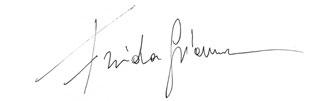

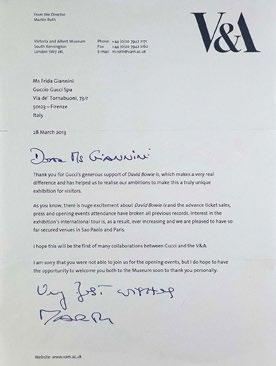

FRIDA GIANNINI

THE YEAR OF THE BIG BANG

THE YEAR OF THE BIG BANG

BY FRIDA GIANNINI

ROCK & LOVE

ROCK REVOLUTION A NEW ERA . . .

SUBVERSIVE ATTITUDE

REVOLUTIONARY WOMEN

COME AS U ARE FROM SOFT ROCK TO METAL

LES MARINIERS

PSYCHO KILLERS

PERFECTO

UNDERGROUND

MATERIAL GIRL

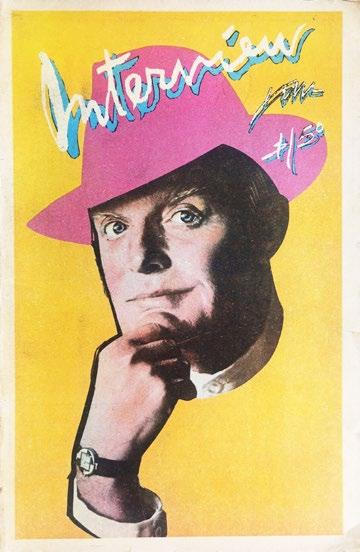

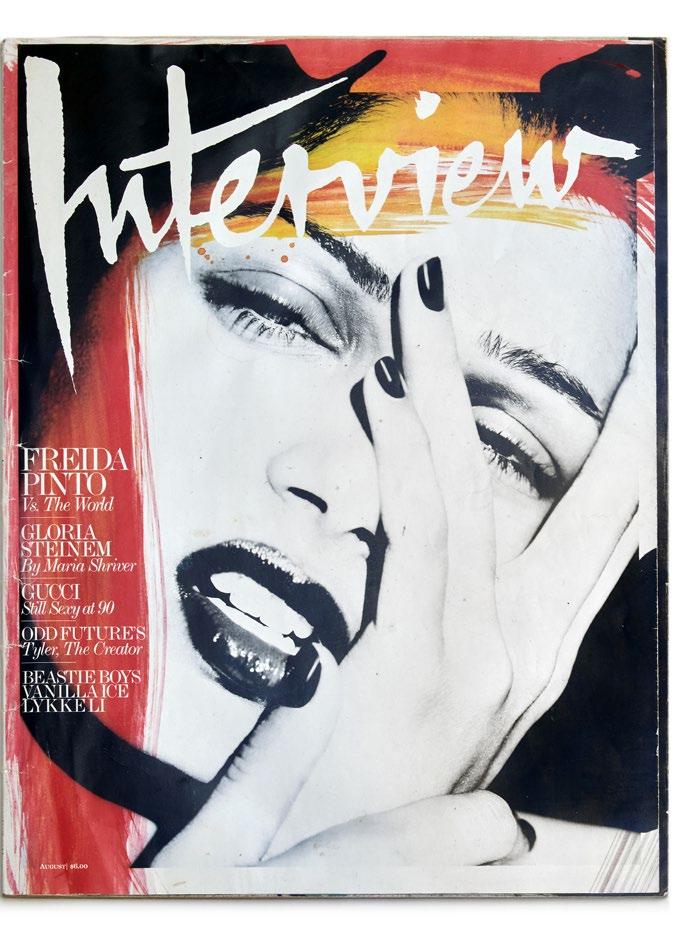

WARHOL’S

My participation in this stellar journey is deeply rooted, bound to my childhood and to a figure who was very important to me for many reasons: my uncle Daniele Vellani.

A music expert, a keen drummer, a famous DJ in the 1970s and 1980s, a refined connoisseur of rock, pop, and disco music, he instilled in me a love of music and of certain musicians in particular. As a young girl, in the company of my beautiful uncle and my older cousin Doriana, who is still to this day my accomplice in music and in life, I did some full-fledged sound immersions in his big room filled with LPs, where the only movement that was allowed was that of my uncle’s hands on the album as he searched for just the right mix.

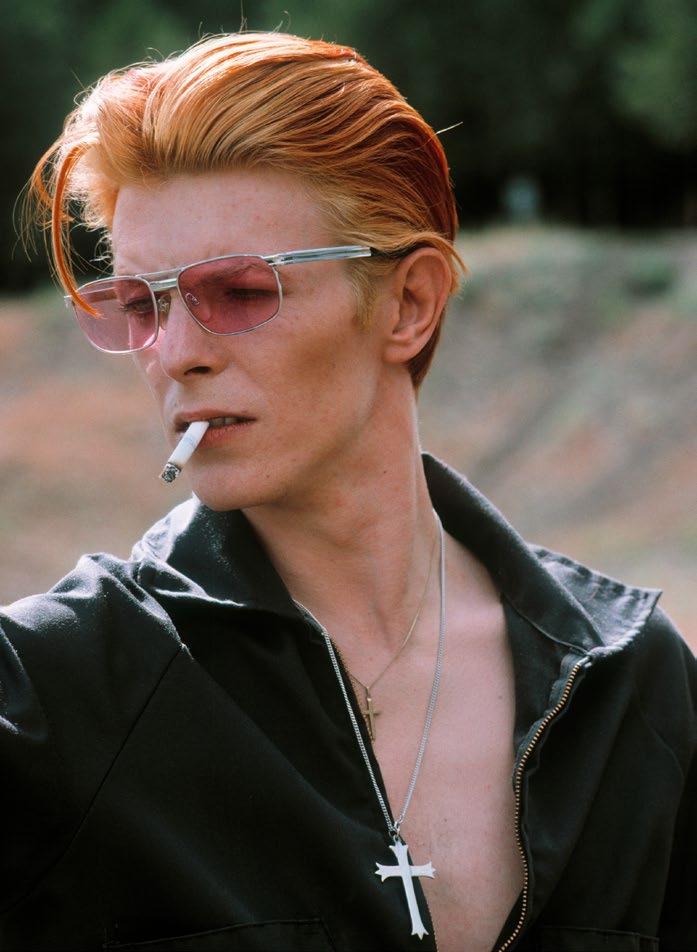

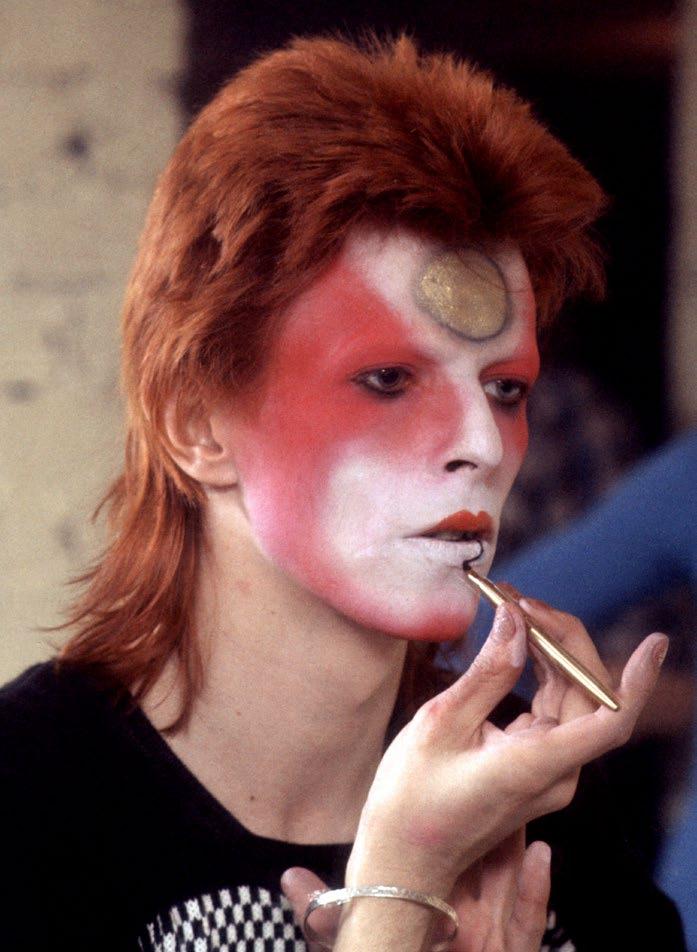

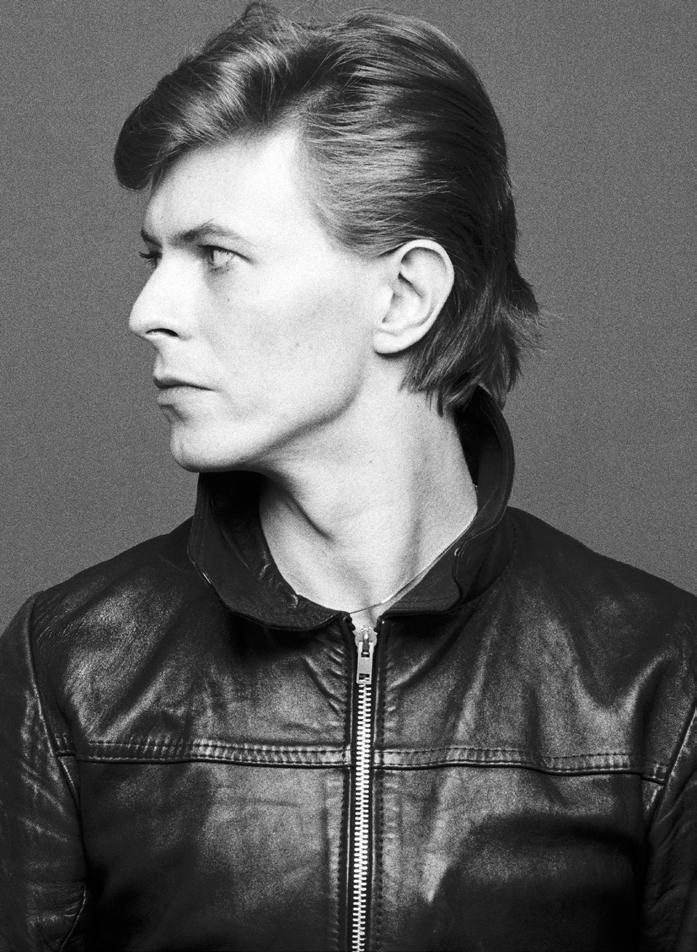

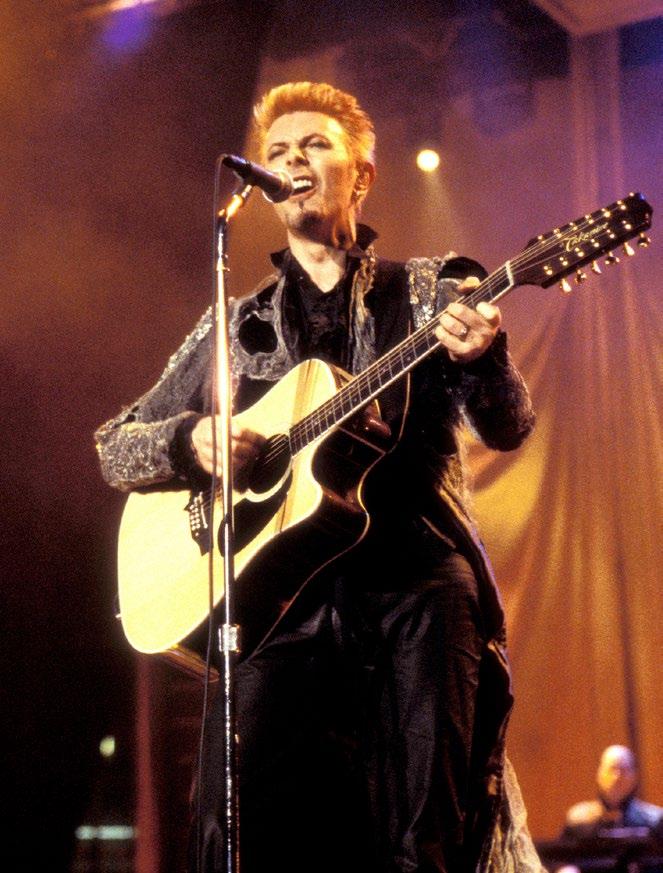

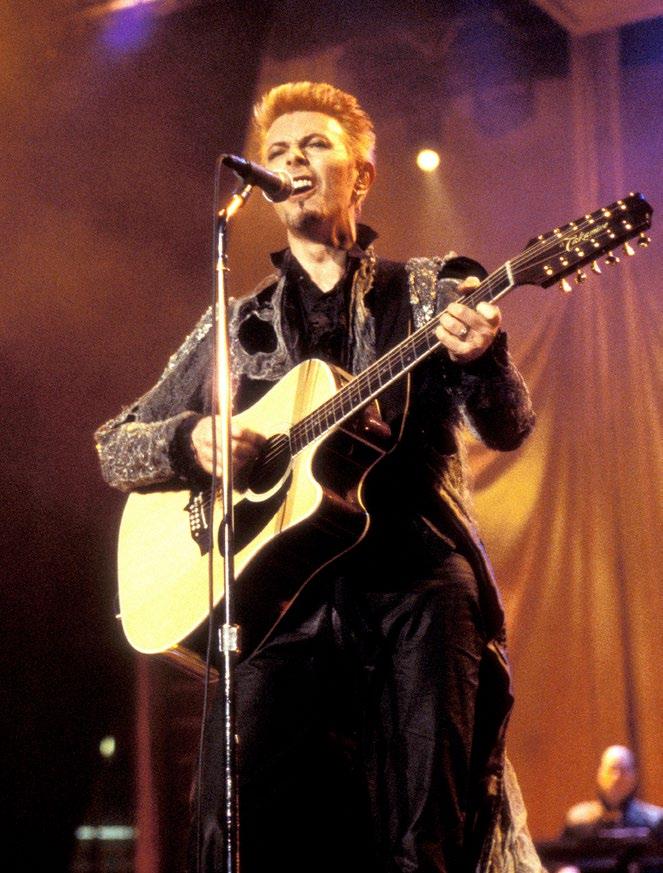

It was a “free” atmosphere, where everything seemed possible and where the hours were like minutes for me. Seated in a corner of that sort of recording studio, I would spend hours listening, hypnotized, to the music that he prepared for his evening’s work, without losing a single step in his movements. And each time the stylus touched the first groove of the record, the emotion I felt was overwhelming. It was Daniele, who left this Earth too soon, who made me fall in love with pop and rock music. Most meaningfully to me, he turned me into a fan of David Bowie when I was a child. Bowie was his favorite musician and mine, too. I grew up to the notes of “Ziggy Stardust,” “Life on Mars?,” “Space Oddity,” all the way to “China Girl” and “Ashes To Ashes.” I bought Bowie records, books, and photos in every corner of the world, delving deeper and deeper into his story as a man and an artist.

Corrado Rizza, a very good friend of my uncle and a DJ, too, wanted to interview me on anecdotes about David Bowie and this is where the idea of the book started. The idea stemmed from the fact that David Bowie, in his final years, lived in Woodstock, far away from his chaotic and hectic life in New York City. I began to lose sleep and started thinking about putting together a new, personal “Big Bang”!

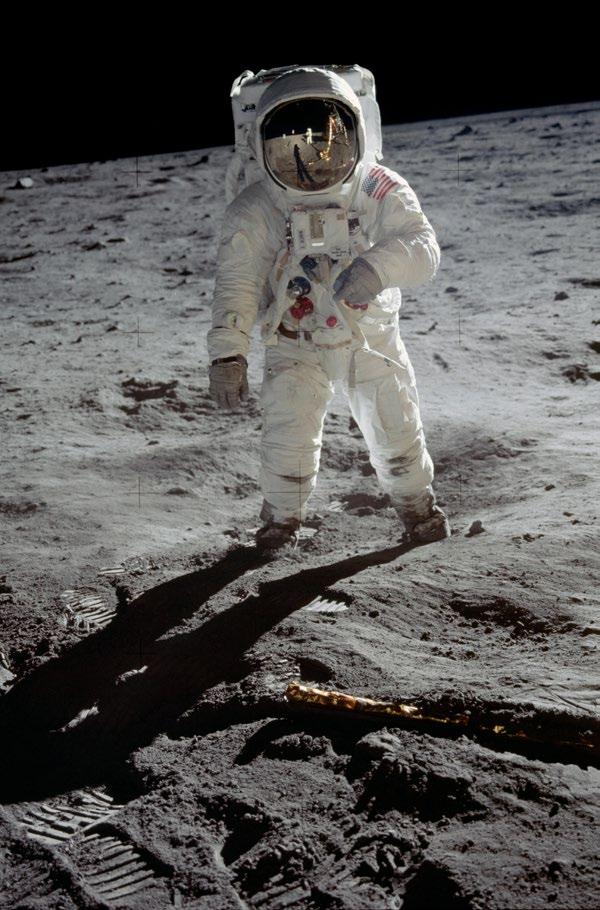

1969: Neil Armstrong, the first man to set foot on the Moon, the pride of NASA and the United States during the Cold War.

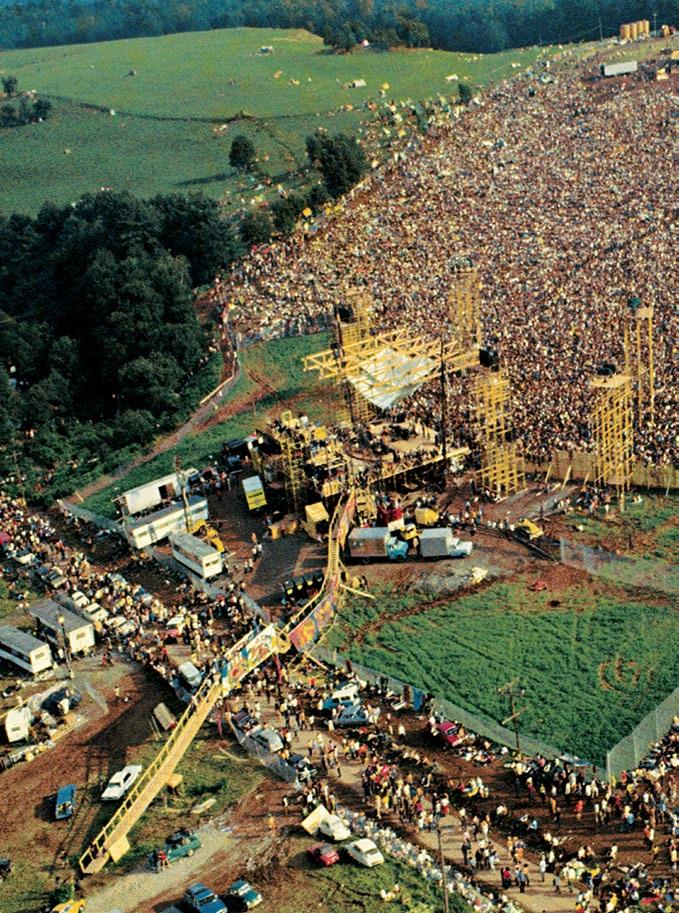

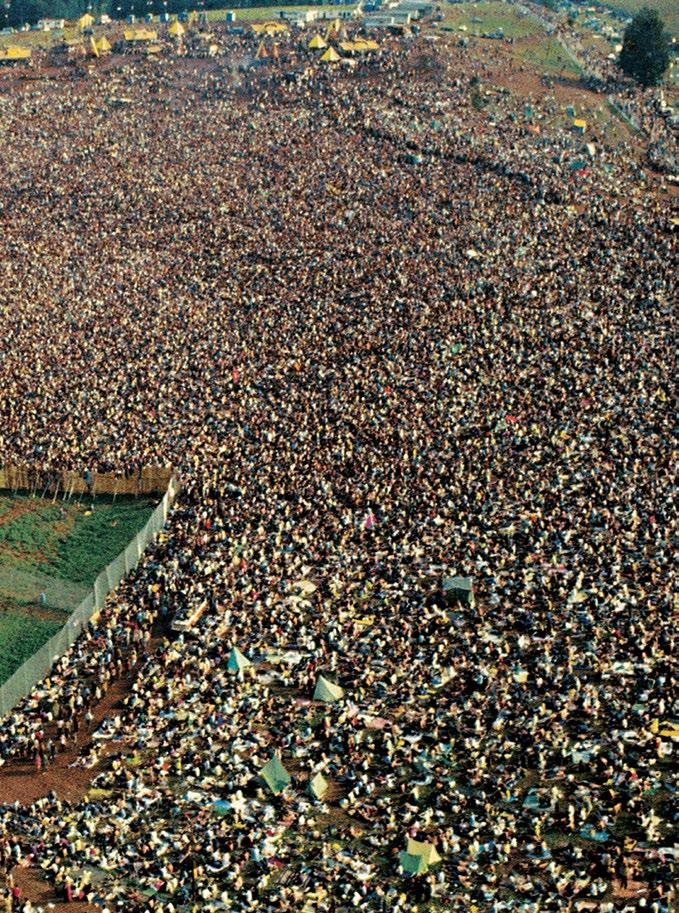

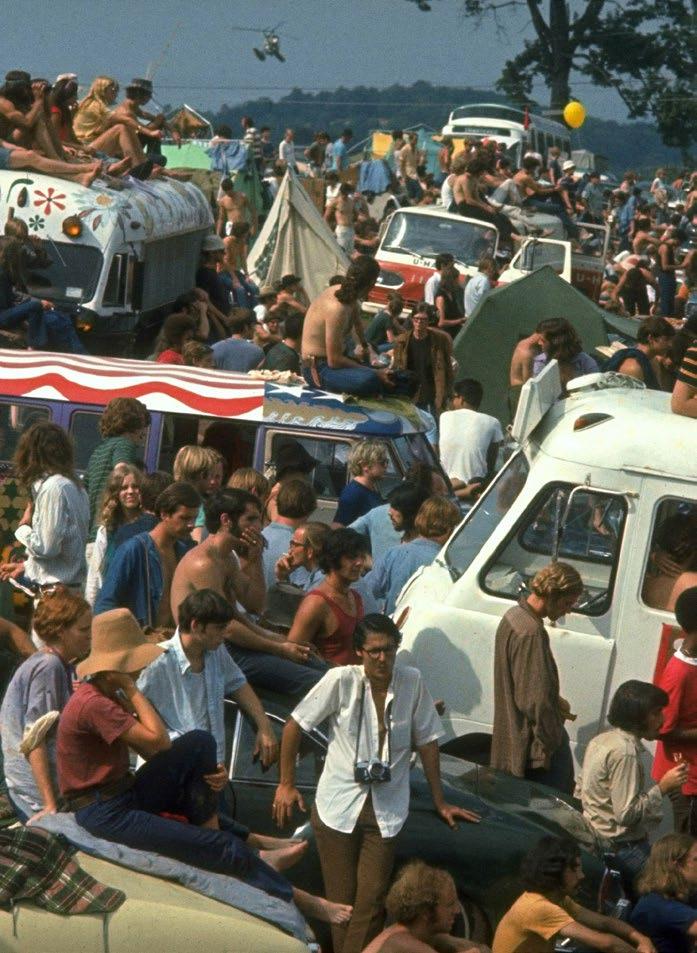

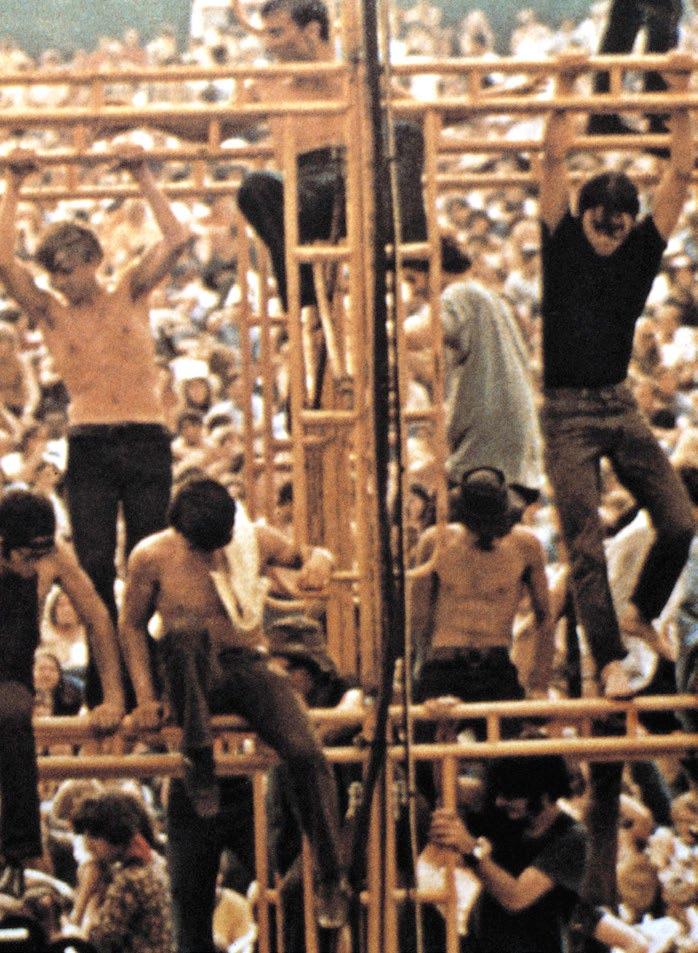

1969: Bowie’s “Space Oddity” is released, another man comes from Mars to the Universe and then falls to Earth and invents a new and personal way of singing, playing, dressing, and performing. 1969: Woodstock, on a huge field in a remote location in Upstate New York, millions of young people camp out to watch the greatest concert of all time. Famous and not-so-famous artists perform with the desire to change the world and leave their mark on the times (hippies, peace&love, sexual liberation). They are the music icons we still listen to today, the artists who generated and influenced much of the music that came afterward.

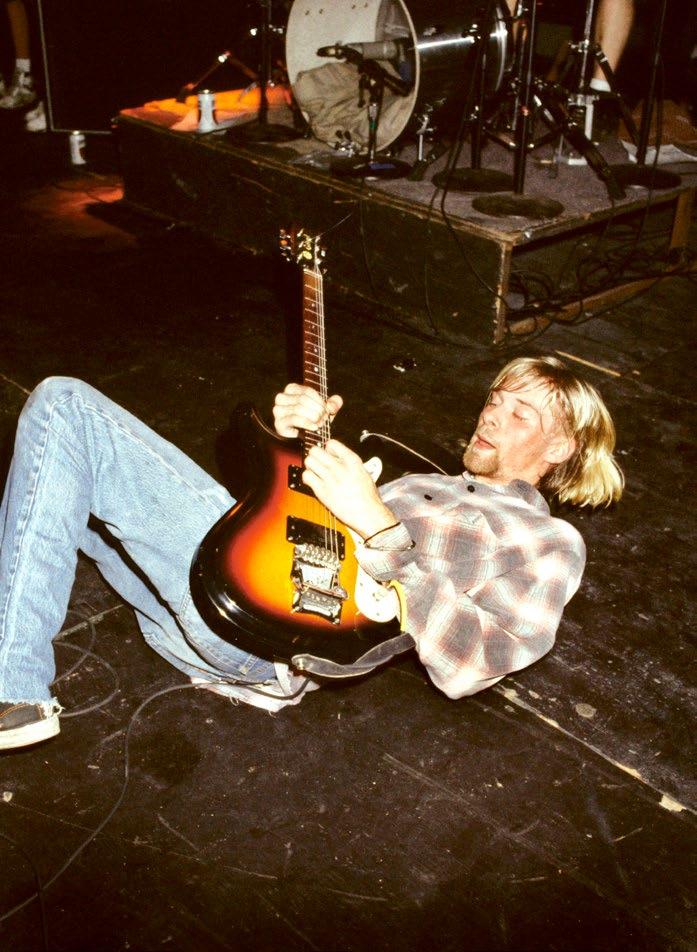

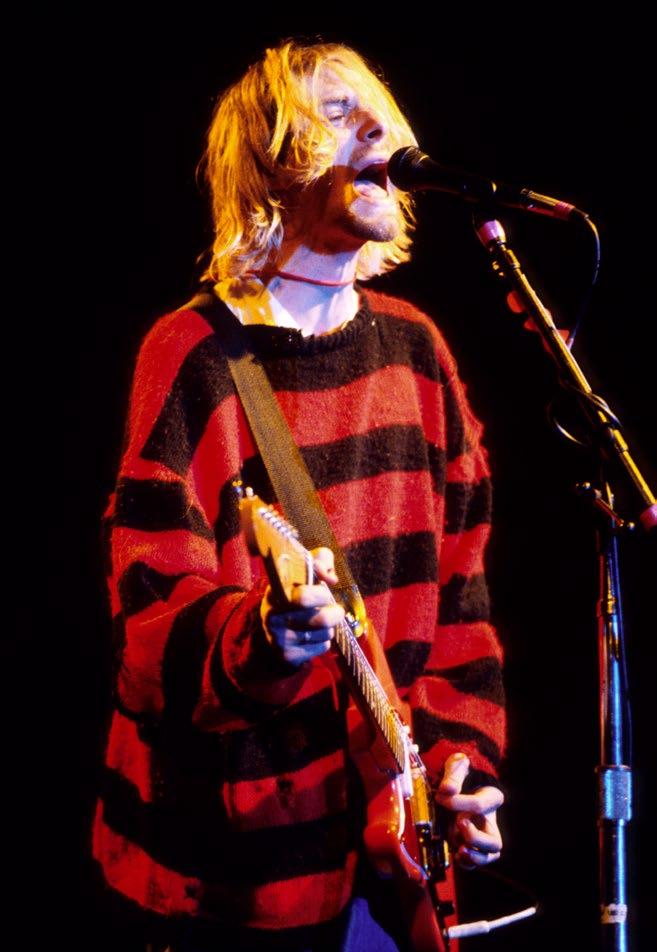

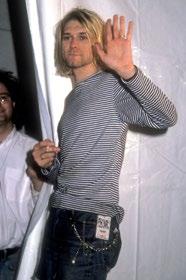

One example? Bowie’s “The Man Who Sold the World,” rearranged by Kurt Cobain decades later, in his unforgettable Unplugged concert, with his sensitivity and ability to reproduce the riff on the guitar, making the same song vibrate on the drums with Dave Grohl. Glam rock and grunge could not have been more distant and yet Kurt gave us this final magic as a tribute to David Bowie.

