‘a sails around O‘ahu’s West Side unites communities and crew members in the revival of Polynesian voyaging.

Pua Aloha

Local Kine Grinds

Kula Kaiapuni ‘o Kapōlei: For the Love of a Language

Kaleo Patterson: The Kahu

LEARN MORE

LETTER FROM JEFFREY R. STONE

Aloha kākou,

As we transition from the cool temperatures of winter to the warmth of spring and summer, our islands’ vibrant flowers begin to bloom— one of my favorite times of year.

Among them is my favorite flower, pua kenikeni, known for its rich, sweet fragrance that I find both tantalizing and soothing. In ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i, pua kenikeni translates to "ten-cent flower," a name that harks back to when a string of these petite blooms could be purchased for just a dime. These blossoms grow on tall trees surrounding my home and hold a special place in my heart.

Over the years, I’ve had the honor of giving hundreds of lei—at high school graduations, family birthdays, political inaugurations, and countless events and brand launches at Ko Olina. When you see someone wearing a lei, it signals the celebration of a special moment. Receiving one is a cherished gift and a truly meaningful gesture.

The Enduring Legacy of Lei

The history of lei in Hawai‘i stretches back to ancient times, when ali‘i (royalty) and akua (deities) exchanged lei as symbols of honor, connection, and reverence. While often associated with flowers, lei are also crafted from feathers, shells, nuts, leaves—even dollar bills and crack seed—each variation carrying its own meaning. Some, like the intricately made Ni‘ihau shell lei—the only shell jewelry insured by Lloyd’s of London—are passed down as heirlooms, preserving legacy through generations.

Giving or receiving a lei is an act of love, respect, and tradition. Lei play a role in celebrations, religious ceremonies, healing practices, hula, music, storytelling, and more. They embody the spirit of aloha and are treasured as expressions of identity and belonging.

Here in Hawai‘i, Lei Day is celebrated in May, where locals and visitors alike honor Hawaiian culture through concerts, lei-making contests, music, and vibrant displays. The day also nods to the international celebration of spring’s return, with fragrant blossoms scenting the air and beauty blooming everywhere.

Today, lei makers are reimagining ancient traditions, adapting to modern challenges like limited farmland and the scarcity of native flowers. These shifts have inspired creative innovation—crafting lei with unique materials, mixing blossoms with unconventional textures, and adding fresh takes on timeless designs. With each strand, Hawai‘i’s lei makers mirror the past while embracing the present.

Wear

Your Lei Proudly

If you’d like to learn more, there are countless ways to explore the history, artistry, and cultural significance of lei—from books and workshops to films, local stories, and community events. Even here at Ko Olina, you might find opportunities to craft your own lei or join local celebrations that share the spirit of aloha. Whether you're making a lei po‘o at a flower bar, reading about traditional featherwork, or simply observing the ways lei are shared across Hawai‘i, each experience deepens your connection to the land and its people.

To be honored with a lei is to receive a gift of beauty and meaning—wear it with gratitude, and know you are a part of a beloved, timehonored tradition that continues to thrive through generations.

Aloha,

Jeffery R. Stone

Master Developer

Ko Olina Resort

Hale is a publication that celebrates O‘ahu’s leeward community—a place rich in diverse stories and home to Ko Olina.

Here in Hawai‘i, it is the people and places that make our island home special. In this issue, our celebration of the West Side continues through its stories. Follow along as we journey mauka (towards the mountain) to experience quiet moments in cool forests, and then wind our way makai (towards the sea) to visit a fish breeding program working diligently to ensure that colorful reef fish can be enjoyed by future generations. Join us as we hear from a kahu (spiritual leader) who brings the Native Hawaiian cultural practice of Makahiki, a season of rest and restoration, to those incarcerated, and be inspired by students deepening their own connection to Hawaiian culture through total language immersion. Our adventure continues on as we stop by a beloved restaurant to savor favorite local dishes served with a side of history, and spend time with a global celebrity proud of his island roots.

These wide-ranging stories, along with others, speak to the pride, hope, legacy, and joy found on the West Side. We invite you, dear reader, to enjoy them and learn more about the people and places at its heart.

ABOUT THE COVER

Honolulu-based photographer Michelle Mishina captures an intimate portrait of Bretman Rock at his home in Mākaha Valley. For more of the photographer’s work, visit michellemishina.com.

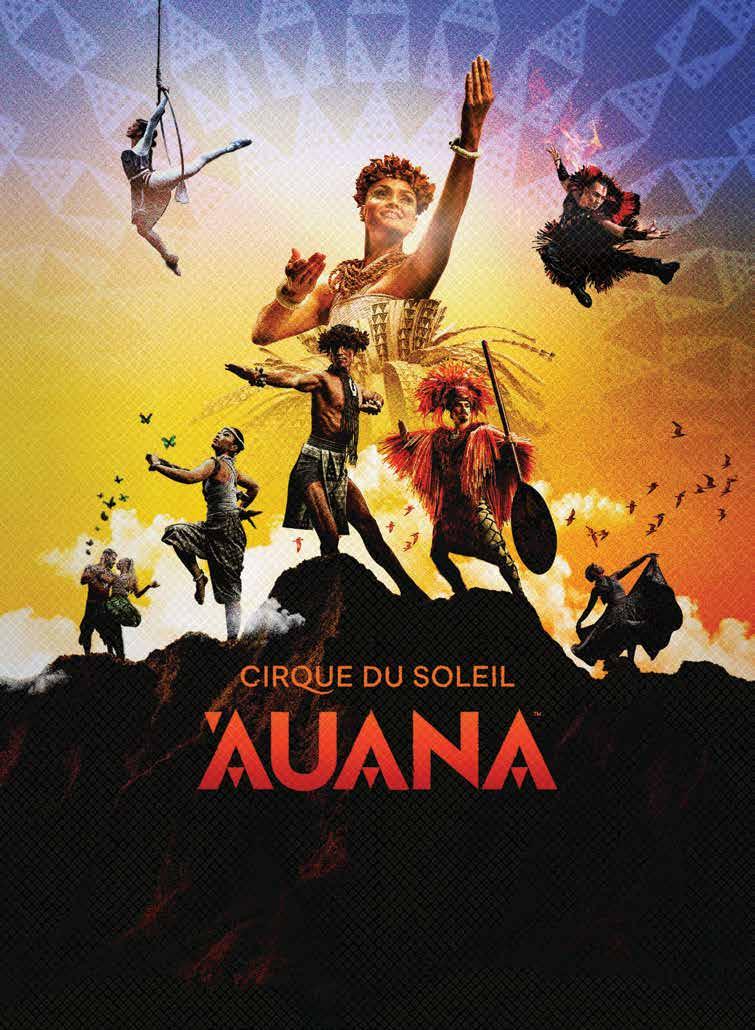

A NEW SUN RISES IN HAWAI’I

A Hawai‘i-inspired production featuring a cast of acrobats, talented musicians and singers, and profound hula dancers. Now performing at the OUTRIGGER eater in Waikīkī.

KoOlina.com

Aulani, A Disney Resort & Spa aulani.com

Beach Villas at Ko Olina beachvillasaoao.com

Four Seasons Resort O‘ahu at Ko Olina fourseasons.com/oahu

Marriott’s Ko Olina Beach Club marriott.com

Ko Olina Golf Club koolinagolf.com

Ko Olina Marina koolinamarina.com

Ko Olina Station + Center koolinashops.com

Newage Ko Olina

The Resort Group theresortgroup.com

CEO & Publisher

Jason Cutinella

Partner & General Manager, Hawai‘i

Joe V. Bock

Editorial Director

Lauren McNally

Senior Editor

Rae Sojot

Senior Photographer

John Hook

Managing Designer

Taylor Niimoto

Designers

Eleazar Herradura

Coby Shimabukuro-Sanchez

Translators

Eri Toyama N. Ha‘alilio Solomon

Advertising

Senior Director, Sales

Alejandro Moxey

Head of Media Solutions & Activations

Francine Beppu

Advertising Director

Simone Perez

Director of Sales

Tacy Bedell

Account Executive

Rachel Lee

Operations & Sales Assistant

Kylie Wong

Sales Inquiries sales@nmgnetwork.com

Operations

Operations Director

Sabrine Rivera

Operations Coordinator

Jessica Lunasco

Traffic Manager Sheri Salmon

Accounts Receivable

Gary Payne

Published by: 41 N. Hotel St. Honolulu, HI 96817

Hale 14 | Spring - Summer

©2025 by NMG Network

Contents of Hale are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. Hale is the exclusive publication of Ko Olina Resort. Visit KoOlina.com for information on accommodations, activities, and special events.

Image by John Hook

“

I always look to nature to see what is there.”

Dale Acoba, lei craftsman

Image by John Hook

Pua Aloha

A Waipahu lei

Text by Viola Gaskell

Images by Viola Gaskell & John Hook

maker draws inspiration from the past to craft lovely strands of lei.

Ho‘oulu ‘ia kona hoihoi e ko ka wā i hala, haku ‘ia he mau lei hiehie e kekahi mea kui pua no Waipahu

ワイパフのレイメーカーは、過去からインスピレーショ ンを得て美しいレイの数々を作り出しています。

On a recent Sunday morning, lei craftsman Dale Acoba arrives at a friend’s birthday party carrying lau hala baskets overflowing with flowers—creamy-hued plumeria, bright purple and green orchids, orange kou, and magenta bougainvillea. On a table, he carefully lays out long lei needles and string. Acoba says a few words on patterning and stringing the blooms, and the friends thread their needles and talk story while partaking in the beloved tradition of making lei.

For Acoba, who moved from the Philippines to O‘ahu in 2006, lei making is both an artistic outlet and a connection to Hawaiian culture. When work at Su-V Expressions, a Honolulu florist, slowed due to the pandemic, he turned to lei making. “I had to figure out a way to stay creative,” Acoba says. What began as gifts for friends quickly blossomed. Drawn to his distinctive style, more and more people began requesting lei.

