2022

LETTER FROM OUR PRESIDENT

Welcome to the 88th year Ceramic Study Club of Boston! So much has changed since 1934, but we remain an enthusiastic group of people sharing our knowledge and questions of all things ceramics. This year we have a series of exciting in-person and virtual presentations that we look forward to sharing with you all.

Anne Lanning created a wonderful and diverse series of nine programs throughout the year based on your suggestions and her extensive knowledge. The series will start off with CSC member Steve Earp presenting on the work and problems of reproduction redwares. Later in the year, we hear Joe Bagley, another CSC member speak on his current research uncovering Charlestown’s 18th century enslaved potters mentioned in Laura Woodside Watkins’ EarlyNew EnglandPottersandtheirWares. In addition to Joe’s research, Jack and Acton pottery in Charlestown was excavated and studied by Steven Pendery during the Big Dig. Research on the enslaved potters of New England continues to grow with new information. If Asian ceramics are your interest, you will have the opportunity to hear from Robert Mowery of the Harvard Art Museum and his program discussing Chinese, Korean and Japanese ceramic traditions. In addition to these programs, we have our traditional Bits and Pieces gatherings and a number of other programs that are not to be missed!

We appreciate all our members eagerness to share knowledge and favorite pieces with us. This is a testament to the talent of all our members and I look forward to seeing people come forward with their research and knowledge in the next year.

We remember our member Dorothy Lee-Jones who passed away this year. Dorothy was a member and president of our club from 1992-1995. My first memories of her were when she visited the Strawbery Banke archaeology center. I was delighted to talk with her as Mary Dupre and I dashed around the room jotting down her astute comparisons and details about each shard. Her fast thinking and quick wit were wonderful and will be remembered fondly. Early this summer, I spent several days at the Warner House in preparation for the season dusting and cleaning, and one afternoon I picked up a Rockingham type spittoon with a Jones Gallery sticker on the bottom. I sat down with a grin on my face and marveled at all the various types of ceramics and glass Dorothy-Lee Jones knew, collected, and taught so many of us. It is a joy to have some of the knowledge that Dorothy-Lee delighted in sharing.

Martha Martha E. Pinello, President

WINTER/SPRING

Page1

JANUARY TALK FROM GERMANY ON PORCELAIN DECORATOR FIDELE DUVIVIER

On January 27, 2022, while anticipating a historic nor’easter, the Ceramics Study Club enjoyed via Zoom our first international program. Independent ceramics researcher and author Charlotte Jacob-Hanson presented an enlightening talk from her home in Frankfurt, Germany on the subject of Fidelle Duvivier Inspired Eye, Gifted Hand. We shared the audience with members of the Ceramics Circle of Frankfurt which Charlotte herself had founded.

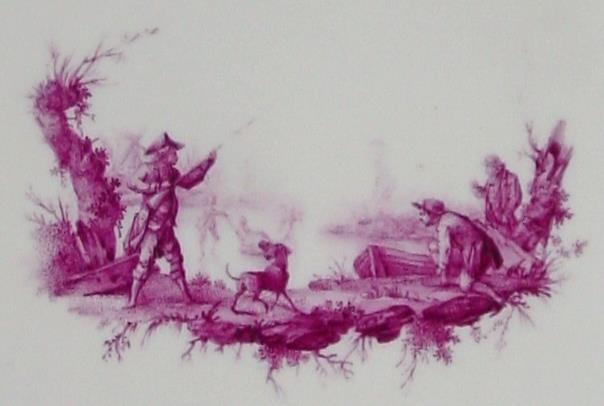

Fidele Duvivier’s rather peripatetic life as a ceramics decorator began in the city of Tournai the Hapsburg Empire’s part of the Netherlands where he was born in 1740. In 1750, Fidele’s older brother, Michel-Joseph Duvivier returned to Tournai from working at the English Chelsea factory to join a newly formed factory founded by one Francois Joseph Peterinck. Fidele was already training there as a painter when his brother arrived. In the beginning the fledgling factory faced many production and marketing challenges, but with Michel-Joseph as their artistic director stylistic elements used at Chelsea were introduced at the Peterinck Factory. One of the most popular techniques was monochromatic painting in what the French called camaieuu-rose landscapes and figural scenes rendered in shades of soft puce enamel.

Although painted a little later in his career, this example is typical of the very popular monochromatic camaieu-rose designs that Fidele Duvivier mastered early in his career at the Peterinck Factory in Tournai. The arching, ‘double-bunch’ stippled foliage trees are indicative of his style.

