How Well is Wayfinding Facilitated in Nursing Homes?

An analysis on care centers built environment and the influence it has on dementia and alzheimer residents navigation and autonomy

By Madeline Bradley

An analysis on care centers built environment and the influence it has on dementia and alzheimer residents navigation and autonomy

By Madeline BradleyHow do we design and accommodate the built environment of elderly residents to better serve their quality of life? When considering assisted living residents, 70 percent of them have cognitive impairments (Davvis,Ohman,Weisbeck 2017). It is important to provide environmental support for residents with physical and(or) cognitive problems when navigating a new place. When residents are moved to a new space it can be disorienting to grasp the new layout and figure out the different sequence of spaces. Residents who have dementia or Alzheimer’s have a bigger obstacle of finding the best route, recognizing the destination once arrived, and finding their way back. These residents are considered to be location dependent and need helpful aids to ease their wayfinding experience.

A main goal for wayfinding in care centers is to have an enhanced autonomous experience for the user and, by this, better staff efficiency. But in order to achieve this result, the design of care centers must change to reach a therapeutic outcome regarding the environmental design. Over the years, the scale of care

centers is changing. Institutional sized nursing homes are starting to break up their wings to be situated in clusters, but the building design still consist of long corridors and non-centralized communal functions. Very few user-friendly design guidelines address ways to support orientation for the elderly and those that do focus more on the signage visibility than the type of signage and guides themselves. How are they being used? Are they salient? Are they too repetitive or not enough?

Spatial orientation plays a key role within wayfinding. It refers to ones ability to mentally develop a cognitive map for a physical setting and their ability to navigate within the built environment.

The design of a floor plan and its overall typology has a big influence on the orientation of the user, but signage, guides, and overall wayfinding aides have just as important of an impact and can alleviate and ease navigation when used correctly.

In current elderly care centers, these design considerations can have a positive influence on all residents and a huge impact on the memory care units to gain back more independence.

Physical features such as small group size, privacy, safety, and accessibility have been linked to a higher level of independence and less agitation, aggression, and fewer psychotic problems (Marquardt,Genside,Dr-Ing 2011). Environmental cues such as signage, lighting, and color can benefit the circulation for the user, help with decision points, and arrive at successful navigation.

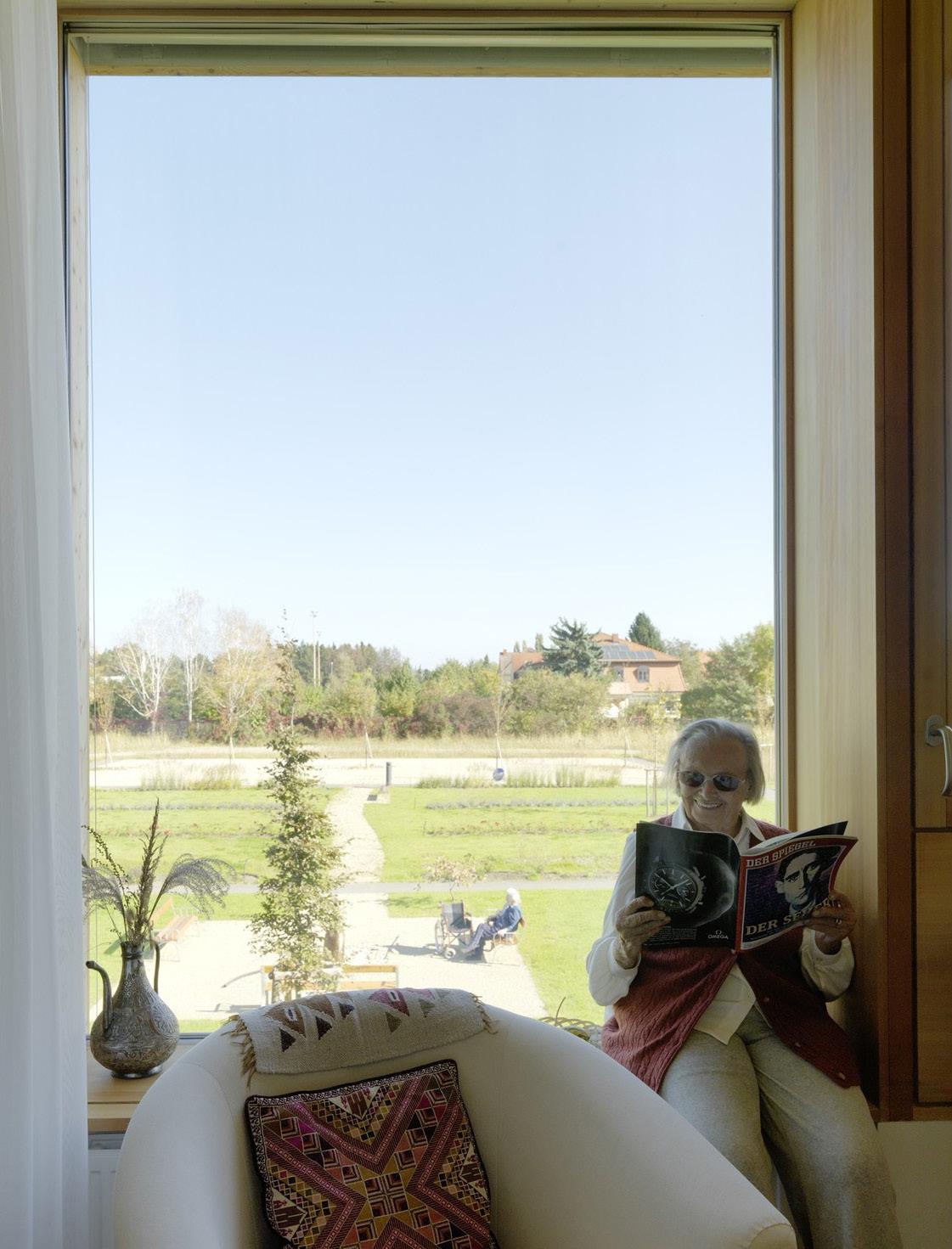

Peter Rosegger Nursing Home | Dietger Wissounig Architekten

Peter Rosegger Nursing Home | Dietger Wissounig Architekten

The aim of this study is to gain insight into how the physical environment of senior housing impacts wayfinding for residence with Dementia and Alzheimer’s. The first part of this report is to identify what factors promote their mobility and autonomy, while identifying which ones distill their navigation. The second part, is to identify knowledge gaps that need more analysis on environmental interventions for long-term care wayfinding that resonate for an enhanced user experience after analyzing existing trends. This will result with design criteria to provide considerations for care facilities

who wish to update their model. Not just for dementia and Alzheimer residence, but any elderly resident in this built environment to better serve their comfortability, mobility, and overall autonomy.

