maine farms

JOURNAL OF MAINE FARMLAND TRUST • 2019

JOURNAL OF MAINE FARMLAND TRUST • 2019

In 1999, a small group of farmers and farm advocates planted the seed of an idea, born from their belief that farmland and farming matters, and should be protected.

Word spread, meetings were held with like minds, and soon, Maine Farmland Trust began as the first and only land trust in the state focused on protecting farmland and supporting farmers. Thanks to the pioneering vision of our founders, the hard work of volunteers and staff, and the support of so many members, Maine Farmland Trust has helped to protect hundreds of farms in every corner of the state, and tens of thousands of acres of precious farmland. In other words, that seed took root and grew.

In the scheme of things, 20 years is not a very long time. And yet, when it comes to Maine’s farming and food landscape, a lot has happened in the last two decades. Consumers in 2019 show a level of awareness and enthusiasm around local food that simply wasn’t there 20 years ago. There are farmers markets in nearly every corner of the state, and consumer demand for local food has grown; as chef Sam Hayward of the pioneering Fore Street Restaurant notes, “it’s almost inconceivable that a new restaurant in Maine wouldn’t at least pay lip-service to local food.”

In some ways, this issue of Maine Farms journal is a testament to how far we’ve come—the fact that this publication exists, there are more stories than we can hope to fit into our page count, and that so many of the voices in this journal carry hope for the future. But this issue is also a testament to the hard work that lies ahead if we’re going to fully realize the potential that farming and food holds for our state. In these pages, you’ll find stories of roadblocks and solutions. Our writers report on the tricky market realities for Maine meat producers (“Of Porkchops and Broilers,” Page 31) and the encouraging possibility of using farm woodlots as a tool to mitigate a changing climate (“Storing Carbon in the Winter Garden,” Page 21). There’s an essay meditating on the skeletons of a farm gone by (“Reading the Stones,” Page 9) that reminds us that today’s farms too could fade into the landscape, bisected by highways and nearly forgotten.

In this and every issue of the journal, we aim to convey equal parts hope and clear-eyed understanding of the many challenges ahead. This dynamic is, in part, what has kept MFT pushing forward for 20 years. While we’ve made so much progress, the urgency for our work is only increasing. The latest Agricultural Census showed a dramatic decrease in the number of farms in Maine, and the number of acres of farmland. But there are bright spots, too. Local and organic markets are growing, and there are more women farming (and counted as farmers) than ever before (“Five Maine Farms,” Page 39). We've learned a lot over the past two decades of working to protect farmland and support farmers, but perhaps our most important lesson is this: There will always be more work to do. The future is still, and will always be, uncertain. But as long as we have our boots on the ground and our hands in the dirt, there's reason to hope that uncertainty will give way to a brighter, greener future.

maine farms

3 field

Snippets from the farming landscape

4 poem

“An Ode to Cider”

ELIZABETH GARBER

5 farm spotlight

Lessons from Crane Brothers Farm in Exeter

KATY KELLEHER & LILY PIEL

9 personal essay

Reading Maine’s stone walls for insight into our past

BEN COSGROVE & JESSICA KLIER

15 future

Local farmers talk about the future of their industry

MFT MEMBERS & KRISTIN DILLON

21 business

How low-impact foresters can help fight climate change

LAURA POPPICK & GRETA RYBUS

31 food

The struggles and pleasures of Maine’s meat economy

WILLY BLACKMORE & KRISTIN DILLON

39 people

Five Maine farms, six talented women

MELISSA COLEMAN & MOLLY HALEY

45 land

One long day on Goranson Farm

KELSEY KOBIK

editors Ellen Sabina

Katy Kelleher

design

Might & Main

writing

Willy Blackmore

Melissa Coleman

Ben Cosgrove

Katy Kelleher

Kelsey Kobik

Laura Poppick

photography

Kristin Dillon

Molly Haley

Kelsey Kobik

Lily Piel

Greta Rybus

illustration

Jessica Klier publisher

Maine Farmland Trust

97 Main Street, Belfast, Maine 04915 (207) 338-6575 mainefarmlandtrust.org info@mainefarmlandtrust.org

Printed on 80# Finch Opaque Bright White Smooth by J.S. McCarthy Printers, Augusta, Maine

All material ©2019 Maine Farmland Trust

The Maine Farms journal is a publication of Maine Farmland Trust, a statewide nonprofit that protects farmland, supports farmers and advances the future of farming.

Ellen Sabina, Outreach Director, Maine Farmland Trust

Ellen Sabina, Outreach Director, Maine Farmland Trust

the

field

snippets from the farming landscape

milestone map

Maine Farmland Trust has protected nearly 300 farms from York County to The County, and has helped to keep over 60,000 acres of farmland in farming while supporting more than 800 farm families with services they need to get on the land and grow strong businesses. Learn more | mainefarmlandtrust20th.org

deb’s delicious rosemary cookies

by the numbers: women in maine agriculture

An Ode to Cider

Farms protected with conservation easements

Farm links between farmland owners and farmland seekers

Farm viability project sites, like business planning workshops

Rosemary is one of my favorite aromatic herbs to grow, to cook with, and to smell. The fragrance of rosemary is uplifting and rejuvenating. When I need to feel hopeful or inspired, I turn to rosemary. Footbaths with rosemary tea are warming and reinvigorating. A fresh ginger root tea with a pinch of fresh rosemary is a wonderful way to begin your day. Rosemary is said to improve memory and bring clarity and openness to our hearts and minds.

Ingredients

· 1 stick organic butter

· 1 cup maple syrup

· 3 cups organic flour (rice, spelt, einkorn)

· 4-5 heaping tablespoons of finely chopped rosemary

Directions

1. Preheat oven to 350 F.

2. Cream the softened butter with maple syrup.

3. Mix the chopped rosemary with the flour and add into the butter and maple syrup mixture.

4. Spoon onto ungreased cookie sheets.

5. Bake for 25-30 minutes or until lightly browned on the bottom. Enjoy!

Recipe excerpted

to

a

The first year that the USDA Agricultural Census compiled data on the sex of primary farm operators.

558 1978

The number of female primary farm operators counted in Maine in 1978.

7,600

The total number of primary farm operators counted in Maine in 2017.

2,830

The number of female primary farm operators counted in Maine in 2017.

507%

Growth in number of female primary farm operators between 1978 and 2017.

by Elizabeth Garber

Grace from the start when blossoms open one sunny day, the only pause from Spring’s deluge. Bees leap into each scalloped furred basin. Gentle summer, sun-bleached denim sky, comfort of brief night, dawn drying breeze, golden afternoon haze, song of grasshopper. Each apple claims a destiny: North West Greening, blood-red wild crab, burnished Rome, peach blush on Tamanga, and galaxies explode across blue-purple Black Oxford.

Leisurely fall, frost forgets to arrive, yellow leaves. The only red is in the orchard where the farmers wed and danced. One Beacon alone produces thirty-five bushels, early bite of white flesh. Quickening frosts intensify the sweetness. Family and tribe gather, scour branches and grassy floor, cheeks glow red, wooden crates fill, Hudson’s Golden Glen, honey-centered Lightning, reliable Baldwin, and sour Starks.

In the belly of the barn, blur of cousins hoist bushels, dangling light, blond beards glint. Rumble, pour, grind, dump, tuck of heavy cloth, wooden grates stack higher until the crushing wheel concentrates the work of bees, the history of a summer into a chilled river of Autumn velvet.

So raise your cups to the farmers!

This cider is a signature of love.

The number of female operators was not provided before the 1978 Census of Agriculture.

4

5

Elizabeth Garber is a lifelong coastal Mainer and the former Poet Laureate of Belfast. She has published three books of poetry, and her work has appeared on NPR’s The Writer’s Almanac and in multiple poetry collections.

By the Numbers sources: Statistics taken from the 1978 and 2017 USDA Census of Agriculture. The farm categories

in

Census

provided are those that appeared as distinct categories

both

versions.

from How

Move Like

Gardener: Planting and Preparing Medicines from Plants by Deb Soule. Soule is an herbalist from Rockport. | avenabotanicals.com.