2

Page

Fidele then moved on to the first of several factories during his career, the Sceaux Factory just outside of Paris. The factory was near an 18th century chateau by that name, belonging to the Duke and Duchess of Maine, the Duchess becoming the factory’s patron during the last five years of her life. Sceaux functioned under a succession three different managers and Charlotte believes that Fidele worked for the last two of them. During the 1760s Sceaux excelled at producing faience tablewares which Fidele handily decorated with landscape and river scenes, birds, animals, fruits, and flowers in puce or polychrome. One typical characteristic of Sceaux plates of this period is a notched edge with a feathered or blue ‘combed’ border. Another recurring theme of Fidele’s work are images of peacocks which appear on Sceaux plates as well as, twenty years later, Newhall pieces. Decorating the Sceaux faience was not that easy as the lead glaze was a rather unforgiving medium to paint upon, one that Fidele apparently mastered readily.

In 1776 the managers at Sceaux leased the Mennecy-Villeroy factory for whom Fidele also worked. The Sceaux decorators were tasked with painting leftovers from the Mennecy stock which explains why Fidele’s hand shows up on those wares as well. One very telltale indicator, besides the peacock motif, of Fidele’s style is an assortment of cut and whole fruits such as berries, quinces, grapes, lemons, plums, or figs as seen here below:

Left: A Sceaux faience plate with notched edge and peignes bleus border. Right: A recurring motif with Duvivier is seen on this Mennecy covered cup: a peacock and whole and cut fruit.

Left: A Sceaux faience plate with notched edge and peignes bleus border. Right: A recurring motif with Duvivier is seen on this Mennecy covered cup: a peacock and whole and cut fruit.

Page 3

By October 1769, Fidele Duvivier was hired by the man who founded the Derby Factory, William Duesbury. Fidele’s exotic bird and fruit decoration shows up on Chelsea porcelain of the period since Duesbury had purchased that factory as well and had his workers painting leftover Chelsea blanks. Duesbury, keen to make Derby wares more fashionable and marketable, asked for more ‘French looking’ designs so Fidele obliged with an array of putti designs in puce in the style of the works of French artist Francois Boucher. This was a very popular motif and there are attributable putti designs by Fidele from almost every factory where he worked. But despite being under contract to Duesbury at Derby, there appears to be evidence that the ambitious Fidele also moonlighted for the James Giles decorating shop in London painting Worcester and Chinese export porcelain blanks. It was also during these years in England that he married an English woman, Elizabeth Thomas.

The Duviviers return to Sceaux by 1775 where a daughter is born. Pieces decorated by Fidele from this five- year period can be recognized by his style and motifs and dated because the factory used an incised SX mark.

By 1780, they are on the road again, relocating to the Netherlands, settling in the town of Loosdrecht where a local church minister started a factory to help employ the locals. The locale had no ceramics-making tradition, and they were in sore need of skilled and experienced talent.

Fidele was most welcome and painted more tea and dinner services here in four years than he did for the Derby factory - landscape vignettes becoming a motif that best exemplify this period. Specific details to look for are simple figures with wide-brimmed hats; vegetation with dangling roots beneath floating landscapes; trees with double bunches of foliage that arch inward framing the scene the foliage rendered in a stippled technique with the pint of a fine brush. One last thing that helps indicate a Duvivier landscape is the artist’s difficulty with animal anatomy cattle are often rendered beyond the crest of a hill because he couldn’t get the legs quite right!

One of Fidele Duvivier’s many versions of French inspired Boucher style camaieu rose putti for Derby.

Page 4

Classic Duvivier landscape from his Loosdrecht period note the ‘floating’ scene with the dangling roots and, faintly in the distance, a windmill.

By 1784, the struggling Loosdrecht factory is dissolved and Fidele makes his last known move back to England, specifically to Staffordshire where he works primarily for the Newhall Factory continuing his popular themes of putti and fruits and exotic birds as well as his landscapes. The only difference being that his Loosdrecht landscapes feature windmills in the background, the Staffordshire scenes feature a smoking kiln.

A Staffordshire Newhall landscape by Duvivier with a smoking kiln in the distance.

A Staffordshire Newhall landscape by Duvivier with a smoking kiln in the distance.

Page 5

After 1796 there is no further mention of this remarkably talented and prolific artist except for letter by Enoch Wood claiming that Fidele Duvivier had moved to America!

For anyone interested in purchasing Charlotte’s newly published book, In the Footsteps of Fidele Duvivier, you can reach Charlotte and her website at www.chjacob-hanson.com

FEBRUARY 2022 BITS ‘N’ PIECES

Our Club’s most popular program Bits ‘n’ Pieces continued again this year from the homes of our members with Zoom-Master Anne Lanning being the MC for the event. Members who wished to share recent acquisitions or had questions about their pieces were asked to present. Many say this is always their favorite meeting of the program year and this year was no exception with a range of objects that showcased the scope of the membership’s interests.

