Yasmine Chouman

In a bustling metro station, I am on a mission to find RoseMary Whalley—an 82-year-old anti-war activist.

A few months ago, I briefly interviewed her for a radio show about her decades of activism. Her story stuck with me—I wanted to know more.

Amongst the sea of people, I recognize her by her little stature and purple hat. There she is, leaning on her cane and reading a book.

To the naked eye, she may just look like any other older woman.

But she is full of stories.

Whalley has been protesting against the use of nuclear weapons for nearly seven decades. At just 14 years old, she was marching the streets of England for the Ban the Bomb movement every weekend.

“A lot of people go to parties when they're young,” Whalley says, “but I went to demos.”

After we walk up and down St. Denis St., she takes me to this quaint vegan buffet.

“I’ve been [protesting] for a hell of a long time,” she says, taking a bite of her food.

After over six decades of protesting outside grocery stores and marching in the streets, Whalley’s energy may be worn—but her spirit isn’t.

She hands out flyers about Canada’s complacency with the war in Gaza three times a week at different metro stations with two other older women.

One of these women, Laurel Thompson, is considered by Whalley to be “the boss” of the group. Thompson is 88 years old, but fierce as ever.

Many of the older women activists we see marching the streets today were once the courageous young activists of the '60s.

They are fighting the fight decades later, but this time with greyer hair, slower steps and more wisdom.

They are called the silent generation, but they are pretty loud about social justice. In 2018, 32 per cent of elders from the silent generation volunteered in some form of activism, averaging 222 hours a year, according to Statistics Canada.

After retirement, older women who are passionate about social justice have been dedicating their time to using their voice for change.

For Whalley and Thompson, this passion of theirs has only grown stronger since they first started protesting in the '60s—the era of revolution.

The student movements of this time came

together in protest against the Vietnam War, and for environmental issues, the women’s rights movement, civil rights and gay rights.

At the time, Whalley focused her activism on opposing war and banning nuclear weapons.

“I grew up knowing the horrors of war,” Whalley says, her eyes turning red and teary, “so doing activism is a no-brainer.”

Genocide and war are not unfamiliar subjects in Whalley’s family.

Many of her family members were murdered in concentration camps, including her grandmother.

Her mother, a Holocaust survivor, fled Berlin, where she met Whalley’s father in England—a British soldier who fought in one of the most violent battles of World War I, the Battle of the Somme.

This family history shaped her worldview and fuels her urgency today.

In today’s political climate, particularly with the ongoing genocide in Palestine, she feels it is her duty to speak out now, perhaps more than ever.

Whalley has never been in a situation where so many people have come together in opposition for a long period like this.

“Mind you, I’ve never seen a genocide like this,” she says. “This is the worst thing that’s ever happened in my life.”

Thompson shares this passion.

During a phone interview, Thompson tells me she has been involved in activism since the Vietnam War, when she was 22 and a student at York University in Toronto.

“As I got older and started to be an independent woman, I just saw stuff that I knew was not right,” Thompson says, “I

knew I wanted to fix it—or try to fix it.”

At the metro station, Thompson boldly talks back to an officer who tries to stop them from giving out flyers.

“He’s full of himself and thinks he's a hotshot, and is going to tell these women to shut up,” Thompson says, turning to us.

“Fuck you,” she whispered, flipping them off.

I was surprised by her vigour. This feistiness has stuck with her since she was in her 20s.

When I asked Thompson about being an older woman activist, she told me it feels the same as it did when she was 22.

“You made me realize I think I’m younger than I am,” she says with a chuckle.

Back at the restaurant, Whalley tells me about the privilege of being an older woman activist.

She says older women’s presumed innocence and fragility allow them to get away with more shenanigans, without the violent repercussions that the younger generation could not.

“It would take a really inhumane cop to beat the shit out of somebody like me,” Whalley says.

I ask her if she’s been harassed by the police before.

”I’ve been arrested a few times,” Whalley says, chewing her noodles casually. “It’s not important—I haven’t been arrested enough.”

Whalley and Thompson are not the only older women activists standing up against human rights abuses in the city today.

One other group—or gaggle, as they say—that is well-loved across North America is the Raging Grannies.

You might catch this large group of older women wearing grandma-like clothing—long skirts, aprons, shawls draped over their shoulders and funky hats with activism-related badges and buttons—and brashly singing “fuck the government” versions of classic tunes.

Sheila Laursen, an 80-year-old Montreal Raging Granny, has been raging since 2010.

At a no-screen cafe, she tells me about what it means to be a Granny. As Laursen explains, it all started with the Victoria Grannies in 1987.

“They were outrageous,” Laursen says. She liked their whole idea. The performative art of activism.

After retiring from the YMCA, she knew her destiny was to be a loud social activist. We sip our coffees and pick at our scones, while she shows me the heavy pile of Raging Granny newspaper archives dating back to the 90s.

For decades, these bold older women have been raging about climate change, national politics, Indigenous rights, women’s rights and anti-war across Canada and, more recently, the United States.

These women have dedicated years of their lives to social justice, yet they are still fighting the same fight Whalley admits.

“In the late '60s there was an upsurge of young people who didn't like the way things were, and decided they wanted to change it,” Thompson says, “and the same thing is happening now.”

She says that because of social media, Gen Z is awake to “what the West does” and its complicity in war and genocide. They choose to continuously fight alongside the younger generation today, in hopes of the future they waited for all those years ago.

“As long as I’m able to walk and talk,” Thompson says, “I’ll be fighting for peace.”

The weekly jam thrives on openness, trust and risk, bringing generations of artists together in one room

Safa Hachi

Onursday nights at O Patro Vys, the music begins without a setlist, but always with purpose.

“A good jam sounds like a song and a bad jam sounds like a jam,” founder and bandleader Vincent Stephen-Ong says.

It’s both a mantra and a challenge, one that has carried the collective through more than a decade of weekly sessions.

Le Cypher X started at Le Belmont in 2014 but took shape at the now-closed Le Bleury bar à vinyle in 2015, before eventually moving to its current home on Mont-Royal.

Stephen-Ong describes the jam as a space that balances openness with musical discipline. Rather than exclusivity, the jam focuses on creating an environment where musicians can thrive together.

“We want to create a space where people are listening, where everyone ampli es each other,” he says. “It’s not just about chops. It’s about serving the music.”

Stephen-Ong is a saxophonist and keyboard player, as well as a freelancer, content creator and performer who has worked with countless groups across Montreal. Alongside performing, he also helped lead workshops with Kalmunity, an improvised collective that blended styles like hip hop, soul, reggae and Afrobeat.

sessions,

In those sessions, he posed a multitude of questions: How do we do what we do? What are our goals, and how do we get out of problem areas when the music breaks down? at process pushed him to think more deeply about the chal-

lenges of improvised music and the strategies needed to turn raw, unpredictable moments into something cohesive.

For drummer Shayne Assouline, Cypher became the place where persistence met mentorship. His introduction was humbling, and he jokingly admitted his rst jam was a mess.

“I really did not do well, like I did such a bad job,” Assouline says.

But instead of shutting the door, Stephen-Ong guided him.

“He’s very approachable, and he’ll tell you what you need to hear, the things a lot of people won’t say, but he does it in a way where you know he cares,” Assouline says.

Over time, he practiced harder, made connections, and learned by watching players who inspired him to keep going.

“My name went up the list, and now I’m beyond the list,” Assouline adds.

Looking back, Assouline credits Le Cypher with shaping his path.

“If I had never gone to Cypher, I would have never started my own jam,” he says. “I built my career from being seen there and from playing with these guys all the time.”

at jam, Growve at Turbo Haüs, is now a weekly xture he runs with Marcus Dillon, one of the collective’s vocalists and MCs, and another Cypher regular, Shem Gordon.

tapped him on the shoulder to wait his turn asked him to host.

“I guess he thought I was a good MC,” Dillon adds. “He saw that I could hold the idea together and help it move forward.” at mix of risk and trust de nes the night. Sometimes the sound is seamless; sometimes it frays.

For Dillon, what matters most is the space created for whoever’s ready.

“If you’re in the front of the crowd and you feel like you could be attached to this song—let me know, and I’ll get you on stage as soon as musically feasible,” Dillon says. at willingness to give the mic to whoever feels ready connects directly to how Le Cypher X began.

“A lot of it came from just being at house parties with other musicians,” Stephen-Ong says. “ at’s the energy I wanted [...] putting di erent talented people together can lead to something unexpected.”

A verse might fall at, a beat might stumble, but the chance that it all clicks and that a song takes shape in the moment makes the night worth it.

For Dillon, the jam represents both stage and classroom, as music didn’t arrive through formal training but through the

love of language.

“I’ve always been fascinated with the good use of lyricism, timing, double entendre and rhetoric. I’ve always loved good words,” Dillon says.

Dillon recalls looping rapper Nas's verses on an MP3 player and rewriting them line for line, sharpening his cra in private before stepping into public.

Stephen-Ong’s projects have always pushed for that balance between precision and play.

When he rst came to Le Cypher, he immediately felt the impact of the lessons.

“I would want to rap so bad that I would get on stage and grab the mic and confuse the whole band. I had no idea what I was doing,” Dillon says.

Alongside Le Cypher X, he leads the Urban Science Brass Band, a New Orleans-style ensemble that brings hip hop into the streets with horns, percussion and MCs. Both projects reflect the same instinct: to make music that feels alive, accessible and communal.

