BAMPTON IN IT’S LANDSCAPE

Bampton is situated in a predominantly rural area of West Oxfordshire; an area characterised by agricultural enclosures, small rural settlement and minimal woodland. In a 1998 Landscape Characterisation study

‘Bampton Vale’ was identified and classified as “an area of distinctly low-lying but gently rolling clay vale between an edge of Limestone to the North and the expansive floodplain landscape which borders the River Thames to the south. The underlying clay geology is reflected in the soils and character of vegetation (oak being the dominant tree species).”

Bampton 6 inch map 1884

A BIRDSEYE VIEW

In this modern aerial photograph of Bampton you can immediately identify a landscape of large fields, bounded by a reasonably strong structure of trees and hedgerows. It is interesting to note that these enclosures are not, unlike those only a few kilometres to the north, bounded in stone walling. Large agricultural enclosures are the most common land use in West Oxfordshire, accounting for 77.5% of the district, and that pattern is evident here. Modern air photography shows a degree of weakening of landscape structure through intensive farming practices, particularly to the north of Bampton.

BAMPTON IN IT’S LANDSCAPE

The area to the South of Bampton is characterised by the River Thames, on approach to which the land opens into very loosely enclosed water meadows. There is a distinct riparian character to this area, and anyone who walks between Bampton and the River Thames will experience a semi-open, pastoral landscape dominated by willows and alders, the former of which are often pollarded in the traditional manner. Many sections of this area have in recent decades been identified by the Forestry Commission as priority meadowland or improved grassland habitats.

Rushey Lock 1878 (Courtesy of Historic England)

Pollarding Willow

Rushey Lock 1878 (Courtesy of Historic England)

Pollarding Willow

TOPOGRAPHIC SURVEYING

This is an example of one of a series of photographs taken by the RAF in 1946.

The RAF initially conducted aerial reconnaissance flights across the UK for military purposes during the Second World War, but they were continued in peacetime once their value for topographic surveying was recognised.

By the end of the war the art had been perfected and the RAF had cameras with a focal length of up to 40 inches - a technology capable of capturing decent images of traffic on the street from 35,000 feet.

With the correct optical viewer the images could be viewed in primitive stereoscope - buildings appeared in 3D.

MODERN BAMPTON

The central core may remain largely unchanged, but outside this area the story is altogether quite different. In 1946 new residential development in Bampton has barely escaped from the historic core.

The most notable additions to the town in the first half of the 20th century were mainly limited to individual developments or direct replacements. The most significant of these perhaps being the rapid expansion of the house known as The Grange.

This house, based around the core of a rather modest 17th or 18th century farmhouse was extensively remodelled and extended in a very accomplished manner throughout the first quarter of the 20th century.

The Grange c1920

AREA CHARACTERISATION

It was not until the 1960s that the issue of managing the future development of Bampton was considered seriously and systematically.

In 1966 the Oxfordshire County Surveyor was commissioned to report on the character of Bampton with a view to recommending the nature and scale of development that may be appropriate.

The author described very much the same as the correspondent for Country Life had almost two decades earlier:

“an attractive limestone-built town with a market square and town hall. The three facades to the main roads are predominantly Georgian…”.

The planner then went on to dilute his praise by noting what he considered the encumbrances of the present age viz:

“…spoilt in a few places by untidy advertisements and disproportionate shop fronts.”.

An attempt at historic area characterisation was made in 1966. In less lucky settlements of Oxfordshire this thinking led to many settlements having their historic cores conserved only to find them subsequently chocked by a ring of insensitive mid-C20 development.

Perhaps Bampton owes a lucky escape from this fate to its relative isolation and the low demand for housing in the 1960s?

Bampton’s first comprehensive planning exercise was conducted at a time that the concept of Conservation areas had first been seriously mooted. Hargreaves (1968) argued that area designations were the response to protecting and managing historic landscapes.

The first Conservation areas were designated in 1967 and Bampton was itself designated a conservation area in 1976.

