VIVIAN HAWES MEMORIAL LECTURE ON IRISH FINE CERAMICS

Each year the Club remembers President, Treasurer, ceramics scholar and friend, Vivian Hawes with a lecture in her honor this time with with a talk via Zoom from Ireland. Mr. Peter Francis, Formerly Research Fellow at the Institute of Irish Studies, Queen’s University, Belfast spoke to us on the subject of Early Irish Fine Ceramics 1697-1840: Delftwares, Creamwares and ‘Stickwares’.

Peter began with a bit of the backstory leading to this subject matter as he was approached in the year 2000 by well-known London dealer Jonathan Horne and asked to produce a catalogue on Irish Delftware for an exhibition Jonathan was preparing in London. What began as an exhibition catalogue of eighty pages ended up taking two years and produced a 200+ page volume with additional research and images by Michael Archer from the V&A Museum.

Most of the Irish ceramic industry Peter discussed focused on the 100-mile stretch between Belfast and Dublin on the east coast of the country. Around 1697 one of the earliest potteries was set up in Dublin by one Matthew Garner. But Garner’s story begins well before that when he appears first around 1666 in London working at a Southwark pottery producing delftwares. In 1687 Garner moves to the Montague Coates Pottery in London, and in 1691 he lost that job and took a place with John Dwight making red stoneware in the manner of the Elers brothers. At some point he loses that job and, bankrupt and homeless, returns to Belfast. Now Belfast had a sugar refinery processing West Indian sugar cane and the town was in need of another industry that could produce trade items to load onto the empty returning ships that brought in the sugar cane. Garner helped set up the ‘Pot House’ in Belfast producing delftwares from locally mined clay deposits. Peter discovered the Pot House kilns were peat fired and thought that unique to Belfast, but later found out that other potteries also employed this method, even some in Holland. Several of the earliest Belfast pieces that were discovered are a pair of delft shoes and a large 20” loving cup now in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Belfast dated 1712. See below: Page

11

Although the Belfast pottery closed in 1725 and its output was small compared to other potteries in Britain, its effect on the pottery industry remained enormous as Belfast clay deposits continued to be mined and the clay went on to supply a plethora of delftware potteries both in England and Ireland such as Liverpool, Lancaster, Dublin, London and Bristol.

At this point the story moves to Dublin which, with a population of 60,000 people was the second largest city in the British Isles. Unemployed potters from Belfast moved to Dublin where an entrepreneur, John Chambers, opens a pottery on the edge of town. One of his earliest ‘masterpieces’ is a large charger bearing the Arms of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (in hopes of attracting some government patronage) which is inscribed Dublin 1735 (pictured below left).

What a difference a big investor makes! Pictured left is the only attributable piece of early Dublin delftware –an armorial charger for the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, 1735. Pictured right, the level of quality now being produced after 1751 with Henry Delamaine’s patronage – this plate is from a service made for Delamaine’s nephew upon his marriage into a wealthy French family.

For the first fifteen years of the pottery’s existence there are no other clues helping identify a specific Dublin piece. It isn’t until when one of Chambers’ successors named Henry Delamaine invests great sums in the company in order to improve the quality of Dublin delft in order to make it competitive with continental wares. What makes this period of Dublin delft a lot easier to recognize is that about half of it bears some small numerical or letter mark on the reverse. Peter surmises that the factory employed decorators on a piecemeal basis and that in order for the workers to get paid they could tally up the number of pieces they had decorated with their specific mark on each. Marks often appeared not on the bottom of a plate but on the reverse side of the plate rim. Monogram marks tend to date from the 1750s; and numerical marks date from the 1760s.

Page 12

Stylistically, Dublin delft attempted to imitate all the fashionable styles and designs of the day. One example is what is called the classic “Irish Landscape” below left. They also attempted a pretty good copy of French Rouen pottery below right.

Dublin’s attempts at imitating English wares such as Worcester were a bit problematic as the factory – unlike Staffordshire -- did not have experienced mold-makers. If Dublin wanted to knockoff a Worcester dish or basket, they actually bought a Worcester piece and made a mold of that. As one can see the molding just lacks that crisp detail. See below left. On a similar note, there is also very little variation in the shapes and sizes of dishes as there were few form-makers and their choices were limited. Below right are some of the other patterns Dublin was emulating – note all the Chinese export designs.

Another Dublin patterns inspired by competitors’ fashionable wares of the time is a distinctive French style floral sprig pattern in blue, yellow and green below left. And their variation of the Liverpool Fitzackerley pattern below right.

Page 13

The Editor apologizes for the dreadful quality of the photo on the left – taken from a monitor screen. The problems with Zoom!

A final note on Dublin patterns, whilst researching the catalogue Peter heard from John Austin at Colonial Williamsburg who presented Peter with Irish delftwares in patterns he had never seen before, quite coarsely painted, but distinctively numbered as the Dublin marks. Many examples were from Colonial Williamsburg, and yet one had been unearthed at the site of a trapper’s cabin in Michigan!! Perhaps some lesser quality wares for shipment to the undiscerning colonials in America?