“At the core, what I hope for is really simple,” Stephen-Ong says. “ at you come, and you have fun. Maybe you meet someone, maybe you take something positive with you, even if it’s the only time you ever come. at’s it.”

Assouline urges jammers to lean into discomfort and surround themselves with people who push them forward.

“Being good is really easy, but getting good is kind of hard— and we should get better at getting good,” Assouline says.

Cypher, he says, is the only space where, no matter your level, there’s going to be someone else there who will inspire you.

Years later, the same band-

leader who

“Everyone wants to be there to kind of experience the same thing as you, so there’s something that connects you and that other person across the room that has a whole di erent thing going on,” Assouline adds.

e jam runs on community as much as it does on sound. Week a er week, strangers become collaborators, and collaborators become friends.

Stephen-Ong o en talks about the generational side of it: how veteran players share the stage with newcomers, and how each group pushes the other to grow.

Le Cypher X exists in that balance of improvisation and structure, risk and reward, chaos and cohesion. For Stephen-Ong, it’s about setting a standard that li s Montreal’s jam culture while keeping it open to anyone ready to take a chance. at same energy carries to the crowd.

“Le Cypher X makes Montreal feel small in the best way,” attendee Luke Savoie-Lopez says. “You realize half the city’s talent is right here, just waiting for a moment to show their skills.”

Or as Dillon puts it, “Your neighbours are crazy with it. And you probably didn’t even know.”

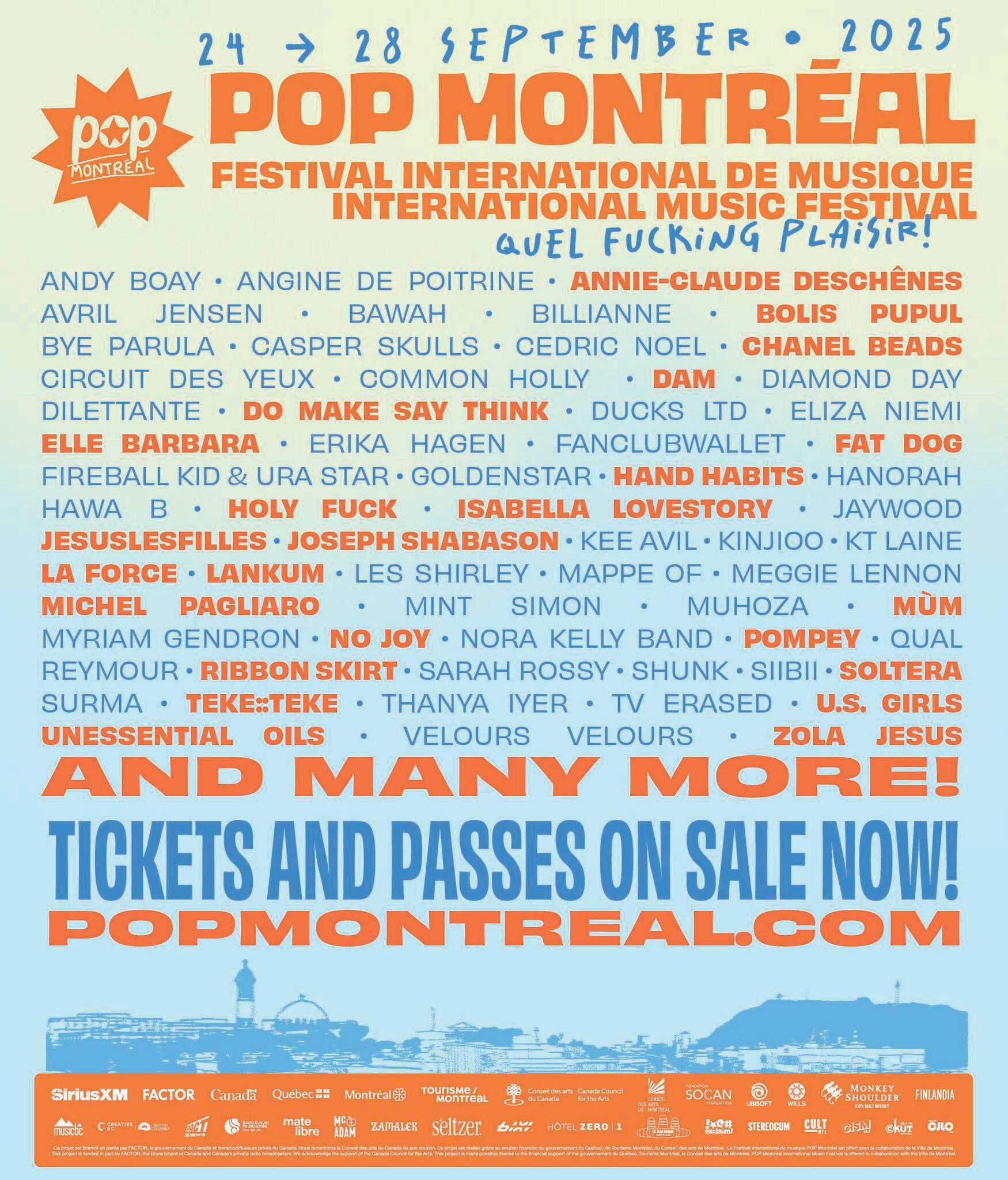

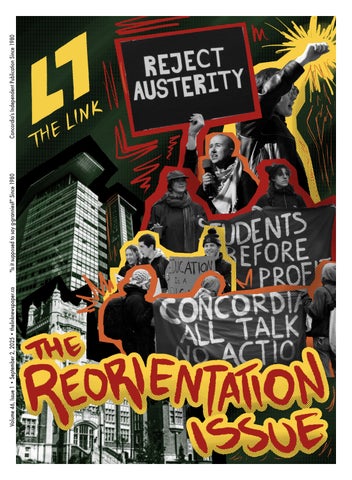

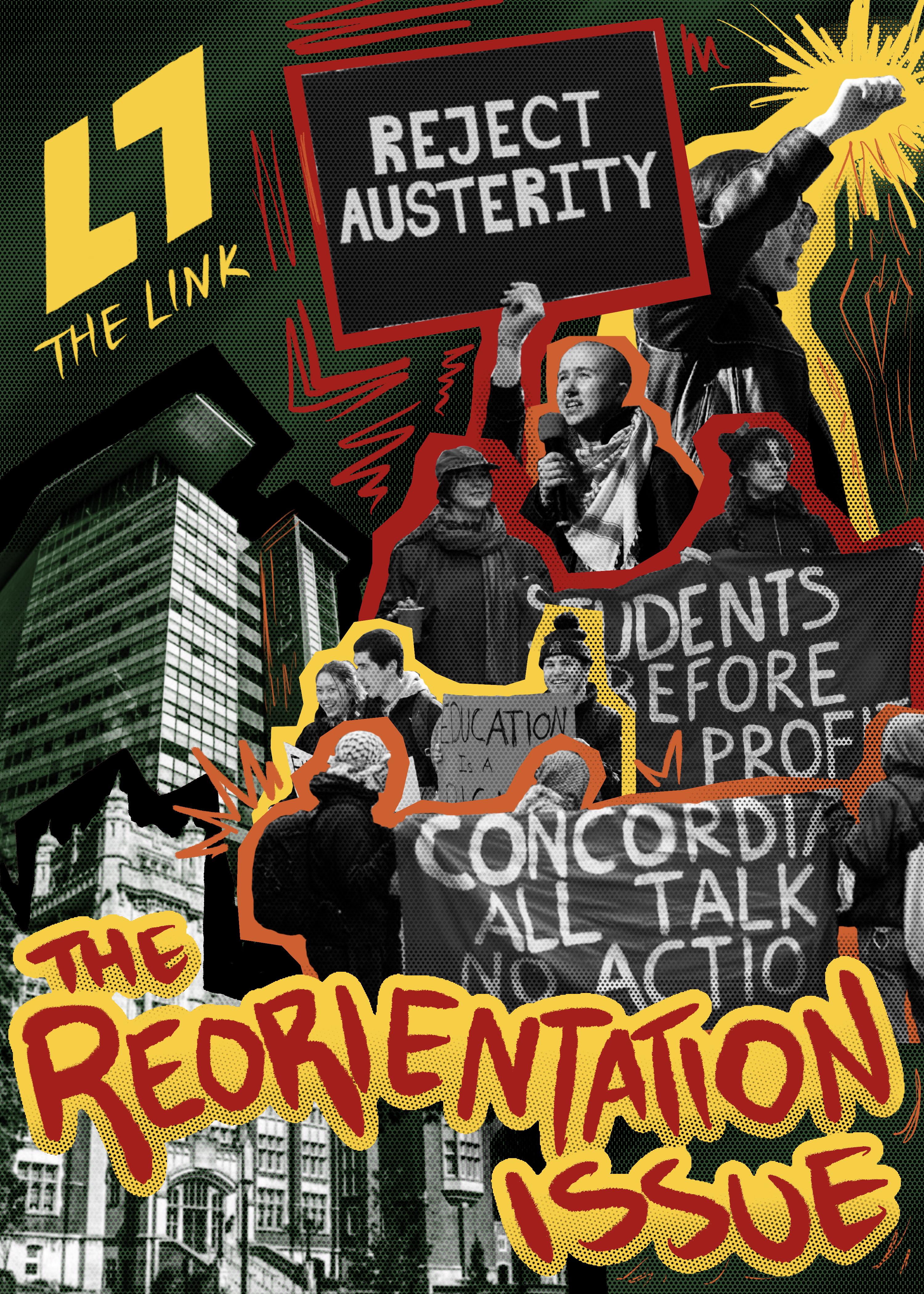

If you’re a student at Concordia University, you’ve probably seen a series of posters and promotional material the university sent out over the summer months.