Bampton - designated a conservation area in 1976

INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS

Visible on mapping, and in aerial photographs, is some of the more informal 20th century settlement in Weald. There are a number of Traveller and Travelling Show people families living in West Oxfordshire on a range of specifically approved sites throughout the District and also in bricks and mortar. Modern strategic planning has a role to play in facilitating the way of life for Travellers, not least in ensuring there are appropriate sites, in suitable locations, available to meet their needs and, from which they can access education, health, welfare and employment infrastructure.

No appreciation of Bampton’s development through time could be complete without adequate reference to the longstanding private authorised Traveller site at The Paddocks, Weald.

Other informal settlement patterns that have become established landscape features can be found to the south of Primrose Lane, Weald, where the development of St Mary’s Court as a caravan site established in 1968 and visible on the 1970 aerial photographs of the area. Judging solely on stylistic grounds perhaps I was witness to one of the last remaining homes dating to the site’s inception being finally and lamentably removed in 2022 without any concerted effort to record its passing. The brutal process of the destruction of a structure, no matter how insignificant invites the reader to reflect on the nature of change as it is experienced in the moment.

Mill Green and Bridge 1898

St Mary’s Court

Plan of the Paddocks

Mill Green and Bridge 1898

St Mary’s Court

Plan of the Paddocks

MAPPING BAMPTON

Mapping of the late 19th Century is perhaps slightly deceptive about the scale of change in Bampton. There was considerable re-building throughout the later 19th Century within the historic core, leading to a sense of general ‘improvement’ being expressed in local sources. Much of this involved the reconstruction of dwellings on their existing footprints, and it takes a keen eye to identify such cases.

Stone remained the primary construction material long after the arrival of the railway allowed brick to be imported at modest cost. The cottages at Mill Green and possibly those on the east of Queen Street were built by the local mason Samuel Spencer in the 1830s, and from the 1850s the Earl of Shrewsbury took the opportunity to develop some of his holdings in Bampton.

Some of the resulting dwellings were quite substantial with Westbrook House on Bridge Street being a good example of polite architecture that would have compared well with anything in the urban centres of Witney or Faringdon.

Other new houses included Windsor Cottages (1887) and Victoria Cottages (1893) on Broad Street, both brick-fronted terraces replacing stone and thatched cottages; Oban (c.1835) and Albion Place (1875) on Bridge Street; Belgrave Cottages (1903) and Bourton Cottages (1906) on Church Street; Eton Villas (1907) on the corner of Church and Broad Streets, and Folly View (1906) and Fleur de Lis Villas (c.1910) south of the market place. These are some of the most notable constructions and re-constructions that began in part to challenge earlier readings of the settlement’s historic core with some demonstrating greater massing or slightly altered alignment to their predecessors.

Broad Street in 1885

Westbrook House Folly View Albion Place Victoria Cottages Fleur De Lis Villas Bourton Cottages

Broad Street in 1885

Westbrook House Folly View Albion Place Victoria Cottages Fleur De Lis Villas Bourton Cottages

BAMPTON IN THE 19th CENTURY

From the 1820s the impact of parliamentary enclosure was felt keenly. Many former commoners relinquished their land and either continued as rural labourers, or abandoned the agricultural economy altogether. This resulted in concentrations of rural labourers in Bampton at dense concentrations in Rosemary Lane and Kerwood’s Yard.

The former was a longstanding area associated with the poor, being mentioned as a site chosen by the parish for a “workhouse capable of employing and housing 60 persons or more” in 1768 before the construction of the later poorhouses on Weald Street.

Both became known as notorious slums during the 19th Century. Pressures on these areas may have fallen in the late 19th Century following a long recession and a national crisis in agricultural productivity that saw the population of Bampton fall from its 1860s peak of 1,713 (accommodated in 393 houses, with another 15 unoccupied). When the 3rd edition map was published in 1921 Bampton’s population was only 1,104.

This latter fall can be identified on the mapping in the abandonment and clearance of areas where very high density labourers’ cottages were provided. Kerwood’s Yard is no longer annotated in 1921 and its site had been cleared. Similarly, the high density labourers’ accommodation in the area around the former workhouse in Rosemary Lane and latterly in Weald Street was consolidated and substantially cleared by the 1920s.

