20 minute read

art

approached the America the Beautiful Fund for financing to launch a more formal residence program in the parks. The fund subsequently provided seed grants to support artists for projects concerned with “preserving the quality of nature and environment.”

Gussow went on to set up the Artists for Environment Foundation, a “creative kibbutz” at the Delaware Water Gap. From 1972 to 1983, Joseph Fiore was visiting artist/critic at the foundation, an experience that helped nurture his passion for the environment and that led to the creation of some of his finest paintings.

Advertisement

••• To further his mission to connect art and the environment, Gussow produced A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land, published by Friends of the Earth in 1972. In this landmark book, he combined paintings with the words of artists—taken from poems, letters, journals, and other sources—in order to highlight the special sense of place that exists between the painter and her or his surroundings. The book covers 400 years of American art and includes more than 20 painters with connections to Maine, including Gussow himself, who painted on Monhegan Island for much of his life.

Among my favorite images in A Sense of Place is Sheridan Lord’s Sagaponack, 1970, a view of potato fields on the South Fork of Long Island. Lord (1926-1994) devoted much of his later life to painting these lovely expanses of green interspersed with barns and farmhouses.

The painting has special resonance for me: I spent the first 30 or so years of my life among the low rolling hills of this part of Long Island. My high school, the Hampton Day School in Bridgehampton, was surrounded by potato fields. I came to cherish those vistas and I still support the Peconic Land Trust, which has sought to save the farmlands from development (the trust was founded by John Halsey, a housemate of mine during my sophomore year at Dartmouth).

Here in Maine, similar pressures exist for farms— and the opportunities for artists to play a part in their preservation increase every year. One marvelous example is the CSA: Community Supporting Arts program launched by the Harlow Gallery and the Kennebec Valley Art Association in 2011. The KVAA matched 14 artists with 13 farms in central Maine, all of them practicing Community Supported Agriculture, the original CSA and inspiration for the arts project. The association displayed the images of the farms in an exhibition at the Harlow Gallery in Hallowell, the Maine Farmland Trust Gallery in Belfast, and six additional venues throughout the state.

“Maine’s artist and farming communities have a lot in common,” said Deborah Fahy, executive director of the Kennebec Valley Art Association and the Harlow Gallery, at the time of the CSA launching. “Both are idealistic and creative groups,” she noted, “and both communities are key to Maine’s unique sense of place.” Fahy and her colleagues looked upon the program as a means for painters and photographers to “use the power of their artistic voices to affect social change—or in this case to promote and celebrate the local foods movement.”

In 2016, the Kennebec Valley Art Association and Harlow Gallery revived the CSA project, once again pairing artists with farms, over the 2017 growing season. This time they partnered with Maine Farmland Trust Gallery in Belfast and Engine in Biddeford to show the resulting work.

Maine Farmland Trust had opened the Joseph A. Fiore Art Center at Rolling Acres Farm in Jefferson in 2016, with a straightforward mission to guide it: “to actively connect the creative worlds of farming and art making.” To accomplish this goal, the trust established an artist-in-residence program. In 2016, they invited four artists to spend a month on the 130acre property on Damariscotta Lake; last summer, six artists stayed at the center, plus a writing resident documenting the history of the farm, and a gardener.

The 2016 cohort included J. Thomas R. Higgins, professor emeritus at the University of Maine at Farmington. A plein air painter, Higgins relishes being “at one” with his surroundings, searching for something that will move him emotionally, “an evocative space, atmosphere, light, mood, etc.” His expressive paintings capture the inherent energy of the landscape; we share in his vision of places in flux.

During his forays into the Jefferson landscape, Higgins discovered “the quiet integrity” of nearby Chimney Farm, former home of three of Maine’s greatest writers, Elizabeth Coatsworth, Henry Beston, and their daughter, Kate Barnes. It was Coatsworth who wrote, “If Americans are to become really at home in America it must be through the devotion of many people to many small, deeply loved places.” These places, she averred, must be “sung and painted and praised until each takes on the gentleness of the thing long loved, and becomes an unconscious part of us and we of it.”

