Editor: John J. Han

Assistant Editor: Susannah Cerutti

Editorial Consultant: C. Clark Triplett

Cover Design: Terrie Jacks, Aurora McCandless

Webmaster: Joel Lindsey

The Right Words is a semiannual online magazine of nonfiction published by the Department of English at Missouri Baptist University, One College Park Dr., St. Louis, MO 63141. Nonfiction encompasses a broad range of literary works based primarily on fact, including essays, biographies, memoirs, documentaries, book reviews, movie reviews, travel stories, photo essays, and aphorisms. Interested students, faculty, and friends of the Department who support the university’s mission may submit previously unpublished works of nonfiction to john.han@mobap.edu for consideration.

For the April issue, we accept up to five nonfiction pieces during the reading period, with each piece ranging from 500 to 2,000 words. The October issue publishes only photo essays; please submit 1-3 photo essays of any length for consideration. Include “RW – your name” in the subject line (e.g., “RW – Jane Haas”). Along with your submission, provide a 100word author bio written in the third person using complete sentences. Below is our publishing schedule:

Reading Period Publication Date

January 1 - March 31 April 15 July 1 – September 30 October 15

Missouri Baptist University reserves the right to publish accepted submissions in The Right Words. Upon publication, copyrights revert to the authors. By submitting, authors certify that the work is their own. All submissions are subject to editing for clarity, grammar, usage, and Christian propriety. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of Missouri Baptist University.

Issue 20, October 2025

© 2025 Missouri Baptist University

“Words satisfy the soul as food satisfies the stomach; the right words on a person’s lips bring satisfaction.”

Proverbs 18:20 (New Living Translation)

“The difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug.”

Mark Twain

“One day I will find the right words, and they will be simple.”

Jack Kerouac

5 Pearl S. Buck Birthplace and House: A Visit to Find Awe

John Zheng

36 An Echo of Courage: A Tribute to My Great-Grandfather

Susannah Cerutti

41 There’s No Place Like Home: A Tribute to Fontbonne University

Susannah Cerutti

48 In the Footsteps of the Reformers: A European Photo Essay

John J. Han

101 Where Writers and Poets Once Trod: A Photo Journey through European Literary Sites

John J. Han

193 Notes on Contributors

By John Zheng

Twenty years ago, as soon as I opened Pearl S. Buck’s My Several Worlds, the very first paragraph about her residence in Green Hills Farm, Pennsylvania attracted me:

This morning I rose early, as is my habit, and as usual I went to the open window and looked out over the land that is to me the fairest I know. I see these hills and fields at dawn and dark, in sunshine and in moonlight, in summer green and winter snow, and yet there is always a new view before my eyes. Today, by the happy coincidence which seems the law of life, I looked at sunshine upon a scene so Chinese that did I not know I live on the other side of the globe, I might have believed it was from my childhood. A mist lay over the big pond under the weeping willows, a frail cloud, through which the water shone a silvered grey, and against this background stood a great white heron, profiled upon one stalk of leg. Centuries of Chinese artists have painted that scene, and here it was before my eyes, upon my land, as American a piece of earth as can be imagined, being now mine, but owned by generations of Americans… (3)

The feeling Buck described reveals her deep nostalgia of a place she had been so emotionally attached to since the age of three months. It is a sense of place attachment and déjà vu, showing her love for the great earth which had been a wellspring for her writing and thinking.

spring rain a seed of nostalgia sprouts before eyes

This past July, my unforgettable impression of Pearl S. Buck’s love for China finally urged me to go on a pilgrimage to her birthplace in Hillsboro, West Virginia and her gravesite in Dublin, Pennsylvania.

mountain road a sudden straight stretch after curve after curve

Pearl S. Buck was born in her maternal grandparents’ house (Figure 1). Buck reminisced in My Several Worlds that the house was a “large white house with its pillared double portico, set in a beautiful landscape of rich green plains and with the Allegheny mountains as a background” (4). Her mother, a twenty-three-year-old young wife who went with her husband on missionary to China had lost three children due to tropical diseases. Frustrated, she and her husband made the decision to return to West Virginia. Two years later, Pearl was born. The young couple then returned to China when Pearl was three months old. It was October 1892.

While growing up in China, little Pearl lived in “a double world.” She said in My Several Worlds: “When I was in the Chinese world I was Chinese, I spoke Chinese and behaved as a Chinese and ate as the Chinese did, and I shared their thoughts and feelings. When I was in the American world, I shut the door between” (10). Having lived a meaningful life in China for so long and become a fiction writer, Buck wrote, as mentioned in her foreword to American Triptych, “so many books about Chinese people that I had become known as a writer only about China.” She admitted that was a natural tendency because China had been deeply woven into her identity and because she “knew no people intimately except the Chinese” since she spent the first half of her life there.

wherever you are you are wherever you are

In 1931, Buck published her second book, The Good Earth, a novel written while living and teaching in Nanking, then the capital city. The story was about peasant life represented by the main character Wang Lung, but as Buck said in her 1944 foreword to the novel, The Good Earth was about Chinese people who “live on, as strong, as resolute, as faithful as ever to the land they love” because she believed that the plain Chinese people had proved “the splendid and heroic qualities” of themselves through their love for the land and their determination to drive out the enemy (Japanese invaders).

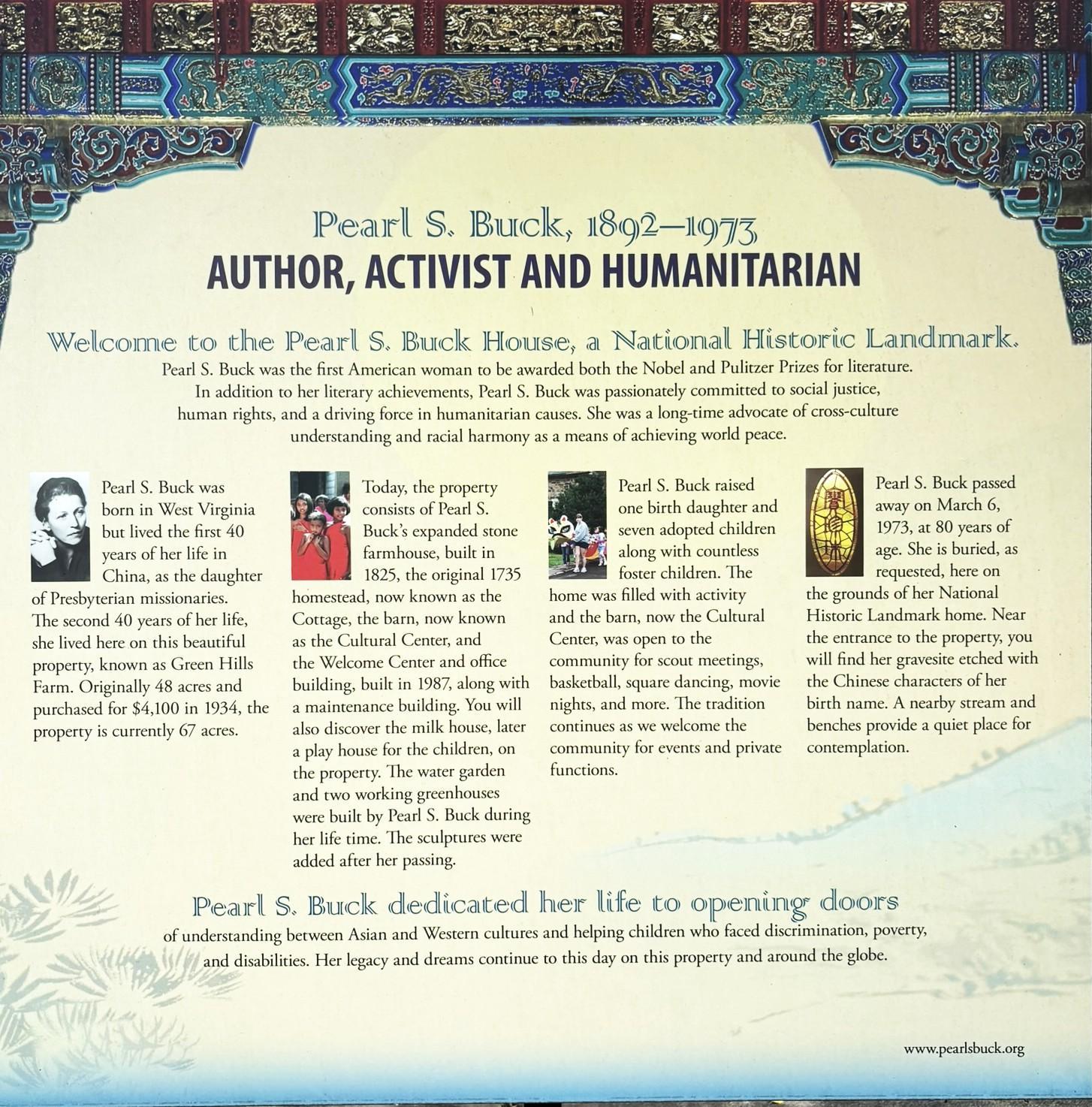

In 1932, The Good Earth won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, and in 1938, the Nobel Prize for Literature. The presentation speech, given on December 10, 1938 by Per Hallström, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy, praised Pearl Buck as a writer who “had found her mission as interpreter to the West of the nature and being of China. She did not turn to it as a literary specialty at all; it came to her naturally…. She has been among the people of China in all their vicissitudes, in good years and in famine years, in the bloody tumults of revolutions and in the delirium of Utopias.… With pure objectivity she has breathed life into her knowledge and given us the peasant epic which has made her world-famous, The Good Earth (1931).” The historic marker erected by Dublin Road (Figure 2), where Pearl S. Buck House is located, highlights these two prizes.

In 1933, Buck purchased the house, known then as Green Hills Farm, which is now a National Historic Landmark (Figures 3, 4 and 5).

finding awe gorgeous sunset at green hills farm

As soon as we arrived, we were greeted by the historic marker and the Visit the Pearl S. Buck House sign (Figure 6). After turning right onto Forest Road, we stopped to snap a shot of the metal gate with the initials of PB for Pearl Buck (Figure 7). Our first stop was the gravesite of Pearl S. Buck, who passed away on March 6, 1973, in Danby, Vermont. The path led us to her grave with a grove of bamboo and a calm stream in the back (Figure 8).

Buck’s gravestone, designed by herself, bears only her birth name in Chinese characters 賽珍珠 (Figure 9), based on her chop, carved in the ancient Chinese seal style. 賽, pronounced as sai, is the sound of the first syllable of her family name Sydenstricker, and 珍珠, pronounced as zhenzhu, means Pearl.

afterlife a state of being and non-being

As we returned to our car, flowers at the gravesite entrance nodded for snapshots, each like a charming smile (Figure 10). For me, I had a feeling that my wish to visit Buck’s grave was finally satisfied.

visitation a dream butterfly over white daisies

Then we drove to the Welcome Center (Figure 11), where we were attracted by the exhibition of the Nobel Prize medal and Buck’s award speech titled “The Chinese Novel” (Figure 12). We were also charmed by the stained glass with her chop inlaid in it. In 1964, Buck purchased a fivestory townhouse in Philadelphia as her home and the headquarters of the Pearl S. Buck Foundation to support her legacy. The house, as stated by the framed information on the wall of the Welcome Center, “included a chapel with eight large stained-glass windows in a floral motif surrounding a central depiction of religious imagery.” To satisfy Buck’s needs, the chapel was remodeled into a breakfast room and the original religious images in the stained-glass windows were replaced with her chop (Figures 13 and 14).

after teneral dragonflies scurry across water

Another attraction is the oil-on-canvas portrait painting of Pearl S. Buck by Freeman Elliot (Figure 15), which was the basis for the Pearl S. Buck stamp deigned by Paul Calle (https://postalmuseum.si.edu/exhibition/women-on-stamps-part-3literature-women-with-a-political-mission/pearl-s-buck). Other exhibited items that attracted us include two special medals. One is the Order of Jade presented in 1941 by the Chinese Ambassador Hu Shih on behalf of the Chinese government in recognition of Buck’s extensive fundraising and humanitarian efforts for China, and the other was the Order of Civil Merit presented by the Republic of Korea in 1967 for her distinguished service in establishing the Opportunity Center and Orphanage in South Korea in 1964 (Figure 16).