Interview with Frida Giannini by Corrado Rizza

CORRADO Where does your love of rock come from?

FRIDA As I already mentioned in my introduction, my love of rock comes from my uncle Daniele Vellani, my mother’s brother. He was a successful DJ in the 1980s, and he passed on to me a love of music in general. I also inherited from him a passion for LPs, especially those by David Bowie, of whom I am a superfan. In my imagination, Bowie has always been a figure of reference, and from a musical point of view, as I grew older I became enthralled with rock and pop. I started buying books, reading the biographies of other singers, too, or of groups like the Rolling Stones, and of musicians who were around in that period.

C. Was it a marvelous time in London?

F. It was a fantastic time, because there was an absolute revolution in style and fashion, and from a musical point of view as well. It was all very experimental because we were coming from the 1960s, from the Beatles, the touchstone of the revolt of the young and of the musical turnaround in terms of modernity. Eighteen-year-old Bowie was dying to make it big, wear makeup, go beyond music, in a “swinging” London that was actually a revolt against British conformist and conservative society.

C. What can you tell me about fashion during that magical time in London?

F. The air was buzzing. There was Twiggy, the first mini-fashion model with very short hair and incredibly thin, totally competing with French models or the statuesque Jane Shrimpton, David Bailey’s muse. Thanks to Antonioni and a grand Vanessa Redgrave, Shrimpton had a part in Blow-Up (she was an inspiring muse), released in 1966. There were the Beatles, of course, and The Who were already famous. The Stones were becoming stars, and there were Zandra Rhodes, Biba, Ossie Clark—my favorites with their extravagant creations—and Malcolm McLaren, who in those years was one of the first to turn the spotlight on Central Saint Martins and who laid the foundations to then become the precursor of the Sex Pistols and of punk rock in the 1970s along with the person who would later become Vivienne Westwood. They then invented vogueing (on which Madonna rebuilt a whole world . ). In short, what more fertile terrain could there be for the ambitions of the young Bowie? From that point onward, thanks to David Bowie, another world opened up. His style was so unique and special that it will always be recognizable. As I grew older, I bought photos and old books about him. Then I bought the original cover of Diamond Dogs photographed by Terry O’Neill in 1974, and wherever I find myself living I always have all my records and my pictures with me. David Bowie is in my heart—so much so that, to give you an idea of my passion for him (a passion that all my friends and acquaintances know about), when he died I was in Barcelona, and I received a series of phone calls of condolences as if he were a close relative of mine! For me it was truly a day of mourning. I cried alone. It was as if I had always known him. Unfortunately, I have met lots of people in music—almost all of them—but I never had the chance to meet him.

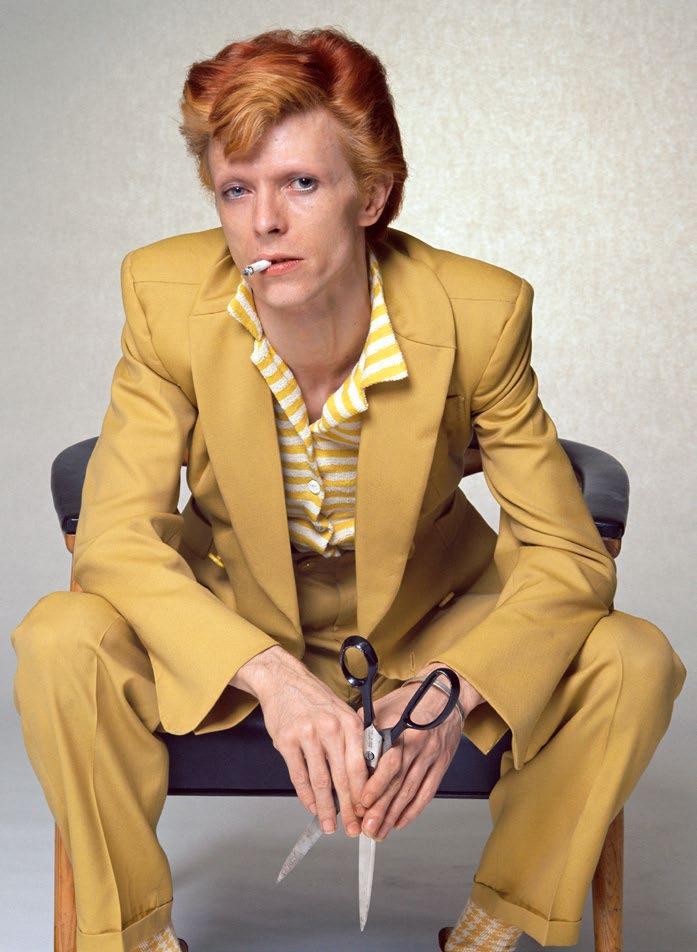

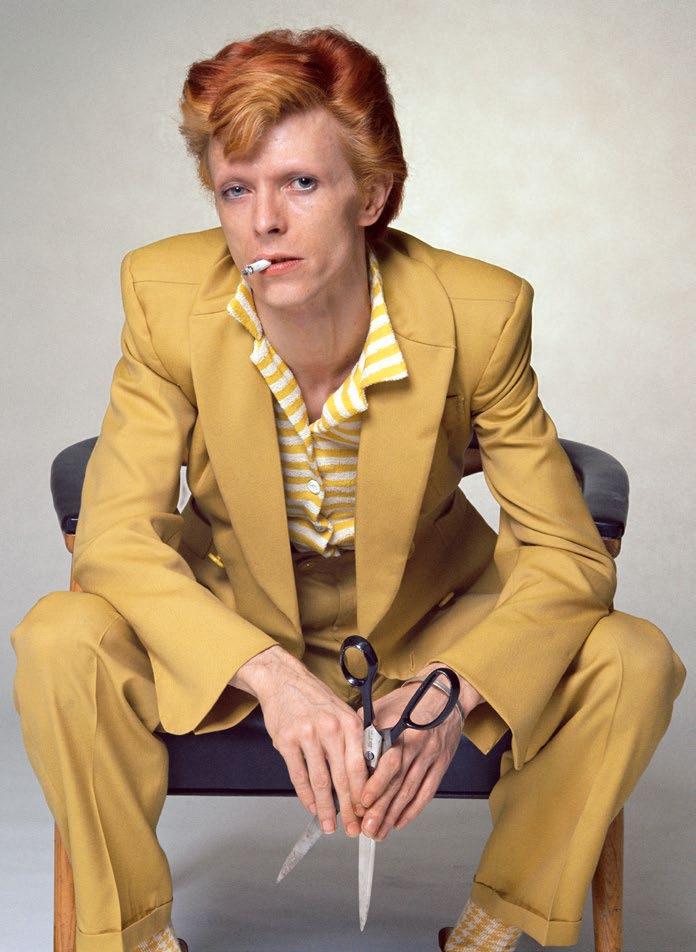

C. Was it because he was a man who fell to Earth, a Martian, that made it hard to meet him? F. He was a Martian in every sense. He was such an innovative Martian that he was the man who came from Mars. Actually, this was also true of the way he lived. He drank milk and ate raw peppers—that was his diet so he could stay thin. It was his diet for years, also because he could swap clothing with his first wife, Angie. He was a borderline anorexic because he had some issues with substance abuse that were associated with these crazy obsessions. He even ended up weighing 108 pounds.

CHIME FOR CHANGE PATRONS, FRIDA GIANNINI AND BEYONCÉ KNOWLES-CARTER, SOUND OF CHANGE LIVE CONCERT, TWICKENHAM STADIUM, LONDON, 2013

FRIDA GIANNINI AND JAY-Z, ROC NATION PRE-GRAMMY BRUNCH, 2011

FROM LEFT: FRIDA GIANNINI, BIANCA BRANDOLINI D’ADDA, GAEL GARCIA BERNAL, LAPO ELKANN, AND PHARRELL WILLIAMS ATTEND THE VANITY FAIR AND GUCCI PARTY HONORING

MARTIN SCORSESE DURING THE 63RD ANNUAL CANNES FILM FESTIVAL AT THE HOTEL DU CAP EDEN ROC, CANNES, 2010

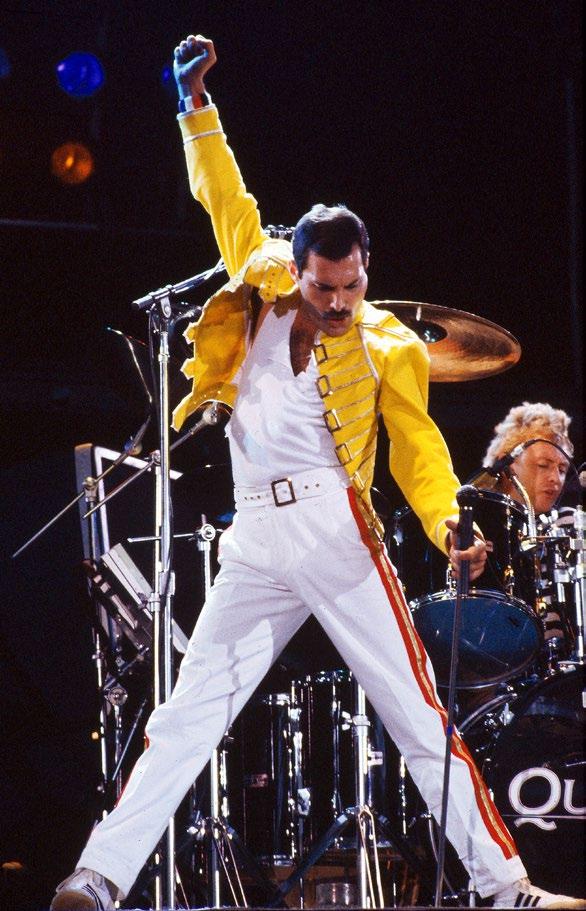

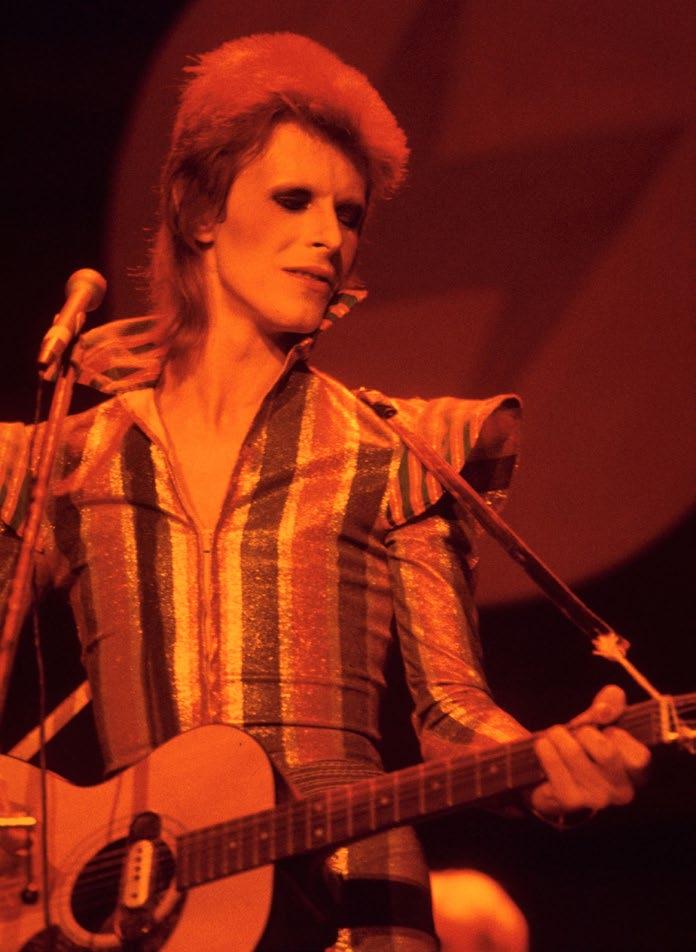

I was also drawn to his tapered, athletic figure, like that of a cat. There were moments when his thinness was truly exaggerated, almost sick-looking, but his hollowed-out face, his differently colored eyes, were totally unique. He was unique in the way he dressed, in the way he moved. He had that chic look in the craziest moments in his life and in the most incredible costumes he wore during his performances. And he had an inborn elegance that others have never had, even though he came from one of the poorest suburbs in England. When he became the famous White Duke, I felt the name was most fitting. David Bowie will always be the White Duke. The name David Bowie is also actually a soubriquet (one of many) of this singing chameleon. His real name was David Robert Jones. You might think you’ve heard it before. Which is the same reason why Bowie decided to change his name. Robert David Jones, better known as Davy Jones, was the leader of The Monkees, a famous pop rock group founded in 1965 in Los Angeles. The risk of not being recognizable and unique enough was not acceptable for someone like the White Duke. But besides this, his aesthetic sense was essential, and I’d like to go back to that and say more about it because my thesis at the Academy was about him, an experience that was helpful to me all the way to starting my career. What fascinated me the most was the uniqueness of his voice, the fact that he went against the tide. There have been different David Bowies but always with the same traits and an inimitable voice. You can listen to a thousand tracks of his, but his voice will always have that intense depth. In the performance he did for the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert singing “Under Pressure,” his voice attracted all the attention and the audience was completely overpowered. I was still too young to know who he was. When I finally did manage to see him perform in Rome, he was getting on in years, and he had some health issues. I was also disappointed because the way the concert was organized was completely wrong. The tickets were really expensive and an artist like him must have suffered to see that the arena was half empty . . .

“BOWIE’S SONGS WERE UNIQUE. HE WAS INCREDIBLY GLAMOROUS, LIKE NO ONE EVER BEFORE OR AFTER HIM.”

C. I actually saw him in 1987 in Rome with Daniele. But getting back to the tribute to Freddie Mercury F. He was wearing a turquoise suit and Annie Lennox had a painted black mask around her eyes and a huge, dramatic, black tulle skirt. They performed the finale together. It was enough to give you goose bumps. That was a very high moment that I love to watch even today. The way he moved, his voice was unique, strong, like Annie Lennox’s. It was one of the most memorable moments in my life. But getting back to my fascination with him and his aesthetic sense, and to all that Bowie meant to me, besides the value of his music, there are some songs that I find to be the most beautiful ones ever written, like “Heroes,” “Life on Mars?,” songs I can lip-sync because I know every single word by heart, and they bring back fond memories (for example about Daniele). They’re songs that make you dream and really look toward the universe. This genre of music is known as Glam Rock. Bowie’s songs were unique. He was incredibly glamorous, like no one ever before or after him. He sewed his clothes himself. He would buy the most bizarre accessories on Portobello Road. He dyed his own hair. He was a totally self-made man. Sometimes he’d wear women’s boots. He had a very feminine body, an androgynous one that was new for those days. This was followed by all the imitations, and today it’s almost normal. I’d say that sometimes it’s even boring now.

The brilliant thing about David Bowie is that he was the one who thought of these things, he was the one who did these things first: his famous makeup with a lightning bolt—that was his work. His other makeup with a gold circle on his forehead—he invented that, too. For my fortieth birthday I was pregnant and the theme was gold so I painted a star over my eye in David Bowie style. He was 100 percent creative, because he was also someone who knew how to draw: he made some amazing paintings.

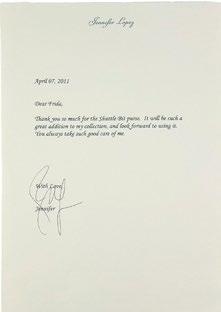

FROM LEFT: CAMILLA BELLE, MARY J. BLIGE, MARC ANTHONY, FRIDA GIANNINI, AND JENNIFER

LOPEZ ATTEND THE FIRST ANNUAL UNICEF WOMEN OF COMPASSION LUNCH, LOS ANGELES, 2011

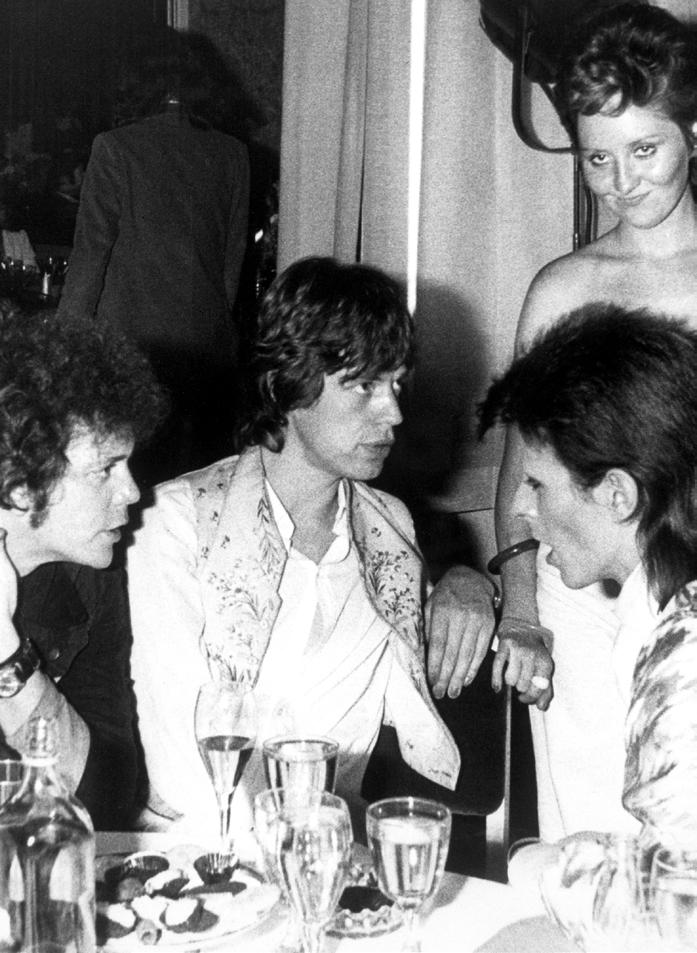

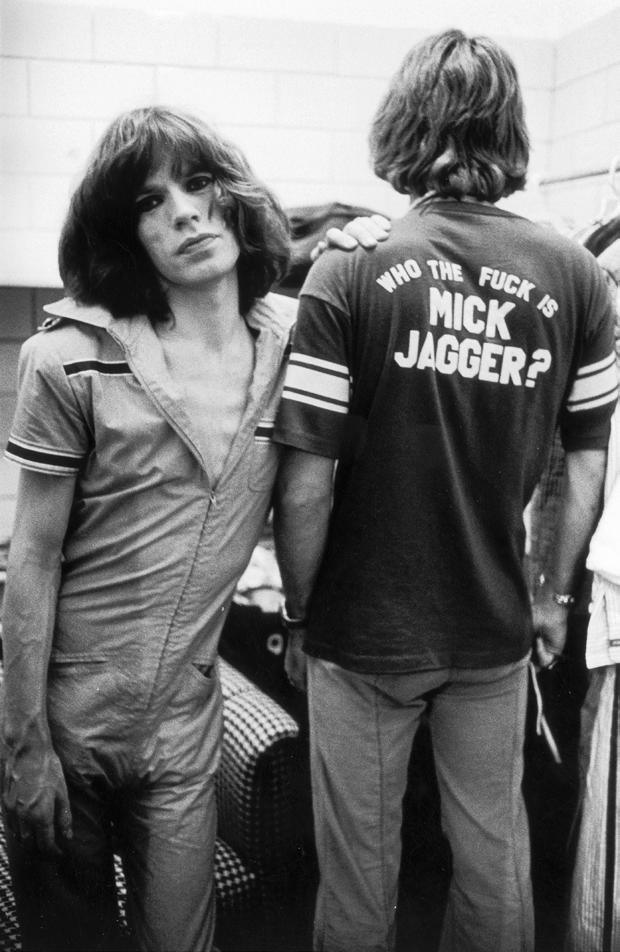

With the eye of an expert he collected bizarre objects. He was very curious. There’s a wonderful interview with him in 1999 by the BBC where he predicts the future of the Internet and social media. He predicts their advantages and their limits. It was one of his rare TV interviews. Not much was known about his private life. We know he loved his wife Angie, even though they broke up suddenly, but we also know that he had some major love affairs with men, and this was proven by some of his fellow artists and singers. In some biographies he seems to confirm it himself. And I believe that his alter ego—with his greater appeal—was Mick Jagger! Angie was jealous of him because she was never invited into their menage.

C. His bisexuality was rather out in the open.

F. Yes, but there again it was the first time that bisexuality was exhibited in such a natural way. Imagine what the UK was like in the late 1960s!

C. What emerges—during my interviews of people close to him, I’m talking about musicians I have interviewed, about Gail Ann Dorsey, the American bass guitarist who worked with him for several years—above all is the Artist.

Do you think they had an intimate relationship, but that maybe this kind of confidence didn’t really exist with him?

F. His private life was very reserved. We know very little about his illness, for instance, and, unfortunately, I didn’t have the chance to meet him personally. It seems that his assistant, Coco Schwab, never abandoned him, and vice versa. I think he carefully chose who was on stage with him.

“BOWIE SEWED HIS CLOTHES HIMSELF. HE WOULD BUY THE MOST BIZARRE ACCESSORIES ON PORTOBELLO ROAD. HE DYED HIS OWN HAIR. HE WAS A TOTALLY SELF-MADE MAN.”

C. That may be the reason why he moved to Woodstock, a place that allows stars to live their lives privately, without people stopping you on the street.

F. You mention Woodstock . . . Today, the idea of Coachella makes me grin, because they were taking more pictures of the Victoria’s Secret Angels disguised as hippies than of the new and emerging Indie bands.

C. But also the DJs themselves.

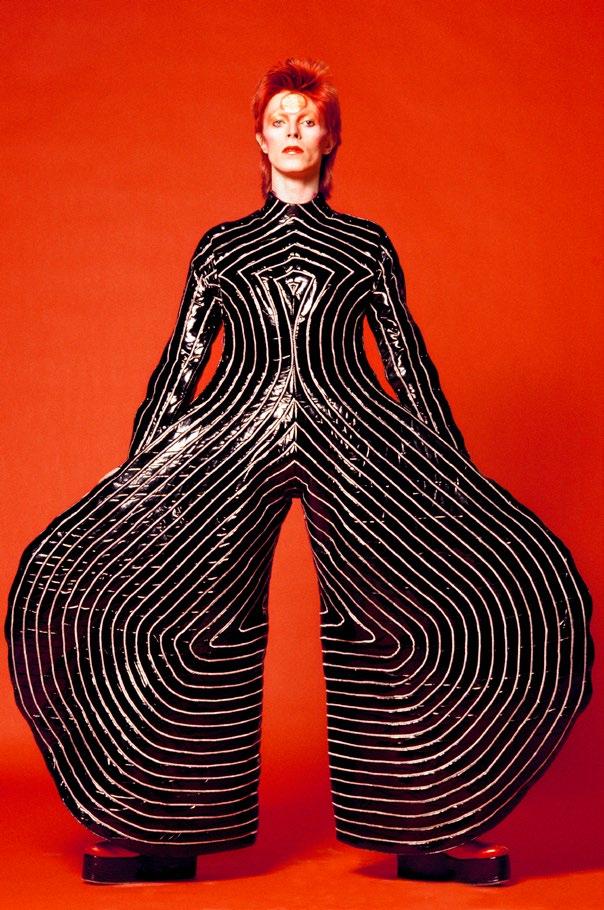

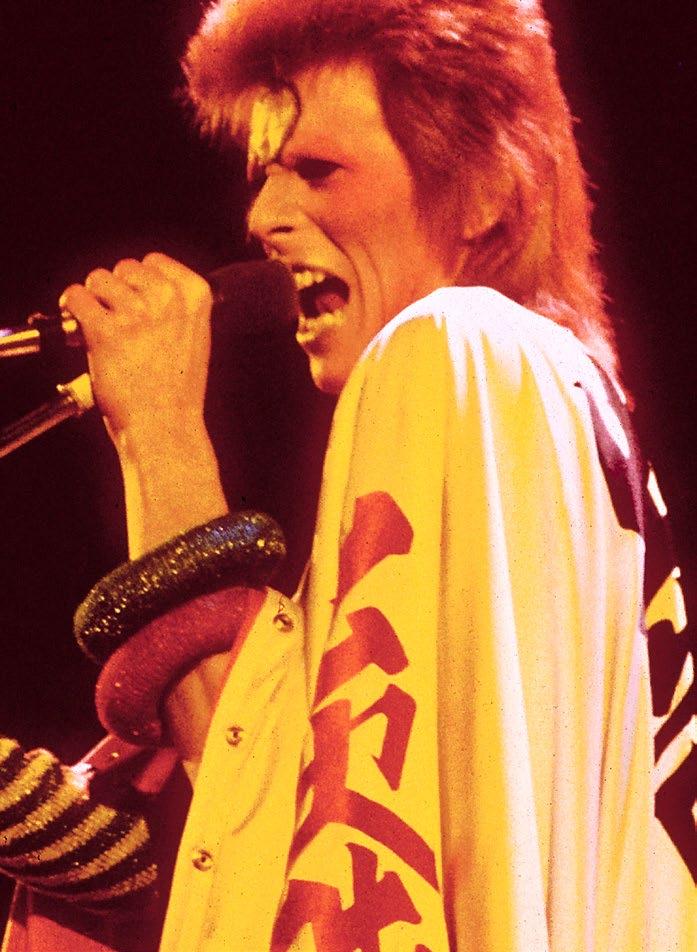

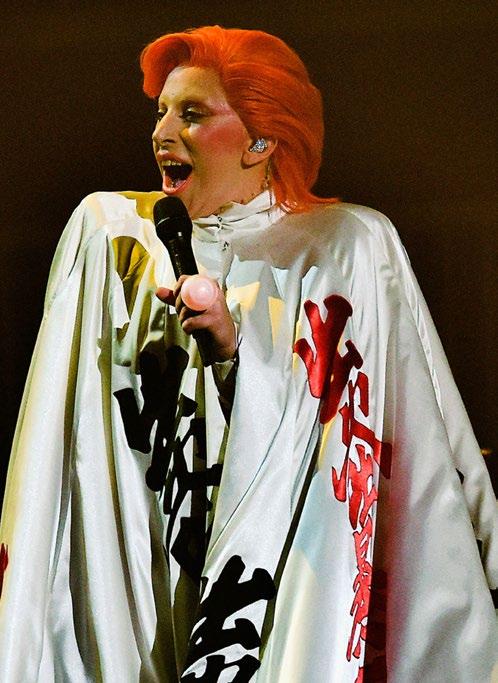

F. Forget about today’s DJs: they act like fashion designers, or at least they try to! In those days, in 1969, it was a time of total revolution in style, mental freedom, and Bowie was an example of all this, to the extent that we all remember the jumpsuits, the turquoise suits with bell bottoms, his fitted jacket with a striped tie, and his red hair, short in the front and long at the back. There’s also the Yamamoto period, which was the only collaboration he did, the first and last. For my thesis at the Academy, I talked about David Bowie the whole time, and I said that for me he set an example, because he invented and created his own look. At a certain point he found Yamamoto to be an interesting partner, but I’m sure it was a mutual collaboration. I’m sure that David designed what he wanted together with Yamamoto. In one biography I learned that his famous Lurex jumpsuit became iconic because before going on stage he cut one of the legs.