つい先日の日曜の朝、レイメーカーのデイル・アコーバさんはあふ れんばかりの花を詰めたラウハラのバスケットを抱えて友人の誕生 パーティにやってきた。なめらかなグラデーションが美しいプルメ リア、鮮やかな紫や緑色のオーキッド、オレンジ色のコウ、そしてマ ジェンタ色のブーゲンビリア。アコーバさんは、レイ用の長い針と糸 を注意深くテーブルの上に並べた。そしてパターンや針の通し方に ついて軽く指示を出すと、友人たちは針に花を通しながらおしゃべ りに興じ、昔から愛されてきたレイ作りという伝統を紡ぎはじめた。

2006年にフィリピンからオアフ島に移り住んだアコーバさんに とって、レイ作りは芸術的な感性のはけ口であり、ハワイ文化を身 近に感じる機会でもあった。アコーバさんがレイ作りをはじめたの は、勤めていたホノルルの生花店〈スーヴィー・エクスプレッション ズ〉がコロナ禍の影響で暇になった時期だ。「クリエイティブでいら れる方法を探していたんです」友人へのプレゼントとして作りはじ めたレイはあっという間に評判になる。独特のスタイルが人気を呼 び、注文は次第に増えていった。

Acoba’s approach to lei making strikes a balance between honoring tradition and embracing innovation. While he always returns to the classic lei as a way of paying tribute to the past, Acoba also seeks out unconventional materials to work with. A small collection of books, including Marie McDonald’s 1985 book Ka Lei: The Leis of Hawaii, provides guidance, inspiration, and reassurance. Through them, Acoba realized the lei makers of old were perhaps as inventive as he is today. “It’s validating because I feel like they thought the same way I do,” he says. “They were just being creative and experimenting with what they had.”

Though Acoba favors certain materials— fragrant blooms such as pīkake, pua kenikeni, pakalana, and ‘ilima—he looks for alternatives when those flowers are out of season. When he first encountered pearl yarrow, which he describes as “giant

アコーバさんのレイは、伝統を重視しつつも新しさを取り入れた絶 妙なバランスが身上。伝統を大切にしたいのでクラシックなレイも よく作るが、あまり見かけたことのない素材にも挑戦する。マリー・ マクドナルドによる1985年出版の『カ・レイ ハワイのレイ』をはじ め、レイに関する書物からインスピレーションを得たり、これでいい んだと納得したりしている。書物を通して、往年のレイメーカーたち も今の自分と同じように独創的だったことがわかった、とアコーバ さん。「彼らも自分と同じように考えていたんだなと思うと、自分の やっていることは間違っていないと安心できます。彼らも感性のお もむくままに、周囲にあるものでいろいろ新しいレイを作ってみた んでしょうね」

香りのいいピーカケやプア・ケニケニ、パカラナ、そしてイリマなど、 アコーバさんにもお気に入りの素材はあるが、こうした花が手に 入らない季節は別の材料を探す。彼が「巨大なカスミソウ」と呼ぶ アール・ヤロウ(セイヨウノコギリソウの一種)に初めて出会ったと き、アコーバさんは花を分解してから糸を通してレイを作り、ピーカ

Envisioning how to transform particular flowers into lei often takes Acoba longer than making the lei itself.

Pua Aloha

baby’s breath,” he saw the potential to deconstruct its blooms, string them into lei, and twist them with pīkake strands, blending the two seamlessly. Although he would love to work exclusively with classic lei flowers, Acoba recognizes the challenge of sourcing them, as fewer people are planting them nowadays. Still, he continues to turn to his archives for inspiration. “I look at pictures of historic lei and try to see if there’s any way of recreating them with the materials that are available right now,” he says. His use of unconventional flora has its appeal: Not only are the blooms beautiful, but Acoba also enjoys introducing people to them through his lei.

ケのレイとねじり合わせて2本でひとつのレイにした。昔からレイ作 りに使われてきた花だけでレイが作れるならそれに越したことはな いが、花を育てる人も減った昨今、手に入らないことも多いのだ。そ れでも、彼はときどき手持ちの書物をあたり、インスピレーションを 得る。「昔のレイの写真を見て、今、手に入る材料でそれに近いもの を作れないかと考えるんです」今までとは違う素材のレイは人を惹 きつける。ただ美しいというだけでなく、アコーバさんはレイを通し て新しい素材を人々に紹介するのが楽しいそうだ。

アコーバさんのレイの素材はほとんどがハワイ産だ。自身もさまざ まな植物を育てているし、庭に花木のある友人宅も頻繁に訪れる。

クリエイティブな感性はフィリピンで生まれ育ったからこそ培われ

Pua Aloha

Today, Acoba sources the majority of his lei materials locally, growing many plants himself and regularly visiting friends with flowering trees in their yards. His creativity was shaped by his Filipino upbringing. “I didn’t grow up with much, and that made me resourceful,” Acoba explains. “I always look to nature to see what is there,” he says. At the birthday party, he points to a lei po‘o (lei worn on the head) embellished with fuchsia accents— tiny blooms plucked from a creeper vine he noticed the night before in a friend’s yard, exclaiming, “They are flowering right now, so you’ll see them everywhere in Honolulu!”

たものだ。「小さい頃からものがありませんでしたから、頭を働かせ て工夫するのが得意になりましたね」と、アコーバさんは話す。「自 然に目を向けて、レイに使えるものを探します」誕生日のパーティ で、アコーバさんが見せてくれたレイ・ポオ(頭にのせるレイ)は、フ クシア色のアクセントが美しかった。それは前の晩に友人宅の庭で 摘んだクリーパー・ヴァインの小さな花たちだった。「今がちょうど 盛りなんです。ホノルルのあちこちで咲いていますよ!」

Acoba typically makes three or four lei per week and hosts lei-making workshops.

Pua Aloha

For Acoba, lei making is methodical and meditative. “I’m in my own space, with no one else around,” he says.

Follow lei craftsman Dale Acoba on Instagram @37vp to see his collection and latest floral works.

Pua Aloha

Local Kine Grinds

Text by Jack Kiyonaga

Images by Laura La Monaca

Waipahu restaurant Highway Inn celebrates 78 years of serving it up Hawaiian style.

Piha

ワイパフのレストラン〈ハイウェイ・イン〉はハワイア ン・スタイルの料理を提供して78年目を迎えます。

Lunchtime at Waipahu’s Highway Inn is lively and loud. Newcomers discuss the menu while longtime patrons, often multigenerational customers, order favorites such as beef stew and lau lau. A toddler enjoys her first taste of squid lū‘au. A tūtū (grandparent) celebrates her birthday with a haupia dessert. It’s a familiar scene, and one that has played out at the Highway Inn for decades.

A local favorite, Highway Inn opened its doors in Waipahu in 1947. Back then, the restaurant was a small operation with just three employees: founder Seiichi Toguchi, his wife Nancy, and a dishwasher. These were the plantation days, when sugar and

お昼時のワイパフ。レストラン〈ハイウェイ・イン〉は、にぎやかな喧 騒に包まれている。メニューを見ながら何にしようか迷う新規のお 客の横で、親の代からの常連客がビーフシチューやラウラウといっ たお気に入りの料理を注文している。初めて食べるスクイッド・ルア ウに舌鼓を打つ女の子。ハウピア(ココナツミルク)のデザートで誕 生日を祝うトゥトゥ(祖父母、年配の人)。〈ハイウェイ・イン〉で何十 年も前から見られる家族の風景だ。

ワイパフの人々に愛されてきた〈ハイウェイ・イン〉の創業は 1947年。当時はわずか3人で切り盛りする小さな店だった。

i ka hale ‘aina ‘o Highway Inn, ma Waipahu, ke 78 o ka makahiki iā ia nō e ho‘okuene nei ma ke ‘ano Hawai‘i.

pineapple reigned king in Hawai‘i. During this time, the multiethnic labor force blended their culinary traditions, creating what we now recognize as local-style food, often referred to as “local grinds,” with dishes that represent a diverse range of cultures. For the nearby plantation communities, Highway Inn offered affordable and satisfying pau hana (postwork) meals, but with one key difference: Instead of serving more popular styles of the time, like American, Japanese, or Chinese dishes, Highway Inn focused on Hawaiian fare.

Seiichi, who was of Okinawan descent, “just loved Hawaiian food and wanted to share it,” explains Monica Toguchi Ryan, his granddaughter and third-generation owner of the Highway Inn. She took over the restaurant from her father, Bobby Toguchi, in 2009.

創業者である渡久地政一(トグチセイイチ)さんと妻ナンシーさん、 そして皿洗いのスタッフ。ハワイでは、砂糖とパイナップルが王様よ りもえらかったプランテーション時代のお話だ。その時代、世界各 地からやってきた労働者がそれぞれの食文化を融合させてハワイ の郷土料理ができあがった。人々が”ローカル・グラインズ”と呼ぶ こうした料理は、ハワイの文化の多様性を映し出している。近くの プランテーションで働く人々に、値段も手ごろでお腹も満足するパ ウ・ハナ(仕事のあと)の食事を提供してきた〈ハイウェイ・イン〉だ が、ほかの店とは決定的に違う点がひとつあった。当時人気だった アメリカ料理や日本料理、中華料理ではなく、ハワイ料理だけしか 出さなかったのだ。

沖縄出身の政一さんは「ハワイ料理が大好きで、その思いを人々 と分かち合いたかったんです」と政一さんの孫娘で〈ハイウェイ・ イン〉三代目のオーナーであるモニカ・渡久地・ライアンさんは語 る。モニカさんは2009年、父親のボビー・渡久地さんから店を引 き継いだ。

Seiichi was 14 when he learned to cook Hawaiian food while working at a local diner. Years later, during World War II, Seiichi and his family were forcibly relocated to internment camps on the U.S. mainland, alongside thousands of fellow Japanese Americans. While they were incarcerated, Seiichi spent years working in the camp kitchens in California and Arkansas, honing his culinary skills and recipes. When the family returned to Hawai‘i in 1946, Seiichi laid plans to open a restaurant along Farrington Highway, serving up ubiquitous comfort foods in contemporary Hawaiian cuisine, like chicken long rice, lomi salmon, and poi.