Moving on, by 1773 the Delamaine family was no longer associated with the factory. All delftware production had pretty much ceased by the autumn of 1772 when they pottery brought in advisors from Staffordshire who helped convert the kiln from delftware to creamware production. Unfortunately, to date Peter has not been able to specifically identify any pieces from this period.

In 1785 when the Dublin factory finally closes, production moves back north to Belfast as a new clay source had been located perfect for creamware production. The new scheme was underwritten by an entrepreneur named Thomas Greg who had very ambitious plans. He not only founded a pottery at one end of the Belfast waterfront, but a glass house at the other end with plans to use the waste from both operations to fill in the swampy, unprofitable coastline in between. Shards from digs into that reclamation land yielded a treasure trove that inspired for Peter’s next book A Pottery by the Lagan; Irish Creamware Pottery from the Downshire Pottery 1787-1806. See below:

Page 14

Working from excavated shards from the Downshire site Peter made a couple observations. First, that the wares had very distinctive molded details so the issue with finding skilled mold-makers must have been resolved, and second, the somewhat limited colors used for decoration. Not having access to the range of enamels that existed in the Staffordshire potteries, Downshire pottery featured a lot of manganese, yellow and blue.

In 1806, creamware manufacturing ceased and the Irish ceramics story now moves back to Dublin again, but on a very limited scale. It seems several of the higher end retailers in town started an enameling kiln and were just importing porcelain blanks and having them decorated for their clients. These pieces are recognizable as they are often signed with the retailer’s name. See below.

Images above representing Downshire Creamware Pottery with molded details on the sauceboat handle and feathered edge plate, and the somewhat limited color palette on the cream jugs, note the somewhat naïve decoration on the pitcher to the far right – perhaps the work of child labor?

Images above representing Downshire Creamware Pottery with molded details on the sauceboat handle and feathered edge plate, and the somewhat limited color palette on the cream jugs, note the somewhat naïve decoration on the pitcher to the far right – perhaps the work of child labor?

15

Page

One of the more successful retailers to do bespoke services signed his wares ‘Jackson’ and imported Worcester porcelain blanks and had a rather skilled decorator on staff judging from this fine plate below – note the charming Irish shamrock detail.

In contrast to the elegant Dublin-decorated Worcester porcelain blank on the left, on the right we have a closeup of the stamped decoration of the Belfast Stickwares.

Peter’s concluding category in his talk brought us back up to Belfast where wares were being produced for a decidedly less affluent market. These brightly colored wares are often referred to as ‘Stickwares’ for their method of decoration which always seems to include variations of small, ribbed, circular stamped designs. Cleverly produced, these graphics were the print of a dried stem of common Cow Parsley which grows wild along the roadsides. The dried stem is ribbed and hollow and when cut horizontally or at an angle creates a perfect natural stamp to decorate with. Also called ‘sponged wares’, this method quickly and cheaply filled as much area as possible with decoration in the least amount of time. This last gasp of Belfast pottery production lasted between 1820 and 1835. It is no coincidence that shortly thereafter pottery called ‘Stick Spatter’ began to appear in production in Scotland.

Page 16

Examples above of the variations of designs achieved by “Stickware’ stamps. Below, actual Stickware stamps created by our speaker from the dried-out stem of the Cow Parsley plant.

In the 1960s when these wares were ‘discovered’ and became a favorite of collectors, masses of it turned up in Canada but were falsely attributed to an unknown factory called Pont Neuf, when in fact they were simply Belfast and Scottish wares that had been brought over from Ireland and Scotland.

NEW GALLERIES AT PEM ON THE PROGRAM IN APRIL

In April the Club hosted an in-person lecture at the King’s Chapel Parish House in Boston welcoming Sarah Chasse, Associate Curator at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem who spoke to the group on a recently unveiled gallery space at the institution, her subject being Seeing Ourselves: American Ceramics in the New Native American and American Art Galleries at PEM.

In March 2022 proudly opened their new 10,000 square foot galleries dedicated to displaying their celebrated collections of Native American and American art. Planning for this path breaking initiative began during the summer of 2018, grounded in the idea that artistic expression has the power to define and redefine our concept of America. We convey our identity - personal, national, and cultural, through diverse objects. Over 350 artworks span in time from 10,000 years ago to today and demonstrate a range of voices, modes of expression, cultures, and media. The galleries explore ideas and themes that explore links, continuities, and disjunctions between historical and contemporary objects across the Native and American art collections. Ceramics play a key role in the gallery and dozens of works are woven throughout all the sections of the installation representing the work of many cultures, communities, and individual artists. Through their selections of Native American and American ceramics PEM can explore the historic and contemporary connections and traditions of creating in this medium across generations. Although Sarah was with us to share this work, she wanted to stress that this was very much a collaborative project. She co-curated the galleries with Karen Kramer, the Stuart W. and Elizabeth F. Pratt Curator of Native American and Oceanic

Page 17

Art and Culture. The descriptions of Native American ceramics detailed here were written by Karen and Sarah also wanted to call out her collaborator in researching and writing about American artworks in the gallery, Lan Morgan, assistant curator at PEM and member of the Ceramics Study Club. The descriptions of American artworks are both her words and Sarah’s.