C. Because he never met Frida Giannini. This is quintessential Frida!

F. Yes, this is quintessential Frida, Corrado.

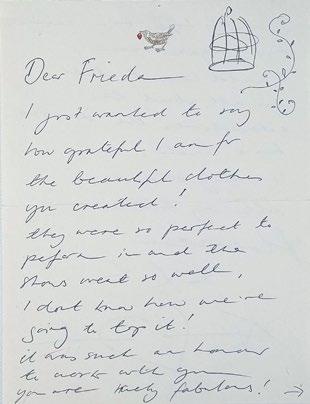

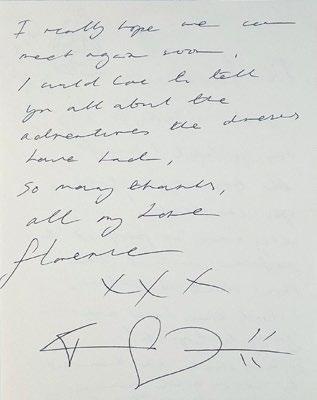

FRIDA GIANNINI AND FLORENCE WELCH ATTEND

THE PRIVATE SCREENING OF JAMES FRANCO’S DOCUMENTARY

FILM THE DIRECTOR: AN EVOLUTION IN THREE ACTS , COHOSTED BY GUCCI AND VOGUE FRANCE, HAUTE COUTURE S/S 2014, HOTEL ROYAL, PARIS FASHION WEEK

GUCCI S/S 2014, MILAN FASHION WEEK

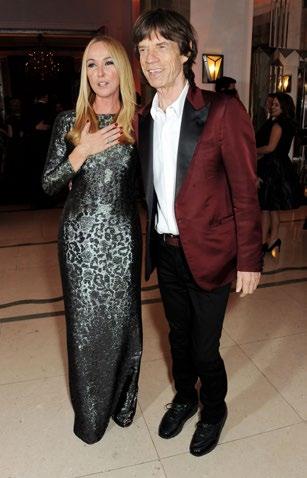

FRIDA GIANNINI AND SIR MICK JAGGER ATTEND THE HARPER’S BAZAAR WOMEN OF THE YEAR AWARDS, CLARIDGE’S HOTEL, LONDON, 2013

C. Was there a moment when you made a professional choice while thinking of him?

F. I designed a collection called glam rock. It’s a collection inspired by Bowie. On my mood boards there were only photos of David Bowie. I made the famous two-piece blue suit with boots and platform heels and a tie and red hair completely gold, the outfits with diagonal stripes. His elegant rock, his glam rock, his being both chic and extreme. He was incredibly ingenious. And there isn’t a single one of David Bowie’s looks that we don’t all remember. Not just in the imagination of a creative person who is also inspired by his work. But there’s no comparison. I love all kinds of music. I’ve never been a snob when it comes to music.

C. But Bowie is Bowie.

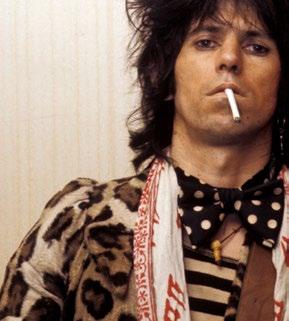

F. I have a beautiful picture of Mick Jagger that I look at now and again. I had my hand over my heart because I thought I’d have a heart attack. There are legends that will always be legends. Part of Johnny Depp’s look has always been his unique scarves, rings—he was inspired by Keith Richards from the Rolling Stones. Led Zeppelin and Robert Plant represented how to dress in the 1970s. Plant was an amazing performer. I saw this with other artists like Jim Morrison rather than Jimi Hendrix, but David Bowie’s uniqueness led me to encourage the company I was working for at the time to sponsor and allow me to devote myself to this exhibition.

C. Tell me about the exhibition.

F. Everyone knew he wasn’t well. I was contacted by the communications department and by the curator of the show, Victoria Brooks. She wanted to talk to me about what David’s worlds meant to me. She interpreted them in an amazing way because there’s a path that accompanies you, how his look was born, how “Life on Mars?” or “Space Oddity” came to be. I knew I had seen something, but not that

“I DESIGNED A COLLECTION CALLED GLAM ROCK. IT’S A COLLECTION INSPIRED BY BOWIE. ON MY MOOD BOARDS THERE WERE ONLY PHOTOS OF DAVID BOWIE.”

much, his wonderful drawings, his self-portraits, works by Basquiat. I found a lot of material, images of his private life rather than his collections, hobbies, makeup. I finally arrived in this room with all the mannequins in his most famous outfits and all these maxi-screens that in a loop continued to tell his story, describe his music, his concerts, and the most famous exhibitions. It was a spine-tingling exhibition and just think, I went there with my three-month-old daughter. I went to the opening by myself, and I went back there after three months. I was very disappointed at the opening because he wasn’t there. I’m assuming he eventually saw the exhibition.

C. He wanted to be on the inside of things!

F. Yes, he wanted to experience them fully, from creation to realization.

C. Which is what happened with the exhibition, with the last thing he did.

F. I think he made some suggestions as to how to set it up and define it. He was a control freak, and rightly so.

C. Even though he did not attend the public event, he gave his blessing. You did an amazing job!

F. I think he was a part of the birth of the exhibition. In fact, I heard that he had collaborated with the curator, visiting the show in the middle of the night, making changes. And when I found out, my joy was solely and instantly: “David Bowie IS,” the title of the exhibition, to which I would add the word “FOREVER.”

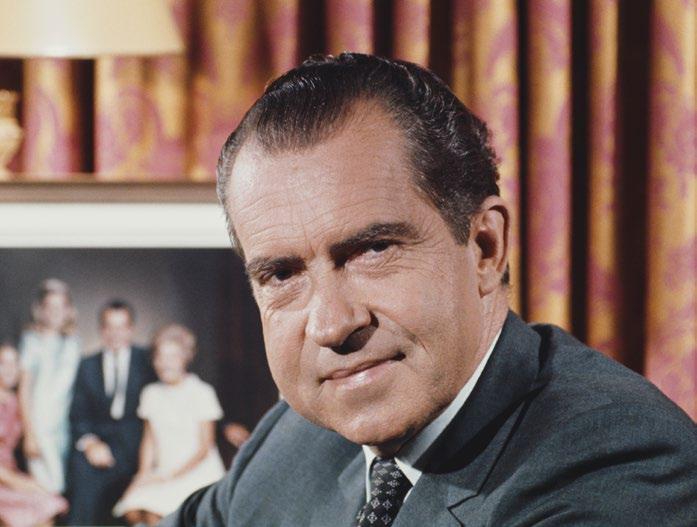

The starting point for this journey is the Apollo 11 landing on July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong became the first man to set foot on the moon’s surface. The American president at the time was Richard Nixon and he strongly supported NASA’s mission. In addition to reasons related to science and foreign affairs, perhaps Nixon was hoping to distract people’s attention from the widespread protests that were raging among young Americans and Vietnam War veterans. The bloody conflict left its mark in the minds and on the bodies of all those who survived it.

This was the context surrounding the first major figures who would become the absolute icons of the twentieth century.

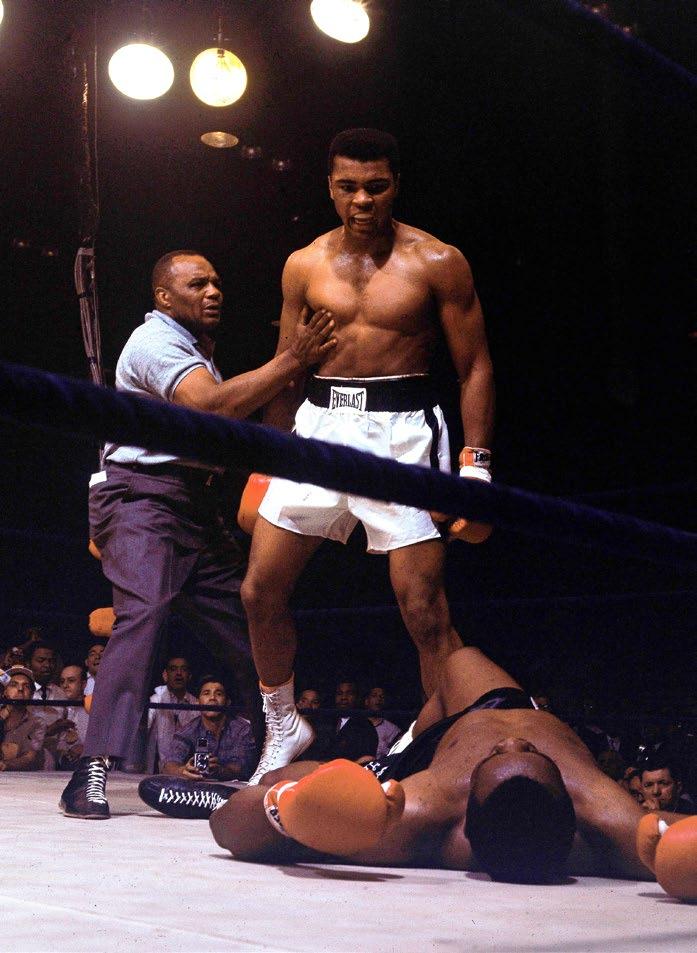

Muhammad Ali became the world heavyweight champion of the world, but for refusing to be drafted to fight in Vietnam he was convicted and stripped of his title. Thanks also to his great charisma, Ali became a reference for the Black Panther movement.

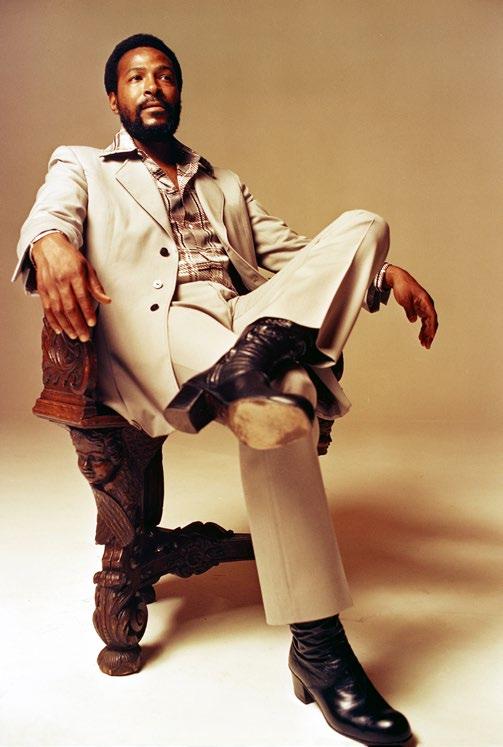

Marvin Gaye, a famous singer for Motown Records, lost his brother in the Vietnam War and later wrote “What’s Going On,” a song that eventually became the protest hymn aligned with the defense of human rights and the Black Revolution. Unfortunately, the lives of both of these men ended sadly. Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 1984, and that same year Marvin Gaye was murdered by his father. Crossed destinies.

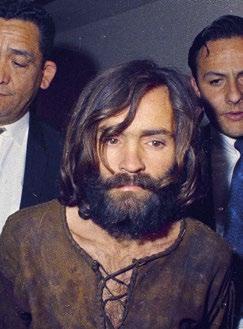

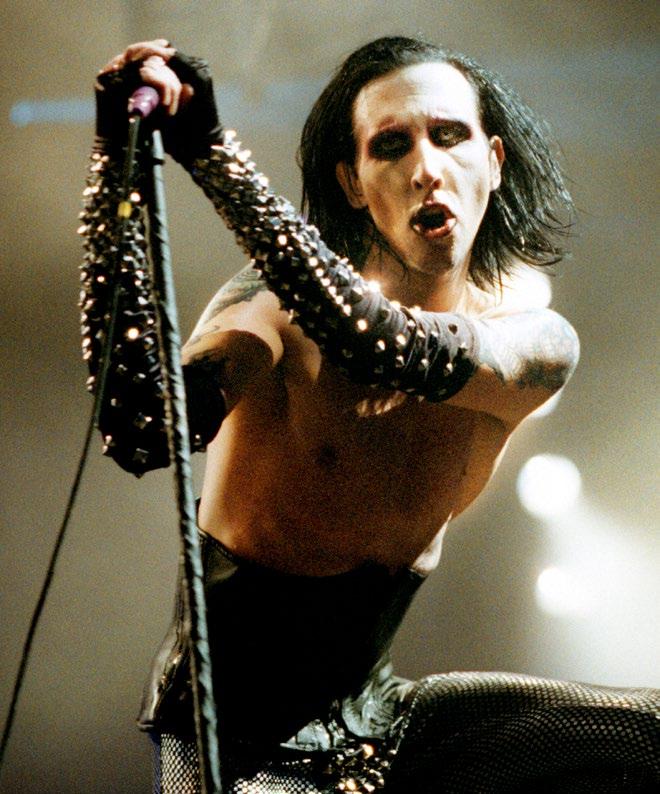

In 1969 Charles Manson and his Satanic cult were responsible for the infamous Bel Air murders of the actress Sharon Tate (Roman Polanski’s wife, who was pregnant at the time) and four of her friends who were at her home, as well as Leno and Rosemary LaBianca the next day. So brutal were the killings there are some who claim they influenced the music of groups like Metallica, Anthrax, the forerunners of Heavy Metal, and even Marilyn Manson created his stage name by combining those of two American icons . . .

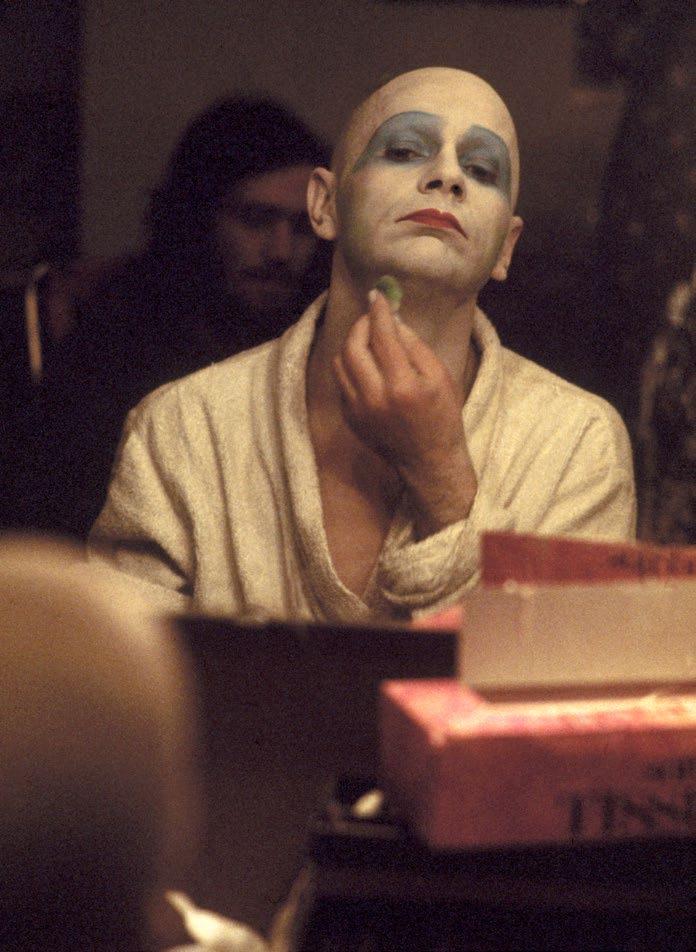

But even before then, the most iconic representative of this trend was Alice Cooper, whose songs were about death, witches, torture, and whose look always featured skulls, bandages, and eyes covered in black mascara, almost a foreshadowing of one of the zombies in Michael Jackson’s video “Thriller.” Alice Cooper performances featured guillotines and other instruments of torture.

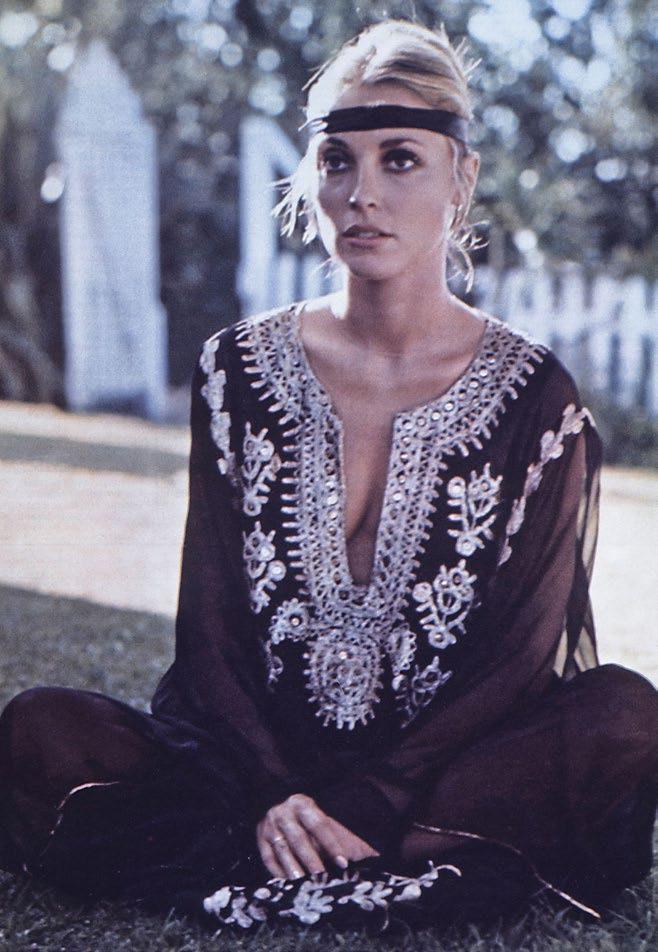

Woodstock, revolution, and revelation: by way of clothing and social conventions, as we shall see further on. Just look at Robert Plant and Janis Joplin—the former in concert in 1971, the latter another celebrity who died at the age of twenty-seven and a member of what has since come to be referred to as the “27 Club”—they look like siblings! With their curly hair, their twists and turns, and the magical way they move their hands. Enraged, grandiose voices that express themselves with extreme, writhing movements and inimitable facial expressions. But not just that! What do they have on?

Who does not own a pair of bellb ottom jeans today, preferably ones that are “distressed”? What young girl has not worn her long hair parted in the middle to cover her breasts? And what about their sandals, belts with studs or fringes, shirts or caftans with Moroccan embroidery or Indian style . . . Although they did not know it, they were laying the groundwork for the fashion of the next forty years. Thanks Janis! Thanks Robert!

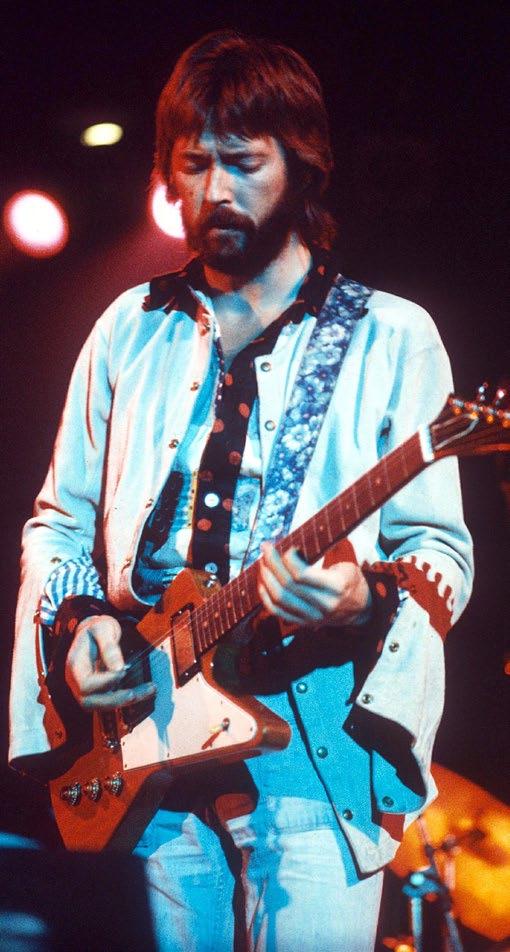

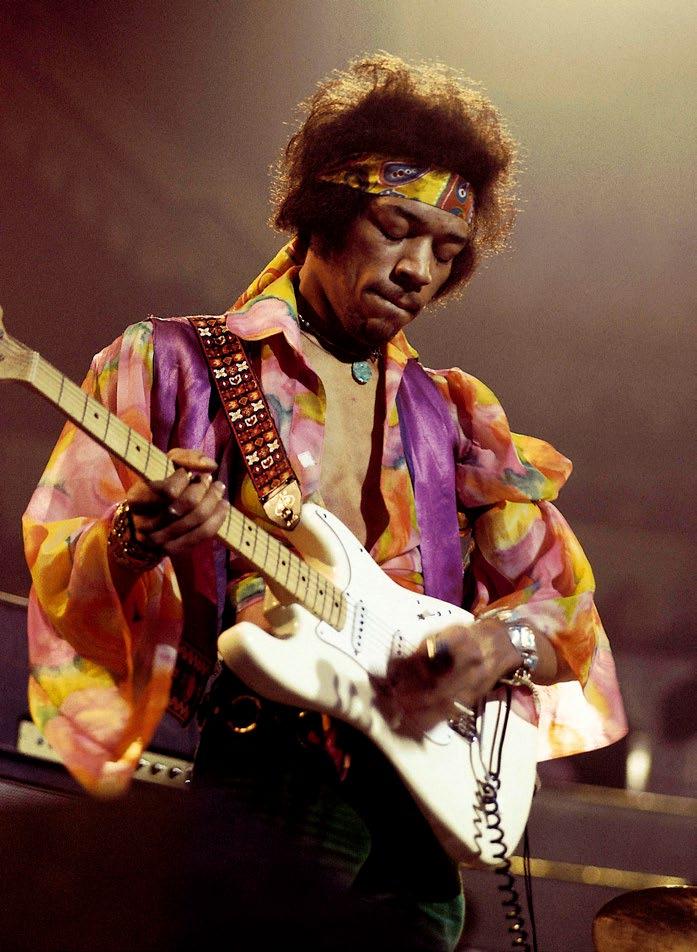

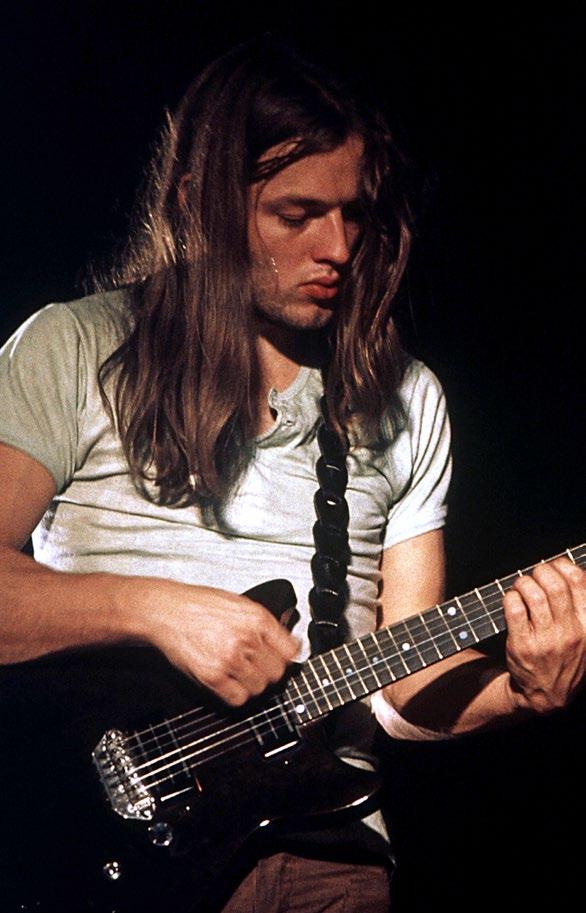

Here we have probably the two greatest guitar players in history. Jimi Hendrix (another star who died at the age of twenty-seven) and Eric Clapton, who always said he was inspired by Jimi. In this picture, with his military tailcoat and scarves, Hendrix reminds us of Prince, even though the pictures taken of him at Woodstock also remind me of what people wear on vacation in Ibiza or Formentera today: leather sandals, studded belts, embroidered shorts, rings, bracelets . . .

