AUTUMN 2023

A FELLOW MEMBER’S COLLECTING ODYSSEY

INAUGURATES OUR 2023-2024 SEASON

The CSC program year began on a lovely autumn afternoon at King’s Chapel Parish House in Boston with a capacity crowd to hear fellow CSC member Nic Johnson speak about his collecting odyssey with a talk entitled Sixty Years with Pots: A Show and Tell. It is always interesting to hear about how a collection is formed, what attracts a collector, and his reasons for the directions he takes (if there ever is any reason to any of it!) and that is just what Nic shared with us as he took us through the various phases of his collection.

Nic was born in the U.K. and his early years were happy ones formed at a progressive coeducational private school in Devon, England called Dartington Hall. It was at Dartington that Nic first encountered pottery: the school strongly encouraged it, as well as all the arts. There was a very well-equipped pottery studio under the direction of Bernard (Bernie) Forrester. Nic admits he wasn’t very good at it, but he became increasingly interested in the craft, purchasing his first piecea black bowl – from Bernie Forrester around 1953.

After college Nic moved from Hampstead to Lambeth in London where he began regular weekly forays to various markets. These were treasure troves with objects brought in from the country by various pickers and dealers. He told us that with a weekly salary of less than 20 pounds sterling a week, economics was a deciding factor in all his early purchases! But he formed a pattern of

Above: A matt black redware bowl, c. 1955 by Nic’s teacher, Bernard Forrester.finding a smaller example of something that interested him, learning about it, forming a small display collection on the subject, and then moving on to the next thing that piqued his interest. The emphasis had to be on small and less fashionable objects. One of these phases of interest were pieces from the Doulton factory which based its original success upon the massive production of sewer pipes. It was Henry Doulton’s friendship with the head of the Lambeth School of Art that led him in 1874 to create a ceramic studio for decoration staffed primarily by young women. Pieces were created by workmen in Doulton’s signature dense stoneware but were mostly decorated by this group of talented women. Nic became rather fixated upon this subject of interest and formed a small collection of these wares which were donated to the MFA, Boston many years later after he had emigrated to the States. Before emigrating, though, many of his earlier Doulton ‘finds’ continued to be discovered at these early morning markets such as Bermondsey where dealers congregated on a Friday morning and where some of the ‘old timers’ spoke of potters and decorators from Doulton because they had actually known some of them! Hannah Barlow was one such figure, and she was able to bring two siblings into the Doulton studio workforce.

Moving on to his second phase of collecting, Nic became interested in the not yet famous Martin Brothers and their highly individual creations. Martinware was made more in a studio rather than an art pottery setting and the division of labor was between the four brothers. Wallace Martin, the eldest brother (and last to die) had previously worked for Doulton and for a while in a Fulham studio before the families moved to a canal-side setting in Southall. Their medium, as with Doulton, was polychrome salt glazed stoneware, but one that became increasingly free. Wallace worked with gargoyles in his youth and liked to sculpt grotesques, while brother Edwin used animals and plants in his delicate sgraffito decoration. Nic was able to buy a lot of small Martin pieces from Sotheby’s in Bond Street, paying about a pound apiece for them, while an ad in he placed in the weekly Exchange Mart led him to a vase which he acquired from a young couple in a basement flat for a little over four pounds! In time prices rose, for Doulton and especially Martin wares and Nic remains grateful to his mother for buying a large Martin bird for him for a hundred pounds – still one of his most cherished possessions.

Above left: A carved Doulton salt-glazed presentation barrel made for a retiring workman. Right: a very functional Doulton stoneware beaker, both circa 1875.

