DAM FINE STREET DESIGN

An investigation into Dutch street design principles in Amsterdam, Netherlands

An investigation into Dutch street design principles in Amsterdam, Netherlands

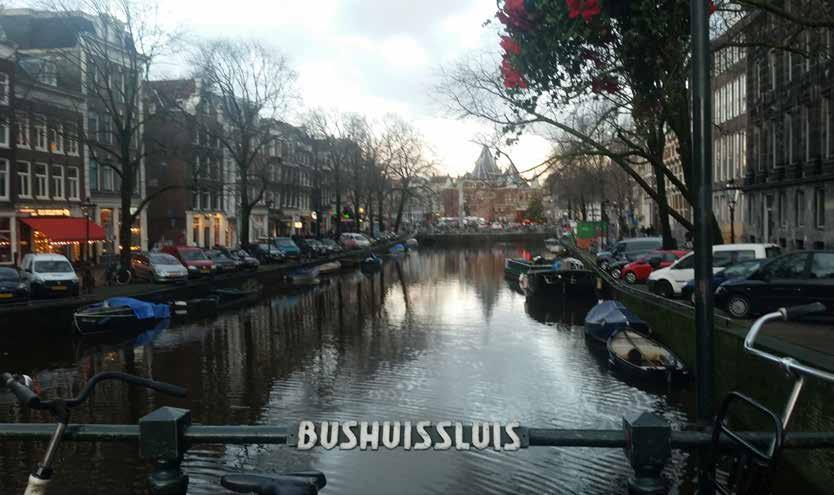

My first experience with the city as a student at the University of Amsterdam

An MKSK TREK to Amsterdam allowed me to dive deeper into how my lingering impression of the city was shaped by intentional urban design and policy

WHAT DOES THIS TREK SEEK TO UNDERSTAND?

Q1: HOW CAN STREETS MAXIMIZE THE SOCIAL LIFE OF A CITY?

Q2: WHAT DESIGN ELEMENTS CAN PROMOTE A COMFORTABLE USER EXPERIENCE?

WHAT DOES THIS TREK SEEK TO UNDERSTAND?

Q1: HOW CAN STREETS MAXIMIZE THE SOCIAL LIFE OF A CITY?

Q2: WHAT DESIGN ELEMENTS CAN PROMOTE A COMFORTABLE USER EXPERIENCE?

Q3: IS STREET DESIGN IN AMSTERDAM HANDLED EQUITABLY?

WHERE AND HOW WOULD I BE INVESTIGATING THESE TOPICS?

MONDAY:

1. Prins Hendrikkade (street)

Oosterpark (Park and

TUESDAY:

2. Waterlooplein (street)

3. Plantage Middenlaan (street)

Bijlmermeer (neighborhood)

WEDNESDAY:

Pijp (neighborhood)

PREPARATION FOR SITE VISITS:

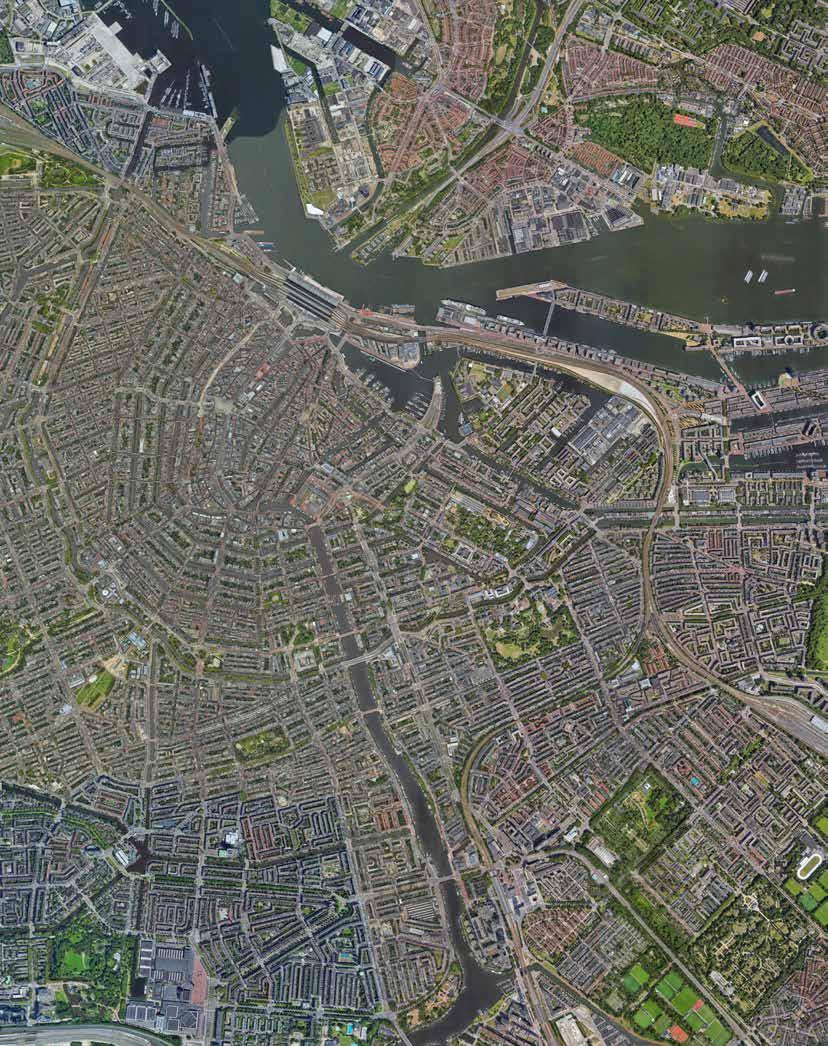

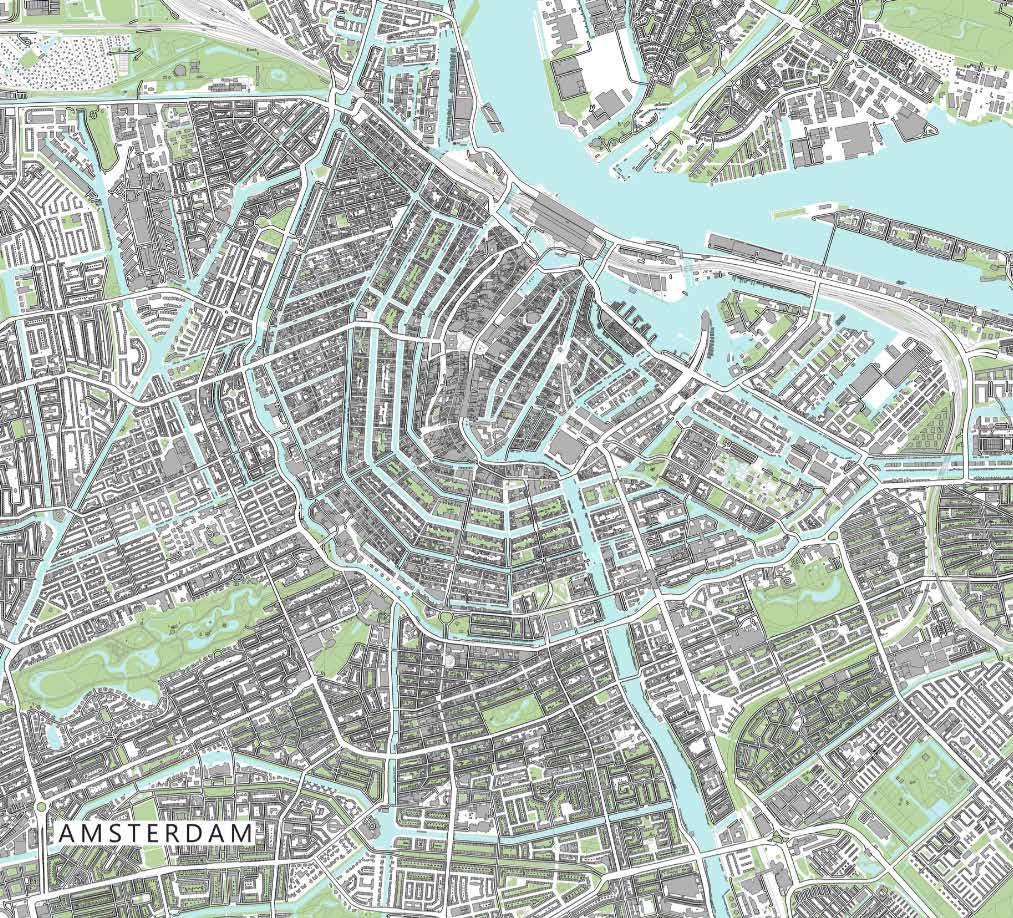

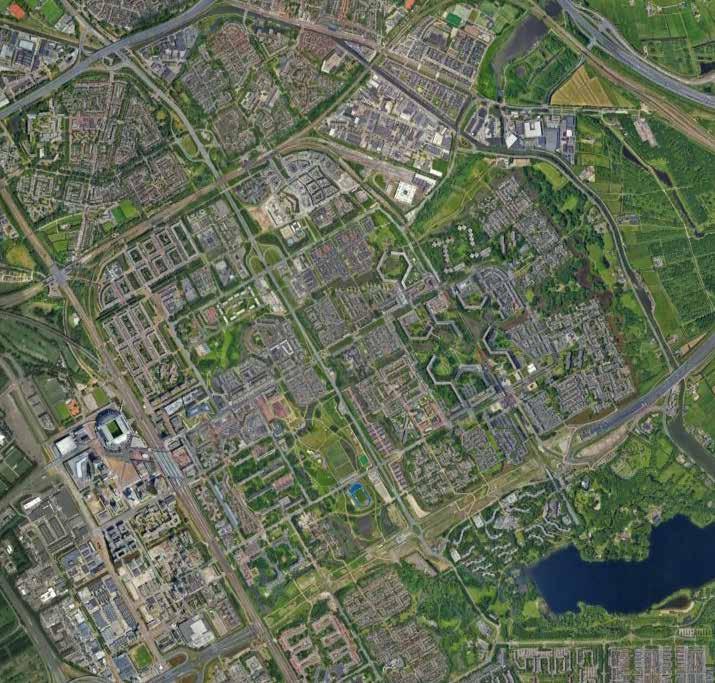

Taking its name from the construction of a dam on the Amstel river, Amsterdam has a population of 918,100 held in a metro area of 65 square miles. The historic city center is only 3 square miles, organized by 9 major canals.

68% 1IN 4 OF DAILY COMMUTES ARE BY BICYCLES OF CITIZENS DO NOT OWN A CAR (IN CITY CENTER)

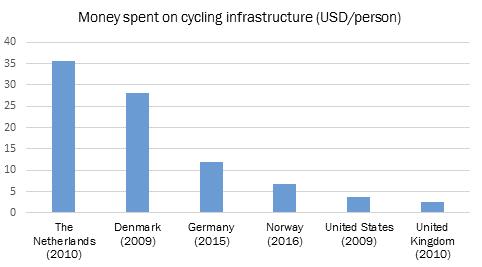

These stats make it easy to forget that Amsterdam had to intentionally move away from the car-centric model that threatened to transform the city in the 1970s.

POPULATION: 918,000

SIZE: 65 SQ MI

DENSITY: 12,710/SQ MI

Amsterdams tram lines are robust, with transfers to bus and railway stops available at many stations. A single ride costs 3.50, with discounts for multi-day, weekly, and monthly rates. The tram is used both by daily commuters and tourists looking for quick connections to museums, city landmarks, and markets throughout the city.

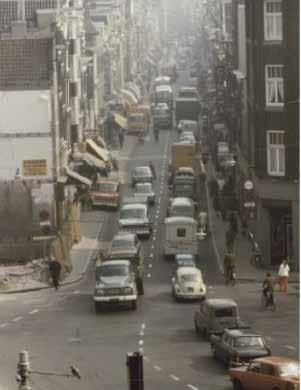

It’s true that Amsterdam was an early adopter of the bike, but so were places like Brooklyn and Copenhagen. As post World War II incomes rose, so did the purchasing of cars, not unlike what was happening in America.

