22 minute read

business

Previous Page A happy customer purchases Hakurei turnips from Fresh Start Farms at a Good Food Bus stop in Westbrook. Eggplant has been another hit in the neighborhood, which is home to many Iraqi immigrants. Above Teenage members of Cultivating Community’s Culinary Crew prepare to deliver meals to recipients of the organization’s Eldershare program.

Program (SNAP, formerly “food stamps”). One of her coworkers today is Athani, a Deering senior.

Advertisement

As the two wait for the elevator, the girls look out over the city, toward the oil tanks of South Portland. Across the river, they spy a high-rise similar to the one whose floors we’re slowly ascending and imagine, correctly, that it’s also subsidized housing. Athani, in a pea-green raincoat and long, flowing skirt, looks pensive. “Who brings food to them?” she asks.

••• One in six Mainers—one in four Maine children— lacks reliable access to adequate food. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Maine is the seventh-most food-insecure state in the nation, a slide from last year’s ninth-worst ranking. As other states see improvement, Maine’s hunger gap is growing, says Chris Hastedt, public policy director at Maine Equal Justice Partners, a legal aid and advocacy group working for low-income Mainers. “We’re heading in the wrong direction.”

In 2016, 14% of Maine residents received SNAP benefits—down from previous years thanks in part to economic recovery but also due to toughening of eligibility requirements. (In 2015, Governor Paul LePage removed waivers on the time limit, asset test, and work or volunteer requirements; the waivers are used by most other eligible states.)

Yet even those who receive SNAP (the average benefit is approximately $1.40 per person per meal) have trouble consistently accessing nutritious food. As a result, hunger relief charities originally intended as stopgaps have become a regular fixture in many Mainers’ lives. Good Shepherd Food Bank now partners with more than 300 food pantries across the state, while Preble Street, in Portland, serves 500,000 meals a year at eight soup kitchens.

At risk are people young and old, black and white, rural and urban—mostly low-income families, seniors, veterans, the disabled, immigrants and refugees, and those living in Maine’s northern-most and far-flung communities.

Food access is a dauntingly complex issue, from farm to factory to fork (and landfill), with far-reaching social, cultural, economic, and ecological implications. The system is broken, and almost everyone agrees that poverty is at the dysfunction’s root.

There is no single solution, says Mark Winne, a longtime community food activist and policy guru who spoke recently at a lecture hosted by University of Southern Maine’s new Food Studies Program— though he’d start with raising the minimum wage.

“Many [food access] programs are Band-Aids that are helping mitigate larger structural problems,” says Shannon Grimes of Maine Farmland Trust, though there is hope and evidence that some programs are having a deeper impact. For lasting systemic change, there must be innovative intervention at every link in the chain.

Hundreds—some estimate thousands—of organizations work to improve food access in Maine. Their efforts are varied and promising, from permaculture experiments such as the Alan Day Community Garden “food forest” in Norway, an eventually self-sustaining edible ecosystem, to 32 winter farmers’ markets making cold-hardy produce like spinach, chard, radishes, and candy-sweet carrots available year-round. There are rooftop gardens and thriving co-ops, food hubs bringing small farms into wholesale and institutional markets, and initiatives to increase production and consumption of locally grown food.

And if activists at one end of the chain are figuring out how to get healthy, locally grown food to market, there are those on the other end working tirelessly— and creatively—to get it from market to table.

Members of the Culinary Crew, many of whom have benefited from food access programs themselves, deliver meals to residents of Portland’s East Bayside neighborhood. Students in the program learn how to harvest, cook, and preserve local foods, some of which are grown in Cultivating Community gardens. They also gain valuable job skills and a better understanding of sustainable food systems.

Left “We’re here for everyone, regardless of income or background. We’re just trying to get good food to people, regardless of who you are,” says Kathleen McKersie, who trailers the Good Food Bus mobile market to 13 weekly stops. Right “A lot of people don’t even think where their food’s coming from,” says Maxine, a Good Food Bus customer. Her family used to grow their own string beans, potatoes, and tomatoes. Top The original Good Food Bus still graces the parking lot of St. Mary’s Nutrition Center in Lewiston. Bottom Health- or age-related mobility issues can be a major obstacle to accessing good, fresh food, making the “we come to you” approach of the mobile market model appealing.

