ET CETERA

CONTENTS

Page 1: Note from the editor

Page 2: Do the human characters in Euripides' plays act of their own free will? Discuss in reference to ‘Hippolytus’ (Addy M-S, Year 13)

Page 6: How Far is Ovid’s Metamorphoses an Epic? (Lauren C, Year 13)

Page 10: The Seeds of Civilisation: Classical Inventions that Shaped the World (Maanvi K, Year 12)

Page 14: Would the flight of Icarus have been physically possible? (Alex D, Year 12)

Page18:“Theonlylanguageswhichdonotchangearedead ones” Howfardoyouagree?(MayaM,Year12)

Page 22: From your reading of Iliad VI, to what extent do you think that Hector is heroic? (Roxana Q, Year 11)

Page 24: Half Term Classics Trip to the Bay of Naples (Eleanor P, Ella C and Esha K, Year 10)

Page 26: A translation of Horaces Ode XI: To Leuconoe (Lauren C, Year 13)

Page 27: ‘The role of fate in the Aeneid reduces suspense and excitement.’ To what extent do you agree? (Preet K, Year 13)

Page 31: Women in Ancient Rome (Edith J, Year 10)

Page 33: Saturn Devouring His Son - Francisco Goya (Deya C, Year 10)

Page 35: To what extent does Enkidu’s death catalyse Gilgamesh’s transformation in ‘The Epic of Gilgamesh’? (Amara G, Year 13)

Page 37: ‘Juvenal should be viewed primarily as an art form’ In your opinion, what dangers are there of taking Juvenal at face value? (Felicity C, Year 13)

Page 40: Classics Reading and Listening Recommendations

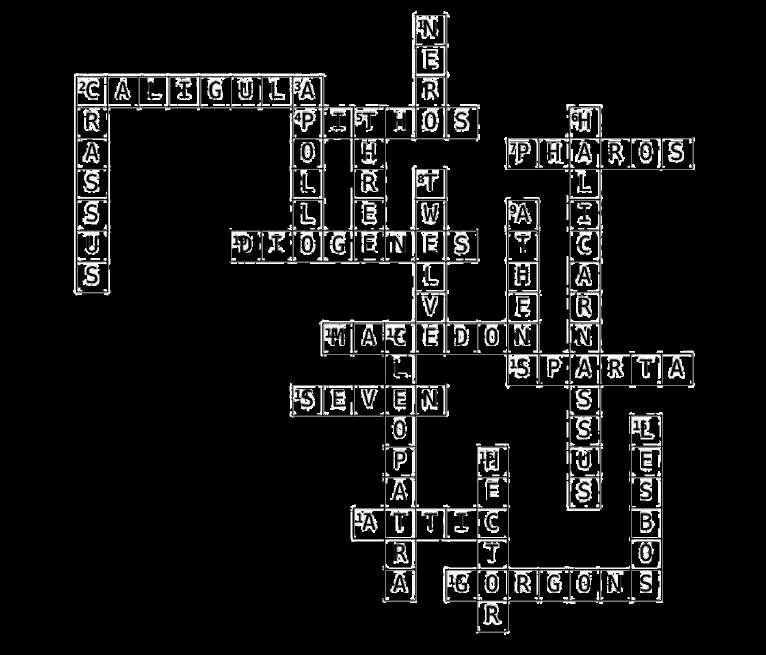

Page 42: Puzzles (and answers!)

Page 45: Classics Playlist

Page 46: Upcoming in Classics...

Page 47: Favourite Classics Memes

Notefrom theeditor Alex Year12

WelcometothefirsteditionofournewClassics publication, ‘et cetera’ where we embark on a journey through the rich and fascinating tapestry of the classical world. This collection is the result of thoughtful collaboration and dedication, reflecting the vibrant opinions and talentsoftheNHEHSSeniorClassicists.

We hope with this publication to develop pupil voiceandleadership,fosteringconfidenceand creativityinexpressingideasaboutthepast.By engaging with the wonders of Antiquity, we aim to widen the knowledge and understanding of the classical world, shedding light on how they continue to shape the world weliveinnow.

Additionally, we invite you to join us in interdisciplinary discussions, linking the classical world with art, literature, philosophy, science, andbeyond.Bymakingtheseconnections,we seek to demonstrate the enduring relevance of classical studies and its power to spark curiosity and innovation across fields; we also aim to explore some lesser-known aspects of the Greek and Latin languages and cultures, uncovering stories and perspectives that may surprise,inspire,orchallenge.

I would also like to say a massive thank you to the teachers of the Classics Department for inspiring all the Senior Classicists, and for giving them the tools, encouragement, and space to explore whatever sparks their curiosity, and to write the brilliant essays featured in this publication. We’re so grateful foryoursupportanddedication!

Ihopeyouenjoythisissue!

Dothehumancharactersin Euripides'playsactoftheir ownfreewill?Discussin referenceto‘Hippolytus’. Addy M-SYear13

Free will is the ability voluntarily to choose between different courses of action Whether the human characters in Greek tragedy possess this ability is heavily disputed This is because of one of the defining characteristics of Greek tragedy which is divine intervention and the control it has over both the narrative and the mortal characters. In order to determine the extent of the impact which the gods have on these mortals, one must observe Euripides’ presentation of gods, humans, and their fate. By showing the gods as physically human on stage, Euripides challenges the previous depictions of Greek deities because they are transformed from an abstract idea to a concrete manifestation Arguably, this is all the gods are in Euripides’ literature They serve as a manifestation of human weakness and the most powerful human emotions The plays of Euripides are a melting pot of human weakness, fate, divine intervention and even gods becoming human in order to further distort the perception of mortal free will

Euripides differs from his preceding tragedians, Aeschylus and Sophocles, in that he portrays gods and goddesses as characters with a physical presence on stage rather than as ideas or concepts. In contrast, Aeschylus and Sophocles often only make mention of the gods or have their mortal characters exhibit prayer or ritual (Divine Deliverance: A New Look at Euripidean Tragedy through Audience Interpretation, pg 6) In making the gods appear more human, Euripides shows them as powerful yet prone to petty human emotions such as jealousy or humiliation. The gods are far from being revered or honoured in Euripidean tragedy but are merely manifestations of human weakness This is seen in the openings of both the ‘Bacchae’ and ‘Hippolytus’ in which the gods Dionysus and Aphrodite, respectively, express their anger at mortals either not believing in their religion or refusing to worship them Immediately the gods are portrayed in a highly vindictive light and will go on to appear extremely cruel, especially in the ‘Bacchae’ in which the god Dionysus orchestrates Pentheus being torn to pieces by his mother. The gods are instrumental to Euripidean tragedy, as by epitomising human emotion, they challenge its rationality Aphrodite even states in the prologue of ‘Hippolytus’ that gods and men share the characteristic of taking ‘pleasure in receiving honour from men ’ (Hippolytus, line 8) This supports the concept of honour being such a strong concern for both mortal and divine entities Thus, when looking at the gods’ impact on mortal free will, the divine can be viewed as a manifestation of human emotion. From the moment that the mortal characters have wronged the god or goddess- an act of free will in itself- they are left with a dual motivation They are controlled by both internal and external motivations simultaneously: while the gods

will events to happen, humans are also acting of their own accord to bring about these events This is seen when Phaedra actively fights against her sexual desires towards Hippolytus which have been inflicted upon her by Aphrodite This then leads to Phaedra’s death However, only the death is preordained by Aphrodite In this way, Euripides’ characters are able to exercise free will within the confines of divine influence.