After watching the introductory video that gives more information about Pearl S. Buck’s life and viewing Buck’s awards, honorary degrees, gowns,

and other exhibits in the gallery and a timeline of significant events in her life, we left the Welcome Center and walked over to the Cultural Center (Figure 17), which was originally a barn constructed in 1827 and later converted into a space for community recreation and a garage for Buck’s vehicles. Now it functions as an event center for Pearl S. Buck International.

Then we paced to the milk house (Figures 18), which was used as a playhouse for Buck’s children, and Buck’s residence house, where we caught a glimpse of the interior (Figures 19 and 20). What impressed us most was the covered breezeway added to the house, showing a Chinese courtyard style and functioned as a lookout for Buck to view the landscape of the valley that reminded her of China (Figure 21).

deep missing morning fog drifting eastward

Secluded in the back of the house is a small Japanese garden with a rusty wrought iron garden chair before the window (Figures 22 and 23). As we walked to the picnic area for a late lunch, I grabbed a shot of the dedication marker that provides a summary of Pearl S. Buck (Figure 24). While I was chewing a sandwich, a sculpture drew me for a snapshot (Figure 25).

Titled “Uplift,” the sculpture by African American artist Selma Burke (1900-1995) represents the unwanted children uplifted by Buck, who once said in My Several Worlds, “For me a house without children cannot be a home” (324). Buck and Burke were good friends. Burke said her sculpture reflects what she saw in Buck who lifted children up with hopes. Today, fifty-two years after her passing, while still celebrated as the first American woman writer to win two prestigious prizes Pulitzer and Nobel, Buck’s legacy as a humanitarian continues, and this legacy is more important when wars created many homeless children.

rite of passage seeds off a dandelion stay aloft

Buck, Pearl S. Foreword. American Triptych. John Day, 1958. ---. Foreword. The Good Earth. 1931. Random House, 1944. . My Several Worlds. John Day, 1954. Hallström, Per. Award Ceremony Speech. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1938/ceremony-speech/.

16. Medals present by Chinese and Korean governments

By Susannah Cerutti

I never got the chance to meet my great-grandfather, James Cerutti II. However, as I got older, I was given opportunities to learn more about him. When I learned that he was in World War II, I became intrigued and had the desire to learn more about him and his involvement in the war.

I learned that my great-grandfather was the battalion sergeant in charge of 50 mess halls between Germany and Belgium. He was also a part of the Normandy Invasion; he arrived on day three of it. He fought in the Battle of the Bulge as well. After the Battle of the Bulge had occurred, the troops began a March to their final destination, which was located at the border of Belgium and Germany. During the March, an American soldier who was ahead of my great-grandpa was shot and killed by a German sniper. My great-grandpa identified where the shot came from - it had come from a nearby church steeple. He called for artillery, and three rounds of it from approximately 2 ½ miles away were fired at the church, completely leveling the building. The March continued to its overnight destination, which was an abandoned four-story brick schoolhouse. The officers were housed in the basement while the enlisted men were on the upper floors of the building. During the night, the building was struck by a German V-2 rocket, which resulted in significant loss of life. My great-grandfather, being in the basement, survived with a slight forehead wound caused by a fragment of the rocket striking him. My great grandpa saved the fragment of the rocket that struck him and had an initial ring made from it for his son (my grandfather) that he was yet to meet.

I also learned that after World War II had ended, my great-grandfather was offered a permanent position as part of the Allied occupation in Italy. He was offered this position due to his officer status and the fact that he spoke both Italian and English. However, he turned the position down since my great-grandmother did not want to move to Italy with my grandpa, who was an infant at that time.

Learning more about my great-grandfather’s involvement in World War II was very fascinating. The fact that he had a ring made from the fragment of

the rocket that struck him for my grandfather was even more fascinating to learn. Serving our country takes a lot of courage, and I admire that my great-grandfather had the courage to do so.

My great-grandpa’s snapshot from WWII

This is a painting based on my great-grandfather’s snapshot. The painting was done in 1993.

The initial ring my great-grandfather had made from the fragment the German V-2 Rocket that struck him.

By Susannah Cerutti

In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy says “There’s no place like home.” For me, home was Fontbonne University. What made Fontbonne University feel like home was the people and the environment. I found two clubs for things I was interested in; I joined Psychology Club and GriffinTHON. I met so many people throughout my one year at Fontbonne University, and I talk to some of them still to this day. I made so many memories in my brief time there, and I still miss it to this day.

To start off my days at Fontbonne, I would go to the library. There was a Starbucks inside of the library, so that is where I would go for coffee most mornings. Some mornings I made coffee in my dorm, but I almost always went to the Starbucks inside of the library. The barista there was so sweet, and she was also so easy to talk to. It was nice to see a familiar face most mornings. I also occasionally spent time together with my friends in the study rooms upstairs. I spent a lot of time in the library, and I will always be thankful for my time spent there. It was also a short distance away from all my classes, so it made sense that I spent a lot of time there.

When I was not in class, the library, my dorm, club meetings, or the dining halls, I was at the gym, watching basketball games. I always went to home games to support the basketball teams and see the dancers or the cheerleaders perform at halftime. When I could not attend basketball games, I watched them on YouTube. I rarely watched any of the other sporting events at Fontbonne. I loved going to watch the basketball teams play; one of my favorite memories was at a tournament when one of the players on the men’s basketball team made a half-court shot right as the buzzer went off for half-time. Aside from going to basketball games and going to classes, Psychology Club and GriffinTHON took up a chunk of my time.

My role in Psychology Club was the student government representative and later, I was the secretary. I also helped plan events, such as self-care night. We had one movie night every semester; we would watch psychological

thrillers. I joined the executive board of the psychology club in late fall of 2023, so I did not get to have very much experience on it. GriffinTHON was a club that raised money for St. Louis Children’s Hospital and SSM Health Cardinal Glennon. I felt called to join GriffinTHON because I had to stay in St. Louis Children’s Hospital when I was little, and I wanted to give back to the doctors and nurses who helped me in my time of need so they could continue to provide the same, if not better, care that I received when I was there. In GriffinTHON, there were participants and morales; the morales had to commit more time to GriffinTHON than the participants did. I was a participant, so I did not have to commit a whole bunch of my time. I raised $1,096 total as a participant, which earned me the Participant of the Year Award. At our main event in April of 2024, we passed our goal of raising $50,000. That was a huge accomplishment for us, and it made me feel good that we’re working to change kids’ health. However, it also made me sad because that was the last GriffinTHON main event I got to attend.

The line “There’s no place like home” describes Fontbonne well. Everything about it felt like home. It was clear to me that other students felt similar about the news of Fontbonne’s closure; there were tears shed by many students, including me when we learned of it. It was in the news before we were informed of it, so some of the students knew before the president broke the news to us. I remember hearing from some of the students that Fontbonne had been sold to Washington University as we waited in the gym to hear it from the president. While Fontbonne is no more, I have the memories I made there to remind me of all the good times had on that campus.

Some of the cheerleaders talking at one of the men’s basketball games

The total amount of money GriffinTHON raised at our main event in April 2024

The certificate I was given for being Participant of the Year

The statue that is outside the library at Fontbonne University

By John J. Han

For the third year in a row, California Prestige University (formerly the Presbyterian Theological Seminary in America, a Korean American institution in Santa Fe Springs, California) organized a study abroad trip from June 11–20, 2025. Forty participants—seminarians and lay church leaders from the United States, Canada, and South Korea—joined the trip, which focused on visiting major Reformation sites in Europe.

Under the guidance of a Korean pastor in Germany, we toured select locations in Germany, France, Switzerland, and Prague, the Czech Republic. Most of our time was spent in Germany and France, which is unsurprising since they are the birthplaces of Martin Luther and John Calvin, respectively the two most prominent figures in the history of the Protestant Reformation. It was also memorable to visit important Swiss sites associated with Calvin and Ulrich Zwingli, as well as Prague, where Jan Hus led a reform movement roughly a century before Luther and Calvin.

Some participants, including my wife and me, arrived two days earlier and stayed three days longer than the official schedule to enjoy additional tours. Those who opted for the extra excursions gathered in Frankfurt, Germany, and visited Rüdesheim am Rhein, a picturesque town about 54 miles west along the Rhine River. After completing the official tour of the Reformation sites, we explored several famous Parisian landmarks, including NotreDame Cathedral, Montmartre Hill, and the Louvre Museum. By the time our group was scheduled to tour the Palace of Versailles, located about 27 miles southwest of Paris, some of us including me had run out of energy and chose to rest at the hotel rather than navigate the complex subway and bus system on a hot day. (Unlike in the United States, Japan, and South Korea, air-conditioning and even public restrooms seemed to be something of a luxury in Europe.)

During the official tour days, we visited many of the best-known Reformation sites, including Worms, Heidelberg, Eisenach, Wartburg,

Stotternheim, Erfurt, Wittenberg, Prague, Zurich, Geneva, Paris, and Noyon. In those places, we experienced history firsthand the same history we had studied in classrooms and churches in Korea and the United States. We gained a deeper appreciation of the risks and sacrifices involved in the Reformation movement, as well as the fruits of the Reformers’ labor, which continue to be reaped worldwide today.

The following pages highlight some of the photos I took on location. I hope the images are both interesting and instructive. Christianity arose in the Middle East and spread to southern Europe before reaching the rest of the continent and, eventually, the world. While Prague and the United Kingdom hold important places in the history of the Reformation, Germany, France, and Switzerland played especially significant roles in shaping the early Protestant movement. Those who have the time and resources should consider visiting these three countries to gain a deeper understanding of the Reformation’s origins and impact. Travelers hesitant to go alone may find an organized package tour more economical and stress-free.

The Diet of Worms of 1521 declared Martin Luther (1483-1546), the Protestant reformer, a heretic. A few years later, Luther’s German New Testament was printed in Worms, and William Tyndale published his English New Testament there as well.

The Luther Monument (Lutherdenkmal) in Worms, erected in 1868, honors Martin Luther and other key figures of the Protestant Reformation, including John Calvin and Ulrich Zwingli. At its center stands the tallest statue of Luther, holding a Bible in his left hand, symbolizing his unwavering stand for Scripture during the Reformation.

“Weeping Magdeburg” (“Trauernde Magdeburg”) is one of the statues at the Luther Monument. The allegorical female figure sits with head bowed, wearing a city crown and holding a blunt sword. She symbolizes the martyrdom of the Protestant city of Magdeburg, Germany, which was sacked by Imperial and Catholic forces during the Thirty Years’ War (1631).

Top: At the Diet of Worms in 1521, held in the Bishop’s Palace adjacent to St. Peter’s Cathedral in Worms, Martin Luther was summoned to appear before Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. When pressed to recant his antiCatholic writings, Luther refused, reportedly declaring, “Here I stand; I can do no other. God help me!” As a result, he was declared a heretic. While the cathedral still stands, the Bishop’s Palace no longer exists.

Bottom: Bronze shoes of Martin Luther in the cathedral’s courtyard.

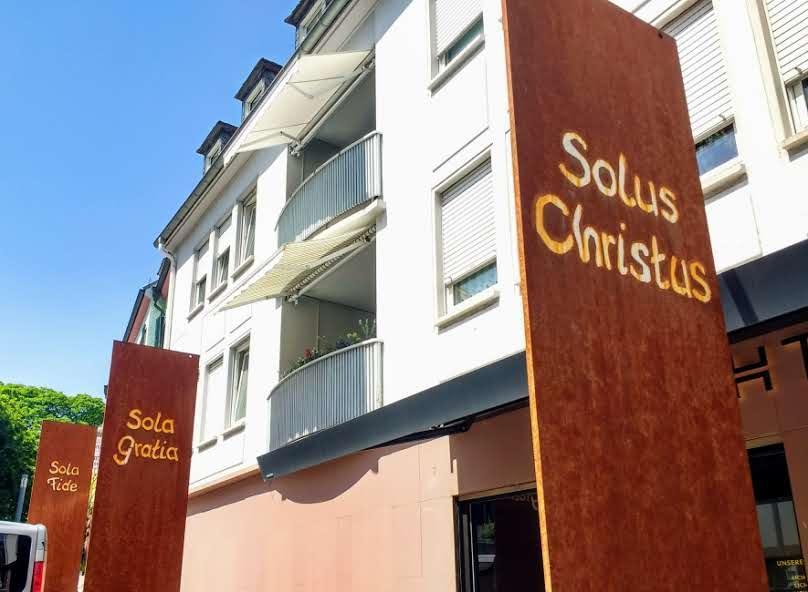

Near the cathedral, through Heylshof Park, and along the route to the large Luther Monument on Lutherplatz, four modern steel structures bear the Protestant slogans: “Sola Scriptura,” “Sola Fide,” “Sola Gratia,” and “Solus Christus.”