“What factors promote their mobility and autonomy, while identifying which ones distill their navigation”Veronica House Elderly Care Facility | F M B Architekten

After reviewing prior literature review, first I will state initial trends regarding wayfinding strategies, measure of design, and measure of success. Then addressing any gaps that were noticed after reviewing. Studies reviewed had to meet the following criteria: (1) considered Dementia or Alzheimer residence in the study (2) analyzed or reviewed wayfinding and environmental interventions (3) took place in a nursing home or had some relation to that setting (4) being published within 1985 to 2022.

Leading trends within literature for signage that was effective in senior housing were considerations to the length of route, width, and shape of the corridor. The main hurdle for residence with or without dementia that struggled to remember their route was due to the long corridor. Some residences were design dependent or location dependent (O’Malley, Wiener, Muir 2018). The design of the building and design factors that ultimately you rely on is considered to be design dependent. Location dependent is when you rely more on the location of rooms or landmarks in relation to where

they are placed. Alzheimer and Dementia patients depending on the stage of their ailment, are a combination of being design and location dependent. The smaller number of residents per living area facilitate orientation and wayfinding (Marquardt, Schmieg 2009). The smaller scale can help location and design dependent elderly by having direct view of their amenities with reduction of length to the sequence of spaces. The shorter the corridor, the better for navigating a space and making it feel less intimidating for residents.

Elevators seem to be a huge contingency in decision making for residents in larger scale

long-term care centers. When elevators are a main access for accessing different floors, some residents have forgotten how to use them and the waiting time to get into elevators exceeds their attention capacities (Passini,Pigot,Rainville,Tetreault 2000). Elevators are mostly inaccessible for most residents due to the overall fear and nervousness it brings even when a staff member accompanies them. When residents get off elevators the metal board in the elevators on which the door runs is known to be an obstacle for some patients (Passini,Pigot,Rainville,Tetreault 2000). The black floor bands mimic a black hole to wandering dementia residents, so they try

to avoid them. In some care centers, staff members use black floor bands to reduce access to certain spaces. Small-scale care centers are highly recommended and supported in most literature that were reviewed due to the likelihood of friendly humancentered care design, the shorter length in corridor, decision making, and increase in patient needs. In the first ever built Green House in Tupelo, Mississippi, the residents’ rooms were no more than a few feet from communal space (Caspi 2014). Some wheelchair residents were even able to stop using their chairs because of the navigation being such a short distance in the household.

There are not many studies on the implementation of lighting and how it impacts the user experience. But one study in a Thai nursing home studied the luminance in relation to wayfinding. The increase in luminance could lead to an increase in wayfinding in the corridor by having it be at least 500 lux of ambient lighting. Natural lighting had its own positive impact, by being able to see natural elements it confirmed a significant effect on wayfinding in corridors. They suggested that natural lighting should be integrated into linear corridor design for promoting the interaction and communication for elderly residents (Tuaycharoen

2020). Natural lighting has a profound impact on the mood. Exposure to natural and bright light has been linked to reduce depression, improvements in sleep, and reduced cost of pain medication (Ulrich et al. 2004). Natural lighting is so important in care centers to connect users to nature and create a therapeutic environment.

Veronica House Elderly Care Facility | F M B Architekten

Veronica House Elderly Care Facility | F M B Architekten

Having a supportive built environment for residence to regain their autonomy is important when considering wayfinding guides and signage within senior care centers. The route to their destination, knowing that you have arrived, and finding your way back are key environmental cues that wayfinding aids that can enhance the navigation process (Brush & Calkins, 2008).

In a study that interviewed advanced dementia of the Alzheimer type, the care center took pictures of the seniors from when they were slightly younger and placed them outside of their private room. Photos taken in the past tend to be more easily recognized by the resident (Passini,Pigot,Rainville,Tetreault 2000). Room numbers did not

seem to be as successful outside of the resident’s room mainly due to them not remembering the number. When the number is there, it is mostly for staff or visitor’s vs the resident. YAH maps (you are here maps) are less important in nursing homes for residents’ wayfinding than it is for visitors. Familiar items and an overall homelike feel to a new space is another great wayfinding aid. In smaller care homes, this is a common tool to help residence orient themselves and have more autonomy. There familial tools give the resident more security and association with a place, in addition, it individualizes their stay and makes it more personable. In most cases, families do have control over what personal items are brought into care centers for dementia residents. Some families are reluctant to bring furniture, valuable possessions in fears that they will go missing

or be stolen from other residents living there (Dincarslan,Inness, Kelly 2011). In cases like this, residence lose autonomy over their valuables and that could lead to an esteem decrease in taking ownership over their treasured items.

It is important to have sensitivity to which floor textures are chosen in care centers. Different floor textures to break up rooms can be another helpful guide. Simple tiles with a consistent line guiding residents to and from a space is helpful to the users who look down at the floor as they walk. The reflectiveness of the floor is another consideration. Many nursing homes are slowly moving away from the institutional model of shiny floors and harsh lighting. The reflection of too much light from the floor can cause anxiety in some residents

The overall goal with care center key spaces is to make them

(Passini,Pigot,Rainville,Tetreault 2000). The overall goal with all of these spaces is to make them memorable, meaningful, and increase comfort.

In bigger nursing homes, the design can be quite repetitive and can be disorienting for users. Finding distinctive signage was key to navigating around the space. Suggestions for existing care centers to assist residents would be landmarks. Landmarks are helpful cues to help the people remember where they are and where their trying to go. Aids such as furniture, plants, wall hangings, artwork, and general items that are attractive and

interesting can be very helpful (O’Malley, Innes, Wiener 2015). Visual aids with less words are considered to be better due to some users not being able to read the landmark from loss in vision or cognitive ability to read.

To ensure a resident’s autonomy having salient cues around the care center is beneficial. Care centers should not make all spaces within the household salient because then it would be too repetitive. Having a nice balance of salient cues at decision making points is key. In some care centers, having to ask permission for certain communal spaces, such as going outside or being able to use certain

spaces, made the resident feel as if they lost some autonomy. Even though this is to ensure the persons safety, it can cause their self-esteem to decrease.

Finding the bathroom was another autonomy issue within care centers for residents. The primary destination that residents had difficulty locating was the toilet. Finding the toilet may prevent one from using it and that can cause distress. Struggling to find their room may prevent them from wanting privacy to use the bathroom or alone time.