It is important to distinguish between the concept of fate and divine intervention Fate’s predetermined nature suggests that any free will exacted by the mortal characters is redundant as neither they, nor the gods, can influence fate. Without the concept of fate the play becomes a story of human behaviour and divine intervention A close link can be drawn between free will and the concepts of moral responsibility and culpability because mortals’ voluntary course of action inevitably warrants consequences. In Hippolytus’ case, it is his own voluntary decision to reject the power of sexuality and desire which angers Aphrodite, leading to Hippolytus becoming a victim of Aphrodite’s anger and divine intervention This

corresponds with the idea that the mortal characters act of their own free will and then use the gods as a way of evading responsibility for their actions Of course, all actions have consequences Therefore in an attempt to evade mortal characters’ responsibility, the dramatic words ‘necessity’ (ἀνάγκη), ‘chance’ (Τυχη) or ‘doom’ (Άτη) are peppered across multiple Greek tragedies. This allows the character, in the case of a destructive outcome, to simply be able to say “it had to be” (Fate and Freedom in Greek Tragedy) The concept of divine intervention is most often used as a facade by Euripides to mask some of the core flaws of humanity which are displayed by free will This can be applied to Hippolytus' aforementioned arrogance and ‘ wrongs ’ to which Aphrodite then attributes her divine intervention and vengeance (Hippolytus) By commencing ‘Hippolytus’ with Aphrodite’s soliloquy, Euripides distracts the audience from Hippolytus’ role as the catalyst to all future horrific events in the play Hippolytus angers Aphrodite- his own free will is what led her to ‘intervene’ and consequently exact revenge on him- therefore he did act of his own free will and that led to the consequence of his death Therefore Euripides presents us with a dichotomy On the one hand, there is an external force, fate, which is greater than the gods themselves and is controlling mortal free will On the other hand, the mortal characters are acting voluntarily which causes a divine response. This leads onto the argument that there is a trigger, and, more specifically, an act of free will, which is exacted by the mortal character, sparking divine intervention and therefore a dual motivation throughout the play This one harmful act committed by that character triggers divine intervention as it appeals to the gods’ petty nature and emotions such as the aforementioned jealousy, love or honour.

Phaedra is a strong example of a mortal taking their fate into their own hands. It is somewhat ironic that the title of the play is ‘Hippolytus’ as it suggests he has the agency when, in reality, Phaedra does Phaedra is autonomous in the play and, aside from the initial event of being enamoured of Hippolytus by Aphrodite, she is determined to orchestrate her own fate ‘When the passion seizes her, she coolly and rationally reviews her situation She classifies her passion as a

’ (disease) that has come over her from outside herself and to cure herself she decides to subdue the passion with her intellectual powers ’ (Human and divine action). When this fails, she chooses to starve herself rather than reveal the secret of her passion The fact that she has acknowledged that her lust has been placed onto her by an external force indicates that she is acting of her own free will from this point onwards She then goes onto kill herself, but leaves a note which accuses Hippolytus of trying to rape her, and so she doesn’t allow herself to die in shame Of course, whether this is morally justified is disputable, but the fact she thinks to do this shows a great amount of agency in conducting her fate. A counter argument to this, of course, is that Aphrodite lays all of this out in her prologue at the beginning of the play, stating that ‘Phaedra must die- with her honour safe

but nevertheless die she must ’ and so Phaedra is arguably just another pawn in Aphrodite’s game. However, in Phaedra’s separate and personal course of action, she has a lot of agency and rationality despite such divine intervention Additionally, Aphrodite is not completely prophetic in her prologue as she states that she ‘shall reveal to Theseus what is happening’ (Hippolytus, line 49-50) but in fact it is Artemis who reveals the truth of the situation not Aphrodite This, most likely, was an intentional move from Euripides to display the subtle holes or inconsistencies in the gods’ omniscient nature, implying that mortals have more free will than the narrative overtly suggests.

The concept of free will, absent or present, is very evident in both ‘Hippolytus’ and ‘the Bacchae’ However, it is much more straightforward in ‘the Bacchae’ as Pentheus and his mother, Agave, hold no free will at all They are both stripped of their free will by Dionysus and this contributes to the tragedy In the Bacchae specifically, it is the contrast between the mortal and the divine and the powerless nature of mortals which makes the play so tragic Contrastingly, in ‘Hippolytus’, there is more ambiguity as to whether it is the gods or mortals who hold more agency. This is seen when King Theseus, of his own accord, capitalises on one of three curses given to him by Poseidon The chosen curse is a sea monster, which surfaces to frighten Hippolytus’ horses thereby causing Hippolytus to lose control of them and be dragged to his death Therefore, in this case, Poseidon as a god is more instrumental, and actually, Theseus holds more agency

The reason why it is so complex to measure the extent to which Euripidean mortal characters hold free will is that the concepts of fate and divine intervention create a paradox. The rationality of the ancient Greeks’ religion is hard to explain since the Greeks did not write down any aspect of their polytheistic faith That is why it was so important to Euripides as a playwright to physically place the gods on stage as a device for showcasing their very human nature and therefore their close intertwinement with the mortals themselves Overall, Euripides’ mortal characters mostly do have free will, but in the face of the divine and of fate, they lose it This is blurred when Euripides presents gods in human form as a dramatic device. Thus the free will of mortals and that of gods become interconnected; whether that is because the gods are responding to mortal acts of free will, or because they are acting as a manifestation of complex and powerful human emotion While in Euripides’ plays you will find human instinct, fate and divine intervention clearly defined, the free will of mortals and that of the gods will forever be intertwined

HowFarisOvid’s Metamorphosesan Epic?

LaurenCYear13

Ovid’s Metamorphoses shares many features with the epic genre in regards to contents, characters and the origin of the actions in the stories. However, his poetry distances itself from the epic genre by mocking the epic tradition and subverting some of the propagandist tropes of epic poetry

The basic contents and stylistic choices of Ovid’s Metamorphoses follow in line with the epic genre

The poem is written in hexameter, closely associated with the epic genre – it is sometimes called heroic hexameter The poem also begins with an invocation to divine beings: “di, coeptis (nam vos mutastis et illas)/ adspirate meis primaque ab origine mundi/ ad mea perpetuum deducite tempora carmen!” (“You heavenly powers, since you were responsible for those changes, as for all else, look favourably on my attempts, and spin an unbroken thread of verse, from the earliest beginnings of the world, down to my own times) An invocation to divine powers is shared with other epic poems, for example The Iliad, which opens with: “Sing, goddess, of the anger of Achilleus”. However, the first variation between Metamorphoses and the epic poem The Iliad is the nature of this invocation

While both invocations suggest divine influence on the writers when crafting their poetry, Homer specifically refers to Calliope, muse of epic poetry, whilst Ovid is more generally referring to the “gods”. This suggests that though Homer aligns his work with epic poetry closely through the invocation, the broadness of Ovid’s invocation suggests he wants to insert quickly divine intervention as one of the key themes of his work instead

As stated above, Ovid’s invocation explores what Metamorphoses shares with the epic genre: divine intervention The origin of the Metamorphoses itself is divine intervention, and the gods are also “responsible for those changes”(Innes) (“nam vos mutastis et illas”) which Ovid is writing about. Metamorphoses includes divine intervention from the Flood in Book 1 (Deucalion notes “it is god’s will” (Innes) “sic visum superis” 1366) to Venus deification of Julius Caesar (“[she] bore [his soul] up to the stars in heaven” (Innes) “animam caelestibus intulit astris” 15846) In a similar way, within the first 10 lines of Book 1 of the Aeneid, the fact that Juno’s wrath has been moved to “thrust on dangers dark and endless toil” onto Aeneas explores how she is responsible for creating the obstacles in the way of the founding of Rome by Aeneas, the events of the epic poem, and thus how the gods are responsible for that epic story. Therefore, in this aspect, Metamorphoses can be regarded as an epic poem.

The heroes, with whose lives these gods interfere, with is another point of argument in how far Metamorphoses is an epic Whilst the epics of Virgil and Homer focus largely on the events in the life of one or two heroes (Achilles, Agamemnon, Odysseus, or Aeneas), Ovid has a significant range of different protagonists since his poem includes over two hundred and fifty myths. The constant change in these protagonists means that their stories are not always elaborated on in great depth, which means that it is harder to create pathos since the reader is not so heavily invested in the story Even Aeneas, obviously so central to the Aeneid and the founding of Rome, is skimmed over by Ovid D King argues that “The Trojans’ time in Carthage is almost nonexistent in the Metamorphoses”, further affirming how brief the descriptions of Aeneas' epic journey are. However, in some respects the protagonists of Metamorphoses are similar to those of epic, considering the poets ’ intentions to create characters exemplifying certain morals and qualities and to explore one of the themes of epic poetry: honour Virgil’s Aeneas represents the piety and duty expected of Roman men; Nicholas Moseley notes that the fifteen times words connected with piety describe Aeneas means “It is evident that the poet meant to impress the reader with this side of his hero’s character” Based on the interpretation that Metamorphoses has

