approached the America the Beautiful Fund for financing to launch a more formal residence program in the parks. The fund subsequently provided seed grants to support artists for projects concerned with “preserving the quality of nature and environment.” Gussow went on to set up the Artists for Environment Foundation, a “creative kibbutz” at the Delaware Water Gap. From 1972 to 1983, Joseph Fiore was visiting artist/critic at the foundation, an experience that helped nurture his passion for the environment and that led to the creation of some of his finest paintings. •••

To further his mission to connect art and the environment, Gussow produced A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land, published by Friends of the Earth in 1972. In this landmark book, he combined paintings with the words of artists—taken from poems, letters, journals, and other sources—in order to highlight the special sense of place that exists between the painter and her or his surroundings. The book covers 400 years of American art and includes more than 20 painters with connections to Maine, including Gussow himself, who painted on Monhegan Island for much of his life. Among my favorite images in A Sense of Place is Sheridan Lord’s Sagaponack, 1970, a view of potato fields on the South Fork of Long Island. Lord (1926-1994) devoted much of his later life to painting these lovely expanses of green interspersed with barns and farmhouses. The painting has special resonance for me: I spent the first 30 or so years of my life among the low rolling hills of this part of Long Island. My high school, the Hampton Day School in Bridgehampton, was surrounded by potato fields. I came to cherish those vistas and I still support the Peconic Land Trust, which has sought to save the farmlands from development (the trust was founded by John Halsey, a housemate of mine during my sophomore year at Dartmouth). Here in Maine, similar pressures exist for farms— and the opportunities for artists to play a part in their preservation increase every year. One marvelous example is the CSA: Community Supporting Arts program launched by the Harlow Gallery and the Kennebec Valley Art Association in 2011. The KVAA matched 14 artists with 13 farms in central Maine, all of them practicing Community Supported Agriculture, the original CSA and inspiration for the arts project. 7

The association displayed the images of the farms in an exhibition at the Harlow Gallery in Hallowell, the Maine Farmland Trust Gallery in Belfast, and six additional venues throughout the state. “Maine’s artist and farming communities have a lot in common,” said Deborah Fahy, executive director of the Kennebec Valley Art Association and the Harlow Gallery, at the time of the CSA launching. “Both are idealistic and creative groups,” she noted, “and both communities are key to Maine’s unique sense of place.” Fahy and her colleagues looked upon the program as a means for painters and photographers to “use the power of their artistic voices to affect social change—or in this case to promote and celebrate the local foods movement.” In 2016, the Kennebec Valley Art Association and Harlow Gallery revived the CSA project, once again pairing artists with farms, over the 2017 growing season. This time they partnered with Maine Farmland Trust Gallery in Belfast and Engine in Biddeford to show the resulting work. Maine Farmland Trust had opened the Joseph A. Fiore Art Center at Rolling Acres Farm in Jefferson in 2016, with a straightforward mission to guide it: “to actively connect the creative worlds of farming and art making.” To accomplish this goal, the trust established an artist-in-residence program. In 2016, they invited four artists to spend a month on the 130acre property on Damariscotta Lake; last summer, six artists stayed at the center, plus a writing resident documenting the history of the farm, and a gardener. The 2016 cohort included J. Thomas R. Higgins, professor emeritus at the University of Maine at Farmington. A plein air painter, Higgins relishes being “at one” with his surroundings, searching for something that will move him emotionally, “an evocative space, atmosphere, light, mood, etc.” His expressive paintings capture the inherent energy of the landscape; we share in his vision of places in flux. During his forays into the Jefferson landscape, Higgins discovered “the quiet integrity” of nearby Chimney Farm, former home of three of Maine’s greatest writers, Elizabeth Coatsworth, Henry Beston, and their daughter, Kate Barnes. It was Coatsworth who wrote, “If Americans are to become really at home in America it must be through the devotion of many people to many small, deeply loved places.” These places, she averred, must be “sung and painted and praised until each takes on the gentleness of the thing long loved, and becomes an unconscious part of us and we of it.” Painter Robert Pollien from Town Hill on Mount Desert Island has conferred that kind of devotion

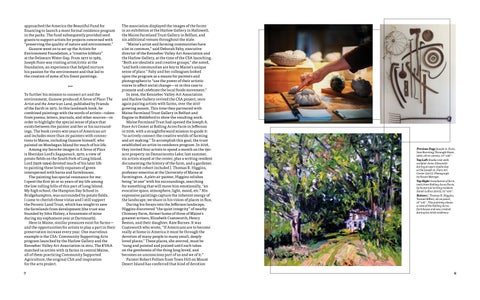

Previous Page Joseph A. Fiore, Sun Burning Through Haze, 1960, oil on canvas, 27"x36". Top Left Studio visit with sculptor Anne Alexander during an open studio day at the Joseph A. Fiore Art Center (2017). Photograph by Susan Metzger. Top Right Installation of farm tools from Rolling Acres Farm, by historical writing resident Sarah Loftus (2017), 75"x50". Bottom J. Thomas R. Higgins, Tunnel Effect, oil on panel, 16"x16". This painting shows a view of the Rolling Acres farmhouse and was created during his 2016 residency.

8