“There weren’t a lot of Hawaiian food restaurants in the 1940s,” Monica says, noting that the menu has barely changed

政一さんは14歳のとき、近くの食堂で働きながらハワイ料理の調 理法を学んだ。やがて第二次世界大戦がはじまり、政一さんとその 家族は数万人の日系アメリカ人とともに米国本土の強制収容所 に移住を強いられた。カリフォルニアとアーカンソーに抑留されて いるあいだ、収容所の食堂で働いて料理の腕を磨き、レパートリー を増やした政一さん。1946年に一家でハワイに引き上げたとき、 ファーリントン・ハイウェイ沿いに食堂を開くことにした。モダンな ハワイ料理に欠かせないチキン・ロング・ライスやロミ・サーモン、 そしてポイといったおなじみの料理を提供する店だ。

「1940年代当時、ハワイ料理を出す食堂はほとんどなかったんで す」モニカさんによれば、この70年間、メニューはほとんど変わって いないそうだ。メニューの基本はあくまでもハワイ料理。「人気があ ろうとなかろうと、うちはずっとハワイ料理一本です」

Highway Inn has been a beloved local haunt for over 75 years.

in the last 70 years. Hawaiian food remains a keystone. “We’ve always been doing this, regardless of its popularity or unpopularity.”

What started as “kind of a hole in the wall,” has since grown into a three-restaurant enterprise serving over 500 meals a day at its locations in Waipahu, Kaka‘ako, and Bishop Museum. Highway Inn’s customer base is wide and diverse. Congressmen drop by. High school sports teams arrive for a post-match fix. But always, there are the beloved regulars ready for their favorite local grinds, especially apparent in Waipahu, where it all started.

“We always consider Waipahu our home,” Monica says with pride.

いわゆる”小さな町の食堂”としてはじまった〈ハイウェイ・イン〉だ

が、今やワイパフ、カカアコ、そしてビショップ博物館内の3店舗を 抱え、1日500食以上を提供する外食企業に成長した。客層も幅 広い。米国議会の議員も立ち寄れば、高校のスポーツチームも試 合のあとに大勢でやってくる。だが、そこにはいつもお気に入りの 料理を食べにくる愛すべき常連客がいる。原点であるワイパフ店で はとくにそうだ。

「わたしたちの本拠地はいつだってワイパフですよ」モニカさんは 誇らしげに言った。

According to Dawn Sakamoto Paiva, Highway Inn’s director of communications, food is a language unto itself. “Here in Hawai‘i, we speak to each other with food. That’s how we show our love.”

Under the leadership of third-generation owner Monica Toguchi Ryan, Highway Inn was named the 2023 Hawai‘i State WomenOwned Business of the Year by the U.S. Small Business Administration.

To learn more about Highway Inn, visit myhighwayinn.com.

Come sailing with us along oahu’s western Coast r elax and enjoy the best sunsets in h awaii Ko olina activity networ K Find us in the 4th l agoon, just steps F rom aulani and Four s easons!

Image by John Hook

“

Going up into the mountains gives me a sense of place and a feeling of being a part of something bigger. All of our problems seem so insignificant up there.”

Josiah Patterson, photographer

Image by Josiah Patterson

A T R E E S U

50 The Mating Game

繁殖ゲーム

O‘ahu’s only private snorkeling lagoon is also a wonderland for fish breeding.

Text by Lindsey Vandal

Images by John Hook

Ho‘okahi nō kai kohola e lu‘u ai ma O‘ahu nei, noa ‘ole i ka lehulehu, he wahi ho‘i e ho‘opi‘i ai i ka i‘a.

オアフ島唯一のプライベートなシュノーケル用珊瑚礁は、魚た ちが次々に命を生み出すワンダーランドです。

Within the pool area of Aulani, a Disney Resort & Spa at Ko Olina, a saltwater lagoon glitters in the midmorning sun. Beneath its surface, hundreds of native tropical fish glide through a 3,800-square-foot reef designed to replicate natural marine habitats. Here, at what the property whimsically calls Rainbow Reef, guests swim and snorkel, immersed in a colorful tableau of angelfish, surgeonfish, and other reef species. While the reef offers guests a captivating experience, it also plays a vital role in Aulani’s sustainability efforts, fostering a thriving fishspawning habitat.

In 2016, Rainbow Reef joined a fishbreeding pilot project led by Rising Tide Conservation and Hawai‘i Pacific University’s Oceanic Institute to test the viability of marine ornamental fish aquaculture, the practice of cultivating marine creatures for the aquarium industry. Though freshwater aquaculture is a common practice for reducing the impacts of wild fish collection, only a small percentage of marine species have been successfully reared through aquaculture to date. The success of the pilot project hinged on two critical stages: the systematic harvesting of fertilized fish eggs by Rainbow Reef and other aquarium partners, and the raising of the embryos into juvenile fish in the

コ・オリナにあるディズニー・リゾート・アンド・スパ、ア ウラニのプールエリアでは、海水の珊瑚礁が昼前の日 差しを受けてまぶしく輝いている。水面下では何百と いうハワイの熱帯魚たちが、彼らの生息地をそっくり 再現したおよそ350平方メートルの珊瑚礁を優雅に 行き来する。〈レインボー・リーフ〉とディズニーらしい 名がつけられたこの珊瑚礁でゲストはシュノーケルを 楽しみ、エンジェルフィッシュやサージョンフィッシュが 描くカラフルな水中の景色を堪能する。ゲストに魅惑 のひとときを提供する珊瑚礁は、魚たちが繁殖しやす い環境がととのっているため、アウラニの環境保護の 取り組み上でも重要な役割を果たしている。

〈レインボー・リーフ〉は、観賞魚産業における海水魚 養殖の可能性を探るため、〈ライジング・タイド・コンサ ヴェーション〉という団体とハワイ・パシフィック大学 海洋研究所が取り組む実験的な繁殖プロジェクトに 2016年から協力している。野生の魚の乱獲を避ける ために淡水魚を養殖するのは一般的だが、養殖に成功 した海水魚の種類はまだとても少ないのだ。

プロジェクトの成功に欠かせないポイントは2つある。 プロジェクトに協力する〈レインボー・リーフ〉や水族 館などで計画的に受精卵が採取できるかという点と、 海洋研究所の水槽で仔魚が稚魚になるまで育てら れるかという点だ。珊瑚礁内の生態系が細心の注意

Oceanic Institute’s nursery. Early in the project, Rainbow Reef emerged as an ideal egg-harvesting partner thanks to its carefully managed ecosystem and abundant egg production.

“Our fish are so happy and comfortable in the lagoon that they don’t really have to think about anything else—they’re just busy producing eggs every day,” says Rafael Jacinto, the animal and water sciences operations manager at Aulani. “We’re great at keeping the parent fish healthy, and the nursery team focuses on the rest—food culture, microalgae, feeding larval fish—which can be major roadblocks in aquaculture. Everybody is doing the best that they can.”

を払って管理されていて、たくさんの卵を採取できる ことから、プロジェクトがはじまった当初から〈レイン ボー・リーフ〉は理想的な受精卵提供者として注目さ れていた。

「珊瑚礁の魚たちは安心して快適に暮らしているの で、それ以外のことを考える必要もないんですよ。毎日 せっせと卵を産んでます」と語るのは、アウラニの生物 および水質科学部門のマネージャー、ラファエル・ハシ ントさん。「親魚の健康管理はわれわれが得意とすると ころです。餌の養殖やマイクロアルジェ(微細藻類)、仔 魚の餌やりなどは海洋研究所の養殖チームの担当で すが、そちらのほうがいろいろ大変なんですよ。それぞ れが最善を尽くしてプロジェクトに取り組んでいます」

Jacinto attributes the fish’s prolific spawning to the meticulous care the Animal Programs staff takes in maintaining a harmonious ecosystem. Additionally, the strategic mix of fish species—mostly herbivores with a few predatory fish, modeled after Hawai‘i’s near-shore ocean environment—plays a key role in ensuring the health and productivity of its inhabitants. According to Spencer Davis, a senior research associate in the Marine Finfish Aquaculture Program at Oceanic Institute, Rainbow Reef’s team was integral in establishing the project’s proof of concept. The shared passion is there too. “There’s a synergy that stems from our crews getting equally excited about what each other was doing,” Davis says.

Such teamwork makes the dream work. Not only was Rainbow Reef the first of the collaborating partners to confirm the feasibility of their egg-collection setup, the pilot project led to the first recorded captive breeding of the Hawaiian cleaner wrasse, a bright blue and yellow fish, and the playful Potter’s angelfish, both endemic to Hawai‘i, as well as the kīkākapu (raccoon butterflyfish) and lauwiliwilinukunuku‘oi‘oi (longnose butterflyfish), two of Hawai‘i’s native fish species.

