Volume 107

Number 6

November/December 2025

How To Not Be

Sexist Outdoors, p. 14

Apps ... Apps ... Apps, p. 17

Build a Better Backcountry First Aid Kit, p. 19

The Art of Passing on Multipitch, p. 21

From Collapse to Confidence: A Mazama Leader’s Food Journey, p. 24

She Climbs High Part II: Mazama Women Hit Their Stride, p. 26

What I Learned Leading Eight Mazamas Through the Enchantments, p. 29

Mount St. Helens Medley, p. 32

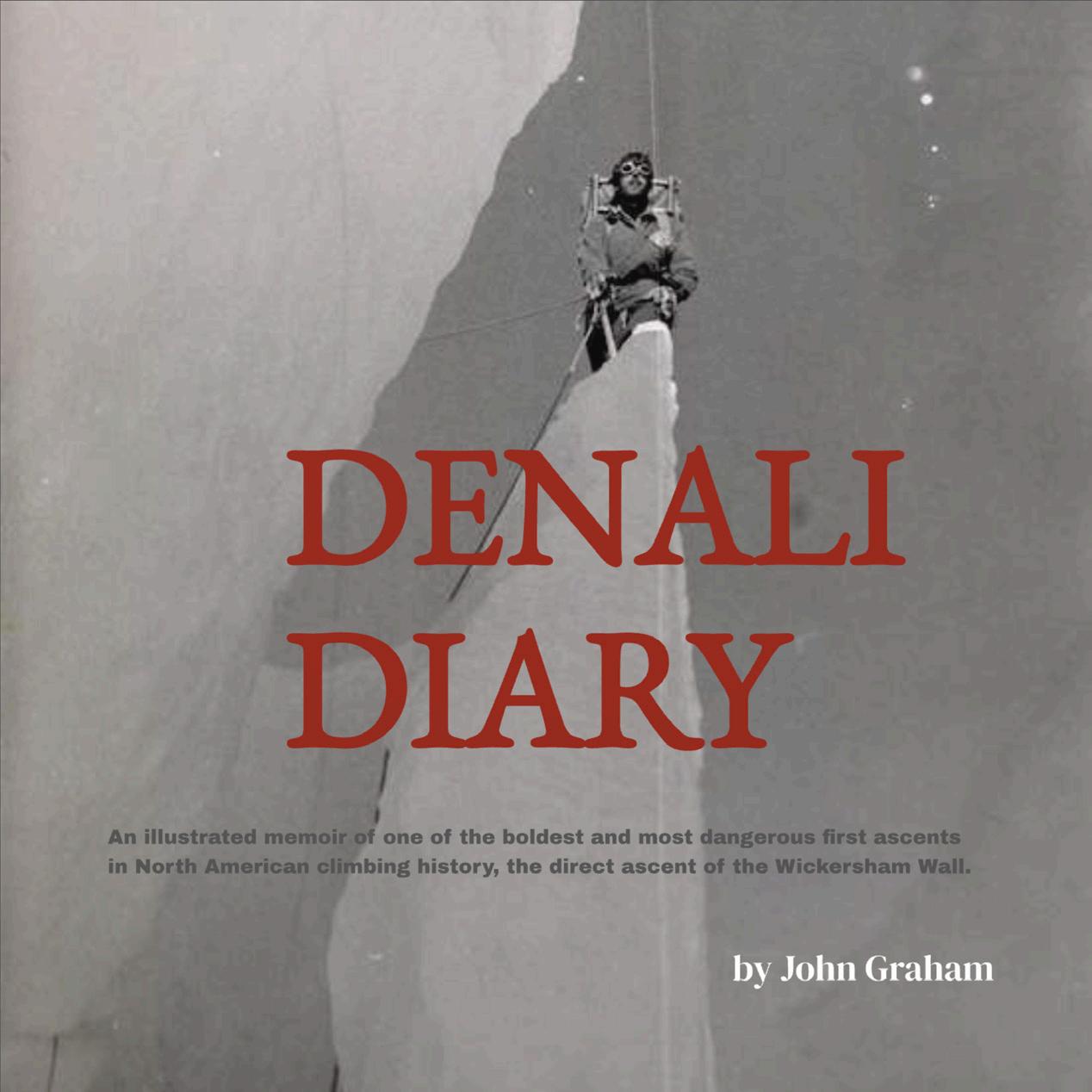

Denali Diary, p. 34

Messenger on the Mountain, p. 36

Mazama Base Camp Fall 2025 Program, p. 4

Upcoming Courses, Activities & Events, p. 6

Mazama Supporters, p. 8

Successful Climbers, p. 10

New Members, p. 11

Critical Incident Stress Management Survey, p. 11

Saying Goodbye, p. 11

Letter from the Editor, p. 13

Board of Directors Minutes, p. 37

Cover: Members of the 2025 Mazama BCEP Team 11, Mount Defiance February 25, 2025.

Photo: Sergey Kiselev

Above: Mountain goat in the Enchantments, 2025.

While most Mazama members are inclusive and supportive of women, there are still opportunities for growth so that we can all feel more comfortable in outdoor spaces.” p. 14

No one told us that we were too young, too inexperienced and too poorly equipped. It wouldn’t have mattered if they had.” p. 34

Sometimes the most enduring memory of a climb is not the view from the top, but the life you meet along the way.” p. 36

by Mathew Brock, Mazama Bulletin Editor

Welcome to the November/ December Mazama Bulletin! As we close out 2025, this issue celebrates the diverse ways we challenge ourselves, support one another, and grow within our community.

We begin with Aimee Frazier’s thoughtful piece on creating more inclusive outdoor spaces (p. 14). Her insights on recognizing and addressing subtle forms of sexism outdoors offer practical guidance for building the welcoming community we aspire to be. It’s a conversation that benefits everyone who ventures into the mountains together.

Technology continues to enhance our outdoor experiences, and Patti Beardsley’s comprehensive guide to outdoor apps (p. 18) equips you with digital tools for everything from navigation and bird identification to avalanche safety and knot tying. Whether you’re a techie or prefer oldschool adventures, these resources can enhance your outdoor experience.

Safety remains paramount in everything the Mazamas do. Duncan Hart and Nick Ostini from the First Aid Committee provide essential guidance for building a wilderness first aid kit (p. 20), while Angie Brown and Damon Greenshields share the nuanced art of passing other parties on multipitch climbs (p. 22)—a skill that requires both technical knowledge and interpersonal grace.

This issue also features deeply personal stories of growth and development. Luke Davis shares his journey of overcoming eating challenges to successfully lead multiday backpacking trips (p. 25), offering insights that may help others facing similar struggles.

We continue our historical series with part two of Amy Brose and Rick Craycraft’s exploration of pioneering Mazama women leaders from the 1940s through 1960s (page 28). These stories of barrier-breaking leaders like Peggy Norene, Marianne Gerke, and Dorothy Rich remind us that today’s inclusive community stands on the

shoulders of those who fought for their place in the mountains.

From the field, Luke Davis returns to recount the challenges and rewards of leading eight Mazamas through the Enchantments (p. 29), while Rex Breunsbach captures the Mount St. Helens Medley tradition (p. 32). John Grahm takes us back to 1963 with excerpts from his memoir of the legendary first ascent of Denali’s north wall (p. 34), and Douglas Filiak shares a memorable wildlife encounter atop Mt. Adams (p. 36).

Throughout these pages, you’ll find the practical resources you’ve come to expect: course announcements, successful climbers, new members, and upcoming Base Camp programs.

This issue reflects what makes the Mazama community special—skill development, historical appreciation, inclusive leadership, and the simple joy of sharing remarkable experiences in unusual places.

Happy reading, and we’ll see you on the trail!

Learn more about how you can integrate charitable giving to support the Mazamas.

Whether you’re considering a bequest in your will, setting up a charitable remainder trust, or exploring other options, by including a planned gift in your legacy, you’ll secure our continued success while ensuring that your passion endures for generations to come.

If you’ve already decided to include the Mazamas in your estate plans, we invite you to let us know. You’ll want to be sure that you’ve recorded the Mazamas with the Tax ID (EIN) 93-0408077.

Even ordinary people can make an extraordinary difference.

Dates: November 12

Time: 7 p.m.

Location: Zoom

Cost: Free

Join us for an informational session about the Advanced Rock Program on Nov. 12 at 7 p.m. via Zoom.

Learn about this comprehensive course that covers the essentials of traditional climbing, including placing gear, building anchors, and performing high-angle rescue techniques. This program prepares climbers for advanced technical skills needed for multi-pitch traditional climbing.

Applications for the 2026 AR class open soon, so this is your opportunity to get details about the course curriculum, admissions process, and requirements. Bring your questions—we’ll have answers.

Applications open: late November, 2025

Dates: February 17–May 19, 2026

Location: Mazama Mountaineering Center

Build your lead-climbing confidence in the Mazama Advanced Rock course. Running February–May, AR develops your skills for single-pitch, multi-pitch, and alpine rock: gear placement, anchor building, lead strategy, rescue, and trip planning. Expect 11 lectures, hands-on demos, and seven weekend field sessions, plus community outings into fall. Admissions testing takes place in early January. Participation in all sessions is required; tuition assistance and payment plans are available. Questions? Email ar@mazamas.org.

Check www.mazamas.org/AR for up-todate info.

Date: Thursday, November 27

Time: 4 p.m., Dinner at 5 p.m.

Location: Mazama Lodge

Cost: Dinner $15 – $30, Lodging $35 – $280

Join us for one of our most cherished traditions—a Thanksgiving celebration where friends and family gather in the heart of the mountains to share warmth, laughter, and an unforgettable feast.

Your day begins at noon when the Lodge opens its doors. Work up an appetite with a scenic 1 p.m. snowshoe adventure or leisurely hike through the winter landscape, returning by 4 p.m. to the cozy comfort of the Lodge.

As the afternoon settles in, savor delicious appetizers at 4 p.m. before sitting down to a bountiful Thanksgiving dinner at 5 p.m. It’s more than a meal—it’s an experience filled with joy, connection, and memories that will last a lifetime. Check the calendar on mazamas.org to learn more and sign up.

Applications close: December 1, 2025

Date: December 2, 2025

Time: 6:30–8 p.m.

Location: Mazama Mountaineering Center

Cost: $40 members / $40 nonmembers

In backcountry emergencies, epinephrine is the only anaphylaxis treatment—and 15 minutes can save a life. Oregon law (ORS 433.800-433.830) permits trained individuals to administer lifesaving treatment when healthcare professionals aren’t available.

Students will attend a December 2 physician-led classroom course. Graduates may obtain epinephrine autoinjectors from pharmacies at their own expense (not covered by Mazamas). The course includes optional naloxone rescue training for opioid overdoses.

Date: Wednesday, December 3, 2025

Time: 6–8 p.m.