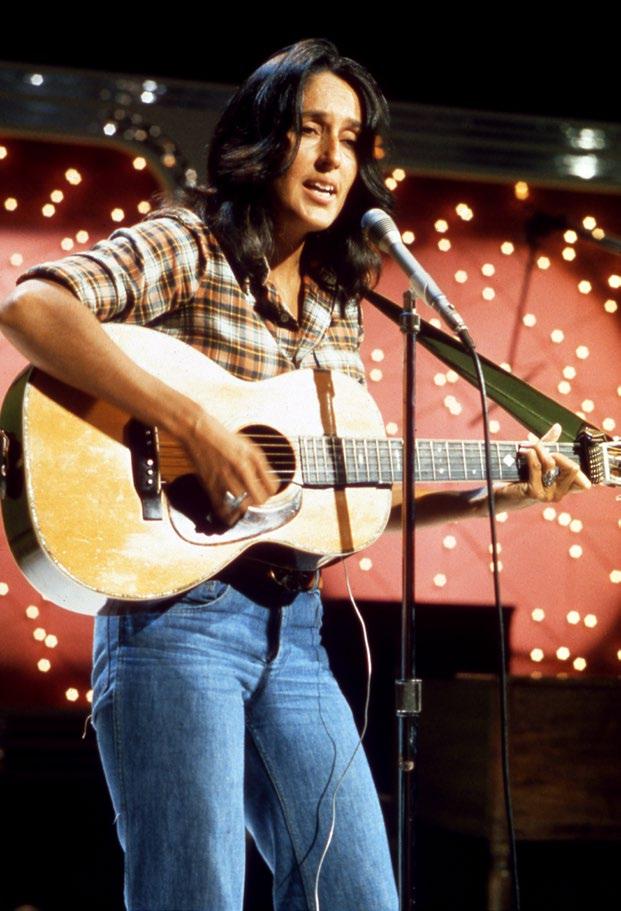

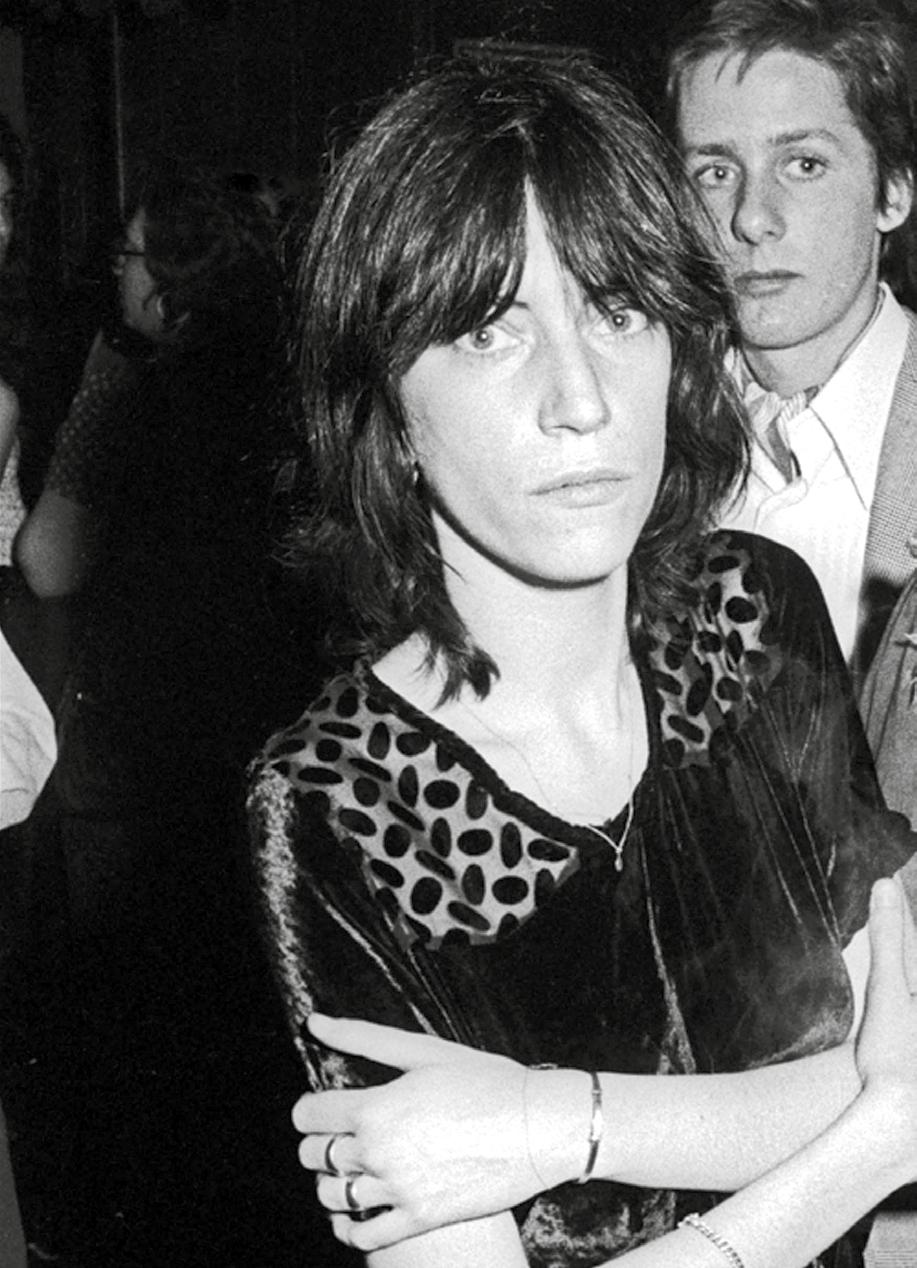

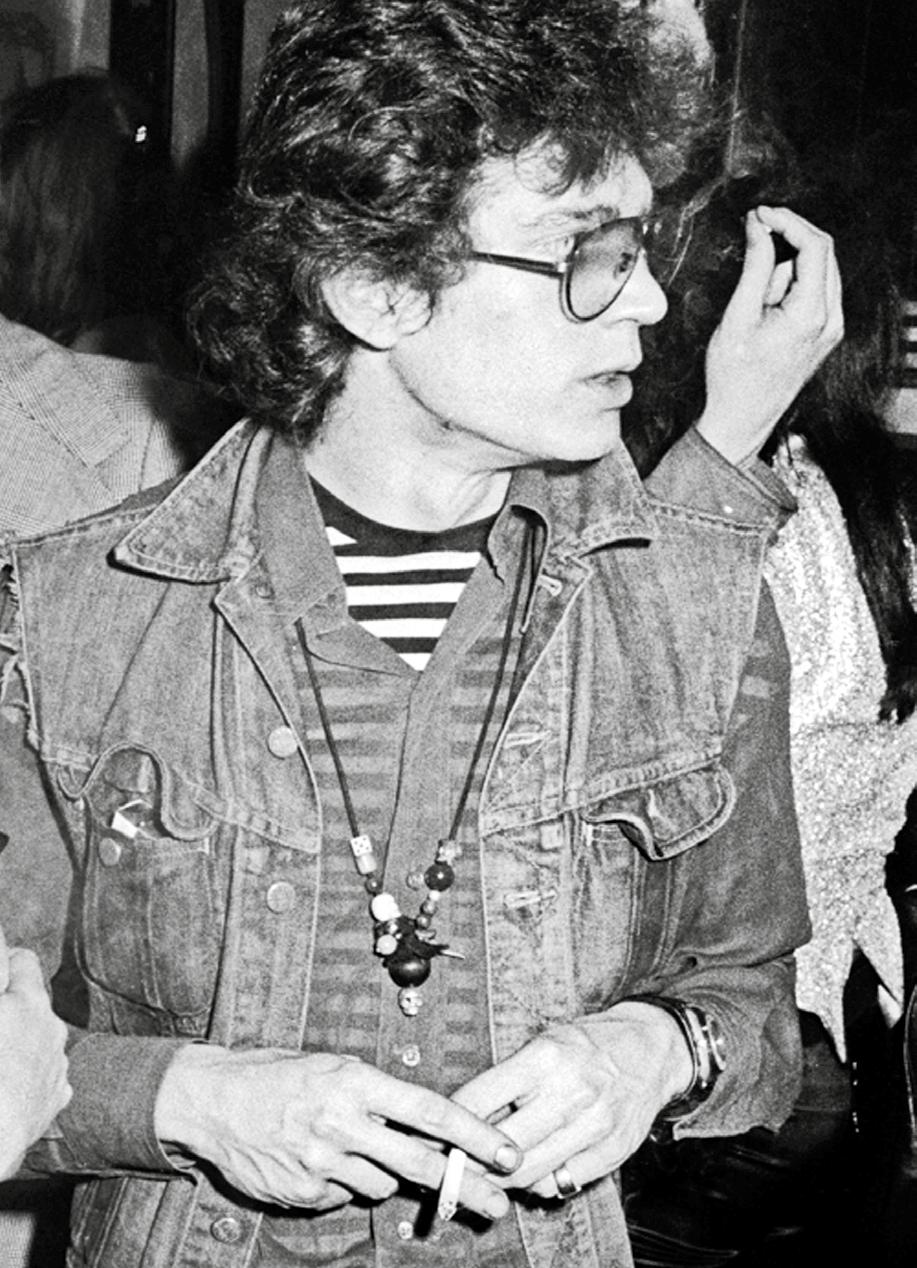

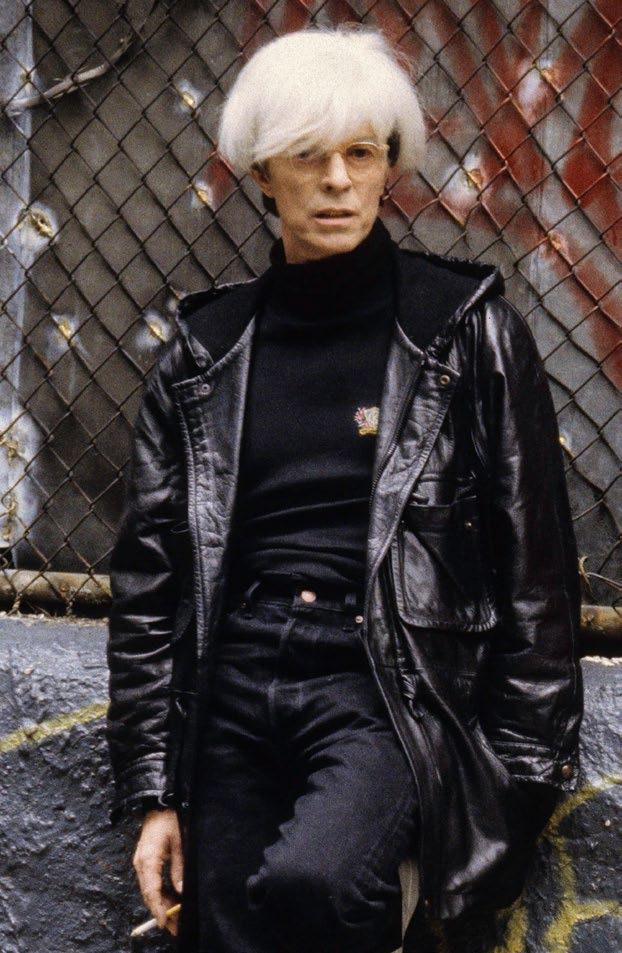

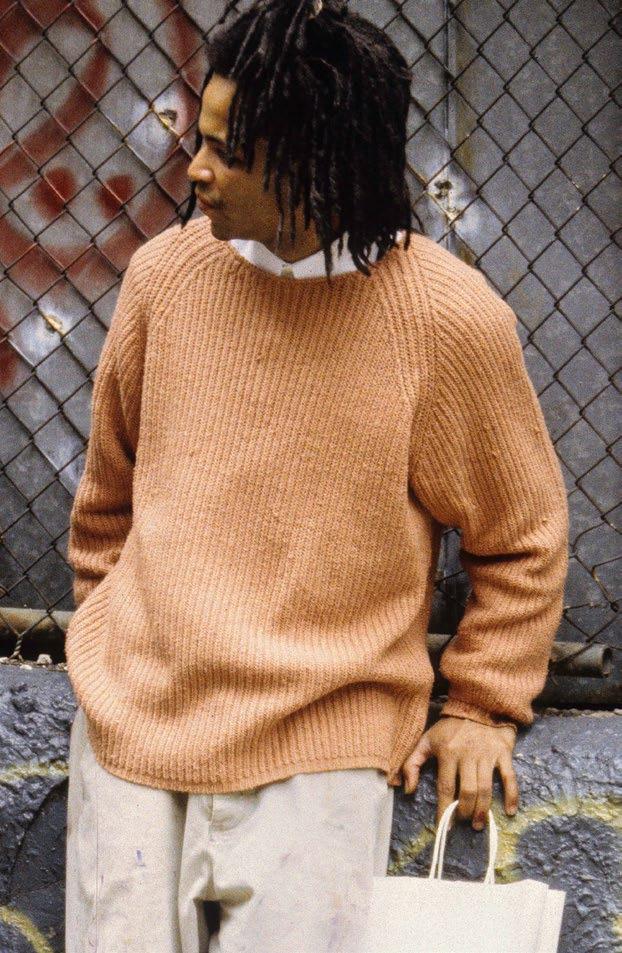

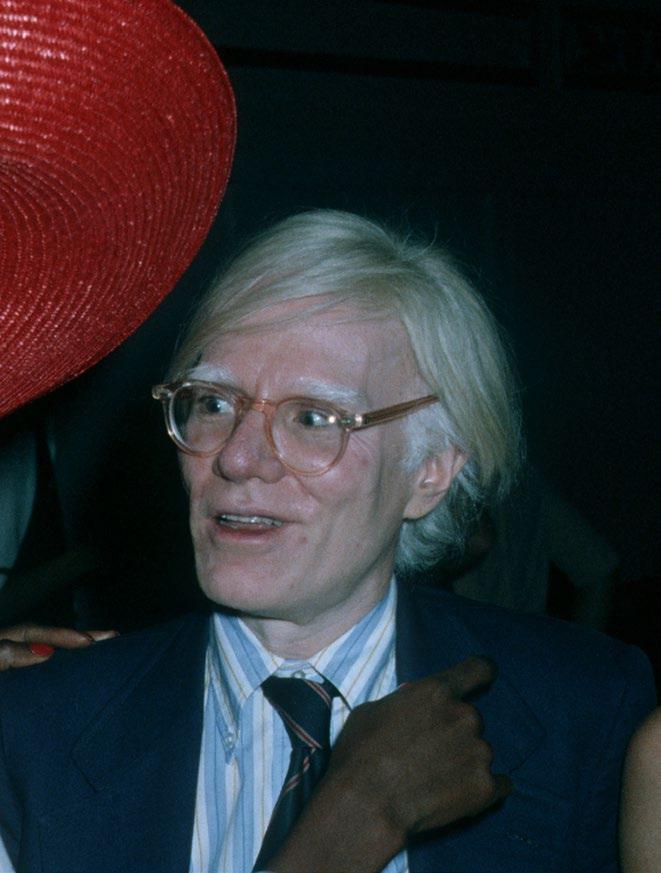

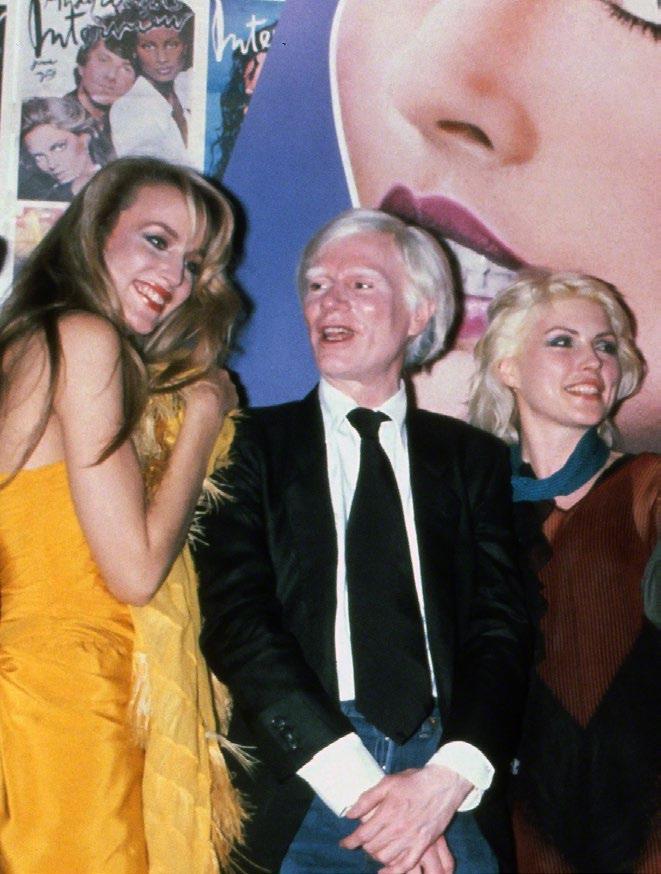

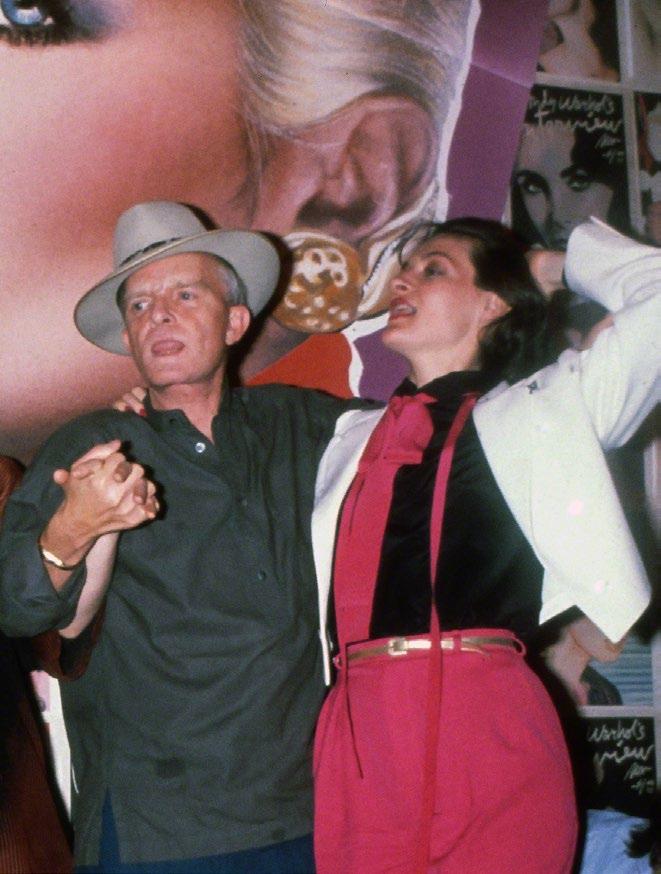

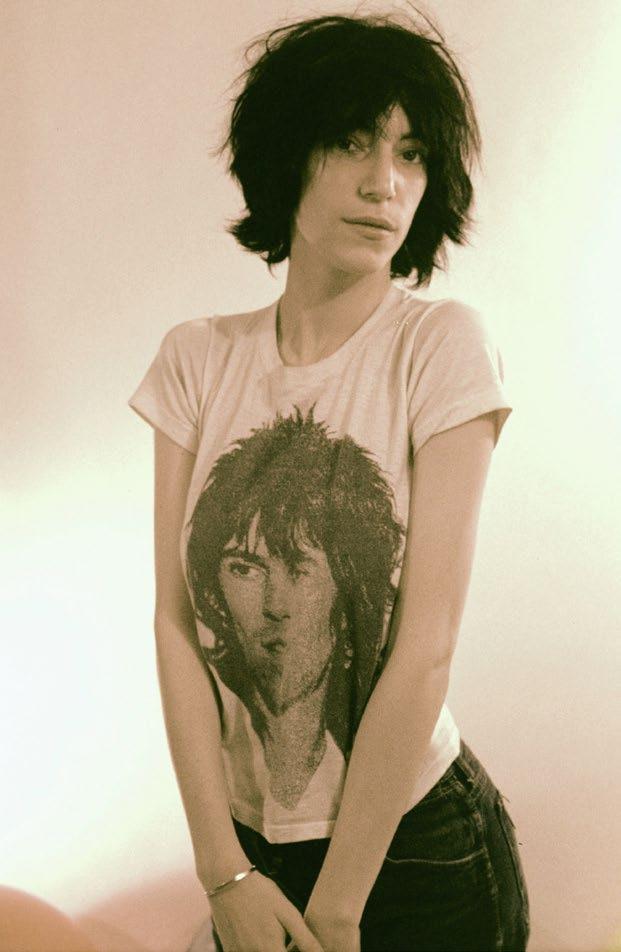

The poetesses of rock, Joan Baez and Patti Smith. In these pictures here (pp. 44, 45) they look like they are the same age and from the same era, with their guitars and distressed jeans, and shoulderlength hair framing their faces. Although they were often photographed wearing rock-star T-shirts and studded belts, their styles and stories were different. Joan Baez’s set at Woodstock in 1969 raised her international musical profile, and she was also in a relationship with Bob Dylan, the two of them sharing their artistic experience. Patti Smith, instead, who came from the small-town American suburbs, moved to New York and the hectic life there in 1975. In the city she shared a room with her closest friend, Robert Mapplethorpe, who was just starting out as a photographer and would later become famous around the world. The two of them lived at the Chelsea Hotel, a go-to destination for artists and musicians at a time when New York City was a cradle for people who would rise to fame in their respective art genres. The city was prey to frenzied artistic activity, and many of the works made then are now auctioned off for millions of dollars. Let us not forget Andy Warhol’s Factory (the American artist was masterfully played by David Bowie in Julian Schnabel’s movie Basquiat ), which hosted the greatest icons and personalities from cinema, art, and music. These same figures would also bring to life the nights at Studio 54, a place where freedom of artistic and visual expression, as well as a whole new way of interpreting objects and clothing, turned them into muses that still inspire us today. Still etched in our minds is the queen of Studio 54: Bianca Jagger’s entrance on a white horse, in sharp contrast with her magnificent fiery red dress—with matching lipstick—made by her friend Halston, the king of jersey, still an inspiration for fashion designers and couturiers around the world.

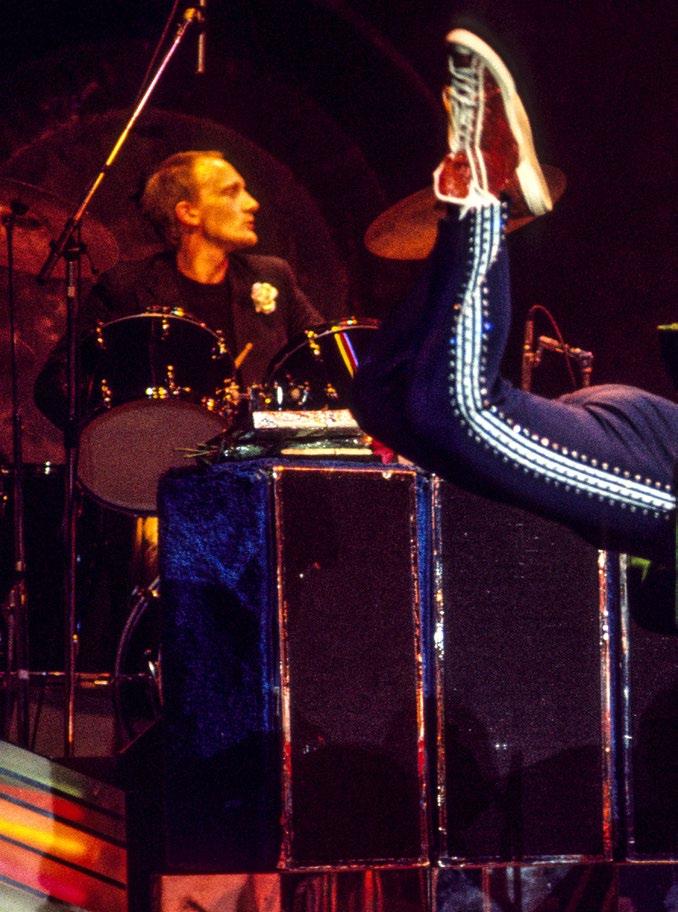

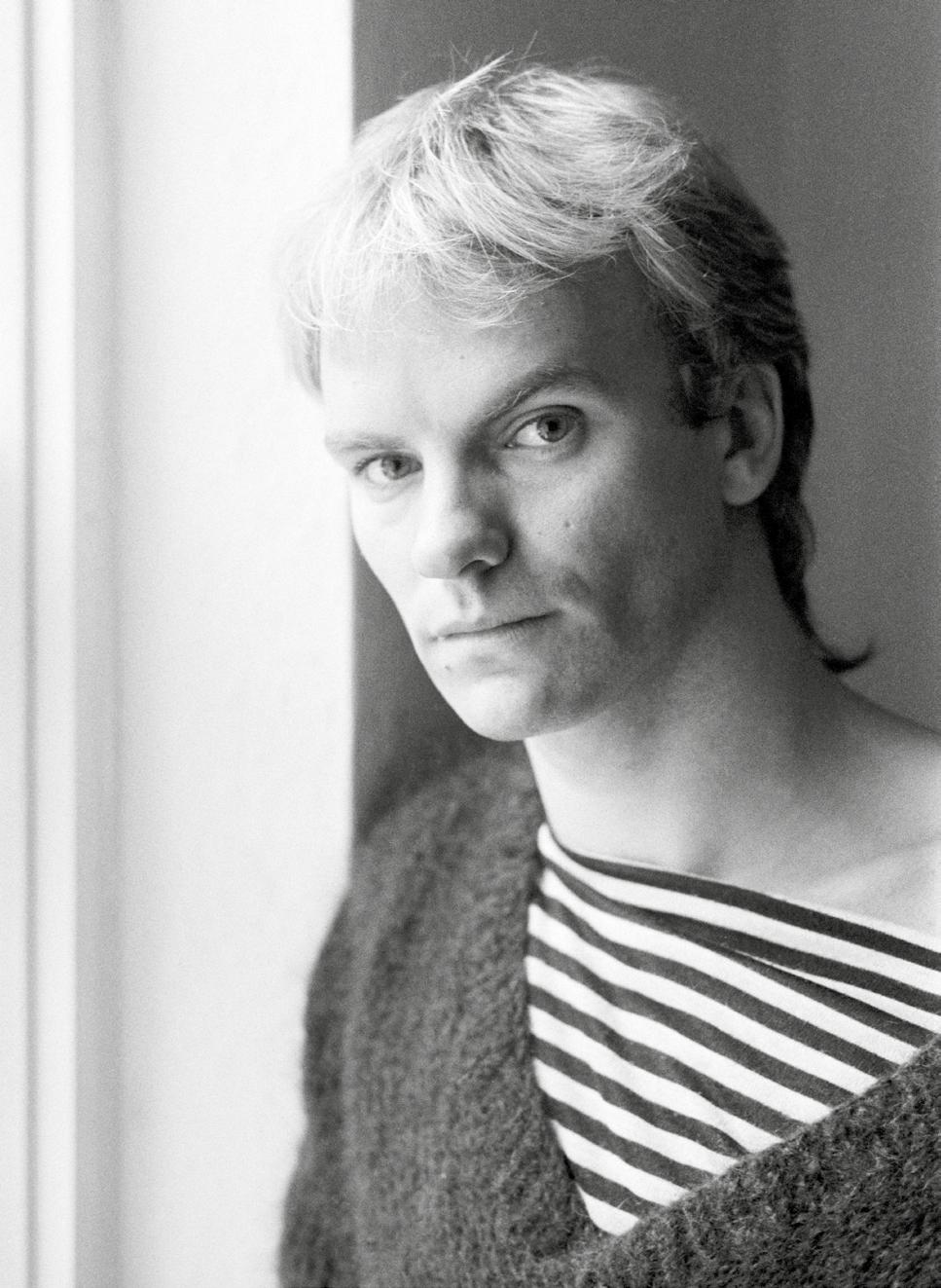

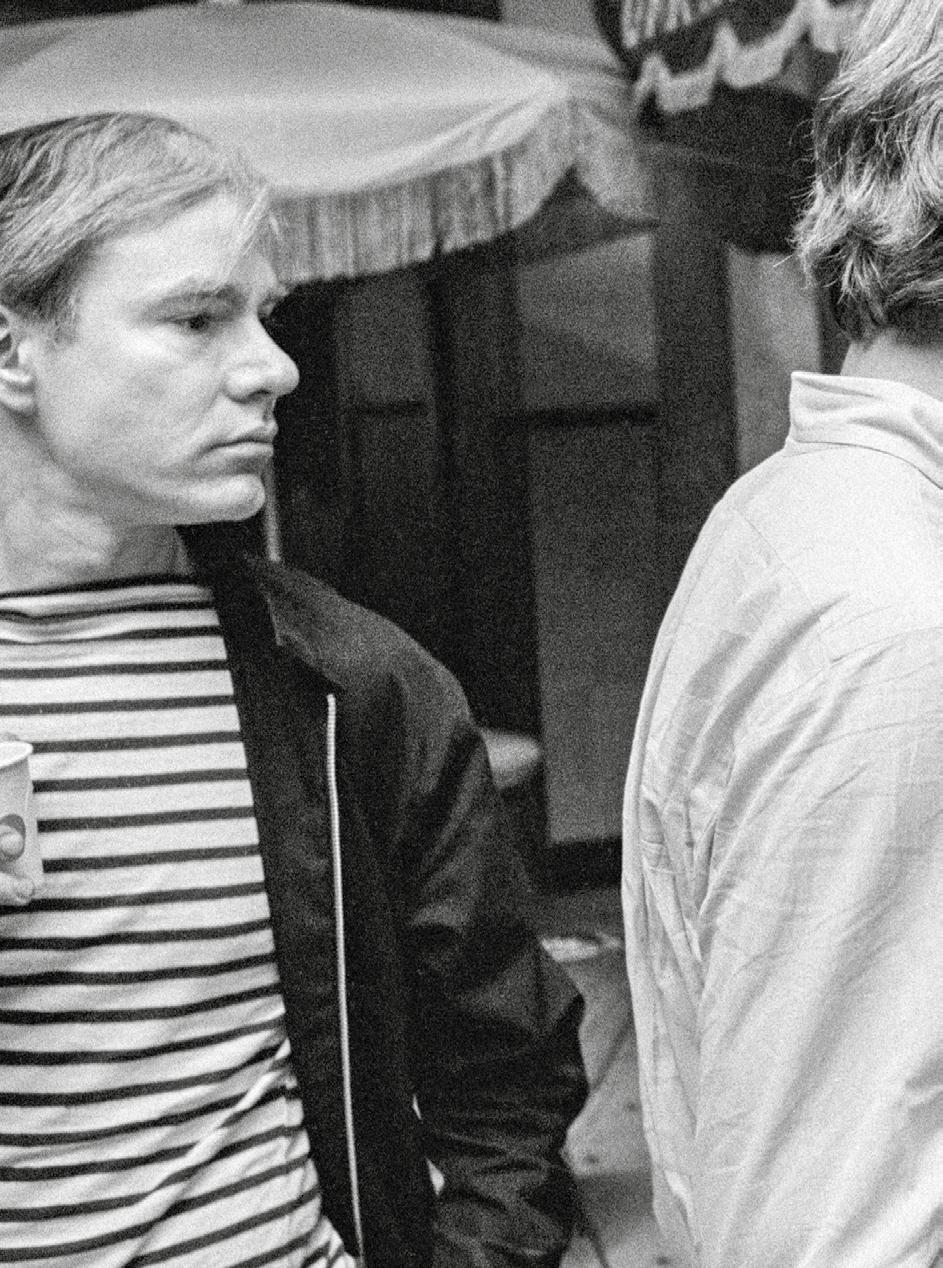

And now a few words about a figure who was as ingenious as he was unique: Pete Townshend. He started out with The Who at Woodstock in 1969, one of the greatest guitar players and performers ever, paving the way for the culture of the Mods, but also the violent language of the Sex Pistols, influencing The Clash first and Pearl Jam later. Because of his progressive, violent approach, Townshend would destroy countless guitars during his career! Oasis and Blur as well were inspired by this musician and his amazing leaps on stage in striped pants and sneakers, as if he were responsible for their sound and bizarre behavior. But even though many of these bands were British like him, Townshend was merciless, unstoppable, no matter who it was. Townshend believed that the Beatles and The Rolling Stones were the creators of fake rock, one that was too melodious and boring . . . Led Zeppelin was accused of copying him, starting from their “pathetic” guitarist (none other than Jimmy Page). To be honest, I have never heard a single riff by Led Zeppelin that reminded me of The Who, and yet . . . He also went after The Police, whose music he called punk rock . . . But to me they were never like that, with their striped T-shirts—one of my absolute favorite items of clothing. I have a thousand colors and

versions, and I am sure T-shirts will forever be a p art of our wardrobes. No one questions Townshend’s talent and his musical influence, but I am certain that if Instagram had been around in the 1970s, he would have had more haters than followers!

Finally, we come to the “spatial” part. David Bowie with his glam rock trying out innovative sounds with means that were rather unusual at the time—as you can see from the jumpsuit Yamamoto designed for him. But we will have more to say about Bowie later . . .