St. Ives

a Bristol

and decorated with a rabbit. Upon a subsequent visit to St Ives at the Leach Studio Museum, a long-time associate of Leach’s identified the piece immediately saying, “That’s Bernard’s hare.” By this point, Leach’s work was becoming more expensive, but the work of Leach’s pupil Michael Cardew was still affordable. Cardew, though of patrician descent, was devoted to the potter’s craft and earned little, leaving his wife to often care for their family for long stints of time. (Cardew learned to throw at Braunton Pottery, of which more later.) Michael finally came into a little money and started his own pottery in Winchcombe, Gloucestershire. He later moved to Wenford bridge in North Cornwall, where Nic and his wife visited him in 1970. Cardew’s prices were always affordable, partly because he advocated for throwing many pieces of the same form. He went on to spend five years in Ghana and Nigeria, establishing at least one pottery that still flourishes today. Bernard Leach continued to pot, occasionally with the help of his son David, who in about 1960 threw a series of lidded jars which his father decorated and signed BL. Nic later found one in an “undistinguished” shop on Cape Cod and acquired it for $25.00.

The next phase started about 1980 when Nic began taking an annual trip to Morocco where the chief pottery centers were in Fez, which produced a white-bodied pottery, and Safi which used a

Above Left: A small, incised vase by Wallace, the oldest of the Martin Brothers from their early Southall Pottery, circa 1880. Right: A small early Martin Brothers beaker vase, circa 1870s. The next phase found Nic becoming more interested in studio pottery as practiced by Bernard Leach in St. Ives from the 1920s. One of Nic’s finds from this period was from junk shop: a small stoneware bowl with the mark Above Left: Stoneware jam pot by Bernard & David Leach, circa 1960. Center: a Safi Dish from Morocco. Right: a footed bowl from the Seghini Pottery, Fez, Morocco, 1980s.local red clay. Many pieces were sold in roadside stands and the prices were affordable, but the shipping, charged by the pound, was more of an issue. Having relocated to New England in the 1970s, Nic tried to continue to collect from his previous phases of interest, but he found the pickings slim. Advice from Robin Hildyard of the V & A led then to an interest in stoneware packaging, bottles, bottle-digging and auctions run by British Bottle Review and a few rivals. Excavated pieces of largely local interest included printed ginger beer bottles from local bottlers; auctions included earlier stonewares including superior slab-sealed flasks and flagons. The EX bottle Nic shared with us, along is a small brown salt-glazed container, perhaps for polish, had an impressed EX to show it was exempt from a tax applied around 1830 on stoneware bottles in order to favor the nascent glass bottle industry. He bought it in a barn in Northwood, N.H. Nic amassed a small collection of anonymous and lustrous Derbyshire stoneware jam jars. They were made by the million and required by the dozen by British housewives but were eventually eclipsed by sturdy and sealable glass jars such as Ball and Kilner. A group of these jars turned up in a Sterling, MA, antique shop which led Nic to wonder if they were exported for use to America in the mid-19th century; There appears to be no historical archeological evidence to support this hypothesis! Stoneware articles were given away as containers for such things as ink, polish, blacking and marmalade, and were often impressed in printer’s’ type to show capacity, manufacturer, customer and even loyalty to a political cause.

Nic also bought and studied brown stoneware hunting mugs, utilitarian pieces from the Midlands to London and Bristol. Another collecting interest concerned the redware pottery of North Devon. First came the Fishley family whose history is outlined in William Fishley Holland’s fascinating 50 Years a Potter. After working in the family pottery in Fremington, WFH was trusted to run a new pottery in Braunton around 1912. Nic went to see the work of George and Edwin Beer Fishley in N. Devon museums, and developed an interest in these men, who, he learned, had helped Edward Elton set up his pottery in Clevedon, not far from Bristol where we were living. I learned that after service in WW1, Holland discovered that people wanted color, which his 1000-degree centigrade kilns could supply better than stoneware competitors working at 1,200C.

Above Left: a 19th century stoneware bottle impressed “EX” as an exemption from a bottle tax as well as a stoneware storage pot with a make-do cover; Right: Two pieces by William Fishley Holland from the Braunton Pottery.Nic’s final phase of collecting (for now) is one with which we are probably the most familiar as he has shared many of his pieces of Kutahya ware with us at Bits ‘n’ Pieces over the years. It was from books and museums that Nic learned of the Kutahya ceramic tradition which goes back probably to the 15th century, reaching its peak in the 18th century, primarily within the Armenian community. One Nic learned of the prices asked for such period pieces, he switched his attention to the revival of these potteries in the late 19th century, about which little had been written.