HOW THINGS

C H A N G E

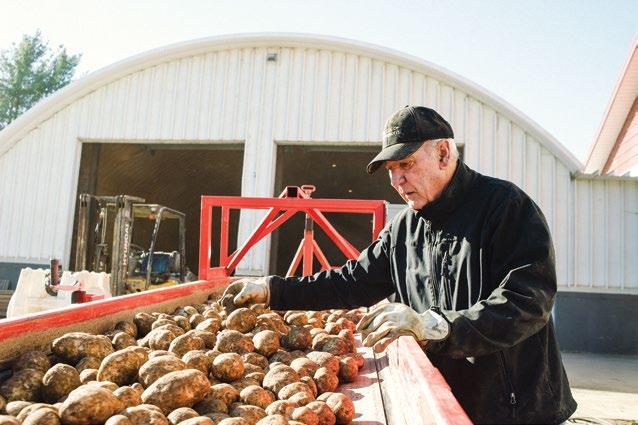

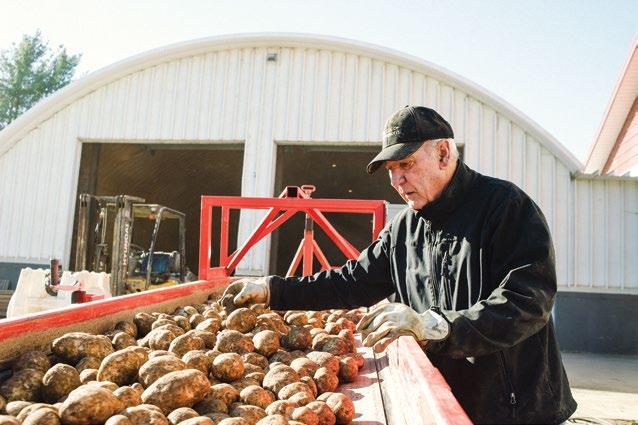

Talking with Neil Crane of Crane Brothers Farm in Exeter

BY KATY KELLEHER PHOTOGRAPHS BY LILY PIEL

I

f you’ve eaten a bag of Frito-Lay chips in the last 60 years, there’s a good chance you’ve crunched on a potato from Crane Brothers Farm. Neil Crane estimates that around 90 percent of his crop goes to this one snack food company. Crane has owned and operated the farm with his brother, Vernon, since they purchased it from their father in the 1940s. In the early 1960s, he began selling Maine potatoes to FritoLay and he hasn’t looked back. “We’re the second longest-term contract with Frito-Lay in the United States,” Crane explains (Frito-Lay’s other longtime supplier is located in the Midwest). “Our potatoes are bred and grown specifically for potato chips.” They have a higher solid content than potatoes you might buy to mash, and lower sugar content. They’re also round, which is important because “a round potato makes a round chip,” as Crane points out.

Now in his 80s, Crane has been farming all his life. He’s worked to expand his father’s small, 200acre farm into a 3,000-acre operation that grows potatoes (on 1,500 acres) and corn (on 1,200 acres). He also rents out some of his land to a nearby dairy farmer. There aren’t many businesses around like Crane Brothers. Most of the old farmers, those who remember when potatoes were stored underground in earthen banks and harvested by hand, have sold their businesses and given up their land. “Back in the early 60s, there were 12 to 15 active potato farmers in the area,” he recalls. “Now there’s only a few left. A lot of farmers retired, and when they retired, their kids didn’t want to take it over.”

Neil and Vernon Crane have been fortunate in this aspect. Their sons, Steve and Jim, are continuing their legacy and working to expand operations at

7

Left Neil Crane has been farming all his life, and he knows potatoes better than almost anyone. Top His crop from Exeter goes primarily towards making chips. A good chip potato is a round potato, he says.

Crane Brothers with the help of their now-adult kids. (In 2015, the Maine Potato Board named Jim’s son Ryan Crane Young Farmer of the Year.) The biggest shift he’s seen, Crane says, has happened in recent years. “The computer age is catching up with us. All the equipment is now computerized, and the tractors have GPS guidance. I would like it if I could figure out how to run it,” he says. “It takes the next generation to put it all together. But it’s good. It’s accurate.” Although he’s technically retired, on the day we spoke Crane had already “changed jobs three times this morning.” He helped fix a mix-up with a conveyer rig, worked to get the grade line going, and pitched in with putting together an irrigation rig. “The job changes hourly,” he says. When asked if he would ever do a different job, Crane jokes, “My wife wishes I would.”

But he’s all-in on farming. Even when he’s on vacation, he’s checking out the alfalfa fields, the irrigation rigs, the lines of corn. “Wherever I go, I try to check out what’s going on in agriculture. We took a trip out to visit five National Parks in Utah and it was beautiful, but for me the highlight of the trip was when we drove through the agricultural area,” he laughs. “I didn’t tell my wife that.”

katy kelleher is the author of Handcrafted Maine and the managing editor of Maine Farms journal. She lives in the woods of Buxton with her two dogs, husband, and daughter.

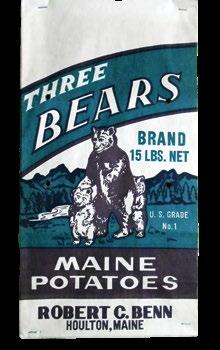

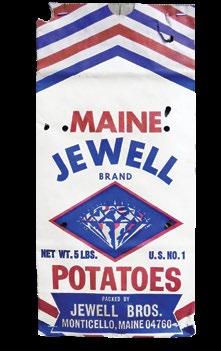

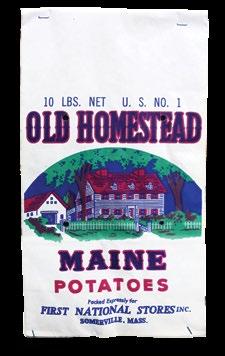

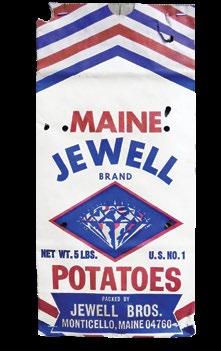

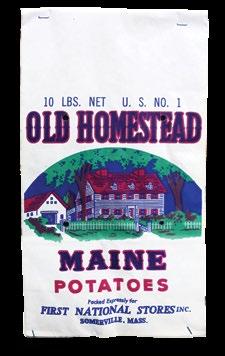

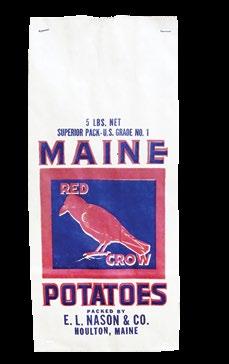

PAST: PACKAGING POTATOES

In the 1940s Maine potato farmers started packaging their potatoes in distinctive bags. The wide variety of bags illustrates the strong interest in distinctive marketing efforts that is still evident today. Even packers outside of the state chose to identify their product with Maine.

8 9

Crane Brothers sells between 250,000 and 300,000 hundredweight of potatoes to Frito Lay annually.

Images and text courtesy of Southern Aroostook Agricultural Museum

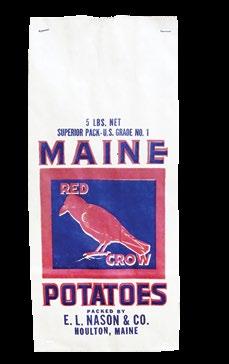

a sudden fascination with a crumbled old wall leads one writer down a winding path into maine’s history

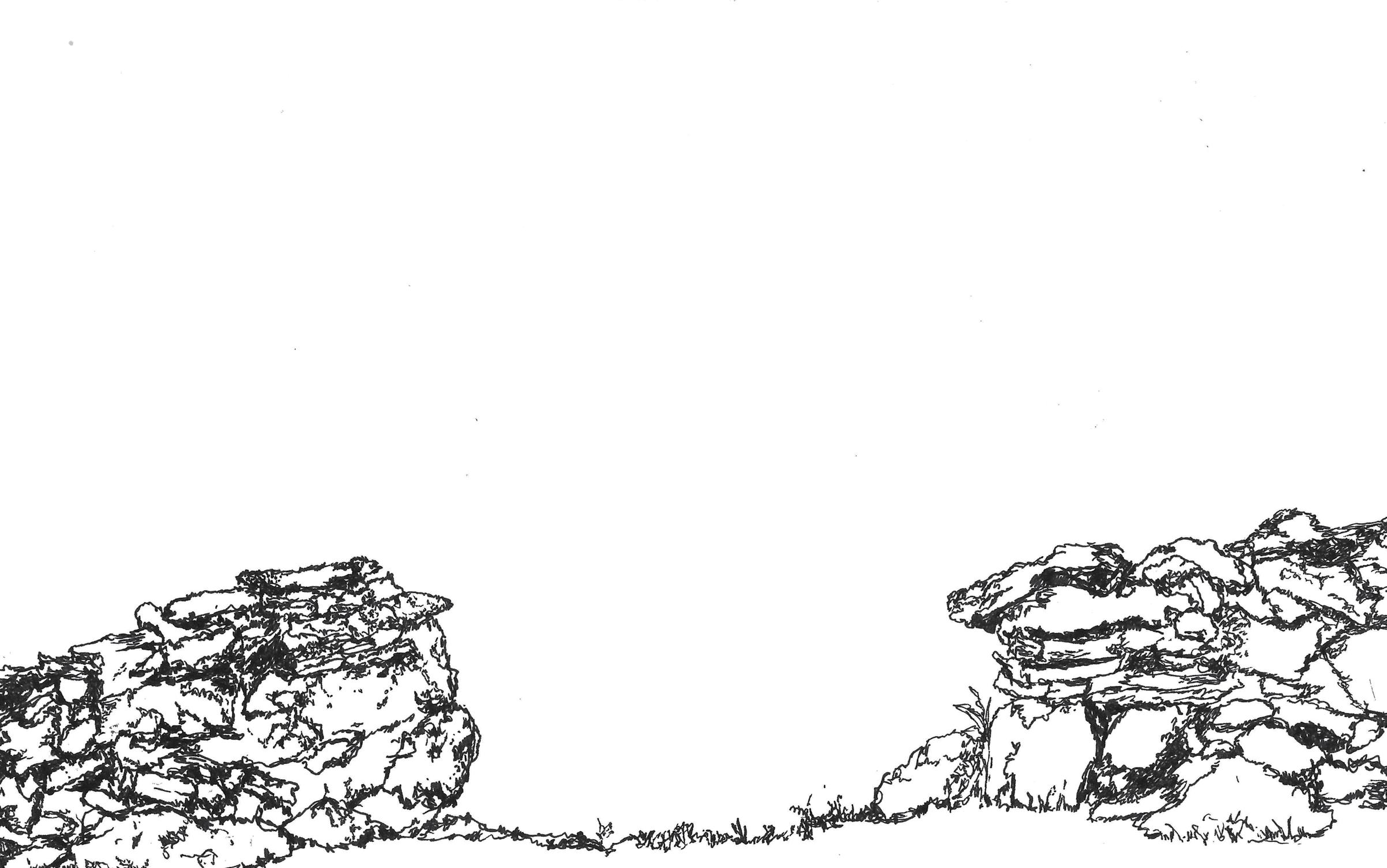

BY BEN COSGROVE | ART BY JESSICA KLIER

The onramp from Desert Road in Freeport to the southbound lanes of I-295 slices diagonally down a hill from the surface road to the interstate, leaving an odd triangle of leftover land between the highway and the access road. Zigzagging across this little gore is a small but stately stone wall that comes up about as high as my knees. It runs south for a few dozen feet, cuts sharply to the left, turns right after parting for what must have been a gate, doubles back again, and dribbles unceremoniously to a stop near where the island peters out into a drainage and the ramp meets the freeway.