Outside the Center for Wisdom’s Women in Lewiston, Maxine rolls a collapsible shopping cart toward a stainless steel trailer painted with a three-foot pumpkin. On her shoulder is a reusable grocery bag fashioned from a tie-dyed T-shirt. Plump zucchini, pert green beans, and picture-perfect peppers set in wooden crates beckon from the trailer’s open windows. On a table beside the trailer sit printed recipes and a pint of exotic husk cherries, free for the sampling.

Two years ago, Maxine blew out her leg when she fell on cement. Now, without work, she, like nearly a third of the population of Lewiston, relies on SNAP. On Wednesdays, she shops the Good Food Bus, a mobile farmers’ market run by nearby St. Mary’s Nutrition Center and Cultivating Community. (Its former incarnation was an actual bus.)

This week Maxine asks about some collard greens her friend Ruth requested; they’ll be stewed in a crockpot with a special seasoning blend Ruth found at the Save-a-Lot. “She’s been talking about them all week.”

Though she grew up on a farm in Jackson, Maine, and wishes she could grow and can tomatoes and string beans the way her mother once did, Maxine doesn’t have space in the small apartment from which, importantly, she can walk to this parking lot.

When it comes to food access, getting there can be more than half the battle. In the last U.S. Census, Maine had the highest percentage of rural residents in the nation, many of them living more than 10 or 20 miles from a grocery store or supercenter, in what experts call “food deserts.” Even with a vehicle, consider the inconvenience and cost of gas, and one can understand how many rural Mainers end up grocery shopping at the local convenience store.

In denser urban areas, public transportation helps alleviate the problem, but seniors and those with limited mobility still often struggle to get to a market less than a mile away. Even when they do, they are limited to what they can carry. For someone working several jobs or odd shifts, getting to a Wednesday afternoon

Fall work in Norway’s three-acre, volunteer-driven Alan Day Community Garden. “We don’t want to be an organization that just gives food out,” says garden coordinator Rocky Crockett. “We want people to have a relationship with the garden.”

Opposite Page A gardener in the hoophouse at Alan Day Community Garden in Norway. The non-profit organization seeks to strike a balance between innovation, education, and approachability, being truly accessible to all kinds of community members. A few years ago it conducted a study to discover any obstacles it might unknowingly create.

farmers’ market might be a ridiculous proposition.

“How do you get [healthy, local food] to where people are?” says Karen Voci, president of the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Foundation, which funds the Good Food Bus.

In 2017, the “bus,” which accepts SNAP and WIC (the supplemental nutrition program for Women, Infants, and Children), had almost 3,000 transactions at 13 weekly stops across LewistonAuburn, Bath, Westbrook, and Gorham and a 42% increase in sales from the year before. After the Center for Wisdom’s Women, the Good Food Bus will head, courtesy of a pickup truck, to a regional medical center and community garden. Later in the week, it will hit Bath Iron Works and a YMCA.

Another mobile model (with a similarly loose definition of “bus”—the program currently runs from volunteers’ cars) is serving Downeast Mainers.

The Magic Food Bus, a program of Healthy Peninsula in partnership with Edible Island, brings free local produce, along with books, to seven towns across the Blue Hill Peninsula and Deer Isle. Each week, staff and volunteers distribute a mix of purchased, donated, and gleaned produce at apartment complexes, community centers, and schools.

“Mobile food initiatives are particularly wellsuited for communities that are spread out,” says Stephanie Aquilina, the program’s island coordinator.

They are also opportunities to introduce consumers to new foods. Aquilina recalls an elementary schooler’s wide-eyed reaction to his first fresh radish. “The whole world should eat this,” he said. That’s the idea.

••• “Our clients, they want to buy broccoli,” says Chris Hastedt, “they want to feed their families healthy meals.”

But accessibility is not just about distribution and cost. What all consumers want—convenience, familiarity, options—these are what go

the final mile toward true accessibility. And in the end, food equality sometimes comes down to good, old-fashioned marketing.

In Lewiston, small vegetable and herb planters cared for by local farmers and businesses run along Lisbon Street. Inspired by Edible Main Street in Norway, Maine, and similar initiatives in the United Kingdom, the program is as much about advertising as about providing access to fresh peas and parsley.