There had been a great decline in pottery production in Kutahya during the 19th century, when a Muslim Turk, Mehmed Hilmi, was charged with helping revive it. Hilmi had previously worked in the book arts and was from a prominent Istanbul family. He was exiled to Kutahya for political reasons, where with an Armenian potter, he established a pottery using the traditional fritware body which when slip-covered provided a good white ground for decoration. The decoration was led by drawing fine outlines using a special black mineral. The outlined shapes were then filled with pigments, often by women workers, covering most of the ground with polychrome designs. Two special features were the use of a raised red made from fine iron-rich clay – possibly fired after glazing at a lower temperature – and the bright Naples yellow which was never employed at Iznik.The three potteries in 1900, two Armenian Christian and one Muslim, worked in competition, but also cooperated on large tile commissions. This multicultural cooperation ended around 1920 when Armenians were largely deported, often with fatal results, and Turkey and Greece were in a war that led to the Greek occupation of Kutahya. Nothing was ever the same; subsequent production has been carried on chiefly by Muslim Turks.

It is very rare to find this Turkish pottery in a shop, and since it is usually unmarked, one needs to employ a variety of e-bay searches, consulted regularly, to snare anything! Nic concluded saying “Each time I’ve been able to invent a new collecting phase – or even craze – I’ve continued my interest in pots from the earlier ones, especially examples of high quality, that ineffable essence we all seek.”

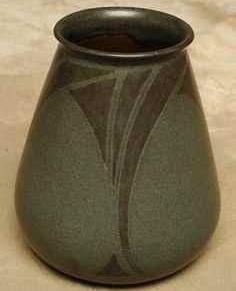

MARBLEHEAD POTTERY AND ITS INFLUENCE

SUBJECT OF NOVEMBER’S TALK

The group’s slated speaker for our November meeting unfortunately had to cancel their zoom lecture with our group but happily our brilliant Program Director Anne Lanning enlisted Marilee Boyd Meyer who successfully stepped into the breach with a zoom presentation entitled Marblehead Pottery: Different From Everything Else”. Immersed in Turn of the Century arts and design for more than 40 years, Ms. Meyer was the founding director of Skinner, Inc’s Arts and Crafts department for 10 yrs. Graduating from Skidmore College in Art History, she worked at the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA) now Historic New England, and was guest curator for several exhibitions including “Inspiring Reform: Boston’s Arts and Crafts Movement” (1997), and on Arthur Wesley Dow: His Art and His Influence (1998). Ms. Meyer, an independent appraiser, consultant and lecturer continues to research Marblehead Pottery and related subjects in the Arts and Crafts Movement. (Photo Crab Tree Farms Foundation)

Determined to produce “Something Different from Everything Else” Marblehead Pottery Director Arthur Eugene Baggs (1866-1947) created a simple ceramic aesthetic grounded in the new 20th century design reform. Emerging from the late 19th century, the Arts and Crafts Movement embraced the home as a holistic harmonious environment. Ceramics became distinctive and “artistic” as opposed to the previously fussy, cluttered Victorian aesthetic. The new overall approach, taught in schools by the 1900, was based on the simplicity and flattened geometric design principles found in Japanese Art permeating the country in the late 19th Century.

Pottery was also part of the new Occupational Therapy, in his case, used at a sanitorium for nervous disorders in the coastal town of Marblehead, Massachusetts. Founded in 1904 by Dr. Herbert Hall (1870-1923), a Harvard graduate, and Miss Jessie Luther (1868-1952), a Rhode Island School of Design graduate, the new treatment hoped to teach discipline, artistic eye and something morally satisfying. In order to create a product of quality, Dr Hall sought out top-notch instructors in all areas.