From pamphlets boasting the university’s global high rankings to campus tours, emails, and Concordia’s carefully curated website, the university o en presents a glowing image of itself.

However, we at e Link believe it's important to remember that promotional material is just that, promotion, and serves as only one side of life at Concordia. As students begin to attend orientation seminars and introductory lectures, we believe it’s important to show you the other side of the story so that you can truly know your university, and not just what it wants you to see.

From this desire, the Reorientation Issue was born. Inside, you’ll nd articles on student activism at Concordia, the millions it collects in late fees and a practical guide to surviving your degree.

e Concordia website touts inclusive spaces and groups, and says it “works hard to foster a safe, accessible and inclusive campus.” While this may be true for some, other students have also reported feeling surveilled on campus in the past year due to police presence during political demonstrations at the university.

e Link also reported that Concordia repeatedly hired security ocers from a rm founded by a former Israel Defense Forces soldier, and even issued them CSPS uniforms.

e university has a long history of pro-Palestinian student activism. In 2002, Concordia students staged a demonstration, now known as the Netanyahu Riot, to protest the invitation of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to speak on campus. is movement has only grown in scope over the past years.

In January 2025, over 800 students gathered in the Hall building atrium and voted in favour of the CSU adopting two Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) motions. ese motions called upon the university to divest from companies complicit in genocide, to defend student activists from sanctions and to declare its support for a full arms embargo.

Following the vote, Concordia president Graham Carr released a statement reiterating Concordia’s position on “such boycott campaigns.” Carr stated that they “are contrary to the value of academic freedom upon which all universities are founded.”

international students, announced in 2023, have also remained a major point of contention at the university. Over 21 student organizations at Concordia went on strike in March of 2024 to show their opposition to the hikes.

e hikes forced Concordia to cut its budget and services, reduce the shuttle bus schedule, freeze hiring, and cut course sections or entire courses altogether. Nonetheless, Carr received a raise of over $30,000 in 2023-24, bringing his total salary to over half a million dollars. e university now faces a starting decit of $84 million for the 2025-26 academic year, to boot.

e statement drew criticism from some activists and student organizations, who said he was seeking to silence pro-Palestine students.

Last year, political action at Concordia went beyond just students. Two workers’ unions at the university, the Concordia University Professional Employees Union and the Concordia Research and Education Workers Union, went on strike to push for better working conditions. Both eventually reached an agreement with the university.

Student unions at the university also faced criticism over the past year, with students raising questions regarding the level of the CSU’s transparency. e student union has also been accused of neglecting trans students.

Last September, three students were arrested at the Guy-Concordia Metro station following a walkout for Palestine. A month later, two students were arrested on campus at a Cops O Campus demonstration. In both instances, the university claimed that arrests only happened following the alleged assault of Campus Safety and Prevention Services (CSPS) o cers by protesters. is all culminated in the Concordia Student Union (CSU) holding a press conference in November, where it accused the university of police brutality and racial discrimination.

Despite this, for two days in November, over 11,000 Concordia students went on strike in support of an international university strike movement for Palestine. Mobilization included picketing classrooms and a rally at the Hall building, where students called for divestment and solidarity with Palestine.

To its credit, the university did disclose its $454 million investment portfolio in April a er pressure from activists. Included in its portfolio are companies that have been accused of complicity in the Palestinian genocide, like BlackRock and Boeing.

e Quebec government’s tuition hikes for out-of-province and

rough this issue, this editorial and our ongoing coverage of the university from which we operate, we invite you to remain critical and resist taking everything at face value. Ensure that you are well-equipped to understand the decisions your university and city make.

e Link has a duty to hold institutions accountable. We hope we have lived up to that responsibility, and that you will continue to hold us to the same standard. We hope this issue enhances your understanding of your university, your city and your place within them.

@india.db

From September 2024 through spring 2025, Concordia University saw on-campus policing, arrests during two protests, the hiring of private security and advisory council resignations.

This retrospective traces the flashpoints, how decisions were justified, who was affected and what demonstrators can take into this year.

The ashpoints

Sept. 25, 2024 – Walkout and three arrests. A daytime Palestine solidarity walkout travelled from the Henry F. Hall Building through campus tunnels and out onto the street. SPVM officers arrested three people at the Guy-Concordia Metro station on allegations of mischief, assault and obstructing a police officer, according to police quoted at the time. The arrested students were aggressively handled by police officers, with one woman yelling that she couldn’t breathe as an officer kneeled on her back, according to eyewitnesses. Concordia later said Campus Safety and Prevention Services (CSPS) had alerted the SPVM in advance and that one CSPS agent was assaulted while intervening in response to vandalism in the tunnel.

Oct. 31, 2024 – Cops O Campus and o arrests. A demonstration opposing police presence on campus ended with two student arrests. e SPVM and a university spokesperson said o cers intervened a er the students allegedly assaulted a CSPS agent. One protester alleged that one CSPS o cer began chasing a student through the tunnels before the student was detained by SPVM o cers in the LB building.

How Concordia’s art gallery entered the picture

e Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery was, perhaps unexpectedly, drawn into the year’s con icts. In November 2024, a scheduled artists’ talk became a surprise silent protest against the arrests of students in the vicinity of the gallery and the dismissal of gallery director Pip Day. Artist Ésery Mondésir criticized the gallery’s use as a “detention centre” during an Oct. 31, 2024, protest and alleged that the community has reason to believe Day was red because of her support for Palestine.

By January 2025, ve of the gallery’s eight advisory council members resigned. In their public letter, they pointed to “disturbing events” during the previous semester, including the arrests and the director’s departure. ey also argued that the university failed “to recognize the legitimate right of the entire Concordia community to peacefully and meaningfully express their solidarity with the Palestinian people.”

e university did not con rm any connection between the director’s dismissal and activism on campus.

More recently, on Aug. 18, artists scheduled for a gallery screening withdrew “in protest against the use of their work to artwash Concordia’s suppression of Palestine solidarity at the Gallery and on campus,” according to an Instagram post by Regards Palestiniens, Artists Against Artwashing, and Academics and Sta for Palestine Concordia.

How Concordia’s securi strategy shi ed

In November 2024, e Link reported that some students, particularly those from marginalized communities, said they felt surveilled and at times mistreated by campus security.

“You can see the shi ,” said a former student union executive at the time. “Security has become more aggressive with students connected to pro-Palestinian activism.”

A Concordia spokesperson told e Link that she encourages students who feel targeted by security to le a complaint with the O ce of Rights and Responsibilities.

For 14 days during the Fall 2024 semester, Concordia hired Perceptage International, an external rm founded by a former Israel Defense Forces soldier. According to university records obtained by e Link, the rm’s agents were issued CSPS logo patches and tasked with “crowd control and special intervention.”

Quebec to ban public prayer

A video posted on Nov. 22, 2024, on the Solidarity for Palestine's Honour and Resistance (SPHR) Instagram page, appeared to show the extent of security o cers’ intervention in student activism. In the video taken during the student strikes for Palestine, Perceptage and other CSPS o cers appear to be aggressively pushing students away from picketing actions and into the stairway of the Hall building, while students shouted: “Don’t touch them, don’t shove them, these are Concordia students.”

Concordia’s deputy spokesperson claimed the Perceptage agents were Canadian Armed Forces veterans and said supplemental sta ng was added a er reports of “aggressive behaviour, assault and vandalism” at demonstrations. Student organizers criticized the optics and reported rough handling during pickets.

Concordia also publicized protest “behaviour guidelines” at the start of the 2024 Fall semester, outlining existing rules for picketing, encampments and classroom access, and noting that breaches can trigger investigations and sanctions.

How student leaders responded

The Quebec government says it will table legislation this fall prohibiting prayer in public spaces. The move follows months of Sunday protests by Montreal4Palestine outside NotreDame Basilica that included group prayers. The Canadian Civil Liberties Association and other civil rights groups said the move would infringe on freedoms of religion and expression, among other freedoms.

LaSalle College fined $30M for breaking English enrolment quotas

Following the September and October 2024 arrests, the Concordia Student Union (CSU) held a press conference with allied groups, alleging police brutality and racial discrimination at the university, while demanding that police be kept o campus.

On Jan. 29, 2025, over 800 undergraduates voted to mandate the CSU to adopt two Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions motions for “ nancial investments which are currently held in funds complicit in or which bene t from militarized violence, war, colonialism, apartheid, and genocide.” Concordia president Graham Carr released a statement the next day saying that such boycott campaigns run “contrary to the value of academic freedom.”

A week later, Concordia opened an investigation into how the special general meeting was conducted and suspended the CSU’s ability to book campus spaces, citing alleged policy breaches, pending the outcome. A er the CSU sent a legal demand and sought relief in court, Concordia temporarily restored limited booking rights so elections could proceed.

Can you s ll protest safely?