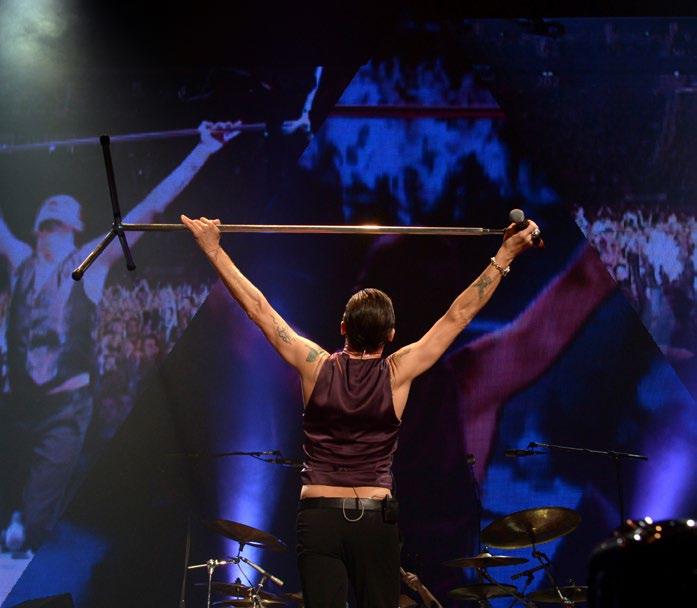

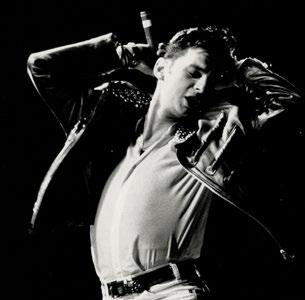

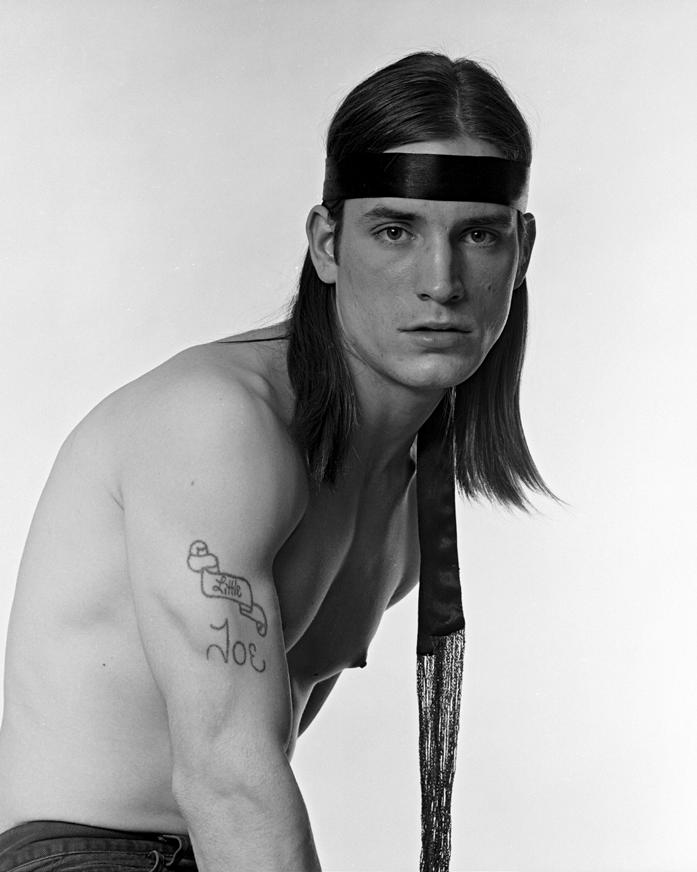

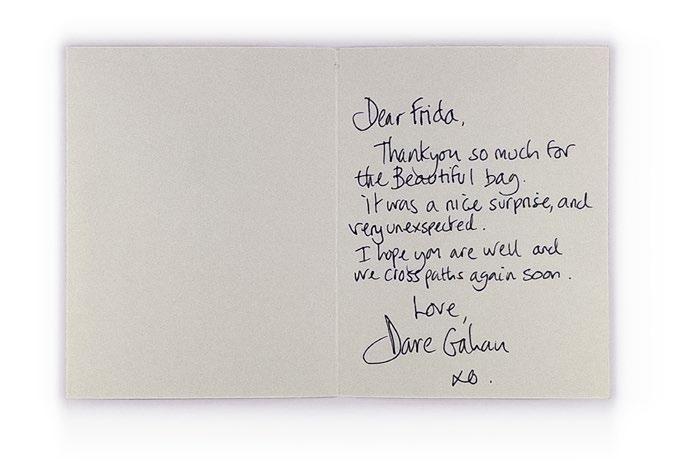

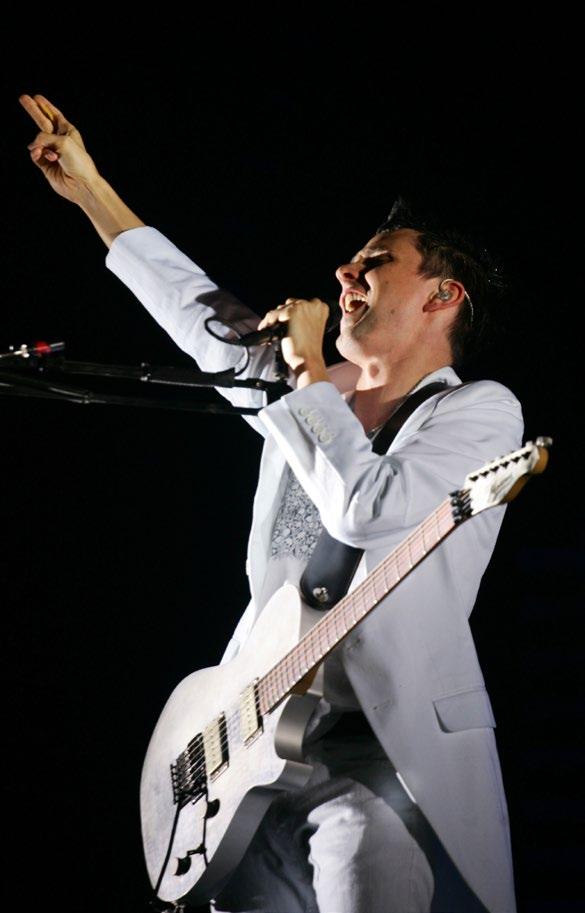

What I find intriguing instead are the most famous bands from the 1980s to today that Bowie inspired. With much more advanced technologies at their disposal, they made electronic music and the use of synthesizers come alive thanks to the talent of musicians like Andy Fletcher and Depeche Mode. Many of their videos and concerts have something futuristic about them. This is also true for the splendid sets created by Anton Corbijn and for the pictures that were taken for their albums. Andy Fletcher on the keyboards is a master, but he always seems to linger in that sexy, romantic aura thanks also to the guitar as it is played by Martin Gore. Known as “the man with the wings” because of his unmistakable all-white or all-black look, he had a pair of feathery wings he wore like a backpack, eyes with black makeup, and black nail polish, which you could see when the camera showed his hands—offset by rugged combat boots. Added to all this was the sensuous, gruff voice of Dave Gahan, who performed wearing sensual black trousers, Beatle boots with a Texan heel designed by me, and a vest over his naked chest, giving us a glimpse of his sexy tattoos.

Remember Gore’s riff “Enjoy the Silence”? Already etched in music history, once it is inside your head you can not get rid of it. And how can we forget Daft Punk, the Banksy of music, who never show their faces, always dressed like astronauts: golden helmets and uniforms like the ones worn at Area 51? And what about “Get Lucky” with Pharrell Williams on vocals and Nile Rodgers on guitar, the lead performer and undisputed guitarist of disco music and r&b in the 1970s and 1980s with Chic—remember Le Freak? (Yes! A masterpiece!). Nile Rodgers was the producer and composer for musicians of the highest caliber, whom he often accompanied to concerts wearing his typical dreadlocks, white Jamaican hat, and unmistakable black-framed eyeglasses. Lucky us, I would say, and the next generations.

Have fun!

Frida

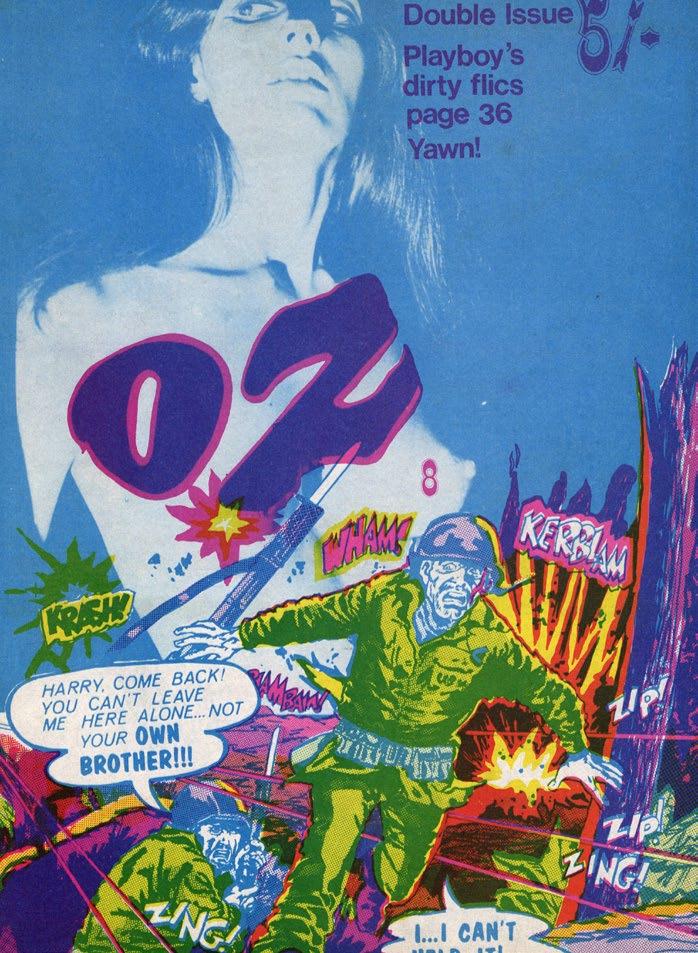

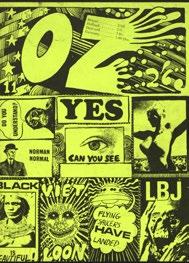

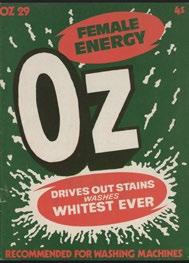

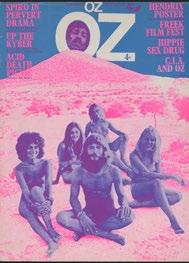

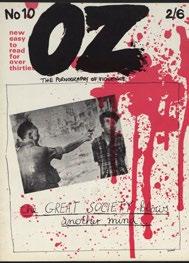

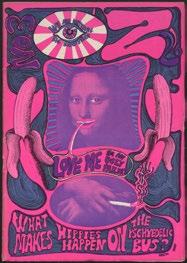

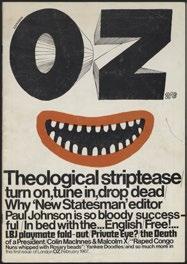

“I wanna be free”: the magazine OZ , founded in 1967, shouted this motto from its covers. Designed by some of the most famous illustrators and cartoonists at the time (it was a sort of Charlie Hebdo back then), it was provocative and featured a freedom of layout that had never been seen before in graphic art for magazines. In fact, OZ ’s covers became some of the most exciting ones in those years and contributed to the emergence of a creative avant-garde that—in conservative London—fueled an underground movement.

The magazine quickly took a stand against the British government with a series of covers that heavily criticized the Vietnam War, or that dealt with the theme of drugs and sex, or ridiculed the public morality propagandized by a government that “deviated” the principles of English children and youths. For this reason, OZ was forced to shut down at the end of a trial for obscenity, but the amazing 80,000 copies that were sold in just a few years’ time turned it into a legend and laid the groundwork for the Swinging London that was coming to life in those very same years of protest.

Those were the years when Bowie released “Oh! You Pretty Things” and moved to Haddon Hall. I believe the 1970s were more important than the 1960s for Bowie. The 1960s led to the birth, in London, of some of the greatest creative and musical names, who would contribute to Bowie’s success: first the Beatles, then lifestyle and design phenomena such as Biba, Zandra Rhodes, the model Twiggy, the photographer David Bailey, the “vogueing” of Malcolm McLaren and his partner, a young fashion designer named Vienne Westwood. In the 1960s Bowie tried to free himself, to perform with different bands, to offer his audiences shows that were innovative. But the world and society were not ready yet, and they still were not ready in the 1970s. In those years the London suburbs were rather poor, and one of those suburbs was Brixton, where Bowie came from. Bowie wanted to invent a way to distract people’s attention from that gloomy reality. Why was glam rock born in the 1970s with David Bowie’s contribution? Precisely because he was a visionary, he was always a visionary, and he always looked farther into the future than many others. He wanted to write songs and do concerts that were so amazing they could somehow disguise the UK’s economic problems in those years.

“Get It On” by Marc Bolan was one of his first approaches to T. Rex with The Spiders, the band he was trying to find stardom with. He was not very successful, however, because the world was not ready for this skinny Martian far removed from any aesthetic canon and who wore makeup and his wife’s clothing. David made every attempt to assert himself, learning to use makeup and eye shadow from Marc Bolan, from his friendship with Lindsey Kemp, who also taught him the art of the stage and transformation, and by testing the sounds of new bands like T. Rex, of which Bolan was the leader. Bowie did all this so that he could go before the public—but, alas, that public was unprepared for his aesthetic and sound. Finally, in 1969, “Space Oddity” was released, launching Bowie into the world of fame just a few months before the Apollo 11 moon landing.

Bowie was against the hippie mentality, which had reached its highest point at Woodstock. He decided he would be one of the organizers of the Glastonbury Festival, in 1970, an event that went against the tide, from which great bands would emerge, especially English ones—Pink Floyd first and foremost. The following year Bowie decided he would participate in the festival as an artist as well, but because his performance was scheduled for the dawn, almost everyone was sleeping and only a few actually watched him singing “Changes.” At the time one of his innumerable artistic transformations was underway, though not many know this, and it would be the start of David Bowie’s epic phase.

Among the artists who took a clear stance were John Lennon with “Imagine,” which he wrote specifically for this moment in history, and The Rolling Stones. The Hells Angels and the disaster of the Altamont Free Concert made it clear that the English band had traveled to an America whose government was tired of being criticized for the Vietnam War by people with long hair. In the meantime, in the UK, an underground movement was coming to light, supported by OZ , which, as we saw before, had to shut down at the end of a trial for obscenity. This shows that although the UK has always had more conservative governments than the United States, it still gave birth, from the 1960s to the present time, to the majority of irreverent, revolutionary, and pioneering artists.

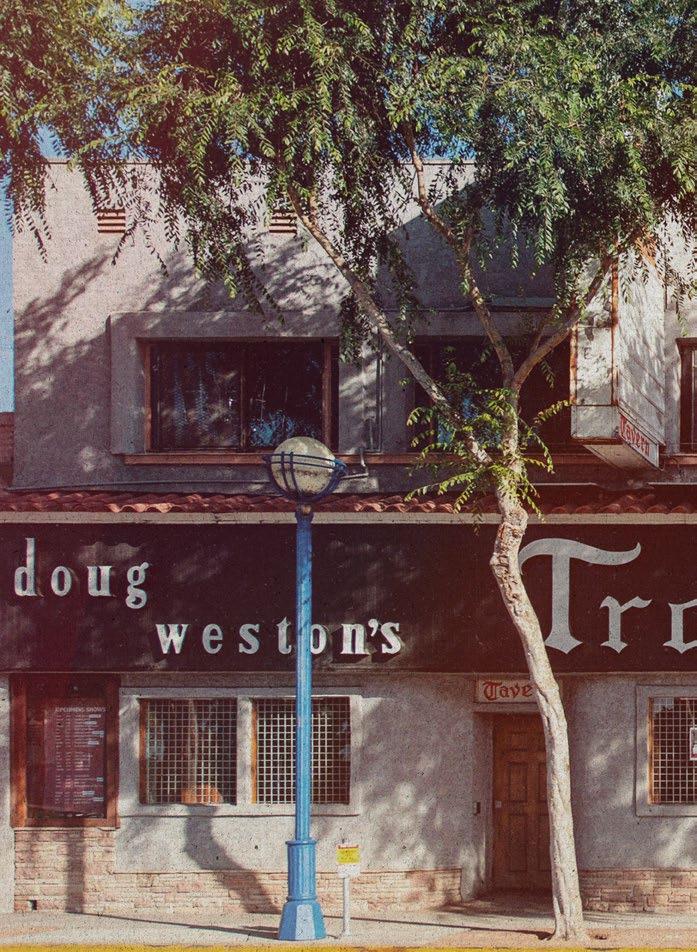

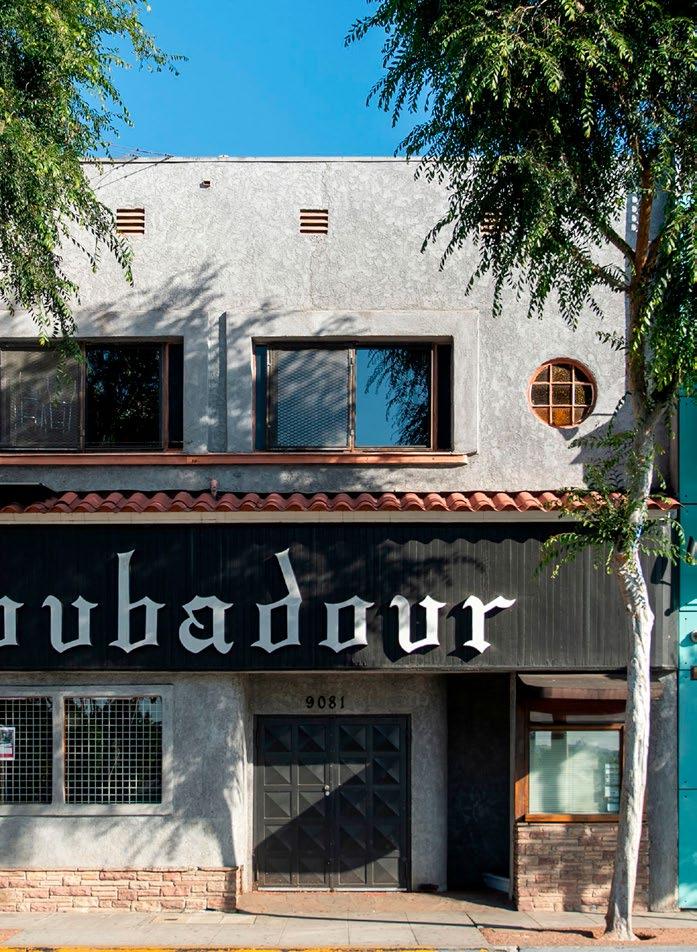

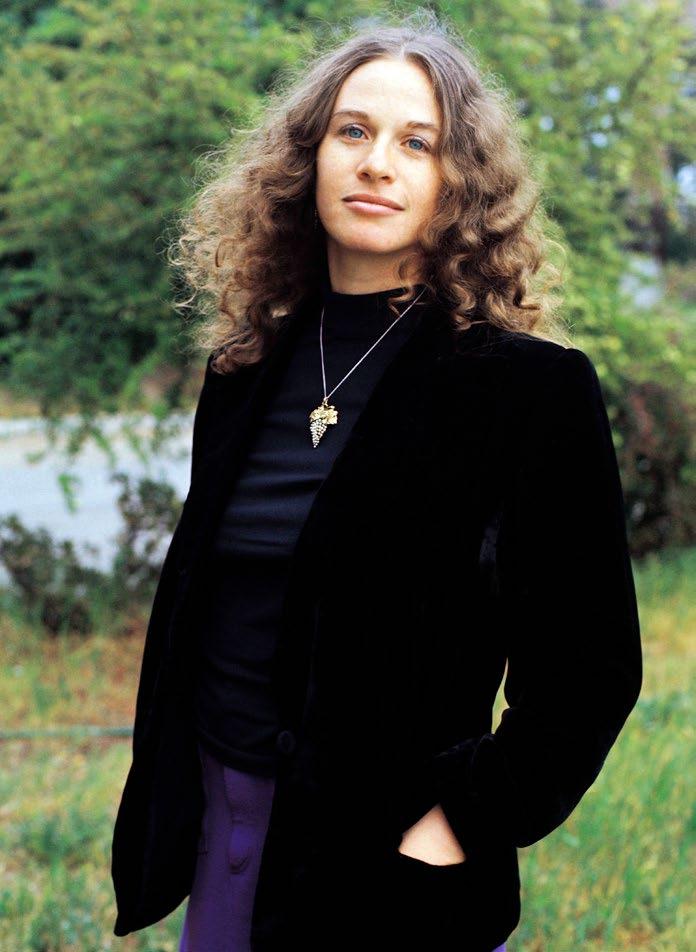

The Troubadour was a Los Angeles nightclub whose owner, Doug Weston, was an enlightened visionary and had no concern for rules, do-gooders, or America’s conservative society, which was even more bigoted than England’s. The Troubadour hosted Carole King’s first public performance, as well as Elton John’s. “Sixty Years On” and “Your Song” were both launched in the early 1970s at The Troubadour, and they also represent the birth of an ambassador for women’s empowerment like Carole King and the voice of LGBTQ rights like Elton John. He, too, was responsible for a huge change, which is also due to the scene that gathered around the LA nightclub starting in the late 1960s.

Carole King with James Taylor in their super contemporary looks: she in a blue velvet jacket, blue turtleneck, navy jeans, and long necklace, her hair always free to follow the rhythm of her hands on the piano, reminding us of Janis Joplin; and James Taylor in the days of his angelic beauty, with jeans, a Navajo belt, long hair, and incredible eyes as they sing “You’ve Got a Friend” . . .

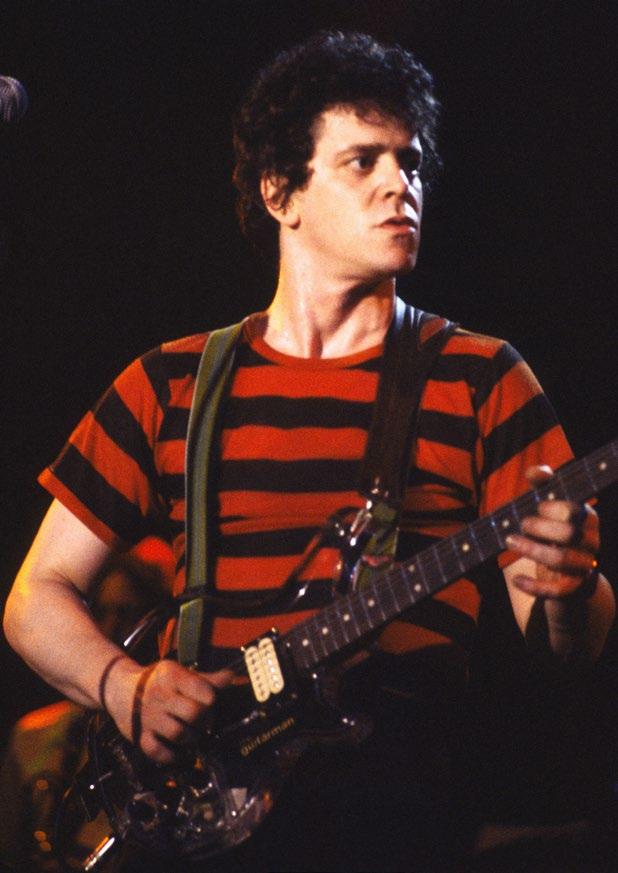

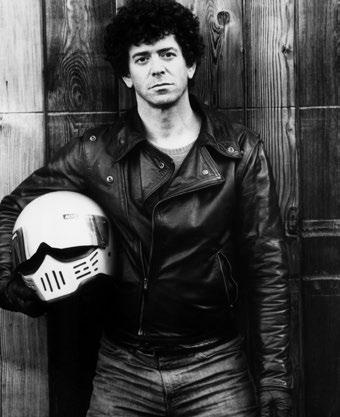

Here we are at the moment New York became a star: 1970–1975. Besides Patti Smith, there was also Lou Reed who wrote “Walk on the Wild Side” for a dear friend of his, the transgender Holly. She, too, was part of Andy Warhol’s Factory, and Lou really admired her. But those were hard times, too. There were huge amounts of illegal drugs in circulation, which took a toll on the art scene (Michael Hutchence and everyone else who did not make it come to mind). The problem still exists today. Maybe we just talk less about it, but the truth is that little has changed. First it was called LSD, now it is called something else. But let us be clear about this: creativity and getting high are not linked.

FOLLOWING PAGES: THE TROUBADOUR, WEST

In those years there was one person who in her songs and in the interviews she gave dealt with topics that were totally out of bounds—dangerous ones—for which she was also attacked: divorce, abortion, work, and the vote. I am talking about Carole King and women’s empowerment. In “Natural Woman,” which was also later sung by Aretha Franklin in a version that has gone down in music history, King describes her commitment to fighting for women’s rights.

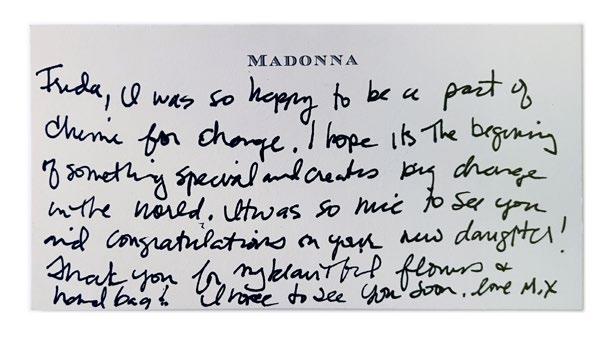

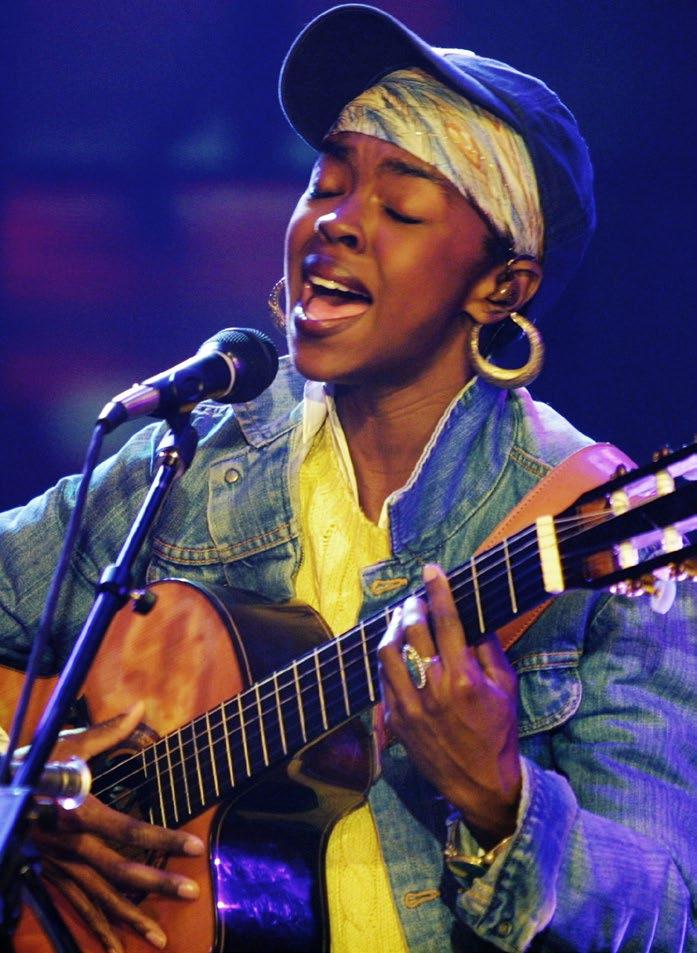

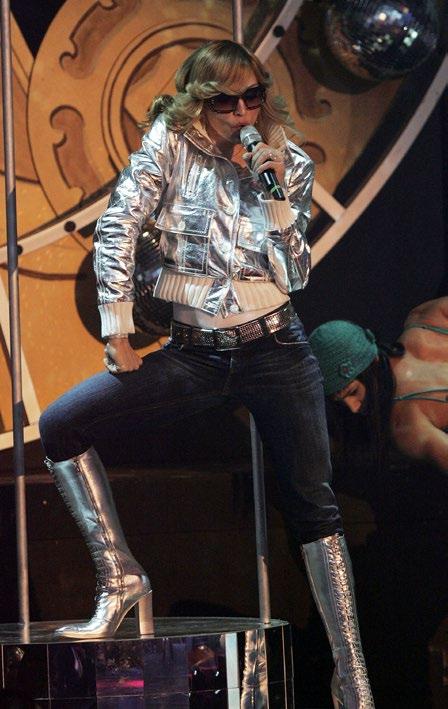

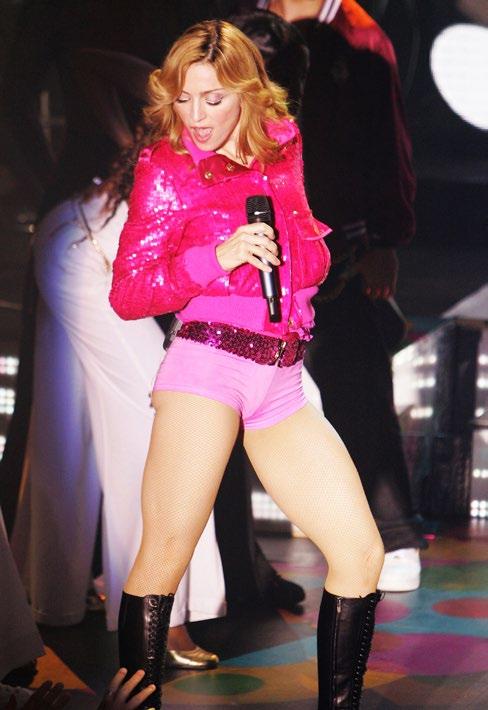

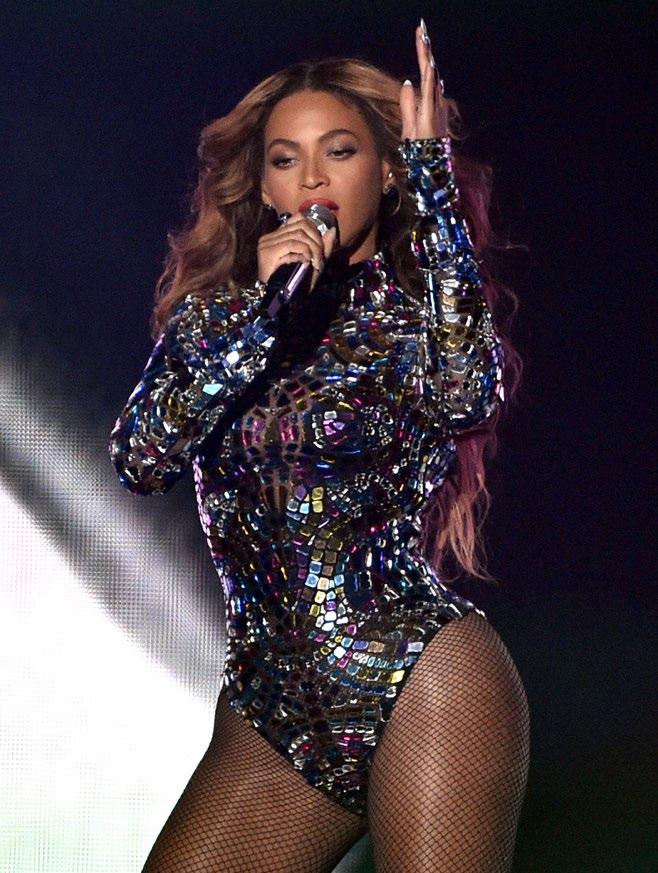

And I think it was Carole King, because of all the battles she waged, who inspired me and gave me a feeling of urgency as a designer involved in human rights to organize the “Chime for Change: The Sound of Change Live” concert that took place on June 1, 2013, at Twickenham Stadium in London. With Bob Geldof’s Live Aid benefit concert in mind, I turned to the same organization, and thanks to Beyoncé and Salma Hayek, I succeeded in bringing to the stage musicians like Beyoncé and Jay-Z, for the first time together, to sing “Crazy in Love.” Not to mention JLo, Mary J. Blige, Florence and The Machine, Madonna, John Legend, Timbaland, and emerging artists like Rita Ora, Ellie Goulding, Iggy Azalea, and others. I personally designed all the artists’ outfits. The target was health and education, and the proceeds from the sold-out concert went to schools, hospitals, and organizations around the world that support young women.