Private Ye San Po Holiday Homes | PaM Design Office

Private Ye San Po Holiday Homes | PaM Design Office

Residents who are location dependent would benefit from a open space by being able to see what they have access to and avoid corridor navigation confusion. The overall distance between resident rooms to communal areas should be minimized based on existing literature of residents having problems with navigating from their room to communal spaces. A study suggested that floorplan complexity negatively affects wayfinding performance and found that the more complex so did the increase in wayfinding performance time, number of wrong turns and back tracking (Jamshidi,Mahnaz,Pati 2020). A suggestion would be to offer visual aids to major spaces and function for patients who’ve lost their cognitive mapping abilities to ease wayfinding at decision points.

Literature review regarding route efficiency indicated that residents walked more than necessary to their destinations. This is mainly due to residents avoiding corridors and taking a longer route to get to their destination more confidently. Service points within the care center can be beneficial by residents being able to make eye contact with a staff member when they are lost or have higher potential of confusion. Circulation patterns should be improved for better wayfinding navigation. The

service points support residents with wayfinding information (Tuaycharoen 2020). Having service spaces and salient signage at decision points should be in separate areas. The service point is a landmark of its own. When it comes to successful signage, having different artwork on the walls and stirring clear of neutral images could decrease disorientation and repetitive sequence of spaces.

The sequence of space is another important measure of design. Newer residents are more likely to get lost at decision points. When finding their room in care centers with multiple wings, a resident is likely to walk to the end of a corridor and then be redirected by a staff member when they are lost (Passini,Pigot,Rainville,Tetreault 2000). When there are multiple decision points in a bigger care center, residents express behaviors of anxiety, confusion, and sometimes panic. In one study, family spoke about the importance of having a choice of space (Dincarslan,Inness, Kelly 2011). This meant a quiet space other than their room; they could go with their relative or a space they could join in with the life of the home while spending time with their relative. In care centers that had residents share a room with another person, they stressed the importance of making their portion of the room a

little more personable and private, whether that was drawing the curtain or situating the furniture a certain way. When it comes to sequence of spaces, having a more open space allows easier views of amenities and better staff efficiency and patient satisfaction with finding such amenities.

The shape of the corridor was measured in a few different ways all but not limited to through comparative floor plan analysis, virtual reality, you are here maps, and interviews. In repetitive designed corridors, patients would mix up their rooms by going down the wrong corridor. This would usually happen in newer arrivals (Passini,Pigot,Rainville,Tetreault 2000). The longer corridors and its narrowness is a main issue among staff and residents. For staff members, the maintenance equipment causes circulation difficulty for people to move around and that causes disorientation and anxiety among wheelchair residents.

The patient’s satisfaction within wayfinding was influenced by their age, sex, culture, and psychological state. It was suggested that women experience more spatial anxiety than men and landmarkguided navigation disrupts their cognitive map guided navigation (Jamshidi,Mahnaz,Pati 2020). The stigma of dementia friendly design suggestions should not be relevant for dementia care solely but instead it should be user friendly for anyone (O’Malley, Wiener, Muir 2018). The implementation of these design considerations will result in a better design for all care centers and benefit a wider spectrum of older adults (O’Malley, Wiener, Muir 2018). Talking directly to the user themselves would result in an increase in resident satisfaction and ultimately a increase in autonomous wayfinding.

In terms of keeping residents cognitive level steady, in a study, residents recommend having a playground visible from the

building where they could go and help if required or having children visit. The positive effects of community contact are important for all care centers. It establishes a strong foundation of belonging and having activities to look forward to. Hosting different amenities and activities inside and outside of the care center is important for location dependent residents to associate different sequence of spaces with the weekly activity and other residents that attend such events.

Small scale layout increases the direct eye contact between staff and resident (Caspi 2014). This scale of design has higher potential to improve staff supervision and help prevent possible confusion of resident’s navigation and potential aggression from confusion. From the literature, measures of successful efficiency were analyzed from comparative floorplan analysis. Studies found that people prefer paths that minimize energy expenditure, longest line of sight and wider and brighter

than available alternatives (Jamshidi,Mahnaz,Pati 2020).

When navigating a room, patients were able to distinguish their room through their personal items. For example, their bed covering seemed like the easiest distinguished. Perritt et al. (2005) evaluated the influence of the carpet texture and patterns on walking time and stability. They found that small motifs and low contrast in level-loop and piletexture carpet could reduce walking time and incidents during walking.

How can the scale of a care center impact the navigation for a resident who is location dependent?

Nursing & Retiree Home | Firma d.o.o.

Veronica House Elderly Care Facility | F M B Architekten

Nursing & Retiree Home | Firma d.o.o.