Location: Nordic Northwest

The Mazamas has hundreds of volunteers, and many have given their time, talent, and expertise for decades. In any given week, they are lecturing, leading climbs, taking people on hikes and rambles, strapping on skis, strategizing about conservation, and more.

The organization could not function without our volunteers, and we can’t wait to honor them. Please mark your calendars and join us for this year’s Volunteer Appreciation Night Wednesday, December 3 at Nordic Northwest in southwest Portland. It’s a night of celebration with great appetizers, drinks, and company. We’ll be unveiling the winners of our prestigious service awards and the newly elected 2026 Board of Directors!

This event is made possible by a generous bequest from Yun Long Ong, whose love for the Mazamas called him to lead climbs on all 16 peaks.

Applications close: December 4, 2025

Dates: January 8–February 15, 2026

Location: Mazama Mountaineering Center

Cost: $230 members / $265 nonmembers

Discover your winter stride with the Mazama Nordic Ski School. Tailored to your current ability, this short program helps you level up—whether you’re brand new, an alpine skier seeking a new challenge, or a nordic skier ready for more. Choose Classic or Nordic Backcountry tracks, attend a mandatory orientation, then two consecutive class sessions with a reserved third date for a make-up or optional tour. Students are grouped by skill for safe, focused learning, with classes in late January/early February. Backcountry emphasizes navigation and confident travel off groomed trails, with flexible weekend scheduling to match conditions. Questions? Email nordic@mazamas.org.

Dates: Early January 2026

Location: Zoom

Cost: Free

Join our virtual Info Night in early January 2026 to learn more about the program and the application process. Check the calender on mazamas.org for more info and a Zoom link.

Applications open: mid-January 2026

Dates: March–May, 2026

Location: Mazama Mountaineering Center

Are you looking to gain new skills and confidence in the outdoors? Our eightweek Basic Climbing Education Program teaches rock and snow skills needed to climb snow-covered peaks, rock-climb, and make safety decisions on outdoor trips.

Taught by experienced Mazama leaders, you’ll be a part of an alpine climbing team and introduced to a future of outdoor opportunities with the Mazamas and beyond!

We envision a vibrant, inclusive community united by a shared love for the mountains, advocating passionately for their exploration and preservation.

INCLUSION

We value every member of our community and foster an open, respectful, and welcoming environment where camaraderie and fun thrive.

SAFETY

We prioritize physical and psychological safety through training, risk management, and sound judgment in all activities.

EDUCATION

We promote learning, skillbuilding, and knowledgesharing to deepen understanding and enjoyment of mountain environments.

SERVICE

We celebrate teamwork and volunteerism, working together to serve our community with expertise and generosity.

SUSTAINABILITY

We champion advocacy and stewardship to protect the mountains and preserve our organization’s legacy.

Building a community that inspires everyone to love and protect the mountains.

We gratefully acknowledge contributions received from the following generous friends between September 1, 2024 – September 15, 2025. If we have inadvertently omitted your name or listed it incorrectly, please notify Lena Toney, Development Director, at 971-420-2505.

Anonymous (21)