Old lady standing near workhouses SEE THE PARISH MAPS ON THE SEPARATE SMALLER BOARDS

BAMPTON IN THE 19th CENTURY

Bampton ceased to be a meaningful market very early in its existence (perhaps as early as the 16th Century) and the various attempts to revive this status - most easily evidenced today by the early 19th Century addition of a market house - appeared to do little to address this. In 1853 Rev Giles complained that the market hall itself was little used and expensive to maintain- noting that it’s meagre income from exhibitions and lectures were “hardly sufficient to heat the room and to pay for the windows, which are broken by the boys congregated in the market place below”. By the late nineteenth century it had become storage for the town’s fire engine and by 1885 it must have presented a rather lamentable sight.

High Street looking east

Market Place

High Street looking west

Market Place looking east

Market Place looking west

High Street east Aerial photograph 1970

High Street looking east

Market Place

High Street looking west

Market Place looking east

Market Place looking west

High Street east Aerial photograph 1970

CHANGING MARKET PLACE

The character of the market place in the 19th century was therefore rather different to today. It was more likely defined by the presence of trades premises, inns and light industry. There has been long-standing infilling of the northern section of the market place; much of it light industrial, but also including an inn (The Bell). The map (and photographic evidence) suggest a rather informal and unattractive appearance. The construction of a war memorial in the 1920s replaced a wheelwright’s shop and in so doing most likely changed the character of this area substantially.

The closure of the Bell Inn and it’s eventual replacement with the Village Hall, probably underscored this area’s change. However, the light-industrial character of this infilling persisted throughout the 20th century where the area was latterly occupied by a motor repair garage.

After the closure of this business there were proposals to “green” the space, but they amounted to nothing and further residential development was permitted.

Market Square Garage 1977

Thornberry Flats 2010

The Bell is behind the railings

Plan of the proposed Greening of Market Place

Market Square Garage 1977

Thornberry Flats 2010

The Bell is behind the railings

Plan of the proposed Greening of Market Place

OTHER OPEN SPACES

Open spaces, largely preserved until the advent of modern roadbuilding, performed an important role throughout Bampton’s history as the location for the annual horse fair. This fair was hosted along the upper part of Broad Street and along Church Lane (modern Church View). Bridge Street being used to ‘run’ horses to prove their soundness before sale. The fair itself can be traced to the 13th century so its continued presence in this specific part of Bampton may represent a relic of considerably older practices.

There are other places shown on these early Ordnance Survey maps that have almost completely disappeared from modern memory. A good example is the area continuously named as Wright’s Hill; known on early Ordnance Survey mapping as situated immediately to the south of the Shillbrook where it is forded (now bridged) by Cheyne Lane and on the very fringe of what could be considered the settlement core. It once consisted of a handful of cottages and agricultural buildings, named for the pre-enclosure field adjacent to which it sat.

At enclosure the field disappeared into the modern field system, and within a generation or two so did the need to describe this peripheral area as a distinct settlement. The cottages standing here were cleared as early as the 1920s. As a name for this part of modern Bampton, it has now therefore effectively disappeared, perhaps in the space of as little as 100 years.