Member Nic Johnson, usually known to share a piece of Iznik pottery with us, or 19th century Doulton, this year surprised us with a colorful array of his three favorite coffee mugs, created by potter Janice Tchalencko who produced brightly colored high-fired stonewares. Janis directed the Dart Pottery in the 1980s which was on the grounds of a private school, Dartington Hall, in Devon, UK which Nic attended as a child in the late 1940s - early 1950s. The Dartington estate was where Bernard Leach had already set up a small pottery, and Nic’s pottery teacher at school was Bernard Forrester, who was trained by Leach. The mugs, interesting in their own right with their complex glazes, brought up the subject of how objects become imbued with certain meaning for their owners, in this case because of Nic’s connections to his school.

SHARDS editor, Jeffrey Brown, shared some of his recently collected ‘covid pieces’. The polychrome Dutch delft pair of vases are marked with an MP on the bottom. One book he found associated the mark with a potter named Pieter Paree, circa 1759 at the Metal Pot Factory which fits nicely with the stylistic details of the pieces. The vases also bear an old Ginsberg Levy label and the custom made covers and bases were a later addition. (See next page)

Page 6

Also, Jeffrey showed a pair of Worcester molded and transfer-printed leaf-shaped dessert dishes in the popular Pine Cone pattern. As is typical of some early Worcester there’s a slight blue cast to the surface due to cobalt in the glaze. Each is marked with a crescent moon “C’ on the reverse, c. 1770

And a third contribution from Jeffrey was two Chinese export porcelain mugs. The ability of the Chinese potters and decorators to cater to any changing design requests is in evidence here: both

Page 6

mugs are after European forms and the decoration reflects changing tastes in the late 18th century. The mug on the right is earlier painted in Famille Rose enamels in a floral pattern, circa 1770s and the mug on the left is in a later European classical taste centered with a classical urn, circa 1780s.

Next, Liz Collins, a member from Hamden, CT. presented an English Staffordshire Lustreware 8” punch bowl decorated with an array of transfer prints depicting George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Lafayette, “The Nation’s Guest”, along with an early version of the Great Seal with an eagle with sixteen stars all around the exterior of the piece. The interior did not disappoint either with a detailed image of The Shipwrights’ Arms. Almost certainly made in commemoration of Lafayette’s visit to America in 1826. Below:

Liz also shared with us an 18th century commemorative snuffbox made of Berlin porcelain painted to the interior with a portrait of Frederick William Great Elector of Prussia and to the exterior with the Prussian eagle and trophies of war and the Elector’s initials as well as dates and names of various battles won. Both pieces from Liz’ family, the bowl purchased in 1952 by Liz’ grandparents, and both pieces with special family connections again, imbued with personal connections beyond their aesthetic and historical interest. The snuff box pictured on the next page.

Page 7

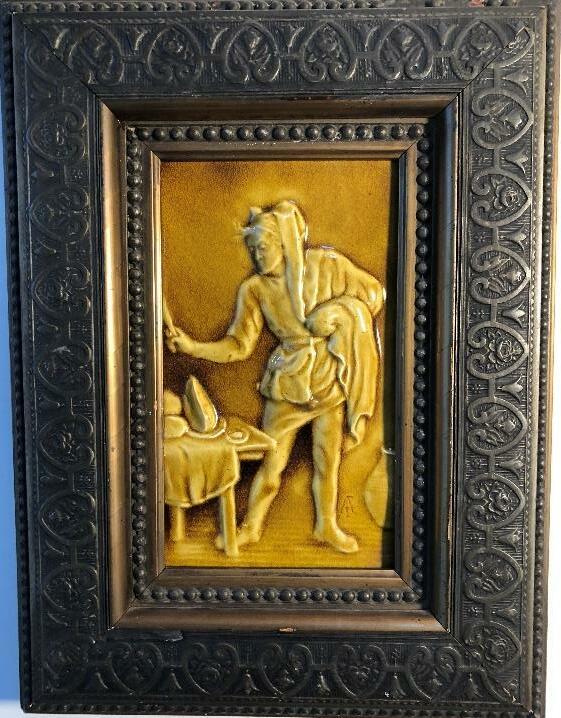

It wouldn’t be a Bits ‘n’ Pieces without our own ‘Dedham Pottery Curator’ Jim Kaufman presenting something intriguing. This year Jim shared an unmarked stoneware tile which he believes was from the precursor to the Dedham Pottery, the Chelsea Keramics Works, circa 18761880. Pictured below, it depicts a figure in medieval garb holding a knife next to a table of food. Jim was asking anyone with any knowledge of a design source a painting or a print - to let him know. Also, another similar tile, with another medieval character holding a knife and a pineapple. This one Jim conjectures was made by the firm of J. G. Low in Chelsea, MA John Low having left Chelsea Keramics in 1878 and started his own pottery. If anyone has seen a similar piece, or a design source, Jim would love to hear from you.