The galleries feature 30 labels that are authored by guest writers from many different perspectives, cultures and experiences. The work of Ben Owen is included in one section looking more closely at American identity and also explores themes of intergenerational connections through ceramic making since Ben is a 4th generation American potter working in Seagrove, NC. They commissioned the artist to write a label for this work and he wrote about the significance of the ancient form of the gourd to humanity since ancient times.

In the Heroes and Histories section they juxtapose artworks from across time and geography, to tell stories of religious persecution and wartime conflicts, and bring forward new ways of looking at the past asking visitors to contemplate if the same stories are repeatedly told, whose stories are missing?

In one of our more provocative pairings, we juxtapose the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 with the Salem Witch Trials of 1692 exploring themes of religious persecution, violence, and the brutal international quest for land in 17th century North America. We elucidate how artists help us imagine historical moments visually.

Page 18

Contemporary ceramics by Virgil Ortiz and Jason Garcia help us visualize stories of the pueblo revolt when Indigenous peoples in the Southwest revolted after nearly 80 years of subjugation, high taxes, and physical punishment by the Spanish church and other colonizers. The legacy of the revolt still burns brightly for Pueblo peoples, symbolizing Indigenous resistance and unity. Cochiti Pueblo artist Virgil Ortiz also refers to the Pueblo Revolt as "America's as First Revolution." His aim is to tell this important but underrecognized history, and honor Po’Pay as its leader in his figural reimagining. Santa Clara Pueblo ceramicist Jason Garcia tells the story of the revolt across seven comic book covers, picturing the Puebloans as superheroes fighting for truth, justice, and the Pueblo worldview. (See below).

Through the galleries ceramics are also in conversation with other media such as Lonnie Vigil’s jar in a grouping with John Sloan’s Arroyo, Santa Fe, and Kay WalkingStick’s Hovenweep, in an exploration of artists’ depictions of the Southwestern desert landscape. And seen below there is Virgil Ortez’ Po’Pay Forseer of 1680 displayed next to Jason Garcia’s Tales of Suspense series.

Page 19

Sarah moved on asking the question “Can a teapot be political?” For the artists represented here, ceramics are the platform of choice for their activism. They express their political sentiment through clay, a versatile material that can be formed, molded, glazed, and decorated to produce myriad designs. The earliest teapot in the display celebrates the repeal of British taxation in the American colonies, circa 1766-1770. In comparison, there is contemporary artist Michelle Erickson’s precarious grouping of tea wares in porcelain, stoneware, earthenware with enamel and goldleaf. Entitled Teapot in Hand, it explores the migration of ideas and cultural influences in the decorative arts creating a playful arena in which fragments of Eastern and Western culture assemble a precarious stairway into the future. A canted blue Delft tea tray offers up a teetering stack of triangular tea bowls, each decorated with a fractured Japanese print. Above, a hand holds this precious cargo and compensates for the imbalance below. A teapot, combining high-fired red earthenware with porcelain agate, references the adaptation of Chinese Yixing tea wares by 17thcentury European potters. Europeans were fascinated with “ceramic gold” as Asian porcelain was then referred to and struggled to imitate it for centuries. Their pursuit of this Holy Grail of ceramic bodies became the single driving force in the development of Western ceramics for the next 200 years and established a unique genre in decorative art. A mischievous guardian lion, indifferent to the potential calamity below, bounces a porcelain cup and saucer at the top of the spire. Fragmented and restored with gold, these pieces reconstruct the past as they arrive in the present. (See below).

Page 20

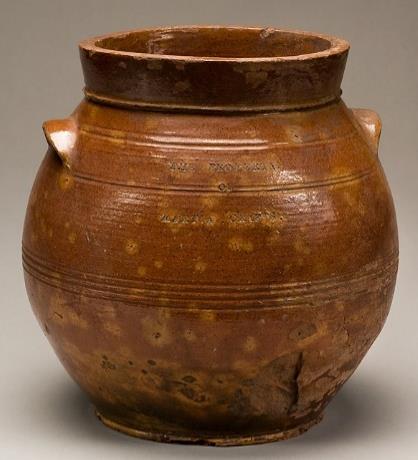

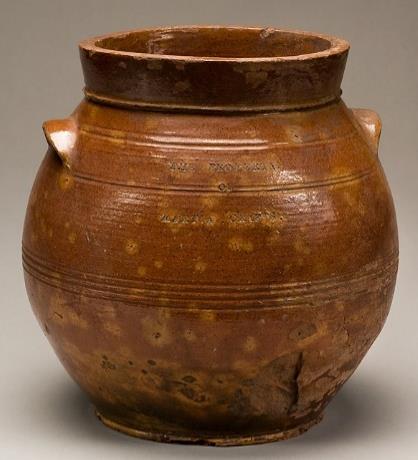

Thomas W. Commeraw is one of a few known free Black potters working in the period before the Civil War. He operated a stoneware pottery kiln in Corlears Hook in Lower Manhattan, a waterfront area near a busy international port and clay repositories. Commeraw was a shrewd businessman, often branding his wares to ensure his name recognition. The utilitarian wares he supplied to merchants and seamen have been discovered as far as Guyana, evidence of the global reach of his objects through trade. (See below).