David W Aaroe and Heidi A Berkman

Patricia Akers

Louis Allen

Stacy Allison

Jerry O Andersen

Dennis H Anderson

Edward L Anderson

Peggy B Anderson

Justin Andrews

Alice Antoinette

Carol M Armatis

Natalie Arndt

Jerry Arnold

Kamilla Aslami

Chuck Aude

Brad Avakian

Gary R Ballou

Tom Bard

Charles & Louis Barker

Dave Barlow

Jerry E Barnes

Michele Scherer Barnett

John E Bauer

Scott R Bauska

Tyler V Bax

Larry Beck

Steven Benson and Lisa Brice

Daven Glenn Berg

Erwin Bergman

Bonnie L Berneck

Bert Berney

Beusse & Porter Foundation

Joesph Bevier

Rachel Bieber

Ken and Nancy Biehler

James F Bily

Pam J. Bishop

Gary Bishop

Bruce H Blank

Anna N. Blumenkron

Peter Boag

Tom G Bode

Andrew Bodien

Barbara Bond

Mike Borden

Jeffrey F Boskind

Brookes Boswell

Steve Boyer

Bob Breivogel

Rex L Breunsbach

Benjamin Briscoe

Scott P. Britell

Alice V Brocoum

Elizabeth Bronder

Richard F Bronder

Amy Brose

Jann O Brown

Anna Browne & Barry Stuart Keller

Barry Buchanan

Carson Bull

Eric Burbano

Joel Burslem

Rick Busing

Neil Cadsawan

Keith Campbell

Patty F Campbell

Ann Marie Caplan

Jeanette E. Caples

Riley Carey

Kenneth S Carlson

Emily Carpenter

John D Carr

Ken Carraro

Marc Carver

Jacob Case

Susan K Cassidy

Rita Charlesworth

Nancy Church

Catherine Ciarlo

Max Ciotti

Matt Cleinman

William F Cloran

Kathleen Cochran

Jeff Coffin

Carol Cogswell

Justin (JC) Colquhoun

Charles Combs

Kristy J Comstock

Brendon Connelly

Toby Contreras

Patti Core Beardsley

Dylan Neil Corbin

Lori Coyner

Darrel M Craft

Adam Cramer

Rick Craycraft

Mark Creevey

Cynthia Cristofani

Tom F Crowder

George Edward Cummings

Julie Dalrymple

Teresa L. Dalsager

Ellen Damaschino

Gail Dana-Sheckley

Alexander S. Danielson

Betty L Davenport

Larry R. Davidson

Tom E Davidson

Howie Davis

Chris Dearth

Edward Decker

Alexander Dedman

Richard G Denman

Sumathi Devarajan

Brad Dewey

Donald Keith Dickson

Sue B Dimin

Jonathan Doman

MaLi Dong

Mark Downing

Robyn Drakeford Wonser

Deborah Driscoll

Keith S Dubanevich

Debbie G. Dwelle & Kirk

Newgard

Richard R Eaton

Heather and Joe Eberhardt

John Egan

Rich Eichen

Toni Eigner

Donna Ellenz

Kent Ellgren

Roland Emetaz

Becky Engel

Mary L Engert

Stephen R Enloe

Bud Erland

Kate Sinnitt Evans

Shelley Everhart

Joshua Ewing

John Facendola

William F Farr

Patrick Feeney

Travis Feracota

Darren Ferris

Aimee Diane Filimoehala

Lilie Chang Fine

Jonathon Fisher

Steven Fisher

Erin Fitzgerald

Ben Fleskes

Peter C Folkestad

Diana Forester

Caroline Foster

Dyanne Foster

Mark Fowler

Joe Frank

Daisy A. Franzini

Aimee Frazier

Michael C. French

Trudi Raz Frengle

Jason Fry

Suzanne Furrer

Brinda Ganesh

Matthew Gantz

Becky Garrett

Kevin Gentry

Paul R Gerdes

Pamela Gilmer

Lise Glancy

Drew Glassroth

John Godino

Zoe Goldblatt

Richard Goldsand

Sandy Gooch

Diana Gordon

Michael Graham

Ali Gray

Dave M Green

Kanjunac Gregga

Shannon Hope Grey

Loren M. Guerriero

Tom & Wendy Guyot

Jacob Wolfgang Haag

Jeff L Hadley

Dan Hafley

Sohaib Haider

Noma L Hanlon

Martin Victor Hanson

Terrance Heath Harrelson

Brook B. Harris

Duncan A Hart

Freda Sherburne & Jeff

Hawkins

Marcus Hecht

Lisa Hefel

Amy Hendrix

Gary Hicks

Elizabeth Hill

Marshall Hill-Tanquist

Maurene Hinds

Natasha Hodas

Frank Hoffman

Gregg A Hoffman

Rick Hoffman

Sue Holcomb

Lehman Holder

Mike Holman

Kris N Holmes

Patty H Holt

Steven Hooker

Michael Hortsch

Charles R Houston

Hal E Howard

Nathan Howell

John A Hubbard

Flora Huber

Chip Hudson

Valoree Hummel

Michael Hynes

Kirsten Jacobson

Rahul Jain

Irene M James-Shultz

Chris Jaworski

Scott Jaworski

Joanne Jene

Brita Johnson

Megan Johnson-Foster

Truth Johnston

Greg J. Jones

Mark Jones

Thomas Jones

Julia Jordan

Nathan Kaul

George Alan Keepers

Anna Browne & Barry Stuart

Keller

Joe Kellar

Jill Kellogg

Shawn Kenner

Charles R Kirk

Sergey Kiselev

Ray Klitzke

Dana S. Knickerbocker

Craig Koon

Chris Kruell

Barbara N Kuehner

Martin Kreidl

Dennis V Kuhnle

Cathy Kurtz

Lori S LaDuke

Richard A LaDuke

Lori A Lahlum

Brenda Jean Lamb

Carol Lane

Jackson Lang

Donald E Lange

Barbara Larrain

Sándor Lau

Nathan Laye

Thuy Le

Petra D LeBaron-Botts

Seth Leonard

Diane M. Lewis

Ernest (Buzz) R Lindahl

Jason N. Linse

Natalie Linton

Margery Linza

Jacob Lippincott

Jeff Litwak

Craig H Llewellyn

Vlad Lobanov

Robert W Lockerby

Christie Lok

Meredith K. Long

Bill E. Lowder

Marine D Lynch

Ted and Kathryn Maas

John L MacDaniels

Alexander L. Macdonald

Christine L Mackert

Joan MacNeill

Patti Magnuson

Ted W Magnuson

Laurie Mapes

Barbara Marquam

Bartholomew “Mac” Martin

Bridget A Martin

Larry G Mastin

James Mater

Donald C. Mather

Allan McAllister

Adam Marion

Robert A McClanathan

Margaret McCue

Mike McGarr

Jamie K. McGilvray

Reed Davaz McGowan

Wesley McNamara

Wilma McNulty

Melanie Means

Jeff I Menashe

Forest Brook MenkeThielman

George T. Mercure

Barbara A Meyer

Daniel J Mick

Dick Miller

James (Jim) Miller

Thomas M. Miller

Sarah A Miller

Jessica L. Minifie

Keith Mischke

Gordy James Molitor

Michael Jeffrey Mongerson

Mary Monnat

Alex Montemayor

Yukiko Morishige

Joanne Morris

Ryan Morrow

Kristen Mullen

Dawn Murai

Megan Nace

Cheryl Nangeroni

Stephan P. Nelsen

Rachael Nelson

David L Nelson

Leah Nelson

Veronika and Jerry Newgard

John and Ginger Niemeyer

Kae Noh

Cait Norman

Patricia M Norman

Ray North

Jim Northrop

Andy A. Nuttbrock

Jennifer Oechsner

Christine Olinghouse

Kathy Olson

Michael Olson

Jim Orsi

Kim Osgood

Nell Ostermeier

Brent Owens

John B Palmer

Alan James Papesh

Patrick Parish

Jooho Park

Nimesh “Nam” Patel

Kellie Peaslee

Ryan Peterson

Phillip Petrides

Theo Pham

Rebekah Phillips & Lars

Campbell

Cindy L Pickens

Robert T Platt

Judith Platt

Steve Polansky

Richard Pope

David Posada

Bronson Potter

Atalanta Powell

Devyn W Powell

William J. Prendergast

Morgan Prescott

Rosemary Prescott

Joe Preston

Frances Prouse

Walker & Madeline Pruett

Emily Grace Pulliam

Michael Quigley

Sarah Raab

Kathy Ragan-Stein

Sandy Ramirez

Cullen Raphael

Walter Raschke

Rahul K Ravel

Stacey M. Reding

Ally Reed

Elizabeth Reed

Ryan Reed

Steph Reinwald

Kristina Rheaume

Anne Richardson

Gary T Riggs

Lisa F Ripps

Echo River

Andy Robbins

Reigh Robitaille

Margaret Rockwood

Jeffery V. Roderick

David Roethig

Kirk C. Rohrig

John Rowland

Steven Ruhl

Gerald Runyan

Mark R Salter

Ellen Satra

Janice E Schermer

Liz Schilling

Bill Schlippert

Janice Schmidt

Ron Schmidt

Michael Schoenheit

Caleb Schott

Michael Schulte

Donna Schuurman

Leigh Schwarz

Greg A Scott & Bonnie

Paisley Scott

Marty Scott

Tim Scott

James E Selby

Astha Sethi

Lucy Shanno

Roger D Sharp

Shahid Sheikh

Joanne Shipley

Rob Shiveley

Richard B Shook

Gary Shumm

Ellen P. Simmons

Patricia Ann Sims

Suresh P Singh

Jeanine Sinnott

Joan D Smith

Rachel Smith

Joseph Hoyt Snyder

Monica Solmonson

Dorothy Sosnowski

Cassie Soucy

Mark Soutter

Carrie Spates

Tony and Mary F Spiering

Tullan Spitz

Mark S Stave

Paul Steger

Bill Stein

Steve Stenkamp

John Sterbis

Lenhardt Stevens

Lee C. Stevenson

Scott Stevenson

John Stewart

Linda Stoltz

George Stonecliffe

Peter W Stott

Celine T Stroinski

Lawrell Studstill

Carol Stull

MaryAnn Sweet

Roger W Swick

Heidi Tansinsin

John G Taylor

Claire Tenscher

Ned Thanhouser

Amanda Carlson Thomas

Lena Toney

Jen Travers

Seth Truby

Gerry Tunstall

Kenneth Umenthum

David A. Urbaniak

Katrin Valdre

Donna Vandall

Stephen A. Wadley

Harlan D Wadley

Jean Waight

Bob Walker

Benjamin Ward

Julie Anne Wear

Cheryl L Weir

Donald G Weir

Dick B Weisbaum

William B Wells

Steve Wenig

Jeffrey W Wessel

Joe Westersund

Guy Wettstein

James P Whinston

Brian White

David White

Joe Whittington

Robin A Wilcox

Gordon Wilde

Debra A Wilkins

Thomas J. Williams

Scott C Willis

Harry Wilson

Richard Wilson

Fendall G Winston

Verena Winter

David Winterling

Gordy Winterrowd

Ingeborg Winters

Liz Wood

Joanne Wright

Jordan Young

Cam (Caroline) M Young

Roberta Zouain

Jason Zuchowski

IN MEMORIAM

In honor of Yun Long Ong for his love of mountains and enthusiastic dedication to the Mazamas, from his husband and fellow Mazama, Bill Bowling.

Katie Barker, by Charles and Louis E Barker

Fred Blank, by Bruce H Blank

Edith Clarke, by Joesph Bevier

Jane Dennis, by Robyn Drakeford Wonser

Brian Holcomb, by Susan Holcomb

Werner & Selma Raz, by Trudi Raz Frengle

Jeff Skoke, by Seth Truby

Ray Mosser, by Keith Mischke

David Schermer, by Janice E Schermer

Will Hough, by Zoe Goldblatt

Will Hough, by Maurene Hinds

IN HONOR

Elva Coombs, by Joanne Shipley

Martin Hanson, by Steven Bensen & Lisa Brice

Greg Scott, by Deborah Driscoll

Rodney Keyser, by William J. Prendergast

Greg Scott, by Anonymous

Ray Sheldon, by Mary F Spiering

Rocky Shorey, by Susan E Koch

Cecilia M, by Jason Zuchowski

George Sweet, by MaryAnn Sweet

Anthony Wright, by Joanne Wright

Robert Skeith Miller, by James (Jim) Miller

Ralph & Ellen Core, by Patti Core Beardsley

Jean Fitzgerald, by Erin Fitzgerald

Krista and Neil, by Sara A Miller

Kevin Mischke, by Brian White

Andrew Robin, by Tullan Spitz

Sharon Herner, by Reed Davaz McGowan

Jean Fitzgerald, by Louise Allen

John Colter, by John Moro

Jared Townsley, by Richard G Denman

Denali, Tundra, & Balto, by Randy Zasloff

IN-KIND DONATIONS

Anonymous

Armin Furrer Family

Barry M Maletzky M.D

Bob Breivogel

Liz A. Crowe and Grant Garrett

George Cummings

Debbie G. Dwelle

Kate Sinnitt Evans

Peter and Mary Green

Tom & Wendy Guyot

Martin Victor Hanson

Duncan A Hart

Jeff Hawkins

Heather Henderson

Mike Holman

Chris Jaworski

Eric Jones

David L Nelson

Gabrielle E. Orsi

Alan & Kristl Plinz

Elizabeth Reed

Richard Sandefur

Greg A Scott

John Sheridan

Steve Stenkamp

Claire Tenscher

Lena Toney

David A. Urbaniak

William B Wells

Owen Wozniak

CORPORATE SUPPORT & MATCHES

Abbott

Apple

Applied Materials

Autodesk

Benevity Community Impact Fund

Broadcom

CGC Financial Services LLC

Edward Jones

Intel

KEEN

Lam Research

McKinstry Charitable Foundation

Microsoft

Nike

Paypal Giving Fund

Portland General Electric

Ravensview Capital Management

Rock Haven Climbing

Springwater Wealth Management

The Standard

Timberline Lodge

Wildflower Meadows, LLC

CORPORATE IN-KIND

Arkangel Technology Group

Better Bar

Broadway Floral and Gifts

Five Stakes

Mountain Shop

Never Coffee Lab

Trailhead Coffee Roasters

Wolfic

ESTATE GIFTS

Katie Foehl

Aug 2, 2025-Mt. Thielsen, West Ridge/ Standard Route. Jeffrey Welter, Leader; Evan McDowell, Assistant Leader. Alex Brauman, Alastair Cox, Allison Wright.

Aug 3, 2025-Mt. Whittier, Norway Pass Traverse. Bill Stein, Leader; Melanie Means, Assistant Leader. Nicole Durchanek, Mike Harley, Sergei Kunsevich, Elizabeth Reed, Seth Truby, William Withington, Mallory Zunino.

Aug 7, 2025-South Sister, Devil’s Lake. Janelle Klaser, Leader; Christin Ritscher, Assistant Leader. Tyler Fitch, Alex Kunsevich, Casey McCreary, MaryBeth Morris, Julia Ronlov, Natalie Rowell, Frank Squeglia.

Aug 8, 2025-Mt. Shuksan, Sulphide Glacier. Pushkar Dixit, Leader; Prajwal Mohan, Assistant Leader. Matthew Delgado, Vlad Lobanov, Cait Norman.

Aug 8, 2025-Santiam Pinnacle South Face. Christin Ritscher, Leader; Janelle Klaser, Assistant Leader. Saad Ahmed, Verna Burden, Brad Dewey, Frank Liao, Andrea Olson, Chris Reigeluth.

Aug 9, 2025-Mt. Adams, South Side. John Sterbis, Leader; Kirk Rohrig, Assistant Leader. Dizzy Bargteil, Elena Ivanova, Diane Peters, Ellen Satra.

Aug 9, 2025-Del Campo And Gothic. Glenn Farley Widener, Leader. Andrew Behr, David Bumpus, Mi Lee, Melanie Means, Elizabeth Reed, Gary Riggs.

Aug 10, 2025-North Sister, South Ridge Hayden Glacier. James Jula, Leader; Janelle Klaser, Assistant Leader. Matt Egeler, Madi Gallagher, Elizabeth Hill.

Aug 12, 2025-Glacier Peak, Cool Glacier. Darren Ferris, Leader; Laetitia Pascal, Assistant Leader. Colin Baker, Berkeley Barnett, Michele Scherer Barnett, Mario DeSimone, Petra LeBaron-Botts, Evan Conway Smith.

Aug 23, 2025-Old Snowy, Snowgrass Flats. Bill Stein, Leader; Donald Kennard, Assistant Leader. Heather Brech, Pete Buckley, Nicole Diggins, Dmitry Medvedev, Alexa Ovchinnikov, Nimesh “Nam” Patel, Echo River, Mallory Zunino.

Aug 23, 2025-Acker Rock, Peregrine Traverse. Andy Nuttbrock, Leader; Justin Colquhoun, Assistant Leader. Midori Watanabe, Assistant Leader. Jen Travers, Assistant Leader. Maxwell Austin, David Bumpus, Alyssa Hausman, Juliana Person, Julian Person, Carrie Spates, Grant Stanaway, Syringa Volk.

Aug 23, 2025-Ingalls Peak, South Face. John Sterbis, Leader; Mark Federman, Assistant Leader. Brad Dewey, Linda Musil, Eleasa Sokolski, Claire Vandevoorde.

Aug 27, 2025-Gilbert Peak (Curtis Gilbert), Klickton Divide. Mark Stave, Leader; Truth Johnston, Melanie Means.

Aug 29, 2025-Middle Sister, Renfrew Glacier/North Ridge. Gary Ballou, Leader; Leesa Tymofichuk, Assistant Leader. Marie Benkley, Sarah Connor, Sylvie Donovan, Bex Gottlieb, Donald Kennard, Casey McCreary, John Meckel, Alexa Ovchinnikov, Rebekah Phillips, Kegan Scowen, Leesa Tymofichuk.

Aug 29, 2025-Santiam Pinnacle South Face. John Sterbis, Leader; Peter Allen, Assistant Leader.Carol Bryan, Assistant Leader. Brad Dewey, Assistant Leader. Leah Brown, Dylan Neil Corbin, Briana Pavlich, Allison Richey.

Aug 30, 2025-Three Fingered Jack, South Ridge. James Jula, Leader; Janelle Klaser, Assistant Leader. Sergei Kunsevich, Frank Squeglia, Kelsey Sullivan.