READING THE STONES

but something about it made it seem strikingly incongruous to the freeway landscape it now occupied. At some point, someone with a different relationship to this patch of land had painstakingly assembled a wall on it, with rocks he had pulled from its ground, and now it was an exclave sitting still in the middle of a different kind of place, hemmed in on all sides by new surfaces dedicated to nothing but movement. I wondered about that wall and how it got here.

I took a somewhat unexplainable interest in the stone wall at Exit 20 towards the end of December of last year, and fell into the habit of pulling over on Desert Road, darting gingerly across the onramp, and wandering around the little tract of land that holds it. For a spot so obviously not meant for pedestrians, the gore is an oddly pleasant place: on the land transected by the wall, majestic white pines and a handful of oak and hemlock trees rise above a needle-carpeted forest floor. Beyond them, past the remnants of a decaying metal fence, a second and much younger grove of evenly spaced, carefully planted pine trees speckles a small bluff that probably formed from excess debris when the freeway was grade-separated from the surface road. Because of the thick evergreen canopy, there is hardly any underbrush. Several times that month, with winter light shining brightly through the pines, I would pull over and poke

around the site. Walking along the jagged length of the wall or examining the two different groves of pines, I was effectively invisible to everyone in the triangle of anonymous vehicular traffic that zipped around me in all directions. I was drawn in part to the bizarre contrast between this small, rocky, forested landscape and the huge, sweeping curves of the highway enfolding it, and struck by the surreal difference between the speed of all the cars flying past and my own as I puttered around among the trees on foot. Maybe it was the comparatively human scale of the wall, or the precision of its angles, all carefully aligned against a now-inscrutable axis,

Stone walls, arguably the single most distinctive feature of the New England landscape, were not the first strategy that the region’s farmers employed for marking their property, or for keeping livestock in and wildlife out. For generations, wooden fences were the standard, but these were prone to rotting and falling apart after enduring a couple of years of New England’s relentlessly rough weather. Years of working the land, however, were gradually contributing to the accretion of a new resource: deforested landscapes suddenly unprotected by trees saw their topsoil rapidly worn down by weather, exposing the rocky landscape below, and years of plowing and tilling also did their part to churn from the fields a slow, steady, and doubtlessly annoying font of mid-sized rocks. In the wake of these developments, stone fences gradually emerged as an elegant means for farmers to solve the fencing issue while simultaneously answering the question of what to do with all of these stupid rocks. (The zigzag

wall at Exit 20, with its clean angles and gateway built in, is probably an example of a stone fence that had been piled around an existing wooden one, which would have used that angular shape as structural support. After the wood rotted away, the rocks remained.) They would double as effective property markers too. While for the most part the earliest English settlements in the region, primarily along shorelines and river valleys, had not produced many stone walls at all—this was partly a consequence of the sandier geology of coastal New England and partly of Puritans’ general preference for communitarian agricultural practices and their corresponding vague disinterest in the notion of private property— by the late eighteenth century, as settlers moved inland and up

north, attitudes toward religion, economics, and land ownership all shifted and New Englanders quickly began to wildly outperform their countrymen in the business of carving up the land among themselves. “In [these] states,” George Washington would note, “landed property is much more divided than it is in the states south of them.”

Before long, New England had grown an exoskeleton of stacked stone lines that was almost impossible in scale: by 1872, the six states together held 240,000 miles of them. By any measure, this is an absurd number; it is a greater distance than that between the earth and the moon.

I went to the Freeport Historical Society to see what I could learn about the provenance of the stone wall on the Exit 20 highway gore, and was helpfully shown a series of old maps that identified the site over time as the property of various generations of a family called Randall. A cemetery bearing the family’s name is preserved on

the other side of the interstate, between another onramp and the edge of the parking lot for a supermarket. After much debate, and a lot of time spent pawing through very old deeds, it was agreed that the wall I was wondering about was probably built by a Randall, though we couldn’t quite figure out which one or when. The family seemed to have farmed the land for a while, slowly calving off pieces of it for successive generations to live and work on. Those acts of subdivision may have been another reason for the wall. An older man who turned out to have lived in Freeport all his life was in the room researching a project of his own while I was there, and he looked on bemusedly as a Historical Society employee assisted me with my highway ramp question. He had thoughts about the Randalls’ wall, which, I found with satisfaction, to be pretty well in line with my own. “Would’ve been there for farming,” he declared immediately and matter-of-factly. “Frost heaves would’ve pushed up all these rocks, and you’ve got to clear the fields before you can get much done. And you needed a fence to keep the animals out. Or in, as the case may be.”

12 13

•••

Something made it seem strikingly incongruous to the freeway landscape it now occupied.

•••

I explained a concurrent interest I’d been developing in the origins of the interstate itself—I had found it hard to imagine this part of Maine without it—and he remembered that when they designed and built that highway in the 1950s, it “mostly went across old farm land that wasn’t being used anymore.” This checks out; as with most interstate projects during that initial wave of construction, the state acquired land by asserting its right of eminent domain. While big highways frequently wrought misery where their construction displaced people and property in dense urban areas, the land requisitioned to carry interstates across rural areas tended to proceed along paths of relatively light resistance, like across fallow farmland.

“A lot of the gravel for it came from up in Topsham,” he went on.

“And North Yarmouth, I suppose. All around here. Point being, it

was good work. I remember one fellow down the road bought six dump trucks to work on the highway. Took them a long time to do the work but they did it.” It didn’t seem to him that the construction of this enormous road was much of an inconvenience to the people in town, with the exception of the people whose property was bisected by the new freeway and now had to travel a considerable and inconvenient distance to get to the different parts of their land. From what I was able to learn, the Randall property would have long fallen out of active use by then, but would certainly have been among those bifurcated tracts. I tried to explain to him and to the Historical Society worker why this particular site seemed so subtly strange to me. It’s relatively uncommon for onramps to be forested, for instance; big trees so near to fast roads present significant liabilities, and so on. But

I also thought it was weird that these old trees—and significantly, this stone wall—had been so well-preserved despite having survived the famously destructive process of laying out an interstate

highway. While today, new highway projects are compelled to perform extensive assessments of the archeological and ecological significance of the sites they will build on, this was not the case in the fifties. Why hadn’t the trees and the wall been buried in debris or knocked over to improve visibility? Or simply to remove a potentially hazardous obstacle?

“I don’t think they would have made an effort to preserve it,” the Historical Society employee said of the stone wall, after thinking for a minute. “Normally, there was very little concern for preserving historic sites, particularly in those days.” The older man nodded and laughed. “You want to know the truth, I’m sure they were just looking at the track they wanted to build on and it just wasn’t in their way.”

Stone walls, left to molder in a field-turned-forest, eventually become part of the environment around them. Centuries of winters and summers cause them to shift and shudder and collapse; things grow on them and up through them, and gradually they take on the characteristics of the landscape that holds them. Ultimately they wind up an inextricable part of it.

“Out of a ruin,” wrote the landscape scholar J.B. Jackson, “a new symbol emerges, and a landscape finds form and comes alive.” I have only been around for the last thirty years, and so my instinctive feeling about stone walls is that they are simply things that one stumbles upon in the woods. They do not make me think of farming, or property lines, or even of people. As someone who grew up in an environment lousy with the things, they have never seemed to me anything but an utterly natural feature of the landscape, as basic and essential as a mountain stream or an erratic boulder. Whenever I’m back in New England after spending time away, stone walls are familiar; an unconscious cue to the fact that I’m back in the forests in which I grew up. And like stone walls, highways like I-295 won’t be relevant forever. The generation I belong to has struck fear into the hearts of auto manufacturers with our demonstrated ambivalence about car ownership. Within my lifetime, self-driving cars are likely to massively reshape the way people think about distance, commuting,

and geographic space. The roads we need now are not necessarily the roads we will need in twenty or fifty or a hundred years. Think of the many miles of decommissioned rail beds around New England that are now paths for recreational cyclists, pedestrians, or snow machine users, and imagine what we will do with 46,876 miles of the U.S. Interstate system once we’ve moved beyond our current, and still relatively new, car-centric moment.