Knowing Concordia’s protest guidelines can be helpful. Being aware of the limits—such as restrictions on blockades or classroom access—can help participants anticipate when police might be called.

Montreal’s LaSalle College has been fined nearly $30 million for exceeding government quotas on English-language programs, with over 1,700 students enrolled beyond the limit for the 2024-25 academic year. The school’s president, Claude Marchand, says the penalties threaten its survival and that he had pleaded for a grace period, as businesses adjusting to Bill 96, Quebec's law to protect the French language, had received. The o ce of the Quebec minister of higher education said the reduced fine rate in the first year was the transitory period.

Poor air quality projected to cut Canadian life expectancy

Documentation is one of the strongest forms of protection. Protesters who record events through video, photography or even audio recordings create a public record that can later be used to clarify disputed accounts. It is also helpful to plan exits in advance and identify safe meeting points should a demonstration be dispersed.

In practice, protests on campus may not be risk-free but no protest is without risk. How 2025-26 feels on campus remains to be seen.

The University of Chicago’s Air Quality Life Index warns that wildfire smoke could reduce life expectancy in parts of Canada. In 2023, the country’s worst wildfire season saw PM2.5 (fine particulate matter) pollution rise by 50 per cent, a ecting half the population. The hardest-hit regions were the Northwest Territories, British Columbia and Alberta.

Manoj Subramaniam

@manojourno

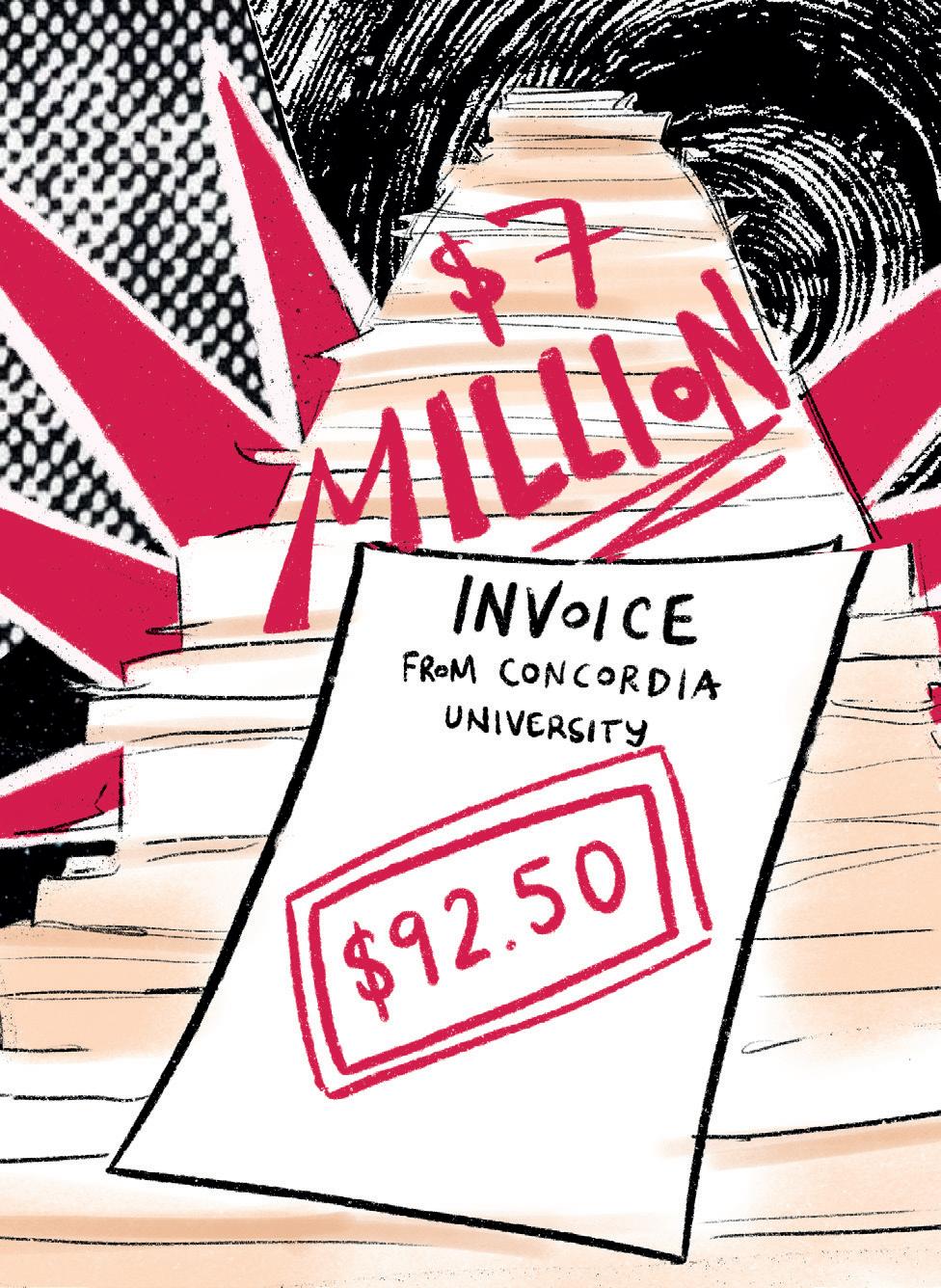

Concordia University collected over $7.2 million from students in late fees and other penalties from 2021 to 2024, according to data obtained through an access to information (ATI) request.

In that four-year period, the university charged over $4.5 million in late fees and collected about $4.3 million of that amount. It levied nearly $3.1 million in interest charges, of which $2.6 million was collected.

Meanwhile, penalties for insu cient funds —when a bank account doesn’t have enough money to cover a payment— totalled $48,345.

Overall, Concordia collected over 91 per cent of the various penalty charges assessed during the period.

e ATI also showed that the university uses a third-party collections agency to recover money owed to it. It declined to disclose the contract or provide data on how much was collected through the agency, however, citing exemptions for “industrial secret” under the ATI law.

Table showing various penalties levied and collected by Concordia University from 2021 to 2024. (Data Courtesy: Concordia University)

Shakya Don, a second-year international student at Concordia, paid the fees for the summer 2025 semester a week a er the deadline. He said he was worried not only about the penalties, but also whether the late payment would a ect his course registrations.

“I was de nitely a bit scared because already it's a big price to pay, and on top of that, I was a bit worried about having to pay even an additional amount,” Don said.

Late fees of $92.70 are applied if a student doesn’t pay their fees within 30 days of the start of a semester, according to the university's policy outlined on its website. e university also charges interest on any unpaid balances at a rate of 8 per cent annually, which gets compounded monthly.

In addition to penalties, the policy states that students with outstanding balances cannot register for additional courses or graduate.

Concordia Student Union (CSU) councillor Nathanael McCooeye said that while he believed some penalty was justied, the $92.70 late fee was steep.

“Students are typically not among the most a uent or autonomous of demographics to be drawing resources from,” McCooeye said.

Another ATI request showed McGill University charged over $6.4 million in late fees and interest on outstanding balances during the same period. However, the school didn’t specify how much of this was collected.

Concordia had a total enrolment of 45,445 students compared to McGill’s 39,380 in 2023, according to their respective websites. e period covering the information requests, 2021-2024, also saw some of the highest in ation rates in decades in Canada, while Montreal’s housing costs surged as vacancy rates dropped to a historic low of 1.5 per cent in 2023.

Youth unemployment also remained high, with Statistics Canada reporting a 14.1 per cent joblessness rate among those aged 15 to 25 in July 2025—more than double the overall rate of 6.9 per cent.

At the same time, the university has also faced cuts in government funding and declining enrolment rates, putting pressure on its nances.

Fortier said that the university may o er a payment agreement to students facing nancial di culties in some cases, if they are unable to pay their outstanding balance. is would remove any holds on their account and allow them to register for classes.

McGill did not provide comment in time for the publication of this article.

Concordia spokesperson Julie Fortier said that, like any organization, the university enforces deadlines and late fees.

“Ensuring we get the revenue we have budgeted has been especially crucial during the period [from 2021 to 2024] since we have faced a deficit for the past few years,” she said in an email to e Link

McCooeye said it would be problematic if the university relied on these penalties as another source of revenue. However, he doubted that was the case, given the amount was small relative to the university’s budget.

“If what they are saying is, ‘In a di cult economic time, Concordia cannot a ord late payments,’” he added. “I think this is understandable.”

The People’s Potato and the Hive Free Lunch say they are at capacity as more students face food insecurity

Kara Brulotte

@kara.brulotte

Free campus food programs at Concordia University, including e People’s Potato and the Hive Free Lunch, say they are struggling to keep up with growing student demand as higher living costs push more students into food insecurity.

A 2023 study conducted by the university found that more than half of Concordia students reported experiencing some level of food insecurity. Another study conducted by Moisson Montreal showed that the proportion of student food bank users has reached 14.1 per cent in 2024.

Since then, the cost of groceries has continued to rise, increasing the pressure on on-campus food programs.

“ e demand for our services is so high that we are not physically able to meet the demand ourselves,” said Simona Bobrow, a member of e People’s Potato collective.

The Potato operates a community garden at the Loyola campus, an emergency food basket program for people in need, and a free lunch service during the school year on the downtown campus.

According to Bobrow, these programs excel, with the lunch program feeding up to 500 people on a good day. Concordia student Marissa Guthrie is one of these students.