Painter Robert Pollien from Town Hill on Mount Desert Island has conferred that kind of devotion

Previous Page Joseph A. Fiore, Sun Burning Through Haze, 1960, oil on canvas, 27"x36" . Top Left Studio visit with sculptor Anne Alexander during an open studio day at the Joseph A. Fiore Art Center (2017). Photograph by Susan Metzger. Top Right Installation of farm tools from Rolling Acres Farm, by historical writing resident Sarah Loftus (2017), 75"x50" . Bottom J. Thomas R. Higgins, Tunnel Effect, oil on panel, 16"x16". This painting shows a view of the Rolling Acres farmhouse and was created during his 2016 residency.

Top Jess Klier, mixed medium installation at Herter Hall, UMass Amherst, thread, plastic bags, yarn, recycled scraps (2017 residency) Bottom Robert Pollien, Flying Crow, graphite on paper, 12"x 18" (2016 residency)

Opposite Page Clockwise from the Top

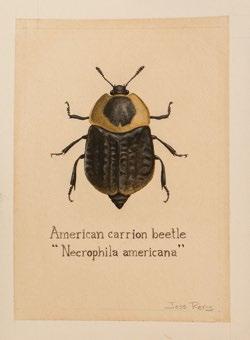

Jude Valentine, Trees in Accord, monoprint with pastel, 22"x30" (2017 residency) Tanja Kuntz, Queen Anne (light and shadow), oil on canvas, 36"x48" (2017 residency) Josselyn Richards Daniels (aka Joss Reny), American Carrion Beetle (Necorphilia americana), watercolor and gouache, 5"x 7" (2017 residency)

9 10

on Acadia National Park since the early 1990s when he served as its first artist in residence. His sense of place encompasses specific characteristics of a locale: “elevation, proximity to water, quality of light, geologic structures, human presence, ground cover and vegetation.” While at Rolling Acres Farm, Pollien found settings on the coast near Bristol and at Pemaquid Point that met his specifications and led to studies that remind us of the beauty of coastal contours and cloud formations.

Like Pollien and Higgins, Thérèse L. Provenzano from Wallagrass in Aroostook County looks for a prompt in the landscape, “a pull or grab, something that stirs.” Her sense of place “can embrace ancestral roots, loneliness, stillness, grace, force, labor, and the till of the soil.” At the Fiore Center, she conveyed these elements through rich pastels, including a view of the curving farm road leading the viewer into the distance.

Provenzano appreciated having the opportunity to get to know one of Maine Farmland Trust’s Forever Farms (a designation for Maine farm properties that are protected with Agricultural Conservation Easements). She also enjoyed an aspect of the residency that is out of the ordinary for these types of programs: having her work viewed by visitors. She relished the weekly interactions, for the social networking that took place, but also for the boost the feedback gave to her confidence.

••• Asked about her sense of place, Jude Valentine from East Machias, a 2017 resident artist, quotes a question landscape architect and Buddhist Dennis Alan Winters posed in his book Searching for the Heart of Sacred Space (2014): “Is it possible, that if the body and mind have the ability to alter the quality of the landscape in which one lives, so does a landscape have the ability to alter the state of one’s body and mind?” This query led her to focus on understanding “the energy” of Rolling Acres Farm “and feeling its qualities” while producing a series of dynamic monoprint landscapes.

One of the functions of an artist, Valentine believes, is to be a “visual translator,” with the result of the translation being “a contemplative icon—a place for the viewer to see a reflection of the world.” The artist serves as a kind of liaison, helping to facilitate the relationship between viewer and place.

Valentine was pleased to be able to disconnect during her residency, to “sit without interruption (or device) in the landscape.” She soaked in “all the nuance of the farm’s ancient time, illusional space, shifting color and light through the whispers of the trees, the land-lake interface, and undulating contours of the fields.”