Stone walls tend to be about thigh-high because of the mechanics of human movement; that’s about as high as a mid-sized man can put a big rock down after lifting it up. Whatever Randall—if indeed it was a Randall—built my stone wall by pulling rocks from the ground and stacking them on top of each other, maybe his actions weren’t so dissimilar to those of the man from Freeport who bought six dump trucks to help build a new, gigantic road out of gravel from North Yarmouth on the same site. These things, so necessary for a moment, will inev-

itably remain in the landscape for long after their intended purpose is served out or forgotten. We walk among ruins whose meaning we’re constantly reevaluating, reimagining, and reinterpreting, and a landscape like Maine’s, so wrought with layers and skeletons, is at any given moment a palimpsest of all these symbols at once. I think this is why I was so compelled by the sight of part of a stone wall stranded on an island hemmed in by the trappings of an interstate highway. The world we navigate today is stacked with the remnants of past and present means of framing the landscape for ourselves: roads and fences, cellar holes and train tracks, buildings and walls. Their shapes are meaningful and instructive even when they’ve outlasted their original function: they add up to a broad and intricate tapestry of awkwardly interlaced lines on the land, each marking out the vectors and dimensions of long-forgotten ways of moving through and being in the world.

ben cosgrove is an essayist and traveling musician who writes music and nonfiction about landscape, place, and environment. | www.bencosgrove.com.

14 15

•••

These things will inevitably remain in the landscape for long after their intended purpose is served out or forgotten.

The Future of Farming IN THEIR OWN WORDS

For 20 years, Maine Farmland Trust has been working with members and farmers to promote and protect local farms and farmland. To honor this milestone, we asked a

few members of our community about how Maine agriculture has changed over the last two decades, and what they hope for the future of farming. Here’s what they told us.

Broadcrest Farm · Ripley

How has farming changed over the last 20 years?

Right now there are currently two operating dairy farms in Ripley. When I was a young kid in the 60s, there were eight. When my father was young, in the 1940s, there were over 40 dairy farms in town. The biggest change I have seen is the age constraint on the older farmers retiring and not having another generation to come along, and that has caused farms to go out of business. Then the land may end up being broken up a bit, and that changes the landscape. And the storms. The weather is changing.

What does the future of agriculture look like in Maine?

We need to eat. We need to have local food. This world is getting so big that we don’t know where our food is coming from. I check labels constantly—Walmart has blueberries from Peru! And here we are in Maine. We need organic, we need conventional, we need big and small. We don’t need super big, but we need it all. We have to stay on the forefront of protecting the land; the public and the landowners need to all be educated on how important it is to protect their land. Without it we won’t have a food supply. Once the farms are broken up, it’s hard to put them back together. We need to able to take care of ourselves, and our state.

17

ANDREW SEVEY

FUTURE 16

PHOTOGRAPHS BY KRISTIN DILLON

STACY BRENNER

In your opinion, how has the landscape changed for farmers in Maine over the past 20 years?

Compared to 20 years ago, there are so many more effective support programs for beginning farmers. We are collectively tackling large issues that are obstacles to launching a career in farming—land access being among the first a farmer experiences. We have a more educated consumer base that is making the connection between buying local products and supporting a vibrant and healthy rural farming landscape in our state.

What are your hopes for Maine agriculture 20 years from now?

My hope is that the shelves of the Hannafords and Shaw’s and Market Baskets around the state are filled with Maine-grown produce, and that only the things we can't grow in Maine are sourced from away. For example, I'd like to see only carrots, onions, and potatoes from Maine sold year round in all stores and not sourced from other states or countries. In addition, I'd like us to have sophisticated production practices and equipment to make the work interesting and to be able to pay farm laborers a living wage.

What are your hopes for Maine agriculture 20 years from now?

We have a vision for robust community-based agriculture that feeds each other in Maine first before it concentrates on exporting food or commodity agriculture. We have a vision of increasing food sovereignty across Maine, building a strong foundation of self-determination over our food policy that prioritizes people’s needs. We hope for better financing and land access systems for beginning farmers. We see Maine increasingly as a destination for aspiring young farmers. With that comes an increasing amount of second-tier economic activity based on farming, like mobile slaughter, food trucks, valued added food, mechanics, etc.

What does the future of farming look like in Maine?

We think the future of farming in Maine hangs in the balance right now. The future very much depends on what we do now in terms of creating supportive policy, attracting more young and beginning farmers, maintaining and increasing the amount of successful farm transfers and farmland protection, continued farm patron education, and the ability of farmers to adapt to climate, financial, infrastructure, and policy challenges.

18 19

HEATHER + PHIL RETBERG

Quill’s End Farm · Penobscot Broadturn Farm · Scarborough

Fore Street & Scales Restaurants · Portland

How has your restaurant and its relationship to Maine farmers and local food changed? What has made that possible and what challenges have you faced?

In the time I’ve been cooking in Maine—that is, since 1974—everything has changed. Back then, almost all food supplies for restaurants came from commercial produce and meat wholesalers, meaning ingredients from onions to lettuce, beef to lamb, originated in industrial California farms and Midwestern feedlots. One fruit and vegetable wholesaler that I used at that time did operate their own family farm in southern New Hampshire and gave purchasers the option of delivering their produce during the short summer growing season.

A flip to the availability of local foods began in my own work in the early 80s, and continues even now. It’s almost inconceivable that a new restaurant would open in Maine that doesn’t give at least lip service to local foods.

Springdale Farm · Waldo

What does the future of farming look like in Maine? What are your hopes for Maine agriculture?

I feel that the Maine brand has really blossomed in the last ten years or so, and my hope is that this trend continues. There is something so special and magnetic about our state and it is really highlighted through our agriculture. I am especially proud to be part of the Maine cheesemaking community. When I moved home, I joined the Maine Cheese Guild immediately and it was a way to connect with other cheesemakers and continue to learn about the craft. The energy and passion within the group really helped fuel my fire to start my own creamery.

My hope is that the reputation and popularity of Maine cheeses continues to grow and reach into markets throughout the Northeast and beyond. There are many challenges facing the dairy industry right now. For me, seeing amazing products being made with Maine milk on all scales, and seeing their growing popularity in the marketplace, is a much-needed ray of hope for such an important industry in our state.

20 21

SAM HAYWARD

CARRIE WHITCOMB

STORING CARBON —in the— WINTER GARDEN

Low-impact foresters across Maine increasingly appreciate the benefits of leaving woodlots intact

BY LAURA POPPICK | PHOTOGRAPHS BY GRETA RYBUS

BY LAURA POPPICK | PHOTOGRAPHS BY GRETA RYBUS

On a clear October morning, I walk with Peter Hagerty down a dirt road on his 100-acre farm in Porterfield, Maine. We make our way past an old barn and a garden, then meander uphill into the dappled light of a forest. That’s when Hagerty starts divulging his favorite facts about the woods. “This is not just a bunch of trees with a bunch of individual roots,” he says with a warm smile. “These roots are all interconnected with one another.”

I try to imagine roots of different species intermingling underground through fungal networks while I take in the stunning oranges and yellows of birch and beech foliage around us. But what may have felt like an ideal fall day is sullied by unseasonable warmth—instead of feeling

a refreshing bite in the air, the humid, 80-degrees-Fahrenheit weather leaves us hot and sweaty. Hagerty and his wife, Marty Tracy, have been harvesting trees from this forest every year since 1976. Over time, Hagerty’s approach to harvesting has shifted, in part because of his mounting concerns about the warming climate. He has always been interested in sustainably harvesting wood, which is why he chooses to harvest with draft horses rather than with heavy machinery (which can compact soil and damage roots more than the trot of a horse). But his harvesting attitudes took a more serious turn after he read the book The Hidden Life of Trees by German forester Peter Wohlleben in 2016. “All of a sudden a light went on,” Hagerty says. What most

22

BUSINESS

Trees have deep roots in Maine culture, and they’re good for more than yielding fruit and syrup.

intrigued him was learning the extent to which trees can slow the rate of climate change by sucking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and storing it in roots and trunks. “We have these huge allies,” he says, “but we don’t even realize that we have them.” With 89 percent of Maine covered in woodland, the state ranks as the most forested in the country and does, indeed, hold great potential in its trees. (New Hampshire comes in second place with 81 percent forested.) Aside from storing carbon, healthy woodlots also help filter drinking water and keep animal communities intact. And while the very best thing for the environment may be to leave all of these forests untouched, Hagerty knows that’s not realistic. That’s why he and others across the state are working to educate landowners about “low impact” forestry, a practice that leaves trees in the ground longer to absorb more carbon, all the while growing in diameter and gaining in value. They ultimately hope to improve quality of life and local business by keeping more

forests intact, and getting locally produced, high-value wood products in the hands of more Mainers. Trees have deep roots in Maine culture. As longtime maple syrup producers, Ed and Pat Jillson understand this intimately. They’ve operated Jillson’s Farm and Sugarhouse in Sabattus for more than 40 years, and each spring, they welcome droves of school groups to their farm so that children can learn about (and taste) Maine’s sweet heritage of tree tapping. When they first opened their doors for Maine Maple Sunday decades ago—an annual springtime tradition when sugarhouses across the state offer tours and community feasts—they were surprised when more than 2,000 people showed up. “From then on, we couldn’t make enough syrup,” Ed says. Syrup, along with apples and other fruits, have a solid place in Maine’s history of agriculture. But, these days, if trees aren’t yielding these types of treats, they’re often viewed as the backdrop of working farms. Hagerty wants to change that mindset.