Veronica House Elderly Care Facility | F M B Architekten

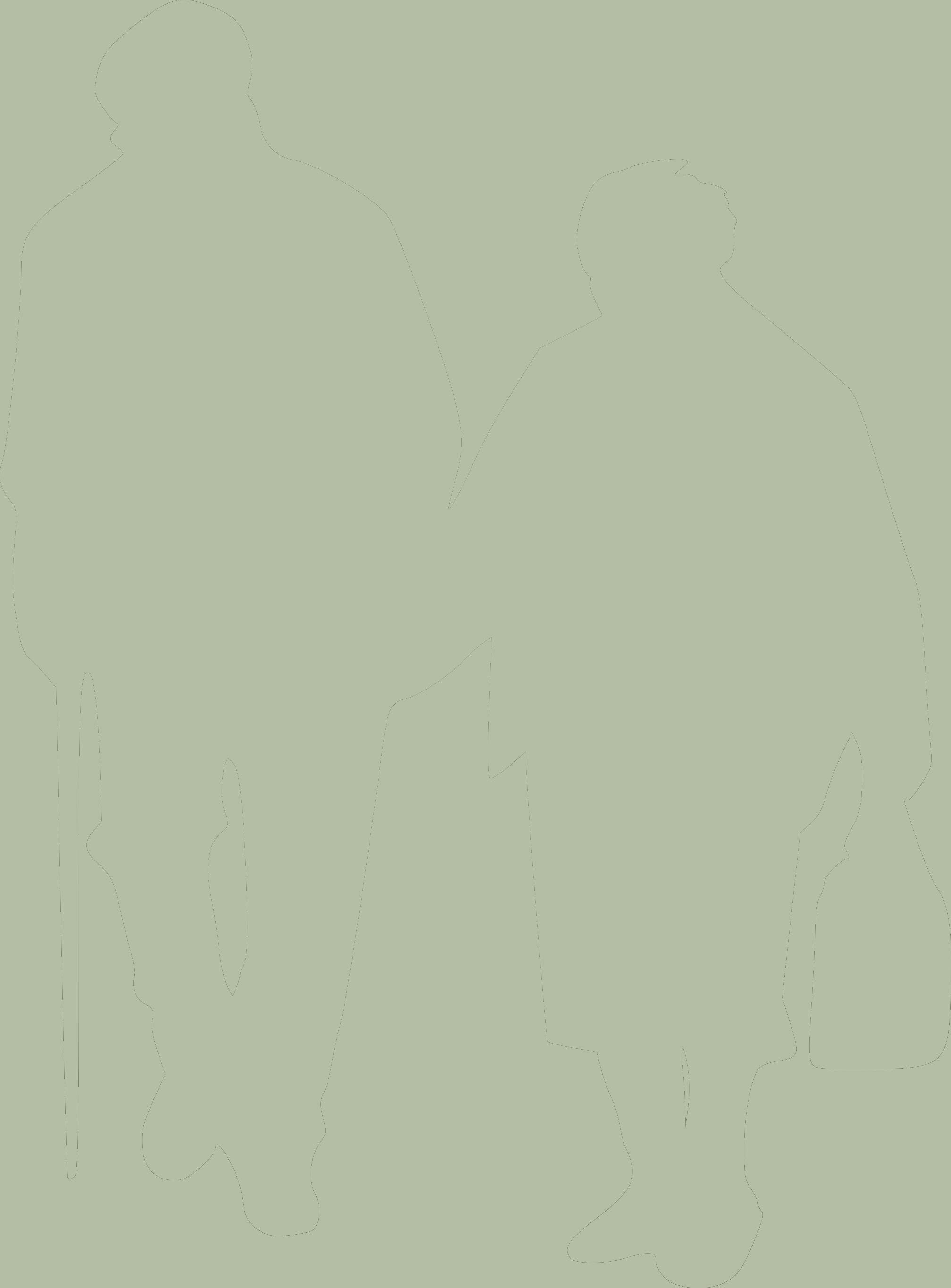

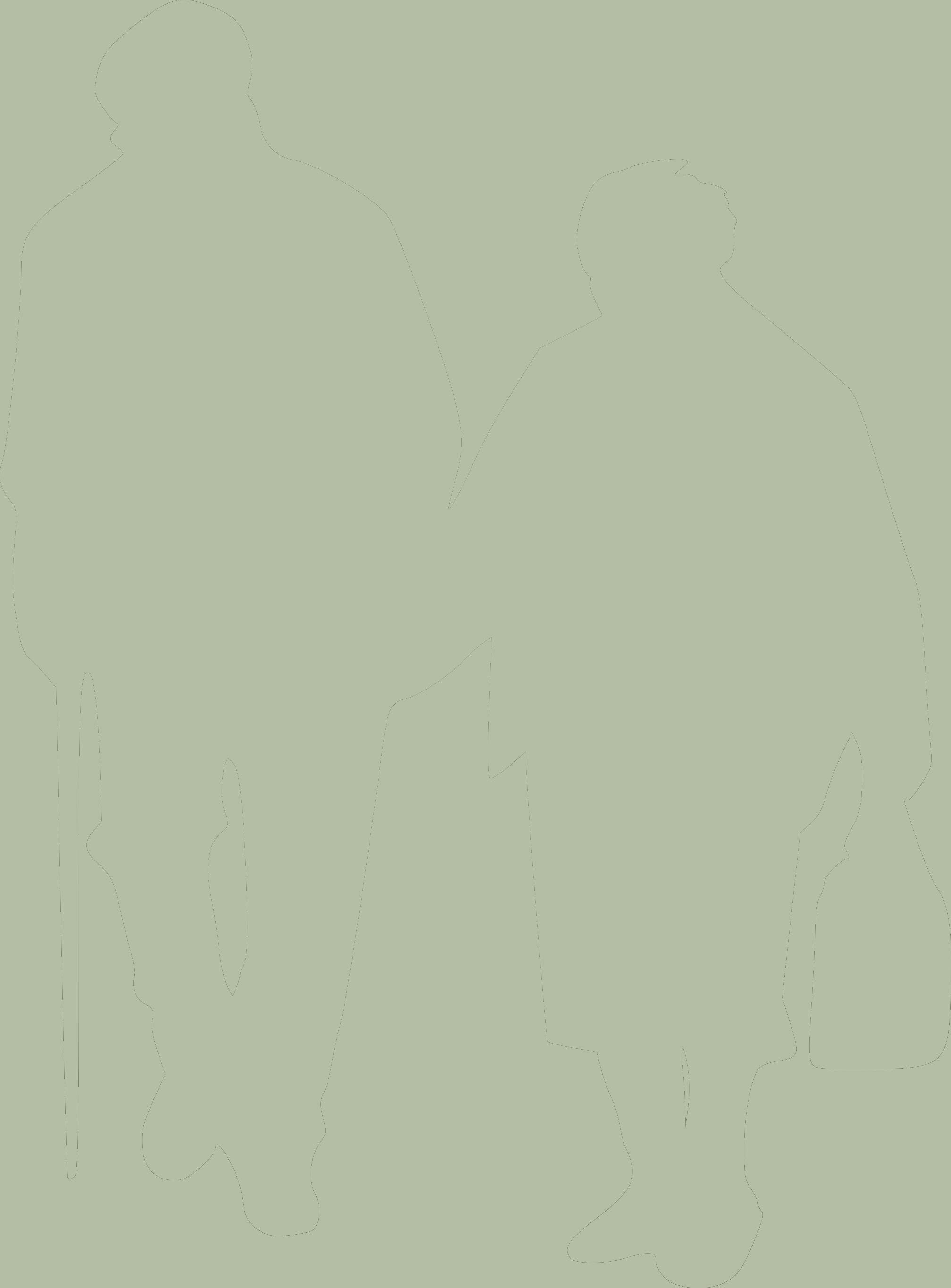

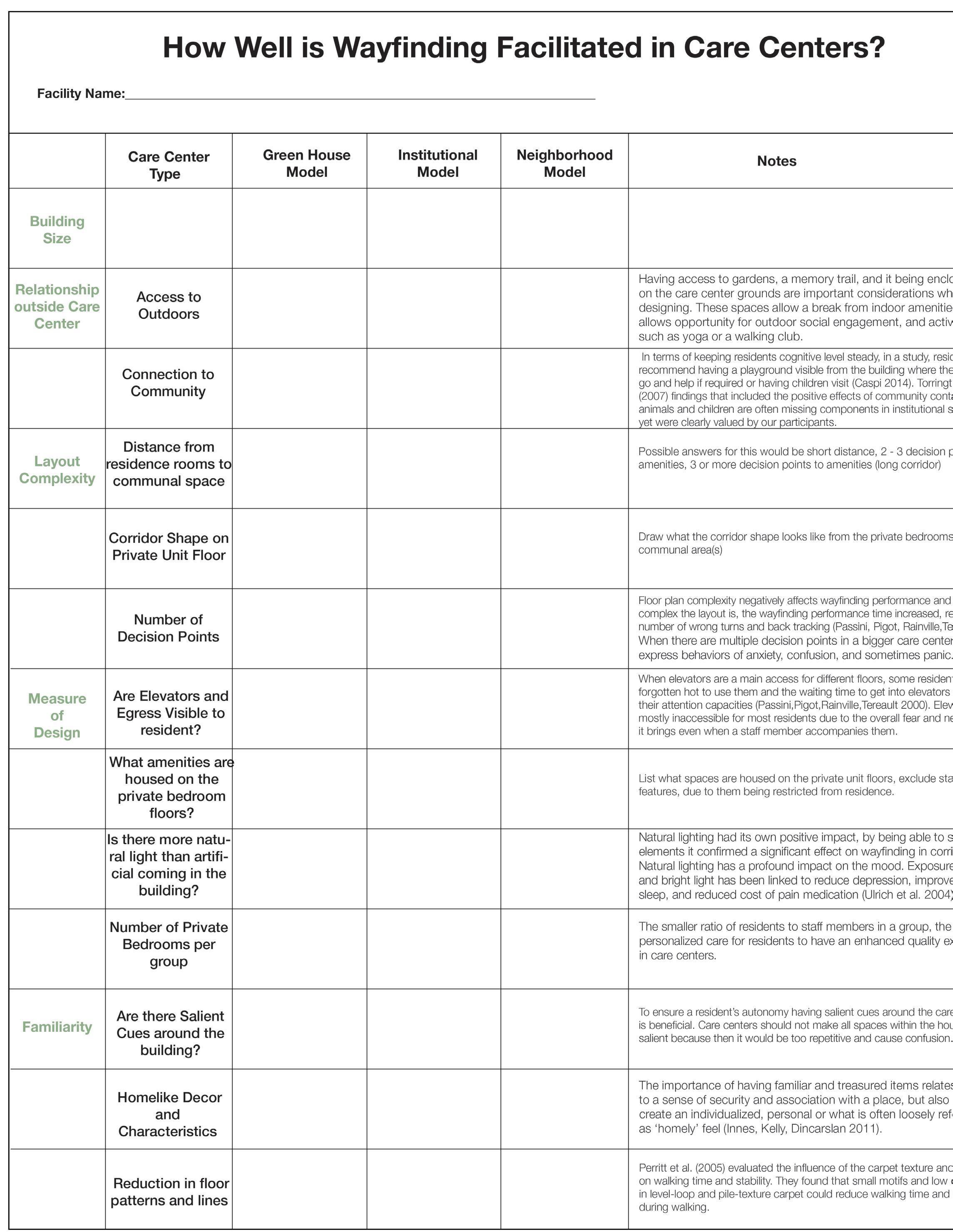

When evaluating nursing home case studies to examine their measure of design, success, and use of signage in relation to prior literature reviews. I created a checklist to compare and contrast between the chosen case studies. This checklist helps put in perspective what considerations the facility chose to better facilitate its residents for better autonomy and quality of life. The case studies are separated by the type of care center, Green House, Institutional, or Neighborhood Model. After completing the checklist, consider the positive and negative implications from each type of care center and how it effects the users.

NORDIC OFFICE OF ARCHITECTURE | 193,750 SQUARE FEET

Carpe Diem Dementia village is a treatment and housing center. Their purpose is to achieve a better and more efficient care system for elderly people with dementia. The buildings and outdoor spaces are designed to help residents increase their activity and master everyday life. Residents have the option of freely walking throughout the facility without closed doors. The care center consist of two levels of care: 136 communal housing units and 22 high-care dementia units. Residents in the communal living areas enjoy their domestic comforts and welcoming common areas such as cafes, community center, fitness facilities, and other amenities.

The rooms all utilize labels to notify the resident which room they are entering. They are placed above eye level which can be harder for a wheelchair resident or person who has started to forget how to read. A suggestion would be to utilize pictograms. With this facility

specifically catering to residents with dementia, this would be a beneficial design change to help all residents navigate more independently. The amenity rooms have a big glass opening to help residents look inside and see what activities are going on. This is helpful for a residents navigation in long corridors. It opens up the space and helps it feel less daunting.