Aug 31, 2025-Mt. Stuart, North Ridge. Pushkar Dixit, Leader; Agreen Ahmadi, Assistant Leader. Stefan Butterbrodt, Dan Dugan, Omar Najar, Alexis Y.

Aug 31, 2025-Ingalls Peak, East Ridge of North Peak. Andrew Leaf, Leader; Matthew Haglund, Margaret Munroe, Kelly Riley, Kevin Swearengin.

Sep 6, 2025-Chief Joseph, Thorp Creek. Bill Stein, Leader; Midori Watanabe, Assistant Leader. Jocelyn Alyse Brackney, Amanda Lovelady.

Sep 12, 2025-Broken Top, Green Lakes / NW Ridge. Duncan Hart, Leader; Evan McDowell, Assistant Leader. Mark Beyer, Luke Davis, Matt Gardner, Matthew Haglund, Truth Johnston, Ryan Popma, Thomas Schwenger.

Sep 13, 2025-Santiam Pinnacle South Face. Brad Dewey, Leader; Ian Edgar, Rahul Jain, Corey Johns, Amanda Lovelady, Chloe Nicolet, Colleen Rawson.

Sep 20, 2025-Mt. Washington, North Ridge. Ryan Reed, Leader; Evan Conway Smith, Assistant Leader. Lindsey Addison, Brian Bizub, Stephen De Herrera, Sean Mychal Kuiawa, Midori Watanabe.

Sep 20, 2025-Mt. Wow, SW Ridge. Andrew Bodien, Leader; Jen Travers, Assistant Leader. Winnie Dong, William Kazanis, Sergei Kunsevich, Alex Kunsevich.

Sep 20, 2025-Santiam Pinnacle South Face. Matthew Gantz, Leader; Ann Marie Caplan, Assistant Leader. Patricia Akers, Matthew Haglund, Evan McDowell, David Urbaniak, Claire Vandevoorde.

Sep 20, 2025-Middle Sister, Hayden Glacier, North Ridge. James Jula, Leader; Janelle Klaser, Assistant Leader. Matt Van Eerden, Jackie Wagoner.

Sep 26, 2025-Mt. Thielsen, West Ridge/Standard Route. Brad Dewey, Leader; Judith Baker, Peter Boag, Martin Fisher, Kirby Kern, Matthew Meyer, Elise Rupp, Bryan Thieme.

Sep 28, 2025-Mt. St. Helens, Swift Creek Worm Flows. Darren Ferris, Leader; Mark Stave, Assistant Leader. Daven Glenn Berg, Erin Courtney, Nathan Howell, Tiffany Lyn McClean, Laetitia Pascal, Del Profitt, Chris Reigeluth.

Help us reduce our environmental footprint by opting out of receiving the printed Mazama Bulletin. By choosing the digital-only version, you'll:

■ Save trees and reduce paper waste

■ Decrease carbon emissions from printing and shipping

■ Access the same great content instantly on any device

■ Support our commitment to responsible environmental stewardship

The digital Bulletin offers enhanced features like searchable text, clickable links, and high-resolution photos while helping preserve the natural spaces we all cherish. Ready to make the switch?

Simply visit tinyurl.com/ MazBulletinOptOut. Thank you for helping us protect the environment we love to explore.

Between August 1, 2024, and September 3, 2025, the Mazamas welcomed 47 new members. Please join us in welcoming them to our community!

Alyssa Aikman

Asa Arrey

Ario Arrey

Susan Bailey

Alex Banks

Molly Bannister

Nick Boyce

June Bradley

Ashwin Budden

Julie Burgmeier

Taylor Capps

Laura Carter

Elaine Chan

Frederick Cohen

Alice Culin-Ellison

Carey Dove

Dave Haglund

Andrew Harris

Shari Katz

Aaron Kirschnick

Justin Laboy

Michael Lee

Heather Mahoney

Dennis Marquez

Tracy Melville

Claudia Miller

John Moro

Abitha Paneerselvam

Robin Pelletier

Jami Petner-Arrey

Drew Plaster

Vetri Pothi

Tobias Pusch

Diego Quintero

Megan Samsel

Trish Satchwell

Michael Scharf

Henry Stark

Sandra Tullis

Craig Vollan

Jordan Volpe

Jackie Wagoner

David Weinstock

Rita Woodruff

Hirut Yehoalashet

Cory Zeller

Alex Zubrow

Have you participated in a CISM debriefing in the past? If so, please consider sharing about your experience of the debriefing process through this brief anonymous survey.

Your input will help the Critical Incident Stress Management Committee better understand what members value about our work and how we can improve the service we offer.

The survey can be accessed by viewing and tapping the QR code on the right using your smartphone's camera app. Feel free to email cism@mazamas.org with any questions or comments about the survey.

MAY 11, 1957 – JUNE 25, 2025

Mike Couch, brother of two-time Mazama president Doug Couch, died in late June after a lengthy struggle with Alzheimer’s. He was a Mazama member for 23 years. Besides climbing, he was an avid fly fisher and outdoor enthusiast. Mike was at his happiest in the natural world. He also lent his carpentry skills to a few projects at the MMC.

In lieu of flowers, you can make donations to the Alzheimer’s Association, Tribute: Mike Couch, 5825 Meadows Road, Lake Oswego, 97035

DECEMBER 29, 1933 – AUGUST 28, 2025

During his lifelong career with the U.S. Forest Service, Kurt worked as a forest ranger, eventually becoming the “Snow Ranger” in charge of the recreational division for the Mt Hood National Forest. He had many duties as a forest ranger, including managing the Mt. Hood Ski Patrol as a liaison for the Forest Service, mountain rescues, and sweeping the

ski runs at the end the day with Ski Patrol. He also managed the building and maintenance of hiking trails, such as the Pacific Crest and Paradise Trails. In his later years with the Forest Service, Kurt worked in the timber division, managing the forest, timber sales, and fire suppression. Kurt joined the Mazamas in 1954 and remained a dedicated member for over 70 years. Over the course of the years between 1967 and 1997 he led 46 hikes for the Mazama, many of which were on Mazama Outings and also on several Round the Mountain events. In July of 1967 he began a series of articles in the Mazama Bulletin which highlighted numerous hike in the Mt. Hood area. After his retirement he was a frequent volunteer at the Mt. Hood Museum in Government Camp. Kurt loved the outdoors. He was an avid skier and hiker, continuing both activities well into his eighties. Kurt lived near Rhododendron, Oregon, close to the mountain he loved. Timberline was his favorite ski area, especially since he was able to ski for free as a senior. He was an outdoor mentor to several of his nieces, nephews, and grandnieces and nephews.

APRIL 9, 1941 – MAY 7, 2025

Base Camp evening programs continue! Halfway through our second successful season in 2025, we’re excited to keep bringing events to the Mazama Mountaineering Center for both Mazamas and members of our community. In the spirit of community, Base Camp events are free of charge and open to all. A donation box will be available to support speaker travel. All Base Camp events are on Wednesdays from 6:30–8:30 p.m. unless noted otherwise.

Anders Carlson and Megan Thayne will discuss Oregon’s rapidly retreating Cascade glaciers and introduce a new mobile app for citizen scientists to track glacier changes through repeat photography. Carlson founded the Oregon Glaciers Institute with 20+ years of cryosphere research experience, while Thayne leads the institute’s digital mapping and education programs.

The Siskiyou Mountain Film Tour features three new short documentaries about public lands across southwest Oregon and northwest California. Siskiyou Mountain Club is a nonprofit managing 400+ miles of trails in the region, using volunteers and staff who backpack to remote sites for trail maintenance, often in post-fire environments, plus fire lookout rebuilds and campground maintenance.

Arlene Blum is a biophysical chemist, author, and mountaineer who has led expeditions to Annapurna I, Denali, and trekked 2,000 miles across the Himalaya. Beyond her climbing achievements, she works to reduce harmful chemicals in consumer products through scientific research and policy advocacy. She shares her adventures and environmental work through talks and her memoirs Annapurna: A Woman’s Place and Breaking Trail: A Climbing Life

Leaders learn the GoBeyond Process to build a positive relationship with fear and communicate more effectively— applying practiced change to leadership, climbing, work, and life.

Valerie Brown is founder of the “Embodied Intelligence Method™” who helps outdoor athletes move smarter and recover faster. This presentation covers recognizing early overtraining signs, nervous system recovery techniques, movement strategies for joint protection, and breathwork for managing stress to improve long-term performance and prevent injury.