“A farm is not just a field,” he says. “A farm is a forest and a field.” He notes that, in his grandfather’s generation, forests received more recognition as an integral part of a farm. “Woodland was the winter garden,” that paid for taxes and kept farmers afloat between growing seasons, he says.

To help landowners sustainably realize the full potential of their land, Hagerty has been involved in the Low Impact Forestry Project of the Maine Organic Farmers and Growers Association (MOFGA) since it was founded 20 years ago. But when this group first launched, they weren’t focused on the climate benefits of forests. “We had no knowledge of how important those trees were to the longterm survival of the environment,” he says.

That’s in part because scientists didn’t understood the extent to which trees can regulate the climate until fairly recently, says Jonathan Thompson, an ecologist at the Harvard Forest in Petersham, Massachusetts. Scientists have long known that trees

suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and store it in their roots and trunks during photosynthesis. But new findings show that forests in the eastern U.S. absorb an astounding 15 to 20 percent of carbon pollution associated with fossil fuel burning each year. And that quantity just keeps increasing over time: As forests age, they suck increasingly more carbon out of the atmosphere. “That’s really news, that wasn’t what we thought would happen,” says Johnson, noting that scientists previously thought trees plateaued in their carbon consumption after about 100 years. This means older forests have always been helpful allies in slowing climate change, but scientists haven’t fully appreciated this fact until recently. The most responsible type of tree harvest would be to leave trees in the ground for as long as possible, Johnson says. But that doesn’t mean a landowner should never thin their woodlot—even waiting an extra five or ten years to thin a stand can offer great benefits to the environment, and to the quality of

25

Left Staying physically active with logging helps keep Hagerty's spirits up amidst the ongoing news of climate change, he says. Right Harvesting only on frozen ground in the winter has helped keep Hagerty's forest so healthy that it's become hard for him to find dead or dying trees to harvest, he says.

Left Ed Jillson tapped the first tree for his farm back in 1976, and has been producing syrup ever since. Right Ed and Pat Jillson operate roughly 2,200 taps across three counties in Maine. They use plastic tubing to help streamline the collection process.

the wood. “Forestry is really a patient person’s game,” he says. “You need to think generations ahead.”

Tracy Moskovitz and Bambi Jones practice this patience at Hidden Valley Nature Center inWhitefield. While their return-on-investment is more drawn out than it might be for a traditional industrial logger, this decision could pay off in the long run, says Jones. “We are constantly improving the woodlot, so the value of the wood is constantly going up, and it is going up faster than most because of our practices,” she adds.

Like Hagerty, this duo didn’t set out with the intent of managing their trees for carbon when they first started logging their 1,000-acre farm about 40 years ago. But they have become more attuned to these climate benefits over the years.

As Moskovitz tours me around their land, he points out various things they do to improve the health of the forest. For example, they only harvest when the ground is solid (preferably frozen) so as not to compact the soil around roots—which can damage or kill organisms living in the soil that also help store

carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. They keep an eye out for branches that need pruning to allow sunlight to reach saplings growing on the forest floor. And they harvest from within a 15-acre area each year, only returning to a given plot after ten years. “In gardens, you think of value during harvest time,” he says. “But we think of standing timber as our greatest asset.”

For that reason, he leaves the healthiest of his trees standing, and weeds out others that aren’t as healthy, trees that are thwarting growth of surrounding trees by blocking sunlight or consuming soil nutrients.

“Conventional foresters take the best and leave the rest, but we do exactly the opposite,” he says.

Moskovitz and Jones have also built numerous culverts and bridges around their property to reduce the impact of their trucks on soil and streambeds; leave some fallen trees for woodpeckers and other creatures to scavenge; and, when school groups visit, build shelter piles for animals using discarded crowns of trees.

For all of these efforts, the couple has won numerous awards including the 2014 State of Maine’s Outstanding Tree Farm from the Maine Tree Farm

26

27

Left Since 1978, Tracy Moskovitz (left) and Bambi Jones (right) have expanded their mostly-wooded farm to include roughly 2,200 acres. “We pretty much like everything about the woods,” says Moskovitz. Right “This is just like driving through a garden,” Moskovitz says of harvesting trees. Opposite Page As a rule of thumb, Moskovitz and Jones try to leave roughly 20 feet between mature trees to allow sunlight to reach the forest floor.

Program. “What makes Hidden Valley unique is that they are taking a long view of what they are doing in every respect,” says Morten Moesswilde, a state forester who works out of the Maine Forest Service’s Jefferson office. Moesswilde hopes these types of practices can become the norm rather than the exception in Maine, and he spends his days working with landowners to educate them about the benefits of these types of low impact forestry practices.

“The trick,” he says, “is getting everyone on the same page.” With increased outreach and public awareness, Moesswilde hopes to elevate an attitude toward locally harvested wood comparable to the rise of the local food movement. “Everything about localism is positive, the tricky part is making those connections for people,” he says. “Everybody eats, but not everybody is paying attention to where wood comes from.”

Theresa Kerchner, executive director of the Kennebec Land Trust, is now working to address this issue by creating a user-friendly tool for Mainers to easily source their wood locally. She launched Local Wood WORKS in 2013, an initiative that connects consumers with local wood providers throughout the northeast through an easy-to-use digital database of products ranging from flooring panels to furniture building materials.

Kerchner is now networking with architects and engineers to spread the word and get this new tool on the radar of more Mainers. She hopes the efforts will help communities return more deeply to their roots in the lumber industry, but this time with a mind towards sustainably harvesting wood for the long-term benefits of our climate. Generations ago, Kerchner notes, small mills scattered throughout Maine towns manufactured

Opposite Page Hagerty gets more than just physical help from his horses—he's formed a strong emotional bond with them as well, he says. This Page Each year, Moskovitz and Jones harvest about 15 acres of forest that together produce roughly 30 cords of pulpwood, 30 cords of firewood, and 6,000 board-feet of lumber.

Opposite Page Hagerty gets more than just physical help from his horses—he's formed a strong emotional bond with them as well, he says. This Page Each year, Moskovitz and Jones harvest about 15 acres of forest that together produce roughly 30 cords of pulpwood, 30 cords of firewood, and 6,000 board-feet of lumber.

products ranging from tool handles, to flooring and beams. That shifted when industrial logging became larger-scale. “My vision is we could bring back some of those small economies in our communities,” she says. “And at the same time, because wood-based economies would be dependent on forests, we get the benefits of keeping forests as forests.”

By keeping forests as forests longer, she hopes to drive up the market value of wood. “I want to find ways for landowners who own forestland and need to derive an income from it to make an income from it,” she says.

Meanwhile, Hagerty has woven carbon storage into his Low Impact Forestry curriculum through MOFGA so that landowners can understand how their thinning practices can help improve the environment. Last fall, a local high school teacher reached out to him to see if she could bring her class to his farm to learn about carbon storage in trees. “These little things are happening now,” he says.

His enthusiasm for the forest is palpable, and it’s hard not to feed off this energy as he tours me around his woodlot. “If you were to look underground,” he continues as we walk through the forest, “you would see this giant map of interconnected organisms that are all working to keep the woodlot in its entirety healthy.”

“There’s more going on than I had ever dreamed,” he adds with genuine awe.

In this way, trees offer Mainers more than just monetary value and ecosystem functions: they provide a source of inspiration and a sense of home.

“The key for all of us,” Kerchner says, “is they provide a sense of beauty and place for our region.”

30

laura poppick is a freelance environmental journalist based in Portland, Maine who's favorite garden snacks are strawberries and sugar snap peas. She contributes to Scientific American, Audubon Magazine and elsewhere.

Pruning trees creates space for trees to grow and expand. Jones estimates she has pruned more than 15,000 trees in her career. "It's a great way to be out in the woods," she says.

AND BROILERS PORK CHOPS

Examining the struggles and pleasures of Maine’s meat economy

BY WILLY BLACKMORE

PHOTOGRAPHS BY KRISTIN DILLON

BY WILLY BLACKMORE

PHOTOGRAPHS BY KRISTIN DILLON

FOOD

OF

33

“Fire up that small skillet in the back, and make a small patty,” Steve Sinisi said over the whir of a motor as he put fistfulls of pork into an electric meat grinder. His four-year-old daughter Minka stood on a chair at the other side of the counter with an eager look on her face. Pork, as Sinisi has pointed out, is not the other white meat—and the trim used for the sausage, cut from a pig raised on his Durham farm, is a stark visual reminder of that fact. Unlike the pale, anemic-looking chops you find shrinkwrapped at the grocery store, the highly marbled cubes of meat, shot through with garlic and chile, were the rich color of a glass of good rosé. This color is the hallmark of a hog that’s lived a life on pasture— basking in the sun, rolling in muck, running around, and rooting in the dirt for some extra food to eat.