Resident rooms are able to be personalized and incorporate furniture from their previous home. This eases the transition and causes less anxiety, confusion, and feelings of sadness. There is not a limit to how much memorabilia the resident can bring into their room, but the facilities does provide furniture for some residents who don’t have the option of bringing their belongings. Some families are hesitant on bringing their family members belongings into nursing homes in fear that it could get stolen or misplaced.

The buildings different exterior material choices can help residents navigate to different buildings by having repetition of amenity buildings all being in one material choice while residential units are in another. The interior utilizes a lot of natural light which is beneficial to the cognitive development of Alzheimer and dementia residents. Due to having floor to ceiling windows that let in natural light, the artificial light doesn’t seem to be needed as much during the day. The floor texture is reduced to a minimum with slight line work from the tile choice in the corridors. The color pattern has light contrast from the wall and ceiling material to ease wayfinding from space to space. There is not much glare from the natural lighting in relation to the floor, which helps hazard or confusion within residents. The archetype of the private resident rooms have high ceilings, a simple floor pattern and floor to ceiling windows. When looking out of their private window, the resident either has a view of the other buildings and can look down into the memory trail or they have views of the dense woods surrounding the facilities.

Elevators can be intimidating for dementia residents to navigate to different floors independently. Each individual building provides a living room, a community space and balcony for its private units. But on days where residents want to interact on the

ground level, navigating there could be tricky. The balcony does provide autonomy for residents to interact outside without leaving their floor. The balconies could incorporate maybe a small garden or provide an activity to where residents have more agency with outdoor activities.