a moral aspect, for example when “Christian morality ultimately took possession of pagan letters” (Ginsberg) in the Middle Ages, then for characters like Daphne their “meaning superseded [their] probability as a person ” (Ginsberg) and a moral was found in their story The decision and interpretation of different protagonists to exemplify morals is found in both Metamorphoses and other epics like The Aeneid It must also be noted that the protagonists in epic poetry are not always perfectly moral or just, and Ovid’s poem shares this When Aeneas kills the weaponless Turnus, “So saying, burning with rage, he buried his sword deep/ in Turnus’s breast” (“ hoc dicens ferrum adverso sub pectore condit/ fervidus” 12950-951), this final image of Aeneas’ rage and brutal killing of the defenceless Turnus is at odds with the ‘clementia’ which is expected of him, and reveals that Aeneas is not always the perfect hero. Similarly, Apollo’s flaying of defenceless Marsyas for his skillful playing of the pipes seems openly cruel – Marsyas cries “pipes are not worth this!” (Innes) “ non est [ ] tibia tanti”(6386) and the weeping of Marsyas’ mourners creating a new spring from their tears further emphasises how harrowing this killing is. Moreover, the killings of Turnus and Marsyas explore the complexity of honour within epic poetry By killing Turnus, Aeneas is avenging Pallas, and also continuing with founding Rome, whilst the music competition between Apollo and Marsyas is to do with the honour of being the better musician. The acts of killing these men are inextricably linked with the honour which will be given to Aeneas and Apollo, and yet this honour is undercut by the brutality of the killings Both Ovid and Virgil use their characters to explore the theme of honour and to exemplify morals, whilst exploring the variation in the nature of their characters and how this can undercut the morality of their actions

Whilst epic poetry may be used to inform morals, it has also been used to interact with political events contemporary to it The Aeneid features many comments on contemporary politics: the accession of Augustus Caesar to emperor in 27 BCE This occurs notably in Book 6, lines 792-794, when Anchises describes the power the Roman empire and “Augustus Caesar, son of the Deified,/who will make a Golden Age again in the fields/where Saturn once reigned/” (“Augustus Caesar, divi genus, aurea condet/saecula qui rursus Latio regnata per arva/ Saturno”); this makes this section of the Aeneid a pro-Augustan piece of propaganda. Similarly, in Metamorphoses, Jupiter announces the destiny of Augustus: “ ‘When the blessing of peace has been bestowed upon the earth, he will turn his attention to the rights of the citizen and will pass laws, eminently just’“ (‘pace data terris animum ad civilia vertet/ iura suum legesque feret iustissimus auctor ’” 15.832-833). Both these works are arguably used as propaganda, creating an epic story for Augustus

alongside the other protagonists they include. However, the use of Aeneas as a propaganda tool in both poems differs In the Aeneid, Aeneas takes on the role of avenger when he kills Turnus in response to the death of Pallas: “‘Pallas te hoc vulnere, Pallas/immolat et poenam scelerato ex sanguine sumit’” (“‘By this wound which I now give, it is Pallas who makes sacrifice of you It is Pallas who exacts the penalty in your guilty blood’” (West), 12 948-949) This role as avenger is similar to the role which Augustus played when he killed the assassins of his adoptive father, Julius Caesar. D. King affirms this by describing how “This accomplishment [the killing of Turnus] at once echoes and foreshadows the real-life exploits of Augustus” However, whilst in the Aeneid Aeneas is the heroic avenger and the poem ends with this act without describing any end to Aeneas, in Metamorphoses, Aeneas’ death is described: “corniger exsequitur Veneris mandata suisque,/quicquid in Aenea fuerat mortale, repurgat/et respersit aquis” (“The horned river carried out the goddess’ requests and, with its waters, sprinkled and cleansed away all that was mortal in Aeneas” (Innes), 14. 602-604). The effect of this could be to remind the reader of the mortal side of this hero despite his apotheosis, and since “Aeneas is a representative for Augustus and the Roman people, Ovid sets bounds on both Augustus’ life and the Empire’s reach” (King), therefore making clear the limits to Augustus’ power Therefore, while both works include propaganda describing the rise of Augustus, through using Aeneas as the embodiment of the Proto-Roman and Augustus, Virgil and Ovid’s portrayal of Augustus differs

However, Ovid’s “lack of high seriousness” (Ginsberg) must also be considered when exploring to what extent his poem is an epic; this humour can be seen through Ovid’s subversion of epic tradition and style Lines 494-759 in Book 2 of Homer’s Iliad features an epic catalogue of all of the units of the Achaean army sailing to Troy. Similarly, Ovid also includes epic catalogues in his poem, but he subverts the epic tradition by including excessive catalogues of unimportant things, such as the eighteen line long catalogue of Actaeon’s hunting dogs: “Melampus and Ichnobates [ ] Lebros and Agriodus and sharp barking Hylactor” (Innes) (“ Melampus / Ichnobatesque [ ] Lebros et Agriodus et acutae vocis Hylactor” 3206-224) Ovid even gives the heritage of each dog, “Icnobates of the Cretan breed, Melampus of the Spartan breed” (“Cnosius Ichnobates, Spartana gente Melampus” (Innes) 3.208), just as other epic writers such as Homer give details about the origins of the heroes in their poems, such as when Nestor is described as the “clear-voiced speaker of Pylos” (Hammond) ( Iliad 1273) In this way, Metamorphoses is not an epic but rather it distances itself from the epic genre by mocking it

Ovid’s Metamorphoses is to some extent an epic poem since it shares many features of epic poetry: an invocation of a muse and divine being; the intervention of divine beings; the variations in the personality and moral significance of heroes; interaction with contemporary events and politics However, the use of multiple heroes and more significantly the way Ovid subverts epic traditions suggests that Ovid is not writing an entirely epic poem and is also trying to mock epic poetry. Thus, Metamorphoses is only to some extent an epic poem.

TheSeedsof Civilisation: Classical Inventions thatshaped theWorld MaanviKYear12

Imagine life without roads, plumbing or even heating. Many of the most ingenious and fundamental inventions seamlessly integrated into our everyday lives today originated with the Greeks and Romans These classical civilisations laid the groundwork for modern society, contributing not only physical inventions but also numerous abstract ideas that continue to shape our world

The Greeks and Romans pioneered many innovations that remain essential today. For instance, the Romans developed the hypocaust system, an early form of central heating, along with the plumbing system, ensuring us access to clean water By making use of an underground fire and concrete pillars, the Romans were able to distribute heat throughout houses, in a similar way to under-floor heating They reinforced this invention by building gaps in walls so that the heat could travel through to the upper floors and eventually escape through the roof With the creation of huge networks of pipes, channels and bridges, the Romans also hugely developed the idea of aqueducts in order to address the critical need for a reliable and efficient water supply. This allowed them to meet demand and support their growing cities and populations

Whilst these contributions are well-known, it may come as much more of a surprise to learn that the Greeks are to thank for a large portion of the machines used in arcades today. During the Hellenistic era, Heron of Alexandria designed a coin operated mechanism that dispensed holy water at temples When worshippers inserted a coin into the slot, it would cause a spigot to open that would release this water due to a shift in weight, meaning, as the coin slid off, the valve closed again and the machine was ready for use by the next customer. Modern day vending machines rely on the same principles to dispense food and merchandise worldwide Similarly, Archimedes of Syracuse outlined the creation of a giant hook from a lever and fulcrum, the mechanics of which can be likened a lot to claw machines used to pick prizes in arcades today. Whilst this was primarily for military use and allowed the Greeks to raise whole enemy ships out of the water, the lever procedure can be implemented in all sorts of applications now As founders of one of the most well known traditions, the Olympic games, the Greeks also invented a gate apparatus called ‘the hysplex’, consisting of wooden posts and tensioned ropes which meant that all competitors would start at the same exact moment, preventing false starts This synchronised release mechanism is used in ball-drop games, along with racing games and even in entrance barriers at many venues. Such inventions illustrate how deeply rooted these civilisations’ ingenuity is in our daily existence

Beyond tangible innovations, the Greeks and Romans introduced a number of abstract concepts that form the basis of civilisation today. Take, for example, the subjects studied in academic institutions all around the world: mathematics, engineering, science, medicine, literature, history, art, theatre, and arguably the most important of all, philosophy

The first idea of mathematics came around as basic arithmetic when the ancient Sumerians of Mesopotamia created a sexagesimal (base-60) number systemgiving us the 60-second minute. Based on the current numerical system, having 100 seconds in a minute would seem more intuitive, especially considering this is the standard for other widely used metric systems, however, this simply proves how influential these founding inventions were to still carry such weight. Furthermore, some of the greatest mathematicians, such as Pythagoras, came from the ancient world and developed theories that remain central to the field

In the realm of engineering, the Greeks developed many of the mechanics behind basic tools and systems still in use today Ramps, levers and buttons are amongst the brilliant gadgets they conceptualised, demonstrating their ability to harness the principles of physics for practical applications.