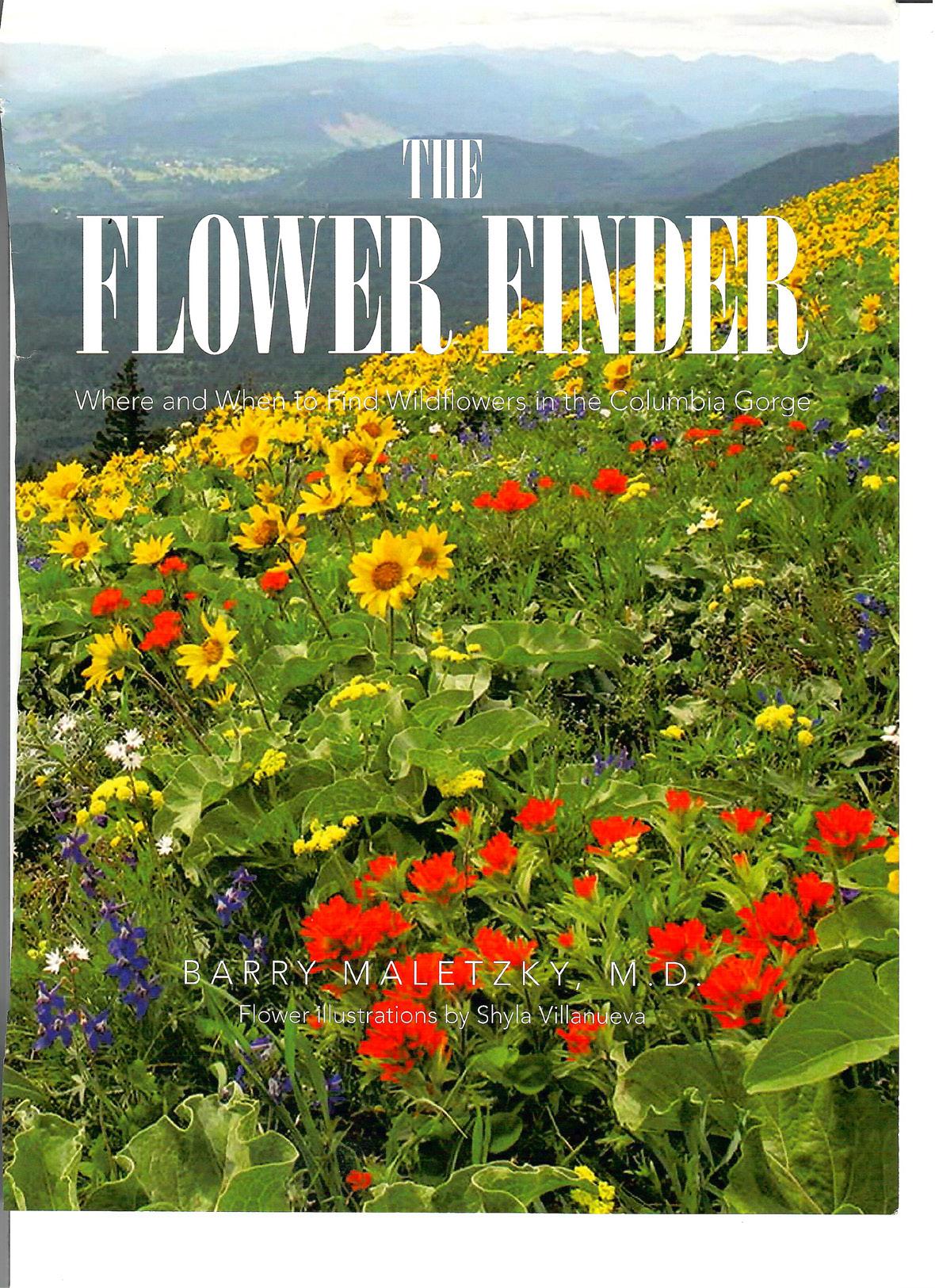

by Barry Maletzky

Discover the Columbia Gorge's Hidden Botanical

Finally, a field guide that answers every hiker’s question: ‘What’s the name of that little blue flower?’ Covering 14 popular trails across Oregon and Washington, this guide pinpoints exactly where to find each species by elevation, mileage, and landmarks.

More than just identification, it explains why plants grow where they do—from evolution to soil fungi. Beautiful illustrations and accessible writing make botany fascinating for curious hikers who want to truly understand the Gorge’s diverse plant life.

Available at Powell’s, Amazon, and bookstores everywhere.

All author royalties support nonprofit conservation organizations.

by Aimee Frazier

It was a beautiful evening in the Wallowa Mountains. Our climbing team was surrounded by towering granite peaks, and to our west the mountains reflected off of the bright blue depths of the alpine lake. After a steep eight-mile hike to camp, where we would sleep before our summit push the next morning, we dropped our packs in a clearing surrounded by stunted alpine trees. The air had shifted from the oppressive daytime heat into a cool breeze as the sun lowered behind the mountains. I inhaled, taking in the mountain air and welcomed the stillness.

After our mosquito-laden dinners of gourmet freeze dried varieties, we each

retreated to our tents to escape from the strong-willed swarms. But it wasn’t long before sexism arrived. That evening, it took the shape of assumptions and unsolicited advice. One of my female teammates, an experienced climber and backpacker, had just set up her tent when one of our male teammates approached. His boots had been disintegrating on the hike in, leaving us quietly wondering whether they would become a liability on the steeper terrain ahead. He glanced at her, and then to her tent anchors, and began offering unsolicited and unnecessary suggestions about how to improve her set up. She politely explained that she was satisfied with her anchors. Rather than accepting this, he doubled down, repeating his advice with the tone of someone who felt strongly in their superior knowledge. She held her ground, reiterating her comfort with her set up. Eventually he shifted to small talk, and asked what she did for work. “I’m an engineer,” she replied. From my tent a few feet away, I couldn’t help but smile at the poetic justice.

I wish I could say this was an isolated moment—a single man making unfounded assumptions about a woman’s abilities outdoors—but my own experiences and the stories of countless women reveal a pattern. The outdoor community is not immune from occasionally, often accidentally, perpetuating the sexism that is embedded within society at large. And while most Mazama members are inclusive and supportive of women, there are still opportunities for growth so that we can all feel more comfortable in outdoor spaces.

The shadow of sexism follows women and gender-queer folks everywhere—even to high elevations within the alpine. It takes different forms in different places, but its roots lie within the same culturally normalized yet inherently harmful perpetuation of power imbalances; the assumption that women aren’t skilled or competent outdoors, the patronizing language used in interactions, the

resistance toward acknowledging the existence of privilege, and the unacknowledged vulnerability that comes with being a woman, given the historical context of societal conditioning that has constricted and oppressed women.

Inspired by the tentside interaction, and many others like it, I wrote this article to offer practical interpersonal guidance on how not to be sexist outdoors. The stories and examples that follow are meant to help people recognize gendered dynamics within mixed groups and learn what not to do, so that everyone can enjoy shared outdoor experiences.

a woman in an overly-confident manner, without recognizing her knowledge or expertise on the subject. And while these interactions are well intentioned,

we are lucky enough to have avoided these experiences, it is very likely that we have a close friend, sister, mother, or grandmother who has experienced them. As social beings, we carry within us the stories of others. As women, we learn to stay alert, scan our surroundings, and have backup plans ready at the drop of a hat.

Years ago, on a steep alpine climb, the leader pointed to a distant cornice and singled me out with a pop quiz: “Why shouldn’t you walk on top of that?” He asked. “Because cornices are highly unstable and can break. And if that one did, I’d fall thousands of feet and probably die,” I answered. He nodded and replied, “Good girl!”—as if he was praising a dog who just performed a trick. While his intent was good, the interaction felt patronizing. If he truly wanted to test qualifying knowledge, he could have asked the entire group. As a 34-year-old woman, I was far from being a girl. I liked the praise, but didn’t like the phrase.

“Let me show you how to do that” one of my BCEP teammates said to me, as I fed a bight of rope through my belay device at Horsethief Butte. He didn’t know that I had 22 years of rock climbing experience, including many years as a professional guide. Mansplaining, a blend of “man” and “explain,” means to explain something to

mansplaining undermines women’s competence. Of course, if you see a safety concern, bring it up, but don’t step in simply because someone’s gender triggers your instinct to “help.” A simple, “Would you like input?” goes a long way toward building respect and trust.

A few months after giving birth to my second child, longing for adventure and a sense of self that had been eroded by sleepless nights and constant caregiving, I joined three strangers from the internet on a Mount St. Helens climb. Meeting three men in a dark parking lot at 2 a.m., I was acutely aware of the risk I was taking and my own vulnerability. As we hiked through the dark forest before dawn, there was a loud rustling in the nearby trees. The men began talking about serial killers, much to the dismay of my nervous system, which was already on high alert.

Many men often forget that women navigate the outdoors with a fundamentally more acute sense of vulnerability. Many women have experienced harassment, domestic violence, assault, or objectification. If

Intentional efforts to build relational safety on the trail go a long way. And this shouldn’t be emotional labor that women carry alone. Even if you personally feel safe, others may not. Take the initiative: ask teammates their names, exchange a story, offer basic kindness. A few minutes of relationship building won’t erase systemic disadvantages or past personal traumas, but it will create a sense of safety in the present moment on the trail.

If we look at the history of women in the outdoors, we see that women have long faced significant social and cultural barriers to entering wild outdoor spaces. For centuries, gender socialization and systemic discrimination confined women to domestic roles, where we were valued primarily for our appearances, compliance toward men, and caretaking roles.

Against this backdrop, women climbing mountains can be seen as a radical and liberating act. It defies traditional gender norms and breaks through the stifling expectations that kept generations of women at home. Mountaineering offers freedom, allowing women to inhabit adventurous spaces that would have been unthinkable just a few generations ago.

Given this historical context, some women and gender-expansive people enter outdoor spaces feeling like vulnerable outsiders. For some people, learning continued on next page

outdoor skills is more easily found in nonmale contexts. Sarah Diver, founder of the She, They, Us affinity group, explains that many people feel safest engaging in the outdoor community without men present.

“One of the biggest challenges women face in the outdoors is the sense that we have to be perfect and excel right off the bat in order to simply justify our participation in mountaineering,” Sarah shared. “Where men are allowed to make mistakes or stumble, many women can feel, at times, that in a learning environment, if we don’t do it right the first time, we’re proving an unspoken fact—we aren’t supposed to be there. For women and gender-queer folks, who might not feel comfortable or accepted from the start, it’s important to explicitly let them know as often as we can that they belong, they’re allowed to learn, and that they’re doing a good job simply by choosing to participate.”

Both literally and figuratively. Have you ever walked side by side on a narrow trail with someone who walks right in the middle, forcing you into the brush? This

taking-up of space, without an awareness of how that impacts others, can be both literal and symbolic. In outdoor spaces, women are sometimes subtly pushed to the margins—left out of decision-making, being talked over, mansplained to, or placed in supporting roles by default. Sharing the space means making room for different voices, and sharing the power of decision making.

“So are you excited to sunbathe when we get to the lake?” one of my male climbing teammates asked with a kind smile. While I appreciated the bid to chat, it felt diminishing toward the 11 hours of climbing with my 30-pound pack that I had just endured. “I’m not here to do that—I’m here for the summit” I said, bypassing his outdated humor. This was a comment he would (likely) never make to a man.

The amount of energy it had taken for me to be there was high: months of BCEP training, countless jogs while pushing my kids in a stroller up the steep neighborhood hills while they spilled goldfish crackers over the seats, taking time away from

work, leaving my children with my partner for half a week. If I wanted to sunbathe, I would have sat in my backyard. I came from a lineage of women who fought against systems of oppression so that I didn’t have to live a constrained life. So no, I will not be sunbathing on this trip, sir. I am here to do what my ancestors couldn’t.

The summit in the Wallowas, which we reached the next morning, was stunning. The white limestone and marble sparkled in the bright sunshine. Layers upon layers of mountains surrounded us in all directions—some jagged and steep, contrasted by another nearby range, green with trees. As I stood on the summit, I felt connected to the unique history of the Wallowa’s formations that had been unfolding over millions of years before I stood in that exact spot. As the Mazamas continue to unfold into the future, I hope that we continue to create supportive environments where every person’s presence is welcomed and valued. Out there, on the trails, endless scree fields, snow and rewarding summits, may we be reminded that we all belong outdoors.

by Patti Beardsley

As we head out into the wild to adventure in endless activities, we are tempted to forget the pounds of maps and field guides that aided us in times past. Now, with a cell phone weighing less than 1/2 pound and apps weighing nothing, we have the luxury of

solving mysteries and being informed at just about any time. When we hear a unique bird call, see a cool critter or flower, view the expansive view of mountains and stars, we can instantly identify and learn. When we need to know how to tie a knot, make a splint, where we are and where to go—there’s an app for that.