Ultimately, On This Ground: Being and Belonging in America is a groundbreaking collaboration between two collections historically separated in our museum. Our collections help us tell more complex stories from broader perspectives, celebrate artistic achievements across time, space, Page 21

and worldviews and create a more expansive definition of American art. Ceramics are prevalent in the gallery, this overview represents just a fraction of the ceramics presented, holding their own with paintings and sculptures as one of the most-represented mediums among over 300 objects and it’s not happenstance. In On This Ground, ceramics, as vessels and sculptures actually made from this ground, do essential work helping us explore the complexities of American identity past and present.

EDITOR’S NOTE: With apologies, I was unable to attend this lecture and our recording equipment (such as it is) did a rather incomplete job. I therefore had to depend upon notes and images kindly supplied to me by our speaker, so the above article is just a small sampling of the images and information attendees got to enjoy that day. One of the most important messages, then, to take away from this is to visit the Peabody Essex Museum in person to indulge yourself in this visually delightful and thought-provoking exhibit.

PROGRAM SEASON ENDS WITH A TALK ON HISTORIC DEERFIELD’S COLLECTIONS

The Club closed out a rather expansive program year – all thanks to the tireless efforts of Program Director Anne Lanning - with our Annual Meeting & Tea at the King’s Chapel Parish House in Boston. Our final talk of the season was presented by CSC member and past President Amanda Lange, the Curatorial Department Director and Curator of Historic Interiors at Historic Deerfield who spoke on the topic of The Latest Dish: Recent Ceramic Acquisitions at Historic Deerfield. Before speaking on the more recent acquisitions, though, Amanda started with a background history of Historic Deerfield, its founders, and original collections.

In May 1948, Henry and Helen Flynt, the founders of Historic Deerfield, opened their first restoration, the Ashley House, to the public. Little in their backgrounds would have predicted that they would become dedicated preservationists and collectors. Henry Flynt (1893-1970) grew up in Monson, Massachusetts, and practiced law in New York City, and Helen Geier Flynt (1895-1986) came from a wealthy Cincinnati manufacturing family. Both had come from collecting families, but the couple vowed early in their married life not to collect. Henry Flynt said, “When Helen and I were married in 1920, I decided that I would devote myself assiduously to ‘not collecting’ and so advised her. Everything went well for a number of years.”

Their interest in the town of Deerfield resulted from their involvement in the boarding school Deerfield Academy. In 1936, their son enrolled in Deerfield Academy and the Flynts formed a lifelong friendship with the headmaster, Frank Boyden (1879- 972). What began as an effort to help the Academy with several building projects led to an enthusiastic restoration of many of the old houses in the village. Over the next twenty years they restored and furnished ten houses. Henry and Helen Flynt strongly believed that Deerfield represented the epitome of frontier American values, and that those values offered an antidote to the Cold War-era spread of Communism.

22

Page

The stories of the colonial British settlement’s early years of conflict and eventual economic success resonated with Henry and Helen Flynt, just as they had with earlier historians and school children alike. While the Flynts’ initial interest in Deerfield involved the restoration and preservation of old houses, their attention soon turned to furnishing those interiors with suitable decorative arts from the 18th and 19th centuries. They enjoyed success acquiring Connecticut River Valley pieces of furniture but locating ceramics with local histories proved more difficult.

The Flynts at home with their collection.

Consequently, the Flynts often purchased English pottery and Chinese porcelains to fill cupboards, pantries, and dining rooms without regard to their appropriateness for the American market. Many of their selections would have never been available to residents of the Connecticut River Valley. Their choices were guided less by the goal of historical accuracy and more by the idea of the creation of beautiful rooms by the standards of the 1950s and 60s. They were also helped and inspired by other dealers, museum curators, and their vast array of friends and rivals such as Henry Francis DuPont, Electra Webb, Ima Hogg, Katharine Prentis Murphy, and Alice Winchester. Buying primarily through American dealers, the Flynts were attracted to colorful pieces of English pottery –- specifically English delftware, English white salt-glazed stoneware -- and Chinese export porcelains. Their purchases often reflected an enthusiasm for early America’s social and political history. The collection contains many pieces of delftware decorated with images of English royalty, such as Charles II, William and Mary, and Anne, and political heroes such as John Wilkes and Major General James Wolfe.

Page 23

There were also tea sets related to important heroes of the American Revolution such as this Chinese export porcelain tea set owned by Dr. David Townsend, a member of the Society of the Cincinnati, a fraternal order of French and American Revolutionary war officers, plus letter from Samuel Shaw giving it to Dr. Townsend (See above). During the 1950s and 1960s, the Flynts amassed a significant collection of Chinese export porcelain. These purchases resulted in several areas of strength in the collection: famille rose wares, armorial porcelains, ink-color wares, European-inspired designs, and pieces for the American market. For example, the collection boasts two Hong-decorated punch bowls. These extremely rare porcelain objects, decorated with scenes of the foreign factories or “hongs” at Canton, are important documents of the area where Western merchants lived and transacted business. Colonial Williamsburg just purchased an example of a Hong Punch Bowl at auction for $138,975. (See below).