That “ancient time” is now better known, thanks to A History of Rolling Acres Farm, researched and authored by the farm’s first writer-in-residence, Sarah Loftus. Drawing on her studies in archeology and anthropology, Loftus offers an enlightening chronicle of this land where the water of Damariscotta Lake “bends and narrows in a patchwork of blue and green,” an image echoed by Valentine’s monoprint, Trees In Accord, reproduced on the cover.

When Maine Farmland Trust acquired the farm, a new chapter in its history began, one that Loftus writes, “represents a broader collective drive to preserve rural farming culture and secure locally produced, environmentally sustainable, affordable, delicious food.” She pays special tribute to Nellie Sweet, the Fiore Art Center’s first resident gardener, who established “a thriving home garden” for the artists in residence, “her hands working the same silty loam” the first owners worked determinedly almost two centuries ago.

Left Elizabeth Hoy, The Advance, oil on panel, 24" x 24" (2017 residency) Right Susan Smith’s “bundles” are comprised of rusty old bits of farm equipment, branches, soil, and plant materials, tightly wrapped into cloth then steamed to create intricate ecoprints (2016 residency) ••• Some of the Fiore residents have taken an organic route in order to inform their—and our—understanding of the land. Dover-Foxcroft artist Susan Smith made “ecoprints” from plant materials found on the farm and rubbings from worn barn wood. She grounds her work in earth because, she writes, “the inability to see ourselves and our future in a handful of dirt or a weed speaks to a loss of an intimate relationship with place, with soil, creating an environment of alienation.”

Creating installations from recycled materials, Jessica Klier, from Northampton, Massachusetts, strives to make palpable her ongoing affection for the visible and the invisible while acknowledging “the waste, overproduction and over-consumption in the world today.” She values knowing how to make something from scratch. Among the highlights of her residency at the Fiore Center was learning how to spin wool into yarn with Maine fiber artist Diane Langley.

Sculptor Anne Alexander also took advantage of local art opportunities while at the farm, meeting up with fellow sculptors. The Windham, Maine-based artist works in wood, stone, and ceramics, abstracting and enlarging natural forms, such as seedpods, to create work that suggests “themes of regeneration, growth, life cycles, and stages of maturation.”

Alexander’s sense of wonder is shared by Yarmouth-based artist Josselyn Richards Daniels, who also works directly from nature, with a special passion for insects. Her natural science illustrations are, in the words of writer Eliza Graumlich, “captivating in their realism and handsome in their aesthetic.” Less realistic but no less tied to natural forms are Portland artist (and chef) Tanja Kunz’s luminous studies of wildflowers and other flora. Again, Graumlich provides eloquent commentary: “Her artwork reads…like photosynthesis distilled.”

••• Over the past couple of years Elizabeth Hoy, who makes her home in Brooklyn, New York, has been painting Superfund sites—“federally designated tragedies of the built environment,” she calls them—in Maine, Vermont, and New York. She played a variation on this quest during her residency, studying the “history of use and the complexities of human influence on the landscape around Jefferson.” Among her activities: collecting bits of trash from the coastline and arranging them in sculptural configurations in her farm studio.

Hoy’s attention to manmade despoliation and her attempts to raise our awareness of it send us back to A Sense of Place. In his introduction to the book, Gussow expressed urgency regarding the need for artists to paint the world. “Nineteenth-century painters went out into the wilderness to bring back reports about a land we did not know,” he wrote. “Painters now report about a land we risk forgetting.”