Page 8

Next, was Tad Baker, archaeologist from the University of New Hampshire who had given us a great talk on early ceramics in the Piscataqua region and the finds from the Demers shipwreck expeditions last October. Tad provided images (below) of pieces from the Demers Collection at the New Castle Historical Society. There were examples of Portuguese faience from the late 17th/early 18th centuries with a popular bird motif decoration, as well as two mystery pieces Tad hoped someone in the group could shed some light on. One shard, a ‘mystery outlier’ as he called it, was a Staffordshire type of rare three colored marbled slipware. The body was coarser than most examples so if anyone had any thoughts on that he’d love to hear from you. And a second mystery piece was a slipware bowl fragment, sadly degraded by saltwater, with green and brown decoration, the pattern slightly incised and colored in. Tad thought that it was perhaps a piece of North Holland slipware and suggested that not enough mention is given to our colonial trade with the Netherlands and the North Sea…any comments or suggestions would be welcomed!

And finally, former CSC President Carolyn Parsons Roy brought a couple of recent acquisitions to share. The first, (below left) was a brown (manganese) and green (copper) sponge--decorated platter with an impressed mark on the reverse DD & Co. for David Dunderdale of the Castleford Pottery in Yorkshire, UK, circa 1790. The second, (below right) was a very handsome foliate molded sauceboat and undertray. All Carolyn could provide us with for a description was Staffordshire, circa 1755 as her research has brought up very few comparable examples.

Page 9

WHISTLER’S ‘PEACOCK ROOM’ SUBJECT FOR OUR MARCH LECTURE

For our March 27th Zoom presentation, we were very fortunate to have Lee Glazer, PhD., Director of the National Archives Museum in Washington, DC speak to us, her talk entitled, From Chinamania to ‘Choice Specimens of Eastern Pottery’ : Whistler’s Peacock Room and Asian Ceramics. The famous ‘Peacock Room’ began life as a dining room in the rather posh London residence of a very successful shipping magnate Frederick Richards Leyland. Despite having come from a rather ordinary Liverpool background, Leyland considered himself as a Medici-style connoisseur and collector; he was a great patron of James McNeil Whistler, and his South Kensington home was packed with art. The dining room was designed by Aesthetic Movement architect Thomas Jeckyll to specifically showcase a Whistler painting and Leyland’s porcelain collection. Jeckyll was inspired by early historical detail and the dining room had a traditional Elizabethan/Jacobean pendant drop and lattice work ceiling and elaborate shelves with display places for the porcelain collection. The room was also inspired by 17th century pavilions designed to display luxurious imported porcelains grouped en masse Bear in mind that this was at the height of the Chinamania craze of the Aesthetic Movement. Blue and white Asian, and especially Chinese, wares were voraciously collected. Leyland was really more of a consumer than a collector when it came to ceramics.

The Leyland dining room as designed by Thomas Jekyll, c.1875

In the 1860s Whistler himself began collecting blue and white to decorate his home. He admired Chinese Kangxi porcelain (1662-1722); these wares provided him with a new artistic identity, design influence and style. You can see this in his painting hanging above the mantle in the Leyland dining room. The subject in The Princess from the Land of Porcelain resembles the elegant ladies with flowing robes, the so-called Long Elizen depicted on Kangxi wares. In another painting, Long Elizen of the Six Marks, the sitter is contemplating a Kangxi vase exemplifying the Chinamania of the period.

Page 10

The dining room as reimagined by Whistler as his complete work of art, Harmony in Blue & Gold. The room’s north end featured the artist’s painting The Princess from the Land of Porcelain over the mantle. Note Leyland’s massing of Chinese Kangxi blue and white porcelains.

But back to the dining room. In 1886, Leyland asked Whistler’s advice in “refreshing” Jeckyll’s original room. Jeckyll had fallen ill and couldn’t take the assignment, and Leyland had de-camped to his country house for the summer season. Whistler basically moved in and instead of refreshing the colors, he completely transformed the room. Over the course of the summer Whistler covered the room in peacock designs, gilded all the traditional woodwork and display shelves and infused the space with pattern everywhere. Whistler considered the entire room a work of art and entitled it Harmony in Blue and Gold. Well, there was little harmony when the artist’s patron returned home; Leyland was shocked at the transformation and at Whistler’s temerity in presenting him with a robust invoice for the work. Artist and patron had a falling out and never spoke again. Whistler managed to get in one last dig when he filled the one last open wall space left in the room with a painting of two peacocks fighting and entitled it The Battle Between Art & Money! Despite their falling out, Leyland never changed the room. He, too, must have realized that it truly was a complete work of art and it remained intact until his death.