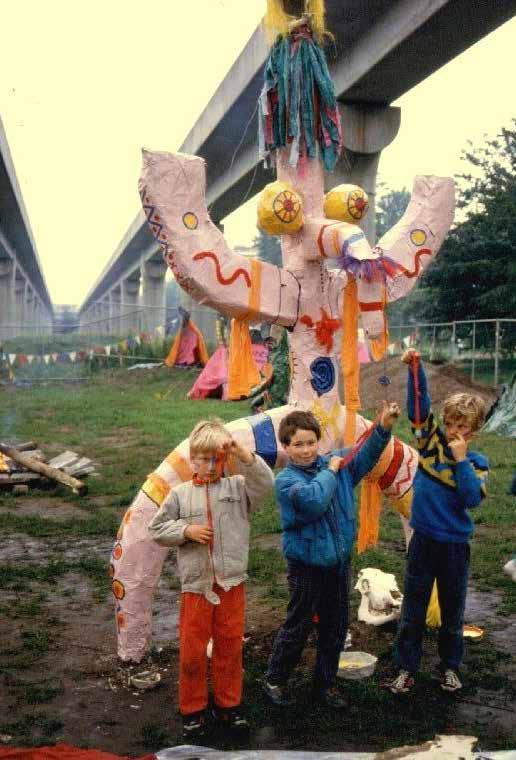

In the 70’s an 80’s the Dutch prepared to tear down parts of the city for highway ramps and replace public spaces with multi-level parking garages. Growing traffic caused a record amount of pedestrian deaths, and there was increasing concern for the safety of children who biked to school. Instead of the response being “I’ll drive my child to school,” Parents and concerned Citizens began to protest in numerous ways. Eventually the city responded with reflective policy changes, for example implementing “car free Sunday’s” to encourage people to enjoy the city at a slower pace. It was not a transformation that happened overnight.

The images displayed to the left illustrate appealing transformation from an auto-centric Amsterdam into the picture we hold of the city today. This street life would not be possible if it weren’t for decades of rejection of modernist ideas, where the car was king. The next slide illustrates the decades of work it took for policy maker and municipal leadership to legitimize the call for safer, human-scale infrastructure investment.

During the post Great War era, bicycle use began to catch on at a mass-scale level. By the mid-1930’s, every second citizen owned a bike Bicycle paths reached 800+ miles and funds were made available for future expansion.

The need to rebuild the country post WWII gave Dutch planners the option to transition the urban fabric into a modern, car based transportation system. The car was framed as the symbol of freedom and an expresion of modernism

The Provo’s, an anarchistic political organization with strong views against mass motorization, painty fifty bikes white and left the unlocked all over amsterdam. Though the “protest” did not last long, the idea resonated all over the country and is considered the first example of a bicycle share program

A prominent news outlet published a plan for a highway system, with a belief that pro-car policies were the way of the future. The outcome was a huge political impact; the financial implications and politial protests created a window for the prioritization of cycling in infrastructure and planning visions.

A 1975 plan for Amsterdam proposed the teardown of a historic district to create offices, university buildings, and luxury shops. The “modernist” vision clashed with the needs of residents; fierce resistence forced the municipality to change the plan to prioritize pedestrians, low speed, and small scale improvements.

CYCLING ON THE POLITICAL AGENDA

Municipalities subsidized up to 80% of cycling infrastructure costs. The city of Delft was the first to draft a cycling plan for its entire city. There with simultaneous plans and policies executed to improve safety, comfort, and integration between public transit and cycling.

HIGH BICYCLE USE POSITIVELY IMPACTS THE HEALTH, LIVABILITY, AND ACCESSABILITY OF DUTCH CITIZENS

At a national level, there are diect economic impacts. The return on investment grows exponentially if you account for social benefits. Not to mention even car users receive a benefit from increased cycling numbers; a study preformed by waze ranks the Netherlands as the least congested contry in the world, due to decreased traffic times for drivers and public transit users alike.

$1.5B $35/CAPITA $20B 24,200 MILES 6 MONTHS 1 IN 4

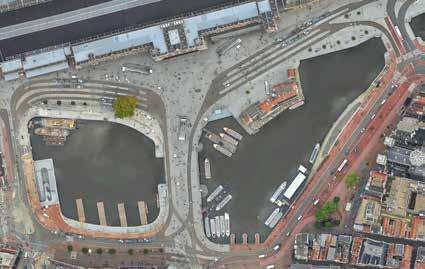

• East/West Connector of Central Station to historic CBD and institutional anchors at the waterfront. Widens and narrows to accommodate boat docks, plazas, canal bridges, and trams, cars, and tourism.

• Busy roadway that experiences congestion during rush hour times and with tourism peaks.

• No steep grade changes, fluctuation of shared vs segregated bike lanes, changes to “complete street” elements where roadway narrows.

TRANSIT TYPES SUPPORTED

Pedestrian Bike Tram Car

• Your first impression of the city; sweeping waterfront views, ornate historic buildings, tourism traps galore, an international melting pot of choices

• Organized chaos - traffic is slow moving, and there is very little organization to the main plaza space off of the entry into Central Station; as if giving no one the right of way will e encourage all users to exercise caution.