The rooms are divided into wings that do not exceed 8 units

to a nurse station. This allows personalized care for those residents and eases wayfinding for users to find their rooms and other amenities easier. Each private room has its own bathroom. By having 8 rooms to a group, this helps residents locate their private bathroom easier and lowers frustration and anxiety. The communal spaces, utilize the contrasting color red for the chairs to help

residents associate where the social spaces are and where they can sit. The interior design utilizes natural colors such as blue and green throughout the entire building. This is proven to help with easing mental and behavioral health in people by lowering their anxiety, depression, and overall sadness. More independent units have connecting balconies for residents to navigate to other buildings without having to go on ground floor to do so. This design strategy is beneficial for staff efficiency to circulate between different staff support areas when necessary.

The moment of decision points for each group is minimized to the community space and eye view of the resident rooms. If a resident

has confusion, they are able to make eye contact with a skilled nurse at any spot within the wing and be redirected to where they are trying to go. When navigating to their room, by the room being personalized with the residents memorabilia and each group not exceeding 8 units. It allows easier identification for residents to locate their room. I suggest a picture of the resident in addition to their name outside of their door to provide less confusion for residents who wander and have more likelihood of getting confused.

Carpe Diem successfully provides the opportunity to interact outside freely. The memory

trail that circulates throughout the buildings, in addition to having places of rest or outdoor activities such as yoga, provides independence for its users. The building typology resembles a residential neighborhood and could ease confusion or anxiety from moving into the facility.

6

Living Room Dining Room Outdoor Deck

193,750 sf Yes No Short No Yes 8 Yes Yes Yes

RLPS ARCHITECTS | 94,400 SQUARE FEET 2012 GREEN HOUSE MODEL

The Leonard Florence Center for Living is a supportive community modeled after an urban apartment house. The facility houses 100 residents and provides skilled nursing care in independently managed houses of ten residents each. On the ground floor, all residents have access to a European day spa, deli, library family room, a 24hour cafe, chapel, and outside patio, in addition to 24-hour room service upon request. There are an abundant of positive distractions and weekly activities such as lectures, games, outings, pub nights, concerts, holiday celebrations, and intergenerational programs. This is the country’s first green house community to be constructed within an urban setting. Their focus is enhancing the quality of life for each resident by providing nursing care within the comfort, privacy, and familiar surroundings of their home.

The private bedrooms are styled like a hotel suite but the

care center highly encourages residents to personalize their room and bring in outside homelike decor and artwork. The small scale of each group can make family more willing to allow new residents to have more of their personal belongings due to more surveillance and less opportunity for their things to get misplaced or stolen compared to a larger scale care center. The short length in corridor has a higher likelihood of residents being able to associate which room is theirs. The care center does not utilize any salient cues to help residents associate which room is theirs. This may be due to the small scale and staff being able to redirect patients easier based on the ratio per group. Each room has a big window letting in a lot of natural light and helps with their cognitive levels. In addition, the natural light helps with the reduction in depression and improvements with their sleep.

Low level carpet is used throughout the private bedroom

floors. The pattern of the flooring changes dependent on what sequence of space you are in. For example, the corridor path is a solid dark gray and on one side if you choose to walk off the corridor path, you walk onto a more complex carpet pattern that is the living room or on the other side, if you wish to go into the kitchen, the flooring is tile. This helps memory care residents to associate flooring with amenity. There are a few carpet pattern choices that look too complex and could confuse, disorient, or scare dementia patients from wanting to walk on the carpet. This choice of pattern could be used to restrict residents from entering certain spaces that are off limits but if used in a inviting space, it might not be the best flooring decision.

The color scheme in the building utilizes warm earthy tones and biophilic elements. The incorporation of accents of green and blues in the furniture and decor around the building provide a therapeutic atmosphere. This

can be helpful for dementia and Alzheimer patients when they have aggressive, anxiety, or depression induced episodes to be surrounded by colors and design that have a bigger potential of reducing such factors.

By having the units hug the communal space, the corridor

has natural light from the living rooms big windows and that makes the path less daunting and dark for users. The building utilizes alcove lighting in major social spaces to reduce glare from the flooring and potential anxiety in the residents.

The reduction of the corridor

length in relation to the sequence of amenity spaces is very short. This allows dementia residents to keep the connection of where they are and where they are headed long enough to successfully navigate to their desired space. In each 10 bed group, the units face into the communal space, giving equal distance of all rooms in relation to major social spaces. For wanderers, there is a fluid rectangular track for them to walk around the floor without fear of them becoming lost or disoriented. The elevators and stairs are out of view for these residents and it is less likely for them to navigate to an area that is off limits. There is a den in addition to the living room, kosher kitchen, and dining room. The den allows a private social space for family to come visit and have auditory privacy from the other residents and their potential guest.

On the ground floor, the majority of the corridors open up into a communal space. This avoids the potential of having long narrow corridors that many dementia or Alzheimer residents avoid. For staff, having corridors that open up into spaces helps have better view of all residents and for them to redirect a confused user. The open concept allows natural light from the communal spaces to pour onto the path and help with navigation.

The small scale care center has many activities that take place in the building and nearby. The strong community base it a positive distraction and provides a lot of agency for the resident to plan how they want to spend their week. The variety of activities also allows for residents to make

connections with the sequence of spaces in relation to what activities will be taking place each week and weekend. Family and friends being incorporated into the residents schedule can ease the transition of new arrivals and help them feel less depressed in a new environment.

94,400 sf Yes Yes Short 4 No No 10 Yes Yes Yes

Living Room Dining Room Kitchen Outdoor Deck Den

DOMINIQUE COULON & ASSOCIES | 62,785 SQUARE FEET 2015 INSTITUTIONAL MODEL

The home for the dependent elderly people is a care home in the heart of Normandy village. To reduce the visual impact of the building, the designers thought it was preferable to divide it up. By using the color green, the building blends into the larger landscape and reflects the rural nature of the surrounding site. There are 115 units and all our connected to a south facing street that is back by the hill. There are 85 private beds for dependent elderly people and 30 private beds for standard elderly residence. The arrangement gives views through the building on one side to the other. The buildings layout has close ties to the surrounding landscape. There is a day center that provides adaptable activities, a treatment facilities, and catering kitchen.

The bold red that circulates throughout the building is the biggest salient cue. The red is broken up by being in major communal spaces and by being on one side of long corridors

to navigate residence. The red can be a bit daunting and cause anxiety in residence. The color white for the choice in flooring, ceiling, and other walls that are not red in major routes can also cause confusion and loose homelike characteristics. The building appears institutional and sterile.