Credit: Google Maps.

Heidelberg occupies a distinctive place in the history of Christianity, especially within the Protestant tradition. The city became an early center of the Reformation when Martin Luther presented his theology at the Heidelberg Disputation in 1518, a milestone that helped disseminate his ideas throughout the Holy Roman Empire.

A generation later, Elector Frederick III transformed Heidelberg into a hub of Reformed thought. Under his leadership, theologians Zacharias Ursinus and Caspar Olevianus produced the Heidelberg Catechism of 1563, whose memorable opening question, “What is your only comfort in life and in death?” continues to echo through Reformed and Presbyterian churches worldwide.

Founded in 1386, Heidelberg University further anchored the city’s significance by serving as one of Europe’s leading intellectual centers during the Reformation. Its faculty trained pastors, scholars, and missionaries who carried Reformed theology across the continent and, eventually, to North America, Africa, and Asia. As a haven for Protestant thinkers during periods of religious conflict, Heidelberg became not only a stronghold of Calvinist influence in Germany but also a global contributor to Christian thought. Today, the city’s Christian heritage remains visible in its institutions, documents, and enduring influence on Protestant belief and practice.

While primarily a civic landmark, Heidelberg’s Old Bridge features subtle Christian symbols, reflecting the medieval tradition of invoking divine protection for travelers.

The tallest building with a spire beyond the bridge is the Church of the Holy Spirit (Heiliggeistkirche). As Heidelberg’s largest church, it dominates the marketplace in the city’s historic old town. Built between 1398 and 1515, the church showcases a blend of Romanesque and Gothic architectural styles.

Credit: Google Maps.

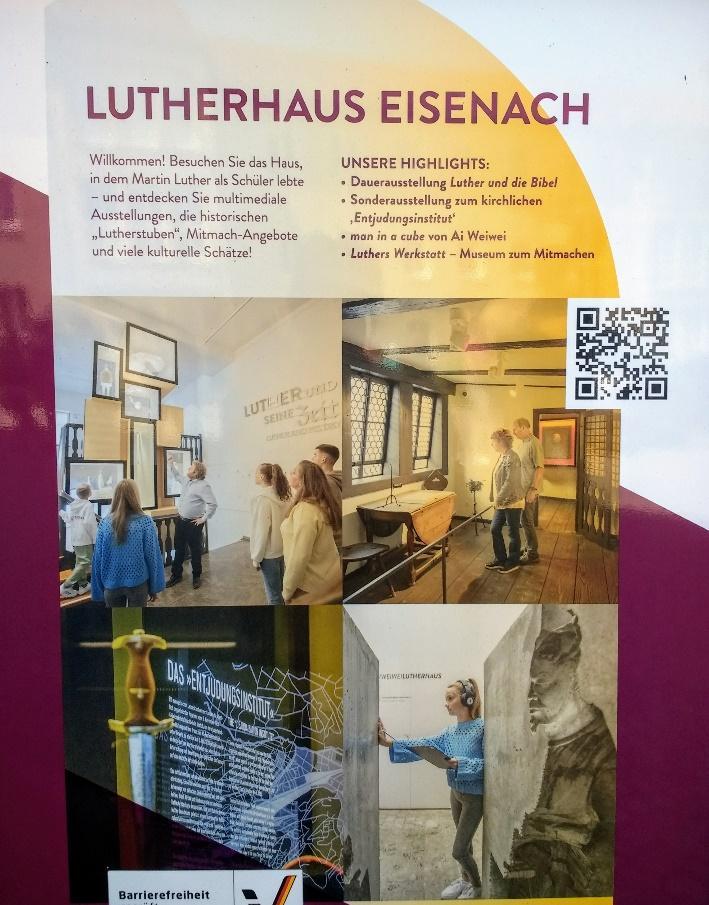

Eisenach, Germany, holds a prominent place in Christian history primarily due to its association with Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation. Luther spent part of his youth in Eisenach at the St. George’s Church (Georgenkirche) and the nearby Luther House (Lutherhaus). St. George’s Church is where Luther was confirmed, and it played a key role in his early spiritual formation. Today, both sites are central to understanding Luther’s life and the broader history of Protestantism in Germany, attracting pilgrims and visitors interested in Reformation history. Beyond Luther, Eisenach is also significant for its Christian musical heritage, particularly through its connection to Johann Sebastian Bach, who was born in the town.

Built around 1182, St. George’s Church in Eisenach began as its original construction and later evolved into the historic Gothic church known for its striking architecture and tall tower. Martin Luther was confirmed here, shaping his early spiritual life, and today the church remains an important site for both worship and Reformation history.

The Luther House was originally a monastery before becoming his residence as a student. It is now a museum in Eisenach showcasing Martin Luther’s life, Reformation history, and artifacts from his time in the city.

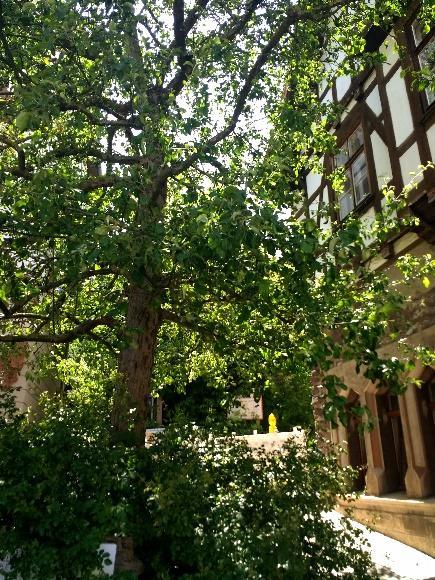

Luther’s Apple Tree at the Luther House is traditionally linked to Martin Luther’s early reflections on faith. The tree stands near the historic building where he lived as a student, a period that shaped his spiritual development. Today, signage at the site provides visitors with context about Luther’s life and the Reformation history connected to Eisenach.

The Johann Sebastian Bach Monument (Bachdenkmal) in Eisenach honors the composer, born in the town in 1685, and celebrates his influence on sacred and classical music. Bach’s early exposure to church music in Eisenach shaped his work, and the town’s historic churches and buildings reflect its long Christian and cultural heritage.

Credit: Google Maps.

Credit: Google Maps.

Wartburg Castle is close to Eisenach, roughly a 10-minute drive (about 3-4 km) from the town center. It sits on a hill overlooking Eisenach.

Wartburg Castle, perched on a hill above Eisenach, is a historic fortress famous for its medieval architecture and scenic views. It is closely linked to Martin Luther, who took refuge there in 1521-22 and translated the New Testament into German. Today, the castle is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a symbol of both Christian history and German cultural heritage.

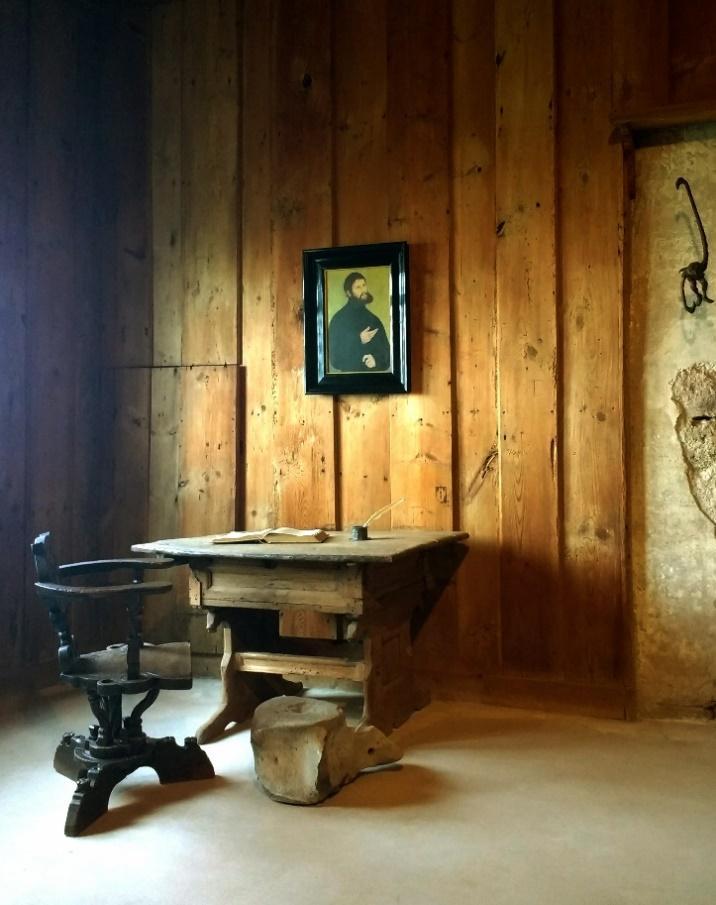

Luther’s Chamber at Wartburg Castle is the room where Martin Luther lived in seclusion during 1521-22 while in hiding from imperial authorities. It was here that he undertook the monumental task of translating the New Testament into German, making the Bible accessible to ordinary people. The chamber is preserved today as a historic site.

These portraits at Wartburg Castle depict Martin Luther and his wife, Katharina von Bora, key figures in the Protestant Reformation. They married in 1525, shortly after Luther returned from Wartburg, breaking with the tradition of clerical celibacy. Katharina, a former nun, managed their household and supported Luther’s work. Together they raised six children in a lively and loving home. Their partnership exemplifies Protestant family life and highlights the importance of marriage in Lutheran teaching.

Credit: Google Maps.

Erfurt holds a central place in Christian history, particularly within the context of the Protestant Reformation. In this city, Martin Luther entered the Augustinian monastery in 1505, a decision sparked by his near-death experience in a thunderstorm in nearby Stotternheim, which ultimately set him on the path to becoming a key Reformation leader.

The city is home to historic churches such as St. Mary’s Cathedral (Mariendom) and the Church of St. Severus, which reflect centuries of Christian worship, medieval architecture, and ecclesiastical influence. Erfurt also became a center for monastic learning and theological study, hosting the Augustinian and other religious communities that shaped early Lutheran thought.

St. Mary’s Cathedral (Mariendom) in Erfurt features a portal adorned with statues of the “wise and foolish virgins,” a visual representation of the Gospel parable. As the city’s larger and more prominent historic church, it showcases Gothic architecture and religious artistry, highlighting the call to vigilance and faith preserved within its centuries-old walls.

Credit: Google Maps.

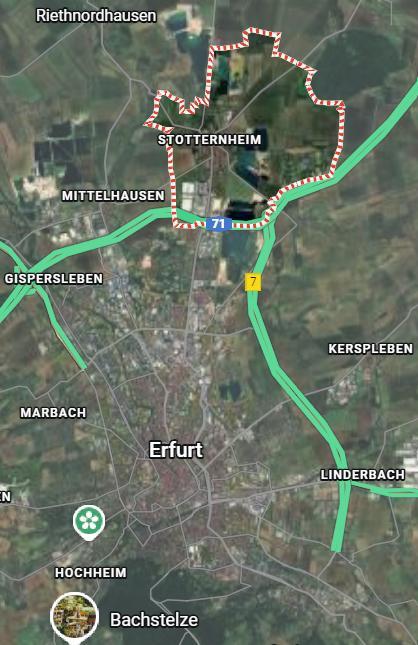

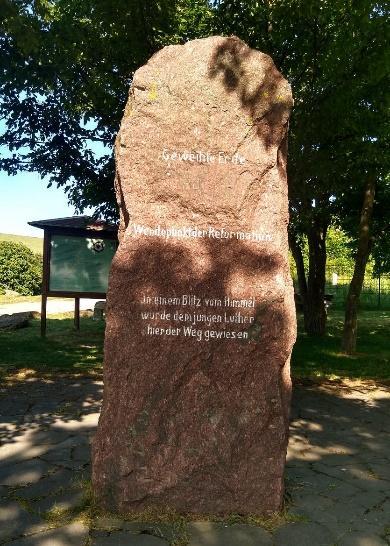

Stotternheim is part of Erfurt, located in an agricultural area north of downtown. This is perhaps the most unique Reformation site there is no church, no university, no castle, and almost no tourists. It is marked by a few stone monuments standing in what feels like “the middle of nowhere.”