Page 24

Several of the collection’s most superlative objects came from Emily “Millie” Manheim, Matthew & Elisabeth Sharpe, Elinor Gordon, and Bernard and S. Dean Levy. Whenever possible the Flynts acquired ceramics with local histories, such as the donation of several pieces from Miss Elizabeth Fuller. A descendant of one Deerfield’s most distinguished families, Miss Fuller generously donated Chinese export porcelain and delftware plates and bowls that had been owned by her ancestor, Dr. Thomas Williams (1718-1775) of Deerfield. Henry and Helen Flynt ensured the future of their Deerfield project by creating an endowment, developing a summer fellowship program for college undergraduates, building a research library, and hiring a professional staff to administer the museum and to assume the duties of acquisitions. Continued study of Connecticut River Valley newspapers, probate inventories, merchants’ accounts, and the archaeological record reveals the presence and usage of many different types of imported ceramics not currently represented in the collection. The museum’s current collecting focus for ceramics emphasizes filling significant documented gaps and acquiring locally owned pieces.

Archaeology can fill in missing pieces in the written record, often correcting biases and frequently revealing surprising information. Prior to 2015, few 17th -century archaeological sites had been excavated in the Connecticut River Valley. Recent discoveries of early English colonial sites in Wethersfield, Windsor, and Glastonbury, Connecticut, have greatly enhanced our understanding of the material world of this time. These excavations turned up a global mix of ceramics from Italy, Portugal, the Netherlands, Germany, and England. For example, the Lieutenant John Hollister site (ca. 1650-1710), in modern-day Glastonbury, Connecticut, was an early fortified, 17th-century farm complex on the border of the “Wilds” or the Pequot homeland. Since 2015, the Connecticut Office of State Archaeology has conducted research excavations there as a public archaeology project. To date, archaeological excavations on the Glastonbury site have identified at least six Cellar holes that were filled around 1710. Identified shards included North Italian marbleized slip-decorated earthenwares, which inspired Historic Deerfield’s purchase of an Italian slipware costrel. (The dishes are much harder to find)

Imported ceramics and glass became precious luxuries at elite levels. The 1679 probate inventory of the Reverend Joseph Haynes (1641-1679) of Hartford, Connecticut, listed “one glass Case wt some glasses & Lisburne ware,” a common term for Portuguese tin-glazed earthenware, that stands apart from the earthenware listed elsewhere. New England merchants exchanged fish and wood products for Portuguese wines, brandy, and tin-glazed plates and dishes. While it is difficult to determine the appearance of Haynes’ “Lisburne” ware, it likely imitated more expensive blue and white Chinese porcelains. Fragments of suspected Portuguese tin-glazed earthenware have also been found at a Sokoki village in Hinsdale, NH – underscoring the value of these ceramics in local trade relationships. (See below image on the left). Page 25

A recent ceramic purchase – with hope of finding evidence in the Connecticut River Valley – is this Spanish olive oil jar. The olive oil jar is an example of Spanish coarseware dating from the early to the mid-17th century. (See above right) Evolving from an amphorae shape, olive oil jars were manufactured in Seville, Spain, from the 16th century. The term olive oil jar is misleading because they were made as shipping containers of more than olives or olive oil. They held other commodities, as well, such as bullets, capers, beans and chickpeas, lard, tar, and wine. In fact, this example still smells of smoky pine pitch. According to ceramics historian C. Malcolm Watkins, owners often described these objects as “money jugs”. Jugs recovered from shipwrecks have been found with coins encased in pitch, a safer way to transport money. Their thickly and quickly potted walls made them cheap; their ovoid shape made them well suited for the curving walls of a ships hold where they could be packed tightly. These storage jars have been recovered from several in New England archaeological sites

English slip-decorated earthenwares, predominately associated with Staffordshire, are common finds in most archaeological sites in the Connecticut River Valley, including Stiles-Ellsworth site in Windsor, Connecticut, dated ca. 1700-1710. The buff-colored earthenware body was coated in a layer of white slip (liquid clay), then decorated with iron-rich brown slips in combed, dotted, or marbleized patterns. A fragment associated with the Stiles site in Windsor exhibits the fine combed and marbled decoration associated with the early 18th -century examples. We purchased a dated example at the 2020 New York Ceramics Fair. English brown stoneware imports to the Valley are most prominently seen with advertisements of “Nottingham” or “brown” stonewares. In Deerfield, Massachusetts, a dated 1757 receipt in Elijah Williams’ papers listed “brown qt mugs,”

Page 26

“brown pint mugs,” “½ pint brown mugs,” and “brown bools.” Those documented source inspired the museum’s first purchase of a Nottingham or Derbyshire brown stoneware mug with grog or potter’s waste applied as decoration. Nottingham wares are known for their lustrous brown glaze.

(See below left).