ハシントさんによれば、〈レインボー・リーフ〉の魚の繁 殖力が高いのは、注意深く生態系の調和をたもってき たスタッフの努力の賜物だ。ハワイ沿岸の環境を模し て、肉食種はほとんど入れず、魚の大半を草食種にす るなど魚種のバランスに気をつけていることも、魚たち の健康と繁殖力の維持に大きく貢献している。

海洋研究所の海洋魚養殖プログラムに上級研究者と してたずさわるスペンサー・デイビスさんは、〈レイン ボー・リーフ〉のチームは、このプロジェクトのコンセプ トが間違っていないことを証明しているという。チーム が一丸となってプロジェクトに取り組んでいる点も見 逃せない。「スタッフみんながお互いの功績を高く評価 している。そのことがすばらしい相乗効果を生み出し ています」

チームワークが夢を現実にした。受精卵の採取予測 が可能であることを最初に立証したのも〈レインボー・ リーフ〉だし、このプロジェクトのおかげで、ハワイ固有 種で鮮やかな青と黄色が美しいハワイアン・クリーナ ー・ラス(ホンソメワケベラのハワイ版)やポッターズ・ エンジェルフィッシュ、さらにはハワイ原産のキーカー カプ(チョウハン)やラウウィリウィリヌクヌクオイオイ (フエヤッコダイ)などの繁殖の様子も初めて記録さ れたのだ。

The Mating Game

Newly spawned fish eggs are captured in nylon mesh jars at various spots around Rainbow Reef. A float test is done to separate the viable eggs from the nonviable ones (the viable eggs will float), then the embryonic fish are bagged in oxygenated water for transport to the nursery. The Rainbow Reef team regularly logs egg-production data as a reliable indicator of the health of the marine life. “If there’s a big drop in egg counts on any given day, we’re checking to see if a change in diet, habitat, or other factor could be causing an imbalance,” Jacinto says. As of 2025, Rainbow Reef is a regular donor in support of Oceanic Institute’s

産卵されたばかりの魚の卵は、ナイロンメッシュの容 器を使って〈レインボー・リーフ〉の数カ所で回収され る。フロートテストを行って受精卵と非受精卵とを分 け(受精卵は浮く)、ふ化した仔魚は海洋研究所への 移動に向けて酸素を注入した水の袋に入れられる。〈 レインボー・リーフ〉では、魚たちの健康状態をきちん と確認するために定期的に産卵数を記録している。「

卵の数が急激に減ったときは、餌や生活環境など、何 かのバランスが崩れていないかを調べます」とハシン トさん。2025年現在、〈レインボー・リーフ〉は一回の 回収ごとに約3万から10万個の受精卵を提供して、海 洋研究所が継続する養殖プログラムへの協力を続け ている。

The

ongoing aquaculture efforts, generating anywhere from 30,000 to more than 100,000 viable eggs per collection.

At Oceanic Institute’s biosecure facility in Waimānalo, the fish eggs are counted, disinfected in a diluted hydrogen peroxide bath, and then placed into 1,000-liter larval-rearing tanks. The most labor-intensive part of egg rearing is farming the plankton for live feeds, Davis explains. In addition to ensuring each species receives the appropriate food, the scientists must provide the fish with larger varietals of plankton as they mature. “These are live animals, so there are no days off,” he adds. “You have to

ワイマナロにある海洋研究所の防菌施設では、数を確 認した魚卵を過酸化水素の水溶液で消毒してから1ト ンの稚魚飼育水槽に入れる。デイヴィスさんによれば、 稚魚の飼育過程でもっとも重労働なのは餌となるプラ ンクトンの栽培だそうだ。種類の違う魚たちにそれぞ れ適した餌を与えるのはもちろん、成長するにつれて プランクトンの種類も増やさなければならない。「生き もの相手ですから休みはありません」デイヴィスさんは つけ加えた。「1日8時間以上、実際にここに来て世話 をしなければならないんです」魚の種類によって期間 は1〜3ヶ月と幅があるが、幼魚の段階にまで成長して やっと粒状の人工餌で対応できるようになる。

Visit Ka Makana Ali’i on our FREE SHOPPING SHUTTLE!

Ask your concierge or book your ride here

AERIE

AMERICAN EAGLE

BATH & BODY WORKS

H&M

MACY’S RIP CURL

VICTORIA’S SECRET

FOODLAND FARMS

REYN SPOONER

CALIFORNIA PIZZA KITCHEN

THE CHEESECAKE FACTORY

GEN KOREAN BBQ

JOHNNY ROCKETS

KICKIN KAJUN

OLIVE GARDEN

TAQUERIA EL RANCHERO

physically be here to care for them for more than eight hours a day.” When the fish reach juvenile stage—in one to three months, depending on the species—they can be transitioned to an artificial diet in pellet form.

At this stage, the cultivated fish are sent to Oceanic Institute’s partners, such as state or federal agencies, public aquariums, fish wholesalers and retailers, and conservation groups. Last fall, Oceanic Institute and Rainbow Reef worked with the Hawai‘i State Department of Land and Natural Resources to release 300 captive-bred juvenile yellow tang in the coastal waters around O‘ahu, including those fronting Aulani. The milestone event marked Hawai‘i’s first documented release of fish aimed at ecosystem restoration, as opposed to population increase. Sediment runoff and toxic substances, like sunscreen containing oxybenzone, contribute to the development of invasive turf algae, which smothers coral. Yellow tang graze on the turf algae to help keep it at bay. “When we first opened Rainbow Reef, we started with around 300 yellow tangs in the lagoon,” Jacinto recalls. “During that one day, we were able to return roughly the same number of yellow tangs back to the ocean. That’s pretty special.”

ここまで成長した養殖魚は、海洋研究所が提携する連 邦政府や州政府機関、公立の水族館、魚の卸売業者 や小売業者、あるいは保護団体が引きとる。昨秋、海洋 研究所と〈レインボー・リーフ〉はハワイ州土地と自然 資源局とともに、養殖したキイロハギ300匹をアウラ ニ前の海も含めてオアフの沿岸各地に放流した。その 目的は、魚の個体数を増やすことではなく、生態系の 回復だ。流出した堆積物や、メトキシケイヒ酸エチルヘ キシルが入っている日焼け止めなどの有害物質は、侵 略的外来種で珊瑚を窒息させるターフ・アルジー(藻 の一種)を増加させてしまう。キイロハギはそのターフ・ アルジーを食べてくれるのだ。

「〈レインボー・リーフ〉のオープン時、約300匹のキイ ロハギがいたんです」ハシントさんは振り返る。「あの 日、わたしたちはほぼ同じ数のキイロハギを海に返す ことができました。とても感慨深かったですよ」

Mountain Meditations

山での瞑想

In the remote reaches of the Wai‘anae Mountain Range, a photographer finds moments of tranquility.

Text by Rae Sojot

Images courtesy of Josiah Patterson

Ma uka ‘iu‘iu o ka pae mauna ‘o Wai‘anae, ma laila nō e ho‘ola‘ila‘i ai kekahi pa‘i ki‘i.

ひと気のないワイアナエ山脈の果てで、写真家は静寂のとき

For Mākaha-based photographer Josiah Patterson, heading mauka, or toward the mountain, is an exercise in calm and repose. While many associate O‘ahu’s West Side with long stretches of sundrenched coast against a brilliant blue sea, Patterson focuses on the often overlooked: a valley’s gentle slopes, the stillness found in the upper forests, the seam of a ridgeline against a swath of sky.

Here, in the nearly four-million-yearold Wai‘anae Mountain Range, the senses become attuned to the cool uplands and their quiet treasures. Patterson notes the joy of discovering an interesting rock and the interstitial light distilled through a forest canopy. He describes psithurism—the sound of wind moving through the trees—and the faint, loamy sweetness that lingers after a rain. As he ascends in elevation, so, too, do his mountain meditations: “Going up into the mountains gives me a sense of place and a feeling of being a part of something bigger,” Patterson shares. “All of our problems seem so insignificant up there.”

マーカハ在住の写真家ジョサイア・パターソンにと って、マウカ、つまり山に向かうことは静けさと平穏を 取り戻すことを意味する。オアフ島のウエストサイドと いえば、鮮やかな青い海を背景に太陽が降り注ぐ長い 海岸線を思い浮かべる人が多いが、彼は人々が見過ご しがちな谷間の穏やかな起伏や山頂に近い森の静け さ、空に浮かぶ尾根の線などに目を向ける。

400万年前からあるワイアナエ山脈で、高原の涼やか さと、そこに静かにたたずむ宝物たちに五感の波長を 合わせる。パターソンが心動かされるのは、不思議な 石のかたちや森の梢から差し込む木漏れ日に気づい たときの喜びだ。伝えたいのは、木立ちを揺らす風の ざわめき。雨のあとで気づく、かすかに土を感じる甘 い香り。標高が上がるにつれ、感覚も研ぎ澄まされる。

「登っていくにつれ周囲との一体感が高まり、自分が 何か大きなものの一部だという感覚にとらわれます」 パターソンは語る。「どんな悩みもたいしたことではな いという気になるんです」

Rock Star

ロックスター

For this Mākahabased celebrity, being multi-faceted means having more than one way to shine.

Text by Rae Sojot

Images by Michelle Mishina

No kēia maka kaulana no Mākaha, he lau a lau kona mau ‘ano, pēlā nō ‘o ia e ‘imo‘imo ai me he hōkū lā.

マーカハ在住のセレブにとって、さまざまな顔を持つことは、 さまざまなかたちで輝けるということなのです。

Filipino American influencer Bretman Rock Sacayanan got a glimpse of his future stardom soon after arriving in Hawai‘i from the Philippines as a child. Right off the plane, the then 8-year-old was swept into a whirlwind of errands: a visit to his new home, a quick detour at the swap meet, enrollment at his new school, and, finally, a run for school supplies. “Girl, when I walked into Walmart and saw the CCTV screen, that was the first time I ever saw myself on TV,” he recalls. “I was in awe. I thought I was in Big Brother, like the world was seeing me.” He preened, posed, and primped, oblivious to the stream of patrons around him—and that his mom had already disappeared down the aisles. Bretman chuckles at the memory. “Honestly, seeing myself on that screen just resonated with me being me. That’s when I knew where I wanted to be and where I belonged.”

Growing up, Bretman recalls that his sunny disposition (“Gay, if you will,” he quips) naturally drew people into his orbit. Living with a large extended family meant there was always someone to play batuhang bola or watch Super Inggo with. His enthusiasm for helping with chores—whether chopping vegetables, feeding the chickens, or preparing guava leaves for his grandmother, an albularyo (Indigenous folk healer), to smudge the house, made him a precocious presence.