Through its gallery in Belfast and its programs in Jefferson, Maine Farmland Trust continues Gussow’s important mission: to ensure that we not only remember but also value and celebrate the land. The trust is building on the remarkable legacy of Joseph Fiore, a painter who once benefited from a residency, whose generosity and vision now enable artists to spend time in a special place where they can practice their art and attain, in Robert Pollien’s words, “a restored sense of clarity and momentum.” A sense of place: that is a great gift.

carl little’s most recent book is Philip Barter: Forever Maine (Marshall Wilkes). He lives and writes on Mount Desert Island.

aving a connection to a farm and its land can be a profound experience. As a kid, I loved running amok in the fields and forest and spending rainy days in the hayloft, building forts out of stacks of square bales. Growing up on a farm felt rich and rewarding in so many ways and difficult in others, but never did I consider that one day our farm might not be a farm anymore. But as my father grew older, it was clear that it was becoming harder for him to continue managing the dairy cow herd and doing all of the heavy chores required to keep the farm running. Several years ago, our family realized that the time had come where something needed to change.

You may be familiar with my family’s story, or just a snapshot of it, as the process of trying to navigate the transfer of my father’s dairy farm to my youngest brother was featured in a film that Maine Farmland Trust produced (before I came to work at Maine Farmland Trust) called Growing Local. This story, filmed over the course of several months in 2013, begins in the middle of what would ultimately be a much longer story, when my father and brother, Adam, were trying to find a way for Adam to purchase the farm so that my father could finally retire.

At that point, Adam had been working full-time off the farm for about five years, making his living as a diesel engine mechanic, as well as helping out on the farm as much as he could. My father had no retirement nest egg as, like many farmers, anything he had left over after the bills were paid went right back into the farm—in fact, the farm was his retirement.

With a young and growing family to support, my brother couldn’t step away from his outside work unless the farm could pay him, too. And yet, for the farm income level to qualify for financing to enable Adam to purchase the farm, the business required more labor—this became a very circular challenge and one they had almost given up on trying to solve.

As I watched them struggling with all of this from the sidelines, I was realizing how deep our connection to this farm was, both as a family and for each of us individually. Vivid images of my father’s many years of working draft horses, clearing land, haying the fields, and dutifully going out to check on the cows one last time every night before bed were deeply ingrained in my mind. Memories of hiking with my siblings across the pasture to round up the cows for milking, spending hours in the barn helping with chores, and putting up bales of hay with the summer crew to sustain the herd through the long winter made it all the more difficult to face the very real possibility that the farm my father had spent decades building—with the hope that one day one of his children would be able to take it over—might not continue to be in our family or even continue at all. When a place holds so much meaning, it’s difficult to imagine life without the ability to spend time there. It is painful to think that the next generation may not grow up on that treasured land, that they won’t be given the same opportunities to learn to appreciate hard work and what it takes to produce good food.

Facing this potential loss was what motivated me to jump in and try to help, and the Growing Local segment shows the initial stages of my efforts to support them in navigating this transfer process. It shows all of us working together to find a way forward, despite the challenges laid before us. But the reality is that, as the credits rolled, the future of this farm was still quite uncertain.

What followed were more years of planning and reaching out for help when we got stuck or needed support. We drew on experiences of other farmers in our community and also enlisted the expertise of knowledgeable staff from various organizations and programs, such as the Maine Department of Agriculture, University of Maine Cooperative Extension, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Maine Farmland Trust, Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association, Farm Service Agency, and others. It was a long journey, but just last fall, Adam and his wife, Jamie, became proud second-generation owners of the farm.

This kind of story of generational succession

Three generations share chores on the farm. Left to right: Richard, Cameron, and Adam Beal.

Adam and Richard Beal stand in front of the newly rebuilt dairy barn, a symbol of success and their hard work to transfer the farm from one generation to the next.

FARM TRANSFER AND SUCCESSION PLANNING RESOURCES

A growing number of resources for farm transfer and succession planning can be accessed through the Farm Transfer Network of New England (farmtransfernewengland.org). Other notable resources include:

Maine Farmland Trust provides a tool to connect farm seekers and farm owners looking to lease or sell their land through the Farmlink program and business planning assistance through the Farm Viability program. In addition, conservation easements purchased through the Farmland Protection program assist in land access for incoming farmers by making farmland more affordable and also ensure that the farmland won’t be developed for non-agricultural use in the future. American Farmland Trust has produced a resource called “Your Land is Your Legacy: A Guide to Planning for the Future of Your Farm.”