Page 11

The south end of the dining room featuring Whistler’s mural The Battle Between Art & Money. Both images above are 1876 1877 interpretations of the room at the Freer Gallery of Art.

The next owner of the house wasn’t too keen on the room either, but by this time it had been published and talked about and she too realized how important it was. So, she advertised the room for sale. And so begins the next chapter in the Peacock Room’s story when American Industrialist Charles Lang Freer bought it in 1904, had it disassembled and shipped across the Atlantic to his home in Detroit. Freer personified the second generation of post-Chinamania collectors and he seemed far more interested in the historical aspect of ceramics and collecting. Eventually he filled the gilded shelves with what he called “Choice specimens of Eastern pottery” with examples from Syria, Iran, Iraq, China, Japan, and Korea. Freer didn’t particularly like the brashness of the stark blue and white porcelains Leyland collected; he preferred ceramics that were chromatically similar. Objects were carefully chosen to display their subtle colors. Texture and chromatic complexity are what Freer found attractive, obviously influenced by Whistler’s later work in his ‘nocturnes’ that he painted. In these subtle juxtapositions were what Freer often called “points of contact across time, place. and historical circumstance”.

Page 12

Previous Page. The Peacock Room as installed in the Freer home in Detroit in 1908. Note the change in aesthetic and collecting taste of Mr. Freer.

Freer died in 1919. The room remained in Detroit until it was dismantled, shipped and reassembled in the Freer Gallery in Washington D.C. and joined other objects from the collection. From 1923 to 1993 the room was used to display a small and changing array of ceramics, but just a few at a time never massed as Whistler, or even Freer, had intended. Following the restoration of the room between 1989-1993, approximately eighty blue and white Chinese porcelains of the Kangxi era were acquired specifically for the Peacock Room and installed to provide a sense of how the room would have appeared in Victorian London (when there were more than 300 blue and white wares on the shelves.

In 2011 an exhibit was mounted entitled The Peacock Room Comes to America trying to recreate Freer’s room from old photos and all the pieces in storage. The effect is quite different from Leyland’s collection of blue and white as Freer’s pieces were carefully chosen and placed to display their chromatic subtlety. And so, the pendulum swung back from Whistler’s “work of art” to Freer’s interpretation of the room and his collection “points of contact across time, place, and historical circumstance”.

Above, a comparison between Leyland’s collection in the Peacock Room (left) and Freer’s collection (right).

Editor’s Note: I found the Peacock Room talk especially interesting. As an appraiser I get to see a lot of homes and I have always been fascinated by how people live with their possessions and their collections. Is the collection its own entity, lined up on shelves, or in a cabinet, or does the collection play a part as an integral part of the space it inhabits? Do you acquire a piece to add to your collection, or do you also consider it for its place in your environment, and what it adds to that space? During our Bits ‘n’ Pieces program we discussed the feelings and sentiments with which we imbue our ceramics and other objects, and now here we have the question of how much importance do they play in the space we inhabit? Any thoughts?

Page 13

A CLAY SCULPTOR SHARES HER WORK WITH US IN APRIL

On Thursday, April 28th, CSC members were invited to join a Zoom meeting with contemporary ceramics sculptor Allison Newsome as she narrated a talk and videos entitled Architectural Clay with Allison Newsome, detailing the source of her inspiration and sharing examples from her very productive and creative career. This started with graduation from the Rhode Island School of Design and included eighteen years of teaching ceramics at Harvard University, as well as numerous shows, installations and workshops.

Allison’s inspiration for her work comes almost entirely from nature and the natural world and she is especially attracted to working with clay and its very tactile qualities. This was best illustrated from the very start of her talk which featured a video of her creating a clay sculpture attached to the side of a large shoreline rock at low tide. The installation has a very fleeting nature as the tide eventually returns and the sculpture washes away; those who were present enjoyed the piece and then it is gone. (See below).

We moved on to another example where in an installation at the Wentworth Coolidge House in New Hampshire Allison created large disc-shaped murals of clay modeled with cornucopia which were then mounted onto the sides of large hay rolls in a field rolling down to the shoreline. She enjoys taking clay outdoors natural forms, made of natural materials, inspired by, and set into nature. She often enjoys collaborating on group installations like this one where artists meet at the site to be inspired and return later with their works. This particular showing spoke to history of the wilderness, and agrarian, industrial and post-industrial history of coastal New Hampshire.

Page 14

One of Allison’s cornucopia pieces at the Wentworth Coolidge Estate in New Hampshire.

On another project Allison was invited to work upon, she ran a workshop at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in conjunction with a Della Robbia exhibit they were hosting. As the famous Italian Renaissance artist ran a thriving workshop, Allison, too, had assistants as they molded clay into parts that came together to form a large Della Robbia style roundel. This was interesting in not only exhibiting how the originals were created, but also how they had to be made differently depending upon whether they were to be installed outside in the elements or displayed or inside.