In the Spring of 1905, Hall contacted Charles Fergus Binns (1857-1934), the director of the newly established (1900) New York School of Clay-working and Ceramics, (Alfred) in Alfred, NY, seeking recommendations to fill the pottery department position which required sufficient training in clay and glazes and who could teach and work independently. Weeks later, undergraduate 18-year-old Arthur Baggs was assigned to the internship, a position he held for the next thirtyone years. By 1908 he became the pottery’s director and in 1915 he purchased the pottery outright from Dr. Hall

It was soon obvious that in order to create something of merit, a reliable workforce was needed which led to several steady hires by 1906. As a “green potter” (which he called himself), Baggs constantly sought guidance and supplies from his mentor, Binns. Eventually, Binns weaned his protégé of his reliance of Alfred glazes and encouraged him to grind his own. These experiments would lead Baggs to independence and a reputation as an expert glazier. (Photo Two Red Roses Foundation)

Self-education was in play the minute he arrived in Boston-considered the epicenter of the Arts and Crafts Movement and home to its influential Society of Arts and Crafts Boston (OR SACB) -which he joined. Baggs visited many cultural institutions and began to network shrewdly within the arts and crafts community. He immediately sought out the ceramics of Adalaide Alsop Robineau exhibiting at the Society showroom and in October 1905, he visited the much-heralded Grueby Pottery and William Grueby, a medal winner in Paris exposition 1900 and legendary for his matt green glaze. He hoped to “visit often and maybe get some good ideas.” (Robineau Eidelberg Collection: Grueby, Private Collection)

More significantly, Baggs had visited Ipswich Summer School near Marblehead, as a guest of his Alfred design teacher, Adelaide Blanchard, who had attended two years earlier. Founded by art educator, Arthur Wesley Dow (1857-1922), a prominent teacher at Pratt Institute in NY, he was a leader in design reform, developing a system of artistic principles based on abstraction, harmony and “COMPOSITION”, publishing his seminal teacher’s manual by the same name in 1899. It became an indispensible resource in the classroom and at Alfred in particular. Baggs, brought with him to Marblehead, Binns’ formal clay technology, glaze chemistry and Blanchard’s lessons based on Dow’s principles of Design. (Dow, Ipswich Summer School, 1903)

In November, sanatorium co-founder Luther who had headed the handicrafts and pottery, departed leaving Baggs with the yeoman job of production and glazing, instead of his preferred drawing and designing. To help with handicrafts, Dr. Hall hired multi-talented Arthur Irvin Hennessey who shared time with both the woodworking and metal workshops. At first Baggs thought Hennessey a “capable” potter and draftsman, but questioned whether he knew very much about design. This blossoming partnership under Baggs’ aesthetic guidance and oversight led to Hennessey becoming a key figure contributing to the pottery’s distinctive identity.

Baggs academic education at Alfred was further supplemented by his attendance in November 1906, of a course called “Theory of Pure Design” by Harvard Art Educator, Denman Waldo Ross (1853-1935), a course Hennessey also attended. Ross had been deeply involved in the movement, designing the “tapestry lion” border for Dedham Pottery in 1897, the same year he co-founded the SACB. Ross, a colleague of Dow’s, had also experimented with systems of abstract design influenced by the budding sciences of botany and mathematics. Cross sections of vegetation, insects and animals became flattened pattern. Taking it one step further, Ross saw design “as a branch of mathematics …particularly geometry”, a direction embraced by the Marblehead potters. The combination of Dow’s and Ross’s lessons championed Japanese forms, simple arrangements of line, proportion, surface pattern, close harmonious tones and geometric simplicity all figuring into the Marblehead pottery aesthetic and creating one of the clearest expressions of Conventionalization in the Arts and Crafts period.

Over the next year, Baggs hired pottery thrower John Swallow, and teacher and designer

(Credit: Arthur Irvin Hennessey, C. 1910, Rago Arts) (Above: Page from Composition 1905 version; vase private collection)Maud Milner. Sarah Tutt and Annie Aldrich, both previous patients, were added to the small staff by 1907. An unofficial, occasional designer, Aldrich produced two iconic vases, one with flying geese and one depicting the Ipswich Marshes. (Above: Image of Maud Milner, Goose, Private collection, Marsh Vase Collection of Two Red Roses Foundation).