BEYONCÉ PERFORMING AT CHIME FOR CHANGE: THE SOUND OF CHANGE LIVE, TWICKENHAM STADIUM, LONDON, 2013

CELEBRITIES PERFORMING AT CHIME FOR CHANGE: THE SOUND OF CHANGE LIVE, TWICKENHAM STADIUM, LONDON, 2013: (FROM TOP ROW TO BOTTOM ROW LEFT TO RIGHT) JESSIE J, FLORENCE WELCH, ELLIE GOULDING; JENNIFER LOPEZ, FRIDA GIANNINI, IGGY AZALEA, MARY J BLIGE; BEYONCÉ, RITA ORA, JAY-Z AND BEYONCÉ, MADONNA

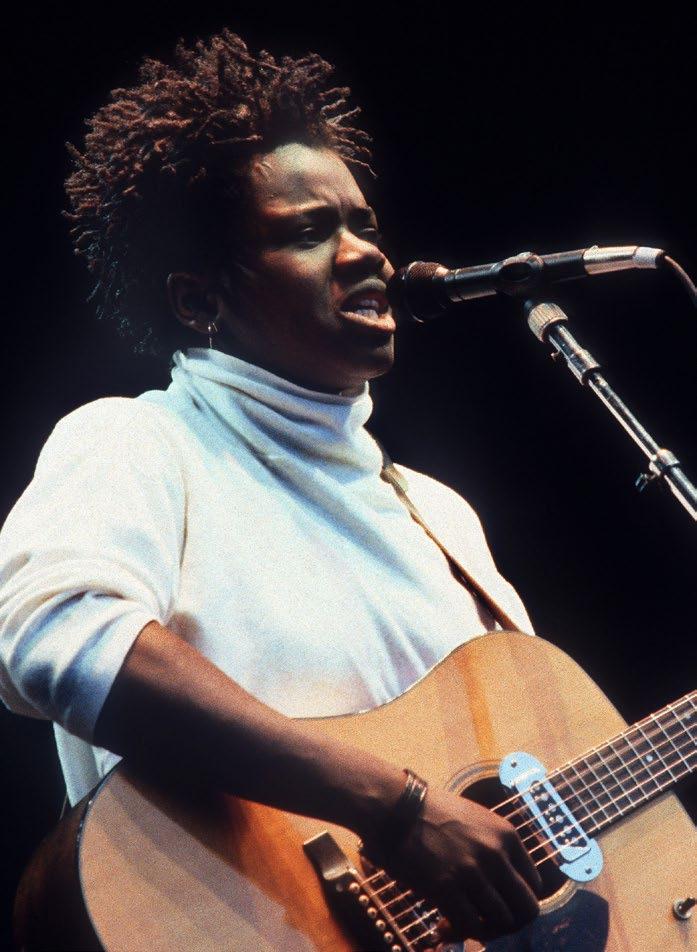

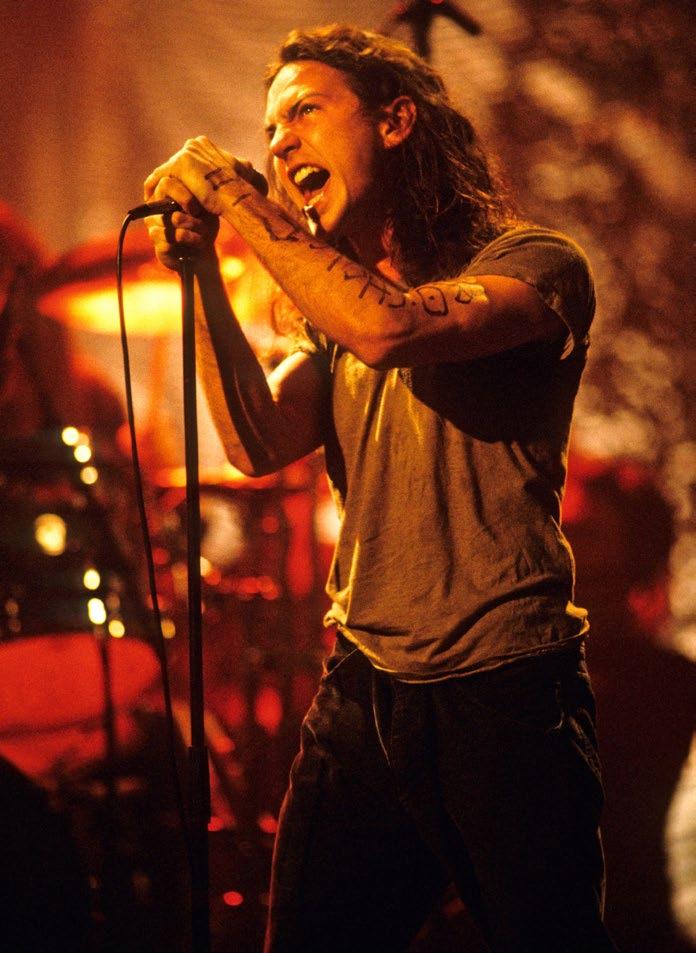

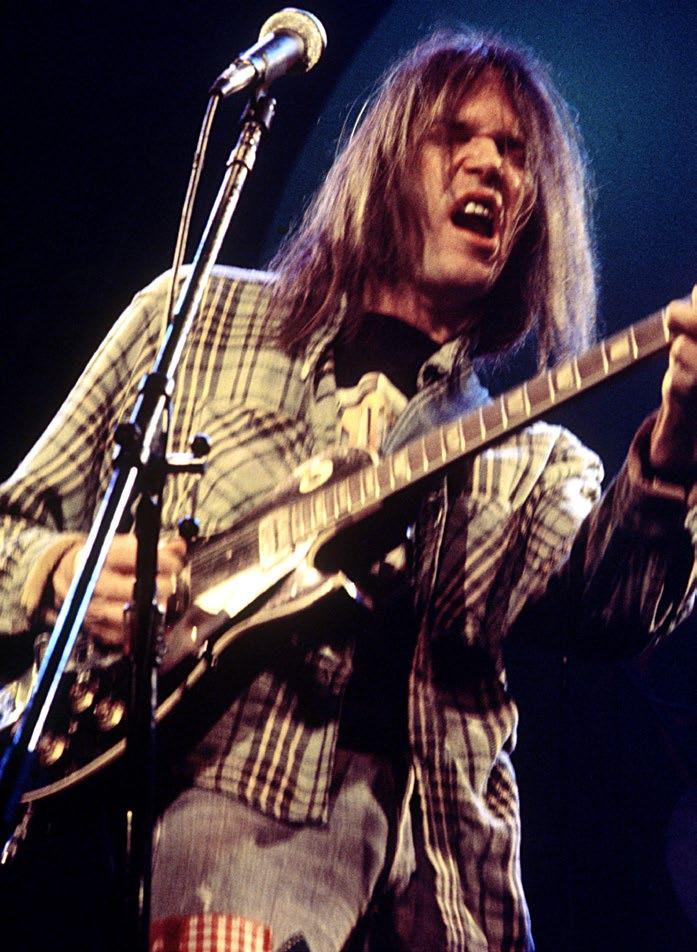

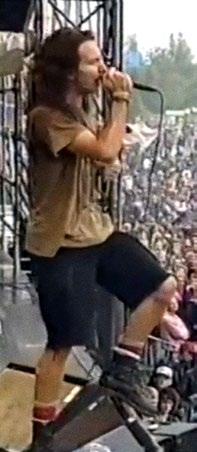

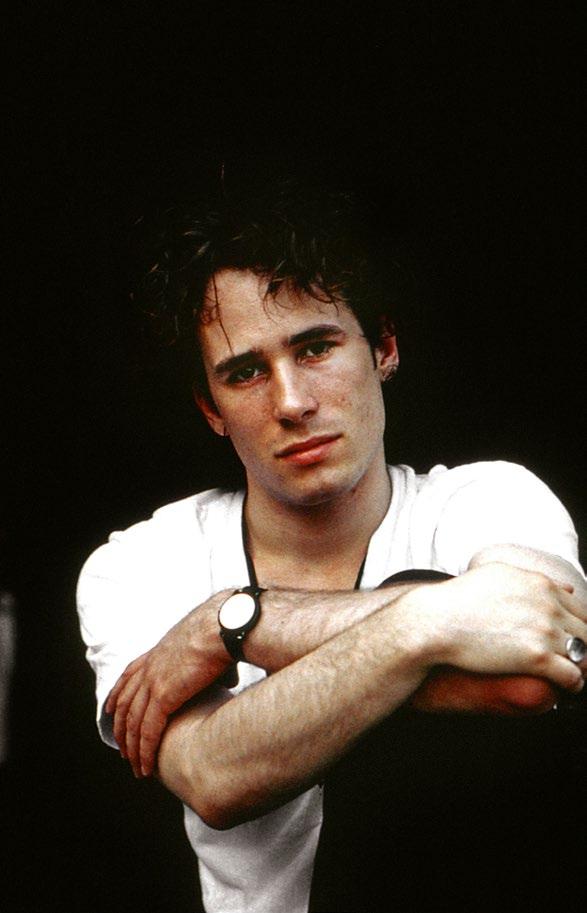

Now we come to a depressed Kurt Cobain, and a dark, marvelous, handsomest of all Neil Young. Who could ever have imagined that one of the most important guitar players in the history of music, who performed at Woodstock in 1969, along with Crosby, Stills, and Nash, would be the visionary forerunner of one of the most innovative musical currents of the past three decades: grunge. If you look at these pictures and listen to their voices and their rage as they scream into the microphone, it is incredible how contemporary they seem even though all this took place decades ago. Like the checked shirt over torn jeans, a symbol, along with the striped crewneck shirt and the distressed cardigan worn by Kurt Cobain (another star who died tragically and member of the “27 Club”), of the grunge aesthetic from Nirvana onward. And let us not forget the marvelous version of the unsurpassable MTV Unplugged in New York , in which Cobain almost outdoes David Bowie in intensity, as he sings and plays “The Man Who Sold the World.” It is all just history repeating itself.

Eddie Vedder, the lead singer of Pearl Jam, never hid the fact that he had been influenced by guitarists like Pete Townshend and singer-songwriters like Cat Stevens and Bob Dylan. Vedder was a member of the grunge movement, with a more aggressive look than Cobain, but just as handsome and talented. A surfer, always wearing either a checked shirt or a printed T-shirt, surfer bracelets, rigorously black converse sneakers or army boots with tennis socks, and cargo shorts. Eddie was very similar to the Nirvana singer because of his melancholy and intense voice and his existential crises, the only difference being that Eddie also took a political stand for human rights and against the Republican party, managing to defeat his depression, or at least learn to live with it. He has collaborated with many artists over the course of his long career, from Bruce Springsteen to Roger Waters, from Beck to Soundgarden . . . That was where his great friendship with the magnificent Chris Cornell was born. Even their way of dressing was very similar: Cornell’s long curly hair framed his bright green eyes. He was another artist who died tragically. A lot has been said about the fact that Vedder did not go to Cornell’s funeral. He did dedicate a ballad to him, however, “Comes Then Goes,” with a lot of the same powerful expressiveness of the hugely famous “Black” (my favorite Pearl Jam song, and I am sure I am not the only one . . . ). Ironically, it was another great artist who sang at Cornell’s funeral, Chester Bennington, of Linkin Park, the indelible authors of “One More Light,” which I personally love to sing at the top of my voice. Bennington committed suicide soon afterward . . . Marvelous, black grunge, forever damned.

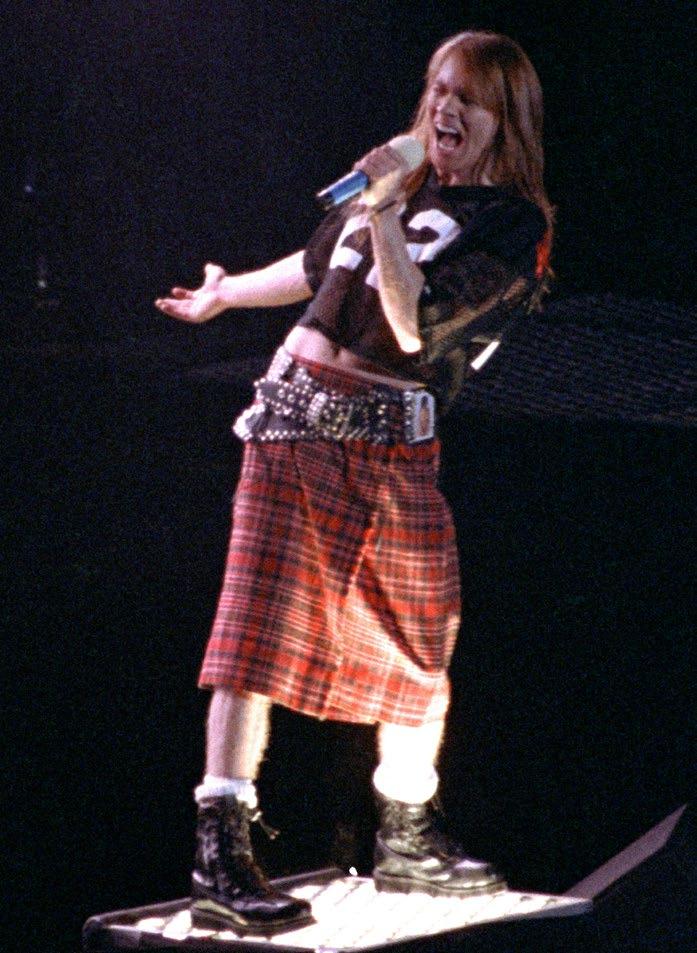

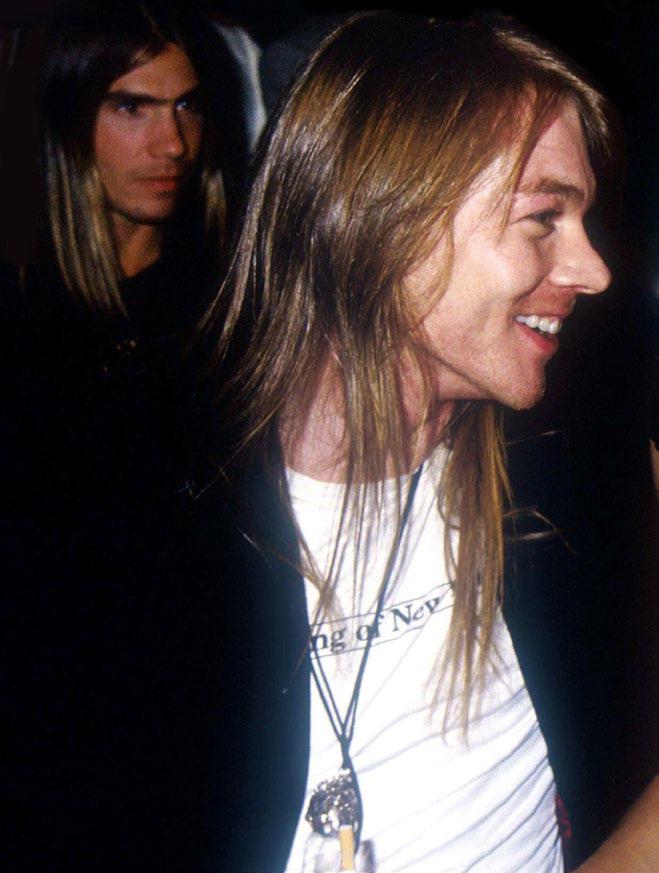

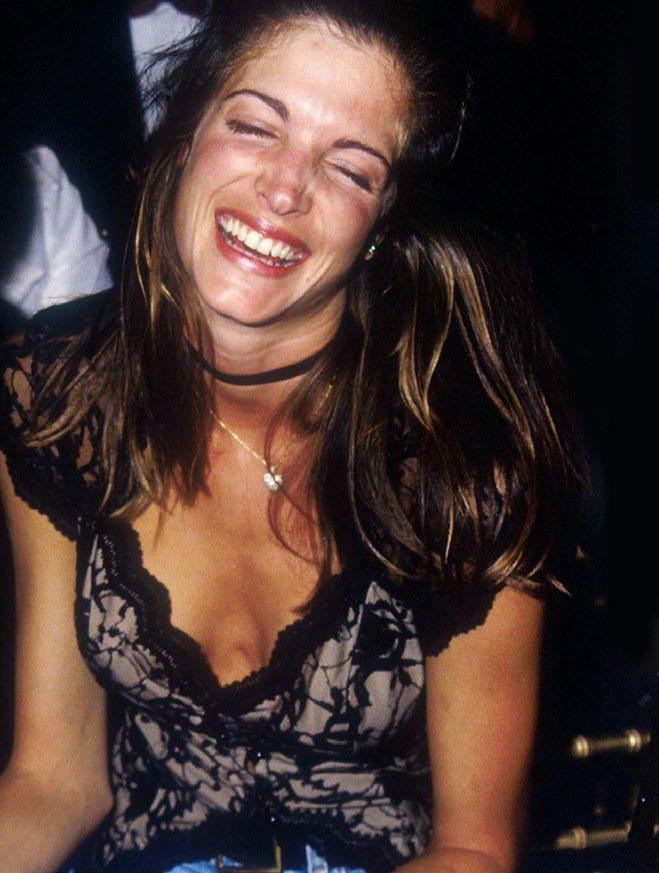

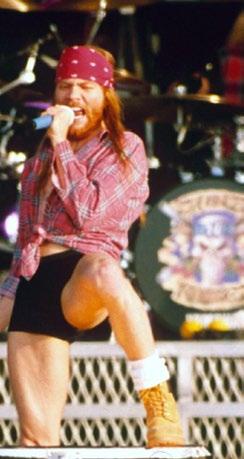

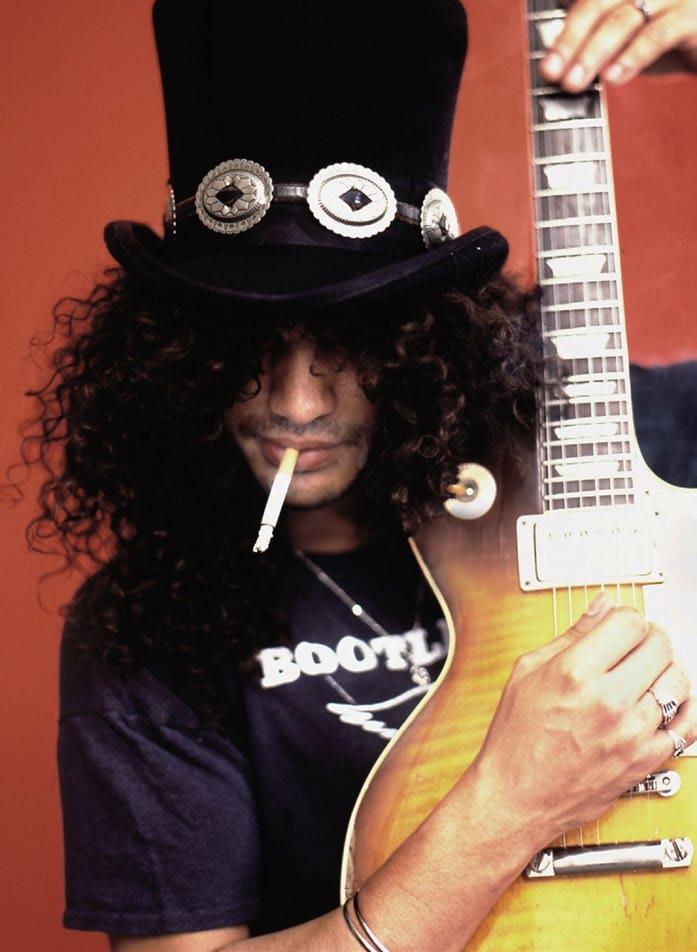

Guns N’ Roses, from Los Angeles, and Bon Jovi, from New Jersey: they burst onto the 1980s scene, between the end of discomania and the start of new wave, and became famous all around the world. And yet they were very different from what was taking place at the time, even though some of their “influences” came from the same place. Guns N’ Roses, led by Axl Rose—truly a bad boy, together with his crazy yet unforgettable guitarist, Slash. His energy was irresistible and he had an incredibly powerful voice. He laid down the law on the matter of trends (their crown of thorns is probably one of the most merchandized logos ever, along with Mick Jagger’s tongue) and looks: who can forget his blond hair and pirate bandana, a baseball cap worn backward, as well as Scottish or leather kilts, combat boots or Dr. Martens? He had some crazy relationships, too, especially the one with Stephanie Seymour, a top model at the height of her career, who even went so far as to have barbed wire tattooed around her right ankle for Axl. One of the band’s biggest hits, “Welcome to the Jungle,” instantly brings to mind “Sympathy for the Devil” by The Stones, which, among other things, they did their own version of in concert.

Quite opposite from this is Jon Bon Jovi, who has been married to Dorothea Hurley since 1989. I was lucky enough to meet them: there is a huge love between them. They are like one soul. And yet rock ’n’ roll turned him into an animal when he was on stage. He was “cleaner,” more of a Good Guy. After all, he did grow up with the “Boss” Bruce Springsteen and with Eric Clapton. But Jon Bon Jovi, too, wore leather chokers and bracelets with studs, combat boots or sneakers of all kinds, as well as long hair that was always disheveled. And obviously very high-rise denim with tank tops.

I have always been intrigued by Axl Rose and his voice, especially the whispered intro in “Patience.” A melodic ballad that is about a love that is over, and that was different from their usual sound. Magical. And “November Rain”: true poetry.

Also impressive was his arrival at the concert in memory of Freddie Mercury, introduced by the legendary Elton John. Together they sang “Bohemian Rhapsody.” Touching.

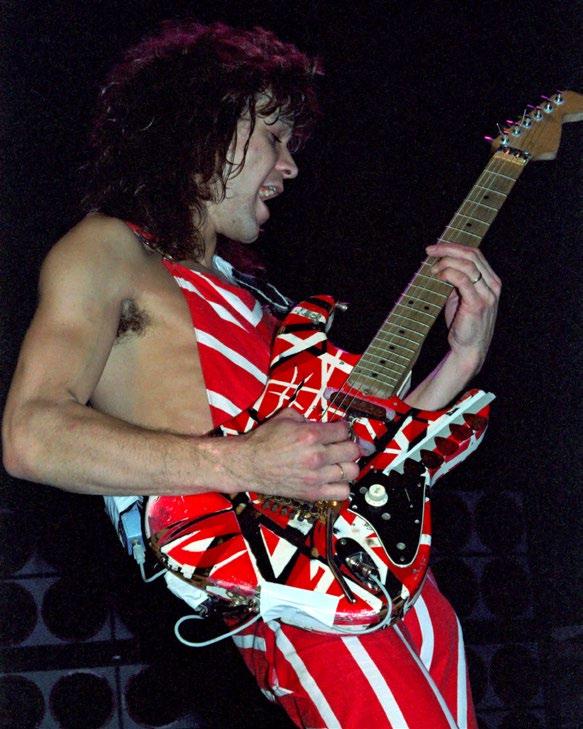

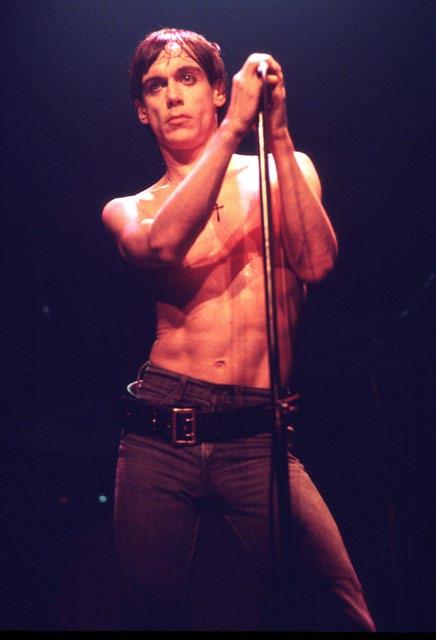

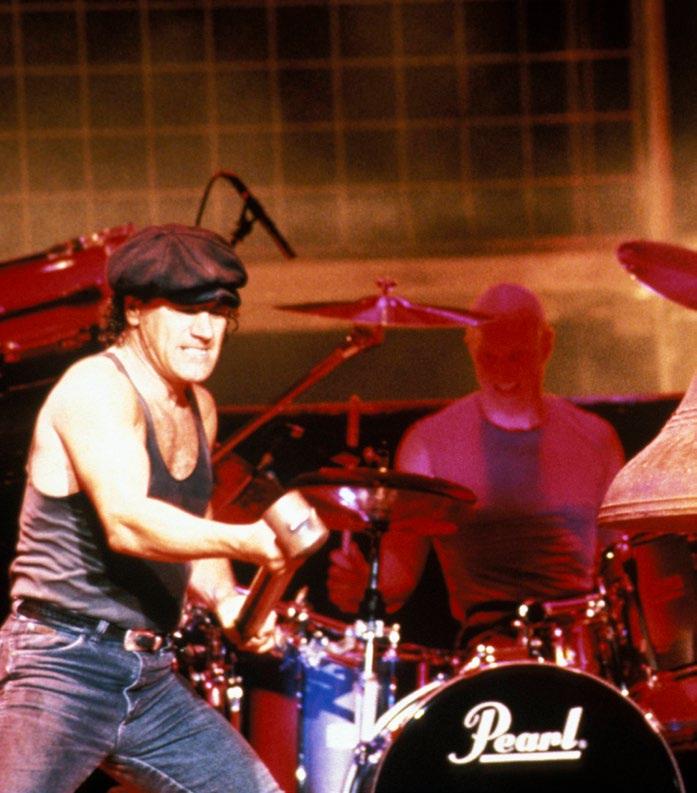

And yet both bands were influenced in a similar way: they started out with Led Zeppelin (“Whole Lotta Love”), Jimi Hendrix, The Doors, Alice Cooper, Iggy Pop, and The Rolling Stones, to then return to David Bowie’s “transformism.” The scene was also filled with new bands like AC/DC and Van Halen, who accentuated the “bad attitude” of both groups. While for Axl Rose, Led Zeppelin was always the starting point, as shown by the guitar style of Slash, which calls to mind Jimmy Page’s, and that is where you always end up . . .

At the same time Alice Cooper was emerging: together with Van Halen and AC/DC, Alice was strongly influenced by Bowie (even though he has always denied it), besides being a great friend of Keith Richards. Appearing on the scene at the same time was Iggy Pop and . . . we also seem to end up with Bowie!

And how can we forget Steven Tyler of Aerosmith with his leggings, bare chest, and bizarre jackets in bold contrast with the total black and Adidas of Run-DMC in their fantastic version of “Walk This Way”? That may have been the first time in history that rock and rap crossed paths.

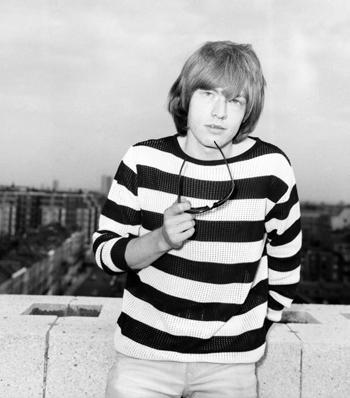

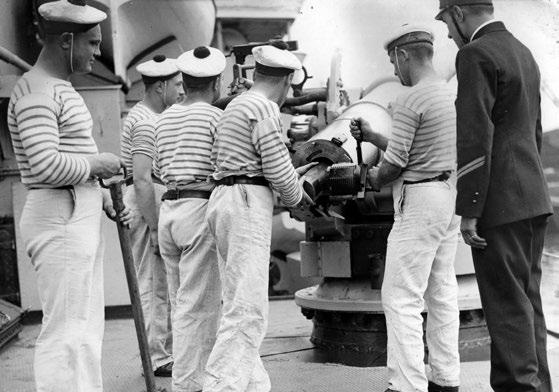

It all started with Breton fishermen, who wore these striped shirts for years, based on the idea that if a man fell overboard, it would be easier to see and therefore rescue him if he were wearing it.