When teaching at Harvard, Allison felt very strongly about visiting museums and their collections in storage to draw on inspiration of earlier works. In one instance she was especially keen that students saw the 17th century sculptor Bernini’s original clay models which he purportedly created with great spontaneity. He desperately wanted to translate the “life” in the clay to the final carved marble product. Allison finds Bernini’s clay models full of that energy and life.

Above Left: Allison in her MFA Della Robbia Workshop. Right: Students studying Bernini’s clay models.

Above Left: Allison in her MFA Della Robbia Workshop. Right: Students studying Bernini’s clay models.

Page 15

One of Allison’s largest outdoor commissions was for a historic building on Newport’s famed Bellevue Avenue. It was a large later 19th century brick building (below) decorated with glazed faience architectural detail in the style of the French Renaissance artist Palissy, including twelve large lions along the roofline.

A hurricane had blown through and destroyed the lions and Allison was commissioned to recreate them. Each one ended up weighing about 500 pounds and she made twenty-three to accommodate any kiln accidents or other problems (they used up three just to decide upon what shade of white they wanted the glaze to be!).

Allison was also honored to be invited to be the first resident artist to work in the Beatrice Wood Center in Ojai, California. Inspired by Wood’s creativity and longevity (she lived over 100 years) Allison created an homage piece to Wood with a female figure beneath a bamboo arch, as well as figural pieces inspired by orange trees in Wood’s garden. Allison wanted to point out two things about these pieces. First, the use of another natural material wicker that she used to impress natural patterns into the clay and the use of color on the clay. She remarked that even when she uses bronze she tries to find a use for color as she finds the dark surface of bronze uninteresting.

500 lb. lion figures in Allison’s studio, before and after their glazing.

500 lb. lion figures in Allison’s studio, before and after their glazing.

Page 16

Inspiration came from another quarter when Allison saw the entire excavated cargo of a Mississippi paddlewheel boat, The Arabia, that sank in the mid-19th century laden with merchandise for general stores along the river. Now seen in its entirety in a Kansas City Museum, Allison became fixated upon all the cards of buttons in the hoard and did a group of pieces based upon 19th century ‘Memory Jugs’ basically simple stoneware jugs adorned with button and ceramic shards and a general mosaic of the bits‘n‘bobs from people’s lives.

Allison’s homage to Beatrice Wood (left) and figural inspiration drawn from the artist’s orange garden (right). In another bronze commission, she cast a life-size wall-mounted spread eagle for a piece in a veterans’ home but included a large colored clay salt marsh mural behind to introduce an expanse of color.

Allison’s veteran’s home eagle installation (left & center) and one of her Memory Jugs (right).

Allison’s homage to Beatrice Wood (left) and figural inspiration drawn from the artist’s orange garden (right). In another bronze commission, she cast a life-size wall-mounted spread eagle for a piece in a veterans’ home but included a large colored clay salt marsh mural behind to introduce an expanse of color.

Allison’s veteran’s home eagle installation (left & center) and one of her Memory Jugs (right).

Page 17

But most recently, Allison was involved with a group show entitled Water, Wind & Solar which led her to the idea of harvesting water in this world of climate change and sustainability. (See above).

sculptures are basically floral inspired forms that collect rainwater and siphon it down their stems into a water ‘bladder’ or receptacle. She has now created a series of these large metal sculptures, some of which gather as much as 500 800 gallons of water and come in all manner of creative forms appearing in public spaces from Boston to Venice.

Another of Allison’s ‘water harvesting’ sculptures. Her inspiration drawn from nature, we can hardly wait to see what Allison comes up with next!

Page 18

‘IT’S A SMALL WORLD AFTER ALL’ MINIATURE CERAMICS CONCLUDE OUR PROGRAM YEAR

Regretfully, another complete CSC program year concluded via Zoom as the lingering repercussions of Covid played out. Still, our talks always seem to enlighten and delight, and our concluding lecture was no exception. In what was to be our Annual Meeting & Tea, fellow member and miniatures artist, Lee Ann Wessel spoke to our group on the subject of Making it Small: Ceramics Study in ½ Scale.

Lee-Ann has combined her two great interests the study of ceramics with her passion for miniatures. The opening image she shared with us summed it all up as it was a photo of her extended hand full of a dozen perfect miniature examples of her work. Examples ranged from a 17TH century monteith to a 20th century Saturday Evening Girls bowl, to mochaware jugs and Arts & Crafts pottery. She has offered them for sale to collectors and at museum gift shops at Colonial Williamsburg and Historic Deerfield as well as giving classes in her art at the Guild School in Castine, ME. Pieces are made in a small home studio with a potter’s wheel and a kiln not much bigger than a microwave oven. She has created tiny molds for slip-casting, either on the wheel or with a small lathe, but is moving away from creating multiples to one-of-a-kind objects.