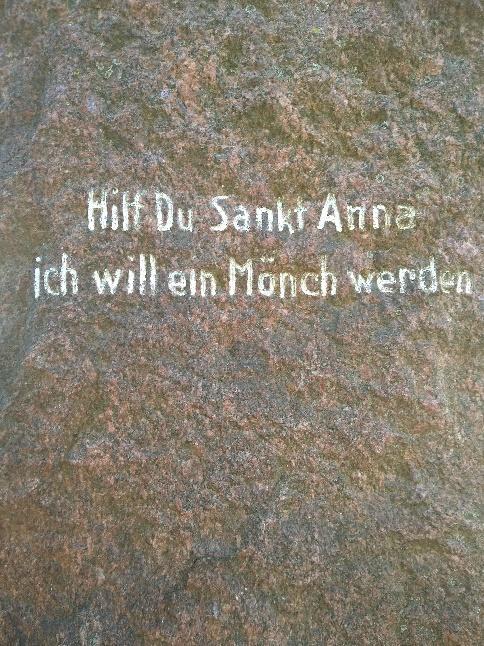

In Stotternheim, Martin Luther experienced a dramatic and life-changing event. As he traveled toward Erfurt in 1505, he was caught in a violent thunderstorm during which his close friend Hans Glaser was reportedly killed. Terrified and believing he might die, Luther cried out, “Help, Saint Anne! I will become a monk!” a desperate vow typical of the late-medieval piety he had been raised in. True to his promise, he entered the Augustinian monastery in Erfurt shortly afterward. Today, the quiet field marked by a few stone monuments commemorates this pivotal moment that set Luther on the path toward the Protestant Reformation.

Left: This monument in Stotternheim marks the place where Martin Luther was caught in a violent thunderstorm in 1505 and vowed, “Help, Saint Anne! I will become a monk!” The event, during which his friend Hans Glaser reportedly died, became a turning point that led him into monastic life and ultimately toward the Reformation.

Right: The monument includes Luther’s plea, “Help, Saint Anne! I will become a monk!” engraved in stone.

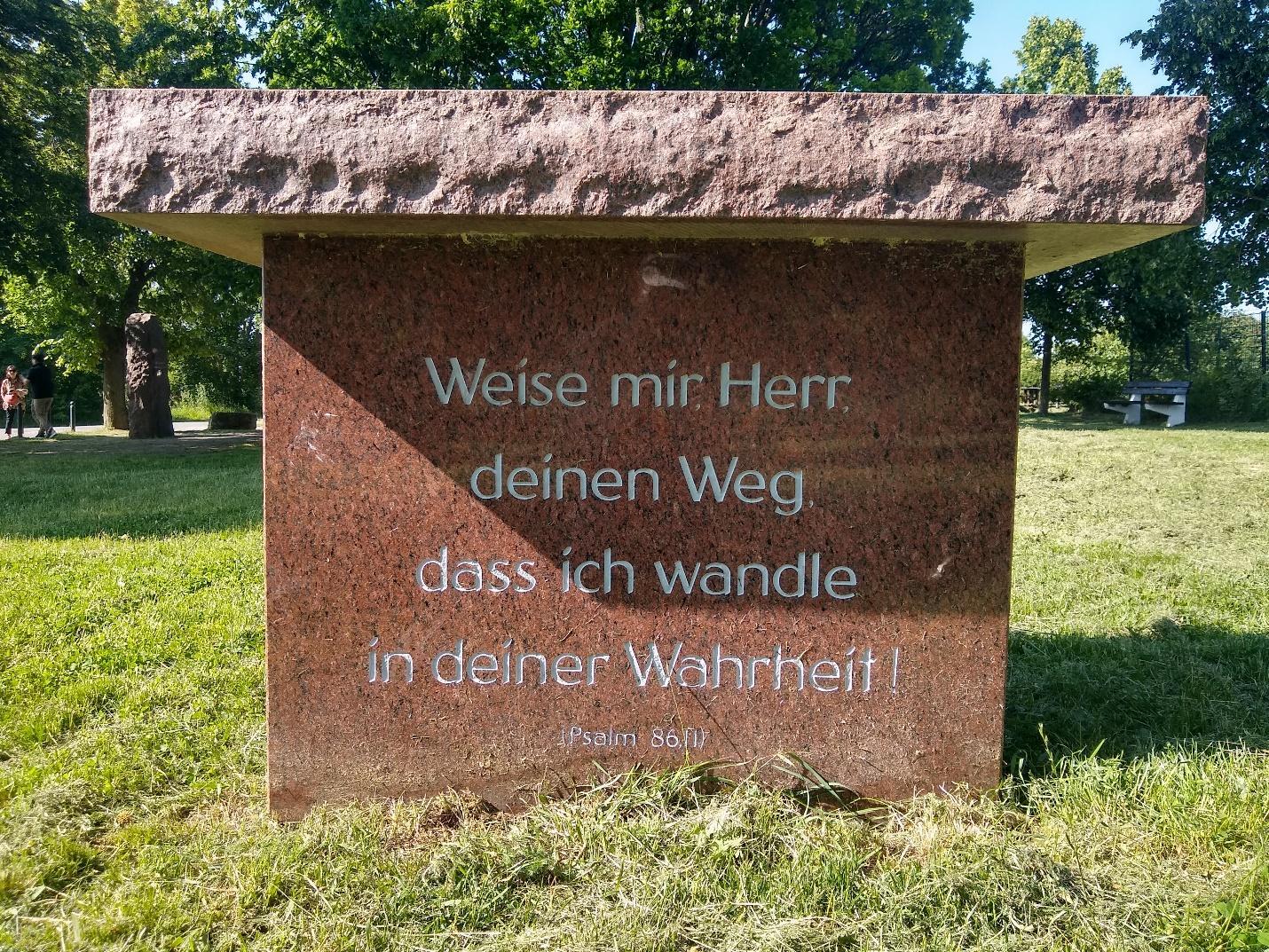

This stone marker bears a verse from Psalm 86:11: “Show me, Lord, your way, that I may walk in your truth.” It reflects the site’s spiritual significance, echoing Luther’s own search for guidance during his transformative experiences near Stotternheim.

The “Luther-Linde” marks a memorial linden tree dedicated to Martin Luther, planted to honor his legacy and the events connected to this site. Though it appears as an ordinary tree, it symbolizes the enduring growth and influence of the Reformation.

The open fields and the path that lead visitors to the historical markers.

Credit: Google Maps.

Wittenberg is one of the most important cities in Christian history, especially for the Protestant Reformation. It was here that Martin Luther famously nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church (Schlosskirche; see the two photos below) in 1517, challenging church practices and sparking widespread religious reform. The city is home to historic churches such as the Castle Church and St. Mary’s Church (Stadtkirche), where Luther preached and shaped his theological ideas. Wittenberg also became a center of Protestant scholarship, attracting reformers, theologians, and students who advanced Reformation teachings across Europe.

The Castle Church door, where Martin Luther famously posted his 95 Theses in 1517, igniting the Protestant Reformation.

Left: The Martin Luther Monument in Wittenberg.

Right: This monument in Wittenberg honors Philipp Melanchthon, Martin Luther’s close collaborator and a key theologian of the Protestant Reformation. Melanchthon played a central role in shaping Protestant education, church organization, and theology.

This bust honors Johannes Bugenhagen, a key figure in the Wittenberg Reformation who served as pastor of the Stadtkirche and helped organize Protestant church life. Wearing an academic cap, Bugenhagen is remembered for his theological leadership and his role in consolidating the early Reformation alongside Martin Luther and Philipp Melanchthon.

Leucorea in Wittenberg, originally founded in 1502 as the Electoral Saxon State University, was named from the Greek leukos oros, meaning “white mountain,” a nod to the city’s name. It became a major center of learning and theology, where Martin Luther began teaching in 1512 and Philipp Melanchthon later joined, helping to shape the early Protestant Reformation. The university played a pivotal role in establishing Wittenberg as a hub of Protestant scholarship and intellectual life. Although the original university merged with another institution in 1817, the Leucorea name endures through a modern foundation that hosts academic conferences, Reformation research, and cultural events, continuing the city’s legacy of theological and scholarly influence.

Inside Leucorea, portraits of Martin Luther and his wife Katharina von Bora honor their pivotal roles in the Protestant Reformation. The display highlights their personal and spiritual partnership, as well as their lasting influence on faith, family life, and the intellectual life of Wittenberg.

The statue of Katharina von Bora with flowers in Leucorea honors her role as Luther’s wife and partner in the Reformation. A former nun, she managed their household, raised six children, and supported Luther’s work, making her an important figure in both the personal and domestic aspects of Reformation history. The flowers decorating the statue symbolize nurturing and devotion, reflecting her care for her family and her contributions to the moral and social example of Protestant family life, while also showing admiration for her lasting legacy.