It’s “to show anyone they can do this,” says Scott Vlaun, of the Center for Ecology-Based Economy, which runs the Norway program. “More than trying to grow food in the community, we’re trying to grow food growers.”

Familiarity and convenience are key. The Good Food Bus carries Marble Family Farms “Hotties,” local and organic savory hand pies akin to healthy Hot Pockets, as well as snack-size baggies of almonds and raisins, while their Anchor Meals, with prepped ingredients and recipes, resemble something from a meal delivery service like Blue Apron.

The FVRx program, piloted in Skowhegan in 2010 by the national organization Wholesome Wave, leverages familiarity in another way. Health care providers offer qualifying patients “prescriptions” for produce in the form of vouchers that can be redeemed at the local farmers’ market or grocery store.

Doctors’ orders carry “a certain weight,” says Jenny Schultz of York County Community Action Corporation, who will coordinate a new FVRx program in Sanford in 2018. Plus, she says, the message can be personalized to address a person’s particular health concerns, such as high blood pressure or diabetes. It’s a kind of hyper-targeted marketing.

Other initiatives run like promotions, similar to a buy-one-get-one deal. There are two nutrition incentive programs in the state: Maine Farmland Trust runs Farm Fresh Rewards in participating stores, and Maine Federation of Farmers' Markets and others facilitate Maine Harvest Bucks at farmers' markets and some farms. The programs effectively double SNAP dollars by offering $5 produce vouchers

One of sixteen Edible Main Street planters in Norway gets some love. “It’s about getting food growing front and center in the community,” says Scott Vlaun of the Center for Ecology-Based Economy. Young gardeners work with urban agriculture specialist Laura Mailander at Boyd Street Urban Garden. Cultivating Community founded this garden in 2004, specifically for residents of the Kennedy Park neighborhood. It strives to make community plots around the city more accessible to low-income gardeners.

for every $5 spent on local products. Maxine at the Good Food Bus is one enthusiastic user.

Of course, the most tried-and-true marketing is word of mouth.

“What makes the biggest difference,” says Shannon Grimes, who manages the Farm Fresh Rewards program, “is to have a community champion.”

In the advertising world, they are called “taste- makers” or “influencers.” Perhaps the biggest influencers are the next generation, which is why much of the focus in food access is on education and youth programs. When it comes to forging healthier habits, “we should forget about adults,” says Ken Morse of the Maine Network of Community Food Councils and Maine Farm to Institution, half-joking, “and just raise a generation of kids who have a new relationship to food.”

••• On a brisk walk back to Cultivating Community after her final meal delivery, Athani talks about the hunger she felt her first year and a half in the United States. Before her family qualified for assistance, they relied heavily on the local Somali community.

“Why are you going to bring us to this country with no food and no place to live?” she wondered. “Now,” she says, with a flutter of her hands, “I feel good.”

With a full stomach, the teen now worries instead about the elderly clients to whom she brings food. Just last week a woman new to the Cultivating Community program told Athani that until the Culinary Crew arrived, she wasn’t sure she’d have anything to eat that day. It’s a story of both validation and urgency for those working tirelessly and creatively to get good food to those who need it most.

kathryn williams is a Maine-based writer and teacher with a special fondness for condiments in small jars. 38

here are as many types of stories as there are storytellers, but one way of cataloging stories places them into two categories: the big and the small. The big stories make the national news—these are tales of international scandal, epic triumph, heartbreaking failure, and earth-shaking events. These stories, while important, can often overshadow that other kind of story: the quiet story of an individual’s struggle, their quest for joy, meaning, and connection. These stories are harder to find, but they exist, swirling nebulously around us at all times. We swim in them like water, and like water, we often forget they are there. But they’re worth noticing, and hundreds of them can be found online in the Salt Story Archive.

The Salt Institute for Documentary Studies has digitized over 400 pieces of student work and has published these pieces online. They cover a wide range of topics presented through a variety of mediums—for example, you might finds a photojournalism project about an immigrant family arriving in Maine, a multimedia piece about a homeless newspaper editor in Portland, or a long-form article about bush pilots in Greenville. There are also dozens of pieces that document farm work and rural life. “Whenever I go into the Salt archives, I’m struck by what an amazing wealth of real people’s stories we have,” says Annie Avilés, program chair of Salt at MECA. “It’s an incredible resource for the state.”