Chuck Huus, Sinisi’s father-in-law, patted out a round to cook on the kitchen’s six-burner stove, the cast-iron pans sitting on top, each slicked with a white cap of rendered pork fat, and pressed it into a hot pan. The loose sausage, which would be packed into plastic sleeves and taped shut by his granddaughter, was destined for Huus’ freezer. Out of the pan, browned and sizzling, the sausage didn’t overwhelm with spice or salt. Instead, it tasted intentensely of the meat itself; the seasoning was less a cover than adornment. More simply put: it’s really good meat.

Burly and tall with a curly, rusty beard, Sinisi talks animatedly about his 70-acre farm, where, in addition to pigs, he raises grass-fed beef. In the summer months, he also raises pastured chickens (his least favorite livestock) to help with cash flow.

(Sinsi was able to buy the farm at an affordable price because it was protected with an easement using Land for Maine’s Future funding.) Now in his eleventh year on the farm, things are starting to get a little bit easier for Sinisi. He has a new barn, which will allow him and his pigs to be inside during the winter time, and to supply pork year-round. Seren Sinisi, Steve’s wife, is spearheading a project to build a tiny house on the property, allowing Old Crow to expand into agrotourism. The farm, unlike so many, is working—but it’s by no means easy. There hasn’t been any kind of significant meat industry in Maine since the bottom fell out of the Belfast-area poultry industry in the late 1980s. The long, grey barns with small square windows that once housed the hundreds of thousands of broilers are now falling in on themselves, or have been repurposed as antique stores or plain-old storage. In 2017, the state ranked 39, 43, and 39, respectively, for poultry and eggs, cattle, and hogs, according to USDA. A livestock survey counted just 4,500 hogs across Maine, which is the equivalent of a single confined-animal feeding operation in leading pork-producing states like Iowa and North Carolina. There are plenty of places like Old Crow Ranch scattered along Maine’s many winding rural roads where you can get a feel for the animal agriculture in the state. There are the small flocks of colorful layers pecking around front yards. There are the Belted Galloways chewing cud in hay fields surrounding weathered old Capes. There are those old poultry barns. But even in aggregate, the sum of these rural scenes reveals only a piece of the Maine Meat Economy.

If you want more than just a glimpse of how—and how much—meat is raised in Maine, there’s a dead-end road outside of Gardiner that is the end of the line for many of the state’s broiler chickens. Here, at Common Wealth Poultry, Maine’s only USDA slaughterhouse for poultry, trucks full of chickens from farms medium and small (no large farms are left) are dropped off daily to be killed and processed for sale. The 35 year-round employees at the slaughterhouse—all New Mainer immigrants from Somalia and elsewhere in Africa—stay plenty busy, but its output is a drop in the bucket compared to big processors, which can kill,

34

•••

Opening Spread There hasn’t been any kind of significant meat industry in Maine since the bottom fell out of the Belfast-area poultry industry in the 1980s. Some farmers are trying slowly, little by little, to bring it back. This Page Old Crow Ranch has a small herd of cold-hearty Mangalitsa pigs, which are renowned for their rich fat. Opposite Page The pigs are so furry that some neighbors thought that Steve (top right) and Seren (bottom right) had started to raise sheep too.

clean, and process between 250,000 to 300,000 birds per day. “They do in a day what I do in a year,” said Ryan Wilson, who co-owns Common Wealth with Gina Simmons. Until recently, when a change in regulations made it possible to send state-inspected birds out-of-state, Common Wealth was the only way for local farmers to sell poultry outside of Maine. All told, there’s only a handful of USDA slaughterhouse facilities in the state. There are exemptions that allow a certain amount of birds to be slaughtered on-farm, but the limited infrastructure overall presents a challenge to Maine farmers. The 2017 report “More Maine Meat” from the Maine Sustainable Agriculture Society found that “the three primary barriers to increasing herds or flocks were feed costs, access to capital and processor availability,” according to a survey of producers in the state, two-thirds of which were operations with fewer than 10 animals. Then there’s the weather. Not only is there winter

to contend with (and the attending need for winter feed and shelter, with different animals having different requirements), but dry summers have been known to tip into drought, which makes maintaining healthy pasture and hay fields throughout the year a more difficult prospect.

“Ecologically, growing birds in Maine has its setbacks,” said Wilson, who got his start on the farming side of the poultry industry, raising pastured chickens and other birds. “The idealism that you can just grow birds in Maine and that's the best way to do it is sort of backward.” Modern meat birds, he said, weren’t bred to withstand a life lived outside, which doesn’t provide the very constant living conditions of a barn. “If you're going to use that bird, I think you owe it to the bird itself to give it the right conditions that it was bred for.”

Raising livestock in Maine has its challenges, but farmers like Sinisi and the poultry producers Common Wealth works with aren’t laboring in

vain. “I think there's potential here,” said Alice Percy, a former hog farmer herself and author of the forthcoming book Happy Pigs Taste Better “Customers are interested. Most people care about animals, and either don't want to think about the conditions of conventional farms, or are actively seeking an alternative.” There is a deep appreciation for local food in the state, thanks in part to institutions like MOFGA, not to mention the young, idealistic farmers who have been drawn to Maine and its comparatively affordable farmland prices since the beginning of the Back to the Land Movement in the 1960s. Finding a market, however, can also be an issue—both because of infrastructure, but cost as well. When Sinisi was working up his business over 10 years ago, he found that just 1.5 percent of Durham residents could afford the kind of meat products he intended to raise. Purchased directly from the farm, a half pig runs $4.75 a pound for 100 to 125 pounds of meat, and whole pigs are $4.70 a pound. “Well, it ain't happening in town!” he thought at the time. Today, Old Crow Ranch ships out 10 pigs a month, the grand majority of which are sold at markets owned (or co-owned) by Ben Slayton: Farmers’ Gate Market in Wales and The Farm Stand in South Portland (of which he is a co-owner). The various Rosemont Market and Bakery locations in the greater Portland area also stock Old Crow Ranch meat. The farm’s proximity to those wealthier Southern Maine markets makes it so the $12 a pound that bone-in pork chops run at The Farm Stand in South Portland (versus just over $3 a pound at Hannaford) is affordable to enough customers so as to keep the whole enterprise running. And Slayton is a steady, understanding buyer. After raising pigs himself, Slayton realized that he could do the most to support a sustainable local meat economy in the state by focusing on the distribution and retail-sales side of things.

“It doesn’t make sense for the Steve Sinisis of the world to build a butcher shop,” Slayton said. “But if we aggregate the Steve Sinisi and other farmers in one location that has good access to consumers, they don’t lose the connection to the farmer—we celebrate that.”

It’s an approach that Percy believes is wise, too. If you sell direct, “you might get a higher price for your product,” she said, “but you're also being a farmer and a salesmen and a distributor”— and farm work itself can be challenging enough.

This Page Ben Slayton of Farmers’ Gate Market and The Farm Stand said, "the kind of farms that are interested in supplying are not going to be able to sustain the kind of market share that we’re going to need." Opposite page At Common Wealth Poultry in Gardiner, many of the workers are so-called New Mainers—immigrants from Somalia and other countries across Africa.

This Page Ben Slayton of Farmers’ Gate Market and The Farm Stand said, "the kind of farms that are interested in supplying are not going to be able to sustain the kind of market share that we’re going to need." Opposite page At Common Wealth Poultry in Gardiner, many of the workers are so-called New Mainers—immigrants from Somalia and other countries across Africa.

In the summer, when the turkey yard is full, Mainely Poultry appears like a cloud of white feathers alongside Route 1 outside Warren. Here, John Barnstein has raised turkey, chickens, and ducks since 1985. “On a small scale, I'm pretty large, but on a big scale, I'm pretty small,” he said of the farm. He processes 800 chickens a week, which isn’t much less than the 1,000 or so Sinisi raises in a year—but it’s a miniscule number compared to the flocks of 20,000-plus birds found in your average contract-farmer poultry barn, which is where nearly all of American broilers are raised. Barnstein got into farming chicken because he thought he could raise a better product than what came out of New England poultry barns. When his wife cooked chicken back in the ‘80s, “it would always smell like she was cooking fish,” he said. This was the result, Barnstein discovered, of the birds being fed waste from a seafood processor

that made breaded fillets and nuggets. Since the beginning of Mainely, he’s been antibiotic- and hormone-free, and didn’t give his birds animal byproducts when that was still allowed. He did manage to raise a chicken that smells like chicken, and has kept at it ever since. “But it's strictly for love of what we do,” he said, “and not for the money.”

At Mainely, labor is Barnstein’s primary concern. He regularly employs international agricultural students through the J1 visa program (one from South Africa and two from the Philippines when we spoke in late 2018), but they can only stay for a year and the process is becoming more difficult as immigration laws are tightened.

Barnstein has also taken advantage of the work program at the nearby Maine State Prison.

While the labor market is tight, Barnstein still manages to find customers at farmers markets and the local brick-and-mortar retailers he supplies

with chicken bearing the farm’s bright-yellow label. “The biggest issue is trying to overcome the fact that Americans have always demanded cheap food, and farmers have been able to produce cheap food,” he said. “But the consequence of producing more cheap food is more antibiotics, more pesticides, more fungicides, and more use of fertilizers.” Buying a bird from Barnstein will cost you a bit more—whole chickens go for $5.25 a pound at local retailers—but he’s convinced customers will earn the difference back in health and longevity.