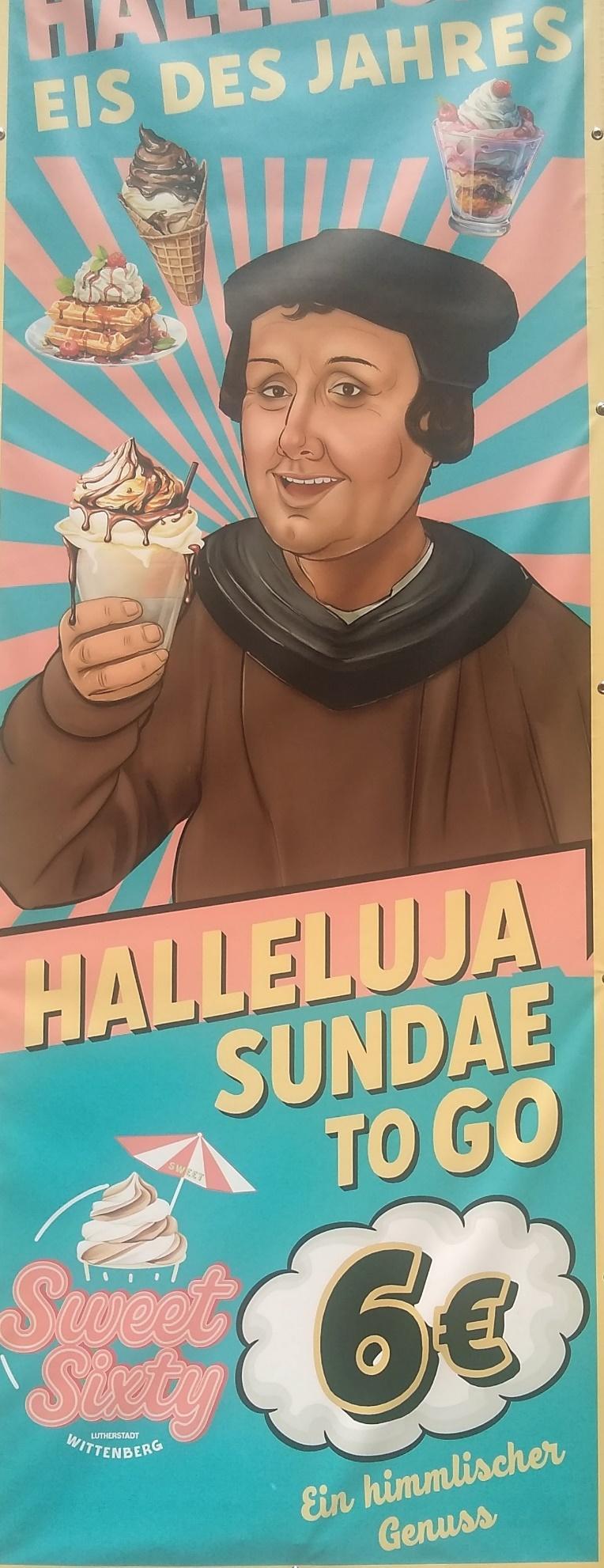

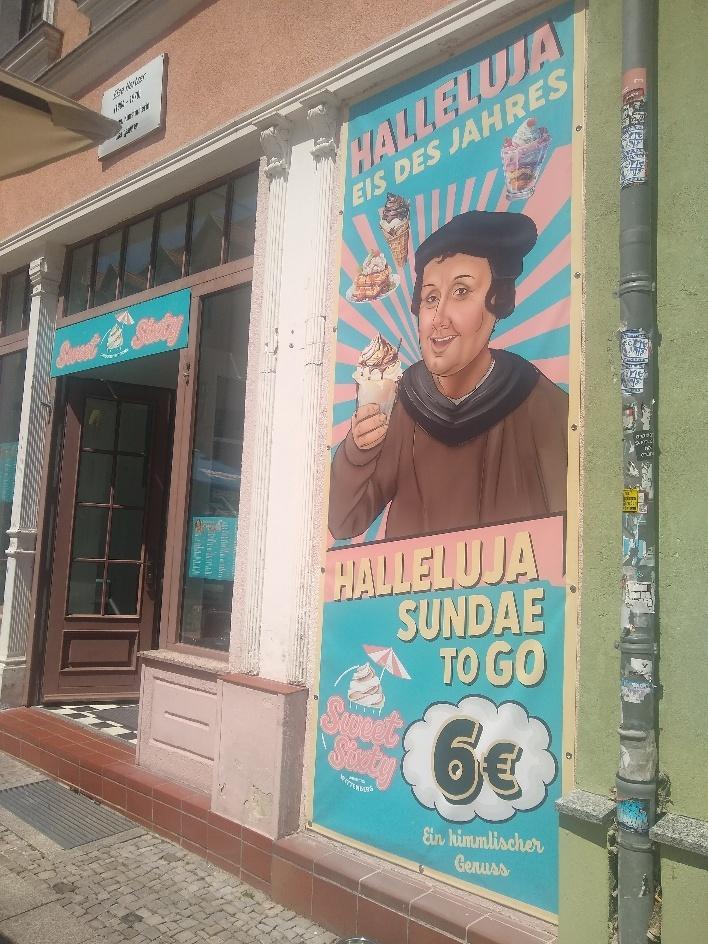

Although Martin Luther is usually depicted with a serious expression in portraits, in this ice cream advertisement in Wittenberg, he wears an inviting smile.

Prague, the Czech Republic

Prague, the capital of the modern Czech Republic, holds a significant place in the history of Protestantism, particularly through its association with the Hussite movement and early reformist thought. In the early 15th century, the city became the center of the Hussite movement, inspired by Jan Hus (1370-1415), a Czech priest and theologian who criticized church corruption and called for reform, predating Martin Luther by a century.

St. Vitus Cathedral (Katedrála svatého Víta), the largest and most important church in Prague. Located within Prague Castle, it is an example of Gothic architecture and has been the seat of the Archbishop of Prague for centuries. Construction began in 1344 and continued over several centuries.

From the vantage point of St. Vitus Cathedral, the cityscape of Prague unfolds with its historic houses, many topped with distinctive red roofs. The view highlights the city’s medieval charm, architectural heritage, and the blend of Gothic, Baroque, and Renaissance influences across the skyline.

Through a narrow slit in the stone walls of Prague Castle, visitors can glimpse part of the city below. Originally built as a defensive feature, this opening allowed guards to observe the surroundings while remaining protected, reflecting the castle’s medieval fortress design.

This statue in Prague’s Old Town Square honors Jan Hus, the 15thcentury Czech reformer whose calls for church reform prefigured the Protestant Reformation. Hus is remembered for his courage in challenging corruption within the church and for inspiring generations of Czech Protestants. The monument bears the inscription “Milujte se, pravdy každému přejte” (“Love one another and wish the truth to everyone”), reflecting Hus’s enduring message of moral integrity, compassion, and commitment to truth.

On the right side of the Jan Hus Monument in Prague, the inscription reads, “Věřím, že po přejití bouří hněvu vláda věcí Tvých k Tobě se zase navrátí, ó lide český” (“I believe that after the storms of rage pass, the governance of your affairs will return to you, O Czech people”). This message reflects Hus’s hope for the moral and spiritual renewal of the Czech nation and his enduring influence on Czech Protestant identity.

Credit: Google Maps.

Zurich holds major Christian significance as the center of the Swiss Reformation, led by the reformer Huldrych Zwingli in the early 16th century. It was here that Zwingli introduced reforms such as preaching directly from Scripture, rejecting certain church traditions, and promoting a simpler form of worship. The city’s churches, especially the Grossmünster, became key sites of Protestant teaching, helping shape Reformed Christianity throughout Switzerland and beyond.

This statue in Zurich honors Huldrych Zwingli, the leading figure of the Swiss Reformation and a major voice in shaping Reformed Christianity. Standing near the shore of Lake Zurich, the monument shows him holding a Bible in one hand and a sword in the other, symbolizing both his devotion to Scripture and his role in defending the Reformation.

The Grossmünster in Zurich is a landmark Reformation church traditionally linked to the city’s conversion under Huldrych Zwingli. Its twin towers and centuries-old architecture make it one of Zurich’s most iconic symbols of Christian history and worship.

Heinrich Bullinger’s image is engraved on the outer wall of the Grossmünster to honor his role as one of Zurich’s most influential Reformation leaders. As Zwingli’s successor, Bullinger guided the church for four decades, shaping Reformed theology and strengthening Protestant communities throughout Europe.

Fraumünster Church in Zurich is a historic Protestant church located on the opposite side of Lake Zurich from the Grossmünster. It is especially famous for its stunning Chagall stained-glass windows, which fill the sanctuary with vibrant color and light.

A view of three of Marc Chagall’s iconic stained-glass windows at Fraumünster Church in Zurich.

This plaque on Lake Zurich commemorates early Anabaptist martyrs, including Hans Landis, who suffered persecution for their faith during the Reformation. Between 1527 and 1532, radical reformers such as Felix Manz were drowned for practicing adult baptism, while Hans Landis was later executed in 1614 for continuing to preach Anabaptist beliefs. The memorial serves as a reminder of the religious intolerance of the period and honors those who stood firm in their convictions despite severe consequences.

Koreans and Korean Americans often bring a banner for photos when traveling in groups. Before leaving Zurich, a group of my fellow travelers from California Prestige University holds a banner they had ordered from a shop in South Korea. The lady holding up her left hand, a current seminarian, served as our MC and entertainer during the bus rides.

Credit: Google Maps.

Geneva was a major center of the Protestant Reformation and became known as a “Protestant Rome” under the leadership of John Calvin. The city offered refuge to persecuted Protestants and developed churches, schools, and social programs based on Calvin’s vision of a disciplined, scripture-centered society. Calvin’s teachings in Geneva influenced church organization, worship, and moral life across Europe and later in North America.

We are on the bus journey from Mont Blanc, France, to Geneva, Switzerland.

This stone wall in Geneva honors the giants of the Protestant Reformation. The four central figures are John Calvin, William Farel, Theodore Beza, and John Knox, who each played pivotal roles in shaping Reformed theology and spreading Protestantism across Europe.

Near the Reformation Wall in Geneva, several busts honor key Protestant reformers who helped shape the Reformed tradition. Among them are Martin Bucer of Strasbourg, Peter Martyr Vermigli of Italy, John Oecolampadius of Basel, and Huldrych Zwingli of Zurich. Collectively, these figures represent the wider network of theologians and leaders whose work spread the influence of the Protestant Reformation throughout Europe.

Gustave Moynier (1826-1910), a Swiss lawyer and philanthropist, was a founder and long-time president of the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva. Although not a Reformation figure, his bust near the Reformation Wall honors his contributions to humanitarian law and reflects Geneva’s enduring legacy of moral and civic leadership.

Adjacent to the Reformation Wall is the University of Geneva’s Bastions campus. Founded in 1559 by John Calvin, the university became a key center of the Protestant Reformation, serving as a hub for Reformed theology and education. It trained pastors, theologians, and scholars who spread Calvinist teachings across Europe, shaping both religious practice and intellectual life in Reformed communities. The statue of Professor Jean Daniel Colladon (1802-93) honors this notable Swiss physicist and engineer, linking Geneva’s rich academic and scientific heritage to its legacy as a center of Reformation thought and education.

Credit: Google Maps.

Noyon, a small city in northern France, holds a notable place in Protestant history primarily as the birthplace of John Calvin (1509-64). Calvin’s theology and leadership helped shape the Reformed tradition, which spread across Europe and influenced Protestant communities worldwide. While Noyon itself remained largely Catholic during his lifetime, the city’s association with Calvin makes it a symbolic site for Protestants, representing the early roots of Reformed thought in France.

Floral displays welcoming visitors at the entrance to Noyon.

John Calvin’s birthplace museum in Noyon.

The Notre-Dame Cathedral in Noyon has a direct connection to John Calvin through his family. Calvin’s father, Gérard Cauvin, worked as a notary in Noyon, and the family was closely tied to the city’s civic and religious life. John Calvin himself was baptized at Notre-Dame Cathedral, which was the central place of worship in Noyon. While the cathedral is a Catholic institution and Calvin would later become a leading Protestant reformer, it nonetheless marks his early religious upbringing and formative environment. The cathedral, therefore, symbolizes the starting point of Calvin’s life and spiritual journey before he embraced the Reformation.

By John J. Han

When I joined the Reformation tour group from June 11-20, 2025 (see the previous photo essay), my main goal was to visit places associated with Luther, Calvin, and other reformers. Unlike most participants, however, I was also eager to photograph literary landmarks along the way. As the cradle of Western civilization, Europe has produced countless authors, artists, and thinkers who have influenced early modern and modern world history more than any other continent. While East Asian countries today are rediscovering their own rich cultural traditions, studying European history and literature both formally and informally remains common practice. The works of Shakespeare, Chaucer, Dante, Hesse, Nietzsche, and Kafka, among many others, have been translated into East Asian languages and have deeply shaped the development of modern Asian literature.

During my high school and college years in Korea in the 1970s, it was fashionable to read European authors such as Arthur Schopenhauer, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Somerset Maugham, Hermann Hesse, Luise Rinser, Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Søren Kierkegaard. We discussed these writers not only in classrooms but also at informal gatherings and parties. Most of their works we read in Korean translation, though in high school I also read several abridged English editions of well-known British novels likely published by Oxford University Press and, as a college freshman, Hesse’s Demian (1919) in English translation. By the time I came to the United States in 1988, I felt well acquainted with Western civilization as well as its Eastern counterpart.