The corridors to the private bedrooms are long and narrow. In addition, the rooms do not use memorabilia to identify residence rooms from one another. The flooring is a solid white laminate tile. With the reduction of artificial light due to maximized natural light, there is less potential for glare when residence are navigating from space to place. The use of strip lighting is very common throughout the building. The strip lighting is on one side of the ceiling and can be used to navigate users to other sequence of spaces if they follow the artificial light.

There is no variation in different floor patterns to ease wayfinding.

On the ground floor, there is eye level labels to help residence find desired spaces. For residence with worsening eye sight, this might not be the best method for wayfinding. In a space with long corridors and the use of the contrasting color red, I would recommend pictograms of amenities at decision points to help users feel confident with their longer route to their desired destination.

Elevators and stairs are in view for residence. The potential of wanderers to go in restricted areas is higher.

There is a lot of natural light in all spaces throughout the building and because of this, artificial light is very minimal. The building feels very empty due to it not having many wall hanging of familial or memorabilia from the residence or provided by the care center. Dementia and Alzheimer residence have a higher chance of disorientation in the scale of this building and by not having

Means of Egress &

&

Stations any other salient cues besides the bold color red.

On the unit floors, all amenities and dining spaces are on the left side. If residence get lost or disoriented, they can follow the corridor and be reassured that eventually they will walk into a communal space on the left side. Residence have access to multiple outdoor decks and seating choices. Private bedrooms face into each other.

There are multiple layouts for how the private bedrooms are sequenced. One corridor might follow a racetrack format while another follows a long dead end corridor layout. The different iterations might be determined on the severity of dependency. The private room iteration with the dead end corridor does not have as much natural light pouring into the corridor until you arrive at the end of the

hallway. For wanderers, this could cause major disorientation and confusion.

There are multiple decision points throughout the building. Service areas should be located at major decision points and divide the long corridors to guide wanders or lost users at the halfway mark to their destination. The private bedrooms allow users to bring in a unlimited amount of their personal items from home. But by not having memorabilia or homelike characteristics any where else in the building invokes cold, institutional, and uninviting feelings. Residence who have lost their cognitive mapping abilities would not benefit from a scale or design of this care center.

Living Room Dining Room Outdoor Deck

Home for Dependant Elderly People | Dominique Coulon & Associes 62,785 sf Yes No Long 17 Yes Yes 74 No No Yes

Wayfinding Facilitated in Care Centers?

When comparing the three case studies regarding their number of decision points based on the type of care center and size, the scale has the leading role in relation to the number of sequence of

spaces and how many turns you have to make to reach them.

RLPS ARCHITECTS | 2012 GREEN HOUSE MODEL

NORDIC OFFICE OF ARCHITECTURE | 2020 NEIGHBORHOOD MODEL

Leonard Florence Center Carpe DiemWith the scale of this model, at decision points it would be important to have contrasting color and(or) signage that can navigate elderly residents to their desired destination. Important

spaces that elderly try to navigate in serious situations might be their private bathroom, room, or a service desk. Having eye level signage with pictures of the destination could be deemed helpful to

residents. Currently a new trend for large scale care centers, is to now break up patient rooms into wings of 12 or less units to provide better staff satisfactory. in regards to ratio and a personable experience

RLPS ARCHITECTS | 2012 GREEN HOUSE MODEL

NORDIC OFFICE OF ARCHITECTURE | 2020 NEIGHBORHOOD MODEL

for dementia patients with higher needs. Avoiding the design of dead end corridors is recommended due to it causing aggression and confusion for wanderers. For existing long corridors, bringing

in natural light can help with overall behavioral results. In addition, placing service desk halfway through long corridors can make them feel less daunting.

Leonard Florence Center Carpe DiemWith the scale of this model, at decision points all sequence of spaces are usually visible to the user. The service desk is in view of all patient rooms and the staff ratio to patient provides a

personable experience. For wanderers, a scale of this care center could provide an ease at navigation if the residents ever gets lost or forgets their desired destination. In this design, the

patients rooms hug the communal space. The patient room that is the farthest from the communal space still has a brief view of the amenity and a short walk to and from the space. Dementia

RLPS ARCHITECTS | 2012 GREEN HOUSE MODEL

NORDIC OFFICE OF ARCHITECTURE | 2020 NEIGHBORHOOD MODEL

residents with higher levels of confusion could have more autonomy in a smaller scale by being able to navigate shorter lengths. With the greenhouse being in a neighborhood setting, this allows residents to

feel apart of a bigger community, even though they are in a care center. This factor is important with managing behavior, instilling routine, and interacting outside the care center with the community.

Leonard Florence Center Carpe DiemNeighborhood Model

With the scale of this model, at decision points inside of the unit, provides easy navigation from patient room to communal space. With the neighborhood model, it allows a choice for residents to wander

either in the unit or in the enclosed larger community setting. Dementia residents with higher potential to get lost might struggle with finding their patient room independently if they leave their building. But

the staff ratio to overall patient population can help residents when they encounter a likely scenario of confusion. The neighborhood model provides a community atmosphere even with it not being in

ARCHITECTS | 2012 GREEN HOUSE MODEL

NORDIC OFFICE OF ARCHITECTURE | 2020 NEIGHBORHOOD MODEL

an actual neighborhood environment. The scale of this model, does not make the care center feel enclosed and provides an abundant of activities for residents to enjoy. On the ground floor, with the majority

of extracurriculars, there are more decision points and no eye level signage, contrasting color, or pictograms to ease dementia residents when navigating spaces. The likelihood of residents needing

assistance is higher due to lack of signage in relation to number of decision points on the ground floor.

Leonard Florence Center Carpe DiemLiterature review covering wayfinding in elderly care centers have similar trends about corridors, familial cues, the scale of the care center, and other trends listed previously in the report. But there are still some knowledge gaps that are left to consider moving forward.

Access to natural lighting shouldn’t just be in private rooms and main social spaces. For existing buildings with long corridors that do not have previous windows that face into the corridor, creating secondary spaces for access of natural light through clear stories could brighten up the corridor and make it feel less daunting.

From the literature review, Lighting to Enhance Wayfinding for Thai Elderly Adults in Nursing Homes by Tuaycharoen, the study claimed that cool colored light (6,500 K), a cool colored surface, and the presence of a view-out of natural elements in rooms could be effectively used as environmental cues for wayfinding purposes for their Thai elderly residents. Color can create different emotions for different

cultures. A warm color, whether light or surface, could remind Thai elderly adults about the strong sunlight in Thailand that might make them feel negative and uncomfortable. Compared to the USA or Europe the association to warm color might vary. Cool color light and surface are calming colors and would possibly make the seniors have cool feelings (Tuaycharoen 2020). Yoto et al. studied the effects of object color stimuli on human brain activities in the perception and attention in Japanese people. They found that blue had the highest arousal compared to red and green (Tuaycharoen 2020). Naturally, people tend to associate a particular emotion with a specific color. This situation would help older people to focus and pay attention to the information that could be remembered (Tuaycharoen 2020). Therefore, Thai elderly adults may prefer and feel more comfortable to be orientated and remember the environmental features in a nursing home with cool color light and surface. When designing nursing homes moving forward, contrasting colors in relation to the location can have a positive effect on elderly behavior and their environment they interact

with in moderation.