The annual Horse Fair from the church looking south

Running horses in Bridge Street

DRAWING THE BOUNDARIES

Bampton and Enclosure

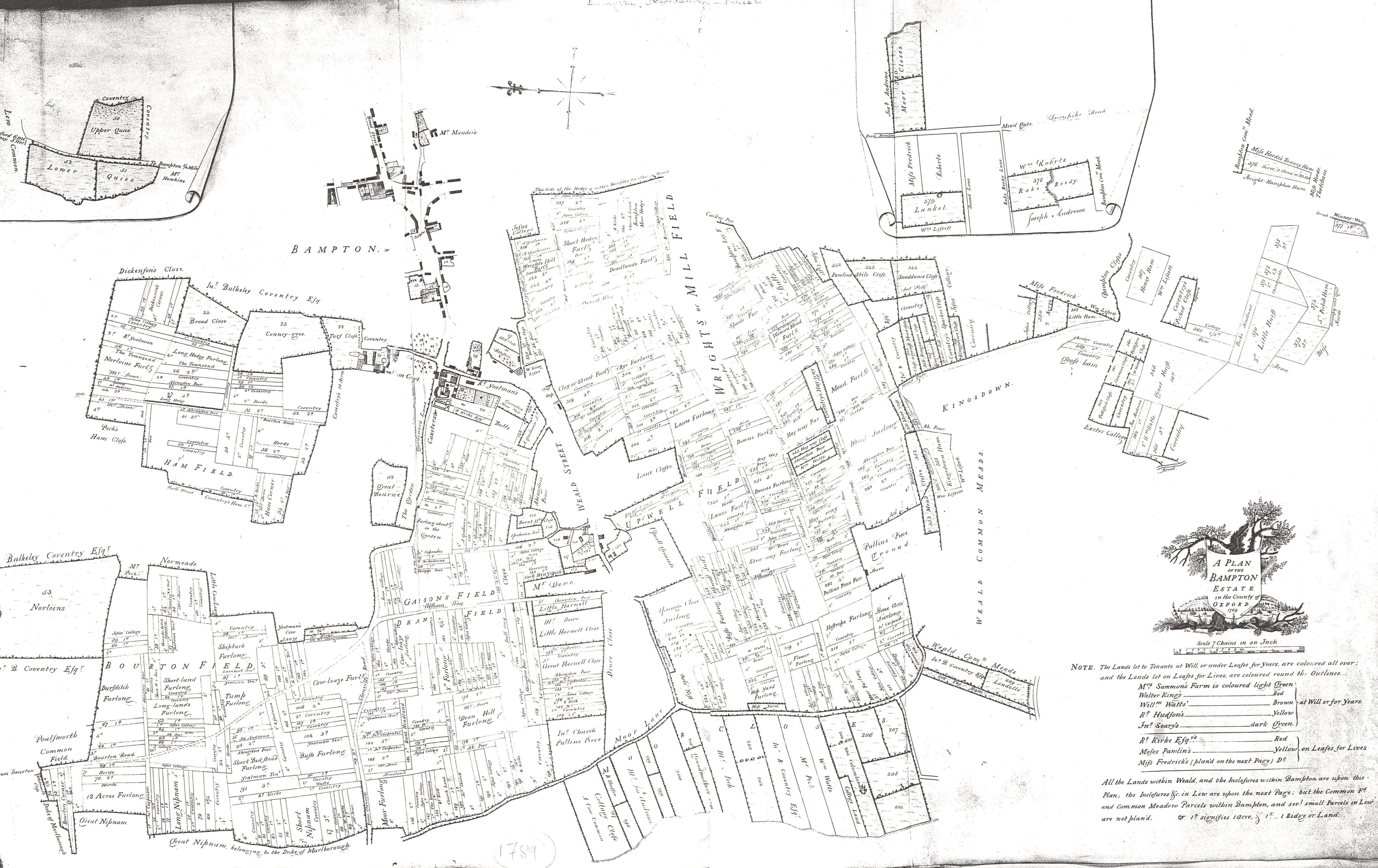

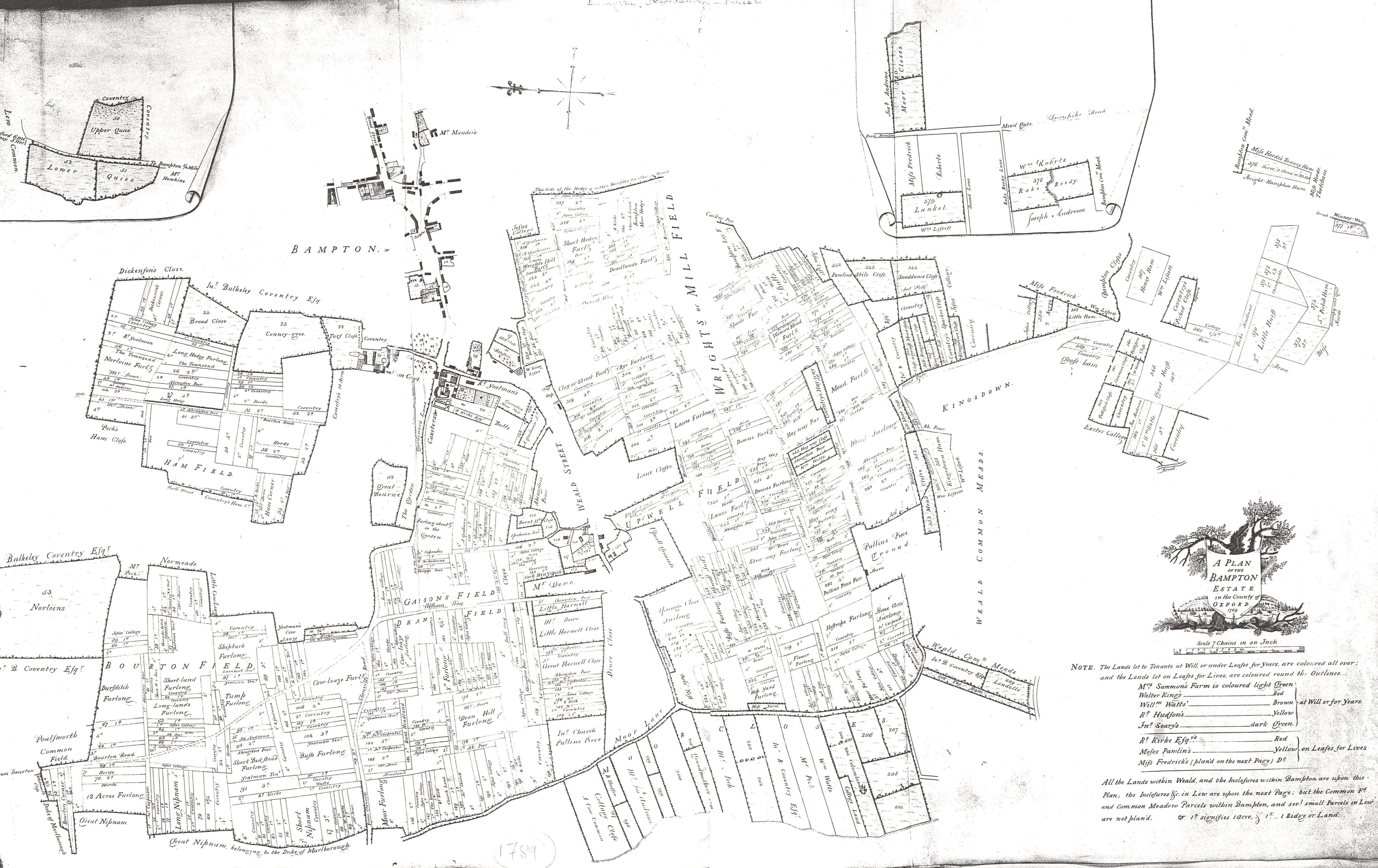

The many early enclosures around the historic core of Bampton were post-medieval or earlier. Much of this enclosure was associated with the arrangement of the three principal manors of Bampton.

Before the late Saxon period Bampton was a single large Royal manor. It became divided in the course of the 10th and 11th centuries to become three manors. The first was Bampton Earls (also known as King’s Bampton, or Bampton Talbot after the family who held it from the 14th century onwards and who became the Earls of Shrewsbury).

The next was Bampton Deanery, a division made by King Eadwig in his grant to Bampton minster between 955 and 957, and so named because it was after the Norman conquest transferred to the Dean and Chapter of Exeter Cathedral. Finally there was Bampton D’Oilly, held by the family of the same name.

Over time these manors were each divided into either moieties (from the Latin mediatus, meaning half) or let out in various parcels of land that resulted in each manor forming a number of distinct estates. The process was complex.

The best surviving example is a survey made for the Earl of Shrewsbury in 1789. This was created to ‘sort out’ once and for all the problem of Shrewsbury and his neighbour at Ham Court, a Mr. Coventry, delineating their holdings. On the ground their respective holdings which had been separated around a 100 years previously in a “most injudicious manner that the estates are most intermixed and interfere with each other in a most inconvenient manner which might have been prevented if it had been carried out by men of judgment”.