Tea and tea drinking equipage became a part of most of elite and aspiring Connecticut River Valley homes around the mid-1740s. The Delftware catalogue pointed out some weak areas of the collection -- Missing delftware tea ware forms try to fill those gaps. William Ellery of Hartford, Connecticut, advertised a wide assortment of delft in the Connecticut Courant of November 5, 1771, including “Delph Tea pots, dishes, flower horns, half gallon, quart, and pint bowls.”

(See above right). English delft cups and saucers were shipped to Britain’s North American colonies in large quantities in the mid-18th century, making them available to consumers in New England and the Connecticut River Valley. Merchant Samuel Colton of Longmeadow, Massachusetts sold delftware punch bowls, teacups and saucers, and plates in 1756. Similarly, Boston merchant Ebenezer Bridgham advertised “Delph bowls of all sizes, plates, dishes, cups & saucers” in the Connecticut Courant in 1772. These wares also appear in local estate records, including the 1790 probate inventory of Northfield, Massachusetts, resident Aaron Whitney, who owned “1 Sett of Delph Tea Cups Saucers.”

Plain undecorated creamware was a ceramic staple of the Connecticut River Valley. This advertisement by William Ellery in 1771 – listed the many forms of creamware he was selling --from fruit baskets to three -leaved pickle stands. Trustee Anne Groves has assisted me in developing the English ceramics collection immeasurably. With the help of Historic Deerfield Trustee Anne Groves, the museum was fortunate to acquire Alistair Sampson’s personal collection of 162 pieces of English creamware in 2006 -- making the museum a significant site for the study and examination of this important art form in the United States.

Page 27

Also supplementing that creamware collection is an 1814 copy of the Leeds Pottery Pattern book. First issued in 1783 with only 45 plates, this publication was one of the earliest pattern books published in England by pottery manufacturers for the use of their travelers, with illustrations of all the articles produced by the firm. These catalogue/pattern books were produced for the use of the wholesale factors and commercial travelers who roamed throughout England and abroad, taking orders for the factory. This copy illustrates 269 designs numbered from 1 to 221 and 1 to 48 for tea ware.

A superlative example from the collection of Liverpool printed wares is this jug’s rare print of a cow and three figures seems to provide commentary on Jefferson’s controversial Embargo Act and the precarious state of trade among America, Britain, and France during the Napoleonic Wars. John Bull (symbolizing England) and Napoleon (symbolizing France) pull the cow, possibly representing commerce, in different directions, while Jefferson sits in the middle milking the cow a scene perhaps highlighting America’s difficult position between these warring foreign powers. As Liverpool printed pottery expert Robert McCauley notes, the cow’s immobile position, precipitated by Jefferson’s Embargo Act, also seems to suggest “commerce at a standstill with no benefit to anyone except the political advantage accruing to Thomas Jefferson.” (See below).

Research in documentary records have also yielded surprises and acquisition opportunities. I spent many fascinating hours poring over the many account books of New York City’s Frederick Rhinelander (1743-1805), one of the most prominent china and glass merchants in colonial America. Copies of Rhinelander’s correspondence and orders survive from 1774 to 1783, providing a fascinating look into American tastes and requirements. Knowing the practical nature of his clientele, Rhinelander focused on tablewares, teawares, and drinking vessels along with a few ornamental wares. Rhinelander had an extensive trade with New England, and Connecticut represented his second largest base of customers outside of New York. What surprised Amandaand what she didn’t expect to see - was two merchants -- William Ellery of Hartford, CT, [1771]

Page 28

and John Atwater of Westfield, Massachusetts [1773], acquired “Cream Cd Pigeon Houses,” “Piggen House,” or creamware dovecotes. The ceramic ornament – priced at 3 shillings a piecemust have been a luxury displayed in a corner cupboard or upon a mantelpiece. Fortunate Colonial Williamsburg owns an example of a dovecote or pigeon house ornament, but I have not seen many others in plain creamware.

As for Deerfield’s “wish list”, the institution is still looking to fill gaps in the collection based upon research carried out during the restoration of Barnard Tavern which provided food, beverages, and lodging for man and beasts from 1795 to 1806. Excavations thereby the University of Massachusetts Amherst Summer field school discovered many small fragments of what collectors call “mochaware” or slip-decorated earthenware, made in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Several had marbleized and combed colored slip designs on the surface. We were fortunate to have collector and author Jonathan Rickard of Deep River, CT, donate several examples of this type of mochware to the collection. His small marmalade pot is displayed on the dining table in the parlor of Barnard Tavern.