As a literary scholar, I had long wished to visit some of Europe’s great literary landmarks, so the Reformation tour provided a golden opportunity to see several of them. Because our schedule was tightly packed, most of my encounters with literary sites were by chance. Before the trip, I knew that Frankfurt was the birthplace of Goethe and that Prague was that of Kafka, and I hoped to glimpse a few related places. Other discoveries such as

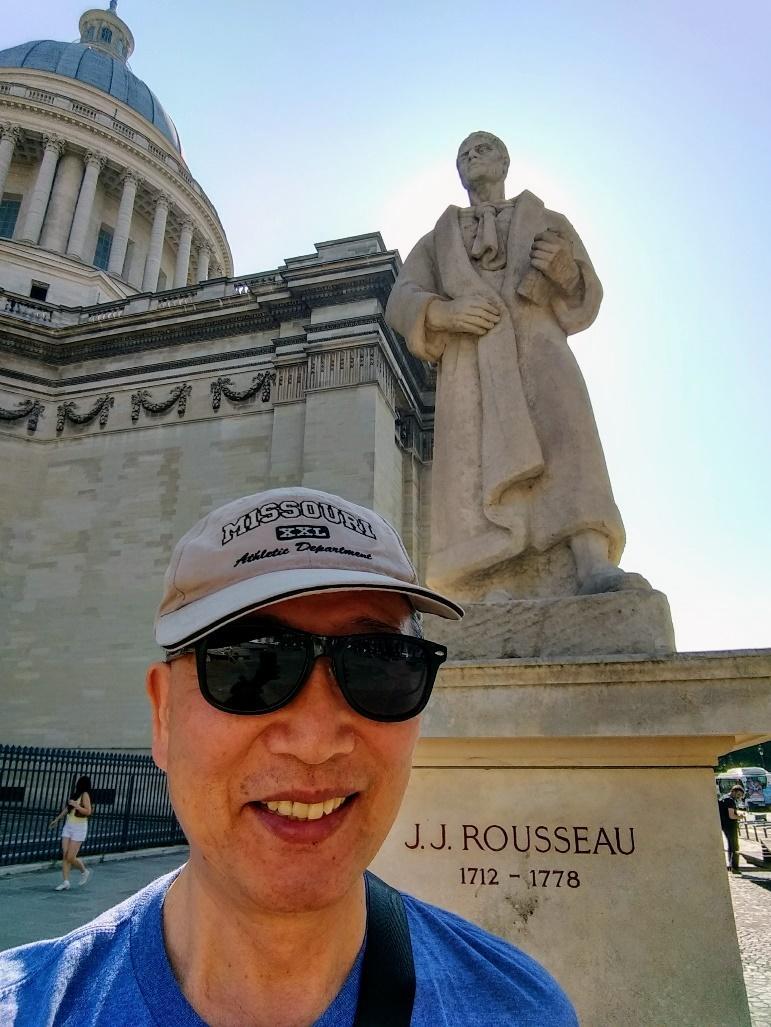

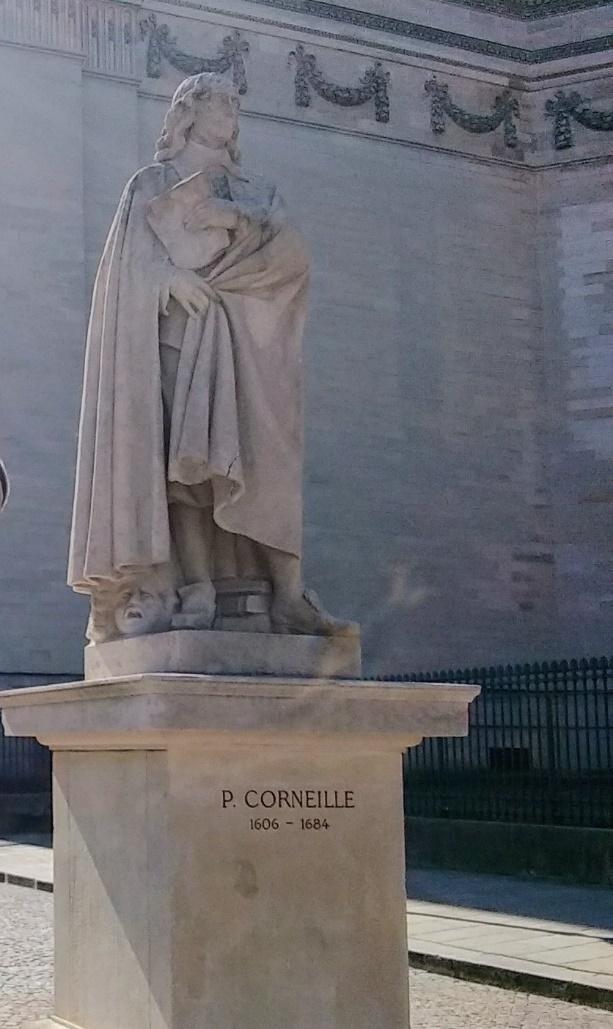

statues of philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau and playwright Pierre Corneille in Paris were pleasant surprises.

This essay presents photographs of literary landmarks I was fortunate to capture during my Christian pilgrimage. Since the tour’s primary focus was not literature, the images may appear somewhat random, yet literaryminded readers will still recognize many familiar sites and perhaps be inspired to visit them in the future. Some of the photos are not directly representative of the landmarks themselves. For instance, I took a picture of a souvenir shop in Prague that sold Kafka-related items, even though our itinerary did not include such significant sites as the Altstädter Deutsches Gymnasium, which Kafka attended; the former home of the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute, where he worked; or the New Jewish Cemetery, where he is buried. Still, for me, it was a lifelong dream fulfilled to see, even briefly, the places connected to some of the greatest authors in European literature.

Credit: Google Maps

While strolling near my hotel, the Hampton, I noticed a restaurant named after Jesse James (1847-82). He was not a literary figure per se, but he appears in many American novels (including dime novels), folktales, and movies. This sign reflects his worldwide fame as a Missouri outlaw, and one could argue that he is indirectly a literary figure.

Near my hotel, I noticed a poster announcing this year’s Anne Frank Day (Anne Frank Tage). Throughout Germany, the country visibly acknowledges the atrocities of Nazi Germany with posters, monuments, and memorials. Anne Frank was born in Frankfurt in 1929 and died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, Germany, in 1945 at the age of 15. Her diary has been translated into more than 70 languages.

The birthplace and childhood home of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) stands at Großer Hirschgraben 23-25 in Frankfurt. The building now houses the Freies Deutsches Hochstift’s Goethe House and Museum. As an early leader of the Sturm und Drang (“Storm and Stress”) movement of German Romanticism, Goethe achieved worldwide fame with his novel The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774).

A white boat on the Main River in Frankfurt bears the name Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

The Main River in Frankfurt. In his autobiography Poetry and Truth from My Own Life (revised translation by Minna Steele Smith, London: George Bell & Sons, 1908), Goethe fondly recalls the Main from his boyhood:

A very inclement winter had frozen over the Main completely, and converted it into a solid surface. The ice became the animated scene of all kinds of business and pleasurable amusements. Endless skating-paths, and wide, smooth frozen plains swarmed with a moving multitude. I was always there from early morning, and, being lightly clad, was really chilled to the bone by the time my mother arrived in her carriage to visit the scene. She sat in the carriage, in her handsome purple velvet fur-trimmed cloak, fastened across the chest by a strong golden cord and tassel. “Give me your furs, dear mother!” I cried out instantly, without a moment’s thought, “I am fearfully cold.” She complied without hesitation, and a moment after I was wrapped in her cloak. Reaching half-way below my knees, with its purple-colour, sable-border, and gold trimmings, it contrasted not unpleasantly with the brown fur cap I wore. Thus attired, I unconcernedly went on skating up and down; the crowd was so great that no especial notice was taken of my strange appearance; still it did not escape notice altogether, for often afterwards it was brought up against me, in jest or earnest, as an example of my eccentricities. (p. 212)

A statue of Friedrich Stoltze (1816-91), a native of Frankfurt, where he was born, lived, and died. A poet, journalist, and political writer, he is best known for Frankfurter Latern, the satirical weekly magazine he published from 1860 until his death. The Stoltze Monument now stands at the Hühnermarkt in the New Old Town.

Credit: Google Maps

The sign marks the entrance to the Weinkellerei Carl Jung in Rüdesheim, a winery founded by Swiss psychologist Dr. Carl Gustav Jung (18751961). In addition to developing alcohol-free wine in 1908, Jung introduced the concept of archetypes universal symbolic patterns which later inspired archetypal approaches to literary criticism.

A cable car ride to the Niederwald Monument, a patriotic landmark, provides a panoramic view of the vineyards and the Rhine River. The Rhine River has inspired countless writers, poets, and musicians over the centuries. Heinrich Heine’s “Die Lorelei” (1824), Victor Hugo’s Le Rhin (1842), and Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876) are among the many works associated with the river.

Aside from its importance in the development of Protestantism, Worms is also renowned as one of the main settings of The Nibelungenlied (Das Nibelungenlied), a Middle High German epic poem from around 1200. In the tale, Prince Siegfried comes to Worms, the court of the Burgundian kings, to win the hand of Princess Kriemhild, succeeding with the help of her brother, King Gunther. Though Siegfried repays Gunther’s kindness, he is later betrayed by him. As is typical of medieval heroic poetry, The Nibelungenlied is steeped in bloodshed and tragedy. Like Beowulf, the Anglo-Saxon epic, it blends Christian and pre-Christian (pagan) elements, reflecting a medieval Christian worldview while preserving older Germanic warrior values that often clash with Christian ideals of forgiveness and humility. Here are four lines from the beginning of the book:

In Worms am Rheine wohnten die Herrn in ihrer Kraft. Von ihren Landen diente viel stolze Ritterschaft Mit rühmlichen Ehren all ihres Lebens Zeit, Bis jämmerlich sie starben durch zweier edeln Frauen Streit.

In Worms upon the Rhine lived the noble lords in their power. From their lands many proud knights served, Winning glorious honor all their lives Until they died miserably in a quarrel between two noble women. (trans. John J. Han)

Top: A rural landscape on the way to Worms. Bottom: Our tour bus approaches the Nibelung Tower, a neo-Romanesque bridge tower located on the Nibelungen Bridge (Nibelungenbrücke).

The Rhine River and the Nibelungen Bridge in Worms. The city looked serene and peaceful, with the river flowing gently beneath the bridge a quiet reminder of the legends and history tied to this ancient place. Inspired by the scene, I composed the following haiku: empty ramparts where soldiers’ cries once scared birds

Credit: Google Maps.

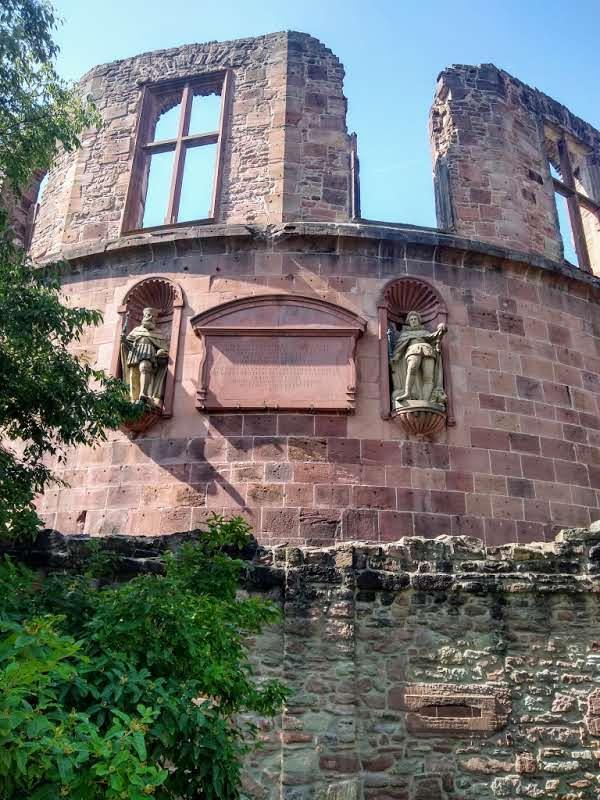

Heidelberg Castle (Schloss Heidelberg) has appeared in or inspired the works of many writers, including Joseph von Eichendorff, Victor Hugo, Mark Twain, and Friedrich Hölderlin. (See more photos on the next page.)

Here is an excerpt from Mark Twain’s A Tramp Abroad, a travelogue published in 1880:

Behind the Castle swells a great dome-shaped hill, forest-clad, and beyond that a nobler and loftier one. The Castle looks down upon the compact brown-roofed town; and from the town two picturesque old bridges span the river. Now the view broadens; through the gateway of the sentinel headlands you gaze out over the wide Rhine plain, which stretches away, softly and richly tinted, grows gradually and dreamily indistinct, and finally melts imperceptibly into the remote horizon.

I have never enjoyed a view which had such a serene and satisfying charm about it as this one gives.

Perched above the city of Heidelberg, the castle commands a view of the Neckar River, a tributary of the Rhine.

A bronze bust of Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe in the gardens of Heidelberg Castle. The inscription on the tablet reads in English translation:

On the terrace a high vaulted arch was once your coming and going

Marianne von Willemer (1784-1860) wrote these poetic lines on August 28, 1824, Goethe’s seventy-fifth birthday, as a reflection on her final meeting with him.

The Old Bridge Gate Towers (Alte Brücke Torhäuser) in Heidelberg appear in literature, especially from the Romantic and nineteenth-century periods.

The Heidelberg Minerva Monument, a stone statue on the Old Bridge, depicts the ancient Roman goddess of wisdom, Minerva (Athena in Greek mythology). An owl, symbolizing wisdom, sits beside her.

The Schlangenweg (“Snake Path”) in Heidelberg is a stone footpath that winds up the hill on the north side of the Neckar River, connecting to the Philosophenweg (“Philosophers’ Walk”) and facing Heidelberg Castle across the river.