Out on trail, maps are your lifeline— especially when service drops. OnX focuses on land ownership, weather, and GPS overlays that help you understand exactly where you stand—crucial when crossing private boundaries or planning access. AllTrails leans into community-sourced routes and current trip reports; the breadth

is excellent, but crowd-sourced data can be uneven, so cross-check before committing to a long objective. TrailForks began with mountain biking, yet its dense trail networks and elevation profiles translate well to hikers who like detail. For off-trail and backcountry navigation, Gaia GPS shines with robust layers, public land overlays, and weather/fire information;

Curiosity turns a hike into a naturalist’s walk. eBird by Cornell lets you log sightings, contribute to conservation datasets, and explore hotspots; it’s a great gateway to community science. Merlin, also by Cornell, excels at sound and

What shall we consider in our choice of apps to carry along? Certainly topics such as bird/plant/insect ID, maps/terrain/night sky/adventure tracking, and essentials such as knot tying/first aid/wildfire reports. Also, how important is the user interface, price, content expertise, and ability to use when out of cell service (offline)?

A small circle of contributors compiled the list below and we are hoping that you all will chime in with your feedback (including additional recommendations) by emailing mazama.bulletin@mazamas.org.

its map accuracy and UI draw mixed reviews, but the offline depth is strong. CalTopo remains the cartographer’s tool— terrain visualization, custom layering, and printable PDFs help you plan with precision and carry paper backups when needed. Across all of these, the paid tiers unlock offline maps; download before departure and verify your area tiles.

photo ID with regional bird packs you download in advance; pair it with eBird to sync your observations. iNaturalist covers the broader web of life—plants, animals, fungi, and bugs—connecting your observations to a global biodiversity project. Seek (by iNaturalist) simplifies

After sunset, the trailhead becomes a planetarium. ISS Dector and NASA’s Spot the Station tell you when the International Space Station will streak overhead—fun

crowd-pleasers on lodge decks or camps. ISS Detector expands the cosmos with comets, planets, Starlink, Hubble, and more; the core ISS features work offline, with add-ons for the rest. Star Walk 2 and Night Sky use your phone’s sensors and

that experience for families and beginners with a kid-friendly interface and offline identification. Obsidentify adds another tool for auto-ID of wild animals and plants. Remember: download species packs and map tiles before heading out, and upload observations when you’re back in service.

camera to overlay constellations, planets, and deep-sky objects—great for learning the sky with guided searches and data sets. Turn on offline star maps and dim your screen; your eyes (and companions) will thank you.

continued on next page

For runners, riders, and multi-sport folks, trackers add structure and social motivation. MapMyRun provides clear pace, elevation, and distance—reliable basics that log offline and sync later. SportsTracker integrates across activities and devices with route sharing

Whether you’re anchoring, securing loads, or teaching Scouts, good knot visuals save time. Knots 3D by NyNix pairs a comprehensive library with controllable, animated steps—slow down, rotate, repeat until it sticks—making it ideal for learning and refreshing under pressure. Animated Knots by Grog adds clean instructions and context stories that help you remember which knot belongs where. Both offer offline, one-time purchases—perfect for the trailhead and the gear room alike.

In fire country, real-time information isn’t optional. Watch Duty, powered by a nonprofit and local observers, offers live wildfire tracking, notifications, and incident details; it’s becoming a staple for anyone traveling during fire season. Inciweb aggregates interagency reporting for fires, floods, hurricanes, and more; it’s credible but not truly real-time, and its interface can feel dated. Disaster Alert zooms out to global incidents, with configurable alerts—handy for broad situational awareness, though fine-tuning to local relevance takes patience. These tools won’t replace local directives, but they help you make go/no-go decisions earlier and stay informed as conditions evolve.

and analytics, giving cross-training a single home. Strava is the community powerhouse: segments, heatmaps, goals, and routes—useful for discovering local lines or benchmarking progress. All three support offline recording; advanced analytics, planning tools, and live features typically sit behind subscriptions.

Standing at a viewpoint, it’s satisfying to name the skyline. PeakFinder offers a global database and camera-guided overlays so you can pan, zoom, and match ridgelines to names—even offline. Peak Visor layers 3D terrain with peaks, trails, and sun paths, offering richer context when planning a route or timing a photo. If you like a quick “what’s that?” in airplane mode, opt for offline-capable versions and pre-download your region.

When something goes sideways, clear instructions matter. The Red Cross app delivers straightforward, offline guidance— basic protocols, short videos, and emergency links—ideal for quick reference when stress is high. GOES (Global Outdoor Emergency Services) takes a wildernessfirst approach with practical visual checklists and assessment tools; offline guides and optional online physician access make it a more comprehensive field companion. For both, practice before you need them: save key pages for offline, and skim flowcharts so you know where to tap in an actual emergency.

Sometimes you just want a quick ID. Google Lens is a handy “point-and-guess” tool for objects and flowers, and its UI is dead simple. Just note that results can be inconsistent and it doesn’t work offline— use it as a starting point, then confirm with more specialized apps when accuracy matters.

■ Match the app to the mission: trip planning (CalTopo, Gaia), infield navigation (OnX, TrailForks, AllTrails), or curiosity (Merlin, iNaturalist, PeakFinder).

■ Think offline first: download maps, species packs, and key guides at home; test airplane mode to confirm what works.

■ Evaluate UI and data quality: community-driven tools are fresh but variable; expert-curated layers can be steadier but require learning the interface.

■ Layer safety: wildfire alerts (Watch Duty), first-aid guides (Red Cross, GOES), and weather overlays help you make conservative calls when conditions change.

■ Keep it simple on trail: two or three well-chosen apps often beat a screenful you don’t use.

Again, your input will help develop this list to be made available as a resource for all Mazamas. Please send your comments to mazama.bulletin@mazamas.org.

by Duncan Hart and Nick Ostini, First Aid Committee

Creating a personal wilderness first aid kit means balancing portability, preparedness, and your specific needs. Here’s a comprehensive guide to building your own kit—whether you’re day hiking, backpacking, or venturing deep into the backcountry.

It is best practice to build your own kit rather than purchase an off-the-shelf kit. Understanding what should go in a wilderness first aid kit starts with training in Wilderness First Aid (WFA) or Wilderness First Responder (WFR), which goes beyond training aimed at urban or industrial settings. Make sure the kit is readily identifiable and easily accessible; placing it at the top of your pack is a good location. When possible, use the patient’s first aid kit contents.

■ First aid manual or wilderness-specific reference card. First aid guides can also be downloaded to a smartphone. The Mazamas offers a First Aid pocket guide through Mazama online merchandise.

■ Waterproof notebook and pencil (for recording injuries, vitals). Mazama leaders are required to carry the Mazama S.O.A.P. note.

■ Emergency contact and medical info card.

■ Trip length: Add more supplies for multi-day trips.

■ Group size: More people means more supplies.

■ Conditions: Snow? Bring foot warmers. Heat? Add hydration tools.

■ Experience level: If you’re WFA/WFR certified, carry gear you know how to use (e.g., splinting tools, triangular bandages).

■ Allergies/conditions: Include personal medications or anaphylaxis kits.

■ Use a waterproof pouch or dry bag (red or marked with a cross for visibility).

■ Organize with zip-top bags or internal dividers:

□ Documentation

□ Body Substance Isolation

□ Bleeding/Wounds

□ Musculoskeletal

□ Medications

□ Blister/Burns

□ Tools

■ Add a checklist inside the kit for easy restocking.

■ Check your kit before each trip. Medications expire and bandages degrade.

■ Know how to use everything you pack. Training matters more than gear.

■ Consider a Wilderness First Aid course from the Mazamas, NOLS, or the Red Cross. Additional training in CPR, EpiPen use, and Stop the Bleed can be helpful.

■ Bag #1: Protection

□ Purpose: A waterproof bag ensures your medical supplies aren’t ruined or made non-sterile in case of submersion.

□ Contents:

▷ Bag #2

▷ Bag #3

■ Bag #2: Preparation

□ Purpose: Contains items to prepare before treatment begins, including Body Substance Isolation (BSI) and record-keeping, so the rescuer can begin the patient assessment prepared.

□ Contents:

▷ Body Substance Isolation:

▷ Gloves (two or three pairs)

▷ Masks (two or three): For both the patient and rescuer

□ Record-keeping:

▷ S.O.A.P. notes (two or three)

▷ For tracking findings and a plan of action for patients

▷ One full page

continued on next page

continued from previous page.

▷ Two smaller, printed on waterproof paper for rainy or snowy conditions

□ Mini mechanical pencils

▷ For writing S.O.A.P. notes

▷ Mechanical pencils won’t break easily when packed

□ Pocket guide: A resource for the patient assessment sequence, how to speak with authorities, and how to diagnose and treat common ailments.

■ Bag #3: First Aid Kit

□ Purpose: Contains medical supplies to properly treat patients.

□ Contents:

▷ Bleeding:

▷ Combine pads: thick pads used to help control major bleeding

▷ QuikClot: gauze with a clotting agent to help control bleeding

▷ Regular gauze: helps control bleeding and clean wounds

▷ Non-adherent gauze: applied to open wounds so dressings don’t remove skin when changed

▷ Roll gauze: helps control bleeding, clean wounds, and wrap wounds

□ Musculoskeletal injury:

▷ Triangular bandage: sling and swath; to help create splints; to help control bleeding

▷ ACE bandage: used to wrap usable injuries, help create splints, and cover wounds

▷ Coban: self-adhering bandage to cover wounds, wrap usable injuries, and help create splints

▷ Flexible medical tape: for wrapping usable ankles and creating an occlusive dressing

□ Wound management:

▷ Antiseptic towelettes: for cleaning around a wound

▷ Povidone-iodine swabs/pads: for disinfecting inside wounds

▷ Sting pad: used to clean sting or bite sites and provide some pain relief

▷ Benzoin tincture: helps tape, Steri-Strips, and bandages adhere to the skin—especially

around difficult areas like the eyes or mouth

▷ Band-Aids: a variety of sizes to help keep wounds clean

▷ Second Skin: for burns

▷ Steri-Strips: to help close wounds

▷ Transparent bandages: for occlusive dressings and to cover wounds while monitoring for infection

▷ Moleskin: to prevent and treat hot spots and blisters

▷ Syringe: for wound irrigation

□ Medication:

▷ Aspirin: for pain, fever reducer, cold and flu discomfort, muscle and joint pain, cramps; cardiac chest pain. Notes: some people are allergic

▷ Tylenol: for pain, fever reducer, cold and flu discomfort, muscle and joint pain, cramps

▷ Ibuprofen: pain, fever reducer, cold and flu discomfort, muscle and joint pain, cramps; inflammation. Note: can be used in conjunction with Tylenol for effective over-the-counter pain relief

▷ Benadryl: temporary relief of allergy symptoms

▷ modium: helps control diarrhea

▷ Antacid: controls heartburn and upset stomach

▷ Medication checklist (WFR only): process for which medication, dosage, and frequency to use before recommending medication to a patient; write each medication’s expiration date in wax pencil to update easily when refilling

□ General:

▷ Compact CPR face shield: to provide breaths to a patient if needed; a one-way valve protects the rescuer from bodily fluids

▷ Trauma shears: for removing clothing from a patient without injuring them

▷ Fever scanner/thermometer: for taking a patient’s

temperature and monitoring over time

▷ Tweezers: for removing ticks, debris, or splinters

▷ Plastic bags: one for trash and used supplies; one for keeping an amputation clean and safe

□ Optional

▷ Purpose: Items to add or subtract based on the owner’s specific concerns for an outing.