フィリピン系アメリカ人のインフルエンサー、ブレット マン・ロック・サカヤナンさんは子供のとき、フィリピン からハワイに移住したその日に、未来のスターダムを 束の間、経験したそうだ。当時8歳のブレットマンさん は、飛行機を降りたその足であちこち連れ回された。 新しい住まいを訪れ、途中でスワップミートに寄り道 し、新しい学校で転入手続きを済ませ、ようやく学校 で使う文房具を買いに出かけた。「ウォルマートの入口 で監視カメラのスクリーンを見たんです。テレビに映る 自分を見たのは初めてでした」ブレットマンさんは振り 返る。「心底びっくりしました。『ビッグ・ブラザー(’90 年代にはじまった米国のリアリティ番組)』に出演して いるみたい、世界中の人が僕を見てる、と思ったんで す」お母さんはとっくの昔に陳列棚の向こうに姿を消 していて、ブレットマンさんは周囲に人が大勢いること も気にせず、髪や服をととのえ、ポーズをとり、カメラに 向かって微笑みかけた。ブレットマンさんはそのときの ことを思い出してくすくす笑う。「スクリーンのなかの自 分を見て、これぞ自分のあるべき姿だと思いました。自 分が何者で、どんな場所にいたいのか、そのとき自覚し たんです」 ブレットマンさんは子供のときから明るい性格で、自然 に人を惹きつけてきた。(「ゲイと言ってもかまわないわ よ」彼はからかうようにつけ加えた。ゲイという単語に は”楽しい、陽気な”という意味がある。)大勢の親戚と 同居していたので、バトゥハン・ボラ(ドッジボール)の 相手や、『スーパー・インゴ(フィリピンのアクションヒー ロー番組)』を一緒に見る人にも困らなかった。野菜を 切ったり、鶏に餌をやったり、アルブラリョ(フィリピン では民間療法の祈祷師をこう呼ぶ)であるお祖母さん

“I was always so excited, like, oh my god, I have a responsibility,” he says of his eagerness to shine, even in the most mundane tasks.

On Sunday mornings, the young Bretman would attend to his most cherished duty: assisting his grandmother as she prepared for church. He’d help her choose between her three Avon lipstick shades and select her stockings, then watch mesmerized from her fainting couch as she applied her makeup. Not wanting to exclude him from this ritual, she’d swirl blush onto a brush from a compact and then gently tap some powder onto his cheeks.

が家屋をいぶして清めるのに使うグアバの葉をそろえ たり、お手伝いも大好きだったせいか、子供のころから 早熟だったそうだ。「いつだってうきうきしながらお手 伝いをしました。すごいわ、こんなに大事なことをまか されちゃったって喜んでいたんです」どんなに普通のこ とをやっていても、きらきら輝いていたかったのだ。

日曜の朝は、若きブレットマンさんが何より楽しみにし ていたお手伝いが待っていた。教会に行く準備をする お祖母さんのアシスタントだ。3本あるエイヴォンの口 紅のなかから色を選び、ストッキングを選び、色褪せた ソファに座って、化粧をするお祖母さんの姿をうっとり 見守った。何もしないで待っているのも可哀想だと思 ってか、お祖母さんはコンパクトの頬紅をブラシにと り、ブレットマンさんの頬にそっとのせてくれた。

He remembers the surge of delight. “Girl, I walked into church thinking, ‘I’m prettier than these angel statues,’” he says, laughing.

It was during these moments of observing his grandmother transform that Bretman fell in love with the concept of “Woman.” The art of beautifying oneself in preparation for the day resonated with him, sketching out the first malleable lines of his gender-fluid identity. “My grandma knew who I was before I even knew who I was,” Bretman says, noting the absence of formalized two-gender pronouns in Tagalog, his native tongue. “In my language, we don’t have a he or she, it’s siya.” He also explains that he never had to “come out” as queer. His family—and culture—served

ブレットマンさんは、天にも昇る心地がしたそうだ。 「”まわりの天使の彫刻より、僕のほうがずっとかわい い”って思いながら教会に入っていきました」彼は楽し そうに笑う。

こうして祖母の変貌を見守るうちに、ブレットマンさ んは”女性”というコンセプトの虜になった。これから 迎える一日のために自分を美しく飾る行為に共感し、 性別にとらわれない彼のアイデンティティを写すス ケッチの、変幻自在な線はこうして描かれていった。

as the keystone to become unequivocally himself. “He, she, they—I’m all of it!”

Beyond his all-encompassing identity, Bretman’s grandma also foresaw an auspicious future, occasionally sharing what she sensed through dreams, visions, or deep intuition. “She’d tell me, ‘A lot of people will know your name,’” he says, adding that in Tagalog, there isn’t a specific term for ‘famous.’ Being named after two of his father’s favorite ’90s wrestling legends—Bret “The Hitman” Hart and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson—was perhaps yet another sign that Bretman was indeed destined for something larger than life.

Since going viral with his social media content as a teenager in 2015, Bretman has amassed a massive fanbase—nearly 19 million followers across Instagram and TikTok. While many influencers are defined by a single niche, Bretman has transcended the beauty content that initially made him famous, evolving into someone who shares all facets of his life. His infectious charm and authenticity have been key to capturing the attention of his doting audience. Once, during a photo shoot, when complimented for his “incandescent” skin—a word he was unfamiliar with—Bretman wasn’t shy about asking for its meaning. Pleased with the definition, he rolled the word around in his mouth with pleasure.

「僕が何者かを僕自身が自覚する前から、祖母にはわ かっていたんです」彼の母国語であるタガログ語には、 性別を区別する代名詞はない。「タガログ語にはhe (彼)もshe(彼女)もなく、みんなsiyaなんです」ブ レットマンさんは、クィアとして”カミングアウト”する 必要もなかったそうだ。彼がありのままの彼自身でい るための土台は、家族とフィリピンの文化が要石と なって支えてくれた。「僕はheであり、sheであり、they でもあるんです!」

すべてを包含する彼のアイデンティティはさておき、 ブレットマンさんのお祖母さんは孫である彼の明る い未来を予知し、夢やビジョン、直感的に感じたこと などをときどき話してくれたそうだ。「”あなたの名前 をたくさんの人が知るようになるよ”って言われてい ました」ブレットマンさんはタガログ語で祖母の言葉 を口にしたが、そこには”有名”という言葉は入ってい なかった。だが、父親が好きだった’90年代のレスリ ングのレジェンド、ブレット・”ザ・ヒットマン”・ハートと ドゥウェイン・”ザ・ロック”・ジョンソンにちなんで名付 けられたことも、脚光を浴びる運命を予兆するサイン だったのかもしれない。

まだティーンエイジャーだった2015年にソーシャルメ ディアのコンテンツが大人気となって以来、ブレットマ ンさんには膨大な数の熱狂的ファンがいる。インスタ グラムとティックトックを合わせてフォロワーが1900 万人。多くのインフルエンサーのコンテンツが特定の 分野に限られているのに対し、ブレットマンさんはもと もと彼を有名にした美容に関するコンテンツを超えて、 日常のあらゆるシーンを紹介している。つい惹き込まれ てしまう人間的魅力と嘘のないコンテンツが、彼を熱

When his walk was described as “jaunty,” he upped the pep to his step, fully leaning into his playful side.

He jokes, too, about his evolving “rock” eras. “When I was small, that was like, Bretman Pebble,” he says. Today, he’s in the midst of his Bretman Rock era, where his diverse interests match his diverse audience. Whether showing how to make his favorite matcha drink or sharing his morning-after reveal of sleeping with a silk hair bonnet, his content reflects his humor, relatability, and curiosity. It’s all part of his everadapting narrative of self-exploration

愛するファンたちの心をとらえて離さないのだ。とある 撮影中に肌が”インカンデセント(光輝く、まばゆい)”だ と褒められた。聞きなれない言葉だったが、臆せず意 味を尋ね、意味を教えられるとうれしそうに何度もそ の言葉をつぶやくのがブレットマンさんなのだ。元気な 歩き方だね、と言われれば、ますます元気に歩いてみせ て、陽気な面をあますことなく発揮する。

“ロック(石)”である自分の進化も、ブレットマンさんは おもしろおかしく解説する。「小さいときは、ブレットマ ン・”ペブル(小石)”だったんです」たくさんの分野に興 味を持ち、さまざまなファンを抱える今の彼は、ブレッ トマン・”ロック”時代の最中にいるそうだ。お気に入り の抹茶ドリンクを紹介したかと思えば、シルクの

and self-celebration—and fans love every moment. Looking ahead, Bretman envisions his future with the same sense of humor and zest for life. “When I’m old, I’ll be Bretman Boulder,” he says, envisioning a life split between Hawai‘i and the Philippines, one where he eventually scales back content creation to savor the fruits of his labor.

In between filming his Da Baddest

Radio podcast and his travel and media engagements, Bretman immerses himself in various projects at home. Landscaping has become a favorite hobby, and he does most of the planting himself. He exercises, tends to his menagerie of animals, and hangs out with family and close friends. A daily journaling habit offers him insight into his evolution as both an individual and influencer, and he sometimes reflects on his grandma’s early predictions. “She said I was going to be a star,” he muses, forever grateful for how his relationship with her laid the foundation for his self-awareness, self-acceptance, and, ultimately, his self-confidence.

But perhaps, in those early visions, it wasn’t exactly a star his grandmother saw—but the making of something even more brilliant, formed by pressure and time: A diamond.

ボンネットをかぶって寝た翌朝の姿を披露するなど、 彼のコンテンツはユーモアたっぷりで、誰もが共感で きて、旺盛な好奇心に満ちている。すべては日々刻々と 変わっていく彼自身の自分探しと自己賛美の物語で、 そこがファンにはたまらないのだ。将来は、と訊かれた ブレットマンさんはおどけた口調で生き生きと答えた。

「歳をとったら、ブレットマン・”ボルダー(岩)”になる つもり」コンテンツ制作の時間は少しずつ減らし、ハワ イとフィリピンを行き来しながら、人生をもっと楽しん でいきたいそうだ。

自身のポッドキャスト『ダ・バッデスト・ラジオ』の収録 や移動、メディア取材の合間を縫って、ブレットマンさ んは自宅でさまざまなプロジェクトに取り組んでいる。

庭いじりは今いちばんお気に入りの趣味で、草花や木 も自身で植える。エクササイズは欠かさず、生きものた ちの世話をし、家族や親しい友人たちとの時間も大切 にしている。毎日、日記をつける習慣は、個人として、ま たインフルエンサーとして、自分がどんな成長を遂げて きたかを振り返る手がかりになるというブレットマンさ んは、ときどきずっと前のお祖母さんの予言を思い出 す。「祖母は、僕がスターになると言っていました」お祖 母さんがいたからこそ、自分が何者かに気づき、自分を 受け入れ、さらには自信を持つこともできた。そのこと に彼は心から感謝しているそうだ。

もしかしたら、ブレットマンさんのお祖母さんが見たの は星ではなかったのかもしれない。星よりずっとまぶし く輝いて、プレッシャーと歳月が作り出すもの。一粒の ダイアモンドではなかっただろうか。

Westward Holoholo

ウエストワードでホロホロ

With visits to O‘ahu’s

West Side and other communities across the island, Hōkūle‘a returns home in an act of solidarity following the Lahaina Wildfires

Text by Lindsey Vandal

Images by John Hook

‘Oiai ia e kipa ana iā Wai‘anae mā ma O‘ahu nei me nā kaiāulu aku ho‘i, ho‘i mai ana ‘o Hōkūle‘a me ke kāko‘o mai ma hope mai o nā ahi i ‘ā wale ma Lahaina.