Shrewsbury Map 1789

Shrewsbury Map 1789

ENCLOSURE

Throughout the early modern period Bampton’s status as a centre of trade (traditionally of tanning and leather glove making) was declining. In 1789 the Earl of Shrewsbury’s surveyor described Bampton quite decisively as a “former market town”. The importance of its agricultural hinterland would become a proportionately more important part of its economy.

By the end of the eighteenth century the enclosures of Bampton were situated in the areas considered to be the richest for agricultural purposes. This broadly defined by the area along the Buckland turnpike road to the south of the settlement in an area named Brookfast Closes - the name being descriptive as the closes are equally spaced perpendicular either side of the route of the Shillbrook. This area of closes appears to have been bounded to the south by Meadow Brook, beyond which to the south was open meadow.

Other early closes are to the south west of Weald, accessed by droveways and known by the 18th century as either the “moor” or “marsh” closes in various sources. The two names appear contradictory, but considering there is also record of the “Maw ditch” in this area, it seems much more likely to be the former, derived as it is from the Saxon word Mōr, used to denote grassland.

To the north of Bampton there were larger enclosures forming the demesnes of the Bampton Manors of the Deanery and Ham Court.

Other important early enclosures include land set aside to fund relief of the poor (“the poor closes”). In 1768, when a poor house was first constructed in Rosemary Lane, this close was used as a source of construction timber.

Beyond the early-enclosed closes of Bampton were large areas of agricultural land. Early county maps illustrate the vastness of the common land around Bampton and Aston. That closest to the settlements of Bampton and Aston were settled into fields that would allow four-field cultivation.

The others, principally towards the south were set aside as meadows. There were also a small number of areas enclosed for coppicing.

1828 Enclosure map showing fish ponds & streams

ENCLOSURE

Parliamentary enclosure delivered a scale of shock to the landscape.

Enclosure redistributed into designated units, consolidating small landholdings into larger farms.

This included the conversion of commons, wasteland and open fields to formally enclosed units of land, the conversion of some arable land to pasture and the partition of large areas of communally farmed land into small fields farmed by individuals.

Commons were places of the poor. Inevitably they were often considered by those in authority as synonymous with people on the margins of mainstream society- known by various names in antiquity. Many of the transient, seasonal or semi-permanent inhabitants of English commons were firmly described in pejorative terms by modern parlance - they are squatters , peddlars, hawkers, tinkers, runaways, Scots, Irish, Egyptians (Gypsies), itinerants, and ultimately, the catch-all term, vagrants.

Commons were increasingly viewed as economically inefficient and hotbeds of lawlessness and immorality, ‘edgy’ places on the edges of parishes, where clandestine or illegal activities took place. In Bampton the commons were used for a myriad of other purposes, including residential and recreational.

Extract from Enclosure showing rectilinear enclosures

An enclosure in a former common field with a hedge and a road

THE OPEN FIELD SYSTEM

The history of the English open-field system (in its dramatic and revolutionary demise through parliamentary enclosure) has generated a great deal of rural mythology throughout the modern age. The reality was this was a system of common regulation and centralised organisation and enforcement.

It relied on its operation by maintaining symbiotic relationships between neighbours; relationships usually managed and regulated by a manorial court. Like any relationships between neighbours ancient or modern, disputes inevitably erupted. Medieval court records of quarrels between neighbours inconvenienced by sharing the same patch of earth are common. Open Field farming was therefore something much more alive, much more in contention than the maps here suggest.

A better sense of what this landscape looked like in practice can once again be found in the modern aerial photography that recorded (and in some areas records still) the rhythm and alignment of ridge and furrow ploughing, much of it demonstrating the characteristic long s-shaped tracks of individual strips.

The townships of Aston, Cote, Shifford and Chimney were not included in the 1821 enclosures, and retained their open fields and commons until the middle 19th century.

LiDAR extract - Ridge and Furrow

LiDAR extract - Ridge and Furrow

EARLY BAMPTON

Bampton is depicted on various county maps of Oxfordshire dating to the 17th and 18th centuries, but detailed early mapping of the settlement eludes the historian.

Where Bampton does appear on an early map, the older the map the less detail with which the settlement is depicted.

The earliest depiction of Bampton is that of Thomas Saxton’s 1574 Map of Oxfordshire.