□ Contents:

▷ Tourniquet: for stopping heavy bleeding when direct pressure doesn’t work

▷ Nuun electrolyte tabs: to help patients struggling with hyponatremia

▷ Powdered gelatin (e.g., Jell-O): for patients with hypoglycemia to raise blood sugar; for patients with hypothermia—or to help prevent shock—add to hot water and have the patient drink (only if they can do so on their own)

▷ Instant glucose: for people experiencing hypoglycemia

▷ Soap sleeves: to clean your hands, clean around a wound, and clean instruments

▷ Hand warmers: can help with hypothermia or frostnip

AI Disclosure: Generative artificial intelligence was used to assist with research and compilation of this article. All content has been reviewed, fact-checked, and approved by the First Aid Committee to ensure accuracy and adherence to our editorial standards.

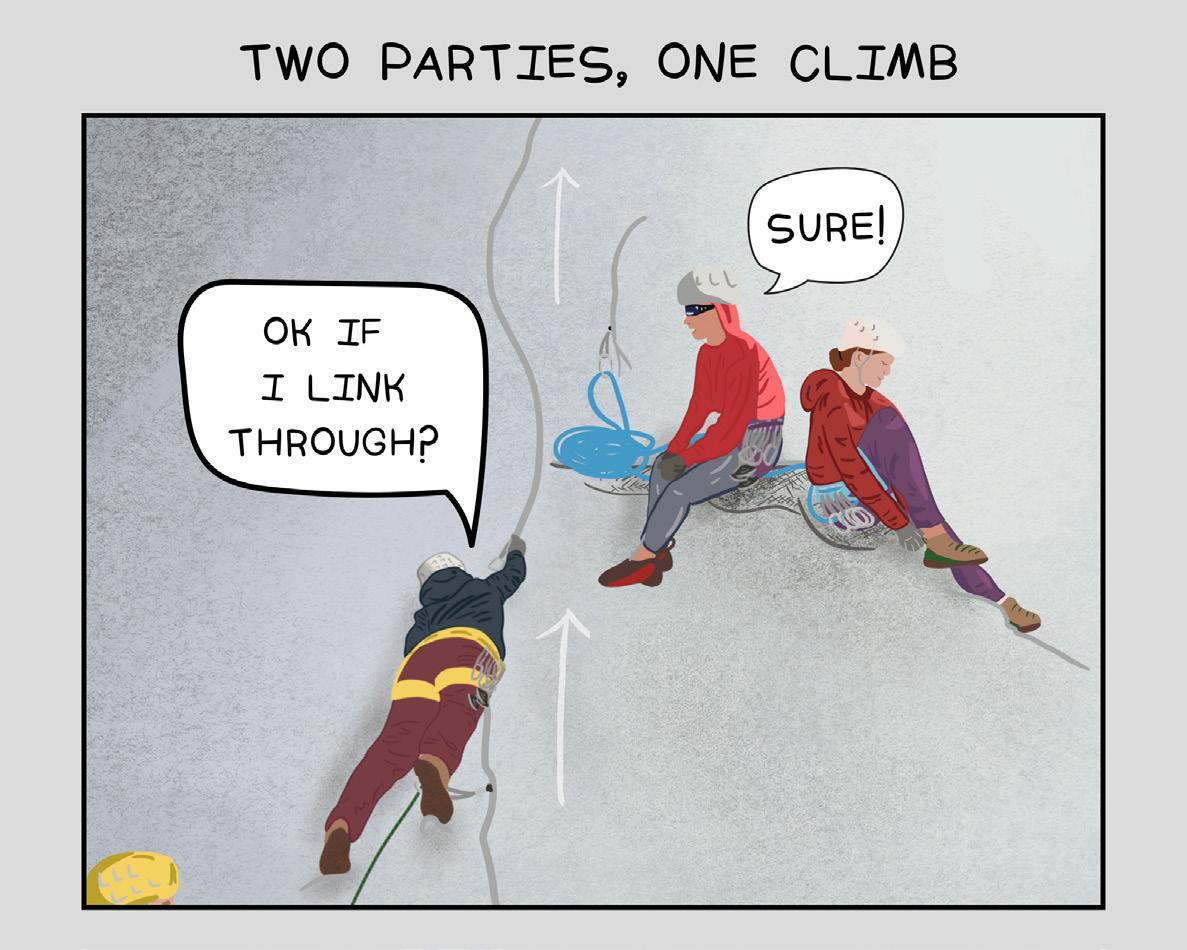

by Angie Brown and Damon Greenshields

Art by Paige Brown Jarreau

If you’re climbing a popular multipitch route, one thing is inevitable: you’re going to want to pass another party, or another party is going to want to pass you. We’ve experienced this dozens of times, under various circumstances. Sometimes multiple parties are on the same route, but going different speeds. Other times, two routes merge near the top, sharing the final pitch(es). Or perhaps one route

crosses another, forcing ropes to mingle as one climber moves across another climber’s line.

What are some efficient, considerate ways to manage these situations? Saying “Hey, we were here first, back off!” Maybe not.

Fear not, we’ve got some suggestions for you. We’ve also got some key considerations to think through, and a bit of advice on how we deal with the challenges to all of this.

Before jumping into the scenarios, let’s talk through some risks. If you’re the passing party, you’re obligated to take on the risk, as opposed to putting the risk on the other party. In addition, in all of the

situations below, you need explicit consent from the other party to accomplish the pass-by safely. It can be tricky. For example, asking the client of a guided party if you can climb up their route would be a bit inconsiderate, putting that client in an unreasonable predicament. But asking two competent climbers if you can find some kind of arrangement to share the climb, yeah that can work well. Regardless of how competent the teams are, using the techniques below to pass could end badly. Crossing another party’s rope, or simulclimbing past another team, could result in pinched ropes, entanglements, and worst, one climber falling on another. As always, use good judgement, and review and practice techniques before you use them in the wild.

continued on next page

Multi, continued from previous page.

It’s not uncommon for separate climbs to merge near the top, where the rock sometimes kicks back into easier, 4th class scrambling. Think of Young Warriors and SE Corner on Beacon Rock, or Rapple Grapple and Beckey Route on Liberty Bell. Parties may meet where those routes converge, causing one party to wait for the other to move through and finish before they can start.

When the terrain is easier, and perhaps wandery (choose-your-own-adventure style), it can work well to simply have two leaders moving at the same time. Let’s say you’re in Party A and your leader is halfway up the pitch when a faster Party B arrives from a converging route. In this situation, Party A’s belayer can offer to Party B’s leader to continue moving up. Party B’s leader should leave ample space between themself and Party A’s leader, and ensure they clip their rope off to one side of Party A’s rope (and maintain it!). When placing gear near the other party’s gear, clip it on an extended draw UNDER the other party’s rope. That way, when Party A’s follower

is moving, they aren’t crawling under and over Party B’s rope because Party B’s leader clipped willy nilly and got the lines twisted (not cool). If the climb is bolted, things are a bit trickier, as bolt hangers rarely allow for multiple carabiners. If they do, the leader of Party B should set their quickdraw under Leader A’s.

Keep in mind that this scenario likely assumes a shared top anchor, so consider whether the next anchor station will be conducive to multiple parties. If it is

If you pick a highly popular route, such as one listed on Roper and Steck’s Fifty Classic Climbs list, you’re bound to have to share. If the climb is low-5th class and wandery, such as West Ridge of Forbidden, you may be able to climb around the other party off to one side, avoiding any kind of

entanglement entirely. But many times, the route is quite distinct, and follows specific bolts or cracks, and you cannot stray off of it. In that case, one of the most effective ways we’ve found to pass another party is by linking pitches. To effectively pass in this manner,

the leader must know the route well, feel confident at the grade, and communicate early. Preparation and timing are critical. As Party A’s follower is climbing, Party B’s leader should lead close behind. Once Party A’s follower arrives at the anchor, with Party B leader arriving, Party B can

not, an option is to clove into the anchor long, using the climbing rope, and use the backside of your clove as the masterpoint, so that you can potentially belay 5-10 feet under the party above, creating more space. (If this is unclear, try Googling “multipitch belay extensions” for some useful writeups).

ask Party A to pass by linking pitches and climbing through. This works well if the pitches are short, and well within comfort grade. Party B can even suggest that Party A’s leader continues their lead behind them, if one was comfortable with that (see Case 1).

But what if the pitches are a touch too long to link, and your 60 meter rope won’t make it? This could be an opportunity to simul-climb. Upon arriving at Party A’s anchor, Party B’s leader will clip the rope to the anchor using a progress-capture device, such as the Petzl Micro Traxion, then continue their lead. Once Party B’s belayer runs out of rope, they can begin climbing, giving the leader the slack needed to reach the next anchor before the follower arrives at the anchor with the Micro Traxion. Even though the leader and follower are simul-climbing, the follower is essentially being belayed by the Micro Traxion. If Party B’s follower falls, Party B’s leader would be unaffected. Party B’s leader will arrive at the next anchor and put the follower on belay like normal. Party B’s follower will have to climb or wait depending on slack in the system; radios can be useful here.