オアフ島ウエストサイドをはじめ、ハワイ諸島の各地を訪れた ホークーレア号はラハイナ火災後の人々の心をひとつにしました。

Less than six months after embarking on the four-year Moananuiākea Voyage, a circumnavigation of the Pacific initiated in June of 2023, Hōkūle‘a—the first wa‘a kaulua (Hawaiian double-hulled canoe) built in modern times—headed back to the Hawaiian Islands. As acting captain at the time, Polynesian Voyaging Society CEO Nainoa Thompson made the tough call to return home, echoing his crew’s desire to offer support and solidarity in the wake of the devastating August 8, 2023 fires in Lahaina, Maui.

Embodying the spirit of ho‘omau, the Hawaiian value of perseverance, the Polynesian Voyaging Society later went on to rekindle its plans for the Moananuiākea Voyage. But before venturing back out into the big, wide world, Hōkūle‘a had to say a proper goodbye: The proud wa‘a kaulua traveled to Lāhainā on August 8, 2024— the one-year anniversary of the fires—

近代に入って初めて建造されたヴァア・カウルア (ハワイ式双胴カヌー)、ホークーレア号は4年をかけ て環太平洋を巡る予定の〈モアナヌイアーケア〉の航 海に出たが、半年もたたないうちにハワイに戻ってき た。2023年8月8日にマウイ島ラハイナに壊滅的な被 害をおよぼした火災のあとで、人々を力づけ、団結の精 神を示したいという乗組員たちの声を受け、暫定的に 船長を務めていたポリネシア航海協会の会長、ナイノ ア・トンプソンさんが苦渋の決断を下した結果だ。

then charted a course for a 7-month, 31-port Pae ‘Āina Statewide Sail that included several stops along the West Side of O‘ahu.

“The Pae ‘Āina speaks to the essence of Hawaiian voyagers of the past,” says Wai‘anae native and regular Hōkūle‘a crew member Isaiah Pule, who participated in the statewide sail.

“Before they went out to sail or find new land, they had to ensure that their home lands were OK. ”

Pule recalls being introduced to Polynesian voyaging as a seventh grader, when his class at Kamaile Academy spent a day on Pōka‘ī Bay, learning from the navigators of E Ala, a 45-foot wa‘a kaulua constructed in 1982 for outreach

ハワイ語で不屈を意味する”ホオマウ”の精神のもと、 ポリネシア航海協会はやがて〈モアナヌイアーケア〉の 航海を再開した。だが、果てしなく広い世界へと再び 船出する前に、きちんと別れを告げる必要があった。 誇り高きヴァア・カウルア、ホークーレア号は、火災から ちょうど1年後の2024年8月8日にラハイナに寄港し、 その後、7ヶ月かけてオアフ島ウエストサイドの数カ所 を含め、ハワイ各地の31の港を巡る〈パエ・アーイナ・ ステイトワイド・セイル〉に出航した。

「〈パエ・アーイナ〉は、ハワイ古来の航海のあり方を 再現しているんです」ワイアナエ出身でホークーレア 号の乗組員としてハワイ各島を訪れているアイゼア・ プレさんは語る。「ハワイアンは、航海に出て新しい土 地を発見する前に、必ず自分たちの島の安全を確かめ たんです」

Westward Holoholo

along the Wai‘anae coast: “Talking to crew members, seeing that E Ala belongs to Wai‘anae, and I belong to Wai‘anae, gave me a connection to my community that was bigger than anything else I had seen. After that day, I was hungry to learn more.”

As executive director of E Ala Voyaging Academy, the Native Hawaiian nonprofit organization offering voyaging training on E Ala, Pule helped to organize Hōkūle‘a’s West Side landing and departure events during the Pae ‘Āina. At Ko Olina, Wai‘anae’s Pōka‘ī Bay, Mākaha, and Nānākuli, families were invited to learn about time-honored Polynesian wayfinding techniques— using natural signs and methods to navigate vast ocean distances without the use of modern technology—straight from Hōkūle‘a’s skilled navigators.

Although E Ala was absent from the Pae ‘Āina events due to ongoing restoration, West Side residents had the opportunity to climb aboard Hōkūle‘a, as well as several smaller canoes designed for short, near-shore sails. These included the 30-foot Kūmau from the youth-focused ocean safety and conservation organization Nā Kama Kai, the 29-foot Kānehūnāmoku from Kānehūnāmoku Voyaging Academy, a wayfinding program for

プレさんは7年生(中学1年生)のときに初めてポリネ シア流の航海術に触れた。通っていた私立の小中高一 貫校、カマイレ・アカデミーがポーカイー湾で校外授業 を行った際に、1982年に建造された全長約14メート ルのヴァア・カウルア、エ・アラ号の航海士たちと交流す る機会を得たのだ。「クルーの人たちの話を聞いて、エ・ アラ号も自分もワイアナエに属しているんだと気づき、 自分とこの場所とのつながりをそれまでよりずっと強く 感じたんです。それ以来、もっと学びたいという思いは 募るばかりでした」

ネイティブ・ハワイアンによる非営利団体として、エ・ アラ号の船上で航海術を教えるエ・アラ航海術アカデ ミーのエグゼクティブディレクターでもあるプレさん は、〈パエ・アーイナ〉の航海中、ホークーレア号がウエ ストサイド各地に寄港する際のイベントなどの準備に もたずさわってきた。近代的なテクノロジーを使わず、 自然の目印や方法だけを使って果てしない大海原を 旅するポリネシア古来の航海術。コ・オリナ、ワイアナ エのポーカイー湾、マーカハ、そしてナーナークリで、 周辺の人々は家族そろってホークーレア号の熟練の 航海士たちから直接、航海の手ほどきを受ける機会に 恵まれた。

エ・アラ号は現在修復中のため〈パエ・アーイナ〉のイ ベントには登場しなかったが、ウエストサイドの住民た ちはホークーレア号だけでなく、青少年向けの海の安 全や保護を中心に活動する団体、ナー・カマ・カイが 所有する長さ約10メートルのクーマウ号、ハワイアン の血を受け継ぐ青少年に航海術を教えるカーネフー ナーモク航海アカデミーに所属する長さ約9メートル のカーネフーナーモク号、ポリネシア文化センター所

Westward Holoholo

Native Hawaiian youth, and Ka ‘Uhane Holokai, the 24-foot training wa‘a kaulua from Polynesian Cultural Center.

“It’s like stringing flowers on a lei. Each community is special in its own way,” says Polynesian Voyaging Society apprentice navigator Kai Hoshijo, who sailed aboard Hōkūle‘a during several West Side legs of the Pae ‘Āina. In Pōka‘i Bay, Hoshijo and her fellow crew members engaged with over 600 secondary students at the Ho‘ākea Mauka to Makai, an annual event featuring dozens of community partners united in their efforts to offer hands-on ocean education grounded in Native Hawaiian values.

有の長さ約8メートルの訓練用ヴァア・カウルア、カー・ ウハネ・ホロカイ号など、沿岸部の短い距離を行き来 するための小さめのカヌーに乗船した。

「花をひとつひとつ糸に通してつくるレイと同じです。 それぞれのコミュニティにはそれぞれのよさがありま す」ポリネシア航海協会の見習い航海士、カイ・ホシジ ョウさんは今回の〈パエ・アーイナ〉の航海でホークー レア号に乗船し、ウエストサイド各地に寄港した。ポー カイー湾では、ハワイ独自の文化にもとづいて海に関 する学びの場を提供する各団体が一堂に会して毎年 行う〈ホアーケア マウカ・トゥ・マカイ(広がり 山か ら海へ)〉のイベントが開催され、ホシジョウさんをはじ めホークーレア号の乗組員は、600人を超える中学生 たちと交流した。

Westward Holoholo

“A big part of modern wayfinding is carrying out our kuleana (personal and collective responsibility) of giving the younger generations access to these voyaging vessels and making sure that canoe culture is present in their life at a young age,” Hoshijo adds. “The West Side is particularly special, since many of the students we serve are Native Hawaiian. Their parents and grandparents have known and loved Hōkūle‘a longer than some of us have been alive. It’s important to listen and hear their stories because, in a way, they’re part of our crew, too.”

In summer of 2025, Hōkūle‘a and her sister canoe, Hikianalia, are set to resume the global Moananuiākea Voyage, with plans to return home in 2028. Though the recently wrapped Pae ‘Āina Statewide Sail marks the last Hōkūle‘a visit to the West Side for a few years, both Pule and Hoshijo are preparing to join various legs of Moananuiākea as crew members. Along the way, they’re hoping to leave a lasting impression on future navigators who may one day follow in their wake. “When I see the kids standing on the ocean looking at the canoes, wanting to learn more, I see myself. And that makes my heart so full,” Pule reflects. “We’re inspiring the next generation to navigate the challenges of not just the ocean, but the challenges that they face every single day.”