The stories at Salt illuminate the reality of life in Maine. While there are interesting pieces that cover life in Portland, Lewiston, and other major cities, there’s a particular poignancy to the pieces that focus on Maine’s far-flung communities and small towns. Avilés points out that the projects on rural life have a particularly strong impact since this is an

tarea that is often misrepresented in national media. “There is a lot of talk now about being rural—good and bad,” she says. “There’s an idea of rural as ‘pure’ or going back to ‘rural values.’ There’s also an idea that rural is dark and at the heart of everything that is wrong in America. Yet so often, people’s ideas about rural life are based on caricature and myth.” The Salt Story Archives showcase the daily lives of dairy farmers and winter gardeners, deer hunters and fishing guides. The stories are deeply humanizing and thoughtful. They’re also incredibly varied; the students who created these documentary pieces come from all walks of life, and each maker brings their own unique voice to the project. To provide readers with a glimpse into the wealth of stories available at Salt, we’ve selected a series of images by Lynn Kippax Jr., Tonee Harbert, Jennie Vosacek, and Christopher Knight. These pictures show blueberry rakers at work in the Gouldsboro fields, apple pickers climbing through orchards in Bridgton and Kents Hill, and a longtime potato farmer on his Aroostook County property. Farm labor is often invisible; we see the final product—the shiny apples, the buttery potatoes, the tart berries—but we don’t often think about the people who handled them or how they got to our table. The photographs in these pages are just a sampling of the work at the Salt Story Archive, but they speak to the mission of the institution. “Our students don’t usually cover stories because they’re in the limelight,” Avilés says. “At Salt, we believe that each person’s life is important. Each person’s experience is important. And that everyone has a story to tell, if you pay attention. That is really what Salt tries to teach.”

BLUEBERRIES

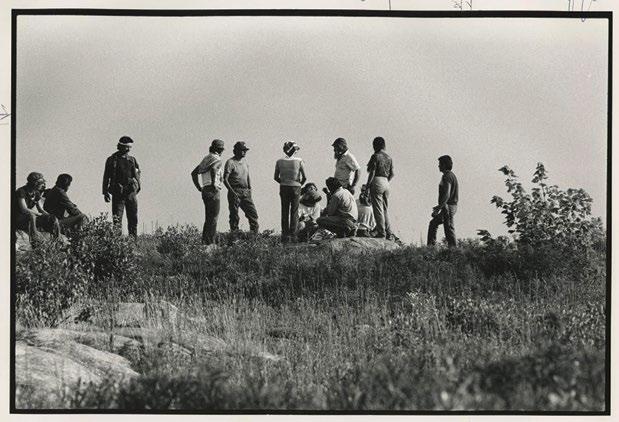

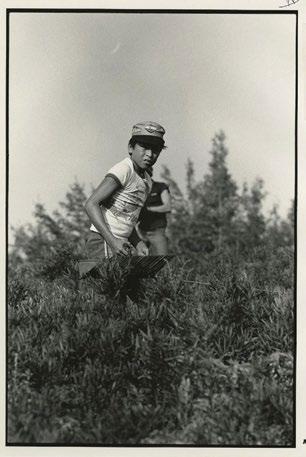

These images shot by photographer Lynn Kippax Jr. show workers harvesting wild blueberries in Gouldsboro, Maine. Kippax collaborated with writer Pamela H. Wood to create a long-form feature about the blueberry industry, which was published in the November 1985 issue of Salt Magazine. The full feature can be read online in the Salt Archives.