“I go to e People’s Potato every day it’s open, regardless if I have a class that day,” Guthrie said. “My experience has been really positive; the food is always good.”

e Hive Café Solidarity Co-op runs a similar program on the Loyola campus. e Hive Free Lunch sees around 200 people a day for free breakfast and between 2 to 500 people for free lunch, according to program coordinator Alanna Silver. Whatever food isn’t used gets put in a community fridge,

so nothing goes to waste, said Silver.

Concordia Student Union (CSU) Loyola coordinator Aya Kidaei said the Hive Free Lunch program is one of her go-tos on campus.

“I eat there every day,” Kidaei said. “It's a very beloved service at Loyola; everyone I know goes there to eat.”

Silver said she hopes to be able to serve free dinner in addition to breakfast and lunch, in order to give students with evening classes a more a ordable food option.

“Success to me would be getting enough funding to do the dinner program,” Silver said, “but also being able to give away free groceries, to fully eliminate food insecurity on the Loyola campus.”

Both groups have had fee levy increases in the last few years, allowing a bigger budget to provide more food for Concordia students.

However, they say budget constraints remain one of their biggest obstacles.

“If we could, we would feed thousands of people every day,” Silver said, “but we have certain budget and kitchen constraints.”

e program coordinator said all the money currently distributed from the CSU and from the Arts and Sciences Federation of Associations (ASFA) fee levies is in use, and more funding would be needed to expand services.

At the same time, the Potato has received requests from students interested in starting similar groups. But Bobrow said kitchen space is limited.

“ e kitchen space is one of the things that makes the Potato possible,” Bobrow said. “ e university was never forthcoming about providing kitchen spaces like that for students because the corporate food supplier is prioritized.”

is food supplier, Aramark, partners with Concordia and currently operates the university cafeterias on both campuses.

According to Silver, the Hive currently receives around 150 thousand dollars of funding per year.

“Budgetwise, I don’t know if it’s possible to expand [the Hive’s budget],” Kidaei said. “ ere’s so much bureaucracy, but I think it’s doable.”

e Potato, though not currently working on introducing any new programs, aims to expand its current services.

With the fee levy increase of 16 cents per credit it put in place last year, the collective was able to hire an extra member and run their emergency food basket program throughout the summer for the rst time.

Guthrie said this made a real difference in her expenses.

budget,” Guthrie said. “Everything I eat there is stuff I’m not buying.”

Despite these e orts, coordinators say food insecurity among students is a structural issue.

“Our projects are successful,” Bobrow said, “but they’re always gonna be a band-aid solution when the system is creating this problem of not being able to meet basic needs.”

With future initiatives put into place, both groups say they hope to continue making food accessible to the student population.

“No one should ever have to choose between paying tuition and paying for groceries,” Silver said. “A lot of students pay tuition, they pay their rent, they pay everything else, and then food comes in last place. You shouldn’t have to put yourself in that position.”

“It does help me save on groceries—probably about a third of my

Concordia University updated its procurement practices to shi away from U.S. suppliers in response to the ongoing U.S.-Canada trade war, according to an access to information (ATI) request.

From advancing purchases and prioritizing local and nonU.S. suppliers to negotiating with vendors, the documents obtained by e Link showed that the university took several measures to avoid future tari -related price hikes and to comply with the Quebec government’s countermeasures.

“We are implementing a number of measures to reduce awarding contracts to U.S. rms,” Caroline Bogner, senior director of procurement services, wrote in response to a question about what impact tari s would have on Concordia, from corporate risk manager Rita Li, in April.

“It would be very di cult to do an overarching analysis on potential nancial impact on us at this time,” Bogner added.

Concordia spokesperson Julie Fortier said in an email that the university expected a reduction in procurement from American companies, but noted that the changes would not have a major impact on academics or campus life.

“We only purchased [4.76 per cent] of goods from the U.S. even before discussions around tari s began,” Fortier said. “So, we do not foresee any major impact.”

within a few days to a couple of weeks to avoid price hikes or renewing contracts ahead of time, anticipating a price increase.

Lander said that advancing purchases was a strategy taken by businesses when faced with a potential price rise or weakening currency.

Last scal year (May 1, 2024, to April 30, 2025), Concordia spent about $10 million on U.S. suppliers and on travel expenses to the U.S., according to Denis Cossette, the university’s chief nancial o cer.

About 90 per cent of the amount went towards goods and services, including about a million apiece on library collections and research databases, lab equipment, so ware and licenses, as well as advertisements for “publicity, exposure, visibility,” according to the ATI.

e remainder of $1 million relates to travel expenses for conferences and research activities.

Economics professor Moshe Lander said that the uncertainty introduced by U.S. President Donald Trump’s ip- opping tari policy since taking o ce in January posed challenges to organizations when making long-term procurement commitments.

With changing tari rates and price hikes, businesses faced uncertainty about signing contracts or spending more resources watching for the best deal.

“You might be stuck with a contract that says, ‘Sorry, you have to buy from us for the next year, two years, ve years, at an agreed-upon price. Too bad [for] you,’” Lander said.

At Concordia, university o cials also acted to place orders

“We've seen it in the GDP data that when Trump was imposing various deadlines, [we] would see this front loading of business where everybody would try and race to beat whatever the deadline was to make sure that it wasn't going to be subject to tari s or disruptions,” he said.

e university o cials also faced uncertainty on whether tari s applied to certain goods.

In an email exchange with a redacted source, Helen McDonald, senior buyer at Concordia’s procurement services department, questioned why the reseller’s price was higher.

“ ere are no counter-tari s on this type of equipment that would a ect price - please tell me if you have evidence that any tari would be in e ect?” McDonald wrote.

In another instance, McDonald received a ve-day deadline to send a purchase order to the vendor.

“I should normally be able to do this quickly, it's just the approvals that can get delayed and overnight refreshes,” she wrote.

Since January, Trump has imposed and paused tari s or changed the rates several times, which the Canadian government has criticized as a violation of the Canada-U.S.-Mexico free trade agreement (CUSMA) signed during his rst term.

Last Friday, a U.S. appeals court ruled that most of Trump’s tari s were illegal, adding to the uncertainty.

e Canadian government, for its part, has backed away from retaliatory tari s against the U.S. tari s.

In August, the Carney government dropped some of the retaliatory tari s on non-CUSMA-compliant goods in the hopes of advancing trade negotiations. In July, the government also scrapped the digital services tax a er Trump ended trade talks abruptly.

However, Lander said that the CUSMA free trade regime still covers the vast majority of goods and services, and therefore is exempt from tari s.

“I don't think that it's having much of an impact on Canadian consumers, of which Concordia is one, in part, because there's just no tari s on a lot of stu ,” Lander said.

Apart from counter-tariffs, federal and provincial governments have also modified their procurement rules for public organizations.

For instance, in March, the Quebec government an-

nounced a slew of measures requiring public institutions like Concordia to change how they purchase goods and services. e university updated its procurement policy, Lignes de conduite, following these to give preference to Montreal- and Quebec-based companies in procurement.

“As per a new government directive, we are also implementing a penalty on U.S. bidders who bid on our public calls for tenders for certain types of procurements, of between 10 to 25 (per cent) if a bidder has a U.S. address,” Bogner wrote in another email exchange shared in response to the ATI.

Under these rules, a product manufactured in the U.S. would not be subject to penalties if imported and sold by a Canadian or Quebec vendor, according to Fortier.

“A Quebec/Canada-based reseller of an American manufactured good is considered a Quebec/Canada vendor, not a U.S. vendor,” she said in an email to e Link

Fortier also said the university would continue to procure some specialized research equipment from the U.S., nonetheless.

“Some goods or services can only be obtained from certain U.S. vendors, especially in a research environment,” she added.

you’re a new arrival at Concordia University this fall or rediscovering campus life, guring out where to go for help can feel overwhelming. Here’s a primer on what to know, where to go, and which free meal you should never say no to.

Academic a airs

If you’re new to Concordia or just trying to find your footing again, here are some things you should know

Start with the Birks Student Service Centre (LB185, SGW Campus or Vanier Library, Loyola Campus). It’s the “Who do I even ask?” desk, handling ID cards, policy and tuition questions, and general triage. Phone them at 514-848-2424 ext. 2668 or email them at students@concordia.ca. Walk-ins are 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. on weekdays at SGW, or by appointment at Loyola.

If you have money questions, the Financial Aid and Awards O ce (GM-230) handles loans, bursaries and scholarships. Walk-ins are 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. on weekdays.

required

Are you an international student? e International Students O ce (GM-330; ext. 3515; iso@concordia.ca) answers questions on immigration documents, study permits, health insurance and settling-in.

For accommodations, the Access Centre for Students with Disabilities supports exam accommodations, note-taking and more—register once and you’re set for your time at Concordia. To access nal exam accommodations for the Fall 2025 term, you must submit all required documentation to acsd.intake@concordia.ca by Oct. 17.

Two other hubs worth knowing are the Otsenhákta Student Centre (H-653; ext. 7327) and the Black Perspectives Ofce (blackperspectives@concordia.ca). e former is for First Nations, Inuit and Métis students, o ering social events, academic support and career advice. e latter is for support, advocacy and mentoring for Black students and those involved in Black-centred research.