「現代の航海で大切なのは、若い世代が航海用の船 に触れる機会を増やし、小さいころからカヌー文化を 身近に感じられるように導いて、わたしたちのクリアナ (個人あるいはグループが共同で担う責任)を果たす ことなんです」ホシジョウさんは付け加えた。「多くの 子供たちがネイティブハワイアンの血を受け継ぐウエ ストサイドでは、その点が特に重要です。子供たちの親 や祖父母の世代は、わたしたちが生まれる前からホー クーレア号に親しんでいます。そうした人々はある意味 でクルー同然ですから、彼らの話に耳を傾け、彼らの 物語を知ることも大切だと思います」

2025年夏、ホークーレア号とそのシスターカヌー、ヒ キアナリア号は世界に向けて〈モアナヌイアーケ〉の旅 を再開する。予定では、ハワイに戻るのは2028年。つ い先日〈パエ・アーイナ・ステイトワイド・セイル〉を終え たホークーレア号が次にウエストサイドを再び訪れる のは数年先になるだろう。プレさんもホシジョウさんも、 〈モアナヌイアーケア〉航海中、いくつかの航路で乗組 員として参加する準備を進めている。航海中、将来の 航海士たちの胸に、いつか自分たちのあとに続こうと 思うような記憶を刻めればいいと願っているそうだ。 「熱心なまなざしでカヌーを見つめる子供たちの姿が かつての自分と重なって胸が熱くなります」プレさんは 語る。「ホークーレア号は、若い世代の青少年が、海の 上だけでなく日々の暮らしなかで試練に直面したとき にも、それを乗り越える力を育んでいるんです」

Image by John Hook

“

Kaleo Patterson, kahu

Hook Hawaiians especially need our culture–it is our life and legacy, and it will be an anchor for us through difficult times.”

Image by John

Kula Kaiapuni ‘o Kapōlei: For the Love of a Language

Intro by Mia Anzalone

Images by John Hook

Ma kekahi kula ma Kapōlei, a‘o ‘ia kamali‘i mā i ka loina Hawai‘i ma o ka ‘ōlelo.

Under the green eaves of the portable classrooms at Kapōlei Middle School, sneakers and rubber slippers are strewn along a shaded walkway. The shoes’ owners, the seventh and eighth-grade students of Kula Kaiapuni ‘o Kapōlei, a Hawaiian language immersion school located on the campus, shuffle barefoot across a lauhala mat. The students fix their eyes upon Kumu (teacher) Kade “Hema” Yam-Lum and Kumu Keonaona Kahawai-Javonero with an unspoken admiration; they offer morning greetings as well as occasional jabs and laughs—all of which are spoken melodically in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i (Hawaiian language).

Here, at Kula Kaiapuni ‘o Kapōlei, class feels less conventional and more communal, a shared learning experience centered on the stewardship of ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i.

Throughout the school day, students speak ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i while studying a standard curriculum of history, math, science, and English through a distinctly Hawaiian lens.

カポーレイにあるハワイ語イマージョンスクール(ハワイ語で授業 を行う学校)では、子供たちが言葉を通して自分たちの文化を学 んでいます。

カポーレイ中学校のプレハブ校舎。緑色のひさしで日陰になった通 路にはスニーカーやビーチサンダルが無造作に散らばっている。靴 やサンダルの持ち主は、同中学校内にあるハワイ語のイマージョン スクール、〈クラ・カイアプニ・オ・カポーレイ〉の7年生と8年生の生 徒たち。ラウハラのゴザの上を裸足で歩く生徒たちは、憧れのまな ざしでクム(先生)のケイド・”ヘマ”・ヤムラムさんとケオナオナ・カハ ヴァイ=ハヴォネロさんを追う。互いにオーレロ・ハワイ(ハワイ語) で朝の挨拶を交わし、ふざけて軽いジャブもお見舞いし合う。

ここ〈クラ・カイアプニ・オ・カポーレイ〉では、授業はオーレロ・ハワ イを中心に行われる。学校にいるあいだはオーレロ・ハワイを話し、 歴史や数学、科学、そして、ハワイ語のレンズを通した英語を学ぶ。 ハウマーナ(生徒)たちがバナナやサトウキビ、キー(ティーリーフ)、 椰子、しょうがなどの手入れをする屋外の畑も学びの場だ。こうし た植物はカヌー・プラントと呼ばれ、かつてポリネシアからハワイへ やってきた人々が食べ物、薬、また道具として、さまざまな用途に活 用したものだ。

The learning continues outdoors, too, as the haumāna (pupils) tend a garden of banana, sugar cane, kī (ti leaf), coconut, and ginger—all canoe plants, introduced to Hawai‘i by early Polynesian settlers for food, medicine, and material resources.

Such immersion in both language and culture has not only been key for students in connecting to their identity as Kānaka Maoli, but also vital for the preservation, promotion, and celebration of Hawaiian traditions. In this Voices selection, we hear from a few students who share what it means to speak ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i and how programs like Kula Kaiapuni ‘o Kapōlei empower them to carry forward their cultural legacy.

ハワイ語、そしてハワイ独自の文化への没入は、生徒たちがカーナ カ・マオリ(ネイティブ・ハワイアン)という自分たちのアイデンティ ティを自覚する鍵となるばかりでなく、ハワイの伝統を守り、奨励 し、大切にしていくためにも欠かせない。オーレロ・ハワイを話すこ とが彼らにとってどんな意味を持つのか。〈クラ・カイアプニ・オ・カ ポーレイ〉のようなプログラムが、彼らの文化や伝統を未来へとつな ぐためにどれだけ役に立っているか。生徒たちの声を聞いてみた。

‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i au ma ke kula i kēlā lā me kēia lā. Makemake wau e komo nui mai ka po‘e i kēia papahana, he mea e pōmaika‘i maoli ai au. He mea maika‘i nō ke a‘o ‘ia kamali‘i i ko lākou mo‘omeheu.”

Kanui, papa 8

“I speak ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i every day at school. I’d like for more people to come to this program, it has done so much for me. It’s good for kids to learn about their culture.”

「学校では毎日オーレロ・ハワイで話しています。もっと大勢 の人にこのプログラムに参加してほしいです。ここでは本当に たくさんのことを学びます。子供たちが自分の文化を知るのは いいことだと思います」

Ma ke Kula Kaiapuni o Kapōlei, nui a‘e ka mea i a‘o ‘ia au ai ma mua o ka mea e a‘o ‘ia ma ke kula ‘ōlelo Pelekane. Makemake wau e ‘ike mai kānaka, ‘a‘ole ka ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i i make, ke ‘ōlelo mau ‘ia nei nō i kēia mau lā. He ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i au ma ke kula, i ka ‘ohana ho‘i. He pōmaika‘i ka mākaukau i ka ‘ōlelo a ka po‘e kūpuna i ‘ōlelo ai.”

‘A‘ali‘i, papa 8

“At Ke Kula Kaiapuni ‘o Kapōlei, I‘ve learned more than when I was at an English-speaking school. I would like others to know that ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i is not a dead language, it is still used to this day. I speak Hawaiian at school and to my family. It is good to know the language your ancestors spoke.”

「〈ケ・クラ・カイアプニ・オ・カポーレイ〉では、英語がベースの学校よりも多くのこと を学んでいます。オーレロ・ハワイが言語として滅びていないこと、今もちゃんと使われ ていることを人々に知ってもらいたいです。学校でも家でもハワイ語を話しています。 先祖たちが話していた言葉を学ぶのはいいことだと思います」

Puni au i ka pilikanaka, no ka mea, a‘o ‘ia mākou i ko ka wā i hala, e la‘a nā ali‘i a me nā akua o Hawai‘i, puni ho‘i au i ke akeakamai, no ka mea he le‘ale‘a ke alu like ‘ana. Ha‘aheo au i ka hele ‘ana i ke kula kaiapuni. ‘A‘ole pēlā ko‘u makua kāne me ko‘u mau kūpuna, ‘o wau na‘e, he wahi nō ko‘u e a‘o

‘ia ai i ka ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i.”

Koa, papa 7

“I enjoy pilikanaka (social studies) because I learn about the past, such the ali‘i and akua of Hawai‘i, and I love akeakamai (science) because of the le‘ale‘a (fun, or amusment) in how we work as a hui. I’m proud to be attending a kula kaiapuni. Unlike my makua (father) and kupuna (elders), I have the chance to learn in Hawaiian.”

「ハワイのアリイ(王族)やアクア(神話)など過去のことを学べるピリカナカ(社会)の 授業、そしてアケアカマイ(科学)の授業も大好きです。フイ(グループ)で勉強するの がレアレア(楽しい)です。〈クラ・カイアプニ(ハワイアン・イマージョン・スクール〉)に 通えるのは誇らしいことです。マクア(両親)やクープナ(祖父母)と違って、ハワイ語を 学ぶ機会があるんですから」

Kaleo Patterson: The Kahu

As told to Elliott Wright Images by John Hook & courtesy of Josiah Patterson

Na ke Kahu Kaleo Patterson e ‘āwili i ka ‘ike ho‘omanamana Hawai‘i me ko ka ‘ao‘ao Kalikiano ma kāna mea e a‘o nei, he ho‘oponopono a he ho‘okuapapa.

In ancient times, Hawaiians structured their lives around nature. When the star cluster Makali‘i (Pleiades) rose over the horizon, the king would cease work island wide, including at the temples, and the season of Makahiki would begin. During this time, royalty would mingle with the common folk, and any warfare would cease. Instead, the people would feast and play games. It was a time to honor Lono, the god of fertility, agriculture, rainfall, music, and peace.

Makahiki programs within the prisons were first conceived in Oklahoma and Arizona prison facilities. Inspired by the cultural traditions practiced by their Native American inmates, such as using sweat lodges, inmates of Hawaiian ancestry felt a need to reconnect with their own cultural ceremonies and practices.