Sara Tutt became the decorator, transferring designs to pots from 1907 until the pottery’s closing in 1936. Her initial “T” was often added to artist initials signifying collaborations between Milner and Tutt (MT) and the prolific Hennessey and Tutt (HT). Baggs’ initials “AB” can be seen with Tutt’s “T” along with the pottery’s ship logo on a small pot with an abstracted wasp design.

Marblehead Pottery was exhibited at both Boston’s 1907 Arts and Crafts Society anniversary exhibition and at the National Society of Craftsmen in New York City December of that year, cementing his reputation with quiet, harmonious, “severely geometric” abstract designs. Ellison Collection, MET

Baggs grasped ideas from many design sources including the Museum of Fine Arts. He had been exposed to the simplicity and honesty of Native American design at Alfredwhich he initially adopted. Tile-making also peaked Baggs’ interest, integrating the fine art of drawing with the handicraft of clay. And Baggs was also drawn to the simple decorative principles from contemporary photography in its contrasts and silhoettes. Dow had advised his students to “treat landscape first as a design, afterwards as a picture”. (See above -Vase Fuldner Collection; three tiles collection of Two Red Roses Foundation)

With loyal staff covering technical and design aspects, Baggs returned to Alfred to resume classes in late 1909 signaling an aesthetic transition. These first four years at Marblehead marked the “incubator period” creating many original designs and a recognizable product.

Baggs remained in Alfred until 1911, the same year he introduced his Majolica glaze, a new white glossy- but short-lived- tin-glaze - under Binns’ tutelage which proved a brilliant background for Hennessey’s painted decoration. Pieces of any consequence were fully signed “Henessey” between 1911-1913 mostly based on Marblehead Maritime and bird motifs and were often included in publications like House Beautiful. By 1912, Marblehead glazes reverted to semi-matt smooth painterly surfaces and the Majolica glaze was discontinued.

Baggs continued his extensive drawings of repeating animals, abstract flowers and empty panels, but unlike Baggs, to date there are no related design studies revealing Hennessey’s work process. Hennessey immersed himself in what Binns called “learning by doing” –initially directly copying designs from the best magazines such as Craftsman and other sources. This page from Keramic Studio gave him a variety of turtles to adapt to this irrigator of 1909. (See Below - Rabbit Vase and drawing courtesy JMW Gallery; Turtle jardinière Ellison Collection MET)

Chinese Lanterns from Keramic Studio, 1913 seem related to this vase with the pods from around the same time. Hennessey’s adaptive ideas help document the legacy and direction of design reform by interpreting the clearest examples from classic resources and may explain why Marblehead designs were so pure. (Vase courtesy Ragoarts)

When Baggs finally purchased the pottery from Dr Hall in 1915, he marked the occasion with a group of statement vases incorporating sea creatures in the now familiar “Marblehead blue” glaze. (See Left). By 1919, a company brochure was published where shapes and colors became standardized though custom pieces were available. (Vase courtesy Ragoarts)

The potter continued to evolve stylistically as he moved from position and institution throughout the teens, twenties and into the thirties, and all the while returning to Marblehead to get rejuvenated. In 1925 Baggs joined Alfred student Guy Cowan at the Cowan Pottery as a glaze

where he introduced a Persian turquoise and black color combination influenced by the Egyptian excavations of 1922. Sgraffito technique and color combination was adopted by Victor Schreckengost for his 1930s Jazz Bowl. Baggs also grew more inventive with sgraffito and incised designs. (See above) Baggs then moved onto Ohio State University where he concluded his career as a Professor of Ceramics, rivaling Alfred, from 1928 until his death 1947. Marblehead Pottery had closed in 1936. (Vase and bowl courtesy Ragoarts)

Design is the process that brings order to the artist’s idea and execution. Both Baggs and Hennessy were master editors of detail resulting in Marblehead’s severely abstracted and geometric style. Their product is highly sought after today for its timeless quality and modern aesthetic.