Pythagoras in the School of Athens fresco

These mechanical advancements reflect their broader philosophical approach to understanding the universe as the idea of science was considered to be the ‘systematic enquiry into the universe’; a system governed by reason and logic Thales of Miletus supposed that all nature must be based on the existence of a single ultimate substance: water; a founding factor of biology. Ptolemy’s geocentric theory forms the basis of our understanding of the motions of stars and planets even a thousand years later, highlighting a clear link to astronomy. The Greeks played a huge role in the advancement of medicine, including the creation of pharmaceuticals, and surgical procedures employing surgical devices to open the human body for medical intervention Hippocrates is considered to be the father of modern medicine, hence the Hippocratic oath taken by professionals upon entering the field He published over 70 books in which he presented, in a scientific manner, many diseases and their treatment following detailed observation.

Literature and history began with the Greeks as the greatest authors of all time, Homer and Herodotus laid the groundwork for western literary tradition Within these uniquely refined texts, both authors established many universal themes which are prevalent in civilisation today Homer created the concepts of honor, heroism, mortality, loyalty, xenia, pathos, identity, and the list could go on Equally as important, Herodotus explored areas now labelled as sociology, anthropology, cultural geography, and ethnography. The development of the inquiry system, involving the use of sources and the removal of bias, led to a whole new area of works branching off predominantly fictional epics of Homer Both verse and prose publications of the ancient world offer us thorough insight into life in antiquity

The Greeks decided very early on that the human form was the most important subject for artistic endeavour, resulting in great statues, vases, ornaments, murals and architectural displays, many of which are still preserved and sought to be recreated today Not only are modern artists finding ways to regenerate such art, but the ideas behind new art are also greatly influenced by the art of ancient Greece Likewise, the earliest origins of performing arts in theatre and drama were found in Athens where ancient hymns were sung in honour of the god Dionysus - they were later adapted for choral processions with the inclusion of costumes and masks. This idea of theatrical performance developed greatly through the Greeks and ultimately led to the establishment of some of the main genres such as tragedy, comedy and satyr plays The theatre of Dionysus stands at the foot of the Acropolis in Athens where the most famous playwrights of the ancient world presented their works in competition

One of the most prominent contributions of the Greeks was the emergence of the first philosophers, including Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, who set the precedent for philosophy as a discipline of problem-solving, logical reasoning, and seeking answers to complex questions These are all fundamental aspects of human knowledge and creativity, illustrating the profound legacy left by the classical world across such a diverse range of fields

Some of the most transformative Greek and Roman contributions are now embedded so deeply within society that it is hard to imagine a time when they didn’t exist. The invention of numbers and time revolutionised human understanding and organisation, forming the basis of almost everything we do The Romans invented numerals along with the calendar year and these same numerical systems remain in place today as the foundation of modern timekeeping from the seconds in a minute to the months in a year Alongside this, other concepts invented by the Greeks, such as democracy - deriving from the greek words δεσμός (people) and κράτος (power) - completely remoulded governance, introducing systems like voting polls and the postal service to enhance societal efficiency. Economic systems also owe much to classical civilisations with the major introduction of coins and the development of a standardized currency system, facilitating the huge expansion of the trading empire During the process of coining, coins were stamped with a royal symbol to give them the sense of authority we would be familiar with today

When comparing modern society to the Stone Age, the substantial changes brought about by the Greeks and Romans mark a stark transformation. Over two millennia, these civilisations introduced tools, systems, and ideas that continue to underpin the way civilisation functions today In many ways, the world as we know it developed more in these 2,000 years than in all the rest of time Their legacy remains as an enduring testament to the brilliance of classical civilisations page13

Wouldtheflightof Icarushavebeen physicallypossible?

AlexDYear12

The Ancient Greek myth of Icarus and Daedalus is a timeless tale of human ambition and the dangers of overreach According to mythology, Daedalus, a brilliant inventor, trapped with his son Icarus by King Minos, was searching for means to escape his captivity. His solution was theoretically great: crafted wings made of feathers and wax so that he and his son could escape from the island of Crete in the air. The myth relates that he warned Icarus not to fly too close to the sun, lest the wax melt, nor too close to the sea, to avoid dampening the feathers Naively, ignoring his father’s advice, Icarus soared too high, the wax melted, and he fell into the sea In every retelling of the myth, Icarus is to blame for his untimely death, but would the crossing even have been physically possible?

To achieve flight, Daedalus would have needed to address two primary forces in aerodynamics: lift and drag The wings Daedalus crafted would need to generate sufficient lift to counteract the force of gravity acting on Icarus’ and Daedalus’ bodies

There is a fair consensus amongst osteologists that the average height of the Graeco-Roman population was approximately 1.67m, which in the modern day BMI scale, would put Daedalus and Icarus at a minimum weight of 55 8kg, and a maximum of 83 7kg Considering they had been in captivity for a considerably long time, it is likely they would be on the lower end of the spectrum Using the minimum value, their weight would be roughly:

��=����

55.8 × 9.81 = 547.4N

For Icarus to maintain flight, the lift produced by his wings would need to at least equal this weight Birds achieve this through both the shape of their wings and the muscle power needed to flap them, creating the necessary velocity to sustain lift Lift can be calculated using the equation:

L = Cl * A * .5 * �� * ��^2

Where ρ is the air density, �� is the relative velocity of air over the wing, A is the wing area, and Cl is the lift coefficient (which depends on the wing shape and angle of attack). However, estimating a feasible wing area for human flight is challenging Based on human mass and the necessary lift coefficient for gliding, wingspans exceeding 20 metres would likely

be needed. Additionally, an extensive knowledge of modern physics would be required for Daedalus to make the optimal shape of wings The Roman poet Ovid describes how Daedalus attaches bird feathers to the wings, "arranging the feathers in order, taking the smallest first; each is less long than the next, and all rise by an insensible gradation Daedalus attaches these feathers, in the middle, with linen, at their tips with wax; he then gives them a slight curve, the better to imitate the wing of birds ” Birds can fly with ease because the structure of their wings is designed for efficient airflow The wing bones are positioned at the front and are covered with a smooth layer of feathers that taper towards the back The rear of the wing consists of a single layer of flight feathers, forming an airfoil shape When air flows directly toward this airfoil, either from flying into the wind or moving swiftly forward, the unique shape causes air to move faster over the top of the wing than underneath it. This faster airflow above lowers the pressure, while the slower air below creates higher pressure, generating lift that allows the bird to ascend.

However, the discovery of this optimum bird shape is most often credited to Sir George Cayley, as the first man to describe the principles of bird flight and wing shape in terms of aerodynamics Considering he lived in the late 18th century to the mid 19th century, and Daedalus is first mentioned in roughly 1400 BC on Linear B tablets, he would not have understood this principle to create his wings accordingly. But even assuming the wings of Icarus and Daedalus were optimally shaped, human physiology lacks the muscle capacity to generate sufficient airspeed by flapping alone In a hypothetical scenario where Daedalus and Icarus could glide on air currents, the wings would need to be very large, far larger than anything described in myth, to provide enough surface area for effective lift, given the density and weight of a human body Such a wing design would make flight nearly impossible without modern materials and a strong enough air current to support them

When Daedalus constructed the wings, his choice of materials was limited Daedalus crafted the wings by fastening feathers with wax- a choice that speaks to the limitations of ancient materials Wax is a malleable substance, but it has a low melting point Most natural waxes begin to soften at around 40°C and melt between 60°C and 80°C While temperatures do not increase significantly with altitude, direct exposure to sunlight would warm the wax, particularly at high altitudes where theres less atmosphere to block solar radiation, the wax would absorb radiative heat from the sun ’ s rays. The rate of energy absorption, due to sunlight can be estimated by:

Where �� is the solar power per unit area, approximately 1361 W/m² at Earth’s surface, and �� is the surface area exposed to sunlight