• The city center requires vigilance among interweaving bike lanes the crowded sidewalk. Here, at the entrance to the city, is an opportunity for assimilation. In getting comfortable with being uncomfortable, you are acclimating to the new invironment in a low stakes environment, because no mode is moving very fast

• Cars are kep to the peremeter of the plaza

Often, the uses of various parts of the road are cued via the style, shape and coloration of paver materials, which are standardized across the city

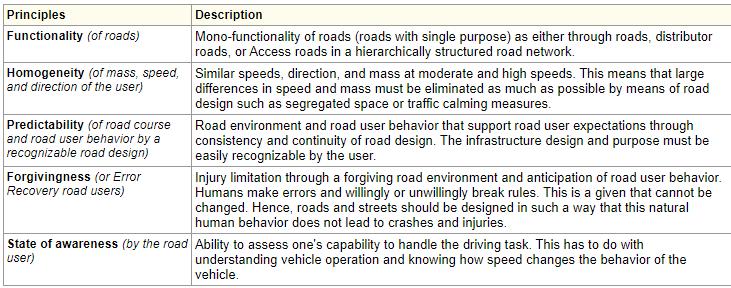

If you step out of line, you are gently coerced back into place. Humans are innately error-prone, so road design must be forgiving, minimizing the ill effects of mistakes.

• A busy connector road serving multiple arts and culture destinations in the city

• A commercially active street with shops, restaurants, performance halls, and daily flea market

• Road widths and traffic patterns are variable; fluctuates from very wide with segregated bike lanes to narrow with integrated lanes for all mode types

TRANSIT TYPES SUPPORTED

• From the bike, options are overwhelming of how to navigate the street and stay out of others way

• Bike lanes remain separate on the higher speed sections of the street, yet converge into shared car and tram lanes where the street narrows

• More instructional signage and traffic signaling present to keep intersections safe

• Wide sidewalks connecting to pedestrian plaza spaces present throughout, prioritizing the comfort of those on foot

• Bikers must remain vigilant to navigate a fluctuating right of way

• Waterlooplein is a higher speed road as it provides many inner city connections, yet does not exceed 30 MPH for automobiles.

Probably due to the nature of the historic city center, wide streets can narrow into a single lane unexpectedly. Pedestrians always get dedicated space

INTERSECTIONS REDUCE POINTS OF CONFLICT WHEREVER POSSIBLE

Multi-modal streets require cars, trams, and bikes to share lanes often; intersections have different requirements

• Located in the quieter plantage neighborhood of Amsterdam, Plantage Middenlan is a comfortable, efficient connector road for the smaller residential streets around it.

• The road itself has less of a presence than its perpendicular offshoots, however there is still strong building frontage along the roads. The environment on and around this street is leisurely, with many children and families enjoying museums, cafes, and views of the canals.

TRANSIT TYPES SUPPORTED

Pedestrian Bike Tram Car

• Traffic noise, stress, and blood pressure drops; this green street visually continues an adjacent park space, connecting it into the Botanical Garden across the street.

• Cars are only banned for about .1 miles of the road; because of its strategic positioning, the impact of traffic at the nearby bridge crossing is much larger

• Since the 1980s, the space for cars has gradually been reallocated to pedestrians, cyclists and the tram. In 2015 cars were banned completely from the first part of Plantage Middenlaan at Wertheimpark. This is a result of the yearlong policy of reducing car traffic in the city.

• Grass in place of asphalt helps to capture water in periods of heavy rainfall –an issue increasingly common due to the impacts of climate change

CAR-BANNED SPACES DO NOT NEED TO BE LARGE TO BE EFFECTIVE

This stretch of road is only .1 miles long, but is used for both traffic mitigation and strengthening of the character and presence of 2 adjacent neighborhood amenities