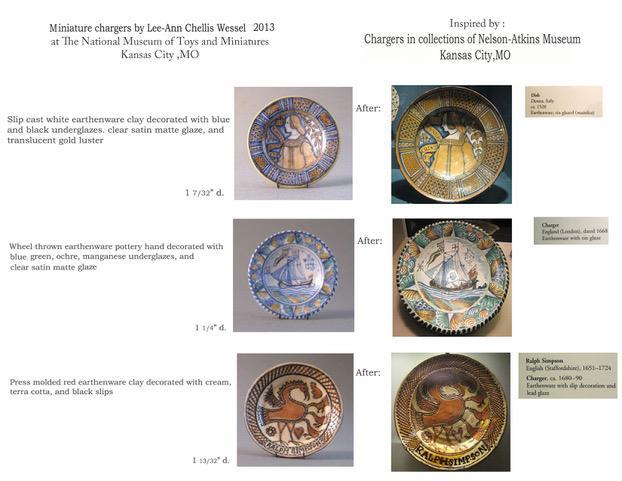

Lee-Ann decided to use her ‘down time’ during covid to filling gaps in her own collection. She has grown a bit tired of doing shows and has since looked to building her own private collection. She shared images with examples of her miniature wonders in Italian lustre, English delft,

Page 19

and slipware by Ralph Simpson inspired by pieces at the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. Lee-Ann finds her inspiration in museum collections as well as in published materials, her research as rewarding as the miniature’s creation itself.

Lee-Ann was honored to be included in a contemporary show called American Clay: Modern Potters, Traditional Pots at the Fuller Craft Museum in Brockton, MA. The exhibit bridged the gap between the two worlds of pottery history and contemporary ceramic fine art. Lee Ann had two cases in the gallery. One was a miniature grain-painted cupboard (made by friends) filled with American redwares and wheel-thrown earthenware a lot of the pieces based upon period originals in the Philadelphia Art Museum. Lee-Ann loves to hand-decorate pieces such as the sgraffito charger and make the models for the fish-shaped flasks. She strives to make her miniatures as accurately as possible; she wants people who know the originals to easily recognize the miniatures.

The other exhibit case she created displayed 16th 17th century Italian maiolica based upon original wares from Montelupo; the chargers and jugs all of similar form, but the decoration, like the originals, varies dependent upon the local village potters’ individual style.

Left: Examples of Lee-Ann’s work for an exhibit at the Fuller Craft Museum illustrating her interpretations of American redware, earthenware and sgraffito pieces. Right: 16th-17th century Italian majolica miniatures. Next page: One of Lee-Ann’s favorite Italian majolica pieces featuring two men, one with a donkey’s head and an inscription reading, “He who washes the head of an ass, wastes soap”.

Page 20

Above: A slide from Lee-Ann’s presentation showing some of the original museum pieces on the right and her miniature interpretations on the left.

Page 21

A present work in progress for Lee-Ann is a collaboration with miniature room specialists Allison Ashby and Steve Judd creating a period room box in the American Arts & Crafts style. They supplied her with an exact replica in foam core so she would know what spaces exactly she had to fill; from a fireplace surround made of circa 1923 Calco inspired peacock tiles, to display cabinets which were to be filed with period pottery, primarily Newcomb and Saturday Evening Girls. There was also an Arts & Crafts tile back sideboard to create and the technique she used here was to use a black wax resist in outlining all the images and then coloring in all the segmented areas. When fired, the wax burns away leaves the outlines without the colors running together, giving Lee-Ann the Saturday Evening Girls ‘look’ that she wanted.

Above Left: The box room model Lee-Ann was given to gauge the size of her pieces for display. Above Right: The room as it actually nears completion. Below: The Calco-inspired fireplace surround and some of Lee Ann’s Arts & Crafts creations.

Page 22

For all these projects Lee-Ann relies heavily upon her research. A devoted bibliophile, she loves her library and researching ceramics, as well as working from original examples as with a Jazz Age bowl that Lee-Ann created after the original by Viktor Schrenkengost, circa 1931. Schrenkengost was an amazingly versatile artist and designer he was a painter and a potter, but he designed everything from tractors and trucks to kiddie peddle cars and bicycles! The Jazz Age bowl was designed for a commission from the Cowan Pottery in Rocky River, Ohio and the artist later found out the piece went to Eleanor Roosevelt. The process he used to create these large bowls was time consuming and somewhat complicated; he then went on to design a template to facilitate production.

Lee Ann’s examples of Schrenkengost’s Jazz Age designs.