Assuming that the wings absorb much of this energy due to the lack of atmospheric interference at higher altitudes, the wax would rapidly heat up The absorbed energy would raise the wax ’ s temperature until it exceeded its melting point, causing it to lose its cohesive properties. As a result, the feathers attached with wax would detach, dismantling the wings This thermodynamic failure demonstrates the importance of material selection in engineering- wax is clearly unsuitable for high-temperature environments In reality, even moderate temperatures in direct sunlight could have led to failure if the wax was the sole adhesive Daedalus’ design, without a more heat-resistant adhesive, was fundamentally flawed

When the wax holding Icarus wings melted, he would have entered free-fall During free-fall, he would have accelerated downward under gravity The distance, fallen after time can be calculated by:

d=0.5*g*t^2

Where g=9.81 m/s^2is (acceleration due to gravity) and t is time. Rearranging the equation to be

t= √d/0 5*g

t= 11277 6/(0 5*9 81^2)

t= 234s

Thus, it would have taken Icarus about 234 seconds to fall after his wings melted. However, even before that happened, as Icarus climbed through the troposphere, the temperature would have dropped by roughly 1°C for every 1,000 feet he ascended Considering the highest recorded altitude for a bird is 37,000 feet (achieved by the Rüppell’s griffon vulture), this altitude therefore marks where the thin air would have made it nearly impossible for Icarus to use his wings effectively. At this height, temperatures would still be decreasing, ranging from -40°C to -60°C, depending on local conditions This suggests that even if Icarus had reached such an altitude without his wings melting, he would likely have frozen to death

Through the myth of Icarus, we see a narrative that, while fictional, aligns in many ways with fundamental principles of physics Daedalus’s attempt at human flight touches on concepts of lift and drag, the limitations of ancient materials, and the hazards of solar radiation. Based upon the knowledge at the time and the sheer force needing to be generated by the wings, the flight of Icarus and Daedalus would have been impossible, meaning that the onus for his death was not completely placed upon Icarus The story captures humanity’s desire to transcend natural limitations, a theme that continues to resonate with modern scientific endeavours The physics of Icarus’ flight highlights the limitations that humans faced before understanding aerodynamics and material science, making it a powerful reminder of both the potential and the peril of human ambition

“Theonlylanguages whichdonotchangeare deadones.” Howfardoyouagree?

MayaMYear12

Language has been evolving ever since we first started using it around 300,000 years ago There are many theories for how we first began speaking, with some suggesting it was imitations of sounds around us whilst others believe that the easiest sounds to make were attached to the most significant objects For example, most languages have some variation of mama , papa for parents, as those are the easiest sounds for babies to make While there is no definitive answer on how or exactly when language developed, it has definitely been long enough to see many languages evolving and dying

English originated from a Proto-Indo-European parent tongue spoken around 5,000 years ago in southeast Europe This later developed into most of the modern and dead European languages that we know today and was the predecessor to the Germanic languages English is a West Germanic language (along with German, Dutch, Flemish and Frisian), and these are relatively analytic (uninflected) when compared to the synthetic Proto-Indo-European parent tongue that they came from In modern English, inflection is used to indicate much less than in other languages like German, Latin and Spanish Whilst we can still see evidence of Old English inflection (take pronouns like, he, his, him) , English has become more flexible over the last few centuries as the amount of inflections used has decreased. The lines between a noun and verb have blurred: one can speak of both “ a dress” and “ to dress” as well as “ to book” and “ a book”, however in all other Indo-European languages (with a few Scandinavian exceptions) this is not possible as their languages require a difference in endings between nouns and verbs This also means that English adapts and takes loan words from other languages very easily It is estimated that ¼ of Modern English words are Germanic in origin, ⅔ from Italic and Romance languages and a large proportion of scientific and technical vocabulary from Greek

Large amounts of the words in the semantic field of politics come from French (which was once the official language of politics) as well as much of our terms for dance, literature and fashion These words did not become part of the English language overnight, and they are the product of hundreds of years of change in both the English language and the world Some of these “loan words” were from people mixing due to trade (the word “tornado” came from Spanish, possibly around the 16th Century when British ships encountered hidalgos on the sea) and others came from the places where exotic plants and products were discovered such as “cigar” (from Latin America through Arizona and California) and “ potato ” (from Spanish patata from Taino batata) More recently, English has changed and adapted due to the internet and SMS messaging Whilst the concept of slang has been around since at least 1734 (the first noted use of the word which meant a low or illiterate language), people have been abbreviating, or creating their own versions of languages, since well before (eg The Thieves Cant which was a system of language used by criminals to keep law enforcement unaware of their movements in the 1600s) The creation and use of new slang has skyrocketed since the internet, and acronyms such as YOLO, LOL, BRB, IRL and LMAO (most of which originated in internet chat rooms in the 1990s) have become so well understood that they are used in normal speech even when not online A study by online language learning platform, Preply, found that 94% of Americans used some form of slang in 2022, and 89% said they had learnt slang from social media The particular slang words that are popular at any given time can also reflect the changes in the real world The highest used slang terms in 2022 included ghosted (to ignore somebody), salty (to be bitter) and catfish (pretending to be somebody you are not online) The English language is an incredible example of a language that changes and adapts frequently, as well as one that has been built upon words from other cultures and languages

The Russian language, on the other hand, is an East Slavic language (as are Ukrainian and Belarusian) which uses the Cyrillic alphabet Russian also came from an Indo-European Language which eventually became Proto-Slavonic as people began to settle in Eastern Europe, some time between 3500 and 2500 BC For centuries, all of the East Slavic languages were nearly indistinguishable from each other and were known as Old Russian It is believed that Ukranian was a fully formed language from as early as 950 BC but was not recognised as one until 1906 (due to a variety of political reasons), and Belarusian was recognised as its own language after the Russian revolution of 1917

A French Example of the Thieves Cant

Venn diagram showing the common glyphs between the Russian Greek and Latin alphabets

Until 862 AD, there was no official written language for the Slavic people Eventually due to a need to translate the Bible, Thessalonian Monks Cyril and Methodius decided to create an alphabet based on the phonemic properties of the dialect they were most familiar with, the Macedonian one (this is in part why both the Greek and the Cyrillic alphabet share several letters) This became known as the OCS (Old Church Slavonic) This was not yet the Cyrillic alphabet used by these languages today (the exact origins of the modern Cyrillic alphabet are still unknown), however OCS was almost certainly a predecessor to it After the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, many scholars emigrated to Moscow and were displeased with irregularities in the language. They attempted to standardise the language and this became known as the “The Second Southern-Slavic Influence This restored old syllables and sounds from Old Russian and removed a few new ones introduced by OCS as well as reintroducing older expressions Under the reign of Peter the Great, almost 400 years later, another massive change was made to the Russian language as he used contemporary Russian and began to remove and simplify letters which did not have a use; this continued until 1918 when even more obsolete letters were removed 1917 brought a revolution to Russia which changed the education system and increased literacy rates which allowed for a wider range of language Russian is another language that has extended its vocabulary through “loaned words”, with some like “ товар ” (commercial goods) and “ лошадь ” (horse) being introduced through the Tartar invasion of the 13th century and others from a variety of languages such as “ рюкзак ” (backpack - from German) and “катастрофа” (catastrophe - from French) This is possibly a result of Russian nobility being well versed in languages, like French, German, and Latin from a very young age, which led to Russian borrowing these words when they offered a better, more precise definitions than their Russian alternatives. Russian, like most modern languages, has its own slang, and whilst some of it is very similar to English (their “hahaha” being “ xaxaxa ” , as x makes a h or kh sound), they also have their own unique slang such as “Круто” (cool) and “Данунафиг!” (to hell with that!) Russian, despite being a completely different language to English, has also evolved dramatically over the centuries and been able to both transliterate and assimilate foreign words into its own language, even when they come from a different alphabet entirely.