Sinisi, who follows a complex series of grazing and cover-crop rotations, represents the more idealistic—and expensive—side of raising meat in Maine, and Barnstein and Common Wealth a more pragmatic approach. But the best path forward for a sustainable meat economy in Maine may bend a bit more toward the conventional side of things than some might imagine.

“The trick is finding the way to supply that demand in a way that's sustainable for the farmers,” Percy said. “Sometimes, that means making some reasonable compromises, and educating both consumers and farmers about what is truly humane husbandry, and what might contribute more to buzzword status than to animal welfare.” For example, she has frequently heard from both would-be farmers and consumers that the ideal is pork raised wholly on pasture—an “ideal” that, in reality, would be impossible, and would leave pigs undernourished.

Inside the barn at Old Crow Ranch, the scene looks a lot different than the picture of summer on the farm as described by Sinisi. On a hot August day, sometimes he’ll be out working—baling hay, or moving cattle—and notice a cloud of dust rising up from the hog pasture. “And you go over and you just see pigs running—they're chasing each other and slamming into each other, and they're just like, playtime!” In the cold of early December, the pigs are more sedate—they actually eat more in the winter, despite the lack of forage—but they gamely snorted at our arrival, the piglets retreating to a pile, while the hogs that would soon fill the cases at Slayton’s shops continued

sniffing at the fences. There’s clean bedding covering the concrete floor, and plenty of rooms in the pens, and yet it’s not anything you’d describe as a bucolic scene, but this set-up works for Sinisi, and that’s what is most important to him. He wants consumers to see how his animals are raised— and he wants them to be comfortable with it.

“There is a farmer out there somewhere for you,” he had said back at the house as we discussed the various ways that people handle confinement, feeding, and forage, and the words they use to describe the product that approach lands them on. “This is how I do it, this is what I do. If you don't like it? Fine! Go find a farmer for you.”

willy blackmore is a freelance writer and editor who covers food, culture, and the environment. He lives in Hope, Maine.

38 39 •••

•••

This Page The cattle at Old Crow Ranch are raised on pasture that's enhanced by the pigs—and their manure. Sinisi's system of rotations and planting grains like millet into his existing fields have made it so he rarely has to buy hay from another farm. Opposite page In the summer, the pigs at Old Crow Ranch run wild and play, but in the winter they’re more sedate.

BY MELISSA COLEMAN PHOTOGRAPHS BY MOLLY HALEY

FIVE MAINE FARMS

Six Talented Women

I n my earliest memories, there are women in the garden. Lots of them. My mother, with her bandana and braids, bending over the earth to dig potatoes. “Like an Easter egg hunt,” she said, as I followed along behind. Then my two stepmothers, too, planting and harvesting over the years. Now it’s my sister, washing baby spinach for market, and carrying on the family business.

Just as there’s an abundance of inspiring female farmers in my life, so too, are we blessed with hard workers in Maine. Some are carrying on the family tradition, others came to it on their own, but they all do their jobs with pride, dedication, and commitment. May they inspire many more to come…

Betsy Bullard

The first thing you notice about Betsy Bullard is how calm she is. That she and her family run a dairy of 600 milk cows is nothing to stress about. Besides, that would not be good for the herd. “Cows like to be bored,” she explains. “It’s my job to make sure they stay that way.” At Brigeen Farms, a 10th generation dairy farm in Turner dating to 1777, this is no small feat. “One of the fantastic things about farming and working with living creatures is that ‘the average day’ is a misnomer,” she says.

After studying animal science at Cornell, where she met her husband Bill, the couple decided to return to Maine in 2000 to partner with Betsy’s parents, Steve and Mary Briggs. They grew the herd from 60 to 600, with nine employees, to become a Dairy Farmers of America wholesale milk provider for brands like Oakhurst and Hood. This means they have to keep their standards high, and their cows bored. Betsy says that’s just how she likes it, too.

40 41 PEOPLE

SPECIALIZATION Dairy SUPERPOWER Staying on schedule

Carolyn and Ramona Snell

It may be an anomaly these days to find three generations of women farmers working together, but at Snell Family Farm in Buxton, it’s business as usual. Henry and Ruth Snell started the farm in 1926, and their grandson, John Jr. runs the farm today, alongside his wife Ramona and their daughter Carolyn (who manages the flower business). Rita, Ramona’s mother, (who turns 90 this year) still helps with the garlic and pumpkins, and John Jr. takes care of the apple orchards.

“It’s a symbiotic relationship,” Carolyn says. “When I do flowers for a wedding, it builds a sense of connection and loyalty. The same people come back for vegetables, apples, and other items.” Customers find them at the farm stand (located on 70 protected acres a mile from the Saco River) or at the Portland Farmer’s Market, where Snell Family Farm has been a vendor since 1980. Now, with daughterin-law Abby in charge of the farm kitchen, the other items for sale include hand pies, raspberry jam, and rhubarb BBQ sauce. Next up, perhaps a fourth generation?

Denise Carpenter

SPECIALIZATION

If you’ve woken up from open heart surgery in the care of nurse Denise Carpenter, you may not have guessed she’s a superhero who just swapped her Carhartts for scrubs. When she’s not at Maine Med, she’s raising 30 cattle on Chellis Brook Farm’s 231-acre protected farm in Newfield. “I can mow a hayfield in the morning and still take a shower and get to work in time,” she says matter-of-factly. The key to a one-woman, parttime farm is in thinking ahead.

Instead of having “to futz around with hitching and unhitching” one tractor, she has five tractors rigged to the tools she needs for making hay and spreading manure. “I can just hop on and go.” At first, she sold steaks at the farmer’s market until colleagues at Maine Med asked if she would raise some cattle to split for quarters of beef. As her business has expanded, she’s made plans to retire to the farm in a few years. But for now, life as a superhero seems to be working just fine.

43

Beef

SUPERPOWER Two

cattle

jobs

SPECIALIZATION Vegetables & flowers SUPERPOWER Three generations

Deb Soule

For Deb Soule, the secret to being an herbalist is “being a teacher so people feel more confident using herbs,” she says. Indeed, she counts with gratitude her own mentors, two famed herbalists, Adele Dawson and Juliette de Baïracli Levy, who passed on their wisdom to her as women healers have done for centuries. After a semester learning traditional healing methods in Nepal, she was inspired to start growing medicinal plants on a friend’s land and making her own herbal preparations. She launched Avena

Botanicals at age 25 by handing out tinctures and herbal salves at the Common Ground Fair. When the small mail order business outgrew her workspace, a friend loaned Deb money to buy her own farm in Rockport in 1995. The gardens were planned as a living classroom, “a healing space that fosters birdlife and pollinators to grow native plants for education and Avena’s apothecary,” she says. In the past 24 years, Avena has become just that—a place to experience and pass on the wisdom of herbs.

Lauren Bruns, age 28, found an unexpected vocation in the low-bush blueberry barrens on her family’s back lot in Gray. After college, she returned to Maine in the heart of blueberry season to a field bursting with tiny ripe berries. “I got so anxious, I couldn’t let it go to waste,” she says. After that first euphoric harvest, she cut back the overgrowth, applied sulfur to lower the pH, and Lost and Found Farm was born.

“I had to have the confidence to ask to be taught certain skills,” she notes. Welding, for example, came in handy for building the custom winnower for cleaning and sorting berries. Lauren wants to keep the berry industry in Maine vibrant, which motivates her to keep growing her own business, and learning more every day. “I cannot wait to be in a position to teach what I've learned,” she adds. We think she’s well on her way.

45

SPECIALIZATION

SUPERPOWER Sharing the wisdom SPECIALIZATION

SUPERPOWER Contagious enthusiasm

Herbs

Blueberries & flowers

Lauren Bruns

melissa coleman is a writer from a family of farmers and writers, and the author of a memoir, This Life Is in Your Hands | melissacoleman.com.

One Long Day on Goranson Farm

4:45 AM FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2018

Another car is in my old parking spot by the sugarhouse, so I pull in next to the farm stand, where at least a hundred pounds of pure loyalty and love comes hurtling through the dark barnyard. The farm dog wedges her muddy body through the car door and into my lap, shrieking and writhing with excitement. Australian Shepherds remember everything, and Lila and I have a long history.

I still remember the night we all drove to North New Portland to pick her out (or let her pick us out) from the litter. I had been working at Goranson Farm for two years, and that was one of the winters when

I was up at the farm every weekend—laughing hysterically in the barn greenhouse with Kiersten over trays of seedlings, learning to cross-country ski with Mike, loading and unloading three trucks a Saturday with Kaite, tagging along with Carl and Göran to magical Whitefield bonfires, cooking elaborate dinners with Jackie for sugar house picnics, helping Rob finish the beer while making PowerPoints for his conferences, and giddily chasing down windblown Reemay through snowy fields with Jan.

Now, two years later, I’m back. It’s late summer, the end of corn season, the beginning of bulk harvesting. I’m visiting on a Friday before a two-market Saturday. All hands on deck. I know how much happens on a day like this, and I want you to know, too. These photos were taken in the span of one day, dawn to dawn.

6:20 AM

“Things are pretty gilly-wampus around here this A.M., for whatever reason. No more than any other Friday, I guess,” shrugs Rob Johanson as he lifts full totes of greens, carrots, radishes, and potatoes onto the truck. After experimenting as an early adopter of organic growing on his own farm in Whitefield, Rob joined forces with Jan (just before they were married in 1987) to convert her family’s conventional potato farm into the thriving diversified organic operation it is today. They now sell their produce at between three and five markets every week, depending on the season. (I’ll let you do the math on how many trucks he’s probably loaded before this one.)