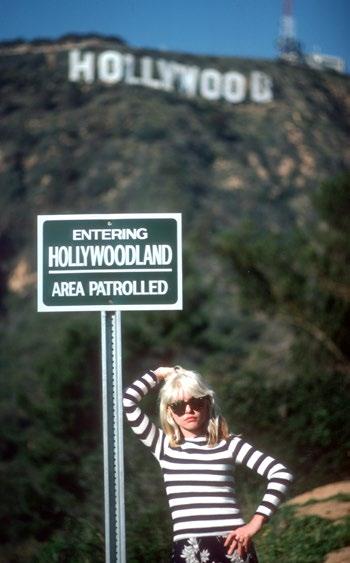

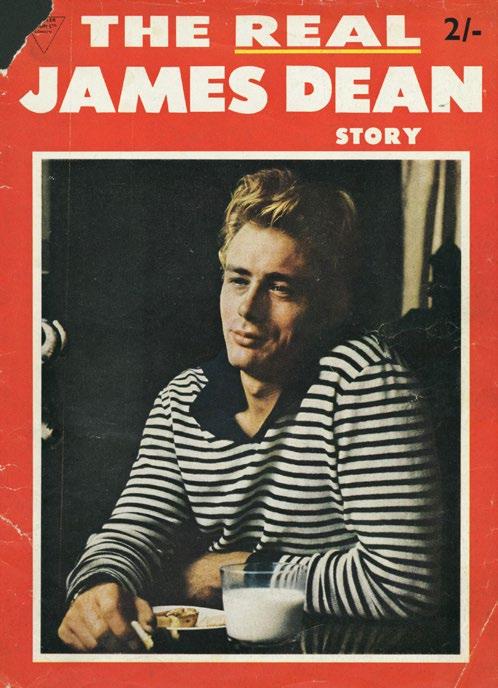

In the late nineteenth century, the French Navy adopted it as part of their official uniform. Throughout history, from the Middle Ages onward, the striped uniform was set aside for prisoners and criminals, the marginalized and prostitutes. People imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps wore a striped uniform. In the late 1920s, one enlightened, visionary woman was the first to understand its elegance and transgression, turning the shirt worn by fishermen into the famous unisex marinière jersey, a must-have for all those spending time in the most fashionable beach resorts—for instance, Deauville in Normandy. Who could this enlightened woman be? Madame Coco Chanel, of course! She transformed a simple shirt into an element so iconic and timeless that even Picasso always wore it to match his eccentric clothes. Later, the marinière became an iconic shirt worn by Marella Agnelli, Jackie Kennedy, and even Greta Garbo, stylishly androgynous as long ago as 1929.

Continuing this discussion about cinema, in Europe the marinière was suddenly everywhere on the Mediterranean coast of France thanks to Brigitte Bardot, who left her mark on the French Nouvelle Vague in Biarritz. And across the ocean even before that it had been spread by transgressive figures like Marlon Brando, James Dean, and Elvis Presley.

In fact, as Coco Chanel taught us, the T-shirt was meant to be an innocent piece of clothing, but it could be sophisticated. It could even rock if worn over leather or denim trousers, or with a classic double-breasted navy-blue blazer.

This piece of clothing also exploded in the world of music: Sting, Patti Smith, Lou Reed, John Lennon, Diana Ross, Bob Dylan, Madonna, Lady Gaga, The Who, and Keith Richards, all the way to the Sex Pistols and Johnny Rotten. Then there were Kurt Cobain, Pearl Jam, and Chris Cornell of Soundgarden for whom the shirt was a banner.

The image of Björn Andrésen in Luchino Visconti’s 1971 masterpiece Death in Venice is unforgettable. On the art scene, besides Picasso, in photographs taken of Andy Warhol in 1970 he is often seen wearing a marinière , just like his muse Edie Sedgwick and the famous photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. From that moment onward the world of fashion once again took over the Breton shirt in designs by Jean Paul Gaultier, Sonia Rykiel, Karl Lagerfeld, and Chanel.

I, too, in my own small way when I designed my first collection as creative director, Spring/Summer 2005, presented colorful striped cashmere sweaters with a white cotton popelin collar, because for me stripes have always represented avant-garde unisex apparel to be worn with everything. In fact, I own a collection of summer and winter marinières , a tribute to the transgressive yet chic style created by Madame Coco Chanel.

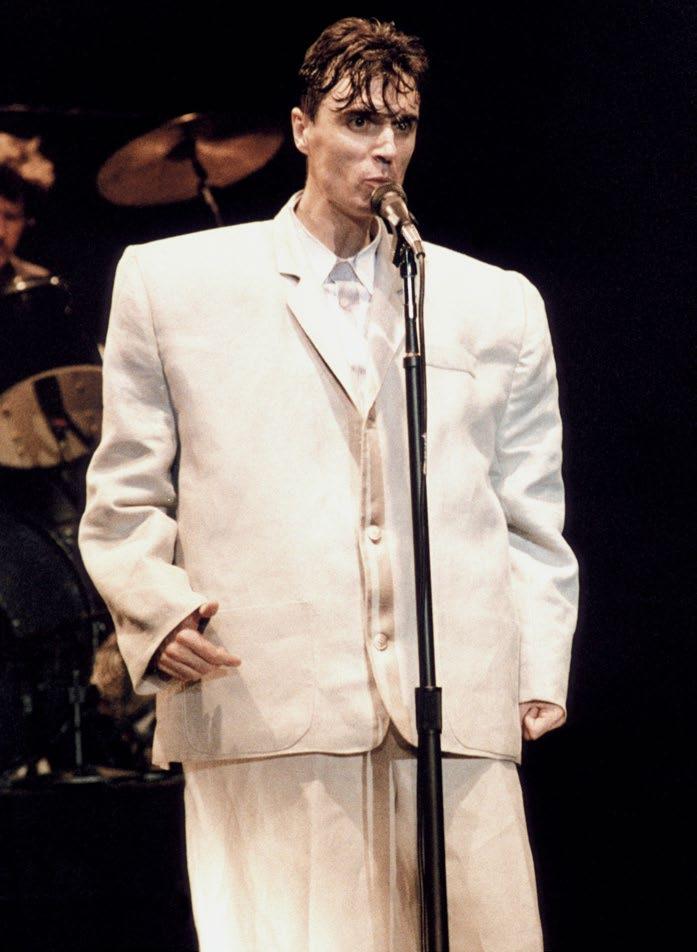

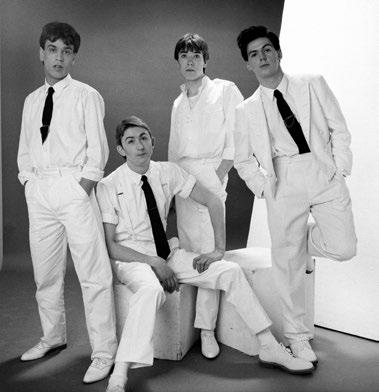

After the dark/gothic movement a sort of hedonism emerged in which artists, besides wanting to express themselves with sounds that were more pop, also wanted to appear more captivating. Thus was born new wave/synth pop, which led to the reappearance of figures from the past, but with new looks characterized by eccentric or very sartorial jackets, with checks or pinstripes, bow ties, and broad shoulders. Those were the years of teased, dyed, and frosted hair like that of David Bowie. During that same period, Gianfranco Ferré, Giorgio Armani, and Gianni Versace brought the “Made in Italy” style to the rest of the world, inventing luxury prêt-à-porter. It is interesting to see just how many musicians reinvented their looks in their own way, tired of studs and piercings à la Sex Pistols.

The Cars: the only American group in the movement, who rose to the top of the charts with “Drive.”

The frontman Ric Ocasek always wore a black jacket, thin tie, and bangs stuck to his forehead.

Talking Heads: led by the genial David Byrne, with his Elvis Presley pompadour hairstyle and one eye on British dandy style. They started out with “Psycho Killer” and no one would ever be able to stop them. My beloved Talk Talk: I adored them. When I was a teenager, I had a poster of Mark Hollis (who died in 2019, sadly) hanging up in my bedroom. He was in a sailor’s cap, the kind I continue to wear today. The group made the navy-blue pea coat famous and wrote some of my favorite songs like “Such a Shame” and “It’s My Life,” to name only two.

The Jam: “Town Called Malice,” with the legendary Paul Weller. Ostensibly inspired by the Beatles, in their look as well, they introduced a more refined, chic rock. For me Weller, with his natural elegance, continues to be an icon of unsurpassable style.

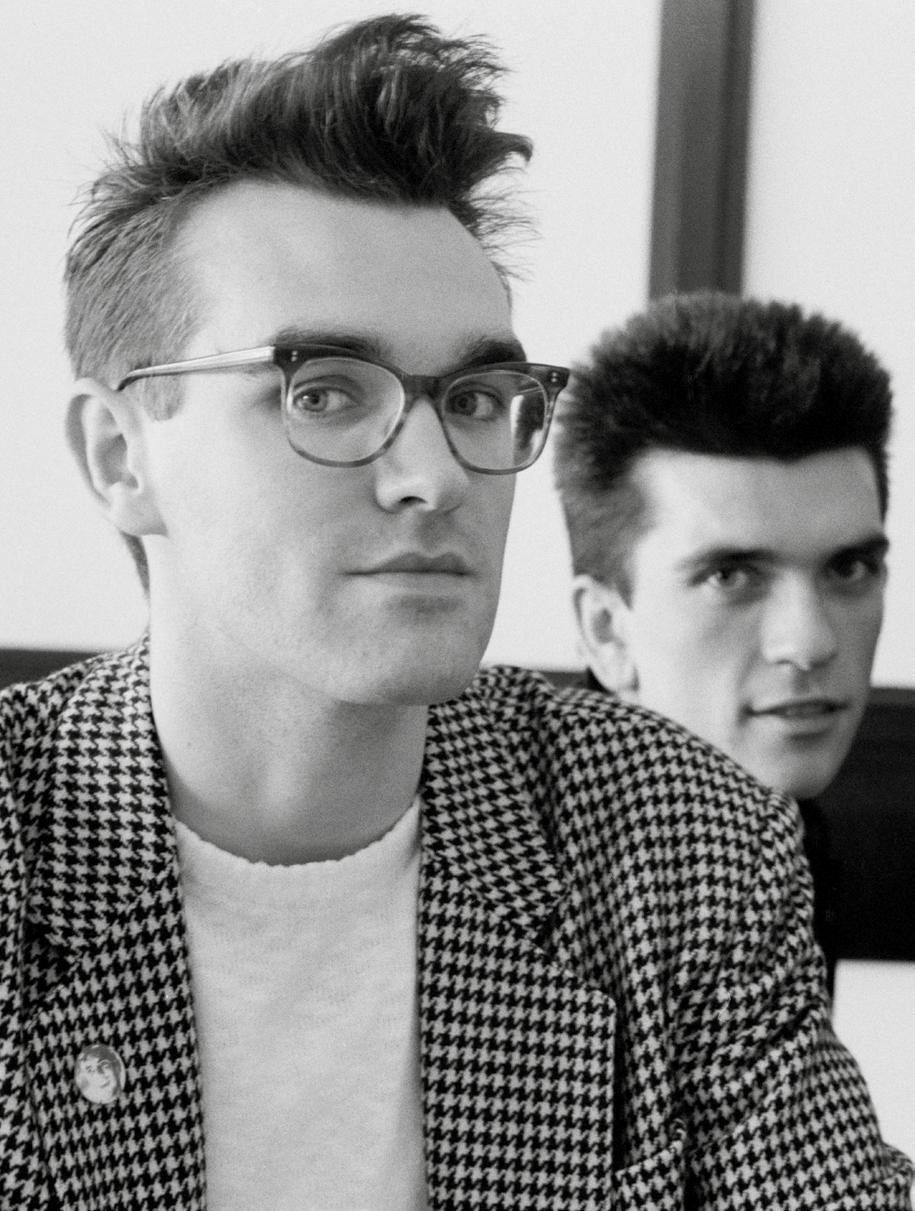

The Smiths: with “This Charming Man” they took Morrissey to the Olympus of pop music. An unmistakable voice and style, with a New Wave shock of hair, white shirt, 1950s eyeglasses that no rocker had ever worn before, he would later become a soloist, inspiring bands of the caliber of Radiohead, Muse, and many others.

Simple Minds: Jim Kerr, the composer of some memorable songs like “Alive and Kicking” and “Don’t You.”

A real super dandy, a great composer and musician, and formerly married to the actress Patsy Kensit. Pet Shop Boys: I give them the Palme d’Or for that period. With pieces like “West End Girls” and “Always On My Mind,” they were a sophisticated, chic, new band on the music scene. With their dandy jackets and bow ties, they seemed discreet but were actually ingenious.

Human League: they came and they left, sort of like a one-hit wonder but with an eccentric and unique dandyism, a perfect look, and even two women in the band!

Marc Almond: another unique one-hit wonder, with “Tainted Love,” played by everyone everywhere, and his pointy face, hat thrown back, lipstick, and black eyeliner. I have always adored him.

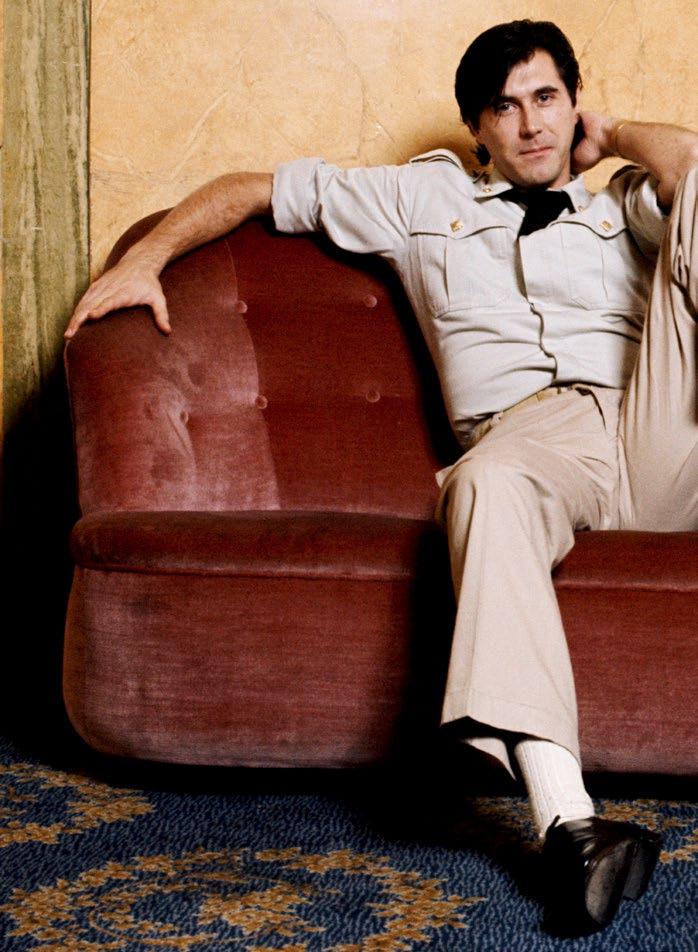

Lastly, just to draw a line because there would be too many names besides Spandau Ballet and Duran Duran, who arrived later and imposed the aesthetic canons of those days, how can we forget Roxy Music and Bryan Ferry: “More Than This” . . . Absolutely the most stylish and effortlessly elegant singer of this era.

ULTRAVOX (FROM LEFT): BILLY CURRIE, CHRIS CROSS, MIDGE URE, AND WARREN CANN, PARIS, 1982

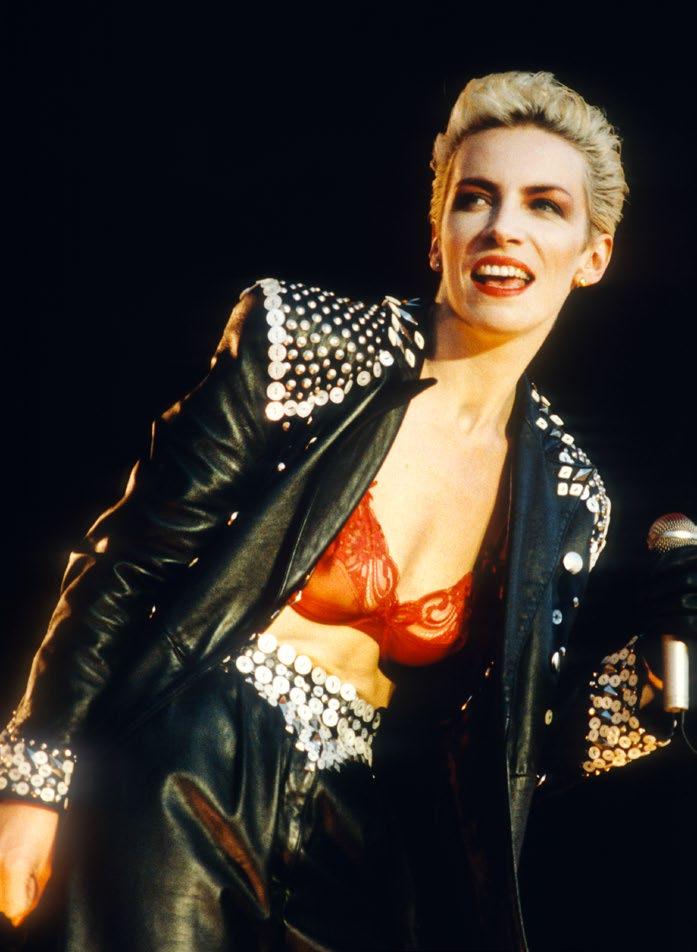

Many of the musicians mentioned up to now had a leather fetish: a bomber, a biker, but, above all, the Perfecto—that is, a black leather motorcycle jacket, one of the most iconic items of clothing ever. Invented by Schott for the US Air Force during World War II, Elvis Presley was one of the first to wear it in the 1950s. In the world of cinema, James Dean, Greta Garbo, Steve McQueen, and Marlon Brando all contributed to turning it into a cult object. Elvis was the breaking point, though, managing to inspire most of the pop culture that followed: the image of the guitarist with his pompadour straddling a motorcycle along with bikers became a common sight. Of course, during one of his performances a motorcycle jacket probably was not the most comfortable thing to have on—I imagine that at the time it was made from horse leather—but it still became a status symbol. I have always loved it, and own several vintage ones, designed both by me and by other designers. The Madonna Bomber jacket—which is not a motorcycle jacket—was truly gratifying. The star wanted it for her tour in every single shade, and it became a must for many years. But just as gratifying was the Perfecto in calfskin, deerskin, and crocodile! However it is worn, the leather jacket has always been popular. Here we see it on David Bowie, Freddie Mercury, and Dave Gahan—and how can we forget the blond-haired Billy Idol and the entire punk movement? Anyway, there is not a single fashion company in the world that has not interpreted this piece of clothing in its own unique way, with or without sleeves, embroidered, studded, in different shades (Michael Jackson’s red jacket!), quilted, with a white fur collar or a fake shearling. The Perfecto is a must-have in everyone’s wardrobe, and even in freezing weather, everyone still insists on wearing it over a T-shirt! Most importantly, everyone can wear it and mix it with whatever they prefer. This is its strength and immortality.

After the fireworks of rock ’n’ roll in the early 1980s with Guns N’ Roses, Bon Jovi, Bruce Springsteen, and many other bands, a new aesthetic musical movement was born, especially in the UK, which was diametrically opposed to its predecessors.

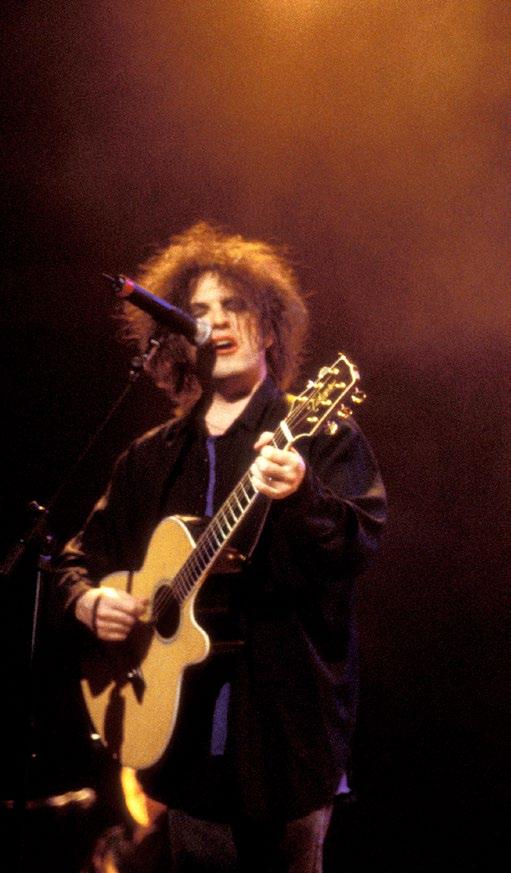

The post-punk/dark movement was born in the underground clubs of London and Manchester, but always in marginal contexts to avoid Thatcherite control.

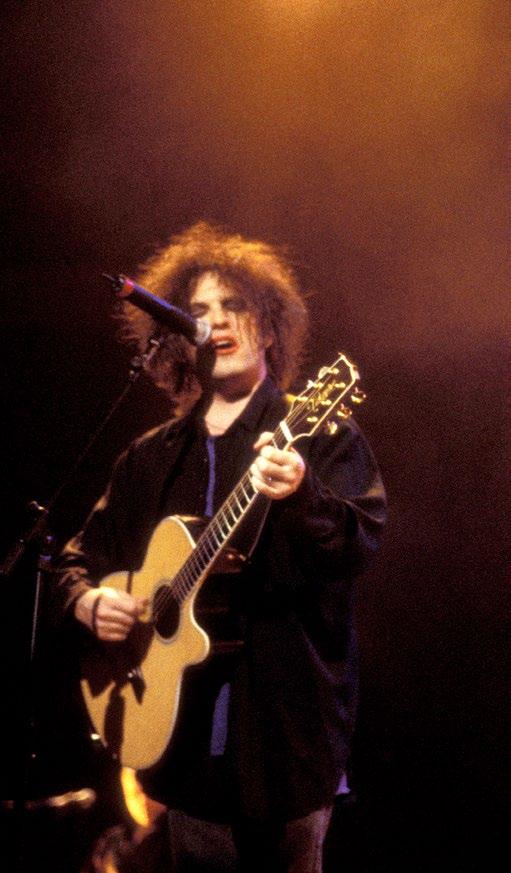

Unquestionably, one of the initiators of the movement was Siouxsie and the Banshees, who claimed the scene and the top of the charts with “The Passenger.” This was alternative rock, also known as Gothic, which would be embraced by so many hugely successful artists in those years. Siouxsie always had dark black hair and eyes that sometimes reminded you of the divine Marchesa Casati, and other times of the makeup worn by Kubrick’s hoodlums in A Clockwork Orange . She never chose one specific designer over another, many of whom were becoming known in those years—like Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren—but rather went to Camden, in north London, to buy all-black outfits, pins, studs, army boots, and to get her tattoos and piercings. Siouxsie also had no qualms about buying leather bondage clothing in sex shops. In those years, probably thanks to her, characters like Jude Blame were born, a stylist and accessories designer, better known as the person who created Boy George’s look, and Zhandra Rodes, a designer who covered her designs with safety pins. But getting back to Siouxsie: where did Robert Smith get his inspiration for his hair? From her. The lead singer of The Cure, as well as composer, musician, and producer, in that period he imposed a very personal aesthetic, with pieces like “Just Like Heaven” and “Lullaby,” which is more romantic. He anticipated the 1990s and has gone down in music history as one of the greats.

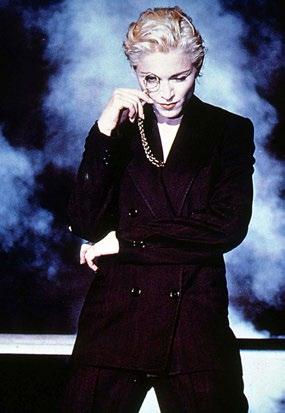

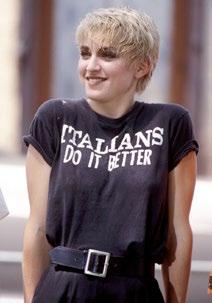

We already talked about The Factory, Warhol, the creative frenzy in New York between the mid-1970s and the early 1980s, from which a group of young artists, who were unknown at the time, emerged. One of them was Jean-Michel Basquiat—innovative, ingenious, and with a bad heroin habit (another member of the infamous “27 Club”), who in a New York City nightclub met a very young Italian-American singer who was just starting out. Their love affair was short but intense, and also encouraged by the artistic fervor of those years. This relationship helped the young artist—Madonna—to come into contact with producers who believed in her, launching her in the firmament of pop music.

I am lucky to have met her and spent time with her, to have collaborated with her on charity projects . . .

A very determined, tough woman, with a dry sense of humor.

The first movie I saw as a teenager was Desperately Seeking Susan: and that is when my Madonna mania began!

I dyed my hair, started wearing leggings below the knees and boots, and teased my hair to hang over my forehead . . .

Those were the days of “Like a Virgin,” “Everybody,” “Lucky Star,” when this girl from Michigan was starting out without having any specific talent (and with a voice that was not so impressive)—but she had a strong personality. She was brazen and had a taste for being provocative and creative and she had her own very personal look. The height of her success came with “Into the Groove,” my absolute favorite disco piece. She has always been like a chameleon: from White Virgin, with lace, corsets, and fishnet stockings, to erotic bondage predator armed with her whip. And then there is the Texas horseback rider with curly hair and a plaid shirt, an acrobatic dancer wearing a high-cut bodysuit and muscle warmers for Confessions on a Dance Floor ; pitch black as Maleficent for Frozen, an actress for Evita, Jean Paul Gaultier’s muse for the “Blond Ambition World Tour,” where she became famous for her corsets with conical-shaped breast cups, fetishes in the world of fashion and style.

She has driven us for forty years, influencing fashion and the look of many young girls from different generations, and the designers for whom she was a muse and an inspiration. She has cut records that have left their mark on the times, won Grammy Awards, is a member of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, sold millions of records . . . And in spite of the many ups and downs, the latter always emphasized by the press and the public with a cynicism that I find unjustified, I would like to portray her the way she is and the way she will always be: a true pop icon. Do not touch Madonna!

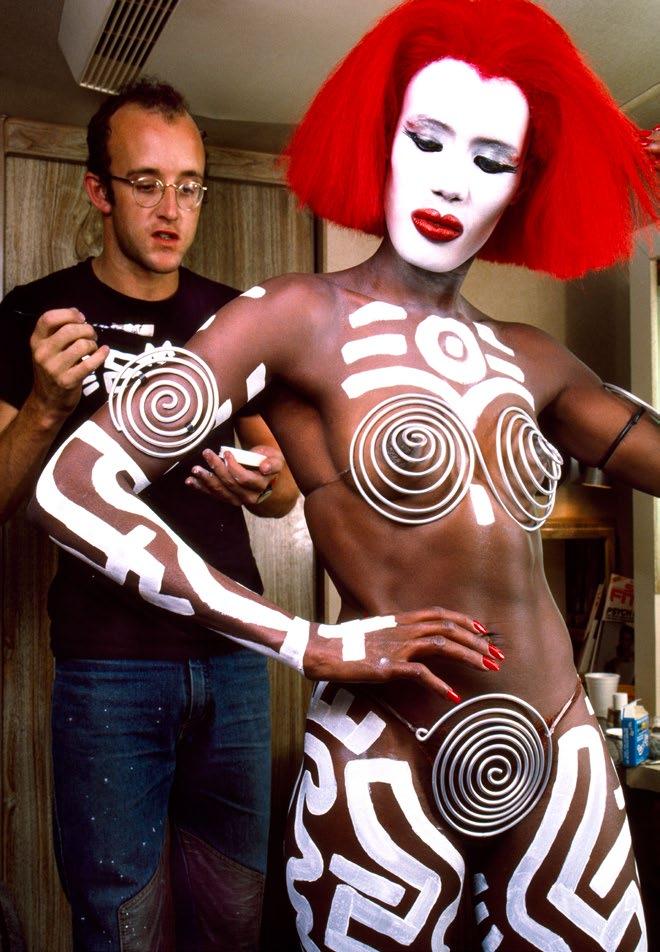

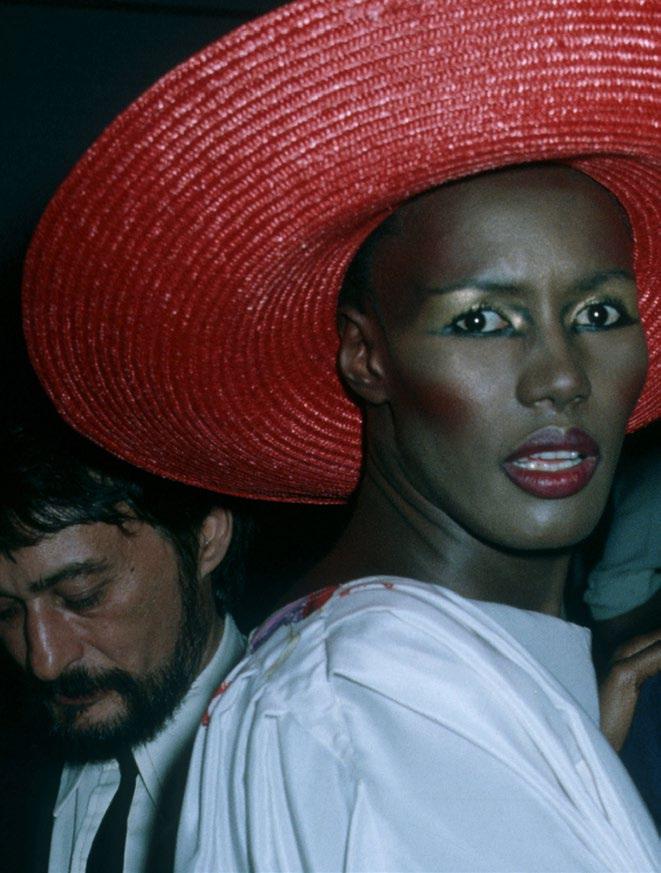

Grace Jones. The legend arrived in Paris from Jamaica, her homeland, and thanks to her diverse and androgynous style and almost-perfect body, she strode down the catwalks for the most famous Parisian fashion designers—YSL, Issey Miyake, Claude Montana—and soon becoming the muse of such great photographers as Helmut Newton and my beloved Guy Bourdin, a visionary master of color. But it would take a wonderful little genius, who passed away in 2017, to make her an icon of her day and age. The partnership between Grace and Azzedine Alaïa would last until the death of this great fashion designer. But for Grace, it was not enough to dominate the catwalks and appear on the covers of magazines like “one of the many.” Enter Jean-Paul Goude, her companion, who, through videos and photos, turned her into New York’s undisputed pop icon in the 1970s and 1980s.