As language itself has been around for centuries, it is unsurprising that some have died out However, even dead languages have been used in legal and religious documents for centuries after people stopped using them as a first language Latin is an Indo-European language that was used throughout the Roman Empire, making it one of the most widespread languages of the ancient world. It was originally Proto-Latin which came from Bronze Age tribes in the area, eventually becoming Old Latin and the Classical Latin which we study and use today It is the base for many of the romance languages such as Italian, Spanish and French and has given Germanic languages like English many words as well Latin itself has never really been removed from circulation as has been studied by scholars and was the language of most sermons for centuries Despite this, it is still considered a dead language, but even dead languages can change The Vatican uses Latin for official documents and because of this it needs to update Latin to contain ideas and words for things that did not exist as the language was evolving naturally The Vatican has created an online dictionary known as “Latinas” This contains Latin words for computer “instrumentum computatórium”, fifty-fifty “aequíssima partítio” and even hot pants “brevíssimae bracae femíneae”! Whilst this is not organic change, and has been created only by necessity, it is still change in a language that is considered dead Hebrew is the only dead language that is now considered revived 150 years ago it survived only in writing and religious texts but now it has millions of speakers Hebrew died out as its native speakers were forced to move around the globe due to oppression and adopted the languages of their new homes or created new ones (like Yiddish which has Hebrew, Slavic and Germanic origins), whilst the knowledge of how to read and write Hebrew was preserved through religious texts In the 19th Century, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda created what is known as Modern Hebrew He raised his son to be the first native Hebrew speaker in almost 2,000 years and created a dictionary of new Hebrew words to adapt to the changing times (which included “ןולימ” - dictionary) The language became standardised and was taught in schools in Jerusalem Now 55% of Israelis speak Hebrew as their first language and there are 15 million Hebrew speakers Despite being considered a dead language for centuries, Hebrew has had such a strong revival that it is now a living language, further proof that even dead languages can change

Language change is inevitable, it has happened all around the globe in both isolated communities and the biggest trading powers. Language change comes hand in hand with progress and happens organically through migration and the spread of cultures As languages grow and change, they can be used to express new ideas or to refer to new objects which allows for better communication; the whole reason why language evolved in the first place On the other hand, change can be considered negative, as it leads to extinct languages, as generations worth of knowledge is lost Some of these languages were fortunate enough to be saved by their last native speakers such as Wichita and Tehuelche, both of which lost their last native speaker within the last 10 years, and only saved their languages from being lost by documenting them with linguists before they passed away Others like Cochin Indo-Portuguese and Akkala Sami are almost undocumented and most of their culture and language was lost when their final native speakers died.

In conclusion, all languages can change, even dead ones Whilst the rate of change is far more rapid in modern languages spoken today (because of the need for more words as new concepts and ideas are created), even dead languages like Latin and Hebrew are changing Language change is inevitable, it is a tool used to reflect the world around us As the world changes, language must also change, otherwise it would cease to be a tool for communication, which is its purpose.

FromyourreadingofIliad VI,towhatextentdoyou thinkthatHectorisheroic? RoxanaQYear11

The majority of Illiad VI lends itself to the idea that Hector is a standard Homeric hero: prideful and masculine However, vital scenes within this book seem to suggest another facet to Hector’s personality which overshadows his heroism; calling into question the driving force behind his heroic acts

Without question, Hector’s deep sense of devotion to Troy and unwavering willingness to fight on its behalf suggests his innately heroic character Hector is frequently described utilising epithets such as “bronze-helmeted”, “glorious” and “man-slaying” all of which suggest his bravery and heroism when fighting Hector himself describes how he was always taught “ to be noble” and “ to fight amongst the leading Trojans ” This suggests how deep-rooted his willingness to fight is; evoking a sense that his supposed heroism is central to his being. He is described as “intending to go out through to the plain,” just after he has returned home, again suggesting his relentless drive to return to war and defend Troy His intense, warrior-like personality suggests a great sense that Hector is immensely heroic

Furthermore, Hector can be seen as heroic due to the fact that, despite his intense love for his wife, Andromache, and son, Astyanax, he still puts his warrior-like duties ahead of his familial duties Despite Andromache’s relentless appeals to Hector; evident when she exclaims “will your courage not destroy you?” and “do you not pity your infant son and my unfortunate self” Hector is not stirred, saying, “ my spirit does not command me thus” when describing his unwillingness to stay on the tower ” all because of his compelling sense of heroism Even when Andromache adopts an extremely commanding tone, especially when considering female roles at the time, saying, “Do not make your son an orphan and your wife a widow.” Hector is unswayed in his decision Considering how much love he has for his family, evident when he is “smiling whilst “looking up at his child in silence” and his devotion to his “excellent wife,” it is extremely significant that this love is not enough to dissuade him: this therefore suggests a great deal that Hector is heroic

However, the idea that Hector is heroic is tainted by his obsession with Kleos, the immortal glory given to warriors who are worthy of it Hector describes how, by acting in a heroic manner and fighting, he earns “ great Kleos both for his father and for himself” This reference therefore suggests an ulterior motive for Hector to act in such a way, calling into question the authenticity of his heroic manner Even when envisioning his son ’ s future prosperity, he imagines Astyanax bringing home “blood-stained spoils” again showing that he is mainly preoccupied on the topic of glory and honour, stopping at nothing to gain it

Moreover, glimmers of Hector’s desperation for recognition amongst others becomes evident, further tarnishing his otherwise heroic nature Hector describes how he does not want to “feel shame in front of the Trojan Women” Hector’s desperation for recognition runs so deep that even the opinion of women, who do not care for war, impresses upon him deeply He refuses to shrink far from the war

and act like a coward This further suggests how important other’s perception of him are, and how therefore he must act in an offensive and heroic manner to maintain his status amongst others When Andromache makes a very logical suggestion to “place the troops next to the fig tree, ” Hector refuses to do so, as this defensive strategy runs the risk of presenting him as weak. One must also consider our modern meaning of Heroism Perhaps to a modern audience, the most heroic thing to do would be to put personal glory aside and do what would be best for the majority Hector’s obsession with not feeling shame and his reputation suggest to the audience that therefore his heroic nature is only implemented by Hector to ensure future glory, rather than being something that is central to him being naturally

Overall, Hector is presented as an enthusiastically bold fighter, with undoubtedly heroic elements to his character. However, his obsession with glory and deep-rooted insecurities marr the audience’s perception of him to the extent that his heroism could be viewed quite simply as just a facade

HalfTerm ClassicsTripto theBayofNaples EleanorP,EllaCandEshaK

Over October half term, 70 of NHEHS s Y8-10 classicists went on a fascinating voyage across both space and time, walking among ancient Romans and practising their Latin!

Well, not really But that was what it felt like (minus speaking Latin – imagine! we chose a dead language for a reason) when we flew to the Bay of Naples for five days and explored many of the stunning sites preserved for us in the future by a volcanic eruption almost 2000 years ago

A very early start on the first day meant that when we landed in Naples, we still had plenty of time to explore the Naples National Archaeological Museum There, we saw a wide variety of mosaics, frescoes and other artefacts from Pompeii, Herculaneum and the surrounding areas affected by the eruption It was great to see so many of the artworks which would have been left in situ if it wasn ’ t for the, ahem, alternative methods of archaeology (making money out of stealing art) from the time when the towns were discovered Some of our favourite items included a mosaic of a skeleton, a lavishly frescoed niche and an impressive scale model of Pompeii, which proved to be helpful for the next day! We then returned to Sorrento, across the Bay from Naples, and enjoyed

our first night at the Hotel La Ripetta The Villa Oplontis, a large Roman villa believed to still be half-buried by archaeologists, was our group ’ s first stop the next day. It is thought to have been the home of Nero’s second wife, Poppaea The villa was one of the largest in the Bay of Naples, and one of the most luxurious, too, with a pool larger than ours at school! After that, we went to our largest site: Pompeii We visited the amphitheatre, lots of villas and thermopolia (fast food shops) with marble table tops We braved the sweltering heat in the forum, exploring the Temple of Jupiter (which was still being rebuilt after an earthquake and the Basilica, important locations to the residents of the ancient town. We even managed to find the house of the notorious Caecilius –although we didn’t see his hortus! (Apparently it’s an inside joke We don’t get it either)

Monday saw everyone visit a local family-run farm where we encountered many animals, discovered how mozzarella is made and (best of all) made our own Italian pizza! After this, we took the long drive to Paestum Paestum was initially a Greek settlement, so is home to amazing Greek temples of Hera and Athena, but also the remains of many other public buildings The architecture was extremely impressive – did you know that the Greeks made their columns bulge in the middle to give the illusion that they were the same width throughout?