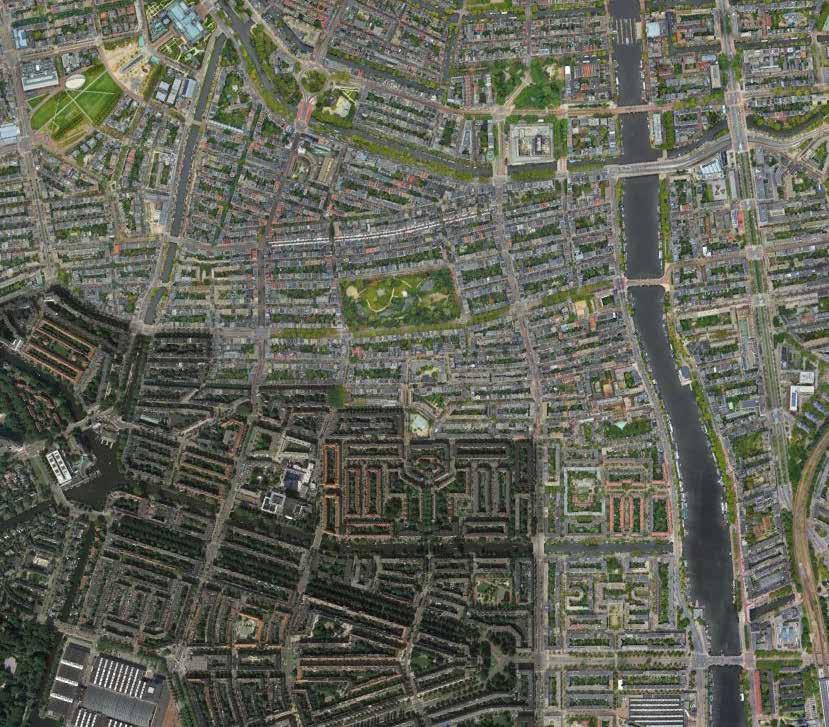

• Once a patch of windmill-studded agricultural land, De Pijp was rapidly redeveloped to make room for Amsterdam’s growing population. The existing canals were filled in by the long roads crammed with tightly-packed workers’ apartments that give the neighborhood its distinct character today.

• The name De Pijp (the pipe) is perhaps a reference to the stream of commuters funneling through the narrow streets each morning.

TRANSIT TYPES SUPPORTED

Woonerf is the dutch term for a living street. Due to the long consistent block patterns of the De Pijp neighborhood, there is great opportunity to convert these streetscapes into woonerf-like designs.

This Dutch concept embraces the idea of a “living street” with room for pedestrians, cyclists and deos not exclude cars. The street is seen as a social space rather than a space for vehicles to get from point A to point B. The woonerf concept was developed in Delft, netherlands in the 1960’s

• Accessible by tram, bus, bike, or foot Oosterpark was the first municipally constructed park and serves the diverse Eastern Amsterdam. Many of the newcomers settle in this part of the city from Suriname, Turkey, Morocco and more recently from Eastern Europe, live in the area.

• Experiencing the neighborhood around the park was calm; minimal traffic signals at intersections, and bike paths traverse in and out of the park, through access points on all sides.

Pedestrian Bike Tram Car

The Bijlmer was envisioned as a modern, functional, ‘radiant city’ for ‘the new man.’

Based on the concepts of Swiss architect Le Corbusier about urban design attuned to modernity and living conditions in crowded cities, the Bijlmer was meant to be a utopia that separated living, work, recreation and transport. It was a unique experiment of urban planning in the Netherlands.

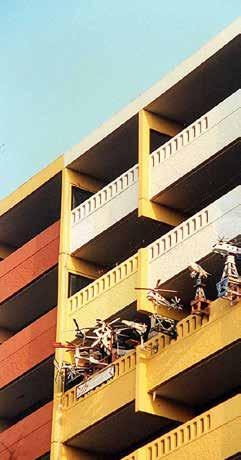

The original design of the Bijlmer was characterized by large high-rise housing blocks with spacious, bright apartments. Motorised traffic was elevated above the living area, parking space was minimised by multi-story garages, and there were different roads for bikes and pedestrians.

1968

Bijlmermeer construction is completed, the first residents move in.

1980s

By the end of the 1980s the Bijlmer had the garnered the reputation of an unruly ghetto. Around 50 percent of Bijlmer residents were unemployed, relying on social benefits to make a living. The Bijlmer was far from a ‘functional and radiant’ city.

1977

The construction of the first metro connection is completed

Poor public transportation infrastructure in a remote neighbourhood translated into barriers to employment, education, social and cultural activities.

1990s

Amsterdam, the city council of South East and the social housing corporations decided for a large scale renewing operation of the Bijlmer area. This plan combined renewal of the physical environment, socio-economic renewal and renewal of the administration of the area. Most crucial in this plan was the decision to depart from the ideal of the functional city and rather to reunite living, working, traffic and recreation.

“My meaning about the Bijlmermeer as I remember it: Flats, Exciting, Mysterious, Grey, Ghostly feeling in the inner streets, Cycling, Lots of Fun, Conviviality, Different Nationalities from which I have also learned something positive, Even though the Bijlmermeer is also negative the news came, I also have a nice reminder of it. It didn’t bore me. It’s a shame that the municipality had a completely wrong policy, now the Bijlmermeer of the time only remains in my thoughts.”