Opposite Page All images by Lynn Kippax Jr. Top Agnatur, officitibus sinvel imin re rectur suntio tem fugiatur. Left Top SExcestium harum que aut hil modi re, in parchil inulparum ree doluptatem Left Bottom Excestium harum que aut hil modi re, in parchil inulparum repel molupta volorerum quiae doluptatem

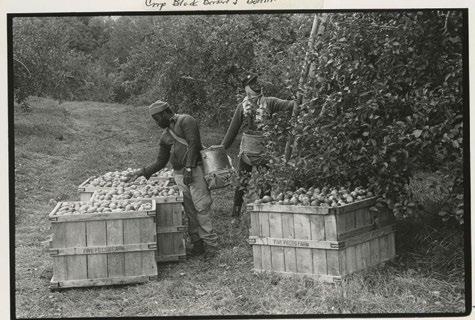

APPLES

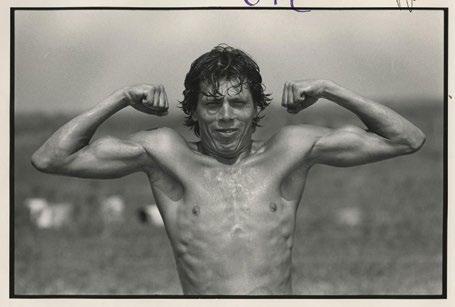

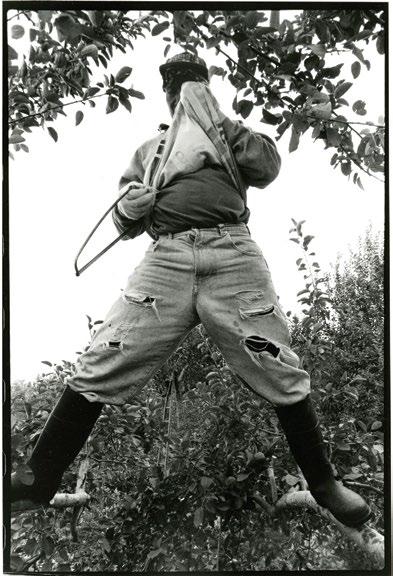

For decades, workers have been coming from Jamaica to harvest fruit, and several Salt-trained photographers have chosen to focus their lenses on this subject. Shooting 13 years apart, Tonee Harbert and Jennie Vosacek each brought their own sensibilities and style to the evergreen topic.

Top Left Jennie Vosacek, Town of Kent's Hill, Kennebec County, 2001 Bottom Left + Right Tonee Harbert,

Town of Bridgton, Cumberland County, Maine, 1988

POTATOES

In December 1990, Salt Magazine published a feature written and photographed by Christopher Knight titled “Death of an American Potato Farm.” This piece captured Aroostook County farmer Mike Brown’s decision to quit the struggling business after years of financial instability.

All Images Christopher Knight, Town of Houlton, Aroostook County, 1988

THE SWEET STORY OF BITTER V I N E S

AROOSTOOK HOPS OWNERS KRISTA DELAHUNTY AND JASON JOHNSTON WORK TO BRING A FRAGRANT NEW CROP TO NORTHERN MAINE

BY LAURA POPPICK | PHOTOGRAPHS BY MOLLY HALEY

It’s a clear September day as I drive north on Route 1 in Aroostook County and potatoes tumble out of the truck in front of me, bouncing to the side of the road like balls spilling from a bin. It’s hard to go a mile without spotting bags of the region’s hallmark crop for sale. But as I approach Westfield, about 9 miles south of Presque Isle, a less expected crop appears over the horizon: rows upon rows of trellises covered in vibrant green hops vines, reaching taller than surrounding trees.

“Most people haven’t seen it before,” says Krista Delahunty of her unusual crop. “So many people drive down this road just to look at it; it’s like a Sunday drive for people.”

Krista and her husband Jason Johnston own Aroostook Hops, one of the largest hops farms in Maine. They started the operation in 2009 and have since expanded from growing just 150 plants to more than 3,000 in five varieties. They sell their organic product to some of the largest breweries in the state, including Allagash and Gritty McDuff’s. With microbreweries popping up across the state, demand continues to increase for their bitter and aromatic harvest.

“If I called the farmers down the road right now and said, ‘Zach, I need a trailer,’ I’d have one in half an hour,” says Jason. He’s talking about his neighbor Zach Smith, owner of Smith’s Farm,

Previous Page The low light of autumn falls beautifully on hops vines but also brings a sense of urgency to harvest before optimal conditions shift to cooler, darker days. Right Jason and Krista rely on a seasonal crew to help tackle fall harvest tasks, from picking unwieldy vines to sorting and drying thousands of cones. the largest broccoli producer in New England. “The farming community here is fantastic. We couldn’t have done what we did without them.”