Historic Deerfield Trustee Anne Groves has been particularly significant to the development of the English ceramics collection. Knowing the institution’s weakness in early English stonewares, Anne recently gave a doubled-walled mug or carved gorge, made by James Morley of Nottingham, England, ca. 1700. At present, only one example of this carved brown salt-glazed stoneware has been located at an American archaeological site. Excavations at the Drummond Planation site in James City County, Virginia yielded a fragment of a double-walled teacup with pierced decoration. She also gave an early English white salt-glazed stoneware mug made by John Dwight of Fulham (London), England, c. 1690. Finely potted white salt-glazed stoneware mugs with tall necks and spherical shaped bodies, such as this example, are known to have been made by the welldocumented London stoneware potter, John Dwight (1633- 1703), who is often credited as the first stoneware potter in England to have achieved commercial success. By the 1680s, Dwight had ended his experiments with porcelain, and began to produce a number of “fine” wares. In a second patent obtained by Dwight in 1684, he included “white Gorges marbled Porcelane Vessels Statues and Figures and fine stone Gorges and Vessels never before made in England or elsewhere.” This stoneware mug is representative of the “white gorges” referenced in Dwight’s second patent. In the 1970s, archaeologists discovered sherds of similar wares at the site of Dwight’s Pottery in Fulham. Dwight’s production of these fine wares was followed in the 1690s with lawsuits against a number of his London, Staffordshire, and Nottingham competitors for patent infringement, suggesting, as one study notes, that “a myriad of makers were producing wares imitating those made at Fulham.

(See below)

Page 29

As for benefactors, Anne couldn’t speak of Historic Deerfield without a mention of Peter Spang, a Founding curator and Trustee, Peter Spang passed away in Beverly, Massachusetts on May 7, 2020. His commitment to Deerfield was the central thread of our institutional history for three generations. Peter was first and foremost a steward of his adopted town of Deerfield. He valued tradition, collectors, and collecting --especially ocean liner memorabilia, architectural pattern books, and a small collection of ceramics – which he bequeathed to the museum. (Below left).

And our dear friend Barbara Cummings (above right), long-time CSC member and Deerfield docent bequeathed fine examples of delftware and black transfer-printed ware including a very rare transfer printing copper plate. Used in the process of transfer printing onto ceramics, this

Page 30

rectangular copper plate is engraved on both sides with a version of the “Willow” pattern. The first step in the transfer printing process involved the creation of a copper plate engraved with a particular design. Ink was then applied to the surface of the plate, and a tissue paper like substance was pressed up against its surface. The tissue paper, carrying a copy of the design, was then removed from the plate and applied to a piece of pottery, thus transferring the design to the pottery’s surface. The design on one side of the copper plate is noticeably more worn compared with the other, suggesting that when one side became unusable, the engraver created a new, but identical design on the reverse. (See below).

For many years Historic Deerfield has been well known for its nationally recognized collections of Chinese export porcelain and English pottery. But since the institution’s founding in 1952, the presence and role of American redware has been underrepresented in our historic houses and museum exhibitions. Redware formed the most common ceramic type in New England households and came in forms ranging from storage jars and milk pans to harvest jugs and chamber pots. These wares were usually coarse, lead glazed and extremely fragile. Frequently damaged and easily broken, redware rarely survives to the present day. Historic Deerfield just didn’t have much to display until the last ten years of our organization’s history when the museum received two large gifts.

William “Bill” T. Brandon (1935-2005) of Concord, Massachusetts, grew up in North Carolina, but lived in Massachusetts for more than 50 years. He graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Northeastern University with degrees in electrical engineering. Bill Brandon

Page 31

became a recognized leader in the field of satellite communications, and was employed by Mitre, Raytheon, and Harris Corporations. One of his most important accomplishments was his work as the project manager for the Apollo Lunar Excursion Module power amplifier, used to return live television from the lunar surface. Brandon’s collection ranged in date from 18th to early 20thcentury examples, focusing predominately on New England-made ceramics, particularly redware, a topic on which he intended to write a book. His widow Sally Brandon Bemis gave the collection to Historic Deerfield in 2013 and 2014.

Pottery production in the Connecticut River Valley was part of the regional economy – usually produced by farmers in the off season to supplement their income. The town of Whately (just south of Deerfield) had an extensive deposit of clay in the southern part of town that accounts in part for the rapid growth in the pottery business there. One object of particular interest to Historic Deerfield is a large jar made by Martin Crafts (1805-1880) of Whately, Massachusetts. The eldest son of potter Thomas Crafts (1781-1861), Martin worked with his father until late 1833, when he left to run potteries in Portland, Maine, Nashua, New Hampshire, and Boston, Massachusetts. In 1857, Martin returned to Whately and ran the Crafts pottery until its close in 1861. This impressive redware jar, marked “The Property of Martin Crafts” and dated “April the 1, 1830,” is a tour-de-force. (See below) Page 32

Examples from the Brandon Collection

Examples from the Brandon Collection

In January 2020 (just before the pandemic began) Historic Deerfield acquired a second private collection of American redware – containing mostly pieces from New England. The donor collected American folk art especially painted furniture, weathervanes, painted tinware, needlework, watercolors, and redware. Although this person maintained a low profile among collectors, the donor had strong relationships with Americana dealers, especially Lew Scranton, an Americana dealer from Killingworth, CT. He was the main supplier of the American redware collection, and the donor emulated his aesthetic sense too. For the most part – it is as you see it today -- a project that is on my to-do list. But one that I am looking forward to. The donor acquired an amazing group of New England redwares (mostly from Bristol County, MA, Hartford and Norwalk, CT) totaling about 200 examples. Redware scholar Justin Thomas has been helping us to identify the collection.