Grace came to Studio 54 wearing an extravagant look and performing in a way that enchanted everyone, from Andy Warhol to Keith Haring. But in those years the New York scene was not limited to the glittering and very exclusive Studio 54. The city also offered different realities, more underground and borderline . . . Keith Haring chose Grace Jones as the protagonist of a performance in which she was completely naked save for the artist’s white graffiti tattoos all over her body. And it was in those years that the androgynous Grace entered the world of music, combining electronic and disco, and performing a magnificent version of “La Vie En Rose.” My favorite song will always be “Slave to the Rhythm,” and I think that she and Bowie, with their sensual, low voices, would have been perfect singing together. However, I realize that “I’m Not Perfect (But I’m Perfect for You)” is the best possible combination of art and creativity for an unforgettable performance. The producer was the untiring Nile Rodgers, who included Warhol and Haring in the video. Haring, in turn, also produced a large-scale canvas for Grace to use as a huge skirt. By mixing the reggae of her native Jamaica, Bowie’s New Wave, and her strong personality, she became a magnetic, sexy, but enigmatic figure, whom I could not possibly overlook along my journey. She reminds me of Gloria Gaynor or Sylvester, whose falsetto was the exact opposite of Grace’s husky one.

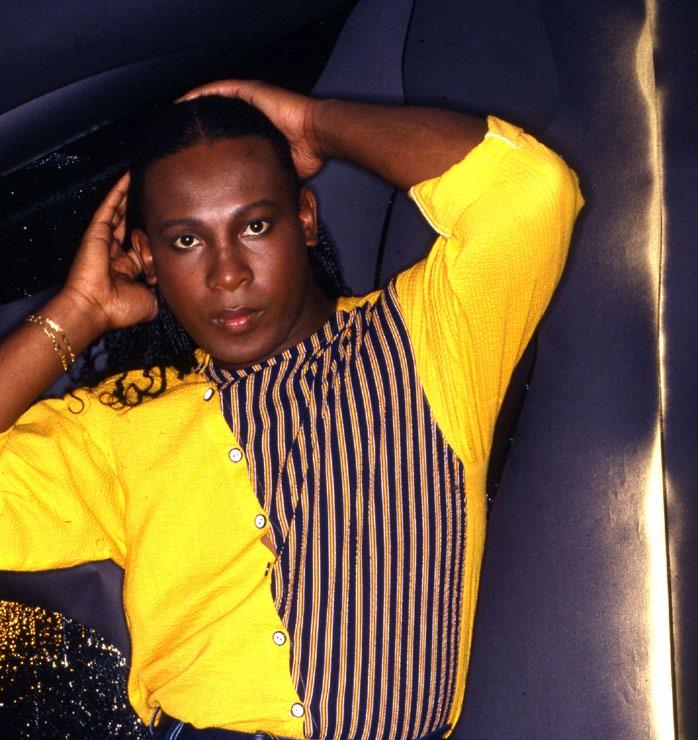

Sylvester was an incredible artist: look at how he changes in the picture on page 161. A predecessor of drag queens Priscilla and RuPaul, he did not come out until he arrived in New York. His family was unsupportive, and in the city he was free to make music and wear what he wanted. Not everyone could get into Studio 54, however: the “cut-off point” was Paradise Garage, where all the most famous members of the underground scene hung out, including Sylvester, Keith Haring, and Robert Mapplethorpe.

AND

Thus far we have talked about Icons, disco music, pop and soul, and rock.

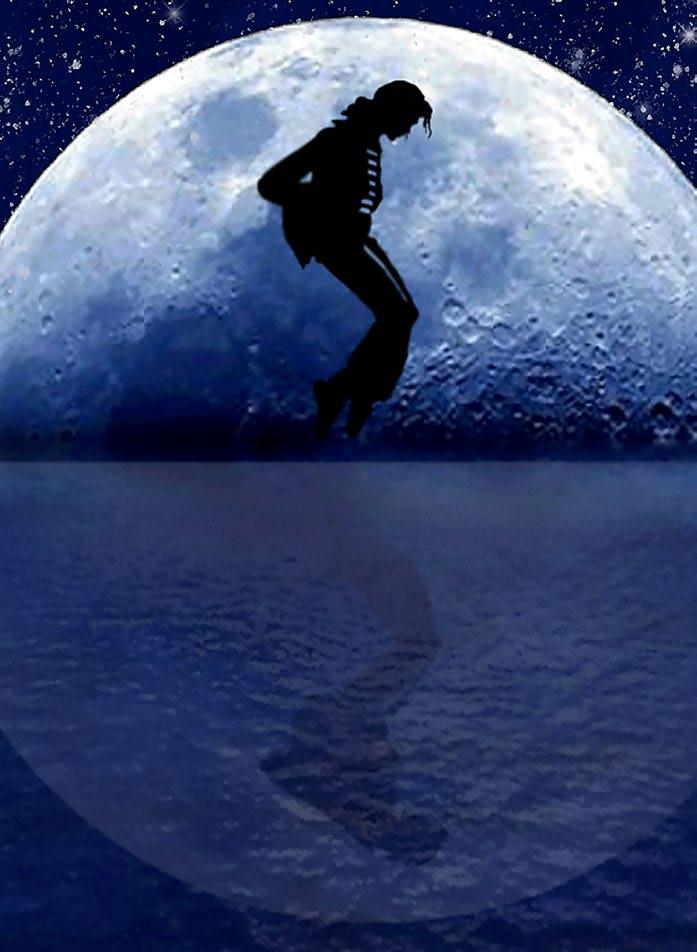

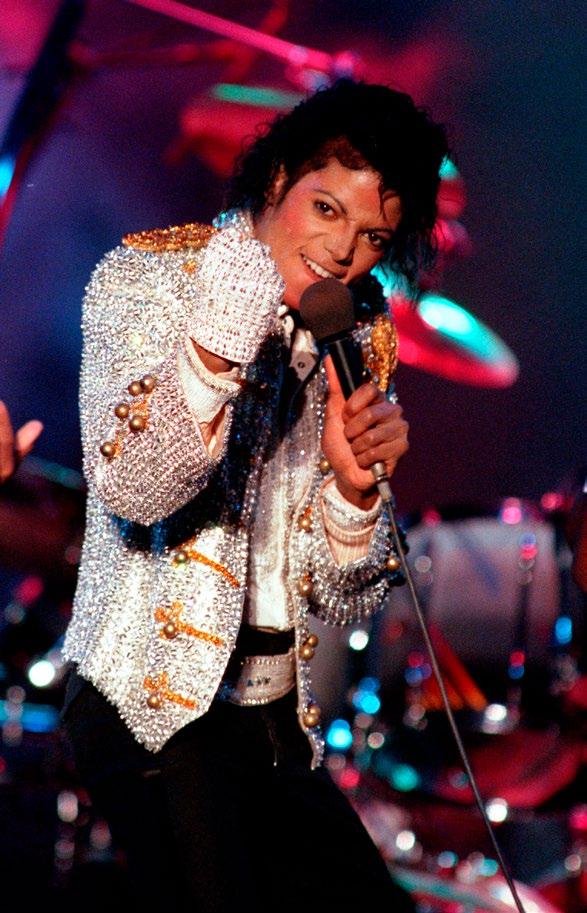

Now to “The Queen” Diana Ross and “The King” Michael Jackson. Legends. Singers we will never forget. Eccentric style, verging on kitsch, but still so “sparkling” their looks have been copied by many. Diana, already a famous star, soon became like a godmother to the young Michael, who was just starting to make a name for himself in the music industry because of his voice and personality as a member of the Jackson 5, the band he had with his brothers.

Diana Ross was influenced by soul and blues music, and by Billie Holiday, and she embarked on her career in the early 1960s with the Supremes. But because she was also inquisitive and smart, she realized the world was changing around her and was drawn to the new music trends. In 1969 (that year again!) she decided to start a career as a soloist, and in 1970 she embraced disco music with a series of hits that we still dance to like crazy today! In 1970 she was ready to sing “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” followed by “Love Hangover,” “Upside Down” . . . by then the Disco Queen was invincible. But still waiting for her was the legendary “I’m Coming Out” produced by who? Why Nile Rodgers, of course . . . Little did she know she would be sending a message to the LGBTQ community, which from that moment onward would use the words “coming out” to express their sexual orientation. So now she was also a gay icon! What else? Here are some of the images of outfits worn by Diana during those years. Later, I am going to tell you who some of her musical and fashion heirs were. She never tied herself to one famous designer—rather, she chose LA designers who mainly dealt with red carpet fashion, like Bob Mackie, her favorite, or Tracy Chambers. Whitney Houston, a sophisticated, unforgettable voice, always elegant, a dramatic life, but without Diana’s vigor, although she was constantly trying to approach her class. Mariah Carey, she as well with a voice that could shatter glass, but not rock, not an icon like Diana (forgive me, Mariah, you know I love you) but the sequins are all they really share . . . Alicia Keys, an excellent artist, when she plays the piano you get goose bumps. But her music is not disco, her songs do not stick in your head, and you do not find yourself humming them in the shower. Donna Summer is more or less from the same generation.

We asked her to sing her most famous piece—”I Feel Love”—for a great perfume video directed by the visionary filmmaker Chris Cunningham, in which her specially designed floral-print dress and the flowers in the surrounding meadow moved to the rhythm of the music. Gloria Gaynor has a great, powerful voice, and “I Will Survive” will live on forever. Donna would rearrange it in 1996. Rihanna is the youngest (I met her when she was just getting started and I collaborated with her on various projects) and she is looking for her own style. She is so fierce that when she does find it she is going to nail it.

How can we forget, after her recent passing, Tina Turner, “Queen of Rock’n’Roll and ’80s Pop.” With great strength and courage, Tina freed herself from the physical and psychological violence Ike Turner subjected her to, becoming a feminist icon, a phoenix who conquered the world with her energy and her famous legs (her nickname was “The Legs”), which her manager even went so far as to have insured.

How can we ever forget her quick moves in minidresses and booties that always left her legs exposed, to the joy of her fans. In a famous interview that has gone down in history, she said: “I am as famous for my legs as much as my voice.” She was simply the best! For her looks, her voice, her performances, and her successes, Beyoncé is the heir to the title of “The Queen.” Great performer, great voice, and already with a series of huge hits. It is a big responsibility to have to follow in the footsteps of “The Queen” Diana Ross, especially as concerns style . . .

But the “Natural Woman” whom all of these great female artists came after and to whom “Respect” is due is the legendary Aretha Franklin. A virtual bow to her.

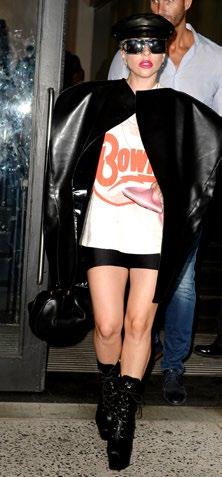

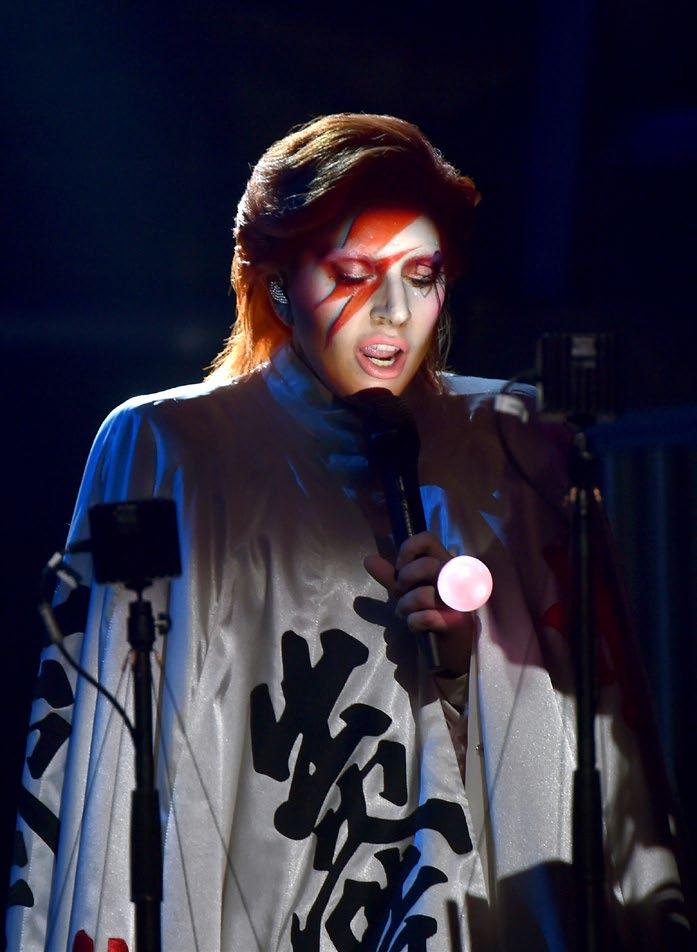

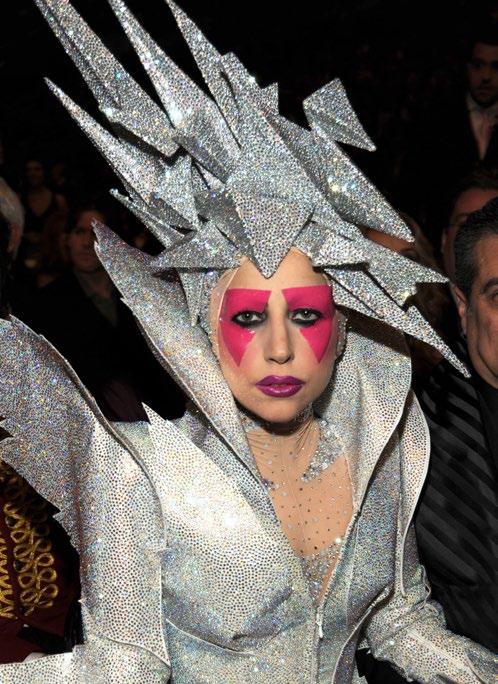

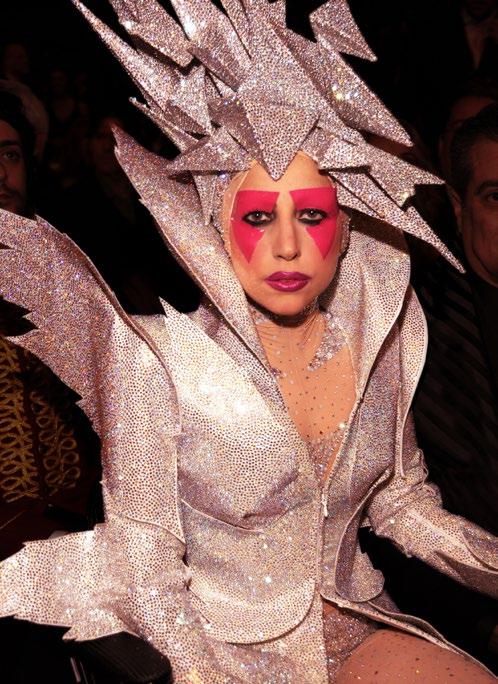

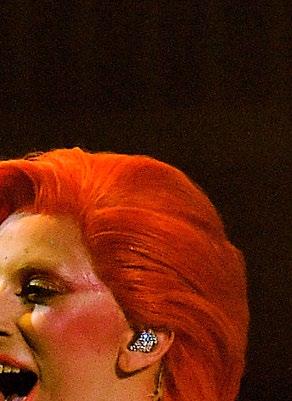

And now to today. After Muse, Daft Punk, Arcade Fire, Beyoncé, I have asked myself this question: who might be David Bowie’s female alter ego on the contemporary scene?

Thanks to her skills as a vocalist, musician, actress, and performer, I have no doubt: Lady Gaga. And she has never hidden the fact that Bowie has influenced her work. As you can see from the images, I have at times copied the same look, the same makeup, and the famous lightning bolt, to which I added a spider

But, above all, leaving her artistic talent aside, we need to acknowledge her amazing ability to completely transform on stage, on her album covers, during photo shoots, where she looks different each time while still maintaining a very strong identity and personality. I came close to meeting her during the Grammy Awards in LA, when I approached this strange and alien sculpture surrounded by models resembling vestals. “Nice to meet you, Gaga,” I said to her, but she was inside a plastic egg and I do not think she heard me. When she got up on the stage, the eggshell broke and out came Gaga. Wow! All covered in buttery latex, her eyebrows dyed so she would look like an otherworldly creature, in a design by Hussein Chalayan to launch her new single “Born This Way” (2011). Whether you like her music or not, we were all on our feet at the Staples Center dancing and cheering. I will never forget the fantastic duet by Eminem and Rihanna, who also won a Grammy for Record of the Year, with Arcade Fire for Best Pop Performance, and the rock moment of a very fit Mick Jagger wearing a peacock jacket and shirt, singing “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love.” What can I say? For me it was like walking on sunshine.

In “Ashes to Ashes” the astronaut from “Space Oddity” is back. The memorial of the ill-fated Major Tom serves as a plot device to describe the “Bowie 1970s”—exciting years professionally, but difficult ones on a personal level. The main character of the piece that accompanies Humanity’s first steps on the Moon is celebrated by Bowie, with a dedication that sounds like a funeral oration—“ashes to ashes, dust to dust”—before he disappears into outer space. The Major in the 1980s song was different from the one in 1969: the first incarnation is closely linked to the positive atmosphere of the hippie years, while the version in Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) is the offspring of Bowie’s bitter analysis of his life up to that point, which included drugs, excesses, and divorce from his wife Angie. Bowie’s Harlequin (for many years his last mask) clearly suffers as he crosses the video clip. This is one of the most expensive and innovative video clips of the 1980s, thanks to the sound/image dialectics, mixed in with fragments of experience and dreamlike-surreal visions, eventually expressing the solitude of the musician locked away in a world of his own.

Bowie does not want to look back, and he says farewell to his great past with an epitaph filled with angst and melancholy, analyzing, between cynicism and severity, the first act of his career (I’ve never done good things / I’ve never done bad things / I never did anything out of the blue)

As concerns Blackstar : “By the time he made his surprise reemergence in 2013 with his first album in a decade, The Next Day, [Bowie] had pulled off a feat that no other rock star has quite managed, regaining all of the heady mystique of his breakthrough years, and then some. He was a legend, a living ghost, hiding in plain sight, walking his daughter to school, taking cabs, exercising alongside ordinary humans in workaday gyms in Manhattan and upstate in Woodstock. With his family, he said, he was David Jones, the person he had been before he assumed his stage name. He had, at last, truly fallen to Earth, and he liked what he found there.” (From Brian Hiatt, “Inside David Bowie’s Final Years,” Rolling Stone, January 27, 2016.)

Indeed, the last three years of life before he died were, for the White Duke, a moment of prolific, amazing inventiveness: “In 2014, he began work on another, even better, album, Blackstar, while also helping bring to life an ambitious off-Broadway show, Lazarus , based around his old and new songs. He died on January 10, two days after the release of Blackstar and a month after the opening of Lazarus . His passing occasioned the kind of worldwide grief not seen since the deaths of Elvis Presley and Michael Jackson. [Anthony Edward] Visconti, who knew of Bowie’s illness, noticed the tone of some of the lyrics early on. ‘You canny bastard,’ Visconti told him. ‘You’re writing a farewell album.’ Bowie simply laughed.” (From Brian Hiatt, “Inside David Bowie’s Final Years,” Rolling Stone, January 27, 2016.)

When you think about rock, you think about the body, too, and when you think about David Bowie, you think about both the body and rock. And from this point of view, the body is in fact one of the key elements in our deepest understanding of rock music, a distinguishing trait that marks the personal and collective identity of a form of sound, where physicality is of primary importance, equal to the musical code itself, both of which are in a dialectic relationship with the languages of the performing arts and media technologies. In short, rock consists of a body on the stage, endowed with artificial appendages, from the electricity to the amplification, from the look to the images. The origin of rock as the music of the body comes from very far away: from jazz music and, before that, from the singing and dancing of Black Africa. In so-called primitive societies, from Senegal to Nigeria, from Mali to the Congo, like in other parts of the planet, music has always expressed a symbolic value with strong magical-religious elements. In the African world the sound is part of a ritual in which the spirit and the flesh, prayer and ceremony, dancing and singing, voice and orchestra are intertwined. In jazz, which, from an anthropological standpoint, developed thanks to the mingling of African and American cultures, the body has only to a certain degree preserved the transcendent aspect of the musical action: in Gospel music and the blues there’s an almost mystical physicality, while in jazz that has evolved thanks to its encounter with European models. The body is sublimated by the musical instrument and at times by the human voice as well. The jazz musician who improvises on the sax or the piano, or the singer who does scat or sings in vocalese, manifests their corporeality at the moment of the performative act, thereby eliminating the traditional (and typically Western) distinction between performance and instantaneous creation. With respect to jazz, rock represents both one step backward and one forward in terms of the body’s expressiveness. Rock can be traced back to African-American music—the blues, boogie, R&B, and jazz itself—simplifying every harmonious, tonal, rhythmical exploration, instead conferring greater credibility, which is often absolute, to the physical impact of the performer: almost always the singer or the guitarist with an electrical instrument. The public, in turn, introjects what it sees, thus dispensing a projective sign vis-à-vis its own idol, assuming the same corporeality while listening live or to recorded music in a public place. But listening is no longer the same in rock; and at the moment of the performance, unlike modern jazz where participating in concerts has become a ceremony much like that of a classical music event, rock shakes the bodies, triggering those on the receiving end of the communication in an almost tribal way: the performer (the rock star) and the listeners (a young audience) become one when the

physical contact occurs, eventually metaphorically identifying with each other. When the metaphor appears weak, it simply means that the performer’s stardom has shed its legendary aura, or it has moved too far away from the sources of inspiration or from the primitive fire. In short, he or she is not a real performer.

“Changes” was a key piece in Bowie’s repertoire, believed by many to be a sort of manifesto of the White Duke’s music. Like many songs over the course of history, at first it almost went unnoticed, but in time it became a symbol of its author and of pop culture. It is important to recall that “Changes” came out as a 45rpm on January 7, 1972, and it was also the first single lifted from the album Hunky Dory (1971), Bowie’s fourth studio album and, like the three previous ones, not a major success. It was, however, reappraised when The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the “Spiders from Mars” came out, which took it to the number three spot in the UK’s top ten list eighteen months after it was first released.

Today, “Changes” is legendary since it is the very last piece that the singer performed live before retiring from the scene.

There has always been a lot of talk around the meaning of “Changes.” Although at first it might sound like an ode to the rapid transformation and never-ending changes in Bowie’s roles, upon closer examination the song reveals a wry reflection on the critical changes in human life. Behind the catchy refrain, Bowie recalls his career and the many false starts (“a million dead-end streets”). But he is not just thinking about his failures and his self-reinventions; he is above all reflecting on the image of the artist as it is perceived by his fans in the many frustrating attempts to create a work that will endure the test of time.

“Changes” is thus an all-important piece in the history of the song, one of the few that joins the traditional pop song structure with genuinely autobiographical lyrics. The author, by referring to himself as almost a liar, seeks an existential balance, underscoring the problem of having to believe in his own public image and at the same time denying the emergence of a genuine identity.

Many music critics have also noticed that the stuttering sound of the line “Ch-ch-ch-ch-changes” might be a nod to the song “My Generation” (1965), written by Pete Townshend for The Who. The phrase “I hope I die before I get old” in the latter composition becomes “Pretty soon now you’re gonna get older” in Bowie’s version. The suggestion here is that even in the world of rock music, time passes for everyone, so it is better to be prepared to accept this stark truth. In addition to its existential-philosophical theme, “Changes” also deals with generational conflict: the clash between the young and the old. This is in part due to the poetics of a young Bob Dylan, for instance in “The Times They Are A-changin.’” And the times really were changing for everyone.

David Bowie died during the early morning hours between January 10 and 11, 2016, just two days after the release of his last great recording effort, Blackstar. The death of the White Duke shocked the entire music and art world, where he left a void that will never again be filled completely. At the time no one knew exactly where he died; the media reported that it was in some unidentified place, presumably a cancer clinic in New York state. As the liver cancer he had been struggling with for years grew worse, Bowie chose euthanasia to put an end to the atrocious pain caused by the illness. In the days following the tragedy, his friend Robert Fox confided that the singer had wanted to try out a new experimental cancer treatment, but that when he realized his end was approaching fast he chose assisted suicide instead. Very few people knew of his decision at the time.

Diamond Dogs by David Bowie. In spite of his importance as a pop star, in the early 1970s Bowie was unable to obtain the rights to adapt the dystopian science-fiction novel by George Orwell, 1984, so that he could turn it into an opera in the glam rock style. Regardless of this setback, Bowie wanted to use the theme of a dystopian society, so he turned to Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis . The results of his efforts were hits like “Rebel Rebel.” Without the original sarcastic comment on atypical cultural values, however, the lyrics, especially on the A side of the LP, seem out of place, capable only of being adapted to a few good ballad or hard-rock riffs. In the second half of the album, the future London minstrel explores Orwell’s ideas via narrative, in the style of William Burroughs, that is rather more explicit, starting with the titles of the pieces that are, unsurprisingly, “1984” and “Big Brother.” And yet it is hard to listen to the album as something very complex or structured, because the songs it contains are not coherent with respect to the themes expressed in the opening track “Future Legend”: the latter song envisions a world with “glitter apocalypse” and humanoid inhabitants in a wild race, like packs of ravenous dogs. Listening to it today, we realize that Diamond Dogs is half-finished with respect to the previous Ziggy Stardust ; however, it continues to be one of the best concept albums ever because of its perfectionist completeness.

David Bowie, going by the name of Edwards. In 1972, David Bowie publishes The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust, a rock “classic” and one of the most successful albums ever according to the public as well as the critics. Forty years later, a cover of “Starman” (one of the best songs on the album) performed in a Soul version by an unknown vocalist named Milky Edwards becomes a huge hit on YouTube. Other covers of Bowie’s work under the name Edwards appear on the web. The narrative created was of an artist, Milky Edwards, who has been gone for decades and has suddenly been reborn. But it is all just a fabrication, discovered after a group of music fans did some research to try to clear things up. The cover of the album, a still image in the YouTube video, seems to represent more of a 1960s style, while the record was released a decade later. The “new” recording can be manipulated digitally, in a totally different way with respect to the sound of vinyl played on an “old” record player. And the fact that Milky and his band The Chamberlings suddenly go from being virtually unknown to the limelight seems too easy, especially when listeners are told that the singer has been dead for years, with the aggravating circumstance that there is no authentic information about him or the members of his group either on the Internet or in books and magazines. Some fans believe, however, that it does not matter whether his recordings are counterfeit. They feel that the music is too great to be ignored, regardless of its possibly fraudulent origin. Still today, Milky Edwards and “his” “Starman” have many listeners on YouTube and on other social media, in spite of the fact that he is likely an abstract entity and therefore a historical impostor.

The music of the younger generations, from the 1950s to the present day, is not disconnected from the epic changes that also revolutionized fashion. Casual, prêt-à-porter, unisex: a more or less spontaneous patchwork transformed bourgeois taste that had once been linked to Parisian couture or to the equally fine styles of Italian dressmakers. Before the fashion designers of the 1980s—Italians, above all, but also Japanese, English, American, who were highly skilled at exploiting the postmodern generational trends for the purpose of showy, superficial, materialistic, and oligarchic hedonism—there was a great deal of creativity in the fashion world, and this included David Bowie as an emblem and a precursor.

Fashion in the days when Bowie first appeared on the stage, with models like Veruschka, Twiggy, and Jane Asher, who were closely tied to the hippie phenomenon, was divided into two major currents. On the one hand, some of the most famous brands even reached into the figurative arts: Paco Rabanne, for instance, was a key figure in op art and programmatic or kinetic art. On the other, there was a more spontaneous taste aimed at more freedom. The “let’s take fashion back” look had actually begun after World War II, and was especially true of men’s fashion, in which middle-class American youths were drawn to a proletarian style, i.e. jeans, T-shirts (Calvin Klein), motorcycle jackets, and sneakers.