Some of Schrenkengost’s pieces were obviously influenced by ancient Egyptian and Persian ceramics and their use of vibrant turquoise glazes such as the turquoise used in the Jazz Bowl. LeeAnn concluded with an image of a collection of her miniatures of ancient ceramics along-side some Jazz Age designs illustrating how similar their styles really are. (See below)

Page 23

Lee-Ann closed her talk with a heart-felt ‘thank you’ to Program Director Anne-Lanning, to whom we all owe our gratitude, for continuing to provide such an outstandingly interesting and diverse roster of speakers each program year. As a ceramic artist herself, Lee-Ann said she loves what she does and loves that our club continues to introduce and celebrate ceramic artists, potteries, and their creations to us all.

Dorothy-Lee Jones Ward, formerly of Wellesley, MA and Sebago, ME, passed away in Nashville, Tennessee on August 4th, 2022, after a decline due to Alzheimer’s. She was 95.

Dorothy-Lee Jones Ward, formerly of Wellesley, MA and Sebago, ME, passed away in Nashville, Tennessee on August 4th, 2022, after a decline due to Alzheimer’s. She was 95.

Page 24

Dorothy-Lee attended The Winsor School in Boston, graduated from Erskine Junior College and took courses at Boston University. While in college she started an antiques business, The Glass Basket, in Douglas Hill (Sebago), Maine. The Glass Basket was very successful, attracting visitors from all over the world and helping her build a reputation as an expert in both antique glass and ceramics.

An early avocation of Dorothy-Lee’s was music, and she trained with Maestro Alberto Saretti in New York in the 1950s and early 1960s. She was a wonderful mezzo soprano, performing in both New York and Boston as well as part of the choir at Park Street Church in Boston.

Dorothy-Lee was very active in a variety of volunteer organizations for decades. They included music-related non-profits in Boston and the Friends of The Deaconess Hospital in the 1960s and 70s. She was President of the Friends at one time and was the buyer for their very successful gift shop.

Dorothy Lee’s real passion though, was glass and ceramics; even as a child she loved seeing interesting antiques. Lowell Innes was a prominent expert on American glass and good friend of her mother’s and helped to fuel her life-long interest. She was active in many collector organizations, including the China Students Club of Boston (now the Ceramics Study Club of Boston), the Wedgwood Society of Boston and the National (Early) American Glass Club, of which she was President (1965-1967) and editor of the Bulletin (1967-1973). Recognizing her accomplishments in the world of glass, she was invited to become an Honorary Fellow of the Corning Museum of Glass, a prestigious group of international experts.

After nearly 30 years running her successful antique shop in Douglas Hill, Maine, she embarked on a daunting task when she founded The Study Gallery: A Museum of Glass and Ceramics in 1978. Wanting to showcase the history and beauty of both glass and ceramics, she loaned her personal collection, alongside gifts and acquisitions by the museum, on display to the public from May to October. While the name was later changed to the Jones Museum of Glass and Ceramics, she acted as Founder-curator and Director for many years. She had had hopes of revitalizing the organization after it was dissolved in the mid-2000s but was regretfully unable to do so.

She had a passion for research and always enjoyed questions about glass and ceramics. When faced with a question from a museum visitor, she would likely drop everything, rush to the well-stocked, reference library and look up details on the piece in question. Despite dyslexia, diagnosed in her 40s, she had a near-photographic memory that allowed her to instantly locate specific images in reference books. She lectured at museums, clubs and symposiums all over the US, and published many articles in a number of glass and ceramics publications. Even when moving into a retirement apartment in 2010, she brought books and pieces with her hoping to work on continuing research.

Her enthusiasm and energy spilled over into other interests as well. She was an avid fan of ice skating and was a member of the Skating Club of Boston, enjoying many trips to skating competitions and exhibitions with her family and other Skating Club members. Dorothy-Lee and her husband Lauriston also were able to go on international trips over the years. Sometimes the trips were glass and ceramic-related, and other times were just to see new and beautiful places.

Page 25

Dorothy-Lee’s life-long joy was in communicating her love, and knowledge, of glass and ceramics. Her dedication to all things of beauty will be missed. She was predeceased by her husband, Lauriston Ward, Jr. and her parents Kathryn and Harry Lee Jones of Newton, Mass. She is survived by her daughter, Lyra Ward Hankins of Nashville, Tennessee.

On another sad note, I passed this sight walking down Boylston Street the destruction of The Women’s Educational & Industrial Union where our club used to hold its monthly meetings when I first joined the organization. One entered through the front door with a gilded swan hanging overhead, up the stairs to a meeting room where many great lectures were heard, and many great friendships were formed. If those walls could talk!

Jeffrey Brown, Editor

Jeffrey Brown, Editor

Page 26