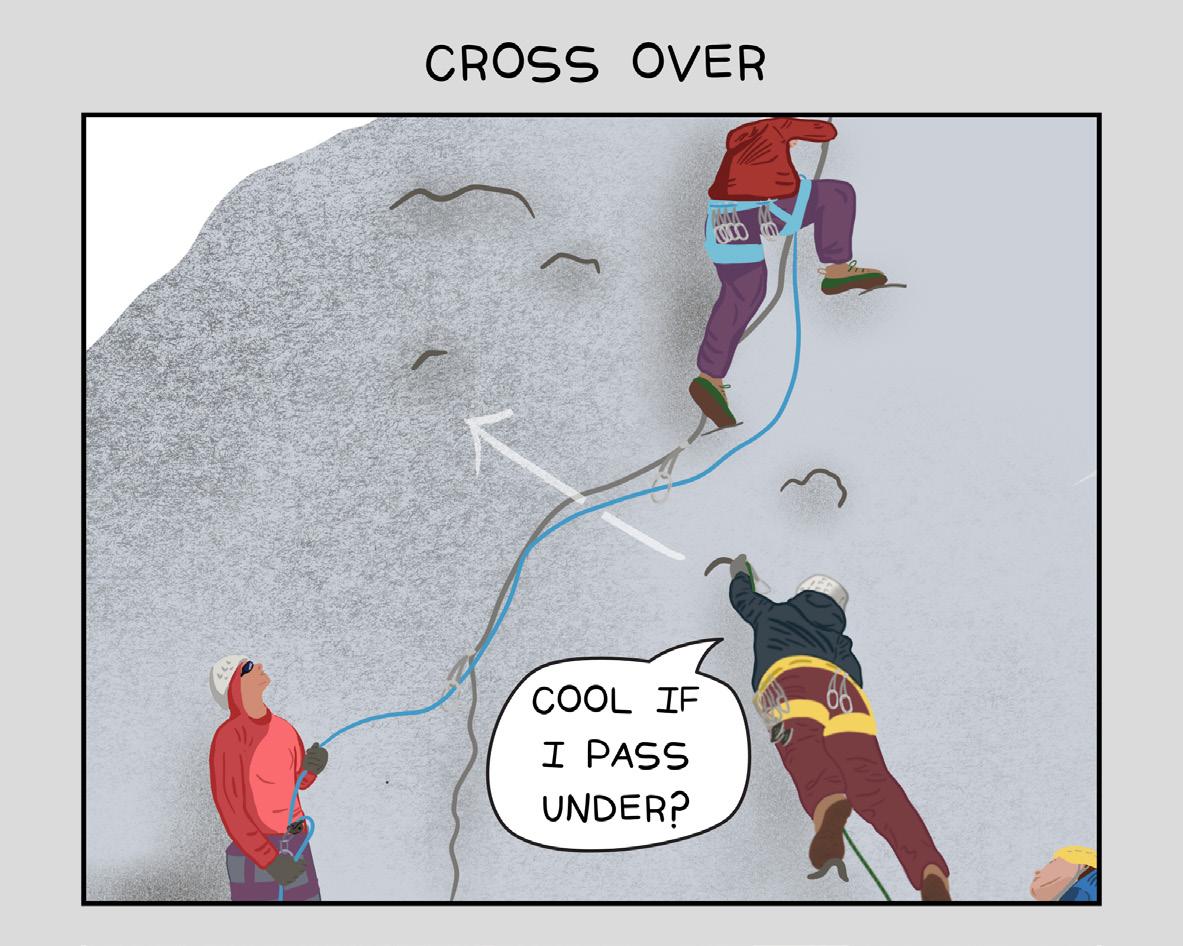

Some routes may not share any pitches, but still have a point where they cross one another—this is very common in Index. In these cases, it would be pretty inefficient and pointless to wait for a party to move through before crossing over and continuing. When the overlap is brief, there’s minor risk in simply moving across the line while another party is climbing, and continuing on. Of course, inform the other party of your plan.

Typically it is considerate for your party (Party B) to pass UNDER Party A’s rope (taking care to place plenty of gear at/near the crossover point), so that Party A’s follower can climb over your line easily when the time comes. This way, if Party B leader takes a fall, they don’t risk pinching Party A’s rope. Of course, in this scenario, if Party A takes a fall, they could conceivably pinch your rope. This is unlikely if the terrain is anywhere near vertical, and still unlikely even on slab. If it does occur, Party B leader might be momentarily shortroped, but that will ease once the other party’s leader begins climbing again. As

Remember, not all climbers are knowledgeable about these possible options, and they may feel unsafe. If you want to pass another party, the best you can do is demonstrate your competency to the other group by climbing fluidly, being efficient in your rope management, and communicating clearly and openly. If you aren’t checking these boxes, it may not be the right time to ask to pass.

When a party is climbing efficiently behind us, that gives us the confidence to allow them to pass without slowing us down. And just in case the situation changes, we like to add a caveat before allowing them to pass: “Yes, absolutely you can pass, but only if you let us pass you if we end up catching back up and moving more quickly.” It’s kind and considerate, yet acknowledges each other’s potential weaknesses or setbacks.

Several times, we’ve gotten push back, or a downright refusal, when asking another party if we could move through, or perhaps share an anchor. Some climbers adopt the restrictive attitude that they own the climb and all its anchor

noted above, the passing party should take on the risks, not the other party.

stations because they got there first. We encourage anyone reading this to treat a long multipitch the way you treat the highway on your way to the climb. Share it. Be considerate. There’s space for all of us. And think about this: you may actually be helping yourself by letting a fast party pass. If you’re following folks who know the route, you’ll minimize any route-finding shenanigans you may have experienced otherwise. It’s also just more fun, and less stressful, to approach climbs in this way. Ultimately, safety is the priority, so if there are risks that you’re not willing to take, there’s no shame in declining to pass someone or get passed. We’re a community, and we can support each other, even when we’re competing for the same summit.

by Luke Davis

When I started college, I ran Division III crosscountry. I’d been distance running since seventh grade and was excited for the big level-up. I got the all-you-can-eat food plan from on-campus dining and ran hard. I was logging about 50 miles per week, plus core, cross-training, and weight room. To match, I was eating about five full meals a day. Halfway through the first week of practice I went to the dining hall and ate for hours straight—I was so hungry.

Partway through track season the next year, I began feeling overwhelmed with classes, I was struggling with my mental health after a friend’s death, and I could feel my body slowly breaking down. I talked about taking a break with my coach, who said that “if I really needed to” I could take one day off. I said that I felt like this was

a bigger problem than a single day. The head coach responded by calling me a “[expletive] [expletive] millennial.” So, I quit. Quitting abruptly changed my relationship with food. Suddenly, eating filled me with fear and guilt. My five full meals a day quickly spiraled into “I should only eat calories that I deserve (i.e., work out intensely for) to eat.” So I didn’t. During my second year of college I would starve myself, almost as a challenge. By the time I really addressed the problem in grad school and started using a calorie tracker, I found that I would typically eat around 1,000 calories per day. Or I’d get depressed or stressed and binge-eat a bunch of junk food and get sick—one or the other.

At the start of 2022, I made it a goal to improve my diet and relationship with food. I made strict rules: no processed foods, no desserts, no red meat, no food that didn’t make me feel good after eating it. After the first month of slight withdrawal, these weren’t too hard to follow. Now I had to figure out what I was going to eat instead. I weighed 122 pounds at the time, and my doctor said I needed to weigh at least 129 to be considered healthy for my sex and height. At first I just tried

"Camping food" by PXHERE is marked with CC0 1.0. to eat more, but I found that I could only force myself (sometimes with tears) to get up to about 1,600 calories per day. So I began going to the gym and running again, thinking that exercising would force me to eat more. It worked. By the end of February, I hit 2,000 calories in a day for the first time that year, according to my tracker. In late April, I finally reached 129 pounds.

Eating and drinking is still a big issue for me today. If I skip a meal and/or don’t drink enough water, I can get dizzy and lethargic. I’ve infamously passed out every time I’ve had COVID, but I’ve also passed out without COVID. For day hiking, it’s usually not too big of an issue; I know to eat a big dinner and breakfast before every hike, and a big dinner and breakfast after, too. But backpacking has always made me nervous. In September 2024 I went on an overnight Mazama climb, and despite meal planning, I didn’t get enough food in me, became unwell, and did not summit. It was an extremely frustrating experience. Considering how many climbs involve at least one night of backpacking, and that I wanted to one day lead backpacks of my

Mountain House x5 2820 3/5 1740

Larabar x14 2720 5/14 920

Turkey Sandwich x2 ~1200 2/2 ~1200

Triscuits 720 Ate about half ~360

Dark Chocolate Bar 1650 Ate 3/4 1200

Dried Mango 1400 Ate 3/4 ~1800

Dates 2420 Ate 3/4 ~1800

Salted Pumpkin Seeds 2848 Ate 1/2 ~1400

Peanut Butter Pretzels ~500 Ate almost all ~400

own, I felt very discouraged. For my next overnight climb, I doubled everything in my meal plan. I did much better, but I was still shocked at how much food I had to go through (and was still hungry on the drive home).

This year, I posted my first Mazama backpacking trips: Paradise Park, the Enchantments, and Hawkeye Point. It was very exciting, but I was nervous about the food part. The Enchantments especially had me nervous because it was two nights, which I had never done before, plus the five-hour drive each way. I brought about 16,200 calories for the trip and ate about 10,200 of them from door to door. I ate and felt much better than I feared or had on previous trips. I woke up feeling a bit strange or weak on the third day but improved as I ate during the first hour of the day. By the time we left camp, I wasn’t even worried anymore.

I wanted to share my experience because I felt it was a huge success to go from a participant on a one-night trip not

Dinner both nights, breakfast on second day. I always felt better after eathing

Supplemental recovery food. Didn’t eat as many because they always ended up on the bottom on the bear cannister.

Bought in Leavenworth before and after trip, and glad I did!

Salty and whole wheat but not dense, I’ve found these are good for me about halfway up a steep slope.

Good for me gefore going up a steep slope and a piece or two immediately after a steep slope. Otherwise int’s not helpful.

This worked really well for me to eat first thing in the morning before anythiong else.

IF you’fe been on a trip with me, you know I like dates! I snack on dates throughout the day, but usually more in the first half, and that’s worked really well for me.

This worked well for me to eat right after a steep slope, the protein and salt together was really great.

Another good way to get quick carbs and salt, with a bit of protein, I bring these on all my trips and sanck through the day.

finishing because of eating problems to a leader on a two-night trip feeling much better. Eating problems differ between people, as do diets and restrictions, but I wanted to share what worked well for me in case anyone else is looking for a reference point. I arrived at these items by testing different foods on day hikes and making some of them part of my daily diet. I encourage you to test, too, before a big trip.

As we headed out on the first hot, muggy day, a few of my participants reported feeling overheated with slight headaches. They self-diagnosed not drinking enough water on the five-hour drive up as part of the problem. I think this is important to mention. Sometimes we want to eat or drink as little as possible on the drive so that we don’t have to stop (or ask to stop), but it’s important to stay up on food and water on a long drive, too. I made sure to drink lots of water, even if it meant running across the parking lot at every rest stop.

The three things I eliminated from my 2024 backpack food were canned sardines, Annie’s mac and cheese, and electrolytes. The canned sardines were too much weight for not enough calories, took a long time to digest, and could be messy to eat. The mac and cheese was replaced by Mountain House, which worked a lot better for me. Electrolytes don’t work for me because I found that the more electrolytes I used, the better I felt and the less I would eat—until suddenly I would crash from too few calories (what I think happened on the first overnight climb). I no longer use electrolytes, which forces me to pay attention to eating more salty food and food in general. This change has worked very well for me.

Again, these are things for my body and my diet. Everyone is different, so please take care of yourself in the best way for you. But I hope that this story and information have been helpful. I hope to see you on the trails, feeling great!

by Amy Brose and Rick Craycraft

Pioneering women set the stage for the explosion of Mazama climb leadership by women in the 1950s and beyond. Our previous article discussed Mazama women breaking down barriers in the early 1900s, and then the 1930s up to 1940. Now we focus on the growing numbers of women in Mazama leadership roles in the post-WWII era through the the 1960s.