33

Examples of a redware collection formed by an anonymous donor and Connecticut dealer Lewis Scranton.

Page

The aesthetics of utilitarian domestic red earthenware are what collectors and museums have been drawn to for more than a century now, although, it was likely an important factor in the marketplace even when red earthenware was originally produced in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. In New England, the wares manufactured in southeastern Massachusetts, Bristol County and Cape Cod were unquestionably at the forefront of the visual appeal of the region’s red earthenware production. The wares produced in this part of Massachusetts have it all: form, glaze, skill and refinement, transforming many of these objects into works of art. This new collection contains some very intriguing examples of Connecticut-made redware. The largest redware kiln sites in Connecticut were located in Hartford and Norwalk, CT. Several redware potteries existed in the Hartford County before the American Revolution. The most famous of the CT potters were the Seymours, the Goodwins and Hervey Brooks, but there were other potters as well. (Justin just wrote a book on the subject) Deerfield has several early examples of pottery attributed to the Seymour pottery of West Hartford, CT. (Attribution is based on a jug in the Wadsworth Atheneum that descended in the potter’s family).

Norwalk Pottery. In 1793, Absalom Day leased property in Norwalk for a pothouse that he ran until 1841. Day was born and trained as a potter in Chatham, New Jersey, and he is thought to bethe originator of the characteristic Norwalk slip-script decoration. Amanda was particularly excited to acquire a number of examples of slip script dishes usually associated with the Asa Smith Pottery of Norwalk, CT, c. 1824 to 1854. These dishes are inscribed for Lafayette, St. Martha Virgin, Sarah’s Dish, Mince Pie, John, ABC, and some with initials. The most significant kiln in Norwalk was owned by Asa A. Smith and was established c. 1825 in what is now downtown Norwalk. Smith had been an apprentice of Absalom Day, and his pottery produced the majority of the slip-script wares. Notice that these dishes are molded using a drape mold, and not thrown on a wheel like other New England plates and dishes.

In 18th- and 19th-century Britain, locally produced ceramics became an important medium for denouncing the horrors of slavery. Founded in 1787, the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in England began a movement that led to the prohibition of the international trade in 1807. This milestone was followed by a second in 1834 when the practice of slavery was abolished (with some exceptions) throughout the British Empire. These changing attitudes towards slavery are poignantly reflected in a group of British ceramics at Historic Deerfield, many of which are recent additions to the collection. A luster-decorated jug with a scene of a seated enslaved man partly bound in chains is accompanied by the phrase, “Am not I a Man and a Brother” a design inspired by a jasperware medallion produced by Josiah Wedgwood (1730-1795) in 1787. This scene, along with a lengthy verse from William Cowper’s (1731-1800) poem “The Negro’s Complaint” (1788) printed on the reverse, highlights the plight of the enslaved while appealing to

Page 34

a sense of common humanity. The jug’s small size suggests it was used as a display piece in the home and was likely purchased at an anti-slavery fair where similar ceramics were available for purchase.

Just like the Flynts experienced in the 1930s, Deerfield continues to inspire visitors looking for symbols of our past and for answers to questions about the New England experience. Deerfield’s sense of place, its authenticity, and grounding in historical documents will assist us in learning more about the context of early New England life and at the same time, enable us to find sanctuary from the rush of modern life.

Page 35

And finally, two recent images from London:

On the Left: For those of you blue and white collectors who have everything, perhaps this may finish off your collections – as seen in a shop window off Pall Mall – a Limited Edition Dolce and Gabbana SMEG Mini-Fridge decorated with 18th century Delftware designs and patterns…place your orders now…all the oligarchs are snapping them up!

On the Right: And for those collectors who think their collections have gotten out-of-hand…this image from one shelf in the V&A Ceramics Department will prove to you that more work needs to be done!

And with deepest appreciation to member Nic Johnson for scrupulously editing each issue of our newsletter and for his maintenance of the CSC website on which all SHARDS issues are archived.

Jeffrey

Brown

Page 36

A map of eastern coastal New England in the 18th century illustrating the number of pottery sites in various towns. Note that Boston and Charlestown had a combined total of 44potteries!

A map of eastern coastal New England in the 18th century illustrating the number of pottery sites in various towns. Note that Boston and Charlestown had a combined total of 44potteries!

Above Right: A rare slip-cast unglazed stoneware mug, Elers, Bradford Wood, Staffordshire, 16931697 was shared by member Bob Barth.

Above Right: A rare slip-cast unglazed stoneware mug, Elers, Bradford Wood, Staffordshire, 16931697 was shared by member Bob Barth.

Images above representing Downshire Creamware Pottery with molded details on the sauceboat handle and feathered edge plate, and the somewhat limited color palette on the cream jugs, note the somewhat naïve decoration on the pitcher to the far right – perhaps the work of child labor?

Images above representing Downshire Creamware Pottery with molded details on the sauceboat handle and feathered edge plate, and the somewhat limited color palette on the cream jugs, note the somewhat naïve decoration on the pitcher to the far right – perhaps the work of child labor?

Examples from the Brandon Collection

Examples from the Brandon Collection