For studying, the Webster (SGW) and Vanier (Loyola) libraries run extended hours, including 24/7 study access during the fall and winter terms (don’t forget to bring your ID for overnight access).

e Student Success Centre (H-745 at SGW; AD-103 at Loyola; ext. 3921/7345) o ers writing help, tutoring, study workshops and career advising.

Know your rights

In the case of an academic dust-up like plagiarism accusations, grade appeals or the general policy maze, there are two lifelines: the Student Advocacy O ce (which o ers con dential guidance) and the CSU Student Advocacy Centre (which is student-run and equally discreet). You can contact them at studentadvocates@concordia.ca and advocacy@csu.qc.ca, respectively.

For con icts beyond the classroom, the Ombuds O ce provides independent, informal mediation (ombuds@concordia.ca; ext. 8658).

Dining on a student budget

e People’s Potato continues to ladle free vegan meals from Monday to ursday, 12:30 p.m. to 2 p.m. on the seventh oor of the Hall building; arrive early with a container. Meals are paid for by donation, though most give nothing but gratitude and tupperware. Emergency food baskets are also available, which is worth remembering the next time your rent is due.

e People’s Potato are also always looking for more volunteers. ose interested can attend their volunteer orientation on Sept. 4 at 3:30 p.m. in their kitchen (seventh oor, Hall building).

Over at Loyola, the Hive Free Lunch hands out free vegan breakfasts and lunches on weekdays, 9:30 a.m. to 10:30 a.m. and 12:30 p.m. to 1:30 p.m. Located at SC 200, they o er nut-free, mostly gluten-free options—bring your own container unless you’re willing to shell out 25 cents for a compostable one.

To volunteer, email hivefreelunch@gmail.com. Volunteers “develop kitchen skills, skip the lunch line, get free co ee and endless gratitude, and make friends,” says the CSU website.

e Hive Café Solidarity Co-op (both SGW and Loyola campuses) invites you to become a member for $10. In return, you’ll earn a 10 per cent discount on food and a vote in its democratic governance. Located in Hall H-Mezzanine (SGW) and SC-200 (Loyola), it serves healthy, a ordable plant-based fare, run cooperatively by students, for students.

Meanwhile, Le Frigo Vert, down on 1440 Mackay St., markets itself as an anti-capitalist, anti-colonial, anti-oppression grocery space. It is open Monday to ursday, noon to 6 p.m., and is a cosy spot to grab a bite and study. Membership, funded automatically for Concordia students through a fee levy, gives you access to discounted groceries, herbs and seeds, workshops, and a vote in their annual general meeting. ey also accept volunteers!

On the matter of mind and body

Health Services is the university’s on-campus clinic (GM200 at SGW; AD-131 at Loyola; ext. 3565/3575) o ering medical care, nursing and referrals. Walk-ins are available downtown. For mental health services (GM-300), start with the men-

tal-health intake— rst-come, rst-served assessments that connect you to counselling, groups and other supports. e Sexual Assault Resource Centre provides con dential support and services for anyone a ected by sexual violence (LB-720; sarcinfo@concordia.ca; ext. 5972).

For prayer and quiet, the Multi-faith and Spirituality Centre hosts drop-ins, community activities and maintains prayer and meditation spaces at H-746 (SGW) and SC-032 (Loyola). e Centre for Gender Advocacy (2110 Mackay; ext. 7431) is student-funded, independent, and is mandated to promote gender equality and empowerment, particularly as it relates to marginalized communities.

Get ng around (and under)

e campus shuttle runs weekdays between SGW (outside the Hall building) and Loyola (on Sherbrooke St.). It’s free with your Concordia ID and takes around 30 minutes to shuttle you between campuses. Check the schedule and arrive on time.

If you’re on the STM, a single one-trip fare is currently $3.75; for reduced fares, set up your student OPUS card through the Student Hub account online.

When winter bites, use the tunnels linking Guy-Concordia Metro to the EV, MB, GM, LB and Hall buildings.

’Til debt do us part

Miss a tuition payment, and you may be introduced to the university’s subsidiary late-fee collection. Consider this your reminder to keep things on time. (For billing questions, contact the Birks Student Service Centre at ext. 2668.)

With that, have a wonderful start to the semester and may your year be lighter than your fees!

Sean Richard

At the heart of Concordia University’s downtown campus is a space where students and community members can learn and engage in activism through the art of lmmaking.

Cinema Politica is a non-pro t media arts organization that hosts screenings of documentaries and lms every Monday at 7 p.m. at H-110 in the Henry F. Hall building during the school semester.

Stefan Christo is an artist, community organizer and graduate student at Concordia who has worked with Cinema Politica since its inception. He believes that it started as a need to ll a void that was present on campus.

“It was pretty clear that there was a need to have a more consistent space to share documentary lms that engaged with social activism [...] both on campus, but also as a way that could bridge the community at large and the campus,” Christo said.

Film has o en been a medium used to educate and inspire others to participate in activism. For Christo , lm allows people to organize in person and promotes political discourse.

“It's not just a lm, it's being in a room with other people,” he said. “It's talking with people a er the screening, and it's the groups and organizations that bring material to the events.”

Cinema Politica is unique in bringing political issues to the screen in ways most cinemas and classrooms do not.

At every screening, sta organize discussions, inviting both the lm’s team and activist groups working on the issues it raises. ese events create a space for students and community members to engage with the material further a er the screening.

Cinema Politica has also collaborated with a number of organizations across the city including SPHR Concordia, the Montreal Amazon Workers Union, Immigrant Workers Centre, Native Montreal, and Learning Disabilities Montreal.

Stephanie Boyd, Canadian lmmaker and activist, has screened several of her lms at Cinema Politica including a screening of her most recent project Karuara, People of the River.

e lm explores the Kukama people in Peru and their ght to preserve the rivers they depend on for survival. At Boyd’s screening last year, activist groups supporting the same causes joined a Q-and-A a er the lm’s screening.

Boyd said that groups like Cuso International and Canadian Senator Rosa Galvez, who is an expert in oil remediation of oil spills and environmental cleanups, were part of the panel.

Cinema Politica is at the forefront of global issues that resonate with students. Last semester, they screened the Academy Award-winning documentary No Other Land, becoming one of the rst cinemas in North America to do so a er distributors in the U.S. refused to pick up the lm.

e organization also aims to connect and engage with issues that a ect the Montreal community.

“Last season, we had a lm that looked at the housing crisis in Montreal,” Christo said. “Yes, we need to talk about what's happening around the world, but we also need to have lms that create space to talk about what's happening in communities here locally.”

While Cinema Politica does not shy away from featuring heavy subject matters in its screenings, the organization also cares deeply for the art of lmmaking.

Aylin Gökmen is a PhD student in Concordia’s lm and

moving image studies program and operations coordinator at Cinema Politica. She says that the programming team at Cinema Politica, who choose which lms will be screened during the semester, care deeply about the aesthetics of the lms they present.

“[ ey] have done a good job showing well-shot, aesthetically pleasing lms and lms that are more chaotic, but with a subject that is so important,” Gökmen said.

e environment that has been cultivated at Cinema Politica encourages lmmakers to return and keep screening their lms.

Nishtha Jain, an Indian lmmaker who has screened Gulabi Gang, e Golden read and Farming the Revolution at Cinema Politica, praised its audience.

“ ey have a very good audience, an audience which is patient, which is not dismissive, which is so eager to know more, learn more, experience more,” Jain said.

Cinema Politica began at Concordia in 2003 and has since expanded to more than 100 locations worldwide. ey have had local screenings in Barcelona, Berlin, Kuwait City, New Delhi and Mombasa.

While this expansion is important in reaching di erent cinema spaces, its core remains the long-lasting community that supports the lmmakers and causes it presents.

“Cinema Politica speaks to the power of consistency and holding a space over a long period of time,” Christo said. “Some screenings will be small, and then some screenings will have hundreds and hundreds of people, [which is] why I’m also involved to help sustain that space.”

Cinema Politica is always looking for more students to help volunteer with screenings, pass out yers, and make classroom announcements. e organization can be reached at info@cinemapolitica.org.

Safa Hachi

Whether you're fresh to Concordia University, new to the city or a long-time local rediscovering Montreal, the nightlife here has something for everyone.

We’re not calling these places underground, but having a guide can help you cut through the noise and nd your next go-to spot with less trial and error.

Some are well-known staples, while others are more tucked away—places you won’t always hear about unless you do some digging. No need to stress! at’s where we come in.

From bars with cheap drinks to DJ-driven dance oors, from casual hangouts to themed nights full of activities, Montreal brims with energy, creativity and community. ink of this as your shortcut to nding the spots worth checking out—whether for the music, the drinks or just the company you’ll nd there.

Part party, part collective, MESSY has quickly carved out a name for itself in Montreal’s queer nightlife scene.

e grassroots collective centres lesbian, queer and trans communities, blending live events with digital media to build spaces that feel both celebratory and intentional.

eir parties are sweaty, glittery and full of energy—bringing DJs, performers and artists together in a setting that’s as much about connection as it is about dancing.

If you’re a er nightlife that highlights creativity and community over the commercial club circuit, MESSY is where to start.

156 Roy St. E

4873 St. Laurent Blvd.

Located in a residential pocket not far from both St. Laurent and St. Denis streets, Else’s is a longtime favourite for anyone who wants a laid-back start to the night.

e bar’s eclectic, cosy feel pairs perfectly with cheap drinks and a ordable food, making it a go-to for students and locals alike.