On Tuesday we split up again: Year 9 and 10 spent some time in Sorrento before trekking up Mount Vesuvius It was a surprisingly steep walk but we braved the rain and managed to make it to the top of the volcano The views were breathtaking (despite the cloud) and we got the chance to visualise the incredibly famous eruption from 79 AD We even saw steam coming out of the crater! In the coach on the way back to our hotel Mrs Goodall read out the two fascinating letters of Pliny the younger describing the eruption In the evening, we enjoyed a night of karaoke, singing only, of course, Latin lyrics!

On our final day, we visited two villas at Stabiae, the Villa San Marco and the Villa Arianna These villas were impressive and everyone enjoyed exploring their elaborate frescoes and learning about the previous inhabitants Finally, before departing for home, we visited Herculaneum Herculaneum was a Roman town covered by pyroclastic flow from Mount Vesuvius’s eruption We enjoyed looking at the Roman spas and houses, as well as seeing how they had invented many useful domestic appliances we still use today, such as central underfloor heating Particularly moving about Herculaneum is that skeletons of many people were discovered hiding in the boathouses – trying to escape but failing – and provide a very dramatic contrast to the deserted town above, reminding us why we can enjoy these sites

Overall, we loved seeing all the different Roman sites around the Bay of Naples! It is incredible how immersive the sites are, and the fact that we can just wander around them two millennia later – it really puts everything in perspective, and frames our studies of Classics (especially seeing Greek colonies in Italy!) Thank you very much to Mrs Goodall and the accompanying teachers for organising this intriguing, enriching experience for us! page25

Atranslationof HoracesOdeXI:To Leuconoe LaurenCYear13

Tu ne quaesieris (scire nefas) quem mihi, quem tibi finem di dederint, Leuconoe, nec Babylonios temptaris numeros. Ut melius quicquid erit pati!

Seu pluris hiemes seu tribuit Iuppiter ultimam, quae nunc oppositis debilitat pumicibus mare 5 Tyrrhenum, sapias, vina liques et spatio brevi spem longam reseces. Dum loquimur, fugerit invida aetas: carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero.

You should not seek (it is unlawful to know) the end the gods have given to me, to you, Leuconoe, nor should you try the Babylonian numbers How much better to suffer whatever happens! Whether Jupiter assigned several more winters or the last, which now erodes the Tyrrhenian sea on opposing cliffs. Wisely, you mix the wine and limit long hope with short life. While we speak, jealous time flees: pluck the day, trusting very little in the future

‘Theroleoffateinthe Aeneidreduces suspenseand excitement.’Towhat extentdoyouagree?

PreetKYear13

In the opening lines of the Aeneid, the eponymous hero, Aeneas, is described to be ‘fato profugus’, clearly conveying to the reader the pivotal role that Fate will play in his journey To simply claim that the lack of agency that Aeneas possesses in his destiny results in the 9,896 lines of the renowned epic not being exciting, would be to disregard entirely why the Aeneid was written Instead, one has to take into account the political context, as this was a piece of work for a patron of the court of Emperor Augustus As a result of the bloody civil wars in Rome and political upheaval, the Aeneid was written with the aim of establishing Augustus’ birthright as ruler Moreover, Virgil is able to take this significant factor of Fate and create a clash between a character’s personal desires and their uncontrollable fate, exploring the idea of human free will and power when faced with divine intervention It is this conflict of desires that incites some of the most emotional, tragic, and magnificent moments of the Aeneid.

Due to the political factors that permeate the Aeneid, arguably it does not matter if Fate reduces its excitement As Virgil had the ulterior motive of endorsing Augustus' divine right to rule, its primary purpose was in fact not to entertain the reader, negating the need for suspense Instead, being written with a political factor in mind, the Aeneid stemmed from the fact that the ‘Principate required a new sort of man, a civic ideal ’ In the wake of political turmoil ranging from the ‘First Triumvirate’, Caesar’s assassination, and finally Rome being embroiled in civil wars for 13 years, the idea that ‘Rome had been founded a second time through the Pax Augusta is one that is reflected through the Augustan ideal of pietas which Aeneas manifests in the highest degree At its core, the Aeneid is indeed a piece of propaganda, rather than an example of ‘l’art pour l’art’. With politics and religion being intrinsically linked in ancient Rome, ‘the deeds of the ancestors (maiores) played an eminent

role in Roman thinking and politics’, leading to the populace judging a ruler based on the extent to which their reign embodied the mos maiorum, ‘the ancestral tradition ’Augustus was able to utilise this to his advantage by giving Virgil the duty of certifying his right to rule in his epic, as shown in the famous scene of Book VI in which Aeneas travels to the Underworld Here his father, Anchises, explains the significance of Aeneas’ journey by showing him the glorious lineage that will follow him, with one of these illustrious spirits being Augustus Caesar who is fated to make a Golden Age again’ Heightened by the comparison to the mythical Golden Age, Virgil effectively traces back Augustus’ lineage not just to Romulus, the first king of Rome, but to Aeneas, founder of the Roman race, creating the notion that the gods have authorised Augustus to rule as ‘princeps’ in place of the Republic This overarching political aim is again reflected in Book VII when Aeneas receives a shield, crafted by Vulcan with indescribable detail from Venus Not only does this gesture directly echo Book XVIII of the Iliad, but the shield’s design also intricately shows scenes from early Roman history - the ‘history of Italy, and Rome’s triumphs’ had been forged onto Aeneas’ shield Most importantly, the centre of the shield depicted the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, describing how ‘Augustus Caesar’ led ‘the Italians to the conflict’ along with the ‘Senate, the people, the household gods, the great gods’ against ‘Antony’ with his ‘barbarous wealth and strange weapons ’ As all of these significant moments on the shield reflect the Roman qualities of bravery, religion, and justice, this central scene reflects ‘the final triumph of the Roman character over alien ways of life at the Battle of Actium ’ Therefore, due to the presence of political motives that permeate the Aeneid, creating suspense is not the aim of the epic

Yet despite the Aeneid being a piece of propaganda first and foremost, the conflict that occurs due to the role of Fate increases the dramatic nature of the epic Although Fate is a pivotal driving force of the epic, Virgil is able to create a dissonance between the character’s desires and their fate which makes the Aeneid engaging - this is clearly seen with the eponymous hero himself Whilst many critics claim that Aeneas is nothing more than an instrument of fate , his character is continually shown to reject his pre-determined journey He differs from previous Homeric heroes in the sense that he is a reluctant hero who does not want to seek eternal glory by founding Rome It is only his sense of pietas that drives him to leave Troy, highlighted in his unwilling abandonment of Dido Here ‘dutiful Aeneas’ explains that ‘if the fates had allowed me to live my life under my own auspices’, he would first have cared for the city of Troy His first choice is not even to stay in Carthage with Dido, but actually never to have left Troy in the first place - Aeneas takes course for Italy ‘ non sponte ’ , ‘ not of [his] own free will’ Dido herself rejects the fact that Aeneas must leave Carthage, despite this being his fate which is sanctioned by the gods, and takes her own life The poignant lamentation by her sister Anna which follows shows the depth of their sisterly bond, illustrating how Virgil is able to utilise the conflict to incite emotion in the reader page28

Moreover, this conflict of Fate and free will is exacerbated by the difference Virgil draws between free will of the gods and free will of mortals; while neither can defy Fate, the gods are shown to interfere much more easily in the lives of humans at their own personal whims, creating drama by showing the lack of agency the characters hold in the face of divine intervention When reflecting upon the devastating consequence of Dido’s love for Aeneas, it is important to note that the gods themselves fashion Dido and Aeneas relationship knowing that he cannot stay in Carthage for long Aeneas in fact only leaves Carthage after Mercury, sent by Jupiter, intervenes and accuses Aeneas of being ‘forgetful of [his] kingdom and fate’ This unfairness of a god’s intervention is one that occurs multiple times during Aeneas’ journey to Italy, and is one of the key factors as to why his journey is so arduous, as seen in his relationship with Dido Venus only makes Dido fall in love with Aeneas so that he is granted safety in Carthage, and Juno only suggests the ‘ pactos hymenaeos to try and delay his arrival in Italy In fact, critics such as Susanna Morton Braund go so far as to state that the Aeneid ‘ can also be read as the story of the wrath of Juno’, a notion which is clearly supported by the start and end of the epic Virgil opens his epic by foregrounding the fact that Aeneas’s journey is ‘ saevae memorem Iunonis ob iram’ and implores the Muse to reveal why the goddess forces him to endure ‘such endless hardship and such suffering’ The end of Book XII again reinforces the idea that Juno’s wrath ultimately engineers Aeneid’s expedition to fulfil his destiny, when Jupiter confronts Juno on her interference in the battle between Aeneas and Turnus He urges her to recognise that Aeneas is ‘ a god of this land’ who is ‘fated to be raised to the stars ’ . It is only at this point that Juno finally yields to fate and allows Aeneas to complete his task of founding the new Roman race, conveying how the free will of the divine is unlike that of mortals Jupiter’s own actions and words in this scene reveal a similar disparity between fate for the gods and for humans He grants Juno’s wish to allow the name of Latium to remain, and says that he does this of his ‘ own free will’, drawing a stark contrast to Aeneas’ own autonomy - neither can drastically alter Fate, but the gods are able to change and resist Fate to a certain extent

utilises the conflict created between Fate and individual wishes to highlight the different layers of free will in order to make the Aeneid dramatic