Credit: Google Maps

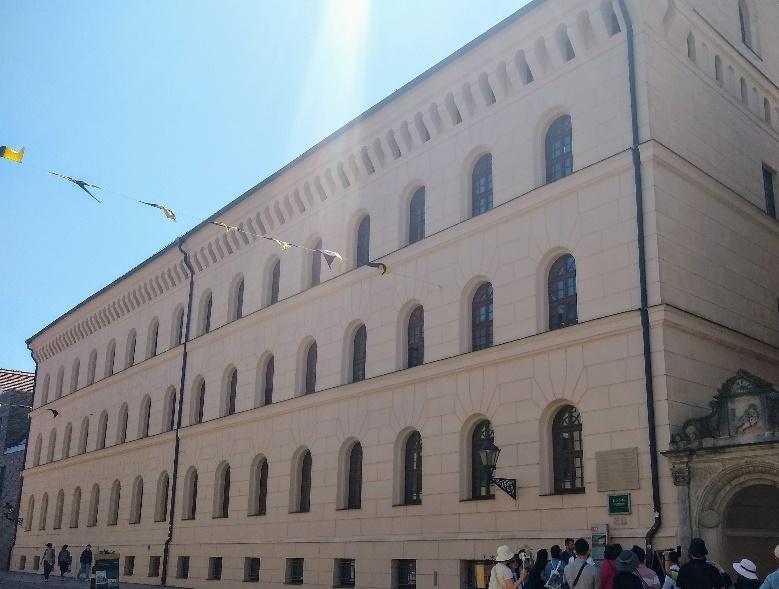

One section of Heidelberg University’s Old Campus, viewed from a courtyard. Founded in 1386, it is renowned for its academic excellence. The university and the city of Heidelberg have been associated with 56 Nobel Prize winners. Many influential thinkers, writers, and artists have also been affiliated with the university, including Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560), John Amos Comenius (1592-1670), Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831), Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-72), Heinrich Hoffmann (1885-1957), José Rizal (1861-96), W. Somerset Maugham (18741965), Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900-2002), and Jürgen Habermas (b. 1929).

Credit: Google Maps

Near the Lutherhaus in Eisenach, I saw a poster for Eine Odyssee, a stage production by the local ensemble Theater am Markt Eisenach (TAM).

Presented as part of TAM’s summer theatre series in the courtyard of the Stadtschloss Eisenach, the play is an adaptation of Homer’s ancient epic

The Odyssey, written by the Dutch author Ad de Bont and translated into German by Barbara Buri.

Credit: Google Maps. Wartburg Castle perches on a hill above the town’s historic center.

Wartburg Castle, originally built in the Middle Ages, stands roughly 1.5 to 2 miles from the town center.

This photo was taken from the castle terrace, looking down toward Eisenach and the Thuringian Basin beyond. The wooded ridge in the foreground belongs to the Thuringian Forest foothills, while the red roofs below mark Eisenach’s historic center. Except for the modern wind turbines in the distance, the view offers a timeless landscape once familiar to Martin Luther, Johann Sebastian Bach, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and many others. Goethe visited Wartburg Castle several times, including a five-week stay in 1777, during which he sketched the castle.

Credit: Google Maps

Erfurt, Germany, was an important, though small and insular, center of humanism focused on literature and philology rather than religious or social reform, producing scholars whose textual expertise later supported biblical humanism in Wittenberg. Key figures associated with Erfurt humanism include Konrad Mutian (1470-1526), Corydons/Mutianist circle members, and Johann von Staupitz (c. 1460-1524). For more information, see Amy Nelson Burnett’s article “Revisiting Humanism and the Urban Reformation” (Lutheran Quarterly, vol. 35, n0, 4, 2021, pp. 373400).

Credit: Google Maps. Weimar is located roughly 15 miles to the east of Erfurt.

Many well-known writers and thinkers are connected to Weimar:

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) lived there for most of his adult life, producing major works, including portions of Faust.

Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805), the great dramatist and poet, moved to Weimar later in life, became close friends with Goethe, and wrote plays such as William Tell (1804) while residing there.

Before Goethe’s and Schiller’s arrival, Christoph Martin Wieland (17331813) an important Enlightenment writer and editor helped establish the city as a literary center.

Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803)—a philosopher, theologian, and critic associated with the Sturm und Drang movement—served as a pastor in Weimar and strongly influenced Goethe as well as later Romantic writers.

The city is also home to the Nietzsche Archive, established by the philosopher’s sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche. (In 1897, after Nietzsche’s mother died, his sister moved him from Naumburg to Weimar, where he died in 1900.)

Finally, Thomas Mann set his novel Lotte in Weimar: The Beloved Returns (1939), a creative response to Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, in this culturally rich city. Below is an excerpt from Chapter 1:

If Frau Councillor but knew the love and veneration which from my birth up, so to speak, I have felt for our prince of poets, the great Goethe; my pride as a citizen of Weimar that we may call this eminent man our own; if she realized what fervent echoes this very work, The Sorrows of Werther, awoke in my heart…. But I say no more. It is not for me to speak though well I know that a masterpiece of feeling like the work in question belongs to high and low and to humanity as a whole, animating it with the most fervid emotions; whereas probably only the upper classes can aspire to such productions as Iphigenie or The Natural Daughter. (trans. H. T. Lowe-Porter, p. 13; ellipsis on original)

In this passage, the speaker gushes about Goethe, expressing lifelong devotion to him as “the prince of poets” and pride that Weimar can claim him. He explains that The Sorrows of Werther moves people of all classes, while Goethe’s more classical works Iphigenie and The Natural Daughter are appreciated mainly by the cultural elite. The speech humorously shows how ordinary Weimar citizens idolize Goethe and speak about him with exaggerated reverence.

Friedrich Wilhelm Riemer (1774-1845), a scholar and literary historian, served as Goethe’s literary assistant and as a tutor to his son in Weimar for nine years.

. Neptune, the Roman god of the sea equivalent to the Greek god Poseidon rises majestically at the center of Weimar’s Market Square, gripping his iconic trident. A child and sea creature at his feet highlight his ancient power over the waters. Framed by historic buildings, the fountain adds classical grandeur to the heart of the city.

The countryside scenery along the route from Weimar to our next destination, Wittenberg, Germany, was captivating. Most passengers on our tour bus took a nap, but as someone who grew up on a rice farm in Asia, I was fascinated by the diverse rural landscapes of Europe. The flatness of the fields, the vast blue sky, and the rusty tool in the lower corner of the photo especially transported me back to my native village, thousands of miles away.

Credit: Google Maps. Wittenberg is located roughly 70 miles to the southwest of Berlin.

Our tour bus crosses the Elbe River as it winds through Wittenberg, Germany, passing over a bridge that spans the historic waterway. The river’s floodplain shapes the surrounding landscape, reflecting both natural beauty and the town’s centuries-old connection to this vital waterway. Travelers crossing here experience the serene flow of one of Central Europe’s major rivers.

Top: Part of Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg.

Bottom: The sign on the building reads, in loose translation: Leucorea

A publicly funded foundation of Martin Luther University HalleWittenberg Scholars’ House

Wittenberg is most famously connected to Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation, but several other authors, theologians, and thinkers are associated with the town as well. They include Philipp Melanchthon (1497-1560), Johannes Bugenhagen (14851558), Justus Jonas (1493-1555), Caspar Cruciger (1504-48), and Christian Thomasius (1655-1728). Wittenberg University (founded 1502) itself attracted many intellectuals and writers during the Renaissance and Reformation, including poets, philosophers, and historians aligned with Protestant humanism.

In Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1623), both Hamlet and Horatio are closely associated with Wittenberg University, though in slightly different ways, and this connection deepens the play’s intellectual atmosphere. Hamlet is explicitly described as a student there, as Claudius discourages him in Act I from returning to his studies:

KING.

[…] For your intent

In going back to school in Wittenberg, It is most retrograde to our desire: And we beseech you bend you to remain Here in the cheer and comfort of our eye, Our chiefest courtier, cousin, and our son.

QUEEN.

Let not thy mother lose her prayers, Hamlet. I pray thee stay with us; go not to Wittenberg.

HAMLET.

I shall in all my best obey you, madam. (SCENE II. Elsinore. A room of state in the Castle)

Horatio, too, identifies himself with Wittenberg when he tells Hamlet he has returned from the university for the king’s funeral, suggesting he is likewise a student or scholar:

HAMLET.

Sir, my good friend; I’ll change that name with you: And what make you from Wittenberg, Horatio?

Marcellus?

MARCELLUS.

My good lord. HAMLET.

I am very glad to see you. Good even, sir. But what, in faith, make you from Wittenberg? (ACT I, SCENE II. Elsinore. A room of state in the Castle)

Shakespeare’s choice of Wittenberg famous as Martin Luther’s university and a center of humanist learning and theological debate places both characters within a world of intellectual inquiry and moral reflection.

Wittenberg’s streets and shops celebrate the town’s historically famous figures, including Martin Luther.

Credit: Google Maps. Prague is the capital of Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia.

We crossed the Czech Republic’s border and headed toward its capital, Prague. The scenery along the way was peaceful.

This is the Prague Astronomical Clock, or Orloj, mounted on the Old Town Hall in Prague’s Old Town Square. Installed in 1410, it is one of the oldest working astronomical clocks in the world. Every hour, it delights visitors with a brief performance featuring moving figures, including the Twelve Apostles. The clock has inspired numerous creative works in literature, from Miloš Urban’s The Devil’s Workshop (2009) to references in Leo Perutz’s The Master of the Day of Judgment (1921) and essays by Karel Čapek. Traditional Czech legends about the Orloj, especially the tale of its blinded clockmaker, have also become part of the city’s rich folklore.

This statue honors Charles IV, King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor, who founded Charles University in 1348, the oldest university in Central Europe. Located near the entrance to the Charles Bridge in Prague, the monument depicts Charles IV surrounded by allegorical figures representing learning and culture. Over the centuries, Charles University has been associated with influential thinkers and writers, including Jan Hus, Franz Kafka, and Karel Čapek. Illuminated at night, the monument reflects the city’s long tradition of scholarship and artistic achievement.

The Vltava River (Czech: Vltava) flows through Prague and is the longest river in the Czech Republic. It is famously crossed by the Charles Bridge, one of Prague’s most iconic landmarks. The river appears in many literary works, both Czech and international. For example, novelist Franz Kafka (1883-1924) rarely names the Vltava explicitly, but his descriptions of Prague’s fog, bridges, and nighttime atmosphere often evoke the river and its embankments.

Near the shore of the Vltava River, I passed a souvenir chop s a specialty gift shop in Prague, themed around Franz Kafka, selling memorabilia, souvenirs, and novelty items inspired by the author. It focuses on Kafkathemed “dark gifts” and collectibles, likely targeting tourists who want quirky literary souvenirs.

"Shakespeare & Synové (Shakespeare & Sons) in Prague is an Englishlanguage bookstore with a mix of new and used books. Its interior includes spaces for browsing and reading. The shop reflects the city’s long-standing literary culture and international connections."

At the base of the Statue of Saint John of Nepomuk on Prague’s Charles Bridge, a bronze relief of a man and dog has become a focal point for visitors rubbing it for luck. The bridge, its statues, and the misty Vltava River evoke the atmospheric Prague that appears in the works of Franz Kafka and Bohumil Hrabal (1914-97; Closely Watched Trains [1965], I Served the King of England [1973]). Though the dog is not part of the original legend, it now embodies the city’s blend of folklore, history, and literary imagination.

Credit: Google Maps. Zurich is the largest city in Switzerland located at the north end of Lake Zurich.

After an overnight stay in Bayreuth, Germany, we traveled toward Zurich, Switzerland. Along the route, we came upon a vast body of water Lake Constance—surrounded by granite-like rocks and verdant foothills of the Alps.

As we neared Zurich, the Alps appeared on the horizon, and road signs for the city became more frequent.

Zurich has long been a hub of literature, philosophy, and psychology. The city is associated with modernist writers such as Friedrich Dürrenmatt (1921-90) and Max Frisch (1911-91), whose plays and novels explored human nature and society. It was also home to influential thinkers like Carl Jung and Alfred Adler, who developed groundbreaking psychological theories here. Literary figures such as Gottfried Keller (1819-90) were part of Zurich’s vibrant 19th-century literary circles. Overall, Zurich’s intellectual and cultural history reflects a rich blend of literary innovation and psychological inquiry.