7:04 AM

Having already logged a few hours this morning answering emails and cutting flowers, Jan is pulling fresh laundry out of the dryer and getting dressed in the kitchen for today’s farmers’ market in Damariscotta. She’ll be outside all morning, and the weather can be finicky this time of year.

“My boot liners! I found my boot liners this morning! I’m so happy! But what do I wear, what’s the weather? What does it say? Do I wear sandals? Everything seems cold.”

Her younger son, Göran Johanson, is working on the day’s pick list and schedule ahead of the all-farm morning meeting. With an even keel demeanor, he knows how to keep his people comfortable. “You could start with socks, Ma,” he says.

Jan shoots him a grateful smile and laughs.

46 47

WORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY KELSEY KOBIK

1 2 3 4 5 6

1. In the carrots 2. Jan makes bouquets before market 3. Carl uses a disc harrow to till the soil 4. Lila ebulliently greets Jackie 5. Rob loads the market truck 6. Carl leads the morning meeting

11:12 AM

Sarah Joyal and Kiersten Savage are picking cucumbers in the South Field when I find a newly hatched monarch butterfly drying its wings on a tomato vine. I bring it over to the pickers and we all moon over it.

“So beautiful!” exclaims Kiersten. “What a good place for you to be!” Kiersten has been working these fields for more than five years. But Sarah is brand new.

“I just got here. I’m from Tennessee,” she explains. “It already feels like fall. Where did the summer go? But it’s still good to be outside.”

We take turns holding the butterfly until I return it to the tomato and let it get on with its first big day as a pollinator.

12:18 PM

As people filter through the prep area to clock out for lunch, Jan jumps in to help her crew leader, Kaite West, clean greens. She knows that Kaite won’t stop for lunch until the greens are bagged and in the cooler, so together they plunge their hands into a mountain of braising mix. They’re using my favorite piece of farm equipment.

“I remember the first one. It was Carl’s. We just started using it one day. Thank you, Carl!” She laughs. “He gave up his kiddie pool for this at the age of two. Very generous of him.”

2:12 PM

At age 72, Maria Escobar embodies charisma, empathy, and experience.

¿Como se sientes estar aqui otra vez? Tengo tantas memorias en este lugar. De este lugar yo recibí todo. Mi dinero para todo. Para mi familia, mi tierra, mis zapatos…Tantas memorias y tanto. Gracias a Dios for ponernos aqui juntos.

“How does it feel to be here again? I have so many memories at this place. From this place I got everything. My money for everything. For my family, my land, my shoes…So many memories and so much. Thanks to God for putting us all here together.”

Me siento mal cuando no puedo estar aquí. Me siento deprimida.

“My family says, ‘Mami, cuando vas a retire? You come live with us!’ But I don’t wanna. Not yet.”

3:58 PM

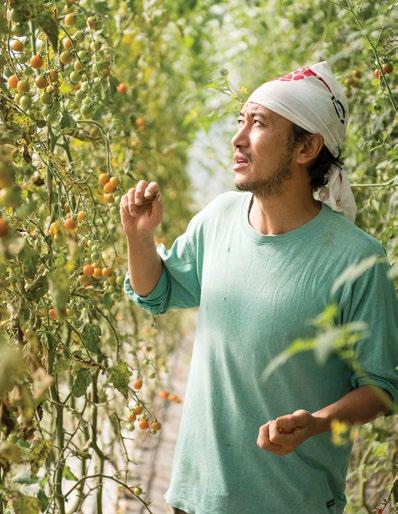

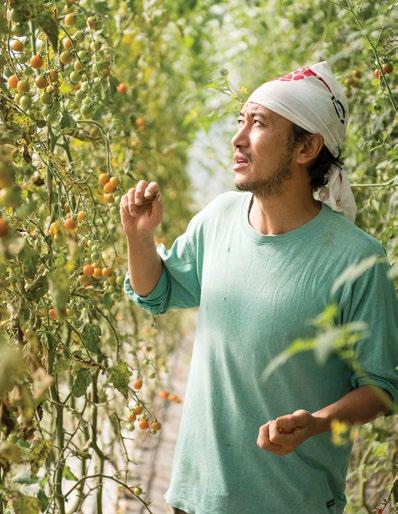

Wangchuk Topden is still picking tomatoes. He grew up as the son of one of the most successful tea farmers in Sikkim, India’s all-organic mountain state. He used to run his own restaurant in Washington, D.C., but came to Maine this spring to work on organic farms and start a cannabis operation.

“Today we worked, just work, nonstop, without a distraction,” he comments, hauling his full basket of heirlooms to the bed of the truck for sorting. “I thought we would get some weeding done after this. But I guess it won’t happen.”

“Really? We have an hour,” his buddy Colby answers from deeper in the greenhouse. It’s Colby’s first season here, too.

“Well then, let’s try to do it!”

“Yes.” Colby is certain. “After this we’ll go to the weeding. They can use the reinforcement.”

48 49

10. Maria weeds the carrots 11. Wan picks cherry tomatoes

7 8 9 10 11

7. Göran and Jan mix greens in the pool 8. Kiersten and Sarah admire a butterfly 9. Kaite fills a washtub

4:30 PM

I find Wan and Colby weeding the southern end of the Wild West field, churning through the end of a very long line of carrots, and singing Bananarama.

4:09 AM

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 2018

Jan looks up from her computer at the kitchen table, “They’re subdividing it. I just got an email. The adjacent farm.”

Jan’s parents bought the tract of silty river bottom in 1960, and stewardship of this peninsula in Merrymeeting Bay has always been a key part of Jan’s work. Jan and Rob’s sons, Carl and Göran, decided years ago that they wanted to keep the farm going, too, but as neighboring farmers retire, the question of what will happen to the rest of the open land along the Kennebec and Eastern Rivers hangs over their heads.

5:46 AM

Jan is hefting full totes off the truck in Deering Oaks Park in Portland. This is her fourth market morning of the week.

“Oh my god, what is that? Feels like rocks. Must be tateys! Yep, tateys. When I’m old and lose my brain, I tell them, just bring me to market. I’ll open the totes with no idea what’s in them. It’ll be like Christmas every day!”

7:14 AM

This market and the simultaneous Bath Farmers’ Market are the last two of the farm’s five weekly markets. What she earns in sales today will go straight back into offsetting the costs of running the farm: paychecks for almost twenty full-time employees, utility bills, fuel and grease for tractors and trucks and irrigation pumps, packing supplies, cover crop seed, animal feed, organic sprays, machine and greenhouse repairs, and maybe a little ice cream for the crew.

Jan reaches to hang the last of her signs as the first customers of the day filter in.

“Ready set? Here we go…”

50 51

15. & 16. Setting up the Portland market 17. Jan hangs her spuds sign

12. Back in the carrots 13. Lauren grabs coffee while Jan checks email 14. Jan helps load the Portland truck

12 13 14 16 15 17

kelsey kobik is a farm photographer and social media consultant in Portland. She uses her camera to support farmers and the businesses that support them. | kelseykobik.com.

We want to hear what you think about the future of farming in Maine. Share your voice at mainefarmlandtrust20th.org

“The future of farming in Maine hangs in the balance. Its future very much depends on what we do now.”

HEATHER & PHIL RETBERG, QUILLS END FARM, PENOBSCOT

JOURNAL OF MAINE FARMLAND TRUST • 2019

JOURNAL OF MAINE FARMLAND TRUST • 2019

Ellen Sabina, Outreach Director, Maine Farmland Trust

Ellen Sabina, Outreach Director, Maine Farmland Trust

BY LAURA POPPICK | PHOTOGRAPHS BY GRETA RYBUS

BY LAURA POPPICK | PHOTOGRAPHS BY GRETA RYBUS

Opposite Page Hagerty gets more than just physical help from his horses—he's formed a strong emotional bond with them as well, he says. This Page Each year, Moskovitz and Jones harvest about 15 acres of forest that together produce roughly 30 cords of pulpwood, 30 cords of firewood, and 6,000 board-feet of lumber.

Opposite Page Hagerty gets more than just physical help from his horses—he's formed a strong emotional bond with them as well, he says. This Page Each year, Moskovitz and Jones harvest about 15 acres of forest that together produce roughly 30 cords of pulpwood, 30 cords of firewood, and 6,000 board-feet of lumber.

BY WILLY BLACKMORE

PHOTOGRAPHS BY KRISTIN DILLON

BY WILLY BLACKMORE

PHOTOGRAPHS BY KRISTIN DILLON

This Page Ben Slayton of Farmers’ Gate Market and The Farm Stand said, "the kind of farms that are interested in supplying are not going to be able to sustain the kind of market share that we’re going to need." Opposite page At Common Wealth Poultry in Gardiner, many of the workers are so-called New Mainers—immigrants from Somalia and other countries across Africa.

This Page Ben Slayton of Farmers’ Gate Market and The Farm Stand said, "the kind of farms that are interested in supplying are not going to be able to sustain the kind of market share that we’re going to need." Opposite page At Common Wealth Poultry in Gardiner, many of the workers are so-called New Mainers—immigrants from Somalia and other countries across Africa.