Community is such an important factor in dementia and Alzheimer care centers. Indoor communal spaces are important but having outlets outside of care centers can provide a sense of belonging to something bigger and outside routine. Being outdoors is great for regulating all ages mental and behavioral health. In enclosed care centers, having spaces for either gardens, public spaces, or other outdoor community enriched spaces has linked to reduction in stress and aggression. (Chalfont & Rodiek, 2005), (Blackman et al., 2003) or on wayfinding (Nolan et al., 2002; Passini, Pigot, Rainville, & Tetreault, 2000)

Children and animals are often missing components in institutional settings yet are clearly valued by residents (Dincarslan, Innes, Kelly 2011). Some newer care center designs incorporate a mixed use design by having early childhood centers on the ground floor and nursing homes above the center. This would allow elderly residents to help out with easy task at the

early childhood center such as reading and playing with children. Currently, nursing homes utilize baby doll therapy for mid-late stages of Alzheimer disease. This therapy address the strong need to nurture and taking care of something living from an earlier time. Doll therapy has been linked to a significant decrease in negative verbalization, wandering, aggression, and obsessions. Having a local playground or early childhood center near the nursing home, if not incorporated into the building, could enhance the quality of life for the residents.

Dependant on the care center, existing signage that uses words primarily to navigate residents can be confusing and disorienting when certain residents can no longer read, see the words, and(or) have language barrier. Different representations of signage that would be beneficial to analyze and conduct would be tactile cues, olfactory, and

auditory guides. Gitlin and Corcoran (1993) reported that tactile cues could benefit both the PwD and their caregivers; however, the details and application of these cues were not reported. Using alarms or sirens with low frequency and suitable pitch were also suggested as potential auditory cues to ensure the safety of PwD with hearing impairments (Mitchell et al., 2003). However, more cautious consideration is needed while applying these devices due to their possible negative influences (e.g., causing anxiety on people) (Lan et al., 2020). Other interventions, like using the smell of food as an olfactory cue to guide the residents to the dining hall might also be effective but has received less scholarly attention.

After conducting this report and establishing the trends and knowledge gaps regarding wayfinding initiatives in nursing

homes through case studies and literature reviews. It would be beneficial to study the specific knowledge gaps and conduct interviews from residents and staff members. Hearing from the users themselves on what would improve their wayfinding and comfort with navigation is key to having the best results with adding to others body of literature. I would like to visit the three care center types that I analyzed, to see how the scale plays a role on the users autonomy. This report was my first phase in gaining insight into how well wayfinding is facilitated in care centers and what needs to be collected moving forward to enhance their mobility while understanding which ones distill them.

“Children and animals are often missing components in institutional settings yet are clearly valued by residents”

Peter Rosegger Nursing Home | Dietger Wissounig

Peter Rosegger Nursing Home | Dietger Wissounig

Buuren, L. V., P., & Mohammadi, M. (2021, September 14). Dementia-friendly design: A set of design criteria and design typologies supporting wayfinding. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/34519238/ Carpman, J. R., & Grant, M. A. (2016). Design That Cares: Planning health facilites for patients and visitors (Third ed.). Jossey-Bass. Caspi, E. (2014, July 13). Wayfinding difficulties among elders with dementia in an assisted living residence. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24858550/ Davis, R., Ohman, J., & Weisbeck, C. (2017, November). Salient cues and wayfinding in alzheimer’s disease within a virtual senior residence. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pmc/articles/PMC5722469/ Hoogdalem, H., Voordt, T., Wegen, H., MooreG.T., SanoffH., Research/Skidmore, Z., . . . Association, B. (2005, July 08). Comparative floorplan-analysis as a means to develop design guidelines. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272494485800153

Innes, A., Kelly, F., & Dincarslan, O. (2011, June 11). Care home design for people with dementia: What do people with dementia and their family carers value? Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://pubmed. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21815846/ Jamshidi, S., M., & Pati, D. (2020, November 6). Wayfinding in Interior Environments: An Integrative Review. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33240147/

Marquardt, G., & Schmieg, P. (2009, June 1). Dementia-friendly architecture: Environments that facilitate wayfinding in nursing homes. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/19487549/

O/Malley, M., Innes, A., & Wiener, J. M. (2016, July 26). Decreasing spatial disorientation in care-home settings: How psychology can guide the development of Dementia Friendly Design Guidelines. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26112167/

O’malley, M., Innes, A., Muir, S., & Wiener, J. (2017, March 28). ‘all the corridors are the same’: A qualitative study of the orientation experiences and design preferences of UK older adults living in a communal retirement development: Ageing & Society. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://www.cambridge. org/core/journals/ageing-and-society/article/abs/all-the-corridors-are-the-same-a-qualitative-study-ofthe-orientation-experiences-and-design-preferences-of-uk-older-adults-living-in-a-communalretirement-development/7E3777AC9F3B6A8E8BA4D73FA22865E8

Passini, R., Pigot, H., Rainville, C., & Tetreault, M. (2000, September). Wayfinding in a Nursing Home for Advanced dementia of the alzheimers type. Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://journals.sagepub. com/doi/10.1177/00139160021972748

Tao Y;Gou Z;Lau SS;Lu Y;Fu J;. (2018, August 11). Legibility of floor plans and wayfinding satisfaction of residents in care and attention homes in Hong Kong. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https:// pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30098224/

Tuaycharoen, N. (2020, June). Lighting to enhance wayfinding for Thai elderly adults in nursing homes. Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341796428_Lighting_to_ Enhance_Wayfinding_for_Thai_Elderly_Adults_in_Nursing_Homes

Wang, W. (2021, October). Influences of physical environmental cues on people ... - sage journals. Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/07334648211050376

Zijlstra, E., Hagedoorn, M., P. Krijen, W., Van der Schans, C., & Mobach, M. (2016, March 31). Route complexity and simulated physical ageing negatively influence wayfinding. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27184311/

| How Well is Wayfinding Facilitated in Care Centers?