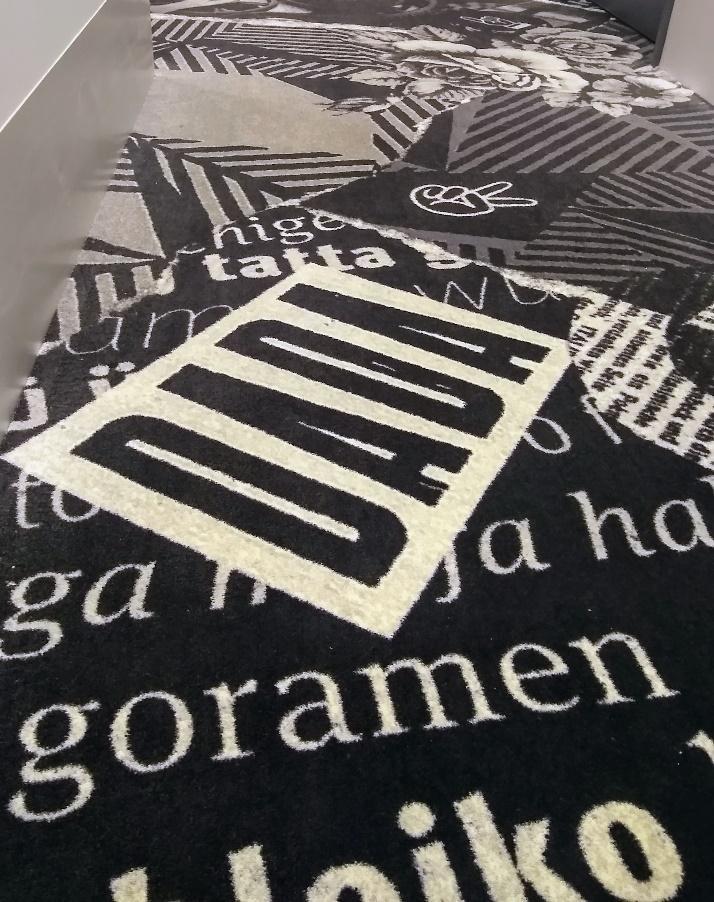

Zurich was a major center of Dadaism during World War I, home to the Cabaret Voltaire where artists like Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara experimented with absurdity, performance, and anti-war art. The city’s neutral status made it a haven for international creatives, fostering a vibrant, chaotic, and revolutionary artistic scene. The word “dada” was displayed throughout the hallways of our hotel, as seen in the photo above.

Lake Zurich is the large lake directly adjacent to the city, stretching southeast from Zurich city center. With its calm waters and graceful swans, it has inspired writers and poets for centuries. Authors such as Gottfried Keller and Friedrich Dürrenmatt evoke the lake and its surrounding cityscape in their works, celebrating its natural beauty and serene atmosphere. The swans we saw on the lake added to the scene, connecting us to the literary appreciation of this iconic Swiss landmark.

During much of World War I, Irish novelist James Joyce resided in Zurich, where he focused on writing Ulysses. The city’s neutral status offered him safety and relative quiet amid the turmoil of Europe. While in Zurich, Joyce interacted with other artists and intellectuals, drawing inspiration from the city’s vibrant cultural life.

Pictured above is the “Bull‑Tamer Fountain” at Bürkliplatz, near the lakefront of Lake Zurich. The statue depicts a young man wrestling a powerful bull, symbolizing humankind’s struggle to tame nature. After exploring Zurich, we headed southwest to Chamonix, France, to visit Mont Blanc. True to expectation, the surrounding landscape was picturesque.

Credit: Google Maps

Credit: Google Maps

Chamonix is a town in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of France, renowned for its skiing and mountaineering. To the south lies Mont Blanc the highest peak in the Alps and Western Europe situated on the French Italian border, though its summit is generally regarded as being in France.

Reaching the peak of Mont Blanc, 15,777 feet above sea level, requires two gondola trips. Some travelers stop at the first station before descending, while others take the second gondola to reach the summit. The journey to the top is not for the faint-hearted, as the gondola sways with several hesitant back-and-forth movements before arriving at a platform perched above a nearly vertical cliff. Although we traveled in June, the mountain’s elevation required us to wear several layers of clothing.

Breathtaking views from the summit of Mont Blanc. Many authors and works engage with Mont Blanc. They include:

• Percy Shelley and Mary Shelley’s History of a Six Weeks’ Tour through a Part of France, Switzerland, Germany and Holland (1817). The book includes Percy Shelley’ s poem Mont Blanc: Lines Written in the Vale of Chamouni.

• Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein (1818).

• Various poems and letters by Lord Byron (1788-1824).

• John Ruskin’s Modern Painters (1843-60) and other works.

Credit: Google Maps

We are on our way from Mont Blac to Gevena, Switzerland.

Top: Geneva Lake, located on the northern side of the Alps, is shared by Switzerland and France.

Bottom: The Monument National in the Jardin Anglais (“English Garden”) in Geneva faces Geneva Lake. The woman on the left symbolizes the Republic of Geneva, while the one on the right, Helvetia, personifies Switzerland.

Many authors have lived in, stayed for an extended time in, or visited Geneva. They include Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-78), Henry James (1843-1916), and Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986). British novelist Graham Greene (1904-91)—the author of Doctor Fischer of Geneva or The Bomb Party (1980) lived in the Lake Geneva region, though not in the city of Geneva itself.

In Chapter 2 of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), the title character describes his childhood and schooling in Geneva. At the beginning of Chapter 3, he explains that his father insisted he leave home to continue his studies in Germany:

When I had attained the age of seventeen my parents resolved that I should become a student at the university of Ingolstadt. I had hitherto attended the schools of Geneva, but my father thought it necessary for the completion of my education that I should be made acquainted with other customs than those of my native country. My departure was therefore fixed at an early date, but before the day resolved upon could arrive, the first misfortune of my life occurred an omen, as it were, of my future misery.

Later, in Chapter 7, Frankenstein returns to his native Geneva after learning that his brother has been murdered:

It was completely dark when I arrived in the environs of Geneva; the gates of the town were already shut; and I was obliged to pass the night at Secheron, a village at the distance of half a league from the city. The sky was serene; and, as I was unable to rest, I resolved to visit the spot where my poor William had been murdered. As I could not pass through the town, I was obliged to cross the lake in a boat to arrive at Plainpalais [a neighborhood in Geneva]. During this short voyage I saw the lightning playing on the summit of Mont Blanc in the most beautiful figures. The storm appeared to approach rapidly, and, on landing, I ascended a low hill, that I might observe its progress. It advanced; the heavens were clouded, and I soon felt the rain coming slowly in large drops, but its violence quickly increased.

Credit: Google Maps.

After leaving Geneva, we traveled northwest to Paris, France. The bus ride took about half a day.

Ascending the Eiffel Tower was an unforgettable, once-in-a-lifetime experience. The Eiffel Tower has appeared in a wide range of literary works, often serving as a powerful symbol of Paris and of modernity itself.

Nineteenth-century writers such as Guy de Maupassant, Jules Verne, Paul Verlaine, and Stéphane Mallarmé reacted to the tower with fascination or skepticism, using it to reflect the cultural tensions of their time. In the twentieth century, authors like Ernest Hemingway and George Orwell wove the tower into their narratives as part of the Parisian landscape that shaped their experiences. More recent works, including Muriel Barbery’s The Elegance of the Hedgehog (French: L'Élégance du hérisson, Gallimard, 2006), continue to feature the tower, using it to evoke beauty, individuality, or the complexities of Parisian life.

From the Eiffel Tower, you can see the Seine River winding through Paris, a city that is mostly flat except for gentle hills like Montmartre.

Paris has occupied a central place in Western literature for centuries, evolving from a medieval religious and political center into a modern symbol of art, culture, and cosmopolitan life. In medieval and early modern texts, Paris often appears as a setting of learning and power, home to the Sorbonne and the royal court. Writers such as François Villon captured the city’s bustling streets and its moral contradictions, while Renaissance authors portrayed Paris as both a refined cultural center and a place of intense religious and political conflict.

By the nineteenth century, Paris emerged as one of literature’s most vividly rendered cities. Romantic and Realist writers including Victor Hugo, Honoré de Balzac, and Émile Zola depicted Paris as a dynamic, often turbulent space shaped by revolution, industrialization, and rapid urban change. Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) immortalized medieval Paris, while Balzac’s La Comédie (1829-48, a multi-volume collection of interlinked novels and short stories) humaine mapped the city’s social hierarchy, and Zola’s novels explored working-class life and modernization. The Impressionist atmosphere of the Belle Époque brought new literary portrayals as well, with poets like Baudelaire transforming the Parisian streets into symbols of modernity, alienation, and artistic inspiration.

In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Paris became synonymous with literary experimentation and expatriate creativity. The Lost Generation Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Stein wrote about the city as a vibrant center of artistic freedom, while postwar authors such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Marguerite Duras explored its existential and psychological dimensions. Contemporary literature continues to portray Paris as a city of contrasts: elegant yet ordinary, historic yet ever-changing. Through centuries of writing, Paris has become not only a setting but also a character—a place that reflects shifting cultural ideals, personal transformations, and the evolving complexities of modern life.

Les Deux Magots in Paris is one of the city’s most historic literary cafés. It was famously frequented by Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, who often met here to write and discuss philosophy. The café became a gathering place for many leading intellectuals of the twentieth century. Its elegant interior and terrace continue to attract visitors from around the world. Today, the square in front of the café is named in honor of Sartre and Beauvoir, reflecting their long association with this iconic spot.

We went inside the café because we needed to use the restroom; public facilities can be difficult to find in Europe. Although our tour guide knew the owner, not all of us were permitted to use it. The group was simply too large for the staff to accommodate.

These statues of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Pierre Corneille stand in Place du Panthéon in Paris’s Latin Quarter, honoring two of France’s most influential writers. Located just outside the Panthéon, a monument dedicated to the nation’s greatest figures, they mark the city’s deep literary and philosophical heritage. Rousseau, the Enlightenment thinker, and Corneille, the great classical dramatist, are commemorated here with dignified stone sculptures that reflect their lasting impact on French culture. Visitors walking through the square encounter these monuments as reminders of Paris’s long-standing devotion to the life of the mind.

The Panthéon in Paris bears the inscription “Aux grands hommes la patrie reconnaissante” on its front pediment. Translated into English, it means “To the great men, the grateful homeland.” This inscription reflects the Panthéon’s role as a mausoleum honoring France’s most distinguished citizens, including writers, scientists, and political figures. It emphasizes the nation’s recognition and gratitude for their contributions to French culture, thought, and history.

This building near the Panthéon displays the names of two major universities, Paris I (Panthéon-Sorbonne) and Paris II (PanthéonAssas), reflecting the historic legacy of the University of Paris. Paris I is known for its programs in humanities, social sciences, law, and economics, while Paris II is particularly renowned for law and political studies. The inscriptions connect the building to centuries of French intellectual and academic tradition.

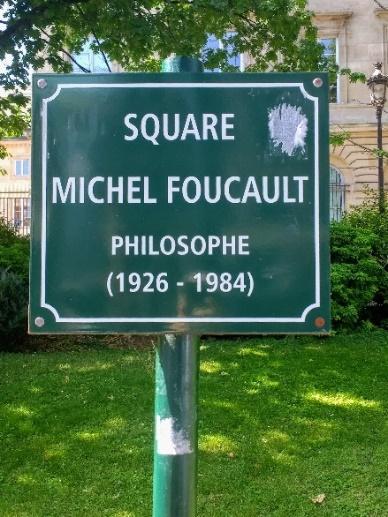

Many notable thinkers, writers, and public figures are associated with these institutions, including Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Michel Foucault, and Raymond Aron. The universities continue to serve as centers of learning and debate, maintaining the Panthéon area’s reputation as a hub of scholarship and culture in Paris.

University of Paris buildings, including those of Sorbonne. The Sorbonne, specifically Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, offers a wide range of programs primarily in the humanities, social sciences, law, and economics.