かつてハワイの人々の暮らしは自然とともに成り立っていました。 マカリイ(プレアデス星団 すばる)が水平線から昇る時期、王は、 神殿も含めて、すべての島民が働くことを禁じました。マカヒキの 季節のはじまりです。この期間は王族も平民たちと交流し、戦さも 休戦となりました。人々は仕事や戦さの代わりに食事を楽しみ、 ゲームに興じました。豊穣と農耕、雨、音楽、平和の神、ロノを祭る 季節ですからね。

刑務所でのマカヒキの儀式は、オクラホマやアリゾナの刑務所で はじまりました。”スウェット・ロッジ”などの伝統的習慣を行うネイ ティブ・アメリカンの囚人仲間に触発されたハワイアンの入所者 たちが、自分たちもハワイの伝統行事や習慣を取り戻そうと考え たのです。

これまでオアフのほとんどの刑務所でマカヒキの行事を開催して きました。初めてのマカヒキは2004年にオアフ・コミュニティ矯正 カレオ・パターソン牧師は、キリスト教の教えにネイティブハワイ アンの精神的なイケ(智恵)を取り込み、和解と再出発の大切さを 人々に説いています。

I’ve introduced our Makahiki program to most of the prisons on O‘ahu. Our first Makahiki took place at O‘ahu Community Correctional Center in 2004, with only a few participants. From there, it expanded to Hālawa and Waiawa Correctional Facilities, where we would regularly have between 40 and 50 pa‘ahao, or incarcerated Hawaiians, attend opening and closing ceremonies.

While Hawai‘i’s prisons have done well in lessening their populations since the pandemic, they are all still crowded, shortstaffed, and more focused on punitive systems than rehabilitation. I’m working to help redesign that. In our island prisons, nearly 40 percent of the inmate population is of Hawaiian ancestry, and many carry the weight of intergenerational trauma rooted in the illegal annexation of Hawai‘i. These inmates often come from poor backgrounds, have had their family land taken, and their lives deeply impacted by non-Hawaiians. As a result, there is a lot of anger.

During our visits, we speak of Makahiki as a time of peace, a time of resetting, and a time to let go of the things that no longer serve us. We encourage forgiveness and the embrace of community. We tailor the cultural practices contextually so that it applies to the restoration and rehabilitation of the incarcerated. Ceremonies include traditional chants, songs, and hakas, or dances.

We share the story of Queen Lili‘uokalani, Hawai‘i’s last reigning monarch, as an example. During the monarchy’s overthrow,

センターで行われましたが、参加者はほんの数人しかいませんでし た。そこからハラヴァとワイアワの刑務所にも広がり、今では開会式 と閉会式に40〜50人前後のパアハオ(服役中のハワイアン)が参加 するのが普通になりました。

パンデミック以来、ハワイの刑務所では囚人の数がだいぶ減りまし たが、施設のなかはあいかわらず人口過密でスタッフも足りず、更生 よりも処罰を重視する傾向にあります。わたしはそこを改善したい のです。ハワイの刑務所では、ハワイアンの血を引く入所者が全体の 40%近くを占めていますが、ハワイが米国に不法に併合されたこと によるトラウマを代々受け継いでいる人が多いのです。多くは貧しい

家庭に育ち、自分たちの土地を奪われたり、外からやってきた人々の せいで人生が大きく変わったりした人たちで、そのため大きな怒りを 抱えています。

刑務所では、マカヒキが平和の季節であることを伝えます。再出発 のタイミング、自分のためにならないことを手放すチャンスなのです。

許すことの大切さを説き、周囲の人々との絆を育むように促します。

入所者の更生や社会復帰につながるように、状況に応じて伝統的な 儀式にアレンジを加えます。儀式では伝統的なチャント(詠唱)や歌、 ハカ(マオリ族の伝統舞踏)や踊りなどを行います。

ハワイを統治した最後の王族、リリウオカラニ女王の例も用います。

ハワイ王国転覆の際、女王は暴力に訴えず、静かに身を引きました。 幽閉されているあいだに讃美歌《ケ・アロハ・オ・カ・ハク》を作曲し、 自分を不当に扱ったものたちの許しを神に乞いました。女王を見 習って怒りから自分を解放し、更生へと向かう道を探るのです。「視 野を広げること。すぐに投げ出さないこと。不当な仕打ちを受けて も、人間らしく解決法を探ればいい」刑務所にいる人々に向けたメッ セージではありますが、旅行者も含め、どんな人にもあてはまります。

マカヒキとは自分を振り返り、修正することを意味するのです。

the Queen stood down and instead promoted nonviolence. While imprisoned, she composed a hymn, “Ke Aloha o ka Haku,” asking the Lord to forgive those who treated her ill. We use her method as an avenue to explore release and rehabilitation. We tell the inmates, “Look at the larger picture, and be patient. Even if you feel that there has been injustice in your life, we are going to work through it as a people.” These messages are tailored to the prisons, but they even apply to the larger community, including visitors to our islands. Makahiki is about self-examination and restoration.

旅行者の皆さんには、ハワイの人々と触れ合う機会を見つけて、本当 の意味での対話をしてほしいですね。ハワイの文化を知っていれば、 避けては通れないハワイ特有の問題に直面したときも、きっとうまく 対応できるでしょう。ハワイの人々はとくに自分たちの文化を必要と しているのです。自分たちの暮らし方や伝統は、困難に直面したとき に心の支えになってくれますからね。

Cafe Hours

Closed Sunday & Monday

Tuesday - Friday 10am - 2:30pm

Saturday Only!

Brunch: 9am - 1pm

Dinner 5:30pm - 7:30pm

Kaka‘ako Farmers Market

1050 Ala Moana Blvd. Honolulu, HI 96814 the corner of Ward and Ala Moana Blvd.

Saturday 8:00am - 12:00pm

Wai‘anae Farmers Market

86-120 Farrington Hwy, Wai‘anae

Saturday 8:00am - 12:00pm

Sourcing produce through an impressive inter-island network of food hubs, vendors, and community partners, Kahumana's intentional approach does more than just fill plates with fresh, flavorful food—it strengthens Hawai‘i's agricultural economy and supports local farmers.

The menu changes with the seasons, reflecting what’s thriving across the islands. From tender greens to tropical fruits, each dish celebrates Hawai‘i's remarkable biodiversity while offering diners exceptional nutrition and flavor.

For those seeking nourishment that goes beyond the ordinary dining experience, Kahumana offers a true farm-to-table journey—one delicious, locally sourced bite at a time.

House Pizza

Chicken Stir Fry

Macadamia Nut Pesto Pasta

Banana French Toast

Community Supported Agriculture

Kahumana Organic Farms

I encourage visitors to make pathways into the community and have genuine interaction. Learning about Hawaiian culture will provide good guidance on how to navigate the storms related to Hawaiian issues that inevitably come. And Hawaiians especially need our culture—it is our life and legacy, and it will be an anchor for us through difficult times.

Kahu Kaleo Patterson is a Native Hawaiian pastor and professor and holds a doctorate in ministry. A vicar at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Wahiawā, he also serves as president of the Pacific Justice and Reconciliation Center, where he teaches Indigenous practices of peacemaking. He and his family live in Mākaha.

カフ・カレオ・パターソンさんはハワイアンの血を引く牧師、教授であ り、神学の博士号を持つ。ワヒアワーにある聖スティーブン聖公会の 牧師を務める一方で、太平洋正義と調和センターの所長としてハワ イ独自の和解の精神を説いている。家族とともにマーカハ在住。

RESORTS

Four Seasons Resort O‘ahu

Aulani, A Disney Resort & Spa

Beach Villas at Ko Olina

Marriott’s Ko Olina Beach Club

WEDDING CHAPELS

Ko Olina Chapel Place of Joy

Ko Olina Aqua Marina

RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITIES

Kai Lani

COMMUNITIES

Ko Olina Marina

Ko Olina Golf Club

Ko Olina Station

Ko Olina Center

Laniwai, A Disney Spa & Mikimiki Fitness Center

Four Seasons Naupaka Spa & Wellness Centre; Four Seasons Tennis Centre

Lanikuhonua Cultural Institute

Grand Lawn

Kai Lani

The Coconut Plantation

Ko Olina Kai Golf Estates & Villas

The Fairways at Ko Olina

The Coconut Plantation Ko Olina

& Villas

The Fairways at Ko Olina

Ko Olina Hillside Villas

The Harry & Jeanette Weinberg

The

& Jeanette Weinberg

Kuleana Coral Restoration Hub

Ko Olina Hillside Villas Centre / Four Seasons

Ko Olina is the only resort in Hawai‘i owned by a local family raising generations of keiki in the islands. We are surrounded by the hearts of a Hawaiian community: we mālama our culture and community ʻohana

by embracing neighbors, guests and employees with aloha. As stewards of the ‘āina and ocean, we honor the foundations of our wellbeing.

We invite you to experience our Place of Joy, where aloha lives.

Aulani, A Disney Resort & Spa

Beach Villas at Ko Olina

Four Seasons Resort O‘ahu at Ko Olina

Marriott’s Ko Olina Beach Club

Lanikūhonua

A HAWAIIAN PARADISE WHERE DREAMS WERE REALIZED, LIVES WERE LIVED AND TIMES WERE SHARED.

Located in Ko Olina, or “Place of Joy,” Lanikūhonua was known to be a tranquil retreat for Hawai‘i’s chiefs. It was said that Queen Ka‘ahumanu, the favorite wife of King Kamehameha I, bathed in the “sacred pools,” the three ocean coves that front the property.

In 1939, Alice Kamokila Campbell, the daughter of business pioneer, James Campbell, leased a portion of the land to use as her private residence. She named her slice of paradise, “Lanikūhonua,” as she felt it was the place “Where Heaven Meets the Earth.”

Today, across 10 beautiful acres, Lanikūhonua continues on as a place that preserves and promotes the cultural traditions of Hawai‘i. It allows visitors from around the world an opportunity to experience the rich, cultural history and lush, natural surroundings of this beautiful property.

FIND YOUR PLACE OF JOY

Shops, Restaurants, and Services to indulge your senses.

Hours: 6AM-11PM; Open Daily. Ko Olina Center 92-1047 Olani Street. Ko Olina, HI. 96707 Ko Olina Station 92-1048 Olani Street. Ko Olina, HI. 96707

Image by John Hook