Finally, Virgil’s ability to make the central focus of the Aeneid be Aeneas journey itself rather than the journey’s outcome allows it to be exciting in spite of the role of Fate While one does know that Aeneas is ultimately going to reach Italy and find a new race, the captivating events that lead up to this result are what Virgil chooses to address in his epic. The fall of Troy and subsequent founding of Rome was not an original story, but rather one which had been told many times by ancient writers well before Virgil’s time, such as in the Iliou Persis Yet seeing as many plays and stories written in the ancient period were usually based on mythology, one has to take into account that much of the entertainment the ancient Romans consumed would have been watched with the knowledge of the ending A prime example of this is Oedipus Rex by Sophocles, a play that retells one of the most famous myths and still manages to invoke shock, horror, and pity in an audience Cited by Aristotle as the ideal tragedy, Sophocles achieves such a gripping play by focusing on Oedipus’ gradual realisation of his fate brought about arguably through no fault of his own. Whilst there is an explicit difference in genre (Oedipus Rex being a play and the Aeneid being an epic poem), a similar technique can be found in Virgi’s epic page29

The Aeneid concerns itself with Aeneas own struggle to accept his preordained destiny, revealing the restraints of his own free will and creating excitement. Interestingly, it is only after Anchises’ revelation of Aeneas’ destiny in Book VI that Aeneas ‘ never falters’ and that ‘his cooperation is willing ’ Prior to this, Aeneas tries to resist his fate on more than one occasion: he does not adhere to Hector’s warning to flee in Book II and attempts to fight; he only leaves Carthage after another instance of divine intervention as discussed above; lastly, he hesitates in Book V and considers ‘oblitus fatorum’, wanting to settle in Sicily instead. George E. Duckworth compiles these and such pieces of evidence to support his claim that ‘prior to the revelation in VI, Aeneas is no puppet but very human in his weaknesses’ Here the change in Aeneas’ character that occurs after Book VI portrays how Virgil reconciles the role of Fate with excitement by centering his epic on Aeneas’ personal struggle with his destiny - Virgil’s choice of focusing on the decisions that Aeneas makes in an attempt to avoid his fate, establishes a real human portrayal of this glorified ‘proto-Roman’ character After all, it is only in Book VIII that Aeneas declares to Evander that fatis egere volentem , that his cooperation is now of his own accord Thus, by exploring Aeneas’ journey in accepting his inevitable fate, Virgil creates a multi-faceted protagonist that an audience can empathise with, allowing for a dramatic epic regardless of the role of Fate

Overall, the role of Fate in the Aeneid may diminish its suspense, but allows Virgil to incorporate political motives that give a whole new layer to the epic - it is how Virgil manipulates the notion of destiny to endorse the rule of Emperor Augustus that arguably makes the Aeneid so nuanced Fundamentally, Fate and the characters’ rejection of it, coupled with the capricious emotions of the gods, lead to many of the emotional and captivating events of the Aeneid Although ultimately being written as a piece of propaganda to ratify the rule of Augustus, Virgil creates such a dramatic and revered epic by exploring Aeneas’ journey, both the choices or lack thereof, to fulfil his fate.

Womenin AncientRome EdithJYear10

Ancient Rome is often associated with high morals and the rule of law - think Cicero and the formidable Roman legions However this concept of Rome is very male dominated–all the famous figures such as emperors and academics seem to be men–so what was a woman ' s role in society? Broadly speaking they were oppressed, used for political alliances and heirs, and never given a second thought Women could marry at twelve, and, despite being cives (citizens), they could not vote or hold office They were mostly controlled by their fathers, even after marriage Under Augustus, women had to have three children (becoming an 'ius liberorum') before they were granted freedom from guardianship While women could divorce simply because they wanted to, free of social criticism, the man would gain custody of their children unless deemed 'worthless' The Romans were fanatics when it came to justice, and I believe women in the later Roman empire had more rights than they have had in our more recent societieslaws and obligations more like those of Regency era England That being said, women were still treated as social capital and were defined by their marriage. Rome was still very much a misogynistic society, as seen by the idolisation of the tale of Lucretia, a woman who killed herself after being raped due to loss of honor The Roman standard for women is important to think about when considering how much our modern society and law is based on the Roman judicial system But, there is more to the story of Roman women

There were some awe inspiring women in the Roman era who rebelled against Rome's sexist expectations These include women such as Fulvia, known for her key role in the civil wars of the late Roman Republic, whose face was immortalised on a coin, or Boudicca who brought Rome to its knees in Britain. But there were other women in ancient Rome who defied their misogynistic societal standards

Cleopatra is often stereotyped as an ancient beauty, killing herself for love like the Juliet of the ancient world But is this true? Cleopatra was born into royalty, one of five, meaning she was never expected to be Queen in her own right, especially since two of her siblings were men She was only supposed to be Queen by marriage to one of her brothers, Ptolemy XIII and Ptolemy XIV However she ended up being Queen after enlisting the help of the Roman general Julius Caesar to defeat Ptolemy in the civil war An act of love or a strategic alliance? Cleopatra was a highly educated woman, having been tutored by the best scholars of the Hellenistic period Her teacher was Philostratus, philosopher and Greek orator of the arts. She spoke over ten languages, and was believed to be the only member of page31

her family, which was mostly Greek, to speak the native language of the Egyptian people Other languages she spoke included Hebrew, Latin, Parthian and Syrian She studied in the Mouseion of Alexandria, home to the library of Alexandria She would have been taught about history and politics, as well as the sciences of the time She produced an heir with Julius Caesar named Caesarion to secure her alliance with Rome, though it is thought that this wasn't actually Caesar's child All of this would indicate Cleopatra was a master political strategist, acutely aware of her political surroundings, rather than simply a charismatic ancient beauty

But it wasn't just exceptional women that defied Rome’s sexist mores. There were certain groups of women with considerably more legal autonomy throughout the duration of the empire The Vestal Virgins are fascinating historical figures; an all female, powerful Roman cult They were the priestesses of Vesta–goddess of the hearth, home and family–tasked with keeping the flame of Vesta alive If this went out, they were killed They were selected between the ages of six and ten to be raised and trained by the older Vestal Virgins in their last ten years of service. They were chosen by the Pontifex Maximus or, in imperial times, the emperor himself, and answered only to him In addition to tending the flame, during their 30 years of service they had an important role to play in many religious events They were given powers unlike any other women; they could vote, own land, and testify in court without taking an oath They could free slaves and war criminals just by looking at them, and, at one point, the reigning Vestal Virgins even pardoned Julius Caesar from being banished They were given special seats at events and their own house behind the temple of Vesta They had huge political and cultural influence, though it is more complicated than that The Romans' obsession with the priestesses’ virginity emphasises how important the purity of women was, and illustrates to the modern person how Rome viewed women based on how they could best serve men As a consequence of this misogynistic mindset, the Vestal Virgins were frequently scapegoated Due to them being considered holy, with their flesh being that of Rome, their blood could not be spilled However, if they were thought to have broken their law of celibacy or let the flame go out, which coincidentally coincided with a strategic or military failure, they were killed So, they were either burnt alive, or - more commonlyburied alive This was a Roman way of condemning women to manage the consequences of the men ' s actions and failures Nevertheless, the Vestal Virgins had immense influence on Roman society, especially for women, and were often allowed to retire peacefully along with their extra rights page32

SaturnDevouring HisSonFranciscoGoya DeyaCYear10