Currently the Bijlmer hosts more then 130 different nationalities. This information in itself is impressive but the multiculturalism of the Bijlmer can be appreciated a lot more after chatting with people on the street who invariably point out the Bijlmer is their home. Institutions celebrating the history of the neighborhood, regardless of being public condemned, celebrating what once was, a snapshot of history in what was blossomed out of a “falure” of a design idea

The vision of the architecturally determined renewal of the Bijlmer should be criticized in two ways. Firstly, the Bijlmer is portrayed as a quasi-historical area that it has never been and will never become. Secondly, the Bijlmer’s renewal scheme is depicted as an ‘organic model’, referring to a form of natural growth of the existing neighbourhood. Yet replacing almost all of the Bijlmer’s urban tissue is nothing less than just another technocratic ‘drawing board plan’ that waits to be written off as a success or a failure.

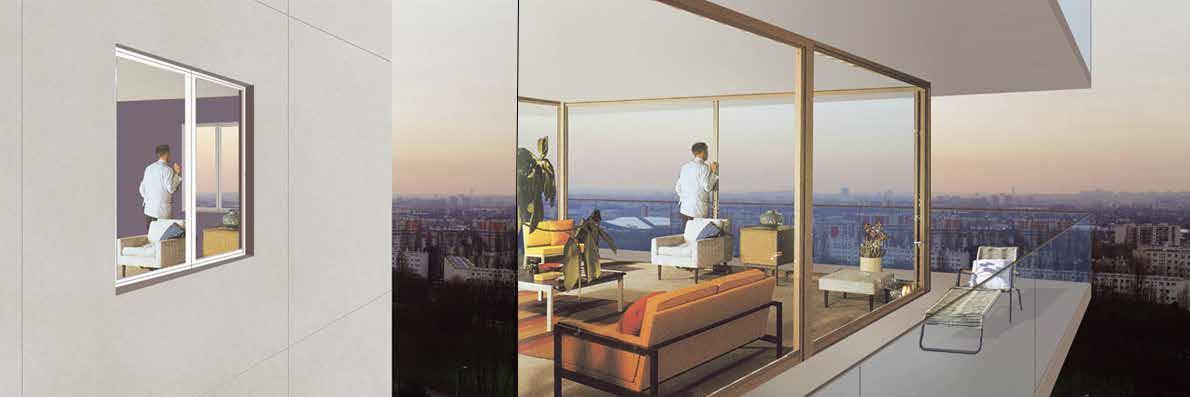

The neighborhood has been studied by urban institutions through a lense of design; among the solutions presented are 1) infil of stepped down residential structures in the wide open spaces to create opportunitites for street life and character within public spaces 2) the renovation of high rises and treatment of exterior building facades to introduce more airy materials such as glass.

The roads are wider, and there is a feeling of living living outside of the dutch fairy tale. The rules of efficiency from the CBD of Amsterdam to accomodate large distances; a hatchwork of streets going in the same direction are required to make connections between living quarters, amenity spaces, and main roades. For its distadvanges to bikers and pedestrians, points of conflict between cars and other users is virtually non-existent.

points of interest and activity are grouped together for walkabilities sake by today’s residents, which the rest of the network is sprawling; public food markets, places of worship, and reently installed recreation facilities occupy the same .25 miles, even though the nieghborhood of Bijlmermeer allows these amenities to spread out if desired.

Surface parking lots do exist in Amsterdam! Roundabouts rule! You can see the inspiration modernist planners felt at the time to build cities that were less focused on small scale beauty and more impressive from a wide-lense vantage point.

EXPERIENTIAL INSIGHTS

DESIGN SHOULD BE SELF EXPLANATORY:

As planners we communicate where and how to use the road through materials and straightforward networks. Language can only accompany clarity of design

EXPERIENTIAL INSIGHTS

DESIGN SHOULD BE SELF EXPLANATORY:

As planners we communicate where and how to use the road through materials and straightforward networks. Language can only accompany clarity of design

MINIMALISM IS SUSTAINABLE:

There isnt room for mistakes on roads with as many constraints as Amsterdam

EXPERIENTIAL INSIGHTS

DESIGN SHOULD BE SELF EXPLANATORY:

As planners we communicate where and how to use the road through materials and straightforward networks. Language can only accompany clarity of design

MINIMALISM IS SUSTAINABLE:

There isnt room for mistakes on roads with as many constraints as Amsterdam

REMOVE POINTS OF DECISION MAKING:

There is no problem where bikes, cars, and trams share lanes and roadspace, as long as users aren’t able to make conflicting decisions at intersections of where their lanes cross

DESIGN LESSONS LEARNED

CONSCIOUS MOBILITY NETWORK PLANNING:

1. Encourage the design of street networks that take up as little space as possible, while working efficiently

2. Place discomfort on cars in shared street designs

3. Create networks that move at a slow pace

DUTCH POLICY SUPPORT

CONSCIOUS MOBILITY NETWORK PLANNING:

The Dutch have ratings of the appropriate degree of separation for multi-modal streets; the appropriate use of each is determined through a matrix of sustainable safety, and implemented with a set of design standards

DESIGN LESSONS LEARNED

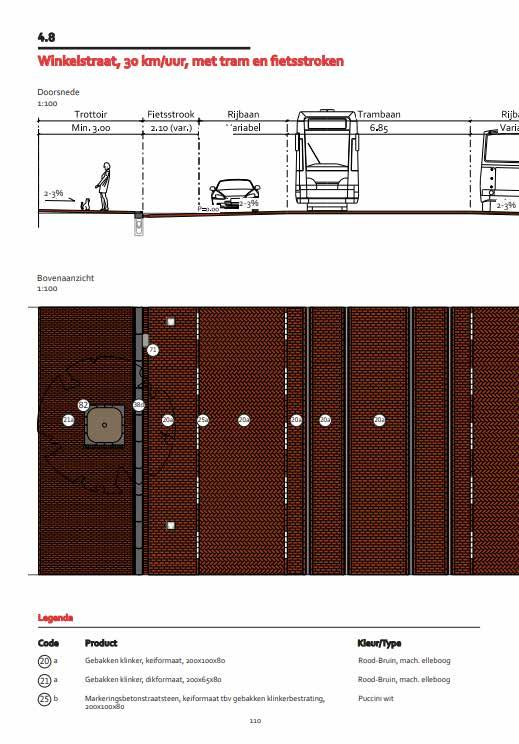

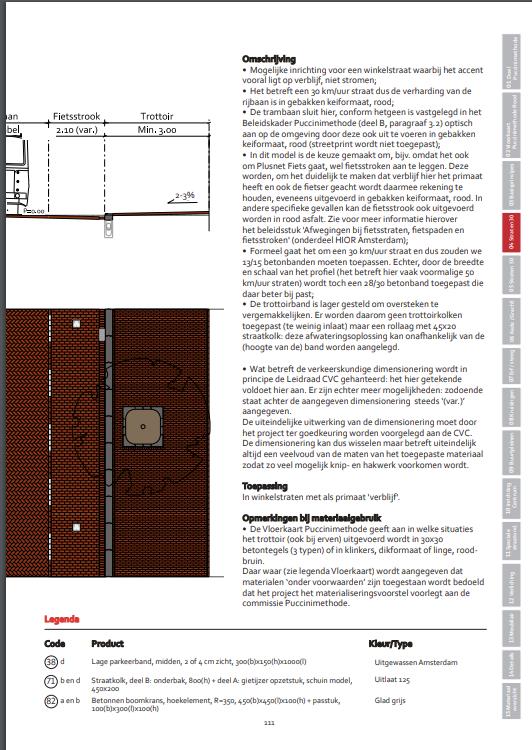

THE PUCCINI STANDARD:

The Dutch have a users manual to the Puccini Standard, their design standards for planning streets for the entirety of the city

The manual breaks down the city into zones, and includes detailing for paver types, landscaping, street networking patters, and any other visualizations of street design

THE PUCCINI STANDARD:

The Dutch have a users manual to the Puccini Standard, their design standards for planning streets for the entirety of the city

The manual breaks down the city into zones, and includes detailing for paver types, landscaping, street networking patters, and any other visualizations of street design

DESIGN LESSON LEARNED

YES, BUT THE CITY HAS ITS FLAWS:

Walking, cycling, and public transit may be inherently more equitable ways to get around the city; depending on the mobility of the individual.

However, Amsterdam is an old city, and struggles with acessibility due to the preserved original urban fabric

OPPORTUNITY FOR PUBLIC INPUT:

Amsterdam has ongoing portals for public input about how their streets should look, and what design elements are desired

There are robust programs for replacing broken pavers, patching damages to traffic lanes, constant restriping of crosswalks

Amsterdam’s history of human-oreinted street design is rooted in public protest, of call and response between the residents and city leadership leadership

• sociallifeproject.org

• amsterdam.nl

• urbancyclinginstitute.org

• international.fhwa.dot.gov/pubs

• streets-alive-yarra.org

• echo-urbandesign.com

• dutchreview.com/culture

• uva.nl/en

• bijlmermuseum.files.wordpress.com

QUESTIONS?