When I arrive at Aroostook Hops, the glow of the afternoon sun streams through the trellises. Jason and his crew of high school and college students busily run the harvesting machine, a boxy metal contraption made of several rows of loudly rattling rubber belts and metal claws that mechanically remove hops cones from vines— when all runs smoothly, that is. “The harvester has been really cantankerous today. It’s certainly not a perfect machine,” says Jason with a smile.

Still, the crew gets the job done. As they work, they’re surrounded on all sides by a distinct zesty aroma, one that I associate with pubs, not farm fields. The scent comes from a bright yellow substance called lupulin that coats the harvesting machine and the crew’s hands. Lupulin is what gives hops its distinct taste. It’s why brewers add hops to their beers, and can range in flavor from floral to citrus to spicy to bitter, depending on the variety. It’s mostly farmed for beer, but can also be found in various herbal remedies, the occasional restaurant dish, and soaps, which Krista and Jason make and sell on their website.

I take a quick turn picking leaves out of the harvest and get my own hands covered in sticky lupulin powder before Krista and I walk away from the commotion and out to some of the yet-to-beharvested fields. Their two daughters, Kathleen and Marie, join us on the tour, along with baby Elise, who is currently strapped to Krista’s chest.

Crickets chirp noisily around us as we look down an impressive field of 40 rows of hops, each 250 feet long and about 20 feet high.

“They grow so quickly, it’s incredible,” says Krista. She explains that they begin planting rhizomes in April, and by the second week in May, they train the plants to grow upward by wrapping them around lines hung from above. It’s labor-intensive to do the process manually but, once trained, the plants take off on their own. “By late June, they reach the top of the trellis and start making their side arms,” she explains.

The harvest season comes in a rush in August and September, when the cones are fully mature and have the right moisture content for optimal flavor. But Jason works full-time at the University of Maine at Presque Isle as an environmental science professor, and Krista also works part-time teaching an online biology course, so harvesting can only happen in the early mornings, evenings, and weekends. Pressures aside, they are glad to be part of this booming business, which they got into as a way to supplement their income and out of

Left Krista Delahunty and Jason Johnson pose with their children, surrounded by hops vines. They have been growing hops on their Aroostook County farm since 2009. genuine interest in the biology of the hops plant. “There is so much to know about it,” says Jason.

Jason had dabbled in growing a couple of plants for homebrewing and then, on a winter’s day in 2009 (just a month after their first daughter, Kathleen, was born), he and Krista started toying with the idea of expanding their crop—a notion they now attribute to the crazy ideas that grow like weeds during long Maine winters.

“We thought, well, the only way we can make any money off of this is to at least have an acre,” says Jason. “And then when we got to an acre, we realized that we really needed more gear and equipment and the only way to support that was to have at least 4 acres, which is where we are at now.”

For now, beers with Aroostook Hops are generally available on draft, and have included Gritty McDuff’s County Wet Hop and Geaghan Brothers’ Aroostook Hop Harvest, both IPAs. Jason and Krista hope to eventually grow to a scale that would allow them to be in more bottles and cans, but first they need to be sure that they can consistently meet the demand of brewers they sell to. “The breweries have to know that year-round, they can get the same hops for their beer, for quality control,” Jason says. “Customers want their beer to taste exactly the same.”

After leaving the family with the sun setting on their front porch, I drive further north to Caribou. On their recommendation, I go to Northern Maine Brewing for dinner. The menu is not only great, they say, but this brewery uses Aroostook Hops in essentially all of its beers.

Chris Bell, co-founder of the brewery, says it was a no-brainer to use Krista and Jason’s hops in their brews as a way to support local business in The County, and because it’s a tasty product. “I love their hops, they are really very good,” he tells me as he serves me a flight.

I settle in and sip, enjoying the citrusy tanginess of my Maine Logger (a Pilsner-style lager with malt and “low hop bitterness”). This beer, matched with an order of potato-encrusted haddock served with a side of smashed potatoes, showcases the best flavors to come from The County, all in one starchy, hoppy meal.

laura poppick is a freelance journalist based in Portland, Maine who covers science and the environment. | laurapoppick.com