18th century maps of Bampton all characterise Bampton in very similar ways. What features they chose to include when constrained by small scales are very interesting. All maps show the convergence of the three routes into Bampton on the market place. All make a point of describing the road today known as Landells as it makes a distinctive curved track around the perimeter of the churchyard.

There are also usually concerted efforts to show the tracks of Broad Street and Church View as distinct and running parallel to each other, with the latter terminating at the church.

Interestingly, most early small scale maps make an attempt to depict the track or path heading east from the settlement core to Beam Cottage.

The 1767 ‘New Map’ actually depicts Beam Cottage, standing in isolation at the end of this track. Weald is depicted variously as a semi-separate settlement, perhaps centred on its own green. All of these features, taken together can be used to infer much earlier landscape features.

Thomas Saxton’s 1574 Map of Oxfordshire

New map of Bampton 1767

MAPS GIVING HERITAGE DATA

Through a combination of studies it has been suggested that the chief east-west route through Bampton once formed part of an inferred minor Roman road which crossed the river Windrush at Gill Mill and continued through Weald towards Lechlade, entering Bampton from the north-east perhaps along the later Kingsway Lane, and passing just south of the present market place.

The name Kingsway implies that the lane, a minor track in the 19th century, was once an important route associated with the Royal Manor, and its projected course south of the later market place passes close to where an early Anglo-Saxon house has been discovered by excavation in the grounds of modern Folly House (the site of the later medieval D’Oilly manor).

Another early route probably ran from Cowleaze Corner north eastwards past the site of the “Lady Well”, skirting to the north of the Deanery. The modern roads north to Brize Norton and north east to Lew were also likely to be ancient in their origins even if the specific alignments have shifted through later history.

Earlier Saxon settlement at Bampton probably focused on the area around modern Beam Cottage, where a sizeable Saxon burial ground has been identified in excavations laying over the site of even earlier Romano-British settlement. The Thames Valley Mapping Project recorded extensive landscape features as cropmarks in this area. The name Beam is what gives the later settlement of Bampton its name.

LiDAR extract showing Track from Cowleaze

Extract from ArcGIS

The developing religious community plugged into an earlier topography of routes and devotional sites, creating a complex settlement pattern that is arranged axially east-west.

Blair reconstruction

LiDAR extract showing Track from Cowleaze

Extract from ArcGIS

The developing religious community plugged into an earlier topography of routes and devotional sites, creating a complex settlement pattern that is arranged axially east-west.

Blair reconstruction

Rushey Lock 1878 (Courtesy of Historic England)

Pollarding Willow

Rushey Lock 1878 (Courtesy of Historic England)

Pollarding Willow

Mill Green and Bridge 1898

St Mary’s Court

Plan of the Paddocks

Mill Green and Bridge 1898

St Mary’s Court

Plan of the Paddocks

Broad Street in 1885

Westbrook House Folly View Albion Place Victoria Cottages Fleur De Lis Villas Bourton Cottages

Broad Street in 1885

Westbrook House Folly View Albion Place Victoria Cottages Fleur De Lis Villas Bourton Cottages

High Street looking east

Market Place

High Street looking west

Market Place looking east

Market Place looking west

High Street east Aerial photograph 1970

High Street looking east

Market Place

High Street looking west

Market Place looking east

Market Place looking west

High Street east Aerial photograph 1970

Market Square Garage 1977

Thornberry Flats 2010

The Bell is behind the railings

Plan of the proposed Greening of Market Place

Market Square Garage 1977

Thornberry Flats 2010

The Bell is behind the railings

Plan of the proposed Greening of Market Place

Shrewsbury Map 1789

Shrewsbury Map 1789

LiDAR extract - Ridge and Furrow

LiDAR extract - Ridge and Furrow

LiDAR extract showing Track from Cowleaze

Extract from ArcGIS

The developing religious community plugged into an earlier topography of routes and devotional sites, creating a complex settlement pattern that is arranged axially east-west.

Blair reconstruction

LiDAR extract showing Track from Cowleaze

Extract from ArcGIS

The developing religious community plugged into an earlier topography of routes and devotional sites, creating a complex settlement pattern that is arranged axially east-west.

Blair reconstruction