It isn’t exactly a hidden gem, but always worth remembering when you want a night out that doesn’t drain your wallet.

Translating to “house of the people,” this bar has been a staple for Montreal’s independent and experimental music scene for over 25 years.

Equal parts venue, bar and café, it’s the kind of spot where you can grab a drink, catch a weekend DJ set, or discover a standout performance from a local artist. With its cosy, intimate vibe, Casa is a perfect night out with friends.

3956 St. Laurent Blvd.

2040 St. Denis St.

If bars are more your thing, there’s Champs, a lively queer-friendly sports bar with plenty happening week to week. It is also home to some of Montreal’s most creative queer programming, such as SATURGAYS.

Champs’ calendar spans trivia, themed nights, fundraisers and watch parties. is includes favourites like Dyke Night with free pool and Meat Market, a playful dating showcase where singles can present themselves (or a friend) in creative ways for the chance to win a free rst date.

SATURGAYS layers on their signature air at Champs with winter formals, Rocky Horror dance parties and live drunk readings of lms like But I’m a Cheerleader and Twilight—all with a queer twist. Together, they make Champs more than just a bar, but a hub where silly, sexy and community-driven nights come to life.

4685 Notre-Dame St. W.

If you’re looking to step outside of the student-heavy core, Bar Courcelle in Saint-Henri is a cosy spot with plenty to keep you busy.

eir weekly deals span everything from cocktail specials to oyster and hot dog happy hours, making it easy to keep things a ordable.

Beyond the food and drinks, you’ll nd live band open mics on Sundays, trivia nights on Tuesdays and karaoke on ursdays.

ey even host free live music on occasion, so keep an eye out; you might catch a show while you are there!

Turbo Haüs is equal parts venue and community hub, known for cheap drinks and a ordable shows, and as a space that truly cares about keeping Montreal’s arts scene alive.

Owner Sergio Da Silva is vocal about defending local music against noise complaints, making the bar a trusted spot for concerts.

e venue also hosts free live band karaoke on Mondays and the weekly Growve jam on Wednesdays.

eir motto, “anti-mosh, pro dance,” sums it up perfectly: a place where you can dive into alternative sound or just come dance without taking things too seriously.

Sweet Like Honey creates intentional spaces where lesbian, sapphic and BIPOC communities can gather and thrive.

eir events range from strip-club nights and dance parties to karaoke and picnics, always spotlighting local BIPOC artists and businesses.

More than the party itself, they’ve built a culture of care, enforcing rules against transphobia, racism and body shaming to make their events feel safe, welcoming and grounded in respect.

In a nightlife scene that too o en sidelines these communities, Sweet Like Honey ensures diversity and representation remain at the centre.

WhenMinza Haque saw a bicycle protest for Gaza for the rst time in her Plateau-Mont-Royal neighbourhood, it surprised her.

She was surprised not only because they were on bikes, but also because the protesters had come to her neighbourhood to begin with.

Haque, who has been going to monthly marches in support of Palestine since 2023, says the bike protests allow participants to cover more ground compared to protests on foot, resulting in them visiting areas that most demonstrations don’t typically frequent.

“ e marches are good, but it’s always the same route that you take,” she said. “It’s always within the same perimeter, near downtown. With the bike protests, it’s very di erent. Being on a bike is a very freeing experience.”

Haque, who had always been curious if there were other ways to mass mobilize, has been participating in the rides ever since she rst saw them in the street.

Damarice, Bill and Aymen, granted last-name anonymity for safety reasons, organize the events for Bikers for Palestine. e initiative got its start in October 2024 to draw attention to the war in Gaza through public rides.

A er discussing with each other and other participants, the organizers recognized a clear community interest in continuing the bike protests on a more regular basis.

In the spring of 2025, they launched the initiative once again, this time with the idea of it becoming a monthly event.

“You can look at it as an anti-racist form of cycling advocacy that looks at the ways Canada would be complicit in the hardships that people are facing in Gaza,” Bill added.

Damarice explained another reason why the bike connection comes so naturally to these protests.

“Gaza is not a place that feels so di erent and backwards; they literally bike just like us,” she said. “For me, it's important that we're using a medium that is one of their mediums too.”

Although protesting on bicycles carries symbolic meaning, it also brings a distinct atmosphere. According to Bill, passers-by engage more with the bike protests, and he even nds the ambiance joyous.

“A lot of us are horri ed watching what’s happening in Gaza, and sometimes it’s almost like there’s a sense of guilt that comes from just simple things,” Bill said. “So, it’s nice to have an act of joy, but it’s not the kind of joy where you're sticking your head in the sand and trying not to deal with reality.”

e bike protests also di er in the amount of territory they can cover.

“We can cover way more streets in Montreal and go places where protests don’t usually go,” Aymen said, referencing the Rosemont and Plateau-Mont-Royal neighbourhoods.

“People are surprised, and a lot of people lm us,” Aymen added. “ ey're happy to see us, and they're happy to see us in places where they don't really expect us.”

However, Bikers for Palestine was not the rst group to pursue this initiative.

In 2018, an Israeli sniper shot Palestinian cyclist Alaa al-Dali in the leg during the Great March of Return.

Al-Dali had hoped to achieve his goal of representing Palestine at the 2018 Asian Games in Indonesia, but had the lower half of his right leg amputated due to the injury. His dream now unattainable, he formed a para-cycling team called the Gaza Sunbirds with 18 other members who experienced similar injuries to al-Dali’s.

Today, the para-cycling team has dedicated its resources to providing aid to Gaza.

ey formed the Great Ride of Return, a global, non-violent, family-friendly movement in support of Palestine. e campaign unites communities from 35 countries. eir medium? Bike protests.

Bikers for Palestine has a simple mission in Montreal: draw public attention to the situation in Gaza.

“It is something that is relevant to cyclists,” organizer Bill said, “and you can’t talk about cycling in Gaza without talking about occupation, you can’t talk about it without talking about the Great Ride of Return, and you can’t talk about it without talking about the siege.”

He explained that the rides are not only about visibility, but also about accountability.

Despite having longer routes than traditional protests, Bikers for Palestine designs theirs to be inclusive for people of all skill levels and of all ages. Many people also use di erent mediums, such as skateboards, rollerblades and even wheelchairs.

Mechanics also maintain a presence during the protests to help anyone who may encounter bike issues during the ride.

Damarice says the bike protests provide a great opportunity to meet new people.

“During the two hours of the protest, you're going to be next to literally every person in the ride,” she said. “So, you do kind of have funny encounters, and we stop, and we chant, and we clap, and then suddenly there's someone new next to you.”

Haque witnessed this sense of solidarity rsthand during one of her rst rides. e ag attached to her bike got caught in her back wheel, and she had to stop. Fellow protesters quickly came to her aid.

“It happened so fast, someone pulled out one tool, the other person pulled out another tool, they took my wheel apart and did everything,” Haque said. “Within a couple of minutes, I was back in the protest. I know those people now, and they're my friends.”

However, Bikers for Palestine’s story doesn’t always revolve around the bikes, but about raising awareness about the situation in Gaza.

“ e Gaza Sunbirds have become a symbol of steadfastness and resistance,” Aymen said. “ ey use cycling to amplify the voices of athletes with disabilities, but also the voices of the people

of Gaza in general. And that's a bit of what we're trying to do.”

Haque agreed.

“ e bikers in Montreal are not the story,” Haque said. “ e story is that people come out in very large numbers to mass mobilize because there is an ongoing genocide and most of us can’t sit and watch it.”

and keep

e next bike protest will be held on Friday, Sept. 6, at 1 p.m. and will depart from the George-Étienne Cartier statue in Mount Royal Park.

“We're going to keep doing this until Palestine is free,” Bill said. “And I feel happy and con dent knowing that there's going to be one day in my lifetime when I'm not going to have to come to this ride anymore.”

coaches and administrators discuss the steps in the recruiting process

Samuel Kayll

@sdubk24

From the looks of the recruiting form on the Concordia University athletics website, anyone could put their name in the hat to become a Stinger.

On the surface, it seems simple: a multi-question document to gather basic information from a prospective recruit. But that form represents just the tip of the Stingers’ recruiting iceberg.

Behind it lies a lengthy process of lm study, multiple visits to facilities and in-depth discussions about the future—repeated for every recruit the team chooses to pursue.

Concordia’s recruiting begins at the top. Before and during the season, athletic administrators meet with each program’s coaching sta to determine the best allocation of resources, providing a baseline for identifying each team’s needs.

D’Arcy Ryan, Concordia’s director of recreation and athletics, explains that the cost of recruiting varies based not only on team needs, but also on each program’s network of support outside the school: scouts, former players-turned-coaches, and external camps and showcases.

“We'll have conversations with the coaches to see what the next year's needs are going to be,” Ryan said. “ is way, we know what our baseline level of support will look like.

While Concordia scans rosters from across the country, they focus primarily on Montreal and its surrounding areas--a talent-rich pool that’s close to home.

“We're lucky—we do a lot of recruiting in our own backyard,” Ryan said. “It helps keep the cost down because we have a great pool of talent at the CEGEP level, so we don't have to go too far out.”

Once teams narrow their recruiting lists, they begin a deep dive into each individual player.

ey study game tape, talk to their previous coaches and evaluate their cultural t. From this process, each team creates its “wish list,” the recruits deemed the most valuable or compatible with the Stingers locker room.