Maine Agricultural Mediation Program of the Volunteers of America Northern New

England offers mediation and conflict resolution assistance specifically for the farming community, which can be useful in navigating difficult discussions in the succession planning process. plays out over and over again here in Maine, to varying degrees of success, as families navigate their own unique circumstances. What is clear is that there is a tremendous amount of farmland that will be changing hands, one way or another, in the coming years. A 2016 assessment by American Farmland Trust verified that over 400,000 acres of farmland in Maine will likely move from one generation to the next over the course of this decade.

What I learned from my own family’s experience is that we can’t expect that the success of this point of transfer will be a given. There are many factors that can complicate such a process, regardless of whether a successor has been identified, within or outside the family. This can also be an especially important and vulnerable point in time for a farm and its future, particularly if the amount of time and level of planning detail needed is underestimated. Farms that have extensive and costly infrastructure and a large land base and perhaps even livestock, such as dairy farms, can require a much longer timescale for transfer than a smaller produce operation. In these cases it may even take multiple decades to successfully transfer a whole farm, which illuminates why it is so important to begin the planning and transfer process early.

In my family’s situation, one element that made this transition possible was having an identified successor, and one that our whole family supported in taking over the farm. However, according to the American Farmland Trust report, “In Maine, farmers age 65 and older own or manage nearly one-third of the farms, and most are farming

University of Maine Cooperative Extension

also offers support for succession planning and has been doing so for many years. In addition to collaborating with the Farm Transfer Network of New England, Extension offers a daylong estate planning conference for farmers, supporting the development of a farm transfer plan, and holds follow-up meetings with families to support them in their succession goals.

Land for Good is a regional organization that has built a “Toolbox for Farm Transfer Planning” and offers one-on-one support with transfer planning and holds workshops on this topic; Land for Good also serves as the administrator for the broader Farm Transfer Network of New England. without a young farmer alongside them.” In fact, “…92 percent of Maine’s 2,367 senior farmers do not have a young (under 45) farm operator working with them.”

But even having an identified successor does not make farm transfers easy, nor guarantee success. There are often still conversations to be had with siblings and other family members to ensure buy-in for the overall succession plan. And sometimes the best laid plans can undergo change when personal circumstances shift, whether related to health issues, growing families, divorce, or other unforeseen opportunities or hurdles emerging.

Other challenges can encroach, as well. For new farmers, access to capital and carrying student loan and other personal debt can be barriers that take time to overcome. For the retiring farmer, it can be difficult to let go of the business they have spent their life building and the deep and long-lasting relationship they have formed with the land. If the farm business has contracted over the years as the landowner has aged, farm viability may also be a factor and need to be addressed in transferring to the next generation.

Family dynamics, communication styles, and differing visions for the future of the farm can take time to work through. These are also exactly the kinds of challenges that can cause a farmer to delay succession planning, as they are complex issues that can feel overwhelming if trying to navigate them without support. In short, some farm ownership transitions are simple, but most are not.

There are many components to think about when contemplating a farm transfer, but one of the biggest takeaways is that succession planning and implementation can take much longer than one might think. Although not a foolproof strategy, in most cases, more lead time means more options for everyone involved. It is never too early to start the process, and although a transition like this can be challenging, the good news is that there are a number of supportive people and programs to help farmers work their way through this process, once they are ready to begin.

Elevating the importance of succession planning in the life cycle of a farm business is a good way to help ensure a future for that farm and for yet another generation to have the rich experience of growing good food and other agricultural products for themselves and their community and enjoying the meaningful process of working with their hands in the soil—and that is something that benefits us all.

amanda beal is President and CEO of Maine Farmland Trust and owner of Fieldstone Farm in Warren, Maine.