While teams analyze skill and potential, they also look into players’ academic goals and individual personalities.

Brad Collinson emphasized the importance of creating mean-

ingful relationships with recruits. e Stingers’ head football coach wants players to feel appreciated throughout their recruitment and to solidify the team’s connection to each prospect.

“We set up meetings—a Zoom or phone call to get to know them,” Collinson said. “We try to make it a more personable process than just, ‘Hey, we like you as a football player and we want to get you here.’”

Along with meetings and tape evaluation, programs pitch themselves through on-campus events. Whether through tours or games, each team aims to give its prospects an accurate depiction of life at Concordia.

Greg Sutton handles soccer operations for both the men’s and women’s teams at Concordia. He appreciates the connection brought by a face-to-face visit, as it provides a more personal touch to a meeting or interaction.

“We'll have a number of players that will come this fall for the following season, to give them a sense of what the gameday atmosphere is like,” Sutton said. “And we have a lot of players that will hang out with some of our current players. We nd that having them on campus is a big advantage for us when we're trying to lock up a recruit.”

But athletics only covers a portion of a recruit’s experience at Concordia. Collinson also uses these meetings to highlight the school’s academic o erings, showcasing programs and opportunities that complement an athlete’s career both on and o the eld.

“We look at the programs that we o er—we're highly touted in engineering and business,” Collinson said. “And then you have your arts and science programs that no one else o ers—I always give the example of the leisure studies program.”

Ryan prioritizes academics alongside the athletic benets of attending Concordia. He takes recruiting visits as an opportunity to remind student-athletes of the many resources a orded to Stingers players, such as academic advising, access to athletic therapy and leadership workshops.

“We're continuously reminding them of these services so

they're able to succeed academically and make it through their program with the support that they feel is necessary,” Ryan said.

But coaches want recruits to make their own decision to choose Concordia. Sutton prioritizes honesty throughout the process to keep expectations realistic and provide an unbiased and transparent view of the program and life as a Stinger.

“I don't like to force the hand of the recruit. I think it's a big step for them and a big decision for them,” Sutton said. “And we don't want to ll their heads with false promises just to get them to commit to our school because in the end, that doesn't end well most times.”

Collinson agreed, noting that the team’s honesty and clarity o en dissuade decommitments by gaining the respect and trust of recruits.

“We're never going to hold a kid here who doesn't want to be here—I don't think that's right,” Collinson said. “But I think if you do your job properly and you create those personal relationships, those are few and far between.”

And through the prioritization of those relationships, Concordia’s recruiting has taken a turn for the better. Sutton noted the in ux of new recruits from around the city through the team’s relationship with Quebec-born players.

“One of our biggest challenges is to recruit [Quebec-born] players to come to an English-speaking school. Over the last three or four years, we've had a lot of success,” Sutton said. “And when you do that, you attract others because the future recruits see that we've got a number of French-speaking players on our team.”

For each recruit, the journey di ers. But regardless of the sport, Ryan lets every prospect know how Concordia prepares them for the future.

“I want them to understand that the three or four years that they're here are going to be eventful,” Ryan said. “ ey're going to be able to compete for a position from day one and graduate with a fantastic degree. Hopefully, they’ve enjoyed their student-athlete experience so that they graduate as a well-rounded contributing member to society.”

Low turnout, insider rules, and closed circles make Concordia’s student democracy feel hollow Mani

Asadieraghi

It’s campaign week at Concordia University.

Bright posters plaster the Hall Building stairwell walls, which most people pass by without turning their heads or even giving them a second glance. Online, Instagram feeds cycle through candidate reels—smiling headshots, pastel slogans, promises of “transparency” and “community.” For most students, it’s just another week of their winter semester. Ballots land in their inboxes and move to the trash without a thought.

When the turnout is released, Winter 2025’s general election records a 14.7 per cent turnout from more than 30,000 undergrads. at’s a slight improvement over 11.2 per cent in Fall 2024 and 12.4 per cent in Winter 2024. Still, over 85 per cent of students didn’t participate. Low numbers can o en be read as apathy.

But what if they’re telling us that the system itself discourages engagement?

On paper, student associations appear democratic: constitutions, elected executives and governing councils. In practice, they centralize power in small groups and bury the rules in procedural language.

e Concordia Student Union (CSU) bylaws require students who want to run for executive or council positions to gather physical signatures during a narrow, o en poorly advertised window—sometimes right in the middle of midterm season. Miss it, and you’re out for the year.

To bring a motion forward—whether to a Regular or Special Council Meeting—you must submit it in writing, with supporting signatures, before a hard deadline that’s tucked away in PDFs.

For those already involved, these hurdles are known. For everyone else, they’re invisible.

Leadership pipelines o en run through the same social circles, making elections less about winning over the student body and more about mobilizing networks. is continuity keeps the machine running but narrows the range of voices in decision-making.

e contrast becomes obvious when the stakes feel real.

In January 2025, nearly 1,000 students packed a special general meeting to debate Concordia’s relationship with Israel. A er hours of discussion, voters cast over 800 ballots in support of two Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) motions. Students will show up when they believe their participation can directly change the university’s direction.

So why can’t regular elections do the same?

If student democracy and its impact want to evolve beyond a ballot once a year, Concordia needs more than symbolic xes—it needs structural change.

While students can technically access meetings through Zoom, the system doesn’t make it easy to follow along. e minutes are supposed to be publicly available, but they haven’t been updated since 2024—leaving a backlog that makes it impossible for students to stay up to date. Recordings, minutes and agendas should be archived in a single searchable space, with plain-language summaries so students can quickly catch up and get involved before decisions are nalized.

Even though the CSU already sets aside money for student-led initiatives, most students never see where that money actually goes—the budget hasn’t been updated online in years. Giving students more power to pitch ideas and decide where the money ows would turn abstract “engagement” into something you can actually see and use.

Power also needs to become decentralized. Faculty associations, departmental groups and recognized collectives should have the right to bring motions directly to the CSU council without executive approval.

Universities are civic training grounds. e habits we form here—whether active engagement or quiet resignation—follow us long a er graduation.

Low turnout isn’t proof that students don’t care; it’s proof that our system isn’t worth most students’ time. If we can’t get democracy right at Concordia, how can we expect to get it right anywhere else?

e next election is your chance to make that change happen. Show up. Speak up. Make it count.

Legacy of student activism shows funding and dissent are not mutually exclusive

Jocelyn Gardner

Funded by the system they’re meant to confront, student unions like Concordia University’s are caught in a paradox.

It’s natural to wonder: how can students hold universities accountable when their operations depend on them? Isn’t that a con ict of interest? Yet, history shows that student unions can—and o en do—navigate this tension e ectively.

Funding does not automatically equate to submission. In fact, institutional support can provide student unions with the resources, legitimacy and platform necessary to o er vital services and drive systemic change.

For example, Concordia’s institutional funding has enabled the Concordia Student Union (CSU) to establish programs such as the Legal Information Clinic, the Student Advocacy Centre, on-campus childcare and other essential initiatives. ough the CSU receives a portion of student fees administered through the university, it retains autonomy in how it organizes, advocates and agitates. is model—common across Canadian universities—has o en strengthened rather than silenced student activism.

Consider the Quebec student strikes of 2012. Students across the province, including those from Concordia, played a central role in one of the largest acts of civil disobedience in Canadian history, protesting tuition hikes proposed by then-premier Jean Charest’s government.

While funding structures remained intact, the political climate shi ed. Student unions like the CSU and the Fédération étudiante universitaire du Québec used their resources to coordinate mass mobilizations, strikes and negotiations— ultimately forcing the provincial government to shelve its tuition increase plans.

e CSU has also taken on broader social justice issues beyond tuition.

In 2024, they accused the university of police brutality, called for the removal of all police o cers on campus and increased support for mental health services. ese were controversial demands that directly challenged Concordia’s operational priorities. e CSU has also backed divestment campaigns and supported marginalized student communities, even when these stances con icted with university policy or public image.

And yet, funding didn’t stop; if anything, the union’s high-prole actions o en strengthened student support and legitimacy.

What makes this tension between funding and freedom navigable is the structure. Most Canadian student unions are democratically governed by elected student leaders who are accountable to their peers, not university administrators.

Still, a funded union is not a powerless one. It o en has a stronger platform to organize, advocate and apply pressure than an unfunded or underground alternative would. is was demonstrated in February 2025 when student unions across Alberta leveraged their collective resources and legitimacy to demand expanded government funding in an e ort to make postsecondary education more a ordable. is action shows how student unions can band together to push for systemic change. With structural safeguards and democratic governance, institutional funding can empower more than it restricts. Concordia’s student body has proven time and again that it can and will bite the hand that feeds it; not out of disloyalty, but out of a commitment to equity, justice and a stronger community. Money doesn’t dictate the ght—students do. @jocelyn.lhg

In Quebec, student union funding is o en legally protected, meaning universities cannot easily defund them without triggering major political or legal consequences.

Of course, risks still exist. Universities can attempt to control or suppress dissent through bureaucratic hurdles or public-relations pressure, and student leaders must always guard against co-optation.

Zoya Ramadan

Intellectual discourse is shrinking into quick videos, punchy tweets and shocking headlines, rewarding trendiness over truth.